DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.06.028

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39043180

تاريخ النشر: 2024-07-22

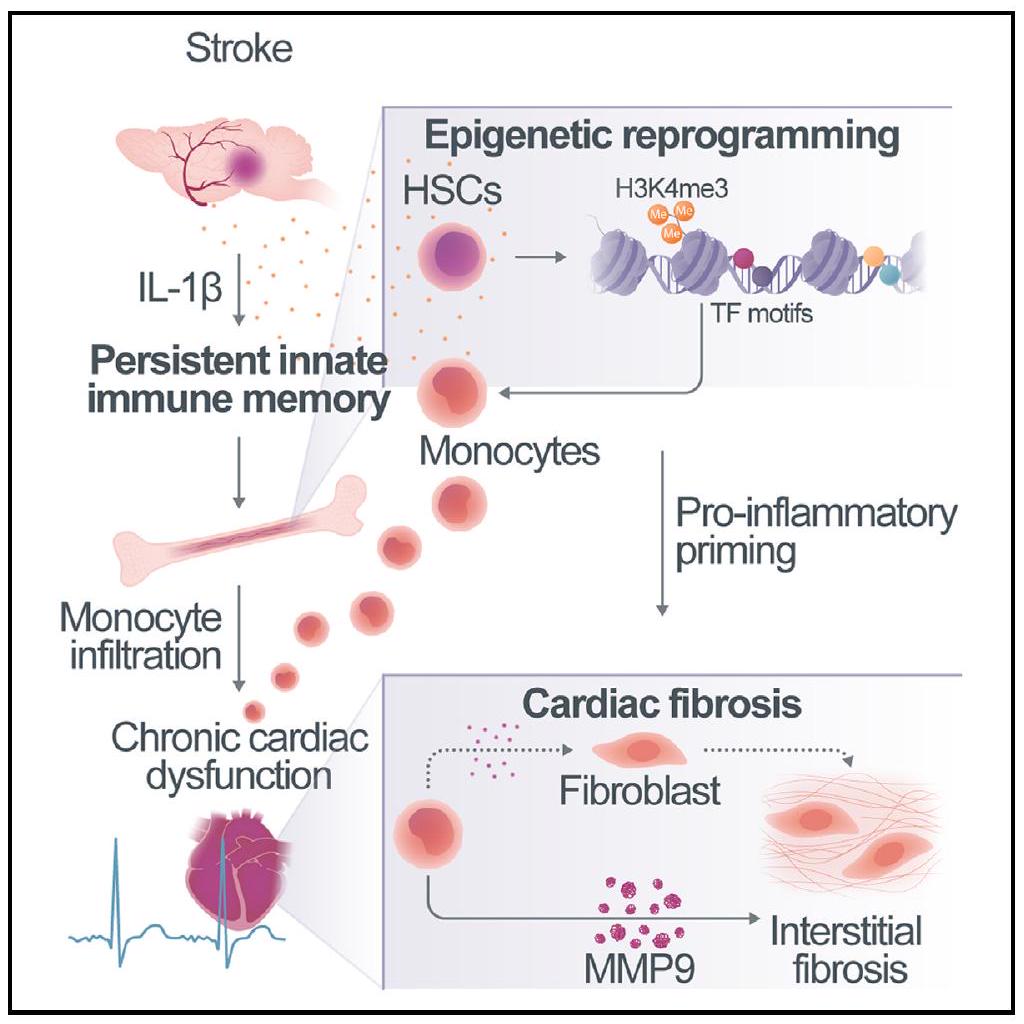

الذاكرة المناعية الفطرية بعد إصابة الدماغ تؤدي إلى خلل التوتر القلبي الالتهابي

أهم النقاط

- نقص التروية الدماغية الحاد يؤدي إلى ذاكرة مناعية فطرية مستمرة

- الذاكرة المناعية الفطرية تسبب خللًا قلبيًا مزمنًا بعد السكتة الدماغية

- IL-1

يحفز المناعة المدربة بعد السكتة الدماغية من خلال التعديلات الجينية - حجب IL-13 أو تجنيد وحيدات النوى يمنع ضعف القلب

المؤلفون

المراسلات

باختصار

الذاكرة المناعية الفطرية بعد إصابة الدماغ تؤدي إلى خلل التوتر القلبي الالتهابي

الملخص

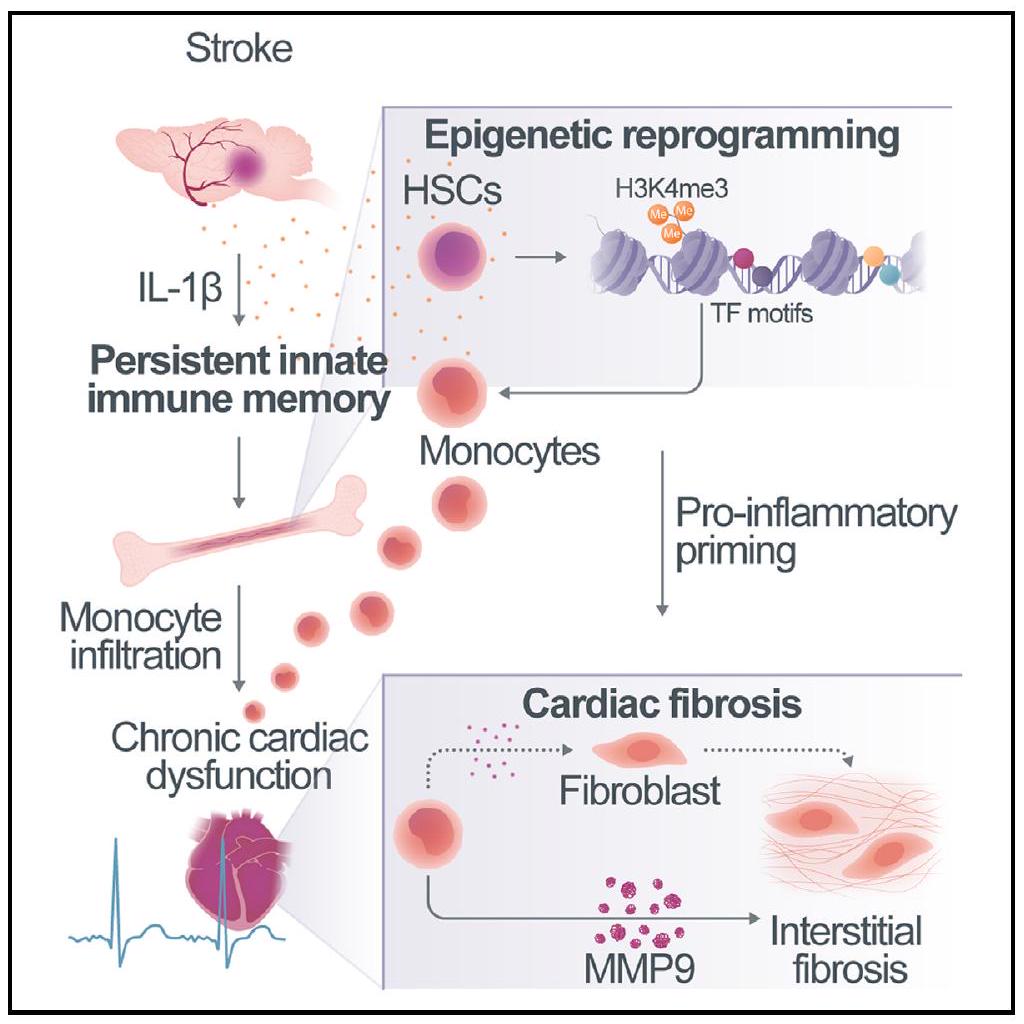

الملخص إن العبء الطبي للسكتة الدماغية يتجاوز الإصابة الدماغية نفسها ويتحدد إلى حد كبير بواسطة الأمراض المصاحبة المزمنة التي تتطور بشكل ثانوي. لقد افترضنا أن هذه الأمراض المصاحبة قد تشترك في سبب مناعي مشترك، ومع ذلك فإن الآثار المزمنة بعد السكتة الدماغية على المناعة الجهازية لم تُستكشف بشكل كافٍ. هنا، نحدد ذاكرة المناعة الفطرية المايلويدية كسبب لخلل الأعضاء البعيدة بعد السكتة الدماغية. كشفت تسلسلات الخلايا المفردة عن تغييرات التهابية مستمرة في المونوسيتات/البلاعم في عدة أعضاء حتى 3 أشهر بعد الإصابة الدماغية، وخاصة في القلب، مما أدى إلى تليف القلب وخلل في كل من الفئران ومرضى السكتة الدماغية. IL-1

مقدمة

النتائج

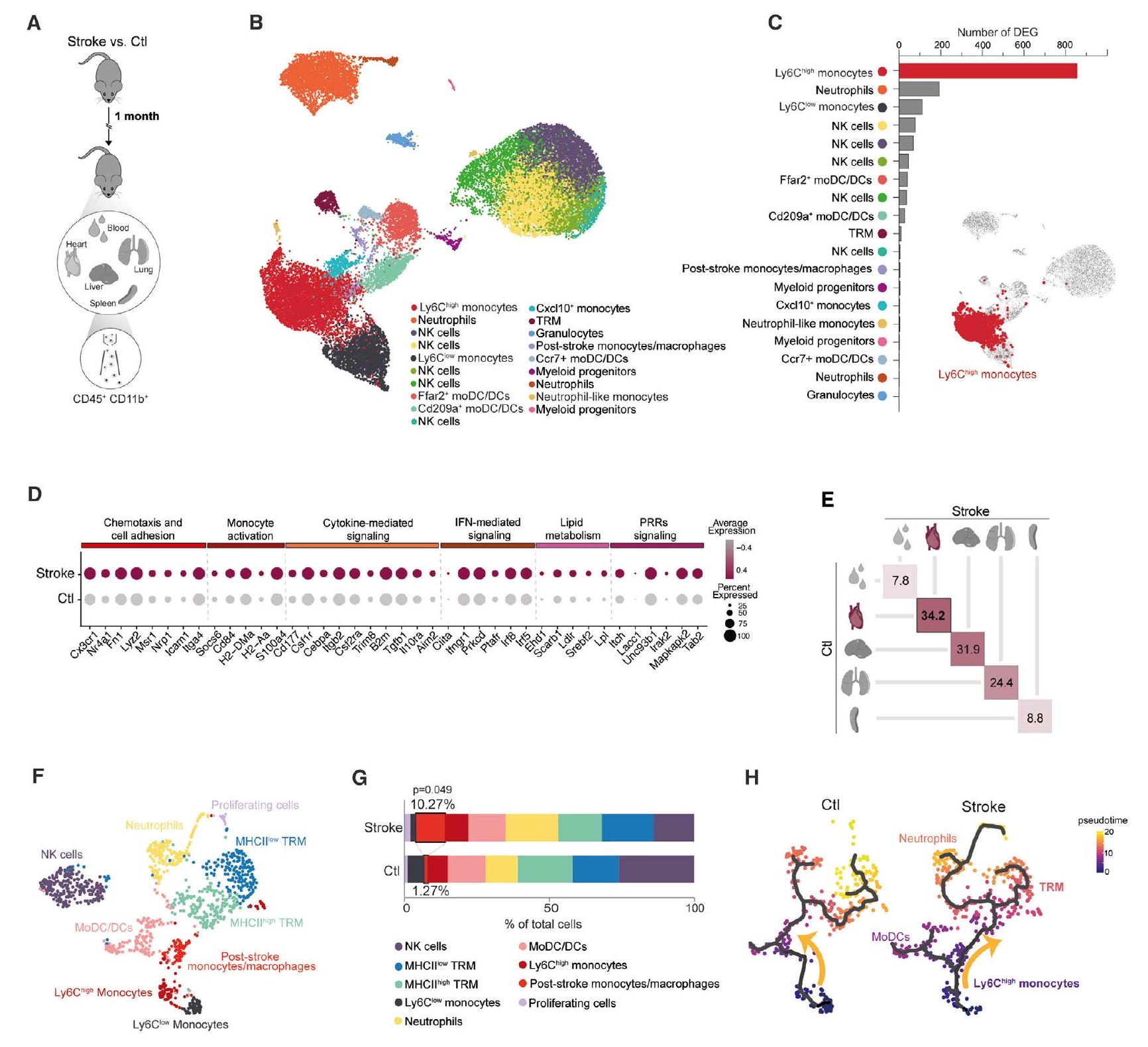

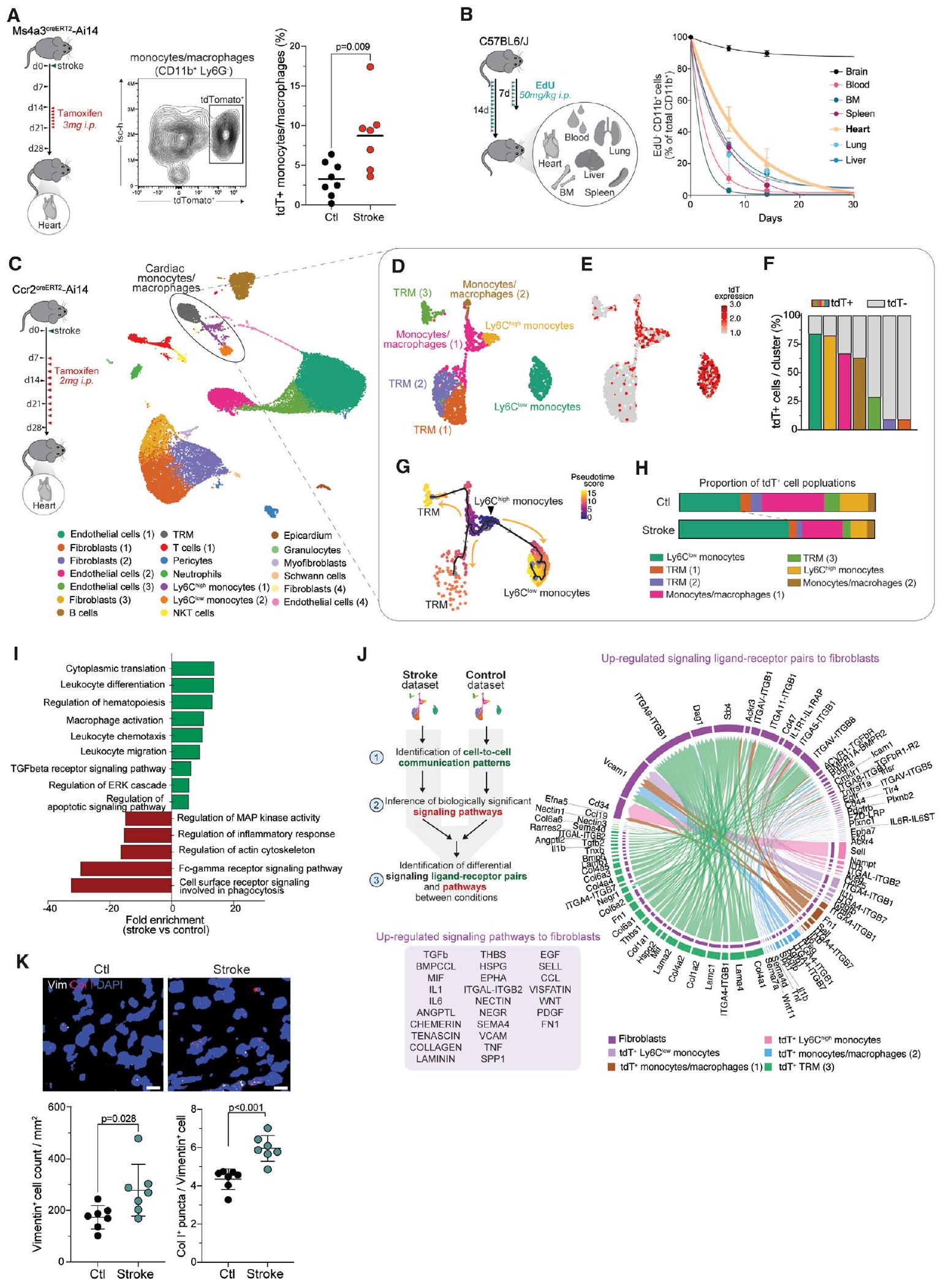

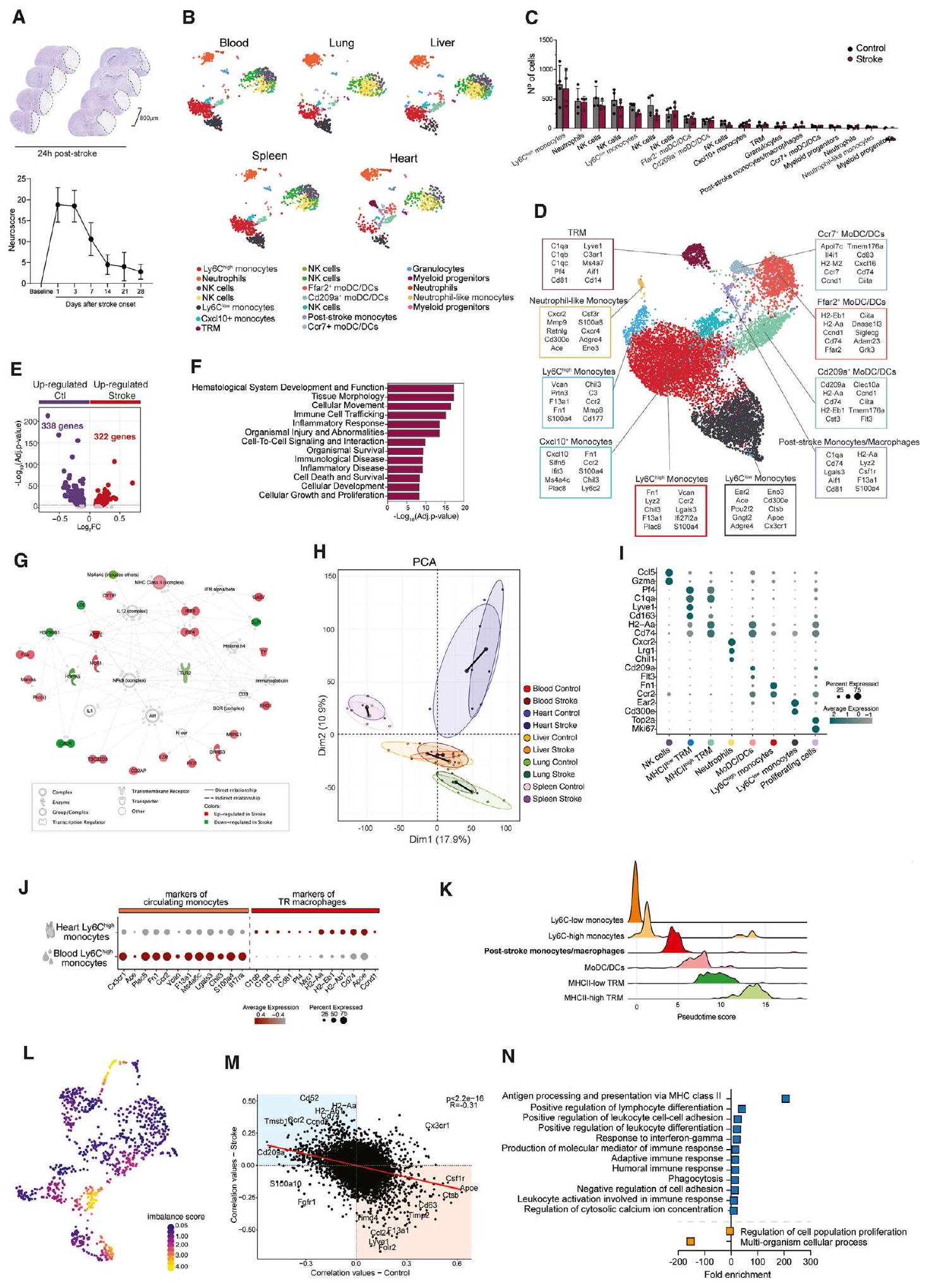

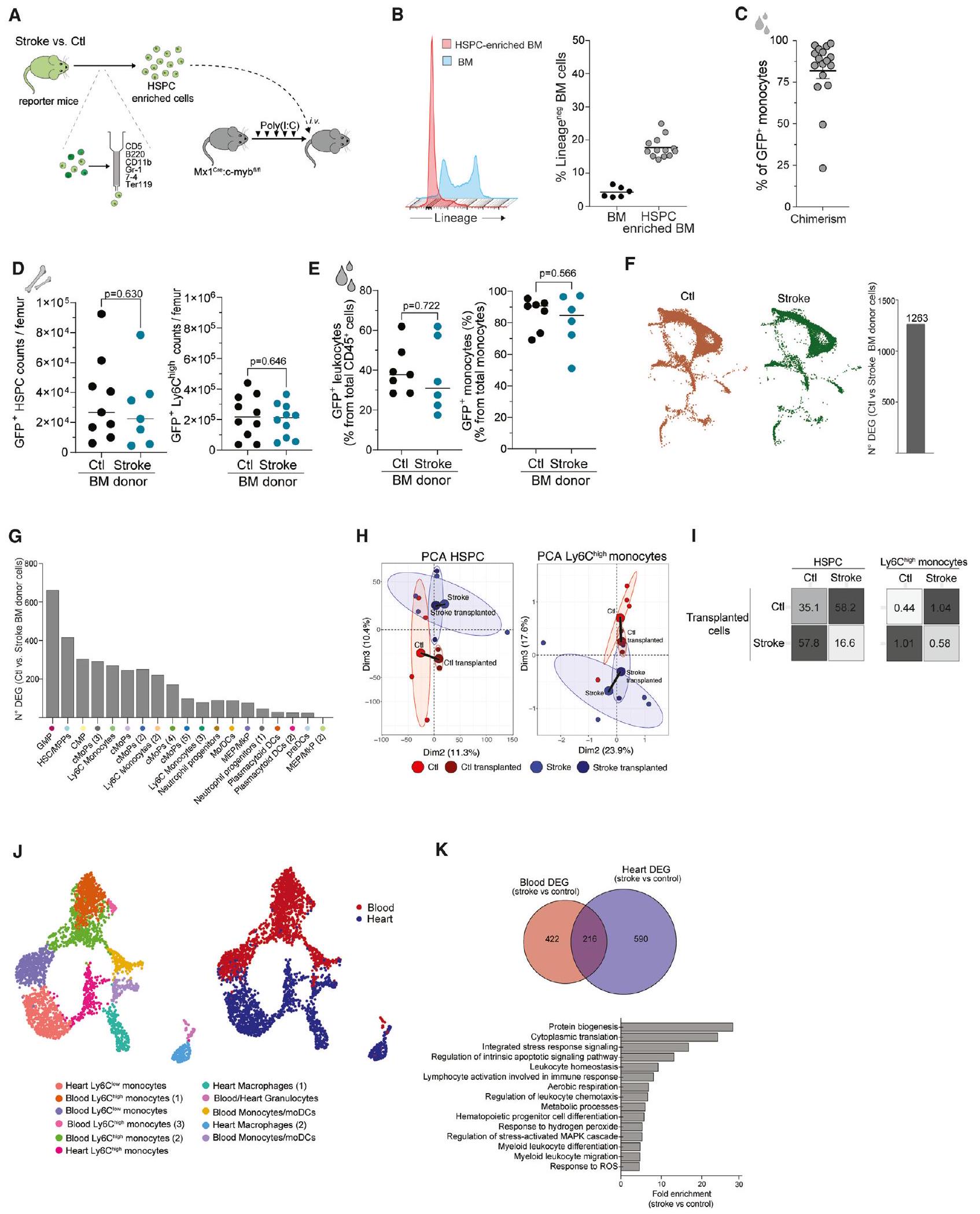

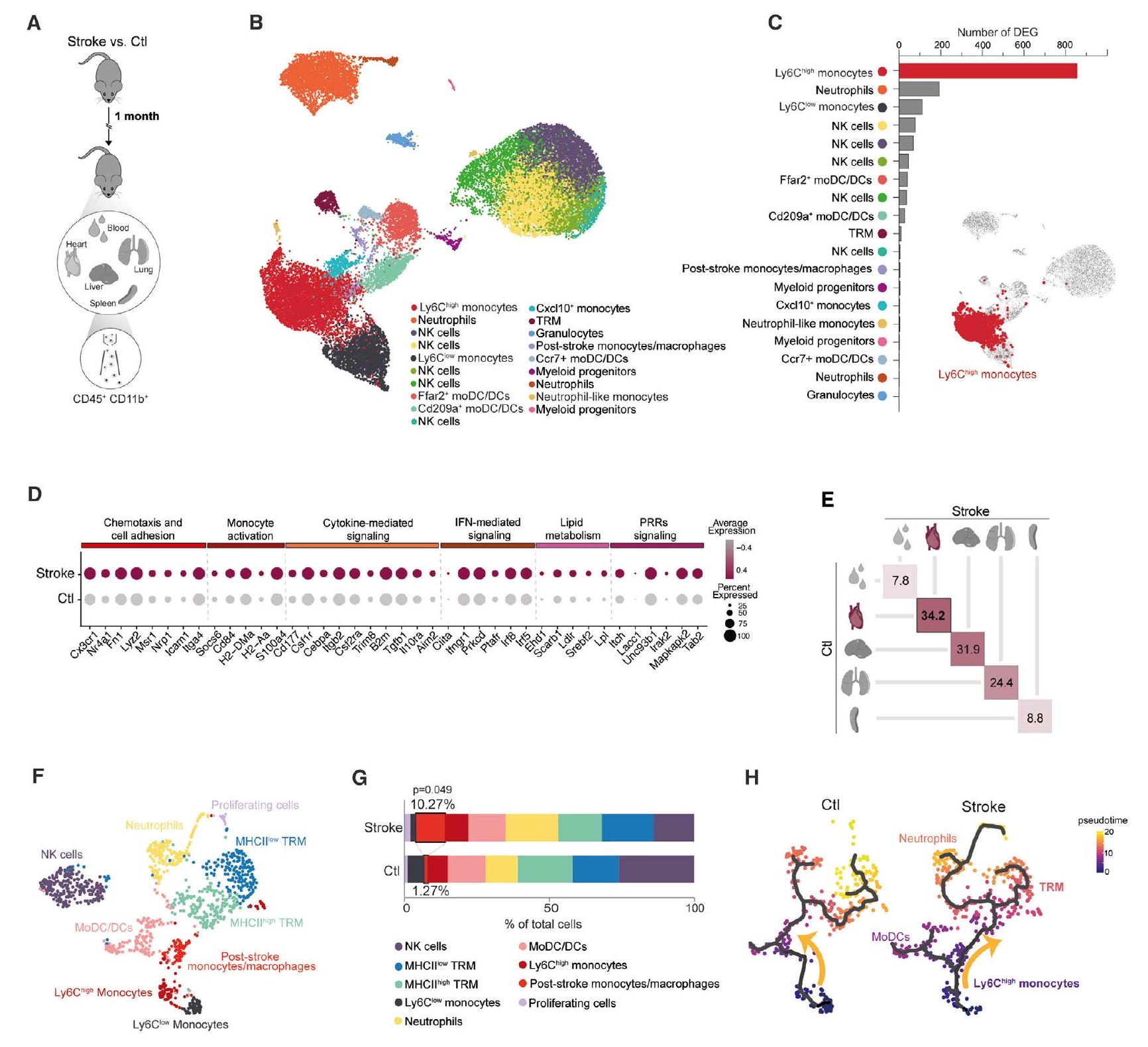

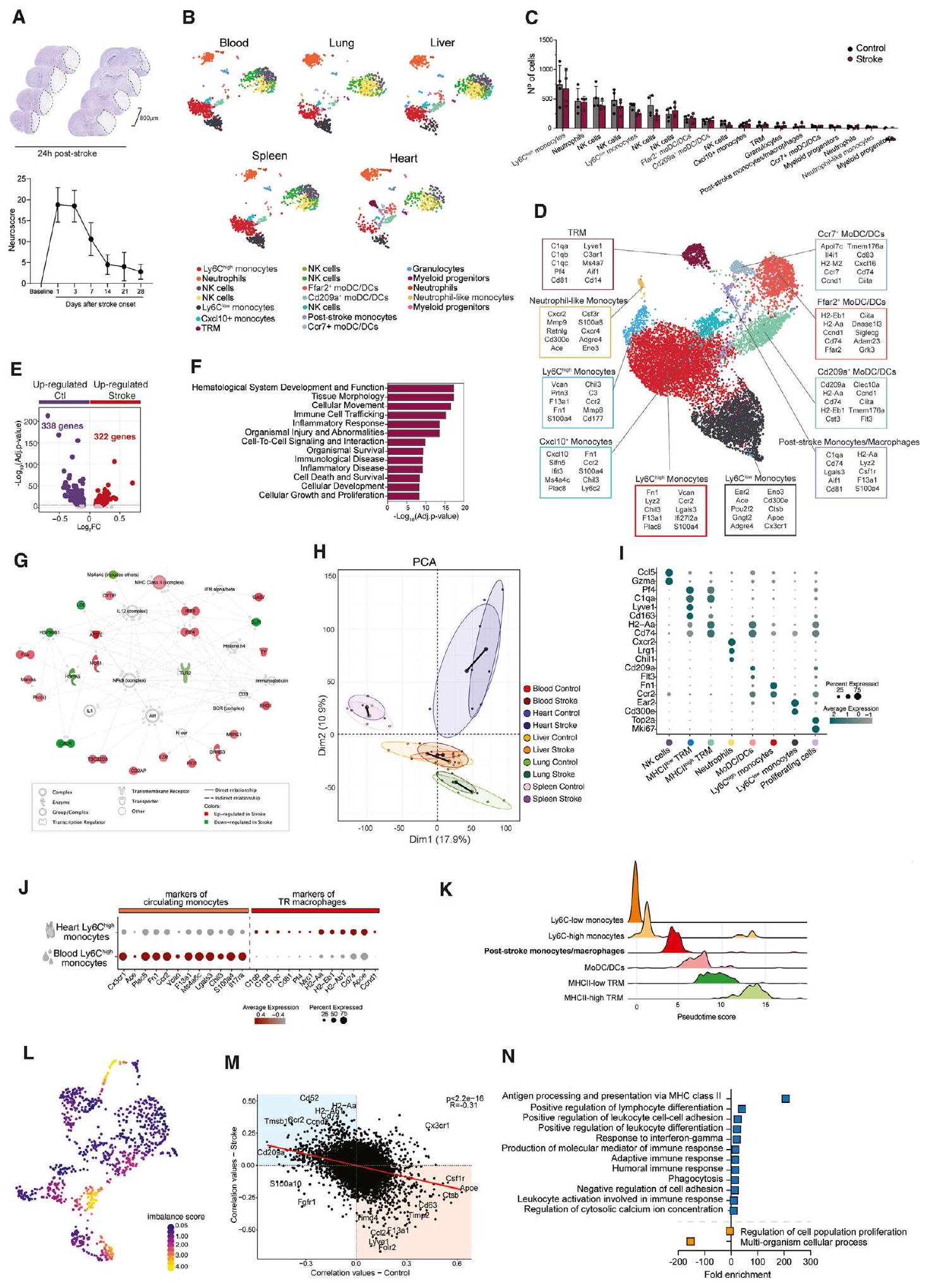

السكتة الدماغية تسبب تغييرات التهابية طويلة الأمد في المونوسيتات/البلاعم الجهازية

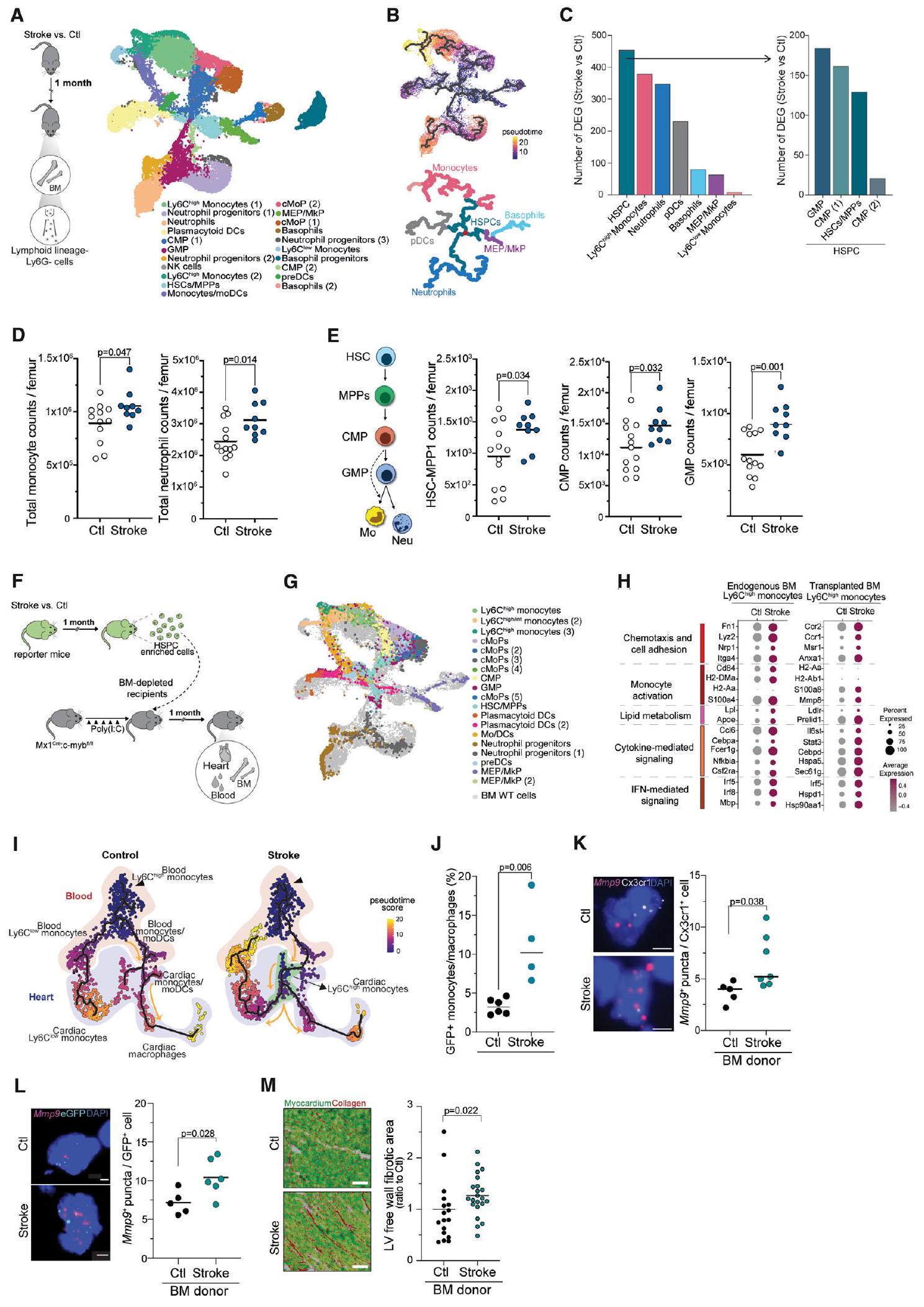

تحليل تسلسل خلايا المايلويد CD45+CD11b+ من الدم والعديد من الأعضاء الطرفية بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية الإقفارية التجريبية، والتي تم ربطها سابقًا بالعواقب الالتهابية لإصابة الدماغ في المرحلة الحادة (الشكل 1A).

(أ) تم فرز الخلايا النخاعية من الدم والأعضاء الطرفية بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية الإقفارية التجريبية

(ب) رسم UMAP لـ

(C) عدد الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف (DEGs) بين الظروف لكل مجموعة محددة (adj.p < 0.05). Ly6C

مستويات التعبير للجينات المختارة في Ly6C

(E) المسافات الإقليدية في فضاء تحليل المكونات الرئيسية بين السكتة الدماغية والتحكم لكل عضو. تم حساب تحليل المكونات الرئيسية من إجمالي 18,834 جينًا تم تحديدها في جميع CD45

(

(H) ترتيب زمني زائف لـ CD45 باستخدام Monocle3

انظر أيضًا الشكل S1.

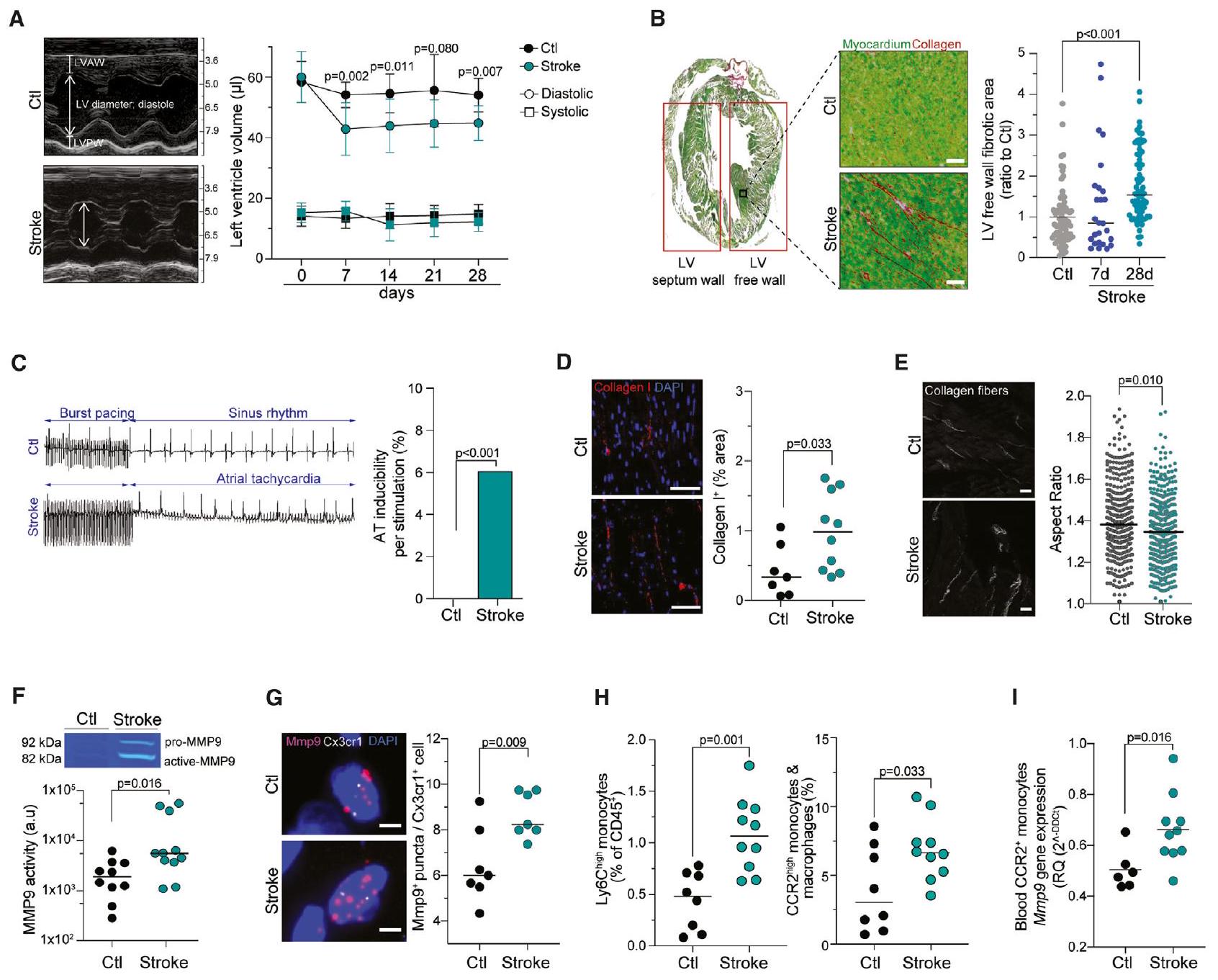

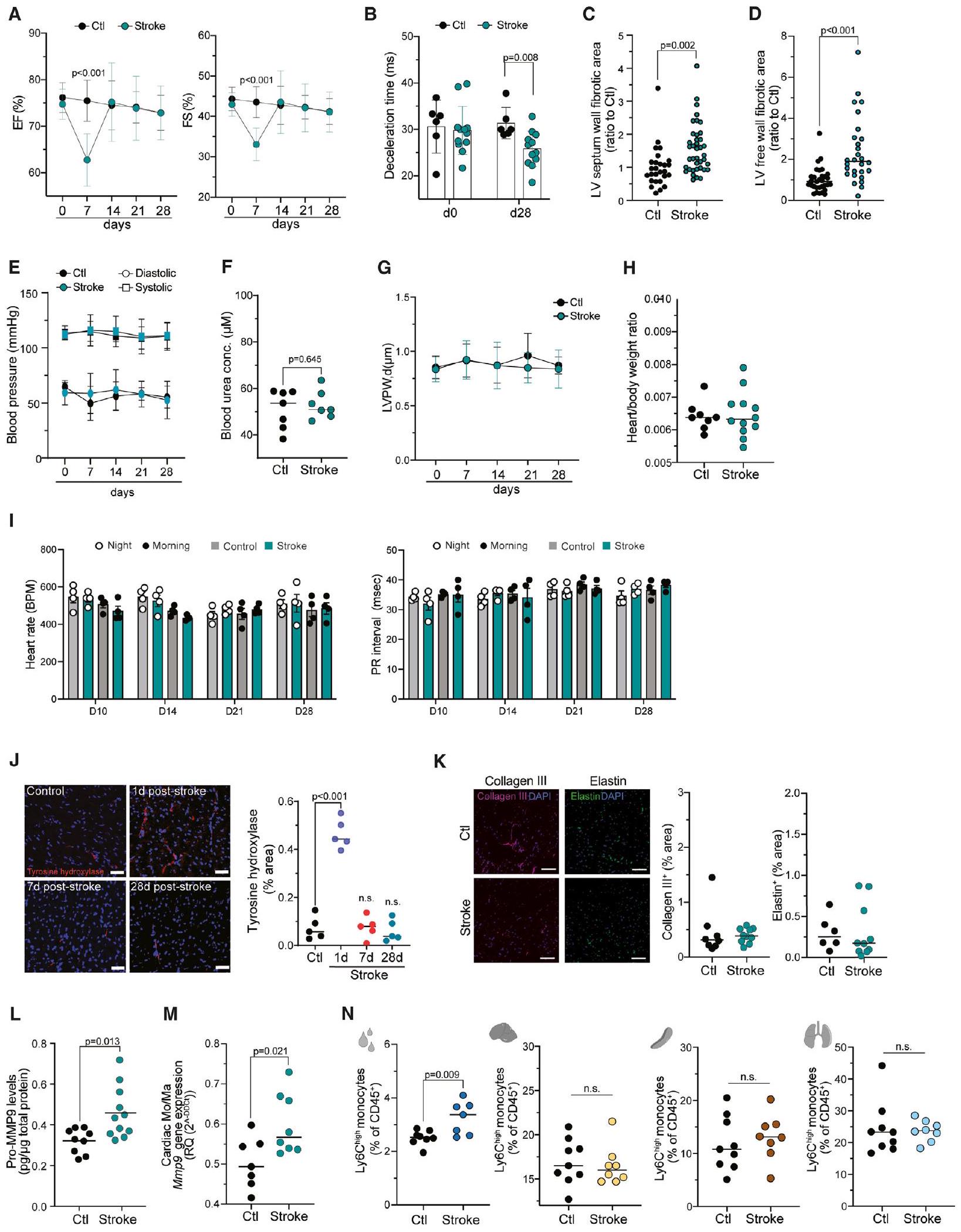

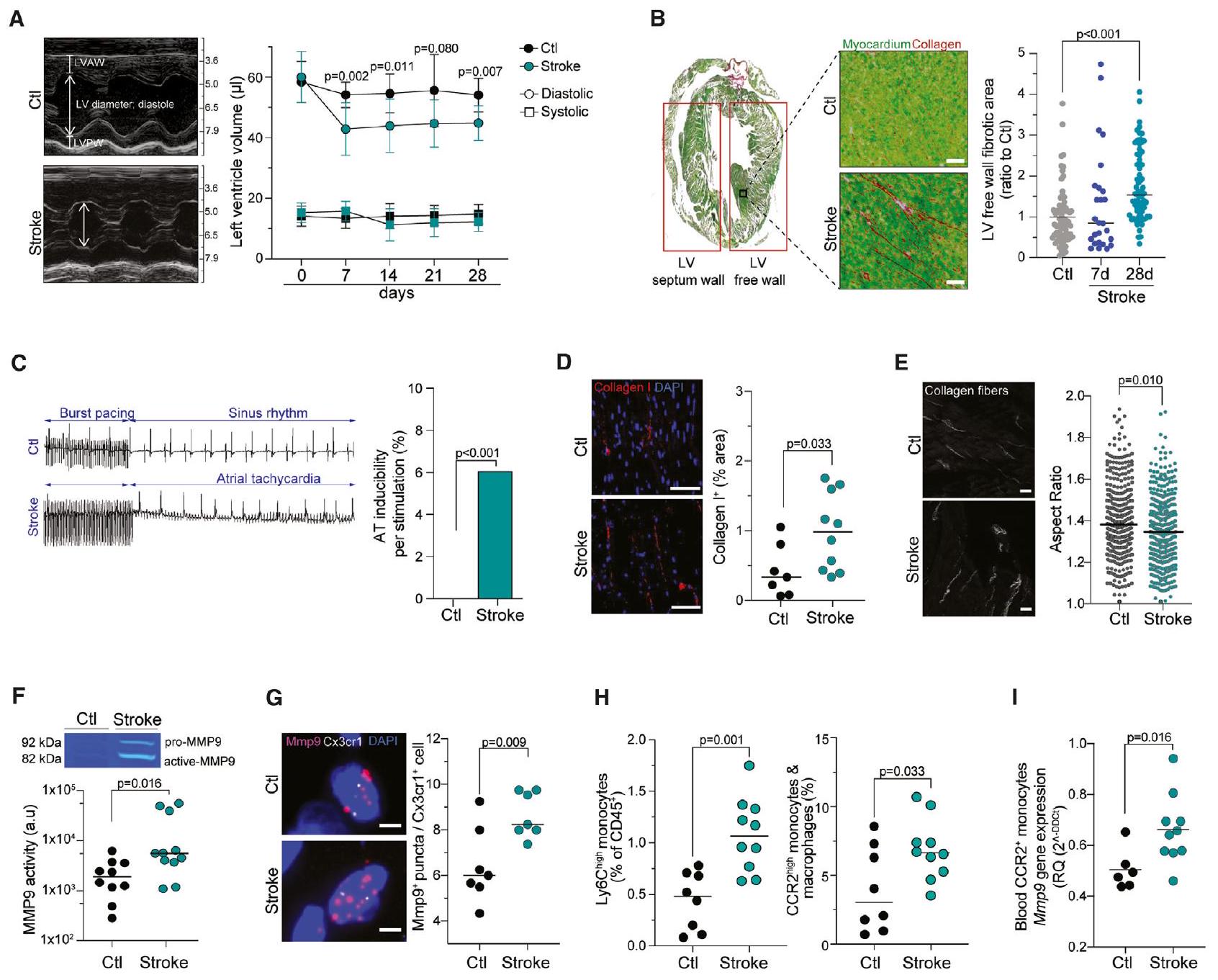

تم قياس الوظيفة القلبية، من خلال نسبة الطرد والتقصير النسبي، وكانت متأثرة بشكل مؤقت فقط بالسكتة الدماغية في المرحلة الحادة (الأشكال 2A و S2A؛ الجدول S1). تشير هذه النتائج إلى

صور الموجات فوق الصوتية التمثيلية (وضع M) التي تم إجراؤها في النقاط الزمنية المحددة (

(ب) صور تمثيلية (صبغة سيريوس الأحمر/الأخضر السريع) وقياس تليف القلب في جدار البطين الأيسر الحر

(ج) صورة تمثيلية لعلم كهرباء القلب بعد شهر واحد من السكتة الدماغية أو التحكم

“(د) صورة تمثيلية وقياس لمحتوى الكولاجين I، معبرًا عنه كنسبة مئوية من المساحة الإجمالية لجدار البطين الأيسر (مقاييس)

(E) صور توليد التوافقيات الثاني (SHG) التمثيلية للكشف عن تنظيم الكولاجين الليفي وقياس نسبة الأبعاد (أشرطة القياس،

النشاط الإنزيمي لمركب MMP9 باستخدام زيموغرافيا الهلام لعينات القلب بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية أو التحكم

(G) صور تمثيلية لتقنية التهجين الموضعي بالفلوريسنس لجزيء واحد (smFISH) وقياس عدد نقاط mRNA لـ Mmp9 لكل Cx3cr1

(H) قياس تدفق السيتومتر لـ Ly6C

تعبير mRNA لـ Mmp9 (RT-qPCR) في CCR2 المصفاة من الدم

انظر أيضًا الشكل S2.

لكن ضعف الانبساط غالبًا ما يرتبط بتليف القلب، مما يعيق ملء البطين الأيسر بسرعة بسبب زيادة صلابة عضلة القلب.

التي ظلت مرتفعة حتى 3 أشهر بعد السكتة الدماغية (الأشكال 2B و S2C و S2D). من المهم أن هذه التليفات القلبية التي لوحظت بعد السكتة الدماغية لم تكن مرتبطة بخلل في وظائف الكلى، أو تغييرات تشريحية كبيرة في القلب، أو اضطرابات مستمرة في الإمداد العصبي الذاتي للقلب بعد المرحلة الحادة بعد السكتة الدماغية (الأشكال S2E-S2J). لاختبار التأثير المحتمل لتليف القلب بعد السكتة الدماغية، أجرينا بعد ذلك دراسة كهربائية قلبية (EP) غازية بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية. بما يتماشى مع دراسة سابقة تحدد دور الالتهاب القلبي كعامل خطر لرجفان الأذين،

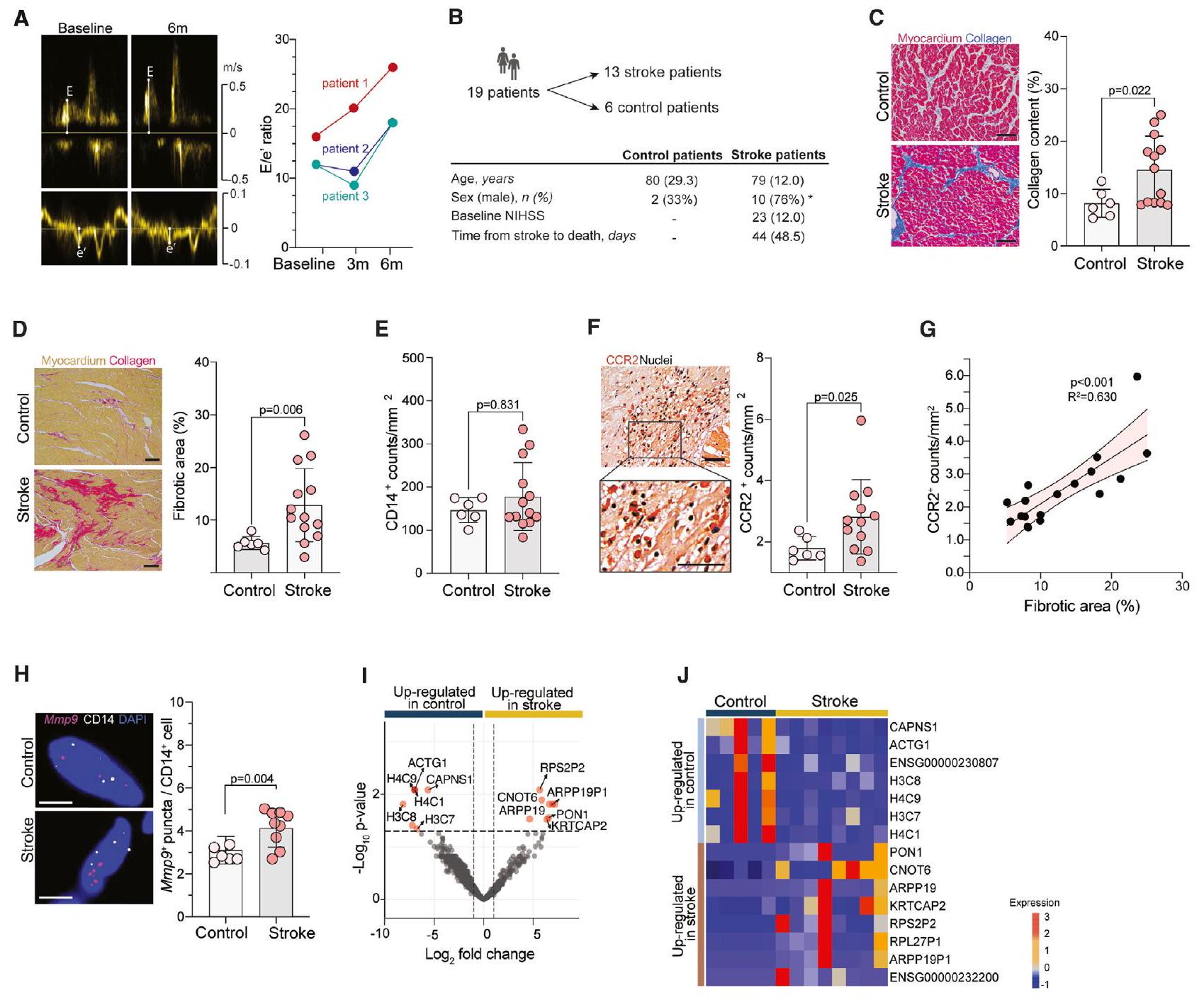

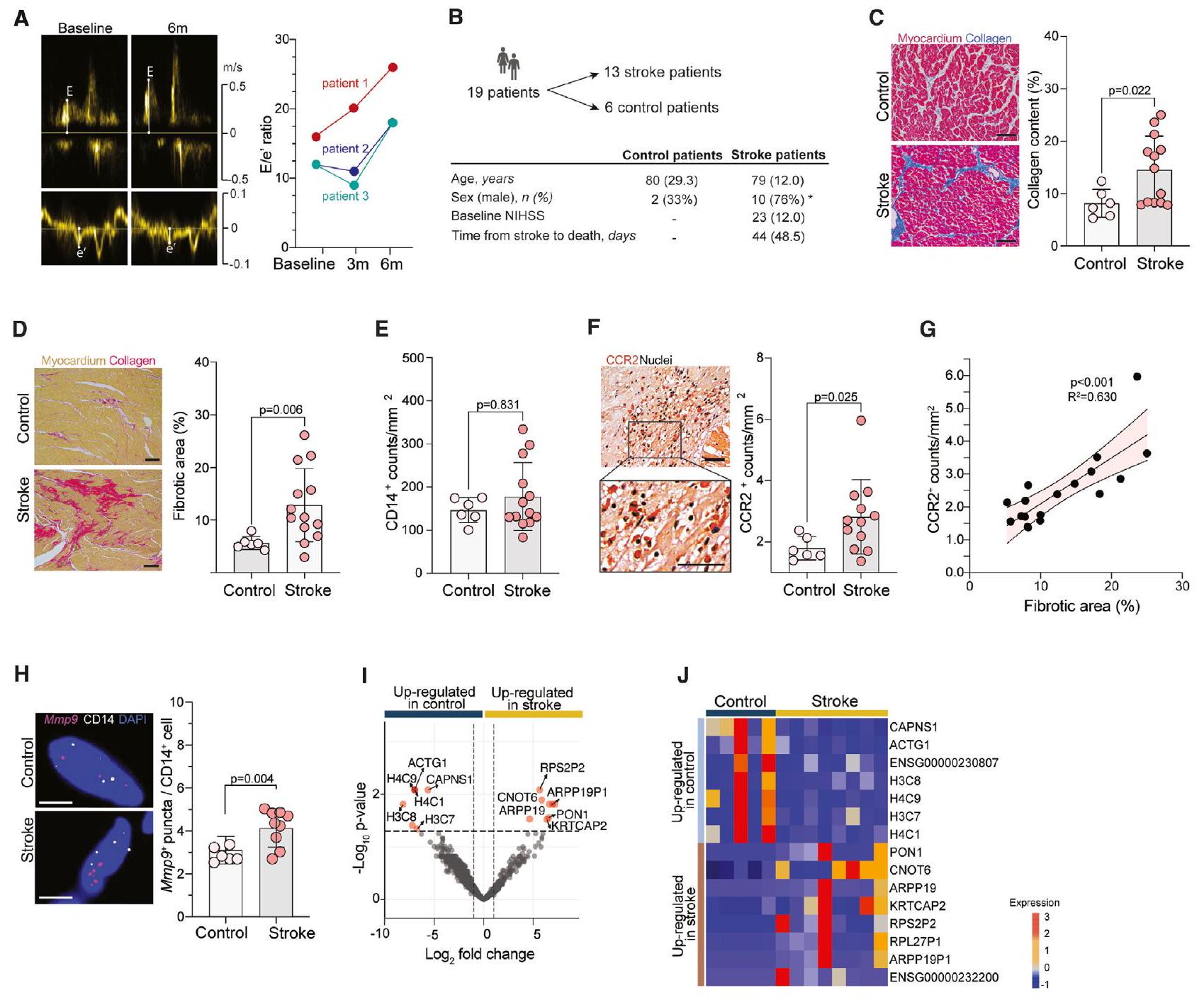

تم استخدام تسلسل الأنسجة المجاورة المستخدمة في التحليلات النسيجية أعلاه ووجدت اختلافات تعبيرية كبيرة بين الموضوعات الضابطة وبعد السكتة الدماغية (الأشكال 3I و3J). ومن المثير للاهتمام أن العديد من الجينات التي تم تنظيمها بشكل زائد في مرضى السكتة الدماغية كانت مرتبطة بإعادة تشكيل المصفوفة خارج الخلوية، بما في ذلك باراكسوناز 1 (PON1) وبروتين مرتبط بالخلايا الكيراتينية 2 (KRTCAP2). مجتمعة، لاحظنا تليف قلبي ملحوظ وإعادة تشكيل المصفوفة خارج الخلوية في كل من الفئران التجريبية ومرضى السكتة الدماغية، والذي ارتبط بشكل أكبر بخلل انبساطي بعد السكتة الدماغية التجريبية. علامة مميزة لهذه الأمراض القلبية الثانوية بعد السكتة الدماغية هي زيادة تجنيد وملف التهابية برو-التهابية للوحيدات/macrophages القلبية.

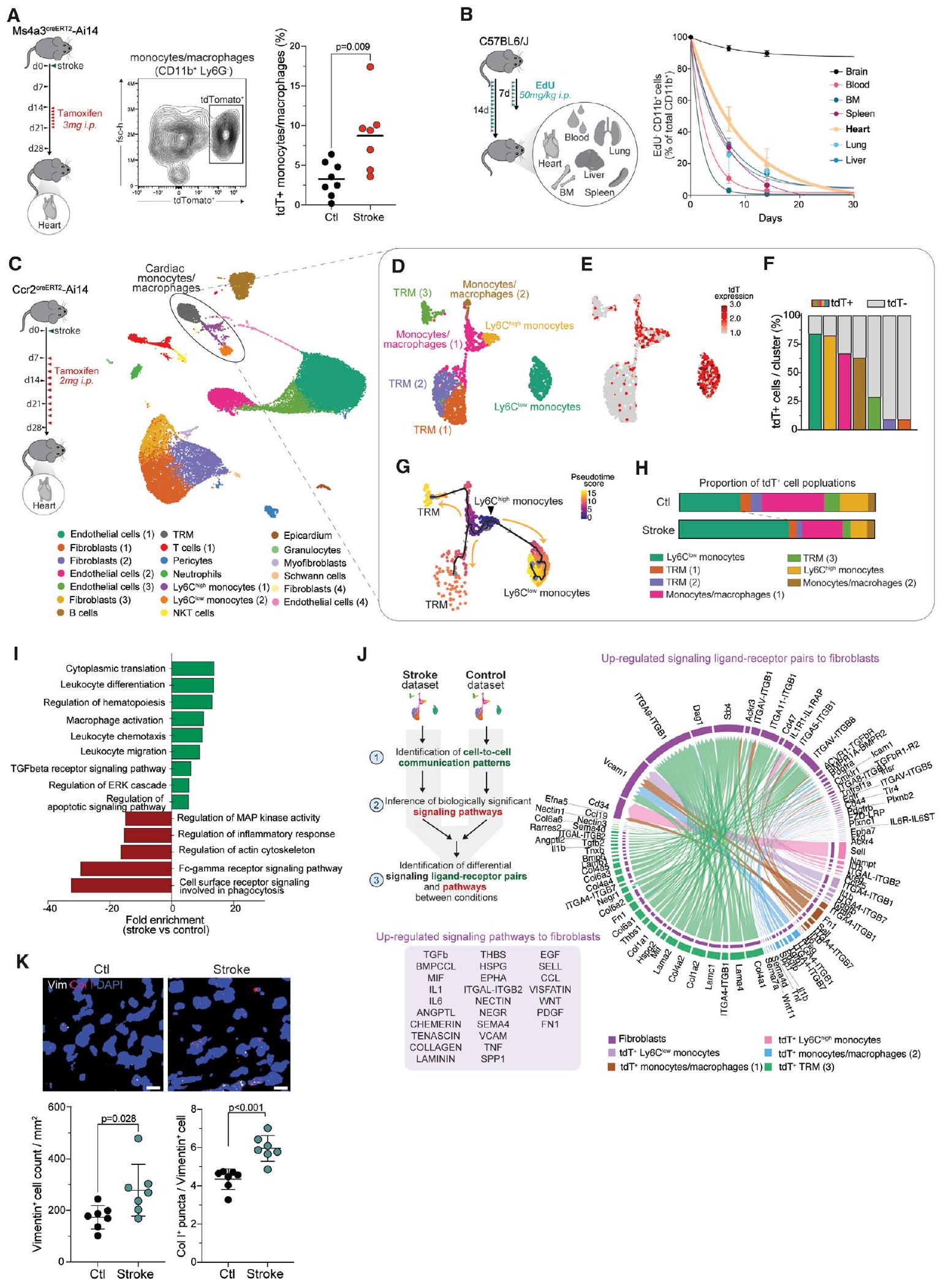

السكتة الدماغية تعزز تجنيد المونوسيتات المزمنة إلى القلب

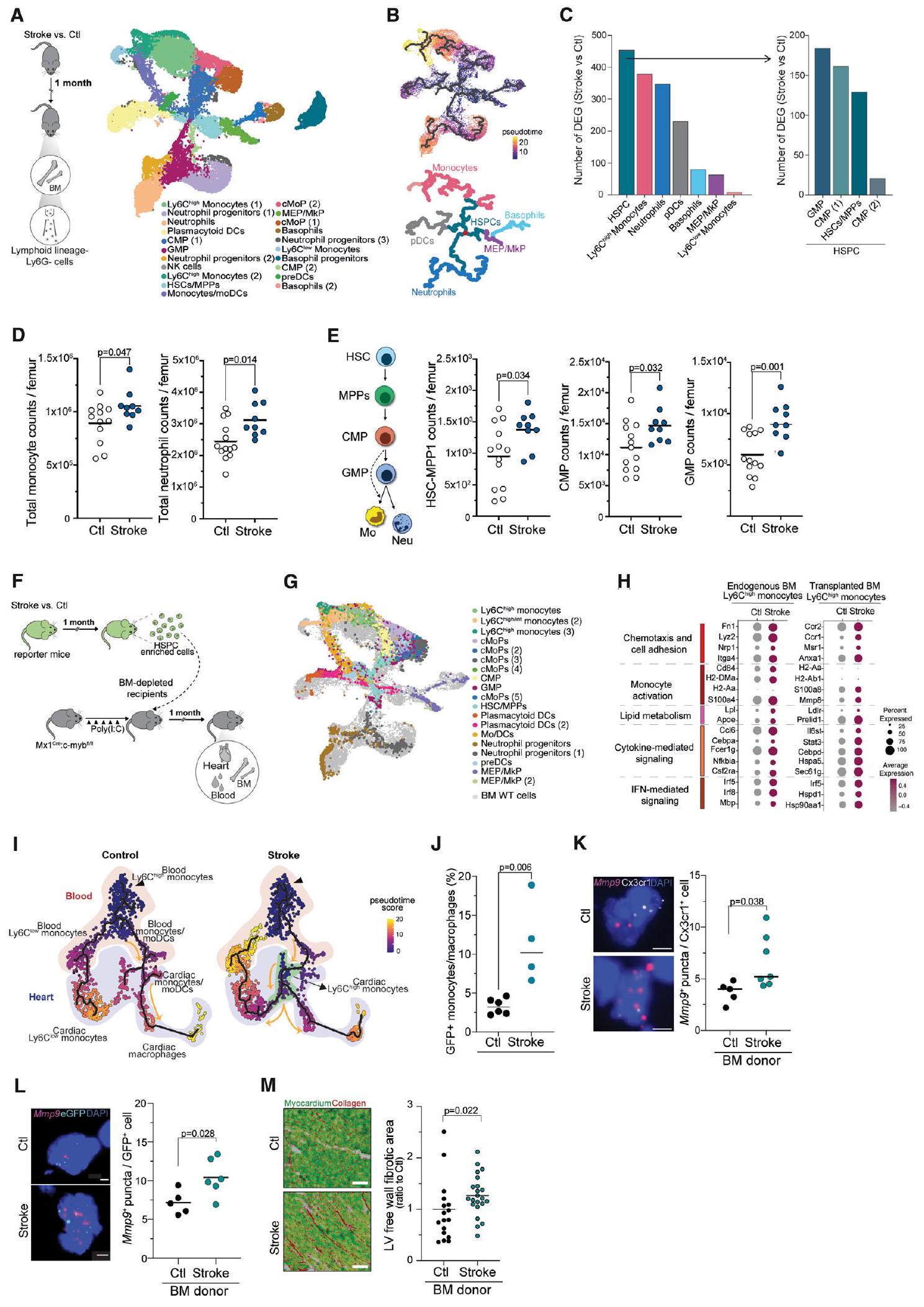

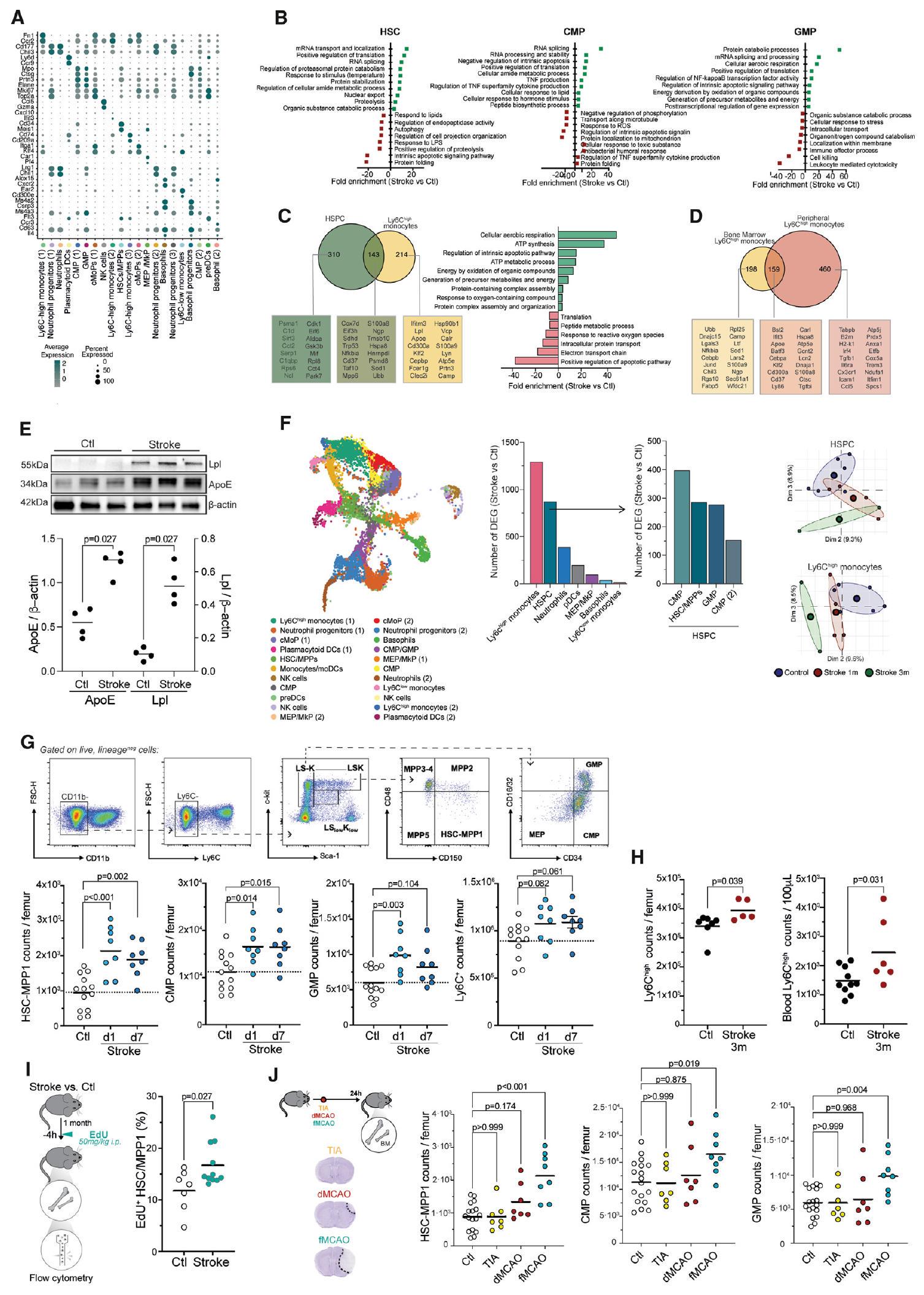

تتغير الخلوية والوظيفة في نخاع العظام بشكل مزمن بعد السكتة الدماغية

(أ) صور تمثيلية للمريض الذي يعاني من خلل انبساطي مزمن تم تجنيده من قبل مجموعة دراسة فشل القلب الناتج عن السكتة الدماغية (SICFAIL). التقدير المقابل لـ

(ب) تم جمع عينات تشريح القلب من إجمالي 19 مريضًا: 12 مريضًا بسكتة دماغية إقفارية و7 ضوابط، توفوا دون اضطراب قلبي أو دماغي (تم تأكيده بواسطة التشريح). يتم توضيح الخصائص الديموغرافية والسريرية الأساسية. يتم التعبير عن البيانات كوسيط (نطاق الربيع بين الربعين [IQR])، ما لم يُذكر خلاف ذلك. *p < 0.05 (اختبار كاي-تربيع).

(ج) صور تمثيلية (صبغة ماسون ثلاثية الألوان، قضبان القياس، 0.1 مم) وقياس محتوى الكولاجين (

(د) صور تمثيلية (صبغة سيريوس الحمراء/اللون الأخضر السريع، قضبان القياس، 0.2 مم) وقياس محتوى الكولاجين المعبر عنه كنسبة مئوية من المساحة القلبية الكلية (اختبار t).

(هـ) قياس CD14

صورة تمثيلية (أشرطة القياس، 0.05 مم) والتquantification (اختبار t) لـ

(G) ارتباط CCR2

(H) صور تمثيلية وقياس لتقنية التهجين الفلوري في الموقع لجزيء واحد (smFISH) للكشف عن تعبير نقاط mRNA لـ Mmp9 في CD14

مخطط البركان (I) يظهر الجينات المنظمة في عضلة القلب بين مرضى احتشاء العضلة القلبية ومرضى التحكم. الجينات الملونة هي

(ج) خريطة حرارية تظهر أهم الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف في القلب بين مرضى السكتة الدماغية والمرضى الضابطين.

غطت بصمة نسخية مميزة في Ly6C

مرحلة ما بعد السكتة الدماغية، والتي كانت مرتبطة بمسارات التهابية (الأشكال S4B و S4C). علاوة على ذلك، كانت بصمة النسخ الجيني بعد السكتة الدماغية في العدلات الناضجة من نخاع العظام محفوظة بشكل كبير في العدلات الدائرة والعدلات المتمايزة التي تم استقطابها إلى الأعضاء الطرفية (الشكل S4D). كانت بروتينات الأبوليبوبروتين E (ApoE) والليباز البروتيني (Lpl) مرتفعة بشكل مستمر على مستوى النسخ بعد السكتة الدماغية، وهو ما تم تأكيده أيضًا على مستوى البروتين (الشكل S4E). استمرت التغيرات النسخية الناتجة عن السكتة الدماغية في خلايا الدم الجذعية المكونة للدم والعدلات الناضجة حتى 3 أشهر بعد السكتة الدماغية، مما يشير إلى تأثير مستمر وربما متزايد للسكتة الدماغية على مشهد النسخ الجيني في نخاع العظام (الشكل S4F).

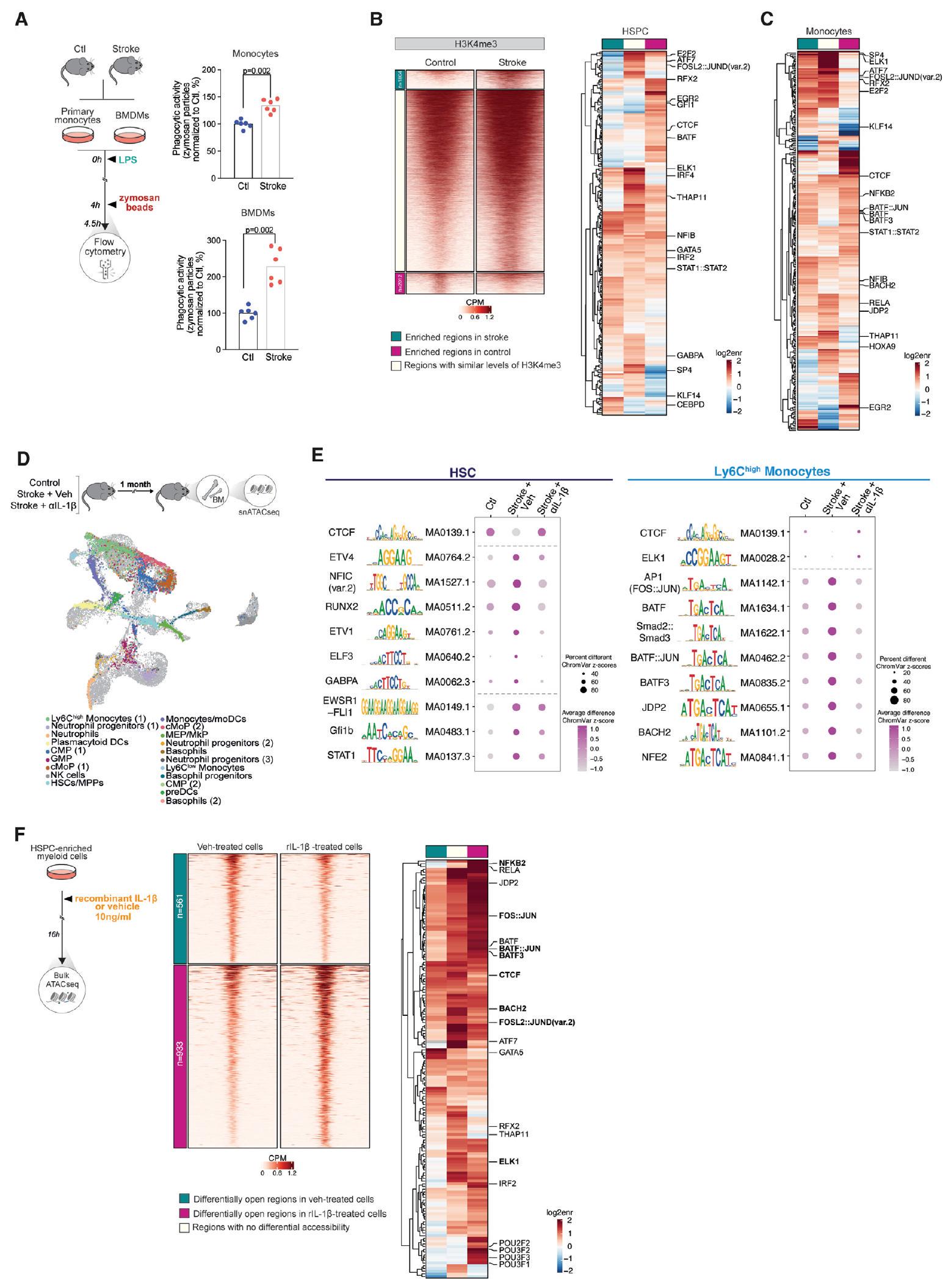

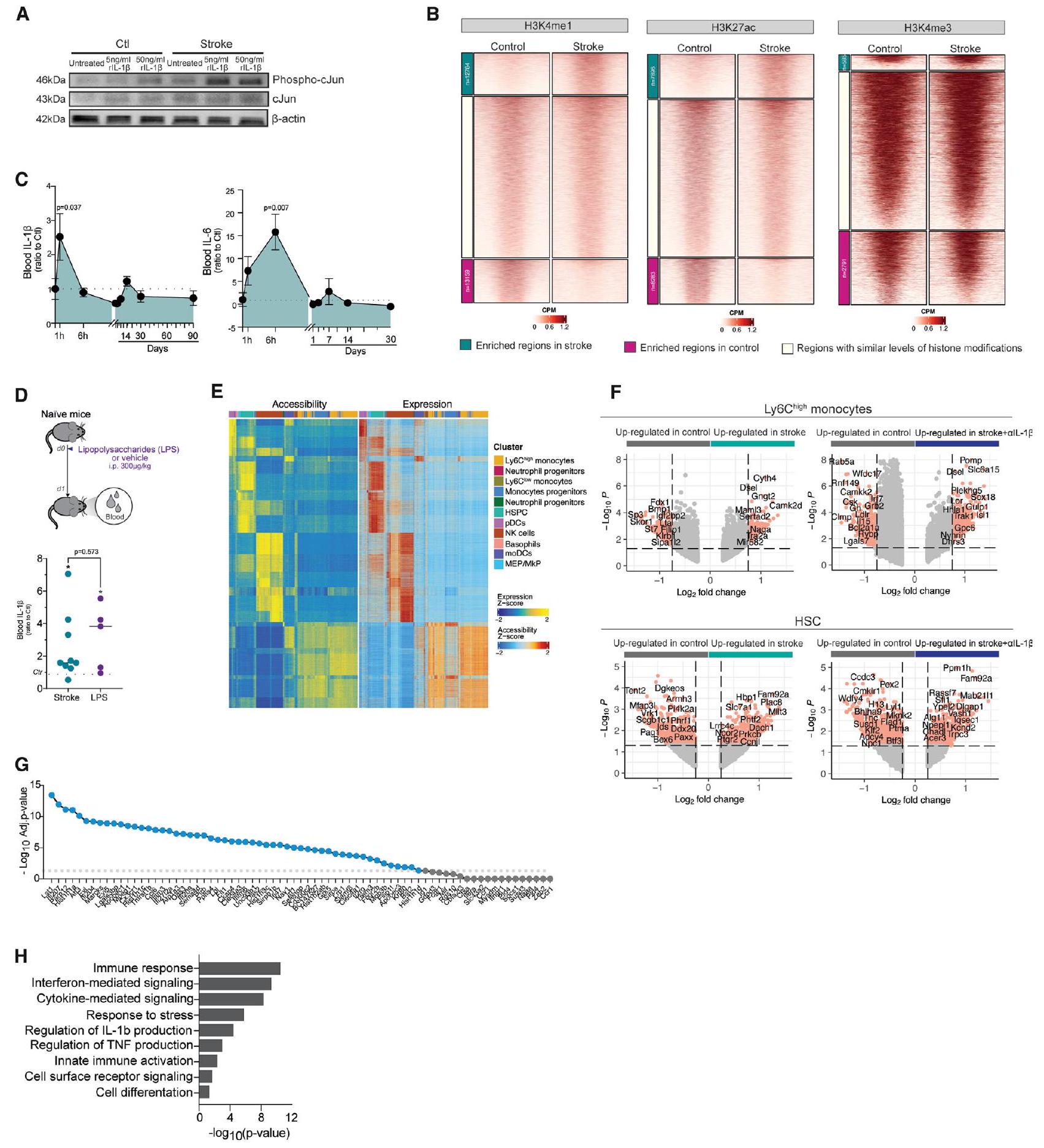

السكتة الدماغية تحفز ذاكرة مناعية فطرية مستمرة

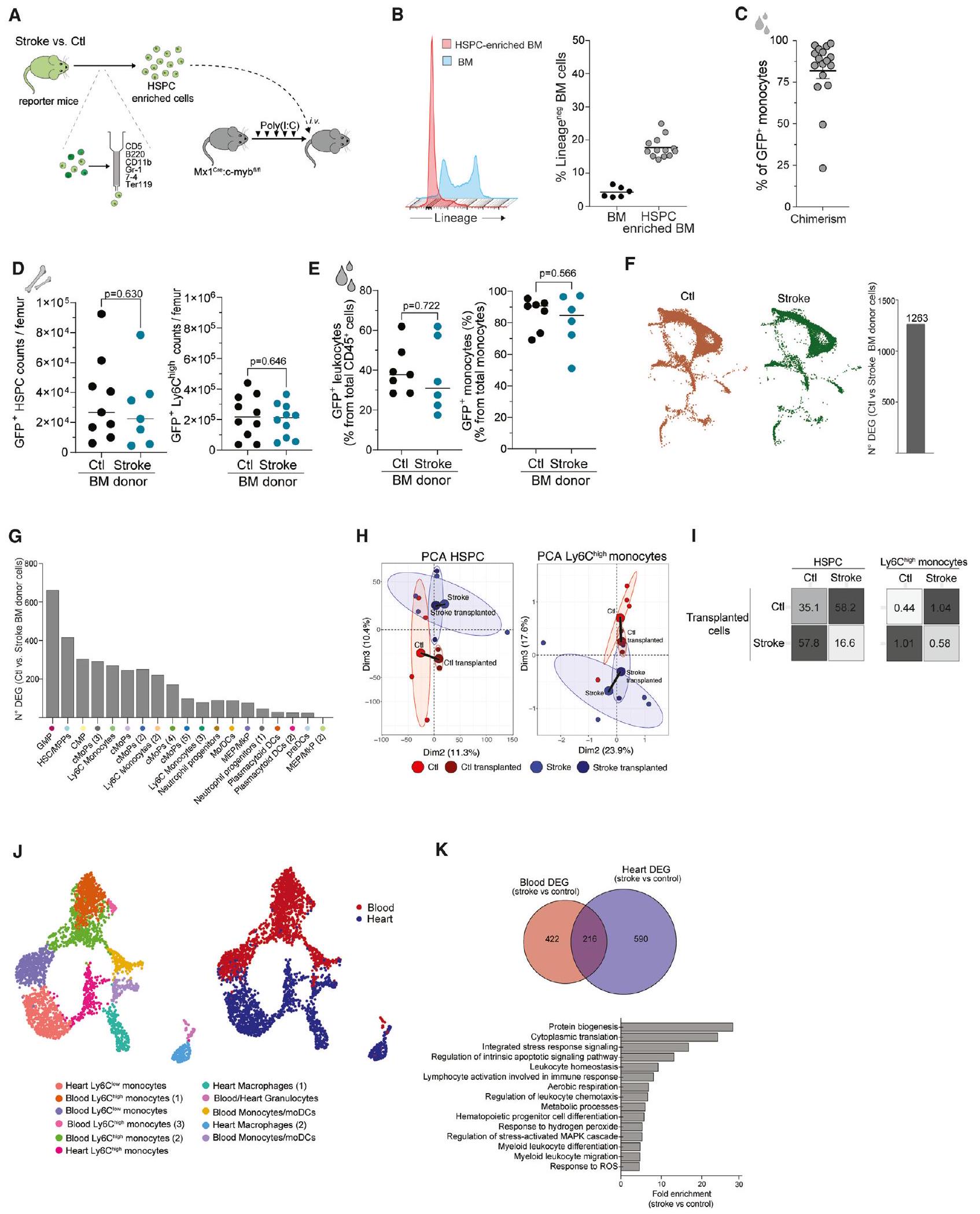

كشفت المسارات النسخية بين الفئران المزروعة والفروق الأصلية بين الحيوانات بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية وجراحة التحكم عن نمط ظاهري محفوظ بشكل كبير في الخلايا المزروعة بعد السكتة الدماغية (الشكل 5H). احتفظت كل من خلايا نخاع العظام من الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية وخلايا نخاع العظام من الفئران المستقبلة المزروعة بخلايا نخاع العظام من الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية بنمط ظاهري نشط مؤيد للالتهابات. عند إسقاط جميع العينات الفردية في فضاء ثنائي الأبعاد باستخدام تحليل المكونات الرئيسية، وجدنا أن الخلايا من الفئران المزروعة بخلايا نخاع العظام من الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية أظهرت قربًا مكانيًا من الخلايا من الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية (الأشكال S4H و S4I)، مما يؤكد أن الخلايا النخاعية تكتسب نمطًا ظاهريًا مميزًا مؤيدًا للالتهابات بعد السكتة الدماغية يمكن نقله عن طريق زراعة نخاع العظام.

لم تتغير فقط بشكل مستقر بعد السكتة الدماغية، ولكن هذه التغيرات في حجرة النخاع الشوكي كافية لتحفيز التليف القلبي الثانوي.

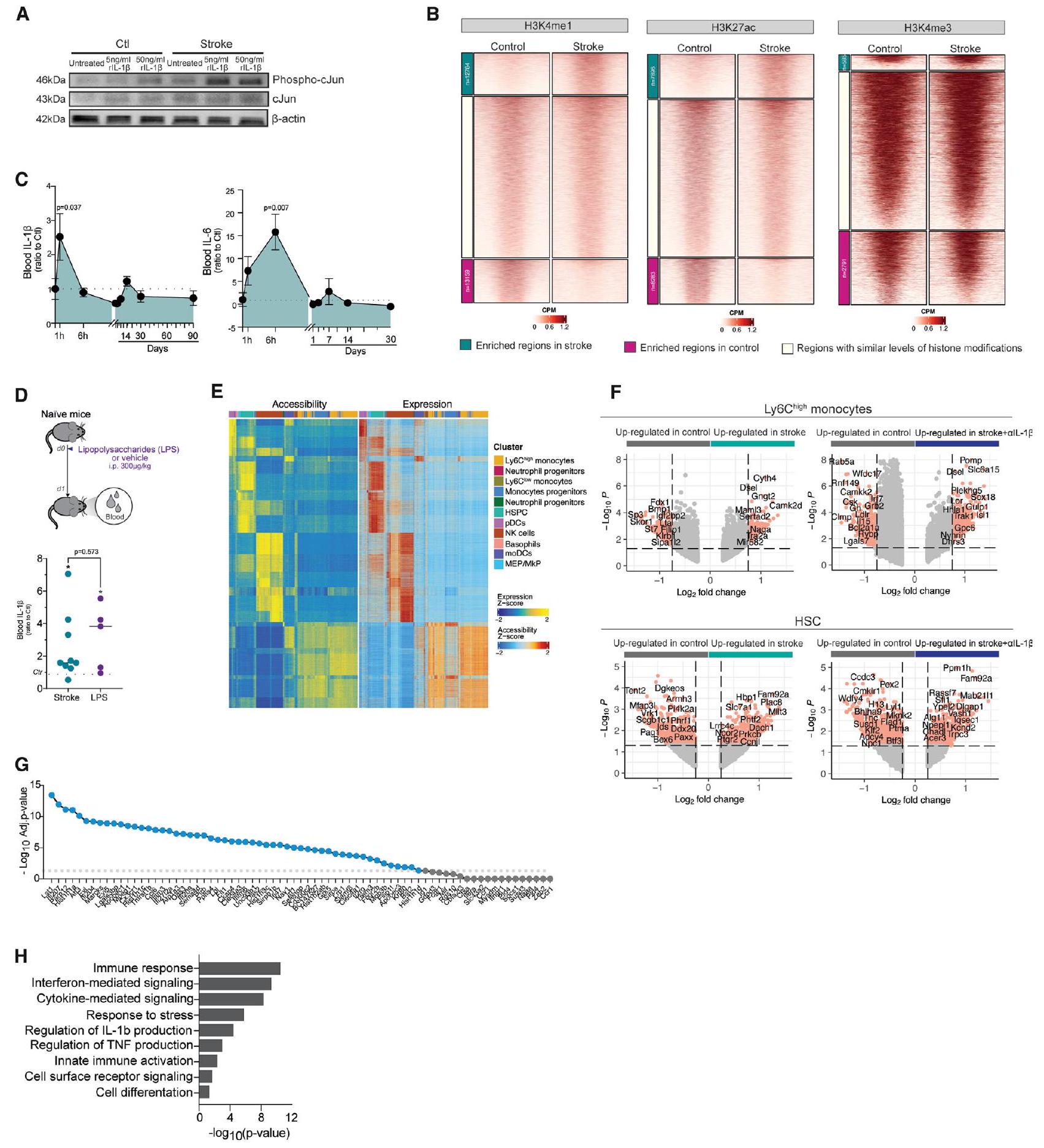

الذاكرة المناعية الفطرية تتوسطها IL-1 المبكر بعد السكتة الدماغية

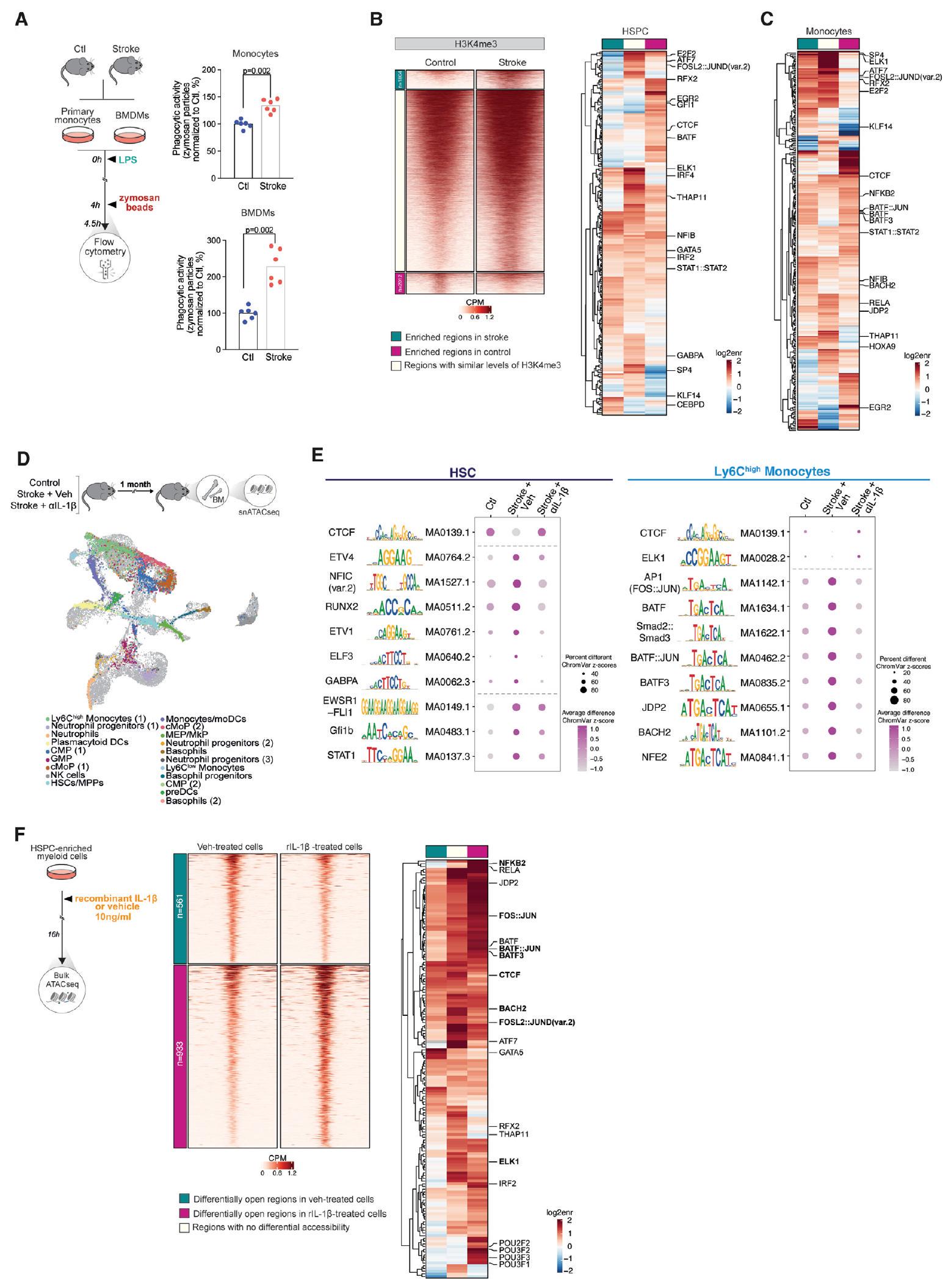

وجدنا أن مستويات H3K4me3 في الوحيدات كانت مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بأنماط TF متنوعة بعد السكتة الدماغية، بما في ذلك CTCF والعديد من المناطق المرتبطة بمسارات إشارات NF-кb و IL-1 واستجابة التهابية، مثل E2F2 و ATF7 و STAT1 و KLF14 (الشكل 6C).

غيرت الضربة المشهد الإبيجينيتيكي للناضجين

IL-1

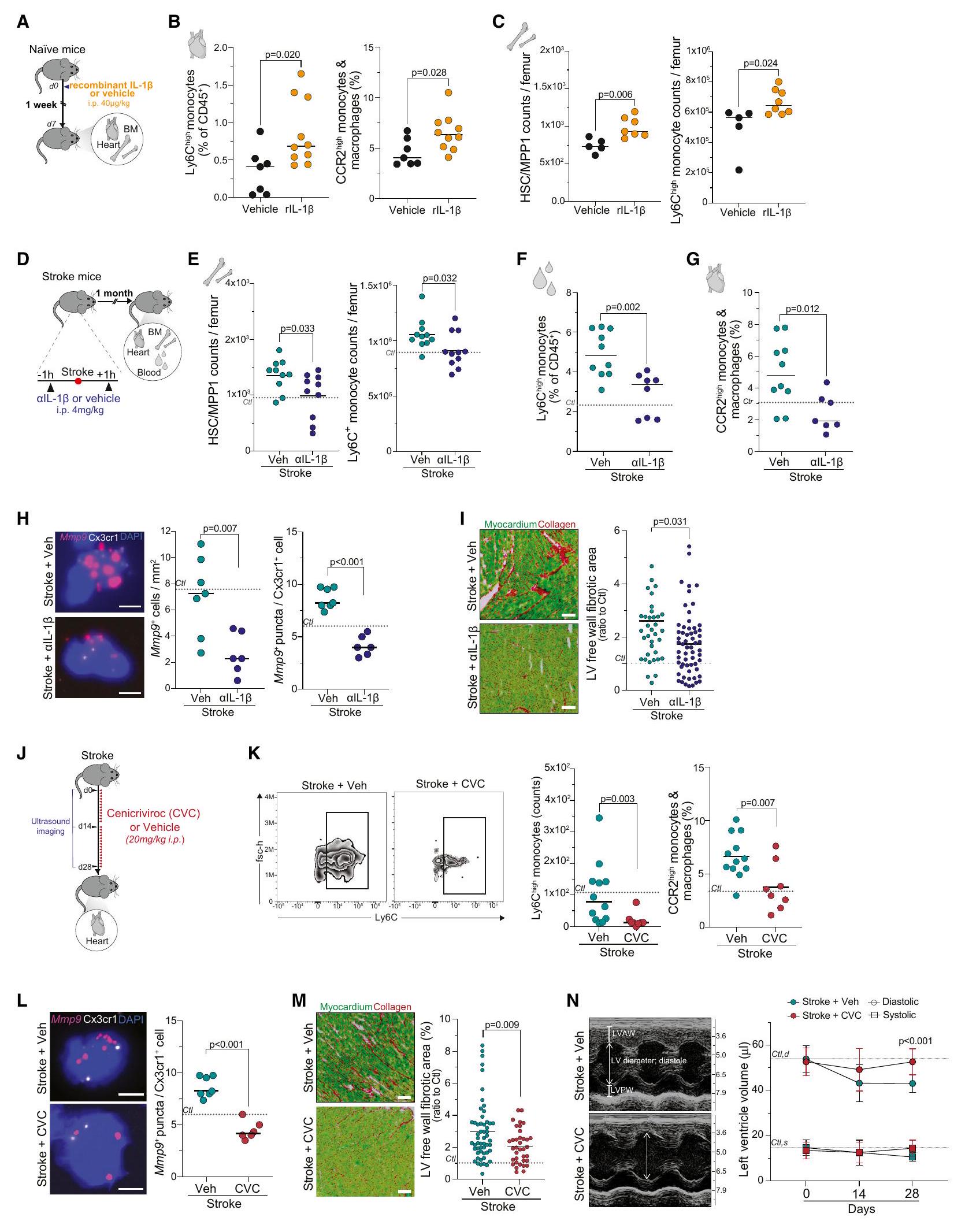

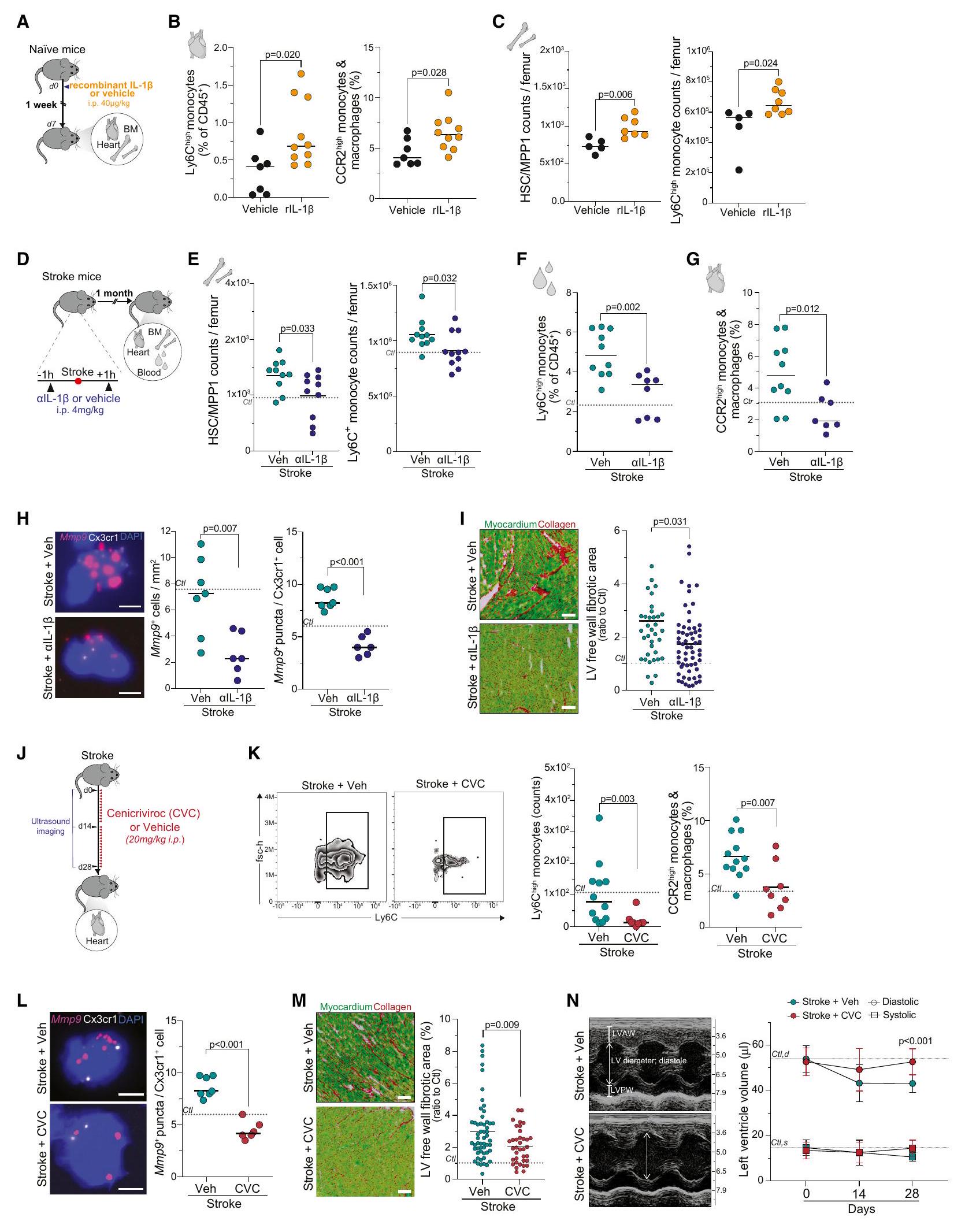

عدد المونوسيتات بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية (الشكل 7F)، وزيادة CCR2 بعد السكتة الدماغية

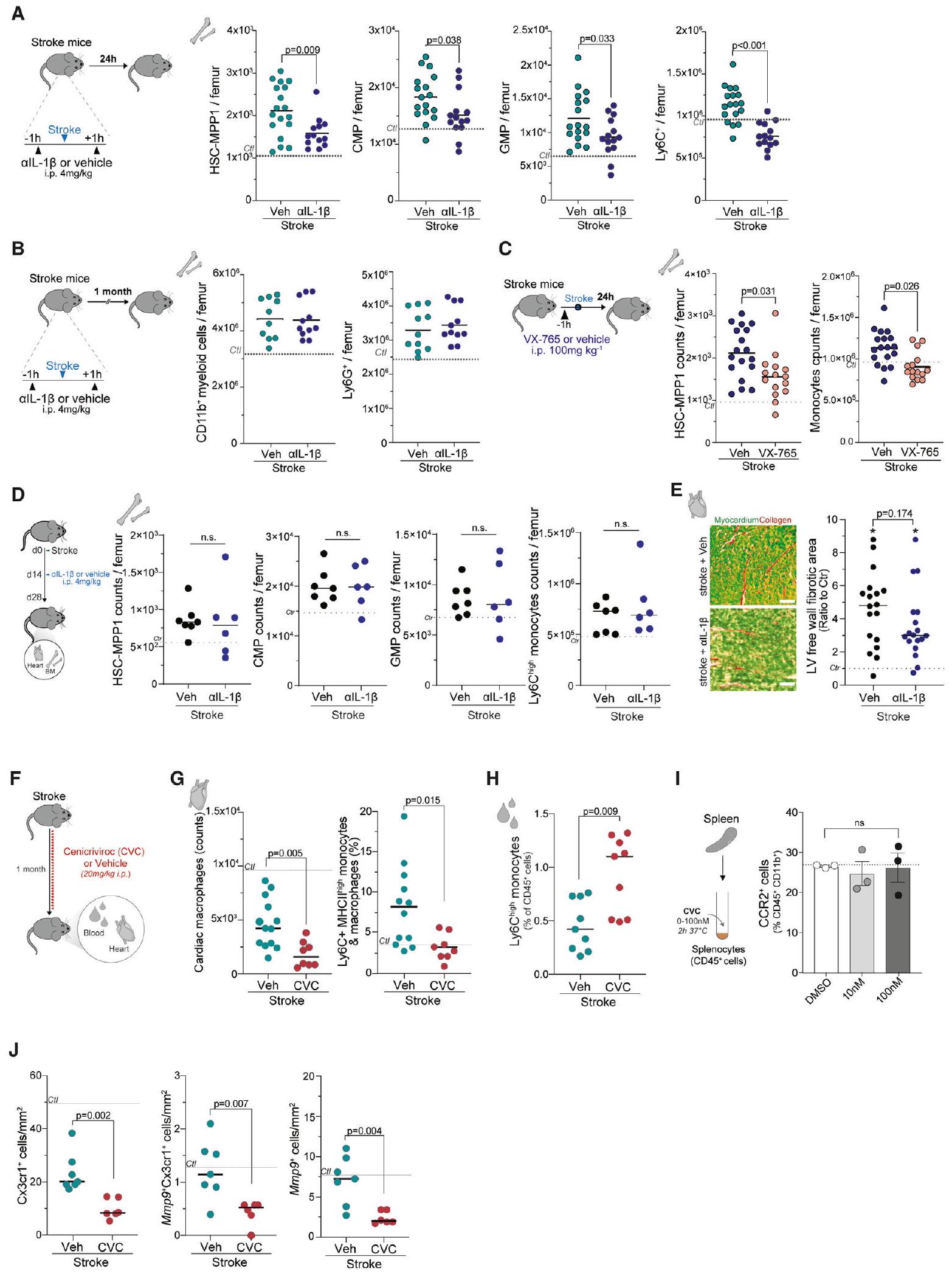

حجب نقل الخلايا الوحيدة من النخاع إلى القلب يمنع ضعف القلب بعد السكتة الدماغية

إعادة تشكيل ECM القلبي بواسطة CVC حسنت أيضًا بشكل كبير وظيفة القلب الانبساطية في المرحلة المزمنة بعد السكتة الدماغية إلى مستويات قابلة للمقارنة مع الفئران الضابطة التي لم تتعرض لسكتة دماغية (الشكل 7N). باختصار، تظهر هذه النتائج الإمكانات العلاجية لحجب هجرة الخلايا الوحيدة المبرمجة المؤيدة للالتهاب من نخاع العظام إلى القلب كاستراتيجية لمنع الأمراض القلبية الثانوية بعد السكتة الدماغية.

نقاش

حدث سلبي قلبي.

قيود الدراسة

إلى حالات أخرى من إصابة الأنسجة الحادة أو نماذج العدوى. أيضًا، الآليات الجزيئية الدقيقة التي من خلالها يعمل IL-1

طرق النجوم

- جدول الموارد الرئيسية

- توافر الموارد

- جهة الاتصال الرئيسية

- توفر المواد

- توفر البيانات والشيفرة

- تفاصيل النموذج التجريبي و المشاركين في الدراسة

- السكان المرضى السريريين

- تجارب الحيوانات

- تفاصيل الطريقة

- نموذج انسداد الشريان الدماغي القريب العابر

- نموذج انسداد الشريان الدماغي البعيد الدائم

- إدارات الأدوية

- تاموكسيفين

- تخطيط صدى القلب

- تخطيط القلب عن بُعد

- دراسات كهربائية القلب

- قياسات ضغط الدم غير الغازية

- زراعة نخاع العظم

- جمع الأعضاء والأنسجة

- عزل الخلايا

- فرز الخلايا

- تدفق الخلايا

- تسلسل RNA على مستوى الخلية الواحدة

- تحليل بيانات تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية

- تسلسل ATAC للأنوية المفردة

- تحليل بيانات ATAC-seq أحادي النواة

- تسلسل ATAC بالجملة

- تسلسل CUT&tag

- تصوير الميكروسكوب لتوليد التوافقي الثاني

- شرائح نسيجية لقلب الفأر

- شرائح نسيجية لقلب الإنسان

- صبغة بيكروسيريوس الحمراء

- صبغة الهيماتوكسيلين والإيوزين

- تلطيخ المناعة الفلورية

- صبغة المناعية النسيجية

- تضخيم الفلورسنت في الموقع للحمض النووي الريبي

- الزيموجرافيا الجيلاتينية لـ MMP9

- قياس اليوريا في الدم

- اختبار الامتصاص المناعي المرتبط بالإنزيم

qPCR

عزل الخلايا الطحالية والحضانة مع CVC

عزل خلايا BMDM والوحيدات الأولية

اختبار بلع الخلايا البلعمية المستمدة من نخاع العظم والوحيدات الأولية

تحفيز BMDM بواسطة IL-1

تحليل الترحيل الغربي

تسلسل الحمض النووي الريبي المرسال بكميات كبيرة من عينات قلب الإنسان

تحليل بيانات تسلسل mRNA بالجملة - التكميم والتحليل الإحصائي

معلومات إضافية

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

إعلان المصالح

تاريخ الاستلام: 29 يونيو 2023

تمت المراجعة: 22 أبريل 2024

تم القبول: 21 يونيو 2024

نُشر: 22 يوليو 2024

REFERENCES

- Simats, A., and Liesz, A. (2022). Systemic inflammation after stroke: implications for post-stroke comorbidities. EMBO Mol. Med. 14, e16269. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.202216269.

- Roth, S., Cao, J., Singh, V., Tiedt, S., Hundeshagen, G., Li, T., Boehme, J.D., Chauhan, D., Zhu, J., Ricci, A., et al. (2021). Post-injury immunosuppression and secondary infections are caused by an AIM2 inflammasomedriven signaling cascade. Immunity 54, 648-659.e8. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.immuni.2021.02.004.

- Iadecola, C., Buckwalter, M.S., and Anrather, J. (2020). Immune responses to stroke: mechanisms, modulation, and therapeutic potential. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 2777-2788. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCl135530.

- Liesz, A., Rüger, H., Purrucker, J., Zorn, M., Dalpke, A., Möhlenbruch, M., Englert, S., Nawroth, P.P., and Veltkamp, R. (2013). Stress mediators and immune dysfunction in patients with acute cerebrovascular diseases. PLoS One 8, e74839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074839.

- Stanne, T.M., Angerfors, A., Andersson, B., Brännmark, C., Holmegaard, L., and Jern, C. (2022). Longitudinal study reveals long-term proinflammatory proteomic signature after ischemic stroke across subtypes. Stroke 53, 2847-2858. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.038349.

- Roth, S., Singh, V., Tiedt, S., Schindler, L., Huber, G., Geerlof, A., Antoine, D.J., Anfray, A., Orset, C., Gauberti, M., et al. (2018). Brain-released alarmins and stress response synergize in accelerating atherosclerosis progression after stroke. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, 1-12. https://doi.org/10. 1126/scitransImed.aao1313.

- Holmegaard, L., Stanne, T.M., Andreasson, U., Zetterberg, H., Blennow, K., Blomstrand, C., Jood, K., and Jern, C. (2021). Proinflammatory protein signatures in cryptogenic and large artery atherosclerosis stroke. Acta Neurol. Scand. 143, 303-312. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.13366.

- Tatemichi, T.K., Paik, M., Bagiella, E., Desmond, D.W., Pirro, M., and Hanzawa, L.K. (1994). Dementia after stroke is a predictor of long-term survival. Stroke 25, 1915-1919. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.25.10.1915.

- Braga, G.P., Gonçalves, R.S., Minicucci, M.F., Bazan, R., and Zornoff, L.A.M. (2020). Strain pattern and T-wave alterations are predictors of mortality and poor neurologic outcome following stroke. Clin. Cardiol. 43, 568-573. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.23348.

- Prosser, J., MacGregor, L., Lees, K.R., Diener, H.C., Hacke, W., and Davis, S. (2007). Predictors of early cardiac morbidity and mortality after ischemic stroke. Stroke 38, 2295-2302. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA. 106. 471813.

- Suissa, L., Panicucci, E., Perot, C., Romero, G., Gazzola, S., Laksiri, N., Rey, C., Doche, E., Mahagne, M.-H., Pelletier, J., et al. (2020). Effect of hyperglycemia on stroke outcome is not homogeneous to all patients treated with mechanical thrombectomy. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 194, 105750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105750.

- Hackett, M.L., and Pickles, K. (2014). Part I: frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Stroke 9, 1017-1025. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12357.

- Netea, M.G., Joosten, L.A.B., Latz, E., Mills, K.H.G., Natoli, G., Stunnenberg, H.G., O’Neill, L.A.J., and Xavier, R.J. (2016). Trained immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science 352, aaf1098. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf1098.

- Netea, M.G., Domínguez-Andrés, J., Barreiro, L.B., Chavakis, T., Divangahi, M., Fuchs, E., Joosten, L.A.B., van der Meer, J.W.M., Mhlanga, M.M., Mulder, W.J.M., et al. (2020). Defining trained immunity and its role in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 375-388. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41577-020-0285-6.

- Ochando, J., Fayad, Z.A., Madsen, J.C., Netea, M.G., and Mulder, W.J.M. (2020). Trained immunity in organ transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 20, 10-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt. 15620.

- Leung, Y.T., Shi, L., Maurer, K., Song, L., Zhang, Z., Petri, M., and Sullivan, K.E. (2015). Interferon regulatory factor 1 and histone H4 acetylation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Epigenetics 10, 191-199. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/15592294.2015.1009764.

- Li, X., Wang, H., Yu, X., Saha, G., Kalafati, L., Ioannidis, C., Mitroulis, I., Netea, M.G., Chavakis, T., and Hajishengallis, G. (2022). Maladaptive innate immune training of myelopoiesis links inflammatory comorbidities. Cell 185, 1709-1727.e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.043.

- Murphy, A.J., and Tall, A.R. (2016). Disordered haematopoiesis and athero-thrombosis. Eur. Heart J. 37, 1113-1121. https://doi.org/10. 1093/eurheartj/ehv718.

- Winklewski, P.J., Radkowski, M., and Demkow, U. (2014). Cross-talk between the inflammatory response, sympathetic activation and pulmonary infection in the ischemic stroke. J. Neuroinflammation 11, 213. https://doi. org/10.1186/s12974-014-0213-4.

- Seifert, H.A., and Offner, H. (2018). The splenic response to stroke: from rodents to stroke subjects. J. Neuroinflammation 15, 195. https://doi. org/10.1186/s12974-018-1239-9.

- Austin, V., Ku, J.M., Miller, A.A., and Vlahos, R. (2019). Ischaemic stroke in mice induces lung inflammation but not acute lung injury. Sci. Rep. 9, 3622. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-40392-1.

- Llovera, G., Hofmann, K., Roth, S., Salas-Pérdomo, A., Ferrer-Ferrer, M., Perego, C., Zanier, E.R., Mamrak, U., Rex, A., Party, H., et al. (2015). Results of a preclinical randomized controlled multicenter trial (pRCT): anti-CD49d treatment for acute brain ischemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 299ra121. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitransImed.aaa9853.

- Ginhoux, F., Schultze, J.L., Murray, P.J., Ochando, J., and Biswas, S.K. (2016). New insights into the multidimensional concept of macrophage ontogeny, activation and function. Nat. Immunol. 17, 34-40. https://doi. org/10.1038/ni.3324.

- Hoyer, F.F., Naxerova, K., Schloss, M.J., Hulsmans, M., Nair, A.V., Dutta, P., Calcagno, D.M., Herisson, F., Anzai, A., Sun, Y., et al. (2019). Tissuespecific macrophage responses to remote injury impact the outcome of subsequent local immune challenge. Immunity 51, 899-914.e7. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2019.10.010.

- Paulus, W.J., and Tschöpe, C. (2013). A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62, 263-271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc. 2013.02.092.

- Sharma, K., and Kass, D.A. (2014). Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: mechanisms, clinical features, and therapies. Circ. Res. 115, 79-96. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.302922.

- Hulsmans, M., Schloss, M.J., Lee, I.-H., Bapat, A., Iwamoto, Y., Vinegoni, C., Paccalet, A., Yamazoe, M., Grune, J., Pabel, S., et al. (2023). Recruited macrophages elicit atrial fibrillation. Science 381, 231-239. https://doi. org/10.1126/science.abq3061.

- Epelman, S., Lavine, K.J., Beaudin, A.E., Sojka, D.K., Carrero, J.A., Calderon, B., Brija, T., Gautier, E.L., Ivanov, S., Satpathy, A.T., et al. (2014). Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation. Immunity 40, 91-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.019.

- Park, M.D., Silvin, A., Ginhoux, F., and Merad, M. (2022). Macrophages in health and disease. Cell 185, 4259-4279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell. 2022.10.007.

- Stik, G., Vidal, E., Barrero, M., Cuartero, S., Vila-Casadesús, M., Men-dieta-Esteban, J., Tian, T.V., Choi, J., Berenguer, C., Abad, A., et al. (2020). CTCF is dispensable for immune cell transdifferentiation but facilitates an acute inflammatory response. Nat. Genet. 52, 655-661. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-0643-0.

- Jaitin, D.A., Weiner, A., Yofe, I., Lara-Astiaso, D., Keren-Shaul, H., David, E., Salame, T.M., Tanay, A., Van Oudenaarden, A., and Amit, I. (2016). Dissecting immune circuits by linking CRISPR-pooled screens with single-cell RNA-seq. Cell 167, 1883-1896.e15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016. 11.039.

- Yuan, Y., Fan, G., Liu, Y., Liu, L., Zhang, T., Liu, P., Tu, Q., Zhang, X., Luo, S., Yao, L., et al. (2022). The transcription factor KLF14 regulates macrophage glycolysis and immune function by inhibiting HK2 in sepsis. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 19, 504-515. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-021-00806-5.

- Yang, Z.-F., Drumea, K., Cormier, J., Wang, J., Zhu, X., and Rosmarin, A.G. (2011). GABP transcription factor is required for myeloid differentiation, in part, through its control of Gfi-1 expression. Blood 118, 22432253. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-07-298802.

- Chen, S., Yang, J., Wei, Y., and Wei, X. (2020). Epigenetic regulation of macrophages: from homeostasis maintenance to host defense. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 17, 36-49. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-019-0315-0.

- Yoshida, K., and Ishii, S. (2016). Innate immune memory via ATF7-dependent epigenetic changes. Cell Cycle 15, 3-4. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 15384101.2015.1112687.

- Li, W., Moorlag, S.J.C.F.M., Koeken, V.A.C.M., Röring, R.J., De Bree, L.C.J., Mourits, V.P., Gupta, M.K., Zhang, B., Fu, J., Zhang, Z., et al. (2023). A single-cell view on host immune transcriptional response to in vivo BCG-induced trained immunity. Cell Rep. 42, 112487. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112487.

- Schep, A.N., Wu, B., Buenrostro, J.D., and Greenleaf, W.J. (2017). chromVAR: inferring transcription-factor-associated accessibility from singlecell epigenomic data. Nat. Methods 14, 975-978. https://doi.org/10. 1038/nmeth. 4401.

- Omatsu, Y., Aiba, S., Maeta, T., Higaki, K., Aoki, K., Watanabe, H., Kondoh, G., Nishimura, R., Takeda, S., Chung, U.I., et al. (2022). Runx1 and Runx2 inhibit fibrotic conversion of cellular niches for hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Commun. 13, 2654. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30266-y.

- Ciau-Uitz, A., Wang, L., Patient, R., and Liu, F. (2013). ETS transcription factors in hematopoietic stem cell development. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 51, 248-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcmd.2013.07.010.

- Ohlsson, R., Renkawitz, R., and Lobanenkov, V. (2001). CTCF is a uniquely versatile transcription regulator linked to epigenetics and disease. Trends Genet. 17, 520-527. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02366-6.

- Baillie, J.K., Arner, E., Daub, C., De Hoon, M., Itoh, M., Kawaji, H., Lassmann, T., Carninci, P., Forrest, A.R.R., Hayashizaki, Y., et al. (2017). Analysis of the human monocyte-derived macrophage transcriptome and response to lipopolysaccharide provides new insights into genetic aetiology of inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006641. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen. 1006641.

- An, Y., Ni, Y., Xu, Z., Shi, S., He, J., Liu, Y., Deng, K.-Y., Fu, M., Jiang, M., and Xin, H.-B. (2020). TRIM59 expression is regulated by Sp1 and Nrf1 in LPS-activated macrophages through JNK signaling pathway. Cell. Signal. 67, 109522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.109522.

- Nikolic, T., Movita, D., Lambers, M.E.H., Ribeiro de Almeida, C.R., Biesta, P., Kreefft, K., De Bruijn, M.J.W., Bergen, I., Galjart, N., Boonstra, A., et al. (2014). The DNA-binding factor Ctcf critically controls gene expression in macrophages. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 11, 58-70. https://doi.org/10.1038/ cmi.2013.41.

- Dekkers, K.F., Neele, A.E., Jukema, J.W., Heijmans, B.T., and De Winther, M.P.J. (2019). Human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation involves highly localized gain and loss of DNA methylation at transcription factor binding sites. Epigenetics Chromatin 12, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/ s13072-019-0279-4.

- Liao, J., Humphrey, S.E., Poston, S., and Taparowsky, E.J. (2011). Batf promotes growth arrest and terminal differentiation of mouse myeloid leukemia cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 9, 350-363. https://doi.org/10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0375.

- Behmoaras, J., Bhangal, G., Smith, J., McDonald, K., Mutch, B., Lai, P.C., Domin, J., Game, L., Salama, A., Foxwell, B.M., et al. (2008). Jund is a determinant of macrophage activation and is associated with glomerulonephritis susceptibility. Nat. Genet. 40, 553-559. https://doi.org/10. 1038/ng. 137.

- Ridker, P.M., MacFadyen, J.G., Thuren, T., Everett, B.M., Libby, P., Glynn, R.J., Lorenzatti, A., Krum, H., and Varigos, J. (2017). Effect of interleukin

inhibition with canakinumab on incident lung cancer in patients with atherosclerosis: exploratory results from a randomised, double-blind, pla-cebo-controlled trial. Lancet 390, 1833-1842. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(17)32247-X. - Thompson, M., Saag, M., DeJesus, E., Gathe, J., Lalezari, J., Landay, A.L., Cade, J., Enejosa, J., Lefebvre, E., and Feinberg, J. (2016). A 48-week randomized phase 2b study evaluating cenicriviroc versus efavirenz in treatment-naive HIV-infected adults with C-C chemokine receptor type 5-tropic virus. AIDS 30, 869-878. https://doi.org/10.1097/ QAD. 0000000000000988.

- Sherman, K.E., Abdel-Hameed, E., Rouster, S.D., Shata, M.T.M., Blackard, J.T., Safaie, P., Kroner, B., Preiss, L., Horn, P.S., and Kottilil, S. (2019). Improvement in hepatic fibrosis biomarkers associated with chemokine receptor inactivation through mutation or therapeutic blockade. Clin. Infect. Dis. 68, 1911-1918. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy807.

- Friedman, S.L., Ratziu, V., Harrison, S.A., Abdelmalek, M.F., Aithal, G.P., Caballeria, J., Francque, S., Farrell, G., Kowdley, K.V., Craxi, A., et al. (2018). A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of cenicriviroc for treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with fibrosis. Hepatology 67, 1754-1767. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29477.

- Dziedzic, T. (2015). Systemic inflammation as a therapeutic target in acute ischemic stroke. Expert Rev. Neurotherapeutics 15, 523-531. https://doi. org/10.1586/14737175.2015.1035712.

- Anrather, J., and Iadecola, C. (2016). Inflammation and stroke: an overview. Neurotherapeutics 13, 661-670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-016-0483-x.

- Chugh, S.S., Roth, G.A., Gillum, R.F., and Mensah, G.A. (2014). Global burden of atrial fibrillation in developed and developing nations. Glob. Heart 9, 113-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2014.01.004.

- Kim, W., and Kim, E.J. (2018). Heart failure as a risk factor for stroke. J. Stroke 20, 33-45. https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2017.02810.

- Kallmünzer, B., Breuer, L., Kahl, N., Bobinger, T., Raaz-Schrauder, D., Huttner, H.B., Schwab, S., and Köhrmann, M. (2012). Serious cardiac arrhythmias after stroke: incidence, time course, and predictors-a systematic, prospective analysis. Stroke 43, 2892-2897. https://doi.org/10. 1161/STROKEAHA.112.664318.

- Buckley, B.J.R., Harrison, S.L., Hill, A., Underhill, P., Lane, D.A., and Lip, G.Y.H. (2022). Stroke-heart syndrome: incidence and clinical outcomes of cardiac complications following stroke. Stroke 53, 1759-1763. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.037316.

- Ruthirago, D., Julayanont, P., Tantrachoti, P., Kim, J., and Nugent, K. (2016). Cardiac arrhythmias and abnormal electrocardiograms after acute stroke. Am. J. Med. Sci. 351, 112-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjms. 2015.10.020.

- Bieber, M., Werner, R.A., Tanai, E., Hofmann, U., Higuchi, T., Schuh, K., Heuschmann, P.U., Frantz, S., Ritter, O., Kraft, P., et al. (2017). Strokeinduced chronic systolic dysfunction driven by sympathetic overactivity. Ann. Neurol. 82, 729-743. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.25073.

- Veltkamp, R., Uhlmann, S., Marinescu, M., Sticht, C., Finke, D., Gretz, N., Gröne, H.J., Katus, H.A., Backs, J., and Lehmann, L.H. (2019). Experimental ischaemic stroke induces transient cardiac atrophy and dysfunction. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 10, 54-62. https://doi.org/10.1002/ jcsm. 12335.

- Heuschmann, P.U., Montellano, F.A., Ungethüm, K., Rücker, V., Wiedmann, S., Mackenrodt, D., Quilitzsch, A., Ludwig, T., Kraft, P., Albert, J., et al. (2021). Prevalence and determinants of systolic and diastolic cardiac dysfunction and heart failure in acute ischemic stroke patients: the SICFAIL study. ESC Heart Fail. 8, 1117-1129. https://doi.org/10.1002/ ehf2.13145.

- Jeong, E.-M., and Dudley, S.C., Jr. (2015). Diastolic dysfunction. Circ. J. 79, 470-477. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0064.

- Thomas, L., Marwick, T.H., Popescu, B.A., Donal, E., and Badano, L.P. (2019). Left atrial structure and function, and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 1961-1977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.059.

- Kirchgesner, J., Beaugerie, L., Carrat, F., Andersen, N.N., Jess, T., Schwarzinger, M., Bouvier, A.M., Buisson, A., Carbonnel, F., and Cosnes, J. (2018). Increased risk of acute arterial events in young patients and severely active IBD: a nationwide French cohort study ibd. Gut 67, 1261-1268. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314015.

- Moorlag, S.J.C.F.M., Khan, N., Novakovic, B., Kaufmann, E., Jansen, T., Van Crevel, R., Divangahi, M., and Netea, M.G. (2020).

-glucan induces protective trained immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection:

a key role for IL-1. Cell Rep. 31, 107634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep. 2020.107634. - Mitroulis, I., Ruppova, K., Wang, B., Chen, L.S., Grzybek, M., Grinenko, T., Eugster, A., Troullinaki, M., Palladini, A., Kourtzelis, I., et al. (2018). Modulation of myelopoiesis progenitors is an integral component of trained immunity. Cell 172, 147-161.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.034.

- Georgakis, M.K., Bernhagen, J., Heitman, L.H., Weber, C., and Dichgans, M. (2022). Targeting the CCL2-CCR2 axis for atheroprotection. Eur. Heart J. 43, 1799-1808. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac094.

- Stuart, T., Butler, A., Hoffman, P., Hafemeister, C., Papalexi, E., Mauck, W.M., Hao, Y., Stoeckius, M., Smibert, P., and Satija, R. (2019). Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell 177, 1888-1902.e21. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031.

- Stuart, T., Srivastava, A., Madad, S., Lareau, C.A., and Satija, R. (2021). Single-cell chromatin state analysis with Signac. Nat. Methods 18, 1333-1341. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01282-5.

- Cao, J., Spielmann, M., Qiu, X., Huang, X., Ibrahim, D.M., Hill, A.J., Zhang, F., Mundlos, S., Christiansen, L., Steemers, F.J., et al. (2019). The singlecell transcriptional landscape of mammalian organogenesis. Nature 566, 496-502. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0969-x.

- Granja, J.M., Corces, M.R., Pierce, S.E., Bagdatli, S.T., Choudhry, H., Chang, H.Y., and Greenleaf, W.J. (2021). ArchR is a scalable software package for integrative single-cell chromatin accessibility analysis. Nat. Genet. 53, 403-411. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00790-6.

- Lange, M., Bergen, V., Klein, M., Setty, M., Reuter, B., Bakhti, M., Lickert, H., Ansari, M., Schniering, J., Schiller, H.B., et al. (2022). CellRank for directed single-cell fate mapping. Nat. Methods 19, 159-170. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41592-021-01346-6.

- Jin, S., Guerrero-Juarez, C.F., Zhang, L., Chang, I., Ramos, R., Kuan, C.-H., Myung, P., Plikus, M.V., and Nie, Q. (2021). Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 12, 1088. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21246-9.

- Machlab, D., Burger, L., Soneson, C., Rijli, F.M., Schübeler, D., and Stadler, M.B. (2022). monaLisa: an R/Bioconductor package for identifying regulatory motifs. Bioinformatics 38, 2624-2625. https://doi.org/10. 1093/bioinformatics/btac102.

- Lun, A.T.L., and Smyth, G.K. (2016). csaw: a Bioconductor package for differential binding analysis of ChIP-seq data using sliding windows. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e45. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1191.

- Andrews, S. (2010). FastQC: a Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data (Babraham Bioinformatics).

- Dobin, A., Davis, C.A., Schlesinger, F., Drenkow, J., Zaleski, C., Jha, S., Batut, P., Chaisson, M., and Gingeras, T.R. (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15-21. https://doi.org/10.1093/ bioinformatics/bts635.

- Martin, M. (2011). Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from highthroughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. j. 17. https://doi.org/10.14806/ ej.17.1.200.

- Liao, Y., Smyth, G.K., and Shi, W. (2014). featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923-930. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656.

- Love, M.I., Huber, W., and Anders, S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8.

- Ge, S.X., Jung, D., and Yao, R. (2020). ShinyGO: a graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants. Bioinformatics 36, 2628-2629. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz931.

- Raudvere, U., Kolberg, L., Kuzmin, I., Arak, T., Adler, P., Peterson, H., and Vilo, J. (2019). g:profiler: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and conversions of gene lists (2019 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W191-W198. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz369.

- Nagueh, S.F., Smiseth, O.A., Appleton, C.P., Byrd, B.F., Dokainish, H., Edvardsen, T., Flachskampf, F.A., Gillebert, T.C., Klein, A.L., Lancellotti, P., et al. (2016). Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular lmaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 17, 1321-1360. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ehjci/jew082.

- Llovera, G., Roth, S., Plesnila, N., Veltkamp, R., and Liesz, A. (2014). Modeling stroke in mice: permanent coagulation of the distal middle cerebral artery. J. Vis. Exp., e51729. https://doi.org/10.3791/51729.

- Tomsits, P., Volz, L., Xia, R., Chivukula, A., Schüttler, D., and Clauß, S. (2023). Medetomidine/midazolam/fentanyl narcosis alters cardiac autonomic tone leading to conduction disorders and arrhythmias in mice. Lab Anim. (NY) 52, 85-92. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41684-023-01141-0.

- Tomsits, P., Sharma Chivukula, A., Raj Chataut, K., Simahendra, A., Weckbach, L.T., Brunner, S., and Clauss, S. (2022). Real-time electrocardiogram monitoring during treadmill training in mice. J. Vis. Exp. https:// doi.org/10.3791/63873.

- Tomsits, P., Chataut, K.R., Chivukula, A.S., Mo, L., Xia, R., Schüttler, D., and Clauss, S. (2021). Analyzing long-term electrocardiography record-

ings to detect arrhythmias in mice. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10. 3791/62386. - Ramírez, F., Ryan, D.P., Grüning, B., Bhardwaj, V., Kilpert, F., Richter, A.S., Heyne, S., Dündar, F., and Manke, T. (2016). deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W160-W165. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw257.

- Skene, P.J., Henikoff, J.G., and Henikoff, S. (2018). Targeted in situ genome-wide profiling with high efficiency for low cell numbers. Nat. Protoc. 13, 1006-1019. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2018.015.

- Kaya-Okur, H.S., Janssens, D.H., Henikoff, J.G., Ahmad, K., and Henikoff, S. (2020). Efficient low-cost chromatin profiling with CUT&Tag. Nat. Protoc. 15, 3264-3283. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-020-0373-x.

- Yu, F., Sankaran, V.G., and Yuan, G.-C. (2021). CUT&RUNTools 2.0: a pipeline for single-cell and bulk-level CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag data analysis. Bioinformatics 38, 252-254. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/ btab507.

- Stempor, P., and Ahringer, J. (2016). SeqPlots – Interactive software for exploratory data analyses, pattern discovery and visualization in genomics. Wellcome Open Res. 1, 14. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.10004.1.

طرق النجوم

جدول الموارد الرئيسية

| كاشف أو مورد | المصدر | معرف |

| الأجسام المضادة | ||

| مضاد الفأر CD45 (30-F11)، فلور

|

إي بايوساينس | رقم المنتج: 48-0451-82؛ RRID: AB_1518806 |

| مضاد الفأر CD16/CD32 (2.4G2)، BV480 | بي دي بيوساينس | الرقم التعريفي# 746324؛ RRID: AB_2743648 |

| مضاد CD11b للفأر (M1/70)، FITC | بايو ليجند | رقم القطعة 557396؛ RRID: AB_396679 |

| مضاد الماوس Ly6C (HK1.4)، فيوليت لامع 570

|

بايو ليجند | رقم القطعة 128029؛ RRID: AB_10896061 |

| مضاد الماوس Ly6G (1A8-Ly6g)، PE-eFluor

|

ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | القطعة رقم 61-9668-82؛ RRID: AB_2574679 |

| مضاد الماوس Sca1 (D7)، بنفسجي لامع

|

بايو ليجند | القطعة رقم 108127؛ RRID: AB_10898327 |

| مضاد الفأر CD115 (AFS98)، BV711 | بي دي بيوساينس | رقم المنتج: 750890؛ RRID: AB_2874986 |

| مضاد الفأر CD150 (TC15-12F12.2)، PE | بايو ليجند | القطعة رقم 115903؛ RRID: AB_313682 |

| مضاد الماوس ckit (CD117) (2B8)، PE-Cy

|

بي دي بيوساينس | رقم القطعة 558163؛ RRID: AB_647250 |

| مضاد الفأر CD135 (A2F10)، APC | بايو ليجند | رقم القطعة 135309؛ RRID: AB_1953264 |

| مضاد الفأر CD11c (N418)، بنفسجي لامع

|

بايو ليجند | الرقم التعريفي# 117339؛ RRID: AB_2562414 |

| مضاد الفأر CD127 (A7R34)، بنفسجي لامع

|

بايو ليجند | رقم القطعة 135037؛ RRID: AB_2565269 |

| CD48 المضاد للفأر (HM48-1)، PerCP | إلابساينس | القطعة# E-AB-F1017UF; RRID: AB_3106916 |

| مضاد الفأر CD34 (RAM34)، أليكسافلور® 700 | بي دي بيوساينس | رقم المنتج: 560518؛ RRID: AB_1727471 |

| مضاد الفأر CD3 (17A2)، APC-eFluor

|

إي بايوساينس | رقم القطعة: 47-0032-80؛ RRID: AB_1272217 |

| مضاد CD4 للفأر (RM4-5)، APC-eFluor

|

إنفيتروجين | القطعة رقم 47-0042-82؛ RRID: AB_1272183 |

| مضاد الفأر CD8a (53-6.7)، APC/Cyanine7 | بايو ليجند | القطعة رقم 100714؛ RRID: AB_312753 |

| مضاد الفأر CD19 (eBio1D3 (1D3))، APC-eFluor

|

إنفيتروجين | القطعة رقم 47-0193-82؛ RRID: AB_10853189 |

| خلايا مضادة للفأر TER-119/خلايا حمراء (TER-119)، APC-Cy

|

بي دي بيوساينس | رقم القطعة 560509؛ RRID: AB_1645230 |

| مضاد الفأر CD16/CD32(93) | إنفيتروجين | القطعة رقم 14-0161-86؛ RRID: AB_467135 |

| مضاد CD11b للفأر (93)، APC-Cyanine7 | إي بايوساينس | القطعة# A15390; RRID: AB_2534404 |

| مضاد الماوس Ly6C (HK1.4)، PerCP/Cyanine5.5 | بايو ليجند | رقم القطعة 128011؛ RRID: AB_1659242 |

| مضاد الفأر F4/80 (BM8)، PE-Cyanine7 | إي بايوساينس | قطة # 25-4801-82؛ RRID: AB_469653 |

| مضاد CCR2 للفأر (SA203G11) (بريليانت فiolet

|

بايو ليجند | قطة # 150621؛ RRID: AB_2721565 |

| مضاد لمولد الضد الفأري من الفئة الثانية (NIMR-4)، PE | إي بايوساينس | القطة رقم 12-5322-81؛ RRID: AB_465930 |

| مضاد CCR2 للفأر (SA203G11)، APC | بايو ليجند | قطة رقم 150628؛ RRID: AB_2810415 |

| مضاد CD45 للفأر (30-F11)، APC-Cy7 | بايو ليجند | قطة # 103116؛ RRID: AB_312981 |

| مضاد الفأر CD11b (M1/70)، BV510 | بي دي بيوساينس | قط #562950؛ RRID: AB_2737913 |

| مضاد الكولاجين I للفئران | إنفيتروجين | قطة # PA5-95137; RRID: AB_2806942 |

| مضاد الكولاجين III للفئران | أبكام | القط # ab184993؛ RRID: AB_2895112 |

| إيلاستين مضاد للفأر | ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | قطة # BS-1756R؛ RRID: AB_10856940 |

| أجسام مضادة لمادة هيدروكسيلاز التيروزين | سيغما-ألدريتش | قطة # AB152؛ RRID: AB_390204 |

| جسم مضاد مضاد لـ GFP مرتبط بـ أليكسافلور® 488 (معزز GFP) | كروموتيك | القط# gb2AF488; RRID: AB_2827573 |

| الأجسام المضادة لمؤشر الفأر 1 TotalSeq-B0301 (M1/42) | بايو ليجند | رقم القطعة 155831؛ RRID: AB_2814067 |

| أجسام مضادة لمؤشر مضاد الفأر 2 TotalSeq-B0302 (M1/42) | بايو ليجند | رقم القطعة 155833؛ RRID: AB_2814068 |

| أجسام مضادة لمؤشر الفأر 3 TotalSeq-B0303 (M1/42) | بايو ليجند | رقم القطعة 155835؛ RRID: AB_2814069 |

| أجسام مضادة لمؤشر مضاد الفأر 4 TotalSeq-B0304 (M1/42) | بايو ليجند | الرقم المرجعي# 155837؛ RRID: AB_2814070 |

| أجسام مضادة لمؤشر الفأر 5 TotalSeq-A0305 (M1/42) | بايو ليجند | الرقم المرجعي# 155809؛ RRID: AB_2750036 |

| أجسام مضادة لـ H3K27ac (pAb) | موضع نشط | قط#39134; RRID: AB_2722569 |

| أجسام مضادة للهستون H3K4me1 (pAb) | موضع نشط | قط#39297; RRID: AB_2615075 |

| أجسام مضادة للهستون H3K4me3 (pAb) | ثيرمو فيشر | قط#PA5-27029; RRID: AB_2544505 |

| أجسام مضادة ضد IgG (H+L) من خنازير غينيا | نوفوس بايو | قط#NBP1-72763; RRID: AB_11024108 |

| مضاد الإنسان CD14 | نوفوس بايو | قط# NBP2-67630; RRID: AB_3106915 |

| CCR2 مضاد للبشر | أنظمة البحث والتطوير | القطعة# MAB150، RRID: AB_2247178 |

| مستمر | ||

| كاشف أو مورد | المصدر | معرف |

| الأجسام المضادة الثانوية المعاد امتصاصها المتقاطعة من الماعز ضد الأرانب (H+L) | أبكام | رقم القطعة 214880؛ RRID: AB_3106917 |

| أليكسا فلور 647 مضاد ثانوي ضد الأرانب | إنفيتروجين | قط # A-21247؛ RRID: AB_141778 |

| مضاد IL-1 للفئران/الجرذان

|

بايوكسل | قط # BE0246; RRID: AB_2687727 |

| أجسام مضادة للبروتين الدهني الليباز/ LPL للبشر/الفئران | بايو-تيكني | قطة # AF7197؛ RRID: AB_10972480 |

| أجسام مضادة متعددة النسائل لـ APOE | إنفيتروجين | قطة # PA5-78803؛ RRID: AB_2745919 |

| فوسفو-سي-جون (سير73) | إشارات الخلايا | قطة # 3270؛ RRID: AB_2129575 |

| أحادي النسيلة المضاد لـ

|

سيغما-ألدريتش | قطة # T4026; RRID: AB_477577 |

|

|

إشارات الخلايا | قطة رقم 8457؛ RRID: AB_10950489 |

| اختبارات تجارية حاسمة | ||

| مجموعة صبغة بيكرو-سيريوس الحمراء (عضلة القلب) | أبكام | القط# ab245887 |

| بيرس

|

ثيرمو فيشر | القط# 23227 |

| طقم صبغة الكولوديل الأزرق | إنفيتروجين | قط# LC6025 |

| طقم النسخ العكسي cDNA عالي السعة | أنظمة البيولوجيا التطبيقية | القط# 4368814 |

| أطقم PCR QuantiTect SYBR® Green | كياغن | القط# 204143 |

| مجموعة الكشف المتعدد الفلوري RNAscope(R) النسخة 2 | ACDbio | القط# 323110 |

| طقم محلول تفاعل RNAscope(R) TSA | ACDbio | القط# 322810 |

| مجموعة كشف TSA Plus Cyanine 3 (Cy3) | بيركين إلمر | القط# NEL744001KT |

| مجموعة كشف TSA Plus Cyanine 5 (Cy5) | بيركين إلمر | القط# NEL745001KT |

| طقم ELISA للفأر الخاص بـ MMP-9 | ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | قط# EMMMP9 |

| طقم ELISA لمستوى IL-1 بيتا في الفئران | أبكام | القط# ab197742 |

| طقم ELISA لمستوى IL-6 في الفئران | أبكام | قط# ab100712 |

| ELISA للتعبير عن HMGB1 | تيكان | القط# 30164033 |

| طقم اختبار اليوريا | أبكام | قط# ab83362 |

| EasySep

|

خلايا جذعية | قط #19761 |

| مجموعة إزالة خلايا السلالة، فأر | ميلتيني بيولوجي | القط# 130-090-858 |

| طقم إزالة الخلايا الميتة | ميلتيني بيولوجي | القط# 130-090-101 |

| مجموعة شريحة الخلية الفردية Chromium Next GEM Chip G | 10x جينومكس | القط# 1000127 |

| مجموعة خلايا مفردة شريحة كروميم نكست جيم | 10x جينومكس | القط# 1000162 |

| مجموعة كروميم نيكست جيم للخلايا المفردة ATAC الإصدار 2 | 10x جينوميات | القط# 1000406 |

| مجموعة باركود 3′ | 10x جينوميكس | القط# 1000262 |

| مجموعة بناء المكتبة | 10x جينومكس | القط# 1000190 |

| مجموعة طقم المؤشر الفردي T A | 10x جينومكس | القط# 1000213 |

| مجموعة مؤشر فردي N Set A | 10x جينومكس | القط# 1000212 |

| مجموعة ATAC-Seq | موضع نشط | قط#53150 |

| انقر عليه

|

إنفيتروجين | القط# C10419 |

| مجموعة Agilent عالية الحساسية للحمض النووي | أجيليت | القط# 5067-4626 |

| خرز من الفولاذ المقاوم للصدأ 5 مم | كياغن | القط# 69989 |

| عينات بيولوجية | ||

| شرائح بارافين قلب الإنسان | NCBN (اليابان) | (يرجى الاطلاع على التفاصيل في قسم طرق STAR) |

| كتل البارافين لقلب الإنسان | جامعة لودفيغ ماكسيميليان في ميونيخ | (يرجى الاطلاع على التفاصيل في قسم طرق STAR) |

| المواد الكيميائية، الببتيدات، والبروتينات المؤتلفة | ||

| بروتين IL-1 بيتا/IL-1F2 الفأري المؤتلف | بايو-تيكني | القط# 401-ML-010/CF |

| سينيكريفيروك | بيوربايت | قط# orb402001 |

| كوليبيور | سيغما ألدريتش | القط# 5135 |

| إنترلوكين-1 بيتا المؤتلف من الفئران | أنظمة البحث والتطوير | القط# 401-ML |

| 5-إيثينيل-2′-ديوكسي يوريدين (EdU) | إنفيتروجين | القط# E10187 |

| تاموكسيفين | سيغما ألدريتش | القط# 85256 |

| بوليمر (I:C) عالي الوزن الجزيئي | إنفيفوجين | قط# trl-pic |

| مستمر | ||

| المُعَايِن أو المورد | المصدر | معرف |

| ميغليول 812 | كايلو | القط# 3274 |

| الليبوبوليسكاريدات من الإشريكية القولونية O111:B4 | سيغما ألدريتش | القطعة# L2630-10MG |

| كولاجيناز النوع الحادي عشر | سيغما ألدريتش | القط# C7657 |

| كولاجيناز النوع الأول | سيغما ألدريتش | القط# SCR103 |

| ديؤوكسي ريبونوكلياز I | سيغما ألدريتش | الرقم المرجعي# 9003-98-9 |

| هيالورونيداز | سيغما ألدريتش | رقم الكات 37326-33-3 |

| هيستوباك

|

سيغما ألدريتش | القط# 10771 |

| زومبي نير | بايو ليجند | القط# 423105 |

| بروميد البروبيديوم | إي بايوساينسز | القط# 00-6990-42 |

| 7-AAD (7-أمينوأكتينوميسين D) | ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | قط# A1310 |

| BD هورايزون

|

بي دي بيوساينس | القط# 563794 |

| محلول صبغ الخلايا | بايو ليجند | القط# 420201 |

| فاست جرين FCF (0.1 %) | مورفيستو | القط# 16596 |

| محلول الإيوسين Y (1%) | كارل روث | رقم الكات 17372-87-1 |

| محلول هيماتوكسيلين ماير | سيغما ألدريتش | قط# MHS32 |

| حمض الأسيتيك | كارل روث | القط# 64-19-7 |

| إيثانول | SAV سائل | قط# 64-17-5 |

| بارافورمالدهيد | مورفيستو | القط# 11762.00100 |

| أغاروز | كيماويات VWR | الرقم التعريفي# 9012-36-6 |

| مصل الماعز | ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | القط# 16210064 |

| ألبومين مصل البقر | سيغما ألدريتش | قط# 9048-46-8 |

| دي إم إي إم، جلوكوز عالي، غلوتا ماكس

|

جيبكو | القط# 31966021 |

| جنتاميسين | جيبكو | القط# 15750-045 |

| مصل الجنين البقري | جيبكو | قط# A5256701 |

| pHrodo

|

إنفيتروجين

|

القط# P35364 |

| ستيم سبان

|

تكنولوجيا الخلايا الجذعية | قط#09600 |

| DAPI (4′-6-دياميدينو-2-فينيل إندول-ديهيدروكلوريد) | ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | القط# D3571 |

| تيروبويتين الفأر المؤتلف | ثيرمو فيشر | قط#315-14 |

| SCF الموريني المؤتلف | ثيرمو فيشر | قط#250-03 |

| بريوميسين | إنفيتروجين | قط#نمل-بم-05 |

| جيلاتين من جلد الأسماك الباردة | سيغما ألدريتش | الرقم المرجعي# 9000-70-8 |

| يوكيت

|

سيغما ألدريتش | رقم الكات 25608-33-7 |

| مثبطات البروتياز والفوسفاتاز | ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | قط# A32959 |

| محلول تحليل/استخراج RIPA | ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | القط# 89900 |

| زيموجرام بلس (جيلاتين) هلام 10% | إنفيتروجين | قط# ZY00102BOX |

| محلول إعادة تشكيل الزيموجرام (10X) | إنفيتروجين | القط# LC2670 |

| محلول تطوير الزيموجرام (10X) | إنفيتروجين | القط# LC2671 |

| نوفكس

|

إنفيتروجين | القط# LC2676 |

| آر إن إيه سكيب

|

ACDbio | القط# 315941-C2 |

| آر إن إيه سكوبي

|

ACDbio | القط# 314221 |

| بروبي RNAscope® – Hs-MMP9 | ACDbio | القط# 311331 |

| بروبي RNAscope® – Hs-CD14 | ACDbio | القط# 418808-C2 |

| آر إن إيه سكوبي

|

ACDbio | القط# 457961 |

| بروبي RNAscope® – Mm-Collagen I-C2 | ACDbio | القط# 537041-C2 |

| ARNاسكوب

|

ACDbio | القط# 310091 |

| ARNاسكوب

|

ACDbio | القط# 322000 |

| توين-20 | بايو راد | القط# 1662404 |

| ديجيتونين 5% | ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | القط# BN2006 |

| محلول تحليل النوى EZ | سيغما ألدريتش | قط# NUC-01 |

| محلول ملحي مخفف بالفوسفات لدولبيكو | سيغما ألدريتش | قطعة# D8537-500مل |

| مستمر | ||

| كاشف أو مورد | المصدر | معرف |

| مصل الجنين البقري (FBS) | جي بي سي أو | القط# 105000-064 |

| بيوماج® بلس كونكانافالين أ | ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | قط#86057-3 |

| CUTANA pAG-Tn5 لـ CUT&tag | إيبيسايفر | قط#15-1017 |

| NEBNext® مزيج ماستر PCR عالي الدقة 2X | مختبرات نيو إنجلاند البيولوجية | قط#M0541S |

| خرز AMPureXP (بيكمان كولتر، A63881) | بيكمان كولتر | قط#A63881 |

| بافر PKD | كياجن | القط# 1034963 |

| بروتياز K | كياغن | القط# 19131 |

| دينابيدز

|

ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | القط# 61005 |

| مثبط RNase المؤتلف | تاكارا | القط# 2313A |

| ألترا بيور

|

ثيرمو فيشر ساينتيفيك | قط#15591043 |

| نماذج تجريبية: الكائنات/السلالات | ||

| فأر: C57BL6/J | نهر تشارلز | السلالة #: 000664 |

| فأر: eGFP (C57BL/6-Tg(CAG-EGFP)131Osb/LeySopJ) | جاكس | السلالة #: 006567 |

| فأر: Mx1Cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Mx1-cre)1Cgn/J) | جاكس | السلالة #: 003556 |

| فأر: ماي ب

|

جاكس | السلالة #: 028881 |

| فأر: Ccr2tm1(cre/ERT2,mKate2)Arte | مختبر بيشر، جامعة زيورخ، سويسرا | MGI: 6314378 |

| فأر: KikGR (Tg(CAG-KikGR)33Hadj) | جاكس | السلالة #: 013753 |

| فأر: Ai14 (B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J) | جاكس | السلالة #: 007914 |

| فأر: Ms4a3(creERT2) | هذه الورقة | غير متوفر |

| أوليغونوكليوتيدات | ||

| Mmp9: الأمامية 5′ GCT CCT GGC TCT CCT GGC TT 3′ العكسية 5′ GTC CCA CCT GAG GCC TTT GA 3′ | ميتبيون | غير متوفر |

| Ppia: الأمام 5′ ACA CGC CAT AAT GGC ACT GG 3′ العكس 5′ ATT TGC CAT GGA CAA GAT GC 3′ | ميتبيون | غير متوفر |

| البرمجيات والخوارزميات | ||

| فلو جو الإصدار 10.6 | تريستار إنك. | غير متوفر |

| جراف باد بريزم 9 | جراباد إنك. | غير متوفر |

| صورة J 1.53c | المعهد الوطني للصحة | غير متوفر |

| زين | زايس | غير متوفر |

| مكتب LAS X | لايكا | غير متوفر |

| فيفو لاب 5.5.0 | فوجي فيلم فيجوال سونيكس | غير متوفر |

| برنامج بونيمه الإصدار 6.42 | شركة هارفارد للعلوم الحيوية | غير متوفر |

| برنامج LabChart Pro الإصدار 8 | أد إنسترومنتس | غير متوفر |

| سيل رينجر v.7.1.0 | 10x جينومكس | غير متوفر |

| سيل رينجر ATAC الإصدار 2.1.0 | 10x جينومكس | غير متوفر |

| حزمة R Seurat 4.2.0 | ستيوارت وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| حزمة R Signac 1.9.0 | ستيوارت وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| مونكل 3 الإصدار 1.3.1 | كاو وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| حزمة R ArchR الإصدار 1.0.1 | جرانجا وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| سيل رانك | لانج وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| حزمة R CellChat | جين وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| حزمة R مونا ليزا | ماخلاب وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| حزمة R csaw | لون وسمايث

|

غير متوفر |

| فاست كيو سي | أندروز

|

غير متوفر |

| نجم | دوبي وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| كوتادابت | مارتن

|

غير متوفر |

| featureCounts | لياو وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| DESeq2 | حب وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| مستمر | ||

| كاشف أو مورد | المصدر | معرف |

| تحليل مسار البراعة | كياغن | غير متوفر |

| شينيغو | جي وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| ج:بروفايلر | راودفير وآخرون

|

غير متوفر |

| البيانات المودعة | ||

| بيانات تسلسل RNA المرسال من خلية مفردة خام | هذه الورقة | GSE232098، GSE262599، GSE262727، GSE263035 |

| بيانات ATACseq للنوى الفردية الخام | هذه الورقة | GSE230692 |

| بيانات تسلسل mRNA الخام | هذه الورقة | GSE232550 |

| بيانات ATACseq الخام | هذه الورقة | GSE264093 |

| بيانات تسلسل CUT&tag | هذه الورقة | GSE264418 |

| آخرون | ||

| ألياف أحادية مغلفة بمطاط السيليكون | دوكول | قط# 602223PK10Re |

| أجهزة إرسال البيانات عن بُعد (PhysiolTel ETA-F10) | شركة هارفارد للعلوم الحيوية | قطعة# ETA-F10 |

| قسطرة أوكتابولار | أدوات ميلار | القط# EPR-800 |

| مضخات ألزيت الميكرو-أسموزية | ألزيت | قط#1007D |

توفر الموارد

جهة الاتصال الرئيسية

توفر المواد

توفر البيانات والشيفرة

تفاصيل النموذج التجريبي و المشاركين في الدراسة

السكان المرضى السريريين

| المريض 1 | المريض 2 | المريض 3 | |

| نطاق العمر، سنوات | ٧٠-٨٠ | ٧٠-٨٠ | 60-70 |

| جنس | ذكر | ذكر | ذكر |

| خط الأساس لمقياس السكتة الدماغية الوطني | 9 | 0 | ٤ |

| HS-CRP | غير متوفر | 0.26 | 0.17 |

| NT-proBNP | غير متوفر | ٩٠٨ | ٢٧٠ |

| سكتة دماغية (

|

تحكم (

|

|

| العمر، سنوات | 79 (12) | 80 (29.3) |

| الجنس (ذكر)،

|

76% (10) | 33% (2) |

| خط الأساس NIHSS | 23 (12) | غير متوفر |

| الوقت من السكتة الدماغية إلى الوفاة، أيام | 44 (48.5) | غير متوفر |

| مبين كوسيط (نطاق الربيع الربعي، IQR)، ما لم يُذكر خلاف ذلك | ||

تجارب الحيوانات

تفاصيل الطريقة

نموذج انسداد الشريان الدماغي القريب العابر

نموذج انسداد الشريان الدماغي البعيد الدائم

إدارة الأدوية

5-إيثينيل-2′-ديوكسي يوريدين

مضاد IL-1

IL-1 المؤتلف

تلقى الفئران حقنة واحدة عن طريق الحقن داخل الصفاق من IL-1 المؤتلف

ليبوبوليسكاريد

تلقى الفئران حقنًا يومية عن طريق الحقن داخل الصفاق من CVC أو المركبة

تاموكسيفين

تخطيط صدى القلب

تخطيط القلب عن بُعد

دراسات الفيزيولوجيا الكهربائية القلبية

تم وضعها في الوريد، تلاها تقدم تدريجي إلى القلب حتى تم تحديد طرف القسطرة في قمة البطين الأيمن. تم تأكيد الوضع الصحيح للقسطرة بواسطة التخطيط الكهربائي المحلي.

تم قياس ضغط الدم غير الغازي

زراعة نخاع العظام

جمع الأعضاء والأنسجة

عزل الخلايا

فرز الخلايا

تدفق السيتومترية

تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية

تحليل بيانات RNA-seq للخلايا المفردة

ATAC-seq للنوى المفردة

تحليل بيانات ATAC-seq للنوى المفردة

تسلسل ATAC بالجملة

تسلسل CUT&tag

تبع ذلك حضانة لمدة 30 دقيقة في درجة حرارة الغرفة على جهاز تدوير. ثم تم حضانة العينات مع

تصوير الميكروسكوب لتوليد التوافقيات الثانية

شرائح نسيجية لقلب الفأر

شرائح نسيجية لقلب الإنسان

صبغة بيكروسيريوس الحمراء

صبغة الهيماتوكسيلين والإيوزين

تلطيخ المناعة الفلورية

صبغة المناعية النسيجية

تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل الفلوري في الموقع

زيموجرافيا الجيلاتين MMP9

قياس اليوريا في الدم

اختبار الامتصاص المناعي المرتبط بالإنزيم

qPCR

عزل الخلايا الطحالية والحضانة مع CVC

عزل خلايا المونوسيت الأولية و BMDM

اختبار ابتلاع الخلايا البلعمية المستمدة من نخاع العظام والوحيدات الأولية

تحفيز BMDM بواسطة IL-1

تحليل الترحيل الغربي

تسلسل الحمض النووي الريبي المرسال بكميات كبيرة من عينات قلب الإنسان

تحليل بيانات تسلسل mRNA بالجملة

التكميم والتحليل الإحصائي

الرسوم التوضيحية التكميلية

خلية

مقالة

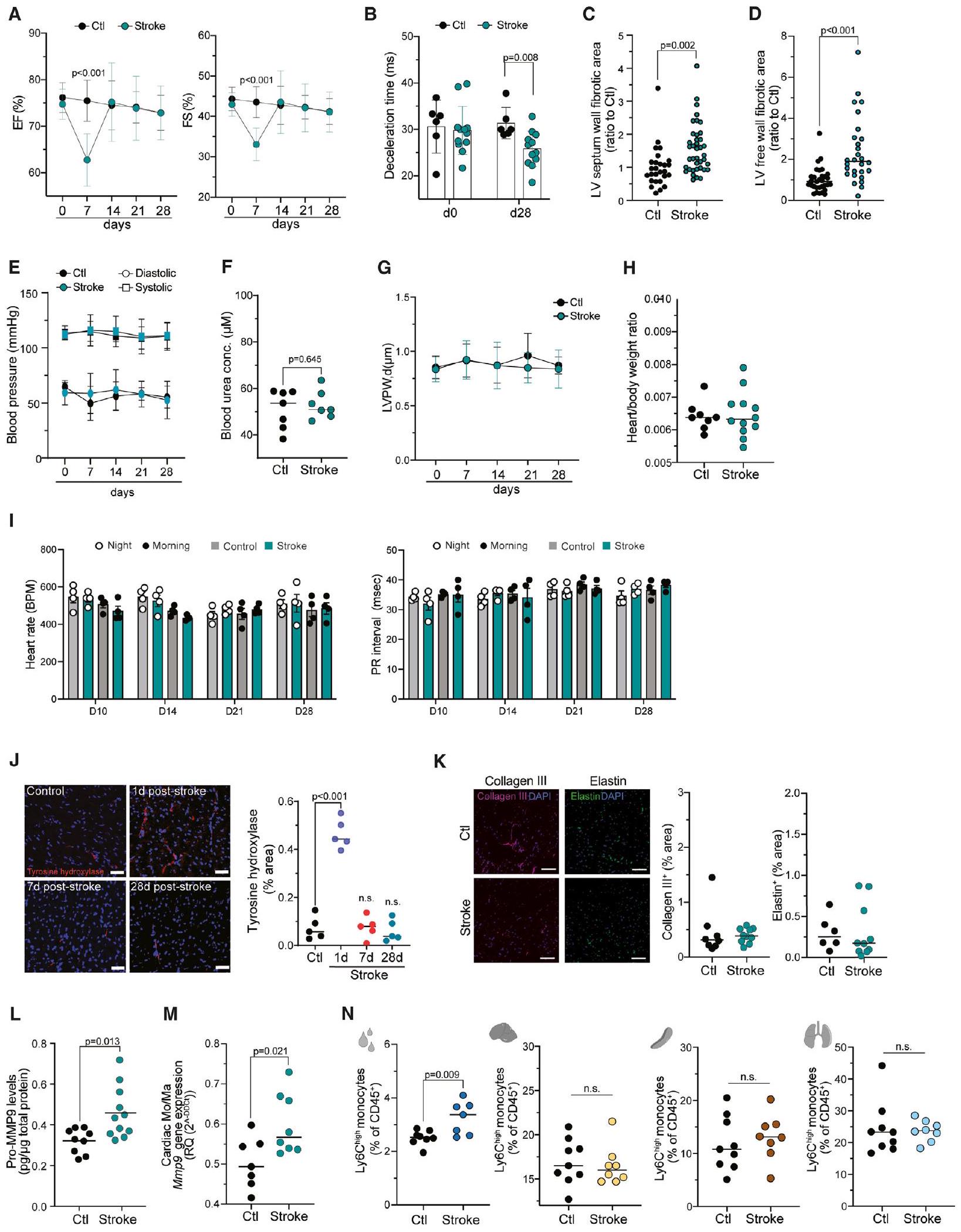

(أ) قياس الكسر القذفي (EF، يسار) والانكماش النسبي (FS، يمين) في النقاط الزمنية المحددة (الأيام) قبل (اليوم 0) وبعد السكتة الدماغية، والتحكم (اختبارات U،

(ب) قياس زمن التباطؤ عبر الصمام التاجي في اليومين 0 و28 في الفئران الضابطة وفئران السكتة الدماغية

(ج) قياس تليف القلب في جدار الحاجز البطيني الأيسر بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية والمجموعة الضابطة (اختبار t،

(د) قياس تليف القلب في جدار البطين الأيسر بعد 3 أشهر من السكتة الدماغية والمجموعة الضابطة (اختبار t،

(E) قياس ضغط الدم في النقاط الزمنية المحددة (الأيام) قبل (اليوم 0) وبعد السكتة الدماغية، وظروف التحكم (

(F) تم قياس تركيز اليوريا في الدم في الفئران بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية أو في الفئران الضابطة (اختبار t،

(G) قياس سمك الجدار الخلفي للبطين الأيسر في نهاية الانبساط (LVPW, d) في النقاط الزمنية المحددة (الأيام) قبل (اليوم 0) وبعد السكتة الدماغية، والفئران الضابطة (اختبارات U،

تم قياس نسبة القلب إلى الجسم في الفئران بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية والفئران الضابطة (اختبارات t،

تحديد معدل ضربات القلب (يمين) وفترة PR (يسار) في النقاط الزمنية المحددة (الأيام) بعد السكتة الدماغية والتحكم، باستخدام تخطيط القلب الكهربائي المستمر (اختبارات U،

(ج) صور مناعية مضيئة تمثيلية لإنزيم هيدروكسيلاز التيروزين (TH) في القلب في النقاط الزمنية المحددة (الأيام) بعد السكتة الدماغية والمجموعة الضابطة. تم استخدام DAPI كصبغة نووية (يسار، قضبان القياس،

(L) تم قياس مستويات بروتين البرو-MMP9 الكلية في عينات القلب من الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية والفئران الضابطة. تم تطبيع مستويات بروتين البرو-MMP9 إلى محتوى البروتين الكلي (اختبار U،

تم إجراء RT-qPCR على المونوسيتات/البلاعم المفروزة

(N) قياس Ly6C

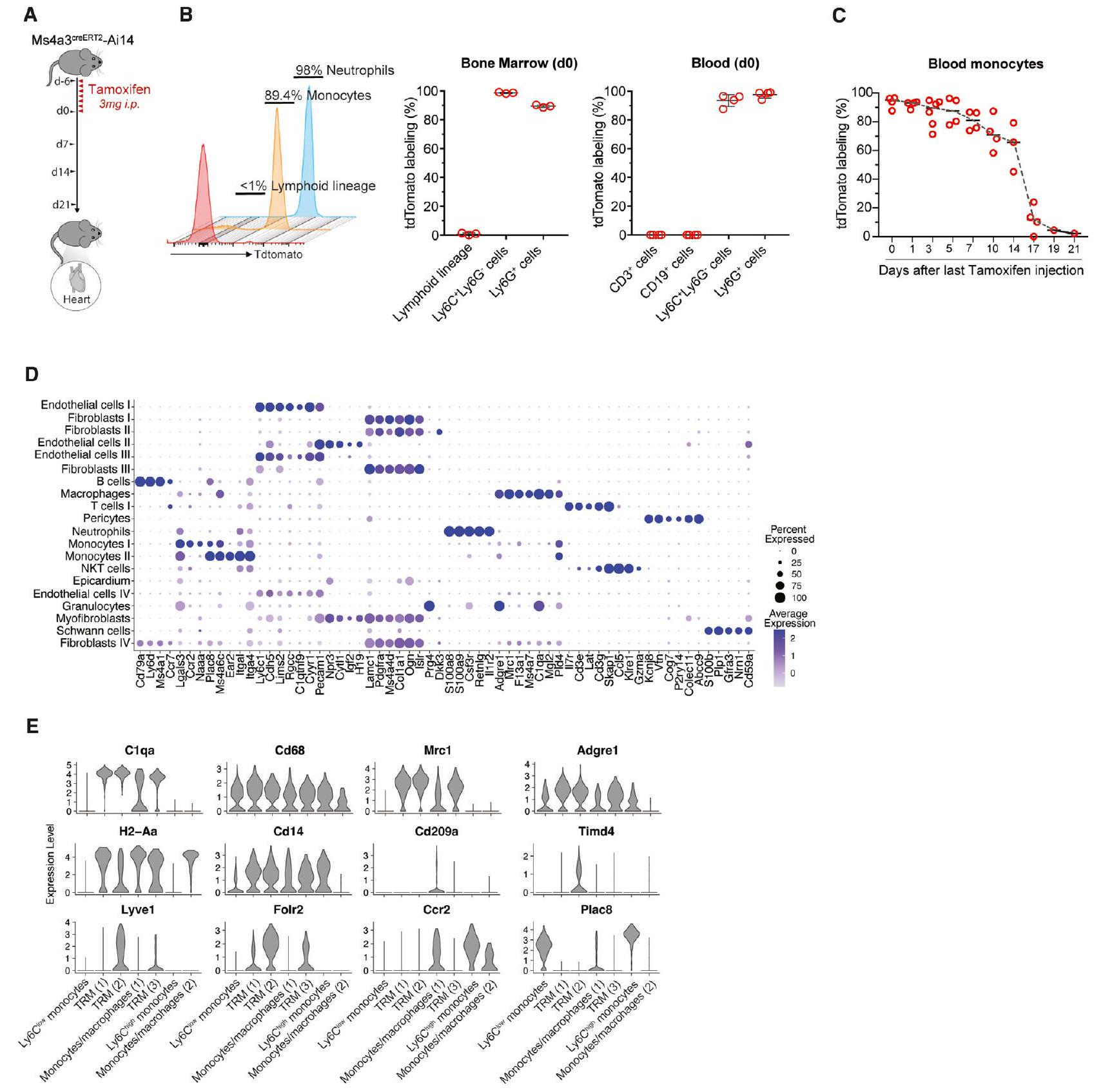

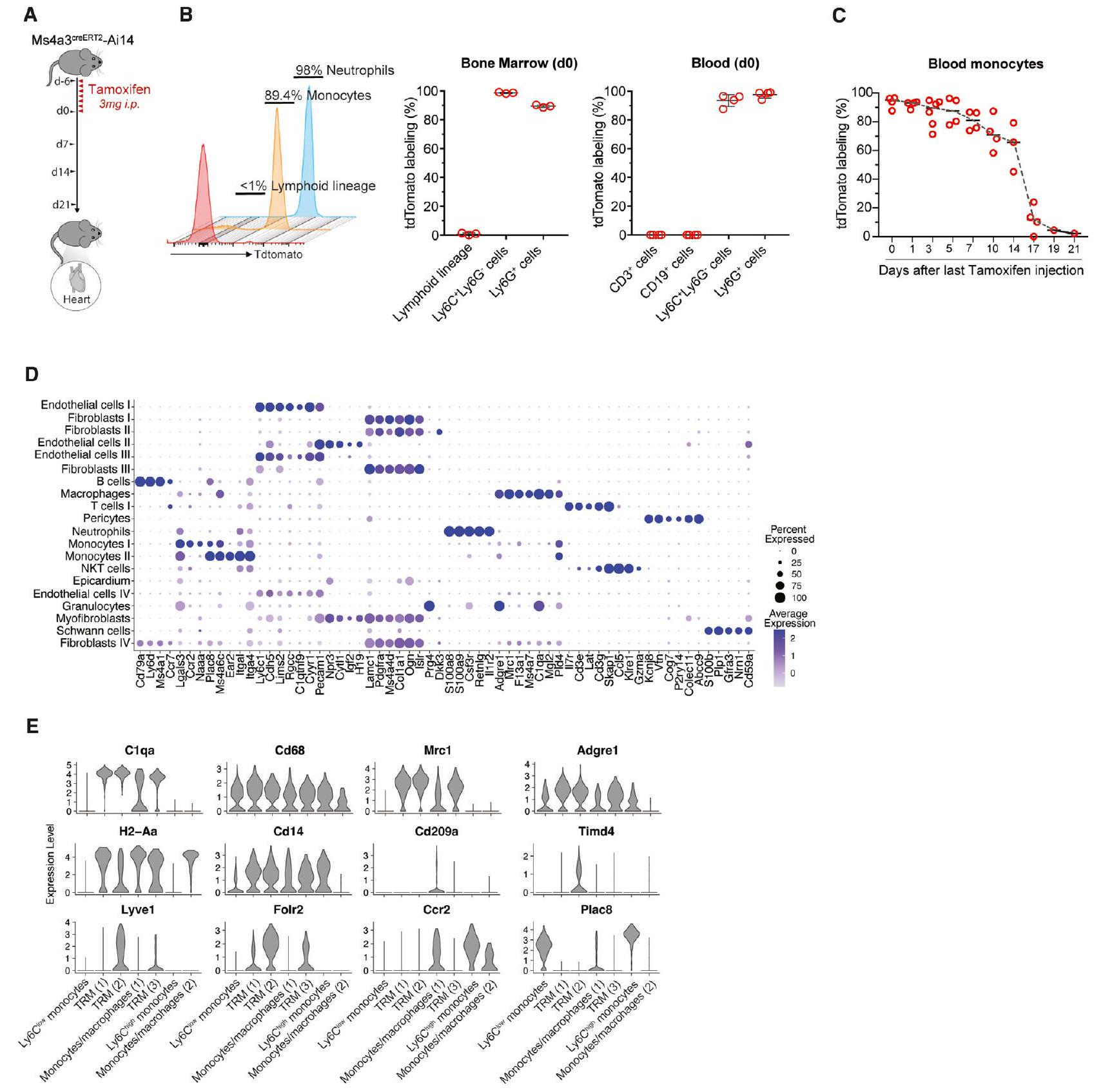

(أ) تصميم تجريبي تخطيطي: Ms4a3

(ب) وسم tdTomato للخلايا اللمفاوية (CD3+، CD4+، CD8a+، CD19+، وTer119+)، وحيدات النوى (Ly6C+Ly6G-)، والعدلات (Ly6C+Ly6G+) في نخاع العظام (الوسط) والدم (اليمين) بعد 7 جرعات يومية من التاموكسيفين (

(C) وسم tdTomato للوحيدات (Ly6C+Ly6G-) في الدم على مدار الوقت بعد 7 جرعات يومية من التاموكسيفين (

(D) رسم نقطي يوضح ملف التعبير للجينات الرئيسية المختارة لتحديد مجموعات الخلايا من خلايا القلب البينية التي تم فرزها من القلوب بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية أو جراحة التحكم في Ccr2

رسوم بيانية على شكل كمان تظهر مستويات التعبير للجينات الرئيسية المختارة لتحديد تجمعات المونوسيتات القلبية والبلاعم.

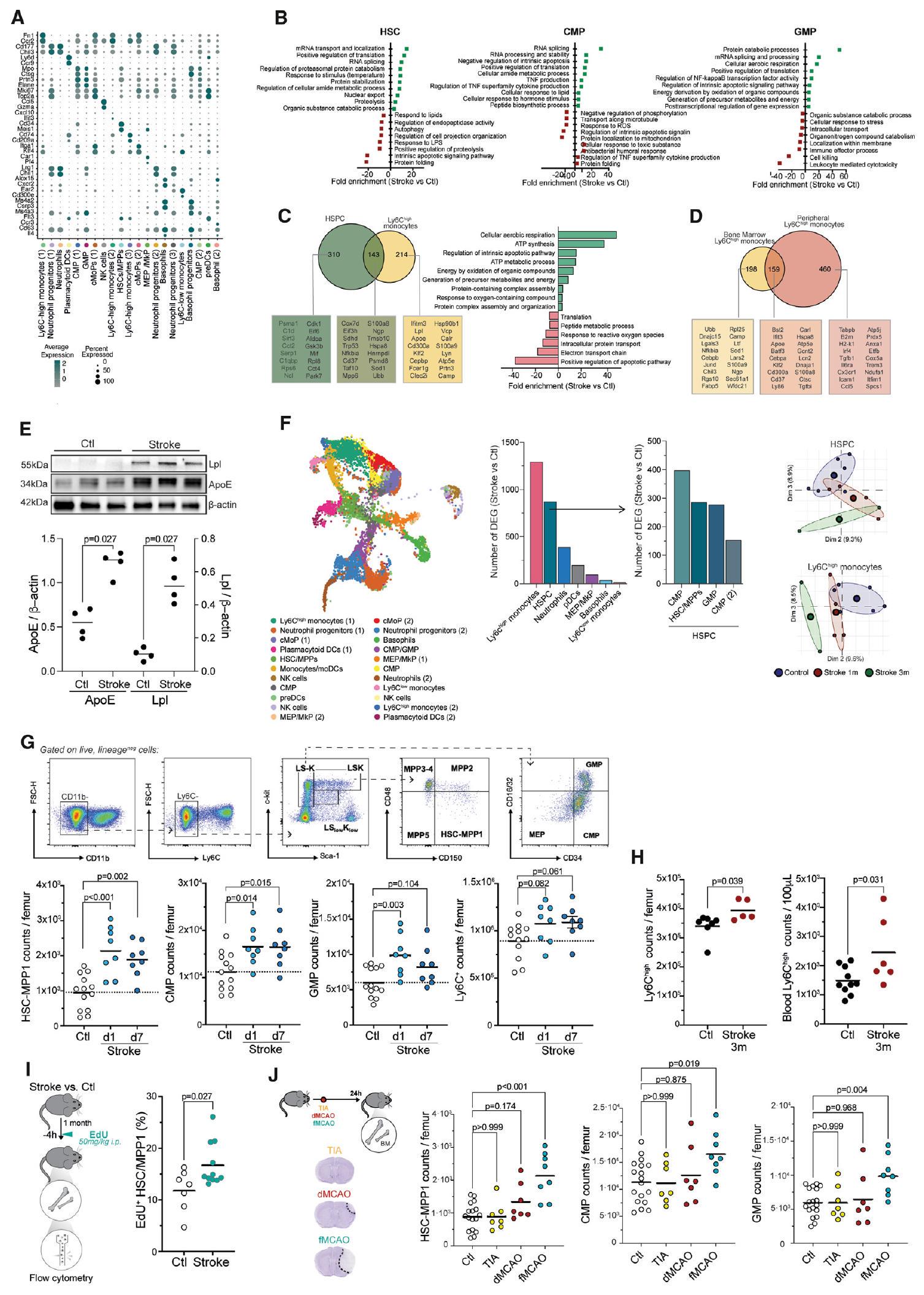

(أ) رسم نقطي يوضح ملف التعبير للجينات الرئيسية المختارة لتحديد تجمعات الخلايا اللمفاوية (CD3، CD4، CD8a، CD19، وTer119) والخلايا النخاعية السلبية (Ly6G) التي تم فرزها من نقي العظام للفئران الضابطة وفئران السكتة الدماغية بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية.

(ب) تم إجراء تحليل المسار باستخدام الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف بين حالات السكتة الدماغية وحالات التحكم في خلايا الدم الجذعية (HSCs) ، والسلائف المايلويدية الشائعة (CMPs) ، وسلائف العدلات-وحيدات النوى (GMPs). تم تجميع العمليات البيولوجية وتصنيفها بواسطة

(C) تحليل فين يوضح الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف المشتركة بين حالات السكتة الدماغية وظروف التحكم في كل من خلايا الدم الجذعية وLy6C

(د) مخطط فين يوضح الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مشترك بين حالات السكتة الدماغية وظروف التحكم في نخاع العظام (BM) وLy6C المتداولة (الدم)

رسم بياني تمثيلي للمناعية لبروتين الربط (Lpl) والبروتين الدهني ApoE (APOE) في البلعميات المشتقة من نخاع العظم (BMDMs) المعزولة من الفئران بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية والفئران الضابطة (الأعلى). التقدير المقابل لشدة APOE وLpl المعدلة.

(G) استراتيجية البوابة التمثيلية لخلايا السلف في نخاع العظم وقياسات عدد خلايا السلف الدموية – السلف المتعدد القدرات 1 (HSC-MPP1)، السلف النقوي الشائع (CMPs)، السلفات الحبيبية-وحيدة النواة (GMPs)، وLy6C

(H) تقدير عدد الخلايا في نخاع العظام (يسار، اختبار t،

(I) التصميم التجريبي التخطيطي: تم إعطاء الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية والفئران الضابطة EdU قبل 4 ساعات من التضحية. بعد ذلك، تم عزل خلايا نخاع العظام وتحليلها بواسطة قياس التدفق الخلوي (يسار). التقدير المقابل لنسبة خلايا EdU+ من HSC/MPP1 في الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية والفئران الضابطة (اختبار U؛

(أ) تصميم تجريبي تخطيطي: تم عزل خلايا نخاع العظام (BM) من الفئران التي تحمل جين actin-eGFP أو kikGR كتحكم، وكذلك من الفئران التي تعرضت للسكتة الدماغية بعد شهر من السكتة، وتم إثراء هذه الخلايا لخلايا الجذع والخلية السلفية الدموية (HSPCs). تم زرع خلايا GFP+ الغنية بـ HSPC في فئران Mx1 Cre:c-myb التي تم استنزاف نخاع العظام منها.

(ب) هيستوجرام للخلايا قبل وبعد إثراء HSPC يظهر نسبة السلالة

(ج) تشوه الدم بعد شهر من زراعة نخاع العظم، موضحًا كنسبة من GFP

(د) نسبة GFP

(هـ) نسبة eGFP المتداولة

رسم UMAP لخلايا النخاع العظمي من الفئران المزروعة، مقسمة حسب الحالة (يسار) وعدد الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف (DEGs) بين السكتة الدماغية والتحكم (المعدلة

(G) عدد الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف بين حالات السكتة الدماغية وحالات التحكم لكل نوع من الخلايا.

(H) رسم PCA يعرض عينات فردية من نخاع العظام للفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية (أزرق فاتح) والفئران الضابطة (أحمر فاتح) ونخاع العظام للفئران المستقبلة المزروعة بالسكتة الدماغية (أزرق داكن) والضابطة (أحمر داكن) GFP

(I) المسافات الإقليدية في فضاء تحليل المكونات الرئيسية بين عينات السكتة الدماغية وعينات التحكم وعينات من الفئران المتلقية المزروعة بسكتة دماغية وGFP التحكم

(ج) رسم UMAP لإجمالي

رسم بياني فين يوضح الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف المشتركة بين الدم والقلب GFP

(أ) رسم بياني تمثيلي لمستويات البروتينات لـ c-Jun وphospho-c-Jun في البلعميات المشتقة من نخاع العظام (BMDMs) المعزولة من الفئران بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية والفئران الضابطة، وبعد التحفيز بـ 5 أو

(ب) خرائط كثافة الحرارة

(ج) IL-1 في البلازما

(د) التصميم التجريبي التخطيطي: تلقت الفئران حقنة واحدة عن طريق الحقن البريتوني (i.p.) من الليببوليسكاريد (LPSs). بعد 24 ساعة، تم التضحية بالفئران، وجُمعت الدم (الأعلى). بلازما IL-

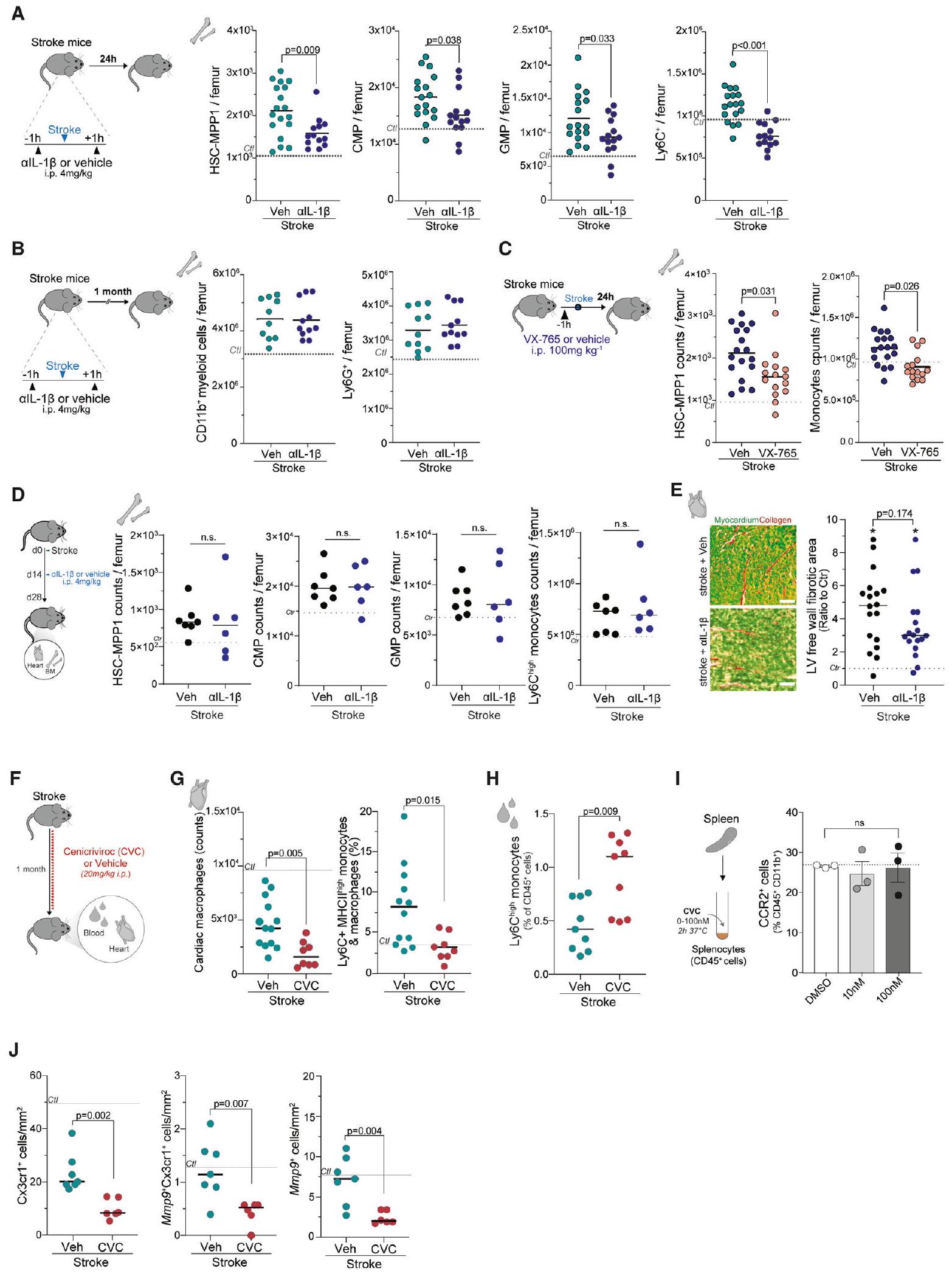

- الشكل 4. السكتة الدماغية تعزز تجنيد المونوسيتات المزمنة إلى القلب

Ms4a3-تم إعطاء فئران السكتة الدماغية والتحكم يوميًا التاموكسيفين لمدة 7 أيام متتالية بدءًا من اليوم 14 بعد السكتة. تم تحليل خلايا النخاع القلبي بواسطة قياس التدفق بعد شهر من السكتة أو التحكم. لكل مجموعة). استراتيجية البوابة التمثيلية لـ tdTomato (tdT الخلايا الوحيدة/ البلعميات القلبية (CD45 Ly6G CD11b ، الوسط) وقياس tdT البلاعم/المونوسيتات القلبية (يمين).

(ب) تم إعطاء الفئران يوميًا EdU لمدة 7 أو 14 يومًا بعد السكتة الدماغية. تم تحليل خلايا المايلويد السلبية النسب من الدم والأعضاء الطرفية بواسطة قياس التدفق لتحديد نسبة خلايا EdU+ CD11b+ في كل نقطة زمنية.لكل عضو).

(ج) CCR2تلقت فئران Ai14 المراسلين التاموكسيفين كل يومين بدءًا من اليوم السابع بعد السكتة الدماغية أو جراحة التحكم حتى شهر واحد، وتم تحليل خلايا القلب البينية باستخدام تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية. فئران/مجموعة).

(د) رسم UMAP لمجموع 34,927 خلية بينية قلبية، ملونة حسب المجموعات المحددة، و(د) رسم UMAP لمجموعات أحادية النواة/البلاعم القلبية.

رسم UMAP يوضح تعبير tdT داخل المونوسيتات/البلاعم القلبية.

نسبة الـخلايا لكل مجموعة فرعية من الخلايا.

(G) ترتيب زمني زائف لـ tdT باستخدام Monocle3الخلايا الوحيدة/البلاعم القلبية مكدسة على مخطط UMAP. يتم تلوين الخلايا بناءً على تقدمها على طول الفضاء الزمني الزائف.

رسم بياني عمودي مكدس لنسبة الخلايا لكل مجموعة سكانية.

تحليل المسارات للجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف (tDEGs) بين الظروف فيالبلاعم/وحيدات النوى القلبية. تم تجميع العمليات البيولوجية وتصنيفها بواسطة قيمة.

تصميم تخطيطي لتحليل تفاعل الخلايا (الزاوية العليا اليسرى) ورسم بياني يوضح أزواج الليغاند-المستقبلات التي تم تنظيمها لأعلى من tdTتجمعات المونوسيتات/البلاعم القلبية إلى الألياف بعد السكتة الدماغية. قائمة المسارات الإشارية التي تم تنظيمها لأعلى من tdT تجمعات المونوسيتات/البلاعم القلبية إلى الألياف بعد السكتة الدماغية.

(ك) صور تمثيلية وقياس لتقنية التهجين الفلوري الجزيئي الفردي في الموقع (smFISH) لاكتشاف عدد الفيمينتينالخلايا الليفية القلبية وتعبير mRNA للكولاجين I في الفيمينتين الخلايا الليفية بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية أو التحكم (مقاييس الرسم، اختبار، /مجموعة).

انظر أيضًا الشكل S4. - الشكل 5. السكتة الدماغية تحفز ذاكرة المناعة الفطرية المستمرة

(أ) تصميم تجريبي تخطيطي: تم فرز خلايا النخاع العظمي السلبية من خط الخلايا اللمفاوية (CD3، CD4، CD8a، CD19، وTer119) وخلايا العدلات (Ly6G) من نخاع العظام للفئران الضابطة وفئران السكتة الدماغية بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية.) لتسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية. رسم UMAP لـ 22,169 خلية نقيية تم فرزها من نقي العظام للفئران الضابطة وفئران السكتة الدماغية.

(ب) ترتيب زمني زائف لخلايا نخاع العظم المكونة للدم باستخدام Monocle3، متراكب على مخطط UMAP. يتم تلوين الخلايا بناءً على تقدمها في الفضاء الزمني الزائف (يسار) أو حسب أنواع الخلايا (يمين).

(ج) عدد الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف (DEGs) بين الظروف لكل نوع خلية (معدل)).

(د) قياس عدد الخلايا الوحيدة والخلايا المتعادلة بين الظروف (اختبار U؛لكل مجموعة).

(E) مخطط مسار تمايز خلايا الجذع الدموية (HSCs) نحو وحيدات النوى (Mo) والعدلات (Neu) (يسار) وقياسات خلايا السلف متعددة القدرات 1 (MPP1) والخلايا السلفية المايلويدية الشائعة (CMPs) وخلايا السلف المحببة-وحيدة النوى (GMPs) (اختبار U؛لكل مجموعة).

(F) التصميم التجريبي التخطيطي: تم عزل خلايا نخاع العظام (BM) الغنية بخلايا السلف الجذعية الدموية (HSPCs) من فئران السكتة الدماغية وفئران التحكم الحاملة للبروتين الفلوري الأخضر (actin-GFP) وزرعها في نخاع العظام المنزوع.الفئران. بعد شهر من الزرع، تم التضحية بالفئران، وتم عزل وتحليل خلايا المايلويد الإيجابية لـ GFP من نخاع العظام، والدم، والقلب باستخدام تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية وقياس التدفق الخلوي.

(G) رسم UMAP لـ 25,358 خلية ميويد GFP+ من نقي العظام (BM) للفئران المزروعة، ملونة حسب المجموعات المحددة ومطبوعة على رسم UMAP لخلايا الميويد من نقي العظام الداخلي (الخلايا باللون الرمادي، الشكل 5A للرجوع إليه).

(H) رسم نقطي يوضح تعبير الجينات المختارة في Ly6Cالسكان وحيدة النواة من نخاع العظام الداخلي للفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية والفئران الضابطة (العمود الأيسر) ونخاع العظام للفئران المتلقية المزروعة مع السكتة الدماغية وضبط GFP خلايا نخاع العظام الغنية بـ HSPC (العمود الأيمن). تم اختيار الجينات من مصطلحات GO الغنية في مجموعة DEGs بين الظروف في Ly6C. وحيدات النواة (معدلة حجم النقطة يتناسب مع نسبة الخلايا ضمن كل حالة، واللون يشير إلى التعبير المتوسط.

(I) الترتيب الزمني الزائف لـ GFP باستخدام Monocle3الخلايا من الفئران المتلقية، مكدسة على مخطط UMAP ومقسمة حسب الحالة. يتم تلوين الخلايا بناءً على تقدمها على طول الفضاء الزمني الزائف.

(ج) قياس تحليل تدفق الخلايا باستخدام GFPالمونوسيتات/البلاعم القلبية من الفئران المتلقية المزروعة بخلايا نخاع العظام الناتجة عن السكتة الدماغية أو التحكم. (K و L) صور تمثيلية لتقنية التهجين الموضعي بالفلوروسينس (smFISH) (يسار، وحدات القياس، ) وقياس عدد نقاط Mmp9 لكل خلايا قلبية اختبار، لكل مجموعة) و GFP خلايا قلبية اختبار، لكل مجموعة).

(م) صور تمثيلية (تلطيخ سيريوس الأحمر/الأخضر السريع) وقياس تليف القلب في جدار البطين الأيسر (LV) من الفئران المتلقية (اختبار t،لكل مجموعة، 3/4 من أقسام القلب لكل فأر).

انظر أيضًا الأشكال S4 و S5. - الشكل 6. الذاكرة المناعية الفطرية تتوسطها IL-1 المبكر بعد السكتة الدماغية

إفراز

(أ) تصميم تجريبي تخطيطي: تم عزل البلعميات المشتقة من نخاع العظم (BMDMs) والوحيدات الأولية من الفئران بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية أو السيطرة. تم قياس امتصاص كريات الزيموزان بواسطة قياس التدفق الخلوي (اختبار t،لكل مجموعة).

(ب) خرائط كثافة الحرارة لقيم H3K4me3 الغنية في قمم الخلايا اللمفاوية – (CD3، CD4، CD8a، CD19، وTer119) والخلايا النخاعية السلبية – (Ly6G) من الفئران بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية (أعلى، أخضر) أو الفئران الضابطة (أسفل، وردي)، مقسمة حسب الحالة.

(C) خريطة حرارية لتراكم الأنماط لمناطق H3K4me3 لخلية HSPCs بين الفئران بعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية والفئران الضابطة و(C) خريطة حرارية مقابلة لـ Ly6Cوحيدات النواة.

(د) تصميم تجريبي تخطيطي: تلقت الفئران IL-1الأجسام المضادة المعادلة أو المركب قبل ساعة واحدة وبعد ساعة واحدة من تحفيز السكتة الدماغية. بعد شهر واحد، تم عزل النوى من خلايا المايلويد السلبية النسب. مجموعة) لتسلسل ATAC للنوى المفردة. رسم UMAP لـ 13,520 نواة نقيعية، ملونة حسب السكان المحددين ومطبوعة على رسم UMAP لخلايا النقي من نقي العظام الداخلي للفئران الضابطة وفئران السكتة الدماغية (الخلايا باللون الرمادي، الشكل 5A).

رسم نقطي يوضح درجات نشاط النمط التفاضلي لكل خلية بين الظروف التجريبية في خلايا HSCs (يسار) وLy6Cالخلايا الوحيدة (يمين). تم تمثيل الأنماط المحددة ذات أعلى وأدنى درجات النشاط بين السكتات الدماغية المعالجة بالتحكم والمعالجة بالسيارة (معدل). ).

“تصميم تجريبي تخطيطي: تم زراعة خلايا المايلويد الغنية بـ HSPC مع إما IL-1 المؤتلف (r)”.أو مركبة لمدة 16 ساعة وتم تحليلها بواسطة تسلسل ATAC (يسار). خرائط كثافة حرارية لمناطق الكروماتين المفتوحة بشكل مختلف مقسمة حسب الحالة (وسط). خريطة حرارية لثراء الأنماط لمناطق الوصول المختلفة بين المجموعات (يمين).

انظر أيضًا الشكل S6. - الشكل 7. IL-1

الذاكرة المناعية الفطرية المدفوعة تؤدي إلى خلل في القلب بعد السكتة الدماغية

(أ) تصميم تجريبي تخطيطي: تلقت الفئران البرية الساذجة rIL-1أو السيارة داخل الصفاق (i.p.) وتم جمع الأعضاء بعد 7 أيام لإجراء تحليل تدفق الخلايا.

(ب) قياس Ly6Cوحيدات النوى (CD45 Ly6G CD11b F4/80 Ly6C ) و CCR2 وحيدات النواة/البلاعم (CD45 Ly6G CCR2 ) بين المجموعات (اختبار t، لكل مجموعة).

(ج) قياس الخلايا الجذعية المكونة للدم متعددة القدرات 1 (HSC-MPP1) وLy6Cوحيدات النوى في نخاع العظام (اختبار t، لكل مجموعة).

(د) التصميم التجريبي التخطيطي: تلقت الفئران IL-1أجسام مضادة محايدة محددة أو مركب ناقل قبل ساعة واحدة وبعد ساعة واحدة من تحفيز السكتة الدماغية، وتم جمع الأعضاء للتحليل بعد شهر واحد.

(E-G) (E) خلايا السلف متعددة القدرات 1 (HSC-MPP1) والوحيدات الكلية في نخاع العظام من الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية (اختبار U؛لكل مجموعة) و (F) Ly6C وحيدات النوى (CD45 Ly6G CD11b Ly6C ) في الدم (اختبار t؛ لكل مجموعة) و (G) CCR2 وحيدات النواة/البلاعم (CD45 Ly6G CD11b F4/80 CCR2 ) في القلوب (اختبار t؛ لكل مجموعة).

(H) صور تمثيلية وقياس تعبير mRNA لـ Mmp9 في خلايا المايلويد القلبية Cx3cr1+ بين مجموعات العلاج بواسطة تقنية الهجين الفلوري في الموقع بجزيء واحد (smFISH، قضبان القياس،اختبار U لكل مجموعة).

(I) صور تمثيلية (تلطيخ سيريوس الأحمر/الأخضر السريع) وقياس تليف القلب في جدار البطين الأيسر (LV) الحر (اختبار t،لكل مجموعة، 4 أقسام قلب لكل فأر.

(ج) التصميم التجريبي التخطيطي: تم إعطاء الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية يوميًا مضاد مستقبلات الكيموكين الثنائي من النوع 2 و5، سينيكريفيروك (سكتة دماغية + CVC) أو المركب الضابطة (سكتة دماغية + Veh) لمدة 28 يومًا. تم إجراء تصوير بالموجات فوق الصوتية للقلب في الأيام 0 و14 و28. تم جمع القلوب في اليوم 28 لإجراء تحليل تدفق الخلايا والتحليل النسيجي.

استراتيجية البوابة لـ Ly6Cوحيدات النواة في الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية المعالجة بـ CVC والمركبة المقابلة والتquantification المقابلة (اختبار U؛ لكل مجموعة).

(L) صور smFISH التمثيلية وقياس عدد نقاط Mmp9 لكل Cx3cr1خلية نقي القلب اختبار، لكل مجموعة).

(M) صور تمثيلية (تلطيخ سيريوس الأحمر/الأخضر السريع) وقياس تليف القلب في جدار البطين الأيسر في الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية المعالجة بـ CVC والمركبة. الخط المنقط يشير إلى النسبة المئوية المتوسطة للمنطقة التليفية في الفئران الضابطة (اختبار t،لكل مجموعة، 4 أقسام قلب لكل فأر.

(N) صور الموجات فوق الصوتية التمثيلية (وضع M) التي أجريت في الأيام 0 و 14 و 28 بعد السكتة الدماغية على الفئران المعالجة بـ CVC والمركبة (يسار). قياس حجم البطين الأيسر (LV) في الانقباض (مربعات) والانبساط (دوائر). الخط المنقط يشير إلى متوسط حجم LV في الفئران الضابطة في اليوم 28. اختبارات t المتعددة،لكل مجموعة. LVAW، الجدار الأمامي للبطين الأيسر؛ LVPW، الجدار الخلفي للبطين الأيسر.

انظر أيضًا الشكل S7. - الشكل S1. السكتة الدماغية تسبب تغييرات التهابية طويلة الأمد في العدلات/البلاعم من الأعضاء الطرفية، المتعلقة بالشكل 1

(أ) صور تمثيلية لآفات السكتة الدماغية الإقفارية من نموذج سكتة الفأر الناتجة عن انسداد الشريان الدماغي الأوسط المؤقت (tMCAo) (الأعلى). رسم بياني يوضح العجز العصبي للفئران على مر الزمن بعد السكتة، تم تقييمه بواسطة اختبار النيوروسكور.

(ب) مخططات تقريب وتوقع متعدد الأشكال الموحد (UMAP) لمجموعة تمثيلية منالخلايا لكل عضو محيطي، ملونة حسب المجموعات المحددة.

(ج) عدد الخلايا لكل مجموعة محددة، مقسمة حسب الحالة.

رسم UMAP لمجموعات العدلات والبلاعم المحددة في الأعضاء الطرفية، مع توضيح الجينات الرئيسية المعبر عنها لكل مجموعة.

مخطط البركان (E) يظهر الجينات المرتفعة (322 جين، أحمر) والجينات المنخفضة (338 جين، أرجواني) لـ Ly6Cالخلايا الوحيدة من الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية والفئران الضابطة. الجينات الملونة هي و |تغيير-الطية| .

تم إجراء تحليل المسار باستخدام تحليل المسار الذكي (IPA، كياجن) باستخدام DEG من Ly6Cوحيدات النواة، مع تعديل و |تغيير_الطيات . الفئات الرئيسية للأمراض والوظائف مرتبة حسب تُعرض القيم.

(G) تحليل شبكة التفاعل الجيني الوظيفي باستخدام IPA. يتم تلوين الجينات بناءً على قيم التغير النسبي التي تم تحديدها من خلال تحليل تسلسل mRNA على مستوى الخلية الواحدة، حيث يشير اللون الأحمر إلى زيادة في السكتة الدماغية واللون الأخضر في الحيوانات الضابطة.

(H) رسم PCA يعرض جميع العينات التي تم تحليلها من جميع الأعضاء الطرفية. تم حساب PCA من إجمالي 18,834 جينًا تم تحديدها في CD45 الطرفي.CD11b الخلايا النخاعية. يتم الإشارة إلى المسافات الإقليدية بين مجموعات السكتة الدماغية والمجموعة الضابطة لكل عضو بخطوط سوداء.

(I) رسم نقطي يوضح ملف التعبير للجينات المختارة الرئيسية لتحديد تجمعات الخلايا في القلب. حجم النقطة يتناسب مع نسبة الخلايا ضمن كل حالة التي تعبر عن النسخة المحددة، واللون يشير إلى متوسط التعبير.

(ج) رسم نقطي يوضح مستويات التعبير لميزات الجينات المختارة في Ly6Cالخلايا الوحيدة من القلب والدم. تم اختيار الجينات من قائمة الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف بين كلا مجموعتي الخلايا. حجم النقطة يتناسب مع نسبة الخلايا ضمن كل حالة التي تعبر عن النسخة المحددة، واللون يشير إلى متوسط التعبير.

رسوم بيانية توضح توزيع درجات الزمن الزائف في كل مجموعة خلوية تم تحديدها في القلب.

رسم UMAP يوضح درجة عدم التوازن.

(م) قيم الارتباط لجينات السائق المسار بين حالات السكتة الدماغية وظروف التحكم.

تحليل المسار باستخدام ShinyGO لجينات السائق المختلفة بين حالات السكتة الدماغية وظروف التحكم. - الشكل S7. IL-1

الذاكرة المناعية الفطرية المدفوعة تؤدي إلى خلل في الأعضاء البعيدة بعد السكتة الدماغية، المرتبطة بالشكل 7

(أ) تصميم تجريبي تخطيطي: تلقت الفئران IL--أجسام مضادة محايدة محددة أو مركب 1 ساعة قبل و1 ساعة بعد تحفيز السكتة الدماغية. بعد 24 ساعة، تم عزل خلايا نخاع العظم لتحليل التدفق الخلوي (يسار). تم إجراء قياسات عدد الخلايا لخلايا الجذع الدموية – السلفيات المتعددة القدرات 1 (HSC-MPP1)، السلفيات المايلويدية الشائعة (CMPs)، السلفيات الحبيبية-وحيدة النواة (GMPs)، وإجمالي Ly6C. وحيدات النوى في نخاع العظم من مضاد IL-1 أو الفئران المعالجة بالمركبات (اختبار U؛ لكل مجموعة).

(ب) نفس تصميم التجربة كما في (أ)، ولكن تم جمع نسيج الدم 1 شهرًا بعد السكتة الدماغية لإجراء قياسات عدد الخلايا باستخدام تقنية الفلوسيتومتر الكمي لإجمالي CD11bالخلايا النخاعية وLy6G العدلات (اختبار U؛ لكل مجموعة).

(C) التصميم التجريبي التخطيطي: تلقت الفئران مثبط الكاسبيز-1 VX-765 أو المركب الوهمي قبل ساعة من تحفيز السكتة الدماغية. بعد 24 ساعة، تم جمع نقي العظام لتحليل تدفق الخلايا (يسار). تم حساب عدد خلايا HSC-MPP1 وإجمالي Ly6C.وحيدات النواة في نخاع العظام من الفئران المعالجة بـ VX-765 أو المركبة (اختبار U؛ لكل مجموعة).

(د) التصميم التجريبي التخطيطي: تلقت الفئران IL-1الأجسام المضادة المعادلة أو المركبة بعد 14 يومًا من السكتة الدماغية. بعد أسبوعين، وبعد شهر من السكتة الدماغية، تم جمع نقي العظام والقلوب لإجراء تحليل تدفق الخلايا وصبغ الأنسجة، على التوالي (يسار). تم حساب عدد الخلايا لـ HSC-MPP1 و CMP و GMP و Ly6C. وحيدات النوى في نخاع العظام من مضاد IL-1 أو الفئران المعالجة بالمركبات (اختبار t؛ لكل مجموعة).

(E) صور تمثيلية لصبغة الكولاجين الحمراء/الخضراء السريعة من سيريوس التي تم إجراؤها على مقاطع قلبية محورية من مضادات IL المتأخرة-والفئران المعالجة بالمركبات المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية (يسار). قياس تليف القلب في جدار البطين الأيسر في مضاد IL- والفئران المعالجة بالجلطة الدماغية. الخط المتقطع يشير إلى النسبة المئوية المتوسطة للمنطقة الليفية في الفئران الضابطة، * تشير إلى فرق ذو دلالة إحصائية بين الفئران المصابة بالجلطة والفئران الضابطة لكل حالة علاجية (اختبار t، لكل مجموعة، 3-4 أقسام قلبية لكل فأر.

(F) التصميم التجريبي التخطيطي: تم إعطاء الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية يوميًا مضاد مستقبلات الكيموكين المزدوجة من النوع 2 و5، سينكريفيروك (سكتة دماغية + CVC) أو محلول التحكم (سكتة دماغية) لمدة 28 يومًا. تم التضحية بالفئران في اليوم 28، وتم جمع القلب والدم لإجراء تحليل تدفق الخلايا والتحليل النسيجي.

تحليل تدفق الخلايا لعدد CCR2 الكليو Ly6C MHC-II وحيدات النواة/البلاعم في قلب الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية المعالجة بـ CVC أو المركبة (اختبار t؛ لكل مجموعة).

(H) قياس التدفق الخلوي لـ Ly6C المتداولةوحيدات النوى في الفئران المصابة بالسكتة الدماغية المعالجة بـ CVC أو المركب، معبراً عنها كنسبة من إجمالي CD45 المتداول الخلايا. الخطوط المتقطعة تشير إلى القيم المتوسطة في الفئران الضابطة (اختبار t؛ لكل مجموعة).

(I) التصميم التجريبي التخطيطي: تم عزل الخلايا الطحالية حديثًا من الفئران السليمة وتم معالجتها بـ CVC بجرعة 0 (DMSO)، 10، و100 نانومتر. بعد ساعتين من المعالجة، كانت نسبة CCR2 الحيةتم تقييم الخلايا بواسطة تحليل تدفق الخلايا.

(ج) قياس smFISH لاكتشاف إجمالي Cx3cr1الخلايا (يسار)، الخلايا (الوسط)، و الخلايا (يمين) في قلوب الفئران المعالجة بـ CVC أو المركبة بعد السكتة الدماغية. تم استخدام DAPI كصبغة نووية. الخطوط المتقطعة تشير إلى القيم المتوسطة في الفئران الضابطة (اختبار t، لكل مجموعة).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.06.028

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39043180

Publication Date: 2024-07-22

Innate immune memory after brain injury drives inflammatory cardiac dysfunction

Highlights

- Acute brain ischemia leads to persistent innate immune memory

- Innate immune memory causes chronic post-stroke cardiac dysfunction

- IL-1

induces post-stroke-trained immunity through epigenetic modifications - Blocking IL-13 or monocyte recruitment prevents cardiac dysfunction

Authors

Correspondence

In brief

Innate immune memory after brain injury drives inflammatory cardiac dysfunction

Abstract

SUMMARY The medical burden of stroke extends beyond the brain injury itself and is largely determined by chronic comorbidities that develop secondarily. We hypothesized that these comorbidities might share a common immunological cause, yet chronic effects post-stroke on systemic immunity are underexplored. Here, we identify myeloid innate immune memory as a cause of remote organ dysfunction after stroke. Single-cell sequencing revealed persistent pro-inflammatory changes in monocytes/macrophages in multiple organs up to 3 months after brain injury, notably in the heart, leading to cardiac fibrosis and dysfunction in both mice and stroke patients. IL-1

INTRODUCTION

RESULTS

Stroke induces long-term inflammatory changes in systemic monocytes/macrophages

sequencing analysis of CD45+CD11b+ myeloid cells from blood and multiple peripheral organs 1 month after experimental ischemic stroke, which have previously been associated with inflammatory consequences of brain injury in the acute phase (Figure 1A).

(A) Myeloid cells were sorted from blood and peripheral organs 1 month after experimental ischemic stroke (

(B) UMAP plot of

(C) Number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between conditions per identified population (adj.p < 0.05). Ly6C

(D) Expression levels of selected genes in the Ly6C

(E) Euclidian distances in the PCA space between the stroke and control per organ. The PCA was calculated from a total of 18,834 genes identified in all CD45

(

(H) Monocle3 pseudo-temporal ordering of CD45

See also Figure S1.

tion, measured by the ejection fraction and fractional shortening, was only transiently affected by stroke in the acute phase (Figures 2A and S2A; Table S1). These findings suggest the

(A) Representative ultrasound images (M-mode) performed at indicated time points (

(B) Representative images (Sirius red/fast green staining) and quantification of cardiac fibrosis in the LV free wall (

(C) Representative image of cardiac electrophysiology at 1 month after stroke or control (

(D) Representative image and quantification of collagen I content, expressed in percentage of total area of the LV free wall (scale bars,

(E) Representative second harmonic generation (SHG) images for the detection of the organization of fibrillar collagen and quantification of the aspect ratio (scale bars,

(F) Enzymatic MMP9 activity using gel zymography of heart samples 1 month after stroke or control (

(G) Representative images of single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) and quantification of the number of Mmp9 mRNA puncta per Cx3cr1

(H) Quantification of flow cytometry for Ly6C

(I) Mmp9 mRNA expression (RT-qPCR) in sorted blood CCR2

See also Figure S2.

tion fraction but diastolic dysfunction is commonly associated with cardiac fibrosis, which impairs the rapid LV filling due to increased myocardial stiffness.

which remained increased still at 3 months post-stroke (Figures 2B, S2C, and S2D). Importantly, this observed post-stroke cardiac fibrosis was not associated with renal dysfunction, gross anatomical cardiac alterations, or persistent perturbations in autonomous cardiac innervation beyond the acute post-stroke phase (Figures S2E-S2J). To test the potential impact of post-stroke cardiac fibrosis, we next conducted an invasive electrophysiological (EP) study 1 month after stroke. In line with a previous study identifying the role of cardiac inflammation as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation,

sequencing on adjacent tissue sections used for the histological analyses above and found significant transcriptional differences between control subjects and after stroke (Figures 3I and 3J). Interestingly, several of the upregulated genes in stroke patients were associated with ECM remodeling, including paraoxonase 1 (PON1) and keratinocyte-associated protein 2 (KRTCAP2). Taken together, we observed marked cardiac fibrosis and ECM remodeling in both experimental mice and stroke patients, which was further associated with diastolic dysfunction after experimental stroke. A hallmark of this secondary cardiac pathology after stroke is the increased recruitment and pro-inflammatory profile of cardiac monocytes/macrophages.

Stroke promotes chronic monocyte recruitment into the heart

BM cellularity and function are chronically altered after stroke

(A) Representative images of the patient with chronic diastolic dysfunction recruited by the Stroke-Induced Cardiac Failure (SICFAIL) study consortium. Corresponding quantification of the

(B) Myocardial autopsy samples were collected from a total of 19 patients: 12 ischemic stroke (IS) patients and 7 controls, who died without cardiac or brain disorder (confirmed by autopsy). Basic demographical and clinical characteristics are depicted. Data are expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]), unless stated otherwise. *p < 0.05 (chi-square test).

(C) Representative images (Masson trichrome staining, scale bars, 0.1 mm ) and quantification of collagen content (

(D) Representative images (Sirius red/fast green staining, scale bars, 0.2 mm ) and quantification of the collagen content expressed as percentage of total cardiac area (t test).

(E) Quantification of CD14

(F) Representative image (scale bars, 0.05 mm ) and quantification (t test) of

(G) Correlation of CCR2

(H) Representative images and quantification of single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) for the detection of Mmp9 mRNA puncta expression in CD14

(I) Volcano plot showing regulated genes in the myocardium between IS and control patients. Colored genes are

(J) Heatmap showing the top differentially expressed genes in the heart between IS and control patients.