DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53202-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38307882

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-02

افتح

الخصائص السكانية والسريرية للمرضى الذين يعانون من نقص الزنك: تحليل لقاعدة بيانات المطالبات الطبية الوطنية اليابانية

الملخص

هيروهيدي يوكوكاوا

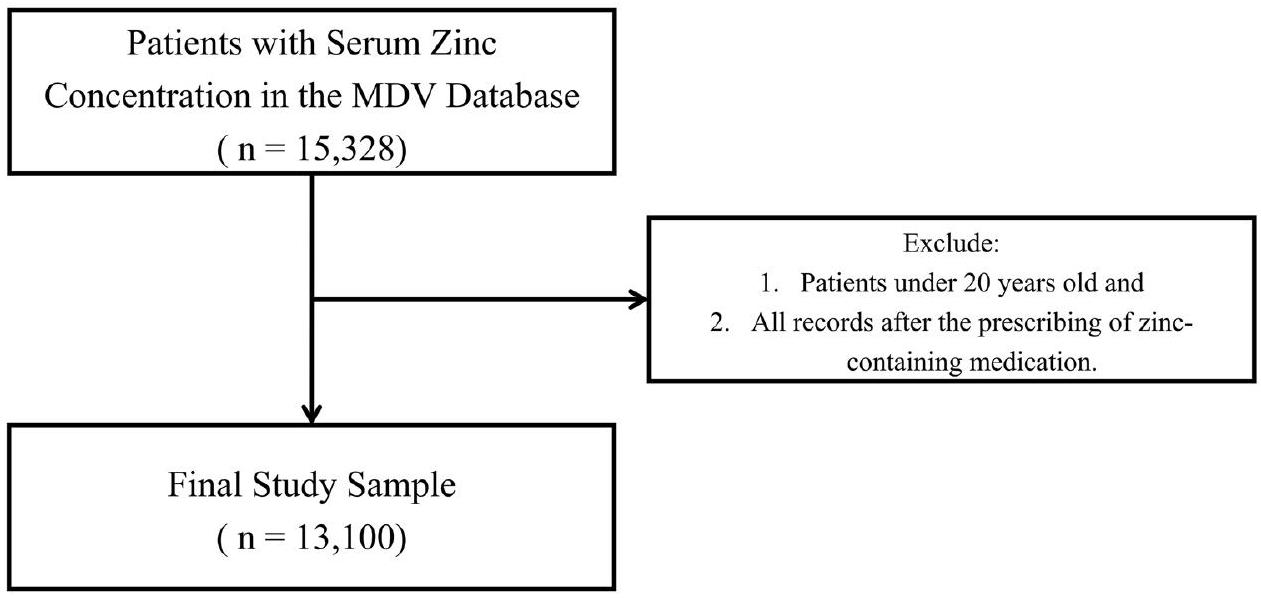

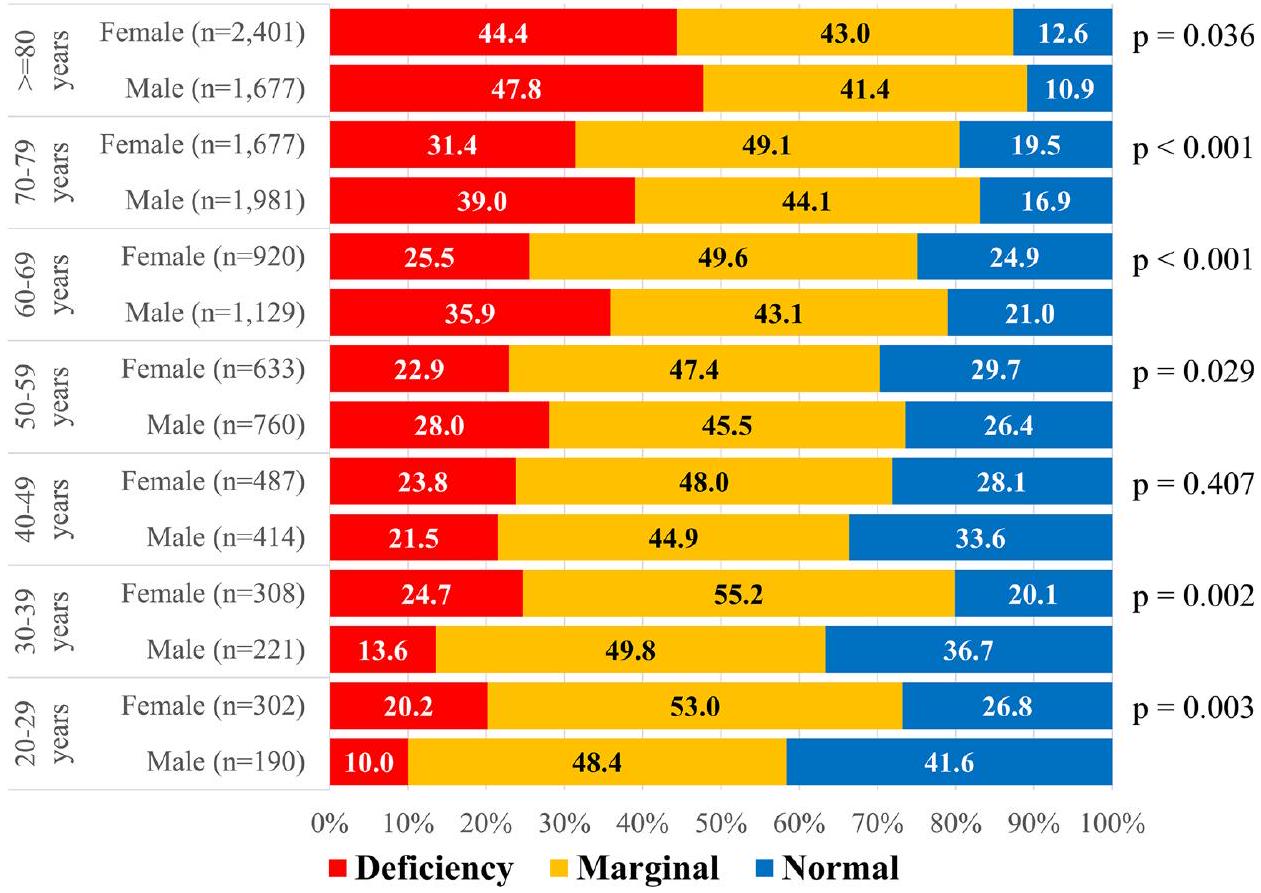

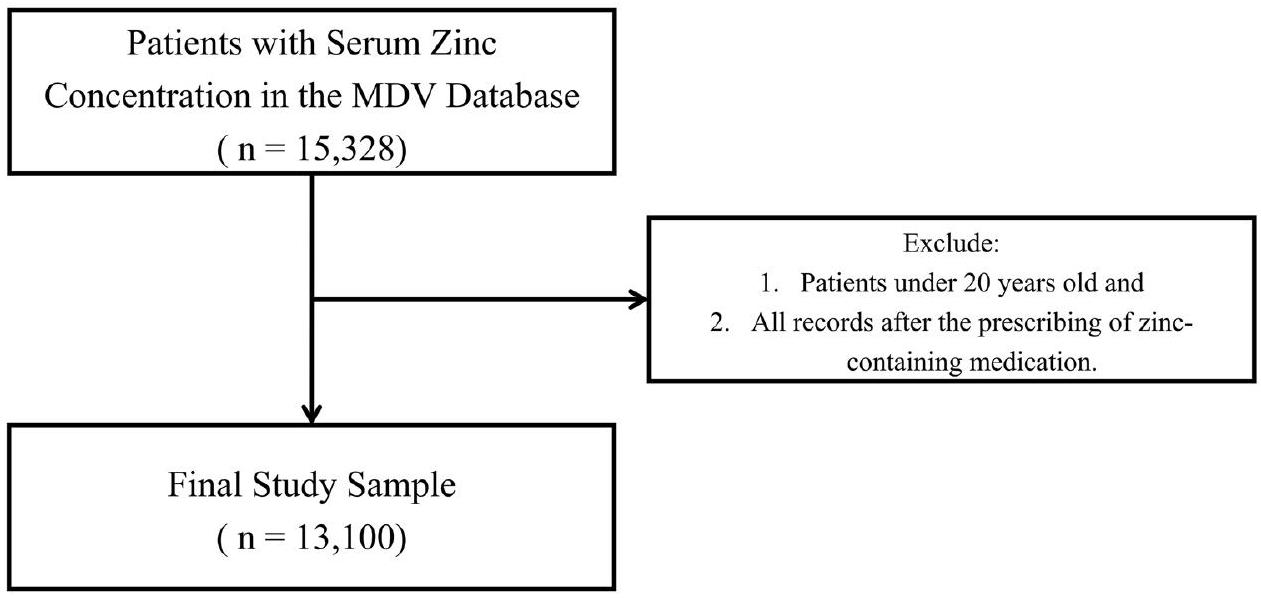

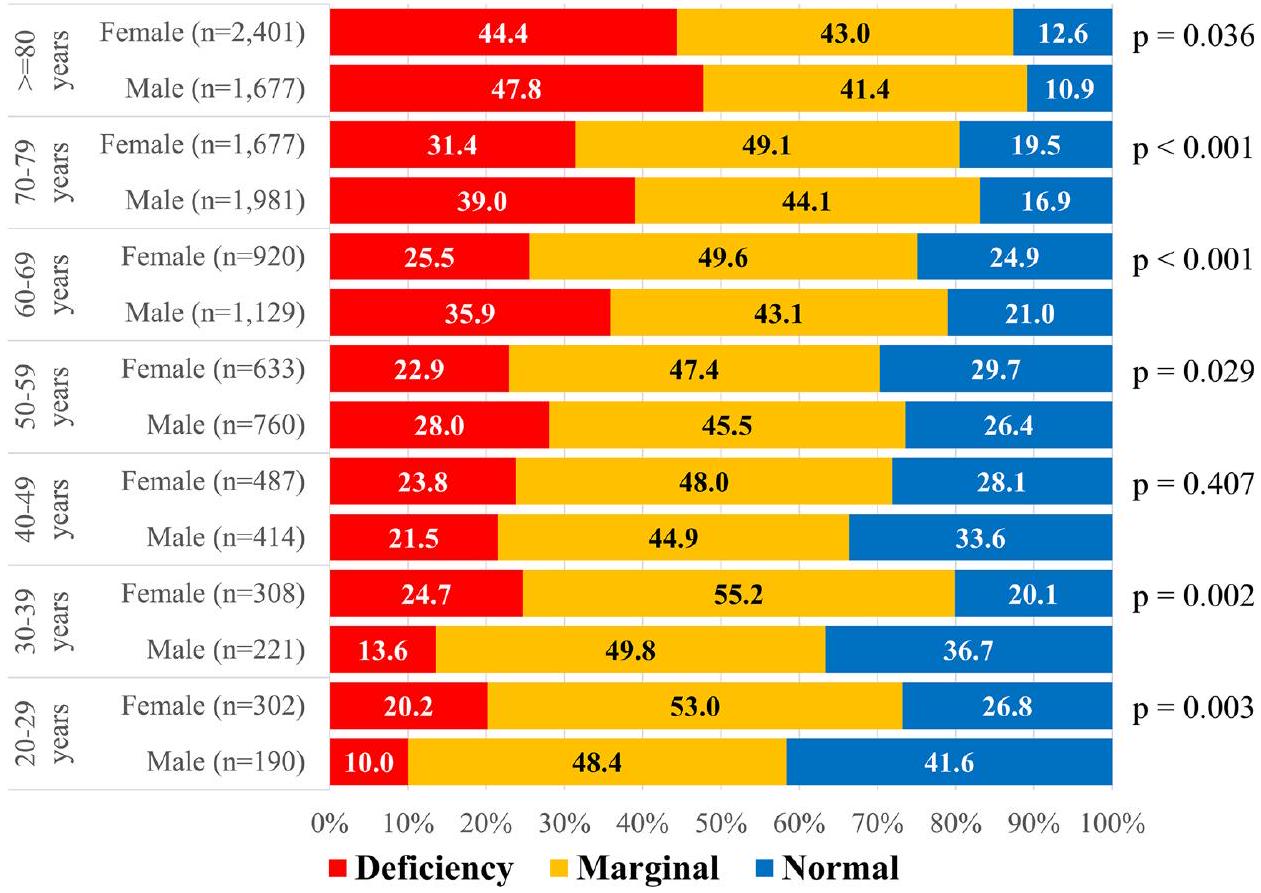

نقص الزنك، الذي يؤثر على أكثر من 2 مليار شخص على مستوى العالم، يشكل عبئًا كبيرًا على الصحة العامة بسبب تأثيراته السلبية العديدة، مثل ضعف وظيفة المناعة، واضطرابات التذوق والشم، والالتهاب الرئوي، وتأخر النمو، وضعف البصر، واضطرابات الجلد. على الرغم من دوره الحاسم، لا تزال الدراسات الكبيرة النطاق التي تحقق في العلاقة بين خصائص المرضى ونقص الزنك بحاجة إلى إكمال. أجرينا دراسة استرجاعية، مقطعية، قائمة على الملاحظة باستخدام قاعدة بيانات المطالبات الوطنية اليابانية من يناير 2019 إلى ديسمبر 2021. شملت عينة الدراسة 13,100 مريض مع بيانات متاحة عن تركيز الزنك في المصل، مستبعدين الأفراد تحت سن 20 والذين تم تقييمهم لتركزات الزنك بعد وصف أدوية تحتوي على الزنك. لوحظت ارتباطات كبيرة مع نقص الزنك بين كبار السن، والذكور، والمرضى الداخليين. أظهرت التحليلات المتعددة المتغيرات، مع تعديل العمر والجنس، ارتباطات كبيرة مع الأمراض المصاحبة، بما في ذلك التهاب الرئة بسبب المواد الصلبة والسوائل مع نسبة الأرجحية المعدلة (aOR) تبلغ 2.959؛ قرحة الضغط والمنطقة المعرضة للضغط (aOR 2.403)، الساركوبينيا (aOR 2.217)، COVID-19 (aOR 1.889)، وأمراض الكلى المزمنة (aOR 1.835). كما وُجدت ارتباطات كبيرة مع الأدوية، بما في ذلك سبيرونولاكتون (aOR 2.523)، والمضادات الحيوية الجهازية (aOR 2.419)، وفوروسيميد (aOR 2.138)، والتحضيرات المضادة لفقر الدم (aOR 2.027)، وهرمونات الغدة الدرقية (aOR 1.864). قد تساعد هذه النتائج الأطباء في تحديد المرضى المعرضين لخطر نقص الزنك، مما قد يحسن نتائج الرعاية.

طرق

تصميم الدراسة ومصدر البيانات

معايير الشمول/الاستبعاد

المتغيرات

الاعتبارات الأخلاقية

طرق إحصائية

تم إجراء دراسات حول الأمراض المصاحبة والأدوية، مقسمة حسب فئة العمر، الجنس، وحالة المريض (داخلي/خارجي). كان الهدف هو تحديد المتغيرات المرتبطة بنقص الزنك التي تتعلق بالجنس، العمر، وحالة المريض. تم تقييم العلاقة بين تركيز الزنك في المصل والمعايير المخبرية باستخدام معامل ارتباط سبيرمان. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم فحص العلاقة بين الهيموغلوبين ومستويات الزنك في المصل من خلال تصنيف الهيموغلوبين على أنه ‘منخفض’ أو ‘طبيعي’ وفقًا لمعايير منظمة الصحة العالمية.

النتائج

| الخصائص السكانية/السريرية | ن (%) | الخصائص السكانية/السريرية | ن (%) |

| إجمالي المرضى | 13,100 | قصور الغدد التناسلية | ٨٨ (٠.٧) |

| قصر القامة | 81 (0.6) | ||

| زنك المصل

|

فرط شحميات الدم | 1252 (9.6) | |

| متوسط

|

|

أمراض ارتفاع ضغط الدم | 2447 (18.7) |

| مستوى الزنك في المصل | احتشاء عضلة القلب الحاد | 873 (6.7) | |

| نقص

|

4557 (34.8) | الرجفان الأذيني والرفرفة | 662 (5.1) |

| هامشي

|

5964 (45.5) | فشل القلب | 2365 (18.1) |

| عادي (

|

2579 (19.7) | أمراض الأوعية الدموية الدماغية | ١٣٣١ (١٠.٢) |

| الإنفلونزا والالتهاب الرئوي | ٢٠٨٨ (١٥.٩) | ||

| جنس | كوفيد-19 | 3640 (27.8) | |

| ذكر | 6372 (48.6) | التهاب الرئة الناتج عن المواد الصلبة والسوائل | ٤٣٩ (٣.٤) |

| أنثى | 6728 (51.4) | التهاب الفم والآفات المرتبطة | 247 (1.9) |

| مرض الكبد | 2657 (20.3) | ||

| العمر (بالسنوات) (في يوم قياس مستوى الزنك في المصل) | التهاب الجلد والأكزيما | 645 (4.9) | |

| متوسط

|

|

الثعلبة البقعية | 76 (0.6) |

| الفئة العمرية (في يوم قياس مستوى الزنك في المصل) | قرحة الضغط ومنطقة الضغط | 265 (2.0) | |

| 20-29 سنة | ٤٩٢ (٣.٨) | تآكل العضلات وضمور العضلات، غير مصنف في مكان آخر (الساركوبينيا) | 1166 (8.9) |

| 30-39 سنة | 529 (4.0) | هشاشة العظام | 823 (6.3) |

| 40-49 سنة | 901 (6.9) | مرض الكلى المزمن | 1321 (10.1) |

| 50-59 سنة | 1393 (10.6) | اضطرابات الشم والتذوق | ٤٩٢ (٣.٨) |

| 60-69 سنة | 2049 (15.6) | فقدان الشهية | 296 (2.3) |

| 70-79 سنة | 3658 (27.9) | إصابات الرأس | 185 (1.4) |

|

|

4078 (31.1) | كسر | 834 (6.4) |

| الوزن (كجم) | |||

| متوسط

|

|

الأدوية (خلال 60 يومًا قبل قياس مستوى الزنك في المصل) | |

| مؤشر كتلة الجسم (BMI)

|

مضادات ارتفاع سكر الدم | ٢١٩١ (١٦.٧) | |

| معدل

|

|

عوامل خافضة للضغط | 5053 (38.6) |

| مجموعة BMI | سبيرونولاكتون | 818 (6.2) | |

| <25 | 3750 (28.6) | فوروسيميد | ٢٠٨١ (١٥.٩) |

|

|

926 (7.1) | مثبطات ACE | ٣٢٤ (٢.٥) |

| مفقود | 8424 (64.3) | حاصرات مستقبلات الأنجيوتنسين II | 1862 (14.2) |

| أدوية خافضة للدهون | 2148 (16.4) | ||

| المرضى الداخليين/المرضى الخارجيين | ستاتينات | 1861 (14.2) | |

| مريض داخلي | 5614 (42.9) | عوامل مضادة للتخثر | 3859 (29.5) |

| خارج المستشفى | 7420 (56.6) | حاصرات H2 | 930 (7.1) |

| مفقود | 66 (0.5) | مثبطات مضخة البروتون | 4273 (32.6) |

| تحضيرات مضادة لفقر الدم | 1935 (14.8) | ||

| الترافق المرضي (خلال 60 يومًا قبل قياس مستوى الزنك في المصل) | الكورتيكوستيرويدات | 1125 (8.6) | |

| الأمراض المعدية المعوية | 639 (4.9) | هرمونات الغدة الدرقية | 410 (3.1) |

| التهاب الأمعاء غير المعدي والتهاب القولون | 135 (1.0) | المضادات الحيوية الجهازية | 3981 (30.4) |

| السل | ٢٨٣ (٢.٢) | أدوية لعلاج أمراض العظام | ٤٨٤ (٣.٧) |

| الأورام الخبيثة للأعضاء الهضمية | 2536 (19.4) | عوامل مضادة لباركنسون | 215 (1.6) |

| فقر الدم الغذائي | 4144 (31.6) | مضادات الذهان | ١٠٩٧ (٨.٤) |

| داء السكري | 4224 (32.2) | مهدئات القلق | 2442 (18.6) |

| مستوى الزنك في المصل | نقص الزنك

|

||||||

| بشكل عام | نقص | هامشي | عادي | نسبة الأرجحية | فترة الثقة 95% |

|

|

| ن | ن (%) | ن (%) | ن (%) | ||||

| إجمالي المرضى | |||||||

| – | 13,100 | 4557 (34.8) | 5964 (45.5) | 2579 (19.7) | |||

| زنك المصل | |||||||

| يعني

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| جنس | |||||||

| ذكر | 6372 | 2330 (36.6) | 2789 (43.8) | 1253 (19.7) | 1.165 | (1.084, 1.252) | <. 001 |

| أنثى | 6728 | 2227 (33.1) | 3175 (47.2) | 1326 (19.7) | مرجع | ||

| العمر (بالسنوات) (في يوم قياس مستوى الزنك في المصل) | |||||||

| متوسط

|

|

|

|

|

1.301 (العمر/10) | (1.270, 1.332) | <. 001 |

| الفئة العمرية (في يوم قياس مستوى الزنك في المصل) | |||||||

| 20-29 سنة | 492 | 80 (16.3) | 252 (51.2) | ١٦٠ (٣٢.٥) | مرجع | ||

| 30-39 سنة | 529 | ١٠٦ (٢٠.٠) | 280 (52.9) | 143 (27.0) | 1.290 | (0.937, 1.778) | 0.119 |

| 40-49 سنة | 901 | 205 (22.8) | 420 (46.6) | 276 (30.6) | 1.517 | (1.140, 2.018) | 0.004 |

| 50-59 سنة | ١٣٩٣ | 358 (25.7) | 646 (46.4) | 389 (27.9) | 1.781 | (1.363, 2.329) | <. 001 |

| 60-69 سنة | ٢٠٤٩ | 640 (31.2) | 943 (46.0) | ٤٦٦ (٢٢.٧) | ٢.٣٣٩ | (1.809, 3.025) | <. 001 |

| 70-79 سنة | ٣٦٥٨ | 1300 (35.5) | ١٦٩٧ (٤٦.٤) | 661 (18.1) | 2.839 | (2.214, 3.641) | <. 001 |

|

|

٤٠٧٨ | 1868 (45.8) | 1726 (42.3) | ٤٨٤ (١١.٩) | ٤.٣٥٣ | (3.399, 5.574) | <. 001 |

| الوزن (كجم) | |||||||

| متوسط

|

|

|

|

|

0.906 (الوزن/5) | (0.887, 0.925) | <. 001 |

| مؤشر كتلة الجسم

|

|||||||

| معدل

|

|

|

|

|

0.903 (مؤشر كتلة الجسم/2) | (0.879, 0.927) | <. 001 |

| مجموعة BMI | |||||||

| <25 | ٣٧٥٠ | 1950 (52.0) | 1307 (34.9) | 493 (13.1) | 1.443 | (1.249, 1.669) | <. 001 |

|

|

926 | 397 (42.9) | 365 (39.4) | 164 (17.7) | مرجع | ||

| مفقود | 8424 | 2210 (26.2) | 4292 (50.9) | 1922 (22.8) | 0.474 | (0.413, 0.545) | <. 001 |

| التدخين | |||||||

| لا | 2897 | 1481 (51.1) | ١٠٣٣ (٣٥.٧) | ٣٨٣ (١٣.٢) | مرجع | ||

| نعم | 1723 | 844 (49.0) | 628 (36.4) | ٢٥١ (١٤.٦) | 0.918 | (0.815, 1.034) | 0.160 |

| مفقود | 8480 | ٢٢٣٢ (٢٦.٣) | 4303 (50.7) | 1945 (22.9) | 0.342 | (0.313, 0.373) | <. 001 |

| المرضى الداخليين/المرضى الخارجيين | |||||||

| مريض داخلي | 5614 | 2822 (50.3) | 1995 (35.5) | 797 (14.2) | 3.367 | (3.123, 3.630) | <. 001 |

| خارج المستشفى | 7420 | 1713 (23.1) | 3938 (53.1) | 1769 (23.8) | مرجع | ||

| مفقود | 66 | 22 (33.3) | 31 (47.0) | 13 (19.7) | 1.666 | (0.996, 2.787) | 0.052 |

نقاش

| مستوى الزنك في المصل | ||||

| بشكل عام | نقص | هامشي | عادي | |

| ن | ن (%) | ن (%) | ن (%) | |

| إجمالي المرضى | 13,100 | 4557 (34.8) | 5964 (45.5) | 2579 (19.7) |

| الترافق المرضي (خلال 60 يومًا قبل يوم قياس مستوى الزنك في المصل) | ||||

| الأمراض المعدية المعوية | 639 | 281 (44.0) | 233 (36.5) | 125 (19.6) |

| التهاب الأمعاء غير المعدي والتهاب القولون | 135 | ٤٩ (٣٦.٣) | ٥٥ (٤٠.٧) | 31 (23.0) |

| السل | ٢٨٣ | 124 (43.8) | 120 (42.4) | ٣٩ (١٣.٨) |

| الأورام الخبيثة لأعضاء الجهاز الهضمي | 2536 | 1009 (39.8) | ١٠٢٢ (٤٠.٣) | 505 (19.9) |

| فقر الدم الغذائي | 4144 | 1380 (33.3) | 1995 (48.1) | 769 (18.6) |

| داء السكري | ٤٢٢٤ | 1427 (33.8) | 1974 (46.7) | 823 (19.5) |

| قصور الغدد التناسلية | ٨٨ | ٢٨ (٣١.٨) | 44 (50.0) | 16 (18.2) |

| قصر القامة | 81 | ٢٧ (٣٣.٣) | ٣٩ (٤٨.١) | 15 (18.5) |

| فرط شحميات الدم | 1252 | 491 (39.2) | ٥٢٦ (٤٢.٠) | 235 (18.8) |

| أمراض ارتفاع ضغط الدم | 2447 | 1147 (46.9) | 923 (37.7) | 377 (15.4) |

| احتشاء عضلة القلب الحاد | 873 | 259 (29.7) | 445 (51.0) | 169 (19.4) |

| الرجفان الأذيني والرفرفة | 662 | 300 (45.3) | ٢٦٨ (٤٠.٥) | 94 (14.2) |

| فشل القلب | 2365 | 1074 (45.4) | 960 (40.6) | ٣٣١ (١٤.٠) |

| أمراض الأوعية الدموية الدماغية | ١٣٣١ | 604 (45.4) | 524 (39.4) | ٢٠٣ (١٥.٣) |

| الإنفلونزا والالتهاب الرئوي | ٢٠٨٨ | ٨٣٨ (٤٠.١) | 921 (44.1) | ٣٢٩ (١٥.٨) |

| كوفيد-19 | ٣٦٤٠ | 1554 (42.7) | 1507 (41.4) | 579 (15.9) |

| التهاب الرئة الناتج عن المواد الصلبة والسوائل | ٤٣٩ | ٢٩٢ (٦٦.٥) | 116 (26.4) | 31 (7.1) |

| التهاب الفم والآفات المرتبطة | 247 | 63 (25.5) | 121 (49.0) | 63 (25.5) |

| مرض الكبد | ٢٦٥٧ | 934 (35.2) | 1155 (43.5) | 568 (21.4) |

| التهاب الجلد والأكزيما | 645 | 238 (36.9) | ٢٧٦ (٤٢.٨) | 131 (20.3) |

| الثعلبة البقعية | 76 | 7 (9.2) | ٣٦ (٤٧.٤) | ٣٣ (٤٣.٤) |

| قرحة الضغط ومنطقة الضغط | ٢٦٥ | 160 (60.4) | ٨٣ (٣١.٣) | 22 (8.3) |

| تآكل العضلات وضمور العضلات، غير مصنف في مكان آخر (الساركوبينيا) | 1166 | 661 (56.7) | 371 (31.8) | ١٣٤ (١١.٥) |

| هشاشة العظام | ٨٢٣ | ٣٤٩ (٤٢.٤) | ٣٣٩ (٤١.٢) | 135 (16.4) |

| مرض الكلى المزمن | 1321 | 676 (51.2) | ٤٩٢ (٣٧.٢) | 153 (11.6) |

| اضطرابات الشم والتذوق | 492 | ٨٣ (١٦.٩) | 260 (52.8) | 149 (30.3) |

| فقدان الشهية | ٢٩٦ | ١١٥ (٣٨.٩) | 123 (41.6) | ٥٨ (١٩.٦) |

| إصابات الرأس | 185 | 89 (48.1) | 69 (37.3) | 27 (14.6) |

| كسر | 834 | ٣٨٠ (٤٥.٦) | ٣٢٢ (٣٨.٦) | ١٣٢ (١٥.٨) |

| مستوى الزنك في المصل | ||||

| بشكل عام | نقص | هامشي | عادي | |

| ن | ن (%) | ن (%) | ن (%) | |

| إجمالي المرضى | 13,100 | 4557 (34.8) | 5964 (45.5) | 2579 (19.7) |

| الأدوية (خلال 60 يومًا قبل يوم قياس مستوى الزنك في المصل) | ||||

| مضادات ارتفاع سكر الدم | ٢١٩١ | 793 (36.2) | 972 (44.4) | 426 (19.4) |

| عوامل خافضة للضغط | 5053 | 2165 (42.8) | 2105 (41.7) | 783 (15.5) |

| سبيرونولاكتون | 818 | 478 (58.4) | 257 (31.4) | 83 (10.1) |

| فوروسيميد | ٢٠٨١ | 1117 (53.7) | 741 (35.6) | ٢٢٣ (١٠.٧) |

| مثبطات ACE | ٣٢٤ | 127 (39.2) | 148 (45.7) | ٤٩ (١٥.١) |

| حاصرات مستقبلات الأنجيوتنسين II | 1862 | 693 (37.2) | 826 (44.4) | 343 (18.4) |

| أدوية خافضة للدهون | 2148 | 634 (29.5) | ١٠٥٩ (٤٩.٣) | 455 (21.2) |

| ستاتينات | 1861 | ٥٥٨ (٣٠.٠) | 924 (49.7) | ٣٧٩ (٢٠.٤) |

| عوامل مضادة للتخثر | ٣٨٥٩ | 1767 (45.8) | 1512 (39.2) | 580 (15.0) |

| حاصرات H2 | 930 | ٣٥٢ (٣٧.٨) | ٤٠٦ (٤٣.٧) | 172 (18.5) |

| مثبطات مضخة البروتون | 4273 | 1860 (43.5) | ١٦٩٧ (٣٩.٧) | 716 (16.8) |

| تحضيرات مضادة لفقر الدم | 1935 | 989 (51.1) | 730 (37.7) | 216 (11.2) |

| الكورتيكوستيرويدات | ١١٢٥ | ٤٨٢ (٤٢.٨) | 474 (42.1) | ١٦٩ (١٥.٠) |

| هرمونات الغدة الدرقية | 410 | 212 (51.7) | 141 (34.4) | 57 (13.9) |

| المضادات الحيوية الجهازية | ٣٩٨١ | 2006 (50.4) | 1420 (35.7) | 555 (13.9) |

| أدوية لعلاج أمراض العظام | ٤٨٤ | 164 (33.9) | 240 (49.6) | 80 (16.5) |

| عوامل مضادة لباركنسون | 215 | ١٠١ (٤٧.٠) | 91 (42.3) | 23 (10.7) |

| مضادات الذهان | ١٠٩٧ | 487 (44.4) | 424 (38.7) | 186 (17.0) |

| مهدئات القلق | 2442 | 1055 (43.2) | 998 (40.9) | 389 (15.9) |

| نقص الزنك

|

تحليل أحادي غير معدل | تحليل معدل

|

||||

| نسبة الأرجحية* | فترة الثقة 95% |

|

نسبة الأرجحية* | فترة الثقة 95% |

|

|

| الترافق المرضي (خلال 60 يومًا قبل يوم قياس مستوى الزنك في المصل) | ||||||

| الأمراض المعدية المعوية | 1.502 | (1.280, 1.764) | <. 001 | 1.733 | (1.468, 2.045) | <. 001 |

| التهاب الأمعاء غير المعدي والتهاب القولون | 1.070 | (0.752, 1.522) | 0.709 | 1.309 | (0.910, 1.883) | 0.147 |

| السل | 1.475 | (1.163, 1.871) | 0.001 | 1.480 | (1.160, 1.888) | 0.002 |

| الأورام الخبيثة للأعضاء الهضمية | 1.307 | (1.195, 1.429) | <. 001 | 1.202 | (1.097, 1.318) | <. 001 |

| فقر الدم الغذائي | 0.908 | (0.840, 0.982) | 0.015 | 0.929 | (0.858, 1.006) | 0.069 |

| داء السكري | 0.937 | (0.867, 1.012) | 0.096 | 0.917 | (0.847, 0.992) | 0.031 |

| قصور الغدد التناسلية | 0.874 | (0.557, 1.371) | 0.558 | 0.960 | (0.606, 1.522) | 0.864 |

| قصر القامة | 0.938 | (0.590, 1.490) | 0.785 | 0.996 | (0.620, 1.600) | 0.986 |

| فرط شحميات الدم | 1.235 | (1.096, 1.392) | <. 001 | 1.133 | (1.003, 1.281) | 0.044 |

| أمراض ارتفاع ضغط الدم | 1.874 | (1.714, 2.049) | <. 001 | 1.566 | (1.429, 1.717) | <. 001 |

| احتشاء عضلة القلب الحاد | 0.778 | (0.670, 0.904) | 0.001 | 0.868 | (0.744, 1.013) | 0.073 |

| الرجفان الأذيني والرفرفة | 1.593 | (1.361, 1.864) | <. 001 | 1.215 | (1.035, 1.427) | 0.017 |

| فشل القلب | 1.732 | (1.582, 1.896) | <. 001 | 1.470 | (1.339, 1.613) | <. 001 |

| أمراض الأوعية الدموية الدماغية | 1.643 | (1.465, 1.842) | <. 001 | 1.376 | (1.223, 1.547) | <. 001 |

| الإنفلونزا والالتهاب الرئوي | 1.315 | (1.194, 1.447) | <. 001 | 1.490 | (1.348, 1.648) | <. 001 |

| كوفيد-19 | 1.602 | (1.481, 1.733) | <. 001 | 1.889 | (1.738, 2.054) | <. 001 |

| التهاب الرئة الناتج عن المواد الصلبة والسوائل | ٣.٩١٠ | (3.196, 4.784) | <. 001 | 2.959 | (2.410, 3.634) | <. 001 |

| التهاب الفم والآفات المرتبطة | 0.637 | (0.477, 0.850) | 0.002 | 0.710 | (0.529, 0.952) | 0.022 |

| مرض الكبد | 1.020 | (0.933, 1.116) | 0.657 | 1.242 | (1.131, 1.364) | <. 001 |

| التهاب الجلد والأكزيما | 1.102 | (0.935, 1.298) | 0.248 | 1.115 | (0.943, 1.318) | 0.202 |

| الثعلبة البقعية | 0.190 | (0.087, 0.412) | <. 001 | 0.306 | (0.139, 0.673) | 0.003 |

| قرحة الضغط ومنطقة الضغط | 2.922 | (2.278, 3.748) | <. 001 | 2.403 | (1.866, 3.094) | < . 001 |

| تآكل العضلات وضمور العضلات، غير مصنف في مكان آخر (الساركوبينيا) | ٢.٦٩٩ | (2.389, 3.050) | <. 001 | ٢.٢١٧ | (1.957, 2.512) | <. 001 |

| هشاشة العظام | 1.412 | (1.224, 1.629) | <. 001 | 1.302 | (1.123, 1.509) | <. 001 |

| مرض الكلى المزمن | ٢.١٣٣ | (1.902, 2.392) | <. 001 | 1.835 | (1.632, 2.063) | <. 001 |

| اضطرابات الشم والتذوق | 0.369 | (0.291, 0.468) | <. 001 | 0.416 | (0.327, 0.531) | <. 001 |

| فقدان الشهية | 1.196 | (0.944, 1.515) | 0.138 | 1.042 | (0.819, 1.325) | 0.740 |

| إصابات الرأس | 1.753 | (1.311, 2.344) | <. 001 | 1.541 | (1.144, 2.074) | 0.004 |

| كسر | 1.621 | (1.407, 1.867) | <. 001 | 1.330 | (1.150, 1.539) | <. 001 |

| نقص الزنك

|

تحليل أحادي غير معدل | تحليل معدل

|

||||

| نسبة الأرجحية* | فترة الثقة 95% |

|

نسبة الأرجحية* | فترة الثقة 95% |

|

|

| الأدوية (خلال 60 يومًا قبل يوم قياس مستوى الزنك في المصل) | ||||||

| مضادات ارتفاع سكر الدم | 1.077 | (0.979, 1.185) | 0.130 | 0.955 | (0.865, 1.054) | 0.356 |

| عوامل خافضة للضغط | 1.772 | (1.647, 1.907) | <. 001 | 1.467 | (1.358, 1.584) | <. 001 |

| سبيرونولاكتون | ٢.٨٢٦ | (2.447, 3.264) | <. 001 | ٢.٥٢٣ | (2.179, 2.922) | <. 001 |

| فوروسيميد | ٢.٥٥٢ | (2.321, 2.807) | <. 001 | ٢.١٣٨ | (1.939, 2.357) | <. 001 |

| مثبطات ACE | 1.215 | (0.969, 1.523) | 0.092 | 0.974 | (0.775, 1.225) | 0.822 |

| حاصرات مستقبلات الأنجيوتنسين II | 1.131 | (1.022, 1.252) | 0.017 | 0.987 | (0.889, 1.095) | 0.806 |

| أدوية خافضة للدهون | 0.750 | (0.679, 0.830) | <. 001 | 0.664 | (0.599, 0.736) | <. 001 |

| ستاتينات | 0.775 | (0.697, 0.862) | <. 001 | 0.685 | (0.614, 0.764) | <. 001 |

| عوامل مضادة للتخثر | 1.953 | (1.808, 2.110) | <. 001 | 1.621 | (1.496, 1.757) | <. 001 |

| حاصرات H2 | 1.154 | (1.005, 1.324) | 0.042 | 1.108 | (0.962, 1.275) | 0.154 |

| مثبطات مضخة البروتون | 1.752 | (1.625, 1.890) | <. 001 | 1.553 | (1.436, 1.678) | <. 001 |

| تحضيرات مضادة لفقر الدم | ٢.٢٢٦ | (2.019, 2.454) | <. 001 | 2.027 | (1.835, 2.239) | <. 001 |

| الكورتيكوستيرويدات | 1.453 | (1.284, 1.645) | <. 001 | 1.504 | (1.325, 1.708) | <. 001 |

| هرمونات الغدة الدرقية | 2.056 | (1.688, 2.504) | <. 001 | 1.864 | (1.524, 2.280) | <. 001 |

| المضادات الحيوية الجهازية | ٢.٦١٥ | (2.421, 2.825) | <. 001 | ٢.٤١٩ | (2.235, 2.617) | <. 001 |

| أدوية لعلاج أمراض العظام | 0.960 | (0.792, 1.162) | 0.673 | 0.849 | (0.698, 1.033) | 0.102 |

| عوامل مضادة لباركنسون | 1.676 | (1.279, 2.196) | <. 001 | 1.494 | (1.134, 1.968) | 0.004 |

| مضادات الذهان | 1.556 | (1.373, 1.763) | <. 001 | 1.411 | (1.242, 1.603) | <. 001 |

| مهدئات القلق | 1.554 | (1.421, 1.700) | <. 001 | 1.372 | (1.251, 1.503) | <. 001 |

الخاتمة

توفر البيانات

نُشر على الإنترنت: 02 فبراير 2024

References

- Prasad, A. S. Discovery of human zinc deficiency: 50 years later. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 26, 66-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jtemb.2012.04.004 (2012).

- Kumssa, D. B. et al. Dietary calcium and zinc deficiency risks are decreasing but remain prevalent. Sci. Rep. 5, 10974. https://doi. org/10.1038/srep10974 (2015).

- Wessells, K. R. & Brown, K. H. Estimating the global prevalence of zinc deficiency: results based on zinc availability in national food supplies and the prevalence of stunting. PLoS One 7, e50568. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0050568 (2012).

- Chen, W. et al. Association between dietary zinc intake and abdominal aortic calcification in US adults. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 35, 1171-1178. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz134 (2020).

- Sarukura, N. et al. Dietary zinc intake and its effects on zinc nutrition in healthy Japanese living in the central area of Japan. J. Med. Invest. 58, 203-209. https://doi.org/10.2152/jmi.58.203 (2011).

- Ackland, M. L. & Michalczyk, A. A. Zinc and infant nutrition. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 611, 51-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb. 2016.06.011 (2016).

- Shankar, H. et al. Association of dietary intake below recommendations and micronutrient deficiencies during pregnancy and low birthweight. J. Perinat. Med. 47, 724-731. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2019-0053 (2019).

- Kvamme, J. M., Gronli, O., Jacobsen, B. K. & Florholmen, J. Risk of malnutrition and zinc deficiency in community-living elderly men and women: The Tromso study. Public Health Nutr. 18, 1907-1913. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980014002420 (2015).

- Olechnowicz, J., Tinkov, A., Skalny, A. & Suliburska, J. Zinc status is associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, lipid, and glucose metabolism. J. Physiol. Sci. 68, 19-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-017-0571-7 (2018).

- Shankar, A. H. & Prasad, A. S. Zinc and immune function: The biological basis of altered resistance to infection. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 68, 447S-463S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/68.2.447S (1998).

- Black, M. M. Zinc deficiency and child development. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 68, 464S-469S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/68.2.464S (1998).

- Henkin, R. I. Zinc in taste function: A critical review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 6, 263-280. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02917511 (1984).

- Lin, P. H. et al. Zinc in wound healing modulation. Nutrients 10, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010016 (2017).

- Berger, M. M. et al. ESPEN micronutrient guideline. Clin. Nutr. 41, 1357-1424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2022.02.015 (2022).

- Tuerk, M. J. & Fazel, N. Zinc deficiency. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 25, 136-143. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0b013e328321b395 (2009).

- Meydani, S. N. et al. Serum zinc and pneumonia in nursing home elderly. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 86, 1167-1173. https://doi.org/10. 1093/ajcn/86.4.1167 (2007).

- McClain, C. J., McClain, M., Barve, S. & Boosalis, M. G. Trace metals and the elderly. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 18, 801-818. https://doi. org/10.1016/s0749-0690(02)00040-x (2002).

- Hosui, A. et al. Oral zinc supplementation decreases the risk of HCC development in patients with HCV eradicated by DAA. Hepatol. Commun. 5, 2001-2008. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1782 (2021).

- Siva, S., Rubin, D. T., Gulotta, G., Wroblewski, K. & Pekow, J. Zinc deficiency is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 23, 152-157. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000989 (2017).

- Kodama, H., Tanaka, M., Naito, Y., Katayama, K. & Moriyama, M. Japan’s practical guidelines for zinc deficiency with a particular focus on taste disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, and liver cirrhosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 2941. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms2 1082941 (2020).

- Tokuyama, A. et al. Effect of zinc deficiency on chronic kidney disease progression and effect modification by hypoalbuminemia. PLoS One 16, e0251554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0251554 (2021).

- Braun, L. A. & Rosenfeldt, F. Pharmaco-nutrient interactions: A systematic review of zinc and antihypertensive therapy. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 67, 717-725. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp. 12040 (2013).

- Li, J. et al. Zinc Intakes and health outcomes: An umbrella review. Front. Nutr. 9, 798078. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.798078 (2022).

- Bhutta, Z. A. et al. Prevention of diarrhea and pneumonia by zinc supplementation in children in developing countries: Pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Zinc investigators’ collaborative group. J. Pediatr. 135, 689-697. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0022-3476(99)70086-7 (1999).

- Santos, H. O. Therapeutic supplementation with zinc in the management of COVID-19-related diarrhea and ageusia/dysgeusia: Mechanisms and clues for a personalized dosage regimen. Nutr. Rev. 80, 1086-1093. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuab054 (2022).

- Salzman, M. B., Smith, E. M. & Koo, C. Excessive oral zinc supplementation. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 24, 582-584. https://doi. org/10.1097/00043426-200210000-00020 (2002).

- Hennigar, S. R., Lieberman, H. R., Fulgoni, V. L. 3rd. & McClung, J. P. Serum zinc concentrations in the US population are related to sex, age, and time of blood draw but not dietary or supplemental zinc. J. Nutr. 148, 1341-1351. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/ nxy105 (2018).

- Yokokawa, H. et al. Serum zinc concentrations and characteristics of zinc deficiency/marginal deficiency among Japanese subjects. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 21, 248-255. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgf2.377 (2020).

- Bailey, R. L. et al. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003-2006. J. Nutr. 141, 261-266. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110. 133025 (2011).

- Wang, X., Schmerold, L. & Naito, T. Real-world medication persistence among HIV-1 patients initiating integrase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 28, 1464-1470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2022.07.005 (2022).

- Ruzicka, D. J., Kuroishi, N., Oshima, N., Sakuma, R. & Naito, T. Switch rates, time-to-switch, and switch patterns of antiretroviral therapy in people living with human immunodeficiency virus in Japan, in a hospital-claim database. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 505. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4129-6 (2019).

- The Japanese Society of Clinical Nutrition. The Treatment Guideline of Zinc Deficiency 2018 (in Japanese). http://jscn.gr.jp/pdf/ aen2018.pdf (2018).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. The Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subject (in Japanese). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/001077424.pdf (2023).

- World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310, 2191-2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053 (2013).

- World Health Organization. Haemoglobin Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anaemia and Assessment of Severity. https://www. who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-MNM-11.1 (2011).

- Kogirima, M. et al. Ratio of low serum zinc levels in elderly Japanese people living in the central part of Japan. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 61, 375-381. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn. 1602520 (2007).

- Giacconi, R. et al. Main biomarkers associated with age-related plasma zinc decrease and copper/zinc ratio in healthy elderly from ZincAge study. Eur. J. Nutr. 56, 2457-2466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-016-1281-2 (2017).

- Ho, E., Wong, C. P. & King, J. C. Impact of zinc on DNA integrity and age-related inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 178, 391-397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.12.256 (2022).

- Yasuda, H. & Tsutsui, T. Infants and elderlies are susceptible to zinc deficiency. Sci. Rep. 6, 21850. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep2 1850 (2016).

- Demircan, K. et al. Association of COVID-19 mortality with serum selenium, zinc and copper: Six observational studies across Europe. Front. Immunol. 13, 1022673. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1022673 (2022).

- Olczak-Pruc, M. et al. The effect of zinc supplementation on the course of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 29, 568-574. https://doi.org/10.26444/aaem/155846 (2022).

- Ben Abdallah, S. et al. Twice-Daily oral zinc in the treatment of patients with coronavirus disease 2019: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, 185-191. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac807 (2023).

- Thomas, D. C. et al. Dysgeusia: A review in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 153, 251-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. adaj.2021.08.009 (2022).

- Matsuda, Y. et al. Symptomatic characteristics of hypozincemia detected in long COVID patients. J. Clin. Med. 12, 2062. https:// doi.org/10.3390/jcm12052062 (2023).

- Yasui, Y. et al. Analysis of the predictive factors for a critical illness of COVID-19 during treatment: relationship between serum zinc level and critical illness of COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 100, 230-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.008 (2020).

- Sadeghsoltani, F. et al. Zinc and respiratory viral infections: Important trace element in anti-viral response and immune regulation. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 200, 2556-2571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-021-02859-z (2022).

- Gengenbacher, M., Stahelin, H. B., Scholer, A. & Seiler, W. O. Low biochemical nutritional parameters in acutely ill hospitalized elderly patients with and without stage III to IV pressure ulcers. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 14, 420-423. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF033 24471 (2002).

- Kawaguchi, M. et al. Relationship between serum zinc levels/nutrition index parameters and pressure ulcer in hospitalized patients with malnutrition. Metallomics Res. 2, reg11-reg18. https://doi.org/10.11299/metallomicsresearch.MR202117 (2022).

- European Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guideline. The International Guideline. (ed. Haesler, E.). (EPUAP/ NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

- Jackson, M. J. Physiology of zinc: General aspects. In Zinc in Human Biology ILSI Human Nutrition Reviews (ed. Mills, C. F.) (Springer, 1989).

- Prasad, A. S. Zinc is an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent: Its role in human health. Front. Nutr. 1, 14. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fnut.2014.00014 (2014).

- Lai, J. C. et al. Malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis: 2021 Practice guidance by the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 74, 1611-1644. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep. 32049 (2021).

- Waters, D. L. et al. Sexually dimorphic patterns of nutritional intake and eating behaviors in community-dwelling older adults with normal and slow gait speed. J. Nutr. Health Aging 18, 228-233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-014-0004-8 (2014).

- Chaput, J. P. et al. Relationship between antioxidant intakes and class I sarcopenia in elderly men and women. J. Nutr. Health Aging 11, 363-369 (2007).

- Fact-finding Committee of the Japanese Society of Pressure Ulcers et al. Nationwide time-series surveys of pressure ulcer prevalence in Japan. J. Wound Care 31, S40-S47. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2022.31.Sup12.S40 (2022).

- Kitamura, A. et al. Sarcopenia: Prevalence, associated factors, and the risk of mortality and disability in Japanese older adults. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 12, 30-38. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm. 12651 (2021).

- Tanabe, N. et al. Importance of nutrition support team in pressure ulcer control: Examination at one long-term care hospital in Yamaguchi prefecture. Bull. Yamaguchi Med. Sch. 69, 37-43 (2022).

- Maruyama, Y., Nakashima, A., Fukui, A. & Yokoo, T. Zinc deficiency: Its prevalence and relationship to renal function in Japan. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 25, 771-778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-021-02046-3 (2021).

- Ume, A. C., Wenegieme, T. Y., Adams, D. N., Adesina, S. E. & Williams, C. R. Zinc deficiency: A potential hidden driver of the detrimental cycle of chronic kidney disease and hypertension. Kidney 360 4, 398-404. https://doi.org/10.34067/kid.0007812021 (2023).

- Severo, J. S. et al. The role of zinc in thyroid hormones metabolism. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 89, 80-88. https://doi.org/10.1024/ 0300-9831/a000262 (2019).

- Chiba, M. et al. Diuretics aggravate zinc deficiency in patients with liver cirrhosis by increasing zinc excretion in urine. Hepatol. Res. 43, 365-373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01093.x (2013).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. NDB Open Data (in Japanese). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/ 0000177221_00011.html.

- VanderWeele, T. J. Principles of confounder selection. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 34, 211-219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00494-6 (2019).

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة علىwww.nature.com/reprints.

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

قسم الطب العام، كلية الطب، جامعة جنتندو، طوكيو، اليابان. قسم علوم البيانات، شركة نوبيلفارما المحدودة، طوكيو، اليابان. قسم الخدمات الأكاديمية، 4DIN المحدودة، #805 مبنى شينباشيكيماي 1 2-20-15 شينبashi ميناتو-كو، طوكيو 105-0004، اليابان. مركز تعزيز علوم البيانات، جامعة جونديندو، كلية الطب، طوكيو، اليابان. البريد الإلكتروني:nfukui@4din.com

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53202-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38307882

Publication Date: 2024-02-02

OPEN

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with zinc deficiency: analysis of a nationwide Japanese medical claims database

Abstract

Hirohide Yokokawa

Zinc deficiency, affecting more than 2 billion people globally, poses a significant public health burden due to its numerous unfavorable effects, such as impaired immune function, taste and smell disorders, pneumonia, growth retardation, visual impairment, and skin disorders. Despite its critical role, extensive large-scale studies investigating the correlation between patient characteristics and zinc deficiency still need to be completed. We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional observational study using a nationwide Japanese claims database from January 2019 to December 2021. The study population included 13,100 patients with available serum zinc concentration data, excluding individuals under 20 and those assessed for zinc concentrations after being prescribed zinc-containing medication. Significant associations with zinc deficiency were noted among older adults, males, and inpatients. Multivariate analysis, adjusting for age and sex, indicated significant associations with comorbidities, including pneumonitis due to solids and liquids with an adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) of 2.959; decubitus ulcer and pressure area (aOR 2.403), sarcopenia (aOR 2.217), COVID-19 (aOR 1.889), and chronic kidney disease (aOR 1.835). Significant association with medications, including spironolactone (aOR 2.523), systemic antibacterials (aOR 2.419), furosemide (aOR 2.138), antianemic preparations (aOR 2.027), and thyroid hormones (aOR 1.864) were also found. These results may aid clinicians in identifying patients at risk of zinc deficiency, potentially improving care outcomes.

Methods

Study design and data source

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Variables

Ethical considerations

Statistical methods

were conducted for comorbidities and medications, stratified by age group, sex, and inpatient/outpatient status. The objective was to identify variables associated with zinc deficiency that are specific to sex, age, and inpatient/ outpatient status. The correlation between serum zinc concentration and laboratory parameters was assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Additionally, the relationship between hemoglobin and serum zinc levels was examined by categorizing hemoglobin as ‘low’ or ‘normal’ according to WHO criteria

Results

| Demographic/clinical characteristic | n (%) | Demographic/clinical characteristic | n (%) |

| Total patients | 13,100 | Hypogonadism | 88 (0.7) |

| Short stature | 81 (0.6) | ||

| Serum zinc (

|

Hyperlipidemia | 1252 (9.6) | |

| Mean

|

|

Hypertensive diseases | 2447 (18.7) |

| Serum zinc level | Acute myocardial infarction | 873 (6.7) | |

| Deficiency (

|

4557 (34.8) | Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 662 (5.1) |

| Marginal (

|

5964 (45.5) | Heart failure | 2365 (18.1) |

| Normal (

|

2579 (19.7) | Cerebrovascular diseases | 1331 (10.2) |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 2088 (15.9) | ||

| Sex | COVID-19 | 3640 (27.8) | |

| Male | 6372 (48.6) | Pneumonitis due to solids and liquids | 439 (3.4) |

| Female | 6728 (51.4) | Stomatitis and related lesions | 247 (1.9) |

| Liver disease | 2657 (20.3) | ||

| Age (years) (on serum zinc-measurement day) | Dermatitis and eczema | 645 (4.9) | |

| Mean

|

|

Alopecia areata | 76 (0.6) |

| Age group (on serum zinc-measurement day) | Decubitus ulcer and pressure area | 265 (2.0) | |

| 20-29 years | 492 (3.8) | Muscle wasting and atrophy, not elsewhere classified (Sarcopenia) | 1166 (8.9) |

| 30-39 years | 529 (4.0) | Osteoporosis | 823 (6.3) |

| 40-49 years | 901 (6.9) | Chronic kidney disease | 1321 (10.1) |

| 50-59 years | 1393 (10.6) | Disturbances of smell and taste | 492 (3.8) |

| 60-69 years | 2049 (15.6) | Anorexia | 296 (2.3) |

| 70-79 years | 3658 (27.9) | Injuries to the head | 185 (1.4) |

|

|

4078 (31.1) | Fracture | 834 (6.4) |

| Weight (kg) | |||

| Mean

|

|

Medication (within 60 days before serum zinc-measurement) | |

| BMI (

|

Antihyperglycemics | 2191 (16.7) | |

| Mean

|

|

Antihypertensive agents | 5053 (38.6) |

| BMI group | Spironolactone | 818 (6.2) | |

| <25 | 3750 (28.6) | Furosemide | 2081 (15.9) |

|

|

926 (7.1) | ACE inhibitors | 324 (2.5) |

| Missing | 8424 (64.3) | Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 1862 (14.2) |

| Antihyperlipidemics | 2148 (16.4) | ||

| Inpatient/Outpatient | Statins | 1861 (14.2) | |

| Inpatient | 5614 (42.9) | Antithrombotic agents | 3859 (29.5) |

| Outpatient | 7420 (56.6) | H2 blockers | 930 (7.1) |

| Missing | 66 (0.5) | Proton pump inhibitors | 4273 (32.6) |

| Antianemic preparations | 1935 (14.8) | ||

| Comorbidity (within 60 days before serum zinc-measurement) | Corticosteroids | 1125 (8.6) | |

| Intestinal infectious diseases | 639 (4.9) | Thyroid hormones | 410 (3.1) |

| Noninfective enteritis and colitis | 135 (1.0) | Systemic antibacterials | 3981 (30.4) |

| Tuberculosis | 283 (2.2) | Drugs for treatment of bone diseases | 484 (3.7) |

| Malignant neoplasms of digestive organs | 2536 (19.4) | Anti-Parkinson agents | 215 (1.6) |

| Nutritional anemias | 4144 (31.6) | Antipsychotics | 1097 (8.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4224 (32.2) | Anxiolytics | 2442 (18.6) |

| Serum zinc level | Zinc deficiency (

|

||||||

| Overall | Deficiency | Marginal | Normal | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|

|

| n | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Total patients | |||||||

| – | 13,100 | 4557 (34.8) | 5964 (45.5) | 2579 (19.7) | |||

| Serum zinc | |||||||

| Mean

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 6372 | 2330 (36.6) | 2789 (43.8) | 1253 (19.7) | 1.165 | (1.084, 1.252) | <. 001 |

| Female | 6728 | 2227 (33.1) | 3175 (47.2) | 1326 (19.7) | Ref | ||

| Age (years) (on serum-zinc measurement day) | |||||||

| Mean

|

|

|

|

|

1.301 (Age/10) | (1.270, 1.332) | <. 001 |

| Age group (on serum-zinc measurement day) | |||||||

| 20-29 years | 492 | 80 (16.3) | 252 (51.2) | 160 (32.5) | Ref | ||

| 30-39 years | 529 | 106 (20.0) | 280 (52.9) | 143 (27.0) | 1.290 | (0.937, 1.778) | 0.119 |

| 40-49 years | 901 | 205 (22.8) | 420 (46.6) | 276 (30.6) | 1.517 | (1.140, 2.018) | 0.004 |

| 50-59 years | 1393 | 358 (25.7) | 646 (46.4) | 389 (27.9) | 1.781 | (1.363, 2.329) | <. 001 |

| 60-69 years | 2049 | 640 (31.2) | 943 (46.0) | 466 (22.7) | 2.339 | (1.809, 3.025) | <. 001 |

| 70-79 years | 3658 | 1300 (35.5) | 1697 (46.4) | 661 (18.1) | 2.839 | (2.214, 3.641) | <. 001 |

|

|

4078 | 1868 (45.8) | 1726 (42.3) | 484 (11.9) | 4.353 | (3.399, 5.574) | <. 001 |

| Weight(kg) | |||||||

| Mean

|

|

|

|

|

0.906 (Weight/5) | (0.887, 0.925) | <. 001 |

| BMI(

|

|||||||

| Mean

|

|

|

|

|

0.903 (BMI/2) | (0.879, 0.927) | <. 001 |

| BMI group | |||||||

| <25 | 3750 | 1950 (52.0) | 1307 (34.9) | 493 (13.1) | 1.443 | (1.249, 1.669) | <. 001 |

|

|

926 | 397 (42.9) | 365 (39.4) | 164 (17.7) | Ref | ||

| Missing | 8424 | 2210 (26.2) | 4292 (50.9) | 1922 (22.8) | 0.474 | (0.413, 0.545) | <. 001 |

| Smoking | |||||||

| No | 2897 | 1481 (51.1) | 1033 (35.7) | 383 (13.2) | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1723 | 844 (49.0) | 628 (36.4) | 251 (14.6) | 0.918 | (0.815, 1.034) | 0.160 |

| Missing | 8480 | 2232 (26.3) | 4303 (50.7) | 1945 (22.9) | 0.342 | (0.313, 0.373) | <. 001 |

| Inpatients/outpatients | |||||||

| Inpatient | 5614 | 2822 (50.3) | 1995 (35.5) | 797 (14.2) | 3.367 | (3.123, 3.630) | <. 001 |

| Outpatient | 7420 | 1713 (23.1) | 3938 (53.1) | 1769 (23.8) | Ref | ||

| Missing | 66 | 22 (33.3) | 31 (47.0) | 13 (19.7) | 1.666 | (0.996, 2.787) | 0.052 |

Discussion

| Serum zinc level | ||||

| Overall | Deficiency | Marginal | Normal | |

| n | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Total patients | 13,100 | 4557 (34.8) | 5964 (45.5) | 2579 (19.7) |

| Comorbidity (within 60 days before serum zinc-measurement day) | ||||

| Intestinal infectious diseases | 639 | 281 (44.0) | 233 (36.5) | 125 (19.6) |

| Noninfective enteritis and colitis | 135 | 49 (36.3) | 55 (40.7) | 31 (23.0) |

| Tuberculosis | 283 | 124 (43.8) | 120 (42.4) | 39 (13.8) |

| Malignant neoplasms of digestive organs | 2536 | 1009 (39.8) | 1022 (40.3) | 505 (19.9) |

| Nutritional anemias | 4144 | 1380 (33.3) | 1995 (48.1) | 769 (18.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4224 | 1427 (33.8) | 1974 (46.7) | 823 (19.5) |

| Hypogonadism | 88 | 28 (31.8) | 44 (50.0) | 16 (18.2) |

| Short stature | 81 | 27 (33.3) | 39 (48.1) | 15 (18.5) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1252 | 491 (39.2) | 526 (42.0) | 235 (18.8) |

| Hypertensive diseases | 2447 | 1147 (46.9) | 923 (37.7) | 377 (15.4) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 873 | 259 (29.7) | 445 (51.0) | 169 (19.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 662 | 300 (45.3) | 268 (40.5) | 94 (14.2) |

| Heart failure | 2365 | 1074 (45.4) | 960 (40.6) | 331 (14.0) |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 1331 | 604 (45.4) | 524 (39.4) | 203 (15.3) |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 2088 | 838 (40.1) | 921 (44.1) | 329 (15.8) |

| COVID-19 | 3640 | 1554 (42.7) | 1507 (41.4) | 579 (15.9) |

| Pneumonitis due to solids and liquids | 439 | 292 (66.5) | 116 (26.4) | 31 (7.1) |

| Stomatitis and related lesions | 247 | 63 (25.5) | 121 (49.0) | 63 (25.5) |

| Liver disease | 2657 | 934 (35.2) | 1155 (43.5) | 568 (21.4) |

| Dermatitis and eczema | 645 | 238 (36.9) | 276 (42.8) | 131 (20.3) |

| Alopecia areata | 76 | 7 (9.2) | 36 (47.4) | 33 (43.4) |

| Decubitus ulcer and pressure area | 265 | 160 (60.4) | 83 (31.3) | 22 (8.3) |

| Muscle wasting and atrophy, not elsewhere classified (Sarcopenia) | 1166 | 661 (56.7) | 371 (31.8) | 134 (11.5) |

| Osteoporosis | 823 | 349 (42.4) | 339 (41.2) | 135 (16.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1321 | 676 (51.2) | 492 (37.2) | 153 (11.6) |

| Disturbances of smell and taste | 492 | 83 (16.9) | 260 (52.8) | 149 (30.3) |

| Anorexia | 296 | 115 (38.9) | 123 (41.6) | 58 (19.6) |

| Injuries to the head | 185 | 89 (48.1) | 69 (37.3) | 27 (14.6) |

| Fracture | 834 | 380 (45.6) | 322 (38.6) | 132 (15.8) |

| Serum zinc level | ||||

| Overall | Deficiency | Marginal | Normal | |

| n | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Total patients | 13,100 | 4557 (34.8) | 5964 (45.5) | 2579 (19.7) |

| Medication (within 60 days before serum zinc-measurement day) | ||||

| Antihyperglycemics | 2191 | 793 (36.2) | 972 (44.4) | 426 (19.4) |

| Antihypertensive agents | 5053 | 2165 (42.8) | 2105 (41.7) | 783 (15.5) |

| Spironolactone | 818 | 478 (58.4) | 257 (31.4) | 83 (10.1) |

| Furosemide | 2081 | 1117 (53.7) | 741 (35.6) | 223 (10.7) |

| ACE inhibitors | 324 | 127 (39.2) | 148 (45.7) | 49 (15.1) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 1862 | 693 (37.2) | 826 (44.4) | 343 (18.4) |

| Antihyperlipidemics | 2148 | 634 (29.5) | 1059 (49.3) | 455 (21.2) |

| Statins | 1861 | 558 (30.0) | 924 (49.7) | 379 (20.4) |

| Antithrombotic agents | 3859 | 1767 (45.8) | 1512 (39.2) | 580 (15.0) |

| H2 blockers | 930 | 352 (37.8) | 406 (43.7) | 172 (18.5) |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 4273 | 1860 (43.5) | 1697 (39.7) | 716 (16.8) |

| Antianemic preparations | 1935 | 989 (51.1) | 730 (37.7) | 216 (11.2) |

| Corticosteroids | 1125 | 482 (42.8) | 474 (42.1) | 169 (15.0) |

| Thyroid hormones | 410 | 212 (51.7) | 141 (34.4) | 57 (13.9) |

| Systemic antibacterials | 3981 | 2006 (50.4) | 1420 (35.7) | 555 (13.9) |

| Drugs for treatment of bone diseases | 484 | 164 (33.9) | 240 (49.6) | 80 (16.5) |

| Anti-Parkinson agents | 215 | 101 (47.0) | 91 (42.3) | 23 (10.7) |

| Antipsychotics | 1097 | 487 (44.4) | 424 (38.7) | 186 (17.0) |

| Anxiolytics | 2442 | 1055 (43.2) | 998 (40.9) | 389 (15.9) |

| Zinc deficiency (

|

Unadjusted univariate analysis | Adjusted analysis

|

||||

| Odds ratio* | 95% confidence interval |

|

Odds ratio* | 95% Confidence interval |

|

|

| Comorbidity (within 60 days before serum zinc-measurement day) | ||||||

| Intestinal infectious diseases | 1.502 | (1.280, 1.764) | <. 001 | 1.733 | (1.468, 2.045) | <. 001 |

| Noninfective enteritis and colitis | 1.070 | (0.752, 1.522) | 0.709 | 1.309 | (0.910, 1.883) | 0.147 |

| Tuberculosis | 1.475 | (1.163, 1.871) | 0.001 | 1.480 | (1.160, 1.888) | 0.002 |

| Malignant neoplasms of digestive organs | 1.307 | (1.195, 1.429) | <. 001 | 1.202 | (1.097, 1.318) | <. 001 |

| Nutritional anemias | 0.908 | (0.840, 0.982) | 0.015 | 0.929 | (0.858, 1.006) | 0.069 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.937 | (0.867, 1.012) | 0.096 | 0.917 | (0.847, 0.992) | 0.031 |

| Hypogonadism | 0.874 | (0.557, 1.371) | 0.558 | 0.960 | (0.606, 1.522) | 0.864 |

| Short stature | 0.938 | (0.590, 1.490) | 0.785 | 0.996 | (0.620, 1.600) | 0.986 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.235 | (1.096, 1.392) | <. 001 | 1.133 | (1.003, 1.281) | 0.044 |

| Hypertensive diseases | 1.874 | (1.714, 2.049) | <. 001 | 1.566 | (1.429, 1.717) | <. 001 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 0.778 | (0.670, 0.904) | 0.001 | 0.868 | (0.744, 1.013) | 0.073 |

| Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 1.593 | (1.361, 1.864) | <. 001 | 1.215 | (1.035, 1.427) | 0.017 |

| Heart failure | 1.732 | (1.582, 1.896) | <. 001 | 1.470 | (1.339, 1.613) | <. 001 |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 1.643 | (1.465, 1.842) | <. 001 | 1.376 | (1.223, 1.547) | <. 001 |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 1.315 | (1.194, 1.447) | <. 001 | 1.490 | (1.348, 1.648) | <. 001 |

| COVID-19 | 1.602 | (1.481, 1.733) | <. 001 | 1.889 | (1.738, 2.054) | <. 001 |

| Pneumonitis due to solids and liquids | 3.910 | (3.196, 4.784) | <. 001 | 2.959 | (2.410, 3.634) | <. 001 |

| Stomatitis and related lesions | 0.637 | (0.477, 0.850) | 0.002 | 0.710 | (0.529, 0.952) | 0.022 |

| Liver disease | 1.020 | (0.933, 1.116) | 0.657 | 1.242 | (1.131, 1.364) | <. 001 |

| Dermatitis and eczema | 1.102 | (0.935, 1.298) | 0.248 | 1.115 | (0.943, 1.318) | 0.202 |

| Alopecia areata | 0.190 | (0.087, 0.412) | <. 001 | 0.306 | (0.139, 0.673) | 0.003 |

| Decubitus ulcer and pressure area | 2.922 | (2.278, 3.748) | <. 001 | 2.403 | (1.866, 3.094) | < . 001 |

| Muscle wasting and atrophy, not elsewhere classified (Sarcopenia) | 2.699 | (2.389, 3.050) | <. 001 | 2.217 | (1.957, 2.512) | <. 001 |

| Osteoporosis | 1.412 | (1.224, 1.629) | <. 001 | 1.302 | (1.123, 1.509) | <. 001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2.133 | (1.902, 2.392) | <. 001 | 1.835 | (1.632, 2.063) | <. 001 |

| Disturbances of smell and taste | 0.369 | (0.291, 0.468) | <. 001 | 0.416 | (0.327, 0.531) | <. 001 |

| Anorexia | 1.196 | (0.944, 1.515) | 0.138 | 1.042 | (0.819, 1.325) | 0.740 |

| Injuries to the head | 1.753 | (1.311, 2.344) | <. 001 | 1.541 | (1.144, 2.074) | 0.004 |

| Fracture | 1.621 | (1.407, 1.867) | <. 001 | 1.330 | (1.150, 1.539) | <. 001 |

| Zinc deficiency (

|

Unadjusted univariate analysis | Adjusted analysis

|

||||

| Odds ratio* | 95% confidence interval |

|

Odds ratio* | 95% confidence interval |

|

|

| Medication (within 60 days before serum zinc-measurement day) | ||||||

| Antihyperglycemics | 1.077 | (0.979, 1.185) | 0.130 | 0.955 | (0.865, 1.054) | 0.356 |

| Antihypertensive agents | 1.772 | (1.647, 1.907) | <. 001 | 1.467 | (1.358, 1.584) | <. 001 |

| Spironolactone | 2.826 | (2.447, 3.264) | <. 001 | 2.523 | (2.179, 2.922) | <. 001 |

| Furosemide | 2.552 | (2.321, 2.807) | <. 001 | 2.138 | (1.939, 2.357) | <. 001 |

| ACE inhibitors | 1.215 | (0.969, 1.523) | 0.092 | 0.974 | (0.775, 1.225) | 0.822 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 1.131 | (1.022, 1.252) | 0.017 | 0.987 | (0.889, 1.095) | 0.806 |

| Antihyperlipidemics | 0.750 | (0.679, 0.830) | <. 001 | 0.664 | (0.599, 0.736) | <. 001 |

| Statins | 0.775 | (0.697, 0.862) | <. 001 | 0.685 | (0.614, 0.764) | <. 001 |

| Antithrombotic agents | 1.953 | (1.808, 2.110) | <. 001 | 1.621 | (1.496, 1.757) | <. 001 |

| H2 blockers | 1.154 | (1.005, 1.324) | 0.042 | 1.108 | (0.962, 1.275) | 0.154 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 1.752 | (1.625, 1.890) | <. 001 | 1.553 | (1.436, 1.678) | <. 001 |

| Antianemic preparations | 2.226 | (2.019, 2.454) | <. 001 | 2.027 | (1.835, 2.239) | <. 001 |

| Corticosteroids | 1.453 | (1.284, 1.645) | <. 001 | 1.504 | (1.325, 1.708) | <. 001 |

| Thyroid hormones | 2.056 | (1.688, 2.504) | <. 001 | 1.864 | (1.524, 2.280) | <. 001 |

| Systemic antibacterials | 2.615 | (2.421, 2.825) | <. 001 | 2.419 | (2.235, 2.617) | <. 001 |

| Drugs for treatment of bone diseases | 0.960 | (0.792, 1.162) | 0.673 | 0.849 | (0.698, 1.033) | 0.102 |

| Anti-Parkinson agents | 1.676 | (1.279, 2.196) | <. 001 | 1.494 | (1.134, 1.968) | 0.004 |

| Antipsychotics | 1.556 | (1.373, 1.763) | <. 001 | 1.411 | (1.242, 1.603) | <. 001 |

| Anxiolytics | 1.554 | (1.421, 1.700) | <. 001 | 1.372 | (1.251, 1.503) | <. 001 |

Conclusion

Data availability

Published online: 02 February 2024

References

- Prasad, A. S. Discovery of human zinc deficiency: 50 years later. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 26, 66-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jtemb.2012.04.004 (2012).

- Kumssa, D. B. et al. Dietary calcium and zinc deficiency risks are decreasing but remain prevalent. Sci. Rep. 5, 10974. https://doi. org/10.1038/srep10974 (2015).

- Wessells, K. R. & Brown, K. H. Estimating the global prevalence of zinc deficiency: results based on zinc availability in national food supplies and the prevalence of stunting. PLoS One 7, e50568. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0050568 (2012).

- Chen, W. et al. Association between dietary zinc intake and abdominal aortic calcification in US adults. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 35, 1171-1178. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz134 (2020).

- Sarukura, N. et al. Dietary zinc intake and its effects on zinc nutrition in healthy Japanese living in the central area of Japan. J. Med. Invest. 58, 203-209. https://doi.org/10.2152/jmi.58.203 (2011).

- Ackland, M. L. & Michalczyk, A. A. Zinc and infant nutrition. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 611, 51-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb. 2016.06.011 (2016).

- Shankar, H. et al. Association of dietary intake below recommendations and micronutrient deficiencies during pregnancy and low birthweight. J. Perinat. Med. 47, 724-731. https://doi.org/10.1515/jpm-2019-0053 (2019).

- Kvamme, J. M., Gronli, O., Jacobsen, B. K. & Florholmen, J. Risk of malnutrition and zinc deficiency in community-living elderly men and women: The Tromso study. Public Health Nutr. 18, 1907-1913. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980014002420 (2015).

- Olechnowicz, J., Tinkov, A., Skalny, A. & Suliburska, J. Zinc status is associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, lipid, and glucose metabolism. J. Physiol. Sci. 68, 19-31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-017-0571-7 (2018).

- Shankar, A. H. & Prasad, A. S. Zinc and immune function: The biological basis of altered resistance to infection. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 68, 447S-463S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/68.2.447S (1998).

- Black, M. M. Zinc deficiency and child development. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 68, 464S-469S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/68.2.464S (1998).

- Henkin, R. I. Zinc in taste function: A critical review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 6, 263-280. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02917511 (1984).

- Lin, P. H. et al. Zinc in wound healing modulation. Nutrients 10, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010016 (2017).

- Berger, M. M. et al. ESPEN micronutrient guideline. Clin. Nutr. 41, 1357-1424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2022.02.015 (2022).

- Tuerk, M. J. & Fazel, N. Zinc deficiency. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 25, 136-143. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0b013e328321b395 (2009).

- Meydani, S. N. et al. Serum zinc and pneumonia in nursing home elderly. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 86, 1167-1173. https://doi.org/10. 1093/ajcn/86.4.1167 (2007).

- McClain, C. J., McClain, M., Barve, S. & Boosalis, M. G. Trace metals and the elderly. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 18, 801-818. https://doi. org/10.1016/s0749-0690(02)00040-x (2002).

- Hosui, A. et al. Oral zinc supplementation decreases the risk of HCC development in patients with HCV eradicated by DAA. Hepatol. Commun. 5, 2001-2008. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1782 (2021).

- Siva, S., Rubin, D. T., Gulotta, G., Wroblewski, K. & Pekow, J. Zinc deficiency is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 23, 152-157. https://doi.org/10.1097/MIB.0000000000000989 (2017).

- Kodama, H., Tanaka, M., Naito, Y., Katayama, K. & Moriyama, M. Japan’s practical guidelines for zinc deficiency with a particular focus on taste disorders, inflammatory bowel disease, and liver cirrhosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 2941. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms2 1082941 (2020).

- Tokuyama, A. et al. Effect of zinc deficiency on chronic kidney disease progression and effect modification by hypoalbuminemia. PLoS One 16, e0251554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0251554 (2021).

- Braun, L. A. & Rosenfeldt, F. Pharmaco-nutrient interactions: A systematic review of zinc and antihypertensive therapy. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 67, 717-725. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp. 12040 (2013).

- Li, J. et al. Zinc Intakes and health outcomes: An umbrella review. Front. Nutr. 9, 798078. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.798078 (2022).

- Bhutta, Z. A. et al. Prevention of diarrhea and pneumonia by zinc supplementation in children in developing countries: Pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Zinc investigators’ collaborative group. J. Pediatr. 135, 689-697. https://doi.org/10.1016/ s0022-3476(99)70086-7 (1999).

- Santos, H. O. Therapeutic supplementation with zinc in the management of COVID-19-related diarrhea and ageusia/dysgeusia: Mechanisms and clues for a personalized dosage regimen. Nutr. Rev. 80, 1086-1093. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuab054 (2022).

- Salzman, M. B., Smith, E. M. & Koo, C. Excessive oral zinc supplementation. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 24, 582-584. https://doi. org/10.1097/00043426-200210000-00020 (2002).

- Hennigar, S. R., Lieberman, H. R., Fulgoni, V. L. 3rd. & McClung, J. P. Serum zinc concentrations in the US population are related to sex, age, and time of blood draw but not dietary or supplemental zinc. J. Nutr. 148, 1341-1351. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/ nxy105 (2018).

- Yokokawa, H. et al. Serum zinc concentrations and characteristics of zinc deficiency/marginal deficiency among Japanese subjects. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 21, 248-255. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgf2.377 (2020).

- Bailey, R. L. et al. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003-2006. J. Nutr. 141, 261-266. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110. 133025 (2011).

- Wang, X., Schmerold, L. & Naito, T. Real-world medication persistence among HIV-1 patients initiating integrase inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 28, 1464-1470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2022.07.005 (2022).

- Ruzicka, D. J., Kuroishi, N., Oshima, N., Sakuma, R. & Naito, T. Switch rates, time-to-switch, and switch patterns of antiretroviral therapy in people living with human immunodeficiency virus in Japan, in a hospital-claim database. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 505. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4129-6 (2019).

- The Japanese Society of Clinical Nutrition. The Treatment Guideline of Zinc Deficiency 2018 (in Japanese). http://jscn.gr.jp/pdf/ aen2018.pdf (2018).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. The Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subject (in Japanese). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/001077424.pdf (2023).

- World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310, 2191-2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053 (2013).

- World Health Organization. Haemoglobin Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anaemia and Assessment of Severity. https://www. who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-MNM-11.1 (2011).

- Kogirima, M. et al. Ratio of low serum zinc levels in elderly Japanese people living in the central part of Japan. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 61, 375-381. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn. 1602520 (2007).

- Giacconi, R. et al. Main biomarkers associated with age-related plasma zinc decrease and copper/zinc ratio in healthy elderly from ZincAge study. Eur. J. Nutr. 56, 2457-2466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-016-1281-2 (2017).

- Ho, E., Wong, C. P. & King, J. C. Impact of zinc on DNA integrity and age-related inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 178, 391-397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.12.256 (2022).

- Yasuda, H. & Tsutsui, T. Infants and elderlies are susceptible to zinc deficiency. Sci. Rep. 6, 21850. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep2 1850 (2016).

- Demircan, K. et al. Association of COVID-19 mortality with serum selenium, zinc and copper: Six observational studies across Europe. Front. Immunol. 13, 1022673. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1022673 (2022).

- Olczak-Pruc, M. et al. The effect of zinc supplementation on the course of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 29, 568-574. https://doi.org/10.26444/aaem/155846 (2022).

- Ben Abdallah, S. et al. Twice-Daily oral zinc in the treatment of patients with coronavirus disease 2019: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, 185-191. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac807 (2023).

- Thomas, D. C. et al. Dysgeusia: A review in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 153, 251-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. adaj.2021.08.009 (2022).

- Matsuda, Y. et al. Symptomatic characteristics of hypozincemia detected in long COVID patients. J. Clin. Med. 12, 2062. https:// doi.org/10.3390/jcm12052062 (2023).

- Yasui, Y. et al. Analysis of the predictive factors for a critical illness of COVID-19 during treatment: relationship between serum zinc level and critical illness of COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 100, 230-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.008 (2020).

- Sadeghsoltani, F. et al. Zinc and respiratory viral infections: Important trace element in anti-viral response and immune regulation. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 200, 2556-2571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-021-02859-z (2022).

- Gengenbacher, M., Stahelin, H. B., Scholer, A. & Seiler, W. O. Low biochemical nutritional parameters in acutely ill hospitalized elderly patients with and without stage III to IV pressure ulcers. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 14, 420-423. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF033 24471 (2002).

- Kawaguchi, M. et al. Relationship between serum zinc levels/nutrition index parameters and pressure ulcer in hospitalized patients with malnutrition. Metallomics Res. 2, reg11-reg18. https://doi.org/10.11299/metallomicsresearch.MR202117 (2022).

- European Pressure Injury Advisory Panel, National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guideline. The International Guideline. (ed. Haesler, E.). (EPUAP/ NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

- Jackson, M. J. Physiology of zinc: General aspects. In Zinc in Human Biology ILSI Human Nutrition Reviews (ed. Mills, C. F.) (Springer, 1989).

- Prasad, A. S. Zinc is an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agent: Its role in human health. Front. Nutr. 1, 14. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fnut.2014.00014 (2014).

- Lai, J. C. et al. Malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis: 2021 Practice guidance by the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 74, 1611-1644. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep. 32049 (2021).

- Waters, D. L. et al. Sexually dimorphic patterns of nutritional intake and eating behaviors in community-dwelling older adults with normal and slow gait speed. J. Nutr. Health Aging 18, 228-233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-014-0004-8 (2014).

- Chaput, J. P. et al. Relationship between antioxidant intakes and class I sarcopenia in elderly men and women. J. Nutr. Health Aging 11, 363-369 (2007).

- Fact-finding Committee of the Japanese Society of Pressure Ulcers et al. Nationwide time-series surveys of pressure ulcer prevalence in Japan. J. Wound Care 31, S40-S47. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2022.31.Sup12.S40 (2022).

- Kitamura, A. et al. Sarcopenia: Prevalence, associated factors, and the risk of mortality and disability in Japanese older adults. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 12, 30-38. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm. 12651 (2021).

- Tanabe, N. et al. Importance of nutrition support team in pressure ulcer control: Examination at one long-term care hospital in Yamaguchi prefecture. Bull. Yamaguchi Med. Sch. 69, 37-43 (2022).

- Maruyama, Y., Nakashima, A., Fukui, A. & Yokoo, T. Zinc deficiency: Its prevalence and relationship to renal function in Japan. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 25, 771-778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-021-02046-3 (2021).

- Ume, A. C., Wenegieme, T. Y., Adams, D. N., Adesina, S. E. & Williams, C. R. Zinc deficiency: A potential hidden driver of the detrimental cycle of chronic kidney disease and hypertension. Kidney 360 4, 398-404. https://doi.org/10.34067/kid.0007812021 (2023).

- Severo, J. S. et al. The role of zinc in thyroid hormones metabolism. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 89, 80-88. https://doi.org/10.1024/ 0300-9831/a000262 (2019).

- Chiba, M. et al. Diuretics aggravate zinc deficiency in patients with liver cirrhosis by increasing zinc excretion in urine. Hepatol. Res. 43, 365-373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.01093.x (2013).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. NDB Open Data (in Japanese). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/ 0000177221_00011.html.

- VanderWeele, T. J. Principles of confounder selection. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 34, 211-219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00494-6 (2019).

Author contributions

Funding

Competing interests

Additional information

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

© The Author(s) 2024

Department of General Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Juntendo University, Tokyo, Japan. Department of Data Science, Nobelpharma Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan. Department of Academic Services, 4DIN Ltd., #805 Shinbashiekimae Bldg. 1 2-20-15 Shinbashi Minato-ku, Tokyo 105-0004, Japan. Center for Promotion of Data Science, Juntendo University Graduate School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan. email: nfukui@4din.com