DOI: https://doi.org/10.2186/jpr.jpr_d_23_00119

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38346729

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-01

التصنيع الإضافي للسيراميك السني في طب الأسنان التعويضي: الوضع الراهن والمستقبل

الملخص

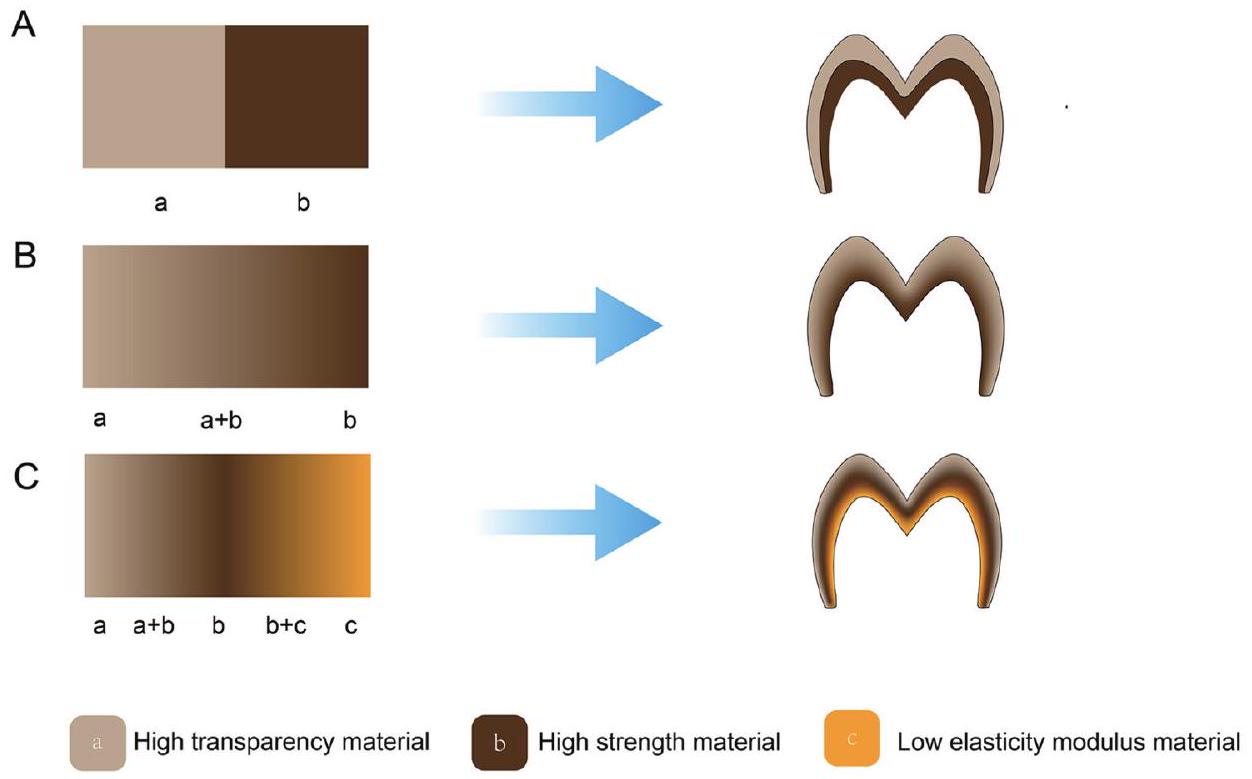

الغرض: تهدف هذه المراجعة إلى تلخيص التقنيات المتاحة، فئات المواد، وتطبيقات التعويضات السنية في تصنيع المواد المضافة (AM) من السيراميك السني، وتقييم الدقة القابلة للتحقيق والخصائص الميكانيكية مقارنةً بأساليب التصنيع التقليدية الحالية المعتمدة على التصميم المدعوم بالحاسوب/التصنيع المدعوم بالحاسوب (CAD/CAM) وطرق التصنيع الناقصة (SM)، ومناقشة الآفاق والاتجاهات المستقبلية. اختيار الدراسة: تستند هذه الورقة إلى أحدث المراجعات، الأبحاث المتطورة، والمعايير الدولية الحالية حول تقنيات AM وتطبيقات التعويضات السنية من السيراميك. كانت PubMed وWeb of Science وScienceDirect من بين المصادر التي تم البحث فيها عن المراجعات السردية. النتائج: تتوفر تقنيات AM بشكل نسبي محدود وتقتصر تطبيقاتها على التيجان والأطقم الجزئية الثابتة. على الرغم من أن دقة وقوة السيراميك السني من AM قابلة للمقارنة مع تلك الخاصة بـ SM، إلا أن لديها قيودًا تتمثل في دقة سطح منحني أقل نسبيًا وموثوقية قوة منخفضة. علاوة على ذلك، فإن التصنيع الإضافي ذو التدرج الوظيفي (FGAM)، وهو اتجاه محتمل لـ AM، يمكّن من تحقيق هياكل تحاكي الطبيعة، مثل الأسنان الطبيعية؛ ومع ذلك، تفتقر الدراسات المحددة حاليًا. الاستنتاجات: لم يتم تطوير السيراميك السني من AM بشكل كافٍ للتطبيقات السريرية على نطاق واسع. ومع ذلك، مع المزيد من الأبحاث، قد يكون من الممكن أن يحل AM محل SM كتقنية التصنيع الرئيسية لترميمات السيراميك.

1. المقدمة

ماذا يُعرف بالفعل عن الموضوع؟

ماذا تضيف هذه الدراسة؟

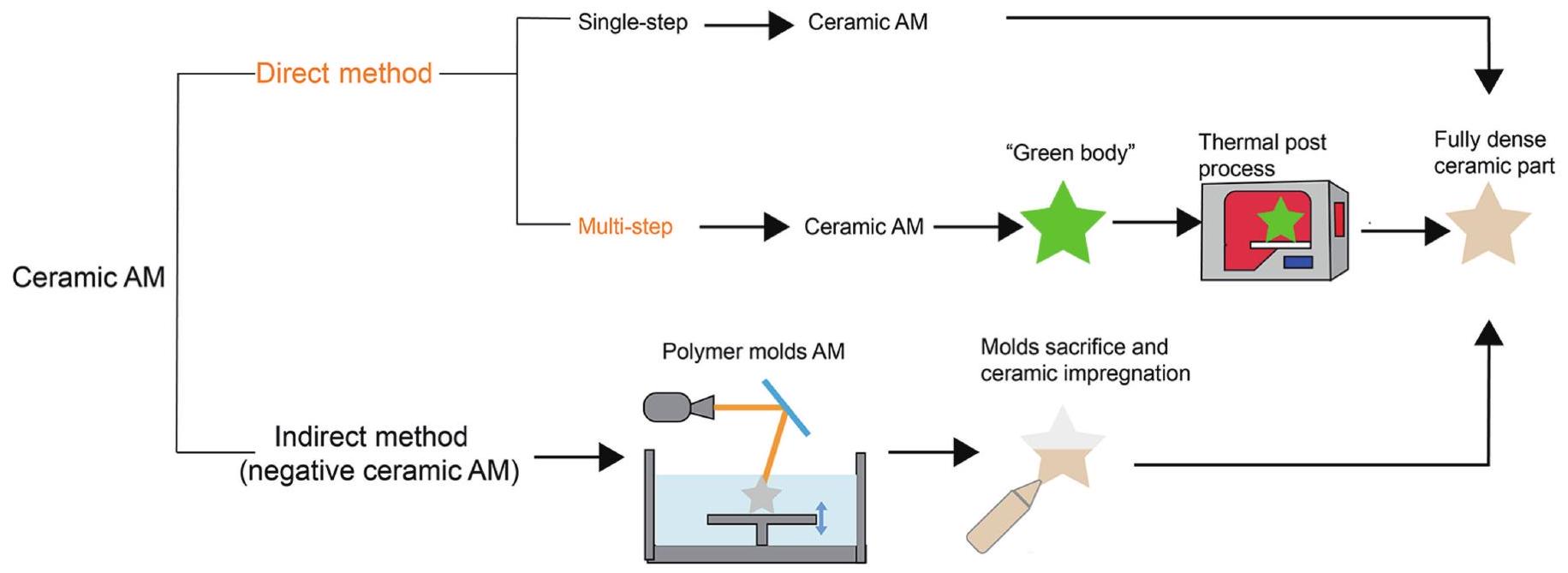

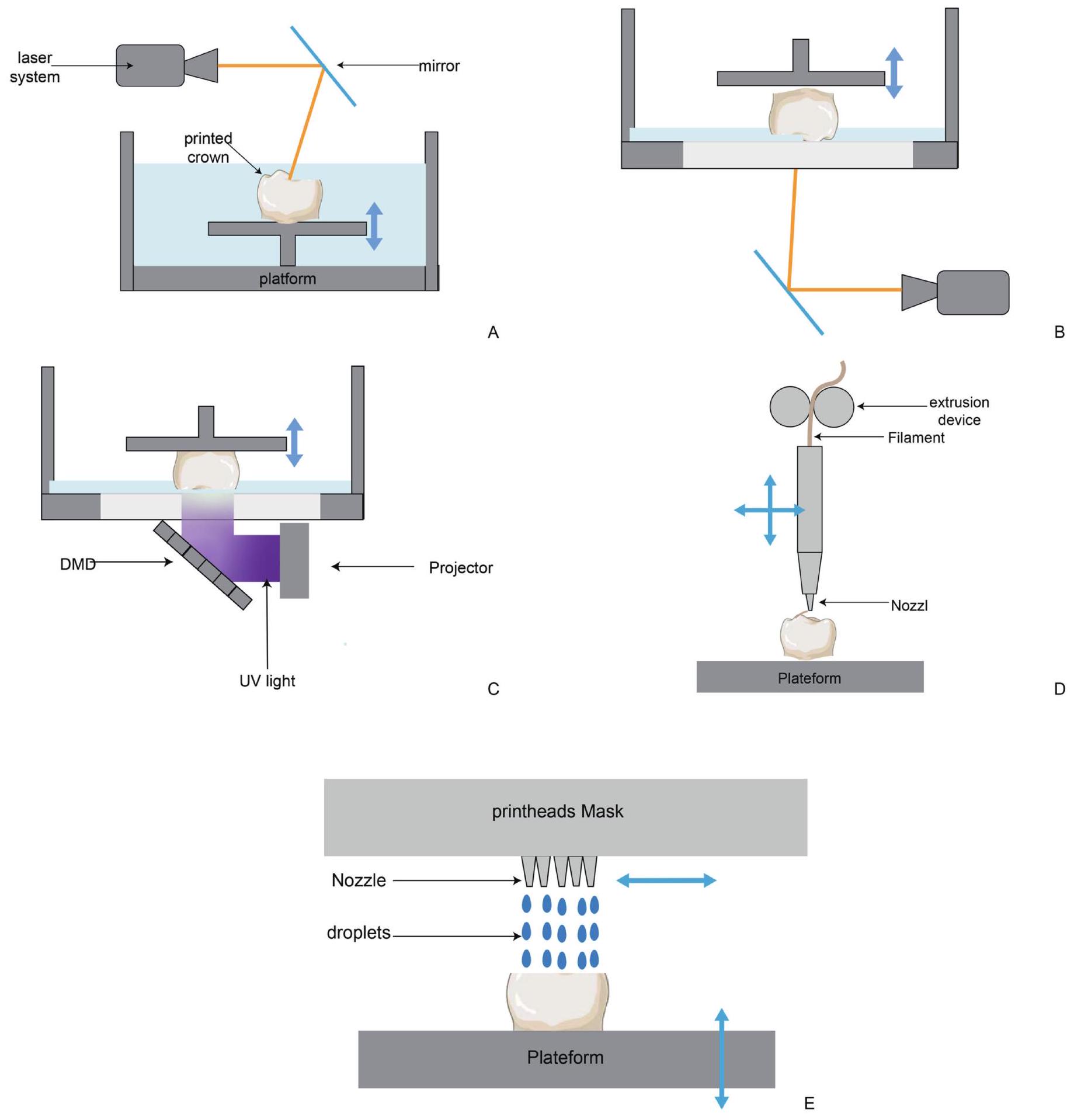

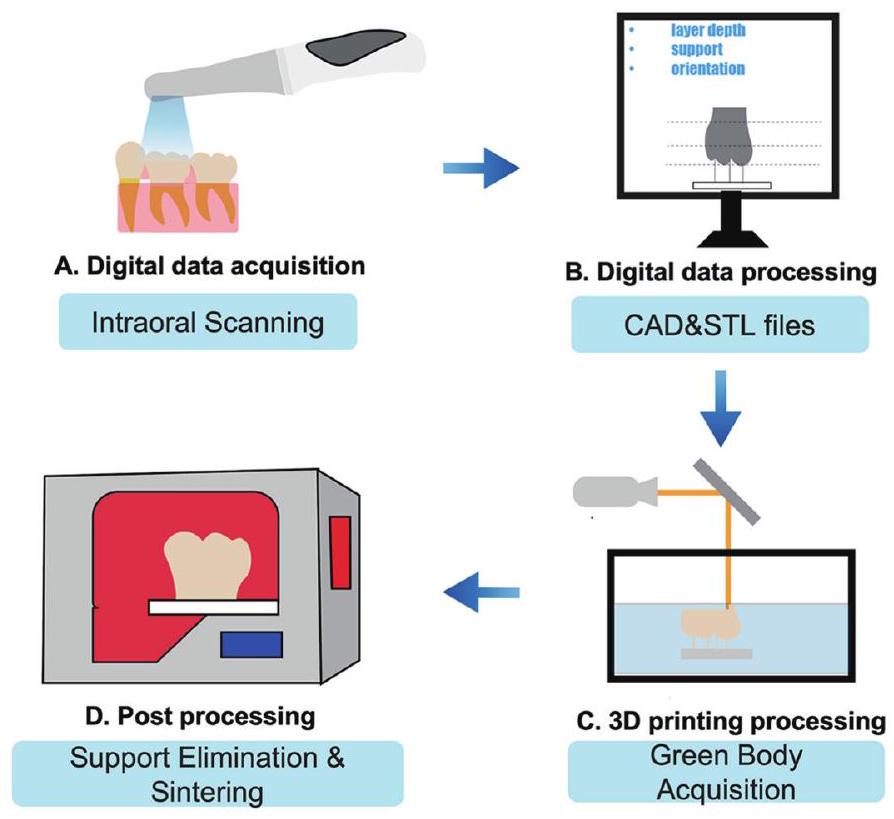

2. تقنيات التصنيع المضافة المستخدمة في السيراميك السني

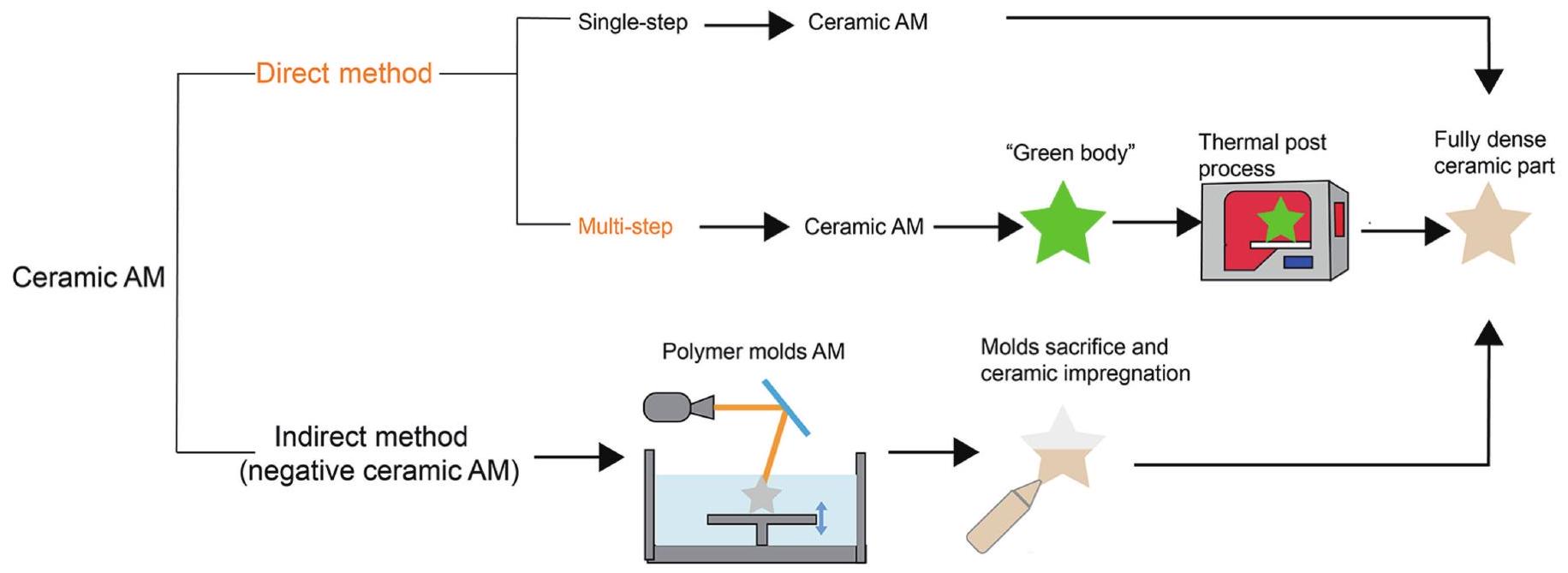

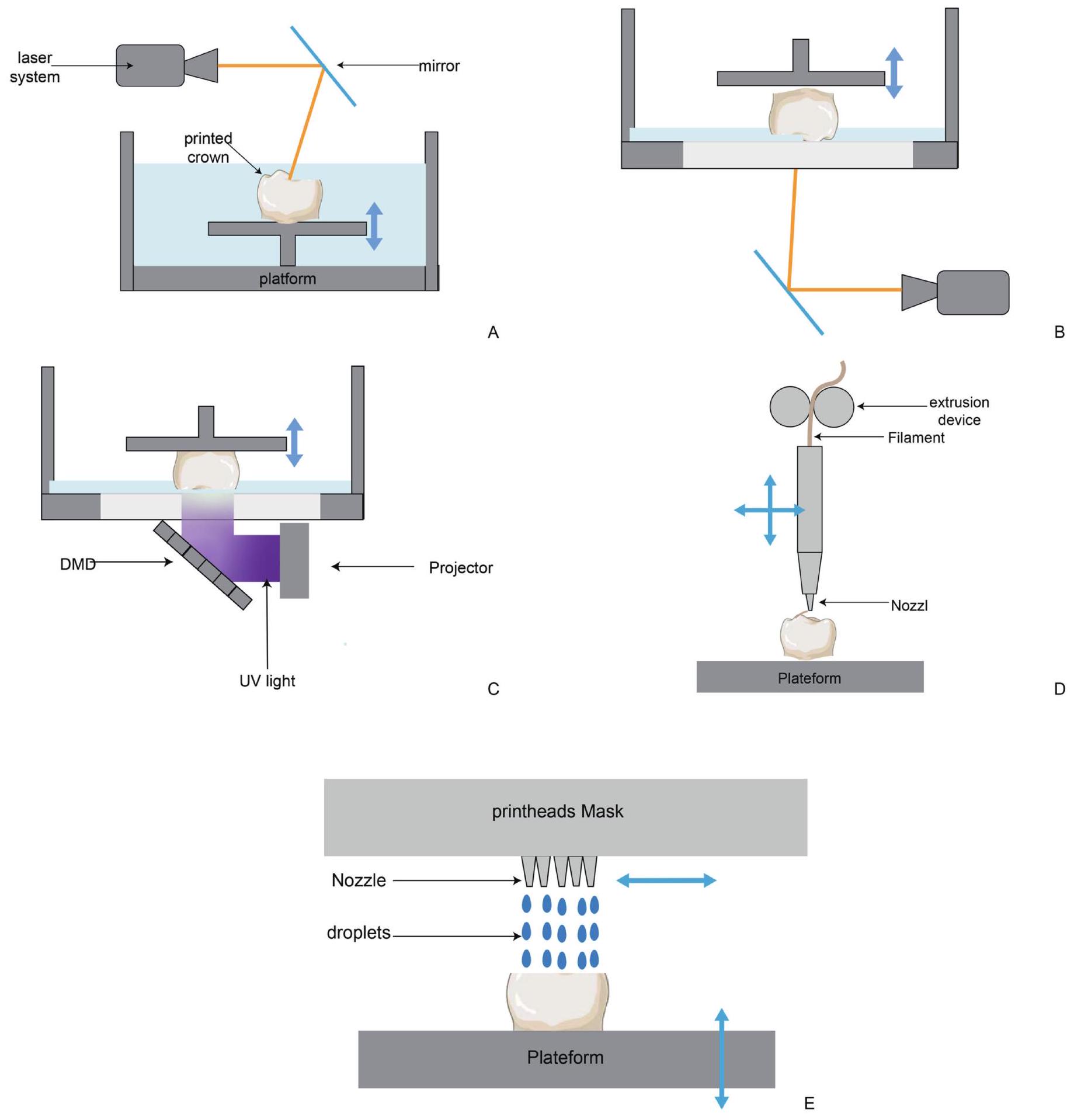

التقنيات مثل الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد (VPP)، واستخراج المواد (MEX)، ورش المواد (MJT)، ورش المواد الرابطة (BJT)، ودمج المسحوق (PBF)، وإيداع الطاقة الموجهة (DED)، وت laminating الورق (SHL). ومع ذلك، نظرًا للمتطلبات الصارمة للسيراميك السني، فإن عددًا قليلاً فقط من تقنيات التصنيع الإضافي للسيراميك تلبي المعايير السريرية لطب الأسنان الاصطناعي، بما في ذلك الاستريوليثوغرافي (SLA)، ومعالجة الضوء الرقمي (DLP) في VPP، والطباعة المباشرة بالحبر النفاث (DIP) في MJT، والطباعة الهلامية ثلاثية الأبعاد (3DGP) في MEX. المبادئ الأساسية لهذه التقنيات موضحة في الشكل 2 وسيتم توضيحها بعد ذلك. تعتمد تقنيات التصنيع الإضافي الأخرى، مثل PBF وDED، على دمج المسحوق باستخدام الطاقة الحرارية (مثل الليزر). تستخدم BJT مادة رابطة سائلة لإيداع المواد الخام، وSHL تقطع وتربط المواد الورقية لتشكيل الأجزاء. ومع ذلك، نظرًا لأن هذه التقنيات لا يمكن استخدامها حاليًا لتصنيع سيراميك أسنان عالي الجودة، فهي خارج نطاق هذه المراجعة.

2.1. VPP

2.1.1. اتفاقية مستوى الخدمة

لتحسين الدقة. ومع ذلك، يجب فصل الطبقات عن قاع الحاوية بعد معالجة كل طبقة، مما يزيد من الوقت الإجمالي للتصنيع. والأسوأ من ذلك، أنه يمكن أن يؤدي إلى تشوهات غير مرغوب فيها وإجهاد أو حتى التسبب في انفصال جزء، مما يؤثر على الخصائص الميكانيكية والحفاظ على الشكل المطلوب أثناء التصنيع. مقارنةً بالطريقة من الأسفل إلى الأعلى، يمكن لطريقة SLA من الأعلى إلى الأسفل تحقيق وقت أقصر.

وقت التصنيع وقوة ميكانيكية أعلى، ولكن سمك سطح طبقة التصنيع عمومًا يصعب التحكم فيه بسبب الخصائص الريولوجية لمعلق السيراميك، مما يؤدي إلى دقة نسبية أقل.

2.1.2.

2.1.3. المعلمات المؤثرة على VPP

الإشارة إلى حدوث عيوب خلال عملية إزالة الربط. أفاد هان وآخرون أن قوة الانحناء لعينات الزركونيا زادت من 302 إلى 1150 ميغاباسكال مع إضافة

2.2. MJT

2.2.1. المعلمات المؤثرة على DIP

بخصائص السلوك الريولوجي للتعليقات، كما يعبر عنه بعدد أونيسورغ (Oh). أفاد برساد وآخرون[57] أنه يمكن تشكيل قطرات مستقرة عندما

2.3. MEX

تم تطوير البثق (CODE). على عكس DIW، يقوم CODE ببثق السيراميك داخل خزان يحتوي على زيت. يمنع الزيت الجفاف غير المرغوب فيه من جوانب الطبقات المبثوقة، ويتم استخدام الإشعاع تحت الأحمر لتجفيف هذه الطبقات[65]. تساهم نسبة المواد الصلبة العالية ودرجة حرارة البثق المنخفضة في البثق القائم على الماء في زيادة الكثافة مع تقليل الانكماش وتجنب تأثير الإجهاد الحراري المتبقي على الأجزاء. ومع ذلك، بسبب قيود قطر الفوهة الكبير وتأثير الدرجات، لا تزال دقة التصنيع وتشطيب السطح لـ DIW و CODE أقل من تلك الخاصة بـ VPP أو DIP، مما يجعل من الصعب تصنيع ترميمات سيراميكية عالية الجودة لا تزال مناسبة لدعامات الأنسجة العظمية[66].

2.3.1. المعلمات المؤثرة على MEX

3. المواد السيراميكية السنية للتصنيع الإضافي

4. معلمات سلسلة العملية التي تؤثر على خصائص السيراميك في التصنيع الإضافي

4.1. معالجة البيانات

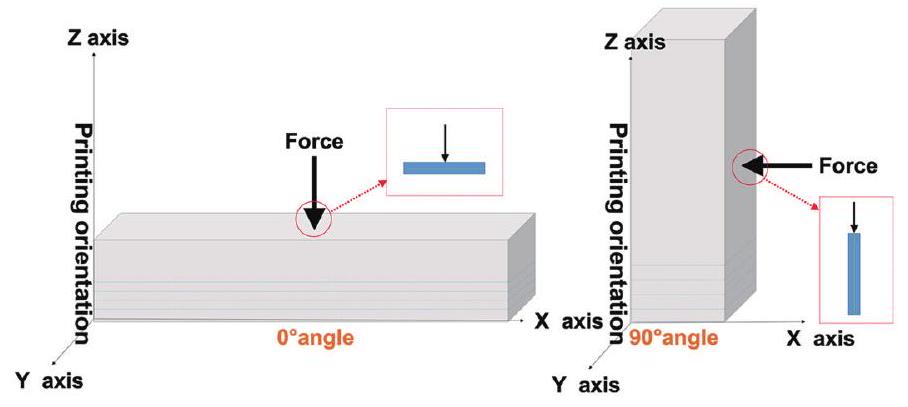

4.1.1. اتجاه البناء

4.1.2. سمك الطبقة

4.2.

4.3. المعالجة اللاحقة

4.3.1. إزالة الدعم

4.3.2. إزالة الربط والتلبيد

| الشركة المصنعة | جهاز AM | التقنيات | الدقة / م | سمك الطبقة الدنيا /

|

المواد | |||||||

| Xjet | Xjet Carmel 1400 | NPJ، بناءً على DIP | 16 | 10.5 | 3Y-TZPAlumina | |||||||

| Lithoz |

|

LCM، بناءً على DLP | 40 | 10 | 3Y-TZPAlumina | |||||||

| 3DCeram |

|

SLA | 35um (قطر بقعة الليزر) | 20 |

|

|||||||

| Porimy | CSL100/150/200 | SLA | 40 | 25 | 3Y-TZP | |||||||

| Admaflex | Admaflex130/300 | DLP | 35 | 10 | 3Y-TZPAlumina | |||||||

| Octave Light | Octave Light R1 | DLP | 30 | 25 | 3Y-TZPAlumina | |||||||

| Exone |

|

طباعة ربط | 30 | 30 | 3Y-TZP | |||||||

| Prodways | Promaker 10 | تقنية الضوء المتحرك، بناءً على DLP | 42 | 10 | 3Y-TZP | |||||||

| AON |

|

DLP | 40 | 25 | 3Y-TZPAlumina |

5. تطبيق سيراميك AM في طب الأسنان الاصطناعية

تقييمات الجمالية نادرة نسبيًا.

يشمل تقييم الدقة في المختبر بشكل أساسي تقييم الدقة والضبط[97]، بينما في طب الأسنان، يتم تمثيل الأخير عادةً من خلال ملاءمة التاج (التكيف الداخلي والملاءمة الهامشية). يتم تحديد الدقة من خلال تحليل الانحراف ثلاثي الأبعاد بين النماذج المقاسة ونموذج CAD الأصلي، وتشير قيمة الدقة المنخفضة إلى دقة متفوقة. تعتبر ملاءمة التاج في الأساس سمك الأسمنت بين الأسنان الداعمة والترميمات ولها أهمية سريرية مباشرة. تلعب الملاءمة الهامشية دورًا مهمًا في التأثير الترميمي، حيث أن الملاءمة الهامشية السيئة تسبب انحلال الأسمنت، وتسوس ثانوي، والتهاب لب الأسنان، والتهاب اللثة، والتهاب دواعم الأسنان، وتغير لون الحواف، مما يؤثر بشدة على صحة الفم والمظهر الجمالي[98-102]. من المتعارف عليه عالميًا أن الملاءمة الهامشية المقبولة سريريًا يجب أن تكون

| المؤلف/ السنوات | تكنولوجيا (شركة) | جهاز AM | مادة | الصدق / الجذر التربيعي لمتوسط المربعات

|

||||||

| وانغ/2019[117] | SLA (3DCeram) | CERAMAKER900 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| باومغارتنر/2020[122] | DLP (ليثوز) | نظام سيرا فاب S65 | ثنائي سيليكات الليثيوم | <50 | ||||||

| ليرنر/2020[120] | DLP (ليثوز) | نظام سيرا فاب S65 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| لي/2020[115] | SLA (بوريماي) | CSL100 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| لي/2020[124] | 3DGP (ERRAN) | زركونيا ذاتية التزجيج | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| وانغ/2021[106] | DLP (ليثوز) | سيرا فاب 7500 | الألومينا |

|

||||||

| SLA (بوريماي) | CSL150 | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||||||

| لي/2022[30] | SLA (ZRapid) | AMC150 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| كيم/2022[123] | SLA (3DCeram) |

|

3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

|

أوكتاف لايت R1 | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||||||

| القمر/2022[121] | DLP (AON) | إنّي-اثنان | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| مينغ/2022[25] | DLP (NP) | NP | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| لي/2022[87] | SLA (بوريماي) | سي إس إل 100 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| أبو السعود/2022[119] | SLA (3DCeram) | ماسح مختبر الأسنان 3Shape E3 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| كامارغو/2022[56] | NPJ (Xjet) | كارمل 1400 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Lv/2023[55] | NPJ (Xjet) | كارمل 1400 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| DLP (جونجينج) | ج2 د140ل سيراميك | 3Y-TZP |

|

معلمات مهمة تؤثر على الأداء طويل الأمد لترميمات السيراميك المصنوعة بإضافة المواد، ولكن الدراسات المتعلقة بهذا الموضوع محدودة أيضًا.

5.1. التيجان

5.1.1. دقة تيجان SLA

| المؤلف/السنوات | تكنولوجيا/ شركة | طريقة التقييم | مادة | تناسب التاج

|

||||||

| لي/2019[115] | SLA (بوريماي) | تقنية التحليل الطوبوغرافي ثلاثي الأبعاد (ماسح داخل الفم + هلام السيليكا) | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Revilla-León/2020 [116] | SLA (3DCeram) |

|

3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| وانغ/2021[106] | DLP (ليثوز) | تقنية النسخ السيليكوني | الألومينا |

|

||||||

| SLA (بوريماي) | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||||

| مينغ/2022[25] | DLP (NP) | فيلم مطاط السيليكون ميكرو CT+ | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| لي/2022[87] | SLA (بوريماي) | طريقة المسح الثلاثي | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| الأحد/2022[125] | 3DGP (ERRAN) | تقنية العرض المباشر + تقنية النسخة السيليكونية | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| أبو السعود/2022[119] | SLA (3DCeram) | تقنية التحليل الطردي ثلاثي الأبعاد | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| كامارغو/2022[56] | NPJ (XJet) | الميكرو-سي تي | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Lv/2023[55] | NPJ (XJet) | تقنية التحليل الطردي ثلاثي الأبعاد | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| DLP (جونجينج) |

|

تمت مقارنة خطوط النهاية المختلفة (حافة مائلة، كتف دائري، وحافة حادة) مع دقة تيجان الزركونيا SM بنفس التصميم. أظهرت النتائج أن دقة التيجان تأثرت بشكل أساسي بتصميم الحافة بدلاً من طريقة التصنيع. من بين التصاميم الثلاثة للحواف، حصلت الحافة الحادة على أكبر الفروقات، ولم تتمكن كل من SLA وSM من الحصول على حافة حادة عالية الجودة. بعد ذلك، صمم لي وآخرون قاعدة داعمة بالكامل وصنعوا تيجان زركونيا SLA باستخدام نفس جهاز التصنيع الإضافي. وأفادوا أن تيجان SLA بتصميم هذه القاعدة الداعمة بالكامل كانت لها دقة سطح خارجي مشابهة وتناسب تاج مماثل لتلك الخاصة بتاج الزركونيا SM.

نتائج إيجابية. استخدموا تقنيات تكرار هلام السيليكا لتقييم ملاءمة التاج لتيجان الزركونيا المصنوعة بنفس الجهاز (Ceramaker900، 3DCeram)، ووجدوا الملاءمة الهامشية (

5.1.2. دقة تيجان DLP

تصنيع السيراميك (LCM، تقنية DLP السيراميكية الحاصلة على براءة اختراع) تيجان الزركونيا (نظام CeraFab S65، Lithoz، فيينا، النمسا) مع تيجان SM. أظهرت النتائج أن دقة LCM كانت أقل من مجموعة التحكم SM، على الرغم من أنها احتفظت بقيمة منخفضة نسبياً (السطح الخارجي:

5.1.3. دقة تيجان 3DGP

5.1.4. دقة تيجان DIP

5.2. وحدة متعددة من FPD

| المؤلف/السنة | تقنية/شركة | مادة | النتيجة الرئيسية | |||||

| ليان/2019[85] | DLP/NP | 3Y-TZP | خطأ الأبعاد المتوسط:

|

|||||

| لي/2020[124] | 3DGP/إيران | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||||

| جيانغ/2021[127] | DLP/NP | 3Y-TZP | الملاءمة الهامشية:

|

|||||

| لوختنبورغ/2022[54] | SLA/3DCeram | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||||

| NPJ/Xjet | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| LCM/ليثوز | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| دي إل بي / جامعة برمنغهام | 3Y-TZP |

|

5.3. حشوة، قشرة، وقشرة إطباقية

قشور LD المصنعة (LCM) المستندة إلى بيانات المسح لستة أسنان أمامية سفلية من مريض سريري، وتم تقييم الملاءمة الهامشية والتكيف الداخلي باستخدام طرق التجربة داخل الفم والمسح الثلاثي. أظهرت النتائج أن هناك ملاءمة هامشية وتكيف داخلي مناسب، حيث كانت الغالبية تقع تحت

5.4. الخصائص الميكانيكية للسيراميك السني المُصنّع بإضافة

لم يتم إثبات أن تيجان الزركونيا DLP لديها قدرة كسر أفضل من تيجان الزركونيا SM. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أفاد زاندينجاد وآخرون أن تيجان الزركونيا المدعومة بالزرع المصنعة باستخدام SLA (CeraMaker 900، 3D Cream) كانت لديها قدرة كسر قابلة للمقارنة مع تلك الخاصة بتاج الزركونيا SM وتاج الليثيوم ديسليكات SM. وجد زاندينجاد وآخرون ورابل وآخرون أن الجسور الثابتة ثلاثية الأبعاد (3DGP FPDs) حققت قدرات كسر تفوق تلك الخاصة بجسور الزركونيا SM. قام إيوانيديس وآخرون بتصنيع قشور الزركونيا LCM وقارنوا قدرات كسرها مع تلك الخاصة بالزركونيا SM وLD المعالجة بالحرارة. أظهرت نتائجهم أن مجموعة LCM العلوية كانت لديها قدرة كسر أعلى بشكل ملحوظ من مجموعتي الزركونيا SM وLD المعالجة بالحرارة. أظهرت الدراسات المذكورة أعلاه القوة الموثوقة والقيمة التطبيقية المحتملة لترميمات السيراميك AM؛ ومع ذلك، هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من الدراسات لتأكيد هذه النتائج.

5.4.1. الخصائص الميكانيكية للسيراميك SLA

5.4.2. الخصائص الميكانيكية للسيراميك DLP

5.4.3. الخصائص الميكانيكية للسيراميك DIP و 3DGP

5.5. أداء الجمالية لمواد السيراميك السنية المضافة

| تكنولوجيا | المؤلف/السنة | جهاز AM / شركة | مادة | مقاومة الانحناء (ميغاباسكال) | صلابة الكسر (ميغاباسكال)

|

معامل ويبول |

| اتفاقية مستوى الخدمة | زينغ/2017 [143] | سيرامايكر300/3DCeram | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

|

| ليان/2018 [46] | SPS450B/هينغتونغ | 3Y-TZP | ٢٠٠.١٤ | |||

| لي/2019 [115] | CSL 150/بوريماي | 3Y-TZP |

|

7.44 | ||

| ناكاي/2021 [77] | سيرامايكر900/3دي سيرام | 3Y-TZP | 1071.1* | 16.3 | ||

| لي/2022 [30] | AMC150/ZRapid | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

||

| زهاي/2021 [139] | CSL 150/بوري مي | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||

| Revilla/2021[140] | سيرامايكر900/3دي سيرام | 3Y-TZP |

|

8.7 | ||

| وانغ/ 2023 [144] | C100 EASY/3DCeram | 5Y-PSZ |

|

11.4 | ||

| ماريون/2017[145] | كريو سيرام / كريو بيريل | الألومينا |

|

5-15 | ||

| ماريون/2020[74] | كريو سيرام/كريو بيريل | الألومينا |

|

|

13.7 | |

| DLP | هارر/2017[150] | سيرا فاب 7500/ليثوز | 3Y-TZP | 878* |

|

11.1 |

| عثمان/2018[74] | أدما فليكس 2.0 / أدما تك | 3Y-TPZ |

|

٧.٠ | ||

| جانغ/2019 [40] | R1/ضوء الأوكتاف | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||

| ليان/2019 [85] | NP | 3Y-TZP |

|

3.68 | ||

| لو/2020 [137] | NP/عروض سريعة | 3Y-TZP |

|

9.3 | ||

| بيرغلر/2021[147] | سيرافاب7500/ليثوز | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||

| الأحد/2021 [138] | منزلية | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

16.4 | |

| زهاي/2021 [139] | سيرافاب7500/ليثوز | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||

| زينثوفر/2022[142] | سيرافاب7500/ليثوز | 3Y-TZP |

|

5.12 | ||

| RevillaLeón/2022 [146] | سيرا فاب S65/ليثوز | 3Y-TZP |

|

6.95 | ||

| كيم/2020 [151] | منزلية | 4Y-TZP |

|

8.3 | ||

| يانغ/2022 [148] | فيلتس 3D/إنشيون | 4Y-TZP |

|

|||

| يونغ/2022 [149] | فيلتس 3D/إنشيون | 5Y-TZP |

|

7.9 | ||

| باومغارتنر/2020[122] | NP/ليثوز | LD |

|

7.2 | ||

| غمس | إيبرت/2009 [52] | ديكست جيت 930/إتش بي | 3Y-TZP | 763* |

|

٣.٥ |

| أوزكول/2012[126] | ديك جيت 930/HP | 3Y-TZP | 843* | 3.6 | ||

| ويلمز/2021[49] | كارمل 1400/XJet | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

10.5 | |

| تشونغ/2022[50] | كارمل 1400/XJet | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

||

| بايسال/2022[141] | كارمل 1400/XJet | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||

| 3DGP | شين/2017 [152] | 3GDP/ERRAN | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

18 |

| *:القوى المميزة. SLA: الطباعة الحجرية الضوئية، DLP: معالجة الضوء الرقمي، DIP: الطباعة المباشرة بالحبر النفاث، 3DGP: الطباعة بالهلام ثلاثي الأبعاد، 3Y-TZP: زيركونيا رباعية الأبعاد المدعمة باليترية بنسبة 3 مول%. | ||||||

6. الإمكانيات وآفاق المستقبل

المعروف من قبل المؤلفين، الحد الأدنى لسمك الطبقة في الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد السيراميكية الحالية هو

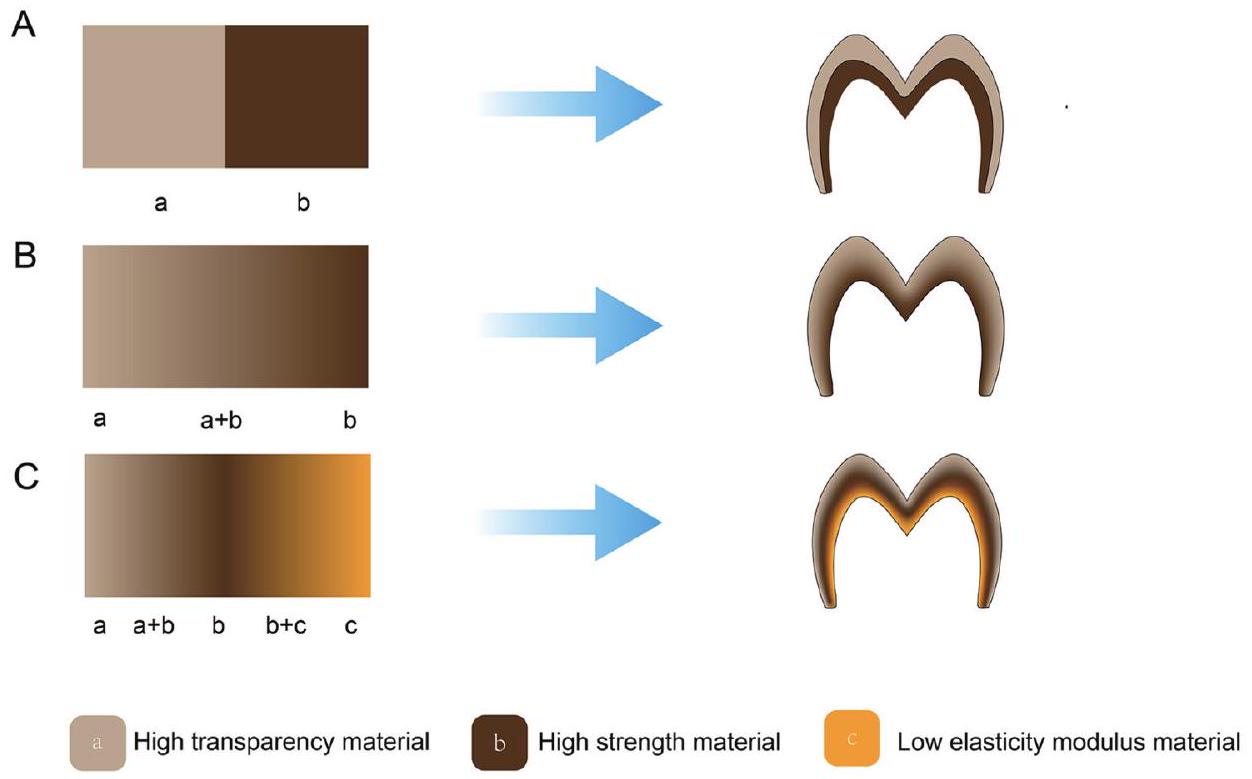

ومن المتوقع أن يتم تصنيع التيجان متعددة التدرجات في المستقبل بناءً على مزيد من الأبحاث.

الشكر والتقدير

تضارب المصالح

References

[2] Deckers J, Vleugels J, Kruthl JP. Additive manufacturing of ceramics: a review. J Ceram Sci Technol. 2014;5:245-60.

[3] Stansbury JW, Idacavage MJ. 3D printing with polymers: challenges among expanding options and opportunities. Dent Mater. 2016;32:54-64. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2015.09.018, PMID:26494268

[4] Alageel O, Abdallah MN, Alsheghri A, Song J, Caron E, Tamimi F. Removable partial denture alloys processed by laser-sintering technique. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2018;106:1174-85. https://doi.org/10.1002/ jbm.b.33929, PMID:28561993

[5] Ozan O, Turkyilmaz I, Ersoy AE, McGlumphy EA, Rosenstiel SF. Clinical accuracy of 3 different types of computed tomography-derived stereolithographic surgical guides in implant placement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:394-401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.033, PMID:19138616

[6] Kabir SMF, Kavita Mathur, Abdel-Fattah M. A critical review on 3D printed continuous fiber-reinforced composites: history, mechanism, materials and properties. Compos Struct. 2020;232:0263-8223.

[7] Additive manufacturing – General principles – Fundamentals and vocabulary; ISO/ASTM 52900:2021.

[8] Oberoi G, Nitsch S, Edelmayer M, Janjić K, Müller AS, Agis H. 3D printingencompassing the facets of dentistry. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2018;6:172. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2018.00172, PMID:30525032

[9] Juste E, Petit F, Lardot V, Cambier F. Shaping of ceramic parts by selective laser melting of powder bed. J Mater Res. 2014;29:2086-94. https://doi. org/10.1557/jmr.2014.127

[10] Lakhdar Y, Tuck C, Binner J, Terry A, Goodridge R. Additive manufacturing of advanced ceramic materials. Prog Mater Sci. 2021;116:100736. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100736

[11] Homsy FR, Özcan M, Khoury M, Majzoub ZAK. Marginal and internal fit of pressed lithium disilicate inlays fabricated with milling, 3D printing, and conventional technologies. J Prosthet Dent. 2018;119:783-90. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2017.07.025, PMID:28969918

[12] Gingter P, Wätjen AM, Kramer M, Telle R. Functionally graded ceramic structures by direct thermal inkjet printing. J Ceram Sci Technol. 2015;6:119-24.

[13] Weingarten S, Scheithauer U, Johne R, Abel J, Schwarzer E, Moritz T, et al. Multi-material ceramic-based components – additive manufacturing of black-and-white zirconia components by thermoplastic 3D-printing (CerAM – T3DP). J Vis Exp. 2019;7:143. PMID:30663650

[14] Hu K, Zhao P, Li J, Lu Z. High-resolution multiceramic additive manufacturing based on digital light processing. Addit Manuf. 2022;54:102732. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.102732

[15] Loh GH, Pei E, Harrison D, Monzón MD. An overview of functionally graded additive manufacturing. Addit Manuf. 2018;23:34-44. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.addma.2018.06.023

[16] Wu H, Cheng Y, Liu W, He R, Zhou M, Wu S, et al. Effect of the particle size and the debinding process on the density of alumina ceramics fabricated by 3D printing based on stereolithography. Ceram Int. 2016;42:17290-4. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.08.024

[17] Sakly A, Kenzari S, Bonina D, Corbel S, Fournée V. A novel quasicrystalresin composite for stereolithography. Materials & Design (1980-2015). 2014;56:280-5.

[18] Santoliquido O, Colombo P, Ortona A. Additive Manufacturing of ceramic components by Digital Light Processing: A comparison between the “bot-tom-up” and the “top-down” approaches. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2019;39:2140-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2019.01.044

[19] Lian Q, Yang F, Xin H, Li D. Oxygen-controlled bottom-up mask-projection stereolithography for ceramic 3D printing. Ceram Int. 2017;43:14956-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.08.014

[20] Della Bona A, Cantelli V, Britto VT, Collares KF, Stansbury JW. 3D printing restorative materials using a stereolithographic technique: a systematic review. Dent Mater. 2021;37:336-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2020.11.030, PMID:33353734

[21] Florence JM, Yoder LA. Display system architectures for digital micromirror device (DMD)-based projectors. In Projection displays II 1996 Mar 29 (Vol. 2650, pp. 193-208). SPIE.

[22] Lu Y, Mapili G, Suhali G, Chen S, Roy K. A digital micro-mirror device-based system for the microfabrication of complex, spatially patterned tissue engineering scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;77A:396-405. https://doi. org/10.1002/jbm.a.30601, PMID:16444679

[23] Melchels FPW, Feijen J, Grijpma DW. A review on stereolithography and its applications in biomedical engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6121-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.050, PMID:20478613

[24] Chen F, Zhu H, Wu JM, Chen S, Cheng LJ, Shi YS, et al. Preparation and biological evaluation of

[25] Meng J, Lian Q, Xi S, Yi Y, Lu Y, Wu G. Crown fit and dimensional accuracy of zirconia fixed crowns based on the digital light processing technology. Ceram Int. 2022;48:17852-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.03.057

[26] Zhang K, Xie C, Wang G, He R, Ding G, Wang M, et al. High solid loading, low viscosity photosensitive

[27] Hinczewski C, Corbel S, Chartier T. Stereolithography for the fabrication of ceramic three- dimensional parts. Rapid Prototyping J. 1998;4:104-11. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552549810222867

[28] Xu X, Zhou S, Wu J, Zhang C, Liu X. Inter-particle interactions of alumina powders in UV-curable suspensions for DLP stereolithography and its effect on rheology, solid loading, and self-leveling behavior. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41:2763-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.12.004

[29] Zhang K, He R, Xie C, Wang G, Ding G, Wang M, et al. Photosensitive ZrO2 suspensions for stereolithography. Ceram Int. 2019;45:12189-95. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.03.123

[30] Li W, Liu M, Liu W, Zhou H, Li M, Chen Y, et al. High-performance integrated manufacturing of a 3Y-TZP ceramic crown through viscoelastic pastebased vat photopolymerization with a conformal contactless support. Addit Manuf. 2022;59:103143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.103143

[31] Song S, Park M, Lee J, Yun J. A Study on the rheological and mechanical properties of photo-curable ceramic/polymer composites with different silane coupling agents for SLA 3D Printing Technology. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2018;8:93. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8020093, PMID:29414912

[32] Kim J, Gal CW, Choi YJ, Park H, Yoon SY, Yun H. Effect of non-reactive diluent on defect-free debinding process of 3D printed ceramics. Addit Manuf. 2023;67:103475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2023.103475

[33] Nie J, Li M, Liu W, Li W, Xing Z. The role of plasticizer in optimizing the rheological behavior of ceramic pastes intended for stereolithography-based additive manufacturing. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41:646-54. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.08.013

[34] Han Z, Liu S, Qiu K, Liu J, Zou R, Wang Y, et al. The enhanced ZrO2 produced by DLP via a reliable plasticizer and its dental application. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2023;141:105751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jmbbm.2023.105751, PMID:36921555

[35] Ji SH, Kim DS, Park MS, Yun JS. Sintering process optimization for 3YSZ ceramic 3D-printed objects manufactured by stereolithography. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021;11:192. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11010192, PMID:33466603

[36] Kang JH, Sakthiabirami K, Kim HA, Hosseini Toopghara SA, Jun MJ, Lim HP, et al. Effects of UV absorber on zirconia fabricated with digital light processing additive manufacturing. Materials (Basel). 2022;15:8726. https://doi. org/10.3390/ma15248726, PMID:36556530

[37] Li K, Zhao Z. The effect of the surfactants on the formulation of UVcurable SLA alumina suspension. Ceram Int. 2017;43:4761-7. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.11.143

[38] Gentry SP, Halloran JW. Light scattering in absorbing ceramic suspensions: effect on the width and depth of photopolymerized features. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2015;35:1895-904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2014.12.006

[39] Chartier T, Badev A, Abouliatim Y, Lebaudy P, Lecamp L. Stereolithography process: influence of the rheology of silica suspensions and of the medium on polymerization kinetics – Cured depth and width. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2012;32:1625-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2012.01.010

[40] Jang KJ, Kang JH, Fisher JG, Park SW. Effect of the volume fraction of zirconia suspensions on the microstructure and physical properties of products produced by additive manufacturing. Dent Mater. 2019;35:e97-106. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2019.02.001, PMID:30833011

[41] Zhang K, Meng Q, Zhang X, Qu Z, Jing S, He R. Roles of solid loading in stereolithography additive manufacturing of ZrO2 ceramic. Int J Refract Hard Met. 2021;99:105604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmhm.2021.105604

[42] Borlaf M, Serra-Capdevila A, Colominas C, Graule T. Development of UV-curable ZrO2 slurries for additive manufacturing (LCM-DLP) technology. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2019;39:3797-803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2019.05.023

[43] Mitteramskogler G, Gmeiner R, Felzmann R, Gruber S, Hofstetter C, Stampfl J, et al. Light curing strategies for lithography-based additive manufacturing of customized ceramics. Addit Manuf. 2014;1-4:110-8. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.addma.2014.08.003

[44] Chartier T, Chaput C, Doreau F, Loiseau M. Stereolithography of structural complex ceramic parts. J Mater Sci. 2002;37:3141-7. https://doi. org/10.1023/A:1016102210277

[45] Sun J, Binner J, Bai J. 3D printing of zirconia via digital light processing: optimization of slurry and debinding process. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2020;40:583744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.05.079

[46] Lian Q, Sui W, Wu X, Yang F, Yang S. Additive manufacturing of ZrO

[47] Derby B. Inkjet printing ceramics: from drops to solid. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2011;31:2543-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2011.01.016

[48] Graf D, Jung J, Hanemann T. Formulation of a ceramic ink for 3D inkjet printing. Micromachines (Basel). 2021;12:1136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ mi12091136, PMID:34577779

[49] Willems E, Turon-Vinas M, Camargo dos Santos B, Van Hooreweder B, Zhang F, Van Meerbeek B, et al. Additive manufacturing of zirconia ceramics by material jetting. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41:5292-306. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2021.04.018

[50] Wätjen AM, Gingter P, Kramer M, Telle R. Novel prospects and possibilities in additive manufacturing of ceramics by means of direct inkjet printing. Adv Mech Eng. 2014;6:141346. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/141346

[51] Lee JH, Kim JH, Hwang KT, Hwang HJ, Han KS. Digital inkjet printing in three dimensions with multiple ceramic compositions. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41:1490-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.09.044

[52] Ebert J, Özkol E, Zeichner A, Uibel K, Weiss Ö, Koops U, et al. Direct inkjet printing of dental prostheses made of zirconia. J Dent Res. 2009;88:673-6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034509339988, PMID:19641157

[53] Zhong S, Shi Q, Deng Y, Sun Y, Politis C, Yang S. High-performance zirconia ceramic additively manufactured via NanoParticle Jetting. Ceram Int. 2022;48:33485-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.07.294

[54] Lüchtenborg J, Willems E, Zhang F, Wesemann C, Weiss F, Nold J, et al. Accuracy of additively manufactured zirconia four-unit fixed dental prostheses fabricated by stereolithography, digital light processing and material jetting compared with subtractive manufacturing. Dent Mater. 2022;38:1459-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2022.06.026, PMID:35798578

[55] Lyu J, Yang X, Li Y. Dimensional accuracy and clinical adaptation of monolithic zirconia crowns fabricated with the nanoparticle jetting technique. J Prosthet Dent. 2023;S0022-3913(23)00260-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. prosdent.2023.04.008 ,

[56] Camargo B, Willems E, Jacobs W, Van Landuyt K, Peumans M, Zhang F, et al. 3D printing and milling accuracy influence full-contour zirconia crown adaptation. Dent Mater. 2022;38:1963-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2022.11.002, PMID:36411148

[57] Prasad PSRK, Reddy AV, Rajesh PK, Ponnambalam P, Prakasan K. Studies on rheology of ceramic inks and spread of ink droplets for direct ceramic ink jet printing. J Mater Process Technol. 2006;176:222-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jmatprotec.2006.04.001

[58] Özkol E, Ebert J, Telle R. An experimental analysis of the influence of the ink properties on the drop formation for direct thermal inkjet printing of high solid content aqueous 3Y-TZP suspensions. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2010;30:166978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2010.01.004

[59] Seerden KAM, Reis N, Derby B, Grant PS, Halloran JW, Evans JRG. Direct inkjet deposition of ceramic green bodies: I-Formulation of build materials. Proc MRS. 1998;542:141-6. https://doi.org/10.1557/PROC-542-141 OPL

[60] Lejeune M, Chartier T, Dossou-Yovo C, Noguera R. Ink-jet printing of ceramic micro-pillar arrays. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2009;29:905-11. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2008.07.040

[61] Magdassi S, ed. The chemistry of inkjet inks. World scientific; 2009 Jul 31.

[62] He Q, Jiang J, Yang X, Zhang L, Zhou Z, Zhong Y, et al. Additive manufacturing of dense zirconia ceramics by fused deposition modeling via screw extrusion. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41:1033-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jeurceramsoc.2020.09.018

[63] Shahzad A, Lazoglu I. Direct ink writing (DIW) of structural and functional ceramics: recent achievements and future challenges. Compos, Part B Eng. 2021;225:109249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109249

[64] Feilden E, Blanca EGT, Giuliani F, Saiz E, Vandeperre L. Robocasting of structural ceramic parts with hydrogel inks. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2016;36:2525-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2016.03.001

[65] Ghazanfari A, Li W, Leu MC, Watts JL, Hilmas GE. Additive manufacturing and mechanical characterization of high density fully stabilized zirconia. Ceram Int. 2017;43:6082-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.01.154

[66] Montero J, Becerro A, Dib A, Quispe-López N, Borrajo J, Benito Garzón L. Preliminary results of customized bone graft made by robocasting hydroxyapatite and tricalcium phosphates for oral surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2023;135:192-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. oooo.2022.06.002, PMID:36089487

[67] Shao H, Zhao D, Lin T, He J, Wu J. 3D gel-printing of zirconia ceramic parts. Ceram Int. 2017;43:13938-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.07.124

[68] Cui X, Shen Z, Wang X. Esthetic appearances of anatomic contour zirconia crowns made by additive wet deposition and subtractive dry milling: A self-controlled clinical trial. J Prosthet Dent. 2020;123:442-8. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.02.016, PMID:31307809

[69] Tidehag P, Shen Z. Digital dentistry calls the change of ceramics and ceramic processes. Adv Appl Ceramics. 2019;118:83-90. https://doi.org/10.10 80/17436753.2018.1511337

[70] Rabel K, Nold J, Pehlke D, Shen J, Abram A, Kocjan A, et al. Zirconia fixed dental prostheses fabricated by 3D gel deposition show higher fracture strength than conventionally milled counterparts. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2022;135:105456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2022.105456, PMID:36150323

[71] Rueschhoff L, Costakis W, Michie M, Youngblood J, Trice R. Additive manufacturing of dense ceramic parts via direct ink writing of aqueous alumina suspensions. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2016;13:821-30. https://doi. org/10.1111/ijac. 12557

[72] Liao J,Chen H,Luo H,Wang X, Zhou K, Zhang D. Direct ink writing of zirconia three-dimensional structures. J Mater Chem C Mater Opt Electron Devices. 2017;5:5867-71. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7TC01545C

[73] Bose S, Ke D, Sahasrabudhe H, Bandyopadhyay A. Additive manufacturing of biomaterials. Prog Mater Sci. 2018;93:45-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. pmatsci.2017.08.003, PMID:31406390

[74] Dehurtevent M, Robberecht L, Thuault A, Deveaux E, Leriche A, Petit F, et al. Effect of build orientation on the manufacturing process and the properties of stereolithographic dental ceramics for crown frameworks. J Prosthet Dent. 2021;125:453-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2020.01.024, PMID:32265125

[75] Xiang D, Xu Y, Bai W, Lin H. Dental zirconia fabricated by stereolithography: Accuracy, translucency and mechanical properties in different build orientations. Ceram Int. 2021;47:28837-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.07.044

[76] Osman RB, van der Veen AJ, Huiberts D, Wismeijer D, Alharbi N. 3D-printing zirconia implants; a dream or a reality? An in-vitro study evaluating the dimensional accuracy, surface topography and mechanical properties of printed zirconia implant and discs.J Mech Behav Biomed Mater.2017;75:5218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2017.08.018, PMID:28846981

[77] Nakai H, Inokoshi M, Nozaki K, Komatsu K, Kamijo S, Liu H, et al. Additively manufactured zirconia for dental applications. Materials (Basel). 2021;14:3694. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14133694, PMID:34279264

[78] Miura S, Shinya A, Ishida Y, Fujisawa M. Mechanical and surface properties of additive manufactured zirconia under the different building directions. J Prosthodont Res. 2022;67:410-7. https://doi.org/10.2186/jpr. JPR_D_22_00166,

[79] Lee HB, Bea EJ, Lee WS, Kim JH. Trueness of stereolithography ZrO<sub>2</ sub> crowns with different build directions. Dent Mater J. 2023;42:42-8. https://doi.org/10.4012/dmj.2022-041, PMID:36288942

[80] Li H, Song L, Sun J, Ma J, Shen Z. Stereolithography-fabricated zirconia dental prostheses: concerns based on clinical requirements. Adv Appl Ceramics. 2020;119:236-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/17436753.2019.1709687

[81] Zhang Z, Li P, Chu F, Shen G. Influence of the three-dimensional printing technique and printing layer thickness on model accuracy. J Orofac Orthop. 2019;80:194-204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-019-00180-y, PMID:31172199

[82] Alazzawi MK, Beyoglu B, Haber RA. A study in a tape casting based stereolithography apparatus: role of layer thickness and casting shear rate. J Manuf Process. 2021;64:1196-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2021.02.040

[83] Su CY, Wang JC, Chen DS, Chuang CC, Lin CK. Additive manufacturing of dental prosthesis using pristine and recycled zirconia solvent-based slurry stereolithography. Ceram Int. 2020;46:28701-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ceramint.2020.08.030

[84] Wilkes J, Hagedorn YC, Meiners W, Wissenbach K. Additive manufacturing of

[85] Lian Q, Wu X, Li D, He X, Meng J, Liu X, et al. Accurate printing of a zirconia molar crown bridge using three-part auxiliary supports and ceramic mask projection stereolithography. Ceram Int. 2019;45:18814-22. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.06.111

[86] Schönherr JA, Baumgartner S, Hartmann M, Stampfl J. Stereolithographic additive manufacturing of high precision glass ceramic parts. Materials (Basel). 2020;13:1492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13071492, PMID:32218270

[87] Li R, Xu T, Wang Y, Sun Y. Accuracy of zirconia crowns manufactured by stereolithography with an occlusal full-supporting structure: an in vitro study. J Prosthet Dent. 2023;130:902-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2022.01.015,

[88] Li W, Armani A, McMillen D, Leu M, Hilmas G, Watts J. Additive manufacturing of zirconia parts with organic sacrificial supports. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2020;17:1544-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijac. 13520

[89] Zhang L, Huang J, Xiao Z, He Y, Liu K, He B, et al. Effects of debinding condition on microstructure and densification of alumina ceramics shaped with photopolymerization-based additive manufacturing technology. Ceram Int. 2022;48:14026-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.01.288

[90] Wang K, Qiu M, Jiao C, Gu J, Xie D, Wang C, et al. Study on defect-free debinding green body of ceramic formed by DLP technology. Ceram Int. 2020;46:2438-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.09.237

[91] Zhou M, Liu W, Wu H, Song X, Chen Y, Cheng L, et al. Preparation of a defectfree alumina cutting tool via additive manufacturing based on stereolithography – Optimization of the drying and debinding processes. Ceram Int. 2016;42:11598-602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.04.050

[92] Li H, Liu Y, Liu Y, Zeng Q, Hu K, Lu Z, et al. Influence of debinding holding time on mechanical properties of 3D-printed alumina ceramic cores. Ceram Int. 2021;47:4884-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.10.061

[93] Zhang L, Liu H, Yao H, Zeng Y, Chen J. 3D printing of hollow lattice structures of ZrO2(3Y)/Al2O3 ceramics by vat photopolymerization: process optimization, microstructure evolution and mechanical properties. J Manuf Process. 2022;83:756-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2022.09.047

[94] Stawarczyk B, Özcan M, Hallmann L, Ender A, Mehl A, Hämmerlet CHF. The effect of zirconia sintering temperature on flexural strength, grain size, and contrast ratio. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:269-74. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s00784-012-0692-6, PMID:22358379

[95] Wang SF, Zhang J, Luo DW, Gu F, Tang DY, Dong ZL, et al. Transparent ceramics: Processing, materials and applications. Prog Solid State Chem. 2013;41:20-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progsolidstchem.2012.12.002

[96] Yoshida M, Hada M, Sakurada O, Morita K. Transparent tetragonal zirconia prepared by sinter forging at

[97] International organization for standardization. ISO 5725-4:2020 Accuracy (trueness and precision) of measurement methods and results – Part 4: Basic methods for the determination of the trueness of a standard measurement method

[98] Jacobs MS, Windeler AS. An investigation of dental luting cement solubility as a function of the marginal gap. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;65:436-42. https:// doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(91)90239-S, PMID:2056466

[99] Valderhaug J, Heløe LA. Oral hygiene in a group of supervised patients with fixed prostheses. J Periodontol. 1977;48:221-4. https://doi.org/10.1902/ jop.1977.48.4.221, PMID:265390

[100] Felton DA, Kanoy BE, Bayne SC, Wirthman GP. Effect of in vivo crown margin discrepancies on periodontal health. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;65:357-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(91)90225-L, PMID:2056454

[101] Lang NP, Kiel RA, Anderhalden K. Clinical and microbiological effects of subgingival restorations with overhanging or clinically perfect margins. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:563-78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.1983. tb01295.x, PMID:6581173

[102] BergenholtzG,CoxCF,LoescheWJ,SyedSA.Bacterial leakage around dental restorations: its effect on the dental pulp. J Oral Pathol Med. 1982;11:439-50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.1982.tb00188.x, PMID:6819352

[103] Beuer F, Naumann M, Gernet W, Sorensen JA. Precision of fit: zirconia threeunit fixed dental prostheses. Clin Oral Investig. 2009;13:343-9. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00784-008-0224-6, PMID:18769946

[104] McLean JW, von F. The estimation of cement film thickness by an in vivo technique. Br Dent J. 1971;131:107-11. https://doi.org/10.1038/ sj.bdj.4802708, PMID:5283545

[105] Tuntiprawon M, Wilson PR. The effect of cement thickness on the fracture strength of all-ceramic crowns. Aust Dent J. 1995;40:17-21. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1834-7819.1995.tb05607.x, PMID:7710410

[106] Wang W, Sun J. Dimensional accuracy and clinical adaptation of ceramic crowns fabricated with the stereolithography technique. J Prosthet Dent. 2021;125:657-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2020.02.032, PMID:32418664

[107] Daou EE, Ounsi H, Özcan M, Al-Haj Husain N, Salameh Z. Marginal and internal fit of pre-sintered

[108] Mously HA, Finkelman M, Zandparsa R, Hirayama H. Marginal and internal adaptation of ceramic crown restorations fabricated with CAD/CAM technology and the heat-press technique. J Prosthet Dent. 2014;112:249-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.03.017, PMID:24795263

[109] Sorensen JA, Munksgaard EC. Interfacial gaps of resin cemented ceramic inlays. Eur J Oral Sci. 1995;103:116-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0722.1995. tb00128.x, PMID:7767706

[110] Souza ROA, Özcan M, Pavanelli CA, Buso L, Lombardo GHL, Michida SMA, et al. Marginal and internal discrepancies related to margin design of ceramic crowns fabricated by a CAD/CAM system. J Prosthodont. 2012;21:94-100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-849X.2011.00793.x, PMID:22050205

[111] ISO 6872: 2015 Dentistry – Ceramic materials. ISO; 2015. p. 28.

[112] Shi HY, Pang R, Yang J,Fan D, Cai H, Jiang HB, et al. Overview of several typical ceramic materials for restorative dentistry. BioMed Res Int. 2022;2022:1-18. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8451445, PMID:35898679

[113] Alghazzawi TF, Janowski GM, Eberhardt AW. An experimental study of flexural strength and hardness of zirconia and their relation to crown failure loads. J Prosthet Dent; Online ahead of print. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. prosdent.2022.04.005,

[114] Tan X, Zhao Y, Lu Y, Yu P, Mei Z, Yu H. Physical and biological implications of accelerated aging on stereolithographic additive-manufactured zirconia for dental implant abutment. J Prosthodont Res. 2021;66:600-9. https://doi. org/10.2186/jpr.JPR_D_21_00240, PMID:34924492

[115] Li R, Wang Y, Hu M, Wang Y, Xv Y, Liu Y, et al. Strength and adaptation of stereolithography-fabricated zirconia dental crowns: an in vitro study. Int J Prosthodont. 2019;32:439-43. https://doi.org/10.11607/ijp.6262, PMID:31486816

[116] Li R, Chen H, Wang Y, Sun Y. Performance of stereolithography and milling in fabricating monolithic zirconia crowns with different finish line designs. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021;115:104255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jmbbm.2020.104255, PMID:33340775

[117] Wang W, Yu H, Liu Y, Jiang X, Gao B. Trueness analysis of zirconia crowns fabricated with 3-dimensional printing. J Prosthet Dent. 2019;121:285-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2018.04.012, PMID:30017167

[118] Revilla-León M, Methani MM, Morton D, Zandinejad A. Internal and marginal discrepancies associated with stereolithography (SLA) additively manufactured zirconia crowns. J Prosthet Dent. 2020;124:730-7. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2019.09.018, PMID:31980204

[119] Abualsaud R, Alalawi H. Fit, precision, and trueness of 3D-printed zirconia crowns compared to milled counterparts. Dent J. 2022;10:215. https://doi. org/10.3390/dj10110215, PMID:36421402

[120] Lerner H, Nagy K, Pranno N, Zarone F, Admakin O, Mangano F. Trueness and precision of 3D-printed versus milled monolithic zirconia crowns: an in vitro study. J Dent. 2021;113:103792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2021.103792, PMID:34481929

[121] Moon JM, Jeong CS, Lee HJ, Bae JM, Choi EJ, Kim ST, et al. A comparative study of additive and subtractive manufacturing techniques for a zirconia dental product: an analysis of the manufacturing accuracy and the bond strength of porcelain to zirconia. Materials (Basel). 2022;15:5398. https://doi. org/10.3390/ma15155398, PMID:35955331

[122] Baumgartner S, Gmeiner R, Schönherr JA, Stampfl J. Stereolithographybased additive manufacturing of lithium disilicate glass ceramic for dental applications. Mater Sci Eng C. 2020;116:111180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. msec.2020.111180, PMID:32806296

[123] Kim YK, Han JS, Yoon HI. Evaluation of intaglio surface trueness, wear, and fracture resistance of zirconia crown under simulated mastication: a comparative analysis between subtractive and additive manufacturing. J Adv Prosthodont. 2022;14:122-32. https://doi.org/10.4047/jap.2022.14.2.122, PMID:35601347

[124] Li R, Chen H, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Shen Z, Sun Y. Three-dimensional trueness and margin quality of monolithic zirconia restorations fabricated by additive 3D gel deposition. J Prosthodont Res. 2020;64:478-84. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jpor.2020.01.002, PMID:32063530

[125] Sun Z, Shen Z, Zhao J, Zheng Y. Adaptation and uniformity of monolithic zirconia crowns fabricated by additive 3-dimensional gel deposition. J Prosthet Dent. 2023;130:859-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2021.11.023,

[126] Özkol E, Zhang W, Ebert J, Telle R. Potentials of the “Direct inkjet printing” method for manufacturing 3Y-TZP based dental restorations. J Eur Ceram Soc.2012;32:2193-201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2012.03.006

[127] Jiang CP, Hentihu MFR, Cheng YC, Lei TY, Lin R, Chen Z. Development of 3D slurry printing technology with submersion-light apparatus in dental application. Materials (Basel). 2021;14:7873. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14247873, PMID:34947467

[128] Goujat A, Abouelleil H, Colon P, Jeannin C, Pradelle N, Seux D, et al. Marginal and internal fit of CAD-CAM inlay/onlay restorations: A systematic review of in vitro studies. J Prosthet Dent. 2019;121:590-597.e3. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2018.06.006, PMID:30509548

[129] Ban S. Development and characterization of ultra-high translucent zirconia using new manufacturing technology. Dent Mater J. 2023;42:1-10. https:// doi.org/10.4012/dmj.2022-243, PMID:36631076

[130] Alenezi A, Yehya M. Evaluating the accuracy of dental restorations manufactured by two CAD/CAM milling systems and their prototypes fabricated by 3D printing methods: an in vitro study. Int J Prosthodont. 2023;36:293-300. https://doi.org/10.11607/ijp.7633, PMID:34919097

[131] Unkovskiy A, Beuer F, Metin DS, Bomze D, Hey J, Schmidt F. Additive manufacturing of lithium disilicate with the LCM process for classic and non-prep veneers: preliminary technical and clinical case experience. Materials (Basel). 2022;15:6034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15176034, PMID:36079415

[132] Sasse M, Krummel A, Klosa K, Kern M. Influence of restoration thickness and dental bonding surface on the fracture resistance of full-coverage occlusal veneers made from lithium disilicate ceramic. Dent Mater. 2015;31:907-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2015.04.017, PMID:26051232

[133] Zamzam H, Olivares A, Fok A. Load capacity of occlusal veneers of different restorative CAD/CAM materials under lateral static loading. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2021;115:104290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jmbbm.2020.104290, PMID:33440327

[134] loannidis A,Park JM, Hüsler J,Bomze D, Mühlemann S, Özcan M. An in vitro comparison of the marginal and internal adaptation of ultrathin occlusal veneers made of 3D-printed zirconia, milled zirconia, and heat-pressed lithium disilicate. J Prosthet Dent. 2022;128:709-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. prosdent.2020.09.053, PMID:33741143

[135] Zandinejad A, Methani MM, Schneiderman ED, Revilla-León M, Bds DM. Fracture resistance of additively manufactured zirconia crowns when cemented to implant supported zirconia abutments: an in vitro study. J Prosthodont. 2019;28:893-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13103, PMID:31430001

[136] loannidis A, Bomze D, Hämmerle CHF, Hüsler J, Birrer O, Mühlemann S. Load-bearing capacity of CAD/CAM 3D-printed zirconia, CAD/CAM milled zirconia, and heat-pressed lithium disilicate ultra-thin occlusal veneers on molars. Dent Mater. 2020;36:e109-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2020.01.016, PMID:31992483

[137] Lu Y, Mei Z, Zhang J, Gao S, Yang X, Dong B, et al. Flexural strength and Weibull analysis of Y-TZP fabricated by stereolithographic additive manufacturing and subtractive manufacturing. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2020;40:826-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2019.10.058

[138] Sun J, Chen X, Wade-Zhu J, Binner J, Bai J. A comprehensive study of dense zirconia components fabricated by additive manufacturing. Addit Manuf. 2021;43:101994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2021.101994

[139] Zhai Z, Sun J. Research on the low-temperature degradation of dental zirconia ceramics fabricated by stereolithography. J Prosthet Dent. 2023;130:629-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2021.11.012, PMID:34933748

[140] Revilla-León M, Al-Haj Husain N, Ceballos L, Özcan M. Flexural strength and Weibull characteristics of stereolithography additive manufactured versus milled zirconia. J Prosthet Dent. 2021;125:685-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. prosdent.2020.01.019, PMID:32434662

[141] Baysal N, Tuğba Kalyoncuoğlu Ü, Ayyıldız S. Mechanical properties and bond strength of additively manufactured and milled dental zirconia: A pilot study. J Prosthodont. 2022;31:629-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13472, PMID:34940979

[142] Zenthöfer A, Schwindling FS, Schmitt C, Ilani A, Zehender N, Rammelsberg P, et al. Strength and reliability of zirconia fabricated by additive manufacturing technology. Dent Mater. 2022;38:1565-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. dental.2022.07.004, PMID:35933222

[143] Xing H, Zou B, Li S, Fu X. Study on surface quality, precision and mechanical properties of 3D printed ZrO2 ceramic components by laser scanning stereolithography. Ceram Int. 2017;43:16340-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ceramint.2017.09.007

[144] Wang L, Yu H, Hao Z, Tang W, Dou R. Fabrication of highly translucent yttria-stabilized zirconia ceramics using stereolithography-based additive manufacturing. Ceram Int. 2023;49:17174-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ceramint.2023.02.081

[145] Dehurtevent M, Robberecht L, Hornez JC, Thuault A, Deveaux E, Béhin P. Stereolithography: A new method for processing dental ceramics by additive computer-aided manufacturing. Dent Mater. 2017;33:477-85. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2017.01.018, PMID:28318544

[146] Revilla-León M, Al-Haj Husain N, Barmak AB, Pérez-López J, Raigrodski AJ, Özcan M. Chemical composition and flexural strength discrepancies between milled and lithography-based additively manufactured zirconia. J Prosthodont. 2022;31:778-83. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13482, PMID:35068002

[147] Bergler M, Korostoff J, Torrecillas-Martinez L, Mante F. Ceramic printingcomparative study of the flexural strength of 3D-printed and milled zirconia. Int J Prosthodont. 2022;35:777-83. https://doi.org/10.11607/ijp.6749, PMID:33616569

[148] Yang SY, Koh YH, Kim HE. Digital light processing of zirconia suspensions containing photocurable monomer/camphor vehicle for dental applications. Materials (Basel). 2023;16:402. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16010402, PMID:36614741

[149] Jung JM, Kim GN, Koh YH, Kim HE. Manufacturing and characterization of dental crowns made of

[150] Harrer W, Schwentenwein M, Lube T, Danzer R. Fractography of zirconiaspecimens made using additive manufacturing (LCM) technology. J Eur Ceram Soc.2017;37:4331-8.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2017.03.018

[151] Kim JH, Maeng WY, Koh YH, Kim HE. Digital light processing of zirconia prostheses with high strength and translucency for dental applications. Ceram Int. 2020;46:28211-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.07.321

[152] Shen Z, Liu L, Xu X, Zhao J, Eriksson M, Zhong Y, et al. Fractography of selfglazed zirconia with improved reliability. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2017;37:4339-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2017.03.008

[153] Sun Z, Wu L, Zhao J, Zheng Y. Aesthetic restoration of anterior teeth with different coloured substrates using digital monolithic zirconia crowns: two case reports. Adv Appl Ceramics. 2021;120:169-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/1 7436753.2021.1915086

[154] Scherrer SS, Cattani-Lorente M, Yoon S, Karvonen L, Pokrant S, Rothbrust F, et al. Post-hot isostatic pressing: A healing treatment for process related defects and laboratory grinding damage of dental zirconia? Dent Mater. 2013;29:e180-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2013.04.014, PMID:23726128

[155] Zhang Y, Lawn BR. Novel zirconia materials in dentistry. J Dent Res. 2018;97:140-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034517737483, PMID:29035694

[156] Wang L,Liu Y,Si W,Feng H,Tao Y,Ma Z. Friction and wear behaviors of dental ceramics against natural tooth enamel. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2012;32:2599-606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2012.03.021

[157] Lohbauer U, Scherrer SS, Della Bona A, Tholey M, van Noort R, Vichi A, et al. ADM guidance-Ceramics: all-ceramic multilayer interfaces in dentistry. Dent Mater. 2017;33:585-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2017.03.005, PMID:28431686

[158] Rueda AO, Anglada M, Jimenez-Pique E. Contact fatigue of veneer feldspathic porcelain on dental zirconia. Dent Mater. 2015;31:217-24. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2014.12.006, PMID:25557277

[159] He LH, Yin ZH, Jansen van Vuuren L, Carter EA, Liang XW. A natural functionally graded biocomposite coating – Human enamel. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:6330-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2012.12.029, PMID:23291490

[160] Cui C, Sun J. Optimizing the design of bio-inspired functionally graded material (FGM) layer in all-ceramic dental restorations. Dent Mater J. 2014;33:173-8. https://doi.org/10.4012/dmj.2013-264, PMID:24583648

[161] Fabris D, Souza JCM, Silva FS, Fredel M, Mesquita-Guimarães J, Zhang Y, et al. The bending stress distribution in bilayered and graded zirconia-based dental ceramics. Ceram Int. 2016;42:11025-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ceramint.2016.03.245, PMID:28104926

[162] Fabris D, Souza JCM, Silva FS, Fredel M, Mesquita-Guimarães J, Zhang Y, et al. Thermal residual stresses in bilayered, trilayered and graded dental ceramics. Ceram Int. 2017;43:3670-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.11.209, PMID:28163345

[163] Scheithauer U, Weingarten S, Johne R, Schwarzer E, Abel J, Richter HJ, et al. Ceramic-based 4D components: additive manufacturing (AM) of ceramicbased functionally graded materials (FGM) by thermoplastic 3D printing (T3DP). Materials (Basel). 2017;10:1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10121368, PMID:29182541

[164] Li W, Armani A, Martin A, Kroehler B, Henderson A, Huang T, et al. Extrusionbased additive manufacturing of functionally graded ceramics. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41:2049-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.10.029

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.2186/jpr.JPR_D_23_00119

These authors contributed equally to this work

*Corresponding author: Fuming He, No.166, QiuTao Rd(N), Shangcheng District, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province 310020, P.R. China.

E-mail address: hfm@zju.edu.cn

*Corresponding author: Yong He, No.166, QiuTao Rd(N), Shangcheng District, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province 310020, P.R. China.

E-mail address: yongqin@zju.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2186/jpr.jpr_d_23_00119

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38346729

Publication Date: 2024-01-01

Additive manufacturing of dental ceramics in prosthodontics: The status quo and the future

Abstract

Purpose: This review aims to summarize the available technologies, material categories, and prosthodontic applications of additive manufacturing (AM) dental ceramics, evaluate the achievable accuracy and mechanical properties in comparison with current mainstream computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) subtractive manufacturing (SM) methods, and discuss future prospects and directions. Study selection: This paper is based on the latest reviews, state-of-the-art research, and existing ISO standards on AM technologies and prosthodontic applications of dental ceramics. PubMed, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect were amongst the sources searched for narrative reviews. Results: Relatively few AM technologies are available and their applications are limited to crowns and fixed partial dentures. Although the accuracy and strength of AM dental ceramics are comparable to those of SM, they have the limitations of relatively inferior curved surface accuracy and low strength reliability. Furthermore, functionally graded additive manufacturing (FGAM), a potential direction for AM, enables the realization of biomimetic structures, such as natural teeth; however, specific studies are currently lacking. Conclusions: AM dental ceramics are not sufficiently developed for large-scale clinical applications. However, with additional research, it may be possible for AM to replace SM as the mainstream manufacturing technology for ceramic restorations.

1. Introduction

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS?

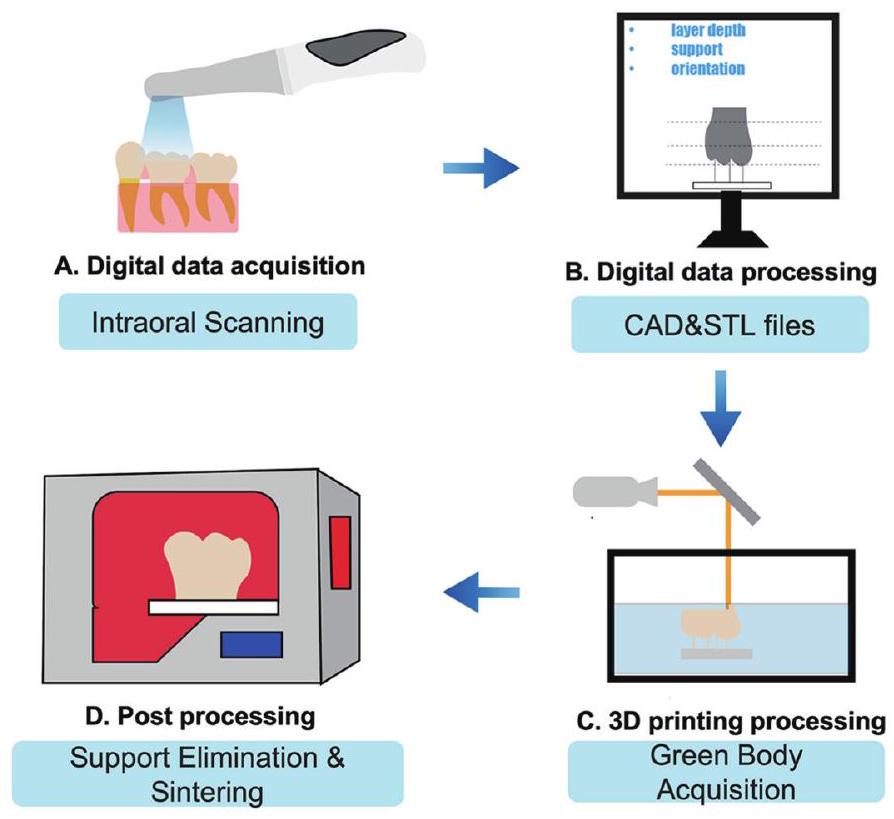

2. AM technologies used for dental ceramics

tion (VPP), material extrusion (MEX), material jetting (MJT), binder jetting (BJT), powder bed fusion (PBF), directed energy deposition (DED), and sheet lamination (SHL). However, owing to the stringent requirements for dental ceramics, only a few ceramic AM technologies meet the clinical standards of prosthodontics, including stereolithography (SLA), digital light processing (DLP) in VPP, direct inkjet printing (DIP) in MJT, and 3D gel printing (3DGP) in MEX. The basic principles of these techniques are shown in Figure 2 and will be elaborated on thereafter. Other AM technologies, such as PBF and DED, are based on powder fusion using thermal energy (such as lasers). BJT uses a liquid bonding agent to deposit power feedstocks, and SHL cuts and bonds sheet materials to form parts. However, as such technologies cannot be used to fabricate high-quality dental ceramics at present, they are beyond the scope of this review.

2.1. VPP

2.1.1. SLA

cial for accuracy enhancement[18,19]. However, the layers must be separated from the bottom of the container after curing each layer, which increases the total fabrication time. Worse still, it can introduce unwanted deformation and stress or even cause the possible detachment of a part, thus affecting the mechanical properties and maintenance of the desired shape during fabrication[18]. Compared with the bottom-up method, top-down SLA can achieve a shorter

fabrication time and higher mechanical strength, but the thickness of the fabricating layer surface is generally difficult to control due to the rheological properties of ceramic slurry, leading to relatively inferior accuracy.

2.1.2.

2.1.3. Parameters affecting VPP

iting the occurrence of flaws during the debinding process[32-35]. Han et al.[34] reported that the flexural strength of zirconia specimens increased from 302 to 1150 MPa with the addition of

2.2. MJT

2.2.1. Parameters affecting DIP

to the rheological properties of the suspensions, as expressed by the Ohnesorge number (Oh). Prasad et al.[57] reported that stable droplets can be formed when

2.3. MEX

extrusion (CODE) has been developed. In contrast to DIW, CODE extrudes ceramics inside a tank with oil. The oil prevents undesirable dehydration from the sides of the extruded layers, and infrared radiation is employed to dry these layers[65]. The high solid ratio and low extrusion temperature of water-based extrusion contribute to a higher density with lower shrinkage and avoid the influence of thermal residual stress on the parts. However, owing to the limitations of a large nozzle diameter and the staircase effect, the fabrication accuracy and surface finish of DIW and CODE are still inferior to those of VPP or DIP, making it difficult to manufacture high-quality ceramic restorations that are still suitable for bone-tissue scaffolding[66].

2.3.1. Parameters affecting MEX

3. Dental ceramic materials for AM

4. Parameters of the process chain influencing the properties of AM ceramics

4.1. Data processing

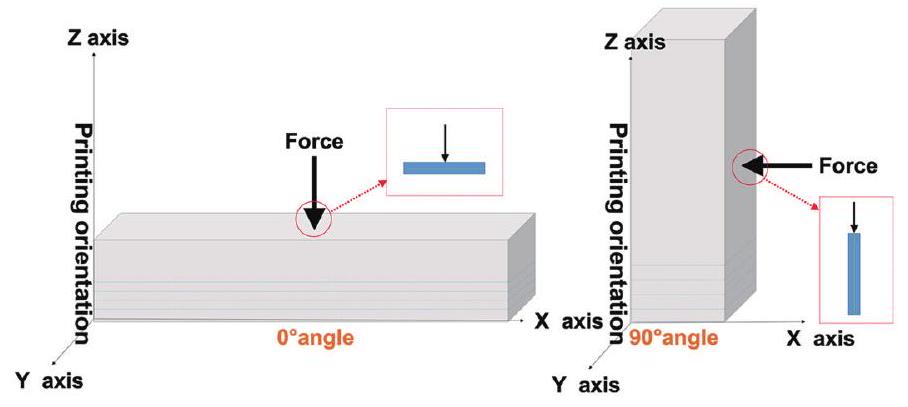

4.1.1. Build orientation

4.1.2. Layer thickness

4.2.

4.3. Post-processing

4.3.1. Support removal

4.3.2. Debinding and sintering

| Manufacturer | AM apparatus | Technologies | Resolution / m | Minimum layer thickness /

|

Materials | |||||||

| Xjet | Xjet Carmel 1400 | NPJ, based on DIP | 16 | 10.5 | 3Y-TZPAlumina | |||||||

| Lithoz |

|

LCM, based on DLP | 40 | 10 | 3Y-TZPAlumina | |||||||

| 3DCeram |

|

SLA | 35um (aser spot diameter) | 20 |

|

|||||||

| Porimy | CSL100/150/200 | SLA | 40 | 25 | 3Y-TZP | |||||||

| Admaflex | Admaflex130/300 | DLP | 35 | 10 | 3Y-TZPAlumina | |||||||

| Octave Light | Octave Light R1 | DLP | 30 | 25 | 3Y-TZPAlumina | |||||||

| Exone |

|

Binder jetting | 30 | 30 | 3Y-TZP | |||||||

| Prodways | Promaker 10 | Moving Light technology, based on DLP | 42 | 10 | 3Y-TZP | |||||||

| AON |

|

DLP | 40 | 25 | 3Y-TZPAlumina |

5. Application of AM ceramics in prosthodontics

aesthetic evaluations are relatively scarce.

In vitro accuracy assessment mainly includes the evaluation of trueness and precision[97], whereas in dentistry, the latter is usually represented by crown fit (internal adaptation and marginal fit). Trueness is established by a 3D deviation analysis between the measured models and the original CAD model, and a lower trueness value indicates superior accuracy. Crown fit is essentially the cement thickness between the abutment teeth and restorations and is of direct clinical significance. Marginal fit plays an important role in the restorative effect, as poor marginal fit causes cement dissolution, secondary caries, pulpitis, gingivitis, periodontitis, and margin discoloration, severely affecting oral health and aesthetic appearance[98-102]. It is universally acknowledged that the clinical acceptable marginal fit should be

| Author/ years | Technology (company) | AM apparatus | Material | Trueness/ RMS (

|

||||||

| Wang/2019[117] | SLA (3DCeram) | CERAMAKER900 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Baumgartner/2020[122] | DLP (Lithoz) | CeraFab System S65 | Lithium disilicate | <50 | ||||||

| Lerner/2020[120] | DLP (Lithoz) | CeraFab System S65 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Li/2020[115] | SLA (Porimy) | CSL100 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Li/2020[124] | 3DGP (ERRAN) | Self-glazed Zirconia | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Wang/2021[106] | DLP (Lithoz) | CeraFab7500 | Alumina |

|

||||||

| SLA (Porimy) | CSL150 | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||||||

| Li/2022[30] | SLA (ZRapid) | AMC150 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Kim/2022[123] | SLA (3DCeram) |

|

3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

|

Octave Light R1 | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||||||

| Moon/2022[121] | DLP (AON) | INNI-II | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Meng/2022[25] | DLP (NP) | NP | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Li/2022[87] | SLA (Porimy) | CSL 100 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Abualsaud/2022[119] | SLA (3DCeram) | 3Shape E3 Dental Lab Scanner | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Camargo/2022[56] | NPJ (Xjet) | Carmel 1400 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Lv/2023[55] | NPJ (Xjet) | Carmel 1400 | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| DLP (Junjing) | J2 D140L CERAMICS | 3Y-TZP |

|

important parameters influencing the long-term performance of AM ceramic restorations, but related studies on this topic are also limited[114].

5.1. Crowns

5.1.1. Accuracy of SLA crowns

| Author/years | Technology/ company | Evaluation method | Material | Crown fit (

|

||||||

| Li/2019[115] | SLA (Porimy) | 3D subtractive analysis technique (intraoral scanner+ silica gel) | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Revilla-León/2020 [116] | SLA (3DCeram) |

|

3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Wang/2021[106] | DLP (Lithoz) | Silicone replica technique | Alumina |

|

||||||

| SLA (Porimy) | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||||

| Meng/2022[25] | DLP (NP) | Micro CT+ silicone rubber film | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Li/2022[87] | SLA (Porimy) | Triple-scan method | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Sun/2022[125] | 3DGP (ERRAN) | Direct-view technique+ silicone replica technique | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Abualsaud/2022[119] | SLA (3DCeram) | 3D subtractive analysis technique | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Camargo/2022[56] | NPJ (XJet) | Micro-CT | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| Lv/2023[55] | NPJ (XJet) | 3D subtractive analysis technique | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| DLP (Junjing) |

|

different finish lines (chamfer, rounded shoulder, and knife-edge), and their trueness was compared with SM zirconia crowns with the same design. The results demonstrated that crown trueness was affected primarily by the margin design rather than the manufacturing method. Among the three marginal designs, knife-edge acquired the maximum discrepancies, and neither SLA nor SM could obtain a high-quality knife-edge. Subsequently, Li et al.[87] designed a fully supporting base and fabricated SLA zirconia crowns using the same additive manufacture apparatus. They reported that SLA crowns with this fully supporting base design had similar external surface trueness and crown fit as SM zirconia crowns.

posite results. They used silica gel replication techniques to evaluate the crown fit of zirconia crowns fabricated with the same apparatus (Ceramaker900, 3DCeram), and found the marginal fit (

5.1.2. Accuracy of DLP crowns

ceramic manufacturing (LCM, a patented ceramic DLP technology) zirconia crowns (CeraFab System S65, Lithoz, Vienna, Austria) with SM crowns. The results showed that the trueness of LCM was inferior to the SM control group, though it retained a relatively low value (external surface:

5.1.3. Accuracy of 3DGP crowns

5.1.4. Accuracy of DIP crowns

5.2. Multiple-unit FPD

| Author/year | Technique/company | Material | Main finding | |||||

| Lian/2019[85] | DLP/NP | 3Y-TZP | Average dimensional error:

|

|||||

| Li/2020[124] | 3DGP/Erran | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||||

| Jiang/2021[127] | DLP/NP | 3Y-TZP | Marginal fit:

|

|||||

| Lüchtenborg/2022[54] | SLA/3DCeram | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||||

| NPJ/Xjet | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| LCM/Lithoz | 3Y-TZP |

|

||||||

| DLP/University of Birmingham | 3Y-TZP |

|

5.3. Inlay, veneer, and occlusal veneer

fabricated LD veneers (LCM) based on the scan data of six lower anterior teeth from a clinical patient, and the marginal fit and internal adaptation were evaluated using the intraoral try-in and triple-scan methods. The results revealed that an appropriate marginal fit and internal adaption, with the majority falling below

5.4. Mechanical properties of AM dental ceramics

could not be proven that DLP zirconia crowns have a better fracture load than SM zirconia crowns. In addition, Zandinejad et al.[135] reported that implant-supported zirconia crowns manufactured using SLA (CeraMaker 900, 3D Cream) had a fracture load comparable to that of SM zirconia crowns and SM lithium disilicate crowns. Zandinejad et al.[135] and Rabel et al.[70] found that 3DGP FPDs achieved fracture loads superior to SM zirconia-FPDs. Ioannidis et al.[136] manufactured LCM zirconia occlusal veneers and compared their fracture loads with those of SM zirconia and heat-press LD. Their results showed that the occlusal LCM group had a significantly higher fracture load than the SM zirconia and heat-press LD groups. The above studies demonstrated the reliable strength and possible application value of AM ceramic restorations; however, more studies are needed to confirm these findings.

5.4.1. Mechanical properties of SLA ceramics

5.4.2. Mechanical properties of DLP ceramics

5.4.3. Mechanical properties of DIP and 3DGP ceramics

5.5. Aesthetics performance of AM dental ceramics

| Technology | Author/year | AM Apparatus/ company | Material | Flexural strength (MPa) | Fracture toughness (MPa

|

Weibull modulu |

| SLA | Xing/2017 [143] | Ceramaker300/3DCeram | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

|

| Lian/2018 [46] | SPS450B/Hengtong | 3Y-TZP | 200.14 | |||

| Li/2019 [115] | CSL 150/Porimy | 3Y-TZP |

|

7.44 | ||

| Nakai/2021 [77] | Ceramaker900/3DCeram | 3Y-TZP | 1071.1* | 16.3 | ||

| Li/2022 [30] | AMC150/ZRapid | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

||

| Zhai/2021 [139] | CSL 150/Porimy | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||

| Revilla/2021[140] | Ceramaker900/3DCeram | 3Y-TZP |

|

8.7 | ||

| Wang/ 2023 [144] | C100 EASY/3DCeram | 5Y-PSZ |

|

11.4 | ||

| Marion/2017[145] | CryoCeram/CryoBeryl | Alumina |

|

5-15 | ||

| Marion/2020[74] | CryoCeram/CryoBeryl | Alumina |

|

|

13.7 | |

| DLP | Harrer/2017[150] | CeraFab 7500/Lithoz | 3Y-TZP | 878* |

|

11.1 |

| Osman/2018[74] | Admaflex2.0/Admatec | 3Y-TPZ |

|

7.0 | ||

| Jang/2019 [40] | R1/Octave Light | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||

| Lian/2019 [85] | NP | 3Y-TZP |

|

3.68 | ||

| Lu/2020 [137] | NP/QuickDemos | 3Y-TZP |

|

9.3 | ||

| Bergler/2021[147] | Cerafab7500/Lithoz | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||

| Sun/2021 [138] | Homemade | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

16.4 | |

| Zhai/2021 [139] | Cerafab7500/Lithoz | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||

| Zenthöfer/2022[142] | Cerafab7500/Lithoz | 3Y-TZP |

|

5.12 | ||

| RevillaLeón/2022 [146] | CeraFab S65/Lithoz | 3Y-TZP |

|

6.95 | ||

| Kim/2020 [151] | Homemade | 4Y-TZP |

|

8.3 | ||

| Yang/2022 [148] | Veltz3D/Incheon | 4Y-TZP |

|

|||

| Jung/2022 [149] | Veltz3D/Incheon | 5Y-TZP |

|

7.9 | ||

| Baumgartner/2020[122] | NP/Lithoz | LD |

|

7.2 | ||

| DIP | Ebert/2009 [52] | DeskJet 930/HP | 3Y-TZP | 763* |

|

3.5 |

| Özkol/2012[126] | DeskJet 930/HP | 3Y-TZP | 843* | 3.6 | ||

| Willems/2021[49] | Carmel 1400/XJet | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

10.5 | |

| Zhong/2022[50] | Carmel 1400/XJet | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

||

| Baysal/2022[141] | Carmel 1400/XJet | 3Y-TZP |

|

|||

| 3DGP | Shen/2017 [152] | 3GDP/ERRAN | 3Y-TZP |

|

|

18 |

| *:Characteristic strengths. SLA: stereolithography, DLP: digital light processing, DIP: direct inkjet printing, 3DGP: 3D gel printing, 3Y-TZP: 3 mol% yttriastabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystal. | ||||||

6. Potential and future outlook

known by the authors, the minimum layer thickness of the current ceramic AM is

and MEX[163,164]. It is expected that the manufacture of multigradient crowns will be realized in the future based on further research.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

References

[2] Deckers J, Vleugels J, Kruthl JP. Additive manufacturing of ceramics: a review. J Ceram Sci Technol. 2014;5:245-60.

[3] Stansbury JW, Idacavage MJ. 3D printing with polymers: challenges among expanding options and opportunities. Dent Mater. 2016;32:54-64. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2015.09.018, PMID:26494268

[4] Alageel O, Abdallah MN, Alsheghri A, Song J, Caron E, Tamimi F. Removable partial denture alloys processed by laser-sintering technique. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2018;106:1174-85. https://doi.org/10.1002/ jbm.b.33929, PMID:28561993

[5] Ozan O, Turkyilmaz I, Ersoy AE, McGlumphy EA, Rosenstiel SF. Clinical accuracy of 3 different types of computed tomography-derived stereolithographic surgical guides in implant placement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:394-401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.033, PMID:19138616

[6] Kabir SMF, Kavita Mathur, Abdel-Fattah M. A critical review on 3D printed continuous fiber-reinforced composites: history, mechanism, materials and properties. Compos Struct. 2020;232:0263-8223.

[7] Additive manufacturing – General principles – Fundamentals and vocabulary; ISO/ASTM 52900:2021.

[8] Oberoi G, Nitsch S, Edelmayer M, Janjić K, Müller AS, Agis H. 3D printingencompassing the facets of dentistry. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2018;6:172. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2018.00172, PMID:30525032

[9] Juste E, Petit F, Lardot V, Cambier F. Shaping of ceramic parts by selective laser melting of powder bed. J Mater Res. 2014;29:2086-94. https://doi. org/10.1557/jmr.2014.127

[10] Lakhdar Y, Tuck C, Binner J, Terry A, Goodridge R. Additive manufacturing of advanced ceramic materials. Prog Mater Sci. 2021;116:100736. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100736

[11] Homsy FR, Özcan M, Khoury M, Majzoub ZAK. Marginal and internal fit of pressed lithium disilicate inlays fabricated with milling, 3D printing, and conventional technologies. J Prosthet Dent. 2018;119:783-90. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2017.07.025, PMID:28969918

[12] Gingter P, Wätjen AM, Kramer M, Telle R. Functionally graded ceramic structures by direct thermal inkjet printing. J Ceram Sci Technol. 2015;6:119-24.

[13] Weingarten S, Scheithauer U, Johne R, Abel J, Schwarzer E, Moritz T, et al. Multi-material ceramic-based components – additive manufacturing of black-and-white zirconia components by thermoplastic 3D-printing (CerAM – T3DP). J Vis Exp. 2019;7:143. PMID:30663650

[14] Hu K, Zhao P, Li J, Lu Z. High-resolution multiceramic additive manufacturing based on digital light processing. Addit Manuf. 2022;54:102732. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.102732

[15] Loh GH, Pei E, Harrison D, Monzón MD. An overview of functionally graded additive manufacturing. Addit Manuf. 2018;23:34-44. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.addma.2018.06.023

[16] Wu H, Cheng Y, Liu W, He R, Zhou M, Wu S, et al. Effect of the particle size and the debinding process on the density of alumina ceramics fabricated by 3D printing based on stereolithography. Ceram Int. 2016;42:17290-4. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.08.024

[17] Sakly A, Kenzari S, Bonina D, Corbel S, Fournée V. A novel quasicrystalresin composite for stereolithography. Materials & Design (1980-2015). 2014;56:280-5.

[18] Santoliquido O, Colombo P, Ortona A. Additive Manufacturing of ceramic components by Digital Light Processing: A comparison between the “bot-tom-up” and the “top-down” approaches. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2019;39:2140-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2019.01.044

[19] Lian Q, Yang F, Xin H, Li D. Oxygen-controlled bottom-up mask-projection stereolithography for ceramic 3D printing. Ceram Int. 2017;43:14956-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.08.014

[20] Della Bona A, Cantelli V, Britto VT, Collares KF, Stansbury JW. 3D printing restorative materials using a stereolithographic technique: a systematic review. Dent Mater. 2021;37:336-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2020.11.030, PMID:33353734

[21] Florence JM, Yoder LA. Display system architectures for digital micromirror device (DMD)-based projectors. In Projection displays II 1996 Mar 29 (Vol. 2650, pp. 193-208). SPIE.

[22] Lu Y, Mapili G, Suhali G, Chen S, Roy K. A digital micro-mirror device-based system for the microfabrication of complex, spatially patterned tissue engineering scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;77A:396-405. https://doi. org/10.1002/jbm.a.30601, PMID:16444679

[23] Melchels FPW, Feijen J, Grijpma DW. A review on stereolithography and its applications in biomedical engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6121-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.050, PMID:20478613

[24] Chen F, Zhu H, Wu JM, Chen S, Cheng LJ, Shi YS, et al. Preparation and biological evaluation of

[25] Meng J, Lian Q, Xi S, Yi Y, Lu Y, Wu G. Crown fit and dimensional accuracy of zirconia fixed crowns based on the digital light processing technology. Ceram Int. 2022;48:17852-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.03.057

[26] Zhang K, Xie C, Wang G, He R, Ding G, Wang M, et al. High solid loading, low viscosity photosensitive

[27] Hinczewski C, Corbel S, Chartier T. Stereolithography for the fabrication of ceramic three- dimensional parts. Rapid Prototyping J. 1998;4:104-11. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552549810222867

[28] Xu X, Zhou S, Wu J, Zhang C, Liu X. Inter-particle interactions of alumina powders in UV-curable suspensions for DLP stereolithography and its effect on rheology, solid loading, and self-leveling behavior. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41:2763-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.12.004

[29] Zhang K, He R, Xie C, Wang G, Ding G, Wang M, et al. Photosensitive ZrO2 suspensions for stereolithography. Ceram Int. 2019;45:12189-95. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.03.123

[30] Li W, Liu M, Liu W, Zhou H, Li M, Chen Y, et al. High-performance integrated manufacturing of a 3Y-TZP ceramic crown through viscoelastic pastebased vat photopolymerization with a conformal contactless support. Addit Manuf. 2022;59:103143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2022.103143

[31] Song S, Park M, Lee J, Yun J. A Study on the rheological and mechanical properties of photo-curable ceramic/polymer composites with different silane coupling agents for SLA 3D Printing Technology. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2018;8:93. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8020093, PMID:29414912

[32] Kim J, Gal CW, Choi YJ, Park H, Yoon SY, Yun H. Effect of non-reactive diluent on defect-free debinding process of 3D printed ceramics. Addit Manuf. 2023;67:103475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2023.103475

[33] Nie J, Li M, Liu W, Li W, Xing Z. The role of plasticizer in optimizing the rheological behavior of ceramic pastes intended for stereolithography-based additive manufacturing. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41:646-54. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.08.013

[34] Han Z, Liu S, Qiu K, Liu J, Zou R, Wang Y, et al. The enhanced ZrO2 produced by DLP via a reliable plasticizer and its dental application. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2023;141:105751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jmbbm.2023.105751, PMID:36921555

[35] Ji SH, Kim DS, Park MS, Yun JS. Sintering process optimization for 3YSZ ceramic 3D-printed objects manufactured by stereolithography. Nanomaterials (Basel). 2021;11:192. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11010192, PMID:33466603

[36] Kang JH, Sakthiabirami K, Kim HA, Hosseini Toopghara SA, Jun MJ, Lim HP, et al. Effects of UV absorber on zirconia fabricated with digital light processing additive manufacturing. Materials (Basel). 2022;15:8726. https://doi. org/10.3390/ma15248726, PMID:36556530

[37] Li K, Zhao Z. The effect of the surfactants on the formulation of UVcurable SLA alumina suspension. Ceram Int. 2017;43:4761-7. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.11.143

[38] Gentry SP, Halloran JW. Light scattering in absorbing ceramic suspensions: effect on the width and depth of photopolymerized features. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2015;35:1895-904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2014.12.006

[39] Chartier T, Badev A, Abouliatim Y, Lebaudy P, Lecamp L. Stereolithography process: influence of the rheology of silica suspensions and of the medium on polymerization kinetics – Cured depth and width. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2012;32:1625-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2012.01.010

[40] Jang KJ, Kang JH, Fisher JG, Park SW. Effect of the volume fraction of zirconia suspensions on the microstructure and physical properties of products produced by additive manufacturing. Dent Mater. 2019;35:e97-106. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2019.02.001, PMID:30833011

[41] Zhang K, Meng Q, Zhang X, Qu Z, Jing S, He R. Roles of solid loading in stereolithography additive manufacturing of ZrO2 ceramic. Int J Refract Hard Met. 2021;99:105604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmhm.2021.105604

[42] Borlaf M, Serra-Capdevila A, Colominas C, Graule T. Development of UV-curable ZrO2 slurries for additive manufacturing (LCM-DLP) technology. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2019;39:3797-803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2019.05.023

[43] Mitteramskogler G, Gmeiner R, Felzmann R, Gruber S, Hofstetter C, Stampfl J, et al. Light curing strategies for lithography-based additive manufacturing of customized ceramics. Addit Manuf. 2014;1-4:110-8. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.addma.2014.08.003

[44] Chartier T, Chaput C, Doreau F, Loiseau M. Stereolithography of structural complex ceramic parts. J Mater Sci. 2002;37:3141-7. https://doi. org/10.1023/A:1016102210277

[45] Sun J, Binner J, Bai J. 3D printing of zirconia via digital light processing: optimization of slurry and debinding process. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2020;40:583744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.05.079

[46] Lian Q, Sui W, Wu X, Yang F, Yang S. Additive manufacturing of ZrO