DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.109040

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-04

الكشف التلقائي عن العرج في الأبقار الحلوب باستخدام الفيديو وتقدير الوضعية وخصائص الحركة المتعددة

الملخص

تقدم هذه الدراسة نظام كشف تلقائي عن العرج يستخدم تقنيات معالجة الصور العميقة لاستخراج خصائص الحركة المتعددة المرتبطة بالعرج. باستخدام نموذج تقدير الوضع T-LEAP، تم استخراج حركة تسع نقاط رئيسية من مقاطع الفيديو للأبقار التي تمشي. تم تسجيل مقاطع الفيديو في الهواء الطلق، مع ظروف إضاءة متغيرة، واستخرج T-LEAP

1. المقدمة

[9، 11، 7]. على حد علمنا، تستخدم جميع الدراسات تقريبًا حول كشف العرج من مقاطع الفيديو خاصية واحدة فقط كميزة لتسجيل العرج، وحتى الآن، فقط [23، [17]، و [8] دمجت خصائص الحركة المتعددة.

2. المواد

2.1. جمع البيانات

2.2. تقييم الحركة

| مراقب | درجة الحركة | |||||

| 1 | 2 | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ | إجمالي | |

| أ | ١١٥ | 99 | 27 | 31 | 0 | |

| ب | ١٠٩ | ٨٠ | ٥٤ | 26 | ٣ | 272 |

| ج | ١٠١ | ١١٩ | ٣٤ | 15 | ٣ | 272 |

| D | 141 | ٨٠ | ٣٨ | 12 | 1 | 272 |

| توزيع |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.3. موثوقية المراقبين والاتفاق

| مراقب | (أ، ب، ج، د) | أ | ب | ج | D |

| كريبندورف

|

0.602 | 0.611 | 0.552 | 0.653 | 0.585 |

| نسبة الاتفاق | ٥٥.٨ | ٥٦.٤ | ٤٩.١ | 60.0 | ٥٨.٢ |

2.4. دمج درجات الحركة

3. الطرق

3.1. تقدير الوضع

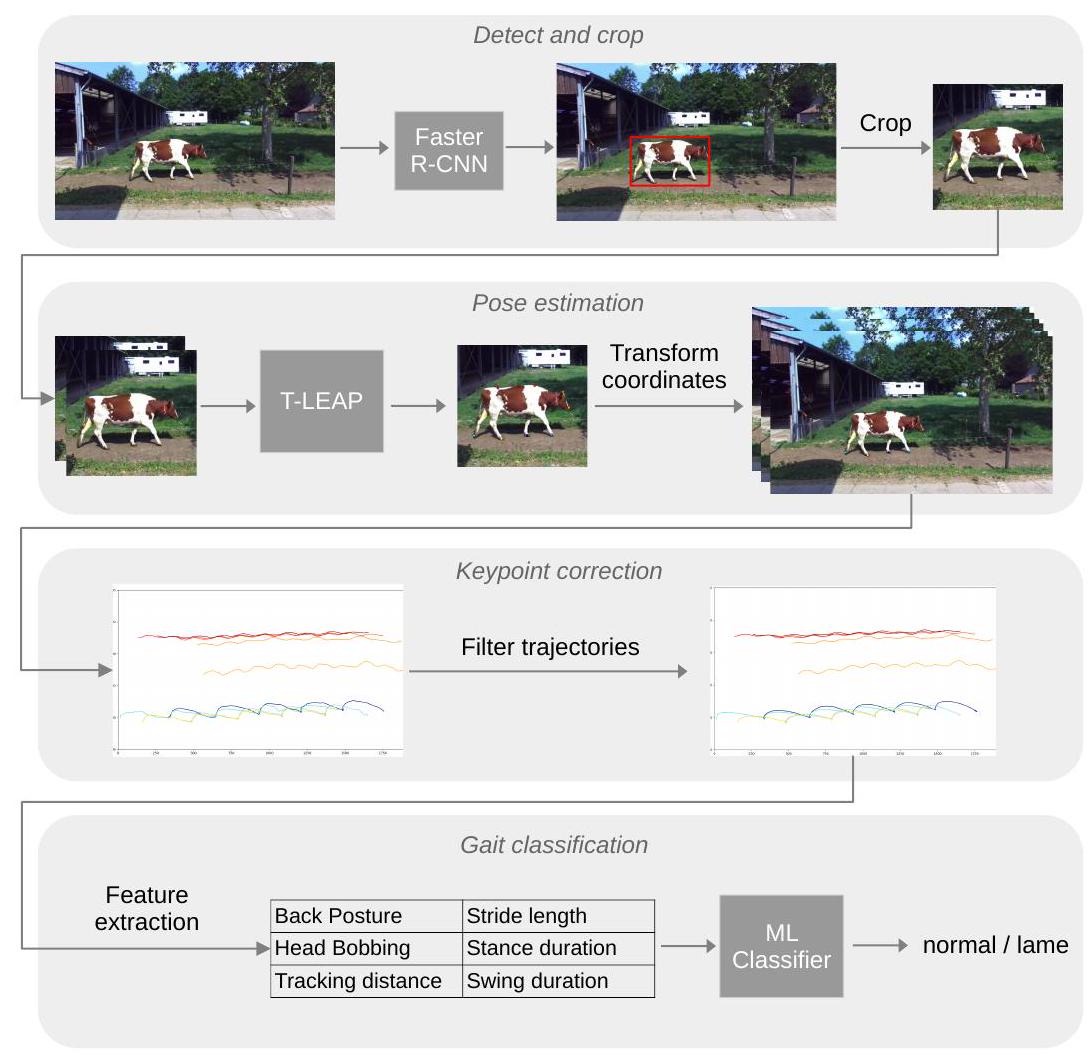

3.1.1. الكشف والقص

إطارات الفيديو باستخدام شبكة الأعصاب التلافيفية المعتمدة على المناطق الأسرع (Faster R-CNN)، وهو نموذج للكشف عن الأجسام يعيد إحداثيات صندوق محيط (bbox) حول كل جسم مثير للاهتمام (هنا، الأبقار). استخدمنا نموذج Faster R-CNN (مع هيكل ResNeXt-101) المدرب على مجموعة بيانات COCO-2017 من مكتبة Detectron2 [31]. احتوت مجموعة بيانات COCO-2017 على 118 ألف صورة تدريب مع تعليقات توضيحية لـ 80 فئة من الأجسام، من بينها 8014 تعليق توضيحي لصناديق محيط للأبقار. عمل نموذج Faster R-CNN من Detectron2 بشكل مباشر وكان قادرًا على اكتشاف الأبقار في إطارات الفيديو لدينا دون الحاجة إلى ضبط دقيق. تم إدخال كل إطار من كل فيديو إلى نموذج الكشف عن الأجسام، الذي أعاد قائمة بصناديق المحيط، واحدة لكل بقرة تم اكتشافها. لكل إطار، تم جعل صندوق المحيط مربعًا عن طريق تمديد الإحداثيات العلوية والسفلية لتتناسب مع العرض مع الحفاظ على البقرة في المنتصف عموديًا. تمت إضافة حشوة بكسل 100 إلى جميع الجوانب الأربعة لضمان رؤية جسم البقرة بالكامل في المنطقة المقتطعة. تم قص الصورة إلى إحداثيات صندوق المحيط الممدود وإعادة قياسها إلى حجم

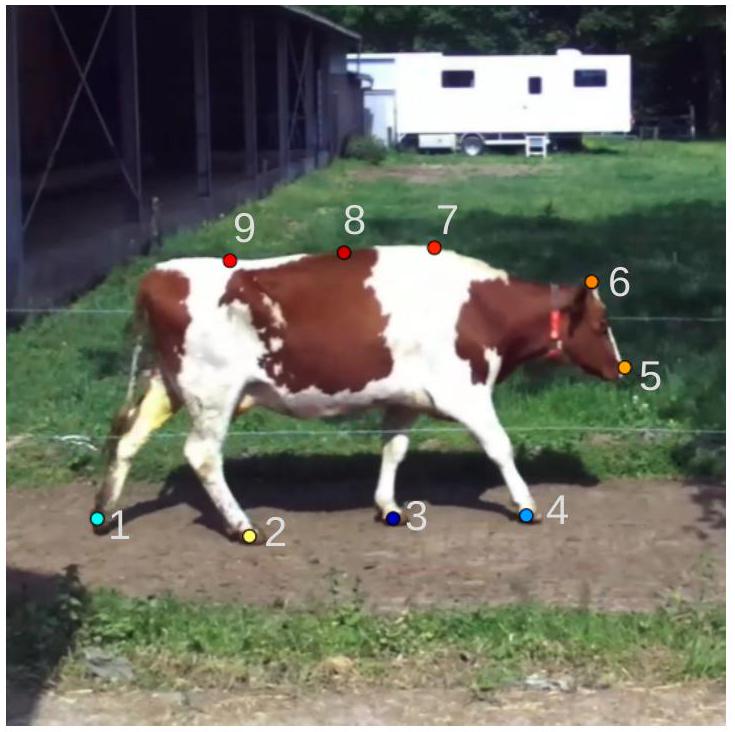

3.1.2. كشف النقاط الرئيسية

وتم إدخال تسلسلات من إطارين متتاليين إلى نموذج تقدير الوضع. ثم تم تحويل إحداثيات النقاط الرئيسية التي تنبأ بها النموذج إلى الإحداثيات الحقيقية للفيديو. لكل فيديو، أسفر ذلك عن إحداثيات

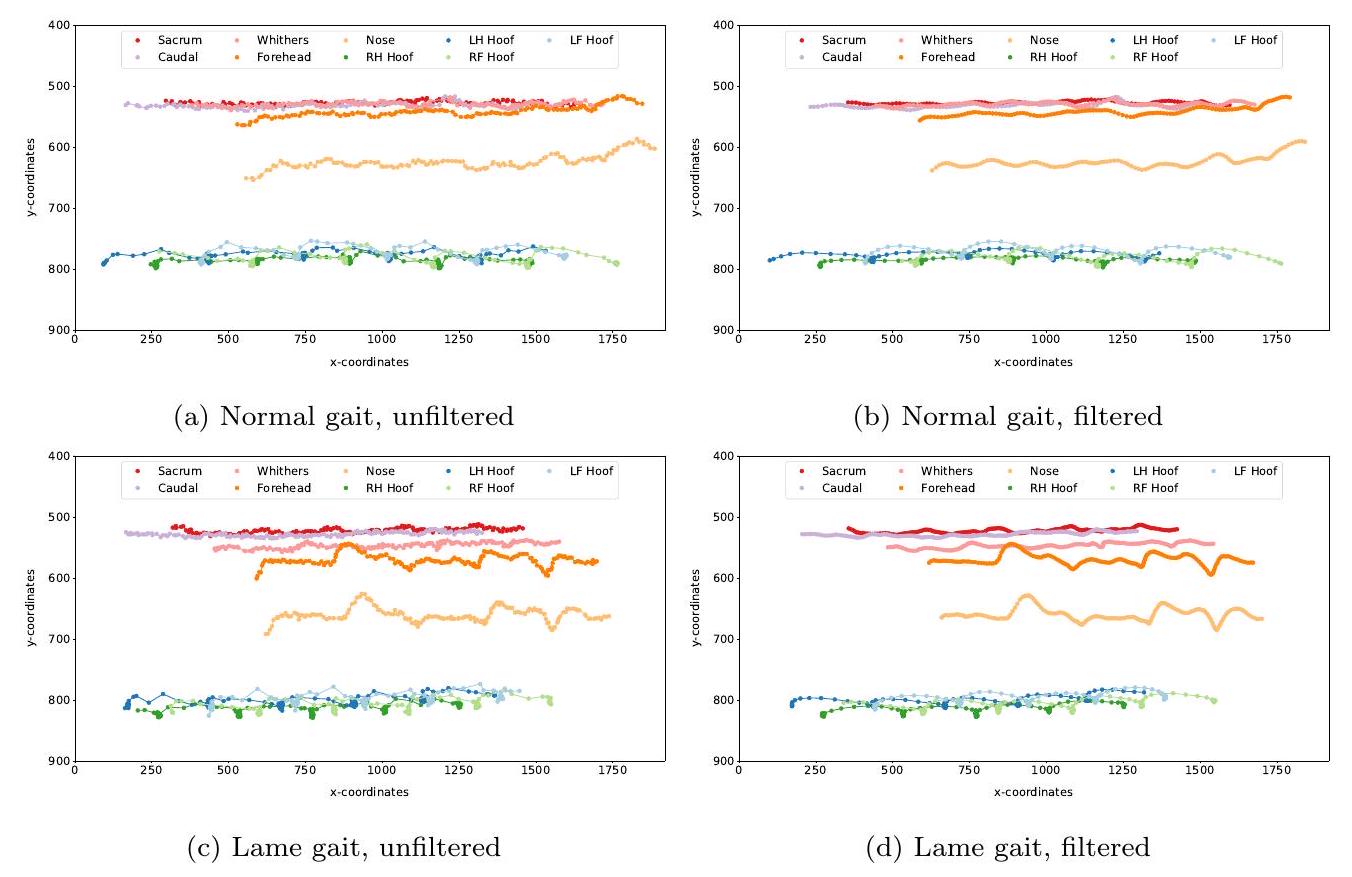

3.1.3. تصحيح النقاط الرئيسية

(النافذة=10، الترتيب=3) لتنعيم المسارات زمنياً. يوضح الشكل 3 أمثلة على المسارات مع القيم الشاذة قبل وبعد تطبيق الفلاتر.

3.2. استخراج ميزات المشي

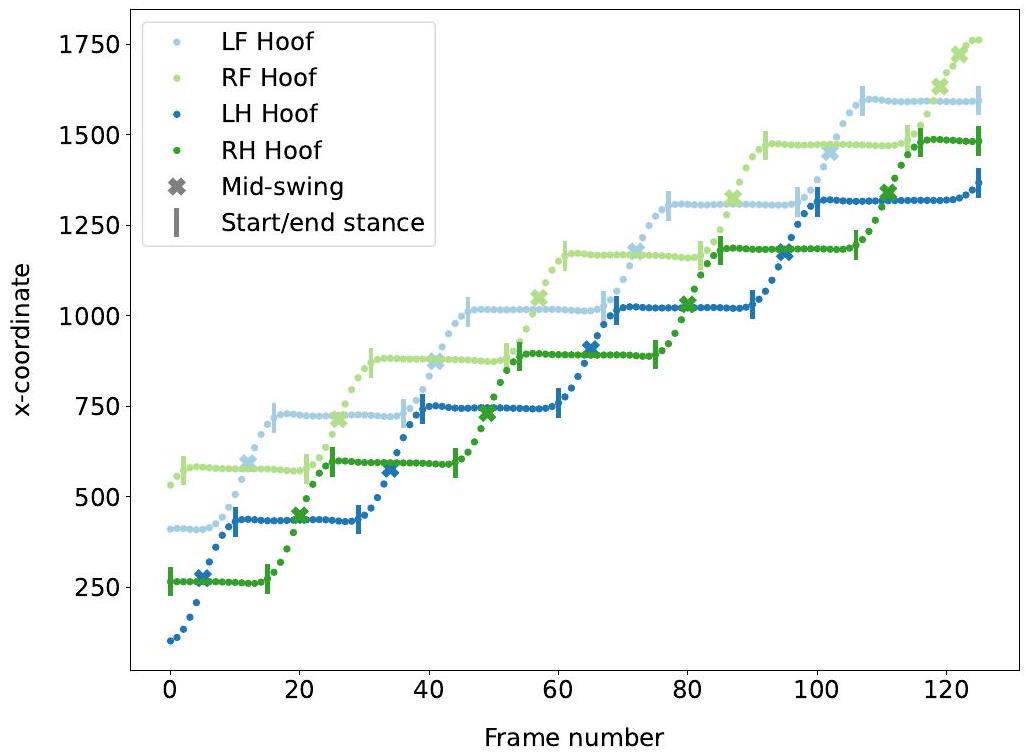

3.2.1. اكتشاف الخطوات

طوال مدة مرحلة التأرجح حتى تهبط وتبقى ثابتة لمرحلة وقوف أخرى. تم اكتشاف إطارات بداية ونهاية مراحل الوقوف من خلال العثور على متى ظلت إحداثيات x للحافر كما هي، أي من خلال العثور على هضاب من 10 إطارات على الأقل حيث كانت الفروق المطلقة في إحداثيات x بين إطارين هي

3.2.2. تصحيح الخطوات

في تلبية هذه المتطلبات، كان ذلك يشير إلى أن توقعات النقاط الرئيسية كانت صاخبة جدًا على تلك الحافر. تم العثور على أربعة فيديوهات فقط بها اكتشاف خطوات مشكلة. ثم تمت إزالة الإطارات ذات الخطوات المشكلة من مسارات النقاط الرئيسية، مما أسفر عن مسارات بها فجوة واحدة أو أكثر. ثم تم تقليم المسارات إلى الجزء الذي يحتوي على أكبر عدد من الإطارات المتبقية.

3.2.3. قياس وضع الظهر (BPM)

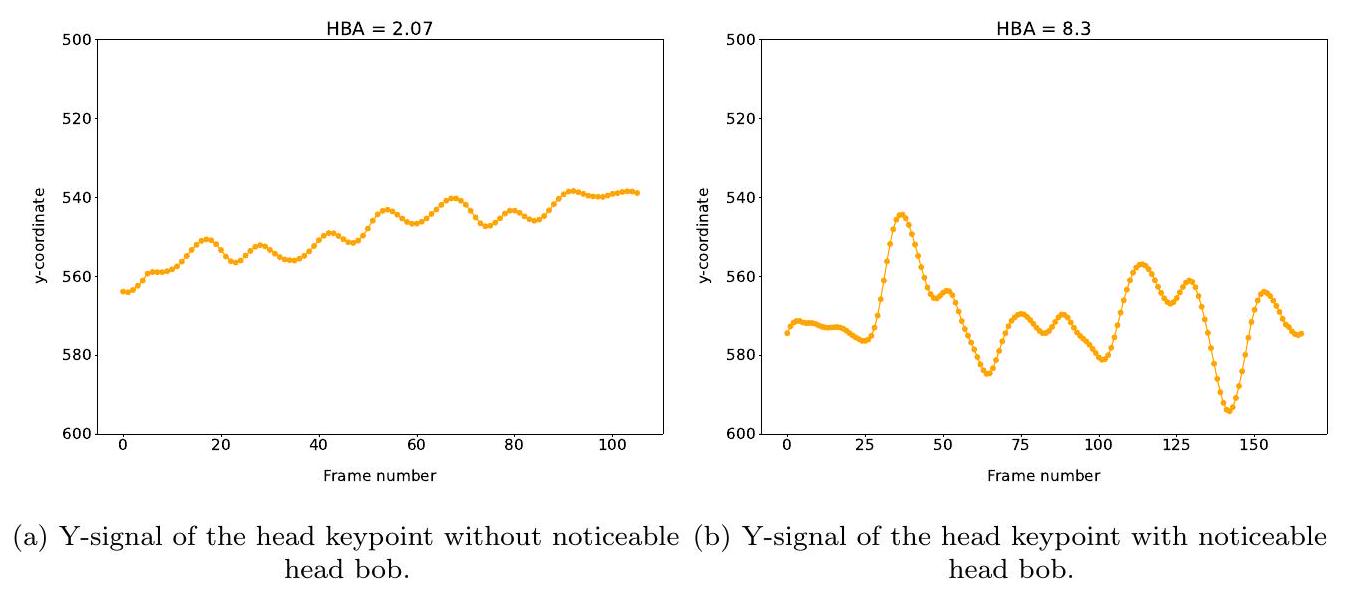

3.2.4. سعة اهتزاز الرأس (HBA)

3.2.5. مسافة التتبع (TRK)

3.2.6. فرق طول الخطوة (STL)

3.2.7. فرق مدة الوقوف (STD)

3.2.8. فرق مدة التأرجح (SWD)

| الميزة | الوصف |

| BPM | قياس وضع الظهر |

| HBA | سعة اهتزاز الرأس |

| TRK

|

مسافة التتبع على الجانب الأيسر |

| TRK

|

مسافة التتبع على الجانب الأيمن |

|

|

فرق طول الخطوة بين الحوافر الأمامية اليسرى واليمنى |

|

|

فرق طول الخطوة بين الحوافر الخلفية اليسرى واليمنى |

|

|

فرق مدة الوقوف بين الحوافر الأمامية اليسرى واليمنى |

|

|

فرق مدة الوقوف بين الحوافر الخلفية اليسرى واليمنى |

|

|

فرق مدة التأرجح بين الحوافر الأمامية اليسرى واليمنى |

|

|

فرق مدة التأرجح بين الحوافر الخلفية اليسرى واليمنى |

3.3. تصنيف العرج

3.3.1. إعداد البيانات

3.3.2. نماذج التصنيف

3.3.3. مقاييس التقييم

3.3.4. أهمية الميزات

4. النتائج

4.1. تقدير الوضع

إلى القيمة المتوسطة للنافذة الزمنية. بسبب نقص تعليقات النقاط الرئيسية على جميع الفيديوهات، لم يكن من الممكن تقييم تصحيح النقاط الرئيسية إلا نوعيًا. تم رسم مسارات النقاط الرئيسية قبل وبعد التصفية لكل فيديو وتم التحكم فيها بصريًا. تم اعتبار جودة المسارات المصفاة متوازنة، حيث كان من الممكن تصحيح معظم القيم الشاذة وبدت المسارات سلسة، دون تصحيح مفرط أو تسطيح. أدت القيم الشاذة التي لم يكن من الممكن تصحيحها بشكل كافٍ إلى اكتشاف خطوة خاطئة. تم بعد ذلك التخلص من هذه الخطوات من المسارات، كما هو مفصل في القسم 3.2.

| نقطة رئيسية |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

متوسط |

| PCKh@0.2 | 98.45 | 1 | 99.48 | 98.45 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.60 |

4.2. اكتشاف العرج

| النموذج | الدقة | درجة F1 | الحساسية | الخصوصية |

| الانحدار اللوجستي | 78.49 | 77.26 | 77.33 | 77.90 |

| SVM مع نواة خطية | 77.25 | 76.31 | 75.39 | 77.90 |

| SVM مع نواة شعاعية |

|

|

76.78 |

|

| الغابات العشوائية | 79.66 | 78.44 | 83.68 | 74.64 |

| تعزيز التدرج | 79.12 | 77.79 |

|

72.05 |

| الشبكة العصبية متعددة الطبقات | 78.97 | 77.60 | 80.74 | 74.59 |

4.3. أهمية الميزات

| ميزات SVM-R | الدقة | درجة F1 | الحساسية | الخصوصية |

| BPM | 76.66 | 74.81 | 63.26 | 86.69 |

| BPM، HBA | 79.31 | 77.50 | 77.42 | 77.32 |

| BPM، HBA، TRK | 79.87 | 78.22 | 76.35 | 80.14 |

| BPM، HBA، TRK، STD | 79.47 | 77.87 | 77.09 | 78.89 |

| BPM، HBA، TRK، STD، STL | 79.18 | 78.03 | 78.31 | 79.17 |

| BPM، HBA، TRK، STD، STL، SWD | 80.07 | 78.70 | 76.78 | 81.15 |

5. المناقشة

5.1. معالجة الفيديو

المشي الطوعي. في الممارسة العملية، يمكن تنفيذ هذه القيود عن طريق تخطي مقاطع الفيديو حيث تكشف Faster-R-CNN (أو أي كاشف كائن آخر) عن أكثر من بقرة واحدة، أو كما تم القيام به في 17، من خلال تنفيذ خوارزمية تتبع تتبع كل بقرة عبر الفيديو.

5.2. تسجيل الحركة

5.3. اكتشاف العرج

تسجيل المشي الدقيق. تم ترك تسجيل الحركة الدقيق للبحث المستقبلي حيث سيتطلب جمع المزيد من لقطات الفيديو مع أمثلة كافية من درجات المشي 3 وما فوق.

5.4. أهمية الميزات

أهمية أكثر من تلك الموجودة على الجانب الأيمن (TRK-R). قد يشير هذا إلى أنه في مجموعة البيانات الخاصة بنا، كان هناك المزيد من الأبقار تتجه للأعلى على الجانب الأيسر مقارنةً بالجانب الأيمن.

5.5. المقارنة مع الأعمال ذات الصلة

نقارن نتائجنا مع الأعمال السابقة التي نعتبرها مرتبطة مباشرة بأعمالنا.

تم استخراج السعة من المسار بالكامل. تم إجراء اختيار الميزات على النحو التالي: تم إجراء اختبار كاي-تربيع على مجموعة البيانات الكاملة. أظهر الاختبار أن قياس وضعية الظهر وحركة الرأس كانت الميزات الأكثر أهمية. بالمقابل، وجدنا أن إضافة تتبع الرأس إلى الميزتين الأخريين أدى إلى نتائج أفضل على مجموعة بياناتنا. قد يعني ذلك أنه في مجموعة بياناتهم، لم يكن الأشخاص المعاقون يتتبعون الرأس. تفسير آخر قد يكون أنه مع زيادة عدد الصفات، تزداد تعقيد البيانات، وقد يكون من الضروري استخدام مصنف غير خطي، مثل SVM-R. تم تدريب عدة مصنفات باستخدام انحناء الظهر وحركة الرأس، وعاد مصنف الانحدار اللوجستي بأفضل النتائج، مع دقة تصنيف تبلغ

قمنا بتجميع القيم في القيمة الوسيطة للفيديو. في ضوء الأداء الممتاز لمصنفاتهم، فإن اتجاهًا واعدًا لتوسيع عملنا سيكون استخراج المزيد من الميزات الإحصائية من سمات الحركة، مثل المتوسط، والانحراف المعياري، والقيم الدنيا والقصوى، لتحسين أداء تصنيفنا بشكل أكبر.

6. الخاتمة

الشكر والتقدير

إعلان المصالح

References

[2] H. R. Whay, J. K. Shearer, The impact of lameness on welfare of the dairy cow, Veterinary Clinics: Food Animal Practice 33 (2) (2017) 153-164.

[3] H. Enting, D. Kooij, A. Dijkhuizen, R. Huirne, E. Noordhuizen-Stassen, Economic losses due to clinical lameness in dairy cattle, Livestock production science 49 (3) (1997) 259-267.

[4] J. Huxley, Impact of lameness and claw lesions in cows on health and production, Livestock Science 156 (1-3) (2013) 64-70.

[5] X. Song, T. Leroy, E. Vranken, W. Maertens, B. Sonck, D. Berckmans, Automatic detection of lameness in dairy cattle-Vision-based trackway analysis in cow’s locomotion, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 64 (1) (2008) 39-44, iSBN: 0168-1699 eprint: 9809069v1. doi:10.1016/j.compag. 2008.05.016

[6] A. Poursaberi, C. Bahr, A. Pluk, A. V. Nuffel, D. Berckmans, A. Van Nuffel, D. Berckmans, Real-time automatic lameness detection based on back posture extraction in dairy cattle: Shape analysis of cow with image processing techniques, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 74 (1) (2010) 110-119, iSBN: 0168-1699 Publisher: Elsevier B.V. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2010.07.004 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2010.07.004

[7] Z. Zheng, X. Zhang, L. Qin, S. Yue, P. Zeng, Cows’ legs tracking and lameness detection in dairy cattle using video analysis and Siamese neural networks, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 205 (2023) 107618. doi: 10.1016/j. compag. 2023.107618. URL haps://uvs sciencedirect com/science/article/pil S0168169923000066

[8] K. Zhao, M. Zhang, J. Ji, R. Zhang, J. M. Bewley, Automatic lameness scoring of dairy cows based on the analysis of head- and back-hoof linkage features using machine learning methods, Biosystems Engineering 230 (2023) 424-441. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2023.05.003

URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S153751102300106X

[9] N. Blackie, E. Bleach, J. Amory, J. Scaife, Associations between locomotion score and kinematic measures in dairy cows with varying hoof lesion types, Journal of Dairy Science 96 (6) (2013) 3564-3572, iSBN: 0022-0302 Publisher: Elsevier. doi:10.3168/jds.2012-5597.

URL http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022030213002282

[10] Y. Karoui, A. A. B. Jacques, A. B. Diallo, E. Shepley, E. Vasseur, A Deep Learning Framework for Improving Lameness Identification in Dairy Cattle, Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 35 (18) (2021) 15811-15812, number: 18.

[11] D. Wu, Q. Wu, X. Yin, B. Jiang, H. Wang, D. He, H. Song, Lameness detection of dairy cows based on the YOLOv3 deep learning algorithm and a relative step size characteristic vector, Biosystems Engineering 189 (2020) 150-163, publisher: Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng. 2019.11.017.

URL https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2019.11.017

[12] X. Kang, X. D. Zhang, G. Liu, Accurate detection of lameness in dairy cattle with computer vision: A new and individualized detection strategy based on the analysis of the supporting phase, Journal of Dairy Science 103 (11) (2020) 10628-10638, publisher: Elsevier. doi:10.3168/jds. 2020-18288.

URL https://www-journalofdairyscience-org.ezproxy.library.wur.nl/ article/S0022-0302(20)30713-X/abstract

[13] B. Jiang, H. Song, H. Wang, C. Li, Dairy cow lameness detection using a back curvature feature, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 194 (2022) 106729. doi:10.1016/j.compag. 2022.106729

URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0168169922000461

[14] E. Arazo, R. Aly, K. McGuinness, Segmentation Enhanced Lameness Detection in Dairy Cows from RGB and Depth Video, arXiv:2206.04449 [cs] (Jun. 2022). doi:10.48550/arXiv.2206.04449.

URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2206.04449

[15] A. Mathis, P. Mamidanna, K. M. Cury, T. Abe, V. N. Murthy, M. W. Mathis, M. Bethge, DeepLabCut: markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning, Nature Neuroscience 21 (9) (2018) 1281-1289, number: 9 Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0209-y.

URL https://www.nature.com/articles/s41593-018-0209-y.

[16] H. Russello, R. van der Tol, G. Kootstra, T-LEAP: Occlusion-robust pose estimation of walking cows using temporal information, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 192 (2022) 106559. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2021.106559

URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0168169921005767

[17] S. Barney, S. Dlay, A. Crowe, I. Kyriazakis, M. Leach, Deep learning pose estimation for multi-cattle lameness detection, Scientific Reports 13 (1) (2023) 4499.

[18] M. Taghavi, H. Russello, W. Ouweltjes, C. Kamphuis, I. Adriaens, Cow key point detection in indoor housing conditions with a deep learning model, Journal of Dairy Science (2023).

[19] S. Viazzi, C. Bahr, A. Schlageter-Tello, T. Van Hertem, C. Romanini, A. Pluk, I. Halachmi, C. Lokhorst, D. Berckmans, Analysis of individual classification of lameness using automatic measurement of back posture in dairy cattle, Journal of Dairy Science 96 (1) (2012) 257-266, publisher: Elsevier. doi:10.3168/jds 2012-5806.

URL http://dx.doi.org/10.3168/jds.2012-5806

[20] T. Van Hertem, S. Viazzi, M. Steensels, E. Maltz, A. Antler, V. Alchanatis, A. A. Schlageter-Tello, K. Lokhorst, E. C. Romanini, C. Bahr, D. Berckmans, I. Halachmi, Automatic lameness detection based on consecutive 3D-video recordings, Biosystems Engineering 119 (2014) 108-116, iSBN: 9789088263330 Publisher: IAgrE. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2014.01.009.

[21] S. Viazzi, C. Bahr, T. Van Hertem, A. Schlageter-Tello, C. E. B. Romanini, I. Halachmi, C. Lokhorst, D. Berckmans, Comparison of a three-dimensional and twodimensional camera system for automated measurement of back posture in dairy cows. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 100 (2014) 139-147, iSBN: 0168-1699

URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2013.11.005

[22] T. Van Hertem, A. S. Tello, S. Viazzi, M. Steensels, C. Bahr, C. E. B. Romanini, K. Lokhorst, E. Maltz, I. Halachmi, D. Berckmans, A. Schlageter Tello, S. Viazzi, M. Steensels, C. Bahr, C. E. B. Romanini, K. Lokhorst, E. Maltz, I. Halachmi, D. Berckmans, Implementation of an automatic 3D vision monitor for dairy cow locomotion in a commercial farm, Biosystems Engineering 173 (2018) 166-175, iSBN: 1537-5110 Publisher: Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2017.08.011.

[23] K. Zhao, J. Bewley, D. He, X. Jin, Automatic lameness detection in dairy cattle based on leg swing analysis with an image processing technique, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 148 (2018) 226-236.

[24] A. Schlageter-Tello, E. A. Bokkers, P. W. Groot Koerkamp, T. Van Hertem, S. Viazzi, C. E. Romanini, I. Halachmi, C. Bahr, D. Berckmans, K. Lokhorst, Effect of merging levels of locomotion scores for dairy cows on intra- and interrater reliability and agreement, Journal of Dairy Science 97 (9) (2014) 5533-5542, publisher: Elsevier. doi:10.3168/jds.2014-8129.

URL http://dx.doi.org/10.3168/jds.2014-8129

[25] A. Schlageter-Tello, E. A. Bokkers, P. W. Groot Koerkamp, T. Van Hertem, S. Viazzi, C. E. Romanini, I. Halachmi, C. Bahr, D. Berckmans, K. Lokhorst, Relation between observed locomotion traits and locomotion score in dairy cows, Journal of Dairy Science 98 (12) (2015) 8623-8633. doi:10.3168/jds.2014-9059

URL https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022030215006633

[26] D. Sprecher, D. Hostetler, J. Kaneene, A LAMENESS SCORING SYSTEM THAT USES POSTURE AND GAIT TO PREDICT DAIRY CATTLE REPRODUCTIVE PERFORMANCE, Science (97) (1997).

[27] P. Thomsen, L. Munksgaard, F. Tøgersen, Evaluation of a lameness scoring system for dairy cows, Journal of dairy science 91 (1) (2008) 119-126.

[28] F. C. Flower, D. M. Weary, Effect of Hoof Pathologies on Subjective Assessments of Dairy Cow Gait, Journal of Dairy Science 89 (1) (2006) 139-146. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72077-X.

URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S002203020672077X

[29] K. Krippendorff, Computing krippendorff’s alpha-reliability (2011).

[30] B. Engel, G. Bruin, G. Andre, W. Buist, Assessment of observer performance in a subjective scoring system: visual classification of the gait of cows, The Journal of Agricultural Science 140 (3) (2003) 317-333, publisher: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/S0021859603002983.

URL http://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/

journal-of-agricultural-science/article/assessment-of-observer-performance-in-a-subjectiv A4C2BDAAE4803FE2DFE34013FC8F6DE9#access-block

[31] Y. Wu, A. Kirillov, F. Massa, W.-Y. Lo, R. Girshick, Detectron2, https://github com/facebookresearch/detectron2 (2019).

[32] A. Savitzky, M. J. Golay, Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures., Analytical chemistry 36 (8) (1964) 1627-1639.

[33] J. W. Cooley, J. W. Tukey, An algorithm for the machine calculation of complex fourier series, Mathematics of computation 19 (90) (1965) 297-301.

[34] L. Buitinck, G. Louppe, M. Blondel, F. Pedregosa, A. Mueller, O. Grisel, V. Niculae, P. Prettenhofer, A. Gramfort, J. Grobler, et al., Api design for machine learning software: experiences from the scikit-learn project, arXiv preprint arXiv:1309.0238 (2013).

[35] N. V. Chawla, K. W. Bowyer, L. O. Hall, W. P. Kegelmeyer, Smote: synthetic minority over-sampling technique, Journal of artificial intelligence research 16 (2002) 321-357.

[36] F. Pedregosa, G. Varoquaux, A. Gramfort, V. Michel, B. Thirion, O. Grisel, M. Blondel, P. Prettenhofer, R. Weiss, V. Dubourg, J. Vanderplas, A. Passos, D. Cournapeau, M. Brucher, M. Perrot, E. Duchesnay, Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python, Journal of Machine Learning Research 12 (2011) 2825-2830.

[37] J. Wainer, G. Cawley, Nested cross-validation when selecting classifiers is overzealous for most practical applications, Expert Systems with Applications 182 (2021) 115222.

[38] L. Breiman, Random forests, Machine learning 45 (2001) 5-32.

[39] A. Schlageter-Tello, E. Bokkers, P. G. Koerkamp, T. Van Hertem, S. Viazzi, C. Romanini, I. Halachmi, C. Bahr, D. Berckmans, K. Lokhorst, Comparison of locomotion scoring for dairy cows by experienced and inexperienced raters using live or video observation methods, Animal Welfare 24 (1) (2015) 69-79.

[40] J. Wainer, Comparison of 14 different families of classification algorithms on 115 binary datasets, arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.00930 (2016).

[41] D. H. Wolpert, The lack of a priori distinctions between learning algorithms, Neural computation 8 (7) (1996) 1341-1390.

[42] T. Borderas, A. Fournier, J. Rushen, A. De Passille, Effect of lameness on dairy cows’ visits to automatic milking systems, Canadian Journal of Animal Science 88 (1) (2008) 1-8.

[43] N. Chapinal, A. De Passille, D. Weary, M. Von Keyserlingk, J. Rushen, Using gait score, walking speed, and lying behavior to detect hoof lesions in dairy cows, Journal of dairy science 92 (9) (2009) 4365-4374.

[44] A. Nejati, A. Bradtmueller, E. Shepley, E. Vasseur, Technology applications in bovine gait analysis: A scoping review, Plos one 18 (1) (2023) e0266287.

[45] Q. Wang, H. Bovenhuis, Validation strategy can result in an overoptimistic view of the ability of milk infrared spectra to predict methane emission of dairy cattle, Journal of dairy science 102 (7) (2019) 6288-6295.

- *Corresponding authors

Email addresses: helena.russello@wur.nl (Helena Russello ), gert.kootstra@wur.nl (Gert Kootstra )

Preprint submitted to Elsevier

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.109040

Publication Date: 2024-06-04

Video-based Automatic Lameness Detection of Dairy Cows using Pose Estimation and Multiple Locomotion Traits

Abstract

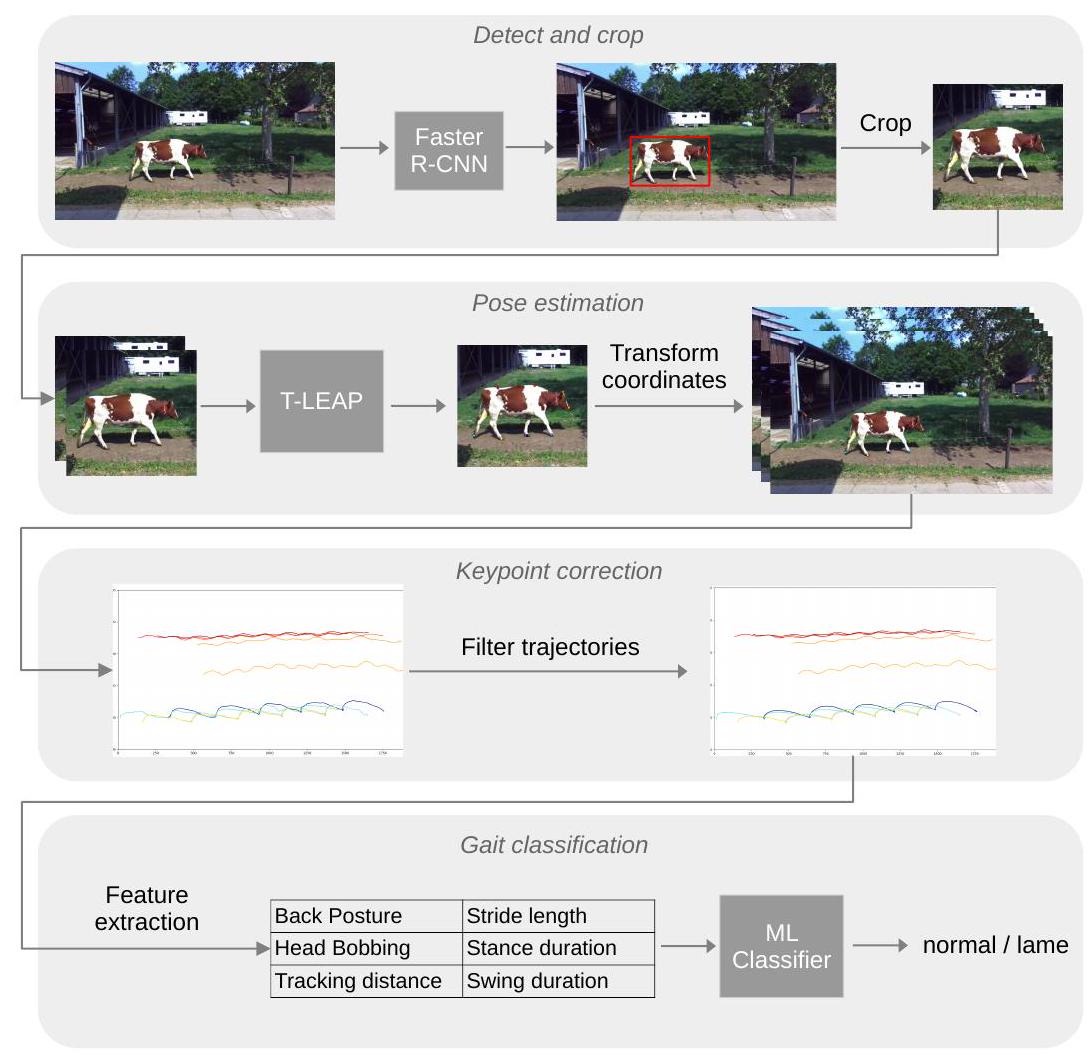

This study presents an automated lameness detection system that uses deep-learning image processing techniques to extract multiple locomotion traits associated with lameness. Using the T-LEAP pose estimation model, the motion of nine keypoints was extracted from videos of walking cows. The videos were recorded outdoors, with varying illumination conditions, and T-LEAP extracted

1. Introduction

length [9, 11, 7]. To the best of our knowledge, almost all studies on lameness detection from videos use only one locomotion trait as a feature to score lameness, and so far, only [23, [17], and [8] combined multiple locomotion traits.

2. Materials

2.1. Data acquisition

2.2. Locomotion scoring

| Observer | Locomotion score | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total | |

| A | 115 | 99 | 27 | 31 | 0 | |

| B | 109 | 80 | 54 | 26 | 3 | 272 |

| C | 101 | 119 | 34 | 15 | 3 | 272 |

| D | 141 | 80 | 38 | 12 | 1 | 272 |

| Distribution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.3. Observers reliability and agreement

| Observer | (A,B,C,D) | A | B | C | D |

| Krippendorff’s

|

0.602 | 0.611 | 0.552 | 0.653 | 0.585 |

| Percentage of Agreement | 55.8 | 56.4 | 49.1 | 60.0 | 58.2 |

2.4. Merging the locomotion scores

3. Methods

3.1. Pose estimation

3.1.1. Detect-and-crop

video frames using the Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (Faster R-CNN), an object-detection model that returns the coordinates of a bounding box (bbox) around each object of interest (here, cows). We used the Faster R-CNN model (with ResNeXt-101 backbone) trained on the COCO-2017 dataset from the Detectron2 library [31]. The COCO-2017 dataset contained 118 K training images with annotations for 80 categories of objects, among which 8014 bounding-box annotations of cows. The Faster R-CNN model from Detectron2 worked out of the box and could detect the cows in our video frames without fine-tuning. Each frame of each video was fed to the object-detection model, which returned a list of bounding boxes, one for each detected cow. For each frame, the bounding box was made square by extending the top and bottom coordinates to match the width while keeping the cow vertically centered. A 100-pixel padding was added to all four sides to ensure that the body of the cow was fully visible in the cropped area. The image was cropped to the coordinates of the extended bounding box and re-scaled to a size of

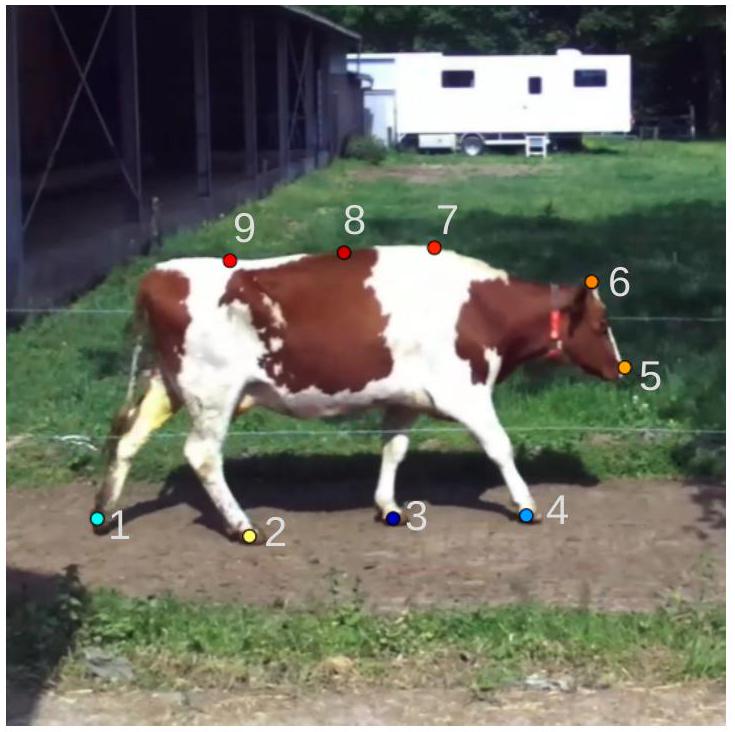

3.1.2. Keypoint detection

and sequences of 2 consecutive frames were fed to the pose estimation model. The keypoint coordinates predicted by the model were then transformed to the true coordinates of the video. For each video, this resulted in the coordinates

3.1.3. Keypoint correction

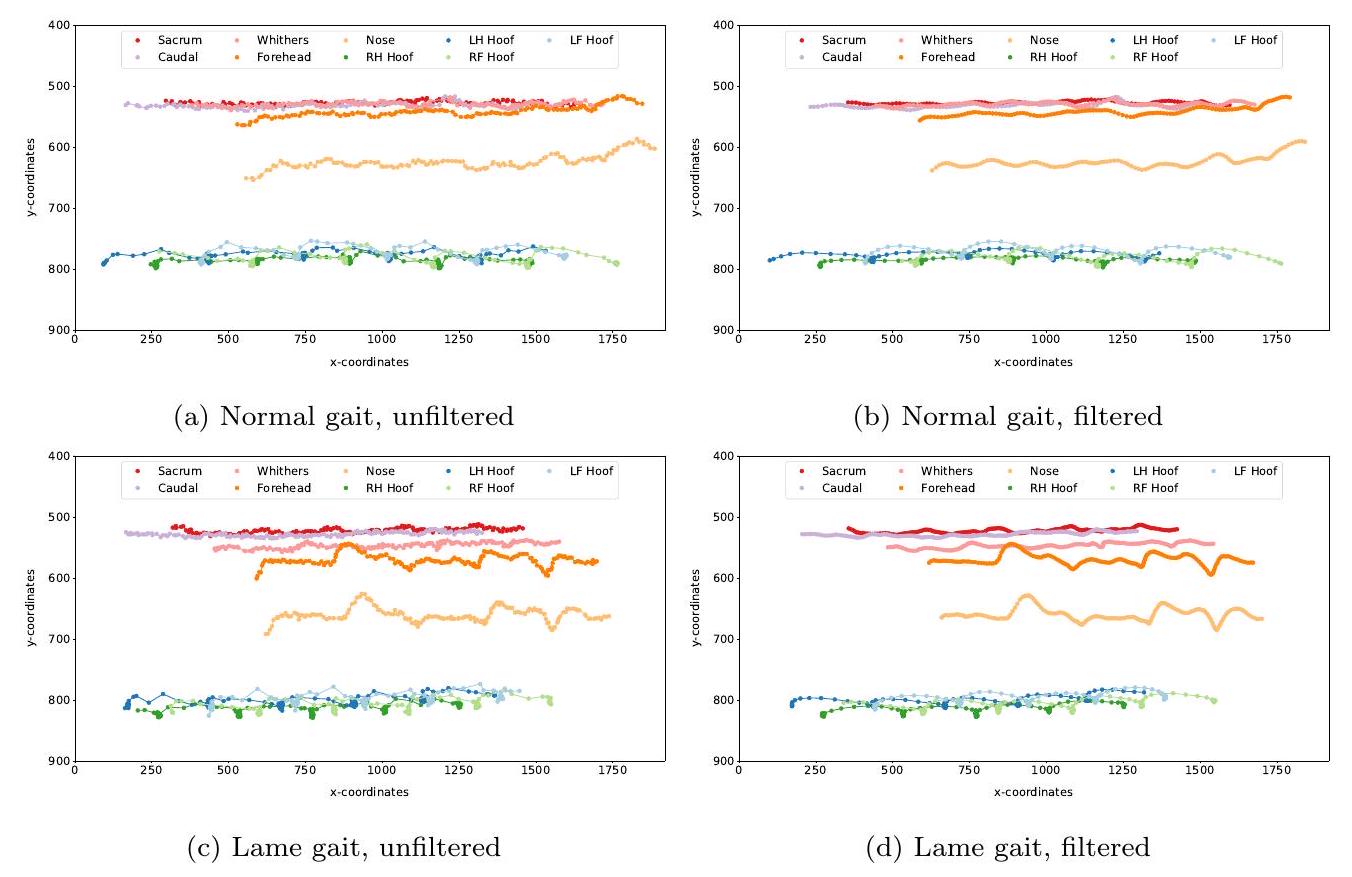

(window=10, order=3) to smooth the trajectories temporally. Figure 3 shows examples of trajectories with outliers before and after applying the filters.

3.2. Gait features extraction

3.2.1. Step detection

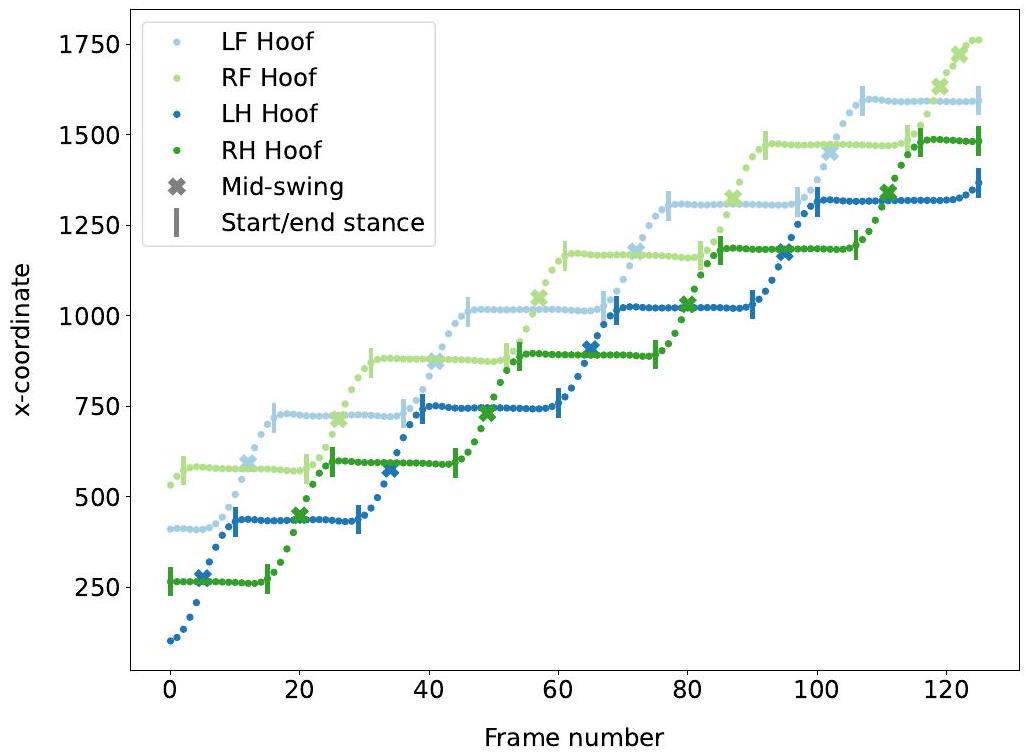

for the whole duration of the swing phase until it lands and remains still for another stance phase. The start and end frames of the stance phases were detected by finding when the x-coordinates of the hoof remained the same, that is, by finding plateaus of at least 10 frames where the absolute difference in x-coordinates between two frames was

3.2.2. Step correction

failed to meet these requirements, this indicated that the keypoint predictions were too noisy on that hoof. Only four videos were found to have problematic step detection. The frames with problematic steps were then removed from the keypoint trajectories, resulting in trajectories with one or several gaps. The trajectories were then trimmed to the part with the most remaining frames.

3.2.3. Back posture measurement (BPM)

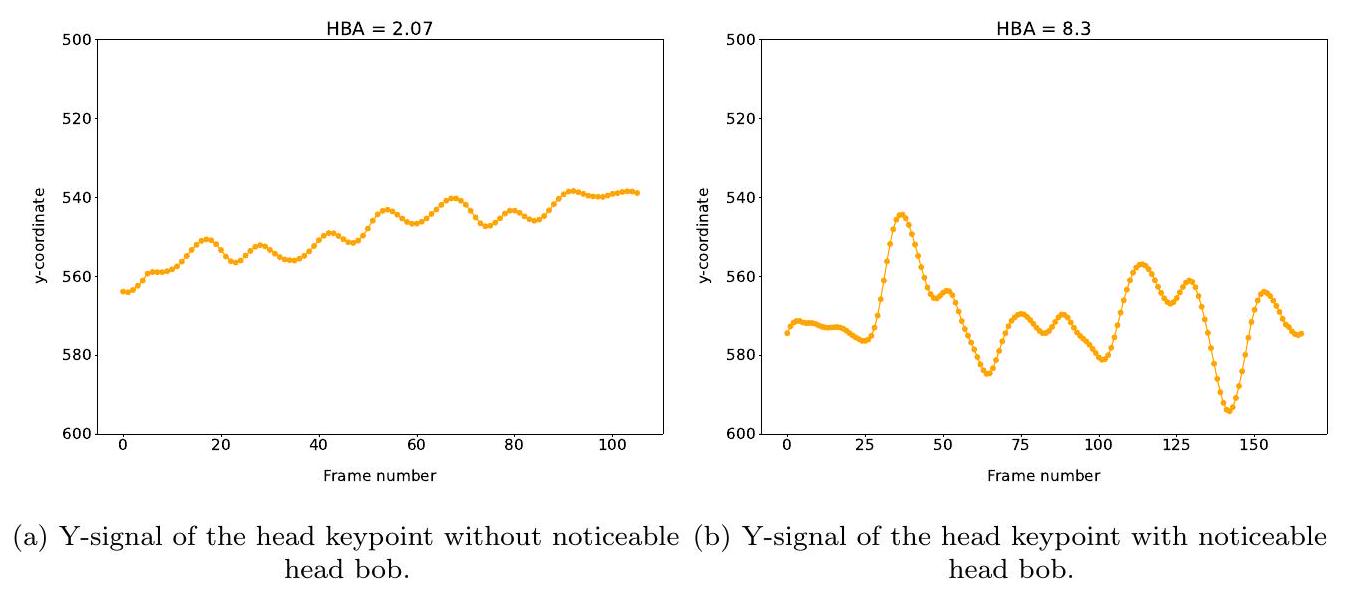

3.2.4. Head bobbing amplitude (HBA)

3.2.5. Tracking distance (TRK)

3.2.6. Stride length difference (STL)

3.2.7. Stance duration difference (STD)

3.2.8. Swing duration difference (SWD)

| Feature | Description |

| BPM | Back posture measurement |

| HBA | Head bobbing amplitude |

| TRK

|

Tracking distance on the left side |

| TRK

|

Tracking distance on the right side |

|

|

Stride length difference between left- and right-front hooves |

|

|

Stride length difference between left- and right-hind hooves |

|

|

Stance duration difference between left- and right-front hooves |

|

|

Stance duration difference between left- and right-hind hooves |

|

|

Swing duration difference between left- and right-front hooves |

|

|

Swing duration difference between left- and right-hind hooves |

3.3. Lameness classification

3.3.1. Data preparation

3.3.2. Classification models

3.3.3. Evaluation metrics

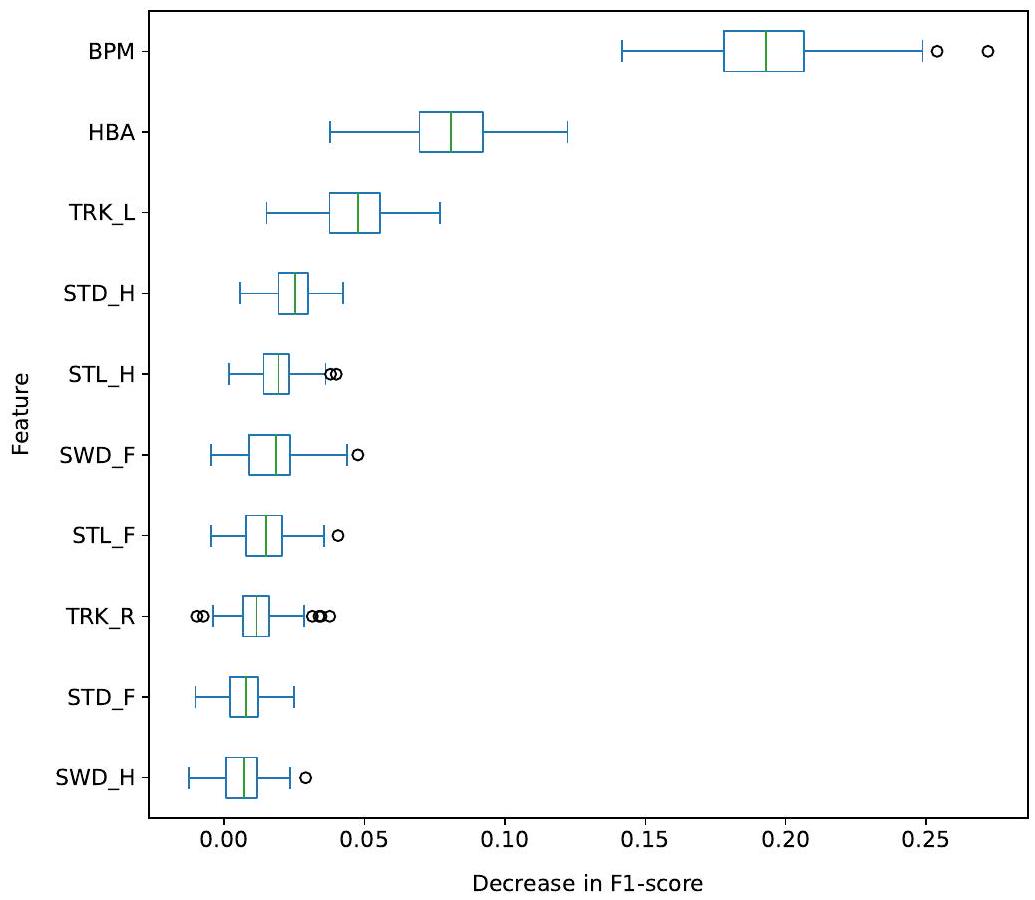

3.3.4. Feature importance

4. Results

4.1. Pose estimation

to the median value of the temporal window. Because of the lack of keypoint annotations on all videos, the keypoint correction could only be assessed qualitatively. The trajectories of the keypoints before and after the filtering were plotted for each video and controlled visually. The quality of the filtered trajectories was deemed balanced, in that most of the outliers could be corrected and the trajectories appeared smooth, without over-correction or flattening. The outliers that could not be corrected sufficiently led to a wrong step detection. These steps were then discarded from trajectories, as detailed in section 3.2.

| Keypoint |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mean |

| PCKh@0.2 | 98.45 | 1 | 99.48 | 98.45 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.60 |

4.2. Lameness detection

| Model | Accuracy | F1-score | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| Logistic Regression | 78.49 | 77.26 | 77.33 | 77.90 |

| SVM linear kernel | 77.25 | 76.31 | 75.39 | 77.90 |

| SVM radial kernel |

|

|

76.78 |

|

| Random Forests | 79.66 | 78.44 | 83.68 | 74.64 |

| Gradient Boosting | 79.12 | 77.79 |

|

72.05 |

| Multi-Layer Perceptron | 78.97 | 77.60 | 80.74 | 74.59 |

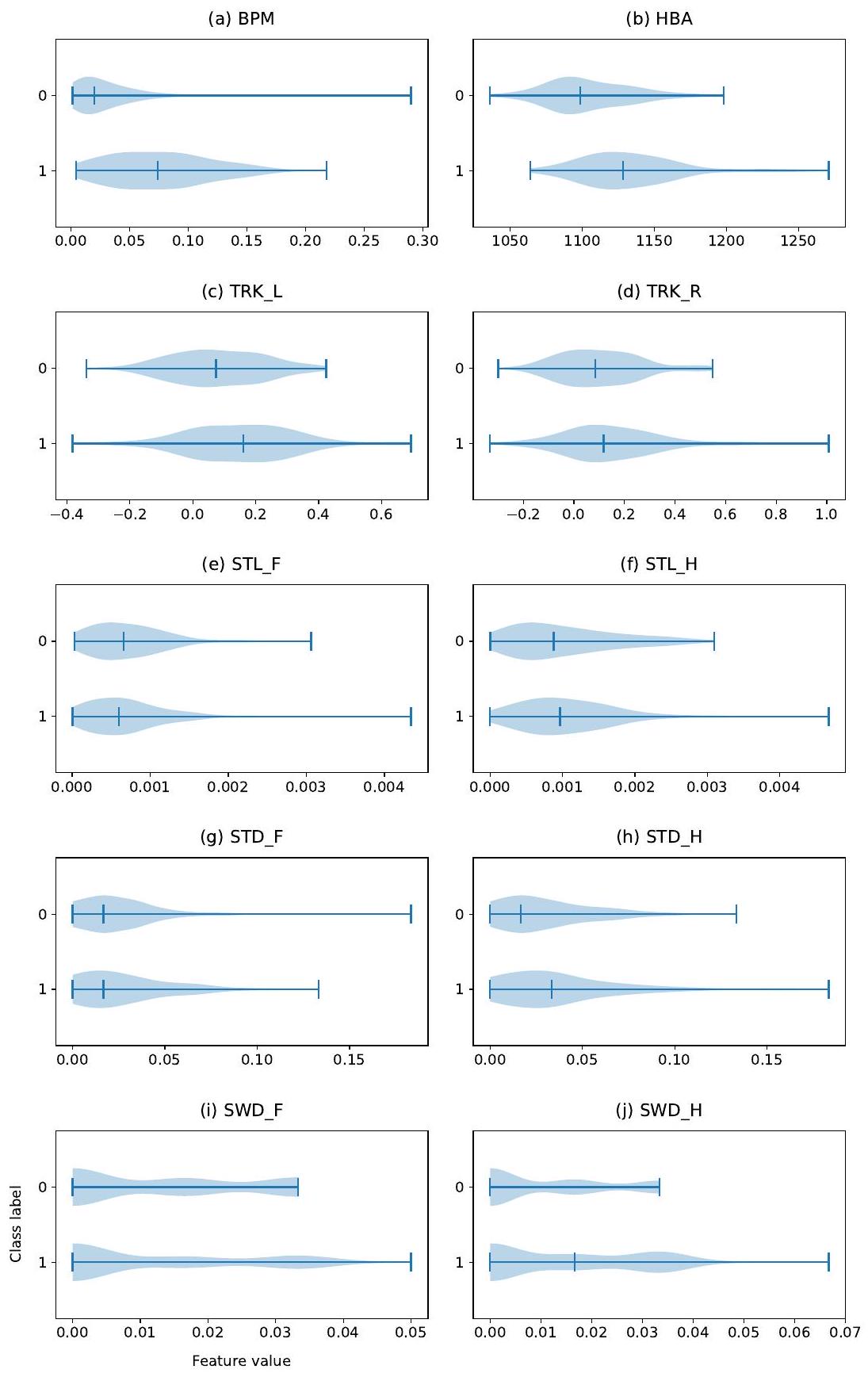

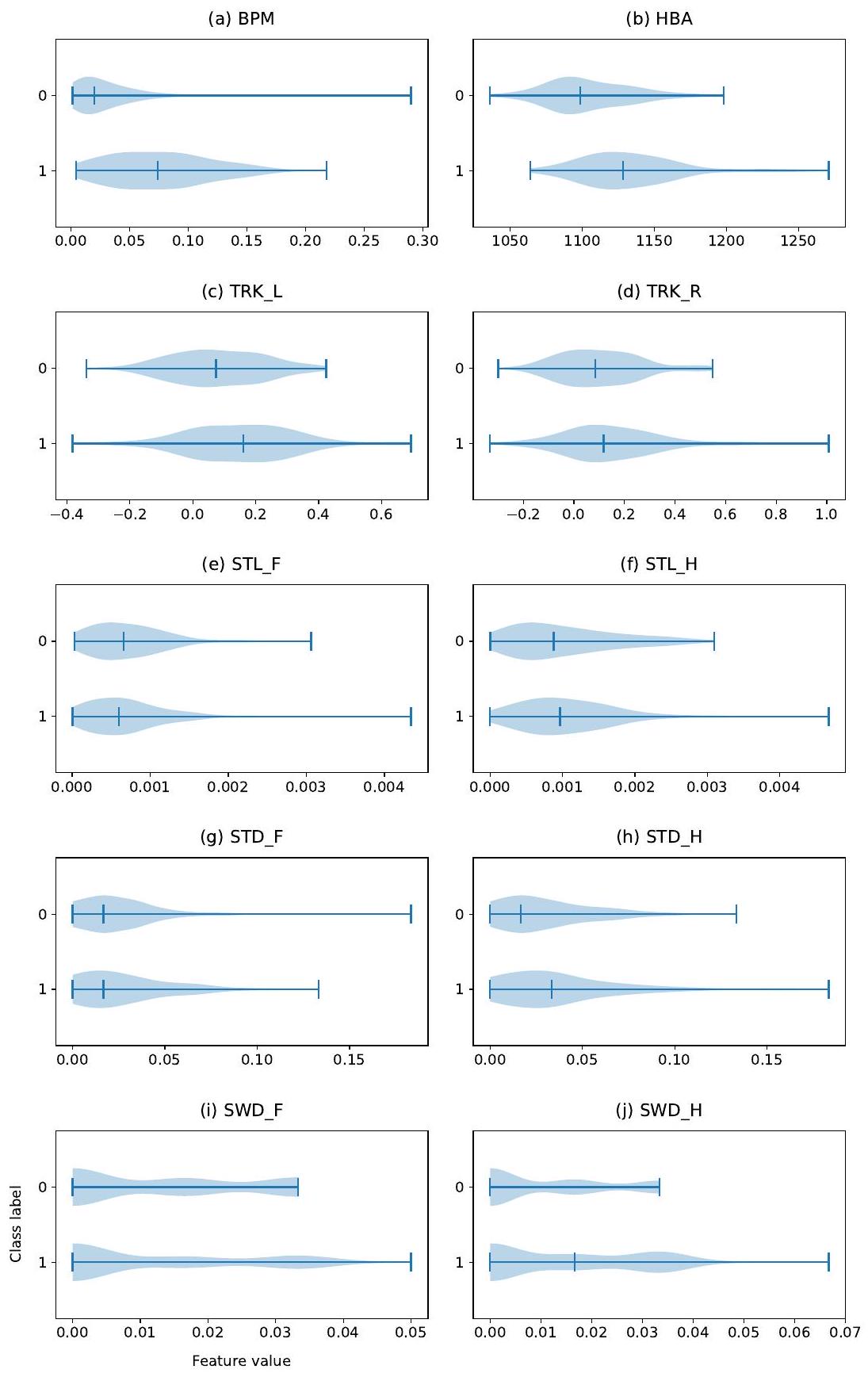

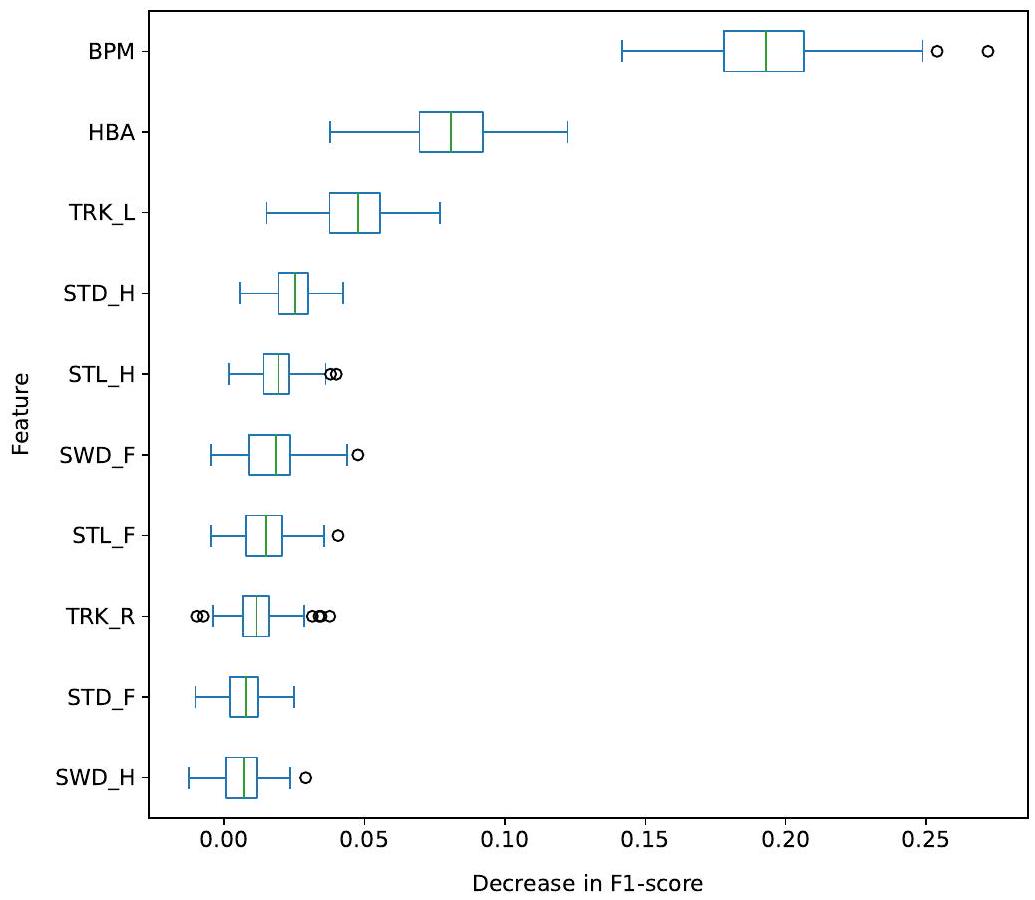

4.3. Feature importance

| SVM-R Features | Accuracy | F1-score | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| BPM | 76.66 | 74.81 | 63.26 | 86.69 |

| BPM, HBA | 79.31 | 77.50 | 77.42 | 77.32 |

| BPM, HBA, TRK | 79.87 | 78.22 | 76.35 | 80.14 |

| BPM, HBA, TRK, STD | 79.47 | 77.87 | 77.09 | 78.89 |

| BPM, HBA, TRK, STD, STL | 79.18 | 78.03 | 78.31 | 79.17 |

| BPM, HBA, TRK, STD, STL, SWD | 80.07 | 78.70 | 76.78 | 81.15 |

5. Discussion

5.1. Video processing

voluntary gait. In practice, this constraint could be implemented by skipping the videos where the Faster-R-CNN (or any other object detector) detects more than one cow, or as done in 17, by implementing a tracking algorithm that follows each cow through the video.

5.2. Locomotion scoring

5.3. Lameness detection

fine-grained gait scoring. Fine-grained locomotion scoring is left for future research as it would require collecting more video footage with sufficient examples of gait scores of 3 and above.

5.4. Feature importance

importance than the one on the right side (TRK-R). This could indicate that, in our dataset, there were more cows tracking-up on the left than on the right side.

5.5. Comparison with related work

contrast our findings with previous work that we deem directly related to ours.

amplitude was extracted from the entire trajectory. The feature selection was performed as follows: a Chi-square test was run on the whole dataset. The test revealed that back posture measurement and head bobbing were the most important features. In contrast, we found that adding tracking-up to the other two features led to better results on our dataset. This could mean that, in their dataset, lame subjects were not tracking up. Another explanation could be that as the number of traits increases, the complexity of the data increases, and a non-linear classifier, such as SVM-R, would be needed. Several classifiers were trained with the back curvature and head bobbing, and the logistic regression classifier returned the best results, with a classification accuracy of

aggregated the values into the median value of the video. In light of their classifiers’ excellent performance, a promising direction for extending our work would be to extract more statistical features from the locomotion traits, such as mean, standard deviation, and min and max values, to improve our classification performance further.

6. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Declaration of interests

References

[2] H. R. Whay, J. K. Shearer, The impact of lameness on welfare of the dairy cow, Veterinary Clinics: Food Animal Practice 33 (2) (2017) 153-164.

[3] H. Enting, D. Kooij, A. Dijkhuizen, R. Huirne, E. Noordhuizen-Stassen, Economic losses due to clinical lameness in dairy cattle, Livestock production science 49 (3) (1997) 259-267.

[4] J. Huxley, Impact of lameness and claw lesions in cows on health and production, Livestock Science 156 (1-3) (2013) 64-70.

[5] X. Song, T. Leroy, E. Vranken, W. Maertens, B. Sonck, D. Berckmans, Automatic detection of lameness in dairy cattle-Vision-based trackway analysis in cow’s locomotion, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 64 (1) (2008) 39-44, iSBN: 0168-1699 eprint: 9809069v1. doi:10.1016/j.compag. 2008.05.016

[6] A. Poursaberi, C. Bahr, A. Pluk, A. V. Nuffel, D. Berckmans, A. Van Nuffel, D. Berckmans, Real-time automatic lameness detection based on back posture extraction in dairy cattle: Shape analysis of cow with image processing techniques, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 74 (1) (2010) 110-119, iSBN: 0168-1699 Publisher: Elsevier B.V. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2010.07.004 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2010.07.004

[7] Z. Zheng, X. Zhang, L. Qin, S. Yue, P. Zeng, Cows’ legs tracking and lameness detection in dairy cattle using video analysis and Siamese neural networks, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 205 (2023) 107618. doi: 10.1016/j. compag. 2023.107618. URL haps://uvs sciencedirect com/science/article/pil S0168169923000066

[8] K. Zhao, M. Zhang, J. Ji, R. Zhang, J. M. Bewley, Automatic lameness scoring of dairy cows based on the analysis of head- and back-hoof linkage features using machine learning methods, Biosystems Engineering 230 (2023) 424-441. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2023.05.003

URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S153751102300106X

[9] N. Blackie, E. Bleach, J. Amory, J. Scaife, Associations between locomotion score and kinematic measures in dairy cows with varying hoof lesion types, Journal of Dairy Science 96 (6) (2013) 3564-3572, iSBN: 0022-0302 Publisher: Elsevier. doi:10.3168/jds.2012-5597.

URL http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022030213002282

[10] Y. Karoui, A. A. B. Jacques, A. B. Diallo, E. Shepley, E. Vasseur, A Deep Learning Framework for Improving Lameness Identification in Dairy Cattle, Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 35 (18) (2021) 15811-15812, number: 18.

[11] D. Wu, Q. Wu, X. Yin, B. Jiang, H. Wang, D. He, H. Song, Lameness detection of dairy cows based on the YOLOv3 deep learning algorithm and a relative step size characteristic vector, Biosystems Engineering 189 (2020) 150-163, publisher: Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng. 2019.11.017.

URL https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2019.11.017

[12] X. Kang, X. D. Zhang, G. Liu, Accurate detection of lameness in dairy cattle with computer vision: A new and individualized detection strategy based on the analysis of the supporting phase, Journal of Dairy Science 103 (11) (2020) 10628-10638, publisher: Elsevier. doi:10.3168/jds. 2020-18288.

URL https://www-journalofdairyscience-org.ezproxy.library.wur.nl/ article/S0022-0302(20)30713-X/abstract

[13] B. Jiang, H. Song, H. Wang, C. Li, Dairy cow lameness detection using a back curvature feature, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 194 (2022) 106729. doi:10.1016/j.compag. 2022.106729

URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0168169922000461

[14] E. Arazo, R. Aly, K. McGuinness, Segmentation Enhanced Lameness Detection in Dairy Cows from RGB and Depth Video, arXiv:2206.04449 [cs] (Jun. 2022). doi:10.48550/arXiv.2206.04449.

URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2206.04449

[15] A. Mathis, P. Mamidanna, K. M. Cury, T. Abe, V. N. Murthy, M. W. Mathis, M. Bethge, DeepLabCut: markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning, Nature Neuroscience 21 (9) (2018) 1281-1289, number: 9 Publisher: Nature Publishing Group. doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0209-y.

URL https://www.nature.com/articles/s41593-018-0209-y.

[16] H. Russello, R. van der Tol, G. Kootstra, T-LEAP: Occlusion-robust pose estimation of walking cows using temporal information, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 192 (2022) 106559. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2021.106559

URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0168169921005767

[17] S. Barney, S. Dlay, A. Crowe, I. Kyriazakis, M. Leach, Deep learning pose estimation for multi-cattle lameness detection, Scientific Reports 13 (1) (2023) 4499.

[18] M. Taghavi, H. Russello, W. Ouweltjes, C. Kamphuis, I. Adriaens, Cow key point detection in indoor housing conditions with a deep learning model, Journal of Dairy Science (2023).

[19] S. Viazzi, C. Bahr, A. Schlageter-Tello, T. Van Hertem, C. Romanini, A. Pluk, I. Halachmi, C. Lokhorst, D. Berckmans, Analysis of individual classification of lameness using automatic measurement of back posture in dairy cattle, Journal of Dairy Science 96 (1) (2012) 257-266, publisher: Elsevier. doi:10.3168/jds 2012-5806.

URL http://dx.doi.org/10.3168/jds.2012-5806

[20] T. Van Hertem, S. Viazzi, M. Steensels, E. Maltz, A. Antler, V. Alchanatis, A. A. Schlageter-Tello, K. Lokhorst, E. C. Romanini, C. Bahr, D. Berckmans, I. Halachmi, Automatic lameness detection based on consecutive 3D-video recordings, Biosystems Engineering 119 (2014) 108-116, iSBN: 9789088263330 Publisher: IAgrE. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2014.01.009.

[21] S. Viazzi, C. Bahr, T. Van Hertem, A. Schlageter-Tello, C. E. B. Romanini, I. Halachmi, C. Lokhorst, D. Berckmans, Comparison of a three-dimensional and twodimensional camera system for automated measurement of back posture in dairy cows. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 100 (2014) 139-147, iSBN: 0168-1699

URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2013.11.005

[22] T. Van Hertem, A. S. Tello, S. Viazzi, M. Steensels, C. Bahr, C. E. B. Romanini, K. Lokhorst, E. Maltz, I. Halachmi, D. Berckmans, A. Schlageter Tello, S. Viazzi, M. Steensels, C. Bahr, C. E. B. Romanini, K. Lokhorst, E. Maltz, I. Halachmi, D. Berckmans, Implementation of an automatic 3D vision monitor for dairy cow locomotion in a commercial farm, Biosystems Engineering 173 (2018) 166-175, iSBN: 1537-5110 Publisher: Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2017.08.011.

[23] K. Zhao, J. Bewley, D. He, X. Jin, Automatic lameness detection in dairy cattle based on leg swing analysis with an image processing technique, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 148 (2018) 226-236.

[24] A. Schlageter-Tello, E. A. Bokkers, P. W. Groot Koerkamp, T. Van Hertem, S. Viazzi, C. E. Romanini, I. Halachmi, C. Bahr, D. Berckmans, K. Lokhorst, Effect of merging levels of locomotion scores for dairy cows on intra- and interrater reliability and agreement, Journal of Dairy Science 97 (9) (2014) 5533-5542, publisher: Elsevier. doi:10.3168/jds.2014-8129.

URL http://dx.doi.org/10.3168/jds.2014-8129

[25] A. Schlageter-Tello, E. A. Bokkers, P. W. Groot Koerkamp, T. Van Hertem, S. Viazzi, C. E. Romanini, I. Halachmi, C. Bahr, D. Berckmans, K. Lokhorst, Relation between observed locomotion traits and locomotion score in dairy cows, Journal of Dairy Science 98 (12) (2015) 8623-8633. doi:10.3168/jds.2014-9059

URL https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022030215006633

[26] D. Sprecher, D. Hostetler, J. Kaneene, A LAMENESS SCORING SYSTEM THAT USES POSTURE AND GAIT TO PREDICT DAIRY CATTLE REPRODUCTIVE PERFORMANCE, Science (97) (1997).

[27] P. Thomsen, L. Munksgaard, F. Tøgersen, Evaluation of a lameness scoring system for dairy cows, Journal of dairy science 91 (1) (2008) 119-126.

[28] F. C. Flower, D. M. Weary, Effect of Hoof Pathologies on Subjective Assessments of Dairy Cow Gait, Journal of Dairy Science 89 (1) (2006) 139-146. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72077-X.

URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S002203020672077X

[29] K. Krippendorff, Computing krippendorff’s alpha-reliability (2011).

[30] B. Engel, G. Bruin, G. Andre, W. Buist, Assessment of observer performance in a subjective scoring system: visual classification of the gait of cows, The Journal of Agricultural Science 140 (3) (2003) 317-333, publisher: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/S0021859603002983.

URL http://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/

journal-of-agricultural-science/article/assessment-of-observer-performance-in-a-subjectiv A4C2BDAAE4803FE2DFE34013FC8F6DE9#access-block

[31] Y. Wu, A. Kirillov, F. Massa, W.-Y. Lo, R. Girshick, Detectron2, https://github com/facebookresearch/detectron2 (2019).

[32] A. Savitzky, M. J. Golay, Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures., Analytical chemistry 36 (8) (1964) 1627-1639.

[33] J. W. Cooley, J. W. Tukey, An algorithm for the machine calculation of complex fourier series, Mathematics of computation 19 (90) (1965) 297-301.

[34] L. Buitinck, G. Louppe, M. Blondel, F. Pedregosa, A. Mueller, O. Grisel, V. Niculae, P. Prettenhofer, A. Gramfort, J. Grobler, et al., Api design for machine learning software: experiences from the scikit-learn project, arXiv preprint arXiv:1309.0238 (2013).

[35] N. V. Chawla, K. W. Bowyer, L. O. Hall, W. P. Kegelmeyer, Smote: synthetic minority over-sampling technique, Journal of artificial intelligence research 16 (2002) 321-357.

[36] F. Pedregosa, G. Varoquaux, A. Gramfort, V. Michel, B. Thirion, O. Grisel, M. Blondel, P. Prettenhofer, R. Weiss, V. Dubourg, J. Vanderplas, A. Passos, D. Cournapeau, M. Brucher, M. Perrot, E. Duchesnay, Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python, Journal of Machine Learning Research 12 (2011) 2825-2830.

[37] J. Wainer, G. Cawley, Nested cross-validation when selecting classifiers is overzealous for most practical applications, Expert Systems with Applications 182 (2021) 115222.

[38] L. Breiman, Random forests, Machine learning 45 (2001) 5-32.

[39] A. Schlageter-Tello, E. Bokkers, P. G. Koerkamp, T. Van Hertem, S. Viazzi, C. Romanini, I. Halachmi, C. Bahr, D. Berckmans, K. Lokhorst, Comparison of locomotion scoring for dairy cows by experienced and inexperienced raters using live or video observation methods, Animal Welfare 24 (1) (2015) 69-79.

[40] J. Wainer, Comparison of 14 different families of classification algorithms on 115 binary datasets, arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.00930 (2016).

[41] D. H. Wolpert, The lack of a priori distinctions between learning algorithms, Neural computation 8 (7) (1996) 1341-1390.

[42] T. Borderas, A. Fournier, J. Rushen, A. De Passille, Effect of lameness on dairy cows’ visits to automatic milking systems, Canadian Journal of Animal Science 88 (1) (2008) 1-8.

[43] N. Chapinal, A. De Passille, D. Weary, M. Von Keyserlingk, J. Rushen, Using gait score, walking speed, and lying behavior to detect hoof lesions in dairy cows, Journal of dairy science 92 (9) (2009) 4365-4374.

[44] A. Nejati, A. Bradtmueller, E. Shepley, E. Vasseur, Technology applications in bovine gait analysis: A scoping review, Plos one 18 (1) (2023) e0266287.

[45] Q. Wang, H. Bovenhuis, Validation strategy can result in an overoptimistic view of the ability of milk infrared spectra to predict methane emission of dairy cattle, Journal of dairy science 102 (7) (2019) 6288-6295.

- *Corresponding authors

Email addresses: helena.russello@wur.nl (Helena Russello ), gert.kootstra@wur.nl (Gert Kootstra )

Preprint submitted to Elsevier