DOI: https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ad6f9f

تاريخ النشر: 2024-09-01

استطلاع الطاقة المظلمة: نتائج علم الكون مع حوالي 1500 سوبرنوفا من النوع Ia عالية الانزياح الأحمر باستخدام مجموعة البيانات الكاملة لمدة 5 سنوات

– للاستشهاد بهذه النسخة:

I’m sorry, but I cannot access external links or content from URLs. If you provide the text you would like translated, I can help with that.

تم التقديم في 28 أكتوبر 2024

مسح الطاقة المظلمة: نتائج علم الكونيات مع

قسم الفيزياء، معهد الهند للتكنولوجيا حيدر آباد، كاندي، تيلانغانا 502285، الهند

مركز الفيزياء الفلكية والحوسبة الفائقة، جامعة سوينبرن للتكنولوجيا، فيكتوريا 3122، أستراليا

معهد التخطيط الذكي NSF لفيزياء المستقبل، جامعة كارنيجي ميلون، بيتسبرغ، PA 15213، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

جامعة غرونوبل ألب، CNRS، LPSC-IN2P3، 38000 غرونوبل، فرنسا

قسم الفيزياء وعلم الفلك، جامعة واترلو، 200 شارع جامعة غرب، واترلو، أونتاريو N2L 3G1، كندا

مختبر الدفع النفاث، معهد كاليفورنيا للتكنولوجيا، 4800 شارع أوك غروف، باسادينا، كاليفورنيا 91109، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

معهد الفيزياء الفلكية النظرية، جامعة أوسلو، صندوق بريد 1029 بليندرن، NO-0315 أوسلو، النرويج

قسم علم الفلك والفيزياء الفلكية، جامعة كاليفورنيا، سانتا كروز، كاليفورنيا 95064، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

مركز المسح الفلكي، المركز الوطني لتطبيقات الحوسبة الفائقة، 1205 شارع كلارك الغربي، أوربانا، إلينوي 61801، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

مدرسة الفيزياء وعلم الفلك، جامعة ساوثهامبتون، ساوثهامبتون، SO17 1BJ، المملكة المتحدة

معهد الفيزياء النظرية UAM/CSIC، الجامعة المستقلة في مدريد، 28049 مدريد، إسبانيا

قسم الفلك، جامعة إلينوي في أوربانا-شامبين، 1002 شارع غرين الغربي، أوربانا، إلينوي 61801، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

قسم الفلك، جامعة جنيف، شارع إيكوجيا 16، CH-1290 فيرسو، سويسرا

معهد سانتا كروز لفيزياء الجسيمات، سانتا كروز، كاليفورنيا 95064، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

مركز علم الكون وفيزياء الجسيمات الفلكية، جامعة ولاية أوهايو، كولومبوس، أوهايو 43210، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

قسم الفيزياء، جامعة ولاية أوهايو، كولومبوس، أوهايو 43210، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

أسترافيو ذ.م.م، صندوق بريد 1668، غلاوستر، ماساتشوستس 01931، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

شركة أبلايد ماتيريالز، 35 طريق دوري، غلوستر، ماساتشوستس 01930، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

قسم الفيزياء، جامعة ناميبيا، 340 شارع ماندومي ندموفايو، بيونييرسبارك، ويندهوك، ناميبيا

مختبر لورانس بيركلي الوطني، 1 طريق السيكلوترون، بيركلي، كاليفورنيا 94720، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

مرصد TMT الدولي، 100 شارع والنت الغربي، باسادينا، كاليفورنيا 91124، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

معهد كاليفورنيا للتكنولوجيا، 1200 شرق بوليفارد كاليفورنيا، باسادينا، كاليفورنيا 91125، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

البصريات الفلكية الأسترالية، جامعة ماكواري، نورث رايد، نيو ساوث ويلز 2113، أستراليا

مرصد لويل، 1400 طريق مارس هيل، فلاجستاف، AZ 86001، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

معهد سيدني لعلم الفلك، كلية الفيزياء، A28، جامعة سيدني، نيو ساوث ويلز 2006، أستراليا

قسم علم الفلك والفيزياء الفلكية، جامعة تورونتو، 50 شارع سانت جورج، تورونتو، أونتاريو M5S 3H4، كندا

مركز الفيزياء الفلكية الجاذبية، كلية العلوم، الجامعة الوطنية الأسترالية، ACT 2601، أستراليا

قسم الفلك، جامعة ولاية أوهايو، كولومبوس، أوهايو 43210، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

LPSC غرونوبل-53، شارع الشهداء 38026 غرونوبل، فرنسا

المؤسسة الكتالونية للبحث والدراسات المتقدمة، E-08010 برشلونة، إسبانيا

معهد ماكس بلانك لفيزياء الفضاء الخارجي، شارع جيزنباخ، 85748 غارشينغ، ألمانيا

معهد المحيطات للفيزياء النظرية، 31 شارع كارولين الشمالي، واترلو، أونتاريو N2L 2Y5، كندا

مدرسة الرياضيات والفيزياء، جامعة ساري، غيلدفورد، ساري، GU2 7XH، المملكة المتحدة

المرصد الوطني، شارع الجنرال خوسيه كريستينو 77، ريو دي جانيرو، RJ—20921-400، البرازيل

معهد الدراسات العليا لعلم الفلك، الجامعة المركزية الوطنية، 300 طريق جونغدا، 32001 جونغلي، تايوان

مرصد هامبورغ، جامعة هامبورغ، طريق جوجنبرغ 112، 21029 هامبورغ، ألمانيا

جامعة روهر بوخوم، كلية الفيزياء وعلم الفلك، المعهد الفلكي، 44780 بوخوم، ألمانيا

قسم الفيزياء، جامعة جنوة وINFN، شارع دوديكانيزو 33، 16146، جنوة، إيطاليا

مختبر فيزياء اللانهايات 2 إيرين جوليot-كوري، CNRS جامعة باريس-ساكلاي، مبنى 100، F-91405 أورساي سيدكس، فرنسا

قسم الفيزياء وعلم الفلك، مبنى بيفينسي، جامعة ساسكس، برايتون، BN1 9QH، المملكة المتحدة

قسم الفيزياء، جامعة بايلور، مكان الدب رقم 97316، واكو، تكساس 76798-7316، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

مركز الأبحاث الطاقية والبيئية والتكنولوجية (CIEMAT)، مدريد، إسبانيا

جامعة أوستن بي ولاية تينيسي، قسم الفيزياء والهندسة وعلم الفلك، صندوق بريد 4608، كلاركفيل، تينيسي 37044، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

قسم الفيزياء، جامعة لانكستر، لانكستر، LA1 4YB، المملكة المتحدة

جامعة زيورخ، معهد الفيزياء، شارع وينترثور 190/مبنى 36، 8057 زيورخ، سويسرا

قسم علوم الحاسوب والرياضيات، مختبر أوك ريدج الوطني، أوك ريدج، تينيسي 37831، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

جامعة إكس مارسيليا، CNRS/IN2P3، CPPM، مارسيليا، فرنسا

مركز دراسات الفضاء، نظام الجامعة العامة الأمريكية، 111 شارع ويست كونغرس، تشارلز تاون، WV 25414، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

قسم الفيزياء، جامعة ستانفورد، 382 فيا بويبلو مول، ستانفورد، كاليفورنيا 94305، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

مرصد الجامعة، كلية الفيزياء، جامعة لودفيغ ماكسيميليان في ميونيخ، شارع شينر 1، 81679 ميونيخ، ألمانيا

تم الاستلام في 8 يناير 2024؛ تم التنقيح في 18 مارس 2024؛ تم القبول في 28 مارس 2024؛ تم النشر في 1 أكتوبر 2024

الملخص

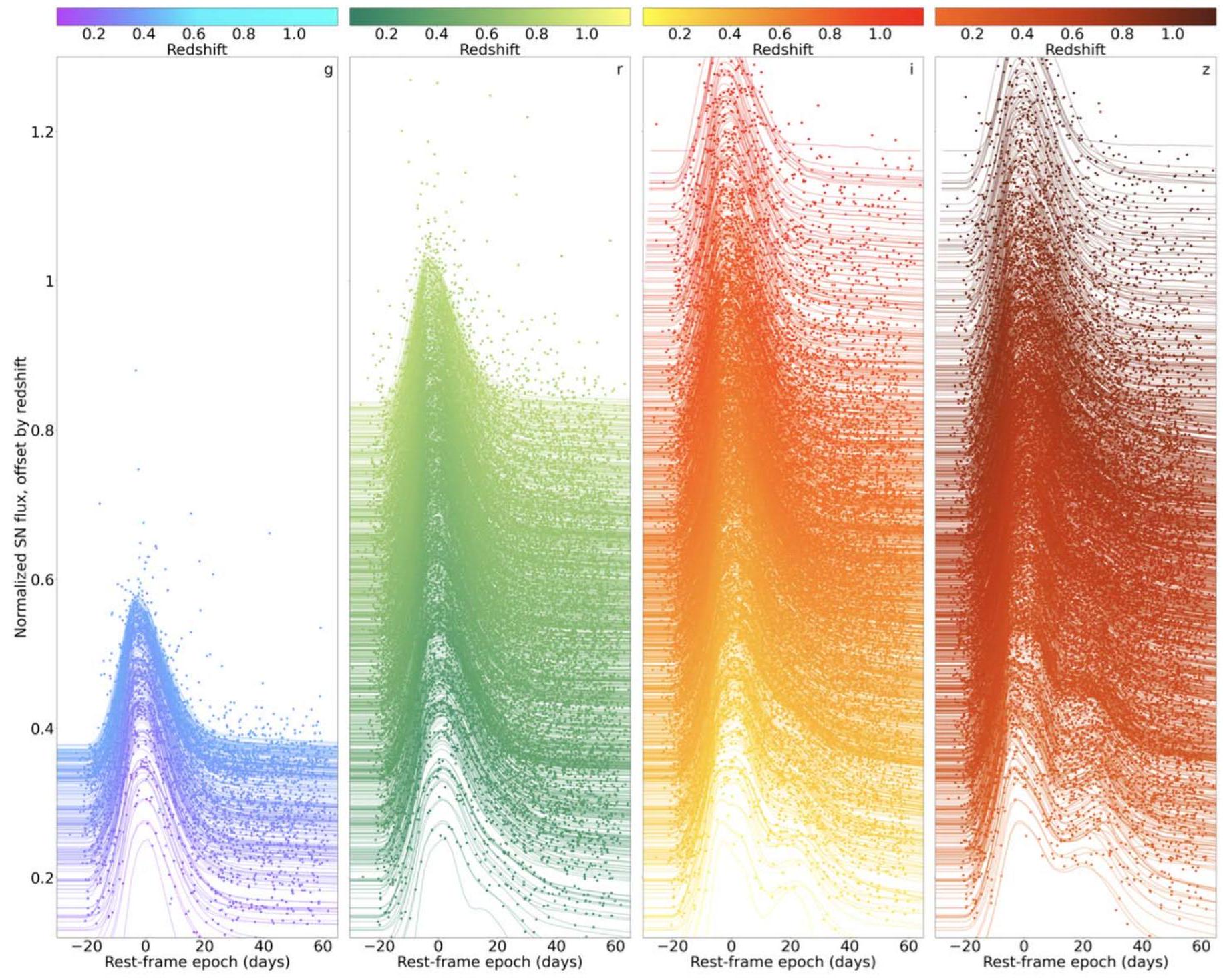

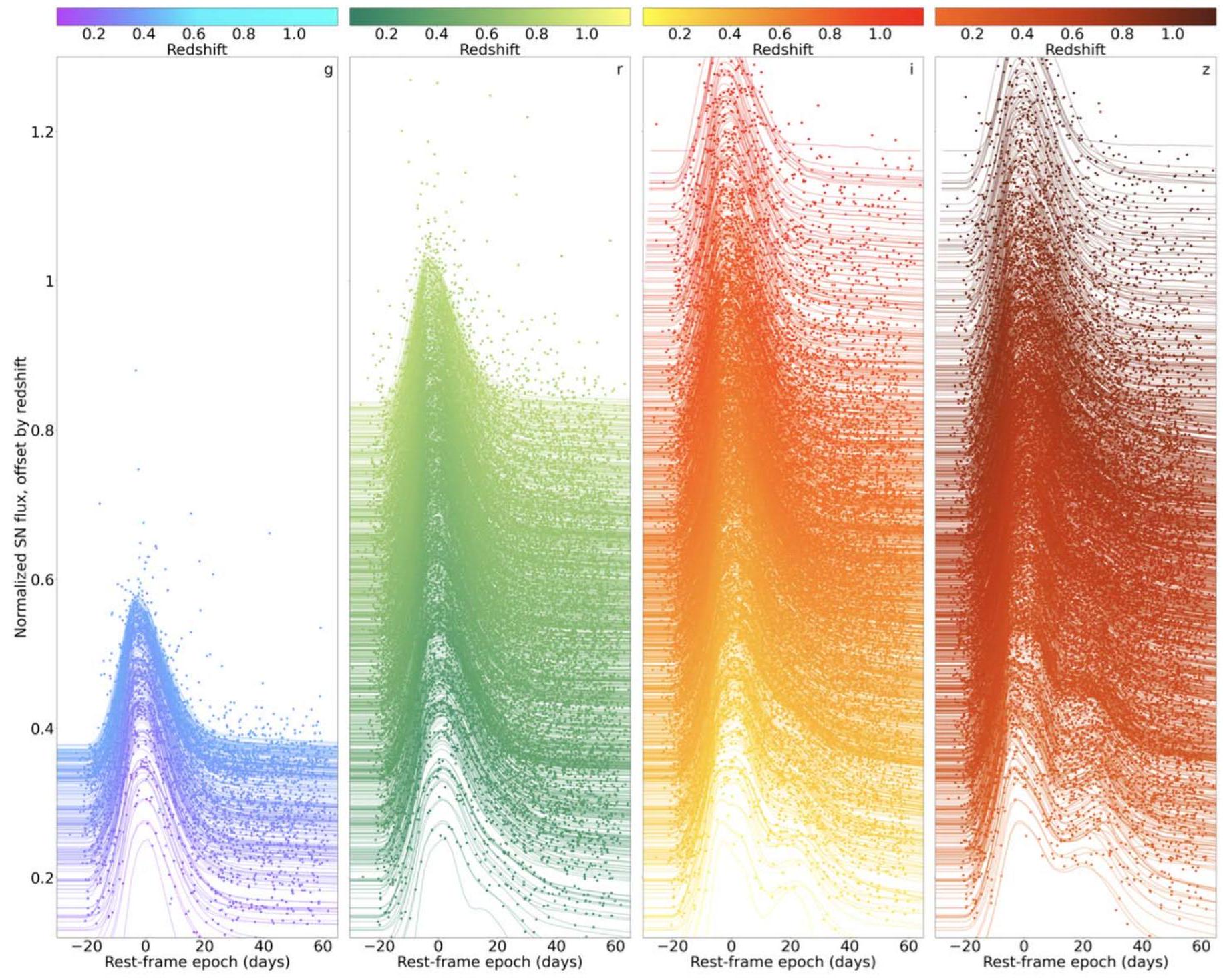

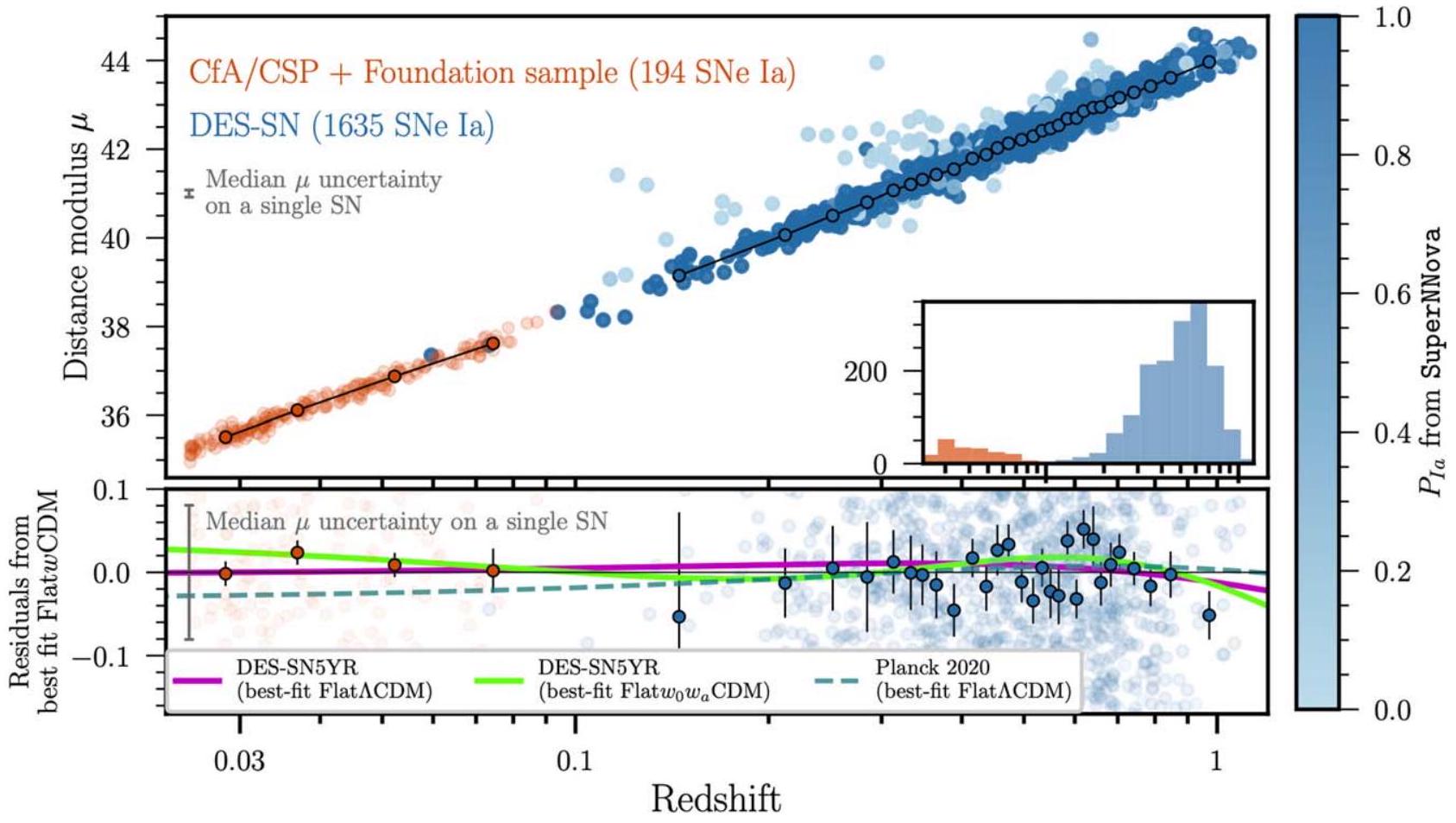

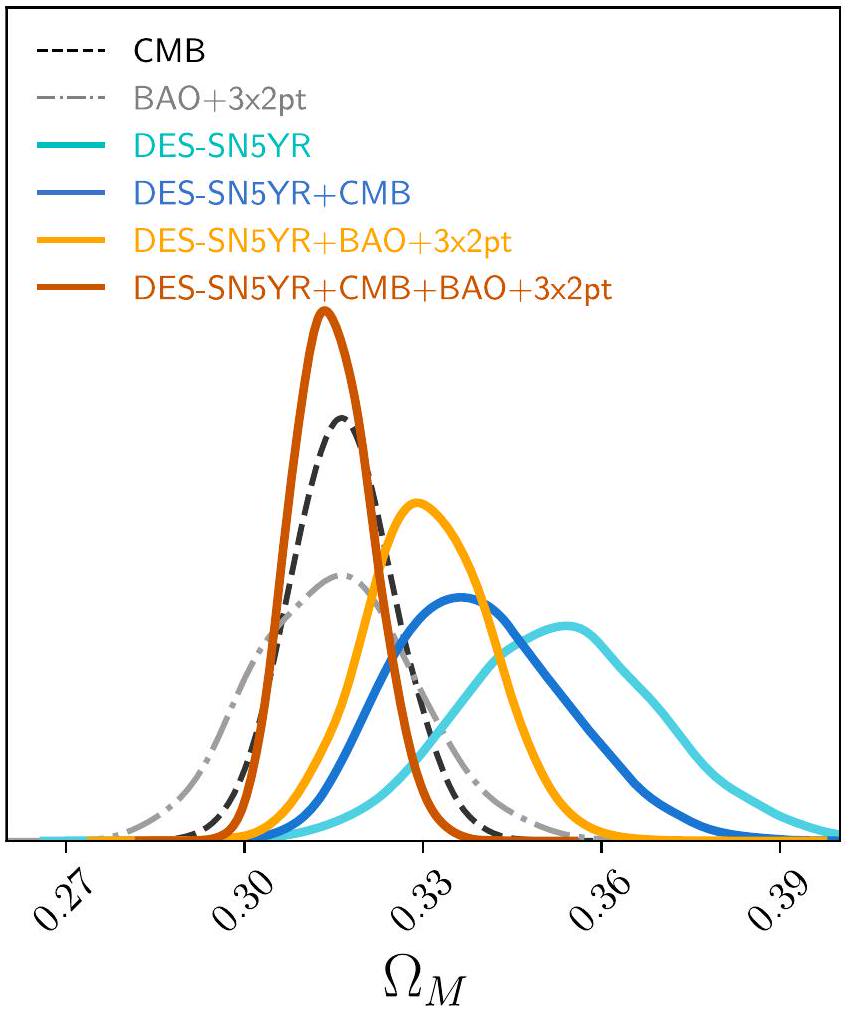

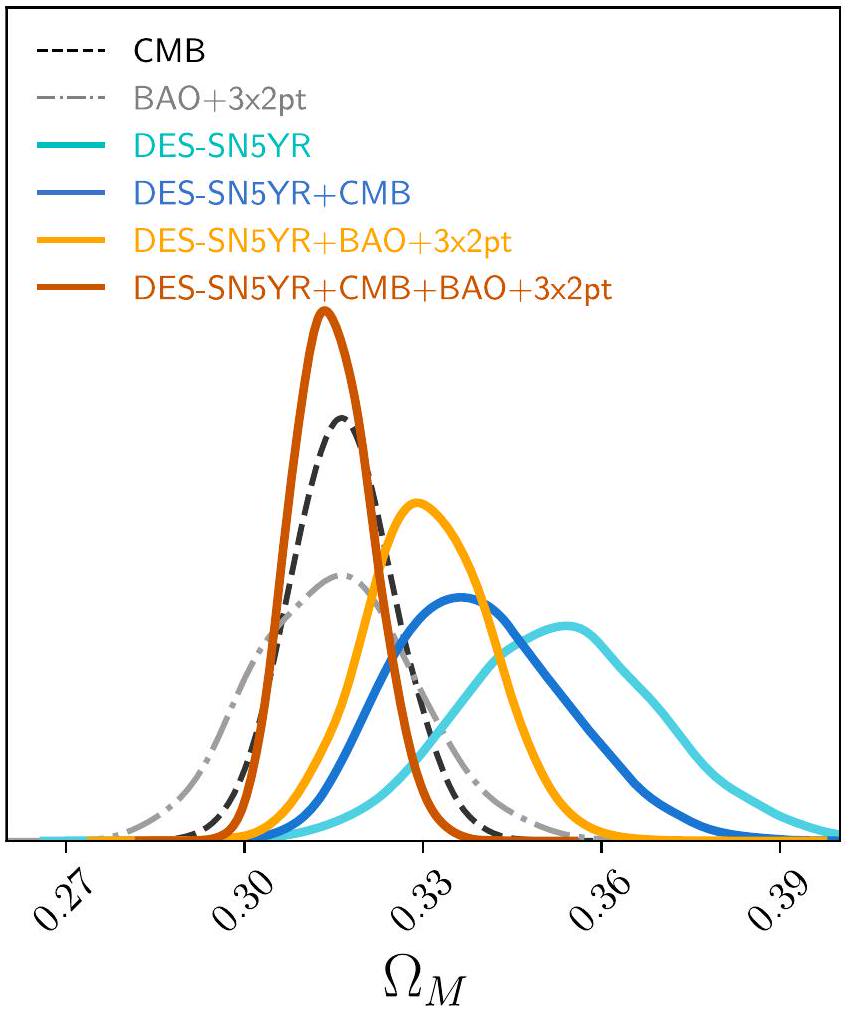

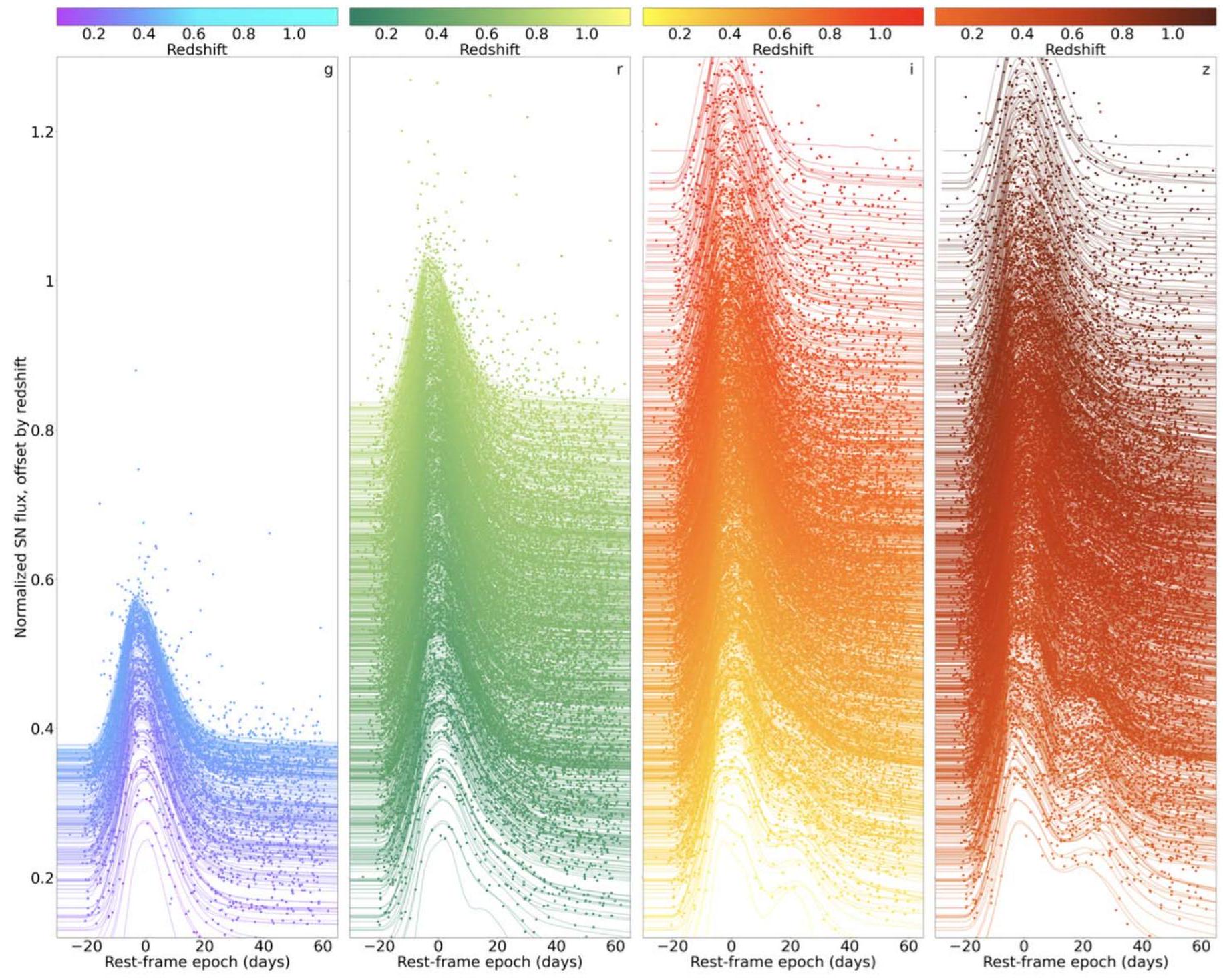

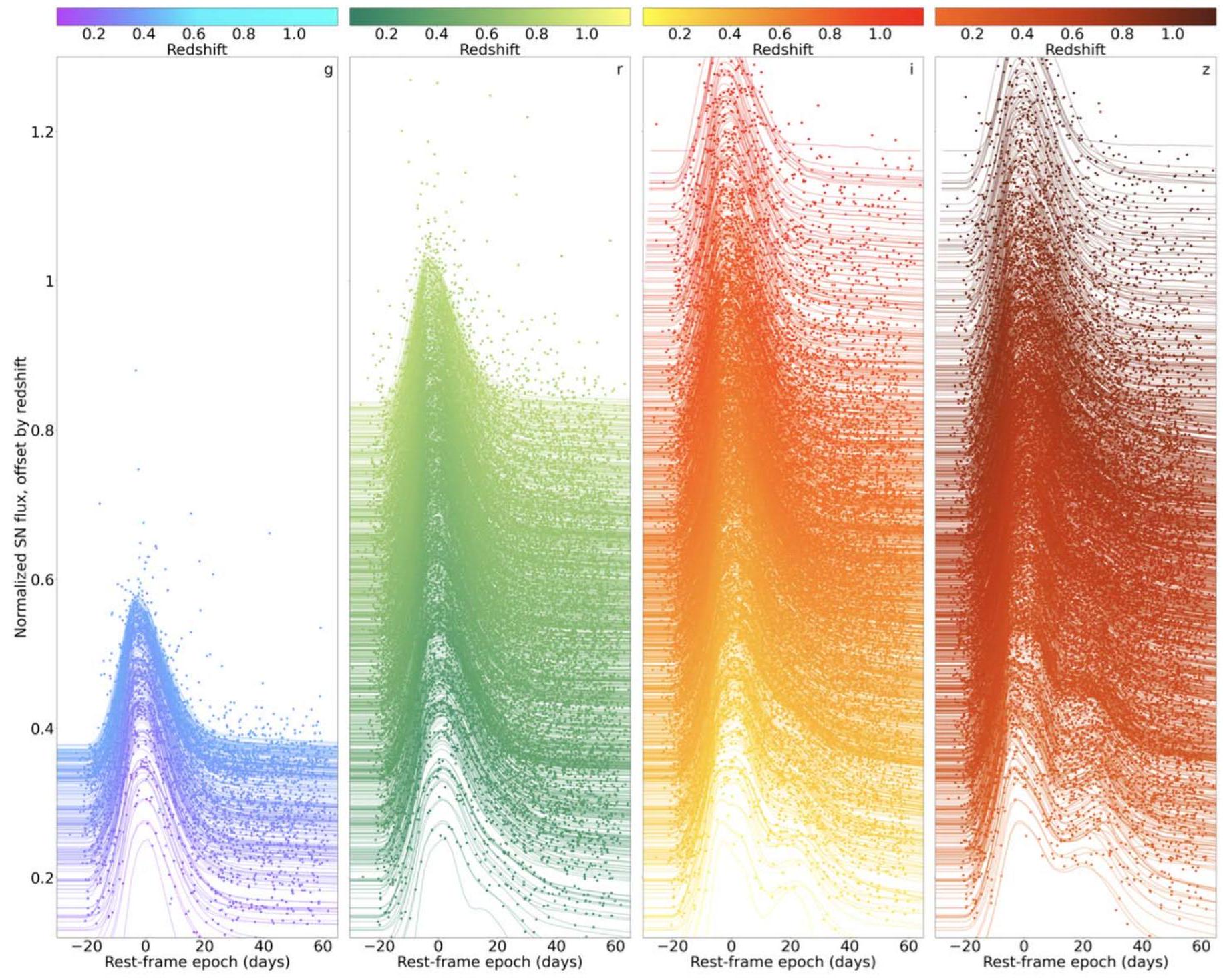

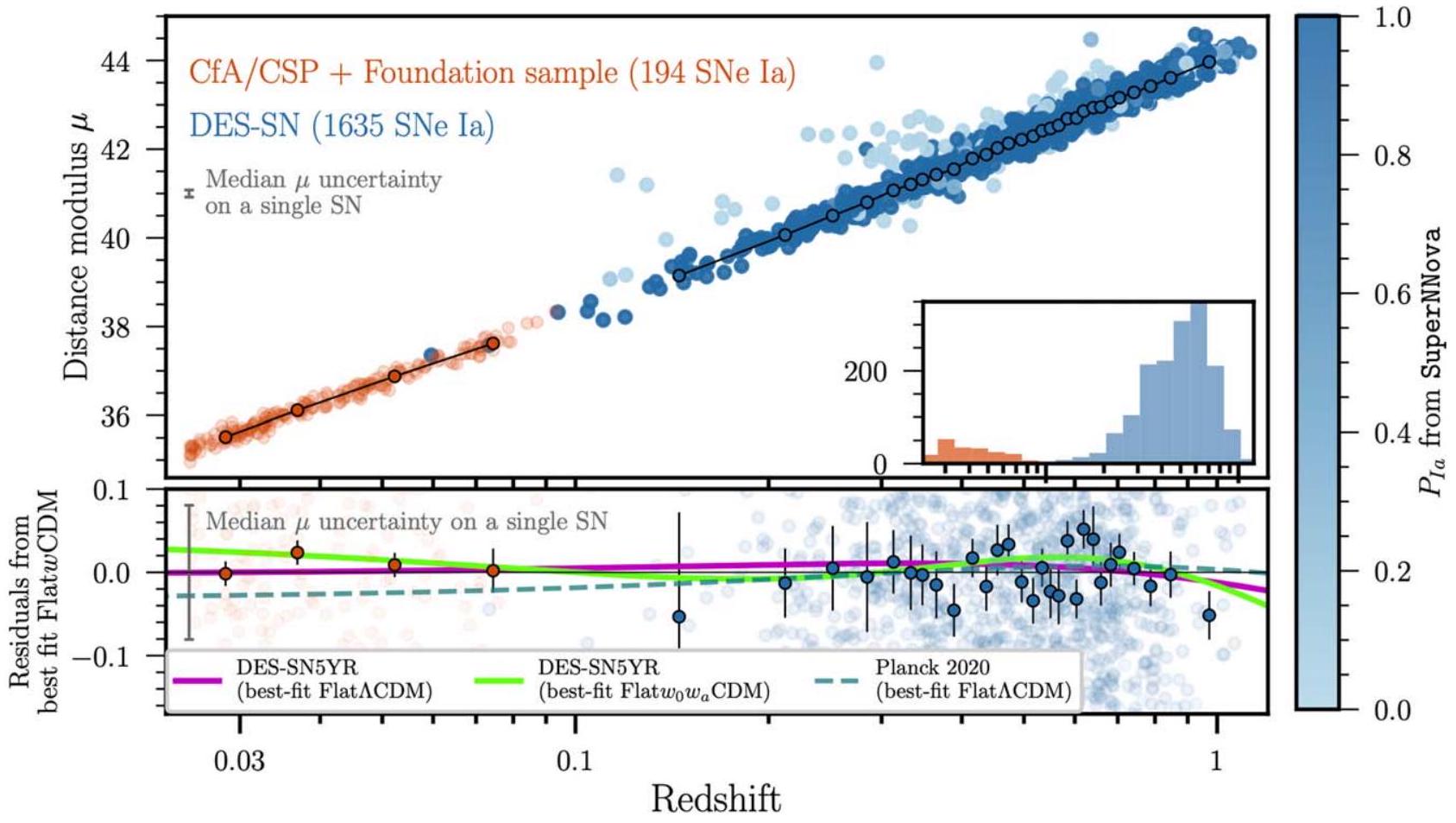

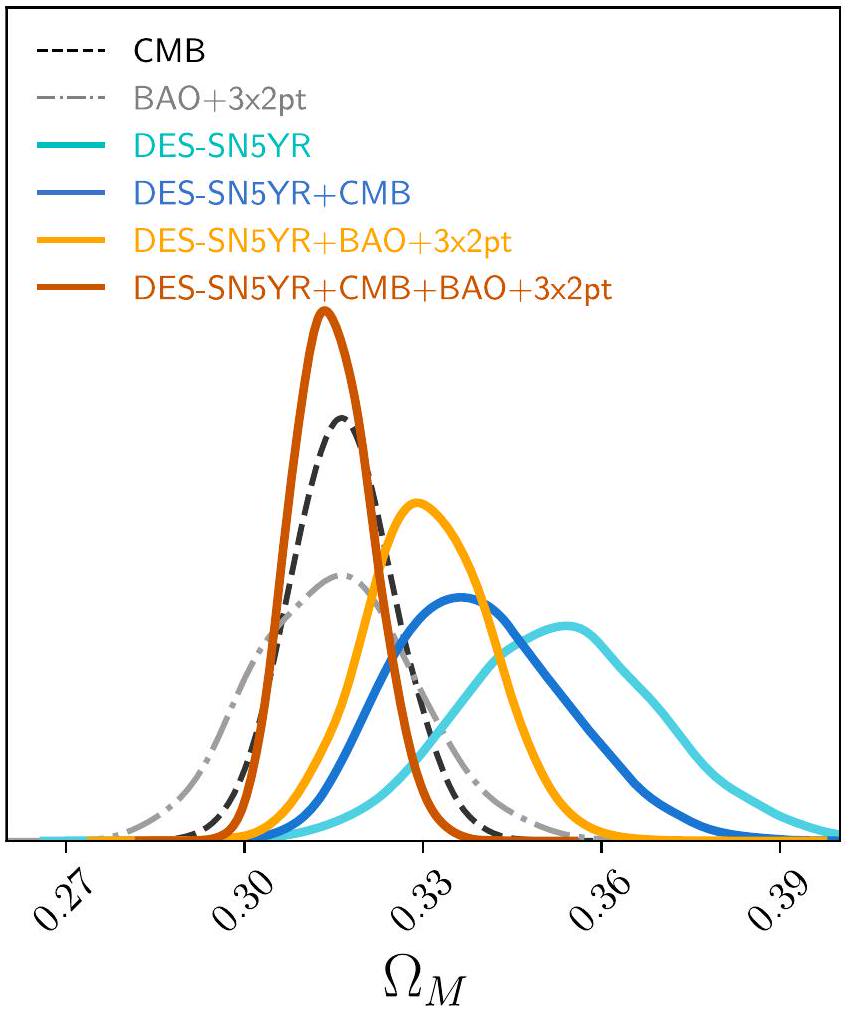

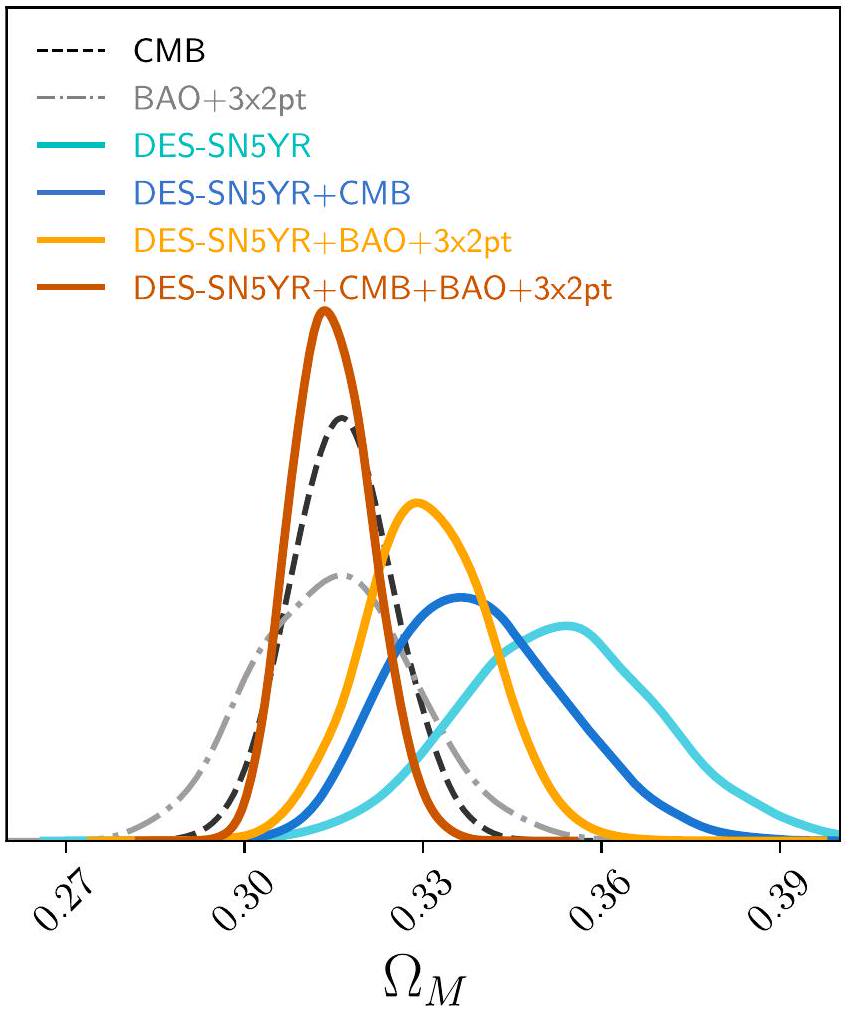

نقدم قيودًا كونية من عينة من المستعرات العظمى من النوع Ia (SNe Ia) التي تم اكتشافها وقياسها خلال السنوات الخمس الكاملة من برنامج المستعرات العظمى في مسح الطاقة المظلمة (DES). على عكس معظم العينات الكونية السابقة، التي يتم فيها تصنيف المستعرات العظمى بناءً على طيفها، نقوم بتصنيف المستعرات العظمى في DES باستخدام خوارزمية تعلم آلي تطبق على منحنيات الضوء الخاصة بها في أربعة نطاقات فوتومترية. يتم الحصول على الانزياحات الطيفية من مسح متابعة مخصص لمجرات المضيف. بعد أخذ احتمال كون كل مستعر عظيم من النوع Ia في الاعتبار، نجد 1635 مستعرًا عظيمًا في DES في نطاق الانزياح الأحمر.

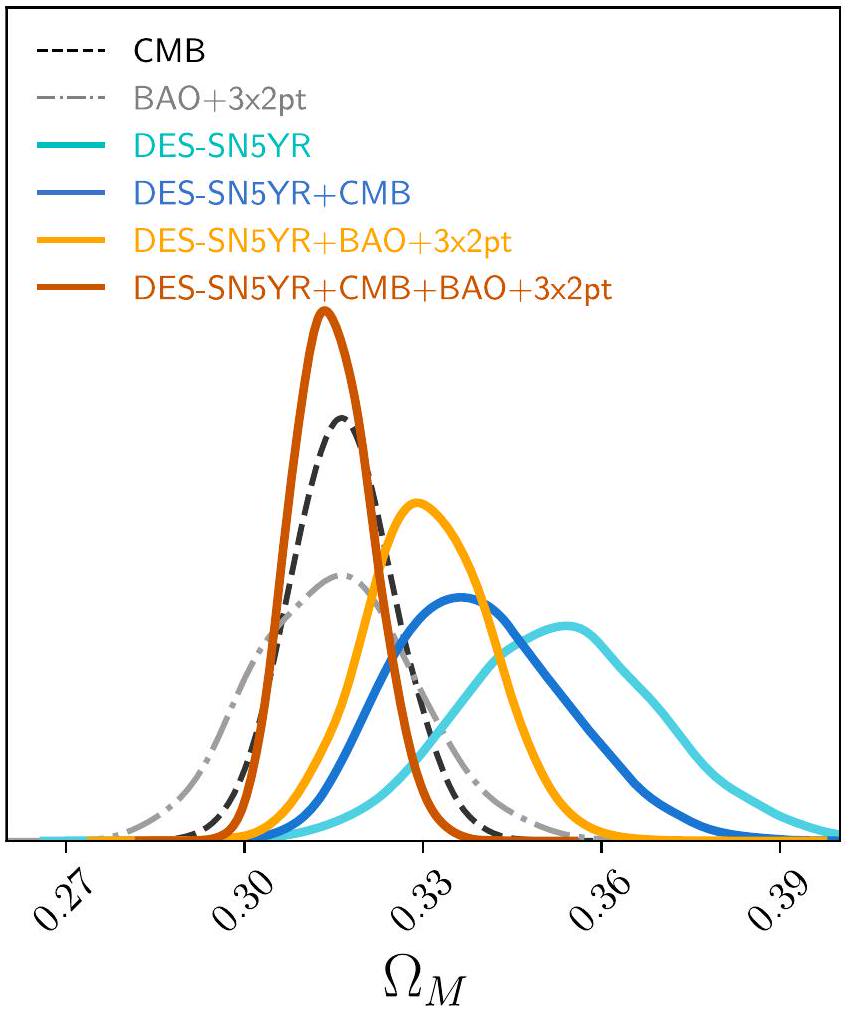

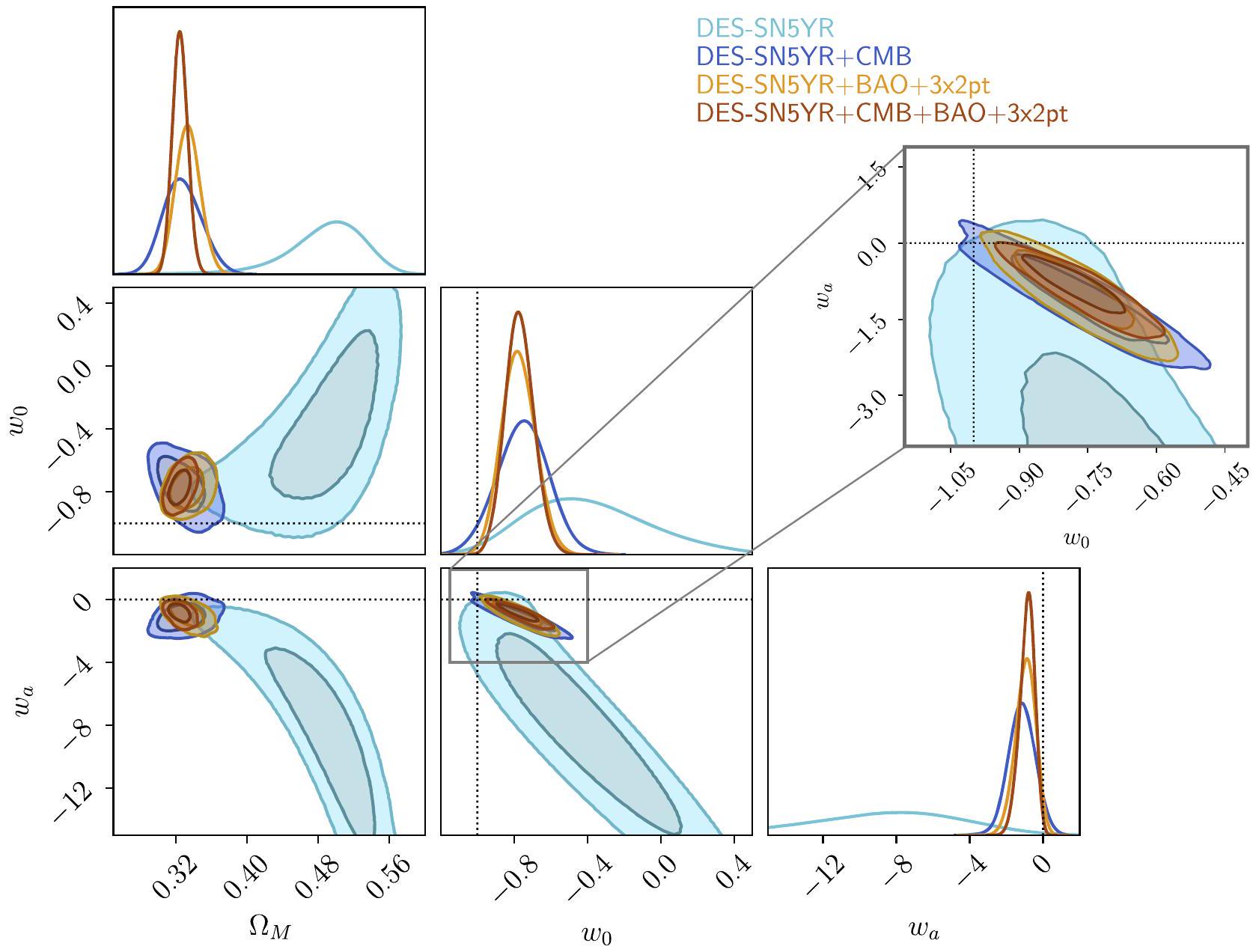

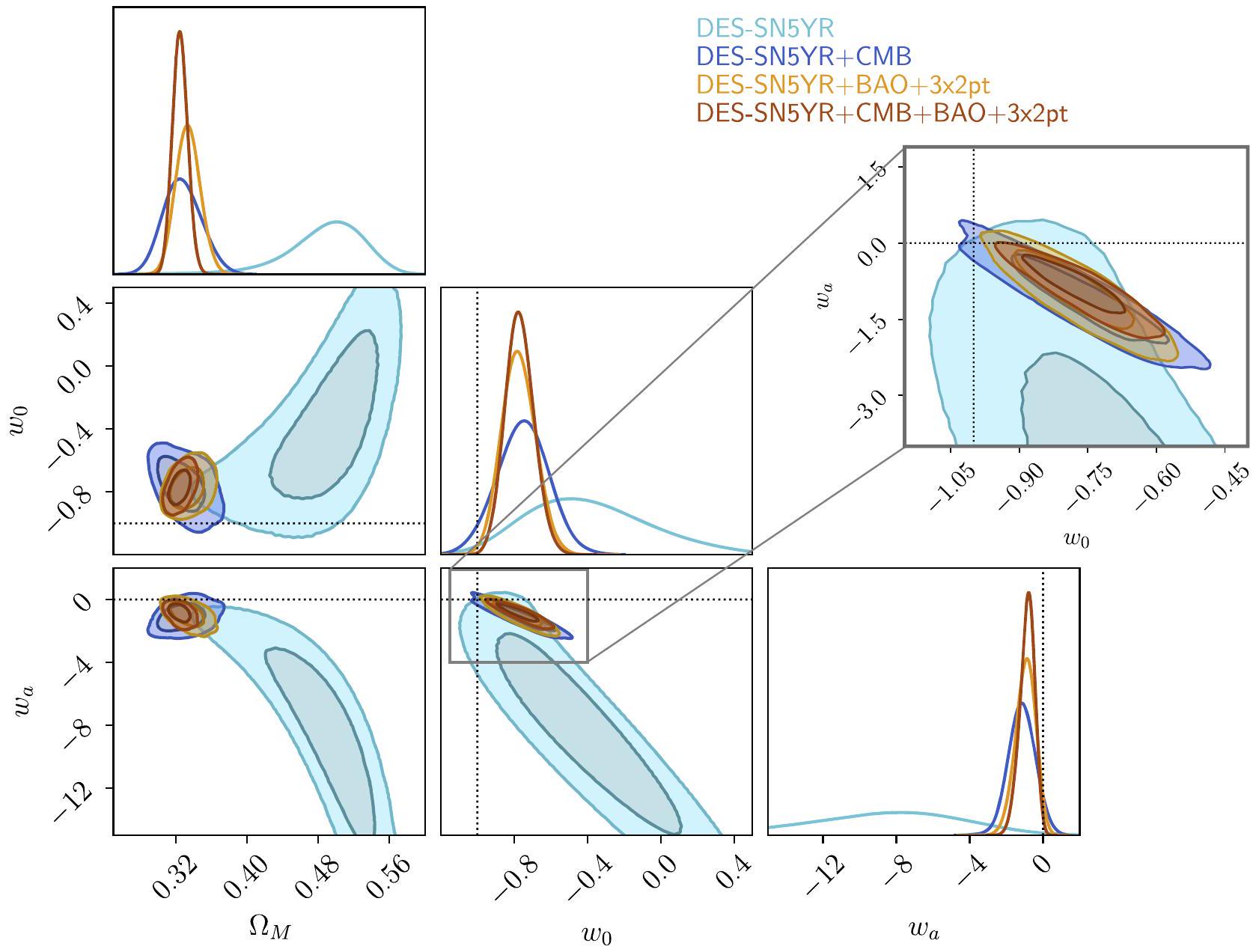

. بما في ذلك خلفية بلانك الكونية الميكروويفية، وتذبذبات الباريونات الصوتية من مسح سلوان الرقمي للسماء، وDES بيانات pt تعطي . في جميع الحالات، الطاقة المظلمة متوافقة مع ثابت كوني ضمن الأخطاء المنهجية في المعلمات الكونية تعتبر ثانوية مقارنة بالأخطاء الإحصائية؛ وبالتالي، تمهد هذه النتائج الطريق لتحليلات سوبرنوفا المصنفة فوتوغرافيًا في المستقبل.

1. المقدمة

(M. Betoule وآخرون 2014؛ D. M. Scolnic وآخرون 2018؛ تعاون مسح الطاقة المظلمة 2019). كما نبرز أن المصادر الأكثر أهمية للأنظمة هي تلك المتعلقة بنقص عينة منخفضة الزاوية متجانسة ومضبوطة بشكل جيد.

2. البيانات والتحليل

2.1. DES و SNe ذات الانزياح الأحمر المنخفض

نظرة عامة على تحليل DES-SN5YR

البيانات:

- المعايرة (بورك وآخرون 2018، بروت وآخرون 2022، ريكوف وآخرون 2023)

- فوتومترية المستعرات العظمى (براؤت وآخرون 2019، سانشيز وآخرون 2024)

- طيف SN (سميث وآخرون 2020أ)

- DCR وكروم (لاسكر وآخرون 2018، لي وآسيفيدو وآخرون 2023)

- تحولات الطيف الأحمر وخصائص المجرات المضيفة (ليدمان وآخرون 2020، كار وآخرون 2021، ويسمان وآخرون 2020/2021، كيلسي وآخرون 2023)

المحاكاة:

- آثار اختيار الاستطلاع (كيسلر وآخرون 2019أ، فينشنزي وآخرون 2020)

- خصائص SN Ia الجوهرية والغبارية (Brout&Scolnic 2021، Popovic et al. 2021a/b، Wiseman et al. 2022) ومعدلاتها (Wiseman et al. 2021)

- التلوث (فينشينزي وآخرون 2019/2020، كيسلر وآخرون 2019ب)

تحليل:

- توافق منحنى الضوء (تايلور وآخرون 2023)

- “BEAMS” وتصحيحات التحيز (كيسلر وسكلونيك 2017)، فك تجميع مخطط هابل لنجوم السوبرنوفا (بروت وآخرون 2020، كيسلر وآخرون 2023)

-آثار عدم تطابق المجرة المضيفة (Qu et al. 2023) - تحقق من حدود الكوزمولوجيا (أرمسترونغ وآخرون 2023)

نتائج كونية: تعاون DES 2024

2.2. من منحنيات الضوء إلى مخطط هابل

فوق الخطوة أو – إذا كان أدناه. تم وصف هذا التصحيح تاريخيًا بأنه “خطوة كتلة”، لكننا نعتبر أيضًا إمكانية أن تكون “خطوة لون” (انظر القسم 2.2 من M. Vincenzi وآخرون 2024)،

انظر الجدول 10 والقسم 7.1.5 من M. Vincenzi وآخرون 2024). يتم تدريب المصنفات باستخدام محاكاة الانهيار الجذعي وSNe Ia الغريبة بناءً على M. Vincenzi وآخرون (2021) وقوالب SED المتطورة من R. Kessler وآخرون (2019b) وM. Vincenzi وآخرون (2019). هذه المحاكاة DES هي الأولى التي تعيد إنتاج التلوث الملحوظ في بقايا هابل بشكل موثوق (M. Vincenzi وآخرون 2021، 2024، الجدول 10).

يقدم ب. أرمسترونغ وآخرون (2023) التحقق من الحدود الكونية التي أنتجها خط أنابيبنا. يظهر التحقق من أن خط تحليلنا غير حساس للنموذج الكوني المفترض في محاكاة تصحيح التحيز لدينا في ر. كاميليري وآخرون (2024).

2.3. معايير فك التعمية

- دقة المحاكاة. تم تقليل

يجب أن تكون العلاقة بين توزيع البيانات والمحاكاة عبر مجموعة متنوعة من الملاحظات (الانزياح الأحمر، معلمات SALT3 وجودة الملاءمة، الحد الأقصى لنسبة الإشارة إلى الضوضاء عند الذروة، كتلة النجوم المضيفة) بين 0.7 و 3.0 (انظر الأشكال 3 و 4 من M. Vincenzi وآخرون 2024). - التحقق من خط الأنابيب باستخدام محاكاة DES. إثبات أن خط الأنابيب لدينا يستعيد علم الكونيات المدخل. نحن ننتج 25 عينة محاكاة بحجم بيانات (مستقلة إحصائيًا) بافتراض مسطح

كون CDM مع قيمة بلانك الأفضل ملاءمة ونحللها بنفس الطريقة التي نحلل بها البيانات الحقيقية. نقوم بتناسب كل مخطط هابل بافتراض مسطح نموذج CDM مع أولوية بلانك والعثور على انحياز متوسط قدره ، حيث هو القيمة المتوسطة لل posterior المهمش لمعلمة حالة معادلة الطاقة المظلمة عبر 25 عينة و هو القيمة النموذجية لذلك المعامل المدخل إلى المحاكاة. - تحقق من الحدود. ضمان أن حدود عدم اليقين لدينا تمثل بدقة احتمال النماذج (P. Armstrong et al. 2023).

- استقلالية علم الكون المرجعي. ضمان أن تكون نتائجنا مستقلة بما فيه الكفاية عن الافتراضات الكونية التي تدخل في محاكاة تصحيح التحيز لدينا (R. Camilleri et al. 2024).

2.4. دمج المستعرات العظمى مع أدوات كونية أخرى

- قياسات الخلفية الكونية الميكروية (CMB) لدرجات الحرارة وطيف الاستقطاب (TTTEEE) المقدمة من قبل تعاون بلانك (2020). نستخدم تنفيذ بايثون لـ Plik_lite الخاص ببلانك لعام 2015 (H. Prince & J. Dunkley 2019).

- قياسات العدسات الضعيفة وتجمع المجرات من DES3

عينة عدسات محدودة الحجم للسنة الثالثة (MagLim)؛ تشير pt إلى التوافق المتزامن لثلاث دوال ارتباط نقطتين، وهي ارتباطات المجرات-المجرات، والمجرات-العدسات، والعدسات-العدسات (تعاون مسح الطاقة المظلمة 2022، 2023). - قياسات تذبذبات الباريون الصوتية (BAO) كما تم تقديمها في ورقة البحث الخاصة بمسح طيف تذبذبات الباريون الموسع (eBOSS) (K. S. Dawson وآخرون 2016؛ S. Alam وآخرون 2021)، والتي تضيف نتائج BAO من مسح سلوين الرقمي للسماء (SDSS)-IV (M. R. Blanton وآخرون 2017) إلى بيانات BAO السابقة من SDSS. على وجه التحديد، نستخدم “BAO” للإشارة إلى قياسات BAO فقط من عينة المجرات الرئيسية (A. J. Ross وآخرون 2015)، BOSS (SDSS-III؛ S. Alam وآخرون 2017)، eBOSS LRG (J. E. Bautista وآخرون 2021)، eBOSS ELG (A. de Mattia وآخرون 2021)، eBOSS QSO (J. Hou وآخرون 2021)، و eBOSS Lya (H. du Mas des Bourboux وآخرون 2020).

3. النماذج والنظرية

التنوعات على النموذج الكوني القياسي التي تم اختبارها في هذه الرسالة، ومعادلات فريدمان، والمعلمات الحرة في الملاءمة

| النموذج الكوني | معادلة فريدمان:

|

معلمات الملاءمة

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| شقة

|

|

|

| شقة

|

|

|

4. النتائج

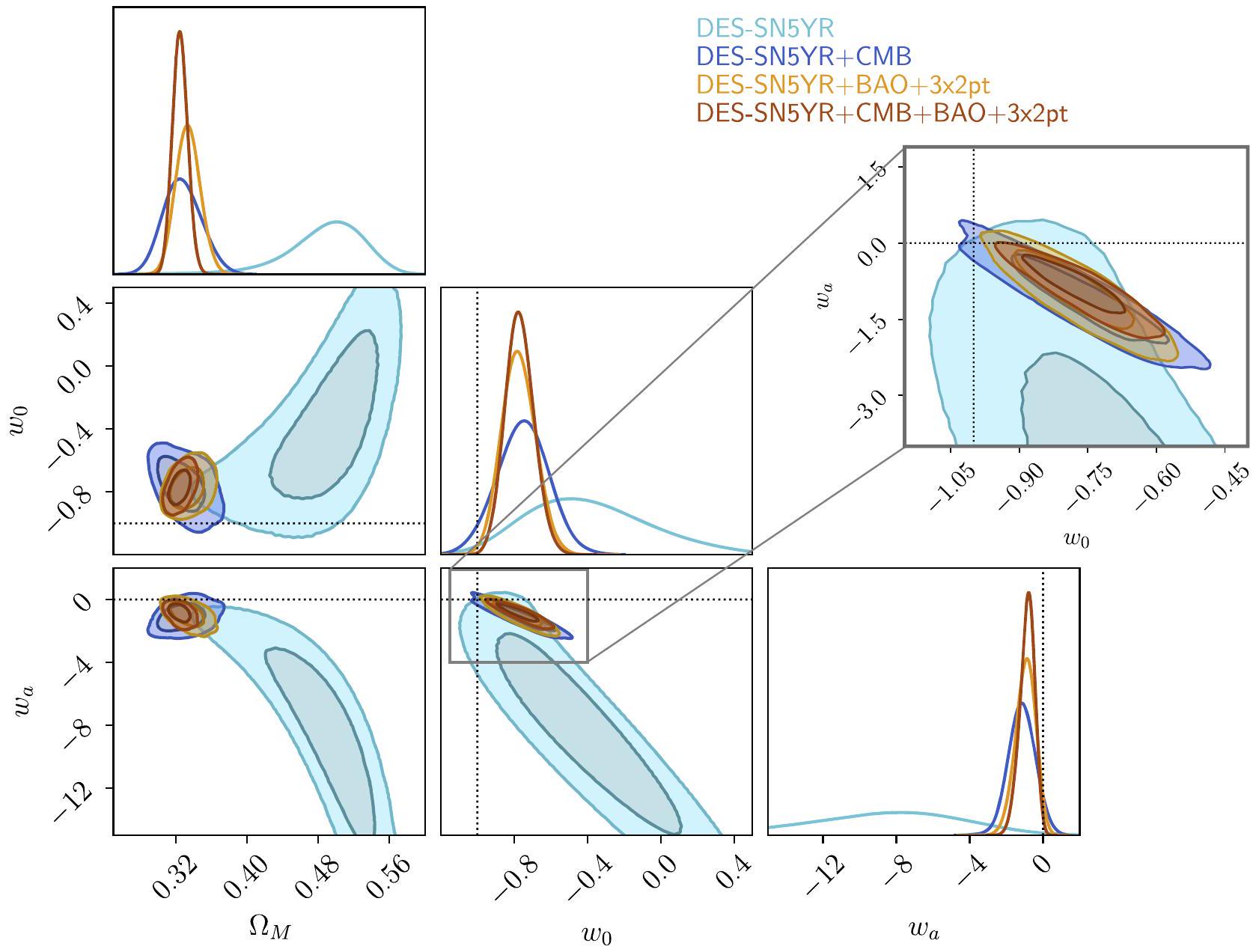

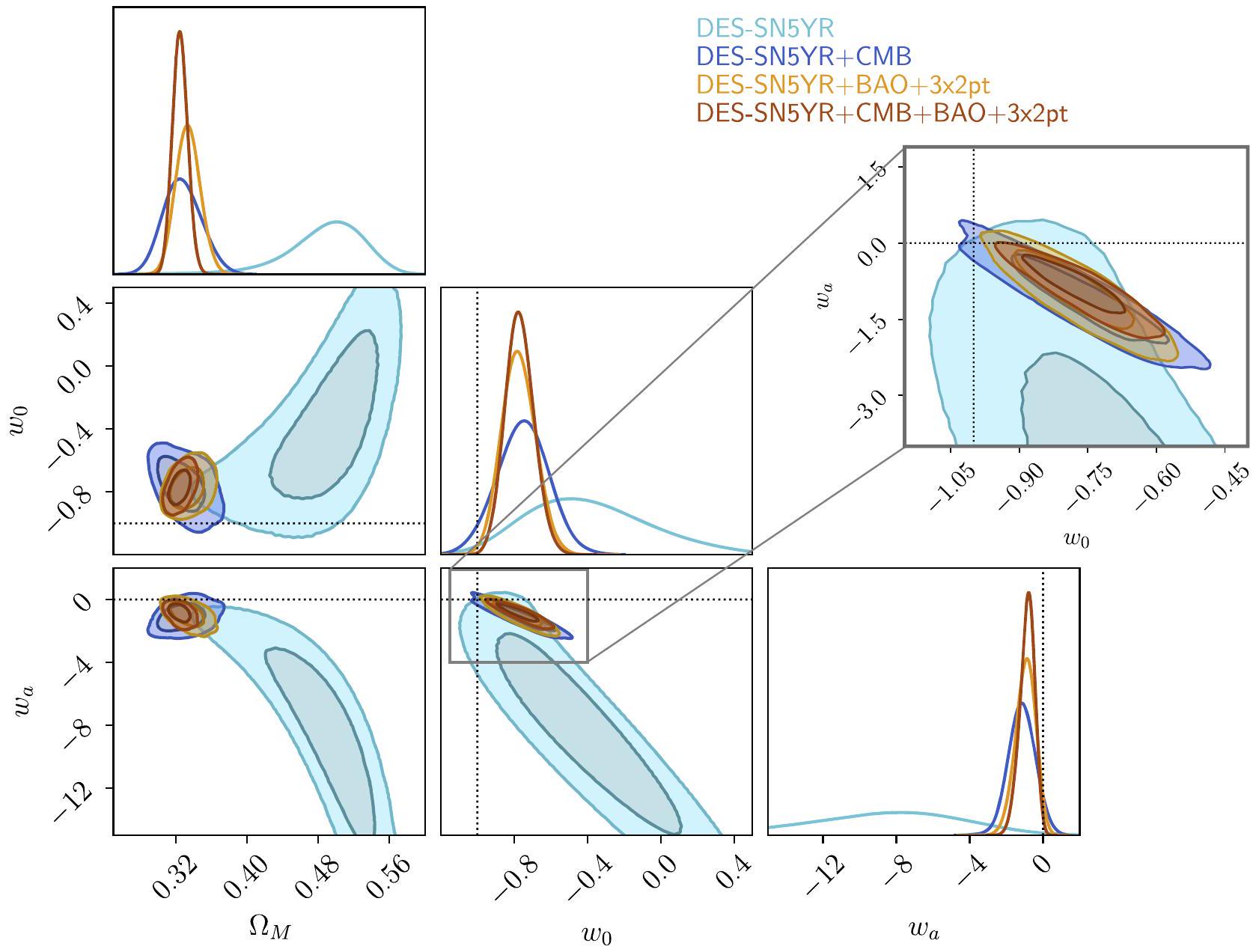

4.1. القيود على المعلمات الكونية

4.1.1. مسطح

4.1.2.

4.1.3. شقة

نتائج لأربعة نماذج كونية مختلفة، مرتبة في أقسام لمجموعات مختلفة من القيود الرصدية

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DES-SN5YR (لا توجد أولويات خارجية) | |||||

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| شقة

|

|

… |

|

… |

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DES-SN5YR + بلانك 2020 | |||||

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

… |

|

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

… |

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DES-SN5YR + SDSS BAO و DES Y3

|

|||||

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

… |

|

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DES-SN5YR + بلانك 2020 + SDSS BAO و DES Y3

|

|||||

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

|

قيمة واحدة، خالية تقريبًا من الانحراف.

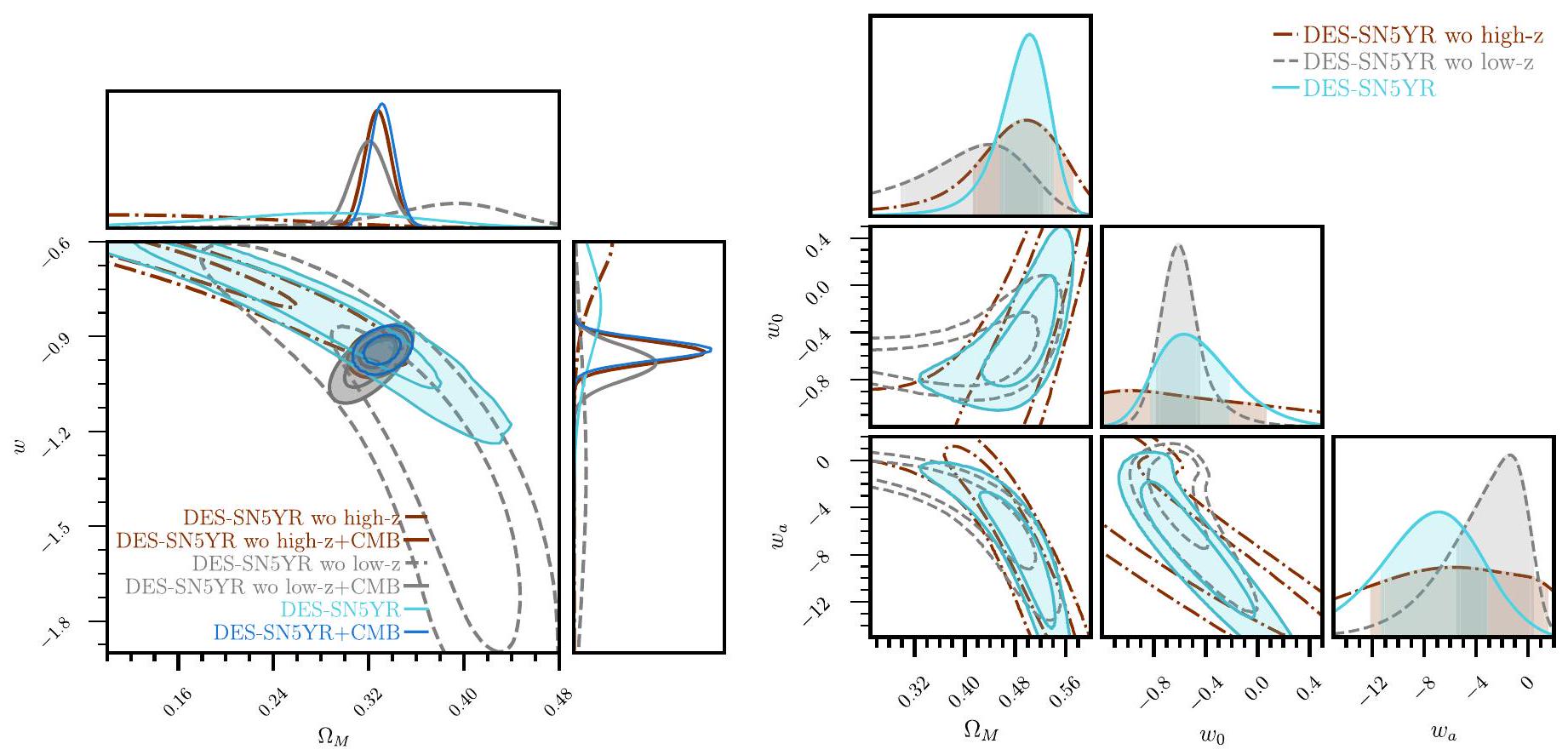

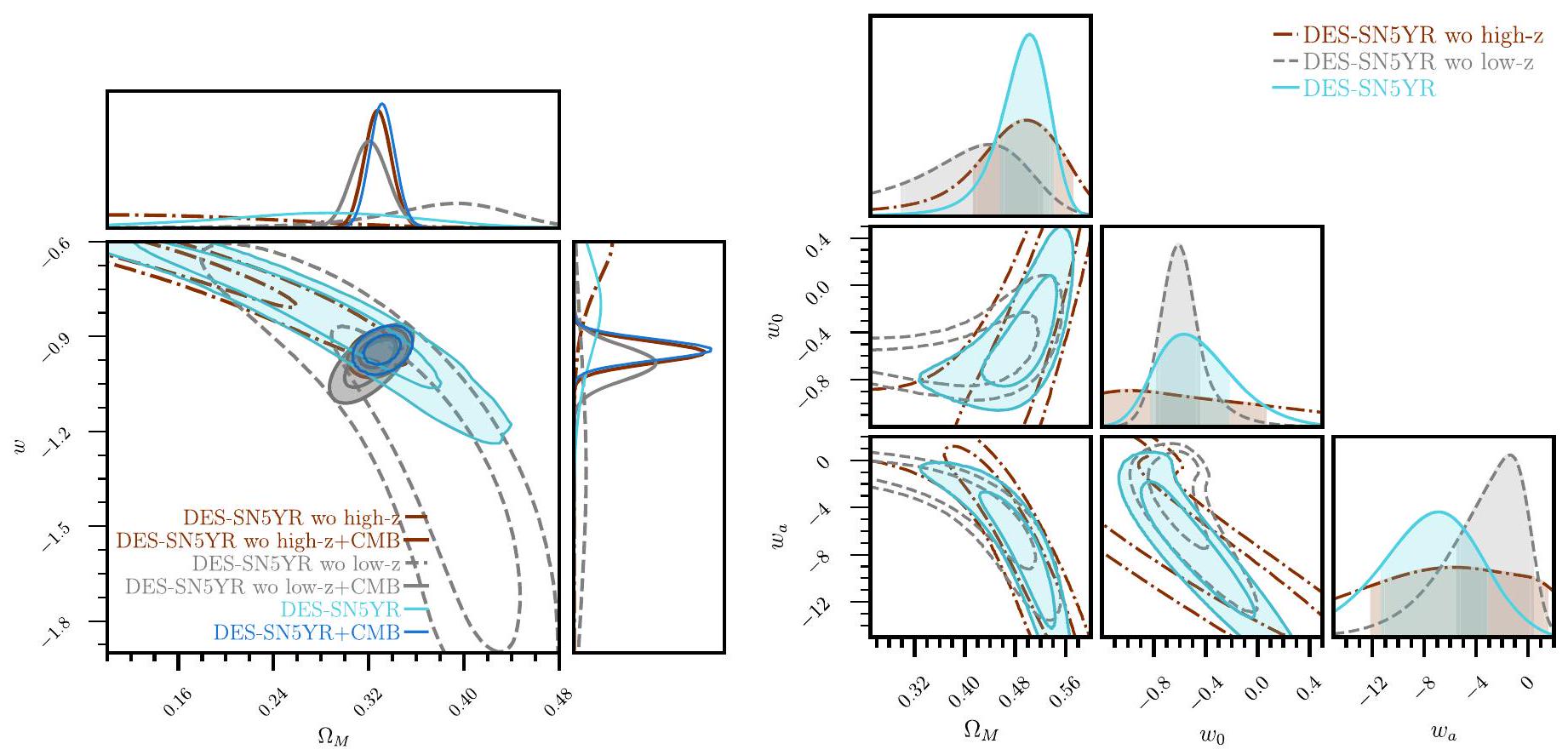

4.1.4. مسطح

4.2. جودة الملاءمة والتوتر

4.2.1.

4.2.2. الشك

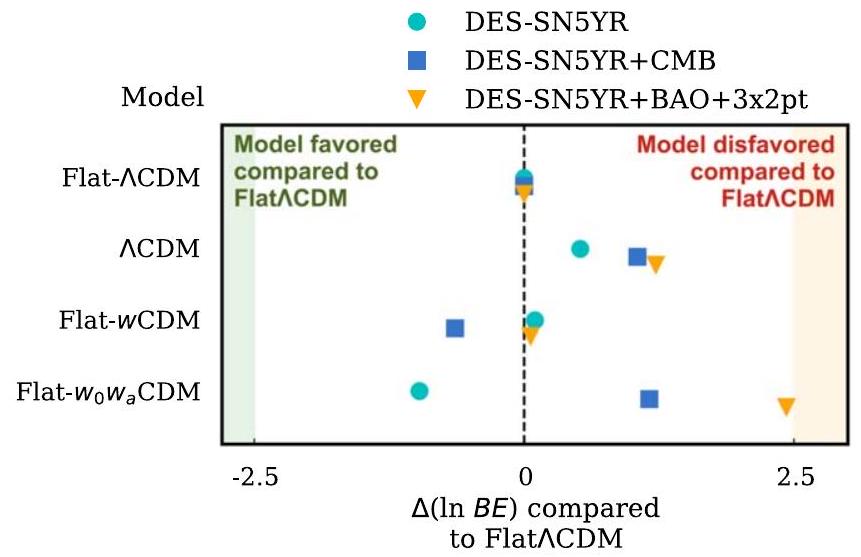

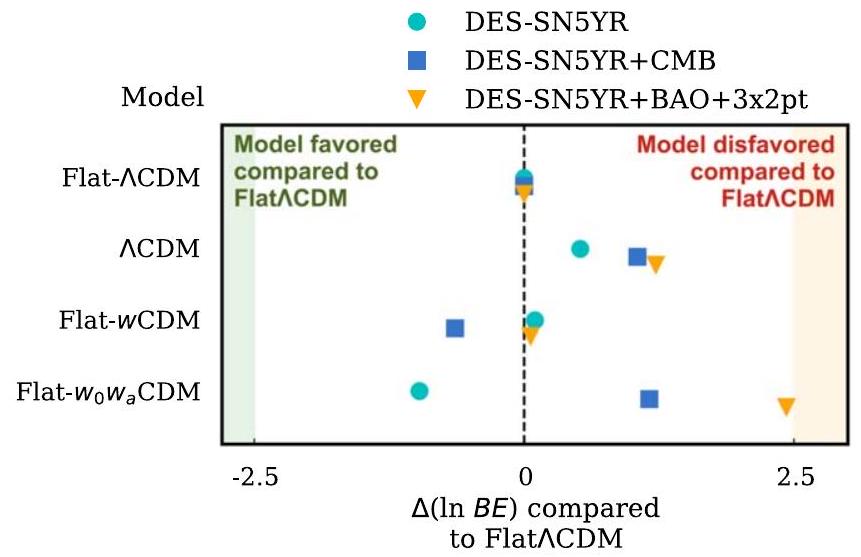

4.3. اختيار النموذج

-2.5) هو دليل معتدل ضد (في دعم) النموذج الأكثر تعقيدًا، بينما

5. المناقشة

5.1. الأسئلة الكبيرة

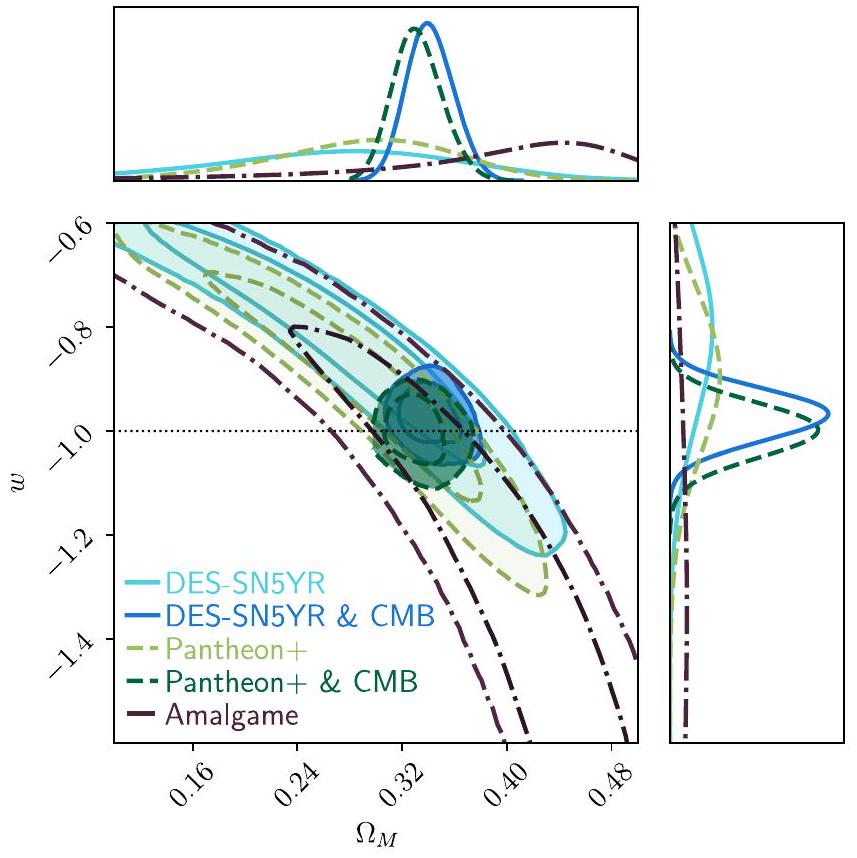

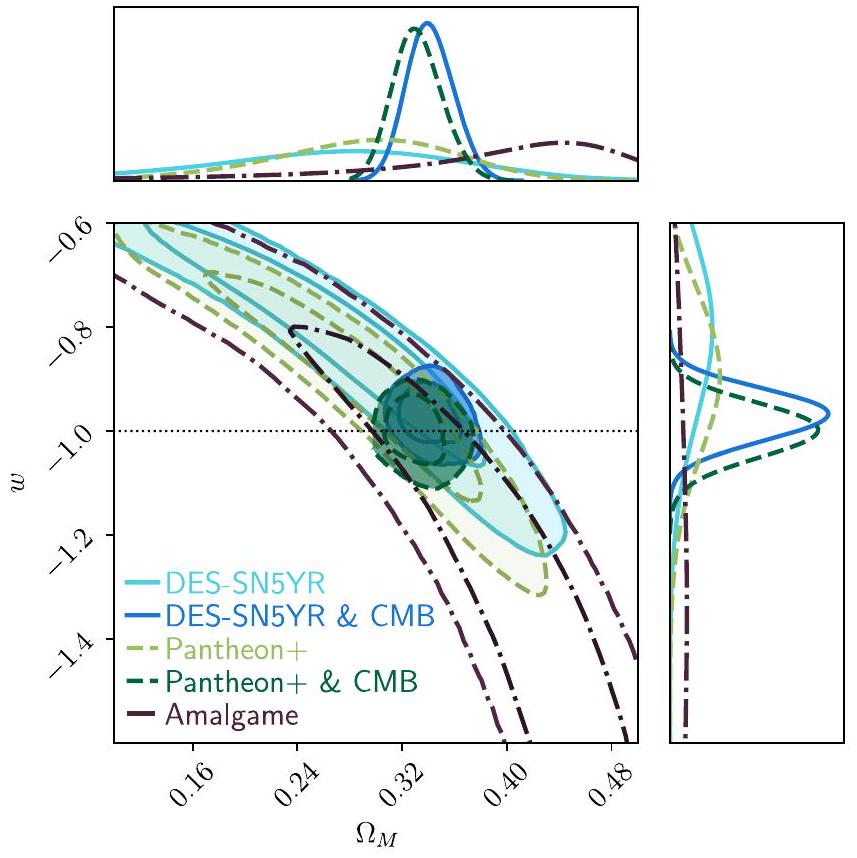

5.1.2. هل الطاقة المظلمة ثابت كوني؟

5.1.3. كم عمر الكون؟

5.1.4. هل يحل أفضل ملاءمة لدينا توتر هابل؟

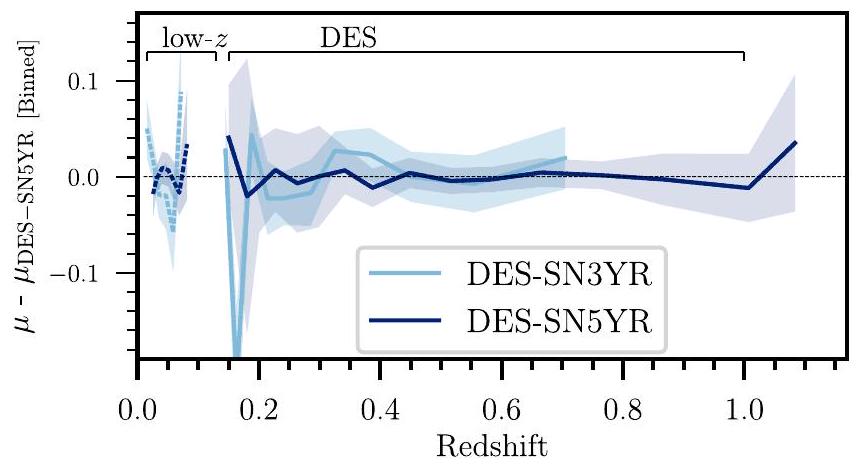

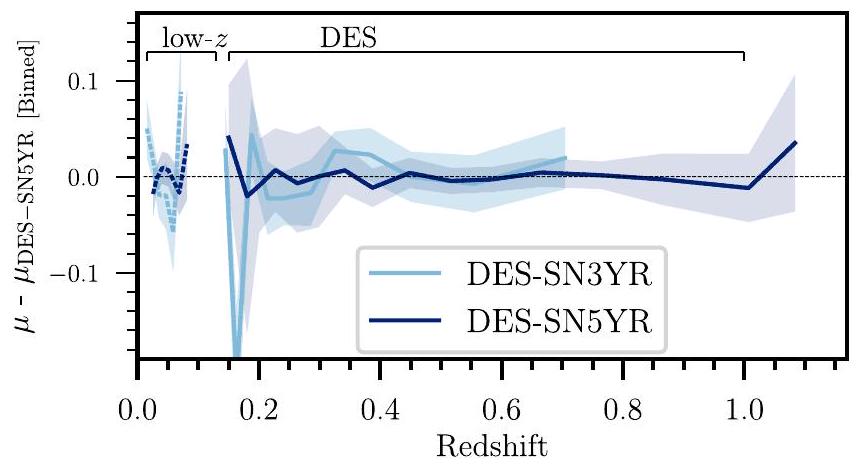

5.2. المقارنة مع DES-SN3YR و Pantheon +

5.3. عينات DES والجيل القادم من SN

تم العمل عليه في P. Armstrong وآخرون (2024، قيد الإعداد)، والذي يمكن أن يغير جميع المعلمات النظامية، والمعلمات المزعجة، والمعلمات الكونية في نفس الوقت للمقارنة مع البيانات.

6. الاستنتاجات

شكر وتقدير

يقر كل من T.M.D. وA.C. وR.C. وS.H. بالدعم المقدم من منحة زمالة أسترالية من مجلس الأبحاث الأسترالي (FL180100168) الممولة من الحكومة الأسترالية، وA.M. مدعوم من منحة جائزة الباحث المبكر من ARC Discovery (DECRA) رقم المشروع DE230100055. M.S. وH.Q. وJ.L. مدعومون من منحة DOE رقم DE-FOA-0002424 ومنحة NSF رقم AST-2108094. R.K. مدعوم من منحة DOE رقم DE-SC0009924. تم دعم M.V. جزئيًا من قبل NASA من خلال منحة زمالة هابل من NASA Hubble Fellowship grant HST-HF2-51546.001-A الممنوحة من معهد علوم التلسكوب الفضائي، الذي تديره جمعية الجامعات للبحث في علم الفلك، بموجب عقد NASA NAS5-26555. تشكر L.K. زمالة قادة المستقبل من UKRI على الدعم من خلال المنحة MR/T01881X/1. يقر L.G. بالدعم المالي من وزارة العلوم والابتكار الإسبانية (MCIN) ووكالة الدولة للبحث (AEI) 10.13039/501100011033، وصندوق الاتحاد الأوروبي الاجتماعي (ESF) “الاستثمار في مستقبلك” بموجب برنامج رامون وكاجال 2019 RYC2019-027683-I ومشروع PID2020-115253GA-I00 HOSTFLOWS، من المركز العالي للبحوث العلمية (CSIC) بموجب مشروع PIE 20215AT016، وبرنامج وحدة التميز ماريا دي مايتزو CEX2020-001058-M، ومن قسم البحث والجامعات في حكومة كاتالونيا من خلال منحة 2021-SGR-01270. تم دعم R.J.F. وD.S. جزئيًا من قبل منحة NASA رقم 14-WPS140048. يتم دعم فريق UCSC جزئيًا من خلال منح NASA NNG16PJ34G وNNG17PX03C الممنوحة من خلال برنامج فرق التحقيق العلمي لرومان؛ ومنح NSF AST-1518052 وAST-1815935؛ وNASA من خلال المنحة رقم AR-14296 من معهد علوم التلسكوب الفضائي، الذي تديره AURA، Inc. بموجب عقد NASA NAS 5-26555؛ ومؤسسة غوردون وبيتي مور؛ ومؤسسة هايسينغ-سيمونز؛ وزمالات من مؤسسة ألفريد ب. سلون ومؤسسة ديفيد ولوسيلي باكارد إلى R.J.F. نقر بفضل مركز الحوسبة البحثية بجامعة شيكاغو على دعمهم لهذا العمل.

بين معهد كاليفورنيا للتكنولوجيا، وجامعة كاليفورنيا، وإدارة الطيران والفضاء الوطنية (PIs: Foley، Kirshner، وNugent). تم تحقيق المرصد بفضل الدعم المالي السخي من مؤسسة W. M. Keck. تتضمن هذه الرسالة نتائج مستندة إلى البيانات التي تم جمعها باستخدام تلسكوبات ماجيلان 6.5 م الموجودة في مرصد لاس كامباناس، شيلي (PI: Foley)، والتلسكوب الكبير في جنوب أفريقيا (SALT؛ PIs: M. Smith & E. Kasai). يرغب المؤلفون في الاعتراف بالدور الثقافي الكبير والاحترام الذي كان دائمًا لقمة ماونا كيا داخل المجتمع الأصلي هاواي. نحن محظوظون جدًا لأن لدينا الفرصة لإجراء الملاحظات من هذه الجبل.

الملحق أ

إصدار البيانات وكيفية استخدام بيانات DES-SN5YR

الملحق ب: التوزيعات السابقة

المقدمات

| معامل | سابق | ||

| علم الكونيات – الأساس | |||

|

|

مسطح | (0.55, 0.91) | |

|

|

مسطح | (0.1, 0.9) | |

|

|

مسطح | (0.5, 5.0) | |

|

|

مسطح | (0.87, 1.07) | |

|

|

مسطح | (0.03, 0.07) | |

|

|

غوسي | (0.067, 0.023) | |

|

|

مسطح | (0.06, 0.6) | |

| تحيز عدسة المجرة | |||

|

|

مسطح | (0.8, 3.0) | |

| تكبير العدسة | |||

|

|

ثابت | 0.42 | |

|

|

ثابت | 0.30 | |

|

|

ثابت | 1.76 | |

|

|

ثابت | 1.94 | |

| عدسة فوتو-ز | |||

|

|

غوسي | (-0.9, 0.7) | |

|

|

غوسي | (-3.5, 1.1) | |

|

|

غوسي | (-0.5, 0.6) | |

|

|

غوسي | (-0.7, 0.6) | |

|

|

غوسي | (0.98, 0.06) | |

|

|

غوسي | (1.31, 0.09) | |

|

|

غوسي | (0.87, 0.05) | |

|

|

غوسي | (0.92, 0.05) | |

| التوافق الجوهري | |||

|

|

مسطح | (-5, 5) | |

|

|

مسطح | (-5, 5) | |

|

|

مسطح |

|

|

|

|

ثابت | 0.62 | |

| صورة المصدر-ز | |||

|

|

غوسي | (0.0, 1.8) | |

|

|

غوسي | (0.0, 1.5) | |

|

|

غوسي | (0.0, 1.1) | |

|

|

غوسي | (0.0, 1.7) | |

| معايرة القص | |||

|

|

غوسي | (-0.6, 0.9) | |

|

|

غوسي | (-2.0, 0.8) | |

|

|

غوسي | (-2.4, 0.8) | |

|

|

غوسي | (-3.7, 0.8) | |

| نموذج | معامل | سابق | |

| النماذج الموسعة | |||

|

|

|

مسطح | (-0.5, 0.5) |

| شقة

|

|

مسطح | (-2, 0) |

| شقة

|

|

مسطح | (-10, 5) |

|

|

مسطح | (-20, 10) | |

حيث تفترض الخطوة الأخيرة وجود أولوية ثابتة لكل من

حيث استخدام (

الملحق ج

اختبارات على مجموعات فرعية من بياناتنا

النتائج باستخدام بيانات DES فقط (باستثناء المنخفضة-

|

|

|

|

أهمية التحول | |

| DES SNe بدون Low-z | ||||

| شقة

|

|

… | … |

|

| شقة

|

|

|

… |

|

| شقة

|

|

|

… |

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

| DES SNe بدون High-z | ||||

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

| شقة

|

|

|

|

|

بهذا النهج، نقيس

نستخدم تقريبًا لسابقة مشابهة لظاهرة الخلفية الكونية الميكروية التي تستخدم

الشقة

معرفات ORCID

أ. ألفيس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7394-9466

ج. أنيس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0609-3987

ب. أرمسترونغ ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1997-3649

ك. بيشتول ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8156-0429

P. H. برناردينيلي ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0743-9422

جي. إم. بيرنشتاين ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8613-8259

E. برتين ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3602-3664

س. بوكويه (10)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4900-805X

دي. بروكس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8458-5047

د. بروت ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5201-8374

دي. إل. بيرك ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1866-1950

أ. كارnero روسيل ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3044-5150

دي. كارولو ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4710-132X

أ. كارhttps://orcid.org/0000-0003-4074-5659

ج. كاريرتو ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3130-0204

ف. ج. كاستاندر ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7316-4573

سي. تشانغ ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7887-0896

ر. تشين ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3917-0966

سي. كونسيليس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1949-7638

ل. ن. دا كوستا ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7731-277X

م. كروتشي (10)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9745-6228

ت. م. ديفيس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4213-8783

س. ديساي ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0466-3288

H. T. Diehl ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8357-7467

C. دوكس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4480-0096

أ. درليكا-واجنر ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8251-933X

ج. إلفين-بول ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5148-9203

آي. فيريرو ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1295-1132

R. J. فولي ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2445-5275

ب. فوسالبا (10)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1510-5214

دي. فريدل ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3632-7668

C. فروماير ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9553-4723

ج. غارسيا-بيليدو ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9370-8360

إ. غازتاناغا ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9632-0815

ك. غلازبروك ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3254-9044

أ. غراور ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4391-6137

ر. أ. غريندل ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4588-6517

س. ر. هينتون ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2071-9349

دي. إل. هوليوود ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9369-4157

دي. هوتيرر ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6558-0112

دي. جي. جيمس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5160-4486

س. كينت ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4207-7420

R. كيسلر ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3221-0419

أ. ج. كيم (10)https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6315-8743

إ. كوفاكس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2545-1989

ك. كوين ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0120-0808

ج. لي ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6633-9793

جي. إف. لويس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3081-9319

ت. س. لي ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9110-6163

سي. ليدمان ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1731-0497

H. لين ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7825-3206

ب. مارتيني ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0194-4017

ج. مينا-فرناندز ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9497-7266

ف. مينانتو ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1372-2534

ر. ميكيل ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6610-4836

ج. مولد (10)https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3820-1740

إ. نيلسن ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7357-0317

ب. نوجنت ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3389-0586

ر. ل. س. أوغاندو ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2120-1154

ي.-س. بان ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8415-6720

أ. بييرس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9186-6042

H. Qu ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1899-9791

أ. ك. رومر ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9328-879X

أ. رودمان ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5326-3486

م. ساكو ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2764-7093

E. سانشيز ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9646-8198

ج. ألين. سميث ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6261-4601

م. سميث ©https://orcid.org/000-0002-3321-1432

م. سوارس-سانتوس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6082-8529

إي. سوشيتا ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7047-9358

م. سوليفان ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9053-4820

ن. سونتسيف ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8102-181

م. إ. س. سوانسون (10)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1488-8552

ج. تارل ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1704-078

د. توماس ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6325-5671

C. إلى ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7836-2261

ب. إ. توكر (10)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4283-5159

دي. إل. تاكر ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7211-5729

س. أ. عدي (10)https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9413-4186

أ. ر. ووكر ©https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7123-8943

ن. ويفرديك ©https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9382-5199

ر. هـ. ويشسلر ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2229-011X

W. ويستر ©https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0072-6736

References

Alam, S., Aubert, M., Avila, S., et al. 2021, PhRvD, 103, 083533

Alard, C., & Lupton, R. H. 1998, ApJ, 503, 325

Aleo, P. D., Malanchev, K., Sharief, S., et al. 2023, ApJS, 266, 9

Armstrong, P., Qu, H., Brout, D., et al. 2023, PASA, 40, e038

Astropy Collaboration 2013, A&A, 558, A33

Astropy Collaboration 2018, AJ, 156, 123

Bautista, J. E., Paviot, R., Vargas Magaña, M., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 500, 736

Bernstein, J. P., Kessler, R., Kuhlmann, S., et al. 2012, ApJ, 753, 152

Bertin, E., & Arnouts, S. 1996, A&AS, 117, 393

Betoule, M., Kessler, R., Guy, J., et al. 2014, A&A, 568, A22

Blanton, M. R., Bershady, M. A., Abolfathi, B., et al. 2017, AJ, 154, 28

Brout, D., Hinton, S. R., & Scolnic, D. 2021, ApJL, 912, L26

Brout, D., & Scolnic, D. 2021, ApJ, 909, 26

Brout, D., Scolnic, D., Kessler, R., et al. 2019a, ApJ, 874, 150

Brout, D., Sako, M., Scolnic, D., et al. 2019b, ApJ, 874, 106

Brout, D., Scolnic, D., Popovic, B., et al. 2022a, ApJ, 938, 110

Brout, D., Taylor, G., Scolnic, D., et al. 2022b, ApJ, 938, 111

Burke, D. L., Rykoff, E. S., Allam, S., et al. 2018, AJ, 155, 41

Camilleri, R., Davis, T. M., Vincenzi, M., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 533, 2615

Chaboyer, B., Demarque, P., Kernan, P. J., & Krauss, L. M. 1998, ApJ, 494, 96

Chen, R., Scolnic, D., Rozo, E., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, 62

Chen, R., Scolnic, D., Rozo, E., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, 62

Chevallier, M., & Polarski, D. 2001, IJMPD, 10, 213

Childress, M. J., Lidman, C., Davis, T. M., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 472, 273

Cimatti, A., & Moresco, M. 2023, ApJ, 953, 149

Conley, A., Guy, J., Sullivan, M., et al. 2011, ApJS, 192, 1

Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2016, MNRAS, 460, 1270

Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2019, ApJL, 872, L30

Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2022, PhRvD, 105, 023520

Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2023, PhRvD, 107, 083504

Dawson, K. S., Kneib, J.-P., Percival, W. J., et al. 2016, AJ, 151, 44

de Mattia, A., Ruhlmann-Kleider, V., Raichoor, A., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 501, 5616

Di Valentino, E., Mena, O., Pan, S., et al. 2021, CQGra, 38, 153001

Diehl, H. T., Neilsen, E., Gruendl, R., et al. 2016, Proc. SPIE, 9910, 99101D

Diehl, H. T., Neilsen, E., Gruendl, R. A., et al. 2018, Proc. SPIE, 10704, 107040D

Dixon, M., Lidman, C., Mould, J., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 517, 4291

du Mas des Bourboux, H., Rich, J., Font-Ribera, A., et al. 2020, ApJ, 901, 153

Duarte, J., González-Gaitán, S., Mourao, A., et al. 2023, A&A, 680, A56

Fioc, M., & Rocca-Volmerange, B. 1999, arXiv:astro-ph/9912179

Flaugher, B., Diehl, H. T., Honscheid, K., et al. 2015, AJ, 150, 150

Foley, R. J., Scolnic, D., Rest, A., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 475, 193

Foreman-Mackey, D., Hogg, D. W., Lang, D., & Goodman, J. 2013, PASP, 125, 306

Ganeshalingam, M., Li, W., & Filippenko, A. V. 2013, MNRAS, 433, 2240

Gilliland, R. L., Nugent, P. E., & Phillips, M. M. 1999, ApJ, 521, 30

Gratton, R. G., Pecci, F. F., Carretta, E., et al. 1997, ApJ, 491, 749

Gupta, R. R., Kuhlmann, S., Kovacs, E., et al. 2016, AJ, 152, 154

Handley, W. 2019, JOSS, 4, 1414

Handley, W., & Lemos, P. 2019, PhRvD, 100, 023512

Handley, W. J., Hobson, M. P., & Lasenby, A. N. 2015, MNRAS, 450, L61

Harris, C. R., Millman, K. J., van der Walt, S. J., et al. 2020, Natur, 585, 357

Hicken, M., Challis, P., Jha, S., et al. 2009, ApJ, 700, 331

Hicken, M., Challis, P., Kirshner, R. P., et al. 2012, ApJS, 200, 12

Hinton, S., & Brout, D. 2020, JOSS, 5, 2122

Hinton, S. 2016, JOSS, 1, 00045

Hlozek, R., Kunz, M., Bassett, B., et al. 2012, ApJ, 752, 79

Hou, J., Sánchez, A. G., Ross, A. J., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 500, 1201

Hunter, J. D. 2007, CSE, 9, 90

Ivezić, Ž., Kahn, S. M., Tyson, J. A., et al. 2019, ApJ, 873, 111

James, F., & Roos, M. 1975, CoPhC, 10, 343

Jennings, E., Wolf, R., & Sako, M. 2016, arXiv:1611.03087

Jones, D. O., Foley, R. J., Narayan, G., et al. 2021, ApJ, 908, 143

Jones, D. O., Scolnic, D. M., Foley, R. J., et al. 2019, ApJ, 881, 19

Jones, D. O., Scolnic, D. M., Riess, A. G., et al. 2018, ApJ, 857, 51

Kelsey, L., Sullivan, M., Wiseman, P., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 519, 3046

Kenworthy, W. D., Jones, D. O., Dai, M., et al. 2021, ApJ, 923, 265

Kessler, R., & Brout, D. 2020, SNDATA_ROOT for SNANA software, v4, Zenodo, doi:10.5281/zenodo. 4015325

Kessler, R., Bernstein, J. P., Cinabro, D., et al. 2009, PASP, 121, 1028

Kessler, R., Brout, D., D’Andrea, C. B., et al. 2019a, MNRAS, 485, 1171

Kessler, R., Guy, J., Marriner, J., et al. 2013, ApJ, 764, 48

Kessler, R., Marriner, J., Childress, M., et al. 2015, AJ, 150, 172

Kessler, R., Narayan, G., Avelino, A., et al. 2019b, PASP, 131, 094501

Kessler, R., & Scolnic, D. 2017, ApJ, 836, 56

Kessler, R., Vincenzi, M., & Armstrong, P. 2023, ApJL, 952, L8

Komatsu, E., Dunkley, J., Nolta, M. R., et al. 2009, ApJS, 180, 330

Krisciunas, K., Contreras, C., Burns, C. R., et al. 2017, AJ, 154, 211

Kunz, M., Bassett, B. A., & Hlozek, R. A. 2007, PhRvD, 75, 103508

Kunz, M., Hlozek, R., Bassett, B. A., et al. 2012, in Astrostatistical Challenges for the New Astronomy, ed. J. M. Hilbe (New York: Springer), 63

Lahav, O., Calder, L., Mayers, J., & Frieman, J. 2020, The Dark Energy Survey (Singapore: World Scientific), https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/pdf/ 10.1142/q0247

Lee, J., Acevedo, M., Sako, M., et al. 2023, AJ, 165, 222

Lemos, P., Raveri, M., Campos, A., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 505, 6179

Lidman, C., Tucker, B. E., Davis, T. M., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 496, 19

Linder, E. V. 2003, PhRvL, 90, 091301

Marriner, J., Bernstein, J. P., Kessler, R., et al. 2011, ApJ, 740, 72

Meldorf, C., Palmese, A., Brout, D., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 518, 1985

Mitra, A., Kessler, R., More, S., Hlozek, R. & LSST Dark Energy Science Collaboration 2023, ApJ, 944, 212

Möller, A., & de Boissiere, T. 2020, MNRAS, 491, 4277

Möller, A., Smith, M., Sako, M., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 514, 5159

Pandas development team 2020, Zenodo: pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas, v2.2.2, Zenodo, doi:10.5281/zenodo. 3509134

Perlmutter, S., Aldering, G., Goldhaber, G., et al. 1999, ApJ, 517, 565

Phillips, M. M., Lira, P., Suntzeff, N. B., et al. 1999, AJ, 118, 1766

Planck Collaboration 2020, A&A, 641, A6

Popovic, B., Brout, D., Kessler, R., & Scolnic, D. 2023, ApJ, 945, 84

Popovic, B., Brout, D., Kessler, R., Scolnic, D., & Lu, L. 2021, ApJ, 913, 49

Popovic, B., Scolnic, D., Vincenzi, M., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 529, 2100

Prince, H., & Dunkley, J. 2019, PhRvD, 100, 083502

Pskovskii, I. P. 1977, SvA, 21, 675

Qu, H., Sako, M., Möller, A., & Doux, C. 2021, AJ, 162, 67

Qu, H., Sako, M., Vincenzi, M., et al. 2024, ApJ, 964, 134

Riess, A. G., Filippenko, A. V., Challis, P., et al. 1998, AJ, 116, 1009

Riess, A. G., Nugent, P. E., Gilliland, R. L., et al. 2001, ApJ, 560, 49

Riess, A. G., Rodney, S. A., Scolnic, D. M., et al. 2018, ApJ, 853, 126

Riess, A. G., Strolger, L.-G., Tonry, J., et al. 2004, ApJ, 607, 665

Riess, A. G., Strolger, L.-G., Casertano, S., et al. 2007, ApJ, 659, 98

Rose, B. M., Baltay, C., Hounsell, R., et al. 2021, arXiv:2111.03081

Ross, A. J., Samushia, L., Howlett, C., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 449, 835

Rubin, D., Aldering, G., Betoule, M., et al. 2023, arXiv:2311.12098

Ruhlmann-Kleider, V., Lidman, C., & Möller, A. 2022, JCAP, 2022, 065

Rust, B. W. 1974, PhD thesis, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Tennessee

Rykoff, E. S. 2023, Rykoff, Eli S. 2023. “The Dark Energy Survey Six-Year Calibration Star Catalog”, FERMILAB-TM-2784-PPD-SCD, Fermi Technical Note, doi:10.2172/1973601

Sako, M., Bassett, B., Becker, A. C., et al. 2018, PASP, 130, 064002

Sánchez, B. O., Brout, D., Vincenzi, M., et al. 2024, arXiv:2406.05046

Sánchez, B. O., Kessler, R., Scolnic, D., et al. 2022, ApJ, 934, 96

Scolnic, D., Brout, D., Carr, A., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, 113

Scolnic, D. M., Jones, D. O., Rest, A., et al. 2018, ApJ, 859, 101

Sevilla-Noarbe, I., Bechtol, K., Kind, M. C., et al. 2021, ApJS, 254, 24

Smith, M., D’Andrea, C. B., Sullivan, M., et al. 2020a, AJ, 160, 267

Smith, M., Sullivan, M., Wiseman, P., et al. 2020b, MNRAS, 494, 4426

Stevens, A. R. H., Bellstedt, S., Elahi, P. J., & Murphy, M. T. 2020, NatAs, 4, 843

Sullivan, M., Le Borgne, D., Pritchet, C. J., et al. 2006, ApJ, 648, 868

Sullivan, M., Guy, J., Conley, A., et al. 2011, ApJ, 737, 102

Suzuki, N., Rubin, D., Lidman, C., et al. 2012, ApJ, 746, 85

Swann, E., Sullivan, M., Carrick, J., et al. 2019, Msngr, 175, 58

Taylor, G., Jones, D. O., Popovic, B., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 520, 5209

The Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2005, arXiv:astro-ph/0510346

Tripp, R. 1998, A&A, 331, 815

Trotta, R. 2008, ConPh, 49, 71

Valcin, D., Bernal, J. L., Jimenez, R., Verde, L., & Wandelt, B. D. 2020, JCAP, 2020, 002

VandenBerg, D. A., Bolte, M., & Stetson, P. B. 1996, ARA&A, 34, 461

Vincenzi, M., Sullivan, M., Firth, R. E., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 489, 5802

Vincenzi, M., Sullivan, M., Graur, O., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 505, 2819

Vincenzi, M., Sullivan, M., Möller, A., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 518, 1106

Vincenzi, M., Brout, D., Armstrong, P., et al. 2024, arXiv:2401.02945

Virtanen, P., Gommers, R., Oliphant, T. E., et al. 2020, NatMe, 17, 261

Wiseman, P., Smith, M., Childress, M., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 495, 4040

Wiseman, P., Sullivan, M., Smith, M., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 506, 3330

Wiseman, P., Vincenzi, M., Sullivan, M., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 515, 4587

Ying, J. M., Chaboyer, B., Boudreaux, E. M., et al. 2023, AJ, 166, 18

Yuan, F., Lidman, C., Davis, T. M., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 452, 3047

Zuntz, J., Paterno, M., Jennings, E., et al. 2015, A&C, 12, 45

The SALT3 model consists of a spectral flux density as a function of phase and wavelength for SNe Ia. Its three components are describing the mean SN light curve, describing the deviations from that are correlated with light-curve width, and CL describing the color dependence. See Equation (1) of G. Taylor et al. (2023). - 93 Following J. Marriner et al. (2011), we replace the traditional

notation with , because in the SALT2 and SALT3 models, the amplitude term, , is not related to any particular filter band. Applying a binary-classification-based cut (SN Ia or not) is not optimal, as it assumes that the classification is perfect. However, we test the binary-cut-based approach by using only the 1499 SNe classified with and assuming they are a pure SN Ia sample. We show that the measured shift in is small compared to the statistical uncertainties (Table 11 of M. Vincenzi et al. 2024). When , the term becomes and can be calculated directly from Equation (2), bypassing the infinite . For each emcee fit, we use a number of walkers that is at least twice the number of parameters and ensure that the number of samples in the chain is greater than 50 times the autocorrelation function, . For each PolyChord fit, we use a minimum of 60 live points, 30 repeats, and an evidence tolerance requirement of 0.1 (except for CDM with all data sets combined, for which we accepted a slightly weaker tolerance because convergence was too slow). When combining with other data sets, we run simultaneous MCMC chains including all relevant data vectors. Flat priors that encapsulate at least the confidence region were chosen in each case, and we summarize those priors in Appendix B.

The main advantage of emcee is that it gives a slightly more accurate bestfit than PolyChord. However, we decided that the tiny improvement in accuracy was not worth the environmental impact (A. R. H. Stevens et al. 2020) of the extra compute time (which was substantial for the many-dataset fits). - 98 The distribution of points around the Hubble diagram is not perfectly Gaussian, as it is skewed due to lensing magnification and non-SN-Ia contamination. This means that the

values (especially at high ) are only approximate. Similar to the parameter used in lensing studies to approximate constraints. Suspiciousness, , is related to the Bayes ratio and Bayesian information and is defined as . If . If , Gyr. Not all events included in the DES-SN3YR analysis are included in the DES-SN5YR analysis, and vice versa. This is due to the two analyses implementing different sample cuts. For example, the cut and the requirement for a host galaxy redshift in DES-SN5YR exclude, respectively, 44 and 29 low-z SNe that were in the DES-SN3YR sample. DES-SN5YR also uses a new SALT model (which affects the SALT-based cuts) and is restricted to SNe that pass selection cuts across all systematic tests (see Table 4 in M. Vincenzi et al. 2024).

The redshift at which the Universe began accelerating in CDM is . These upcoming low- surveys are magnitude-limited rather than targeted; therefore, they provide SN samples with a well-defined selection function. - Note.

We also used some specific variations of the above baseline priors. For the CDM model using the DES-SN5YR only, ; using DESSN5YR + SDSS BAO and DES Y3 ; and using DES-SN5YR + Planck SDSS BAO and DES Y3 pt, . For the flat CDM model using DES-SN5YR + Planck , and finally, for the flat model using DESSN5YR + SDSS BAO and DES Y3 .

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ad6f9f

Publication Date: 2024-09-01

The Dark Energy Survey: Cosmology Results With 1500 New High-redshift Type Ia Supernovae Using The Full 5-year Dataset

– To cite this version:

The Dark Energy Survey: Cosmology Results with

Department of Physics, IIT Hyderabad, Kandi, Telangana 502285, India

Centre for Astrophysics & Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, VIC 3122, Australia

NSF AI Planning Institute for Physics of the Future, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA

Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, LPSC-IN2P3, 38000 Grenoble, France

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA

Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1029 Blindern, NO-0315 Oslo, Norway

Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA

Center for Astrophysical Surveys, National Center for Supercomputing Applications, 1205 West Clark Street, Urbana, IL 61801, USA

School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Southampton, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK

Instituto de Fisica Teorica UAM/CSIC, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, 28049 Madrid, Spain

Department of Astronomy, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1002 West Green Street, Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Department of Astronomy, University of Geneva, ch. d’Écogia 16, CH-1290 Versoix, Switzerland

Santa Cruz Institute for Particle Physics, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA

Center for Cosmology and Astro-Particle Physics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

Department of Physics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

ASTRAVEO LLC, P.O. Box 1668, Gloucester, MA 01931, USA

Applied Materials Inc., 35 Dory Road, Gloucester, MA 01930, USA

Department of Physics, University of Namibia, 340 Mandume Ndemufayo Avenue, Pionierspark, Windhoek, Namibia

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 1 Cyclotron Road, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA

TMT International Observatory, 100 West Walnut Street, Pasadena, CA 91124, USA

California Institute of Technology, 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA

Australian Astronomical Optics, Macquarie University, North Ryde, NSW 2113, Australia

Lowell Observatory, 1400 Mars Hill Road, Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA

Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics, A28, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia

Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Toronto, 50 St. George Street, Toronto, ON M5S 3H4, Canada

Centre for Gravitational Astrophysics, College of Science, The Australian National University, ACT 2601, Australia

Department of Astronomy, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

LPSC Grenoble-53, Avenue des Martyrs 38026 Grenoble, France

Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats, E-08010 Barcelona, Spain

Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Giessenbachstrasse, 85748 Garching, Germany

Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, 31 Caroline Street North, Waterloo, ON N2L 2Y5, Canada

School of Mathematics and Physics, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey, GU2 7XH, UK

Observatório Nacional, Rua Gal. José Cristino 77, Rio de Janeiro, RJ—20921-400, Brazil

Graduate Institute of Astronomy, National Central University, 300 Jhongda Road, 32001 Jhongli, Taiwan

Hamburger Sternwarte, Universität Hamburg, Gojenbergsweg 112, 21029 Hamburg, Germany

Ruhr University Bochum, Faculty of Physics and Astronomy, Astronomical Institute, 44780 Bochum, Germany

Department of Physics, University of Genova and INFN, Via Dodecaneso 33, 16146, Genova, Italy

Laboratoire de physique des 2 infinis Irène Joliot-Curie, CNRS Université Paris-Saclay, Bât. 100, F-91405 Orsay Cedex, France

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Pevensey Building, University of Sussex, Brighton, BN1 9QH, UK

Department of Physics, Baylor University, One Bear Place #97316, Waco, TX 76798-7316, USA

Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas, Medioambientales y Tecnológicas (CIEMAT), Madrid, Spain

Austin Peay State University, Department of Physics, Engineering and Astronomy, P.O. Box 4608, Clarksville, TN 37044, USA

Physics Department, Lancaster University, Lancaster, LA1 4YB, UK

University of Zurich, Physics Institute, Winterthurerstrasse 190/Building 36, 8057 Zürich, Switzerland

Computer Science and Mathematics Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN 37831, USA

Aix Marseille Univ, CNRS/IN2P3, CPPM, Marseille, France

Centre for Space Studies, American Public University System, 111 West Congress Street, Charles Town, WV 25414, USA

Department of Physics, Stanford University, 382 Via Pueblo Mall, Stanford, CA 94305, USA

Universitäts-Sternwarte, Fakultät für Physik, Ludwig-Maximilians Universität München, Scheinerstr. 1, 81679 München, Germany

Received 2024 January 8; revised 2024 March 18; accepted 2024 March 28; published 2024 October 1

Abstract

We present cosmological constraints from the sample of Type Ia supernovae ( SNe Ia) discovered and measured during the full 5 yr of the Dark Energy Survey (DES) SN program. In contrast to most previous cosmological samples, in which SNe are classified based on their spectra, we classify the DES SNe using a machine learning algorithm applied to their light curves in four photometric bands. Spectroscopic redshifts are acquired from a dedicated follow-up survey of the host galaxies. After accounting for the likelihood of each SN being an SN Ia, we find 1635 DES SNe in the redshift range

. Including Planck cosmic microwave background, Sloan Digital Sky Survey baryon acoustic oscillation, and DES pt data gives . In all cases, dark energy is consistent with a cosmological constant to within . Systematic errors on cosmological parameters are subdominant compared to statistical errors; these results thus pave the way for future photometrically classified SN analyses.

1. Introduction

(M. Betoule et al. 2014; D. M. Scolnic et al. 2018; Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2019). We also highlight that the most critical sources of systematics are those related to the lack of a homogeneous and well-calibrated low-z sample.

2. Data and Analysis

2.1. DES and Low-redshift SNe

DES-SN5YR analysis overview

Data:

- Calibration (Burke et al. 2018, Brout et al. 2022, Rykoff et al. 2023)

- SN photometry (Brout et al. 2019, Sanchez et al. 2024)

- SN spectroscopy (Smith et al. 2020a)

- DCR and chrom (Lasker et al. 2018, Lee&Acevedo et al. 2023)

- Host galaxy redshifts and properties (Lidman et al. 2020, Carr et al. 2021, Wiseman et al. 2020/2021, Kelsey et al. 2023)

Simulations:

- Survey selection effects (Kessler et al. 2019a, Vincenzi et al. 2020)

- SN Ia intrinsic and dust properties (Brout&Scolnic 2021, Popovic et al. 2021a/b, Wiseman et al. 2022) and rates (Wiseman et al. 2021)

- Contamination (Vincenzi et al. 2019/2020, Kessler et al. 2019b)

Analysis:

- Light-curve fitting (Taylor et al. 2023)

- “BEAMS” and bias corrections (Kessler & Scolnic 2017), unbinning the SN Hubble diagram (Brout et al. 2020, Kessler et al. 2023)

-Effects of host galaxy mismatch (Qu et al. 2023) - Cosmological contour validation (Armstrong et al. 2023)

Cosmological results: DES Collaboration 2024

2.2. From Light Curves to Hubble Diagram

above the step or – if below. This correction has historically been described as a “mass step,” but we also consider the possibility that it is a “color step” (see Section 2.2 of M. Vincenzi et al. 2024),

see Table 10 and Section 7.1.5 of M. Vincenzi et al. 2024). Classifiers are trained using core-collapse and peculiar SN Ia simulations based on M. Vincenzi et al. (2021) and state-of-theart SED templates by R. Kessler et al. (2019b) and M. Vincenzi et al. (2019). These DES simulations are the first to robustly reproduce the contamination observed in the Hubble residuals (M. Vincenzi et al. 2021, 2024, Table 10).

P. Armstrong et al. (2023) present validation of the cosmological contours produced by our pipeline. Validation that our analysis pipeline is insensitive to the cosmological model assumed in our bias correction simulation appears in R. Camilleri et al. (2024).

2.3. Unblinding Criteria

- Accuracy of simulations. The reduced

between the distribution of data and simulations across a variety of observables (redshift, SALT3 parameters and goodness of fit, maximum signal-to-noise ratio at peak, host stellar mass) is required to be between 0.7 and 3.0 (see Figures 3 and 4 of M. Vincenzi et al. 2024). - Pipeline validation using DES simulations. Demonstrate that our pipeline recovers the input cosmology. We produce 25 data-size simulated samples (statistically independent) assuming a flat

CDM Universe with a best-fit Planck value of and analyze them the same way as real data. We fit each Hubble diagram assuming a flat CDM model with a Planck prior and find a mean bias of , where is the mean value of the marginalized posterior of the dark energy equation-of-state parameter over the 25 samples and is the model value of that parameter input to the simulation. - Validation of contours. Ensuring that our uncertainty limits accurately represent the likelihood of the models (P. Armstrong et al. 2023).

- Independence of reference cosmology. Ensuring that our results are sufficiently independent of cosmological assumptions that enter our bias correction simulations (R. Camilleri et al. 2024).

2.4. Combining SNe with Other Cosmological Probes

- Cosmic microwave background (CMB) measurements of the temperature and polarization power spectra (TTTEEE) presented by the Planck Collaboration (2020). We use the Python implementation of Planck’s 2015 Plik_lite (H. Prince & J. Dunkley 2019).

- Weak-lensing and galaxy clustering measurements from the DES3

pt year 3 magnitude-limited (MagLim) lens sample; pt refers to the simultaneous fit of three two-point correlation functions, namely, galaxy-galaxy, galaxy-lensing, and lensing-lensing correlations (Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2022, 2023). - Baryon acoustic oscillation (BAO) measurements as presented in the extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (eBOSS) paper (K. S. Dawson et al. 2016; S. Alam et al. 2021), which adds the BAO results from Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS)-IV (M. R. Blanton et al. 2017) to earlier SDSS BAO data. Specifically, we use “BAO” to refer to the BAO-only measurements from the main galaxy sample (A. J. Ross et al. 2015), BOSS (SDSS-III; S. Alam et al. 2017), eBOSS LRG (J. E. Bautista et al. 2021), eBOSS ELG (A. de Mattia et al. 2021), eBOSS QSO (J. Hou et al. 2021), and eBOSS Lya (H. du Mas des Bourboux et al. 2020).

3. Models and Theory

Variations on the Standard Cosmological Model that Are Tested in This Letter, Their Friedmann Equations, and the Free Parameters in the Fit

| Cosmological Model | Friedmann Equation:

|

Fit Parameters

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Flat

|

|

|

| Flat

|

|

|

4. Results

4.1. Constraints on Cosmological Parameters

4.1.1. Flat

4.1.2.

4.1.3. Flat

Results for Four Different Cosmological Models, Sorted into Sections for Different Combinations of Observational Constraints

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DES-SN5YR (No External Priors) | |||||

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Flat

|

|

… |

|

… |

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DES-SN5YR + Planck 2020 | |||||

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

… |

|

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

… |

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DES-SN5YR + SDSS BAO and DES Y3

|

|||||

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

… |

|

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DES-SN5YR + Planck 2020 + SDSS BAO and DES Y3

|

|||||

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

|

a single, almost degeneracy-free value.

4.1.4. Flat

4.2. Goodness of Fit and Tension

4.2.1.

4.2.2. Suspiciousness

4.3. Model Selection

-2.5) is moderate evidence against (in support of) the more complex model, whereas

5. Discussion

5.1. The Big Questions

5.1.2. Is Dark Energy a Cosmological Constant?

5.1.3. How Old Is the Universe?

5.1.4. Does Our Best Fit Resolve the Hubble Tension?

5.2. Comparison with DES-SN3YR and Pantheon +

5.3. DES and Next-generation SN Samples

worked on in P. Armstrong et al. (2024, in preparation), which could vary all systematics, nuisance, and cosmological parameters at the same time to compare against the data.

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

T.M.D., A.C., R.C., and S.H. acknowledge the support of an Australian Research Council Australian Laureate Fellowship (FL180100168) funded by the Australian Government, and A.M. is supported by the ARC Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) project No. DE230100055. M.S., H.Q., and J.L. are supported by DOE grant DE-FOA-0002424 and NSF grant AST-2108094. R.K. is supported by DOE grant DE-SC0009924. M.V. was partly supported by NASA through the NASA Hubble Fellowship grant HST-HF2-51546.001-A awarded by the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under NASA contract NAS5-26555. L.K. thanks the UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship for support through the grant MR/T01881X/1. L.G. acknowledges financial support from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MCIN), the Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) 10.13039/501100011033, and the European Social Fund (ESF) “Investing in your future” under the 2019 Ramón y Cajal program RYC2019-027683-I and the PID2020-115253GA-I00 HOSTFLOWS project, from Centro Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC) under the PIE project 20215AT016, and the program Unidad de Excelencia María de Maeztu CEX2020-001058-M, and from the Departament de Recerca i Universitats de la Generalitat de Catalunya through the 2021-SGR-01270 grant. R.J.F. and D.S. were supported in part by NASA grant 14-WPS140048. The UCSC team is supported in part by NASA grants NNG16PJ34G and NNG17PX03C issued through the Roman Science Investigation Teams Program; NSF grants AST-1518052 and AST-1815935; NASA through grant No. AR-14296 from the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by AURA, Inc., under NASA contract NAS 5-26555; the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation; the Heising-Simons Foundation; and fellowships from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation to R.J.F. We acknowledge the University of Chicago’s Research Computing Center for their support of this work.

among the California Institute of Technology, the University of California, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (PIs: Foley, Kirshner, and Nugent). The Observatory was made possible by the generous financial support of the W. M. Keck Foundation. This Letter includes results based on data gathered with the 6.5 m Magellan Telescopes located at Las Campanas Observatory, Chile (PI: Foley), and the Southern African Large Telescope (SALT; PIs: M. Smith & E. Kasai). The authors wish to recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that the summit of Maunakea has always had within the Native Hawaiian community. We are most fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct observations from this mountain.

Appendix A

Data Release and How to Use the DES-SN5YR Data

Appendix B Priors

Priors

| Parameter | Prior | ||

| Cosmology—baseline | |||

|

|

Flat | (0.55, 0.91) | |

|

|

Flat | (0.1, 0.9) | |

|

|

Flat | (0.5, 5.0) | |

|

|

Flat | (0.87, 1.07) | |

|

|

Flat | (0.03, 0.07) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (0.067, 0.023) | |

|

|

Flat | (0.06, 0.6) | |

| Lens Galaxy Bias | |||

|

|

Flat | (0.8, 3.0) | |

| Lens Magnification | |||

|

|

Fixed | 0.42 | |

|

|

Fixed | 0.30 | |

|

|

Fixed | 1.76 | |

|

|

Fixed | 1.94 | |

| Lens photo-z | |||

|

|

Gaussian | (-0.9, 0.7) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (-3.5, 1.1) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (-0.5, 0.6) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (-0.7, 0.6) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (0.98, 0.06) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (1.31, 0.09) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (0.87, 0.05) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (0.92, 0.05) | |

| Intrinsic Alignment | |||

|

|

Flat | (-5, 5) | |

|

|

Flat | (-5, 5) | |

|

|

Flat |

|

|

|

|

Fixed | 0.62 | |

| Source photo-z | |||

|

|

Gaussian | (0.0, 1.8) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (0.0, 1.5) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (0.0, 1.1) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (0.0, 1.7) | |

| Shear Calibration | |||

|

|

Gaussian | (-0.6, 0.9) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (-2.0, 0.8) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (-2.4, 0.8) | |

|

|

Gaussian | (-3.7, 0.8) | |

| Model | Parameter | Prior | |

| Extended Models | |||

|

|

|

Flat | (-0.5, 0.5) |

| Flat

|

|

Flat | (-2, 0) |

| Flat

|

|

Flat | (-10, 5) |

|

|

Flat | (-20, 10) | |

where the last step assumes a constant prior for each of the

where using (

Appendix C

Tests on Subsets of Our Data

Results Using DES Data Alone (Excluding Low-

|

|

|

|

Shift Significance | |

| DES SNe without Low-z | ||||

| Flat

|

|

… | … |

|

| Flat

|

|

|

… |

|

| Flat

|

|

|

… |

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

| DES SNe without High-z | ||||

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

| Flat

|

|

|

|

|

this approach, we measure a

we use an approximation of a CMB-like prior that uses the

the flat

ORCID iDs

O. Alves © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7394-9466

J. Annis © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0609-3987

P. Armstrong © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1997-3649

K. Bechtol © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8156-0429

P. H. Bernardinelli © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0743-9422

G. M. Bernstein © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8613-8259

E. Bertin © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3602-3664

S. Bocquet (10) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4900-805X

D. Brooks © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8458-5047

D. Brout © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5201-8374

D. L. Burke © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1866-1950

A. Carnero Rosell © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3044-5150

D. Carollo © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4710-132X

A. Carr © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4074-5659

J. Carretero © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3130-0204

F. J. Castander © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7316-4573

C. Chang © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7887-0896

R. Chen © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3917-0966

C. Conselice © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1949-7638

L. N. da Costa © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7731-277X

M. Crocce (10) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9745-6228

T. M. Davis © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4213-8783

S. Desai © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0466-3288

H. T. Diehl © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8357-7467

C. Doux © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4480-0096

A. Drlica-Wagner © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8251-933X

J. Elvin-Poole © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5148-9203

I. Ferrero © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1295-1132

R. J. Foley © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2445-5275

P. Fosalba (10) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1510-5214

D. Friedel © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3632-7668

C. Frohmaier © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9553-4723

J. García-Bellido © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9370-8360

E. Gaztanaga © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9632-0815

K. Glazebrook © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3254-9044

O. Graur © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4391-6137

R. A. Gruendl © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4588-6517

S. R. Hinton © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2071-9349

D. L. Hollowood © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9369-4157

D. Huterer © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6558-0112

D. J. James © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5160-4486

S. Kent © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4207-7420

R. Kessler © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3221-0419

A. G. Kim (10) https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6315-8743

E. Kovacs © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2545-1989

K. Kuehn © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0120-0808

J. Lee © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6633-9793

G. F. Lewis © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3081-9319

T. S. Li © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9110-6163

C. Lidman © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1731-0497

H. Lin © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7825-3206

P. Martini © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0194-4017

J. Mena-Fernández © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9497-7266

F. Menanteau © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1372-2534

R. Miquel © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6610-4836

J. Mould (10) https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3820-1740

E. Neilsen © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7357-0317

P. Nugent © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3389-0586

R. L. C. Ogando © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2120-1154

Y.-C. Pan © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8415-6720

A. Pieres © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9186-6042

H. Qu © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1899-9791

A. K. Romer © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9328-879X

A. Roodman © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5326-3486

M. Sako © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2764-7093

E. Sanchez © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9646-8198

J. Allyn. Smith © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6261-4601

M. Smith © https://orcid.org/000-0002-3321-1432

M. Soares-Santos © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6082-8529

E. Suchyta © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7047-9358

M. Sullivan © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9053-4820

N. Suntzeff © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8102-181

M. E. C. Swanson (10) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1488-8552

G. Tarle © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1704-078

D. Thomas © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6325-5671

C. To © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7836-2261

B. E. Tucker (10) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4283-5159

D. L. Tucker © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7211-5729

S. A. Uddin (10) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9413-4186

A. R. Walker © https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7123-8943

N. Weaverdyck © https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9382-5199

R. H. Wechsler © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2229-011X

W. Wester © https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0072-6736

References

Alam, S., Aubert, M., Avila, S., et al. 2021, PhRvD, 103, 083533

Alard, C., & Lupton, R. H. 1998, ApJ, 503, 325

Aleo, P. D., Malanchev, K., Sharief, S., et al. 2023, ApJS, 266, 9

Armstrong, P., Qu, H., Brout, D., et al. 2023, PASA, 40, e038

Astropy Collaboration 2013, A&A, 558, A33

Astropy Collaboration 2018, AJ, 156, 123

Bautista, J. E., Paviot, R., Vargas Magaña, M., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 500, 736

Bernstein, J. P., Kessler, R., Kuhlmann, S., et al. 2012, ApJ, 753, 152

Bertin, E., & Arnouts, S. 1996, A&AS, 117, 393

Betoule, M., Kessler, R., Guy, J., et al. 2014, A&A, 568, A22

Blanton, M. R., Bershady, M. A., Abolfathi, B., et al. 2017, AJ, 154, 28

Brout, D., Hinton, S. R., & Scolnic, D. 2021, ApJL, 912, L26

Brout, D., & Scolnic, D. 2021, ApJ, 909, 26

Brout, D., Scolnic, D., Kessler, R., et al. 2019a, ApJ, 874, 150

Brout, D., Sako, M., Scolnic, D., et al. 2019b, ApJ, 874, 106

Brout, D., Scolnic, D., Popovic, B., et al. 2022a, ApJ, 938, 110

Brout, D., Taylor, G., Scolnic, D., et al. 2022b, ApJ, 938, 111

Burke, D. L., Rykoff, E. S., Allam, S., et al. 2018, AJ, 155, 41

Camilleri, R., Davis, T. M., Vincenzi, M., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 533, 2615

Chaboyer, B., Demarque, P., Kernan, P. J., & Krauss, L. M. 1998, ApJ, 494, 96

Chen, R., Scolnic, D., Rozo, E., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, 62

Chen, R., Scolnic, D., Rozo, E., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, 62

Chevallier, M., & Polarski, D. 2001, IJMPD, 10, 213

Childress, M. J., Lidman, C., Davis, T. M., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 472, 273

Cimatti, A., & Moresco, M. 2023, ApJ, 953, 149

Conley, A., Guy, J., Sullivan, M., et al. 2011, ApJS, 192, 1

Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2016, MNRAS, 460, 1270

Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2019, ApJL, 872, L30

Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2022, PhRvD, 105, 023520

Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2023, PhRvD, 107, 083504

Dawson, K. S., Kneib, J.-P., Percival, W. J., et al. 2016, AJ, 151, 44

de Mattia, A., Ruhlmann-Kleider, V., Raichoor, A., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 501, 5616

Di Valentino, E., Mena, O., Pan, S., et al. 2021, CQGra, 38, 153001

Diehl, H. T., Neilsen, E., Gruendl, R., et al. 2016, Proc. SPIE, 9910, 99101D

Diehl, H. T., Neilsen, E., Gruendl, R. A., et al. 2018, Proc. SPIE, 10704, 107040D

Dixon, M., Lidman, C., Mould, J., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 517, 4291

du Mas des Bourboux, H., Rich, J., Font-Ribera, A., et al. 2020, ApJ, 901, 153

Duarte, J., González-Gaitán, S., Mourao, A., et al. 2023, A&A, 680, A56

Fioc, M., & Rocca-Volmerange, B. 1999, arXiv:astro-ph/9912179

Flaugher, B., Diehl, H. T., Honscheid, K., et al. 2015, AJ, 150, 150

Foley, R. J., Scolnic, D., Rest, A., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 475, 193

Foreman-Mackey, D., Hogg, D. W., Lang, D., & Goodman, J. 2013, PASP, 125, 306

Ganeshalingam, M., Li, W., & Filippenko, A. V. 2013, MNRAS, 433, 2240

Gilliland, R. L., Nugent, P. E., & Phillips, M. M. 1999, ApJ, 521, 30

Gratton, R. G., Pecci, F. F., Carretta, E., et al. 1997, ApJ, 491, 749

Gupta, R. R., Kuhlmann, S., Kovacs, E., et al. 2016, AJ, 152, 154

Handley, W. 2019, JOSS, 4, 1414

Handley, W., & Lemos, P. 2019, PhRvD, 100, 023512

Handley, W. J., Hobson, M. P., & Lasenby, A. N. 2015, MNRAS, 450, L61

Harris, C. R., Millman, K. J., van der Walt, S. J., et al. 2020, Natur, 585, 357

Hicken, M., Challis, P., Jha, S., et al. 2009, ApJ, 700, 331

Hicken, M., Challis, P., Kirshner, R. P., et al. 2012, ApJS, 200, 12

Hinton, S., & Brout, D. 2020, JOSS, 5, 2122

Hinton, S. 2016, JOSS, 1, 00045

Hlozek, R., Kunz, M., Bassett, B., et al. 2012, ApJ, 752, 79

Hou, J., Sánchez, A. G., Ross, A. J., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 500, 1201

Hunter, J. D. 2007, CSE, 9, 90

Ivezić, Ž., Kahn, S. M., Tyson, J. A., et al. 2019, ApJ, 873, 111

James, F., & Roos, M. 1975, CoPhC, 10, 343

Jennings, E., Wolf, R., & Sako, M. 2016, arXiv:1611.03087

Jones, D. O., Foley, R. J., Narayan, G., et al. 2021, ApJ, 908, 143

Jones, D. O., Scolnic, D. M., Foley, R. J., et al. 2019, ApJ, 881, 19

Jones, D. O., Scolnic, D. M., Riess, A. G., et al. 2018, ApJ, 857, 51

Kelsey, L., Sullivan, M., Wiseman, P., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 519, 3046

Kenworthy, W. D., Jones, D. O., Dai, M., et al. 2021, ApJ, 923, 265

Kessler, R., & Brout, D. 2020, SNDATA_ROOT for SNANA software, v4, Zenodo, doi:10.5281/zenodo. 4015325

Kessler, R., Bernstein, J. P., Cinabro, D., et al. 2009, PASP, 121, 1028

Kessler, R., Brout, D., D’Andrea, C. B., et al. 2019a, MNRAS, 485, 1171

Kessler, R., Guy, J., Marriner, J., et al. 2013, ApJ, 764, 48

Kessler, R., Marriner, J., Childress, M., et al. 2015, AJ, 150, 172

Kessler, R., Narayan, G., Avelino, A., et al. 2019b, PASP, 131, 094501

Kessler, R., & Scolnic, D. 2017, ApJ, 836, 56

Kessler, R., Vincenzi, M., & Armstrong, P. 2023, ApJL, 952, L8

Komatsu, E., Dunkley, J., Nolta, M. R., et al. 2009, ApJS, 180, 330

Krisciunas, K., Contreras, C., Burns, C. R., et al. 2017, AJ, 154, 211

Kunz, M., Bassett, B. A., & Hlozek, R. A. 2007, PhRvD, 75, 103508

Kunz, M., Hlozek, R., Bassett, B. A., et al. 2012, in Astrostatistical Challenges for the New Astronomy, ed. J. M. Hilbe (New York: Springer), 63

Lahav, O., Calder, L., Mayers, J., & Frieman, J. 2020, The Dark Energy Survey (Singapore: World Scientific), https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/pdf/ 10.1142/q0247

Lee, J., Acevedo, M., Sako, M., et al. 2023, AJ, 165, 222

Lemos, P., Raveri, M., Campos, A., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 505, 6179

Lidman, C., Tucker, B. E., Davis, T. M., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 496, 19

Linder, E. V. 2003, PhRvL, 90, 091301

Marriner, J., Bernstein, J. P., Kessler, R., et al. 2011, ApJ, 740, 72

Meldorf, C., Palmese, A., Brout, D., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 518, 1985

Mitra, A., Kessler, R., More, S., Hlozek, R. & LSST Dark Energy Science Collaboration 2023, ApJ, 944, 212

Möller, A., & de Boissiere, T. 2020, MNRAS, 491, 4277

Möller, A., Smith, M., Sako, M., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 514, 5159

Pandas development team 2020, Zenodo: pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas, v2.2.2, Zenodo, doi:10.5281/zenodo. 3509134

Perlmutter, S., Aldering, G., Goldhaber, G., et al. 1999, ApJ, 517, 565

Phillips, M. M., Lira, P., Suntzeff, N. B., et al. 1999, AJ, 118, 1766

Planck Collaboration 2020, A&A, 641, A6

Popovic, B., Brout, D., Kessler, R., & Scolnic, D. 2023, ApJ, 945, 84

Popovic, B., Brout, D., Kessler, R., Scolnic, D., & Lu, L. 2021, ApJ, 913, 49

Popovic, B., Scolnic, D., Vincenzi, M., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 529, 2100

Prince, H., & Dunkley, J. 2019, PhRvD, 100, 083502

Pskovskii, I. P. 1977, SvA, 21, 675

Qu, H., Sako, M., Möller, A., & Doux, C. 2021, AJ, 162, 67

Qu, H., Sako, M., Vincenzi, M., et al. 2024, ApJ, 964, 134

Riess, A. G., Filippenko, A. V., Challis, P., et al. 1998, AJ, 116, 1009

Riess, A. G., Nugent, P. E., Gilliland, R. L., et al. 2001, ApJ, 560, 49

Riess, A. G., Rodney, S. A., Scolnic, D. M., et al. 2018, ApJ, 853, 126

Riess, A. G., Strolger, L.-G., Tonry, J., et al. 2004, ApJ, 607, 665

Riess, A. G., Strolger, L.-G., Casertano, S., et al. 2007, ApJ, 659, 98

Rose, B. M., Baltay, C., Hounsell, R., et al. 2021, arXiv:2111.03081

Ross, A. J., Samushia, L., Howlett, C., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 449, 835

Rubin, D., Aldering, G., Betoule, M., et al. 2023, arXiv:2311.12098

Ruhlmann-Kleider, V., Lidman, C., & Möller, A. 2022, JCAP, 2022, 065

Rust, B. W. 1974, PhD thesis, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Tennessee

Rykoff, E. S. 2023, Rykoff, Eli S. 2023. “The Dark Energy Survey Six-Year Calibration Star Catalog”, FERMILAB-TM-2784-PPD-SCD, Fermi Technical Note, doi:10.2172/1973601

Sako, M., Bassett, B., Becker, A. C., et al. 2018, PASP, 130, 064002

Sánchez, B. O., Brout, D., Vincenzi, M., et al. 2024, arXiv:2406.05046

Sánchez, B. O., Kessler, R., Scolnic, D., et al. 2022, ApJ, 934, 96

Scolnic, D., Brout, D., Carr, A., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, 113

Scolnic, D. M., Jones, D. O., Rest, A., et al. 2018, ApJ, 859, 101

Sevilla-Noarbe, I., Bechtol, K., Kind, M. C., et al. 2021, ApJS, 254, 24

Smith, M., D’Andrea, C. B., Sullivan, M., et al. 2020a, AJ, 160, 267

Smith, M., Sullivan, M., Wiseman, P., et al. 2020b, MNRAS, 494, 4426

Stevens, A. R. H., Bellstedt, S., Elahi, P. J., & Murphy, M. T. 2020, NatAs, 4, 843

Sullivan, M., Le Borgne, D., Pritchet, C. J., et al. 2006, ApJ, 648, 868

Sullivan, M., Guy, J., Conley, A., et al. 2011, ApJ, 737, 102

Suzuki, N., Rubin, D., Lidman, C., et al. 2012, ApJ, 746, 85

Swann, E., Sullivan, M., Carrick, J., et al. 2019, Msngr, 175, 58

Taylor, G., Jones, D. O., Popovic, B., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 520, 5209

The Dark Energy Survey Collaboration 2005, arXiv:astro-ph/0510346

Tripp, R. 1998, A&A, 331, 815

Trotta, R. 2008, ConPh, 49, 71

Valcin, D., Bernal, J. L., Jimenez, R., Verde, L., & Wandelt, B. D. 2020, JCAP, 2020, 002

VandenBerg, D. A., Bolte, M., & Stetson, P. B. 1996, ARA&A, 34, 461

Vincenzi, M., Sullivan, M., Firth, R. E., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 489, 5802

Vincenzi, M., Sullivan, M., Graur, O., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 505, 2819

Vincenzi, M., Sullivan, M., Möller, A., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 518, 1106

Vincenzi, M., Brout, D., Armstrong, P., et al. 2024, arXiv:2401.02945

Virtanen, P., Gommers, R., Oliphant, T. E., et al. 2020, NatMe, 17, 261

Wiseman, P., Smith, M., Childress, M., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 495, 4040

Wiseman, P., Sullivan, M., Smith, M., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 506, 3330

Wiseman, P., Vincenzi, M., Sullivan, M., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 515, 4587

Ying, J. M., Chaboyer, B., Boudreaux, E. M., et al. 2023, AJ, 166, 18

Yuan, F., Lidman, C., Davis, T. M., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 452, 3047

Zuntz, J., Paterno, M., Jennings, E., et al. 2015, A&C, 12, 45

The SALT3 model consists of a spectral flux density as a function of phase and wavelength for SNe Ia. Its three components are describing the mean SN light curve, describing the deviations from that are correlated with light-curve width, and CL describing the color dependence. See Equation (1) of G. Taylor et al. (2023). - 93 Following J. Marriner et al. (2011), we replace the traditional

notation with , because in the SALT2 and SALT3 models, the amplitude term, , is not related to any particular filter band. Applying a binary-classification-based cut (SN Ia or not) is not optimal, as it assumes that the classification is perfect. However, we test the binary-cut-based approach by using only the 1499 SNe classified with and assuming they are a pure SN Ia sample. We show that the measured shift in is small compared to the statistical uncertainties (Table 11 of M. Vincenzi et al. 2024). When , the term becomes and can be calculated directly from Equation (2), bypassing the infinite . For each emcee fit, we use a number of walkers that is at least twice the number of parameters and ensure that the number of samples in the chain is greater than 50 times the autocorrelation function, . For each PolyChord fit, we use a minimum of 60 live points, 30 repeats, and an evidence tolerance requirement of 0.1 (except for CDM with all data sets combined, for which we accepted a slightly weaker tolerance because convergence was too slow). When combining with other data sets, we run simultaneous MCMC chains including all relevant data vectors. Flat priors that encapsulate at least the confidence region were chosen in each case, and we summarize those priors in Appendix B.

The main advantage of emcee is that it gives a slightly more accurate bestfit than PolyChord. However, we decided that the tiny improvement in accuracy was not worth the environmental impact (A. R. H. Stevens et al. 2020) of the extra compute time (which was substantial for the many-dataset fits). - 98 The distribution of points around the Hubble diagram is not perfectly Gaussian, as it is skewed due to lensing magnification and non-SN-Ia contamination. This means that the

values (especially at high ) are only approximate. Similar to the parameter used in lensing studies to approximate constraints. Suspiciousness, , is related to the Bayes ratio and Bayesian information and is defined as . If . If , Gyr. Not all events included in the DES-SN3YR analysis are included in the DES-SN5YR analysis, and vice versa. This is due to the two analyses implementing different sample cuts. For example, the cut and the requirement for a host galaxy redshift in DES-SN5YR exclude, respectively, 44 and 29 low-z SNe that were in the DES-SN3YR sample. DES-SN5YR also uses a new SALT model (which affects the SALT-based cuts) and is restricted to SNe that pass selection cuts across all systematic tests (see Table 4 in M. Vincenzi et al. 2024).

The redshift at which the Universe began accelerating in CDM is . These upcoming low- surveys are magnitude-limited rather than targeted; therefore, they provide SN samples with a well-defined selection function. - Note.

We also used some specific variations of the above baseline priors. For the CDM model using the DES-SN5YR only, ; using DESSN5YR + SDSS BAO and DES Y3 ; and using DES-SN5YR + Planck SDSS BAO and DES Y3 pt, . For the flat CDM model using DES-SN5YR + Planck , and finally, for the flat model using DESSN5YR + SDSS BAO and DES Y3 .