DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7402-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38789756

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-24

التهاب الغشاء المخاطي حول الزرع والتهاب الأنسجة المحيطة بالزرع: السمات الرئيسية والاختلافات

النقاط الرئيسية

الملخص

تعتبر الأمراض المحيطة بالزرعات من المضاعفات الشائعة التي تحدث حول الزرعات العظمية المتكاملة، وهي نتيجة لعدم التوازن بين التحدي البكتيري واستجابة المضيف. يمكن أن تؤثر الأمراض المحيطة بالزرعات على الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرعة فقط (التهاب الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرعة) أو تشمل أيضًا العظم الداعم (التهاب العظم المحيط بالزرعة). إن الكشف المبكر عن الأمراض المحيطة بالزرعات والعلاج في الوقت المناسب مهم لنجاح علاج زرع الأسنان. يعتبر قياس عمق الجيوب المحيطة بالزرعة أمرًا أساسيًا لتقييم حالة الصحة المحيطة بالزرعة ويجب أن يتم في كل زيارة متابعة. يجب أن يكون أطباء الأسنان على دراية بالميزات السريرية والأشعة لكلتا الحالتين من أجل إجراء تشخيص دقيق وتحديد العلاج المناسب المطلوب. يهدف هذا المقال إلى تزويد الأطباء بفهم الفروق الرئيسية بين صحة الزرعة، والتهاب الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرعة، والتهاب العظم المحيط بالزرعة.

مقدمة

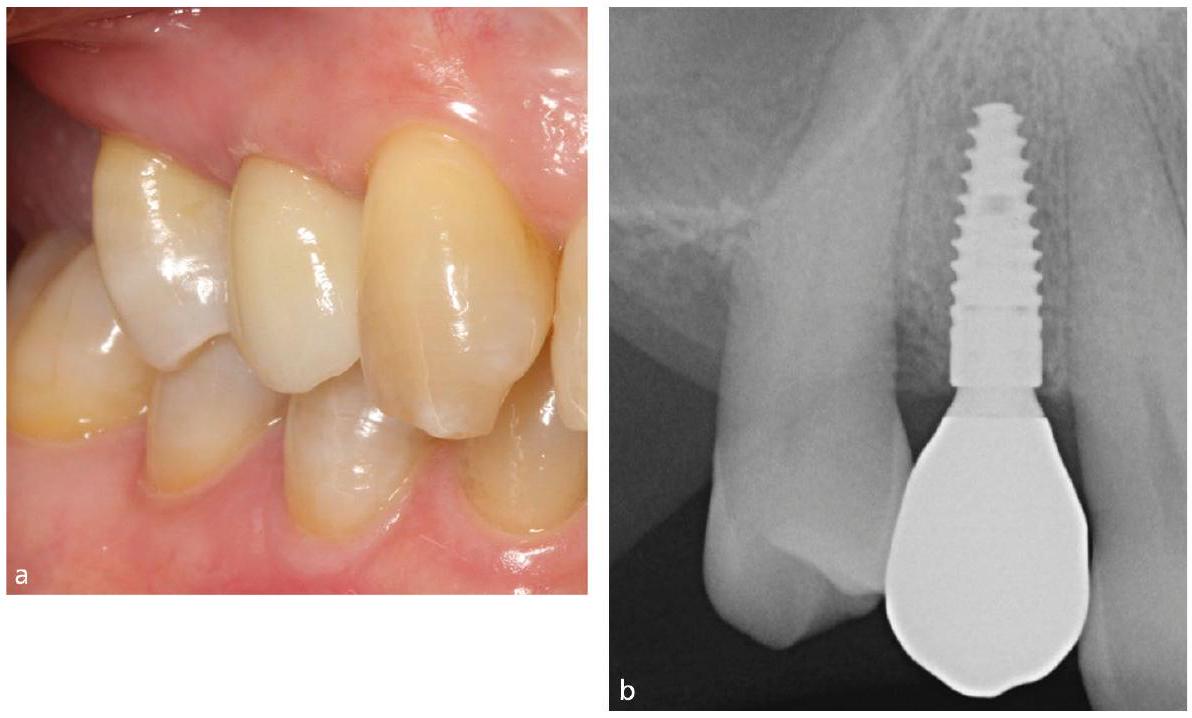

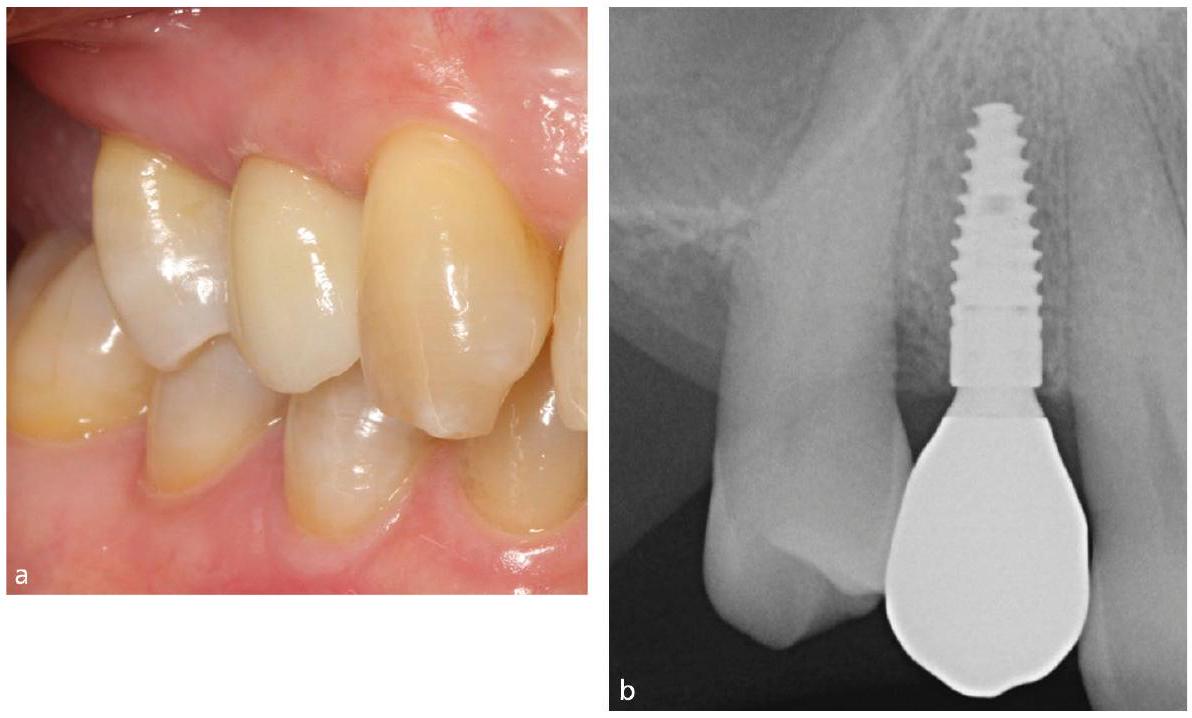

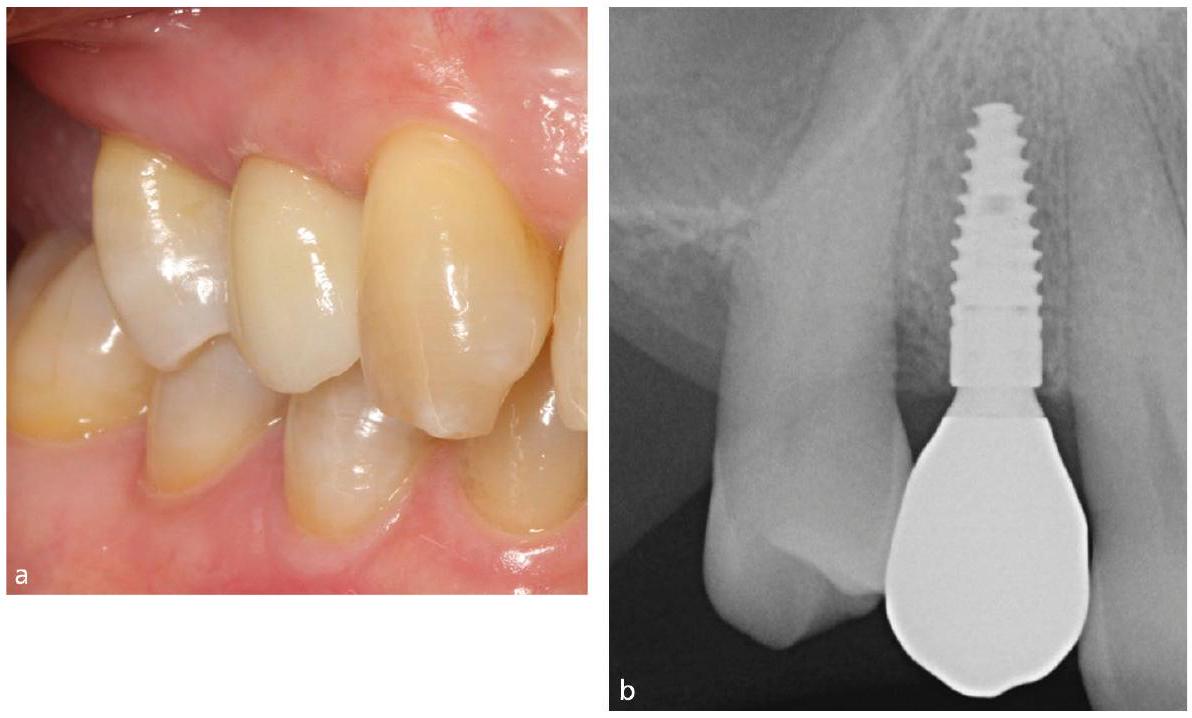

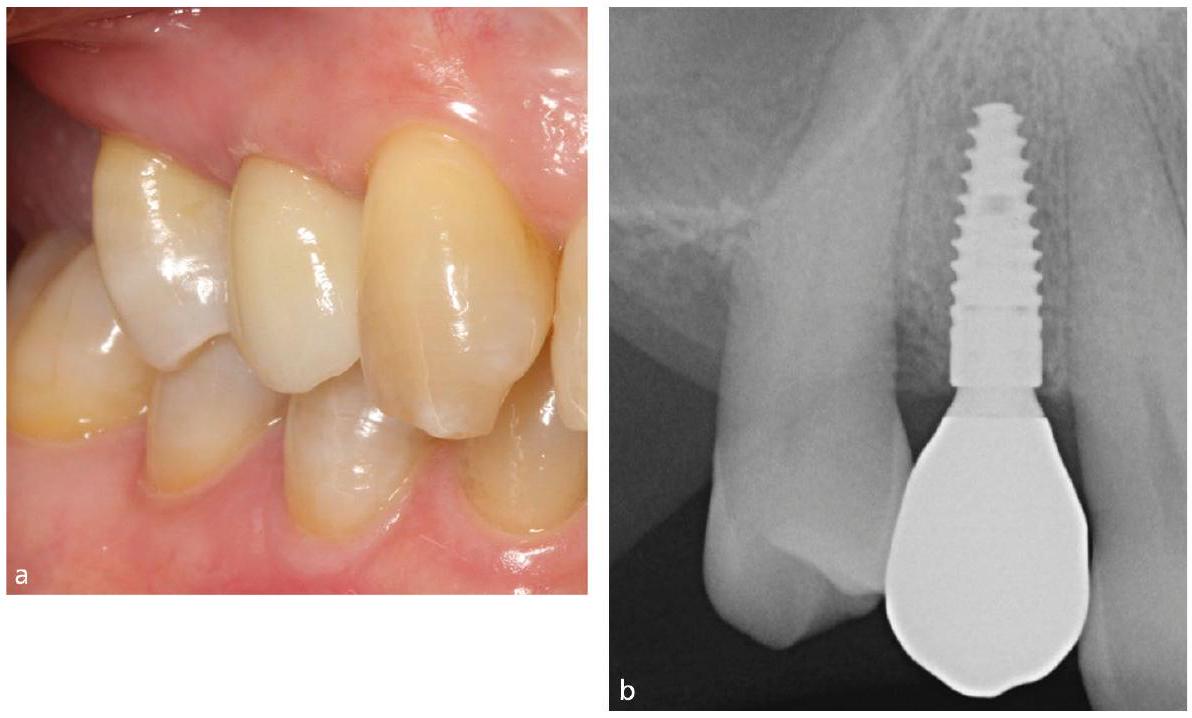

علامات سريرية لصحة ما حول الزرع

علامات الأشعة السينية لصحة ما حول الزرع

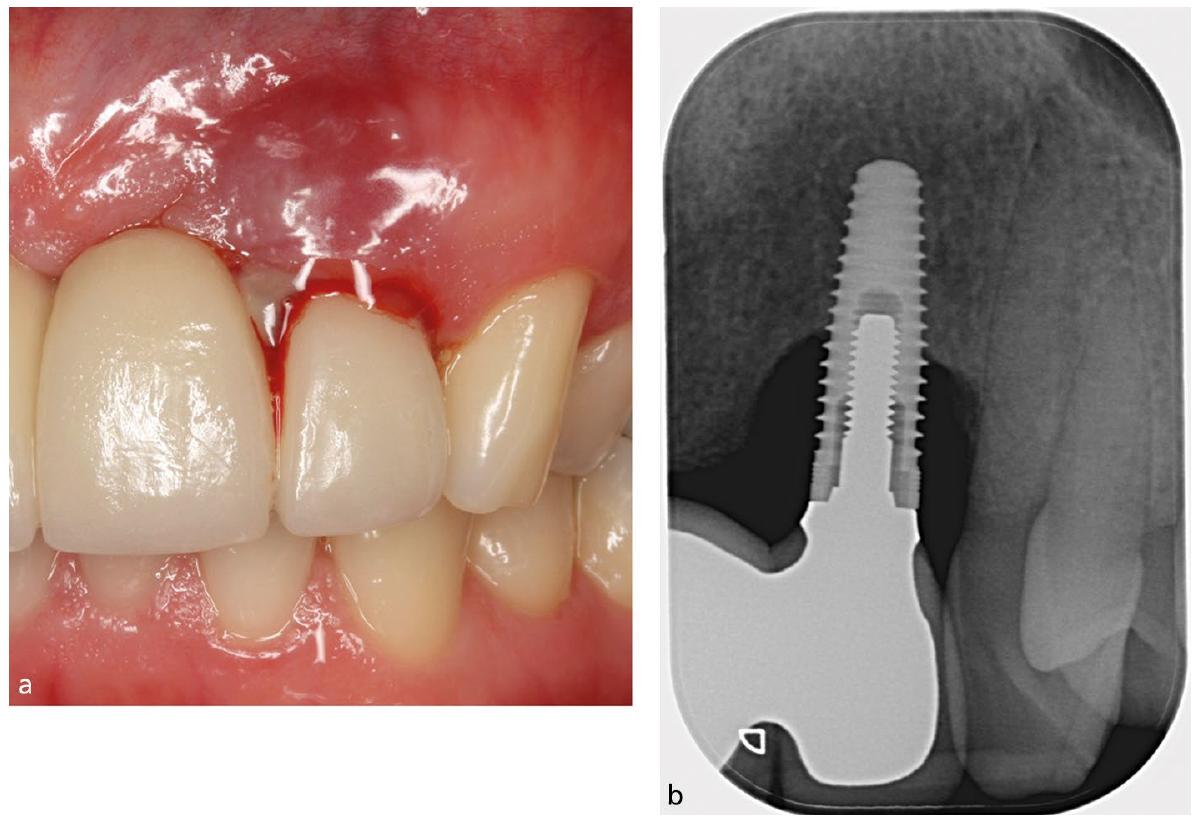

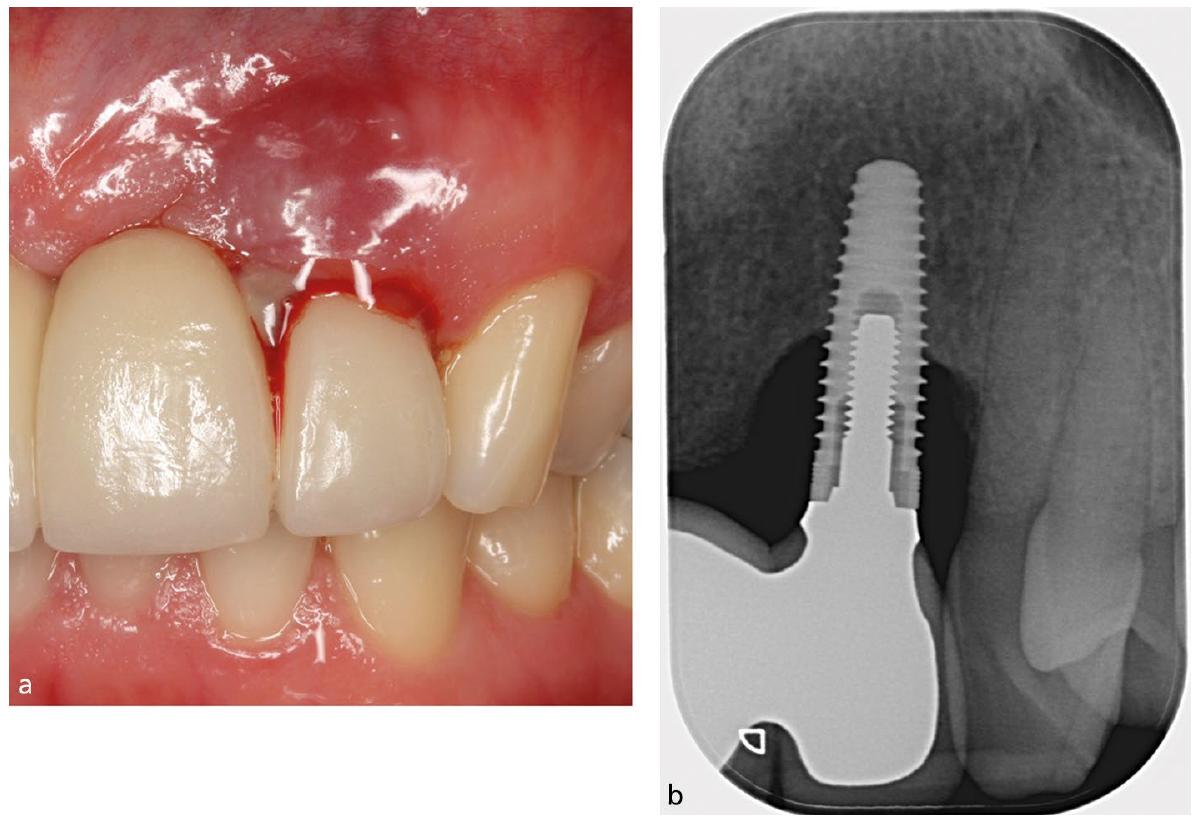

علامات سريرية وإشعاعية لالتهاب الغشاء المخاطي حول الزرع

الميزات النسيجية لالتهاب الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرع

في البشر، أظهرت الدراسات أنه بعد إزالة البيوفيلم، يحدث تراجع في ارتفاع مؤشرات الالتهاب المقاسة في سائل الجيب المحيط بالزرع.

قد يكون من الصعب تحقيقه، كما هو موضح في دراسة تجريبية حول التهاب الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرع، عندما لم تؤدِ السيطرة على البايوفيلم لمدة ثلاثة أسابيع إلى حل كامل على المستوى السريري.

علامات سريرية وإشعاعية للالتهاب المحيط بالزرع

المستويات. قد توفر الأشعة ثلاثية الأبعاد، مثل التصوير المقطعي المحوسب باستخدام شعاع المخروط (CBCT)، معلومات حول مستويات العظم الوجهية والفموية ولكن لا يُوصى بمسحات CBCT كطريقة تقييم روتينية.

الميزات النسيجية للالتهاب المحيط بالزرع والمقارنة بالتهاب الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرع

الخاتمة

- يؤثر التهاب الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرع على الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرع (الأنسجة الرخوة) ويتميز بعلامات سريرية للالتهاب (BoP) دون فقدان العظم الداعم.

- يتميز الالتهاب المحيط بالزرع بعلامات سريرية للالتهاب (BoP) بالإضافة إلى فقدان العظم التدريجي.

- بينما لا تتقدم جميع آفات التهاب الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرع إلى الالتهاب المحيط بالزرع، يُعتبر التهاب الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرع مقدمة وعامل خطر للالتهاب المحيط بالزرع.

- قد يحدث ظهور الالتهاب المحيط بالزرع مبكرًا (خلال السنوات الثلاث الأولى) وقد يكون التقدم سريعًا. تختلف آفات الالتهاب المحيط بالزرع عن آفات التهاب الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرع من حيث أنها تمتد إلى ما وراء الظهارة الجيبية، ولها حجم أكبر من تسلل الخلايا الالتهابية وتتميز بنسب كبيرة من خلايا البلازما.

- يوصى بالحصول على صور شعاعية أساسية وقياسات فحص حول الزرع بعد الانتهاء من علاج الزرع. يمكن أن تكون هذه البيانات المسجلة بمثابة مرجع لمراقبة واكتشاف التغيرات في مستويات العظم الهامشي وعمق الفحص مع مرور الوقت، مما يمكّن من التشخيص المبكر لأمراض الزرع.

- يعد فحص الزرع باستخدام مسبار لثوي بقوة خفيفة (حوالي 0.2 نيوتن) أمرًا ضروريًا لتشخيص حالة صحة الزرع ويجب أن يتم في كل زيارة متابعة.

- عند اكتشاف علامات سريرية للالتهاب (BoP، عمق فحص متزايد)، تؤكد صورة شعاعية داخل الفم

التشخيص اعتمادًا على ما إذا كان هناك فقدان تدريجي أو مستمر للعظم المحيط بالزرع (الالتهاب المحيط بالزرع) أم لا (التهاب الغشاء المخاطي المحيط بالزرع).

إعلان الأخلاقيات

معلومات التمويل

References

- Derks J, Tomasi C. Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology. J Clin Periodontol 2015; 42: 158-171.

- Araujo M G, de Souza D F N, Souza LP, Matarazzoa F. Characteristics of healthy peri-implant tissues. Br Dent J 2024; 236: 759-763.

- Heitz-Mayfield L J A, Salvi G E. Peri-implant mucositis. J Periodontol 2018; 89: 257-266.

- Herrera D, Berglundh T, Schwarz F et al. Prevention and treatment of peri-implant diseases -The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J Clin Periodontol 2023; 50: 4-76.

- Pontoriero R, Tonelli M P, Carnevale G, Mombelli A, Nyman S R, Lang N P. Experimentally induced periimplant mucositis. A clinical study in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res 1994; 5: 254-259.

- Salvi G E, Aglietta M, Eick S, Sculean A, Lang N P, Ramseier CA. Reversibility of experimental peri-implant mucositis compared with experimental gingivitis in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res 2012; 23: 182-190.

- Zitzmann

, Berglundh T, Marinello ( P, Lindhe J. Experimental peri-implant mucositis in man. J Clin Periodontol 2001; 28: 517-523. - Meyer S, Giannopoulou C, Courvoisier D, Schimmel M, Muller F, Mombelli A. Experimental mucositis and experimental gingivitis in persons aged 70 or over.

9. Gualini F, Berglundh T. Immunohistochemical characteristics of inflammatory lesions at implants. J Clin Periodontol 2003; 30: 14-18.

10. Seymour G J, Gemmell E, Lenz L J, Henry P, Bower R, Yamazaki K. Immunohistologic analysis of the inflammatory infiltrates associated with osseointegrated implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1989; 4: 191-198.

11. Chan D, Pelekos G, Ho D, Cortellini P, Tonetti M S. The depth of the implant mucosal tunnel modifies the development and resolution of experimental peri-implant mucositis: A case-control study. J Clin Periodontol 2019; 46: 248-255.

12. Schwarz F, Derks J, Monje A, Wang H-L. Peri-implantitis. J Clin Periodontol 2018; 45: 246-266.

13. Berglundh T, Armitage G, Araujo M G et al. Periimplant diseases and conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Clin Periodontol 2018; 45: 286-291.

14. Derks J, Schaller D, Håkansson J, Wennström J L, Tomasi C, Berglundh T. Peri-implantitis – onset and pattern of progression. J Clin Periodontol 2016; 43: 383-388.

15. Berglundh T, Gislason O, Lekholm U, Sennerby L, Lindhe J. Histopathological observations of human periimplantitis lesions. J Clin Periodontol 2004; 31: 341-347.

16. Konttinen Y T, Lappalainen R, Laine P, Kitti U, Santavirta

17. Albouy J-P, Abrahamsson I, Persson L G, Berglundh T. Spontaneous progression of ligatured induced peri-implantitis at implants with different surface characteristics. An experimental study in dogs II: histological observations. Clin Oral Implants Res 2009; 20: 366-371.

18. Lindhe J, Berglundh T, Ericsson I, Liljenberg B, Marinello C. Experimental breakdown of peri-implant and periodontal tissues. A study in the beagle dog. Clin Oral Implants Res 1992; 3: 9-16.

19. Heitz-Mayfield L J, Lang N P. Comparative biology of chronic and aggressive periodontitis vs. peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000 2010; 53: 167-181.

The University of Western Australia, International Research Collaborative, Oral Health and Equity, School of Human Anatomy and Biology, Crawley, WA, Australia; The University of Sydney, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Medicine and Health, NSW, Australia. Correspondence to: Lisa J. A. Heitz-Mayfield Email address: heitz.mayfield@iinet.net.au Refereed Paper.

Submitted 24 December 2023

Revised 12 April 2024

Accepted 17 April 2024

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7402-z

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7402-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38789756

Publication Date: 2024-05-24

Peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: key features and differences

Key points

Abstract

Peri-implant diseases are frequent complications that occur around osseointegrated endosseous implants and are the result of an imbalance between the bacterial challenge and host response. Peri-implant diseases may affect the peri-implant mucosa only (peri-implant mucositis) or also involve the supporting bone (peri-implantitis). Early detection of peri-implant diseases and timely treatment is important for the success of dental implant treatment. Peri-implant probing is essential to assess the peri-implant health status and should be done at each recall visit. Dental practitioners should be familiar with the clinical and radiological features of both conditions in order to make an accurate diagnosis and determine the appropriate treatment required. This article aims to provide clinicians with an understanding of the key differences between peri-implant health, peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis.

Introduction

Clinical signs of peri-implant health

Radiologic signs of peri-implant health

Clinical and radiologic signs of periimplant mucositis

Histologic features of peri-implant mucositis

in humans have shown that, following biofilm removal, there is a reversal of the elevation of inflammatory biomarkers measured in the periimplant sulcular fluid.

may be more difficult to achieve, as shown in an experimental peri-implant mucositis study, when biofilm control for three weeks did not result in complete resolution at a clinical level.

Clinical and radiologic signs of periimplantitis

levels. Three-dimensional radiography, such as cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), may provide information regarding the facial and oral bone levels but CBCT scans are not recommended as a routine evaluation method.

Histologic features of periimplantitis and comparison to periimplant mucositis

Conclusion

- Peri-implant mucositis affects the peri-implant mucosa (soft tissues) and is characterised by clinical signs of inflammation (BoP) without loss of supporting bone

- Peri-implantitis is characterised by clinical signs of inflammation (BoP) in addition to progressive bone loss

- While not all peri-implant mucositis lesions progress to peri-implantitis, peri-implant mucositis is considered a precursor and risk factor for peri-implantitis

- The onset of peri-implantitis may occur early (within the first three years) and progression may be rapid. Peri-implantitis lesions differ from peri-implant mucositis lesions in that they extend beyond the pocket epithelium, have a larger size of inflammatory cell infiltrate and are characterised by large proportions of plasma cells

- It is recommended to obtain baseline radiographs and peri-implant probing measurements following completion of implant therapy. These recorded baseline data can serve as a reference for monitoring and detecting changes in marginal bone levels and probing depths over time, enabling early diagnosis of peri-implant diseases

- Peri-implant probing using a periodontal probe with light force (approximately 0.2 N ) is essential for the diagnosis of the periimplant health status and should be performed at each recall visit

- When clinical signs of inflammation are detected (BoP, deepening probing depths), an intra-oral radiograph confirms a

diagnosis depending on whether there has been progressive or continuing peri-implant bone loss (peri-implantitis) or not (periimplant mucositis).

Ethics declaration

Funding information

References

- Derks J, Tomasi C. Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology. J Clin Periodontol 2015; 42: 158-171.

- Araujo M G, de Souza D F N, Souza LP, Matarazzoa F. Characteristics of healthy peri-implant tissues. Br Dent J 2024; 236: 759-763.

- Heitz-Mayfield L J A, Salvi G E. Peri-implant mucositis. J Periodontol 2018; 89: 257-266.

- Herrera D, Berglundh T, Schwarz F et al. Prevention and treatment of peri-implant diseases -The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J Clin Periodontol 2023; 50: 4-76.

- Pontoriero R, Tonelli M P, Carnevale G, Mombelli A, Nyman S R, Lang N P. Experimentally induced periimplant mucositis. A clinical study in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res 1994; 5: 254-259.

- Salvi G E, Aglietta M, Eick S, Sculean A, Lang N P, Ramseier CA. Reversibility of experimental peri-implant mucositis compared with experimental gingivitis in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res 2012; 23: 182-190.

- Zitzmann

, Berglundh T, Marinello ( P, Lindhe J. Experimental peri-implant mucositis in man. J Clin Periodontol 2001; 28: 517-523. - Meyer S, Giannopoulou C, Courvoisier D, Schimmel M, Muller F, Mombelli A. Experimental mucositis and experimental gingivitis in persons aged 70 or over.

9. Gualini F, Berglundh T. Immunohistochemical characteristics of inflammatory lesions at implants. J Clin Periodontol 2003; 30: 14-18.

10. Seymour G J, Gemmell E, Lenz L J, Henry P, Bower R, Yamazaki K. Immunohistologic analysis of the inflammatory infiltrates associated with osseointegrated implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1989; 4: 191-198.

11. Chan D, Pelekos G, Ho D, Cortellini P, Tonetti M S. The depth of the implant mucosal tunnel modifies the development and resolution of experimental peri-implant mucositis: A case-control study. J Clin Periodontol 2019; 46: 248-255.

12. Schwarz F, Derks J, Monje A, Wang H-L. Peri-implantitis. J Clin Periodontol 2018; 45: 246-266.

13. Berglundh T, Armitage G, Araujo M G et al. Periimplant diseases and conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Clin Periodontol 2018; 45: 286-291.

14. Derks J, Schaller D, Håkansson J, Wennström J L, Tomasi C, Berglundh T. Peri-implantitis – onset and pattern of progression. J Clin Periodontol 2016; 43: 383-388.

15. Berglundh T, Gislason O, Lekholm U, Sennerby L, Lindhe J. Histopathological observations of human periimplantitis lesions. J Clin Periodontol 2004; 31: 341-347.

16. Konttinen Y T, Lappalainen R, Laine P, Kitti U, Santavirta

17. Albouy J-P, Abrahamsson I, Persson L G, Berglundh T. Spontaneous progression of ligatured induced peri-implantitis at implants with different surface characteristics. An experimental study in dogs II: histological observations. Clin Oral Implants Res 2009; 20: 366-371.

18. Lindhe J, Berglundh T, Ericsson I, Liljenberg B, Marinello C. Experimental breakdown of peri-implant and periodontal tissues. A study in the beagle dog. Clin Oral Implants Res 1992; 3: 9-16.

19. Heitz-Mayfield L J, Lang N P. Comparative biology of chronic and aggressive periodontitis vs. peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000 2010; 53: 167-181.

The University of Western Australia, International Research Collaborative, Oral Health and Equity, School of Human Anatomy and Biology, Crawley, WA, Australia; The University of Sydney, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Medicine and Health, NSW, Australia. Correspondence to: Lisa J. A. Heitz-Mayfield Email address: heitz.mayfield@iinet.net.au Refereed Paper.

Submitted 24 December 2023

Revised 12 April 2024

Accepted 17 April 2024

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7402-z