DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-024-00963-y

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-15

الإدراك البصري في نماذج اللغة الكبيرة متعددة الوسائط

تاريخ القبول: 25 نوفمبر 2024

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 15 يناير 2025

تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

هدف رئيسي من الذكاء الاصطناعي هو بناء آلات تفكر مثل البشر. ومع ذلك، تم الإشارة إلى أن هياكل الشبكات العصبية العميقة تفشل في تحقيق ذلك. وقد أكد الباحثون على قيود هذه النماذج في مجالات التفكير السببي، والفيزياء الحدسية، وعلم النفس الحدسي. ومع ذلك، فإن التقدمات الأخيرة، ولا سيما ظهور نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، وخاصة تلك المصممة للمعالجة البصرية، قد أعادت إشعال الاهتمام في الإمكانية لتقليد القدرات الإدراكية البشرية. تقيم هذه الورقة الحالة الحالية لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة المعتمدة على الرؤية في مجالات الفيزياء الحدسية، والتفكير السببي، وعلم النفس الحدسي. من خلال سلسلة من التجارب المنضبطة، نحقق في مدى فهم هذه النماذج الحديثة للتفاعلات الفيزيائية المعقدة، والعلاقات السببية، والفهم الحدسي لتفضيلات الآخرين. تكشف نتائجنا أنه، بينما تظهر بعض هذه النماذج كفاءة ملحوظة في معالجة وتفسير البيانات البصرية، إلا أنها لا تزال تقصر عن القدرات البشرية في هذه المجالات. تؤكد نتائجنا على الحاجة إلى دمج آليات أكثر قوة لفهم السببية، والديناميات الفيزيائية، والإدراك الاجتماعي في نماذج اللغة المعتمدة على الرؤية الحديثة، وتشير إلى أهمية المعايير المستوحاة من الإدراك.

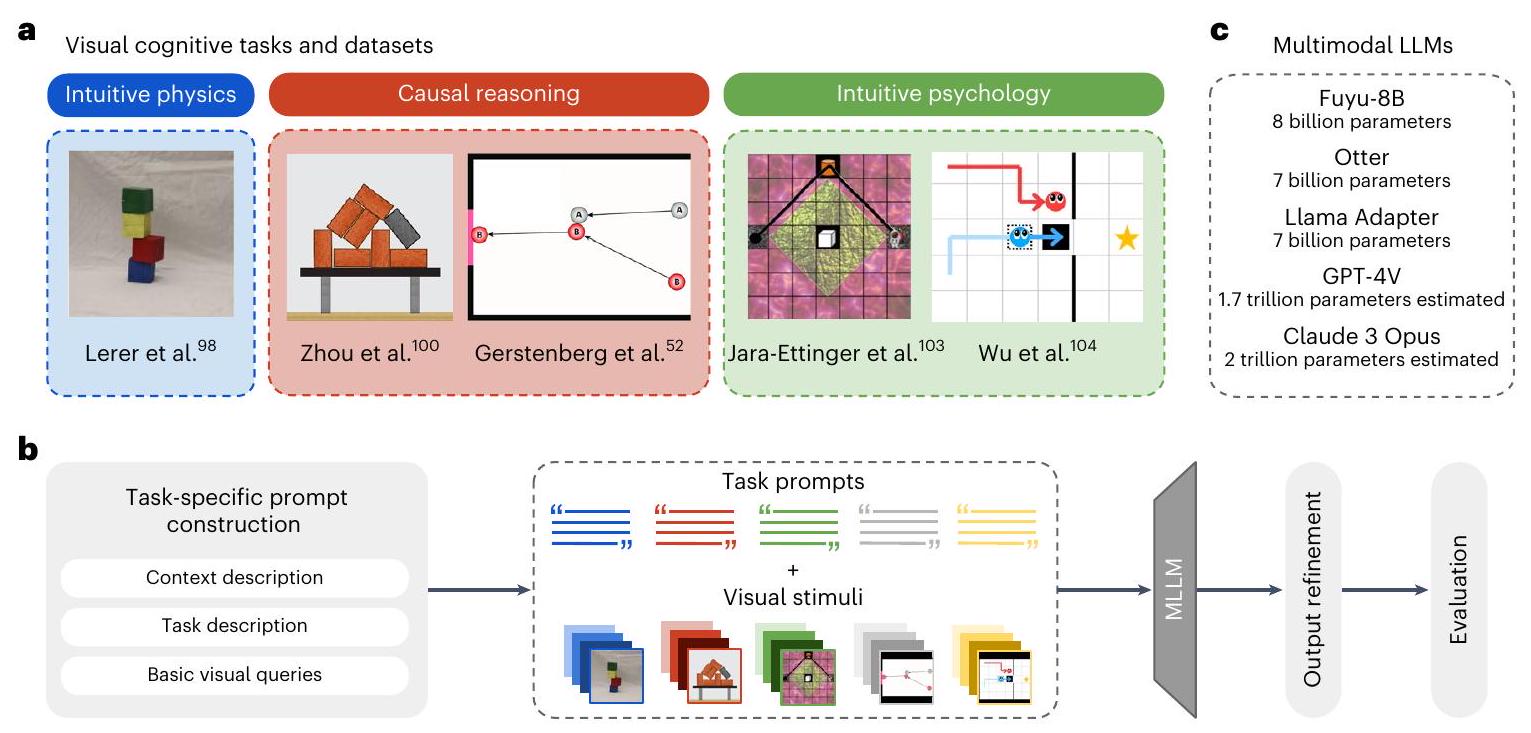

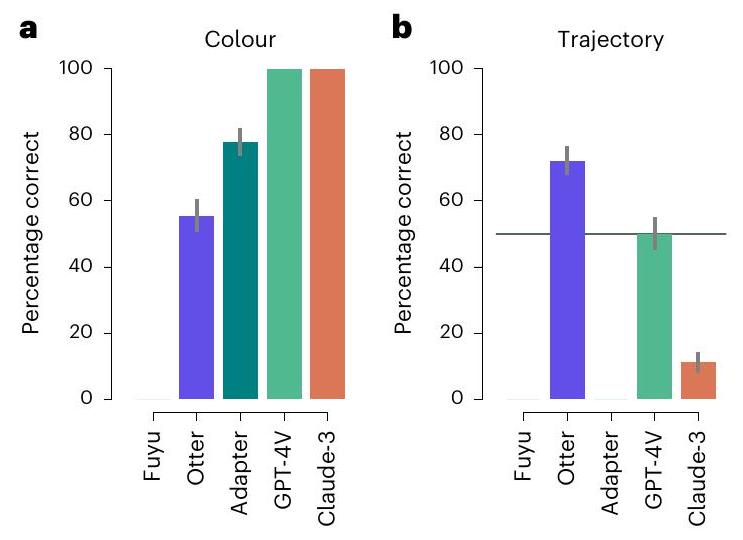

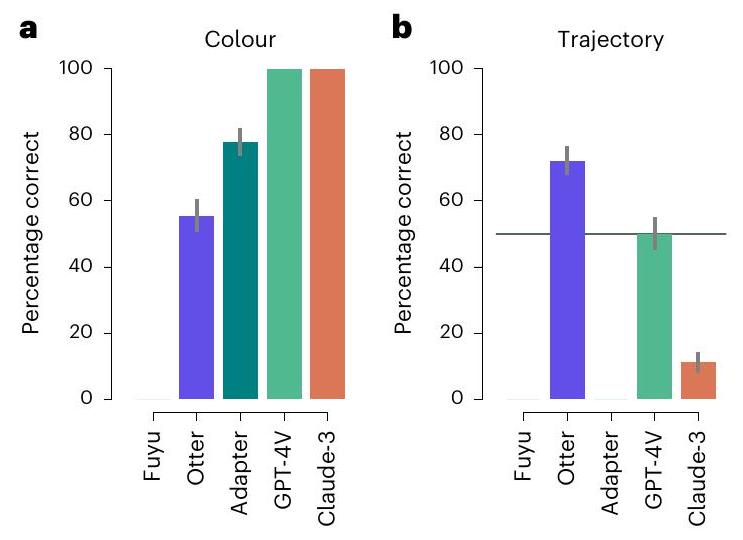

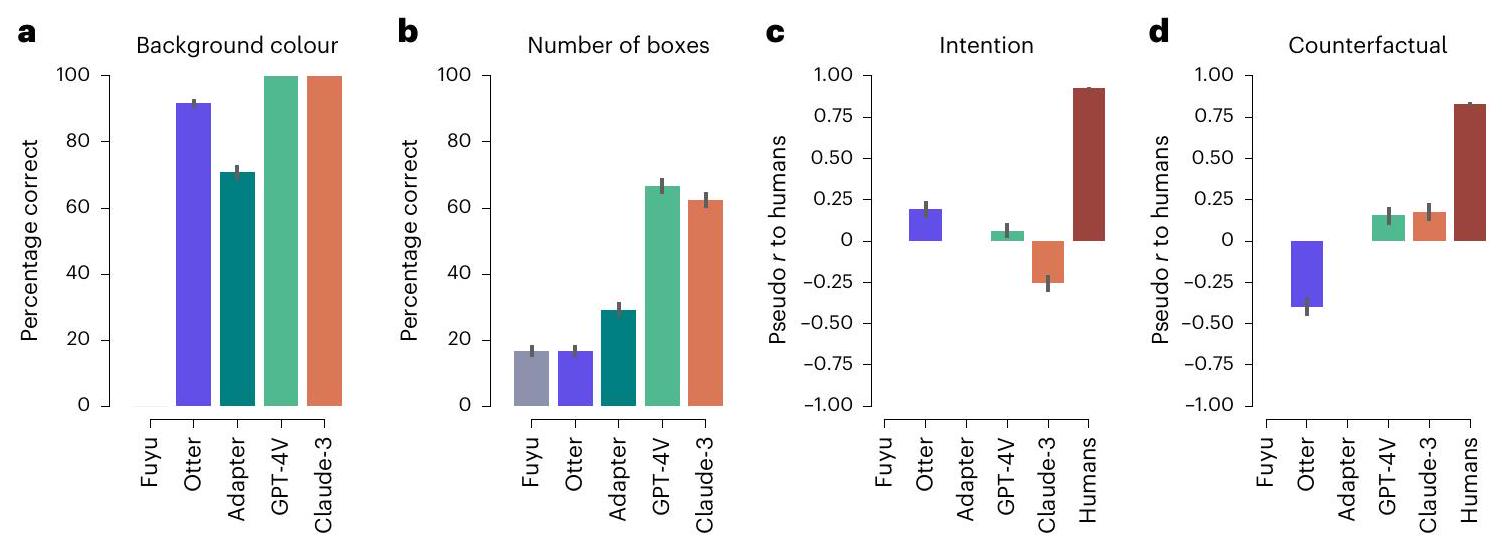

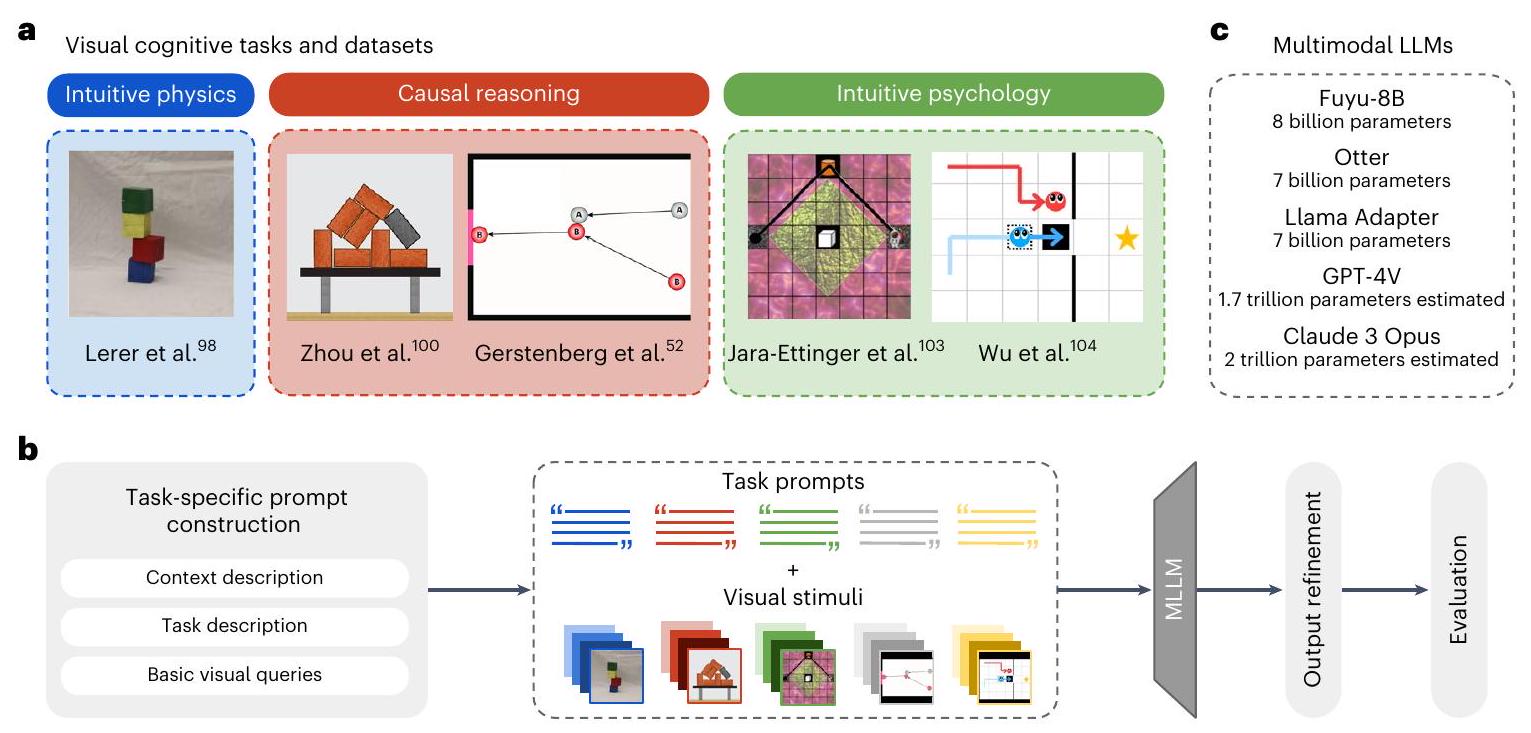

النهج. لكل استفسار، تم تقديم صورة إلى النموذج، وتم طرح أسئلة مختلفة حول الصورة، أي أننا قمنا بإجراء إجابة على سؤال بصري. ج، استخدمت نماذج LLM متعددة الوسائط وحجمها. MLLM، LLM متعددة الوسائط.

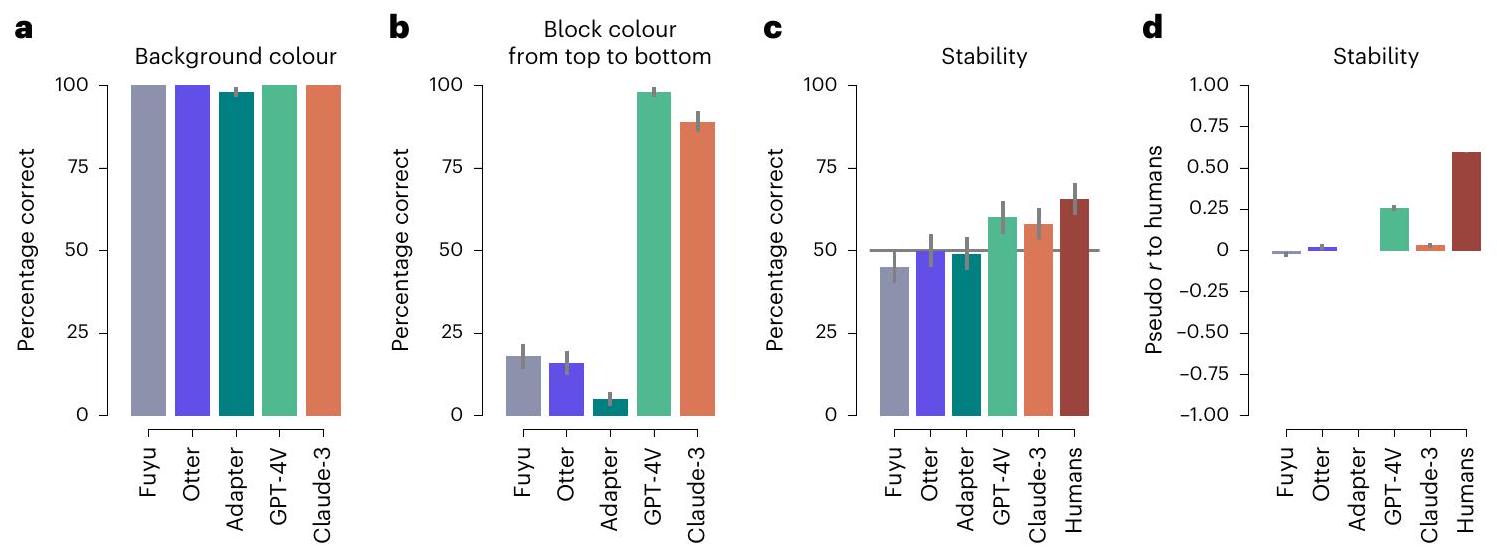

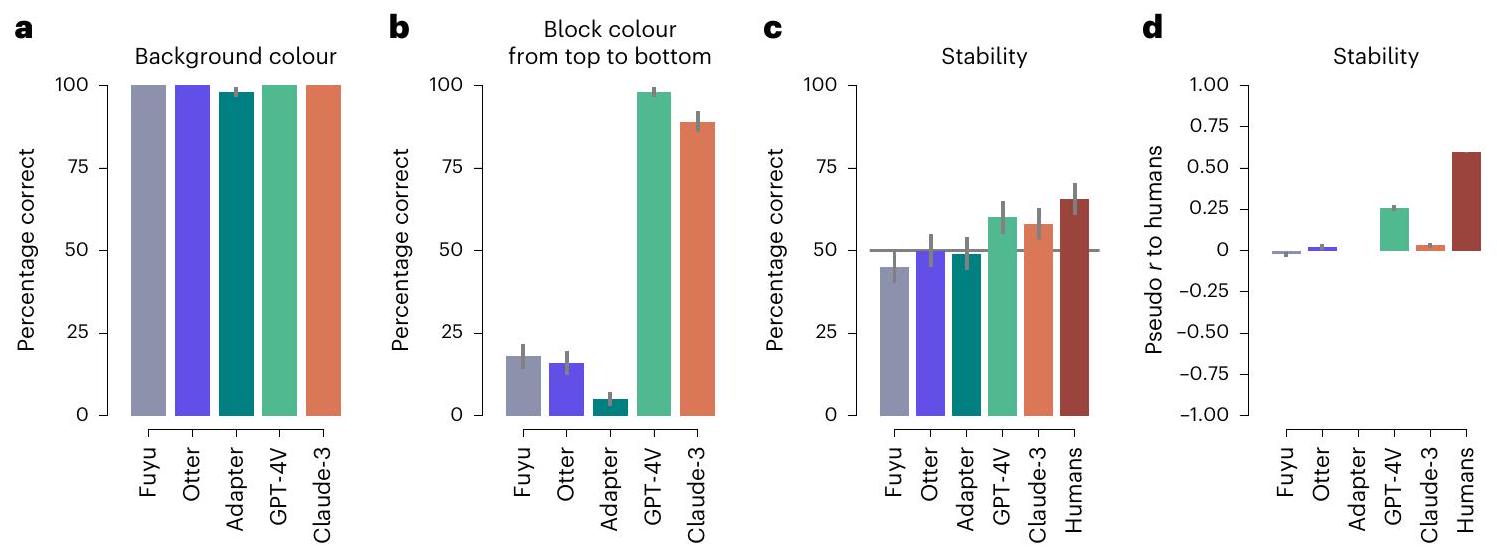

في هذا المجال تتضمن اختبار أحكام الناس حول استقرار أبراج الكتل

قمنا بتقديمها إلى بعض من أكثر نماذج LLMs تقدمًا حاليًا. لتقييم ما إذا كانت نماذج LLMs تظهر أداءً يشبه البشر في هذه المجالات، نتبع النهج الموضح في المرجع 73: نتعامل مع النماذج كمشاركين في التجارب النفسية. وهذا يسمح لنا بإجراء مقارنات مباشرة مع سلوك البشر في هذه المهام. نظرًا لأن المهام مصممة لاختبار القدرات في مجالات معرفية محددة، فإن هذه المقارنة تسمح لنا بالتحقيق في المجالات التي تؤدي فيها نماذج LLMs متعددة الوسائط بشكل مشابه للبشر، وفي أي منها لا تفعل ذلك. أظهرت نتائجنا أن هذه النماذج يمكنها، على الأقل جزئيًا، حل هذه المهام. على وجه الخصوص، تمكن اثنان من أكبر النماذج المتاحة حاليًا، نموذج OpenAI’s Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT-4) وAnthropic’s Claude-3 Opus، من الأداء بشكل قوي فوق الصدفة في اثنين من المجالات الثلاثة. ومع ذلك، ظهرت اختلافات حاسمة. أولاً، لم تتطابق أي من النماذج مع أداء مستوى البشر في أي من المجالات. ثانيًا، لم تلتقط أي من النماذج سلوك البشر بالكامل، مما يترك مجالًا لنماذج الإدراك الخاصة بالمجالات مثل النماذج البايزية التي اقترحت في الأصل للمهام.

الأعمال ذات الصلة

وشولز

النتائج

فيزياء بديهية مع أبراج الكتل

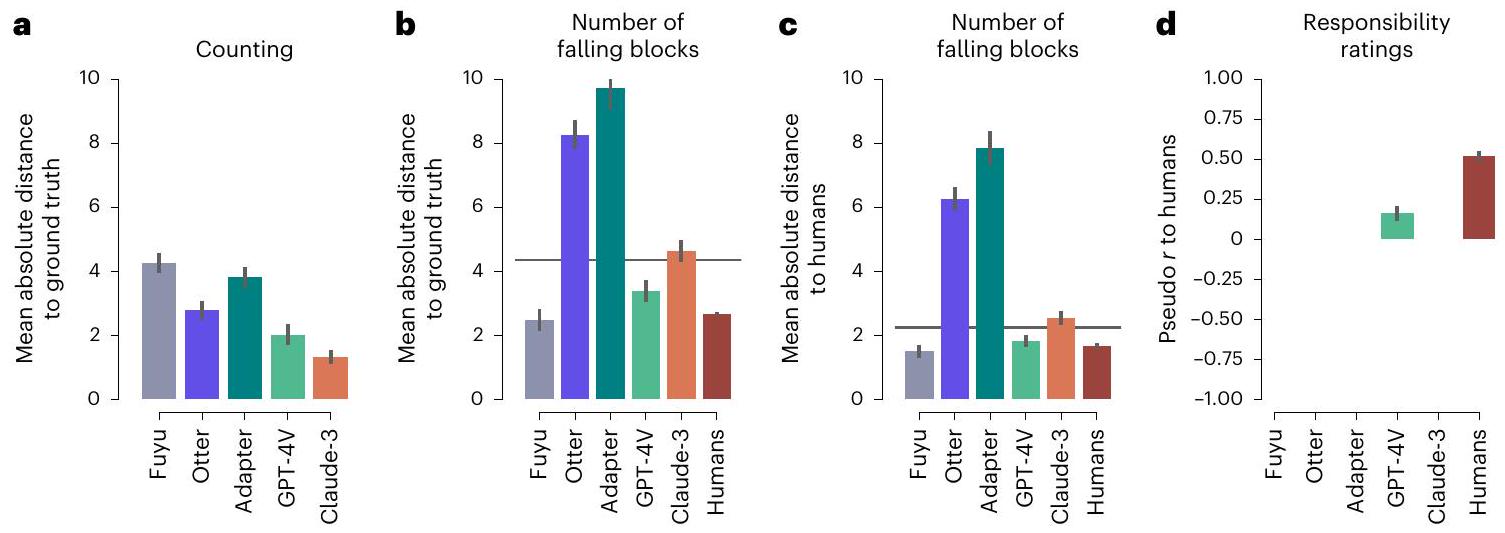

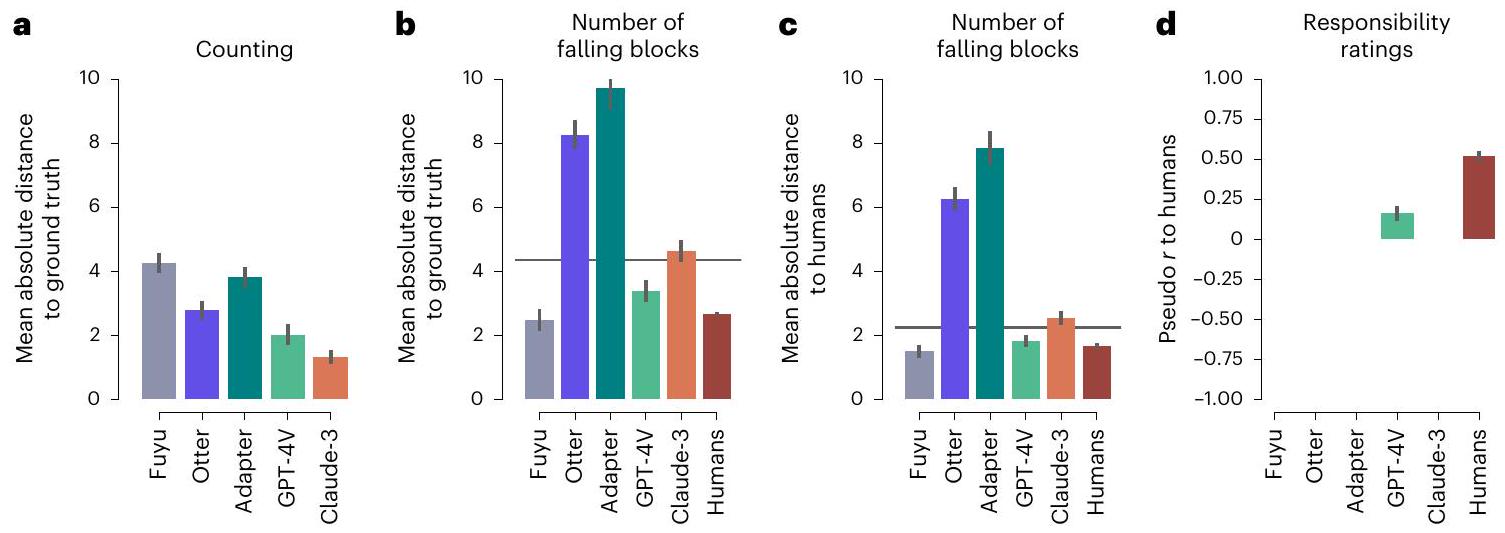

الاستدلال السببي مع جينغا

قارب الحقيقة الأرضية، وإن كان نادراً ما يتطابق معها تماماً. لذلك، نبلغ عن متوسط المسافة المطلقة إلى الحقيقة الأرضية بدلاً من نسبة الإجابات الصحيحة (الشكل 3أ). أظهرت أداء النماذج الطبيعة التحديّة لهذه المهمة، حيث كانت أفضل نموذج (كلود-3) لا يزال في المتوسط أكثر من كتلة واحدة بعيداً.

الاستدلال السببي مع ميشوت

‘منتصف البوابة’ (إذا دخلت الكرة B البوابة) أو ‘الكرة B فاتتها البوابة تمامًا’ (إذا فاتت الكرة B البوابة) (الشكل 4c). لا يوجد نموذج يحقق نتائج قريبة من النتائج البشرية المبلغ عنها في المرجع 52. أفضل نموذج أداء هو Fuyu مع معامل انحدار قدره 0.26 (

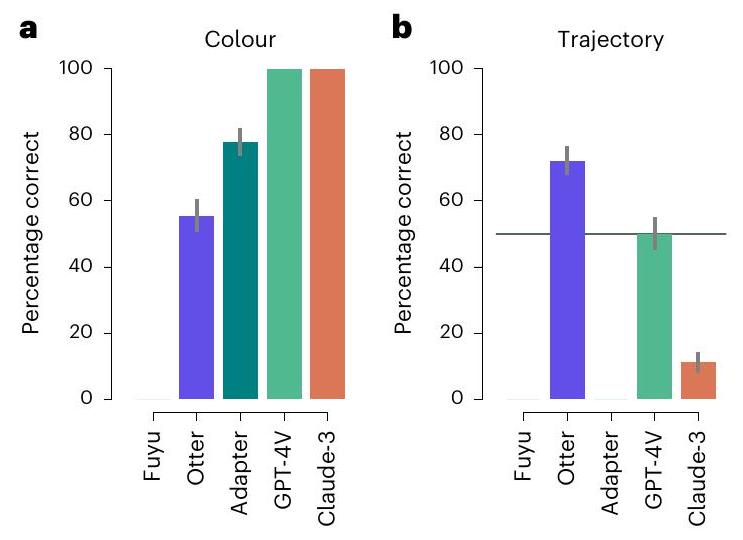

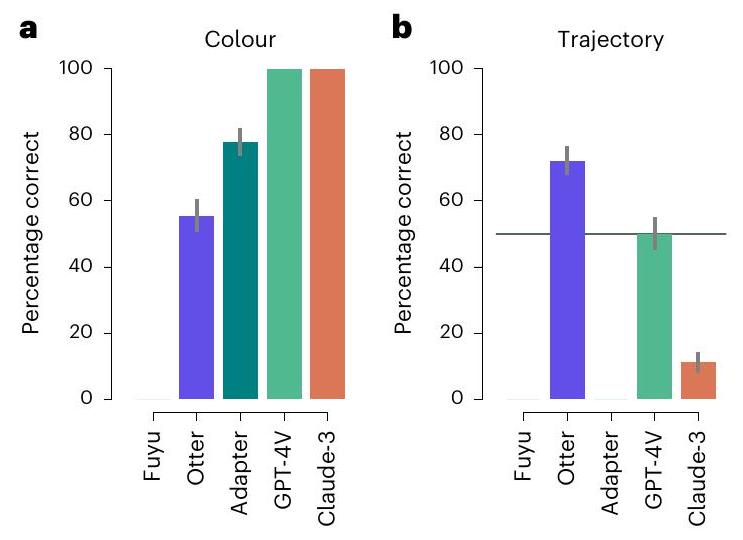

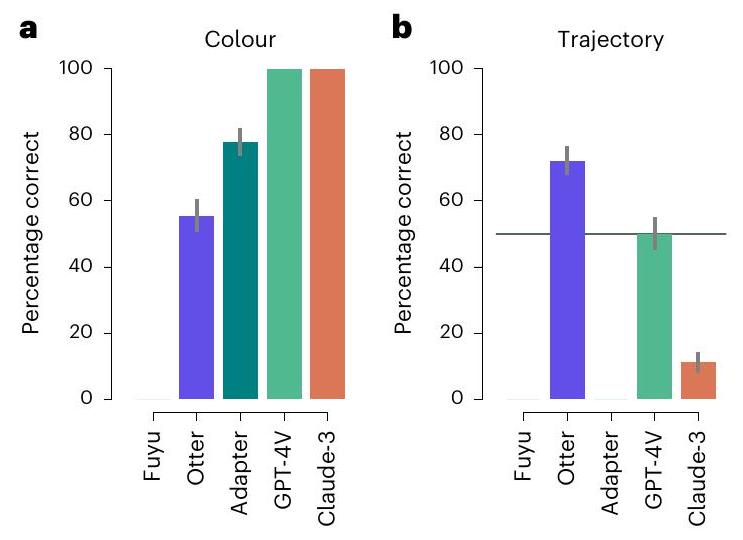

علم النفس الحدسي مع مهمة رائد الفضاء

معاملات النماذج مع

علم النفس الحدسي مع مهمة المساعدة أو العائق

من المأخوذ من المرجع 104. الأعمدة في الرسوم البيانية

نقاش

كنت أتوقع أن تؤدي النماذج بشكل أفضل إذا كانت المحفزات تحتوي على صور أكثر واقعية للأشخاص، وهو ما أظهرته الدراسات السابقة أنه يعمل بشكل أفضل.

بين البشر والآلات

طرق

كود

نماذج

مجموعات البيانات

المشاهد: كلفناهم بتحديد لون الخلفية وعدد الكتل في الصورة. لاختبار فهمهم الفيزيائي، اختبرناهم على نفس المهمة كما في الدراسة الأصلية: طلبنا منهم إعطاء تقييم ثنائي حول استقرار أبراج الكتل المرسومة. بالنسبة للمهمتين الأوليين، حسبنا نسبة الإجابات الصحيحة لكل من النماذج. بالنسبة للمهمة الثالثة، حسبنا انحدار بايزي الخطي المختلط بين إجابات البشر والنماذج.

تصطدم بالكرة

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الكود

References

- Mitchell, M. Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans (Penguin, 2019).

- Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proc. 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers) (eds Burstein, J. et al.) 4171-4186 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019).

- Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017) (eds Guyon, I. et al.) 5998-6008 (2017).

- Brown, T. et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020) (eds Larochelle, H. et al.) 1877-1901 (Curran Associates, 2020).

- Bubeck, S. et al. Sparks of artificial general intelligence: early experiments with GPT-4. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/ abs/2303.12712 (2023).

- Wei, J. et al. Emergent abilities of large language models. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. https://openreview.net/forum?id=yzkSU5zdwD (2022).

- Katz, D. M., Bommarito, M. J., Gao, S. & Arredondo, P. GPT-4 passes the bar exam. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 382, 2270 (2024).

- Sawicki, P. et al. On the power of special-purpose gpt models to create and evaluate new poetry in old styles. In Proc. 14th International Conference on Computational Creativity (ICCC’23) (eds Pease, A. et al.) 10-19 (Association for Computational Creativity, 2023).

- Borsos, Z. et al. Audiolm: a language modeling approach to audio generation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process 31, 2523-2533 (2023).

- Poldrack, R. A., Lu, T. & Beguš, G. Ai-assisted coding: experiments with GPT-4. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.13187 (2023).

- Kasneci, E. et al. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 103, 102274 (2023).

- Bommasani, R. et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07258 (2021).

- Elkins, K. & Chun, J. Can GPT-3 pass a writer’s Turing test? J. Cult. Anal. 5, 2 (2020).

- Dell’Acqua, F. et al. Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality. Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Mgt. Unit Working Paper (Harvard Business School, 2023).

- Bašić, Ž., Banovac, A., Kružić, I. & Jerković, I. Better by you, better than me? ChatGPT-3.5 as writing assistance in students’ essays. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 10, 750 (2023).

- Akata, E. et al. Playing repeated games with large language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.16867 (2023).

- Simon, H. A. Cognitive science: the newest science of the artificial. Cogn. Sci. 4, 33-46 (1980).

- Rumelhart, D. E. et al. Parallel Distributed Processing, Vol.1 (MIT Press, 1987).

- Wichmann, F. A. & Geirhos, R. Are deep neural networks adequate behavioral models of human visual perception? Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 9, 501-524 (2023).

- Bowers, J. S. et al. On the importance of severely testing deep learning models of cognition. Cogn. Syst. Res. 82, 101158 (2023).

- Marcus, G. Deep learning: a critical appraisal. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.00631 (2018).

- Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Gershman, S. J. Building machines that learn and think like people. Behav. Brain Sci. 40, e253 (2017).

- Sejnowski, T. J. The Deep Learning Revolution (MIT, 2018).

- Smith, K. A., Battaglia, P. W. & Vul, E. Different physical intuitions exist between tasks, not domains. Comput. Brain Behav. 1, 101-118 (2018).

- Bates, C. J., Yildirim, I., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Battaglia, P. Modeling human intuitions about liquid flow with particle-based simulation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15, e1007210 (2019).

- Battaglia, P. et al. Computational models of intuitive physics. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 34, 32-33 (2012).

- Bramley, N. R., Gerstenberg, T., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Gureckis, T. M. Intuitive experimentation in the physical world. Cogn. Psychol. 105, 9-38 (2018).

- Ullman, T. D. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Bayesian models of conceptual development: learning as building models of the world. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2, 533-558 (2020).

- Ullman, T. D., Spelke, E., Battaglia, P. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Mind games: game engines as an architecture for intuitive physics. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 649-665 (2017).

- Hamrick, J., Battaglia, P. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Probabilistic internal physics models guide judgments about object dynamics. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 33, 1545-1550 (2011).

- Mildenhall, P. & Williams, J. Instability in students’ use of intuitive and Newtonian models to predict motion: the critical effect of the parameters involved. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 23, 643-660 (2001).

- Todd, J. T. & Warren, W. H. Jr Visual perception of relative mass in dynamic events. Perception 11, 325-335 (1982).

- Battaglia, P. W., Hamrick, J. B. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Simulation as an engine of physical scene understanding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 18327-18332 (2013).

- Hamrick, J. B., Battaglia, P. W., Griffiths, T. L. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Inferring mass in complex scenes by mental simulation. Cognition 157, 61-76 (2016).

- Bakhtin, A., van der Maaten, L., Johnson, J., Gustafson, L. & Girshick, R. PHYRE: a new benchmark for physical reasoning. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (NeurIPS 2019) (eds Wallach, H. et al.) 5082-5093 (Curran Associates, 2019).

- Riochet, R. et al. Intphys: a framework and benchmark for visual intuitive physics reasoning. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/ abs/1803.07616 (2018).

- Schulze Buschoff, L. M., Schulz, E. & Binz, M. The acquisition of physical knowledge in generative neural networks. In Proc. 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Krause, A. et al.) 202, 30321-30341 (JMLR, 2023).

- Waldmann, M. The Oxford Handbook of Causal Reasoning (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017).

- Cheng, P. W. From covariation to causation: a causal power theory. Psychol. Rev. 104, 367 (1997).

- Holyoak, K. J. & Cheng, P. W. Causal learning and inference as a rational process: the new synthesis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 62, 135-163 (2011).

- Pearl, J. Causality (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009).

- Griffiths, T. L. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Theory-based causal induction. Psychol. Rev. 116, 661 (2009).

- Lagnado, D. A., Waldmann, M. R., Hagmayer, Y. & Sloman, S. A. in Causal Learning: Psychology, Philosophy, and Computation (eds Gopnik, A. and Schulz, L.) 154-172 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2007).

- Carey, S. On the Origin of Causal Understanding (Clarendon Press/ Oxford Univ. Press, 1995).

- Gopnik, A. et al. A theory of causal learning in children: causal maps and Bayes nets. Psychol. Rev. 111, 3 (2004).

- Lucas, C. G. & Griffiths, T. L. Learning the form of causal relationships using hierarchical bayesian models. Cogn. Sci. 34, 113-147 (2010).

- Bramley, N. R., Gerstenberg, T., Mayrhofer, R. & Lagnado, D. A. Time in causal structure learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 44, 1880 (2018).

- Griffiths, T. L. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Structure and strength in causal induction. Cogn. Psychol. 51, 334-384 (2005).

- Schulz, L., Kushnir, T. & Gopnik, A. in Causal Learning: Psychology, Philosophy, and Computation (eds Gopnik, A. and Schulz, L.) 67-85 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2007).

- Bramley, N. R., Dayan, P., Griffiths, T. L. & Lagnado, D. A. Formalizing Neurath’s ship: approximate algorithms for online causal learning. Psychol. Rev. 124, 301 (2017).

- Gerstenberg, T. What would have happened? Counterfactuals, hypotheticals and causal judgements. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 377, 20210339 (2022).

- Gerstenberg, T., Peterson, M. F., Goodman, N. D., Lagnado, D. A. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Eye-tracking causality. Psychol. Sci. 28, 1731-1744 (2017).

- Gerstenberg, T., Goodman, N. D., Lagnado, D. A. & Tenenbaum, J. B. A counterfactual simulation model of causal judgments for physical events. Psychol. Rev. 128, 936 (2021).

- Jin, Z. et al. CLadder: Assessing causal reasoning in language models. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023) (eds Oh, A. et al.) 31038-31065 (Curran Associates, 2023).

- Dasgupta, I. et al. Causal reasoning from meta-reinforcement learning. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.08162 (2019).

- Baker, C. L. & Tenenbaum, J. B. in Plan, Activity, and Intent Recognition: Theory and Practice (eds Sukthankar, G. et al.) 177-204 (Morgan Kaufmann, 2014).

- Jern, A. & Kemp, C. A decision network account of reasoning about other people’s choices. Cognition 142, 12-38 (2015).

- Vélez, N. & Gweon, H. Learning from other minds: an optimistic critique of reinforcement learning models of social learning. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 38, 110-115 (2021).

- Spelke, E. S., Bernier, E. P. & Skerry, A. Core Social Cognition (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

- Baker, C., Saxe, R. & Tenenbaum, J. Bayesian theory of mind: modeling joint belief-desire attribution. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 33, 2469-2474 (2011).

- Frith, C. & Frith, U. Theory of mind. Curr. Biol. 15, R644-R645 (2005).

- Saxe, R. & Houlihan, S. D. Formalizing emotion concepts within a Bayesian model of theory of mind. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 17, 15-21 (2017).

- Baker, C. L. et al. Intuitive theories of mind: a rational approach to false belief. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 28, 69k8c7v6 (2006).

- Shum, M., Kleiman-Weiner, M., Littman, M. L. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Theory of minds: understanding behavior in groups through inverse planning. In Proc. 33rd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 6163-6170 (Curran Associates, 2019).

- Baker, C. L., Jara-Ettinger, J., Saxe, R. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Rational quantitative attribution of beliefs, desires and percepts in human mentalizing. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 0064 (2017).

- Zhi-Xuan, T. et al. Solving the baby intuitions benchmark with a hierarchically Bayesian theory of mind. Preprint at https://arxiv. org/abs/2208.02914 (2022).

- Rabinowitz, N. et al. Machine theory of mind. In Proc. 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Dy, J. & Krause, A.) 80, 4218-4227 (JMLR, 2018).

- Kosinski, M. Theory of mind may have spontaneously emerged in large language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/ 2302.02083 (2023).

- Ullman, T. Large language models fail on trivial alterations to theory-of-mind tasks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.08399 (2023).

- Schulz, L. The origins of inquiry: inductive inference and exploration in early childhood. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16, 382-389 (2012).

- Ullman, T. D. On the Nature and Origin of Intuitive Theories: Learning, Physics and Psychology. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2015).

- Tenenbaum, J. B., Kemp, C., Griffiths, T. L. & Goodman, N. D. How to grow a mind: statistics, structure, and abstraction. Science 331, 1279-1285 (2011).

- Binz, M. & Schulz, E. Using cognitive psychology to understand GPT-3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2218523120 (2023).

- Huang, J. & Chang, K. C.-C. Towards reasoning in large language models: a survey. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023 (eds Rogers, A. et al.) 1049-1065 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023).

- Sawada, T. et al. ARB: Advanced reasoning benchmark for large language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.13692 (2023).

- Wei, J. et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2022) (eds Koyejo, S. et al.) 24824-24837 (Curran Associates, 2022).

- Webb, T., Holyoak, K. J. & Lu, H. Emergent analogical reasoning in large language models. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1526-1541 (2023).

- Coda-Forno, J. et al. Inducing anxiety in large language models increases exploration and bias. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/ abs/2304.11111 (2023).

- Eisape, T. et al. A systematic comparison of syllogistic reasoning in humans and language models. In Proc. 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds Duh, K. et al.) 8425-8444 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024).

- Hagendorff, T., Fabi, S. & Kosinski, M. Human-like intuitive behavior and reasoning biases emerged in large language models but disappeared in ChatGPT. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 833-838 (2023).

- Ettinger, A. What BERT is not: Lessons from a new suite of psycholinguistic diagnostics for language models. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 8, 34-48 (2020).

- Jones, C. R. et al. Distrubutional semantics still can’t account for affordances. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 44, 482-489 (2022).

- Rahwan, I. et al. Machine behaviour. Nature 568, 477-486 (2019).

- Schulz, E. & Dayan, P. Computational psychiatry for computers. iScience 23, 12 (2020).

- Rich, A. S. & Gureckis, T. M. Lessons for artificial intelligence from the study of natural stupidity. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 174-180 (2019).

- Zhang, Y., Pan, J., Zhou, Y., Pan, R. & Chai, J. Grounding visual illusions in language: do vision-language models perceive illusions like humans? In Proc. 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language (eds Bouamor, H. et al.) 5718-5728 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023).

- Mitchell, M., Palmarini, A. B. & Moskvichev, A. Comparing humans, GPT-4, and GPT-4v on abstraction and reasoning tasks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.09247 (2023).

- Zečević, M., Willig, M., Dhami, D. S. & Kersting, K. Causal parrots: large language models may talk causality but are not causal. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. https://openreview.net/ pdf?id=tv46tCzs83 (2023).

- Zhang, C., Wong, L., Grand, G. & Tenenbaum, J. Grounded physical language understanding with probabilistic programs and simulated worlds. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 45, 3476-3483 (2023).

- Jassim, S. et al. GRASP: a novel benchmark for evaluating language grounding and situated physics understanding in multimodal language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/ abs/2311.09048 (2023).

- Kosoy, E. et al. Towards understanding how machines can learn causal overhypotheses. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 45, 363-374 (2023).

- Gandhi, K., Fränken, J.-P., Gerstenberg, T. & Goodman, N. D. Understanding social reasoning in language models with language models. In Proc. 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS ’23) (eds Oh, A. et al.) 13518-13529 (Curran Associates, 2024).

- Srivastava, A. et al. Beyond the imitation game: quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.04615 (2022).

- Baltrušaitis, T., Ahuja, C. & Morency, L.-P. Multimodal machine learning: a survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 41, 423-443 (2018).

- Reed, S. et al. Generative adversarial text to image synthesis. In Proc. 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Balcan, M. F. & Weinberger, K. Q.) 48, 1060-1069 (JMLR, 2016).

- Wu, Q. et al. Visual question answering: a survey of methods and datasets. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 163, 21-40 (2017).

- Manmadhan, S. & Kovoor, B. C. Visual question answering: a state-of-the-art review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53, 5705-5745 (2020).

- Lerer, A., Gross, S. & Fergus, R. Learning physical intuition of block towers by example. In Proc. 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Balcan, M. F. & Weinberger, K. Q.) 48, 430-438 (JMLR, 2016).

- Gelman, A., Goodrich, B., Gabry, J. & Vehtari, A. R-squared for Bayesian regression models. Am. Stat. 73, 307-309 (2019).

- Zhou, L., Smith, K. A., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Gerstenberg, T. Mental Jenga: a counterfactual simulation model of causal judgments about physical support. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 152, 2237 (2023).

- Gerstenberg, T., Zhou, L., Smith, K. A. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Faulty towers: A hypothetical simulation model of physical support. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 39, 409-414 (2017).

- Michotte, A. The Perception of Causality (Basic Books, 1963).

- Jara-Ettinger, J., Schulz, L. E. & Tenenbaum, J. B. The naïve utility calculus as a unified, quantitative framework for action understanding. Cogn. Psychol. 123, 101334 (2020).

- Wu, S. A., Sridhar, S. & Gerstenberg, T. A computational model of responsibility judgments from counterfactual simulations and intention inferences. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 45, 3375-3382 (2023).

- Sutton, R. The bitter lesson. Incomplete Ideas http://www. incompleteideas.net/Incldeas/BitterLesson.html (2019).

- Kaplan, J. et al. Scaling laws for neural language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.08361 (2020).

- Binz, M. & Schulz, E. Turning large language models into cognitive models. In Proc. 12th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) https://openreview.net/ forum?id=eiC4BKypf1 (OpenReview, 2024).

- Rahmanzadehgervi, P., Bolton, L., Taesiri, M. R. & Nguyen, A. T. Vision language models are blind. In Proc. Asian Conference on Computer Vision (ACCV) 18-34 (Computer Vision Foundation, 2024).

- Ju, C., Han, T., Zheng, K., Zhang, Y. & Xie, W. Prompting visual-language models for efficient video understanding. In Proc. Computer Vision – ECCV 2022: 17th European Conference (eds Avidan, S. et al.) 105-124 (Springer, 2022).

- Meding, K., Bruijns, S. A., Schölkopf, B., Berens, P. & Wichmann, F. A. Phenomenal causality and sensory realism. Iperception 11, 2041669520927038 (2020).

- Allen, K. R. et al. Using games to understand the mind. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 1035-1043 (2024).

- Maaz, M., Rasheed, H., Khan, S. & Khan, F. Video-ChatGPT: Towards detailed video understanding via large vision and language models. In Proc. 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds Ku, L.-W. et al.) 12585-12602 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024).

- Golan, T., Raju, P. C. & Kriegeskorte, N. Controversial stimuli: pitting neural networks against each other as models of human cognition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 29330-29337 (2020).

- Golan, T., Siegelman, M., Kriegeskorte, N. & Baldassano, C. Testing the limits of natural language models for predicting human language judgements. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 952-964 (2023).

- Reynolds, L. & McDonell, K. Prompt programming for large language models: beyond the few-shot paradigm. In Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (eds Kitamura, Y. et al.) 314 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2021).

- Strobelt, H. et al. Interactive and visual prompt engineering for ad-hoc task adaptation with large language models. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 29, 1146-1156 (2022).

- Webson, A. & Pavlick, E. Do prompt-based models really understand the meaning of their prompts? In Proc. 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (eds Carpuat, M. et al.) 2300-2344 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022).

- Liu, P. et al. Pre-train, prompt, and predict: a systematic survey of prompting methods in natural language processing. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 195 (2023).

- Gu, J. et al. A systematic survey of prompt engineering on vision-language foundation models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/ abs/2307.12980 (2023).

- Coda-Forno, J. et al. Meta-in-context learning in large language models. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023) (eds Oh, A. et al.) 65189-65201 (Curran Associates, 2023).

- Geirhos, R. et al. Partial success in closing the gap between human and machine vision. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (NeurIPS 2021) (eds Ranzato, M. et al.) 23885-23899 (Curran Associates, 2021).

- Balestriero, R. et al. A cookbook of self-supervised learning. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.12210 (2023).

- Wong, L. et al. From word models to world models: translating from natural language to the probabilistic language of thought. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.12672 (2023).

- Carta, T. et al. Grounding large language models in interactive environments with online reinforcement learning. In Proc. 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Krause, A. et al.) 202, 3676-3713 (JMLR, 2023).

- Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (NeurIPS 2019) (eds Wallach, H. et al.) 8026-8037 (Curran Associates, 2019).

- Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357-362 (2020).

- Pandas Development Team. pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 3509134 (2020).

- Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261-272 (2020).

- Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90-95 (2007).

- Waskom, M. L. seaborn: statistical data visualization. J. Open Source Softw 6, 3021 (2021).

- Bürkner, P.-C. brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v080.i01 (2017).

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

- Schulze Buschoff, L. M. et al. lsbuschoff/multimodal: First release. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14050104 (2024).

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© المؤلفون 2025

natureportfolio

آخر تحديث من المؤلفين: 7 نوفمبر 2024

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

□ X

□

□ X

□

□

□

□

□

□

□

حجم العينة الدقيقة

بيان حول ما إذا كانت القياسات قد أُخذت من عينات متميزة أو ما إذا كانت نفس العينة قد تم قياسها عدة مرات

اختبار(ات) الإحصائية المستخدمة وما إذا كانت أحادية الجانب أو ثنائية الجانب

يجب وصف الاختبارات الشائعة فقط بالاسم؛ وصف تقنيات أكثر تعقيدًا في قسم الطرق.

وصف جميع المتغيرات المرافقة التي تم اختبارها

وصف أي افتراضات أو تصحيحات، مثل اختبارات الطبيعية والتعديل للمقارنات المتعددة

وصف كامل للمعلمات الإحصائية بما في ذلك الاتجاه المركزي (مثل المتوسطات) أو تقديرات أساسية أخرى (مثل معامل الانحدار) و التباين (مثل الانحراف المعياري) أو تقديرات مرتبطة بعدم اليقين (مثل فترات الثقة)

للتصاميم الهرمية والمعقدة، تحديد المستوى المناسب للاختبارات والتقارير الكاملة للنتائج

تقديرات أحجام التأثير (مثل حجم تأثير كوهين

تحتوي مجموعة الويب الخاصة بنا حول الإحصائيات لعلماء الأحياء على مقالات حول العديد من النقاط المذكورة أعلاه.

البرمجيات والشيفرات

جمع البيانات

nature portfolio | ملخص التقرير مارس 202

البيانات

معلومات السياسة حول توفر البيانات

- رموز الوصول، معرفات فريدة، أو روابط ويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتماشى مع سياستنا

المشاركون في البحث البشري

107 موضوعًا (55 أنثى و52 ذكرًا)، لم يتم إجراء أي تحليلات قائمة على الجنس أو النوع

متحدثون أصليون باللغة الإنجليزية بمتوسط عمر 27.73 (

تم تجنيد المشاركين من Prolific مع شرط الحاجة إلى متحدثين أصليين باللغة الإنجليزية

لجنة الأخلاقيات في كلية الطب، جامعة إبرهارد كارل توبنغن

يرجى ملاحظة أنه يجب أيضًا تقديم معلومات كاملة حول الموافقة على بروتوكول الدراسة في المخطوطة.

التقرير الخاص بالمجال

□ العلوم الحياتية

العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية □ العلوم البيئية والتطورية والبيئية

لنسخة مرجعية من الوثيقة مع جميع الأقسام، انظر nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

تصميم دراسة العلوم السلوكية والاجتماعية

| وصف الدراسة | دراسة كمية: تقييم نماذج اللغة البصرية على المجالات المعرفية ومقارنتها بالبيانات البشرية | |||

| عينة البحث | خمسة نماذج لغوية متعددة الوسائط متطورة. تم اختيار هذه العينة من النماذج بحيث تمثل بشكل كافٍ النماذج الحالية SOTA (كبيرة وصغيرة، مفتوحة المصدر ومغلقة المصدر). | |||

| استراتيجية العينة | لم يتم إجراء حساب لحجم العينة. تم تحديد العينات من خلال مجموعات البيانات المتاحة في المجالات المعنية. | |||

| جمع البيانات |

|

|||

| التوقيت | تم جمع البيانات بشكل رئيسي في أكتوبر ونوفمبر 2023 ومرة أخرى في مايو ويونيو 2024. | |||

| استبعاد البيانات | تم تحليل الإجابات الخام من النماذج اللغوية الكبيرة وتم تسجيل الإجابات غير المفهومة كـ N/A. تم استبعاد المشاركين البشريين إذا لم يكملوا التجربة. | |||

| عدم المشاركة | بالنسبة للتجربة البشرية، بدأ 11 مشاركًا التجربة ولكن لم يكملوها. |

التقرير عن مواد وأنظمة وطرق محددة

| المواد والأنظمة التجريبية | طرق | ||

| غير متاح | مشارك في الدراسة | غير متاح | مشارك في الدراسة |

| X | □ |  |

□ |

| X | □ | – | □ |

| X | □ |  |

□ |

| X | □ | ||

| X | □ | ||

| X | □ | ||

- ¹معهد ماكس بلانك لعلم السيبرنتيك الحيوية، توبنغن، ألمانيا.

معهد الذكاء الاصطناعي الموجه نحو الإنسان، هيلمهولتز ميونيخ، أوبيرشلايسهايم، ألمانيا. جامعة توبنغن، توبنغن، ألمانيا. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: لوكا م. شولتز بوشوف، إليف أكاتا.

□ البريد الإلكتروني: lucaschulzebuschoff@gmail.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-024-00963-y

Publication Date: 2025-01-15

Visual cognition in multimodal large language models

Accepted: 25 November 2024

Published online: 15 January 2025

Check for updates

Abstract

A chief goal of artificial intelligence is to build machines that think like people. Yet it has been argued that deep neural network architectures fail to accomplish this. Researchers have asserted these models’ limitations in the domains of causal reasoning, intuitive physics and intuitive psychology. Yet recent advancements, namely the rise of large language models, particularly those designed for visual processing, have rekindled interest in the potential to emulate human-like cognitive abilities. This paper evaluates the current state of vision-based large language models in the domains of intuitive physics, causal reasoning and intuitive psychology. Through a series of controlled experiments, we investigate the extent to which these modern models grasp complex physical interactions, causal relationships and intuitive understanding of others’ preferences. Our findings reveal that, while some of these models demonstrate a notable proficiency in processing and interpreting visual data, they still fall short of human capabilities in these areas. Our results emphasize the need for integrating more robust mechanisms for understanding causality, physical dynamics and social cognition into modern-day, vision-based language models, and point out the importance of cognitively inspired benchmarks.

approach. For every query, an image was submitted to the model, and different questions were asked about the image, that is, we performed visual question answering.c, Used multimodal LLMs and their size. MLLM, multimodal LLM.

in this domain involve testing people’s judgements about the stability of block towers

questions. We submitted them to some of the currently most advanced LLMs. To evaluate whether the LLMs show human-like performance in these domains, we follow the approach outlined in ref.73: we treat the models as participants in psychological experiments. This allows us to draw direct comparisons with human behaviour on these tasks. Since the tasks are designed to test abilities in specific cognitive domains, this comparison allows us to investigate in which domains multimodal LLMs perform similar to humans, and in which they don’t. Our results showed that these models can, at least partially, solve these tasks. In particular, two of the largest currently available models, OpenAl’s Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT-4) and Anthropic’s Claude-3 Opus, managed to perform robustly above chance in two of the three domains. Yet crucial differences emerged. First, none of the models matched human-level performance in any of the domains. Second, none of the models fully captured human behaviour, leaving room for domain-specific models of cognition such as the Bayesian models originally proposed for the tasks.

Related work

and Schulz

Results

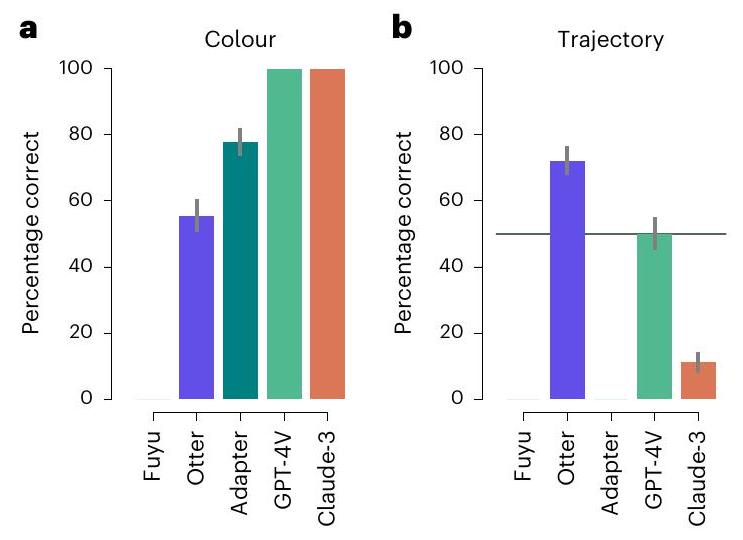

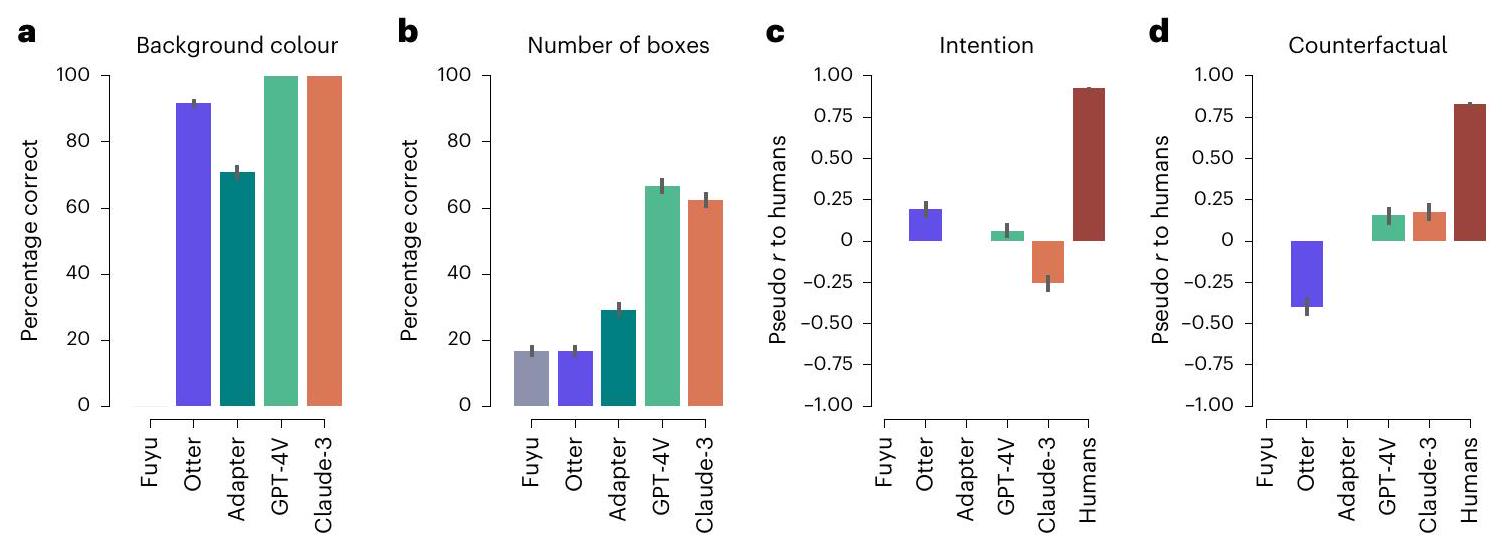

Intuitive physics with block towers

Causal reasoning with Jenga

approximated the ground truth, albeit rarely matching it exactly. Therefore, we report the mean absolute distance to the ground truth instead of the percentage of correct answers (Fig. 3a). The models’ performance highlighted the challenging nature of this task, with the best performing model (Claude-3) still being on average more than one block off.

Causal reasoning with Michotte

middle of the gate’ (if ball B entered the gate) or ‘Ball B completely missed the gate’ (if ball B missed the gate) (Fig. 4c). No model performs close to the human results reported in ref. 52. The best performing model is Fuyu with a regression coefficient of 0.26 (

Intuitive psychology with the astronaut task

coefficients of the models with the

Intuitive psychology with the help or hinder task

from taken from ref. 104. Bars in plots

Discussion

would expect the models to perform better if the stimuli contained more realistic images of people, which has been shown to work better in previous studies

between humans and machines

Methods

Code

Models

Datasets

scenes: we tasked them with determining the background colour and the number of blocks in the image. To test their physical understanding, we tested them on the same task as the original study: we asked them to give a binary rating on the stability of the depicted block towers. For the first two tasks, we calculated the percentage of correct answers for each of the models. For the third task, we calculated a Bayesian linear mixed effects regression between human and model answers.

collided with ball

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Mitchell, M. Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking Humans (Penguin, 2019).

- Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proc. 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers) (eds Burstein, J. et al.) 4171-4186 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019).

- Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017) (eds Guyon, I. et al.) 5998-6008 (2017).

- Brown, T. et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020) (eds Larochelle, H. et al.) 1877-1901 (Curran Associates, 2020).

- Bubeck, S. et al. Sparks of artificial general intelligence: early experiments with GPT-4. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/ abs/2303.12712 (2023).

- Wei, J. et al. Emergent abilities of large language models. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. https://openreview.net/forum?id=yzkSU5zdwD (2022).

- Katz, D. M., Bommarito, M. J., Gao, S. & Arredondo, P. GPT-4 passes the bar exam. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 382, 2270 (2024).

- Sawicki, P. et al. On the power of special-purpose gpt models to create and evaluate new poetry in old styles. In Proc. 14th International Conference on Computational Creativity (ICCC’23) (eds Pease, A. et al.) 10-19 (Association for Computational Creativity, 2023).

- Borsos, Z. et al. Audiolm: a language modeling approach to audio generation. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process 31, 2523-2533 (2023).

- Poldrack, R. A., Lu, T. & Beguš, G. Ai-assisted coding: experiments with GPT-4. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.13187 (2023).

- Kasneci, E. et al. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 103, 102274 (2023).

- Bommasani, R. et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07258 (2021).

- Elkins, K. & Chun, J. Can GPT-3 pass a writer’s Turing test? J. Cult. Anal. 5, 2 (2020).

- Dell’Acqua, F. et al. Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality. Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Mgt. Unit Working Paper (Harvard Business School, 2023).

- Bašić, Ž., Banovac, A., Kružić, I. & Jerković, I. Better by you, better than me? ChatGPT-3.5 as writing assistance in students’ essays. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 10, 750 (2023).

- Akata, E. et al. Playing repeated games with large language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.16867 (2023).

- Simon, H. A. Cognitive science: the newest science of the artificial. Cogn. Sci. 4, 33-46 (1980).

- Rumelhart, D. E. et al. Parallel Distributed Processing, Vol.1 (MIT Press, 1987).

- Wichmann, F. A. & Geirhos, R. Are deep neural networks adequate behavioral models of human visual perception? Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 9, 501-524 (2023).

- Bowers, J. S. et al. On the importance of severely testing deep learning models of cognition. Cogn. Syst. Res. 82, 101158 (2023).

- Marcus, G. Deep learning: a critical appraisal. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.00631 (2018).

- Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Gershman, S. J. Building machines that learn and think like people. Behav. Brain Sci. 40, e253 (2017).

- Sejnowski, T. J. The Deep Learning Revolution (MIT, 2018).

- Smith, K. A., Battaglia, P. W. & Vul, E. Different physical intuitions exist between tasks, not domains. Comput. Brain Behav. 1, 101-118 (2018).

- Bates, C. J., Yildirim, I., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Battaglia, P. Modeling human intuitions about liquid flow with particle-based simulation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15, e1007210 (2019).

- Battaglia, P. et al. Computational models of intuitive physics. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 34, 32-33 (2012).

- Bramley, N. R., Gerstenberg, T., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Gureckis, T. M. Intuitive experimentation in the physical world. Cogn. Psychol. 105, 9-38 (2018).

- Ullman, T. D. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Bayesian models of conceptual development: learning as building models of the world. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2, 533-558 (2020).

- Ullman, T. D., Spelke, E., Battaglia, P. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Mind games: game engines as an architecture for intuitive physics. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 649-665 (2017).

- Hamrick, J., Battaglia, P. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Probabilistic internal physics models guide judgments about object dynamics. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 33, 1545-1550 (2011).

- Mildenhall, P. & Williams, J. Instability in students’ use of intuitive and Newtonian models to predict motion: the critical effect of the parameters involved. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 23, 643-660 (2001).

- Todd, J. T. & Warren, W. H. Jr Visual perception of relative mass in dynamic events. Perception 11, 325-335 (1982).

- Battaglia, P. W., Hamrick, J. B. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Simulation as an engine of physical scene understanding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 18327-18332 (2013).

- Hamrick, J. B., Battaglia, P. W., Griffiths, T. L. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Inferring mass in complex scenes by mental simulation. Cognition 157, 61-76 (2016).

- Bakhtin, A., van der Maaten, L., Johnson, J., Gustafson, L. & Girshick, R. PHYRE: a new benchmark for physical reasoning. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (NeurIPS 2019) (eds Wallach, H. et al.) 5082-5093 (Curran Associates, 2019).

- Riochet, R. et al. Intphys: a framework and benchmark for visual intuitive physics reasoning. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/ abs/1803.07616 (2018).

- Schulze Buschoff, L. M., Schulz, E. & Binz, M. The acquisition of physical knowledge in generative neural networks. In Proc. 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Krause, A. et al.) 202, 30321-30341 (JMLR, 2023).

- Waldmann, M. The Oxford Handbook of Causal Reasoning (Oxford Univ. Press, 2017).

- Cheng, P. W. From covariation to causation: a causal power theory. Psychol. Rev. 104, 367 (1997).

- Holyoak, K. J. & Cheng, P. W. Causal learning and inference as a rational process: the new synthesis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 62, 135-163 (2011).

- Pearl, J. Causality (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009).

- Griffiths, T. L. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Theory-based causal induction. Psychol. Rev. 116, 661 (2009).

- Lagnado, D. A., Waldmann, M. R., Hagmayer, Y. & Sloman, S. A. in Causal Learning: Psychology, Philosophy, and Computation (eds Gopnik, A. and Schulz, L.) 154-172 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2007).

- Carey, S. On the Origin of Causal Understanding (Clarendon Press/ Oxford Univ. Press, 1995).

- Gopnik, A. et al. A theory of causal learning in children: causal maps and Bayes nets. Psychol. Rev. 111, 3 (2004).

- Lucas, C. G. & Griffiths, T. L. Learning the form of causal relationships using hierarchical bayesian models. Cogn. Sci. 34, 113-147 (2010).

- Bramley, N. R., Gerstenberg, T., Mayrhofer, R. & Lagnado, D. A. Time in causal structure learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 44, 1880 (2018).

- Griffiths, T. L. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Structure and strength in causal induction. Cogn. Psychol. 51, 334-384 (2005).

- Schulz, L., Kushnir, T. & Gopnik, A. in Causal Learning: Psychology, Philosophy, and Computation (eds Gopnik, A. and Schulz, L.) 67-85 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2007).

- Bramley, N. R., Dayan, P., Griffiths, T. L. & Lagnado, D. A. Formalizing Neurath’s ship: approximate algorithms for online causal learning. Psychol. Rev. 124, 301 (2017).

- Gerstenberg, T. What would have happened? Counterfactuals, hypotheticals and causal judgements. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 377, 20210339 (2022).

- Gerstenberg, T., Peterson, M. F., Goodman, N. D., Lagnado, D. A. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Eye-tracking causality. Psychol. Sci. 28, 1731-1744 (2017).

- Gerstenberg, T., Goodman, N. D., Lagnado, D. A. & Tenenbaum, J. B. A counterfactual simulation model of causal judgments for physical events. Psychol. Rev. 128, 936 (2021).

- Jin, Z. et al. CLadder: Assessing causal reasoning in language models. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023) (eds Oh, A. et al.) 31038-31065 (Curran Associates, 2023).

- Dasgupta, I. et al. Causal reasoning from meta-reinforcement learning. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.08162 (2019).

- Baker, C. L. & Tenenbaum, J. B. in Plan, Activity, and Intent Recognition: Theory and Practice (eds Sukthankar, G. et al.) 177-204 (Morgan Kaufmann, 2014).

- Jern, A. & Kemp, C. A decision network account of reasoning about other people’s choices. Cognition 142, 12-38 (2015).

- Vélez, N. & Gweon, H. Learning from other minds: an optimistic critique of reinforcement learning models of social learning. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 38, 110-115 (2021).

- Spelke, E. S., Bernier, E. P. & Skerry, A. Core Social Cognition (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

- Baker, C., Saxe, R. & Tenenbaum, J. Bayesian theory of mind: modeling joint belief-desire attribution. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 33, 2469-2474 (2011).

- Frith, C. & Frith, U. Theory of mind. Curr. Biol. 15, R644-R645 (2005).

- Saxe, R. & Houlihan, S. D. Formalizing emotion concepts within a Bayesian model of theory of mind. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 17, 15-21 (2017).

- Baker, C. L. et al. Intuitive theories of mind: a rational approach to false belief. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 28, 69k8c7v6 (2006).

- Shum, M., Kleiman-Weiner, M., Littman, M. L. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Theory of minds: understanding behavior in groups through inverse planning. In Proc. 33rd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 6163-6170 (Curran Associates, 2019).

- Baker, C. L., Jara-Ettinger, J., Saxe, R. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Rational quantitative attribution of beliefs, desires and percepts in human mentalizing. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1, 0064 (2017).

- Zhi-Xuan, T. et al. Solving the baby intuitions benchmark with a hierarchically Bayesian theory of mind. Preprint at https://arxiv. org/abs/2208.02914 (2022).

- Rabinowitz, N. et al. Machine theory of mind. In Proc. 35th International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Dy, J. & Krause, A.) 80, 4218-4227 (JMLR, 2018).

- Kosinski, M. Theory of mind may have spontaneously emerged in large language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/ 2302.02083 (2023).

- Ullman, T. Large language models fail on trivial alterations to theory-of-mind tasks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.08399 (2023).

- Schulz, L. The origins of inquiry: inductive inference and exploration in early childhood. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16, 382-389 (2012).

- Ullman, T. D. On the Nature and Origin of Intuitive Theories: Learning, Physics and Psychology. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2015).

- Tenenbaum, J. B., Kemp, C., Griffiths, T. L. & Goodman, N. D. How to grow a mind: statistics, structure, and abstraction. Science 331, 1279-1285 (2011).

- Binz, M. & Schulz, E. Using cognitive psychology to understand GPT-3. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2218523120 (2023).

- Huang, J. & Chang, K. C.-C. Towards reasoning in large language models: a survey. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023 (eds Rogers, A. et al.) 1049-1065 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023).

- Sawada, T. et al. ARB: Advanced reasoning benchmark for large language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.13692 (2023).

- Wei, J. et al. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2022) (eds Koyejo, S. et al.) 24824-24837 (Curran Associates, 2022).

- Webb, T., Holyoak, K. J. & Lu, H. Emergent analogical reasoning in large language models. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1526-1541 (2023).

- Coda-Forno, J. et al. Inducing anxiety in large language models increases exploration and bias. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/ abs/2304.11111 (2023).

- Eisape, T. et al. A systematic comparison of syllogistic reasoning in humans and language models. In Proc. 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds Duh, K. et al.) 8425-8444 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024).

- Hagendorff, T., Fabi, S. & Kosinski, M. Human-like intuitive behavior and reasoning biases emerged in large language models but disappeared in ChatGPT. Nat. Comput. Sci. 3, 833-838 (2023).

- Ettinger, A. What BERT is not: Lessons from a new suite of psycholinguistic diagnostics for language models. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 8, 34-48 (2020).

- Jones, C. R. et al. Distrubutional semantics still can’t account for affordances. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 44, 482-489 (2022).

- Rahwan, I. et al. Machine behaviour. Nature 568, 477-486 (2019).

- Schulz, E. & Dayan, P. Computational psychiatry for computers. iScience 23, 12 (2020).

- Rich, A. S. & Gureckis, T. M. Lessons for artificial intelligence from the study of natural stupidity. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 174-180 (2019).

- Zhang, Y., Pan, J., Zhou, Y., Pan, R. & Chai, J. Grounding visual illusions in language: do vision-language models perceive illusions like humans? In Proc. 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language (eds Bouamor, H. et al.) 5718-5728 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023).

- Mitchell, M., Palmarini, A. B. & Moskvichev, A. Comparing humans, GPT-4, and GPT-4v on abstraction and reasoning tasks. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.09247 (2023).

- Zečević, M., Willig, M., Dhami, D. S. & Kersting, K. Causal parrots: large language models may talk causality but are not causal. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. https://openreview.net/ pdf?id=tv46tCzs83 (2023).

- Zhang, C., Wong, L., Grand, G. & Tenenbaum, J. Grounded physical language understanding with probabilistic programs and simulated worlds. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 45, 3476-3483 (2023).

- Jassim, S. et al. GRASP: a novel benchmark for evaluating language grounding and situated physics understanding in multimodal language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/ abs/2311.09048 (2023).

- Kosoy, E. et al. Towards understanding how machines can learn causal overhypotheses. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 45, 363-374 (2023).

- Gandhi, K., Fränken, J.-P., Gerstenberg, T. & Goodman, N. D. Understanding social reasoning in language models with language models. In Proc. 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS ’23) (eds Oh, A. et al.) 13518-13529 (Curran Associates, 2024).

- Srivastava, A. et al. Beyond the imitation game: quantifying and extrapolating the capabilities of language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.04615 (2022).

- Baltrušaitis, T., Ahuja, C. & Morency, L.-P. Multimodal machine learning: a survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 41, 423-443 (2018).

- Reed, S. et al. Generative adversarial text to image synthesis. In Proc. 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Balcan, M. F. & Weinberger, K. Q.) 48, 1060-1069 (JMLR, 2016).

- Wu, Q. et al. Visual question answering: a survey of methods and datasets. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 163, 21-40 (2017).

- Manmadhan, S. & Kovoor, B. C. Visual question answering: a state-of-the-art review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53, 5705-5745 (2020).

- Lerer, A., Gross, S. & Fergus, R. Learning physical intuition of block towers by example. In Proc. 33rd International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Balcan, M. F. & Weinberger, K. Q.) 48, 430-438 (JMLR, 2016).

- Gelman, A., Goodrich, B., Gabry, J. & Vehtari, A. R-squared for Bayesian regression models. Am. Stat. 73, 307-309 (2019).

- Zhou, L., Smith, K. A., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Gerstenberg, T. Mental Jenga: a counterfactual simulation model of causal judgments about physical support. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 152, 2237 (2023).

- Gerstenberg, T., Zhou, L., Smith, K. A. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Faulty towers: A hypothetical simulation model of physical support. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 39, 409-414 (2017).

- Michotte, A. The Perception of Causality (Basic Books, 1963).

- Jara-Ettinger, J., Schulz, L. E. & Tenenbaum, J. B. The naïve utility calculus as a unified, quantitative framework for action understanding. Cogn. Psychol. 123, 101334 (2020).

- Wu, S. A., Sridhar, S. & Gerstenberg, T. A computational model of responsibility judgments from counterfactual simulations and intention inferences. Proc. Annu. Meet. Cogn. Sci. Soc. 45, 3375-3382 (2023).

- Sutton, R. The bitter lesson. Incomplete Ideas http://www. incompleteideas.net/Incldeas/BitterLesson.html (2019).

- Kaplan, J. et al. Scaling laws for neural language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.08361 (2020).

- Binz, M. & Schulz, E. Turning large language models into cognitive models. In Proc. 12th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) https://openreview.net/ forum?id=eiC4BKypf1 (OpenReview, 2024).

- Rahmanzadehgervi, P., Bolton, L., Taesiri, M. R. & Nguyen, A. T. Vision language models are blind. In Proc. Asian Conference on Computer Vision (ACCV) 18-34 (Computer Vision Foundation, 2024).

- Ju, C., Han, T., Zheng, K., Zhang, Y. & Xie, W. Prompting visual-language models for efficient video understanding. In Proc. Computer Vision – ECCV 2022: 17th European Conference (eds Avidan, S. et al.) 105-124 (Springer, 2022).

- Meding, K., Bruijns, S. A., Schölkopf, B., Berens, P. & Wichmann, F. A. Phenomenal causality and sensory realism. Iperception 11, 2041669520927038 (2020).

- Allen, K. R. et al. Using games to understand the mind. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 1035-1043 (2024).

- Maaz, M., Rasheed, H., Khan, S. & Khan, F. Video-ChatGPT: Towards detailed video understanding via large vision and language models. In Proc. 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers) (eds Ku, L.-W. et al.) 12585-12602 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024).

- Golan, T., Raju, P. C. & Kriegeskorte, N. Controversial stimuli: pitting neural networks against each other as models of human cognition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 29330-29337 (2020).

- Golan, T., Siegelman, M., Kriegeskorte, N. & Baldassano, C. Testing the limits of natural language models for predicting human language judgements. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 952-964 (2023).

- Reynolds, L. & McDonell, K. Prompt programming for large language models: beyond the few-shot paradigm. In Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (eds Kitamura, Y. et al.) 314 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2021).

- Strobelt, H. et al. Interactive and visual prompt engineering for ad-hoc task adaptation with large language models. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 29, 1146-1156 (2022).

- Webson, A. & Pavlick, E. Do prompt-based models really understand the meaning of their prompts? In Proc. 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (eds Carpuat, M. et al.) 2300-2344 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2022).

- Liu, P. et al. Pre-train, prompt, and predict: a systematic survey of prompting methods in natural language processing. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 195 (2023).

- Gu, J. et al. A systematic survey of prompt engineering on vision-language foundation models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/ abs/2307.12980 (2023).

- Coda-Forno, J. et al. Meta-in-context learning in large language models. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023) (eds Oh, A. et al.) 65189-65201 (Curran Associates, 2023).

- Geirhos, R. et al. Partial success in closing the gap between human and machine vision. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (NeurIPS 2021) (eds Ranzato, M. et al.) 23885-23899 (Curran Associates, 2021).

- Balestriero, R. et al. A cookbook of self-supervised learning. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.12210 (2023).

- Wong, L. et al. From word models to world models: translating from natural language to the probabilistic language of thought. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.12672 (2023).

- Carta, T. et al. Grounding large language models in interactive environments with online reinforcement learning. In Proc. 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Krause, A. et al.) 202, 3676-3713 (JMLR, 2023).

- Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32 (NeurIPS 2019) (eds Wallach, H. et al.) 8026-8037 (Curran Associates, 2019).

- Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357-362 (2020).

- Pandas Development Team. pandas-dev/pandas: Pandas. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 3509134 (2020).

- Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261-272 (2020).

- Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90-95 (2007).

- Waskom, M. L. seaborn: statistical data visualization. J. Open Source Softw 6, 3021 (2021).

- Bürkner, P.-C. brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v080.i01 (2017).

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2021).

- Schulze Buschoff, L. M. et al. lsbuschoff/multimodal: First release. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 14050104 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Competing interests

Additional information

© The Author(s) 2025

natureportfolio

Last updated by author(s): Nov 7, 2024

Reporting Summary

Statistics

□ X

□

□ X

□

□

□

□

□

□

□

The exact sample size

A statement on whether measurements were taken from distinct samples or whether the same sample was measured repeatedly

The statistical test(s) used AND whether they are one- or two-sided

Only common tests should be described solely by name; describe more complex techniques in the Methods section.

A description of all covariates tested

A description of any assumptions or corrections, such as tests of normality and adjustment for multiple comparisons

A full description of the statistical parameters including central tendency (e.g. means) or other basic estimates (e.g. regression coefficient) AND variation (e.g. standard deviation) or associated estimates of uncertainty (e.g. confidence intervals)

For hierarchical and complex designs, identification of the appropriate level for tests and full reporting of outcomes

Estimates of effect sizes (e.g. Cohen’s

Our web collection on statistics for biologists contains articles on many of the points above.

Software and code

Data collection

nature portfolio | reporting summary March 202

Data

Policy information about availability of data

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

Human research participants

107 subjects (55 female and 52 male), no sex or gender based analyses were performed

native English speakers with a mean age of 27.73 (

Participants were recruited from Prolific with the constraint of requiring native English speakers

Ethics commission at the faculty of medicine, Eberhard Karls University Tübingen

Note that full information on the approval of the study protocol must also be provided in the manuscript.

Field-specific reporting

□ Life sciences

Behavioural & social sciences □ Ecological, evolutionary & environmental sciences

For a reference copy of the document with all sections, see nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

Behavioural & social sciences study design

| Study description | Quantitative study: evaluation of vision language models on cognitive domains and comparison to human data | |||

| Research sample | Five state of the art multimodal large language models. This sample of models were chosen so that they adequately represent current SOTA models (large and small, open source and closed source). | |||

| Sampling strategy | No sample size calculation was performed. Samples were determined by the available data sets in the respective domains. | |||

| Data collection |

|

|||

| Timing | Data collection mainly took place in October and November of 2023 and again in May and June of 2024. | |||

| Data exclusions | The raw answers from the large language models were parsed and non-intelligible answers were registered as N/A. Human subjects were excluded if they did not complete the experiment. | |||

| Non-participation | For the human experiment, 11 participants started the experiment but did not complete it. |

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

| Materials & experimental systems | Methods | ||

| n/a | Involved in the study | n/a | Involved in the study |

| X | □ |  |

□ |

| X | □ | – | □ |

| X | □ |  |

□ |

| X | □ | ||

| X | □ | ||

| X | □ | ||

- ¹Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics, Tübingen, Germany.

Institute for Human-Centered AI, Helmholtz Munich, Oberschleißheim, Germany. University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany. These authors contributed equally: Luca M. Schulze Buschoff, Elif Akata.

□ e-mail: lucaschulzebuschoff@gmail.com