DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2024.3391130

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-01

الصيانة التنبؤية القابلة للتفسير: استعراض للطرق الحالية، التحديات والفرص

وجهات النظر والاستنتاجات الواردة هنا هي آراء المؤلفين ولا ينبغي تفسيرها على أنها تمثل بالضرورة السياسات الرسمية أو التأييدات، سواء كانت صريحة أو ضمنية، للجيش الأمريكي ERDC أو وزارة الدفاع الأمريكية. كما يود المؤلفون أن يشكروا

مختبر جامعة ولاية ميسيسيبي لتحليلات البيانات التنبؤية ودمج التكنولوجيا (PATENT) لدعمه.

الملخص

الصيانة التنبؤية هي مجموعة مدروسة جيدًا من التقنيات التي تهدف إلى إطالة عمر النظام الميكانيكي من خلال استخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي وتعلم الآلة للتنبؤ بالوقت الأمثل لأداء الصيانة. تسمح هذه الطرق لمشغلي الأنظمة والأجهزة بتقليل التكاليف المالية والزمنية للصيانة. مع اعتماد هذه الطرق لتطبيقات أكثر خطورة وقد تكون مهددة للحياة، يحتاج المشغلون البشريون إلى الثقة في النظام التنبؤي. وهذا يجذب مجال الذكاء الاصطناعي القابل للتفسير (XAI) لإدخال القابلية للتفسير والفهم في النظام التنبؤي. يقدم XAI طرقًا في مجال الصيانة التنبؤية يمكن أن تعزز الثقة لدى المستخدمين مع الحفاظ على أنظمة ذات أداء جيد. تستعرض هذه الدراسة حول الصيانة التنبؤية القابلة للتفسير (XPM) وتقدم الطرق الحالية لـ XAI كما تم تطبيقها على الصيانة التنبؤية مع اتباع إرشادات العناصر المفضلة للتقارير للمراجعات المنهجية والتحليلات التلوية (PRISMA) 2020. نقوم بتصنيف طرق XPM المختلفة إلى مجموعات تتبع أدبيات XAI. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، ندرج التحديات الحالية ونقاشًا حول اتجاهات البحث المستقبلية في XPM.

المقدمة

الصيانة التنبؤية (PdM). تشمل PdM العديد من المشكلات المختلفة في مجال الصيانة، ولكن التمثيل الشامل لـ PdM يتضمن مراقبة النظام كما هو في الوقت الحاضر وتنبيه المستخدمين لأي مشكلات محتملة مثل شذوذ معين أو الوقت المتبقي حتى الفشل [1]، [6]. بينما تم دراسة هذه المشكلة الموجودة في المجال السيبراني الفيزيائي بشكل جيد من منظور نماذج التعلم العميق، والنماذج الإحصائية، وأكثر من ذلك، فإن الأشخاص الذين يتأثرون بهذه الأنظمة قد حصلوا على اهتمام أقل بكثير. يقودنا هذا التغيير في التركيز إلى الثورة الصناعية الخامسة أو الصناعة 5.0.

II. الخلفية

أ. الشرح وقابلية التفسير في الذكاء الاصطناعي

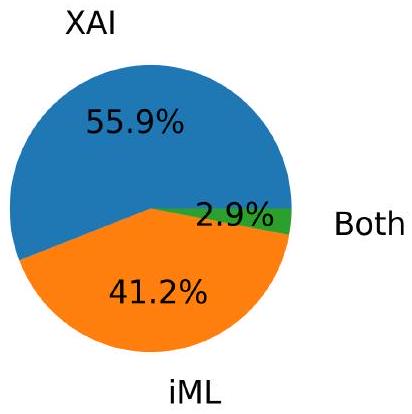

1) الذكاء الاصطناعي القابل للتفسير

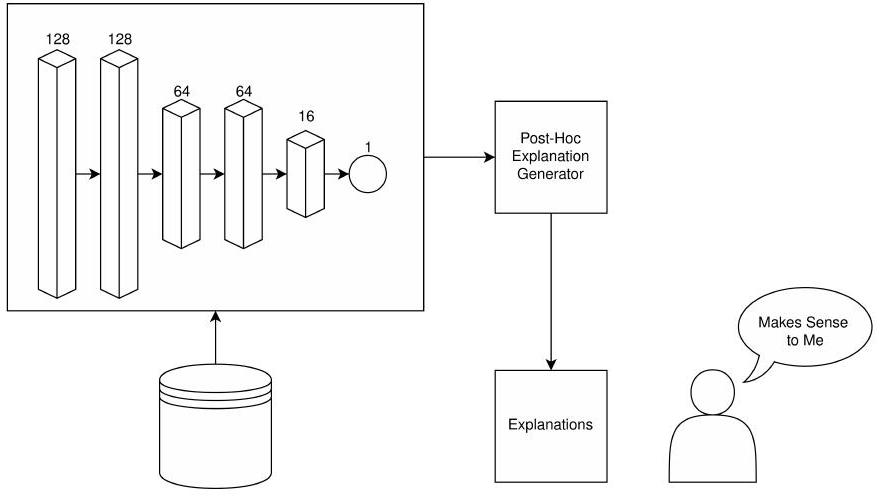

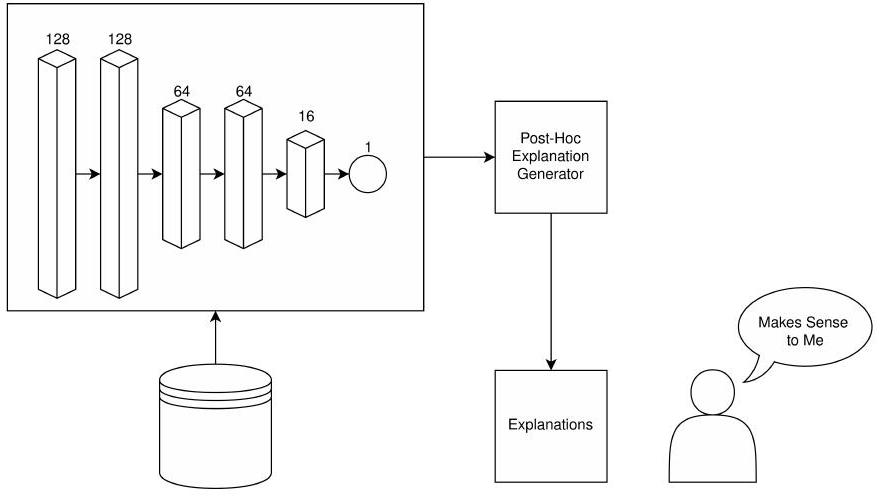

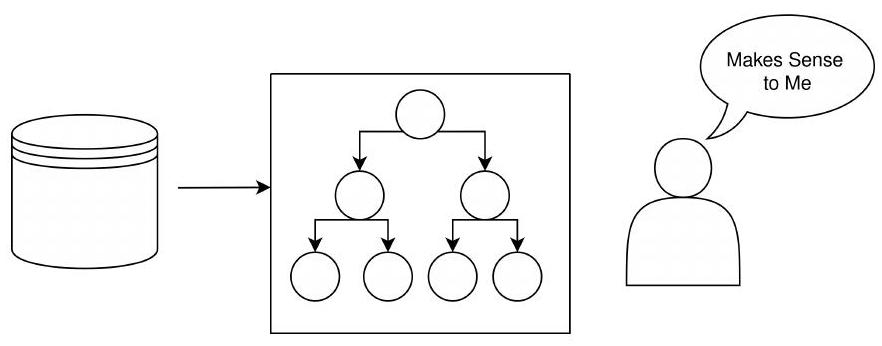

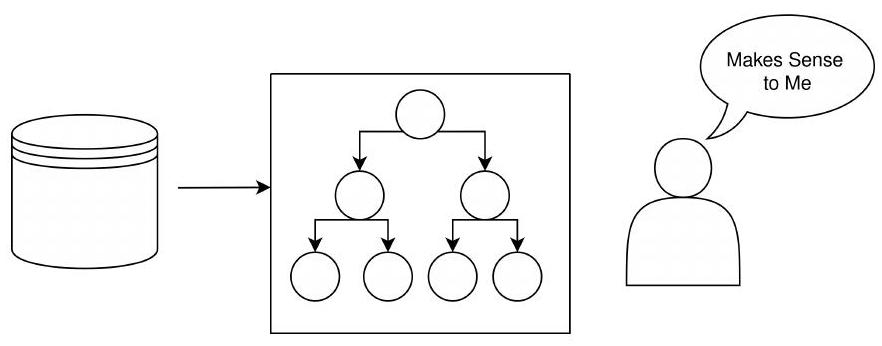

تتمثل هذه الطرق في السعي لتفسير آليات نموذج تم تدريبه بالفعل. كما أوضح سوكول وآخرون باختصار، فإن القابلية للتفسير تتعلق بمخرجات النموذج. من منظور تحليلي أكثر، تشمل الذكاء الاصطناعي القابل للتفسير بشكل أساسي استراتيجيات ما بعد التفسير لتسليط الضوء على النماذج الغامضة، المعروفة بصندوق الأسود. يتم توضيح هذا النموذج في الشكل 1، حيث يتم بناء تفسيرات النموذج لتعزيز فهم المستخدم.

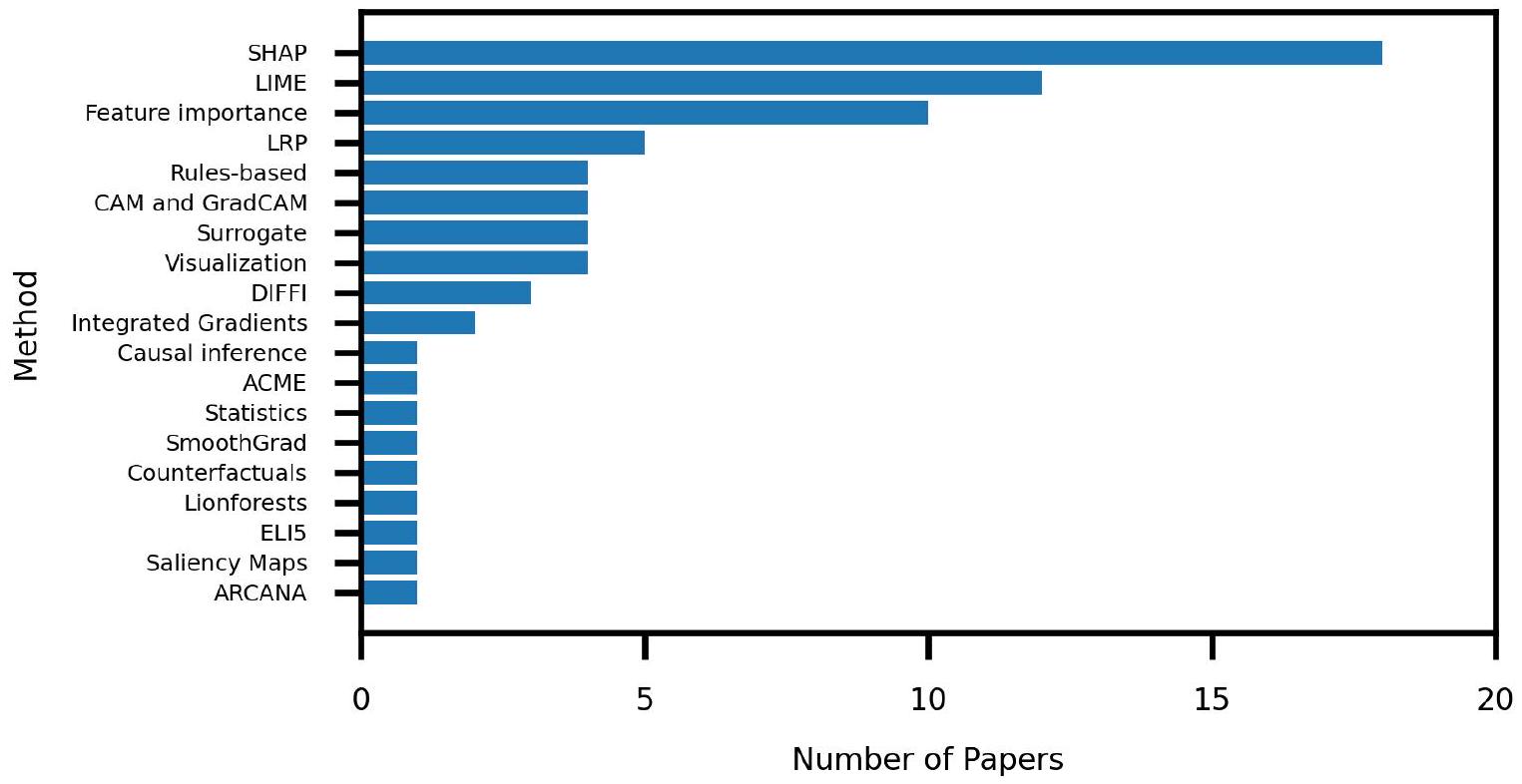

يمكن تصنيف الطرق القابلة للتفسير بناءً على ملاءمتها لمعالجة أنواع مختلفة من نماذج الصندوق الأسود. تُسمى الطرق التي تنطبق على النماذج بغض النظر عن هيكلها بالطرق غير المعتمدة على النموذج. تشمل الطرق الشائعة التي تندرج تحت هذه الفئة تفسيرات شابلي الإضافية (SHAP) [23] وتفسيرات النماذج القابلة للتفسير محليًا وغير المعتمدة على النموذج (LIME) [24]. يتم وصف هذه الطرق وطرق أخرى غير معتمدة على النموذج في القسم V-A. يُعرف عكس هذه الطرق بالطرق المعتمدة على النموذج. تم تصميم الطرق المعتمدة على النموذج مثل رسم تنشيط الفئة (CAM) [25] لشبكات الأعصاب التلافيفية (CNNs) للاستفادة من الهيكل الموجود بالفعل لتوفير التفسير. يتم وصف هذه الطرق وغيرها في القسم V-B.

b: التفسيرات المحلية والتفسيرات العالمية.

c: مثال على XAI

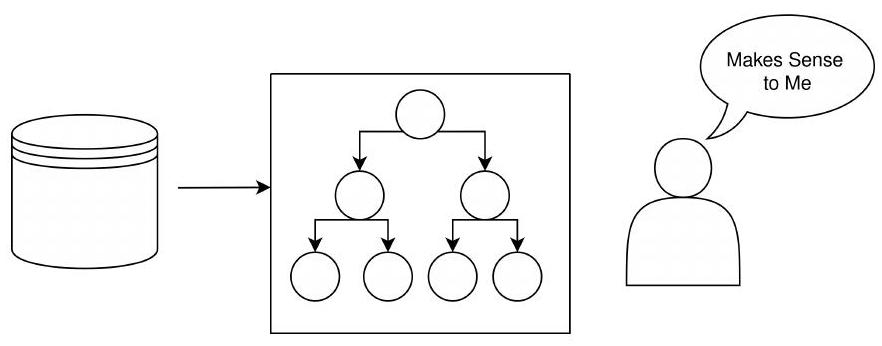

شجرة القرار، إلخ، لتكون بمثابة بديل للتفسيرات اللاحقة. سيتم تقديم هذه التفسيرات بعد ذلك للمستخدم/المطور/المعنيين لشرح سلوك هيكل الصندوق الأسود الكامن بشكل أفضل.

2) التعلم الآلي القابل للتفسير

B. الصيانة التنبؤية

يتعامل التنبؤ مع توقع العمر المتبقي المفيد (RUL) أو الوقت حتى الفشل [1]، [6]، [28]. هذا يضع التنبؤ في نطاق مشاكل الانحدار. الآن بعد أن تم تعريف هذه المصطلحات وتصنيفها إلى مشاكلها المختلفة، يمكننا مناقشة البحث المنهجي المتوافق مع PRISMA الذي قمنا به.

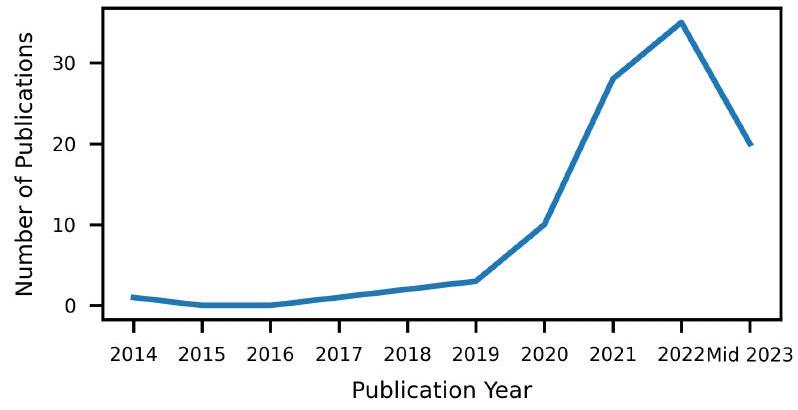

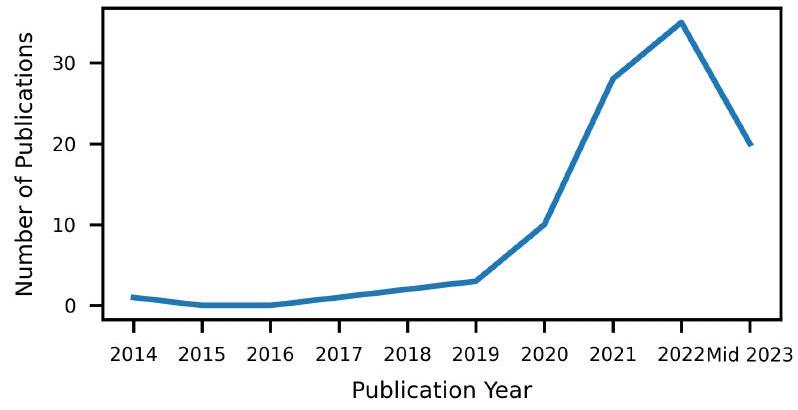

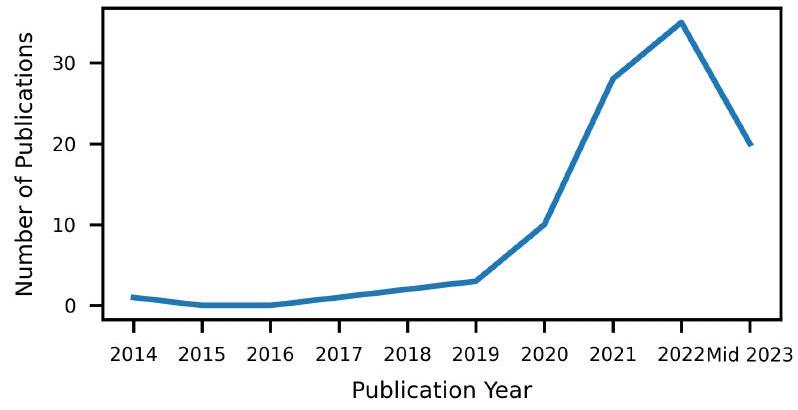

III. البحث المنهجي

A. التعرف

B. معايير الاستبعاد والفحص

- لا يعد XAI أو iML محورًا رئيسيًا للمقال.

- المقالات ليست دراسات حالة لـ PdM.

- لا يتم تقديم أي تفسير أو تفسير.

- ثلاثة يذكرون XAI/iML في الملخص لكنهم لا يستخدمون أي طرق يمكننا العثور عليها.

- اثنان لم يكونا لا XAI ولا iML. تذكر هذه المصطلحات البحثية في الملخصات، لكنها لا تبني عليها.

- ثلاثة لا يقدمون أي تفسيرات لطريقتهم التفسيرية.

- يذكر اثنان PdM في الملخص لكن لا يركزان على PdM في تجربة.

- لم تكن واحدة دراسة حالة.

ج. الشمولية

IV. نتائج البحث

V. الذكاء الاصطناعي القابل للتفسير في الصيانة التنبؤية

أ. غير معتمد على النموذج

- تفسيرات شابلي الإضافية (SHAP).

| مجموعات البيانات | مقالات |

| محامل و PRONOSTIA [39]، 40] | |41|-|53 |

| [33]، [37]، [54]، |55] | |

| المركبات أو نظام فرعي للمركبة | [56]-|68 |

| CMAPSS [69] | [35]-|37], |70|-|79| |

| [80] | |

| أعطال وآخطاء الآلات العامة 81 | [42]، [48]، |82|-|86] |

| قطارات | [٣٤]، |٨٧-|٩٢ |

| صناديق التروس [93] | |42|، 45، 48، |94| |

| مجموعة بيانات اصطناعية | [٤٤، ٩٥، ٩٦ |

| الصلب المدرفل على الساخن أو البارد | [72]، |95|، |97| |

| مضخة ميكانيكية | [98-|100] |

| طائرة | [52],101 |

| ألعاب الملاهي | [102],103 |

| مسارعات الجسيمات | [104, 1105 |

| مصنع كيميائي | [١٠٦، ١٠٧ |

| بحري | [108-110 |

| أشباه الموصلات |111| | |112|, 113 |

| مكيفات الهواء | ٥٦ |

| الأقراص الصلبة [114] | [٣٨، [٧٠]، |١١٥] |

| عملية تينيسي إيستمان |116 | 70 |

| آلات الضغط | ١٠٣ |

| مستودع تعلم الآلة UCI [117] | 1118 |

| توربينات الرياح [119] | [120]-|122 |

| محولات | |123 |

| بطاريات الليثيوم أيون [124] | [٣٧، |١٢٥|، |١٢٦|] |

| سخانات | 127 |

| بيانات التحكم الرقمي بالكمبيوتر | 128 |

| الأقمشة | ١٢٩ |

| آلات بثق البلاستيك | ١٣٠ |

| آلة الضغط | 131 |

| آلات الفحم | 132 |

| ثلاجات | ١١٣٣ |

| ضواغط الغاز | 134 |

| أنظمة هيدروليكية | 135 |

| أفران صناعة الحديد | 1136 |

| أدوات القطع | ١٣٧ |

| خطوط الطاقة [138] | ١٣٩ |

| معدات الاتصالات | ١٤٠ |

| مضخة مياه | 141 |

| معدات حفر النفط | 142 |

| صمامات تعمل بالملف اللولبي | 143 |

| نواقل الفحم | ١٤٤ |

| أجهزة مراقبة درجة الحرارة | 145 |

| وحدة التقطير | 146 |

| أنابيب المياه [147] | 148 |

| طريقة | مقالات | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

2) تفسيرات نموذجية قابلة للتفسير محليًا (LIME). تم تقديم LIME من قبل ريبيرو وآخرون كوسيلة لشرح أي نموذج باستخدام تمثيل محلي حول التنبؤ [24]. يتم ذلك عن طريق أخذ عينات حول بيانات الإدخال المعطاة وتدريب نموذج خطي باستخدام البيانات المأخوذة. من خلال القيام بذلك، يمكنهم توليد تفسير يتوافق مع ذلك التنبؤ بينما يستخدمون فقط المعلومات المستمدة من النموذج الأصلي.

الأعطال التي تعكس الأعطال الفيزيائية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أظهروا أن LIME ستواجه صعوبة أكبر في تصنيف الميزات المهمة عندما تم تطبيقها على مقاطع بدون أعطال حيث يمكن أن يحدث أي شيء في المستقبل.

3) أهمية الميزات.

4) انتشار الصلة على مستوى الطبقة (LRP).

5) المفسرات القائمة على القواعد.

محركات التوربين. أدت هذه الطريقة إلى أداء رائع مع تفسيرات قائمة على القواعد.

6) نماذج الوكلاء.

7) التدرجات المتكاملة.

تُحسب التدرجات المتكاملة من خلال جمعات صغيرة عبر تدرجات الطبقات، مع وضع هذه البديهيات في الاعتبار.

8) الاستدلال السببي.

9) التصور.

10) تفسيرات نموذجية غير محددة متسارعة (ACME).

باستخدام ACME مع جميع البيانات بينما سيكون SHAP أبطأ حتى مع الوصول إلى

11) الإحصائيات.

12) تدرجات سلسة (SmoothGrad).

13) الافتراضات المضادة.

تفسير لنتيجة النموذج، لكن هذه القدرة الإضافية تجعل العوامل المضادة فريدة جدًا في مجال طرق الذكاء الاصطناعي القابلة للتفسير.

14) اشرح لي كأني في الخامسة (ELI5).

ب. نموذج محدد

1) رسم تفعيل الفئة (CAM) ورسم تفعيل الفئة المدعوم بالتدرج (GradCAM).

2) أهمية الميزات المستندة إلى عمق غابة العزل (DIFFI). تم تقديم DIFFI بواسطة كارليتي وآخرين [160] كطريقة قابلة للتفسير لغابات العزل. غابات العزل هي مجموعة من أشجار العزل التي تتعلم النقاط الشاذة من خلال عزلها عن النقاط العادية. يعتمد DIFFI على فرضيتين لتعريف أهمية الميزات حيث يجب أن: تؤدي إلى عزل النقاط الشاذة عند عمق صغير (أي، بالقرب من الجذر) وتنتج عدم توازن أعلى على النقاط الشاذة بينما تكون عديمة الفائدة على النقاط العادية [160]. ستسمح هذه الفرضيات بتقديم تفسيرات للبيانات الشاذة مما سيمكن من تقديم تفسيرات للنقاط الشاذة أو البيانات المعيبة.

واللحظات العليا للإشارات مثل الكورتوز. تقوم FSCA باختيار الميزات بشكل تكراري لزيادة مقدار التباين المفسر. أخيرًا، يتم استخدام غابة العزل لاكتشاف القيم الشاذة التي يتم التعامل معها كأحداث خاطئة. يتم شرح هذه من خلال DIFFI. لقد طبقوا طريقتهم على سنتين من بيانات التحكم الرقمي بالحاسوب مما أسفر عن

3) غابات الأسد.

4) خرائط البروز.

5) تحليل السبب الجذري للانحرافات القائم على التشفير التلقائي (ARCANA).

الفرق بين ناتج المشفر التلقائي والمدخلات، يضيفون هذا المتجه المنحاز إلى بيانات المدخلات للحصول على مدخلات مصححة. علاوة على ذلك، يظهر المنحاز ميزات “غير صحيحة” بناءً على الناتج؛ لذلك، يمكن أن يفسر المنحاز سلوك المشفر التلقائي من خلال إظهار الميزات التي تجعل الناتج شاذًا.

ج. دمج الطرق

اتفاق حول الشرح لنتيجة النموذج، لكنهم لم يتقدموا أكثر في السؤال عن أيهما أفضل.

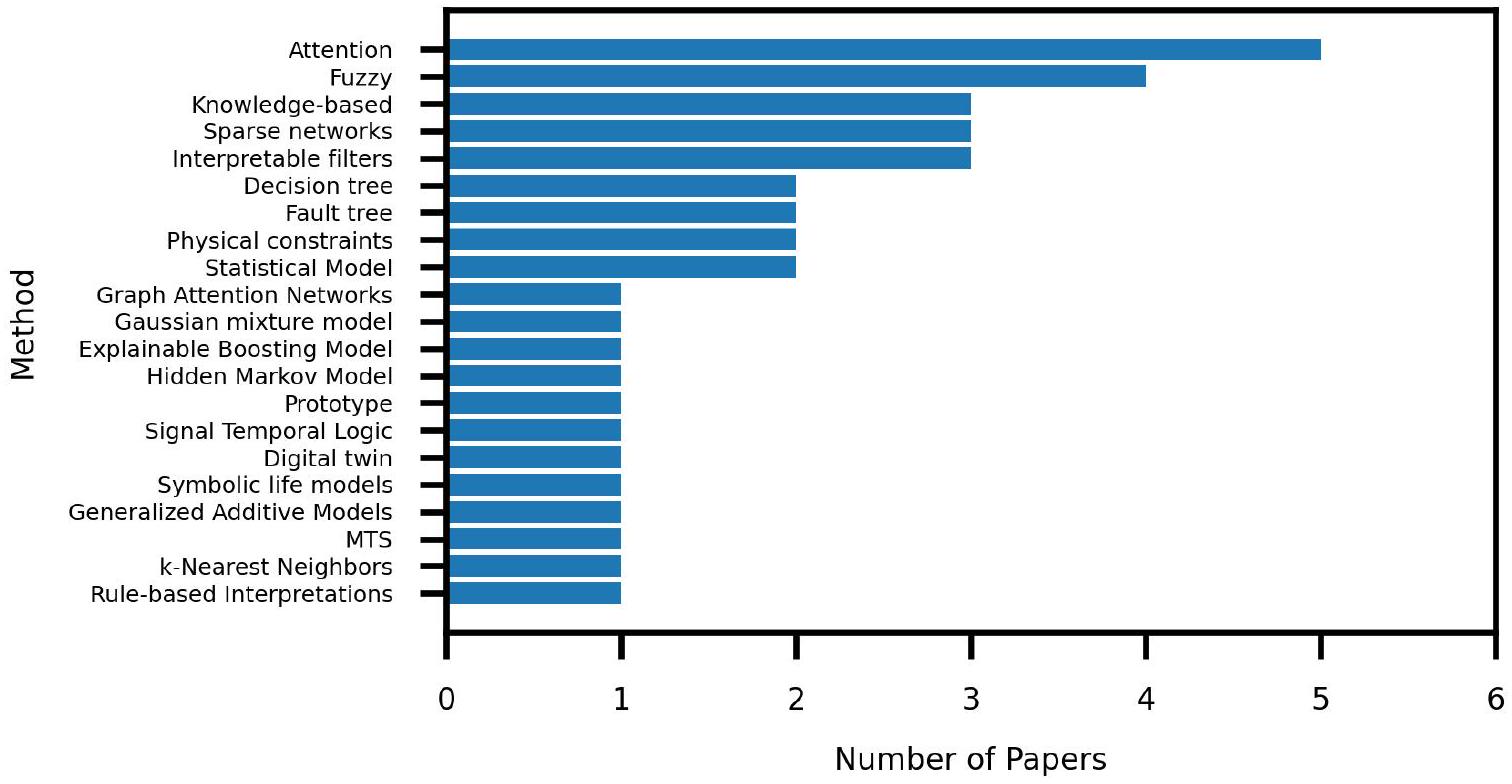

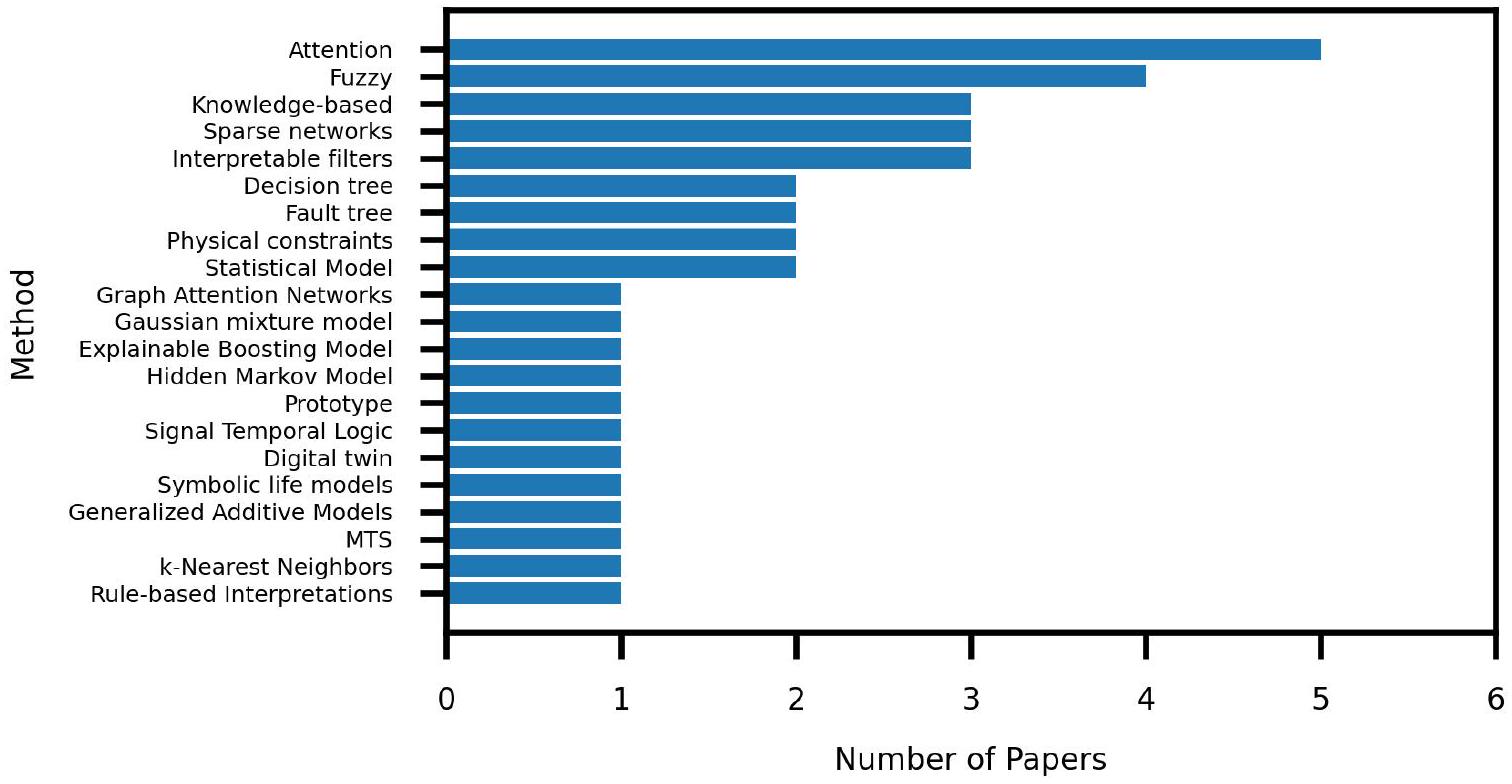

VI. التعلم الآلي القابل للتفسير في الصيانة التنبؤية

أ. انتباه.

آليات ويمكن استخدامها لإضافة قابلية التفسير لسبب إخراج الشبكة لـ DTC.

ب. قائم على الضبابية.

ج. قائمة على المعرفة.

بين الميزات المختلفة حيث تأخذ الروابط شكل رابط عند مناقشة الرسوم البيانية أو قواعد الإنتاج عند مناقشة أنظمة الإنتاج. تنتج هذه الطرق تفسيرًا من خلال توفير هذه الاتصالات داخل الميزات، عادةً في شكل لغة طبيعية.

يتكون قاعدة قواعد السجل من استخراج القواعد من خلال تعدين السجل المتكرر، وترجمة القواعد إلى قواعد SWRL، واستخدام الدقة (عدد القواعد الصحيحة) والتغطية (عدد القواعد الصحيحة الشاملة) لاختيار أفضل القواعد جودة. شملت عملية دمج قواعد الخبراء تلقي المدخلات من الخبراء وتطبيق نفس القيود على قواعدهم. أخيرًا، تم استخدام القواعد لتوقع الشذوذ في أشباه الموصلات.

| طريقة | مقالات | ||

| انتباه VI-A | |56|، |58|، |64|، |78|، 133 | ||

| فوزي VI-B |

|

||

| VI-C المعتمد على المعرفة | 99، 1131، 142 | ||

| الشبكات النادرة (VI-M) | ٤٦، ١٠٠، ١٢١ | ||

| مرشحات قابلة للتفسير VI-D | ٤٥، ٤٩، [٦٠] | ||

| شجرة القرار VI-E | [٥٧، |١٥] | ||

| شجرة العيوب (VI-F) | 79، 127 | ||

| القيود الفيزيائية VI-G | ٩٨، ١٤٣ | ||

| النموذج الإحصائي VI-H | 41، |55 | ||

| شبكات الانتباه البيانية VI-I | 87 | ||

| نموذج المزيج الغاوسي VI-J | 125] | ||

| آلة التعزيز القابلة للتفسير (VI-K) | 76 | ||

| نموذج ماركوف المخفي VI-L | 80 | ||

| نموذج أولي VI-N | 62 | ||

| منطق الإشارة الزمنية VI-O | 136 | ||

| التوأم الرقمي VI-P | 144] | ||

| نموذج الحياة الرمزي VI-Q | 33 | ||

| نموذج الجمع العام (VI-R) | 43 | ||

| MTS (VI-S) | 118 | ||

| أقرب الجيران k- VI-T | 145 | ||

| تفسيرات قائمة على القواعد VI-U. | 146] |

D. المرشحات القابلة للتفسير.

التتبع العكسي. تحتوي هذه الشبكة على 1) معنى قابل للتفسير من طبقة التحويل الموجي، 2) طبقات كبسولة تسمح بفصل الخطأ المركب، و3) تتبع عكسي يساعد في تفسير المخرجات من خلال التركيز على العلاقات بين الميزات وظروف الصحة. لم يكن إطارهم قادرًا فقط على تحقيق دقة عالية في جميع الظروف، بما في ذلك الأخطاء المركبة، ولكنهم أظهروا أيضًا أن طريقة التتبع العكسي يمكن أن تفصل طبقات الكبسولة بشكل فعال.

E. أشجار القرار.

مختلفة بين الفئات. تم استخدام هذه الميزات لتدريب آلة تعزيز التدرج الخفيف (LightGBM) وهي نوع من شجرة قرار تعزيز التدرج التي قدمها كي وآخرون [170]. تتيح هذه الطريقة المراقبة المستمرة لأهمية الميزات أثناء التدريب والتي يمكن استخدامها لتفسير النتائج.

F. أشجار الأخطاء.

G. القيود الفيزيائية.

إلى دمج النهج المعتمدة على النموذج والنهج المعتمدة على البيانات من خلال إرفاق الخصائص الرياضية للنظام بالبيانات في النهج المعتمدة على البيانات [98].

H. الطرق الإحصائية.

I. شبكات انتباه الرسم البياني (GATS).

| العنوان | الهدف | المساهمة |

| أثر الاعتماد المتبادل: منظور نظام متعدد المكونات نحو الصيانة التنبؤية المعتمدة على التعلم الآلي وXAI [112] | تنفيذ الصيانة التنبؤية من خلال نمذجة الاعتماد المتبادل واختبار أهميتها | أظهر مع دلالة إحصائية أن نمذجة الاعتماد المتبادل تزيد من أداء وفهم النموذج |

| تقدير العمر المتبقي القابل للتفسير والمساعد بالذكاء الاصطناعي لمحركات الطائرات [35] | حساب RUL لمجموعة بيانات CMAPSS لمحركات التوربينات مع LIME لشرح الأداء | أظهر أن LIME كان أداؤه ضعيفًا عند تطبيقه على مقاطع بدون أعطال ولكنه كان جيدًا عند تصنيف الميزات مع تسلسلات فاشلة |

| تحسين النموذج المدفوع بالشرح لتقدير SOH لبطارية الليثيوم أيون [126] | تنفيذ الصيانة التنبؤية من خلال تضمين الشروحات في حلقة التدريب | قدم فكرة التدريب المدفوع بالشرح للصيانة التنبؤية |

| شرح الشذوذ عبر الإنترنت: دراسة حالة على الصيانة التنبؤية [65] | تطبيق طرق XAI على عملية التعلم عبر الإنترنت | أظهر أن الشروحات المحلية والعالمية يمكن إضافتها إلى نموذج التعلم عبر الإنترنت |

| شرح غابة عشوائية مع فرق نموذجين ARIMA في سيناريو اكتشاف الأعطال الصناعية [82] | استخدام نموذجين ARIMA بديلين لشرح قدرات نموذج الغابة العشوائية | قدم طريقة لوضع نموذج بين بديلين لإظهار أين يفشل النموذج في الأداء الجيد |

| اقتراح قائم على الذكاء الحدي لتشخيص سعة التداخل على متن القطار [89] | اختبار XAI على الحوسبة الحدي لتشخيص الأعطال | قدم طريقة لتنفيذ XAI في مثال الحوسبة الحدي مقترنًا بمكتبات AutoML |

| خوارزميات الذكاء الاصطناعي القابلة للتفسير لاكتشاف الأعطال المستندة إلى الاهتزاز: طرق متكيفة مع حالات الاستخدام وتقييم نقدي [44] | اكتشاف إمكانية طرق XAI في شرح مخرجات هياكل CNN | أظهر LRP ميزات غير قابلة للتمييز، وأظهر LIME ميزات غير مهمة، وأظهر GradCAM الميزات المهمة |

| حول صحة XAI في التنبؤات وإدارة الصحة (PHM) [37] | مقارنة طرق XAI المختلفة لمجموعة بيانات CMAPSS وبطارية الليثيوم أيون | أظهر مقاييس مختلفة لمقارنة الشروحات التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة طرق XAI المختلفة وأظهر أن GradCAM كان الأفضل في أداءه على هياكل CNN |

| تفسير تقديرات العمر المتبقي القابل للتفسير بالجمع بين الذكاء الاصطناعي القابل للتفسير والمعرفة الميدانية في الآلات الصناعية [51] | تنفيذ RUL للمحامل من خلال نماذج وأساليب تفسيرية متعددة مختلفة | أظهر أهمية تطبيق الشروحات العالمية والمحلية لتفسير أداء النماذج من جميع الجوانب |

| تقييم أدوات الذكاء الاصطناعي القابلة للتفسير لصيانة محركات الأقراص الصلبة التنبؤية [38] | تحليل فعالية طرق الشرح لنماذج الشبكات العصبية المتكررة لتنبؤ RUL | استخدمت ثلاث مقاييس لمقارنة الشروحات من LIME وSHAP وأظهرت أين يتألق كل منها على الآخر |

| نظام صيانة تنبؤية تلقائي وقابل للتفسير [66] | هدفت إلى دمج القابلية للتفسير في بيئة AutoML | عرفت سير عمل لنظام صيانة تنبؤية تلقائي قابل للتفسير |

| DTCEncoder: هيكل سكين الجيش السويسري لاستكشاف DTC، التنبؤ، البحث وتفسير النموذج [64] | تنفيذ اكتشاف الأعطال من خلال تصنيف DTCs | صممت DTCEncoder التي تستخدم آلية انتباه لتوفير مساحة خفية قابلة للتفسير حول سبب إخراج DTC |

| تعلم متباين عميق متعدد الحالات مع انتباه مزدوج لاكتشاف الشذوذ [133] | تنفيذ اكتشاف الشذوذ واكتشاف سلف الشذوذ | نفذت اكتشاف سلف الشذوذ من خلال التعلم متعدد الحالات مع شروحات تم التحقق منها من خلال خبراء المجال |

| نظام ذكاء اصطناعي قابل للتفسير قائم على الضبابية من النوع 2 للصيانة التنبؤية في صناعة ضخ المياه [141] | استخدام خوارزمية تطورية لتحسين نظام المنطق الضبابي الخاص بهم لتنبؤ الأعطال | استخدم نظام منطق ضبابي من النوع 2 وتحسين تطوري لتوليد قواعد ضبابية لتنبؤ الأعطال |

| Waveletkernelnet: شبكة عصبية عميقة قابلة للتفسير للتشخيص الذكي الصناعي [45] | تحسين طرق قائمة على CNN للصيانة الصحية | صممت التحويلة الموجية المستمرة لإضافة تفسيرات فيزيائية إلى الطبقة الأولى من هياكل CNN |

| شبكات متفرقة مقيدة لتشخيص أعطال المحامل الدوارة [46] | تنفيذ اكتشاف الأعطال باستخدام شبكة متفرقة | استكشفت فضاء التردد المتقطع المقيد واستخدمت التحويل إلى هذه المساحة لتدريب شبكة من طبقتين تؤدي بشكل متساوٍ مع CNN-LSTM |

| تعلم تسلسلي قابل للتفسير وقابل للتوجيه عبر النماذج الأولية [62] | بناء نموذج تعلم عميق مع قابلية تفسير مدمجة لتشخيص الأعطال عبر DTCs | قدمت شبكة تسلسل النموذج الأولي (ProSeNet) التي تستخدم تشابه النموذج الأولي في تدريب الشبكة وأكدت قابلية تفسير نهجهم من خلال دراسة مستخدمين على Amazon MTurk |

| قواعد سببية وقابلة للتفسير لتحليل السلاسل الزمنية [146] | تنفيذ الصيانة التنبؤية مع الاستفادة من القواعد السببية للتفسيرات | صممت خوارزمية APriori لتقاطع الحالة للصيانة التنبؤية والتي أظهرت أن الأداء الأعلى يحدث عند وجود قواعد مضافة ومطروحة على المخرجات |

رسم بياني موجه غير دوري. يقوم انتباه السبب المفكك (DC-Attention) بتجميع المتغيرات السببية لتوليد تمثيلات المتغيرات التأثيرية. يقوم انتباه DC-Attention بإخراج حالة النظام (معطلة أو غير معطلة). ثم يستخدمون دالة خسارة مخصصة تحسب المسافة بين الدعم الحالي للتمثيلات ودعمه المفكك نظريًا.

نموذج المزيج الغاوسي.

آلة التعزيز القابلة للتفسير (EBM).

نموذج ماركوف المخفي.

تعلم الوكيل التعليمي سياسة للصيانة بناءً على الأعطال. التحدي الأول في هذا النهج يتضمن تمثيل الصيانة التنبؤية كمشكلة تعلم معزز. يتم ذلك من خلال تمثيل الإجراءات المحتملة كالإبقاء، الإصلاح، أو الاستبدال، وإنشاء دالة مكافأة بناءً على الإبقاء، الاستبدال المبكر والاستبدال بعد الفشل، وقياس التكلفة بناءً على هذه الدوال المكافأة. يتم استخدام نموذج ماركوف المخفي لتفسير مخرجات نموذجهم من خلال ملاحظة الميزات التي أدت بالنموذج إلى اكتشاف حالة الفشل.

شبكات متفرقة.

ن. تعلم النموذج الأولي.

من خلال المقارنة مع مثال تمثيلي. تحديد أفضل النماذج الأولية هو مشكلة بحد ذاته، لكن القابلية للتفسير التي يجلبها واضحة. سيكون ناتج إدخال محدد مشابهًا لناتج أقرب نموذج أولي له؛ لذلك، فإن السبب وراء أن بيانات الإدخال لها ناتج معين هو بسبب ناتج قطعة بيانات مشابهة جدًا. وهذا يجلب القابلية للتفسير من خلال المقارنة مع النموذج الأولي.

O. منطق الإشارة الزمنية (STL).

P. التوأم الرقمي.

الأصل ونظام رقمي يحمل المعلومات حول النظام المادي. باستخدام التوائم الرقمية، يمكن للمرء مراقبة أداء النظام المادي دون الحاجة إلى مراقبة الأصل فعليًا.

Q. نموذج الحياة الرمزي.

R. النموذج الإضافي العام (GAM).

لتنبؤ RUL وتشخيص الأعطال. أدت طريقتهم بشكل جيد مقارنة بالطرق الأخرى وسمحت بمستوى من القابلية للتفسير.

S. نظام ماهالانوبس-تاجوتشي (MTS).

T. الجيران الأقرب K (KNN).

U. التفسيرات القائمة على القواعد.

VII. التحديات والاتجاهات البحثية للصيانة التنبؤية القابلة للتفسير

A. غرض التفسيرات

المجالات الفيزيائية والزمنية إلى معلومات مجردة على مستوى أعلى.

| المقاييس | وجهة النظر | الوصف |

| D | موضوعي | الفرق بين أداء النموذج وأداء التفسير |

| R | موضوعي | عدد القواعد في التفسيرات |

| F | موضوعي | عدد الميزات في التفسير |

| S | موضوعي | استقرار التفسير |

| الحساسية | موضوعي | قياس الدرجة التي تتأثر بها التفسيرات بالتغييرات الصغيرة في نقاط الاختبار |

| الصلابة | موضوعي | يجب أن تكون المدخلات المماثلة لها تفسيرات مماثلة |

| التزايدية | موضوعي | يجب أن تكون نسب الميزات تزايدية؛ وإلا، فإن الأهمية الصحيحة لا تُحسب |

| صحة التفسير | موضوعي | الحساسية والولاء |

| الولاء | موضوعي | تصف التفسيرات النموذج بشكل صحيح؛ الميزات ونسبها مرتبطة |

| العمومية | موضوعي | مدى إبلاغ تفسير واحد عن الآخرين |

| الثقة | ذاتي | يتم قياسها من خلال استبيانات المستخدمين |

| الفعالية | ذاتي | تقيس فائدة التفسيرات |

| الرضا | ذاتي | سهولة الاستخدام |

B. تقييم التفسيرات

C. إضافة مشاركة الإنسان

د. قيود الدراسة

ثامناً. الخاتمة

REFERENCES

[2] J. Leng, W. Sha, B. Wang, P. Zheng, C. Zhuang, Q. Liu, T. Wuest, D. Mourtzis, and L. Wang, “Industry 5.0: Prospect and retrospect,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, vol. 65, pp. 279-295, Oct. 2022.

[3] F. Longo, A. Padovano, and S. Umbrello, “Value-Oriented and ethical technology engineering in industry 5.0: A Human-Centric perspective for the design of the factory of the future,” NATO Adv. Sci. Inst. Ser. E Appl. Sci., vol. 10, no. 12, p. 4182, Jun. 2020.

[4] S. Nahavandi, “Industry 5.0-a Human-Centric solution,” Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy, vol. 11, no. 16, p. 4371, Aug. 2019.

[5] A. Lavopa and M. Delera, “What is the Fourth Industrial Revolution? | Industrial Analytics Platform,” 2021. [Online]. Available: https: //iap.unido.org/articles/what-fourth-industrial-revolution

[6] L. Cummins, B. Killen, K. Thomas, P. Barrett, S. Rahimi, and M. Seale, “Deep learning approaches to remaining useful life prediction: A survey,” in 2021 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), 2021, pp. 1-9.

[7] T. Speith, “A review of taxonomies of explainable artificial intelligence (xai) methods,” in Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2022, pp. 2239-2250.

[8] J. Zhou, A. H. Gandomi, F. Chen, and A. Holzinger, “Evaluating the quality of machine learning explanations: A survey on methods and metrics,” Electronics, vol. 10, no. 5, p. 593, 2021.

[9] M. Nauta, J. Trienes, S. Pathak, E. Nguyen, M. Peters, Y. Schmitt, J. Schlötterer, M. van Keulen, and C. Seifert, “From anecdotal evidence to quantitative evaluation methods: A systematic review on evaluating explainable ai,” ACM Computing Surveys, 2022.

[10] Y. Rong, T. Leemann, T.-t. Nguyen, L. Fiedler, T. Seidel, G. Kasneci, and E. Kasneci, “Towards human-centered explainable ai: user studies for model explanations,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.11584, 2022.

[11] J. Sharma, M. L. Mittal, and G. Soni, “Condition-based maintenance using machine learning and role of interpretability: a review,” International Journal of System Assurance Engineering and Management, Dec. 2022.

[12] R. Marcinkevičs and J. E. Vogt, “Interpretable and explainable machine learning: A methods-centric overview with concrete examples,” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, p. e1493, 2023.

[13] M. Clinciu and H. Hastie, “A survey of explainable ai terminology,” in Proceedings of the 1st workshop on interactive natural language technology for explainable artificial intelligence (NLAXAI 2019), 2019, pp. 8-13.

[14] S. S. Kim, E. A. Watkins, O. Russakovsky, R. Fong, and A. MonroyHernández, “” help me help the ai”: Understanding how explainability can support human-ai interaction,” in Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2023, pp. 1-17.

[15] S. Neupane, J. Ables, W. Anderson, S. Mittal, and others, “Explainable intrusion detection systems (x-ids): A survey of current methods, challenges, and opportunities,” IEEE, 2022.

[16] A. K. M. Nor, S. R. Pedapati, M. Muhammad, and V. Leiva, “Overview of explainable artificial intelligence for prognostic and health management of industrial assets based on preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 23, Dec. 2021.

[17] S. Ali, T. Abuhmed, S. El-Sappagh, K. Muhammad, J. M. Alonso-Moral, R. Confalonieri, R. Guidotti, J. D. Ser, N. Díaz-Rodríguez, and F. Herrera, “Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI): What we know and what is left to attain trustworthy artificial intelligence,” Inf. Fusion, p. 101805, Apr. 2023.

[18] T. Rojat, R. Puget, D. Filliat, J. Del Ser, R. Gelin, and N. Díaz-Rodríguez, “Explainable artificial intelligence (xai) on timeseries data: A survey,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.00950, 2021.

[19] K. Sokol and P. Flach, “Explainability is in the mind of the beholder: Establishing the foundations of explainable artificial intelligence,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.14466, 2021.

[20] T. A. Schoonderwoerd, W. Jorritsma, M. A. Neerincx, and K. Van Den Bosch, “Human-centered xai: Developing design patterns for explanations of clinical decision support systems,” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, vol. 154, p. 102684, 2021.

[21] P. Lopes, E. Silva, C. Braga, T. Oliveira, and L. Rosado, “Xai systems evaluation: A review of human and computer-centred methods,” Applied Sciences, vol. 12, no. 19, p. 9423, 2022.

[22] S. Vollert, M. Atzmueller, and A. Theissler, “Interpretable machine learning: A brief survey from the predictive maintenance perspective,” in 2021 26th IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA). ieeexplore.ieee.org, Sep. 2021, pp. 01-08.

[23] S. M. Lundberg and S.-I. Lee, “A unified approach to interpreting model predictions,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 30, 2017.

[24] M. T. Ribeiro, S. Singh, and C. Guestrin, “” why should i trust you?” explaining the predictions of any classifier,” in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 2016, pp. 1135-1144.

[25] B. Zhou, A. Khosla, A. Lapedriza, A. Oliva, and A. Torralba, “Learning deep features for discriminative localization,” in 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE, Jun. 2016, pp. 2921-2929.

[26] C. Molnar, Interpretable machine learning. Lulu. com, 2020.

[27] S. B. Ramezani, L. Cummins, B. Killen, R. Carley, S. Rahimi, and M. Seale, “Similarity based methods for faulty pattern detection in predictive maintenance,” in 2021 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), 2021, pp. 207-213.

[28] Y. Wen, F. Rahman, H. Xu, and T.-L. B. Tseng, “Recent advances and trends of predictive maintenance from data-driven machine prognostics perspective,” Measurement, vol. 187, p. 110276, Jan. 2022.

[29] S. B. Ramezani, B. Killen, L. Cummins, S. Rahimi, A. Amirlatifi, and M. Seale, “A survey of hmm-based algorithms in machinery fault prediction,” in 2021 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), 2021, pp. 1-9.

[30] K. L. Tsui, N. Chen, Q. Zhou, Y. Hai, W. Wang et al., “Prognostics and health management: A review on data driven approaches,” Mathematical Problems in Engineering, vol. 2015, 2015.

[31] M. J. Page, D. Moher, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. C. Hoffmann, C. D. Mulrow, L. Shamseer, J. M. Tetzlaff, E. A. Akl, S. E. Brennan et al., “Prisma 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews,” bmj, vol. 372, 2021.

[32] N. R. Haddaway, M. J. Page, C. C. Pritchard, and L. A. McGuinness, “Prisma2020: An r package and shiny app for producing prisma 2020compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis,” Campbell Systematic Reviews, vol. 18, no. 2, p. e1230, 2022.

[33] P. Ding, M. Jia, and H. Wang, “A dynamic structure-adaptive symbolic approach for slewing bearings’ life prediction under variable working conditions,” Structural Health Monitoring, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 273-302, Jan. 2021.

[34] G. Manco, E. Ritacco, P. Rullo, L. Gallucci, W. Astill, D. Kimber, and M. Antonelli, “Fault detection and explanation through big data analysis on sensor streams,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 87, pp. 141156, 2017.

[35] G. Protopapadakis and A. I. Kalfas, “Explainable and interpretable AIAssisted remaining useful life estimation for aeroengines,” ASME Turbo Expo 2022: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, p. V002T05A002, Oct. 2022.

[36] T. Khan, K. Ahmad, J. Khan, I. Khan, and N. Ahmad, “An explainable regression framework for predicting remaining useful life of machines,” in 2022 27th International Conference on Automation and Computing (ICAC). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1-6.

[37] D. Solís-Martín, J. Galán-Páez, and J. Borrego-Díaz, “On the soundness of XAI in prognostics and health management (PHM),” Information, vol. 14, no. 5, p. 256, Apr. 2023.

[38] A. Ferraro, A. Galli, V. Moscato, and G. Sperlì, “Evaluating explainable artificial intelligence tools for hard disk drive predictive maintenance,” Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 56, no. 7, pp. 7279-7314, Jul. 2023.

[39] P. Nectoux, R. Gouriveau, K. Medjaher, E. Ramasso, B. Chebel-Morello, N. Zerhouni, and C. Varnier, “Pronostia: An experimental platform for bearings accelerated degradation tests.” in IEEE International Conference on Prognostics and Health Management, PHM’12. IEEE Catalog Number: CPF12PHM-CDR, 2012, pp. 1-8.

[40] H. Qiu, J. Lee, J. Lin, and G. Yu, “Wavelet filter-based weak signature detection method and its application on rolling element bearing prognostics,” Journal of Sound and Vibration, vol. 289, no. 4, pp. 1066-1090, 2006. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/pii/S0022460X0500221X

[41] R. Yao, H. Jiang, C. Yang, H. Zhu, and C. Liu, “An integrated framework via key-spectrum entropy and statistical properties for bearing dynamic health monitoring and performance degradation assessment,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 187, p. 109955, 2023.

[42] L. C. Brito, G. A. Susto, J. N. Brito, and M. A. Duarte, “An explainable artificial intelligence approach for unsupervised fault detection and diagnosis in rotating machinery,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 163, p. 108105, 2022.

[43] J. Yang, Z. Yue, and Y. Yuan, “Noise-aware sparse gaussian processes and application to reliable industrial machinery health monitoring,” IEEE

[44] O. Mey and D. Neufeld, “Explainable ai algorithms for vibration data-based fault detection: Use case-adadpted methods and critical evaluation,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 23, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/22/23/9037

[45] T. Li, Z. Zhao, C. Sun, L. Cheng, X. Chen, R. Yan, and R. X. Gao, “Waveletkernelnet: An interpretable deep neural network for industrial intelligent diagnosis,” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 2302-2312, 2022.

[46] H. Pu, K. Zhang, and Y. An, “Restricted sparse networks for rolling bearing fault diagnosis,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, pp. 1-11, 2023.

[47] G. Xin, Z. Li, L. Jia, Q. Zhong, H. Dong, N. Hamzaoui, and J. Antoni, “Fault diagnosis of wheelset bearings in high-speed trains using logarithmic short-time fourier transform and modified self-calibrated residual network,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 18, no. 10, pp. 7285-7295, 2022.

[48] L. C. Brito, G. A. Susto, J. N. Brito, and M. A. V. Duarte, “Fault diagnosis using explainable ai: A transfer learning-based approach for rotating machinery exploiting augmented synthetic data,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 232, p. 120860, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0957417423013623

[49] F. Ben Abid, M. Sallem, and A. Braham, “An end-to-end bearing fault diagnosis and severity assessment with interpretable deep learning.” Journal of Electrical Systems, vol. 18, no. 4, 2022.

[50] D. C. Sanakkayala, V. Varadarajan, N. Kumar, Karan, G. Soni, P. Kamat, S. Kumar, S. Patil, and K. Kotecha, “Explainable ai for bearing fault prognosis using deep learning techniques,” Micromachines, vol. 13, no. 9, p. 1471, 2022.

[51] O. Serradilla, E. Zugasti, C. Cernuda, A. Aranburu, J. R. de Okariz, and U. Zurutuza, “Interpreting remaining useful life estimations combining explainable artificial intelligence and domain knowledge in industrial machinery,” in 2020 IEEE international conference on fuzzy systems (FUZZ-IEEE). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1-8.

[52] R. Kothamasu and S. H. Huang, “Adaptive mamdani fuzzy model for condition-based maintenance,” Fuzzy sets and Systems, vol. 158, no. 24, pp. 2715-2733, 2007.

[53] E. Lughofer, P. Zorn, and E. Marth, “Transfer learning of fuzzy classifiers for optimized joint representation of simulated and measured data in anomaly detection of motor phase currents,” Applied Soft Computing, vol. 124, p. 109013, 2022.

[54] A. L. Alfeo, M. G. C. A. Cimino, and G. Vaglini, “Degradation stage classification via interpretable feature learning,” Journal of Manufacturing Systems, vol. 62, pp. 972-983, Jan. 2022.

[55] J. Wang, M. Xu, C. Zhang, B. Huang, and F. Gu, “Online bearing clearance monitoring based on an accurate vibration analysis,” Energies, vol. 13, no. 2, p. 389, 2020.

[56] W. Wang, Z. Peng, S. Wang, H. Li, M. Liu, L. Xue, and N. Zhang, “Ifpadac: A two-stage interpretable fault prediction model for multivariate time series,” in 2021 22nd IEEE International Conference on Mobile Data Management (MDM). IEEE, 2021, pp. 29-38.

[57] C. Panda and T. R. Singh, “Ml-based vehicle downtime reduction: A case of air compressor failure detection,” Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, vol. 122, p. 106031, 2023.

[58] S. Xia, X. Zhou, H. Shi, S. Li, and C. Xu, “A fault diagnosis method with multi-source data fusion based on hierarchical attention for auv,” Ocean Engineering, vol. 266, p. 112595, 2022.

[59] Y. Fan, H. Sarmadi, and S. Nowaczyk, “Incorporating physics-based models into data driven approaches for air leak detection in city buses,” in Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. Springer, 2022, pp. 438-450.

[60] W. Li, H. Lan, J. Chen, K. Feng, and R. Huang, “Wavcapsnet: An interpretable intelligent compound fault diagnosis method by backward tracking,” IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 72, pp. 1-11, 2023.

[61] G. B. Jang and S. B. Cho, “Anomaly detection of 2.41 diesel engine using one-class svm with variational autoencoder,” in Proc. Annual Conference of the Prognostics and Health Management Society, vol. 11, no. 1, 2019.

[62] Y. Ming, P. Xu, H. Qu, and L. Ren, “Interpretable and steerable sequence learning via prototypes,” in Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 2019, pp. 903-913.

[63] C. Oh, J. Moon, and J. Jeong, “Explainable process monitoring based on class activation map: Garbage in, garbage out,” in IoT Streams for DataDriven Predictive Maintenance and IoT, Edge, and Mobile for Embedded Machine Learning, J. Gama, S. Pashami, A. Bifet, M. Sayed-Mouchawe, H. Fröning, F. Pernkopf, G. Schiele, and M. Blott, Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020, pp. 93-105.

[64] A. B. Hafeez, E. Alonso, and A. Riaz, “Dtcencoder: A swiss army knife architecture for dtc exploration, prediction, search and model interpretation,” in 2022 21st IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 519-524.

[65] R. P. Ribeiro, S. M. Mastelini, N. Davari, E. Aminian, B. Veloso, and J. Gama, “Online anomaly explanation: A case study on predictive maintenance,” in Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. Springer, 2022, pp. 383-399.

[66] X. Li, Y. Sun, and W. Yu, “Automatic and interpretable predictive maintenance system,” in SAE Technical Paper Series, no. 2021-01-0247. 400 Commonwealth Drive, Warrendale, PA, United States: SAE International, Apr. 2021.

[67] S. Voronov, D. Jung, and E. Frisk, “A forest-based algorithm for selecting informative variables using variable depth distribution,” Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence, vol. 97, p. 104073, 2021.

[68] J.-H. Han, S.-U. Park, and S.-K. Hong, “A study on the effectiveness of current data in motor mechanical fault diagnosis using XAI,” Journal of Electrical Engineering & Technology, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 3329-3335, Nov. 2022.

[69] A. Saxena and K. Goebel, “Turbofan engine degradation simulation data set,” NASA ames prognostics data repository, vol. 18, 2008.

[70] A. Brunello, D. Della Monica, A. Montanari, N. Saccomanno, and A. Urgolo, “Monitors that learn from failures: Pairing stl and genetic programming,” IEEE Access, 2023.

[71] Z. Wu, H. Luo, Y. Yang, P. Lv, X. Zhu, Y. Ji, and B. Wu, “K-pdm: Kpioriented machinery deterioration estimation framework for predictive maintenance using cluster-based hidden markov model,” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 41676-41687, 2018.

[72] J. Jakubowski, P. Stanisz, S. Bobek, and G. J. Nalepa, “Anomaly detection in asset degradation process using variational autoencoder and explanations,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 291, 2021.

[73] A. Brunello, D. Della Monica, A. Montanari, and A. Urgolo, “Learning how to monitor: Pairing monitoring and learning for online system verification.” in OVERLAY, 2020, pp. 83-88.

[74] N. Costa and L. Sánchez, “Variational encoding approach for interpretable assessment of remaining useful life estimation,” Reliability Engineering & System Safety, vol. 222, p. 108353, 2022.

[75] M. Sayed-Mouchaweh and L. Rajaoarisoa, “Explainable decision support tool for iot predictive maintenance within the context of industry 4.0,” in 2022 21st IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1492-1497.

[76] J. Jakubowski, P. Stanisz, S. Bobek, and G. J. Nalepa, “Performance of explainable AI methods in asset failure prediction,” in Computational Science – ICCS 2022. Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 472485.

[77] E. Kononov, A. Klyuev, and M. Tashkinov, “Prediction of technical state of mechanical systems based on interpretive neural network model,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 4, Feb. 2023.

[78] T. Jing, P. Zheng, L. Xia, and T. Liu, “Transformer-based hierarchical latent space VAE for interpretable remaining useful life prediction,” Advanced Engineering Informatics, vol. 54, p. 101781, Oct. 2022.

[79] K. Waghen and M.-S. Ouali, “A Data-Driven fault tree for a time causality analysis in an aging system,” Algorithms, vol. 15, no. 6, p. 178, May 2022.

[80] A. N. Abbas, G. C. Chasparis, and J. D. Kelleher, “Interpretable InputOutput hidden markov Model-Based deep reinforcement learning for the predictive maintenance of turbofan engines,” in Big Data Analytics and Knowledge Discovery. Springer International Publishing, 2022, pp. 133148.

[81] J. Brito and R. Pederiva, “Using artificial intelligence tools to detect problems in induction motors,” in Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Soft Computing and Intelligent Systems (International Session of 8th SOFT Fuzzy Systems Symposium) and 3rd International Symposium on Advanced Intelligent Systems (SCIS and ISIS 2002), vol. 1, 2002, pp. 1-6.

[82] A.-C. Glock, “Explaining a random forest with the difference of two arima models in an industrial fault detection scenario,” Procedia Computer Science, vol. 180, pp. 476-481, 2021.

[83] S. Matzka, “Explainable artificial intelligence for predictive maintenance applications,” in 2020 third international conference on artificial intelligence for industries (ai4i). IEEE, 2020, pp. 69-74.

[84] A. Torcianti and S. Matzka, “Explainable artificial intelligence for predictive maintenance applications using a local surrogate model,” in 2021 4th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence for Industries (AI4I). IEEE, 2021, pp. 86-88.

[85] Y. Remil, A. Bendimerad, M. Plantevit, C. Robardet, and M. Kaytoue, “Interpretable summaries of black box incident triaging with subgroup discovery,” in 2021 IEEE 8th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Oct. 2021, pp. 1-10.

[86] B. Ghasemkhani, O. Aktas, and D. Birant, “Balanced K-Star: An explainable machine learning method for Internet-of-Things-Enabled predictive maintenance in manufacturing,” Machines, vol. 11, no. 3, p. 322, Feb. 2023.

[87] J. Liu, S. Zheng, and C. Wang, “Causal graph attention network with disentangled representations for complex systems fault detection,” Reliability Engineering & System Safety, vol. 235, p. 109232, 2023.

[88] A. Trilla, N. Mijatovic, and X. Vilasis-Cardona, “Unsupervised probabilistic anomaly detection over nominal subsystem events through a hierarchical variational autoencoder,” International Journal of Prognostics and Health Management, vol. 14, no. 1, 2023.

[89] I. Errandonea, P. Ciáurriz, U. Alvarado, S. Beltrán, and S. Arrizabalaga, “Edge intelligence-based proposal for onboard catenary stagger amplitude diagnosis,” Computers in Industry, vol. 144, p. 103781, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0166361522001774

[90] B. Steenwinckel, D. De Paepe, S. V. Hautte, P. Heyvaert, M. Bentefrit, P. Moens, A. Dimou, B. Van Den Bossche, F. De Turck, S. Van Hoecke et al., “Flags: A methodology for adaptive anomaly detection and root cause analysis on sensor data streams by fusing expert knowledge with machine learning,” Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 116, pp. 30-48, 2021.

[91] H. Li, D. Parikh, Q. He, B. Qian, Z. Li, D. Fang, and A. Hampapur, “Improving rail network velocity: A machine learning approach to predictive maintenance,” Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, vol. 45, pp. 17-26, 2014.

[92] Z. Allah Bukhsh, A. Saeed, I. Stipanovic, and A. G. Doree, “Predictive maintenance using tree-based classification techniques: A case of railway switches,” Transp. Res. Part C: Emerg. Technol., vol. 101, pp. 35-54, Apr. 2019.

[93] P. Cao, S. Zhang, and J. Tang, “Preprocessing-free gear fault diagnosis using small datasets with deep convolutional neural network-based transfer learning,” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 26241-26253, 2018.

[94] G. Hajgató, R. Wéber, B. Szilágyi, B. Tóthpál, B. Gyires-Tóth, and C. Hős, “PredMaX: Predictive maintenance with explainable deep convolutional autoencoders,” Advanced Engineering Informatics, vol. 54, p. 101778, Oct. 2022.

[95] J. Jakubowski, P. Stanisz, S. Bobek, and G. J. Nalepa, “Explainable anomaly detection for hot-rolling industrial process,” in 2021 IEEE 8th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1-10.

[96] N. Mylonas, I. Mollas, N. Bassiliades, and G. Tsoumakas, “Local multilabel explanations for random forest,” in Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. Springer, 2022, pp. 369-384.

[97] J. Jakubowski, P. Stanisz, S. Bobek, and G. J. Nalepa, “Roll wear prediction in strip cold rolling with physics-informed autoencoder and counterfactual explanations,” in 2022 IEEE 9th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1-10.

[98] W. Xu, Z. Zhou, T. Li, C. Sun, X. Chen, and R. Yan, “Physics-constraint variational neural network for wear state assessment of external gear pump,” IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 2022.

[99] J. M. F. Salido and S. Murakami, “A comparison of two learning mechanisms for the automatic design of fuzzy diagnosis systems for rotating machinery,” Applied Soft Computing, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 413-422, 2004.

[100] R. Langone, A. Cuzzocrea, and N. Skantzos, “Interpretable anomaly prediction: Predicting anomalous behavior in industry 4.0 settings via regularized logistic regression tools,” Data & Knowledge Engineering, vol. 130, p. 101850, 2020.

[101] V. M. Janakiraman, “Explaining aviation safety incidents using deep temporal multiple instance learning,” in Proceedings of the 24th ACM

[102] M. Berno, M. Canil, N. Chiarello, L. Piazzon, F. Berti, F. Ferrari, A. Zaupa, N. Ferro, M. Rossi, and G. A. Susto, “A machine learning-based approach for advanced monitoring of automated equipment for the entertainment industry,” in 2021 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 & IoT (MetroInd4. 0&IoT). IEEE, 2021, pp. 386-391.

[103] E. Anello, C. Masiero, F. Ferro, F. Ferrari, B. Mukaj, A. Beghi, and G. A. Susto, “Anomaly detection for the industrial internet of things: an unsupervised approach for fast root cause analysis,” in 2022 IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications (CCTA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1366-1371.

[104] D. Marcato, G. Arena, D. Bortolato, F. Gelain, V. Martinelli, E. Munaron, M. Roetta, G. Savarese, and G. A. Susto, “Machine learning-based anomaly detection for particle accelerators,” in 2021 IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications (CCTA). IEEE, 2021, pp. 240246.

[105] L. Felsberger, A. Apollonio, T. Cartier-Michaud, A. Müller, B. Todd, and D. Kranzlmüller, “Explainable deep learning for fault prognostics in complex systems: A particle accelerator use-case,” in Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction: 4th IFIP TC 5, TC 12, WG 8.4, WG 8.9, WG 12.9 International Cross-Domain Conference, CD-MAKE 2020, Dublin, Ireland, August 25-28, 2020, Proceedings 4. Springer, 2020, pp. 139158.

[106] P. Bellini, D. Cenni, L. A. I. Palesi, P. Nesi, and G. Pantaleo, “A deep learning approach for short term prediction of industrial plant working status,” in 2021 IEEE Seventh International Conference on Big Data Computing Service and Applications (BigDataService). IEEE, 2021, pp. 9-16.

[107] H. Choi, D. Kim, J. Kim, J. Kim, and P. Kang, “Explainable anomaly detection framework for predictive maintenance in manufacturing systems,” Applied Soft Computing, vol. 125, p. 109147, 2022.

[108] D. Kim, G. Antariksa, M. P. Handayani, S. Lee, and J. Lee, “Explainable anomaly detection framework for maritime main engine sensor data,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 15, p. 5200, 2021.

[109] K. Michałowska, S. Riemer-Sørensen, C. Sterud, and O. M. Hjellset, “Anomaly detection with unknown anomalies: Application to maritime machinery,” IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 54, no. 16, pp. 105-111, 2021.

[110] A. Bakdi, N. B. Kristensen, and M. Stakkeland, “Multiple instance learning with random forest for event logs analysis and predictive maintenance in ship electric propulsion system,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf., vol. 18, no. 11, pp. 7718-7728, Nov. 2022.

[111] M. McCann and A. Johnston, “SECOM,” UCI Machine Learning Repository, 2008, DOI: https://doi.org/10.24432/C54305.

[112] M. Gashi, B. Mutlu, and S. Thalmann, “Impact of interdependencies: Multi-component system perspective toward predictive maintenance based on machine learning and xai,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 5, p. 3088, 2023.

[113] Q. Cao, C. Zanni-Merk, A. Samet, F. d. B. de Beuvron, and C. Reich, “Using rule quality measures for rule base refinement in knowledgebased predictive maintenance systems,” Cybernetics and Systems, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 161-176, 2020.

[114] A. Klein, “Hard drive failure rates: A look at drive reliability,” Jul 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.backblaze.com/blog/ backblaze-hard-drive-stats-q1-2020/

[115] M. Amram, J. Dunn, J. J. Toledano, and Y. D. Zhuo, “Interpretable predictive maintenance for hard drives,” Machine Learning with Applications, vol. 5, p. 100042, Sep. 2021.

[116] I. Katser, V. Kozitsin, V. Lobachev, and I. Maksimov, “Unsupervised offline changepoint detection ensembles,” Applied Sciences, vol. 11, no. 9, p. 4280, 2021.

[117] D. Dua and C. Graff, “Uci machine learning repository,” 2017. [Online]. Available: http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml

[118] K. Scott, D. Kakde, S. Peredriy, and A. Chaudhuri, “Computational enhancements to the mahalanobis-taguchi system to improve fault detection and diagnostics,” in 2023 Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium (RAMS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1-7.

[119] K. S. Hansen, N. Vasiljevic, and S. A. Sørensen, “Wind farm measurements,” May 2021. [Online]. Available: https://data.dtu.dk/ collections/Wind_Farm_measurements/5405418/3

[120] C. M. Roelofs, M.-A. Lutz, S. Faulstich, and S. Vogt, “Autoencoder-based anomaly root cause analysis for wind turbines,” Energy and AI, vol. 4, p. 100065, 2021.

[121] M. Beretta, A. Julian, J. Sepulveda, J. Cusidó, and O. Porro, “An ensemble learning solution for predictive maintenance of wind turbines main bearing,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 4, Feb. 2021.

[122] M. Beretta, Y. Vidal, J. Sepulveda, O. Porro, and J. Cusidó, “Improved ensemble learning for wind turbine main bearing fault diagnosis,” Applied Sciences, vol. 11, no. 16, 2021. [Online]. Available: https: //www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/11/16/7523

[123] S. J. Upasane, H. Hagras, M. H. Anisi, S. Savill, I. Taylor, and K. Manousakis, “A big bang-big crunch type-2 fuzzy logic system for explainable predictive maintenance,” in 2021 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems (FUZZ-IEEE). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1-8.

[124] P. M. Attia, A. Grover, N. Jin, K. A. Severson, T. M. Markov, Y.-H. Liao, M. H. Chen, B. Cheong, N. Perkins, Z. Yang et al., “Closedloop optimization of fast-charging protocols for batteries with machine learning,” Nature, vol. 578, no. 7795, pp. 397-402, 2020.

[125] R. Csalódi, Z. Bagyura, and J. Abonyi, “Mixture of survival analysis models-cluster-weighted weibull distributions,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 152288-152299, 2021.

[126] F. Wang, Z. Zhao, Z. Zhai, Z. Shang, R. Yan, and X. Chen, “Explainability-driven model improvement for SOH estimation of lithium-ion battery,” Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf., vol. 232, p. 109046, Apr. 2023.

[127] B. Verkuil, C. E. Budde, and D. Bucur, “Automated fault tree learning from continuous-valued sensor data: a case study on domestic heaters,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.07374, 2022.

[128] L. Lorenti, G. De Rossi, A. Annoni, S. Rigutto, and G. A. Susto, “Cuadmo: Continuos unsupervised anomaly detection on machining operations,” in 2022 IEEE Conference on Control Technology and Applications (CCTA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 881-886.

[129] B. A. ugli Olimov, K. C. Veluvolu, A. Paul, and J. Kim, “Uzadl: Anomaly detection and localization using graph laplacian matrix-based unsupervised learning method,” Computers & Industrial Engineering, vol. 171, p. 108313, 2022.

[130] A. Lourenço, M. Fernandes, A. Canito, A. Almeida, and G. Marreiros, “Using an explainable machine learning approach to minimize opportunistic maintenance interventions,” in International Conference on Practical Applications of Agents and Multi-Agent Systems. Springer, 2022, pp. 41-54.

[131] O. Serradilla, E. Zugasti, J. Ramirez de Okariz, J. Rodriguez, and U. Zurutuza, “Adaptable and explainable predictive maintenance: Semisupervised deep learning for anomaly detection and diagnosis in press machine data,” Applied Sciences, vol. 11, no. 16, p. 7376, 2021.

[132] M. Hermansa, M. Kozielski, M. Michalak, K. Szczyrba, Ł. Wróbel, and M. Sikora, “Sensor-based predictive maintenance with reduction of false alarms-a case study in heavy industry,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 226, 2021.

[133] D. Xu, W. Cheng, J. Ni, D. Luo, M. Natsumeda, D. Song, B. Zong, H. Chen, and X. Zhang, “Deep multi-instance contrastive learning with dual attention for anomaly precursor detection,” in Proceedings of the 2021 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining (SDM). SIAM, 2021, pp. 91-99.

[134] B. Steurtewagen and D. Van den Poel, “Adding interpretability to predictive maintenance by machine learning on sensor data,” Computers & Chemical Engineering, vol. 152, p. 107381, 2021.

[135] A. T. Keleko, B. Kamsu-Foguem, R. H. Ngouna, and A. Tongne, “Health condition monitoring of a complex hydraulic system using deep neural network and deepshap explainable xai,” Advances in Engineering Software, vol. 175, p. 103339, 2023.

[136] G. Chen, M. Liu, and Z. Kong, “Temporal-logic-based semantic fault diagnosis with time-series data from industrial internet of things,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 68, no. 5, pp. 4393-4403, 2020.

[137] A. Schmetz, C. Vahl, Z. Zhen, D. Reibert, S. Mayer, D. Zontar, J. Garcke, and C. Brecher, “Decision support by interpretable machine learning in acoustic emission based cutting tool wear prediction,” in 2021 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM). ieeexplore.ieee.org, Dec. 2021, pp. 629-633.

[138] T. V. Addison Howard, Sohier Dane, “Vsb power line fault detection,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://kaggle.com/competitions/ vsb-power-line-fault-detection

[139] S. Simmons, L. Jarvis, D. Dempsey, and A. W. Kempa-Liehr, “Data mining on extremely long Time-Series,” in 2021 International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), Dec. 2021, pp. 1057-1066.

[140] Y. Zhang, P. Wang, K. Liang, Y. He, and S. Ma, “An alarm and fault association rule extraction method for power equipment based on explainable decision tree,” in 2021 11th International Conference on Power and Energy Systems (ICPES), Dec. 2021, pp. 442-446.

[141] S. J. Upasane, H. Hagras, M. H. Anisi, S. Savill, I. Taylor, and K. Manousakis, “A type-2 fuzzy based explainable AI system for predictive maintenance within the water pumping industry,” IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, pp. 1-14, 2023.

[142] L. Xia, Y. Liang, J. Leng, and P. Zheng, “Maintenance planning recommendation of complex industrial equipment based on knowledge graph and graph neural network,” Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf., vol. 232, p. 109068, Apr. 2023.

[143] G. Tod, A. P. Ompusunggu, and E. Hostens, “An improved first-principle model of AC powered solenoid operated valves for maintenance applications,” ISA Trans., vol. 135, pp. 551-566, Apr. 2023.

[144] M. Mahmoodian, F. Shahrivar, S. Setunge, and S. Mazaheri, “Development of digital twin for intelligent maintenance of civil infrastructure,” Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy, vol. 14, no. 14, p. 8664, Jul. 2022.

[145] I. Konovalenko and A. Ludwig, “Generating decision support for alarm processing in cold supply chains using a hybrid

[146] A. Dhaou, A. Bertoncello, S. Gourvénec, J. Garnier, and E. Le Pennec, “Causal and interpretable rules for time series analysis,” in Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, ser. KDD ’21. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, Aug. 2021, pp. 2764-2772.

[147] [Online]. Available: https://catalogue.data.wa.gov.au/dataset/ water-pipe-wcorp-002

[148] P. Castle, J. Ham, M. Hodkiewicz, and A. Polpo, “Interpretable survival models for predictive maintenance,” in 30th European Safety and Reliability Conference and 15th Probabilistic Safety Assessment and Management Conference. research-repository.uwa.edu.au, 2020, pp. 3392-3399.

[149] V. Belle and I. Papantonis, “Principles and practice of explainable machine learning,” Front Big Data, vol. 4, p. 688969, Jul. 2021.

[150] A. Saabas, “Interpreting random forests,” Oct 2014. [Online]. Available: http://blog.datadive.net/interpreting-random-forests/

[151] S. Bach, A. Binder, G. Montavon, F. Klauschen, K.-R. Müller, and W. Samek, “On Pixel-Wise explanations for Non-Linear classifier decisions by Layer-Wise relevance propagation,” PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 7, p. e0130140, Jul. 2015.

[152] Y. LeCun, L. Bottou, Y. Bengio, and P. Haffner, “Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 86, no. 11, pp. 2278-2324, 1998.

[153] M. Sundararajan, A. Taly, and Q. Yan, “Axiomatic attribution for deep networks,” in Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, ser. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, D. Precup and Y. W. Teh, Eds., vol. 70. PMLR, 2017, pp. 3319-3328.

[154] D. Janzing, D. Balduzzi, M. Grosse-Wentrup, and B. Schölkopf, “Quantifying causal influences,” aos, vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 2324-2358, Oct. 2013.

[155] D. Dandolo, C. Masiero, M. Carletti, D. Dalle Pezze, and G. A. Susto, “AcME-Accelerated model-agnostic explanations: Fast whitening of the machine-learning black box,” Expert Syst. Appl., vol. 214, p. 119115, Mar. 2023.

[156] D. Smilkov, N. Thorat, B. Kim, F. Viégas, and M. Wattenberg, “Smoothgrad: removing noise by adding noise,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.03825, 2017.

[157] S. Wachter, B. Mittelstadt, and C. Russell, “Counterfactual explanations without opening the black box: Automated decisions and the GDPR,” Harv. JL & Tech., 2017.

[158] TeamHG-Memex, “Teamhg-memex/eli5: A library for debugging/inspecting machine learning classifiers and explaining their predictions.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/TeamHG-Memex/eli5

[159] R. R. Selvaraju, M. Cogswell, A. Das, R. Vedantam, D. Parikh, and D. Batra, “Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradientbased localization,” Int. J. Comput. Vis., vol. 128, no. 2, pp. 336-359, Feb. 2020.

[160] M. Carletti, M. Terzi, and G. A. Susto, “Interpretable anomaly detection with DIFFI: Depth-based feature importance of isolation forest,” Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell., vol. 119, p. 105730, Mar. 2023.

[161] I. Mollas, N. Bassiliades, and G. Tsoumakas, “Conclusive local interpretation rules for random forests,” Data Min. Knowl. Discov., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 1521-1574, Jul. 2022.

[162] “AI4I 2020 Predictive Maintenance Dataset,” UCI Machine Learning Repository, 2020, DOI: https://doi.org/10.24432/C5HS5C.

[163] K. Simonyan, A. Vedaldi, and A. Zisserman, “Deep inside convolutional networks: Visualising image classification models and saliency maps,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6034, 2013.

[164] Vaswani, Shazeer, Parmar, and others, “Attention is all you need,” Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst., 2017.

[165] L. A. Zadeh, “Fuzzy logic,” Computer, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 83-93, Apr. 1988.

[166] M. Ravanelli and Y. Bengio, “Speaker recognition from raw waveform with sincnet,” in 2018 IEEE spoken language technology workshop (SLT). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1021-1028.

[167] J. N. Morgan and J. A. Sonquist, “Problems in the analysis of survey data, and a proposal,” Journal of the American statistical association, vol. 58, no. 302, pp. 415-434, 1963.

[168] D. Bertsimas and J. Dunn, “Optimal classification trees,” Machine Learning, vol. 106, pp. 1039-1082, 2017.

[169] D. Bertsimas, J. Dunn, E. Gibson, and A. Orfanoudaki, “Optimal survival trees,” Machine Learning, vol. 111, no. 8, pp. 2951-3023, 2022.

[170] G. Ke, Q. Meng, T. Finley, T. Wang, W. Chen, W. Ma, Q. Ye, and T.Y. Liu, “Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 30, 2017.

[171] H. A. Watson et al., “Launch control safety study,” Bell labs, 1961.

[172] Student, “The probable error of a mean,” Biometrika, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1-25, 1908.

[173] K. Pearson, “X. on the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling,” The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, vol. 50, no. 302, pp. 157-175, 1900.

[174] P. Veličković, G. Cucurull, A. Casanova, A. Romero, P. Lio, and Y. Bengio, “Graph attention networks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.10903, 2017.

[175] D. A. Reynolds et al., “Gaussian mixture models.” Encyclopedia of biometrics, vol. 741, no. 659-663, 2009.

[176] H. Nori, S. Jenkins, P. Koch, and R. Caruana, “Interpretml: A unified framework for machine learning interpretability,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.09223, 2019.

[177] L. E. Baum and T. Petrie, “Statistical inference for probabilistic functions of finite state markov chains,” The annals of mathematical statistics, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 1554-1563, 1966.

[178] O. Maler and D. Nickovic, “Monitoring temporal properties of continuous signals,” in International Symposium on Formal Techniques in RealTime and Fault-Tolerant Systems. Springer, 2004, pp. 152-166.

[179] M. Grieves and J. Vickers, “Digital twin: Mitigating unpredictable, undesirable emergent behavior in complex systems,” Transdisciplinary perspectives on complex systems: New findings and approaches, pp. 85113, 2017.

[180] D. A. Augusto and H. J. Barbosa, “Symbolic regression via genetic programming,” in Proceedings. Vol. 1. Sixth Brazilian symposium on neural networks. IEEE, 2000, pp. 173-178.

[181] T. Hastie and R. Tibshirani, “Generalized additive models,” Stat. Sci., vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 297-310, Aug. 1986.

[182] G. Taguchi, G. Taguchi, and R. Jugulum, The Mahalanobis-Taguchi strategy: A pattern technology system. John Wiley & Sons, 2002.

[183] E. Fix and J. L. Hodges, “Discriminatory analysis. nonparametric discrimination: Consistency properties,” International Statistical Review/Revue Internationale de Statistique, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 238-247, 1989.

[184] A. Barredo Arrieta, N. Díaz-Rodríguez, J. Del Ser, A. Bennetot, S. Tabik, A. Barbado, S. Garcia, S. Gil-Lopez, D. Molina, R. Benjamins, R. Chatila, and F. Herrera, “Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI,” Inf. Fusion, vol. 58, pp. 82-115, Jun. 2020.

[185] T. Miller, “Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences,” Artif. Intell., vol. 267, pp. 1-38, Feb. 2019.

[186] L. Coroama and A. Groza, “Evaluation metrics in explainable artificial intelligence (xai),” in International Conference on Advanced Research in Technologies, Information, Innovation and Sustainability. Springer, 2022, pp. 401-413.

[187] M. Sisk, M. Majlis, C. Page, and A. Yazdinejad, “Analyzing xai metrics: Summary of the literature review,” TechRxiv preprint techrxiv.21262041.v1, 2022.

[188] M. A. Kadir, A. Mosavi, and D. Sonntag, “Assessing xai: Unveiling evaluation metrics for local explanation, taxonomies, key concepts, and practical applications,” engrXiv preprint, 2023.

[189] R. R. Hoffman, S. T. Mueller, G. Klein, and J. Litman, “Metrics for explainable ai: Challenges and prospects,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.04608, 2018.

their B.S. degree in Computer Science and Engineering from Mississippi State University. They are currently pursuing a Ph.D degree in Computer Science at Mississippi State University with a minor in Cognitive Science.

ceived his B.S. in Computer Science from Saint Vincent Collage and his M.S. in Computer Science from Southern Illinois University. He is pursuing A Ph.D. in Computer Science at Mississippi State University with a concentration in machine learning.

IEEE) received the B.S. degree in computer engineering and the M.S. degree in information technology engineering from the Iran University of Science and Technology, in 2004 and 2008, respectively. She is currently pursuing the Ph.D. degree in computer science with Mississippi State University.

He is a member of the IEEE New Standards Committee in Computational Intelligence. He provides advice to staff and administration at the federal government on predictive analytics for foreign policy. He was a recipient of the 2016 Illinois Rising Star Award from ISBA, selected among 100s of highly qualified candidates. His intelligent algorithm for patient flow optimization and hospital staffing is currently used in over 1000 emergency departments across the nation. He was named one of the top ten AI technology for healthcare, in 2018, by HealthTech Magazine. He has secured over

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2024.3391130

Publication Date: 2024-01-01

Explainable Predictive Maintenance: A Survey of Current Methods, Challenges and Opportunities

The views and conclusions contained herein are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Army ERDC or the U.S. DoD. Authors would also like to thank

Mississippi State University’s Predictive Analytics and Technology Integration (PATENT) Laboratory for its support.

Abstract

Predictive maintenance is a well studied collection of techniques that aims to prolong the life of a mechanical system by using artificial intelligence and machine learning to predict the optimal time to perform maintenance. The methods allow maintainers of systems and hardware to reduce financial and time costs of upkeep. As these methods are adopted for more serious and potentially life-threatening applications, the human operators need trust the predictive system. This attracts the field of Explainable AI (XAI) to introduce explainability and interpretability into the predictive system. XAI brings methods to the field of predictive maintenance that can amplify trust in the users while maintaining well-performing systems. This survey on explainable predictive maintenance (XPM) discusses and presents the current methods of XAI as applied to predictive maintenance while following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. We categorize the different XPM methods into groups that follow the XAI literature. Additionally, we include current challenges and a discussion on future research directions in XPM.

I. INTRODUCTION

tive maintenance ( Pd M ). PdM encompasses many different problems in the field of maintenance, but an overarching representation of PdM involves monitoring the system as it is in the present and alerting for any potential problems such as a specific anomaly or time until failure [1], [6]. While this problem that exists in the cyber-physical realm has been well studied from the perspective of deep learning models, statistical models, and more, the people that get impacted by these systems have had considerably less attention. This change of focus leads us into the fifth industrial revolution or Industry 5.0.

II. BACKGROUND

A. EXPLAINABILITY AND INTERPRETABILITY IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

1) Explainable Artificial Intelligence

these methods is the endeavor to interpret the workings of an already-trained model. As Sokol et al. succinctly put it, explainability is for the model’s output [19]. From a more analytical standpoint, XAI predominantly encompasses posthoc strategies to shed light on otherwise opaque, black-box models [16]. This paradigm is illustrated in Figure 1, where a model’s explanations are constructed to enhance user comprehension.

Explainable methods can be categorized based on their suitability for addressing various types of black-box models. Methods that are applicable to models regardless of their architecture are called model-agnostic. Common methods that fall into this category are Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) [23] and Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) [24]. These methods and additional modelagnostic methods are described in Section V-A. The opposite of these methods are known as model-specific. Modelspecific methods such as Class Activation Mapping (CAM) [25] for Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are designed to take advantage of the architecture already to provide explainability. These methods and others are described in Section V-B.

b: Local Explanations and Global Explanations.

c: XAI Example

decision tree, etc., to serve as a surrogate for post-hoc explanations. These explanations would then be presented to the user/developer/stakeholder to better explain the behavior of an inherent black-box architecture.

2) Interpretable Machine Learning

B. PREDICTIVE MAINTENANCE

deals with predicting the remaining useful life (RUL) or time until failure [1], [6], [28]. This puts prognosis in the domain of regression problems. Now that these terms are defined and categorized into their different problems, we can discuss the PRISMA compliant systematic search that we performed.

III. SYSTEMATIC SEARCH

A. IDENTIFICATION

B. EXCLUSION CRITERIA AND SCREENING

- Neither XAI nor iML are a main focus of the article.

- Articles are not PdM case studies.

- No explanation or interpretation is provided.

- Three mention XAI/iML in the abstract but do not utilize any methods that we could find.

- Two were neither XAI nor iML. These mention search terms in the abstracts, but do not build on them.

- Three offer no interpretations of their interpretive method.

- Two mention PdM in the abstract but do not focus on PdM in an experiment.

- One was not a case study.

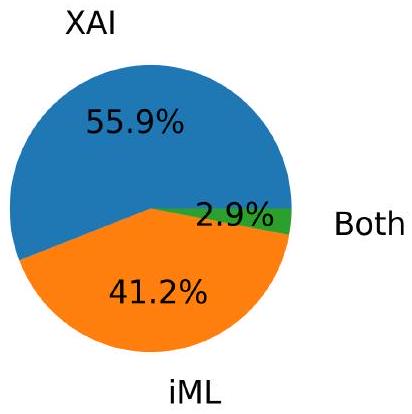

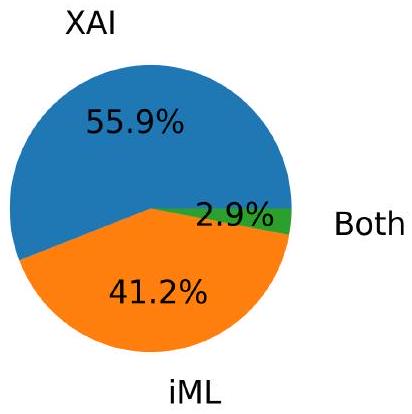

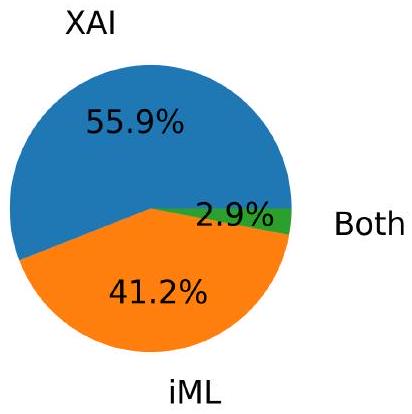

C. INCLUSION

IV. SEARCH RESULTS

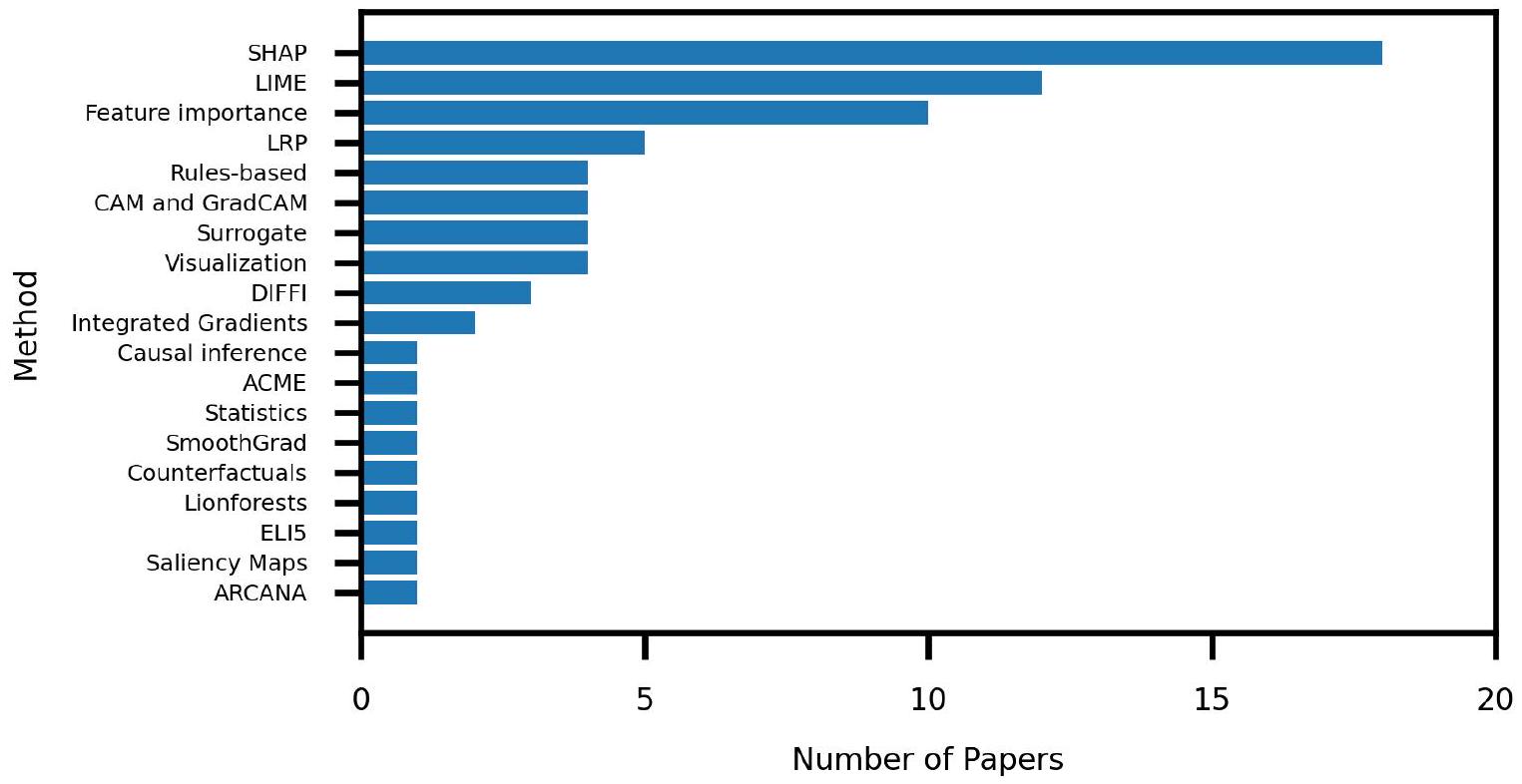

V. EXPLAINABLE AI IN PREDICTIVE MAINTENANCE

A. MODEL-AGNOSTIC

- Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP).

| Datasets | Articles |

| Bearings and PRONOSTIA [39], 40] | |41|-|53 |

| [33], [37], [54], |55] | |

| Vehicles or vehicle subsystem | [56]-|68 |

| CMAPSS [69] | [35]-|37], |70|-|79| |

| [80] | |

| General Machine Faults and Failures 81 | [42], [48], |82|-|86] |

| Trains | [34], |87-|92 |

| Gearboxes [93] | |42|, 45, 48, |94| |

| Artificial Dataset | [44, 95, 96 |

| Hot or Cold Rolling Steel | [72], |95|, |97] |

| Mechanical Pump | [98-|100] |

| Aircraft | [52],101 |

| Amusement Park Rides | [102],103 |

| Particle Accelerators | [104, 1105 |

| Chemical plant | [106, 107 |

| Maritime | [108-110 |

| Semi-conductors |111| | |112|, 113 |

| Air Conditioners | 56 |

| Hard Drives [114] | [38, [70], |115] |

| Tennessee Eastman Process |116 | 70 |

| Compacting Machines | 103 |

| UCI Machine Learning Repository [117] | 1118 |

| Wind Turbines [119] | [120]-|122 |

| Transducers | |123 |

| Lithium-ion Batteries [124] | [37, |125|, |126] |

| Heaters | 127 |

| Computer Numerical Control data | 128 |

| Textiles | 129 |

| Plastic Extruders | 130 |

| Press Machine | 131 |

| Coal Machinery | 132 |

| Refrigerators | 1133 |

| Gas Compressors | 134 |

| Hydraulic Systems | 135 |

| Iron Making Furnaces | 1136 |

| Cutting Tools | 137 |

| Power Lines [138] | 139 |

| Communication Equipment | 140 |

| Water Pump | 141 |

| Oil Drilling Equipment | 142 |

| Solenoid operated valves | 143 |

| Coal Conveyors | 144 |

| Temperature Monitoring Devices | 145 |

| Distillation Unit | 146 |

| Water Pipes [147] | 148 |

| Method | Articles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

2) Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME). LIME was introduced by Ribeiro et al. as a way of explaining any model using a local representation around the prediction [24]. This is done by sampling around the given input data and training a linear model with the sampled data. In doing this, they can generate an explanation that is faithful to that prediction while using only information gained from the original model.

failures that reflected the physical faults. Additionally, they showed that LIME would have a more difficult time labeling the important features when it was applied to segments with no faults as anything could occur in the future.

3) Feature Importance.

4) Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP).

5) Rule-based Explainers.

turbofans. This method led to great performance with rulebased explanations.

6) Surrogate Models.

7) Integrated Gradients.

tical for two functionally equivalent networks. With these axioms in mind, the integrated gradients are calculated via small summations through the layers’ gradients.

8) Causal Inference.

9) Visualization.

10) Accelerated Model-agnostic Explanations (ACME).

by using ACME with all of the data while SHAP would be slower even with access to

11) Statistics.

12) Smooth Gradients (SmoothGrad).

13) Counterfactuals.

an explanation for the output of the model, but this extra capability makes counterfactuals very unique in realm of XAI methods.

14) Explain Like I’m 5 (ELI5).

B. MODEL-SPECIFIC

1) Class Activation Mapping (CAM) and Gradient-weighted Cam (GradCAM).

2) Depth-based Isolation Forrest Feature Importance (DIFFI). DIFFI was introduced by Carletti et al. [160] as an explanable method for isolation forests. Isolation forests are an ensemble of isolation trees which learn outliers by isolating them from the inliers. DIFFI relies on two hypotheses to define feature importance where a feature must: induce the isolation of anomalous data points at small depth (i.e., close to the root) and produce a higher imbalance on anomalous data points while being useless on regular points [160]. These hypotheses would allow explanations for anomalous data which would allow for explanations of outliers or faulty data.

and higher order moments of the signals such as Kurtosis. FSCA iteratively selects features to maximize the amount of variance explained. Finally, the Isolation Forest is used to detect outliers which are handled as faulty events. These are explained via DIFFI. They applied their method to 2 years of computer numerical control data resulting in a

3) LionForests.

4) Saliency Maps.

5) Autoencoder-based Anomaly Root Cause Analysis (ARCANA).

the difference between the output of the autoencoder and the input, they add this bias vector to the input data as to have a corrected input. Moreover, the bias shows “incorrect” features based on the output; therefore, the bias would explain the behavior of the autoencoder by showing which features are making the output anomalous.

C. COMBINATION OF METHODS

agreement about the explanation for the model’s output, but they did not move further in asking which is better.

VI. INTERPRETABLE ML IN PREDICTIVE MAINTENANCE

A. ATTENTION.

mechanisms and could be used to add interpretability of why the network output the DTC.

B. FUZZY-BASED.

C. KNOWLEDGE-BASED.

between different features where the links take the form of a link when discussing graphs or production rules when discussing production systems. These methods produce interpretation by providing these connections within the features, usually in the form of natural language.

chronicle rule base consists of mining the rules with frequent chronicle mining, translating the rules into SWRL rules, and using accuracy (how many true rules) and coverage (how many true encompassing rules) to select the best quality rules. The integration of expert rules involved receiving input from the experts and placing the same restrictions on their rules. Finally, the rules were used for anomaly prediction of semiconductors.

| Method | Articles | ||

| Attention VI-A | |56|, |58|, |64|, |78|, 133 | ||

| Fuzzy VI-B |

|

||

| Knowledge-based VI-C | 99, 1131, 142 | ||

| Sparse Networks (VI-M) | 46, 100, 121 | ||

| Interpretable Filters VI-D | 45, 49, [60] | ||

| Decision Tree VI-E | [57, |15] | ||

| Fault Tree (VI-F) | 79, 127 | ||

| Physical Constraints VI-G | 98, 143 | ||

| Statistical Model VI-H | 41, |55 | ||

| Graph Attention Networks VI-I | 87 | ||

| Gaussian Mixture Model VI-J | 125] | ||

| Explainable Boosting Machıne (VI-K) | 76 | ||

| Hidden Markov Model VI-L | 80 | ||

| Prototype VI-N | 62 | ||

| Signal Temporal Logic VI-O | 136 | ||

| Digital Twin VI-P | 144] | ||

| Symbolic Life Model VI-Q | 33 | ||

| Generalized Additive Model (VI-R) | 43 | ||

| MTS (VI-S) | 118 | ||

| k-Nearest Neighbors VI-T | 145 | ||

| Rule-based Interpretations VI-U. | 146] |

D. INTERPRETABLE FILTERS.

backward tracking. This network has 1) interpretable meaning from the wavelet kernel convolutional layer, 2) capsule layers that allow decoupling of the compound fault, and 3) backward tracking which helps interpret output by focusing on the relationships between the features and health conditions. Not only was their framework able to achieve high accuracy on all conditions, including compound faults, but also they showed that the backward tracking method can decouple the capsule layers effectively.

E. DECISION TREES.

different between classes. These features were used to train a Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) which is a type of gradient boosting decision tree introduced by Ke et al. [170]. This method allows for constant monitoring of feature importance during training which can be used for interpreting the results.

F. FAULT TREES.

G. PHYSICAL CONSTRAINTS.

models aim to combine model-based and data-driven approaches by attaching the mathematical properties of the system to the data in data-driven approaches [98].

H. STATISTICAL METHODS.

I. GRAPH ATTENTION NETWORKS (GATS).

| Title | Objective | Contribution |

| Impact of Interdependencies: Multi-Component System Perspective Toward Predictive Maintenance Based on Machine Learning and XAI [112] | Perform predictive maintenance by modeling interdependencies and test their importance | Showed with statistical significance that interdependency modeling increases performance and understandability of a model |

| Explainable and Interpretable AI-Assisted Remaining Useful Life Estimation for Aeroengines [35] | Compute RUL of the CMAPSS turbofan dataset with LIME explaining the performance | Showed that LIME performed poorly when applied to segments with no faults but performed well when labeling features with failing sequences |

| Explainability-driven Model Improvement for SOH Estimation of Lithium-ion Battery [126] | Perform predictive maintenance by embedding explanations into the training loop | Introduced the idea of explainability-driven training for predictive maintenance |

| Online Anomaly Explanation: A Case Study on Predictive Maintenance [65] | Apply XAI methods to the online learning process | Showed that local and global explanations could be added into the online learning paradigm |

| Explaining a Random Forest with the Difference of Two ARIMA Models in an Industrial Fault Detection Scenario [82] | Utilize two ARIMA surrogate models to explain the capabilities of a random forest model | Introduced a method of sandwiching a model between two surrogates to show where a model fails to perform well |

| Edge Intelligence-based Proposal for Onboard Catenary Stagger Amplitude Diagnosis [89] | Test XAI on edge computing for fault diagnosis | Provided a method of performing XAI in an edge computing example coupled with AutoML libraries |

| Explainable AI Algorithms for Vibration Databased Fault Detection: Use Case-adapted Methods and Critical Evaluation [44] | Discover the plausibility of XAI methods explaining the output of CNN architectures | LRP showed non-distinguishable features, LIME showed unimportant features, and GradCAM showed the important features |

| On the Soundness of XAI in Prognostics and Health Management (PHM) [37] | Compare different XAI methods for the CMAPSS and lithium-ion battery dataset | Showed different metrics for comparing explanations generated by different XAI methods and showed GradCAM to perform the best on CNN architectures |

| Interpreting Remaining Useful Life Estimations Combining Explainable Artificial Intelligence and Domain Knowledge in Industrial Machinery [51] | Perform RUL of bushings through multiple different models and explanatory methods | Showed the importance of applying global and local explanations to interpret performances of models from all aspects |

| Evaluating Explainable Artificial Intelligence Tools for Hard Disk Drive Predictive Maintenance [38] | Analyze the effectiveness of explainability methods for recurrent neural network based models for RUL prediction | Utilized three metrics to compare explanations from LIME and SHAP and showed where each of them shine over the others |

| Automatic and Interpretable Predictive Maintenance System [66] | Aimed to integrate explainability into an AutoML environment | Defined a workflow for an automatic explainable predictive maintenance system |

| DTCEncoder: A Swiss Army Knife Architecture for DTC Exploration, Prediction, Search and Model interpretation [64] | Perform fault detection by classifying DTCs | Designed the DTCEncoder that utilizes an attention mechanism to provide an interpretable latent space as to why the a DTC is output |

| Deep Multi-Instance Contrastive Learning with Dual Attention for Anomaly Precursor Detection [133] | Perform anomaly detection and anomaly precursor detection | Performed anomaly precursor detection through multi-instance learning with verified explanations through domain experts |