DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-023-03171-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38216871

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-12

الجسيمات النانوية السيلينيوم البيوجينية وكونجوجيت السيلينيوم/الكيتوزان التي تم تخليقها حيوياً بواسطة ستربتوميسيس بارفولوس MAR4 مع إمكانيات مضادة للميكروبات ومضادة للسرطان

الملخص

الخلفية: مع تراجع فعالية المضادات الحيوية والعلاج الكيميائي، تعتبر الكائنات الحية المقاومة لمتعدد الأدوية (MDR) والسرطان حاليًا من أخطر التهديدات لحياة الإنسان. في هذه الدراسة، تم اقتراح أن تكون جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية (SeNPs) التي تم تخليقها حيويًا بواسطة Streptomyces parvulus MAR4، والناانو-كيتوزان (NCh)، وموحدهما النانوي (Se/Ch-nanoconjugate) عوامل مضادة للميكروبات ومضادة للسرطان فعالة. النتائج: تم تحقيق جزيئات SeNPs التي تم تخليقها حيويًا بواسطة Streptomyces parvulus MAR4 وNCh بنجاح وتوحيدها. كانت جزيئات SeNPs الكروية الشكل بمتوسط قطر 94.2 نانومتر واستقرار عالٍ. ومع ذلك، كان موحد Se/Ch-nanoconjugate شبه كروي بمتوسط قطر 74.9 نانومتر واستقرار أعلى بكثير. أظهرت جزيئات SeNPs وNCh وموحد Se/Chnanoconjugate نشاطًا مضادًا للميكروبات ملحوظًا ضد مجموعة متنوعة من الكائنات الحية الدقيقة مع تأثير مثبط قوي على إنزيماتها الرئيسية المختبرة [إيزوميراز الفوسفوغلوكوز (PGI)، ديهيدروجيناز البيروفات (PDH)، ديهيدروجيناز الجلوكوز-6-فوسفات (G6PDH) والاختزال النيتري (NR)]; كان موحد Se/Ch-nanoconjugate هو الأكثر قوة. علاوة على ذلك، أظهرت جزيئات SeNPs سمية خلوية قوية ضد HepG2.

مقدمة

حالياً، يتم استخدام تكنولوجيا النانو في مجالات متعددة تتعلق بالإنسان، مثل الطب الحيوي، والتغذية، والكيماويات، والبيولوجيا، والميكانيكا، والبصريات، والبيئة، والزراعة [6-8]. نظراً لوظيفتها المتميزة وتفاعليتها، تم استخدام جزيئات النانو المعدنية (NPs) على نطاق واسع في أغراض طبية حيوية متنوعة، بما في ذلك مضادات البكتيريا، ومضادات الأكسدة، ومضادات السرطان، ومضادات التخثر، أو كحاملات لمركبات نشطة حيوياً [8-11].

تم الإبلاغ عن عدة طرق لتخليق الجسيمات النانوية، بما في ذلك الطرق الكيميائية والفيزيائية والبيولوجية. عادةً ما تكون العمليات الكيميائية والفيزيائية معقدة ومكلفة، مما يؤدي إلى إطلاق نواتج ثانوية خطرة تهدد الأنظمة البيئية. بالمقابل، يمكن للطريقة البيولوجية باستخدام عوامل بيولوجية، مثل البوليمرات الحيوية، مستخلصات النباتات، الكائنات الدقيقة، الطحالب، أو مشتقاتها، أن تتغلب بنجاح على معظم المشاكل المرتبطة بالطرق الكيميائية والفيزيائية، مما يوفر طرقًا بسيطة وصديقة للبيئة وعالية العائد واقتصادية. تعتبر الأكتينوميسيتات بكتيريا موجبة الجرام ذات تباين عالٍ، واستقرار قوي، وسهولة في التعامل. تنتج الأكتينوميسيتات، وخاصةً الأنواع من جنس ستربتوميسيس، عدة مستقلبات ثانوية، مثل الإنزيمات والبروتينات، التي يمكن استخدامها لتقليل الأيونات وتغطية المعادن على النانو مقياس.

السيلينيوم (Se) هو عنصر غذائي دقيق حيوي يحافظ على صحة الإنسان ووظائف الجسم (مع نطاق ضيق بين مستويات السمية ونقص التغذية يبلغ 400 و

الكيتوزان (Ch) هو بوليمر حيوي غير سام ذو شحنة موجبة وله مجموعة واسعة من الاستخدامات البيولوجية بسبب أصله الكيميائي الفريد وشحنته الإيجابية ووجوده

يمكن الحصول على Ch من إزالة الأسيتيل من الكيتين الموجود في قشور القشريات (مثل السلطعون، والجراد، والروبيان) ومجموعة متنوعة من الكائنات الحية (مثل الحشرات والفطريات). علاوة على ذلك، يتم تسويق Ch لخصائصه الاستثنائية، بما في ذلك القابلية للتحلل البيولوجي، والتوافق الحيوي، والقدرة على تشكيل الأفلام، والامتصاص، وشفاء الجروح، ومكافحة البكتيريا، ومكافحة السرطان، ومضادات الأكسدة.

المواد والطرق

المادة

تم الحصول على النيستاتين وخطوط الخلايا من شركة سيغما-ألدريش (سانت لويس، ميزوري، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية). تم الحصول على مصل الجنين البقري (FBS) وMTT من جيبكو، المملكة المتحدة. تم الحصول على مجموعة Qiagen DNeasy للدم والأنسجة من كياجن، هيلدن، ألمانيا. تم الحصول على جميع المذيبات والمخازن والمواد الكيميائية من شركة النصر للكيماويات الدوائية (القاهرة، مصر).

جمع عينات بحرية وعزل الأكتينوميسيتات

تخليق الجسيمات النانوية من السيلينيوم (SeNPs)

تحديد السلالة المحتملة

تحضير النانو-كيتوزان (NCh) والنانوكونجوجيت

توصيف الجسيمات النانوية (NPs) والنانوكونجوجيت

النشاط المضاد للميكروبات

تأثير الجسيمات النانوية المصنعة على نشاط إنزيمات الأيض للميكروبات الممرضة المختبرة إعداد مستخلصات الإنزيمات

تم تلقيح S. aureus و E. coli و S. typhi و P. vulgaris في وسط LB وتم حضنها طوال الليل في

اختبار الإنزيمات

تحديد نشاط إنزيم البيروفات ديهيدروجيناز (PDH)

تحديد نشاط إنزيم جلوكوز-6-فوسفات ديهيدروجيناز (G6PD)

معلومات عند 340 نانومتر. كان حجم خليط التفاعل 3 مل، والذي احتوى على 1.5 مل من

تحديد نشاط نازعة نترات (NR)

تحديد محتوى البروتين القابل للذوبان الكلي

النشاط السمي للخلايا

كان متاحًا من قبل EXL 800، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. تم تقديم البيانات كمتوسط

التحليل الإحصائي

النتائج

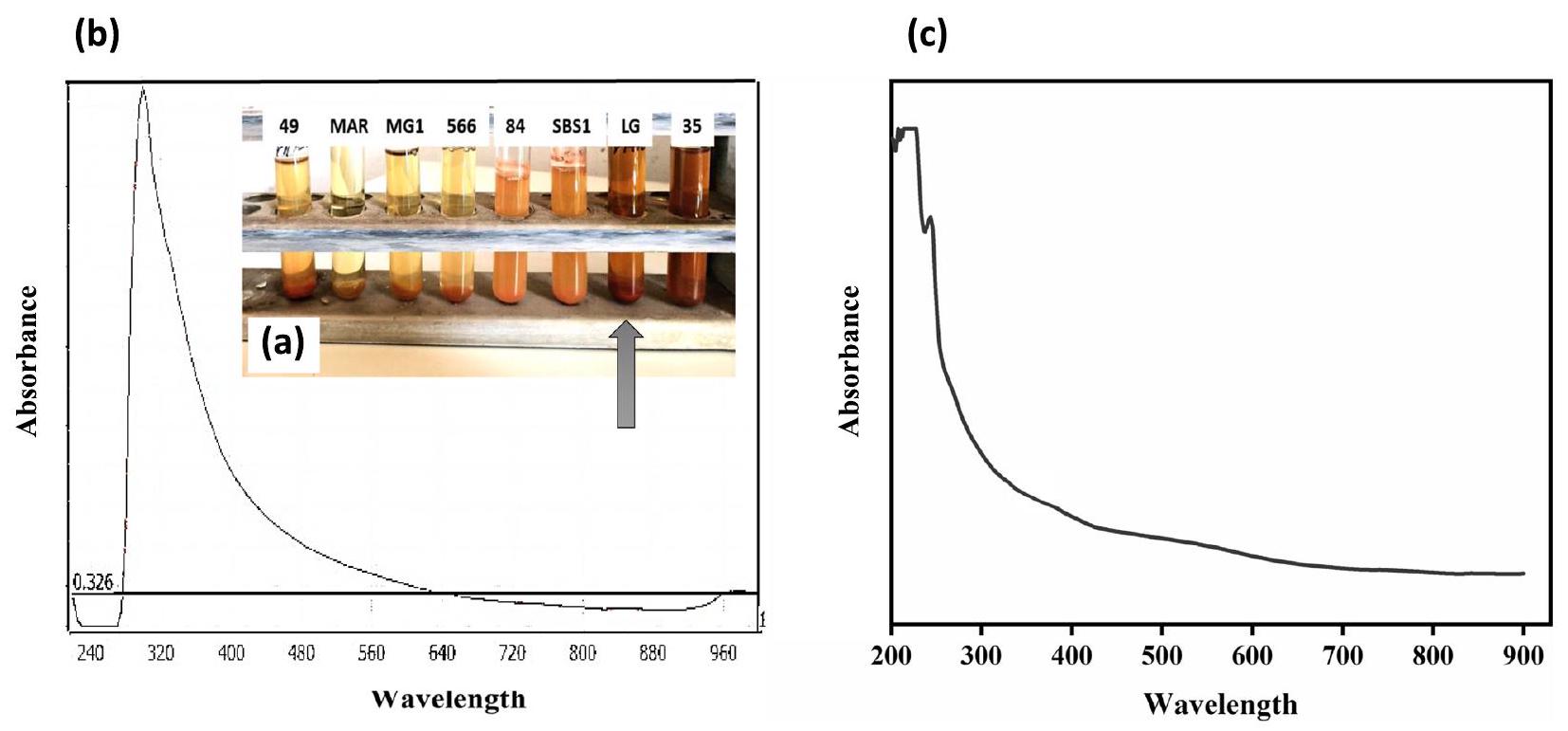

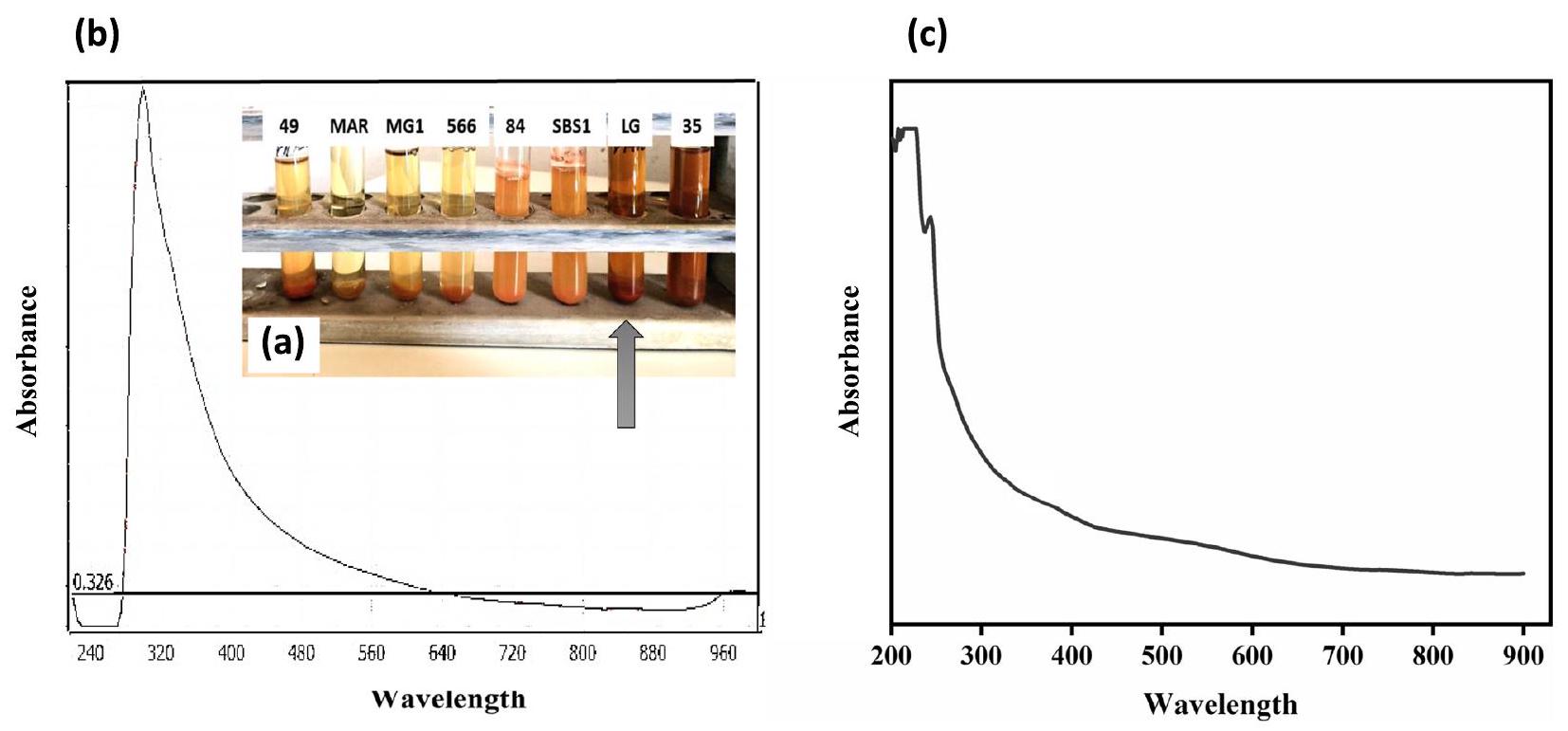

تخليق الجسيمات النانوية السيلينيوم وتحليل الطيف المرئي فوق البنفسجي

تحديد العزلة المحتملة

تحليل النشوء والتطور، العزلة LG وStreptomyces parvulus مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا من الناحية الجينية.

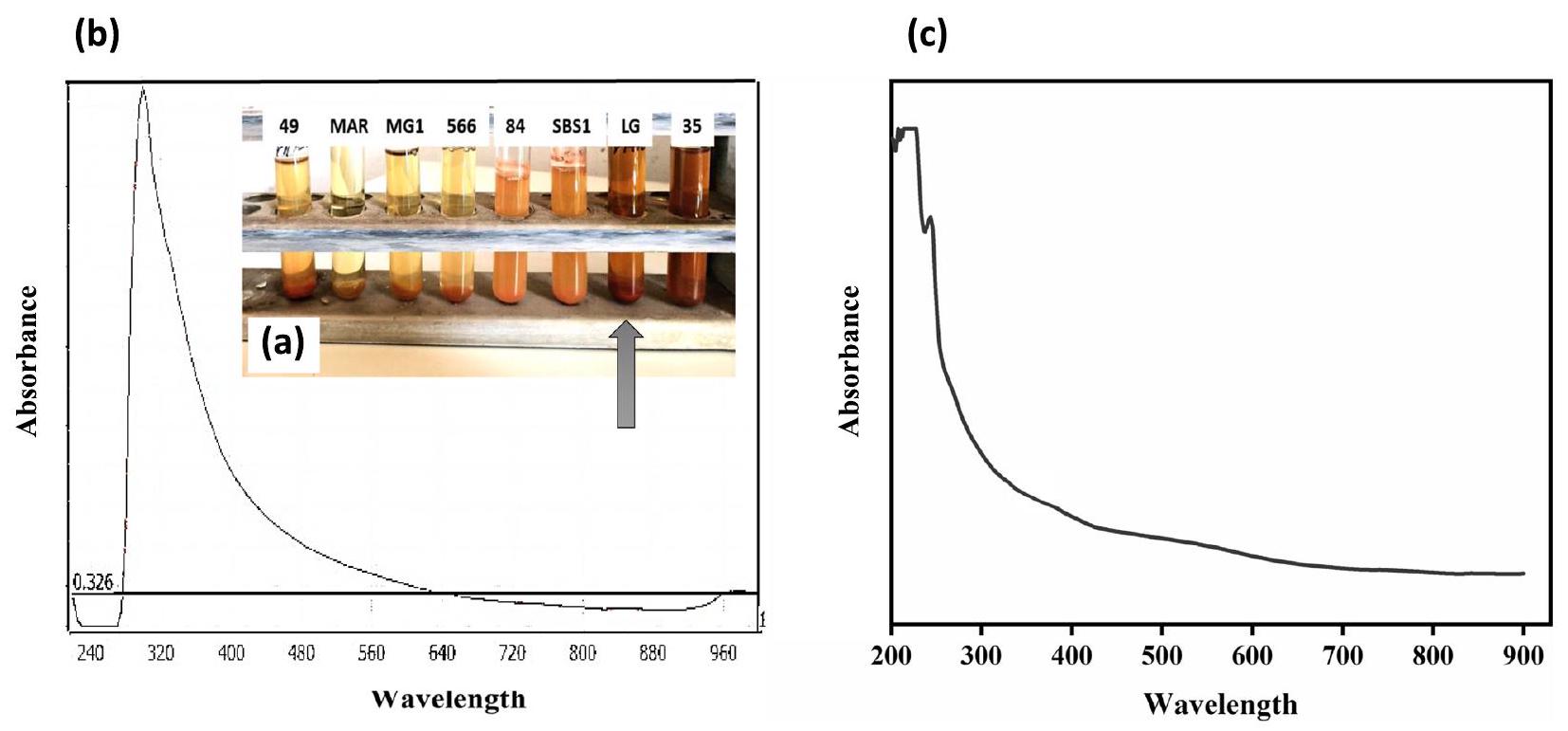

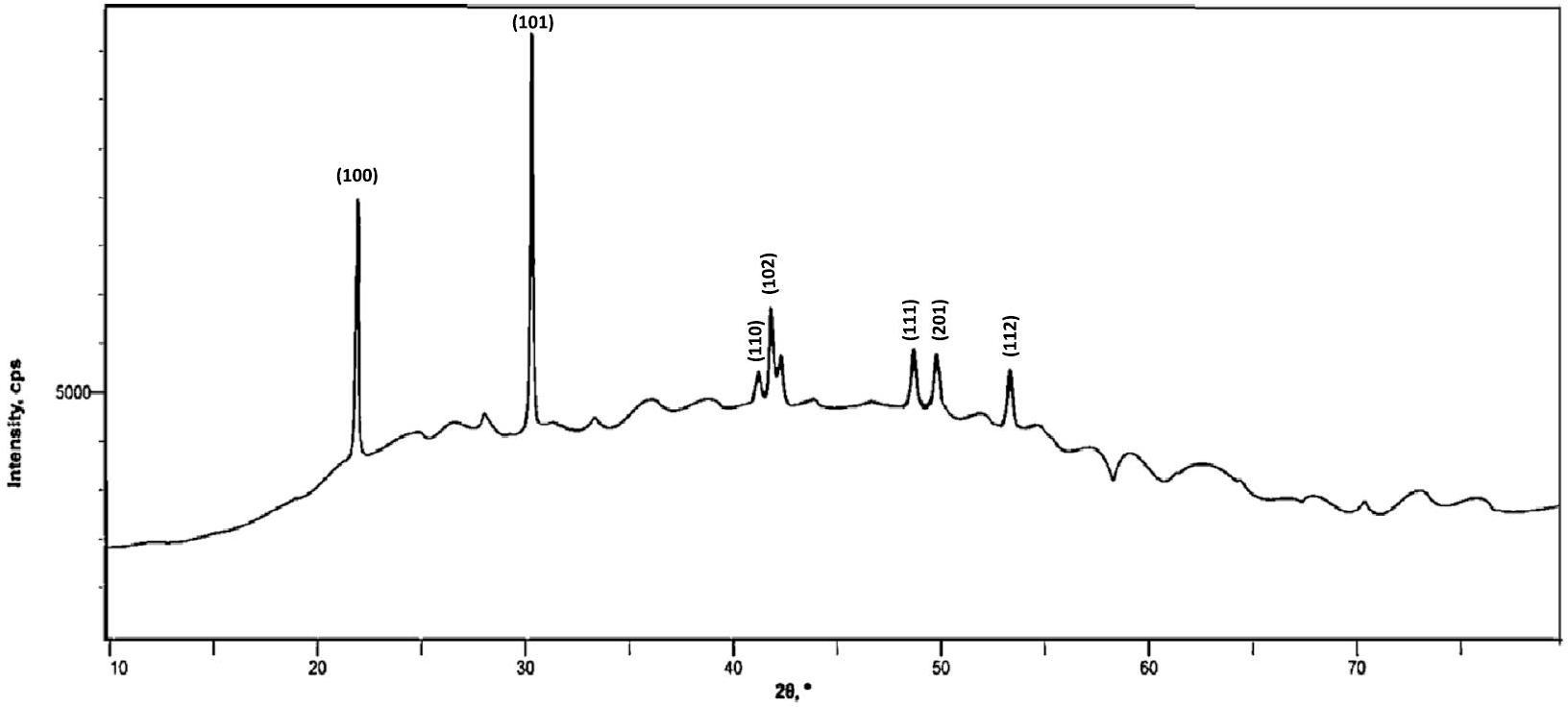

تحليل حيود الأشعة السينية

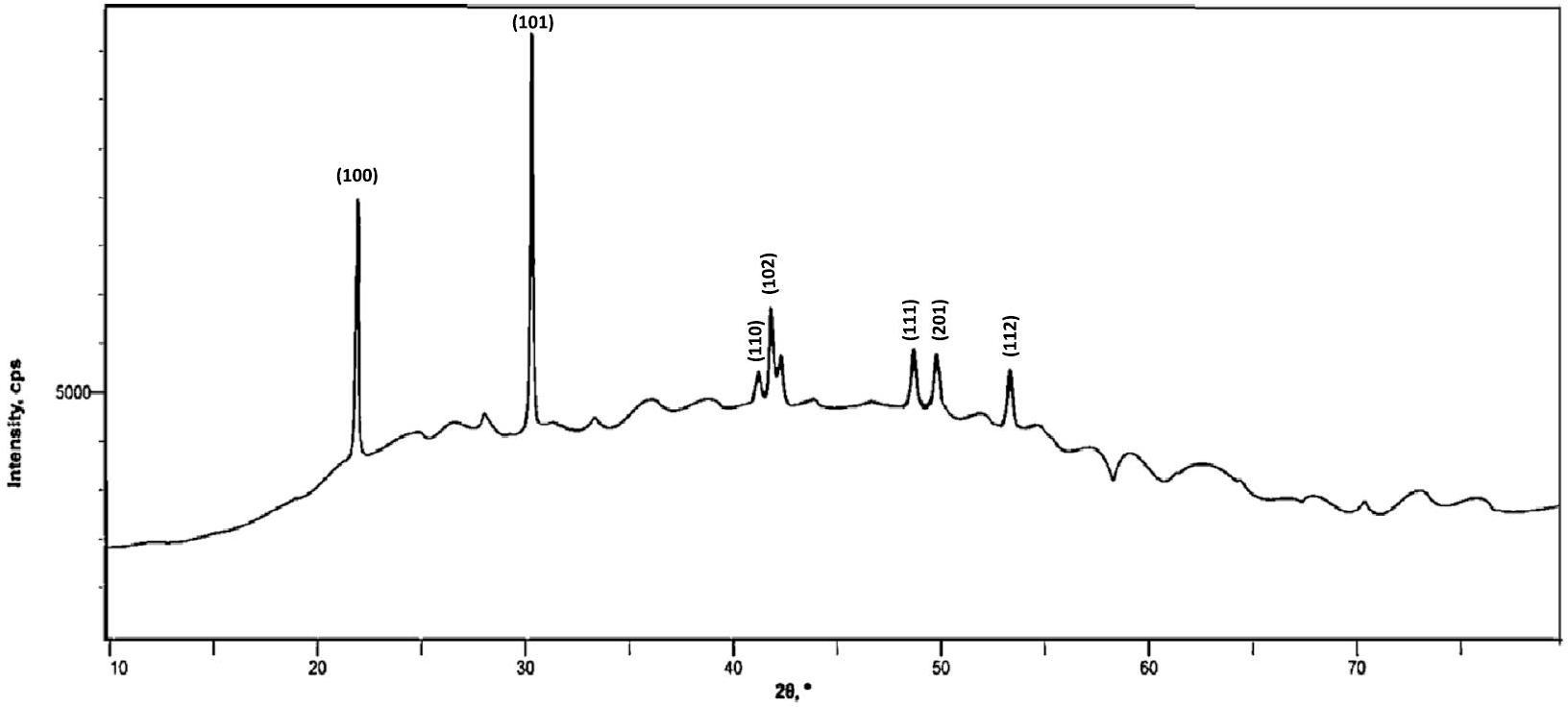

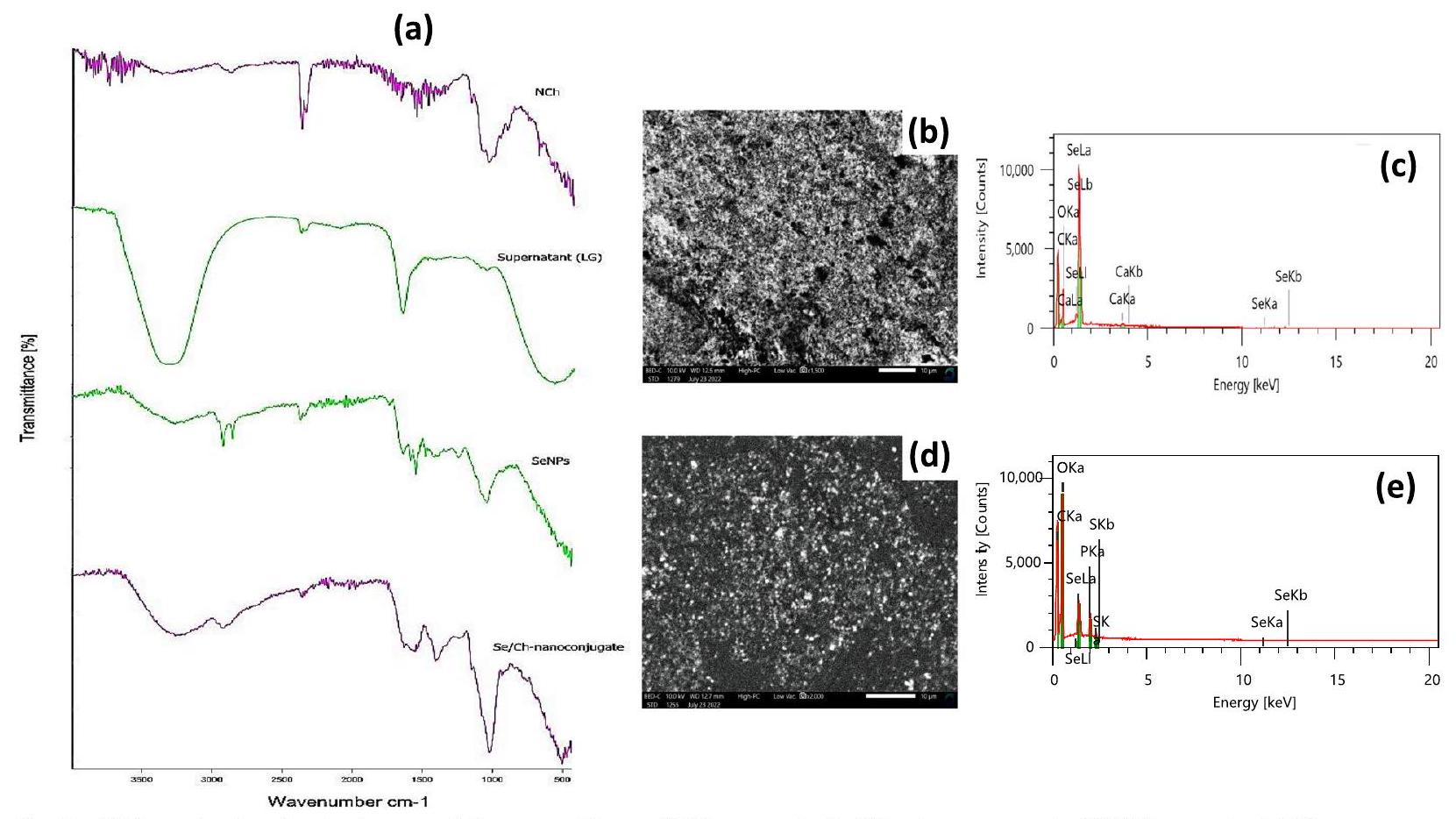

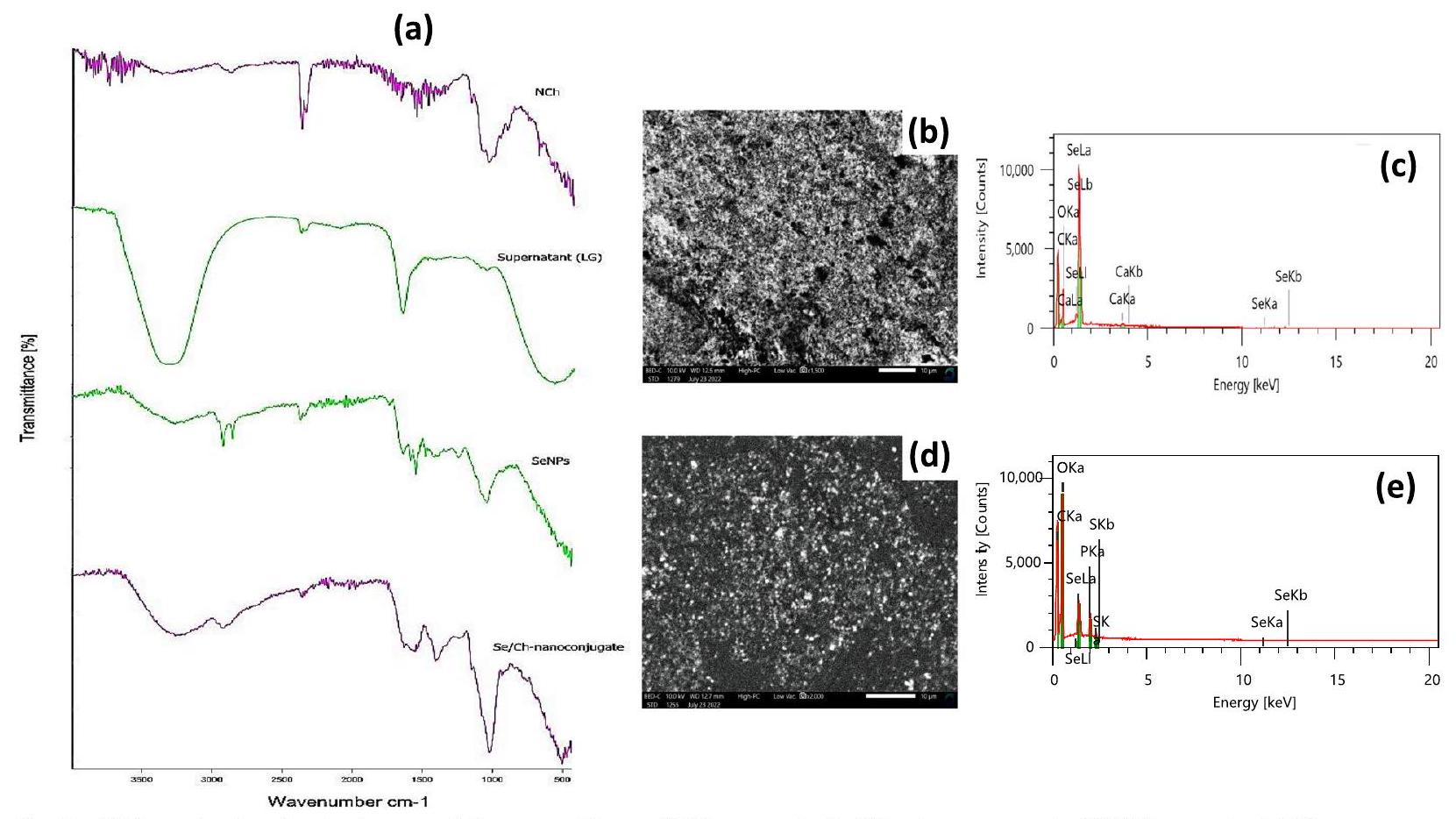

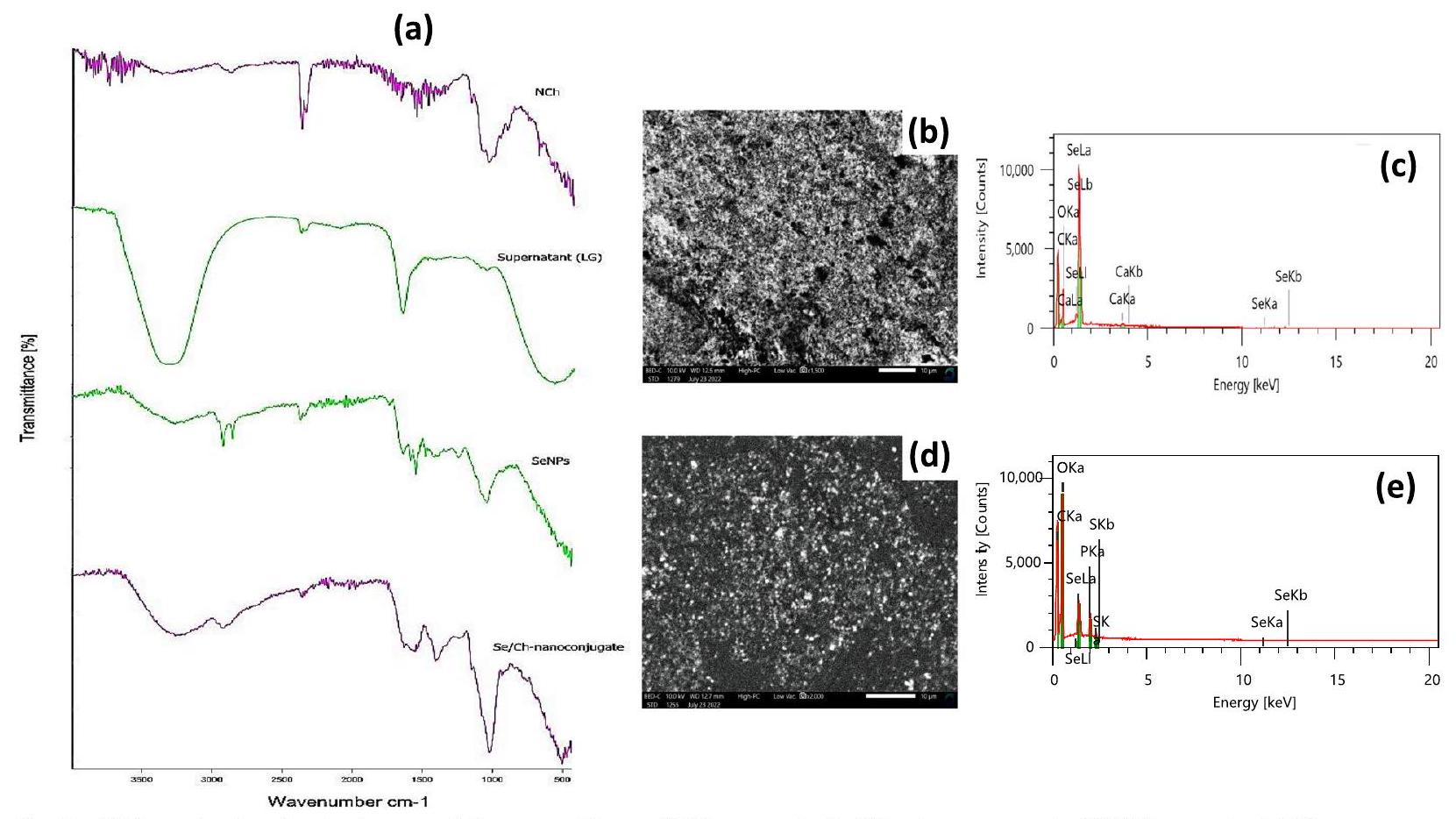

تحليل FTIR

المجموعات الوظيفية اللازمة لـ

تحليل TEM

تحليلات SEM و EDX

| NPs |

|

PDI | (الجهد (ملي فولت | ||

| جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية | 196,2 | 0.252 | ٣٧.٠٨ | ||

|

٤٧٦.٦ | 0.264 | ٥٥.٩١ |

قطر هيدرو ديناميكي وزيتا (

يتم تقدير تجانس المحلول بواسطة مؤشر التوزيع المتعدد (PDI). تتراوح قيمة PDI من 0 إلى 1، حيث يمثل 0 محلولًا مثاليًا يحتوي على جزيئات متساوية الحجم، ويمثل 1 محلولًا متنوعًا للغاية يحتوي على جزيئات بأحجام مختلفة. تعتبر القيم التي تقل عن 0.5 أحادية التوزيع، بينما تعتبر القيم التي تزيد عن 0.7 متعددة التوزيع بشكل كبير [73]. أظهرت جزيئات نانو السيلينيوم (SeNPs) والجزيئات النانوية المرتبطة بالسيلينيوم/الكيتوزان (Se/Ch-nanoconjugate) قيم PDI أقل من 0.5 (0.252 و0.264 على التوالي)، مما يشير إلى أنها كانت أحادية التوزيع، مستقرة، ومتساوية الحجم في المحلول.

من خلال قياس

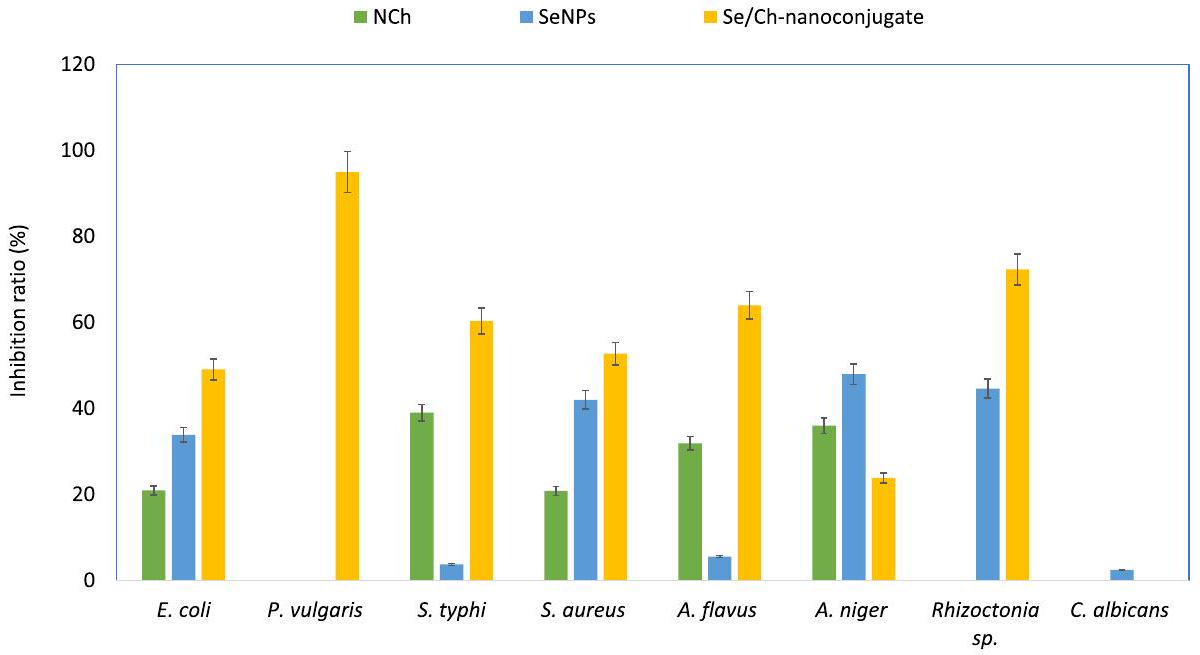

النشاط المضاد للميكروبات

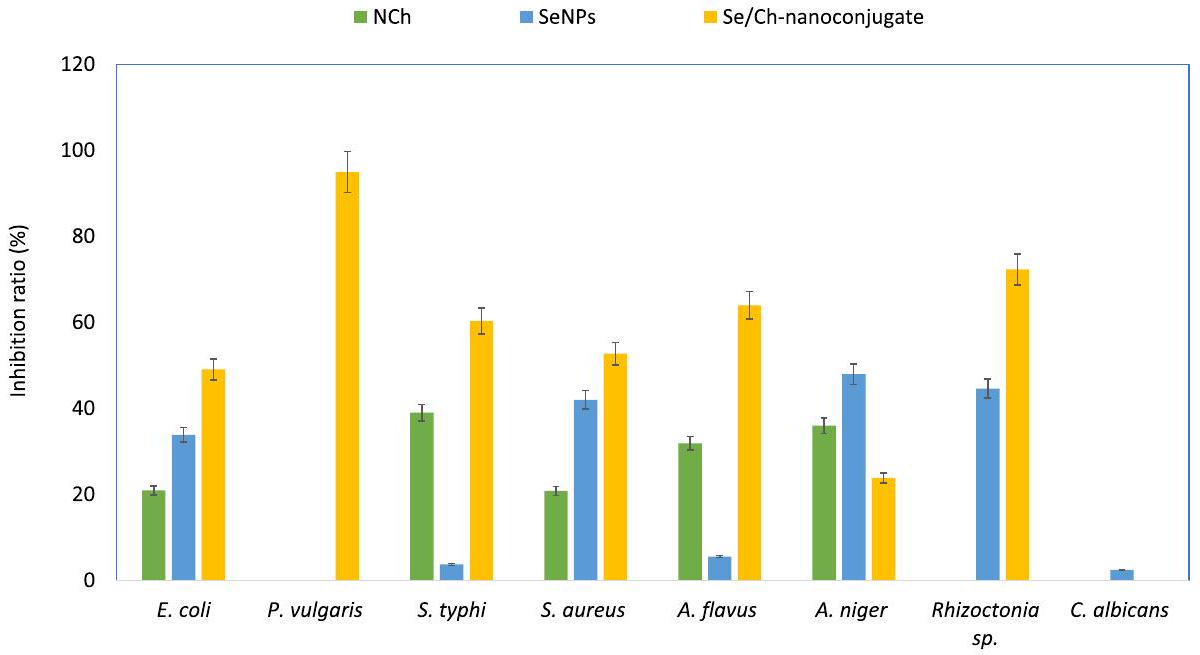

نطاق واسع من النشاط المضاد للميكروبات ضد كل من السلالات البكتيرية والفطرية (الشكل 6). أظهر مركب Se/Ch-النانو أعلى فعالية وقدم نشاطًا مضادًا للميكروبات متفوقًا ضد معظم مسببات الأمراض الميكروبية المختبرة. أظهر مركب Se/Ch-النانو تأثيرًا مضادًا للبكتيريا أقوى من تأثيره المضاد للفطريات.

تأثير الجسيمات النانوية المصنعة على نشاط إنزيمات الأيض للميكروبات الممرضة المختبرة

| NPs المختبرة | % تثبيط PGI | |||||||

| E. coli | ب. فالجريس | س. التيفية | المكورات العنقودية الذهبية | أ. فلافوس | أ. نيجر | رايزوكطونيا | المبيضات البيضاء | |

| NCh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| مركب نانو سيلينيوم/كربون |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NPs المختبرة | % تثبيط PDH | |||||||

| E. coli | ب. فالجريس | س. التيفي | المكورات العنقودية الذهبية | أ. فلافوس | أ. نيجر | رايزوكطونيا | المبيضات البيضاء | |

| NCh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| مركب نانو سيلينيوم/كربون |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NPs المختبرة | % تثبيط G6PDH | |||||||

| E. كولاي | ب. فulgariس | س. التيفي | المكورات العنقودية الذهبية | أ. فلافوس | أ. نيجر | رايزوكطونيا | المبيضات البيض | |

| NCh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| مركب النانو Se/Ch |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NPs المختبرة | % تثبيط NR | |||||||

| E. coli | ب. فulgariس | س. التيفي | المكورات العنقودية الذهبية | أ. فلافوس | أ. نيجر | رايزوكطونيا | المبيضات البيض | |

| NCh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| مركب نانو سيلينيوم/كربون |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

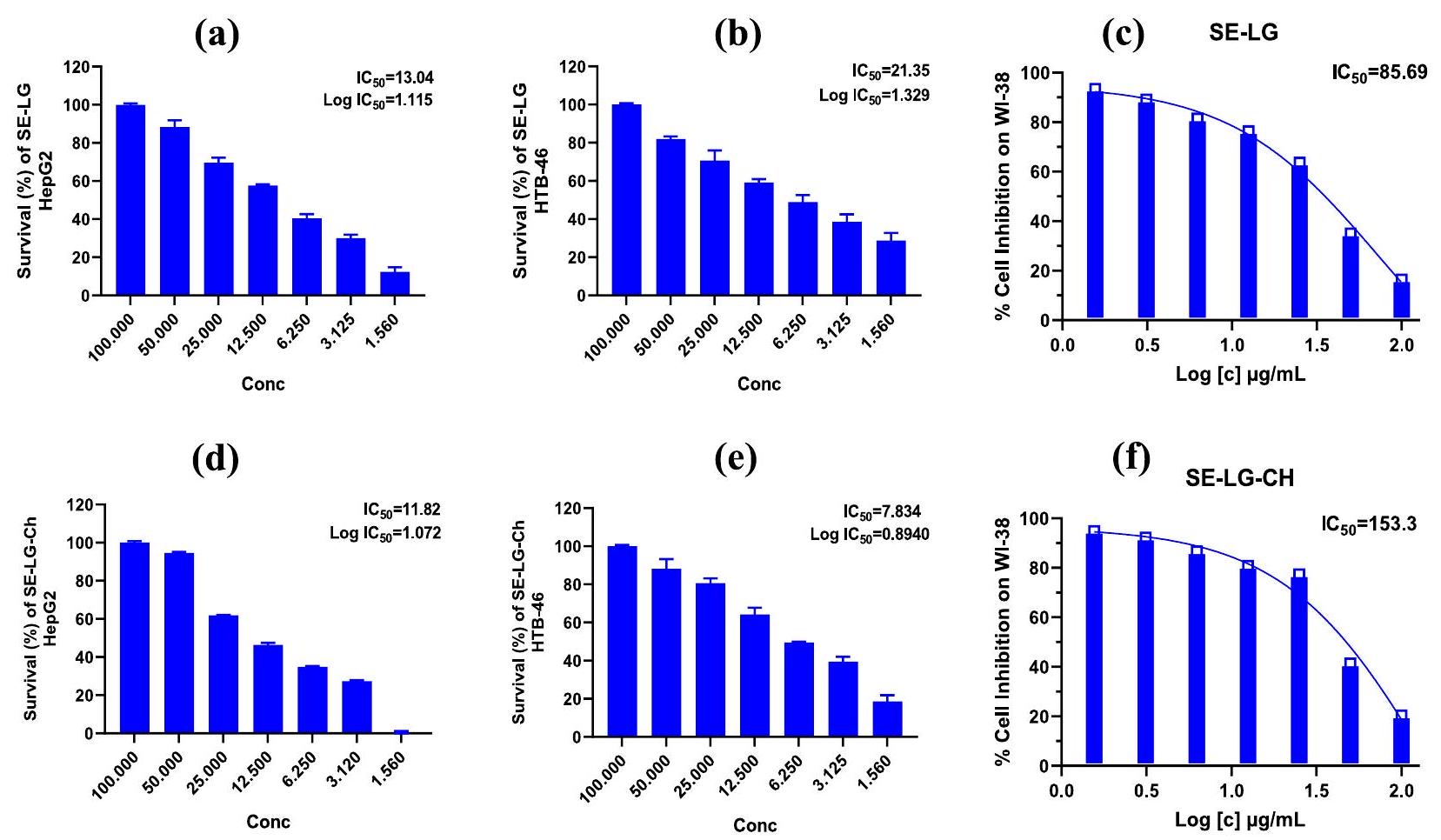

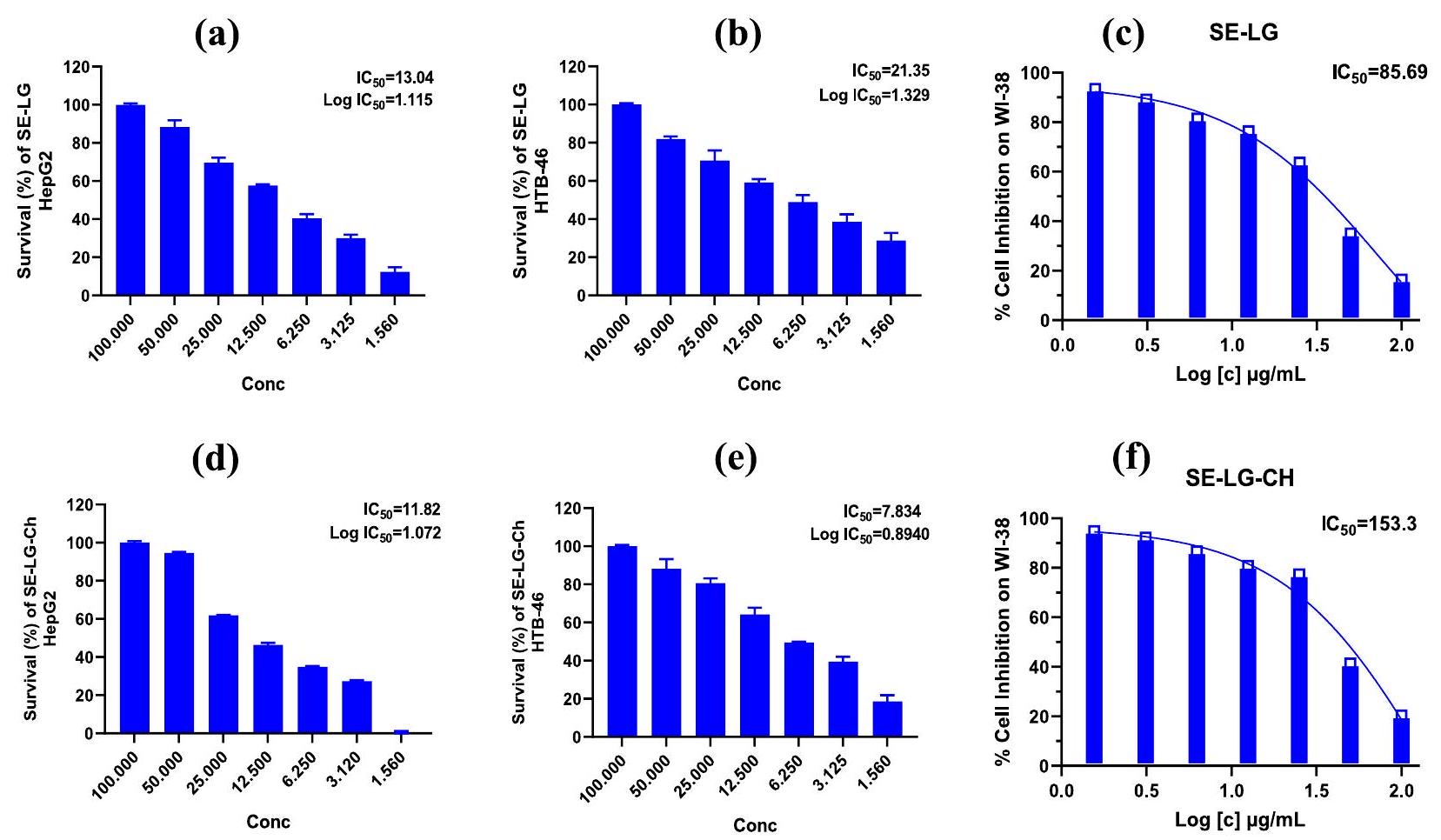

النشاط السمي للخلايا

| NPs المختبرة | هي بي جي – 2 | السُمية الخلوية في المختبر | |

| IC

|

|||

| HTB-46 | WI-38 | ||

| جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية | 13.04 | 21.35 | 85.69 |

| مركب نانو سيلينيوم/كربون | 11.82 | 7.83 | 153.3 |

نقاش

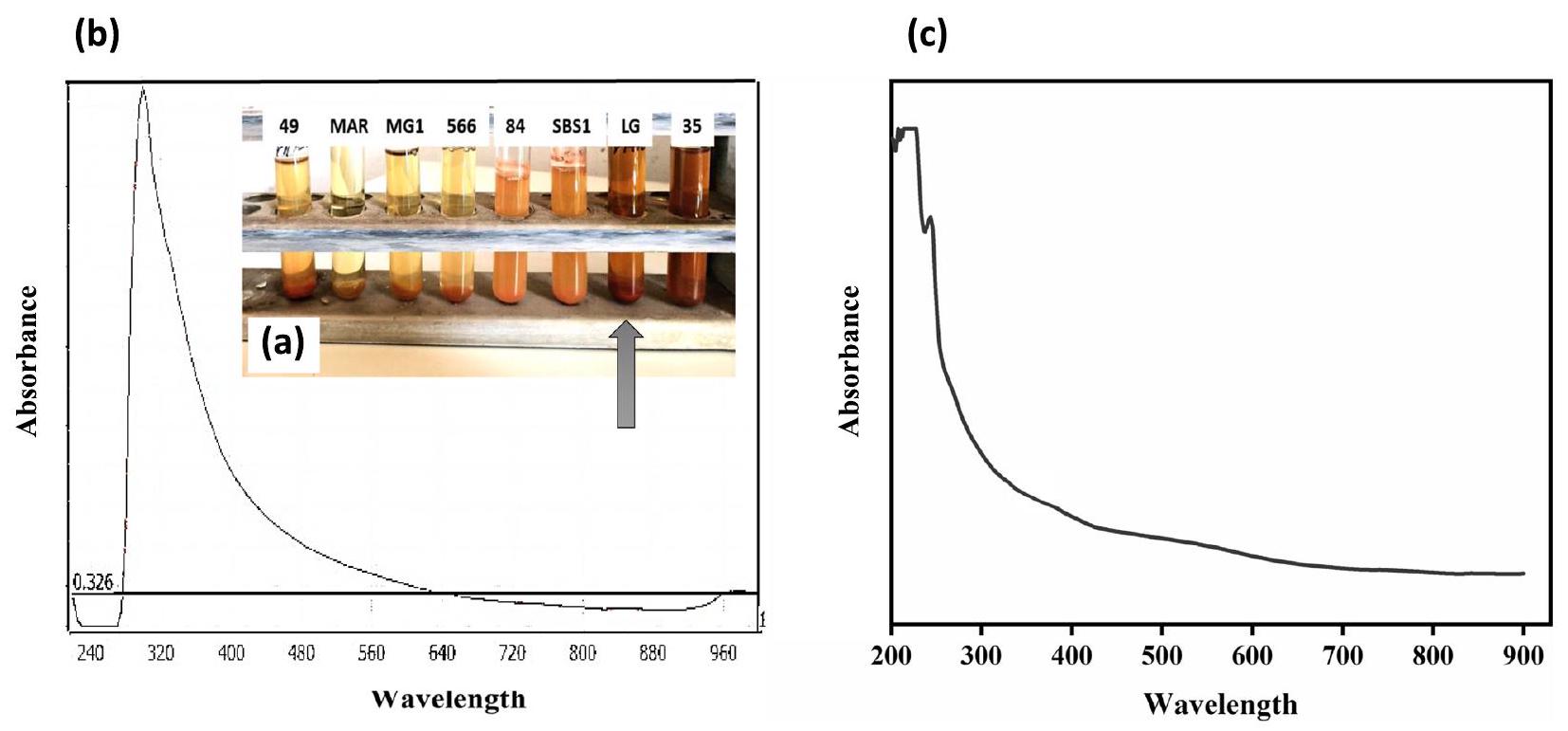

أظهرت الجسيمات النانوية من السيلينيوم التي تم تخليقها حيوياً قمة امتصاص حادة عند 300 نانومتر، وهو ما يتماشى مع الدراسات السابقة للجسيمات النانوية من السيلينيوم التي تم تخليقها بواسطة البكتيريا. وعلى العكس، أظهرت الأطياف فوق البنفسجية-المرئية للجسيمات النانوية من السيلينيوم التي تم تخليقها خارج الخلية بواسطة بكتيريا الزائفة الزنجارية وبكتيريا العصوية الشديدة اختلافاً في قمم الامتصاص عند 520 نانومتر و590 نانومتر، على التوالي. وبالتالي، تختلف الأطياف فوق البنفسجية-المرئية للجسيمات النانوية من السيلينيوم التي تم تخليقها حيوياً اعتماداً على هيكلها الذري.

وتخليق SeNPs اللاحق (الشكل 4a، السائل العلوي (LG)). تم توضيح الإنزيمات المعتمدة على NADH و/أو البروتينات المحتوية على الكبريت، التي تتمتع بخصائص اختزال ممتازة وتعمل كعوامل مساعدة في اختزال أيونات السيلينيد، من خلال اهتزاز OH وNH عند

تم الكشف عن التخليق الحيوي لجزيئات نانو السيلينيوم (SeNPs) وتكوين روابط جديدة مع جزيئات البيومولكولات في السائل الفائق (LG) من خلال طيف FTIR لجزيئات نانو السيلينيوم (شكل 4أ، SeNPs). النطاق العريض القوي عند

أكد مخطط EDX للنانوكونجوجيت (الشكل 4e) تشكيل NCh من خلال الربط المتقاطع مع TPP [98، 99].

تم الإبلاغ عن الفعالية المضادة للبكتيريا لـ NCh ضد مجموعة متنوعة من مسببات الأمراض الميكروبية، وتم توثيق عدة آليات مفترضة [115-117]. يُعتبر التفاعل الكهروستاتيكي بين مجموعة الأمين الموجبة الشحنة لـ NCT والأغشية الخلوية الميكروبية السالبة الشحنة واحدًا من الآليات الرئيسية المضادة للميكروبات، والتي تسبب تلف الخلايا من خلال تسرب البروتينات ومكونات خلوية أخرى [118، 119]. قد يعمل NCh أيضًا كعامل خالب، حيث يرتبط بالمعادن النادرة ويولد سمومًا تعيق نمو الميكروبات [120]. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن لـ NCT حمل والتحكم في إطلاق العوامل الحيوية النشطة [121].

نتيجة لذلك، يمكن لـ NCh بسهولة اختراق مسام غشاء الخلية الميكروبية حاملاً الجسيمات النانوية SeNPs التي تم تصنيعها حيوياً وإطلاقها هناك. وبناءً عليه، فإن النانوكونجوجيت له تأثيرات مباشرة على الخلايا؛ يمكن أن يتداخل مع تخليق ATP، ويؤثر على انقسام الخلايا، ويسبب تحلل الخلايا. علاوة على ذلك، فإن الشحنة الإيجابية الكبيرة لجسيمات Se/Ch-nanoconjugate يمكن أن تتفاعل كهربائياً مع الأغشية الخلوية السالبة الشحنة مما يسبب تلف الخلايا. وبالتالي، تم إثبات أن جسيمات Se/Ch-nanoconjugate هي أقوى عامل مضاد للميكروبات.

مؤخراً، حظيت الجسيمات النانوية من السيلينيوم التي تم تصنيعها حيوياً (SeNPs) بالكثير من الاهتمام كعامل محتمل لمكافحة السرطان بسبب نشاطها البيولوجي الملحوظ، وتوافقها الحيوي، وانخفاض سمّيتها. علاوة على ذلك، تم الإبلاغ عن عدم وجود آثار جانبية على الخلايا الطبيعية بينما تثبط بشكل محدد نمو الورم. في الدراسة الحالية، تم تحميل NCh لتحسين الخصائص البيولوجية للجسيمات النانوية من السيلينيوم التي تم تصنيعها حيوياً. أظهرت الجسيمات النانوية من السيلينيوم وSe/Ch-nanoconjugate نشاطاً مضاداً للسرطان متميزاً ضد خطوط خلايا الورم HepG2 وCaki-1 (HTB-46)؛ وكانت النانوكونجوجيت.

الأكثر قوة مع

الخاتمة

يمكن أن تُعزى الآليات إلى وجود عدة عوامل حيوية نشطة مجتمعة ذات طرق عمل متنوعة. كما أن الربط قلل من السمية وزاد من التوافق الحيوي والسلامة والنشاط البيولوجي لكل عامل فردي. علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن يتفاعل الشحنة الإيجابية الكبيرة للنانوربط بشكل كهربائي مع أغشية الخلايا السالبة الشحنة، مما يؤدي إلى تلف الخلايا. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم إثبات أن تثبيط الإنزيمات الأيضية الرئيسية كان أحد آلياتها المضادة للميكروبات من خلال التداخل مع هذه الإنزيمات وتعطيل العمليات الأيضية، مما يسبب تثبيط نمو وتكاثر الميكروبات. بشكل عام، يمكن تطبيق نانو-الربط Se/Ch كعامل طبي واعد له خصائص مضادة للميكروبات ومضادة للسرطان. ومع ذلك، هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من الدراسات المتعمقة لتوضيح الآليات الدقيقة الكامنة وراء تأثيراته المضادة للميكروبات والمضادة للسرطان بشكل كامل.

الاختصارات

| MDR | مقاوم متعدد الأدوية |

| جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية | جزيئات السيلينيوم النانوية |

| تش | كيتوزان |

| NCh | نانوشيتوزان |

| PGI | إيزوميراز الفوسفوغلوكوز |

| PDH | ديهيدروجيناز البيروفات |

| G6PDH | إنزيم جلوكوز-6-فوسفات ديهيدروجيناز |

| NR | نترات ريدوكتاز |

| الشراكة عبر المحيط الهادئ | ثلاثي فوسفات |

| تم | ميكروسكوبية الإلكترون الناقل |

| SEM | المجهر الإلكتروني الماسح |

| EDX | أشعة إكس المشتتة للطاقة |

| FTIR | طيف الأشعة تحت الحمراء بواسطة تحويل فورييه |

| CCG | شبكات نحاسية مغطاة بالكربون |

| لب | مرق ليسوجينيا |

| هيب جي 2 | خط الخلايا السرطانية الكبدية |

| كاكي-1 | خط الخلايا السرطانية للكلى |

| روس | أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية |

| FBS | مصل الجنين البقري |

شكر وتقدير

بيان توفر البيانات

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

نُشر على الإنترنت: 12 يناير 2024

References

- Pang T, Guindon GE. Globalization and risks to health: as borders disappear, people and goods are increasingly free to move, creating new challenges to global health. These cannot be met by national governments alone but must be dealt with instead by international organizations and agreements. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(S1):S11-6.

- Sroor FM, Othman AM, Aboelenin MM, Mahrous KF. Anticancer and antimicrobial activities of new thiazolyl-urea deriv-atives: gene expression, DNA damage, DNA fragmentation and SAR studies. Med Chem Res. 2022;31(3):400-15.

- Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. Pharm Therapeut. 2015;40(4):277.

- Housman G, Byler S, Heerboth S, Lapinska K, Longacre M, Snyder N, et al. Drug resistance in cancer: an overview. Cancers. 2014;6(3):1769-92.

- Garcia-Oliveira P, Otero P, Pereira AG, Chamorro F, Carpena M, Echave J, et al. Status and challenges of plant-anticancer compounds in cancer treatment. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(2):157.

- Sharma VP, Sharma U, Chattopadhyay M, Shukla VN. Advance applications of nanomaterials: a review. Mater Today: Proc. 2018;5(2):6376-80.

- Kumar A, Choudhary A, Kaur H, Mehta S, Husen A. Metal-based nanoparticles, sensors, and their multifaceted application in food packaging. Nanobiotechnology. 2021;19(1):256.

- Salem SS, Fouda A. Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles and their prospective biotechnological applications: an overview. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021;199:344-70.

- Baptista PV, McCusker MP, Carvalho A, Ferreira DA, Mohan NM, Martins M, et al. Nano-strategies to fight multidrug resistant bacteria-“a Battle of the titans”. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1441.

- Marinescu L, Ficai D, Oprea O, Marin A, Ficai A, Andronescu E, et al. Optimized synthesis approaches of metal nanoparticles with antimicrobial applications. Nanomaterials. 2020;2020:1-14.

- EISaied BE, Diab AM, Tayel AA, Alghuthaymi MA, Moussa SH. Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract. Green Process Synthesis. 2021;10(1):49-60.

- Khanna P, Kaur A, Goyal D. Algae-based metallic nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and applications. Microbiol Methods. 2019;163:105656.

- Bisht N, Phalswal P, Khanna PK. Selenium nanoparticles: a review on synthesis and biomedical applications. Mater Adv. 2022;3(3):1415-31.

- Saratale RG, Karuppusamy I, Saratale GD, Pugazhendhi A, Kumar G, Park Y, et al. A comprehensive review on green nanomaterials using biological systems: recent perception and their future applications. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces. 2018;170:20-35.

- Fahimirad S, Ajalloueian F, Ghorbanpour M. Synthesis and therapeutic potential of silver nanomaterials derived from plant extracts. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;168:260-78.

- Bahrulolum H, Nooraei S, Javanshir N, Tarrahimofrad H, Mirbagheri VS, Easton AJ, et al. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using microorganisms and their application in the agrifood sector. Nanobiotechnology. 2021;19(1):1-26.

- Składanowski M, Wypij M, Laskowski D, Golińska P, Dahm H, Rai M. Silver and gold nanoparticles synthesized from Streptomyces sp. isolated from acid forest soil with special reference to its antibacterial activity against pathogens. Cluster. Science. 2017;28:59-79.

- Gu H, Chen X, Chen F, Zhou X, Parsaee Z. Ultrasound-assisted biosynthesis of CuO-NPs using brown alga Cystoseira trinodis: characterization, photocatalytic AOP, DPPH scavenging and antibacterial investigations. Ultrason Sonochem. 2018;41:109-19.

- Fouda A, Hassan SED, Eid AM, El-Din EE. The interaction between plants and bacterial endophytes under salinity stress. Endophytes Second Metab. 2019:1-18.

- Zhang J, Wang H, Yan X, Zhang L. Comparison of short-term toxicity between Nano-se and selenite in mice. Life Sci. 2005;76(10):1099-109.

- Manivasagan

, Oh J. Production of a novel fucoidanase for the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles by Streptomyces sp. and its cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells. Marine drugs. 2015;13(11):6818-37. - Zhang J, Zhang SY, Xu JJ, Chen HY. A new method for the synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and the application to construction of

2 biosensor. Chin Chem Lett. 2004;15(11):1345-8. - Romero I, de Francisco P, Gutiérrez JC, Martín-González A. Selenium cytotoxicity in Tetrahymena thermophila: new clues about its biological effects and cellular resistance mechanisms. Sci Total Environ. 2019;671:850-65.

- Gautam PK, Kumar S, Tomar MS, Singh RK, Acharya A, Ram B. Selenium nanoparticles induce suppressed function of tumor associated macrophages and inhibit Dalton’s lymphoma proliferation. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2017;12:172-84.

- Hashem AH, Selim TA, Alruhaili MH, Selim S, Alkhalifah DHM, AI Jaouni SK, et al. Unveiling antimicrobial and insecticidal activities of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using prickly pear peel waste. Function Biomater. 2022;13(3):112.

- Salem SS. A mini review on green nanotechnology and its development in biological effects. Arch Microbiol. 2023;205(4):128.

- Abu-Elghait M, Hasanin M, Hashem AH, Salem SS. Ecofriendly novel synthesis of tertiary composite based on cellulose and myco-synthesized selenium nanoparticles: characterization, antibiofilm and biocompatibility. Biol Macromol. 2021;175:294-303.

- Elakraa AA, Salem SS, El-Sayyad GS, Attia MS. Cefotaxime incorporated bimetallic silver-selenium nanoparticles: promising antimicrobial synergism, antibiofilm activity, and bacterial membrane leakage reaction mechanism. RSC Adv. 2022;12(41):26603-19.

- Salem SS. Bio-fabrication of selenium nanoparticles using Baker’s yeast extract and its antimicrobial efficacy on food borne pathogens. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;194(5):1898-910.

- Cruz LY, Wang D, Liu J. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles, characterization and X-ray induced radiotherapy for the treatment of lung cancer with interstitial lung disease. Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2019;191:123-7.

- Ferro C, Florindo HF, Santos HA. Selenium nanoparticles for biomedical applications: from development and characterization to therapeutics. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2021;10(16):2100598.

- Chaudhary S, Umar A, Mehta SK. Surface functionalized selenium nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomed Nanotechnol. 2014;10(10):3004-42.

- Martínez-Esquivias F, Guzmán-Flores JM, Pérez-Larios A, González Silva N, Becerra-Ruiz JS. A review of the antimicrobial activity of selenium nanoparticles. Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2021;21(11):5383-98.

- Rout SK. Physicochemical, functional and spectroscopic analysis of crawfish chitin and chitosan as affected by process modification. Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College; 2001. p. 3042648.

- Lopez-Moya F, Suarez-Fernandez M, Lopez-Llorca LV. Molecular mechanisms of chitosan interactions with fungi and plants. Int J Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(2):332.

- Saeedi M, Vahidi O, Moghbeli M, Ahmadi S, Asadnia M, Akhavan O, et al. Customizing nano-chitosan for sustainable drug delivery. Control Release. 2022;350:175-92.

- Hashem AH, Shehabeldine AM, Ali OM, Salem SS. Synthesis of chitosanbased gold nanoparticles: antimicrobial and wound-healing activities. Polymers. 2022;14(11):2293.

- Shehabeldine AM, Salem SS, Ali OM, Abd-Elsalam KA, Elkady FM, Hashem AH. Multifunctional silver nanoparticles based on chitosan: antibacterial, antibiofilm, antifungal, antioxidant, and wound-healing activities. Fungi. 2022;8(6):612.

- Torzsas TL, Kendall CWC, Sugano M, Iwamoto Y, Rao AV. The influence of high and low molecular weight chitosan on colonic cell proliferation and aberrant crypt foci development in CF1 mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 1996;34(1):73-7.

- Maeda Y, Kimura Y. Antitumor effects of various low-molecular-weight chitosans are due to increased natural killer activity of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes in sarcoma 180-bearing mice. Nutrition. 2004;134(4):945-50.

- Rangrazi A, Bagheri H, Ghazvini K, Boruziniat A, Darroudi M. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of colloidal selenium nanoparticles in chitosan solution: a new antibacterial agent. Mater Res Express. 2020;6(12):1250h3.

- Sivanesan I, Gopal J, Muthu M, Shin J, Mari S, Oh J. Green synthesized chitosan/chitosan nanoforms/nanocomposites for drug delivery applications. Polymers. 2021;13(14):2256.

- Alalawy AI, El Rabey HA, Almutairi FM, Tayel AA, AI-Duais MA, Zidan NS, et al. Effectual anticancer potentiality of loaded bee venom onto fungal chitosan nanoparticles. Polymer Sci. 2020;2020 https://doi.org/10.1155/ 2020/2785304.

- Oladele IO, Omotosho TF, Adediran AA. Polymer-based composites: an indispensable material for present and future applications. Polymer Sci. 2020;2020:1-12.

- Alghuthaymi MA, Diab AM, Elzahy AF, Mazrou KE, Tayel AA, Moussa SH. Green biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles by cinnamon extract and their antimicrobial activity and application as edible coatings with nano-chitosan. Food Quality. 2021;2021:1-10.

- Chubukov V, Gerosa L, Kochanowski K, Sauer U. Coordination of microbial metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12(5):327-40.

- Zhou Y, Yan K, Qin Q, Raimi OG, Du C, Wang B, et al. Phosphoglucose isomerase is important for aspergillus fumigatus cell wall biogenesis. Mbio. 2022;13(4):e01426-2.

- Yuan W, Du Y, Yu K, Xu S, Liu M, Wang S, et al. The production of pyruvate in biological technology: a critical review. Microorganisms. 2022;10(12):2454.

- Ortiz-Ramírez P, Hernández-Ochoa B, Ortega-Cuellar D, González-Valdez A, Martínez-Rosas V, Morales-Luna L, et al. Biochemical and kinetic characterization of the Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from helicobacter pylori strain 29CaP. Microorganisms., 1359. 2022;10(7)

- You Y, Chu S, Khalid M, Hayat K, Yang X, Zhang D, et al. A sustainable approach for removing nitrate: studying the nitrate transformation and metabolic potential under different carbon source by microorganism. Clean Prod. 2022;346:131169.

- Hamed AA, Abdel-Aziz MS, Fadel M, Ghali MF. Antimicrobial, antidermatophytic, and cytotoxic activities from Streptomyces sp. MER4 isolated from Egyptian local environment. Bull Natl Res Centre. 2018;42:1-10.

- Hamed AA, Eskander DM, Badawy MSEM. Isolation of secondary metabolites from marine Streptomyces sparsus ASD203 and evaluation its bioactivity. Egypt J Chem. 2022;65(3):539-47.

- Hamed AA, Kabary H, Khedr M, Emam AN. Antibiofilm, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of extracellular green-synthesized silver nanoparticles by two marine-derived actinomycete. RSC Adv. 2020;10(17):10361-7.

- Ramya

, Shanmugasundaram , Balagurunathan R. Biomedical potential of actinobacterially synthesized selenium nanoparticles with special reference to anti-biofilm, anti-oxidant, wound healing, cytotoxic and anti-viral activities. T.race Elements Med Biol. 2015;32:30-9. - Ranjitha VR, Ravishankar VR. Extracellular synthesis of selenium nanoparticles from an actinomycetes streptomyces griseoruber and

evaluation of its cytotoxicity on HT-29 cell line. Pharmac Nanotechnol. 2018;6(1):61-8. - Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870-4.

- Salem MF, Abd-Elraoof WA, Tayel AA, Alzuaibr FM, Abonama OM. Antifungal application of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles with pomegranate peels and nanochitosan as edible coatings for citrus green mold protection. Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):182.

- Mostafa EM, Abdelgawad MA, Musa A, Alotaibi NH, Elkomy MH, Ghoneim MM, et al. Chitosan silver and gold nanoparticle formation using endophytic fungi as powerful antimicrobial and anti-biofilm potentialities. Antibiotics. 2022;11(5):668.

- Alhadrami HA, Orfali R, Hamed AA, Ghoneim MM, Hassan HM, Hassane ASI, et al. Flavonoid-coated gold nanoparticles as efficient antibiotics against gram-negative bacteria-evidence from in silico-supported in vitro studies. Antibiotics. 2021;2021:10.

- Abdel-Nasser M, Abdel-Maksoud G, Abdel-Aziz MS, Darwish SS, Hamed AA, Youssef AM. Evaluation of the efficiency of nanoparticles for increasing a-amylase enzyme activity for removing starch stain from paper artifacts. Cultural Heritage. 2022;53:14-23.

- Abdelaziz MS, Hamed AA, Radwan AA, Khaled E, Hassan RY. Biosynthesis and bio-sensing applications of silver and gold metal nanoparticles. Egypt J Chem. 2021;64(2):1057-63.

- Khedr WE, Shaheen MN, Elmahdy EM, Bendary MAE, Hamed AA, Mohamedin AH. Silver and gold nanoparticles: eco-friendly synthesis, antibiofilm, antiviral, and anticancer bioactivities. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2023:1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826068.2023.2248238.

- Hamed AA, Soldatou S, Qader MM, Arjunan S, Miranda KJ, Casolari F, et al. Screening fungal endophytes derived from under-explored Egyptian marine habitats for antimicrobial and antioxidant properties in factionalised textiles. Microorganisms. 2020;8(10):1617.

- El-Shora HM, El-Sharkawy RM, Khateb AM, Darwish DB. Production and immobilization of

-glucanase from aspergil-lus Niger with its applications in bioethanol production and biocontrol of phytopathogenic fungi. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21000. - Lima TC, Ferreira AR, Silva DF, Lima EO, de Sousa DP. Antifungal activity of cinnamic acid and benzoic acid esters against Candida albicans strains. Nat Prod Res. 2018;32(5):572-5.

- Sezonov G, Joseleau-Petit D, d’Ari R. Escherichia coli physiology in LuriaBertani broth. Bacteriology. 2007;189(23):8746-9.

- Gohil K, Jones DA. A sensitive spectorophotometric assay for pyruvate dehydrogenase and oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complexes. Biosci Rep. 1983;3(1):1-9.

- Betke K, Beutler E, Brewer GJ, Kirkman HN, Luzzatto L, Motulsky AG, et al. Standardization of procedures for the study of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Report of a WHO scientific group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1967;366(1)

- Lewis OAM, Watson EF, Hewitt EJ. Determination of nitrate reductase activity in barley leaves and roots. Ann Bot. 1982;49(1):31-7.

- Bradford MM . A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72(1-2):248-54.

- El-Bendary MA, Afifi SS, Moharam ME, Abo El-Ola SM, Salama A, Omara EA, et al. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using isolated Bacillus subtilis: characterization, antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity, and their performance as antimicrobial agent for textile materials. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2021;51(1):54-68.

- Oka M, Maeda S, Koga N, Kato K, Saito T. A modified colorimetric MTT assay adapted for primary cultured hepatocytes: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1992;56(9):1472-3.

- Danaei M, Dehghankhold M, Ataei S, Hasanzadeh Davarani F, Javanmard R, Dokhani A, et al. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(2):57.

- Lin ZH, Wang CC. Evidence on the size-dependent absorption spectral evolution of selenium nanoparticles. Mater Chem Phys. 2005;92(2-3):591-4.

- Ikram M, Javed B. Raja NI biomedical potential of plant-based selenium nanoparticles: a comprehensive review on therapeutic and mechanistic aspects. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:249.

- Abdel-Moneim AME, El-Saadony MT, Shehata AM, Saad AM, Aldhumri SA, Ouda SM, et al. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Spirulina platensis extracts and biogenic selenium nanoparticles against selected pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29(2):1197-209.

- Sumithra D, Bharathi S, Kaviyarasan P, Suresh G. Biofabrication of Selenium Nanoparticles Using Marine Streptomyces sp. and Assessment of Its Antibacterial, Antibiofilm, Antioxidant, and In Vivo Cytotoxic Potential. Geomicrobiology. 2023;40(5):485-92.

- Dhanjal S, Cameotra SS. Aerobic biogenesis of selenium nanospheres by Bacillus cereus isolated from coalmine soil. Microb Cell Factories. 2010;9(1):1-11.

- Kora AJ, Rastogi L. Biomimetic synthesis of selenium nanoparticles by Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853: an approach for conversion of selenite. Environ Manag. 2016;181:231-6.

- Jiang F, Cai W, Tan G. Facile synthesis and optical properties of small selenium nanocrystals and nanorods. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2017;12:1-6.

- Nogueira GD, Duarte CR, Barrozo MA. Hydrothermal carbonization of acerola (Malphigia emarginata DC) wastes and its application as an adsorbent. Waste Manag. 2019;95:466-75.

- Prasad KS, Selvaraj K. Biogenic synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their effect on as (III)-induced toxicity on human lymphocytes. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;157:275-83.

- Fresneda MAR, Martín JD, Bolívar JG, Cantos MVF, Bosch-Estévez G, Moreno MFM, et al. Green synthesis and biotransformation of amorphous se nanospheres to trigonal 1D se nanostructures: impact on se mobility within the concept of radioactive waste disposal. Environ Sci: Nano. 2018;5(9):2103-16.

- Salama A, Hasanin M, Hesemann P. Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of new chitosan derivatives containing guani-dinium groups. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;241:116363.

- Tayel AA, Elzahy AF, Moussa SH, Al-Saggaf MS, Diab AM. Biopreservation of shrimps using composed edible coatings from chitosan nanoparticles and cloves extract. Food Quality. 2020;2020:1-10.

- Shehabeldine AM, Hashem AH, Wassel AR, Hasanin M. Antimicrobial and antiviral activities of durable cotton fabrics treated with nanocomposite based on zinc oxide nanoparticles, acyclovir, nanochitosan, and clove oil. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;194 https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12010-021-03649-y.

- Shehabeldine A, Hasanin M. Green synthesis of hydrolyzed starchchitosan nano-composite as drug delivery system to gram negative bacteria. Environ Nanotechnol Monitor Manag. 2019;12:100252.

- Potrč S, Glaser TK, Vesel A, Ulrih NP, Zemljič LF. Two-layer functional coatings of chitosan particles with embedded catechin and pomegranate extracts for potential active packaging. Polymers. 2020;12(9):1855.

- Elsharawy K, Abou-Dobara M, El-Gammal H, Hyder A. Chitosan coating does not prevent the effect of the transfer of green silver nanoparticles biosynthesized by Streptomyces malachitus into fetuses via the placenta. Reprod Biol. 2020;20(1):97-105.

- Siddiqi KS, Husen A, Rao RA. A review on biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biocidal properties. Nanobiotechnology. 2018;16(1):1-28.

- Gad HA, Tayel AA, AI-Saggaf MS, Moussa SH, Diab AM. Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens. Green Process Synthesis. 2021;10(1):529-37.

- Shetta A, Kegere J, Mamdouh W. Comparative study of encapsulated peppermint and green tea essential oils in chitosan nanoparticles: encapsulation, thermal stability, in-vitro release, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Int J Biological Macromolecules. 2019;126:731-42.

- Joshi SM, De Britto S, Jogaiah S, Ito SI. Mycogenic selenium nanoparticles as potential new generation broad spectrum antifungal molecules. Biomolecules. 2019;9(9):419.

- Zhang H, Zhou H, Bai J, Li Y, Yang J, Ma Q, et al. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles mediated by fungus Mariannaea sp. HJ and their characterization. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2019;571:9-16.

- Koukaras EN, Papadimitriou SA, Bikiaris DN, Froudakis GE. Insight on the formation of chitosan nanoparticles through ionotropic gelation with tripolyphosphate. Mol Pharm. 2012;9(10):2856-62.

- Hnain A, Brooks J, Lefebvre DD. The synthesis of elemental selenium particles by Synechococcus leopoliensis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:10511-9.

- Pandey S, Awasthee N, Shekher A, Rai LC, Gupta SC, Dubey SK. Biogenic synthesis and characterization of selenium nanoparticles and their applications with special reference to antibacterial, antioxidant, anticancer and photocatalytic activity. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2021;44:2679-96.

- MubarakAli D, LewisOscar F, Gopinath V, Alharbi NS, Alharbi SA, Thajuddin N. An inhibitory action of chitosan nanoparticles against pathogenic bacteria and fungi and their potential applications as biocompatible antioxidants. Microb Pathog. 2018;114:323-7.

- Villegas-Peralta Y, López-Cervantes J, Santana TJM, Sánchez-Duarte RG, Sánchez-Machado DI, Martínez-Macías MDR, et al. Impact of the molecular weight on the size of chitosan nanoparticles: characterization and its solid-state application. Polym Bull. 2021;78:813-32.

- Guisbiers G, Wang Q, Khachatryan E, Mimun LC, Mendoza-Cruz R, Larese-Casanova P, et al. Inhibition of E. Coli and S. Aureus with selenium nanoparticles synthesized by pulsed laser ablation in deionized water. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016:3731-6.

- Skoglund S, Hedberg J, Yunda E, Godymchuk A, Blomberg E, Odnevall WI. Difficulties and flaws in performing accurate determinations of zeta potentials of metal nanoparticles in complex solutions-four case studies. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181735.

- Chen W, Yue L, Jiang Q, Liu X, Xia W. Synthesis of varisized chitosanselenium nanocomposites through heating treatment and evaluation of their antioxidant properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;114:751-8.

- Jardim KV, Siqueira JLN, Báo SN, Parize AL. In vitro cytotoxic and antioxidant evaluation of quercetin loaded in ionic cross-linked chitosan nanoparticles. Drug Del Sci Technol. 2022;74:103561.

- Chudobova D, Cihalova K, Dostalova S, Ruttkay-Nedecky B, Merlos Rodrigo MA, Tmejova K, et al. Comparison of the effects of silver phosphate and selenium nanoparticles on Staphylococcus aureus growth reveals potential for selenium particles to prevent infection. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2014;351(2):195-201.

- Al-Saggaf MS. Nanoconjugation between fungal Nanochitosan and biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles with Hibiscus sabdariffa extract for effectual control of multidrug-resistant Bacteria. Nanomaterials. 2022;2022 https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7583032.

- Portillo-Torres LA, Bernardino-Nicanor A, Mercado-Monroy J, GómezAldapa CA, González-Cruz L, Rangel-Vargas E, et al. Antimicrobial effects of aqueous extract from calyces of Hibiscus sabdariffa in CD-1 mice infected with multidrug-resistant Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli and salmonella Typhimurium. Medicinal Food. 2022;25(9):902-9.

- Hashem AH, Salem SS. Green and ecofriendly biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using Urtica dioica (stinging nettle) leaf extract: antimicrobial and anticancer activity. Biotechnology. 2022;17(2):2100432.

- Cremonini E, Zonaro E, Donini M, Lampis S, Boaretti M, Dusi S, et al. Biogenic selenium nanoparticles: characterization, antimicrobial activity and effects on human dendritic cells and fibroblasts. Microb Biotechnol. 2016;9(6):758-71.

- Khiralla GM, El-Deeb BA. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm effects of selenium nanoparticles on some foodborne pathogens. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2015;63(2):1001-7.

- El-Sayed ESR, Abdelhakim HK, Ahmed AS. Solid-state fermentation for enhanced production of selenium nanoparticles by gamma-irradiated Monascus purpureus and their biological evaluation and photocatalytic activities. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2020;43:797-809.

- Huang T, Holden JA, Heath DE, O’Brien-Simpson NM, O’Connor AJ. Engineering highly effective antimicrobial selenium nanoparticles through control of particle size. Nanoscale. 2019;11(31):14937-51.

- Deepa T, Mohan S, Manimaran P. A crucial role of selenium nanoparticles for future perspectives. Results Chem. 2022;4:100367.

- Nikam PB, Salunkhe JD, Marathe KR, Alghuthaymi MA, Abd-Elsalam KA, Patil SV. Rhizobium pusense-Mediated Selenium NanoparticlesAntibiotics Combinations against Acanthamoeba sp. Microorganisms. 2022;10(12):2502.

- Saad EL, Salem SS, Fouda A, Awad MA, El-Gamal MS, Abdo AM. New approach for antimicrobial activity and bio-control of various pathogens by biosynthesized copper nanoparticles using endophytic actinomycetes. J Radiat Res Appl. 2018;11 (3):262-70.

- Alarfaj AA. Antibacterial effect of chitosan nanoparticles against food spoilage bacteria. Pure Appl Microbiol. 2019;13(2):1273-8.

- Ma S, Moser D, Han F, Leonhard M, Schneider-Stickler B, Tan Y. Preparation and antibiofilm studies of curcumin loaded chitosan nanoparticles against polymicrobial biofilms of Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;241:116254.

- Wrońska N, Katir N, Miłowska K, Hammi N, Nowak M, Kędzierska M, et al. Antimicrobial effect of chitosan films on food spoilage bacteria. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11):5839.

- Orellano MS, Isaac P, Breser ML, Bohl LP, Conesa A, Falcone RD, et al. Chitosan nanoparticles enhance the antibacterial activity of the native polymer against bovine mastitis pathogens. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;213:1-9.

- Abdallah Y, Liu M, Ogunyemi SO, Ahmed T, Fouad H, Abdelazez A, et al. Bioinspired green synthesis of chitosan and zinc oxide nanoparticles with strong antibacterial activity against rice pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae. Molecules. 2020;25(20):4795.

- Divya K, Vijayan S, George TK, Jisha MS. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan nanoparticles: mode of action and factors affecting activity. Fibers Polymers. 2017;18:221-30.

- Bhumkar DR, Pokharkar VB. Studies on effect of pH on cross-linking of chitosan with sodium tripolyphosphate: a technical note. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2006;7:E138-43.

- Gunti L, Dass RS, Kalagatur NK. Phytofabrication of selenium nanoparticles from Emblica officinalis fruit extract and exploring its biopotential applications: antioxidant, antimicrobial, and biocompatibility. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:931.

- Aboul-Fadl T. Selenium derivatives as cancer preventive agents. Curr Med Chem Anticancer. 2005;5(6):637-52.

- Huang Y, He L, Liu W, Fan C, Zheng W, Wong YS, et al. Selective cellular uptake and induction of apoptosis of cancer-targeted selenium nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2013;34(29):7106-16.

- Wang H, He Y, Liu L, Tao W, Wang G, Sun W, et al. Prooxidation and cytotoxicity of selenium nanoparticles at nonlethal level in Sprague-dawley rats and buffalo rat liver cells. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020 https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7680276.

- Kamath PR, Sunil D. Nano-chitosan particles in anticancer drug delivery: an up-to-date review. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2017;17(15):1457-87.

- Tan HW, Mo HY, Lau AT, Xu YM. Selenium species: current status and potentials in cancer prevention and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;20(1):75.

- LiT, Xu H. Selenium-containing nanomaterials for cancer treatment. Cell Rep Phys Sci. 2020;1(7)

- Hashem AH, Khalil AMA, Reyad AM, Salem SS. Biomedical applications of mycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Penicillium expansum ATTC 36200. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021:1-11. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s12011-020-02506-z.

- Hassanien R, Abed-Elmageed AA, Husein DZ. Eco-friendly approach to synthesize selenium nanoparticles: photocatalytic degradation of sunset yellow azo dye and anticancer activity. ChemistrySelect. 2019;4(31):9018-26.

- Khurana A, Tekula S, Saifi MA, Venkatesh P, Godugu C. Therapeutic applications of selenium nanoparticles. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;111:802-12.

- Menon S, Shanmugam V. Cytotoxicity analysis of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles towards A549 lung cancer cell line. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater. 2020;30(5):1852-64.

- Cao J, Zhou NJ. Progress in antitumor studies of chitosan. Chin J Biochem Pharmac. 2005;26(2):127.

- Wang JJ, Zeng ZW, Xiao RZ, Xie T, Zhou GL, Zhan XR, et al. Recent advances of chitosan nanoparticles as drug carriers. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6 https://doi.org/10.2147/JJN.S17296.

- Qi L, Xu Z, Chen M. In vitro and in vivo suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma growth by chitosan nanoparticles. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(1):184-93.

- Yu B, Zhang Y, Zheng W, Fan C, Chen T. Positive surface charge enhances selective cellular uptake and anticancer efficacy of selenium nanoparticles. Inorg Chem. 2012;51(16):8956-63.

- Fröhlich E. The role of surface charge in cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of medical nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7 https://doi.org/10. 2147/IJN.S36111.

- He C, Hu Y, Yin L, Tang C, Yin C. Effects of particle size and surface charge on cellular uptake and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2010;31(13):3657-66.

ملاحظة الناشر

هل أنت مستعد لتقديم بحثك؟ اختر BMC واستفد من:

- تقديم سريع ومريح عبر الإنترنت

- مراجعة دقيقة من قبل باحثين ذوي خبرة في مجالك

- نشر سريع عند القبول

- دعم بيانات البحث، بما في ذلك أنواع البيانات الكبيرة والمعقدة

- الوصول المفتوح الذهبي الذي يعزز التعاون الأوسع وزيادة الاقتباسات

- أقصى رؤية لبحثك: أكثر من 100 مليون مشاهدة للموقع سنويًا

في BMC، البحث مستمر دائمًا.

بي إم سي

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-023-03171-7

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38216871

Publication Date: 2024-01-12

Biogenic selenium nanoparticles and selenium/chitosan-Nanoconjugate biosynthesized by Streptomyces parvulus MAR4 with antimicrobial and anticancer potential updates

Abstract

Background As antibiotics and chemotherapeutics are no longer as efficient as they once were, multidrug resistant (MDR) pathogens and cancer are presently considered as two of the most dangerous threats to human life. In this study, Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) biosynthesized by Streptomyces parvulus MAR4, nano-chitosan (NCh), and their nanoconjugate (Se/Ch-nanoconjugate) were suggested to be efficacious antimicrobial and anticancer agents. Results SeNPs biosynthesized by Streptomyces parvulus MAR4 and NCh were successfully achieved and conjugated. The biosynthesized SeNPs were spherical with a mean diameter of 94.2 nm and high stability. Yet, Se/Ch-nanoconjugate was semispherical with a 74.9 nm mean diameter and much higher stability. The SeNPs, NCh, and Se/Chnanoconjugate showed significant antimicrobial activity against various microbial pathogens with strong inhibitory effect on their tested metabolic key enzymes [phosphoglucose isomerase (PGI), pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) and nitrate reductase (NR)]; Se/Ch-nanoconjugate was the most powerful agent. Furthermore, SeNPs revealed strong cytotoxicity against HepG2 (

Introduction

Currently, nanotechnology is employed in various human-related sectors, such as biomedical, nutritional, chemical, biological, mechanical, optical, environmental, and agricultural [6-8]. Due to their outstanding functionality and reactivity, metal nanoparticles (NPs) have been widely used in various biomedical purposes, including antibacterial, antioxidant, anticancer, anticoagulant, or carriers for bioactive compounds [8-11].

Several methods have been reported for NPs synthesis, including chemical, physical, and biological [12]. The chemical and physical processes are usually complicated and expensive causing the release of hazardous byproducts that threaten ecological systems [13]. In contrast, biological method using biogenic agents, such as biopolymers, plant extracts, microorganisms, algae, or their derivative could successfully overcome most problems with chemical and physical methods, providing simple, environmentally friendly, high yielded, and economical approaches [14-16]. Actinomycetes are Gram-positive bacteria with high polydispersity, strong stability, and easy handling [17]. Actinomycetes, in particular Streptomyces sp., produce several secondary metabolites, such as enzymes and proteins, that can be employed for ion reduction and capping of metals at nanoscale [18-21].

Selenium (Se) is a crucial micronutrient which maintains human health and body functions (with a small range between toxic levels and nutritional deficiency of 400 and

Chitosan (Ch) is a nontoxic polycationic biopolymer which has a wide range of biological uses because of its unique chemical origin, positive charge, and presence of

reactive hydroxyl and amino groups. Ch can be obtained by deacetylation of chitin which is found in shells of crustaceans (crab, lobster, and shrimp) and various organisms (insects and fungi). Furthermore, Ch is marketed for its exceptional properties, including biodegradability, biocompatibility, ability to form films, adsorption, wound healing, antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant [34-36].

Material and methods

Material

nystatin, and cell lines were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and MTT were obtained from GIBCO, UK. The Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit were gotten from Qiagen, Hilden, Germany. All solvents, buffers and reagents were obtained from El Nasr Pharmaceutical Chemicals Company (Cairo, Egypt).

Marine samples collection and actinomycetes isolation

Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs)

Identification of potential strain

Preparation of nano-chitosan (NCh) and nanoconjugate

Characterization of synthesized nanoparticles (NPs) and nanoconjugate

Antimicrobial activity

Influence of synthesized NPs on metabolic enzymes activity of tested microbial pathogens Preparation of enzymes extracts

S. aureus, E. coli, S. typhi, and P. vulgaris were inoculated in LB media and incubated overnight at

Enzymes assay

Determination of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activity

Determination of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activity

formation at 340 nm . The reaction mixture was in 3 ml volume, which contained 1.5 ml of

Determination of nitrate reductase (NR) activity

Determination of total soluble protein content

Cytotoxic activity

was obtainable by EXL 800, USA. Data were given as a mean

Statistical analysis

Results

Biosynthesis of SeNPs and UV-visible spectroscopic analysis

Identification of potential isolate

phylogenetic analysis, LG isolate and Streptomyces parvulus are closely linked genetically.

XRD analysis

FTIR analysis

The functional groups necessary for the

TEM analysis

SEM and EDX analyses

| NPs |

|

PDI | (potential (mV) | ||

| SeNPs | 196,2 | 0.252 | 37.08 | ||

|

476.6 | 0.264 | 55.91 |

Hydrodynamic diameter and zeta (

The solution homogeneity is estimated by the polydispersity index (PDI). PDI value ranges from 0 to 1 , which 0 represents an ideal solution with same-sized particles, and 1 represents a highly polydisperse solution with various sized particles. Values below 0.5 are regarded as monodispersed, whereas those above 0.7 are regarded as substantially polydisperse [73]. SeNPs and Se/Ch-nanoconjugate showed PDI values below 0.5 ( 0.252 and 0.264, respectively), indicating that they were monodispersed, stable, and uniformly sized in the solution.

By measuring the

Antimicrobial activity

broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity against both bacterial and fungal strains (Fig. 6). The Se/Ch-nanoconjugate showed the highest effectiveness and exhibited superior antimicrobial activity against most tested microbial pathogens. The Se/Ch-nanoconjugate showed stronger antibacterial than antifungal action.

Influence of synthesized NPs on metabolic enzymes activity of tested microbial pathogens

| Tested NPs | % Inhibition of PGI | |||||||

| E. coli | P. vulgaris | S. typhi | S. aureus | A. flavus | A. niger | Rhizoctonia sp. | C. albicans | |

| NCh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SeNPs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Se/Ch-nanoconjugate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tested NPs | % Inhibition of PDH | |||||||

| E. coli | P. vulgaris | S. typhi | S. aureus | A. flavus | A. niger | Rhizoctonia sp. | C. albicans | |

| NCh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SeNPs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Se/Ch-nanoconjugate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tested NPs | % Inhibition of G6PDH | |||||||

| E. coli | P. vulgaris | S. typhi | S. aureus | A. flavus | A. niger | Rhizoctonia sp. | C. albicans | |

| NCh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SeNPs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Se/Ch-nanoconjugate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tested NPs | % Inhibition of NR | |||||||

| E. coli | P. vulgaris | S. typhi | S. aureus | A. flavus | A. niger | Rhizoctonia sp. | C. albicans | |

| NCh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| SeNPs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Se/Ch-nanoconjugate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cytotoxic activity

| Tested NPs | HePG-2 | In vitro Cytotoxicity, | |

| IC

|

|||

| HTB-46 | WI-38 | ||

| SeNPs | 13.04 | 21.35 | 85.69 |

| Se/Ch-nanoconjugate | 11.82 | 7.83 | 153.3 |

Discussion

of the biosynthesized SeNPs showed a sharp absorption peak at 300 nm which is consistent with previous studies for bacterially-synthesized SeNPs [76, 77]. Conversely, the UV-visible spectra of SeNPs extracellularly synthesized by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Bacillus cereus exhibited different absorption peaks at 520 nm and 590 nm , respectively [78, 79]. Consequently, UV-visible spectra of biosynthesized SeNPs vary depending on their atomic structure [54].

and subsequent SeNPs synthesis (Fig. 4a, supernatant (LG)). NADH-dependent enzymes and/or Sulfur-containing proteins, which had superb redox characteristics serving as cofactors in selenide ions reduction, were exemplified by OH and NH stretching at

The biosynthesis of SeNPs and formation of novel bonds with supernatant (LG) biomolecules were revealed by the SeNPs FTIR spectrum (Fig. 4a, SeNPs). The broad strong band at

nanoconjugate EDX diagram (Fig. 4e) confirmed the formation of NCh by cross-linking with TPP [98, 99].

The antibacterial action of NCh was reported against various microbial pathogens, and several hypothesized mechanisms were documented [115-117]. The electrostatic interaction between the NCT positively charged amino group and the negatively charged microbial cell membranes is considered to be one of the main antimicrobial mechanisms, which causes cell damage through the leakage of proteinaceous and other intracellular components [118, 119]. The NCh may also act as a chelating agent, binding to trace metals and generating toxins that inhibit microbial growth [120]. Additionally, NCT can carry and control the release of bioactive agents [121].

As a result, the NCh can easily penetrate the microbial cell membrane pores carrying the biosynthesized SeNPs and release them there. Accordingly, the nanoconjugate has direct effects on the cells; it can interfere with ATP synthesis, affect cell division, and cause cell lysis [45, 57, 98, 122]. Furthermore, the substantial positive charge of Se/Ch-nanoconjugate could electrostatically interact with the negatively charged cell membranes causing cell damage. Consequently, the Se/Ch-nanoconjugate was proved to be the most powerful antimicrobial agent.

Recently, biosynthesized SeNPs have been receiving a lot of attention as a potential anticancer agent due to their remarkable biological activity, biocompatibility, and low toxicity [82, 122, 123]. Furthermore, it was reported that they have no side effects on normal cells while specifically inhibiting the tumor growth [124, 125]. In the current study, the NCh was loaded to improve the biological properties of the biosynthesized SeNPs [126]. The biosynthesized SeNPs and Se/Ch-nanoconjugate exhibited outstanding anticancer activity against HepG2 and Caki-1 (HTB-46) tumor cell lines; the nanoconjugate was

the most powerful with

Conclusion

mechanisms can be attributed to the presence of multiple combined bioactive agents with diverse modes of action. The conjugation also decreased toxicity and enhanced biocompatibility, safety, and biological activity of each individual agent. Furthermore, the nanoconjugate significant positive charge could electrostatically interact with negatively charged cell membranes, resulting in cell damage. Moreover, the inhibition of key metabolic enzymes was proven to be one of their antimicrobial mechanisms through interfering with these enzymes and disrupting metabolic processes, causing inhibition of microbial growth and proliferation. Overall, the Se/Ch-nanoconjugate can be applied as a promising biomedical agent with both antimicrobial and anticancer properties. However, further in-depth studies are required to fully elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying its antimicrobial and anticancer effects.

Abbreviations

| MDR | Multidrug resistant |

| SeNPs | Selenium nanoparticles |

| Ch | Chitosan |

| NCh | nano-chitosan |

| PGI | Phosphoglucose isomerase |

| PDH | Pyruvate dehydrogenase |

| G6PDH | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| NR | Nitrate reductase |

| TPP | tripolyphosphate |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| EDX | Energy dispersive X-ray |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| CCG | Carbon-coated copper grids |

| LB | Lysogenia broth |

| HepG2 | Hepatocellular carcinoma cell line |

| Caki-1 | Renal cell carcinoma cell line |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| FBS | Foetal Bovine Serum |

Acknowledgments

Data availability statement

Authors’ contributions

Funding

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 12 January 2024

References

- Pang T, Guindon GE. Globalization and risks to health: as borders disappear, people and goods are increasingly free to move, creating new challenges to global health. These cannot be met by national governments alone but must be dealt with instead by international organizations and agreements. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(S1):S11-6.

- Sroor FM, Othman AM, Aboelenin MM, Mahrous KF. Anticancer and antimicrobial activities of new thiazolyl-urea deriv-atives: gene expression, DNA damage, DNA fragmentation and SAR studies. Med Chem Res. 2022;31(3):400-15.

- Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. Pharm Therapeut. 2015;40(4):277.

- Housman G, Byler S, Heerboth S, Lapinska K, Longacre M, Snyder N, et al. Drug resistance in cancer: an overview. Cancers. 2014;6(3):1769-92.

- Garcia-Oliveira P, Otero P, Pereira AG, Chamorro F, Carpena M, Echave J, et al. Status and challenges of plant-anticancer compounds in cancer treatment. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(2):157.

- Sharma VP, Sharma U, Chattopadhyay M, Shukla VN. Advance applications of nanomaterials: a review. Mater Today: Proc. 2018;5(2):6376-80.

- Kumar A, Choudhary A, Kaur H, Mehta S, Husen A. Metal-based nanoparticles, sensors, and their multifaceted application in food packaging. Nanobiotechnology. 2021;19(1):256.

- Salem SS, Fouda A. Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles and their prospective biotechnological applications: an overview. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021;199:344-70.

- Baptista PV, McCusker MP, Carvalho A, Ferreira DA, Mohan NM, Martins M, et al. Nano-strategies to fight multidrug resistant bacteria-“a Battle of the titans”. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1441.

- Marinescu L, Ficai D, Oprea O, Marin A, Ficai A, Andronescu E, et al. Optimized synthesis approaches of metal nanoparticles with antimicrobial applications. Nanomaterials. 2020;2020:1-14.

- EISaied BE, Diab AM, Tayel AA, Alghuthaymi MA, Moussa SH. Potent antibacterial action of phycosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Spirulina platensis extract. Green Process Synthesis. 2021;10(1):49-60.

- Khanna P, Kaur A, Goyal D. Algae-based metallic nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and applications. Microbiol Methods. 2019;163:105656.

- Bisht N, Phalswal P, Khanna PK. Selenium nanoparticles: a review on synthesis and biomedical applications. Mater Adv. 2022;3(3):1415-31.

- Saratale RG, Karuppusamy I, Saratale GD, Pugazhendhi A, Kumar G, Park Y, et al. A comprehensive review on green nanomaterials using biological systems: recent perception and their future applications. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces. 2018;170:20-35.

- Fahimirad S, Ajalloueian F, Ghorbanpour M. Synthesis and therapeutic potential of silver nanomaterials derived from plant extracts. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;168:260-78.

- Bahrulolum H, Nooraei S, Javanshir N, Tarrahimofrad H, Mirbagheri VS, Easton AJ, et al. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using microorganisms and their application in the agrifood sector. Nanobiotechnology. 2021;19(1):1-26.

- Składanowski M, Wypij M, Laskowski D, Golińska P, Dahm H, Rai M. Silver and gold nanoparticles synthesized from Streptomyces sp. isolated from acid forest soil with special reference to its antibacterial activity against pathogens. Cluster. Science. 2017;28:59-79.

- Gu H, Chen X, Chen F, Zhou X, Parsaee Z. Ultrasound-assisted biosynthesis of CuO-NPs using brown alga Cystoseira trinodis: characterization, photocatalytic AOP, DPPH scavenging and antibacterial investigations. Ultrason Sonochem. 2018;41:109-19.

- Fouda A, Hassan SED, Eid AM, El-Din EE. The interaction between plants and bacterial endophytes under salinity stress. Endophytes Second Metab. 2019:1-18.

- Zhang J, Wang H, Yan X, Zhang L. Comparison of short-term toxicity between Nano-se and selenite in mice. Life Sci. 2005;76(10):1099-109.

- Manivasagan

, Oh J. Production of a novel fucoidanase for the green synthesis of gold nanoparticles by Streptomyces sp. and its cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells. Marine drugs. 2015;13(11):6818-37. - Zhang J, Zhang SY, Xu JJ, Chen HY. A new method for the synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and the application to construction of

2 biosensor. Chin Chem Lett. 2004;15(11):1345-8. - Romero I, de Francisco P, Gutiérrez JC, Martín-González A. Selenium cytotoxicity in Tetrahymena thermophila: new clues about its biological effects and cellular resistance mechanisms. Sci Total Environ. 2019;671:850-65.

- Gautam PK, Kumar S, Tomar MS, Singh RK, Acharya A, Ram B. Selenium nanoparticles induce suppressed function of tumor associated macrophages and inhibit Dalton’s lymphoma proliferation. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2017;12:172-84.

- Hashem AH, Selim TA, Alruhaili MH, Selim S, Alkhalifah DHM, AI Jaouni SK, et al. Unveiling antimicrobial and insecticidal activities of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using prickly pear peel waste. Function Biomater. 2022;13(3):112.

- Salem SS. A mini review on green nanotechnology and its development in biological effects. Arch Microbiol. 2023;205(4):128.

- Abu-Elghait M, Hasanin M, Hashem AH, Salem SS. Ecofriendly novel synthesis of tertiary composite based on cellulose and myco-synthesized selenium nanoparticles: characterization, antibiofilm and biocompatibility. Biol Macromol. 2021;175:294-303.

- Elakraa AA, Salem SS, El-Sayyad GS, Attia MS. Cefotaxime incorporated bimetallic silver-selenium nanoparticles: promising antimicrobial synergism, antibiofilm activity, and bacterial membrane leakage reaction mechanism. RSC Adv. 2022;12(41):26603-19.

- Salem SS. Bio-fabrication of selenium nanoparticles using Baker’s yeast extract and its antimicrobial efficacy on food borne pathogens. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;194(5):1898-910.

- Cruz LY, Wang D, Liu J. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles, characterization and X-ray induced radiotherapy for the treatment of lung cancer with interstitial lung disease. Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2019;191:123-7.

- Ferro C, Florindo HF, Santos HA. Selenium nanoparticles for biomedical applications: from development and characterization to therapeutics. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2021;10(16):2100598.

- Chaudhary S, Umar A, Mehta SK. Surface functionalized selenium nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomed Nanotechnol. 2014;10(10):3004-42.

- Martínez-Esquivias F, Guzmán-Flores JM, Pérez-Larios A, González Silva N, Becerra-Ruiz JS. A review of the antimicrobial activity of selenium nanoparticles. Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2021;21(11):5383-98.

- Rout SK. Physicochemical, functional and spectroscopic analysis of crawfish chitin and chitosan as affected by process modification. Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College; 2001. p. 3042648.

- Lopez-Moya F, Suarez-Fernandez M, Lopez-Llorca LV. Molecular mechanisms of chitosan interactions with fungi and plants. Int J Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(2):332.

- Saeedi M, Vahidi O, Moghbeli M, Ahmadi S, Asadnia M, Akhavan O, et al. Customizing nano-chitosan for sustainable drug delivery. Control Release. 2022;350:175-92.

- Hashem AH, Shehabeldine AM, Ali OM, Salem SS. Synthesis of chitosanbased gold nanoparticles: antimicrobial and wound-healing activities. Polymers. 2022;14(11):2293.

- Shehabeldine AM, Salem SS, Ali OM, Abd-Elsalam KA, Elkady FM, Hashem AH. Multifunctional silver nanoparticles based on chitosan: antibacterial, antibiofilm, antifungal, antioxidant, and wound-healing activities. Fungi. 2022;8(6):612.

- Torzsas TL, Kendall CWC, Sugano M, Iwamoto Y, Rao AV. The influence of high and low molecular weight chitosan on colonic cell proliferation and aberrant crypt foci development in CF1 mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 1996;34(1):73-7.

- Maeda Y, Kimura Y. Antitumor effects of various low-molecular-weight chitosans are due to increased natural killer activity of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes in sarcoma 180-bearing mice. Nutrition. 2004;134(4):945-50.

- Rangrazi A, Bagheri H, Ghazvini K, Boruziniat A, Darroudi M. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of colloidal selenium nanoparticles in chitosan solution: a new antibacterial agent. Mater Res Express. 2020;6(12):1250h3.

- Sivanesan I, Gopal J, Muthu M, Shin J, Mari S, Oh J. Green synthesized chitosan/chitosan nanoforms/nanocomposites for drug delivery applications. Polymers. 2021;13(14):2256.

- Alalawy AI, El Rabey HA, Almutairi FM, Tayel AA, AI-Duais MA, Zidan NS, et al. Effectual anticancer potentiality of loaded bee venom onto fungal chitosan nanoparticles. Polymer Sci. 2020;2020 https://doi.org/10.1155/ 2020/2785304.

- Oladele IO, Omotosho TF, Adediran AA. Polymer-based composites: an indispensable material for present and future applications. Polymer Sci. 2020;2020:1-12.

- Alghuthaymi MA, Diab AM, Elzahy AF, Mazrou KE, Tayel AA, Moussa SH. Green biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles by cinnamon extract and their antimicrobial activity and application as edible coatings with nano-chitosan. Food Quality. 2021;2021:1-10.

- Chubukov V, Gerosa L, Kochanowski K, Sauer U. Coordination of microbial metabolism. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12(5):327-40.

- Zhou Y, Yan K, Qin Q, Raimi OG, Du C, Wang B, et al. Phosphoglucose isomerase is important for aspergillus fumigatus cell wall biogenesis. Mbio. 2022;13(4):e01426-2.

- Yuan W, Du Y, Yu K, Xu S, Liu M, Wang S, et al. The production of pyruvate in biological technology: a critical review. Microorganisms. 2022;10(12):2454.

- Ortiz-Ramírez P, Hernández-Ochoa B, Ortega-Cuellar D, González-Valdez A, Martínez-Rosas V, Morales-Luna L, et al. Biochemical and kinetic characterization of the Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from helicobacter pylori strain 29CaP. Microorganisms., 1359. 2022;10(7)

- You Y, Chu S, Khalid M, Hayat K, Yang X, Zhang D, et al. A sustainable approach for removing nitrate: studying the nitrate transformation and metabolic potential under different carbon source by microorganism. Clean Prod. 2022;346:131169.

- Hamed AA, Abdel-Aziz MS, Fadel M, Ghali MF. Antimicrobial, antidermatophytic, and cytotoxic activities from Streptomyces sp. MER4 isolated from Egyptian local environment. Bull Natl Res Centre. 2018;42:1-10.

- Hamed AA, Eskander DM, Badawy MSEM. Isolation of secondary metabolites from marine Streptomyces sparsus ASD203 and evaluation its bioactivity. Egypt J Chem. 2022;65(3):539-47.

- Hamed AA, Kabary H, Khedr M, Emam AN. Antibiofilm, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity of extracellular green-synthesized silver nanoparticles by two marine-derived actinomycete. RSC Adv. 2020;10(17):10361-7.

- Ramya

, Shanmugasundaram , Balagurunathan R. Biomedical potential of actinobacterially synthesized selenium nanoparticles with special reference to anti-biofilm, anti-oxidant, wound healing, cytotoxic and anti-viral activities. T.race Elements Med Biol. 2015;32:30-9. - Ranjitha VR, Ravishankar VR. Extracellular synthesis of selenium nanoparticles from an actinomycetes streptomyces griseoruber and

evaluation of its cytotoxicity on HT-29 cell line. Pharmac Nanotechnol. 2018;6(1):61-8. - Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870-4.

- Salem MF, Abd-Elraoof WA, Tayel AA, Alzuaibr FM, Abonama OM. Antifungal application of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles with pomegranate peels and nanochitosan as edible coatings for citrus green mold protection. Nanobiotechnology. 2022;20(1):182.

- Mostafa EM, Abdelgawad MA, Musa A, Alotaibi NH, Elkomy MH, Ghoneim MM, et al. Chitosan silver and gold nanoparticle formation using endophytic fungi as powerful antimicrobial and anti-biofilm potentialities. Antibiotics. 2022;11(5):668.

- Alhadrami HA, Orfali R, Hamed AA, Ghoneim MM, Hassan HM, Hassane ASI, et al. Flavonoid-coated gold nanoparticles as efficient antibiotics against gram-negative bacteria-evidence from in silico-supported in vitro studies. Antibiotics. 2021;2021:10.

- Abdel-Nasser M, Abdel-Maksoud G, Abdel-Aziz MS, Darwish SS, Hamed AA, Youssef AM. Evaluation of the efficiency of nanoparticles for increasing a-amylase enzyme activity for removing starch stain from paper artifacts. Cultural Heritage. 2022;53:14-23.

- Abdelaziz MS, Hamed AA, Radwan AA, Khaled E, Hassan RY. Biosynthesis and bio-sensing applications of silver and gold metal nanoparticles. Egypt J Chem. 2021;64(2):1057-63.

- Khedr WE, Shaheen MN, Elmahdy EM, Bendary MAE, Hamed AA, Mohamedin AH. Silver and gold nanoparticles: eco-friendly synthesis, antibiofilm, antiviral, and anticancer bioactivities. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2023:1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826068.2023.2248238.

- Hamed AA, Soldatou S, Qader MM, Arjunan S, Miranda KJ, Casolari F, et al. Screening fungal endophytes derived from under-explored Egyptian marine habitats for antimicrobial and antioxidant properties in factionalised textiles. Microorganisms. 2020;8(10):1617.

- El-Shora HM, El-Sharkawy RM, Khateb AM, Darwish DB. Production and immobilization of

-glucanase from aspergil-lus Niger with its applications in bioethanol production and biocontrol of phytopathogenic fungi. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21000. - Lima TC, Ferreira AR, Silva DF, Lima EO, de Sousa DP. Antifungal activity of cinnamic acid and benzoic acid esters against Candida albicans strains. Nat Prod Res. 2018;32(5):572-5.

- Sezonov G, Joseleau-Petit D, d’Ari R. Escherichia coli physiology in LuriaBertani broth. Bacteriology. 2007;189(23):8746-9.

- Gohil K, Jones DA. A sensitive spectorophotometric assay for pyruvate dehydrogenase and oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complexes. Biosci Rep. 1983;3(1):1-9.

- Betke K, Beutler E, Brewer GJ, Kirkman HN, Luzzatto L, Motulsky AG, et al. Standardization of procedures for the study of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Report of a WHO scientific group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1967;366(1)

- Lewis OAM, Watson EF, Hewitt EJ. Determination of nitrate reductase activity in barley leaves and roots. Ann Bot. 1982;49(1):31-7.

- Bradford MM . A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72(1-2):248-54.

- El-Bendary MA, Afifi SS, Moharam ME, Abo El-Ola SM, Salama A, Omara EA, et al. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using isolated Bacillus subtilis: characterization, antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity, and their performance as antimicrobial agent for textile materials. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2021;51(1):54-68.

- Oka M, Maeda S, Koga N, Kato K, Saito T. A modified colorimetric MTT assay adapted for primary cultured hepatocytes: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1992;56(9):1472-3.

- Danaei M, Dehghankhold M, Ataei S, Hasanzadeh Davarani F, Javanmard R, Dokhani A, et al. Impact of particle size and polydispersity index on the clinical applications of lipidic nanocarrier systems. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(2):57.

- Lin ZH, Wang CC. Evidence on the size-dependent absorption spectral evolution of selenium nanoparticles. Mater Chem Phys. 2005;92(2-3):591-4.

- Ikram M, Javed B. Raja NI biomedical potential of plant-based selenium nanoparticles: a comprehensive review on therapeutic and mechanistic aspects. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:249.

- Abdel-Moneim AME, El-Saadony MT, Shehata AM, Saad AM, Aldhumri SA, Ouda SM, et al. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Spirulina platensis extracts and biogenic selenium nanoparticles against selected pathogenic bacteria and fungi. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29(2):1197-209.

- Sumithra D, Bharathi S, Kaviyarasan P, Suresh G. Biofabrication of Selenium Nanoparticles Using Marine Streptomyces sp. and Assessment of Its Antibacterial, Antibiofilm, Antioxidant, and In Vivo Cytotoxic Potential. Geomicrobiology. 2023;40(5):485-92.

- Dhanjal S, Cameotra SS. Aerobic biogenesis of selenium nanospheres by Bacillus cereus isolated from coalmine soil. Microb Cell Factories. 2010;9(1):1-11.

- Kora AJ, Rastogi L. Biomimetic synthesis of selenium nanoparticles by Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853: an approach for conversion of selenite. Environ Manag. 2016;181:231-6.

- Jiang F, Cai W, Tan G. Facile synthesis and optical properties of small selenium nanocrystals and nanorods. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2017;12:1-6.

- Nogueira GD, Duarte CR, Barrozo MA. Hydrothermal carbonization of acerola (Malphigia emarginata DC) wastes and its application as an adsorbent. Waste Manag. 2019;95:466-75.

- Prasad KS, Selvaraj K. Biogenic synthesis of selenium nanoparticles and their effect on as (III)-induced toxicity on human lymphocytes. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;157:275-83.

- Fresneda MAR, Martín JD, Bolívar JG, Cantos MVF, Bosch-Estévez G, Moreno MFM, et al. Green synthesis and biotransformation of amorphous se nanospheres to trigonal 1D se nanostructures: impact on se mobility within the concept of radioactive waste disposal. Environ Sci: Nano. 2018;5(9):2103-16.

- Salama A, Hasanin M, Hesemann P. Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of new chitosan derivatives containing guani-dinium groups. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;241:116363.

- Tayel AA, Elzahy AF, Moussa SH, Al-Saggaf MS, Diab AM. Biopreservation of shrimps using composed edible coatings from chitosan nanoparticles and cloves extract. Food Quality. 2020;2020:1-10.

- Shehabeldine AM, Hashem AH, Wassel AR, Hasanin M. Antimicrobial and antiviral activities of durable cotton fabrics treated with nanocomposite based on zinc oxide nanoparticles, acyclovir, nanochitosan, and clove oil. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;194 https://doi.org/10.1007/ s12010-021-03649-y.

- Shehabeldine A, Hasanin M. Green synthesis of hydrolyzed starchchitosan nano-composite as drug delivery system to gram negative bacteria. Environ Nanotechnol Monitor Manag. 2019;12:100252.

- Potrč S, Glaser TK, Vesel A, Ulrih NP, Zemljič LF. Two-layer functional coatings of chitosan particles with embedded catechin and pomegranate extracts for potential active packaging. Polymers. 2020;12(9):1855.

- Elsharawy K, Abou-Dobara M, El-Gammal H, Hyder A. Chitosan coating does not prevent the effect of the transfer of green silver nanoparticles biosynthesized by Streptomyces malachitus into fetuses via the placenta. Reprod Biol. 2020;20(1):97-105.

- Siddiqi KS, Husen A, Rao RA. A review on biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biocidal properties. Nanobiotechnology. 2018;16(1):1-28.

- Gad HA, Tayel AA, AI-Saggaf MS, Moussa SH, Diab AM. Phyto-fabrication of selenium nanorods using extract of pomegranate rind wastes and their potentialities for inhibiting fish-borne pathogens. Green Process Synthesis. 2021;10(1):529-37.

- Shetta A, Kegere J, Mamdouh W. Comparative study of encapsulated peppermint and green tea essential oils in chitosan nanoparticles: encapsulation, thermal stability, in-vitro release, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Int J Biological Macromolecules. 2019;126:731-42.

- Joshi SM, De Britto S, Jogaiah S, Ito SI. Mycogenic selenium nanoparticles as potential new generation broad spectrum antifungal molecules. Biomolecules. 2019;9(9):419.

- Zhang H, Zhou H, Bai J, Li Y, Yang J, Ma Q, et al. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles mediated by fungus Mariannaea sp. HJ and their characterization. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2019;571:9-16.

- Koukaras EN, Papadimitriou SA, Bikiaris DN, Froudakis GE. Insight on the formation of chitosan nanoparticles through ionotropic gelation with tripolyphosphate. Mol Pharm. 2012;9(10):2856-62.

- Hnain A, Brooks J, Lefebvre DD. The synthesis of elemental selenium particles by Synechococcus leopoliensis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:10511-9.

- Pandey S, Awasthee N, Shekher A, Rai LC, Gupta SC, Dubey SK. Biogenic synthesis and characterization of selenium nanoparticles and their applications with special reference to antibacterial, antioxidant, anticancer and photocatalytic activity. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2021;44:2679-96.

- MubarakAli D, LewisOscar F, Gopinath V, Alharbi NS, Alharbi SA, Thajuddin N. An inhibitory action of chitosan nanoparticles against pathogenic bacteria and fungi and their potential applications as biocompatible antioxidants. Microb Pathog. 2018;114:323-7.

- Villegas-Peralta Y, López-Cervantes J, Santana TJM, Sánchez-Duarte RG, Sánchez-Machado DI, Martínez-Macías MDR, et al. Impact of the molecular weight on the size of chitosan nanoparticles: characterization and its solid-state application. Polym Bull. 2021;78:813-32.

- Guisbiers G, Wang Q, Khachatryan E, Mimun LC, Mendoza-Cruz R, Larese-Casanova P, et al. Inhibition of E. Coli and S. Aureus with selenium nanoparticles synthesized by pulsed laser ablation in deionized water. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016:3731-6.

- Skoglund S, Hedberg J, Yunda E, Godymchuk A, Blomberg E, Odnevall WI. Difficulties and flaws in performing accurate determinations of zeta potentials of metal nanoparticles in complex solutions-four case studies. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181735.

- Chen W, Yue L, Jiang Q, Liu X, Xia W. Synthesis of varisized chitosanselenium nanocomposites through heating treatment and evaluation of their antioxidant properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;114:751-8.

- Jardim KV, Siqueira JLN, Báo SN, Parize AL. In vitro cytotoxic and antioxidant evaluation of quercetin loaded in ionic cross-linked chitosan nanoparticles. Drug Del Sci Technol. 2022;74:103561.

- Chudobova D, Cihalova K, Dostalova S, Ruttkay-Nedecky B, Merlos Rodrigo MA, Tmejova K, et al. Comparison of the effects of silver phosphate and selenium nanoparticles on Staphylococcus aureus growth reveals potential for selenium particles to prevent infection. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2014;351(2):195-201.

- Al-Saggaf MS. Nanoconjugation between fungal Nanochitosan and biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles with Hibiscus sabdariffa extract for effectual control of multidrug-resistant Bacteria. Nanomaterials. 2022;2022 https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7583032.

- Portillo-Torres LA, Bernardino-Nicanor A, Mercado-Monroy J, GómezAldapa CA, González-Cruz L, Rangel-Vargas E, et al. Antimicrobial effects of aqueous extract from calyces of Hibiscus sabdariffa in CD-1 mice infected with multidrug-resistant Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli and salmonella Typhimurium. Medicinal Food. 2022;25(9):902-9.

- Hashem AH, Salem SS. Green and ecofriendly biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles using Urtica dioica (stinging nettle) leaf extract: antimicrobial and anticancer activity. Biotechnology. 2022;17(2):2100432.

- Cremonini E, Zonaro E, Donini M, Lampis S, Boaretti M, Dusi S, et al. Biogenic selenium nanoparticles: characterization, antimicrobial activity and effects on human dendritic cells and fibroblasts. Microb Biotechnol. 2016;9(6):758-71.

- Khiralla GM, El-Deeb BA. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm effects of selenium nanoparticles on some foodborne pathogens. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2015;63(2):1001-7.

- El-Sayed ESR, Abdelhakim HK, Ahmed AS. Solid-state fermentation for enhanced production of selenium nanoparticles by gamma-irradiated Monascus purpureus and their biological evaluation and photocatalytic activities. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2020;43:797-809.

- Huang T, Holden JA, Heath DE, O’Brien-Simpson NM, O’Connor AJ. Engineering highly effective antimicrobial selenium nanoparticles through control of particle size. Nanoscale. 2019;11(31):14937-51.

- Deepa T, Mohan S, Manimaran P. A crucial role of selenium nanoparticles for future perspectives. Results Chem. 2022;4:100367.

- Nikam PB, Salunkhe JD, Marathe KR, Alghuthaymi MA, Abd-Elsalam KA, Patil SV. Rhizobium pusense-Mediated Selenium NanoparticlesAntibiotics Combinations against Acanthamoeba sp. Microorganisms. 2022;10(12):2502.

- Saad EL, Salem SS, Fouda A, Awad MA, El-Gamal MS, Abdo AM. New approach for antimicrobial activity and bio-control of various pathogens by biosynthesized copper nanoparticles using endophytic actinomycetes. J Radiat Res Appl. 2018;11 (3):262-70.

- Alarfaj AA. Antibacterial effect of chitosan nanoparticles against food spoilage bacteria. Pure Appl Microbiol. 2019;13(2):1273-8.