المجلة: Humanities and Social Sciences Communications، المجلد: 12، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04948-z

تاريخ النشر: 2025-05-10

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04948-z

تاريخ النشر: 2025-05-10

استكشاف استمتاع طلاب الجامعات الصينية باللغات الأجنبية، وانخراطهم، ورغبتهم في التواصل في دروس المحادثة باللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية

لقد ركزت الأبحاث المتزايدة على دراسة دور العواطف في اكتساب اللغة الثانية (SLA)، مع التركيز بشكل خاص على العواطف الإيجابية وانخراط الطلاب كعوامل مهمة في تعزيز جوانب مختلفة من السلوك البشري والإدراك. على الرغم من أهمية الرغبة في التواصل (WTC) في فهم سلوكيات المتعلمين التواصلية في لغة أجنبية، لا تزال هناك فجوات في فهم كيفية ارتباط العواطف الإيجابية مثل استمتاع اللغة الأجنبية (FLE) والانخراط السلوكي بـ WTC. تبحث هذه الدراسة في العلاقات بين FLE والانخراط السلوكي وWTC في سياق اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية (EFL) في الصين، مستندة إلى نظرية التوسع والبناء. لذلك، قامت الدراسة بفحص كيفية إدراك 690 طالبًا صينيًا في الجامعات لـ FLE والانخراط السلوكي المتعلق بـ WTC باستخدام طريقة كمية. كشفت النتائج عن علاقات إيجابية كبيرة بين FLE والانخراط السلوكي مع WTC، حيث أظهر FLE ارتباطًا أقوى من الانخراط السلوكي. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن يتنبأ FLE وWTC بشكل كبير وقوي بـ WTC. تقدم هذه النتائج رؤى قيمة للممارسات التعليمية وتطوير السياسات، مما يشير إلى الفوائد المحتملة لدمج استراتيجيات تركز على الاستمتاع في تعلم اللغة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تساهم هذه الأبحاث في فهمنا لكيفية عمل العواطف الإيجابية، وخاصة الاستمتاع، جنبًا إلى جنب مع عوامل أخرى لتعزيز كفاءة الطلاب التواصلية وتجربتهم العامة في تعلم اللغة.

مقدمة

تلعب العواطف دورًا أساسيًا في تعليم اللغة. تشمل هذه المتغيرات العاطفية العواطف الإيجابية والسلبية، وتعتبر مركزية في عملية التعلم (دراخشان وآخرون، 2022؛ هوانغ وآخرون، 2024؛ لين ووانغ، 2024). بينما تم تجاهل العواطف تاريخيًا بسبب النظرة المعرفية السائدة لتعلم اللغة، ألهم إدخال فرضية الفلتر العاطفي لكراشين (1985) في اكتساب اللغة الثانية (SLA) العلماء للاعتراف بالدور المحوري للعواطف في تعلم اللغة الثانية (L2)، خاصة فيما يتعلق بالعواطف السلبية مثل القلق، مما زاد من التعرف على العوامل العاطفية، وخاصة القلق (ماكنتاير وآخرون، 2019). وفقًا لماكنتاير وغريغرسن (2012)، فإن دمج علم النفس الإيجابي في أبحاث SLA قد سلط الضوء على الدور الحاسم للعواطف الإيجابية في تعزيز نتائج تعلم اللغة ورفاهية المتعلمين. يعكس هذا التحول من التركيز فقط على العواطف السلبية إلى تضمين العواطف الإيجابية التطورات الأوسع في علم النفس التي تعترف بالمساهمات الفريدة للتجارب العاطفية الإيجابية في التعلم والتطور.

لقد حفز انتشار علم النفس الإيجابي ونظرياته الأساسية العديد من العلماء على دمج العواطف الإيجابية، وخاصة الاستمتاع، في أبحاث SLA. خاصة، توفر نظرية التوسع والبناء لفريدريكسون (2001) إطارًا شاملاً لفهم كيفية عمل العواطف الإيجابية في تعلم اللغة. في سياق تعلم اللغة، عندما يشعر الطلاب بالاستمتاع، يكونون أكثر ميلًا لاستكشاف والتفاعل مع اللغة المستهدفة، مما يخلق ظروفًا مثالية للمعالجة المعرفية، والتحفيز، والتفاعل الاجتماعي (ماكنتاير وغريغرسن، 2012). لقد امتد هذا الإطار النظري إلى ما هو أبعد من الأساليب التقليدية التي تركز على القلق ويبرز منظورًا أكثر شمولية حول العواطف الإيجابية في تعلم اللغة. وبالتالي، تركزت الأبحاث الحديثة في L2 بشكل متزايد على دراسة العواطف الإيجابية في سياقات تعلم اللغة (لي، 2021).

بعيدًا عن فهم مفهوم ودور العواطف الإيجابية، قامت العديد من الأبحاث بفحص التفاعل بين العواطف الإيجابية، وخاصة الاستمتاع، وغيرها من المتغيرات الرئيسية في تعلم اللغة (يو، 2022). كما اقترح ماكنتاير وتشاروس (1996)، فإن الهدف الرئيسي من تعليم اللغة هو تحقيق القدرة على استخدام اللغة للتواصل، بغض النظر عن غرض تعلم اللغة. يؤكد ديويل وديويل (2018) أن تعلم اللغة يمكن أن يتم تسهيله من خلال التأثيرات الإيجابية للعواطف على رغبة المتعلمين في التواصل (WTC)، خاصة عندما يحفز المعلمون بشكل فعال الاستجابات العاطفية الإيجابية (ديويل، 2015). علاوة على ذلك، تم التحقق تجريبيًا من هذه العلاقة بين العواطف الإيجابية، وخاصة الاستمتاع كأكثر العواطف الإيجابية انتشارًا (ديويل وماكنتاير، 2019)، وWTC عبر دراسات متعددة (بن سالم، 2022؛ ديويل وبافيلسكو، 2021؛ كون وآخرون، 2020). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يعمل الانخراط كوسيط حاسم بين عمليات التعليم والتعلم (هايفر وآخرون، 2021). تشير الأبحاث الحديثة إلى أن العواطف تتنبأ بشكل كبير بمستويات الانخراط (دراخشان وفاتي، 2023؛ بيكرون، 2006)، حيث تسهل العواطف الإيجابية استكشاف الموارد والقدرات التكيفية، بينما قد تعيق العواطف السلبية التعلم من خلال تقليل التركيز المعرفي (دينغ ووانغ، 2024؛ فريدريكسون، 2001؛ ريشلي وآخرون، 2008). نظرًا للدور الأساسي للاستمتاع على نتائج التعلم والرفاهية النفسية (سيليغمان، 2018)، فإن دراسة هذه العوامل أمر ضروري للحصول على رؤى أساسية في أبحاث SLA.

ومع ذلك، لا تزال الأبحاث في SLA غير كافية لفهم كيفية ارتباط استمتاع الطلاب باللغة الأجنبية (FLE) والانخراط بالنتائج التعليمية اللاحقة مثل WTC. على الرغم من أن الأدبيات الحالية قد بحثت في الروابط بين العواطف والانخراط (ديويل ولي، 2021؛

فينغ وهونغ، 2022؛ قوه، 2021؛ خاجافي، 2021) وبين الاستمتاع وWTC (لي وآخرون، 2022؛ خاجافي وآخرون، 2018؛ بينغ ووانغ، 2024)، فقد تم توجيه اهتمام تجريبي محدود نحو العلاقات المتبادلة بين هذه المتغيرات. هذه الفجوة البحثية ذات صلة خاصة في سياقات اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية (EFL) في الصين، حيث لم يتم التحقيق بعد في التفاعل بين FLE والانخراط السلوكي وWTC.

لذلك، استنادًا إلى نظرية التوسع والبناء لفريدريكسون (2001)، تسعى هذه الأبحاث إلى توسيع الإطار النظري للاستمتاع من خلال دراسة علاقته بالمتغيرات الخاصة بـ L2، وخاصة الانخراط السلوكي وWTC. تركزت هذه الدراسة بشكل خاص على الانخراط السلوكي، حيث يؤثر بشكل واضح على ديناميات التفاعل في الفصل الدراسي والبيئة التعليمية الأوسع. استخدمت الأبحاث نهجًا منهجيًا كميًا لفحص العلاقات المتبادلة بين الانخراط السلوكي، والاستمتاع، وWTC بين الطلاب الجامعيين الصينيين في الفصول الدراسية الناطقة باللغة الإنجليزية. تم اختبار النموذج المفترض الذي يدمج المتغيرات الثلاثة باستخدام نمذجة المعادلات الهيكلية (SEM). لذلك، فإن أسئلة البحث هي كما يلي:

RQ1: هل هناك أي علاقات متبادلة كبيرة بين FLE والانخراط السلوكي وWTC بين متعلمي اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين؟

RQ2: هل يتنبأ FLE والانخراط السلوكي بشكل كبير برغبة الطلاب الصينيين في التواصل (WTC)؟

مراجعة الأدبيات

علم النفس الإيجابي في اكتساب اللغة الثانية ونظرية التوسع والبناء. لقد ظهر علم النفس الإيجابي كإطار أساسي لفهم عمليات تعلم اللغة، مما يمثل تحولًا كبيرًا عن الأساليب التقليدية التي كانت تركز بشكل أساسي على المشاعر السلبية في اكتساب اللغة الثانية. هذا التحول، الذي بدأ بعمل سيلجمان وتشكسينتمهالي (2000) الرائد، أعاد توجيه الانتباه نحو نقاط القوة البشرية والأداء الأمثل بدلاً من الضعف (بولي وآخرون، 2009). في سياق اكتساب اللغة الثانية، فإن هذا التوجه الجديد له أهمية خاصة لأن المشاعر، على الرغم من كونها حاسمة في تعلم اللغة (ديويل، 2015)، كانت تاريخيًا تُعتبر عناصر غير معقولة (جو وآخرون، 2017). منذ تقديمه في أبحاث اكتساب اللغة الثانية، حول هذا الفهم لكيفية تأثير المشاعر الإيجابية على نجاح تعلم اللغة ورفاهية الطلاب (لي، 2018).

تستند الدراسة نظريًا إلى نظرية التوسع والبناء لفريدريكسون (2001)، التي نشأت من حركة علم النفس الإيجابي في تعلم اللغة الثانية. تتماشى النظرية مع هدف علم النفس الإيجابي في تعزيز العوامل التي تسهم في ازدهار الإنسان، موضحة كيف يمكن أن تبني المشاعر الإيجابية في تعلم اللغة موارد شخصية دائمة وتعزز نتائج التعلم (ماكنتاير وغريغرسن، 2012). لقد أدى دمج مبادئ علم النفس الإيجابي ونظرية التوسع والبناء في أبحاث تعلم اللغة الثانية إلى خلق “موجة عاطفية” (ماكنتاير وآخرون، 2016)، مما يبرز الحاجة إلى مراعاة كل من المشاعر الإيجابية والسلبية في فهم عمليات تعلم اللغة وتفاعلاتها المعقدة في عملية التعلم (لي وآخرون، 2018).

نظرية التوسع والبناء تقدم منظورًا مميزًا حول كيفية تسهيل المشاعر الإيجابية لتعلم اللغة من خلال اقتراح أن المشاعر الإيجابية تؤدي وظيفتين متكاملتين: فهي ‘توسع’ نطاق تفكير المتعلمين و’تبني’ مواردهم الشخصية الدائمة (فريدريكسون وآخرون، 2008). تميز النظرية بين وظائف المشاعر الإيجابية والسلبية في تعلم اللغة. بينما تضيق المشاعر السلبية الانتباه وتعزز ميول سلوكية محددة، تخلق المشاعر الإيجابية ميولًا نحو الاستكشاف واللعب، وتوسع الانتباه، وتبني موارد للعمل المستقبلي (فريدريكسون، 2001). هذه الموارد

يمكن أن تشمل الدعم الاجتماعي، مهارات التكيف، والكفاءة الذاتية، التي تعزز مرونة المتعلمين في تعلم اللغة (فريدريكسون، 2001). على وجه التحديد، تقترح النظرية أن المشاعر الإيجابية مثل الفرح في تعلم اللغة يمكن أن تسهل تعلم اللغة من خلال خلق ظروف مثالية للمعالجة المعرفية، التحفيز، والتفاعل الاجتماعي (ماكنتاير وغريغرسن، 2012). والأهم من ذلك، أن نظرية التوسع والبناء قد قدمت رؤى حاسمة لفهم الديناميات العاطفية في فصول اللغة في أبحاث اكتساب اللغة الثانية (ديويلي وماكنتاير، 2014) وكيف تتفاعل التجارب العاطفية مع متغيرات أخرى حاسمة في تعلم اللغة، مثل الانخراط ورغبة التواصل، مما يؤثر في النهاية على نتائج التعلم والسلوك التواصلي. هذه الإطار النظري ذو صلة خاصة بدراستنا لأنه يساعد في تفسير كيف يمكن أن يعزز الفرح في تعلم اللغة كل من الانخراط ورغبة التواصل في فصول اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين.

يمكن أن تشمل الدعم الاجتماعي، مهارات التكيف، والكفاءة الذاتية، التي تعزز مرونة المتعلمين في تعلم اللغة (فريدريكسون، 2001). على وجه التحديد، تقترح النظرية أن المشاعر الإيجابية مثل الفرح في تعلم اللغة يمكن أن تسهل تعلم اللغة من خلال خلق ظروف مثالية للمعالجة المعرفية، التحفيز، والتفاعل الاجتماعي (ماكنتاير وغريغرسن، 2012). والأهم من ذلك، أن نظرية التوسع والبناء قد قدمت رؤى حاسمة لفهم الديناميات العاطفية في فصول اللغة في أبحاث اكتساب اللغة الثانية (ديويلي وماكنتاير، 2014) وكيف تتفاعل التجارب العاطفية مع متغيرات أخرى حاسمة في تعلم اللغة، مثل الانخراط ورغبة التواصل، مما يؤثر في النهاية على نتائج التعلم والسلوك التواصلي. هذه الإطار النظري ذو صلة خاصة بدراستنا لأنه يساعد في تفسير كيف يمكن أن يعزز الفرح في تعلم اللغة كل من الانخراط ورغبة التواصل في فصول اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين.

استمتاع اللغة الأجنبية. تلعب المشاعر الإيجابية دورًا أساسيًا في اكتساب اللغة الثانية، لا سيما في توسيع العمليات المعرفية للمتعلمين وبناء كفاءاتهم اللغوية (فريدريكسون، 2001). وقد درس العلماء الوظائف المختلفة وتأثيرات المشاعر الإيجابية في دراساتهم (ديويلي وماكينتاير، 2014؛ لي، 2020؛ وانغ وآخرون، 2021، 2022).

من بين هذه المشاعر الإيجابية، برزت FLE كعنصر مهم بشكل خاص في أبحاث تعلم اللغة الثانية. حدد ديويل وماكنتاير (2019) الاستمتاع كأكثر المشاعر الإيجابية التي تم ملاحظتها في فصول اللغة، خاصة كتعويض عن القلق التقليدي المرتبط بتعلم اللغات الأجنبية. تم تعريف FLE من قبل لي وآخرين (2018) كمشاعر إيجابية تتأثر بـ “الأقران، والمعلمين، والبيئة، وإحساس بالإنجاز” (ص. 193). لقد حظي هذا المفهوم باهتمام متزايد ضمن حركة علم النفس الإيجابي في تعلم اللغة الثانية على مدى السنوات العشر الماضية (ديويل وآخرون، 2017).

تدعم الأدلة التجريبية بقوة التأثير الإيجابي للفرح في التعلم على نتائج التعلم المختلفة ضمن إطار علم النفس الإيجابي. أظهرت الأبحاث الرائدة التي أجراها ديويل وماكنتاير (2014) أن المشاعر الإيجابية والسلبية تؤدي وظائف متميزة في تعلم اللغة بدلاً من أن تكون أقطابًا متعارضة على نفس المحور. على وجه التحديد، أظهرت العديد من الأبحاث التأثير الإيجابي للمشاعر الإيجابية على الدافع، والانخراط، والإنجاز الأكاديمي (لي، 2020). تكمن الأسس النظرية لهذه التأثيرات في قدرة المتعة على توسيع مجموعة أفكار المتعلمين، مما يعزز قدرتهم على تطوير موارد اللغة وتسهيل التعلم (ماكنتاير وغريغرسن، 2012). علاوة على ذلك، فإن تطوير وتأكيد مقياس الفرح في التعلم الصيني المعدل ثقافيًا من قبل لي وآخرين (2018) يقدم إطارًا ثلاثي الأبعاد يشمل الجوانب الخاصة، والمعلم، والجو، مما يساهم في تصورات محددة للسياق للفرح في التعلم.

لذلك، يكشف أنه على الرغم من التقدم الكبير الذي تم إحرازه في فهم الفرح في تعلم اللغة، لا تزال هناك فجوات كبيرة في الأبحاث الحالية. بينما تدعم الأدلة الكبيرة تأثيره الإيجابي على نتائج تعلم اللغة، لا يزال الشبكة النمائية للمتعة غير مستكشفة بالكامل. على وجه الخصوص، تحتاج العلاقات المعقدة بين الفرح في تعلم اللغة والمتغيرات الأخرى في سياقات اللغة الثانية إلى مزيد من التحقيق، مما يشير إلى اتجاه واعد للبحوث المستقبلية في هذا المجال. بعبارة أخرى، بينما ظهر الفرح في تعلم اللغة كعنصر حاسم في أبحاث اكتساب اللغة الثانية، هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من الدراسات لفهم تفاعلاته المعقدة بالكامل ضمن مجال اكتساب اللغة الثانية.

الانخراط. كما تم الإشارة سابقًا، يُعتبر الانخراط عنصرًا رئيسيًا في علم النفس الإيجابي (سيلجمان، 2011؛ وانغ وانغ، 2024). في البداية، كان يُعتبر مفهومًا جديدًا نسبيًا مقارنةً بمفاهيم مثل الدافع (ريشلي وكريستنسون، 2012)، وقد حظي الانخراط باهتمام متزايد من الباحثين و

لقد أصبح أكثر بروزًا في أبحاث التعليم (بان وآخرون، 2023؛ بيكرون ولينينبرينك-غارسيا، 2012؛ وانغ وآخرون، 2024؛ وو وآخرون، 2024). يُعرف الانخراط بأنه مفهوم “مدى انخراط الطالب بنشاط في مهمة تعليمية ومدى توجيه تلك الأنشطة الجسدية والعقلية نحو أهداف محددة وذات مغزى” (هايفر وآخرون، 2021، ص. 3). تؤكد هذه التعريف على أهمية كل من المشاركة الجسدية والاستثمار المعرفي، مما يشير إلى الحاجة إلى أهداف واضحة ومعنى شخصي في الأنشطة التعليمية (غاو وآخرون، 2025؛ قوه وانغ، 2024؛ وانغ وآخرون، 2025؛ وانغ وريينولدز، 2024). لقد تطور مفهوم انخراط الطلاب في تعلم اللغة الثانية من بعدين – سلوكي وعاطفي (فان أودن وآخرون، 2013) إلى ثلاثة، مع إضافة الجوانب المعرفية (فريدريكس وآخرون، 2004). مؤخرًا، تم تضمين نموذج رباعي الأبعاد يشمل الانخراط الفاعل (ريف، 2013). أظهر هذا التحول أن تعلم اللغة الثانية يمثل تفاعلًا معقدًا بين المتغيرات المعرفية والعاطفية والاجتماعية (ساتو، 2017). والأهم من ذلك، أن الانخراط السلوكي هو الأكثر ارتباطًا بالأداء الأكاديمي (لي، 2014) وإنجاز المتعلم (وانغ وآخرون، 2024). يتميز هذا البعد عمومًا بالاستمرارية الملحوظة والجهد الذي يستثمره المتعلمون في الأنشطة التعليمية (هيوز وآخرون، 2008).

لقد أصبح أكثر بروزًا في أبحاث التعليم (بان وآخرون، 2023؛ بيكرون ولينينبرينك-غارسيا، 2012؛ وانغ وآخرون، 2024؛ وو وآخرون، 2024). يُعرف الانخراط بأنه مفهوم “مدى انخراط الطالب بنشاط في مهمة تعليمية ومدى توجيه تلك الأنشطة الجسدية والعقلية نحو أهداف محددة وذات مغزى” (هايفر وآخرون، 2021، ص. 3). تؤكد هذه التعريف على أهمية كل من المشاركة الجسدية والاستثمار المعرفي، مما يشير إلى الحاجة إلى أهداف واضحة ومعنى شخصي في الأنشطة التعليمية (غاو وآخرون، 2025؛ قوه وانغ، 2024؛ وانغ وآخرون، 2025؛ وانغ وريينولدز، 2024). لقد تطور مفهوم انخراط الطلاب في تعلم اللغة الثانية من بعدين – سلوكي وعاطفي (فان أودن وآخرون، 2013) إلى ثلاثة، مع إضافة الجوانب المعرفية (فريدريكس وآخرون، 2004). مؤخرًا، تم تضمين نموذج رباعي الأبعاد يشمل الانخراط الفاعل (ريف، 2013). أظهر هذا التحول أن تعلم اللغة الثانية يمثل تفاعلًا معقدًا بين المتغيرات المعرفية والعاطفية والاجتماعية (ساتو، 2017). والأهم من ذلك، أن الانخراط السلوكي هو الأكثر ارتباطًا بالأداء الأكاديمي (لي، 2014) وإنجاز المتعلم (وانغ وآخرون، 2024). يتميز هذا البعد عمومًا بالاستمرارية الملحوظة والجهد الذي يستثمره المتعلمون في الأنشطة التعليمية (هيوز وآخرون، 2008).

من الجدير بالذكر أن الانخراط يعمل كجسر حاسم بين التعليم والتعلم، مما يسهل تجارب التعلم ذات المعنى (Hiver et al., 2021). لقد درس العديد من الباحثين علاقته الإيجابية مع نتائج التعلم المتعددة عبر المجالات الأكاديمية والاجتماعية والعاطفية (Reeve, 2012). على وجه التحديد، تم ربط الانخراط بالتحصيل والدافع والكفاءة الذاتية (Mystkowska-Wiertelak, 2021). بمعنى آخر، يُعتبر الانخراط غالبًا وسيطًا نفسيًا يؤثر على أداء الطلاب من خلال العديد من العوامل السياقية (Reyes et al., 2012; Benner et al., 2008).

الأهم من ذلك، تعتبر العواطف والانخراط مكونات حاسمة في أبحاث اكتساب اللغة الثانية، تؤثر بشكل كبير على كل من التعلم والرفاه النفسي (فينغ وهونغ، 2022). يبرز بويكيرتس (2016) أن كل من العواطف الإيجابية والسلبية تؤثر بشكل كبير على الانخراط. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن الانخراط مرتبط بشكل إيجابي بالمتعة في تعلم اللغة (فينغ وهونغ، 2022؛ خاجافي، 2021؛ لينينبرينك-غارسيا وآخرون، 2011). عند دراسة الانخراط، يحتاج الباحثون إلى استكشاف كيف يمكن أن تؤثر العواطف الإيجابية على انخراط الطلاب (بويكيرتس، 2016). على سبيل المثال، وجد خاجافي (2021) أن المتعة تنبأت بشكل إيجابي بالانخراط بين متعلمي اللغة الثانية الإيرانيين. في سياق اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين، أظهر فينج وهونغ (2022) هذه العلاقة مع الإشارة إلى أن الطلاب الصينيين عمومًا أبلغوا عن مستويات استمتاع أقل مقارنة بنظرائهم الغربيين. علاوة على ذلك، تدعم هذه العلاقة نظرية توسيع وبناء فريدريكسون (2001)، التي تجادل بأن العواطف الإيجابية من الاستمتاع يمكن أن تعزز الانخراط. بخلاف ذلك، فإن الأبحاث التي تفحص العلاقة بين الانخراط والاستعداد للتحدث (WTC) ضرورية لفهم ديناميات التفاعل في الفصل الدراسي. وجدت دراسة ميستكوفسكا-ويرتيلاك (2021) لطلاب اللغة الإنجليزية الرئيسيين ارتباطات كبيرة بين الانخراط وأبعاد الاستعداد للتحدث ووجدت أن هذه المفاهيم تأثرت أيضًا بشكل كبير بالعوامل الاجتماعية. على الرغم من أن الأبحاث السابقة استكشفت بشكل أساسي العلاقات الثنائية بين الاستمتاع والانخراط (دو وشالرت، 2004) أو العلاقات بين الانخراط والاستعداد للتحدث، لا تزال هناك دراسات تجريبية قليلة تحقق في الآليات الكامنة وراء هذه العلاقات. لذلك، من الضروري التحقيق في الآليات المعقدة التي تكمن وراء هذه المفاهيم.

باختصار، ركزت الدراسات السابقة في SLA بشكل أساسي على الجوانب اللغوية للانخراط، مثل الميزات النحوية والمعجمية. ومع ذلك، فإن التعريف الأوسع للانخراط في التعليم يشمل الأبعاد النفسية، التي تم تجاهلها غالبًا. في هذه الدراسة، نركز بشكل أساسي على

الانخراط السلوكي، الذي يُعرف بأنه “وقت المشاركة، والمثابرة في الأنشطة التعليمية، وجهود المشاركة” (تينغ ووانغ، 2021، ص. 3). ويشمل المشاركة في التفاعلات مع زملاء الدراسة والمعلمين، وجودة هذه التفاعلات الاجتماعية. الانخراط السلوكي ذو صلة خاصة لأنه يؤثر بشكل مباشر على ديناميات التفاعل في الفصل الدراسي والبيئة التعليمية بشكل عام. تكمن المبررات للتركيز على الانخراط السلوكي في هذه الدراسة في أنه أكثر قابلية للملاحظة والقياس من الأبعاد الأخرى، ويمكن أن يسهل التقييم والتحليل المنهجي ضمن سياق تعليمي (فريدريكس وآخرون، 2004). علاوة على ذلك، وُجد أن الانخراط السلوكي مرتبط بشكل جوهري بالنجاح الأكاديمي (هيوز وآخرون، 2008)، حيث إن الطلاب الذين يشاركون بشكل سلوكي أكبر قد يظهرون مثابرة وجهودًا ومشاركة نشطة أكبر، وكلها أمور حاسمة للتعلم الفعال (ريف، 2012). نظرًا لأن الانخراط أمر حاسم للنجاح الأكاديمي، فإنه من الضروري دراسة أبعاده النفسية ضمن تعلم اللغة الثانية للحصول على رؤى أعمق في هذا المجال.

الانخراط السلوكي، الذي يُعرف بأنه “وقت المشاركة، والمثابرة في الأنشطة التعليمية، وجهود المشاركة” (تينغ ووانغ، 2021، ص. 3). ويشمل المشاركة في التفاعلات مع زملاء الدراسة والمعلمين، وجودة هذه التفاعلات الاجتماعية. الانخراط السلوكي ذو صلة خاصة لأنه يؤثر بشكل مباشر على ديناميات التفاعل في الفصل الدراسي والبيئة التعليمية بشكل عام. تكمن المبررات للتركيز على الانخراط السلوكي في هذه الدراسة في أنه أكثر قابلية للملاحظة والقياس من الأبعاد الأخرى، ويمكن أن يسهل التقييم والتحليل المنهجي ضمن سياق تعليمي (فريدريكس وآخرون، 2004). علاوة على ذلك، وُجد أن الانخراط السلوكي مرتبط بشكل جوهري بالنجاح الأكاديمي (هيوز وآخرون، 2008)، حيث إن الطلاب الذين يشاركون بشكل سلوكي أكبر قد يظهرون مثابرة وجهودًا ومشاركة نشطة أكبر، وكلها أمور حاسمة للتعلم الفعال (ريف، 2012). نظرًا لأن الانخراط أمر حاسم للنجاح الأكاديمي، فإنه من الضروري دراسة أبعاده النفسية ضمن تعلم اللغة الثانية للحصول على رؤى أعمق في هذا المجال.

الاستعداد للتواصل (WTC). يمثل WTC في تعلم اللغة الثانية مفهومًا معقدًا وديناميكيًا يؤثر بشكل كبير على نتائج تدريس وتعلم اللغات الأجنبية. تم تصوره في البداية من قبل مكروسكي وريتشمان (1987) كصفة مستقرة في سياقات اللغة الأم، وقد تطور WTC ليشمل “استعدادًا للدخول في حوار في وقت معين مع شخص أو أشخاص محددين، باستخدام لغة ثانية” في سياقات اللغة الثانية (ماكنتاير وآخرون، 1998، ص. 547). تعكس هذه التطورات الاعتراف بأن WTC في اللغة الثانية يختلف بشكل كبير بين المتعلمين بسبب تنوع كفاءاتهم اللغوية وفرصهم التواصلية (خاجافي وآخرون، 2018).

لقد شهد الإطار النظري لرغبة التواصل بلغة ثانية (L2 WTC) تطورًا كبيرًا على مدار العشرين عامًا الماضية، حيث تحول من رؤيته كمتغير سياقي وسمتي (MacIntyre et al., 1998) إلى تضمين وجهات نظر عملية، بيئية، وديناميكية (Cao and Philp, 2006; Cao, 2009; MacIntyre and Legatto, 2011). يؤكد هذا النموذج على أن التواصل الفعال بلغة ثانية يتطلب ليس فقط الكفاءة اللغوية ولكن أيضًا الاستعداد النفسي (Khajavy et al., 2018). علاوة على ذلك، يقترح نموذج الهرم أن تباينات الرغبة في التواصل تنشأ من التفاعلات بين العوامل اللغوية، والتواصلية، والسياقية (Khajavy et al., 2018). وقد تم التحقق من ذلك عبر سياقات متنوعة، بما في ذلك السياق الكوري (Joe et al., 2017)، والسياق الصيني (Peng and Woodrow, 2010)، والسياق الياباني (Yashima, 2002) والسياق الإيراني (Khajavy et al., 2016).

لقد حددت الأبحاث التجريبية العديد من العوامل التي تؤثر على الرغبة في التواصل بلغة ثانية (L2 WTC)، بما في ذلك العمليات طويلة الأمد والمتغيرات السياقية الفورية (خاجافي وآخرون، 2018). في سياقات اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين، أظهر بينغ وودرو (2010) الدور التنبؤي لبيئة الفصل الدراسي في تطوير الرغبة في التواصل، بينما أظهر وانغ (2019) الطبيعة الديناميكية للرغبة في التواصل من خلال التقلبات اللحظية. ومع ذلك، لا يزال هناك فجوة بحثية كبيرة في فهم العلاقة بين العوامل النفسية السياقية، وخاصة المتعة، والرغبة في التواصل بلغة ثانية. بينما اقترح ديوالي وماكنتاير (2016) أن المعلمين يمكنهم التأثير بشكل أكثر فعالية على متعة الطلاب في اللغة مقارنة بالقلق، لا تزال التفاعلات المعقدة بين المشاعر الإيجابية والرغبة في التواصل غير مستكشفة بشكل كافٍ. هذه القيود ملحوظة بشكل خاص نظرًا للعدد الكبير من المتنبئين المحتملين للرغبة في التواصل. لذلك، من الضروري استكشاف الروابط بين المتعة والرغبة في التواصل عبر سياقات التعلم المتنوعة، مما قد يعزز فهمنا لبيئات التواصل الفعالة بلغة ثانية. تلعب المشاعر والانخراط أدوارًا حاسمة في التعلم والرفاه النفسي (فينغ وهونغ، 2022)، ومع ذلك، توجد فجوة بحثية كبيرة في فهم الشبكة النمائية للمتعة في

SLA (بوتس وآخرون، 2020). بينما كانت الدراسات السابقة غالبًا ما تفحص العلاقات الثنائية البسيطة بين هذه المتغيرات، تشير الأبحاث الحديثة إلى وجود ترابطات أكثر تعقيدًا بين الانخراط العاطفي والسلوكي، والاستعداد للتواصل في سياقات تعلم اللغة.

لقد تم دعم العلاقة الإيجابية بين FLE والانخراط باستمرار عبر دراسات متعددة (Feng و Hong، 2022؛ Khajavy، 2021؛ Nalipay وآخرون، 2021). هذا التوافق مع نظرية توسيع وبناء فريدريكسون (2001) يظهر أن المشاعر الإيجابية تعزز الانخراط من خلال زيادة المشاركة في أنشطة التعلم. وبالمثل، أظهرت الأبحاث باستمرار وجود علاقات إيجابية بين FLE و WTC في فصول اللغة (Bensalem، 2022؛ Dewaele و Pavelescu، 2021؛ Peng و Wang، 2024)، حيث تم تحديد المتعة كأكثر المشاعر الإيجابية انتشارًا التي تسهل الرغبة في التواصل (Dewaele و MacIntyre، 2019). ومع ذلك، تظهر عدة تناقضات في الأدبيات. أولاً، بينما يظهر FLE عمومًا آثارًا إيجابية عبر السياقات، تكشف الدراسات عن اختلافات ثقافية كبيرة. وجد Feng و Hong (2022) أن الطلاب الصينيين يبلغون عن قلق أعلى ومتعة أقل مقارنةً بالعينات الغربية، مما يشير إلى أن العلاقة بين المشاعر والانخراط قد تكون متوسطة ثقافيًا. ثانيًا، توجد نتائج متناقضة بشأن استقرار هذه العلاقات. بينما تقدم بعض الدراسات هذه العلاقات على أنها مستقرة نسبيًا (Khajavy وآخرون، 2018)، تكشف أبحاث Dewaele و Pavelescu (2021) الطولية أن المشاعر وارتباطها بـ WTC ديناميكية للغاية وتتقلب مع مرور الوقت. ثالثًا، بينما وجد Kun وآخرون (2020) علاقات إيجابية قوية بين FLE و WTC بين الطلاب الصينيين في التعليم العالي الذين لديهم مستويات عالية من FLE، تختلف العلاقة بشكل كبير بين الطلاب بمستويات كفاءة مختلفة وفي سياقات تعلم مختلفة.

لا تزال هناك عدة فجوات بحثية. أولاً، بينما تم إثبات الطبيعة الديناميكية للمشاعر فيما يتعلق بـ WTC، لا تزال الآليات المحددة التي تحرك هذه التقلبات غير واضحة، خاصة في سياق EFL الصيني. ثانيًا، تفحص معظم الدراسات هذه المتغيرات في أزواج بدلاً من التحقيق في تفاعلاتها المتزامنة في فصول المحادثة. لذلك، فإن هذا التفاعل المعقد بين المشاعر والانخراط و WTC، جنبًا إلى جنب مع النتائج المتناقضة في سياقات مختلفة، يتطلب نهجًا أكثر شمولية لفهم كيفية عمل هذه المتغيرات معًا في تعلم اللغة. من الضروري تطوير ممارسات تدريس أكثر فعالية تأخذ في الاعتبار النطاق الكامل للديناميات العاطفية والسلوكية في بيئات تعلم اللغة.

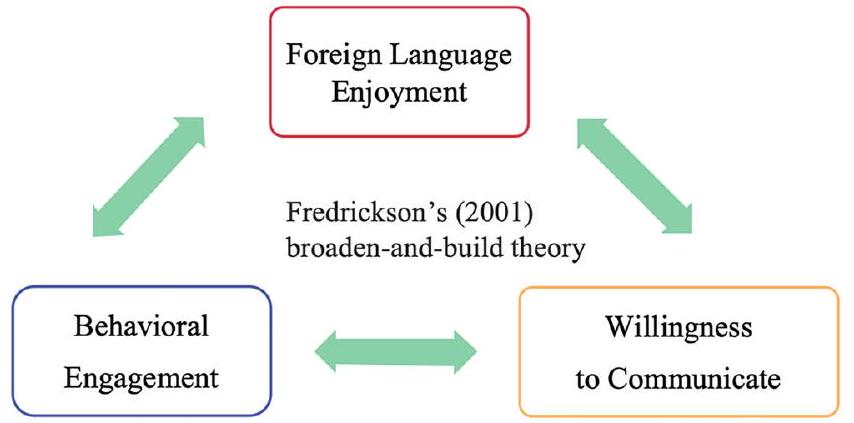

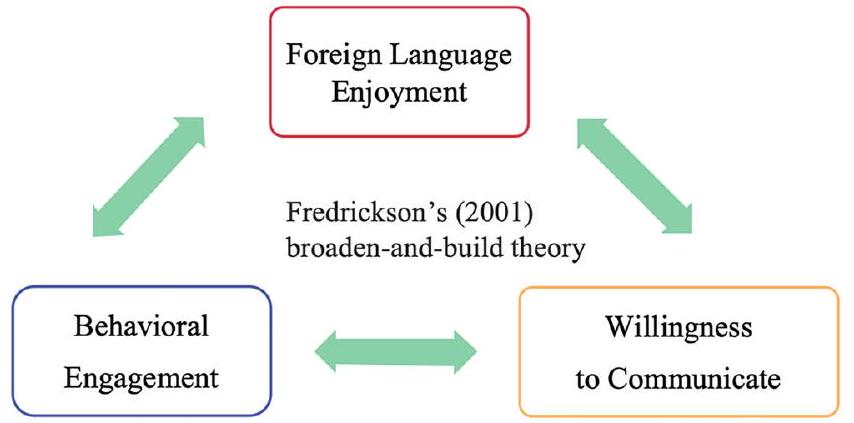

الإطار المفاهيمي. اختيار FLE والانخراط السلوكي و WTC كأبعاد رئيسية في هذه الدراسة مستند نظريًا إلى نظرية توسيع وبناء فريدريكسون (2001) ومبرر بشكل خاص من خلال أدوارها الحاسمة في سياقات المحادثة في EFL. تشكل هذه الأبعاد الثلاثة إطارًا مترابطًا يلتقط كل من الأبعاد العاطفية والسلوكية لتعلم اللغة. تم اختيار FLE لأنه يمثل أكثر المشاعر الإيجابية انتشارًا في فصول اللغة (Dewaele و MacIntyre، 2019) ويتماشى مع وظيفة التوسيع. في سياق EFL الصيني، حيث يعمل القلق من التحدث غالبًا كحاجز (Jiang و Dewaele، 2019)، فإن قدرة FLE على مواجهة المشاعر السلبية تجعلها ذات صلة خاصة. الانخراط السلوكي، الذي يُعرف بمشاركة الطلاب النشطة في أنشطة تعلم اللغة، هو أكثر قابلية للرصد والقياس من الأبعاد الأخرى للانخراط. هذا الجانب السلوكي مهم بشكل خاص في فصول EFL الصينية، حيث قد تحد الطرق التعليمية التقليدية من فرص المشاركة النشطة. تم اختيار WTC كمتغير ناتج لأنه يجسد جانب ‘البناء’ من النظرية ويمثل الهدف النهائي من التعليم اللغوي: استعداد الطلاب للانخراط.

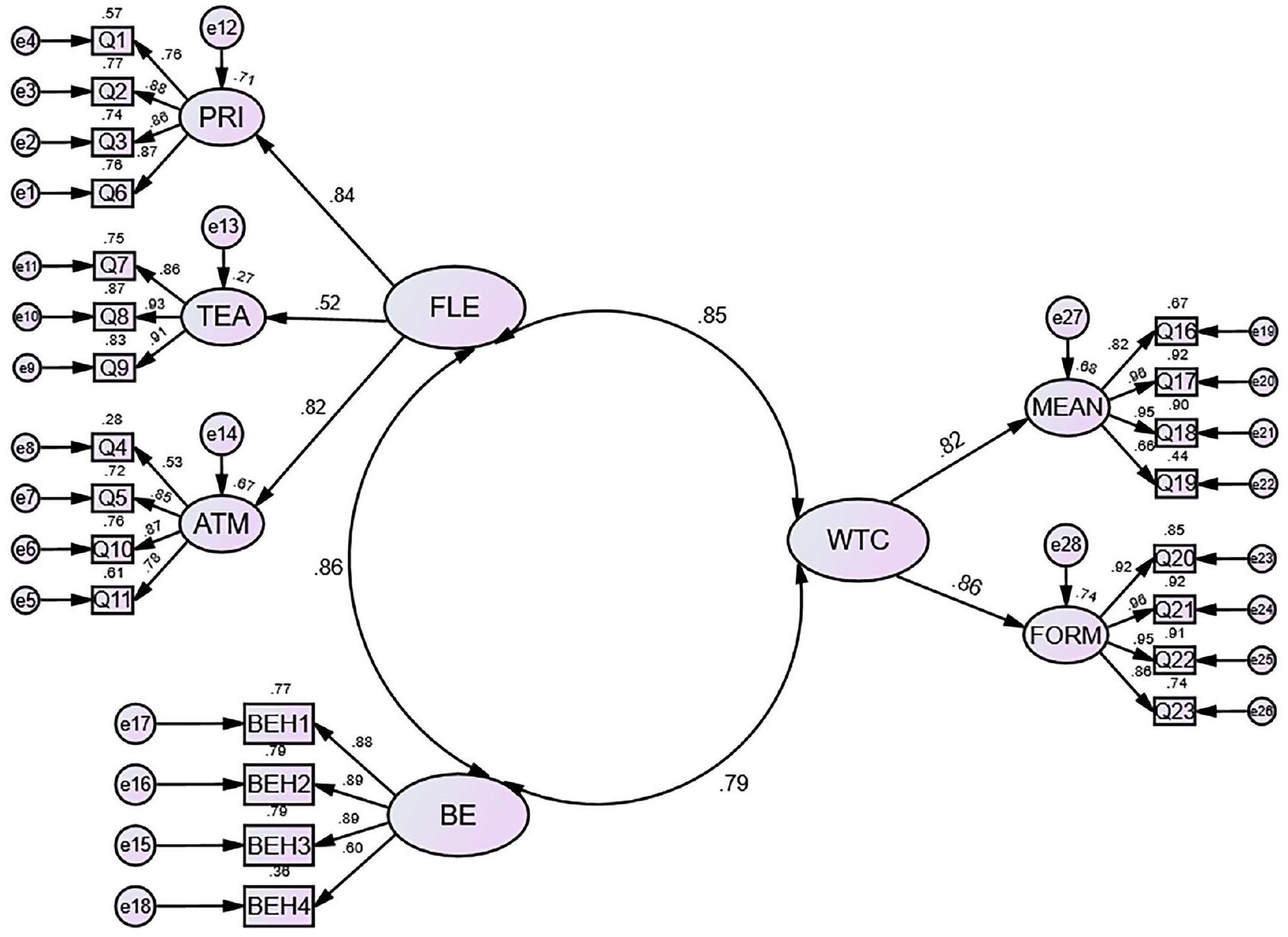

الشكل 1 الإطار المفاهيمي للدراسة. يوضح هذا الشكل العلاقات المفترضة بين الأبعاد الرئيسية التي تم فحصها في هذه البحث.

| الجدول 1 الخصائص الديموغرافية للمشاركين (

|

|||

| المتغيرات | المستوى | التكرار | النسبة المئوية |

| الجنس | ذكر | 231 | 33.5% |

| أنثى | 459 | 66.5% | |

| العمر | الحد الأقصى. | الحد الأدنى. | المتوسط. |

| 26 | 17 | 19.97 | |

| السنة الدراسية | السنة الأولى | 335 | 48.6% |

| السنة الثانية | 186 | 27.0% | |

| السنة الثالثة | 69 | 10.0% | |

| السنة الرابعة | 100 | 14.5% | |

| درجة CET-4 | أقل من 425 | 187 | 27.1% |

| 425-550 | 415 | 60.1% | |

| أعلى من 550 | 88 | 12.8% | |

| درجة CET-6 | أقل من 425 | 300 | 43.5% |

| 425-550 | 313 | 45.4% | |

| أعلى من 550 | 77 | 11.2% | |

في التواصل بلغة L2، وهو أمر مهم بشكل خاص في سياق EFL الصيني حيث يظهر الطلاب غالبًا كفاءة لغوية عالية ولكن رغبة أقل في التواصل (MacIntyre وآخرون، 2019). لذلك، في سياق هذه الدراسة، من المحتمل أن يسهل FLE زيادة الانخراط السلوكي في أنشطة الفصل الدراسي، مما يؤدي بدوره إلى تطوير رغبة الطلاب في التواصل في تعلم اللغة.

يوضح الشكل 1 الإطار المفاهيمي للدراسة. يقسم الإطار الحالي WTC إلى بعدين وفقًا لنموذج Peng و Woodrow (2010): الأنشطة التي تركز على الشكل، والتي تركز على ميزات اللغة المحددة والأنشطة التي تركز على المعنى، والتي تركز على تبادل الرسائل. يتكون المتغير FLE من ثلاثة أبعاد، تم تحديدها من مقياس FLE الصيني في دراسة Li وآخرون (2018). يتم تعريف هذه الأبعاد على النحو التالي: FLE-خاص، وهو المتعة الشخصية من التقدم والأداء؛ FLE-معلم، وهو المتعة من دعم معلم EFL؛ FLE-جو، وهو الاستمتاع من جو الفصل الإيجابي. تم تعديل المتغير الانخراط السلوكي من مقياس Khajavy (2021)، بما في ذلك أربعة عناصر تقيس الانخراط في الجوانب السلوكية.

المنهجية

المشاركون. شملت الدراسة 690 طالبًا جامعيًا صينيًا في EFL (أنثى

طلابًا جامعيين في مستويات أكاديمية مختلفة، تتراوح من السنة الأولى إلى السنة الرابعة، ضمن سياق EFL. تم اختيار المشاركين بناءً على اعتبارين. أولاً، ركزنا على طلاب الجامعات الصينية في EFL حيث يمثلون شريحة كبيرة في تعليم اللغة الإنجليزية، مما يسمح لنا بفحص تجربة تعلم اللغة للمتعلمين الصينيين في سياق تعلم حقيقي. ثانيًا، من خلال تضمين طلاب من مؤسسات متعددة عبر مناطق مختلفة من الصين، هدفنا إلى التقاط عينة متنوعة تعكس السياقات المؤسسية والإقليمية المتنوعة، ويمكن أن تعزز من تعميم نتائجنا ضمن سياق EFL الصيني. تم أخذ عينة من 919 طالبًا جامعيًا يدرسون دورات المحادثة باللغة الإنجليزية من سبع جامعات عبر ست مقاطعات (هوبى، قوانغدونغ، خنان، خبي، تشجيانغ، وشانشي). بعد استبعاد 229 طالبًا

طلابًا جامعيين في مستويات أكاديمية مختلفة، تتراوح من السنة الأولى إلى السنة الرابعة، ضمن سياق EFL. تم اختيار المشاركين بناءً على اعتبارين. أولاً، ركزنا على طلاب الجامعات الصينية في EFL حيث يمثلون شريحة كبيرة في تعليم اللغة الإنجليزية، مما يسمح لنا بفحص تجربة تعلم اللغة للمتعلمين الصينيين في سياق تعلم حقيقي. ثانيًا، من خلال تضمين طلاب من مؤسسات متعددة عبر مناطق مختلفة من الصين، هدفنا إلى التقاط عينة متنوعة تعكس السياقات المؤسسية والإقليمية المتنوعة، ويمكن أن تعزز من تعميم نتائجنا ضمن سياق EFL الصيني. تم أخذ عينة من 919 طالبًا جامعيًا يدرسون دورات المحادثة باللغة الإنجليزية من سبع جامعات عبر ست مقاطعات (هوبى، قوانغدونغ، خنان، خبي، تشجيانغ، وشانشي). بعد استبعاد 229 طالبًا

تكونت العينة النهائية من 690 طالبًا جامعيًا (انظر الجدول 1 للحصول على خصائص ديموغرافية مفصلة). عكست العينة التوزيع الجنسى النموذجي في برامج اللغات الأجنبية الصينية، حيث شكلت الطالبات حوالي ثلثي المشاركين. كان متوسط العمر

الأدوات. استخدمت الدراسة الحالية ثلاثة استبيانات معدلة ومصادق عليها لجمع البيانات، جميعها مقدمة باللغة الصينية، لضمان الفهم الدقيق. تألف الاستبيان من جزئين، بما في ذلك المعلومات الديموغرافية والثلاثة مقاييس: FLE، WTC، والانخراط السلوكي. تم تصميم نموذج المعلومات الديموغرافية من قبل الباحثين لجمع البيانات حول جنس المشاركين، وعمرهم، وسنتهم الدراسية، ودرجة CET-4، ودرجة CET-6. تم قياس جميع العناصر على مقياس ليكرت من خمس نقاط (من

لأغراض هذه الدراسة، تم استخدام ثلاثة استبيانات معدلة ومصادق عليها لجمع البيانات، بما في ذلك ثلاثة أبعاد: FLE، والانخراط، وWTC، بما في ذلك 23 عنصرًا.

مقياس الاستمتاع باللغة الأجنبية. تم تعديل المقياس لتقييم FLE من مقياس FLE الصيني في دراسة لي وآخرون (2018). يتضمن المقياس 11 عنصرًا من ثلاثة أبعاد: خاص، معلم، وجو. أحد أمثلة التعديلات على المقاييس كان تغيير “لقد تعلمت أشياء مثيرة” إلى “لقد تعلمت معلومات مثيرة في الدروس”) لتعزيز الوضوح والدقة في سياق الفصل الدراسي للغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن موثوقية مقياس FLE المعدل في هذه الدراسة تم حسابها على أنها 0.91 للخاص، 0.93 للمعلم، و0.83 للجو، مما يشير إلى موثوقية عالية للعناصر.

مقياس WTC. تم تصميم المقياس لتقييم استعداد الطلاب للتحدث باللغة الإنجليزية في دروس المحادثة، وتم تعديله من مقياس بينغ وودرو (2010). يتضمن المقياس 10 عناصر تقيس WTC من بعدين: الأنشطة الموجهة نحو المعنى والأنشطة الموجهة نحو الشكل. كما خضع مقياس WTC للترجمة والترجمة العكسية من قبل خبيرين ثنائيي اللغة. إنه

الجدول 2 موثوقية الاستبيانات.

| البناءات | البعد | العناصر | معامل كرونباخ |

| FLE | خاص | Q1 | 0.91 |

| Q2 | |||

| Q3 | |||

| Q6 | |||

| معلم | Q7 | 0.93 | |

| Q8 | |||

| Q9 | |||

| جو | Q4 | 0.83 | |

| Q5 | |||

| Q10 | |||

| Q11 | |||

| سلوكي | Q12 | 0.88 | |

| Q13 | |||

| Q14 | |||

| WTC | موجه نحو المعنى | Q16 | 0.91 |

| Q17 | |||

| Q18 | |||

| Q19 | |||

| موجه نحو الشكل | Q20 | 0.96 | |

| Q21 | |||

| Q22 | |||

| Q23 |

من الجدير بالذكر أن دراسة سابقة أفادت بمعاملات موثوقية لمقياس WTC كانت 0.91 للأنشطة الموجهة نحو المعنى، و0.96 للأنشطة الموجهة نحو الشكل، مما يشير إلى موثوقية عالية.

مقياس الانخراط السلوكي. تم تعديل مقياس الانخراط السلوكي من خاجافي (2021). يتضمن المقياس 4 عناصر، تقيس الانخراط السلوكي داخل فصل المحادثة بلغة L2 (على سبيل المثال، ‘أبذل جهدًا في تعلم الإنجليزية’). في هذه الدراسة، كانت موثوقية المقياس المعدل 0.88 للعناصر في الانخراط السلوكي، مما يشير إلى أن العناصر تظهر موثوقية عالية.

يوضح الجدول 2 موثوقية مقاييس FLE وWTC والانخراط السلوكي. يعرض هذا الجدول قيم ألفا كرونباخ لثلاثة مقاييس مصادق عليها، مما يدل على اتساق داخلي موثوق.

جمع البيانات. تم إجراء الدراسة عبر الإنترنت باستخدام منصة الاستبيان وينجوانشين (www.wjx.cn). تم تجنيد المشاركين من خلال أخذ عينات ملائمة من دورات اللغة الإنجليزية الجامعية من مؤسسات تعليمية متعددة في مناطق مختلفة من الصين، لاختيار المشاركين بناءً على سهولة الوصول والقرب (إتيكان وآخرون، 2016). تضمنت استراتيجية أخذ العينات التعاون مع معلمي EFL الذين وافقوا على مشاركة رابط الاستبيان مع طلابهم عبر مختلف الأقسام الأكاديمية. تم جمع البيانات من الطلاب الذين كانوا متاحين بسهولة واختاروا المشاركة طواعية في الدراسة. قبل جمع البيانات، تم الحصول على موافقة أخلاقية من لجنة أخلاقيات البحث في جامعة شمال الصين لموارد المياه والطاقة الكهربائية، وقدم جميع المشاركين موافقة مستنيرة. تم إجراء دراسة تجريبية أولية مع ثلاثة طلاب لاكتشاف أي مشاكل محتملة مع الأدوات قبل البحث الرئيسي. تم إبلاغ المشاركين بأهداف الدراسة وقدموا موافقتهم المستنيرة قبل توزيع الاستبيان. تم جمع الملاحظات من طلاب المجموعة التجريبية بشأن أي أسئلة غير واضحة أو مضللة. تم إجراء مراجعات على جميع الأدوات بناءً على نتائج الدراسة التجريبية وملاحظات المشاركين. تم تقديم المقاييس النهائية لجميع المشاركين في الدراسة الفعلية. تم الحفاظ على سرية وهوية

الجدول 3 علاقات FLE والانخراط السلوكي وWTC.

| المتغير | FLE | BE | WTC |

| FLE | 1 | ||

| BE |

|

1 | |

| WTC |

|

|

1 |

|

|

تظل المعلومات الشخصية للمشاركين محفوظة بشكل صارم، مما يضمن المبادئ الأخلاقية المتكاملة للدراسة.

تحليل البيانات. استخدمت الدراسة تصميم بحث بأسلوب كمي لفهم العلاقة بين FLE والانخراط السلوكي وWTC بين طلاب EFL الصينيين. تم إجراء تحليل البيانات باستخدام حزم البرمجيات SPSS 27 وAMOS 27. أولاً، تمت إزالة الاستجابات غير الصالحة، وتم تحديد القيم الشاذة لاختبار التوزيع الطبيعي لضمان جودة البيانات (كولير، 2020). أظهرت البيانات توزيعًا طبيعيًا، مما يلبي متطلبات التحليل اللاحق (هو وبنتلر، 1999). ثم تم استخدام التحليل الوصفي لتقييم تكرار العناصر في المتغيرات الثلاثة. بعد ذلك، تم قياس الموثوقية والصلاحية باستخدام ألفا كرونباخ (

النتائج

العلاقات المتبادلة بين FLE والانخراط السلوكي وWTC. في البداية، تم تطبيق تقنيات مراجعة البيانات لتحديد أي معلومات مفقودة أو قيم شاذة ولتقييم التوزيع الطبيعي لمجموعة البيانات. كانت هذه العملية الشاملة مصممة لضمان نزاهة وموثوقية مجموعة البيانات، مما يسهل التحليلات اللاحقة (كلين، 2015). أظهر تحليلنا الأولي أن قيم الانحراف والتفرطح كانت جميعها ضمن النطاقات المقبولة (الانحراف

وفقًا للجدول 3، هناك علاقات قوية بين FLE والانخراط السلوكي وWTC. أولاً، توجد علاقة إيجابية كبيرة بين FLE والانخراط السلوكي (0.656**). لوحظت علاقة إيجابية مماثلة بين FLE وWTC (0.656**). علاوة على ذلك، تم العثور أيضًا على علاقة إيجابية قوية بين الانخراط السلوكي وWTC (

التأثير التنبؤي لـ FLE والانخراط السلوكي على WTC. بالنسبة لـ CFA وSEM اللاحقين، تم تأكيد ملاءمة العينة من خلال اختبار كايزر-ماير-أولكين

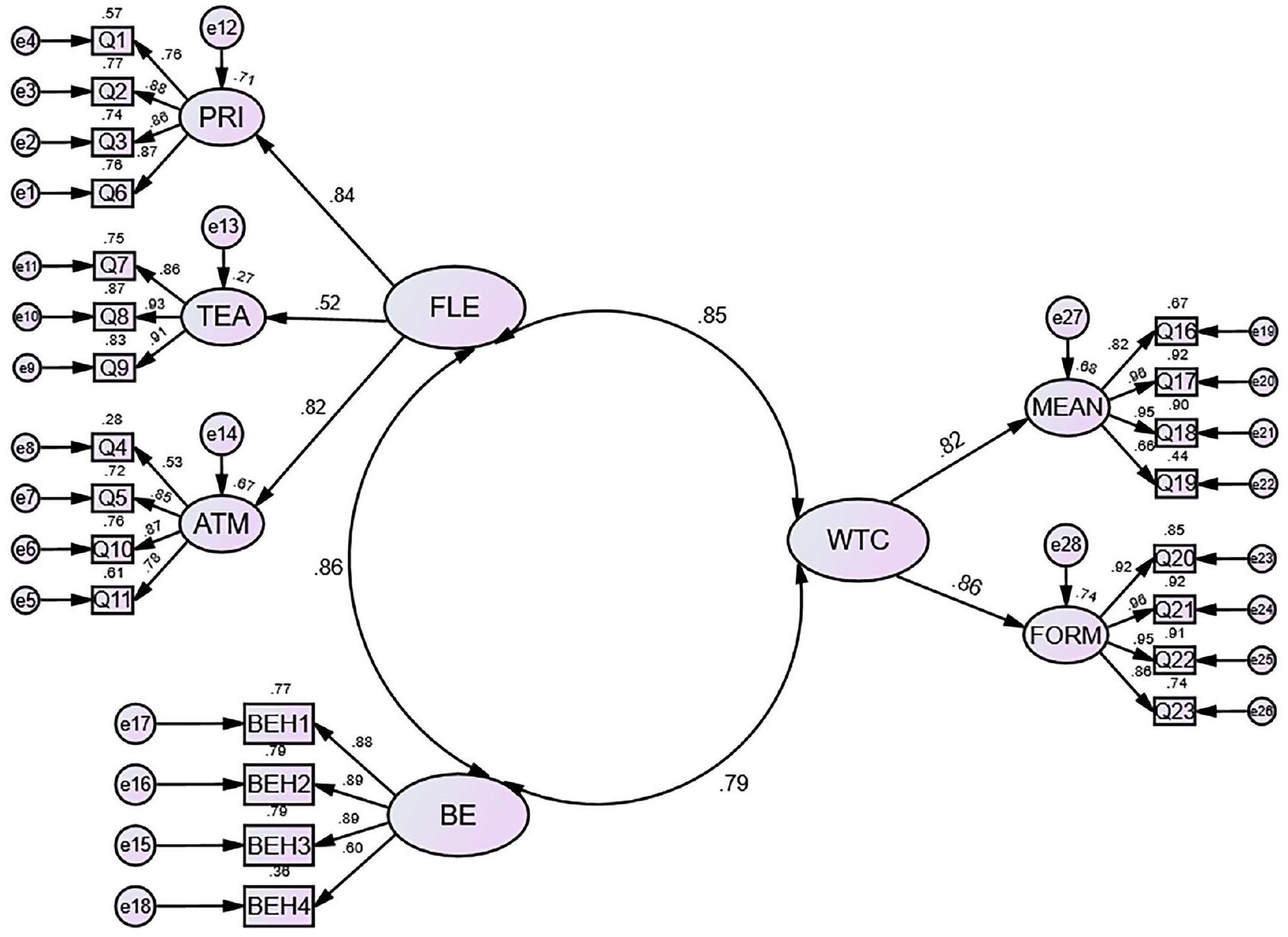

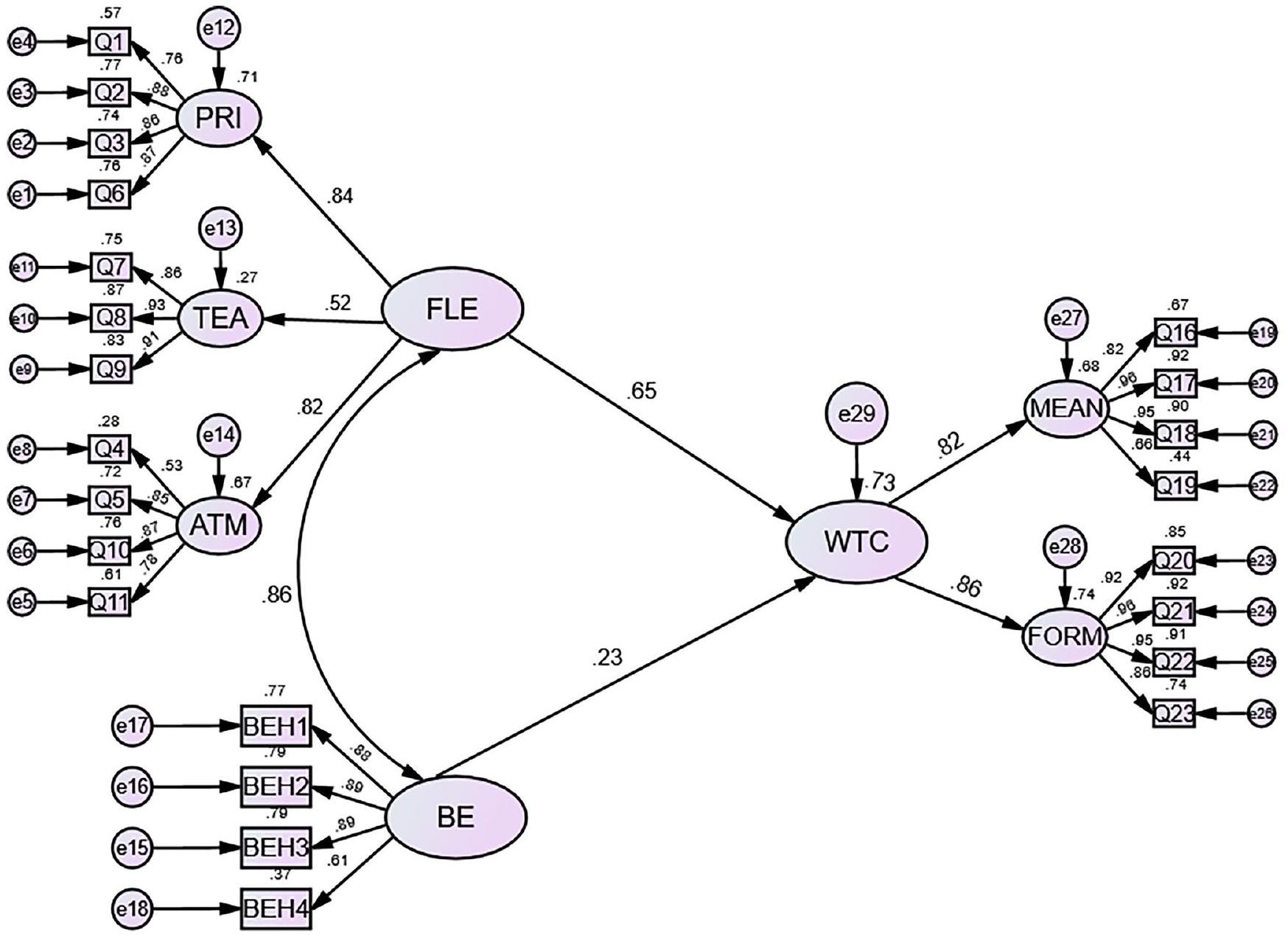

تم بناء نموذج القياس بعد ذلك بواسطة AMOS. يشير النموذج الأولي إلى توافق جيد مع البيانات، كما هو موضح في الشكل 2. تم الإشارة إلى جودة التوافق من خلال عدة عناصر رئيسية، كما هو موضح

في الجدول 4. نسبة CMIN/df، التي تمثل إحصائية كاي-تربيع مقسومة على درجات الحرية، هي 4.87، مما يلبي متطلبات أن تكون أقل من أو تساوي 5.0 (مارش وهوكيفار، 1985). وهذا يشير إلى أن الفجوة بين مصفوفات التغاير المرصودة والمتوقعة يمكن قبولها. RMSEA هو 0.075، ضمن النطاق المقبول الذي يقل عن 0.080، مما يشير إلى خطأ تقريبي معقول. CFI، الذي يأخذ في الاعتبار حجم العينة، هو 0.942، متجاوزًا الحد الأدنى المطلوب وهو 0.9، مما يشير إلى أن النموذج يتناسب مع البيانات بشكل جيد مقارنةً بنموذج مستقل. PNFI، الذي يعدل مؤشر الملاءمة المعياري لتعقيد النموذج، هو 0.814، وهو أعلى بكثير من المتطلب الذي يزيد عن 0.5، مما يوحي بأن

في الجدول 4. نسبة CMIN/df، التي تمثل إحصائية كاي-تربيع مقسومة على درجات الحرية، هي 4.87، مما يلبي متطلبات أن تكون أقل من أو تساوي 5.0 (مارش وهوكيفار، 1985). وهذا يشير إلى أن الفجوة بين مصفوفات التغاير المرصودة والمتوقعة يمكن قبولها. RMSEA هو 0.075، ضمن النطاق المقبول الذي يقل عن 0.080، مما يشير إلى خطأ تقريبي معقول. CFI، الذي يأخذ في الاعتبار حجم العينة، هو 0.942، متجاوزًا الحد الأدنى المطلوب وهو 0.9، مما يشير إلى أن النموذج يتناسب مع البيانات بشكل جيد مقارنةً بنموذج مستقل. PNFI، الذي يعدل مؤشر الملاءمة المعياري لتعقيد النموذج، هو 0.814، وهو أعلى بكثير من المتطلب الذي يزيد عن 0.5، مما يوحي بأن

عتبة

الجدول 4 تقييم ملاءمة نموذج CFA.

| معايير | رهيب | مقبول | ممتاز | تقييم | |

| سيمن | ١٠٨١.١٧١ | ||||

| df | 222 | ||||

| CMIN/df | ٤.٨٧ | >5 | >3 | <1 | مقبول |

| RMSEA | 0.075 | >0.08 | <0.08 | <0.06 | مقبول |

| جي إف آي | 0.883 | <0.9 | >0.9 | >0.95 | ممتاز |

| CFI | 0.942 | <0.9 | >0.9 | >0.95 | ممتاز |

| PNFI | 0.814 | <0.5 | >0.5 | مقبول | |

| TLI | 0.934 | <0.9 | >0.9 | >0.95 | ممتاز |

النموذج متسق مع البيانات بشكل جيد على الرغم من تعقيده. أخيرًا، مؤشر TLI، وهو مؤشر ملاءمة مقارن يعاقب على تعقيد النموذج، هو 0.934، متجاوزًا العتبة المطلوبة البالغة 0.9، مما يشير إلى ملاءمة جيدة جدًا. بشكل عام، كل مقياس لملاءمة النموذج يتماشى مع المعايير المحددة أو يتجاوزها، مما يدل على أن النموذج يلبي جميع المعايير بشكل مرضٍ. على الرغم من أن قيمة GFI هي 0.88، وهي أقل بقليل من 0.9، إلا أن جميع مؤشرات ملاءمة النموذج الأخرى تقع ضمن النطاقات المقبولة، ومن الجدير بالذكر أن GFI حساس لحجم العينة وغالبًا ما يعتبر مؤشرًا أقل موثوقية لملاءمة النموذج (تومس وآخرون، 2006). نظرًا لأن هذا نموذج من الدرجة الثانية مع زيادة التعقيد، يمكن اعتبار قيمة GFI المحصل عليها مقبولة، حيث تم اعتبار القيم التي تزيد عن 0.80 مناسبة للنماذج المعقدة (بيرن، 2013).

تم استخدام CFA لتقييم موثوقية التركيب (CR) ومتوسط التباين المستخرج (AVE) لكل عامل، وفقًا لإرشادات الإجراءات التي وضعها كولير (2020). تقدم الجدول 5 تقييمًا للصلاحية التمييزية وCR لكل بناء. أظهرت النتائج أن جميع البنى تلبي عتبات CR.

الشكل 2 نموذج CFA النهائي المعدل مع التقديرات المعيارية. يعرض هذا الشكل نموذج تحليل العوامل التأكيدي بعد التعديلات، موضحًا العلاقات بين المتغيرات الكامنة ومؤشراتها.

| الجدول 5 موثوقية مركبة وصلاحية تمييز المتغيرات. | |||||

| متغير | الموثوقية المركبة | صلاحية التمييز | |||

| سي آر | AVE | كن | FLE | برج التجارة العالمي | |

| FLE | 0.779 | 0.550 | 0.742 | ||

| كن | 0.891 | 0.677 | 0.703*** | 0.822 | |

| برج التجارة العالمي | 0.829 | 0.708 | 0.656*** | 0.685*** | 0.841 |

| ***

|

|||||

| الجدول 6 تقييم جودة ملاءمة نموذج SEM. | |||||

| عتبة | |||||

| معايير | رهيب | مقبول | ممتاز | تقييم | |

| سيمن | ١٠٨١.٥٤ | ||||

| df | 222 | ||||

| CMIN/df | ٤.٨٧ | >5 | >3 | <1 | مقبول |

| RMSEA | 0.075 | >0.08 | <0.08 | <0.06 | مقبول |

| جي إف آي | 0.883 | <0.9 | >0.9 | >0.95 | ممتاز |

| CFI | 0.942 | <0.9 | >0.9 | >0.95 | ممتاز |

| PNFI | 0.814 | <0.5 | >0.5 | مقبول | |

| TLI | 0.934 | <0.9 | >0.9 | >0.95 | ممتاز |

ثم تم بناؤه بواسطة AMOS. يشير نموذج القياس إلى توافق جيد مع البيانات، كما هو موضح في الشكل 2.

كما ذُكر سابقًا، قبل تحليل البيانات في النموذج الهيكلي، تم تأكيد افتراضات SEM. تم عرض نتائج تقييم ملاءمة SEM في الجدول 6.

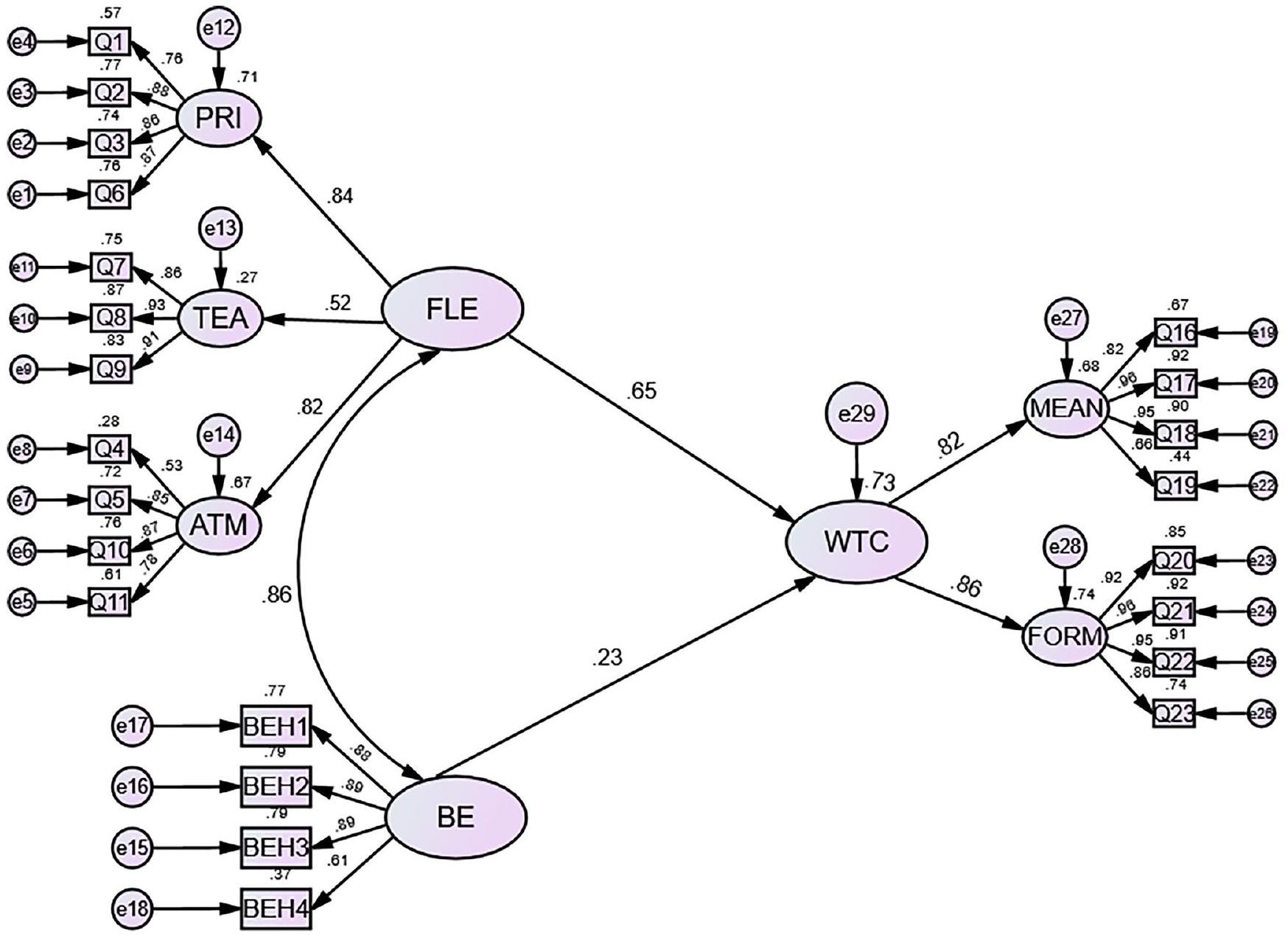

بعد ذلك، تم بناء النموذج الهيكلي بواسطة AMOS. أظهر نموذج القياس خصائص ملائمة مرضية بشكل عام، كما هو موضح في الشكل 3 والجدول 6. نسبة كاي-تربيع (CMIN/df

يظهر SEM لهذا التحليل في الشكل 3. تكشف الجدول 7 أن العلاقة بين FLE و WTC ذات دلالة إحصائية.

نقاش

تدرس هذه الدراسة دور FLE والانخراط السلوكي في WTC من خلال استخدام نهج كمي بين متعلمي اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين.

تعلم الطلاب في الكلية. على وجه التحديد، استكشفت الدراسة العلاقات المهمة بين الفرح في التعلم، والانخراط، والاستعداد للتواصل بين طلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية الصينيين في الفصول الدراسية الناطقة باللغة الإنجليزية. أظهرت النتائج وجود علاقات إيجابية كبيرة بين كل من الفرح في التعلم والانخراط السلوكي مع الاستعداد للتواصل، حيث أظهر الفرح في التعلم ارتباطًا أقوى من الانخراط السلوكي. والأهم من ذلك، أنه يظهر تأثير الفرح في التعلم والانخراط السلوكي على الاستعداد للتواصل. هذه الدراسة مهمة بشكل خاص لأنها تضع الفرح في التعلم في إطار نظري نظرية التوسع والبناء لفريدريكسون (2001) في سياق تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين. وفقًا لهذه النظرية، فإن المشاعر الإيجابية مثل الاستمتاع تؤدي وظيفتين حاسمتين: فهي توسع من نطاق تفكير الطلاب وإجراءاتهم اللحظية وتبني مواردهم الشخصية المستدامة. في سياق دراستنا، عندما يستمتع الطلاب بعملية التعلم، فإن هذه المشاعر الإيجابية توسع من منظورهم حول تعلم اللغة، مما يجعلهم أكثر احتمالًا لرؤية التواصل كفرصة بدلاً من تهديد. ثم يبني هذا التأثير التوسعي موارد تعليمية دائمة، بما في ذلك زيادة الثقة والاستعداد للتواصل. تساعد هذه النظرية في تفسير سبب كون الاستمتاع يمكن أن يلعب دورًا حاسمًا في كسر الحواجز التواصلية، خاصة في البيئات الجامعية الصينية حيث قد يكون الطلاب تقليديًا مترددين في التحدث. يبرز هذا المنظور النظري الدور المحوري للاستمتاع في إثراء تجربة الفصل الدراسي وتعزيز انخراط الطلاب السلوكي واستعدادهم للتواصل.

تعلم الطلاب في الكلية. على وجه التحديد، استكشفت الدراسة العلاقات المهمة بين الفرح في التعلم، والانخراط، والاستعداد للتواصل بين طلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية الصينيين في الفصول الدراسية الناطقة باللغة الإنجليزية. أظهرت النتائج وجود علاقات إيجابية كبيرة بين كل من الفرح في التعلم والانخراط السلوكي مع الاستعداد للتواصل، حيث أظهر الفرح في التعلم ارتباطًا أقوى من الانخراط السلوكي. والأهم من ذلك، أنه يظهر تأثير الفرح في التعلم والانخراط السلوكي على الاستعداد للتواصل. هذه الدراسة مهمة بشكل خاص لأنها تضع الفرح في التعلم في إطار نظري نظرية التوسع والبناء لفريدريكسون (2001) في سياق تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين. وفقًا لهذه النظرية، فإن المشاعر الإيجابية مثل الاستمتاع تؤدي وظيفتين حاسمتين: فهي توسع من نطاق تفكير الطلاب وإجراءاتهم اللحظية وتبني مواردهم الشخصية المستدامة. في سياق دراستنا، عندما يستمتع الطلاب بعملية التعلم، فإن هذه المشاعر الإيجابية توسع من منظورهم حول تعلم اللغة، مما يجعلهم أكثر احتمالًا لرؤية التواصل كفرصة بدلاً من تهديد. ثم يبني هذا التأثير التوسعي موارد تعليمية دائمة، بما في ذلك زيادة الثقة والاستعداد للتواصل. تساعد هذه النظرية في تفسير سبب كون الاستمتاع يمكن أن يلعب دورًا حاسمًا في كسر الحواجز التواصلية، خاصة في البيئات الجامعية الصينية حيث قد يكون الطلاب تقليديًا مترددين في التحدث. يبرز هذا المنظور النظري الدور المحوري للاستمتاع في إثراء تجربة الفصل الدراسي وتعزيز انخراط الطلاب السلوكي واستعدادهم للتواصل.

أولاً، أشارت النتائج إلى وجود ارتباط إيجابي ذو دلالة إحصائية، معتدل الأهمية، بين الفرح في التعلم والاستعداد للتواصل. وقد أشار الارتباط الإيجابي إلى أن مستويات أعلى من الفرح في التعلم تتوافق مع زيادة مستويات الاستعداد للتواصل بين طلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. يتماشى هذا الاكتشاف مع توقعات نظرية التوسع والبناء، مما يشير إلى أن المتعة المستمدة من عملية التعلم تؤثر بشكل كبير على استعداد الطلاب للمشاركة في الأنشطة التواصلية، خاصة في السياق التعليمي الصيني حيث تعتبر المحافظة على الوجه وتجنب الأخطاء اعتبارات ثقافية مهمة. من الملحوظ أن المشاعر الإيجابية (أي المتعة) الناتجة عن المتعة الشخصية المستمدة من التقدم والأداء، وبيئات التعلم الممتعة، وعلاقات المعلم والطالب الداعمة تلعب دورًا محوريًا في هذه الديناميكية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تشير الأبحاث السابقة إلى أن المتعلمين الذين يبلغون عن مستويات أعلى من المتعة قد يكونون أكثر ميلاً للتواصل برغبة في دروس لغتهم (ديوايلي، 2019). يمكن تفسير ذلك من خلال حقيقة أن المشاعر الإيجابية تقلل من القلق وتزيد من الثقة، مما يسهل المشاعر الإيجابية، مما يجعل الطلاب يشعرون بمزيد من الراحة والدافع للتواصل (فريدريكسون، 2001). علاوة على ذلك، يؤكد هذا الاكتشاف التأثير التنبؤي الحاسم للفرح في التعلم على الاستعداد للتواصل بلغة ثانية، كما تم الإبلاغ عنه في عدة دراسات (بن سالم، 2022؛ ديوايلي، 2019؛ ديوايلي وبافيلسكو، 2021؛ كون وآخرون، 2020؛ بينغ ووانغ، 2024). وفقًا لبينغ (2012)، فإن بيئة الفصل الدراسي التي تعطي الأولوية للمتعة من خلال الأنشطة التفاعلية والمثيرة تعزز شعور المجتمع وتخفض الفلتر العاطفي، مما يزيد من الاستعداد للتواصل. تشجع هذه البيئة الداعمة الطلاب على اتخاذ مخاطر لغوية ورؤية التواصل كفرصة للنمو بدلاً من تحدٍ (ديوايلي، 2015). والأهم من ذلك، أن هذه العلاقة الإيجابية بين الفرح في التعلم والاستعداد للتواصل مدعومة بنظرية فريدريكسون (2001) للتوسع والبناء. يمكن تفسير هذا التأثير الإيجابي للمتعة على الاستعداد للتواصل من خلال نظرية فريدريكسون (2001)، التي تبرز التأثير الكبير للمشاعر الإيجابية على نتائج التعلم. يبرز التفاعل بين الفرح في التعلم والاستعداد للتواصل الدور الحاسم للرفاهية العاطفية في اكتساب اللغة، كما تؤكده أطر علم النفس الإيجابي (ماكنتاير وغريغرسن، 2012). لذلك، من الضروري عدم التركيز فقط على كفاءة اللغة ولكن أيضًا على تنمية تجربة تعلم مبهجة.

الشكل 3 نموذج القياس النهائي مع التقديرات الموحدة. يعرض هذا الشكل نموذج القياس المعتمد مع معاملات المسار الموحدة.

الجدول 7 نتائج SEM.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| الاستعداد للتواصل |

|

الفرح في التعلم | 0.713 | 0.650 | 0.113 | 0.000 | 6.282 |

| الاستعداد للتواصل |

|

BE | 0.190 | 0.228 | 0.077 | 0.014 | 2.457 |

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كان هناك ارتباط إيجابي بين المشاركة السلوكية والاستعداد للتواصل في هذه الدراسة، متماشيًا مع الأبحاث السابقة في السياق البولندي (ميستكوفسكا-ويرتيلاك وبيلاك، 2023). يبدو أن المشاركة السلوكية، التي تشمل المشاركة النشطة، والجهد المستمر، والمثابرة في أنشطة تعلم اللغة، مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بمختلف جوانب الاستعداد للتواصل. كشفت البيانات أن الطلاب الذين أظهروا هذه السلوكيات المشاركة في دروس اللغة الإنجليزية في الجامعة كانوا أكثر احتمالًا لإظهار الاستعداد للتواصل، على الرغم من التحديات التي غالبًا ما تكون موجودة في سياقات اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين مثل أحجام الفصول الكبيرة والفرص المحدودة للتحدث. أحد التفسيرات للاختلاف الإيجابي بين المشاركة السلوكية والاستعداد للتواصل هو أن الطلاب الذين يظهرون مستويات أعلى من المشاركة يختبرون مشاعر إيجابية أكثر خلال عملية التعلم، مما يوسع بدوره من مجموعة أفكارهم وأفعالهم ويبني موارد شخصية دائمة. بعبارة أخرى، الطلاب الذين يشاركون سلوكيًا في الفصول الدراسية يختبرون المزيد من الفرص للتجارب العاطفية الإيجابية، مما يؤدي بهم إلى تطوير مواقف أكثر إيجابية تجاه كل من عمليات التعلم والتفاعلات التواصلية. الانتقال إلى

تحليل أعمق، أحد الأسباب الثقافية في سياق اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين هو أن الطلاب تقليديًا يحافظون على أدوار سلبية في الفصول الدراسية (ليو وجاكسون، 2011)، ومع ذلك، فإن أولئك الذين يظهرون مستويات أعلى من المشاركة يبدأون في التغلب على أنماط التعلم التقليدية. يميلون إلى رؤية أنشطة الفصل الدراسي كأمور ذات صلة وقيمة، مما يعزز شعور الاستثمار والحماس (فريدريكس وآخرون، 2004). هذا مهم بشكل خاص في سياق يتم فيه تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية بشكل أساسي كلغة أجنبية مع تعرض محدود خارج الفصل الدراسي (وين وكلمنت، 2003). في جوهره، يتغلب الطلاب الصينيون الذين يشاركون سلوكيًا في الفصول الدراسية تدريجيًا على التردد الثقافي ويصبحون أكثر استعدادًا لتولي المهام التواصلية (لي وجيا، 2006)، بدءًا من رؤية المشاركة النشطة كجزء لا يتجزأ من تعلمهم. والأهم من ذلك، أن هذا يتماشى مع نظرية فريدريكسون (2001)، حيث أن المشاعر الإيجابية الناتجة عن تجارب المشاركة الناجحة تخلق حلقة تصاعدية: عندما يشارك الطلاب سلوكيًا، يختبرون المزيد من الفرص للتجارب العاطفية الإيجابية في الفصل الدراسي. ثم توسع هذه المشاعر الإيجابية من مجموعة أفكارهم وأفعالهم، مما يجعلهم أكثر انفتاحًا على الفرص التواصلية ويبني مواردهم الشخصية الدائمة مثل الثقة والكفاءة اللغوية. هذا يخلق دورة تعزز الذات حيث تؤدي المشاركة إلى مشاعر إيجابية، مما يسهل بدوره زيادة الاستعداد للتواصل. مع استمرار هذه الدورة، تمتد الفوائد إلى ما هو أبعد من المشاركة الفورية في الفصل الدراسي. تعمل هذه المشاركة المعززة على تحسين كل من النتائج اللغوية، مثل الكفاءة والكفاءة التواصلية، والنتائج غير اللغوية،

بما في ذلك الرفاهية النفسية والمعرفة الثقافية الاجتماعية. بعد ذلك، تعزز هذه النتائج المجمعة التفاعل الأكبر مع مجتمع اللغة المستهدفة وتزيد من استعداد المتعلمين للتواصل. لذلك، تسلط العلاقة بين المشاركة السلوكية والاستعداد للتواصل الضوء على أن بيئة الفصل الدراسي الجذابة التي تعزز تفاعل الطلاب والتجارب العاطفية الإيجابية ضرورية لاكتساب اللغة بشكل فعال (بينغ، 2012). بعبارة أخرى، يصبح الطلاب أكثر تمكينًا للتواصل والتعاون في بيئة تعلم تفاعلية وجذابة، حيث تبني هذه التجارب الإيجابية ثقتهم وتوسع من مجموعة تواصلهم. بينما تعتبر هذه النتائج ذات صلة خاصة بسياقات الجامعات الصينية والسياقات المماثلة، إلا أنها قد تحمل تداعيات أوسع على بيئات اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية الأخرى حيث تؤثر العوامل الثقافية والمؤسسية على استعداد الطلاب للتواصل. يمكن أن تستكشف الأبحاث المستقبلية كيف تتجلى هذه العلاقات في سياقات ثقافية ومؤسسية مختلفة، خاصة في بيئات تعليمية آسيوية أخرى ذات قيم ثقافية مماثلة.

تحليل أعمق، أحد الأسباب الثقافية في سياق اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين هو أن الطلاب تقليديًا يحافظون على أدوار سلبية في الفصول الدراسية (ليو وجاكسون، 2011)، ومع ذلك، فإن أولئك الذين يظهرون مستويات أعلى من المشاركة يبدأون في التغلب على أنماط التعلم التقليدية. يميلون إلى رؤية أنشطة الفصل الدراسي كأمور ذات صلة وقيمة، مما يعزز شعور الاستثمار والحماس (فريدريكس وآخرون، 2004). هذا مهم بشكل خاص في سياق يتم فيه تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية بشكل أساسي كلغة أجنبية مع تعرض محدود خارج الفصل الدراسي (وين وكلمنت، 2003). في جوهره، يتغلب الطلاب الصينيون الذين يشاركون سلوكيًا في الفصول الدراسية تدريجيًا على التردد الثقافي ويصبحون أكثر استعدادًا لتولي المهام التواصلية (لي وجيا، 2006)، بدءًا من رؤية المشاركة النشطة كجزء لا يتجزأ من تعلمهم. والأهم من ذلك، أن هذا يتماشى مع نظرية فريدريكسون (2001)، حيث أن المشاعر الإيجابية الناتجة عن تجارب المشاركة الناجحة تخلق حلقة تصاعدية: عندما يشارك الطلاب سلوكيًا، يختبرون المزيد من الفرص للتجارب العاطفية الإيجابية في الفصل الدراسي. ثم توسع هذه المشاعر الإيجابية من مجموعة أفكارهم وأفعالهم، مما يجعلهم أكثر انفتاحًا على الفرص التواصلية ويبني مواردهم الشخصية الدائمة مثل الثقة والكفاءة اللغوية. هذا يخلق دورة تعزز الذات حيث تؤدي المشاركة إلى مشاعر إيجابية، مما يسهل بدوره زيادة الاستعداد للتواصل. مع استمرار هذه الدورة، تمتد الفوائد إلى ما هو أبعد من المشاركة الفورية في الفصل الدراسي. تعمل هذه المشاركة المعززة على تحسين كل من النتائج اللغوية، مثل الكفاءة والكفاءة التواصلية، والنتائج غير اللغوية،

بما في ذلك الرفاهية النفسية والمعرفة الثقافية الاجتماعية. بعد ذلك، تعزز هذه النتائج المجمعة التفاعل الأكبر مع مجتمع اللغة المستهدفة وتزيد من استعداد المتعلمين للتواصل. لذلك، تسلط العلاقة بين المشاركة السلوكية والاستعداد للتواصل الضوء على أن بيئة الفصل الدراسي الجذابة التي تعزز تفاعل الطلاب والتجارب العاطفية الإيجابية ضرورية لاكتساب اللغة بشكل فعال (بينغ، 2012). بعبارة أخرى، يصبح الطلاب أكثر تمكينًا للتواصل والتعاون في بيئة تعلم تفاعلية وجذابة، حيث تبني هذه التجارب الإيجابية ثقتهم وتوسع من مجموعة تواصلهم. بينما تعتبر هذه النتائج ذات صلة خاصة بسياقات الجامعات الصينية والسياقات المماثلة، إلا أنها قد تحمل تداعيات أوسع على بيئات اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية الأخرى حيث تؤثر العوامل الثقافية والمؤسسية على استعداد الطلاب للتواصل. يمكن أن تستكشف الأبحاث المستقبلية كيف تتجلى هذه العلاقات في سياقات ثقافية ومؤسسية مختلفة، خاصة في بيئات تعليمية آسيوية أخرى ذات قيم ثقافية مماثلة.

الخاتمة

تقدم هذه الدراسة رؤى قيمة حول العلاقات بين الفرح في التعلم (FLE) والانخراط السلوكي (behavioral engagement) والرغبة في التواصل (WTC) بين طلاب اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية (EFL) في الصين، بالإضافة إلى العوامل التي تشكل الرغبة في التواصل. أظهرت النتائج أن تعزيز المشاعر الإيجابية ورعاية الانخراط السلوكي يمكن أن يؤثر بشكل كبير وإيجابي على رغبة الطلاب في التواصل. تسلط هذه النتائج الضوء على التفاعل بين الفرح في التعلم والانخراط السلوكي في تشكيل الرغبة في التواصل، مما يبرز الحاجة إلى مراعاة كل من المنظورات العاطفية والسلوكية في أبحاث الرغبة في التواصل. تسهم هذه الدراسة في الأدبيات الموجودة من خلال التأكيد على التأثير الكبير للفرح في التعلم والانخراط السلوكي كعوامل رئيسية تؤثر على الرغبة في التواصل. نظرًا لأن المشاعر غالبًا ما تكون مؤقتة وقصيرة الأمد في تعليم اللغة، فإن الفرح في التعلم، كونه تجربة عاطفية إيجابية نسبياً، يمكن أن يؤثر بشكل كبير على سلوكيات التواصل لدى متعلمي اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين. عادةً ما يظهر المتعلمون الذين يتمتعون بمستويات عالية من الفرح في التعلم حماسًا وثقة أكبر في استخدام اللغة المستهدفة. تجعل هذه الحالة العاطفية منهم أقل عرضة للتأثيرات السلبية للقلق والمشاعر السلبية الأخرى، مما يحمي رغبتهم في التواصل في عملية تعلم اللغة. علاوة على ذلك، لا يمكن المبالغة في أهمية الانخراط السلوكي في تشكيل الرغبة في التواصل. تشجع المشاركة النشطة في الأنشطة الصفية المتعلمين على ممارسة وتطوير مهاراتهم اللغوية، مما يزيد من ثقتهم ورغبتهم في التواصل. يعزز بيئة التعلم التي تتميز بتجارب عاطفية إيجابية والانخراط النشط من استعداد الفرد للمشاركة، وثقته بنفسه، وكفاءته التواصلية العامة. علاوة على ذلك، فإن المستويات المرتفعة من الفرح في التعلم والانخراط السلوكي داخل الفصل لا تسهم فقط في تحسين الأداء الأكاديمي والتطور المعرفي، بل تعزز أيضًا الرفاهية العاطفية للمتعلمين. وهذا بدوره يشجع على المشاركة النشطة والتعاون بين الطلاب، مما يعزز مهاراتهم الاجتماعية وذكائهم العاطفي، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى بيئة تعليمية أكثر تماسكًا وفعالية.

تتمتع هذه الدراسة بعدة تداعيات على المستويين النظري والعملي. من الناحية النظرية، تساهم في الأدبيات الموجودة حول علم النفس الإيجابي في تعليم اللغة من خلال تسليط الضوء على أهمية الفرح في التعلم والمشاركة السلوكية في تعزيز الرغبة في التواصل بين متعلمي اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. تسلط النتائج الضوء على الدور الحاسم الذي تلعبه مفاهيم علم النفس الإيجابي في السياق الصيني لتعليم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية، مما يوفر رؤى قيمة حول كيفية تعزيز هذه المفاهيم لتحسين تعليم اللغة. عمليًا، تقدم هذه البحث تداعيات هامة لتعزيز الرغبة في التواصل في السياقات الصينية لتعليم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. أولاً، تشير هذه الدراسة إلى أن تعزيز الفرح في التعلم داخل الفصل يمكن أن يزيد بشكل كبير من رغبة الطلاب في التواصل. النتائج

يتوافق مع نظرية فريدريكسون (2001) للتوسع والبناء، التي تقترح أن تعزيز تجربة التعلم الإيجابية يمكن أن يساعد الطلاب في بناء موارد دائمة مثل الكفاءة اللغوية، والروابط الاجتماعية، والثقة. يمكن للمعلمين تحقيق ذلك من خلال دمج أنشطة جذابة وممتعة في دروسهم، مثل الألعاب التفاعلية، والمشاريع التعاونية، والمحتوى الثقافي الغني. علاوة على ذلك، فإن التعرف على إنجازات الطلاب والاحتفال بها، مهما كانت صغيرة، يمكن أن يعزز المشاعر الإيجابية ويعزز جوًا أكثر تواصلًا. ثانيًا، فإن الانخراط السلوكي أمر حاسم لتعزيز الرغبة في التواصل. المشاركة النشطة في الأنشطة الصفية تحسن من الكفاءة اللغوية وتزيد من رغبة الطلاب في التواصل. يمكن أن تعزز استراتيجيات مثل المناقشات الجماعية، وتمثيل الأدوار، ومهام حل المشكلات الانخراط النشط وتوفر فرصًا للطلاب لممارسة التواصل في بيئة داعمة. لتنفيذ هذه الاستراتيجيات بفعالية، يجب أن تتضمن برامج تدريب المعلمين وحدات شاملة حول نظرية فريدريكسون (2001) للتوسع والبناء وتطبيقاتها في تدريس اللغة. يجب أن يكون المعلمون مستعدين بفهم نظري وموارد مفيدة لإنشاء بيئة صفية تعزز الانخراط السلوكي وتجربة التعلم الإيجابية وبالتالي تعزز الرغبة في التواصل.

يتوافق مع نظرية فريدريكسون (2001) للتوسع والبناء، التي تقترح أن تعزيز تجربة التعلم الإيجابية يمكن أن يساعد الطلاب في بناء موارد دائمة مثل الكفاءة اللغوية، والروابط الاجتماعية، والثقة. يمكن للمعلمين تحقيق ذلك من خلال دمج أنشطة جذابة وممتعة في دروسهم، مثل الألعاب التفاعلية، والمشاريع التعاونية، والمحتوى الثقافي الغني. علاوة على ذلك، فإن التعرف على إنجازات الطلاب والاحتفال بها، مهما كانت صغيرة، يمكن أن يعزز المشاعر الإيجابية ويعزز جوًا أكثر تواصلًا. ثانيًا، فإن الانخراط السلوكي أمر حاسم لتعزيز الرغبة في التواصل. المشاركة النشطة في الأنشطة الصفية تحسن من الكفاءة اللغوية وتزيد من رغبة الطلاب في التواصل. يمكن أن تعزز استراتيجيات مثل المناقشات الجماعية، وتمثيل الأدوار، ومهام حل المشكلات الانخراط النشط وتوفر فرصًا للطلاب لممارسة التواصل في بيئة داعمة. لتنفيذ هذه الاستراتيجيات بفعالية، يجب أن تتضمن برامج تدريب المعلمين وحدات شاملة حول نظرية فريدريكسون (2001) للتوسع والبناء وتطبيقاتها في تدريس اللغة. يجب أن يكون المعلمون مستعدين بفهم نظري وموارد مفيدة لإنشاء بيئة صفية تعزز الانخراط السلوكي وتجربة التعلم الإيجابية وبالتالي تعزز الرغبة في التواصل.

ومع ذلك، فإن الدراسة لها عدة قيود. أولاً، على الرغم من أن النموذج أظهر مؤشرات ملائمة عامة مرضية، فإن قيمة GFI المنخفضة نسبياً تشير إلى فرص محتملة لتحسين تحديد النموذج في الدراسات التجريبية المستقبلية. ثانياً، فإن استخدام مقاييس ذاتية التقرير كطريقة رئيسية لجمع البيانات يقدم قيوداً منهجية، خاصة فيما يتعلق بتحيز الرغبة الاجتماعية وموثوقية القياس. قد تفكر الدراسات اللاحقة في استخدام مؤشرات موضوعية لهذه المتغيرات، مثل الملاحظات السلوكية المباشرة والتقييمات المعتمدة على الأداء. ثالثاً، على الرغم من أن هذه الدراسة هي تحقيق كمي واسع النطاق يشمل عدة مشاركين، فإن اعتمادها على جمع وتحليل البيانات الرقمية يقدم بعض القيود. قد لا تتمكن المنهجيات التقليدية الثابتة من التقاط التعقيدات الديناميكية والسياقية وال constructs المتأصلة في عمليات تعلم اللغة بشكل كافٍ. يجب أن تدمج الأبحاث المستقبلية أساليب مختلطة وتقنيات جمع البيانات في الوقت الحقيقي لتوفير فهم أكثر شمولاً. علاوة على ذلك، بينما تفسر نظرية التوسع والبناء نتائجنا بشكل فعال، يمكن أن تستفيد الأبحاث المستقبلية من دمج أطر نظرية إضافية، مثل نظرية تحديد الذات (SDT)، لدراسة كيفية تأثير الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية على علاقة الانخراط-الاستعداد للتواصل، أو نموذج PERMA لسليغمان (2011) لفهم كيفية عمل المشاعر الإيجابية والانخراط ضمن السياق الأوسع لرفاهية تعلم اللغة الثانية. علاوة على ذلك، نظراً لتركيزها المحدد على سياقات تعليم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الصين، قد تكون قابلية تطبيق النتائج في هذه الدراسة على سياقات اجتماعية ثقافية ولغوية أخرى محدودة. يجب أن تحقق الأبحاث المستقبلية في تأثيرات الفرح في التعلم والانخراط السلوكي في تشكيل الاستعداد للتواصل في سياقات متنوعة.

توفر البيانات

تتوفر مجموعات البيانات التي تم إنشاؤها و/أو تحليلها خلال الدراسة الحالية من المؤلف المراسل عند الطلب المعقول.

تاريخ الاستلام: 20 نوفمبر 2024؛ تاريخ القبول: 25 أبريل 2025؛ تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 10 مايو 2025

References

Benner AD, Graham S, Mistry RS (2008) Discerning direct and mediated effects of ecological structures and processes on adolescents’ educational outcomes. Dev. Psychol 44:840-854. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.3. 840

Bensalem E (2022) The impact of enjoyment and anxiety on English-language learners’ willingness to communicate. Vivat Acad (155), 6. https://doi.org/10. 15178/va.2022.155.e1310

Best JW, Kahn JV (2006) Research in education, 10th edn. Pearson Education, Inc, Boston

Boekaerts M (2016) Engagement as an inherent aspect of the learning process. Learn Instr 43:76-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.001

Botes E, Dewaele J-M, Greiff S (2020) The Power to Improve: Effects of Multilingualism and Perceived Proficiency on Enjoyment and Anxiety in Foreign Language Learning. Eur J Educ 8(2):279-306. https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2020-0003

Byrne BM (2013) Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Psychology Press

Cao Y, Philp J (2006) Interactional context and willingness to communicate: a comparison of behavior in whole class, group and dyadic interaction. System 34(4):480-493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2006.05.002

Cao Y (2009) An ecological view of situational willingness to communicate in a second language classroom. Making a difference: challenges for applied linguistics. 199-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2006.05.002

Collier JE (2020) Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS: basic to advanced techniques. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018414

Derakhshan A, Dewaele JM, Noughabi MA (2022) Modeling the contribution of resilience, well-being, and L2 grit to foreign language teaching enjoyment among Iranian English language teachers. System 109:102890. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.system.2022.102890

Best JW, Kahn JV (2006) Research in education, 10th edn. Pearson Education, Inc, Boston

Boekaerts M (2016) Engagement as an inherent aspect of the learning process. Learn Instr 43:76-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.001

Botes E, Dewaele J-M, Greiff S (2020) The Power to Improve: Effects of Multilingualism and Perceived Proficiency on Enjoyment and Anxiety in Foreign Language Learning. Eur J Educ 8(2):279-306. https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2020-0003

Byrne BM (2013) Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Psychology Press

Cao Y, Philp J (2006) Interactional context and willingness to communicate: a comparison of behavior in whole class, group and dyadic interaction. System 34(4):480-493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2006.05.002

Cao Y (2009) An ecological view of situational willingness to communicate in a second language classroom. Making a difference: challenges for applied linguistics. 199-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2006.05.002

Collier JE (2020) Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS: basic to advanced techniques. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018414

Derakhshan A, Dewaele JM, Noughabi MA (2022) Modeling the contribution of resilience, well-being, and L2 grit to foreign language teaching enjoyment among Iranian English language teachers. System 109:102890. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.system.2022.102890

Derakhshan A, Fathi J (2023) Grit and foreign language enjoyment as predictors of EFL learners’ online engagement: the mediating role of online learning selfefficacy. Asia Pacific Edu Res 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-023-00745-x

Dewaele JM (2019) The effect of classroom emotions, attitudes toward English, and teacher behavior on willingness to communicate among English foreign language learners. J Lang Soc Psychol 38(4):523-535. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0261927×19864996

Dewaele JM, Li C (2021) Teacher enthusiasm and students’ social-behavioral learning engagement: the mediating role of student enjoyment and boredom in Chinese EFL classes. Lang Teach Res 25(6):922-945. https://doi.org/10. 1177/13621688211014538

Dewaele J-M (2015) On emotions in foreign language learning and use. Lang Teach 39(3):13-15. https://jalt-publications.org/tlt/issues/2015-05_39.3

Dewaele J-M, MacIntyre PD (2014) The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach 4(2):237-274. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.5

Dewaele J-M, Dewaele L (2018) Learner-internal and learner external predictors of willingness to communicate in the FL classroom. J Eur Second Lang Assoc 2:1-14. https://doi.org/10.22599/jesla. 37

Dewaele J-M, Pavelescu LM (2021) The relationship between incommensurable emotions and willingness to communicate in English as a foreign language: a multiple case study. Innov Lang Learn Teach 15(1):66-80. https://doi.org/10. 1080/17501229.2019.1675667

Dewaele J-M, Witney J, Saito K, Dewaele L (2017) Foreign language enjoyment and anxiety: the effect of teacher and learner variables. Lang Teach Res 22(6):676-697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817692161

Dewaele JM, MacIntyre PD (2016) Foreign language enjoyment and foreign language classroom anxiety: the right and left feet of the language learner. Positive psychology in SLA, vol 215(236), https://doi.org/10.21832/ 9781783095360-010

Dewaele JM, MacIntyre PD (2019) The predictive power of multicultural personality traits, learner and teacher variables on foreign language enjoyment and anxiety. In Evidence-based second language pedagogy. Routledge, pp 263-286. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351190558-12

Ding L, Wang Y (2024) Unveiling Chinese EFL students’ academic burnout and its prediction by anxiety, boredom, and hopelessness: a latent growth curve modeling. Innov Lang Learn Teach 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229. 2024.2407811

Dewaele JM (2019) The effect of classroom emotions, attitudes toward English, and teacher behavior on willingness to communicate among English foreign language learners. J Lang Soc Psychol 38(4):523-535. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0261927×19864996

Dewaele JM, Li C (2021) Teacher enthusiasm and students’ social-behavioral learning engagement: the mediating role of student enjoyment and boredom in Chinese EFL classes. Lang Teach Res 25(6):922-945. https://doi.org/10. 1177/13621688211014538

Dewaele J-M (2015) On emotions in foreign language learning and use. Lang Teach 39(3):13-15. https://jalt-publications.org/tlt/issues/2015-05_39.3

Dewaele J-M, MacIntyre PD (2014) The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach 4(2):237-274. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.5

Dewaele J-M, Dewaele L (2018) Learner-internal and learner external predictors of willingness to communicate in the FL classroom. J Eur Second Lang Assoc 2:1-14. https://doi.org/10.22599/jesla. 37

Dewaele J-M, Pavelescu LM (2021) The relationship between incommensurable emotions and willingness to communicate in English as a foreign language: a multiple case study. Innov Lang Learn Teach 15(1):66-80. https://doi.org/10. 1080/17501229.2019.1675667

Dewaele J-M, Witney J, Saito K, Dewaele L (2017) Foreign language enjoyment and anxiety: the effect of teacher and learner variables. Lang Teach Res 22(6):676-697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817692161

Dewaele JM, MacIntyre PD (2016) Foreign language enjoyment and foreign language classroom anxiety: the right and left feet of the language learner. Positive psychology in SLA, vol 215(236), https://doi.org/10.21832/ 9781783095360-010

Dewaele JM, MacIntyre PD (2019) The predictive power of multicultural personality traits, learner and teacher variables on foreign language enjoyment and anxiety. In Evidence-based second language pedagogy. Routledge, pp 263-286. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351190558-12

Ding L, Wang Y (2024) Unveiling Chinese EFL students’ academic burnout and its prediction by anxiety, boredom, and hopelessness: a latent growth curve modeling. Innov Lang Learn Teach 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229. 2024.2407811

Do S, Schallert D (2004) Emotions and classroom talk: toward a model of the role of affect in students’ experiences of classroom discussions. J Educ Psychol 96(4):619-634. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.619

Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS (2016) Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat 5(1):1-4

Feng E, Hong G (2022) Engagement mediates the relationship between emotion and achievement of Chinese EFL learners. Front Psychol 13:895594. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.895594

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39-50. https:// doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH (2004) School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev Educ Res 74(1):59-109. https://doi.org/10. 3102/00346543074001059

Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS (2016) Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat 5(1):1-4

Feng E, Hong G (2022) Engagement mediates the relationship between emotion and achievement of Chinese EFL learners. Front Psychol 13:895594. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.895594

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39-50. https:// doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH (2004) School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev Educ Res 74(1):59-109. https://doi.org/10. 3102/00346543074001059

Fredrickson BL (2001) The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 56(3):218-226. 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218

Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, Finkel SM (2008) Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J Personal Soc Psychol 95(5):1045. https:// doi.org/10.1037/a0013262

Gao Y, Wang X, Reynolds BL (2025) The mediating roles of resilience and flow in linking basic psychological needs to tertiary EFL learners’ engagement in the informal digital learning of English: a mixed-methods study. Behav Sci 15(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010085

Guo Y (2021) Exploring the dynamic interplay between foreign language enjoyment and learner engagement with regard to EFL achievement and absenteeism: a sequential mixed methods study. Front Psychol 12:766058. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.766058

Guo Y, Wang Y (2024) Exploring the effects of artificial intelligence application on EFL students’ academic engagement and emotional experiences: a mixed-methods study. Eur J Educ 60(1):e12812. https://doi.org/10.1111/ ejed. 12812

Hiver P, Al-Hoorie AH, Vitta JP, Wu J (2021) Engagement in language learning: a systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Lang Teach Res 136216882110012. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211001289

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang F, Wang Y, Zhang H (2024) Modeling generative AI acceptance, perceived teachers’ enthusiasm, and self-efficacy to English as foreign language learners’ well-being in the digital era. Eur J Edu. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed. 12770

Hughes JN, Luo W, Kwok OM, Loyd LK (2008) Teacher-student support, effortful engagement, and achievement: a 3-year longitudinal study. J Educ Psychol 100(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.1

Jiang Y, Dewaele J-M (2019) How unique is the foreign language classroom enjoyment and anxiety of Chinese EFL learners? System 82:13-25. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.system.2019.02.017

Joe H-K, Hiver P, Al-Hoorie AH (2017) Classroom social climate, self-determined motivation, willingness to communicate, and achievement: A study of structural relationships in instructed second language settings. Learn Individ Differ 53:133-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.11.005

Kaiser HF (1974) An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39(1):31-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02291575

Khajavy GH, MacIntyre PD, Barabadi E (2018) Role of the emotions and classroom environment in willingness to communicate: applying doubly latent multilevel analysis in second language acquisition research. Stud Second Lang Acquis 40(3):605-624. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263117000304

Khajavy GH, Ghonsooly B, Hosseini Fatemi A, Choi CW (2016) Willingness to communicate in English: a microsystem model in the Iranian EFL classroom context. Tesol Q 50(1):154-180. https://doi.org/10.1002/ tesq. 204

Khajavy GH (2021) Modeling the relations between foreign language engagement, emotions, grit and reading achievement. Student engagement in the language classroom, pp 241-259. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788923613-016

Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2012.687667

Krashen SD (1985) The input hypothesis: issues and implications. TESOL Q 20(1):116. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586393

Kun Y, Senom F, Peng CF (2020) Relationship between willingness to communicate in english and foreign language enjoyment. Univers J Educ Res 10. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081057

Lee JS (2014) The relationship between student engagement and academic performance: is it a myth or reality? J Educ Res 107(3):177-185. https://doi-org. ezproxy.eduhk.hk/10.1080/00220671.2013.807491

Li C (2018) A positive psychology perspective on Chinese students’ emotional intelligence, classroom Emotions, and EFL learning achievement. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Xiamen University, Xiamen

Li C (2020) A Positive Psychology perspective on Chinese EFL students’ trait emotional intelligence, foreign language enjoyment and EFL learning achievement. J Multiling Multicult Dev 41(3):246-263. https://doi.org/10. 1080/01434632.2019.1614187

Li C (2021) A Control-Value Theory approach to boredom in English classes among university students in China. Mod Lang J 105(1):317-334. https://doi. org/10.1111/modl. 12693

Li C, Jiang G, Dewaele J-M (2018) Understanding Chinese high school students’ Foreign Language Enjoyment: Validation of the Chinese version of the Foreign Language Enjoyment scale. System 76:183-196. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.system.2018.06.004

Li X, Jia X (2006) Why don’t you speak up?: East Asian students’ participation patterns in American and Chinese ESL classrooms. Intercult Commun Stud 15(1):192

Gao Y, Wang X, Reynolds BL (2025) The mediating roles of resilience and flow in linking basic psychological needs to tertiary EFL learners’ engagement in the informal digital learning of English: a mixed-methods study. Behav Sci 15(1):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15010085

Guo Y (2021) Exploring the dynamic interplay between foreign language enjoyment and learner engagement with regard to EFL achievement and absenteeism: a sequential mixed methods study. Front Psychol 12:766058. https:// doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.766058

Guo Y, Wang Y (2024) Exploring the effects of artificial intelligence application on EFL students’ academic engagement and emotional experiences: a mixed-methods study. Eur J Educ 60(1):e12812. https://doi.org/10.1111/ ejed. 12812

Hiver P, Al-Hoorie AH, Vitta JP, Wu J (2021) Engagement in language learning: a systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Lang Teach Res 136216882110012. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211001289

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang F, Wang Y, Zhang H (2024) Modeling generative AI acceptance, perceived teachers’ enthusiasm, and self-efficacy to English as foreign language learners’ well-being in the digital era. Eur J Edu. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed. 12770

Hughes JN, Luo W, Kwok OM, Loyd LK (2008) Teacher-student support, effortful engagement, and achievement: a 3-year longitudinal study. J Educ Psychol 100(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.1

Jiang Y, Dewaele J-M (2019) How unique is the foreign language classroom enjoyment and anxiety of Chinese EFL learners? System 82:13-25. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.system.2019.02.017

Joe H-K, Hiver P, Al-Hoorie AH (2017) Classroom social climate, self-determined motivation, willingness to communicate, and achievement: A study of structural relationships in instructed second language settings. Learn Individ Differ 53:133-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.11.005

Kaiser HF (1974) An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39(1):31-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02291575

Khajavy GH, MacIntyre PD, Barabadi E (2018) Role of the emotions and classroom environment in willingness to communicate: applying doubly latent multilevel analysis in second language acquisition research. Stud Second Lang Acquis 40(3):605-624. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263117000304

Khajavy GH, Ghonsooly B, Hosseini Fatemi A, Choi CW (2016) Willingness to communicate in English: a microsystem model in the Iranian EFL classroom context. Tesol Q 50(1):154-180. https://doi.org/10.1002/ tesq. 204

Khajavy GH (2021) Modeling the relations between foreign language engagement, emotions, grit and reading achievement. Student engagement in the language classroom, pp 241-259. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788923613-016

Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2012.687667

Krashen SD (1985) The input hypothesis: issues and implications. TESOL Q 20(1):116. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586393

Kun Y, Senom F, Peng CF (2020) Relationship between willingness to communicate in english and foreign language enjoyment. Univers J Educ Res 10. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081057

Lee JS (2014) The relationship between student engagement and academic performance: is it a myth or reality? J Educ Res 107(3):177-185. https://doi-org. ezproxy.eduhk.hk/10.1080/00220671.2013.807491

Li C (2018) A positive psychology perspective on Chinese students’ emotional intelligence, classroom Emotions, and EFL learning achievement. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Xiamen University, Xiamen

Li C (2020) A Positive Psychology perspective on Chinese EFL students’ trait emotional intelligence, foreign language enjoyment and EFL learning achievement. J Multiling Multicult Dev 41(3):246-263. https://doi.org/10. 1080/01434632.2019.1614187

Li C (2021) A Control-Value Theory approach to boredom in English classes among university students in China. Mod Lang J 105(1):317-334. https://doi. org/10.1111/modl. 12693

Li C, Jiang G, Dewaele J-M (2018) Understanding Chinese high school students’ Foreign Language Enjoyment: Validation of the Chinese version of the Foreign Language Enjoyment scale. System 76:183-196. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.system.2018.06.004

Li X, Jia X (2006) Why don’t you speak up?: East Asian students’ participation patterns in American and Chinese ESL classrooms. Intercult Commun Stud 15(1):192

Li C, Dewaele J-M, Pawlak M, Kruk M (2022) Classroom environment and willingness to communicate in English: the mediating role of emotions experienced by university students in China. Lang Teach Res 136216882211116. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221111623

Lin J, Wang YL (2024) Unpacking the mediating role of classroom interaction between student satisfaction and perceived online learning among Chinese EFL tertiary learners in the normal of post-COVID-19. Acta Psychol 245:104233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104233. 1-10

Linnenbrink-Garcia L, Rogat TK, Koskey KLK (2011) Affect and engagement during small group instruction. Contemp Educ Psychol 36(1):13-24. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.09.001

Liu M, Jackson J (2011) Reticence and anxiety in oral English lessons: a case study in China. Researching Chinese learners: skills, perceptions and intercultural adaptations. pp 119-137. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230299481_6

Macintyre PD, Gregersen T, Mercer S (2019) Setting an agenda for positive psychology in SLA: theory, practice, and research. Mod Lang J 103(1):262-274. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl. 12544

MacIntyre P, Gregersen T (2012) Emotions that facilitate language learning: the positive-broadening power of the imagination. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach 2(2):193-213. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.4

MacIntyre PD, Charos C (1996) Personality, attitudes, and affect as predictors of second language communication. J Lang Soc Psychol 15(1):3-26. https://doi. org/10.1177/0261927×960151001

MacIntyre PD, Legatto JJ (2011) A dynamic system approach to willingness to communicate: developing an idiodynamic method to capture rapidly changing affect. Appl Linguist 32(2):149-171. https://doi.org/10.1093/ applin/amq037

MacIntyre PD, Dörnyei Z, Clément R, Noels KA (1998) Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: a situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. Mod Lang J 82(4):545-562. https://doi.org/10.2307/330224

MacIntyre PD, Dewaele JM, Macmillan N, Li C (2019) The emotional underpinnings of Gardner’s attitudes and motivation test battery. Contemp Lang Motiv Theory 60:57-79. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788925211-008

MacIntyre PD, Gregersen T, Mercer S (2016) Positive psychology in SLA. Multilingual Matters, Bristol, UK. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783095360

Marsh HW, Hocevar D (1985) Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: first-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychol Bull 97(3):562. 10.1037//00332909.97.3.562

Lin J, Wang YL (2024) Unpacking the mediating role of classroom interaction between student satisfaction and perceived online learning among Chinese EFL tertiary learners in the normal of post-COVID-19. Acta Psychol 245:104233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104233. 1-10

Linnenbrink-Garcia L, Rogat TK, Koskey KLK (2011) Affect and engagement during small group instruction. Contemp Educ Psychol 36(1):13-24. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.09.001

Liu M, Jackson J (2011) Reticence and anxiety in oral English lessons: a case study in China. Researching Chinese learners: skills, perceptions and intercultural adaptations. pp 119-137. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230299481_6

Macintyre PD, Gregersen T, Mercer S (2019) Setting an agenda for positive psychology in SLA: theory, practice, and research. Mod Lang J 103(1):262-274. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl. 12544

MacIntyre P, Gregersen T (2012) Emotions that facilitate language learning: the positive-broadening power of the imagination. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach 2(2):193-213. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.4

MacIntyre PD, Charos C (1996) Personality, attitudes, and affect as predictors of second language communication. J Lang Soc Psychol 15(1):3-26. https://doi. org/10.1177/0261927×960151001

MacIntyre PD, Legatto JJ (2011) A dynamic system approach to willingness to communicate: developing an idiodynamic method to capture rapidly changing affect. Appl Linguist 32(2):149-171. https://doi.org/10.1093/ applin/amq037

MacIntyre PD, Dörnyei Z, Clément R, Noels KA (1998) Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: a situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. Mod Lang J 82(4):545-562. https://doi.org/10.2307/330224

MacIntyre PD, Dewaele JM, Macmillan N, Li C (2019) The emotional underpinnings of Gardner’s attitudes and motivation test battery. Contemp Lang Motiv Theory 60:57-79. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781788925211-008

MacIntyre PD, Gregersen T, Mercer S (2016) Positive psychology in SLA. Multilingual Matters, Bristol, UK. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783095360

Marsh HW, Hocevar D (1985) Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: first-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychol Bull 97(3):562. 10.1037//00332909.97.3.562

McCroskey JC, Richmond VP (1987) Willingness to communicate. In: McCroskey JC, Daly JA (eds) Personality and interpersonal communication. Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp 129-156

Mystkowska-Wiertelak A (2021) The link between different facets of willingness to communicate, engagement and communicative behavior in task performance. Positive psychology in second and foreign language education, pp 95-113. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64444-4_6

Mystkowska-Wiertelak A, Bielak J (2023) Investigating the link between L2 WtC, learner engagement and selected aspects of the classroom context. In: Contemporary issues in foreign language education: festschrift in honour of Anna Michońska-Stadnik. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 163-189. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28655-1_10