DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-023-01091-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38198038

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-10

ارتباطات قوية لبروتين السيلينوبروتين P في المصل مع الوفيات بسبب جميع الأسباب والوفيات الناتجة عن السرطان وأمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية وأمراض الجهاز التنفسي والجهاز الهضمي لدى كبار السن الألمان

© المؤلف(ون) 2023

الملخص

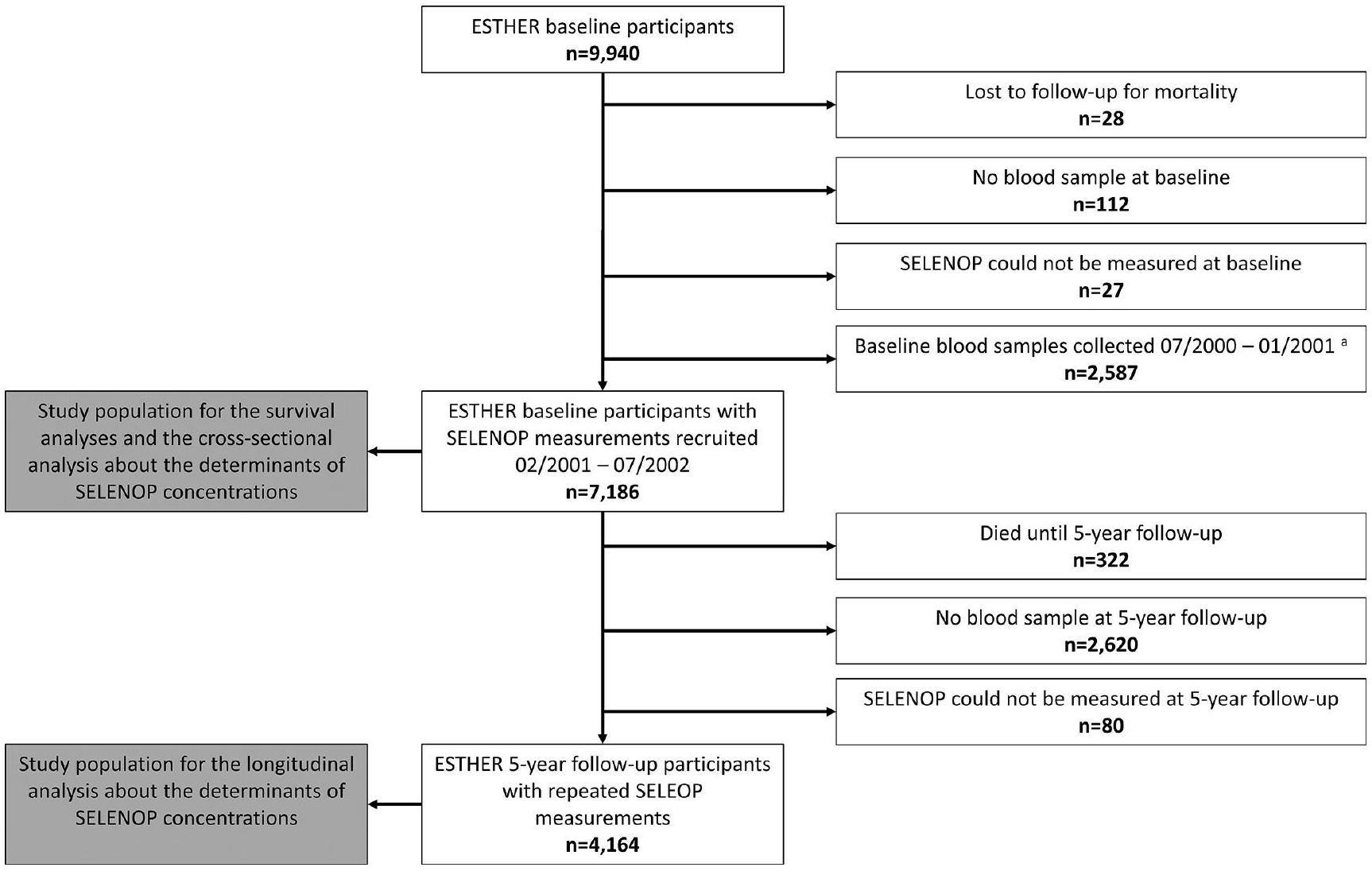

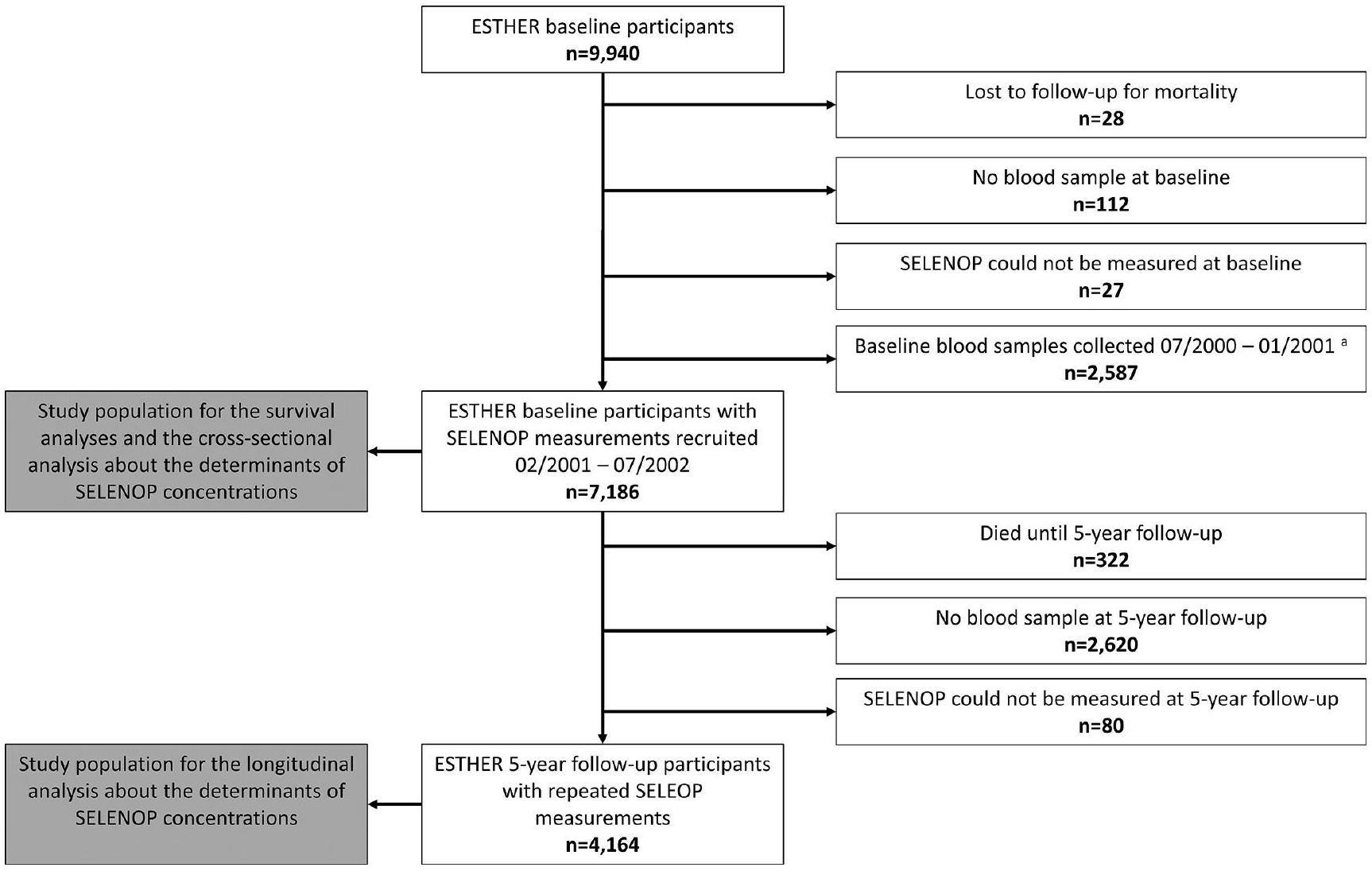

خلفية السيلينيوم هو معدن أساسي نادر. الوظيفة الرئيسية لبروتين السيلينوب (SELENOP) هي نقل السيلينيوم، ولكن تم وصفه أيضًا بتأثيرات مضادة للأكسدة. الطرق لتقييم العلاقة بين قياسات متكررة لتركيز SELENOP في المصل مع الوفيات الناتجة عن جميع الأسباب والوفيات المحددة بسبب السبب، تم قياس SELENOP في المصل عند خط الأساس والمتابعة بعد 5 سنوات في 7,186 و 4,164 مشاركًا من دراسة ESTHER، وهي دراسة قائمة على السكان الألمان تتراوح أعمارهم بين 50-74 عامًا عند خط الأساس. النتائج خلال 17.3 عامًا من المتابعة، توفي 2,126 من المشاركين في الدراسة (

| قائمة الاختصارات | |

| فترة الثقة 95% | فترة الثقة 95% |

| بيرنه | الدراسة البلجيكية بين الجامعات حول التغذية والصحة |

| كوف | معامل التباين |

| مرض القلب والأوعية الدموية | أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية |

| تصفية الكرياتينين التقديرية | معدل تصفية الكلى المقدر |

| إستير | دراسة وبائية حول فرص |

| الوقاية، الكشف المبكر والتحسين | |

| الأطباء العامون | الأطباء العامون |

| جي بي إكس | إنزيم الجلوتاثيون بيروكسيداز |

| الموارد البشرية | نسبة المخاطر |

| المنظمة الدولية للهجرة | معهد الطب |

| NHANES | |

| المسح الوطني للصحة والتغذية | |

| MPP | مشروع مالمو الوقائي |

| السيد | التوزيع العشوائي المندلي |

| أو | نسبة الأرجحية |

| PREVEND | الوقاية من مرض الكلى والأوعية الدموية في المرحلة النهائية |

| التجارب السريرية العشوائية | التجارب السريرية العشوائية المضبوطة |

| اختر | تجربة الوقاية من السرطان باستخدام السيلينيوم وفيتامين E |

| سيلينوب | سيلينوبروتين P |

الخلفية

الأشخاص الذين يعانون من تعبير غير طبيعي لجين GPX1 لديهم كميات عالية من الدهون المؤكسدة في الكبد وزيادة في إطلاق بيروكسيد الهيدروجين إلى النظام الدوري. هناك أدلة متزايدة على أن GPX1 هو حجر الزاوية الضروري لنظام الدفاع المضاد للأكسدة في الإنسان. تم ربط التعبير غير الطبيعي لـ GPX3 المشتق من الكلى، على سبيل المثال، بتعزيز thrombosis الشرياني المعتمد على الصفائح الدموية، والتصلب الجانبي الضموري، والسرطان. قد تؤثر الوظائف المضادة للأكسدة لأعضاء عائلة GPX وبروتينات السيلينيوم الأخرى على عمر الفرد. وفقًا لنظرية الجذور الحرة للشيخوخة، يمكن أن يؤدي عدم التوازن بين القدرات المؤكسدة والمضادة للأكسدة في الخلايا إلى تلف الحمض النووي والبروتينات والدهون الغشائية، مما يمكن أن يؤدي إلى شيخوخة الخلايا، وظهور الأمراض المرتبطة بالعمر، وفي النهاية وفاة مبكرة.

طرق

تصميم الدراسة

جميع الأشخاص الذين لديهم تأمين صحي قانوني والأشخاص الذين لديهم تأمين صحي خاص عادة ما يتم تعويض تكاليفهم. في الفئة العمرية لدراسة ESTHER (50-75 سنة)، الفروق في استخدام الفحص الصحي حسب الجنس والحالة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية صغيرة جداً [26]، مما يشير إلى عدم وجود انحياز في الاختيار بسبب سلوك الوعي الصحي. علاوة على ذلك، كانت انتشار الأمراض المزمنة الشائعة في دراسة ESTHER، مثل ارتفاع ضغط الدم ومرض السكري، مشابهة لتلك المبلغ عنها لمجموعات عمرية مماثلة من خلال المسح الوطني الألماني للمقابلات الصحية والفحوصات 1998 (BGS98) [27، 28]، وهو مسح تمثيلي لألمانيا. معدل المشاركة الفعلي لدراسة ESTHER في البداية غير معروف لأن الأطباء العامين لم يوثقوا عدد المشاركين المحتملين الذين اقتربوا منهم. نفترض أنه أعلى بكثير من معدل المشاركة في BGS98، الذي كان

تقييم المتغيرات المشتركة

تم تسجيل مرض السكري لتكملة معلومات التشخيص. تم تعريف مرض القلب والأوعية الدموية السائد (CVD) من خلال تقارير الأطباء عن مرض الشريان التاجي، وتاريخ ذاتي للإصابة بالنوبات القلبية، أو السكتة الدماغية، أو إعادة توعية الشرايين التاجية (تجاوز أو دعامة). تم توفير معلومات عن تاريخ الحياة الكامل للسرطان (رموز ICD-10 C00-C97، باستثناء C44) من قبل سجل سرطان سارلاند. تم قياس بروتين سي التفاعلي بواسطة التوربيديمترية في كل من الأساس والمتابعة بعد 5 سنوات، وتم تعريف الالتهاب على أنه مستويات بروتين سي التفاعلي.

قياسات SELENOP

لأنها كانت مرتبطة بتركيزات البروتين الكلي في العينات (

تحديد الوفيات

التحليلات الإحصائية

| الخصائص الأساسية |

|

ن (%) | يعني

|

| العمر (بالسنوات) | 7186 |

|

|

| الجنس (ذكر) | 7186 | 3219 (44.8) | |

| التعليم المدرسي (السنوات) | ٧٠٠٠ | ||

|

|

٥٢٦٤ (٧٥.٢) | ||

| 10-11 | 952 (13.6) | ||

|

|

784 (11.2) | ||

| مؤشر كتلة الجسم (BMI)

|

7178 |

|

|

| < 25 | 1955 (27.2) | ||

| 25-<30 | ٣٣٧٥ (٤٧.٠) | ||

|

|

1848 (25.8) | ||

| سلوك التدخين | 6989 | ||

| مدخن أبداً | 3548 (50.8) | ||

| مدخن سابق | 2299 (32.9) | ||

| مدخن حالي | 1142 (16.3) | ||

| النشاط البدني

|

7163 | ||

| غير نشط | 1571 (21.9) | ||

| منخفض | ٣٢٨١ (٤٥.٨) | ||

| متوسط أو عالي | 2311 (32.3) | ||

| استهلاك الكحول

|

٦٤٧٨ | ||

| ممتنع | 2135 (33.0) | ||

| معتدل | 3909 (60.3) | ||

| عالي | ٣٣٤ (٥.٢) | ||

| مرتفع جداً | 100 (1.5) | ||

| التغذية (الحصص اليومية) | |||

| لحم | 6456 |

|

|

| خبز | 5980 |

|

|

| حليب/جبن/بيض | 6539 |

|

|

| الفواكه/الخضروات | 6813 |

|

|

| سمك | 6754 |

|

|

| مكملات الفيتامينات/المعادن (يوميًا) | 7017 | 991 (14.1) | |

| الأمراض/الحالات | |||

| سرطان

|

7186 | 458 (6.4) | |

| مرض القلب والأوعية الدموية

|

7185 | 1200 (16.7) | |

| داء السكري | 7073 | 1062 (15.0) | |

| خلل شحميات الدم | 7075 | 3100 (43.8) | |

| ارتفاع ضغط الدم | 7071 | 3132 (44.3) | |

| فشل القلب | 7136 | 755 (10.6) | |

| ضعف الكلى

|

7165 | ١١٩٤ (١٦.٧) | |

| التهاب

|

7097 | ٢٧٦٨ (٣٩.٠) | |

| حالة فيتامين د

|

7020 |

|

|

| كافٍ | 2795 (39.8) | ||

| غير كافٍ | 3146 (44.8) | ||

| نقص | 1079 (15.4) | ||

| إجمالي البروتين (غ/ل) | 7186 |

|

| الخصائص الأساسية |

|

ن (%) | يعني

|

| خط الأساس SELENOP (ملغ/لتر) | 7186 |

|

|

| متابعة لمدة 5 سنوات SELENOP (ملغ/لتر) | 4164 |

|

|

| الاختصارات: مؤشر كتلة الجسم (BMI)؛ مرض القلب والأوعية الدموية (CVD)؛

|

|||

| نساء

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

نموذج يعتمد على الزمن باستخدام إما فقط الوفيات التي حدثت في وقت سابق (السنة 1-9) أو لاحقًا (السنة 10-18) خلال فترة المتابعة.

النتائج

خصائص عينة الدراسة

| خاصية | تحليل مقطعي

|

تحليل طولي

|

| OR (95%CI)

|

OR (95%CI)

|

|

| العمر (لكل 10 سنوات) | 1.15 (1.06; 1.24) | 1.26 (1.12; 1.41) |

| الجنس (ذكر) | 1.53 (1.37; 1.71) | – |

| مؤشر كتلة الجسم (BMI)

|

||

| < 25 | مرجع | – |

| 25-<30 | 0.79 (0.70; 0.89) | – |

|

|

0.65 (0.57; 0.76) | – |

| سلوك التدخين | ||

| مدخن أبداً | – | مرجع |

| مدخن سابق | – | مرجع |

| مدخن حالي | – | 1.41 (1.15; 1.73) |

| النشاط البدني | ||

| غير نشط | مرجع | – |

| منخفض | مرجع | – |

| متوسط أو عالي | 0.81 (0.73; 0.91) | – |

| استهلاك الكحول | ||

| ممتنع | 1.18 (1.05; 1.33) | – |

| معتدل | مرجع | – |

| عالي | مرجع | – |

| مرتفع جداً | 1.76 (1.17; 2.64) | – |

| مكملات الفيتامينات/المعادن المتعددة (يوميًا) | 0.63 (0.54; 0.74) | – |

| الأمراض/الحالات | ||

| سرطان | – | 1.35 (1.02; 1.79) |

| مرض القلب والأوعية الدموية | 1.31 (1.14; 1.50) | 1.30 (1.08; 1.56) |

| داء السكري | 0.57 (0.49; 0.67) | – |

| خلل شحميات الدم | – | 0.82 (0.71; 0.94) |

| التهاب

|

1.36 (1.22; 1.51) | – |

| حالة فيتامين د

|

||

| كافٍ | مرجع | مرجع |

| غير كافٍ | 1.18 (1.05; 1.32) | مرجع |

| ناقص | 1.73 (1.50; 2.01) | 1.39 (1.13; 1.70) |

| خط الأساس SELENOP (حسب

|

غير متوفر | 0.55 (0.51; 0.58) |

توزيع SELENOP

عوامل تركيز السيلينوب

ارتباط تركيز السيلينوب مع الوفيات

للموت المحدد بسبب السبب. كانت الفئة السفلية من SELENOP مرتبطة فقط بوفيات السرطان التي حدثت لاحقًا في المتابعة. على النقيض من ذلك، كانت العلاقات بين تركيز SELENOP ووفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية ووفيات غير الناتجة عن الأمراض القلبية الوعائية أو السرطان أقوى مع الوفيات التي حدثت في وقت مبكر من المتابعة، ولكن كانت العلاقة لا تزال قابلة للاكتشاف مع الوفيات اللاحقة (على الرغم من أنها لم تكن ذات دلالة إحصائية لوفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية).

| نتيجة | الثلاثيات SELENOP

|

|

|

نموذج معدل حسب العمر والجنس | النموذج الرئيسي

|

| HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | ||||

| الوفيات لجميع الأسباب | تي 1 | ٢٣٩٥ | 857 (35.8) | 1.48 (1.33; 1.64) | 1.35 (1.21; 1.50) |

| T2 | ٢٣٩٥ | 653 (27.3) | 1.02 (0.91; 1.14) | 1.02 (0.91; 1.14) | |

| T3 | ٢٣٩٦ | 616 (25.7) | مرجع | مرجع | |

| وفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية

|

تي 1 | ٢٣٩٥ | 275 (11.5) | 1.33 (1.12; 1.59) | 1.24 (1.04; 1.49) |

| T2 | ٢٣٩٥ | 217 (9.1) | 0.85 (0.70; 1.04) | 0.86 (0.71; 1.05) | |

| T3 | ٢٣٩٦ | 217 (9.1) | مرجع | مرجع | |

| وفيات السرطان

|

تي 1 | ٢٣٩٥ | 271 (11.3) | 1.47 (1.22; 1.77) | 1.31 (1.09; 1.58) |

| T2 | ٢٣٩٥ | 225 (9.4) | 1.11 (0.91; 1.35) | 1.12 (0.92; 1.36) | |

| T3 | ٢٣٩٦ | 200 (8.4) | مرجع | مرجع | |

| وفيات الأمراض التنفسية

|

تي 1 | ٢٣٩٥ | 61 (2.6) | 2.37 (1.49; 3.77) | 2.06 (1.28; 3.32) |

| T2 | ٢٣٩٥ | 19 (0.8) | 0.88 (0.50; 1.55) | 0.87 (0.49; 1.53) | |

| T3 | ٢٣٩٦ | 31 (1.3) | مرجع | مرجع | |

| وفيات الأمراض المعوية

|

تي 1 | ٢٣٩٥ | 54 (2.2) | 2.22 (1.37; 3.59) | 2.04 (1.25; 3.32) |

| T2 | ٢٣٩٥ | 25 (1.0) | 1.05 (0.60; 1.83) | 1.03 (0.59; 1.80) | |

| T3 | ٢٣٩٦ | ٢٦ (١.١) | مرجع | مرجع | |

| وفيات الأمراض النفسية/العصبية

|

T1 | ٢٣٩٥ | ٤٨ (٢.٠) | 1.47 (0.95; 2.29) | 1.40 (0.89; 2.19) |

| T2 | ٢٣٩٥ | ٤٤ (١.٨) | 1.15 (0.72; 1.82) | 1.15 (0.73; 1.84) | |

| T3 | ٢٣٩٦ | 31 (1.3) | مرجع | مرجع | |

| سبب الوفاة الآخر/غير المعروف

|

تي 1 | ٢٣٩٥ | 148 (6.2) | 1.34 (1.04; 1.72) | 1.27 (0.98; 1.63) |

| T2 | ٢٣٩٥ | 123 (5.1) | 1.16 (0.89; 1.49) | 1.18 (0.91; 1.53) | |

| T3 | ٢٣٩٦ | 111 (4.6) | مرجع | مرجع |

مطبوع بخط عريض: ذو دلالة إحصائية

كانت الوفيات أعلى بين الأشخاص الذين ليس لديهم تاريخ مرضي للسرطان مقارنة بالأشخاص الذين لديهم تاريخ مرضي للسرطان.

نقاش

ملخص

تم العثور على ارتباط غير خطي عكسي مع الوفيات يبدأ في الزيادة بشكل ملحوظ عند تركيزات SELENOP أقل من

مقارنة عامة مع الدراسات السابقة والجدة

| مجموعة فرعية |

|

الوفيات لجميع الأسباب | وفيات الأمراض القلبية الوعائية | وفيات السرطان | |||

|

|

الموارد البشرية

|

|

الموارد البشرية

|

|

الموارد البشرية

|

||

| إجمالي السكان | 7186 | 2126 (29.6) | 1.35 (1.21; 1.50) | 709 (9.9) | 1.24 (1.04; 1.49) | 696 (9.7) | 1.31 (1.09; 1.58) |

| نساء | 3967 | 912 (23.0) | 1.20 (1.03; 1.42) | ٣٠٣ (٧.٦) | 1.22 (0.92; 1.61) | 284 (7.2) | 1.16 (0.86; 1.55) |

| رجال | ٣٢١٩ | 1214 (37.7) | 1.47 (1.28; 1.70) | ٤٠٦ (١٢.٦) | 1.27 (1.01; 1.62) | 412 (12.8) | 1.42 (1.11; 1.82) |

| < 65 سنة | ٤٣٢٤ | 802 (18.6) | 1.48 (1.24; 1.75) | 210 (4.9) | 1.45 (1.04; 2.04) | 336 (7.8) | 1.25 (0.95; 1.64) |

|

|

2862 | 1324 (46.3) | 1.26 (1.10; 1.44) | 499 (17.4) | 1.15 (0.93; 1.42) | 360 (12.6) | 1.33 (1.03; 1.73) |

| لا أمراض قلبية وعائية | 6010 | 1525 (25.4) | 1.30 (1.15; 1.47) | ٤٥٩ (٧.٦) | 1.20 (0.95; 1.49) | ٥٤٨ (٩.١) | 1.26 (1.02; 1.55) |

| مرض القلب والأوعية الدموية | 1176 | 601 (51.1) | 1.52 (1.24; 1.86) | 250 (21.3) | 1.33 (0.98; 1.80) | 148 (12.6) | 1.58 (1.02; 2.45) |

| لا تاريخ للإصابة بالسرطان | 6728 | 1897 (28.2) | 1.36 (1.21; 1.52) | 652 (9.7) | 1.20 (1.00; 1.45) | 575 (8.6) | 1.32 (1.08; 1.63) |

| تاريخ السرطان | ٤٥٨ | 229 (50.0) | 1.26 (0.91; 1.73) | 57 (12.5) | 1.60 (0.77; 3.32) | 121 (26.4) | 1.21 (0.78; 1.88) |

مطبوع بخط عريض: ذو دلالة إحصائية

الدراسة (

العمر و SELENOP

علاقة حالة السيلينيوم بالوفيات

تم ملاحظة النتيجة في نموذج معدل حسب العمر والجنس (HR [95%CI] لكل زيادة بمقدار 1 SD: 0.65 [0.51؛ 0.82]) لكنها فقدت دلالتها الإحصائية في نموذج معدل بشكل أكثر شمولاً (OR لم يتم الإبلاغ عنه).

التفاعل مع الجنس

في اتجاه اختلاف الجنس [68]. كانت ORs [95%CIs] 0.74 (0.64؛ 0.86) و 0.90 (0.86؛ 0.95) بين الرجال والنساء، على التوالي، وتداخلت بشكل ضئيل. لقد تم وصف تأثيرات مضادة للسرطان للسيلينيوم من خلال تأثيراته المضادة للأكسدة وتأثيراته على استقرار الحمض النووي [69].

تحليلات تتناول إمكانية العكس في السببية

نقاط القوة والقيود

تمكننا المتابعة من الحصول على تقديرات دقيقة للتأثير ومعالجة المزيد من أسباب الوفاة بدلاً من أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية والسرطان فقط.

آثار الصحة العامة

تأسيس علاقات بين تركيزات السيلينيوم المحددة وراثيًا والأمراض (مثل سرطان القولون والمستقيم، مرض الكبد الدهني غير الكحولي، داء السكري من النوع 2، مرض الكلى المزمن، التهاب القولون التقرحي، والفصام [7782]). المشكلة نفسها المتمثلة في عدم اعتبار العلاقة على شكل حرف L بين تركيزات السيلينيوم والوفيات تؤثر أيضًا على دراسات MR. يمكن تعلم درس من مستويات 25(OH)D، التي لها أيضًا علاقة على شكل حرف L مع الوفيات. على عكس العديد من دراسات MR الأخرى، التي استخدمت النطاق الكامل من

الاستنتاجات

الإعلانات

References

- Labunskyy VM, Gladyshev VN. Role of reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling in aging. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(12):1362-72. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2012.4891

- Hinojosa Reyes L, Marchante-Gayon JM, Garcia Alonso JI, SanzMedel A. Quantitative speciation of selenium in human serum by affinity chromatography coupled to post-column isotope dilution analysis ICP-MS. J Anal at Spectrom. 2003;18:1210-6. https:// doi.org/10.1039/B305455A

- Letsiou S, Nomikos T, Panagiotakos DB, Pergantis SA, Fragopoulou E, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C, Antonopoulou S. Gen-der-specific distribution of selenium to serum selenoproteins: associations with total selenium levels, age, Smoking, body mass index, and physical activity. BioFactors. 2014;40:524-35. https:// doi.org/10.1002/biof. 1176

- Schomburg L, Selenoprotein. P – selenium transport protein, enzyme and biomarker of selenium status. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;191:150-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. freeradbiomed.2022.08.022

- Hurst R, Armah CN, Dainty JR, Hart DJ, Teucher B, Goldson AJ, Broadley MR, Motley AK, Fairweather-Tait SJ. Establishing optimal selenium status: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:923-31. https:// doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28169

- Toh P, Nicholson JL, Vetter AM, Berry MJ, Torres DJ. Selenium in Bodily Homeostasis: Hypothalamus, hormones, and highways of communication. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijms232315445

- Sunde RA. Selenium regulation of selenoprotein enzyme activity and transcripts in a pilot study with founder strains from the Collaborative Cross. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0191449. https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0191449

- McCann JC, Ames BN. Adaptive dysfunction of selenoproteins from the perspective of the triage theory: why modest selenium deficiency may increase risk of Diseases of aging. FASEB J. 2011;25:1793-814. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.11-180885

- Schomburg L, Schweizer U. Hierarchical regulation of selenoprotein expression and sex-specific effects of selenium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1453-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. bbagen.2009.03.015

- Esposito LA, Kokoszka JE, Waymire KG, Cottrell B, MacGregor GR, Wallace DC. Mitochondrial oxidative stress in mice lacking the glutathione peroxidase-1 gene. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:754-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0891-5849(00)00161-1

- Lubos E, Loscalzo J, Handy DE. Glutathione peroxidase-1 in health and Disease: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1957-97. https:// doi.org/10.1089/ars.2010.3586

- Jin RC, Mahoney CE, Coleman Anderson L, Ottaviano F, Croce K, Leopold JA, Zhang YY, Tang SS, Handy DE, Loscalzo J. Glutathione peroxidase-3 deficiency promotes platelet-dependent Thrombosis in vivo. Circulation. 2011;123:1963-73. https://doi. org/10.1161/circulationaha.110.000034

- Restuadi R, Steyn FJ, Kabashi E, Ngo ST, Cheng FF, Nabais MF, Thompson MJ, Qi T, Wu Y, Henders AK, et al. Functional characterisation of the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis risk locus GPX3/TNIP1. Genome Med. 2022;14. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s13073-021-01006-6

- Chang C, Worley BL, Phaëton R, Hempel N. Extracellular glutathione peroxidase GPx 3 and its role in Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082197

- Zhang L, Zeng H, Cheng WH. Beneficial and paradoxical roles of selenium at nutritional levels of intake in healthspan and longevity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. freeradbiomed.2018.05.067

- Wang N, Tan HY, Li S, Xu Y, Guo W, Feng Y. Supplementation of Micronutrient Selenium in Metabolic Diseases: Its Role as an Antioxidant. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017;2017:7478523. https:// doi.org/10.1155/2017/7478523

- Barja G. Updating the mitochondrial free radical theory of aging: an integrated view, key aspects, and confounding concepts. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:1420-45. https://doi.org/10.1089/ ars.2012.5148

- Schöttker B, Brenner H, Jansen EH, Gardiner J, Peasey A, Kubinova R, Pajak A, Topor-Madry R, Tamosiunas A, Saum KU, et al. Evidence for the free radical/oxidative stress theory of ageing from the CHANCES consortium: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMC Med. 2015;13. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12916-015-0537-7

- Rayman MP. The importance of selenium to human health. Lancet. 2000;356:233-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0140-6736(00)02490-9

- Rayman MP. Selenium and human health. Lancet. 2012;379:125668. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61452-9

- Wolters M, Hermann S, Golf S, Katz N, Hahn A. Selenium and antioxidant vitamin status of elderly German women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;60:85. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn. 1602271

- Goyal A, Terry MB, Siegel AB. Serum antioxidant nutrients, vitamin A, and mortality in U.S. adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:2202-11. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965. epi-13-0381

- Xing X, Xu M, Yang L, Shao C, Wang Y, Qi M, Niu X, Gao D. Association of selenium and cadmium with Heart Failure and mortality based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2023;36:1496-506. https://doi. org/10.1111/jhn. 13107

- Schöttker B, Haug U, Schomburg L, Köhrle J, Perna L, Müller H, et al. Strong associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer, and Respiratory Disease mortality in a large cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:78293. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.047712

- Zhu A, Kuznia S, Niedermaier T, Holleczek B, Schöttker B, Brenner H. Vitamin D-binding protein, total, nonbioavailable, bioavailable, and free 25 -hydroxyvitamin D , and mortality in a large population-based cohort of older adults. J Intern Med. 2022;292:463-76. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim. 13494

- Kahl H, Holling H, Kamtsiuris P. [Utilization of health screening studies and measures for health promotion]. Gesundheitswesen 1999, 61 Spec No:S163-8, S163-S168.

- Neuhauser H, Diederichs C, Boeing H, Felix SB, Jünger C, Lorbeer R, Meisinger C, Peters A, Völzke H, Weikert C, et al. Hypertension in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:809-15. https:// doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2016.0809

- Icks A, Moebus S, Feuersenger A, Haastert B, Jöckel KH, Giani G. Diabetes prevalence and association with social status-widening of a social gradient? German national health surveys 19901992 and 1998. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;78:293-7. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2007.04.005

- Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO, Criqui III, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107:499-511. https://www.ahajournals.org/ doi/10.1161/01.CIR.0000052939.59093.45

- Schöttker B, Jansen EH, Haug U, Schomburg L, Köhrle J, Brenner H. Standardization of misleading immunoassay based 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels with liquid chromatography tan-dem-mass spectrometry in a large cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48774. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0048774

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2011.

- Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, Tighiouart H, Wang D, Sang Y, Crews DC, Doria A, Estrella MM, Froissart M, et al. New Cre-atinine- and cystatin C-Based equations to Estimate GFR without Race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1737-49. https://doi.org/10.1056/ NEJMoa2102953

- Hybsier S, Schulz T, Wu Z, Demuth I, Minich WB, Renko K, Rijntjes E, Kohrle J, Strasburger CJ, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, et al. Sex-specific and inter-individual differences in biomarkers of selenium status identified by a calibrated ELISA for selenoprotein P. Redox Biol. 2017;11:403-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. redox.2016.12.025

- Ballihaut G, Kilpatrick LE, Davis WC. Detection, identification, and quantification of selenoproteins in a candidate human plasma standard reference material. Anal Chem. 2011;83:8667-74. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac2021147

- SAS OnlineDoc® Version 8. Chapter 49: The PHREG procedure. Institute Inc SAS, Cary, NC, USA. 2023. p. 2622-2635. http:// www.math.wpi.edu/saspdf/stat/chap49.pdf. Accessed Dec 2023.

- Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med. 2010;29:1037-57. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim. 3841

- Müller SM, Dawczynski C, Wiest J, Lorkowski S, Kipp AP, Schwerdtle T. Functional biomarkers for the Selenium Status in a human nutritional intervention study. Nutrients. 2020;12. https:// doi.org/10.3390/nu12030676

- Schomburg L, Orho-Melander M, Struck J, Bergmann A, Melander O. Selenoprotein-P Deficiency predicts Cardiovascular Disease and Death. Nutrients. 2019;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ nu11081852

- Brodin O, Hackler J, Misra S, Wendt S, Sun Q, Laaf E, Stoppe C, Björnstedt M, Schomburg L. Selenoprotein P as Biomarker of Selenium Status in clinical trials with therapeutic dosages of Selenite. Nutrients. 2020;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041067

- Demircan K, Bengtsson Y, Sun Q, Brange A, Vallon-Christersson J, Rijntjes E, Malmberg M, Saal LH, Rydén L, Borg

, et al. Serum selenium, selenoprotein P and glutathione peroxidase 3 as predictors of mortality and recurrence following Breast cancer diagnosis: a multicentre cohort study. Redox Biol. 2021;47:102145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2021.102145 - Hughes DJ, Fedirko V, Jenab M, Schomburg L, Méplan C, Freisling H, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Hybsier S, Becker NP, Czuban M, et al. Selenium status is associated with Colorectal cancer risk in the European prospective investigation of cancer and nutrition cohort. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1149-61. https://doi.org/10.1002/ ijc. 29071

- Al-Mubarak AA, Grote Beverborg N, Suthahar N, Gansevoort RT, Bakker SJL, Touw DJ, de Boer RA, van der Meer P, Bomer N. High selenium levels associate with reduced risk of mortality and new-onset Heart Failure: data from PREVEND. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24:299-307. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf. 2405

- Isobe Y, Asakura H, Tsujiguchi H, Kannon T, Takayama H, Takeshita Y, Ishii KA, Kanamori T, Hara A, Yamashita T, et al. Alcohol intake is Associated with elevated serum levels of selenium and selenoprotein P in humans. Front Nutr. 2021;8:633703. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.633703

- Rasmussen LB, Hollenbach B, Laurberg P, Carlé A, Hög A, Jørgensen T, Vejbjerg P, Ovesen L, Schomburg L. Serum selenium and selenoprotein P status in adult Danes -8-year followup. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2009;23:265-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jtemb.2009.03.009

- Lloyd B, Lloyd RS, Clayton BE. Effect of Smoking, alcohol, and other factors on the selenium status of a healthy population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1983;37:213-7. https://doi. org/10.1136/jech.37.3.213

- Ray AL, Semba RD, Walston J, Ferrucci L, Cappola AR, Ricks MO, Xue QL, Fried LP. Low serum selenium and total carotenoids predict mortality among older women living in the community: the women’s health and aging studies. J Nutr. 2006;136:172-6. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.1.172

- Bleys J, Navas-Acien A, Guallar E. Serum selenium levels and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality among US adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:404-10. https://doi.org/10.1001/ archinternmed.2007.74

- Zhao S, Wang S, Yang X, Shen L. Dose-response relationship between multiple trace elements and risk of all-cause mortality: a prospective cohort study. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1205537. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1205537

- Marniemi J, Järvisalo J, Toikka T, Räihä I, Ahotupa M, Sourander L. Blood vitamins, mineral elements and inflammation markers as risk factors of vascular and non-vascular Disease mortality in an elderly population. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:799-807. https:// doi.org/10.1093/ije/27.5.799

- Wei WQ, Abnet CC, Qiao YL, Dawsey SM, Dong ZW, Sun XD, Fan JH, Gunter EW, Taylor PR, Mark SD. Prospective study of

serum selenium concentrations and esophageal and gastric cardia cancer, Heart Disease, stroke, and total death. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:80-5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.1.80 - González S, Huerta JM, Fernández S, Patterson AM, Lasheras C. Homocysteine increases the risk of mortality in elderly individuals. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:1138-43. https://doi.org/10.1017/ s0007114507691958

- Suadicani P, Hein HO, Gyntelberg F. Serum selenium level and risk of Lung cancer mortality: a 16-year follow-up of the Copenhagen Male Study. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1443-8. https://doi. org/10.1183/09031936.00102711

- Kilander L, Berglund L, Boberg M, Vessby B, Lithell H. Education, lifestyle factors and mortality from Cardiovascular Disease and cancer. A 25-year follow-up of Swedish 50-year-old men. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1119-26. https://doi.org/10.1093/ ije/30.5.1119

- Akbaraly NT, Arnaud J, Hininger-Favier I, Gourlet V, Roussel AM, Berr C. Selenium and mortality in the elderly: results from the EVA study. Clin Chem. 2005;51:2117-23. https://doi. org/10.1373/clinchem.2005.055301

- Walston J, Xue Q, Semba RD, Ferrucci L, Cappola AR, Ricks M, Guralnik J, Fried LP. Serum antioxidants, inflammation, and total mortality in older women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:18-26. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwj007

- Lauretani F, Semba RD, Bandinelli S, Ray AL, Ruggiero C, Cherubini A, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Low plasma selenium concentrations and mortality among older community-dwelling adults: the InCHIANTI Study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2008;20:1538. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03324762

- Bates CJ, Hamer M, Mishra GD. Redox-modulatory vitamins and minerals that prospectively predict mortality in older British people: the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of people aged 65 years and over. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:123-32. https://doi. org/10.1017/s0007114510003053

- Alehagen U, Johansson P, Bjornstedt M, Rosen A, Post C, Aaseth J. Relatively high mortality risk in elderly Swedish subjects with low selenium status. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:91-6. https://doi. org/10.1038/ejcn.2015.92

- Giovannini S, Onder G, Lattanzio F, Bustacchini S, Di Stefano G, Moresi R, Russo A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Selenium concentrations and mortality among Community-Dwelling older adults: results from IlSIRENTE Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22:608-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1021-9

- Virtamo J, Valkeila E, Alfthan G, Punsar S, Huttunen JK, Karvonen MJ. Serum selenium and the risk of coronary Heart Disease and Stroke. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:276-82. https://doi. org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114099

- Shi L, Yuan Y, Xiao Y, Long P, Li W, Yu Y, Liu Y, Liu K, Wang H, Zhou L, et al. Associations of plasma metal concentrations with the risks of all-cause and Cardiovascular Disease mortality in Chinese adults. Environ Int. 2021;157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. envint.2021.106808

- Kok FJ, de Bruijn AM, Vermeeren R, Hofman A, van Laar A, de Bruin M, Hermus RJ, Valkenburg HA. Serum selenium, vitamin antioxidants, and cardiovascular mortality: a 9-year follow-up study in the Netherlands. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:462-8. https:// doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/45.2.462

- Salonen JT, Alfthan G, Huttunen JK, Pikkarainen J, Puska P. Association between cardiovascular death and Myocardial Infarction and serum selenium in a matched-pair longitudinal study. Lancet. 1982;2:175-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91028-5

- Criqui MH, Bangdiwala S, Goodman DS, Blaner WS, Morris JS, Kritchevsky S, Lippel K, Mebane I, Tyroler HA. Selenium, retinol, retinol-binding protein, and uric acid. Associations with cancer mortality in a population-based prospective

case-control study. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:385-93. https://doi. org/10.1016/1047-2797(91)90008-z - Kornitzer M, Valente F, De Bacquer D, Neve J, De Backer G. Serum selenium and cancer mortality: a nested case-control study within an age- and sex-stratified sample of the Belgian adult population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:98-104. https://doi. org/10.1038/sj.ejcn. 1601754

- Kok FJ, de Bruijn AM; Hofman, A.; Vermeeren, R.; Valkenburg, H.A. Is serum selenium a risk factor for cancer in men only? Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125:12-16. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114493

- Brown DG, Burk RF. Selenium retention in tissues and sperm of rats fed a Torula yeast diet. J Nutr. 1973;103:102-8. https://doi. org/10.1093/jn/103.1.102

- Cai X, Wang C, Yu W, Fan W, Wang S, Shen N, Wu P, Li X, Wang F. Selenium exposure and Cancer risk: an updated Meta-analysis and Meta-regression. Sci Rep. 2016;6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ srep19213

- Whanger PD. Selenium and its relationship to cancer: an update. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:11-28. https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn20031015

- Xiang S, Dai Z, Man C, Fan Y. Circulating Selenium and Cardiovascular or all-cause mortality in the General Population: a Meta-analysis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2020;195:55-62. https://doi. org/10.1007/s12011-019-01847-8

- Kuria A, Tian H, Li M, Wang Y, Aaseth JO, Zang J, Cao Y. Selenium status in the body and Cardiovascular Disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021;61:361625. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1803200

- Vinceti M, Filippini T, Del Giovane C, Dennert G, Zwahlen M, Brinkman M, Zeegers MP, Horneber M, D’Amico R, Crespi CM. Selenium for preventing cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1(Cd005195). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858. CD005195.pub4

- Jenkins DJA, Kitts D, Giovannucci EL, Sahye-Pudaruth S, Paquette M, Blanco Mejia S, Patel D, Kavanagh M, Tsirakis T, Kendall CWC, et al. Selenium, antioxidants, Cardiovascular Disease, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112:1642-52. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa245

- Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, Lucia MS, Thompson IM, Ford LG, Parnes HL, Minasian LM, Gaziano JM, Hartline JA, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of Prostate cancer and other cancers: the selenium and vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2009;301:39-51. https://doi. org/10.1001/jama.2008.864

- Duffield AJ, Thomson CD, Hill KE, Williams S. An estimation of selenium requirements for New zealanders. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:896-903. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/70.5.896

- Yu Z, Zhang F, Xu C, Wang Y. Association between circulating antioxidants and longevity: insight from mendelian randomization study. Bio Med Res Int. 2022;2022:4012603. https://doi. org/10.1155/2022/4012603

- Cornish AJ, Law PJ, Timofeeva M, Palin K, Farrington SM, Palles C, Jenkins MA, Casey G, Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, et al. Modifiable pathways for Colorectal cancer: a mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:5562. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(19)30294-8

- Rath AA, Lam HS, Schooling CM. Effects of selenium on coronary artery Disease, type 2 Diabetes and their risk factors: a mendelian randomization study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75:1668-78. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-021-00882-w

- Chen L, Fan Z, Sun X, Qiu W, Mu W, Chai K, Cao Y, Wang G, Lv G. Diet-derived antioxidants and nonalcoholic fatty Liver Disease: a mendelian randomization study. Hepatol Int. 2023;17:326-38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-022-10443-3

- Fu S, Zhang L, Ma F, Xue S, Sun T, Xu Z. Effects of Selenium on chronic Kidney Disease: a mendelian randomization study. Nutrients. 2022;14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214458

- Deng MG, Cui HT, Nie JQ, Liang Y, Chai C. Genetic association between circulating selenium level and the risk of schizophrenia in the European population: a two-sample mendelian randomization study. Front Nutr. 2022;9:969887. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fnut.2022.969887

- Chen J, Ruan X, Yuan S, Deng M, Zhang H, Sun J, Yu L, Satsangi J, Larsson SC, Therdoratou E, et al. Antioxidants, minerals

and vitamins in relation to Crohn’s Disease and ulcerative Colitis: a mendelian randomization study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;57:399-408. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt. 17392 - Sutherland JP, Zhou A, Hyppönen E, Vitamin D. Deficiency increases Mortality Risk in the UK Biobank: a nonlinear mendelian randomization study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:1552-9. https://doi.org/10.7326/m21-3324

- Josef K?hrle, Lutz Schomburg and Hermann Brenner are shared last authorship.

- Ben Schöttker

b.schoettker@dkfz.de1 Division of Clinical Epidemiology and Aging Research, German Cancer Research Center, Im Neuenheimer Feld 581, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany2 Saarland Cancer Registry, Neugeländstraße 9, 66117 Saarbrücken, Germany

Institut für Experimentelle Endokrinologie, Max Rubner Center (MRC) for Cardiovascular Metabolic Renal Research, Charité University Medicine Berlin, CCM, Hessische Straße 4A, 10115 Berlin, Germany 4 Division of Preventive Oncology, German Cancer Research Center, Im Neuenheimer Feld 460, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-023-01091-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38198038

Publication Date: 2024-01-10

Strong associations of serum selenoprotein P with all-cause mortality and mortality due to cancer, cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases in older German adults

© The Author(s) 2023

Abstract

Background Selenium is an essential trace mineral. The main function of selenoprotein P (SELENOP) is to transport selenium but it has also been ascribed anti-oxidative effects. Methods To assess the association of repeated measurements of serum SELENOP concentration with all-cause and causespecific mortality serum SELENOP was measured at baseline and 5-year follow-up in 7,186 and 4,164 participants of the ESTHER study, a German population-based cohort aged 50-74 years at baseline. Results During 17.3 years of follow-up, 2,126 study participants (

| List of Abbreviations | |

| 95%CI | 95% confidence interval |

| BIRNH | Belgian Interuniversity Study on Nutrition and Health |

| COV | Coefficient of variation |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| ESTHER | Epidemiologische Studie zu Chancen der |

| Verhütung, Früherkennung und optimierten | |

| GPs | General practitioners |

| GPX | Glutathione peroxidase |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| IOM | Institute of Medicine |

| NHANES | |

| National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey | |

| MPP | Malmö Preventive Project |

| MR | Mendelian Randomization |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PREVEND | Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-Stage Disease |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| SELECT | Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial |

| SELENOP | Selenoprotein P |

Background

with impaired GPX1 gene expression have high amounts of peroxidized lipids in the liver and an increased release of hydrogen peroxide into the circulatory system [10]. There is emerging evidence that GPX1 is an indispensable cornerstone of the human antioxidant defense system [11]. Impaired expression of kidney-derived GPX3 has been associated with e.g. promoting platelet-dependent arterial thrombosis [12], amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [13] and cancer [14]. The anti-oxidative functions of the GPX family members and other selenoproteins may have an impact on the lifespan [15, 16]. According to the free radical theory of ageing, an imbalance of oxidative and anti-oxidative capacities in cells can lead to damage to DNA, proteins and membrane lipids, which can result in cell senescence, the manifestation of age-related diseases and ultimately a premature death [17, 18].

Methods

Study design

all with statutory health insurance and people with private health insurance usually get the costs reimbursed. In the age range of the ESTHER study (50-75 years), differences in the utilization of the health check-up according to sex and socioeconomic status are very small [26], speaking against a selection bias by health-conscious behavior. Furthermore, the prevalences of common chronic diseases in the ESTHER study, like hypertension and diabetes mellitus, were similar to those reported for comparable age groups by the population-based German National Health Interview and Examination Survey 1998 (BGS98) [27, 28], which is a representative survey for Germany. The actual participation rate of the ESTHER study at baseline is unknown because the GPs did not document how many potential study participants they approached. We assume that it is much higher than the participation rate of the BGS98, which was

Assessment of covariates

and diabetes mellitus were recorded to complement diagnosis information. Prevalent cardiovascular disease (CVD) was defined by physician-reported coronary heart disease, a self-reported history of myocardial infarction, stroke, or revascularisation of the coronary arteries (bypass or stent). Information on a life-time history of cancer (ICD-10-codes C00-C97, except C44) was provided by the Saarland Cancer Registry. C-reactive protein was measured by turbidimetry at both baseline and 5-year follow-up and inflammation was defined as C-reactive protein levels

SELENOP measurements

because they correlated with the total protein concentrations of the samples (

Mortality ascertainment

Statistical analyses

| Baseline characteristics |

|

n (%) | Mean

|

| Age (years) | 7186 |

|

|

| Sex (Male) | 7186 | 3219 (44.8) | |

| School education (years) | 7000 | ||

|

|

5264 (75.2) | ||

| 10-11 | 952 (13.6) | ||

|

|

784 (11.2) | ||

| BMI (

|

7178 |

|

|

| < 25 | 1955 (27.2) | ||

| 25-<30 | 3375 (47.0) | ||

|

|

1848 (25.8) | ||

| Smoking behaviour | 6989 | ||

| Never smoker | 3548 (50.8) | ||

| Former smoker | 2299 (32.9) | ||

| Current smoker | 1142 (16.3) | ||

| Physical activity

|

7163 | ||

| Inactive | 1571 (21.9) | ||

| Low | 3281 (45.8) | ||

| Medium or high | 2311 (32.3) | ||

| Alcohol consumption

|

6478 | ||

| Abstainer | 2135 (33.0) | ||

| Moderate | 3909 (60.3) | ||

| High | 334 (5.2) | ||

| Very high | 100 (1.5) | ||

| Nutrition (portions per day) | |||

| Meat | 6456 |

|

|

| Bread | 5980 |

|

|

| Milk/cheese/eggs | 6539 |

|

|

| Fruits/vegetables | 6813 |

|

|

| Fish | 6754 |

|

|

| Multivitamin/mineral supplements (daily) | 7017 | 991 (14.1) | |

| Diseases/conditions | |||

| Cancer

|

7186 | 458 (6.4) | |

| CVD

|

7185 | 1200 (16.7) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7073 | 1062 (15.0) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 7075 | 3100 (43.8) | |

| Hypertension | 7071 | 3132 (44.3) | |

| Heart failure | 7136 | 755 (10.6) | |

| Renal impairment

|

7165 | 1194 (16.7) | |

| Inflammation

|

7097 | 2768 (39.0) | |

| Vitamin D status

|

7020 |

|

|

| Sufficient | 2795 (39.8) | ||

| Insufficient | 3146 (44.8) | ||

| Deficient | 1079 (15.4) | ||

| Total protein (g/L) | 7186 |

|

| Baseline characteristics |

|

n (%) | Mean

|

| Baseline SELENOP (mg/L) | 7186 |

|

|

| 5-year follow-up SELENOP (mg/L) | 4164 |

|

|

| Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease;

|

|||

| women

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

time-dependent modelling using either only deaths that occurred earlier (year 1-9) or later (year 10-18) during follow-up.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic | Cross-sectional analysis

|

Longitudinal analysis (

|

| OR (95%CI)

|

OR (95%CI)

|

|

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.15 (1.06; 1.24) | 1.26 (1.12; 1.41) |

| Sex (Male) | 1.53 (1.37; 1.71) | – |

| BMI (

|

||

| < 25 | Ref | – |

| 25-<30 | 0.79 (0.70; 0.89) | – |

|

|

0.65 (0.57; 0.76) | – |

| Smoking behaviour | ||

| Never smoker | – | Ref |

| Former smoker | – | Ref |

| Current smoker | – | 1.41 (1.15; 1.73) |

| Physical activity | ||

| Inactive | Ref | – |

| Low | Ref | – |

| Medium or high | 0.81 (0.73; 0.91) | – |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| Abstainer | 1.18 (1.05; 1.33) | – |

| Moderate | Ref | – |

| High | Ref | – |

| Very high | 1.76 (1.17; 2.64) | – |

| Multivitamin/-mineral supplements (daily) | 0.63 (0.54; 0.74) | – |

| Diseases/conditions | ||

| Cancer | – | 1.35 (1.02; 1.79) |

| CVD | 1.31 (1.14; 1.50) | 1.30 (1.08; 1.56) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.57 (0.49; 0.67) | – |

| Dyslipidemia | – | 0.82 (0.71; 0.94) |

| Inflammation

|

1.36 (1.22; 1.51) | – |

| Vitamin D status

|

||

| Sufficient | Ref | Ref |

| Insufficient | 1.18 (1.05; 1.32) | Ref |

| Deficient | 1.73 (1.50; 2.01) | 1.39 (1.13; 1.70) |

| Baseline SELENOP (per

|

NA | 0.55 (0.51; 0.58) |

Distribution of SELENOP

Determinants of SELENOP concentration

Association of SELENOP concentration with mortality

for cause-specific mortality. The bottom SELENOP tertile was only associated with cancer deaths that occurred later in follow-up. In contrast, the associations of the SELENOP concentration with CVD mortality and with deaths neither caused by CVD nor cancer were stronger with deaths that occurred earlier in the follow-up but an association was still detectable with later deaths (albeit not statistical significantly for CVD mortality).

| Outcome | SELENOP tertiles

|

|

|

Age and sex adjusted model | Main model

|

| HR (95%CI) | HR (95%CI) | ||||

| All-cause mortality | T1 | 2395 | 857 (35.8) | 1.48 (1.33; 1.64) | 1.35 (1.21; 1.50) |

| T2 | 2395 | 653 (27.3) | 1.02 (0.91; 1.14) | 1.02 (0.91; 1.14) | |

| T3 | 2396 | 616 (25.7) | Ref | Ref | |

| CVD mortality

|

T1 | 2395 | 275 (11.5) | 1.33 (1.12; 1.59) | 1.24 (1.04; 1.49) |

| T2 | 2395 | 217 (9.1) | 0.85 (0.70; 1.04) | 0.86 (0.71; 1.05) | |

| T3 | 2396 | 217 (9.1) | Ref | Ref | |

| Cancer mortality

|

T1 | 2395 | 271 (11.3) | 1.47 (1.22; 1.77) | 1.31 (1.09; 1.58) |

| T2 | 2395 | 225 (9.4) | 1.11 (0.91; 1.35) | 1.12 (0.92; 1.36) | |

| T3 | 2396 | 200 (8.4) | Ref | Ref | |

| Respiratory disease mortality

|

T1 | 2395 | 61 (2.6) | 2.37 (1.49; 3.77) | 2.06 (1.28; 3.32) |

| T2 | 2395 | 19 (0.8) | 0.88 (0.50; 1.55) | 0.87 (0.49; 1.53) | |

| T3 | 2396 | 31 (1.3) | Ref | Ref | |

| Gastrointestinal disease mortality

|

T1 | 2395 | 54 (2.2) | 2.22 (1.37; 3.59) | 2.04 (1.25; 3.32) |

| T2 | 2395 | 25 (1.0) | 1.05 (0.60; 1.83) | 1.03 (0.59; 1.80) | |

| T3 | 2396 | 26 (1.1) | Ref | Ref | |

| Psychiatric/neurological disease mortality

|

T1 | 2395 | 48 (2.0) | 1.47 (0.95; 2.29) | 1.40 (0.89; 2.19) |

| T2 | 2395 | 44 (1.8) | 1.15 (0.72; 1.82) | 1.15 (0.73; 1.84) | |

| T3 | 2396 | 31 (1.3) | Ref | Ref | |

| Other/unknown cause of death

|

T1 | 2395 | 148 (6.2) | 1.34 (1.04; 1.72) | 1.27 (0.98; 1.63) |

| T2 | 2395 | 123 (5.1) | 1.16 (0.89; 1.49) | 1.18 (0.91; 1.53) | |

| T3 | 2396 | 111 (4.6) | Ref | Ref |

Printed in bold: Statistically significant (

mortality was stronger among subjects without a history of cancer compared to subjects with a history of cancer.

Discussion

Summary

found to be a non-linear inverse association with mortality starting to increase significantly at SELENOP concentrations below

General comparison with previous studies & novelty

| Subgroup |

|

All-cause mortality | CVD mortality | Cancer mortality | |||

|

|

HR

|

|

HR

|

|

HR

|

||

| Total population | 7186 | 2126 (29.6) | 1.35 (1.21; 1.50) | 709 (9.9) | 1.24 (1.04; 1.49) | 696 (9.7) | 1.31 (1.09; 1.58) |

| Women | 3967 | 912 (23.0) | 1.20 (1.03; 1.42) | 303 (7.6) | 1.22 (0.92; 1.61) | 284 (7.2) | 1.16 (0.86; 1.55) |

| Men | 3219 | 1214 (37.7) | 1.47 (1.28; 1.70) | 406 (12.6) | 1.27 (1.01; 1.62) | 412 (12.8) | 1.42 (1.11; 1.82) |

| < 65 years | 4324 | 802 (18.6) | 1.48 (1.24; 1.75) | 210 (4.9) | 1.45 (1.04; 2.04) | 336 (7.8) | 1.25 (0.95; 1.64) |

|

|

2862 | 1324 (46.3) | 1.26 (1.10; 1.44) | 499 (17.4) | 1.15 (0.93; 1.42) | 360 (12.6) | 1.33 (1.03; 1.73) |

| No CVD | 6010 | 1525 (25.4) | 1.30 (1.15; 1.47) | 459 (7.6) | 1.20 (0.95; 1.49) | 548 (9.1) | 1.26 (1.02; 1.55) |

| CVD | 1176 | 601 (51.1) | 1.52 (1.24; 1.86) | 250 (21.3) | 1.33 (0.98; 1.80) | 148 (12.6) | 1.58 (1.02; 2.45) |

| No history of cancer | 6728 | 1897 (28.2) | 1.36 (1.21; 1.52) | 652 (9.7) | 1.20 (1.00; 1.45) | 575 (8.6) | 1.32 (1.08; 1.63) |

| History of cancer | 458 | 229 (50.0) | 1.26 (0.91; 1.73) | 57 (12.5) | 1.60 (0.77; 3.32) | 121 (26.4) | 1.21 (0.78; 1.88) |

Printed in bold: Statistically significant (

study (

Age and SELENOP

Association of selenium status with mortality

outcome was observed in an age- and sex-adjusted model (HR [95%CI] per 1 SD increase: 0.65 [0.51; 0.82]) but it lost its statistical significance in a more comprehensively adjusted model (OR not reported).

Interaction with sex

in the direction of a sex difference [68]. The ORs [95%CIs] were 0.74 (0.64; 0.86) and 0.90 (0.86; 0.95) among men and women, respectively, and overlapped just minimally. Selenium has been ascribed anti-cancerogenic effects by antioxidative effects and effects on DNA stability [69].

Analyses addressing potential reverse causality

Strengths and limitations

of follow-up enabled us to obtain precise effect estimates and address more causes of death than just CVD and cancer.

Public health implications

establish relationships between genetically determined selenium concentrations and diseases (e.g., for colorectal cancer, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, ulcerative colitis, and schizophrenia [7782]). The same problem of not considering the L-shaped association of selenium concentrations with mortality also affects MR studies. A lesson can be learned from 25(OH)D levels, which also have an L-shaped association with mortality. In contrast to several other MR studies, which used the whole range of

Conclusions

Declarations

References

- Labunskyy VM, Gladyshev VN. Role of reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling in aging. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(12):1362-72. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2012.4891

- Hinojosa Reyes L, Marchante-Gayon JM, Garcia Alonso JI, SanzMedel A. Quantitative speciation of selenium in human serum by affinity chromatography coupled to post-column isotope dilution analysis ICP-MS. J Anal at Spectrom. 2003;18:1210-6. https:// doi.org/10.1039/B305455A

- Letsiou S, Nomikos T, Panagiotakos DB, Pergantis SA, Fragopoulou E, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C, Antonopoulou S. Gen-der-specific distribution of selenium to serum selenoproteins: associations with total selenium levels, age, Smoking, body mass index, and physical activity. BioFactors. 2014;40:524-35. https:// doi.org/10.1002/biof. 1176

- Schomburg L, Selenoprotein. P – selenium transport protein, enzyme and biomarker of selenium status. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;191:150-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. freeradbiomed.2022.08.022

- Hurst R, Armah CN, Dainty JR, Hart DJ, Teucher B, Goldson AJ, Broadley MR, Motley AK, Fairweather-Tait SJ. Establishing optimal selenium status: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:923-31. https:// doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28169

- Toh P, Nicholson JL, Vetter AM, Berry MJ, Torres DJ. Selenium in Bodily Homeostasis: Hypothalamus, hormones, and highways of communication. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijms232315445

- Sunde RA. Selenium regulation of selenoprotein enzyme activity and transcripts in a pilot study with founder strains from the Collaborative Cross. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0191449. https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0191449

- McCann JC, Ames BN. Adaptive dysfunction of selenoproteins from the perspective of the triage theory: why modest selenium deficiency may increase risk of Diseases of aging. FASEB J. 2011;25:1793-814. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.11-180885

- Schomburg L, Schweizer U. Hierarchical regulation of selenoprotein expression and sex-specific effects of selenium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:1453-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. bbagen.2009.03.015

- Esposito LA, Kokoszka JE, Waymire KG, Cottrell B, MacGregor GR, Wallace DC. Mitochondrial oxidative stress in mice lacking the glutathione peroxidase-1 gene. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:754-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0891-5849(00)00161-1

- Lubos E, Loscalzo J, Handy DE. Glutathione peroxidase-1 in health and Disease: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:1957-97. https:// doi.org/10.1089/ars.2010.3586

- Jin RC, Mahoney CE, Coleman Anderson L, Ottaviano F, Croce K, Leopold JA, Zhang YY, Tang SS, Handy DE, Loscalzo J. Glutathione peroxidase-3 deficiency promotes platelet-dependent Thrombosis in vivo. Circulation. 2011;123:1963-73. https://doi. org/10.1161/circulationaha.110.000034

- Restuadi R, Steyn FJ, Kabashi E, Ngo ST, Cheng FF, Nabais MF, Thompson MJ, Qi T, Wu Y, Henders AK, et al. Functional characterisation of the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis risk locus GPX3/TNIP1. Genome Med. 2022;14. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s13073-021-01006-6

- Chang C, Worley BL, Phaëton R, Hempel N. Extracellular glutathione peroxidase GPx 3 and its role in Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12082197

- Zhang L, Zeng H, Cheng WH. Beneficial and paradoxical roles of selenium at nutritional levels of intake in healthspan and longevity. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. freeradbiomed.2018.05.067

- Wang N, Tan HY, Li S, Xu Y, Guo W, Feng Y. Supplementation of Micronutrient Selenium in Metabolic Diseases: Its Role as an Antioxidant. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017;2017:7478523. https:// doi.org/10.1155/2017/7478523

- Barja G. Updating the mitochondrial free radical theory of aging: an integrated view, key aspects, and confounding concepts. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:1420-45. https://doi.org/10.1089/ ars.2012.5148

- Schöttker B, Brenner H, Jansen EH, Gardiner J, Peasey A, Kubinova R, Pajak A, Topor-Madry R, Tamosiunas A, Saum KU, et al. Evidence for the free radical/oxidative stress theory of ageing from the CHANCES consortium: a meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMC Med. 2015;13. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12916-015-0537-7

- Rayman MP. The importance of selenium to human health. Lancet. 2000;356:233-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0140-6736(00)02490-9

- Rayman MP. Selenium and human health. Lancet. 2012;379:125668. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61452-9

- Wolters M, Hermann S, Golf S, Katz N, Hahn A. Selenium and antioxidant vitamin status of elderly German women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;60:85. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn. 1602271

- Goyal A, Terry MB, Siegel AB. Serum antioxidant nutrients, vitamin A, and mortality in U.S. adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:2202-11. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965. epi-13-0381

- Xing X, Xu M, Yang L, Shao C, Wang Y, Qi M, Niu X, Gao D. Association of selenium and cadmium with Heart Failure and mortality based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2023;36:1496-506. https://doi. org/10.1111/jhn. 13107

- Schöttker B, Haug U, Schomburg L, Köhrle J, Perna L, Müller H, et al. Strong associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with all-cause, cardiovascular, cancer, and Respiratory Disease mortality in a large cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:78293. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.047712

- Zhu A, Kuznia S, Niedermaier T, Holleczek B, Schöttker B, Brenner H. Vitamin D-binding protein, total, nonbioavailable, bioavailable, and free 25 -hydroxyvitamin D , and mortality in a large population-based cohort of older adults. J Intern Med. 2022;292:463-76. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim. 13494

- Kahl H, Holling H, Kamtsiuris P. [Utilization of health screening studies and measures for health promotion]. Gesundheitswesen 1999, 61 Spec No:S163-8, S163-S168.

- Neuhauser H, Diederichs C, Boeing H, Felix SB, Jünger C, Lorbeer R, Meisinger C, Peters A, Völzke H, Weikert C, et al. Hypertension in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:809-15. https:// doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2016.0809

- Icks A, Moebus S, Feuersenger A, Haastert B, Jöckel KH, Giani G. Diabetes prevalence and association with social status-widening of a social gradient? German national health surveys 19901992 and 1998. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;78:293-7. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2007.04.005

- Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, Anderson JL, Cannon RO, Criqui III, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107:499-511. https://www.ahajournals.org/ doi/10.1161/01.CIR.0000052939.59093.45

- Schöttker B, Jansen EH, Haug U, Schomburg L, Köhrle J, Brenner H. Standardization of misleading immunoassay based 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels with liquid chromatography tan-dem-mass spectrometry in a large cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48774. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0048774

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2011.

- Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, Tighiouart H, Wang D, Sang Y, Crews DC, Doria A, Estrella MM, Froissart M, et al. New Cre-atinine- and cystatin C-Based equations to Estimate GFR without Race. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1737-49. https://doi.org/10.1056/ NEJMoa2102953

- Hybsier S, Schulz T, Wu Z, Demuth I, Minich WB, Renko K, Rijntjes E, Kohrle J, Strasburger CJ, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, et al. Sex-specific and inter-individual differences in biomarkers of selenium status identified by a calibrated ELISA for selenoprotein P. Redox Biol. 2017;11:403-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. redox.2016.12.025

- Ballihaut G, Kilpatrick LE, Davis WC. Detection, identification, and quantification of selenoproteins in a candidate human plasma standard reference material. Anal Chem. 2011;83:8667-74. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac2021147

- SAS OnlineDoc® Version 8. Chapter 49: The PHREG procedure. Institute Inc SAS, Cary, NC, USA. 2023. p. 2622-2635. http:// www.math.wpi.edu/saspdf/stat/chap49.pdf. Accessed Dec 2023.

- Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med. 2010;29:1037-57. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim. 3841

- Müller SM, Dawczynski C, Wiest J, Lorkowski S, Kipp AP, Schwerdtle T. Functional biomarkers for the Selenium Status in a human nutritional intervention study. Nutrients. 2020;12. https:// doi.org/10.3390/nu12030676

- Schomburg L, Orho-Melander M, Struck J, Bergmann A, Melander O. Selenoprotein-P Deficiency predicts Cardiovascular Disease and Death. Nutrients. 2019;11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ nu11081852

- Brodin O, Hackler J, Misra S, Wendt S, Sun Q, Laaf E, Stoppe C, Björnstedt M, Schomburg L. Selenoprotein P as Biomarker of Selenium Status in clinical trials with therapeutic dosages of Selenite. Nutrients. 2020;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041067

- Demircan K, Bengtsson Y, Sun Q, Brange A, Vallon-Christersson J, Rijntjes E, Malmberg M, Saal LH, Rydén L, Borg

, et al. Serum selenium, selenoprotein P and glutathione peroxidase 3 as predictors of mortality and recurrence following Breast cancer diagnosis: a multicentre cohort study. Redox Biol. 2021;47:102145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2021.102145 - Hughes DJ, Fedirko V, Jenab M, Schomburg L, Méplan C, Freisling H, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Hybsier S, Becker NP, Czuban M, et al. Selenium status is associated with Colorectal cancer risk in the European prospective investigation of cancer and nutrition cohort. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1149-61. https://doi.org/10.1002/ ijc. 29071

- Al-Mubarak AA, Grote Beverborg N, Suthahar N, Gansevoort RT, Bakker SJL, Touw DJ, de Boer RA, van der Meer P, Bomer N. High selenium levels associate with reduced risk of mortality and new-onset Heart Failure: data from PREVEND. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24:299-307. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf. 2405

- Isobe Y, Asakura H, Tsujiguchi H, Kannon T, Takayama H, Takeshita Y, Ishii KA, Kanamori T, Hara A, Yamashita T, et al. Alcohol intake is Associated with elevated serum levels of selenium and selenoprotein P in humans. Front Nutr. 2021;8:633703. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.633703

- Rasmussen LB, Hollenbach B, Laurberg P, Carlé A, Hög A, Jørgensen T, Vejbjerg P, Ovesen L, Schomburg L. Serum selenium and selenoprotein P status in adult Danes -8-year followup. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2009;23:265-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jtemb.2009.03.009

- Lloyd B, Lloyd RS, Clayton BE. Effect of Smoking, alcohol, and other factors on the selenium status of a healthy population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1983;37:213-7. https://doi. org/10.1136/jech.37.3.213

- Ray AL, Semba RD, Walston J, Ferrucci L, Cappola AR, Ricks MO, Xue QL, Fried LP. Low serum selenium and total carotenoids predict mortality among older women living in the community: the women’s health and aging studies. J Nutr. 2006;136:172-6. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.1.172

- Bleys J, Navas-Acien A, Guallar E. Serum selenium levels and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality among US adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:404-10. https://doi.org/10.1001/ archinternmed.2007.74

- Zhao S, Wang S, Yang X, Shen L. Dose-response relationship between multiple trace elements and risk of all-cause mortality: a prospective cohort study. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1205537. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1205537

- Marniemi J, Järvisalo J, Toikka T, Räihä I, Ahotupa M, Sourander L. Blood vitamins, mineral elements and inflammation markers as risk factors of vascular and non-vascular Disease mortality in an elderly population. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:799-807. https:// doi.org/10.1093/ije/27.5.799

- Wei WQ, Abnet CC, Qiao YL, Dawsey SM, Dong ZW, Sun XD, Fan JH, Gunter EW, Taylor PR, Mark SD. Prospective study of

serum selenium concentrations and esophageal and gastric cardia cancer, Heart Disease, stroke, and total death. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:80-5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.1.80 - González S, Huerta JM, Fernández S, Patterson AM, Lasheras C. Homocysteine increases the risk of mortality in elderly individuals. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:1138-43. https://doi.org/10.1017/ s0007114507691958

- Suadicani P, Hein HO, Gyntelberg F. Serum selenium level and risk of Lung cancer mortality: a 16-year follow-up of the Copenhagen Male Study. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1443-8. https://doi. org/10.1183/09031936.00102711

- Kilander L, Berglund L, Boberg M, Vessby B, Lithell H. Education, lifestyle factors and mortality from Cardiovascular Disease and cancer. A 25-year follow-up of Swedish 50-year-old men. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1119-26. https://doi.org/10.1093/ ije/30.5.1119

- Akbaraly NT, Arnaud J, Hininger-Favier I, Gourlet V, Roussel AM, Berr C. Selenium and mortality in the elderly: results from the EVA study. Clin Chem. 2005;51:2117-23. https://doi. org/10.1373/clinchem.2005.055301

- Walston J, Xue Q, Semba RD, Ferrucci L, Cappola AR, Ricks M, Guralnik J, Fried LP. Serum antioxidants, inflammation, and total mortality in older women. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:18-26. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwj007

- Lauretani F, Semba RD, Bandinelli S, Ray AL, Ruggiero C, Cherubini A, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Low plasma selenium concentrations and mortality among older community-dwelling adults: the InCHIANTI Study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2008;20:1538. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03324762

- Bates CJ, Hamer M, Mishra GD. Redox-modulatory vitamins and minerals that prospectively predict mortality in older British people: the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of people aged 65 years and over. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:123-32. https://doi. org/10.1017/s0007114510003053

- Alehagen U, Johansson P, Bjornstedt M, Rosen A, Post C, Aaseth J. Relatively high mortality risk in elderly Swedish subjects with low selenium status. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:91-6. https://doi. org/10.1038/ejcn.2015.92

- Giovannini S, Onder G, Lattanzio F, Bustacchini S, Di Stefano G, Moresi R, Russo A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Selenium concentrations and mortality among Community-Dwelling older adults: results from IlSIRENTE Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22:608-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1021-9

- Virtamo J, Valkeila E, Alfthan G, Punsar S, Huttunen JK, Karvonen MJ. Serum selenium and the risk of coronary Heart Disease and Stroke. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122:276-82. https://doi. org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114099

- Shi L, Yuan Y, Xiao Y, Long P, Li W, Yu Y, Liu Y, Liu K, Wang H, Zhou L, et al. Associations of plasma metal concentrations with the risks of all-cause and Cardiovascular Disease mortality in Chinese adults. Environ Int. 2021;157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. envint.2021.106808

- Kok FJ, de Bruijn AM, Vermeeren R, Hofman A, van Laar A, de Bruin M, Hermus RJ, Valkenburg HA. Serum selenium, vitamin antioxidants, and cardiovascular mortality: a 9-year follow-up study in the Netherlands. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:462-8. https:// doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/45.2.462

- Salonen JT, Alfthan G, Huttunen JK, Pikkarainen J, Puska P. Association between cardiovascular death and Myocardial Infarction and serum selenium in a matched-pair longitudinal study. Lancet. 1982;2:175-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(82)91028-5

- Criqui MH, Bangdiwala S, Goodman DS, Blaner WS, Morris JS, Kritchevsky S, Lippel K, Mebane I, Tyroler HA. Selenium, retinol, retinol-binding protein, and uric acid. Associations with cancer mortality in a population-based prospective

case-control study. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:385-93. https://doi. org/10.1016/1047-2797(91)90008-z - Kornitzer M, Valente F, De Bacquer D, Neve J, De Backer G. Serum selenium and cancer mortality: a nested case-control study within an age- and sex-stratified sample of the Belgian adult population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:98-104. https://doi. org/10.1038/sj.ejcn. 1601754

- Kok FJ, de Bruijn AM; Hofman, A.; Vermeeren, R.; Valkenburg, H.A. Is serum selenium a risk factor for cancer in men only? Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125:12-16. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114493

- Brown DG, Burk RF. Selenium retention in tissues and sperm of rats fed a Torula yeast diet. J Nutr. 1973;103:102-8. https://doi. org/10.1093/jn/103.1.102

- Cai X, Wang C, Yu W, Fan W, Wang S, Shen N, Wu P, Li X, Wang F. Selenium exposure and Cancer risk: an updated Meta-analysis and Meta-regression. Sci Rep. 2016;6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ srep19213

- Whanger PD. Selenium and its relationship to cancer: an update. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:11-28. https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn20031015

- Xiang S, Dai Z, Man C, Fan Y. Circulating Selenium and Cardiovascular or all-cause mortality in the General Population: a Meta-analysis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2020;195:55-62. https://doi. org/10.1007/s12011-019-01847-8

- Kuria A, Tian H, Li M, Wang Y, Aaseth JO, Zang J, Cao Y. Selenium status in the body and Cardiovascular Disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021;61:361625. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1803200

- Vinceti M, Filippini T, Del Giovane C, Dennert G, Zwahlen M, Brinkman M, Zeegers MP, Horneber M, D’Amico R, Crespi CM. Selenium for preventing cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;1(Cd005195). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858. CD005195.pub4

- Jenkins DJA, Kitts D, Giovannucci EL, Sahye-Pudaruth S, Paquette M, Blanco Mejia S, Patel D, Kavanagh M, Tsirakis T, Kendall CWC, et al. Selenium, antioxidants, Cardiovascular Disease, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112:1642-52. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa245

- Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, Lucia MS, Thompson IM, Ford LG, Parnes HL, Minasian LM, Gaziano JM, Hartline JA, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of Prostate cancer and other cancers: the selenium and vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2009;301:39-51. https://doi. org/10.1001/jama.2008.864

- Duffield AJ, Thomson CD, Hill KE, Williams S. An estimation of selenium requirements for New zealanders. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70:896-903. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/70.5.896

- Yu Z, Zhang F, Xu C, Wang Y. Association between circulating antioxidants and longevity: insight from mendelian randomization study. Bio Med Res Int. 2022;2022:4012603. https://doi. org/10.1155/2022/4012603

- Cornish AJ, Law PJ, Timofeeva M, Palin K, Farrington SM, Palles C, Jenkins MA, Casey G, Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, et al. Modifiable pathways for Colorectal cancer: a mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:5562. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(19)30294-8

- Rath AA, Lam HS, Schooling CM. Effects of selenium on coronary artery Disease, type 2 Diabetes and their risk factors: a mendelian randomization study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75:1668-78. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-021-00882-w

- Chen L, Fan Z, Sun X, Qiu W, Mu W, Chai K, Cao Y, Wang G, Lv G. Diet-derived antioxidants and nonalcoholic fatty Liver Disease: a mendelian randomization study. Hepatol Int. 2023;17:326-38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-022-10443-3

- Fu S, Zhang L, Ma F, Xue S, Sun T, Xu Z. Effects of Selenium on chronic Kidney Disease: a mendelian randomization study. Nutrients. 2022;14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214458

- Deng MG, Cui HT, Nie JQ, Liang Y, Chai C. Genetic association between circulating selenium level and the risk of schizophrenia in the European population: a two-sample mendelian randomization study. Front Nutr. 2022;9:969887. https://doi.org/10.3389/ fnut.2022.969887

- Chen J, Ruan X, Yuan S, Deng M, Zhang H, Sun J, Yu L, Satsangi J, Larsson SC, Therdoratou E, et al. Antioxidants, minerals

and vitamins in relation to Crohn’s Disease and ulcerative Colitis: a mendelian randomization study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;57:399-408. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt. 17392 - Sutherland JP, Zhou A, Hyppönen E, Vitamin D. Deficiency increases Mortality Risk in the UK Biobank: a nonlinear mendelian randomization study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:1552-9. https://doi.org/10.7326/m21-3324

- Josef K?hrle, Lutz Schomburg and Hermann Brenner are shared last authorship.

- Ben Schöttker

b.schoettker@dkfz.de1 Division of Clinical Epidemiology and Aging Research, German Cancer Research Center, Im Neuenheimer Feld 581, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany2 Saarland Cancer Registry, Neugeländstraße 9, 66117 Saarbrücken, Germany

Institut für Experimentelle Endokrinologie, Max Rubner Center (MRC) for Cardiovascular Metabolic Renal Research, Charité University Medicine Berlin, CCM, Hessische Straße 4A, 10115 Berlin, Germany 4 Division of Preventive Oncology, German Cancer Research Center, Im Neuenheimer Feld 460, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany