الكتابة الذهنية المعززة بالذكاء الاصطناعي: دراسة استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في توليد الأفكار الجماعية

الملخص

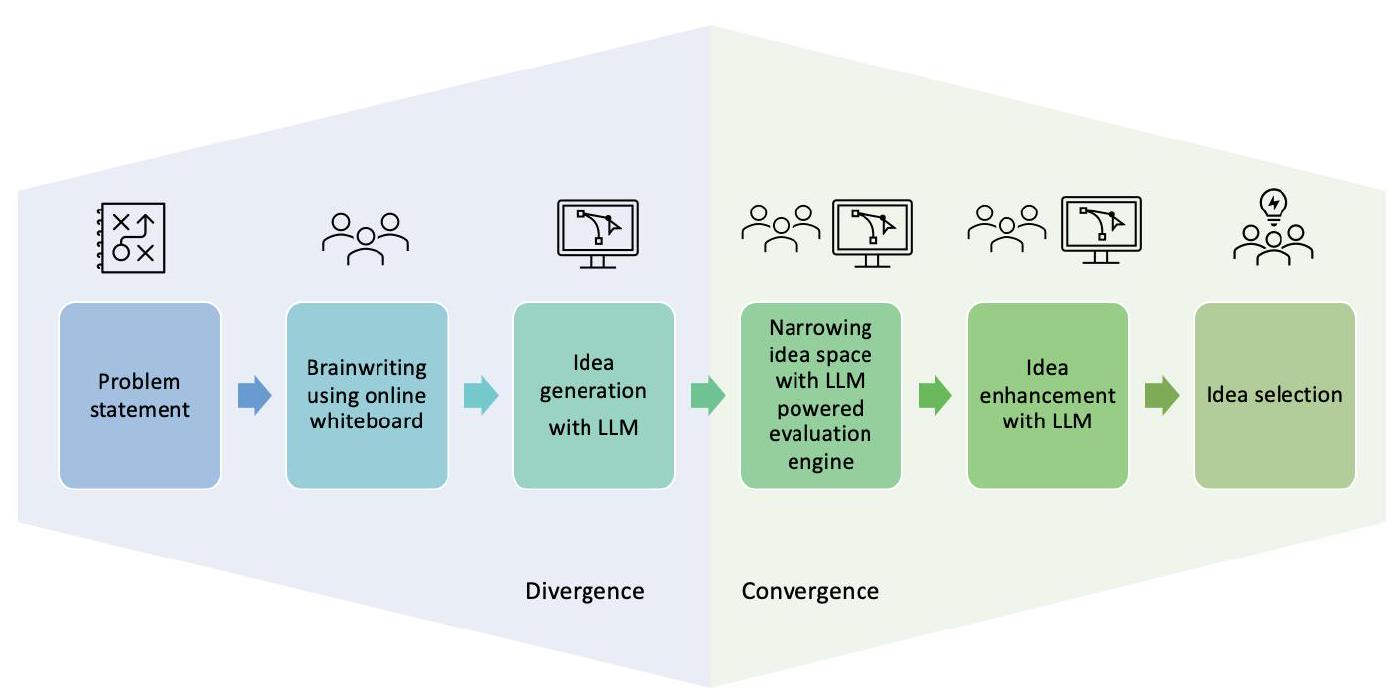

توافر تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدية مثل نماذج اللغة الكبيرة له آثار كبيرة على العمل الإبداعي. تستكشف هذه الورقة جوانب دمج نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في العملية الإبداعية – مرحلة التباين في توليد الأفكار، ومرحلة التقارب في تقييم واختيار الأفكار. قمنا بتصميم إطار عمل للكتابة الجماعية المعززة بالذكاء الاصطناعي، والذي دمج نموذج لغة كبيرة كتعزيز في عملية توليد الأفكار الجماعية، وقيمنا عملية توليد الأفكار والمساحة الناتجة عن الحلول. لتقييم إمكانية استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في عملية تقييم الأفكار، قمنا بتصميم محرك تقييم وقارناه بتقييمات الأفكار التي منحها ثلاثة خبراء وستة مقيمين مبتدئين. تشير نتائجنا إلى أن دمج نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في الكتابة الجماعية يمكن أن يعزز كل من عملية توليد الأفكار ونتائجها. كما نقدم أدلة على أن نماذج اللغة الكبيرة يمكن أن تدعم تقييم الأفكار. نختتم بمناقشة الآثار المترتبة على تعليم وممارسة تفاعل الإنسان مع الكمبيوتر.

1 المقدمة

RQ2: كيف يمكن أن تساعد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في تقييم الأفكار خلال مرحلة التقارب في عملية الكتابة الجماعية التعاونية؟

2 الأعمال ذات الصلة

2.1 الأساليب المنظمة لتوليد الأفكار

2.2 التعاون بين البشر والذكاء الاصطناعي

2.3 أساليب لتقييم الأفكار

3 تصميم إطار عمل كتابة الأفكار التعاونية بين المجموعات والذكاء الاصطناعي

3.1 مرحلة تباين الكتابة الجماعية

كيف يعمل

اضبط المؤقت على 10 دقائق. يجب على كل عضو في الفريق قراءة جميع الأفكار على السبورة.

5 ناقش وابتكر معًا على الأقل ثلاث أفكار جديدة أو مصقولة. أضف الأفكار إلى الملاحظات اللاصقة في قسم الأفكار التعاونية. اضبط المؤقت على 5 دقائق إضافية وابتكر على الأقل ثلاث أفكار أخرى.

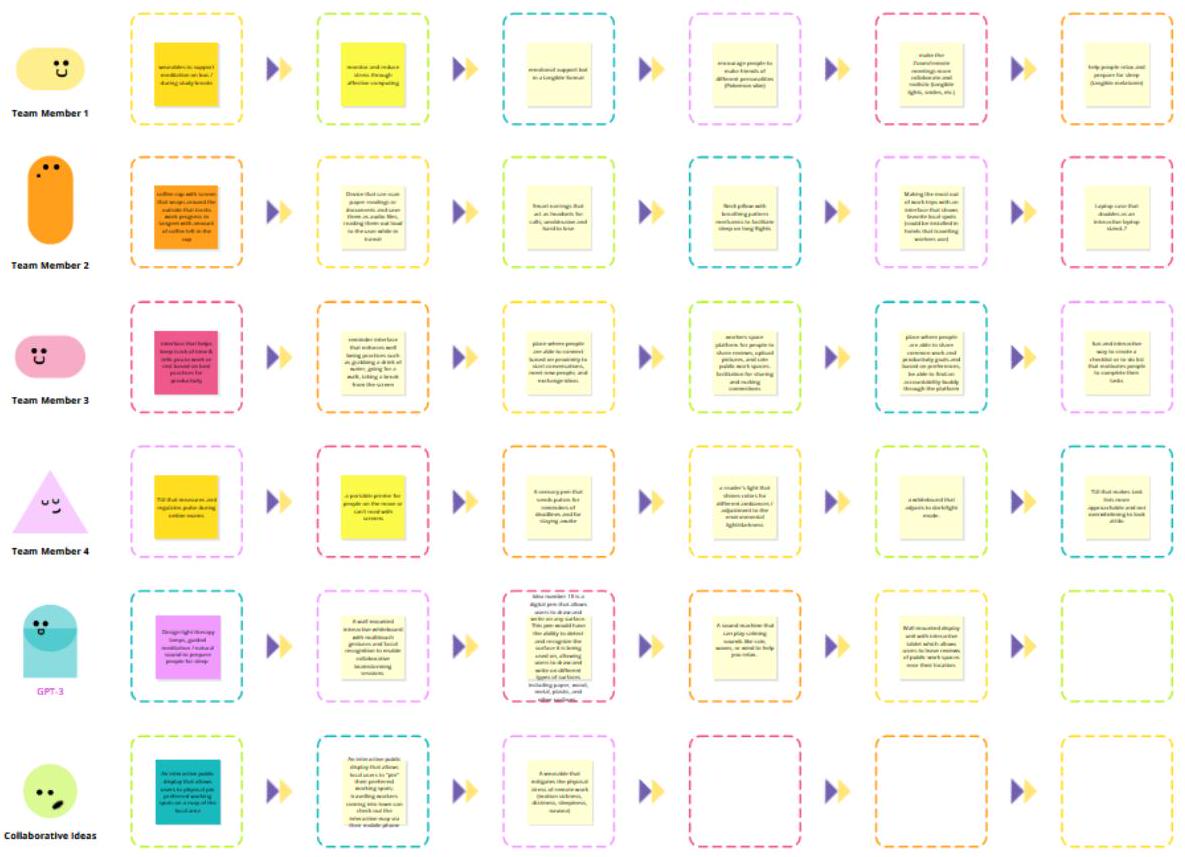

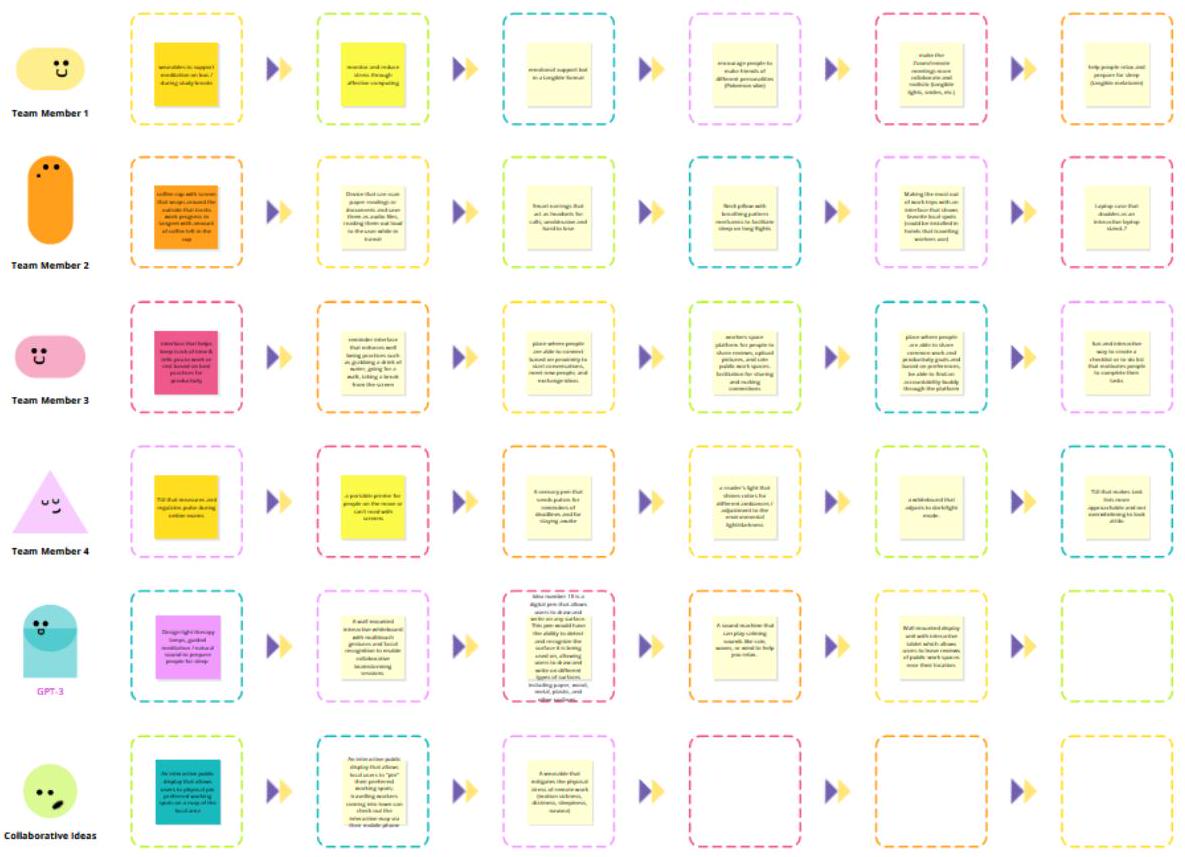

(ب) مخطط العملية

3.1.2 المرحلة 2: تعزيز الأفكار باستخدام LLM. في هذه المرحلة، يُطلب من كل مجموعة استخدام LLM (OpenAI Playground GPT-3) لتوليد أفكار إضافية. يتم تشجيع المشاركين على التكرار على مطالباتهم لـ LLM ويتعرضون، قبل جلسة الكتابة الجماعية، لمواد نظرة عامة حول هندسة المطالبات. يتم نسخ الأفكار المولدة ولصقها في

mلاحظات لاصقة على السبورة. قمنا بتعديل القالب الأصلي للكتابة الجماعية الذي قدمته Conceptboard ليعكس هذا الإطار الجديد للكتابة الجماعية باستخدام LLM من أجل تعزيز الأفكار.

3.2 مرحلة تقارب الكتابة الجماعية

3.3 هل يمكن أن تساعد LLMs في التقارب؟ تطوير وتنفيذ محرك تقييم مدعوم بـ LLM

معايير محددة جيدًا: سيتم توجيه المحرك لتقييم الأفكار وفقًا لمجموعة محددة جيدًا من المعايير، والتي غالبًا ما يستخدمها البشر لتحديد الأفكار الجيدة والمبتكرة والإبداعية. اخترنا استخدام معيارين من إطار تقييم دين وآخرون [10]: الملاءمة والابتكار. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، اخترنا معيارًا ثالثًا، البصيرة، استنادًا إلى أبحاث داير وآخرون حول أصل المشاريع الابتكارية [16]. كل من هذه المعايير تتطلب تعريفًا واضحًا.

تعريف المقياس × المعايير: يجب أن يكون كل قيمة مقياس لكل معيار محددة جيدًا، وبالتفصيل.

(1) قمنا أولاً بتطوير فقرات وصفية أولية لكل معيار – الملاءمة، الابتكار، البصيرة، استنادًا إلى التعريفات في الأدبيات الموجودة، وأنشأنا مرساة وصفية لكل قيمة مقياس.

(2) قام ثلاثة مقيمين هم مراجعين خبراء (باحثين في HCI)، يعملون بشكل مستقل، بتقييم عينة صغيرة من الأفكار باستخدام التعريفات الأولية والمرساة.

(3) اجتمعنا مع الباحثين كمجموعة لمناقشة تقييماتهم للعينة، مع التركيز على مجالات الاختلاف، وتوصلنا إلى اتفاق مشترك حول التعريف العام لكل معيار وما تعنيه كل من مرساة قيمتها.

(4) باستخدام هذه التعريفات الجديدة، طلبنا من GPT-4 تقييم عينة من الأفكار وتقديم تفسير وتبرير لتقييمه المعين لكل معيار لكل فكرة. ثم اخترنا الصفات التقييمية والأسماء الوصفية من كل تفسير، واستخدمناها في تعريف مصقول لمطالبة معدلة. التعريفات المعطاة في المطالبة هي: الملاءمة: إلى أي مدى تعكس الفكرة مدى ارتباط الفكرة بالأهداف أو المتطلبات أو التحديات لبيان المشكلة؟ الابتكار: إلى أي مدى تعكس الفكرة مدى أصالة وإبداع الفكرة، مبتعدة عن الحلول التقليدية أو الموجودة لبيان المشكلة؟ والبصيرة: إلى أي مدى تعكس الفكرة فهمًا عميقًا ودقيقًا لبيان المشكلة؟

كررنا العملية حوالي ثلاث مرات لكل مقياس حتى كانت المرساة لكل قيمة متميزة بما فيه الكفاية. توضح المعلومات التكميلية الشكل 1 المطالبة مع التفسيرات للتقييمات المختلفة لكل معيار المعطاة لمحرك تقييم GPT-4. الشكل 3 يصور تقييم فكرة باستخدام محرك تقييم GPT-4.

3.3.1 التنفيذ. في هذه المرحلة اخترنا GPT-4. في الوقت الذي أجرينا فيه هذا التجربة (يونيو 2023)، كان متاحًا فقط للمشتركين، وقام الباحثون بشراء اشتراك. تم اختيار GPT-4 لمرحلة التقارب بدلاً من النسخة المجانية GPT-3 نظرًا لقدراته الأكثر تقدمًا في التفكير. استخدمنا واجهة برمجة التطبيقات OpenAI لكتابة برنامج بايثون يستخدم الموجه لتقييم مجموعة من الأفكار المقروءة من ملف نصي. يقوم البرنامج بإخراج ملف CSV يحتوي على ثلاثة تقييمات لكل فكرة (للملائمة، والابتكار، والرؤية)، وملف نصي يحتوي على تبريرات GPT-4 لتلك التقييمات. يمكن للمستخدم تحديد عدد المرات لتكرار العملية؛ كل تكرار سيفتح سياقًا جديدًا لـ GPT-4 وينتج مجموعة جديدة من التقييمات.

4 دراسة المستخدم: عملية الكتابة الجماعية بالتعاون مع الذكاء الاصطناعي

4.1 التباين: جلسة الكتابة الجماعية

استراحات.

الأهمية (1-5):

التبرير: الفكرة تتناول بشكل مباشر جانب الرفاهية في بيان المشكلة من خلال تشجيع الحركة وأخذ فترات راحة. هذا الأمر ذو صلة خاصة لأولئك الذين يعملون أو يدرسون في بيئات متنقلة، حيث قد يكونون عرضة لفترات جلوس طويلة. ومع ذلك، فإنها لا تتناول بشكل مباشر الإنتاجية أو الإبداع.

الابتكار (1-5):

التبرير: مفهوم الأجهزة أو التطبيقات التي تذكر المستخدمين بأخذ فترات راحة بعد فترات طويلة من الجلوس ليس جديدًا تمامًا. على سبيل المثال، غالبًا ما تحتوي الساعات الذكية على مثل هذه التذكيرات. وبالتالي، فإن الفكرة تظهر ابتكارًا ضئيلًا عن الحلول الموجودة.

البصيرة (1-5):

التبرير: الفكرة تعترف بمسألة أساسية تتعلق بالجلوس لفترات طويلة وتأثيراته الصحية المحتملة. ومع ذلك، فهي لا تتناول التحديات الدقيقة للعمل أو الدراسة في بيئات متنقلة، كما أنها لا تقدم رؤى حول كيفية تأثير هذه الاستراحات على الإنتاجية والإبداع.

يواجه المصممون عند العمل مع الذكاء الاصطناعي كمواد تصميم

طلبت منهم مراجعة ومناقشة واختيار ونسخ ولصق أفضل الأفكار في لوحة جانبية وبدء تطوير هذه الأفكار بشكل أكبر بمساعدة GPT-3.

| إنسان | جي بي تي-3 | تعاوني | إجمالي عدد الأفكار | |

| الفريق 1 | 20 | ٤ | 2 | 26 |

| الفريق 2 | ١٨ | 11 | 11 | 40 |

| الفريق 3 | 17 | 2 | 0 | 19 |

| الفريق 4 | ٢٤ | ٦ | ٦ | ٣٦ |

| الفريق 5 | 18 | ٦ | ٣ | 27 |

4.2 التقارب: تقييم الأفكار واختيارها

| تم إنشاؤه بواسطة | الملاءمة | ابتكار | بصير | |||

| متوسط | معيار | متوسط | معيار | متوسط | معيار | |

| إنسان | ٤.٨١ | 0.40 | ٤.٣١ | 0.70 | ٤.٣٧ | 0.61 |

| جي بي تي-3 | ٤.٥٦ | 0.51 | ٤.٢٥ | 0.68 | ٤.١٨ | 0.65 |

| تعاون | ٤.٨٧ | 0.34 | ٤.٨١ | 0.40 | ٤.٨١ | 0.40 |

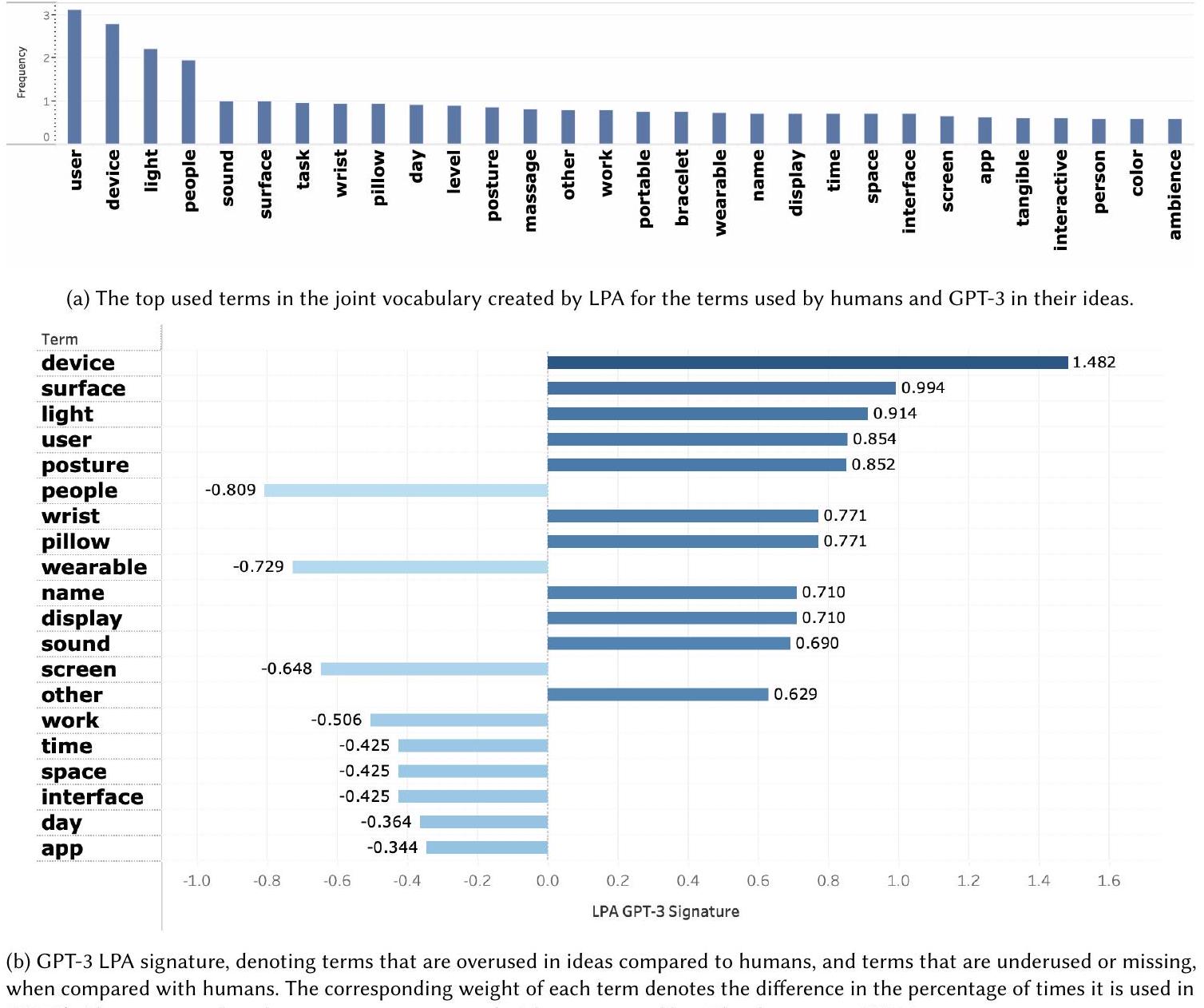

5 تقييم الإطار

قمنا بتقييم التباين من خلال فحص التوزيع الدلالي للأفكار التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة البشر وGPT-3. كما حددنا المصطلحات الفريدة المستخدمة في مساحات الحل المختلفة. ثم نستكشف، في الجزء الثاني من التقييم، كيف يمكن استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة للمساعدة في تقييم الأفكار خلال مرحلة التقارب (RQ2).

5.1 البيانات والأساليب

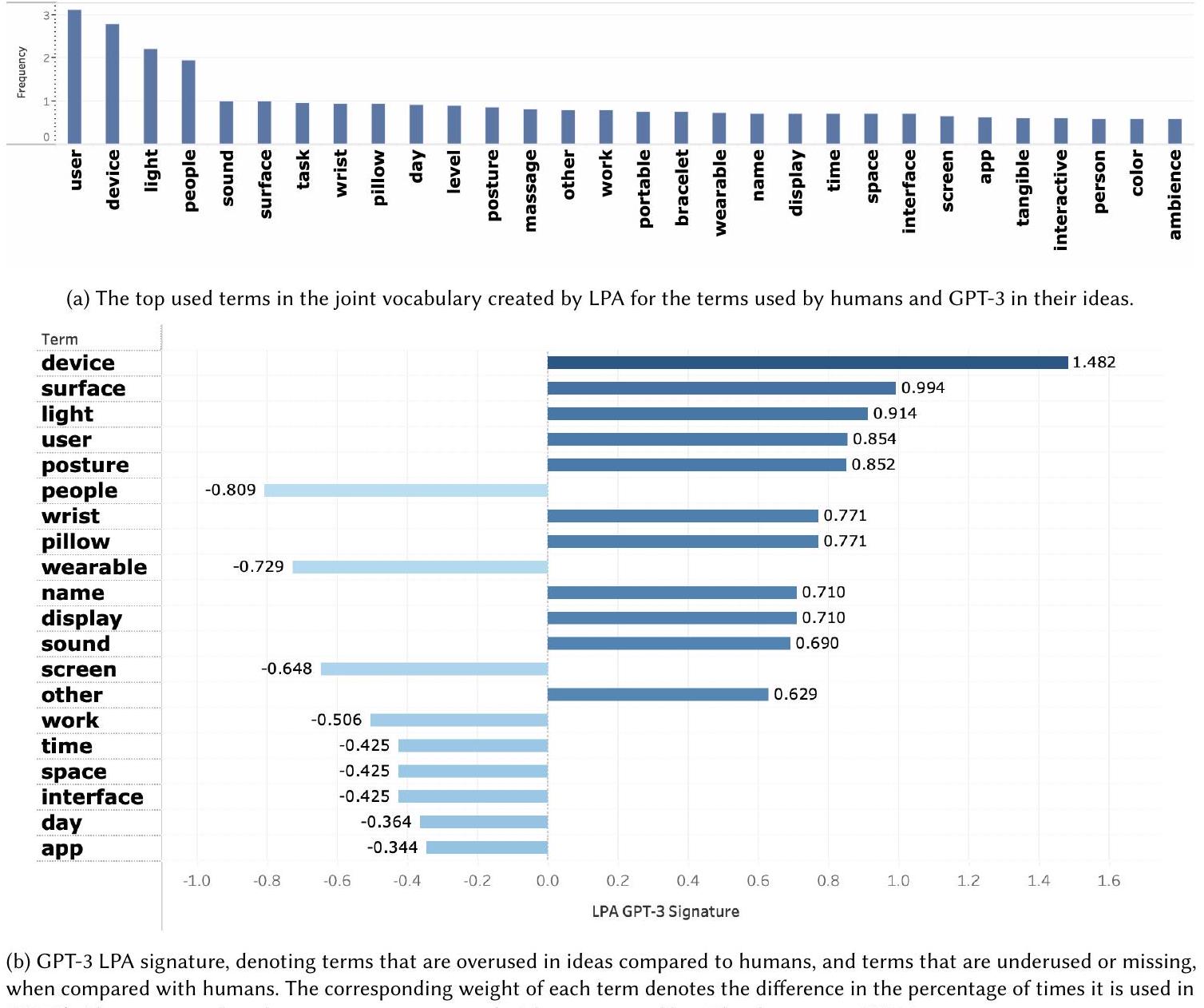

مصطلح شائع يتم استخدامه بشكل غير كافٍ أو لا يُستخدم على الإطلاق (مفقود) في الوثيقة. تتكون مجموعة المصطلحات ذات الوزن المطلق الأعلى من توقيع الوثيقة، كل منها مع توقيعها المقابل.

5.2 نتائج RQ1: هل يعزز استخدام نموذج اللغة الكبير خلال مرحلة التباين في الكتابة الجماعية التعاونية عملية توليد الأفكار ونتائجها؟

5.2.1 تأملات الطلاب. نظرًا لأن دراسة المستخدم أجريت في إطار تعليمي، فإن تقييمنا لآراء الطلاب حول إطار عمل الكتابة الجماعية بالذكاء الاصطناعي هذا شمل أيضًا تقييم تعلمهم وتفاعلهم النقدي مع الذكاء الاصطناعي. في ورقة منفصلة [تحت المراجعة حاليًا لمؤتمر مختلف]، وضعنا استخدام هذا الإطار في سياق أوسع لدمج الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي في دورة تفاعل ملموس، وناقشنا تأملات الطلاب وتعلمهم. هنا، نلخص آراء الطلاب حول عملية الكتابة الجماعية بالذكاء الاصطناعي. على وجه التحديد، نقوم بتحليل ردود الطلاب على سؤال طرحناه مباشرة بعد جلسة توليد الأفكار (Q1): “بأي طرق ساهم استخدام GPT-3 في أو أعاق جلسة توليد الأفكار؟” كما نقوم بتحليل ردهم على سؤال طرح في نهاية الفصل الدراسي (Q2): “عند التفكير في توليد الأفكار الأصلي الخاص بك مع GPT-3: إلى أي مدى تشعر أن تعاونك مع الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي للنصوص أثر على اتجاه مشروعك؟”

جميع الطلاب أجابوا على هذا السؤال (

5.2.2 نتائج التفكير. كانت نتيجة عملية التفكير بين الإنسان ونموذج اللغة الكبير مجموعة من الأفكار المختارة – حيث اختار كل فريق فكرة واحدة لاستكشافها في مشروع يستمر طوال الفصل الدراسي. يوضح الجدول 3 الفكرة المختارة لكل فريق، ويصف تصور كل فكرة من حيث أصلها البشري و/أو أصلها من GPT-3. بشكل عام، تم تطوير 3 من أصل 5 أفكار مختارة من خلال دمج فكرة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الإنسان وفكرة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-3. تم تطوير فكرة واحدة من خلال دمج عدة أفكار تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الإنسان وأفكار متعددة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-3. أخيرًا، واحدة من بين 5 أفكار تعتمد فقط على فكرة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-3.

5.2.3 استكشاف المساحات الحلول البشرية و LLM. لاستكشاف تباين الأفكار والمساحة الحلول المستكشفة مع وبدون LLMs، قمنا بتقييم التوزيع الدلالي للأفكار التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة البشر و GPT-3، والمصطلحات المستخدمة في المساحات الحلول المختلفة باستخدام LPA.

| الفكرة المختارة | تحسين | وصف | |

| الفريق 1 | عرض عام تفاعلي يتيح للمستخدمين المحليين ‘تثبيت’ أماكن العمل المفضلة لديهم؛ يمكن للعمال المسافرين القادمين إلى المدينة الاطلاع على الخريطة التفاعلية عبر هواتفهم المحمولة. | البشر والذكاء الاصطناعي المشترك | مستوحى من دمج فكرة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الإنسان، وهي منصة لتقييم أماكن العمل، مع فكرة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-3، وهي عرض تفاعلي عام. |

| الفريق 2 | وسادة وضعية تتعقب أنماط الوضعية وتذكر المستخدم بتغيير وضعه أو أخذ استراحة | LLM | مستوحى من فكرة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-3 لوسادة ذكية يمكنها اكتشاف الوضعية |

| الفريق 3 | مكتب محمول لطلاب التنقل مع ميزات الثبات وتخفيف دوار الحركة ونقطة اتصال واي فاي مدمجة | البشر والذكاء الاصطناعي المشترك | لم يتم تقديمه مع مجموعة فكرة الورشة الأصلية، ولكن تم تقديمه مع اقتراح المشروع كمزيج من فكرة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الإنسان (“مكتب محمول مستقر في الرحلات الوعرة”) وفكرة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-3 (“تثبيت جهاز توجيه لاسلكي أو نقطة وصول داخل مكتب محمول”) |

| الفريق 4 | حامل مفاتيح على شكل دمية محشوة/كرة ضغط يمكن للمستخدمين الإمساك بها؛ تطلق العلاج بالروائح وتتواصل أيضًا مع المستخدم الذي يحمل واحدة أخرى ليشعر بنبض قلبه أو بنفس إحساس الضغط. | البشر والذكاء الاصطناعي المتقدم | مستوحاة من دمج عدد من الأفكار التي تم توليدها بواسطة البشر وGPT-3 تتعلق بالعلاج بالروائح للتوتر والأجهزة المتصلة التي تنقل نبضات المستخدمين. على عكس الفرق الأخرى، قامت هذه الفريق بدمج عدة أفكار معًا. |

| الفريق 5 | قناع عين للنوم يتغير درجة حرارته بناءً على مكانك في رحلتك ويهتز ليوقظك قبل توقفك | البشر والذكاء الاصطناعي المتقدم | مستوحى من دمج فكرة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة الإنسان، وهي جهاز قابل للارتداء لإخطار المستخدم عندما تقترب محطة النقل العام الخاصة به، مع فكرة تم إنشاؤها بواسطة GPT-3، وهي قناع نوم يتحكم في درجة الحرارة. |

تجميع

5.2.4 تحليل المطالبات. للحصول على مزيد من الرؤية حول الفروق بين الأفكار التي أنشأها البشر وتلك التي أنشأها GPT-3، قمنا بتحليل المطالبات المستخدمة من قبل الطلاب لتوليد أفكار جديدة والتكرار على الأفكار الموجودة، وحددنا بعض الأساليب المميزة. عادةً، استخدم الطلاب أحد نهجين لبدء تفاعلهم مع GPT-3: 1) مطالبات واسعة النطاق، أو 2) مطالبات محددة للحل.

5.2.5 ملخص النتائج لـ RQ1. بعد الجلسة،

5.3 RQ2: كيف يمكن أن تساعد LLMs في تقييم الأفكار خلال مرحلة التقارب في عملية العصف الذهني الجماعي؟

5.3.1 اتساق محرك تقييم GPT-4. أولاً، نقيم الاتساق الداخلي لـ 29 تقييمًا من GPT-4 للأفكار على المعايير الثلاثة للملاءمة، والابتكار، والعمق. لتقييم الاتساق، نتعامل مع التقييمات كعناصر استبيان ونحللها باستخدام معاملات كابا لفليس لتقييم اتفاق المقيمين. تظهر تحليلاتنا مستوى معتدل من الاتساق في أداء GPT-4، مع تجاوز جميع قيم كابا لفليس عتبة 0.4. كانت قيم كابا لفليس المحددة للمعايير المختلفة كما يلي. الملاءمة: 0.42، الابتكار: 0.40، والعمق: 0.49. وبالتالي، يمكن اعتبار تقييمات GPT-4 متسقة عبر المعايير الثلاثة.

5.3.2 التحليل المقارن لتقييمات GPT-4 مقابل التقييمات من المقيّمين المبتدئين والخبراء. نقارن التقييمات التي منحها GPT-4 بتلك التي منحها المبتدئون والخبراء للأفكار الـ 148 التي تم توليدها إما بواسطة البشر، أو GPT-3، أو بالتعاون. تم منح التقييمات لكل فكرة وفقًا للمعايير الثلاثة: الصلة، والابتكار، وعمق الفكرة. لمقارنة تقييمات GPT-4 مع المقيّمين البشريين، قمنا بتنفيذ الخطوات التالية: (أ) مقارنة توزيعات التقييمات المعطاة، (ب) مقارنة التقييمات لأفضل وأسوأ الأفكار كما تم تصنيفها بواسطة تقييمات الخبراء؛ (ج) حساب معامل الارتباط بيرسون بين تصنيف GPT-4 للأفكار وتصنيف الخبراء؛ (د) مقارنة التقييمات التي منحها GPT-4 والمبتدئون والخبراء عبر المعايير الثلاثة، للأفكار التي اختارها الفرق كأفكارهم النهائية.

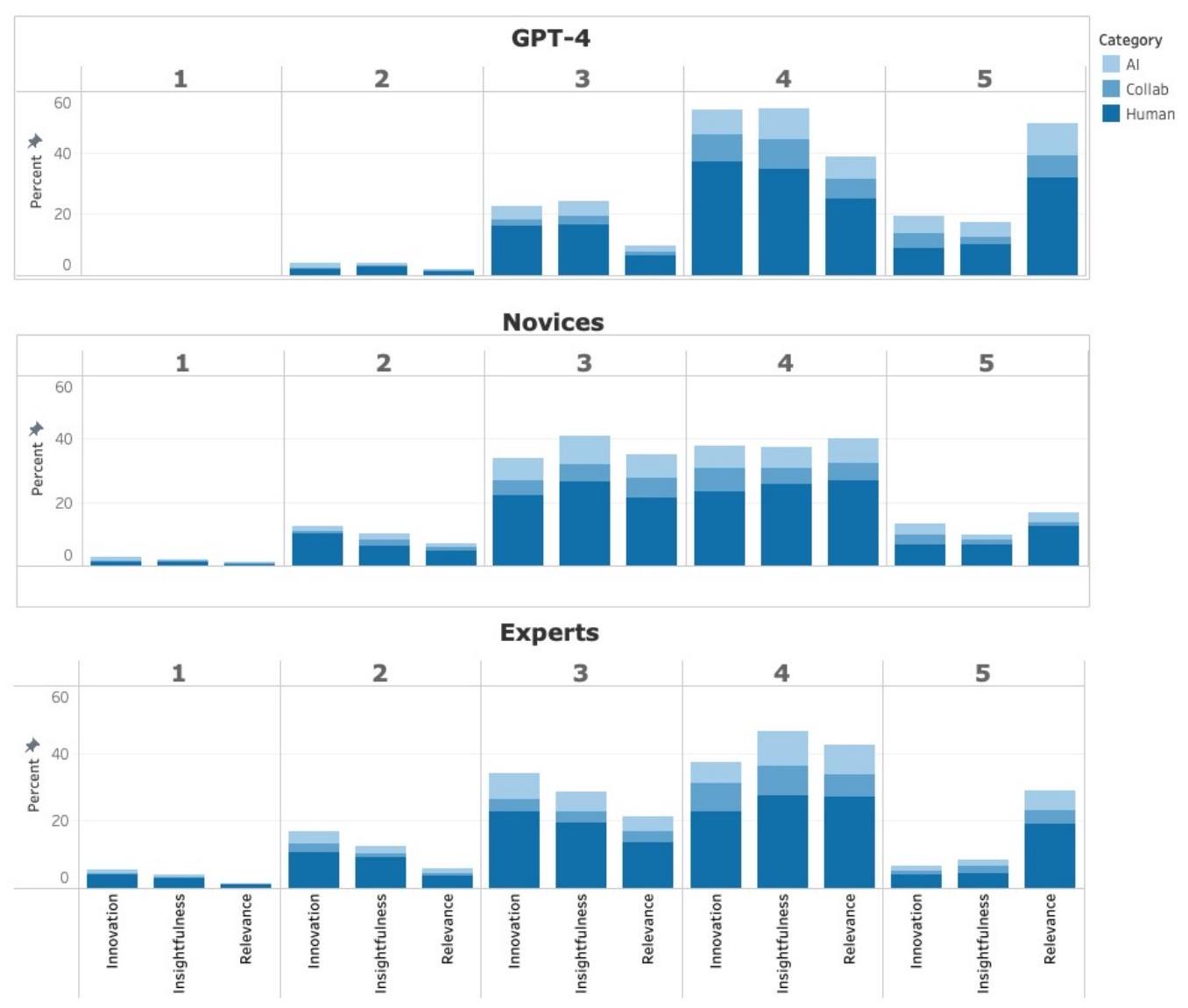

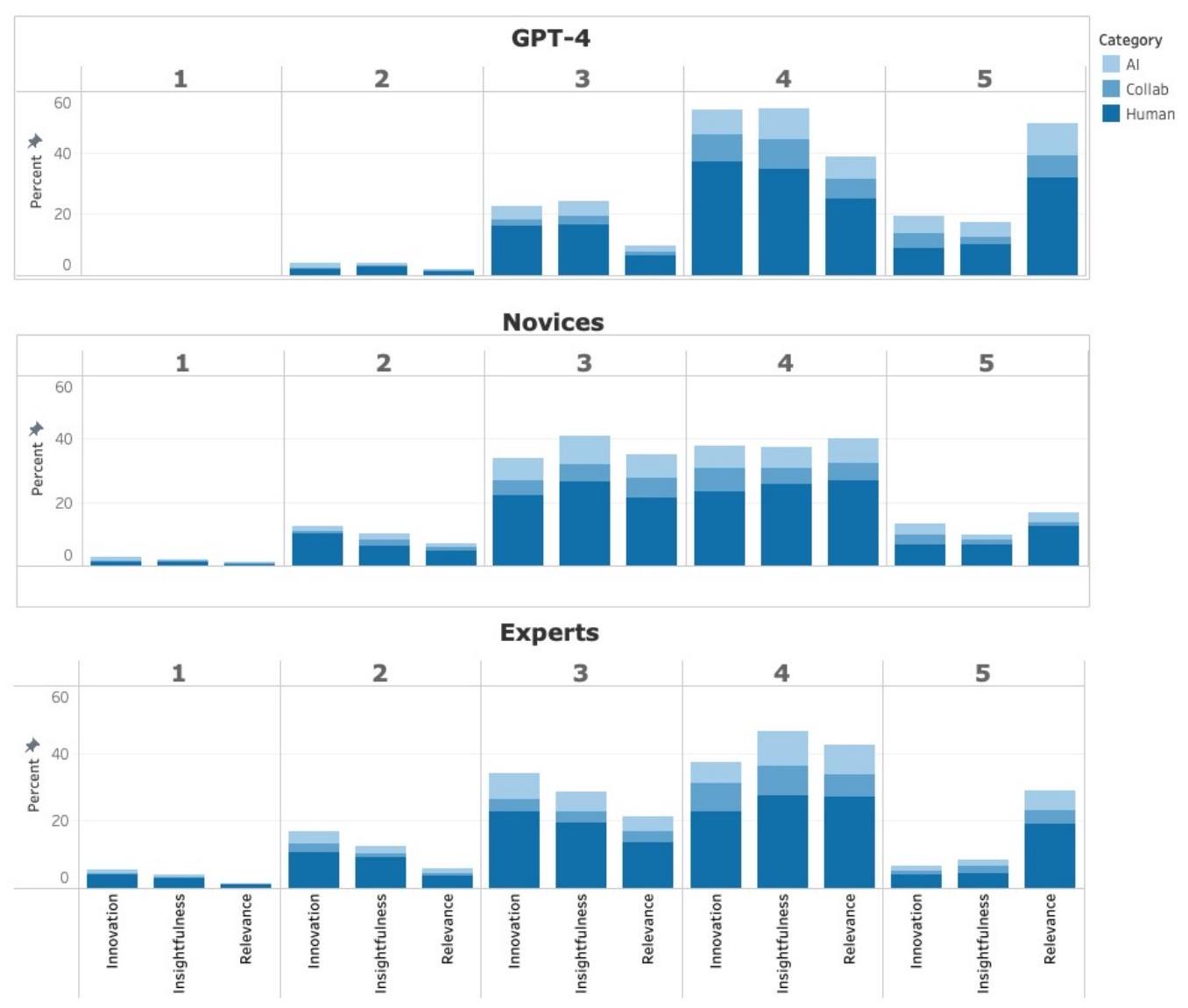

(أ) أولاً، نقارن توزيعات التقييمات عبر مجموعات المقيمين. توضح الشكل 5 توزيع التقييمات على مقياس ليكرت من 1 إلى 5 الذي قدمه الخبراء (الجزء السفلي)، والمبتدئون (الجزء الأوسط)، وGPT-4 (الجزء العلوي) للأفكار الـ148 عبر المعايير الثلاثة. بالنسبة لكل فكرة ومعيار، تم حساب التقييم كمتوسط التقييمات المقدمة من مجموعة المقيمين المعنية، سواء كانت خبراء أو مبتدئين أو GPT-4، لتلك الفكرة. تُظهر توزيعات التقييمات أن الخبراء كانوا أكثر انتقادًا من المبتدئين وأن GPT-4 يمنح تقييمات مرتفعة نسبيًا للأفكار. قدم GPT-4 عددًا أكبر بكثير من التقييمات 5 مقارنة بالمبتدئين والخبراء، وعددًا أقل بكثير من التقييمات 2 و1. على وجه التحديد، أعطى تقييمًا أقل من 1 لفكرة واحدة فقط، بسبب عمقها. قدم GPT-4 متوسط تقييم قدره 4.19 للملاءمة، و3.72 للابتكار، و3.68 للعمق.

(ب) قمنا بإنشاء تصنيف للأفكار لكل مجموعة من المقيمين، الخبراء، المبتدئين، وGPT-4. تم حساب تصنيف الأفكار على النحو التالي. لكل مجموعة من المقيمين، تم حساب تقييم فكرة من قبل تلك المجموعة من المقيمين من خلال متوسط التقييمات التي قدمها أعضاء المجموعة لكل من المعايير، ثم جمع هذه القيم. على سبيل المثال، في حالة مجموعة المقيمين الخبراء، تم حساب متوسط التقييم الذي قدمه الخبراء الثلاثة لكل من المعايير: الصلة، الابتكار، وعمق الفهم، وتم حساب التقييم النهائي للفكرة كمجموع لهذه القيم المتوسطة الثلاث. وبالتالي، حصلت فكرة على متوسط تقييم من الخبراء قدره 4 للصلة، و2.75 للابتكار، و2.375 لعمق الفهم، مما أدى إلى حصولها على تقييم مجمع قدره 9.125، وتم تصنيفها في المرتبة 24 من بين 148 فكرة.

(ج) لقياس العلاقة بين التقييمات المقدمة من مجموعات مختلفة، قمنا بحساب معاملات ارتباط بيرسون. أسفرت المقارنة عن معامل قدره 0.556 بين تقييمات الخبراء وGPT-4، و0.547 بين تقييمات المبتدئين وGPT-4، و0.602 بين تقييمات الخبراء والمبتدئين. تشير هذه النتائج إلى وجود علاقة خطية إيجابية معتدلة بين القوائم الثلاثة المصنفة.

(د) أخيرًا، نقوم بفحص التقييمات التي قدمها محرك تقييم GPT-4 للأفكار التي تم اختيارها في النهاية من قبل فرق الطلاب، ونقارنها بتقييمات الخبراء والمبتدئين المقابلة. تلخص الجدول 4 تقييمات الأفكار النهائية التي اختارتها الفرق. في الغالب، قامت جميع مجموعات المقيمين، وهي الخبراء والمبتدئين ومحرك تقييم GPT-4، بتعيين تقييمات أعلى للأفكار المختارة النهائية مقارنةً بالتقييم المتوسط الذي منحوه لجميع الأفكار.

| مقيّم | معيار | الفريق 1 | الفريق 2 | الفريق 3 | الفريق 4 | الفريق 5 | المتوسط لجميع الأفكار | |

| خبير | الملاءمة | متوسط | 3.75 | ٤.٢٥ | ٤.٠٠ | 3.67 | ٣.٠٠ | ٣.٥٧ |

| الانحراف المعياري | 0.96 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 1.83 | 1.10 | ||

| ابتكار | متوسط | ٣.٠٠ | ٣.٢٥ | 3.33 | ٣.٠٠ | 2.00 | 2.79 | |

| الانحراف المعياري | 1.41 | 0.96 | 2.08 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.10 | ||

| فطنة | متوسط | ٣.٠٠ | ٣.٢٥ | ٣.٦٧ | 3.67 | ٢.٢٥ | 3.01 | |

| الانحراف المعياري | 1.15 | 1.26 | 1.53 | 0.58 | 1.26 | 1.11 | ||

| مبتدئ | الملاءمة | متوسط | 3.67 | ٣.٥٠ | ٤.١٧ | 3.17 | 3.33 | 3.38 |

| الانحراف المعياري | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.95 | ||

| ابتكار | متوسط | 2.83 | 3.67 | ٣.٥٠ | 3.83 | 3.83 | 3.11 | |

| الانحراف المعياري | 0.98 | 0.52 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 1.07 | ||

| فطنة | متوسط | ٣.٥٠ | 3.67 | ٣.٥٠ | 3.33 | 3.17 | 3.13 | |

| الانحراف المعياري | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.84 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 0.96 | ||

| جي بي تي-4 | الملاءمة | متوسط | ٤.٨٠ | ٤.٧٣ | ٤.٥٢ | ٤.٠٣ | ٤.٥٧ | ٤.١٩ |

| الانحراف المعياري | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.50 | 0.82 | ||

| ابتكار | متوسط | 3.77 | 3.90 | 3.52 | ٤.٥٧ | ٤.٩٣ | 3.72 | |

| الانحراف المعياري | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.80 | ||

| فطنة | متوسط | 3.87 | ٤.٢٧ | 3.93 | 3.87 | ٤.٣٣ | 3.68 | |

| الانحراف المعياري | 0.43 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.80 | ||

6 المناقشة

6.1 مناقشة النتائج لـ RQ1: هل يعزز استخدام نموذج لغوي كبير خلال مرحلة التباين في كتابة الأفكار الجماعية التعاونية عملية توليد الأفكار ونتائجها؟

6.2 مناقشة النتائج لـ RQ2: كيف يمكن أن تساعد النماذج اللغوية الكبيرة في تقييم الأفكار خلال مرحلة التقارب في عملية كتابة الأفكار الجماعية التعاونية؟

6.3 الآثار المترتبة على التعليم والممارسة في HCl

6.3.1 توسيع الأفكار. تظهر نتائجنا أن دمج عمليات المشاركة في الإبداع مع الذكاء الاصطناعي في عملية توليد الأفكار للمصممين المبتدئين، يمكن أن يعزز مرحلة التباين حيث يتم استكشاف مجموعة أوسع من الأفكار المختلفة.

6.3.2 هندسة المطالبات. توضح التعليقات التي قدمها الطلاب في دراستنا أنهم أحيانًا واجهوا صعوبة في إنشاء مطالبات فعالة لـ GPT-3. هذه قضية مهمة، حيث أن هدفنا هو دعم الإبداع للفرق ذات مستويات خبرة متنوعة في العمل مع نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، وليس فقط المحترفين المدربين على استخدام أحدث تقنيات نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. بينما يُعتبر التوجيه من الخلف نهجًا لمعالجة هذا التحدي، من الواضح أن المصممين المبتدئين يحتاجون أيضًا إلى تعليم حول كيفية بناء مطالبات فعالة. لذلك، من المهم تطوير مواد تدريبية لـ

مصممو التفاعل في أفضل ممارسات هندسة المطالبات ولتشجيعهم على التفكير في كيفية تقديم كلمات رئيسية محددة بالنطاق، والمهمة، وأسلوب التفاعل مع مطالباتهم.

6.3.3 زيادة الإبداع من خلال تغيير الانتباه. يقترح تفرسكي وتشاو أن تغيير الانتباه بين مشكلات مختلفة يعزز التفكير المتباين ويزيد من الإبداع. يمكن أن تتضمن التعديلات المستقبلية على الإطار المقترح لكتابة الأفكار الجماعية بالتعاون مع الذكاء الاصطناعي، تغيير انتباه المجموعة بحيث يتم تحفيز نموذج اللغة الكبير عدة مرات، حيث يركز كل تحفيز على مشكلة أو جانب مختلف من المشكلة. يجب أن تستكشف الأبحاث المستقبلية مثل هذه الاستراتيجيات لزيادة إبداع الأفكار التي ينتجها نموذج اللغة الكبير.

6.3.4 قيود الوكلاء غير البشريين. يمكن اعتبار عملية الكتابة الجماعية باستخدام الذكاء الاصطناعي المقترحة ضمن نطاق طرق تصميم التفاعل ما بعد الإنسانية، حيث يتم توزيع الوكالة بين البشر والوكلاء غير البشريين مثل نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. عند تطبيق مثل هذه الطرق، من المهم أن نتذكر أن الوكلاء غير البشريين المعتمدين على الذكاء الاصطناعي يتم تدريبهم على أشكال منطقية ولغوية تقليدية وإنسانية. وبالتالي، قد تؤدي عمليات توليد الأفكار المشتركة إلى أفكار تجسد وتعزز التحيزات الاجتماعية البشرية. بينما لم نحدد تحيزات اجتماعية محددة في الأفكار التي تم إنتاجها من خلال التعاون المقترح بين المجموعة والذكاء الاصطناعي استجابةً للبيان المعطى، يجب أن تستكشف الأعمال المستقبلية الأفكار التي تحتوي على تحيزات تجاه مجموعات أو مفاهيم معينة. يمكن أن تطور الأعمال المستقبلية أيضًا طرقًا لتصفية الأفكار التي تحتوي على مثل هذا التحيز.

6.3.5 تقييم الأفكار. في دراستنا، استخدمنا محرك تقييم GPT-4 فقط بعد الانتهاء من جلسات توليد الأفكار، لذا لم تكن هذه التقييمات متاحة للفرق. بينما نواصل العمل على توفير مثل هذه التقييمات التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة نماذج اللغة الكبيرة للمستخدمين، هناك عدة قضايا يجب أخذها بعين الاعتبار. أولاً، يقع هذا الاستخدام لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة ضمن الاتجاه الذي حددته يانسن وآخرون [33] بأن الأتمتة تُستخدم بشكل متزايد من قبل المستخدمين بمستويات خبرة متنوعة في استخدام الأدوات الآلية والمزودة بالذكاء الاصطناعي. تحتاج التعليقات التي تم إنشاؤها بواسطة نماذج اللغة الكبيرة إلى تفسير للمصممين بمستويات تدريب مختلفة، بحيث يمكنهم ضبط ثقتهم في النظام بشكل مناسب [38، 42]، وفهمه، وتطبيقه بفعالية [25]. ثانياً، تُظهر نتائجنا أن تقييم الأفكار القائم على نماذج اللغة الكبيرة يمكن أن يقوم بتصفية الأفكار ذات التقييم المنخفض في المراحل المبكرة من العملية. وهذا يعد واعدًا، حيث يمكن لفرق المصممين المستقبليين أو المبتدئين تلقي تعليقات مبكرة، مما يوفر توجيهًا ويسمح لهم بتركيز وقتهم على تطوير الأفكار الأكثر وعدًا. أخيرًا، كما يحذرنا فان ديك، لا تزال الوكلاء غير البشرية تجسد التحيزات البشرية [77]، قبل جعل محرك تقييم الأفكار القائم على نماذج اللغة الكبيرة متاحًا للمستخدمين، من المهم استكشاف وتحديد التحيزات المحتملة في مخرجاته.

6.4 القيود

7 الخاتمة

شكر وتقدير

REFERENCES

[2] Kristina Andersen, Ron Wakkary, Laura Devendorf, and Alex McLean. 2019. Digital Crafts-Machine-Ship: Creative Collaborations with Machines. Interactions 27, 1 (dec 2019), 30-35. https://doi.org/10.1145/3373644

[3] Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke. 2012. Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C.

[4] CompVis Group and Runway and Stability AI. 2022. Stable Diffusion Online. https://stablediffusionweb.com/. Accessed: 02-08-2023.

[5] Conceptboard. 2023. Brainwriting Technique Free Template. https://conceptboard.com/blog/brainwriting-technique-free-template/. Accessed: 12-09-2023.

[6] Conceptboard. 2023. Secure Collaboration Tool for Hybrid Teams – Conceptboard. https://conceptboard.com/. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[7] Lauren E Coursey, Ryan T Gertner, Belinda C Williams, Jared B Kenworthy, Paul B Paulus, and Simona Doboli. 2019. Linking the divergent and convergent processes of collaborative creativity: The impact of expertise levels and elaboration processes. Frontiers in Psychology 10 (2019), 699.

[8] David H. Cropley, Caroline Theurer, Sven Mathijssen, and Rebecca L. Marrone. 2023. Fit-for-Purpose Creativity Assessment: Using Machine Learning to Score a Figural Creativity Test. PsyArXiv Preprints N/A, N/A (2023), N/A. Available online at PsyArXiv.

[9] Edward De Bono. 1999. Six Thinking Hats. Back Bay Books, New York.

[10] Douglas L. Dean, Jillian M. Hender, Thomas Lee Rodgers, and Eric L. Santanen. 2006. Identifying Quality, Novel, and Creative Ideas: Constructs and Scales for Idea Evaluation. 7. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 7 (2006), 30. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:15910404

[11] Dennis J. Devine, Laura D. Clayton, Jennifer L. Philips, Benjamin B. Dunford, and Sarah B. Melner. 1999. Teams in Organizations. Small Group Research 30, 6 (dec 1999), 678-711. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649649903000602

[12] Michael Diehl and Wolfgang Stroebe. 1987. Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: Toward the solution of a riddle. 7ournal of personality and social psychology 53, 3 (1987), 497.

[13] Anil R Doshi and Oliver Hauser. 2023. Generative artificial intelligence enhances creativity. Available at SSRN N/A, N/A (2023), N/A.

[14] Graham Dove, Kim Halskov, Jodi Forlizzi, and John Zimmerman. 2017. UX Design Innovation: Challenges for Working with Machine Learning as a Design Material. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Denver, Colorado, USA) (CHI ’17). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 278-288. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025739

[15] Steven Dow, Julie Fortuna, Dan Schwartz, Beth Altringer, Daniel Schwartz, and Scott Klemmer. 2011. Prototyping Dynamics: Sharing Multiple Designs Improves Exploration, Group Rapport, and Results. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Vancouver, BC, Canada) (CHI ’11). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2807-2816. https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979359

[16] Jeffrey H. Dyer, Hal B Gregersen, and Clayton Christensen. 2008. Entrepreneur behaviors, opportunity recognition, and the origins of innovative ventures. Strategic Entrepreneurship Fournal 2, 4 (2008), 317-338. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej. 59 arXiv:https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/sej. 59

[17] Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner. 1998. Conceptual integration networks. Cognitive Science 22, 2 (1998), 133-187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0364-0213(99)80038-X

[18] Rahel Flechtner and Aeneas Stankowski. 2023. AI Is Not a Wildcard: Challenges for Integrating AI into the Design Curriculum. In Proceedings of the 5th Annual Symposium on HCI Education (Hamburg, Germany) (EduCHI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 72-77. https://doi.org/10.1145/3587399.3587410

[19] Elisa Giaccardi and Johan Redström. 2020. Technology and More-Than-Human Design. Design Issues 36, 4 (09 2020), 33-44. https://doi.org/10.1162/ desi_a_00612 arXiv:https://direct.mit.edu/desi/article- pdf/36/4/33/1857682/desi_a_00612.pdf

[20] Rony Ginosar, Hila Kloper, and Amit Zoran. 2018. PARAMETRIC HABITAT: Virtual Catalog of Design Prototypes. In Proceedings of the 2018 Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Hong Kong, China) (DIS ’18). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1121-1133. https://doi.org/10.1145/3196709.3196813

[21] K Girotra, L Meincke, C Terwiesch, and KT Ulrich. 2023. Ideas are dimes a dozen: large language models for idea generation in innovation (SSRN Scholarly Paper 4526071).

[22] Toshali Goel, Orit Shaer, Catherine Delcourt, Quan Gu, and Angel Cooper. 2023. Preparing Future Designers for Human-AI Collaboration in Persona Creation. In Proceedings of the 2nd Annual Meeting of the Symposium on Human-Computer Interaction for Work. ACM Press, New York, NY, USA, 1-14.

[23] Google. 2023. Bard: Chat-Based AI Tool from Google, Powered by PaLM 2. https://bard.google.com/. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[24] Jieun Han, Haneul Yoo, Yoo Lae Kim, Jun-Hee Myung, Minsun Kim, Hyunseung Lim, Juho Kim, Tak Yeon Lee, Hwajung Hong, So-Yeon Ahn, and Alice H. Oh. 2023. RECIPE: How to Integrate ChatGPT into EFL Writing Education. In Proceedings of the Tenth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 1-8. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:258823196

[25] AKM Bahalul Haque, AKM Najmul Islam, and Patrick Mikalef. 2023. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) from a user perspective: A synthesis of prior literature and problematizing avenues for future research. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 186 (2023), 122120.

[26] Andrew Hargadon. 2003. How breakthroughs happen: The surprising truth about how companies innovate. Harvard Business Press, Boston, MA.

[27] Harvard Business Review. 2022. How Generative AI Is Changing Creative Work. https://hbr.org/2022/11/how-generative-ai-is-changing-creativework. Accessed: 01-08-2023.

[28] Scarlett R. Herring, Chia-Chen Chang, Jesse Krantzler, and Brian P. Bailey. 2009. Getting Inspired! Understanding How and Why Examples Are Used in Creative Design Practice. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Boston, MA, USA) (CHI ’09). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 87-96. https://doi.org/10.1145/1518701.1518717

[29] Peter A. Heslin. 2009. Better than brainstorming? Potential contextual boundary conditions to brainwriting for idea generation in organizations. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 82, 1 (2009), 129-145. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X285642 arXiv:https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1348/096317908X285642

[30] Sarah Homewood, Marika Hedemyr, Maja Fagerberg Ranten, and Susan Kozel. 2021. Tracing Conceptions of the Body in HCI: From User to More-Than-Human. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Yokohama, Japan) (CHI ’21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 258, 12 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445656

[31] Charles McLaughlin Hymes and Gary M Olson. 1992. Unblocking brainstorming through the use of a simple group editor. In Proceedings of the 1992 ACM conference on Computer-supported cooperative work. ACM Press, New York, NY, USA, 99-106.

[32] Nanna Inie, Jeanette Falk, and Steve Tanimoto. 2023. Designing Participatory AI: Creative Professionals’ Worries and Expectations about Generative AI. In Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Hamburg, Germany) (CHI EA ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 82, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544549.3585657

[33] Christian P Janssen, Stella F Donker, Duncan P Brumby, and Andrew L Kun. 2019. History and future of human-automation interaction. International journal of human-computer studies 131 (2019), 99-107.

[34] Frans Johansson. 2004. The medici effect. Penerbit Serambi, Jakarta, Indonesia.

[35] Martin Jonsson and Jakob Tholander. 2022. Cracking the Code: Co-Coding with AI in Creative Programming Education. In Proceedings of the 14th Conference on Creativity and Cognition (Venice, Italy) (C&C ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3527927.3532801

[36] Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass R Sunstein. 2021. Noise: a flaw in human judgment. Hachette UK, London, UK.

[37] Jingoog Kim and Mary Lou Maher. 2023. The effect of AI-based inspiration on human design ideation. International fournal of Design Creativity and Innovation 11, 2 (2023), 81-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2023.2167124 arXiv:https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2023.2167124

[38] Lars Krupp, Steffen Steinert, Maximilian Kiefer-Emmanouilidis, Karina E Avila, Paul Lukowicz, Jochen Kuhn, Stefan Küchemann, and Jakob Karolus. 2023. Unreflected Acceptance-Investigating the Negative Consequences of ChatGPT-Assisted Problem Solving in Physics Education. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.03087 N/A, N/A (2023), N/A.

[39] Solomon Kullback and Richard A Leibler. 1951. On information and sufficiency. The annals of mathematical statistics 22, 1 (1951), 79-86.

[40] Harsh Kumar, Ilya Musabirov, Mohi Reza, Jiakai Shi, Anastasia Kuzminykh, Joseph Jay Williams, and Michael Liut. 2023. Impact of guidance and interaction strategies for LLM use on Learner Performance and perception. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.13712

[41] Brian Lee, Savil Srivastava, Ranjitha Kumar, Ronen Brafman, and Scott R. Klemmer. 2010. Designing with Interactive Example Galleries. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Atlanta, Georgia, USA) (CHI ’10). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2257-2266. https://doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753667

[42] John D Lee and Katrina A See. 2004. Trust in automation: Designing for appropriate reliance. Human factors 46, 1 (2004), 50-80.

[43] J McCormack and A Dorin. 2014. Generative Design: A Paradigm for Design Research. Futureground – DRS International Conference N/A, N/A (2014), 17-21.

[44] Meta Research. 2023. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. https://research.facebook.com/publications/llama-open-and-efficient-foundation-language-models/. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[45] Midjourney. 2022. Midjourney. https://www.midjourney.com/. [Accessed 01-08-2023].

[46] Miro. 2023. First Idea to Final Innovation: It All Lives Here. https://miro.com/product-overview/. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[47] Miro. 2023. Miro AI. https://miro.com/ai/. Accessed: 09-09-2023.

[48] Osnat Mokryn and Hagit Ben-Shoshan. 2021. Domain-based Latent Personal Analysis and its use for impersonation detection in social media. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interactions 31, 4 (2021), 785-828.

[49] René Morkos. 2023. Council Post: Generative AI: It’s Not All ChatGPT – forbes.com. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2023/04/24/ generative-ai-its-not-all-chatgpt/?sh=151ea40a32ef. [Accessed 01-08-2023].

[50] MURAL. 2023. Work Better Together with Mural’s Visual Work Platform. https://www.mural.co/. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[51] Thomas Olsson and Kaisa Väänänen. 2021. How Does AI Challenge Design Practice? Interactions 28, 4 (jun 2021), 62-64. https://doi.org/10.1145/ 3467479

[52] OpenAI. 2022. DALL•E 2. https://openai.com/dall-e-2. Accessed: 2-08-2023.

[53] OpenAI. 2023. GPT-4 – openai.com. https://openai.com/gpt-4. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[54] Alex F Osborn. 1953. Applied imagination. Charles Scribner’s Son’s, New York, USA.

[55] Jeongeon Park, Bryan Min, Xiaojuan Ma, and Juho Kim. 2023. Choicemates: Supporting unfamiliar online decision-making with multi-agent conversational interactions. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.01331

[56] Paul B Paulus and Mary T Dzindolet. 1993. Social influence processes in group brainstorming. 7ournal of personality and social psychology 64, 4 (1993), 575.

[57] Paul B Paulus and Huei-Chuan Yang. 2000. Idea generation in groups: A basis for creativity in organizations. Organizational behavior and human decision processes 82, 1 (2000), 76-87.

[58] Billy Perrigo. 2023. Exclusive: OpenAI Used Kenyan Workers on Less Than $2 Per Hour to Make ChatGPT Less Toxic. https://time.com/6247678/ openai-chatgpt-kenya-workers/

[59] Anuradha Reddy. 2022. Artificial everyday creativity: creative leaps with AI through critical making. Digital Creativity 33, 4 (2022), 295-313. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2022.2138452

[60] Kevin Roose. 2022. The Brilliance and Weirdness of ChatGPT. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/05/technology/chatgpt-ai-twitter.html

[61] root. 2022. noda – mind mapping in virtual reality, solo or group – noda.io. https://noda.io/. [Accessed 09-09-2023].

[62] Vildan Salikutluk, Dorothea Koert, and Frank Jäkel. 2023. Interacting with Large Language Models: A Case Study on AI-Aided Brainstorming for Guesstimation Problems. In HHAI 2023: Augmenting Human Intellect. IOS Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 153-167.

[63] Albrecht Schmidt, Passant Elagroudy, Fiona Draxler, Frauke Kreuter, and Robin Welsch. 2024. Simulating the Human in HCD with ChatGPT: Redesigning Interaction Design with AI. Interactions 31, 1 (jan 2024), 24-31. https://doi.org/10.1145/3637436

[64] Orit Shaer and Angelora Cooper. 2023. Integrating Generative Artificial Intelligence to a Project Based Tangible Interaction Course. IEEE Pervasive Computing 23, 1 (2023), 5. https://doi.org/10.1109/MPRV.2023.3346548

[65] Joon Gi Shin, Janin Koch, Andrés Lucero, Peter Dalsgaard, and Wendy E. Mackay. 2023. Integrating AI in Human-Human Collaborative Ideation. In Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Hamburg, Germany) (CHI EA ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 355, 5 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544549.3573802

[66] Pao Siangliulue, Kenneth C. Arnold, Krzysztof Z. Gajos, and Steven P. Dow. 2015. Toward Collaborative Ideation at Scale: Leveraging Ideas from Others to Generate More Creative and Diverse Ideas. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (Vancouver, BC, Canada) (CSCW ’15). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 937-945. https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675239

[67] Dominik Siemon. 2023. Let the computer evaluate your idea: evaluation apprehension in human-computer collaboration. Behaviour & Information Technology 42, 5 (2023), 459-477.

[68] Wolfgang Stroebe, Bernard A. Nijstad, and Eric F. Rietzschel. 2010. Chapter Four – Beyond Productivity Loss in Brainstorming Groups: The Evolution of a Question. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Mark P. Zanna and James M. Olson (Eds.). Vol. 43. Academic Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 157-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(10)43004-X

[69] Hariharan Subramonyam, Colleen Seifert, and Eytan Adar. 2021. Towards A Process Model for Co-Creating AI Experiences. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Virtual Event, USA) (DIS ’21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1529-1543. https://doi.org/10.1145/3461778.3462012

[70] Ivan E. Sutherland. 1963. Sketchpad: A Man-Machine Graphical Communication System. In Proceedings of the May 21-23, 1963, Spring 7oint Computer Conference (Detroit, Michigan) (AFIPS ’63 (Spring)). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 329-346. https: //doi.org/10.1145/1461551.1461591

[71] Ivan Edward Sutherland. 2003. Sketchpad: A man-machine graphical communication system. Technical Report UCAM-CL-TR-574. University of Cambridge, Computer Laboratory. https://doi.org/10.48456/tr-574

[72] The New York Times. 2023. What’s the Future for A.I.? – nytimes.com. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/31/technology/ai-chatbots-benefitsdangers.html. Accessed: 01-08-2023.

[73] Jakob Tholander and Martin Jonsson. 2023. Design Ideation with AI – Sketching, Thinking and Talking with Generative Machine Learning Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) (DIS ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1930-1940. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596014

[74] Barbara Tversky and Juliet Y. Chou. 2011. Creativity: Depth and Breadth. In Design Creativity 2010, Toshiharu Taura and Yukari Nagai (Eds.). Springer London, London, 209-214.

[75] Brygg Ullmer, Orit Shaer, Ali Mazalek, and Caroline Hummels. 2022. Weaving Fire into Form: Aspirations for Tangible and Embodied Interaction (1 ed.). Vol. 44. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA.

[76] Priyan Vaithilingam, Tianyi Zhang, and Elena L Glassman. 2022. Expectation vs. experience: Evaluating the usability of code generation tools powered by large language models. In Chi conference on human factors in computing systems extended abstracts. ACM, NY, USA, 1-7.

[77] Jelle van Dijk. 2020. Post-Human Interaction Design, Yes, but Cautiously. In Companion Publication of the 2020 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Eindhoven, Netherlands) (DIS’ 20 Companion). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 257-261. https: //doi.org/10.1145/3393914.3395886

[78] Mathias Peter Verheijden and Mathias Funk. 2023. Collaborative Diffusion: Boosting Designerly Co-Creation with Generative AI. In Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Hamburg, Germany) (CHI EA ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 73, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544549.3585680

[79] Ron Wakkary. 2020. Nomadic Practices: A Posthuman Theory for Knowing Design. International fournal of Design 14, 3 (2020), 117.

[80] Ron Wakkary. 2021. Things we could design: For more than human-centered worlds. MIT Press, Boston, MA, USA.

[81] Qiaosi Wang, Michael Madaio, Shaun Kane, Shivani Kapania, Michael Terry, and Lauren Wilcox. 2023. Designing Responsible AI: Adaptations of UX Practice to Meet Responsible AI Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Hamburg, Germany) (CHI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 249, 16 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581278

[82] Sitong Wang, Savvas Petridis, Taeahn Kwon, Xiaojuan Ma, and Lydia B Chilton. 2023. PopBlends: Strategies for Conceptual Blending with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Hamburg, Germany) (CHI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 435,19 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3580948

[83] Chauncey Wilson. 2013. Using Brainwriting For Rapid Idea Generation. https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2013/12/using-brainwriting-for-rapid-idea-generation/

[84] Qian Yang, Aaron Steinfeld, Carolyn Rosé, and John Zimmerman. 2020. Re-Examining Whether, Why, and How Human-AI Interaction Is Uniquely Difficult to Design. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Honolulu, HI, USA) (CHI ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376301

- Authors’ addresses: Orit Shaer, oshaer@wellesley.edu, Wellesley College, 106 Central st., Wellesley, MA, USA, 02481; Angelora Cooper, acooper5@ wellesley.edu, Wellesley College, 106 Central st., Wellesley, MA, USA, 02481; Osnat Mokryn, omokryn@is.haifa.ac.il, University of Haifa, 199 Abba Khushi Ave., Haifa, Israel; Andrew L. Kun, andrew.kun@unh.edu, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA; Hagit Ben Shoshan, hagits@gmail.com, University of Haifa, 199 Abba Khushi Ave., Haifa, Israel.

Al-Augmented Brainwriting: Investigating the use of LLMs in group ideation

Abstract

The growing availability of generative AI technologies such as large language models (LLMs) has significant implications for creative work. This paper explores twofold aspects of integrating LLMs into the creative process – the divergence stage of idea generation, and the convergence stage of evaluation and selection of ideas. We devised a collaborative group-AI Brainwriting ideation framework, which incorporated an LLM as an enhancement into the group ideation process, and evaluated the idea generation process and the resulted solution space. To assess the potential of using LLMs in the idea evaluation process, we design an evaluation engine and compared it to idea ratings assigned by three expert and six novice evaluators. Our findings suggest that integrating LLM in Brainwriting could enhance both the ideation process and its outcome. We also provide evidence that LLMs can support idea evaluation. We conclude by discussing implications for HCI education and practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

RQ2: How can LLMs assist to evaluate ideas during the convergence stage of a collaborative group Brainwriting process?

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Structured Approaches to Ideation

2.2 Human-AI Co-Creation

2.3 Approaches for Evaluating Ideas

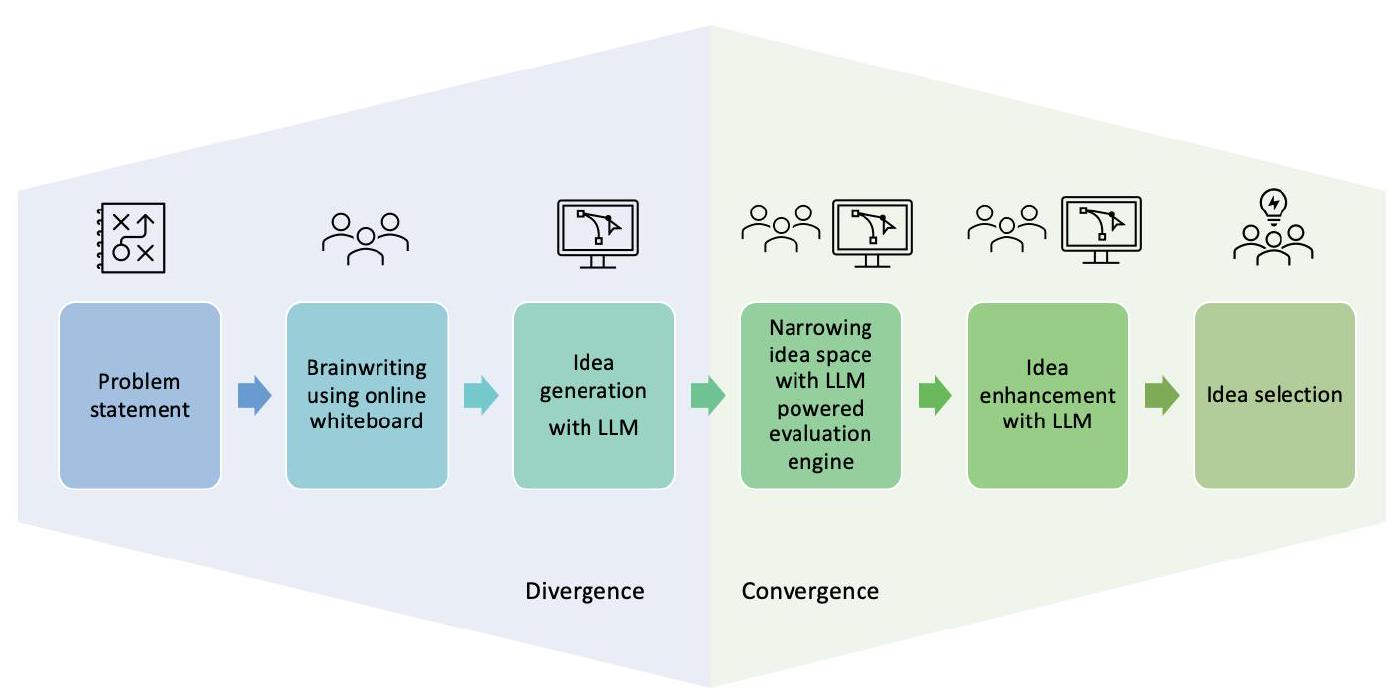

3 COLLABORATIVE GROUP-AI BRAINWRITING FRAMEWORK DESIGN

3.1 Brainwriting Divergence stage

How it works

Set the timer to 10 minutes. Each team member should read all ideas on the board.

5 Discuss and come up together with at least three new or refined ideas. Add the ideas to sticky notes in the collaborative ideas section. Set the timer to an additional 5 minutes and come up with at least three more ideas.

(b) Outline of the process

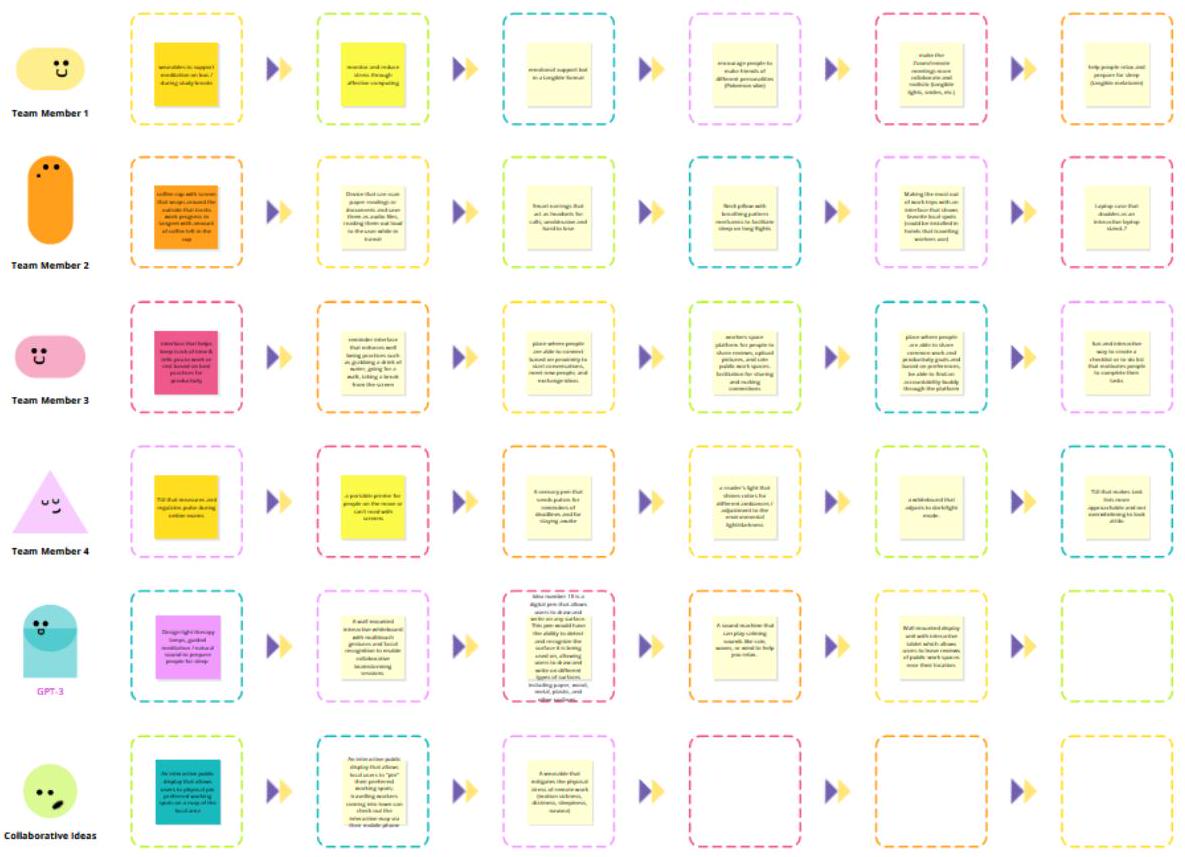

3.1.2 Phase 2: Enhancing Ideas with an LLM. In here, each group is required to use an LLM (OpenAI Playground GPT-3) to generate additional ideas. Participants are encouraged to iterate on their LLM prompts and are exposed, prior to the Brainwriting session, to overview materials on prompt engineering. The generated ideas are copied and pasted into

sticky notes on the board. We modified the original Brainwriting template offered by Conceptboard to reflect this new framework for Brainwriting with LLM for the enhancement of ideas.

3.2 Brainwriting convergence stage

3.3 Can LLMs Help with Convergence? Developing and implementing an LLM Powered Evaluation Engine

Well-defined Criteria: The engine would be prompted to evaluate ideas according to a well defined set of criteria, which is often used by humans to identify quality, innovative, and creative ideas. We chose to use two criteria from Dean et al.’s evaluation framework [10]: relevance and innovation. In addition, we chose a third criterion, insightfulness, based on Dyer et al.’s research on the origin of innovative ventures [16]. Each of these criteria required a clear definition.

Scale x Criteria Definition: Each scale value for each criterion should be well defined, and in detail.

(1) We first developed initial descriptive paragraphs for each criterion – Relevance, Innovation, Insightfulness, based on definitions in existing literature, and created descriptive anchors for each scale value.

(2) Three raters who are expert reviewers (researchers in HCI), working independently, rated a small sample of ideas using the initial definitions and anchors.

(3) We met with the researchers as a group to discuss their sample ratings, focusing on areas of disagreement, and came to a shared agreement on the general definition of each criterion and what each of its scale value anchors meant.

(4) Using these new definitions, we prompted GPT-4 to score a sample of ideas and to provide an explanation and justification for its assigned rating per criterion per idea. We then chose evaluation adjective and descriptive nouns from each explanation, and used these in a refined definition for a revised prompt. The definitions given in the prompt are: Relevance: To what extent does the idea reflect how well the idea is connected with or appropriate for the objectives, requirements, or challenges of the problem statement? Innovation: To what extent does the idea reflect how original and creative the idea is, breaking away from conventional or existing solutions to the problem statement? and Insightfulness: To what extent does the idea reflect a profound and nuanced understanding of the problem statement?

We repeated the process approximately three times for each scale until the anchors for each value were sufficiently differentiated. Supplementary Information Figure 1 shows the prompt with the explanations for the various ratings per each criterion given to the GPT-4 evaluation engine. Figure 3 depicts an idea evaluation using the GPT-4 evaluation engine.

3.3.1 Implementation. For this phase we chose GPT-4. At the time we conducted this experiment (June 2023), it has been available only for subscribers, and the researchers purchased a subscription. GPT-4 was chosen for the convergence phase over the free GPT-3 version due to its more advanced reasoning capabilities. We used the OpenAI API to write a Python program that uses the prompt to rate a set of ideas read in from a text file. The program outputs a CSV file with three ratings for each idea (for Relevance, Innovation, and Insightfulness), and a text file that contains GPT-4’s justifications for those ratings. The user can indicate the number of times to repeat the process; each repetition will open a new GPT-4 context and produce a new set of ratings.

4 USER STUDY: COLLABORATIVE GROUP-AI BRAINWRITING PROCESS

4.1 Divergence: The Collaborative Brainwriting session

breaks.

Relevance (1-5):

Justification: The idea directly addresses the well-being aspect of the problem statement by encouraging mobility and break-taking. This is especially relevant for those working or studying in mobile environments, as they might be prone to long sitting durations. However, it doesn’t directly address productivity or creativity.

Innovation (1-5):

Justification: The concept of devices or apps reminding users to take breaks after prolonged periods of sitting isn’t entirely new. Smartwatches, for instance, often have such reminders. Hence, the idea shows minimal innovation from existing solutions.

Insightfulness (1-5):

Justification: The idea does recognize a fundamental issue of prolonged sitting and its potential health implications. However, it doesn’t delve into the nuanced challenges of working or studying in mobile environments, nor does it offer insights into how productivity and creativity might be impacted by such breaks.

designers face when working with AI as a design material

asked them to review, discuss, select, copy & paste the best ideas to a side panel and start developing these ideas further with the help of GPT-3.

| Human | GPT-3 | Collaborative | Total # of ideas | |

| Team 1 | 20 | 4 | 2 | 26 |

| Team 2 | 18 | 11 | 11 | 40 |

| Team 3 | 17 | 2 | 0 | 19 |

| Team 4 | 24 | 6 | 6 | 36 |

| Team 5 | 18 | 6 | 3 | 27 |

4.2 Convergence: Ideas Evaluation and Selection

| Generated by | Relevance | Innovation | Insightful | |||

| Avg | Std | Avg | Std | Avg | Std | |

| Human | 4.81 | 0.40 | 4.31 | 0.70 | 4.37 | 0.61 |

| GPT-3 | 4.56 | 0.51 | 4.25 | 0.68 | 4.18 | 0.65 |

| Collab | 4.87 | 0.34 | 4.81 | 0.40 | 4.81 | 0.40 |

5 FRAMEWORK EVALUATION

generated [7], we evaluated divergence by examining the semantic distribution of ideas generated by humans and by GPT-3. We also identify the unique terms used in the different solution spaces. We then explore, in the second part of the evaluation, how LLMs can be used to assist in idea evaluation during the convergence stage (RQ2).

5.1 Data and Methods

popular term that is underused or not used at all (missing) at the document. The set of terms with the highest absolute weight comprises the document’s signature, each with its corresponding sign.

5.2 Results RQ1: Does the use of an LLM during the divergence stage of collaborative group Brainwriting enhance the idea generation process and its outcome?

5.2.1 Students’ Reflections. Since the user study was conducted within an educational setting, our evaluation of students’ perceptions of this Group-AI Brainwriting framework also involved assessing their learning and critical engagement with AI. In a separate paper [currently under review for a different conference], we contextualized the use of this framework within a broader integration of generative AI into a tangible interaction course, and discussed students’ reflections and learning. Here, we summarize student perceptions of the Group-AI Brainwriting process. Specifically, we analyze student responses to a question we asked immediately after the ideation session (Q1): “In what ways did using GPT-3 contribute to or hinder the ideation session?” We also analyze their response to a question asked at the end of the semester (Q2): “Thinking back to your original ideation with GPT-3: to what extent do you feel like your collaboration with text-generative AI influenced the direction of your project?”

All students responded to this question (

5.2.2 Ideation outcomes. The outcome of the human-LLM ideation process was a set of chosen ideas – each team chose one idea to explore in a semester long project. Table 3 shows the chosen idea of each team, and describes the conception of each idea in terms of its human and/or GPT-3 origin. Overall, 3 out 5 chosen ideas were developed through merging a Human-Generated idea and a GPT-3-Generated idea. One idea was developed through merging multiple Human-Generated ideas and multiple GPT-3-Generated ideas. Finally, one out of the 5 ideas is based solely on a GPT-3-Generated idea.

5.2.3 Exploring the Human and LLM solution spaces. To explore the divergence of ideas and the solution space explored with and without LLMs, we evaluated the semantic distribution of ideas generated by humans and by GPT-3, and the terms used in the different solution spaces using LPA.

| Chosen idea | Enhancement | Description | |

| Team 1 | An interactive public display that allows local users to “pin” their preferred working spots; travelling workers coming into town can check out the interactive map via their mobile phone | Combined human & LLM | Inspired by the combination of a Human-Generated idea, a platform for rating work spaces, with a GPT-3 Generated idea, an interactive public display |

| Team 2 | Posture pillow that keeps track of posture patterns and reminds user to change their position or take a break | LLM | Inspired by a GPT-3-Generated idea for a smart pillow that can detect posture |

| Team 3 | Portable desk for commuter students with stability and motion sickness-alleviating features and a built-in wifi hotspot | Combined human & LLM | Not submitted with original workshop idea set, but submitted with project proposal as a combination of a Human-Generated idea (“portable desk that is stable on bumpy rides”) and a GPT-3-Generated idea (“installing a wireless router or access point inside a portable desk”) |

| Team 4 | A plushie/stress ball keychain that users can hold onto; releases aromatherapy and also communicates with user holding another one to either feel their heartbeat or the same squeezing sensation | Combined human & LLM | Inspired by combining a number of Human-Generated and GPT-3-Generated ideas having to do with aromatherapy for stress and paired devices that transmit the users’ pulse. Unlike the other teams, this team combined several ideas together |

| Team 5 | Sleeping eye mask that changes temperature based on where you are in your journey and vibrates to wake you before your stop | Combined human & LLM | Inspired by the combination of a Human-Generated idea, a wearable to notify the user when their public transport stop is near, with a GPT-3-Generated idea, a temperature-controlled sleep mask |

clustering of

5.2.4 Prompt analysis. To get further insight into the differences between Human-Generated and GPT-3-Generated ideas, we analyzed the prompts used by students to generate new ideas and iterate on existing ones, and identified a few distinct approaches. Typically, students used one of two approaches to initiate their interaction with GPT-3: 1) broad-area prompts, or 2) solution-specific prompts.

5.2.5 Summary of findings for RQ1. After the session,

5.3 RQ2: How can LLMs assist to evaluate ideas during the convergence stage of a collaborative group Brainwriting process?

5.3.1 Consistency of the GPT-4 evaluation engine. First, we assess the internal consistency of the 29 GPT-4 evaluations for the ideas on the three criteria of Relevance, Innovation, and insightfulness. To evaluate consistency we treat the evaluations as questionnaire items and analyze them with Fleiss’ Kappa coefficients to evaluate rater agreement. Our analysis shows a moderate level of consistency in GPT-4’s performance, with all Fleiss’ Kappa values surpassing the 0.4 threshold. The specific Fleiss’ Kappa values for the different criteria were the following. Relevance: 0.42 , Innovation: 0.40, and Insightfulness: 0.49 . Thus, GPT-4 evaluations can be seen as consistent across the three criteria.

5.3.2 Comparative Analysis of GPT-4’s Evaluations Against Novice and Expert Human Evaluators. We compare the ratings given GPT-4 to those given by novices and experts to the 148 ideas generated by either humans, GPT-3, or in collaboration. The ratings were given to each idea for each of the three criteria: Relevance, Innovation, and Insightfulness. To compare the GPT-4 evaluations to human raters, we conducted the following steps: (a) compared the given rating distributions, (b) compared evaluations for the top and bottom ideas as ranked by the experts’ ratings; (c) computed the Pearson correlation between GPT-4 ranking of ideas and the experts’ ranking; (d) compared the ratings given by GPT-4, novices, and experts, across the three criteria, to the ideas that were chosen by the teams as their final ideas.

(a) First, we compare the ratings distributions across the evaluator groups. Figure 5 depicts the distribution of ratings on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 given by Experts (lower panel), Novices (middle panel), and GPT-4 (upper panel) for the 148 ideas across the three criteria. For each idea and criterion, the rating was calculated as the average of the ratings given by the corresponding rater group, either Experts, Novices, or GPT-4, to that idea. The ratings distributions demonstrate that the Experts were more critical than the Novices and that GPT-4 gives relatively high ratings to ideas. GPT-4 gave much more ratings of 5 than novices and experts and much less ratings of 2 and 1 . Specifically, it gave a lower rating of 1 to only one idea, for its Insightfulness. GPT-4 gave an average rating of 4.19 for relevance, 3.72 for innovation, and 3.68 for insightfulness.

(b) We created a ranking of the ideas for each rater group, Experts, Novices, and GPT-4. The ranking of the ideas was computed as follows. For each rater group, the rating of an idea by that rater group was computed by averaging the ratings given by the group members for each of the criteria and then by summing these values. For example, in the case of the Expert rater group, the average rating given by the three experts to each of the criteria Relevance, Innovation, and Insightfulness was computed, and the idea’s final rating was computed as the sum of these three average values. per each criteria and summing it. Thus, an idea with an Experts average rating of 4 for relevance, 2.75 for innovation, and 2.375 for insightfulness received an aggregated rating of 9.125 , and was ranked 24 out of 148 ideas.

(c) To quantify the relationship between the rankings provided by different groups, we computed Pearson correlation coefficients. The comparison yielded a coefficient of 0.556 between expert and GPT- 4 ratings, 0.547 between novice and GPT-4 ratings, and 0.602 between expert and novice ratings. These results indicate a moderate positive linear relationship among the three ranked lists.

(d) Lastly, we examine the evaluations given by the GPT-4 evaluation engine to the ideas that were ultimately chosen by student teams, and compare these to the expert and novices corresponding ratings. Table 4 summarizes the the ratings of the final ideas chosen by teams. For the majority of instances, all rater groups, namely experts, novices, and the GPT-4 evaluation engine, assigned higher ratings to the final selected ideas compared to the average rating they assigned to all ideas.

| Rater | Criterion | Team 1 | Team 2 | Team 3 | Team 4 | Team 5 | Average over all ideas | |

| Expert | Relevance | Avg | 3.75 | 4.25 | 4.00 | 3.67 | 3.00 | 3.57 |

| Stdev | 0.96 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 1.83 | 1.10 | ||

| Innovation | Avg | 3.00 | 3.25 | 3.33 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 2.79 | |

| Stdev | 1.41 | 0.96 | 2.08 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.10 | ||

| Insightfulness | Avg | 3.00 | 3.25 | 3.67 | 3.67 | 2.25 | 3.01 | |

| Stdev | 1.15 | 1.26 | 1.53 | 0.58 | 1.26 | 1.11 | ||

| Novice | Relevance | Avg | 3.67 | 3.50 | 4.17 | 3.17 | 3.33 | 3.38 |

| Stdev | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.95 | ||

| Innovation | Avg | 2.83 | 3.67 | 3.50 | 3.83 | 3.83 | 3.11 | |

| Stdev | 0.98 | 0.52 | 1.05 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 1.07 | ||

| Insightfulness | Avg | 3.50 | 3.67 | 3.50 | 3.33 | 3.17 | 3.13 | |

| Stdev | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.84 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 0.96 | ||

| GPT-4 | Relevance | Avg | 4.80 | 4.73 | 4.52 | 4.03 | 4.57 | 4.19 |

| Stdev | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.50 | 0.82 | ||

| Innovation | Avg | 3.77 | 3.90 | 3.52 | 4.57 | 4.93 | 3.72 | |

| Stdev | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.80 | ||

| Insightfulness | Avg | 3.87 | 4.27 | 3.93 | 3.87 | 4.33 | 3.68 | |

| Stdev | 0.43 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.80 | ||

6 DISCUSSION

6.1 Discussion of results for RQ1: Does the use of an LLM during the divergence stage of collaborative group Brainwriting enhance the idea generation process and its outcome?

6.2 Discussion of results for RQ2: How can LLMs assist to evaluate ideas during the convergence stage of a collaborative group Brainwriting process?

6.3 Implications for HCl education and practice

6.3.1 Expanding Ideas. Our findings demonstrate that integrating co-creation processes with AI into the ideation process of novice designers, could enhance the divergence stage where a wider range of different ideas is explored.

6.3.2 Prompt Engineering. The comments made by the students in our study make it clear that sometimes they struggled with creating effective prompts for GPT-3. This is an important issue, since our goal is to support ideation for teams with diverse levels of experience working with LLMs, not only professionals with training in the usage of the latest LLM technologies. While back-end prompting is one approach to address this challenge, it is clear that novice designers also require instruction on constructing effective prompts. It is thereby important to develop training materials for

interaction designers in best practices of prompt engineering and to encourage them to consider how best to provide domain, task, and interaction style specific keywords with their prompts.

6.3.3 Increased Creativity through Shifting Attention. Tversky and Chou suggest that shifting attention between different problems fosters divergent thought and enhance creativity [74]. Future variation of our proposed framework for collaborative group-AI Brainwriting, could shift the group attention so that an LLM is prompted multiple times, where each prompt is focused on a different problem or aspect of the problem. Future research should explore such strategies for increasing the creativity of LLM-generated ideas.

6.3.4 Limitations of Non-Human Agents. The proposed group-AI Brainwriting process could be considered within the realm of more-than-human, post-humanist interaction design methods [19,30,79,80] where agency is distributed among humans and non-human agents such as LLMs. When applying such methods it is important to remember that AI-based non-human agents are trained upon and import “traditional, humanist forms of logic and language” [77]. Thus, co-creation ideation processes might yield ideas that embody and amplify human social biases. While we did not identify specific social biases in the ideas produced by the proposed group-AI collaboration in response to the given problem statement, future work should probe for ideas that contain bias regarding specific groups or concepts. Future work could also develop methods of filtering out ideas that contain such bias.

6.3.5 Evaluating Ideas. In our study, we used the GPT-4 evaluation engine only after the ideation sessions were completed, so these evaluations were not available to teams. As we continue to work towards providing such LLMgenerated evaluations to users, there are several issues to consider. First, such use of LLMs falls into the trend identified by Janssen et al. [33] that automation is increasingly being used by users with varied levels of expertise in using automated and AI-powered tools. LLM-generated feedback needs to be explained for designers with varying levels of training, such that they can appropriately calibrate their trust in the system [38, 42], understand it, and apply it effectively [25]. Second, our findings demonstrate that LLM-based idea evaluation could potentially filter out low-rated ideas in early stages of the process. This is promising, since teams of future or novice designers could receive early feedback, which provides direction and allows them to focus their time on developing the more promising ideas. Finally, as van Dijk warns us non-human agent still embody human biases [77], before making an LLM-based idea evaluation engine available to users, it is important to probe for and identify potential biases in its output.

6.4 Limitations

7 CONCLUSION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

REFERENCES

[2] Kristina Andersen, Ron Wakkary, Laura Devendorf, and Alex McLean. 2019. Digital Crafts-Machine-Ship: Creative Collaborations with Machines. Interactions 27, 1 (dec 2019), 30-35. https://doi.org/10.1145/3373644

[3] Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke. 2012. Thematic analysis. American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C.

[4] CompVis Group and Runway and Stability AI. 2022. Stable Diffusion Online. https://stablediffusionweb.com/. Accessed: 02-08-2023.

[5] Conceptboard. 2023. Brainwriting Technique Free Template. https://conceptboard.com/blog/brainwriting-technique-free-template/. Accessed: 12-09-2023.

[6] Conceptboard. 2023. Secure Collaboration Tool for Hybrid Teams – Conceptboard. https://conceptboard.com/. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[7] Lauren E Coursey, Ryan T Gertner, Belinda C Williams, Jared B Kenworthy, Paul B Paulus, and Simona Doboli. 2019. Linking the divergent and convergent processes of collaborative creativity: The impact of expertise levels and elaboration processes. Frontiers in Psychology 10 (2019), 699.

[8] David H. Cropley, Caroline Theurer, Sven Mathijssen, and Rebecca L. Marrone. 2023. Fit-for-Purpose Creativity Assessment: Using Machine Learning to Score a Figural Creativity Test. PsyArXiv Preprints N/A, N/A (2023), N/A. Available online at PsyArXiv.

[9] Edward De Bono. 1999. Six Thinking Hats. Back Bay Books, New York.

[10] Douglas L. Dean, Jillian M. Hender, Thomas Lee Rodgers, and Eric L. Santanen. 2006. Identifying Quality, Novel, and Creative Ideas: Constructs and Scales for Idea Evaluation. 7. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 7 (2006), 30. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:15910404

[11] Dennis J. Devine, Laura D. Clayton, Jennifer L. Philips, Benjamin B. Dunford, and Sarah B. Melner. 1999. Teams in Organizations. Small Group Research 30, 6 (dec 1999), 678-711. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649649903000602

[12] Michael Diehl and Wolfgang Stroebe. 1987. Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: Toward the solution of a riddle. 7ournal of personality and social psychology 53, 3 (1987), 497.

[13] Anil R Doshi and Oliver Hauser. 2023. Generative artificial intelligence enhances creativity. Available at SSRN N/A, N/A (2023), N/A.

[14] Graham Dove, Kim Halskov, Jodi Forlizzi, and John Zimmerman. 2017. UX Design Innovation: Challenges for Working with Machine Learning as a Design Material. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Denver, Colorado, USA) (CHI ’17). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 278-288. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025739

[15] Steven Dow, Julie Fortuna, Dan Schwartz, Beth Altringer, Daniel Schwartz, and Scott Klemmer. 2011. Prototyping Dynamics: Sharing Multiple Designs Improves Exploration, Group Rapport, and Results. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Vancouver, BC, Canada) (CHI ’11). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2807-2816. https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979359

[16] Jeffrey H. Dyer, Hal B Gregersen, and Clayton Christensen. 2008. Entrepreneur behaviors, opportunity recognition, and the origins of innovative ventures. Strategic Entrepreneurship Fournal 2, 4 (2008), 317-338. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej. 59 arXiv:https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/sej. 59

[17] Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner. 1998. Conceptual integration networks. Cognitive Science 22, 2 (1998), 133-187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0364-0213(99)80038-X

[18] Rahel Flechtner and Aeneas Stankowski. 2023. AI Is Not a Wildcard: Challenges for Integrating AI into the Design Curriculum. In Proceedings of the 5th Annual Symposium on HCI Education (Hamburg, Germany) (EduCHI ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 72-77. https://doi.org/10.1145/3587399.3587410

[19] Elisa Giaccardi and Johan Redström. 2020. Technology and More-Than-Human Design. Design Issues 36, 4 (09 2020), 33-44. https://doi.org/10.1162/ desi_a_00612 arXiv:https://direct.mit.edu/desi/article- pdf/36/4/33/1857682/desi_a_00612.pdf

[20] Rony Ginosar, Hila Kloper, and Amit Zoran. 2018. PARAMETRIC HABITAT: Virtual Catalog of Design Prototypes. In Proceedings of the 2018 Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Hong Kong, China) (DIS ’18). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1121-1133. https://doi.org/10.1145/3196709.3196813

[21] K Girotra, L Meincke, C Terwiesch, and KT Ulrich. 2023. Ideas are dimes a dozen: large language models for idea generation in innovation (SSRN Scholarly Paper 4526071).

[22] Toshali Goel, Orit Shaer, Catherine Delcourt, Quan Gu, and Angel Cooper. 2023. Preparing Future Designers for Human-AI Collaboration in Persona Creation. In Proceedings of the 2nd Annual Meeting of the Symposium on Human-Computer Interaction for Work. ACM Press, New York, NY, USA, 1-14.

[23] Google. 2023. Bard: Chat-Based AI Tool from Google, Powered by PaLM 2. https://bard.google.com/. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[24] Jieun Han, Haneul Yoo, Yoo Lae Kim, Jun-Hee Myung, Minsun Kim, Hyunseung Lim, Juho Kim, Tak Yeon Lee, Hwajung Hong, So-Yeon Ahn, and Alice H. Oh. 2023. RECIPE: How to Integrate ChatGPT into EFL Writing Education. In Proceedings of the Tenth ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 1-8. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:258823196

[25] AKM Bahalul Haque, AKM Najmul Islam, and Patrick Mikalef. 2023. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) from a user perspective: A synthesis of prior literature and problematizing avenues for future research. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 186 (2023), 122120.

[26] Andrew Hargadon. 2003. How breakthroughs happen: The surprising truth about how companies innovate. Harvard Business Press, Boston, MA.

[27] Harvard Business Review. 2022. How Generative AI Is Changing Creative Work. https://hbr.org/2022/11/how-generative-ai-is-changing-creativework. Accessed: 01-08-2023.

[28] Scarlett R. Herring, Chia-Chen Chang, Jesse Krantzler, and Brian P. Bailey. 2009. Getting Inspired! Understanding How and Why Examples Are Used in Creative Design Practice. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Boston, MA, USA) (CHI ’09). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 87-96. https://doi.org/10.1145/1518701.1518717

[29] Peter A. Heslin. 2009. Better than brainstorming? Potential contextual boundary conditions to brainwriting for idea generation in organizations. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 82, 1 (2009), 129-145. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317908X285642 arXiv:https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1348/096317908X285642

[30] Sarah Homewood, Marika Hedemyr, Maja Fagerberg Ranten, and Susan Kozel. 2021. Tracing Conceptions of the Body in HCI: From User to More-Than-Human. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Yokohama, Japan) (CHI ’21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 258, 12 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445656

[31] Charles McLaughlin Hymes and Gary M Olson. 1992. Unblocking brainstorming through the use of a simple group editor. In Proceedings of the 1992 ACM conference on Computer-supported cooperative work. ACM Press, New York, NY, USA, 99-106.

[32] Nanna Inie, Jeanette Falk, and Steve Tanimoto. 2023. Designing Participatory AI: Creative Professionals’ Worries and Expectations about Generative AI. In Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Hamburg, Germany) (CHI EA ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 82, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544549.3585657

[33] Christian P Janssen, Stella F Donker, Duncan P Brumby, and Andrew L Kun. 2019. History and future of human-automation interaction. International journal of human-computer studies 131 (2019), 99-107.

[34] Frans Johansson. 2004. The medici effect. Penerbit Serambi, Jakarta, Indonesia.

[35] Martin Jonsson and Jakob Tholander. 2022. Cracking the Code: Co-Coding with AI in Creative Programming Education. In Proceedings of the 14th Conference on Creativity and Cognition (Venice, Italy) (C&C ’22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1145/3527927.3532801

[36] Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass R Sunstein. 2021. Noise: a flaw in human judgment. Hachette UK, London, UK.

[37] Jingoog Kim and Mary Lou Maher. 2023. The effect of AI-based inspiration on human design ideation. International fournal of Design Creativity and Innovation 11, 2 (2023), 81-98. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2023.2167124 arXiv:https://doi.org/10.1080/21650349.2023.2167124

[38] Lars Krupp, Steffen Steinert, Maximilian Kiefer-Emmanouilidis, Karina E Avila, Paul Lukowicz, Jochen Kuhn, Stefan Küchemann, and Jakob Karolus. 2023. Unreflected Acceptance-Investigating the Negative Consequences of ChatGPT-Assisted Problem Solving in Physics Education. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.03087 N/A, N/A (2023), N/A.

[39] Solomon Kullback and Richard A Leibler. 1951. On information and sufficiency. The annals of mathematical statistics 22, 1 (1951), 79-86.

[40] Harsh Kumar, Ilya Musabirov, Mohi Reza, Jiakai Shi, Anastasia Kuzminykh, Joseph Jay Williams, and Michael Liut. 2023. Impact of guidance and interaction strategies for LLM use on Learner Performance and perception. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.13712

[41] Brian Lee, Savil Srivastava, Ranjitha Kumar, Ronen Brafman, and Scott R. Klemmer. 2010. Designing with Interactive Example Galleries. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Atlanta, Georgia, USA) (CHI ’10). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2257-2266. https://doi.org/10.1145/1753326.1753667

[42] John D Lee and Katrina A See. 2004. Trust in automation: Designing for appropriate reliance. Human factors 46, 1 (2004), 50-80.

[43] J McCormack and A Dorin. 2014. Generative Design: A Paradigm for Design Research. Futureground – DRS International Conference N/A, N/A (2014), 17-21.

[44] Meta Research. 2023. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. https://research.facebook.com/publications/llama-open-and-efficient-foundation-language-models/. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[45] Midjourney. 2022. Midjourney. https://www.midjourney.com/. [Accessed 01-08-2023].

[46] Miro. 2023. First Idea to Final Innovation: It All Lives Here. https://miro.com/product-overview/. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[47] Miro. 2023. Miro AI. https://miro.com/ai/. Accessed: 09-09-2023.

[48] Osnat Mokryn and Hagit Ben-Shoshan. 2021. Domain-based Latent Personal Analysis and its use for impersonation detection in social media. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interactions 31, 4 (2021), 785-828.

[49] René Morkos. 2023. Council Post: Generative AI: It’s Not All ChatGPT – forbes.com. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2023/04/24/ generative-ai-its-not-all-chatgpt/?sh=151ea40a32ef. [Accessed 01-08-2023].

[50] MURAL. 2023. Work Better Together with Mural’s Visual Work Platform. https://www.mural.co/. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[51] Thomas Olsson and Kaisa Väänänen. 2021. How Does AI Challenge Design Practice? Interactions 28, 4 (jun 2021), 62-64. https://doi.org/10.1145/ 3467479

[52] OpenAI. 2022. DALL•E 2. https://openai.com/dall-e-2. Accessed: 2-08-2023.

[53] OpenAI. 2023. GPT-4 – openai.com. https://openai.com/gpt-4. Accessed: 14-09-2023.

[54] Alex F Osborn. 1953. Applied imagination. Charles Scribner’s Son’s, New York, USA.

[55] Jeongeon Park, Bryan Min, Xiaojuan Ma, and Juho Kim. 2023. Choicemates: Supporting unfamiliar online decision-making with multi-agent conversational interactions. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.01331

[56] Paul B Paulus and Mary T Dzindolet. 1993. Social influence processes in group brainstorming. 7ournal of personality and social psychology 64, 4 (1993), 575.

[57] Paul B Paulus and Huei-Chuan Yang. 2000. Idea generation in groups: A basis for creativity in organizations. Organizational behavior and human decision processes 82, 1 (2000), 76-87.

[58] Billy Perrigo. 2023. Exclusive: OpenAI Used Kenyan Workers on Less Than $2 Per Hour to Make ChatGPT Less Toxic. https://time.com/6247678/ openai-chatgpt-kenya-workers/

[59] Anuradha Reddy. 2022. Artificial everyday creativity: creative leaps with AI through critical making. Digital Creativity 33, 4 (2022), 295-313. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626268.2022.2138452

[60] Kevin Roose. 2022. The Brilliance and Weirdness of ChatGPT. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/05/technology/chatgpt-ai-twitter.html

[61] root. 2022. noda – mind mapping in virtual reality, solo or group – noda.io. https://noda.io/. [Accessed 09-09-2023].

[62] Vildan Salikutluk, Dorothea Koert, and Frank Jäkel. 2023. Interacting with Large Language Models: A Case Study on AI-Aided Brainstorming for Guesstimation Problems. In HHAI 2023: Augmenting Human Intellect. IOS Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 153-167.

[63] Albrecht Schmidt, Passant Elagroudy, Fiona Draxler, Frauke Kreuter, and Robin Welsch. 2024. Simulating the Human in HCD with ChatGPT: Redesigning Interaction Design with AI. Interactions 31, 1 (jan 2024), 24-31. https://doi.org/10.1145/3637436

[64] Orit Shaer and Angelora Cooper. 2023. Integrating Generative Artificial Intelligence to a Project Based Tangible Interaction Course. IEEE Pervasive Computing 23, 1 (2023), 5. https://doi.org/10.1109/MPRV.2023.3346548

[65] Joon Gi Shin, Janin Koch, Andrés Lucero, Peter Dalsgaard, and Wendy E. Mackay. 2023. Integrating AI in Human-Human Collaborative Ideation. In Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (Hamburg, Germany) (CHI EA ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 355, 5 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544549.3573802

[66] Pao Siangliulue, Kenneth C. Arnold, Krzysztof Z. Gajos, and Steven P. Dow. 2015. Toward Collaborative Ideation at Scale: Leveraging Ideas from Others to Generate More Creative and Diverse Ideas. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (Vancouver, BC, Canada) (CSCW ’15). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 937-945. https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675239

[67] Dominik Siemon. 2023. Let the computer evaluate your idea: evaluation apprehension in human-computer collaboration. Behaviour & Information Technology 42, 5 (2023), 459-477.

[68] Wolfgang Stroebe, Bernard A. Nijstad, and Eric F. Rietzschel. 2010. Chapter Four – Beyond Productivity Loss in Brainstorming Groups: The Evolution of a Question. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Mark P. Zanna and James M. Olson (Eds.). Vol. 43. Academic Press, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 157-203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(10)43004-X

[69] Hariharan Subramonyam, Colleen Seifert, and Eytan Adar. 2021. Towards A Process Model for Co-Creating AI Experiences. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Virtual Event, USA) (DIS ’21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1529-1543. https://doi.org/10.1145/3461778.3462012

[70] Ivan E. Sutherland. 1963. Sketchpad: A Man-Machine Graphical Communication System. In Proceedings of the May 21-23, 1963, Spring 7oint Computer Conference (Detroit, Michigan) (AFIPS ’63 (Spring)). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 329-346. https: //doi.org/10.1145/1461551.1461591

[71] Ivan Edward Sutherland. 2003. Sketchpad: A man-machine graphical communication system. Technical Report UCAM-CL-TR-574. University of Cambridge, Computer Laboratory. https://doi.org/10.48456/tr-574

[72] The New York Times. 2023. What’s the Future for A.I.? – nytimes.com. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/31/technology/ai-chatbots-benefitsdangers.html. Accessed: 01-08-2023.

[73] Jakob Tholander and Martin Jonsson. 2023. Design Ideation with AI – Sketching, Thinking and Talking with Generative Machine Learning Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Pittsburgh, PA, USA) (DIS ’23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1930-1940. https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596014

[74] Barbara Tversky and Juliet Y. Chou. 2011. Creativity: Depth and Breadth. In Design Creativity 2010, Toshiharu Taura and Yukari Nagai (Eds.). Springer London, London, 209-214.

[75] Brygg Ullmer, Orit Shaer, Ali Mazalek, and Caroline Hummels. 2022. Weaving Fire into Form: Aspirations for Tangible and Embodied Interaction (1 ed.). Vol. 44. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA.

[76] Priyan Vaithilingam, Tianyi Zhang, and Elena L Glassman. 2022. Expectation vs. experience: Evaluating the usability of code generation tools powered by large language models. In Chi conference on human factors in computing systems extended abstracts. ACM, NY, USA, 1-7.

[77] Jelle van Dijk. 2020. Post-Human Interaction Design, Yes, but Cautiously. In Companion Publication of the 2020 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (Eindhoven, Netherlands) (DIS’ 20 Companion). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 257-261. https: //doi.org/10.1145/3393914.3395886