DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114520

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-02

المؤثرون الافتراضيون والقضايا البيئية: أدوار دفء الرسالة والثقة في الخبراء

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

التسويق الأخضر

المسافة الاجتماعية النفسية

دفء الرسالة

الثقة في الخبراء

الملخص

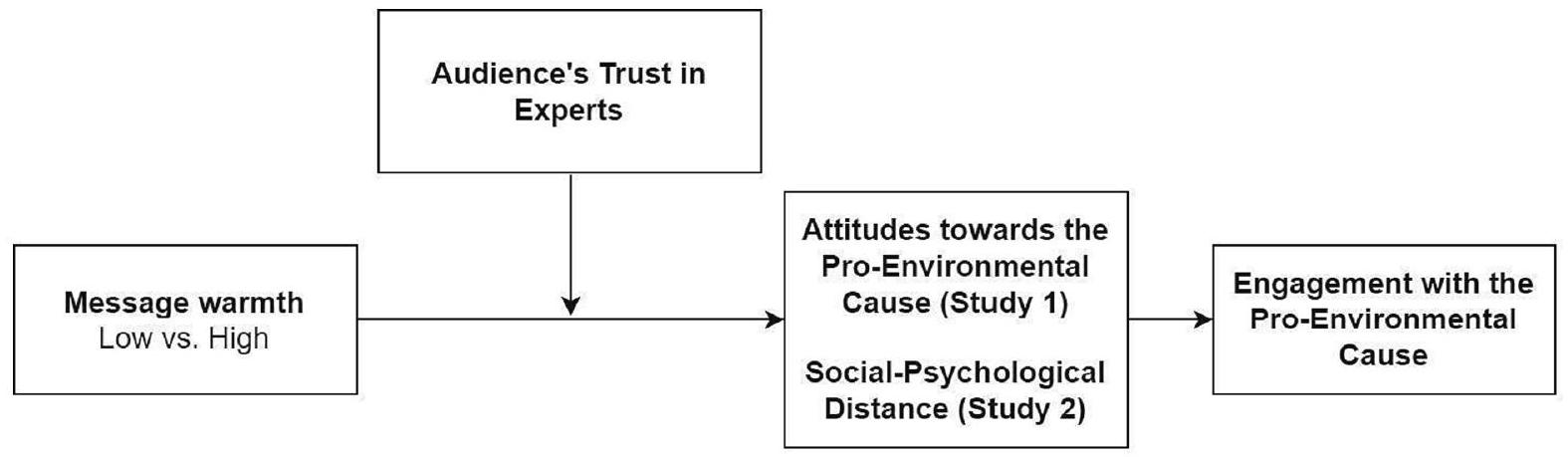

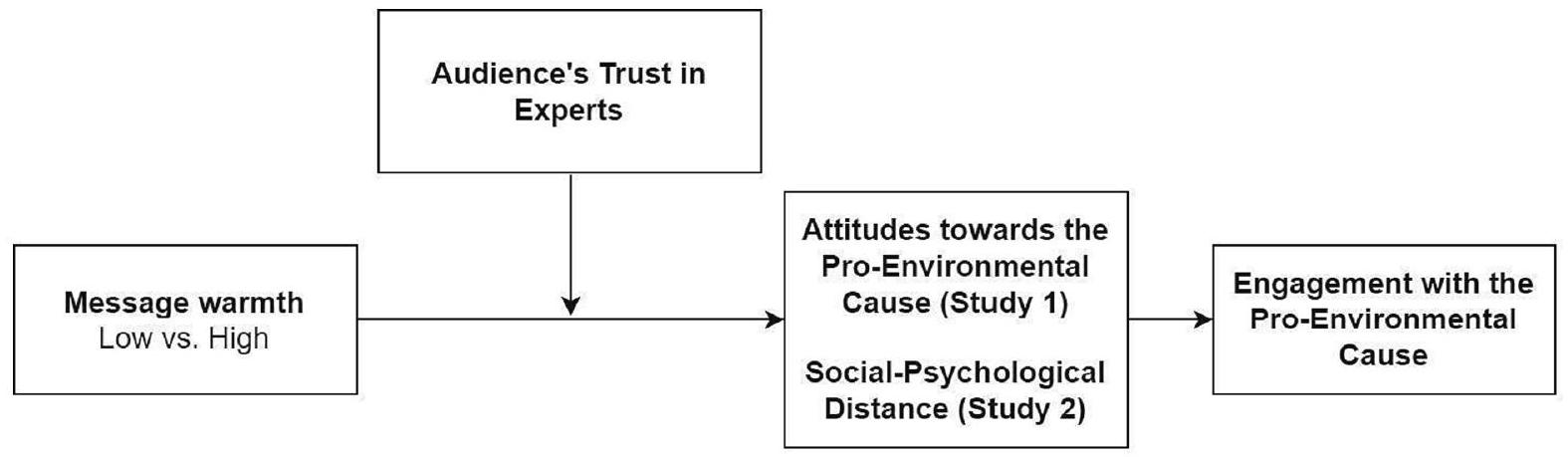

المؤثرون الافتراضيون (VIs) هم شكل متزايد الشعبية من المؤيدين المستخدمين في الحملات التسويقية. مع تورط نظرائهم من المؤثرين البشريين أحيانًا في فضائح وجدل، يمكن أن يكون VIs مصدرًا أكثر موثوقية للترويج للسلوك البيئي المستدام. من خلال اتباع نهج متعدد الطرق، نفحص كيف يتفاعل الأفراد مع VIs التي تروج لحملات بيئية. تؤكد نتائجنا من المقابلات شبه المنظمة الأولية أن الأفراد قد يكونون منفتحين على التعلم عن القضايا الخضراء من VIs. بعد ذلك، نجري تجربتين لاستكشاف كيف يجب على VIs الترويج للقضايا الخضراء اعتمادًا على جمهورهم. نجد أن دفء الرسالة مرتبط إيجابيًا بالمسافة الاجتماعية النفسية، مما يؤدي إلى مستويات أعلى من التفاعل مع القضايا البيئية. علاوة على ذلك، فإن تأثير دفء الرسالة يكون ملحوظًا بشكل خاص للأفراد الذين لديهم ثقة منخفضة في الخبراء. نقترح تداعيات قابلة للتنفيذ لصانعي السياسات وغيرهم من أصحاب المصلحة الذين يفكرون في استخدام VIs للترويج لحملاتهم البيئية.

1. المقدمة

التي تحتفظ بعنصر من السلوك غير المتوقع الذي ينشأ من نقص السيطرة على محتواها وحياتها الشخصية (توماس وفاولر، 2021). قد يكون SMIs البشرية متورطين في فضائح وقد يرتكبون حتى تجاوزات قد تؤدي إلى أضرار سمعة وخسائر مالية (توماس وفاولر، 2021). في سياق القضايا البيئية، قد تتعرض مصداقية المؤثرين للتقويض بسبب التناقضات بين القضايا الخضراء التي يروجون لها وممارساتهم غير المستدامة (أودريزيت وآخرون، 2020؛ جيراث وأسرى، 2021؛ ليونغ وآخرون، 2022)، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى تقليل النوايا البيئية لجمهورهم (بوميران وآخرون، 2022). على سبيل المثال، تعرضت المؤثرة لورا ويتيمور للانتقاد لترويجها للسلوك البيئي بينما كانت سفيرة لعلامة الأزياء السريعة برايمارك (مصطفى، 2021). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قد تؤدي حالات استثارة ردود فعل سلبية من المستهلكين عند ترويج المؤثرين للقضايا الخضراء إلى أن تكون رادعًا لمؤثرين آخرين يفكرون في الترويج للقضايا البيئية. لذلك، فإن الحاجة إلى توسيع الفهم حول كيفية أن يساعد تسويق المؤثرين بشكل فعال في الترويج للقضايا البيئية أصبحت ملحة.

2. نظرية وتطوير الفرضيات

2.1. المؤثرون والقضايا البيئية

2.2. المؤثرون الافتراضيون (VIs)

2.3. دفء رسالة المؤثر والمسافة الاجتماعية النفسية

تتداخل “الدفء” مع مصطلح “الأخلاق” (فيزك وآخرون، 2007).

قد تؤثر دفء المؤثرين الافتراضيين على ردود فعل الجمهور تجاه الحملات البيئية، حيث يحدد الناس ما إذا كان الآخرون ذوي نوايا حسنة أم لا من خلال دفئهم المدرك (فيش وآخرون، 2002؛ جيرشون وكرايدر، 2018). تشير الأبحاث السابقة حول الدفء في الأحكام الاجتماعية إلى أن الناس يقيمون الشخصيات ذات الدفء العالي بشكل أكثر إيجابية من نظرائهم ذوي الدفء المنخفض (جيرشون وكرايدر، 2018). حتى إذا تصرف الممثلون ذوو الدفء المنخفض بشكل اجتماعي، قد يحكم عليهم الآخرون بأن لديهم دوافع خفية بدلاً من نوايا حسنة (كودي وآخرون، 2011). والأهم من ذلك، مع تزايد الشكوك حول النداءات البيئية والإعلانات الخضراء (أي، الغسل الأخضر؛ لافير، 2003) (ديلماس وبوربانو، 2011)، قد يعبر الناس عن ردود فعل سلبية وإنكار للرسالة إذا أدركوا النداءات على أنها تلاعبية (كلي وويكلوند، 1980). لذلك، يبدو أن دفء المؤثرين البيئيين أكثر أهمية حيث يمكن أن يرتبط الدفء العالي بموثوقية عالية ونوايا حسنة (فيش وآخرون، 2007؛ جيرشون وكرايدر، 2018)، مما يقلل من ردود الفعل غير المتوقعة. تشير الأدلة التجريبية إلى أن الناس يظهرون دوافع ونوايا اجتماعية أكبر (مثل تأييد العلامات التجارية غير الربحية [بيرنريتر وآخرون، 2016]؛ التبرع [تشو وآخرون، 2019]) بسبب تعزيز إدراك الدفء. ومع ذلك، على حد علمنا، لم يتم إجراء أي بحث حتى الآن لفحص كيف يؤثر دفء المؤثرين الافتراضيين على فعاليتهم في تعزيز القضايا البيئية.

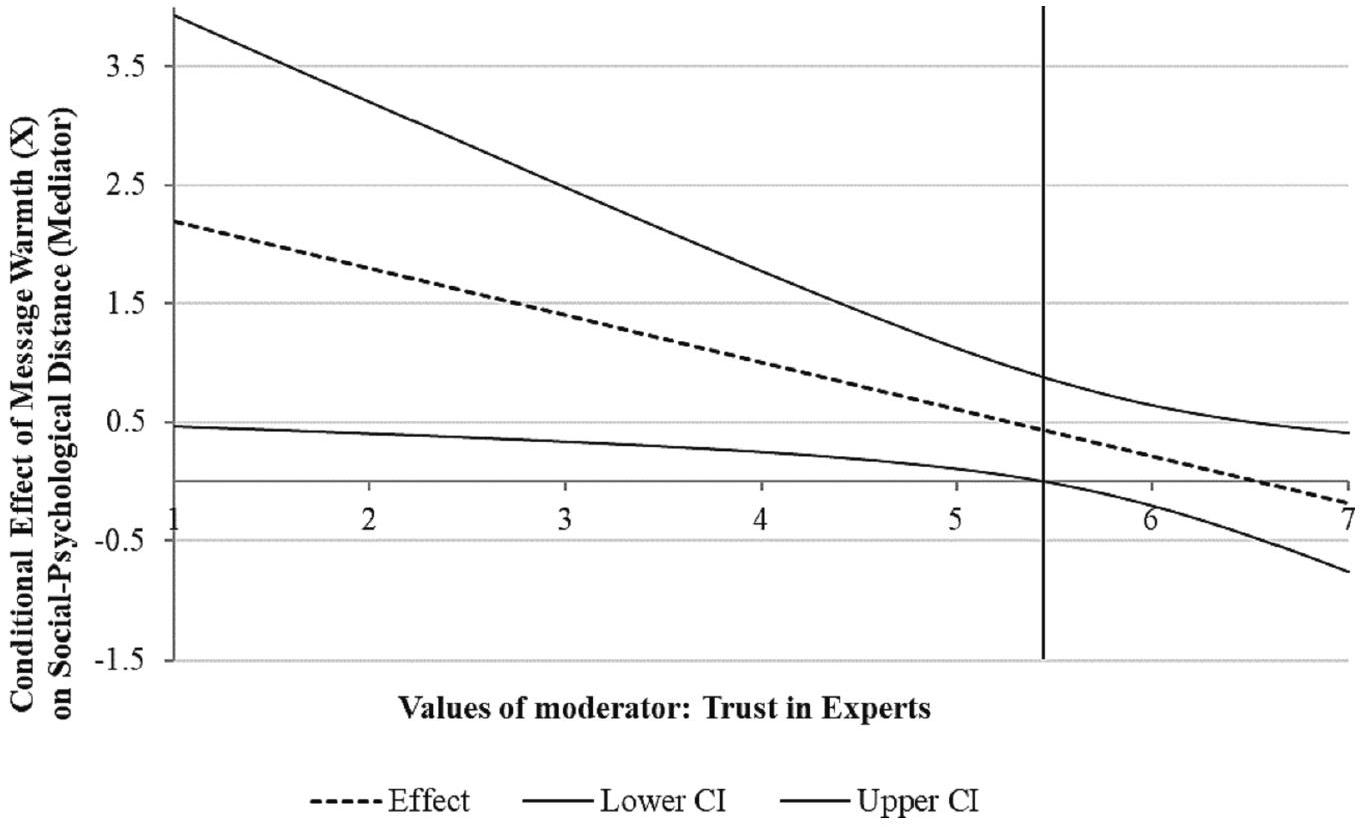

نحن نفترض أن العلاقة بين دفء رسالة VI ومشاركة الفرد في القضايا البيئية تفسرها المسافة الاجتماعية النفسية التي يدركها الفرد.

2.4. دور الثقة في الخبراء

الأسباب التي تروج لها VI. من ناحية أخرى، الأفراد الذين يثقون بشكل كبير في الخبراء من المحتمل أن يعطوا وزناً وتفضيلاً أكبر للمعلومات الموضوعية والقابلة للتحقق (لوبيّا وآخرون، 1998؛ ميركلي ولوين، 2021؛ وينتريتش وآخرون، 2012)، مما يضعف هذه العلاقة.

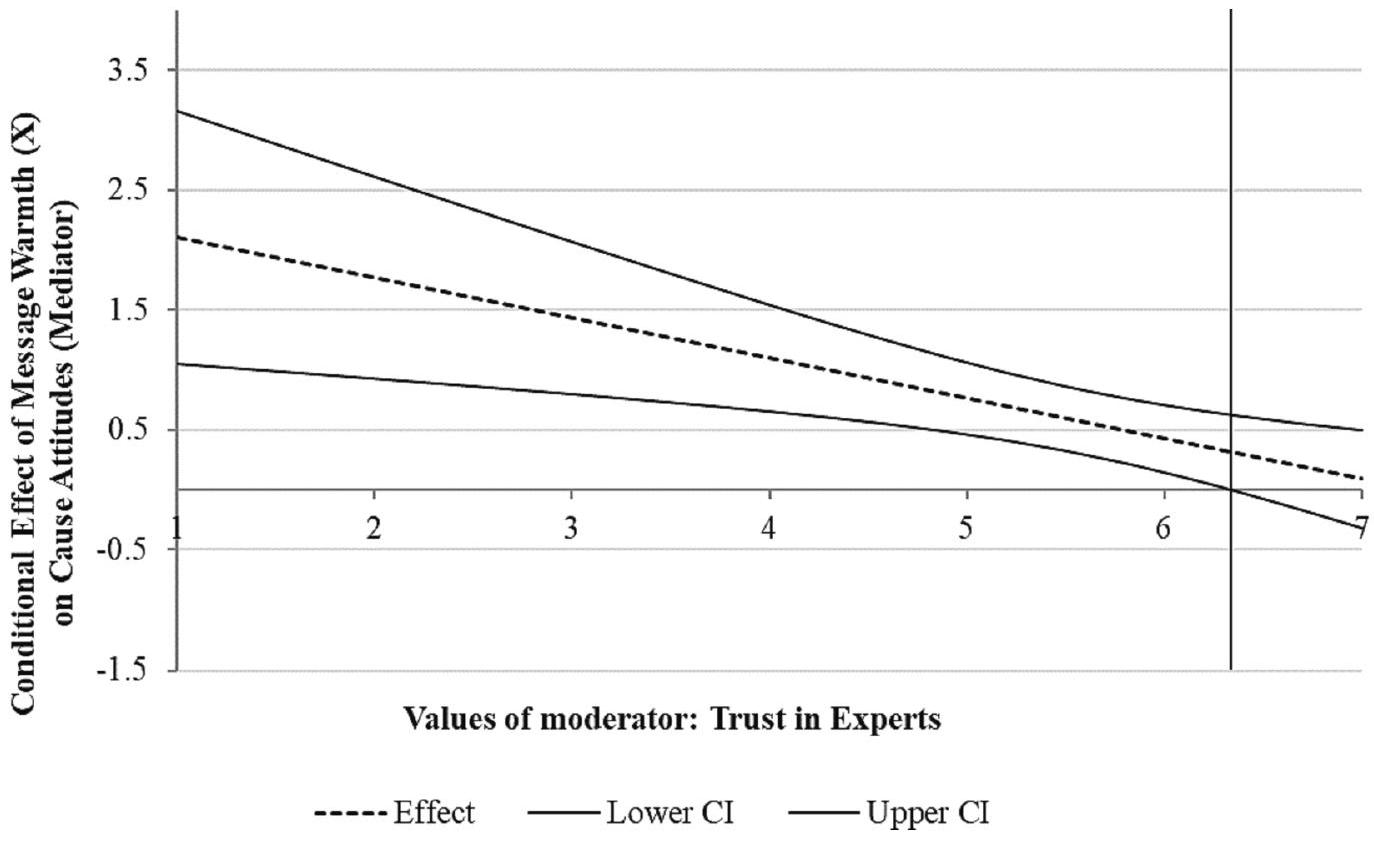

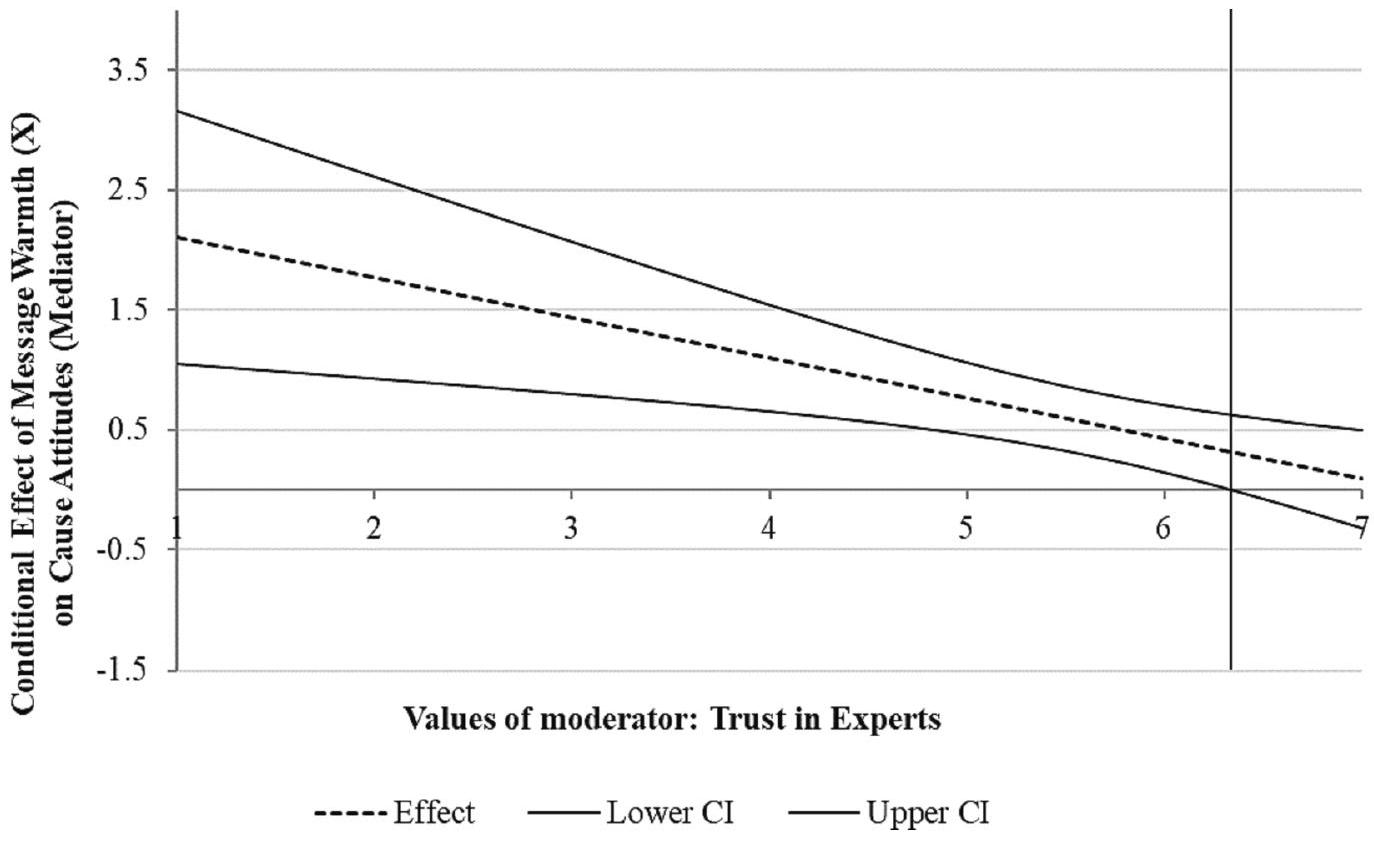

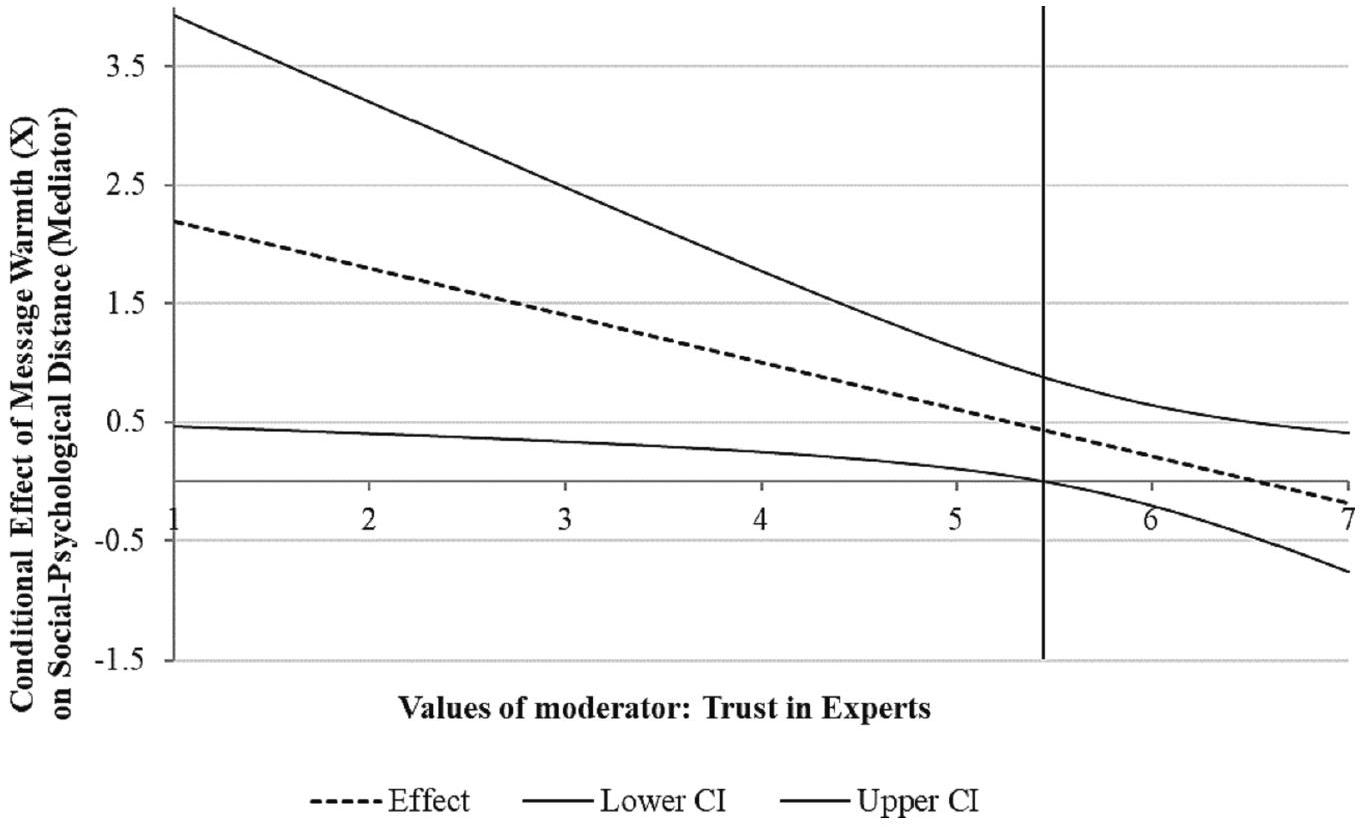

H2a. موقف الجمهور تجاه القضية البيئية يعمل كوسيط بين دفء الرسالة والانخراط مع القضية، خاصة إذا كان الناس يثقون بالخبراء أقل.

3. نظرة عامة على الدراسات

4. الدراسة الأولية: مقابلات استكشافية

4.1. المستجيبون والإجراء

4.2. النتائج

يجعلني أشعر بالضياع والاكتئاب، [ويبدو] أنه لا يوجد فائدة أو ميزة…. سأنظر إليه ثم أستمر في التمرير لرؤية شيء مختلف. (R6)

لا أذهب إلى الإنترنت [وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي] لرؤية أشياء تزعجني…. إذا كانت المعلومات قد تم تقديمها بطريقة مثيرة للاهتمام، حسنًا، لكنها تستمر في القول إننا مسؤولون. (R13)

أعتقد أنهم [SMIs] يفعلون ذلك عندما يعود عليهم بالنفع لأنه رائج…. يمكن أن يجعل القضية المهمة تبدو كـ “أشياء تافهة” مثل الأشياء الرائعة ولكن دون أي اهتمام حقيقي…. يمكنك أن ترى أنهم ينشرون قصصًا وأشياء تظهر أنهم ليسوا مهتمين حقًا. (R5)

أحب المؤثرين، أتابع الكثير [منهم] ولديهم معلومات جيدة ولكن يمكنك أن ترى أنهم [لا] يهتمون بالقضايا وليس من الجيد للقضايا…. سيفكر الناس أن هذه قضية خاصة بالمؤثرين وليست جدية عندما يقولون لا تشتري البلاستيك ثم يقومون بمراجعة أو يقولون “اشترِ المنتجات التي تحتوي على البلاستيك.” (R8)

يمكنك أن تراهم [المؤثرين] ينشرون صورًا على طائرات خاصة وطائرات، ثم سيقولون أشياء مثل “يجب أن نحمي كوكبنا” في يوم الأرض و”أحب الحيوانات”، لكنهم لا يظهرون أنهم يهتمون، ويمكننا أن نرى ذلك…. إنه مزعج، يجعلني أرغب في تجاهله. (R11) يمكنك أن ترى عائلة كارداشيان تنشر عن الحب والاهتمام، لكنهم لا يكونون مستدامين بأنفسهم. إذا كانوا يهتمون، لماذا لا يغيرون ما يفعلونه أولاً ثم يخبروننا؟ إنه يزعجني حقًا. (R12)

لن يقوموا بالتحقق من الحقائق بشكل صحيح ويقومون بالترويج أو الإدلاء ببيانات خاطئة يمكن للناس بعد ذلك الإشارة إليها والقول، “انظروا؟ هم مخطئون” … هم [SMIs] لن يعرفوا عما يتحدثون…. القضايا [البيئية] مهمة، لكن بيان خاطئ واحد وسيتعامل الناس معه. (R1)

أعتقد أن [الرسائل البيئية] مهمة جدًا. هناك مؤثرون ينشرون عنها [القضايا البيئية] وهم على حق، لكنهم ليسوا مثاليين، والناس من الجانب الآخر يستخدمون ذلك…. سيستخدمون صورة لشخص يفعل شيئًا غير سياسي أو يضر بالبيئة وسيقولون إن الرسالة سيئة، وهذا يقلقني. (R16)

سيكون من الجيد إذا تحدثوا عن القضايا الإيجابية؛ فهم يعرفون أي الطرق تعمل بشكل أفضل للتأثير على الناس ولديهم متابعون كثر.

يوجد الكثير من نفس المحتوى [على وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي] بحيث أن التكنولوجيا المولدة بواسطة الكمبيوتر جيدة، لذا ستجعلني ألتفت وأتوقف لأنظر، ثم يصبح الأمر مثيرًا للاهتمام، وسأنظر إليه وأقرأ المعلومات. (R7)

أرى أن الواقعية، نعم، ليست حقيقية، ولكن مثل شخصية في لعبة فيديو يستخدمها شخص ما لإظهار شخصيته الحقيقية. هناك شخص خلفها، وأعتقد أن ذلك يساعدهم على أن يكونوا أكثر واقعية وصدقًا لأنهم يمكنهم البقاء مخفيين وعدم القلق بشأن الحكم…. لذا فإن الشخص خلفها هو الحقيقي.

4.3. المناقشة

5. الدراسة 1

5.1. المشاركون والإجراءات

الدفء، استخدمنا تسميات منشورات إنستغرام من الاختبار الأول. كما هو موضح في الاختبار الأول، استخدمت التسمية في حالة الدفء العالي للرسالة لغة أكثر تعاطفًا ورعاية ومساعدة وإخلاصًا لتعزيز تصورات الدفء. على وجه التحديد، في حالة الدفء العالي للرسالة، نصت التسمية أسفل منشور إنستغرام (أي، التسمية) على: “أنا قلق حقًا بشأن ما قرأته عن أحدث تقرير المناخ للأمم المتحدة. تغير المناخ هو شيء أهتم به بعمق. نحتاج إلى حماية كوكبنا العزيز. يرجى دعم حملة “العمل المناخي” في كفاحهم ضد تغير المناخ. لمزيد من المعلومات، يرجى زيارةhttps://www.climateacti on.gov.uk. #إعلان.” في حالة دفء الرسالة المنخفضة، ذكرت التسمية: “لقد قرأت للتو أحدث تقرير من الأمم المتحدة حول المناخ. مستوى ثاني أكسيد الكربون في الغلاف الجوي العالمي ارتفع إلى

5.2. النتائج

المواقف، أجرينا تحليل تباين ثنائي الاتجاه (ANOVA) مع دفء الرسالة ونوع مظهر VI كمتغيرات مستقلة. أشارت النتائج إلى تأثير رئيسي كبير لدفء الرسالة على مواقف السبب (

5.3. المناقشة

6. الدراسة 2

6.1. المشاركون والإجراءات

بتوزيعهم عشوائيًا لفحص واحدة من أربع (أي، دفء الرسالة المنخفض مع SMI البشرية؛ دفء الرسالة العالي مع SMI البشرية؛ دفء الرسالة المنخفض مع VI؛ دفء الرسالة العالي مع VI) نسخ من منشور خيالي على إنستغرام. كما في الدراسة 1، تم التلاعب بتعليق منشور إنستغرام لدفء الرسالة المنخفض مقابل المرتفع. علاوة على ذلك، كانت صورة منشور إنستغرام تحتوي إما على SMI البشرية أو VI (كما تم اختباره مسبقًا في الملحق E). يوفر الملحق F عينات من المحفزات.

6.2. النتائج

في دعم H 1 ، أظهرت النتائج تأثيرًا رئيسيًا كبيرًا لدفء الرسالة على الانخراط في القضية

التأثير غير المباشر في حالة انخفاض الثقة في الخبراء

6.3. المناقشات

7. المناقشات العامة

7.1. المساهمات النظرية

7.2. الآثار المترتبة على أصحاب المصلحة

7.2.1. هل تسويق المؤثرين نهج فعال للترويج للقضايا البيئية؟

7.2.2. كيف يمكن لأصحاب المصلحة جذب الجماهير التي لا تثق بالخبراء؟

7.3. القيود وسبل البحث المستقبلية

تغير المناخ موجود حتى لو قال العلماء والخبراء عكس ذلك (كينيدي وآخرون، 2022؛ تريموليير وجيريوات، 2021). لذلك، تعتبر الثقة في الخبراء عاملًا مهمًا في هذا البحث. ثالثًا، تشير نتائج الدراسة الأولية إلى أن معظم المستجيبين سيكونون منفتحين ويرغبون في رؤية المؤثرين يشاركون محتوى حول القضايا البيئية.

بيان مساهمة المؤلفين

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

شكر وتقدير

الملاحق. المواد التكميلية

References

Ameen, N., Cheah, J. H., Ali, F., El-Manstrly, D., & Kulyciute, R. (2023). Risk, trust, and the roles of human versus virtual influencers. Journal of Travel Research. https://doi. org/10.1177/00472875231190601

Ameen, N., Hosany, S., & Tarhini, A. (2021). Consumer interaction with cutting-edge technologies: Implications for future research. Computers in Human Behavior, 120, Article 106761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106761

Appel, G., Grewal, L., Hadi, R., & Stephen, A. T. (2020). The future of social media in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(1), 79-95. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11747-019-00695-1

Arsel, Z. (2017). Asking questions with reflexive focus. Journal of Consumer Research, 44 (4), 939-948. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx096

Audrezet, A., & Koles, B. (2023). Virtual influencer as a brand avatar in interactive marketing. In C. L. Wang (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of interactive marketing (pp. 353-376). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14961-0_16.

Aw, E. C. X., & Chuah, S. H. W. (2021). “Stop the unattainable ideal for an ordinary me!” Fostering parasocial relationships with social media influencers: The role of selfdiscrepancy. Journal of Business Research, 132, 146-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbusres.2021.04.025

Ballestar, M. T., Martín-Llaguno, M., & Sainz, J. (2022). An artificial intelligence analysis of climate-change influencers’ marketing on Twitter. Psychology & Marketing, 39(12), 2273-2283. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar. 21735

Bernritter, S. F., Verlegh, P. W., & Smit, E. G. (2016). Why nonprofits are easier to endorse on social media: The roles of warmth and brand symbolism. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 33(1), 27-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2015.10.002

Boerman, S. C., Meijers, M. H., & Zwart, W. (2022). The importance of influencermessage congruence when employing greenfluencers to promote pro-environmental behavior. Environmental Communication, 16(7), 920-941. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 17524032.2022.2115525

Breves, P., & Liebers, N. (2022). #Greenfluencing. The impact of parasocial relationships with social media influencers on advertising effectiveness and followers’ proenvironmental intentions. Environmental Communication, 16(6), 773-787. https:// doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2022.2109708

Buys, L., Aird, R., van Megen, K., Miller, E., & Sommerfeld, J. (2014). Perceptions of climate change and trust in information providers in rural Australia. Public Understanding of Science, 23(2), 170-188. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0963662512449948

Byun, K. J., & Ahn, S. J. (2023). A systematic review of virtual influencers: Similarities and differences between human and virtual influencers in interactive advertising. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 15252019.2023.2236102

Cascio Rizzo, G. L. C., Berger, J., & Villarroel, F. (2023). What drives virtual influencer’s impact? Working paper, LUISS Guido Carli University. https://doi.org/10.4855 0/arXiv.2301.09874.

Castelo, N., Bos, M. W., & Lehmann, D. R. (2019). Task-dependent algorithm aversion. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(5), 809-825. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0022243719851788

Chang, Y., Li, Y., Yan, J., & Kumar, V. (2019). Getting more likes: The impact of narrative person and brand image on customer-brand interactions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(6), 1027-1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00632-2

Clark, M. S. (1984). Record keeping in two types of relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(3), 549-557. https://doi.org/10.1037/00223514.47.3.549

Cologna, V., & Siegrist, M. (2020). The role of trust for climate change mitigation and adaptation behaviour: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 69, Article 101428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101428

Conde, R., & Casais, B. (2023). Micro, macro and mega-influencers on Instagram: The power of persuasion via the parasocial relationship. Journal of Business Research, 158, Article 113708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113708

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64-87. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64

Dubois, D., Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2016). Dynamics of communicator and audience power: The persuasiveness of competence versus warmth. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(1), 68-85. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw006

Edwards, S. M., Lee, J. K., & Ferle, C. L. (2009). Does place matter when shopping online? Perceptions of similarity and familiarity as indicators of psychological distance. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 10(1), 35-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 15252019.2009.10722161

Fage-Butler, A., Ledderer, L., & Nielsen, K. H. (2022). Public trust and mistrust of climate science: A meta-narrative review. Public Understanding of Science, 31(7), 832-846. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625221110028

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77-83. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Gerrath, M. H. E. E., & Usrey, B. (2021). The impact of influencer motives and commonness perceptions on follower reactions toward incentivized reviews. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 38(3), 531-548, doi:10.1016/j. ijresmar.2020.09.010.

Gershon, R., & Cryder, C. (2018). Goods donations increase charitable credit for lowwarmth donors. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(2), 451-469. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/jcr/ucx126

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G., & Fielding, K. S. (2016). Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nature Climate Change, 6(6), 622-626. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2943

Hsieh, S. H., & Chang, A. (2016). The psychological mechanism of brand co-creation engagement. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 33, 13-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. intmar.2015.10.001

Hu, T.-Y., Li, J., Jia, H., & Xie, X. (2016). Helping others, warming yourself: Altruistic behaviors increase warmth feelings of the ambient environment. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1349-1349, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01349.

Huang, R., & Ha, S. (2020). The effects of warmth-oriented and competence-oriented service recovery messages on observers on online platforms. Journal of Business Research, 121, 616-627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.04.034

Hughes, C., Swaminathan, V., & Brooks, G. (2019). Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. Journal of Marketing, 83(5), 78-96. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0022242919854374

Jin, S. V., & Ryu, E. (2020). “I’ll buy what she’s# wearing”: The roles of envy toward and parasocial interaction with influencers in Instagram celebrity-based brand endorsement and social commerce. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, Article 102121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102121

Karagür, Z., Becker, J. M., Klein, K., & Edeling, A. (2022). How, why, and when disclosure type matters for influencer marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 39(2), 313-335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2021.09.006

Kennedy, B., Tyson, A., & Funk, C. (2022). Americans’ Trust in Scientists, Other Groups Declines. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/02/15/ame ricans-trust-in-scientists-other-groups-declines/.

Kim, D. Y., & Kim, H. Y. (2021). Trust me, trust me not: A nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. Journal of Business Research, 134, 223-232. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.024

Kim, E., Duffy, M., & Thorson, E. (2021). Under the influence: Social media influencers’ impact on response to corporate reputation advertising. Journal of Advertising, 50(2), 119-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2020.1868026

Kim, S. Y., Schmitt, B. H., & Thalmann, N. M. (2019). Eliza in the uncanny valley: Anthropomorphizing consumer robots increases their perceived warmth but decreases liking. Marketing Letters, 30(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-019-09485-9

Kim, Y., Kwak, S. S., & Kim, M. (2013). Am I acceptable to you? Effect of a robot’s verbal language forms on people’s social distance from robots. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1091-1101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.001

Knupfer, H., Neureiter, A., & Matthes, J. (2023). From social media diet to public riot? Engagement with “greenfluencers” and young social media users’ environmental activism. Computers in Human Behavior, 139, Article 107527. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107527

Kull, A. J., Romero, M., & Monahan, L. (2021). How may I help you? Driving brand engagement through the warmth of an initial chatbot message. Journal of Business Research, 135, 840-850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.005

Lee, S. A., & Oh, H. (2021). Anthropomorphism and its implications for advertising hotel brands. Journal of Business Research, 129, 455-464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbusres.2019.09.053

Leung, F. F., Gu, F. F., & Palmatier, R. W. (2022). Online influencer marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(2), 226-251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00829-4

Lewandowsky, S. (2021). Climate change disinformation and how to combat it. Annual Review of Public Health, 42, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102409

Lou, C., Kiew, S. T. J., Chen, T., Lee, T. Y. M., Ong, J. E. C., & Phua, Z. (2023). Authentically fake? How consumers respond to the influence of virtual influencers. Journal of Advertising, 52(4), 540-557. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00913367.2022 .2149641

Maiella, R., La Malva, P., Marchetti, D., Pomarico, E., Di Crosta, A., Palumbo, R., … Verrocchio, M. C. (2020). The psychological distance and climate change: A systematic review on the mitigation and adaptation behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568899

McDonald, R. I., Chai, H. Y., & Newell, B. R. (2015). Personal experience and the ‘psychological distance’ of climate change: An integrative review. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 44, 109-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jenvp.2015.10.003

McKenna, B., Myers, M. D., & Newman, M. (2017). Social media in qualitative research: Challenges and recommendations. Information and Organization, 27(2), 87-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2017.03.001

Merkley, E. (2020). Anti-intellectualism, populism, and motivated resistance to expert consensus. Public Opinion Quarterly, 84(1), 24-48. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/ nfz053

Merkley, E., & Loewen, P. J. (2021). Anti-intellectualism and the mass public’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(6), 706-715. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41562-021-01112-w

Miao, F., Kozlenkova, I. V., Wang, H., Xie, T., & Palmatier, R. W. (2022). An emerging theory of avatar marketing. Journal of Marketing, 86(1), 67-90. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0022242921996646

Muniz, F., Stewart, K., & Magalhães, L. (2023). Are they humans or are they robots? The effect of virtual influencer disclosure on brand trust. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb. 2271

Mustafa, T. (2021). Are fast fashion brands trying to greenwash us? Retrieved February 6, 2023 from https://metro.co.uk/2021/04/08/are-fast-fashion-brands-trying-to-greenwash-us-14369109/.

Nagy, P., & Koles, B. (2014). “My avatar and her beloved possession”: Characteristics of attachment to virtual objects. Psychology & Marketing, 31(12), 1122-1135. https:// doi.org/10.1002/mar. 20759

Nerlich, B., Koteyko, N., & Brown, B. (2010). Theory and language of climate change communication. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 1(1), 97-110. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc. 2

Oliver, J. E., & Rahn, W. M. (2016). Rise of the Trumpenvolk: Populism in the 2016 election. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667(1), 189-206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216662639

Orlove, B., Shwom, R., Markowitz, E., & Cheong, S. M. (2020). Climate decision-making. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 45, 271-303. https://doi.org/10.1146/ annurev-environ-012320-085130

Park, C. W., Eisingerich, A. B., & Park, J. W. (2013). Attachment-aversion (AA) model of customer-brand relationships. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(2), 229-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2013.01.002

Pittman, M., & Abell, A. (2021). More trust in fewer followers: Diverging effects of popularity metrics and green orientation social media influencers. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 56, 70-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2021.05.002

Pogacar, R., Angle, J., Lowrey, T. M., Shrum, L. J., & Kardes, F. R. (2021). Is Nestlé a lady? The feminine brand name advantage. Journal of Marketing, 85(6), 101-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242921993060

Ren, S., Karimi, S., Velázquez, A. B., & Cai, J. (2023). Endorsement effectiveness of different social media influencers: The moderating effect of brand competence and warmth. Journal of Business Research, 156, Article 113476. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jbusres. 2022.113476

Scheufele, D. A., & Krause, N. M. (2019). Science audiences, misinformation, and fake news. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(16), 7662-7669.

Shah, Z., Olya, H., & Le Monkhouse, L. (2023). Developing strategies for international celebrity branding: A comparative analysis between Western and South Asian cultures. International Marketing Review, 40(1), 102-126. https://doi.org/10.1108/ IMR-08-2021-0261

Spence, A., Poortinga, W., & Pidgeon, N. (2012). The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Analysis, 32(6), 957-972. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.15396924.2011.01695.x

Thomas, V. L., & Fowler, K. (2021). Close encounters of the AI kind: Use of AI influencers as brand endorsers. Journal of Advertising, 50(1), 11-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00913367.2020.1810595

Till, B. D., & Busler, M. (2000). The match-up hypothesis: Physical attractiveness, expertise, and the role of fit on brand attitude, purchase intent and brand beliefs. Journal of Advertising, 29(3), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00913367.2000 .10673613

Trémolière, B., & Djeriouat, H. (2021). Exploring the roles of analytic cognitive style, climate science literacy, illusion of knowledge, and political orientation in climate change skepticism. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 74, Article 101561. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101561

Trimble, C. S., & Rifon, N. J. (2006). Consumer perceptions of compatibility in causerelated marketing messages. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 11(1), 29-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm. 42

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440-463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018963

van Valkengoed, A. M., & Steg, L. (2019). Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nature Climate Change, 9(2), 158-163. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41558-018-0371-y

Whang, C., & Im, H. (2021). “I like your suggestion!” The role of humanlikeness and parasocial relationship on the website versus voice shopper’s perception of recommendations. Psychology & Marketing, 38(4), 581-595. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/mar. 21437

Winterich, K. P., Zhang, Y., & Mittal, V. (2012). How political identity and charity positioning increase donations: Insights from moral foundations theory. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(4), 346-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ijresmar.2012.05.002

Wojciszke, B., Dowhyluk, M., & Jaworski, M. (1998). Moral competence-related traits: How do they differ? Polish Psychological Bulletin, 29(4), 283-294.

Ybarra, O., Chan, E., & Park, D. (2001). Young and old adults’ concerns about morality and competence. Motivation and Emotion, 25(2), 85-100. https://doi.org/10.1023/A: 1010633908298

Zhang, W., Chintagunta, P. K., & Kalwani, M. U. (2021). Social media, influencers, and adoption of an eco-friendly product: Field experiment evidence from rural China. Journal of Marketing, 85(3), 10-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242920985784

Zhou, X., Kim, S., & Wang, L. (2019). Money helps when money feels: Money anthropomorphism increases charitable giving. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(5), 953-972. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy012

- Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: m.gerrath@leeds.ac.uk (M.H.E.E. Gerrath), h.olya@sheffield.ac.uk (H. Olya), zahra.shah@sheffield.ac.uk (Z. Shah), hli176@sheffield.ac.uk (H. Li).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.114520

Publication Date: 2024-02-02

Virtual influencers and pro-environmental causes: The roles of message warmth and trust in experts

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Green marketing

Social-psychological distance

Message warmth

Trust in experts

Abstract

Virtual influencers (VIs) are an increasingly popular form of endorsers used in marketing campaigns. With their human influencer counterparts sometimes involved in scandals and controversy, VIs can be a more reliable source to promote pro-environmental and sustainable behavior. Taking a multi-methods approach, we examine how individuals react to VIs promoting pro-environmental campaigns. Our findings from initial semi-structured interviews confirm that individuals may be open to learning about green causes from VIs. Following this, we conduct two experiments to explore how VIs should promote green causes depending on their audience. We find that message warmth is positively associated with social-psychological distance, resulting in higher levels of engagement with pro-environmental causes. Moreover, the effect of message warmth is particularly pronounced for individuals with low trust in experts. We propose actionable implications for policy makers and other stakeholders considering employing VIs to promote their pro-environmental campaigns.

1. Introduction

retaining an element of unpredictable behavior which stems from a lack of control over their content and personal life (Thomas & Fowler, 2021). Human SMIs might be involved in scandals and even commit transgressions that could result in reputational damages and financial losses (Thomas & Fowler, 2021). In the context of pro-environmental causes, influencers’ authenticity could be undermined by inconsistencies between the green causes they promote and their unsustainable practices (Audrezet et al., 2020; Gerrath & Usrey, 2021; Leung et al., 2022), ultimately resulting in reduced pro-environmental intentions of their audiences (Boerman et al., 2022). For example, influencer Laura Whitmore was criticized for promoting pro-environmental behavior while being an ambassador for the fast-fashion brand Primark (Mustafa, 2021). Additionally, occurrences of influencers eliciting consumer backlash when promoting green causes may act as deterrents for other influencers considering promoting pro-environmental causes. Therefore, the need to expand understanding of how influencer marketing can effectively help promote pro-environmental causes is becoming incumbent.

2. Theory and hypotheses development

2.1. Influencers and pro-environmental causes

2.2. Virtual influencers (VIs)

2.3. Influencer’s message warmth and social-psychological distance

“warmth” overlaps with the term “morality” (Fiske et al., 2007).

A VI’s warmth may shape the audience’s reactions to proenvironmental campaigns, as people determine whether others are well-intentioned or not by their perceived warmth (Fiske et al., 2002; Gershon & Cryder, 2018). Prior research on warmth in social judgments suggests that people evaluate high-warmth characters more favorably than their low-warmth counterparts (Gershon & Cryder, 2018). Even if low-warmth actors behave prosocially, others might judge them as having ulterior motives rather than good intentions (Cuddy et al., 2011). More important, as the skepticism about pro-environmental appeals and green advertising (i.e., greenwashing; Laufer, 2003) grows (Delmas & Burbano, 2011), people may express reactance and message denial if they perceive appeals as manipulative (Clee & Wicklund, 1980). Green influencers’ warmth, therefore, appears more crucial as high warmth can be associated with high trustworthiness and good intentions (Fiske et al., 2007; Gershon & Cryder, 2018), thereby mitigating unexpected reactance. Empirical evidence indicates that people exhibit greater prosocial motivations and intentions (e.g., the endorsement of nonprofit brands [Bernritter et al., 2016]; donation [Zhou et al., 2019]) due to enhanced warmth perceptions. However, to the best of our knowledge, no research to date has examined how VIs’ warmth affects their effectiveness in promoting pro-environmental causes.

their actions (Hu et al., 2016). We thus posit that the relationship between VI’s message warmth and an individual’s pro-environmental engagement is explained by their perceived social-psychological distance.

2.4. Role of trust in experts

causes promoted by the VI. On the other hand, individuals who have high trust in experts are likely to give more weight and preference to objective and verifiable information (Lupia et al., 1998; Merkley & Loewen, 2021; Winterich et al., 2012), thus weakening this relationship.

H2a. The audience’s attitude towards the pro-environmental cause acts as a mediator between message warmth and engagement with the cause, especially if people trust experts less.

3. Overview of studies

4. Preliminary study: Exploratory interviews

4.1. Respondents and procedure

4.2. Findings

It makes me feel lost and depressed, [and] there seems to be no upside or advantage…. I will look at it and then keep scrolling to see something different. (R6)

I don’t go online [social media] to see things which upset me…. If the information was done in an interesting way, fine, but it keeps on saying we are responsible. (R13)

I think they [SMIs] do it when it will benefit them because it’s trending…. It can make the important issue seen as “fluff” things like cool but without any real concern…. You can see they post stories and things which show they are not really into it. (R5)

I like influencers, I follow a lot [of them] and they have good information but you can see they [do] not care about issues and it is not good for issues…. People will think this is an issue just for influencers and not serious when they say don’t buy plastic and then they are reviewing or saying “buy products which have plastic.” (R8)

You can see them [influencers] posting pictures on private jets and planes, and then they will be saying things like “We should protect our Earth” on Earth Day and “I love animals,” but they are not showing they care, and we can see that…. It’s off-putting, it makes me want to ignore it. (R11) You can see the Kardashians posting about love and care, but they are not being sustainable themselves. If they care, why don’t they change what they do first and then tell us? It really annoys me. (R12)

They won’t do proper fact-checking and promote or make false statements which people can then point to and say, “See? They are wrong” … they [the SMIs] won’t know what they are talking about…. The [proenvironmental] causes are important, but one wrong statement and people will use it. (R1)

I think it [pro-environmental messaging] is very important. There are influencers who post about it [environmental issues] and they are right, but they are not perfect, and people on the other side use that…. They will use a picture of someone doing something which is unpolitical or harming the environment and they will say the message is bad, and it worries me. (R16)

It would be good if they [VIs] talk about positive issues; they know which methods work best to influence people and they have large followings. (R4)

There is so much of the same [content on social media that] computergenerated technology is good, so it will make me pay attention and stop to look and then the thing becomes interesting, and I will look at it and read the information. (R7)

I see that realness, yes, it’s [VIs] not real, but like a video game character someone is using to show their real personality. There is a person behind it, and I think it helps them be more real and honest because they can stay hidden and not worry about judgment…. So the person behind it is real. (R14)

4.3. Discussion

5. Study 1

5.1. Participants and procedures

warmth, we used the Instagram post captions from Pretest 1. As described in Pretest 1, the caption in the high message warmth condition used more empathetic, caring, helpful, and sincere language to enhance warmth perceptions. Specifically, in the high message warmth condition, the text underneath the Instagram post (i.e., caption) stated: “I am really worried about what I read about the UN’s latest climate report. Climate change is something I care deeply about. We need to protect our beloved planet. Please support the “Climate Action” campaign in their fight against climate change. For more information, please visit https://www.climateacti on.gov.uk. #ad.”. In the low message warmth condition, the caption stated: “I just read the UN’s latest climate report. The global atmospheric carbon dioxide level rose to

5.2. Results

attitudes, we ran a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with message warmth and VI appearance as independent variables. The results indicated a significant main effect of message warmth on cause attitudes (

5.3. Discussion

6. Study 2

6.1. Participants and procedures

randomly allocated them to examine one of four (i.e., low message warmth with human SMI; high message warmth with human SMI; low message warmth with VI; high message warmth with VI) versions of a fictitious Instagram post. As in Study 1, the Instagram post’s caption manipulated low vs. high message warmth. Moreover, the Instagram post’s image featured either a human SMI or a VI (as pretested in Appendix E). Appendix F provides samples of the stimuli.

6.2. Results

variables. In support of H 1 , the results indicated a significant main effect of message warmth on cause engagement

the indirect effect for the case of low trust in experts (

6.3. Discussions

7. General discussions

7.1. Theoretical contributions

7.2. Implications for stakeholders

7.2.1. Is VI marketing an effective approach to promote green causes?

7.2.2. How can stakeholders engage audiences who mistrust experts?

7.3. Limitations and avenues for further research

climate change exists even if scientists and experts say otherwise (Kennedy et al., 2022; Trémolière & Djeriouat, 2021). Trust in experts is therefore an important factor in this research. Third, the results of the Preliminary Study suggest that most respondents would be open to and like to see VIs share content on pro-environmental causes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

Acknowledgement

Appendices. Supplementary material

References

Ameen, N., Cheah, J. H., Ali, F., El-Manstrly, D., & Kulyciute, R. (2023). Risk, trust, and the roles of human versus virtual influencers. Journal of Travel Research. https://doi. org/10.1177/00472875231190601

Ameen, N., Hosany, S., & Tarhini, A. (2021). Consumer interaction with cutting-edge technologies: Implications for future research. Computers in Human Behavior, 120, Article 106761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106761

Appel, G., Grewal, L., Hadi, R., & Stephen, A. T. (2020). The future of social media in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(1), 79-95. https://doi. org/10.1007/s11747-019-00695-1

Arsel, Z. (2017). Asking questions with reflexive focus. Journal of Consumer Research, 44 (4), 939-948. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx096

Audrezet, A., & Koles, B. (2023). Virtual influencer as a brand avatar in interactive marketing. In C. L. Wang (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of interactive marketing (pp. 353-376). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-14961-0_16.

Aw, E. C. X., & Chuah, S. H. W. (2021). “Stop the unattainable ideal for an ordinary me!” Fostering parasocial relationships with social media influencers: The role of selfdiscrepancy. Journal of Business Research, 132, 146-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbusres.2021.04.025

Ballestar, M. T., Martín-Llaguno, M., & Sainz, J. (2022). An artificial intelligence analysis of climate-change influencers’ marketing on Twitter. Psychology & Marketing, 39(12), 2273-2283. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar. 21735

Bernritter, S. F., Verlegh, P. W., & Smit, E. G. (2016). Why nonprofits are easier to endorse on social media: The roles of warmth and brand symbolism. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 33(1), 27-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2015.10.002

Boerman, S. C., Meijers, M. H., & Zwart, W. (2022). The importance of influencermessage congruence when employing greenfluencers to promote pro-environmental behavior. Environmental Communication, 16(7), 920-941. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 17524032.2022.2115525

Breves, P., & Liebers, N. (2022). #Greenfluencing. The impact of parasocial relationships with social media influencers on advertising effectiveness and followers’ proenvironmental intentions. Environmental Communication, 16(6), 773-787. https:// doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2022.2109708

Buys, L., Aird, R., van Megen, K., Miller, E., & Sommerfeld, J. (2014). Perceptions of climate change and trust in information providers in rural Australia. Public Understanding of Science, 23(2), 170-188. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0963662512449948

Byun, K. J., & Ahn, S. J. (2023). A systematic review of virtual influencers: Similarities and differences between human and virtual influencers in interactive advertising. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 15252019.2023.2236102

Cascio Rizzo, G. L. C., Berger, J., & Villarroel, F. (2023). What drives virtual influencer’s impact? Working paper, LUISS Guido Carli University. https://doi.org/10.4855 0/arXiv.2301.09874.

Castelo, N., Bos, M. W., & Lehmann, D. R. (2019). Task-dependent algorithm aversion. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(5), 809-825. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0022243719851788

Chang, Y., Li, Y., Yan, J., & Kumar, V. (2019). Getting more likes: The impact of narrative person and brand image on customer-brand interactions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(6), 1027-1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00632-2

Clark, M. S. (1984). Record keeping in two types of relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(3), 549-557. https://doi.org/10.1037/00223514.47.3.549

Cologna, V., & Siegrist, M. (2020). The role of trust for climate change mitigation and adaptation behaviour: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 69, Article 101428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101428

Conde, R., & Casais, B. (2023). Micro, macro and mega-influencers on Instagram: The power of persuasion via the parasocial relationship. Journal of Business Research, 158, Article 113708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113708

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Delmas, M. A., & Burbano, V. C. (2011). The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1), 64-87. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2011.54.1.64

Dubois, D., Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2016). Dynamics of communicator and audience power: The persuasiveness of competence versus warmth. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(1), 68-85. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw006

Edwards, S. M., Lee, J. K., & Ferle, C. L. (2009). Does place matter when shopping online? Perceptions of similarity and familiarity as indicators of psychological distance. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 10(1), 35-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 15252019.2009.10722161

Fage-Butler, A., Ledderer, L., & Nielsen, K. H. (2022). Public trust and mistrust of climate science: A meta-narrative review. Public Understanding of Science, 31(7), 832-846. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625221110028

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77-83. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Gerrath, M. H. E. E., & Usrey, B. (2021). The impact of influencer motives and commonness perceptions on follower reactions toward incentivized reviews. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 38(3), 531-548, doi:10.1016/j. ijresmar.2020.09.010.

Gershon, R., & Cryder, C. (2018). Goods donations increase charitable credit for lowwarmth donors. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(2), 451-469. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/jcr/ucx126

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis (3rd ed.). Guilford Press.

Hornsey, M. J., Harris, E. A., Bain, P. G., & Fielding, K. S. (2016). Meta-analyses of the determinants and outcomes of belief in climate change. Nature Climate Change, 6(6), 622-626. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2943

Hsieh, S. H., & Chang, A. (2016). The psychological mechanism of brand co-creation engagement. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 33, 13-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. intmar.2015.10.001

Hu, T.-Y., Li, J., Jia, H., & Xie, X. (2016). Helping others, warming yourself: Altruistic behaviors increase warmth feelings of the ambient environment. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1349-1349, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01349.

Huang, R., & Ha, S. (2020). The effects of warmth-oriented and competence-oriented service recovery messages on observers on online platforms. Journal of Business Research, 121, 616-627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.04.034

Hughes, C., Swaminathan, V., & Brooks, G. (2019). Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. Journal of Marketing, 83(5), 78-96. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0022242919854374

Jin, S. V., & Ryu, E. (2020). “I’ll buy what she’s# wearing”: The roles of envy toward and parasocial interaction with influencers in Instagram celebrity-based brand endorsement and social commerce. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, Article 102121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102121

Karagür, Z., Becker, J. M., Klein, K., & Edeling, A. (2022). How, why, and when disclosure type matters for influencer marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 39(2), 313-335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2021.09.006

Kennedy, B., Tyson, A., & Funk, C. (2022). Americans’ Trust in Scientists, Other Groups Declines. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/02/15/ame ricans-trust-in-scientists-other-groups-declines/.

Kim, D. Y., & Kim, H. Y. (2021). Trust me, trust me not: A nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. Journal of Business Research, 134, 223-232. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.024

Kim, E., Duffy, M., & Thorson, E. (2021). Under the influence: Social media influencers’ impact on response to corporate reputation advertising. Journal of Advertising, 50(2), 119-138. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2020.1868026

Kim, S. Y., Schmitt, B. H., & Thalmann, N. M. (2019). Eliza in the uncanny valley: Anthropomorphizing consumer robots increases their perceived warmth but decreases liking. Marketing Letters, 30(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-019-09485-9

Kim, Y., Kwak, S. S., & Kim, M. (2013). Am I acceptable to you? Effect of a robot’s verbal language forms on people’s social distance from robots. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 1091-1101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.001

Knupfer, H., Neureiter, A., & Matthes, J. (2023). From social media diet to public riot? Engagement with “greenfluencers” and young social media users’ environmental activism. Computers in Human Behavior, 139, Article 107527. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107527

Kull, A. J., Romero, M., & Monahan, L. (2021). How may I help you? Driving brand engagement through the warmth of an initial chatbot message. Journal of Business Research, 135, 840-850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.005

Lee, S. A., & Oh, H. (2021). Anthropomorphism and its implications for advertising hotel brands. Journal of Business Research, 129, 455-464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jbusres.2019.09.053

Leung, F. F., Gu, F. F., & Palmatier, R. W. (2022). Online influencer marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(2), 226-251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00829-4

Lewandowsky, S. (2021). Climate change disinformation and how to combat it. Annual Review of Public Health, 42, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102409

Lou, C., Kiew, S. T. J., Chen, T., Lee, T. Y. M., Ong, J. E. C., & Phua, Z. (2023). Authentically fake? How consumers respond to the influence of virtual influencers. Journal of Advertising, 52(4), 540-557. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00913367.2022 .2149641

Maiella, R., La Malva, P., Marchetti, D., Pomarico, E., Di Crosta, A., Palumbo, R., … Verrocchio, M. C. (2020). The psychological distance and climate change: A systematic review on the mitigation and adaptation behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568899

McDonald, R. I., Chai, H. Y., & Newell, B. R. (2015). Personal experience and the ‘psychological distance’ of climate change: An integrative review. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 44, 109-118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jenvp.2015.10.003

McKenna, B., Myers, M. D., & Newman, M. (2017). Social media in qualitative research: Challenges and recommendations. Information and Organization, 27(2), 87-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2017.03.001

Merkley, E. (2020). Anti-intellectualism, populism, and motivated resistance to expert consensus. Public Opinion Quarterly, 84(1), 24-48. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/ nfz053

Merkley, E., & Loewen, P. J. (2021). Anti-intellectualism and the mass public’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(6), 706-715. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41562-021-01112-w

Miao, F., Kozlenkova, I. V., Wang, H., Xie, T., & Palmatier, R. W. (2022). An emerging theory of avatar marketing. Journal of Marketing, 86(1), 67-90. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0022242921996646

Muniz, F., Stewart, K., & Magalhães, L. (2023). Are they humans or are they robots? The effect of virtual influencer disclosure on brand trust. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb. 2271

Mustafa, T. (2021). Are fast fashion brands trying to greenwash us? Retrieved February 6, 2023 from https://metro.co.uk/2021/04/08/are-fast-fashion-brands-trying-to-greenwash-us-14369109/.

Nagy, P., & Koles, B. (2014). “My avatar and her beloved possession”: Characteristics of attachment to virtual objects. Psychology & Marketing, 31(12), 1122-1135. https:// doi.org/10.1002/mar. 20759

Nerlich, B., Koteyko, N., & Brown, B. (2010). Theory and language of climate change communication. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 1(1), 97-110. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc. 2

Oliver, J. E., & Rahn, W. M. (2016). Rise of the Trumpenvolk: Populism in the 2016 election. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667(1), 189-206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216662639

Orlove, B., Shwom, R., Markowitz, E., & Cheong, S. M. (2020). Climate decision-making. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 45, 271-303. https://doi.org/10.1146/ annurev-environ-012320-085130

Park, C. W., Eisingerich, A. B., & Park, J. W. (2013). Attachment-aversion (AA) model of customer-brand relationships. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(2), 229-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2013.01.002

Pittman, M., & Abell, A. (2021). More trust in fewer followers: Diverging effects of popularity metrics and green orientation social media influencers. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 56, 70-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2021.05.002

Pogacar, R., Angle, J., Lowrey, T. M., Shrum, L. J., & Kardes, F. R. (2021). Is Nestlé a lady? The feminine brand name advantage. Journal of Marketing, 85(6), 101-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242921993060

Ren, S., Karimi, S., Velázquez, A. B., & Cai, J. (2023). Endorsement effectiveness of different social media influencers: The moderating effect of brand competence and warmth. Journal of Business Research, 156, Article 113476. https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jbusres. 2022.113476

Scheufele, D. A., & Krause, N. M. (2019). Science audiences, misinformation, and fake news. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(16), 7662-7669.

Shah, Z., Olya, H., & Le Monkhouse, L. (2023). Developing strategies for international celebrity branding: A comparative analysis between Western and South Asian cultures. International Marketing Review, 40(1), 102-126. https://doi.org/10.1108/ IMR-08-2021-0261

Spence, A., Poortinga, W., & Pidgeon, N. (2012). The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Analysis, 32(6), 957-972. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.15396924.2011.01695.x

Thomas, V. L., & Fowler, K. (2021). Close encounters of the AI kind: Use of AI influencers as brand endorsers. Journal of Advertising, 50(1), 11-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00913367.2020.1810595

Till, B. D., & Busler, M. (2000). The match-up hypothesis: Physical attractiveness, expertise, and the role of fit on brand attitude, purchase intent and brand beliefs. Journal of Advertising, 29(3), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00913367.2000 .10673613

Trémolière, B., & Djeriouat, H. (2021). Exploring the roles of analytic cognitive style, climate science literacy, illusion of knowledge, and political orientation in climate change skepticism. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 74, Article 101561. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101561

Trimble, C. S., & Rifon, N. J. (2006). Consumer perceptions of compatibility in causerelated marketing messages. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 11(1), 29-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm. 42

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440-463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018963

van Valkengoed, A. M., & Steg, L. (2019). Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nature Climate Change, 9(2), 158-163. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41558-018-0371-y

Whang, C., & Im, H. (2021). “I like your suggestion!” The role of humanlikeness and parasocial relationship on the website versus voice shopper’s perception of recommendations. Psychology & Marketing, 38(4), 581-595. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/mar. 21437

Winterich, K. P., Zhang, Y., & Mittal, V. (2012). How political identity and charity positioning increase donations: Insights from moral foundations theory. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(4), 346-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ijresmar.2012.05.002

Wojciszke, B., Dowhyluk, M., & Jaworski, M. (1998). Moral competence-related traits: How do they differ? Polish Psychological Bulletin, 29(4), 283-294.

Ybarra, O., Chan, E., & Park, D. (2001). Young and old adults’ concerns about morality and competence. Motivation and Emotion, 25(2), 85-100. https://doi.org/10.1023/A: 1010633908298

Zhang, W., Chintagunta, P. K., & Kalwani, M. U. (2021). Social media, influencers, and adoption of an eco-friendly product: Field experiment evidence from rural China. Journal of Marketing, 85(3), 10-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242920985784

Zhou, X., Kim, S., & Wang, L. (2019). Money helps when money feels: Money anthropomorphism increases charitable giving. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(5), 953-972. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucy012

- Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: m.gerrath@leeds.ac.uk (M.H.E.E. Gerrath), h.olya@sheffield.ac.uk (H. Olya), zahra.shah@sheffield.ac.uk (Z. Shah), hli176@sheffield.ac.uk (H. Li).