DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-025-05864-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40186217

تاريخ النشر: 2025-04-04

العبء العالمي والاتجاهات المتعلقة بالاضطرابات الفموية بين المراهقين والشباب (من 10 إلى 24 عامًا) من 1990 إلى 2021

الملخص

الهدف: تحديد الأنماط والاتجاهات في العبء العالمي والإقليمي والوطني للأمراض الفموية بين المراهقين والشباب (AYA) من 1990 إلى 2021. الطرق: هذه دراسة وبائية رصدية تحللت انتشار الأمراض الفموية سنويًا وسنوات الحياة المعدلة حسب الإعاقة (DALYs) للأمراض الفموية – بما في ذلك تسوس الأسنان، وأمراض اللثة، وفقدان الأسنان، وغيرها من الحالات الفموية – بين المراهقين والشباب (الأعمار من 10 إلى 24) من 1990 إلى 2021. تم الحصول على البيانات من دراسة العبء العالمي للأمراض (GBD) 2021. لتقييم الاتجاهات الزمنية، تم حساب التغيرات النسبية السنوية المقدرة (EAPC) في معدلات الانتشار المعدلة حسب العمر ومعدلات DALY على المستويات العالمية والإقليمية والوطنية. كما توفر GBD 2021 بيانات عن المؤشر الاجتماعي والاقتصادي (SDI) عبر 204 دول وأقاليم. تم إجراء تحليلات الارتباط بيرسون لاستكشاف العلاقات بين معدلات الانتشار المعدلة حسب العمر ومعدلات DALY مع SDI وEAPCs الخاصة بهم. النتائج: عالميًا، زادت الحالات السائدة للأمراض الفموية بنسبة 17.1%، من 549.2 مليون في 1990 إلى 643.3 مليون في 2021، وارتفعت DALYs بنسبة 22.2%، من 1.4 مليون في 1990 إلى 1.7 مليون في 2021. انخفض معدل الانتشار المعدل حسب العمر (EAPC

الاستنتاجات: زادت معدلات الانتشار وDALYs للأمراض الفموية بين AYA على مدى العقود الثلاثة الماضية، خاصة بسبب العبء المتزايد لالتهاب اللثة وفقدان الأسنان. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن أكبر الزيادات لوحظت في أمريكا اللاتينية الجنوبية وجنوب آسيا. بينما أدى الانخفاض العالمي في تسوس الأسنان إلى تقليل ASPR، لا يزال العبء المتزايد لأمراض اللثة وفقدان الأسنان مصدر قلق كبير. تؤكد هذه الاتجاهات على الحاجة الملحة لاستراتيجيات مبتكرة للوقاية والتدخل لتحسين صحة الفم لهذه الفئة السكانية على مستوى العالم.

المقدمة

الأمراض الفموية، وخاصة تسوس الأسنان، شائعة بين AYA، حيث يصل تسوس الأسنان غير المعالج إلى ذروته بين سن 15 و19 ويؤثر على الملايين حول العالم [3]. على الرغم من أن التهاب اللثة وفقدان الأسنان أقل شيوعًا في هذه المجموعة، إلا أنها تظل قضايا صحية فموية هامة [5]. بشكل مقلق، يتزايد التهاب اللثة بين البالغين الأصغر سنًا، مما يبرز الحاجة الملحة لاستراتيجيات وقائية مبكرة [6]. التأثيرات النفسية والاجتماعية للأمراض الفموية في AYA، بما في ذلك تسوس الأسنان والتهاب اللثة، شديدة بشكل خاص [7]. يمكن أن تؤدي هذه الحالات إلى ضغوط عاطفية كبيرة، تؤثر سلبًا على تقدير الذات، والتفاعلات الاجتماعية، ورضا الحياة بشكل عام. قد يكون لصحة الفم السيئة في AYA عواقب طويلة الأمد، تمتد إلى صحتهم النفسية ورفاهيتهم الاجتماعية.

علاوة على ذلك، فإن الآثار الأوسع للأمراض الفموية غير المعالجة مثيرة للقلق، حيث غالبًا ما تتفاقم هذه الحالات مع تقدم العمر [8]. يميل تسوس الأسنان غير المعالج، وأمراض اللثة، وفقدان الأسنان في المراحل المبكرة لدى الشباب إلى التقدم إلى أشكال أكثر حدة، مما يزيد من خطر الإصابة بحالات مزمنة مثل فقدان الأسنان والأمراض الجهازية. العلاقة بين صحة الفم والصحة العامة – بما في ذلك حالات مثل السكري والسمنة – مثيرة للقلق بشكل خاص، حيث ترتبط صحة الفم السيئة في AYA بزيادة خطر تطوير هذه الحالات، والتي يمكن أن يكون لها عواقب مدى الحياة [7،9].

هناك تفاوتات صارخة في صحة الفم عبر المناطق والدول، حيث تؤثر الأمراض الفموية بشكل غير متناسب على المناطق الفقيرة وتزيد من تفاقم عدم المساواة الصحية [3، 10]. في الدول ذات الدخل المرتفع، غالبًا ما تهيمن أنظمة الرعاية الصحية الفموية على الأساليب التي تركز على العلاج وتزداد اعتمادًا على التكنولوجيا. ومع ذلك، تميل هذه الأنظمة إلى أن تكون محاصرة في دورة تدخلية لا تعالج الأسباب الجذرية للأمراض الفموية ولا تخدم بشكل كافٍ شرائح كبيرة من السكان [11]. في العديد من الدول ذات الدخل المتوسط، يكون عبء الأمراض الفموية كبيرًا، ومع ذلك تظل أنظمة الرعاية الصحية الفموية

غير متطورة وغير ميسورة التكلفة بالنسبة للأغلبية [12]. الوضع هو الأكثر سوءًا في الدول ذات الدخل المنخفض، حيث يكون الوصول إلى الرعاية الفموية محدودًا بشدة، مما يترك العديد بدون علاج أو وقاية أساسية [13]. علاوة على ذلك، قد تؤدي التغيرات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية والتجارية الأوسع في الدول ذات الدخل المنخفض والمتوسط إلى زيادة خطر الإصابة بالأمراض الفموية [14]. عالميًا، عدد AYA في أعلى مستوى له على الإطلاق ومن المتوقع أن يستمر في النمو في العقود القادمة. سيكون هذا الزيادة أكثر وضوحًا في الدول ذات الدخل المنخفض، حيث حدثت تخفيضات كبيرة في معدلات وفيات الأطفال دون سن 5 سنوات، بينما تظل معدلات الخصوبة مرتفعة نسبيًا [15]. نتيجة لذلك، فإن التقييمات الشاملة لعبء الأمراض الفموية بين AYA عبر مناطق مختلفة أمر بالغ الأهمية لتطوير استراتيجيات وقائية ورقابية أكثر استهدافًا وفعالية.

يمثل AYA مجموعة سكانية حيوية، حيث أن الاستثمار في صحتهم لا يجلب فوائد فورية فحسب، بل يدعم أيضًا رفاهيتهم في مرحلة البلوغ ويؤثر بشكل إيجابي على صحة الأجيال القادمة [16]. لذلك، يمكن أن يؤدي تنفيذ تدخلات فعالة للأمراض الفموية خلال هذه المرحلة التنموية الحاسمة إلى تحسين نتائج صحة الفم العالمية بشكل كبير والمساهمة في رفاهية السكان بشكل أوسع [17]. ومع ذلك، كانت صحة الفم بين AYA لفترة طويلة موضوعًا غير مستكشف في أبحاث الصحة العالمية، خاصة فيما يتعلق بالتباينات الإقليمية، والاتجاهات الزمنية، والعوامل الاجتماعية والاقتصادية الأوسع التي تؤثر على انتشار الأمراض الفموية [18]. ركزت الدراسات السابقة إلى حد كبير على التقييمات المقطعية أو البيانات الإقليمية التي تفشل في التقاط الاتجاهات طويلة الأمد. هذه الفجوة واضحة بشكل خاص في ندرة البيانات حول عبء الأمراض الفموية مثل التهاب اللثة وفقدان الأسنان في الفئات السكانية الأصغر سنًا [19، 20]. على الرغم من أن العديد من الدراسات استكشفت العلاقة بين الوضع الاجتماعي والاقتصادي وصحة الفم، إلا أن تأثير التغيرات الاجتماعية والاقتصادية العالمية بمرور الوقت على أعباء صحة الفم في AYA لا يزال غير واضح [21، 22].

تقدم دراسة العبء العالمي للأمراض (GBD) تقييمًا شاملاً لعبء الاضطرابات الفموية عبر 204 دول وأقاليم، مما يوفر فرصة قيمة لتحليل الاتجاهات في صحة الفم على مدى العقود الأخيرة. في هذه الدراسة، نركز على ثلاثة حالات فموية شائعة – تسوس الأسنان الدائمة، التهاب اللثة، وفقدان الأسنان – ونسعى لتقدير الأنماط والاتجاهات في انتشارها وسنوات الحياة المعدلة حسب الإعاقة (DALYs) بين المراهقين والشباب. الهدف من هذه الدراسة هو تحديد الأنماط والاتجاهات في العبء العالمي والإقليمي والوطني للاضطرابات الفموية، وبشكل خاص تسوس الأسنان، التهاب اللثة، وفقدان الأسنان بين المراهقين والشباب (الأعمار من 10 إلى 24) من 1990 إلى 2021، من أجل إبلاغ استراتيجيات الوقاية والتدخل المستهدفة.

طرق

نظرة عامة

التعاريف

جمع البيانات

التحليل الإحصائي

يُفترض أن اللوغاريتم الطبيعي للتغيرات في ASR يتبع اتجاهًا خطيًا على مر الزمن، ممثلاً بالمعادلة

إلى 21 منطقة عالمية بناءً على تصنيف GBD، مما يتيح لنا دراسة الفروق الإقليمية في عبء الاضطرابات الفموية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، على المستوى الوطني، قمنا بتقييم الاتجاهات في نتائج صحة الفم باستخدام بيانات من 204 دول وأقاليم. قمنا بتصنيف معدل الوفيات المعدل حسب العمر (ASR) على أنه في تزايد أو تناقص إذا كان كل من معدل النمو السنوي المتوقع (EAPC) وفترة الثقة 95% الخاصة به بالكامل فوق أو تحت الصفر، على التوالي. إذا كانت فترة الثقة 95% تتضمن الصفر، فإن التغيير في ASR اعتُبر غير ذي دلالة إحصائية.

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم استخدام نموذج التنعيم بالوزن المحلي لنقاط التشتت (LOWESS) لفحص العلاقة بين عبء الاضطرابات الفموية بين الشباب والمراهقين (AYA) ومؤشر التنمية المستدامة (SDI) عبر 21 منطقة و204 دول وأقاليم [30]. تم إجراء تحليل الارتباط لبيرسون لحساب

علاوة على ذلك، تم تقدير معدل انتشار الاضطرابات الفموية المعدل حسب العمر (ASPR) بين الشباب والمراهقين من 2022 إلى 2040 باستخدام نموذج بايزي للفترة العمرية-الجيل (BAPC) مع تقريبات لابلاس المتداخلة. يقدر نموذج BAPC توزيعات احتمالية افتراضية بناءً على ثلاثة عوامل رئيسية – العمر، الفترة، والجيل – من خلال دمج المعرفة السابقة مع بيانات العينة لاستنتاج توزيعات لاحقة. تم الحصول على بيانات السكان العالمية المعدلة حسب العمر من قاعدة بيانات المعايير العالمية، التي طورتها منظمة الصحة العالمية.https://seer. cancer.gov/stdpopulations/world.who.html)، وتم الحصول على بيانات توقعات السكان من بيانات الخصوبة والوفيات والهجرة وتوقعات السكان العالمية من GBD للفترة 2017-2100 [32]. تم استخدام حزمة “BAPC” R لتنفيذ النموذج، مما أتاح إنشاء توقعات احتمالية جيدة المعايرة مع فترات عدم يقين ضيقة نسبيًا.

تم إجراء جميع التحليلات الإحصائية ورسم الخرائط باستخدام

النتائج

العبء العالمي والإقليمي والوطني للاضطرابات العامة بين الشباب والمراهقين

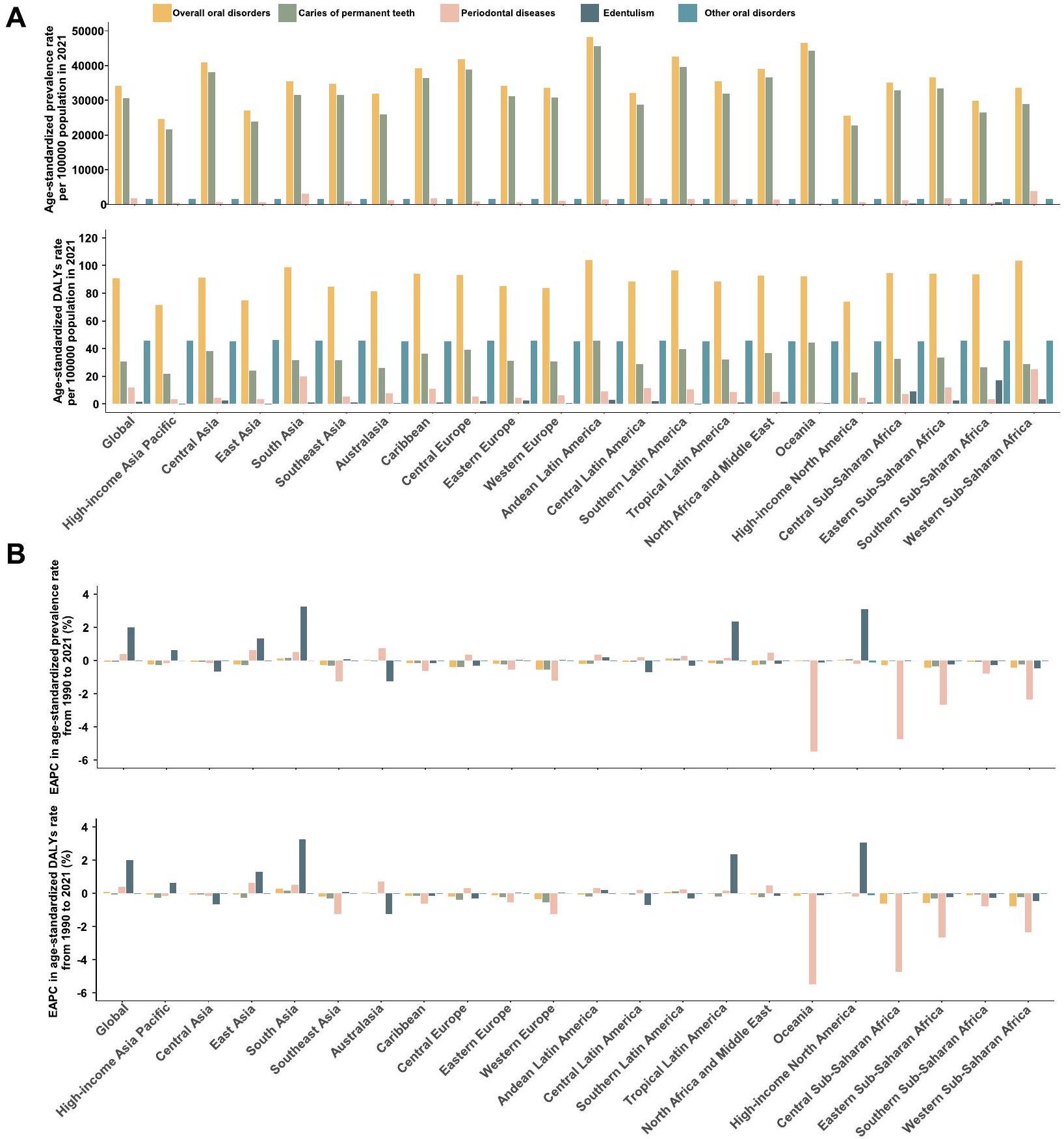

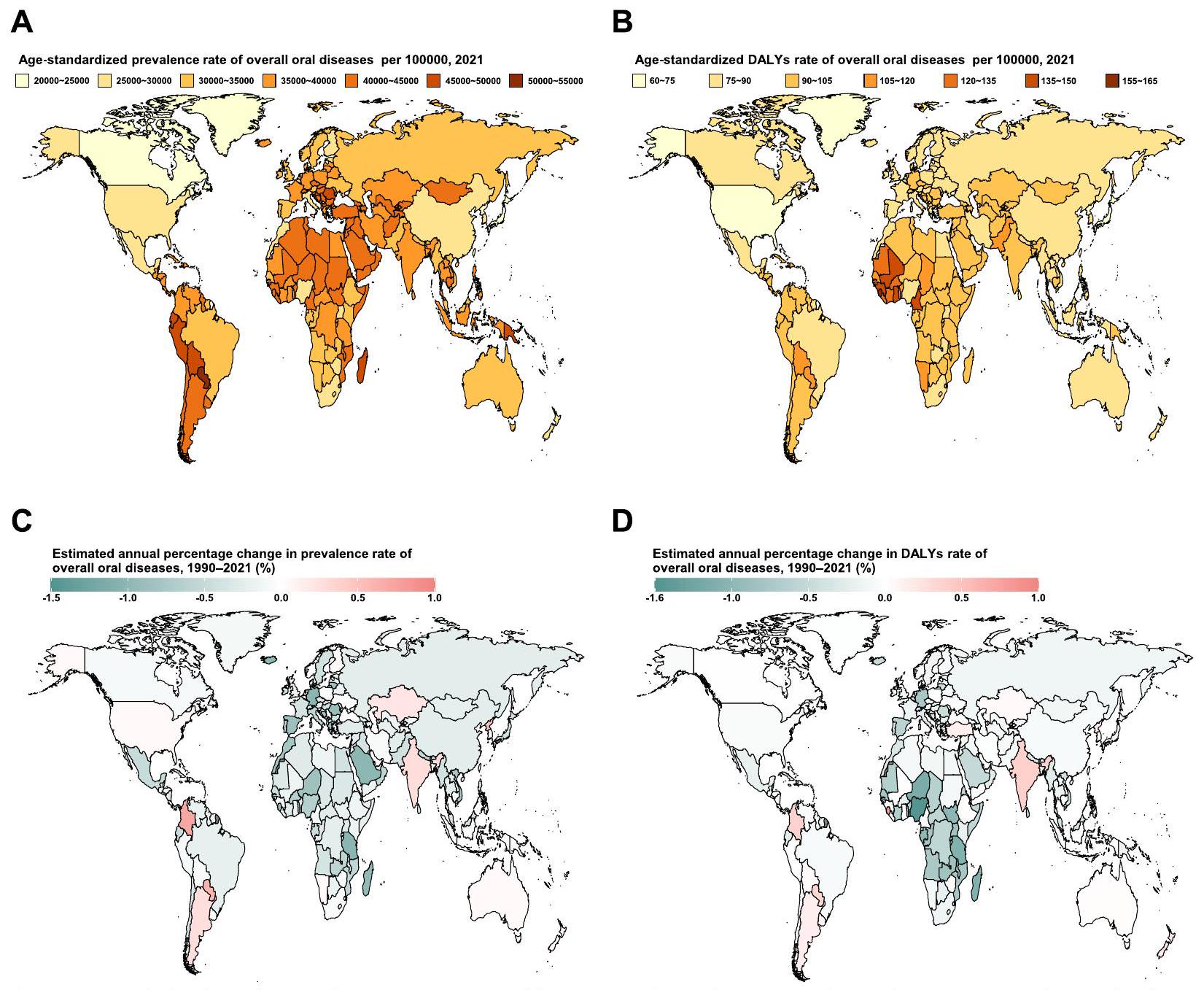

على مستوى الدول، أظهرت باراغواي أعلى معدل للوفاة المعدل حسب العمر (ASPR) بمعدل 54,007.6 (فترة الثقة 95%، من 53,905.5 إلى 54,109.8) لكل 100,000، بينما كانت سيراليون لديها أعلى معدل للوفاة المعدل حسب العمر (ASDR) مسجلاً 158 (فترة الثقة 95%، من 153.4 إلى 162.7) لكل 100,000 (الأشكال 2A وB، الجدول التكميلي S3).

من 1990 إلى 2021، انخفض معدل انتشار الاضطرابات الفموية عالميًا بمعدل متوسط قدره

الفوارق الإقليمية في عبء أربعة اضطرابات فموية بين الشباب والمراهقين

| خصائص | انتشار | سنوات الحياة المعدلة بالإعاقة | ||||||||

| عدد الحالات في عام 1990 (مليون) | معدل موحد العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 1990 | عدد الحالات في 2021 (مليون) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 2021 | التغير السنوي المقدر كنسبة مئوية، 1990-2021 | عدد الحالات في عام 1990 (ألف) | معدل موحد العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 1990 | عدد الحالات في 2021 (ألف) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 2021 | التغير السنوي المقدر كنسبة مئوية، 1990-2021 | |

| عالمي | 549.17 | ٣٥,٤٦٩ (٣٥,٤٦٦ إلى ٣٥,٤٧١.٩) | 643.29 | 34,076.8 (34,074.2 إلى 34,079.4) | -0.07 (-0.12 إلى -0.03) | ١٤٠٠.٥٣ | 90.3 (90.1 إلى 90.4) | 1711.71 | 90.7 (90.5 إلى 90.8) | 0.06 (0.02 إلى 0.11) |

| جنس | ||||||||||

| أنثى | ٢٧٤.٤٢ | ٣٥,٩٩٨.٥ (٣٥,٩٩٤.٢ إلى ٣٦,٠٠٢.٨) | 317.91 | 34,506.8 (34,503 إلى

|

-0.09 (-0.14 إلى -0.04) | 720.99 | 94.3 (94.1 إلى 94.5) | 871.67 | 94.5 (94.3 إلى 94.7) | 0.05 (0.01 إلى 0.09) |

| ذكر | ٢٧٤.٧٥ | 34,956.4 (34,952.3 إلى

|

٣٢٥.٣٨ | 33,667.8 (33,664.2 إلى

|

-0.06 (-0.11 إلى -0.01) | 679.54 | 86.4 (86.2 إلى 86.6) | 840.05 | 87 (86.8 إلى 87.2) | 0.08 (0.03 إلى 0.12) |

| عمر | ||||||||||

| 10-14 سنة | 168.7 | 31,492.9 (21,831.1 إلى 43,160.6) | 188.5 | 28,276.5 (19,990.5 إلى 39,064.1) | -0.24 (-0.3 إلى -0.17) | ٣٢٦.٠٣ | 60.9 (33.6 إلى 105.8) | ٣٨٦.٥١ | 58 (32.4 إلى 99.3) | -0.1 (-0.13 إلى -0.07) |

| 15-19 سنة | ١٦٩.٤٤ | 32,621 (22,828.8 إلى 44,722.2) | 204.16 | 32,719 (23,558.9 إلى 43,569.8) | 0.07 (0 إلى 0.13) | ٤٤٨ | 86.2 (45.4 إلى 144.1) | ٥٤٥.٠٨ | ٨٧.٤ (٤٧.١ إلى ١٤٦.٧) | 0.07 (0.03 إلى 0.1) |

| 20-24 سنة | 211.02 | 42,883.6 (32,284.2 إلى 54,395.7) | ٢٥٠.٦٣ | 41,970.8 (33,125.5 إلى 52,185.8) | -0.06 (-0.1 إلى -0.02) | 626.5 | 127.3 (68.7 إلى 214.2) | 780.12 | 130.6 (71.1 إلى 216.6) | 0.15 (0.09 إلى 0.2) |

| أسباب | ||||||||||

| تسوس الأسنان الدائمة | 494.54 | 31,918 (31,915.2 إلى 31,920.8) | 578.76 | 30,658.1 (30,655.6 إلى 30,660.6) | -0.07 (-0.12 إلى -0.01) | 495.06 | 32 (31.9 إلى 32) | 579.6 | 30.7 (30.6 إلى 30.8) | -0.06 (-0.12 إلى -0.01) |

| أمراض اللثة | ٢٤.١٩ | 1551.3 (1550.7 إلى 1551.9) | ٣٣.٨٨ | 1794.7 (1794.1 إلى 1795.3) | 0.4 (0.26 إلى 0.54) | 161.24 | 10.3 (10.3 إلى 10.4) | ٢٢٥.٤ | 11.9 (11.9 إلى 12) | 0.4 (0.26 إلى 0.54) |

| فقدان الأسنان | 0.8 | 51.2 (51.1 إلى 51.3) | 1.14 | 60.4 (60.3 إلى 60.5) | 1.99 (1.19 إلى 2.8) | 23.12 | 1.5 (1.5 إلى 1.5) | ٣٣.١٥ | 1.8 (1.7 إلى 1.8) | 2 (1.2 إلى 2.8) |

| اضطرابات فموية أخرى | ٢٤.٠٦ | 1550.9 (1550.3 إلى 1551.6) | ٢٩.٢٥ | 1549.6 (1549 إلى 1550.1) | -0.01 (-0.01 إلى -0.01) | ٧٠٨.٦٨ | ٤٥.٧ (٤٥.٦ إلى ٤٥.٨) | 861.86 | ٤٥.٧ (٤٥.٦ إلى ٤٥.٨) | 0 (-0.01 إلى 0) |

| مؤشر سوسيو-ديموغرافي | ||||||||||

| عالي | 63.52 | 32,107 (32,099 إلى

|

٥٥.٤ | 29,486.5 (29,478.7 إلى 29,494.3) | -0.25 (-0.34 إلى -0.16) | 165.15 | 82.3 (81.9 إلى 82.7) | ١٤٩.٣٤ | 78.7 (78.3 إلى 79.1) | -0.15 (-0.2 إلى -0.1) |

| خصائص | انتشار | سنوات الحياة المعدلة بالإعاقة | ||||||||

| عدد الحالات في عام 1990 (مليون) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 1990 | عدد الحالات في 2021 (مليون) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 2021 | التغير السنوي المقدر كنسبة مئوية، 1990-2021 | عدد الحالات في عام 1990 (ألف) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 1990 | عدد الحالات في 2021 (ألف) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 2021 | التغير السنوي المقدر كنسبة مئوية، 1990-2021 | |

| عالي-متوسط | 100.76 | 35,285.6 (35,278.6 إلى 35,292.5) | ٧٤.٩٢ | 33,005.9 (32,998.4 إلى 33,013.4) | -0.18 (-0.22 إلى -0.14) | 244.86 | 84.7 (84.4 إلى 85.1) | 189.73 | 83.3 (83 إلى 83.7) | -0.02 (-0.04 إلى 0) |

| وسط | 191.79 | 34,847.1 (34,842.2 إلى 34,852.1) | 185.29 | 33,467.5 (33,462.7 إلى 33,472.3) | -0.07 (-0.13 إلى 0) | ٤٨١.٣٨ | 87 (86.7 إلى 87.2) | ٤٨٤.١ | 87.3 (87.1 إلى 87.6) | 0.08 (0.03 إلى 0.13) |

| منخفض-متوسط | ١٣٢.٤٨ | 37,013.5 (37,007.2 إلى 37,019.8) | 193.14 | 34,925.3 (34,920.4 إلى 34,930.2) | -0.06 (-0.17 إلى 0.06) | ٣٤٦.٤٣ | 98.2 (97.9 إلى 98.5) | 532.81 | 96.3 (96 إلى 96.5) | 0.05 (-0.04 إلى 0.14) |

| منخفض | 60.03 | 39,294.5 (39,284.5 إلى 39,304.5) | ١٣٣.٩٨ | ٣٦,٧٧٩.٧ (٣٦,٧٧٣.٤ إلى

|

-0.26 (-0.31 إلى -0.2) | 161.4 | ١٠٨.٥ (١٠٧.٩ إلى ١٠٩) | ٣٥٤.٤٥ | 98.8 (98.4 إلى 99.1) | -0.34 (-0.39 إلى -0.29) |

| مناطق GBD | ||||||||||

| آسيا والمحيط الهادئ ذات الدخل المرتفع | 11.61 | 27,303.2 (27,287.5 إلى 27,319) | 6.54 | 24,550.7 (24,531.8 إلى 24,569.7) | -0.24 (-0.31 إلى -0.17) | 31.82 | 74.2 (73.4 إلى 75) | 19.22 | 71.5 (70.5 إلى 72.5) | -0.09 (-0.11 إلى -0.07) |

| آسيا الوسطى | 8.33 | 42,182.1 (42,153.5 إلى 42,210.8) | 9.02 | 40,855.9 (40,829.2 إلى 40,882.6) | -0.08 (-0.13 إلى -0.03) | 18.37 | 93.4 (92.1 إلى 94.8) | 20.11 | 91.4 (90.2 إلى 92.7) | -0.06 (-0.09 إلى -0.04) |

| شرق آسيا | ١١٣.٨٥ | 29,961.2 (29,955.6 إلى 29,966.7) | ٦٥.٥٧ | 27,073.9 (27,067.3 إلى 27,080.5) | -0.24 (-0.34 إلى -0.14) | 298.62 | 77.5 (77.2 إلى 77.8) | 180.84 | 74.8 (74.4 إلى 75.1) | -0.07 (-0.11 إلى -0.02) |

| جنوب آسيا | 121.49 | 36,664.6 (36,658 إلى 36,671.1) | ١٨٧.٩٥ | 35,566.5 (35,561.5 إلى 35,571.6) | 0.13 (-0.07 إلى 0.33) | ٣٢٢.٣٥ | 98.4 (98.1 إلى 98.8) | ٥٢٥.٥٢ | 98.9 (98.6 إلى 99.2) | 0.26 (0.09 إلى 0.43) |

| جنوب شرق آسيا | ٥٥.٢٨ | 37,364 (37,354.1 إلى 37,373.9) | ٥٩.٥٩ | 34,750.8 (34,741.9 إلى 34,759.6) | -0.28 (-0.34 إلى -0.23) | ١٣٠.٦٧ | 88.9 (88.4 إلى 89.4) | ١٤٦.٣١ | 84.9 (84.5 إلى 85.3) | -0.19 (-0.23 إلى -0.16) |

| أسترالاسيا | 1.65 | 33,875.9 (33,824.2 إلى 33,927.8) | 1.85 | 31,973.4 (31,927.3 إلى 32,019.6) | 0.05 (-0.13 إلى 0.23) | ٤.٠٩ | 83.3 (80.8 إلى 85.9) | ٤.٧٤ | 81.3 (79 إلى 83.7) | 0.05 (-0.04 إلى 0.13) |

| الكاريبي | ٤.٥ | 42,075.8 (42,036.9 إلى 42,114.7) | ٤.٤٧ | 39,167 (39,130.6 إلى 39,203.3) | -0.16 (-0.19 إلى -0.13) | 10.7 | 99.4 (97.5 إلى 101.3) | 10.83 | 94.3 (92.5 إلى 96.1) | -0.15 (-0.17 إلى -0.12) |

| خصائص | انتشار | سنوات الحياة المعدلة بالإعاقة | ||||||||

| عدد الحالات في عام 1990 (مليون) | معدل موحد العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 1990 | عدد الحالات في 2021 (مليون) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 2021 | التغير السنوي المقدر كنسبة مئوية، 1990-2021 | عدد الحالات في عام 1990 (ألف) | معدل موحد العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 1990 | عدد الحالات في 2021 (ألف) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 2021 | التغير السنوي المقدر كنسبة مئوية، 1990-2021 | |

| أوروبا الوسطى | 14.13 | 48,490.7 (48,465.4 إلى 48,516) | ٧.٦ | 41,760.4 (41,730.7 إلى 41,790.1) | -0.39 (-0.43 إلى -0.35) | ٢٩.٠١ | 99.9 (98.7 إلى 101) | 17 | 93.1 (91.7 إلى 94.5) | -0.18 (-0.2 إلى -0.16) |

| أوروبا | 17.19 | ٣٦,٤٠٠.٣ (٣٦,٣٨٣.١ إلى ٣٦,٤١٧.٥) | 11.23 | 34,211.5 (34,191.5 إلى 34,231.6) | -0.21 (-0.28 إلى -0.13) | 41.61 | ٨٨ (٨٧.٢ إلى ٨٨.٩) | 27.75 | 85.2 (84.2 إلى 86.2) | -0.11 (-0.14 إلى -0.08) |

| أوروبا الغربية | 31.61 | 38,137.6 (38,124.2 إلى 38,151) | ٢٤.٣٦ | 33,574 (33,560.6 إلى 33,587.3) | -0.56 (-0.61 إلى -0.51) | ٧٧.٦٣ | 91.3 (90.7 إلى 92) | 61.13 | 83.6 (82.9 إلى 84.2) | -0.33 (-0.37 إلى -0.3) |

| أمريكا اللاتينية الأنديزية | 6.02 | 49,089.5 (49,050.3 إلى 49,128.8) | 8.36 | 48,254.2 (48,221.4 إلى 48,286.9) | -0.19 (-0.24 إلى -0.13) | 12.66 | 104.3 (102.5 إلى 106.2) | 18.13 | ١٠٣.٨ (١٠٢.٣ إلى ١٠٥.٣) | -0.06 (-0.09 إلى -0.04) |

| أمريكا الوسطى | 18.93 | 35,184.2 (35,168.3 إلى 35,200.1) | 21.06 | 32,171.5 (32,157.8 إلى 32,185.3) | -0.08 (-0.18 إلى 0.02) | ٤٨.٨٥ | 91.7 (90.9 إلى 92.5) | ٥٨.٣٦ | 88.7 (88 إلى 89.4) | -0.02 (-0.07 إلى 0.03) |

| أمريكا اللاتينية الجنوبية | ٥.٦٦ | 42,850.5 (42,815.2 إلى 42,885.8) | 6.57 | 42,611.1 (42,578.4 إلى 42,643.7) | 0.1 (0.04 إلى 0.16) | 12.58 | 95.7 (94 إلى 97.4) | 15.02 | 96.4 (94.9 إلى 98) | 0.07 (0.03 إلى 0.11) |

| أمريكا اللاتينية الاستوائية | 17.4 | ٣٦,٤٩٢.٧ (٣٦,٤٧٥.٥ إلى ٣٦,٥٠٩.٨) | 18.12 | 35,475.9 (35,459.5 إلى 35,492.3) | -0.15 (-0.24 إلى -0.07) | ٤١.٧١ | 88.1 (87.3 إلى 89) | ٤٥.٧٤ | 88.3 (87.5 إلى 89.1) | -0.04 (-0.13 إلى 0.05) |

| شمال أفريقيا والشرق الأوسط | ٤٥.٠٢ | 41,611.6 (41,599.4 إلى 41,623.8) | 63.26 | 39,060 (39,050.3 إلى 39,069.6) | -0.29 (-0.34 إلى -0.24) | 100.62 | 94.2 (93.7 إلى 94.8) | ١٤٩.٣٧ | 92.6 (92.1 إلى 93) | -0.08 (-0.11 إلى -0.05) |

| أمريكا الشمالية ذات الدخل المرتفع | 17.79 | 28,813.2 (28,799.8 إلى 28,826.7) | 18.47 | 25,627.7 (25,616 إلى 25,639.4) | 0.03 (-0.27 إلى 0.33) | ٤٨.٠٦ | 76.8 (76.1 إلى 77.5) | 53.59 | 73.9 (73.2 إلى 74.5) | -0.04 (-0.17 إلى 0.08) |

| أوقيانوسيا | 0.98 | 47,081.8 (46,988.5 إلى 47,175.3) | 1.87 | 46,465.9 (46,399.3 إلى 46,532.6) | -0.04 (-0.06 إلى -0.02) | 1.97 | 95.4 (91.2 إلى 99.7) | 3.7 | 92.2 (89.2 إلى 95.2) | -0.15 (-0.17 إلى -0.12) |

| وسط أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء | 6.31 | 37,235.9 (37,206.8 إلى 37,265.1) | 15.35 | 35,039.8 (35,022.1 إلى 35,057.4) | -0.28 (-0.34 إلى -0.22) | 18.07 | 108.9 (107.3 إلى 110.5) | ٤٠.٨٦ | 94.7 (93.8 إلى 95.6) | -0.62 (-0.73 إلى -0.52) |

| خصائص | انتشار | سنوات الحياة المعدلة بالإعاقة | ||||||||

| عدد الحالات في عام 1990 (مليون) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 1990 | عدد الحالات في 2021 (مليون) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 2021 | التغير السنوي المقدر كنسبة مئوية، 1990-2021 | عدد الحالات في عام 1990 (ألف) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 1990 | عدد الحالات في 2021 (ألف) | معدل موحد حسب العمر لكل 100,000 نسمة، 2021 | التغير السنوي المقدر كنسبة مئوية، 1990-2021 | |

| شرق أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء | ٢٤.٥١ | 40,304.6 (40,288.5 إلى 40,320.7) | 52.5 | ٣٦،٥٦٠.٨ (٣٦،٥٥٠.٩ إلى

|

-0.43 (-0.47 إلى -0.38) | 63.83 | ١٠٨ (١٠٧.٢ إلى ١٠٨.٩) | ١٣٣.٣٥ | 94.1 (93.6 إلى 94.6) | -0.57 (-0.63 إلى -0.51) |

| جنوب الصحراء الكبرى الأفريقية | ٤.٩٩ | 29,669.3 (29,643.2 إلى 29,695.4) | 6.47 | 29,795.7 (29,772.7 إلى 29,818.6) | -0.08 (-0.21 إلى 0.05) | 15.87 | 95.5 (94 إلى 97) | ٢٠.٢٤ | 93.6 (92.3 إلى 94.9) | -0.1 (-0.37 إلى 0.16) |

| غرب أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء | 21.92 | 37,496.6 (37,480.8 إلى 37,512.4) | 53.08 | 33,634 (33,624.9 إلى 33,643.1) | -0.45 (-0.49 إلى -0.41) | 71.46 | 125.5 (124.6 إلى 126.5) | 159.92 | ١٠٣.٥ (١٠٢.٩ إلى ١٠٤) | -0.79 (-0.86 إلى -0.71) |

بين عامي 1990 و2021، انخفضت معدلات الإصابة بالتهاب الأسنان الدائم بشكل كبير، مع معدل التغير السنوي المتوقع -0.07 و -0.06.

على التوالي. في المقابل، ظلت معدلات الاضطرابات الفموية الأخرى مستقرة، مع معدلات النمو السنوي المقدرة -0.01 و0. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن هناك اتجاهًا تصاعديًا ملحوظًا لأمراض اللثة.

على المستوى الوطني في عام 2021، تم الإبلاغ عن أعلى معدل انتشار تسوس الأسنان (ASPR) ومعدل الوفيات بسبب تسوس الأسنان (ASDR) لكل 100,000 نسمة في الأسنان الدائمة في باراغواي.

قادت معدلات فقدان الأسنان (1020.5 و 29.6). من 1990 إلى 2021، تم ملاحظة أكبر الزيادات في كل من معدل الإصابة بالأسنان الدائمة ومعدل الوفيات بسبب تسوس الأسنان في كولومبيا، بينما شهدت سيراليون أعلى الزيادات في الأمراض اللثوية، والسويد في فقدان الأسنان (الشكل التوضيحي التكميلي S1-S3، الجدول S8-S10). من حيث الاضطرابات الفموية الأخرى، كانت نيجيريا لديها أعلى معدل إصابة بلغ 1564.1 لكل 100,000، وأبلغت الصين عن أعلى معدل وفيات بلغ 45.99 لكل 100,000. خلال نفس الفترة، شهدت الجمهورية العربية السورية أسرع زيادة سنوية في معدل الإصابة.

العلاقة بين ASR و EAPC و SDI

مؤشر SDI يبلغ 70. بالمقابل، انخفض معدل ASDR العام بشكل أسي مع زيادة SDI (الشكل التوضيحي S5). بالنسبة للتسوس في الأسنان الدائمة، ارتفع كل من ASPR و ASDR في البداية قبل أن ينخفضا عند SDI يبلغ 70.

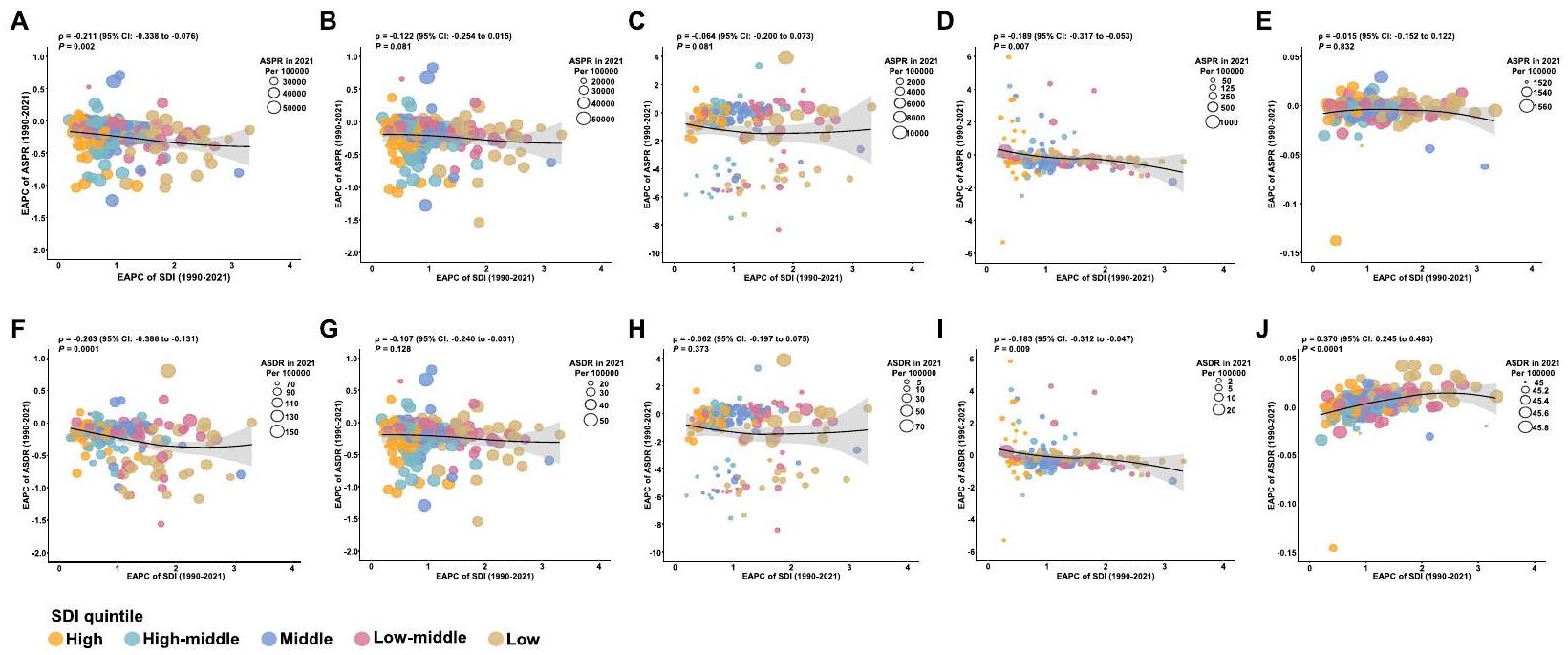

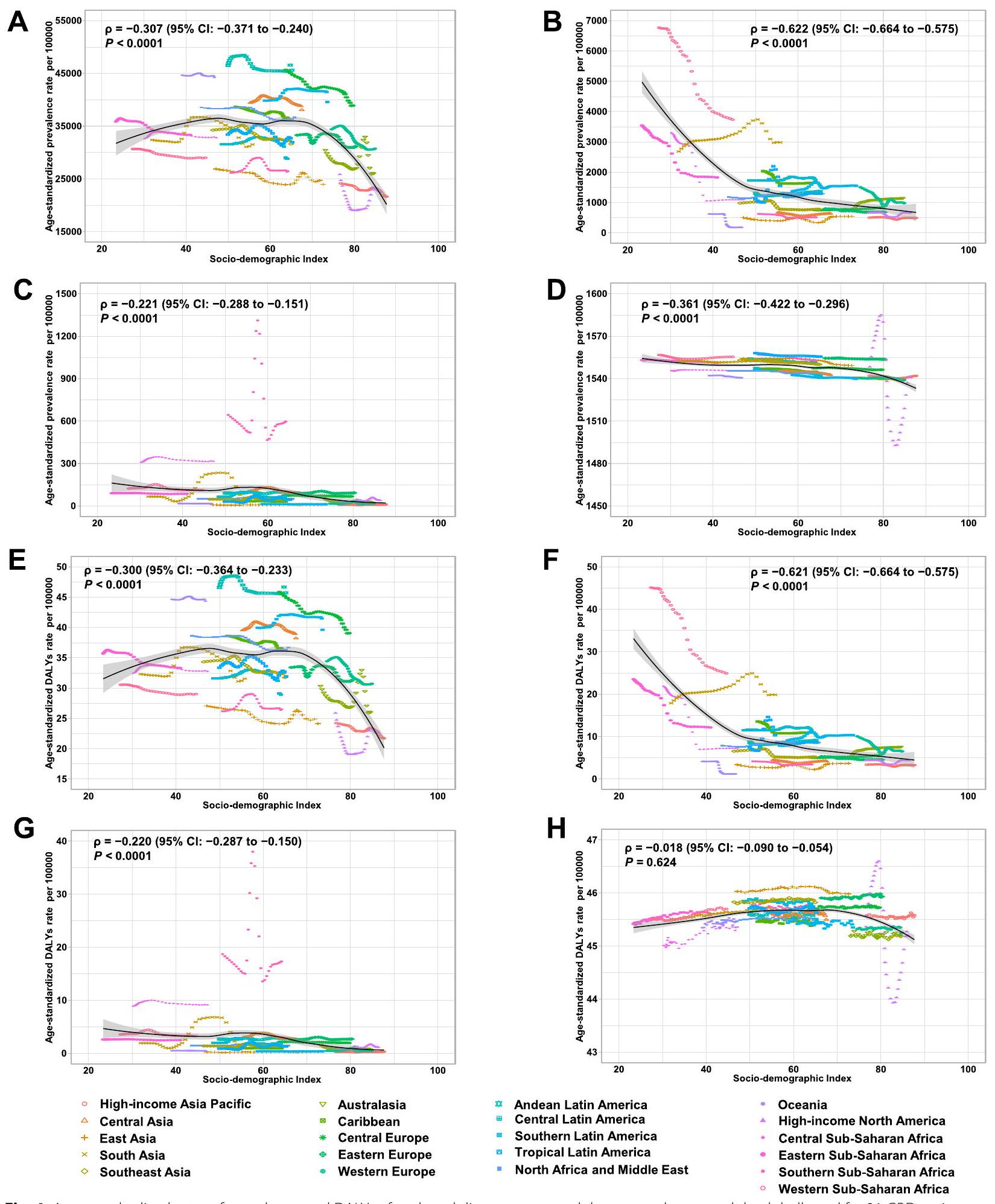

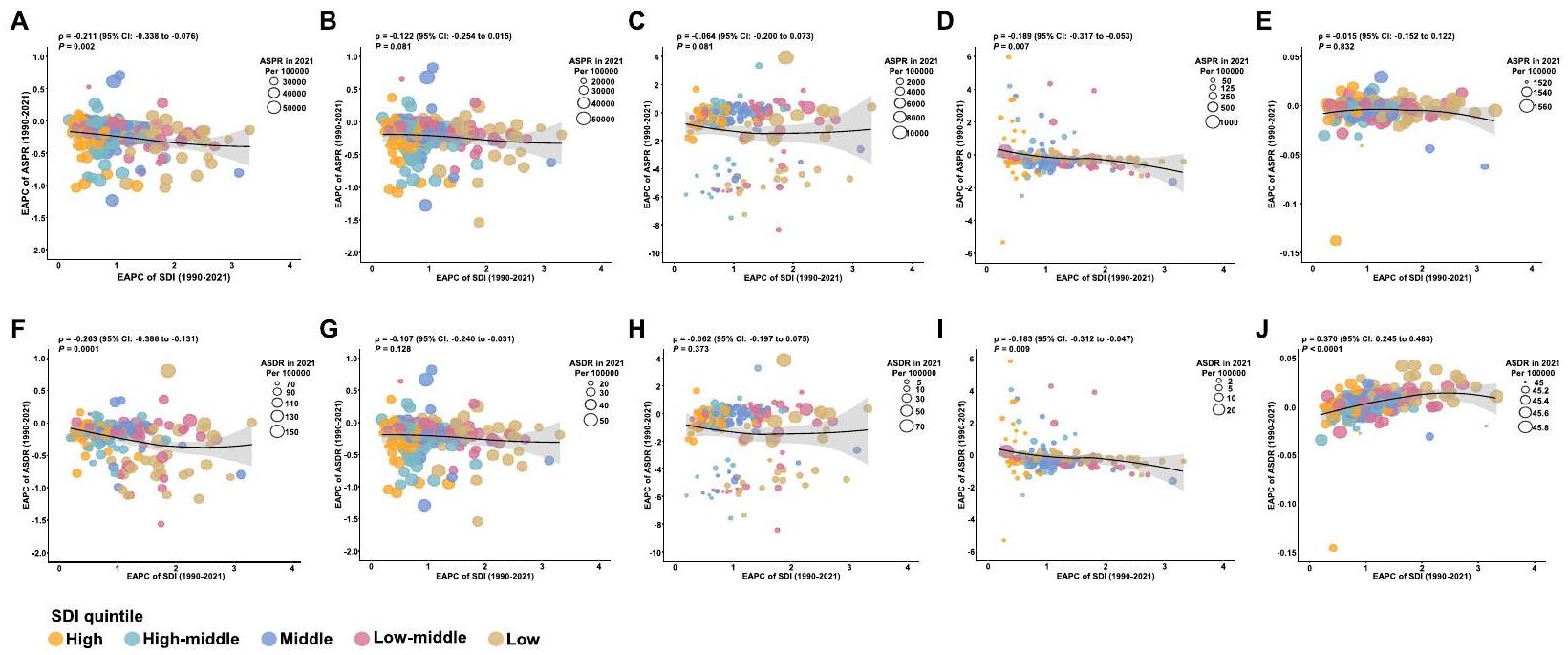

فيما يتعلق بـ 204 دول وإقليم في عام 2021، انخفض كل من معدل الوفيات المعدل حسب العمر (ASPR) ومعدل الوفيات المعدل حسب العمر (ASDR) للاضطرابات الفموية بشكل عام، وكذلك لكل اضطراب فموي محدد، مع ارتفاع مؤشر التنمية الاجتماعية (SDI) (الشكل التوضيحي S6-S10). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، شهدت الدول ذات مستويات SDI الأعلى زيادة سنوية أسرع في ASDR للتسوس في الأسنان الدائمة، فضلاً عن ASPR و ASDR لأمراض اللثة من 1990 إلى 2021 (الشكل التوضيحي S6-S10). علاوة على ذلك، لوحظت ارتباطات سلبية بين التغيرات السنوية المقدرة في النسب المئوية (EAPCs) لـ ASPR أو ASDR والـ SDI للاضطرابات الفموية بشكل عام وفقدان الأسنان من 1990 إلى 2021، بينما لوحظ ارتباط إيجابي بين EAPCs لـ ASDR لاضطرابات فموية أخرى و SDI خلال نفس الفترة (الشكل 5).

من 1990 إلى 2021، زادت نسبة انتشار الاضطرابات الفموية العامة فقط لدى الأفراد الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين

التوقعات لمعدل انتشار الاضطرابات الفموية العامة بين الشباب والمراهقين حتى عام 2040

نقاش

لحالات الاضطرابات الفموية وDALYs بمعدل

تشير نتائجنا إلى أن الانخفاض العالمي في معدل انتشار الاضطرابات الفموية بين الشباب والمراهقين من 1990 إلى 2021 يمكن أن يُعزى إلى حد كبير إلى تقليل تسوس الأسنان في الأسنان الدائمة. تسوس الأسنان هو مرض معقد ومتعدد العوامل مدفوع بتكوين الأغشية الحيوية واستهلاك السكر، مما يؤدي إلى إزالة المعادن وإعادة المعادن في هياكل الأسنان، مما يسبب أعباء اقتصادية كبيرة وتأثيرات على جودة الحياة [33]. لذلك، فإن تقليل تأثير تسوس الأسنان مهم بشكل خاص خلال فترة الشباب. إن فهم أفضل لانتشاره على المستويات الإقليمية والوطنية أمر بالغ الأهمية لتحسين الوصول إلى رعاية الفم الفعالة. يرتبط الانخفاض العالمي في انتشار التسوس إلى حد كبير بتحسينات في نظافة الفم، وتغييرات في النظام الغذائي، وتدخلات الصحة العامة، وخاصة زيادة استخدام الفلورايد [34]. أحد العوامل الرئيسية التي تسهم في هذا الانخفاض هو الاعتماد الواسع على تنظيف الأسنان بالفرشاة بانتظام، خاصة مع معجون الأسنان بالفلورايد. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، ساعدت التقدمات في المواد السنية المضادة للميكروبات التي تطلق عوامل، وتقتل البكتيريا عند الاتصال، أو تجمع بين استراتيجيات متعددة في منع الالتصاق البكتيري الأولي وتكوين الأغشية الحيوية [35]. كان إدخال الفلورة في إمدادات المياه العامة أيضًا واحدًا من أكثر التدابير الصحية العامة فعالية في تقليل تسوس الأسنان [36]. علاوة على ذلك، كان هناك تحول عالمي نحو تقليل استهلاك السكر، مدفوعًا بحملات صحية، وتغييرات في النظام الغذائي، وتدخلات سياسية مثل ضرائب السكر وتنظيمات وضع العلامات الغذائية [37]. أدى هذا الانخفاض في الوجبات الخفيفة السكرية، والمشروبات الغازية، والأطعمة المعالجة إلى تقليل الهجمات الحمضية على الأسنان وتكوين الأغشية الحيوية، مما ساهم بشكل أكبر في انخفاض معدلات التسوس. ومع ذلك، على الرغم من هذه المكاسب، لا يزال تسوس الأسنان يمثل تحديًا كبيرًا لصحة الفم، خاصة بين الشباب والمراهقين، ويستمر في تمثيل أكثر من ثلاثة أرباع الاضطرابات الفموية السائدة في هذه الفئة العمرية. للتخفيف بشكل أكثر فعالية من عبء تسوس الأسنان بين الشباب والمراهقين، من الضروري اتباع نهج متعدد الجوانب. يجب أن يتضمن ذلك تعزيز المراقبة، وتحسين استراتيجيات الوقاية، وتوسيع الوصول إلى رعاية الأسنان، وتدخلات سلوكية. يمكن أن يساعد التركيز على الفئات عالية المخاطر، وزيادة الوصول إلى علاجات الفلورايد، وتعزيز الأنظمة الغذائية الأكثر صحة، واستغلال التقنيات الجديدة في تقليل انتشار التسوس ومنع

أظهر معدل انتشار الاضطرابات الفموية العالمي انخفاضًا طفيفًا على مدى العقود الثلاثة الماضية؛ ومع ذلك، زاد معدل الوفيات بسببها بشكل متناقض، مما يشير إلى أنه بينما قد يكون معدل انتشار الأمراض الفموية بشكل عام في انخفاض في بعض السياقات، فإن شدتها وعواقبها على صحة الشباب والمراهقين تتزايد. تسلط هذه الاتجاهات الضوء على التأثير المتزايد للأمراض الفموية، خاصة في المناطق ذات مؤشر التنمية الاجتماعية المتوسط. يمكن أن يُعزى انخفاض معدل انتشار الاضطرابات الفموية إلى عدة تحسينات في الصحة العامة، بما في ذلك تحسين ممارسات نظافة الفم، واستخدام الفلورايد، وتغييرات في النظام الغذائي، وبرامج الوقاية. قد يكون الزيادة في معدل الوفيات بسبب الاضطرابات الفموية ناتجة عن عبء متزايد من الحالات الفموية الأكثر شدة، مثل الأمراض اللثوية وفقدان الأسنان، والتي تكون أقل قابلية للتقليل من خلال تدابير الوقاية البسيطة مثل استخدام الفلورايد وتتطلب رعاية طويلة الأمد أكثر تعقيدًا. من الجدير بالذكر أن عبء كل من التهاب اللثة وفقدان الأسنان قد ارتفع بشكل غير متوقع بين الشباب والمراهقين عالميًا من 1990 إلى 2021. التدخين هو أحد أهم عوامل الخطر لالتهاب اللثة، حيث ترتبط معدلات التدخين الأعلى بزيادة حالات الأمراض اللثوية [38]. يضعف التدخين الجهاز المناعي، ويعيق تدفق الدم إلى اللثة، ويعزز نمو البكتيريا الضارة في الفم، مما يسرع من تدمير اللثة. على الرغم من الجهود الكبيرة في الصحة العامة لتقليل تدخين السجائر بين الشباب، يُقدر أن 155 مليون

شخصًا تتراوح أعمارهم بين 15-24 عامًا كانوا مدخنين عالميًا في عام 2019 [39]. من بين هؤلاء،

إلى زيادة في فقدان الأسنان. مع تقدم التهاب اللثة، يمكن أن يسبب ضررًا كبيرًا للثة وفقدان العظام، مما يؤدي إلى فقدان الأسنان الذي لا يمكن استعادته.

هذه الحالات أكثر تعقيدًا وشدة من تسوس الأسنان وترتبط بتأثيرات كبيرة

تؤدي التأثيرات الوظيفية والجمالية غالبًا إلى فقدان الأسنان الدائم (فقدان الأسنان) أو تلف طويل الأمد للهياكل الفموية (التهاب اللثة). وقد ارتبطت أمراض اللثة، على وجه الخصوص، بعوامل خطر مثل التدخين والسمنة والأمراض الأيضية، التي تزداد انتشارًا بين الشباب والمراهقين عالميًا. على الرغم من التقدم الكبير في السيطرة على تسوس الأسنان، فإن أمراض اللثة غالبًا ما تزداد سوءًا مع تغييرات نمط الحياة (مثل زيادة استهلاك التبغ والكحول) والحالات المزمنة، مما يسهم في شدتها وبالتالي تأثيرها على الإعاقة. يتطلب معالجة هذا الاتجاه المقلق استراتيجيات شاملة تركز على الكشف المبكر، وتحسين التعليم الصحي الفموي، وزيادة الوصول إلى الرعاية الوقائية، وإدارة أفضل لعوامل الخطر مثل التدخين والنظام الغذائي وقلة النشاط البدني. من خلال اعتماد نهج متعدد الجوانب للوقاية وإدارة أمراض اللثة، يمكننا تقليل عبء التهاب اللثة وفقدان الأسنان بشكل فعال بين الشباب والمراهقين.

بشكل عام، تميل عبء الاضطرابات الفموية بين الشباب والمراهقين إلى الانخفاض مع ارتفاع مؤشر التنمية الاجتماعية، ولكن المناطق ذات المؤشر المنخفض تشهد انخفاضًا أسرع في النسبة المئوية السنوية لمعدل الوفيات المعدلة حسب العمر (ASDR) للاضطرابات الفموية. لقد تم توثيق هذه الفجوة بشكل موسع في الدراسات السابقة، التي سلطت الضوء على العلاقات السببية بين الوضع الاجتماعي والاقتصادي ونتائج الصحة الفموية. بينما تبدأ المناطق ذات المؤشر المنخفض في وضع غير مواتٍ بسبب الوصول المحدود إلى رعاية الأسنان الجيدة، فإنها غالبًا ما تشهد تحسينات أسرع في الصحة الفموية مع تطور أنظمة الرعاية الصحية. حتى التقدم المتواضع، مثل إدخال تدابير وقائية أساسية، يمكن أن يؤدي إلى تقليص كبير في أعباء الصحة الفموية في هذه المناطق. في هذه البيئات، يمكن أن يكون لتحسينات صغيرة تأثير كبير بشكل غير متناسب، مما يؤدي إلى انخفاض أسرع في معدل الوفيات المعدلة حسب العمر، على الرغم من أن العبء العام يبقى أعلى مقارنة بالمناطق ذات المؤشر العالي. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تكون المناطق ذات المؤشر المنخفض عادة في مراحل مبكرة من الانتقال الوبائي، حيث يكون عبء الأمراض المعدية والاضطرابات الفموية القابلة للتجنب أكثر وضوحًا. مع تقدم هذه المناطق خلال الانتقال، غالبًا ما تؤدي التحسينات في البنية التحتية الأساسية للرعاية الصحية وزيادة الوصول إلى رعاية الأسنان إلى انخفاضات سريعة في حدوث الأمراض الفموية. على سبيل المثال، مع انخفاض عبء تسوس الأسنان غير المعالج وأمراض اللثة بسبب تحسين ممارسات النظافة الفموية وتوسيع خدمات الأسنان، يتسارع معدل الانخفاض السنوي في معدل الوفيات المعدلة حسب العمر. بالمقابل، تكون المناطق ذات المؤشر العالي قد مرت عادة بالفعل عبر المراحل الأولية من الانتقال الوبائي. في هذه المناطق، قد يكون عبء الأمراض الفموية المزمنة، مثل التهاب اللثة وفقدان الأسنان، في تزايد، حيث أن هذه الحالات أكثر تعقيدًا وتتطلب إدارة مستمرة. وغالبًا ما ترتبط هذه الأمراض بعوامل خطر مثل التدخين والسكري والسمنة. نتيجة لذلك، فإن التحسينات في معدل الوفيات المعدلة حسب العمر تكون أقل وضوحًا.

في المناطق ذات المؤشر العالي للصحة العامة لأن السكان قد استفادوا بالفعل من التدخلات الأساسية، ويتحول التركيز إلى إدارة قضايا صحة الفم الأكثر تعقيدًا واستمرارية.

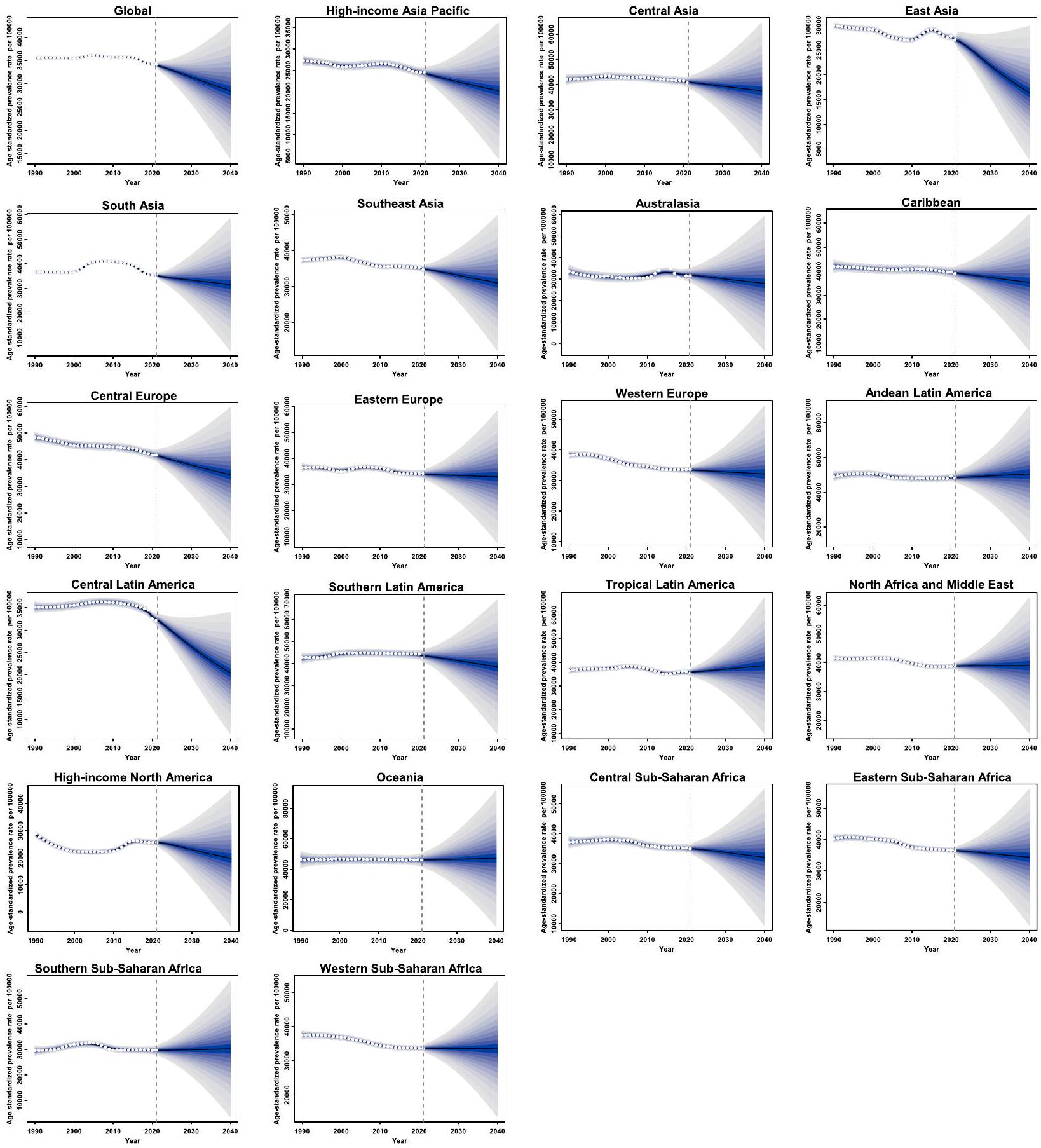

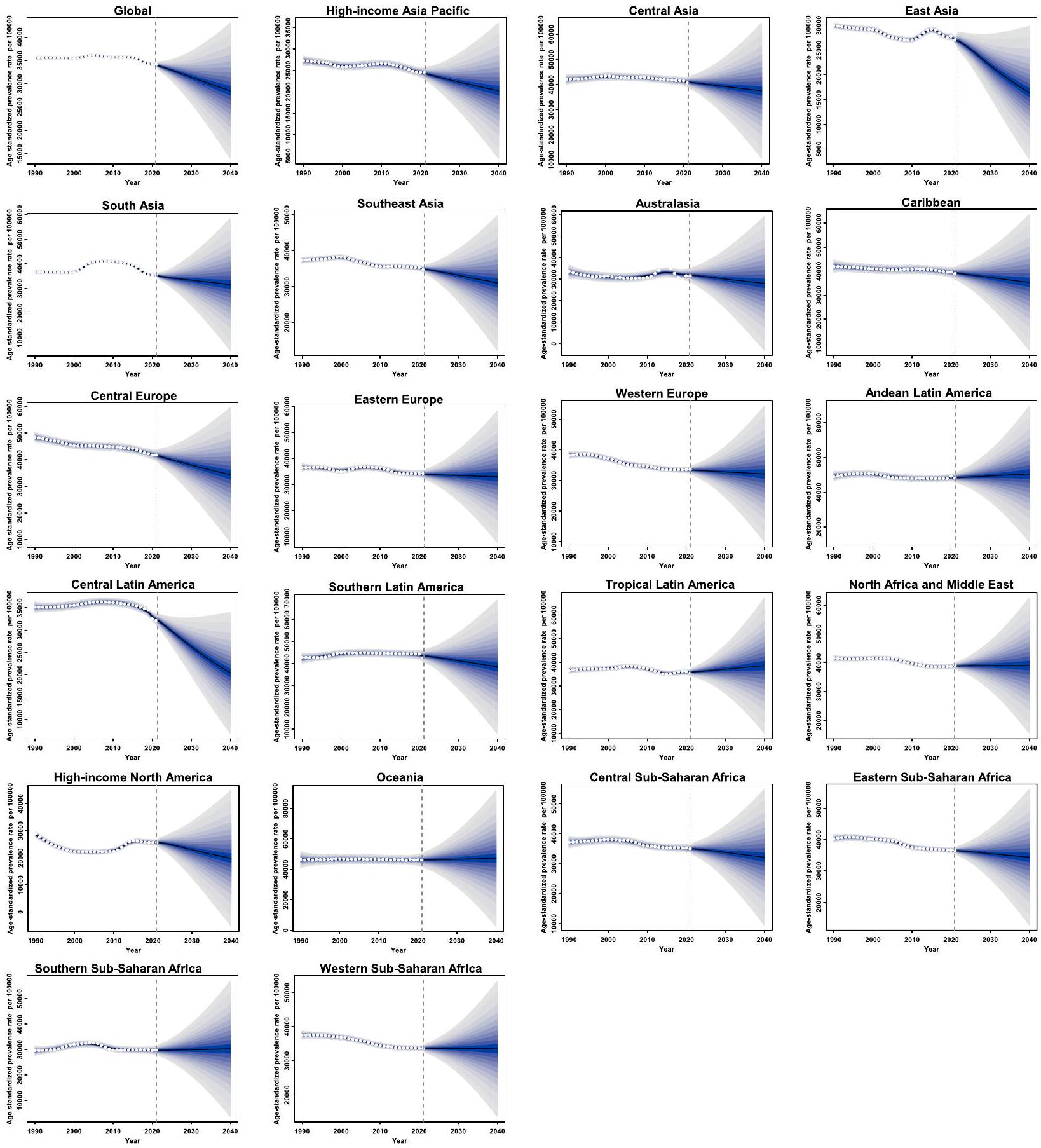

تظهر نتائجنا وجود تفاوتات إقليمية كبيرة في انتشار وأعباء الأمراض الفموية، مما يبرز الحاجة الملحة للتدخلات الصحية العامة المستهدفة. وعند النظر إلى المستقبل، تشير توقعاتنا إلى استمرار الانخفاض العالمي في معدل انتشار الأمراض الفموية حتى عام 2040، مع استثناءات ملحوظة في أمريكا اللاتينية الاستوائية وأوقيانوسيا. يمكن أن يُعزى العبء المتزايد للأمراض الفموية في هذه المناطق إلى عدة عوامل، بما في ذلك محدودية الوصول إلى رعاية الأسنان، والتحولات الغذائية، وزيادة استخدام التبغ، ونقص برامج الصحة العامة، والتأثيرات البيئية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن التحضر السريع واعتماد أنماط الحياة الغربية، جنبًا إلى جنب مع ارتفاع معدلات السمنة والأمراض المزمنة مثل السكري، يدفعان أيضًا نحو زيادة انتشار الأمراض الفموية. إن الزيادة المتوقعة في أعباء الأمراض الفموية في هذه المناطق تشير إلى تحديات محتملة في الصحة العامة تتطلب استراتيجيات استباقية. وهذا يبرز أهمية مراقبة الاتجاهات عن كثب وتكييف التدخلات مع السياقات المحلية، لضمان أنها تعالج بفعالية الاحتياجات الصحية الناشئة وعوامل الخطر المتطورة.

تتمتع مناطق مثل أمريكا اللاتينية الأنديز وبعض مناطق أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء بمعدلات انتشار موحدة للعمر (ASPR) عالية للاضطرابات الفموية. لمعالجة هذه التحديات، نوصي بتنفيذ تدابير وقائية أكثر شمولاً في هذه المناطق عالية المخاطر، بما في ذلك: دمج الحملات التعليمية في المناهج الدراسية والبرامج الصحية المجتمعية، توسيع مبادرات الفلورايد، تقديم سياسات مثل ضرائب السكر ووضع ملصقات غذائية أوضح لتنظيم تسويق المنتجات السكرية، وتحسين الوصول إلى رعاية الأسنان بأسعار معقولة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن الزيادة في انتشار الأمراض اللثوية بين الشباب والمراهقين، خاصة في مناطق مثل جنوب آسيا وأمريكا اللاتينية الجنوبية، تستدعي اتخاذ إجراءات مستهدفة. إن زيادة الفحص والتشخيص المبكر للأمراض اللثوية في الفئات السكانية عالية المخاطر أمر حاسم لتمكين التدخلات في الوقت المناسب ومنع المضاعفات طويلة الأمد مثل فقدان الأسنان. كما تؤكد دراستنا على التأثير الكبير للعوامل الاجتماعية والاقتصادية على نتائج الصحة الفموية. لذلك، فإن السياسات التي تعالج المحددات الاجتماعية الأوسع للصحة ضرورية لتحسين الصحة الفموية بين الشباب والمراهقين. لتعزيز البيانات المستقبلية حول عبء الأمراض الفموية وتقييم فعالية التدخلات، نوصي بتقوية أنظمة مراقبة الصحة الفموية لتوفير بيانات أكثر دقة وفي الوقت المناسب حول انتشار وشدة الأمراض الفموية بين الشباب والمراهقين.

لخفض العبء المتزايد للأمراض الفموية بين الشباب والمراهقين بشكل فعال، نقترح استراتيجية شاملة متعددة الجوانب،

تجمع بين مبادرات الصحة العامة، وتدابير السياسة، وجهود الوقاية المستهدفة. تشمل هذه الاستراتيجيات: (1) تنفيذ برامج قائمة على المدارس، مثل تنظيف الأسنان تحت الإشراف وتعليم الصحة الفموية، للانخراط بشكل فعال مع الشباب والمراهقين. (2) تعزيز اللوائح المتعلقة بإعلانات التبغ والسجائر الإلكترونية، وزيادة الضرائب على منتجات التبغ، وإطلاق حملات توعية لتثبيط تدخين الشباب. (3) تقديم ضرائب على السكر، وتحسين سياسات وضع العلامات الغذائية، وتقييد تسويق المشروبات والوجبات الخفيفة السكرية للسكان الأصغر سناً. (4) توسيع تغطية التأمين لرعاية الأسنان الوقائية ودمج خدمات الصحة الفموية في أنظمة الرعاية الصحية الأولية لتسهيل التدخل المبكر والحد من تقدم الأمراض الفموية الشديدة. (5) تعزيز النشاط البدني وبرامج التغذية الصحية للتخفيف من الاضطرابات الأيضية المرتبطة بالصحة الفموية السيئة. (6) تعزيز جمع البيانات وأنظمة المراقبة لتتبع الاتجاهات الناشئة في الأمراض الفموية وإبلاغ التدخلات المستهدفة.

ومع ذلك، فإن الدراسة الحالية لها عدة قيود. أولاً، كانت دقة وقوة التقديرات لانتشار وDALYs الاضطرابات الفموية مقيدة بتوافر وجودة البيانات، مما قد يؤدي إلى تحيزات، خاصة في المناطق التي تفتقر إلى المراقبة الوطنية أو الدراسات السكانية. للتخفيف من ذلك، تم استخدام طرق معدلة مختلفة، بما في ذلك تصحيحات التصنيف الخاطئ وإعادة توزيع الرموز غير المفيدة، لتقليل التحيز. ثانياً، تعتمد الدراسة على بيانات مجمعة على المستويات الوطنية والإقليمية، مما قد يحجب التباينات المحلية في نتائج الصحة الفموية. ثالثاً، قد يكون استخدام التغيرات النسبية السنوية لتقييم الاتجاهات طويلة الأجل من 1990 إلى 2021 قد أغفل التحولات القصيرة الأجل الأخيرة التي قد تعكس فعالية التدخلات الوقائية. رابعاً، بينما تشير التوقعات للاتجاهات المستقبلية إلى استمرار الانخفاض العالمي في ASPR للاضطرابات الفموية، فإن هذه التوقعات تستند إلى الاتجاهات الحالية والافتراضات، والتي قد لا تأخذ في الاعتبار التغييرات المستقبلية المحتملة في سياسات الصحة العامة، أو التقدم التكنولوجي، أو الأحداث غير المتوقعة التي قد تؤثر على نتائج الصحة الفموية. أخيراً، بينما يتماشى تقسيمنا العمري (10-14، 15-19، 20-24 سنة) مع إطار عمل الصحة المراهقة لمنظمة الصحة العالمية من حيث أهمية السياسة، فإننا نعترف بأن التباينات البيولوجية والفسيولوجية الكبيرة داخل نطاق العمر 10-24 قد تؤثر على نتائج الصحة الفموية. كل مجموعة فرعية تظهر تبايناً بيولوجياً، مثل الانتقال من الأسنان المختلطة إلى الأسنان الدائمة الكاملة (10-14 مقابل 20-24 سنة) [52]، والتباينات في أنماط بزوغ الأسنان (مثل بزوغ الضرس الثالث في أواخر المراهقة) [53]، والتغيرات الهرمونية [54]، بما في ذلك التحولات المدفوعة بالبلوغ في الميكروبيوم الفموي التي قد تؤثر على القابلية للتسوس والتهاب اللثة. ومع ذلك، فإن تصميم دراستنا الملاحظة قيدت القدرة على إجراء

تحليلات أكثر تفصيلاً حسب العمر. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن الطبيعة العرضية لبيانات GBD تقيد الاستنتاجات السببية بين التغيرات البيولوجية المرتبطة بالعمر ومسارات الأمراض الفموية.

الخاتمة

معلومات إضافية

الشكر والتقدير

رقم التجربة السريرية

بيان مصادر التمويل للدراسة

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

نشر على الإنترنت: 04 أبريل 2025

References

- Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, Listl S, Celeste RK, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Kearns C, et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):249-60.

- Chimbinha ÍGM, Ferreira BNC, Miranda GP, Guedes RS. Oral-healthrelated quality of life in adolescents: umbrella review. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1603.

- Kassebaum NJ, Smith AGC, Bernabé E, Fleming TD, Reynolds AE, Vos T, Murray CJL, Marcenes W, Abyu GY, Alsharif U, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence, incidence, and disability-adjusted life years for oral conditions for 195 countries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. J Dent Res. 2017;96(4):380-7.

- Freitag-Wolf S, Munz M, Wiehe R, Junge O, Graetz C, Jockel-Schneider Y, Staufenbiel I, Bruckmann C, Lieb W, Franke A, et al. Smoking modifies the genetic risk for early-onset periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2019;98(12):1332-9

- Nascimento GG, Alves-Costa S, Romandini M. Burden of severe periodontitis and edentulism in 2021, with projections up to 2050: the global burden of disease 2021 study. J Periodontal Res. 2024;59(5):823-67.

- Wu L, Zhang S-Q, Zhao L, Ren Z-H, Hu C-Y. Global, regional, and national burden of periodontitis from 1990 to 2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. J Periodontol. 2022;93(10):1445-54.

- Kaur P, Singh S, Mathur A, Makkar DK, Aggarwal VP, Batra M, Sharma A, Goyal N. Impact of dental disorders and its influence on self esteem levels among adolescents. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(4):Zc05-zc08.

- López R, Smith PC, Göstemeyer G, Schwendicke F. Ageing, dental caries and periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(Suppl 18):S145-s152.

- Borgnakke WS. IDF diabetes atlas: diabetes and oral health – a two-way relationship of clinical importance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157: 107839.

- Bernabe E, Marcenes W, Hernandez CR, Bailey J, Abreu LG, Alipour V, Amini S, Arabloo J, Arefi Z, Arora A, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease 2017 study. J Dent Res. 2020;99(4):362-73.

- Watt RG, Daly B, Allison P, Macpherson LMD, Venturelli R, Listl S, Weyant RJ, Mathur MR, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Celeste RK, et al. Ending the neglect of global oral health: time for radical action. The Lancet. 2019;394(10194):261-72.

- Hosseinpoor AR, Itani L, Petersen PE. Socio-economic inequality in oral healthcare coverage: results from the world health survey. J Dent Res. 2011;91(3):275-81.

- Luan Y, Sardana D, Jivraj A, Liu D, Abeyweera N, Zhao Y, Cellini J, Bass M, Wang J, Lu X, et al. Universal coverage for oral health care in 27 low-income countries: a scoping review. Global Health Res Policy. 2024;9(1):34.

- Watt RG, Sheiham A. Integrating the common risk factor approach into a social determinants framework. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40(4):289-96.

- Weiss HA, Ferrand RA. Improving adolescent health: an evidence-based call to action. Lancet. 2019;393(10176):1073-5.

- Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, Arora M, Azzopardi P, Baldwin W, Bonell C, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. The Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2423-78.

- Botelho J, Mascarenhas P, Viana J, Proença L, Orlandi M, Leira Y, Chambrone L, Mendes JJ, Machado V. An umbrella review of the evidence linking oral health and systemic noncommunicable diseases. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):7614.

- The Lancet Child Adolescent Health. Oral health: oft overlooked. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(10):663.

- Jain N, Dutt U, Radenkov I, Jain S. WHO’s global oral health status report 2022: actions, discussion and implementation. Oral Dis. 2024;30(2):73-9.

- Jin LJ, Lamster IB, Greenspan JS, Pitts NB, Scully C, Warnakulasuriya S. Global burden of oral diseases: emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral Dis. 2016;22(7):609-19.

- Knorst JK, Sfreddo CS, de F Meira G, Zanatta FB, Vettore MV, Ardenghi TM. Socioeconomic status and oral health-related quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2021;49(2):95-102.

- Heaton LJ, Santoro M, Tiwari T, Preston R, Schroeder K, Randall CL, Sonnek A, Tranby EP. Mental health, socioeconomic position, and oral health: a path analysis. Prev Chronic Dis. 2024;21:E76.

- Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Aali A, Abate YH, Abbafati C, Abbastabar H, Abd ElHafeez S, Abdelmasseh M, Abd-Elsalam S, Abdollahi A, et al. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disabilityadjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403(10440):2133-61.

- Murray CJL. The global burden of disease study at 30 years. Nat Med. 2022;28(10):2019-26.

- Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolescent Health. 2018;2(3):223-8.

- Wang H, Song Y, Ma J, Ma S, Shen L, Huang Y, Thangaraju P, Basharat Z, Hu Y, Lin Y, et al. Burden of non-communicable diseases among adolescents and young adults aged 10-24 years in the South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2023;7(9):621-35.

- GBD 2019 Adolescent Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national mortality among young people aged 10-24 years, 1950-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2021;398(10311):1593-618.

- Schumacher AE, Kyu HH, Aali A, Abbafati C, Abbas J, Abbasgholizadeh R, Abbasi MA, Abbasian M, Abd ElHafeez S, Abdelmasseh M, et al. Global age-sex-specific mortality, life expectancy, and population estimates in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1950-2021, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. The Lancet. 2024;403(10440):1989-2056.

- Hankey BF, Ries LA, Kosary CL, Feuer EJ, Merrill RM, Clegg LX, Edwards BK. Partitioning linear trends in age-adjusted rates. Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11(1):31-5.

- Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J Am Stat Assoc. 1979;74(368):829-36.

- Riebler A, Held L. Projecting the future burden of cancer: Bayesian age-period-cohort analysis with integrated nested Laplace approximations. Biom J. 2017;59(3):531-49.

- Vollset SE, Goren E, Yuan C-W, Cao J, Smith AE, Hsiao T, Bisignano C, Azhar GS, Castro E, Chalek J, et al. Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the global burden of disease study. The Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1285-306.

- Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD, Ekstrand K, Weintraub JA, Ramos-Gomez F, Tagami J, Twetman S, Tsakos G, Ismail A. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(1):17030.

- Frencken JE, Sharma P, Stenhouse L, Green D, Laverty D, Dietrich T. Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis – a comprehensive review. J Clin Periodontol. 2017;44(S18):S94-105.

- Jiao Y, Tay FR, Niu LN, Chen JH. Advancing antimicrobial strategies for managing oral biofilm infections. Int J Oral Sci. 2019;11(3):28.

- Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Walsh T, Lewis SR, Riley P, Boyers D, Clarkson JE, Worthington HV, Glenny AM, O’Malley L. Water fluoridation for the prevention of dental caries. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2024;10(10):CD010856.

- Chaloupka FJ, Powell LM, Warner KE. The use of excise taxes to reduce tobacco, alcohol, and sugary beverage consumption. Ann Rev Public Health. 2019;40:187-201.

- Leite FRM, Nascimento GG, Scheutz F, López R. Effect of smoking on periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-regression. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6):831-41.

- Reitsma MB, Flor LS, Mullany EC, Gupta V, Hay SI, Gakidou E. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and initiation among young people in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(7):e472-81.

- Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, Chang JT, Anic GM, Wang TW, Creamer MR, Jamal A, Ambrose BK, King BA. e-Cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2095-103.

- Shabil M, Khatib MN, Ballal S, Bansal P, Tomar BS, Ashraf A, Kumar MR, Sinha A, Rawat P, Gaidhane AM, et al. The impact of electronic cigarette use on periodontitis and periodontal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):1197.

- van Sluijs EMF, Ekelund U, Crochemore-Silva I, Guthold R, Ha A, Lubans D, Oyeyemi AL, Ding D, Katzmarzyk PT. Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: current evidence and opportunities for intervention. Lancet. 2021;398(10298):429-42.

- Azzopardi PS, Hearps SJC, Francis KL, Kennedy EC, Mokdad AH, Kassebaum NJ, Lim S, Irvine CMS, Vos T, Brown AD, et al. Progress in adolescent health and wellbeing: tracking 12 headline indicators for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016. The Lancet. 2019;393(10176):1101-18.

- Tison GH, Barrios J, Avram R, Kuhar P, Bostjancic B, Marcus GM, Pletcher MJ, Olgin JE. Worldwide physical activity trends since COVID-19 onset. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10(10):e1381-2.

- Ganesan SM, Vazana S, Stuhr S. Waistline to the gumline: relationship between obesity and periodontal disease-biological and management considerations. Periodontology 2000. 2021;87(1):299-314.

- Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JR, Lontchi-Yimagou E, Nkeck JR, Nyaga UF, Ngouo AT, Tounouga DN, Tianyi FL, Foka AJ, Ndoadoumgue AL, et al. Global, regional, and country estimates of metabolic syndrome burden in children and adolescents in 2020: a systematic review and modelling analysis. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2022;6(3):158-70.

- Marruganti C, Suvan JE, D’Aiuto F. Periodontitis and metabolic diseases (diabetes and obesity): tackling multimorbidity. Periodontol 2000. 2023;00:1-16.

- Albandar JM, Brown LJ, Löe H. Dental caries and tooth loss in adolescents with early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1996;67(10):960-7.

- Seminario AL, DeRouen T, Cholera M, Liu J, Phantumvanit P, Kemoli A, Castillo J, Pitiphat W. Mitigating global oral health inequalities: research training programs in low- and middle-income countries. Ann Glob Health. 2020;86(1):141.

- Jebeile H, Kelly AS, O’Malley G, Baur LA. Obesity in children and adolescents: epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(5):351-65.

- Xie J, Wang M, Long Z, Ning H, Li J, Cao Y, Liao Y, Liu G, Wang F, Pan A. Global burden of type 2 diabetes in adolescents and young adults, 1990-2019: systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. BMJ. 2022;379: e072385.

- Lynch RJ. The primary and mixed dentition, post-eruptive enamel maturation and dental caries: a review. Int Dent J. 2013;63 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):3-13.

- Alsaegh MA, Abushweme DA, Ahmed KO, Ahmed SO. The pattern of mandibular third molar impaction and its relationship with the development of distal caries in adjacent second molars among Emiratis: a retrospective study. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):306.

- Al-Ghutaimel H, Riba H, Al-Kahtani S, Al-Duhaimi S. Common periodontal diseases of children and adolescents. Int J Dent. 2014;2014: 850674.

ملاحظة الناشر

زينغزو داي ومانكيونغ داي ساهموا بالتساوي في هذا العمل.

*المراسلة:

وانغهونغ تشاو

wanghong_zhao@sina.com

القائمة الكاملة لمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقال

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-025-05864-z

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40186217

Publication Date: 2025-04-04

Global burden and trends of oral disorders among adolescent and young adult (1024 years old) from 1990 to 2021

Abstract

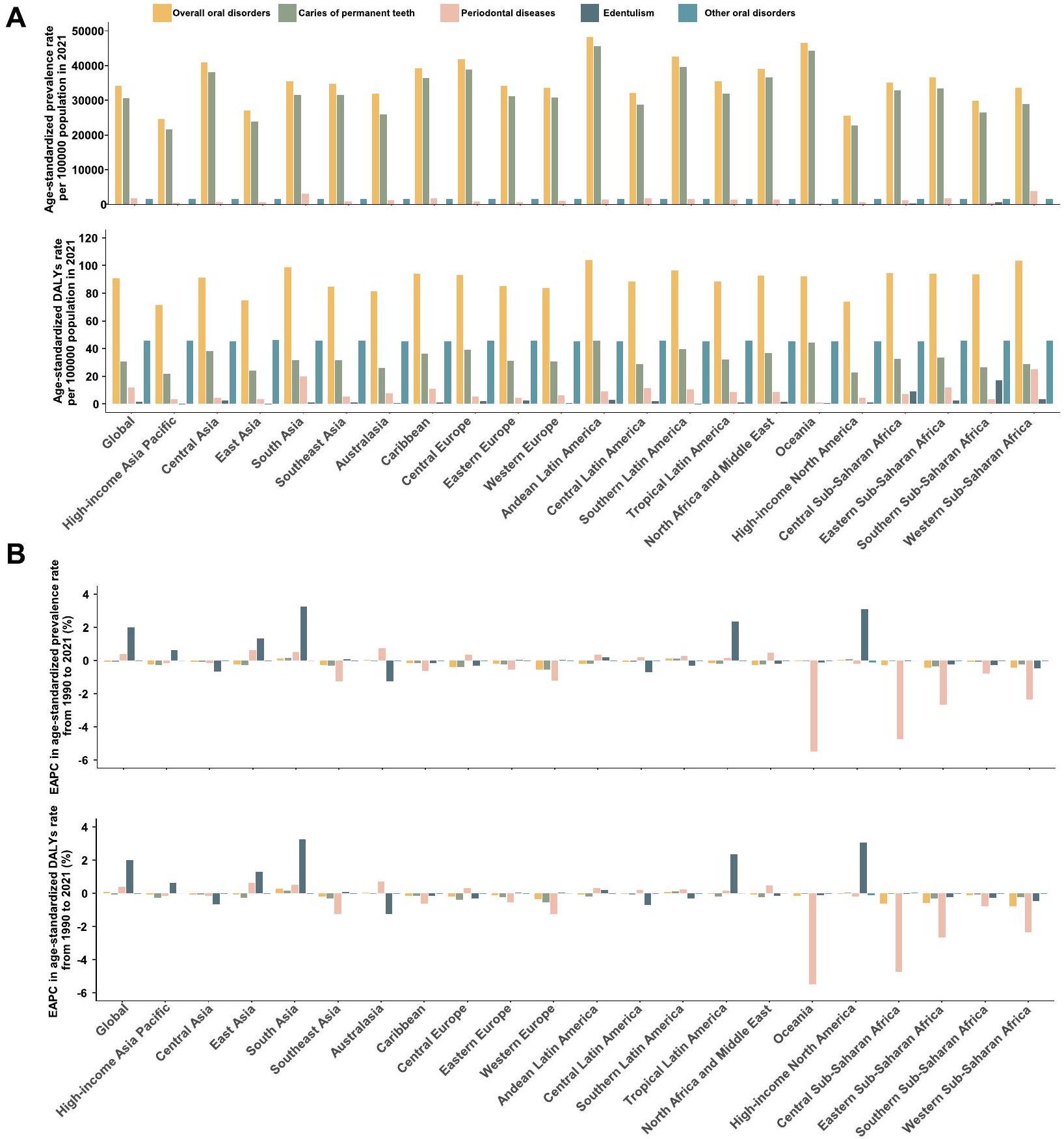

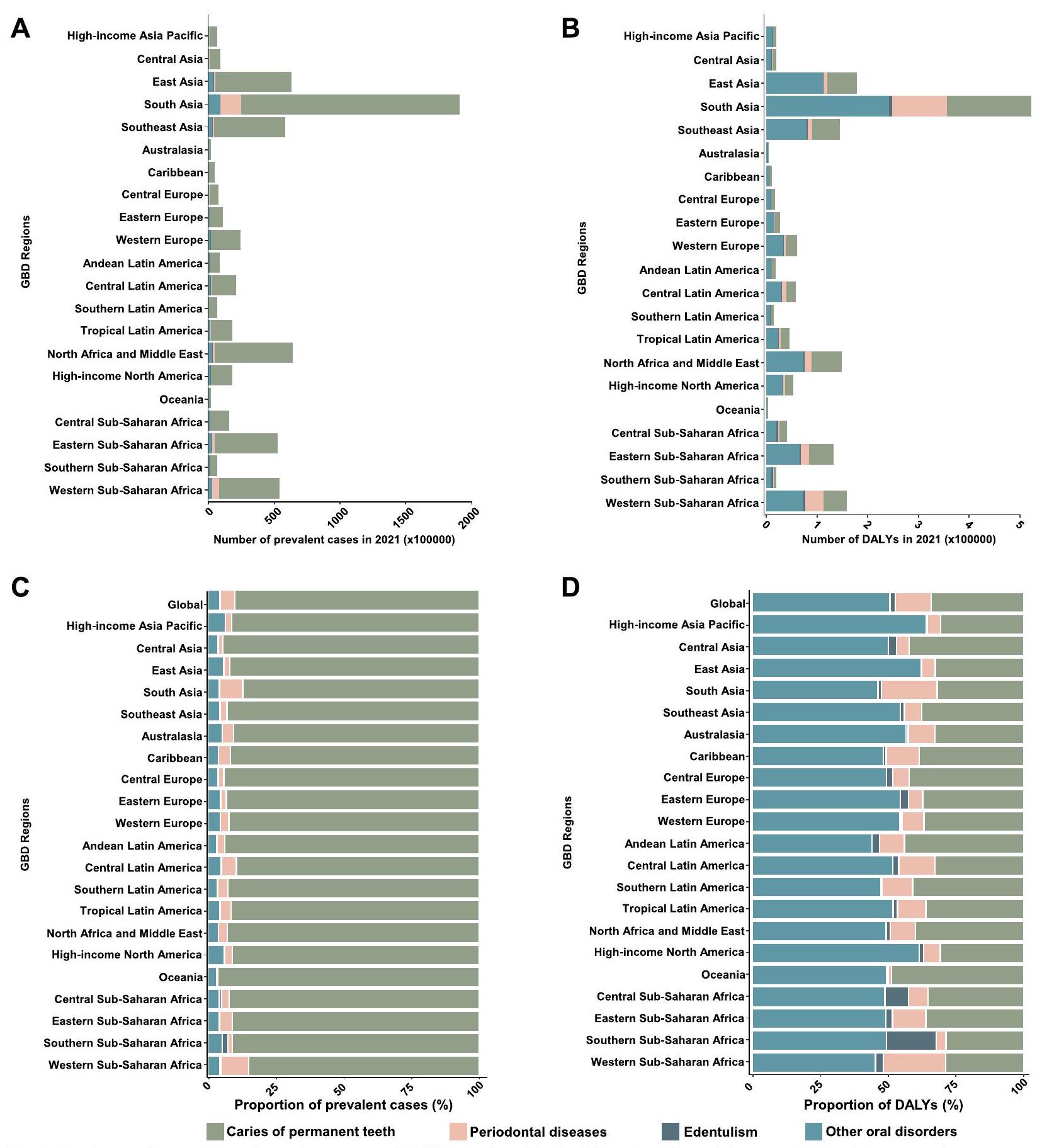

Objective To determine the patterns and trends in the global, regional, and national burden of oral disorders among adolescents and young adults (AYA) from 1990 to 2021. Methods This is an epidemiological observational study that analyzed annual prevalence and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for oral disorders—including dental caries, periodontal disease, edentulism, and other oral conditions—among adolescents and young adults (ages 10-24) from 1990 to 2021. Data were sourced from the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) 2021. To assess temporal trends, the estimated annual percentage changes (EAPC) in age-standardized prevalence and DALY rates were calculated at global, regional, and national levels. The GBD 2021 also provides sociodemographic index (SDI) data across 204 countries and territories. Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to explore the relationships between age-standardized prevalence and DALY rates with the SDI and their respective EAPCs. Results Globally, the prevalent cases of oral disorders increased by 17.1%, from 549.2 million in 1990 to 643.3 million in 2021, and DALYs rose by 22.2%, from 1.4 million in 1990 to 1.7 million in 2021. The overall age-standardized prevalence rate (EAPC

Conclusions The prevalence and DALYs of oral disorders among AYA have risen over the past three decades, particularly due to the growing burden of periodontitis and edentulism. Notably, the most significant increases have been observed in Southern Latin America and South Asia. While the global decline in dental caries has led to a reduction in ASPR, the escalating burden of periodontal disease and edentulism remains a critical concern. These trends emphasize the urgent need for innovative prevention and intervention strategies to improve oral health for this demographic worldwide.

Introduction

Oral diseases, particularly dental caries, are widespread among AYAs, with untreated caries peaking between the ages of 15 and 19 and affecting millions worldwide [3]. Although periodontitis and edentulism are less common in this group, they remain significant oral health concerns [5]. Alarmingly, periodontitis is on the rise among younger adults, underscoring the urgent need for early preventive strategies [6]. The psychosocial impacts of oral disorders in AYAs, including dental caries and periodontitis, are especially severe [7]. These conditions can lead to significant emotional distress, negatively affecting self-esteem, social interactions, and overall life satisfaction. Poor oral health in AYAs may have long-lasting consequences, extending to their mental health and social well-being.

Furthermore, the broader implications of untreated oral disorders are concerning, as these conditions often worsen with age [8]. Untreated caries, periodontal disease, and early-stage edentulism in young individuals tend to progress into more severe forms, increasing the risk of chronic conditions such as tooth loss and systemic diseases. The link between oral health and overall health-including conditions like diabetes and obesityis particularly concerning, as poor oral health in AYAs is associated with an increased risk of developing these conditions, which can have lifelong consequences [7,9].

There are stark disparities in oral health across regions and countries, with oral diseases disproportionately affecting impoverished areas and further exacerbating health inequalities [3, 10]. In high-income countries, oral healthcare systems are often dominated by treatmentfocused and increasingly technology-driven approaches. However, these systems tend to be trapped in an interventionist cycle that neither addresses the root causes of oral diseases nor adequately serves large segments of the population [11]. In many middle-income countries, the burden of oral diseases is considerable, yet oral healthcare

systems remain underdeveloped and unaffordable for the majority [12]. The situation is most dire in low-income countries, where access to oral care is severely limited, leaving many without essential treatment or prevention [13]. Moreover, broader social, economic, and commercial changes in low- and middle-income countries may be increasing the risk of oral disease [14]. Globally, the number of AYA is at an all-time high and is expected to continue growing in the coming decades. This increase will be most pronounced in low-income countries, where significant reductions in under- 5 and child mortality rates have occurred, while fertility rates remain relatively high [15]. As a result, comprehensive assessments of the burden of oral disorders among AYA across different regions are crucial for developing more targeted and effective prevention and control strategies.

AYA represent a crucial demographic group, where investing in their health not only brings immediate benefits but also supports their wellbeing into adulthood and positively influences the health of future generations [16]. Therefore, implementing effective interventions for oral disorders during this pivotal developmental stage can significantly improve global oral health outcomes and contribute to broader population wellbeing [17]. However, oral health among AYA has long been underexplored in global health research, particularly with regard to regional variations, temporal trends, and the broader socio-economic determinants influencing oral disease prevalence [18]. Previous studies have largely focused on cross-sectional assessments or regional data that fail to capture long-term trends. This gap is especially evident in the scarcity of data on the burden of oral diseases such as periodontitis and edentulism in younger populations [19, 20]. Although numerous studies have explored the relationship between socio-economic status and oral health, the impact of global socio-economic changes over time on the oral health burdens in AYA remains unclear [21, 22].

The Global Burden of Diseases Study (GBD) offers a thorough evaluation of the burden of oral disorders across 204 countries and territories, providing a valuable opportunity to analyze trends in oral health over recent decades [23]. In this study, we focus on three common oral conditions-caries of permanent teeth, periodontitis, and edentulism-and aim to estimate the patterns and trends in their prevalence and disabilityadjusted life-years (DALYs) among AYA. The objective of this study is to determine the patterns and trends in the global, regional, and national burden of oral disordersspecifically dental caries, periodontitis, and edentulismamong adolescents and young adults (ages 10-24) from 1990 to 2021, in order to inform targeted prevention and intervention strategies.

Methods

Overview

Definitions

Data collection

Statistical analysis

The natural logarithm of changes in ASR is assumed to follow a linear trend over time, represented by the equation

into 21 world regions based on the GBD classification, allowing us to examine regional differences in the burden of oral disorders. Additionally, at the national level, we evaluated trends in oral health outcomes using data from 204 countries and territories. We classified an ASR as increasing or decreasing if both the EAPC and its 95% CI were entirely above or below zero, respectively. If the 95% CI included zero, the change in ASR was considered statistically insignificant.

Additionally, a Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing (LOWESS) model was used to examine the correlation between the burden of oral disorders among AYA and the SDI across 21 regions and 204 countries and territories [30]. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to calculate the

Furthermore, the age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR) of oral disorders among AYA from 2022 to 2040 was projected using the Bayesian age-period-cohort (BAPC) model with nested Laplace approximations [31]. The BAPC model estimates hypothetical probability distributions based on three key factors-age, period, and cohort-by combining prior knowledge with sample data to derive posterior distributions [31]. Global age-standardized population data were sourced from the World Standards database, developed by the WHO (https://seer. cancer.gov/stdpopulations/world.who.html), and population forecast data were obtained from the GBD Global Fertility, Mortality, Migration, and Population Forecasts for 2017-2100 [32]. The “BAPC” R package was used to implement the model, enabling the creation of wellcalibrated probabilistic forecasts with relatively narrow uncertainty intervals.

All statistical analyses and mapping were conducted using

Results

Global, regional, and national burden of overall disorders among AYA

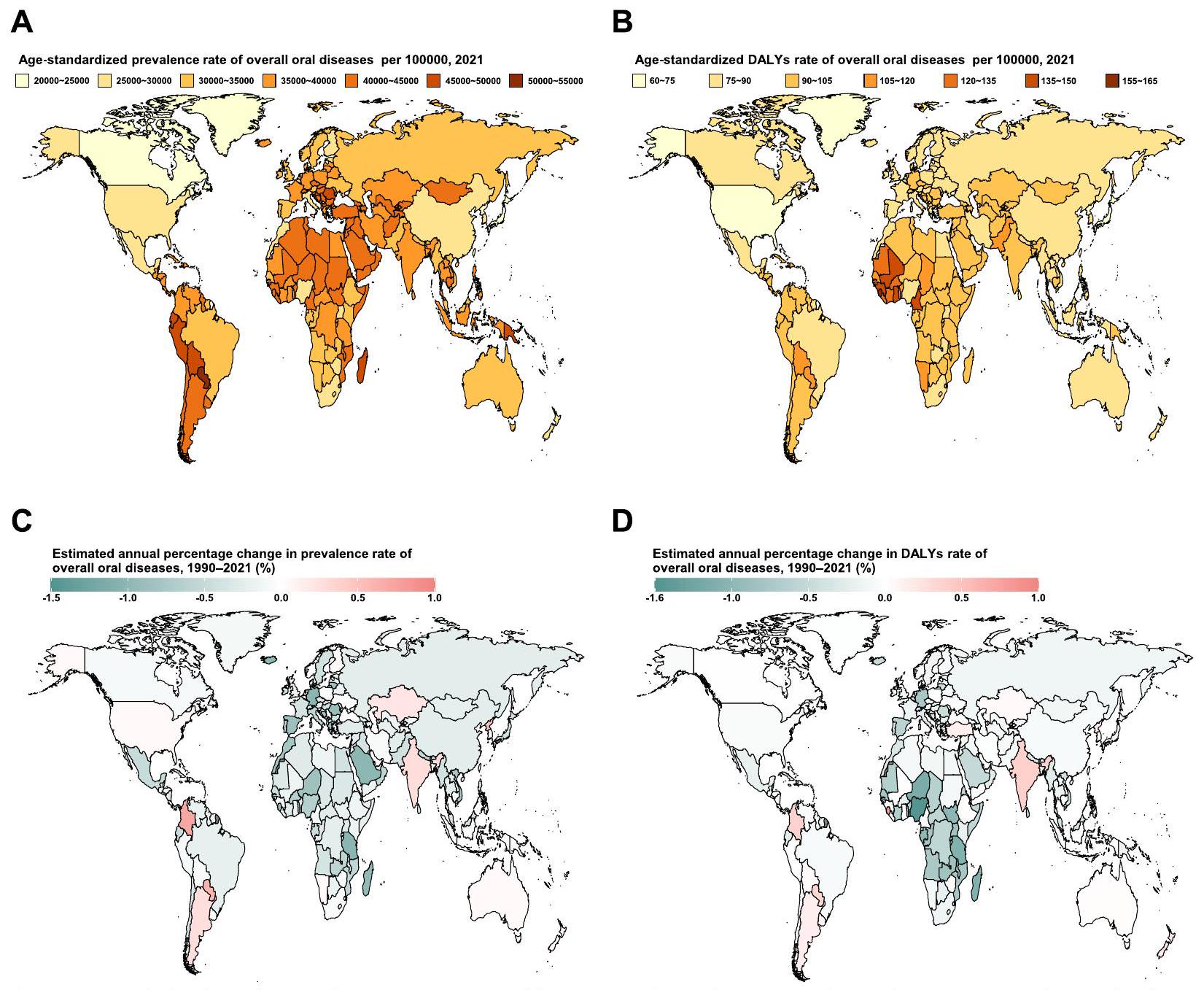

country level, Paraguay exhibited the highest ASPR at 54,007.6 (95% UI, 53,905.5 to 54,109.8) per 100,000, while Sierra Leone had the highest ASDR, recorded at 158 (95% UI, 153.4 to 162.7 ) per 100,000 (Figs. 2A and B, Supplementary Table S3).

From 1990 to 2021, the global ASPR of oral disorders decreased by an average of

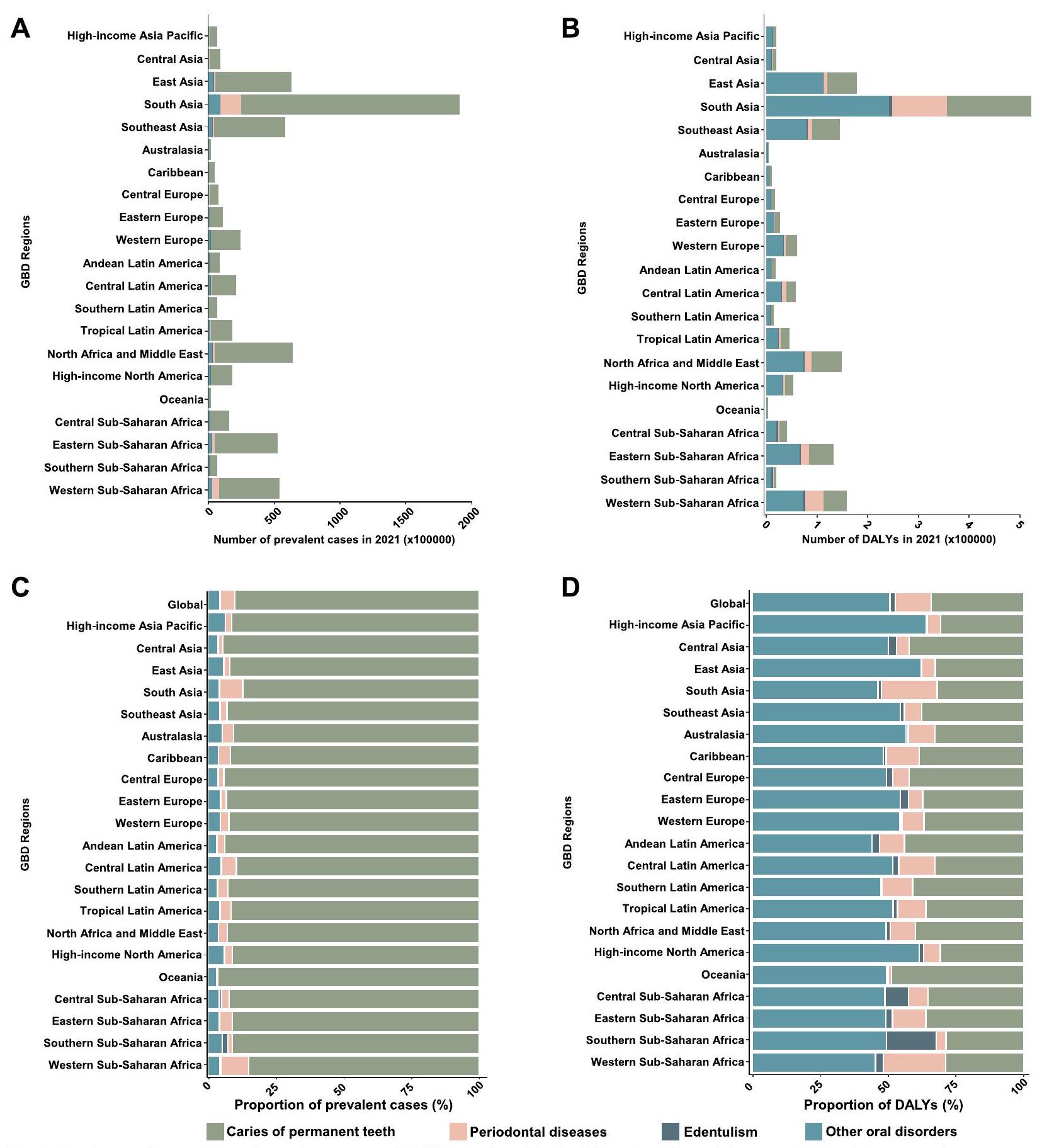

Regional disparities in the burden of four oral disorders among AYA

| Characteristics | Prevalence | DALYs | ||||||||

| Number of cases in 1990 (Million) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 1990 | Number of cases in 2021 (Million) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 2021 | Estimated annual percentage change, 1990-2021 | Number of cases in 1990 (Thousand) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 1990 | Number of cases in 2021 (Thousand) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 2021 | Estimated annual percentage change, 1990-2021 | |

| Global | 549.17 | 35,469 (35,466 to 35,471.9) | 643.29 | 34,076.8 (34,074.2 to 34,079.4) | -0.07 (-0.12 to -0.03) | 1400.53 | 90.3 (90.1 to 90.4) | 1711.71 | 90.7 (90.5 to 90.8) | 0.06 (0.02 to 0.11) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 274.42 | 35,998.5 (35,994.2 to 36,002.8) | 317.91 | 34,506.8 (34,503 to

|

-0.09 (-0.14 to -0.04) | 720.99 | 94.3 (94.1 to 94.5) | 871.67 | 94.5 (94.3 to 94.7) | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.09) |

| Male | 274.75 | 34,956.4 (34,952.3 to

|

325.38 | 33,667.8 (33,664.2 to

|

-0.06 (-0.11 to -0.01) | 679.54 | 86.4 (86.2 to 86.6) | 840.05 | 87 (86.8 to 87.2) | 0.08 (0.03 to 0.12) |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 10-14 years | 168.7 | 31,492.9 (21,831.1 to 43,160.6) | 188.5 | 28,276.5 (19,990.5 to 39,064.1) | -0.24 (-0.3 to -0.17) | 326.03 | 60.9 (33.6 to 105.8) | 386.51 | 58 (32.4 to 99.3) | -0.1 (-0.13 to -0.07) |

| 15-19 years | 169.44 | 32,621 (22,828.8 to 44,722.2) | 204.16 | 32,719 (23,558.9 to 43,569.8) | 0.07 (0 to 0.13) | 448 | 86.2 (45.4 to 144.1) | 545.08 | 87.4 (47.1 to 146.7) | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.1) |

| 20-24 years | 211.02 | 42,883.6 (32,284.2 to 54,395.7) | 250.63 | 41,970.8 (33,125.5 to 52,185.8) | -0.06 (-0.1 to -0.02) | 626.5 | 127.3 (68.7 to 214.2) | 780.12 | 130.6 (71.1 to 216.6) | 0.15 (0.09 to 0.2) |

| Causes | ||||||||||

| Caries of permanent teeth | 494.54 | 31,918 (31,915.2 to 31,920.8) | 578.76 | 30,658.1 (30,655.6 to 30,660.6) | -0.07 (-0.12 to -0.01) | 495.06 | 32 (31.9 to 32) | 579.6 | 30.7 (30.6 to 30.8) | -0.06 (-0.12 to -0.01) |

| Periodontal diseases | 24.19 | 1551.3 (1550.7 to 1551.9) | 33.88 | 1794.7 (1794.1 to 1795.3) | 0.4 (0.26 to 0.54) | 161.24 | 10.3 (10.3 to 10.4) | 225.4 | 11.9 (11.9 to 12) | 0.4 (0.26 to 0.54) |

| Edentulism | 0.8 | 51.2 (51.1 to 51.3) | 1.14 | 60.4 (60.3 to 60.5) | 1.99 (1.19 to 2.8) | 23.12 | 1.5 (1.5 to 1.5) | 33.15 | 1.8 (1.7 to 1.8) | 2 (1.2 to 2.8) |

| Other oral disorders | 24.06 | 1550.9 (1550.3 to 1551.6) | 29.25 | 1549.6 (1549 to 1550.1) | -0.01 (-0.01 to -0.01) | 708.68 | 45.7 (45.6 to 45.8) | 861.86 | 45.7 (45.6 to 45.8) | 0 (-0.01 to 0) |

| Socio-demographic index | ||||||||||

| High | 63.52 | 32,107 (32,099 to

|

55.4 | 29,486.5 (29,478.7 to 29,494.3) | -0.25 (-0.34 to -0.16 ) | 165.15 | 82.3 (81.9 to 82.7) | 149.34 | 78.7 (78.3 to 79.1) | -0.15 (-0.2 to -0.1) |

| Characteristics | Prevalence | DALYs | ||||||||

| Number of cases in 1990 (Million) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 1990 | Number of cases in 2021 (Million) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 2021 | Estimated annual percentage change, 1990-2021 | Number of cases in 1990 (Thousand) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 1990 | Number of cases in 2021 (Thousand) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 2021 | Estimated annual percentage change, 1990-2021 | |

| High-middle | 100.76 | 35,285.6 (35,278.6 to 35,292.5) | 74.92 | 33,005.9 (32,998.4 to 33,013.4) | -0.18 (-0.22 to -0.14) | 244.86 | 84.7 (84.4 to 85.1) | 189.73 | 83.3 (83 to 83.7) | -0.02 (-0.04 to 0) |

| Middle | 191.79 | 34,847.1 (34,842.2 to 34,852.1) | 185.29 | 33,467.5 (33,462.7 to 33,472.3) | -0.07 (-0.13 to 0 ) | 481.38 | 87 (86.7 to 87.2) | 484.1 | 87.3 (87.1 to 87.6) | 0.08 (0.03 to 0.13) |

| Low-middle | 132.48 | 37,013.5 (37,007.2 to 37,019.8) | 193.14 | 34,925.3 (34,920.4 to 34,930.2) | -0.06 (-0.17 to 0.06) | 346.43 | 98.2 (97.9 to 98.5) | 532.81 | 96.3 (96 to 96.5) | 0.05 (-0.04 to 0.14) |

| Low | 60.03 | 39,294.5 (39,284.5 to 39,304.5) | 133.98 | 36,779.7 (36,773.4 to

|

-0.26 (-0.31 to -0.2) | 161.4 | 108.5 (107.9 to 109) | 354.45 | 98.8 (98.4 to 99.1) | -0.34 (-0.39 to -0.29) |

| GBD regions | ||||||||||

| High-income Asia Pacific | 11.61 | 27,303.2 (27,287.5 to 27,319) | 6.54 | 24,550.7 (24,531.8 to 24,569.7) | -0.24 (-0.31 to -0.17 ) | 31.82 | 74.2 (73.4 to 75) | 19.22 | 71.5 (70.5 to 72.5) | -0.09 (-0.11 to -0.07) |

| Central Asia | 8.33 | 42,182.1 (42,153.5 to 42,210.8) | 9.02 | 40,855.9 (40,829.2 to 40,882.6) | -0.08 (-0.13 to -0.03) | 18.37 | 93.4 (92.1 to 94.8) | 20.11 | 91.4 (90.2 to 92.7) | -0.06 (-0.09 to -0.04) |

| East Asia | 113.85 | 29,961.2 (29,955.6 to 29,966.7) | 65.57 | 27,073.9 (27,067.3 to 27,080.5) | -0.24 (-0.34 to -0.14) | 298.62 | 77.5 (77.2 to 77.8) | 180.84 | 74.8 (74.4 to 75.1) | -0.07 (-0.11 to -0.02) |

| South Asia | 121.49 | 36,664.6 (36,658 to 36,671.1) | 187.95 | 35,566.5 (35,561.5 to 35,571.6) | 0.13 (-0.07 to 0.33) | 322.35 | 98.4 (98.1 to 98.8) | 525.52 | 98.9 (98.6 to 99.2) | 0.26 (0.09 to 0.43) |

| Southeast Asia | 55.28 | 37,364 (37,354.1 to 37,373.9) | 59.59 | 34,750.8 (34,741.9 to 34,759.6) | -0.28 (-0.34 to -0.23) | 130.67 | 88.9 (88.4 to 89.4) | 146.31 | 84.9 (84.5 to 85.3) | -0.19 (-0.23 to -0.16) |

| Australasia | 1.65 | 33,875.9 (33,824.2 to 33,927.8) | 1.85 | 31,973.4 (31,927.3 to 32,019.6) | 0.05 (-0.13 to 0.23) | 4.09 | 83.3 (80.8 to 85.9) | 4.74 | 81.3 (79 to 83.7) | 0.05 (-0.04 to 0.13) |

| Caribbean | 4.5 | 42,075.8 (42,036.9 to 42,114.7) | 4.47 | 39,167 (39,130.6 to 39,203.3) | -0.16 (-0.19 to -0.13) | 10.7 | 99.4 (97.5 to 101.3) | 10.83 | 94.3 (92.5 to 96.1) | -0.15 (-0.17 to -0.12) |

| Characteristics | Prevalence | DALYs | ||||||||

| Number of cases in 1990 (Million) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 1990 | Number of cases in 2021 (Million) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 2021 | Estimated annual percentage change, 1990-2021 | Number of cases in 1990 (Thousand) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 1990 | Number of cases in 2021 (Thousand) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 2021 | Estimated annual percentage change, 1990-2021 | |

| Central Europe | 14.13 | 48,490.7 (48,465.4 to 48,516) | 7.6 | 41,760.4 (41,730.7 to 41,790.1) | -0.39 (-0.43 to -0.35) | 29.01 | 99.9 (98.7 to 101) | 17 | 93.1 (91.7 to 94.5) | -0.18 (-0.2 to -0.16) |

| Europe | 17.19 | 36,400.3 (36,383.1 to 36,417.5) | 11.23 | 34,211.5 (34,191.5 to 34,231.6) | -0.21 (-0.28 to -0.13) | 41.61 | 88 (87.2 to 88.9) | 27.75 | 85.2 (84.2 to 86.2) | -0.11 (-0.14 to -0.08) |

| Western Europe | 31.61 | 38,137.6 (38,124.2 to 38,151) | 24.36 | 33,574 (33,560.6 to 33,587.3) | -0.56 (-0.61 to -0.51) | 77.63 | 91.3 (90.7 to 92) | 61.13 | 83.6 (82.9 to 84.2) | -0.33 (-0.37 to -0.3) |

| Andean Latin America | 6.02 | 49,089.5 (49,050.3 to 49,128.8) | 8.36 | 48,254.2 (48,221.4 to 48,286.9) | -0.19 (-0.24 to -0.13) | 12.66 | 104.3 (102.5 to 106.2) | 18.13 | 103.8 (102.3 to 105.3) | -0.06 (-0.09 to -0.04) |

| Central Latin America | 18.93 | 35,184.2 (35,168.3 to 35,200.1) | 21.06 | 32,171.5 (32,157.8 to 32,185.3) | -0.08 (-0.18 to 0.02) | 48.85 | 91.7 (90.9 to 92.5) | 58.36 | 88.7 (88 to 89.4) | -0.02 (-0.07 to 0.03) |

| Southern Latin America | 5.66 | 42,850.5 (42,815.2 to 42,885.8) | 6.57 | 42,611.1 (42,578.4 to 42,643.7) | 0.1 (0.04 to 0.16) | 12.58 | 95.7 (94 to 97.4) | 15.02 | 96.4 (94.9 to 98) | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.11) |

| Tropical Latin America | 17.4 | 36,492.7 (36,475.5 to 36,509.8) | 18.12 | 35,475.9 (35,459.5 to 35,492.3) | -0.15 (-0.24 to -0.07) | 41.71 | 88.1 (87.3 to 89) | 45.74 | 88.3 (87.5 to 89.1) | -0.04 (-0.13 to 0.05) |

| North Africa and Middle East | 45.02 | 41,611.6 (41,599.4 to 41,623.8) | 63.26 | 39,060 (39,050.3 to 39,069.6) | -0.29 (-0.34 to -0.24) | 100.62 | 94.2 (93.7 to 94.8) | 149.37 | 92.6 (92.1 to 93) | -0.08 (-0.11 to -0.05) |

| High-income North America | 17.79 | 28,813.2 (28,799.8 to 28,826.7) | 18.47 | 25,627.7 (25,616 to 25,639.4) | 0.03 (-0.27 to 0.33) | 48.06 | 76.8 (76.1 to 77.5) | 53.59 | 73.9 (73.2 to 74.5) | -0.04 (-0.17 to 0.08) |

| Oceania | 0.98 | 47,081.8 (46,988.5 to 47,175.3) | 1.87 | 46,465.9 (46,399.3 to 46,532.6) | -0.04 (-0.06 to -0.02) | 1.97 | 95.4 (91.2 to 99.7) | 3.7 | 92.2 (89.2 to 95.2) | -0.15 (-0.17 to -0.12) |

| Central SubSaharan Africa | 6.31 | 37,235.9 (37,206.8 to 37,265.1) | 15.35 | 35,039.8 (35,022.1 to 35,057.4) | -0.28 (-0.34 to -0.22) | 18.07 | 108.9 (107.3 to 110.5) | 40.86 | 94.7 (93.8 to 95.6) | -0.62 (-0.73 to -0.52) |

| Characteristics | Prevalence | DALYs | ||||||||

| Number of cases in 1990 (Million) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 1990 | Number of cases in 2021 (Million) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 2021 | Estimated annual percentage change, 1990-2021 | Number of cases in 1990 (Thousand) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 1990 | Number of cases in 2021 (Thousand) | Agestandardized rate per 100,000 population, 2021 | Estimated annual percentage change, 1990-2021 | |

| Eastern SubSaharan Africa | 24.51 | 40,304.6 (40,288.5 to 40,320.7) | 52.5 | 36,560.8 (36,550.9 to

|

-0.43 (-0.47 to -0.38) | 63.83 | 108 (107.2 to 108.9) | 133.35 | 94.1 (93.6 to 94.6) | -0.57 (-0.63 to -0.51) |

| Southern Sub-Saharan Africa | 4.99 | 29,669.3 (29,643.2 to 29,695.4) | 6.47 | 29,795.7 (29,772.7 to 29,818.6) | -0.08 (-0.21 to 0.05) | 15.87 | 95.5 (94 to 97) | 20.24 | 93.6 (92.3 to 94.9) | -0.1 (-0.37 to 0.16) |

| Western SubSaharan Africa | 21.92 | 37,496.6 (37,480.8 to 37,512.4) | 53.08 | 33,634 (33,624.9 to 33,643.1) | -0.45 (-0.49 to -0.41 ) | 71.46 | 125.5 (124.6 to 126.5) | 159.92 | 103.5 (102.9 to 104) | -0.79 (-0.86 to -0.71) |

Between 1990 and 2021, the global ASPR and ASDR significantly decreased for caries in permanent teeth significantly decreased, with EAPC of -0.07 and -0.06 ,

respectively. In contrast, the rates for other oral disorders remained stable, with EAPCs of -0.01 and 0 . Notably, there was a significant upward trend for periodontal diseases

At the national level in 2021, the highest ASPR and ASDR per 100,000 population for caries in permanent teeth were reported in Paraguay (

led in edentulism rates (1020.5 and 29.6). From 1990 to 2021, the most significant increases in both ASPR and ASDR for caries of permanent teeth were observed in Colombia, while Sierra Leone saw the highest increases for periodontal diseases, and Sweden for edentulism (Supplementary Figure S1-S3, Table S8-S10). In terms of other oral disorders, Nigeria had the highest ASPR at 1564.1 per 100,000, and China reported the highest ASDR at 45.99 per 100,000 . During the same period, the Syrian Arab Republic experienced the fastest annual increase in ASPR at

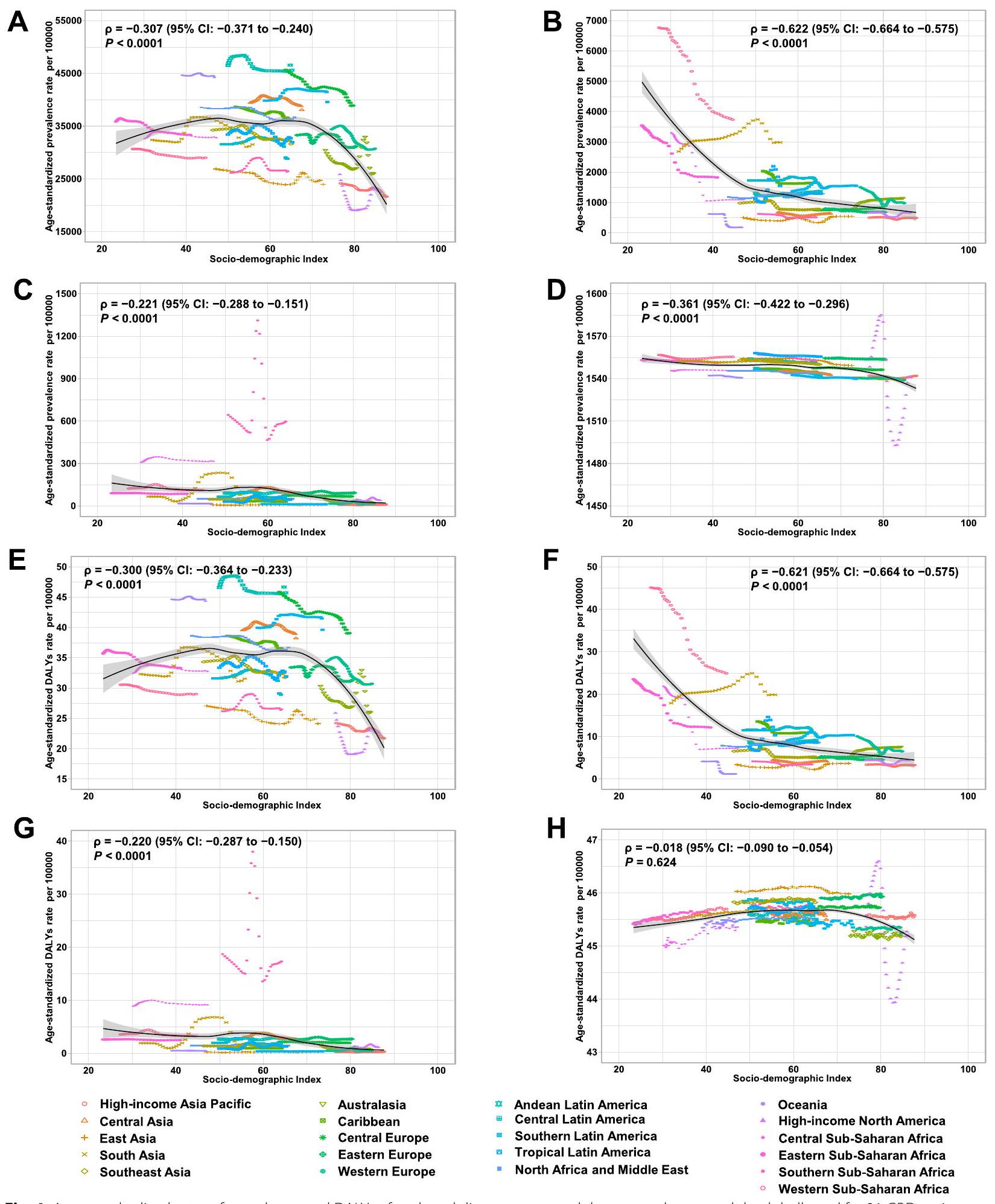

The association between ASR, EAPC, and SDI

an SDI of 70. In contrast, the overall ASDR decreased exponentially with increasing SDI (Supplementary Figure S5). For caries in permanent teeth, both ASPR and ASDR initially rose before declining at an SDI of 70.

In terms of the 204 countries and territories in 2021, both the ASPR and ASDR for overall oral disorders, as well as for each specific oral disorder, decreased with rising SDI (Supplementary Figure S6-S10). Additionally, countries with higher SDI levels experienced a faster annual increase in the ASDR for caries in permanent teeth, as well as in the ASPR and ASDR for periodontal diseases from 1990 to 2021 (Supplementary Figure S6-S10). Furthermore, negative associations were observed between the estimated annual percentage changes (EAPCs) of ASPR or ASDR and SDI for overall oral disorders and edentulism from 1990 to 2021, while a positive association was noted between the EAPCs of ASDR for other oral disorders and SDI during the same period (Fig. 5).

From 1990 to 2021, the ASPR of overall oral disorders increased only in individuals aged

Projected ASPR of overall oral disorders among AYA through 2040

Discussion

number of prevalent cases and DALYs for oral disorders rose by

Our findings suggest that the global decline in the ASPR of oral disorders among AYA between 1990 and 2021 can largely be attributed to the reduction in dental caries of permanent teeth. Dental caries is a complex, multifactorial disease driven by biofilm formation and sugar consumption, which leads to the demineralization and remineralization of tooth structures, causing substantial economic and quality-of-life burdens [33]. Therefore, reducing the impact of dental caries is especially important during youth. A better understanding of its prevalence at regional and national levels is crucial for improving access to effective oral care. The global decline in caries prevalence is largely linked to improvements in oral hygiene, dietary changes, and public health interventions, particularly the increased use of fluoride [34]. One of the key factors contributing to this decline is the widespread adoption of regular tooth brushing, especially with fluoride toothpaste. Additionally, advances in antimicrobial dental materials that release agents, kill bacteria on contact, or combine multiple strategies have helped prevent initial bacterial attachment and biofilm formation [35]. The introduction of fluoridation in public water supplies has also been one of the most effective public health measures for reducing dental caries [36]. Moreover, there has been a global shift toward reduced sugar consumption, driven by health campaigns, dietary changes, and policy interventions such as sugar taxes and food labeling regulations [37]. This reduction in sugary snacks, sodas, and processed foods has led to fewer acid attacks on teeth and less biofilm formation, further contributing to lower caries rates. However, despite these gains, dental caries remains a major oral health challenge, particularly among AYA, and continues to account for more than three-quarters of prevalent oral disorders in this age group. To more effectively mitigate the burden of dental caries in AYA, a multi-faceted approach is essential. This should include enhanced surveillance, improved preventive strategies, expanded access to dental care, and behavioral interventions. Focusing on highrisk groups, increasing access to fluoride treatments, promoting healthier diets, and leveraging new technologies can all help reduce caries prevalence and prevent its

The global ASPR of oral disorders has shown a slight decline over the past three decades; however, the ASDR has paradoxically increased, indicating that while the overall prevalence of oral diseases may be decreasing in certain contexts, their severity and consequences on AYA health are intensifying. These trends highlight the growing impact of oral diseases, particularly in regions with a middle SDI. The decline of ASPR can be attributed to several public health improvements, including better oral hygiene practices, fluoride use, dietary changes, and preventive programs. The increase in ASDR may be due to an increasing burden of more severe oral conditions, such as periodontal diseases and edentulism, which are less amenable to simple prevention measures like fluoride use and require more complex long-term care. Notably, the burden of both periodontitis and edentulism has unexpectedly risen among AYA globally from 1990 to 2021. Smoking is one of the most significant risk factors for periodontitis, with higher smoking rates correlating with increased incidences of periodontal disease [38]. Smoking weakens the immune system, impairs blood flow to the gums, and fosters the growth of harmful oral bacteria, all of which accelerate periodontal destruction. Despite substantial public health efforts to reduce cigarette smoking among youth, an estimated 155 million

individuals aged 15-24 were tobacco smokers globally in 2019 [39]. Of these,

to a rise in edentulism. As periodontitis progresses, it can cause significant gum damage and bone loss, leading to tooth loss that cannot be restored.

These conditions are more complex and severe than dental caries and are associated with significant

functional and aesthetic impacts, often leading to permanent tooth loss (edentulism) or long-term damage to oral structures (periodontitis). Periodontal disease, in particular, has been linked to risk factors such as smoking, obesity, and metabolic diseases, which are increasingly prevalent among AYA globally. Despite substantial progress in controlling caries, periodontal disease often worsens with lifestyle changes (e.g., increased tobacco and alcohol consumption) and chronic systemic conditions, which contribute to its severity and, therefore, its disability impact. Addressing this concerning trend requires comprehensive strategies that focus on early detection, improved oral health education, greater access to preventive care, and better management of risk factors such as smoking, diet, and physical inactivity. By adopting a multi-faceted approach to the prevention and management of periodontal disease, we can effectively reduce the burden of periodontitis and edentulism among AYA.

In general, the burden of oral disorders among AYA tends to decrease with higher SDI, but regions with lower SDI experience a faster annual percentage decrease in the ASDR for oral disorders. This disparity has been extensively documented in previous studies, which have highlighted the causal relationships between socioeconomic status and oral health outcomes [1]. While regions with lower SDI start at a disadvantage due to limited access to quality dental care, they often see more rapid improvements in oral health as healthcare systems develop. Even modest advancements, such as the introduction of basic preventive measures, can lead to substantial reductions in oral health burdens in these regions [49]. In these settings, small improvements can have a disproportionately large effect, resulting in a faster decline in ASDR, despite the overall burden remaining higher compared to highSDI regions. Additionally, regions with lower SDI are typically in earlier stages of the epidemiological transition, where the burden of infectious diseases and preventable oral disorders is more pronounced. As these regions progress through the transition, improvements in basic healthcare infrastructure and increased access to dental care often led to rapid declines in oral disease incidence [13]. For example, as the burden of untreated dental caries and periodontal disease decreases due to better oral hygiene practices and expanded dental services, the annual rate of decline in ASDR accelerates. In contrast, regions with higher SDI have usually already passed through the initial stages of the epidemiological transition. In these areas, the burden of chronic oral diseases, such as periodontitis and edentulism, may be increasing, as these conditions are more complex and require ongoing management. These diseases are often linked to risk factors such as smoking, diabetes, and obesity. As a result, improvements in ASDR are less pronounced

in high-SDI regions because the population has already benefited from basic interventions, and the focus shifts to managing more complex and persistent oral health issues [11].

Our findings reveal significant regional disparities in the prevalence and DALYs of oral diseases, underscoring the urgent need for targeted public health interventions. Looking ahead, our projections suggest a continued global decline in the ASPR for oral disorders through 2040, with notable exceptions in Tropical Latin America and Oceania. The rising burden of oral disorders in these regions can be attributed to several factors, including limited access to dental care, dietary shifts, increasing tobacco use, insufficient public health programs, and environmental influences [39]. Additionally, the rapid urbanization and adoption of Westernized lifestyles, combined with escalating rates of obesity and chronic diseases like diabetes, are further driving the growing prevalence of oral disorders [50,51]. The anticipated rise in oral disease burdens in these regions signals potential public health challenges that require proactive strategies. This highlights the importance of closely monitoring trends and tailoring interventions to local contexts, ensuring that they effectively address emerging health needs and evolving risk factors.

Regions like Andean Latin America and certain areas of Sub-Saharan Africa have high age-standardized prevalence rates (ASPR) of oral disorders. To address these challenges, we recommend implementing more comprehensive preventive measures in these high-risk areas, including: integrating educational campaigns into school curricula and community-based health programs, expanding fluoride initiatives, introducing policies such as sugar taxes and clearer food labeling to regulate the marketing of sugary products, and improving access to affordable dental care. Additionally, the rising prevalence of periodontal diseases among AYAs, especially in regions like South Asia and Southern Latin America, warrants targeted action. Increased screening and early diagnosis of periodontal diseases in high-risk populations are critical for enabling timely interventions and preventing long-term complications such as tooth loss. Our study also underscores the significant impact of socioeconomic factors on oral health outcomes. Therefore, policies addressing the broader social determinants of health are essential for improving oral health among AYAs. To enhance future data on the burden of oral diseases and assess the effectiveness of interventions, we recommend strengthening oral health surveillance systems to provide more accurate and timely data on the prevalence and severity of oral diseases in AYAs.

To effectively reduce the growing burden of oral diseases among AYA, we propose a comprehensive,

multi-pronged strategy that combines public health initiatives, policy measures, and targeted prevention efforts. These strategies include: (1) Implementing school-based programs, such as supervised toothbrushing and oral health education, to effectively engage AYA. (2) Strengthening regulations on tobacco and e-cigarette advertising, increasing taxation on tobacco products, and launching awareness campaigns to discourage youth smoking. (3) Introducing sugar taxes, improving food labeling policies, and restricting the marketing of sugary beverages and snacks to younger populations. (4) Expanding insurance coverage for preventive dental care and integrating oral health services into primary healthcare systems to facilitate early intervention and curb the progression of severe oral diseases. (5) Promoting physical activity and healthy nutrition programs to mitigate metabolic disorders associated with poor oral health. (6) Strengthening data collection and monitoring systems to track emerging trends in oral diseases and inform targeted interventions.

Nevertheless, the current study has several limitations. First, the accuracy and robustness of the estimates for the prevalence and DALYs of oral disorders were constrained by the availability and quality of data, which could lead to biases, particularly in regions where national surveillance or population-based studies are lacking. To mitigate this, various adjusted methods, including misclassification corrections and redistribution of garbage codes, were employed to reduce bias. Second, the study relies on aggregated data at the national and regional levels, which may obscure local variations in oral health outcomes. Third, the use of annual percentage changes to assess long-term trends from 1990 to 2021 may have overlooked recent short-term shifts that could reflect the effectiveness of prevention interventions. Fourthly, while the projections of future trends suggest a continued global decline in the ASPR for oral disorders, these projections are based on current trends and assumptions, which may not fully account for potential future changes in public health policies, technological advances, or unexpected events that could impact oral health outcomes. Lastly, while our age stratification (10-14, 15-19, 20-24 years) aligns with the WHO adolescent health framework for policy relevance, we acknowledge that significant biological and physiological variations within the 10-24 age range may impact oral health outcomes. Each subgroup exhibits biological heterogeneity, such as the transition from mixed to full permanent dentition (10-14 vs. 20-24 years) [52], variations in tooth eruption patterns (e.g., third molar emergence in late adolescence) [53], and hormonal changes [54], including pubertydriven shifts in the oral microbiome that may affect susceptibility to caries and periodontitis. However, our observational study design limited the ability to perform

more granular age-stratified analyses. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the GBD data restricts causal inference between age-related biological changes and oral disease trajectories.

Conclusion

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Clinical trial number

Statement of sources of funding for the study

Authors’ contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 04 April 2025

References