DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38390241

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-01

الأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة المستمدة من ميكروبات الأمعاء والاكتئاب: نظرة عميقة على الآليات البيولوجية والتطبيقات المحتملة

- المواد الإضافية التكميلية تُنشر عبر الإنترنت فقط. لعرضها، يرجى زيارة المجلة على الإنترنت (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374).

JC و HH هما المؤلفان الرئيسيان المشتركين.

تم الاستلام في 04 أكتوبر 2023

تم القبول في 25 ديسمبر 2023

© المؤلفون (أو أصحاب العمل) 2024. يُسمح بإعادة الاستخدام بموجب CC BY-NC. لا يُسمح بإعادة الاستخدام التجاري. انظر الحقوق والتصاريح. نُشر بواسطة BMJ.

الملخص

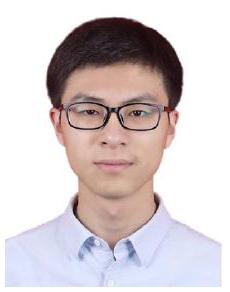

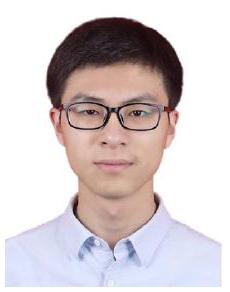

الميكروبيوم المعوي هو نظام بيئي معقد وديناميكي يعرف باسم ‘الدماغ الثاني’. يتكون محور الميكروبيوم المعوي-الدماغ، حيث ينظم الميكروبيوم المعوي ومستقلباته الجهاز العصبي المركزي من خلال مسارات عصبية وغدد صماء ومناعية لضمان الوظيفة الطبيعية للكائن الحي، مما يؤثر على صحة الأفراد وحالة المرض. الأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة (SCFAs)، وهي المستقلبات الحيوية الرئيسية للميكروبيوم المعوي، تشارك في عدة اضطرابات نفسية عصبية، بما في ذلك الاكتئاب. للأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة تأثيرات أساسية على كل مكون من مكونات محور الميكروبيوم المعوي-الدماغ في الاكتئاب. في هذه المراجعة، يتم تلخيص أدوار الأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة الرئيسية (الأسيتات، البروبيونات والبيوتيرات) في الفيزيولوجيا المرضية للاكتئاب فيما يتعلق بنقص تروية الدماغ المزمن، والالتهاب العصبي، والإيبيجينوم المضيف، والتغيرات العصبية الغدد الصماء. نأمل أن تتناول الملاحظات الختامية حول الآليات البيولوجية المتعلقة بالميكروبيوم المعوي القيمة السريرية للعلاجات المرتبطة بالميكروبيوم للاكتئاب.

مقدمة

لقد تم توضيح التكيف الذي يعتمد على الدوائر الدماغية تدريجياً. تلخص هذه المراجعة التفاعل بين المستقلبات الرئيسية لميكروبات الأمعاء – الأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة (SCFAs) – والآليات البيولوجية للاكتئاب. نأمل أن يساهم توضيح الآليات البيولوجية المتعلقة بالأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة من ميكروبات الأمعاء في إلقاء الضوء على استراتيجيات علاجية جديدة للاكتئاب.

الميكروبيوم المعوي وعملياته الأيضية غير الطبيعية في الاكتئاب

خلل ميكروبات الأمعاء

خلل التوازن الميكروبي، يظهر تنوعًا أقل ولكن كثافة أعلى من الميكروبات المعوية على سطح الغشاء المخاطي المعوي.

الطب النفسي العام: نُشر لأول مرة كـ 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 في 19 فبراير 2024. تم تنزيله منhttps://gpsych.bmj.com في 29 أغسطس 2025 بواسطة ضيف. محمي بموجب حقوق الطبع والنشر، بما في ذلك الاستخدامات المتعلقة بتعدين النصوص والبيانات، وتدريب الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتقنيات المماثلة.

أن الوفرة النسبية لبكتيريا Bacteroidetes كانت أقل لدى المرضى الذين يعانون من الاكتئاب مقارنة بالضوابط الصحية. قد تُعزى هذه النتائج المتضاربة إلى اختلافات في أحجام العينات، والفروق الديموغرافية، ومعايير الفحص للمرضى المجندين، وتقنيات التسلسل والمعلومات الحيوية المختلفة. ومع ذلك، تم الإشارة باستمرار إلى أن الاكتئاب يتوافق مع تغييرات ملحوظة في تكوين الميكروبات المعوية.

أثر الأحماض الدهنية القصيرة المشتقة من الميكروبات المعوية على الاكتئاب: التمثيل الغذائي والآثار الفسيولوجية للأحماض الدهنية القصيرة

نقل العناصر الغذائية والجزيئات المشاركة في الحفاظ على سلامة BBB، مما يؤثر بشكل مباشر على تطوير الدماغ وتوازن الجهاز العصبي المركزي.

دور الأحماض الدهنية القصيرة في الآليات المرضية الكامنة وراء الاكتئاب المرتبط بالميكروبات المعوية

الأحماض الدهنية القصيرة ونقص تروية الدماغ المزمن

الطب النفسي العام: نُشر لأول مرة كـ 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 في 19 فبراير 2024. تم التنزيل منhttps://gpsych.bmj.comفي 29 أغسطس 2025 بواسطة ضيف. محمي بموجب حقوق الطبع والنشر، بما في ذلك الاستخدامات المتعلقة بتعدين النصوص والبيانات، وتدريب الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتقنيات المماثلة.

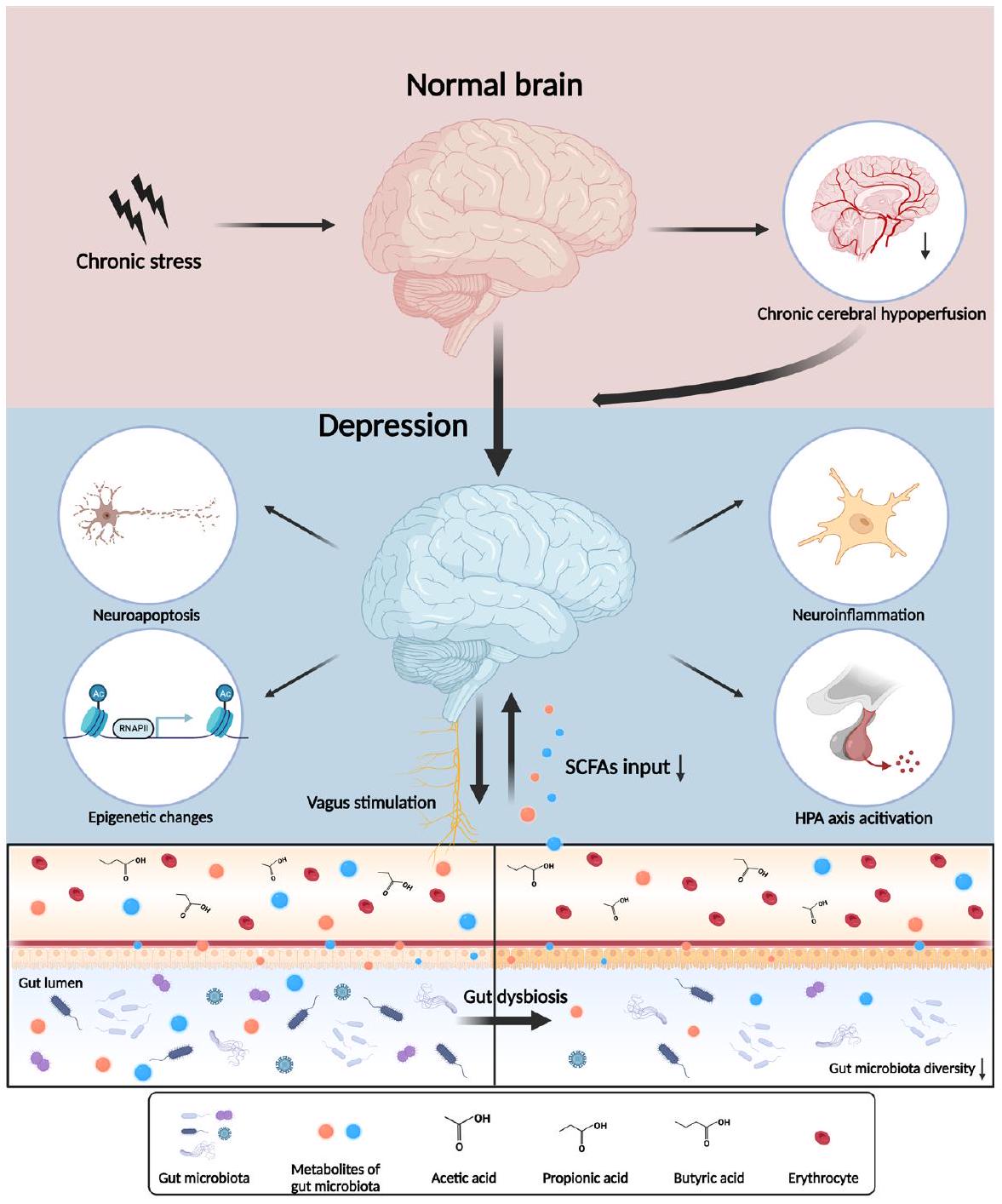

لقد تم التحقيق على نطاق واسع في الدور الأساسي للالتهاب في الاكتئاب في العقود الأخيرة، حيث برز محور الميكروبيوتا-الأمعاء-الدماغ كمنظم وسيط رئيسي.

في الضوابط الصحية.

تم الإبلاغ عن أنها تظهر تأثيرات واقية على الحاجز المعوي كمصادر للطاقة.

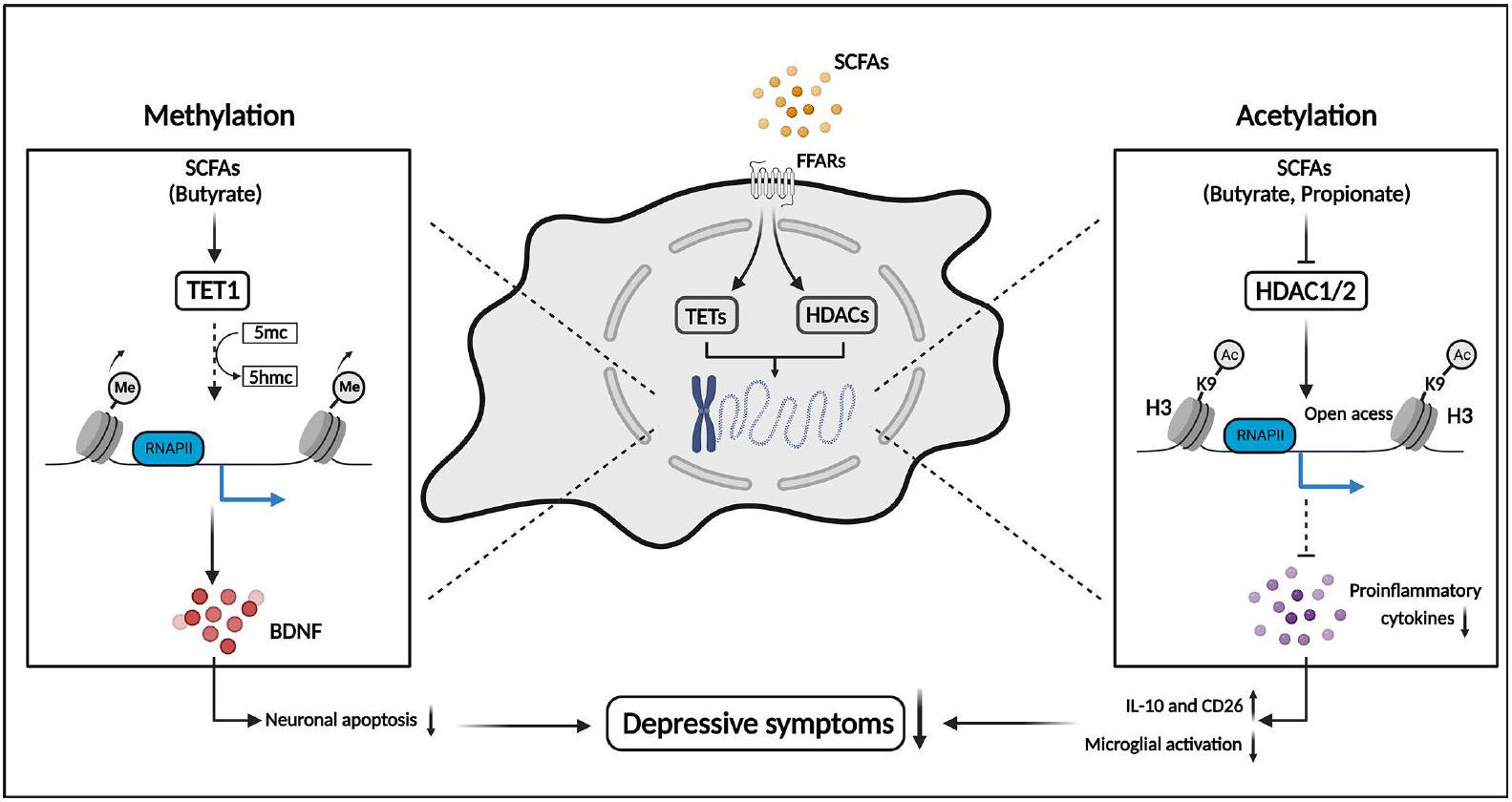

الأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة والجينوم الوبائي للمضيف

الطب النفسي العام: نُشر لأول مرة كـ 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 في 19 فبراير 2024. تم التنزيل منhttps://gpsych.bmj.comفي 29 أغسطس 2025 بواسطة ضيف. محمي بموجب حقوق الطبع والنشر، بما في ذلك الاستخدامات المتعلقة بتعدين النصوص والبيانات، وتدريب الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتقنيات المماثلة.

تعديلات الهيستون

لخلايا الدبق والخلايا المناعية خلال الاستجابة الالتهابية.

الطب النفسي العام: نُشر لأول مرة كـ 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 في 19 فبراير 2024. تم التنزيل منhttps://gpsych.bmj.comفي 29 أغسطس 2025 بواسطة ضيف محمي بموجب حقوق الطبع والنشر، بما في ذلك الاستخدامات المتعلقة بتعدين النصوص والبيانات، وتدريب الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتقنيات المماثلة.

ميثيلation الحمض النووي

الطب النفسي العام: نُشر لأول مرة كـ 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 في 19 فبراير 2024. تم التنزيل منhttps://gpsych.bmj.comفي 29 أغسطس 2025 بواسطة ضيف. محمي بموجب حقوق الطبع والنشر، بما في ذلك الاستخدامات المتعلقة بتعدين النصوص والبيانات، وتدريب الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتقنيات المماثلة.

ممارسة تأثيرات مشابهة لمضادات الاكتئاب.

RNA غير مشفر

من الدماغ من خلال المسارات الوراثية البيئية. قد يفسر التأخير في إضافة أو حذف التعديلات الوراثية البيئية التطور البطيء والآثار الأولية غير المهمة لمضادات الاكتئاب في علاج الاكتئاب. يؤدي اضطراب توازن الأمعاء إلى تحفيز منظمات وراثية بيئية متغيرة يتم تصنيعها بواسطة ميكروبات الأمعاء، مثل الأسيتات، والبيوتيرات، والبروبيونات، بعد تنشيط الالتهاب العصبي ومسارات أخرى من خلال إعادة برمجة وراثية بيئية. قد تلعب الآليات الأساسية في محور الميكروبات-الأمعاء-الدماغ دورًا مهمًا في اللدونة المشبكية غير الطبيعية على المدى الطويل والاستجابة السلوكية للتوتر في الاكتئاب.

الأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة والتغيرات العصبية الهرمونية

الطب النفسي العام: نُشر لأول مرة كـ 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 في 19 فبراير 2024. تم التنزيل منhttps://gpsych.bmj.comفي 29 أغسطس 2025 بواسطة ضيف. محمي بموجب حقوق الطبع والنشر، بما في ذلك الاستخدامات المتعلقة بتعدين النصوص والبيانات، وتدريب الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتقنيات المماثلة.

لقد تم توضيح تأثير ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء بشكل جيد، لكن كيفية تنظيم الكيتامين لعملية الأيض في ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء ومستقلباتها، مثل الأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة، غير واضحة. لذلك، يجب أن تركز الدراسات المستقبلية على الآليات التي ينظم بها الكيتامين عملية الأيض في ميكروبيوتا الأمعاء ومستقلباتها كعامل واعد لمكافحة الاكتئاب.

الاستخدام المحتمل لميكروبيوم الأمعاء والأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة في علاج الاكتئاب

التدخلات الغذائية

الطب النفسي العام: نُشر لأول مرة كـ 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 في 19 فبراير 2024. تم التنزيل منhttps://gpsych.bmj.comفي 29 أغسطس 2025 بواسطة ضيف. محمي بموجب حقوق الطبع والنشر، بما في ذلك الاستخدامات المتعلقة بتعدين النصوص والبيانات، وتدريب الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتقنيات المماثلة.

زراعة ميكروبات البراز

البروبيوتيك والبريبايوتيك

في إنتاج الأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة.

الاستنتاجات والرؤية المستقبلية

الطب النفسي العام: نُشر لأول مرة كـ 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 في 19 فبراير 2024. تم التنزيل منhttps://gpsych.bmj.comفي 29 أغسطس 2025 بواسطة ضيف. محمي بموجب حقوق الطبع والنشر، بما في ذلك الاستخدامات المتعلقة بتعدين النصوص والبيانات، وتدريب الذكاء الاصطناعي، والتقنيات المماثلة.

في بداية وتطور الاكتئاب. على الرغم من أننا فهمنا بشكل أولي التفاعلات بين الميكروبات المعوية والأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة والاكتئاب، لا تزال هناك عدة مشاكل تعيق الانتقال من النتائج المخبرية إلى التطبيقات السريرية. في الواقع، من الصعب تقدير التأثير المباشر وغير المباشر لتمثيل الميكروبات المعوية على الجهاز العصبي المركزي. نظرًا للتواصل المعقد بين الميكروبات المعوية، والمناعة، والأنظمة الغدد الصماء والعصبية، من الصعب توضيح تأثيرات الأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة في أي جانب واحد. في الوقت نفسه، قامت عدد من الدراسات بالتحقيق في التغيرات في تركيب ووفرة الميكروبات المعوية لدى المرضى الذين يعانون من الاكتئاب، لكن التغيرات تظهر نتائج متشعبة تحير الباحثين وقد تؤدي إلى عواقب غير مرغوب فيها في العلاج الميكروبي. نظرًا لتعقيد الفسيولوجيا البشرية، تؤثر عدة عوامل، بما في ذلك النظام الغذائي، والتمارين الرياضية، والشيخوخة، والمزاج، على تركيب ووفرة الميكروبات المعوية. بمساعدة طرق جديدة، مثل التسلسل عالي الإنتاجية، والنهج متعددة الأوميات، وتقنية زراعة الميكروبات، يمكن أن تعزل الأبحاث المستقبلية السلالات المسببة للأمراض والضارة المرتبطة بالاكتئاب وتوضح التفاعلات بين الميكروبات، ومحور الأمعاء والدماغ، والأنظمة الأخرى.

تمويل تم تمويل هذه الدراسة من قبل المؤسسة الوطنية للعلوم الطبيعية في الصين (82001437 و 82371535)، مشاريع STI2030 الكبرى (2021ZD0202000)، وبرنامج الابتكار العلمي والتكنولوجي لمقاطعة هونان (2023RC3083).

المصالح المتنافسة لم يتم الإعلان عنها.

موافقة المريض للنشر غير قابلة للتطبيق.

موافقة الأخلاقيات غير قابلة للتطبيق.

الأصل والمراجعة من قبل الأقران لم يتم تكليفه؛ تمت مراجعته من قبل الأقران خارجيًا.

الوصول المفتوح هذه مقالة مفتوحة الوصول موزعة وفقًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام غير التجاري (CC BY-NC 4.0)، والتي تسمح للآخرين بتوزيع وإعادة مزج وتكييف وبناء على هذا العمل بشكل غير تجاري، وترخيص أعمالهم المشتقة بشروط مختلفة، شريطة أن يتم الاستشهاد بالعمل الأصلي بشكل صحيح، ومنح الائتمان المناسب، والإشارة إلى أي تغييرات تم إجراؤها، وأن يكون الاستخدام غير تجاري. انظر: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

بانغشان ليوhttp://orcid.org/0000-0002-9355-2183

REFERENCES

2 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical Manual of mental disorders. In: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, VA, US: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3 World Health Organization. Depressive disorder (depression). 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ depression [Accessed 18 Aug 2023].

4 Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet 2018;392:2299-312.

5 Baquero F, Nombela C. The microbiome as a human organ. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18 Suppl 4:2-4.

6 Paone P, Cani PD. Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners? Gut 2020;69:2232-43.

7 Weersma RK, Zhernakova A, Fu J. Interaction between drugs and the gut microbiome. Gut 2020;69:1510-9.

8 Wang S, Zhang C, Yang J, et al. Sodium butyrate protects the intestinal barrier by modulating intestinal host defense peptide expression and gut microbiota after a challenge with deoxynivalenol in weaned piglets. J Agric Food Chem 2020;68:4515-27.

9 Wang H-X, Wang Y-P. Gut microbiota-brain axis. Chinese Medical Journal 2016;129:2373-80.

10 Farzi A, Fröhlich EE, Holzer P. Gut microbiota and the neuroendocrine system. Neurotherapeutics 2018;15:5-22.

11 Needham BD, Funabashi M, Adame MD, et al. A gut-derived metabolite alters brain activity and anxiety behaviour in mice. Nature 2022;602:647-53.

12 Li Z, Lai J, Zhang P, et al. Multi-omics analyses of serum metabolome, gut microbiome and brain function reveal dysregulated microbiota-gut-brain axis in bipolar depression. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:4123-35.

13 Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, et al. The microbiota-gutbrain axis. Physiol Rev 2019;99:1877-2013.

14 Turna J, Grosman Kaplan K, Anglin R, et al. The gut microbiome and inflammation in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients

compared to age- and sex-matched controls: a pilot study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2020;142:337-47.

15 Yu Z, Chen W, Zhang L, et al. Gut-derived bacterial LPS attenuates incubation of methamphetamine craving via modulating microglia. Brain Behav Immun 2023;111:101-15.

16 McGuinness AJ, Davis JA, Dawson SL, et al. A systematic review of gut microbiota composition in observational studies of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:1920-35.

17 Modesto Lowe V, Chaplin M, Sgambato D. Major depressive disorder and the gut microbiome: what is the link? Gen Psychiatr 2023;36:e100973.

18 Miller TL, Wolin MJ. Pathways of acetate, propionate, and butyrate formation by the human fecal microbial flora. Appl Environ Microbiol 1996;62:1589-92.

19 Le Poul E, Loison C, Struyf S, et al. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J Biol Chem 2003;278:25481-9.

20 Kimura I, Ichimura A, Ohue-Kitano R, et al. Free fatty acid receptors in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2020;100:171-210.

21 Brown AJ, Goldsworthy SM, Barnes AA, et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J Biol Chem 2003;278:11312-9.

22 Tian D, Xu W, Pan W, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation enhances cell therapy in a rat model of hypoganglionosis by SCFAinduced Mek1/2 signaling pathway. EMBO J 2023;42:e111139.

23 Morais LH, Schreiber HL 4th, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiotabrain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021;19:241-55.

24 Stewart CJ, Ajami NJ, O’Brien JL, et al. Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature 2018;562:583-8.

25 Yu LW, Agirman G, Hsiao EY. The gut microbiome as a regulator of the neuroimmune landscape. Annu Rev Immunol 2022;40:143-67.

26 Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011;473:174-80.

27 Korem T, Zeevi D, Suez J, et al. Growth dynamics of gut microbiota in health and disease inferred from single metagenomic samples. Science 2015;349:1101-6.

28 Yu X, Jiang W, Kosik RO, et al. Gut microbiota changes and its potential relations with thyroid carcinoma. J Adv Res 2022;35:61-70.

29 Zmora N, Suez J, Elinav E. You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16:35-56.

30 Gao X, Cao Q, Cheng Y, et al. Chronic stress promotes colitis by disturbing the gut microbiota and triggering immune system response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E2960-9.

31 O’Toole PW, Jeffery IB. Gut microbiota and aging. Science 2015;350:1214-5.

32 Reyman M, van Houten MA, Watson RL, et al. Effects of early-life antibiotics on the developing infant gut microbiome and resistome: a randomized trial. Nat Commun 2022;13:893.

33 Zhao Y, Wang C, Goel A. Role of gut microbiota in epigenetic regulation of colorectal cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Reviews on Cancer 2021;1875:188490.

35 Fan Y, Støving RK, Berreira Ibraim S, et al. The gut microbiota contributes to the pathogenesis of anorexia nervosa in humans and mice. Nat Microbiol 2023;8:787-802.

36 Kosuge A, Kunisawa K, Arai S, et al. Heat-sterilized Bifidobacterium breve prevents depression-like behavior and interleukin-1B expression in mice exposed to chronic social defeat stress. Brain Behav Immun 2021;96:200-11.

37 Schoeler M, Caesar R. Dietary lipids, gut microbiota and lipid metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2019;20:461-72.

38 Fröhlich EE, Farzi A, Mayerhofer R, et al. Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication. Brain Behav Immun 2016;56:140-55.

39 Schirmer M, Garner A, Vlamakis H, et al. Microbial genes and pathways in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019;17:497-511.

40 Kilinçarslan S, Evrensel A. The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: an experimental study. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2020;48:1-7.

41 Lurie I, Yang Y-X, Haynes K, et al. Antibiotic exposure and the risk for depression, anxiety, or psychosis: a nested case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:1522-8.

43 Lou M, Cao A, Jin C, et al. Deviated and early unsustainable stunted development of gut microbiota in children with autism spectrum disorder. Gut 2022;71:1588-99.

44 Zheng P , Zeng B , Liu M , et al. The gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia modulates the glutamate-glutamine-GABA cycle and schizophrenia-relevant behaviors in mice. Sci Adv 2019;5:eaau8317.

45 Singh A, Dawson TM, Kulkarni S. Neurodegenerative disorders and gut-brain interactions. J Clin Invest 2021;131:13.

46 Zhao N, Chen Q-G, Chen X, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis mediates cognitive impairment via the intestine and brain NLRP3 inflammasome activation in chronic sleep deprivation. Brain Behav Immun 2023;108:98-117.

47 Chen Y, Xu J, Chen Y. Regulation of neurotransmitters by the gut microbiota and effects on cognition in neurological disorders. Nutrients 2021;13:2099.

48 Wang Y, Li N, Yang J-J, et al. Probiotics and fructo-oligosaccharide intervention modulate the microbiota-gut brain axis to improve autism spectrum reducing also the hyper-serotonergic state and the dopamine metabolism disorder. Pharmacological Research 2020;157:104784.

49 Liu Y, Xu F, Liu S, et al. Significance of gastrointestinal tract in the therapeutic mechanisms of exercise in depression: synchronism between brain and intestine through GBA. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2020;103:109971.

50 Zeissig S, Bürgel N, Günzel D, et al. Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn’s disease. Gut 2007;56:61-72.

51 Shan Y, Lee M, Chang EB. The gut microbiome and inflammatory bowel diseases. Annu Rev Med 2022;73:455-68.

52 Sperner-Unterweger B, Kohl C, Fuchs D. Immune changes and neurotransmitters: possible interactions in depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2014;48:268-76.

53 Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun 2015;48:186-94.

54 Liu Y, Zhang L, Wang X, et al. Similar fecal microbiota signatures in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and patients with depression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1602-11.

55 Nikolova VL, Smith MRB, Hall LJ, et al. Perturbations in gut microbiota composition in psychiatric disorders: a review and metaanalysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:1343-54.

56 Kelly JR, Borre Y, O’ Brien C, et al. Transferring the blues: depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J Psychiatr Res 2016;82:109-18.

57 Zheng P, Zeng B, Zhou C, et al. Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host’s metabolism. Mol Psychiatry 2016;21:786-96.

58 Simpson CA, Diaz-Arteche C, Eliby D, et al. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression – a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2021;83:101943.

59 Valles-Colomer M, Falony G, Darzi Y, et al. The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nat Microbiol 2019;4:623-32.

60 Kim C-S, Cha L, Sim M, et al. Probiotic supplementation improves cognitive function and mood with changes in gut microbiota in community-dwelling older adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2021;76:32-40.

61 Rudzki L, Ostrowska L, Pawlak D, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum 299 V decreases kynurenine concentration and improves cognitive functions in patients with major depression: a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019;100:213-22.

62 Kazemi A, Noorbala AA, Azam K, et al. Effect of probiotic and prebiotic vs placebo on psychological outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Clinical Nutrition 2019;38:522-8.

63 Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, et al. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 1987;28:1221-7.

64 Macfarlane S, Macfarlane GT. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc Nutr Soc 2003;62:67-72.

65 Itoh Y, Kawamata Y, Harada M, et al. Free fatty acids regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells through GPR40. Nature 2003;422:173-6.

67 Li H-B, Xu M-L, Xu X-D, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii attenuates CKD via butyrate-renal GPR43 axis. Circ Res 2022;131:e120-34.

68 Hou Y-F, Shan C, Zhuang S-Y, et al. Gut microbiota-derived propionate mediates the neuroprotective effect of osteocalcin in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Microbiome 2021;9:34.

69 Vijay N, Morris ME. Role of monocarboxylate transporters in drug delivery to the brain. Curr Pharm Des 2014;20:1487-98.

70 Schönfeld P, Wojtczak L. Short- and medium-chain fatty acids in energy metabolism: the cellular perspective. J Lipid Res 2016;57:943-54.

71 Doifode T, Giridharan VV, Generoso JS, et al. The impact of the microbiota-gut-brain axis on Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. Pharmacol Res 2021;164:105314.

72 Mitchell RW, On NC, Del Bigio MR, et al. Fatty acid transport protein expression in human brain and potential role in fatty acid transport across human brain microvessel endothelial cells. J Neurochem 2011;117:735-46.

73 Kekuda R, Manoharan P, Baseler W, et al. Monocarboxylate 4 mediated butyrate transport in a rat intestinal epithelial cell line. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:660-7.

74 Fock E, Parnova R. Mechanisms of blood-brain barrier protection by microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids. Cells 2023;12:657.

75 Serger E, Luengo-Gutierrez L, Chadwick JS, et al. The gut metabolite indole-3 propionate promotes nerve regeneration and repair. Nature 2022;607:585-92.

76 Wu M, Tian T, Mao Q, et al. Associations between disordered gut microbiota and changes of neurotransmitters and short-chain fatty acids in depressed mice. Transl Psychiatry 2020;10:350.

77 Agus A, Clément K, Sokol H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut 2021;70:1174-82.

78 Awata S, Ito H, Konno M, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow abnormalities in late-life depression: relation to refractoriness and chronification. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998;52:97-105.

79 Rajeev V, Fann DY, Dinh QN, et al. Pathophysiology of blood brain barrier dysfunction during chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in vascular cognitive impairment. Theranostics 2022;12:1639-58.

80 Ren C, Liu Y, Stone C, et al. Limb remote ischemic conditioning ameliorates cognitive impairment in rats with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion by regulating glucose transport. Aging Dis 2021;12:1197:1197-210…

81 Zhang L-Y, Pan J, Mamtilahun M, et al. Microglia exacerbate white matter injury via complement C3/C3aR pathway after hypoperfusion. Theranostics 2020;10:74-90.

82 Lansdell TA, Dorrance AM. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in male rats results in sustained HPA activation and hyperinsulinemia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2022;322:E24-33.

83 Farrell JS, Colangeli R, Wolff MD, et al. Postictal hypoperfusion/ hypoxia provides the foundation for a unified theory of seizureinduced brain abnormalities and behavioral dysfunction. Epilepsia 2017;58:1493-501.

84 Lan D, Song S, Jia M, et al. Cerebral venous-associated brain damage may lead to anxiety and depression. J Clin Med 2022;11:6927.

85 Lee SR, Choi B, Paul S, et al. Depressive-like behaviors in a rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Transl Stroke Res 2015;6:207-14.

86 Xiao W, Su J, Gao X, et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis participates in chronic cerebral hypoperfusion by disrupting the metabolism of short-chain fatty acids. Microbiome 2022;10:62.

87 Su SH, Chen M, Wu YF, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation and short-chain fatty acids protected against cognitive dysfunction in a rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. CNS Neurosci Ther 2023;29:98-114.

88 Su S-H, Wu Y-F, Lin Q, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation and replenishment of short-chain fatty acids protect against chronic cerebral hypoperfusion-induced colonic dysfunction by regulating gut microbiota, differentiation of Th17 cells, and mitochondrial energy metabolism. J Neuroinflammation 2022;19:313.

89 Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol 2006;27:24-31.

90 Köhler CA, Freitas TH, Maes M, et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017;135:373-87.

91 Cui Y, Yang Y, Ni Z, et al. Astroglial Kir4.1 in the lateral habenula drives neuronal bursts in depression. Nature 2018;554:323-7.

93 Leclercq S, Le Roy T, Furgiuele S, et al. Gut microbiota-induced changes in B-hydroxybutyrate metabolism are linked to altered sociability and depression in alcohol use disorder. Cell Rep 2020;33:108238.

94 Li H, Xiang Y, Zhu Z, et al. Rifaximin-mediated gut microbiota regulation modulates the function of microglia and protects against CUMS-induced depression-like behaviors in adolescent rat. J Neuroinflammation 2021;18:254.

95 Xiao W, Li J, Gao X, et al. Involvement of the gut-brain axis in vascular depression via tryptophan metabolism: a benefit of short chain fatty acids. Exp Neurol 2022;358:114225.

96 Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry 2016;21:1696-709.

97 Beurel E, Lowell JA. Th17 cells in depression. Brain Behav Immun 2018;69:28-34.

98 Peng Z, Peng S, Lin K, et al. Chronic stress-induced depression requires the recruitment of peripheral Th17 cells into the brain.

99 Beurel E, Lowell JA, Jope RS. Distinct characteristics of hippocampal pathogenic

100 Kann O, Almouhanna F, Chausse B. Interferon

101 Wachholz S, Eßlinger M, Plümper J, et al. Microglia activation is associated with IFN-

102 Liu Z, Qiu A-W, Huang Y, et al. IL-17A exacerbates neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration by activating microglia in rodent models of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav Immun 2019;81:630-45.

103 Wu J, Li J, Gaurav C, et al. CUMS and dexamethasone induce depression-like phenotypes in mice by differentially altering gut microbiota and triggering macroglia activation. Gen Psychiatr 2021;34:e100529.

104 Wang H, He Y, Sun Z, et al. Microglia in depression: an overview of microglia in the pathogenesis and treatment of depression. J Neuroinflammation 2022;19:132.

105 Ikeda Y, Saigo N, Nagasaki Y. Direct evidence for the involvement of intestinal reactive oxygen species in the progress of depression via the gut-brain axis. Biomaterials 2023;295.

106 Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, et al. Acetylcholinesynthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science 2011;334:98-101.

107 Pu Y, Tan Y, Qu Y, et al. A role of the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve in depression-like phenotypes in mice after fecal microbiota transplantation from Chrna7 knock-out mice with depression-like phenotypes. Brain Behav Immun 2021;94:318-26.

108 Sternberg EM. Neural regulation of innate immunity: a coordinated nonspecific host response to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 2006;6:318-28.

109 Bernik TR, Friedman SG, Ochani M, et al. Pharmacological stimulation of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway. J Exp Med 2002;195:781-8.

110 Yang Y, Eguchi A, Wan X, et al. A role of gut-microbiota-brain axis via subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve in depression-like phenotypes in Chrna7 knock-out mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2023;120:110652.

111 Zhang J, Ma L, Chang L, et al. A key role of the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve in the depression-like phenotype and abnormal composition of gut microbiota in mice after lipopolysaccharide administration. Trans/ Psychiatry 2020;10:186.

112 Marwaha S, Palmer E, Suppes T, et al. Novel and emerging treatments for major depression. Lancet 2023;401:141-53.

113 Hashimoto K. Neuroinflammation through the vagus nervedependent gut-microbiota-brain axis in treatment-resistant depression. Prog Brain Res 2023;278:61-77.

114 Frost G, Sleeth ML, Sahuri-Arisoylu M, et al. The short-chain fatty acid acetate reduces appetite via a central homeostatic mechanism. Nat Commun 2014;5:3611.

115 Li J-M, Yu R, Zhang L-P, et al. Dietary fructose-induced gut dysbiosis promotes mouse hippocampal neuroinflammation: a benefit of short-chain fatty acids. Microbiome 2019;7:98.

116 Aho VTE, Houser MC, Pereira PAB, et al. Relationships of gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, inflammation, and the gut barrier in Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 2021;16:6.

General Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 on 19 February 2024. Downloaded from https://gpsych.bmj.com on 29 August 2025 by guest Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

118 Hoyles L, Snelling T, Umlai U-K, et al. Microbiome-host systems interactions: protective effects of propionate upon the blood-brain barrier. Microbiome 2018;6:55.

119 Erny D, Hrabě de Angelis AL, Jaitin D, et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat Neurosci 2015;18:965-77.

120 Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature 2009;461:1282-6.

121 Liu J, Li H, Gong T, et al. Anti-neuroinflammatory effect of shortchain fatty acid acetate against Alzheimer’s disease via upregulating GPR41 and inhibiting ERK/JNK/NF-кB. J Agric Food Chem 2020;68:7152-61.

122 Fu S-P, Wang J-F, Xue W-J, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of BHBA in both in vivo and in vitro Parkinson’s disease models are mediated by Gpr109A-dependent mechanisms. J Neuroinflammation 2015;12:9.

123 Wang P , Zhang Y , Gong Y , et al. Sodium butyrate triggers a functional elongation of microglial process via Akt-small RhoGTPase activation and HDACs inhibition. Neurobiol Dis 2018;111:12-25.

124 van der Hee B, Wells JM. Microbial regulation of host physiology by short-chain fatty acids. Trends Microbiol 2021;29:700-12.

125 Weaver ICG, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci 2004;7:847-54.

126 Yin H, Galfalvy H, Zhang B, et al. Interactions of the GABRG2 polymorphisms and childhood trauma on suicide attempt and related traits in depressed patients. J Affect Disord 2020;266:447-55.

127 Kronman H, Torres-Berrío A, Sidoli S, et al. Long-term behavioral and cell-type-specific molecular effects of early life stress are mediated by H3K79Me2 dynamics in medium spiny neurons. Nat Neurosci 2021;24:753-4.

128 Alameda L, Trotta G, Quigley H, et al. Can epigenetics shine a light on the biological pathways underlying major mental disorders Psychol Med 2022;52:1645-65.

129 Massart R, Mongeau R, Lanfumey L. Beyond the monoaminergic hypothesis: neuroplasticity and epigenetic changes in a transgenic mouse model of depression. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2012;367:2485-94.

130 Jeong S, Chokkalla AK, Davis CK, et al. Post-stroke depression: epigenetic and epitranscriptomic modifications and their interplay with gut microbiota[online ahead of print]. Mol Psychiatry May 15, 2023.

132 Cheng J, He Z, Chen Q, et al. Histone modifications in cocaine, methamphetamine and opioids. Heliyon 2023;9:e16407.

133 Soliman ML, Smith MD, Houdek HM, et al. Acetate supplementation modulates brain histone acetylation and decreases interleukin1B expression in a rat model of neuroinflammation.

134 Zhao Y-T, Deng J, Liu H-M, et al. Adaptation of prelimbic cortex mediated by IL-6/Stat3/Acp5 pathway contributes to the comorbidity of neuropathic pain and depression in rats. J Neuroinflammation 2022;19:144.

135 Faraco G, Pittelli M, Cavone L, et al. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors reduce the glial inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Neurobiol Dis 2009;36:269-79.

136 Vinolo MAR, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, et al. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients 2011;3:858-76.

137 Schroeder FA, Lin CL, Crusio WE, et al. Antidepressant-like effects of the histone deacetylase inhibitor, sodium butyrate, in the mouse. Biol Psychiatry 2007;62:55-64.

138 Edelmann E, Cepeda-Prado E, Franck M, et al. Theta burst firing recruits BDNF release and signaling in postsynaptic Ca1 neurons in spike-timing-dependent LTP. Neuron 2015;86:1041-54.

139 Mizui T, Ishikawa Y, Kumanogoh H, et al. BDNF pro-peptide actions facilitate hippocampal LTD and are altered by the common BDNF polymorphism Val66Met. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:E3067-74.

140 Bus BAA, Molendijk ML, Tendolkar I, et al. Chronic depression is associated with a pronounced decrease in serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor over time. Mol Psychiatry 2015;20:602-8.

141 Diniz BS, Teixeira AL, Machado-Vieira R, et al. Reduced cerebrospinal fluid levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor is associated with cognitive impairment in late-life major depression.

143 Song L, Sun Q, Zheng H, et al. Roseburia hominis alleviates neuroinflammation via short-chain fatty acids through histone deacetylase inhibition. Mol Nutr Food Res 2022;66.

144 Carrard A, Elsayed M, Margineanu M, et al. Peripheral administration of lactate produces antidepressant-like effects. Mol Psychiatry 2018;23:488.

145 Karnib N, El-Ghandour R, El Hayek L, et al. Lactate is an antidepressant that mediates resilience to stress by modulating the hippocampal levels and activity of histone deacetylases. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019;44:1152-62.

146 Paoli C, Misztak P, Mazzini G, et al. DNA methylation in depression and depressive-like phenotype: biomarker or target of pharmacological intervention? Curr Neuropharmacol 2022;20:2267-91.

147 Zhu J-H, Bo H-H, Liu B-P, et al. The associations between DNA methylation and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

148 Tomoda T, Sumitomo A, Shukla R, et al. BDNF controls GABA A trafficking and related cognitive processes via autophagic regulation of p62. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022;47:553-63.

149 Januar V, Ancelin M-L, Ritchie K, et al. BDNF promoter methylation and genetic variation in late-life depression. Transl Psychiatry 2015;5:e619.

150 Wei Y, Melas PA, Wegener G, et al. Antidepressant-like effect of sodium butyrate is associated with an increase in TET1 and in 5-hydroxymethylation levels in the BDNF gene. Int

151 Li Y, Fan C, Wang L, et al. Microrna-26A-3P rescues depressionlike behaviors in male rats via preventing hippocampal neuronal anomalies. J Clin Invest 2021;131:e148853:16.:.

152 Issler O, van der Zee YY, Ramakrishnan A, et al. Sex-specific role for the long non-coding RNA Linc00473 in depression. Neuron 2020;106:912-26.

153 Yu X, Bai Y, Han B, et al. Extracellular vesicle-mediated delivery of circDYM alleviates CUS-induced depressive-like behaviours. J Extracell Vesicles 2022;11:e12185.

154 Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, et al. A ceRNA hypothesis: the rosetta stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell 2011;146:353-8.

155 Liu L, Wang H, Chen X, et al. Integrative analysis of long noncoding RNAs, Messenger RNAs, and MicroRNAs Indicates the neurodevelopmental dysfunction in the hippocampus of gut microbiota-dysbiosis mice. Front Mol Neurosci 2021;14:745437.

156 Uchida S, Yamagata H, Seki T, et al. Epigenetic mechanisms of major depression: targeting neuronal plasticity. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2018;72:212-27.

157 Thangaraju M, Cresci GA, Liu K, et al. GPR109A is a G-proteincoupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate and functions as a tumor suppressor in colon. Cancer Res 2009;69:2826-32.

158 Pluznick JL, Protzko RJ, Gevorgyan H, et al. Olfactory receptor responding to gut microbiota-derived signals plays a role in renin secretion and blood pressure regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:4410-5.

159 Fleischer J, Bumbalo R, Bautze V, et al. Expression of odorant receptor Olfr78 in enteroendocrine cells of the colon. Cell Tissue Res 2015;361:697-710.

160 Zhao Y, Chen F, Wu W, et al. GPR43 mediates microbiota metabolite SCFA regulation of antimicrobial peptide expression in intestinal epithelial cells via activation of mTOR and STAT3. Mucosal Immunol 2018;11:752-62.

161 Cani PD, Knauf C. How gut microbes talk to organs: the role of endocrine and nervous routes. Mol Metab 2016;5:743-52.

162 Peng L, Li Z-R, Green RS, et al. Butyrate enhances the intestinal barrier by facilitating tight junction assembly via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J Nutr 2009;139:1619-25.

163 Tolhurst G, Heffron H, Lam YS, et al. Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the G-proteincoupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes 2012;61:364-71.

164 Jiao A, Yu B, He J, et al. Short chain fatty acids could prevent fat deposition in pigs via regulating related hormones and genes. Food Funct 2020;11:1845-55.

165 Yano JM, Yu K, Donaldson GP, et al. Indigenous bacteria from the gut microbiota regulate host serotonin biosynthesis. Cell 2015;161:264-76.

166 Lahiri S, Kim H, Garcia-Perez I, et al. The gut microbiota influences skeletal muscle mass and function in mice. Sci Transl Med 2019;11:502.

168 Essien BE, Grasberger H, Romain RD, et al. ZBP-89 regulates expression of tryptophan hydroxylase I and mucosal defense against salmonella typhimurium in mice. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1466-77.

169 Williams EK, Chang RB, Strochlic DE, et al. Sensory neurons that detect stretch and nutrients in the digestive system. Cell 2016;166:209-21.

170 Colle R, Masson P, Verstuyft C, et al. Peripheral tryptophan, serotonin, kynurenine, and their metabolites in major depression: a case-control study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2020;74:112-7.

171 Tian T, Mao Q, Xie J, et al. Multi-omics data reveals the disturbance of glycerophospholipid metabolism caused by disordered gut microbiota in depressed mice. Journal of Advanced Research 2022;39:135-45.

172 Cowen PJ. Serotonin and depression: pathophysiological mechanism or marketing myth? Trends Pharmacol Sci 2008;29:433-6.

173 Sudo N, Chida Y, Aiba Y, et al. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J Physiol 2004;558(Pt 1):263-75.

174 van de Wouw M, Boehme M, Lyte JM, et al. Short-chain fatty acids: microbial metabolites that alleviate stress-induced brain-gut axis alterations. J Physiol 2018;596:4923-44.

175 O’Connor DB, Thayer JF, Vedhara K. Stress and health: a review of psychobiological processes. Annu Rev Psychol 2021;72:663-88.

176 Dalile B, Vervliet B, Bergonzelli G, et al. Colon-delivered shortchain fatty acids attenuate the cortisol response to psychosocial stress in healthy men: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020;45:2257-66.

177 Wei Y, Chang L, Hashimoto K. Molecular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant actions of arketamine: beyond the NMDA receptor. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:559-73.

178 Hashimoto K. Rapid-acting antidepressant ketamine, its metabolites and other candidates: a historical overview and future perspective. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2019;73:613-27.

179 Qu Y, Yang C, Ren Q, et al. Comparison of (R)-ketamine and lanicemine on depression-like phenotype and abnormal composition of gut microbiota in a social defeat stress model. Sci Rep 2017;7:15725.

180 Huang N, Hua D, Zhan G, et al. Role of actinobacteria and coriobacteriia in the antidepressant effects of ketamine in an inflammation model of depression. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2019;176:93-100.

181 Cash RFH, Cocchi L, Lv J, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging-guided personalization of transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment for depression. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:337-9.

182 UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Lancet 2003;361:799-808.

183 Cuijpers P, Clignet F, van Meijel B, et al. Psychological treatment of depression in inpatients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:353-60.

184 Marx W, Lane M, Hockey M, et al. Diet and depression: exploring the biological mechanisms of action. Mol Psychiatry 2021;26:134-50.

185 Firth J, Gangwisch JE, Borisini A, et al. Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing? BMJ 2020;369:m2382.

186 Yao S, Zhang M, Dong S-S, et al. Bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis identifies causal associations between relative carbohydrate intake and depression. Nat Hum Behav 2022;6:1569-76.

187 Ghosh TS, Rampelli S, Jeffery IB, et al. Mediterranean diet intervention alters the gut microbiome in older people reducing frailty and improving health status: the NU-AGE 1-year dietary intervention across five European countries. Gut 2020;69:1218-28.

188 Yin W, Löf M, Chen R, et al. Mediterranean diet and depression: a population-based cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2021;18:153.

189 Gibson-Smith D, Bot M, Brouwer IA, et al. Association of food groups with depression and anxiety disorders. Eur J Nutr 2020;59:767-78.

190 Bayes J, Schloss J, Sibbritt D. The effect of A Mediterranean diet on the symptoms of depression in young males (the “AMMend: a mediterranean diet in men with depression” study): a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2022;116:572-80.

191 Psaltopoulou T, Sergentanis TN, Panagiotakos DB, et al. Mediterranean diet, stroke, cognitive impairment, and depression: a meta-analysis. Ann Neurol 2013;74:580-91.

193 Cristiano C, Cuozzo M, Coretti L, et al. Oral sodium butyrate supplementation ameliorates paclitaxel-induced behavioral and intestinal dysfunction. Biomed Pharmacother 2022;153:113528.

194 Liu J, Fang Y, Cui L, et al. Butyrate emerges as a crucial effector of Zhi-Zi-Chi decoctions to ameliorate depression via multiple pathways of brain-gut axis. Biomed Pharmacother 2022;149:112861.

195 Qiu J, Liu R, Ma Y, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressionlike behaviors is ameliorated by sodium butyrate via inhibiting neuroinflammation and oxido-nitrosative stress. Pharmacology 2020;105:550-60.

196 Watson H, Mitra S, Croden FC, et al. A randomised trial of the effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplements on the human intestinal microbiota. Gut 2018;67:1974-83.

197 Xie L, Xu C, Fan Y, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with slow transit constipation and the relative mechanisms based on the protein digestion and absorption pathway. J Transl Med 2021;19:490.

198 Hu B, Das P, Lv X, et al. Effects of ‘healthy’ fecal Microbiota transplantation against the deterioration of depression in fawnhooded rats. mSystems 2022;7:e00953-22.

199 Cai T, Zheng S-P, Shi X, et al. Therapeutic effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depression. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022;12:900652.

200 Lin H, Guo Q, Wen Z, et al. The multiple effects of fecal microbiota transplantation on diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) patients with anxiety and depression behaviors. Microb Cell Fact 2021;20:233.

201 Guo Q, Lin H, Chen P, et al. Dynamic changes of intestinal flora in patients with irritable bowel syndrome combined with anxiety and depression after oral administration of enterobacteria capsules. Bioengineered 2021;12:11885-97.

202 Green JE, Berk M, Mohebbi M, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and safety of faecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Can J Psychiatry 2023;68:315-26.

203 Liu L, Wang H, Zhang H, et al. Toward a deeper understanding of gut microbiome in depression: the promise of clinical applicability. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2022;9:e2203707.

204 Pinto-Sanchez MI, Hall GB, Ghajar K, et al. Probiotic bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 reduces depression scores and alters brain activity: a pilot study in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2017;153:S0016-5085(17)35557-9:448-459..

205 Tian P, Chen Y, Zhu H, et al. Bifidobacterium breve CCFM1025 attenuates major depression disorder via regulating gut microbiome and tryptophan metabolism: a randomized clinical trial. Brain Behav Immun 2022;100:233-41.

206 Okubo R, Koga M, Katsumata N, et al. Effect of bifidobacterium breve A-1 on anxiety and depressive symptoms in schizophrenia: a proof-of-concept study. Journal of Affective Disorders 2019;245:377-85.

207 Steenbergen L, Sellaro R, van Hemert S, et al. A randomized controlled trial to test the effect of multispecies probiotics on cognitive reactivity to sad mood. Brain Behav Immun 2015;48:258-64.

208 Schaub A-C, Schneider E, Vazquez-Castellanos JF, et al. Clinical, gut microbial and neural effects of a probiotic add-on therapy in depressed patients: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry 2022;12:227.

209 Sun J, Wang F, Hu X, et al. Clostridium butyricum attenuates chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depressive-like behavior in mice via the gut-brain axis. J Agric Food Chem 2018;66:8415-21.

210 Tian T, Xu B, Qin Y, et al. Clostridium butyricum miyairi 588 has preventive effects on chronic social defeat stress-induced depressive-like behaviour and modulates microglial activation in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019;516:430-6.

211 Zhang W, Ding T, Zhang H, et al. Clostridium butyricum RH2 alleviates chronic foot shock stress-induced behavioral deficits in rats via PAI-1. Front Pharmacol 2022;13:845221.

212 Hao Z, Wang W, Guo R, et al. Faecalibacterium Prausnitzii (ATCC 27766) has preventive and therapeutic effects on chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depression-like and anxiety-like behavior in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019;104:132-42.

213 Slykerman RF, Hood F, Wickens K, et al. Effect of lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 in pregnancy on postpartum symptoms of

depression and anxiety: a randomised double-blind placebocontrolled trial. EBioMedicine 2017;24:159-65.

214 Vicariotto F, Malfa P, Torricelli M, et al. Beneficial effects of limosilactobacillus reuteri PBS072 and bifidobacterium breve BB077 on mood imbalance, self-confidence, and breastfeeding in women during the first trimester postpartum. Nutrients 2023;15:16.

215 Dailey FE, Turse EP, Daglilar E, et al. The dirty aspects of fecal microbiota transplantation: a review of its adverse effects and complications. Current Opinion in Pharmacology 2019;49:29-33.

216 Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, et al. Expert consensus document: the international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;14:491-502.

218 Burokas A, Arboleya S, Moloney RD, et al. Targeting the microbiota-gut-brain axis: prebiotics have anxiolytic and antidepressant-like effects and reverse the impact of chronic stress in mice. Biol Psychiatry 2017;82:472-87.

219 Savignac HM, Corona G, Mills H, et al. Prebiotic feeding elevates central brain derived neurotrophic factor, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits and D-Serine. Neurochem Int 2013;63:756-64.

220 Liu L, Wang H, Chen X, et al. Gut microbiota and its metabolites in depression: from pathogenesis to treatment. EBioMedicine 2023;90:104527.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38390241

Publication Date: 2024-02-01

Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and depression: deep insight into biological mechanisms and potential applications

- Additional supplemental material is published online only. To view, please visit the journal online (http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/ gpsych-2023-101374).

JC and HH are joint first authors.

Received 04 October 2023

Accepted 25 December 2023

© Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2024. Re-use permitted under CC BY-NC. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by BMJ.

Abstract

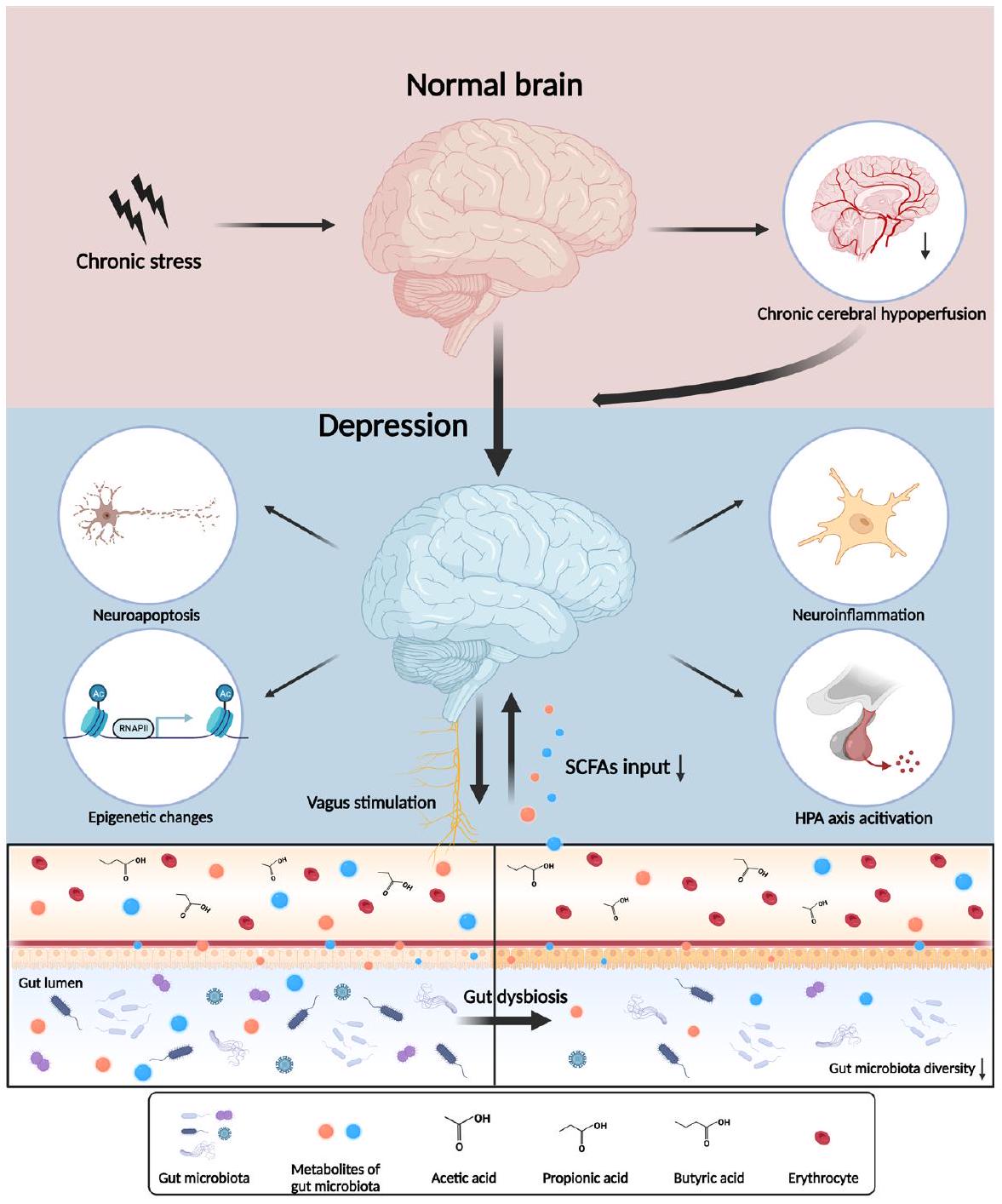

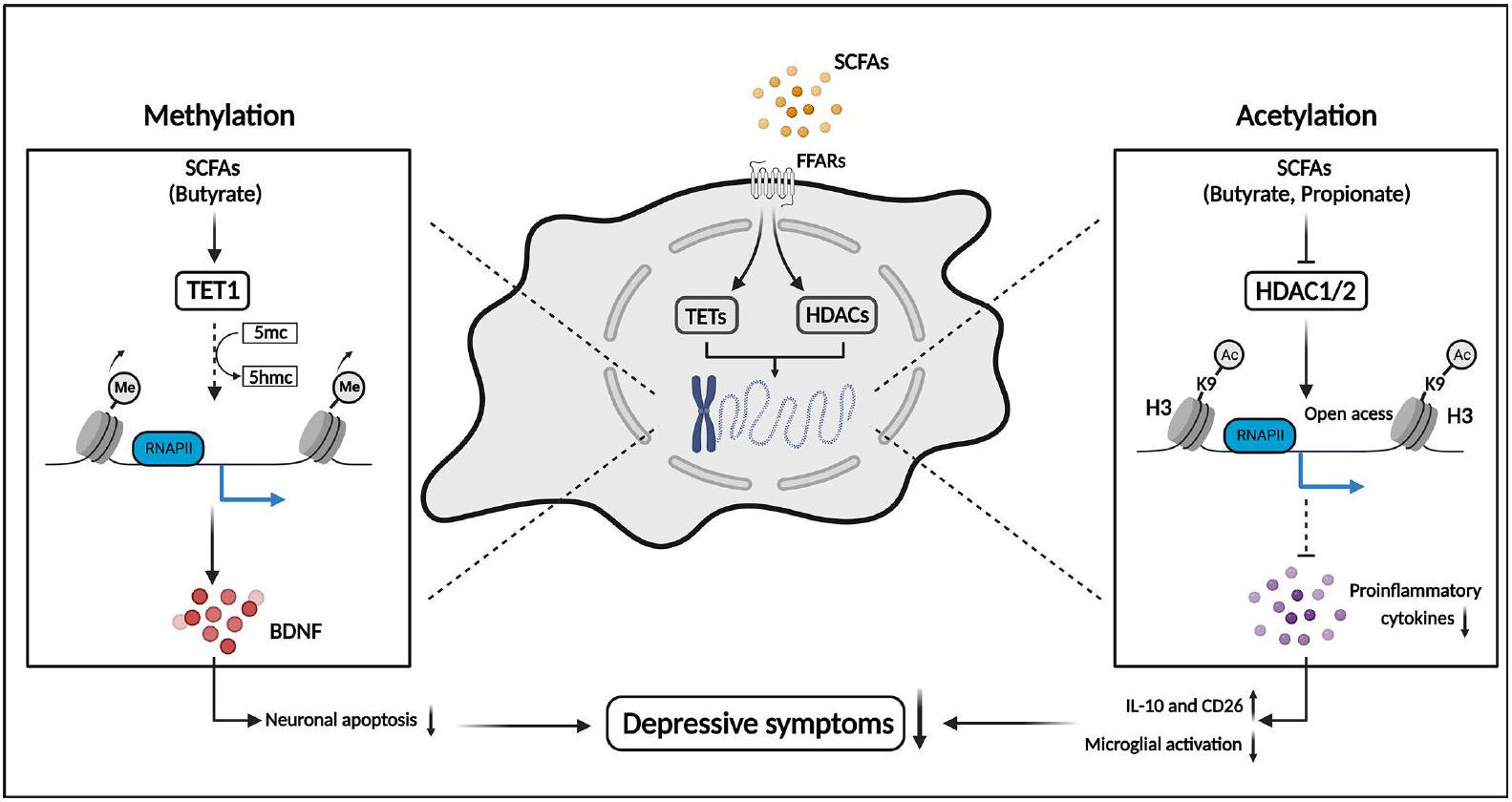

The gut microbiota is a complex and dynamic ecosystem known as the ‘second brain’. Composing the microbiota-gut-brain axis, the gut microbiota and its metabolites regulate the central nervous system through neural, endocrine and immune pathways to ensure the normal functioning of the organism, tuning individuals’ health and disease status. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), the main bioactive metabolites of the gut microbiota, are involved in several neuropsychiatric disorders, including depression. SCFAs have essential effects on each component of the microbiota-gut-brain axis in depression. In the present review, the roles of major SCFAs (acetate, propionate and butyrate) in the pathophysiology of depression are summarised with respect to chronic cerebral hypoperfusion, neuroinflammation, host epigenome and neuroendocrine alterations. Concluding remarks on the biological mechanisms related to gut microbiota will hopefully address the clinical value of microbiota-related treatments for depression.

INTRODUCTION

adaptation underlying brain circuitry has gradually been elucidated. This review summarises the interplay between the main gut microbiota metabolites-SCFAs, and the biological mechanisms of depression. We hope that illustrating the biological mechanisms related to SCFAs from the gut microbiota will shed light on novel treatment strategies for depression.

GUT MICROBIOTA AND ITS ABNORMAL METABOLISM IN DEPRESSION Gut microbiota

Gut dysbiosis

dysbiosis, exhibiting lower diversity but a higher density of gut microorganisms on the surface of the intestinal mucosa.

General Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 on 19 February 2024. Downloaded from https://gpsych.bmj.com on 29 August 2025 by guest. Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

that the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes was lower in patients with depression than in healthy controls. These conflicting results may be attributed to differences in sample sizes, demographic disparities, screening criteria of the recruited patients and disparate sequencing and bioinformatics techniques. Nevertheless, it has been consistently indicated that depression corresponds with marked alterations in gut microbiota composition.

EFFECT OF GUT MICROBIOTA-DERIVED SCFAS ON DEPRESSION Metabolism and physiological effects of SCFAs

regulate the transfer of nutrients and molecules involved in the maintenance of BBB integrity, directly influencing brain development and CNS homeostasis.

The role of SCFAs in the pathological mechanisms underlying gut microbiota-associated depression

SCFAs and chronic cerebral hypoperfusion

General Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 on 19 February 2024. Downloaded from https://gpsych.bmj.com on 29 August 2025 by guest. Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

The essential role of inflammation in depression has been widely investigated in recent decades, with the microbiota-gut-brain axis emerging as a key intermediate regulator.

in healthy controls.

been reported to exhibit protective effects on the intestinal barrier as energy substrates.

SCFAs and host epigenome

General Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 on 19 February 2024. Downloaded from https://gpsych.bmj.com on 29 August 2025 by guest. Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

Histone modifications

of glia and immune cells during the pro-inflammatory response.

General Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 on 19 February 2024. Downloaded from https://gpsych.bmj.com on 29 August 2025 by guest Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

DNA methylation

General Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 on 19 February 2024. Downloaded from https://gpsych.bmj.com on 29 August 2025 by guest. Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

exerting antidepressant-like effects.

Non-coding RNA

of the brain through epigenetic pathways. Delayed addition or deletion of epigenetic modifications may explain the slow development and insignificant initial effects of antidepressants in treating depression. Disrupted gut homeostasis induces altered epigenetic regulators synthesised by the gut microbiota, such as acetate, butyrate and propionate, following the activation of neuroinflammation and other pathways by epigenetic reprogramming. The underlying mechanisms in the microbiota-gutbrain axis may play an important role in the long-term abnormal synaptic plasticity and behavioural response to stress in depression.

SCFAs and neuroendocrine alterations

General Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 on 19 February 2024. Downloaded from https://gpsych.bmj.com on 29 August 2025 by guest. Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

of gut microbiota has been well illustrated, how ketamine regulates the metabolism of gut microbiota and its metabolites, such as SCFAs, is unclear. Hence, further studies should concentrate on the mechanisms by which ketamine regulates the metabolism of gut microbiota and its metabolites as a promising antidepression agent.

POTENTIAL APPLICATION OF GUT MICROBIOTA AND SCFAS IN DEPRESSION TREATMENT

Dietary interventions

General Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 on 19 February 2024. Downloaded from https://gpsych.bmj.com on 29 August 2025 by guest. Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

Faecal microbiota transplantation

Probiotics and prebiotics

in the production of SCFAs.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVE

General Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 on 19 February 2024. Downloaded from https://gpsych.bmj.com on 29 August 2025 by guest. Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

in the onset and progression of depression. Although we have preliminarily understood the interactions between microbiota, SCFAs and depression, there are still several problems that obscure the translation from laboratory findings to clinical applications. Indeed, it is difficult to estimate the direct and indirect influence of gut microbial metabolism on the CNS. Owing to the intricate crosstalk concerning the gut microbiota, immunity, endocrine and nervous systems, it is difficult to elaborate on the effects of SCFAs in any single aspect. Meanwhile, a number of studies have investigated alterations in the composition and abundance of gut microbiota in patients with depression, but the alterations exhibit ramified results that puzzle researchers and may lead to undesirable consequences in microbial treatment. Given the complexity of human physiology, several factors, including diet, exercise, ageing and mood, affect the composition and abundance of gut microbiota. With the help of novel methods, such as high-throughput sequencing, multi-omics approaches and microbial culture technology, further research could isolate the pathogenic and harmful strains involved in depression and elaborate the interactions between the microbiota, gut-brain axis and other systems,

Funding This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82001437 and 82371535), STI2030-Major Projects (2021ZD0202000), and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (2023RC3083).

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not applicable.

Ethics approval Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Open access This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Bangshan Liu http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9355-2183

REFERENCES

2 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical Manual of mental disorders. In: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, VA, US: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3 World Health Organization. Depressive disorder (depression). 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ depression [Accessed 18 Aug 2023].

4 Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet 2018;392:2299-312.

5 Baquero F, Nombela C. The microbiome as a human organ. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012;18 Suppl 4:2-4.

6 Paone P, Cani PD. Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners? Gut 2020;69:2232-43.

7 Weersma RK, Zhernakova A, Fu J. Interaction between drugs and the gut microbiome. Gut 2020;69:1510-9.

8 Wang S, Zhang C, Yang J, et al. Sodium butyrate protects the intestinal barrier by modulating intestinal host defense peptide expression and gut microbiota after a challenge with deoxynivalenol in weaned piglets. J Agric Food Chem 2020;68:4515-27.

9 Wang H-X, Wang Y-P. Gut microbiota-brain axis. Chinese Medical Journal 2016;129:2373-80.

10 Farzi A, Fröhlich EE, Holzer P. Gut microbiota and the neuroendocrine system. Neurotherapeutics 2018;15:5-22.

11 Needham BD, Funabashi M, Adame MD, et al. A gut-derived metabolite alters brain activity and anxiety behaviour in mice. Nature 2022;602:647-53.

12 Li Z, Lai J, Zhang P, et al. Multi-omics analyses of serum metabolome, gut microbiome and brain function reveal dysregulated microbiota-gut-brain axis in bipolar depression. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:4123-35.

13 Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, et al. The microbiota-gutbrain axis. Physiol Rev 2019;99:1877-2013.

14 Turna J, Grosman Kaplan K, Anglin R, et al. The gut microbiome and inflammation in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients

compared to age- and sex-matched controls: a pilot study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2020;142:337-47.

15 Yu Z, Chen W, Zhang L, et al. Gut-derived bacterial LPS attenuates incubation of methamphetamine craving via modulating microglia. Brain Behav Immun 2023;111:101-15.

16 McGuinness AJ, Davis JA, Dawson SL, et al. A systematic review of gut microbiota composition in observational studies of major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:1920-35.

17 Modesto Lowe V, Chaplin M, Sgambato D. Major depressive disorder and the gut microbiome: what is the link? Gen Psychiatr 2023;36:e100973.

18 Miller TL, Wolin MJ. Pathways of acetate, propionate, and butyrate formation by the human fecal microbial flora. Appl Environ Microbiol 1996;62:1589-92.

19 Le Poul E, Loison C, Struyf S, et al. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. J Biol Chem 2003;278:25481-9.

20 Kimura I, Ichimura A, Ohue-Kitano R, et al. Free fatty acid receptors in health and disease. Physiol Rev 2020;100:171-210.

21 Brown AJ, Goldsworthy SM, Barnes AA, et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J Biol Chem 2003;278:11312-9.

22 Tian D, Xu W, Pan W, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation enhances cell therapy in a rat model of hypoganglionosis by SCFAinduced Mek1/2 signaling pathway. EMBO J 2023;42:e111139.

23 Morais LH, Schreiber HL 4th, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiotabrain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021;19:241-55.

24 Stewart CJ, Ajami NJ, O’Brien JL, et al. Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature 2018;562:583-8.

25 Yu LW, Agirman G, Hsiao EY. The gut microbiome as a regulator of the neuroimmune landscape. Annu Rev Immunol 2022;40:143-67.

26 Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 2011;473:174-80.

27 Korem T, Zeevi D, Suez J, et al. Growth dynamics of gut microbiota in health and disease inferred from single metagenomic samples. Science 2015;349:1101-6.

28 Yu X, Jiang W, Kosik RO, et al. Gut microbiota changes and its potential relations with thyroid carcinoma. J Adv Res 2022;35:61-70.

29 Zmora N, Suez J, Elinav E. You are what you eat: diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16:35-56.

30 Gao X, Cao Q, Cheng Y, et al. Chronic stress promotes colitis by disturbing the gut microbiota and triggering immune system response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E2960-9.

31 O’Toole PW, Jeffery IB. Gut microbiota and aging. Science 2015;350:1214-5.

32 Reyman M, van Houten MA, Watson RL, et al. Effects of early-life antibiotics on the developing infant gut microbiome and resistome: a randomized trial. Nat Commun 2022;13:893.

33 Zhao Y, Wang C, Goel A. Role of gut microbiota in epigenetic regulation of colorectal cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Reviews on Cancer 2021;1875:188490.

35 Fan Y, Støving RK, Berreira Ibraim S, et al. The gut microbiota contributes to the pathogenesis of anorexia nervosa in humans and mice. Nat Microbiol 2023;8:787-802.

36 Kosuge A, Kunisawa K, Arai S, et al. Heat-sterilized Bifidobacterium breve prevents depression-like behavior and interleukin-1B expression in mice exposed to chronic social defeat stress. Brain Behav Immun 2021;96:200-11.

37 Schoeler M, Caesar R. Dietary lipids, gut microbiota and lipid metabolism. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2019;20:461-72.

38 Fröhlich EE, Farzi A, Mayerhofer R, et al. Cognitive impairment by antibiotic-induced gut dysbiosis: analysis of gut microbiota-brain communication. Brain Behav Immun 2016;56:140-55.

39 Schirmer M, Garner A, Vlamakis H, et al. Microbial genes and pathways in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019;17:497-511.

40 Kilinçarslan S, Evrensel A. The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: an experimental study. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2020;48:1-7.

41 Lurie I, Yang Y-X, Haynes K, et al. Antibiotic exposure and the risk for depression, anxiety, or psychosis: a nested case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:1522-8.

43 Lou M, Cao A, Jin C, et al. Deviated and early unsustainable stunted development of gut microbiota in children with autism spectrum disorder. Gut 2022;71:1588-99.

44 Zheng P , Zeng B , Liu M , et al. The gut microbiome from patients with schizophrenia modulates the glutamate-glutamine-GABA cycle and schizophrenia-relevant behaviors in mice. Sci Adv 2019;5:eaau8317.

45 Singh A, Dawson TM, Kulkarni S. Neurodegenerative disorders and gut-brain interactions. J Clin Invest 2021;131:13.

46 Zhao N, Chen Q-G, Chen X, et al. Intestinal dysbiosis mediates cognitive impairment via the intestine and brain NLRP3 inflammasome activation in chronic sleep deprivation. Brain Behav Immun 2023;108:98-117.

47 Chen Y, Xu J, Chen Y. Regulation of neurotransmitters by the gut microbiota and effects on cognition in neurological disorders. Nutrients 2021;13:2099.

48 Wang Y, Li N, Yang J-J, et al. Probiotics and fructo-oligosaccharide intervention modulate the microbiota-gut brain axis to improve autism spectrum reducing also the hyper-serotonergic state and the dopamine metabolism disorder. Pharmacological Research 2020;157:104784.

49 Liu Y, Xu F, Liu S, et al. Significance of gastrointestinal tract in the therapeutic mechanisms of exercise in depression: synchronism between brain and intestine through GBA. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2020;103:109971.

50 Zeissig S, Bürgel N, Günzel D, et al. Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn’s disease. Gut 2007;56:61-72.

51 Shan Y, Lee M, Chang EB. The gut microbiome and inflammatory bowel diseases. Annu Rev Med 2022;73:455-68.

52 Sperner-Unterweger B, Kohl C, Fuchs D. Immune changes and neurotransmitters: possible interactions in depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2014;48:268-76.

53 Jiang H, Ling Z, Zhang Y, et al. Altered fecal microbiota composition in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav Immun 2015;48:186-94.

54 Liu Y, Zhang L, Wang X, et al. Similar fecal microbiota signatures in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and patients with depression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1602-11.

55 Nikolova VL, Smith MRB, Hall LJ, et al. Perturbations in gut microbiota composition in psychiatric disorders: a review and metaanalysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021;78:1343-54.

56 Kelly JR, Borre Y, O’ Brien C, et al. Transferring the blues: depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J Psychiatr Res 2016;82:109-18.

57 Zheng P, Zeng B, Zhou C, et al. Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host’s metabolism. Mol Psychiatry 2016;21:786-96.

58 Simpson CA, Diaz-Arteche C, Eliby D, et al. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression – a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2021;83:101943.

59 Valles-Colomer M, Falony G, Darzi Y, et al. The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nat Microbiol 2019;4:623-32.

60 Kim C-S, Cha L, Sim M, et al. Probiotic supplementation improves cognitive function and mood with changes in gut microbiota in community-dwelling older adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2021;76:32-40.

61 Rudzki L, Ostrowska L, Pawlak D, et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum 299 V decreases kynurenine concentration and improves cognitive functions in patients with major depression: a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019;100:213-22.

62 Kazemi A, Noorbala AA, Azam K, et al. Effect of probiotic and prebiotic vs placebo on psychological outcomes in patients with major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Clinical Nutrition 2019;38:522-8.

63 Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, et al. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut 1987;28:1221-7.

64 Macfarlane S, Macfarlane GT. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc Nutr Soc 2003;62:67-72.

65 Itoh Y, Kawamata Y, Harada M, et al. Free fatty acids regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells through GPR40. Nature 2003;422:173-6.

67 Li H-B, Xu M-L, Xu X-D, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii attenuates CKD via butyrate-renal GPR43 axis. Circ Res 2022;131:e120-34.

68 Hou Y-F, Shan C, Zhuang S-Y, et al. Gut microbiota-derived propionate mediates the neuroprotective effect of osteocalcin in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Microbiome 2021;9:34.

69 Vijay N, Morris ME. Role of monocarboxylate transporters in drug delivery to the brain. Curr Pharm Des 2014;20:1487-98.

70 Schönfeld P, Wojtczak L. Short- and medium-chain fatty acids in energy metabolism: the cellular perspective. J Lipid Res 2016;57:943-54.

71 Doifode T, Giridharan VV, Generoso JS, et al. The impact of the microbiota-gut-brain axis on Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology. Pharmacol Res 2021;164:105314.

72 Mitchell RW, On NC, Del Bigio MR, et al. Fatty acid transport protein expression in human brain and potential role in fatty acid transport across human brain microvessel endothelial cells. J Neurochem 2011;117:735-46.

73 Kekuda R, Manoharan P, Baseler W, et al. Monocarboxylate 4 mediated butyrate transport in a rat intestinal epithelial cell line. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:660-7.

74 Fock E, Parnova R. Mechanisms of blood-brain barrier protection by microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids. Cells 2023;12:657.

75 Serger E, Luengo-Gutierrez L, Chadwick JS, et al. The gut metabolite indole-3 propionate promotes nerve regeneration and repair. Nature 2022;607:585-92.

76 Wu M, Tian T, Mao Q, et al. Associations between disordered gut microbiota and changes of neurotransmitters and short-chain fatty acids in depressed mice. Transl Psychiatry 2020;10:350.

77 Agus A, Clément K, Sokol H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as central regulators in metabolic disorders. Gut 2021;70:1174-82.

78 Awata S, Ito H, Konno M, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow abnormalities in late-life depression: relation to refractoriness and chronification. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998;52:97-105.

79 Rajeev V, Fann DY, Dinh QN, et al. Pathophysiology of blood brain barrier dysfunction during chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in vascular cognitive impairment. Theranostics 2022;12:1639-58.

80 Ren C, Liu Y, Stone C, et al. Limb remote ischemic conditioning ameliorates cognitive impairment in rats with chronic cerebral hypoperfusion by regulating glucose transport. Aging Dis 2021;12:1197:1197-210…

81 Zhang L-Y, Pan J, Mamtilahun M, et al. Microglia exacerbate white matter injury via complement C3/C3aR pathway after hypoperfusion. Theranostics 2020;10:74-90.

82 Lansdell TA, Dorrance AM. Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in male rats results in sustained HPA activation and hyperinsulinemia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2022;322:E24-33.

83 Farrell JS, Colangeli R, Wolff MD, et al. Postictal hypoperfusion/ hypoxia provides the foundation for a unified theory of seizureinduced brain abnormalities and behavioral dysfunction. Epilepsia 2017;58:1493-501.

84 Lan D, Song S, Jia M, et al. Cerebral venous-associated brain damage may lead to anxiety and depression. J Clin Med 2022;11:6927.

85 Lee SR, Choi B, Paul S, et al. Depressive-like behaviors in a rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Transl Stroke Res 2015;6:207-14.

86 Xiao W, Su J, Gao X, et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis participates in chronic cerebral hypoperfusion by disrupting the metabolism of short-chain fatty acids. Microbiome 2022;10:62.

87 Su SH, Chen M, Wu YF, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation and short-chain fatty acids protected against cognitive dysfunction in a rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. CNS Neurosci Ther 2023;29:98-114.

88 Su S-H, Wu Y-F, Lin Q, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation and replenishment of short-chain fatty acids protect against chronic cerebral hypoperfusion-induced colonic dysfunction by regulating gut microbiota, differentiation of Th17 cells, and mitochondrial energy metabolism. J Neuroinflammation 2022;19:313.

89 Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol 2006;27:24-31.

90 Köhler CA, Freitas TH, Maes M, et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017;135:373-87.

91 Cui Y, Yang Y, Ni Z, et al. Astroglial Kir4.1 in the lateral habenula drives neuronal bursts in depression. Nature 2018;554:323-7.

93 Leclercq S, Le Roy T, Furgiuele S, et al. Gut microbiota-induced changes in B-hydroxybutyrate metabolism are linked to altered sociability and depression in alcohol use disorder. Cell Rep 2020;33:108238.

94 Li H, Xiang Y, Zhu Z, et al. Rifaximin-mediated gut microbiota regulation modulates the function of microglia and protects against CUMS-induced depression-like behaviors in adolescent rat. J Neuroinflammation 2021;18:254.

95 Xiao W, Li J, Gao X, et al. Involvement of the gut-brain axis in vascular depression via tryptophan metabolism: a benefit of short chain fatty acids. Exp Neurol 2022;358:114225.

96 Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry 2016;21:1696-709.

97 Beurel E, Lowell JA. Th17 cells in depression. Brain Behav Immun 2018;69:28-34.

98 Peng Z, Peng S, Lin K, et al. Chronic stress-induced depression requires the recruitment of peripheral Th17 cells into the brain.

99 Beurel E, Lowell JA, Jope RS. Distinct characteristics of hippocampal pathogenic

100 Kann O, Almouhanna F, Chausse B. Interferon

101 Wachholz S, Eßlinger M, Plümper J, et al. Microglia activation is associated with IFN-

102 Liu Z, Qiu A-W, Huang Y, et al. IL-17A exacerbates neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration by activating microglia in rodent models of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav Immun 2019;81:630-45.

103 Wu J, Li J, Gaurav C, et al. CUMS and dexamethasone induce depression-like phenotypes in mice by differentially altering gut microbiota and triggering macroglia activation. Gen Psychiatr 2021;34:e100529.

104 Wang H, He Y, Sun Z, et al. Microglia in depression: an overview of microglia in the pathogenesis and treatment of depression. J Neuroinflammation 2022;19:132.

105 Ikeda Y, Saigo N, Nagasaki Y. Direct evidence for the involvement of intestinal reactive oxygen species in the progress of depression via the gut-brain axis. Biomaterials 2023;295.

106 Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, et al. Acetylcholinesynthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science 2011;334:98-101.

107 Pu Y, Tan Y, Qu Y, et al. A role of the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve in depression-like phenotypes in mice after fecal microbiota transplantation from Chrna7 knock-out mice with depression-like phenotypes. Brain Behav Immun 2021;94:318-26.

108 Sternberg EM. Neural regulation of innate immunity: a coordinated nonspecific host response to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol 2006;6:318-28.

109 Bernik TR, Friedman SG, Ochani M, et al. Pharmacological stimulation of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway. J Exp Med 2002;195:781-8.

110 Yang Y, Eguchi A, Wan X, et al. A role of gut-microbiota-brain axis via subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve in depression-like phenotypes in Chrna7 knock-out mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2023;120:110652.

111 Zhang J, Ma L, Chang L, et al. A key role of the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve in the depression-like phenotype and abnormal composition of gut microbiota in mice after lipopolysaccharide administration. Trans/ Psychiatry 2020;10:186.

112 Marwaha S, Palmer E, Suppes T, et al. Novel and emerging treatments for major depression. Lancet 2023;401:141-53.

113 Hashimoto K. Neuroinflammation through the vagus nervedependent gut-microbiota-brain axis in treatment-resistant depression. Prog Brain Res 2023;278:61-77.

114 Frost G, Sleeth ML, Sahuri-Arisoylu M, et al. The short-chain fatty acid acetate reduces appetite via a central homeostatic mechanism. Nat Commun 2014;5:3611.

115 Li J-M, Yu R, Zhang L-P, et al. Dietary fructose-induced gut dysbiosis promotes mouse hippocampal neuroinflammation: a benefit of short-chain fatty acids. Microbiome 2019;7:98.

116 Aho VTE, Houser MC, Pereira PAB, et al. Relationships of gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, inflammation, and the gut barrier in Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 2021;16:6.

General Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/gpsych-2023-101374 on 19 February 2024. Downloaded from https://gpsych.bmj.com on 29 August 2025 by guest Protected by copyright, including for uses related to text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

118 Hoyles L, Snelling T, Umlai U-K, et al. Microbiome-host systems interactions: protective effects of propionate upon the blood-brain barrier. Microbiome 2018;6:55.

119 Erny D, Hrabě de Angelis AL, Jaitin D, et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat Neurosci 2015;18:965-77.

120 Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature 2009;461:1282-6.

121 Liu J, Li H, Gong T, et al. Anti-neuroinflammatory effect of shortchain fatty acid acetate against Alzheimer’s disease via upregulating GPR41 and inhibiting ERK/JNK/NF-кB. J Agric Food Chem 2020;68:7152-61.

122 Fu S-P, Wang J-F, Xue W-J, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of BHBA in both in vivo and in vitro Parkinson’s disease models are mediated by Gpr109A-dependent mechanisms. J Neuroinflammation 2015;12:9.

123 Wang P , Zhang Y , Gong Y , et al. Sodium butyrate triggers a functional elongation of microglial process via Akt-small RhoGTPase activation and HDACs inhibition. Neurobiol Dis 2018;111:12-25.

124 van der Hee B, Wells JM. Microbial regulation of host physiology by short-chain fatty acids. Trends Microbiol 2021;29:700-12.

125 Weaver ICG, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, et al. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nat Neurosci 2004;7:847-54.

126 Yin H, Galfalvy H, Zhang B, et al. Interactions of the GABRG2 polymorphisms and childhood trauma on suicide attempt and related traits in depressed patients. J Affect Disord 2020;266:447-55.

127 Kronman H, Torres-Berrío A, Sidoli S, et al. Long-term behavioral and cell-type-specific molecular effects of early life stress are mediated by H3K79Me2 dynamics in medium spiny neurons. Nat Neurosci 2021;24:753-4.

128 Alameda L, Trotta G, Quigley H, et al. Can epigenetics shine a light on the biological pathways underlying major mental disorders Psychol Med 2022;52:1645-65.

129 Massart R, Mongeau R, Lanfumey L. Beyond the monoaminergic hypothesis: neuroplasticity and epigenetic changes in a transgenic mouse model of depression. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2012;367:2485-94.

130 Jeong S, Chokkalla AK, Davis CK, et al. Post-stroke depression: epigenetic and epitranscriptomic modifications and their interplay with gut microbiota[online ahead of print]. Mol Psychiatry May 15, 2023.

132 Cheng J, He Z, Chen Q, et al. Histone modifications in cocaine, methamphetamine and opioids. Heliyon 2023;9:e16407.

133 Soliman ML, Smith MD, Houdek HM, et al. Acetate supplementation modulates brain histone acetylation and decreases interleukin1B expression in a rat model of neuroinflammation.

134 Zhao Y-T, Deng J, Liu H-M, et al. Adaptation of prelimbic cortex mediated by IL-6/Stat3/Acp5 pathway contributes to the comorbidity of neuropathic pain and depression in rats. J Neuroinflammation 2022;19:144.

135 Faraco G, Pittelli M, Cavone L, et al. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors reduce the glial inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Neurobiol Dis 2009;36:269-79.

136 Vinolo MAR, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, et al. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients 2011;3:858-76.

137 Schroeder FA, Lin CL, Crusio WE, et al. Antidepressant-like effects of the histone deacetylase inhibitor, sodium butyrate, in the mouse. Biol Psychiatry 2007;62:55-64.