DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05124-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38685022

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-29

العلاقة بين الميكروبيوم المهبلي والفموي لدى مرضى عدوى فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري (HPV) وسرطان عنق الرحم

الملخص

الخلفية كان الهدف من هذه الدراسة هو تقييم التغيرات الميكروبية والبيوماركرات في البيئات المهبلية والفموية للمرضى المصابين بفيروس الورم الحليمي البشري (HPV) وسرطان عنق الرحم (CC) وتطوير نماذج تنبؤية جديدة. المواد والأساليب شملت هذه الدراسة 164 عينة تم جمعها من كل من القناة المهبلية واللويحة تحت اللثة الفموية من 82 امرأة. تم تقسيم المشاركات إلى أربع مجموعات متميزة بناءً على عيناتهن المهبلية والفموية: مجموعة التحكم (Z/KZ،

الخاتمة: تؤثر عدوى فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري وسرطان عنق الرحم على كل من الميكروبيوم المهبلي والفموي، مما يؤثر على الأيض الجهازي والتآزر بين البكتيريا. وهذا يشير إلى أن استخدام علامات الفلورا الفموية هو أداة فحص محتملة لتشخيص سرطان عنق الرحم.

مقدمة

تعتبر تجويف الفم نظامًا مفتوحًا طبيعيًا يتكون من ميكروبيوم معقد يتألف من أكثر من 800 نوع من البكتيريا. لقد تم ربط هذه الميكروبات الفموية ليس فقط بأمراض اللثة ولكن أيضًا بحالات نظامية تشمل الأمراض الدموية، والأورام اللمفاوية، وأورام الرئة، والبنكرياس، والثدي.

تُعتبر التغيرات في تركيبة الميكروبيوم الفموي الآن مؤشرات حيوية محتملة للسرطانات، بما في ذلك سرطان القولون والمستقيم (CRC)، حيث يتميز بزيادة وفرة بكتيريا Fusobacterium nucleatum. وبالمثل، تم ربط التحولات التي تفضل مسببات الأمراض الفموية مثل أجناس Porphyromonas وFusobacterium وPrevotella بزيادة حدوث سرطان القولون، على الرغم من أن الآليات الكامنة وراء ذلك لا تزال غير مفهومة جيدًا، كما أن هذه المسببات للأمراض الفموية تسبب أيضًا مرض اللثة. أظهرت الدراسات السابقة وجود علاقة بين البكتيريا المهبلية والتهاب اللثة، حيث لا يقتصر فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري (HPV) على غزو الخلايا القاعدية في الظهارة المهبلية، بل يصيب أيضًا الأنسجة اللثوية ويحتفظ بالفيروس في حالة كامنة. قد توفر البيئات الفموية والمهبلية ظروفًا مشابهة للاستعمار والنمو، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة كبيرة في خطر الإصابة بمرض اللثة والسرطان. ومع ذلك، هناك عدد قليل نسبيًا من الدراسات التي تتناول التغيرات في الميكروبيوم الفموي عندما يتم تحويل الميكروبيوم المهبل خلال مسار عدوى HPV إلى تطور سرطان القولون، مما يشير إلى الحاجة إلى مزيد من البحث في هذا المجال.

يتم تنفيذ فحص سرطان عنق الرحم القائم على السكان كأولوية للصحة العامة في الصين [17]، وأفضل استراتيجية هي استخدام اختبار علم الخلايا القائم على السوائل (TCT) مع فحص فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري (HPV) [18، 19]. على الرغم من أن تقنية الفحص المدمجة متقدمة وفعالة، إلا أنها مكلفة ومناسبة للمناطق التي تتوفر فيها الرعاية الطبية والصحية الكافية. ومع ذلك، لا تزال هناك العديد من المناطق الأقل تطورًا اقتصاديًا (المناطق الريفية) في الصين، وهناك حاجة ملحة

يجب العثور على طريقة عالية الجودة وغير مكلفة. قد تقدم التغيرات في تنوع الميكروبات الفموية القابلة للاكتشاف من خلال التحليل منخفض التكلفة قيمة إضافية كعلامات حيوية للت screening المبكر، والتشخيص، ومراقبة عدوى فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري وحتى سرطان عنق الرحم. كان الهدف من هذه الدراسة هو تقييم الفروق والارتباطات بين الميكروبات المهبلية والفموية في المرضى المصابين بفيروس الورم الحليمي البشري ومرضى سرطان عنق الرحم. قد تساهم زيادة الفهم لعلم البيئة الميكروبية في تحسين دقة فحص سرطان عنق الرحم وتوفير تدخلات منقذة للحياة للمجموعات الضعيفة.

المواد والأساليب

تصميم الدراسة وجمع العينات

تم إدخال جهاز القياس في جانب اللسان من الضرس الأول السفلي تحت اللثة لإزالة اللويحات السنية وتم منع تلوث الدم أثناء عملية الجمع. لجمع عينة من الإفرازات المهبلية، تم إدخال منظار disposable، وتم أخذ عينة مسحة معقمة من القبو الخلفي للمهبل. تم تخزين جميع العينات على الفور في

تسلسل 16S الكامل ومعالجة البيانات

التحليل الإحصائي

تعقيد الأنواع. تم استخدام تحليل التباين الأحادي (ANOVA) لمقارنة وفرة البكتيريا وتنوعها. تم تطبيق تحليل التمييز الخطي (LDA) مع حجم التأثير (LEfSe) لتقييم الأنواع ذات الوفرة المختلفة. درجة LDA

النتائج

خصائص الموضوعات

| عادي (

|

الإجهاض

|

فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري (HPV)

|

سرطان

|

قيمة P | |

| العمر (سنة) |

|

|

|

|

0.395 |

| أمة | |||||

| القومية الهانية | ٢٢ (١٠٠) | 17 (100) | 21 (100) | 17 (77.27) | 0.003 |

| قوميون آخرون | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (22.73) | |

| مستوى التعليم | |||||

| المدرسة الابتدائية | 1 (4.55) | 6 (35.29) | 13 (61.90) | 19 (86.36) | <0.001 |

| المدرسة الثانوية | 8 (36.36) | 6 (35.29) | 3 (14.29) | 2 (9.09) | |

| درجة جامعية | 13 (59.09) | 5 (29.41) | 5 (23.81) | 1 (4.55) | |

| الحمل |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

| الإجهاض الجراحي |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

| التكافؤ |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

| العمر الجنسي (سنة) |

|

|

|

|

0.556 |

| مؤشر كتلة الجسم (BMI)

|

|

|

|

|

0.02 |

| التدخين | 2 (9.09) | 3 (17.65) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.059 |

| الشرب | 4 (18.19) | 6 (35.30) | 3 (14.29) | 4 (18.19) | 0.481 |

| تاريخ العائلة لسرطان الثدي (%) | 1 (4.54) | 2 (11.76) | 2 (9.52) | 0 (0) | 0.365 |

| CRP (ملغ/دل) |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

| WBC (4.5 إلى

|

|

|

|

|

0.635 |

| RBC |

|

|

|

|

0.068 |

| HGB |

|

|

|

|

0.122 |

| نيوتر% |

|

|

|

|

0.014 |

| LYM% |

|

|

|

|

0.079 |

| مونو% |

|

|

|

|

0.461 |

| نسبة EOS% |

|

|

|

|

0.048 |

| BASO% |

|

|

|

|

0.118 |

| PLT |

|

|

|

|

0.158 |

| التسوس (%) | 3 (13.64) | 2 (11.76) | 1 (4.76) | 2 (9.09) | 0.663 |

| التهاب اللثة (%) | 3 (13.64) | 3 (17.65) | 5 (23.81) | 8 (36.36) | 0.34 |

| تكرار تنظيف الأسنان (%) | |||||

|

|

3 (13.64) | 8 (47.06) | 8 (38.10) | 16 (72.73) | <0.001 |

| مرتين في اليوم | 19 (86.36) | 9 (52.94) | 13 (61.90) | 6 (27.27) | |

| وقت الفرشاة (%) | |||||

|

|

1 (4.55) | 3 (17.65) | 12 (57.14) | 9 (40.91) | <0.001 |

| دقيقتان | 7 (31.82) | 7 (41.18) | 6 (28.57) | 11 (50.00) | |

|

|

14 (63.66) | 7 (41.18) | 3 (14.29) | 2 (9.09) | |

| نزيف اللثة (%) | |||||

| لا | 16 (72.73) | 9 (52.94) | 7 (33.33) | 15 (68.18) | 0.043 |

| نعم | 6 (27.27) | 8 (47.06) | 14 (66.67) | 7 (31.82) | |

| تنظيف الأسنان الاحترافي (%) | |||||

| لا | 16 (72.73) | 12 (70.59) | 18 (85.71) | 22 (100) | 0.039 |

| مرة في السنة | 5 (22.73) | 2 (11.76) | 3 (14.29) | 0 | |

| 2-4 سنوات/مرات | 0 | 1 (5.89) | 0 | 0 | |

|

|

1 (4.55) | 2 (11.76) | 0 | 0 | |

| ألم الأسنان أو حساسية الأسنان (%) | |||||

| لا | 20 (90.91) | 15 (88.24) | 17 (80.95) | 17 (77.27) | 0.768 |

| نعم | 2 (9.09) | 2 (11.76) | 4 (19.05) | 5 (22.73) | |

| أنماط فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري | |||||

| 16 | – | – | 13 (61.90) | 12 (54.55) | – |

| ١٨ | – | – | 4 (19.05) | 6 (27.27) | |

| عادي (

|

الإجهاض

|

فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري (HPV)

|

سرطان

|

قيمة P | |

| ٣٣ | – | – | 1 (4.76) | 1 (4.55) | |

| 51 | – | – | 1 (4.76) | 1 (4.55) | |

| 52 | – | – | 1 (4.76) | 0 | |

| 53 | – | – | 1 (4.76) | 2 (9.09) | |

| ٥٨ | – | – | 3 (14.29) | 5 (22.73) |

يتم حساب قيمة P بواسطة ANOVA، واختبار فيشر للاحتمالات الدقيقة. القيمة بالخط العريض تشير إلى أن قيمة P أقل من 0.05

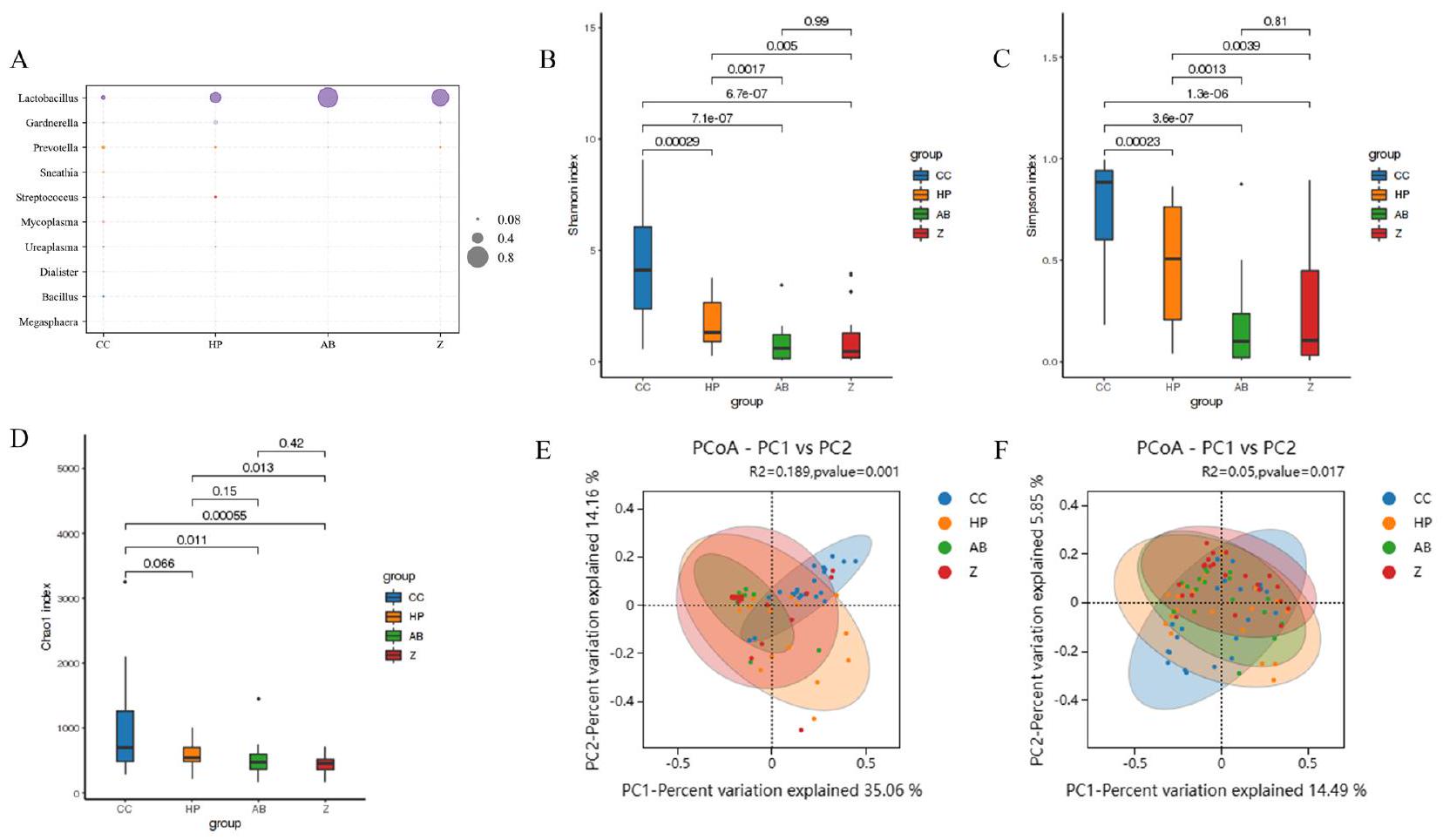

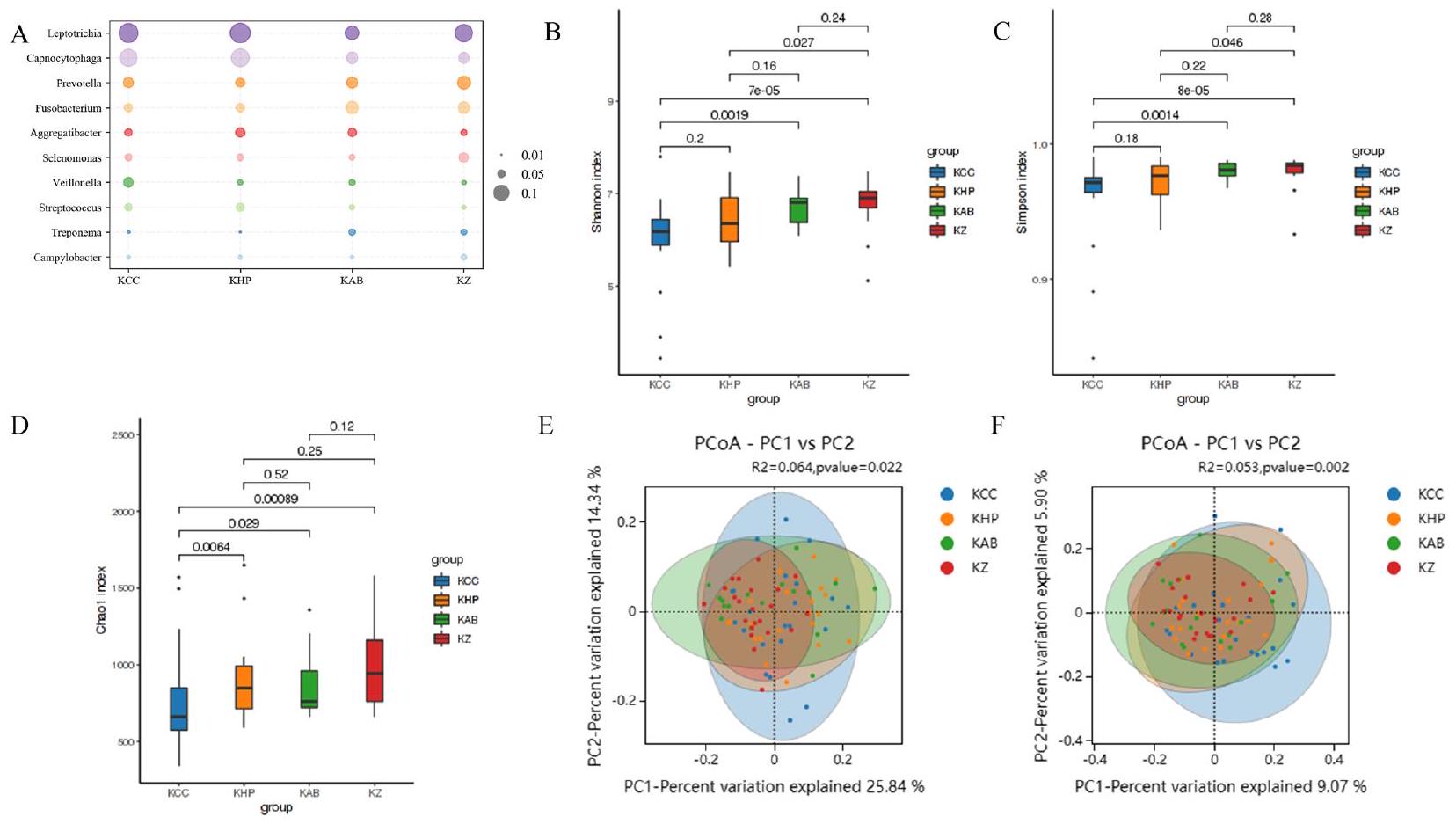

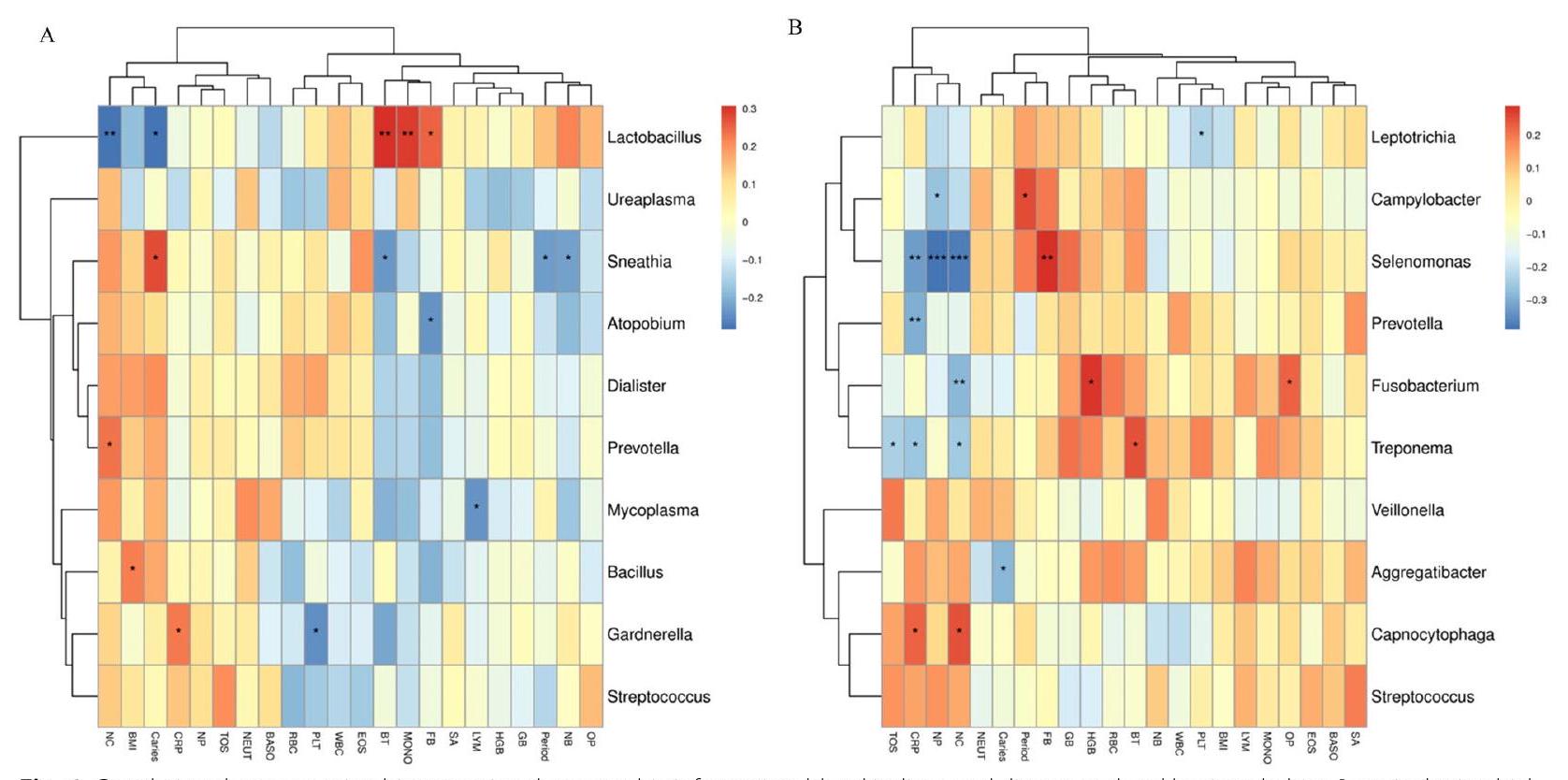

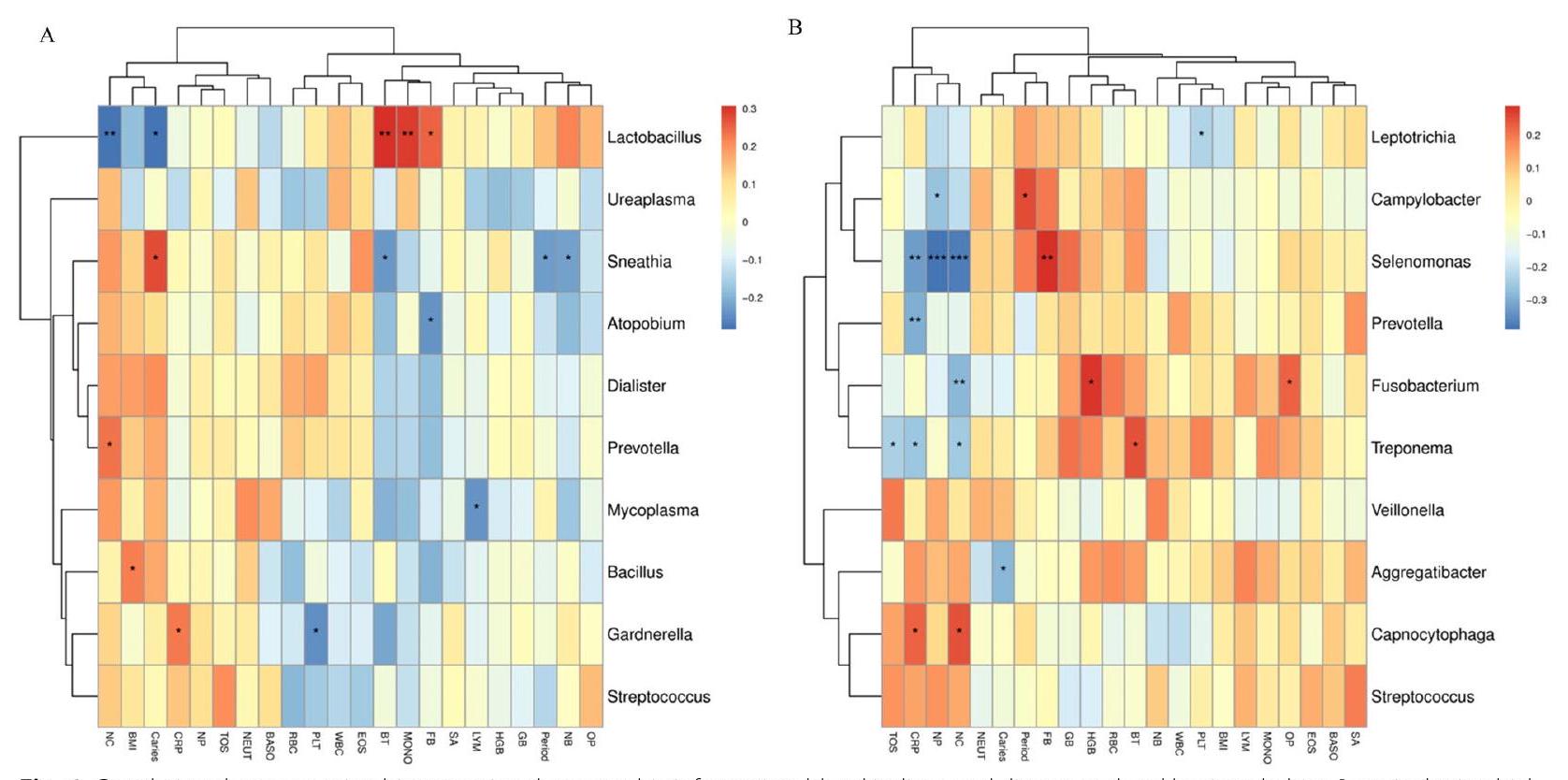

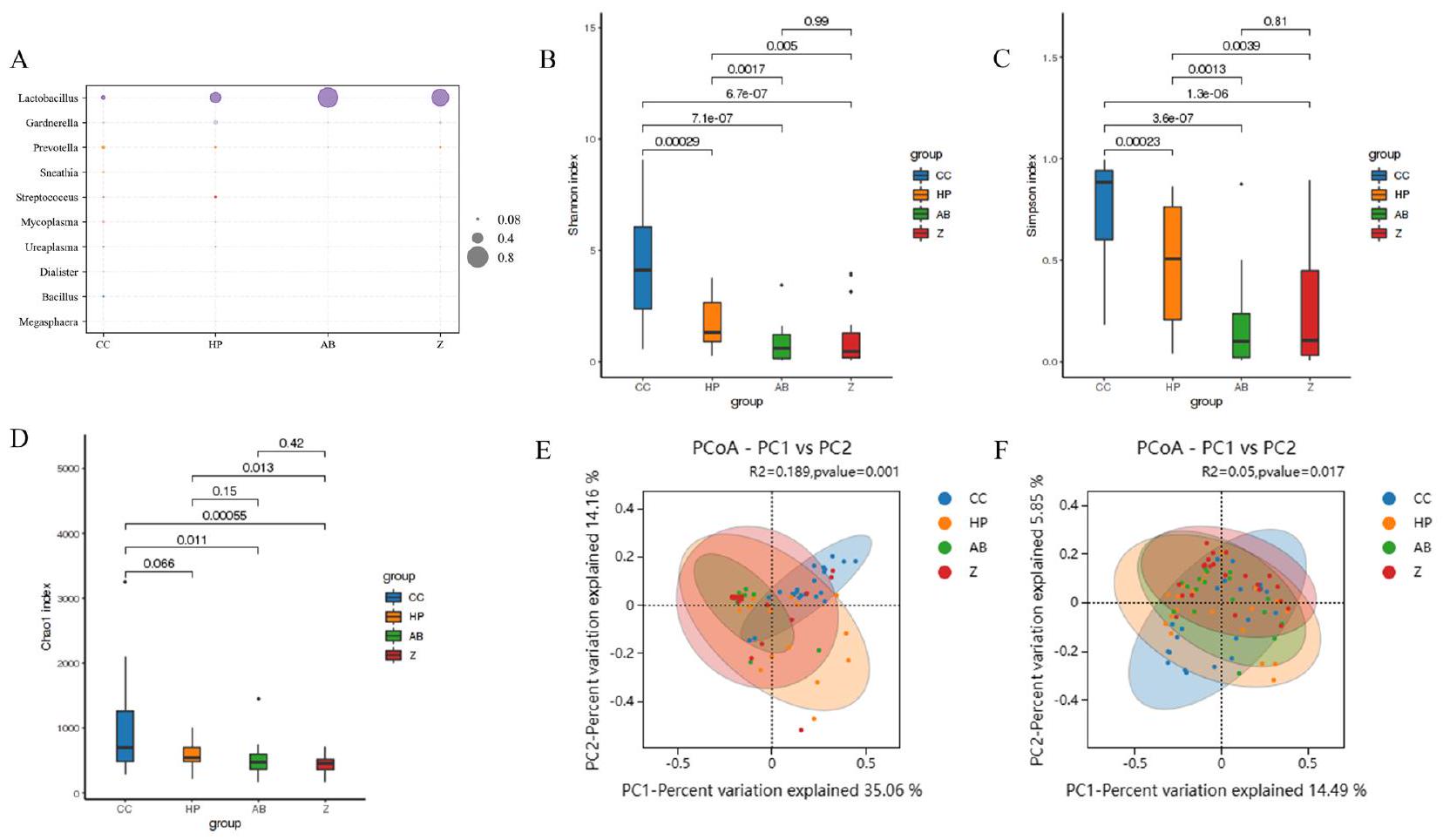

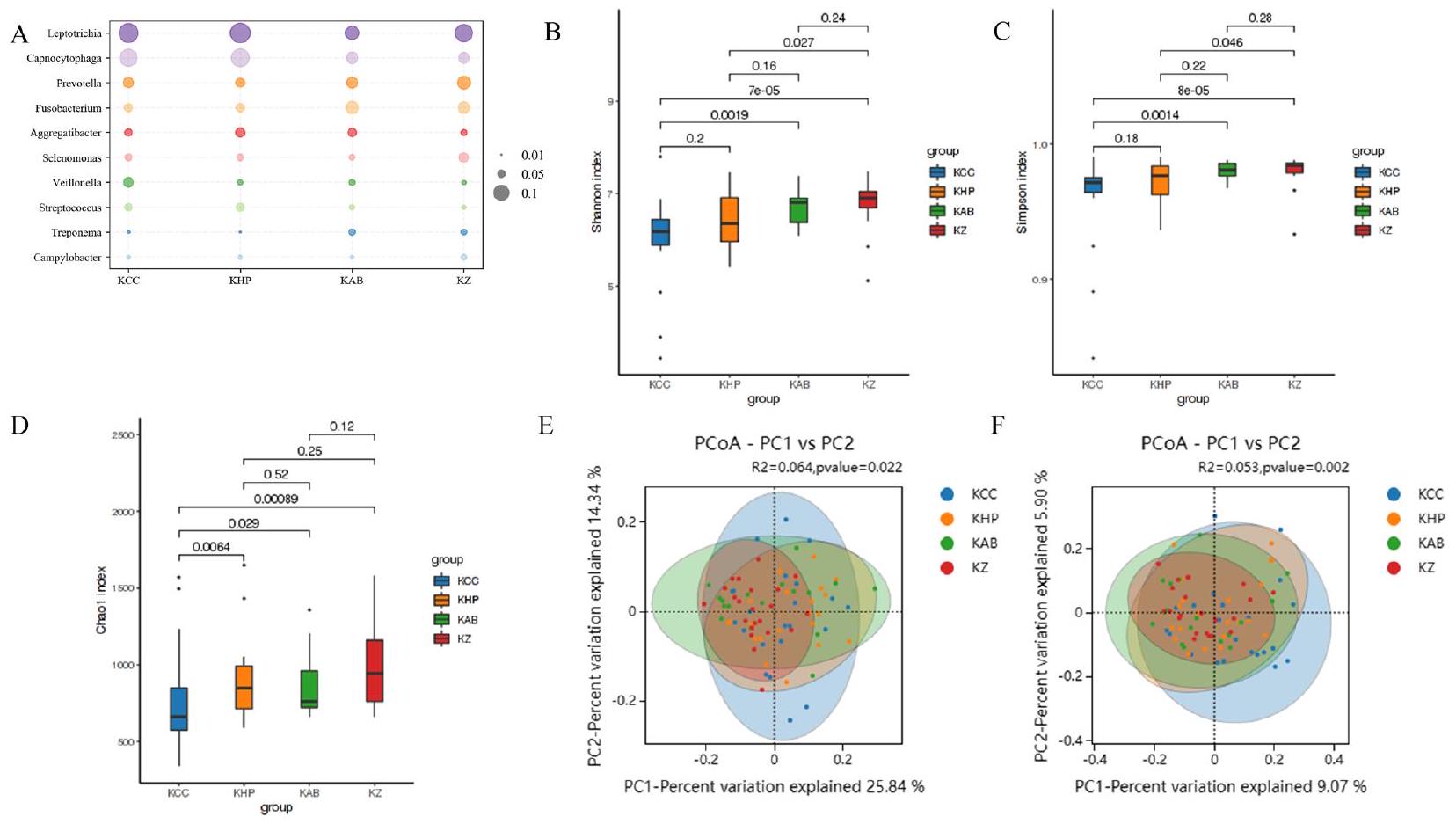

تركيب وتنوع الميكروبات المهبلية والفموية

وانخفضت وفرتها بشكل كبير في عينات CC

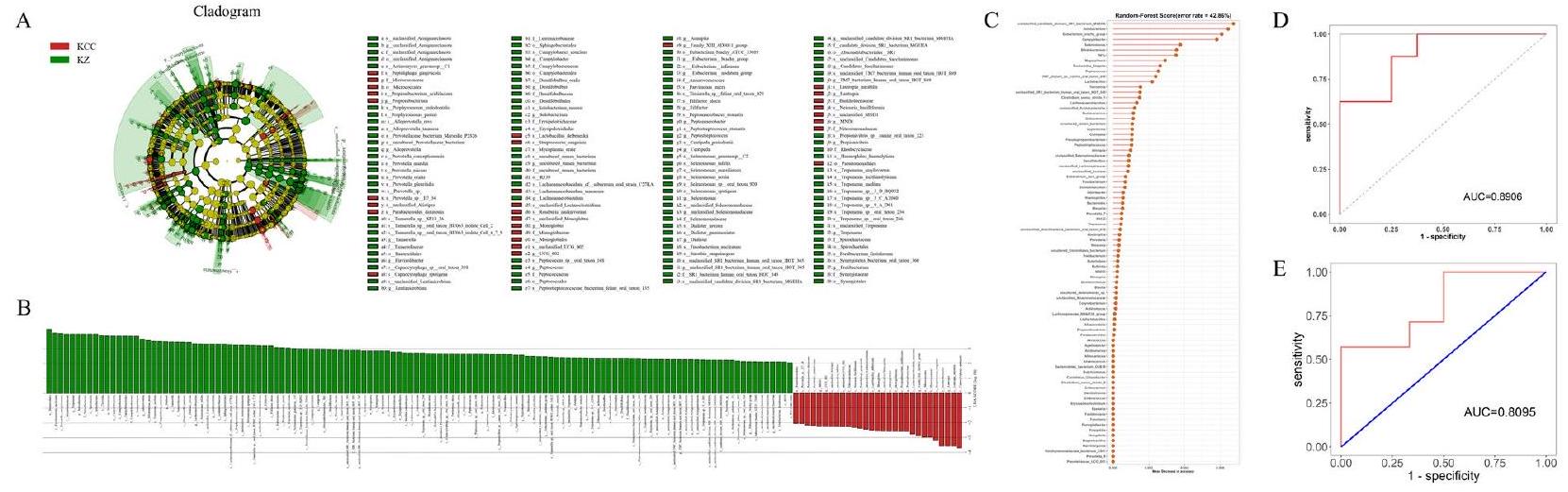

تحديد مرضى Z و CC بناءً على الميكروبات المهبلية والميكروبات الفموية

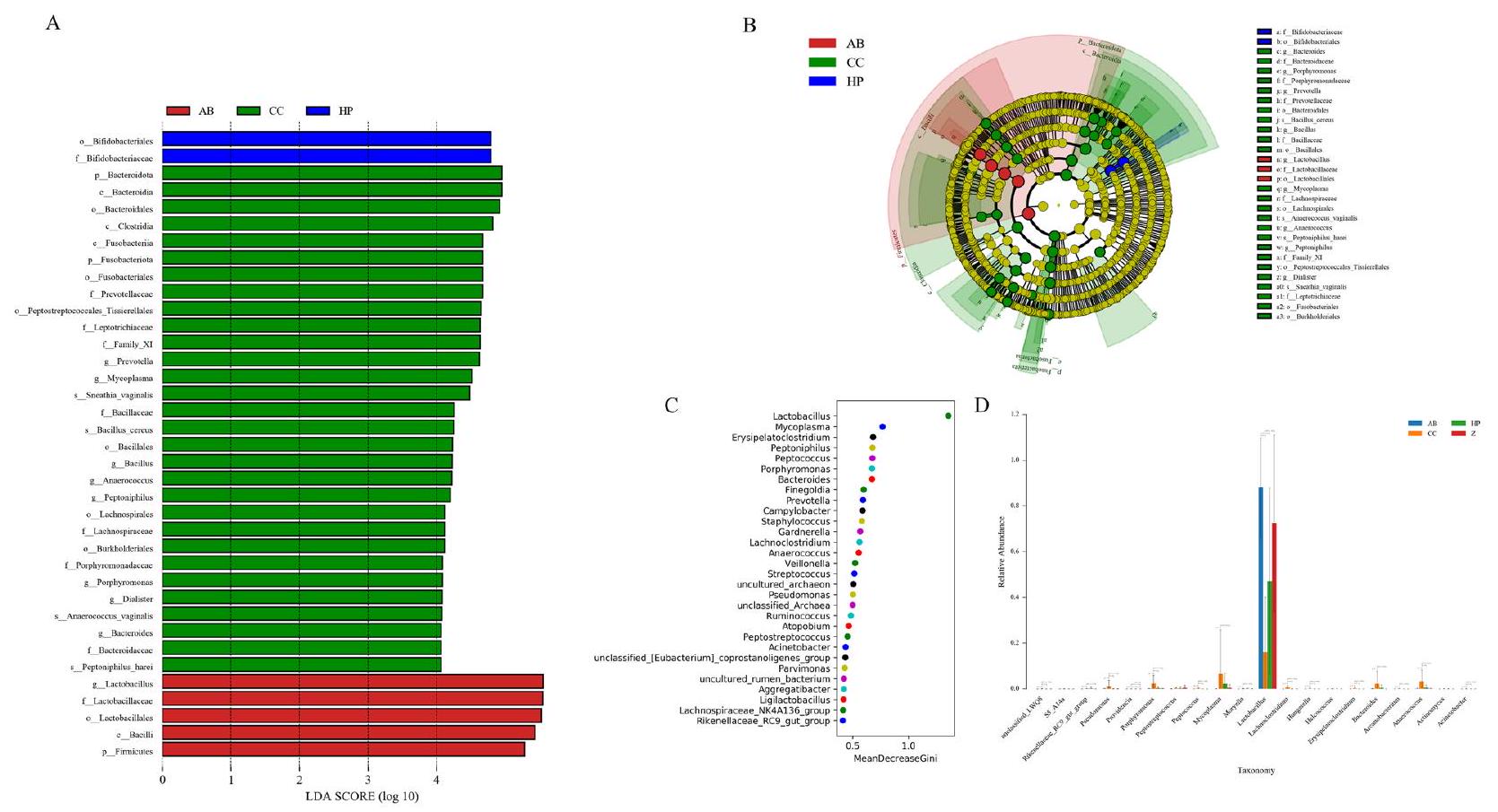

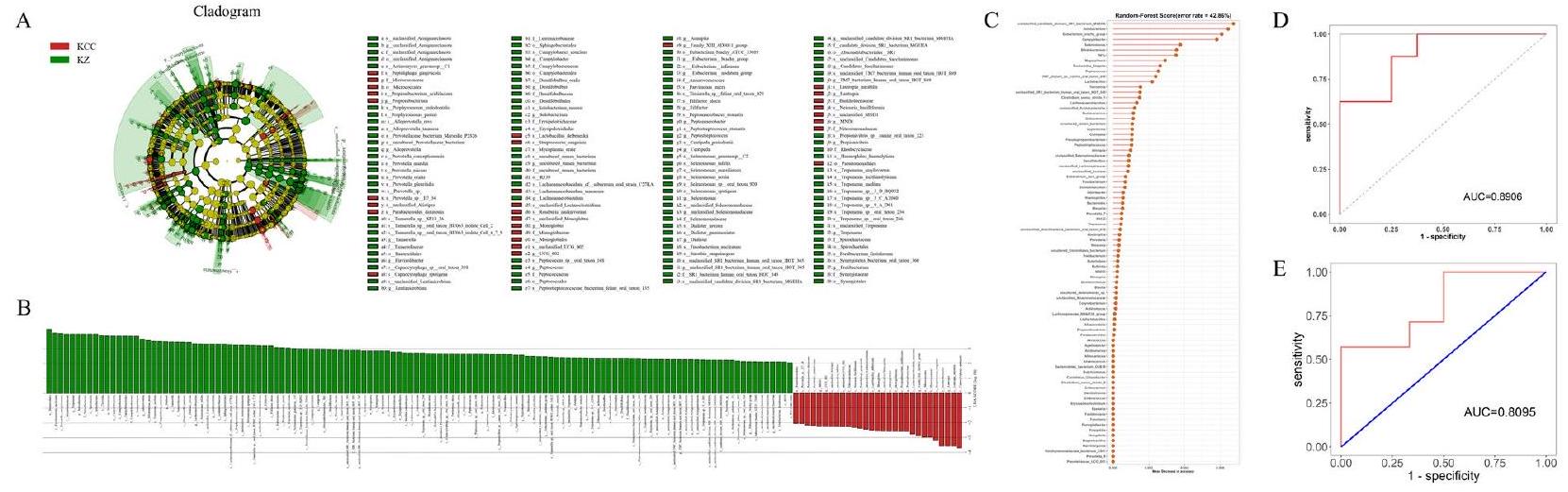

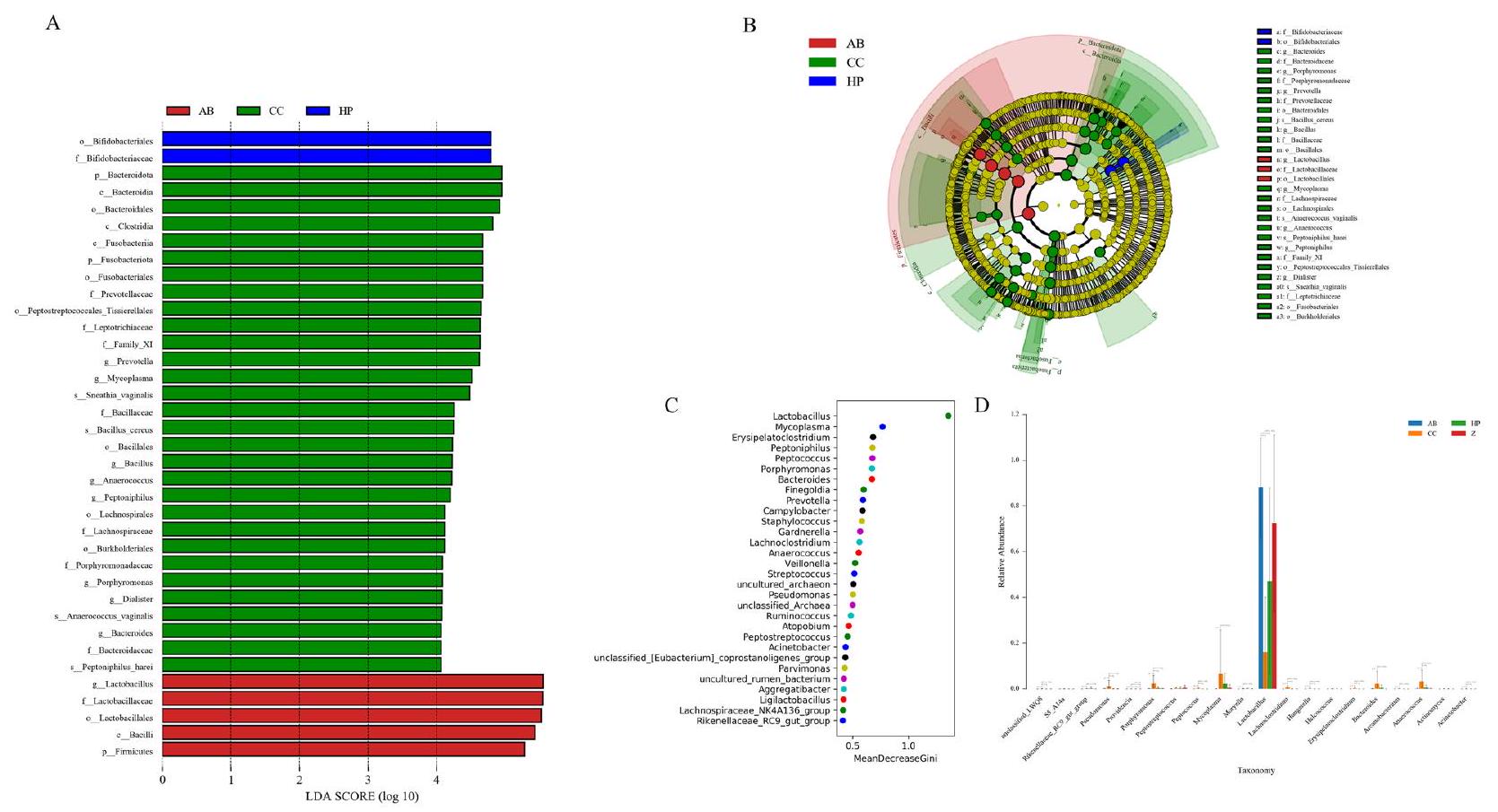

تباينت علامات LDA وLEfSe للميكروبيوم تحت اللثة بشكل عكسي مع تلك الخاصة بالميكروبيوم المهبلي، حيث كانت اللويحات في مجموعة التحكم (KZZ) تحتوي على أكثر الأنواع تميزًا، بما في ذلك Prevotella وSelenomonas وSaccharibacteria وCampylobacter وAmnipila وCentipeda.

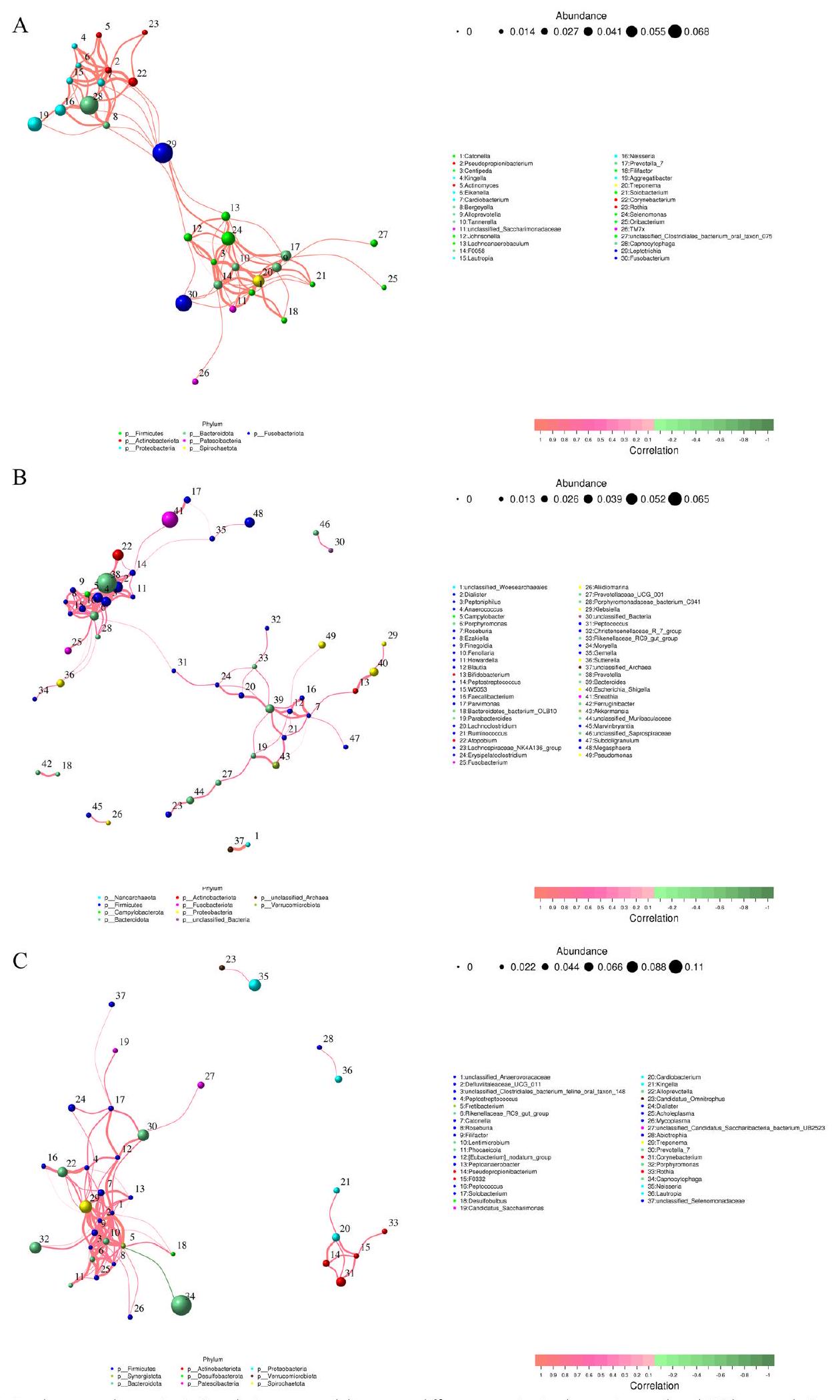

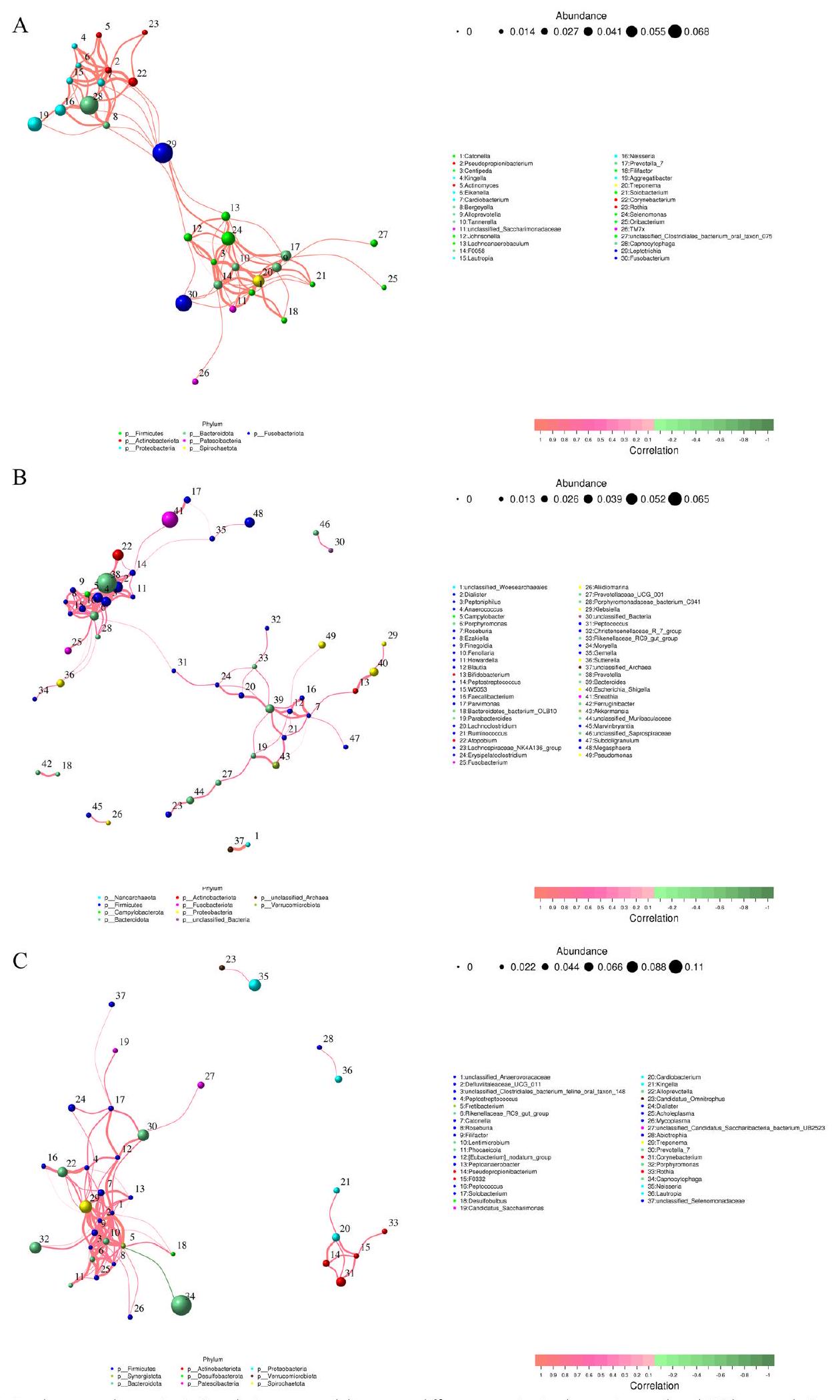

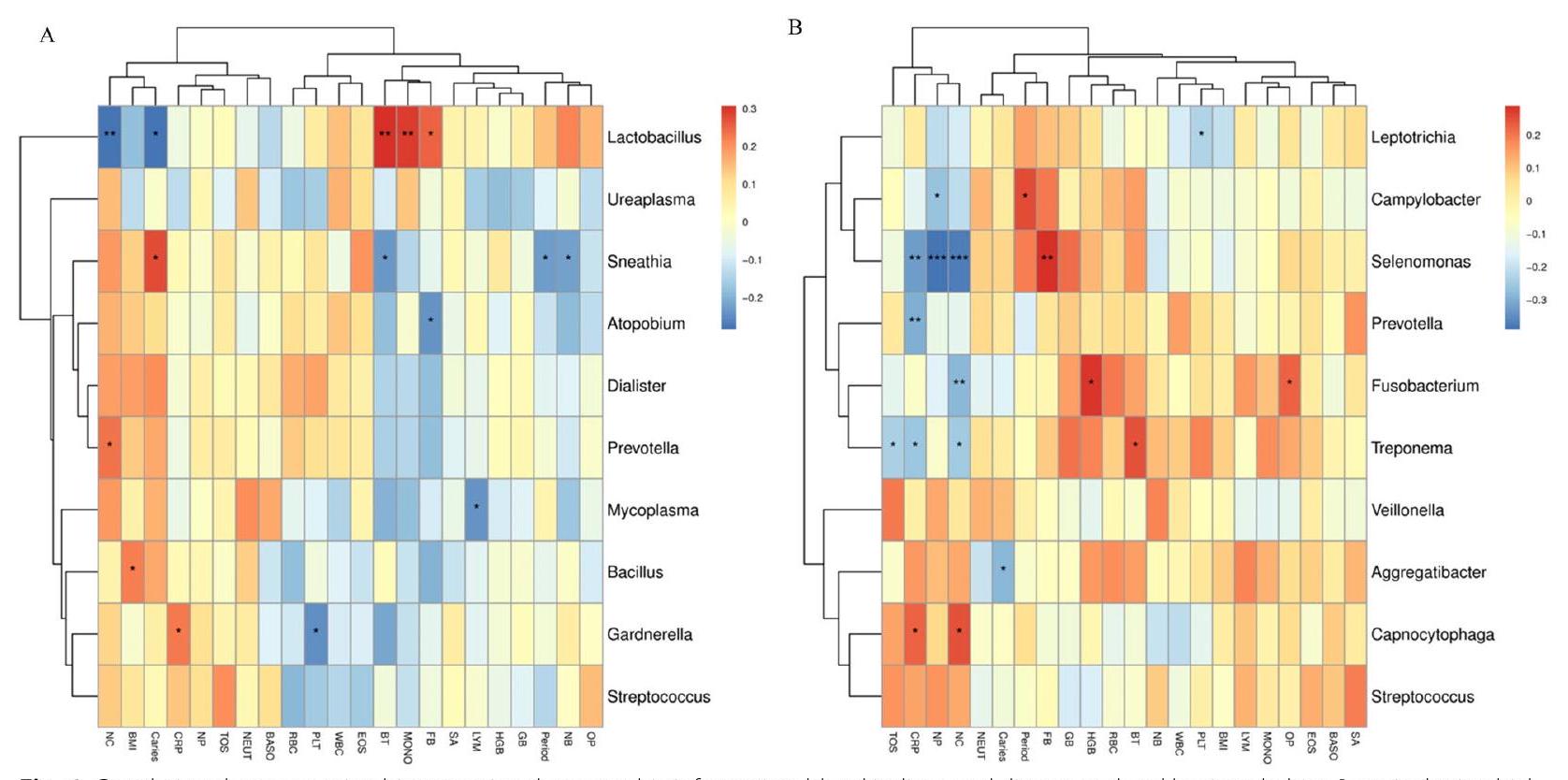

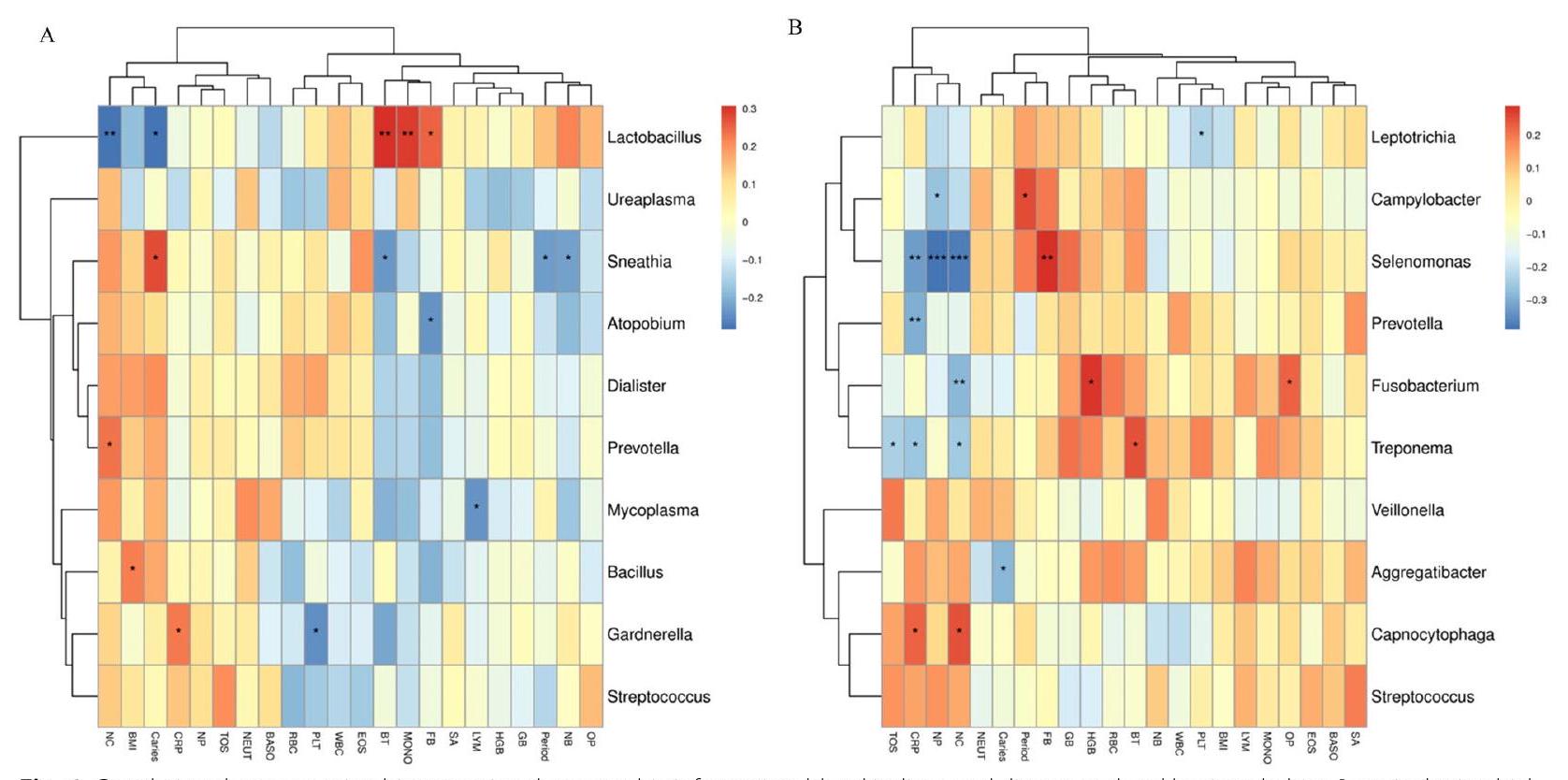

العلاقة بين الكائنات الدقيقة والعوامل البيئية

(بي تي) (

تحليل وظيفة التنبؤ

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أظهرت مجموعة CC وفرة أكبر من الجينات المتعلقة بتمثيل الأحماض الأمينية مقارنة بمجموعة HP ومجموعة AB. كانت الجينات الوظيفية في المسارات الأيضية لمرضى CC أكثر غنى في الخرائط العالمية والشاملة، وتمثيل الأحماض الأمينية، وتمثيل العوامل المساعدة والفيتامينات، وكانت تلك الموجودة في مجموعة HP أكثر غنى في الخرائط العالمية والشاملة وتمثيل الأحماض الأمينية مقارنة بتلك الموجودة في مجموعة AB (الملف الإضافي 1: الشكل S4). وهذا يشير إلى أن وجود بعض البكتيريا قد يلعب دورًا في العمليات الأيضية لمرضى السرطان. كان هناك فرق كبير في هيكل الفلورا الميكروبية الفموية بين مجموعة KCC ومجموعة KZ، بينما بالمقارنة مع المجموعات الأخرى، كانت هناك اختلافات مشابهة. ومع ذلك، نظرًا لصغر حجم العينة، يجب تفسير هذه النتائج بحذر.

المناقشات

تشارك المهبل مجتمعًا ميكروبيًا مشتركًا وهناك أيضًا تبادل متبادل لمجتمعات ميكروبية ذات صلة. كانت الميكروبات اللعابية للمشاركين الذين يعانون من التهاب المهبل البكتيري (BV) أكثر تنوعًا من تلك الخاصة بالمشاركين الذين لا يعانون من BV، وكانت Prevotella intermedia وPorphyromonas endodontalis أكثر وفرة في الميكروبات اللثوية تحت اللثة لدى النساء المصابات بـ BV مقارنة بالنساء غير المصابات بـ BV، مما يشير إلى وجود محور مهبلي فموي. علاوة على ذلك، ثبت أن Porphyromonas وPrevotella لهما قدرة مسرطنة عبر عدة آليات مختلفة. على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن تحافظ Porphyromonas على عدوى لثوية مزمنة، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة التعبير عن جزيئات مؤيدة للالتهابات مثل IL-6 وIL-8 وIL-1.

تمت دراسة تحولات الميكروبيوم المهبلي على طول مسار سرطان عنق الرحم، ولكن التأثيرات المرتبطة بها على الفم لا تزال غير مستكشفة بشكل كاف. كشفت هذه الدراسة أن تجويف الفم يحتوي على عدد أكبر بكثير من الأنواع البكتيرية مقارنة بالمهبل، وكشفت عن تبادل واسع الاتجاه بين المجتمعات الميكروبية بين التجويفين المهبلي والفموي من خلال محور مهبلي فموي ناشئ. توفر هذه الدراسة رؤى حول المجتمع الميكروبي المشترك بين الأجزاء الفموية والمهبلية من جسم الإنسان، فضلاً عن تبادل المجتمعات الميكروبية ذات الصلة. كشفت هذه الدراسة أن عدوى فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري المهبلي والعديد من حالات الإجهاض لم يكن لهما تأثير واضح على الفلورا الفموية للمرضى. ومع ذلك، فإن وجود سرطان عنق الرحم يمكن أن يسبب تغييرات كبيرة في تركيب ووفرة الميكروبات الفموية، مما يؤدي إلى تنوع أقل في الميكروبيوم الفموي مقارنة بالسكان الطبيعيين، وهو ما يتعارض مع التغيرات في الميكروبيوم المهبلي. زادت نسبة مسببات الأمراض اللثوية بشكل ملحوظ في المرضى الذين يعانون من سرطان عنق الرحم.

وفقًا لنتائج كل من تحليل LEfSe والغابات العشوائية، تم تحديد الفصيلة البكتيرية Fusobacterium وCampylobacter وCapnocytophaga وVeillonella وStreptococcus وLachnoanaerobaculum وPropionibacterium وPrevotella وLactobacillus وNeisser كعلامات بكتيرية فموية لسرطان القولون. يمكن أن تؤدي التغيرات في نسب هذه البكتيريا إلى اختلال ميكروبيوم الفم وترتبط أيضًا بجميع الأمراض الجهازية، بما في ذلك السرطان. ترتبط بكتيريا مختلفة، مثل Fusobacterium nucleatum وPeriodonticum وStreptococcus salivarius وPorphyromonas وأنواع مختلفة من Lactobacillus، بتشخيص هذا النوع من السرطان. تعتبر مسببات الأمراض اللثوية Fusobacterium nucleatum وCampylobacter وPseudomonas aeruginosa وPorphyromonas “ميكروبيوتا متحركة” لأنها تنشأ في تجويف الفم ولكنها مرتبطة أيضًا بالعدوى والالتهابات خارج الفم. هناك آليات مختلفة لتكوين الأورام مرتبطة بالميكروبيوم الفموي، تشمل بشكل رئيسي زيادة عوامل الخلايا وعوامل الالتهاب، الالتهاب المزمن، تكاثر الخلايا، تغييرات في مسارات الأيض، نواتج البكتيريا المسببة للأمراض، قمع الاستجابة المناعية، تحفيز تلف الجينات الورمية، وتغيير الحواجز الظهارية. تركز معظم الأبحاث الحالية على كيفية تأثير خلل الميكروبات الفموية على الأعضاء والأنظمة الرئيسية في الجسم ككل. ومع ذلك، هناك علاقة ثنائية الاتجاه بين الصحة الفموية والصحة العامة، وكيف تؤثر الأمراض الجهازية سلبًا على الميكروبات الفموية يحتاج إلى مزيد من الاستكشاف.

عدد إشارات استشعار الكائنات الدقيقة التي تؤدي إلى زيادة المقاومة ضد الجهاز المناعي، والمضادات الحيوية، أو الاتصال المباشر بين الكائنات الدقيقة لتعزيز التآزر. وبالتالي، فإن التأثير الشامل لاثنين أو أكثر من الكائنات الدقيقة على المرض يكون أكثر حدة من تأثير كائن دقيق واحد، وقد تعزز الشبكة التفاعلية المعقدة من قدرة الأمراض الميكروبية المتعددة على التسبب في المرض، مما يؤثر في النهاية على بدء المرض وتطوره. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن هذه الدراسات تستند إلى بكتيريا مختلفة في نفس الموقع، بينما يتباين تكوين الميكروبيوم المهبلي عن تكوين الميكروبيوم الفموي، وهناك حاجة إلى مزيد من الدراسات لتوضيح آليات عمل الميكروبيوم في مواقع مختلفة.

تسبب الالتهاب الجهازي (مثل الآفات العنقية وعدوى فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري) في تباين كبير في تركيز بروتين سي التفاعلي عبر جميع المجموعات. يمكن أن يؤدي زيادة عدد الحمل والولادات والإجهاضات بسهولة إلى إزعاج الميكروبيوم المهبلي، وتقليل وفرة اللاكتوباسيلس، وزيادة نسب البكتيريا اللاهوائية مثل بريفوتيلا وغاردنريلا. يرتبط الالتهاب الجهازي والمحلي الشديد ارتباطًا وثيقًا بعدم التوازن في الميكروبيوم المهبلي. وبالمثل، عندما كانت نظافة الفم جيدة وتكرار الفرشاة مرتفعًا، انخفضت وفرة الكائنات الدقيقة المسببة للأمراض المرتبطة بأمراض اللثة، مثل سيلينوموناس وبريفوتيلا وتريبونيما وأغريغاتيبكتير؛ وذلك بسبب انتقال الكائنات الدقيقة الفموية أو نواتجها الأيضية مباشرة عبر الدم أو تأثيرها غير المباشر على الوسائط الالتهابية المنتجة في تجويف الفم.

استهلاك الجليكوجين العالي [60]، وPorphyromonas وPrevotella وFusobacterium مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بالاختلافات في المستقلبات. يتم زيادة استقلاب البيريميدين بشكل ملحوظ في المرضى الذين يعانون من سرطان القولون والمستقيم (CC) وهو مرتبط إيجابيًا بأمراض اللثة [61]. كما أن استقلاب الجلوتامات والهستيدين والتيروزين يشارك أيضًا في تطور التهاب اللثة. تؤدي الآفات العنقية إلى تغييرات في البيئة الدقيقة الفموية، مما قد يزيد من التأثير الممرض للبكتيريا اللثوية، ويحفز النمو والتكاثر الانتقائي للعوامل الممرضة الفموية، وينتج ميكروبيوم أكثر مرضية، وحتى ينتج “تأثير واربورغ”.

القيود

الاستنتاجات

تُظهر خرائط النظرة العامة، بالإضافة إلى استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية واستقلاب العوامل المساعدة والفيتامينات، وفرة عالية في مرضى سرطان عنق الرحم، مع تقلبات في الميكروبات. يمكن أن يؤدي ذلك إلى انخفاض في تنوع الميكروبات الفموية وزيادة في تكوين الكائنات الدقيقة المسببة للأمراض، مما يزيد من خطر العدوى والسرطان. في المستقبل، من المتوقع أن يتم فحص سرطان عنق الرحم من خلال علامات الفلورا الفموية.

معلومات إضافية

الملف الإضافي 4: الشكل S4. يستنتج PICRUSt الوظائف الخلوية للمجتمعات البكتيرية في مجموعات مختلفة. (أ) مجموعة AB ومجموعة CC؛ (ب) مجموعة CC ومجموعة HP؛ (ج) مجموعة AB ومجموعة HP.

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

نُشر على الإنترنت: 29 أبريل 2024

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6): 394424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492.

- Araldi RP, Sant’Ana TA, Módolo DG, de Melo TC, Spadacci-Morena DD, de Cassia SR, Cerutti JM, de Souza EB. The human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancer biology: an overview. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:1537-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.149.

- Quinlan JD. Human papillomavirus: screening, testing, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(2):152-9.

- Economopoulou P, Kotsantis I, Psyrri A. Special issue about head and neck cancers: HPV positive cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3388. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijms21093388.

- Baker JL, Mark Welch JL, Kauffman KM, McLean JS, He X. The oral microbiome: diversity, biogeography and human health. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00963-6.

- Desvarieux M, Demmer RT, Rundek T, Boden-Albala B, Jacobs DR Jr, Sacco RL, Papapanou PN. Periodontal microbiota and carotid intima-media thickness: the Oral Infections and Vascular Disease Epidemiology Study (INVEST). Circulation. 2005;111:576-82. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR. 0000154582.37101.15.

- Maisonneuve P, Amar S, Lowenfels AB. Periodontal disease, edentulism, and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:985-95. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx019.

- Shi J, Yang Y, Xie H, Wang X, Wu J, Long J, Courtney R, Shu XO, Zheng W, Blot WJ, Cai Q. Association of oral microbiota with lung cancer risk in a low-income population in the Southeastern USA. Cancer Causes Control. 2021;32:1423-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-021-01490-6.

- Fan X, Alekseyenko AV, Wu J, Peters BA, Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM, Purdue MP, Abnet CC, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Miller G, et al. Human oral microbiome and prospective risk for pancreatic cancer: a population-based nested case-control study. Gut. 2018;67:120-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/ gutjnl-2016-312580.

- Shi T, Min M, Sun C, Zhang Y, Liang M, Sun Y. Periodontal disease and susceptibility to breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:1025-33. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12982.

- Yang J, He P, Zhou M, Li S, Zhang J, Tao X, Wang A, Wu X. Variations in oral microbiome and its predictive functions between tumorous and healthy individuals. J Med Microbiol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.001568.

- Shang FM, Liu HL. Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: a review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;10:71-81. https://doi.org/10. 4251/wjgo.v10.i3.71.

- Wu S, Ding X, Kong Y, Acharya S, Wu H, Huang C, Liang Y, Nong X, Chen H. The feature of cervical microbiota associated with the progression of cervical cancer among reproductive females. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;163:34857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.08.016.

- Chattopadhyay I, Lu W, Manikam R, Malarvili MB, Ambati RR, Gundamaraju R. Can metagenomics unravel the impact of oral bacteriome in

human diseases? Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2023;39(1):85-117. https:// doi.org/10.1080/02648725.2022.2102877. - Persson R, Hitti J, Verhelst R, Vaneechoutte M, Persson R, Hirschi R, Weibel M , Rothen M , Temmerman M , Paul K , Eschenbach D . The vaginal microflora in relation to gingivitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:6. https://doi.org/10. 1186/1471-2334-9-6.

- Yusuf K, Sampath V, Umar S. Bacterial infections and cancer: exploring this association and its implications for cancer patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24043110.

- Organization WH. Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. World Health Organization; 2020.

- Egemen D, Cheung LC, Chen X, et al. Risk estimates supporting the 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24(2):132-43. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0000000000000529.

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(5):321-46. https://doi.org/10. 3322/caac.21628.

- Pitts N. “ICDAS”-an international system for caries detection and assessment being developed to facilitate caries epidemiology, research and appropriate clinical management. Community Dent Health. 2004;21(3):193-8.

- Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S159-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER. 18-0006.

- Krog MC, Hugerth LW, Fransson E, Bashir Z, Nyboe Andersen A, Edfeldt G, Engstrand L, Schuppe-Koistinen I, Nielsen HS. The healthy female microbiome across body sites: effect of hormonal contraceptives and the menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod. 2022;37(7):1525-43. https://doi.org/10. 1093/humrep/deac094.

- Mei L, Wang T, Chen Y, Wei D, Zhang Y, Cui T, Meng J, Zhang X, Liu Y, Ding L, Niu X. Dysbiosis of vaginal microbiota associated with persistent highrisk human papilloma virus infection. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):12. https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12967-021-03201-w.

- Mitra A, MacIntyre DA, Ntritsos G, Smith A, Tsilidis KK, Marchesi JR, Bennett PR, Moscicki AB, Kyrgiou M. The vaginal microbiota associates with the regression of untreated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 lesions. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1999. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15856-y.

- Camargo M, Vega L, Muñoz M, Sánchez R, Patarroyo ME, Ramírez JD, Patarroyo MA. Changes in the cervical microbiota of women with different high-risk human papillomavirus loads. Viruses. 2022;14(12):2674. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14122674.

- Karpinets TV, Wu X, Solley T, El Alam MB, Sims TT, Yoshida-Court K, Lynn E, Ahmed-Kaddar M, Biegert G, Yue J, et al. Metagenomes of rectal swabs in larger, advanced stage cervical cancers have enhanced mucus degrading functionalities and distinct taxonomic structure. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):945. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09997-0.

- Zhang Y, Xu X, Yu L, Shi X, Min M, Xiong L, Pan J, Zhang Y, Liu P, Wu G, Gao G. Vaginal microbiota changes caused by HPV infection in Chinese women. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12: 814668. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fcimb.2022.814668.

- Wei Z-T, Chen H-L, Wang C-F, Yang G-L, Han S-M, Zhang S-L. Depiction of vaginal microbiota in women with high-risk human papillomavirus infection. Front Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020. 587298.

- Ivanov MK, Brenner EV, Hodkevich AA, Dzyubenko VV, Krasilnikov SE, Mansurova AS, Vakhturova IE, Agletdinov EF, Shumeikina AO, Chernyshova AL, Titov SE. Cervicovaginal-microbiome analysis by 16 S sequencing and real-time PCR in patients from novosibirsk (Russia) with cervical lesions and several years after cancer treatment. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(1):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13010140.

- Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Delgado S, Ruiz L, Ruas-Madiedo P, Sánchez B, Margolles A. Bifidobacteria and their health-promoting effects. Microbiol Spectr. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.BAD-0010-2016.

- Chao X, Wang L, Wang S, Lang J, Tan X, Fan Q, Shi H. Research of the potential vaginal microbiome biomarkers for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8: 565001. https://doi. org/10.3389/fmed.2021.565001.

- Curty G, Costa RL, Siqueira JD, Meyrelles AI, Machado ES, Soares EA, Soares MA. Analysis of the cervical microbiome and potential

biomarkers from postpartum HIV-positive women displaying cervical intraepithelial lesions. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17364. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-017-17351-9. - Wang W, Liu Y, Yang Y, Ren J, Zhou H. Changes in vaginal microbiome after focused ultrasound treatment of high-risk human papillomavirus infection-related low-grade cervical lesions. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07937-8.

- Freitas AC, Hill JE. Quantification, isolation and characterization of Bifidobacterium from the vaginal microbiomes of reproductive aged women. Anaerobe. 2017;47:145-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.05. 012.

- Srinivasan U, Misra D, Marazita ML, Foxman B. Vaginal and oral microbes, host genotype and preterm birth. Med Hypotheses. 2009;73(6):963-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2009.06.017.

- Balle C, Esra R, Havyarimana E, Jaumdally SZ, Lennard K, Konstantinus IN, Barnabas SL, Happel AU, Gill K, Pidwell T, et al. Relationship between the oral and vaginal microbiota of south African adolescents with high prevalence of bacterial vaginosis. Microorganisms. 2020;8(7):1004. https://doi. org/10.3390/microorganisms8071004.

- Takada K, Melnikov VG, Kobayashi R, Komine-Aizawa S, Tsuji NM, Hayakawa S. Female reproductive tract-organ axes. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1110001. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1110001.

- Hoare A, Soto C, Rojas-Celis V, Bravo D. Chronic inflammation as a link between periodontitis and carcinogenesis. Mediators Inflamm. 2019;2019:1029857. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1029857.

- Inaba H, Amano A, Lamont RJ, Murakami Y. Involvement of proteaseactivated receptor 4 in over-expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2015;204(5):605-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00430-015-0389-y.

- Chattopadhyay I, Verma M, Panda M. Role of oral microbiome signatures in diagnosis and prognosis of oral cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2019;18:1533033819867354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533033819867354.

- Lo CH, Wu DC, Jao SW, Wu CC, Lin CY, Chuang CH, Lin YB, Chen CH, Chen YT, Chen JH, et al. Enrichment of Prevotella intermedia in human colorectal cancer and its additive effects with Fusobacterium nucleatum on the malignant transformation of colorectal adenomas. J Biomed Sci. 2022;29(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-022-00869-0.

- Castañeda-Corzo GJ, Infante-Rodríguez LF, Villamil-Poveda JC, Bustillo J, Cid-Arregui A, García-Robayo DA. Association of Prevotella intermedia with oropharyngeal cancer: a patient-control study. Heliyon. 2023;9(3): e14293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14293.

- Tuominen H, Rautava J. Oral microbiota and cancer development. Pathobiology. 2021;88(2):116-26. https://doi.org/10.1159/000510979.

- Cullin N, Azevedo Antunes C, Straussman R, Stein-Thoeringer CK, Elinav E. Microbiome and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(10):1317-41. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ccell.2021.08.006.

- Pignatelli P, Romei FM, Bondi D, Giuliani M, Piattelli A, Curia MC. Microbiota and oral cancer as a complex and dynamic microenvironment: a narrative review from etiology to prognosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15):8323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158323.

- Jolivet-Gougeon A, Bonnaure-Mallet M. Screening for prevalence and abundance of Capnocytophaga spp. by analyzing NGS data: a scoping review. Oral Dis. 2021;27(7):1621-30. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13573.

- Irfan M, Delgado RZR, Frias-Lopez J. The oral microbiome and cancer. Front Immunol. 2020;11: 591088. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020. 591088.

- Radaic A, Kapila YL. The oralome and its dysbiosis: new insights into oral microbiome-host interactions. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:1335-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2021.02.010.

- Radaic A, Ganther S, Kamarajan P, Grandis J, Yom SS, Kapila YL. Paradigm shift in the pathogenesis and treatment of oral cancer and other cancers focused on the oralome and antimicrobial-based therapeutics. Periodontol 2000. 2021;87(1):76-93. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12388.

- El-Awady A, de Sousa RM, Meghil MM, Rajendran M, Elashiry M, Stadler AF, Foz AM, Susin C, Romito GA, Arce RM, Cutler CW. Polymicrobial synergy within oral biofilm promotes invasion of dendritic cells and survival of consortia members. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019;5(1):11. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41522-019-0084-7.

- Wright CJ, Xue P, Hirano T, Liu C, Whitmore SE, Hackett M, Lamont RJ. Characterization of a bacterial tyrosine kinase in Porphyromonas gingivalis

involved in polymicrobial synergy. Microbiologyopen. 2014;3(3):383-94. https://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.177. - Rosca AS, Castro J, França Â, Vaneechoutte M, Cerca N. Gardnerella vaginalis dominates multi-species biofilms in both pre-conditioned and competitive in vitro biofilm formation models. Microb Ecol. 2022;84(4):127887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-021-01917-2.

- Murray JL, Connell JL, Stacy A, Turner KH, Whiteley M. Mechanisms of synergy in polymicrobial infections. J Microbiol. 2014;52(3):188-99. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s12275-014-4067-3.

- Audirac-Chalifour A, Torres-Poveda K, Bahena-Roman M, Tellez-Sosa J, Martinez-Barnetche J, Cortina-Ceballos B, Lopez-Estrada G, DelgadoRomero K, Burguete-Garcia AI, Cantu D, et al. Cervical microbiome and cytokine profile at various stages of cervical cancer: a pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4): e0153274. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 01532 74.

- Xu B, Han YW. Oral bacteria, oral health, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Periodontol 2000. 2022;89(1):181-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd. 12436.

- Yu L, Chen X, Sun X, Wang L, Chen S. The glycolytic switch in tumors: how many players are involved? J Cancer. 2017;8(17):3430-40. https://doi.org/ 10.7150/jca. 21125.

- Park NJ, Choi Y, Lee D, Park JY, Kim JM, Lee YH, Hong DG, Chong GO, Han HS. Transcriptomic network analysis using exfoliative cervical cells could discriminate a potential risk of progression to cancer in HPV-related cervical lesions: a pilot study. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2023;20(1):75-87. https://doi.org/10.21873/cgp.20366.

- Chen X, Yi C, Yang MJ, Sun X, Liu X, Ma H, Li Y, Li H, Wang C, He Y, et al. Metabolomics study reveals the potential evidence of metabolic reprogramming towards the Warburg effect in precancerous lesions. J Cancer. 2021;12(5):1563-74. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.54252.

- Ilhan ZE, Łaniewski P, Thomas N, Roe DJ, Chase DM, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Deciphering the complex interplay between microbiota, HPV, inflammation and cancer through cervicovaginal metabolic profiling. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:675-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.04.028.

- Spratt DA, Greenman J, Schaffer AG. Capnocytophaga gingivalis: effects of glucose concentration on growth and hydrolytic enzyme production. Microbiology (Reading). 1996;142:2161-4. https://doi.org/10.1099/13500 872-142-8-2161.

- Pei J, Li F, Xie Y, Liu J, Yu T, Feng X. Microbial and metabolomic analysis of gingival crevicular fluid in general chronic periodontitis patients: lessons for a predictive, preventive, and personalized medical approach. EPMA J. 2020;11(2):197-215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13167-020-00202-5.

- Hübbers CU, Akgül B. HPV and cancer of the oral cavity. Virulence. 2015;6(3):244-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2014.999570.

- Eggersmann TK, Sharaf K, Baumeister P, Thaler C, Dannecker CJ, Jeschke U, Mahner S, Weyerstahl K, Weyerstahl T, Bergauer F, Gallwas JA-O. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in cervical HPV positive women and their sexual partners. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299(6):1659-65. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00404-019-05135-7.

ملاحظة الناشر

ساهم وي زانغ ويانفاي يين بالتساوي في هذا العمل.

*المراسلة:

بين ليو

liubkq@lzu.edu.cn

لي هي ياو

13639317172@163.com

قائمة كاملة بمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقال

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05124-8

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38685022

Publication Date: 2024-04-29

Relationship between vaginal and oral microbiome in patients of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and cervical cancer

Abstract

Background The aim of this study was to assess the microbial variations and biomarkers in the vaginal and oral environments of patients with human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer (CC) and to develop novel prediction models. Materials and methods This study included 164 samples collected from both the vaginal tract and oral subgingival plaque of 82 women. The participants were divided into four distinct groups based on their vaginal and oral samples: the control group (Z/KZ,

Conclusion HPV infection and CC impact both the vaginal and oral microenvironments, affecting systemic metabolism and the synergy between bacteria. This suggests that the use of oral flora markers is a potential screening tool for the diagnosis of CC.

Introduction

The oral cavity is a natural open system composed of a complex microbiome consisting of more than 800 bacterial species [5]. This oral microbiota has been implicated not only in periodontal disease but also in systemic conditions including haematological diseases, and lymphatic, lung, pancreatic and breast cancers [6-10].

Changes in the composition of the oral microbiome are now recognized as potential biomarkers for cancers, including colorectal cancer (CRC), marked by increased Fusobacterium nucleatum abundance [11, 12]. Similarly, shifts favouring oral pathogens such as the genera Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium and Prevotella have been correlated with the incidence of CC, although the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood [13], these oral pathogens also cause the periodontal disease [14]. Previous studies have shown a correlation between vaginal bacteria and gingival inflammation [15], HPV not only invades the basal cells of the vaginal epithelium, but also infects the periodontal tissue and keeps the virus in a latent state [5]. The oral and vaginal environments may provide similar colonization and growth conditions, resulting in a significantly increased risk of periodontal disease and cancer [16]. However, relatively few studies exist on changes in the oral microbiome when the vaginal microbiota is transformed during the course of HPV infection to CC development, suggesting that more research is needed in this area.

Population-based CC screening is implemented as a public health priority in China [17], and the best strategy is the use of a liquid-based cytology test (TCT) combined with HPV screening [18, 19]. The combined screening technology, although advanced and effective, is costly and suitable for areas with adequate medical and health care. However, there are still many less economically developed areas (rural areas) in China, and there is an urgent

need to find a high-quality and inexpensive method. Changes in oral microbial diversity that are detectable through low-cost profiling may offer additional value as biomarkers for early screening, diagnosis and monitoring of HPV infection and even CC. The aim of this study was to evaluate the differences and associations between vaginal and oral microorganisms in HPV-infected patients and CC patients. An increased understanding of microbial ecology may contribute to improving the accuracy of CC screening and providing life-saving interventions to vulnerable groups.

Materials and methods

Study design and specimen collection

scaler penetrated the tongue side of the mandibular first molar below the gum to remove dental plaque and blood contamination was prevented during the collection process. For vaginal secretion sample collection, a disposable speculum was inserted, and a sterile swab sample was taken from the posterior vaginal fornix. All specimens were stored immediately at

Full-length 16 S sequencing and data processing

Statistical analysis

species complexity. One-way ANOVA was used to compare bacterial abundance and diversity. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) coupled with effect size (LEfSe) was applied to evaluate the differentially abundant taxa. An LDA score

Results

Characteristics of the subjects

| Normal (

|

Abortion (

|

HPV (

|

Cancer (

|

P value | |

| Age (year) |

|

|

|

|

0.395 |

| Nation | |||||

| Han nationality | 22 (100) | 17 (100) | 21 (100) | 17 (77.27) | 0.003 |

| Other nationalist | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (22.73) | |

| Level of education | |||||

| Primary school | 1 (4.55) | 6 (35.29) | 13 (61.90) | 19 (86.36) | <0.001 |

| High school | 8 (36.36) | 6 (35.29) | 3 (14.29) | 2 (9.09) | |

| College degree | 13 (59.09) | 5 (29.41) | 5 (23.81) | 1 (4.55) | |

| Gravidity |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

| Surgical abortions |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

| Parity |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

| Sexual age (year) |

|

|

|

|

0.556 |

| BMI (

|

|

|

|

|

0.02 |

| Smoking | 2 (9.09) | 3 (17.65) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.059 |

| Drinking | 4 (18.19) | 6 (35.30) | 3 (14.29) | 4 (18.19) | 0.481 |

| Family history of CC (%) | 1 (4.54) | 2 (11.76) | 2 (9.52) | 0 (0) | 0.365 |

| CRP (mg/dL) |

|

|

|

|

<0.01 |

| WBC (4.5 to

|

|

|

|

|

0.635 |

| RBC |

|

|

|

|

0.068 |

| HGB |

|

|

|

|

0.122 |

| NEUT% |

|

|

|

|

0.014 |

| LYM% |

|

|

|

|

0.079 |

| MONO% |

|

|

|

|

0.461 |

| EOS% |

|

|

|

|

0.048 |

| BASO% |

|

|

|

|

0.118 |

| PLT |

|

|

|

|

0.158 |

| Caries (%) | 3 (13.64) | 2 (11.76) | 1 (4.76) | 2 (9.09) | 0.663 |

| Periodontitis (%) | 3 (13.64) | 3 (17.65) | 5 (23.81) | 8 (36.36) | 0.34 |

| Frequency of tooth brushing (%) | |||||

|

|

3 (13.64) | 8 (47.06) | 8 (38.10) | 16 (72.73) | <0.001 |

| 2 times/day | 19 (86.36) | 9 (52.94) | 13 (61.90) | 6 (27.27) | |

| Brushing time (%) | |||||

|

|

1 (4.55) | 3 (17.65) | 12 (57.14) | 9 (40.91) | <0.001 |

| 2 min | 7 (31.82) | 7 (41.18) | 6 (28.57) | 11 (50.00) | |

|

|

14 (63.66) | 7 (41.18) | 3 (14.29) | 2 (9.09) | |

| Gingival bleeding (%) | |||||

| No | 16 (72.73) | 9 (52.94) | 7 (33.33) | 15 (68.18) | 0.043 |

| Yes | 6 (27.27) | 8 (47.06) | 14 (66.67) | 7 (31.82) | |

| Professional dental cleaning (%) | |||||

| No | 16 (72.73) | 12 (70.59) | 18 (85.71) | 22 (100) | 0.039 |

| Once a year | 5 (22.73) | 2 (11.76) | 3 (14.29) | 0 | |

| 2-4 years/times | 0 | 1 (5.89) | 0 | 0 | |

|

|

1 (4.55) | 2 (11.76) | 0 | 0 | |

| Toothache or sensitivity of tooth (%) | |||||

| No | 20 (90.91) | 15 (88.24) | 17 (80.95) | 17 (77.27) | 0.768 |

| Yes | 2 (9.09) | 2 (11.76) | 4 (19.05) | 5 (22.73) | |

| HPV subtypes | |||||

| 16 | – | – | 13 (61.90) | 12 (54.55) | – |

| 18 | – | – | 4 (19.05) | 6 (27.27) | |

| Normal (

|

Abortion (

|

HPV (

|

Cancer (

|

P value | |

| 33 | – | – | 1 (4.76) | 1 (4.55) | |

| 51 | – | – | 1 (4.76) | 1 (4.55) | |

| 52 | – | – | 1 (4.76) | 0 | |

| 53 | – | – | 1 (4.76) | 2 (9.09) | |

| 58 | – | – | 3 (14.29) | 5 (22.73) |

The P -value is calculated by ANOVA, Fisher exact probability test. Bold value indicates that P value is less than 0.05

Composition and diversity of vaginal and oral microbiota

and its abundance declined drastically in the CC samples

Identification of Z and CC patients based on cervical microbiota and oral microbiota

Subgingival microbiome LDA and LEfSe markers varied inversely to those of the vaginal microbiome, with control (KZZ group) plaques harbouring the most distinct taxa, including Prevotella, Selenomonas, Saccharibacteria, Campylobacter, Amnipila, and Centipeda (

Association between microorganisms and environmental factors

(BT) (

Predictive function analysis

In addition, the CC group exhibited a greater abundance of genes related to amino acid metabolism than did the HP group and the AB group. The functional genes in metabolic pathways of CC patients were still more enriched in global and overview maps, amino acid metabolism, and metabolism of cofactors and vitamins, and those in the HP group were more enriched in global and overview maps and amino acid metabolism than those in the AB group (Additional file 1: Figure S4). This suggests that the presence of certain bacteria may play a role in the metabolic processes of cancer patients. There was a significant difference in the oral microbial flora structure between the KCC group and the KZ group, while in comparison with the other groups, there were similar differences. However, due to the small sample size, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

Discussions

vagina share a common microbial community and that there is also a reciprocal exchange of related microbial communities. The salivary microbiota of participants with bacterial vaginosis (BV) was more diverse than that of BV-negative participants [36], and Prevotella intermedia and Porphyromonas endodontalis were enriched in the subgingival gingival microbiota of BV-infected women compared to women without BV, which indicates the presence of a vagino-oral axis [37]. Moreover, Porphyromonas and Prevotella have been proven to have carcinogenic potential via several different mechanisms. For example, Porphyromonas can maintain chronic periodontal infection, leading to increased expression of proinflammatory molecules such as IL-6, IL-8, IL-1

Vaginal microbiome transformations along the cervical carcinogenesis route have been characterized, but the associated impacts on the oral niche remain underexplored. This study revealed that the oral cavity contains a significantly greater number of bacterial species than does the vagina and revealed extensive bidirectional sharing of microbial communities between the vaginal and oral cavities through an emerging vagino-oral axis [37]. This study provides insight into the microbial community shared between the oral and vaginal parts of the human body, as well as the exchange of related microbial communities. This study revealed that vaginal HPV infection and multiple abortions had no obvious impact on the oral flora of patients. However, the presence of CC can cause significant changes in the composition and abundance of oral microorganisms, leading to a lower diversity of the oral microbiome compared to that of the normal population, which is contrary to the changes in the vaginal microbiota. The prevalence of periodontal pathogens significantly increased in patients with CC. According

to the results of both LEfSe and random forest analysis, Fusobacterium, Campylobacter, Capnocytophaga, Veillonella, Streptococcus, Lachnoanaerobaculum, Propionibacterium, Prevotella, Lactobacillus and Neisser were identified as oral bacterial markers for CC. Changes in the proportions of these bacteria can cause oral microflora dysbiosis and are also associated with all systemic diseases, including cancer [5, 38, 40, 44-47]. Different bacteria, such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, Periodonticum, Streptococcus salivarius, Porphyromonas, and different Lactobacillus subspecies, are associated with the diagnosis of this type of cancer. The periodontal pathogens Fusobacterium nucleatum, Campylobacter, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Porphyromonas are considered “mobile microbiota” because they originate in the oral cavity but are also associated with extraoral infections and inflammation [45]. There are various tumorigenesis mechanisms associated with the oral microbiome, mainly including increased cell factors and inflammatory factors, chronic inflammation, cell proliferation, metabolic pathway changes, pathogenic bacterial metabolites, suppression of the immune response, induction of tumour genetic damage, and alteration of epithelial barriers [4749]. Most of the current research focuses on how dysfunction of oral microorganisms affects major organs and systems of the whole body. However, there is a bidirectional relationship between oral and general health, and how systemic diseases adversely affect oral microorganisms needs further exploration.

number of microbiota quorum-sensing signals that result in enhanced resistance against the immune system, antibiotics, or direct contact between microorganisms to promote synergy [53]. Thus, the comprehensive impact of two or more microorganisms on disease is more severe than that of a single microorganism, and the complex interaction network may enhance the pathogenicity of multiple microbial infections, ultimately affecting disease initiation and progression. Notably, these studies are based on different bacteria at the same site, while the composition of the vaginal microbiome is different from that of the oral microbiome, and more studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms of action of the microbiome at different sites.

Systemic inflammation (such as cervical lesions and HPV infection) caused significant variation in the CRP concentration across all the groups. An increase in the number of pregnancies, childbirths and abortions can easily disturb the vaginal microenvironment, decrease the abundance of Lactobacillus, and increase the proportions of the anaerobic bacteria Prevotella and Gardnerella. Severe systemic and local inflammation are closely related to imbalances in the vaginal microbiome [54]. Similarly, when oral hygiene was good and brushing frequency was high, the abundance of pathogenic microorganisms associated with periodontal disease, such as Selenomonas, Prevotella, Treponema, and Aggregatibacter, decreased; this is due to oral microorganisms or their metabolites directly migrating through the blood or indirectly affecting the inflammatory mediators produced in the oral cavity [55].

high glycogen consumption [60], and Porphyromonas, Prevotella and Fusobacterium are closely related to differences in metabolites. Pyrimidine metabolism is significantly increased in patients with CC and is positively correlated with periodontal disease [61]. Glutamate, histidine, and tyrosine metabolism are also involved in the development of periodontitis. Cervical lesions lead to changes in the oral microenvironment, which may increase the pathogenic effect of periodontal bacteria, induce the selective growth and reproduction of oral pathogens, produce a more pathogenic microbiome, and even produce the “Warburg effect”.

Limitations

Conclusions

overview maps, as well as amino acid metabolism and the metabolism of cofactors and vitamins, are highly abundant in CC patients, exhibiting fluctuations in the microbiota. This can lead to a decrease in oral microbial diversity and an increase in the composition of pathogenic microorganisms, increasing the risk of infections and cancer. In the future, it is expected to screen cervical cancer through oral flora markers.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 4: Figure S4. PICRUSt infers the cellular functions of bacterial communities in different groups. (A) AB group and CC group; (B) CC group and HP group; (C) AB group and HP group.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 29 April 2024

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6): 394424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492.

- Araldi RP, Sant’Ana TA, Módolo DG, de Melo TC, Spadacci-Morena DD, de Cassia SR, Cerutti JM, de Souza EB. The human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancer biology: an overview. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:1537-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.149.

- Quinlan JD. Human papillomavirus: screening, testing, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(2):152-9.

- Economopoulou P, Kotsantis I, Psyrri A. Special issue about head and neck cancers: HPV positive cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3388. https://doi. org/10.3390/ijms21093388.

- Baker JL, Mark Welch JL, Kauffman KM, McLean JS, He X. The oral microbiome: diversity, biogeography and human health. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-023-00963-6.

- Desvarieux M, Demmer RT, Rundek T, Boden-Albala B, Jacobs DR Jr, Sacco RL, Papapanou PN. Periodontal microbiota and carotid intima-media thickness: the Oral Infections and Vascular Disease Epidemiology Study (INVEST). Circulation. 2005;111:576-82. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR. 0000154582.37101.15.

- Maisonneuve P, Amar S, Lowenfels AB. Periodontal disease, edentulism, and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:985-95. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx019.

- Shi J, Yang Y, Xie H, Wang X, Wu J, Long J, Courtney R, Shu XO, Zheng W, Blot WJ, Cai Q. Association of oral microbiota with lung cancer risk in a low-income population in the Southeastern USA. Cancer Causes Control. 2021;32:1423-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-021-01490-6.

- Fan X, Alekseyenko AV, Wu J, Peters BA, Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM, Purdue MP, Abnet CC, Stolzenberg-Solomon R, Miller G, et al. Human oral microbiome and prospective risk for pancreatic cancer: a population-based nested case-control study. Gut. 2018;67:120-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/ gutjnl-2016-312580.

- Shi T, Min M, Sun C, Zhang Y, Liang M, Sun Y. Periodontal disease and susceptibility to breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:1025-33. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12982.

- Yang J, He P, Zhou M, Li S, Zhang J, Tao X, Wang A, Wu X. Variations in oral microbiome and its predictive functions between tumorous and healthy individuals. J Med Microbiol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.001568.

- Shang FM, Liu HL. Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: a review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;10:71-81. https://doi.org/10. 4251/wjgo.v10.i3.71.

- Wu S, Ding X, Kong Y, Acharya S, Wu H, Huang C, Liang Y, Nong X, Chen H. The feature of cervical microbiota associated with the progression of cervical cancer among reproductive females. Gynecol Oncol. 2021;163:34857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.08.016.

- Chattopadhyay I, Lu W, Manikam R, Malarvili MB, Ambati RR, Gundamaraju R. Can metagenomics unravel the impact of oral bacteriome in

human diseases? Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 2023;39(1):85-117. https:// doi.org/10.1080/02648725.2022.2102877. - Persson R, Hitti J, Verhelst R, Vaneechoutte M, Persson R, Hirschi R, Weibel M , Rothen M , Temmerman M , Paul K , Eschenbach D . The vaginal microflora in relation to gingivitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:6. https://doi.org/10. 1186/1471-2334-9-6.

- Yusuf K, Sampath V, Umar S. Bacterial infections and cancer: exploring this association and its implications for cancer patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24043110.

- Organization WH. Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. World Health Organization; 2020.

- Egemen D, Cheung LC, Chen X, et al. Risk estimates supporting the 2019 ASCCP risk-based management consensus guidelines. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2020;24(2):132-43. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0000000000000529.

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(5):321-46. https://doi.org/10. 3322/caac.21628.

- Pitts N. “ICDAS”-an international system for caries detection and assessment being developed to facilitate caries epidemiology, research and appropriate clinical management. Community Dent Health. 2004;21(3):193-8.

- Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S159-72. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER. 18-0006.

- Krog MC, Hugerth LW, Fransson E, Bashir Z, Nyboe Andersen A, Edfeldt G, Engstrand L, Schuppe-Koistinen I, Nielsen HS. The healthy female microbiome across body sites: effect of hormonal contraceptives and the menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod. 2022;37(7):1525-43. https://doi.org/10. 1093/humrep/deac094.

- Mei L, Wang T, Chen Y, Wei D, Zhang Y, Cui T, Meng J, Zhang X, Liu Y, Ding L, Niu X. Dysbiosis of vaginal microbiota associated with persistent highrisk human papilloma virus infection. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):12. https:// doi.org/10.1186/s12967-021-03201-w.

- Mitra A, MacIntyre DA, Ntritsos G, Smith A, Tsilidis KK, Marchesi JR, Bennett PR, Moscicki AB, Kyrgiou M. The vaginal microbiota associates with the regression of untreated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 lesions. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1999. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15856-y.

- Camargo M, Vega L, Muñoz M, Sánchez R, Patarroyo ME, Ramírez JD, Patarroyo MA. Changes in the cervical microbiota of women with different high-risk human papillomavirus loads. Viruses. 2022;14(12):2674. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14122674.

- Karpinets TV, Wu X, Solley T, El Alam MB, Sims TT, Yoshida-Court K, Lynn E, Ahmed-Kaddar M, Biegert G, Yue J, et al. Metagenomes of rectal swabs in larger, advanced stage cervical cancers have enhanced mucus degrading functionalities and distinct taxonomic structure. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):945. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09997-0.

- Zhang Y, Xu X, Yu L, Shi X, Min M, Xiong L, Pan J, Zhang Y, Liu P, Wu G, Gao G. Vaginal microbiota changes caused by HPV infection in Chinese women. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12: 814668. https://doi.org/10. 3389/fcimb.2022.814668.

- Wei Z-T, Chen H-L, Wang C-F, Yang G-L, Han S-M, Zhang S-L. Depiction of vaginal microbiota in women with high-risk human papillomavirus infection. Front Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020. 587298.

- Ivanov MK, Brenner EV, Hodkevich AA, Dzyubenko VV, Krasilnikov SE, Mansurova AS, Vakhturova IE, Agletdinov EF, Shumeikina AO, Chernyshova AL, Titov SE. Cervicovaginal-microbiome analysis by 16 S sequencing and real-time PCR in patients from novosibirsk (Russia) with cervical lesions and several years after cancer treatment. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(1):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13010140.

- Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Delgado S, Ruiz L, Ruas-Madiedo P, Sánchez B, Margolles A. Bifidobacteria and their health-promoting effects. Microbiol Spectr. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.BAD-0010-2016.

- Chao X, Wang L, Wang S, Lang J, Tan X, Fan Q, Shi H. Research of the potential vaginal microbiome biomarkers for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8: 565001. https://doi. org/10.3389/fmed.2021.565001.

- Curty G, Costa RL, Siqueira JD, Meyrelles AI, Machado ES, Soares EA, Soares MA. Analysis of the cervical microbiome and potential

biomarkers from postpartum HIV-positive women displaying cervical intraepithelial lesions. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17364. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-017-17351-9. - Wang W, Liu Y, Yang Y, Ren J, Zhou H. Changes in vaginal microbiome after focused ultrasound treatment of high-risk human papillomavirus infection-related low-grade cervical lesions. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-022-07937-8.

- Freitas AC, Hill JE. Quantification, isolation and characterization of Bifidobacterium from the vaginal microbiomes of reproductive aged women. Anaerobe. 2017;47:145-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2017.05. 012.

- Srinivasan U, Misra D, Marazita ML, Foxman B. Vaginal and oral microbes, host genotype and preterm birth. Med Hypotheses. 2009;73(6):963-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2009.06.017.

- Balle C, Esra R, Havyarimana E, Jaumdally SZ, Lennard K, Konstantinus IN, Barnabas SL, Happel AU, Gill K, Pidwell T, et al. Relationship between the oral and vaginal microbiota of south African adolescents with high prevalence of bacterial vaginosis. Microorganisms. 2020;8(7):1004. https://doi. org/10.3390/microorganisms8071004.

- Takada K, Melnikov VG, Kobayashi R, Komine-Aizawa S, Tsuji NM, Hayakawa S. Female reproductive tract-organ axes. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1110001. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1110001.

- Hoare A, Soto C, Rojas-Celis V, Bravo D. Chronic inflammation as a link between periodontitis and carcinogenesis. Mediators Inflamm. 2019;2019:1029857. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1029857.

- Inaba H, Amano A, Lamont RJ, Murakami Y. Involvement of proteaseactivated receptor 4 in over-expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2015;204(5):605-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00430-015-0389-y.

- Chattopadhyay I, Verma M, Panda M. Role of oral microbiome signatures in diagnosis and prognosis of oral cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2019;18:1533033819867354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533033819867354.

- Lo CH, Wu DC, Jao SW, Wu CC, Lin CY, Chuang CH, Lin YB, Chen CH, Chen YT, Chen JH, et al. Enrichment of Prevotella intermedia in human colorectal cancer and its additive effects with Fusobacterium nucleatum on the malignant transformation of colorectal adenomas. J Biomed Sci. 2022;29(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-022-00869-0.

- Castañeda-Corzo GJ, Infante-Rodríguez LF, Villamil-Poveda JC, Bustillo J, Cid-Arregui A, García-Robayo DA. Association of Prevotella intermedia with oropharyngeal cancer: a patient-control study. Heliyon. 2023;9(3): e14293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14293.

- Tuominen H, Rautava J. Oral microbiota and cancer development. Pathobiology. 2021;88(2):116-26. https://doi.org/10.1159/000510979.

- Cullin N, Azevedo Antunes C, Straussman R, Stein-Thoeringer CK, Elinav E. Microbiome and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(10):1317-41. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ccell.2021.08.006.

- Pignatelli P, Romei FM, Bondi D, Giuliani M, Piattelli A, Curia MC. Microbiota and oral cancer as a complex and dynamic microenvironment: a narrative review from etiology to prognosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15):8323. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158323.

- Jolivet-Gougeon A, Bonnaure-Mallet M. Screening for prevalence and abundance of Capnocytophaga spp. by analyzing NGS data: a scoping review. Oral Dis. 2021;27(7):1621-30. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13573.

- Irfan M, Delgado RZR, Frias-Lopez J. The oral microbiome and cancer. Front Immunol. 2020;11: 591088. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020. 591088.

- Radaic A, Kapila YL. The oralome and its dysbiosis: new insights into oral microbiome-host interactions. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:1335-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2021.02.010.

- Radaic A, Ganther S, Kamarajan P, Grandis J, Yom SS, Kapila YL. Paradigm shift in the pathogenesis and treatment of oral cancer and other cancers focused on the oralome and antimicrobial-based therapeutics. Periodontol 2000. 2021;87(1):76-93. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12388.

- El-Awady A, de Sousa RM, Meghil MM, Rajendran M, Elashiry M, Stadler AF, Foz AM, Susin C, Romito GA, Arce RM, Cutler CW. Polymicrobial synergy within oral biofilm promotes invasion of dendritic cells and survival of consortia members. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019;5(1):11. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41522-019-0084-7.

- Wright CJ, Xue P, Hirano T, Liu C, Whitmore SE, Hackett M, Lamont RJ. Characterization of a bacterial tyrosine kinase in Porphyromonas gingivalis

involved in polymicrobial synergy. Microbiologyopen. 2014;3(3):383-94. https://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.177. - Rosca AS, Castro J, França Â, Vaneechoutte M, Cerca N. Gardnerella vaginalis dominates multi-species biofilms in both pre-conditioned and competitive in vitro biofilm formation models. Microb Ecol. 2022;84(4):127887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-021-01917-2.

- Murray JL, Connell JL, Stacy A, Turner KH, Whiteley M. Mechanisms of synergy in polymicrobial infections. J Microbiol. 2014;52(3):188-99. https:// doi.org/10.1007/s12275-014-4067-3.

- Audirac-Chalifour A, Torres-Poveda K, Bahena-Roman M, Tellez-Sosa J, Martinez-Barnetche J, Cortina-Ceballos B, Lopez-Estrada G, DelgadoRomero K, Burguete-Garcia AI, Cantu D, et al. Cervical microbiome and cytokine profile at various stages of cervical cancer: a pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4): e0153274. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 01532 74.

- Xu B, Han YW. Oral bacteria, oral health, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Periodontol 2000. 2022;89(1):181-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd. 12436.

- Yu L, Chen X, Sun X, Wang L, Chen S. The glycolytic switch in tumors: how many players are involved? J Cancer. 2017;8(17):3430-40. https://doi.org/ 10.7150/jca. 21125.

- Park NJ, Choi Y, Lee D, Park JY, Kim JM, Lee YH, Hong DG, Chong GO, Han HS. Transcriptomic network analysis using exfoliative cervical cells could discriminate a potential risk of progression to cancer in HPV-related cervical lesions: a pilot study. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2023;20(1):75-87. https://doi.org/10.21873/cgp.20366.

- Chen X, Yi C, Yang MJ, Sun X, Liu X, Ma H, Li Y, Li H, Wang C, He Y, et al. Metabolomics study reveals the potential evidence of metabolic reprogramming towards the Warburg effect in precancerous lesions. J Cancer. 2021;12(5):1563-74. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.54252.

- Ilhan ZE, Łaniewski P, Thomas N, Roe DJ, Chase DM, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Deciphering the complex interplay between microbiota, HPV, inflammation and cancer through cervicovaginal metabolic profiling. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:675-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.04.028.

- Spratt DA, Greenman J, Schaffer AG. Capnocytophaga gingivalis: effects of glucose concentration on growth and hydrolytic enzyme production. Microbiology (Reading). 1996;142:2161-4. https://doi.org/10.1099/13500 872-142-8-2161.

- Pei J, Li F, Xie Y, Liu J, Yu T, Feng X. Microbial and metabolomic analysis of gingival crevicular fluid in general chronic periodontitis patients: lessons for a predictive, preventive, and personalized medical approach. EPMA J. 2020;11(2):197-215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13167-020-00202-5.

- Hübbers CU, Akgül B. HPV and cancer of the oral cavity. Virulence. 2015;6(3):244-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2014.999570.

- Eggersmann TK, Sharaf K, Baumeister P, Thaler C, Dannecker CJ, Jeschke U, Mahner S, Weyerstahl K, Weyerstahl T, Bergauer F, Gallwas JA-O. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in cervical HPV positive women and their sexual partners. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019;299(6):1659-65. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00404-019-05135-7.

Publisher’s Note

Wei Zhang and Yanfei Yin contributed equally to this work.

*Correspondence:

Bin Liu

liubkq@lzu.edu.cn

Lihe Yao

13639317172@163.com

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article