المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 15، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85359-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39863636

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-25

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85359-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39863636

تاريخ النشر: 2025-01-25

افتح

التوافق الحيوي لسمك متغير من جهاز تقويم الأسنان المطبوعة مباشرةً

تقدم القوالب المطبوعة مباشرة (DPAs) فوائد مثل القدرة على تغيير سمك الطبقات داخل DPA واحد وطباعتها ثلاثية الأبعاد لأجهزة تقويم الأسنان القابلة للإزالة المصنوعة حسب الطلب. تعتمد التوافق الحيوي للأجهزة المصنوعة من Tera Harz TA-28 (Graphy Inc.، سيول، كوريا الجنوبية) على الالتزام الصارم ببروتوكول إنتاج وما بعد الإنتاج القياسي، بما في ذلك المعالجة بالأشعة فوق البنفسجية. كان هدفنا هو تقييم ما إذا كانت التعديلات التصميمية التي تزيد من سمك الطبقة تتطلب وقت معالجة بالأشعة فوق البنفسجية أطول لضمان التوافق الحيوي. تم طباعة عينات بسمك طبقات متنوع بدقة عالية باستخدام Tera Harz TA-28 وطابعة Asiga MAX ثلاثية الأبعاد (تكنولوجيا Asiga SPS ™، سيدني، أستراليا). تم ضبط فترات المعالجة بالأشعة فوق البنفسجية على 20 و30 و60 دقيقة. تم تقييم السمية الخلوية باستخدام اختبار AlamarBlue على الخلايا الليفية اللثوية البشرية. انخفضت حيوية الخلايا مع زيادة سمك العينة (مهم لسمك 2 مم).

الكلمات الرئيسية: تقويم الأسنان الرقمي، الأقواس المطبوعة ثلاثية الأبعاد، الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد، الأقواس الشفافة، علاج الأقواس، الأقواس المطبوعة مباشرة، التوافق الحيوي، السمية الخلوية، الراتنج

لقد أصبحت علاج التقويم الشفاف وسيلة علاجية تزداد شعبية بين أطباء التقويم وكذلك المرضى الذين يسعون للحصول على رعاية تقويم الأسنان في جميع أنحاء العالم.

في السنوات الأخيرة، مكنت الابتكارات التكنولوجية الكبرى في الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد، وخاصة المتعلقة بتصميم الكمبيوتر، والمواد الحيوية، وتقنيات التصنيع، من إنتاج أجهزة تقويم الأسنان القابلة للطباعة مباشرة في العيادة (DPAs) – مما يمثل ابتكارًا مقارنةً بأجهزة التقويم التقليدية المصنوعة من الحرارة.

مؤخراً، أطلقت شركة جرافي نسخة محدثة ومعدلة من راتنجها، تيرا هارز TA-28 (جرافي إنك، سيول، كوريا الجنوبية). بينما تشترك TA-28 و TC-85 في العديد من مكوناتهما وخصائصهما الفيزيائية، قد تؤدي التعديلات إلى اختلافات في الخصائص البيوميكانيكية لـ DPAs، والأداء، والتوافق الحيوي.

البروتينات في الخلايا

تُشير المواد المصنوعة من راتنجات جرافي إلى عصر جديد في علاج التقويم الشفاف، حيث تقدم عددًا من المزايا البيوميكانيكية مقارنةً بنظيراتها المصنوعة بالتشكيل الحراري.

على الرغم من هذه الفوائد المغرية، فإنه من غير المعروف حاليًا ما إذا كانت مثل هذه التعديلات على سمك المAligner الشفاف الشائع

على الرغم من أن الزيادة في شعبية راتنج جرافي في السنوات الأخيرة قد أدت إلى أبحاث واسعة حول الخصائص البيوميكانيكية، والتوافق الحيوي، وعمليات الشيخوخة داخل الفم للأجهزة السنية المصنوعة من تيرا هارز TC-85 (جرافي إنك، سيول، كوريا الجنوبية)، إلا أنه حتى الآن، لم تقيم أي دراسات تأثير تغييرات التصميم التي تتضمن زيادة سمك المادة على التوافق الحيوي والسُمية الخلوية للأجهزة السنية.

لذا، فإن تصنيع واستخدام أجهزة DPAs أو أجهزة وظيفية مخصصة وفقًا للاحتياجات الفردية للمريض يحمل دائمًا خطر التعرض لمواد سامة للخلايا. بالنظر إلى تهيج الغشاء المخاطي السابق في عدة مرضى، فإن تقييم التوافق الحيوي الإضافي هو في غاية الأهمية والأهمية السريرية.

لذلك، كان هدفنا هو تقييم التوافق الحيوي والسمية الخلوية لراتنج المحاذاة الجديد Tera Harz TA-28 من Graphy وتحديد ما إذا كانت التعديلات التصميمية، التي تتطلب زيادة في سمك المادة، تؤدي إلى أي انخفاض في التوافق الحيوي عندما لا يتم تعديل المعالجة اللاحقة بشكل مناسب.

لمعالجة هذا الهدف، قمنا باختبار الفرضيات الصفرية التالية:

- تمديد مدة المعالجة بالأشعة فوق البنفسجية خلال المعالجة اللاحقة لا يؤثر على التوافق الحيوي للمواد DPAs المصنوعة من Tera Harz TA-28 (Graphy Inc.، سيول، كوريا الجنوبية).

- زيادة سمك الطبقة من DPAs المصنوعة من Tera Harz TA-28 (Graphy Inc.، سيول، كوريا الجنوبية) لا تتطلب معالجة بالأشعة فوق البنفسجية لفترة طويلة أثناء المعالجة اللاحقة للحفاظ على التوافق الحيوي.

- يمكن طباعة النماذج المصممة رقميًا، المصنوعة من Tera Harz TA-28 (Graphy Inc.، سيول، كوريا الجنوبية)، بتقنية الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد بدقة عالية، بغض النظر عن التعديلات في مدة المعالجة بالأشعة فوق البنفسجية أو سمك المادة.

طرق

التصميم الرقمي، الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد والمعالجة اللاحقة للنماذج

عينات دائرية بقطر 1 سم وسماكات متفاوتة من

زراعة الخلايا

تم زراعة الخلايا الليفية اللثوية البشرية المكتسبة تجارياً (HGFs، CLS Cell Lines Service GmbH، إيبيلهايم، ألمانيا) في وسط ديلبيكو المعدل (DMEM؛ ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك، كارلسباد، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) يحتوي على

اختبار العينات

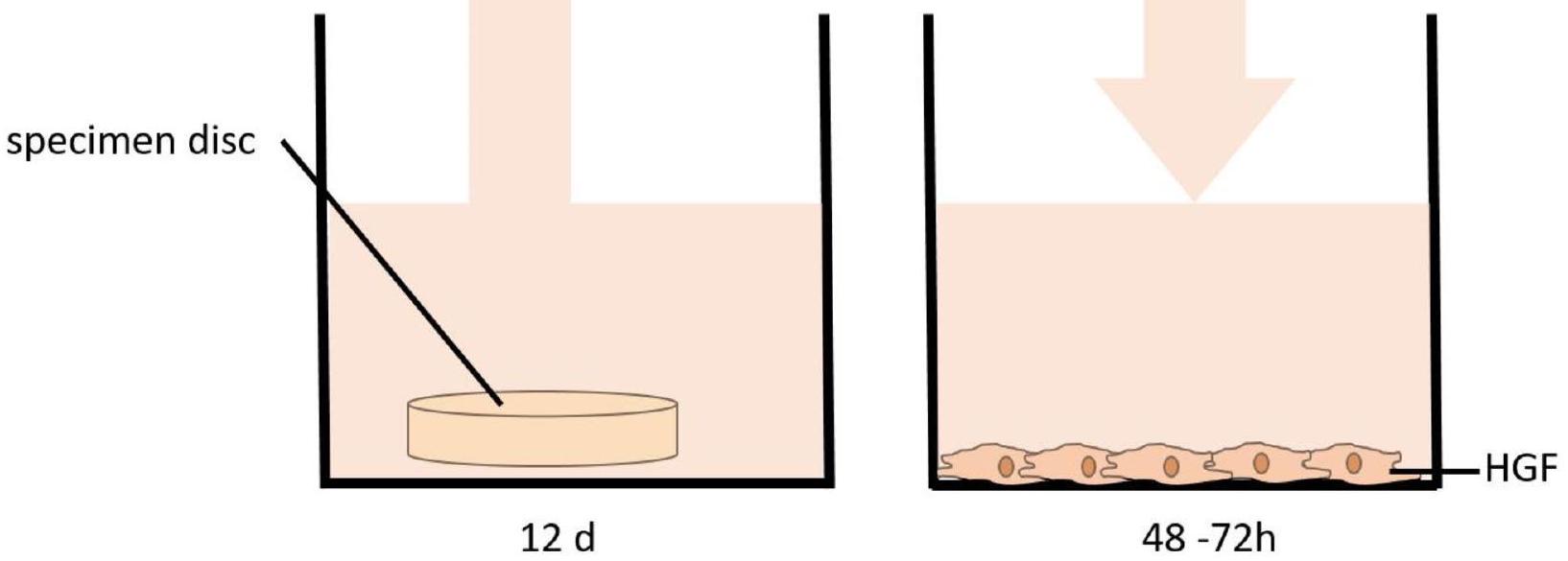

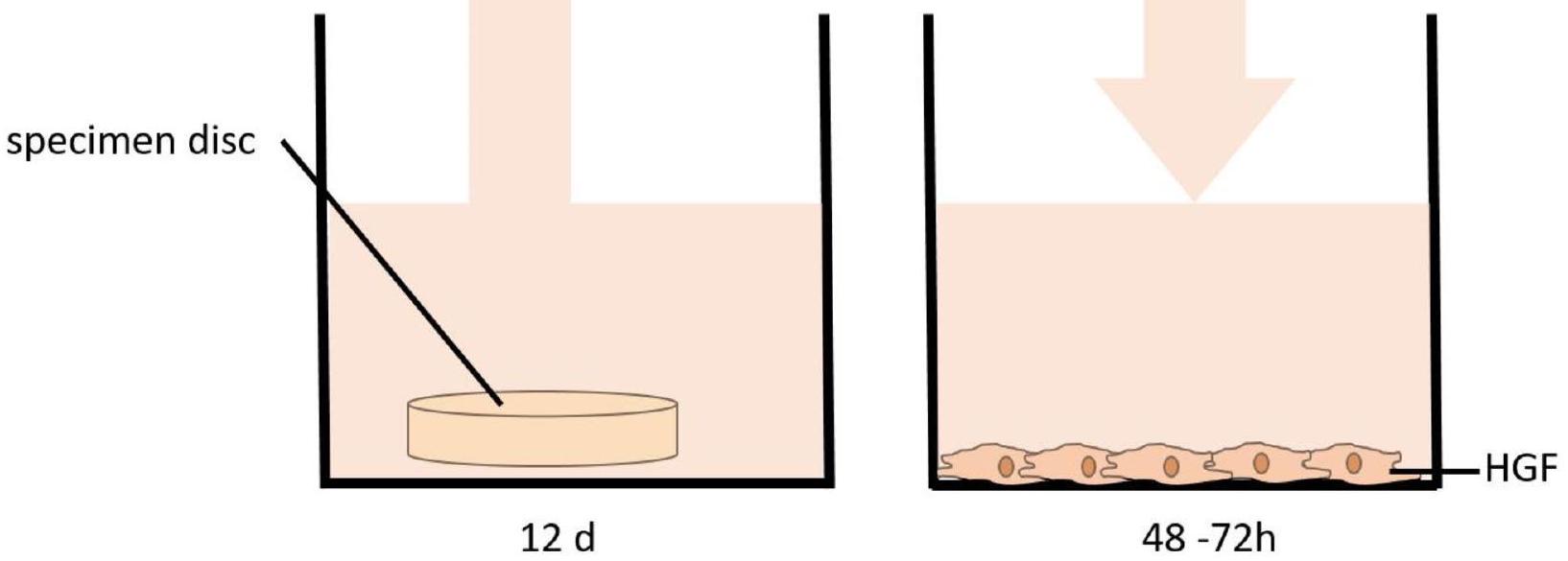

تم حضانة العينات في وسط الزراعة مع اهتزاز متقطع لمدة 12 يومًا، محاكاة مدة التآكل للموصلات الشفافة أثناء العلاج التقويمي النشط. لتقييم التأثير المحتمل لتعرض اللعاب على السمية الخلوية، تم حضانة عينات إضافية في اللعاب لمدة الفترة المقابلة، وتقييم تأثيره على حيوية الخلايا. بعد فترة الحضانة، تم نقل الوسط أو اللعاب (

تم مراقبة تكاثر الخلايا باستمرار بناءً على الزيادة في التوافق الملحوظ باستخدام جهاز تصوير الخلايا الحية إنكوسايت (إنكوسايت، سارتوريوس، غوتينغن، ألمانيا). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم قياس حيوية الخلايا باستخدام اختبار حيوية الخلايا ألاماربلو (ألاماربلو؛ ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) بعد

اختبار حيوية الخلايا ألاماربلو

تم تقييم حيوية خلايا HGFs بشكل كمي باستخدام اختبار لوني (ألاماربلو؛ ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) وفقًا لبروتوكول الشركة المصنعة. مادة اختبار حيوية الخلايا ألاماربلو

وسط زراعة الخلايا المشروطة

الشكل 1. اختبار العينات لتقييم تأثير مادة الموصل على الخلايا الليفية اللثوية البشرية (HGF).

(ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) هو صبغة إنديغو غير سامة وقابلة للاختراق للخلايا (ريزازورين) تستخدم للتحليل الكمي لحيوية الخلايا وتكاثرها. إنها تقيس معدل التمثيل الغذائي للخلايا الحية بناءً على قدرتها على الاختزال. عند دخولها إلى الخلايا الحية، يتم اختزال ريزازورين إلى ريزوروفين، وهو مركب أحمر وعالي الفلورية. يمكن اكتشاف التغيرات في الحيوية بسهولة باستخدام قارئ صفيحة الفلورية (التحفيز عند 537 نانومتر والانبعاث عند 600 نانومتر، قارئ صفيحة فيرسامكس؛ مولكيولار ديفايسز، سوني فالي، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية). تمت إضافة مادة ألاماربلو المخلوطة مسبقًا إلى الوسط فوق الخلايا بتركيز

التحليل الإحصائي

لتحديد الفروق بين المجموعات، تم إجراء اختبار t غير المقترن أو ANOVA أحادي الاتجاه متبوعًا باختبار توكي بعد ذلك. تم حساب الخطأ القياسي للمتوسط باستخدام GraphPad PRISM (GraphPad Software، بوسطن، ماساتشوستس، الولايات المتحدة).

النتائج

دقة العينة

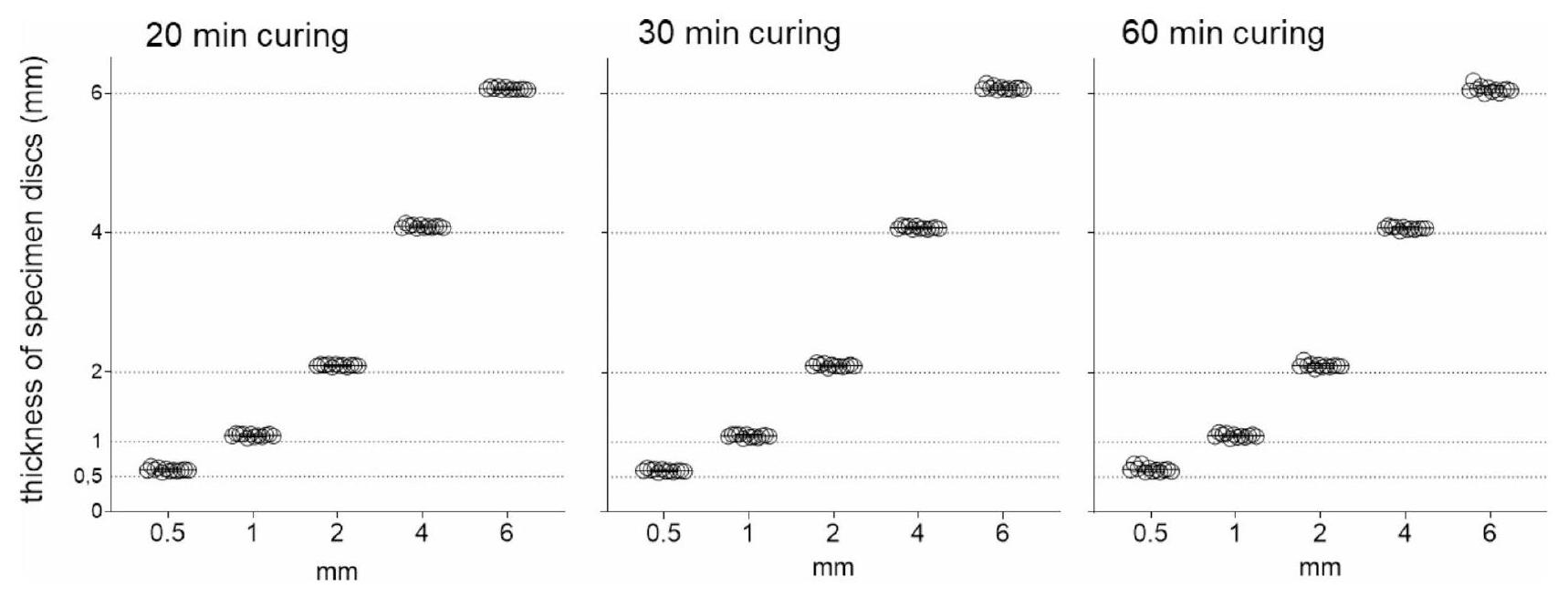

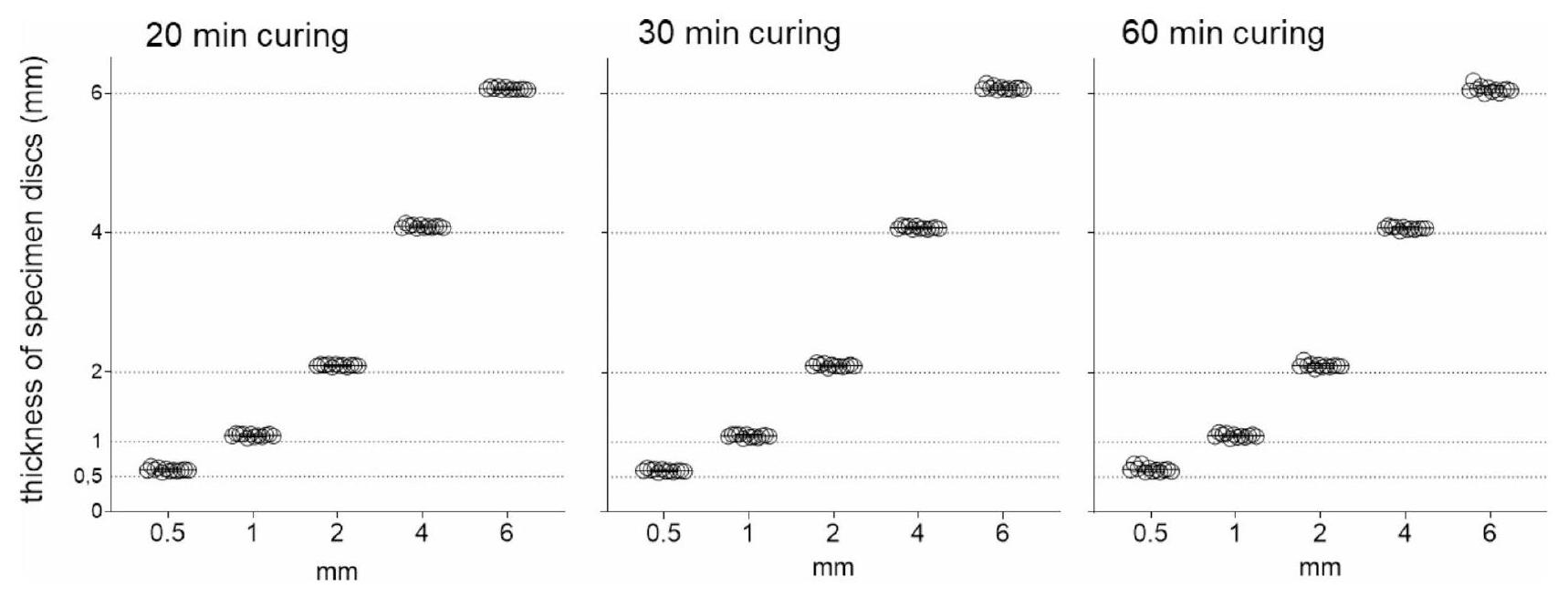

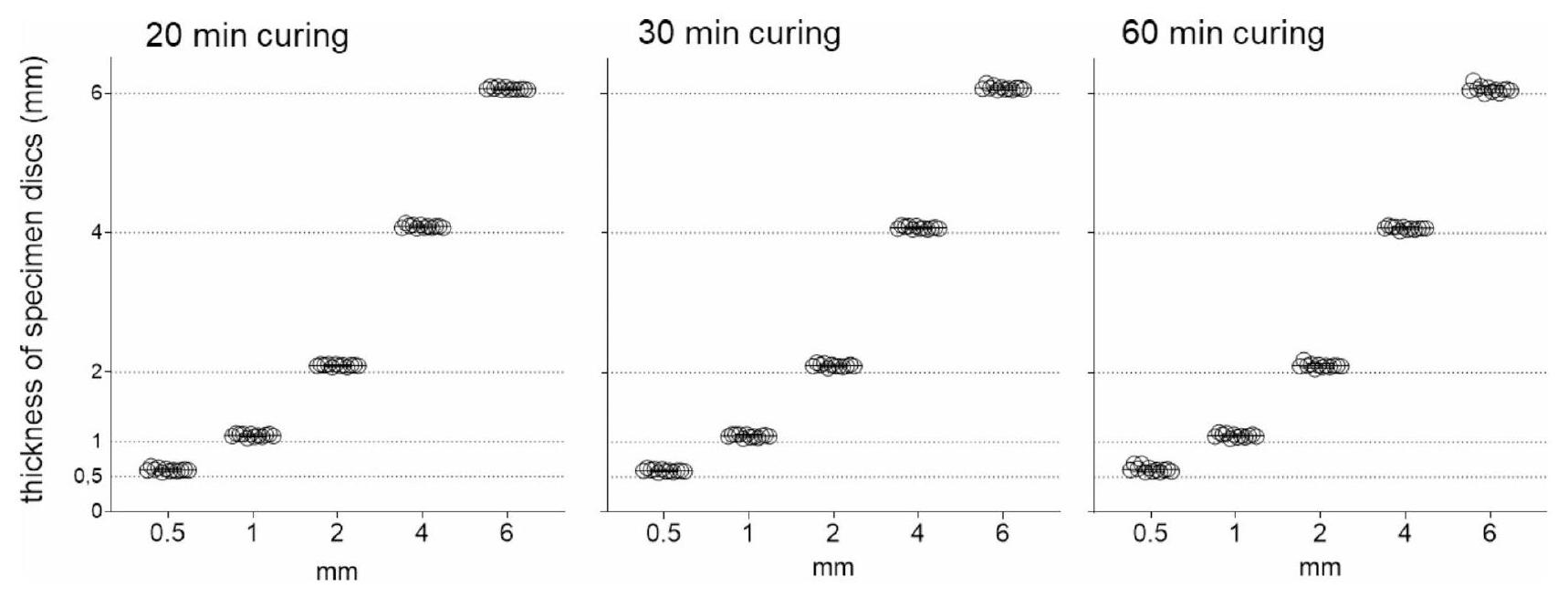

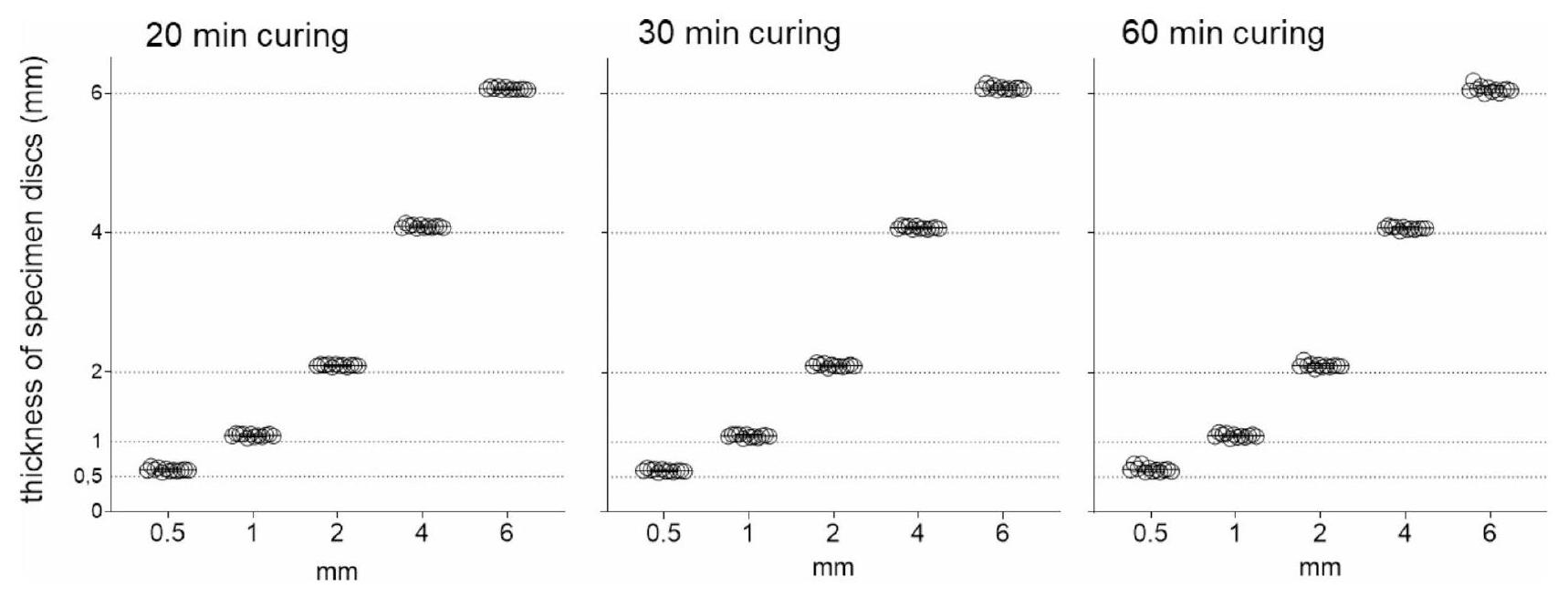

تم قياس العينات يدويًا باستخدام مقياس كاليبر رقمي وأظهرت دقة عالية حيث وصلت إلى القطر المطلوب 1 سم بالإضافة إلى سمك مختلف من

تكاثر الخلايا وحيويتها

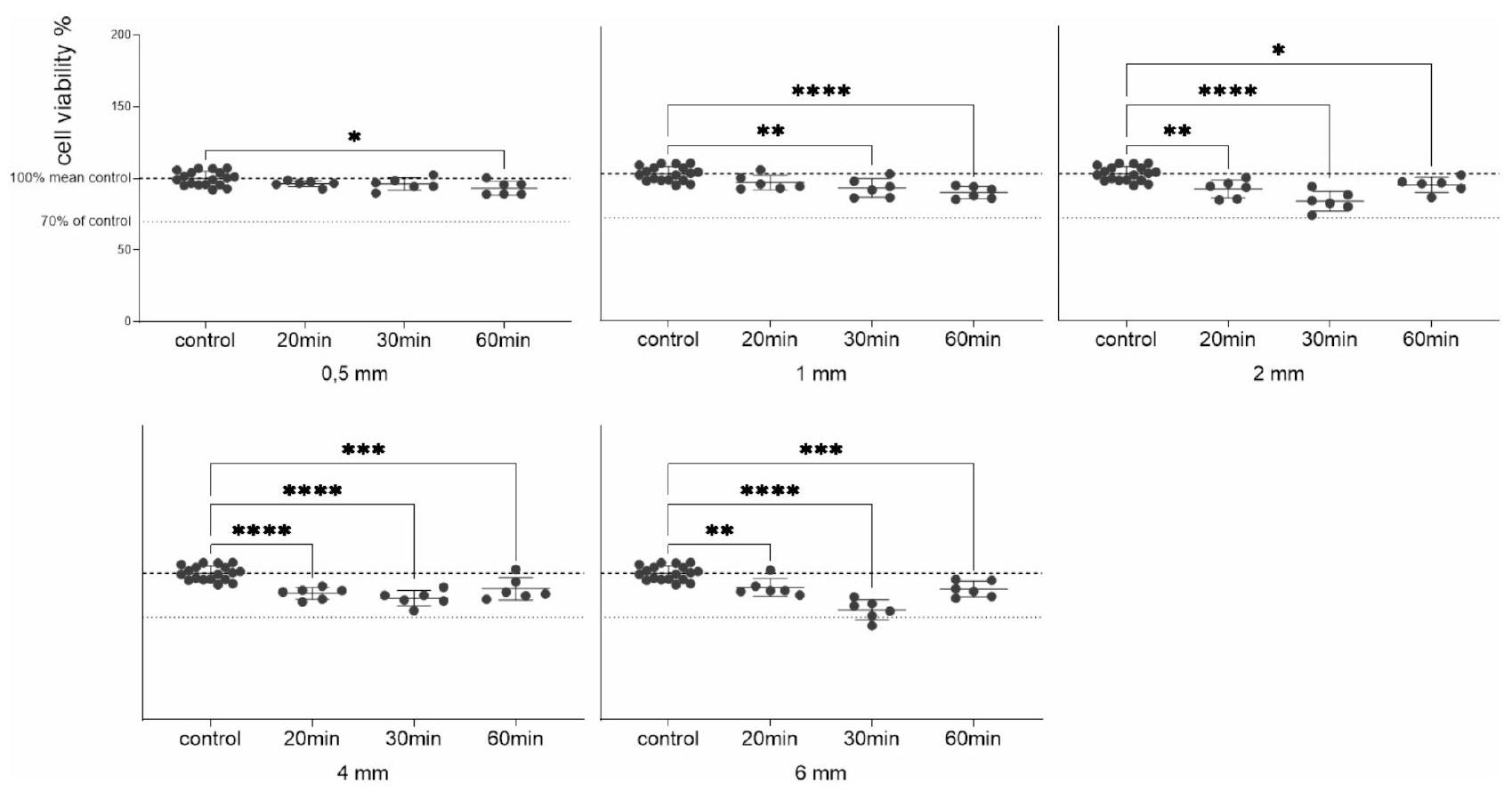

في البداية، تم تقييم تأثير راتنج الموصل من غرافي على الخلايا الليفية اللثوية الفموية (HGF) باستخدام عينات من سمك مادة مختلفة (

أظهر تصوير الخلايا الحية على مدى 72 ساعة أيضًا أن الخلايا تكاثرت تحت جميع الظروف (الشكل 3B)، دون ملاحظة أي تغييرات شكلية ودون انفصال أي خلايا عن قاع البئر.

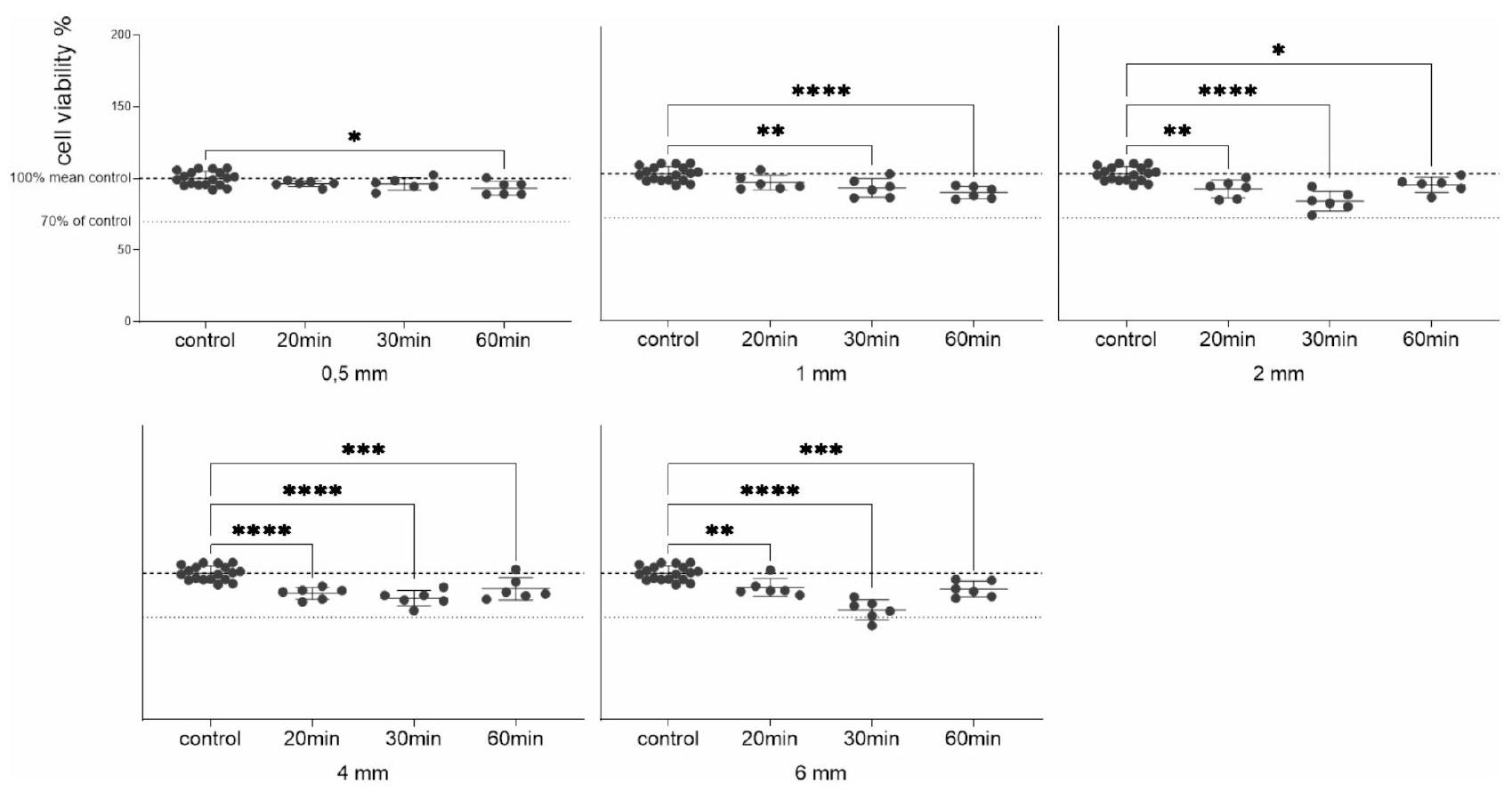

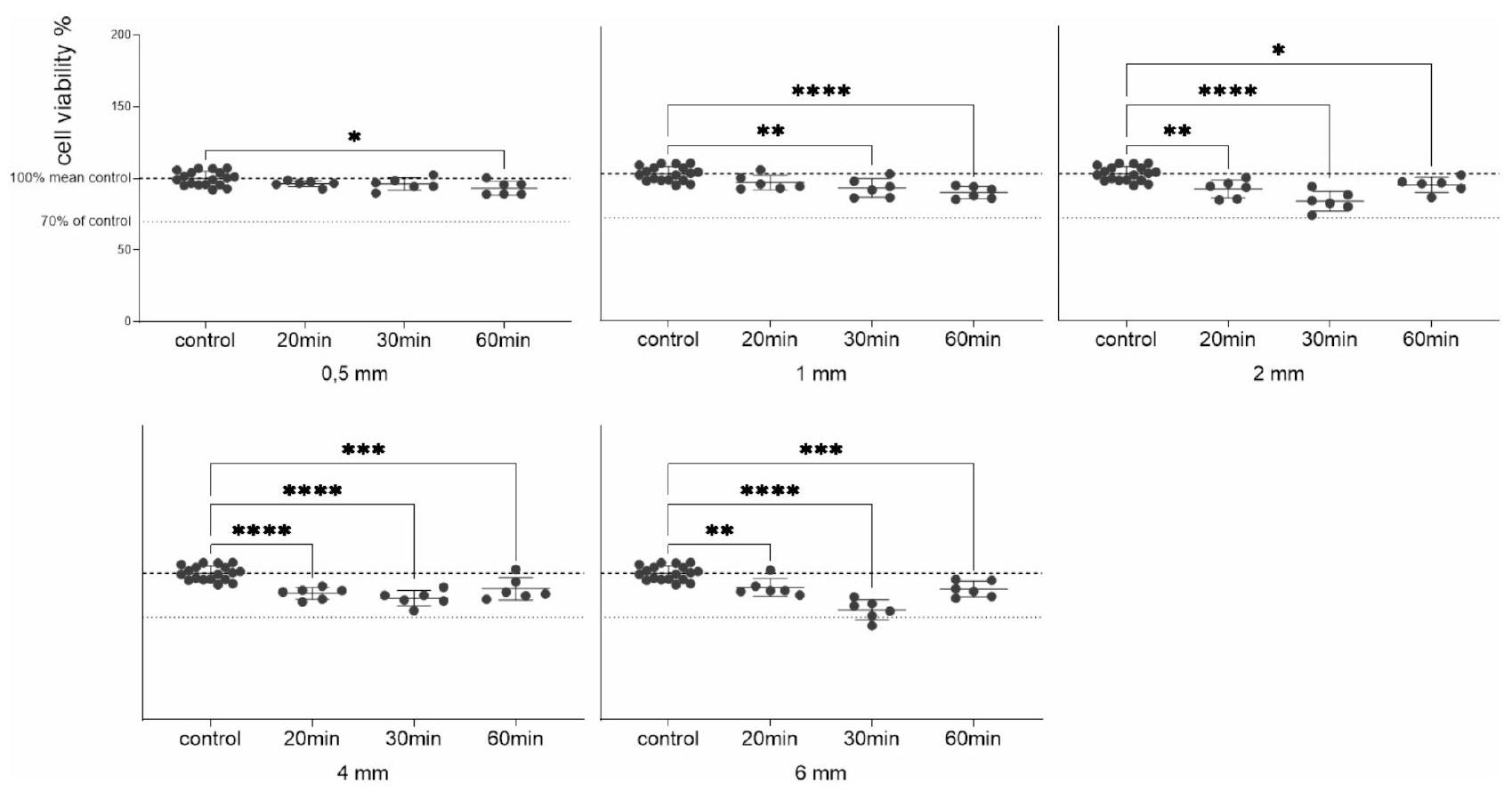

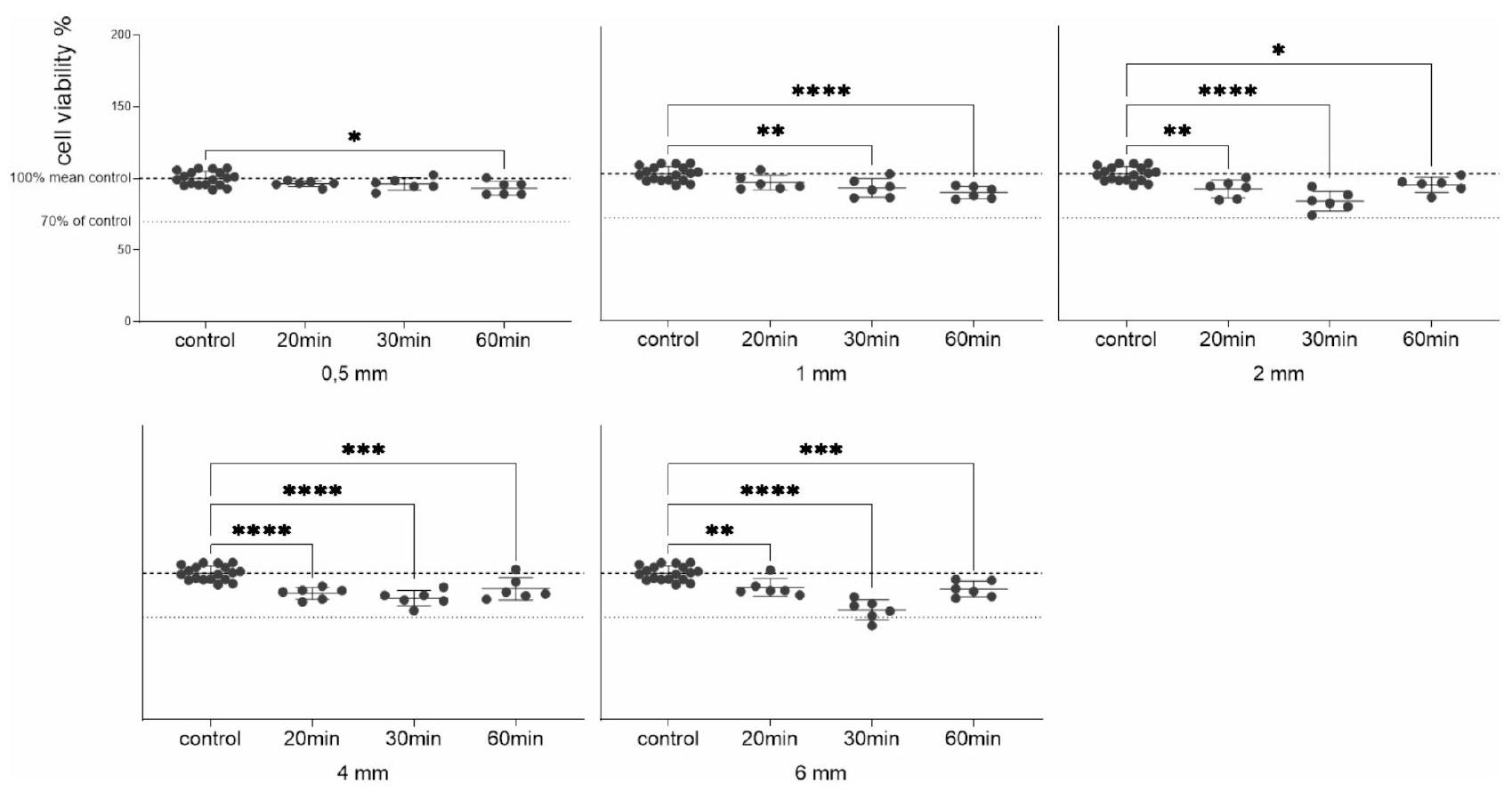

بعد ذلك، تم تغيير مدة المعالجة بالأشعة فوق البنفسجية (20، 30 و60 دقيقة). مرة أخرى، لم يُلاحظ أي انخفاض في حيوية الخلايا يتجاوز 30% (الشكل 4). انخفضت حيوية الخلايا مع زيادة وقت المعالجة لجميع المواد

الشكل 2. سمك العينات المقاسة (

الشكل 3. حيوية الخلايا لـ HGF المعرضة لـ “Tera Harz TA-28”. (A) عينات من سمكات مختلفة (

سمكات، مع العينات بسمك 2 و4 و6 مم تظهر أكبر فقدان في حيوية الخلايا عند المعالجة لمدة 30 دقيقة. ومع ذلك، أظهرت المعالجة لمدة 60 دقيقة زيادة لاحقة في حيوية الخلايا.

في نهج آخر، بحثنا في تأثير اللعاب على الإفراج المحتمل عن مواد نشطة بيولوجيًا من مادة الموصل. لذلك، تم معالجة عينات من جميع السماكات المختلفة (

المناقشة

من المتوقع أن تكون DPAs علامة فارقة في علاج الموصلات الشفافة بسبب مزاياها المتعددة، مثل تحسين الدقة والملاءمة، مقارنةً بالموصلات الشفافة التقليدية المنتجة في عملية تشكيل حراري

الشكل 4. تباين في حيوية الخلايا تم تقييمه بعد المعالجة اللاحقة (التصلب بالأشعة فوق البنفسجية) لفترات زمنية مختلفة (20، 30، 60 دقيقة). تم وضع العينات في الوسط لمدة 12 يومًا وعلاج HGFs بالوسط المشروط (

الشكل 5. حيوية الخلايا لـ HGFs المعرضة لـ “Tera Harz TA-28” في اللعاب. (A)

الاختلافات في الخصائص، من المحتمل أن تتأثر هذه التباينات بعوامل مثل اختيار الطابعة، إعدادات الطابعة وبروتوكولات المعالجة اللاحقة المطبقة

بالإضافة إلى مناطق الضغط المخصصة، فإن التباين في التصميم الرقمي لـ DPAs يسمح لأطباء تقويم الأسنان بإنتاج أي نوع من الأجهزة القابلة للإزالة المخصصة: على سبيل المثال، يمكن استخدام كتل العض الخلفية المصممة عن طريق زيادة سمك طبقة الإطباق الخلفية بشكل كبير حتى عدة مليمترات لإنشاء ميكانيكا من الفئة الثانية مشابهة لـ Twin-Block أو أداة التقدم الفك السفلي (Invisalign، Align Technology، سان خوسيه، كاليفورنيا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية). يمكن تسهيل انغماس الأضراس في المرضى الذين يعانون من عض مفتوح أمامي أيضًا.

ومع ذلك، من وجهة نظرنا، تأتي هذه الفوائد مع خطر تعريض المرضى لمونومرات سامة للخلايا حيث قد تكون مدة التصلب بالأشعة فوق البنفسجية الأطول مطلوبة لتبلمر كامل الحجم في مناطق سمك المادة الأعلى. قد يؤدي التصلب غير الكافي أو غير المكتمل للرواسب إلى زيادة احتمال حدوث آثار جانبية سلبية.

أثناء العلاج النشط، فإن الالتزام الصارم بالوقت الأساسي للارتداء لمدة

تقيم هذه الدراسة التوافق الحيوي لـ DPAs المصنوعة من راتنج المحاذاة الجديد من Graphy، Tera Harz TA-28، بالإضافة إلى تقييم تأثيرات سمك المادة المختلفة على حيوية الخلايا. ستساهم هذه النتائج في فهم أعمق لخصائص المادة وتطبيقاتها السريرية المحتملة. حتى الآن، لم يكن من الواضح ما إذا كانت مثل هذه التعديلات التصميمية ستتطلب تغييرات كبيرة في عملية التصلب اللاحق لضمان الاستخدام الآمن بيولوجيًا لدى المرضى. عند اتباع إرشادات التصلب الخاصة بالشركة ومعالجة العينات لمدة 20 دقيقة لكل منها، يتم اكتشاف فقدان طفيف في حيوية الخلايا مع زيادة السمك. لتقييم التفاعل بين سمك DPAs، ووقت التصلب، والسُمية الخلوية الناتجة بمزيد من التفصيل، تم تحليل تأثيرات المستخلصات من عينات بسمك مختلف، تم معالجتها لمدة 20، 30، أو 60 دقيقة، على HGFs. بالنسبة للعينات بسمك 0.5 مم و1 مم، انخفضت حيوية الخلايا مع زيادة وقت التصلب. ومع ذلك، أظهرت العينات بسمك 2، 4، أو 6 مم أكبر فقدان في حيوية الخلايا عند وقت تصلب قدره 30 دقيقة، مع زيادة الحيوية مرة أخرى عند 60 دقيقة (الشكل 3). على الرغم من أن الانخفاض في حيوية الخلايا لجميع التركيبات كان أقل من

على غرار الأبحاث السابقة، فإن أحد قيود الدراسة الحالية، كونها في المختبر، هو عدم القدرة على محاكاة جميع التأثيرات المحتملة داخل الفم بما في ذلك قوى المضغ وصريف الأسنان التي قد تتلف سطح DPAs مما يكشف عن الطبقات الداخلية التي قد لا تكون قد تم تصلبها بالكامل، الرقم الهيدروجيني، تقلبات درجة الحرارة، النشاط الميكروبي وكذلك التفاعلات الإنزيمية (مثل الإسترازات)

الاستنتاجات

إن إدخال أجهزة التقويم القابلة للتعديل باستخدام راتنجات Graphy يمثل ابتكارًا كبيرًا مقارنةً بأجهزة التقويم التقليدية المصنوعة بالتشكيل الحراري. أكدت الدراسة الحالية دقة طريقة الإنتاج العالية، حيث حقق جميع النماذج أبعادها المستهدفة بغض النظر عن وقت المعالجة بالأشعة فوق البنفسجية. كانت بروتوكولات المعالجة بالأشعة فوق البنفسجية القياسية لمدة 20 دقيقة كافية لضمان التوافق الحيوي، وبالتالي سلامة المرضى لسمك المواد يصل إلى 6 مم.

توفر البيانات

جميع مجموعات البيانات متاحة عند الطلب من المؤلف المراسل.

تاريخ الاستلام: 22 أكتوبر 2024؛ تاريخ القبول: 2 يناير 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 25 يناير 2025

تاريخ الاستلام: 22 أكتوبر 2024؛ تاريخ القبول: 2 يناير 2025

نُشر على الإنترنت: 25 يناير 2025

References

- Castroflorio, T., Parrini, S. & Rossini, G. Aligner biomechanics: where we are now and where we are heading for. J. World Fed. Orthod.. 13 (2), 57-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejwf.2023.12.005 (2024).

- Bichu, Y. et al. Advances in orthodontic clear aligner materials. Bioactive Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.10.006

- Weir, T. Clear aligners in orthodontic treatment. Aust Dent. J. 62 (Suppl 1), 58-62. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj. 12480 (2017).

- Rosvall, M. D., Fields, H. W., Ziuchkovski, J., Rosenstiel, S. F. & Johnston, W. M. Mar. Attractiveness, acceptability, and value of orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 135(3): e1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.09.020 (2009).

- Abbate, G. M. et al. Periodontal health in teenagers treated with removable aligners and fixed orthodontic appliances. J. Orofac. Orthop.. 76 (3), 240-250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-015-0285-5 (2015).

- Shokeen, B. et al. The impact of fixed orthodontic appliances and clear aligners on the oral microbiome and the association with clinical parameters: a longitudinal comparative study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 161 (5), e475-e485. https://doi.org/10.101 6/j.ajodo.2021.10.015 (2022).

- Tartaglia, G. M. et al. Direct 3D Printing of Clear Orthodontic aligners: current state and future possibilities. Materials https://doi .org/10.3390/ma14071799 (2021).

- Tera Harz Clear. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf24/K240597.pdf

- Luo, K. et al. Effect of post-curing conditions on surface characteristics, physico-mechanical properties, and cytotoxicity of a 3D-printed denture base polymer. Dent. Mater. 40 (3), 500-507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2023.12.017 (2024).

- Grant, J. et al. Forces and moments generated by 3D direct printed clear aligners of varying labial and lingual thicknesses during lingual movement of maxillary central incisor: an in vitro study. Prog Orthod.. 10 (1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-023-004 75-2 (2023).

- Koenig, N. et al. Comparison of dimensional accuracy between direct-printed and thermoformed aligners. Korean J. Orthod. 25 (4), 249-257. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod21.269 (2022).

- Hertan, E., McCray, J., Bankhead, B. & Kim, K. B. Force profile assessment of direct-printed aligners versus thermoformed aligners and the effects of non-engaged surface patterns. Prog. Orthodont. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-022-00443-2 (2022).

- Lee, S. Y. et al. Thermo-mechanical properties of 3D printed photocurable shape memory resin for clear aligners. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 6246. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09831-4 (2022).

- Can, E. et al. In-house 3D-printed aligners: effect of in vivo ageing on mechanical properties. Eur. J. Orthod. 25 (1), 51-55. https:/ /doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjab022 (2022).

- Zinelis, S., Panayi, N., Polychronis, G., Papageorgiou, S. N. & Eliades, T. Comparative analysis of mechanical properties of orthodontic aligners produced by different contemporary 3D printers. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 25 (3), 336-341. https://doi.org/10. 1111/ocr. 12537 (2022).

- Narongdej, P., Hassanpour, M., Alterman, N., Rawlins-Buchanan, F. & Barjasteh, E. Advancements in Clear Aligner fabrication: a comprehensive review of Direct-3D Printing technologies. Polymers. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16030371 (2024).

- Alessandra, C. et al. Comparison of the cytotoxicity of 3D-printed aligners using different post-curing procedures: an in vitro study. Australas. Orthod. J. 39 (2), 49-56. https://doi.org/10.2478/aoj-2023-0026 (2023).

- Pratsinis, H. et al. Cytotoxicity and estrogenicity of a novel 3-dimensional printed orthodontic aligner. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 162 (3), e116-e122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.06.014 (2022).

- Iodice, G. et al. Effect of post-printing curing time on cytotoxicity of direct printed aligners: a pilot study. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/ocr. 12819 (2024).

- Willi, A. et al. Leaching from a 3D-printed aligner resin. Eur. J. Orthod. 31 (3), 244-249. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjac056 (2023).

- Park, S. Y. et al. Comparison of translucency, thickness, and gap width of thermoformed and 3D-printed clear aligners using micro-CT and spectrophotometer. Sci. Rep. 5 (1), 10921. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36851-5 (2023).

- Sayahpour, B. et al. Effects of intraoral aging on mechanical properties of directly printed aligners vs. thermoformed aligners: an in vivo prospective investigation. Eur. J. Orthod. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjad063 (2024).

- Shirey, N., Mendonca, G., Groth, C. & Kim-Berman, H. Comparison of mechanical properties of 3-dimensional printed and thermoformed orthodontic aligners. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 163 (5), 720-728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.12.008 (May 2023).

- Edelmann, A., English, J. D., Chen, S. J. & Kasper, F. K. Analysis of the thickness of 3-dimensional-printed orthodontic aligners. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop.. 158 (5), e91-e98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.07.029 (2020).

- McCarty, M. C., Chen, S. J., English, J. D. & Kasper, F. Effect of print orientation and duration of ultraviolet curing on the dimensional accuracy of a 3-dimensionally printed orthodontic clear aligner design. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 158 (6), 889-897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.03.023 (2020).

- Mattle, M. et al. Effect of heat treatment and nitrogen atmosphere during post-curing on mechanical properties of 3D-printed orthodontic aligners. Eur. J. Orthod. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjad074 (2024).

- Graphy, T. C. 85 Certification Workshop. FORESTADENT. https://www.forestadent.com/de-de/kurse-kongresse/event/zertifizie rungsworkshop-graphy-tc-85-direct-print-aligner/

شكر وتقدير

يشكر المؤلفون السيدة سونيا هوخ-كرافت، والسيدة راهل ريجيتز على دعمهما الفني الممتاز، والسيد كريستيان جيركه، والسيد ماتياس كواس، وكارستن موهر على طباعة النماذج ثلاثية الأبعاد.

مساهمات المؤلفين

تصور: م.ب، ج.و-ج، ف.ك، ب.ل و ج.هـ؛ التصميم: ج.و-ج و ج.هـ؛ المنهجية: ج.و-ج؛ بيانات ا-

التحقيق: C.W-J.; التحقق: C.W-J.، M.B.، V.K. و C.E.; تحليل البيانات، التفسير والتصور: C.W-J.; الكتابة، المراجعة والتحرير: M.B.، C.W-J.، V.K.، B.L. و C.E.; الموارد: C.E. و B.L.; إدارة المشروع: C.E. و B.L. جميع المؤلفين قرأوا ووافقوا على النسخة المنشورة من المخطوطة.

التحقيق: C.W-J.; التحقق: C.W-J.، M.B.، V.K. و C.E.; تحليل البيانات، التفسير والتصور: C.W-J.; الكتابة، المراجعة والتحرير: M.B.، C.W-J.، V.K.، B.L. و C.E.; الموارد: C.E. و B.L.; إدارة المشروع: C.E. و B.L. جميع المؤلفين قرأوا ووافقوا على النسخة المنشورة من المخطوطة.

تمويل

تم تمويل الوصول المفتوح وتنظيمه بواسطة مشروع DEAL.

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى م.ب. أو س.و.-ج.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىwww.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينغر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىwww.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر: تظل شركة سبرينغر ناتشر محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي النسب 4.0 الدولية، التي تسمح بالاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج بأي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح إذا ما تم إجراء تغييرات. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمواد. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي الخاصة بالمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، فسيتعين عليك الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارةhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© المؤلف(ون) 2025

© المؤلف(ون) 2025

قسم تقويم الأسنان وطب الأسنان الوجهية، المركز الطبي الجامعي لجامعة يوهانس غوتنبرغ ماينز، أوغسطس بلاتز 2، 55131 ماينز، ألمانيا. ²قسم تقويم الأسنان، جامعة هومبورغ، زار، ألمانيا. ممارسة خاصة لطب تقويم الأسنان، أم بانهوف 54، 56841 ترابن-تراباخ، ألمانيا. ماكسيميليان بليلوبي، كلوديا ويلتي-جزيك ساهموا بالتساوي في هذا العمل. البريد الإلكتروني:maximilian.bleiloeb@unimedizin-mainz.de; Claudia.Welte-Jzyk@unimedizin-mainz.de

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 15, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85359-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39863636

Publication Date: 2025-01-25

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85359-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39863636

Publication Date: 2025-01-25

OPEN

Biocompatibility of variable thicknesses of a novel directly printed aligner in orthodontics

Direct printed aligners (DPAs) offer benefits like the ability to vary layer thickness within a single DPA and to 3D print custom-made removable orthodontic appliances. The biocompatibility of appliances made from Tera Harz TA-28 (Graphy Inc., Seoul, South Korea) depends on strict adherence to a standardized production and post-production protocol, including UV curing. Our aim was to evaluate whether design modifications that increase layer thickness require a longer UV curing time to ensure biocompatibility. Specimens with varying layer thickness were printed to high accuracy using Tera Harz TA-28 and the Asiga MAX 3D printer (Asiga SPS ™ technology, Sydney, Australia). UV curing durations were set at 20, 30 and 60 min . Cytotoxicity was evaluated using the AlamarBlue assay on human gingival fibroblasts. Cell viability decreased with increasing specimen thickness (significant for 2 mm

Keywords Digital orthodontics, 3D printed aligners, 3D printing, Clear aligner, Aligner therapy, Direct printed aligners, Biocompatibility, Cytotoxicity, Resin

Clear aligner therapy has become an increasingly popular treatment method among orthodontists as well as patients seeking orthodontic care worldwide

In recent years, major technological innovations in 3D printing, especially related to computer-aided design, biomaterials and manufacturing techniques, have enabled the production of in-office direct to print aligners (DPAs) – representing an innovation compared to the traditional thermoformed aligners

Recently, Graphy has launched an updated and modified version of its resin, Tera Harz TA-28 (Graphy Inc., Seoul, South Korea). While TA-28 and TC-85 share many of their components and physical properties, the modifications may result in differences in the DPAs biomechanical properties, performance and biocompatibilitiy

proteins in cells

DPAs made from Graphy’s resins herald a new era in clear aligner therapy offering a number of biomechanical advantages compared to their thermoformed counterparts

Despite these wooed benefits, it is currently unknown if such adaptations to the common clear aligner thickness of

Although the increased popularity of Graphy’s resin in recent years has led to extensive reasearch on the biomechanical properties, biocompatibility and intraoral ageing processes of DPAs made from Tera Harz TC-85 (Graphy Inc, Seoul, South Korea), to date, no studies have evaluated the influence of design changes involving increased material thickness on the DPAs’ biocompatibility and cytotoxicity

Thus, manufacturing and using customized DPAs or functional appliances according to the patient’s individual needs always bears the risk of exposing cytotoxic materials. Considering previous mucosa irritation in multiple patients, further biocompatibility assessment is of utmost importance and clinical relevance

Therefore, our objective was to evaluate the biocompatibility and cytotoxicity of Graphy’s new Tera Harz TA-28 aligner resin and to determine whether design adaptations, which require increases in material thickness, result in any reductions in biocompatibility when post-processing is not adapted appropriately.

To address this aim, we tested the following null hypotheses:

- The extension of the duration of UV curing during post-processing does not affect the biocompatibility of DPAs made from Tera Harz TA-28 (Graphy Inc., Seoul, South Korea).

- The increase in layer thickness of DPAs made from Tera Harz TA-28 (Graphy Inc., Seoul, South Korea) does not require prolonged UV curing during post-processing to maintain biocompatibility.

- Digitally designed specimens, made from Tera Harz TA-28 (Graphy Inc., Seoul, South Korea), can be 3D printed to a high degree of accuracy, regardless of modifications in UV curing duration or material thickness.

Methods

Digital design, 3D-printing and post-processing of the specimens

Circular specimens with a diameter of 1 cm and varying thicknesses of

Cell culture

Commercially acquired human gingival fibroblasts (HGFs, CLS Cell Lines Service GmbH, Eppelheim, Germany) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing

Specimen testing

The specimens were incubated in culture medium with intermittent shaking for 12 days, simulating the wear duration of clear aligners during active orthodontic treatment. To assess the potential impact of saliva exposure on cytotoxicity, additional samples were incubated in saliva for the corresponding period, evaluating its influence on cell viability. Following the incubation period, the medium or saliva (

Cell proliferation was monitored continuously based on the increase in confluence observed with the life-cell imaging device Incucyte (Incucyte, Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). In addition, cell viability was measured using the AlamarBlue cell viability assay (AlamarBlue; ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA) after

AlamarBlue cell viability assay

Cell viability of the HGFs was assessed quantitatively using a colorimetric assay (AlamarBlu; ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The AlamarBlue cell viability reagent

Conditioned cell culture medium

Fig. 1. Specimen testing to evaluate the influence of the aligner material on human gingival fibroblasts (HGF).

(ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA) is a non-toxic, cell-permeable indigo dye (Resazurin) used for quantitative analysis of cell viability and proliferation. It quantifies the metabolic turnover of living cells based on their reducing power. Upon entering living cells, Resazurin is reduced to Resorufin, a red and highly fluorescent compound. Changes in viability are easily detected with a fluorescence plate reader (excitation at 537 nm and emission at 600 nm , VersaMax Microplate Reader; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, USA). The premixed AlamarBlue reagent was added to the media above the cells in a dilution of

Statistical analysis

To identify differences between groups, an unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was performed. The standard error of the mean was calculated using GraphPad PRISM (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, United States).

Results

Accuracy of specimen

The specimens were manually measured using a digital caliper gauge and demonstrated high accuracy as they reached the desired diameter of 1 cm as well as various thicknesses of

Cell proliferation and viability

Initially, the effect of Graphy’s aligner resin Tera Harz TA-28 on oral gingival fibroblasts (HGF) was assessed using specimens of different material thicknesses (

Live cell imaging over 72 h also showed that the cells proliferated under all conditions (Fig. 3B), with no morphological changes observed and no cells detaching from the well bottom.

Subsequently, the UV curing duration was varied (20, 30 and 60 min ). Once again, no reduction in cell viability exceeding 30% was observed (Fig. 4). Cell viability decreased with increasing curing time for all material

Fig. 2. Measured thickness of specimens (

Fig. 3. Cell viability of HGF exposed to “Tera Harz TA-28”. (A) Specimens of various thicknesses (

thicknesses, with specimens of 2,4 and 6 mm showing the greatest loss in cell viability when cured for 30 min . Curing for 60 min , however, showed a subsequent increase in cell viability.

In a further approach, we investigated the influence of saliva on the potential release of biologically active substances from the aligner material. Therefore, specimens of all different thicknesses (

Discussion

DPAs are anticipated to be a milestone in clear aligner therapy due to their multiple advantages, such as improved precision and fit, compared to traditional clear aligners produced in a thermoforming process

Fig. 4. Variation in cell viability assessed following post processing (UV curing) for different durations (20, 30, 60 min ). Specimens in media for 12 days and treatment of HGFs with the conditioned media (

Fig. 5. Cell viability of HGFs exposed to “Tera Harz TA-28” in saliva. (A)

differences in properties, such variations are likely influenced by factors such as the choice of printer, printer settings and the post-processing protocols applied

In addition to customized pressure zones, the variability in the DPAs’ digital design allows orthodontists to produce almost any kind of desired, custom-made removable orthodontic appliance: For instance, posterior bite blocks designed by increasing posterior occlusal layer thickness significantly up to several millimeters can be used to create Class II mechanics similar to the Twin-Block or the Mandibular Advancement Tool (Invisalign, Align Technology, San Joé, CA, USA). Molar intrusion in patients with anterior open bite can be facilitated as well.

However, from our perspective, these benefits come with the risk of exposing patients to cytotoxic monomers as a longer UV curing duration might be needed for the UV light to fully polymerize the whole volume in areas of higher material thickness. Insufficient or incomplete curing of the resin may increase the potential for adverse side effects.

During active treatment, strict adherence to the essential wearing time of

This study evaluates the biocompatibility of DPAs made from Graphy’s new aligner resin, Tera Harz TA-28, as well as assesses the effects of different material thicknesses on cell viability. These findings will contribute to a deeper understanding of the material’s properties and its potential clinical applications. Until now, it was unclear whether such design adaptations would require significant alterations in the post-curing process to still guarantee biological safe use in patients. When following the company’s curing guidelines and curing the specimens for 20 min each, a slight loss of cell vitality is detected with increasing thickness. To further evaluate the interplay between DPAs’ thickness, curing time, and the resulting cytotoxicity in more detail, the effects of eluates from specimens of different thicknesses, cured for either 20, 30 , or 60 min , on HGFs were analyzed. For specimens with 0.5 mm and 1 mm thickness, cell viability decreased with increasing curing time. However, specimens with a thickness of 2,4 , or 6 mm showed the greatest loss in cell viability at a curing time of 30 min , with viability increasing again at 60 min (Fig. 3). Although the decrease in cell viability for all combinations was less than

Similar to previous research, one limitation of the current study, being in-vitro, is the inability to fully simulate all potential intraoral influences including chewing forces and bruxism which may damage the DPAs surface exposing inner layers that might not be fully cured, pH , temperature fluctuations, microbial activity as well as enzymatic reactions (e.g. esterases)

Conclusions

The introduction of DPAs using Graphy’s aligner resins marks a significant innovation over traditional thermoformed aligners. The current study confirmed the high accuracy of the production method, as all specimens achieved their target dimensions irrespective of the UV curing time. The standard 20 -minute UV curing protocol was sufficient to ensure biocompatibility and, thus, patient safety for material thicknesses up to 6 mm .

Data availability

All datasets are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Received: 22 October 2024; Accepted: 2 January 2025

Published online: 25 January 2025

Received: 22 October 2024; Accepted: 2 January 2025

Published online: 25 January 2025

References

- Castroflorio, T., Parrini, S. & Rossini, G. Aligner biomechanics: where we are now and where we are heading for. J. World Fed. Orthod.. 13 (2), 57-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejwf.2023.12.005 (2024).

- Bichu, Y. et al. Advances in orthodontic clear aligner materials. Bioactive Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.10.006

- Weir, T. Clear aligners in orthodontic treatment. Aust Dent. J. 62 (Suppl 1), 58-62. https://doi.org/10.1111/adj. 12480 (2017).

- Rosvall, M. D., Fields, H. W., Ziuchkovski, J., Rosenstiel, S. F. & Johnston, W. M. Mar. Attractiveness, acceptability, and value of orthodontic appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 135(3): e1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.09.020 (2009).

- Abbate, G. M. et al. Periodontal health in teenagers treated with removable aligners and fixed orthodontic appliances. J. Orofac. Orthop.. 76 (3), 240-250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-015-0285-5 (2015).

- Shokeen, B. et al. The impact of fixed orthodontic appliances and clear aligners on the oral microbiome and the association with clinical parameters: a longitudinal comparative study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 161 (5), e475-e485. https://doi.org/10.101 6/j.ajodo.2021.10.015 (2022).

- Tartaglia, G. M. et al. Direct 3D Printing of Clear Orthodontic aligners: current state and future possibilities. Materials https://doi .org/10.3390/ma14071799 (2021).

- Tera Harz Clear. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf24/K240597.pdf

- Luo, K. et al. Effect of post-curing conditions on surface characteristics, physico-mechanical properties, and cytotoxicity of a 3D-printed denture base polymer. Dent. Mater. 40 (3), 500-507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2023.12.017 (2024).

- Grant, J. et al. Forces and moments generated by 3D direct printed clear aligners of varying labial and lingual thicknesses during lingual movement of maxillary central incisor: an in vitro study. Prog Orthod.. 10 (1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-023-004 75-2 (2023).

- Koenig, N. et al. Comparison of dimensional accuracy between direct-printed and thermoformed aligners. Korean J. Orthod. 25 (4), 249-257. https://doi.org/10.4041/kjod21.269 (2022).

- Hertan, E., McCray, J., Bankhead, B. & Kim, K. B. Force profile assessment of direct-printed aligners versus thermoformed aligners and the effects of non-engaged surface patterns. Prog. Orthodont. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40510-022-00443-2 (2022).

- Lee, S. Y. et al. Thermo-mechanical properties of 3D printed photocurable shape memory resin for clear aligners. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 6246. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09831-4 (2022).

- Can, E. et al. In-house 3D-printed aligners: effect of in vivo ageing on mechanical properties. Eur. J. Orthod. 25 (1), 51-55. https:/ /doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjab022 (2022).

- Zinelis, S., Panayi, N., Polychronis, G., Papageorgiou, S. N. & Eliades, T. Comparative analysis of mechanical properties of orthodontic aligners produced by different contemporary 3D printers. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 25 (3), 336-341. https://doi.org/10. 1111/ocr. 12537 (2022).

- Narongdej, P., Hassanpour, M., Alterman, N., Rawlins-Buchanan, F. & Barjasteh, E. Advancements in Clear Aligner fabrication: a comprehensive review of Direct-3D Printing technologies. Polymers. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym16030371 (2024).

- Alessandra, C. et al. Comparison of the cytotoxicity of 3D-printed aligners using different post-curing procedures: an in vitro study. Australas. Orthod. J. 39 (2), 49-56. https://doi.org/10.2478/aoj-2023-0026 (2023).

- Pratsinis, H. et al. Cytotoxicity and estrogenicity of a novel 3-dimensional printed orthodontic aligner. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 162 (3), e116-e122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.06.014 (2022).

- Iodice, G. et al. Effect of post-printing curing time on cytotoxicity of direct printed aligners: a pilot study. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/ocr. 12819 (2024).

- Willi, A. et al. Leaching from a 3D-printed aligner resin. Eur. J. Orthod. 31 (3), 244-249. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjac056 (2023).

- Park, S. Y. et al. Comparison of translucency, thickness, and gap width of thermoformed and 3D-printed clear aligners using micro-CT and spectrophotometer. Sci. Rep. 5 (1), 10921. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36851-5 (2023).

- Sayahpour, B. et al. Effects of intraoral aging on mechanical properties of directly printed aligners vs. thermoformed aligners: an in vivo prospective investigation. Eur. J. Orthod. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjad063 (2024).

- Shirey, N., Mendonca, G., Groth, C. & Kim-Berman, H. Comparison of mechanical properties of 3-dimensional printed and thermoformed orthodontic aligners. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 163 (5), 720-728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2022.12.008 (May 2023).

- Edelmann, A., English, J. D., Chen, S. J. & Kasper, F. K. Analysis of the thickness of 3-dimensional-printed orthodontic aligners. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop.. 158 (5), e91-e98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.07.029 (2020).

- McCarty, M. C., Chen, S. J., English, J. D. & Kasper, F. Effect of print orientation and duration of ultraviolet curing on the dimensional accuracy of a 3-dimensionally printed orthodontic clear aligner design. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 158 (6), 889-897. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.03.023 (2020).

- Mattle, M. et al. Effect of heat treatment and nitrogen atmosphere during post-curing on mechanical properties of 3D-printed orthodontic aligners. Eur. J. Orthod. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjad074 (2024).

- Graphy, T. C. 85 Certification Workshop. FORESTADENT. https://www.forestadent.com/de-de/kurse-kongresse/event/zertifizie rungsworkshop-graphy-tc-85-direct-print-aligner/

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms Sonja Hoch-Kraft, Ms Rahel Regitz for their excellent technical support and Mr Christian Gehrke, Mr Matthias Quoß and Carsten Mohr for 3D printing the specimens.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M.B., C.W-J., V.K., B.L and C.E.; Design: C.W-J. and C.E.; Methodology: C.W-J.; Data ac-

quisition C.W-J.; Validation: C.W-J., M.B., V.K., and C.E.; Data analysis, interpretation and visualisation C.W-J.; Writing, review and editing: M.B., C.W-J., V.K., B.L. and C.E.; Resources: C.E. and B.L.; Project administration: C.E. and B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

quisition C.W-J.; Validation: C.W-J., M.B., V.K., and C.E.; Data analysis, interpretation and visualisation C.W-J.; Writing, review and editing: M.B., C.W-J., V.K., B.L. and C.E.; Resources: C.E. and B.L.; Project administration: C.E. and B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.B. or C.W.-J.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2025

© The Author(s) 2025

Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, University Medical Center of the Johannes GutenbergUniversity Mainz, Augustusplatz 2, 55131 Mainz, Germany. ²Department of Orthodontics, University of Homburg, Saar, Germany. Private Practice of Orthodontics, Am Bahnhof 54, 56841 Traben-Trarbach, Germany. Maximilian Bleilöb, Claudia Welte-Jzyk contributed equally to this work. email: maximilian.bleiloeb@unimedizin-mainz.de; Claudia.Welte-Jzyk@unimedizin-mainz.de