DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0267190524000072

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-15

الإنجليزية خارج المنهج كمتغير اختلاف فردي في أبحاث اللغة الثانية: أهمية المنهجية

الملخص

في ضوء النتائج المستخلصة من الأبحاث حول تعلم اللغة الأجنبية/الثانية غير الرسمي (L2)، مع التركيز على الإنجليزية كلغة مستهدفة واستخدام مفهوم الإنجليزية الخارجية (EE)، يجادل هذا البحث بأن انخراط المتعلمين في EE (من خلال أنشطة مثل مشاهدة التلفزيون أو الأفلام أو لعب الألعاب الرقمية) يشكل متغير اختلاف فردي مهم (ID) يجب تضمينه في الدراسات التي تهدف إلى قياس كفاءة أو تطوير اللغة الإنجليزية L2. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يُقترح أنه إذا تم استبعاد EE كمتغير ID في مثل هذه الدراسات في المستقبل، يجب أن يتم توضيح مبررات الاستبعاد بوضوح. يناقش هذا البحث أيضًا أدوات البحث والأساليب المستخدمة في هذا المجال من البحث، وفوائد وعيوب الأساليب المختلفة، ويحدد الفجوات البحثية والمجموعات التعليمية التي لم يتم البحث فيها بشكل كافٍ. علاوة على ذلك، يُجادل بأن EE في بعض السياقات قد حلت محل الأنشطة الصفية كنقطة انطلاق وأساس لتعلم اللغة الإنجليزية.

الملخص

الملخص السويدي بناءً على نتائج من الأبحاث حول التعلم غير الرسمي للغات الأجنبية/الثانية، مع التركيز على الإنجليزية كلغة مستهدفة واستخدام مفهوم الإنجليزية الخارجية (EE)، يجادل هذا ‘الموقف’ بأن انخراط الطلاب في EE (على سبيل المثال، من خلال أنشطة مثل مشاهدة التلفزيون أو الأفلام، أو لعب الألعاب الرقمية) يشكل اختلافًا فرديًا مهمًا (متغير ID) يجب تضمينه في الدراسات التي تهدف إلى قياس كفاءة اللغة أو تطويرها في الإنجليزية L2. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يُقترح أنه إذا تم استبعاد EE كمتغير ID في مثل هذه الدراسات في المستقبل، يجب أن يتم توضيح مبررات الاستبعاد بوضوح. يناقش هذا ‘الموقف’ أيضًا أدوات البحث والأساليب المستخدمة في هذا المجال، بالإضافة إلى مزايا وعيوب الأساليب المختلفة، ويحدد الفجوات البحثية والمجموعات التعليمية التي لم يتم البحث فيها بشكل كافٍ. علاوة على ذلك، يُجادل بأن EE في بعض السياقات قد حلت محل الأنشطة الصفية كنقطة انطلاق وأساس لتعلم اللغة الإنجليزية.

أبحاث الإنجليزية الخارجية

ليشمل الانخراط في EE، الذي يتم تنظيمه ذاتيًا أيضًا. لقد أظهرت زيادة التعرض، والانتباه، والوقت المستثمَر في أنشطة EE المحددة أنها تعزز اكتساب القدرات والمعرفة المحتوى المرتبطة بها. تعكس التكرارية التي يشارك فيها المتعلم في أنشطة EE الانخراط السلوكي، وتعكس الطبيعة الطوعية للمشاركة الانخراط العاطفي. يميل المتعلمون إلى الانخراط في الأنشطة التي يستمتعون بها ولكنهم يتوقفون عن المشاركة بمجرد أن يتناقص ارتباطهم العاطفي (سوندكفيست، 2019). علاوة على ذلك، أي شكل من أشكال الانخراط في EE يعني الانخراط المعرفي، حيث يستخدم المتعلمون مهاراتهم في اللغة الثانية. تتطلب بعض أنشطة EE مستويات أعلى من الطلب المعرفي، خاصة عندما يكون التفاعل مع الآخرين متضمنًا (فرضية التفاعل، انظر، على سبيل المثال، غاس وماكي، 2006).

تغيير هيكلي

المدرسة (Puimège & Peters، 2019)، وبعضهم بالفعل يحصل على مستوى A2 وفقًا للإطار الأوروبي المرجعي المشترك (مجلس أوروبا، 2020) لفهم الاستماع، والكتابة، والتحدث قبل حتى بدء تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية كلغة ثانية بشكل رسمي في المدرسة (De Wilde et al.، 2020b). لا تؤثر هذه التغيرات في التعرض للغة الإنجليزية على الجوانب التربوية فحسب، بل تؤثر أيضًا على كيفية بحثنا في التعليم باللغة الإنجليزية. من الواضح أن الوضع يتطلب أدوات وأساليب جديدة لالتقاط وقياس انخراط المتعلمين في أنشطة التعليم باللغة الإنجليزية المختلفة. لاقتباس بوب ديلان (1964): “[ت] الأوقات تتغير”.

تعتبر المنهجية مهمة

النهج الهرمي والنهج التراكمي في البحث الطبيعي والتأكيد

المتغيرات المستقلة – أي، IDs – والمتغيرات التابعة، مثل مقاييس تعلم L2). علاوة على ذلك، يطرح إليس تقليدين عامين في أبحاث ID: البحث الطبيعي والبحث التأكيدي. بدأت أبحاث EE في التقليد الطبيعي، متبنية نهجًا تراكميًا. كان من الشائع أن تكون هناك دراسات استكشافية تحدد كيف يشارك الشباب في أنشطة EE المختلفة في أوقات فراغهم، غالبًا في المنزل، وتحلل العلاقة بين بيانات EE ومقاييس جوانب مختلفة من كفاءة اللغة الإنجليزية L2 (انظر، على سبيل المثال، دي وايلد وإيكمانز، 2017؛ هانيبال جنسن، 2017؛ وسوندكفيست، 2009). هذا النهج البحثي ثم النظري، بالمقارنة مع النهج الهرمي، يتبنى موقفًا أقل توجيهًا ويشجع على جمع بيانات واسعة وصياغة تعميمات واسعة. ومع ذلك، فإن عيب هذا النهج هو أن الباحث قد يواجه صعوبة بسبب وفرة البيانات، مع القليل من الإرشادات حول كيفية المضي قدمًا. بينما ستكون النقطة النهائية لتصميم بحث EE هي تصميم نظرية ثم بحث، يبدو أن أبحاث EE الحالية في ما يشير إليه سكيهان (1991) باسم “مرحلة تطهير الأرض” (ص. 296). ويؤكد أن هذه المرحلة ضرورية للوصول إلى النقطة النهائية، وفي الوقت الحالي، فإن استكشاف طرق جديدة للمضي قدمًا في أبحاث EE مرحب به.

طرق، أدوات البحث، وطرق المضي قدمًا

البيانات في تلك اللحظة، ويحدث ذلك كل يوم لفترة من الوقت (مثل أسبوع). إحدى فوائد هذا النهج هي أن التجارب في الوقت الحقيقي يتم الإبلاغ عنها، مما يعني صلاحية بيئية عالية (أرندت وآخرون، 2023). تقلل الطريقة من تأثير تحيز الاسترجاع ويمكن أن تؤدي إلى بيانات أكثر موثوقية، مما يسمح للباحثين بدراسة ديناميات الأنشطة والتجارب على مر الزمن. علاوة على ذلك، يقترح أرندت وآخرون (2023) أن ESM يسمح بأنواع جديدة من التحليلات بسبب هيكل البيانات “المتداخل” ثلاثي المستويات: عدة استجابات/لحظات في اليوم وعدة أيام لكل مشارك. الافتراض هو أن “القياسات من المحتمل أن تكون أكثر تشابهًا إذا كانت تأتي من نفس الفرد مقارنة بمشاركين مختلفين، وإذا تم جمعها في نفس اليوم مقابل أيام مختلفة” (أرندت وآخرون، 2023، ص. 43). ومع ذلك، كما ناقش المؤلفون، هناك عيوب أيضًا، مثل العبء الذي يقع على المشاركين للاستجابة بشكل متكرر لأسئلة الاستبيان، مما قد يؤدي إلى الانسحاب وتعطيل سلوك المشاركين الطبيعي. هناك أيضًا خطر التحيز في الاختيار، ويمكن أن تكون هناك آثار عادية أو تفاعلية، مما يعني أن المشاركين قد يصبحون أكثر انتباهاً لتجاربهم وقد يبدأون في تغيير سلوكياتهم، بوعي أو بدون وعي.

(للاستثناء، انظر Dressman، 2020). بالإضافة إلى الحاجة لاستكشاف مناطق جديدة والاختلافات الإقليمية، سيكون من المفيد أيضًا النظر في الاختلافات الاجتماعية الاقتصادية أو الطبقية، وسؤال الوصول إلى أشكال مختلفة من EE (بما في ذلك الموارد الرقمية والإنترنت) داخل مناطق أو دول معينة، حيث قد يُنظر إلى التعرض لـ EE على أنه شكل عالمي من رأس المال الاجتماعي والثقافي (انظر Bourdieu، 1973).

الخاتمة

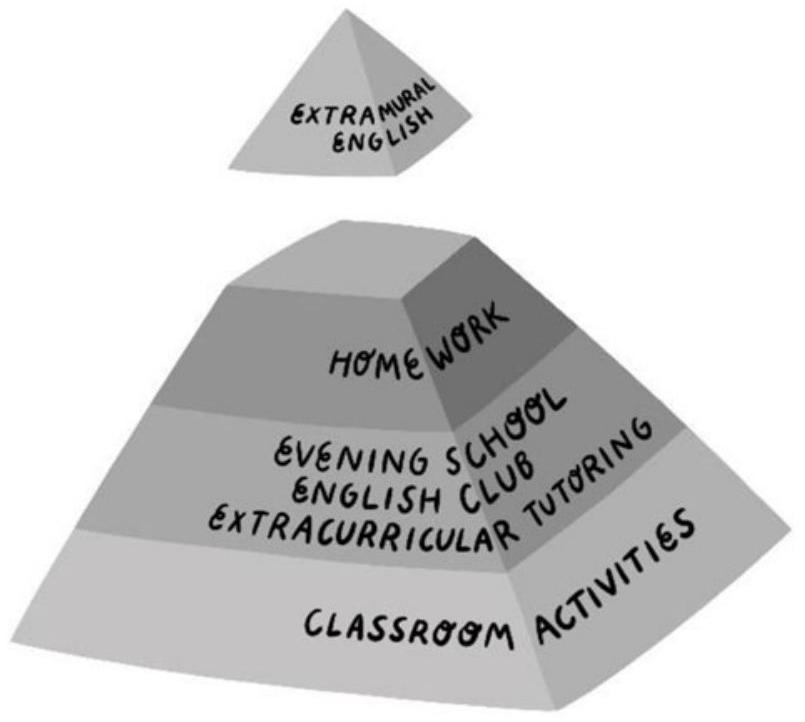

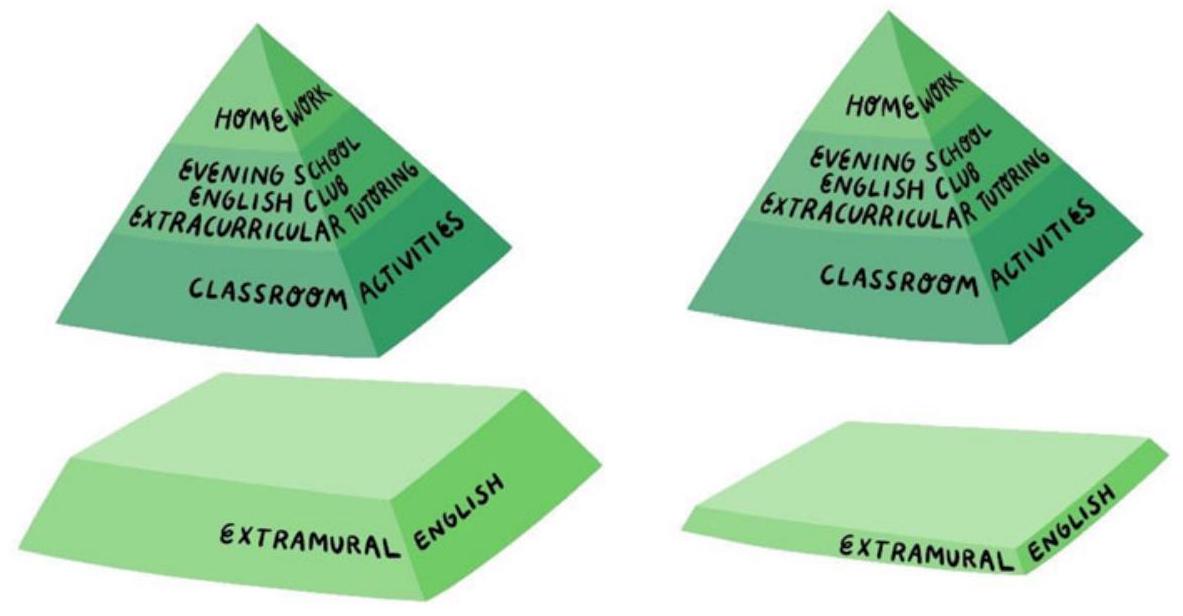

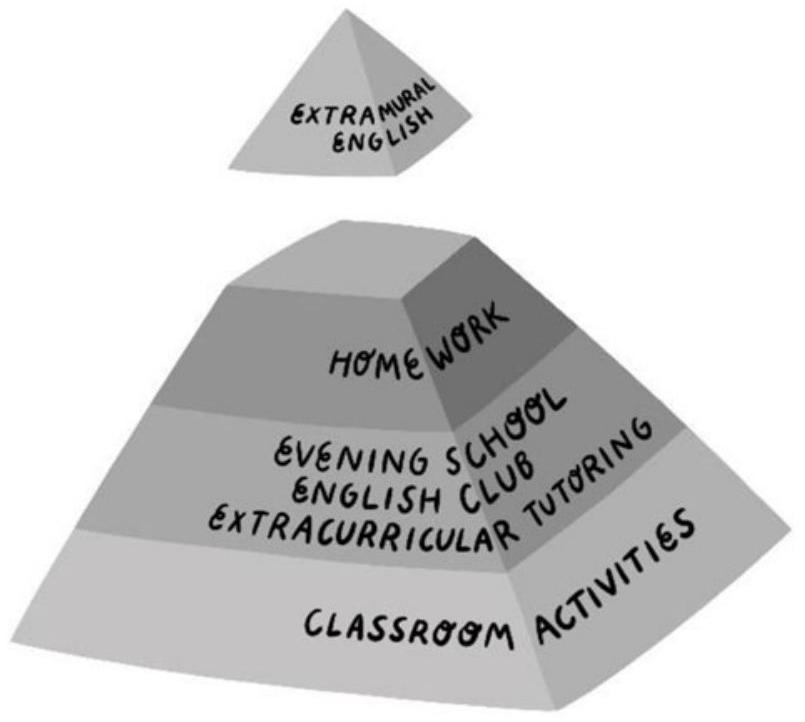

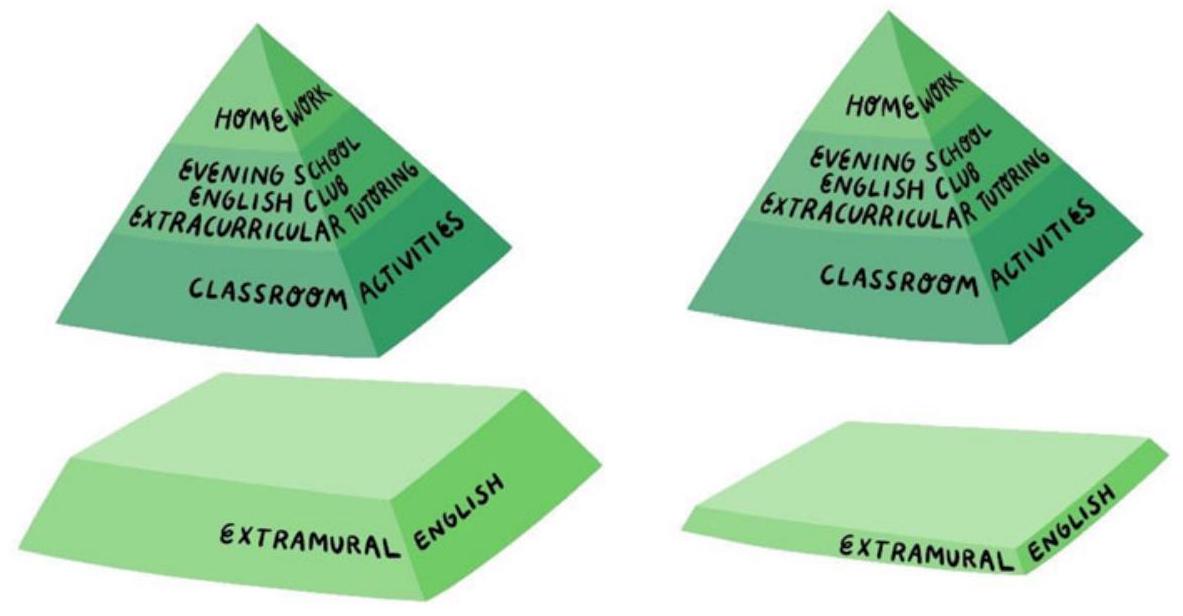

من كفاءة اللغة الثانية وكذلك مع العوامل المعرفية والعاطفية. في ضوء الإنجليزية كلغة عالمية، والرقمنة، ونتائج أبحاث EE، أ argue أن تغييرًا هيكليًا قد حدث في البيئات التي يتعرض فيها المتعلمون للكثير من الإنجليزية، مما يعني باختصار أن EE قد حلت محل الأنشطة الصفية في المدرسة كنقطة انطلاق وأساس لتعلم الإنجليزية، وهو ما تم توضيحه مع هرم تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية المعدل المقدم في الشكل 2 (استنادًا إلى هرم التعلم الأصلي الذي تم تقديمه في Sundqvist & Sylvén، 2016). تم تقديم بعض الاقتراحات حول كيفية التحقيق في EE وكيف يمكن التحقيق فيها في المستقبل. وبالتالي، في فترة زمنية قصيرة نسبيًا، تحولت EE إلى متغير ID مهم في أبحاث SLA لا ينبغي تجاهله. ستظل نقطة تركيز مهمة في هذا المجال لفهم التباين في نتائج التعلم وتحديد العوامل التي تساهم في تعلم اللغة الإنجليزية بنجاح.

References

Arndt, H. L. (2023). Construction and validation of a questionnaire to study engagement in informal second language learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(5), 1456-1480.

Arndt, H. L., Granfeldt, J., & Gullberg, M. (2023). Reviewing the potential of the Experience Sampling Method (ESM) for capturing second language exposure and use. Second Language Research, 39(1), 39-58.

Arndt, H. L., & Woore, R. (2018). Vocabulary learning from watching YouTube videos and reading blog posts. Language Learning & Technology, 22(1), 124-142.

Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In R. Brown (Ed.), Knowledge, education, and cultural change: Papers in the sociology of education (pp. 71-112). Tavistock Publications.

Butler, Y. G. (2014). Socioeconomic disparities and early English education: A case in Changzhou, China. In N. Murray & A. Scarino (Eds.), Dynamic ecologies: A relational perspective on language education in the Asia-Pacific region (pp. 95-115). Springer.

Cadierno, T., Hansen, M., Lauridsen, J. T., Eskildsen, S. W., Fenyvesi, K., Hannibal Jensen, S., & Aus der Wieschen, M. V. (2020). Does younger mean better? Age of onset, learning rate and short-term L2 proficiency in Danish young learners of English. Vigo International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 17, 57-86.

Chapelle, C. A., & Duff, P. A. (2003). Some guidelines for conducting quantitative and qualitative research in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 37(1), 157-178.

Council of Europe. (2020). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment – Companion volume. Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://www.coe.int/en/web/ common-european-framework-reference-languages

De Wilde, V., Brysbaert, M., & Eyckmans, J. (2020a). Learning English through out-of-school exposure: How do word-related variables and proficiency influence receptive vocabulary learning? Language Learning, 70(2), 349-381.

De Wilde, V., Brysbaert, M., & Eyckmans, J. (2020b). Learning English through out-of-school exposure. Which levels of language proficiency are attained and which types of input are important? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 23(1), 171-185.

De Wilde, V., Brysbaert, M., & Eyckmans, J. (2021). Young learners’ L2 English after the onset of instruction: Longitudinal development of L2 proficiency and the role of individual differences. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 24(3), 439-453.

De Wilde, V., & Eyckmans, J. (2017). Game on! Young learners’ incidental language learning of English prior to instruction. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 7(4), 673-694.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford University Press.

Dressman, M. (2020). Informal English learning among Moroccan youth. In M. Dressman & R. W. Sadler (Eds.), The handbook of informal language learning (pp. 303-318). John Wiley & Sons.

Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford University Press.

European Union (2018). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Retrieved December 28, 2023, from http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/2016-05-04

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: And sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll (4th ed.). sage.

Fredricks, J. A., Filsecker, M., & Lawson, M. A. (2016). Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learning and Instruction, 43, 1-4.

Gass, S., Loewen, S., & Plonsky, L. (2021). Coming of age: The past, present, and future of quantitative SLA research. Language Teaching, 54(2), 245-258.

Gass, S., & Mackey, A. (2006). Input, interaction and output: An overview. AILA Review, 19, 3-17.

Graddol, D. (2006). English next. British Council.

Hannibal Jensen, S. (2017). Gaming as an English language learning resource among young children in Denmark. CALICO Journal, 34(1), 1-19.

Hannibal Jensen, S. (2019). Language learning in the wild: A young user perspective. Language Learning & Technology, 23(1), 72-86.

Hughes, C. (2023). Largest YouTube user bases APAC 2023, by country [Chart]. Retrieved March 9, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1334225/apac-number-of-youtube-users-by-country/ #statisticContainer

Lai, C., & Zheng, D. (2018). Self-directed use of mobile devices for language learning beyond the classroom. ReCALL, 30(3), 299-318.

Lai, C., Zhu, W., & Gong, G. (2015). Understanding the quality of out-of-class English learning. TESOL Quarterly, 49(2), 278-308.

Lee, J. S. (2022). Evaluation of instruments for researching learners’ LBC. In H. Reinders, C. Lai & P. Sundqvist (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language learning and teaching beyond the classroom (pp. 312-326). Routledge.

Lee, J. S., & Drajati, N. A. (2020). Willingness to communicate in digital and non-digital EFL contexts: Scale development and psychometric testing. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(7), 688-707.

Lee, J. S., & Dressman, M. (2018). When IDLE hands make an English workshop: Informal digital learning of English and language proficiency. TESOL Quarterly, 52(2), 435-445.

Lee, J. S., & Taylor, T. (2022). Positive psychology constructs and Extramural English as predictors of primary school students’ willingness to communicate. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2079650

Lindgren, E., & Muñoz, C. (2013). The influence of exposure, parents, and linguistic distance on young European learners’ foreign language comprehension. International Journal of Multilingualism, 10(1), 105-129.

Lyrigkou, C. (2019). Not to be overlooked: Agency in informal language contact. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 13(3), 237-252.

Mackey, A. M., & Gass, S. M. (Eds.). (2023). Current approaches in second language acquisition research:

Muñoz, C. (2020). Boys like games and girls like movies: Age and gender differences in out-of-school contact with English. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics, 33(1), 171-201.

Muñoz, C., Cadierno, T., & Casas, I. (2018). Different starting points for English language learning: A comparative study of Danish and Spanish young learners. Language Learning, 68(4), 1076-1109.

Norris, J. M., Plonsky, L., Ross, S. J., & Schoonen, R. (2015). Guidelines for reporting quantitative methods and results in primary research. Language Learning, 65(2), 470-476.

Norwegian Media Authority. (2022). Barn og medier 2022 – En undersøkelse om 9-18-åringers medievaner [Children and media 2022 – an investigation of 9-18-year-olds’ media habits]. [Report]. Retrieved December 28, 2023, from https://www.medietilsynet.no/globalassets/publikasjoner/barn-og-medier-undersokelser/2022/231002_barn-og-medier_2022.pdf

Olsson, E., & Sylvén, L. K. (2015). Extramural English and academic vocabulary. A longitudinal study of CLIL and non-CLIL students in Sweden. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies, 9(2), 77-103.

Peters, E. (2018). The effect of out-of-class exposure to English language media on learners’ vocabulary knowledge. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 169(1), 142-167.

Peters, E., Noreillie, A.-S., Heylen, K., Bulté, B., & Desmet, P. (2019). The impact of instruction and out-ofschool exposure to foreign language input on learners’ vocabulary knowledge in two languages. Language Learning, 69(3), 747-782.

Plonsky, L., & Oswald, F. L. (2014). How big is “big”? Interpreting effect sizes in L2 research. Language Learning, 64(4), 878-912.

Puimège, E., & Peters, E. (2019). Learners’ English vocabulary knowledge prior to formal instruction: The role of learner-related and word-related factors. Language Learning, 69(4), 943-977.

Rothoni, A. (2017). The interplay of global forms of pop culture and media in teenagers’ ‘interest-driven’ everyday literacy practices with English in Greece. Linguistics and Education, 38, 92-103.

Saferinternet.at. (2022). Jugend-Internet-Monitor: Welche sozialen netzwerke nutzen Österreichs Jugendliche? [Youth-Internet-Monitor: Which social networks do young people in Austria use?]. Retrieved November 23, 2023, from https://www.saferinternet.at/services/jugend-internet-monitor/

Salaberry, M. R., & Kunitz, S. (Eds.) (2019). Teaching and testing L2 interactional competence: Bridging theory and practice. Routledge.

Schmitt, N. (2008). Review article: Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language Teaching Research, 12(3), 329-363.

Schurz, A., & Sundqvist, P. (2022). Connecting extramural English with ELT: Teacher reports from Austria, Finland, France, and Sweden. Applied Linguistics, 43(5), 934-957.

Schwarz, M. (2020). Beyond the walls: A mixed methods study of teenagers’ extramural English practices and their vocabulary knowledge [Doctoral dissertation, University of Vienna]. Retrieved January 11, 2022, from https://utheses.univie.ac.at/detail/56447

Skehan, P. (1989). Individual differences in second-language learning. Edward Arnold.

Skehan, P. (1991). Individual differences in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 13(2), 275-298.

Soyoof, A. (2023). Iranian EFL students’ perception of willingness to communicate in an extramural digital context. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(9), 5922-5939.

Soyoof, A., Reynolds, B. L., Shadiev, R., & Vazquez-Calvo, B. (2024). A mixed-methods study of the incidental acquisition of foreign language vocabulary and healthcare knowledge through serious game play. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(1-2), 27-60.

Sundqvist, P. (2009). Extramural English matters: Out-of-school English and its impact on Swedish ninth graders’ oral proficiency and vocabulary. [Doctoral dissertation, Karlstad University]. https://www.divaportal.org/smash/get/diva2:275141/FULLTEXT03.pdf

Sundqvist, P. (2015). About a boy: A gamer and L2 English speaker coming into being by use of self-access. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6(4), 352-364.

Sundqvist, P. (2019). Commercial-off-the-shelf games in the digital wild and L2 learner vocabulary. Language Learning & Technology, 23(1), 87-113.

Sundqvist, P., & Sylvén, L. K. (2016). Extramural English in teaching and learning: From theory and research to practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

Sundqvist, P., & Uztosun, M. S. (2023). Extramural English in Scandinavia and Asia: Scale development, learner engagement, and perceived speaking ability. TESOL Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq. 3296

Sundqvist, P., & Wikström, P. (2015). Out-of-school digital gameplay and in-school L2 English vocabulary outcomes. System, 51, 65-76.

Swedish Media Council. (2023). Ungar & medier 2023 [Youth and media 2023]. [Report]. Retrieved December 13, 2023, from https://www.statensmedierad.se/rapporter-och-analyser/material-rapporter-och-analyser/2023/ungar-medier-2023

Sylvén, L. K., & Sundqvist, P. (2012). Gaming as extramural English L2 learning and L2 proficiency among young learners. ReCALL, 24(3), 302-321.

Twining, P., Heller, R. S., Nussbaum, M., & Tsai, -C.-C. (2017). Some guidance on conducting and reporting qualitative studies. Computers and Education, 106, A1-A9.

Zhang, Y., & Liu, G. (2022). Revisiting informal digital learning of English (IDLE): A structural equation modeling approach in a university EFL context. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-33. https://doi. org/10.1080/09588221.2022.2134424

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0267190524000072

Publication Date: 2024-04-15

Extramural English as an individual difference variable in L2 research: Methodology matters

Abstract

In light of findings from research on informal foreign/second language (L2) learning, with a focus on English as a target language and using the concept of extramural English (EE), this position paper argues that learners’ engagement in EE (through activities such as watching television or films or playing digital games) constitutes an important individual difference (ID) variable that needs to be included in studies that aim to measure L2 English proficiency or development. In addition, it is suggested that if EE as an ID variable is left out in such studies in the future, the rationale for exclusion should be clearly stated. This position paper also discusses research instruments and methods used in this area of research, the benefits and drawbacks of different methods, and identifies research gaps and underresearched learner groups. Further, it is argued that in some contexts, EE has replaced classroom activities as the starting point for and foundation of learning English.

Abstract

Swedish Abstract Baserat på resultat från forskning om informellt lärande av främmande-/andraspråk och med fokus på engelska som målspråk samt med användning av begreppet extramural engelska (EE), argumenterar detta ‘position paper’ för att elevers engagemang i EE (exempelvis genom aktiviteter såsom att se på tv eller film, eller att spela dataspel) utgör en viktig individuell skillnad (en ID-variabel), som bör inkluderas i studier som syftar till att mäta språkfärdighet eller utveckling i L2 engelska. Dessutom föreslås det att ifall EE som ID-variabel exkluderas i sådana studier i framtiden, bör motiveringen för exkluderingen tydligt anges. Detta ‘position paper’ diskuterar dessutom olika forskningsinstrument och metoder som används inom forskningsfältet samt för- och nackdelar med olika metoder, och det identifierar även forskningsluckor och underbeforskade elev- och studentgrupper. Vidare argumenteras det för att EE i vissa sammanhang har ersatt klassrumsaktiviteter som utgångspunkt och bas för att lära sig engelska.

Extramural English research

can be extended to EE engagement, which is also self-regulated. Increased exposure, attention, and time invested in specific EE activities have been shown to enhance the acquisition of abilities and content knowledge associated with them. The frequency at which a learner engages in EE activities reflects behavioral engagement, and the voluntary nature of participation reflects emotional engagement. Learners tend to engage in activities they enjoy but discontinue their involvement once their emotional connection diminishes (Sundqvist, 2019). Moreover, any form of EE engagement implies cognitive engagement, as learners utilize their L2 skills. Certain EE activities necessitate higher levels of cognitive demand, particularly when interaction with others is involved (the interaction hypothesis, see, e.g., Gass & Mackey, 2006).

A structural change

school (Puimège & Peters, 2019), and some already score at level A2 according to the Common European Framework of Reference (Council of Europe, 2020) for listening comprehension, writing, and speaking before even beginning formal English L2 learning in school (De Wilde et al., 2020b). Not only does this change in exposure to English have pedagogical implications but it also affects how we research EE. Clearly, the situation calls for new tools and methods to capture and measure learners’ engagement in different EE activities. To quote Bob Dylan (1964): “[t]he times they are a-changin””

Methodology matters

Hierarchical and concatenative approaches in naturalistic and confirmatory research

independent variables – i.e., the IDs – and dependent variables, such as measures of L2 learning). Further, Ellis brings up two general traditions in ID research: naturalistic and confirmatory research. Research on EE started out in the naturalistic tradition, adopting a concatenative approach. It was common with exploratory studies that mapped how young people engage in various EE activities in their spare time, often in the home, and analyzed the relationship between EE data and measures of different aspects of L2 English proficiency (see, e.g., De Wilde & Eyckmans, 2017; Hannibal Jensen, 2017; and Sundqvist, 2009). This research-then-theory approach, in comparison with the hierarchical approach, adopts a less prescriptive stance and encourages extensive data collection and the formulation of broad generalizations. However, a drawback of the approach is that the researcher risks being overwhelmed by an abundance of data, with little guidance about how to move forward. While the endpoint for an EE research design would be a theory-then-research design, current EE research appears to be in what Skehan (1991) refers to as a “ground-clearing phase” (p. 296). He argues that this phase is necessary in order to reach the endpoint, and at present, exploring new ways forward in EE research is, thus, welcomed.

Methods, research instruments, and ways forward

data right then in the moment, and this happens every day for a period of time (e.g., for a week). One benefit of this approach is that real-time experiences are reported, which means high ecological validity (Arndt et al., 2023). The method minimizes the impact of recall bias and can lead to more reliable data, allowing researchers to examine the dynamics of activities and experiences over time. Further, Arndt et al. (2023) propose that ESM allows for new types of analyses because of a three-level “nested” structure of data: several responses/moments per day and several days per participant. The assumption is that “measurements are likely to be more similar if they stem from the same individual than across different participants, and if they are collected on the same day versus different days” (Arndt et al., 2023, p. 43). However, as discussed by the authors, there are drawbacks too, such as the burden put on participants to frequently respond to survey questions, which risks leading to attrition and disrupting participants’ natural behavior. There is also a risk of selection bias, and there can be habitual effects or reactivity, which means that participants might become more attentive to their experiences and can potentially start changing their behaviors, consciously or subconsciously.

(for an exception, see Dressman, 2020). In addition to the need to explore new regions and regional differences, it would be valuable to consider socioeconomic or class differences as well, and the question of access to various forms of EE (including digital resources and the internet) within particular regions or countries, as EE exposure may be viewed as a global form of social and cultural capital (cf. Bourdieu, 1973).

Conclusion

of L2 proficiency as well as with cognitive and affective factors. In light of English as a global language, digitization, and results from EE research, I argue that a structural change has taken place in settings where learners are exposed to a lot of English, which, in short, means that EE has replaced classroom activities in school as the starting point and foundation for learning English, which was illustrated with revised L2 English language learning pyramids presented in Figure 2 (based on the original learning pyramid introduced in Sundqvist & Sylvén, 2016). Some suggestions for how EE has been investigated and may be investigated in the future were also presented. Thus, in a relatively short time, EE has turned into an important ID variable in SLA research that should not be overlooked. It will continue to be an important focus in the field for understanding the variability in learning outcomes and determining the factors that contribute to successful L2 English learning.

References

Arndt, H. L. (2023). Construction and validation of a questionnaire to study engagement in informal second language learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(5), 1456-1480.

Arndt, H. L., Granfeldt, J., & Gullberg, M. (2023). Reviewing the potential of the Experience Sampling Method (ESM) for capturing second language exposure and use. Second Language Research, 39(1), 39-58.

Arndt, H. L., & Woore, R. (2018). Vocabulary learning from watching YouTube videos and reading blog posts. Language Learning & Technology, 22(1), 124-142.

Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In R. Brown (Ed.), Knowledge, education, and cultural change: Papers in the sociology of education (pp. 71-112). Tavistock Publications.

Butler, Y. G. (2014). Socioeconomic disparities and early English education: A case in Changzhou, China. In N. Murray & A. Scarino (Eds.), Dynamic ecologies: A relational perspective on language education in the Asia-Pacific region (pp. 95-115). Springer.

Cadierno, T., Hansen, M., Lauridsen, J. T., Eskildsen, S. W., Fenyvesi, K., Hannibal Jensen, S., & Aus der Wieschen, M. V. (2020). Does younger mean better? Age of onset, learning rate and short-term L2 proficiency in Danish young learners of English. Vigo International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 17, 57-86.

Chapelle, C. A., & Duff, P. A. (2003). Some guidelines for conducting quantitative and qualitative research in TESOL. TESOL Quarterly, 37(1), 157-178.

Council of Europe. (2020). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment – Companion volume. Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://www.coe.int/en/web/ common-european-framework-reference-languages

De Wilde, V., Brysbaert, M., & Eyckmans, J. (2020a). Learning English through out-of-school exposure: How do word-related variables and proficiency influence receptive vocabulary learning? Language Learning, 70(2), 349-381.

De Wilde, V., Brysbaert, M., & Eyckmans, J. (2020b). Learning English through out-of-school exposure. Which levels of language proficiency are attained and which types of input are important? Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 23(1), 171-185.

De Wilde, V., Brysbaert, M., & Eyckmans, J. (2021). Young learners’ L2 English after the onset of instruction: Longitudinal development of L2 proficiency and the role of individual differences. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 24(3), 439-453.

De Wilde, V., & Eyckmans, J. (2017). Game on! Young learners’ incidental language learning of English prior to instruction. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 7(4), 673-694.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford University Press.

Dressman, M. (2020). Informal English learning among Moroccan youth. In M. Dressman & R. W. Sadler (Eds.), The handbook of informal language learning (pp. 303-318). John Wiley & Sons.

Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford University Press.

European Union (2018). General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Retrieved December 28, 2023, from http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/2016-05-04

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: And sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll (4th ed.). sage.

Fredricks, J. A., Filsecker, M., & Lawson, M. A. (2016). Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learning and Instruction, 43, 1-4.

Gass, S., Loewen, S., & Plonsky, L. (2021). Coming of age: The past, present, and future of quantitative SLA research. Language Teaching, 54(2), 245-258.

Gass, S., & Mackey, A. (2006). Input, interaction and output: An overview. AILA Review, 19, 3-17.

Graddol, D. (2006). English next. British Council.

Hannibal Jensen, S. (2017). Gaming as an English language learning resource among young children in Denmark. CALICO Journal, 34(1), 1-19.

Hannibal Jensen, S. (2019). Language learning in the wild: A young user perspective. Language Learning & Technology, 23(1), 72-86.

Hughes, C. (2023). Largest YouTube user bases APAC 2023, by country [Chart]. Retrieved March 9, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1334225/apac-number-of-youtube-users-by-country/ #statisticContainer

Lai, C., & Zheng, D. (2018). Self-directed use of mobile devices for language learning beyond the classroom. ReCALL, 30(3), 299-318.

Lai, C., Zhu, W., & Gong, G. (2015). Understanding the quality of out-of-class English learning. TESOL Quarterly, 49(2), 278-308.

Lee, J. S. (2022). Evaluation of instruments for researching learners’ LBC. In H. Reinders, C. Lai & P. Sundqvist (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language learning and teaching beyond the classroom (pp. 312-326). Routledge.

Lee, J. S., & Drajati, N. A. (2020). Willingness to communicate in digital and non-digital EFL contexts: Scale development and psychometric testing. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(7), 688-707.

Lee, J. S., & Dressman, M. (2018). When IDLE hands make an English workshop: Informal digital learning of English and language proficiency. TESOL Quarterly, 52(2), 435-445.

Lee, J. S., & Taylor, T. (2022). Positive psychology constructs and Extramural English as predictors of primary school students’ willingness to communicate. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2022.2079650

Lindgren, E., & Muñoz, C. (2013). The influence of exposure, parents, and linguistic distance on young European learners’ foreign language comprehension. International Journal of Multilingualism, 10(1), 105-129.

Lyrigkou, C. (2019). Not to be overlooked: Agency in informal language contact. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 13(3), 237-252.

Mackey, A. M., & Gass, S. M. (Eds.). (2023). Current approaches in second language acquisition research:

Muñoz, C. (2020). Boys like games and girls like movies: Age and gender differences in out-of-school contact with English. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics, 33(1), 171-201.

Muñoz, C., Cadierno, T., & Casas, I. (2018). Different starting points for English language learning: A comparative study of Danish and Spanish young learners. Language Learning, 68(4), 1076-1109.

Norris, J. M., Plonsky, L., Ross, S. J., & Schoonen, R. (2015). Guidelines for reporting quantitative methods and results in primary research. Language Learning, 65(2), 470-476.

Norwegian Media Authority. (2022). Barn og medier 2022 – En undersøkelse om 9-18-åringers medievaner [Children and media 2022 – an investigation of 9-18-year-olds’ media habits]. [Report]. Retrieved December 28, 2023, from https://www.medietilsynet.no/globalassets/publikasjoner/barn-og-medier-undersokelser/2022/231002_barn-og-medier_2022.pdf

Olsson, E., & Sylvén, L. K. (2015). Extramural English and academic vocabulary. A longitudinal study of CLIL and non-CLIL students in Sweden. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies, 9(2), 77-103.

Peters, E. (2018). The effect of out-of-class exposure to English language media on learners’ vocabulary knowledge. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 169(1), 142-167.

Peters, E., Noreillie, A.-S., Heylen, K., Bulté, B., & Desmet, P. (2019). The impact of instruction and out-ofschool exposure to foreign language input on learners’ vocabulary knowledge in two languages. Language Learning, 69(3), 747-782.

Plonsky, L., & Oswald, F. L. (2014). How big is “big”? Interpreting effect sizes in L2 research. Language Learning, 64(4), 878-912.

Puimège, E., & Peters, E. (2019). Learners’ English vocabulary knowledge prior to formal instruction: The role of learner-related and word-related factors. Language Learning, 69(4), 943-977.

Rothoni, A. (2017). The interplay of global forms of pop culture and media in teenagers’ ‘interest-driven’ everyday literacy practices with English in Greece. Linguistics and Education, 38, 92-103.

Saferinternet.at. (2022). Jugend-Internet-Monitor: Welche sozialen netzwerke nutzen Österreichs Jugendliche? [Youth-Internet-Monitor: Which social networks do young people in Austria use?]. Retrieved November 23, 2023, from https://www.saferinternet.at/services/jugend-internet-monitor/

Salaberry, M. R., & Kunitz, S. (Eds.) (2019). Teaching and testing L2 interactional competence: Bridging theory and practice. Routledge.

Schmitt, N. (2008). Review article: Instructed second language vocabulary learning. Language Teaching Research, 12(3), 329-363.

Schurz, A., & Sundqvist, P. (2022). Connecting extramural English with ELT: Teacher reports from Austria, Finland, France, and Sweden. Applied Linguistics, 43(5), 934-957.

Schwarz, M. (2020). Beyond the walls: A mixed methods study of teenagers’ extramural English practices and their vocabulary knowledge [Doctoral dissertation, University of Vienna]. Retrieved January 11, 2022, from https://utheses.univie.ac.at/detail/56447

Skehan, P. (1989). Individual differences in second-language learning. Edward Arnold.

Skehan, P. (1991). Individual differences in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 13(2), 275-298.

Soyoof, A. (2023). Iranian EFL students’ perception of willingness to communicate in an extramural digital context. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(9), 5922-5939.

Soyoof, A., Reynolds, B. L., Shadiev, R., & Vazquez-Calvo, B. (2024). A mixed-methods study of the incidental acquisition of foreign language vocabulary and healthcare knowledge through serious game play. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(1-2), 27-60.

Sundqvist, P. (2009). Extramural English matters: Out-of-school English and its impact on Swedish ninth graders’ oral proficiency and vocabulary. [Doctoral dissertation, Karlstad University]. https://www.divaportal.org/smash/get/diva2:275141/FULLTEXT03.pdf

Sundqvist, P. (2015). About a boy: A gamer and L2 English speaker coming into being by use of self-access. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6(4), 352-364.

Sundqvist, P. (2019). Commercial-off-the-shelf games in the digital wild and L2 learner vocabulary. Language Learning & Technology, 23(1), 87-113.

Sundqvist, P., & Sylvén, L. K. (2016). Extramural English in teaching and learning: From theory and research to practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

Sundqvist, P., & Uztosun, M. S. (2023). Extramural English in Scandinavia and Asia: Scale development, learner engagement, and perceived speaking ability. TESOL Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq. 3296

Sundqvist, P., & Wikström, P. (2015). Out-of-school digital gameplay and in-school L2 English vocabulary outcomes. System, 51, 65-76.

Swedish Media Council. (2023). Ungar & medier 2023 [Youth and media 2023]. [Report]. Retrieved December 13, 2023, from https://www.statensmedierad.se/rapporter-och-analyser/material-rapporter-och-analyser/2023/ungar-medier-2023

Sylvén, L. K., & Sundqvist, P. (2012). Gaming as extramural English L2 learning and L2 proficiency among young learners. ReCALL, 24(3), 302-321.

Twining, P., Heller, R. S., Nussbaum, M., & Tsai, -C.-C. (2017). Some guidance on conducting and reporting qualitative studies. Computers and Education, 106, A1-A9.

Zhang, Y., & Liu, G. (2022). Revisiting informal digital learning of English (IDLE): A structural equation modeling approach in a university EFL context. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-33. https://doi. org/10.1080/09588221.2022.2134424