DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09842-1

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-17

الماضي والحاضر والمستقبل لنظرية الإدراك في التعلم متعدد الوسائط

© المؤلفون 2024

الملخص

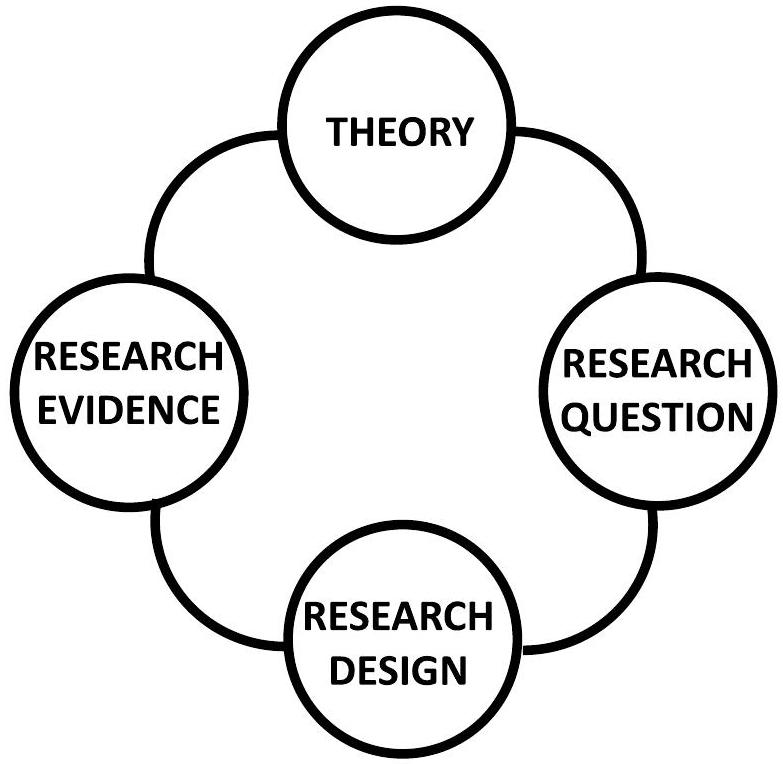

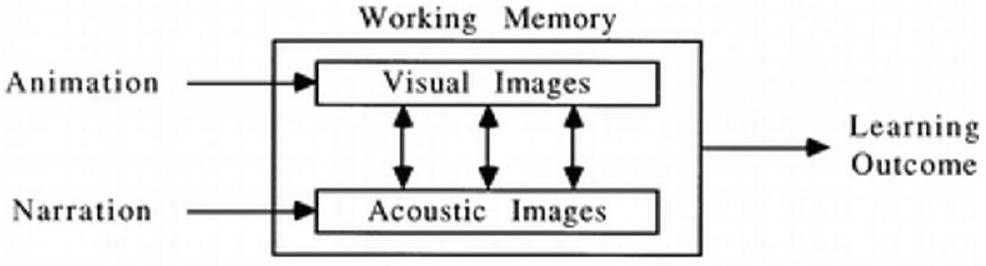

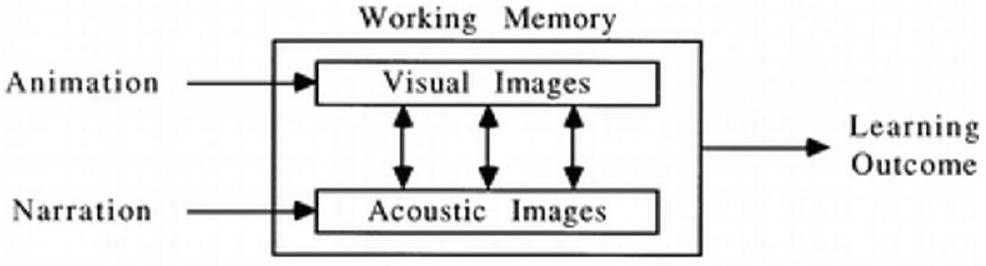

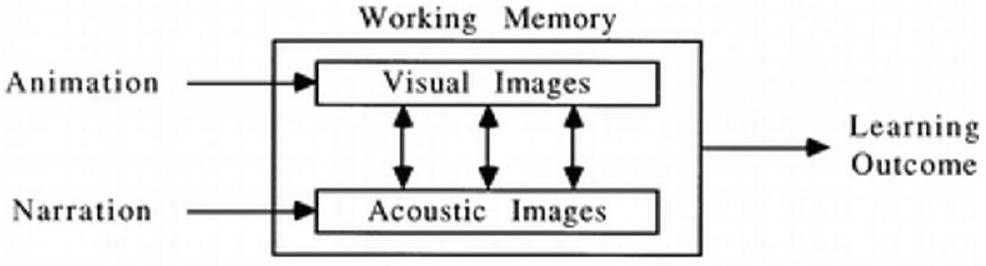

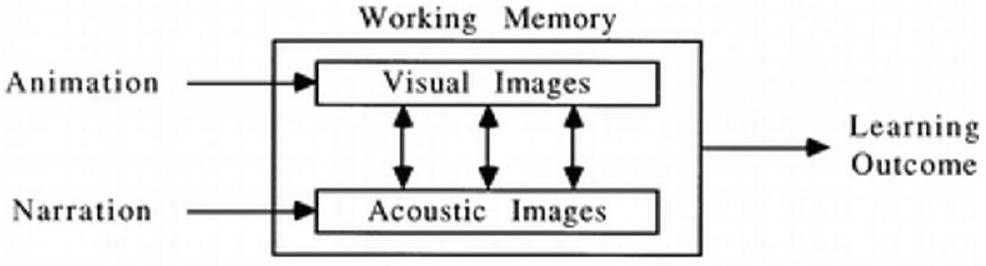

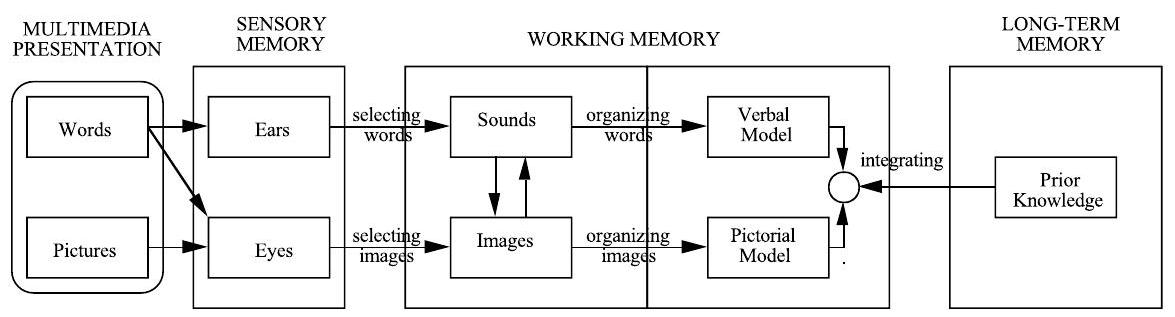

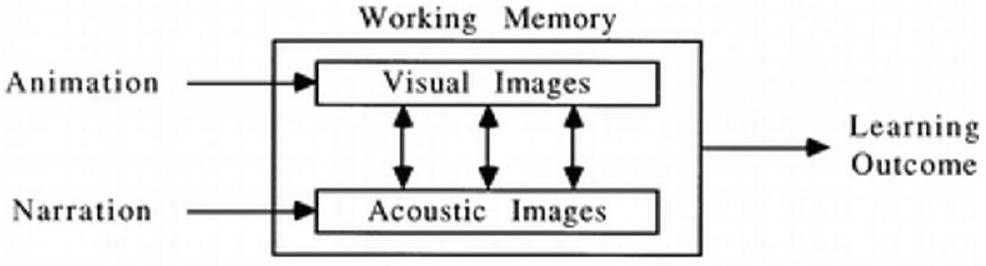

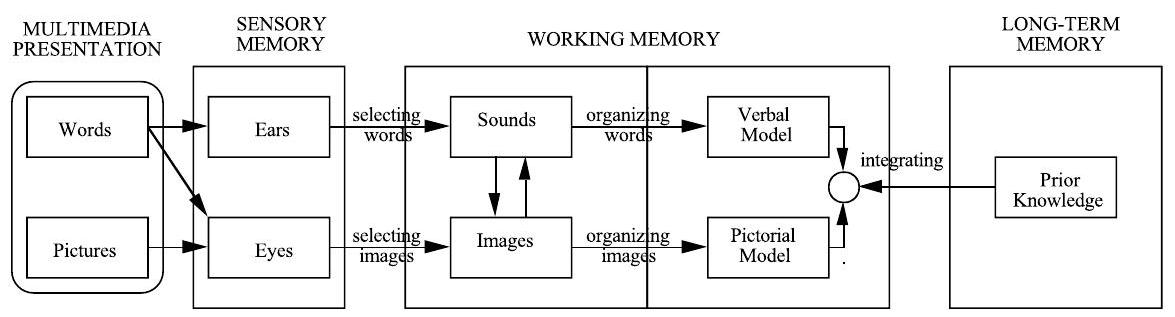

نظرية التعلم المتعدد الوسائط المعرفية (ماير، 2021، 2022)، التي تسعى لشرح كيفية تعلم الناس للمواد الأكاديمية من الكلمات والرسوم البيانية، قد تطورت على مدى الأربعة عقود الماضية. على الرغم من أن اسم النظرية وتمثيلها الرسومي قد تطورا على مر السنين، إلا أن الأفكار الأساسية ظلت ثابتة – قنوات مزدوجة (أي أن البشر لديهم قنوات معالجة معلومات منفصلة للمعلومات اللفظية والمرئية)، سعة محدودة (أي أن سعة المعالجة محدودة بشدة)، ومعالجة نشطة (أي أن التعلم المعنوي يتضمن اختيار المواد ذات الصلة ليتم معالجتها في الذاكرة العاملة، وتنظيم المواد عقليًا في هياكل لفظية ومرئية متماسكة، ودمجها مع بعضها البعض ومع المعرفة ذات الصلة المفعلة من الذاكرة طويلة المدى). تصف هذه المراجعة كيف تطورت النظرية (أي، الماضي)، والحالة الحالية للنظرية (أي، الحاضر)، والاتجاهات الجديدة للتطوير المستقبلي (أي، المستقبل). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تتضمن المراجعة أمثلة على الأحداث والنتائج التي أدت إلى تغييرات في النظرية. يتم مناقشة الآثار المترتبة على علم النفس التربوي، بما في ذلك 15 مبدأً قائمًا على الأدلة لتصميم الوسائط المتعددة.

مقدمة في نظرية التعلم المتعدد الوسائط المعرفية

قوة النظريات تكمن في أنها تمتلك القدرة على البقاء صالحة وذات صلة عبر الأجيال، بينما قوة النظريات الجديدة تكمن في أنها تبني على تلك النظريات القديمة وتوسعها. يمكنك أن تقول إن النظريات القديمة هي العمالقة الذين يقف على أكتافهم النظريات الجديدة، وبالتالي العمالقة الجدد. يمكن اعتبار نظرية التعلم المتعدد الوسائط المعرفية (CTML) … واحدة من هؤلاء العمالقة الجدد.

الرؤية 1: بناء النظرية يعتمد على الفضول الفكري

كعالم نفس، حظيت بفرصة جيدة لأخذ دورة بعنوان نماذج التفكير، التي قام بتدريسها مستشاري، جيم غرينو. جعلتني هذه الدورة أفكر في كيفية قدرة الناس على التوصل إلى حلول إبداعية للمشكلات، مما قادني إلى سؤال أساسي: “كيف يمكننا مساعدة الناس على التعلم بطرق تمكنهم من أخذ ما تعلموه وتطبيقه على مواقف جديدة؟” هذا السؤال حول التعليم من أجل النقل، الذي تشكل في ذهني خلال تلك الدورة، ظل معي طوال هذه السنوات وقد دفع أبحاثي. اكتشفت قريبًا أن هذه قضية كلاسيكية، وإن كانت مراوغة، في كل من علم النفس والتعليم تعود إلى الأيام الأولى من البحث في التعلم والتعليم.

الرؤية 2: بناء النظرية مستند إلى أفكار قديمة

الرؤية 3: بناء النظرية ليس مسارًا مستقيمًا مخططًا له

خطة، وبالتأكيد لم تظهر في رأسي يومًا ما في حزمة مصقولة جميلة. بل خرجت على شكل نوبات متقطعة، مع سلسلة طويلة من المراجعات، والتنقيحات، والتوضيحات، والحذف، والإضافات.

البصيرة 4: بناء النظرية هو مشكلة هندسية

تحول من وجهات نظر سلوكية إلى وجهات نظر معرفية حول كيفية عمل التعلم – ولكن بعد ذلك على مدى جميع هذه السنوات اللاحقة، كان يتضمن تحسينًا مستمرًا على فكرتي الأصلية.

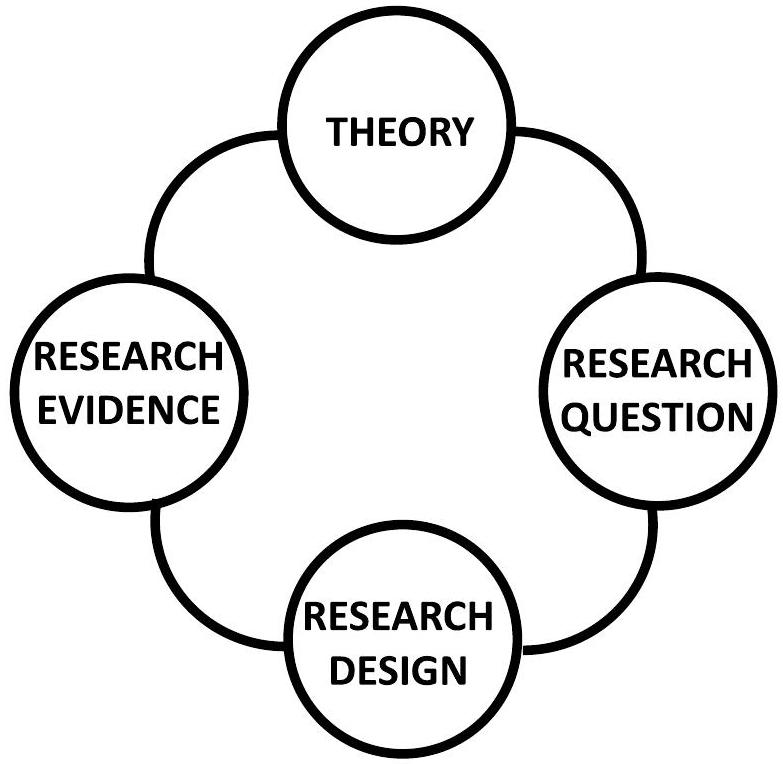

البصيرة 5: بناء النظرية هو عملية تكرارية تتضمن التفاعل المستمر بين البحث والنظرية

البصيرة 6: بناء النظرية يعتمد على الاستمرارية في جمع أدلة البحث الجديدة

الرؤية 7: بناء النظرية هو نشاط جماعي

الذي يمثل فيه العديد من الأشخاص في الإصدارات المختلفة من دليل كامبريدج للتعلم متعدد الوسائط (ماير، 2005، 2014؛ ماير وفيوريلا، 2022). كما استفاد CTML من الأفكار من النظريات المتنافسة مثل نظرية الحمل المعرفي (باس وسويلر، 2022؛ سويلر، 1999، قيد النشر؛ سويلر وآخرون، 2011) أو النموذج المتكامل لفهم النص والصورة (شنتز، 2022، 2023). جزء من بناء النظرية هو القدرة على إقناع أقرانك وأن تكون مقتنعًا بهم.

ماضي النظرية المعرفية للتعلم متعدد الوسائط

الصدام باسم النظرية

| الجدول 1 تغييرات الأسماء التي أدت إلى النظرية المعرفية للتعلم متعدد الوسائط وما بعدها | ||

| الاسم | التركيز | المصدر (المصادر) الأولية |

| نموذج التعلم المعنوي | الظروف للتعليم من أجل التعلم المعنوي | ماير (1989) |

| نموذج الظروف للتوضيحات الفعالة | الظروف للتعليم من أجل التعلم المعنوي | ماير وغاليني (1990) |

| نموذج الترميز المزدوج | الترميز المزدوج | ماير وأندرسون

|

| نموذج المعالجة المزدوجة للتعلم متعدد الوسائط أو نموذج المعالجة المزدوجة للذاكرة العاملة | الترميز المزدوج | ماير ومورينو (1998); |

| نموذج SOI | العمليات التوليدية | ماير (1996) |

| نظرية التوليد | العمليات التوليدية | ماير وآخرون (1995) |

| نظرية التوليد للتعلم متعدد الوسائط | العمليات التوليدية | ماير (1997)؛ بلاس وآخرون (1998) |

| نظرية التعلم التوليدية | العمليات التوليدية | فيوريلا وماير (2015، 2016); |

| نظرية التوليد للتعلم | العمليات التوليدية | ماير (2010) |

| النظرية المعرفية للتعلم متعدد الوسائط | العمليات التوليدية | ماير (1997)؛ ماير وآخرون، (1996، 1999)؛ مورينو وماير (2000)؛ ماير (2001)؛ ماير وآخرون (2001)؛ ماير ومورينو، 2003) |

| اسم | تأكيد | المصدر (المصادر) الأولية |

| نظرية الوكالة الاجتماعية | المعالجة الاجتماعية | ماير وآخرون (2003)؛ أتكينسون وآخرون (2005) |

| النموذج المعرفي العاطفي للتعلم باستخدام الوسائط | المعالجة العاطفية | مورينو وماير (2007) |

| النموذج المعرفي العاطفي للتعلم الإلكتروني | المعالجة العاطفية | لاوسون وآخرون (2021)؛ لاوسون وماير (2022) |

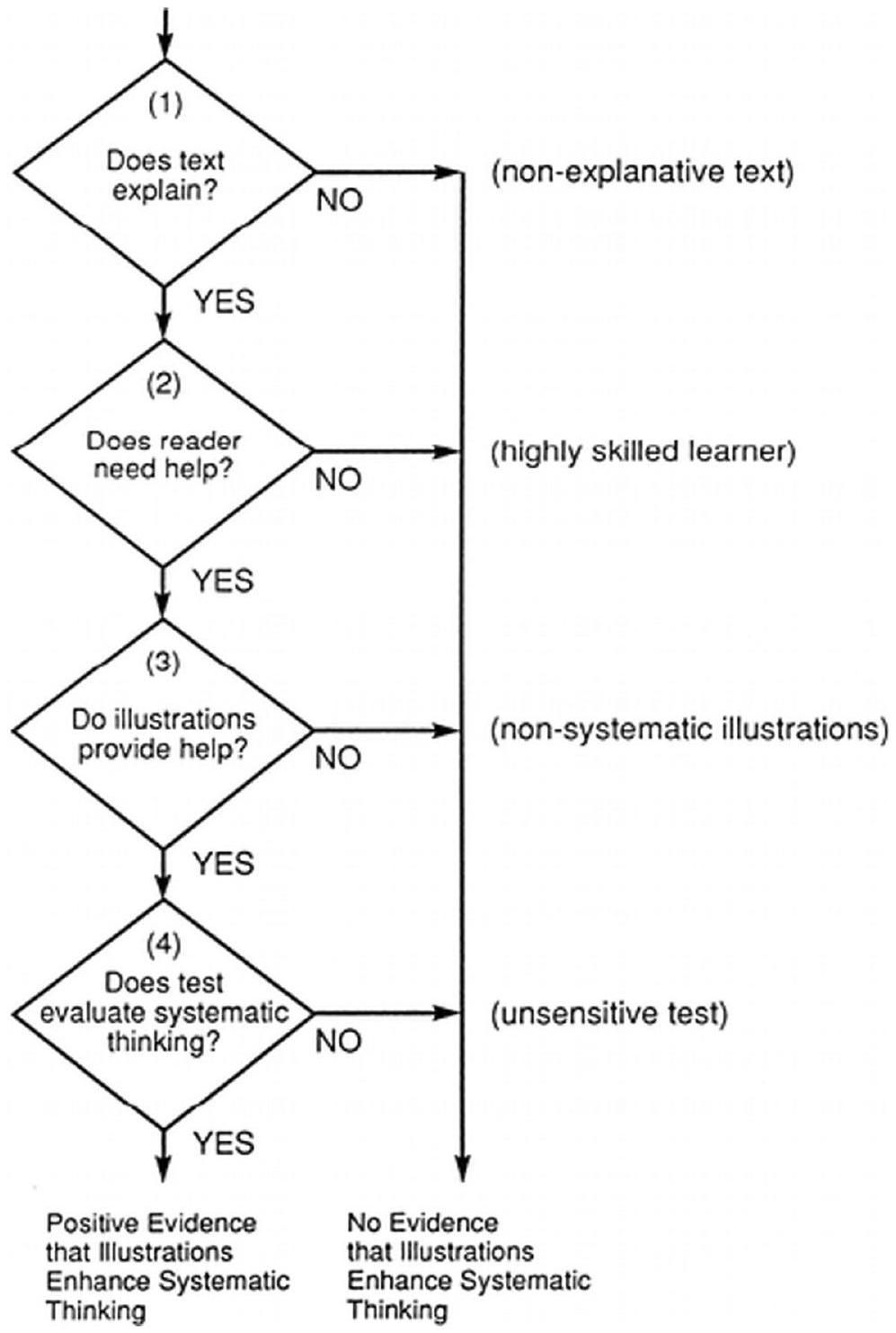

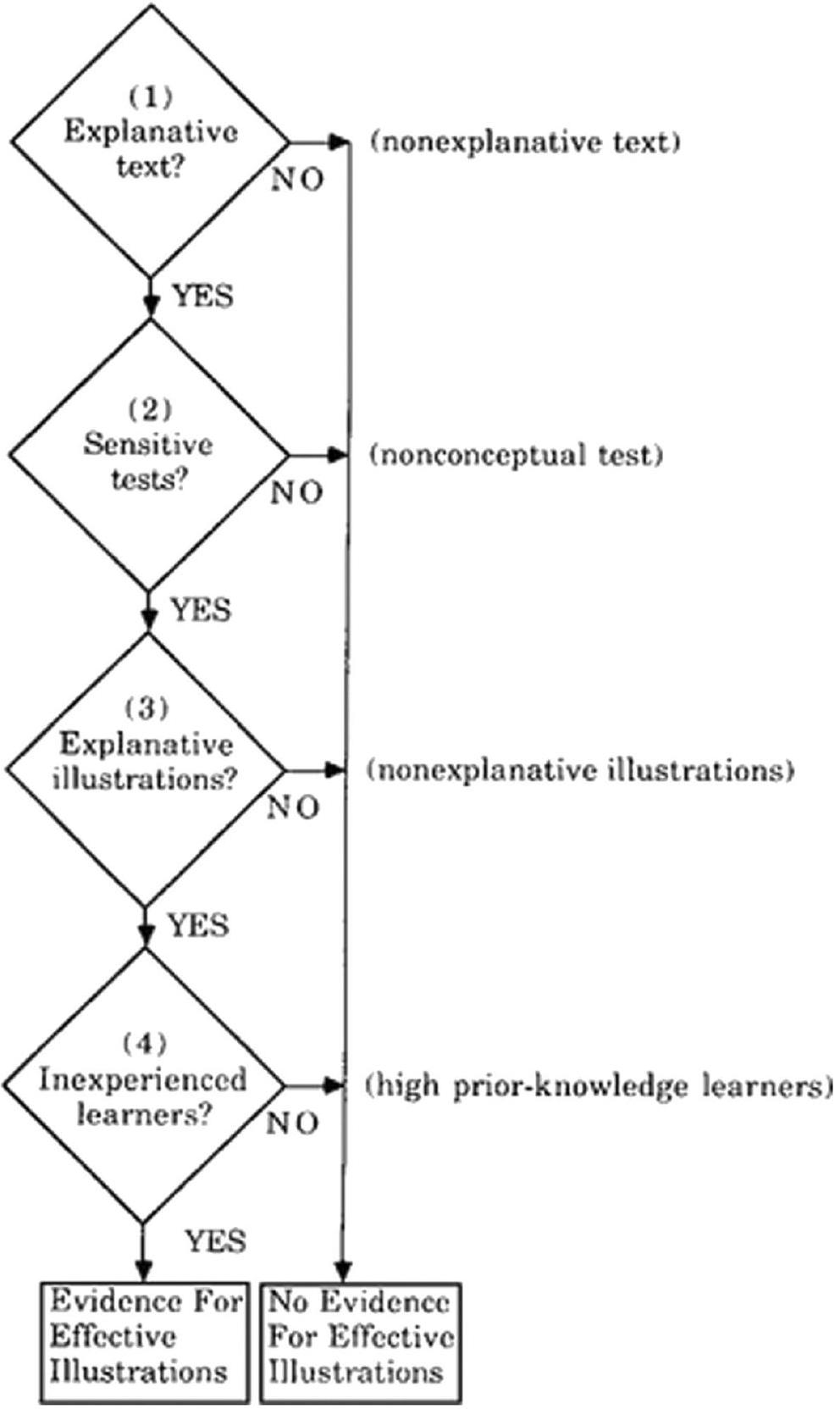

التقدم نحو تمثيل بصري للنظرية

إضافة إلى قاعدة البحث

| طبعة | سنة |

|

|

||||

| 1 | 2001 | ٤٥ | ٧ | ||||

| 2 | 2009 | 93 | 12 | ||||

| ٣ | ٢٠٢١ | ٢٠١ | 15 |

| مبدأ | الطبعة الأولى (2001) | الطبعة الثانية (2009) | الطبعة الثالثة (2021) |

| وسائط متعددة | إكس | إكس | إكس |

| التماسك | إكس | إكس | إكس |

| الإشارة | إكس | إكس | |

| الازدواجية | إكس | إكس | إكس |

| التجاور المكاني | إكس | إكس | إكس |

| التجاور الزمني | إكس | إكس | إكس |

| تقسيم | إكس | إكس | |

| التدريب المسبق | إكس | إكس | |

| الأسلوب | إكس | إكس | إكس |

| التخصيص | إكس | إكس | |

| صوت | إكس | إكس | |

| صورة | إكس | إكس | |

| تجسيد | إكس | ||

| الانغماس |

|

||

| نشاط توليدي | إكس |

الحالة الحالية لنظرية التعلم المعرفي متعدد الوسائط

| الطبعة | السنة | الفصول | المبادئ | المؤلفون |

| 1 | 2005 | 35 | 22 | 46 |

| 2 | 2014 | 34 | 25 | 52 |

| 3 | 2022 | 46 | 31 | 60 |

الافتراضات التوجيهية لنظرية التعلم المعرفي متعدد الوسائط

ثلاثة مخازن للذاكرة في نظرية التعلم المعرفي متعدد الوسائط

خمسة عمليات معرفية في نظرية التعلم المعرفي متعدد الوسائط

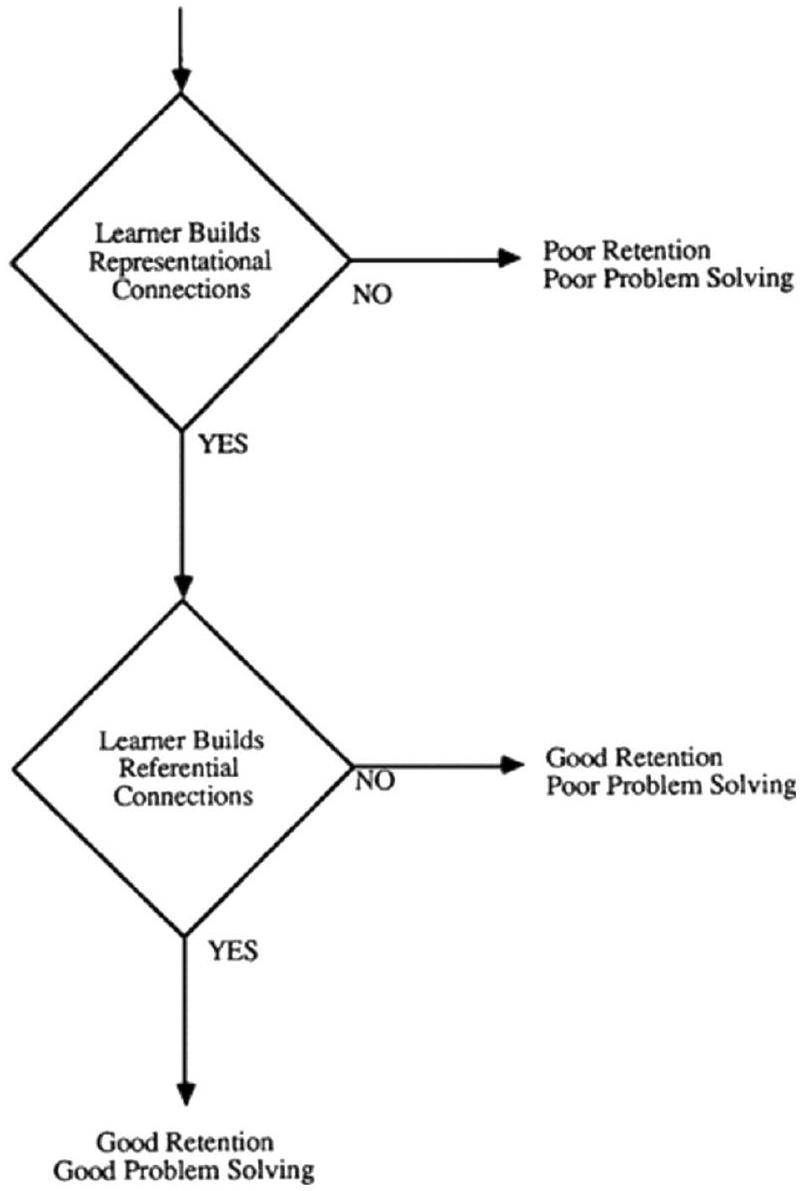

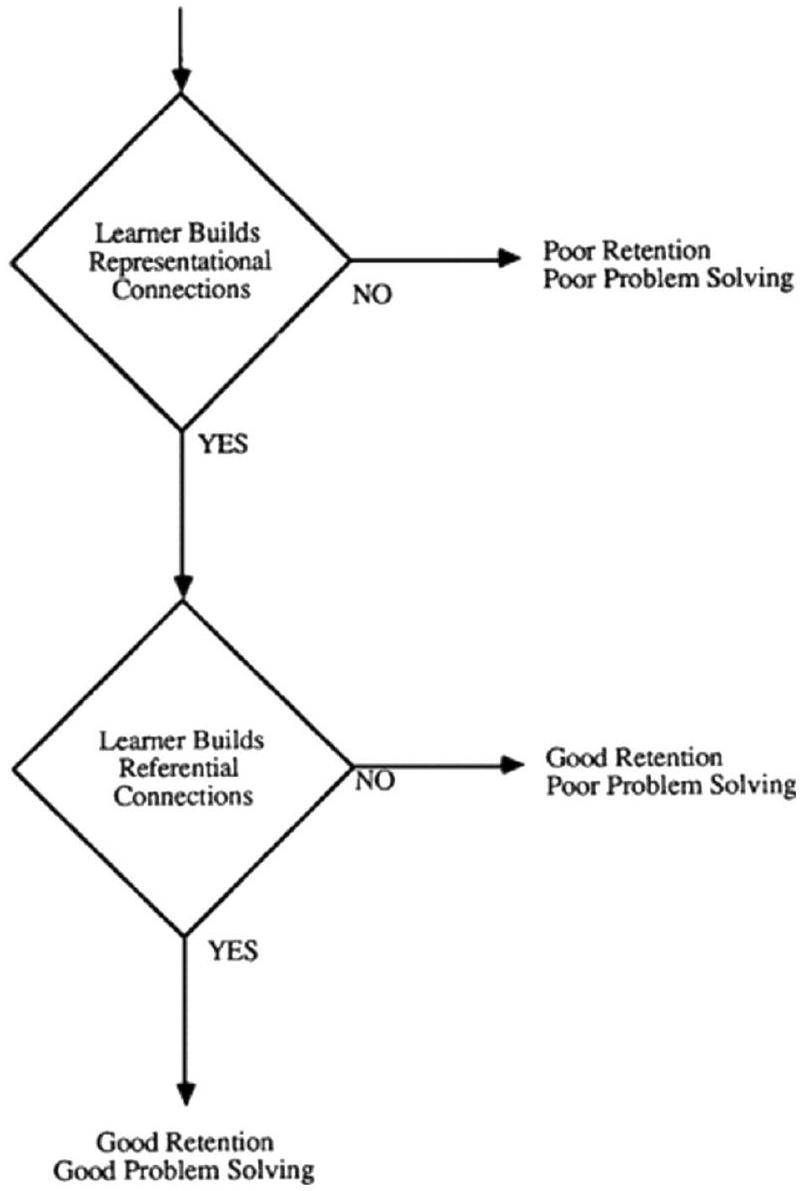

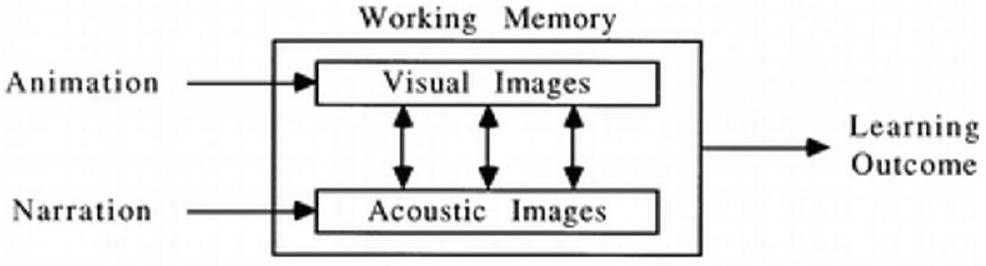

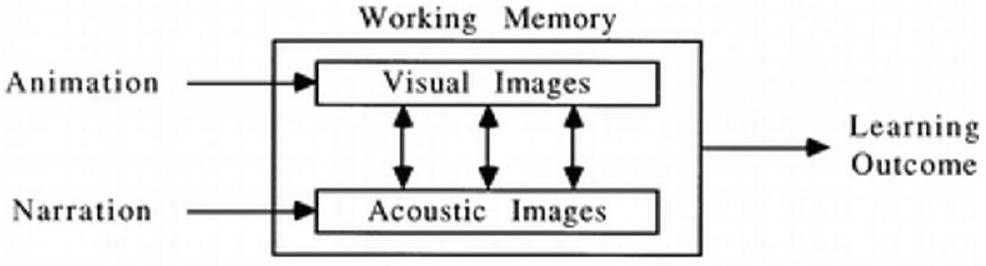

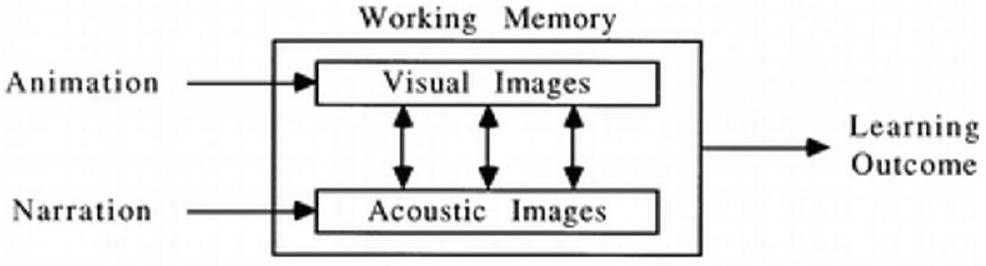

dمج. يشير اختيار الكلمات إلى الانتباه إلى الأجزاء ذات الصلة من النص المطبوع، ويشير اختيار الصور إلى الانتباه إلى الأجزاء ذات الصلة من الرسوم البيانية المعروضة. يشير تنظيم الكلمات إلى ترتيب الكلمات ذات الصلة في نموذج لفظي في الذاكرة العاملة، ويشير تنظيم الصور إلى ترتيب الأجزاء ذات الصلة من الرسوم البيانية في نموذج تصويري في الذاكرة العاملة. يشير الدمج إلى إنشاء اتصالات بين التمثيلات اللفظية والتصويرية المقابلة في الذاكرة العاملة بالإضافة إلى المعرفة ذات الصلة من الذاكرة طويلة المدى. يعتمد التعلم المعنوي على انخراط المتعلم في معالجة معرفية مناسبة تتضمن الاختيار والتنظيم والدمج. يهدف تصميم التعليم إلى توجيه هذه العمليات.

ثلاثة مطالب على السعة المعرفية

ثلاثة أهداف تعليمية

إدارة المعالجة الأساسية. يمكن تحقيق ذلك، على سبيل المثال، من خلال تقسيم درس مستمر إلى أجزاء قابلة للإدارة يمكن أن يتم ضبطها من قبل المتعلم.

خمسة عشر مبدأ لتصميم التعليم المتعدد الوسائط

مستقبل نظرية التعلم المتعدد الوسائط المعرفية

دمج مكونات جديدة في نظرية التعلم المتعدد الوسائط المعرفية

| مبدأ لتقليل المعالجة الزائدة | حجم التأثير | اختبارات |

| 1. مبدأ التماسك: يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل عندما يتم استبعاد المواد الزائدة بدلاً من تضمينها | 0.86 | 19 |

| 2. مبدأ الإشارة: يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل عندما تتم إضافة إشارات تبرز تنظيم المادة الأساسية | 0.69 | 16 |

| 3. مبدأ التكرار: لا يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل عندما يتم إضافة نص مطبوع إلى الرسوم البيانية والسرد؛ يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل من الرسوم البيانية والسرد مقارنة بالرسوم البيانية والسرد والنص المطبوع، عندما يكون الدرس سريعًا | 0.10 | 12 |

| 4. مبدأ القرب المكاني: يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل عندما يتم تقديم الكلمات والصور المتطابقة بالقرب من بعضها البعض بدلاً من بعيدًا عن بعضها على الصفحة أو الشاشة | 0.82 | 9 |

| 5. مبدأ القرب الزمني: يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل عندما يتم تقديم الكلمات والصور المتطابقة في وقت واحد بدلاً من بالتتابع | 1.31 | 8 |

| مبادئ إدارة المعالجة الأساسية | حجم التأثير | اختبارات |

| 6. مبدأ التقسيم: يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل عندما يتم تقديم درس متعدد الوسائط في أجزاء يمكن للمتعلم ضبطها بدلاً من وحدة مستمرة | 0.67 | 7 |

| 7. مبدأ التدريب المسبق: يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل من درس متعدد الوسائط عندما يعرفون أسماء وخصائص المفاهيم الرئيسية | 0.78 | 10 |

| 8. مبدأ الوسائط: يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل من الرسوم البيانية والسرد مقارنة بالرسوم البيانية والنص على الشاشة | 1.00 | 19 |

| مبادئ إدارة المعالجة الأساسية | حجم التأثير | اختبارات |

| 9. مبدأ الوسائط المتعددة: يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل من الكلمات والصور مقارنة بالكلمات وحدها | 1.35 | 13 |

| 10. مبدأ التخصيص: يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل من دروس متعددة الوسائط عندما تكون الكلمات بأسلوب محادثة بدلاً من أسلوب رسمي | 1.00 | 15 |

| 11. مبدأ الصوت: يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل عندما يتم سرد الدروس متعددة الوسائط بصوت إنساني ودود بدلاً من صوت آلة | 0.74 | 7 |

| 12. مبدأ الصورة: لا يتعلم الناس بالضرورة بشكل أفضل من درس متعدد الوسائط عندما تتم إضافة صورة المتحدث إلى الشاشة | 0.20 | 7 |

| 13. مبدأ التجسيد: يتعلم الناس بشكل أعمق من العروض التقديمية متعددة الوسائط عندما يظهر المعلم على الشاشة تجسيدًا عاليًا بدلاً من تجسيد منخفض | 0.58 | 17 |

| 14. مبدأ الانغماس: لا يتعلم الناس بالضرورة بشكل أفضل في الواقع الافتراضي الغامر ثلاثي الأبعاد مقارنة بعرض ثنائي الأبعاد المقابل على سطح المكتب | -0.10 | 9 |

| 15. مبدأ النشاط التوليدي: يتعلم الناس بشكل أفضل عندما يتم توجيههم في تنفيذ أنشطة التعلم التوليدية أثناء التعلم | 0.71 | 44 |

توسيع منهجيات البحث لمراقبة عمليات التعلم

توسيع قاعدة المعرفة

الخاتمة

References

Ausubel, D. P. (1968). Educational psychology: A cognitive view. Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Baddeley, A. (1986). Working memory. Oxford University Press.

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering. Cambridge University Press.

Camp, G., Surma, T., & Kirschner, P. A. (2022). Foundations of multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed., pp. 17-24). Cambridge University Press.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2003). e-Learning and the science of instruction. Jossey-Bass.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2008). e-Learning and the science of instruction (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2011). e-Learning and the science of instruction (3rd ed.). Pfeiffer.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). e-Learning and the science of instruction (4th ed.). Wiley.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2024). e-Learning and the science of instruction (5th ed.). Wiley.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1913 [1885]). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Teachers College Columbia University.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2015). Learning as a generative activity: Eight learning strategies that promote understanding. Cambridge University Press.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). Eight ways to promote generative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 717-741.

Greene, J. A. (2022). What can educational psychology learn from, and contribute to, theory development scholarship. Educational Psychology Review, 34, 3011-3035.

Horovitz, T., & Mayer, R. E. (2021). Learning with human and virtual instructors who display happy or bored emotions in video lectures. Computers in Human Behavior, 119, 106724.

Huang, X., & Mayer, R. E. (2019). Adding self-efficacy features to an online statistics lesson. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57, 1003-1037.

Huang, X., Mayer, R. E., & Esher, E. (2020). Better together: Effects of four self-efficacy building strategies on online statistical learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 63, 101924.

Johnson, C., & Mayer, R. E. (2012). An eye movement analysis of the spatial contiguity effect in multimedia learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 18, 178-191.

Katona, G. (1940). Organizing and memorizing. Columbia University Press.

Kuhlmann, S. L., Bernacki, M. L., Greene, J. A., Hogan, K. A., Evans, M., Plumley, R., …, & Panter, A. (2023). How do students’ achievement goals relate to learning from well-designed instructional videos and subsequent exam performance?. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 73, 102162.

Kuhn, T. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Lawson, A., & Mayer, R. E. (2022). Does the emotional stance of human and virtual instructors in instructional videos affect learning processes and outcomes? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 70, 102080.

Lawson, A. P., Mayer, R. E., Adamo-Villani, N., Benes, B., Lei, X., & Cheng, J. (2021). The positivity principle: Do positive instructors improve learning from video lectures? Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(6), 3101-3129.

Li, W., Wang, F., Mayer, R. E., & Liu, T. (2022). Animated pedagogical agents enhance learning outcomes and brain activity during learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38, 621-637.

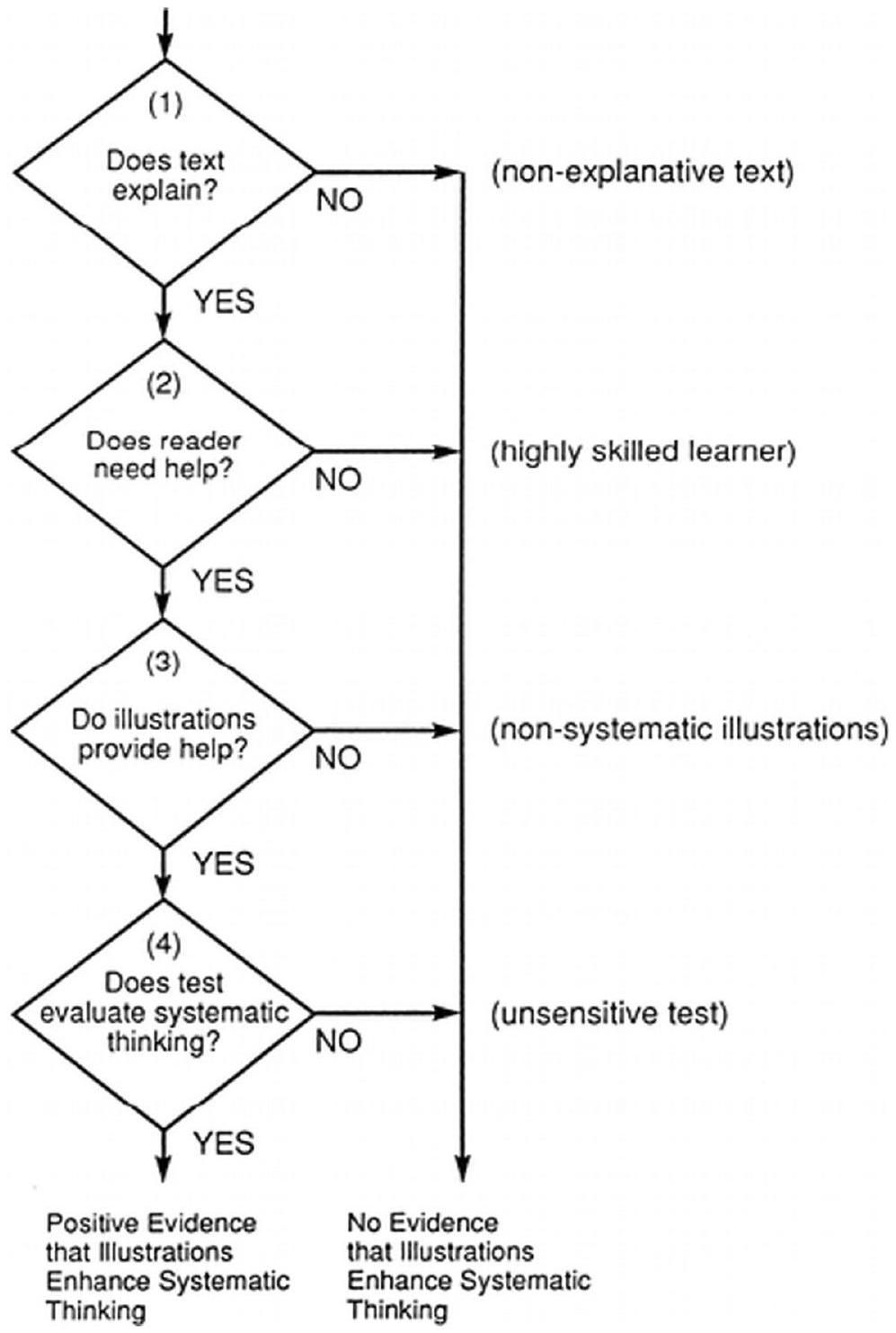

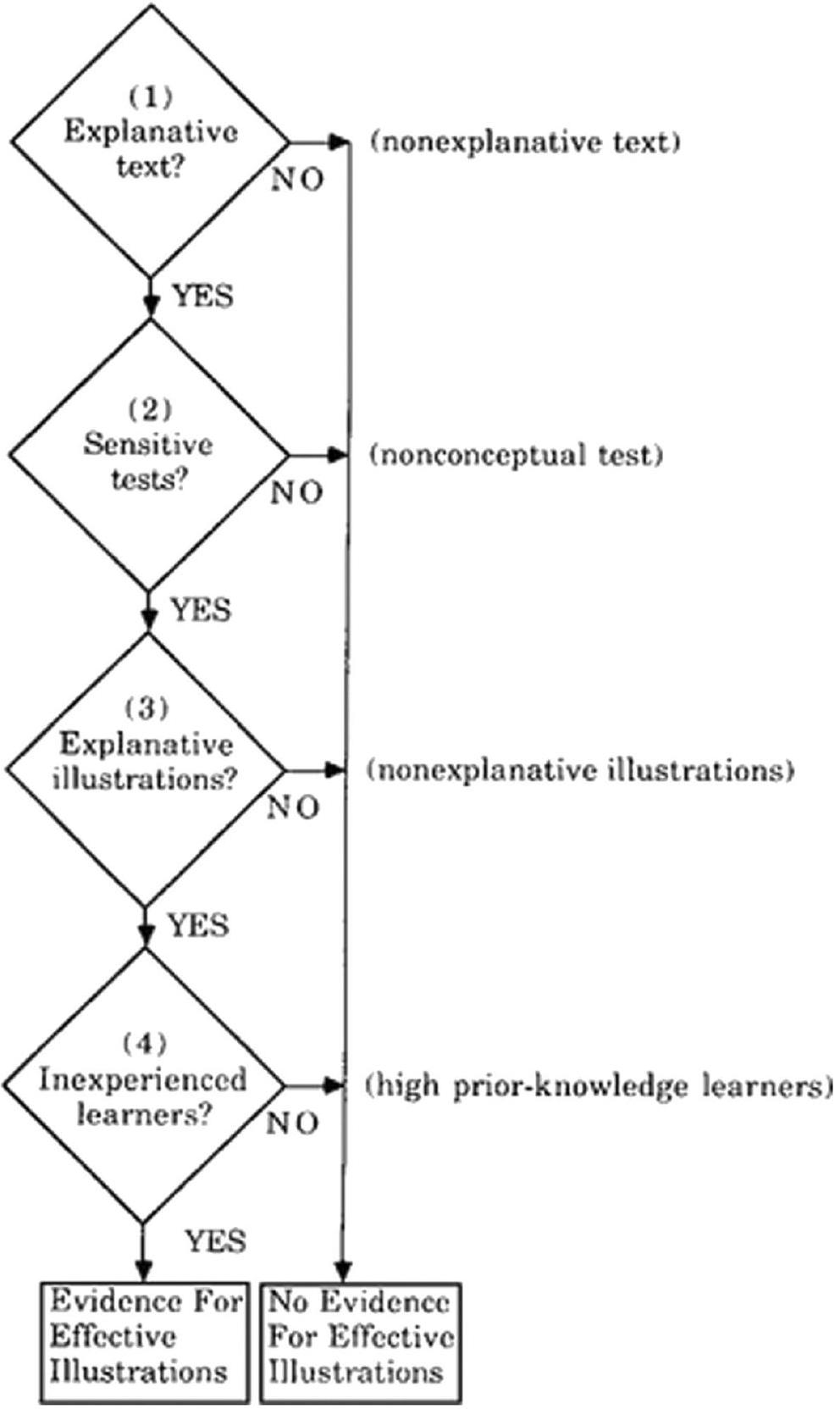

Mayer, R. E. (1989). Systematic thinking fostered by illustrations in scientific text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 240-246.

Mayer, R. E. (1996). Learning strategies for making sense out of expository text: The SOI model for guiding three cognitive processes in knowledge construction. Educational Psychology Review, 8(4), 357-371.

Mayer, R. E. (1997). Multimedia learning: Are we asking the right questions? Educational Psychologist, 32, 1-19.

Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia learning. Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (Ed.). (2005). The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning. Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (Ed.). (2014). The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (2021). Multimedia learning (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (2022). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed., pp. 57-72). Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E., & Fiorella, L. (Eds.). (2022). The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E., & Anderson, A. B. (1991). Animations need narrations: An experimental test of a dualcoding hypothesis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83, 484-490.

Mayer, R. E., & Anderson, A. B. (1992). The instructive animation: Helping students build connections between words and pictures in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 444-452.

Mayer, R. E., & Gallini, J. (1990). When is an illustration worth ten thousand words? Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 715-727.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (1998). A split-attention effect in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 312-320.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38, 43-52.

Mayer, R. E., Steinhoff, K., Bower, G., & Mars, R. (1995). A generative theory of textbook design: Using annotated illustrations to foster meaningful learning of science text. Educational Technology Research and Development, 43, 31-43.

Mayer, R. E., Bove, W., Bryman, A., Mars, R., & Tapangco, L. (1996). When less is more: Meaningful learning from visual and verbal summaries. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 64-73.

Mayer, R. E., Moreno, R., Boire, M., & Vagge, S. (1999). Maximizing constructivist learning from multimedia communications by minimizing cognitive load. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 638-643.

Mayer, R. E., Heiser, J., & Lonn, S. (2001). Cognitive constraints on multimedia learning: When presenting more material results in less understanding. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 187-198.

Mayer, R. E., Sobko, K., & Mautone, P. D. (2003). Social cues in multimedia learning: Role of speaker’s voice. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 419-425.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81-97.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. E. (2000). A coherence effect in multimedia learning: The case for minimizing irrelevant sounds in the design of multimedia instructional messages. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 117-125.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. (2007). Interactive multimodal learning environments: Special issue on interactive learning environments: Contemporary issues and trends. Educational Psychology Review, 19(3), 309-326.

Paas, F., & Sweller, J. (2022). Implications of cognitive load theory for multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed., pp. 73-81). Cambridge University Press.

Paivio, A. (1986). Mental representations: A dual-coding approach. Oxford University Press.

Parong, J., & Mayer, R. E. (2021a). Cognitive and affective processes for learning science in immersive virtual reality. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37, 226-241.

Parong, J., & Mayer, R. E. (2021b). Learning about history in immersive virtual reality: Does immersion facilitate learning? Educational Technology Research and Development, 69, 1433-1451.

Piaget, J. (1926). The language and thought of the child. Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner and Company.

Pilegard, C., & Mayer, R. E. (2015a). Within-subject and between-subject conceptions of metacomprehension accuracy. Learning and Individual Differences, 41, 54-61.

Pilegard, C., & Mayer, R. E. (2015b). Adding judgments of understanding to the metacognitive toolbox. Learning and Individual Differences, 41, 62-72.

Plass, J. L., Chun, D. M., Mayer, R. E., & Leutner, D. (1998). Supporting visual and verbal learning preferences in a second language multimedia learning environment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 25-36.

Schnotz, W. (2022). Integrated model of text and picture comprehension. In R. E. Mayer & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed., pp. 82-99). Cambridge University Press.

Schnotz, W. (2023). Multimedia comprehension. Cambridge University Press.

Stull, A., & Mayer, R. E. (2021). The case for embodied instruction: The instructor as a source of attentional and social cues in video lectures. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113, 1441-1453.

Stull, A., Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2018). An eye-tracking analysis of instructor presence in video lectures. Computers in Human Behavior, 88, 263-272.

Sweller, J. (1999). Instructional design in technical areas. ACER Press.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Springer.

Sweller, J. (in press). The development of cognitive load theory: Replication crises and incorporation of other theories can lead to theory expansion. Educational Psychology Review.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Harvard University Press.

Wertheimer, M. (1959). Productive thinking. Harper & Row.

Wittrock, M. C. (1974). Learning as a generative activity. Educational Psychologist, 11, 87-95.

Wittrock, M. C. (1989). Generative processes of comprehension. Educational Psychologist, 24, 345-376.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- This article is part of the Topical Collection on Theory Development in Educational Psychology.

Richard E. Mayer

mayer@psych.ucsb.edu

1 University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, USA

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09842-1

Publication Date: 2024-01-17

The Past, Present, and Future of the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

© The Author(s) 2024

Abstract

The cognitive theory of multimedia learning (Mayer, 2021, 2022), which seeks to explain how people learn academic material from words and graphics, has developed over the past four decades. Although the name and graphical representation of the theory have evolved over the years, the core ideas have been constant-dual channels (i.e., humans have separate information processing channels for verbal and visual information), limited capacity (i.e., processing capacity is severely limited), and active processing (i.e., meaningful learning involves selecting relevant material to be processed in working memory, mentally organizing the material into coherent verbal and visual structures, and integrating them with each other and with relevant knowledge activated from long-term memory). This review describes how the theory has developed (i.e., the past), the current state of the theory (i.e., the present), and new directions for future development (i.e., the future). In addition, the review includes examples of the events and findings that led to changes in the theory. Implications for educational psychology are discussed, including 15 evidence-based principles of multimedia design.

Introduction to the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

The power of theories is that they have the potential to remain valid and relevant through generations, while the power of new theories is that they build upon and expand those old theories. You might say that the old theories are the giants upon whose shoulders new theories, and thus new giants, stand. The cognitive theory of multimedia learning (CTML) …can be regarded as one such new giant.

Insight 1: Theory Building Depends on Intellectual Curiosity

psychologist, I had the good fortune to take a course entitled, Models of Thinking, taught by my advisor, Jim Greeno. That course got me thinking about how people are able to come up with creative solutions to problems, which lead me to a basic question: “How can we help people learn in ways so that they can take what they have learned and apply it to new situations?” This question about teaching for transfer, which formed in my mind during that course, has stuck with me all these years and has driven my research. I soon discovered that this is a classic, albeit elusive, issue both in psychology and in education that dates back to early days of research in learning and instruction.

Insight 2: Theory Building Is Grounded in Old Ideas

Insight 3: Theory Building Is Not a Straight, Planned-Out Path

plan, and it certainly did not pop out of my head one day all in one nice polished package. It came out in fits and starts, with a long series of revisions, refinements, clarifications, deletions, and additions.

Insight 4: Theory Building Is an Engineering Problem

shift from behaviorist to cognitive views of how learning works-but then for all these ensuing years has involved continually improving on my original idea.

Insight 5: Theory Building Is an Iterative Process Involving the Persistent Interplay Between Research and Theory

Insight 6: Theory Building Depends on Persistence in Collecting New Research Evidence

Insight 7: Theory Building Is a Team Activity

many of whom are represented in the various editions of The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (Mayer, 2005, 2014; Mayer & Fiorella, 2022). CTML also has benefitted from ideas from competing theories such as cognitive load theory (Paas & Sweller, 2022; Sweller, 1999, in press; Sweller et al., 2011) or the integrated model of text and picture comprehension (Schnotz, 2022, 2023). Part of theory building is being able to convince your peers and to be convinced by them.

The Past of the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

Stumbling Upon a Name for the Theory

| Table 1 Name changes leading to the cognitive theory of multimedia learning and beyond | ||

| Name | Emphasis | Initial source(s) |

| Model of meaningful learning | Conditions for instruction for meaningful learning | Mayer (1989) |

| Model of conditions for effective illustrations | Conditions for instruction for meaningful learning | Mayer & Gallini (1990) |

| Dual-coding model | Dual-coding | Mayer & Anderson

|

| Dual-processing model of multimedia learning or dual-processing model of working memory | Dual-coding | Mayer & Moreno (1998); |

| SOI model | Generative processes | Mayer (1996) |

| Generative theory | Generative processes | Mayer et al. (1995) |

| Generative theory of multimedia learning | Generative processes | Mayer (1997); Plass et al. (1998) |

| Generative learning theory | Generative processes | Fiorella & Mayer (2015, 2016); |

| Generative theory of learning | Generative processes | Mayer (2010) |

| Cognitive theory of multimedia learning | Generative processes | Mayer (1997); Mayer et al., (1996, 1999); Moreno & Mayer (2000); Mayer (2001); Mayer, et al. (2001); Mayer & Moreno, 2003) |

| Name | Emphasis | Initial source(s) |

| Social agency theory | Social processing | Mayer et al. (2003); Atkinson et al. (2005) |

| Cognitive affective model of learning with media | Affective processing | Moreno & Mayer (2007) |

| Cognitive affective model of e-learning | Affective processing | Lawson et al. (2021); Lawson & Mayer (2022) |

Inching Towards a Visual Representation of the Theory

Adding to the Research Base

| Edition | Year |

|

|

||||

| 1 | 2001 | 45 | 7 | ||||

| 2 | 2009 | 93 | 12 | ||||

| 3 | 2021 | 201 | 15 |

| Principle | First edition (2001) | Second edition (2009) | Third edition (2021) |

| Multimedia | X | X | X |

| Coherence | X | X | X |

| Signaling | X | X | |

| Redundancy | X | X | X |

| Spatial contiguity | X | X | X |

| Temporal contiguity | X | X | X |

| Segmenting | X | X | |

| Pretraining | X | X | |

| Modality | X | X | X |

| Personalization | X | X | |

| Voice | X | X | |

| Image | X | X | |

| Embodiment | X | ||

| Immersion |

|

||

| Generative Activity | X |

The Present State of the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

| Edition | Year | Chapters | Principles | Authors |

| 1 | 2005 | 35 | 22 | 46 |

| 2 | 2014 | 34 | 25 | 52 |

| 3 | 2022 | 46 | 31 | 60 |

Guiding Assumptions of the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

Three Memory Stores in the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

Five Cognitive Processes in the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

integrating. Selecting words refers to attending to relevant parts of the printed text, and selecting images refers to attending to relevant parts of the presented graphics. Organizing words refers to arranging the relevant words in to a verbal model in working memory, and organizing images refers to arranging the relevant parts of the graphics into a pictorial model in working memory. Integrating refers to making connections between corresponding verbal and pictorial representations in working memory as well as relevant knowledge from long-term memory. Meaningful learning depends on the learner engaging in appropriate cognitive processing involving selecting, organizing, and integrating. Instructional design is intended to guide these processes.

Three Demands on Cognitive Capacity

Three Instructional Goals

manage essential processing. This can be accomplished, for example, by breaking a continuous lesson into manageable chunks that can be paced by the learner.

Fifteen Multimedia Instructional Design Principles

The Future of the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

Integrating New Components into the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

| Principle for reducing extraneous processing | Effect size | Tests |

| 1. Coherence principle: People learn better when extraneous material is excluded rather than included | 0.86 | 19 |

| 2. Signaling principle: People learn better when cues are added that highlight the organization of the essential material | 0.69 | 16 |

| 3. Redundancy principle: People do not learn better when printed text is added to graphics and narration; people learn better from graphics and narration than from graphics, narration, and printed text, when the lesson is fast-paced | 0.10 | 12 |

| 4. Spatial contiguity principle: People learn better when corresponding words and pictures are presented near rather than far from each other on the page or screen | 0.82 | 9 |

| 5. Temporal contiguity principle: People learn better when corresponding words and pictures are presented simultaneously rather than successively | 1.31 | 8 |

| Principles for managing essential processing | Effect size | Tests |

| 6. Segmenting principle: People learn better when a multimedia lesson is presented in user-paced segments rather than as a continuous unit | 0.67 | 7 |

| 7. Pretraining principle: People learn better from a multimedia lesson when they know the names and characteristics of the main concepts | 0.78 | 10 |

| 8. Modality principle: People learn better from graphics and narration than from graphics and on-screen text | 1.00 | 19 |

| Principles for managing essential processing | Effect size | Tests |

| 9. Multimedia principle: People learn better from words and pictures than from words alone | 1.35 | 13 |

| 10. Personalization principle: People learn better from multimedia lessons when words are in conversational style rather than formal style | 1.00 | 15 |

| 11. Voice principle: People learn better when the narration in multimedia lessons is spoken in a friendly human voice rather than a machine voice | 0.74 | 7 |

| 12. Image principle: People do not necessarily learn better from a multimedia lesson when the speaker’s image is added to the screen | 0.20 | 7 |

| 13. Embodiment principle: People learn more deeply from multimedia presentations when an onscreen instructor displays high embodiment rather than low embodiment | 0.58 | 17 |

| 14. Immersion principle: People do not necessarily learn better in 3D immersive virtual reality than with a corresponding 2D desktop presentation | -0.10 | 9 |

| 15. Generative activity principle: People learn better when they are guided in carrying out generative learning activities during learning | 0.71 | 44 |

Expanding Research Methodologies to Monitor Learning Processes

Expanding the Knowledge Base

Conclusion

References

Ausubel, D. P. (1968). Educational psychology: A cognitive view. Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Baddeley, A. (1986). Working memory. Oxford University Press.

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering. Cambridge University Press.

Camp, G., Surma, T., & Kirschner, P. A. (2022). Foundations of multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed., pp. 17-24). Cambridge University Press.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2003). e-Learning and the science of instruction. Jossey-Bass.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2008). e-Learning and the science of instruction (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2011). e-Learning and the science of instruction (3rd ed.). Pfeiffer.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). e-Learning and the science of instruction (4th ed.). Wiley.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2024). e-Learning and the science of instruction (5th ed.). Wiley.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1913 [1885]). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. Teachers College Columbia University.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2015). Learning as a generative activity: Eight learning strategies that promote understanding. Cambridge University Press.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). Eight ways to promote generative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 717-741.

Greene, J. A. (2022). What can educational psychology learn from, and contribute to, theory development scholarship. Educational Psychology Review, 34, 3011-3035.

Horovitz, T., & Mayer, R. E. (2021). Learning with human and virtual instructors who display happy or bored emotions in video lectures. Computers in Human Behavior, 119, 106724.

Huang, X., & Mayer, R. E. (2019). Adding self-efficacy features to an online statistics lesson. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57, 1003-1037.

Huang, X., Mayer, R. E., & Esher, E. (2020). Better together: Effects of four self-efficacy building strategies on online statistical learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 63, 101924.

Johnson, C., & Mayer, R. E. (2012). An eye movement analysis of the spatial contiguity effect in multimedia learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 18, 178-191.

Katona, G. (1940). Organizing and memorizing. Columbia University Press.

Kuhlmann, S. L., Bernacki, M. L., Greene, J. A., Hogan, K. A., Evans, M., Plumley, R., …, & Panter, A. (2023). How do students’ achievement goals relate to learning from well-designed instructional videos and subsequent exam performance?. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 73, 102162.

Kuhn, T. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Lawson, A., & Mayer, R. E. (2022). Does the emotional stance of human and virtual instructors in instructional videos affect learning processes and outcomes? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 70, 102080.

Lawson, A. P., Mayer, R. E., Adamo-Villani, N., Benes, B., Lei, X., & Cheng, J. (2021). The positivity principle: Do positive instructors improve learning from video lectures? Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(6), 3101-3129.

Li, W., Wang, F., Mayer, R. E., & Liu, T. (2022). Animated pedagogical agents enhance learning outcomes and brain activity during learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38, 621-637.

Mayer, R. E. (1989). Systematic thinking fostered by illustrations in scientific text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 240-246.

Mayer, R. E. (1996). Learning strategies for making sense out of expository text: The SOI model for guiding three cognitive processes in knowledge construction. Educational Psychology Review, 8(4), 357-371.

Mayer, R. E. (1997). Multimedia learning: Are we asking the right questions? Educational Psychologist, 32, 1-19.

Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia learning. Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (Ed.). (2005). The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning. Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (Ed.). (2014). The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (2021). Multimedia learning (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E. (2022). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed., pp. 57-72). Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E., & Fiorella, L. (Eds.). (2022). The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Mayer, R. E., & Anderson, A. B. (1991). Animations need narrations: An experimental test of a dualcoding hypothesis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83, 484-490.

Mayer, R. E., & Anderson, A. B. (1992). The instructive animation: Helping students build connections between words and pictures in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 444-452.

Mayer, R. E., & Gallini, J. (1990). When is an illustration worth ten thousand words? Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 715-727.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (1998). A split-attention effect in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 312-320.

Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38, 43-52.

Mayer, R. E., Steinhoff, K., Bower, G., & Mars, R. (1995). A generative theory of textbook design: Using annotated illustrations to foster meaningful learning of science text. Educational Technology Research and Development, 43, 31-43.

Mayer, R. E., Bove, W., Bryman, A., Mars, R., & Tapangco, L. (1996). When less is more: Meaningful learning from visual and verbal summaries. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 64-73.

Mayer, R. E., Moreno, R., Boire, M., & Vagge, S. (1999). Maximizing constructivist learning from multimedia communications by minimizing cognitive load. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91, 638-643.

Mayer, R. E., Heiser, J., & Lonn, S. (2001). Cognitive constraints on multimedia learning: When presenting more material results in less understanding. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 187-198.

Mayer, R. E., Sobko, K., & Mautone, P. D. (2003). Social cues in multimedia learning: Role of speaker’s voice. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 419-425.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63(2), 81-97.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. E. (2000). A coherence effect in multimedia learning: The case for minimizing irrelevant sounds in the design of multimedia instructional messages. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 117-125.

Moreno, R., & Mayer, R. (2007). Interactive multimodal learning environments: Special issue on interactive learning environments: Contemporary issues and trends. Educational Psychology Review, 19(3), 309-326.

Paas, F., & Sweller, J. (2022). Implications of cognitive load theory for multimedia learning. In R. E. Mayer & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed., pp. 73-81). Cambridge University Press.

Paivio, A. (1986). Mental representations: A dual-coding approach. Oxford University Press.

Parong, J., & Mayer, R. E. (2021a). Cognitive and affective processes for learning science in immersive virtual reality. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37, 226-241.

Parong, J., & Mayer, R. E. (2021b). Learning about history in immersive virtual reality: Does immersion facilitate learning? Educational Technology Research and Development, 69, 1433-1451.

Piaget, J. (1926). The language and thought of the child. Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner and Company.

Pilegard, C., & Mayer, R. E. (2015a). Within-subject and between-subject conceptions of metacomprehension accuracy. Learning and Individual Differences, 41, 54-61.

Pilegard, C., & Mayer, R. E. (2015b). Adding judgments of understanding to the metacognitive toolbox. Learning and Individual Differences, 41, 62-72.

Plass, J. L., Chun, D. M., Mayer, R. E., & Leutner, D. (1998). Supporting visual and verbal learning preferences in a second language multimedia learning environment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 25-36.

Schnotz, W. (2022). Integrated model of text and picture comprehension. In R. E. Mayer & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (3rd ed., pp. 82-99). Cambridge University Press.

Schnotz, W. (2023). Multimedia comprehension. Cambridge University Press.

Stull, A., & Mayer, R. E. (2021). The case for embodied instruction: The instructor as a source of attentional and social cues in video lectures. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113, 1441-1453.

Stull, A., Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2018). An eye-tracking analysis of instructor presence in video lectures. Computers in Human Behavior, 88, 263-272.

Sweller, J. (1999). Instructional design in technical areas. ACER Press.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory. Springer.

Sweller, J. (in press). The development of cognitive load theory: Replication crises and incorporation of other theories can lead to theory expansion. Educational Psychology Review.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Harvard University Press.

Wertheimer, M. (1959). Productive thinking. Harper & Row.

Wittrock, M. C. (1974). Learning as a generative activity. Educational Psychologist, 11, 87-95.

Wittrock, M. C. (1989). Generative processes of comprehension. Educational Psychologist, 24, 345-376.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- This article is part of the Topical Collection on Theory Development in Educational Psychology.

Richard E. Mayer

mayer@psych.ucsb.edu

1 University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, USA