DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01679-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38169461

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-03

الأيض الخلوي للزنك وإشارات الزنك: من الوظائف البيولوجية إلى الأمراض والأهداف العلاجية

الملخص

يعد أيض الزنك على المستوى الخلوي أمرًا حيويًا للعديد من العمليات البيولوجية في الجسم. من الملاحظات الرئيسية هو اضطراب التوازن الخلوي، الذي غالبًا ما يتزامن مع تقدم المرض. باعتباره عاملًا أساسيًا في الحفاظ على التوازن الخلوي، أصبح الزنك الخلوي محط اهتمام متزايد في سياق تطور الأمراض. تشير الأبحاث المكثفة إلى تورط الزنك في تعزيز الخباثة والغزو في خلايا السرطان، على الرغم من تركيزه المنخفض في الأنسجة. وقد أدى ذلك إلى تزايد الأدبيات التي تحقق في أيض الزنك الخلوي، لا سيما وظائف ناقلات الزنك وآليات التخزين خلال تقدم السرطان. يخضع نقل الزنك لسيطرة عائلتين رئيسيتين من الناقلات: SLC30 (ZnT) لإفراز الزنك وSLC39 (ZIP) لامتصاص الزنك. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يتم تخزين هذا العنصر الأساسي بشكل رئيسي بواسطة الميتالوثيونينات (MTs). تجمع هذه المراجعة المعرفة حول الوظائف الحيوية لإشارات الزنك الخلوية وتبرز المسارات الجزيئية المحتملة التي تربط أيض الزنك بتقدم المرض، مع تركيز خاص على السرطان. كما نلخص التجارب السريرية التي تشمل أيونات الزنك. نظرًا للتموضع الرئيسي لناقلات الزنك على غشاء الخلية، فإن الإمكانيات للعلاجات المستهدفة، بما في ذلك الجزيئات الصغيرة والأجسام المضادة وحيدة النسيلة، تقدم آفاقًا واعدة للاستكشاف المستقبلي.

مقدمة

(ZnT) وSLC39 (بروتينات شبيهة بـ Zrt وIrt/ZIP)، بالإضافة إلى البروتينات المرتبطة بالزنك (MTs).

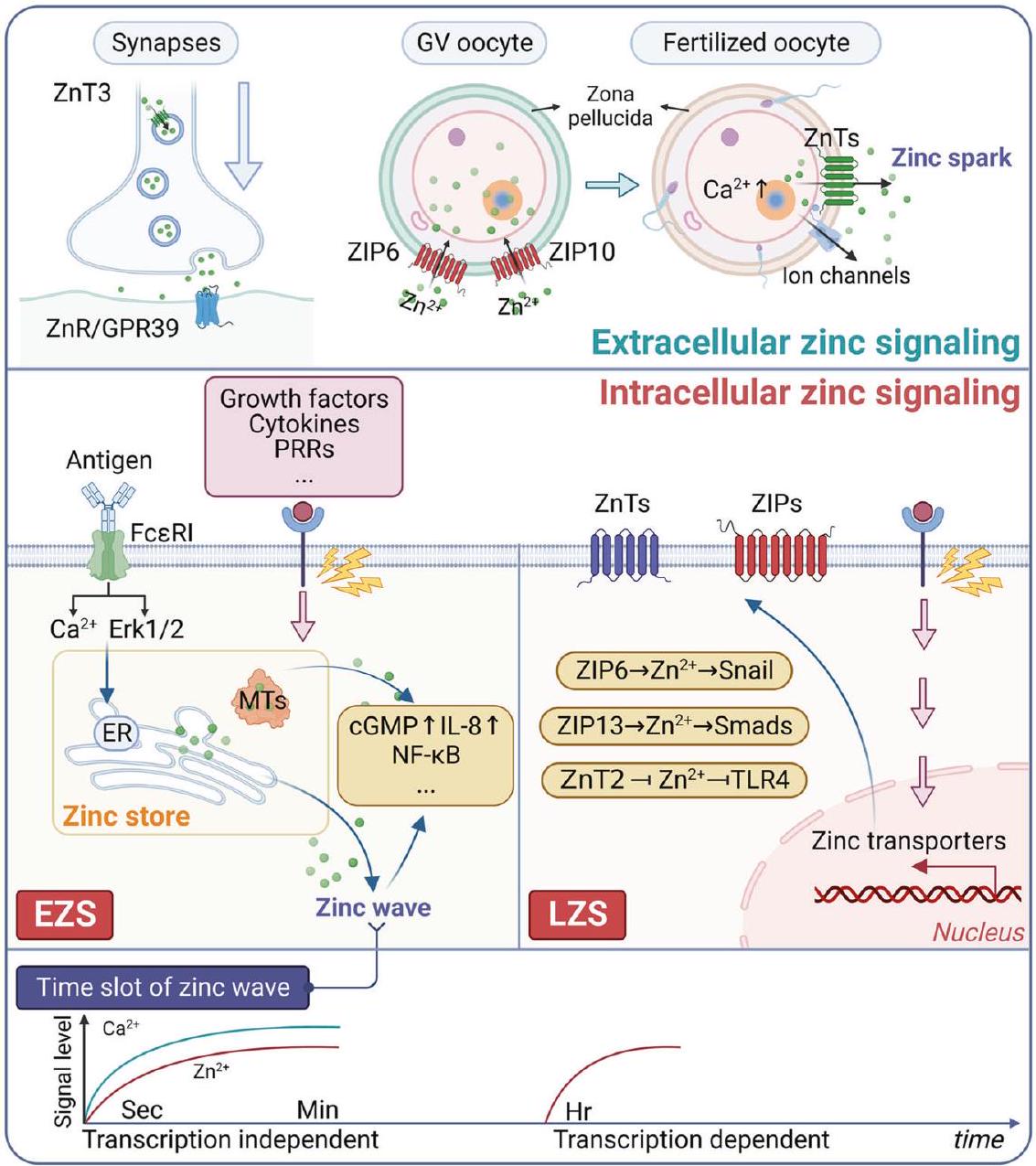

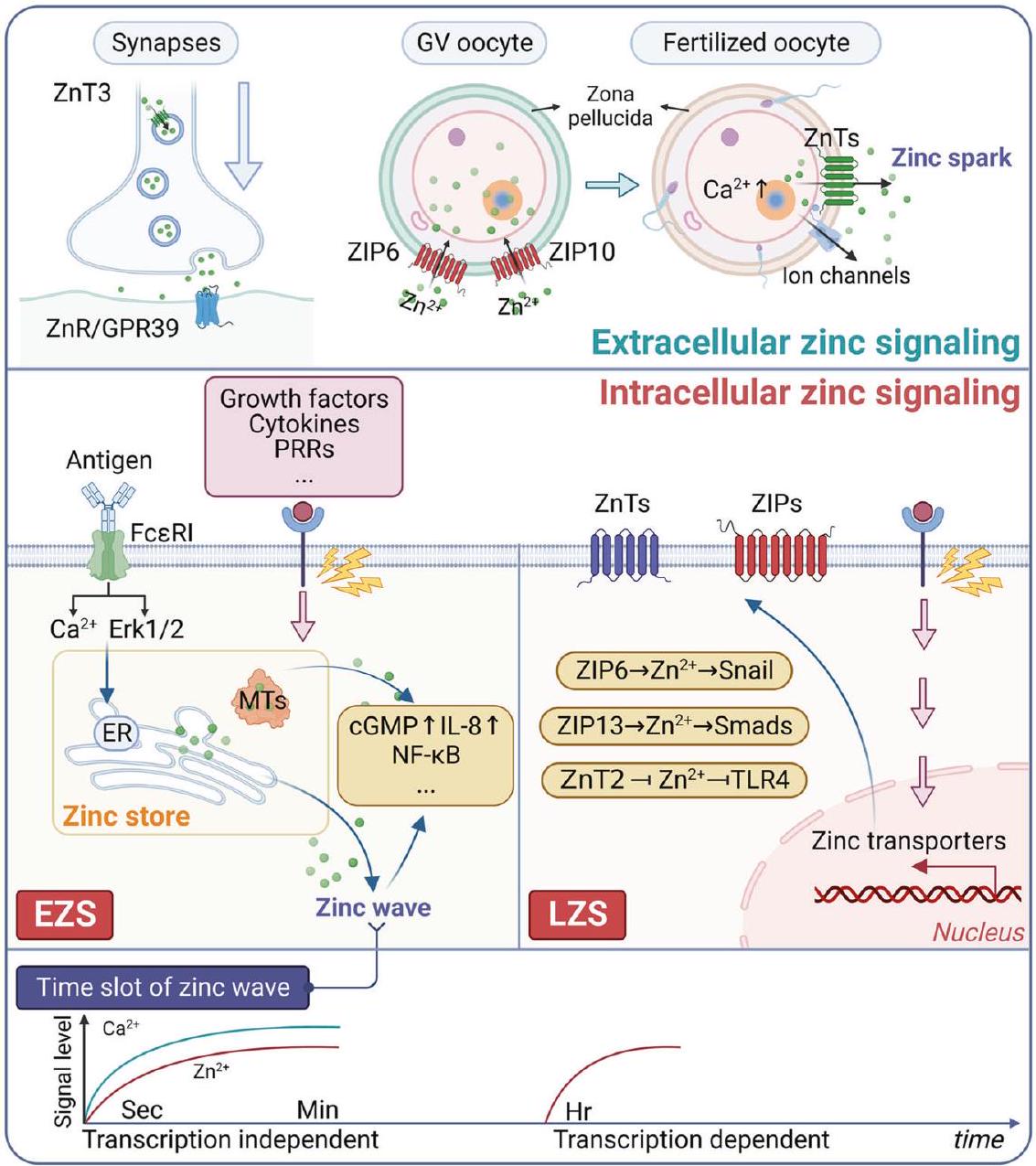

تنظيم إشارات الزنك الخلوية

توزيع الزنك

الإشارات الخلوية للزنك

الذي يساعد في الحفاظ على تركيز الزنك في نطاق البيكو مول في السيتوسول.

الإشارات الزنك خارج الخلية

الإشارات الزنك وتكوّن الأورام

تجسيد الأنشطة الحالية للخلايا، مثل الوظيفة، والنمو، والتكاثر. تفسر عدة آليات الوظيفة المضادة للأورام للزنك، وتشمل تلف الحمض النووي، وإصلاح الحمض النووي، ووظيفة الجهاز المناعي، والإجهاد التأكسدي، والالتهاب.

المسار في سرطان البلعوم الأنفي (NPC).

تنظيم أيض الزنك الخلوي

مُجمّعات ZIP. تتألف عائلة SLC39 من أربع مجموعات متميزة بناءً على تشابه تسلسل الأحماض الأمينية: العائلة الفرعية الأولى (ZIP9)؛ العائلة الفرعية الثانية (ZIP1، 2، و3)؛ العائلة الفرعية LIV-1 (ZIP4، 5، 6، 7، 8، 10، 12، 13، و14)؛ والعائلة الفرعية gufA التي تحتوي على ZIP11.

امتصاص أيونات المعادن إلى داخل الخلايا. يقع ZIP7 في جهاز جولجي والشبكة الإندوبلازمية، بينما ZIP13، الأقرب تطوريًا إلى ZIP7، يتموضع في جهاز جولجي والحويصلات السيتوبلازمية.

في تخزين الأنسولين، ZnT 4 في إفراز البروستاتا، وZnT 2 في الرضاعة.

عضو في بروتينات ناقل الزنك ZnT في الثدييات.

المتالثيونينات الثديية هي عائلة فائقة من الببتيدات غير الإنزيمية التي تتكون عادة من 61-68 حمضًا أمينيًا.

دور أيض الزنك الخلوي تحت الظروف الفسيولوجية

دعم وظيفة الجهاز المناعي. تعتبر الخلايا التائية مكونًا حيويًا في الجهاز المناعي.

متمركزة بشكل رئيسي في طوافات الدهون المشاركة في تكوين المشبك المناعي (IS) بعد تحفيز مستقبلات الخلايا التائية (TCR).

يتم التوسط بواسطة ZIP7، حيث أن ZIP7 يتواجد بشكل رئيسي في الشبكة الإندوبلازمية، ومنع إسكات ZIP باستخدام siRNA حدوث موجة الزنك.

وتشوهات في العظام والأنسجة الضامة، تعكس الأنماط الظاهرية التي لوحظت في مرضى متلازمة إهلرز-دانلوس المرتبطة بمرض الخلايا المنجلية.

المشاركة في تكاثر الخلايا، التمايز، والموت المبرمج. أظهرت العديد من الدراسات أن البروتينات المعدنية (MTs) تنظم الزنك، لا سيما فيما يتعلق بتنظيم دورة الخلية وتكاثر الخلايا.

التفريق هو وظيفة غير مباشرة، تتضمن كبت PPAR

إزالة السموم من المعادن الثقيلة، وخاصة الكادميوم والزرنيخ.

كما ذُكر سابقًا، هناك علاقة بين تغيرات مستويات الزنك وتقدم السرطان. ومع ذلك، من الضروري الاعتراف بأن طبيعة هذه العلاقة قد تختلف بين أنواع السرطان المختلفة. تؤكد التأثيرات المتعددة الأوجه للزنك في تعزيز أو تثبيط نمو الأورام على هذه التعقيدات، مع وجود آليات مميزة تعمل في أنواع السرطان المختلفة. تتراكم الأدلة الحديثة التي تشير إلى وجود صلة بين نقص الزنك وتطور السرطانات. تشارك العديد من العمليات في النشاط المضاد للأورام للزنك، بما في ذلك تلف وإصلاح الحمض النووي، التأكسج، المناعة، وعملية الالتهاب.

يُلاحظ ارتفاع تنظيمه في سرطانات الثدي الإيجابية لمستقبلات الإستروجين ويظهر ارتباطًا إيجابيًا مع حالة مستقبلات الإستروجين. خلال التكوّن الجنيني في سمك الزبرا، يتم تنشيط zip6 بواسطة STAT3. يؤدي التعبير المرتفع لـ zip6 إلى احتجاز نووي لـ Snail، المعروف أيضًا بأنه عامل نسخ يحتوي على إصبع زنك، والذي يقوم بعد ذلك بكبت تعبير E-cadherin، مما يؤدي إلى هجرة الخلايا.

تم العثور على نسيج الدماغ بمعدل ضعف ما هو موجود في خط خلايا سرطان الثدي الثلاثي السلبية MDA-MB231. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم إثبات زيادة التعبير عن ZIP8 وZIP9 وZIP13 في خلايا BrM2. يُفترض وجود علاقة بين تركيز الزنك داخل الخلايا وإمكانات انتقال خلايا سرطان الثدي.

لوحظ انخفاض التنظيم في تضخم البروستاتا الحميد (BPH)، وخلايا PC-3، والأنسجة الخبيثة للبروستاتا البشرية. يتم تعزيز تعبير MT1/2 بشكل ملحوظ بواسطة علاج الزنك في كل من خلايا PC-3 وBPH، بالتزامن مع استعادة تركيزات الزنك داخل الخلايا. على وجه التحديد، في خلايا BPH، تم تحديد MT3، الذي يعمل كعامل مثبط للنمو، وكانت مستوياته مرتفعة بفعل الزنك. علاوة على ذلك، يُعد تعبير MT3 سمة مميزة توجد حصريًا في خلايا BPH.

الأنماط الظاهرية والنتائج السريرية السيئة لدى مرضى سرطان القولون والمستقيم.

الأيض. ومن المثير للاهتمام أن هذه البروتينات الغنية بالميثيونين غالبًا ما تعمل كجينات كابحة للأورام في سرطان القولون والمستقيم. تم تحديد علاقة ملحوظة بين انخفاض تعبير MT1B أو MT1H أو MT1L وزيادة خطر النتائج السلبية.

أن MT1M لديها القدرة على تقليل الخباثة وخصائص الخلايا الجذعية لسرطان المعدة عن طريق تثبيط GLI1، وهو مكون من مكونات مسار إشارات Hedgehog، المعروف بعدد كبير من مجالات الزنك الإصبعي.

تشن وآخرون

تم التضاعف المشترك لجين SLC30A8 وSLC39A4 في جميع مرضى السرطان تقريبًا. ومن المثير للاهتمام أن الحالات التي تظهر حذفًا لجين SLC39A14 تبدو أكثر من تلك التي تظهر تضاعفًا (الشكل 8). على الرغم من أن بروتينات ZIP تُعتبر عادةً جينات مسرطنة في السرطان، إلا أن سرطان البروستاتا يشكل استثناءً. كما أشارت الدراسات إلى أن وظيفة ناقلات الزنك قد تكون متناقضة بين أنواع السرطان المختلفة. أثناء تعمقنا في التغيرات الجينية في MTs، يجذب انتباهنا التباين المذهل والمتسق الذي لوحظ بين جميع أعضاء MTs (الشكل 8). ومن الجدير بالذكر أن مجموعة البيانات القوية من مرضى الأورام النموذجيين تعرض اتجاهات متجانسة بشكل ملحوظ في التغيرات الجينية بين جميع أعضاء MTs. وتتمثل هذه التغيرات بشكل رئيسي في…

تشمل التوسعات والتسلسلات العميقة، مما يشير إلى أدوار محورية للبروتينات المعدنية في سياق السرطانات. على الرغم من الاتجاهات المماثلة في تغيرات الجينات، لوحظت ملفات تعبير mRNA مختلفة لأعضاء البروتينات المعدنية المختلفة. تشير هذه الملاحظة المثيرة إلى تورط آليات تنظيم نسخ معقدة تتحكم في جينات البروتينات المعدنية. قد تنشأ التنوع في مستويات تعبير mRNA بسبب عوامل عديدة، قد تكون مرتبطة بالسياق الخلوي، خصوصية الأنسجة، وحتى أنواع السرطان. لذلك، لا يزال البحث في ناقلات الزنك والبروتينات المعدنية في تكوين الأورام في بداياته.

الأيض الخلوي للزنك في أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية

لقد تم اقتراح أن تقليل إنتاج أكسيد النيتريك في المناطق المعرضة للتصلب العصيدي، إلى جانب زيادة تعبير ZnT 1 وMT، قد يؤدي إلى انخفاض الزنك الحر داخل الخلايا.

الصمامات من مرضى تضيق الصمام التاجي التكلسي (CAVD). التأثير المضاد للتكلس للزنك على تكلس خلايا بينية الصمام البشري (hVIC) يتم، على الأقل جزئياً، من خلال تثبيط الاستماتة والتمايز العظمي عبر مسار الإشارة ERK1/2 المعتمد على GPR39. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يلعب كل من ZIP13 وZIP14 أدوارًا مهمة في تكلس hVIC والتمايز العظمي في المختبر.

يلعب الزنك أدوارًا مختلفة في الأمراض المناعية الذاتية، بما في ذلك دوره كعامل مؤثر في الجهاز المناعي والالتهاب والتمثيل الغذائي. كما ذُكر سابقًا، تعمل عائلة ZIP وعائلة ZnT والبروتينات المعدنية (MTs) كمنظمات حاسمة لمستويات الزنك وتشارك في تطور أمراض مناعية ذاتية مختلفة، مثل إنتاج الأجسام المضادة الذاتية والاستجابات الالتهابية.

يعكس الفقدان المستمر لـ

الأيض الخلوي للزنك في الأمراض المعدية

استعادة حساسية الكاربابينيم في الأكنيتوباكتر بوماني وتحسن البقاء على قيد الحياة في الفئران المصابة بالأسبيرجيلوس فوميغاتوس عندما تم تجويع الممرضات بمُخلبات الزنك.

الحويصلات البلعومية عبر بروتينات ZIP.

تم اقتراح أن التغيرات في توازن الزنك مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بتطور بعض الأمراض التنكسية العصبية.

الأهداف العلاجية لأيض الزنك الخلوي

ناقلات الزنك

| الجدول 1. مستويات التعبير، الارتباطات السريرية المرضية، والجزيئات الصغيرة المحتملة لناقلات الزنك في التسرطن | ||||||

| عضو | نوع السرطان | تعبير | علامة تشخيصية | علامة تنبؤية | جزيئات صغيرة | المراجع |

| زيب4 | سرطان الخلايا الكبدية | مرتفع التعبير | – |

|

– | ٣٩٧ |

| الأورام الدبقية | مرتفع التعبير |

|

|

– | ٦٧٩ | |

| قيادة العمليات الخاصة التابعة للجيش الأمريكي | مرتفع التعبير |

|

– | – | ٥٨٥ | |

| الحاسوب الشخصي | مرتفع التعبير |

|

|

– | ٣٩١، ٣٩٣، ٣٩٤، ٣٩٦، ٣٩٩ | |

| شخصية غير قابلة للعب | مرتفع التعبير |

|

|

– | ٧٧ | |

| سرطان الرئة غير صغير الخلايا | مرتفع التعبير | – |

|

– | ٥٨٣ | |

| ZIP5 | ESCC | مرتفع التعبير | – | – | مي آر-193ب | ٥٩٦ |

| زيب6 | ESCC | مرتفع التعبير | – |

|

– | ٤٤٧ |

| قبل الميلاد | مرتفع التعبير |

|

|

SGN-LIV1A/LV (NCT01969643، NCT03310957، NCT03424005، NCT01042379، NCT04032704، NCT02093858) | ١٥٦٬٦٠١٬٦٨٠ | |

| جسم مضاد ZIP6-Y | ١٥٦ | |||||

| فاسلوديكس، 4-هيدروكسي تاموكسيفين | ١٥٧ | |||||

| M1S9 | ٦٠٢ | |||||

| زيب7 | قبل الميلاد | مرتفع التعبير |

|

|

دي إم إيه تي، تي بي بي | ١٦٨ |

| اللمفوما التائية الحادة | مرتفع التعبير | – |

|

NVS-ZP7-4 | ٦٠٣ | |

| زيب9 | سرطان الخلايا الكبدية | مرتفع التعبير | – |

|

– | ٦٨١ |

| سرطان المثانة | مرتفع التعبير | – |

|

دوتاستيريد | ٦٠٤٬٦٠٥ | |

| الميلانوما | مرتفع التعبير | بيكالوتاميد | ٤٦١ | |||

| زيب10 | سرطان العظم | مرتفع التعبير | – |

|

666-15، GSK690693 | ٥٨٩ |

| قبل الميلاد | مرتفع التعبير | – |

|

جسم مضاد ZIP10B | ١٥٦٬٣٣٤ | |

| GC | مرتفع التعبير | – |

|

إكس واي إيه-2 | ٦٨٢ | |

| زيب13 | سرطان المبيض | مرتفع التعبير | – |

|

– | ٧٣ |

| زيب14 | CRC تعني “رمز تصحيح الخطأ الدوري” | مرتفع التعبير | – |

|

– | ٤١٧٬٦٨٣ |

البيئة الدقيقة، تساعد خلايا السرطان على توليد مقاومة كيميائية من خلال تنظيم تركيز الزنك.

الانتشار.

| الجدول 2. إمكانية استهداف استقلاب الزنك في عدة أمراض | |||||||

| بروتين | مرض | تعبير | القيمة الحالية أو المحتملة للاستهداف | ||||

| ZIP5 | داء السكري | منخفض التعبير | الهدف العلاجي المحتمل للأمراض المرتبطة بالسكري.

|

||||

| زيب10 | مرض الدم النخاعي | منخفض التعبير | استهداف ZIP10 قد يكون استراتيجية علاجية جديدة ضد فقر الدم الجنيني المبكر.

|

||||

| زيب14 | العضلات التنكسية | مرتفع التعبير | يؤكد على أهمية تنظيم توازن الزنك في ضمور العضلات الناجم عن السرطان النقيلي ويقترح مسار علاج جديد من خلال استهداف ZIP14.

|

||||

| تليف الكبد | مرتفع التعبير | طريق علاجي جديد محتمل لمنع تليف الكبد الناجم عن موت الحديد.

|

|||||

| ZnT8 | السكري | منخفض النشاط |

|

||||

| MT1/2 | ميلادي | – | تعديل تعبير MT-I/II هو هدف علاجي محتمل لعلاج بداية وتطور ضعف الإدراك.

|

||||

| تكوّن أوعية دموية جديدة في العين | – | MT1/2 هو هدف علاجي جديد محتمل للأمراض التي تنطوي على تكوّن الأوعية الدموية في العين.

|

|||||

الإمكانات العلاجية للبروتينات الغنية بالميثيونين

العلاجات القائمة على الزنك والقياس

تشن وآخرون

| مرض | الجرعة وأنواع الزنك | التأثير/التعليقات | رقم تسجيل التجربة | المراجع |

| التطبيقات السريرية لمكملات الزنك | ||||

| مرحلة ما قبل السكري | 30 ملغ جلوكونات الزنك/يوم، 90 يومًا. | أدى تناول مكملات الزنك إلى انخفاض كبير في مؤشر كتلة الجسم وتحسن في مستوى الجلوكوز الصائم، والجلوكوز بعد ساعتين من الأكل، والهيموغلوبين السكري، والأنسولين، وحساسية الأنسولين، ومقاومة الأنسولين. | – | ٦٨٤ |

| داء السكري من النوع الثاني | 30 ملغ كبريتات الزنك/يوم، 6 أشهر. | تحسين مكملات الزنك لتركيز الجلوكوز الصائم ومؤشر HOMA. كما أظهرت وظيفة خلايا بيتا، وحساسية الأنسولين، ومقاومة الأنسولين تحسناً ملحوظاً. | – | ٦٨٥ |

| 40 ملغ كبريتات الزنك/يوم، 12 أسبوعًا. | لم يُلاحظ تأثير لمكملات الزنك على تركيزات مؤشرات الالتهاب أو التغير النسبي في تعبير جينات ناقل الزنك وجينات البروتين المرتبط بالميتالوثيونين. | NCT01505803 | 686 | |

| 50 ملغ جلوكونات الزنك/يوم، 8 أسابيع. | تم رفع السعة الكلية لمضادات الأكسدة بشكل ملحوظ (

|

IRCT2015083102 | ٦٨٧ | |

| السكري مع الثلاسيميا | 25 ملغ كبريتات الزنك/يوم، 3 أشهر. | مكملات الزنك تحسن توازن الجلوكوز في الثلاسيميا. | NCT01772680 | ٦٨٨ |

| كما | 45 ملغ من جلوكونات الزنك/يوم، لمدة 6 أشهر. | أدى تناول مكملات الزنك إلى خفض مستويات بروتين سي التفاعلي (CRP) والإنترلوكين-6 (IL-6) في البلازما لدى الرجال والنساء. قد يكون للزنك تأثير وقائي على تصلب الشرايين بسبب وظائفه المضادة للالتهابات والمضادة للأكسدة. | – | ٦٨٩ |

| كوفيد-19 | 25 ملغ من الزنك العنصري على شكل كبسولة/يوم، لمدة 15 يومًا. | يمكن أن يقلل الزنك الفموي من معدل الوفاة خلال 30 يومًا، ومعدل دخول وحدة العناية المركزة، ويمكن أن يختصر مدة الأعراض. | NCT05212480. | ٦٩٠ |

| كوفيد-19 | 15 ملغ من الزنك في منتج نشط/يوم، 30 يومًا. | إدارة منتج نشط (ABB C1

|

NCT04798677 | ٦٩١ |

| مرض بهجت | 30 ملغ جلوكونات الزنك/يوم، 12 أسبوعًا. | يمكن اعتبار مكملات جلوكونات الزنك كعلاج مساعد في تخفيف الالتهاب والقرح التناسلية لدى مرضى داء بهجت. | – | ٦٩٢ |

| 30 ملغ جلوكونات الزنك/يوم، 12 أسبوعًا. | أدى تناول مكملات الزنك إلى تحسن كبير في درجة مرض بهجت غير العيني وتعبير TLR-2. | NCT05098678 | ٦٩٣ | |

| فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية-1 | 10 ملغ كبريتات الزنك/يوم، 6 أشهر. | لا يؤدي تناول مكملات الزنك إلى زيادة في الحمل الفيروسي لفيروس HIV-1 في البلازما وقد يقلل من المراضة الناجمة عن الإسهال. | – | ٦٩٤ |

| الكوليرا | 30 ملغ أسيتات الزنك/يوم، حتى زوال الإسهال أو لمدة تصل إلى سبعة أيام. | أدى تناول مكملات الزنك إلى تقليل مدة الإسهال وكمية البراز بشكل كبير لدى الأطفال المصابين بالكوليرا. | NCT00226616 | ٦٩٥ |

| الملاريا | 10 ملغ جلوكونات الزنك/يوم، متوسط فترة المتابعة: 331 يومًا | لم يؤثر الزنك ولا المغذيات المتعددة على معدلات الملاريا | NCT00623857 | ٦٩٦ |

| الثلاسيميا الكبرى | 25 ملغ كبريتات الزنك/يوم، 18 شهرًا. | أدى تناول مكملات الزنك إلى زيادة أكبر في كتلة العظام الكلية للجسم لدى المرضى الشباب المصابين بمرض الثلاسيميا الكبرى. | NCT00459732 | ٦٩٧ |

| الغسيل الكلوي | 78 ملغ من جلوكونات الزنك/يوم، لمدة شهرين. | تكملة الزنك تحسن من تركيزات الألفا-1 البلازمية المرتفعة بشكل غير طبيعي والإجهاد التأكسدي وتحسن حالة السيلينيوم لدى مرضى الغسيل الكلوي طويل الأمد. | – | ٦٩٨ |

| 34 ملغ غسيل دموي/يوم، 12 شهرًا. | يقلل تناول مكملات الزنك من مؤشر استجابة الإريثروبويتين لدى المرضى الذين يخضعون لغسيل الكلى وقد يكون استراتيجية علاجية جديدة للمرضى الذين يعانون من فقر الدم الكلوي وانخفاض مستويات الزنك في الدم. | – | ٦٩٩ | |

| سرطانات الرأس والعنق | 25 ملغ برو-زينك (مسحوق مستخلص من غدة البروستاتا البقرية ثم مرتبط بالزنك) / يوم، لمدة شهرين. | يمكن أن يؤخر تناول مكملات الزنك مع العلاج الإشعاعي تطور التهاب الغشاء المخاطي والتهاب الجلد الشديد لدى المرضى المصابين بسرطانات الرأس والعنق. | – | ٧٠٠ |

| سرطان القولون والمستقيم | 308 ملغ كبريتات الزنك/يوم، 108 أيام. | أدى تناول مكملات الزنك خلال دورات العلاج الكيميائي إلى زيادة نشاط إنزيم SOD والحفاظ على تركيزات فيتامين E، مما يشير إلى إنتاج جذور حرة مستقرة، والتي قد يكون لها تأثير إيجابي على علاج السرطان. | NCT02106806 | ٧٠١ |

| 70 ملغ كبريتات الزنك/يوم، 16 أسبوعًا | مكملات الزنك على مؤشرات الإجهاد التأكسدي في سرطان القولون والمستقيم بعد الجراحة خلال دورات العلاج الكيميائي. | NCT02106806 | – | |

| غلوكونات الزنك، جرعة غير معروفة، 8 أسابيع. | مكمل الزنك في مريض سرطان القولون والمستقيم النقيلي المعالج بريجورافينيب (ZnCORRECT). | NCT03898102 | – | |

| 70 ملغ كبريتات الزنك/يوم، 4 أشهر. | تعديل الاستجابة المناعية عن طريق مكملات الزنك الفموية في العلاج الكيميائي لسرطان القولون والمستقيم. | NCT01261962 | – | |

| ESCC و GC | 22.5 ملغ أكسيد الزنك/يوم، 15.25 سنة. | كان تناول مكملات الزنك مرتبطًا بزيادة في إجمالي الوفيات ووفيات السكتة الدماغية. | – | ٧٠٢ |

| سرطان الجهاز الهضمي | كبريتات الزنك، الجرعة غير معروفة | تأثيرات مكملات الزنك على جودة الحياة لدى مرضى سرطان الجهاز الهضمي. | NCT03819088 | – |

| التطبيق السريري لمُخلِّبات الزنك | ||||

| الصرع | أسبوعان

|

لفحص النشاط المضاد للنوبات المحتمل لكليوكينول في مجموعة صغيرة من المراهقين المصابين بالصرع المقاوم للأدوية | NCT05727943 | – |

| السرطان الدموي | 800 ملغ كليوكينول/يوم، 28 يومًا. | لتقييم السمية المحددة للجرعة، والجرعة القصوى المحتملة التحمل، والجرعة الموصى بها للمرحلة الثانية من عقار الكليوكينول في المرضى الذين يعانون من أمراض دموية خبيثة متكررة أو مقاومة للعلاج. | NCT00963495 | – |

| الفئة | الاسم | كد | العُضيّات المستهدفة | المراجع |

| فريت | زيف |

|

– | ٧٠٣ |

| زاب سي واي 1 |

|

جولجي، الشبكة الإندوبلازمية، الميتوكوندريا | ٦٧٢٬٦٧٨ | |

| eCALWY-4 |

|

قسم الطوارئ، الميتوكوندريا | ٦٧٥ | |

| eZinCh-2 |

|

الطوارئ، الميتوكوندريا | ٦٧٦ | |

| GZnP1 |

|

– | ٧٠٤ | |

| بريت | BLZinCh-1 |

|

الطوارئ، الميتوكوندريا | ٦٧١ |

| BLZinCh-2 |

|

الطوارئ، الميتوكوندريا | ٦٧١ | |

| BLZinCh-3 |

|

قسم الطوارئ، الميتوكوندريا | ٦٧١ | |

| LMW | فلوازين-3-إيه إم |

|

الطوارئ، الميتوكوندريا | ٧٠٥ |

| زينباير (ZP) |

|

جولجي، الميتوكوندريا | ٧٠٦ | |

| ZnAF |

|

– | ٧٠٧ | |

| رودزين-353 | – | الميتوكوندريا | ٧٠٨،٧٠٩ | |

| زيرف |

|

– | ٧١٠ | |

| TSQ | – | السيتوبلازم | ٧١١ |

يخفف من التوتر المعدني والأكسدي في أنسجة الكلى لدى الفئران المصابة بالسكري الناتج عن الستربتوزوتوسين، مما يمنع تطور اعتلال الكلية السكري.

نحاس.

وبروتينات الفلورسنت المشفرة وراثيًا.

الخاتمة والاتجاه المستقبلي

الميثلة في سرطان القولون والمستقيم. التعبير الشاذ أو فرط تنشيط ناقلات الزنك قد يساهم أيضًا في مقاومة الورم، مما قد يكون عاملًا سيئًا في توقعات المرضى المصابين بالسرطان. لذلك، من المتوقع أن يؤدي استهداف ناقلات الزنك إلى تحسين فعالية علاجات الأورام. في الوقت نفسه، نظرًا لأن بروتينات ناقلات الزنك موزعة بشكل رئيسي على أغشية الخلايا، فإن تطوير جزيئات صغيرة أو أجسام مضادة وحيدة النسيلة للاستهداف المحدد أمر ممكن.

الشكر والتقدير

مجموعات البيانات والتحليل. تم إنشاء جزء من الصور بواسطة BioRender (https:// biorender.com/) و GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#isoform). نحن نقدر أيضًا الدعم الفني من قسم المرافق الأساسية لجينوميات السرطان والبيولوجيا المرضية في قسم علم الأمراض التشريحي والخلوي، الجامعة الصينية في هونغ كونغ.

مساهمات المؤلف

معلومات إضافية

REFERENCES

- Huang, L. & Tepaamorndech, S. The SLC30 family of zinc transporters – a review of current understanding of their biological and pathophysiological roles. Mol. Asp. Med. 34, 548-560 (2013).

- Kambe, T., Tsuji, T., Hashimoto, A. & Itsumura, N. The Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Roles of Zinc Transporters in Zinc Homeostasis and Metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 95, 749-784 (2015).

- Kimura, T. & Kambe, T. The Functions of Metallothionein and ZIP and ZnT Transporters: An Overview and Perspective. Int J. Mol. Sci. 17, 336 (2016).

- Hu, H. et al. New anti-cancer explorations based on metal ions. J. Nanobiotechnol. 20, 457 (2022).

- Stockwell, B. R., Jiang, X. & Gu, W. Emerging mechanisms and disease relevance of ferroptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 30, 478-490 (2020).

- Andreini, C., Bertini, I. & Rosato, A. Metalloproteomes: a bioinformatic approach. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 1471-1479 (2009).

- Angus-Hill, M. L. et al. A Rsc3/Rsc30 zinc cluster dimer reveals novel roles for the chromatin remodeler RSC in gene expression and cell cycle control. Mol. Cell. 7, 741-751 (2001).

- Kim, A. M. et al. Zinc sparks are triggered by fertilization and facilitate cell cycle resumption in mammalian eggs. ACS Chem. Biol. 6, 716-723 (2011).

- Lo, M. N. et al. Single cell analysis reveals multiple requirements for zinc in the mammalian cell cycle. Elife 9, e51107 (2020).

- Haase, H. & Rink, L. Multiple impacts of zinc on immune function. Metallomics 6, 1175-1180 (2014).

- Que, E. L. et al. Quantitative mapping of zinc fluxes in the mammalian egg reveals the origin of fertilization-induced zinc sparks. Nat. Chem. 7, 130-139 (2015).

- Maret, W. Analyzing free zinc(II) ion concentrations in cell biology with fluorescent chelating molecules. Metallomics 7, 202-211 (2015).

- Hennigar, S. R., Kelley, A. M. & McClung, J. P. Metallothionein and zinc transporter expression in circulating human blood cells as biomarkers of zinc status: a systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 7, 735-746 (2016).

- Bafaro, E., Liu, Y., Xu, Y. & Dempski, R. E. The emerging role of zinc transporters in cellular homeostasis and cancer. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2, 17029- (2017).

- Calesnick, B. & Dinan, A. M. Zinc deficiency and zinc toxicity. Am. Fam. Physician 37, 267-270 (1988).

- Stefanidou, M., Maravelias, C., Dona, A. & Spiliopoulou, C. Zinc: a multipurpose trace element. Arch. Toxicol. 80, 1-9 (2006).

- Gilbert, R., Peto, T., Lengyel, I. & Emri, E. Zinc nutrition and inflammation in the aging retina. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 63, e1801049 (2019).

- Pfeiffer, C. C. & Braverman, E. R. Zinc, the brain and behavior. Biol. Psychiatry 17, 513-532 (1982).

- Tapiero, H. & Tew, K. D. Trace elements in human physiology and pathology: zinc and metallothioneins. Biomed. Pharmacother. 57, 399-411 (2003).

- Costello, L. C., Fenselau, C. C. & Franklin, R. B. Evidence for operation of the direct zinc ligand exchange mechanism for trafficking, transport, and reactivity of zinc in mammalian cells. J. Inorg. Biochem. 105, 589-599 (2011).

- Maret, W. Zinc coordination environments in proteins as redox sensors and signal transducers. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 8, 1419-1441 (2006).

- Turan, B. & Tuncay, E. Impact of labile zinc on heart function: from physiology to pathophysiology. Int J. Mol. Sci. 18, 2395 (2017).

- Coyle, P., Philcox, J. C., Carey, L. C. & Rofe, A. M. Metallothionein: the multipurpose protein. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 59, 627-647 (2002).

- Outten, C. E. & O’Halloran, T. V. Femtomolar sensitivity of metalloregulatory proteins controlling zinc homeostasis. Science 292, 2488-2492 (2001).

30

25. Blindauer, C. A. & Leszczyszyn, O. I. Metallothioneins: unparalleled diversity in structures and functions for metal ion homeostasis and more. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27, 720-741 (2010).

26. Wang, X. L., Schnoor, M. & Yin, L. M. Metallothionein-2: an emerging target in inflammatory diseases and cancers. Pharm. Ther. 244, 108374 (2023).

27. Amagai, Y. et al. Zinc homeostasis governed by Golgi-resident ZnT family members regulates ERp44-mediated proteostasis at the ER-Golgi interface. Nat. Commun. 14, 2683 (2023).

28. Fang, H. et al. Simultaneous

29. Frederickson, C. J., Koh, J. Y. & Bush, A. I. The neurobiology of zinc in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 449-462 (2005).

30. Eide, D. J. The SLC39 family of metal ion transporters. Pflug. Arch. 447, 796-800 (2004).

31. Bin, B. H. et al. Molecular pathogenesis of spondylocheirodysplastic EhlersDanlos syndrome caused by mutant ZIP13 proteins. EMBO Mol. Med. 6, 1028-1042 (2014).

32. Wang, Z., Tymianski, M., Jones, O. T. & Nedergaard, M. Impact of cytoplasmic calcium buffering on the spatial and temporal characteristics of intercellular calcium signals in astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 17, 7359-7371 (1997).

33. Krezel, A. & Maret, W. Zinc-buffering capacity of a eukaryotic cell at physiological pZn. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 11, 1049-1062 (2006).

34. Atrián-Blasco, E. et al. Chemistry of mammalian metallothioneins and their interaction with amyloidogenic peptides and proteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 7683-7693 (2017).

35. Krezel, A. & Maret, W. Dual nanomolar and picomolar

36. Colvin, R. A., Holmes, W. R., Fontaine, C. P. & Maret, W. Cytosolic zinc buffering and muffling: their role in intracellular zinc homeostasis. Metallomics 2, 306-317 (2010).

37. Ueda, S. et al. Early secretory pathway-resident Zn transporter proteins contribute to cellular sphingolipid metabolism through activation of sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 322, C948-c959 (2022).

38. Wagatsuma, T. et al. Pigmentation and TYRP1 expression are mediated by zinc through the early secretory pathway-resident ZNT proteins. Commun. Biol. 6, 403 (2023).

39. Chandler, P. et al. Subtype-specific accumulation of intracellular zinc pools is associated with the malignant phenotype in breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 15, 2 (2016).

40. Beyer, N. et al. ZnT 3 mRNA levels are reduced in Alzheimer’s disease postmortem brain. Mol. Neurodegener. 4, 53 (2009).

41. Chimienti, F., Devergnas, S., Favier, A. & Seve, M. Identification and cloning of a beta-cell-specific zinc transporter,

42. Maret, W. Redox biochemistry of mammalian metallothioneins. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 16, 1079-1086 (2011).

43. Hirano, T. et al. Roles of zinc and zinc signaling in immunity: zinc as an intracellular signaling molecule. Adv. Immunol. 97, 149-176 (2008).

44. Yamasaki, S. et al. Zinc is a novel intracellular second messenger. J. Cell Biol. 177, 637-645 (2007).

45. Bonaventura, P., Benedetti, G., Albarède, F. & Miossec, P. Zinc and its role in immunity and inflammation. Autoimmun. Rev. 14, 277-285 (2015).

46. Liu, W. et al. Lactate regulates cell cycle by remodelling the anaphase promoting complex. Nature 616, 790-797 (2023).

47. Wang, L. et al. Co-implantation of magnesium and zinc ions into titanium regulates the behaviors of human gingival fibroblasts. Bioact. Mater. 6, 64-74 (2021).

48. Xiao, W. et al. Therapeutic targeting of the USP2-E2F4 axis inhibits autophagic machinery essential for zinc homeostasis in cancer progression. Autophagy 18, 2615-2635 (2022).

49. Supasai, S. et al. Zinc deficiency affects the STAT1/3 signaling pathways in part through redox-mediated mechanisms. Redox Biol. 11, 469-481 (2017).

50. He, X. et al. The zinc transporter SLC39A10 plays an essential role in embryonic hematopoiesis. Adv. Sci. 10, e2205345 (2023).

51. Feske, S., Wulff, H. & Skolnik, E. Y. Ion channels in innate and adaptive immunity. Annu Rev. Immunol. 33, 291-353 (2015).

52. Chaigne-Delalande, B. & Lenardo, M. J. Divalent cation signaling in immune cells. Trends Immunol. 35, 332-344 (2014).

53. Ma, T. et al. A pair of transporters controls mitochondrial

54. Chen, H. C. et al. Sub-acute restraint stress progressively increases oxidative/ nitrosative stress and inflammatory markers while transiently upregulating antioxidant gene expression in the rat hippocampus. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 130, 446-457 (2019).

55. Si, M. & Lang, J. The roles of metallothioneins in carcinogenesis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 11, 107 (2018).

56. Aras, M. A. & Aizenman, E. Redox regulation of intracellular zinc: molecular signaling in the life and death of neurons. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 15, 2249-2263 (2011).

57. McCord, M. C. & Aizenman, E. Convergent Ca2+ and

58. Millward, D. J. Nutrition, infection and stunting: the roles of deficiencies of individual nutrients and foods, and of inflammation, as determinants of reduced linear growth of children. Nutr. Res Rev. 30, 50-72 (2017).

59. Ren, M. et al. Associations between hair levels of trace elements and the risk of preterm birth among pregnant Wwomen: a prospective nested case-control study in Beijing Birth Cohort (BBC), China. Environ. Int. 158, 106965 (2022).

60. Chorin, E. et al. Upregulation of KCC2 activity by zinc-mediated neurotransmission via the mZnR/GPR39 receptor. J. Neurosci. 31, 12916-12926 (2011).

61. Anderson, C. T. et al. Modulation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors by synaptic and tonic zinc. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 112, E2705-E2714 (2015).

62. Medvedeva, Y. V., Ji, S. G., Yin, H. Z. & Weiss, J. H. Differential vulnerability of CA1 versus CA3 pyramidal neurons after ischemia: possible relationship to sources of

63. Michelotti, F. C. et al. PET/MRI enables simultaneous in vivo quantification of

64. Carver, C. M., Chuang, S. H. & Reddy, D. S. Zinc selectively blocks neurosteroidsensitive extrasynaptic

65. Dostalova, Z. et al. Human

66. Sensi, S. L., Paoletti, P., Bush, A. I. & Sekler, I. Zinc in the physiology and pathology of the CNS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 780-791 (2009).

67. Olesen, R. H. et al. Obesity and age-related alterations in the gene expression of zinc-transporter proteins in the human brain. Transl. Psychiatry 6, e838 (2016).

68. Ren, L. et al. Amperometric measurements and dynamic models reveal a mechanism for how zinc alters neurotransmitter release. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 59, 3083-3087 (2020).

69. Hershfinkel, M. The zinc sensing receptor, ZnR/GPR39, in health and disease. Int J. Mol. Sci. 19, 439 (2018).

70. Ho, E. & Ames, B. N. Low intracellular zinc induces oxidative DNA damage, disrupts p53, NFkappa B, and AP1 DNA binding, and affects DNA repair in a rat glioma cell line. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 99, 16770-16775 (2002).

71. Nuñez, N. N. et al. The zinc linchpin motif in the DNA repair glycosylase MUTYH: identifying the

72. Lecane, P. S. et al. Motexafin gadolinium and zinc induce oxidative stress responses and apoptosis in B-cell lymphoma lines. Cancer Res. 65, 11676-11688 (2005).

73. Cheng, X. et al. Zinc transporter SLC39A13/ZIP13 facilitates the metastasis of human ovarian cancer cells via activating Src/FAK signaling pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 40, 199 (2021).

74. Liu, M. et al. Zinc-dependent regulation of ZEB1 and YAP1 coactivation promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition plasticity and metastasis in pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 160, 1771-1783.e1771 (2021).

75. Yang, J. et al. ZIP4 promotes muscle wasting and cachexia in mice with orthotopic pancreatic tumors by stimulating RAB27B-regulated release of extracellular vesicles from cancer cells. Gastroenterology 156, 722-734.e726 (2019).

76. Wagner, E. F. & Nebreda, A. R. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 537-549 (2009).

77. Zeng, Q. et al. Inhibition of ZIP4 reverses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and enhances the radiosensitivity in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 10, 588 (2019).

78. Qi, J. et al. MCOLN1/TRPML1 finely controls oncogenic autophagy in cancer by mediating zinc influx. Autophagy 17, 4401-4422 (2021).

79. Su, X. et al. Disruption of zinc homeostasis by a novel platinum(IV)-terthiophene complex for antitumor immunity. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 62, e202216917 (2023).

80. Jeong, J. & Eide, D. J. The SLC39 family of zinc transporters. Mol. Asp. Med. 34, 612-619 (2013).

81. Zhang, T., Sui, D. & Hu, J. Structural insights of ZIP4 extracellular domain critical for optimal zinc transport. Nat. Commun. 7, 11979 (2016).

82. Zhang, T. et al. Crystal structures of a ZIP zinc transporter reveal a binuclear metal center in the transport pathway. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700344 (2017).

83. Pang, C. et al. Structural mechanism of intracellular autoregulation of zinc uptake in ZIP transporters. Nat. Commun. 14, 3404 (2023).

84. Bogdan, A. R., Miyazawa, M., Hashimoto, K. & Tsuji, Y. Regulators of iron homeostasis: new players in metabolism, cell death, and disease. Trends Biochem Sci. 41, 274-286 (2016).

85. Jeong, J. et al. Promotion of vesicular zinc efflux by ZIP13 and its implications for spondylocheiro dysplastic Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 109, E3530-E3538 (2012).

86. Bin, B. H. et al. Biochemical characterization of human ZIP13 protein: a homodimerized zinc transporter involved in the spondylocheiro dysplastic EhlersDanlos syndrome. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40255-40265 (2011).

87. Lichten, L. A. et al. MTF-1-mediated repression of the zinc transporter Zip10 is alleviated by zinc restriction. PLoS One 6, e21526 (2011).

88. Ryu, M. S., Lichten, L. A., Liuzzi, J. P. & Cousins, R. J. Zinc transporters ZnT1 (Slc30a1), Zip8 (SIc39a8), and Zip10 (SIc39a10) in mouse red blood cells are differentially regulated during erythroid development and by dietary zinc deficiency. J. Nutr. 138, 2076-2083 (2008).

89. Liuzzi, J. P. et al. Responsive transporter genes within the murine intestinalpancreatic axis form a basis of zinc homeostasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 101, 14355-14360 (2004).

90. Taylor, K. M. & Nicholson, R. I. The LZT proteins; the LIV-1 subfamily of zinc transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1611, 16-30 (2003).

91. Xin, Y. et al. Manganese transporter Slc39a14 deficiency revealed its key role in maintaining manganese homeostasis in mice. Cell Discov. 3, 17025 (2017).

92. Polesel, M. et al. Functional characterization of SLC39 family members ZIP5 and ZIP10 in overexpressing HEK293 cells reveals selective copper transport activity. Biometals 36, 227-237 (2023).

93. Boycott, K. M. et al. Autosomal-recessive intellectual disability with cerebellar atrophy syndrome caused by mutation of the manganese and zinc transporter gene SLC39A8. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 97, 886-893 (2015).

94. Jorge-Nebert, L. F. et al. Comparing gene expression during cadmium uptake and distribution: untreated versus oral Cd-treated wild-type and ZIP14 knockout mice. Toxicol. Sci. 143, 26-35 (2015).

95. Himeno, S., Yanagiya, T. & Fujishiro, H. The role of zinc transporters in cadmium and manganese transport in mammalian cells. Biochimie 91, 1218-1222 (2009).

96. Nebert, D. W. & Liu, Z. SLC39A8 gene encoding a metal ion transporter: discovery and bench to bedside. Hum. Genomics. 13, 51 (2019).

97. Liu, Z. et al. Cd2+ versus Zn2+ uptake by the ZIP8 HCO3-dependent symporter: kinetics, electrogenicity and trafficking. Biochem. Biophys. Res Commun. 365, 814-820 (2008).

98. Napolitano, J. R. et al. Cadmium-mediated toxicity of lung epithelia is enhanced through NF-кB-mediated transcriptional activation of the human zinc transporter ZIP8. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 302, L909-L918 (2012).

99. Girijashanker, K. et al. Slc39a14 gene encodes ZIP14, a metal/bicarbonate symporter: similarities to the ZIP8 transporter. Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 1413-1423 (2008).

100. Pinilla-Tenas, J. J. et al. Zip14 is a complex broad-scope metal-ion transporter whose functional properties support roles in the cellular uptake of zinc and nontransferrin-bound iron. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 301, C862-C871 (2011).

101. Liuzzi, J. P. et al. Zip14 (SIc39a14) mediates non-transferrin-bound iron uptake into cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 103, 13612-13617 (2006).

102. Wang, C. Y. et al. ZIP8 is an iron and zinc transporter whose cell-surface expression is up-regulated by cellular iron loading. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 34032-34043 (2012).

103. Jenkitkasemwong, S. et al. SLC39A14 is required for the development of hepatocellular iron overload in murine models of hereditary hemochromatosis. Cell Metab. 22, 138-150 (2015).

104. Kambe, T., Matsunaga, M. & Takeda, T. A. Understanding the contribution of zinc transporters in the function of the early secretory pathway. Int J. Mol. Sci. 18, 2179 (2017).

105. Davidson, H. W., Wenzlau, J. M. & O’Brien, R. M. Zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8) and beta cell function. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 25, 415-424 (2014).

106. Suzuki, T. et al. Zinc transporters, ZnT5 and ZnT7, are required for the activation of alkaline phosphatases, zinc-requiring enzymes that are glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 637-643 (2005).

107. Nishito, Y. & Kambe, T. Zinc transporter 1 (ZNT1) expression on the cell surface is elaborately controlled by cellular zinc levels. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 15686-15697 (2019).

108. Lichten, L. A. & Cousins, R. J. Mammalian zinc transporters: nutritional and physiologic regulation. Annu Rev. Nutr. 29, 153-176 (2009).

109. Wang, Y. et al. Zinc application alleviates the adverse renal effects of arsenic stress in a protein quality control way in common carp. Environ. Res. 191, 110063 (2020).

110. Dwivedi, O. P. et al. Loss of ZnT 8 function protects against diabetes by enhanced insulin secretion. Nat. Genet. 51, 1596-1606 (2019).

111. Henshall, S. M. et al. Expression of the zinc transporter ZnT 4 is decreased in the progression from early prostate disease to invasive prostate cancer. Oncogene 22, 6005-6012 (2003).

112. Sanchez, V. B., Ali, S., Escobar, A. & Cuajungco, M. P. Transmembrane 163 (TMEM163) protein effluxes zinc. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 677, 108166 (2019).

113. Styrpejko, D. J. & Cuajungco, M. P. Transmembrane 163 (TMEM163) protein: a new member of the zinc efflux transporter family. Biomedicines 9, 220 (2021).

114. do Rosario, M. C. et al. Variants in the zinc transporter TMEM163 cause a hypomyelinating leukodystrophy. Brain 145, 4202-4209 (2022).

115. Kia, D. A. et al. Identification of candidate Parkinson disease genes by integrating genome-wide association study, expression, and epigenetic data sets. JAMA Neurol. 78, 464-472 (2021).

116. Yuan, Y. et al. A zinc transporter, transmembrane protein 163, is critical for the biogenesis of platelet dense granules. Blood 137, 1804-1817 (2021).

117. Braun, W. et al. Comparison of the NMR solution structure and the x-ray crystal structure of rat metallothionein-2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 89, 10124-10128 (1992).

118. Krężel, A. & Maret, W. The bioinorganic chemistry of mammalian metallothioneins. Chem. Rev. 121, 14594-14648 (2021).

119. Merlos Rodrigo, M. A. et al. Metallothionein isoforms as double agents – their roles in carcinogenesis, cancer progression and chemoresistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 52, 100691 (2020).

120. Go, Y. M., Chandler, J. D. & Jones, D. P. The cysteine proteome. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 84, 227-245 (2015).

121. Marreiro, D. D. et al. Zinc and oxidative stress: current mechanisms. Antioxidants. 6, 24 (2017).

122. Guo, L. et al. STAT5-glucocorticoid receptor interaction and MTF-1 regulate the expression of ZnT2 (Slc30a2) in pancreatic acinar cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 107, 2818-2823 (2010).

123. Lu, Y. J. et al. Coordinative modulation of human zinc transporter 2 gene expression through active and suppressive regulators. J. Nutr. Biochem. 26, 351-359 (2015).

124. Mocchegiani, E., Giacconi, R. & Malavolta, M. Zinc signalling and subcellular distribution: emerging targets in type 2 diabetes. Trends Mol. Med. 14, 419-428 (2008).

125. O’Donnell, J. S., Teng, M. W. L. & Smyth, M. J. Cancer immunoediting and resistance to T cell-based immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 16, 151-167 (2019).

126. Kim, B., Kim, H. Y. & Lee, W. W. Zap70 regulates TCR-mediated Zip6 activation at the immunological synapse. Front. Immunol. 12, 687367 (2021).

127. Lee, W. W. et al. Age-dependent signature of metallothionein expression in primary CD4 T cell responses is due to sustained zinc signaling. Rejuvenation Res. 11, 1001-1011 (2008).

128. Pommier, A. et al. Inflammatory monocytes are potent antitumor effectors controlled by regulatory CD4+ T cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 110, 13085-13090 (2013).

129. Aydemir, T. B., Liuzzi, J. P., McClellan, S. & Cousins, R. J. Zinc transporter ZIP8 (SLC39A8) and zinc influence IFN-gamma expression in activated human T cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 86, 337-348 (2009).

130. Liu, M. J. et al. ZIP8 regulates host defense through zinc-mediated inhibition of NF-kappaB. Cell Rep. 3, 386-400 (2013).

131. Begum, N. A. et al. Mycobacterium bovis BCG cell wall and lipopolysaccharide induce a novel gene, BIGM103, encoding a 7-TM protein: identification of a new protein family having Zn-transporter and Zn-metalloprotease signatures. Genomics 80, 630-645 (2002).

132. Kim, B. et al. Cytoplasmic zinc promotes IL-1 beta production by monocytes and macrophages through mTORC1-induced glycolysis in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci. Signal. 15, eabi7400 (2022).

133. Kang, J. A. et al. ZIP8 exacerbates collagen-induced arthritis by increasing pathogenic T cell responses. Exp. Mol. Med. 53, 560-571 (2021).

134. Abd El-Rehim, D. M. et al. High-throughput protein expression analysis using tissue microarray technology of a large well-characterised series identifies biologically distinct classes of breast cancer confirming recent cDNA expression analyses. Int J. Cancer 116, 340-350 (2005).

135. Lee, D. S. W., Rojas, O. L. & Gommerman, J. L. B cell depletion therapies in autoimmune disease: advances and mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 179-199 (2021).

136. Taniguchi, M. et al. Essential role of the zinc transporter ZIP9/SLC39A9 in regulating the activations of Akt and Erk in B-cell receptor signaling pathway in DT40 cells. PLoS One 8, e58022 (2013).

137. Miyai, T. et al. Zinc transporter SLC39A10/ZIP10 facilitates antiapoptotic signaling during early B-cell development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 11780-11785 (2014).

138. Hojyo, S. et al. Zinc transporter SLC39A10/ZIP10 controls humoral immunity by modulating B-cell receptor signal strength. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 111, 11786-11791 (2014).

139. Ma, Z. et al. SLC39A10 upregulation predicts poor prognosis, promotes proliferation and migration, and correlates with immune infiltration in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 8, 899-912 (2021).

140. Stafford, S. L. et al. Metal ions in macrophage antimicrobial pathways: emerging roles for zinc and copper. Biosci. Rep. 33, e00049 (2013).

141. Locati, M., Curtale, G. & Mantovani, A. Diversity, mechanisms, and significance of macrophage plasticity. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 15, 123-147 (2020).

142. Gao, H. et al. Metal transporter Slc39a10 regulates susceptibility to inflammatory stimuli by controlling macrophage survival. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 114, 12940-12945 (2017).

143. Sriskandan, S. & Altmann, D. M. The immunology of sepsis. J. Pathol. 214, 211-223 (2008).

144. Wong, H. R. et al. Genome-level expression profiles in pediatric septic shock indicate a role for altered zinc homeostasis in poor outcome. Physiol. Genomics. 30, 146-155 (2007).

145. Besecker, B. et al. The human zinc transporter SLC39A8 (Zip8) is critical in zincmediated cytoprotection in lung epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 294, L1127-L1136 (2008).

146. Besecker, B. Y. et al. A comparison of zinc metabolism, inflammation, and disease severity in critically ill infected and noninfected adults early after intensive care unit admission. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 93, 1356-1364 (2011).

147. Wessels, I. & Cousins, R. J. Zinc dyshomeostasis during polymicrobial sepsis in mice involves zinc transporter Zip14 and can be overcome by zinc supplementation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 309, G768-G778 (2015).

148. Hogstrand, C., Kille, P., Nicholson, R. I. & Taylor, K. M. Zinc transporters and cancer: a potential role for ZIP7 as a hub for tyrosine kinase activation. Trends Mol. Med. 15, 101-111 (2009).

149. Adulcikas, J. et al. The zinc transporter SLC39A7 (ZIP7) harbours a highlyconserved histidine-rich N-terminal region that potentially contributes to zinc homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum. Comput Biol. Med. 100, 196-202 (2018).

150. Uchida, R. et al. L-type calcium channel-mediated zinc wave is involved in the regulation of IL-6 by stimulating non-IgE with LPS and IL-33 in mast cells and dendritic cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 42, 87-93 (2019).

151. Levy, S. et al. Molecular basis for zinc transporter 1 action as an endogenous inhibitor of L-type calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 32434-32443 (2009).

152. Maret, W. Zinc in cellular regulation: the nature and significance of “zinc signals”. Int J. Mol. Sci. 18, 2285 (2017).

153. Kim, A. M., Vogt, S., O’Halloran, T. V. & Woodruff, T. K. Zinc availability regulates exit from meiosis in maturing mammalian oocytes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 674-681 (2010).

154. Taylor, K. M. et al. Zinc transporter ZIP10 forms a heteromer with ZIP6 which regulates embryonic development and cell migration. Biochem J. 473, 2531-2544 (2016).

155. Kong, B. Y. et al. Maternally-derived zinc transporters ZIP6 and ZIP10 drive the mammalian oocyte-to-egg transition. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 20, 1077-1089 (2014).

156. Nimmanon, T. et al. The ZIP6/ZIP10 heteromer is essential for the zinc-mediated trigger of mitosis. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 78, 1781-1798 (2021).

157. Hogstrand, C. et al. A mechanism for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and anoikis resistance in breast cancer triggered by zinc channel ZIP6 and STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3). Biochem. J. 455, 229-237 (2013).

158. Mulay, I. L. et al. Trace-metal analysis of cancerous and noncancerous human tissues. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 47, 1-13 (1971).

159. Chen, P. H. et al. Zinc transporter ZIP7 is a novel determinant of ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 12, 198 (2021).

160. Makhov, P. et al. Zinc chelation induces rapid depletion of the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis and sensitizes prostate cancer cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 15, 1745-1751 (2008).

161. Zhang, R. et al. Zinc regulates primary ovarian tumor growth and metastasis through the epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 160, 775-783 (2020).

162. Hernandez-Camacho, J. D., Vicente-Garcia, C., Parsons, D. S. & Navas-Enamorado, I. Zinc at the crossroads of exercise and proteostasis. Redox Biol. 35, 101529 (2020).

163. Ohashi, K. et al. Zinc promotes proliferation and activation of myogenic cells via the PI3K/Akt and ERK signaling cascade. Exp. Cell Res. 333, 228-237 (2015).

164. Lee, H. Y. et al. Deletion of Jazf1 gene causes early growth retardation and insulin resistance in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 119, e2213628119 (2022).

165. Jinno, N., Nagata, M. & Takahashi, T. Marginal zinc deficiency negatively affects recovery from muscle injury in mice. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 158, 65-72 (2014).

166. Lin, P. H. et al. Zinc in wound healing modulation. Nutrients 10, 16 (2017).

167. Postigo, A. A. & Dean, D. C. Differential expression and function of members of the zfh-1 family of zinc finger/homeodomain repressors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 97, 6391-6396 (2000).

168. Taylor, K. M. et al. Protein kinase CK2 triggers cytosolic zinc signaling pathways by phosphorylation of zinc channel ZIP7. Sci. Signal. 5, ra11 (2012).

169. Mnatsakanyan, H., Serra, R. S. I., Rico, P. & Salmeron-Sanchez, M. Zinc uptake promotes myoblast differentiation via Zip7 transporter and activation of Akt signalling transduction pathway. Sci. Rep. 8, 13642 (2018).

170. Nimmanon, T. et al. Phosphorylation of zinc channel ZIP7 drives MAPK, PI3K and mTOR growth and proliferation signalling. Metallomics 9, 471-481 (2017).

171. Mapley, J. I., Wagner, P., Officer, D. L. & Gordon, K. C. Computational and spectroscopic analysis of beta-indandione modified zinc porphyrins. J. Phys. Chem. A. 122, 4448-4456 (2018).

172. Giunta, C. et al. Spondylocheiro dysplastic form of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome-an autosomal-recessive entity caused by mutations in the zinc transporter gene SLC39A13. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82, 1290-1305 (2008).

173. Fukada, T. et al. The zinc transporter SLC39A13/ZIP13 is required for connective tissue development; its involvement in BMP/TGF-beta signaling pathways. PLoS One 3, e3642 (2008).

174. Shusterman, E. et al. Zinc transport and the inhibition of the L-type calcium channel are two separable functions of ZnT-1. Metallomics 9, 228-238 (2017).

175. Hennigar, S. R. & McClung, J. P. Zinc transport in the mammalian intestine. Compr. Physiol. 9, 59-74 (2018).

176. Geiser, J., Venken, K. J., De Lisle, R. C. & Andrews, G. K. A mouse model of acrodermatitis enteropathica: loss of intestine zinc transporter ZIP4 (SIc39a4) disrupts the stem cell niche and intestine integrity. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002766 (2012).

177. Dufner-Beattie, J., Kuo, Y. M., Gitschier, J. & Andrews, G. K. The adaptive response to dietary zinc in mice involves the differential cellular localization and zinc regulation of the zinc transporters ZIP4 and ZIP5. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49082-49090 (2004).

178. Dufner-Beattie, J. et al. The acrodermatitis enteropathica gene ZIP4 encodes a tissue-specific, zinc-regulated zinc transporter in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33474-33481 (2003).

179. Kury, S. et al. Identification of SLC39A4, a gene involved in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Nat. Genet. 31, 239-240 (2002).

180. Wang, K. et al. A novel member of a zinc transporter family is defective in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71, 66-73 (2002).

181. Weaver, B. P., Dufner-Beattie, J., Kambe, T. & Andrews, G. K. Novel zincresponsive post-transcriptional mechanisms reciprocally regulate expression of the mouse Slc39a4 and Slc39a5 zinc transporters (Zip4 and Zip5). Biol. Chem. 388, 1301-1312 (2007).

182. Yu, Y. Y., Kirschke, C. P. & Huang, L. Immunohistochemical analysis of ZnT1, 4, 5, 6, and 7 in the mouse gastrointestinal tract. J. Histochem Cytochem. 55, 223-234 (2007).

183. McMahon, R. J. & Cousins, R. J. Regulation of the zinc transporter

184. Wu, J., Ma, N., Johnston, L. J. & Ma, X. Dietary nutrients mediate intestinal host defense peptide expression. Adv. Nutr. 11, 92-102 (2020).

185. Podany, A. B. et al. ZnT2-mediated zinc import into paneth cell granules is necessary for coordinated secretion and paneth cell function in mice. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2, 369-383 (2016).

186. Hennigar, S. R. & Kelleher, S. L. TNFalpha post-translationally targets ZnT2 to accumulate zinc in lysosomes. J. Cell Physiol. 230, 2345-2350 (2015).

187. Ohashi, W. et al. Zinc transporter SLC39A7/ZIP7 promotes intestinal epithelial self-renewal by resolving ER stress. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006349 (2016).

188. Turner, J. R. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 799-809 (2009).

189. Higashimura, Y. et al. Zinc deficiency activates the IL-23/Th17 axis to aggravate experimental colitis in mice. J. Crohns Colitis 14, 856-866 (2020).

190. Hering, N. A., Fromm, M. & Schulzke, J. D. Determinants of colonic barrier function in inflammatory bowel disease and potential therapeutics. J. Physiol. 590, 1035-1044 (2012).

191. Guthrie, G. J. et al. Influence of ZIP14 (slc39A14) on intestinal zinc processing and barrier function. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 308, G171-G178 (2015).

192. Kim, J. et al. Deletion of metal transporter Zip14 (SIc39a14) produces skeletal muscle wasting, endotoxemia, Mef2c activation and induction of miR-675 and Hspb7. Sci. Rep. 10, 4050 (2020).

193. Aydemir, T. B. & Cousins, R. J. The multiple faces of the metal transporter ZIP14 (SLC39A14). J. Nutr. 148, 174-184 (2018).

194. McGourty, K. et al. ZnT2 is critical for TLR4-mediated cytokine expression in colonocytes and modulates mucosal inflammation in mice. Int J. Mol. Sci. 23, 11467 (2022).

195. Hennigar, S. R. et al. ZnT 2 is a critical mediator of lysosomal-mediated cell death during early mammary gland involution. Sci. Rep. 5, 8033 (2015).

196. Liu, M. J. et al. ZIP8 regulates host defense through zinc-mediated inhibition of NF-кВ. Cell Rep. 3, 386-400 (2013).

197. Li, D. et al. A pleiotropic missense variant in SLC39A8 is associated with Crohn’s disease and human gut microbiome composition. Gastroenterology 151, 724-732 (2016).

198. Vergnano, A. M. et al. Zinc dynamics and action at excitatory synapses. Neuron 82, 1101-1114 (2014).

199. Kalappa, B. I. et al. AMPA receptor inhibition by synaptically released zinc. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 112, 15749-15754 (2015).

200. Huang, Y. Z., Pan, E., Xiong, Z. Q. & McNamara, J. O. Zinc-mediated transactivation of TrkB potentiates the hippocampal mossy fiber-CA3 pyramid synapse. Neuron 57, 546-558 (2008).

201. Pan, E. et al. Vesicular zinc promotes presynaptic and inhibits postsynaptic longterm potentiation of mossy fiber-CA3 synapse. Neuron 71, 1116-1126 (2011).

202. Eom, K. et al. Intracellular

203. Anderson, C. T., Kumar, M., Xiong, S. & Tzounopoulos, T. Cell-specific gain modulation by synaptically released zinc in cortical circuits of audition. Elife 6, e29893 (2017).

204. Kumar, M., Xiong, S., Tzounopoulos, T. & Anderson, C. T. Fine control of sound frequency tuning and frequency discrimination acuity by synaptic zinc signaling in mouse auditory cortex. J. Neurosci. 39, 854-865 (2019).

205. Besser, L. et al. Synaptically released zinc triggers metabotropic signaling via a zinc-sensing receptor in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 29, 2890-2901 (2009).

206. Palmiter, R. D., Cole, T. B., Quaife, C. J. & Findley, S. D. ZnT-3, a putative transporter of zinc into synaptic vesicles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 93, 14934-14939 (1996).

207. Sikora, J., Kieffer, B. L., Paoletti, P. & Ouagazzal, A. M. Synaptic zinc contributes to motor and cognitive deficits in 6-hydroxydopamine mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 134, 104681 (2020).

208. Upmanyu, N. et al. Colocalization of different neurotransmitter transporters on synaptic vesicles is sparse except for VGLUT1 and ZnT3. Neuron 110, 1483-1497.e1487 (2022).

209. McAllister, B. B. & Dyck, R. H. Zinc transporter 3 (ZnT3) and vesicular zinc in central nervous system function. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 80, 329-350 (2017).

210. Perez-Rosello, T. et al. Tonic zinc inhibits spontaneous firing in dorsal cochlear nucleus principal neurons by enhancing glycinergic neurotransmission. Neurobiol. Dis. 81, 14-19 (2015).

211. Sindreu, C., Palmiter, R. D. & Storm, D. R. Zinc transporter ZnT-3 regulates presynaptic Erk1/2 signaling and hippocampus-dependent memory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 108, 3366-3370 (2011).

212. Mellone, M. et al. Zinc transporter-1: a novel NMDA receptor-binding protein at the postsynaptic density. J. Neurochem. 132, 159-168 (2015).

213. Krall, R. F. et al. Synaptic zinc inhibition of NMDA receptors depends on the association of GluN2A with the zinc transporter ZnT1. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb1515 (2020).

214. Chowanadisai, W. et al. Neurulation and neurite extension require the zinc transporter ZIP12 (slc39a12). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 110, 9903-9908 (2013).

215. Kambe, T., Yamaguchi-Iwai, Y., Sasaki, R. & Nagao, M. Overview of mammalian zinc transporters. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 61, 49-68 (2004).

216. Scarr, E. et al. Increased cortical expression of the zinc transporter SLC39A12 suggests a breakdown in zinc cellular homeostasis as part of the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. NPJ Schizophr. 2, 16002 (2016).

217. Bogdanovic, M. et al. The ZIP3 zinc transporter is localized to mossy fiber terminals and is required for kainate-induced degeneration of CA3 neurons. J. Neurosci. 42, 2824-2834 (2022).

218. De Benedictis, C. A. et al. Expression analysis of zinc transporters in nervous tissue cells reveals neuronal and synaptic localization of ZIP4. Int J. Mol. Sci. 22, 4511 (2021).

219. Pickrell, J. K. et al. Detection and interpretation of shared genetic influences on 42 human traits. Nat. Genet. 48, 709-717 (2016).

220. Park, J. H. et al. SLC39A8 deficiency: a disorder of manganese transport and glycosylation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 97, 894-903 (2015).

221. Müller, N. Inflammation and the glutamate system in schizophrenia: implications for therapeutic targets and drug development. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 12, 1497-1507 (2008).

222. Tseng, W. C. et al. Schizophrenia-associated SLC39A8 polymorphism is a loss-offunction allele altering glutamate receptor and innate immune signaling. Transl. Psychiatry 11, 136 (2021).

223. Derewenda, U. et al. Phenol stabilizes more helix in a new symmetrical zinc insulin hexamer. Nature 338, 594-596 (1989).

224. Barman, S. & Srinivasan, K. Diabetes and zinc dyshomeostasis: can zinc supplementation mitigate diabetic complications? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 1046-1061 (2022).

225. Davidson, H. W., Wenzlau, J. M. & O’Brien, R. M. Zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8) and

226. Rutter, G. A. & Chimienti, F. SLC30A8 mutations in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 58, 31-36 (2015).

227. Tamaki, M. et al. The diabetes-susceptible gene SLC30A8/ZnT8 regulates hepatic insulin clearance. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 4513-4524 (2013).

228. Sladek, R. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature 445, 881-885 (2007).

229. Fukunaka, A. & Fujitani, Y. Role of zinc homeostasis in the pathogenesis of diabetes and obesity. Int J. Mol. Sci. 19, 476 (2018).

230. Ma, Q. et al. ZnT8 loss-of-function accelerates functional maturation of hESCderived

231. Regnell, S. E. & Lernmark, Å. Early prediction of autoimmune (type 1) diabetes. Diabetologia 60, 1370-1381 (2017).

232. Lemaire, K. et al. Insulin crystallization depends on zinc transporter ZnT8 expression, but is not required for normal glucose homeostasis in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 106, 14872-14877 (2009).

233. Wenzlau, J. M. et al. The cation efflux transporter

234. Smidt, K. et al. SLC30A3 responds to glucose- and zinc variations in beta-cells and is critical for insulin production and in vivo glucose-metabolism during beta-cell stress. PLoS One 4, e5684 (2009).

235. Petersen, A. B. et al. siRNA-mediated knock-down of ZnT 3 and ZnT 8 affects production and secretion of insulin and apoptosis in INS-1E cells. Apmis 119, 93-102 (2011).

236. Hardy, A. B. et al. Zip4 mediated zinc influx stimulates insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells. PLoS One 10, e0119136 (2015).

237. Liu, Y. et al. Characterization of zinc influx transporters (ZIPs) in pancreatic

238. Gyulkhandanyan, A. V. et al. Investigation of transport mechanisms and regulation of intracellular

239. Solomou, A. et al. Over-expression of Slc30a8/ZnT8 selectively in the mouse a cell impairs glucagon release and responses to hypoglycemia. Nutr. Metab. 13, 46 (2016).

240. Balaz, M. et al. Subcutaneous adipose tissue zinc-a2-glycoprotein is associated with adipose tissue and whole-body insulin sensitivity. Obesity 22, 1821-1829 (2014).

241. Wang, W. & Seale, P. Control of brown and beige fat development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 691-702 (2016).

242. Fukunaka, A. et al. Zinc transporter ZIP13 suppresses beige adipocyte biogenesis and energy expenditure by regulating C/EBP-

243. Hay, N. Reprogramming glucose metabolism in cancer: can it be exploited for cancer therapy? Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 635-649 (2016).

244. Luo, X. et al. Emerging roles of lipid metabolism in cancer metastasis. Mol. Cancer 16, 76 (2017).

245. Gumulec, J. et al. Insight to physiology and pathology of zinc(II) ions and their actions in breast and prostate carcinoma. Curr. Med. Chem. 18, 5041-5051 (2011).

246. Takahashi, Y., Ogra, Y. & Suzuki, K. T. Nuclear trafficking of metallothionein requires oxidation of a cytosolic partner. J. Cell Physiol. 202, 563-569 (2005).

247. Nagel, W. W. & Vallee, B. L. Cell cycle regulation of metallothionein in human colonic cancer cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 92, 579-583 (1995).

248. Formigari, A., Santon, A. & Irato, P. Efficacy of zinc treatment against ironinduced toxicity in rat hepatoma cell line H4-II-E-C3. Liver Int. 27, 120-127 (2007).

249. Chen, W. Y. et al. Expression of metallothionein gene during embryonic and early larval development in zebrafish. Aquat. Toxicol. 69, 215-227 (2004).

250. Chen, W. Y., John, J. A., Lin, C. H. & Chang, C. Y. Expression pattern of metallothionein, MTF-1 nuclear translocation, and its dna-binding activity in zebrafish (Danio rerio) induced by zinc and cadmium. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 26, 110-117 (2007).

251. Xia, N., Liu, L., Yi, X. & Wang, J. Studies of interaction of tumor suppressor p53 with apo-MT using surface plasmon resonance. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 395, 2569-2575 (2009).

252. Rana, U. et al. Zinc binding ligands and cellular zinc trafficking: apo-metallothionein, glutathione, TPEN, proteomic zinc, and Zn-Sp1. J. Inorg. Biochem. 102, 489-499 (2008).

253. Huang, M., Shaw, I. C. & Petering, D. H. Interprotein metal exchange between transcription factor Illa and apo-metallothionein. J. Inorg. Biochem. 98, 639-648 (2004).

254. Parreno, V., Martinez, A. M. & Cavalli, G. Mechanisms of Polycomb group protein function in cancer. Cell Res. 32, 231-253 (2022).

34

255. Di Foggia, V. et al. Bmi1 enhances skeletal muscle regeneration through MT1mediated oxidative stress protection in a mouse model of dystrophinopathy. J. Exp. Med. 211, 2617-2633 (2014).

256. Dünkelberg, S. et al. The interaction of sodium and zinc in the priming of T cell subpopulations regarding Th17 and treg cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 64, e1900245 (2020).

257. Spiering, R. et al. Membrane-bound metallothionein 1 of murine dendritic cells promotes the expansion of regulatory T cells in vitro. Toxicol. Sci. 138, 69-75 (2014).

258. Li, S. et al. Metallothionein 3 promotes osteoblast differentiation in C2C12 cells via reduction of oxidative stress. Int J. Mol. Sci. 22, 4312 (2021).

259. Shin, C. H. et al. Identification of XAF1-MT2A mutual antagonism as a molecular switch in cell-fate decisions under stressful conditions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 114, 5683-5688 (2017).

260. Korkola, N. C. & Stillman, M. J. Structural role of cadmium and zinc in metallothionein oxidation by hydrogen peroxide: the resilience of metal-thiolate clusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6383-6397 (2023).

261. Ma, H. et al. HMBOX1 interacts with MT2A to regulate autophagy and apoptosis in vascular endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 5, 15121 (2015).

262. Murphy, M. P. et al. Guidelines for measuring reactive oxygen species and oxidative damage in cells and in vivo. Nat. Metab. 4, 651-662 (2022).

263. Song, Q. X. et al. Potential role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of diabetic bladder dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Urol. 19, 581-596 (2022).

264. Vatner, S. F. et al. Healthful aging mediated by inhibition of oxidative stress. Ageing Res. Rev. 64, 101194 (2020).

265. Niu, B. et al. Application of glutathione depletion in cancer therapy: enhanced ROS-based therapy, ferroptosis, and chemotherapy. Biomaterials 277, 121110 (2021).

266. Otterbein, L. E., Foresti, R. & Motterlini, R. Heme oxygenase-1 and carbon monoxide in the heart: the balancing act between danger signaling and prosurvival. Circ. Res. 118, 1940-1959 (2016).

267. Maret, W. & Li, Y. Coordination dynamics of zinc in proteins. Chem. Rev. 109, 4682-4707 (2009).

268. Pluth, M. D., Tomat, E. & Lippard, S. J. Biochemistry of mobile zinc and nitric oxide revealed by fluorescent sensors. Annu Rev. Biochem. 80, 333-355 (2011).

269. Rowsell, S. et al. Crystal structure of human MMP9 in complex with a reverse hydroxamate inhibitor. J. Mol. Biol. 319, 173-181 (2002).

270. Choi, S., Liu, X. & Pan, Z. Zinc deficiency and cellular oxidative stress: prognostic implications in cardiovascular diseases. Acta Pharm. Sin. 39, 1120-1132 (2018).

271. D’Amico, E., Factor-Litvak, P., Santella, R. M. & Mitsumoto, H. Clinical perspective on oxidative stress in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 65, 509-527 (2013).

272. Wu, W., Bromberg, P. A. & Samet, J. M. Zinc ions as effectors of environmental oxidative lung injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 65, 57-69 (2013).

273. Roel, M. et al. Crambescin C1 exerts a cytoprotective effect on HepG2 cells through metallothionein induction. Mar. Drugs 13, 4633-4653 (2015).

274. Cavalca, E. et al. Metallothioneins are neuroprotective agents in lysosomal storage disorders. Ann. Neurol. 83, 418-432 (2018).

275. Yang, M. & Chitambar, C. R. Role of oxidative stress in the induction of metallothionein-2A and heme oxygenase-1 gene expression by the antineoplastic agent gallium nitrate in human lymphoma cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45, 763-772 (2008).

276. Qu, W., Pi, J. & Waalkes, M. P. Metallothionein blocks oxidative DNA damage in vitro. Arch. Toxicol. 87, 311-321 (2013).

277. Koh, J. Y. & Lee, S. J. Metallothionein-3 as a multifunctional player in the control of cellular processes and diseases. Mol. Brain. 13, 116 (2020).

278. Álvarez-Barrios, A. et al. Antioxidant defenses in the human eye: a focus on metallothioneins. Antioxidants 10, 89 (2021).

279. Maret, W. The redox biology of redox-inert zinc ions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 134, 311-326 (2019).

280. Oteiza, P. I. Zinc and the modulation of redox homeostasis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 53, 1748-1759 (2012).

281. Hübner, C. & Haase, H. Interactions of zinc- and redox-signaling pathways. Redox Biol. 41, 101916 (2021).

282. Kim, H. G. et al. The epigenetic regulator SIRT6 protects the liver from alcoholinduced tissue injury by reducing oxidative stress in mice. J. Hepatol. 71, 960-969 (2019).

283. Hwang, S. et al. Interleukin-22 ameliorates neutrophil-driven nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through multiple targets. Hepatology 72, 412-429 (2020).

284. Wang, B. et al. D609 protects retinal pigmented epithelium as a potential therapy for age-related macular degeneration. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 5, 20 (2020).

285. Phillippi, J. A. et al. Basal and oxidative stress-induced expression of metallothionein is decreased in ascending aortic aneurysms of bicuspid aortic valve patients. Circulation 119, 2498-2506 (2009).

286. Bahadorani, S., Mukai, S., Egli, D. & Hilliker, A. J. Overexpression of metalresponsive transcription factor (MTF-1) in Drosophila melanogaster ameliorates life-span reductions associated with oxidative stress and metal toxicity. Neurobiol. Aging 31, 1215-1226 (2010).

287. Esposito, K. et al. Inflammatory cytokine concentrations are acutely increased by hyperglycemia in humans: role of oxidative stress. Circulation 106, 2067-2072 (2002).

288. Stankovic, R. K., Chung, R. S. & Penkowa, M. Metallothioneins I and II: neuroprotective significance during CNS pathology. Int J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 484-489 (2007).

289. Inoue, K., Takano, H. & Satoh, M. Protective role of metallothionein in coagulatory disturbance accompanied by acute liver injury induced by LPS/D-GalN. Thromb. Haemost. 99, 980-983 (2008).

290. Inoue, K. et al. Role of metallothionein in coagulatory disturbance and systemic inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. Faseb J. 20, 533-535 (2006).

291. Takano, H. et al. Protective role of metallothionein in acute lung injury induced by bacterial endotoxin. Thorax 59, 1057-1062 (2004).

292. Subramanian Vignesh, K. et al. Granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor induced Zn sequestration enhances macrophage superoxide and limits intracellular pathogen survival. Immunity 39, 697-710 (2013).

293. Liu, Y. et al. EOLA1 protects lipopolysaccharide induced IL-6 production and apoptosis by regulation of MT2A in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Mol. Cell Biochem. 395, 45-51 (2014).

294. Wu, H. et al. Metallothionein deletion exacerbates intermittent hypoxia-induced renal injury in mice. Toxicol. Lett. 232, 340-348 (2015).

295. Vasto, S. et al. Zinc and inflammatory/immune response in aging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1100, 111-122 (2007).

296. Majumder, S. et al. Loss of metallothionein predisposes mice to diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis by activating NF-kappaB target genes. Cancer Res. 70, 10265-10276 (2010).

297. Butcher, H. L. et al. Metallothionein mediates the level and activity of nuclear factor kappa B in murine fibroblasts. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 310, 589-598 (2004).

298. Pan, Y. et al. Metallothionein 2 A inhibits

299. Toh, P. P. et al. Modulation of metallothionein isoforms is associated with collagen deposition in proliferating keloid fibroblasts in vitro. Exp. Dermatol. 19, 987-993 (2010).

300. Cong, W. et al. Metallothionein prevents age-associated cardiomyopathy via inhibiting NF-kB pathway activation and associated nitrative damage to 2-OGD. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 25, 936-952 (2016).

301. Read, S. A. et al. Zinc is a potent and specific inhibitor of IFN-

302. Chen, Q. Y., DesMarais, T. & Costa, M. Metals and mechanisms of carcinogenesis. Annu. Rev. Pharm. Toxicol. 59, 537-554 (2019).

303. Ganger, R. et al. Protective effects of zinc against acute arsenic toxicity by regulating antioxidant defense system and cumulative metallothionein expression. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 169, 218-229 (2016).

304. Polykretis, P. et al. Cadmium effects on superoxide dismutase 1 in human cells revealed by NMR. Redox Biol. 21, 101102 (2019).

305. Petering, D. H., Loftsgaarden, J., Schneider, J. & Fowler, B. Metabolism of cadmium, zinc and copper in the rat kidney: the role of metallothionein and other binding sites. Environ. Health Perspect. 54, 73-81 (1984).

306. Chen, X. et al. The association between renal tubular dysfunction and zinc level in a Chinese population environmentally exposed to cadmium. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 186, 114-121 (2018).

307. Hu, Y. et al. The role of reactive oxygen species in arsenic toxicity. Biomolecules 10, 240 (2020).

308. Rahman, M. T. & De Ley, M. Arsenic induction of metallothionein and metallothionein induction against arsenic cytotoxicity. Rev. Environ. Contam Toxicol. 240, 151-168 (2017).

309. Ho, E. Zinc deficiency, DNA damage and cancer risk. J. Nutr. Biochem. 15, 572-578 (2004).

310. Song, Y. et al. Marginal zinc deficiency increases oxidative DNA damage in the prostate after chronic exercise. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 48, 82-88 (2010).

311. Stepien, M. et al. Circulating copper and zinc levels and risk of hepatobiliary cancers in Europeans. Br. J. Cancer 116, 688-696 (2017).

312. Jayaraman, A. K. & Jayaraman, S. Increased level of exogenous zinc induces cytotoxicity and up-regulates the expression of the

313. Wu, X., Tang, J. & Xie, M. Serum and hair zinc levels in breast cancer: a metaanalysis. Sci. Rep. 5, 12249 (2015).

314. Seeler, J. F. et al. Metal ion fluxes controlling amphibian fertilization. Nat. Chem. 13, 683-691 (2021).

315. Kambe, T., Hashimoto, A. & Fujimoto, S. Current understanding of ZIP and ZnT zinc transporters in human health and diseases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 71, 3281-3295 (2014).

316. Margalioth, E. J., Schenker, J. G. & Chevion, M. Copper and zinc levels in normal and malignant tissues. Cancer 52, 868-872 (1983).

317. Gammoh, N. Z. & Rink, L. Zinc in infection and inflammation. Nutrients 9, 624 (2017).

318. Cui, Y. et al. Levels of zinc, selenium, calcium, and iron in benign breast tissue and risk of subsequent breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 16, 1682-1685 (2007).

319. Santoliquido, P. M., Southwick, H. W. & Olwin, J. H. Trace metal levels in cancer of the breast. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 142, 65-70 (1976).

320. Taylor, K. M. et al. The emerging role of the LIV-1 subfamily of zinc transporters in breast cancer. Mol. Med. 13, 396-406 (2007).

321. Kasper, G. et al. Expression levels of the putative zinc transporter LIV-1 are associated with a better outcome of breast cancer patients. Int J. Cancer 117, 961-973 (2005).

322. Yamashita, S. et al. Zinc transporter LIVI controls epithelial-mesenchymal transition in zebrafish gastrula organizer. Nature 429, 298-302 (2004).

323. Kowalski, P. J., Rubin, M. A. & Kleer, C. G. E-cadherin expression in primary carcinomas of the breast and its distant metastases. Breast Cancer Res. 5, R217-R222 (2003).

324. Oka, H. et al. Expression of E-cadherin cell adhesion molecules in human breast cancer tissues and its relationship to metastasis. Cancer Res. 53, 1696-1701 (1993).

325. Lopez, V. & Kelleher, S. L. Zip6-attenuation promotes epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in ductal breast tumor (T47D) cells. Exp. Cell Res. 316, 366-375 (2010).

326. Shen, H., Qin, H. & Guo, J. Concordant correlation of LIV-1 and E-cadherin expression in human breast cancer cell MCF-7. Mol. Biol. Rep. 36, 653-659 (2009).

327. Matsui, C. et al. Zinc and its transporter ZIP6 are key mediators of breast cancer cell survival under high glucose conditions. FEBS Lett. 591, 3348-3359 (2017).

328. Gao, T. et al. The mechanism between epithelial mesenchymal transition in breast cancer and hypoxia microenvironment. Biomed. Pharmacother. 80, 393-405 (2016).

329. Dave, B., Mittal, V., Tan, N. M. & Chang, J. C. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, cancer stem cells and treatment resistance. Breast Cancer Res. 14, 202 (2012).

330. Chung, C. H., Bernard, P. S. & Perou, C. M. Molecular portraits and the family tree of cancer. Nat. Genet. 32, 533-540 (2002).

331. Tozlu, S. et al. Identification of novel genes that co-cluster with estrogen receptor alpha in breast tumor biopsy specimens, using a large-scale real-time reverse transcription-PCR approach. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 13, 1109-1120 (2006).

332. Althobiti, M. et al. Oestrogen-regulated protein SLC39A6: a biomarker of good prognosis in luminal breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 189, 621-630 (2021).

333. Kambe, T. [Overview of and update on the physiological functions of mammalian zinc transporters]. Nihon Eiseigaku Zasshi. 68, 92-102 (2013).

334. Kagara, N., Tanaka, N., Noguchi, S. & Hirano, T. Zinc and its transporter ZIP10 are involved in invasive behavior of breast cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 98, 692-697 (2007).

335. Pal, D., Sharma, U., Singh, S. K. & Prasad, R. Association between ZIP10 gene expression and tumor aggressiveness in renal cell carcinoma. Gene 552, 195-198 (2014).

336. Pawlus, M. R., Wang, L. & Hu, C. J. STAT3 and HIF1alpha cooperatively activate HIF1 target genes in MDA-MB-231 and RCC4 cells. Oncogene 33, 1670-1679 (2014).

337. Armanious, H. et al. STAT3 upregulates the protein expression and transcriptional activity of beta-catenin in breast cancer. Int J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 3, 654-664 (2010).

338. Chung, S. S., Giehl, N., Wu, Y. & Vadgama, J. V. STAT3 activation in HER2overexpressing breast cancer promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell traits. Int J. Oncol. 44, 403-411 (2014).

339. Taylor, K. M. et al. ZIP7-mediated intracellular zinc transport contributes to aberrant growth factor signaling in antihormone-resistant breast cancer Cells. Endocrinology 149, 4912-4920 (2008).

340. Ziliotto, S. et al. Activated zinc transporter ZIP7 as an indicator of anti-hormone resistance in breast cancer. Metallomics 11, 1579-1592 (2019).

341. Huang, L., Kirschke, C. P., Zhang, Y. & Yu, Y. Y. The ZIP7 gene (SIc39a7) encodes a zinc transporter involved in zinc homeostasis of the Golgi apparatus. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 15456-15463 (2005).

342. de Nonneville, A. et al. Prognostic and predictive value of LIV1 expression in early breast cancer and by molecular subtype. Pharmaceutics 15, 938 (2023).

343. Vogel-Gonzalez, M., Musa-Afaneh, D., Rivera Gil, P. & Vicente, R. Zinc favors triple-negative breast cancer’s microenvironment modulation and cell plasticity. Int J. Mol. Sci. 22, 9188 (2021).

344. Yap, X. et al. Over-expression of metallothionein predicts chemoresistance in breast cancer. J. Pathol. 217, 563-570 (2009).

345. Jadhav, R. R. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis reveals estrogenmediated epigenetic repression of metallothionein-1 gene cluster in breast cancer. Clin. Epigenetics. 7, 13 (2015).

346. Lopez, V., Foolad, F. & Kelleher, S. L. ZnT2-overexpression represses the cytotoxic effects of zinc hyper-accumulation in malignant metallothionein-null T47D breast tumor cells. Cancer Lett. 304, 41-51 (2011).

347. Lim, D., Jocelyn, K. M., Yip, G. W. & Bay, B. H. Silencing the Metallothionein-2A gene inhibits cell cycle progression from G1- to S-phase involving ATM and cdc25A signaling in breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 276, 109-117 (2009).

348. Sun, L. et al. Zinc regulates the ability of Cdc25C to activate MPF/cdk1. J. Cell Physiol. 213, 98-104 (2007).

349. Banin, S. et al. Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 by ATM in response to DNA damage. Science 281, 1674-1677 (1998).

350. Deng, C. et al. Mice lacking p21CIP1/WAF1 undergo normal development, but are defective in G1 checkpoint control. Cell 82, 675-684 (1995).

351. Li, D., Stovall, D. B., Wang, W. & Sui, G. Advances of zinc signaling studies in prostate cancer. Int J. Mol. Sci. 21, 667 (2020).

352. Zhao, J. et al. Comparative study of serum zinc concentrations in benign and malignant prostate disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 25778 (2016).

353. McNeal, J. E. Normal histology of the prostate. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 12, 619-633 (1988).

354. Costello, L. C. & Franklin, R. B. A comprehensive review of the role of zinc in normal prostate function and metabolism; and its implications in prostate cancer. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 611, 100-112 (2016).

355. Vartsky, D. et al. Prostatic zinc and prostate specific antigen: an experimental evaluation of their combined diagnostic value. J. Urol. 170, 2258-2262 (2003).

356. Dakubo, G. D. et al. Altered metabolism and mitochondrial genome in prostate cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 59, 10-16 (2006).

357. Feng, P. et al. The involvement of Bax in zinc-induced mitochondrial apoptogenesis in malignant prostate cells. Mol. Cancer 7, 25 (2008).

358. Nardinocchi, L. et al. Zinc downregulates HIF-1alpha and inhibits its activity in tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 5, e15048 (2010).

359. Uzzo, R. G. et al. Zinc inhibits nuclear factor-kappa B activation and sensitizes prostate cancer cells to cytotoxic agents. Clin. Cancer Res. 8, 3579-3583 (2002).

360. Ishii, K. et al. Evidence that the prostate-specific antigen (PSA)/Zn2+ axis may play a role in human prostate cancer cell invasion. Cancer Lett. 207, 79-87 (2004).

361. Uzzo, R. G. et al. Diverse effects of zinc on NF-kappaB and AP-1 transcription factors: implications for prostate cancer progression. Carcinogenesis 27, 1980-1990 (2006).

362. Ishii, K. et al. Inhibition of aminopeptidase N (AP-N) and urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) by zinc suppresses the invasion activity in human urological cancer cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 24, 226-230 (2001).

363. Singh, K. K., Desouki, M. M., Franklin, R. B. & Costello, L. C. Mitochondrial aconitase and citrate metabolism in malignant and nonmalignant human prostate tissues. Mol. Cancer 5, 14 (2006).

364. Fontana, F., Anselmi, M. & Limonta, P. Unraveling the peculiar features of mitochondrial metabolism and dynamics in prostate cancer. Cancers. 15, 1192 (2023).

365. Costello, L. C. et al. Human prostate cancer ZIP1/zinc/citrate genetic/metabolic relationship in the TRAMP prostate cancer animal model. Cancer Biol. Ther. 12, 1078-1084 (2011).

366. Costello, L. C. & Franklin, R. B. The clinical relevance of the metabolism of prostate cancer; zinc and tumor suppression: connecting the dots. Mol. Cancer 5, 17 (2006).

367. Franklin, R. B. et al. hZIP1 zinc uptake transporter down regulation and zinc depletion in prostate cancer. Mol. Cancer 4, 32 (2005).