DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49556-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38902254

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-20

الاستدامة البيئية والاقتصادية والاجتماعية في تربية الأحياء المائية: مؤشرات أداء تربية الأحياء المائية

تاريخ القبول: 10 يونيو 2024

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 20 يونيو 2024

الملخص

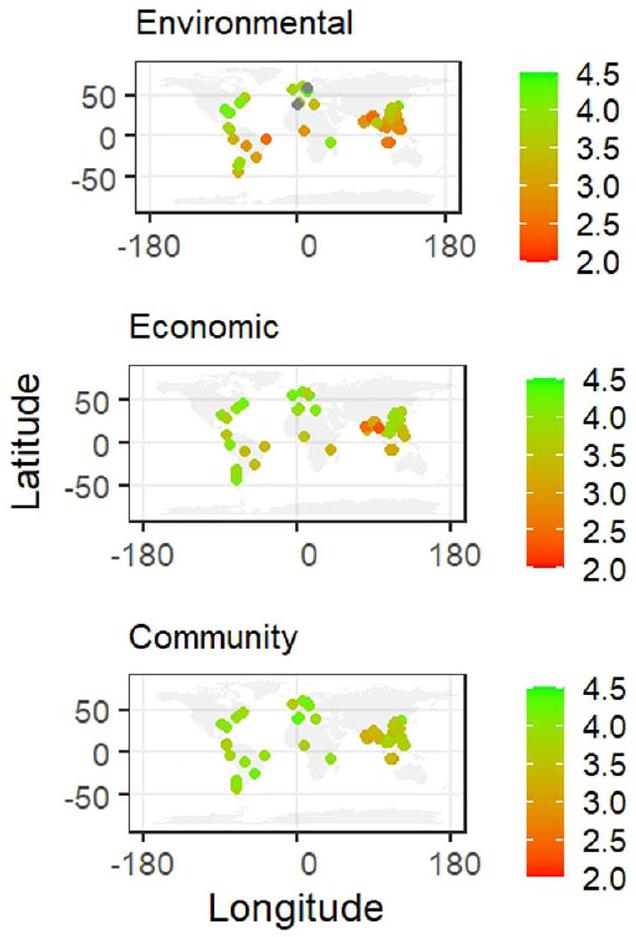

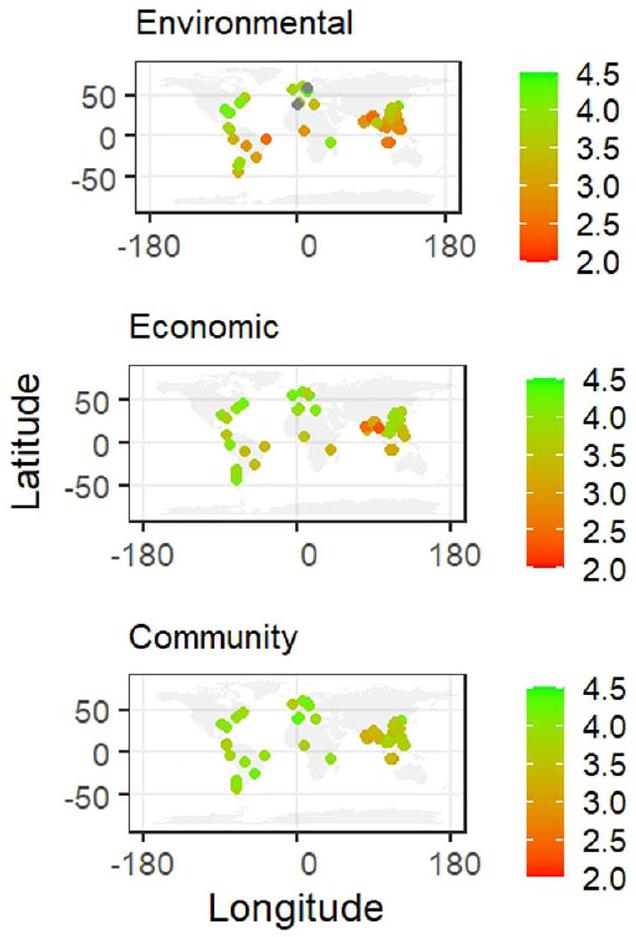

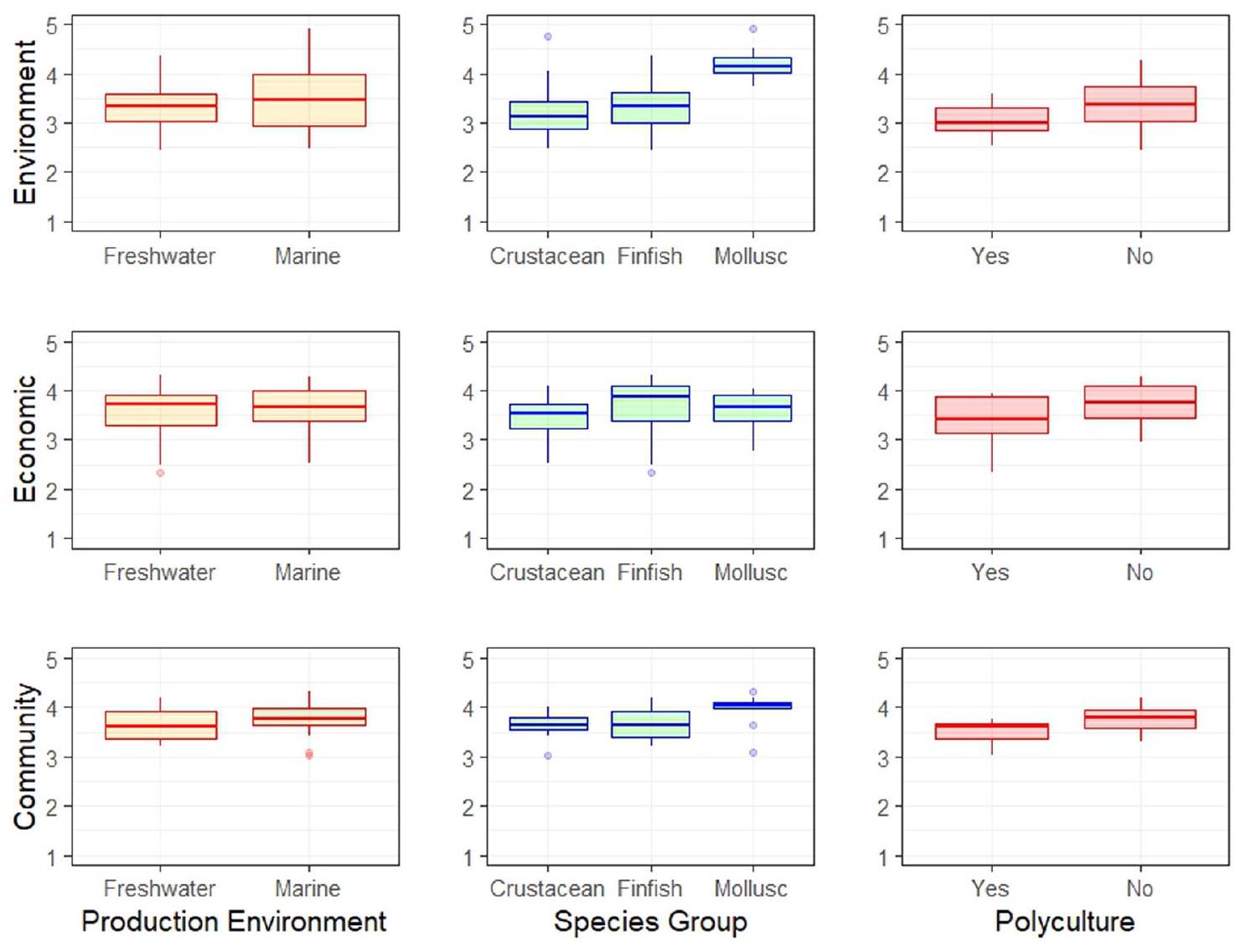

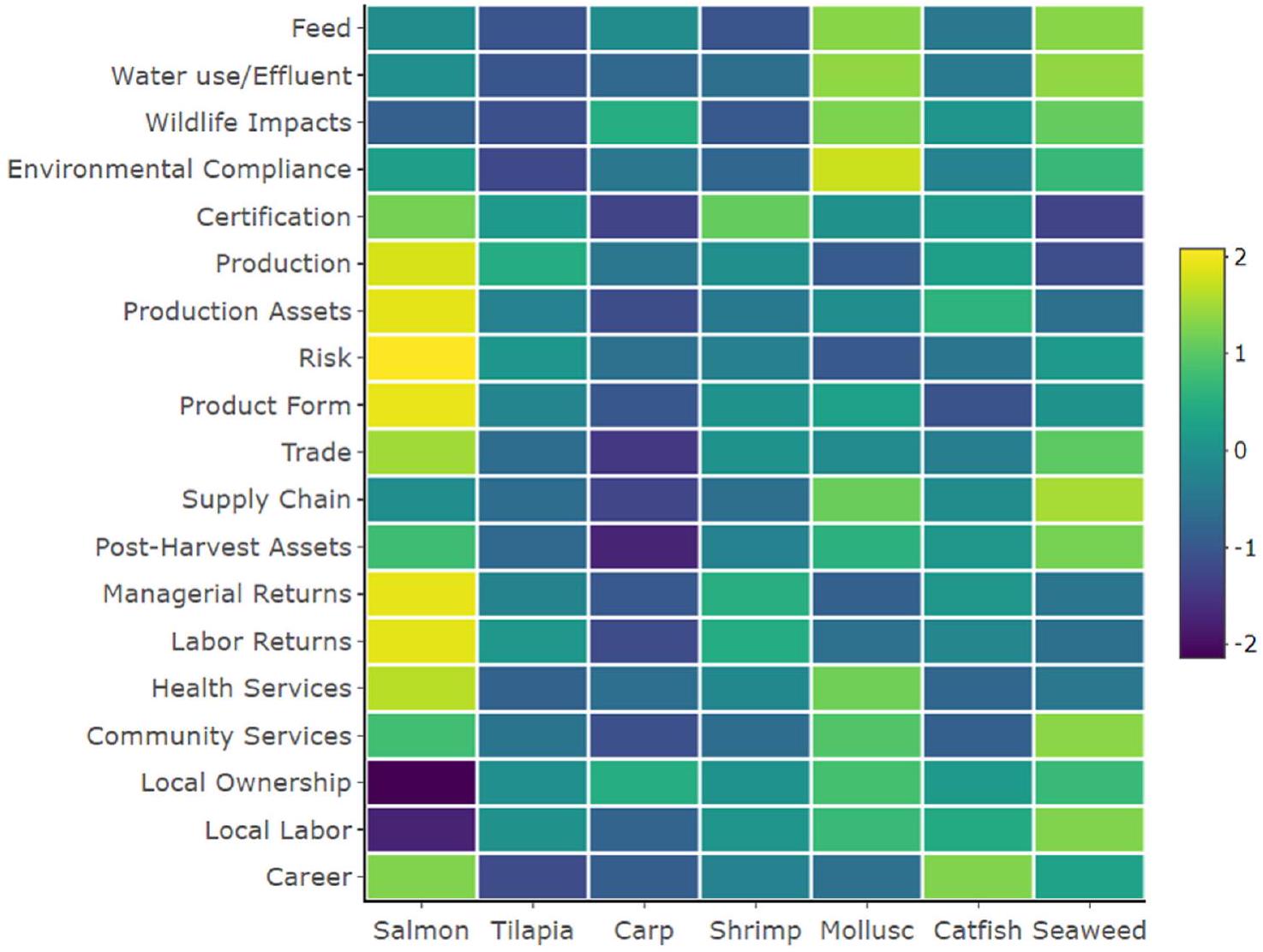

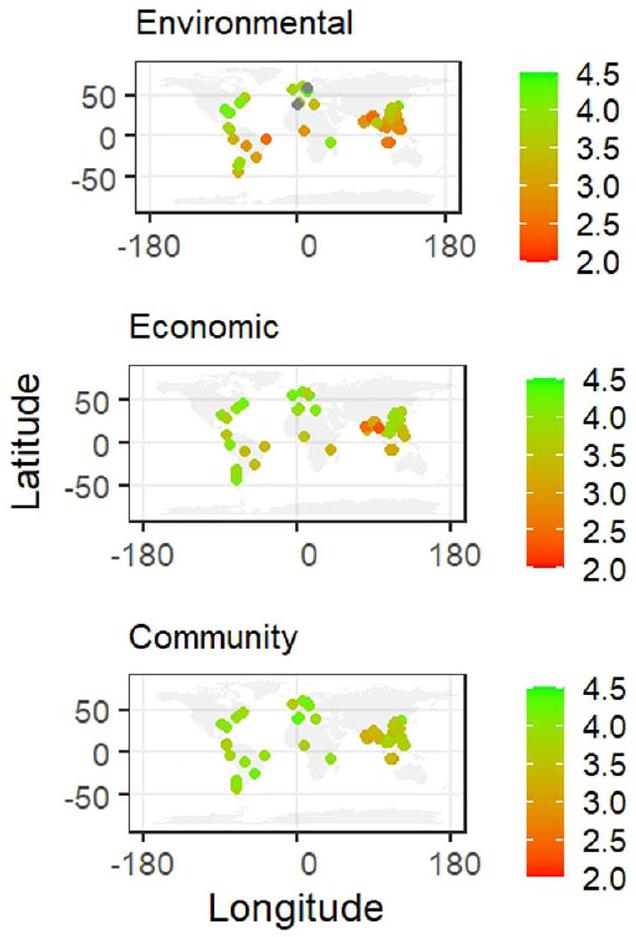

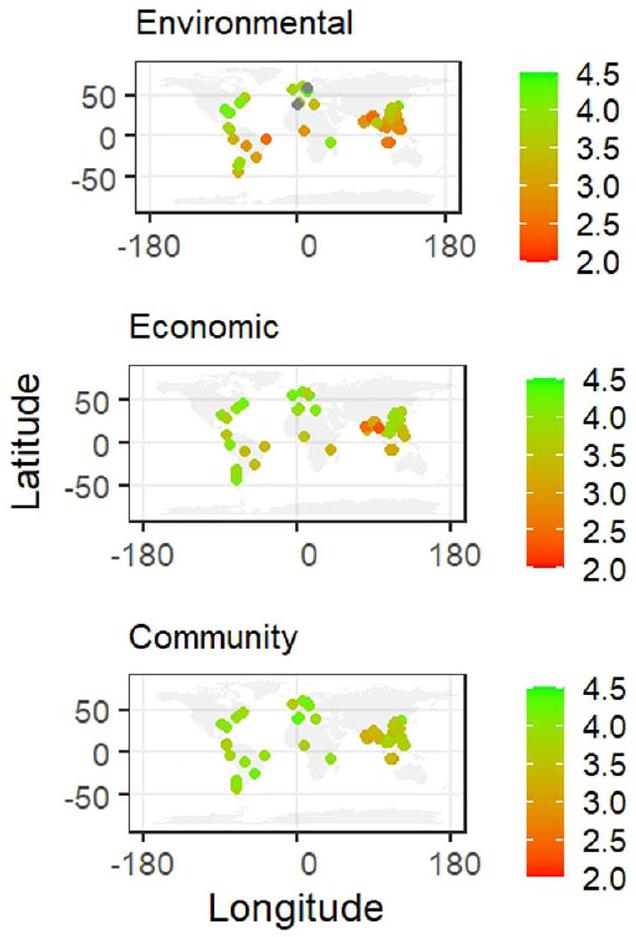

تربية الأحياء المائية هي تقنية إنتاج غذائي تنمو بسرعة، ولكن هناك مخاوف كبيرة تتعلق بتأثيرها البيئي وآثارها الاجتماعية السلبية. نحن نفحص نتائج تربية الأحياء المائية في إطار ثلاثة أعمدة للاستدامة من خلال تحليل البيانات التي تم جمعها باستخدام مؤشرات أداء تربية الأحياء المائية. باستخدام هذا النهج، تم جمع بيانات قابلة للمقارنة لـ 57 نظامًا لتربية الأحياء المائية في جميع أنحاء العالم على 88 مقياسًا يقيس النتائج الاجتماعية أو الاقتصادية أو البيئية. نحن نفحص أولاً العلاقات بين الأعمدة الثلاثة للاستدامة ثم نحلل الأداء في الأعمدة الثلاثة حسب التكنولوجيا والأنواع. تظهر النتائج أن النتائج الاقتصادية والاجتماعية والبيئية، في المتوسط، تعزز بعضها البعض في أنظمة تربية الأحياء المائية العالمية. ومع ذلك، تظهر التحليلات أيضًا تباينًا كبيرًا في درجة الاستدامة في أنظمة تربية الأحياء المائية المختلفة، وأن الأداء الضعيف لبعض أنظمة الإنتاج في بعض الأبعاد يوفر فرصة لتدابير سياسية مبتكرة واستثمار لمزيد من توافق أهداف الاستدامة.

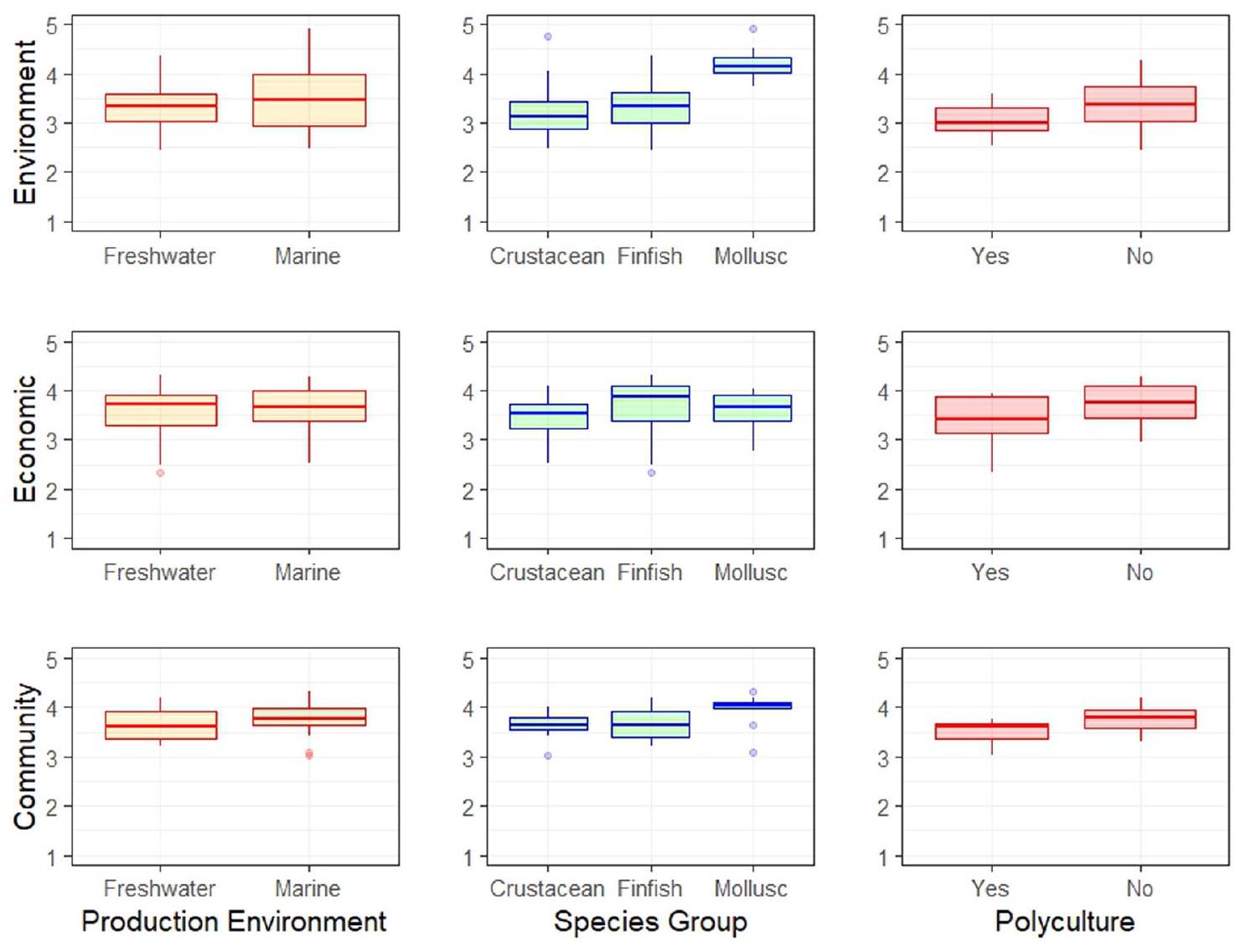

العلاقات بين أعمدة الاستدامة تختلف تمامًا في تربية الأحياء المائية عن مصايد الأسماك، وهي التقنية الرئيسية الأخرى لإنتاج المأكولات البحرية. على وجه الخصوص، هناك علاقة أضعف بكثير بين الاستدامة البيئية والاقتصادية وعلاقة أقوى بكثير بين الاستدامة الاجتماعية والبيئية. كما تسهل مؤشرات الأداء التحقيق في العديد من الموضوعات المثيرة للجدل حول تطوير تربية الأحياء المائية. على سبيل المثال، تشير نتائجنا إلى أن تربية الأحياء المائية للمياه العذبة والبحرية متكافئة من منظور الاستدامة، وأن الزراعة الأحادية تفضل على الزراعة المتعددة. نحن نحدد أنواع تربية الأحياء المائية ذات الأداء العالي والأنواع ونبرز الفرص لتحسين الأداء الاقتصادي والاجتماعي والبيئي. تدعم نتائجنا الصورة الدقيقة لصناعة غير متجانسة كما أشار نيلور وآخرون.

القضايا المتعلقة بالأعمدة الثلاثة للاستدامة، وبالتالي تسهل المقارنات العالمية. مؤشرات الأداء هي امتداد لمؤشرات أداء مصايد الأسماك (FPIs) لأندرسون وآخرين.

النتائج

التآزر والمفاضلات بين الأعمدة الثلاثة للاستدامة

بواسطة الصيادين

بيئة الإنتاج، والتقنيات، والأنواع

لقد انخفض استخدام المكونات البحرية بشكل كبير

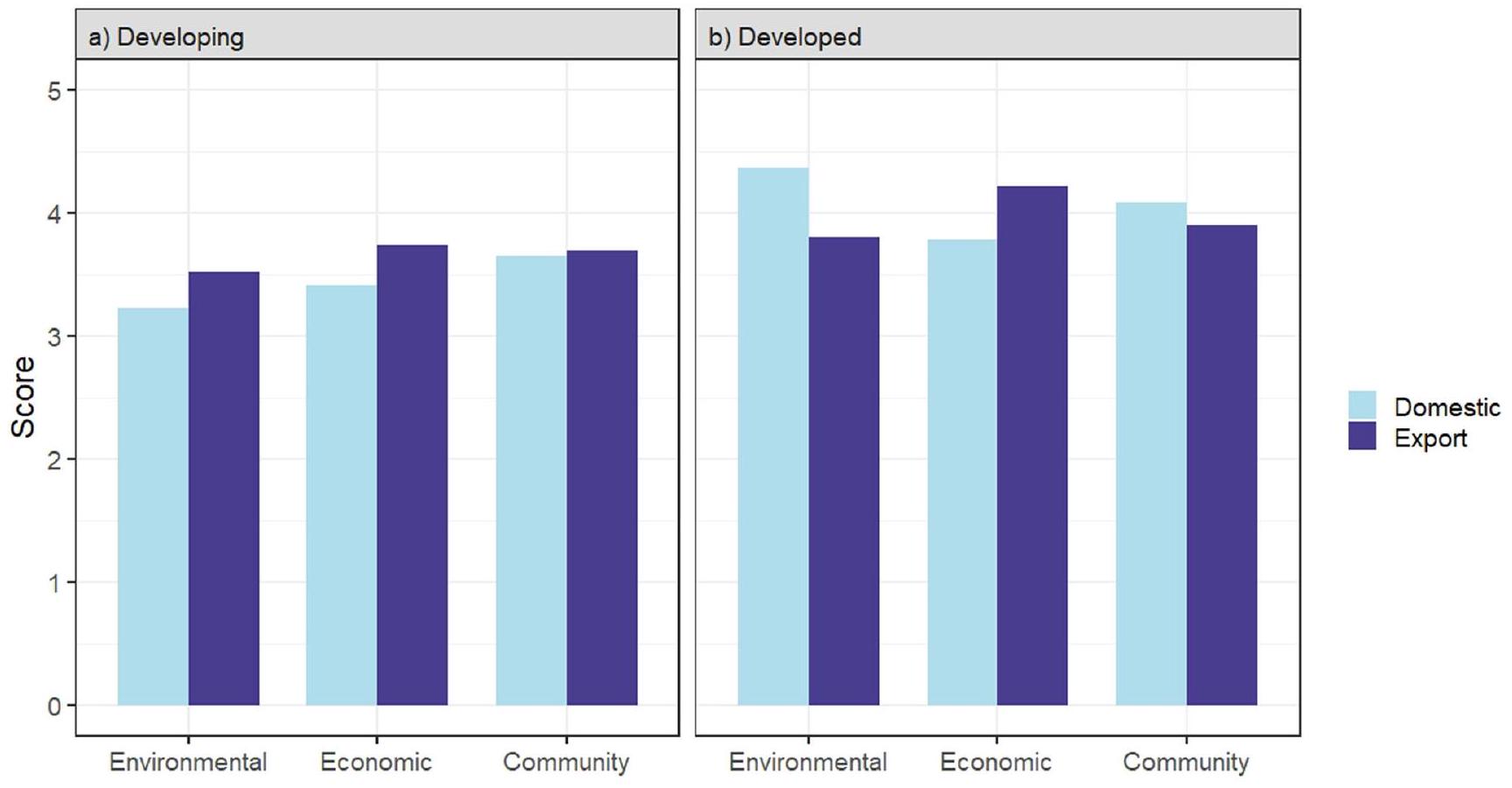

التجارة الدولية

يتم توحيد الدرجات حسب الصف من خلال طرح المتوسط والقسمة على

الانحراف المعياري. وبالتالي، فإن الدرجة المعيارية تعكس المسافة من المتوسط بوحدات الانحراف المعياري. راجع المواد التكميلية للقياسات الفردية التي تشكل كل بُعد.

المناطق الفقيرة في العالم

نقاش

طرق

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Rome, FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0461en. (2022).

- Belton, B., Bush, S. R. & Little, D. C. Not just for the wealthy: rethinking farmed fish consumption in the Global South. Glob. Food Secur. 16, 85 (2018).

- Golden, C. D. et al. Aquatic foods to nourish nations. Nature 598, 315 (2021).

- Gephart, J. A. et al. Environmental performance of blue foods. Nature 597, 360 (2021).

- Thomas, N. et al. Distribution and drivers of global mangrove forest change 1996-2010. PloS One 12, e0179302 (2017).

- Ahmed, N., Thompson, S. & Glaser, M. Global aquaculture productivity, sustainability, and climate change adaptation. Environ. Manag. 63, 159 (2019).

- Tacon, A. G. J. Trends in global aquaculture and aquafeed production: 2000-2017. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 28, 43 (2020).

- Wang, J., Beusen, A. H. W., Liu, X. & Bouwan, A. F. Aquaculture production is a large, spatially concentrated source of nutrients in Chinese freshwater and coastal seas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 1464 (2020).

- Beveridge, M. C. M. et al. Meeting the food and nutrition needs of the poor: the role of fish and the opportunities and challenges emerging from the rise of aquaculture. J. Fish. Biol. 83, 1067 (2013).

- Troell, M. Integrated marine and brackishwater aquaculture in tropical regions: research, implementation and prospects. In: Soto, D. (ed) integrated mariculture: a global review. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper, no 529. FAO, Rome. (2009).

- Naylor, R. L. et al. A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature 591, 551 (2021).

- Asche, F. Farming the sea. Mar. Resour. Econ. 23, 527 (2008).

- Garlock, T. et al. Aquaculture: the missing contributor in the food security agenda. Glob. Food Security 32, 10062 (2022).

- Belton, B. & Little, D. C. Immanent and interventionist inland Asian aquaculture development and its outcomes. Dev. Policy Rev. 29, 459 (2011).

- Anderson, J. L., Asche, F. & Garlock, T. Globalization and commoditization: the transformation of the seafood market. J. Commod. Mark. 12, 2 (2018).

- Asche, F., Eggert, H., Oglend, A., Roheim, C. A. & Smith, M. D. Aquaculture: externalities and policy options. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 16, 282 (2022).

- Naylor, R., Fang, S. & Fanzo, J. A global view of aquaculture policy. Food Policy 116, 102422 (2023).

- FAO. The world’s mangroves 1980-2005: a thematic study prepared in the framework of the Global Forest Resource Assessment 2005. FAO Forestry Paper 153, Rome, FAO. (2007).

- Hilborn, R. et al. Effective fisheries management instrumental in improving fish stock status. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 2218 (2020).

- Koehn, J. S., Allison, E. H., Golden, C. D. & Hilborn, R. The role of seafood in sustainable diets. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 035003 (2022).

- Belton, B. et al. Farming fish in sea will not nourish the world. Nat. Commun. 11, 5804 (2020).

- Kaminski, A. M., Kruijssen, F., Cole, S. M., Beveridge, M. C. M. & Dawson, C. A review of inclusive business models and their application in aquaculture development. Rev. Aquac. 12, 1881 (2020).

- Prodhan, Md. M. H., Khan, Md. A., Palash, Md. S., Hossain, M. I. & Kumar, G. Supply chain performance of fishing industry in Bangladesh: emphasizing on information sharing and commitment. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 27, 523 (2023).

- Clark, T. P. & Longo, S. B. Global labor value chains, commodification, and the socioecological structure of severe exploitation. A case study of the Thai seafood sector. J. Peasant Stud. 49, 652 (2022).

- Ceballos, A., Dresdner-Cid, J. D. & Quiroga-Suazo, M. Á. Does the location of salmon farms contribute to the reduction of poverty in remote coastal areas? An impact assessment using a Chilean case study. Food Policy 75, 68 (2018).

- Filipski, M. & Belton, B. Give a man a fish pond: modeling the impacts of aquaculture in the rural economy. World Dev. 110, 205 (2018).

- Cárdenas-Retamal, R., Dresdner-Cid, J. D. & Ceballos-Concha, A. Impact assessment of salmon farming on income distribution of remote coastal areas. The Chilean case. Food Policy 101, 102078 (2021).

- Hegde, S. et al. Economic contribution of the US catfish industry. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 26, 384 (2022).

- Toufique, K. A. & Belton, B. Is aquaculture pro-poor? Empirical evidence of impacts on fish consumption in Bangladesh. World Dev. 64, 609 (2014).

- Anderson, J. L., Anderson, C. M., Chu, J. & Meredith, J. The fishery performance indicators: a management tool for triple bottom line outcomes. PLoS ONE 10, e0122809 (2015).

- Asche, F. et al. The three pillars of sustainability in fisheries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 11221 (2018).

- Garlock, T. et al. Global insights on managing fishery systems for the three pillars of sustainability. Fish. Fish. 23, 899 (2022).

- McCluney, J. K., Anderson, C. M. & Anderson, J. L. The fishery performance indicators for global tuna fisheries. Nat. Commun. 10, 1641 (2019).

- Asche, F., Garlock, T. M. & Akpalu, W. Fisheries performance in Africa: an analysis based on data from 14 countries. Mar. Policy 125, 104263 (2021).

- Volpe, J. P. et al. Global aquaculture performance index (GAPI): the first global environmental assessment of marine fish farming. Sustainability 5, 3976 (2013).

- FAO World Aquaculture Performance Indicators (WAPI) Information, knowledge and capacity for Blue Growth. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/I9622EN/i9622en.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2023) (2017).

- Stentiford, G. D. et al. Sustainable aquaculture through the One Health lens. Nat. Food 1, 468 (2020).

- Garlock, T. et al. A global blue revolution: Aquaculture growth across regions, species and countries. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 28, 107 (2020).

- Costello, C., Gaines, S. D. & Lynham, J. Can catch shares prevent fisheries collapse? Science 321, 1678 (2008).

- Birkenbach, A. M., Kaczan, D. J. & Smith, M. D. Catch shares slow the race to fish. Nature 544, 1067 (2017).

- Pincinato, R. B., Asche, F. & Roll, K. H. Escapees in salmon aquaculture: a multi-output approach. Land Econ. 97, 425 (2021).

- Bush, S. R. et al. Certify sustainable aquaculture? Science 341, 1067 (2013).

- Asche, F., Bronnmann, J. & Cojocaru, A. L. The value of responsibly farmed fish: a hedonic price study of ASC-certified whitefish. Ecol. Econ. 188, 107135 (2021).

- Ruff, E. O., Gentry, R. R. & Lester, S. E. Understanding the role of socioeconomic and governance conditions in countrylevel marine aquaculture production. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 1040a8 (2020).

- Zhang, W. B. et al. Aquaculture will continue to depend more on land than sea. Nature 603, E2 (2022).

- Costa-Pierce, B. A. et al. A fishy story promoting a false dichotomy to policy-makers: it is not freshwater vs. marine aquaculture. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 30, 429 (2022).

- Chopin, T., Cooper, J. A., Reid, G., Cross, S. & Moore, C. Open-water integrated multi-trophic aquaculture: environmental biomitigation and economic diversification of fed aquaculture by extractive aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 4, 209 (2012).

- Knowler, D. et al. The economics of integrated multi-trophic aquaculture: where are we now and where do we need to go? Rev. Aquac. 12, 1579 (2020).

- Gephart, J. E. et al. Scenarios for global aquaculture and its role in human nutrition. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 29, 122 (2021b).

- Naylor, R. L. et al. Feeding aquaculture in an era of finite resources. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 106, 15103 (2009).

- Barrett, L. T. et al. Sustainable growth of non-fed aquaculture can generate valuable ecosystem benefits. Ecosyst. Serv. 53, 101396 (2022).

- Advelas, L. et al. The decline of mussel aquaculture in the European Union: causes, economic impacts and opportunities. Rev. Aquac. 13, 91 (2021).

- Moor, J., Ropicki, A., Anderson, J. L. & Asche, F. Stochastic modeling and financial viability of mollusk aquaculture. Aquaculture 552, 737963 (2022).

- Moor, J., Ropicki, A. & Garlock, T. Clam aquaculture profitability under changing environmental risks. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 26, 283 (2022).

- Botta, R., Asche, F., Borsum, J. S. & Camp, E. V. A review of global oyster aquaculture production and consumption. Mar. Policy 117, 103952 (2020).

- Parker, M. & Bricker, S. Sustainable oyster aquaculture, water quality improvement, and ecosystem service value potential in Maryland Chesapeake Bay. J. Shellfish Res. 39, 269 (2020).

- Ytrestøyl, T., Aas, T. S. & Åsgård, T. Utilisation of feed resources in production of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in Norway. Aquaculture 448, 365 (2015).

- Kumar, G. & Engle, C. R. Technological advances that led to growth of shrimp, salmon, and tilapia farming. Rev. Fish. Sci. 24, 134 (2016).

- Kumar, G., Engle, C. R. & Tucker, C. S. Factors driving aquaculturetechnology adoption. J. World Aquac. Soc. 49, 447 (2018).

- Phyne, J. A comparative political economy of rural capitalism: Salmon aquaculture in Norway, Chile and Ireland. Acta Sociol. 53, 160 (2010).

- Hishamunda, N. et al. Improving governance of aquaculture employment: A global assessment. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper 575, Rome. (2014).

- Young, N. et al. Limitations to growth: Social-ecological challenges to aquaculture development in five wealthy nations. Mar. Policy 104, 216 (2019).

- Quiñones, R., Fuentes, M., Montes, R. M., Soto, D. & León-Muñoz, J. Environmental issues in Chilean salmon farming: a review. Rev. Aquac. 11, 375 (2019).

- Gephart, J. A. & Pace, M. L. Structure and evolution of the global seafood trade network. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 125014 (2015).

- Belton, B. & Little, D. C. The development of aquaculture in central Thailand: domestic demand versus export-led production. J. Agrar. Change 8, 123 (2008).

- Primavera, J. H. Socio-economic impacts of shrimp culture. Aquac. Res. 28, 815 (1997).

- van Mulekom, L. et al. Trade and export orientation of fisheries in Southeast Asia: under-priced export at the expense of domestic food security and local economies. Ocean Coast. Manag. 49, 546 (2006).

- Rivera-Ferre, M. G. Can export-oriented aquaculture in developing countries be sustainable and promote sustainable development? The shrimp case. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 22, 201 (2009).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

جمع البيانات، وكتب الورقة. صمم J.L.A. البحث، جمع البيانات، حلل البيانات، وكتب الورقة. صمم H.E. البحث، جمع البيانات، حلل البيانات، وكتب الورقة. جمع T.M.A. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع B.C. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع C.A.C. البيانات، حلل البيانات، وكتب الورقة. جمع J.C. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع N.C. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع M.M.D. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع K.F. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع J.F. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع J.G. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع G.K. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع L.L. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع I.L. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع L.N. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع R.N. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع R.B.M.P. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع P.O.S. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع B.T. البيانات وكتب الورقة. جمع R.T. البيانات وكتب الورقة. يتشارك T.M.G. و F.A. في تأليف الورقة.

تمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© المؤلفون 2024، نشر مصحح 2024

- تظهر قائمة كاملة بالانتماءات في نهاية الورقة.

البريد الإلكتروني: فرانك.أش@ufl.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49556-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38902254

Publication Date: 2024-06-20

Environmental, economic, and social sustainability in aquaculture: the aquaculture performance indicators

Accepted: 10 June 2024

Published online: 20 June 2024

Abstract

Aquaculture is a rapidly growing food production technology, but there are significant concerns related to its environmental impact and adverse social effects. We examine aquaculture outcomes in a three pillars of sustainability framework by analyzing data collected using the Aquaculture Performance Indicators. Using this approach, comparable data has been collected for 57 aquaculture systems worldwide on 88 metrics that measure social, economic, or environmental outcomes. We first examine the relationships among the three pillars of sustainability and then analyze performance in the three pillars by technology and species. The results show that economic, social, and environmental outcomes are, on average, mutually reinforced in global aquaculture systems. However, the analysis also shows significant variation in the degree of sustainability in different aquaculture systems, and weak performance of some production systems in some dimensions provides opportunity for innovative policy measures and investment to further align sustainability objectives.

relationships between the sustainability pillars is quite different in aquaculture from fisheries, the other main production technology for seafood. In particular, there is a much weaker relationship between environmental and economic sustainability and a much stronger relationship between social and environmental sustainability. The APIs also facilitate the investigation of several controversial topics about aquaculture development. For instance, our results suggest that freshwater and marine aquaculture are equivalent from a sustainability perspective, and monoculture is preferable to polyculture. We identify high-performing aquaculture typologies and species and highlight opportunities to improve economic, social, and environmental performance. Our results support the nuanced picture of a heterogenous industry indicated by Naylor et al.

issues related to the three pillars of sustainability and, therefore, facilitates global comparisons. The APIs are an extension of the Fishery Performance Indicators (FPIs) of Anderson et al.

Results

Synergies and trade-offs among the three pillars of sustainability

by fishers

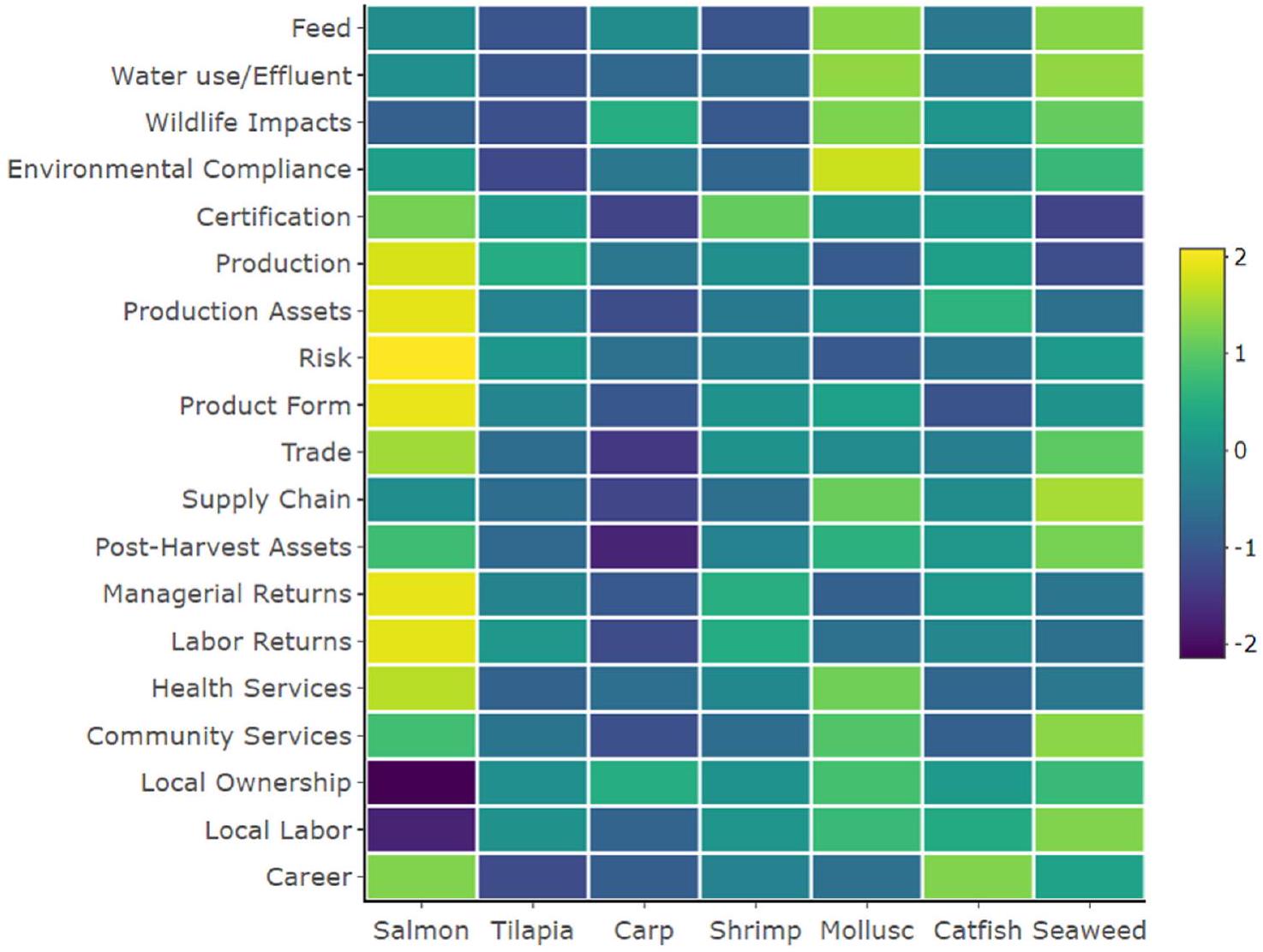

Production environment, technologies, and species

the use of marine ingredients have declined significantly

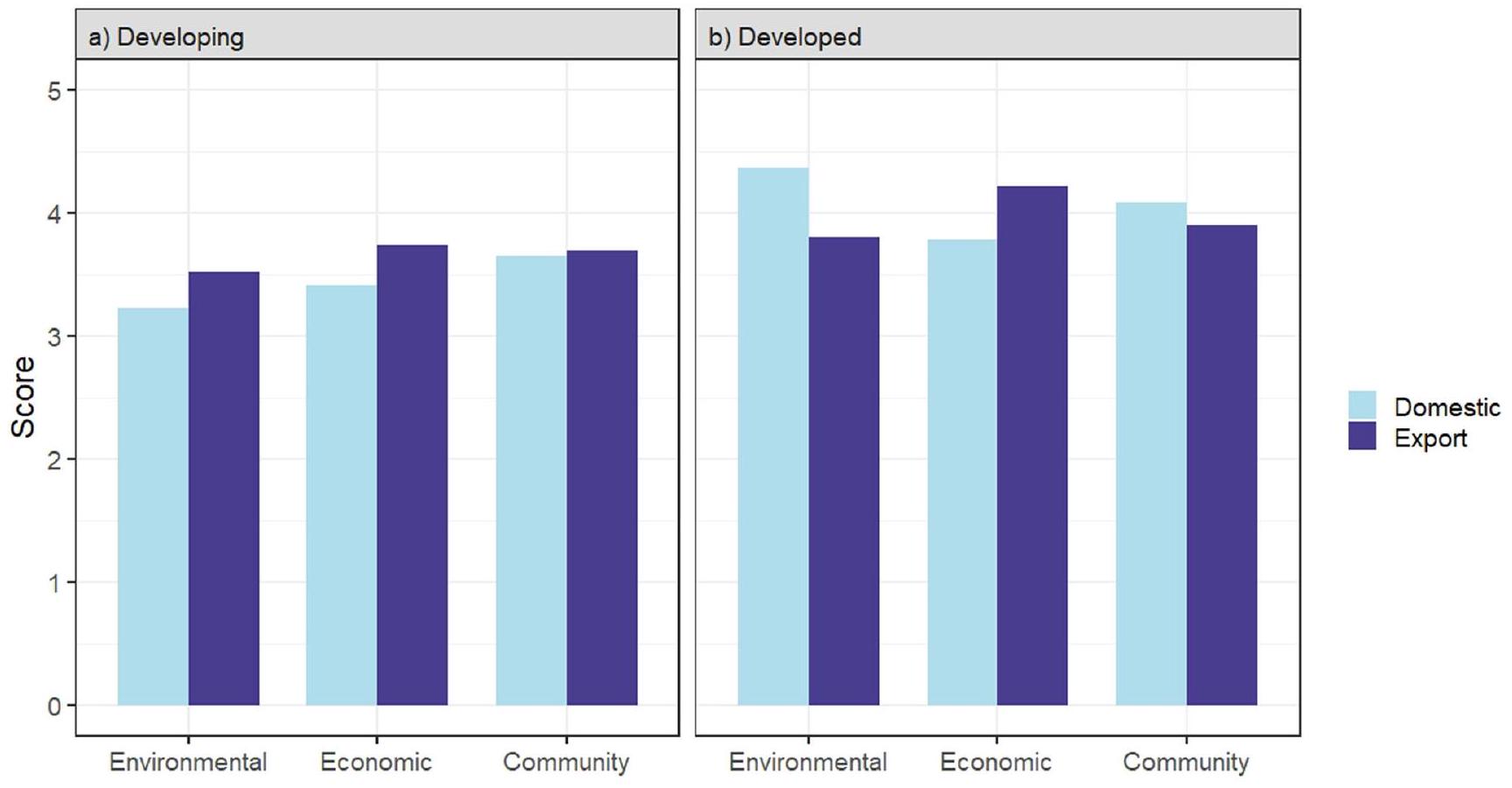

International trade

Scores are standardized by row by subtracting the mean and dividing by the

standard deviation. Thus, the standardized score reflects the distance from the mean in units of standard deviation. See the Supplementary materials for the individual metrics comprising each dimension.

poor regions of the world

Discussion

Methods

Reporting summary

Data availability

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Rome, FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0461en. (2022).

- Belton, B., Bush, S. R. & Little, D. C. Not just for the wealthy: rethinking farmed fish consumption in the Global South. Glob. Food Secur. 16, 85 (2018).

- Golden, C. D. et al. Aquatic foods to nourish nations. Nature 598, 315 (2021).

- Gephart, J. A. et al. Environmental performance of blue foods. Nature 597, 360 (2021).

- Thomas, N. et al. Distribution and drivers of global mangrove forest change 1996-2010. PloS One 12, e0179302 (2017).

- Ahmed, N., Thompson, S. & Glaser, M. Global aquaculture productivity, sustainability, and climate change adaptation. Environ. Manag. 63, 159 (2019).

- Tacon, A. G. J. Trends in global aquaculture and aquafeed production: 2000-2017. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 28, 43 (2020).

- Wang, J., Beusen, A. H. W., Liu, X. & Bouwan, A. F. Aquaculture production is a large, spatially concentrated source of nutrients in Chinese freshwater and coastal seas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 1464 (2020).

- Beveridge, M. C. M. et al. Meeting the food and nutrition needs of the poor: the role of fish and the opportunities and challenges emerging from the rise of aquaculture. J. Fish. Biol. 83, 1067 (2013).

- Troell, M. Integrated marine and brackishwater aquaculture in tropical regions: research, implementation and prospects. In: Soto, D. (ed) integrated mariculture: a global review. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper, no 529. FAO, Rome. (2009).

- Naylor, R. L. et al. A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature 591, 551 (2021).

- Asche, F. Farming the sea. Mar. Resour. Econ. 23, 527 (2008).

- Garlock, T. et al. Aquaculture: the missing contributor in the food security agenda. Glob. Food Security 32, 10062 (2022).

- Belton, B. & Little, D. C. Immanent and interventionist inland Asian aquaculture development and its outcomes. Dev. Policy Rev. 29, 459 (2011).

- Anderson, J. L., Asche, F. & Garlock, T. Globalization and commoditization: the transformation of the seafood market. J. Commod. Mark. 12, 2 (2018).

- Asche, F., Eggert, H., Oglend, A., Roheim, C. A. & Smith, M. D. Aquaculture: externalities and policy options. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 16, 282 (2022).

- Naylor, R., Fang, S. & Fanzo, J. A global view of aquaculture policy. Food Policy 116, 102422 (2023).

- FAO. The world’s mangroves 1980-2005: a thematic study prepared in the framework of the Global Forest Resource Assessment 2005. FAO Forestry Paper 153, Rome, FAO. (2007).

- Hilborn, R. et al. Effective fisheries management instrumental in improving fish stock status. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 2218 (2020).

- Koehn, J. S., Allison, E. H., Golden, C. D. & Hilborn, R. The role of seafood in sustainable diets. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 035003 (2022).

- Belton, B. et al. Farming fish in sea will not nourish the world. Nat. Commun. 11, 5804 (2020).

- Kaminski, A. M., Kruijssen, F., Cole, S. M., Beveridge, M. C. M. & Dawson, C. A review of inclusive business models and their application in aquaculture development. Rev. Aquac. 12, 1881 (2020).

- Prodhan, Md. M. H., Khan, Md. A., Palash, Md. S., Hossain, M. I. & Kumar, G. Supply chain performance of fishing industry in Bangladesh: emphasizing on information sharing and commitment. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 27, 523 (2023).

- Clark, T. P. & Longo, S. B. Global labor value chains, commodification, and the socioecological structure of severe exploitation. A case study of the Thai seafood sector. J. Peasant Stud. 49, 652 (2022).

- Ceballos, A., Dresdner-Cid, J. D. & Quiroga-Suazo, M. Á. Does the location of salmon farms contribute to the reduction of poverty in remote coastal areas? An impact assessment using a Chilean case study. Food Policy 75, 68 (2018).

- Filipski, M. & Belton, B. Give a man a fish pond: modeling the impacts of aquaculture in the rural economy. World Dev. 110, 205 (2018).

- Cárdenas-Retamal, R., Dresdner-Cid, J. D. & Ceballos-Concha, A. Impact assessment of salmon farming on income distribution of remote coastal areas. The Chilean case. Food Policy 101, 102078 (2021).

- Hegde, S. et al. Economic contribution of the US catfish industry. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 26, 384 (2022).

- Toufique, K. A. & Belton, B. Is aquaculture pro-poor? Empirical evidence of impacts on fish consumption in Bangladesh. World Dev. 64, 609 (2014).

- Anderson, J. L., Anderson, C. M., Chu, J. & Meredith, J. The fishery performance indicators: a management tool for triple bottom line outcomes. PLoS ONE 10, e0122809 (2015).

- Asche, F. et al. The three pillars of sustainability in fisheries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, 11221 (2018).

- Garlock, T. et al. Global insights on managing fishery systems for the three pillars of sustainability. Fish. Fish. 23, 899 (2022).

- McCluney, J. K., Anderson, C. M. & Anderson, J. L. The fishery performance indicators for global tuna fisheries. Nat. Commun. 10, 1641 (2019).

- Asche, F., Garlock, T. M. & Akpalu, W. Fisheries performance in Africa: an analysis based on data from 14 countries. Mar. Policy 125, 104263 (2021).

- Volpe, J. P. et al. Global aquaculture performance index (GAPI): the first global environmental assessment of marine fish farming. Sustainability 5, 3976 (2013).

- FAO World Aquaculture Performance Indicators (WAPI) Information, knowledge and capacity for Blue Growth. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/I9622EN/i9622en.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2023) (2017).

- Stentiford, G. D. et al. Sustainable aquaculture through the One Health lens. Nat. Food 1, 468 (2020).

- Garlock, T. et al. A global blue revolution: Aquaculture growth across regions, species and countries. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 28, 107 (2020).

- Costello, C., Gaines, S. D. & Lynham, J. Can catch shares prevent fisheries collapse? Science 321, 1678 (2008).

- Birkenbach, A. M., Kaczan, D. J. & Smith, M. D. Catch shares slow the race to fish. Nature 544, 1067 (2017).

- Pincinato, R. B., Asche, F. & Roll, K. H. Escapees in salmon aquaculture: a multi-output approach. Land Econ. 97, 425 (2021).

- Bush, S. R. et al. Certify sustainable aquaculture? Science 341, 1067 (2013).

- Asche, F., Bronnmann, J. & Cojocaru, A. L. The value of responsibly farmed fish: a hedonic price study of ASC-certified whitefish. Ecol. Econ. 188, 107135 (2021).

- Ruff, E. O., Gentry, R. R. & Lester, S. E. Understanding the role of socioeconomic and governance conditions in countrylevel marine aquaculture production. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 1040a8 (2020).

- Zhang, W. B. et al. Aquaculture will continue to depend more on land than sea. Nature 603, E2 (2022).

- Costa-Pierce, B. A. et al. A fishy story promoting a false dichotomy to policy-makers: it is not freshwater vs. marine aquaculture. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 30, 429 (2022).

- Chopin, T., Cooper, J. A., Reid, G., Cross, S. & Moore, C. Open-water integrated multi-trophic aquaculture: environmental biomitigation and economic diversification of fed aquaculture by extractive aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 4, 209 (2012).

- Knowler, D. et al. The economics of integrated multi-trophic aquaculture: where are we now and where do we need to go? Rev. Aquac. 12, 1579 (2020).

- Gephart, J. E. et al. Scenarios for global aquaculture and its role in human nutrition. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 29, 122 (2021b).

- Naylor, R. L. et al. Feeding aquaculture in an era of finite resources. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 106, 15103 (2009).

- Barrett, L. T. et al. Sustainable growth of non-fed aquaculture can generate valuable ecosystem benefits. Ecosyst. Serv. 53, 101396 (2022).

- Advelas, L. et al. The decline of mussel aquaculture in the European Union: causes, economic impacts and opportunities. Rev. Aquac. 13, 91 (2021).

- Moor, J., Ropicki, A., Anderson, J. L. & Asche, F. Stochastic modeling and financial viability of mollusk aquaculture. Aquaculture 552, 737963 (2022).

- Moor, J., Ropicki, A. & Garlock, T. Clam aquaculture profitability under changing environmental risks. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 26, 283 (2022).

- Botta, R., Asche, F., Borsum, J. S. & Camp, E. V. A review of global oyster aquaculture production and consumption. Mar. Policy 117, 103952 (2020).

- Parker, M. & Bricker, S. Sustainable oyster aquaculture, water quality improvement, and ecosystem service value potential in Maryland Chesapeake Bay. J. Shellfish Res. 39, 269 (2020).

- Ytrestøyl, T., Aas, T. S. & Åsgård, T. Utilisation of feed resources in production of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in Norway. Aquaculture 448, 365 (2015).

- Kumar, G. & Engle, C. R. Technological advances that led to growth of shrimp, salmon, and tilapia farming. Rev. Fish. Sci. 24, 134 (2016).

- Kumar, G., Engle, C. R. & Tucker, C. S. Factors driving aquaculturetechnology adoption. J. World Aquac. Soc. 49, 447 (2018).

- Phyne, J. A comparative political economy of rural capitalism: Salmon aquaculture in Norway, Chile and Ireland. Acta Sociol. 53, 160 (2010).

- Hishamunda, N. et al. Improving governance of aquaculture employment: A global assessment. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper 575, Rome. (2014).

- Young, N. et al. Limitations to growth: Social-ecological challenges to aquaculture development in five wealthy nations. Mar. Policy 104, 216 (2019).

- Quiñones, R., Fuentes, M., Montes, R. M., Soto, D. & León-Muñoz, J. Environmental issues in Chilean salmon farming: a review. Rev. Aquac. 11, 375 (2019).

- Gephart, J. A. & Pace, M. L. Structure and evolution of the global seafood trade network. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 125014 (2015).

- Belton, B. & Little, D. C. The development of aquaculture in central Thailand: domestic demand versus export-led production. J. Agrar. Change 8, 123 (2008).

- Primavera, J. H. Socio-economic impacts of shrimp culture. Aquac. Res. 28, 815 (1997).

- van Mulekom, L. et al. Trade and export orientation of fisheries in Southeast Asia: under-priced export at the expense of domestic food security and local economies. Ocean Coast. Manag. 49, 546 (2006).

- Rivera-Ferre, M. G. Can export-oriented aquaculture in developing countries be sustainable and promote sustainable development? The shrimp case. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 22, 201 (2009).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

the data, and wrote the paper. J.L.A. designed the research, collected data, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. H.E. designed the research, collected the data, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. T.M.A. collected data and wrote the paper. B.C. collected data and wrote the paper. C.A.C. collected data, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. J.C. collected data and wrote the paper. N.C. collected data and wrote the paper. M.M.D. collected data and wrote the paper. K.F. collected data and wrote the paper. J.F. collected data and wrote the paper. J.G. collected data and wrote the paper. G.K. collected data and wrote the paper. L.L. collected data and wrote the paper. I.L. collected data and wrote the paper. L.N. collected data and wrote the paper. R.N. collected data and wrote the paper. R.B.M.P. collected data and wrote the paper. P.O.S. collected data and wrote the paper. B.T. collected data and wrote the paper. R.T. collected data and wrote the paper. T.M.G. and F.A. share first authorship.

Funding

Competing interests

Additional information

© The Author(s) 2024, corrected publication 2024

- A full list of affiliations appears at the end of the paper.

e-mail: frank.asche@ufl.edu