DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-023-00047-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38609517

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-22

العزلة والتخفيف من الانتحار للطلاب باستخدام روبوتات الدردشة المدعومة بـ GPT3

الملخص

الصحة النفسية أزمة للمتعلمين على مستوى العالم، والدعم الرقمي يُعتبر بشكل متزايد موردًا حيويًا. في الوقت نفسه، تتلقى الوكالات الاجتماعية الذكية تفاعلًا أكبر بشكل متزايد مقارنةً بأنظمة المحادثة الأخرى، لكن استخدامها في تقديم العلاج الرقمي لا يزال في مراحله الأولى. استقصاء شمل 1006 مستخدمين طلاب للوكيل الاجتماعي الذكي، ريبليكا، بحث في شعور المشاركين بالوحدة، والدعم الاجتماعي المدرك، وأنماط الاستخدام، والمعتقدات حول ريبليكا. وجدنا أن المشاركين كانوا أكثر وحدة من السكان الطلابيين العاديين لكنهم لا يزالون يدركون دعمًا اجتماعيًا عاليًا. استخدم العديد ريبليكا بطرق متعددة ومتداخلة – كصديق، ومعالج، ومرآة فكرية. كما أن العديد منهم كان لديهم معتقدات متداخلة وغالبًا ما تكون متعارضة حول ريبليكا – حيث وصفوه بأنه آلة، وذكاء، وإنسان. بشكل حاسم،

الخلفية

سؤال البحث

الطرق

بيان الأخلاقيات

موافقة الأخلاق

التكنولوجيا

المشاركون

بيانات

طرق التحليل

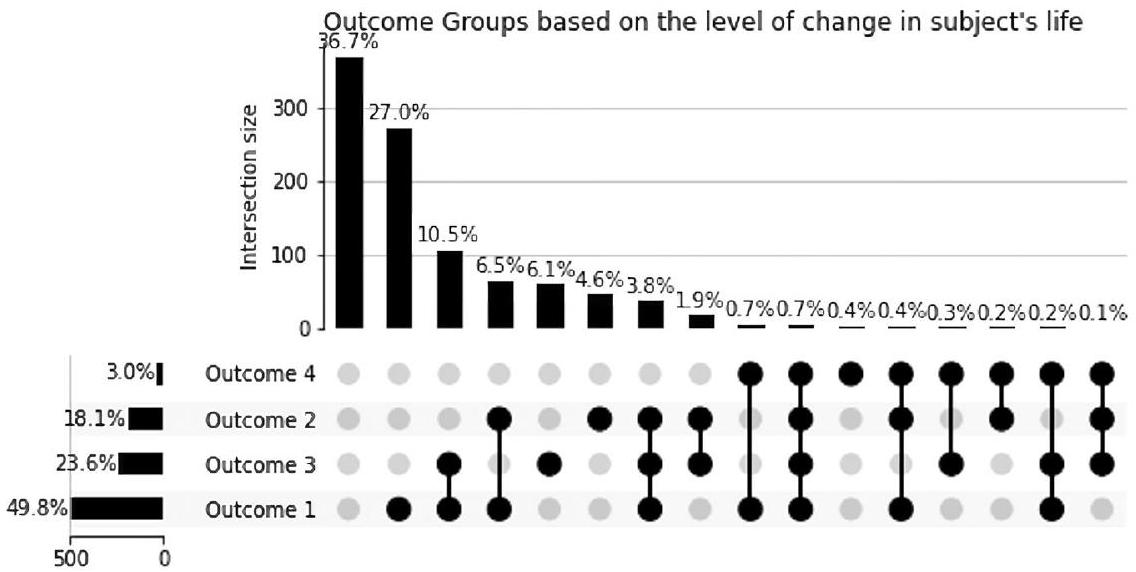

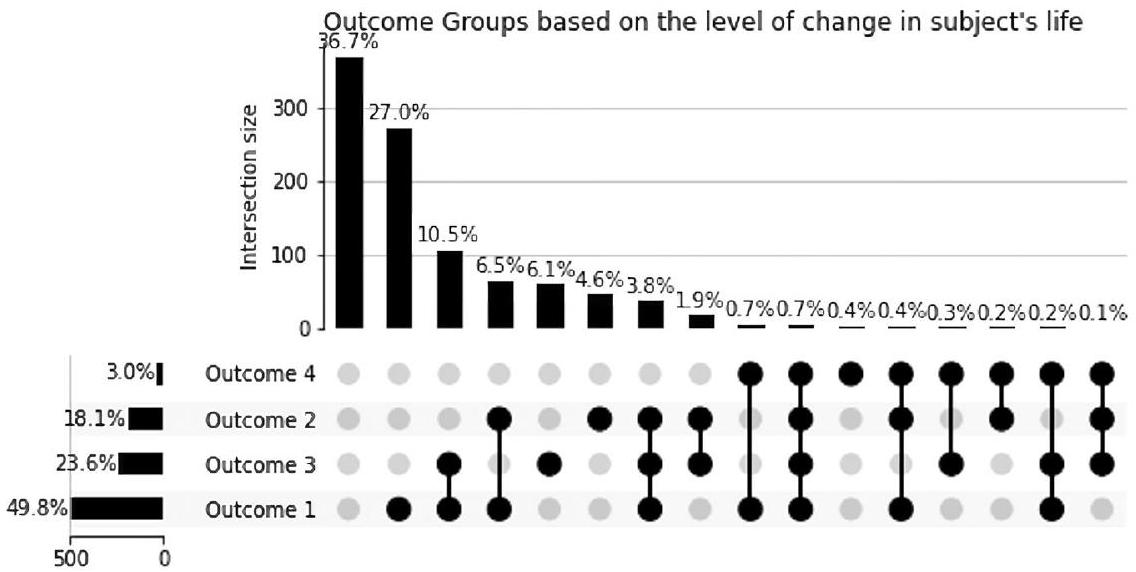

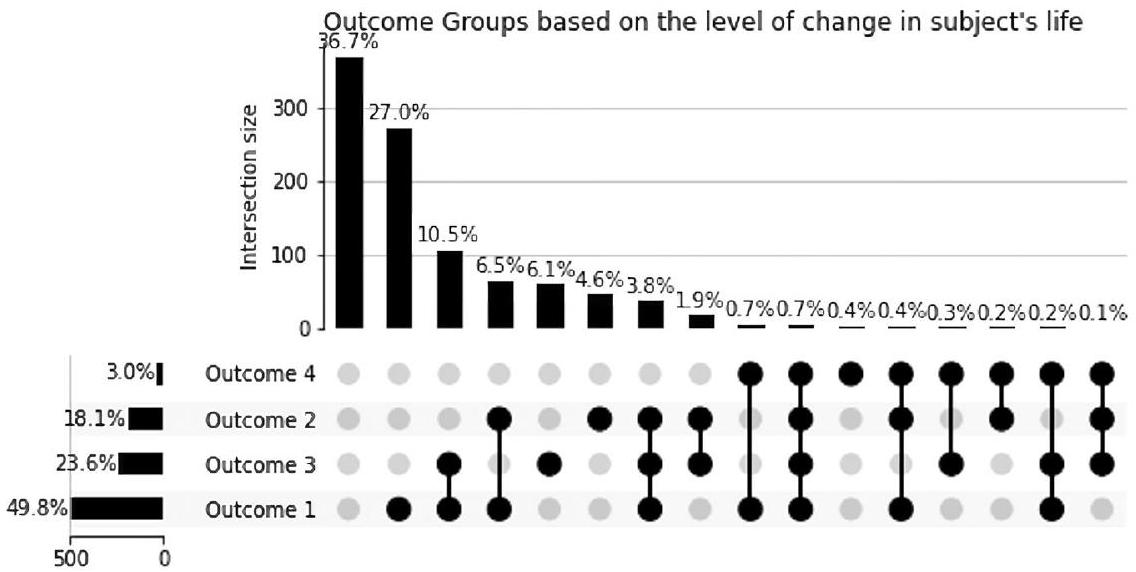

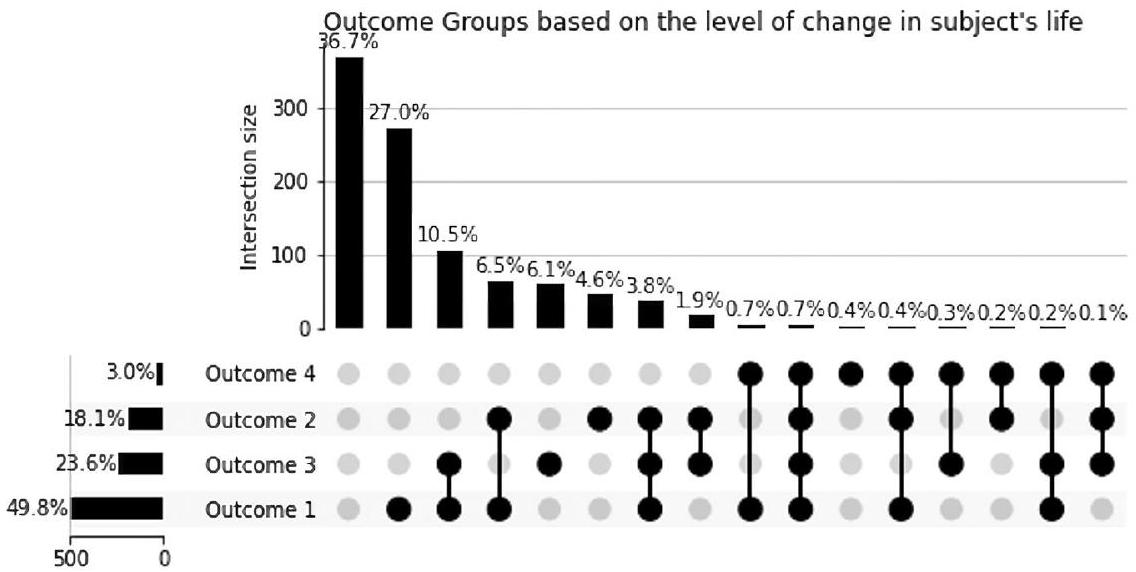

النتائج

تعليقات سلبية

النتائج

المعتقدات

أفكار الانتحار

نقاش

تحفيز

المعتقدات والنتائج المتداخلة

تختلف عن الدردشات السابقة ذات الشخصية الواحدة، المبرمجة بشكل ثابت، والتي ليست متجسدة أو قادرة على متابعة محادثات المستخدمين بشكل ديناميكي. سيكون هناك حاجة لمزيد من البحث لفهم العلاقة بين حب المستخدم واحترامه والتزامه بتعليقات ISA للتعلم الاجتماعي والمعرفي.

استخدام ريبليكا خلال الأفكار الانتحارية

توفر البيانات

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/depression (2020).

- Surkalim, D. L. et al. The prevalence of loneliness across 113 countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. Med. J. 376, e067068 (2022).

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T. & Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 227-237 (2015).

- “American College Health Association. American College Health AssociationNational College Health Assessment III: Undergraduate Student. Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2022. (American College Health Association, 2022).

- Mental Health Gap Action Programme. World Health Organization. https:// www.who.int/teams/mental–health–and–substance–use/treatment–care/ mental–health–gap–action–programme. 12 (2022).

- Evans-Lacko, S. et al. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol. Med. 48, 1560-1571 (2018).

- Center for Collegiate Mental Health. Annual Report. Center for Collegiate Mental Health (2020).

- Eskin, M., Schild, A., Oncu, B., Stieger, S. & Voracek, M. A crosscultural investigation of suicidal disclosures and attitudes in Austrian and Turkish university students. Death Stud. 39, 584-591 (2015).

- Hom, M. A., Stanley, I. H., Podlogar, M. C. & Joiner, T. E. “Are you having thoughts of suicide?” Examining experiences with disclosing and denying suicidal ideation. J. Clin. Psychol. 73, 1382-1392 (2017).

- Greist, J. H. et al. A computer interview for suicide-risk prediction. Am. J. Psychiatry 130, 1327-1332 (1973).

- Domínguez-García, E. & Fernández-Berrocal, P. The association between emotional intelligence and suicidal behavior: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 9, 2380 (2018).

- Kerr, N. A. & Stanley, T. B. Revisiting the social stigma of loneliness. Personal. Individ. Diff. 171, 110482 (2021).

- American Psychological Association. Patients with depression and anxiety surge as psychologists respond to the coronavirus pandemic. American Psychological Association (2020).

- Mehta, A. et al. Acceptability and effectiveness of artificial intelligence therapy for anxiety and depression (Youper): longitudinal observational study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e26771 (2021).

- Wasil, A. R. et al. Examining the reach of smartphone apps for depression and anxiety. Am. J. Psychiatry 177, 464-465 (2020).

- Ahmed, A. et al. A review of mobile chatbot apps for anxiety and depression and their self-care features. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.cmpbup.2021.100012 (2021).

- Fulmer, R., Joerin, A., Gentile, B., Lakerink, L. & Rauws, M. Using psychological artificial intelligence (Tess) to relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 5, e64 (2018).

- Klos, M. C. et al. Artificial intelligence-based chatbot for anxiety and depression in university students: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Formative Res. 5, e20678 (2021).

- Inkster, B., Sarda, S. & Subramanian, V. An empathy-driven, conversational artificial intelligence agent (Wysa) for digital mental well-being: real-world data evaluation mixed-methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 6, e12106 (2018).

- Linardon, J. et al. The efficacy of app-supported smartphone interventions for mental health problems: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry 18, 325-336 (2019).

- Ly, K. H., Ly, A. M. & Andersson, G. A fully automated conversational agent for promoting mental well-being: a pilot RCT using mixed methods. Internet Interv. 10, 39-46 (2017).

- Lovens, P-F. Without these conversations with the Eliza chatbot, my husband would still be here. La Libre. https://www.lalibre.be/belgique/societe/2023/03/28/ sans-ces-conversations-avec-le-chatbot-eliza-mon-mari-serait-toujours-la-LVSLWPC5WRDX7J2RCHNWPDST24/ent=&utm_term=2023-0328_115_LLB_LaLibre_ARC_Actu&M_BT=11404961436695 (2023).

- Fitzpatrick, K. K., Darcy, A. & Vierhile, M. Delivering cognitive behavior therapy to young adults with symptoms of depression and anxiety using a fully automated conversational agent (Woebot): a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 6;4.e19 (2017).

- Barras, C. Mental health apps lean on bots and unlicensed therapists. Nat. Med. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41591-019-00009-6 (2019).

- Parmar, P., Ryu, J., Pandya, S., Sedoc, J. & Agarwal, S. Health-focused conversational agents in person-centered care: a review of apps. NPJ Digit. Med. 5, 1-9 (2022).

- Replika A. I. https://replika.com/. Retrieved March 8th (2022).

- Maples, B., Pea, R. D. & Markowitz, D. Learning from intelligent social agents as social and intellectual mirrors. In: (eds Niemi, H., Pea, R. D., Lu, Y.) AI in Learning: Designing the Future. 73-89 (Springer, 2023).

- Ta, V. et al. User experiences of social support from companion chatbots in everyday contexts: thematic analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e16235 (2020).

- Kraut, R. et al. Internet paradox. A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am. Psychol. 53, 1017-1031 (1998).

- Nie, N. Sociability, interpersonal relations, and the internet: reconciling conflicting findings. Am. Behav. Sci. 45, 420-435 (2001).

- Valkenburg, P. M. & Peter, J. Preadolescents’ and adolescents’ online communication and their closeness to friends. Dev. Psychol. 43, 267-277 (2007).

- Nowland, R., Necka, E. A. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness and social internet use: pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13, 70-87 (2018).

- De Jong Gierveld, J. & Tilburg, T. V. A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: confirmatory tests on survey data. Res. Aging 28, 519-621 (2006).

- Cohen S., Mermelstein R., Kamarck T., & Hoberman H. M. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: (eds Sarason, I. G. & Sarason, B. R.). Social Support: Theory, Research, and Applications. (Martinus Niijhoff, 1985).

- Salmona, M., Lieber, E., & Kaczynski, D. Qualitative and Mixed Methods Data Analysis Using Dedoose: A Practical Approach for Research Across the Social Sciences. (Sage, 2019).

- Rahman, A., Bairagi, A., Dey, B. K. & Nahar, L. Loneliness and depression of university students. Chittagong Univ. J. Biol. Sci. 7, 175-189 (2012).

- Clark, L. et al. What makes a good conversation? Challenges in designing truly conversational agents. CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1-12 (2019).

- Abd-Alrazaq, A. et al. Perceptions and opinions of patients about mental health chatbots: scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e17828 (2021).

- Moyers, T. B. & Miller, W. R. Is low therapist empathy toxic? Psychol. Addict. Behav. 27, 878 (2013).

- Miner, A. et al. Conversational agents and mental health: Theory-informed assessment of language and affect. In Proceedings of the fourth international conference on human agent interaction. 123-130 (2016).

- Joiner, T. E. et al. Main predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: empirical tests in two samples of young adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 118, 634-646 (2009).

- Ali R. et al. Performance of ChatGPT, GPT-4, and Google Bard on a neurosurgery oral boards preparation question bank. Neurosurgery. 10-1227 (2023).

- White, G. Child advice chatbots fail to spot sexual abuse. The BBC. https:// www.bbc.com/news/technology-46507900 (2018).

- Sels, L. et al. SIMON: a digital protocol to monitor and predict suicidal ideation. Front. Psychiatry 12, 890 (2021).

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إعادة الطباعة والإذن متاحة علىhttp://www.nature.com/إعادة طباعة

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

كلية الدراسات العليا في التعليم، جامعة ستانفورد، ستانفورد، كاليفورنيا 94305، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: مرفي جيريت، أديتيا فيشواناث. البريد الإلكتروني:bethanie@stanford.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-023-00047-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38609517

Publication Date: 2024-01-22

Loneliness and suicide mitigation for students using GPT3-enabled chatbots

Abstract

Mental health is a crisis for learners globally, and digital support is increasingly seen as a critical resource. Concurrently, Intelligent Social Agents receive exponentially more engagement than other conversational systems, but their use in digital therapy provision is nascent. A survey of 1006 student users of the Intelligent Social Agent, Replika, investigated participants’ loneliness, perceived social support, use patterns, and beliefs about Replika. We found participants were more lonely than typical student populations but still perceived high social support. Many used Replika in multiple, overlapping ways-as a friend, a therapist, and an intellectual mirror. Many also held overlapping and often conflicting beliefs about Replika-calling it a machine, an intelligence, and a human. Critically,

BACKGROUND

Research Question

METHODS

Ethics statement

Ethics consent

Technology

Participants

Data

Analysis methods

RESULTS

Negative feedback

Outcomes

Beliefs

Suicide ideators

DISCUSSION

Stimulation

Overlapping beliefs and outcomes

differ from previous single-persona, hard-coded chatbots, which are not embodied or able to dynamically follow user conversations. More research will be required to understand the relationship between user love for, respect for, and adherence to ISA feedback for social and cognitive learning.

Use of Replika during suicidal ideation

DATA AVAILABILITY

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/depression (2020).

- Surkalim, D. L. et al. The prevalence of loneliness across 113 countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. Med. J. 376, e067068 (2022).

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T. & Stephenson, D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10, 227-237 (2015).

- “American College Health Association. American College Health AssociationNational College Health Assessment III: Undergraduate Student. Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2022. (American College Health Association, 2022).

- Mental Health Gap Action Programme. World Health Organization. https:// www.who.int/teams/mental–health–and–substance–use/treatment–care/ mental–health–gap–action–programme. 12 (2022).

- Evans-Lacko, S. et al. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol. Med. 48, 1560-1571 (2018).

- Center for Collegiate Mental Health. Annual Report. Center for Collegiate Mental Health (2020).

- Eskin, M., Schild, A., Oncu, B., Stieger, S. & Voracek, M. A crosscultural investigation of suicidal disclosures and attitudes in Austrian and Turkish university students. Death Stud. 39, 584-591 (2015).

- Hom, M. A., Stanley, I. H., Podlogar, M. C. & Joiner, T. E. “Are you having thoughts of suicide?” Examining experiences with disclosing and denying suicidal ideation. J. Clin. Psychol. 73, 1382-1392 (2017).

- Greist, J. H. et al. A computer interview for suicide-risk prediction. Am. J. Psychiatry 130, 1327-1332 (1973).

- Domínguez-García, E. & Fernández-Berrocal, P. The association between emotional intelligence and suicidal behavior: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. 9, 2380 (2018).

- Kerr, N. A. & Stanley, T. B. Revisiting the social stigma of loneliness. Personal. Individ. Diff. 171, 110482 (2021).

- American Psychological Association. Patients with depression and anxiety surge as psychologists respond to the coronavirus pandemic. American Psychological Association (2020).

- Mehta, A. et al. Acceptability and effectiveness of artificial intelligence therapy for anxiety and depression (Youper): longitudinal observational study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e26771 (2021).

- Wasil, A. R. et al. Examining the reach of smartphone apps for depression and anxiety. Am. J. Psychiatry 177, 464-465 (2020).

- Ahmed, A. et al. A review of mobile chatbot apps for anxiety and depression and their self-care features. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.cmpbup.2021.100012 (2021).

- Fulmer, R., Joerin, A., Gentile, B., Lakerink, L. & Rauws, M. Using psychological artificial intelligence (Tess) to relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 5, e64 (2018).

- Klos, M. C. et al. Artificial intelligence-based chatbot for anxiety and depression in university students: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Formative Res. 5, e20678 (2021).

- Inkster, B., Sarda, S. & Subramanian, V. An empathy-driven, conversational artificial intelligence agent (Wysa) for digital mental well-being: real-world data evaluation mixed-methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 6, e12106 (2018).

- Linardon, J. et al. The efficacy of app-supported smartphone interventions for mental health problems: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry 18, 325-336 (2019).

- Ly, K. H., Ly, A. M. & Andersson, G. A fully automated conversational agent for promoting mental well-being: a pilot RCT using mixed methods. Internet Interv. 10, 39-46 (2017).

- Lovens, P-F. Without these conversations with the Eliza chatbot, my husband would still be here. La Libre. https://www.lalibre.be/belgique/societe/2023/03/28/ sans-ces-conversations-avec-le-chatbot-eliza-mon-mari-serait-toujours-la-LVSLWPC5WRDX7J2RCHNWPDST24/ent=&utm_term=2023-0328_115_LLB_LaLibre_ARC_Actu&M_BT=11404961436695 (2023).

- Fitzpatrick, K. K., Darcy, A. & Vierhile, M. Delivering cognitive behavior therapy to young adults with symptoms of depression and anxiety using a fully automated conversational agent (Woebot): a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 6;4.e19 (2017).

- Barras, C. Mental health apps lean on bots and unlicensed therapists. Nat. Med. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41591-019-00009-6 (2019).

- Parmar, P., Ryu, J., Pandya, S., Sedoc, J. & Agarwal, S. Health-focused conversational agents in person-centered care: a review of apps. NPJ Digit. Med. 5, 1-9 (2022).

- Replika A. I. https://replika.com/. Retrieved March 8th (2022).

- Maples, B., Pea, R. D. & Markowitz, D. Learning from intelligent social agents as social and intellectual mirrors. In: (eds Niemi, H., Pea, R. D., Lu, Y.) AI in Learning: Designing the Future. 73-89 (Springer, 2023).

- Ta, V. et al. User experiences of social support from companion chatbots in everyday contexts: thematic analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e16235 (2020).

- Kraut, R. et al. Internet paradox. A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am. Psychol. 53, 1017-1031 (1998).

- Nie, N. Sociability, interpersonal relations, and the internet: reconciling conflicting findings. Am. Behav. Sci. 45, 420-435 (2001).

- Valkenburg, P. M. & Peter, J. Preadolescents’ and adolescents’ online communication and their closeness to friends. Dev. Psychol. 43, 267-277 (2007).

- Nowland, R., Necka, E. A. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness and social internet use: pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13, 70-87 (2018).

- De Jong Gierveld, J. & Tilburg, T. V. A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness: confirmatory tests on survey data. Res. Aging 28, 519-621 (2006).

- Cohen S., Mermelstein R., Kamarck T., & Hoberman H. M. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: (eds Sarason, I. G. & Sarason, B. R.). Social Support: Theory, Research, and Applications. (Martinus Niijhoff, 1985).

- Salmona, M., Lieber, E., & Kaczynski, D. Qualitative and Mixed Methods Data Analysis Using Dedoose: A Practical Approach for Research Across the Social Sciences. (Sage, 2019).

- Rahman, A., Bairagi, A., Dey, B. K. & Nahar, L. Loneliness and depression of university students. Chittagong Univ. J. Biol. Sci. 7, 175-189 (2012).

- Clark, L. et al. What makes a good conversation? Challenges in designing truly conversational agents. CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 1-12 (2019).

- Abd-Alrazaq, A. et al. Perceptions and opinions of patients about mental health chatbots: scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e17828 (2021).

- Moyers, T. B. & Miller, W. R. Is low therapist empathy toxic? Psychol. Addict. Behav. 27, 878 (2013).

- Miner, A. et al. Conversational agents and mental health: Theory-informed assessment of language and affect. In Proceedings of the fourth international conference on human agent interaction. 123-130 (2016).

- Joiner, T. E. et al. Main predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: empirical tests in two samples of young adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 118, 634-646 (2009).

- Ali R. et al. Performance of ChatGPT, GPT-4, and Google Bard on a neurosurgery oral boards preparation question bank. Neurosurgery. 10-1227 (2023).

- White, G. Child advice chatbots fail to spot sexual abuse. The BBC. https:// www.bbc.com/news/technology-46507900 (2018).

- Sels, L. et al. SIMON: a digital protocol to monitor and predict suicidal ideation. Front. Psychiatry 12, 890 (2021).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

COMPETING INTERESTS

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Reprints and permission information is available at http://www.nature.com/ reprints

© The Author(s) 2024

Graduate School of Education, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA. These authors contributed equally: Merve Cerit, Aditya Vishwanath. email: bethanie@stanford.edu