DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48201-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38719858

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-08

التغيرات الزمنية في 24 مرضًا معديًا قابلًا للإبلاغ في الصين قبل وأثناء جائحة COVID-19

تاريخ القبول: 24 أبريل 2024

تاريخ النشر على الإنترنت: 08 مايو 2024

(A) تحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

جائحة مرض فيروس كورونا 2019 (COVID-19)، جنبًا إلى جنب مع تنفيذ تدابير الصحة العامة والاجتماعية (PHSMs)، أعادت تشكيل ديناميات انتقال الأمراض المعدية بشكل ملحوظ. قمنا بتحليل تأثير PHSMs على 24 مرضًا معديًا قابلًا للإبلاغ (NIDs) في البر الرئيسي الصيني، باستخدام نماذج السلاسل الزمنية للتنبؤ باتجاهات الانتقال بدون PHSMs أو جائحة. كشفت نتائجنا عن أنماط موسمية مميزة في حدوث NID، حيث أظهرت الأمراض التنفسية أكبر استجابة لـ PHSMs، بينما استجابت الأمراض المنقولة بالدم والأمراض المنقولة جنسيًا بشكل أكثر اعتدالًا. تم تحديد 8 NIDs على أنها حساسة لـ PHSMs، بما في ذلك مرض اليد والقدم والفم، وحمى الضنك، والحصبة الألمانية، والحمى القرمزية، والسعال الديكي، والنكاف، والملاريا، والتهاب الدماغ الياباني. لم يتسبب إنهاء PHSMs في عودة ظهور NIDs على الفور، باستثناء السعال الديكي، الذي شهد أعلى ذروة له في ديسمبر 2023 منذ يناير 2008. تسلط نتائجنا الضوء على التأثيرات المتنوعة لـ PHSMs على NIDs المختلفة وأهمية استراتيجيات مستدامة وطويلة الأجل، مثل تطوير اللقاحات.

(BSTDs)، والأمراض المعدية الحيوانية المنشأ (ZIDs)

لتحديد NIDs الحساسة لـ PHSMs، وتحليل الارتباط المتبادل لفك شفرة العلاقة بين مؤشر صرامة PHSMs وتأثيرها على NIDs.

النتائج

اتجاهات NID طويلة الأجل قبل جائحة COVID-19

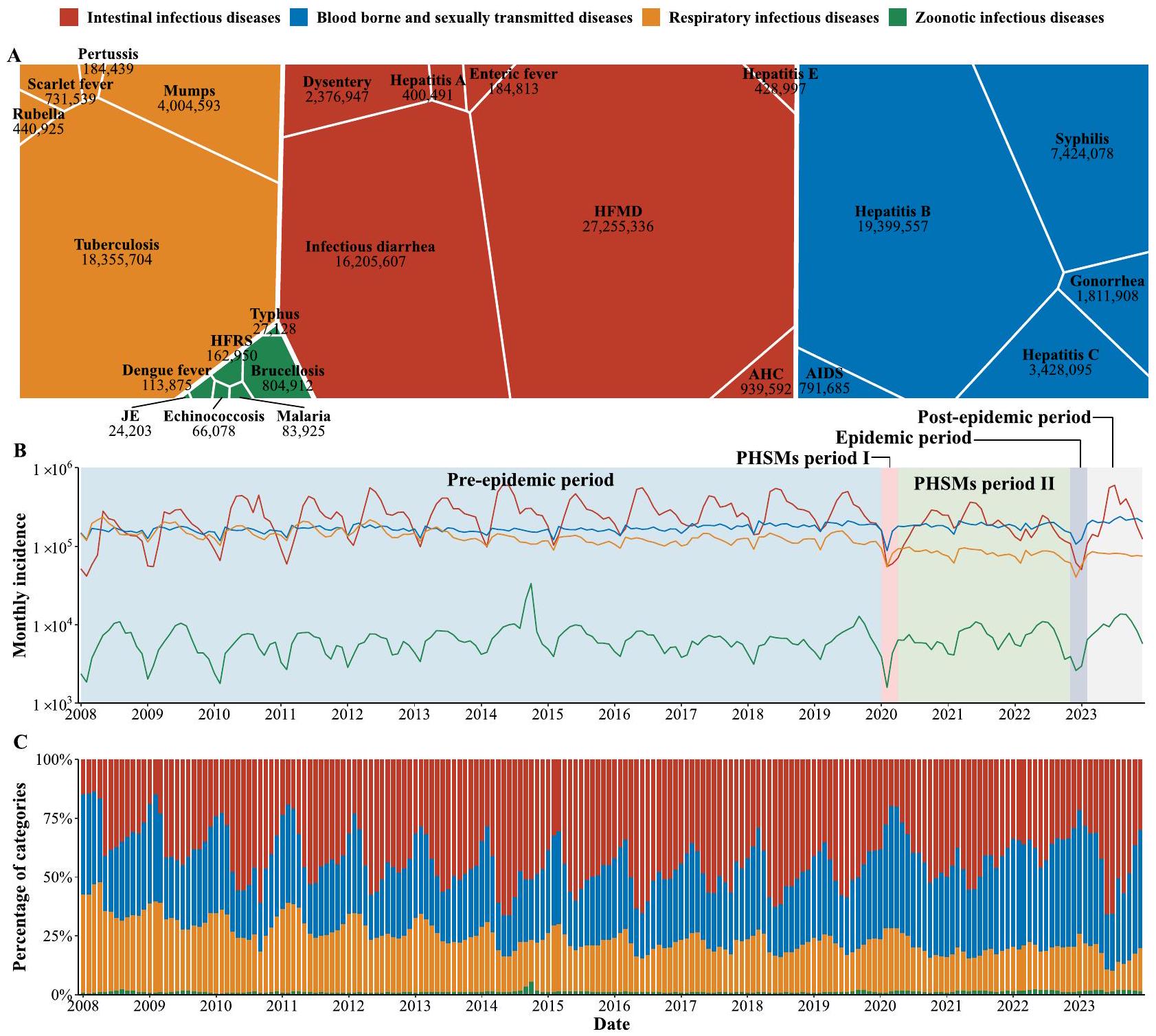

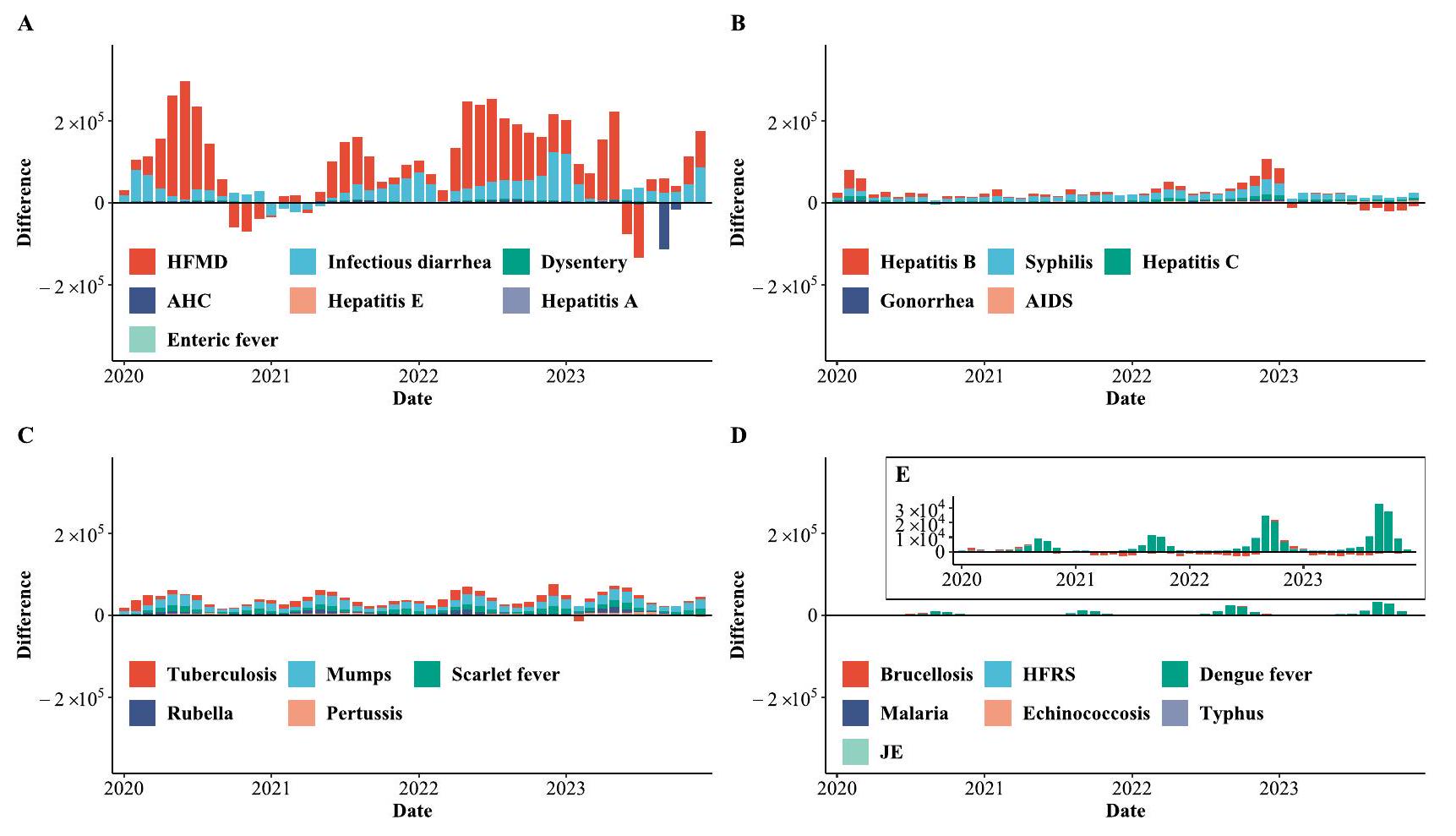

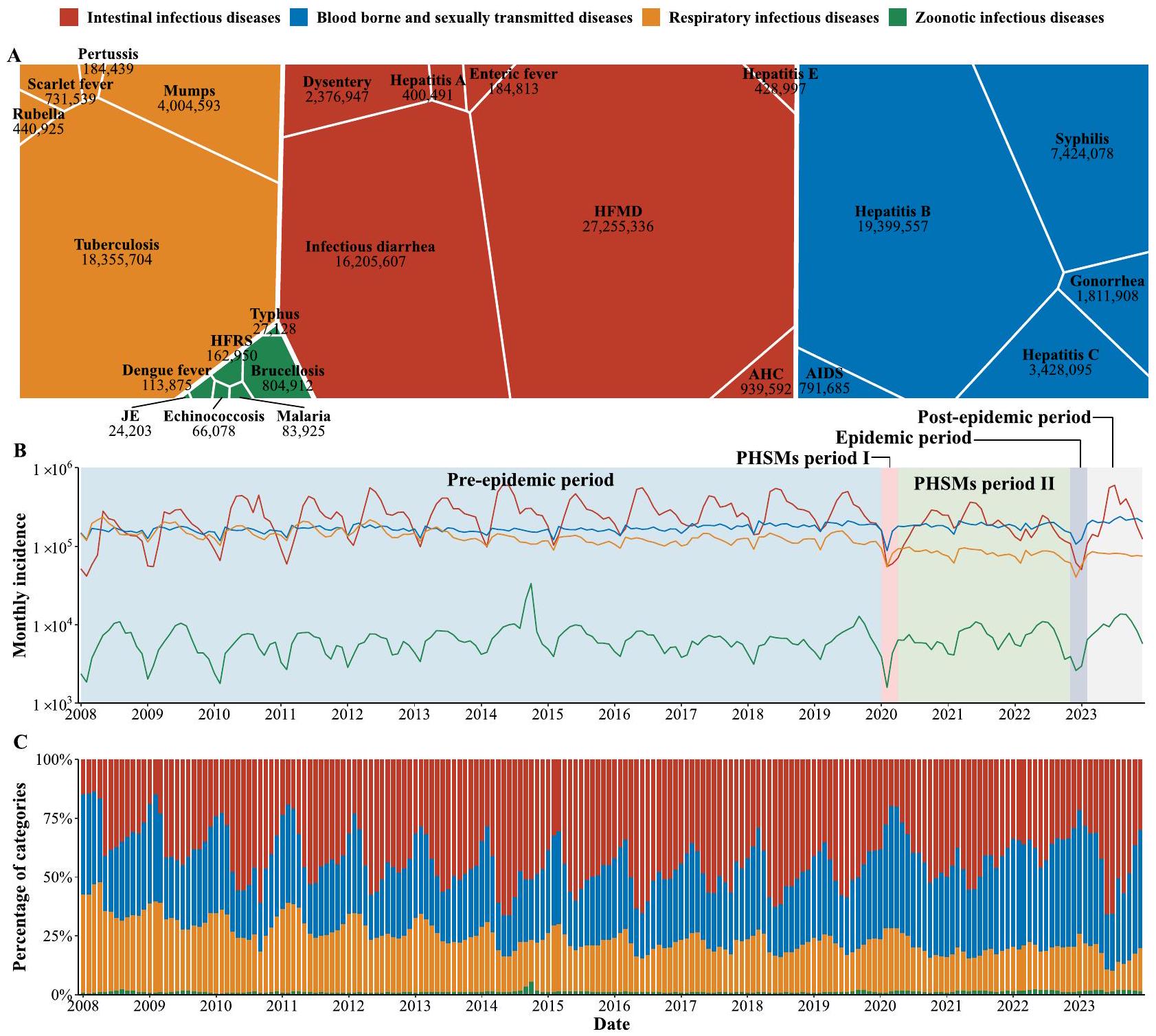

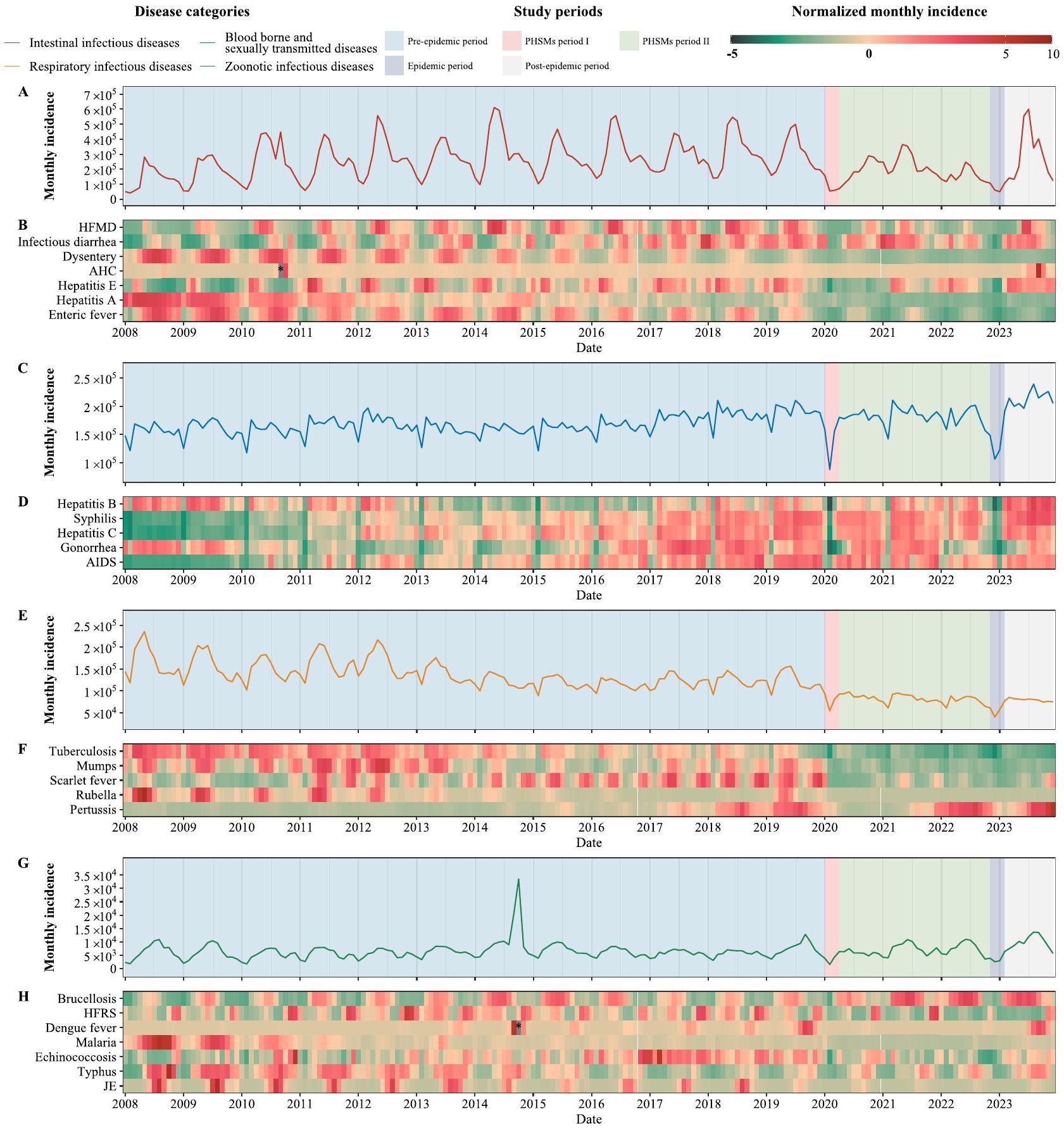

A الحدوث التراكمي لـ 24 NIDs مصنفة حسب طرق انتقالها، على مدار الفترة من يناير 2008 إلى ديسمبر 2023. تمثل حجم ولون كل كتلة الحالات التراكمية ومجموعة الأمراض، على التوالي. الإيدز (متلازمة نقص المناعة المكتسب)، لا تشمل عدوى فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية. تشمل الزحار الزحار البكتيري وزحار الأميبا. الحمى المعوية تُعرف أيضًا بحمى التيفوئيد وحمى بارا التيفوئيد. HFRS

حمى نزفية مع متلازمة الكلى؛ JE التهاب الدماغ الياباني؛ HFMD مرض اليد والقدم والفم؛ AHC التهاب الملتحمة النزفي الحاد. B تم تقسيم منحنيات الوباء لأربع فئات من NIDs إلى 5 فترات متميزة: فترة ما قبل الوباء (يناير 2008 إلى ديسمبر 2019)، فترة PHSMs I (يناير 2020 إلى مارس 2020)، فترة PHSMs II (أبريل 2020 إلى أكتوبر 2022)، فترة الوباء (نوفمبر 2022 إلى يناير 2023)، وفترة ما بعد الوباء (فبراير 2023 إلى ديسمبر 2023). C نسبة الحدوث الشهري لأربع مجموعات من NIDs.

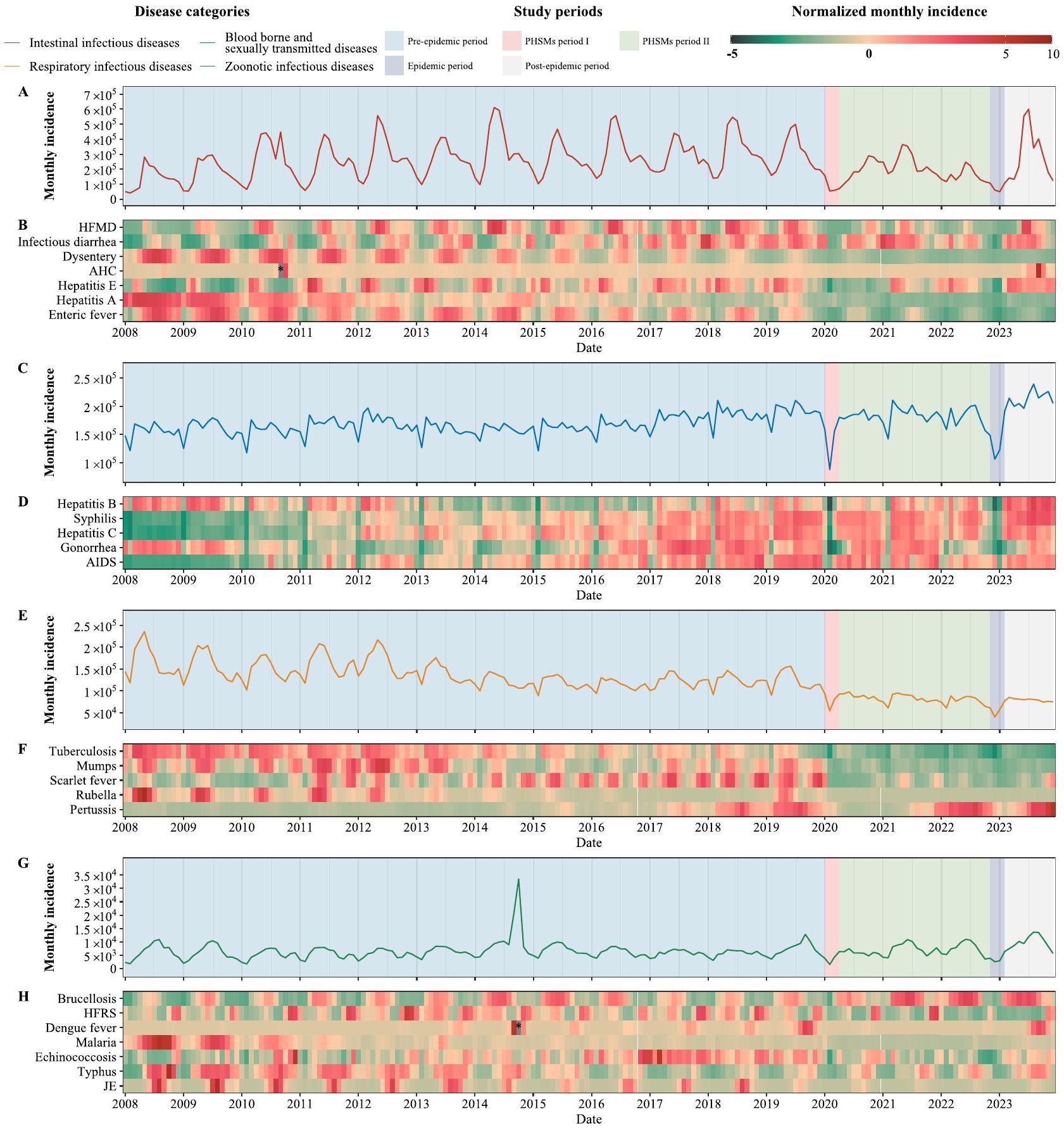

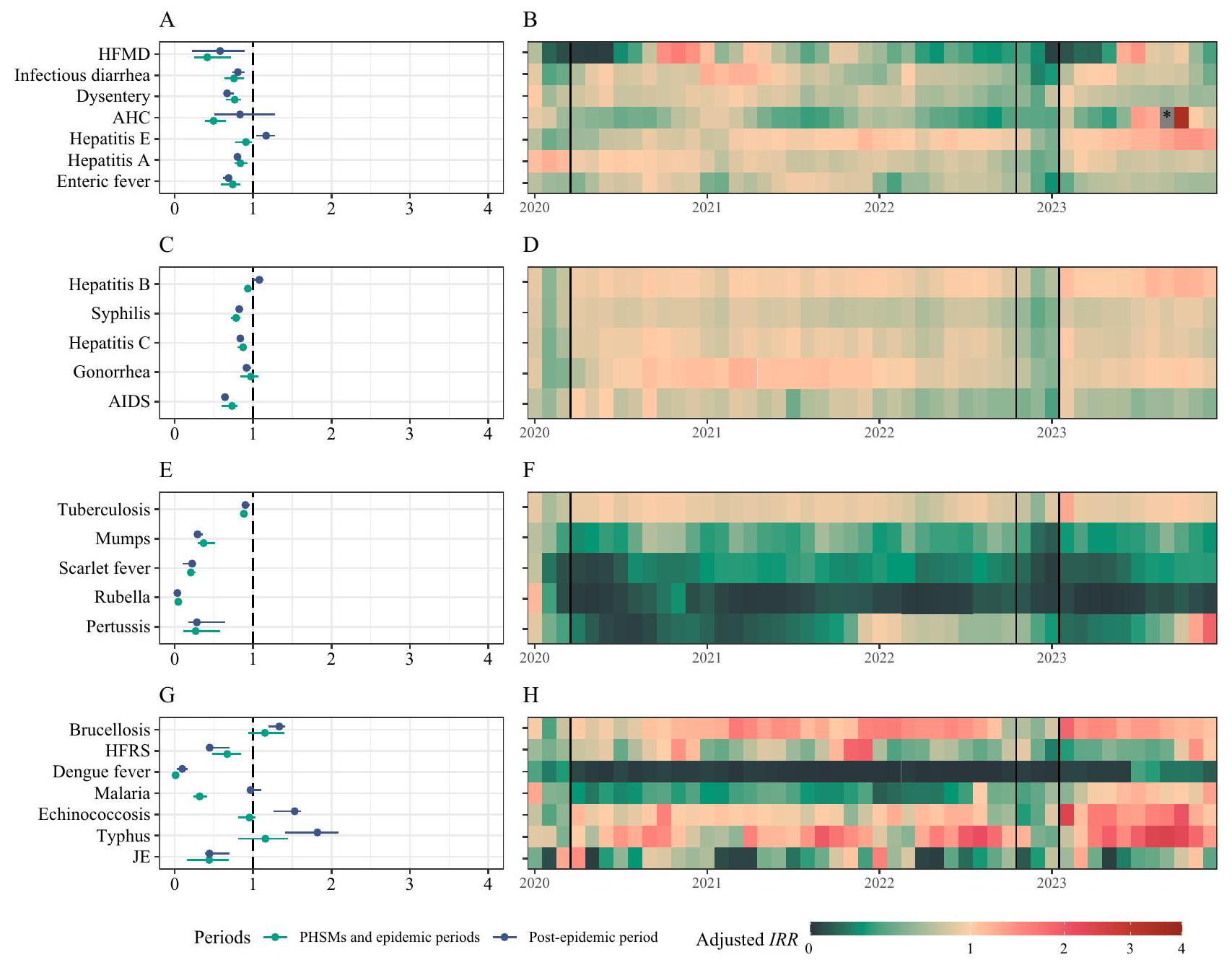

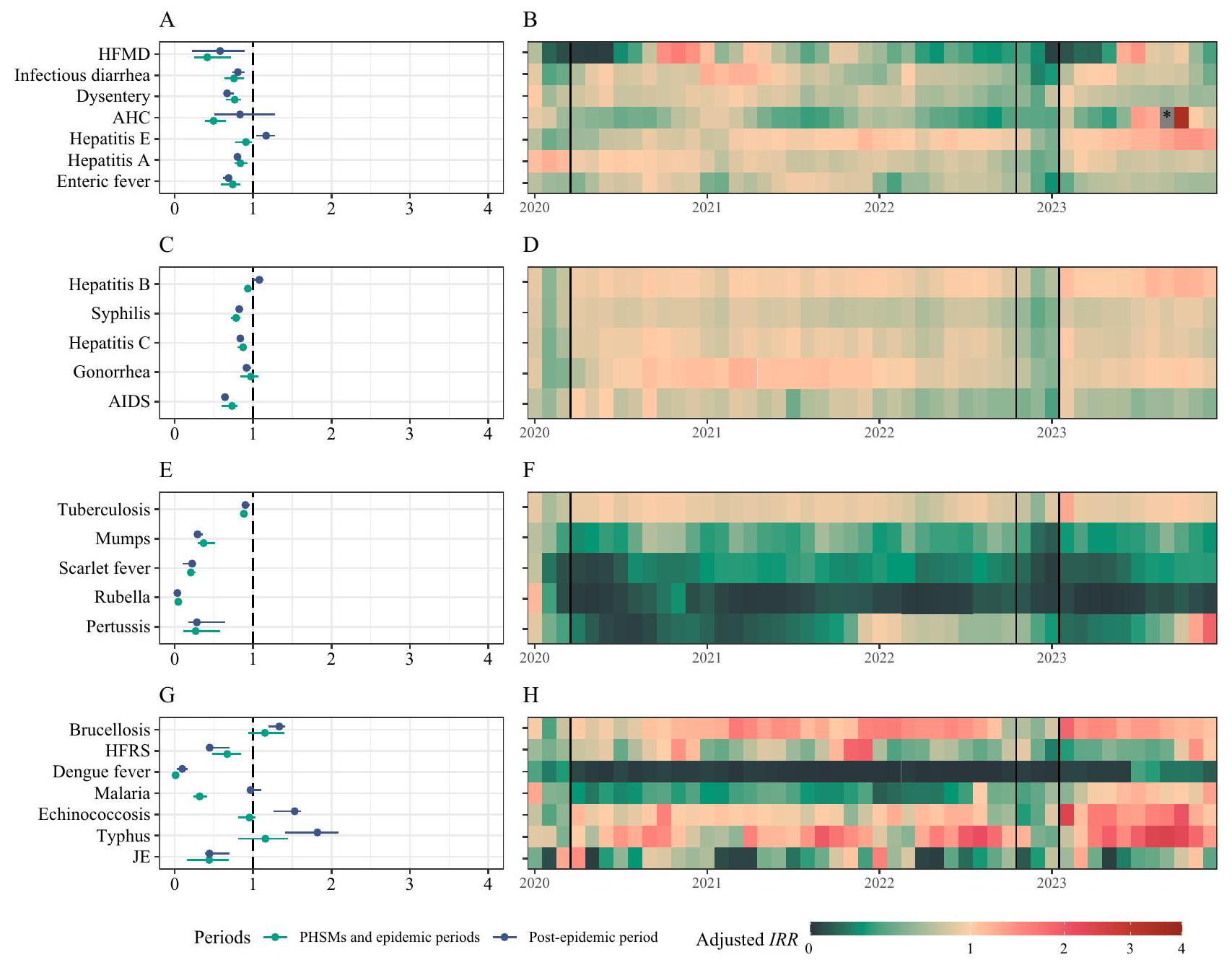

E، F الأمراض المعدية التنفسية. G، H الأمراض المعدية الحيوانية المنشأ.

A، C، E، G تم تقسيم منحنيات الوباء في فترة الدراسة إلى 5 فترات متميزة: فترة ما قبل الوباء (يناير 2008 إلى ديسمبر 2019)، فترة PHSMs I (يناير 2020 إلى مارس 2020)، فترة PHSMs II (أبريل 2020 إلى أكتوبر 2022)،

فترة الوباء (نوفمبر 2022 إلى يناير 2023)، وفترة ما بعد الوباء (فبراير 2023 إلى ديسمبر 2023). B، D، F، H الحدوث الشهري المنظم لكل NIDs، مع كثافة اللون تشير إلى حجم الحدوث الشهري المنظم. يتم حساب التنظيم كفرق بين حدوث NID الشهري ومتوسط الحدوث الشهري، مقسومًا على الانحراف المعياري للحدوث. القيم خارج النطاق -5 إلى 10 يتم الإشارة إليها بصندوق أسود، مع تلك التي تتجاوز 10 محددة بـ *.

جميع IIDs (الشكل 2A، B). أظهرت أمراض محددة مثل التهاب الكبد E، والزحار، والحمى المعوية تقلبات موسمية مميزة. بلغ التهاب الكبد E ذروته من يناير إلى مايو (الشكل التوضيحي 5)، بينما بلغ التهاب الحمى المعوية والزحار ذروته من مايو إلى نوفمبر (الشكل التوضيحي 31، الشكل التوضيحي 27). كانت HFMD ملحوظة لذرواتها نصف السنوية والنمط المتناوب الملحوظ الذي أظهرته عبر السنوات الفردية والزوجية. نظرًا لارتفاع حدوث HFMD مقارنةً بـ IIDs الأخرى، أثر هذا التغيير نصف السنوي بشكل كبير على الاتجاه الإجمالي الملحوظ في

عدوى التهاب الملتحمة النزفي الحاد (AHC) عبر الصين (الشكل التوضيحي 28). جميع المناطق باستثناء التبت شهدت زيادة في AHC، واستمرت ذروات الحالات في 30 مقاطعة المتبقية لمدة 1-2 شهر (الشكل التوضيحي 4). كانت مقاطعتي قوانغشي وقوانغدونغ الأكثر تسجيلاً للحالات، حيث سجلت 79,977 و69,839 حالة، على التوالي، خلال هذه الفترة. لمزيد من المعلومات التفصيلية، انظر البيانات التكميلية 1.

قمم تقليدية مرتبطة بـ ZIDs. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن هناك حالة شاذة من ZIDs في عام 2014 تعود أساسًا إلى تفشي حمى الضنك في مقاطعة قوانغدونغ (الأشكال 1B، 2G، الشكل التكميلي 20). ارتفعت الحالات المبلغ عنها في سبتمبر وأكتوبر 2014 إلى 14,759 و28,796 على التوالي، وهو زيادة كبيرة عن 1289 و1473 حالة في نفس الأشهر من عام 2013 (الشكل التكميلي 44، البيانات التكملية 1). لمزيد من المعلومات التفصيلية، يرجى الرجوع إلى الجدول التكميلي 1.

اتجاهات NID على المدى القصير خلال جائحة COVID-19

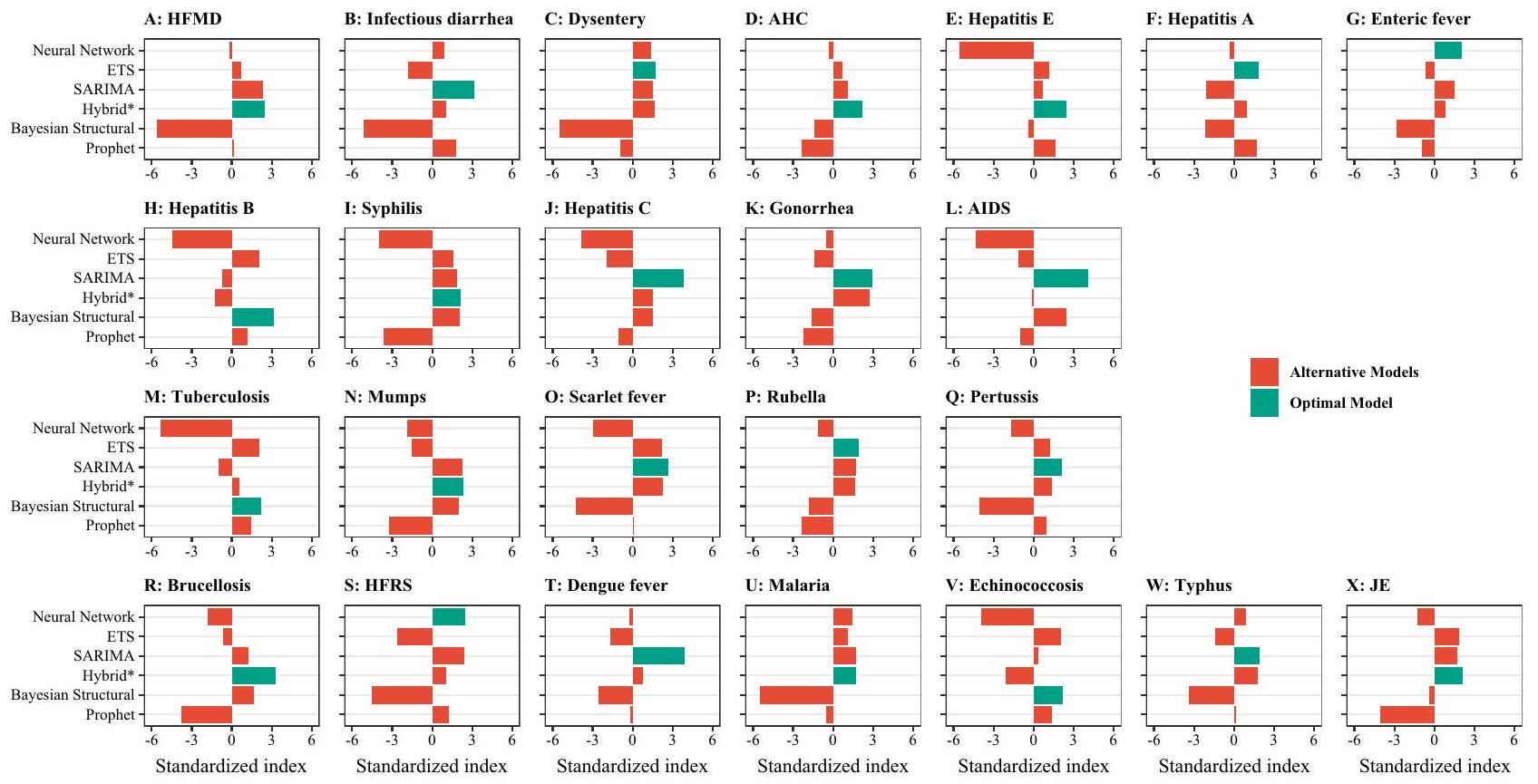

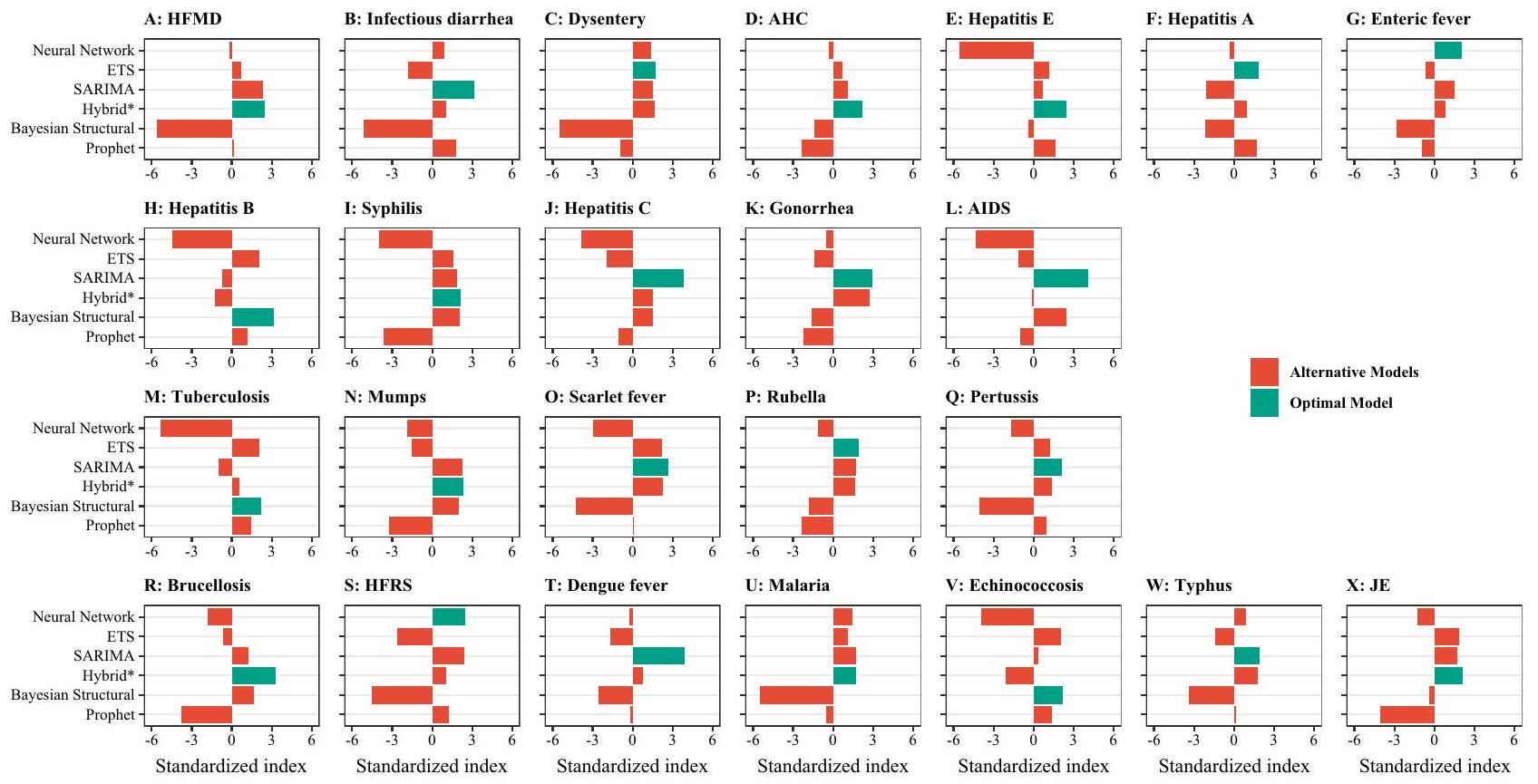

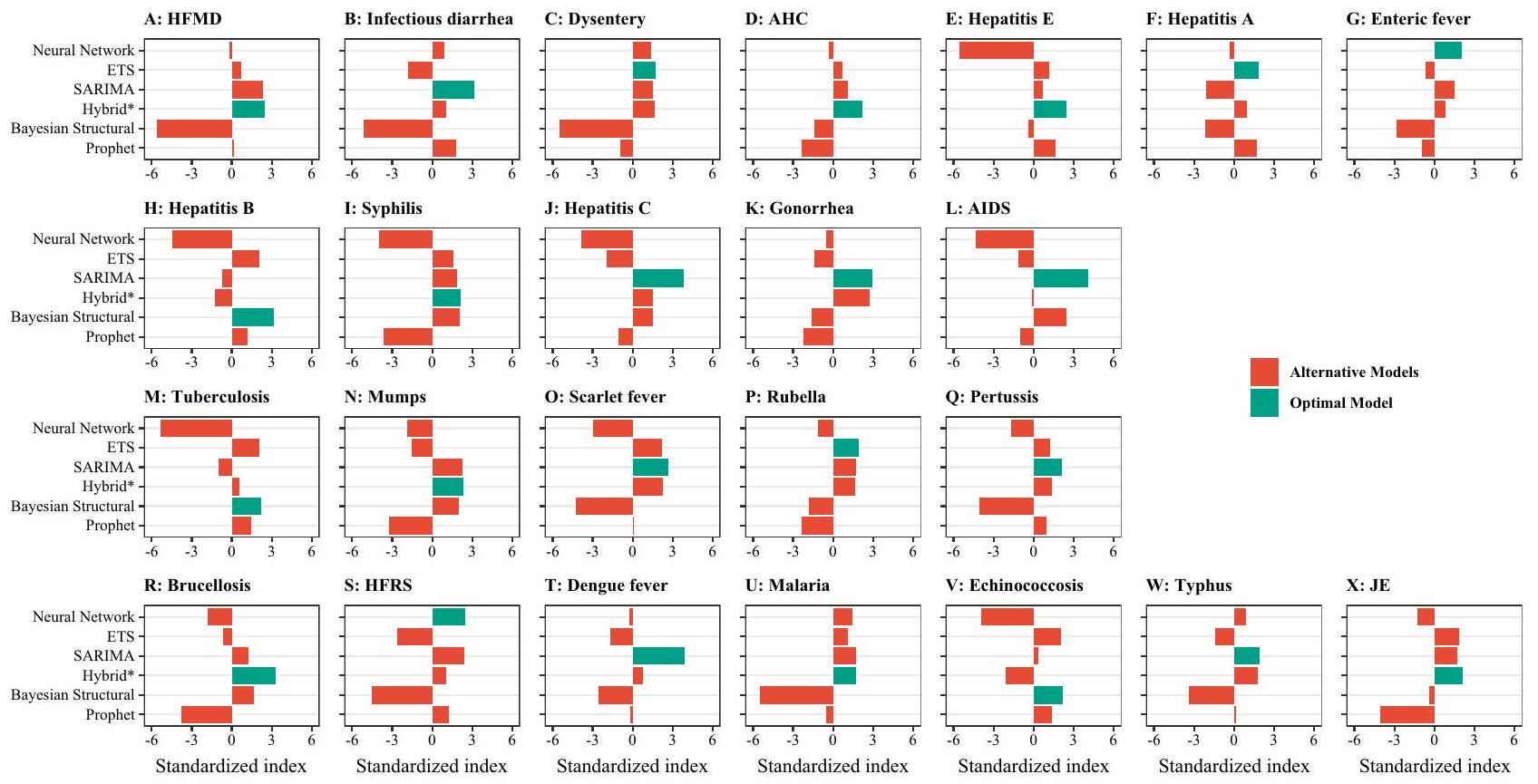

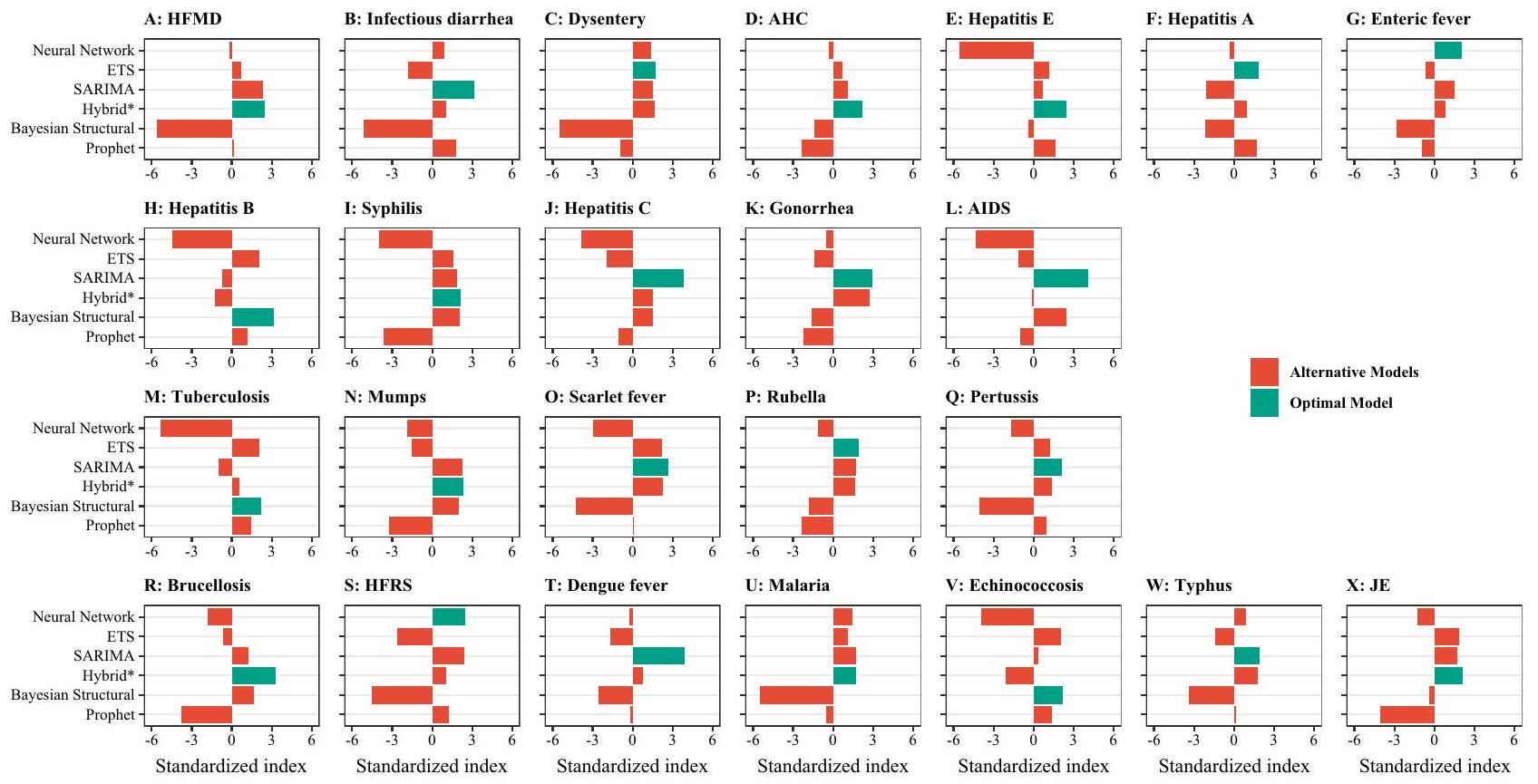

نموذج الانحدار الذاتي المتكامل المتحرك الموسمي؛ هجين: مزيج من SARIMA وETS وSTL (تحليل الاتجاهات والموسمية باستخدام لويس) ونماذج الشبكات العصبية؛ متلازمة نقص المناعة المكتسب (AIDS) دون تضمين عدوى فيروس نقص المناعة البشرية. تشمل الزحار الزحار البكتيري وزحار الأميبا. الحمى المعوية تُعرف أيضًا بحمى التيفوئيد وحمى الباراتيفوئيد. الحمى النزفية مع متلازمة الكلى (HFRS)، التهاب الدماغ الياباني (JE)، مرض اليد والقدم والفم (HFMD)، التهاب الملتحمة النزفي الحاد (AHC).

حمى. HFRS حمى نزفية مع متلازمة الكلى، JE التهاب الدماغ الياباني، HFMD مرض اليد والقدم والفم، AHC التهاب الملتحمة النزفي الحاد. كل لوحة مقسمة إلى خمس فترات: فترة ما قبل الوباء (يناير 2008 إلى ديسمبر 2019)، فترة PHSMs الأولى (يناير 2020 إلى مارس 2020)، فترة PHSMs الثانية (أبريل 2020 إلى أكتوبر 2022)، فترة الوباء (نوفمبر 2022 إلى يناير 2023)، وفترة ما بعد الوباء (فبراير 2023 إلى ديسمبر 2023).

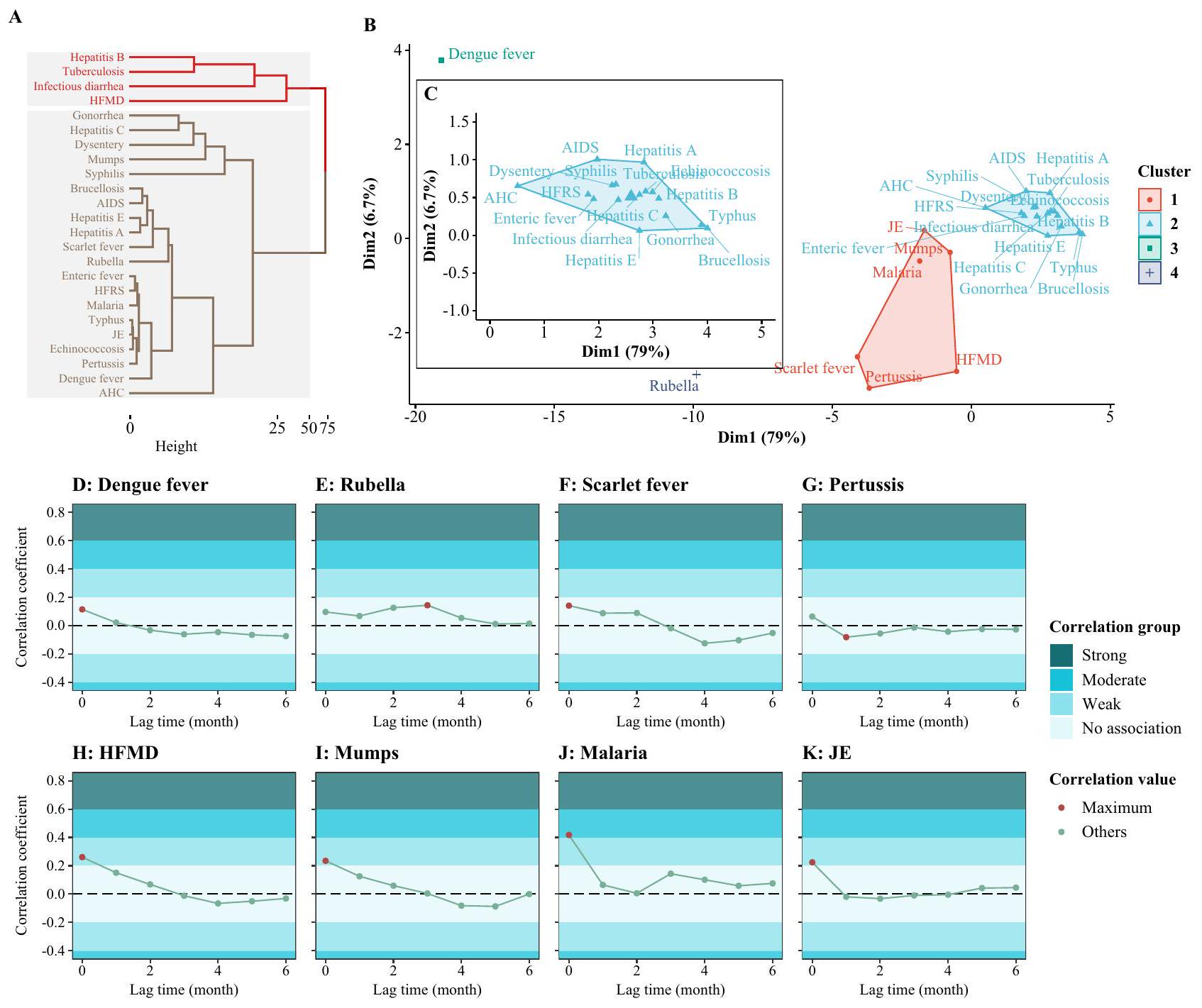

(الشكل 4Q)، والملاريا (الشكل 4U)، التي أظهرت في البداية انخفاضًا في الانتشار ولكنها عادت بعد ذلك تدريجيًا إلى اتجاهاتها الطبيعية. على عكس الأمراض غير المعدية الأخرى، قدمت الحصبة الألمانية وحمى الضنك اتجاهًا فريدًا خلال فترة التدابير الصحية العامة الثانية، حيث اقتربت الحالات المبلغ عنها من الصفر (الشكل 4P، T). تم استبعاد مجموعة بيانات الحصبة الألمانية المستخدمة للاختبار في المرحلة الأولى وإعادة التدريب في المرحلة الثانية من بيانات عام 2019 بسبب التأثير الكبير لتفشي الحصبة الألمانية في عام 2019 على النماذج (الشكل التوضيحي التكميلي 50). ومع ذلك، حتى مع هذا الاستبعاد، أظهر الفرق بين البيانات الملاحظة والنتائج المتوقعة تأثيرًا كبيرًا على الحصبة الألمانية خلال هذه الفترة (الشكل 4P).

0.59-0.80،

العلاقة بين قوة PHSMs ومعدل العائد الداخلي (IRR)

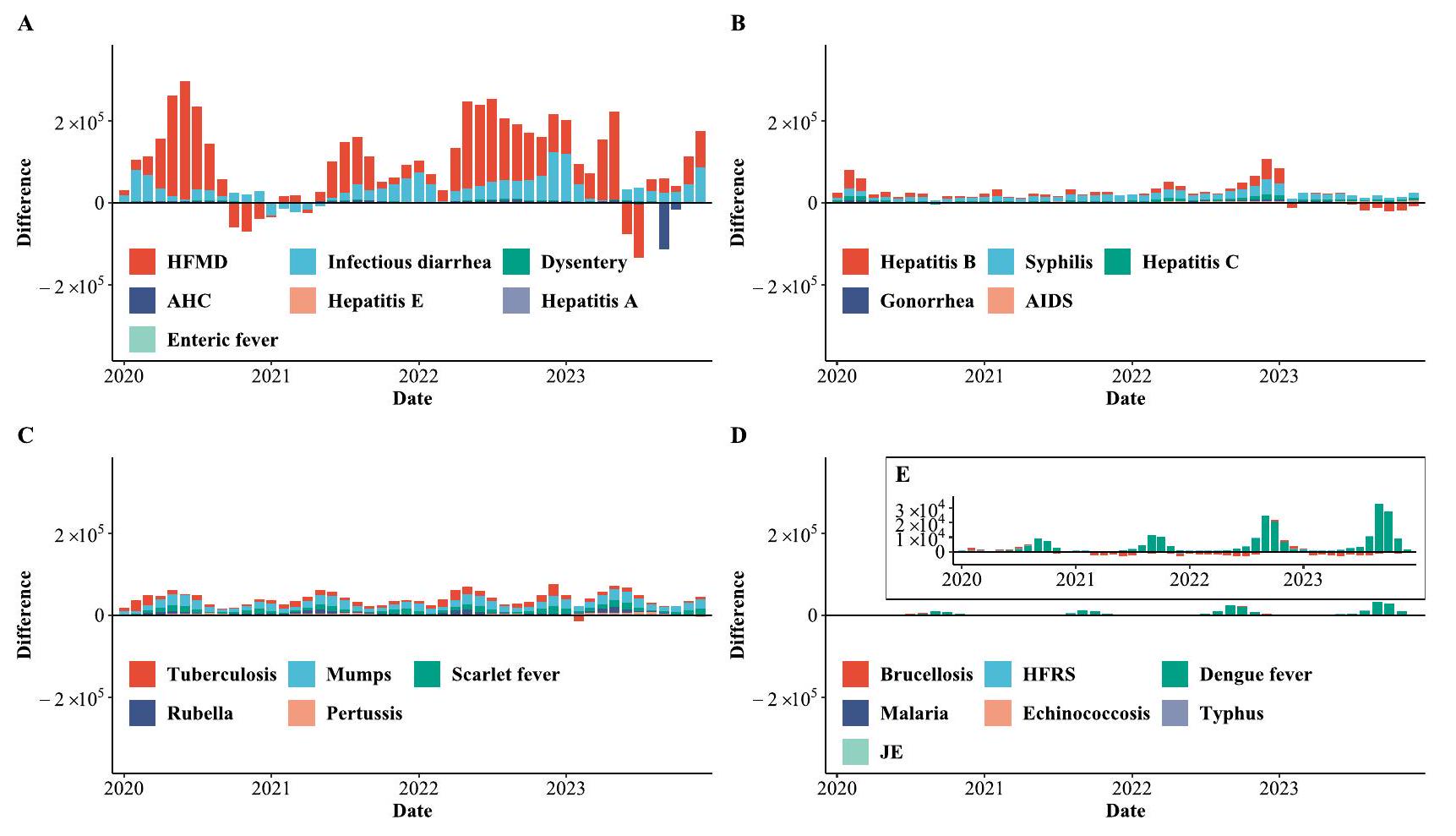

توزيع E و F والتغيرات في النسب النسبية للأمراض المعدية التنفسية.

توزيع G و H والتغيرات في النسب النسبية للأمراض المعدية الحيوانية المنشأ.

نقاش

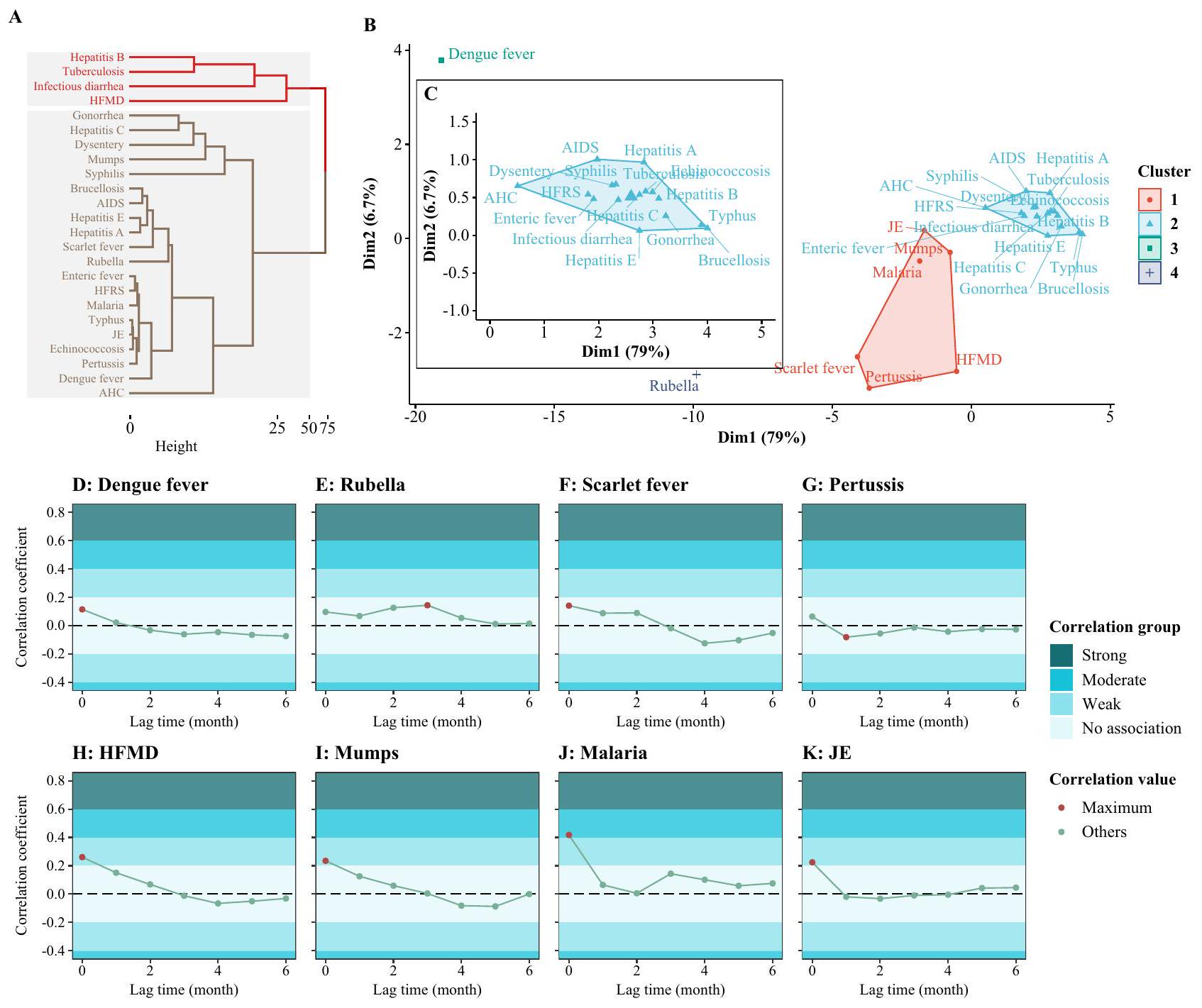

(الشكل 5A). تشير هذه الأنماط غير المنتظمة في مرض اليد والقدم والفم إلى تغيرات وبائية معدلة ليس فقط خلال فترات تدابير الصحة العامة ولكن أيضًا في فترة ما بعد الوباء. يجب التحقق من الشذوذات الملحوظة باستخدام بيانات من عام 2024 لتحديد ما إذا كانت هذه الشذوذات هي قمم صغيرة مضخمة أو تحولات في حدوث القمم الكبرى التي يُتوقع عادةً في السنوات الزوجية من يونيو إلى يوليو. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن الملاريا فقط أظهرت معامل ارتباط معتدل قدره 0.42 دون فترة تأخير (الشكل 7J). كان الانخفاض في حالات الملاريا يُعزى بشكل رئيسي إلى قيود السفر الصارمة. الملاريا هي مرض ينتقل عن طريق البعوض وقد تم القضاء عليه في الصين وينتشر بشكل أساسي من قبل المسافرين الدوليين الذين يصابون في دول أخرى.

فترات الحضانة، التي تسمح بتغيير ديناميات الانتقال بعد تنفيذ تدابير الصحة العامة، لتعكس بسرعة. ومع ذلك، أظهرت الحمى اليابانية، والنكاف، والحصبة الوردية، والحصبة susceptibility لتدابير الصحة العامة، ولم يحدث أي انتعاش يتجاوز التوقعات أو الاتجاهات الوبائية خلال فترة ما قبل الوباء. لا يمكن أن يُعزى هذا الانخفاض فقط إلى تدابير الصحة العامة أو تأثير نظام مراقبة الأمراض القابلة للإبلاغ الوطني. من المحتمل أن يفسر زيادة تغطية التطعيم بلقاح السحائي متعدد السكريات (MPV) ولقاحات الحصبة والنكاف والحصبة الوردية (MMR) الاتجاهات الملحوظة في حالات الحمى اليابانية والنكاف والحصبة الوردية.

التهوية. على النقيض من ذلك، فإن الأمراض التي تنتقل عن طريق الاتصال المباشر (BSTDs)، والتي تنتقل بشكل أساسي من خلال الاتصال المباشر مع سوائل الجسم المصابة، قد لا تكون فعالة في التخفيف من هذه التدابير.

طرق

معايير اختيار الأمراض

جمع البيانات

محدد بانخفاض ملحوظ في معدل إيجابية اختبارات COVID-19، مما يشير إلى تقليل في انتقال الفيروس

بناء النموذج

تظهر أنماط موسمية قوية وتتعامل بشكل جيد مع البيانات المفقودة، وتحولات الاتجاه، والقيم غير العادية

التحليل الإحصائي

لتحسين نهجنا وتقليل مشكلة قيم الحدوث الصفري، قمنا بتطبيق تنعيم لابلاس لضبط حسابات IRR:

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Olsen, S. J. et al. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic-United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Weekly Rep. 69, 1305-1309 (2020).

- Tran, T. Q. et al. Efficacy of face masks against respiratory infectious diseases: a systematic review and network analysis of randomizedcontrolled trials. J. Breath Res. 15, 047102 (2021).

- Jefferson, T. et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11, Cd006207 (2020).

- Lohr, J., Fredrick, N. B., Helm, L. & Cho, J. Health guidelines for travel abroad. Prim. Care 45, 541-554 (2018).

- Mavroidi, N. Transmission of zoonoses through immigration and tourism. Vet. Ital. 44, 651-656 (2008).

- Maharaj, R. et al. The effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on malaria transmission in South Africa. Malaria J. 22, 107 (2023).

- Aiello, A. E., Coulborn, R. M., Perez, V. & Larson, E. L. Effect of hand hygiene on infectious disease risk in the community setting: a metaanalysis. Am. J. Public Health 98, 1372-1381 (2008).

- Curtis, V. & Cairncross, S. Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: a systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3, 275-281 (2003).

- Geng, M. J. et al. Changes in notifiable infectious disease incidence in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Commun. 12, 6923 (2021).

- Liu, W. et al. The indirect impacts of nonpharmacological COVID-19 control measures on other infectious diseases in Yinchuan, Northwest China: a time series study. BMC Public Health 23, 1089 (2023).

- Huang, Q. S. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on influenza and other respiratory viral infections in New Zealand. Nat. Commun. 12, 1001 (2021).

- Feng, L. et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreaks and interventions on influenza in China and the United States. Nat. Commun. 12, 3249 (2021).

- Zhao, X. et al. Changes in temporal properties of notifiable infectious disease epidemics in China During the COVID-19 pandemic: population-based surveillance study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 8, e35343 (2022).

- The Lancet Regional Health-Western P. The end of zero-COVID-19 policy is not the end of COVID-19 for China. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 30, 100702 (2023).

- Su, Q. et al. Assessing the burden of congenital rubella syndrome in China and evaluating mitigation strategies: a metapopulation modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, 1004-1013 (2021).

- Li, J. et al. Meningococcal disease and control in China: findings and updates from the Global Meningococcal Initiative (GMI). J. Infect. 76, 429-437 (2018).

- WHO. Increased incidence of scarlet fever and invasive Group A Streptococcus infection-multi-country. https://www.who.int/ emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON429 (2024).

- Pica, N. & Bouvier, N. M. Environmental factors affecting the transmission of respiratory viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2, 90-95 (2012).

- Lee, W. M. et al. Human rhinovirus species and season of infection determine illness severity. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 186, 886-891 (2012).

- Monto, A. S. The seasonality of rhinovirus infections and its implications for clinical recognition. Clin. Ther. 24, 1987-1997 (2002).

- Dixit, A. K., Espinoza, B., Qiu, Z., Vullikanti, A. & Marathe, M. V. Airborne disease transmission during indoor gatherings over multiple time scales: modeling framework and policy implications. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2216948120 (2023).

- Price RHM, Graham, C. & Ramalingam, S. Association between viral seasonality and meteorological factors. Sci. Rep. 9, 1-11 (2019).

- Nelson, R. J. & Demas, G. E. Seasonal changes in immune function. Q. Rev. Biol. 71, 511-548 (1996).

- Wyse, C., O’Malley, G., Coogan, A. N., McConkey, S. & Smith, D. J. Seasonal and daytime variation in multiple immune parameters in humans: evidence from 329,261 participants of the UK Biobank cohort. iScience 24, 102255 (2021).

- Santana, C. et al. COVID-19 is linked to changes in the time-space dimension of human mobility. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1729-1739 (2023).

- Chen, S., Zhang, X., Zhou, Y., Yang, K. & Lu, X. COVID-19 protective measures prevent the spread of respiratory and intestinal infectious diseases but not sexually transmitted and bloodborne diseases. J. Infect. 83, e37-e39 (2021).

- Yang, C. et al. Exploring the influence of COVID-19 on the spread of hand, foot, and mouth disease with an automatic machine learning prediction model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 30, 20369-20385 (2023).

- Boiko, I. et al. The clinico-epidemiological profile of patients with gonorrhoea and challenges in the management of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in an STI clinic, Ternopil, Ukraine (20132018). J. Med. Life 13, 75-81 (2020).

- CDC. Sexually transmitted infections CDC Yellow Book 2024. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/posttravel-evaluation/sexually-transmitted-infections (2024).

-

. et al. The imported infections among foreign travelers in China: an observational study. Glob. Health 18, 97 (2022). - Li, R. et al. Climate-driven variation in mosquito density predicts the spatiotemporal dynamics of dengue. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 3624-3629 (2019).

- Yang, H. et al. Epidemic characteristics, high-risk areas and spacetime clusters of human Brucellosis-China, 2020-2021. China CDC Weekly 5, 17-22 (2023).

- NPR. ‘We Are Swamped’: coronavirus propels interest in raising backyard chickens for eggs. https://www.npr.org/2020/04/03/ 826925180/we-are-swamped-coronavirus-propels-interest-in-raising-backyard-chickens-for-egg (2020).

- Han, L. et al. Changing epidemiologic patterns of typhus group rickettsiosis and scrub typhus in China, 1950-2022. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 140, 52-61 (2024).

- Boro, P. et al. An outbreak of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis due to Coxsackievirus A24 in a residential school, Naharlagun, Arunachal Pradesh: July 2023. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 48, 100549 (2024).

- Haider, S. A. et al Genomic insights into the 2023 outbreak of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis in Pakistan: identification of coxsackievirus A24 variant through next generation sequencing. Preprint at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.1110.1111. 23296878v23296871 (2023).

- Stein-Zamir, C., Shoob, H., Abramson, N., Brown, E. H. & Zimmermann, Y. Pertussis outbreak mainly in unvaccinated young children in ultra-orthodox Jewish groups, Jerusalem, Israel 2023. Epidemiol. Infect. 151, e166 (2023).

- Huang, W. J. et al. Epidemiological and virological surveillance of influenza viruses in China during 2020-2021. Infect. Dis. Poverty 11, 74 (2022).

- Wang, Q. et al. Increased population susceptibility to seasonal influenza during the COVID-19 pandemic in China and the United States. J. Med. Virol. 95, e29186 (2023).

- Wang, C. & Zhang, H. Analysis on the epidemiological characteristics of non-type virus hepatitis in Xi’an City from 2004 to 2016. Chin. J. Dis. Control Prev. 22, 849 (2018).

- Minta, A. A. Progress toward regional measles eliminationworldwide, 2000-2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 71, 1489-1495 (2022).

- China CDC. Epidemic situation of new coronavirus infection in China. https://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/zl/szkb_11803/jszl_13141/ 202304/t20230422_265534.html (2024).

- Hale, T. et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 529-538 (2021).

- Hyndman, R. J. & Khandakar, Y. Automatic time series forecasting: the forecast package for R. J. Stat. Softw. 27, 1-22 (2008).

- Bates, J. M. & Granger, C. W. J. The combination of forecasts. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 20, 451-468 (1969).

- Harvey, A. C. Forecasting, Structural Time Series Models and the Kalman Filter (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- Taylor, S. J. & Letham, B. Forecasting at scale. Preprint at https:// peerj.com/preprints/3190/ (2017).

- Kassambara, A. Practical Guide to Cluster Analysis in R: Unsupervised Machine Learning (Multivariate Analysis). (STHDA, 2018).

- Venables, W. N., Ripley, B. D. Modern Applied Statistics with S. (Springer, 2000).

- Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 18, 91-93 (2018).

- Li, K. et al. Temporal shifts in 24 notifiable infectious diseases in China before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Zendodo. https:// doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 10970161 (2024).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

المختبر الوطني الرئيسي للقاحات للأمراض المعدية، مختبر شيانغ آن للبيولوجيا الطبية، المختبر الوطني الرئيسي لعلم اللقاحات الجزيئي والتشخيص الجزيئي، المنصة الوطنية للابتكار لدمج الصناعة والتعليم في أبحاث اللقاحات، كلية الصحة العامة، جامعة شيامن، شيامن، الصين. قسم الرعاية الصحية، مستشفى النساء والأطفال، كلية الطب، جامعة شيامن، شيامن، الصين. مركز جيانغشي الطبي للأحداث الصحية العامة الحرجة، المستشفى الأول التابع لكلية جيانغشي الطبية، جامعة نانتشانغ، نانتشانغ، الصين. مستشفى جيانغشي بمستشفى الصداقة الصينية اليابانية، نانتشانغ، الصين. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: كانغ قوه لي، جيا روي، وينتاو سونغ، لي لو. البريد الإلكتروني: ndyfy02258@ncu.edu.cn; chentianmu@xmu.edu.cn

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-48201-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38719858

Publication Date: 2024-05-08

Temporal shifts in 24 notifiable infectious diseases in China before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Accepted: 24 April 2024

Published online: 08 May 2024

(A) Check for updates

Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, along with the implementation of public health and social measures (PHSMs), have markedly reshaped infectious disease transmission dynamics. We analysed the impact of PHSMs on 24 notifiable infectious diseases (NIDs) in the Chinese mainland, using time series models to forecast transmission trends without PHSMs or pandemic. Our findings revealed distinct seasonal patterns in NID incidence, with respiratory diseases showing the greatest response to PHSMs, while bloodborne and sexually transmitted diseases responded more moderately. 8 NIDs were identified as susceptible to PHSMs, including hand, foot, and mouth disease, dengue fever, rubella, scarlet fever, pertussis, mumps, malaria, and Japanese encephalitis. The termination of PHSMs did not cause NIDs resurgence immediately, except for pertussis, which experienced its highest peak in December 2023 since January 2008. Our findings highlight the varied impact of PHSMs on different NIDs and the importance of sustainable, long-term strategies, like vaccine development.

(BSTDs), and zoonotic infectious diseases (ZIDs)

analysis to identify NIDs susceptible to PHSMs, and a cross-correlation analysis to decipher the relationship between PHSMs stringency index and the impact on NIDs.

Results

Long-term NID trends before the COVID-19 pandemic

A Cumulative incidence of 24 NIDs categorized by their respective modes of transmission, over the period from January 2008 to December 2023. The size and color of each block represent the cumulative cases and disease group, respectively. AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome), not including human immunodeficiency virus infections. Dysentery includes bacterial dysentery and ameba dysentery. Enteric fever is also known as typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever. HFRS

hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome; JE Japanese encephalitis; HFMD hand, foot and mouth disease; AHC acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. B Epidemic curves for the four categories of NIDs were segmented into 5 distinct periods: pre-epidemic period (January 2008 to December 2019), PHSMs period I (January 2020 to March 2020), PHSMs period II (April 2020 to October 2022), epidemic period (November 2022 to January 2023), and post-epidemic period (February 2023 to December 2023). C Percentage of monthly incidences for the four groups of NIDs.

E, F Respiratory infectious diseases. G, H Zoonotic infectious diseases.

A, C, E, G Epidemic curves in the study period were segmented into 5 distinct periods: pre-epidemic period (January 2008 to December 2019), PHSMs period I (January 2020 to March 2020), PHSMs period II (April 2020 to October 2022),

epidemic period (November 2022 to January 2023), and post-epidemic period (February 2023 to December 2023). B, D, F, H The normalized monthly incidence for each NIDs, with color intensity indicating the magnitude of the normalized monthly incidence. Normalization is calculated as the difference between the monthly NID incidence and the monthly average incidence, divided by the standard deviation of the incidence. Values outside the -5 to 10 range are denoted by a black box, with those exceeding 10 marked by *.

all IIDs (Fig. 2A, B). Specific diseases such as hepatitis E, dysentery, and enteric fever each exhibited distinct seasonal fluctuations. Hepatitis E peaked from January to May (Supplementary Fig. 5), while enteric fever and dysentery peaked from May to November (Supplementary Fig. 31, Supplementary Fig. 27). HFMD was notable for its biannual peaks and the remarkable alternating pattern it exhibited across odd and even years. Due to the greater incidence of HFMD than other IIDs, this biennial alteration heavily influenced the aggregate trend observed in

acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis (AHC) infections across China (Supplementary Fig. 28). All regions except for Tibet experienced a sore in AHC, and peaks in the remaining 30 provinces lasted 1-2 months (Supplementary Fig. 4). Guangxi and Guangdong provinces had most cases, which are 79,977 and 69,839 cases, respectively, during this period. For detailed information, see Supplementary Data 1.

traditional peaks associated with ZIDs. Notably, an outlier of ZIDs in 2014 primarily attributed to a dengue fever outbreak in Guangdong province (Figs. 1B, 2G, Supplementary Fig. 20). Reported cases in September and October 2014 surged to 14,759 and 28,796 respectively, a significant increase from the 1289 and 1473 cases in the same months of 2013 (Supplementary Fig. 44, Supplementary Data 1). For more detailed information, please refer to Supplementary Table 1.

Short-term NID trends during the COVID-19 pandemic

seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average; Hybrid: combined SARIMA, ETS, STL (seasonal and trend decomposition using loess), and neural network models; AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) not including human immunodeficiency virus infections. Dysentery includes bacterial dysentery and ameba dysentery. Enteric fever is also known as typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever. HFRS hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, JE Japanese encephalitis, HFMD hand, foot and mouth disease, AHC acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis.

fever. HFRS hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, JE Japanese encephalitis, HFMD hand, foot and mouth disease, AHC acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. Each panel is divided into five periods: pre-epidemic period (January 2008 to December 2019), PHSMs period I (January 2020 to March 2020), PHSMs period II (April 2020 to October 2022), epidemic period (November 2022 to January 2023), and postepidemic period (February 2023 to December 2023).

(Fig. 4Q), and malaria (Fig. 4U), which initially showed a decrease in prevalence but subsequently exhibited a gradual return to their normal trends. Distinct from other NIDs, rubella, and dengue fever presented a unique trend during PHSMs period II, with reported cases nearing zero (Fig. 4P, T). The rubella dataset used for testing in the first stage and retraining in the second stage excluded the 2019 data due to the significant impact of the 2019 rubella outbreak on the models (Supplementary Fig. 50). However, even with this exclusion, the difference between observed data and forecasted outcomes revealed a significant impact on rubella during this period (Fig. 4P).

0.59-0.80,

Relationship between PHSMs strength and IRR

E, F Distribution and changes in relative ratios for respiratory infectious diseases.

G, H Distribution and changes in relative ratios for zoonotic infectious diseases.

Discussion

(Fig. 5A). These irregular patterns in HFMD suggest altered epidemiological trends not only during PHSMs periods but also in the postepidemic period. The anomalies observed need to be validated with data from 2024 to determine whether these anomalies are amplified minor peaks or shifts in the occurrence of major peaks typically expected in even-numbered years from June to July. Notably, only malaria exhibited a moderate correlation coefficient of 0.42 without a lag time (Fig. 7J). The decrease in malaria cases was mainly attributed to strict travel restrictions. Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease that has been eliminated in China and is primarily spread by international travelers who are infected in other countries

incubation periods, which allows changes in transmission dynamics following the implementation of PHSMs to be quickly reflected. However, JE, mumps, scarlet fever, and rubella demonstrated susceptibility to PHSMs, and no resurgence exceeding the forecasted or epidemic trends during the pre-epidemic period. This decline cannot be solely attributed to PHSMs or the influence of the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS). The increased vaccination coverage of meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine (MPV) and measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccines likely explains the trends observed in JE, mumps and rubella cases

ventilation. In contrast, BSTDs, which are primarily transmitted through direct contact with infected bodily fluids, may not be as effectively mitigated by these measures

Methods

Disease selection criteria

Data collection

demarcated by a notable decrease in the positive rate of COVID-19 tests, indicating a reduction in viral transmission

Model building

exhibiting strong seasonal patterns and copes well with missing data, trend shifts, and atypical values

Statistical analysis

further refine our approach and mitigate the issue of zero incidence values, we applied Laplace smoothing to adjust the IRR calculations:

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Olsen, S. J. et al. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic-United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. Morb. Mortal. Weekly Rep. 69, 1305-1309 (2020).

- Tran, T. Q. et al. Efficacy of face masks against respiratory infectious diseases: a systematic review and network analysis of randomizedcontrolled trials. J. Breath Res. 15, 047102 (2021).

- Jefferson, T. et al. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11, Cd006207 (2020).

- Lohr, J., Fredrick, N. B., Helm, L. & Cho, J. Health guidelines for travel abroad. Prim. Care 45, 541-554 (2018).

- Mavroidi, N. Transmission of zoonoses through immigration and tourism. Vet. Ital. 44, 651-656 (2008).

- Maharaj, R. et al. The effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on malaria transmission in South Africa. Malaria J. 22, 107 (2023).

- Aiello, A. E., Coulborn, R. M., Perez, V. & Larson, E. L. Effect of hand hygiene on infectious disease risk in the community setting: a metaanalysis. Am. J. Public Health 98, 1372-1381 (2008).

- Curtis, V. & Cairncross, S. Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: a systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3, 275-281 (2003).

- Geng, M. J. et al. Changes in notifiable infectious disease incidence in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Commun. 12, 6923 (2021).

- Liu, W. et al. The indirect impacts of nonpharmacological COVID-19 control measures on other infectious diseases in Yinchuan, Northwest China: a time series study. BMC Public Health 23, 1089 (2023).

- Huang, Q. S. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on influenza and other respiratory viral infections in New Zealand. Nat. Commun. 12, 1001 (2021).

- Feng, L. et al. Impact of COVID-19 outbreaks and interventions on influenza in China and the United States. Nat. Commun. 12, 3249 (2021).

- Zhao, X. et al. Changes in temporal properties of notifiable infectious disease epidemics in China During the COVID-19 pandemic: population-based surveillance study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 8, e35343 (2022).

- The Lancet Regional Health-Western P. The end of zero-COVID-19 policy is not the end of COVID-19 for China. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 30, 100702 (2023).

- Su, Q. et al. Assessing the burden of congenital rubella syndrome in China and evaluating mitigation strategies: a metapopulation modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, 1004-1013 (2021).

- Li, J. et al. Meningococcal disease and control in China: findings and updates from the Global Meningococcal Initiative (GMI). J. Infect. 76, 429-437 (2018).

- WHO. Increased incidence of scarlet fever and invasive Group A Streptococcus infection-multi-country. https://www.who.int/ emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON429 (2024).

- Pica, N. & Bouvier, N. M. Environmental factors affecting the transmission of respiratory viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2, 90-95 (2012).

- Lee, W. M. et al. Human rhinovirus species and season of infection determine illness severity. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 186, 886-891 (2012).

- Monto, A. S. The seasonality of rhinovirus infections and its implications for clinical recognition. Clin. Ther. 24, 1987-1997 (2002).

- Dixit, A. K., Espinoza, B., Qiu, Z., Vullikanti, A. & Marathe, M. V. Airborne disease transmission during indoor gatherings over multiple time scales: modeling framework and policy implications. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2216948120 (2023).

- Price RHM, Graham, C. & Ramalingam, S. Association between viral seasonality and meteorological factors. Sci. Rep. 9, 1-11 (2019).

- Nelson, R. J. & Demas, G. E. Seasonal changes in immune function. Q. Rev. Biol. 71, 511-548 (1996).

- Wyse, C., O’Malley, G., Coogan, A. N., McConkey, S. & Smith, D. J. Seasonal and daytime variation in multiple immune parameters in humans: evidence from 329,261 participants of the UK Biobank cohort. iScience 24, 102255 (2021).

- Santana, C. et al. COVID-19 is linked to changes in the time-space dimension of human mobility. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1729-1739 (2023).

- Chen, S., Zhang, X., Zhou, Y., Yang, K. & Lu, X. COVID-19 protective measures prevent the spread of respiratory and intestinal infectious diseases but not sexually transmitted and bloodborne diseases. J. Infect. 83, e37-e39 (2021).

- Yang, C. et al. Exploring the influence of COVID-19 on the spread of hand, foot, and mouth disease with an automatic machine learning prediction model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 30, 20369-20385 (2023).

- Boiko, I. et al. The clinico-epidemiological profile of patients with gonorrhoea and challenges in the management of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection in an STI clinic, Ternopil, Ukraine (20132018). J. Med. Life 13, 75-81 (2020).

- CDC. Sexually transmitted infections CDC Yellow Book 2024. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/posttravel-evaluation/sexually-transmitted-infections (2024).

-

. et al. The imported infections among foreign travelers in China: an observational study. Glob. Health 18, 97 (2022). - Li, R. et al. Climate-driven variation in mosquito density predicts the spatiotemporal dynamics of dengue. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 3624-3629 (2019).

- Yang, H. et al. Epidemic characteristics, high-risk areas and spacetime clusters of human Brucellosis-China, 2020-2021. China CDC Weekly 5, 17-22 (2023).

- NPR. ‘We Are Swamped’: coronavirus propels interest in raising backyard chickens for eggs. https://www.npr.org/2020/04/03/ 826925180/we-are-swamped-coronavirus-propels-interest-in-raising-backyard-chickens-for-egg (2020).

- Han, L. et al. Changing epidemiologic patterns of typhus group rickettsiosis and scrub typhus in China, 1950-2022. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 140, 52-61 (2024).

- Boro, P. et al. An outbreak of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis due to Coxsackievirus A24 in a residential school, Naharlagun, Arunachal Pradesh: July 2023. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 48, 100549 (2024).

- Haider, S. A. et al Genomic insights into the 2023 outbreak of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis in Pakistan: identification of coxsackievirus A24 variant through next generation sequencing. Preprint at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.1110.1111. 23296878v23296871 (2023).

- Stein-Zamir, C., Shoob, H., Abramson, N., Brown, E. H. & Zimmermann, Y. Pertussis outbreak mainly in unvaccinated young children in ultra-orthodox Jewish groups, Jerusalem, Israel 2023. Epidemiol. Infect. 151, e166 (2023).

- Huang, W. J. et al. Epidemiological and virological surveillance of influenza viruses in China during 2020-2021. Infect. Dis. Poverty 11, 74 (2022).

- Wang, Q. et al. Increased population susceptibility to seasonal influenza during the COVID-19 pandemic in China and the United States. J. Med. Virol. 95, e29186 (2023).

- Wang, C. & Zhang, H. Analysis on the epidemiological characteristics of non-type virus hepatitis in Xi’an City from 2004 to 2016. Chin. J. Dis. Control Prev. 22, 849 (2018).

- Minta, A. A. Progress toward regional measles eliminationworldwide, 2000-2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 71, 1489-1495 (2022).

- China CDC. Epidemic situation of new coronavirus infection in China. https://www.chinacdc.cn/jkzt/crb/zl/szkb_11803/jszl_13141/ 202304/t20230422_265534.html (2024).

- Hale, T. et al. A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nat. Hum. Behav. 5, 529-538 (2021).

- Hyndman, R. J. & Khandakar, Y. Automatic time series forecasting: the forecast package for R. J. Stat. Softw. 27, 1-22 (2008).

- Bates, J. M. & Granger, C. W. J. The combination of forecasts. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 20, 451-468 (1969).

- Harvey, A. C. Forecasting, Structural Time Series Models and the Kalman Filter (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- Taylor, S. J. & Letham, B. Forecasting at scale. Preprint at https:// peerj.com/preprints/3190/ (2017).

- Kassambara, A. Practical Guide to Cluster Analysis in R: Unsupervised Machine Learning (Multivariate Analysis). (STHDA, 2018).

- Venables, W. N., Ripley, B. D. Modern Applied Statistics with S. (Springer, 2000).

- Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 18, 91-93 (2018).

- Li, K. et al. Temporal shifts in 24 notifiable infectious diseases in China before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Zendodo. https:// doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 10970161 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

© The Author(s) 2024

State Key Laboratory of Vaccines for Infectious Diseases, Xiang An Biomedicine Laboratory, State Key Laboratory of Molecular Vaccinology and Molecular Diagnostics, National Innovation Platform for Industry-Education Integration in Vaccine Research, School of Public Health, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China. Health Care Departmen, Women and Children’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China. Jiangxi Medical Center for Critical Public Health Events, The First Affiliated Hospital, Jiangxi Medical College, Nanchang University, Nanchang, China. Jiangxi Hospital of China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Nanchang, China. These authors contributed equally: Kangguo Li, Jia Rui, Wentao Song, Li Luo. e-mail: ndyfy02258@ncu.edu.cn; chentianmu@xmu.edu.cn