DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2024.105000

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-21

الأساليب وعناصر اللعبة المستخدمة لتخصيص الت gamification الرقمية للتعلم: مراجعة أدبية منهجية

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

التعليم والتعلم

نهج مخصص

عناصر اللعبة والعناقيد

مراجعة أدبية منهجية

الملخص

استعرضت المراجعة المنهجية الأبحاث المتعلقة بتخصيص الألعاب الرقمية للتعلم استنادًا إلى 43 مقالة تمت مراجعتها من قبل الأقران نُشرت بين عامي 2013 و2022. كان الهدف من الدراسة هو التحقيق في الأساليب المخصصة وعناصر اللعبة، مما يساهم في استخدام تخصيص الألعاب الرقمية في البيئات التعليمية. تم تصنيف الأساليب المخصصة إلى تخصيص، وتكيف، وتوصية، مع نمذجة المستخدم كأساس لها. تم استخدام خمسة مجموعات من عناصر اللعبة عند استخدام هذه الأساليب المخصصة في الفصول الدراسية المعززة بالألعاب الرقمية. تشير النتائج إلى أن معظم المقالات في هذه المراجعة كانت لا تزال في مرحلة إعداد الفصول وتركزت على المعلومات التي يمكن استخدامها للتخصيص. هناك حاجة لإجراء المزيد من الدراسات التجريبية لفحص التأثيرات المحفزة للفصول الدراسية المعززة بالألعاب الرقمية المخصصة، باستخدام أساليب التخصيص، والتكيف، والتوصية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، وُجدت ثلاثة وعشرون عنصرًا من عناصر اللعبة في هذه الدراسة، من بينها كانت المكافأة الأكثر استخدامًا. ثم تم تجميع هذه العناصر في خمس مجموعات بناءً على وظائفها، وهي: الأداء، والشخصية، والاجتماعية، والبيئية، والخيالية. تعكس مجموعة متنوعة من مجموعات عناصر اللعبة جوانب متعددة من التخصيص. قد يساهم استخدامها في كل أسلوب مخصص في فهم أفضل واختيار عناصر اللعبة عند تخصيص الألعاب الرقمية. توفر هذه النتائج صورة شاملة عن الأساليب الشائعة وعناصر اللعبة ذات الصلة في الفصول الدراسية المعززة بالألعاب الرقمية المخصصة. يمكن للمعلمين ومصممي المناهج الاستفادة من هذه الدراسة من خلال النظر في الأساليب المناسبة وعناصر اللعبة.

1. المقدمة

2. تخصيص الألعاب التعليمية في التعليم

RQ2. ما هي عناصر الألعاب المستخدمة عند استخدام هذه النهج المخصصة؟

3. المنهجية

الأقسام الفرعية التالية.

3.1. معايير الأهلية

3.2. البحث

3.3. الاختيار

جمع قواعد البيانات.

| استراتيجية البحث | عدد المقالات التي تم العثور عليها في قواعد البيانات |

| عمليات البحث الإلكترونية | 1021 |

| SpringerLink

|

26 |

| Taylor & Francies Online

|

18 |

| Wiley Online Library

|

15 |

| SAGE Journals

|

11 |

| Web of Science

|

5 |

| JSTOR (Journal STORage)

|

3 |

| ScienceDirect (Elsevier)

|

3 |

| ProQuest

|

2 |

| Scopus

|

938 |

| قوائم المراجع المتراكمة | 4 |

| المجموع | 1025 |

3.4. تحليل البيانات

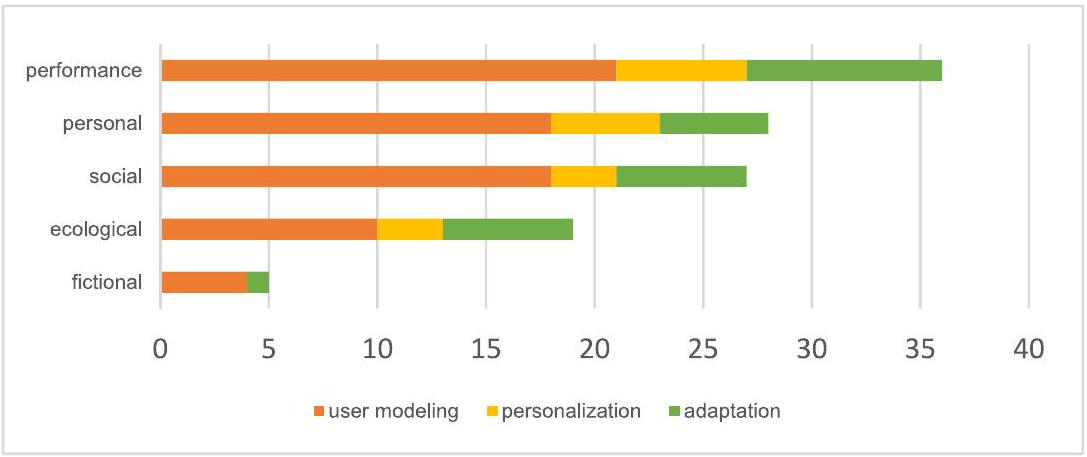

التوافق الداخلي بين الخبراء بشأن وصف عناصر اللعبة التسعة عشر (ألفا كرونباخ> 0.8). ثم قام 5 خبراء بتصنيف عناصر اللعبة التسعة عشر إلى 5 مجموعات. توفر عناصر مجموعة ‘الأداء’ معلومات حول أداء المستخدمين في البيئة الم gamified (مثل: المكافأة، العقوبة)؛ تتعلق مجموعة ‘الشخصية’ بالمتعلم الذي يستخدم البيئة الم gamified (مثل: الهدف الشخصي)؛ توفر مجموعة ‘الاجتماعية’ معلومات حول تفاعل المستخدمين في البيئة الم gamified (التعاون، المنافسة)؛ توفر مجموعة ‘البيئية’ معلومات للمستخدمين حول البيئة الم gamified (مثل: ضغط الوقت)؛ أما مجموعة ‘الخيالية’ فهي بُعد مختلط يتعلق بكل من المستخدم (من خلال السرد) والبيئة (من خلال رواية القصص)، مما يربط تجربة المستخدم بالسياق. يشير السرد إلى القصة الأكبر التي يعمل عليها المستخدم، بينما تجسد رواية القصص هذه القصة الأكبر بمساعدة النص، والوسائط السمعية والبصرية، وغيرها من المحفزات الحسية لوضع السرد في سياقه.

4. النتائج: نظرة عامة على الدراسات

5. النتائج: أساليب تخصيص الألعاب الرقمية في التعليم

نهج مخصص.

| نهج مخصص | دراسات | إجمالي |

| نموذج المستخدم (أساس الأساليب) | باراتا وآخرون (2015)؛ بناني وآخرون (2020)؛ كوديش ورافييد (2014)؛ دي لا بينا وآخرون (2021)؛ ديرميفال وآخرون (2019)؛ ديكينز وآخرون (2021)؛ جيل وآخرون (2015)؛ غونزاليس وآخرون (2016)؛ حمامي وخمجة (2019)؛ إمري (2020)؛ كلوك، غاسباريني، وآخرون (2015)؛ كلوك، دا كونها، وآخرون (2015)؛ كنوتاس وآخرون (2019)؛ مدريد ويسوع (2021)؛ مونتيررات وآخرون (2014)؛ مونتيررات وآخرون (2014ب)؛ مونتيررات وآخرون (2015)؛ رودريغيز وآخرون (2021)؛ سانتوس وآخرون (2018)؛ سانتوس وآخرون (2021)؛ سيزجين ويوزر (2022)؛ تينوريو، ديرميفال، وآخرون (2020)؛ تينوريو وآخرون (2021)؛ زاريتش وآخرون (2017) | 24 (56%) |

| التخصيص | عباسي وآخرون (2021)؛ باكلي ودويل (2017)؛ إيدر وآخرون (2021)؛ هاليفاكس وآخرون (2020)؛ ماهر وآخرون (2020)؛ ميساوي ومعاليل (2021)؛ روستا وآخرون (2016)؛ شبيهي وآخرون (2016) | 8 (19%) |

| تكييف | داغستاني وآخرون (2020)؛ حسن وآخرون (2021)؛ جاكوست وآخرون (2018)؛ كولبيكوفا وآخرون (2019)؛ ماهر وآخرون (2020)؛ ميساوي ومعليل (2021)؛ مونتيررات وآخرون (2017)؛ رودريغيز وآخرون (2022)؛ شي وكريستيا (2016)؛ تان وتشياه (2021)؛ تينوريو، تشالكوشالك وآخرون (2020)؛ شو وآخرون (2017) | 12 (28%) |

| توصية | سو وآخرون (2016) | 1 (2%) |

5.1. التخصيص

5.2. التكيف

5.3. التوصية

عناصر اللعبة في كل مجموعة من عناصر اللعبة.

| مجموعة عناصر اللعبة | عنصر اللعبة | التعريف | الإجمالي |

| الأداء | المكافأة | أي شيء يُعطى للاعب لمدح أفعاله أو نجاحه في التحدي، مما قد يعزز الطلاب للحفاظ على سلوكياتهم وتقويتها لتحقيق المزيد من المكافآت | 30 |

| التقدم | يمكن اللاعبين من تحديد مواقعهم وتقدمهم في الوقت الحقيقي ويظهر نموهم وتحسنهم خلال العملية الم gamified | 27 | |

| التعليقات | تعترف باللاعب على استفساره وصحة أو خطأ أنشطته التعليمية لتشجيع أو تثبيط سلوك معين | 13 | |

| العقوبة | تُفرض عندما يقدم الطلاب إجابة غير صحيحة أو يكسرون قاعدة النشاط الم gamified | 1 | |

| التصويت | عملية طلب تعليقات المستخدمين لتوجيه تطوير أو تقدم النظام الم gamified | 1 | |

| الشخصية | التحدي | مجموعة متنوعة من المواقف أو الأنشطة التي يحتاج الطلاب إلى التغلب عليها أو بذل الجهود للتعامل معها، من أجل تحقيق الأهداف التعليمية | 26 |

| التخصيص | يوفر للطلاب تجارب شخصية من خلال تعيين تحديات تناسب تمامًا مستوى مهاراتهم، وضبط مهام التعلم بناءً على ملاحظات اللاعبين، أو السماح للطلاب بتغيير البيئة الم gamified من خلال إنشاء هوياتهم الخاصة | 13 | |

| الهدف | هدف محدد وواضح ومحدد يعمل كدليل لأفعال الطلاب، ويمكنهم رؤية التأثير المباشر لجهودهم | 10 | |

| حرية الفشل | يخلق مخاطر منخفضة للتقديم للاعبين | 2 | |

| الجدة | معلومات جديدة ومحدثة تُقدم للاعب باستمرار. بعض الأمثلة والمرادفات هي التغييرات، والمفاجآت، والتحديثات | 2 | |

| الإحساس | استخدام حواس اللاعب لإنشاء تجارب جديدة. بعض الأمثلة والمرادفات هي التحفيز البصري، والتحفيز الصوتي | 2 | |

| الاجتماعي | المنافسة | صراع بين اللاعبين نحو هدف مشترك ويحفز اللاعبين على الأداء بشكل أفضل من الآخرين | 26 |

| التواصل الاجتماعي | تتيح الشبكة الاجتماعية للمستخدمين إنشاء ملفاتهم الشخصية، وإضافة الأصدقاء والتفاعل مع بعضهم البعض فيها؛ يتيح الدعم للمستخدمين دعم الآخرين أو طلب الدعم من الآخرين؛ الحالة الاجتماعية تعتمد على تأثير المستخدم الاجتماعي، مثل عدد المتابعين في الشبكات الاجتماعية؛ الضغط الاجتماعي هو الضغط من خلال التفاعلات الاجتماعية مع لاعبين آخرين | 13 | |

| التعاون | عندما يتعاون لاعبان أو أكثر لتحقيق هدف مشترك | 8 | |

| السمعة | الألقاب التي يجمعها اللاعب داخل اللعبة | 2 | |

| البيئي | الوصول | محتوى حصري مشروط بفعل من المستخدم ليكون متاحًا | 8 |

| الاختيار | يمنح المستخدمين إمكانية وجود مسارات متعددة للنجاح، مما يسمح لهم بتحديد كيفية إكمال مهام التعلم | 8 | |

| ضغط الوقت | يتطلب من اللاعبين إكمال مهمة واحدة في وقت محدد | 7 | |

| الفرصة | أي احتمال لاتخاذ إجراءات معينة أو زيادة النتائج ضمن نشاط مُعَشَّق | 5 | |

| التجارة | يمثل المعاملة في النظام المُعَشَّق | 4 | |

| الندرة | الموارد المحدودة والعناصر القابلة للجمع | 2 | |

| خيالي | السرد | ترتيب الأحداث حيث تحدث في لعبة، والتي تتأثر بأفعال اللاعب. | 5 |

| سرد القصص | هي الطريقة التي تُروى بها قصة اللعبة (كنص). تُروى داخل اللعبة، من خلال النص، الصوت، أو الموارد الحسية. | 8 |

6. النتائج: مجموعات من عناصر اللعبة لتخصيص التحفيز الرقمي في التعليم

6.1. مجموعة الأداء من عناصر اللعبة

6.2. مجموعة الاجتماعية من عناصر اللعبة

6.3. مجموعة الشخصية من عناصر اللعبة

6.4. مجموعة العناصر البيئية في اللعبة

6.5. مجموعة العناصر الخيالية في اللعبة

7. المناقشة

الألعاب المخصصة للجميع والألعاب المخصصة.

7.1. النهج لتخصيص الألعاب الرقمية

7.1.1. التخصيص والتكيف

7.1.2. التوصية

7.2. مجموعات عناصر اللعبة

8. القيود والبحوث المستقبلية

الدروس المعززة بالألعاب. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قد تساعد التصاميم التجريبية مع دروس الألعاب غير المخصصة كمرجع في فحص نتائج الطلاب بطريقة صارمة. كما ذكر وي وآخرون (2021)، يلعب تقييم نتائج التعلم دورًا أساسيًا في تقييم إنجازات الطلاب الفعلية وفعالية ممارسات التدريس. في هذه التصاميم البحثية التجريبية، يمكن فحص ليس فقط الأساليب وتركيبات عناصر اللعبة للدروس المعززة بالألعاب، ولكن أيضًا التأثير النسبي لكل عنصر لعبة من خلال مقارنة النتائج في مجموعات الطلاب التي تتنوع فيها عناصر اللعبة.

9. الخاتمة والآثار العملية

بيان مساهمة مؤلفي CRediT

توفر البيانات

الملحق

نظرة عامة على الأساليب المخصصة لت gamification الرقمية في الدراسات التي تم مراجعتها

| المؤلفون(السنة) | بلد | انضباط | المستوى التعليمي | نهج مخصص | تحليل مصادر البيانات وصف البحث | ||

| باراتا وآخرون (2015) | البرتغال | الهندسة | جامعة | النمذجة | ملاحظة | تعلم الآلة | نموذج gamification القائم على نوع اللاعب |

| بنعاني وآخرون (2020) | تونس | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | النمذجة | ملاحظة | الأدب | برنامج أنطولوجيا AGE-Learn |

| كوديش ورافيد (2014) | إسرائيل | إدارة الهندسة الصناعية | جامعة | النمذجة | لا توجد معلومات | الأدب | نموذج gamification القائم على الشخصية |

| درمافال وآخرون (2019) | البرازيل، كندا | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | النمذجة | لا توجد معلومات | السبب الآلي | نموذج موحد للت gamification والتحفيز |

| غونزاليس وآخرون (2016) | المملكة المتحدة | علوم الحاسوب | لا توجد معلومات | النمذجة | بيانات المستخدم، الملاحظة: أوقات تسجيل الدخول، مدة اللعبة، آثار الإجراءات الم gamified | الأدب | نظام تعليمي ذكي معتمد على الألعاب يستند إلى خصائص متعددة للطلاب |

| حمامي وخماجة (2019) | تونس | تكامل النظام والبيانات | جامعة | النمذجة | ملاحظة | منهجية أجايل | نموذج قائم على المهارات والكفاءات والأهداف التعليمية |

| إيمري (2020) | رومانيا | علوم الحاسوب | لا توجد معلومات | النمذجة | لا توجد معلومات | تنقيب البيانات | برنامج تلقائي قائم على الأنطولوجيا مع عناصر الألعاب |

| كلوك، غاسباريني، وآخرون (2015) | البرازيل | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | النمذجة | ملاحظة، شكل، استبيان، بيانات المستخدم، مقابلة | تفاعل الإنسان مع الكمبيوتر | برنامج التكيف على الويب |

| كنوتاس وآخرون (2019) | فنلندا، بلجيكا، إيطاليا | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | النمذجة | استطلاع | الأدب | نموذج قائم على نوع اللاعب |

| مونتيررات وآخرون (2014) | فرنسا | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | النمذجة | ملاحظة | تعلم الآلة | نموذج قائم على نوع اللاعب |

| مونتيررات وآخرون (2014ب) | فرنسا | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | النمذجة | بيانات المستخدم، الملاحظة | تحليل الأثر | نظام مخصص قائم على الألعاب يعتمد على خصائص متعددة |

| مونتيررات وآخرون (2015) | فرنسا | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | النمذجة | اختبار، استبيان | تعلم الآلة (شجرة القرار) | نموذج نظام مخصص للأزياء المعتمدة على الألعاب |

| المؤلفون(السنة) | بلد | انضباط | نهج مخصص | تحليل مصادر البيانات وصف البحث | |||

الجدول 4 (مستمر)

| المؤلفون(السنة) | بلد | انضباط | المستوى التعليمي | نهج مخصص | مصادر البيانات تحليل وصف البحث | ||

| ماهر وآخرون (2020) | مصر | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | تكييف | بيانات المستخدم، الملاحظة: آثار العمل الم gamified | تحليلات التعلم | دراسة تجريبية تعتمد على خصائص متعددة للطلاب |

| مساوي ومعليل (2021) | تونس | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | تكييف | نموذج التسجيل، استبيان، ملاحظة: آثار العمل الم gamified | تعلم الآلة | دراسة حالة حول أنطولوجيا SPOnto استنادًا إلى خصائص متعددة للطلاب |

| مونتيررات وآخرون (2017) | فرنسا | لغة | المدرسة الثانوية | تكييف | ملاحظة: آثار العمل الم gamified | التغير الخطي | دراسة استكشافية قائمة على نوع اللاعب في BrainHex |

| رودريغيز وآخرون (2022) | إسبانيا | علوم الحاسوب، الإدارة | المدرسة الثانوية | تكييف | الملاحظة: سرعة اللعبة، مدة اللعبة، آثار العمل الم gamified | طريقة ضرب المصفوفات | دراسة تجريبية تعتمد على نوع اللاعب لدى الطلاب |

| تان وتشيا (2021) | سنغافورة | تحفيز التعلم من خلال الألعاب في التعليم | جامعة | تكييف | درجة الاختبار، الوقت المستغرق في الاختبارات، المحاولات للاختبارات، تكرار تسجيل الدخول، | حكم المدربين، الأدب | دراسة حالة مدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي تعتمد على سلوكيات الطلاب وأدائهم في الوقت المناسب |

| شو وآخرون (2017) | الصين، البرتغال | علوم الحاسوب | جامعة | تكييف | ملاحظة: طلبات الرصاص والهز لطرح الأسئلة والمساعدة | حكم المعلمين، الأدب | دراسة حالة معتمدة على الألعاب تستند إلى سلوكيات الطلاب وأدائهم في الوقت المناسب |

| سو وآخرون (2016) | تايوان (الصين) | رياضيات | لا توجد معلومات | توصية | لا توجد معلومات | طريقة دلفي | نظام توصية قائم على أسلوب التعلم استخدم دراسة تجريبية |

نظرة عامة على مجموعات عناصر اللعبة للتخصيص الرقمي في الألعاب التعليمية التي تم مراجعتها

| المؤلفون(السنة) | نهج مخصص | عناقيد عناصر اللعبة | عناصر اللعبة | ||

| باراتا وآخرون (2015) | النمذجة | أداء | مكافأة | ||

| تقدم | |||||

| بيئي | ضغط الوقت | ||||

| اجتماعي | المنافسة | ||||

| شخصي | تحدي | ||||

| بنعاني وآخرون (2020) | النمذجة | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | ||

| كوديش ورافيد (2014) | النمذجة | أداء | مكافأة | ||

| تقدم | |||||

| دي لا بينيا وآخرون (2021) | النمذجة | أداء | مكافأة | ||

| تقدم | |||||

| بيئي | الوصول | ||||

| فرصة | |||||

| اجتماعي | المنافسة | ||||

| شخصي | تخصيص | ||||

| درمافال وآخرون (2019) |

|

أداء | مكافأة | ||

| تعليق | |||||

| اجتماعي | المنافسة | ||||

| شخصي | تخصيص | ||||

| تحدي | |||||

| ديكنز وآخرون (2021) | أداء | مكافأة | |||

| تقدم | |||||

| التصويت | |||||

| اجتماعي | مسابقة | ||||

| التفاعل الاجتماعي | |||||

| شخصي | تخصيص | ||||

| تحدي | |||||

| – | سرد القصص/قصة | ||||

| المؤلفون(السنة) | نهج مخصص | عناقيد عناصر اللعبة | عناصر اللعبة | ||

| جيل وآخرون (2015) | النمذجة | أداء | مكافأة | ||

| بيئي | اقتصاد الاختيار/ الوصول إلى التجارة | ||||

| اجتماعي | المنافسة | ||||

| تعاون | |||||

| شخصي | تحدي | ||||

| غونزاليس وآخرون (2016) | النمذجة | أداء | مكافأة | ||

| بيئي | الوصول | ||||

| شخصي | تحدي | ||||

| حمامي وخماجة (2019) | النمذجة | أداء | مكافأة | ||

| بيئي | اختيار | ||||

| اجتماعي | منافسة | ||||

| شخصي | هدف | ||||

| تخصيص | |||||

| تحدي | |||||

| إيمري (2020) | النمذجة | أداء | مكافأة | ||

| تقدم | |||||

| تعليق | |||||

| اجتماعي | المنافسة | ||||

| شخصي | تحدي | ||||

| خيالي | سرد القصص / قصة | ||||

| سرد | |||||

| كلوك، غاسباريني، وآخرون (2015) | النمذجة | أداء | مكافأة | ||

| تقدم |

| المؤلفون(السنة) | مخصص | عناقيد | عنصر اللعبة | عناصر اللعبة | آليات اللعبة | ||||||||||

| اجتماعي | المنافسة | نقطة، ترتيب | |||||||||||||

| المؤلفون(السنة) | نهج مخصص | عناقيد عناصر اللعبة | عناصر اللعبة | آليات اللعبة | |||||||||||

| كلوك، دا كونها، وآخرون (2015) | النمذجة |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| شخصي |

|

||||||||||||||

| كنوتاس وآخرون (2019) | النمذجة |

|

|

نقطة، شارة | |||||||||||

| مدريد ويسوع (2021) | النمذجة |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| بيئي | الاقتصاد/التجارة | شارة | |||||||||||||

| اجتماعي | التفاعل الاجتماعي | الوضع الاجتماعي | |||||||||||||

| شخصي | تخصيص | أفاتار | |||||||||||||

| تحدي | مهمة | ||||||||||||||

| خيالي |

|

||||||||||||||

| مونتيررات وآخرون (2014) | النمذجة |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| شخصي | تخصيص | ||||||||||||||

| هدف | |||||||||||||||

| تحدي | شارة، كأس | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| مونتيررات وآخرون (2014ب) | النمذجة | اجتماعي |

|

||||||||||||

| مونتيررات وآخرون (2015) | النمذجة | أداء |

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| بيئي |

|

||||||||||||||

| مؤقت | |||||||||||||||

| المؤلفون(السنة) | نهج مخصص | عناقيد عناصر اللعبة | عناصر اللعبة | آليات اللعبة | |||||||||||

| اجتماعي | التفاعل الاجتماعي | نصيحة | |||||||||||||

| المنافسة | قائمة المتصدرين | ||||||||||||||

| أداء |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| بيئي | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| اجتماعي | |||||||||||||||

|

الضغط الاجتماعي | ||||||||||||||

| شخصي | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| تحدي | لُغز | ||||||||||||||

| خيالي | سرد القصص/قصة | ||||||||||||||

| سرد | |||||||||||||||

| أداء | مكافأة |

|

|||||||||||||

| تقدم | |||||||||||||||

| اجتماعي | المنافسة | ||||||||||||||

| شخصي | تخصيص | ||||||||||||||

| أداء | |||||||||||||||

| بيئي | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| اجتماعي | المنافسة | ||||||||||||||

| المؤلفون(السنة) | نهج مخصص | عناقيد عناصر اللعبة | عناصر اللعبة | آليات اللعبة | |||||||

| المؤلفون(السنة) | نهج مخصص | عناقيد عناصر اللعبة | عناصر اللعبة | آليات اللعبة | |||||||

|

التفاعل الاجتماعي | الضغط الاجتماعي | |||||||||

| سيزجين ويوزر (2022) | النمذجة | لا توجد معلومات | معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | |||||||

| تينوريو، ديرميفال، وآخرون (2020) | النمذجة | أداء | مكافأة | نقطة، شارة | |||||||

| اجتماعي | المنافسة | قائمة المتصدرين | |||||||||

| – | سرد القصص/قصة | ||||||||||

| تينوريو وآخرون (2021) | النمذجة | شخصي |

|

||||||||

| زارك وآخرون (2017) | النمذجة | أداء |

|

|

|||||||

| – | ضغط الوقت | ||||||||||

| عباسي وآخرون (2021) | التخصيص | أداء |

|

خريطة | |||||||

| تعليق | |||||||||||

| شخصي | تحدي | لُغز | |||||||||

| المؤلفون(السنة) | نهج مخصص | عناقيد عناصر اللعبة | عناصر اللعبة | آليات اللعبة | |||||||

| باكلي ودويل (2017) | التخصيص |

|

|

نقاط، شارة، سلع افتراضية | |||||||

| مسابقة | قائمة المتصدرين | ||||||||||

| تعاون |

|

||||||||||

| شخصي | |||||||||||

| إيدر وآخرون (2021) | التخصيص | أداء | مكافأة | نقطة | |||||||

| تعليق | |||||||||||

| اجتماعي | المنافسة | ||||||||||

| شخصي | تخصيص | أفاتار | |||||||||

| تحدي | |||||||||||

| هاليفاكس وآخرون (2020) | التخصيص | أداء | مكافأة | نقطة، شارة | |||||||

| تقدم | مستوى | ||||||||||

| بيئي | ضغط الوقت | مؤقت | |||||||||

| اجتماعي | المنافسة | نقطة، شارة، لوحة المتصدرين | |||||||||

| ماهر وآخرون (2020) | التخصيص | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | |||||||

| مساوي ومعليل (2021) | التخصيص | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | |||||||

| روستا وآخرون (2016) | التخصيص | أداء | تقدم | شريط التقدم | |||||||

| تعليق | |||||||||||

| شبيهي وآخرون (2016) | التخصيص | أداء |

|

نقطة، شارة | |||||||

| تعليق | |||||||||||

| شخصي | هدف | ||||||||||

| داغستاني وآخرون (2020) | تكييف | أداء |

|

الموارد الخارجية | |||||||

| بيئي |

|

||||||||||

| اجتماعي |

|

|

|||||||||

| المؤلفون(السنة) | نهج مخصص | عناقيد عناصر اللعبة | عناصر اللعبة | آليات اللعبة | |||||||

| شخصي |

|

واجهة الملاحة | |||||||||

| المؤلفون(السنة) | نهج مخصص | عناقيد عناصر اللعبة | عناصر اللعبة | آليات اللعبة | ||||

| حسن وآخرون (2021) | تكييف | أداء |

|

|

||||

|

|

قائمة المتصدرين | ||||||

| جاهوشت وآخرون (2018) | تكييف | أداء |

|

|||||

| بيئي | ضغط الوقت | |||||||

| اجتماعي | منافسة | |||||||

|

||||||||

| خيالي |

|

|||||||

| كولبيكوفا وآخرون (2019) | تكييف | أداء | مكافأة | نقطة | ||||

| ملاحظات | تلميح | |||||||

| بيئي | اختيار | |||||||

| ماهر وآخرون (2020) | تكييف | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | ||||

| مساوي ومعاليل (2021) | تكييف | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | ||||

| مونتيررات وآخرون (2017) | تكييف | أداء | تقدم | مستوى | ||||

| بيئي | اختيار | |||||||

| وصول | مهمة جديدة | |||||||

| اجتماعي | تنافس | لوحة المتصدرين | ||||||

| رودريغيز وآخرون (2022) | تكييف | أداء | مكافأة | نقطة، شارة | ||||

| تقدم | مستوى | |||||||

| بيئي | وصول | لعبة صغيرة، بيضة عيد الفصح | ||||||

| فرصة | يانصيب، مجموعة تطوير | |||||||

| اجتماعي |

|

لوحة المتصدرين | ||||||

| المؤلفون (السنة) | نهج مخصص | مجموعات عناصر اللعبة | عناصر اللعبة | ميكانيكا اللعبة | ||||

| شي وكريستيا (2016) | تكييف | شخصي | اجتماع | شبكة اجتماعية، حالة اجتماعية | ||||

| بيئي |

|

|||||||

| فرصة | ||||||||

| اجتماعي |

|

|||||||

| شخصي |

|

|||||||

| تان وتشياه (2021) | تكييف | أداء |

|

|

||||

| ملاحظات | تلميح | |||||||

| تينوريو، تشالكوشالك وآخرون (2020) | تكييف | شخصي |

|

|||||

| تحدي | مهمة | |||||||

| شو وآخرون (2017) | تكييف | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | ||||

| سو وآخرون (2016) | توصية | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات | لا توجد معلومات |

References

Adomavicius, G., & Tuzhilin, A. (2005). Toward the next generation of recommender systems: A survey of the state-of-the-art and possible extensions. Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 17(6), 734-749.

Aljabali, R. N., & Ahmad, N. (2018). A review on adopting personalized gamified experience in the learning context (pp. 61-66). IEEE Conference on e-Learning, eManagement and e-Services.

Almeida, C., Kalinowski, M., Uchôa, A., & Feijó, B. (2023). Negative effects of gamification in education software: Systematic mapping and practitioner perceptions. Information and Software Technology, 156, Article 107142.

Altaie, M. A., & Jawawi, D. N. A. (2021). Adaptive gamification framework to promote computational thinking in 8-13 year olds. Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society, 17(3), 89-100.

Amiel, T., & Reeves, T. C. (2008). Design-based research and educational technology: Rethinking technology and the research agenda. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 11(4), 29-40.

Azzi, I., Jeghal, A., Radouane, A., Yahyaouy, A., & Tairi, H. (2020). A robust classification to predict learning styles in adaptive E-learning systems. Education and Information Technologies, 25(1), 437-448.

Barata, G., Gama, S., Jorge, J., & Gonçalves, D. (2015). Gamification for smarter learning: Tales from the trenches. Smart Learning Environments, 2(1), 1-23.

Bennani, S., Maalel, A., & Ghezala, H. B. (2020). AGE-Learn: Ontology-based representation of personalized gamification in E-learning. Procedia Computer Science, 176, 1005-1014.

Buckley, P., & Doyle, E. (2017). Individualising gamification: An investigation of the impact of learning styles and personality traits on the efficacy of gamification using a prediction market. Computers & Education, 106, 43-55.

Codish, D., & Ravid, G. (2014). Personality based gamification-Educational gamification for extroverts and introverts. Proceedings of the 9th CHAIS Conference for the Study of Innovation and Learning Technologies: Learning in the Technological Era, 1, 36-44.

Daghestani, L. F., Ibrahim, L. F., Al-Towirgi, R. S., & Salman, H. A. (2020). Adapting gamified learning systems using educational data mining techniques. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 28(3), 568-589.

de la Peña, D., Lizcano, D., & Martínez-Álvarez, I. (2021). Learning through play: Gamification model in university-level distance learning. Entertainment Computing, 39.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In In proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments (pp. 9-15).

Dykens, I. T., Wetzel, A., Dorton, S. L., & Batchelor, E. (2021). Towards a unified model of gamification and motivation. International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 53-70.

Eder, G. M. J., Mirna, M., Héctor, C. R., & Jezreel, M. (2021). Designing a player-persona for gamification learning experiences.

Elliot, A. J., & Murayama, K. (2008). On the measurement of achievement goals: Critique illustration and application. Educational Psychology, 100, 613-628.

Fishman, B. J., Penuel, W. R., Allen, A. R., Cheng, B. H., & Sabelli, N. O. R. A. (2013). Design-based implementation research: An emerging model for transforming the relationship of research and practice. Teachers College Record, 115(14), 136-156.

Gil, B., Cantador, I., & Marczewski, A. (2015). Validating gamification mechanics and player types in an e-learning environment (pp. 568-572). European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning.

González, C. S., Toledo, P., & Muñoz, V. (2016). Enhancing the engagement of intelligent tutorial systems through personalization of gamification. International Journal of Engineering Education, 32(1), 532-541.

Hallifax, S., Lavoué, E., & Serna, A. (2020). To tailor or not to tailor gamification? An analysis of the impact of tailored game elements on learners’ behaviours and motivation. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, 216-227.

Hallifax, S., Serna, A., Marty, J. C., & Lavoué, É. (2019). Adaptive gamification in education: A literature review of current trends and developments (pp. 294-307). European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning.

Hammami, J., & Khemaja, M. (2019). Towards agile and gamified flipped learning design models: Application to the system and data integration course. Procedia Computer Science, 164, 239-244.

Hanus, M. D., & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & education, 80, 152-161.

Hassan, M. A., Habiba, U., Majeed, F., & Shoaib, M. (2021). Adaptive gamification in E-learning based on students’ learning styles. Interactive Learning Environments, 29(4), 545-565.

Imre, Z. (2020). Ontology based UX personalization for gamified education (pp. 415-422). ENASE.

Jagušt, T., Botički, I., & So, H. J. (2018). Examining competitive, collaborative and adaptive gamification in young learners’ math learning. Computers & Education, 125, 444-457.

Klock, A. C. T., da Cunha, L. F., de Cravalho, M. F., Rosa, B. E., Anton, A. J., & Gasparini, I. (2015b). Gamification in E-learning systems: A conceptual model to engage students and its application in an adaptive e-learning system. International Conference on Learning and Collaboration Technologies, 595-607.

Klock, A. C. T., Gasparini, I., Pimenta, M. S., & de Oliveira, J. P. M. (2015). Everybody is playing the game, but nobody’s rules are the same: Towards adaptation of gamification based on users’ characteristics. Bulletin of the Technical Committee on Learning Technology, 17(4), 22-25.

Klock, A. C. T., Gasparini, I., Pimenta, M. S., & Hamari, J. (2020). Tailored gamification: A review of literature. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 144.

Klock, A. C. T., Pimenta, M. S., & Gasparini, I. (2018). A systematic mapping of the customization of game elements in gamified systems. Brazilian Symposium on Computer Games and Digital Entertainment, 11-18.

Knutas, A., Van Roy, R., Hynninen, T., Granato, M., Kasurinen, J., & Ikonen, J. (2019). A process for designing algorithm-based personalized gamification. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 78(10), 13593-13612.

Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191-210.

Kolpikova, E. P., Chen, D. C., & Doherty, J. H. (2019). Does the format of preclass reading quizzes matter? An evaluation of traditional and gamified, adaptive preclass reading quizzes. CBE-life Sciences Education, 18(4), 1-10.

Krath, J., Schürmann, L., & Von Korflesch, H. F. (2021). Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games and game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 125, Article 106963.

Kreuter, M. W., Farrell, D. W., Olevitch, L. R., & Brennan, L. K. (2013). Tailoring health messages: Customizing communication with computer technology. Routledge.

Lopes, V., Reinheimer, W., Medina, R., Bernardi, G., & Nunes, F. B. (2019). Adaptive gamification strategies for education: A systematic literature review. Brazilian Symposium on Computers in Education, 30, 1032-1041.

Madrid, M. A. C., & Jesus, D. M. A. D. (2021). Towards the design and development of an adaptive gamified task management web application to increase student engagement in online learning. International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 215-223.

Maher, Y., Moussa, S. M., & Khalifa, M. E. (2020). Learners on focus: Visualizing analytics through an integrated model for learning analytics in adaptive gamified elearning. IEEE Access, 8, 197597-197616.

Missaoui, S., & Maalel, A. (2021). Student’s profile modeling in an adaptive gamified learning environment. Education and Information Technologies, 26(5), 6367-6381.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group*.. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264-269.

Monterrat, B., Desmarais, M., Lavoué, E., & George, S. (2015). A player model for adaptive gamification in learning environments. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, 297-306.

Monterrat, B., Lavoué, É., & George, S. (2014). Toward an adaptive gamification system for learning environments. International Conference on Computer Supported Education, 115-129.

Monterrat, B., Lavoué, É., & George, S. (2014b). A framework to adapt gamification in learning environments (pp. 578-579). European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning.

Monterrat, B., Lavoué, É., & George, S. (2017). Adaptation of gaming features for motivating learners. Simulation & Gaming, 48(5), 625-656.

Mora, A., Tondello, G. F., Nacke, L. E., & Arnedo-Moreno, J. (2018). Effect of personalized gameful design on student engagement (pp. 1925-1933). IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON).

Oliveira, W., & Bittencourt, I. I. (2019). Tailored gamification to educational technologies. Singapore: Springer.

Oliveira, W., Hamari, J., Shi, L., Toda, A. M., Rodrigues, L., Palomino, P. T., & Isotani, S. (2022). Tailored gamification in education: A literature review and future agenda. Education and Information Technologies, 1-34.

Palomino, P. T., Toda, A. M., Oliveira, W., Cristea, A. I., & Isotani, S. (2019). Narrative for gamification in education: Why should you care? International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), 97-99.

Qiao, S., Yeung, S. S. S., Zainuddin, Z., Ng, D. T. K., & Chu, S. K. W. (2023). Examining the effects of mixed and non-digital gamification on students’ learning performance, cognitive engagement and course satisfaction. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(1), 394-413.

Rodríguez, I., Puig, A., & Rodríguez, À. (2022). Towards adaptive gamification: A method using dynamic player profile and a case study. Applied Sciences, 12(1), 486-504.

Roosta, F., Taghiyareh, F., & Mosharraf, M. (2016). Personalization of gamification-elements in an E-learning environment based on learners’ motivation. International Symposium on Telecommunications (IST), 637-642.

Santos, W. O. D., Bittencourt, I. I., & Vassileva, J. (2018). Design of tailored gamified educational systems based on gamer types (pp. 42-51). CBIE.

Santos, A. C. G., Oliveira, W., Hamari, J., Rodrigues, L., Toda, A. M., Palomino, P. T., & Isotani, S. (2021). The relationship between user types and gamification designs. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 31(5), 907-940.

Sezgin, S., & Yüzer, T. V. (2022). Analysing adaptive gamification design principles for online courses. Behaviour & Information Technology, 41(3),

Shabihi, N., Taghiyareh, F., & Abdoli, M. H. (2016). Analyzing the effect of game-elements in E-learning environments through MBTI-based personalization. International Symposium on Telecommunications (IST), 612-618.

Shi, L., & Cristea, A. I. (2016). Motivational Gamification strategies rooted in self-determination theory for social adaptive E-Learning. Intelligent Tutoring Systems, 294-300.

Su, C. H., Fan, K. K., & Su, P. Y. (2016). A intelligent Gamifying learning recommender system integrated with learning styles and Kelly repertory grid technology. International Conference on Applied System Innovation (ICASI), 1-4.

Tan, D. Y., & Cheah, C. W. (2021). Developing a gamified AI-enabled online learning application to improve students’ perception of university physics. Computers and education: Artificial Intelligence, 2.

Tenório, K., Chalco Challco, G., Dermeval, D., Lemos, B., Nascimento, P., Santos, R., & Pedro da Silva, A. (2020). Helping teachers assist their students in gamified adaptive educational systems: Towards a gamification analytics tool. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, 312-317.

Tenório, K., Dermeval, D., Monteiro, M., Peixoto, A., & Pedro, A. (2020b). Raising teachers empowerment in gamification design of adaptive learning systems: A qualitative research. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, 524-536.

Tenório, K., Dermeval, D., Monteiro, M., Peixoto, A., & Silva, A. P. D. (2021). Exploring design concepts to enable teachers to monitor and adapt gamification in adaptive learning systems: A qualitative research approach. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 1-25.

Toda, A. M., Klock, A. C., Oliveira, W., Palomino, P. T., Rodrigues, L., Shi, L., Bittencourt, lg, Gasparini, I., Isotani, S., & Cristea, A. I. (2019). Analysing gamification elements in educational environments using an existing Gamification taxonomy. Smart Learning Environments, 6(1), 1-14.

Toda, A. M., Valle, P. H. D., & Isotani, S. (2017). The dark side of gamification: An overview of negative effects of gamification in education. In Proceedings of the researcher links workshop (pp. 143-156).

Van Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2018). Need-supporting gamification in education: An assessment of motivational effects over time. Computers & Education, 127, 283-297.

Wei, X., Saab, N., & Admiraal, W. (2021). Assessment of cognitive, behavioral, and affective learning outcomes in massive open online courses: A systematic literature review. Computers & Education, 163, Article 104097.

Xu, H., Song, D., Yu, T., & Tavares, A. (2017). An enjoyable learning experience in personalising learning based on knowledge management: A case study. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(7), 3001-3018.

Xu, Y., & Tang, Y. (2015). Based on action-personality data mining, research of gamification emission reduction mechanism and intelligent personalized action recommendation model. Cross-Cultural Design Methods, Practice and Impact: 7th International Conference, 241-252.

Yildirim, I. (2017). The effects of gamification-based teaching practices on student achievement and students’ attitudes toward lessons. The Internet and Higher Education, 33, 86-92.

Zaric, N., Scepanović, S., Vujicic, T., Ljucovic, J., & Davcev, D. (2017). The model for gamification of E-learning in higher education based on learning styles. International Conference on ICT Innovations, 265-273.

- Corresponding author. at: ICLON, Leiden University Graduate School of Teaching, Leiden University, Kolffpad 1, 2333 BN, Leiden, the Netherlands.

E-mail addresses: y.hong@iclon.leidenuniv.nl (Y. Hong), n.saab@iclon.leidenuniv.nl (N. Saab), wilfried@oslomet.no (W. Admiraal).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2024.105000

Publication Date: 2024-01-21

Approaches and game elements used to tailor digital gamification for learning: A systematic literature review

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Teaching and learning

Tailored approach

Game elements and clusters

Systematic literature review

Abstract

The systematic review examined research on tailored digital gamification for learning based on 43 peer-reviewed articles published between 2013 and 2022. The study aimed to investigate tailored approaches and game elements, contributing to the use of tailored digital gamification in educational settings. The tailored approaches were categorized as personalization, adaptation, and recommendation, with user modeling as their basis. Five clusters of game elements were employed when using these tailored approaches in digital gamified classes. The findings imply that most of the articles in this review were still in the stage of class preparation and focused on what information can be used to tailor. More empirical studies need to be conducted to examine the motivating effects of tailored digital gamifying classes, using the approaches of personalization, adaptation, and recommendation. Additionally, twenty-three game elements were found in this review study, among which reward was the most often used. Then these game elements were grouped into five clusters based on their functions, that is, performance, personal, social, ecological, and fictional cluster. A variety of game element clusters reflect multiple aspects of gamification. The use of them in each tailored approach might contribute to a better understanding and selection of game elements when tailoring digital gamification. These findings provide a holistic picture of common approaches and related game elements in tailored digital gamifying classes. Teachers and curriculum designers can benefit from this study by considering appropriate approaches and game elements.

1. Introduction

2. Tailored gamification in education

RQ2. Which game elements are used when using these tailored approaches?

3. Methodology

described in the following subsections.

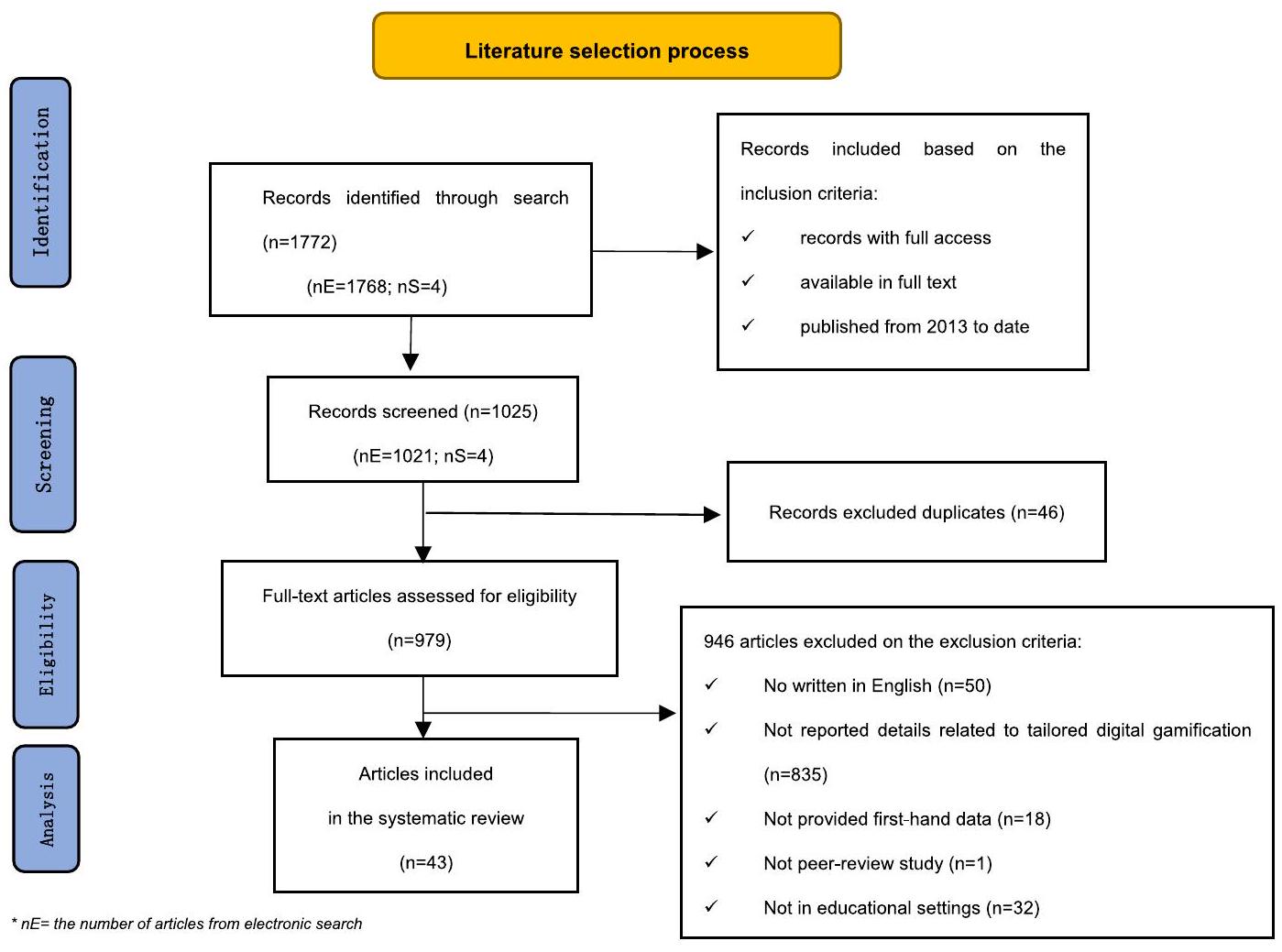

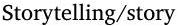

3.1. Eligibility criteria

3.2. Search

3.3. Selection

Databases collection.

| Search strategy | Number of articles found in the databases |

| Electronic searches | 1021 |

| SpringerLink

|

26 |

| Taylor & Francies Online

|

18 |

| Wiley Online Library

|

15 |

| SAGE Journals

|

11 |

| Web of Science

|

5 |

| JSTOR (Journal STORage)

|

3 |

| ScienceDirect (Elsevier)

|

3 |

| ProQuest

|

2 |

| Scopus

|

938 |

| Snowballing Reference lists | 4 |

| Total | 1025 |

3.4. Data analysis

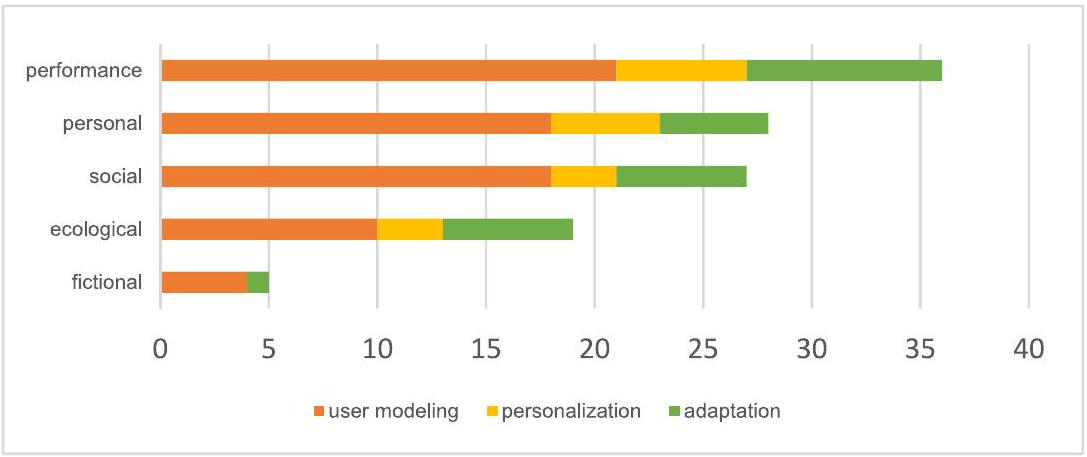

internal consistence among the experts regarding the description of the 19 game elements (Cronbach’s Alpha> 0.8). Then 5 experts, classified the 19 game elements into 5 clusters. The game elements of ‘performance’ cluster provide information about users’ performance in the gamified environment (e.g., reward, punishment); the ‘personal’ cluster is related to the learner who is using the gamified environment (e.g., personal goal); the ‘social’ one provides information about users’ interaction in the gamified environment (cooperation, competition); the ‘ecological’ cluster provides users with the information about the gamified environment (e.g., time pressure); the ‘fictional’ one is a mixed dimension that is related to both the user (through narrative) and the environment (through storytelling), tying the users’ experience with the context. Narrative refers to the larger story the user is working with and storytelling materializes this larger story with the aid of text, audio-visual and other sensorial stimuli to contextualize the narrative.

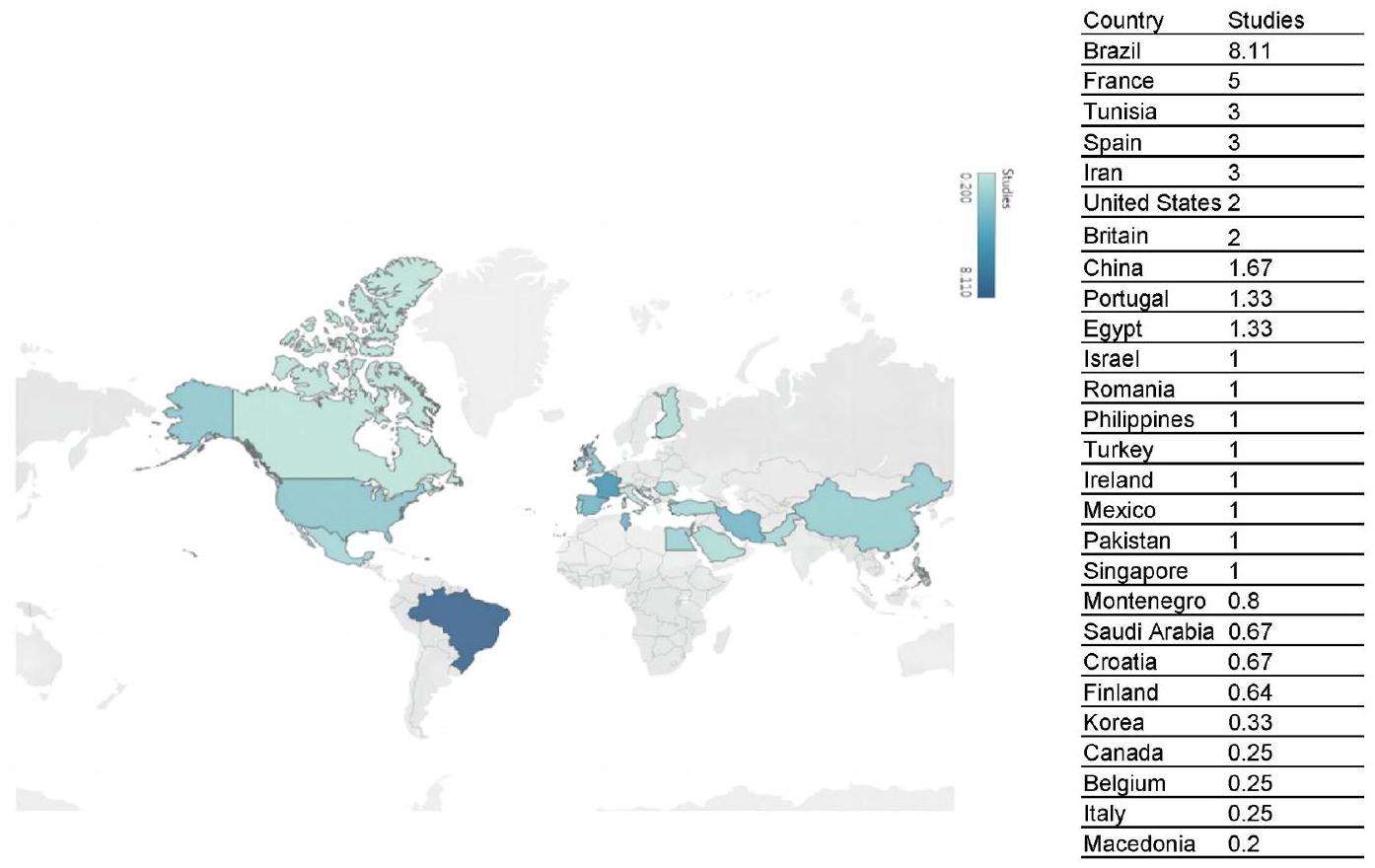

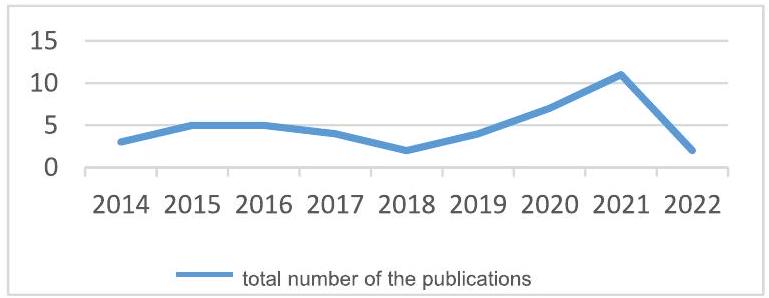

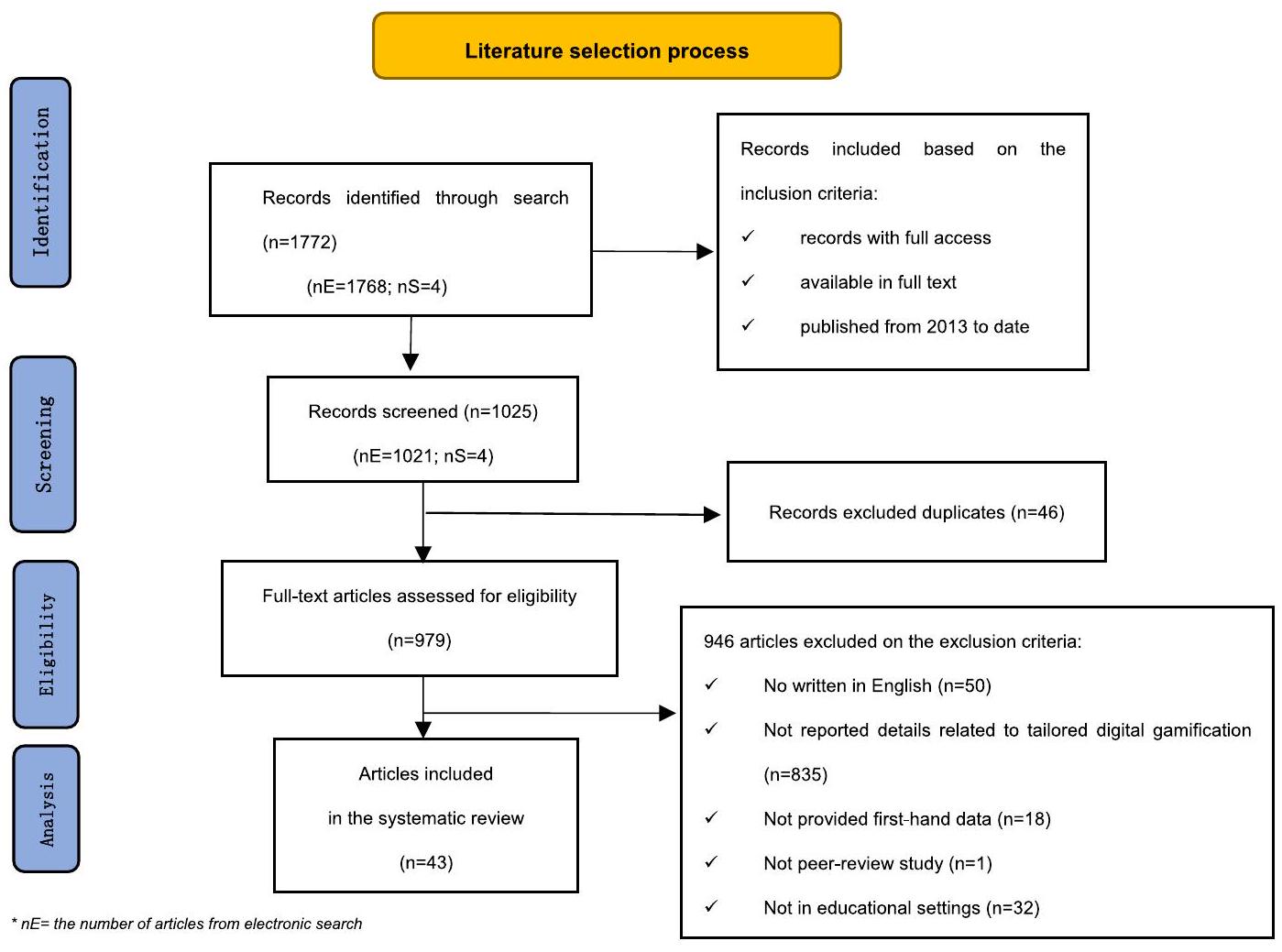

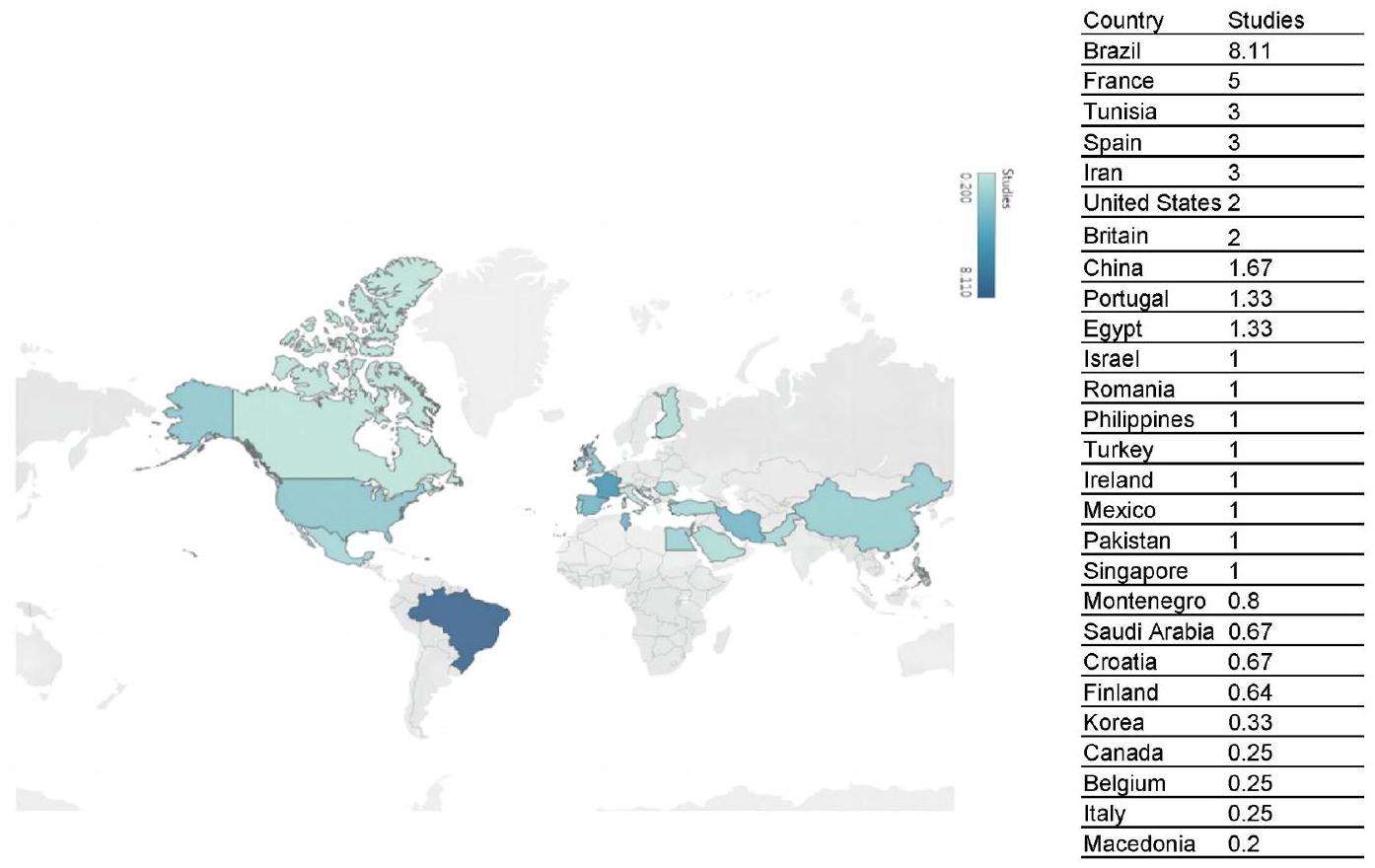

4. Results: studies overview

5. Results: approaches to tailor digital gamification in education

Tailored approaches.

| Tailored approach | Studies | Total |

| User modeling (basis of the approaches) | Barata et al. (2015); Bennani et al. (2020); Codish and Ravid (2014); de la Peña et al. (2021); Dermeval et al. (2019); Dykens et al. (2021); Gil et al. (2015); González et al. (2016); Hammami and Khemaja (2019); Imre (2020); Klock, Gasparini, et al. (2015); Klock, da Cunha, et al. (2015); Knutas et al. (2019); Madrid and Jesus (2021); Monterrat et al. (2014); Monterrat et al. (2014b); Monterrat et al. (2015); Rodrigues et al. (2021); Santos et al. (2018); Santos et al. (2021); Sezgin and Yüzer (2022); Tenório, Dermeval, et al. (2020); Tenório et al. (2021); Zaric et al. (2017) | 24 (56%) |

| Personalization | Abbasi et al. (2021); Buckley and Doyle (2017); Eder et al. (2021); Hallifax et al. (2020); Maher et al. (2020); Missaoui and Maalel (2021); Roosta et al. (2016); Shabihi et al. (2016) | 8 (19%) |

| Adaptation | Daghestani et al. (2020); Hassan et al. (2021); Jagušt et al. (2018); Kolpikova et al. (2019); Maher et al. (2020); Missaoui and Maalel (2021); Monterrat et al. (2017); Rodríguez et al. (2022); Shi and Cristea (2016); Tan and Cheah (2021); Tenório, ChalcoChallco, et al. (2020); Xu et al. (2017) | 12 (28%) |

| Recommendation | Su et al. (2016) | 1 (2%) |

5.1. Personalization

5.2. Adaptation

5.3. Recommendation

Game elements in each game element cluster.

| Game element cluster | Game element | Definition | Total |

| Performance | Reward | Anything given to the player to praise his/her actions or success in the challenge, which could reinforce students to keep and strengthen their behaviors for achieving more rewards | 30 |

| Progress | It enables the players to locate themselves and their real-time progress and demonstrates their growth and improvement during the gamified process | 27 | |

| Feedback | It acknowledges the player for his/her inquiry and the correctness or wrongness of his/her learning activities to encourage or discourage a particular behavior | 13 | |

| Punishment | It is imposed when students give an incorrect answer or break the rule of the gamified activity | 1 | |

| Voting | The process of soliciting user feedback to guide the development or progression of the gamified system | 1 | |

| Personal | Challenge | A variety of situations or activities that the students need to conquer or make efforts to deal with, in order to achieve the learning goals | 26 |

| Customization | It provides students with personal experiences by assigning challenges that perfectly fit their skill level, adjusting learning tasks moderated based on player feedback, or allowing students to change the gamified environment by creating their own identities | 13 | |

| Goal | A specific, clear, and defined goal serves as a guideline for student actions, and they can see the direct impact of their efforts | 10 | |

| Free to fail | It creates a low risk of submission for the players | 2 | |

| Novelty | New, updated information presented to the player continuously. Some examples and synonyms are changes, surprises, updates | 2 | |

| Sensation | Use of player senses to create new experiences. Some examples and synonyms are visual stimulation, sound stimulation | 2 | |

| Social | Competition | A conflict between players towards a common goal and prompts the players to perform better than others | 26 |

| Socialization | Social network allows users to create their profiles, add friends and interact with each other in it; Scaffolding allows the users to support others or ask for support from others; Social status is based on the user’s social influence, such as the number of followers in the social networks; Social pressure is the pressure through social interactions with other players | 13 | |

| Cooperation | When two or more players collaborate to achieve a common goal | 8 | |

| Reputation | Titles that the player accumulates within the game | 2 | |

| Ecological | Access | An exclusive content conditioned to an action of the user to be available | 8 |

| Choice | It gives the users the possibility to have multiple routes to success, allowing them to decide how to complete the learning tasks | 8 | |

| Time pressure | It requires the players to complete one task in a determined time | 7 | |

| Chance | Any probability to take certain actions or increase outcomes within a gamified activity | 5 | |

| Trading | It represents the transaction in the gamified system | 4 | |

| Rarity | Limited resources and collectables | 2 | |

| Fictional | Narrative | Order of events where they happen in a game, which is influenced by the player’s actions. | 5 |

| Storytelling | It is the way the story of the game is told (as a script). It is told within the game, through text, voice, or sensorial resources. | 8 |

6. Results: clusters of game elements to tailor digital gamification in education

6.1. Performance cluster of game elements

6.2. Social cluster of game elements

6.3. Personal cluster of game elements

6.4. Ecological cluster of game elements

6.5. Fictional cluster of game elements

7. Discussion

one-size-fits-all gamification and the tailored one.

7.1. Approaches to tailor digital gamification

7.1.1. Personalization and adaptation

7.1.2. Recommendation

7.2. Game element clusters

8. Limitations and future research

evaluate gamified classes. In addition, experimental designs with non-tailored gamification classes as comparisons might help to examine the student outcomes in a rigorous way. As stated by Wei et al. (2021), the assessment of learning outcomes plays an essential role in the evaluation of students’ actual achievements and the effectiveness of teaching practices. In these experimental research designs, not only approaches and combinations of game elements of gamified classes can be examined, but also the relative effect of each game element by comparing outcomes in student groups in which game elements are varied.

9. Conclusion and practical implications

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Data availability

Appendix

An overview of tailored approaches for digital gamification in the studies reviewed

| Authors(year) | Country | Discipline | Educational level | Tailored approach | Data sources Analyze Research description | ||

| Barata et al. (2015) | Portugal | Engineering | University | Modeling | Observation | Machine learning | Player type-based gamification model |

| Bennani et al. (2020) | Tunisia | No info | No info | Modeling | Observation | Literature | AGE-Learn ontology program |

| Codish and Ravid (2014) | Israel | Industrial management and engineering | University | Modeling | No info | Literature | Personality-based gamification model |

| Dermeval et al. (2019) | Brazil, Canada | No info | No info | Modeling | No info | Automated reason | Unified gamification and motivation model |

| González et al. (2016) | UK | Computer science | No info | Modeling | User data, observation: login times, game duration, gamified action traces | Literature | Gamified intelligent tutorial system based on students’ multiple characteristics |

| Hammami and Khemaja (2019) | Tunisia | System and Data Integration | University | Modeling | Observation | Agile methodology | Skill, competency and learning goalbased model |

| Imre (2020) | Romania | Computer science | No info | Modeling | No info | Data mining | Ontology based automatic gamified program |

| Klock, Gasparini, et al. (2015) | Brazil | No info | No info | Modeling | Observation, form, survey, user data, interview | Human-computer interaction | Adapt Web program |

| Knutas et al. (2019) | Finland, Belgium, Italy | No info | No info | Modeling | Survey | Literature | Player type-based model |

| Monterrat et al. (2014) | France | No info | No info | Modeling | Observation | Machine learning | Player type-based model |

| Monterrat et al. (2014b) | France | No info | No info | Modeling | User data, observation | Trace analysis | Tailored gamified system based on multiple characteristics |

| Monterrat et al. (2015) | France | No info | No info | Modeling | Test, questionnaire | Machine learning (decision tree) | Automated tailoring gamified system model |

| Authors(year) | Country | Discipline | Tailored approach | Data sources Analyze Research description | |||

Table 4 (continued)

| Authors(year) | Country | Discipline | Educational level | Tailored approach | Data sources Analyze Research description | ||

| Maher et al. (2020) | Egypt | No info | No info | Adaptation | User data, observation: gamified action traces | Learning analytics | Experimental study based on students’ multiple characteristics |

| Missaoui and Maalel (2021) | Tunisia | No info | No info | Adaptation | Registration Form, questionnaire, observation: gamified action traces | Machine learning | Case study about SPOnto ontology based on students’ multiple characteristics |

| Monterrat et al. (2017) | France | Language | Secondary school | Adaptation | Observation: gamified action traces | Linear variation | BrainHex Player type-based exploratory study |

| Rodríguez et al. (2022) | Spain | Computer science, management | Secondary school | Adaptation | Observation: game speed, game duration, gamified action traces | Matrix multiplication method | Experimental study based on students’ player type |

| Tan and Cheah (2021) | Singapore | Gamification in education | University | Adaptation | Quiz score, time spent in quizzes, attempts for quizzes, login frequency, | Instructors’ judgment, literature | AI-enabled gamified case study based on students’ timely behaviors and performances |

| Xu et al. (2017) | China, Portugal | Computer science | University | Adaptation | Observation: bullet and shake requests for stating questions and help | Instructors’ judgement, literature | Gamified case study based on students’ timely behaviors and performances |

| Su et al. (2016) | Taiwan (China) | Math | No info | Recommendation | No info | Delphi method | A learning style-based recommendation system used experimental study |

An overview of game element clusters for tailored digital gamification in the studies reviewed

| Authors(year) | Tailored approach | Game element clusters | Game elements | ||

| Barata et al. (2015) | Modeling | Performance | Reward | ||

| Progress | |||||

| Ecological | Time pressure | ||||

| Social | Competition | ||||

| Personal | Challenge | ||||

| Bennani et al. (2020) | Modeling | No info | No info | ||

| Codish and Ravid (2014) | Modeling | Performance | Reward | ||

| Progress | |||||

| de la Peña et al. (2021) | Modeling | Performance | Reward | ||

| Progress | |||||

| Ecological | Access | ||||

| Chance | |||||

| Social | Competition | ||||

| Personal | Customization | ||||

| Dermeval et al. (2019) |

|

Performance | Reward | ||

| Feedback | |||||

| Social | Competition | ||||

| Personal | Customization | ||||

| Challenge | |||||

| Dykens et al. (2021) | Performance | Reward | |||

| Progress | |||||

| Voting | |||||

| Social | Competition | ||||

| Socialization | |||||

| Personal | Customization | ||||

| Challenge | |||||

| – | Storytelling/story | ||||

| Authors(year) | Tailored approach | Game element clusters | Game elements | ||

| Gil et al. (2015) | Modeling | Performance | Reward | ||

| Ecological | Choice Economy/ trading Access | ||||

| Social | Competition | ||||

| Cooperation | |||||

| Personal | Challenge | ||||

| González et al. (2016) | Modeling | Performance | Reward | ||

| Ecological | Access | ||||

| Personal | Challenge | ||||

| Hammami and Khemaja (2019) | Modeling | Performance | Reward | ||

| Ecological | Choice | ||||

| Social | Competition | ||||

| Personal | Goal | ||||

| Customization | |||||

| Challenge | |||||

| Imre (2020) | Modeling | Performance | Reward | ||

| Progress | |||||

| Feedback | |||||

| Social | Competition | ||||

| Personal | Challenge | ||||

| Fictional | Storytelling/ story | ||||

| Narrative | |||||

| Klock, Gasparini, et al. (2015) | Modeling | Performance | Reward | ||

| Progress |

| Authors(year) | Tailored | clusters | Game element | Game elements | Game mechanics | ||||||||||

| Social | Competition | Point, ranking | |||||||||||||

| Authors(year) | Tailored approach | Game element clusters | Game elements | Game mechanics | |||||||||||

| Klock, da Cunha, et al. (2015) | Modeling |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| personal |

|

||||||||||||||

| Knutas et al. (2019) | Modeling |

|

|

Point, badge | |||||||||||

| Madrid and Jesus (2021) | Modeling |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Ecological | Economy/trading | Badge | |||||||||||||

| Social | Socialization | Social status | |||||||||||||

| Personal | Customization | Avatar | |||||||||||||

| Challenge | Quest | ||||||||||||||

| Fictional |

|

||||||||||||||

| Monterrat et al. (2014) | Modeling |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Personal | Customization | ||||||||||||||

| Goal | |||||||||||||||

| Challenge | Badge, cup | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Monterrat et al. (2014b) | Modeling | Social |

|

||||||||||||

| Monterrat et al. (2015) | Modeling | Performance |

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Ecological |

|

||||||||||||||

| Timer | |||||||||||||||

| Authors(year) | Tailored approach | Game element clusters | Game elements | Game mechanics | |||||||||||

| Social | Socialization | Tip | |||||||||||||

| Competition | Leaderboard | ||||||||||||||

| Performance |

|

|

|||||||||||||

| Ecological | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Social | |||||||||||||||

|

Social pressure | ||||||||||||||

| Personal | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Challenge | Puzzle | ||||||||||||||

| Fictional | Storytelling/story | ||||||||||||||

| Narrative | |||||||||||||||

| Performance | Reward |

|

|||||||||||||

| Progress | |||||||||||||||

| Social | Competition | ||||||||||||||

| Personal | Customization | ||||||||||||||

| Performance | |||||||||||||||

| Ecological | |||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Social | Competition | ||||||||||||||

| Authors(year) | Tailored approach | Game element clusters | Game elements | Game mechanics | |||||||

| Authors(year) | Tailored approach | Game element clusters | Game elements | Game mechanics | |||||||

|

Socialization | Social pressure | |||||||||

| Sezgin and Yüzer (2022) | Modeling | No info | Info | No info | |||||||

| Tenório, Dermeval, et al. (2020) | Modeling | Performance | Reward | Point, badge | |||||||

| Social | Competition | Leaderboard | |||||||||

| – | Storytelling/story | ||||||||||

| Tenório et al. (2021) | Modeling | Personal |

|

||||||||

| Zaric et al. (2017) | Modeling | Performance |

|

|

|||||||

| – | Time pressure | ||||||||||

| Abbasi et al. (2021) | Personalization | Performance |

|

Map | |||||||

| Feedback | |||||||||||

| Personal | Challenge | Puzzle | |||||||||

| Authors(year) | Tailored approach | Game element clusters | Game elements | Game mechanics | |||||||

| Buckley and Doyle (2017) | Personalization |

|

|

Point, badge, virtual goods | |||||||

| Competition | Leaderboard | ||||||||||

| Cooperation |

|

||||||||||

| Personal | |||||||||||

| Eder et al. (2021) | Personalization | Performance | Reward | Point | |||||||

| Feedback | |||||||||||

| Social | Competition | ||||||||||

| Personal | Customization | Avatar | |||||||||

| Challenge | |||||||||||

| Hallifax et al. (2020) | Personalization | Performance | Reward | Point, badge | |||||||

| Progress | Level | ||||||||||

| Ecological | Time pressure | Timer | |||||||||

| Social | Competition | Point, badge, leaderboard | |||||||||

| Maher et al. (2020) | Personalization | No info | No info | No info | |||||||

| Missaoui and Maalel (2021) | Personalization | No info | No info | No info | |||||||

| Roosta et al. (2016) | Personalization | Performance | Progress | Progress bar | |||||||

| Feedback | |||||||||||

| Shabihi et al. (2016) | Personalization | Performance |

|

Point, badge | |||||||

| Feedback | |||||||||||

| Personal | Goal | ||||||||||

| Daghestani et al. (2020) | Adaptation | Performance |

|

External resources | |||||||

| Ecological |

|

||||||||||

| Social |

|

|

|||||||||

| Authors(year) | Tailored approach | Game element clusters | Game elements | Game mechanics | |||||||

| Personal |

|

Navigation interface | |||||||||

| Authors(year) | Tailored approach | Game element clusters | Game elements | Game mechanics | ||||

| Hassan et al. (2021) | Adaptation | Performance |

|

|

||||

|

|

Leaderboard | ||||||

| Jahušt et al. (2018) | Adaptation | Performance |

|

|||||

| Ecological | Time pressure | |||||||

| Social | Competition | |||||||

|

||||||||

| Fictional |

|

|||||||

| Kolpikova et al. (2019) | Adaptation | Performance | Reward | Point | ||||

| Feedback | Hint | |||||||

| Ecological | Choice | |||||||

| Maher et al. (2020) | Adaptation | No info | No info | No info | ||||

| Missaoui and Maalel (2021) | Adaptation | No info | No info | No info | ||||

| Monterrat et al. (2017) | Adaptation | Performance | Progress | Level | ||||

| Ecological | Choice | |||||||

| Access | New task | |||||||

| Social | Competition | Leaderboard | ||||||

| Rodríguez et al. (2022) | Adaptation | Performance | Reward | Point, badge | ||||

| Progress | Level | |||||||

| Ecological | Access | Mini-game, Easter egg | ||||||

| Chance | Lottery, development pool | |||||||

| Social |

|

Leaderboard | ||||||

| Authors(year) | Tailored approach | Game element clusters | Game elements | Game mechanics | ||||

| Shi and Cristea (2016) | Adaptation | Personal | Socialization | Social network, social status | ||||

| Ecological |

|

|||||||

| Chance | ||||||||

| Social |

|

|||||||

| Personal |

|

|||||||

| Tan and Cheah (2021) | Adaptation | Performance |

|

|

||||

| Feedback | Hint | |||||||

| Tenório, ChalcoChallco, et al. (2020) | Adaptation | Personal |

|

|||||

| Challenge | Mission | |||||||

| Xu et al. (2017) | Adaptation | No info | No info | No info | ||||

| Su et al. (2016) | Recommendation | No info | No info | No info |

References

Adomavicius, G., & Tuzhilin, A. (2005). Toward the next generation of recommender systems: A survey of the state-of-the-art and possible extensions. Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 17(6), 734-749.

Aljabali, R. N., & Ahmad, N. (2018). A review on adopting personalized gamified experience in the learning context (pp. 61-66). IEEE Conference on e-Learning, eManagement and e-Services.

Almeida, C., Kalinowski, M., Uchôa, A., & Feijó, B. (2023). Negative effects of gamification in education software: Systematic mapping and practitioner perceptions. Information and Software Technology, 156, Article 107142.

Altaie, M. A., & Jawawi, D. N. A. (2021). Adaptive gamification framework to promote computational thinking in 8-13 year olds. Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society, 17(3), 89-100.

Amiel, T., & Reeves, T. C. (2008). Design-based research and educational technology: Rethinking technology and the research agenda. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 11(4), 29-40.

Azzi, I., Jeghal, A., Radouane, A., Yahyaouy, A., & Tairi, H. (2020). A robust classification to predict learning styles in adaptive E-learning systems. Education and Information Technologies, 25(1), 437-448.

Barata, G., Gama, S., Jorge, J., & Gonçalves, D. (2015). Gamification for smarter learning: Tales from the trenches. Smart Learning Environments, 2(1), 1-23.

Bennani, S., Maalel, A., & Ghezala, H. B. (2020). AGE-Learn: Ontology-based representation of personalized gamification in E-learning. Procedia Computer Science, 176, 1005-1014.

Buckley, P., & Doyle, E. (2017). Individualising gamification: An investigation of the impact of learning styles and personality traits on the efficacy of gamification using a prediction market. Computers & Education, 106, 43-55.

Codish, D., & Ravid, G. (2014). Personality based gamification-Educational gamification for extroverts and introverts. Proceedings of the 9th CHAIS Conference for the Study of Innovation and Learning Technologies: Learning in the Technological Era, 1, 36-44.

Daghestani, L. F., Ibrahim, L. F., Al-Towirgi, R. S., & Salman, H. A. (2020). Adapting gamified learning systems using educational data mining techniques. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 28(3), 568-589.

de la Peña, D., Lizcano, D., & Martínez-Álvarez, I. (2021). Learning through play: Gamification model in university-level distance learning. Entertainment Computing, 39.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In In proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments (pp. 9-15).

Dykens, I. T., Wetzel, A., Dorton, S. L., & Batchelor, E. (2021). Towards a unified model of gamification and motivation. International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 53-70.

Eder, G. M. J., Mirna, M., Héctor, C. R., & Jezreel, M. (2021). Designing a player-persona for gamification learning experiences.

Elliot, A. J., & Murayama, K. (2008). On the measurement of achievement goals: Critique illustration and application. Educational Psychology, 100, 613-628.

Fishman, B. J., Penuel, W. R., Allen, A. R., Cheng, B. H., & Sabelli, N. O. R. A. (2013). Design-based implementation research: An emerging model for transforming the relationship of research and practice. Teachers College Record, 115(14), 136-156.

Gil, B., Cantador, I., & Marczewski, A. (2015). Validating gamification mechanics and player types in an e-learning environment (pp. 568-572). European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning.

González, C. S., Toledo, P., & Muñoz, V. (2016). Enhancing the engagement of intelligent tutorial systems through personalization of gamification. International Journal of Engineering Education, 32(1), 532-541.

Hallifax, S., Lavoué, E., & Serna, A. (2020). To tailor or not to tailor gamification? An analysis of the impact of tailored game elements on learners’ behaviours and motivation. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, 216-227.

Hallifax, S., Serna, A., Marty, J. C., & Lavoué, É. (2019). Adaptive gamification in education: A literature review of current trends and developments (pp. 294-307). European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning.

Hammami, J., & Khemaja, M. (2019). Towards agile and gamified flipped learning design models: Application to the system and data integration course. Procedia Computer Science, 164, 239-244.

Hanus, M. D., & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & education, 80, 152-161.

Hassan, M. A., Habiba, U., Majeed, F., & Shoaib, M. (2021). Adaptive gamification in E-learning based on students’ learning styles. Interactive Learning Environments, 29(4), 545-565.

Imre, Z. (2020). Ontology based UX personalization for gamified education (pp. 415-422). ENASE.

Jagušt, T., Botički, I., & So, H. J. (2018). Examining competitive, collaborative and adaptive gamification in young learners’ math learning. Computers & Education, 125, 444-457.

Klock, A. C. T., da Cunha, L. F., de Cravalho, M. F., Rosa, B. E., Anton, A. J., & Gasparini, I. (2015b). Gamification in E-learning systems: A conceptual model to engage students and its application in an adaptive e-learning system. International Conference on Learning and Collaboration Technologies, 595-607.

Klock, A. C. T., Gasparini, I., Pimenta, M. S., & de Oliveira, J. P. M. (2015). Everybody is playing the game, but nobody’s rules are the same: Towards adaptation of gamification based on users’ characteristics. Bulletin of the Technical Committee on Learning Technology, 17(4), 22-25.

Klock, A. C. T., Gasparini, I., Pimenta, M. S., & Hamari, J. (2020). Tailored gamification: A review of literature. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 144.

Klock, A. C. T., Pimenta, M. S., & Gasparini, I. (2018). A systematic mapping of the customization of game elements in gamified systems. Brazilian Symposium on Computer Games and Digital Entertainment, 11-18.

Knutas, A., Van Roy, R., Hynninen, T., Granato, M., Kasurinen, J., & Ikonen, J. (2019). A process for designing algorithm-based personalized gamification. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 78(10), 13593-13612.

Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191-210.

Kolpikova, E. P., Chen, D. C., & Doherty, J. H. (2019). Does the format of preclass reading quizzes matter? An evaluation of traditional and gamified, adaptive preclass reading quizzes. CBE-life Sciences Education, 18(4), 1-10.

Krath, J., Schürmann, L., & Von Korflesch, H. F. (2021). Revealing the theoretical basis of gamification: A systematic review and analysis of theory in research on gamification, serious games and game-based learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 125, Article 106963.

Kreuter, M. W., Farrell, D. W., Olevitch, L. R., & Brennan, L. K. (2013). Tailoring health messages: Customizing communication with computer technology. Routledge.

Lopes, V., Reinheimer, W., Medina, R., Bernardi, G., & Nunes, F. B. (2019). Adaptive gamification strategies for education: A systematic literature review. Brazilian Symposium on Computers in Education, 30, 1032-1041.

Madrid, M. A. C., & Jesus, D. M. A. D. (2021). Towards the design and development of an adaptive gamified task management web application to increase student engagement in online learning. International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 215-223.

Maher, Y., Moussa, S. M., & Khalifa, M. E. (2020). Learners on focus: Visualizing analytics through an integrated model for learning analytics in adaptive gamified elearning. IEEE Access, 8, 197597-197616.

Missaoui, S., & Maalel, A. (2021). Student’s profile modeling in an adaptive gamified learning environment. Education and Information Technologies, 26(5), 6367-6381.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group*.. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264-269.

Monterrat, B., Desmarais, M., Lavoué, E., & George, S. (2015). A player model for adaptive gamification in learning environments. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, 297-306.

Monterrat, B., Lavoué, É., & George, S. (2014). Toward an adaptive gamification system for learning environments. International Conference on Computer Supported Education, 115-129.

Monterrat, B., Lavoué, É., & George, S. (2014b). A framework to adapt gamification in learning environments (pp. 578-579). European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning.

Monterrat, B., Lavoué, É., & George, S. (2017). Adaptation of gaming features for motivating learners. Simulation & Gaming, 48(5), 625-656.

Mora, A., Tondello, G. F., Nacke, L. E., & Arnedo-Moreno, J. (2018). Effect of personalized gameful design on student engagement (pp. 1925-1933). IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON).

Oliveira, W., & Bittencourt, I. I. (2019). Tailored gamification to educational technologies. Singapore: Springer.

Oliveira, W., Hamari, J., Shi, L., Toda, A. M., Rodrigues, L., Palomino, P. T., & Isotani, S. (2022). Tailored gamification in education: A literature review and future agenda. Education and Information Technologies, 1-34.

Palomino, P. T., Toda, A. M., Oliveira, W., Cristea, A. I., & Isotani, S. (2019). Narrative for gamification in education: Why should you care? International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), 97-99.

Qiao, S., Yeung, S. S. S., Zainuddin, Z., Ng, D. T. K., & Chu, S. K. W. (2023). Examining the effects of mixed and non-digital gamification on students’ learning performance, cognitive engagement and course satisfaction. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(1), 394-413.

Rodríguez, I., Puig, A., & Rodríguez, À. (2022). Towards adaptive gamification: A method using dynamic player profile and a case study. Applied Sciences, 12(1), 486-504.

Roosta, F., Taghiyareh, F., & Mosharraf, M. (2016). Personalization of gamification-elements in an E-learning environment based on learners’ motivation. International Symposium on Telecommunications (IST), 637-642.

Santos, W. O. D., Bittencourt, I. I., & Vassileva, J. (2018). Design of tailored gamified educational systems based on gamer types (pp. 42-51). CBIE.

Santos, A. C. G., Oliveira, W., Hamari, J., Rodrigues, L., Toda, A. M., Palomino, P. T., & Isotani, S. (2021). The relationship between user types and gamification designs. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 31(5), 907-940.

Sezgin, S., & Yüzer, T. V. (2022). Analysing adaptive gamification design principles for online courses. Behaviour & Information Technology, 41(3),

Shabihi, N., Taghiyareh, F., & Abdoli, M. H. (2016). Analyzing the effect of game-elements in E-learning environments through MBTI-based personalization. International Symposium on Telecommunications (IST), 612-618.

Shi, L., & Cristea, A. I. (2016). Motivational Gamification strategies rooted in self-determination theory for social adaptive E-Learning. Intelligent Tutoring Systems, 294-300.

Su, C. H., Fan, K. K., & Su, P. Y. (2016). A intelligent Gamifying learning recommender system integrated with learning styles and Kelly repertory grid technology. International Conference on Applied System Innovation (ICASI), 1-4.

Tan, D. Y., & Cheah, C. W. (2021). Developing a gamified AI-enabled online learning application to improve students’ perception of university physics. Computers and education: Artificial Intelligence, 2.

Tenório, K., Chalco Challco, G., Dermeval, D., Lemos, B., Nascimento, P., Santos, R., & Pedro da Silva, A. (2020). Helping teachers assist their students in gamified adaptive educational systems: Towards a gamification analytics tool. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, 312-317.

Tenório, K., Dermeval, D., Monteiro, M., Peixoto, A., & Pedro, A. (2020b). Raising teachers empowerment in gamification design of adaptive learning systems: A qualitative research. International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, 524-536.

Tenório, K., Dermeval, D., Monteiro, M., Peixoto, A., & Silva, A. P. D. (2021). Exploring design concepts to enable teachers to monitor and adapt gamification in adaptive learning systems: A qualitative research approach. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 1-25.

Toda, A. M., Klock, A. C., Oliveira, W., Palomino, P. T., Rodrigues, L., Shi, L., Bittencourt, lg, Gasparini, I., Isotani, S., & Cristea, A. I. (2019). Analysing gamification elements in educational environments using an existing Gamification taxonomy. Smart Learning Environments, 6(1), 1-14.

Toda, A. M., Valle, P. H. D., & Isotani, S. (2017). The dark side of gamification: An overview of negative effects of gamification in education. In Proceedings of the researcher links workshop (pp. 143-156).

Van Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2018). Need-supporting gamification in education: An assessment of motivational effects over time. Computers & Education, 127, 283-297.

Wei, X., Saab, N., & Admiraal, W. (2021). Assessment of cognitive, behavioral, and affective learning outcomes in massive open online courses: A systematic literature review. Computers & Education, 163, Article 104097.

Xu, H., Song, D., Yu, T., & Tavares, A. (2017). An enjoyable learning experience in personalising learning based on knowledge management: A case study. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(7), 3001-3018.

Xu, Y., & Tang, Y. (2015). Based on action-personality data mining, research of gamification emission reduction mechanism and intelligent personalized action recommendation model. Cross-Cultural Design Methods, Practice and Impact: 7th International Conference, 241-252.

Yildirim, I. (2017). The effects of gamification-based teaching practices on student achievement and students’ attitudes toward lessons. The Internet and Higher Education, 33, 86-92.

Zaric, N., Scepanović, S., Vujicic, T., Ljucovic, J., & Davcev, D. (2017). The model for gamification of E-learning in higher education based on learning styles. International Conference on ICT Innovations, 265-273.

- Corresponding author. at: ICLON, Leiden University Graduate School of Teaching, Leiden University, Kolffpad 1, 2333 BN, Leiden, the Netherlands.

E-mail addresses: y.hong@iclon.leidenuniv.nl (Y. Hong), n.saab@iclon.leidenuniv.nl (N. Saab), wilfried@oslomet.no (W. Admiraal).