DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-024-05770-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38884817

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-17

اختلال التوازن الميكروبي الفموي لدى مرضى سرطانات تجويف الفم

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

الملخص

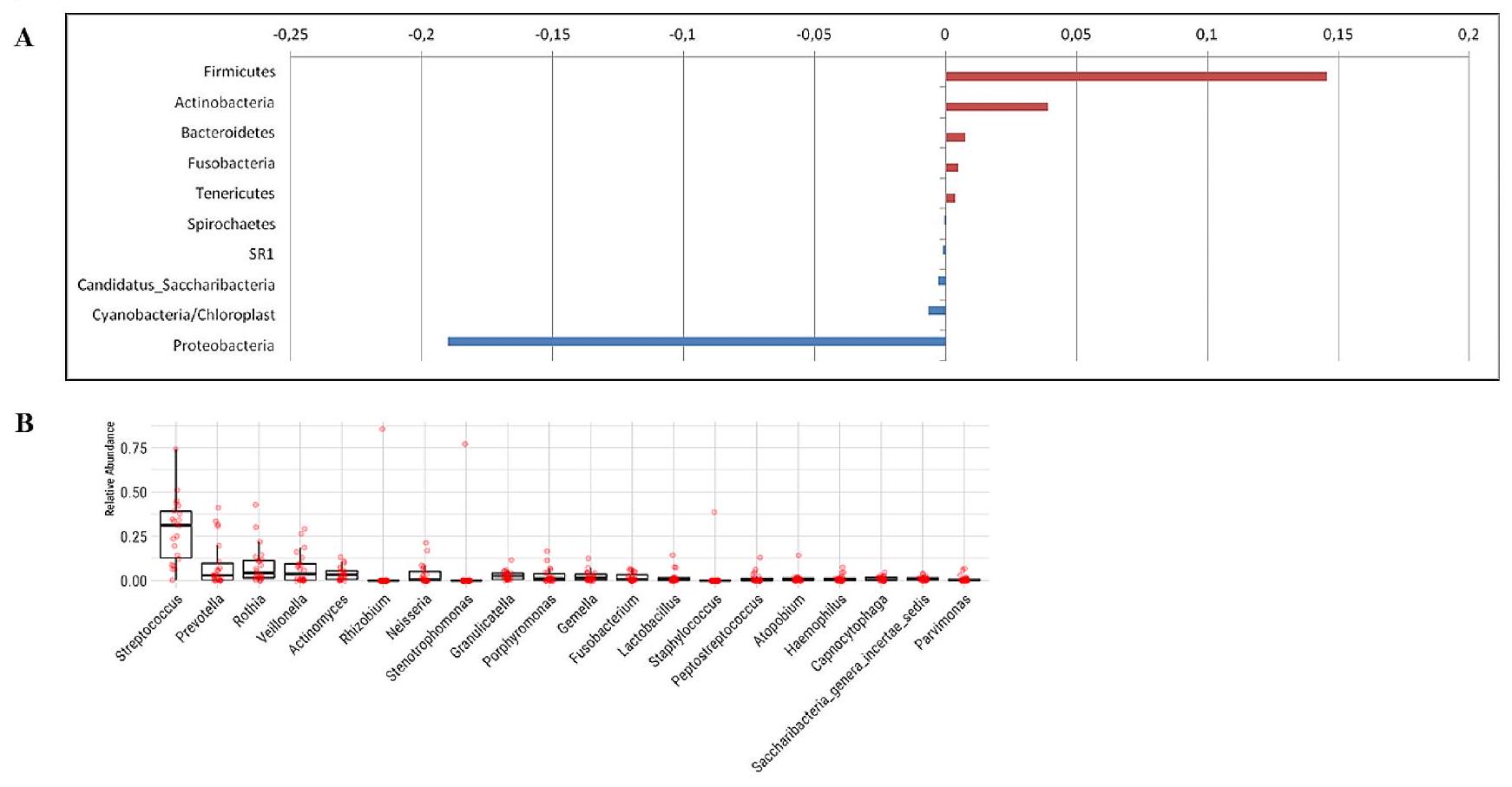

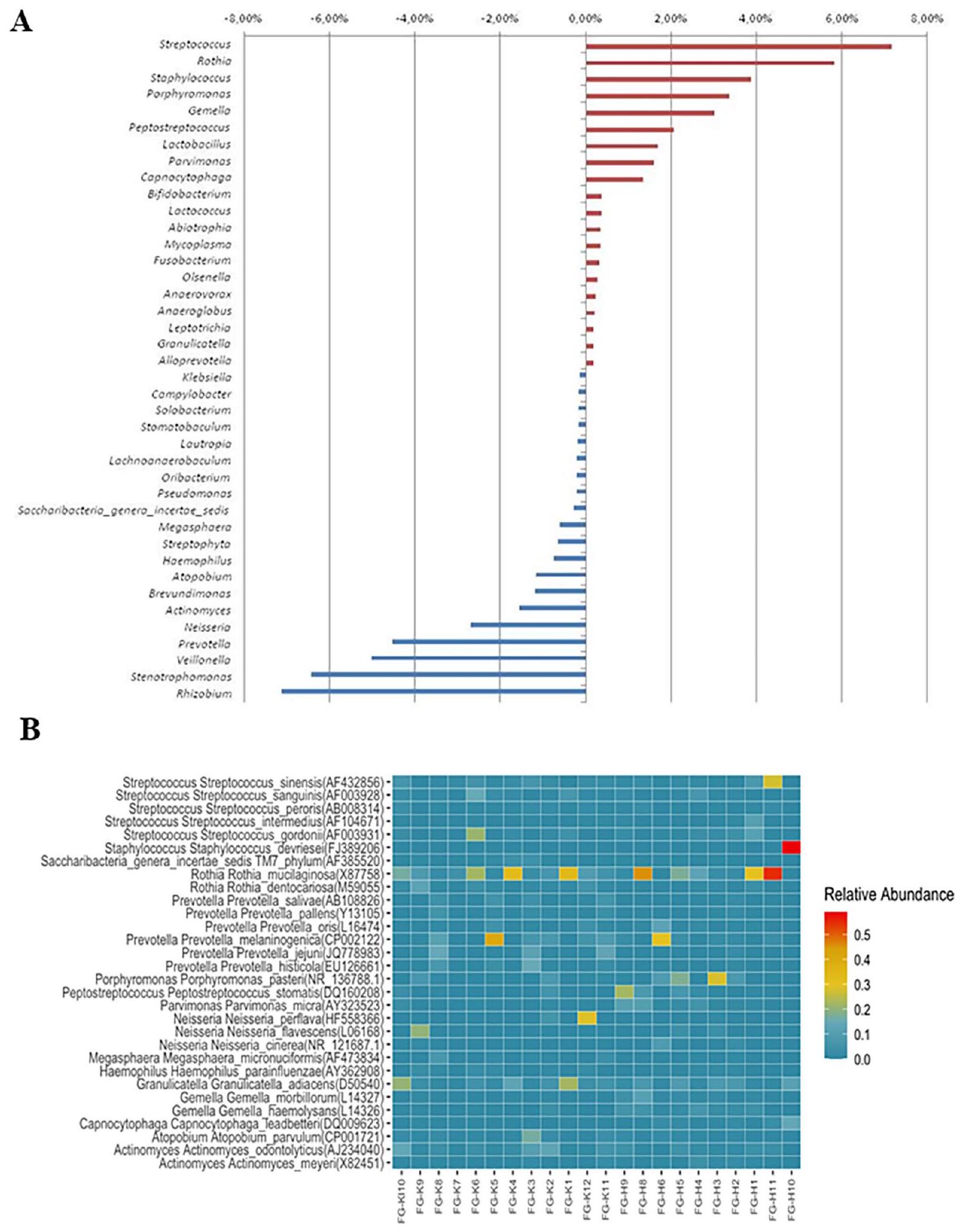

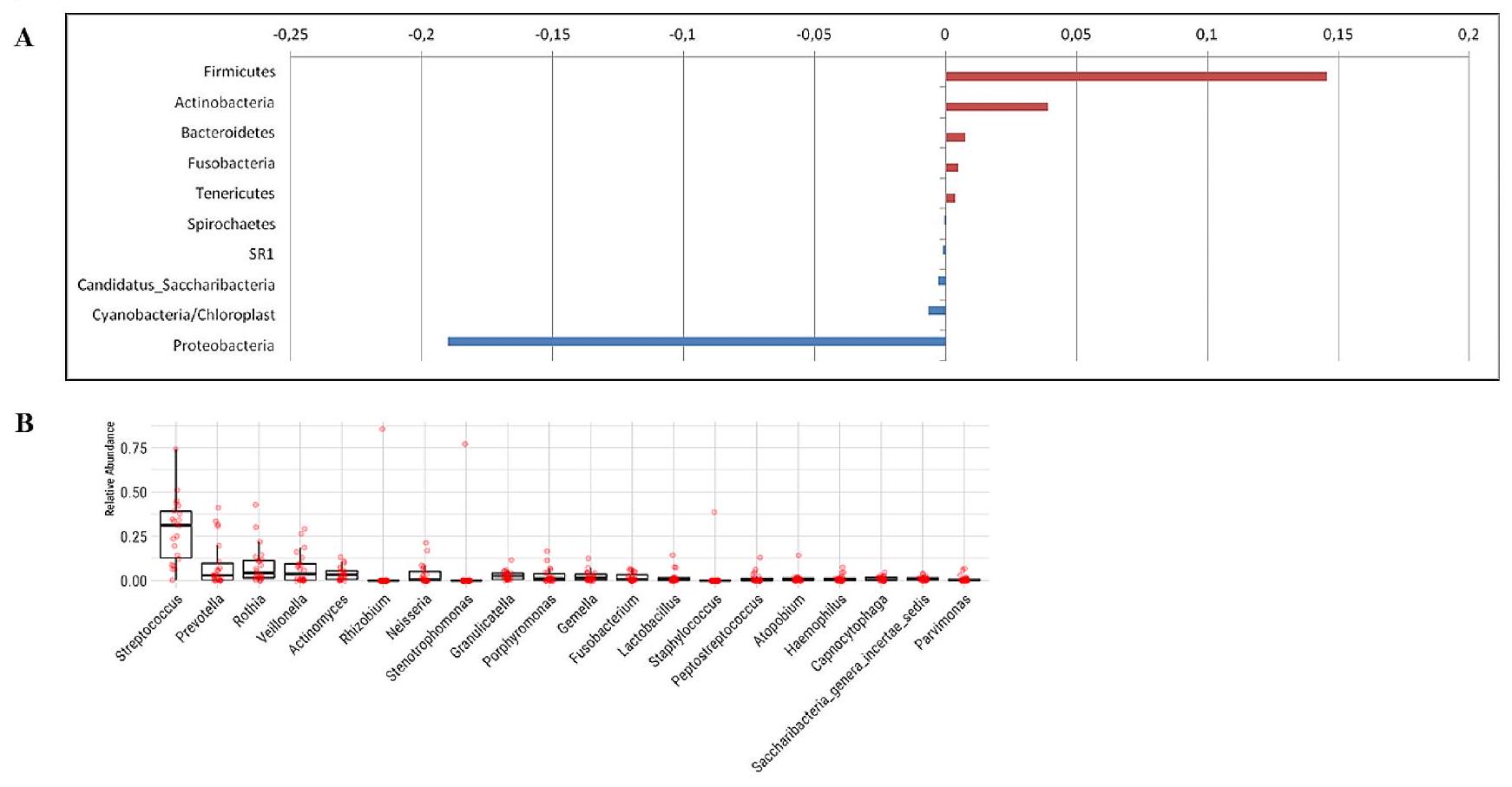

الأهداف إن مسببات سرطان تجويف الفم معقدة. اختبرنا الفرضية القائلة بأن اختلال ميكروبات الفم مرتبط بسرطان تجويف الفم. المواد والأساليب تم تضمين المرضى الذين يعانون من سرطان تجويف الفم الأولي والذين استوفوا معايير الإدراج والاستبعاد في الدراسة. تم تجنيد أفراد أصحاء متطابقين كضوابط. تم جمع بيانات عن العوامل الاجتماعية والديموغرافية والسلوكية، وقياسات اللثة المبلغ عنها ذاتيًا والعادات، والحالة السنية الحالية باستخدام استبيان منظم ورسم بياني للثة. بالإضافة إلى قياسات صحة الفم المبلغ عنها ذاتيًا، خضع كل مشارك لفحص سريري قياسي ومفصل. تم استخراج الحمض النووي من عينات اللعاب من المرضى والضوابط الأصحاء. تم إجراء تسلسل الجيل التالي من خلال استهداف مناطق الجينات V3-V4 من 16 S rRNA مع تحليلات المعلومات الحيوية اللاحقة. النتائج كان لدى المرضى الذين يعانون من سرطانات تجويف الفم جودة صحة فموية أقل من الضوابط الأصحاء. انخفضت مستويات Proteobacteria وAggregatibacter وHaemophilus وNeisseria، بينما زادت Firmicutes وBacteroidetes وActinobacteria وLactobacillus وGemella وFusobacteria في مرضى سرطان الفم. على مستوى الأنواع، كانت C. durum وL. umeaens وN. subflava وA. massiliensis، و

مقدمة

المواد والطرق

تصميم الدراسة والمشاركون

ومستشفى التدريب والبحوث (2017/11/09-1109). تم جمع العينات بعد الحصول على موافقة مستنيرة؛ وتم إجراء التجربة وفقًا لإعلان هلسنكي. تم تجنيد المرضى من عيادات الأنف والأذن والحنجرة في مستشفى باججيلار للتدريب والبحوث ومستشفى إسطنبول للتدريب والبحوث. تم تأكيد تشخيص سرطان تجويف الفم بواسطة علم الأمراض النسيجي، وتم تصنيف الآفات باستخدام نظام TNM [13]. جميع المرضى كانوا حالات تم تشخيصها مؤخرًا ولم يتلق أي منهم أي علاج. كانت معايير الاستبعاد هي فقدان الأسنان الكامل، إجراء عملية جراحية على الغدد اللعابية، تاريخ مرض مناعي ذاتي أو مرض نظامي، الحمل، تاريخ العلاج الإشعاعي أو الكيميائي، العلاج التقويمي الثابت، العلاج بالمضادات الحيوية، أو مضادات الالتهاب، أو العلاج بمضادات التخثر أو استخدام البروبيوتيك خلال الأسابيع الأربعة الماضية، غير البالغين (< 18 عامًا)، العدوى الفيروسية أو البكتيرية أو الفطرية النشطة، وإيجابية فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري (تم اختبارها لفيروس الورم الحليمي باستخدام مجموعة اختبار PCR التجارية). من بين أكثر من 100 مريض تم تجنيدهم، استوفى 10 مرضى بسرطانات تجويف الفم الأولية (6 رجال و4 نساء) معايير الإدراج والاستبعاد في التوصيف السريري، أخذ عينات اللعاب، والتحليلات الميكروبية. تم تجنيد اثني عشر فردًا صحيًا بشكل نظامي بدون سرطان (6 رجال و6 نساء) كضوابط.

الخصائص السكانية وطب الأسنان لمجموعات الدراسة

الفحص السريري للأفراد المشاركين في الدراسة

تضمنت المعايير عمق الاستكشاف (PD) ، مستوى الارتباط السريري (CAL) ، النزيف عند الاستكشاف (BOP) ، تراجع اللثة (GR) ، مؤشر اللويحات (PI) ، ومؤشر اللثة (GI) [19، 20]. تم تقييم المعايير السريرية في جميع الأسنان، باستثناء الأضراس الثالثة. تم تسجيل PI و GI في أربعة مواقع، بينما تم قياس PD و CAL في ستة مواقع لكل سن (الخد، والميزيوبوكال، والدستوبوكال، واللساني، والميزيولساني، والدستولساني). تم قياس BOP من خلال وجود أو عدم وجود نزيف بعد 10 ثوانٍ من الاستكشاف. تم إجراء جميع القياسات باستخدام مسبار لثوي معتمد بالملليمتر (PCP15؛ Hu-Friedy®، شيكاغو، إلينوي، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية)، وتم تقريب القيم إلى أقرب ملليمتر. تم حساب متوسط الدرجة لعمق الاستكشاف في الفم بالكامل، ومستوى الارتباط السريري، ومؤشر اللثة، ومؤشر اللويحات، وBOP، مقسومًا على العدد الإجمالي للمواقع في الفم ومضروبًا في 100، لكل فرد.

جمع العينات، المعالجة، وتسلسل الجيل التالي

تم استخدامه لتنقية منتجات الأمبليكون بعد دورات PCR. تم فحص منتجات PCR لوجود الأشرطة وكثافة الأشرطة النسبية على

المعلوماتية الحيوية والتحليل الإحصائي

النتائج

الخصائص السكانية وصحة الفم لمجموعات الدراسة

| خصائص | المجموعة الضابطة الصحية | مرضى سرطان تجويف الفم |

|

|

|

|

||

| جنس | 0.6911 | ||

| ذكر | 6(50) | 6(60) | |

| أنثى | 6(50) | ٤(٤٠) | |

| العمر (بالسنوات) | 0.1872 | ||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

| مد(الحد الأدنى-الحد الأقصى) | 57(28-71) | 61.5(46-89) | |

| الحالة الاجتماعية | 0.6241 | ||

| متزوج | 10(83.3) | ٧(٧٠) | |

| غير متزوج | 2(16.7) | 3(30) | |

| التعليم | <0.001 | ||

|

|

0(0) | 6(60) | |

| >8 سنوات | 12(100) | ٤(٤٠) | |

| مؤشر كتلة الجسم | 0.3562 | ||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

| مد(الحد الأدنى-الحد الأقصى) | 22.7(18.3832.05) | 25.27(18.69— 34.75) | |

| الأمراض المصاحبة | 1 | ||

| لا | 10(83.3) | 7(77.8) | |

| نعم | 2(16.7) | 2(22.2) | |

| تاريخ عائلي للسرطان | <0.001 | ||

| لا | 12(100) | 1(10) | |

| نعم | 0 | 9(90) | |

| تاريخ التدخين | 0.096 | ||

| لا | ٤(٣٣.٣) | 0(0) | |

| نعم | 8(66.7) | 10(100) | |

| عادة التدخين الحالية | 1 | ||

| لا | 8(66.7) | ٧(٧٠) | |

| نعم | ٤(٣٣.٣) | 3(30) | |

| استهلاك الكحول | 0.646 | ||

| لا | 8(66.7) | 8(80) | |

| نعم | ٤(٣٣.٣) | 2(20) | |

| استهلاك اللحوم الحمراء (أيام في الأسبوع) | 0.619 | ||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

| مد(الحد الأدنى-الحد الأقصى) | 5(3-6) | 5(2-7) | |

| استهلاك الخضروات (أيام في الأسبوع) | 0.886 | ||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

| مد(الحد الأدنى-الحد الأقصى) | 5(2-6) | 5(3-7) | |

| استهلاك الفواكه (أيام في الأسبوع) | 0.489 | ||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

| مد(الحد الأدنى-الحد الأقصى) | 5(4-7) | 5(3-7) | |

| المجموعة الضابطة الصحية

|

مرضى سرطان تجويف الفم

|

|

|

| الصحة الفموية المقيّمة ذاتياً | – | ||

| جيد | 12(100) | 10(100) | |

| نزيف اللثة المبلغ عنه ذاتيًا |

|

||

| لا | 11(91.7) | 0 | |

| نعم | 1(8.3) | 10(100) | |

| تورم اللثة واحمرارها المبلغ عنه ذاتيًا |

|

||

| لا | 11(91.7) | 0 | |

| نعم | 1(8.3) | 10(100) | |

| إجراء فحص الأسنان |

|

||

| لا | 3(25) | ٧(٧٠) | |

| نعم | 9(75) | 3(30) | |

| تنظيف الأسنان |

|

||

| لا | 0 | 6(60) | |

| نعم | 12(100) | ٤(٤٠) | |

| استخدام خيط الأسنان/فرشاة بين الأسنان |

|

||

| لا | 5(41.7) | 10(100) | |

| نعم | 7(58.3) | 0 | |

| تاريخ أمراض اللثة |

|

||

| لا | 7(58.3) | 0 | |

| نعم | 5(41.7) | 10(100) | |

| وجود أطقم الأسنان |

|

||

| لا | 12(100) | 8(80) | |

| نعم | 0 | 2(20) |

النتائج الميكروبيولوجية في مرضى سرطان الفم

| المجموعة الضابطة الصحية | سرطان تجويف الفم |

|

|

| مؤشر اللثة (GI) |

|

||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

| مد(الحد الأدنى-الحد الأقصى) | 0.6(0.5-0.9) | 1.7(1.2-2.4) | |

| مؤشر اللويحات (PI) |

|

||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

| مد(الحد الأدنى-الحد الأقصى) | 0.4(0.02-0.5) | 1.9(1.6-2.7) | |

| النزيف عند الاستكشاف (BOP) |

|

||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

| مد(الحد الأدنى-الحد الأقصى) | 3.3(0-6) | 100(100-100) | |

| عمق الاستكشاف (PD، مم) |

|

||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

| مد(الحد الأدنى-الحد الأقصى) | 1.5(0.3-1.5) | 3.5(3.2-4.3) | |

| مستوى الارتباط السريري (CAL، مم) |

|

||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

| مد(الحد الأدنى-الحد الأقصى) | 1.5(0.3-1.5) | 4.6(4.2-5.5) | |

| تراجع اللثة (GR، مم) |

|

||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

| مد(الحد الأدنى-الحد الأقصى) | 0(0-0) | 1.1(0.1-2.0) | |

في مجموعة المرضى بالتوازي مع الانخفاض الكلي في الشعبة. Fusobacterium، وهو عضو في شعبة Fusobacteria، وLactobacillus، وGemella، وهو عضو في Firmicutes، زادت في مجموعة المرضى بالتوازي مع الشعبة. كان الجنس البكتيري الذي سجل أعلى معدل في مجموعتي المرضى والشهود هو Streptococcus، تلاه Rothia وPrevotella وVeionella. بينما وُجد Streptococcus في

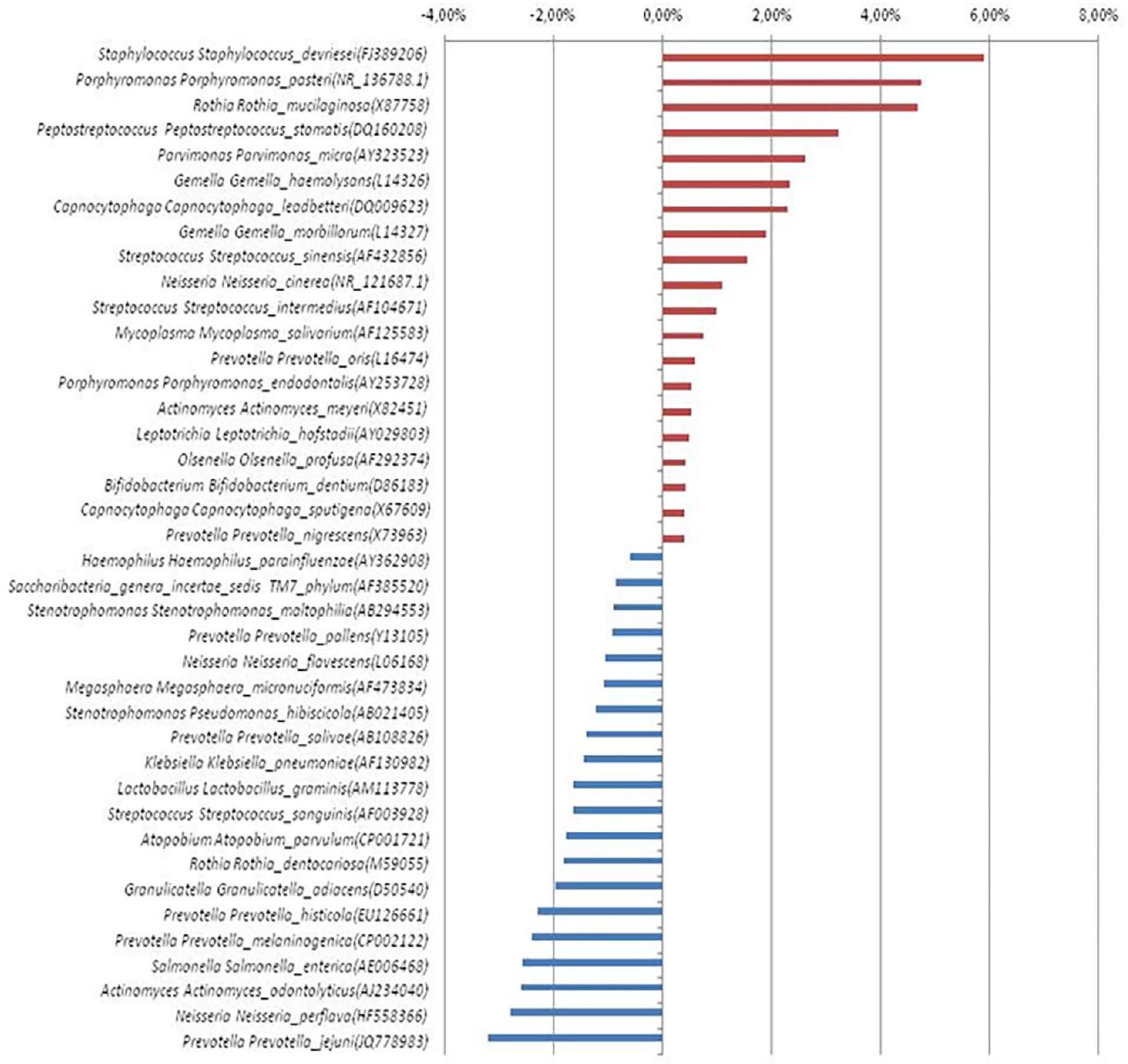

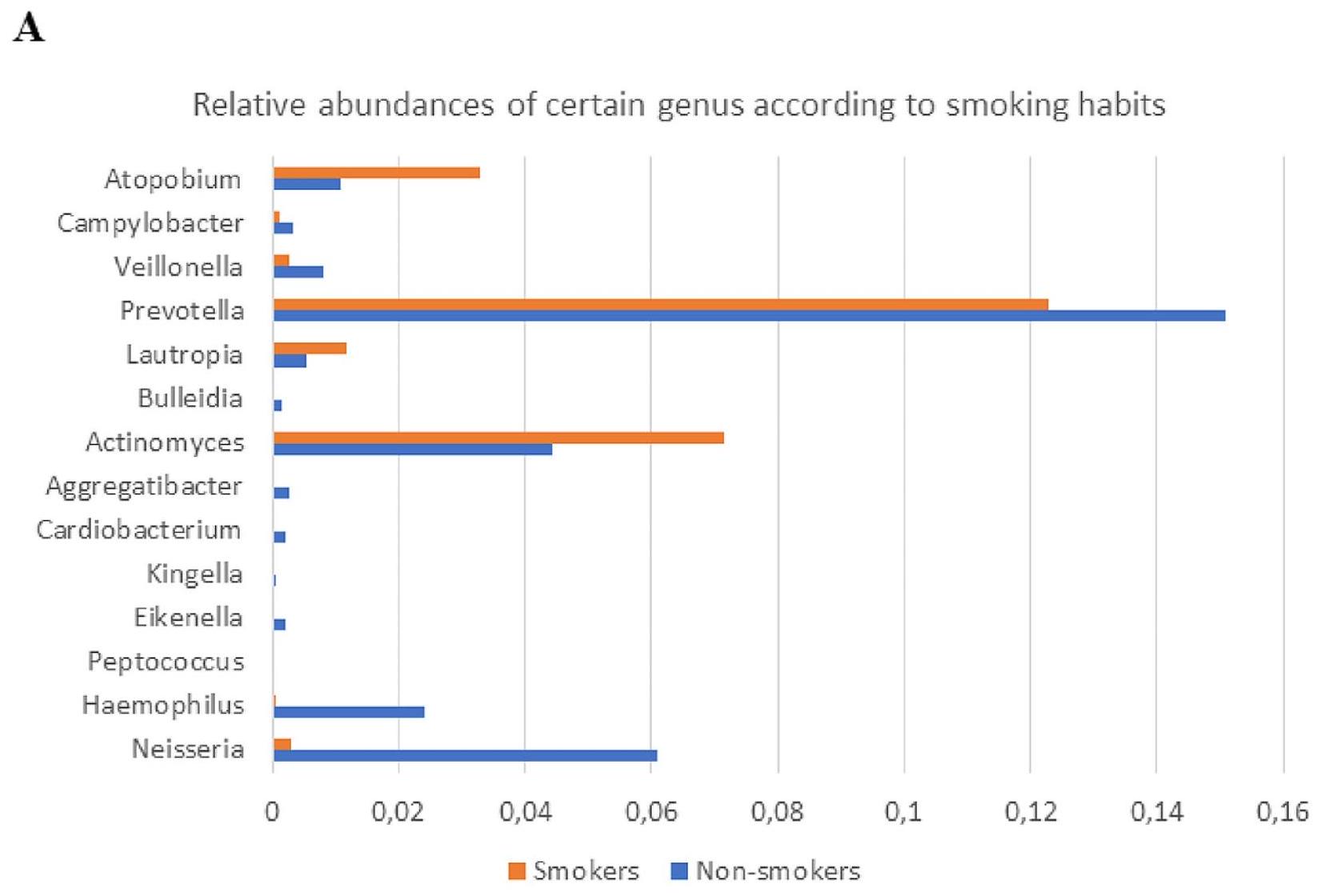

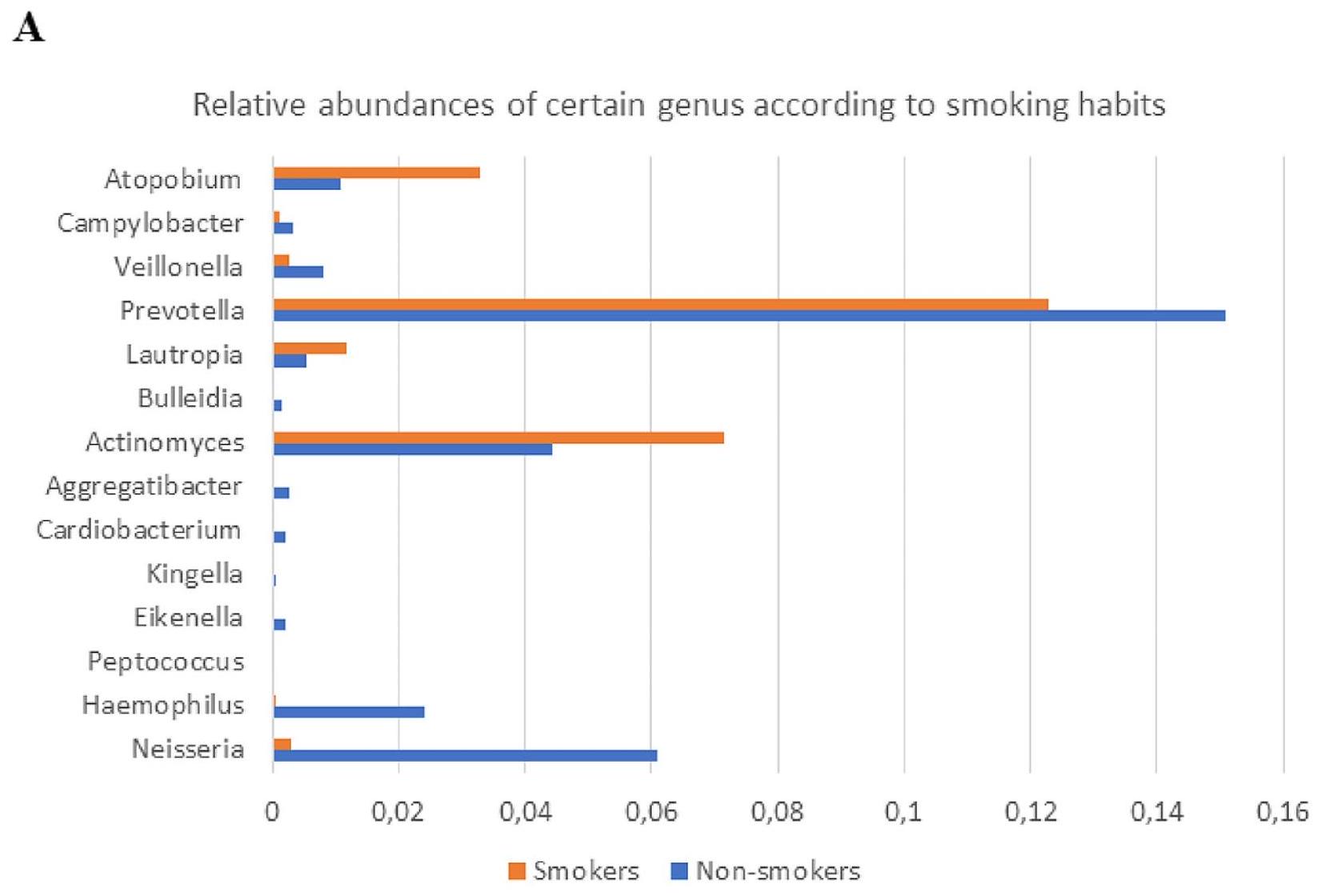

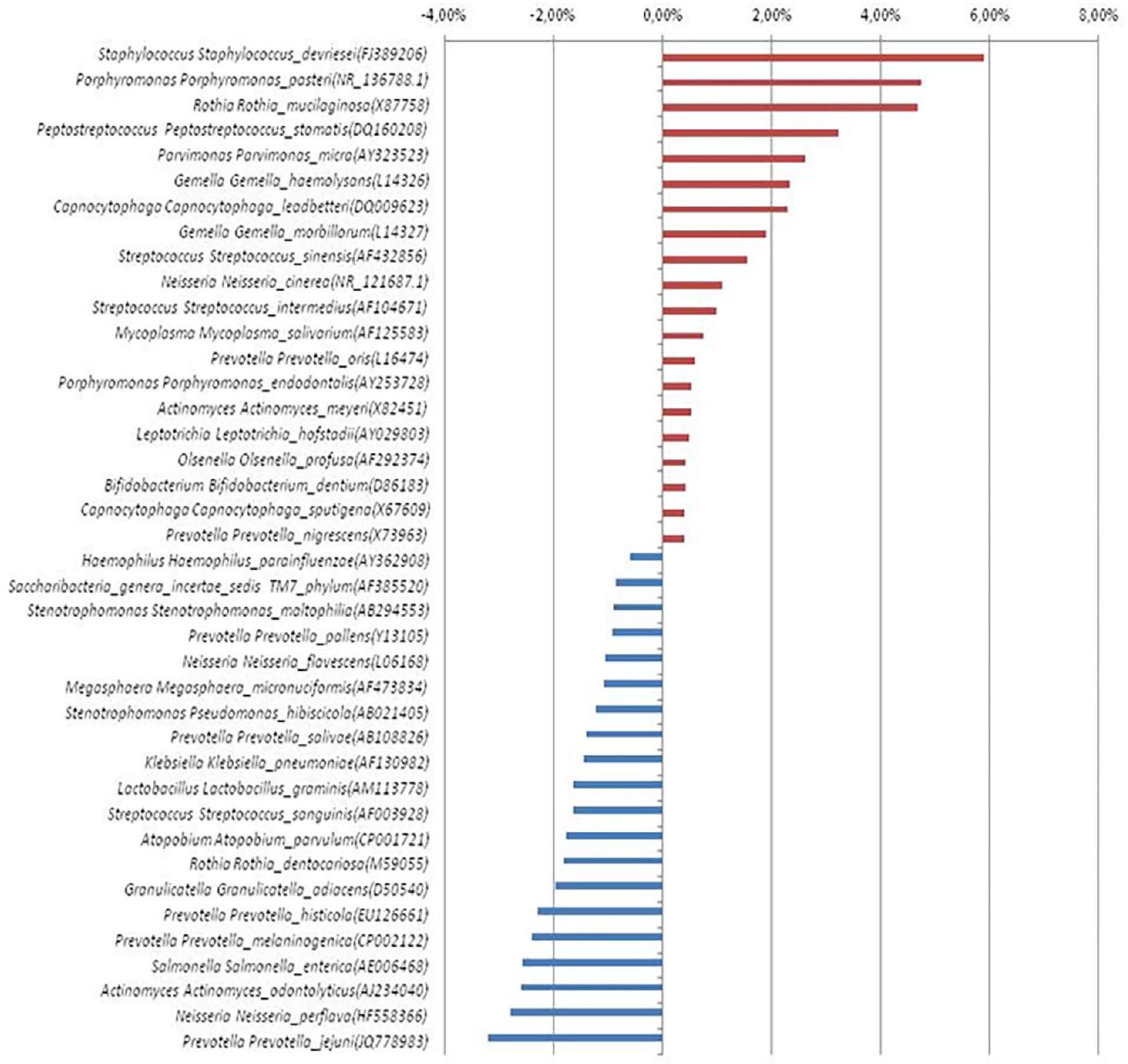

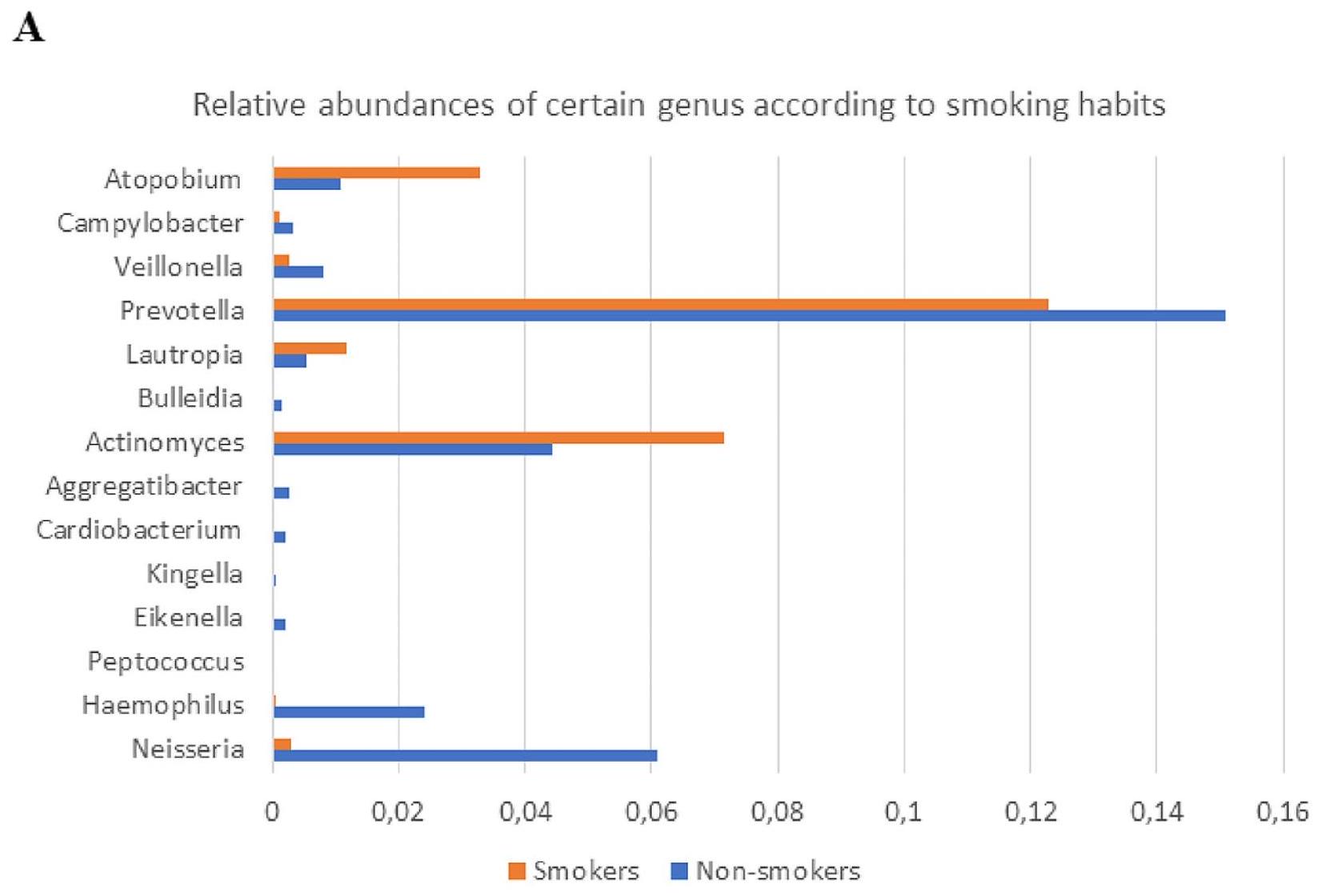

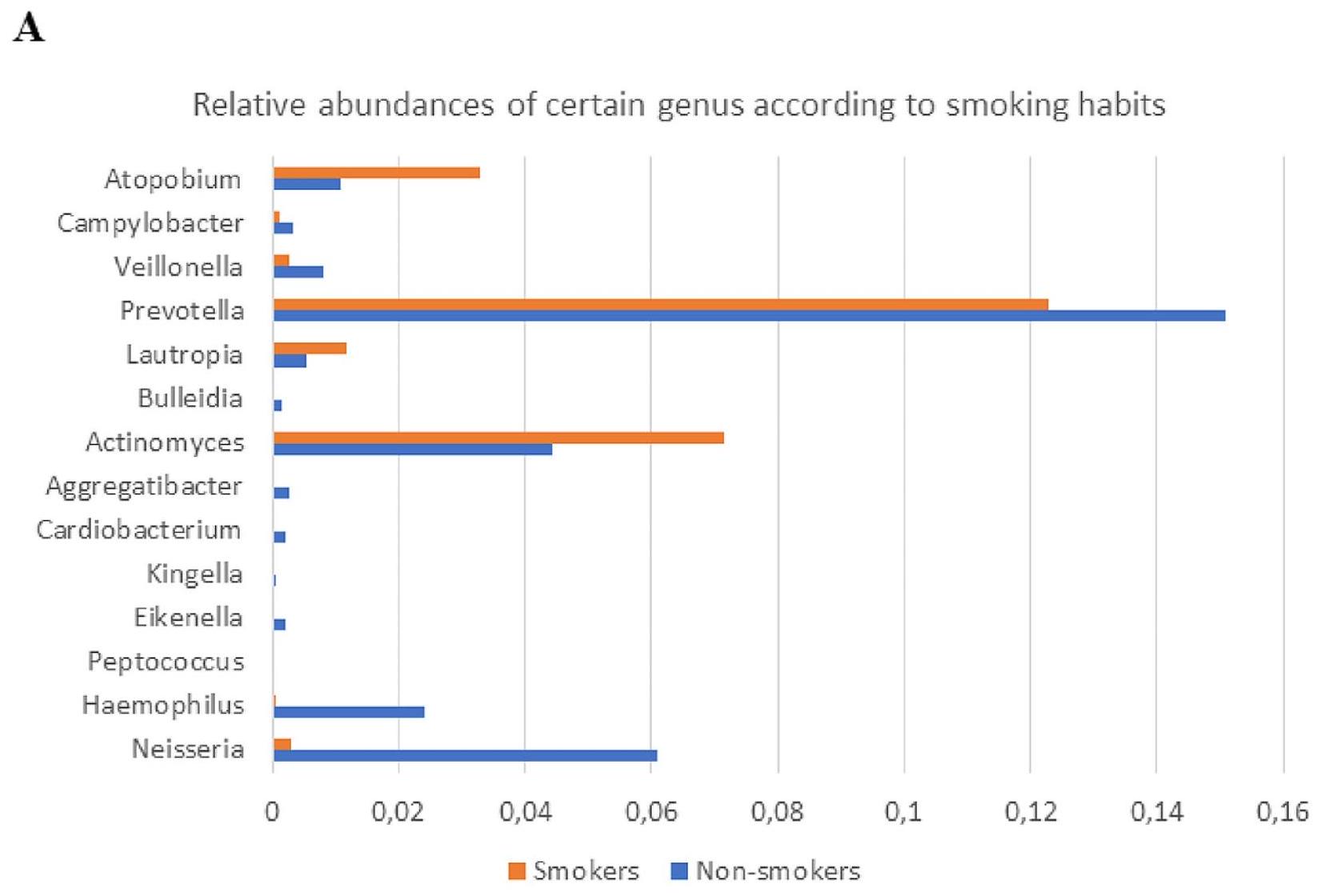

أثر التدخين واستهلاك الكحول على الميكروبات الفموية في سرطان الفم

تم العثور على بكتيريا، جيملا بالاتكانيس، روثيا أيريا، بريفوتيلا ساكاروليتكا، بريفوتيلا ماكولوزا، فوسوبكتيريوم بيريودونتيكوم، بريفوتيلا بريانت، بورفيروموناس باستيري، بريفوتيلا شاهيي، تريبوينما سوكرانسكي، كارديوباكتيريوم هومينيس، أجرجاتيبكتير أفروليفوس، دياليستر نيوموسينتس، فيلونيللا روجوساي، هيموفيلوس سبوتوروم، وأنواع نيسيريا إيلونغاتا كانت موجودة بمستويات أقل بشكل ملحوظ في المدخنين.

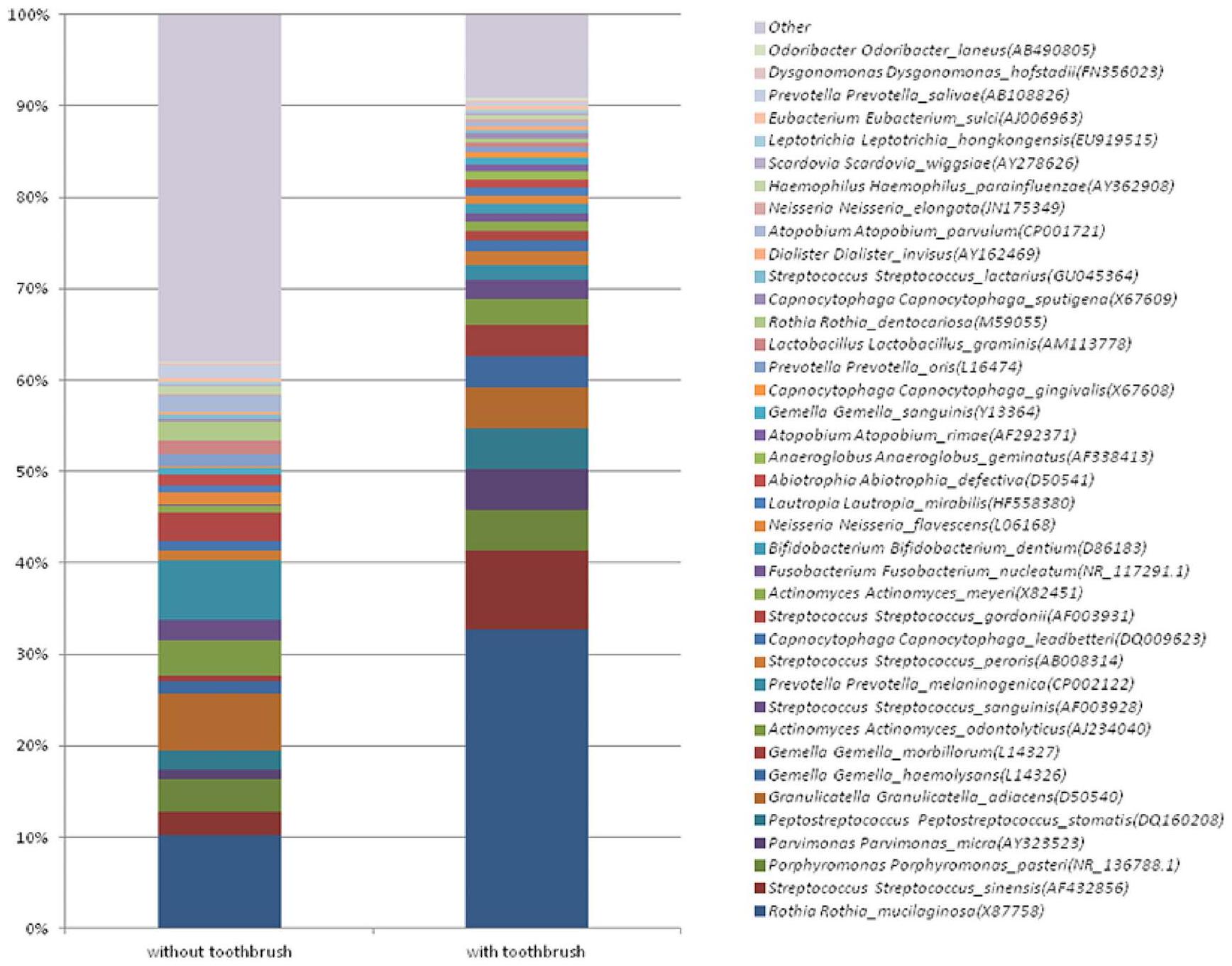

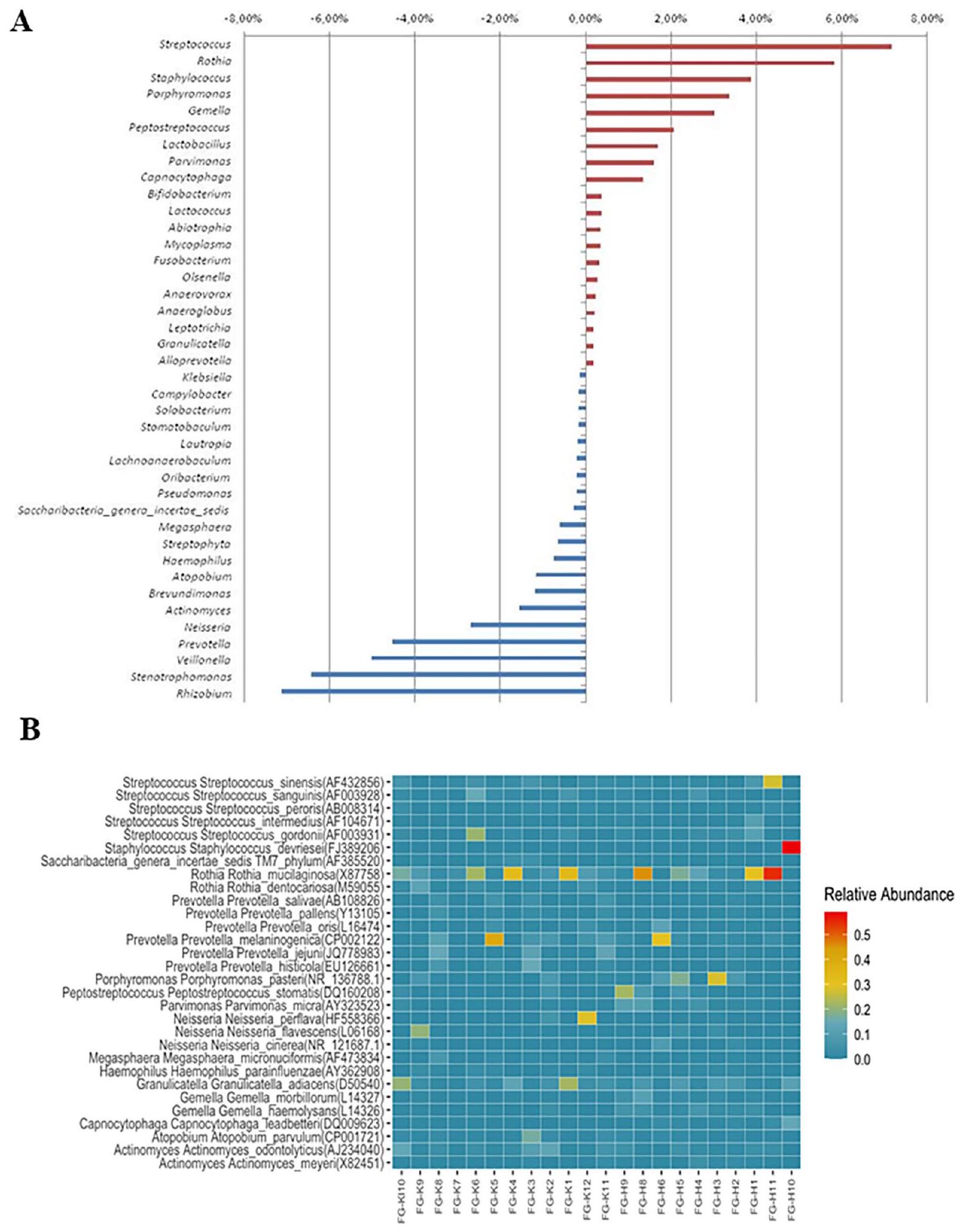

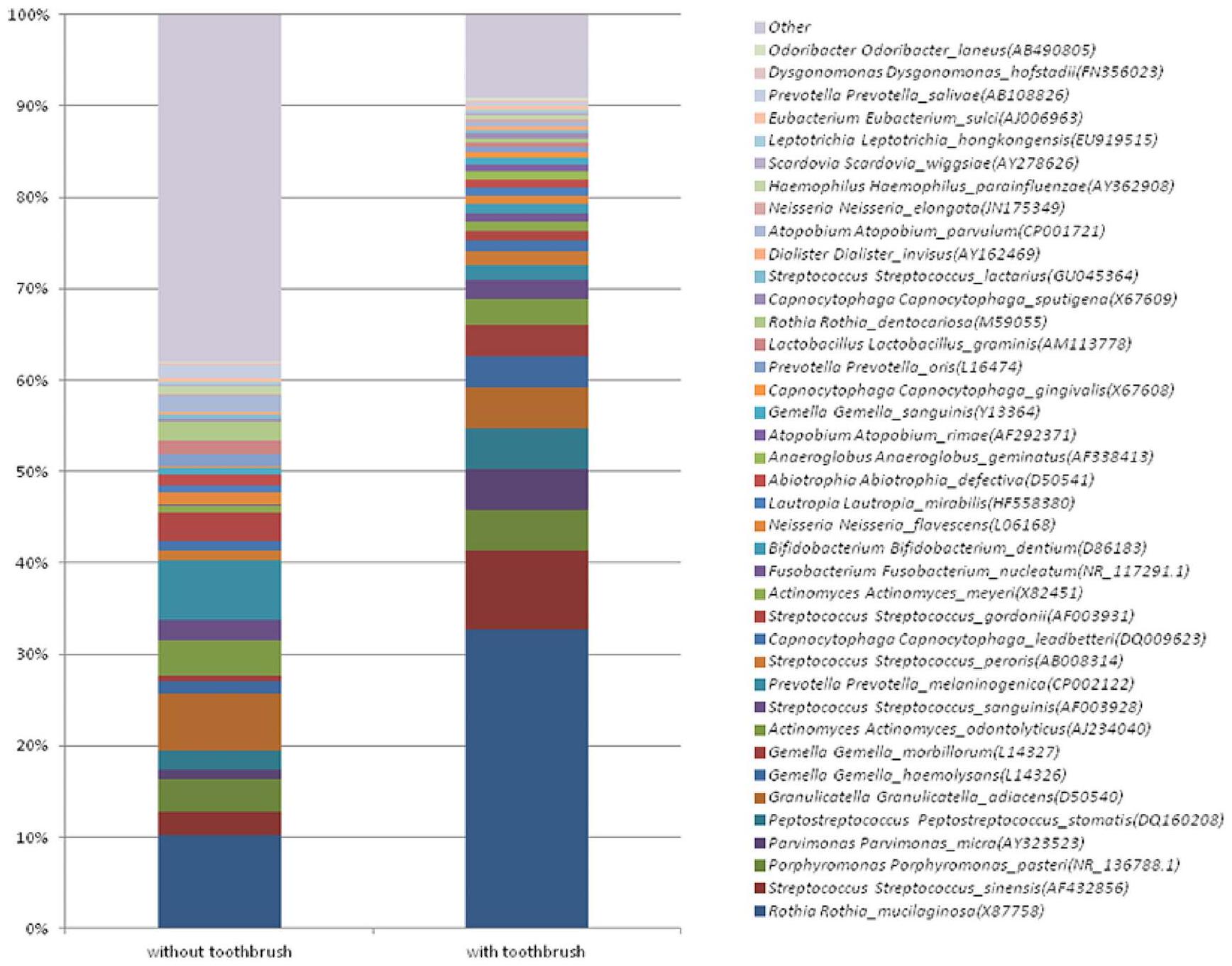

أثر العناية الفموية على الميكروبات الفموية في سرطان الفم

هايموليسانس، جيملا موربيلوروم، أكتينوميس أودونتوليتيكوس، ستربتوكوكوس سانغوينيس، على التوالي. في المرضى الذين لم يكن لديهم عادات تنظيف الأسنان اليومية، كانت الأنواع العشر الأكثر وفرة هي روثيا موكيلاجينوزا، بريفوتيلا ميلانينوجينيكا، جرانوبيكاتيلا أدياسينس، أكتينوميس أودونتوليتيكوس، بورفيروموناس باستيري، ستافيلوكوكوس ديفريسي، ستربتوكوكوس غوردوني، ستربتوكوكوس سينيينس، بريفوتيلا جيجوني، ستربتوكوكوس سانغوينيس، على التوالي. في المرضى الذين يعانون من السرطان الفموي، سواء كانوا ينظفون أسنانهم أو لا، كانت روثيا موكيلاجينوزا هي النوع الأكثر وفرة؛ كانت أعلى بمقدار 3.2 مرة في المشاركين الذين لديهم عادات تنظيف الأسنان اليومية. في المرضى الذين يقومون بالعناية الفموية اليومية، زادت مستويات جيملا موربيلوروم، بارفيموناس ميكرا، جيملا هايموليسانس، وبيبتوستربتوكوكوس ستوماتيس.

نقاش

قد تكون التغيرات الميكروبية الفموية أيضًا مؤشرات على نشوء الأورام. لذلك، يمكن أن يوفر تكوين الميكروبات الفموية والأنواع المحددة لدى المرضى المصابين بسرطان تجويف الفم تقنية تشخيصية غير جراحية لسرطانات تجويف الفم.

وفرة من روثيا في مرضى سرطان تجويف الفم، مما يتناقض مع هذه التقارير السابقة [3].

المدخنين. كانت المستويات المنخفضة من Proteobacteria مرتبطة بتطور سرطانات الفم، مما يشير بشكل جماعي إلى أن التدخين، وهو عامل خطر رئيسي للعديد من السرطانات، قد يؤثر على مستويات بعض الأنواع، مما يؤدي إلى تطور سرطان الفم.

أظهرت دراستنا أن العديد من الأنواع الميكروبية، بما في ذلك الكائنات الدقيقة الرئيسية المرتبطة بشكل جيد بالتهاب اللثة، كانت مرتبطة أيضًا بسرطانات الفم. لم نختار عمدًا مقارنة مرضانا في هذه الدراسة بمجموعة من المرضى الذين يعانون من التهاب اللثة لأن هدف الدراسة لم يكن توضيح دور التهاب اللثة. سمح لنا نهجنا غير المتحيز بتحديد الأنواع الميكروبية المرتبطة بسرطانات الفم مقارنة بتلك التي لا تعاني من أي سرطان فم. نظرًا لأن أيًا من مواضيع التحكم لم يكن لديهم أمراض لثة (كما هو مذكور في الجدول 2)، أظهرنا ارتباطًا واضحًا بين سرطانات الفم وأنواع ميكروبية معينة من تجويف الفم، بعضها مرتبط بمرض اللثة. أظهرت النتائج أنه حتى في غياب التهاب اللثة، كانت الأنواع البكتيرية التي تلعب دورًا في مرض اللثة مرتبطة بسرطان الفم، مما يطرح سؤالًا مثيرًا: هل تقتصر مسببات الأمراض اللثوية فقط على أمراض اللثة في تأثيرها، أم أن تأثيراتها تتجاوز سبب وشدة التهاب اللثة؟ بينما كان هذا السؤال خارج نطاق هذا العمل، ستتركز دراساتنا الجارية على هذا الموضوع. ما إذا كان الخلل الميكروبي هو سبب أو نتيجة للسرطان لا يزال يتعين تحديده؛ ومع ذلك، فإن الروابط بين الأنواع التي أظهرناها حاسمة لفهم علم الأمراض لسرطانات الفم ودور الميكروبيوم الفموي.

الخلاصة

تم توفير تمويل الوصول المفتوح من قبل مجلس البحث العلمي والتكنولوجي في تركيا (TÜBİTAK).

الإعلانات

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام، والمشاركة، والتكيف، والتوزيع، وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت هناك تغييرات قد تم إجراؤها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة واستخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

- Cancer (IARC) (2024) https://gco.iarc.fr/

- Adeoye J, Hui L, Tan JY, Koohi-Moghadam M, Choi SW, Thomson P (2021) Prognostic value of non-smoking, nonalcohol drinking status in oral cavity cancer. Clin Oral Investig 25(12):6909-6918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-021-03981-x

- Guerrero-Preston R, Godoy-Vitorino F, Jedlicka A et al (2016) 16 S rRNA amplicon sequencing identifies microbiota associated with oral cancer, human papilloma virus infection and surgical treatment. Oncotarget 7(32):51320-51334. https://doi. org/10.18632/oncotarget. 9710

- Deng Q, Yan L, Lin J et al (2022) A composite oral hygiene score and the risk of oral cancer and its subtypes: a large-scale propensity score-based study. Clin Oral Investig 26(3):2429-2437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-021-04209-8

- Marques LA, Eluf-Neto J, Figueiredo RAO et al (2008) Oral health, hygiene practices and oral cancer. Rev Saúde Pública 42(3):471479. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102008000300012

- Seymour RA (2010) Is oral health a risk for malignant disease? Dent Update 37(5):279-280. https://doi.org/10.12968/ denu.2010.37.5.279

- Irfan M, Delgado RZR, Frias-Lopez J (2020) The oral microbiome and cancer. Front Immunol. ;11. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/ fimmu.2020.591088

- Zhong X, Lu Q, Zhang Q, He Y, Wei W, Wang Y (2021) Oral microbiota alteration associated with oral cancer and areca chewing. Oral Dis 27(2):226-239. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi. 13545

- Lee YH, Chung SW, Auh QS et al (2021) Progress in oral microbiome related to oral and systemic diseases: an update. Diagn Basel Switz 11(7):1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11071283

- Stasiewicz M, Karpiński TM (2022) The oral microbiota and its role in carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol 86(Pt 3):633-642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.11.002

- Wei W, Li J, Shen X et al (2022) Oral microbiota from periodontitis promote oral squamous cell carcinoma development via

T cell activation. mSystems 7(5):e0046922. https://doi.org/10.1128/ msystems.00469-22 - Chattopadhyay I, Verma M, Panda M (2019) Role of oral microbiome signatures in diagnosis and prognosis of oral cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat 18:1533033819867354. https://doi. org/10.1177/1533033819867354

- Kato MG, Baek CH, Chaturvedi P et al (2020) Update on oral and oropharyngeal cancer staging – international perspectives. World J Otorhinolaryngol – Head Neck Surg 6(1):66-75. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.wjorl.2019.06.001

- OECD (2007) Reviews of national policies for education: basic education in Turkey 2007. OECD. https://doi. org/10.1787/9789264030206-en

- de Moraes RC, Dias FL, Figueredo CM, da Fischer S (2016) Association between chronic periodontitis and oral/oropharyngeal cancer. Braz Dent J 27:261-266. https://doi. org/10.1590/0103-6440201600754

- Peker K, Bermek G (2011) Oral health: locus of control, health behavior, self-rated oral health and socio-demographic factors in Istanbul adults. Acta Odontol Scand 69(1):54-64. https://doi.org/ 10.3109/00016357.2010.535560

- Christensen LB, Jeppe-Jensen D, Petersen PE (2003) Selfreported gingival conditions and self-care in the oral health of Danish women during pregnancy. J Clin Periodontol 30(11):949953. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00404.x

- Chatzopoulos GS, Cisneros A, Sanchez M, Lunos S, Wolff LF (2018) Validity of self-reported periodontal measures, demographic characteristics, and systemic medical conditions. J Periodontol 89(8):924-932. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.17-0586

- Silness J, Löe H (1964) Periodontal disease in pregnancy II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand 22(1):121-135. https://doi. org/10.3109/00016356408993968

- Löe H (1967) The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol 38(6):610-616. https://doi. org/10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610

- Erdem MG, Unlu O, Ates F, Karis D, Demirci M (2023) Oral microbiota signatures in the pathogenesis of euthyroid hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Biomedicines 11(4):1012. https://doi. org/10.3390/biomedicines11041012

- Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T et al (2013) Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res 41(1):e1. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks808

- Wang S, Song F, Gu H et al (2022) Comparative evaluation of the salivary and buccal mucosal microbiota by 16S rRNA sequencing for forensic investigations. Front Microbiol 13. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/https://doi.org/10.3389/ fmicb. 2022.777882

- Kaya D, Genc E, Genc MA, Aktas M, Eroldogan OT, Guroy D (2020) Biofloc technology in recirculating aquaculture system as a culture model for green tiger shrimp, Penaeus semisulcatus: effects of different feeding rates and stocking densities. Aquaculture 528:735526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. aquaculture.2020.735526

- Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K et al (2007) SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 35(21):7188-7196. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm864

- Su SC, Chang LC, Huang HD et al (2021) Oral microbial dysbiosis and its performance in predicting oral cancer. Carcinogenesis 42(1):127-135. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgaa062

- de Rezende CP, Ramos MB, Daguíla CH, Dedivitis RA, Rapoport A (2008) Oral health changes in patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 74(4):596-600. https://doi. org/10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30609-1

- Michaud DS, Liu Y, Meyer M, Giovannucci E, Joshipura K (2008) Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and cancer risk in male health professionals: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 9(6):550-558. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70106-2

- Javed F , Warnakulasuriya S (2016) Is there a relationship between periodontal disease and oral cancer? A systematic review of currently available evidence. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 97:197-205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.08.018

- Ye L, Jiang Y, Liu W, Tao H (2016) Correlation between periodontal disease and oral cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Ther 12(Supplement):C237-C240. https://doi. org/10.4103/0973-1482.200746

- Guha N, Boffetta P, Wünsch Filho V et al (2007) Oral health and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and esophagus: results of two multicentric case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol 166(10):1159-1173. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm193

- Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Eke PI, Thornton-Evans G, Petersen PE (2012) Recording and surveillance systems for periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 60(1):40-53. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1600-0757.2012.00446.x

- Rosenquist K, Wennerberg J, Schildt EB, Bladström A, Hansson B, Andersson G (2005) Oral status, oral infections and some lifestyle factors as risk factors for oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. A population-based case-control study in Southern Sweden. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 125:1327-1336. https:// doi.org/10.1080/00016480510012273

- Shin YJ, Choung HW, Lee JH, Rhyu IC, Kim HD (2019) Association of periodontitis with oral cancer: a case-control study. J Dent Res 98(5):526-533. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034519827565

- Eliot MN, Michaud DS, Langevin SM, McClean MD, Kelsey KT (2013) Periodontal disease and mouthwash use are risk factors for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Causes Control CCC 24(7):1315-1322. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10552-013-0209-x

- Tuominen H, Rautava J (2021) Oral microbiota and cancer development. Pathobiology 88(2):116-126. https://doi. org/10.1159/000510979

- Perera M, Al-Hebshi NN, Speicher DJ, Perera I, Johnson NW (2016) Emerging role of bacteria in oral carcinogenesis: a review

with special reference to perio-pathogenic bacteria. J Oral Microbiol 8:32762. https://doi.org/10.3402/jom.v8.32762 - Gholizadeh P, Eslami H, Kafil HS (2017) Carcinogenesis mechanisms of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother 89:918-925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. biopha.2017.02.102

- Pushalkar S, Ji X, Li Y et al (2012) Comparison of oral microbiota in tumor and non-tumor tissues of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Microbiol 12(1):144. https://doi. org/10.1186/1471-2180-12-144

- Bankvall M, Carda-Diéguez M, Mira A et al (2023) Metataxonomic and metaproteomic profiling of the oral microbiome in oral lichen planus – a pilot study. J Oral Microbiol 15(1):2161726. https://doi.org/10.1080/20002297.2022.2161726

- Wen L, Mu W, Lu H et al (2020) Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes oral squamous cell carcinoma progression in an immune microenvironment. J Dent Res 99(6):666-675. https://doi. org/10.1177/0022034520909312

- Miyoshi T, Oge S, Nakata S et al (2021) Gemella haemolysans inhibits the growth of the periodontal pathogen porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci Rep 11(1):11742. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-021-91267-3

- Panda M, Rai AK, Rahman T et al (2020) Alterations of salivary microbial community associated with oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients. Arch Microbiol 202(4):785-805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-019-01790-1

- Uranga CC, Arroyo P, Duggan BM, Gerwick WH, Edlund A (2020) Commensal oral Rothia mucilaginosa produces enterobactin, a metal-chelating siderophore. mSystems 5(2):e00161e00120. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00161-20

- Nosrati R, Abnous K, Alibolandi M et al (2021) Targeted SPION siderophore conjugate loaded with doxorubicin as a theranostic agent for imaging and treatment of colon carcinoma. Sci Rep 11(1):13065. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92391-w

- Könönen E, Fteita D, Gursoy U, Gursoy M (2022) Prevotella species as oral residents and infectious agents with potential impact on systemic conditions. J Oral Microbiol 14. https://doi.org/10.10 80/20002297.2022.2079814

- Supré K, De Vliegher S, Cleenwerck I et al (2010) Staphylococcus devriesei sp. nov., isolated from teat apices and milk of dairy cows. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 60(12):2739-2744. https://doi. org/10.1099/ijs.0.015982-0

- Schmidt BL, Kuczynski J, Bhattacharya A et al (2014) Changes in abundance of oral microbiota associated with oral cancer. PLoS ONE 9(6):e98741. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0098741

- Kumar PS, Matthews CR, Joshi V, de Jager M, Aspiras M (2011) Tobacco smoking affects bacterial acquisition and colonization in oral biofilms. Infect Immun 79(11):4730-4738. https://doi. org/10.1128/IAI.05371-11

- Wu J, Peters BA, Dominianni C et al (2016) Cigarette smoking and the oral microbiome in a large study of American adults. ISME J 10(10):2435-2446. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2016.37

- Jia YJ, Liao Y, He YQ et al (2021) Association between oral microbiota and cigarette smoking in the Chinese population. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 11. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.658203

- Yokoyama S, Takeuchi K, Shibata Y et al (2018) Characterization of oral microbiota and acetaldehyde production. J Oral Microbiol 10(1):1492316. https://doi.org/10.1080/20002297.2018.1492316

- de Castilhos J, Zamir E, Hippchen T et al (2021) Severe dysbiosis and specific haemophilus and neisseria signatures as hallmarks of the oropharyngeal microbiome in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. Clin Infect Dis. Published Online Oct 25:ciab902. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab902

- Fan X, Peters BA, Jacobs EJ et al (2018) Drinking alcohol is associated with variation in the human oral microbiome in a

large study of American adults. Microbiome 6(1):59. https://doi. org/10.1186/s40168-018-0448-x

- Ozge Unlu

ozge_unlu88@yahoo.com

Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Microbiology, Istanbul Atlas University, Istanbul, Turkey

Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Microbiology, Kırklareli University, Kırklareli, Turkey 3 Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Periodontology, University of Health Sciences, Istanbul, Turkey

4 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Biostatistics, Koc University, Istanbul, Turkey

5 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Otolaryngology, Yeditepe University, Istanbul, Turkey6 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Biology, Balıkesir University, Balıkesir, Turkey

7 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Biology, Bandirma University, Balıkesir, Turkey8 Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Beykent University, Istanbul, Turkey9 Department of Ear, Nose and Throat Diseases, Istanbul Sisli Hamidiye Etfal Research and Training Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

Faculty of Medicine, Department of Ear, Nose and Throat Diseases, Istanbul Aydin University, Istanbul, Turkey 11 ADA Forsyth Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA

12 School of Dental Medicine, Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-024-05770-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38884817

Publication Date: 2024-06-17

Oral microbial dysbiosis in patients with oral cavity cancers

© The Author(s) 2024

Abstract

Objectives The pathogenesis of oral cavity cancers is complex. We tested the hypothesis that oral microbiota dysbiosis is associated with oral cavity cancer. Materials and methods Patients with primary oral cavity cancer who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the study. Matching healthy individuals were recruited as controls. Data on socio-demographic and behavioral factors, self-reported periodontal measures and habits, and current dental status were collected using a structured questionnaire and periodontal chartings. In addition to self-reported oral health measures, each participant received a standard and detailed clinical examination. DNA was extracted from saliva samples from patients and healthy controls. Next-generation sequencing was performed by targeting V3-V4 gene regions of the 16 S rRNA with subsequent bioinformatic analyses. Results Patients with oral cavity cancers had a lower quality of oral health than healthy controls. Proteobacteria, Aggregatibacter, Haemophilus, and Neisseria decreased, while Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Lactobacillus, Gemella, and Fusobacteria increased in oral cancer patients. At the species level, C. durum, L. umeaens, N. subflava, A. massiliensis, and

Introduction

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

and Training Hospital (2017/11/09-1109). Samples were collected after obtaining informed consent; the trial was carried out in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were recruited from the otorhinolaryngology clinics of Bağcılar Research and Training Hospital and Istanbul Research and Training Hospital. Oral cavity cancer diagnosis was confirmed by histopathology, and the lesions were classified using the TNM system [13]. All patients were recently diagnosed cases and none of them received any treatment. The exclusion criteria were complete edentulism, surgical operation on salivary glands, history of autoimmune disease or systemic disease, pregnancy, history of radiotherapy or chemotherapy, fixed orthodontic treatment, antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, and anticoagulant therapy or probiotic use for the past 4 weeks, non-adults (< 18 ages), active viral, bacterial, or fungal infections, and HPV positivity (tested for HPV using a commercial HPV real-time PCR kit). Out of more than 100 patients recruited, 10 patients with primary oral cavity cancers ( 6 men and 4 women) met the inclusion and exclusion criteria in clinical characterization, saliva sampling, and microbial analyses. Twelve systemically healthy individuals with no cancer ( 6 men and 6 women) were recruited as controls.

Demographic and dental characterization of study cohorts

Clinical examination of study individuals

parameters included probing depth (PD), clinical attachment level (CAL), bleeding on probing (BOP), gingival recession (GR), plaque index (PI), and gingival index (GI) [19, 20]. Clinical parameters were evaluated in all teeth, excluding third molars. PI and GI were recorded at four sites, while PD and CAL were measured at six sites per tooth (buccal, mesiobuccal, distobuccal, lingual, mesiolingual, and distolingual). BOP was measured by the presence or absence of bleeding 10 s after probing. All measurements were performed using a calibrated millimeter periodontal probe (PCP15; Hu-Friedy®, Chicago, IL, USA), and the values were rounded up to the nearest millimeter. The average score for whole-mouth PD, CAL, GI, PI, and BOP, divided by the total number of sites per mouth and multiplied by 100, was calculated for each individual.

Sample collection, processing, and next generation sequencing

used to purify the amplicon products following both PCR cycles. PCR products were examined for band presence and relative band intensities on a

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

Results

Demographic characteristics and oral health of study groups

| Characteristics | Healthy Controls | Oral Cavity Cancer Patients |

|

|

|

|

||

| Gender | 0.6911 | ||

| Male | 6(50) | 6(60) | |

| Female | 6(50) | 4(40) | |

| Age (years) | 0.1872 | ||

| mean

|

|

|

|

| Med(min-max) | 57(28-71) | 61.5(46-89) | |

| Marital Status | 0.6241 | ||

| Married | 10(83.3) | 7(70) | |

| Not married | 2(16.7) | 3(30) | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||

|

|

0(0) | 6(60) | |

| >8 years | 12(100) | 4(40) | |

| BMI | 0.3562 | ||

| mean

|

|

|

|

| Med(min-max) | 22.7(18.3832.05) | 25.27(18.69— 34.75) | |

| Comorbidities | 1 | ||

| No | 10(83.3) | 7(77.8) | |

| Yes | 2(16.7) | 2(22.2) | |

| Family history of cancer | <0.001 | ||

| No | 12(100) | 1(10) | |

| Yes | 0 | 9(90) | |

| History of smoking | 0.096 | ||

| No | 4(33.3) | 0(0) | |

| Yes | 8(66.7) | 10(100) | |

| Current smoking habit | 1 | ||

| No | 8(66.7) | 7(70) | |

| Yes | 4(33.3) | 3(30) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.646 | ||

| No | 8(66.7) | 8(80) | |

| Yes | 4(33.3) | 2(20) | |

| Red meat consumption (days per week) | 0.619 | ||

| mean

|

|

|

|

| Med(min-max) | 5(3-6) | 5(2-7) | |

| Vegetable consumption (days per week) | 0.886 | ||

| mean

|

|

|

|

| Med(min-max) | 5(2-6) | 5(3-7) | |

| Fruit consumption (days per week) | 0.489 | ||

| mean

|

|

|

|

| Med(min-max) | 5(4-7) | 5(3-7) | |

| Healthy Controls

|

Oral Cavity Cancer Patients

|

|

|

| Self-rated oral health | – | ||

| Good | 12(100) | 10(100) | |

| Self-reported gingival bleeding |

|

||

| No | 11(91.7) | 0 | |

| Yes | 1(8.3) | 10(100) | |

| Self-reported gum swelling and redness |

|

||

| No | 11(91.7) | 0 | |

| Yes | 1(8.3) | 10(100) | |

| Having dental check-up |

|

||

| No | 3(25) | 7(70) | |

| Yes | 9(75) | 3(30) | |

| Tooth brushing |

|

||

| No | 0 | 6(60) | |

| Yes | 12(100) | 4(40) | |

| Using dental flossing/interdental brush |

|

||

| No | 5(41.7) | 10(100) | |

| Yes | 7(58.3) | 0 | |

| History of periodontal diseases |

|

||

| No | 7(58.3) | 0 | |

| Yes | 5(41.7) | 10(100) | |

| Having dental prosthesis |

|

||

| No | 12(100) | 8(80) | |

| Yes | 0 | 2(20) |

Microbiological findings in oral cancer patients

| Healthy Controls | Oral Cavity Cancer |

|

|

| Gingival Index (GI) |

|

||

| mean

|

|

|

|

| Med(min-max) | 0.6(0.5-0.9) | 1.7(1.2-2.4) | |

| Plaque Index (PI) |

|

||

| mean

|

|

|

|

| Med(min-max) | 0.4(0.02-0.5) | 1.9(1.6-2.7) | |

| Bleeding on probing(BOP) |

|

||

| mean

|

|

|

|

| Med(min-max) | 3.3(0-6) | 100(100-100) | |

| Probing Depth (PD, mm) |

|

||

| mean

|

|

|

|

| Med(min-max) | 1.5(0.3-1.5) | 3.5(3.2-4.3) | |

| Clinical attachment level (CAL, mm) |

|

||

| mean

|

|

|

|

| Med(min-max) | 1.5(0.3-1.5) | 4.6(4.2-5.5) | |

| Gingival recession (GR, mm) |

|

||

| mean

|

|

|

|

| Med(min-max) | 0(0-0) | 1.1(0.1-2.0) | |

in the patient group in parallel with the total decrease in the phylum. Fusobacterium, a member of the phylum of Fusobacteria, Lactobacillus, and Gemella, a member of Firmicutes, increased in the patient group in parallel with the phylum. The bacterial genus with the highest rate in the patient and control groups was Streptococcus, followed by Rothia, Prevotella, and Veionella. While Streptococcus was found in

Impact of smoking and alcohol consumption on oral microbiota in oral cancer

bacterium, Gemella palaticanis, Rothia aeria, Prevotella saccharolytica, Prevotella maculosa, Fusobacterium periodonticum, Prevotella bryantii, Porphyromonas pasteri, Prevotella shahii, Treponema socranskii, Cardiobacterium hominis, Aggregatibacter aphrophilus, Dialister pneumosintes, Veillonella rogosae, Haemophilus sputorum, Neisseria elongata species were found to be significantly lower in smokers (

Impact of oral care on oral microbiota in oral cancer

haemolysans, Gemella morbillorum, Actinomyces odontolyticus, Streptococcus sanguinis, respectively. In patients who did not have daily tooth-brushing habits, the most abundant 10 species were Rothia mucilaginosa, Prevotella melaninogenica, Granulicatella adiacens, Actinomyces odontolyticus, Porphyromonas pasteri, Staphylococcus devriesei, Streptococcus gordonii, Streptococcus sinensis, Prevotella jejuni, Streptococcus sanguinis, respectively. In brushing and non-brushing patients with oral cancer, Rothia mucilaginosa was the most abundant species; it was 3.2fold higher in participants with daily tooth brushing habits. In patients with daily oral care, Gemella morbillorum, Parvimonas micra, Gemella haemolysans, and Peptostreptococcus stomatis levels were increased by

Discussion

of oral microbial shifts may also serve as predictors of oncopathogenesis. Therefore, oral microbiota composition and specific species in patients with oral cavity cancer can provide a non-invasive diagnostic technique for oral cavity cancers [3, 26].

abundance of Rothia in oral cavity cancer patients, contrasting with these previous reports [3]. .

smokers. Lower levels of Proteobacteria were associated with the development of oral cancers, collectively suggesting that smoking, a key risk factor for many cancers, may affect the levels of some species, resulting in the development of oral cancer.

our study demonstrated that several microbial species, including major microorganisms that are well-linked to periodontitis, were also associated with oral cancers. We intentionally did not choose to compare our patients in this study to a group of patients with periodontitis because the goal of the study was not to elucidate the role of periodontitis. Our unbiased approach allowed us to identify microbial species that are associated with oral cancers compared to those without any oral cancer. Since none of the control subjects had periodontal diseases (as mentioned in Table 2), we demonstrated a clear association between oral cancers and specific microbial species of the oral cavity, some of which were linked to periodontal disease. The results demonstrated that even in the absence of periodontitis, bacterial species that play a role in periodontal disease were associated with oral cancer, which posits a fascinating question: Are periodontopathogens only limited to periodontal diseases in their impact, or do their effects go beyond the cause and severity of periodontitis? While this question was beyond the scope of this work, our ongoing studies will be focused on this topic. Whether dysbiosis is a cause or consequence of the malignancy is yet to be determined; however, the interspecies associations that we demonstrated are critical for understanding the pathobiology of oral cancers and the role of oral microbiome.

Conclusion

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK).

Declarations

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

- Cancer (IARC) (2024) https://gco.iarc.fr/

- Adeoye J, Hui L, Tan JY, Koohi-Moghadam M, Choi SW, Thomson P (2021) Prognostic value of non-smoking, nonalcohol drinking status in oral cavity cancer. Clin Oral Investig 25(12):6909-6918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-021-03981-x

- Guerrero-Preston R, Godoy-Vitorino F, Jedlicka A et al (2016) 16 S rRNA amplicon sequencing identifies microbiota associated with oral cancer, human papilloma virus infection and surgical treatment. Oncotarget 7(32):51320-51334. https://doi. org/10.18632/oncotarget. 9710

- Deng Q, Yan L, Lin J et al (2022) A composite oral hygiene score and the risk of oral cancer and its subtypes: a large-scale propensity score-based study. Clin Oral Investig 26(3):2429-2437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-021-04209-8

- Marques LA, Eluf-Neto J, Figueiredo RAO et al (2008) Oral health, hygiene practices and oral cancer. Rev Saúde Pública 42(3):471479. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102008000300012

- Seymour RA (2010) Is oral health a risk for malignant disease? Dent Update 37(5):279-280. https://doi.org/10.12968/ denu.2010.37.5.279

- Irfan M, Delgado RZR, Frias-Lopez J (2020) The oral microbiome and cancer. Front Immunol. ;11. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/ fimmu.2020.591088

- Zhong X, Lu Q, Zhang Q, He Y, Wei W, Wang Y (2021) Oral microbiota alteration associated with oral cancer and areca chewing. Oral Dis 27(2):226-239. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi. 13545

- Lee YH, Chung SW, Auh QS et al (2021) Progress in oral microbiome related to oral and systemic diseases: an update. Diagn Basel Switz 11(7):1283. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11071283

- Stasiewicz M, Karpiński TM (2022) The oral microbiota and its role in carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol 86(Pt 3):633-642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.11.002

- Wei W, Li J, Shen X et al (2022) Oral microbiota from periodontitis promote oral squamous cell carcinoma development via

T cell activation. mSystems 7(5):e0046922. https://doi.org/10.1128/ msystems.00469-22 - Chattopadhyay I, Verma M, Panda M (2019) Role of oral microbiome signatures in diagnosis and prognosis of oral cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat 18:1533033819867354. https://doi. org/10.1177/1533033819867354

- Kato MG, Baek CH, Chaturvedi P et al (2020) Update on oral and oropharyngeal cancer staging – international perspectives. World J Otorhinolaryngol – Head Neck Surg 6(1):66-75. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.wjorl.2019.06.001

- OECD (2007) Reviews of national policies for education: basic education in Turkey 2007. OECD. https://doi. org/10.1787/9789264030206-en

- de Moraes RC, Dias FL, Figueredo CM, da Fischer S (2016) Association between chronic periodontitis and oral/oropharyngeal cancer. Braz Dent J 27:261-266. https://doi. org/10.1590/0103-6440201600754

- Peker K, Bermek G (2011) Oral health: locus of control, health behavior, self-rated oral health and socio-demographic factors in Istanbul adults. Acta Odontol Scand 69(1):54-64. https://doi.org/ 10.3109/00016357.2010.535560

- Christensen LB, Jeppe-Jensen D, Petersen PE (2003) Selfreported gingival conditions and self-care in the oral health of Danish women during pregnancy. J Clin Periodontol 30(11):949953. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00404.x

- Chatzopoulos GS, Cisneros A, Sanchez M, Lunos S, Wolff LF (2018) Validity of self-reported periodontal measures, demographic characteristics, and systemic medical conditions. J Periodontol 89(8):924-932. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.17-0586

- Silness J, Löe H (1964) Periodontal disease in pregnancy II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand 22(1):121-135. https://doi. org/10.3109/00016356408993968

- Löe H (1967) The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol 38(6):610-616. https://doi. org/10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610

- Erdem MG, Unlu O, Ates F, Karis D, Demirci M (2023) Oral microbiota signatures in the pathogenesis of euthyroid hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Biomedicines 11(4):1012. https://doi. org/10.3390/biomedicines11041012

- Klindworth A, Pruesse E, Schweer T et al (2013) Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res 41(1):e1. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gks808

- Wang S, Song F, Gu H et al (2022) Comparative evaluation of the salivary and buccal mucosal microbiota by 16S rRNA sequencing for forensic investigations. Front Microbiol 13. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/https://doi.org/10.3389/ fmicb. 2022.777882

- Kaya D, Genc E, Genc MA, Aktas M, Eroldogan OT, Guroy D (2020) Biofloc technology in recirculating aquaculture system as a culture model for green tiger shrimp, Penaeus semisulcatus: effects of different feeding rates and stocking densities. Aquaculture 528:735526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. aquaculture.2020.735526

- Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K et al (2007) SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res 35(21):7188-7196. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkm864

- Su SC, Chang LC, Huang HD et al (2021) Oral microbial dysbiosis and its performance in predicting oral cancer. Carcinogenesis 42(1):127-135. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgaa062

- de Rezende CP, Ramos MB, Daguíla CH, Dedivitis RA, Rapoport A (2008) Oral health changes in patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 74(4):596-600. https://doi. org/10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30609-1

- Michaud DS, Liu Y, Meyer M, Giovannucci E, Joshipura K (2008) Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and cancer risk in male health professionals: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol 9(6):550-558. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70106-2

- Javed F , Warnakulasuriya S (2016) Is there a relationship between periodontal disease and oral cancer? A systematic review of currently available evidence. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 97:197-205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.08.018

- Ye L, Jiang Y, Liu W, Tao H (2016) Correlation between periodontal disease and oral cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Ther 12(Supplement):C237-C240. https://doi. org/10.4103/0973-1482.200746

- Guha N, Boffetta P, Wünsch Filho V et al (2007) Oral health and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck and esophagus: results of two multicentric case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol 166(10):1159-1173. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm193

- Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Eke PI, Thornton-Evans G, Petersen PE (2012) Recording and surveillance systems for periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 60(1):40-53. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1600-0757.2012.00446.x

- Rosenquist K, Wennerberg J, Schildt EB, Bladström A, Hansson B, Andersson G (2005) Oral status, oral infections and some lifestyle factors as risk factors for oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. A population-based case-control study in Southern Sweden. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 125:1327-1336. https:// doi.org/10.1080/00016480510012273

- Shin YJ, Choung HW, Lee JH, Rhyu IC, Kim HD (2019) Association of periodontitis with oral cancer: a case-control study. J Dent Res 98(5):526-533. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034519827565

- Eliot MN, Michaud DS, Langevin SM, McClean MD, Kelsey KT (2013) Periodontal disease and mouthwash use are risk factors for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Causes Control CCC 24(7):1315-1322. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10552-013-0209-x

- Tuominen H, Rautava J (2021) Oral microbiota and cancer development. Pathobiology 88(2):116-126. https://doi. org/10.1159/000510979

- Perera M, Al-Hebshi NN, Speicher DJ, Perera I, Johnson NW (2016) Emerging role of bacteria in oral carcinogenesis: a review

with special reference to perio-pathogenic bacteria. J Oral Microbiol 8:32762. https://doi.org/10.3402/jom.v8.32762 - Gholizadeh P, Eslami H, Kafil HS (2017) Carcinogenesis mechanisms of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother 89:918-925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. biopha.2017.02.102

- Pushalkar S, Ji X, Li Y et al (2012) Comparison of oral microbiota in tumor and non-tumor tissues of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Microbiol 12(1):144. https://doi. org/10.1186/1471-2180-12-144

- Bankvall M, Carda-Diéguez M, Mira A et al (2023) Metataxonomic and metaproteomic profiling of the oral microbiome in oral lichen planus – a pilot study. J Oral Microbiol 15(1):2161726. https://doi.org/10.1080/20002297.2022.2161726

- Wen L, Mu W, Lu H et al (2020) Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes oral squamous cell carcinoma progression in an immune microenvironment. J Dent Res 99(6):666-675. https://doi. org/10.1177/0022034520909312

- Miyoshi T, Oge S, Nakata S et al (2021) Gemella haemolysans inhibits the growth of the periodontal pathogen porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci Rep 11(1):11742. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-021-91267-3

- Panda M, Rai AK, Rahman T et al (2020) Alterations of salivary microbial community associated with oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma patients. Arch Microbiol 202(4):785-805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-019-01790-1

- Uranga CC, Arroyo P, Duggan BM, Gerwick WH, Edlund A (2020) Commensal oral Rothia mucilaginosa produces enterobactin, a metal-chelating siderophore. mSystems 5(2):e00161e00120. https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00161-20

- Nosrati R, Abnous K, Alibolandi M et al (2021) Targeted SPION siderophore conjugate loaded with doxorubicin as a theranostic agent for imaging and treatment of colon carcinoma. Sci Rep 11(1):13065. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92391-w

- Könönen E, Fteita D, Gursoy U, Gursoy M (2022) Prevotella species as oral residents and infectious agents with potential impact on systemic conditions. J Oral Microbiol 14. https://doi.org/10.10 80/20002297.2022.2079814

- Supré K, De Vliegher S, Cleenwerck I et al (2010) Staphylococcus devriesei sp. nov., isolated from teat apices and milk of dairy cows. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 60(12):2739-2744. https://doi. org/10.1099/ijs.0.015982-0

- Schmidt BL, Kuczynski J, Bhattacharya A et al (2014) Changes in abundance of oral microbiota associated with oral cancer. PLoS ONE 9(6):e98741. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0098741

- Kumar PS, Matthews CR, Joshi V, de Jager M, Aspiras M (2011) Tobacco smoking affects bacterial acquisition and colonization in oral biofilms. Infect Immun 79(11):4730-4738. https://doi. org/10.1128/IAI.05371-11

- Wu J, Peters BA, Dominianni C et al (2016) Cigarette smoking and the oral microbiome in a large study of American adults. ISME J 10(10):2435-2446. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2016.37

- Jia YJ, Liao Y, He YQ et al (2021) Association between oral microbiota and cigarette smoking in the Chinese population. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 11. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.658203

- Yokoyama S, Takeuchi K, Shibata Y et al (2018) Characterization of oral microbiota and acetaldehyde production. J Oral Microbiol 10(1):1492316. https://doi.org/10.1080/20002297.2018.1492316

- de Castilhos J, Zamir E, Hippchen T et al (2021) Severe dysbiosis and specific haemophilus and neisseria signatures as hallmarks of the oropharyngeal microbiome in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. Clin Infect Dis. Published Online Oct 25:ciab902. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab902

- Fan X, Peters BA, Jacobs EJ et al (2018) Drinking alcohol is associated with variation in the human oral microbiome in a

large study of American adults. Microbiome 6(1):59. https://doi. org/10.1186/s40168-018-0448-x

- Ozge Unlu

ozge_unlu88@yahoo.com

Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Microbiology, Istanbul Atlas University, Istanbul, Turkey

Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Microbiology, Kırklareli University, Kırklareli, Turkey 3 Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Periodontology, University of Health Sciences, Istanbul, Turkey

4 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Biostatistics, Koc University, Istanbul, Turkey

5 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Otolaryngology, Yeditepe University, Istanbul, Turkey6 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Biology, Balıkesir University, Balıkesir, Turkey

7 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Medical Biology, Bandirma University, Balıkesir, Turkey8 Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Beykent University, Istanbul, Turkey9 Department of Ear, Nose and Throat Diseases, Istanbul Sisli Hamidiye Etfal Research and Training Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

Faculty of Medicine, Department of Ear, Nose and Throat Diseases, Istanbul Aydin University, Istanbul, Turkey 11 ADA Forsyth Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA

12 School of Dental Medicine, Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA