DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-025-05703-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40055702

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-07

التبييض الداخلي باستخدام أكسالات الكالسيوم وإشعاع الليزر لإدارة تغيرات اللون الناتجة عن تجميع ثلاثي أكسيد المعادن

الملخص

الهدف: درست هذه الدراسة المختبرية تأثير دمج 1% و 3% و 5% من أكسالات الكالسيوم في 15% من بيروكسيد الهيدروجين

المقدمة

تم اقتراح عدة فرضيات لشرح آلية تغير لون الأسنان بعد تطبيق MTA. اقترحت إحدى الفرضيات الأولية أن أكسدة المعادن الثقيلة، مثل الحديد أو المغنيسيوم، هي المسؤولة عن تغير اللون المرتبط بـ MTA الرمادي [3]. لذلك، تم تقديم MTA الأبيض، الذي يحتوي على الحد الأدنى من FeO وMgO وAl2O3 في هيكله، لتقليل تغير اللون. ومع ذلك، لا تزال تحدث تغيرات في اللون بعد استخدام MTA الأبيض، على الرغم من أنها أقل حدة من MTA الرمادي [4]. لذلك، تم الإشارة إلى أكسيد البزموت، وهو المادة المشعة في MTA، كعامل رئيسي في تغير لون الأسنان في MTA الأبيض [3]. يرتبط أكسيد البزموت مع هيدرات سيليكات الكالسيوم ويتم إطلاقه تدريجياً مع تحلله بمرور الوقت [5]. يمكن أن يسبب أكسيد البزموت المحرر تغير لون الأسنان، بشكل أساسي من خلال التفاعل مع كولاجين العاج لتشكيل راسب أسود [6]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قد يتفاعل مع ثاني أكسيد الكربون وينتج كربونات البزموت، مما يؤدي إلى تغير لون الأسنان [3]. قد يتسبب تعرض أكسيد البزموت لإشعاع الضوء ودرجات الحرارة المرتفعة أيضًا في تغير اللون في MTA أو خليط الأسمنت الغني بالكالسيوم (CEM) [3].

التبييض الداخلي هو علاج عملي ومحافظ وفعال من حيث التكلفة لإدارة تغير اللون في الأسنان غير الحيوية. ومع ذلك، فإن هذه الطريقة العلاجية لها آثار جانبية محتملة، مثل امتصاص الجذر العنقي الخارجي، وتغيرات شكل العاج، وتدهور الكولاجين [7، 8]. لتقليل هذه المخاطر، يستكشف الباحثون طرقًا لتقليل مدة العلاج وتركيز عوامل التبييض.

نهج مناسب لمعالجة تغير اللون الناتج عن أكاسيد المعادن هو استخدام عوامل خلب مثل حمض الأكساليك، الذي يرتبط بفعالية بأيونات المعادن [9] مما يسهل إزالة المركبات الأيونية غير القابلة للذوبان من الركائز [10]. تُستخدم الأكسالات على نطاق واسع في صناعات مختلفة، مثل السيراميك وتبييض الورق، لإزالة التلوث المعدني [11، 12]. هناك بعض الدراسات حول تأثير حمض الأكساليك على تحسين نتائج التبييض [9، 13]. ركزت الدراسات حول استخدام حمض الأكساليك في طب الأسنان بشكل أساسي على قدرته على تقليل حساسية الأسنان بعد التبييض [9، 14]. يقلل أكسالات البوتاسيوم، عند تطبيقه على العاج، من نقل الأعصاب ويشكل بلورات أكسالات الكالسيوم التي تسد أنابيب العاج [14]. ومع ذلك، هناك أدلة قليلة على تأثير الأكسالات في التبييض في الممارسة السنية.

دراسات سابقة حول التبييض بمساعدة الليزر درست بشكل أساسي الإجراءات في العيادة، كاشفة عن تأثيرات تبييض أسرع وأقل تعقيدًا في التبييض بمساعدة الليزر مقارنة بالتقنيات التقليدية [16-19]. ومع ذلك، هناك أدلة محدودة ومتضاربة بشأن فعالية الليزر في التبييض الداخلي للأسنان غير الحيوية [20، 21]. علاوة على ذلك، لم تكن هناك دراسات تفحص فعالية التبييض الداخلي باستخدام أكسالات الكالسيوم وإشعاع الليزر الثنائي لتغير لون الأسنان الناتج عن MTA. لذلك، تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى التحقيق في تأثير دمج

المواد والطرق

تحضير العينة

إجراء التلوين

تم وضع سدادة MTA (أنجيلوس دنتال، لوندينا، البرازيل) على عمق 2 مم تحت نقطة التقاء المينا والعاج (CEJ).

تحضير جل التبييض المحتوي على أكسالات الكالسيوم

إجراء تخصيص العينة والتبييض

- المجموعة 1:

. - المجموعة 2:

أكسالات الكالسيوم. - المجموعة 3:

أكسالات الكالسيوم. - المجموعة 4:

أكسالات الكالسيوم. - المجموعة 5:

+ ليزر. - المجموعة 6:

أكسالات الكالسيوم + ليزر. - المجموعة 7:

أكسالات الكالسيوم + ليزر - المجموعة 8:

أكسالات الكالسيوم + ليزر.

في المجموعات 5-8، كانت العملية مشابهة لتلك الموصوفة في المجموعات 1 إلى 4، ولكن تم تنشيط الجل باستخدام ليزر ديود من غاليوم-ألومنيوم-زرنيخ (GaAlAs) (DoctorSmile، Lambda S.p.A.، إيطاليا). كان الليزر ينبعث منه طول موجي قدره 810 نانومتر وتم ضبطه على قوة 2 واط ووضع الموجة المستمرة (CW)، باستخدام أداة تبييض غير تلامسية على بعد تقريبي قدره 1 مم من الجل. تم تعريض الليزر ثلاث مرات لمدة 30 ثانية لكل مرة، مع فواصل زمنية مدتها دقيقة واحدة بين التعريضات [18]. العينات

| المجموعات التجريبية |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| المتوسط ± الانحراف المعياري | فترة الثقة 95% للمتوسط | المتوسط ± الانحراف المعياري | فترة الثقة 95% للمتوسط | المتوسط ± الانحراف المعياري | فترة الثقة 95% للمتوسط | المتوسط ± الانحراف المعياري | فترة الثقة 95% للمتوسط | ||

| 1 |

|

|

2.28 إلى 5.60 |

|

6.06 إلى 9.23 |

|

5.55 إلى 9.53 |

|

1.11 إلى 1.89 |

| ٢ |

|

|

2.74 إلى 4.54 |

|

9.70 إلى 11.91 |

|

8.40 إلى 11.19 |

|

1.45 إلى 2.67 |

| ٣ |

|

|

2.77 إلى 5.60 |

|

6.63 إلى 9.62 |

|

7.18 إلى 9.13 |

|

0.94 إلى 2.17 |

| ٤ |

|

|

3.03 إلى 4.18 |

|

6.92 إلى 9.44 |

|

7.52 إلى 9.65 |

|

0.86 إلى 1.81 |

| ٥ |

|

|

2.68 إلى 6.12 |

|

6.28 إلى 9.11 |

|

6.38 إلى 9.28 |

|

1.30 إلى 2.05 |

| ٦ |

|

|

2.23 إلى 5.96 |

|

9.01 إلى 11.30 |

|

8.48 إلى 10.61 |

|

0.81 إلى 2.03 |

| ٧ |

|

|

4.06 إلى 5.79 |

|

6.92 إلى 10.55 |

|

7.46 إلى 10.59 |

|

0.99 إلى 2.08 |

| ٨ |

|

|

2.28 إلى 5.60 |

|

6.06 إلى 9.23 |

|

5.55 إلى 9.53 |

|

1.11 إلى 1.89 |

| قيمة P | 0.851 | 0.002* | 0.040* | 0.460* | |||||

تم حضنها لمدة 5 أيام، تلتها قياس اللون (T3).

في جميع المجموعات، تم شطف غرفة اللب بعد تطبيق الجل الأول وتم تكرار إجراء التبييض. تم قياس لون السطح بعد تطبيق الجل الثاني (T4).

تقييم تغيير اللون

-

-

-

-

التحليل الإحصائي

النتائج

كشفت المقارنات الثنائية أن

نقاش

في هذه الدراسة، تم استخدام أسنان الأبقار بسبب بعض التحديات المرتبطة بأسنان البشر. يمكن أن يكون الحصول على أسنان بشرية بكميات وجودة كافية صعبًا نظرًا لأنها غالبًا ما تُستخرج بسبب عيوب واسعة. تم اختيار أسنان الأبقار على غيرها من الأنسجة الصلبة غير البشرية بسبب توفرها، وتكوينها الموحد، ومساحتها السطحية الأكبر، وتشابهها مع أسنان البشر، لا سيما فيما يتعلق بمحتوى الكالسيوم. تم استخدام أسنان الأبقار بفعالية في الدراسات التي تقيم التسرب المجهري، وإعادة التمعدن، والصلابة، والتوسع الحراري. وفقًا لفرانشيني بان مارتينيز وآخرين، هناك إمكانية لاستبدال الأسنان البشرية بأسنان الأبقار في الدراسات المتعلقة بالتسرب المجهري، والمحتوى العضوي وغير العضوي للأسنان، ومعامل التمدد الحراري، والفلورومترية الطيفية، والصلابة، والكثافة الإشعاعية. ومع ذلك، يرتبط استخدام أسنان الأبقار ببعض القيود، بما في ذلك التباينات في الشكل، والكثافة الإشعاعية، والخصائص الميكانيكية مقارنة بأسنان البشر. علاوة على ذلك، تتمتع أسنان الأبقار بسمك أكبر، مما قد يعيق التقييم الدقيق للون. في هذه الدراسة، تم إزالة العاج بعناية من تجويف الوصول باستخدام مثقاب دائري عالي السرعة حتى بلغ سمك السطح الخدّي 3 مم، محاكياً سمك سن بشري. أفاد فافوريتو وآخرون أن درجة تغير اللون واختراق بيروكسيد الهيدروجين قابلة للمقارنة بين الأسنان البشرية وأسنان الأبقار، مما يدعم استخدام أسنان الأبقار في تجارب التبييض.

استخدمت هذه الدراسة

الأعلى

يمكن أن يُعزى الأداء المتفوق الذي لوحظ في مجموعات أكسالات الكالسيوم بنسبة 1% إلى قدرة أيونات الأكسالات على تشكيل معقدات مع الكاتيونات المعدنية. الأكسالات هو عامل تشكيل معقدات قوي يُستخدم عادةً في الصناعات مثل السيراميك وتبييض الورق لإزالة الملوثات المعدنية [11، 12، 35]. هناك أيضًا أدلة تتعلق بتأثير التبييض للأكسالات في الأدبيات السنية. أبلغت دراسة عن جل تبييض الأسنان المصنوع من عصائر الفواكه الطبيعية عن كميات ضئيلة من حمض الأكساليك في تركيبها [36]، وبعض علكة تبييض الأسنان تحتوي على أحماض عضوية مثل حمض الأكساليك [9].

تم استخدام MTA الأبيض في هذه الدراسة لأنه يسبب تغير لون الأسنان أقل من MTA الرمادي. وفقًا لتشانغ وآخرون [37]، فإن محتوى الحديد في MTA الرمادي

في الدراسة الحالية، كانت

تركيز أعلى، قد يكون هناك خطر من تكتل جزيئات أكسالات الكالسيوم، مما يؤدي إلى تشبع السطح وخلق طبقة واقية تمنع اختراق عامل التبييض. استخدمت دراسات أخرى أيضًا تركيزات أقل من الأكسالات في علاجات التبييض. على سبيل المثال، استخدم باناهانده وآخرون [9] وأولييفيرا باروس وآخرون [14] 0.24 م من حمض الأكساليك (ما يعادل حوالي

في هذه الدراسة، تم استخدام ملح الكالسيوم لحمض الأكساليك. أظهرت عدة دراسات أن عوامل التبييض تسبب آثارًا سلبية مثل التغيرات السطحية وتقليل محتوى الكالسيوم والفلورايد في بنية الأسنان (8). قد يؤدي إضافة الكالسيوم إلى عوامل التبييض إلى زيادة دمج الكالسيوم في بنية الأسنان، مما يزيد من المقاومة لإزالة المعادن. وجد ألكسندرينو وآخرون [39] أن جلًا

تتفق نتائج هذه الدراسة مع نتائج بعض الدراسات السابقة [9، 13]. استخدم لو جيويديس وآخرون [13] مزيجًا من حمض الأكساليك وجل تبييض ووجدوا أن تنشيط جل التبييض بمصباح LED عزز إجراء التبييض مقارنةً بمجموعة التحكم. ومع ذلك، لم تتضمن دراستهم مجموعة تحكم بدون إضافة حمض الأكساليك. درس باناهانده وآخرون [9] تأثير المعالجة المسبقة مع 0.24 م من حمض الأكساليك و5.25% من هيبوكلوريت الصوديوم قبل التبييض في المكتب باستخدام

في الدراسة الحالية، لم يؤثر إشعاع الليزر الثنائي بشكل ملحوظ على تغيرات لون الأسنان في مجموعات الدراسة. كانت قيم تغير اللون في المجموعات 5 إلى 8، التي تعرضت للإشعاع بالليزر، أقل قليلاً من المجموعات الضابطة المعنية، لكن الفروق لم تكن ذات دلالة. كما وجد سايغلام وآخرون [20] عدم وجود فرق كبير بين مجموعة المساعدة بالليزر الثنائي (30 ثانية) ومجموعة التحكم فيما يتعلق بفعالية التبييض الداخلي. على الرغم من أنه في الدراسة الحالية، تم إجراء إشعاع الليزر ثلاث مرات لمدة 30 ثانية لكل منها، فإن تمديد مدة الإشعاع لم يكن فعالًا في تعزيز تأثيرات التبييض. أفاد سعيدي وآخرون [40] أن

التبييض بمساعدة الليزر في المكتب عند أطوال موجية 810 و940 و980 نانومتر حقق فعالية مماثلة للتبييض التقليدي، ولكن في فترة زمنية أقصر. في المقابل، أشارت عدة دراسات إلى أن إشعاع الليزر يسرع من إطلاق الجذور الحرة من عوامل التبييض أثناء إجراءات التبييض في المكتب [16، 17، 41، 42]. وجد بابادوبولو وآخرون [24] أن تطبيق الليزر الثنائي (445 نانومتر) عزز بشكل كبير نتائج التبييض في المكتب، على الرغم من أن التأثير اعتمد على قوة الليزر ومدة الإشعاع ووقت القياس بعد علاجات التبييض. يبدو أن تأثير تسريع الليزر على التفاعلات الكيميائية أكثر أهمية لإجراءات المكتب حيث يبقى الجل على سطح الأسنان لفترة قصيرة (أقل من ساعة). قد لا يكون هذا التأثير ملحوظًا في عملية التبييض الداخلي لأن عامل التبييض يبقى داخل السن لعدة أيام، وهناك وقت كافٍ للتفاعلات الكيميائية. قد يتسبب إشعاع الليزر أيضًا في ارتباط وتكتل جزيئات أكسالات الكالسيوم، مما يؤدي إلى تشبع السطح ومنع اختراق الأكسالات في بنية العاج. قد تلعب الاختلافات في بنية العاج مقابل المينا أيضًا دورًا في النتائج المختلفة التي تم الحصول عليها بين التبييض الداخلي بمساعدة الليزر والتبييض في المكتب بمساعدة الليزر. فيما يتعلق بفعالية الليزر المختلفة، أظهرت بعض الدراسات أن الليزر الثنائي له أداء مشابه لمصابيح LED [43، 44] وليزر Er، Cr: YSGG [45] في تبييض الأسنان. أظهرت دراسة أخرى أن التبييض الداخلي باستخدام بيربورات الصوديوم المنشط إما بواسطة الليزر الثنائي أو LED أدى إلى فعالية تبييض مماثلة [46]. في المقابل، كشف زانغ وآخرون [47] أن التبييض بمساعدة الليزر باستخدام ليزر فوسفات البوتاسيوم-التيتانيوم (KTP) كان أكثر فعالية من LED والليزر الثنائي في توفير أسنان أكثر بياضًا وفقًا لـ

تشير النتائج الحالية إلى أن إضافة 1% من أكسالات الكالسيوم إلى جل التبييض يحسن تبييض الأسنان المتغيرة اللون وقد يُوصى بها في الإعدادات السريرية. ومع ذلك، يجب مراعاة السلامة عند إضافة الأكسالات إلى عوامل التبييض. قد تشكل التركيزات العالية من الأكسالات التي تتلامس مباشرة مع الأنسجة البشرية مخاطر صحية محتملة، بما في ذلك فقدان الكالسيوم، وتهيج الجلد، واختلال توازن الإلكتروليت، وتغيرات في خلايا الثدي إلى خلايا ورمية، وحصوات الكلى، وأضرار عصبية [48]. عتبة السمية الجهازية لحمض الأكساليك للبشر هي حوالي

كانت لهذه الدراسة بعض القيود، أساسًا بسبب تصميمها في المختبر. بينما يعتبر أكسيد الحديد والبزموت من المساهمين الرئيسيين في تغير اللون الناتج عن MTA، فإن تسرب كريات الدم الحمراء إلى المسام في حالة عدم التصلب

الاستنتاجات

- تسبب MTA الأبيض في تغير لون تاجي ملحوظ في جميع العينات.

- بعد تطبيق الجل الأول والثاني،

- يمكن أن يؤدي دمج

- لم تحسن التركيزات الأعلى (3% و5%) ولا تنشيط مادة التبييض باستخدام ليزر ثنائي بشكل ملحوظ من تغير اللون الناتج عن MTA، ربما بسبب تشبع السطح وبالتالي انخفاض اختراق مادة التبييض في بنية العاج.

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 07 مارس 2025

References

- Sahiba U, Gowri S, Prathap MS, Aphiya A, Aleemuddin M. Comparative evaluation of calcium ion release from three bioceramic cements in simulated immature teeth with open apices. J Dent Mater Tech. 2024;13(3):103-9.

- Khedmat S, Ahmadi E, Meraji N, Fallah ZF. Colorimetric comparison of internal bleaching with and without removing mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) on induced coronal tooth discoloration by MTA. Int J Dent. 2021;2021:1-7.

- Możyńska J, Metlerski M, Lipski M, Nowicka A. Tooth discoloration induced by different calcium Silicate-based cements: A systematic review of in vitro studies. J Endod. 2017;43(10):1593-601.

- Boutsioukis C, Noula G, Lambrianidis T. Ex vivo study of the efficiency of two techniques for the removal of mineral trioxide aggregate used as a root Canal filling material. J Endod. 2008;34(10):1239-42.

- Žižka R, Šedý J, Gregor L, Voborná I. Discoloration after regenerative endodontic procedures: A critical review. Iran Endod J. 2018;13(3):278-84.

- Al-Hiyasat AS, Ahmad DM, Khader YS. The effect of different calcium silicatebased pulp capping materials on tooth discoloration: an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):330-40.

- Amer M. Intracoronal tooth bleaching – A review and treatment guidelines. Aust Dent J. 2023;68(Suppl 1):S141-52.

- Ghanbarzadeh M, Ahrari F, Akbari M, Hamzei H. Microhardness of demineralized enamel following home bleaching and laser-assisted in office bleaching. J Clin Exp Dent. 2015;7(3):e405-9.

- Panahandeh N, Mohammadkhani S, Sedighi S, Nejadkarimi S, Ghasemi A. Comparative effects of three bleaching techniques on tooth discoloration caused by tea. Front Dent. 2023;20:25-35.

- Abdel-Maksoud G, Awad H, Rashed UM. Different cleaning techniques for removal of Iron stain from archaeological bone artifacts: a review. Egypt J Chem. 2022;65(5):69-83.

- Lee SO, Tran T, Jung BH, Kim SJ, Kim MJ. Dissolution of iron oxide using oxalic acid. Hydrometallurgy. 2007;87(3-4):91-9.

- Sultana U, Kurny A. Dissolution kinetics of iron oxides in clay in oxalic acid solutions. Int J Min Met Mater. 2012;19:1083-7.

- LO GIUDICE G, Cicciù D, Cervino G, Lizio A, Panarello C, Cicciu M. Effects of photoactivation in bleaching with hydrogen peroxide. Spectrophotometric Evaluation Dentistry. 2011;1:1-5.

- Oliveira Barros AP, da Silva Pompeu D, Takeuchi EV, de Melo Alencar C, Alves EB, Silva CM. Effect of

- Kiryk J, Kiryk S, Kensy J, Świenc W, Palka B, Zimoląg-Dydak M, et al. Effectiveness of Laser-Assisted teeth bleaching: A systematic review. Appl Sci. 2024;14(20):9219.

- Ahrari F, Akbari M, Mohammadipour HS, Fallahrastegar A, Sekandari S. The efficacy and complications of several bleaching techniques in patients after fixed orthodontic therapy. A randomized clinical trial. Swiss Dent J. 2020;130(6):493-501.

- Ahrari F, Akbari M, Mohammadpour S, Forghani M. The efficacy of laserassisted in-office bleaching and home bleaching on sound and demineralized enamel. Laser Ther. 2015;24(4):257-64.

- Saeedi R, Omrani LR, Abbasi M, Chiniforush N, Kargar M. Effect of three wavelengths of diode laser on the efficacy of bleaching of stained teeth. Front Dent. 2019;16(6):458-64.

- Moosavi H, Arjmand N, Ahrari F, Zakeri M, Maleknejad F. Effect of low-level laser therapy on tooth sensitivity induced by in-office bleaching. Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31(4):713-9.

- Sağlam BC, Koçak MM, Koçak S, Türker SA, Arslan D. Comparison of Nd: YAG and diode laser irradiation during intracoronal bleaching with sodium perborate: color and Raman spectroscopy analysis. Photomed Laser Surg. 2015;33(2):77-81.

- Wajeh AS, Jawad HA. Efficacy of sodium perborate assisted by Er:Cr;YSGG laser induced photoacoustic streaming technique for enhancing the color of internally stained teeth. Laser Dent Sci. 2024;8(1):45.

- Das DK, Goswami P, Barman C, Das B. Methyl red: a fluorescent sensor for hg 2+over Na+, K+, Ca 2+, Mg 2+, Zn 2+, and cd 2+. Environ Eng Res. 2012;17(S1):75-8.

- AlOtaibi FL. Adverse effects of tooth bleaching: A review. Int J Dent Oral Health. 2019;7(2):53-5.

- Papadopoulou A, Dionysopoulos D, Strakas D, Kouros P, Vamvakoudi E, Tsetseli P, et al. Exploring the efficacy of laser-assisted in-office tooth bleaching: A study on varied irradiation times and power settings utilizing a diode laser ( 445 nm ). J Photochem Photobiol B. 2024;257:112970.

- Lima SNL, Ribeiro IS, Grisotto MA, Fernandes ES, Hass V, de Jesus Tavarez RR, et al. Evaluation of several clinical parameters after bleaching with hydrogen peroxide at different concentrations: A randomized clinical trial. J Dent. 2018;68:91-7.

- Asadi M, Majidinia S, Bagheri H, Hoseinzadeh M. The effect of formulated dentin remineralizing gel containing hydroxyapatite, fluoride, and bioactive glass on dentin microhardness: an in vitro study. Int J Dent. 2024;2024:4788668.

- Yassen GH, Platt JA, Hara AT. Bovine teeth as substitute for human teeth in dental research: a review of literature. J Oral Sci. 2011;53(3):273-82.

- Parisay I, Boskabady M, Bagheri H, Babazadeh S, Hoseinzadeh M, Esmaeilzadeh F. Investigating the efficacy of a varnish containing Gallic acid on remineralization of enamel lesions: an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):175-82.

- Franchini Pan Martinez L, KL Ferraz N, Lannes CNL, Rodrigues AC, De Carvalho MF, Zina MG. Can bovine tooth replace human tooth in laboratory studies? A systematic review. J Adhes Sci Tech. 2023;37(7):1279-98.

- Favoreto MW, Cordeiro DCF, Centenaro GG, Bosco LD, Arana-Gordillo LA, Reis A, et al. Evaluating color change and hydrogen peroxide penetration in human and bovine teeth through in-office bleaching procedures. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2024;36(8):1171-8.

- Heravi F, Ahrari F, Tanbakuchi B. Effectiveness of MI paste plus and remin pro on remineralization and color improvement of postorthodontic white spot lesions. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2018;15(2):95-103.

- Mohammadipour HS, Maghrebi ZF, Ramezanian N, Ahrari F, Daluyi RA. The effects of sodium hexametaphosphate combined with other remineralizing agents on the staining and microhardness of early enamel caries: an in vitro modified pH-cycling model. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2019;16(6):398-406.

- Guler AU, Kurt S, Kulunk T. Effects of various finishing procedures on the staining of provisional restorative materials. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;93(5):453-8.

- Meireles SS, Fontes ST, Coimbra LA, Della Bona Á, Demarco FF. Effectiveness of different carbamide peroxide concentrations used for tooth bleaching: an in vitro study. J Appl Oral Sci. 2012;20(2):186-91.

- Kim H-M, Choi T-Y, Park M-J, Jeong D-W. Heavy metal removal using an advanced removal method to obtain recyclable paper incineration Ash. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):12800.

- Filip M, Moldovan M, Vlassa M, Sarosi C, Cojocaru I. HPLC determination of the main organic acids in teeth bleaching gels prepared with the natural fruit juices. Rev Chim. 2016;67:2440-5.

- Chang SW, Shon WJ, Lee W, Kum KY, Baek SH, Bae KS. Analysis of heavy metal contents in Gray and white MTA and 2 kinds of Portland cement: a preliminary study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109(4):642-6.

- Asgary S, Parirokh M, Eghbal MJ, Stowe S, Brink F. A qualitative X-ray analysis of white and grey mineral trioxide aggregate using compositional imaging. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17(2):187-91.

- Alexandrino L, Gomes Y, Alves E, Costi H, Rogez H, Silva C. Effects of a bleaching agent with calcium on bovine enamel. Eur J Dent. 2014;8(3):320-5.

- Saeedi R, Omrani LR, Abbasi M, Chiniforush N, Kargar M. Effect of three wavelengths of diode laser on the efficacy of bleaching of stained teeth. Front Dent. 2019;16(6):458.

- Zhang Q, Liu Y, Ding M, Yuwen L, Wang L. On-Demand free radical release by laser irradiation for Photothermal-Thermodynamic biofilm inactivation and tooth whitening. Gels. 2023;9(7):554-70.

- Maiya R, Attavar SH, Kovoor KL. Comparative analysis of laser activated radical free bleaching agent on surface morphology and calcium phosphate content of enamel. Laser Dent Sci. 2024;8(1):36.

- Tekce AU, Yazici AR. Clinical comparison of diode laser- and LED-activated tooth bleaching: 9-month follow-up. Lasers Med Sci. 2022;37(8):3237-47.

- Oommen TE, Arya A, Jahangeer B, Mishra D, Vamseekrishna KVN, Gupta J. An In-Vitro study on the impact of Light-Emitting diode (LED) and Laser-Activated bleaching techniques on the color change of artificially stained teeth at varying time intervals. Cureus. 2024;16(9):e69851.

- Surmelioglu D, Usumez A. Effectiveness of different Laser-Assisted In-Office bleaching techniques: 1-Year Follow-Up. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg. 2020;38(10):632-9.

- Koçak S, Koçak MM, Sağlam BC. Clinical comparison between the bleaching efficacy of light-emitting diode and diode laser with sodium perborate. Aust Endod J. 2014;40(1):17-20.

- Zhang C, Wang X, Kinoshita J-I, Zhao B, Toko T, Kimura Y, et al. Effects of KTP laser irradiation, diode laser, and LED on tooth bleaching: a comparative study. Photomed Laser Surg. 2007;25(2):91-5.

- Verma A, Kore R, Corbin DR, Shiflett MB. Metal recovery using oxalate chemistry: a technical review. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2019;58(34):15381-93.

- Meraji N, Bolhari B, Sefideh MR, Niavarzi S. Prevention of tooth discoloration due to Calcium-Silicate cements: A review. Dent Hypotheses. 2019;10(1):4-8.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

فرزانه أحراري

Farzaneh.Ahrari@Gmail.com; Ahrarif@mums.ac.ir

سيدة زهراء جمالى

zahrajamali7073@yahoo.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-025-05703-1

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40055702

Publication Date: 2025-03-07

Internal bleaching with calcium oxalate and laser irradiation for managing discolorations induced by mineral trioxide aggregate

Abstract

Aim This in vitro study investigated the effects of incorporating 1%, 3%, and 5% calcium oxalate into 15% hydrogen peroxide

Introduction

Multiple hypotheses have been suggested to explain the mechanism of tooth discoloration after applying MTA. One initial hypothesis suggested that the oxidation of heavy metals, such as iron or magnesium, is responsible for the discoloration associated with grey MTA [3]. Therefore, white MTA, which contains minimal FeO, MgO , and Al 2 O 3 in its structure, was introduced to reduce discoloration. However, color changes still happened after using white MTA, although less intensely than with grey MTA [4]. Therefore, bismuth oxide, the radiopacifier in MTA, was implicated as the key contributor to tooth discoloration in white MTA [3]. Bismuth oxide binds with calcium silicate hydrate and is gradually released as it degrades over time [5]. Released bismuth oxide can cause tooth discoloration, primarily by interacting with dentin collagen to form a black precipitate [6]. Additionally, it may react with carbon dioxide and produce bismuth carbonate, thus leading to tooth discoloration [3]. The exposure of bismuth oxide to light irradiation and higher temperatures may also cause discoloration in MTA or calcium-enriched mixture (CEM) cement [3].

Internal bleaching is a practical, conservative, and costefficient therapy for managing discoloration in non-vital teeth. However, this treatment method has potential adverse effects, such as external cervical root resorption, dentine morphological changes, and collagen degradation [7, 8]. To minimize these risks, researchers are exploring methods to reduce the duration of treatment and concentration of bleaching agents.

A suitable approach to address discoloration from metal oxides is to use chelating agents such as oxalic acid, which effectively binds metal cations [9] facilitating the removal of insoluble ionic compounds from the substrates [10]. Oxalates are widely used in various industries, such as ceramics and paper bleaching, to remove metal contaminations [11, 12]. Thereare a few studies about the effect of oxalic acid on improving bleaching outcomes [9, 13]. Studies on the use of oxalic acid in dentistry have mainly focused on its ability to reduce tooth sensitivity after whitening [9, 14]. Potassium oxalate, when applied to dentin, decreases nerve transmission and forms calcium oxalate crystals that block dentinal tubules [14]. However, little evidence exists on the bleaching effect of oxalate compounds in dental practice.

Previous studies on laser-assisted bleaching primarily examined in-office procedures, revealing faster whitening effects and fewer complications in laser assisted bleaching than in conventional techniques [16-19]. However, there is limited and controversial evidence regarding the efficacy of lasers in the internal bleaching of non-vital teeth [20, 21]. Furthermore, there have been no studies examining the effectiveness of internal bleaching with calcium oxalate and diode laser irradiation for MTAinduced tooth discoloration. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of incorporating

Materials and methods

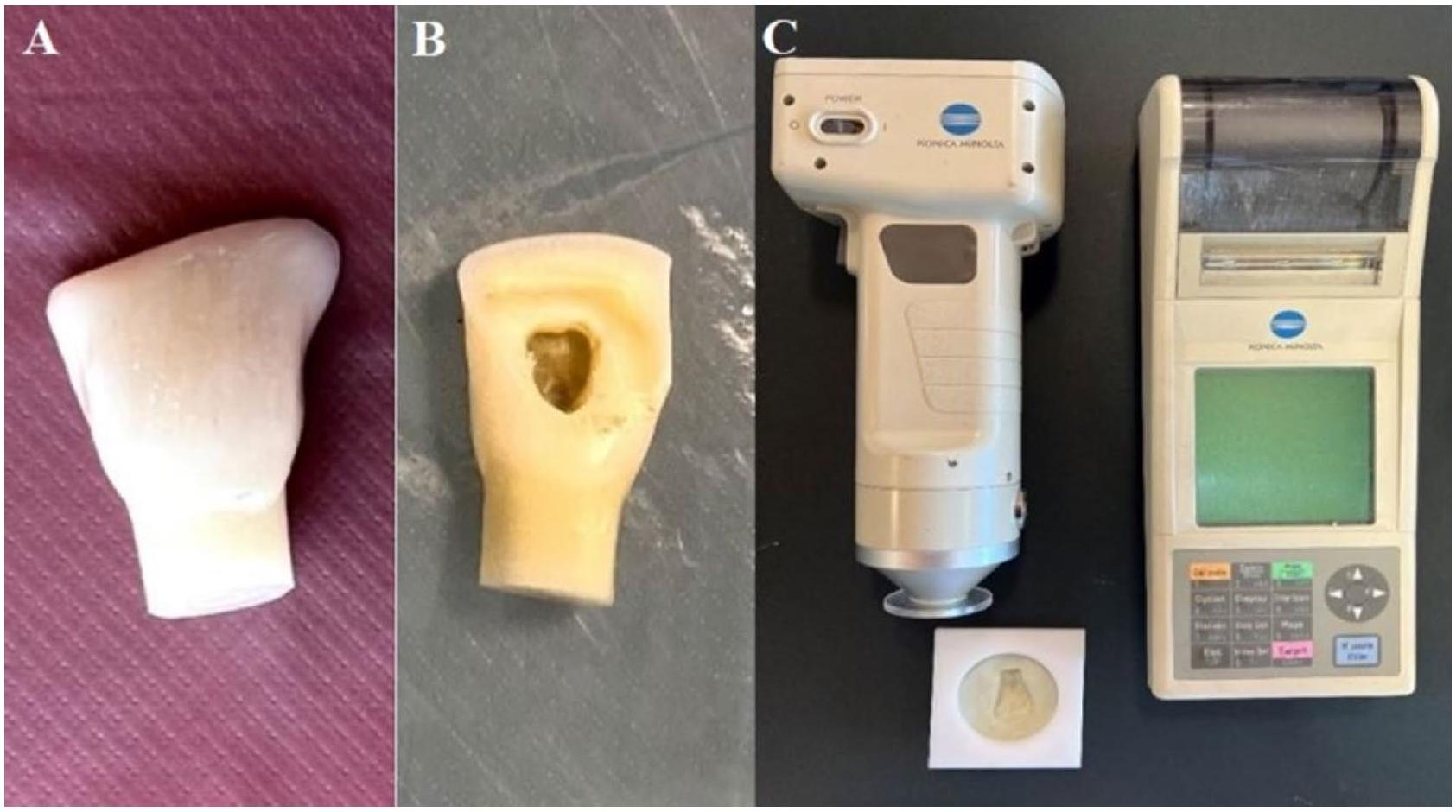

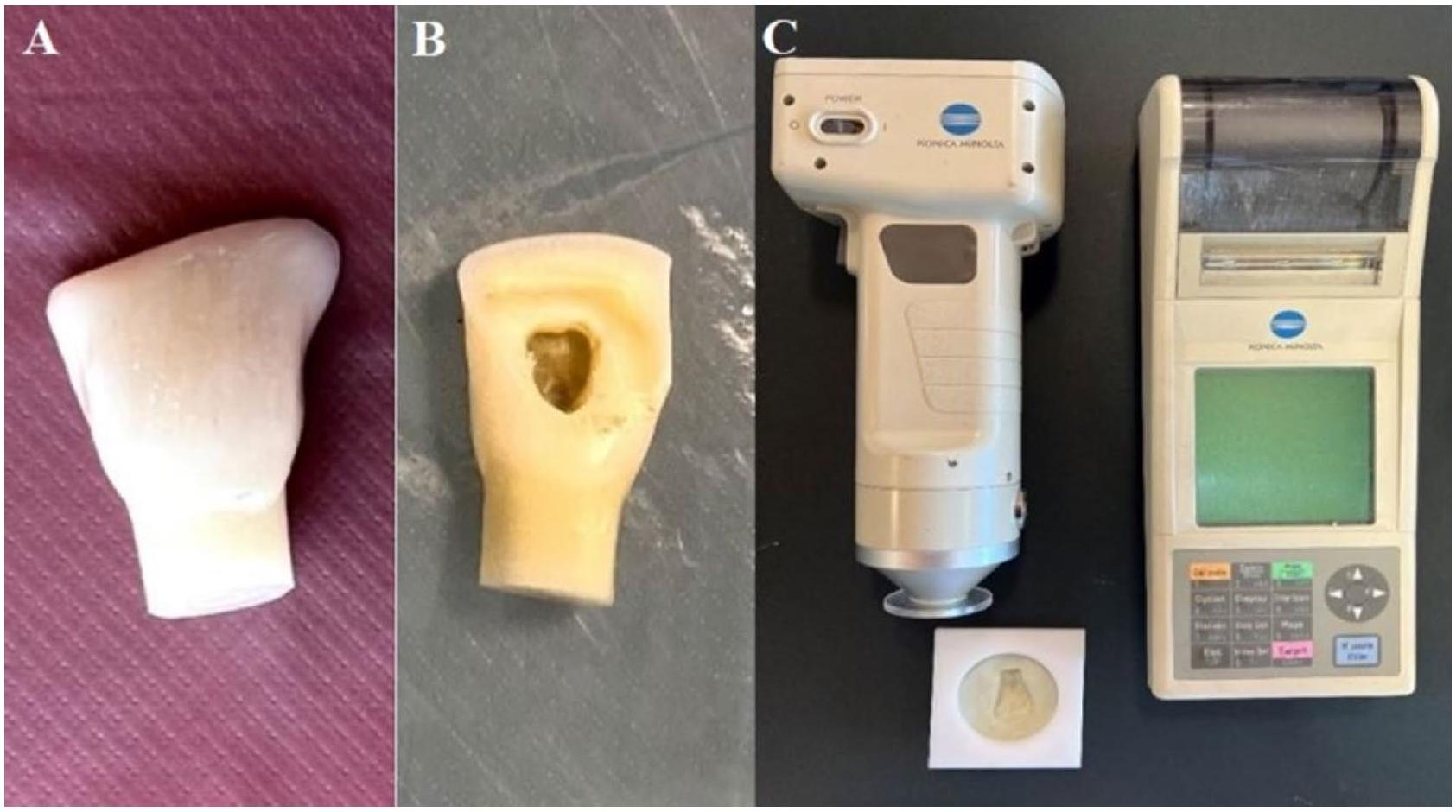

Sample preparation

Staining procedure

An MTA plug (Angelus Dental, Londrina, Brazil) was placed 2 mm below the cementoenamel junction (CEJ).

Preparation of bleaching gel containing calcium oxalate

Sample allocation and bleaching procedure

- Group 1:

- Group 2:

- Group 3:

- Group 4:

- Group 5:

- Group 6:

- Group 7:

- Group 8:

In groups 5-8, the process was similar to that explained in groups 1 to 4, but the gel was activated with a gallium-aluminum-arsenide (GaAlAs) diode laser (DoctorSmile, Lambda S.p.A., Italy). The laser emitted a wavelength of 810 nm and was set at the power of 2 W and continuous wave (CW) mode, using a non-contact bleaching handpiece at the approximate distance of 1 mm from the gel. The laser was irradiated three times for 30 s each, at oneminute intervals between irradiations [18]. The samples

| Experimental groups |

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean ± SD | 95% CI for Mean | Mean ± SD | 95% CI for Mean | Mean ± SD | 95% CI for Mean | Mean ± SD | 95% CI for Mean | ||

| 1 |

|

|

2.28 to 5.60 |

|

6.06 to 9.23 |

|

5.55 to 9.53 |

|

1.11 to 1.89 |

| 2 |

|

|

2.74 to 4.54 |

|

9.70 to 11.91 |

|

8.40 to 11.19 |

|

1.45 to 2.67 |

| 3 |

|

|

2.77 to 5.60 |

|

6.63 to 9.62 |

|

7.18 to 9.13 |

|

0.94 to 2.17 |

| 4 |

|

|

3.03 to 4.18 |

|

6.92 to 9.44 |

|

7.52 to 9.65 |

|

0.86 to 1.81 |

| 5 |

|

|

2.68 to 6.12 |

|

6.28 to 9.11 |

|

6.38 to 9.28 |

|

1.30 to 2.05 |

| 6 |

|

|

2.23 to 5.96 |

|

9.01 to 11.30 |

|

8.48 to 10.61 |

|

0.81 to 2.03 |

| 7 |

|

|

4.06 to 5.79 |

|

6.92 to 10.55 |

|

7.46 to 10.59 |

|

0.99 to 2.08 |

| 8 |

|

|

2.28 to 5.60 |

|

6.06 to 9.23 |

|

5.55 to 9.53 |

|

1.11 to 1.89 |

| P value | 0.851 | 0.002* | 0.040* | 0.460* | |||||

were incubated for 5 days, followed by color measurement (T3).

In all groups, the pulp chamber was rinsed after the first gel application and the bleaching procedure was repeated. The surface color was measured after the second gel application (T4).

Color change assessment

-

-

-

-

Statistical analysis

Results

Pairwise comparisons revealed that

Discussion

In this study, bovine teeth were used due to certain challenges associated with human teeth. Obtaining human teeth in sufficient quantity and quality can be difficult since they are often extracted because of extensive defects. Bovine teeth are chosen over other non-human dental hard tissues because of their availability, uniform composition, higher surface area and their similarity to human teeth, particularly regarding calcium content [26]. Bovine teeth have been used effectively in studies assessing microleakage, remineralization, hardness, and thermal expansion [26-28]. According to Franchini Pan Martinez et al. [29], there is the possibility for replacement of human by bovine teeth in studies concerning microleakage, organic and inorganic tooth content, coefficient of thermal expansion, spectrofluorometry, hardness, and radiodensity. The use of bovine teeth, however, is associated with some limitations, including variations in morphology, radiodensity, and mechanical properties compared to human teeth. Furthermore, bovine teeth have greater thickness, which may hinder accurate color assessment. In this study, dentin was carefully removed from the access cavity using a high-speed round bur until the buccal surface measured 3 mm , simulating the thickness of a human tooth. Favoreto et al. [30] reported that the degree of color change and hydrogen peroxide penetration is comparable between human and bovine teeth, supporting the use of bovine teeth in bleaching experiments.

This study used

The highest

The superior performance observed in the 1% calcium oxalate groups can be attributed to the ability of oxalate ions to chelate metal cations. Oxalate is a potent chelating agent commonly used in industries such as ceramics and paper bleaching to remove metal contaminants [11, 12, 35]. There is also evidence regarding the bleaching effect of oxalate in dental literature. A study on toothwhitening gels made with natural fruit juices reported minor amounts of oxalic acid in their composition [36], and some tooth-whitening chewing gums contain organic acids like oxalic acid [9].

White MTA was used in this study as it causes less tooth discoloration than grey MTA. According to Chang et al. [37], the iron content of grey MTA

In the present study, the

a higher concentration, there might be a risk of calcium oxalate particle agglomeration, leading to surface saturation and creating a protective layer that prevents bleaching agent penetration. Other studies have also used lower concentrations of oxalate in bleaching treatments. For instance, Panahandeh et al. [9] and Oliveira Barros et al. [14] used 0.24 M oxalic acid (equivalent to approximately

In this study, the calcium salt of oxalic acid was used. Several studies demonstrated that bleaching agents cause adverse effects such as surface alterations and reductions in the calcium and fluoride content of tooth structure (8). Adding calcium to bleaching agents may increase calcium incorporation into tooth structure, thus increasing resistance to demineralization. Alexandrino et al. [39] found that a

The outcomes of this study agree with those of some previous studies [9, 13]. Lo Giudice et al. [13] used a combination of oxalic acid and a bleaching gel and found that activation of the bleaching gel with LED lamp enhanced the whitening procedure compared to the control group. However, their study did not have a control group without oxalic acid addition. Panahandeh et al. [9] studied the effect of pretreatment with 0.24 M oxalic acid and 5.25% sodium hypochlorite before in-office bleaching with

In the present study, diode laser irradiation did not significantly affect tooth color changes in the study groups. The color change values in groups 5 to 8, which underwent laser exposure, were somewhat lower than the respective control groups, but the differences were not significant. Sağlam et al. [20] also found no significant difference between the diode laser-assisted group ( 30 s ) and control group regarding the efficacy of intracoronal bleaching. Although in the present study, laser irradiation was performed three times for 30 s each, extending the duration of irradiation was ineffective for enhancing the bleaching effects. Saeedi et al. [40] reported that

laser-assisted in-office bleaching at wavelengths of 810, 940, and 980 nm achieved similar efficacy to conventional bleaching, but in a shorter period. In contrast, several studies have indicated that laser irradiation accelerates the release of free radicals from bleaching agents during in-office bleaching procedures [16, 17, 41, 42]. Papadopoulou et al. [24] found that diode laser application ( 445 nm ) significantly enhanced the results of inoffice bleaching, although the effect depended on the laser power, duration of irradiation, and measurement time after whitening treatments. It appears that the accelerating effect of laser on chemical reactions is more critical for in-office procedures where the gel remains on the tooth surface for a short period (less than one hour). This effect may not be perceivable in the internal bleaching process because the whitening agent remains within the tooth for several days, and there is enough time for chemical reactions. Laser irradiation may also cause binding and agglomeration of calcium oxalate particles, leading to surface saturation and prevention of oxalate penetration into the dentin structure. The difference in the structure of dentin versus enamel may also play a role in the different results obtained between laser-assisted internal bleaching and laser-assisted in-office bleaching. Regarding the efficacy of different lasers, some studies have shown that diode lasers have similar performance to LED [43, 44] and Er, Cr: YSGG laser [45] in tooth bleaching. Another study demonstrated that internal bleaching with sodium perborate activated by either diode laser or LED caused a comparable whitening efficacy [46]. In contrast, Zhang et al. [47] revealed that laser-assisted bleaching using potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) laser was more effective than LED and diode laser at providing brighter teeth according to

The present results indicated that adding 1% calcium oxalate to the bleaching gel improves the whitening of discolored teeth and may be recommended in clinical settings. However, safety should be regarded when adding oxalate to bleaching agents. High concentrations of oxalates in direct contact with human tissue may pose potential health risks, including calcium loss, skin irritation, electrolyte imbalances, changes in breast cells to tumor cells, kidney stones, and neural damage [48]. The systemic toxicity threshold of oxalic acid for humans is approximately

This study had some limitations, primarily due to its in vitro design. While iron and bismuth oxide are considered major contributors to MTA-induced discoloration, erythrocyte infiltration into the porosities of unset

Conclusions

- White MTA caused noticeable coronal discoloration in all samples.

- After the first and second gel applications,

- Incorporating

- Neither higher concentrations (3% and 5%) nor the activation of the bleaching agent with a diode laser significantly improved MTA-induced discoloration, possibly due to surface saturation and, thus, lower penetration of the bleaching agent into the dentin structure.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 07 March 2025

References

- Sahiba U, Gowri S, Prathap MS, Aphiya A, Aleemuddin M. Comparative evaluation of calcium ion release from three bioceramic cements in simulated immature teeth with open apices. J Dent Mater Tech. 2024;13(3):103-9.

- Khedmat S, Ahmadi E, Meraji N, Fallah ZF. Colorimetric comparison of internal bleaching with and without removing mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) on induced coronal tooth discoloration by MTA. Int J Dent. 2021;2021:1-7.

- Możyńska J, Metlerski M, Lipski M, Nowicka A. Tooth discoloration induced by different calcium Silicate-based cements: A systematic review of in vitro studies. J Endod. 2017;43(10):1593-601.

- Boutsioukis C, Noula G, Lambrianidis T. Ex vivo study of the efficiency of two techniques for the removal of mineral trioxide aggregate used as a root Canal filling material. J Endod. 2008;34(10):1239-42.

- Žižka R, Šedý J, Gregor L, Voborná I. Discoloration after regenerative endodontic procedures: A critical review. Iran Endod J. 2018;13(3):278-84.

- Al-Hiyasat AS, Ahmad DM, Khader YS. The effect of different calcium silicatebased pulp capping materials on tooth discoloration: an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):330-40.

- Amer M. Intracoronal tooth bleaching – A review and treatment guidelines. Aust Dent J. 2023;68(Suppl 1):S141-52.

- Ghanbarzadeh M, Ahrari F, Akbari M, Hamzei H. Microhardness of demineralized enamel following home bleaching and laser-assisted in office bleaching. J Clin Exp Dent. 2015;7(3):e405-9.

- Panahandeh N, Mohammadkhani S, Sedighi S, Nejadkarimi S, Ghasemi A. Comparative effects of three bleaching techniques on tooth discoloration caused by tea. Front Dent. 2023;20:25-35.

- Abdel-Maksoud G, Awad H, Rashed UM. Different cleaning techniques for removal of Iron stain from archaeological bone artifacts: a review. Egypt J Chem. 2022;65(5):69-83.

- Lee SO, Tran T, Jung BH, Kim SJ, Kim MJ. Dissolution of iron oxide using oxalic acid. Hydrometallurgy. 2007;87(3-4):91-9.

- Sultana U, Kurny A. Dissolution kinetics of iron oxides in clay in oxalic acid solutions. Int J Min Met Mater. 2012;19:1083-7.

- LO GIUDICE G, Cicciù D, Cervino G, Lizio A, Panarello C, Cicciu M. Effects of photoactivation in bleaching with hydrogen peroxide. Spectrophotometric Evaluation Dentistry. 2011;1:1-5.

- Oliveira Barros AP, da Silva Pompeu D, Takeuchi EV, de Melo Alencar C, Alves EB, Silva CM. Effect of

- Kiryk J, Kiryk S, Kensy J, Świenc W, Palka B, Zimoląg-Dydak M, et al. Effectiveness of Laser-Assisted teeth bleaching: A systematic review. Appl Sci. 2024;14(20):9219.

- Ahrari F, Akbari M, Mohammadipour HS, Fallahrastegar A, Sekandari S. The efficacy and complications of several bleaching techniques in patients after fixed orthodontic therapy. A randomized clinical trial. Swiss Dent J. 2020;130(6):493-501.

- Ahrari F, Akbari M, Mohammadpour S, Forghani M. The efficacy of laserassisted in-office bleaching and home bleaching on sound and demineralized enamel. Laser Ther. 2015;24(4):257-64.

- Saeedi R, Omrani LR, Abbasi M, Chiniforush N, Kargar M. Effect of three wavelengths of diode laser on the efficacy of bleaching of stained teeth. Front Dent. 2019;16(6):458-64.

- Moosavi H, Arjmand N, Ahrari F, Zakeri M, Maleknejad F. Effect of low-level laser therapy on tooth sensitivity induced by in-office bleaching. Lasers Med Sci. 2016;31(4):713-9.

- Sağlam BC, Koçak MM, Koçak S, Türker SA, Arslan D. Comparison of Nd: YAG and diode laser irradiation during intracoronal bleaching with sodium perborate: color and Raman spectroscopy analysis. Photomed Laser Surg. 2015;33(2):77-81.

- Wajeh AS, Jawad HA. Efficacy of sodium perborate assisted by Er:Cr;YSGG laser induced photoacoustic streaming technique for enhancing the color of internally stained teeth. Laser Dent Sci. 2024;8(1):45.

- Das DK, Goswami P, Barman C, Das B. Methyl red: a fluorescent sensor for hg 2+over Na+, K+, Ca 2+, Mg 2+, Zn 2+, and cd 2+. Environ Eng Res. 2012;17(S1):75-8.

- AlOtaibi FL. Adverse effects of tooth bleaching: A review. Int J Dent Oral Health. 2019;7(2):53-5.

- Papadopoulou A, Dionysopoulos D, Strakas D, Kouros P, Vamvakoudi E, Tsetseli P, et al. Exploring the efficacy of laser-assisted in-office tooth bleaching: A study on varied irradiation times and power settings utilizing a diode laser ( 445 nm ). J Photochem Photobiol B. 2024;257:112970.

- Lima SNL, Ribeiro IS, Grisotto MA, Fernandes ES, Hass V, de Jesus Tavarez RR, et al. Evaluation of several clinical parameters after bleaching with hydrogen peroxide at different concentrations: A randomized clinical trial. J Dent. 2018;68:91-7.

- Asadi M, Majidinia S, Bagheri H, Hoseinzadeh M. The effect of formulated dentin remineralizing gel containing hydroxyapatite, fluoride, and bioactive glass on dentin microhardness: an in vitro study. Int J Dent. 2024;2024:4788668.

- Yassen GH, Platt JA, Hara AT. Bovine teeth as substitute for human teeth in dental research: a review of literature. J Oral Sci. 2011;53(3):273-82.

- Parisay I, Boskabady M, Bagheri H, Babazadeh S, Hoseinzadeh M, Esmaeilzadeh F. Investigating the efficacy of a varnish containing Gallic acid on remineralization of enamel lesions: an in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):175-82.

- Franchini Pan Martinez L, KL Ferraz N, Lannes CNL, Rodrigues AC, De Carvalho MF, Zina MG. Can bovine tooth replace human tooth in laboratory studies? A systematic review. J Adhes Sci Tech. 2023;37(7):1279-98.

- Favoreto MW, Cordeiro DCF, Centenaro GG, Bosco LD, Arana-Gordillo LA, Reis A, et al. Evaluating color change and hydrogen peroxide penetration in human and bovine teeth through in-office bleaching procedures. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2024;36(8):1171-8.

- Heravi F, Ahrari F, Tanbakuchi B. Effectiveness of MI paste plus and remin pro on remineralization and color improvement of postorthodontic white spot lesions. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2018;15(2):95-103.

- Mohammadipour HS, Maghrebi ZF, Ramezanian N, Ahrari F, Daluyi RA. The effects of sodium hexametaphosphate combined with other remineralizing agents on the staining and microhardness of early enamel caries: an in vitro modified pH-cycling model. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2019;16(6):398-406.

- Guler AU, Kurt S, Kulunk T. Effects of various finishing procedures on the staining of provisional restorative materials. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;93(5):453-8.

- Meireles SS, Fontes ST, Coimbra LA, Della Bona Á, Demarco FF. Effectiveness of different carbamide peroxide concentrations used for tooth bleaching: an in vitro study. J Appl Oral Sci. 2012;20(2):186-91.

- Kim H-M, Choi T-Y, Park M-J, Jeong D-W. Heavy metal removal using an advanced removal method to obtain recyclable paper incineration Ash. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):12800.

- Filip M, Moldovan M, Vlassa M, Sarosi C, Cojocaru I. HPLC determination of the main organic acids in teeth bleaching gels prepared with the natural fruit juices. Rev Chim. 2016;67:2440-5.

- Chang SW, Shon WJ, Lee W, Kum KY, Baek SH, Bae KS. Analysis of heavy metal contents in Gray and white MTA and 2 kinds of Portland cement: a preliminary study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109(4):642-6.

- Asgary S, Parirokh M, Eghbal MJ, Stowe S, Brink F. A qualitative X-ray analysis of white and grey mineral trioxide aggregate using compositional imaging. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17(2):187-91.

- Alexandrino L, Gomes Y, Alves E, Costi H, Rogez H, Silva C. Effects of a bleaching agent with calcium on bovine enamel. Eur J Dent. 2014;8(3):320-5.

- Saeedi R, Omrani LR, Abbasi M, Chiniforush N, Kargar M. Effect of three wavelengths of diode laser on the efficacy of bleaching of stained teeth. Front Dent. 2019;16(6):458.

- Zhang Q, Liu Y, Ding M, Yuwen L, Wang L. On-Demand free radical release by laser irradiation for Photothermal-Thermodynamic biofilm inactivation and tooth whitening. Gels. 2023;9(7):554-70.

- Maiya R, Attavar SH, Kovoor KL. Comparative analysis of laser activated radical free bleaching agent on surface morphology and calcium phosphate content of enamel. Laser Dent Sci. 2024;8(1):36.

- Tekce AU, Yazici AR. Clinical comparison of diode laser- and LED-activated tooth bleaching: 9-month follow-up. Lasers Med Sci. 2022;37(8):3237-47.

- Oommen TE, Arya A, Jahangeer B, Mishra D, Vamseekrishna KVN, Gupta J. An In-Vitro study on the impact of Light-Emitting diode (LED) and Laser-Activated bleaching techniques on the color change of artificially stained teeth at varying time intervals. Cureus. 2024;16(9):e69851.

- Surmelioglu D, Usumez A. Effectiveness of different Laser-Assisted In-Office bleaching techniques: 1-Year Follow-Up. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg. 2020;38(10):632-9.

- Koçak S, Koçak MM, Sağlam BC. Clinical comparison between the bleaching efficacy of light-emitting diode and diode laser with sodium perborate. Aust Endod J. 2014;40(1):17-20.

- Zhang C, Wang X, Kinoshita J-I, Zhao B, Toko T, Kimura Y, et al. Effects of KTP laser irradiation, diode laser, and LED on tooth bleaching: a comparative study. Photomed Laser Surg. 2007;25(2):91-5.

- Verma A, Kore R, Corbin DR, Shiflett MB. Metal recovery using oxalate chemistry: a technical review. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2019;58(34):15381-93.

- Meraji N, Bolhari B, Sefideh MR, Niavarzi S. Prevention of tooth discoloration due to Calcium-Silicate cements: A review. Dent Hypotheses. 2019;10(1):4-8.

Publisher’s note

- *Correspondence:

Farzaneh Ahrari

Farzaneh.Ahrari@Gmail.com; Ahrarif@mums.ac.ir

Seyyedeh Zahra Jamali

zahrajamali7073@yahoo.com