DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02524-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40022265

تاريخ النشر: 2025-02-28

استكشاف الأدوار الوسيطة للدافع والملل في الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والانخراط السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية: منظور نظرية تحديد الذات

الملخص

في أبحاث اكتساب اللغة الثانية، كانت العوامل النفسية المرتبطة بتعلم اللغة محور تركيز بارز. لقد عزز التحول العاطفي وإدخال علم النفس الإيجابي في هذا المجال البحث حول أدوار العوامل النفسية الإيجابية للمتعلمين (مثل الدافع) في الأداء (مثل الانخراط). ومع ذلك، فإن العدسة النظرية للتحقيق في هذه المتغيرات تتطلب مزيدًا من التوضيح، وقد كانت أدوار بعض المتغيرات (مثل الملل) في تعلم اللغة تحت البحث. مسترشدين بهذا السياق، تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى استكشاف العلاقات المعقدة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية للمتعلمين، والدافع الذاتي، والملل والانخراط السلوكي بين 687 متعلمًا صينيًا في المرحلة الثانوية في اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية من منظور نظرية تحديد الذات (SDT). كشفت جمع البيانات الكمية وتحليلها أن الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية للطلاب تنبأت مباشرة بالانخراط السلوكي. كما تنبأت الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية بشكل غير مباشر بالانخراط السلوكي من خلال الوساطة البسيطة للملل والوساطة المتسلسلة للدافع الذاتي والملل. ومع ذلك، كانت الوساطة البسيطة للدافع الذاتي في العلاقة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والانخراط السلوكي غير ذات دلالة. تعزز النتائج تطبيق SDT في أبحاث انخراط تعلم اللغة، مما يوفر دلالات قيمة للمعلمين والمربين.

المقدمة

ومع ذلك، لم يكن لبعض الدراسات حول انخراط تعلم اللغة أساس نظري واضح. كان التركيز البحثي، بناءً على النتائج التجريبية للدراسات السابقة، على وصف مستويات انخراط تعلم اللغة وعلاقاتها مع عوامل سياقية ونفسية أخرى دون توجيه من نظريات ذات صلة. إن غياب أساس نظري قوي سيكون ضارًا ليس فقط بالملخص المنهجي للدراسات ذات الصلة [34] ولكن أيضًا بانتشار أبحاث انخراط تعلم اللغة الأجنبية. استجابةً لذلك، تتعلق نظرية تحديد الذات (SDT) بكيفية تأثير نفسية الناس وبيئتهم على سلوكياتهم وإنجازاتهم، مما يوفر أساسًا نظريًا قويًا لاستكشاف العلاقة بين الانخراط وعوامل أخرى في تعلم اللغة الأجنبية [35]. من خلال تطبيق SDT، كانت نتيجة بحثية مهمة في مجال التعليم العام وتعلم اللغة الأجنبية هي أن الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية للمتعلمين، بما في ذلك الاستقلالية، والكفاءة، والترابط، ضرورية لشرح سلوكياتهم التعليمية، مثل الانخراط (مثل [36، 37]).

في سياق EFL في المدارس الثانوية الصينية، تعتبر اللغة الإنجليزية مادة إلزامية وجزءًا رئيسيًا من امتحان القبول في الجامعات، مما يخلق ضغطًا وتحديات للعديد من الطلاب. وفقًا لـ SDT، من المحتمل أن يعيق هذا الضغط والتحديات اختيار الطلاب الحر في تعلم EFL، والشعور بالكفاءة، وأجواء التعلم المريحة، من بين أمور أخرى. في هذا السياق عالي المخاطر، كيف يتم تلبية الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية للطلاب وتأثيراتها على نفسية التعلم (مثل الدافع والملل) والسلوكيات (مثل الانخراط السلوكي) تتطلب مزيدًا من التحقيق.

في ضوء خلفية البحث أعلاه ومبادئ SDT، تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى استكشاف الآليات المعقدة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية، والدافع، والملل والانخراط السلوكي بين متعلمي EFL في المدارس الثانوية الصينية لتوسيع الخلفية النظرية لأبحاث تعلم اللغة الأجنبية وتعزيز البحث حول العوامل المؤثرة في انخراط EFL.

مراجعة الأدبيات

نظرية تحديد الذات

أصبح من الضروري للناس تعلم لغة أجنبية، ويتفاوت الدافع للقيام بذلك بين الأفراد. وجد نويلز وآخرون [45] أن SDT تغطي دوافع متنوعة (مثل تكوين المزيد من الأصدقاء وتحقيق إنجازات أفضل) وإنتاجها وتأثيرها على عملية التعلم والنتائج، وبالتالي قدموا SDT في مجال تعلم اللغة الأجنبية. ونتيجة لذلك، تم تطوير الدراسات حول دافع تعلم اللغة الأجنبية من منظور SDT (مثل [9، 46، 47]). وبالتالي، أصبحت إطارًا بحثيًا شاملاً لاستكشاف دافع تعلم اللغة الأجنبية ونتائجه ونتائجه [34، 48].

تركز الدراسة الحالية على العوامل السابقة (أي الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية) والنتائج (أي الملل والانخراط السلوكي) لدافع EFL في

الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية

الدافع

الاهتمام والمتعة. يشير الدافع الخارجي إلى الأفعال المدفوعة لأسباب خارجية بدلاً من الفرح الداخلي والرضا. فيما يتعلق بدرجات التضمين والتكامل للأنظمة الخارجية كجزء من الذات، تصنف نظرية التكامل العضوي الدافع الخارجي إلى أربعة أنواع فرعية: التنظيم الخارجي، والتنظيم المدخل، والتنظيم المحدد، والتنظيم المتكامل (مرتبة من الأقل إلى الأكثر ذاتية التحديد). إذا كان الأفراد خاضعين لتنظيم خارجي، فإن المحفزات الخارجية تجبرهم على العمل. يتجنب الأفراد المدخلون تجربة حالات نفسية سلبية. يقوم الأفراد ذوو التنظيم المحدد بأداء الأفعال عندما يدركون قيمتها وأهميتها. يقوم الأشخاص ذوو التنظيم المتكامل بالأنشطة لأنهم يعتبرون تلك الأنشطة جزءًا من أنفسهم – وهو شيء يتم تجاهله عمومًا في السياقات التعليمية، خاصة بين الطلاب في الصفوف الدنيا، بسبب ميزته غير المميزة ([50] مقتبس من [45]). لذلك، لم يتم تضمين التنظيم المتكامل في هذه الدراسة. في الوقت نفسه، لم تتضمن الدراسة الحالية عدم الدافع لأن المشاركين في هذه الدراسة يختلفون في درجة الدافع الذاتي التحديد بدلاً من أن يكونوا مدفوعين أو لا. التنظيم الداخلي والتنظيم المحدد كلاهما ذاتي التحديد بدرجة عالية ويسمى دافعًا ذاتيًا. الدوافع المدخلة والدوافع الخارجية أقل ذاتية التحديد وتسمى دافعًا خاضعًا.

وفقًا لـ SDT، تؤثر الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية بشكل مباشر على الدافع، وهو ما تم تأكيده في مجال تعلم اللغة الأجنبية. قام نويلز [51] بالتحقيق مع 322 طالبًا يتعلمون الإسبانية كلغة ثانية ووجد أن الاحتياجات للحرية والكفاءة تنبأت بالدافع الداخلي؛ كما تنبأت الحرية بقوة بالتنظيم المحدد. كانت القوة التنبؤية لحاجة الكفاءة للدافع الداخلي أكثر قوة من تلك الخاصة بالدافع الخارجي. حصل كاريرا [52] على نتائج مماثلة بين 505 متعلمًا يابانيًا في المرحلة الابتدائية للغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية؛ حيث حددوا علاقات أقوى بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والدافع الذاتي التحديد العالي. أكد تانكا [53] اكتشاف نويلز [51] بشأن القوة التنبؤية للاحتياجات للحرية والكفاءة للدافع الذاتي في سياق تعلم المفردات المحبط بين 155 متعلمًا يابانيًا غير متخصص في اللغة الإنجليزية. كما كشفت الدراسة أن التأثير السلبي للأقران تنبأ سلبًا بالدافع الذاتي، بينما تنبأ التأثير الإيجابي للأقران بالدافع المدخل. تم تأكيد العلاقة الوثيقة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والدافع الذاتي التحديد العالي من قبل جو وآخرون [54] في سياق اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المدارس الثانوية الكورية ومن قبل العمار [55] بين الطلاب المتخصصين في اللغة الإنجليزية في السياق السعودي.

الملل

علاوة على ذلك، كشفت دراسة العمار ولي [60] الطولية عن الدور الوسيط للدافع الذاتي التحديد في العلاقة بين قلق اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية والإنجاز بين 226 متعلمًا جامعيًا سعوديًا. وبالمثل، أكد وانغ وليو [9] الدور الوسيط للملل في العلاقة بين دافع التعلم الذاتي والانخراط في سياق اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المدرسة الثانوية الصينية. هذه الدراستان تحققان بشكل غير مباشر العلاقة بين الدافع الذاتي التحديد والعواطف. لتلخيص، على الرغم من استكشاف تأثيرات الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والدافع الذاتي التحديد على قلق اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية، إلا أن هناك أبحاثًا محدودة حول تأثير الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والدافع الذاتي التحديد على عواطف أخرى، مثل الملل.

الملل هو عاطفة سلبية تُعرّف بأنها “التجربة المزعجة لوجود رغبة غير مُلباة في الانخراط في نشاط مُرضٍ” [61، ص. 69]، بما في ذلك الانفصال، الإثارة العالية، الإثارة المنخفضة، انخفاض إدراك الوقت وعدم الانتباه [61]. في علم النفس التعليمي، ينشأ الملل مباشرة من تجربة التعلم والأنشطة المتعلقة بالفصل الدراسي [62]. يتميز بعدة مكونات، تشمل العناصر العاطفية والمعرفية والفسيولوجية والدافعية [63]. عندما يشعر المتعلمون بالملل، فإنهم يعانون من مشاعر غير سارة، وانخفاض إدراك الوقت أو نقص في التحفيز العقلي، والإرهاق والانفصال عن أنشطة التعلم. بناءً على ما سبق، في الدراسة الحالية، يُعتبر الملل عاطفة سلبية ناتجة عن الرغبة غير المُلباة في الانخراط في أنشطة تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية مُرضية. كما يتضمن مكونات عاطفية ومعرفية وفسيولوجية ودافعية.

مع التحول العاطفي المتسارع [64] والتحول الإيجابي [4] في اللغويات التطبيقية، بدأ علماء اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الكشف عن الأدوار الإيجابية للعوامل النفسية الإيجابية في عملية تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. ومع ذلك، فقد أولوا اهتمامًا محدودًا للعواطف السلبية بخلاف القلق، وهو التركيز طويل الأمد للباحثين في كلا المجالين،

التعليم العام ومجال اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. على الرغم من أن بعض العواطف السلبية قد جذبت انتباه الباحثين في اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية تدريجيًا في السنوات الأخيرة، مثل الشعور بالذنب والخجل [65] والملل [66،67]، إلا أنها تحتاج إلى مزيد من التحقيق. لقد قيمت معظم الدراسات طلاب الجامعات وافتقرت إلى منظور نظري. كشفت بعض هذه الدراسات، على سبيل المثال، أن التحديات العالية في المهام، وأنشطة التعلم الرتيبة [68] ومشاركة الأقران [69] كانت مسؤولة عن الملل في فصل اللغة، والذي يمكن أيضًا تفسيره من منظور نظرية الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية، والتي ترتبط ارتباطًا وثيقًا بميول المتعلمين نحو المهام متعددة الخيارات، والتحديات المتوسطة، وأجواء التعلم النشطة. نظرًا لأن الملل شائع وصامت في عملية تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية، مما يؤدي بسهولة إلى علم نفس التعلم السلبي [70]، فإنه من الضروري فحص مسبباته ونتائجه عن كثب.

الانخراط السلوكي

على الرغم من أن الانخراط السلوكي في اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية قد تلقى مؤخرًا اهتمامًا ضئيلًا، فقد حققت العديد من الدراسات في العلاقة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية، والدافعية الذاتية، والعواطف ومؤشرات الانخراط السلوكي أو العام في التعلم. في التعليم العام، حدد ريف [36] أن الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية للطلاب كانت مسببات مباشرة للانخراط في التعلم. وقد ظهرت أدلة على ذلك أيضًا في مجال تعلم اللغات الأجنبية. كشفت دراسة العمار [55] عن العلاقة المباشرة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والجهد في تعلم المفردات في سياق تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المملكة العربية السعودية. وأكد زو وآخرون [37] على الرابط المذكور أعلاه بين 686 متعلمًا للغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الجامعات الصينية.

نظرًا لأن الانخراط في التعلم هو التجلي الخارجي للدافعية في التعلم [36، 78]، فقد استكشف العلماء العلاقة بين الدافعية الذاتية والانخراط السلوكي. كشفت دراسة تشين وكراكلاو [79] أن الدافعية الداخلية والتنظيم الخارجي

أثرت إيجابيًا على الجهد بين 276 متعلمًا للغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في الجامعات التايوانية. اعتمد أوجا-بالدوين وفراير [80] نهجًا مركزيًا على الشخص وكشفوا أن الدافعية الذاتية العالية لـ 513 طالبًا عززت الانخراط العام بمرور الوقت. كما أظهرت دراسة نولز وآخرون [81] الطولية العلاقة الإيجابية بين الدافعية الذاتية والجهد في تعلم اللغة الفرنسية كلغة ثانية. أكدت دراسة وانغ وليو [9] النتيجة المذكورة أعلاه. ومع ذلك، لاحظت الدراسات أيضًا القوة التنبؤية للدافعية الخاضعة للسيطرة. على سبيل المثال، كشف سانجايا وآخرون [82] عن القيمة التنبؤية القوية للدافعية الخاضعة للسيطرة مقارنة بالدافعية الذاتية في سياق اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في إندونيسيا.

كما أثبتت الدراسات تأثير العواطف على الانخراط السلوكي في اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية [18]. ومع ذلك، فإن الاستكشافات للعلاقة بين الملل والانخراط السلوكي في اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية محدودة. أظهرت دراسة فنغ وهونغ [33] لـ 633 متعلمًا للغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المدارس الثانوية الصينية وجود علاقة سلبية كبيرة بين القلق والانخراط السلوكي. أكدت دراسة ليو ولي وفانغ [27] لـ 1,157 متعلمًا للغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المدارس الثانوية الصينية العلاقة السلبية بين الملل والانخراط السلوكي. كما أسفرت دراسة أخرى أجراها حامدي وآخرون [28] عن نتائج مماثلة في قراءة اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. كما قدمت الدراسة القيمة التنبؤية الأكبر للملل، مقارنة بالاستمتاع والقلق، على الانخراط.

النموذج المفترض للدراسة

تُفترض العلاقات بين المتغيرات في هذه الدراسة بناءً على ادعاءات نظرية الدافعية الذاتية والأدلة التجريبية. أولاً، تدعي نظرية الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية أن إشباع الفرد للاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية مرتبط ارتباطًا وثيقًا بتطور الرفاهية وغياب المعاناة [43]، والتي تشمل الصفات النفسية الإيجابية (مثل الدافعية الذاتية والعواطف الإيجابية) والسلوكيات (مثل الانخراط) [83،

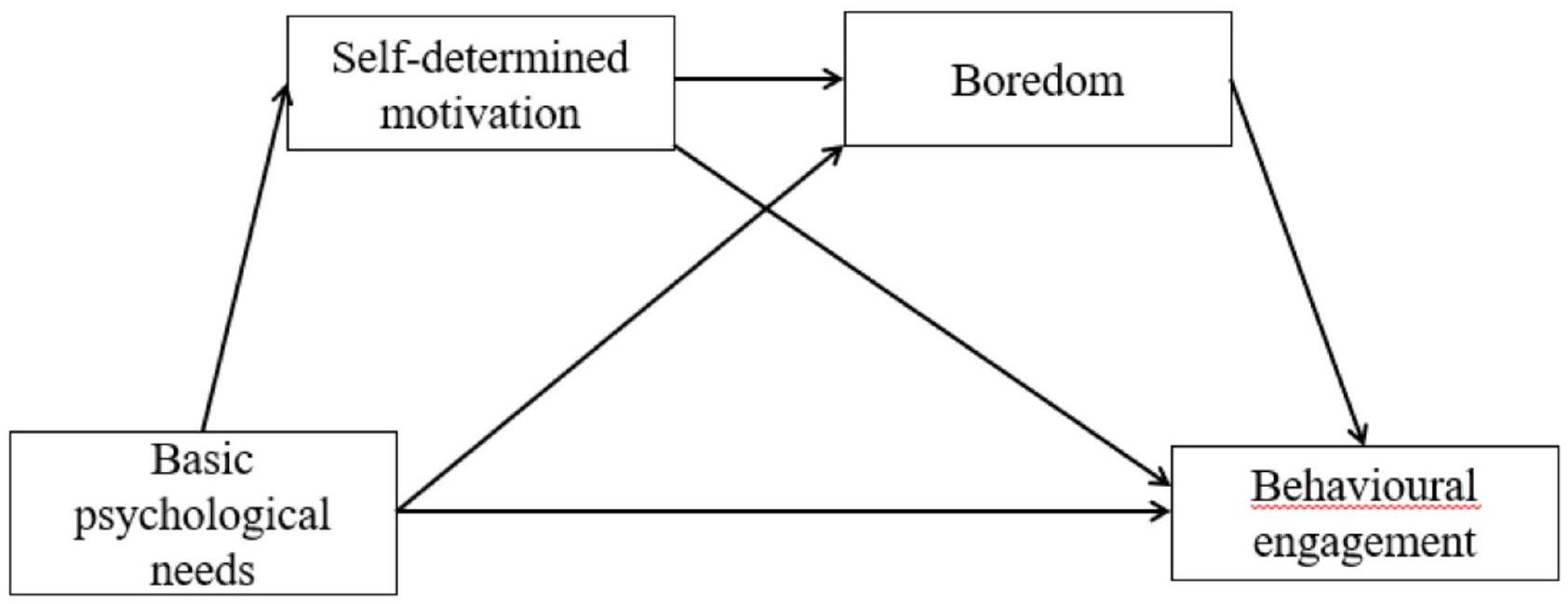

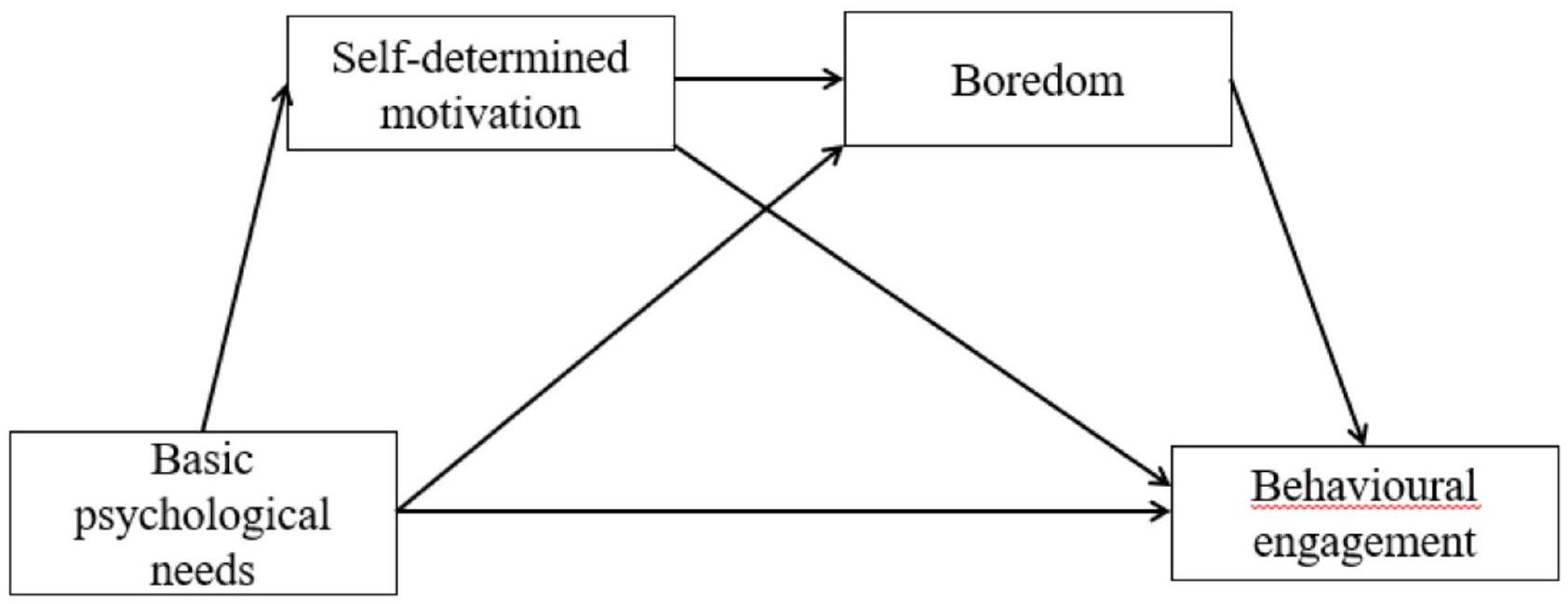

ومع ذلك، كشفت الدراسات التجريبية في تعلم اللغات الأجنبية أن تأثير الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية على الانخراط السلوكي قد يكون مباشرًا [37، 55] وغير مباشر. فيما يتعلق بالصلة غير المباشرة، على سبيل المثال، قد تتنبأ الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية بشكل غير مباشر بالانخراط السلوكي من خلال الدور الوسيط للدافع الذاتي (مثل [52، 80]). قد تتنبأ الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية أيضًا بالانخراط السلوكي من خلال الدور الوسيط للقلق (مثل [33، 58]). ومع ذلك، لم يتم التحقيق بشكل شامل في الآليات المؤثرة المذكورة أعلاه. من بين مشاعر تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية المتعددة، يكتسب الملل، وهو شعور شائع في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية [70]، تدريجياً اهتمام الباحثين ويستحق مزيدًا من التحقيق. بالنظر إلى التأثيرات المماثلة للقلق والملل على تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية، مثل الانخراط السلوكي [28]، ومبادئ نظرية الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية ونظرية التكامل العضوي، تستكشف هذه الدراسة العلاقة المعقدة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والدافع الذاتي والملل والانخراط السلوكي في سياق تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المدارس الثانوية الصينية. النموذج الافتراضي (انظر الشكل 1) والفرضيات البحثية المقابلة هي كما يلي:

الفرضية 2: تؤثر الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية بشكل غير مباشر على انخراط الطلاب السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية، من خلال الدافع.

الفرضية 3: تؤثر الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية بشكل غير مباشر على انخراط الطلاب السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية، من خلال الملل.

الفرضية 4: تؤثر الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية بشكل غير مباشر على انخراط الطلاب السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية، من خلال التحفيز والملل.

تصميم البحث

المشاركون

الأدوات

تم استخدام نظرية تحديد الذات – L2 لألامر [55] لقياس دافع تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. وكانت تتألف من أربعة أبعاد: الدافع الداخلي، الدافع المعرف، الدافع المدخل والدافع الخارجي. مثلت خمسة عناصر كل بعد. في نموذج القياس مع العوامل الأربعة الأصلية، تم حذف العناصر 18 و 24 و 25 و 26 و 31 بسبب تحميلات العوامل المتقاطعة أو عدم التوافق مع نظرية تحديد الذات. على سبيل المثال، كانت العبارة “لأنني أريد الحصول على وظيفة مرموقة تتطلب إتقان اللغة الإنجليزية” محملة على الدافع الداخلي، مما يتعارض مع مبادئ نظرية التكامل العضوي الصغيرة في نظرية تحديد الذات. بعد دمج عاملين – الدافع الداخلي والدافع المعرف – بسبب ارتباطاتهما العالية، وفقًا لنتائج النموذج المقدمة من تحليل العوامل المؤكدة، كانت مؤشرات ملاءمة النموذج مقبولة.

في نظرية التكامل المصغرة في نظرية تحديد الذات، تُسمى الدوافع الذاتية والدوافع المعروفة بالدافع الذاتي. لذلك، تم تسمية البعد الجديد “الدافع الذاتي”. كانت قيم ألفا كرونباخ للأبعاد الثلاثة – الدافع الذاتي، الدافع المدخل، والدافع الخارجي –

تم قياس الملل من خلال تعديل مقياس الملل الخاص بـ Bieleke وآخرين في استبيان مشاعر الإنجاز (الإصدار القصير). شمل مقياس الملل ثمانية عناصر تقيس الملل المتعلق بالتعلم والصف. تم تعديل جميع العناصر الثمانية لتناسب الدراسة الحالية. على سبيل المثال، تم تعديل العنصر الأصلي “أشعر بالملل” ليصبح “أشعر بالملل خلال درس اللغة الإنجليزية”. في نموذج القياس، كانت مؤشرات ملاءمة النموذج مرضية.

تم تعديل مقياس الانخراط السلوكي من المقياس الفرعي المكون من 5 عناصر الذي وضعه ريف و تسينغ. تم تعديل جميع العناصر الخمسة لتناسب الدراسة الحالية. على سبيل المثال، تم تعديل العنصر الأصلي “أستمع بعناية في الفصل” إلى “أستمع بعناية في فصل اللغة الإنجليزية”. في نموذج القياس، كانت مؤشرات ملاءمة النموذج مرضية.

الإجراء

تم الحصول على الاستجابات بعد فحص البيانات للزمن والاستجابات الثابتة.

اتبعت جميع إجراءات جمع البيانات المعايير الأخلاقية للبحث الكمي. قبل جمع البيانات، تم إبلاغ الطلاب بالكامل عن الغرض وتفاصيل الدراسة الحالية. جميعهم أكملوا نموذج الموافقة المكتوبة وشاركوا طواعية في هذه الدراسة. على وجه التحديد، أكمل جميع المشاركين الاستبيان طواعية وتم السماح لهم بالانسحاب في أي وقت من البحث. كما ضمنت هذه الدراسة سرية جميع المشاركين، وتم الاحتفاظ بمعلوماتهم الشخصية وإجاباتهم على الاستبيان بسرية واستخدمت فقط لأغراض أكاديمية دون أي تأثير سلبي عليهم.

لتحليل البيانات، تم اختبار التوزيع الطبيعي للبيانات باستخدام SPSS 24.0 ثم تم إنشاء نماذج القياس. تم إجراء عدة تحليلات عاملية تأكيدية (CFAs) باستخدام Mplus 8.3 لاختبار نماذج القياس. كانت المعايير لمؤشرات ملاءمة النموذج هي CMIN/DF

النتائج

المستويات والارتباطات بين المتغيرات

| M | SD | الانحراف | التفرطح | بي بي إن | راي | بو | كن | |

| بي بي إن | 3.66 | 0.87 | -0.59 | 0.43 | ||||

| راي | 1.08 | 3.41 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.588** | |||

| بو | ٢.٥٠ | 1.05 | 0.56 | -0.23 | -0.545** | -0.583** | ||

| كن | 3.80 | 0.83 | -0.67 | 0.81 | 0.817** | 0.517** | -0.543** |

| طرق | تقدير | SE | 95% ثقة | التأثيرات النسبية |

| التأثير الكلي | 0.779 | 0.021 | [0.738, 0.820] | — |

| الأثر المباشر | 0.706 | 0.027 | [0.654, 0.759] | 90.6 |

| التأثير غير المباشر الكلي | 0.073 | 0.022 | [0.032, 0.119] | 9.4 |

|

|

0.001 | 0.016 | [-0.029, 0.032] | — |

|

|

0.041 | 0.015 | [0.017, 0.074] | 5.3 |

|

|

0.031 | 0.009 | [0.015, 0.050] | ٤.١ |

أظهرت نتائج تحليل الارتباط وجود علاقات ارتباطية كبيرة بين المتغيرات. كانت الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية للطلاب مرتبطة بشكل كبير وإيجابي بالدافع الذاتي والانخراط السلوكي.

اختبار النموذج المفترض

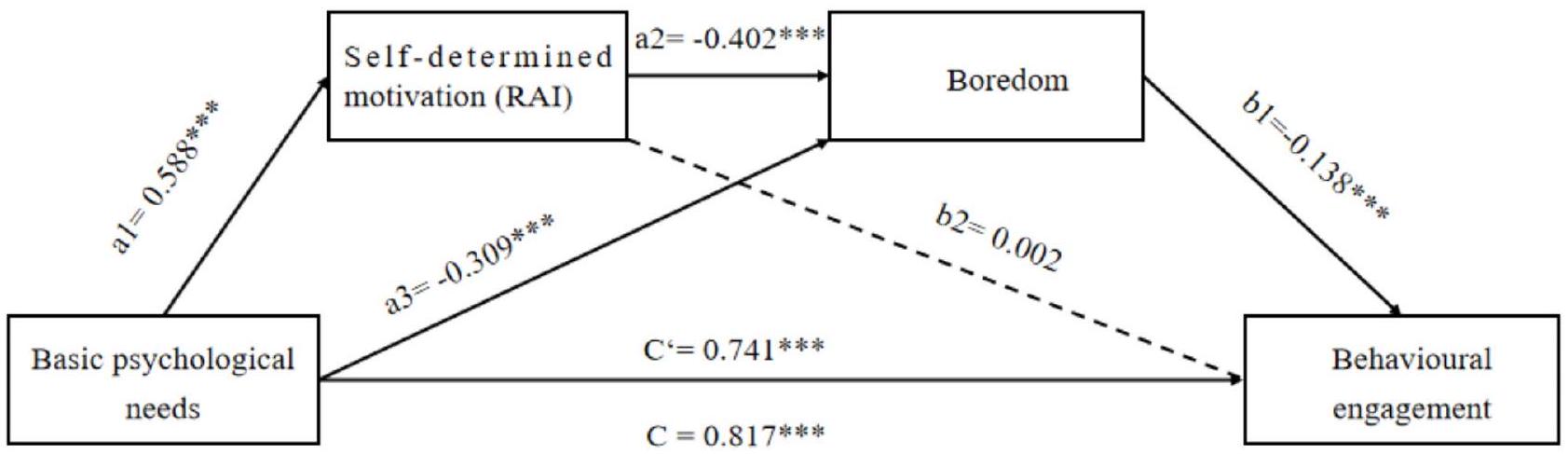

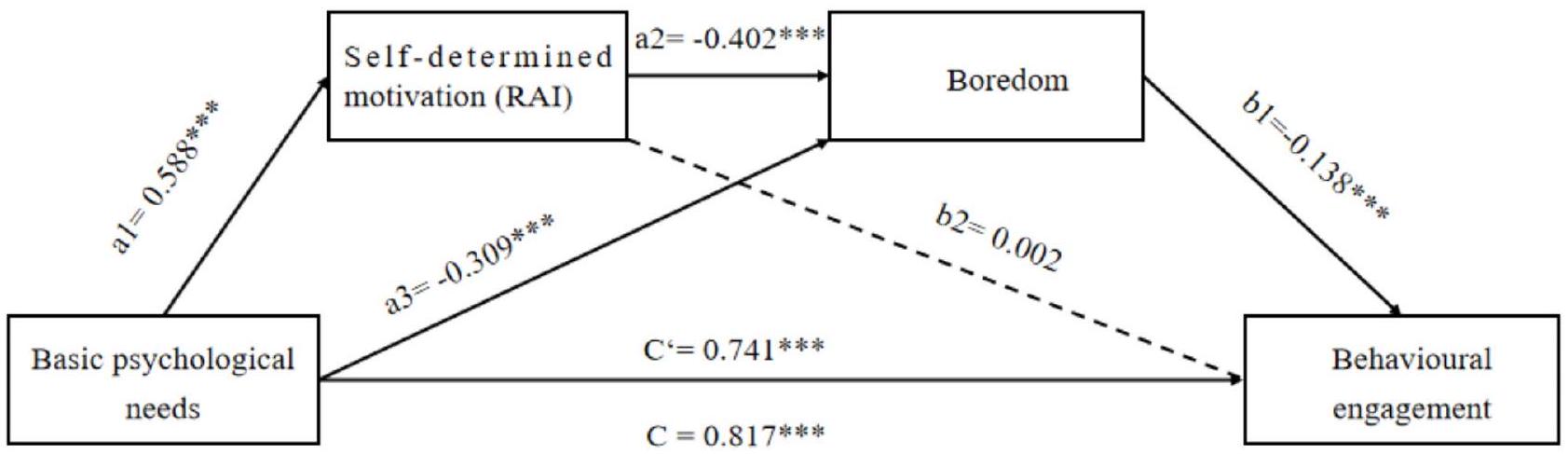

الدافع والملل كوسيطين. أظهرت النتائج أن المسار المؤثر من الدافع الذاتي إلى الانخراط السلوكي كان غير ذي دلالة إحصائية.

أكدت نتائج تحليل الوساطة أن نموذج الوساطة المتسلسل كان ذا دلالة إحصائية (

فيما يتعلق بالأثر غير المباشر للاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية على الانخراط السلوكي، أظهرت النتائج أن الدور الوسيط البسيط للدافع الذاتي لم يكن ذا دلالة إحصائية.

نقاش

كشفت الدراسة الحالية أيضًا أن الوساطة البسيطة للدافع الذاتي في العلاقة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والانخراط السلوكي كانت غير ذات دلالة، مما يشير إلى أن الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية للطلاب لم تؤثر على انخراطهم السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية من خلال الدافع الذاتي. وهذا يتعارض مع ادعاء نظرية الدافع الذاتي بأن كلما زادت درجة الدافع الذاتي، زاد الانخراط في الأنشطة ذات الصلة. قد يكون ذلك بسبب أن الإنجاز في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية يعتبر عاملًا حاسمًا في التنمية الشخصية في بعض السياقات الثقافية (مثل: الوضع الاجتماعي الأعلى). بالنسبة للمشاركين في هذه الدراسة، كان تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية أيضًا أمرًا حيويًا لتحقيق درجات جيدة في امتحان القبول الجامعي، والذي سيكون مرتبطًا ارتباطًا وثيقًا بالوظائف المستقبلية والتنمية الذاتية. لذلك، كان الطلاب الذين لديهم دافع خارجي يشاركون بنشاط في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية خلال المرحلة الثانوية، مما يقلل من درجة الدافع الذاتي في دافع تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. هذه النتيجة تتعارض مع نظرية الدافع الذاتي حيث تم قياس الدافع الذاتي من خلال مؤشر الاستقلال النسبي. ومع ذلك، كانت مستويات الدافع المستقل والمتحكم مرتفعة بين متعلمي اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المدارس الثانوية الصينية. وبالتالي، لم يتمكن الدافع الذاتي من التنبؤ بانخراط الطلاب السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية، على الرغم من أن الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية يمكن أن تتنبأ بشكل كبير بالدافع الذاتي.

تفسير آخر محتمل للنتيجة المذكورة أعلاه هو أن هناك متغيرات وسيطة أخرى موجودة في العلاقة بين الدافع الذاتي والانخراط السلوكي، مثل العواطف. في العديد من الدراسات السابقة، كان للدافع الذاتي تأثير مباشر على الانخراط في التعلم في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. ومع ذلك، في بعض الحالات، لم يكن هناك دعم للحجة القائلة بأن الدافع هو المصدر المباشر للانخراط في التعلم. وذلك لأن بعض الطلاب لديهم دافع ولكن لا يمكنهم تكريس الكثير من الجهد لتعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. على سبيل المثال، في سياق تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المدارس الثانوية الصينية ذات المخاطر العالية، يجب على الطلاب متابعة مواد أخرى للحفاظ على أدائهم الأكاديمي الشامل. إن النتيجة التي تشير إلى أن الدافع الذاتي لم يتمكن من التنبؤ بالانخراط السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية تساهم في تطبيق نظرية الدافع الذاتي في مجال تعلم اللغات من خلال إظهار طبيعتها المحددة ثقافياً وسياقياً.

كشفت الدراسة الحالية أيضًا أن الوساطة البسيطة للملل في العلاقة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والانخراط السلوكي كانت ذات دلالة، مما يشير إلى أن رضا الطلاب عن الاحتياجات الأساسية

ستعيق الاحتياجات النفسية الملل، مما يشجع على انخراطهم السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. يتفق هذا مع نظرية احتياجات النفس الأساسية: إن تلبية الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية ستؤدي إلى مشاعر إيجابية وتخفف من الحالة العاطفية السلبية. استجابت بعض الدراسات التجريبية في اكتساب اللغة الثانية أيضًا لإظهار أن الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية للطلاب تتنبأ سلبًا بقلق المتعلم. من شأن القلق أن يتنبأ سلبًا أيضًا بانخراطهم في تعلم اللغة. نظرًا للأدوار المعيقة المماثلة للقلق والملل، يمكن أن يتوسط الملل العلاقة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والانخراط السلوكي.

أخيرًا، في الدراسة الحالية، كانت الأدوار الوسيطة لسلسلة الدوافع الذاتية المحددة والملل في العلاقة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والانخراط السلوكي أيضًا ذات دلالة، مما يعني أن مستوى الدافع الذاتي المحدد في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية قد تحسن مع تلبية الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية. كما أن الدافع الذاتي المحدد بشكل كبير قلل من الملل، مما حفز الانخراط السلوكي النشط. تُظهر هذه النتيجة أحد أسباب رفض الفرضية 2 في هذه الدراسة. يمكن تفسير ذلك من خلال مبادئ نظرية الدافع الذاتي المحدد والنتائج التجريبية. أظهرت الأدبيات السابقة دورًا تنبؤيًا سلبيًا كبيرًا للملل في الانخراط السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية وكشفت عن وجود علاقات وثيقة بين الدافع الذاتي المحدد والعواطف وبين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والدافع الذاتي المحدد. تدعم نظرية الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية ونظرية التكامل العضوي في نظرية الدافع الذاتي المحدد أيضًا أن تلبية الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية للطلاب تؤدي إلى دافع ذاتي محدد بشكل كبير؛ وهذا بدوره يقلل من مستويات العواطف السلبية التي تعد من العوامل التنبؤية لسلوكيات التعلم. يمكننا أن نؤكد أن احتياجات الطلاب النفسية الأساسية تُلبى في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية، وأن دافعهم يصبح أكثر تحديدًا ذاتيًا، مما من شأنه أن يخفف من تجربة الملل ويعزز الانخراط السلوكي.

الخاتمة

الدافع والانخراط السلوكي، الذي يوسع أبحاث العواطف من منظور نظرية الدافع الذاتي. تم استكشاف آلية معقدة ومؤثرة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية والانخراط السلوكي في سياق تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المدارس الثانوية العليا لإثراء أبحاث الانخراط في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية. النتائج لها تداعيات عملية على تدريس وتعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المدارس الثانوية العليا:

أولاً، يجب تلبية الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية للطلاب. في هذه الدراسة، أثرت الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية لطلاب المرحلة الثانوية بشكل مباشر على انخراطهم السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. في سياق تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في المدارس الثانوية الصينية، يبدو أن تلبية الحاجة إلى الكفاءة أمر أساسي. ومع ذلك، تشير الارتباطات العالية في الدراسة الحالية بين الاستقلالية والكفاءة والترابط إلى أن الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية الثلاثة للطلاب مهمة بنفس القدر. لذلك، يجب على المعلمين إيلاء اهتمام متساوٍ لتلبية جميع الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية الثلاثة. على وجه التحديد، يمكن للمعلمين تنفيذ تعليم متميز وفقًا لقدرات الطلاب في تعلم اللغة لتلبية الحاجة إلى الكفاءة. يمكنهم أيضًا توفير المزيد من الخيارات من المواد ومصادر التعلم لتلبية حاجة الطلاب للاستقلالية، مع إظهار الاحترام والتعاطف تجاه الطلاب لتلبية الحاجة إلى الترابط وبالتالي تعزيز الانخراط السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية.

ثانيًا، يعتبر استيعاب الدافع لتعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية وسيلة أخرى لتحسين مشاركة الطلاب السلوكية. على الرغم من أن الدافع الذاتي لم يؤثر بشكل مباشر على المشاركة السلوكية في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية، إلا أنه كان مفيدًا في تقليل الملل، الذي كان السبب المباشر للمشاركة السلوكية في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. تشير نتائج هذه الدراسة إلى أن الطلاب الذين يتحفزون لتعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية بدرجة عالية من الاستقلالية من المحتمل أن يطوروا نفسية تعلم إيجابية ويزيدوا من مستويات جهدهم وتركيزهم ومشاركتهم. في سياق يركز على الامتحانات، يمكن للمعلمين التأكيد على أهمية تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية لتطوير الطلاب الشخصي أو خلق سياقات تعليمية تتعلق بتجارب الطلاب في الحياة الواقعية. علاوة على ذلك، هناك حاجة إلى تغذية راجعة إيجابية للطلاب في بيئات التعلم ذات المخاطر العالية، وهو ما يعد ذا قيمة لتعزيز المزيد من الدافع الذاتي. سيساعد ذلك في تجنب الملل، الذي يرتبط ارتباطًا وثيقًا بمستوى عالٍ من المشاركة السلوكية.

وأخيرًا وليس آخرًا، فإن تقليل الملل في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية يستحق الجهد، حيث إنه شعور له علاقة مباشرة بالانخراط السلوكي في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية. من المحتمل أن يؤدي السياق التعليمي الموجه نحو الامتحانات إلى إثارة الملل بسبب المواد التعليمية الرتيبة، وأجواء التعلم ذات الضغط العالي، وما إلى ذلك. يمكن للمعلمين استهداف هذه السمة واستخدام العدوى العاطفية لنقل الحماس لتعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية لتحقيق مستويات منخفضة من الملل. يمكن تحقيق ذلك من خلال دمج طرق ومواد تدريس متعددة، والاستفادة الكاملة من الموارد عبر الإنترنت.

تخطيط الأنشطة التي تتماشى مع قدرات الطلاب وتقديم ملاحظات إيجابية.

على الرغم من الدلالات المذكورة أعلاه، إلا أن الدراسة الحالية كانت لها بعض القيود. أولاً، تم فحص الانخراط السلوكي فقط لأنه ضروري لبناء الانخراط في التعلم متعدد الأبعاد. لذلك، فإن العلاقات بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية، والدافع الذاتي، والملل، وأبعاد الانخراط الأخرى تستحق المناقشة في الدراسات المستقبلية. ثانياً، تم اعتماد الملل كمثال لمناقشة أدواره الوسيطة في العلاقة بين الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية، والدافع الذاتي، والانخراط السلوكي. ومع ذلك، يعاني الطلاب من مشاعر متنوعة في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية، ويستحقون مزيدًا من الدراسة [57]. لم يتم استكشاف عدم الدافع والدافع المتكامل في دراستنا، لكنهما موضوعان قيمان في الدراسات المستقبلية التي يمكن أن تفحص مستويات هذه المتغيرات وعلاقاتها مع عوامل نفسية أخرى. فيما يتعلق بأساليب البحث، تم استخدام مقاييس ذاتية كمية فقط لقياس المتغيرات الأربعة؛ لذلك، تحتاج نتائج الدراسة الحالية إلى مزيد من التثليث من خلال اعتماد طرق جمع بيانات أخرى، مثل المقابلات المتعمقة. قيد آخر هو أن هذه الدراسة أجريت في سياق مدرسة ثانوية عليا لتعليم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية في منطقة من الصين. يمكن أن تجند الأبحاث المستقبلية المزيد من الطلاب في مناطق أخرى وتعتبر طلاب المدارس المتوسطة كجزء من المشاركين لتعزيز التمثيلية.

الاختصارات

| SLA | اكتساب اللغة الثانية |

| SDT | نظرية تحديد الذات |

| EFL | اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة أجنبية |

| CFA | تحليل العوامل التأكيدية |

| RAI | مؤشر الاستقلال النسبي |

| CI | فترة الثقة |

معلومات إضافية

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 28 فبراير 2025

References

- Dörnyei Z, Ryan S. The psychology of the language learner revisited. 1st edition. New York: Routledge. 2015.

- Dörnyei Z. The interface of psychology and second language acquisition. In: Gervain J, Csibra G, Kovács K, editors. A life in cognition: studies in cognitive science in honor of Csaba Pléh. Cham: Springer 2022;17-28.

- Pavlenko A. The affective turn in SLA: from ‘affective factors’ to ‘language desire’ and ‘commodification of affect’. In: Gabryś-Barker D, Bielska J, editors. The affective dimension in second language acquisition. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. 2013;3-28.

- Mercer S, MacIntyre PD. Introducing positive psychology to SLA. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach. 2014;4:153-72.

- Dewaele JM, Dewaele L. Are foreign language learners’ enjoyment and anxiety specific to the teacher? An investigation into the dynamics of learners’ classroom emotions. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach. 2020;10:45-65.

- Wang N. How does basic psychological needs satisfaction contribute to EFL learners’ achievement and positive emotions? The mediating role of L2 selfconcept. System. 2024;123:103340.

- Jin Y, Zhang LJ. The dimensions of foreign language classroom enjoyment and their effect on foreign language achievement. Int J Biling Educ Biling. 2021;24:948-62.

- Liu H, Fan J. Al-mediated communication in EFL classrooms: the role of technical and pedagogical stimuli and the mediating effects of AI literacy and enjoyment. Eur J Educ. 2025;60:e12813.

- Wang Y, Liu H. The mediating roles of buoyancy and boredom in the relationship between autonomous motivation and engagement among Chinese senior high school EFL learners. Front Psychol. 2022;13:992279.

- Wang X, Liu H. Exploring the moderating roles of emotions, attitudes, environment, and teachers in the impact of motivation on learning behaviours in students’ English learning. Psychol Rep. 2024;00332941241231714.

- Hasanzadeh S, Shayesteh S, Pishghadam R. Investigating the role of teacher concern in EFL students’ motivation, anxiety, and language achievement through the lens of self-determination theory. Learn Motiv. 2024;86:101992.

- Wang

, Feng , , Liu H. Do residential areas matter? Exploring the differences in motivational factors, motivation, and learning behaviors among urban high school English learners from different regions. Educ Urban Soc. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131245251314194 - Liu H, Han X . Exploring senior high school students’ English academic resilience in the Chinese context. Chin J Appl Linguist. 2022;45:49-68.

- Duan S, Han X, Li X, Liu H. Unveiling student academic resilience in language learning: a structural equation modelling approach. BMC Psychol. 2024;12:177.

- Chu W, Yan Y, Wang H, Liu H. Visiting the studies of resilience in language learning: from concepts to themes. Acta Psychol. 2024;244:104208.

- Liu H, Li X, Yan Y. Demystifying the predictive role of students’ perceived foreign Language teacher support in foreign language anxiety: the mediation of L2 grit. J Multiling Multicult Develop. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/014346 32.2023.2223171

- Li X, Duan S, Liu H. Unveiling the predictive effect of students’ perceived EFL teacher support on academic achievement: the mediating role of academic buoyancy. Sustainability. 2023;15:10205.

- Liu H, Zhu Z, Chen B. Unraveling the mediating role of buoyancy in the relationship between anxiety and EFL students’ learning engagement. Percept Mot Skills. 2025;132:195-217.

- Dörnyei Z, Kormos J. The role of individual and social variables in oral task performance. Lang Teach Res. 2000;4:275-300.

- Tsao JJ, Tseng WT, Hsiao TY, Wang C, Gao AX. Toward a motivation-regulated learner engagement WCF model of L2 writing performance. Sage Open. 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211023172

- Liu H, Zhong Y, Chen H, Wang Y. The mediating roles of resilience and motivation in the relationship between students’ English learning burnout and engagement: a conservation-of-resources perspective. Int Rev Appl Linguist Lang Teach. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2023-0089

- Fan N, Yang C, Kong F, Zhang Y. Low- to mid-level high school first-year EFL learners’ growth language mindset, grit, burnout, and engagement: using serial mediation models to explore their relationships. System. 2024;125:103397.

- Derakhshan A, Fathi J. Grit and foreign language enjoyment as predictors of EFL learners’ online engagement: the mediating role of online learning selfefficacy. Asia-Pacific Edu Res. 2024;33:759-69.

- Liu H, Li X, Guo G. Students’ L2 grit, foreign language anxiety and language learning achievement: A latent profile and mediation analysis. Int Rev Appl Linguist Lang Teach. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2024-0013

- Liu H, Jin L, Han X, Wang H. Unraveling the relationship between English learning burnout and academic achievement: the mediating role of English learning resilience. Behav Sci. 2024;14:1124.

- Liu H, Elahi Shirvan M, Taherian T. Revisiting the relationship between global and specific levels of foreign language boredom and language engagement: a moderated mediation model of academic buoyancy and emotional engagement. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach. 2024. https://doi.org/10.14746/ ssllt. 40195

- Liu H, Li J, Fang F. Examining the complexity between boredom and engagement in English learning: evidence from Chinese high school students. Sustainability. 2022;14:16920.

- Hamedi SM, Pishghadam R, Fadardi JS. The contribution of reading emotions to reading comprehension: the mediating effect of reading engagement using a structural equation modeling approach. Educ Res Policy Prac. 2020;19:211-38.

- Dai K, Wang Y. Enjoyable, anxious, or bored? Investigating Chinese EFL learners’ classroom emotions and their engagement in technology-based EMI classrooms. System. 2024;123:103339.

- Skinner EA, Kindermann TA, Furrer CJ. A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educ Psychol Meas. 2009;69:493-525.

- Oga-Baldwin WLQ. Acting, thinking, feeling, making, collaborating: the engagement process in foreign language learning. System. 2019;86:102128.

- Mercer S, Dörnyei Z. Engaging language learners in contemporary classrooms. 1st edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2020.

- Feng E, Hong G. Engagement mediates the relationship between emotion and achievement of Chinese EFL learners. Front Psychol. 2022;13:895594.

- McEown MS, Oga-Baldwin WLQ. Self-determination for all language learners: new applications for formal language education. System. 2019;86:102124.

- Al-Hoorie AH, Oga-Baldwin WLQ, Hiver P, Vitta JP. Self-determination minitheories in second language learning: a systematic review of three decades of research. Lang Teach Res. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/136216882211026 86

- Reeve J. A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In: Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C, editors. Handbook of research on student engagement. Boston, MA: Springer US. 2012;149-72.

- Zhou SA, Hiver P, Zheng Y. Modeling intra- and inter-individual changes in L2 classroom engagement. Appl Lingusit. 2023;44:1047-76.

- Karimi S, Sotoodeh B. The mediating role of intrinsic motivation in the relationship between basic psychological needs satisfaction and academic engagement in agriculture students. Teach High Educ. 2020;25:959-75.

- Leo FM, Mouratidis A, Pulido JJ, López-Gajardo MA, Sánchez-Oliva D. Perceived teachers’ behavior and students’ engagement in physical education: the mediating role of basic psychological needs and self-determined motivation. Phys Educ Sport Pedag. 2022;27:59-76.

- Zamarripa J, Rodríguez-Medellín R, Otero-Saborido F. Basic psychological needs, motivation, engagement, and disaffection in Mexican students during physical education classes. J Teach Phys Educ. 2022;41:436-45.

- Alrabai F, Algazzaz W. The influence of teacher emotional support on language learners’ basic psychological needs, emotions, and emotional engagement: treatment-based evidence. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach. 2024. https: //doi.org/10.14746/ssllt. 39329

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum; 1985.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL, editors. Self- determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Press. 2017.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Can Psychol / Psychologie Canadienne. 2008;49:182-5.

- Noels KA, Clément R, Pelletier LG. Perceptions of teachers’ communicative style and students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Mod Lang J. 1999;83:23-34.

- Noels KA, Pelletier LG, Clément R, Vallerand RJ. Why are you learning a second Language? Motivational orientations and self-determination theory. Lang Learn. 2000;50:57-85.

- Pae T-I, Shin S-K. Examining the effects of differential instructional methods on the model of foreign language achievement. Learn Individ Differ. 2011;21:215-22.

- Noels KA, Lou NM, Vargas Lascano DI, Chaffee KE, Dincer A, Zhang YSD, et al. Self-determination and motivated engagement in language learning. In: Lamb M, Csizér K, Henry A, Ryan S, editors. The Palgrave handbook of motivation for language learning. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. 2020;95-115.

- Dörnyei Z. The psychology of second language acquisition. 1. publ. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. 2009.

- Vallerand RJ, Blais MR, Brière NM, Pelletier LG. Construction et validation de L’échelle de motivation En éducation (EME). Can J Behav Sci-Rev Can Sci Comport. 1989;21:323-49.

- Noels KA. Learning Spanish as a second language: learners’ orientations and perceptions of their teachers’ communication style. Lang Learn. 2003;53:97-136.

- Carreira JM. Motivational orienations and psychological needs in EFL learning among elementary school students in Japan. System. 2012;40:191-202.

- Tanaka M. Examining EFL vocabulary learning motivation in a demotivating learning environment. System. 2017;65:130-8.

- Joe H-K, Hiver P, Al-Hoorie AH. Classroom social climate, self-determined motivation, willingness to communicate, and achievement: a study of structural relationships in instructed second language settings. Learn Individual Differences. 2017;53:133-44.

- Alamer A. Basic psychological needs, motivational orientations, effort, and vocabulary knowledge: a comprehensive model. Stud Second Lang Acquis. 2022;44:164-84.

- Horwitz EK, Horwitz MB, Cope J. Foreign language classroom anxiety. Mod Lang J. 1986;70:125-32.

- Shao K, Pekrun R, Nicholson LJ. Emotions in classroom language learning: what can we learn from achievement emotion research? System. 2019;86:102121.

- Alamer A, Almulhim F. The interrelation between language anxiety and self-determined motivation; a mixed methods approach. Front Educ. 2021;6:618655.

- Khodadady E, Khajavy GH. Exploring the role of anxiety and motivation in foreign language achievement: a structural equation modeling approach. Porta Linguarum. 2013. https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug. 20240

- Alamer A, Lee J. Language achievement predicts anxiety and not the other way around: a cross-lagged panel analysis approach. Lang Teach Res. 2024;28:1572-93.

- Fahlman SA, Mercer-Lynn KB, Flora DB, Eastwood JD. Development and validation of the multidimensional state boredom scale. Assessment. 2013;20:68-85.

- Goetz T, Hall N. Academic boredom. In: Pekrun R, Lisa, Linnenbrink-Garcia, editors. International handbook of emotions in education. New York: Routledge 2014;311-30.

- Pekrun R, Goetz T, Daniels LM, Stupnisky RH, Perry RP. Boredom in achievement settings: exploring control-value antecedents and performance outcomes of a neglected emotion. J Educ Psychol. 2010;102:531-49.

- White CJ. The emotional turn in applied linguistics and TESOL: significance, challenges and prospects. In: Martínez Agudo JDD, editor. Emotions in second language teaching. Cham: Springer International Publishing. 2018;19-34.

- Teimouri Y. Differential roles of shame and guilt in L2 learning: how bad is bad? Mod Lang J. 2018;102:632-52.

- Kruk M. Variations in motivation, anxiety and boredom in learning English in second life. EuroCALL Rev. 2016;24:25.

- Tsang A, Davis C. Young learners’ well-being and emotions: examining enjoyment and boredom in the foreign language classroom. Asia-Pacific Edu Res. 2024;33:1481-8.

- Liu W, Xie Z. Investigating factors responsible for more boredom in online live EFL classes. Sage Open. 2024;14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244024129290 1

- Derakhshan A, Kruk M, Mehdizadeh M, Pawlak M. Boredom in online classes in the Iranian EFL context: sources and solutions. System. 2021;101:102556.

- Pawlak M, Zawodniak J, Kruk M. The neglected emotion of boredom in teaching English to advanced learners. Int J App Linguist. 2020;30:497-509.

- Reeve J, Tseng C-M. Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2011;36:257-67.

- Philp J, Duchesne S. Exploring engagement in tasks in the language classroom. Annu Rev Appl Linguist. 2016;36:50-72.

- Newmann FM, editor. Student engagement and achievement in American secondary schools. New York: Teachers College. 1992.

- Marks HM. Student engagement in instructional activity: patterns in the elementary, middle, and high school years. Am Educ Res J. 2000;37:153-84.

- Hu S, Kuh GD. Being (dis)engaged in educationally purposeful activities: the influences of student and institutional characteristics. Res High Educt. 2002;43:555-75.

- Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH. School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev Educ Res. 2004;74:59-109.

- Skinner EA, Pitzer JR. Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In: Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C, editors. Handbook of research on student engagement. Boston, MA: Springer US. 2012;21-44.

- Mercer S. Language learner engagement: setting the scene. In: Gao X, editor. Second handbook of English language teaching. Cham: Springer. 2019;1-19.

- Chen Y-LE, Kraklow D. Taiwanese college students’ motivation and engagement for English learning in the context of internationalization at home: a comparison of students in EMI and non-EMI programs. J Stud Int Educ. 2015;19:46-64.

- Oga-Baldwin WLQ, Fryer LK. Schools can improve motivational quality: profile transitions across early foreign language learning experiences. Motiv Emot. 2018;42:527-45.

- Noels KA, Vargas Lascano DI, Saumure K. The development of self-determination across the language course. Stud Second Lang Acquis. 2019;41:821-51.

- Sanjaya INS, Sitawati AAR, Suciani NK, Putra IMA, Yudistira CGP. The effects of L2 pragmatic autonomous and controlled motivations on engagement with pragmatic aspect. TEFLIN J. 2022;33:148.

- Mercer S, MacIntyre P, Gregersen T, Tammy K. Positive language education: combining positive education and language education. Theory Pract Second Lang Acquis. 2018;4:11-31.

- Oxford RL. 2 Toward a psychology of well-being for language learners: the ‘EMPATHICS’ vision. In: MacIntyre PD, Gregersen T, Mercer S, editors. Positive psychology in SLA. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. 2016;10-88.

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2020;61:101860.

- Dörnyei Z, Taguchi T. Questionnaires in second language research: construction, administration, and processing. 2nd edition. New York: Routledge. 2009.

- Leeming P, Harris J. Measuring foreign language students’ self-determination: a Rasch validation study. Lang Learn. 2022;72:646-94.

- Browne MW, Cudeck RA. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol Methods Res. 1992;21:230-58.

- Bieleke M, Gogol K, Goetz T, Daniels L, Pekrun R. The AEQ-S: a short version of the achievement emotions questionnaire. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2021;65:101940.

- Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE. Multivariate data analysis. Eighth edition. Andover, Hampshire: Cengage. 2019.

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Third edition. New York: Guilford Press. 2022.

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Fourth edition. New York: Guilford Press. 2016.

- Vaz A, Pratley P, Alkire S. Measuring women’s autonomy in Chad using the relative autonomy index. Fem Econ. 2016;22:264-94.

- Carreira JM, Ozaki K, Maeda T. Motivational model of English learning among elementary school students in Japan. System. 2013;41:706-19.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

ينغ وانغ

111991055@imu.edu.cn

هاويوي وانغ

wdaisy2023@163.com

كلية اللغات الأجنبية، جامعة سوتشو، سوتشو

215006، الصين

كلية اللغات الأجنبية، جامعة منغوليا الداخلية، هولون، منطقة منغوليا الداخلية ذاتية الحكم، 010021، الصين

كلية اللغات الأجنبية، كلية بودا، جامعة جيلين العادية، سيبينغ، مقاطعة جيلين 136000، الصين

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02524-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40022265

Publication Date: 2025-02-28

Exploring the mediating roles of motivation and boredom in basic psychological needs and behavioural engagement in English learning: a self-determination theory perspective

Abstract

In second language acquisition research, the psychological factors associated with language learning have been a prominent focus. The affective turn in and introduction of positive psychology in this field have further boosted research on the roles of positive learner psychological factors (e.g. motivation) in performance (e.g. engagement). However, the theoretical lens for investigating these variables requires further clarification, and the roles of some variables (e.g. boredom) in language learning have been under-researched. Guided by this background, this study aims to explore the complex relationships between learners’ basic psychological needs, self-determined motivation, boredom and behavioural engagement among 687 Chinese senior high school EFL learners from the perspective of self-determination theory (SDT). Quantitative data collection and analysis revealed that students’ basic psychological needs directly predicted behavioural engagement. Basic psychological needs also indirectly predicted behavioural engagement through the simple mediation of boredom and the chain mediation of self-determined motivation and boredom. However, the simple mediation of self-determined motivation in the relationship between basic psychological needs and behavioural engagement was non-significant. The findings enrich the application of SDT in the language learning engagement research, providing valuable implications for teachers and educators.

Introduction

However, some studies on language learning engagement have not had a clear theoretical basis. The research focus, based on the empirical findings of previous studies, has been on describing language learning engagement levels and their relationships with other contextual and psychological factors without the guidance of related theories. The absence of a solid theoretical foundation would be detrimental not only to the systematic summary of related studies [34] but also to the proliferation of foreign language learning engagement research. In response, self-determination theory (SDT) concerns how people’s behaviours and achievements are influenced by their psychology and environment, offering a solid theoretical foundation for exploring the association between engagement and other factors in foreign language learning [35]. Applying SDT, a significant research result in the general education and foreign language learning field is that learners’ basic psychological needs, including autonomy, competence and relatedness, are essential to explaining their learning behaviours, such as engagement (e.g [36, 37]).

In the Chinese senior high school EFL context, English is a compulsory subject and a major part of the College Entrance Examination, which creates stress and challenges for many students. According to SDT, such stress and challenges are likely to inhibit students’ free choice in EFL learning, the feeling of being competent and the relaxed learning atmosphere, among others. In this highstakes context, how students’ basic psychological needs are satisfied and their effects on learning psychology (e.g. motivation and boredom) and behaviours (e.g. behavioural engagement) require further investigation.

In light of the above research background and SDT principles, this study aims to explore the complex mechanisms between basic psychological needs, motivation, boredom and behavioural engagement among Chinese senior high school EFL learners to extend the theoretical background of foreign language learning research and boost the research on factors influencing EFL engagement.

Literature review

Self-determination theory

It has become necessary for people to learn a foreign language, and the motivation to do so varies among individuals. Noels et al. [45] found that SDT covers various motivations (e.g. making more friends and making better achievements) and their production and influence on the learning process and outcomes, and they accordingly introduced SDT in the foreign language learning field. Consequently, studies on foreign language learning motivation have been advanced from the lens of SDT (e.g [9, 46, 47]). Thus, it has become a comprehensive research framework for exploring foreign language learning motivation and its antecedents and outcomes [34, 48].

The current study focuses on the antecedent (i.e. basic psychological needs) and outcomes (i.e. boredom and behavioural engagement) of EFL motivation in a

Basic psychological needs

Motivation

interest and enjoyment. Extrinsic motivation refers to actions motivated by external reasons rather than internal joy and satisfaction. Regarding the degrees of internalization and integration of external regulations as part of the self, the organismic integration theory further classifies extrinsic motivation into four subtypes: external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation and integrated regulation (ranked from least to most self-determination). If individuals are externally regulated, external stimuli compel them to act. Introjected individuals avoid experiencing negative psychological states. Individuals with identified regulation perform actions when they recognize their value and significance. People with integrated regulation undertake activities because they consider those activities to be part of themselves – something generally neglected in educational contexts, especially among lower-grade students, due to its indistinctive feature ( [50] cited from [45]). Therefore, integrated regulation was not involved in this study. Meanwhile, the current study did not include amotivation because the participants in this study differ in the degree of self-determined motivation rather than being motivated or not. Intrinsic regulation and identified regulation are both highly self-determined and are named autonomous motivation. Introjected and externally regulated motivations are less self-determined and are called controlled motivation.

According to SDT, basic psychological needs directly influence motivation, which has been confirmed in the domain of foreign language learning. Noels [51] investigated 322 students learning Spanish as a second language and found that the needs for autonomy and competence predicted intrinsic motivation; autonomy also strongly predicted identified regulation. The predictive power of the need for competence for intrinsic motivation was more robust than that for extrinsic motivation. Carreira [52] obtained similar results among 505 Japanese primary school EFL learners; they identified stronger correlations between basic psychological needs and highly self-determined motivation. Tanaka [53] confirmed Noels’ [51] finding regarding the predictive power of the needs for autonomy and competence for autonomous motivation in a demotivating vocabulary learning context among 155 Japanese non-English major EFL learners. The study also revealed that negative peer influence negatively predicted autonomous motivation, whereas positive peer influence predicted introjected motivation. The close link between basic psychological needs and highly self-determined motivation was corroborated by Joe et al. [54] in the Korean secondary EFL context and by Alamer [55] among English majors in the Saudi Arabian context.

Boredom

Moreover, Alamer and Lee’s [60] longitudinal study uncovered the moderating role of self-determined motivation in the relationship between EFL anxiety and achievement among 226 Saudi Arabian university learners. Likewise, Wang and Liu [9] confirmed the mediating role of boredom in the relationship between autonomous learning motivation and engagement in the Chinese senior high school EFL context. These two studies indirectly verified the relationship between self-determined motivation and emotions. To summarize, although the effects of basic psychological needs and self-determined motivation on EFL anxiety have been explored, there is limited research on the influence of basic psychological needs and self-determined motivation on other emotions, such as boredom.

Boredom is a negative emotion defined as “the aversive experience of having an unfulfilled desire to be engaged in satisfying activity” [61, p. 69], including disengagement, high arousal, low arousal, low time perception and inattention [61]. In educational psychology, boredom directly arises from the experience of learning and classroom-related activities [62]. It features multiple components, encompassing affective, cognitive, physiological and motivational elements [63]. When learners experience boredom, they have unpleasant feelings, low time perception or lack of mental stimulation, exhaustion and disengagement from learning activities. Based on the above elaboration, in the current study, boredom is a negative emotion generated from the unfulfilled desire to engage in satisfying EFL learning activities. It also includes affective, cognitive, physiological and motivational components.

With the accelerating emotional turn [64] and positive turn [4] in applied linguistics, EFL scholars have begun to uncover the positive roles of positive psychological factors in the EFL process. However, they have paid limited attention to negative emotions other than anxiety, the long-term focus of researchers in both the

general education and EFL fields. Although some negative emotions have gradually attracted EFL researchers’ attention in recent years, such as guilt and shame [65] and boredom [66,67], they need further investigation. Most studies have assessed university students and have lacked a theoretical perspective. Some of these studies revealed, for instance, that high task challenges, monotonous learning activities [68] and peer involvement [69] were responsible for boredom in the language classroom, which could also be explained from the perspective of basic psychological needs theory, which is closely related to learners’ inclination towards multiple choice, moderately challenging tasks and an active learning atmosphere. Considering that boredom is prevalent and silent in the EFL process, thus easily leading to negative learning psychology [70], it is necessary to closely examine its antecedents and outcomes.

Behavioural engagement

Although EFL behavioural engagement has recently received scant attention, many studies have investigated the relationship between basic psychological needs, selfdetermined motivation, emotions and the indicators of behavioural or general learning engagement. In general education, Reeve [36] determined that students’ basic psychological needs were direct antecedents of learning engagement. Evidence of this has also emerged in the field of foreign language learning. Alamer’s [55] investigation revealed the direct relationship between basic psychological needs and effort in vocabulary learning in the Saudi Arabian EFL learning context. Zhou et al. [37] corroborated the above link among 686 Chinese university EFL learners.

As learning engagement is the external manifestation of learning motivation [36, 78], scholars have explored the relationship between self-determined motivation and behavioural engagement. Chen and Kraklow’s [79] survey revealed that intrinsic motivation and external regulation

positively influenced effort among 276 Taiwanese university EFL learners. Oga-Baldwin and Fryer [80] adopted a person-centred approach and uncovered that 513 students’ highly self-determined motivation promoted overall engagement over time. Noels et al.’s [81] longitudinal study also demonstrated the positive relation between self-determined motivation and effort in learning French as a second language. Wang and Liu’s [9] cross-sectional survey affirmed the above result. However, studies have also noted the predictive power of controlled motivation. For instance, Sanjaya et al. [82] disclosed the solid predictive value of controlled motivation over autonomous motivation in the Indonesian EFL context.

Studies have also substantiated the impact of emotions on EFL behavioural engagement [18]. However, explorations of the relationship between boredom and EFL behavioural engagement are limited. Feng and Hong’s [33] investigation of 633 Chinese senior high school EFL learners showed a significant and negative correlation between anxiety and behavioural engagement. Liu, Li and Fang’s [27] investigation of 1,157 Chinese secondary EFL learners verified the negative correlation between boredom and behavioural engagement. Another study by Hamedi et al. [28] yielded similar results in EFL reading. The study also presented the more substantial predictive value of boredom, compared to enjoyment and anxiety, on engagement.

Hypothesized model of the study

The associations between variables in this study are assumed on the basis of SDT claims and empirical evidence. Firstly, the basic psychological needs theory claims that individual’s satisfaction of basic psychological needs is closely related to the development of wellbeing and absence of ill-being [43], which covers positive psychological traits (e.g. self-determined motivation and positive emotions) and behaviours (e.g. engagement) [83,

However, empirical studies in foreign language learning have revealed that the influence of basic psychological needs on behavioural engagement might be direct [37, 55] and indirect. Concerning the indirect link, for example, basic psychological needs may indirectly predict behavioural engagement through the mediating role of self-determined motivation (e.g [52, 80]). Basic psychological needs may also predict behavioural engagement through the mediating role of anxiety (e.g [33,58]). However, the above influential mechanisms have not been comprehensively investigated. Among multiple EFL emotions, boredom, a ubiquitous emotion in EFL [70], is gradually attracting researchers’ attention and merits further investigation. Considering the similar effects of anxiety and boredom on EFL learning, such as behavioural engagement [28], and the principles of basic psychological needs theory and organismic integration theory, this study explores the complex relationship between basic psychological needs, self-determined motivation, boredom and behavioural engagement in the Chinese senior high school EFL context. The hypothetical model (see Fig. 1) and the corresponding research hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 2 Basic psychological needs indirectly affect students’ behavioural engagement in EFL learning, mediated through motivation.

Hypothesis 3 Basic psychological needs indirectly affect students’ behavioural engagement in EFL learning, mediated through boredom.

Hypothesis 4 Basic psychological needs indirectly affect students’ behavioural engagement in EFL learning, mediated through motivation and boredom.

Research design

Participants

Instruments

Alamer’s [55] self-determination theory-L2 was used to measure EFL motivation. It comprised four dimensions: intrinsic motivation, identified motivation, introjected motivation and external motivation. Five items represented each dimension. In the measurement model with the original four factors, items 18, 24, 25, 26 and 31 were deleted for the cross-factor loadings or non-conformity with SDT. For instance, the item “because I want to get a prestigious job that requires English proficiency” was loaded on intrinsic motivation, thus conflicting with the principles of the organismic integration mini-theory in SDT. After combining two factors – intrinsic motivation and identified motivation – due to their high correlations, according to the model results provided by CFA, the model fit indices were acceptable (

integration mini-theory in SDT, intrinsic and identified motivations are named autonomous motivation. Therefore, the new dimension was named “autonomous motivation”. Cronbach’s alphas for the three dimensions – autonomous motivation, introjected motivation and external motivation – were

Boredom was measured by adapting Bieleke et al.’s [89] boredom subscale in their achievement emotion questionnaire (short version). The boredom subscale included eight items measuring learning-related and class-related boredom. All eight items were revised to fit the present study. For instance, the original item “I get bored” was revised as “I get bored during English class”. In the measurement model, the model fit indices were satisfactory

The behavioural engagement scale was adapted from Reeve and Tseng’s [71] 5-item behavioural engagement subscale. All five items were revised to fit the present study. For instance, the original item “I listen carefully in class” was revised as “I listen carefully in English class”. In the measurement model, the model fit indices were satisfactory

Procedure

responses were obtained after screening the data for time and invariant responses.

All the data collection procedures followed the ethical standards of quantitative research. Prior to the data collection, the students were fully informed of the purpose and details of the current study. They all completed the written consent form and voluntarily participated in this study. Specifically, all the participants completed the questionnaire voluntarily and were allowed to withdraw at any time of the research. This study also assured the anonymity of all participants, and their personal information and answers to the questionnaire were kept confidential and simply used for academic purposes without any negative impact on them.

For the data analysis, the normal distribution of the data was tested using SPSS 24.0 and then the measurement models were established. Several confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were conducted using Mplus 8.3 to test the measurement models. The benchmarks for the model fit indices were CMIN/DF

Results

Levels and correlations between variables

| M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | BPN | RAI | BO | BE | |

| BPN | 3.66 | 0.87 | -0.59 | 0.43 | ||||

| RAI | 1.08 | 3.41 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.588** | |||

| BO | 2.50 | 1.05 | 0.56 | -0.23 | -0.545** | -0.583** | ||

| BE | 3.80 | 0.83 | -0.67 | 0.81 | 0.817** | 0.517** | -0.543** |

| Paths | estimate | SE | 95% Cls | Relative effects |

| Total effect | 0.779 | 0.021 | [0.738, 0.820] | — |

| Direct effect | 0.706 | 0.027 | [0.654, 0.759] | 90.6 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.073 | 0.022 | [0.032, 0.119] | 9.4 |

|

|

0.001 | 0.016 | [-0.029, 0.032] | — |

|

|

0.041 | 0.015 | [0.017, 0.074] | 5.3 |

|

|

0.031 | 0.009 | [0.015, 0.050] | 4.1 |

The results of the correlation analysis revealed significant correlations between the variables. Students’ basic psychological needs were significantly and positively correlated with self-determined motivation and behavioural engagement (

Testing the hypothesized model

motivation and boredom as mediators. The results displayed that the influential path from self-determined motivation to behavioural engagement was non-significant (

The results of the mediation analysis confirmed that the chain mediation model was significant (

Regarding the indirect effect of basic psychological needs on behavioural engagement, the results showed that the simple mediating role of self-determined motivation was non-significant (

Discussion

The present study also uncovered that the simple mediation of self-determined motivation in the relationship between basic psychological needs and behavioural engagement was non-significant, indicating that students’ basic psychological needs failed to influence their EFL behavioural engagement through self-determined motivation. This is inconsistent with the claim of SDT that the higher the self-determination, the more engagement there is in related activities. This may be because, in some cultural contexts, achievement in EFL learning is a determinant factor in personal development (e.g. higher social status) [82]. For the participants in this study, EFL learning was also crucial for achieving good scores on the college entrance examination, which would be closely connected with future jobs and self-development. Therefore, students with external motivation would actively engage in EFL learning [79] during senior high school, decreasing the degree of self-determination in EFL motivation. This result contradicts SDT as self-determined motivation was measured by the relative autonomy index. However, the high levels of both autonomous and controlled motivation featured Chinese senior high school EFL learners’ motivation. Consequently, self-determined motivation could not predict students’ EFL behavioural engagement, although basic psychological needs could significantly predict self-determined motivation [51, 52, 54, 55].

Another possible explanation for the above finding is that other mediating variables exist in the relationship between self-determined motivation and behavioural engagement, such as emotions. In many previous studies, self-determined motivation directly influenced learning engagement in EFL learning [9, 20, 79-81]. However, in some cases, there was no support for the argument that motivation is the direct source of learning engagement [36]. This is because some students are motivated but cannot devote much effort to EFL learning. For example, in the high-stakes Chinese senior high school EFL learning context, students must pursue other subjects to maintain their comprehensive academic performance. The finding that self-determined motivation could not predict EFL behavioural engagement contributes to the application of SDT in the language learning field by displaying its culture-specific and context-specific nature [43].

The present study also unveiled that the simple mediation of boredom in the relationship between basic psychological needs and behavioural engagement was significant, suggesting that students’ satisfaction of basic

psychological needs will inhibit boredom, encouraging their EFL behavioural engagement. This agrees with the basic psychological needs theory: basic psychological needs satisfaction will induce positive feelings and attenuate negative affective status [43, 85]. In response, some empirical studies in SLA have also demonstrated that students’ basic psychological needs negatively predicted learner anxiety [58]. The anxiety would further negatively predict language learning engagement [33]. Given the same hindering roles of anxiety and boredom [27, 28], boredom could mediate the relationship between basic psychological needs and behavioural engagement.

Finally, in the current study, the chain mediating roles of self-determined motivation and boredom in the relationship between basic psychological needs and behavioural engagement were also significant, implying that the level of self-determination of EFL motivation improved with the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Highly self-determined motivation further reduced boredom, motivating active behavioural engagement. This result demonstrates one of the reasons for the rejection of hypothesis 2 in this study. This could be explained by the SDT principles and empirical findings. Previous literature has shown a significant negative predictive role of boredom in behavioural engagement in EFL learning [27, 28, 33] and revealed the existence of close relationships between self-determined motivation and emotions [9] and between basic psychological needs and self-determined motivation [54, 94]. Basic psychological needs theory and organismic integration theory in SDT also support that the satisfaction of students’ basic psychological needs leads to highly self-determined motivation; this, in turn, decreases the levels of negative emotions that are among the predictive factors of learning behaviours. We could claim that students’ basic psychological needs are satisfied in EFL learning, and their motivation becomes more self-determined, which would further alleviate the experience of boredom and promote behavioural engagement.

Conclusion

motivation and behavioural engagement, which extends the emotion research from the perspective of SDT. Another complex, influential mechanism between basic psychological needs and behavioural engagement was explored in the context of senior high school EFL to enrich the EFL engagement research. The results have practical implications for senior high school EFL teaching and learning:

First, students’ basic psychological needs should be satisfied. In this study, senior high school students’ basic psychological needs directly influenced their EFL behavioural engagement. In the Chinese senior high school EFL context, the satisfaction of the need for competence seems essential. However, the present study’s high correlations between autonomy, competence and relatedness suggest that students’ three basic psychological needs are equally important. Therefore, teachers should pay equal attention to satisfying all three basic psychological needs. Specifically, teachers can implement differentiated teaching according to students’ language learning abilities to fulfil the need for competence. They can also provide more choices of learning materials and sources to meet students’ need for autonomy while showing respect and empathy towards students to satiate the need for relatedness and thus promote EFL behavioural engagement.

Second, internalizing EFL motivation is another way to improve students’ behavioural engagement. Although self-determined motivation failed to influence EFL behavioural engagement directly, it was beneficial in reducing boredom, which was the direct antecedent of EFL behavioural engagement. The results of this study indicate that students who are motivated to learn EFL with a high degree of self-determination will likely cultivate positive learning psychology and increase their levels of effort, attention and participation. In an examoriented context, teachers can emphasize the significance of learning EFL for students’ personal development or create learning contexts that relate to students’ real-life experiences. Furthermore, positive feedback is needed for students in high-stake learning environments, which is valuable for promoting more self-determined motivation. It will help in avoiding boredom, which is closely related to a high level of behavioural engagement.

Last but not least, reducing boredom in EFL learning is worthwhile as it is an emotion with a direct relationship to EFL behavioural engagement. The exam-oriented EFL learning context will likely trigger boredom because of monotonous learning materials, a high-pressure learning atmosphere, etc. Teachers can target this characteristic and use emotional contagion to transmit enthusiasm for EFL learning to achieve low levels of boredom. This can be achieved by integrating multiple teaching methods and materials, making full use of online resources,

planning activities that align with students’ abilities and providing positive feedback.

Despite the above implications, the present study had some limitiations. First, only behavioural engagement was examined as it is vital to the multidimensional learning engagement construct. Therefore, the relationships between basic psychological needs, self-determined motivation, boredom and other dimensions of engagement are worthy to be discussed in the future studies. Second, boredom was adopted as an example to discuss its mediating roles in the relationship between basic psychological needs, self-determined motivation and behavioural engagement. However, students experience diverse emotions in EFL learning, and they are worthy of further study [57]. Amotivation and integrated motivation were not explored in our study, but they are two valuable topics in the future studies which can examine the levels of these variables and their relationships with other psychological factors. Concerning the research methods, only quantitative self-measures were used to measure the four variables; therefore, the results of the present study need further triangulation by adopting other data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews. Another limitation is that this study was conducted in a senior high school EFL context in an area of China. Future research can recruit more students in other areas and consider the junior high school students as the partcipants to enhance the representativeness.

Abbreviations

| SLA | Second language acquisition |

| SDT | Self-determination theory |

| EFL | English as a foreign language |

| CFA | Confirmatory factor analysis |

| RAI | Relative autonomy index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 28 February 2025

References

- Dörnyei Z, Ryan S. The psychology of the language learner revisited. 1st edition. New York: Routledge. 2015.

- Dörnyei Z. The interface of psychology and second language acquisition. In: Gervain J, Csibra G, Kovács K, editors. A life in cognition: studies in cognitive science in honor of Csaba Pléh. Cham: Springer 2022;17-28.

- Pavlenko A. The affective turn in SLA: from ‘affective factors’ to ‘language desire’ and ‘commodification of affect’. In: Gabryś-Barker D, Bielska J, editors. The affective dimension in second language acquisition. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. 2013;3-28.

- Mercer S, MacIntyre PD. Introducing positive psychology to SLA. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach. 2014;4:153-72.

- Dewaele JM, Dewaele L. Are foreign language learners’ enjoyment and anxiety specific to the teacher? An investigation into the dynamics of learners’ classroom emotions. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach. 2020;10:45-65.

- Wang N. How does basic psychological needs satisfaction contribute to EFL learners’ achievement and positive emotions? The mediating role of L2 selfconcept. System. 2024;123:103340.

- Jin Y, Zhang LJ. The dimensions of foreign language classroom enjoyment and their effect on foreign language achievement. Int J Biling Educ Biling. 2021;24:948-62.

- Liu H, Fan J. Al-mediated communication in EFL classrooms: the role of technical and pedagogical stimuli and the mediating effects of AI literacy and enjoyment. Eur J Educ. 2025;60:e12813.

- Wang Y, Liu H. The mediating roles of buoyancy and boredom in the relationship between autonomous motivation and engagement among Chinese senior high school EFL learners. Front Psychol. 2022;13:992279.

- Wang X, Liu H. Exploring the moderating roles of emotions, attitudes, environment, and teachers in the impact of motivation on learning behaviours in students’ English learning. Psychol Rep. 2024;00332941241231714.

- Hasanzadeh S, Shayesteh S, Pishghadam R. Investigating the role of teacher concern in EFL students’ motivation, anxiety, and language achievement through the lens of self-determination theory. Learn Motiv. 2024;86:101992.

- Wang

, Feng , , Liu H. Do residential areas matter? Exploring the differences in motivational factors, motivation, and learning behaviors among urban high school English learners from different regions. Educ Urban Soc. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131245251314194 - Liu H, Han X . Exploring senior high school students’ English academic resilience in the Chinese context. Chin J Appl Linguist. 2022;45:49-68.

- Duan S, Han X, Li X, Liu H. Unveiling student academic resilience in language learning: a structural equation modelling approach. BMC Psychol. 2024;12:177.

- Chu W, Yan Y, Wang H, Liu H. Visiting the studies of resilience in language learning: from concepts to themes. Acta Psychol. 2024;244:104208.

- Liu H, Li X, Yan Y. Demystifying the predictive role of students’ perceived foreign Language teacher support in foreign language anxiety: the mediation of L2 grit. J Multiling Multicult Develop. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/014346 32.2023.2223171

- Li X, Duan S, Liu H. Unveiling the predictive effect of students’ perceived EFL teacher support on academic achievement: the mediating role of academic buoyancy. Sustainability. 2023;15:10205.

- Liu H, Zhu Z, Chen B. Unraveling the mediating role of buoyancy in the relationship between anxiety and EFL students’ learning engagement. Percept Mot Skills. 2025;132:195-217.

- Dörnyei Z, Kormos J. The role of individual and social variables in oral task performance. Lang Teach Res. 2000;4:275-300.

- Tsao JJ, Tseng WT, Hsiao TY, Wang C, Gao AX. Toward a motivation-regulated learner engagement WCF model of L2 writing performance. Sage Open. 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211023172

- Liu H, Zhong Y, Chen H, Wang Y. The mediating roles of resilience and motivation in the relationship between students’ English learning burnout and engagement: a conservation-of-resources perspective. Int Rev Appl Linguist Lang Teach. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2023-0089

- Fan N, Yang C, Kong F, Zhang Y. Low- to mid-level high school first-year EFL learners’ growth language mindset, grit, burnout, and engagement: using serial mediation models to explore their relationships. System. 2024;125:103397.

- Derakhshan A, Fathi J. Grit and foreign language enjoyment as predictors of EFL learners’ online engagement: the mediating role of online learning selfefficacy. Asia-Pacific Edu Res. 2024;33:759-69.

- Liu H, Li X, Guo G. Students’ L2 grit, foreign language anxiety and language learning achievement: A latent profile and mediation analysis. Int Rev Appl Linguist Lang Teach. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2024-0013

- Liu H, Jin L, Han X, Wang H. Unraveling the relationship between English learning burnout and academic achievement: the mediating role of English learning resilience. Behav Sci. 2024;14:1124.

- Liu H, Elahi Shirvan M, Taherian T. Revisiting the relationship between global and specific levels of foreign language boredom and language engagement: a moderated mediation model of academic buoyancy and emotional engagement. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach. 2024. https://doi.org/10.14746/ ssllt. 40195

- Liu H, Li J, Fang F. Examining the complexity between boredom and engagement in English learning: evidence from Chinese high school students. Sustainability. 2022;14:16920.

- Hamedi SM, Pishghadam R, Fadardi JS. The contribution of reading emotions to reading comprehension: the mediating effect of reading engagement using a structural equation modeling approach. Educ Res Policy Prac. 2020;19:211-38.

- Dai K, Wang Y. Enjoyable, anxious, or bored? Investigating Chinese EFL learners’ classroom emotions and their engagement in technology-based EMI classrooms. System. 2024;123:103339.

- Skinner EA, Kindermann TA, Furrer CJ. A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educ Psychol Meas. 2009;69:493-525.

- Oga-Baldwin WLQ. Acting, thinking, feeling, making, collaborating: the engagement process in foreign language learning. System. 2019;86:102128.

- Mercer S, Dörnyei Z. Engaging language learners in contemporary classrooms. 1st edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2020.

- Feng E, Hong G. Engagement mediates the relationship between emotion and achievement of Chinese EFL learners. Front Psychol. 2022;13:895594.

- McEown MS, Oga-Baldwin WLQ. Self-determination for all language learners: new applications for formal language education. System. 2019;86:102124.

- Al-Hoorie AH, Oga-Baldwin WLQ, Hiver P, Vitta JP. Self-determination minitheories in second language learning: a systematic review of three decades of research. Lang Teach Res. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/136216882211026 86

- Reeve J. A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In: Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C, editors. Handbook of research on student engagement. Boston, MA: Springer US. 2012;149-72.

- Zhou SA, Hiver P, Zheng Y. Modeling intra- and inter-individual changes in L2 classroom engagement. Appl Lingusit. 2023;44:1047-76.