DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.134.116703

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40192380

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-18

المغناطيسية الفيريمغناطيسية المعوضة بالكامل ثنائية الأبعاد

الملخص

لقد كانت الإلكترونيات المغناطيسية المضادة لفترة طويلة موضوعًا لاهتمام بحثي مكثف، وقد أشعلت المقدمة الأخيرة للـ “ألتيرمغناطيسية” الحماس في هذا المجال. ومع ذلك، لم تحظَ الفيريمغناطيسية المعوضة بالكامل، التي تظهر انقسامًا في دوران الشريط ولكنها تتمتع بمغناطيسية صافية صفرية، بالاهتمام الكافي بعد. منذ التحضير التجريبي للمواد المغناطيسية ثنائية الأبعاد (2D) من نوع فان دير واهل في عام 2017، أصبحت المواد المغناطيسية ثنائية الأبعاد، بفضل قابليتها الكبيرة للتعديل، ساحة مهمة للإلكترونيات المغناطيسية. هنا، نوسع مفهوم الفيريمغناطيسية المعوضة بالكامل (fFIM) إلى بعدين ونقترح fFIM المعززة بالتعبئة ثنائية الأبعاد، ونظهر استقرارها وسهولة التلاعب بها، ونقدم ثلاث خطط تنفيذ ممكنة مع مواد مرشحة نموذجية لكل منها. تم تطوير نموذج بسيط للفيريمغناطيسيات المعوضة بالكامل ثنائية الأبعاد (fFIMs). تكشف المزيد من التحقيقات في الخصائص الفيزيائية لـ fFIMs ثنائية الأبعاد أنها لا تظهر فقط استجابة مغناطيسية بصرية كبيرة ولكنها أيضًا تظهر تيارات قطبية بالكامل وتأثير هول الشاذ في الحالات نصف المعدنية، مما يعرض خصائص كانت تقريبًا حصرية سابقًا للمواد الفيرومغناطيسية، مما يوسع بشكل كبير آفاق البحث والتطبيق لمواد الإلكترونيات المغناطيسية.

المواد (mvdW) ذات القابلية الممتازة للتعديل قد جذبت اهتمامًا هائلًا على الفور. حتى الآن، تم تخليق مجموعة أغنى من أنظمة المواد ثنائية الأبعاد (mvdW) [20-22]، بما في ذلك

مغناطيسات فيري مختلفة. عندما يكون للنظام تعبئة مناسبة، أي،

(2) الجهد المتقطع: من خلال تطبيق جهد متقطع، تم تقديمه بواسطة حقل كهربائي أو ركيزة، إلخ، على شبكتين فرعيتين مغناطيسيتين، يتم كسر التناظر الذي يربط بين الشبكتين الفرعيتين، مما يؤدي إلى انقسام الدوران، ويصبح النظام fFIM. من التحليل النظري أعلاه، يمكن رؤية أنه بينما يمكن أن يؤدي جهد متقطع صغير إلى fFIMs مكسورة، يمكن أن يؤدي جهد كبير إلى fFIMs نصف معدنية، كما هو موضح في الأشكال 2(د) و(هـ). على سبيل المثال، في الطبقة الثنائية المضادة المغناطيسية من النوع A التي تم إعدادها تجريبيًا

(3) استبدال عنصر أو سبائك: من خلال استبدال أو سبائك مع عنصر له نفس عدد الإلكترونات التكافؤية أو يختلف بعدد زوجي مقارنة بالذرة المغناطيسية الأصلية، مما يضمن توزيع هذه الإلكترونات بالتساوي عبر قناتي الدوران، يحتفظ النظام بـ

تحدث فقط في الأنظمة الفيرومغناطيسية. لتأكيد هذه الخصائص الفيزيائية الجديدة، نعرض نتائجنا من حيث كل من النموذج الفعال والمواد التمثيلية. الفجوة المذكورة في fFIM

- ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي في هذا العمل.

ccliu@bit.edu.cn

[1] V. بالتز، A. مانشون، M. تسوي، T. مورياما، T. أونو، وY. تسيركوفنياك، سبينترونيك مضاد للمغناطيسية، مراجعة الفيزياء الحديثة 90، 015005 (2018).

[2] ل. شميكال، ج. سينوفا، وت. يونغويرث، المشهد البحثي الناشئ للـ ألترمغناطيسية، فيزي. ريف. إكس 12، 040501 (2022).

[3] I. مازن ومحررو PRX، تحرير: المغناطيسية البديلة – سطر جديد في المغناطيسية الأساسية، فيزي. ريف. X 12، 040002 (2022).

[4] هـ. فان لوكن و ر. أ. دي غروت، مضادات مغناطيسية نصف معدنية، فيزيكال ريفيو ليترز 74، 1171 (1995).

[5] هـ. أكاي وم. أوجورا، أشباه الموصلات المضادة للمغناطيسية المخففة نصف المعدنية، فيزيكال ريفيو ليترز 97، 026401 (2006).

[6] س. وورمهيل، هـ. س. كاندبال، ج. هـ. فيشر، و س. فيلزر، قواعد إلكترونات التكافؤ للتنبؤ بسلوك الفيريمغناطيسية المعوضة نصف المعدنية لمركبات هيوسلر ذات الاستقطاب المغناطيسي الكامل، مجلة الفيزياء: المادة المكثفة 18، 6171 (2006).

[7] و. إ. بيكيت، بحث قائم على دالة كثافة الدوران للمواد المضادة للمغناطيسية نصف المعدنية، فيزي. ريف. ب 57، 10613 (1998).

[8] ي.-م. نيي و إكس. هو، مغناطيس مضاد نصف معدني محتمل في كوبرات بيروفسكايت المدعومة بالثقوب كما تم التنبؤ به من خلال حسابات المبادئ الأولى، فيزي. ريف. ليت. 100، 117203 (2008).

[9] ك. إ. سيفيرسكا، ج. أتشيسون، أ. جها، ك. إيسين، ر. سميث، س. ليني، ن. تيشرت، ج. أوبراين، ج. م. د. كوي، ب. ستامينوف، وك. رود، النظام المغناطيسي والنقل المغناطيسي في أفلام نصف معدنية مغناطيسية مكونة من mn y ru x ga، فيزيكس ريفيو ب 104، 064414 (2021).

[10] م. إ. جامر، ي. ج. وانغ، ج. م. ستيفن، إ. ج. مك دونالد، أ. ج. غروتر، ج. إ. ستيربينسكي، د. أ. أرينا، ج. أ. بورشرز، ب. ج. كيربي، ل. هـ. لويس، ب. باربييليني، أ. بانسيل، ود. هييمان، المغناطيسية الفيريمغناطيسية المعوضة في سبيكة هويزلر ذات الزيرو مومنتفيزي. ريف. أبليد. 7، 064036 (2017).

[11] م. زيتش، ك. رود، ن. ثياغاراجاه، ي.-س. لاو، د. بيتو، ج. م. د. كوي، س. سانفيتو، ك. ج. أوشيا، ج. أ. فيرغسون، د. أ. ماكلارين، و ت. آرتشر، تصميم مغناطيس نصف معدني مع تعويض كامل، فيزيكس ريفيو ب 93، 140202 (2016).

[12] ج. كوي و م. فينكاتيسان، المغناطيسية نصف المعدنية: مثال على(مدعو)، J APPL PHYS 91، 8345 (2002).

[13] إكس. هو، المغناطيس المضاد نصف المعدني كمادة محتملة لتكنولوجيا السبين، مواد متقدمة 24، 294 (2012).

[14] ك. أوزدوغان، إ. شاشيوغلو، و إ. جالاناكيس، دراسة أولية للخصائص الإلكترونية والمغناطيسية لمركبات هيوسليير الفيريمغناطيسية ذات الـ 18 إلكترونًا في حالة التكافؤ والمُعوضة بالكامل: نموذج لمواد فلاتر الدوران، علوم المواد الحاسوبية 110، 77 (2015).

[15] ر. ستينشوف، أ. ك. ناياك، ج. هـ. فيشر، ب. بالكي، س. أواردي، ي. سكورسكي، ت. ناكامورا، و ج. فيلزر، مغناطيسية فيري كاملة التعويض وعبور دوران الشبكة في المركب الهيوسلر نصف المعدنيالمراجعة الفيزيائية ب 95، 060410 (2017).

[16] ك. فليشير، ن. ثياغاراجاه، ي.-س. لاو، د. بيتو، ك. بوريسوف، س. س. سميث، إ. ف. شفيتس، ج. م. د. كوي.

كي. رود، تأثير كير المغناطيسي البصري في فيري مغناطيس ذو لحظة صفرية مستقطبة، فيزيكال ريفيو بي 98، 134445 (2018).

[17] ت. كاوامورا، ك. يوشيمي، ك. هاشيموتو، أ. كوباياشي، و ت. ميساوا، الفيريمغناطيسيات المعوضة مع انقسام دوران ضخم في المركبات العضوية، فيز. ريف. ليت. 132، 156502 (2024).

[18] ب. هوانغ، ج. كلارك، إ. نافارو-موراتالا، د. ر. كلاين، ر. تشينغ، ك. ل. سايلر، د. تشونغ، إ. شميتغال، م. أ. مكغواير، د. هـ. كوبدن، و. ياو، د. شياو، ب. جاريلو-هيريرو، و إكس. شو، المغناطيسية الحديدية المعتمدة على الطبقات في بلورة فان دير وولس حتى حد الطبقة الأحادية، ناتشر 546، 270 (2017).

[19] سي. غونغ، ل. لي، ز. لي، هـ. جي، أ. ستيرن، ي. شيا، ت. كاو، و. باو، سي. وانغ، ي. وانغ، ز. كيو. كيو، ر. ج. كافا، س. ج. لوي، ج. شيا، و إكس. تشانغ، اكتشاف المغناطيسية الذاتية في بلورات فان دير فالس ثنائية الأبعاد، ناتشر 546، 265 (2017).

[20] ي. دينغ، ي. يو، ي. سونغ، ج. تشانغ، ن. ز. وانغ، ز. سون، ي. يي، ي. ز. وو، س. وو، ج. تشو، ج. وانغ، إكس. هـ. تشين، وي. تشانغ، مغناطيسية حديدية قابلة للتعديل عند درجة حرارة الغرفة في الأبعاد الثنائيةطبيعة 563، 94 (2018).

[21] م. بونيلا، س. كوليكار، ي. ما، هـ. سي. دياز، ف. كالا باتيل، ر. داس، ت. إيغرز، هـ. ر. غوتيريز، م.-هـ. فهان، وم. باتزيل، مغناطيسية قوية عند درجة حرارة الغرفة.طبقات أحادية على الركائز من نوع فان دير فال، نات. نانو تكنولوج 13، 289 (2018).

[22] ج. كلاين، ت. فام، ج. د. تومسن، ج. ب. كيرتس، ت. دينولين، م. لوركي، م. فلوريان، أ. شتاينهوف، ر. أ. ويسكونس، ج. لوكسا، ز. سوفر، ف. ياهنكي، ب. نارنج، و ف. م. روس، التحكم في الهيكل ونسيج الدوران في المغناطيس ذو الطبقات فان دير فالس CrSBr، نات كوميون 13، 5420 (2022).

[23] ب. هوانغ، و.-ي. ليو، إكس.-سي. وو، س.-ز. لي، هـ. لي، ز. يانغ، و و.-ب. تشانغ، استقطاب وادي عفوي كبير ودرجة حرارة انتقال مغناطيسي عالية في ferrovalley ثنائي الأبعاد المستقر، و Cl فيزي. ريف. ب 107، 045423 (2023).

[24] ف. د. م. هالدين، نموذج لتأثير هال الكمي بدون مستويات لاندو: تحقيق في المادة المكثفة لـ “شذوذ التماثل”، فيزيكال ريفيو ليترز 61، 2015 (1988).

[25] سي. إل. كاين وإي. جي. ميلي،ترتيب طوبولوجي وتأثير سبين كوانتي هول، مجلة مراجعة الفيزياء. 95، 146802 (2005).

[26] ك. مومّا و ف. إيزومي، فيستا 3 للتصوير ثلاثي الأبعاد لبيانات البلورات والحجم والشكل، مجلة البلورات التطبيقية 44، 1272 (2011).

[27] انظر المواد التكميلية لمزيد من المعلومات التفصيلية حول (I) نموذج الربط الضيق لشبكة مربعة fFIM، (II) التأثير المغناطيسي البصري الملحوظ وتأثير هول الشاذ في نموذج fFIM العام، (III) نموذج الربط الضيق لشبكة سداسية، و (IV) تفاصيل حساب المواد، والتي تشمل المراجع [18، 23، 30، 33-47].

[28] أ.-ي. لو، هـ. زو، ج. شياو، س.-ب. تشو، ي. هان، م.-هـ. تشيو، س.-س. تشينغ، س.-و. يانغ، ك.-هـ. وي، ي. يانغ، ي. وانغ، د. سوكاراس، د. نوردلوند، ب. يانغ، د. أ. مولر، م.-ي. تشو، إكس. تشانغ، و ل.-ج. لي، طبقات أحادية من ثنائي كبريتيد المعادن الانتقالية، نات. نانو تكنولوجول 12، 744 (2017).

[29] س.-د. قوه، ي.-ت. تشو، ك. كوين، وي.-س. أنغ، استجابة بيزوكهربائية كبيرة خارج المستوى في طبقة أحادية من النيكل المغناطيسي، رسائل الفيزياء التطبيقية 120، 232403 (2022).

[30] ت. غوركان، ج. داس، ج. كابيجان، م. أكرم، ج. ف.

[31] ق. سونغ، ج. أ. أوكالييني، إ. إرجين، ب. إلياس، د. أموروسو، ب. باروني، ج. كابيغيان، ك. واتانابي، ت. تانيغوتشي، أ. س. بوتانا، س. بيكوزي، ن. جيديك، ور. كومن، دليل على وجود مادة متعددة ferroic ذات طبقة واحدة من فان دير فال، ناتشر 602، 601 (2022).

[32] س. سيمبوشي، ر. ي. أوميتسو، ي. كاواهito، و هـ. أكاي، نوع جديد من الفيريمغناطيس نصف المعدني المدعوم بالكامل، Sci Rep 12، 10687 (2022).

[33] ب. وانغ، د. وو، ك. تشانغ، و إكس. وو، كبريتيد المعادن الانتقالية الرباعية الأبعاد ثنائية الأبعاد

[34] م.-هـ. كيم، ج. أكباس، م.-هـ. يانغ، إ. أوكوبو، هـ. كريستين، د. ماندروس، م. أ. سكاربولا، أ. د. دوبون، ز. شليسينجر، ب. خليفة، وج. سيرني، تحديد موتر التوصيلية المغناطيسية المعقدة تحت تأثير الأشعة تحت الحمراء في الفيرومغناطيسيات المتنقلة من قياسات فاراداي وكير، فيزيكس ريفيو ب 75، 214416 (2007).

[35] ر. فالديز أغيلار، أ. ف. ستير، و. ليو، ل. س. بيلبرو، د. ك. جورج، ن. بانسال، ل. وو، ج. سيرني، أ. ج. ماركيلز، س. أوه، و ن. ب. أرمتيج، استجابة التيراهيرتز ودوران كير الضخم من حالات السطح للعازل الطوبولوجي

[36] هـ. إيبيرت، التأثيرات المغناطيسية الضوئية في أنظمة المعادن الانتقالية، تقرير تقدم في الفيزياء 59، 1665 (1996).

[37] C. Aversa و J. E. Sipe، الاستجابات البصرية غير الخطية للموصلات نصفية: نتائج مع تحليل بواسطة مقياس الطول، فيزي. ريف. ب 52، 14636 (1995).

[38] ي. ياو، ل. كلاينمان، أ. هـ. ماكدونالد، ج. سينوفا، ت. يونغويرث، د.-س. وانغ، إ. وانغ، و ق. نيو، حسابات من المبادئ الأولى للتوصيل غير العادي في الحديد المغناطيسي البارد bcc، فيزيكال ريفيو ليترز 92، 037204 (2004).

[39] إكس. وانغ، ج. ر. ييتس، آي. سوزا، و د. فاندربيلت، حساب من أول المبدأ للتوصيلية الغريبة باستخدام تقنيات وانير، فيزيكال ريفيو بي 74، 195118 (2006).

[40] ج. كريسه و ج. فورتسمولر، مخططات تكرارية فعالة لحسابات الطاقة الكلية من أولى المبادئ باستخدام مجموعة أساس الموجة المستوية، فيزي. ريف. ب 54، 11169 (1996).

[41] ج. ب. بيردو، ك. بورك، و م. إرنزرهوف، تقريب التدرج العام المبسط، فيزيكال ريفيو ليترز 77، 3865 (1996).

[42] أ. توغو، ف. أوبا، وإي. تانكا، حسابات من المبادئ الأولى للانتقال الفيروالاستيكي بين نوع الروتيل و

[43] ن. مارزاري و د. فاندربيلت، دوال وانيير العامة المحلية بشكل أقصى لشرائط الطاقة المركبة، فيزي. ريف. ب 56، 12847 (1997).

[44] أ. أ. موستوفي، ج. ر. ييتس، ي.-س. لي، إ. سوزا، د. فاندربيلت، و ن. مارزاري، وانير90: أداة للحصول على دوال وانير المحلية بشكل أقصى، اتصالات فيزيائية حاسوبية 178، 685 (2008)، 0708.0650.

[45] I. سوزا، ن. مارزاري، و د. فاندربيلت، دوال وانيير المحلية بشكل أقصى للشرائط الطاقية المتشابكة، فيزي. ريف. ب 65، 035109 (2001).

[46] ك. س. بورش، د. ماندروس، وج. – ج. بارك، المغناطيسية في المواد ثنائية الأبعاد من نوع فان دير وولز، ناتشر 563، 47 (2018).

[47] م. كوكوتشوني و س. دي جيرونكولي، نهج الاستجابة الخطية لحساب التفاعل الفعال

معلمات في طريقة LDA+U، مراجعة الفيزياء B 71، 035105 (2005).

المواد التكميلية لـ “المغناطيسية الفيريمغناطيسية المعوضة بالكامل ثنائية الأبعاد”

نموذج الربط الضيق لشبكة مربعة

عندما تكون المعلمات مضبوطة على

II. التأثير المغناطيسي البصري الملحوظ وتأثير هول الشاذ في نموذج FFIM العام

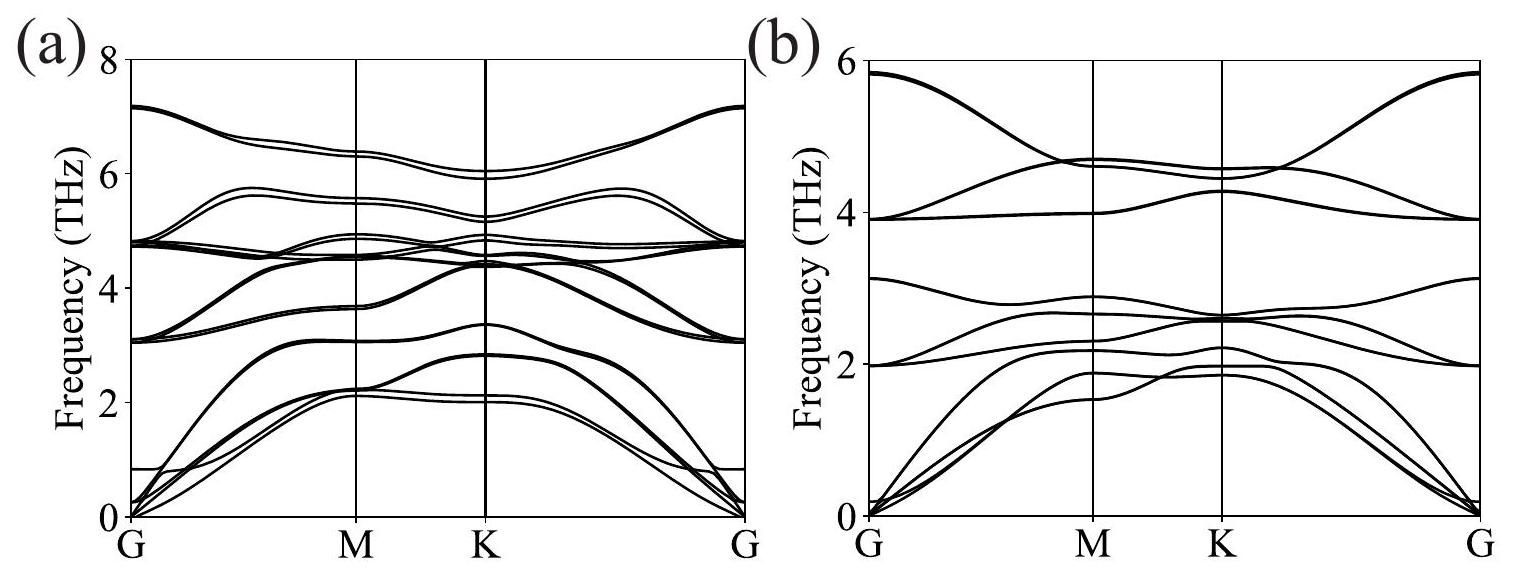

III. نموذج الربط الضيق لشبكة سداسية

الرابع. حساب المواد

[1] C. Aversa و J. E. Sipe، الحساسية البصرية غير الخطية للموصلات نصفية: نتائج مع تحليل بواسطة مقياس الطول، فيزيكال ريفيو B 52، 14636 (1995).

[2] هـ. إيبيرت، التأثيرات المغناطيسية الضوئية في أنظمة المعادن الانتقالية، تقرير تقدم الفيزياء 59، 1665 (1996).

[3] م.-هـ. كيم، ج. أكباس، م.-هـ. يانغ، إ. أوكوبو، هـ. كريستين، د. ماندروس، م. أ. سكاربولا، أ. د. دوبون، ز. شليسينجر، ب. خليفة، وج. سيرني، تحديد موتر التوصيلية المغناطيسية المعقدة تحت الأشعة تحت الحمراء في الفيرومغناطيسيات المتنقلة من قياسات فاراداي وكير، فيزيكس ريفيو ب 75، 214416 (2007).

[4] ر. فالديز أغيلار، أ. ف. ستير، و. ليو، ل. س. بيلبرو، د. ك. جورج، ن. بانسال، ل. وو، ج. سيرني، أ. ج. ماركيلز، س. أوه، و

| نيكل | ||||

| U (eV) | 2 | ٣ | ٤ | ٥ |

| إ

|

-17.713227 | -16.865274 | -16.077713 | -15.348955 |

|

|

-17.714349 | -16.864369 | -16.073680 | -15.341357 |

|

|

0.001122 | -0.000905 | -0.004033 | -0.007598 |

|

|

||||

| U (eV) | 1 | 2 | ٣ | ٤ |

| إ

|

-64.108138 | -62.529771 | -61.062467 | -59.686118 |

|

|

– | -61.917934 | -60.410827 | -58.999141 |

|

|

– | -0.611837 | -0.65164 | -0.686977 |

|

|

||||

| U (eV) | 0 | 1 | 2 | ٣ |

|

|

-27.797280 | -26.962275 | -26.161623 | -25.395336 |

|

|

-27.797266 | -26.962107 | -26.161330 | -25.394878 |

|

|

-0.000014 | -0.000168 | -0.000293 | -0.000458 |

[5] ي. ياو، ل. كلاينمان، أ. هـ. ماكدونالد، ج. سينوفا، ت. يونغويرث، د.-س. وانغ، إ. وانغ، و ق. نيو، حسابات من المبادئ الأولى للتوصيل غير العادي في الحديد المغناطيسي البسيط bcc، فيزيكال ريفيو ليترز 92، 037204 (2004).

[6] إكس. وانغ، ج. ر. ييتس، آي. سوزا، ود. فاندربيلت، حساب من أول المبدأ للتوصيلية الغريبة باستخدام تقنيات وانير، فيزيكال ريفيو بي 74، 195118 (2006).

[7] ج. كريس وج. فورتسمولر، مخططات تكرارية فعالة لحسابات الطاقة الكلية من أولى المبادئ باستخدام مجموعة أساس الموجة المسطحة، فيزي. ريف. ب 54، 11169 (1996).

[8] ج. ب. بيرديو، ك. بورك، و م. إرنزرهوف، تقريب التدرج العام المبسط، فيزيكال ريفيو ليترز 77، 3865 (1996).

[9] أ. توغو، ف. أوبا، وإي. تانكا، حسابات من المبادئ الأولى للانتقال الفيروالاستيكي بين نوع الروتيل و

[10] ن. مارزاري و د. فاندربيلت، دوال وانيير العامة المحلية بشكل أقصى للشرائط الطاقية المركبة، فيزي. ريف. ب 56، 12847 (1997).

[11] أ. أ. موستوفي، ج. ر. ييتس، ي.-س. لي، إ. سوزا، د. فاندربيلت، و ن. مارزاري، وانير90: أداة للحصول على دوال وانير المحلية بشكل أقصى، اتصالات فيزيائية حاسوبية 178، 685 (2008)، 0708.0650.

[12] I. سوزا، ن. مارزاري، و د. فاندربيلت، دوال وانيير المحلية بشكل أقصى للشرائط الطاقية المتشابكة، فيزي. ريف. ب 65، 035109 (2001).

[13] ك. س. بورش، د. ماندروس، وج. – ج. بارك، المغناطيسية في المواد ثنائية الأبعاد من فان دير وولز، ناتشر 563، 47 (2018).

[14] ب. هوانغ، ج. كلارك، إ. نافارو-موراتالا، د. ر. كلاين، ر. تشينغ، ك. ل. سييلر، د. تشونغ، إ. شميتغال، م. أ. مكغواير، د. هـ. كوبدن، و. ياو، د. شياو، ب. جاريلو-هيريرو، و إكس. شو، المغناطيسية الحديدية المعتمدة على الطبقات في بلورة فان دير وولس حتى حد الطبقة الواحدة، ناتشر 546، 270 (2017).

[15] م. كوكوتشوني و س. دي جيرونكولي، نهج الاستجابة الخطية لحساب معلمات التفاعل الفعالة في طريقة LDA+U، مراجعة الفيزياء B 71، 035105 (2005).

[16] ت. غوركان، ج. داس، ج. كابيجان، م. أكرم، ج. ف. بارث، س. تونغاي، إ. أكتورك، أ. إرتين، و أ. س. بوتانا، تشكيل سكريمون في طبقات ثنائية الهاليد جانوس القائمة على النيكل: التفاعل بين الإحباط المغناطيسي وتفاعل دزيالوشينسكي-موريا، فيزيكس ريفيو ماتيير 7، 054006 (2023).

[17] ب. وانغ، د. وو، ك. تشانغ، و إكس. وو، كبريتيد المعادن الانتقالية الرباعية الأبعاد ثنائي الأبعاد

[18] ب. هوانغ، و.-ي. ليو، إكس.-سي. وو، س.-ز. لي، هـ. لي، ز. يانغ، و و.-ب. تشانغ، استقطاب وادي عفوي كبير ودرجة حرارة انتقال مغناطيسي عالية في ferrovalley ثنائي الأبعاد المستقر

- ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي في هذا العمل.

ccliu@bit.edu.cn

- ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي في هذا العمل.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.134.116703

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40192380

Publication Date: 2025-03-18

Two-dimensional fully-compensated Ferrimagnetism

Abstract

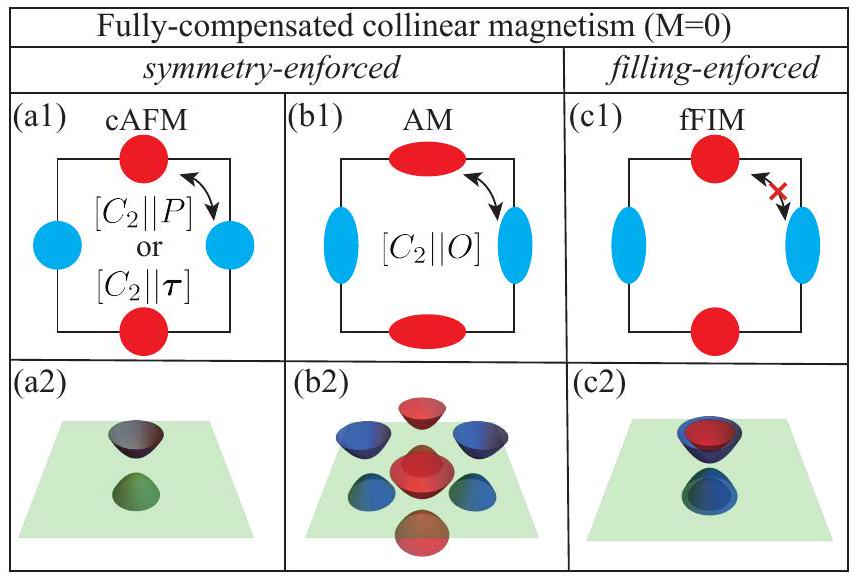

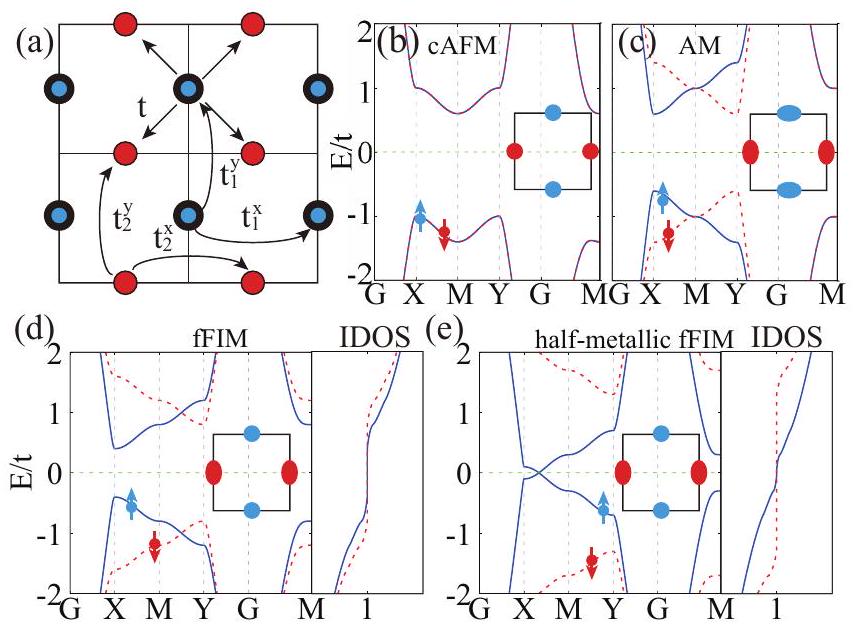

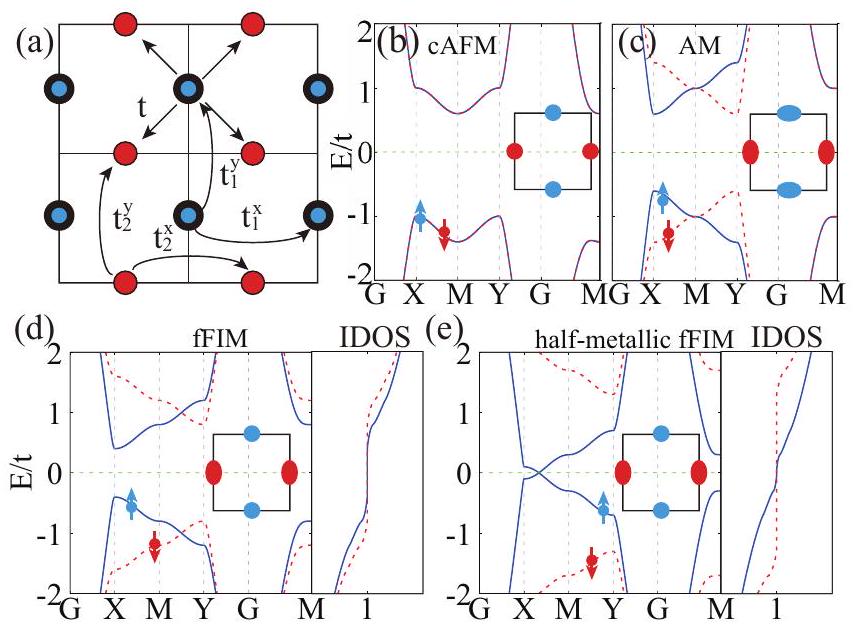

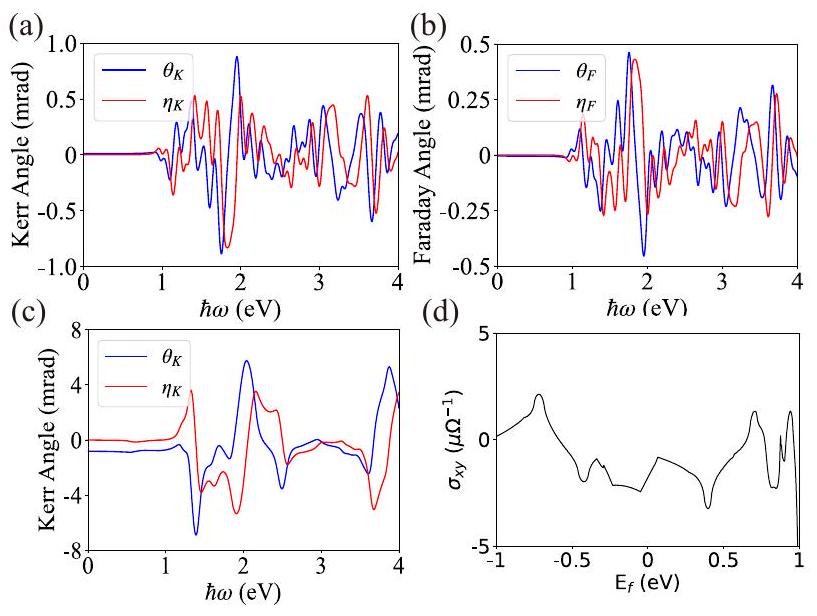

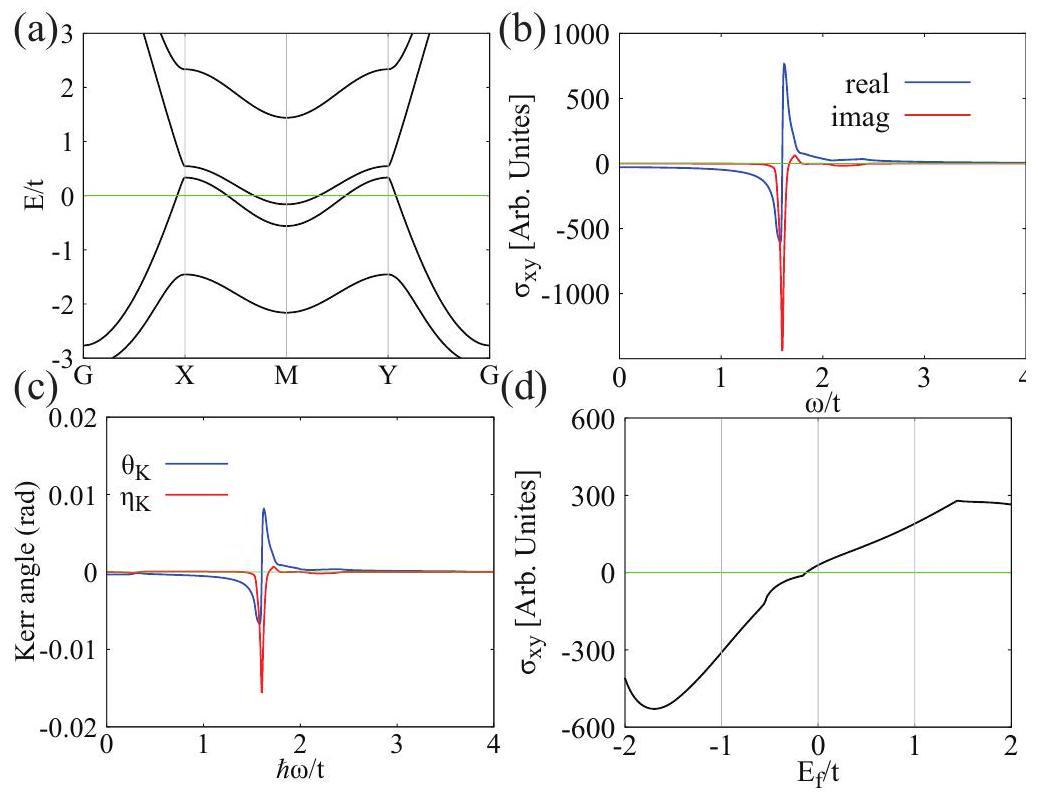

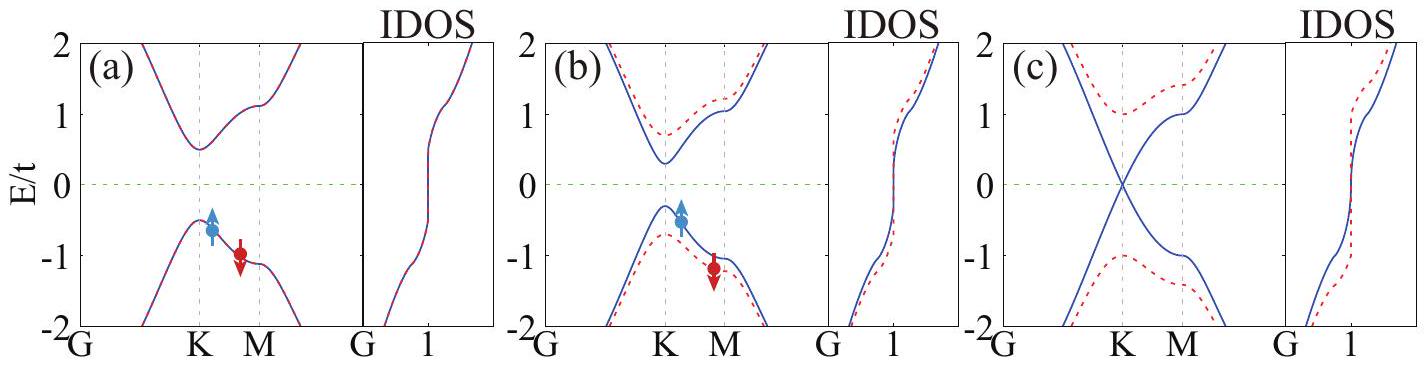

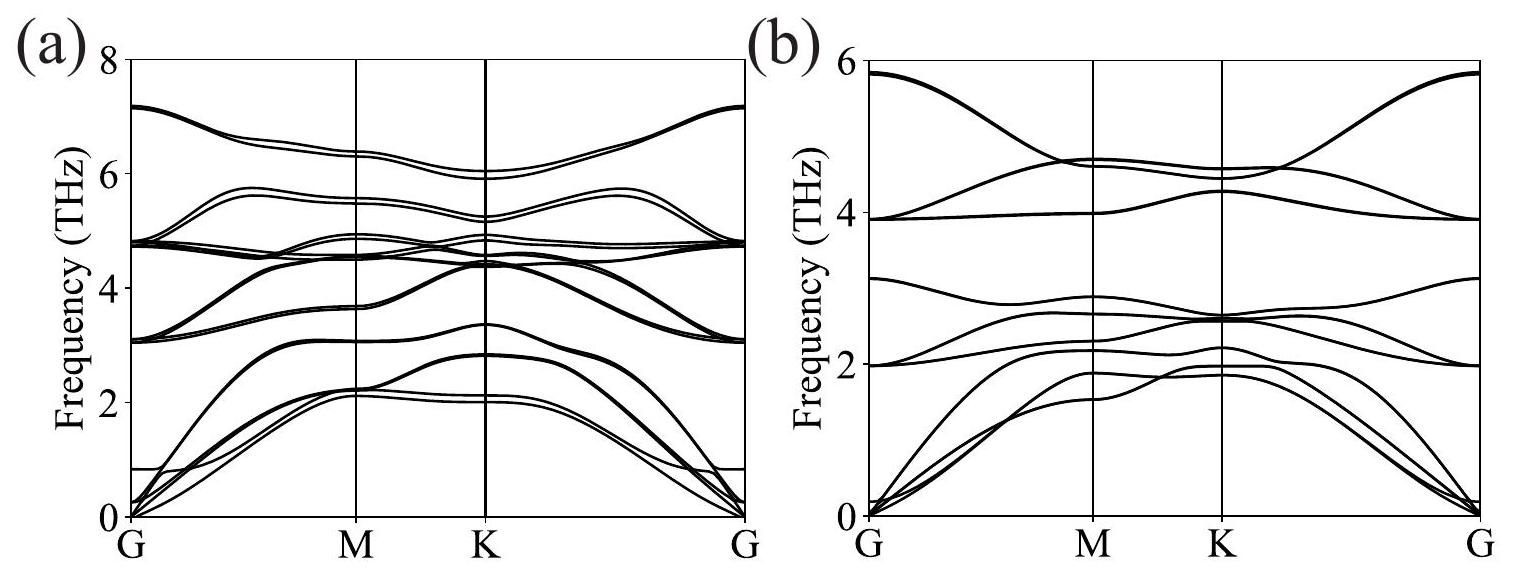

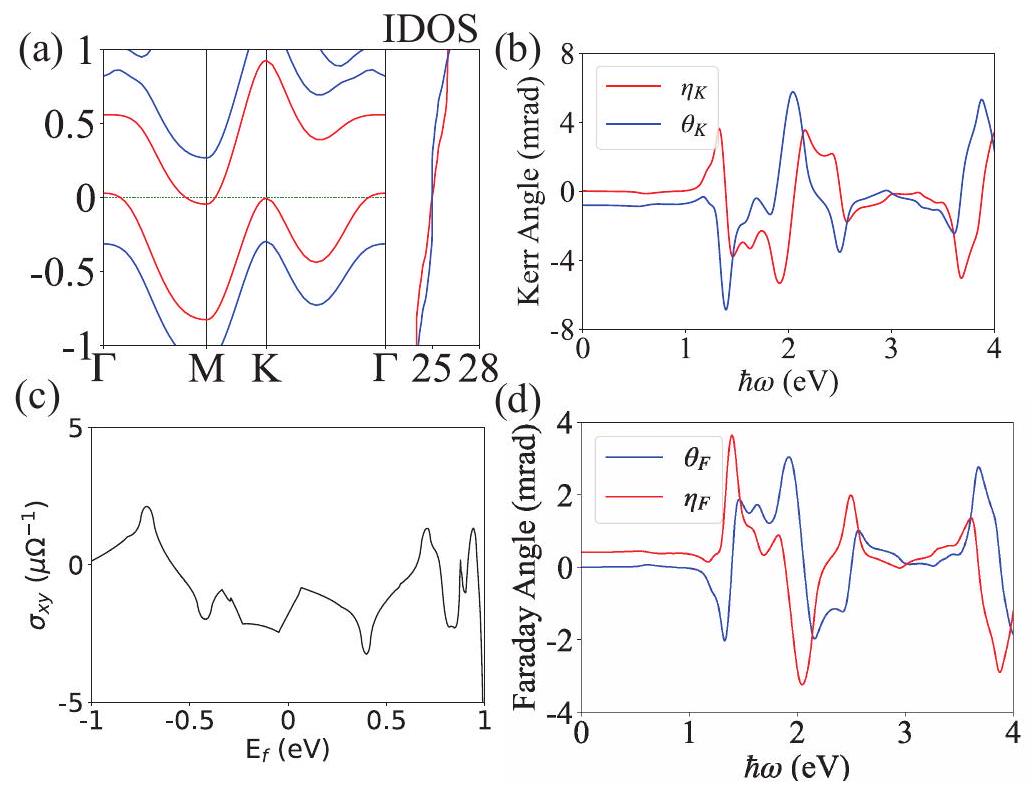

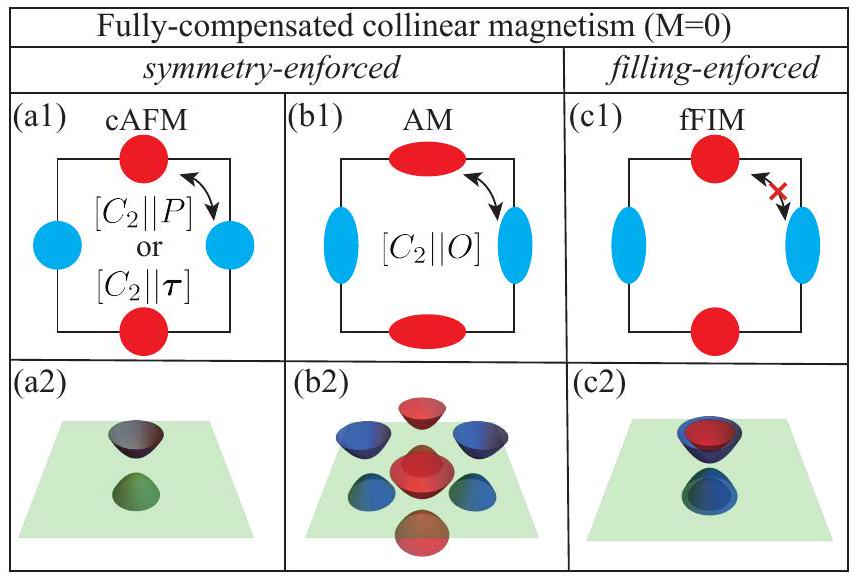

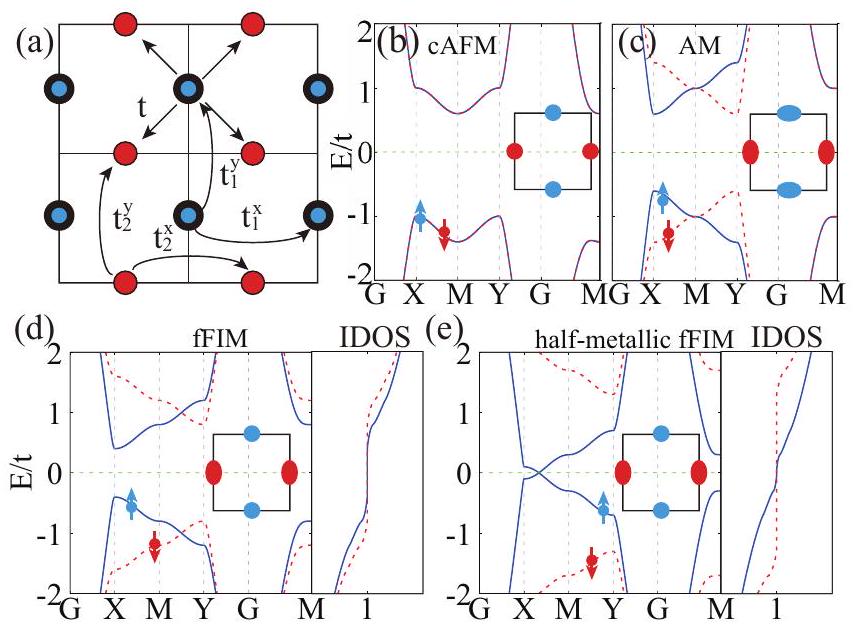

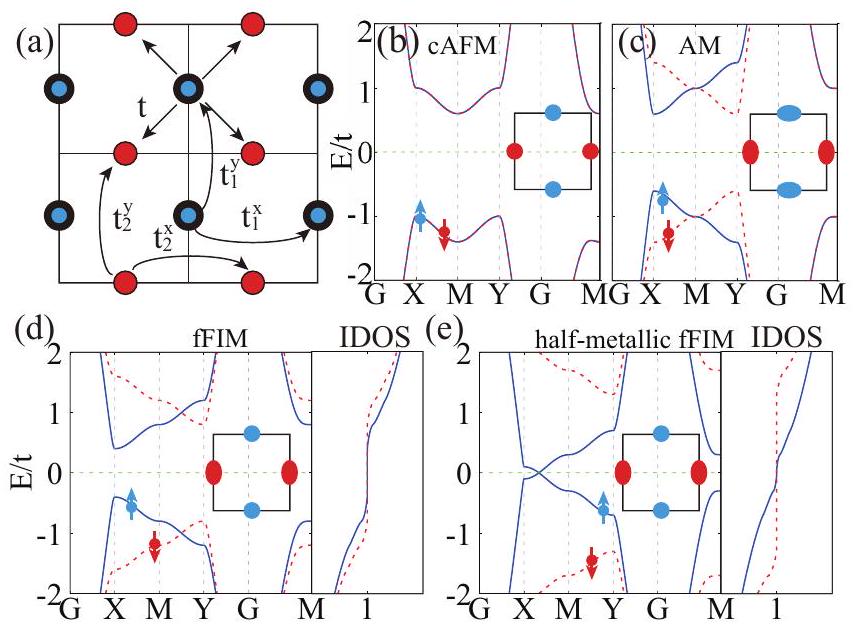

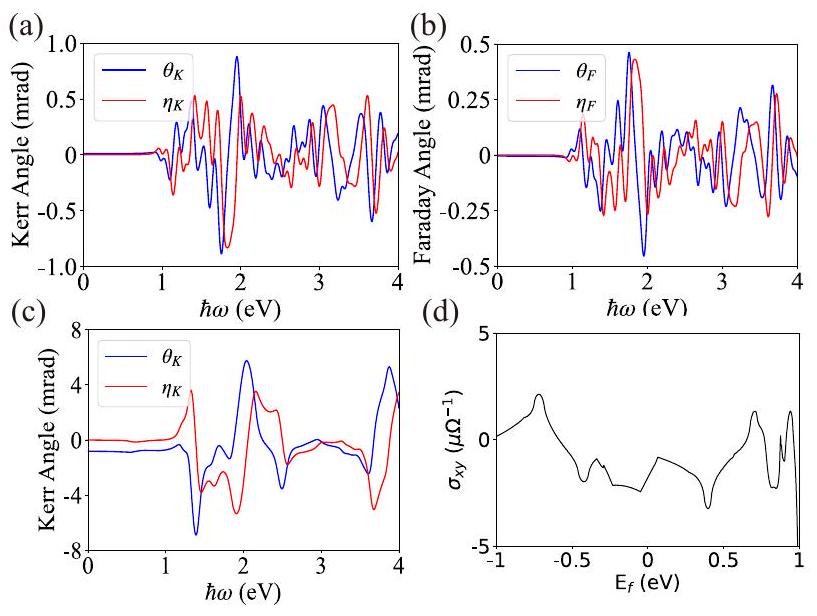

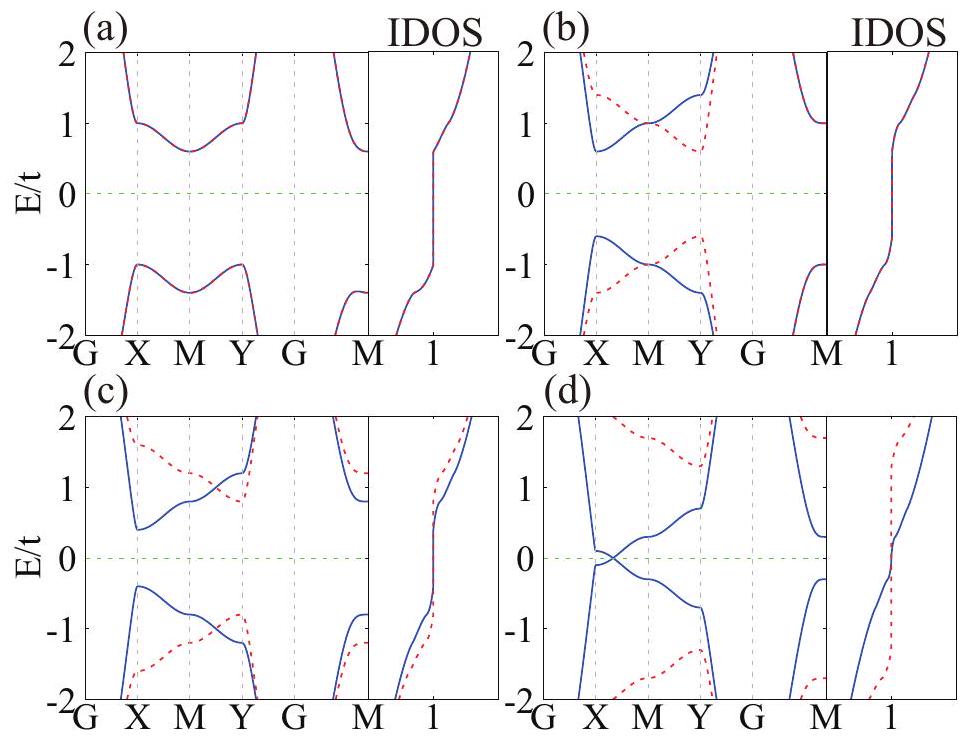

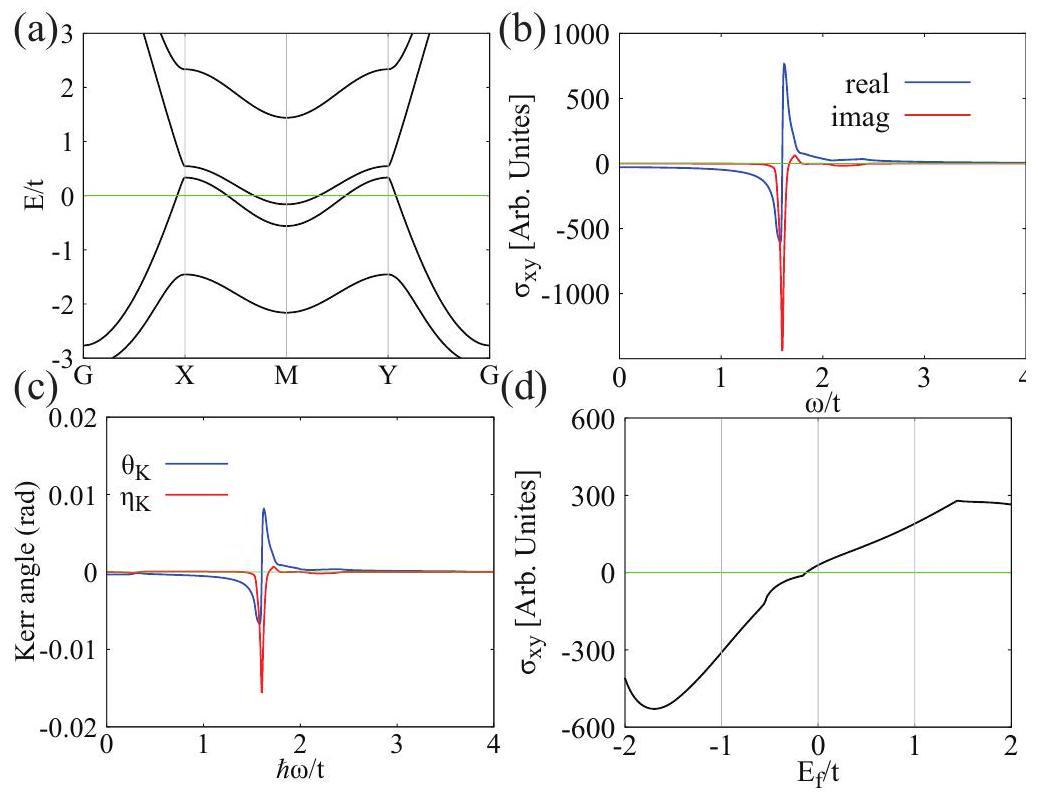

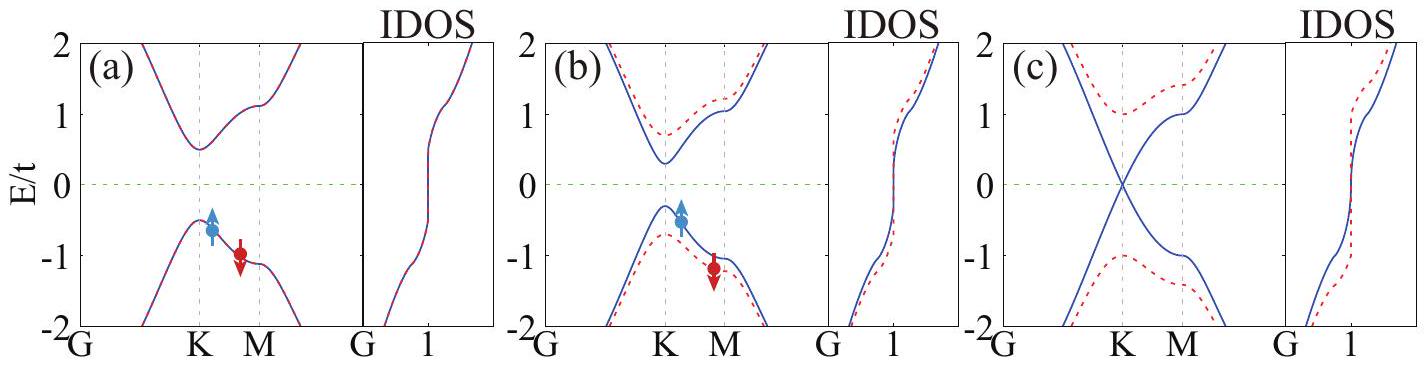

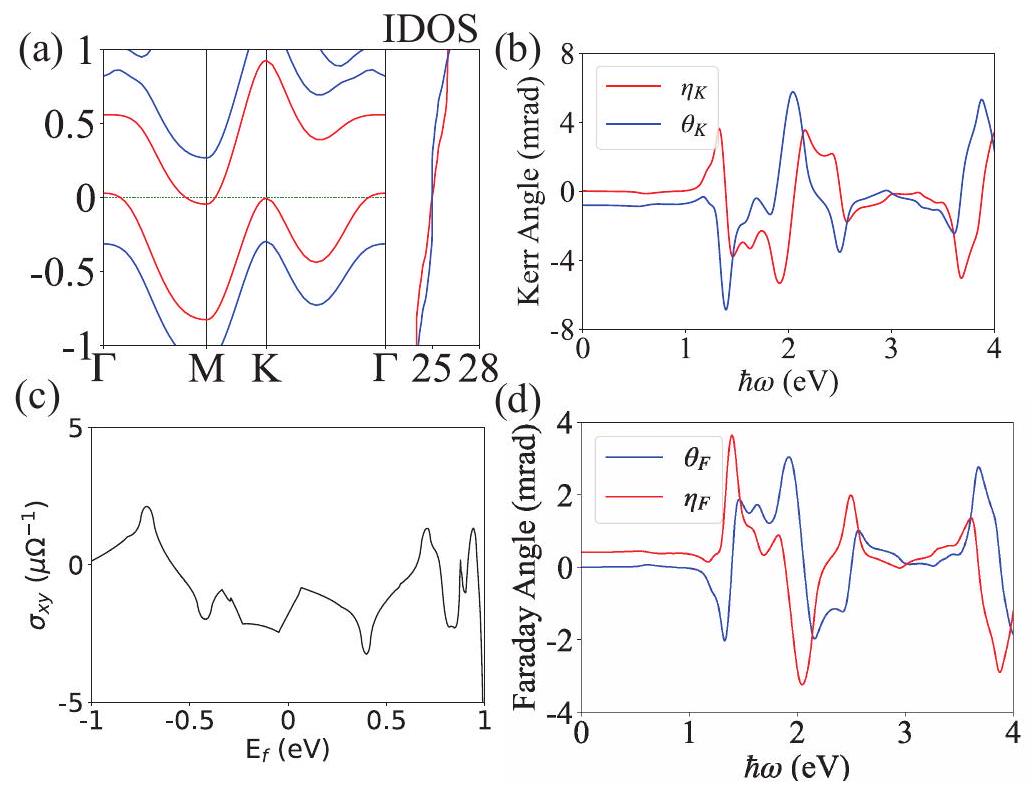

Antiferromagnetic spintronics has long been a subject of intense research interest, and the recent introduction of altermagnetism has further ignited enthusiasm in the field. However, fullycompensated ferrimagnetism, which exhibits band spin splitting but zero net magnetization, has yet to receive enough attention. Since the experimental preparation of two-dimensional (2D) magnetic van der Waals (vdW) materials in 2017, 2D magnetic materials, thanks to their super tunability, have quickly become an important playground for spintronics. Here, we extend the concept of fully-compensated ferrimagnetism (fFIM) to two dimensions and propose 2D filling-enforced fFIM, demonstrate its stability and ease of manipulation, and present three feasible realization schemes with respective exemplary candidate materials. A simple model for 2D fully-compensated ferrimagnets (fFIMs) is developed. Further investigation of 2D fFIMs’ physical properties reveals that they not only exhibit significant magneto-optical response but also show fully spin-polarized currents and the anomalous Hall effect in the half-metallic states, displaying characteristics previously almost exclusive to ferromagnetic materials, greatly broadening the research and application prospects of spintronic materials.

(mvdW) materials with excellent adjustability have immediately attracted tremendous interest. So far, a richer variety of 2D mvdW material systems have been synthesized[20-22], including

different ferrimagnets. When the system has an appropriate filling, i.e.,

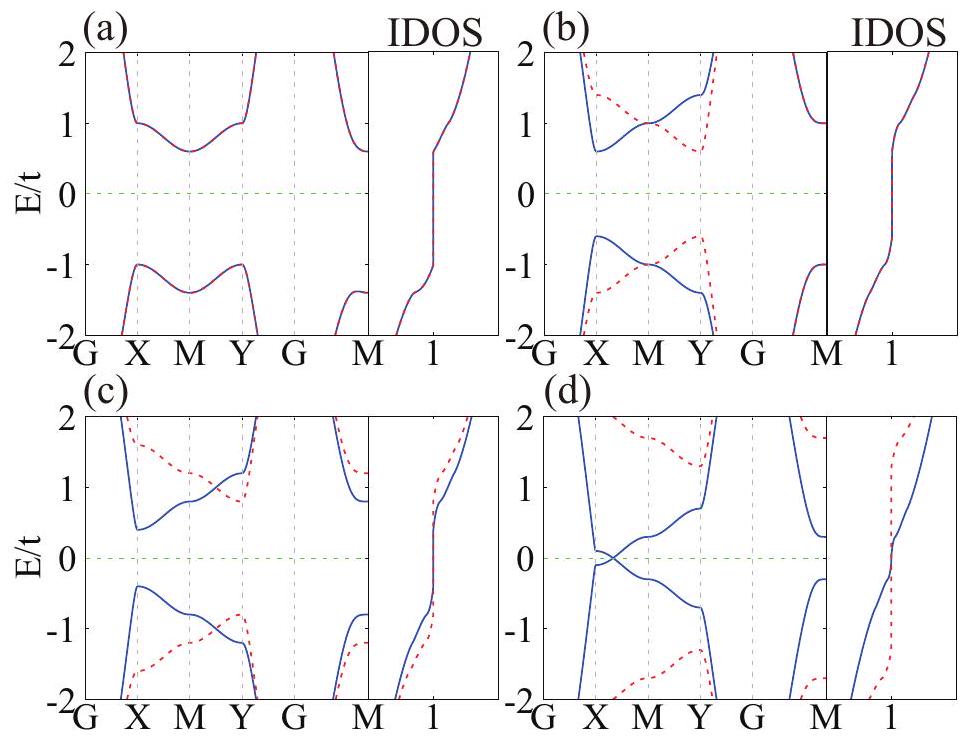

(2) Staggered potential: By applying a staggered potential, introduced by an electric field or substrate, etc., to two magnetic sublattices, the symmetry connecting the two sublattices is broken, leading to spin splitting, and the system becomes a fFIM. From the above theoretical analysis, it can be seen that while a small staggered potential can induce gapped fFIMs, a large one can induce half-metallic fFIMs, as shown in Figs. 2(d) and (e). For example, in experimentally-prepared A-type antiferromagnetic bilayer

(3) Elemental substitution or alloying: By substituting or alloying with an element that either has the same number of valence electrons or differs by an even number compared with the original magnetic atom, ensuring these electrons are evenly distributed across both spin channels, the system maintains

cur only in ferromagnetic systems. To confirm these novel physical properties, we demonstrate our results in terms of both the effective model and representative materials. The above gapped fFIM

- These authors contributed equally to this work.

ccliu@bit.edu.cn

[1] V. Baltz, A. Manchon, M. Tsoi, T. Moriyama, T. Ono, and Y. Tserkovnyak, Antiferromagnetic spintronics, Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015005 (2018).

[2] L. Šmejkal, J. Sinova, and T. Jungwirth, Emerging research landscape of altermagnetism, Phys. Rev. X 12, 040501 (2022).

[3] I. Mazin and The PRX Editors, Editorial: Altermagnetism-a new punch line of fundamental magnetism, Phys. Rev. X 12, 040002 (2022).

[4] H. van Leuken and R. A. de Groot, Half-metallic antiferromagnets, Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 1171 (1995).

[5] H. Akai and M. Ogura, Half-metallic diluted antiferromagnetic semiconductors, Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 026401 (2006).

[6] S. Wurmehl, H. C. Kandpal, G. H. Fecher, and C. Felser, Valence electron rules for prediction of half-metallic compensated-ferrimagnetic behaviour of heusler compounds with complete spin polarization, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 18, 6171 (2006).

[7] W. E. Pickett, Spin-density-functional-based search for half-metallic antiferromagnets, Phys. Rev. B 57, 10613 (1998).

[8] Y.-m. Nie and X. Hu, Possible half metallic antiferromagnet in a hole-doped perovskite cuprate predicted by first-principles calculations, Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 117203 (2008).

[9] K. E. Siewierska, G. Atcheson, A. Jha, K. Esien, R. Smith, S. Lenne, N. Teichert, J. O’Brien, J. M. D. Coey, P. Stamenov, and K. Rode, Magnetic order and magnetotransport in half-metallic ferrimagnetic mn y ru x ga thin films, Phys. Rev. B 104, 064414 (2021).

[10] M. E. Jamer, Y. J. Wang, G. M. Stephen, I. J. McDonald, A. J. Grutter, G. E. Sterbinsky, D. A. Arena, J. A. Borchers, B. J. Kirby, L. H. Lewis, B. Barbiellini, A. Bansil, and D. Heiman, Compensated ferrimagnetism in the zero-moment heusler alloy, Phys. Rev. Appl. 7, 064036 (2017).

[11] M. Žic, K. Rode, N. Thiyagarajah, Y.-C. Lau, D. Betto, J. M. D. Coey, S. Sanvito, K. J. O’Shea, C. A. Ferguson, D. A. MacLaren, and T. Archer, Designing a fully compensated half-metallic ferrimagnet, Phys. Rev. B 93, 140202 (2016).

[12] J. Coey and M. Venkatesan, Half-metallic ferromagnetism:: Example of(invited), J APPL PHYS 91, 8345 (2002).

[13] X. Hu, Half-metallic antiferromagnet as a prospective material for spintronics, Adv Mater 24, 294 (2012).

[14] K. Özdoğan, E. Şaşıoğlu, and I. Galanakis, Ab-initio investigation of electronic and magnetic properties of the 18 -valence-electron fully-compensated ferrimagnetic (crv)xz heusler compounds: A prototype for spin-filter materials, Comput. Mater. Sci 110, 77 (2015).

[15] R. Stinshoff, A. K. Nayak, G. H. Fecher, B. Balke, S. Ouardi, Y. Skourski, T. Nakamura, and C. Felser, Completely compensated ferrimagnetism and sublattice spin crossing in the half-metallic heusler compound, Physical Review B 95, 060410 (2017).

[16] K. Fleischer, N. Thiyagarajah, Y.-C. Lau, D. Betto, K. Borisov, C. C. Smith, I. V. Shvets, J. M. D. Coey, and

K. Rode, Magneto-optic kerr effect in a spin-polarized zero-moment ferrimagnet, Phys. Rev. B 98, 134445 (2018).

[17] T. Kawamura, K. Yoshimi, K. Hashimoto, A. Kobayashi, and T. Misawa, Compensated ferrimagnets with colossal spin splitting in organic compounds, Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 156502 (2024).

[18] B. Huang, G. Clark, E. Navarro-Moratalla, D. R. Klein, R. Cheng, K. L. Seyler, D. Zhong, E. Schmidgall, M. A. McGuire, D. H. Cobden, W. Yao, D. Xiao, P. JarilloHerrero, and X. Xu, Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a van Der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit, Nature 546, 270 (2017).

[19] C. Gong, L. Li, Z. Li, H. Ji, A. Stern, Y. Xia, T. Cao, W. Bao, C. Wang, Y. Wang, Z. Q. Qiu, R. J. Cava, S. G. Louie, J. Xia, and X. Zhang, Discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in two-dimensional van Der Waals crystals, Nature 546, 265 (2017).

[20] Y. Deng, Y. Yu, Y. Song, J. Zhang, N. Z. Wang, Z. Sun, Y. Yi, Y. Z. Wu, S. Wu, J. Zhu, J. Wang, X. H. Chen, and Y. Zhang, Gate-tunable room-temperature ferromagnetism in two-dimensional, Nature 563, 94 (2018).

[21] M. Bonilla, S. Kolekar, Y. Ma, H. C. Diaz, V. Kalappattil, R. Das, T. Eggers, H. R. Gutierrez, M.-H. Phan, and M. Batzill, Strong room-temperature ferromagnetism inmonolayers on van Der Waals Substrates, Nat. Nanotechnol 13, 289 (2018).

[22] J. Klein, T. Pham, J. D. Thomsen, J. B. Curtis, T. Denneulin, M. Lorke, M. Florian, A. Steinhoff, R. A. Wiscons, J. Luxa, Z. Sofer, F. Jahnke, P. Narang, and F. M. Ross, Control of structure and spin texture in the van Der Waals layered magnet CrSBr, Nat Commun 13, 5420 (2022).

[23] B. Huang, W.-Y. Liu, X.-C. Wu, S.-Z. Li, H. Li, Z. Yang, and W.-B. Zhang, Large spontaneous valley polarization and high magnetic transition temperature in stable twodimensional ferrovalley, and Cl , Phys. Rev. B 107, 045423 (2023).

[24] F. D. M. Haldane, Model for a quantum hall effect without landau levels: Condensed-matter realization of the “parity anomaly”, Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2015 (1988).

[25] C. L. Kane and E. J. Mele,topological order and the quantum spin hall effect, Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 146802 (2005).

[26] K. Momma and F. Izumi, Vesta 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data, J. Appl. Crystallogr 44, 1272 (2011).

[27] See Supplemental Material for more detailed information on (I) Square lattice fFIM tight-binding model, (II) The remarkable magneto-optical effect and anomalous Hall effect in general fFIM model, (III) Hexagonal lattice tight-binding model, and (IV) Materials calculation details, which includes Refs.[18, 23, 30, 33-47].

[28] A.-Y. Lu, H. Zhu, J. Xiao, C.-P. Chuu, Y. Han, M.-H. Chiu, C.-C. Cheng, C.-W. Yang, K.-H. Wei, Y. Yang, Y. Wang, D. Sokaras, D. Nordlund, P. Yang, D. A. Muller, M.-Y. Chou, X. Zhang, and L.-J. Li, Janus monolayers of transition metal dichalcogenides, Nat. Nanotechnol 12, 744 (2017).

[29] S.-D. Guo, Y.-T. Zhu, K. Qin, and Y.-S. Ang, Large out-of-plane piezoelectric response in ferromagnetic monolayer nicli, Applied Physics Letters 120, 232403 (2022).

[30] T. Gorkan, J. Das, J. Kapeghian, M. Akram, J. V.

[31] Q. Song, C. A. Occhialini, E. Ergeçen, B. Ilyas, D. Amoroso, P. Barone, J. Kapeghian, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi, A. S. Botana, S. Picozzi, N. Gedik, and R. Comin, Evidence for a single-layer van Der Waals multiferroic, Nature 602, 601 (2022).

[32] S. Semboshi, R. Y. Umetsu, Y. Kawahito, and H. Akai, A new type of half-metallic fully compensated ferrimagnet, Sci Rep 12, 10687 (2022).

[33] P. Wang, D. Wu, K. Zhang, and X. Wu, Two-dimensional quaternary transition metal sulfide

[34] M.-H. Kim, G. Acbas, M.-H. Yang, I. Ohkubo, H. Christen, D. Mandrus, M. A. Scarpulla, O. D. Dubon, Z. Schlesinger, P. Khalifah, and J. Cerne, Determination of the infrared complex magnetoconductivity tensor in itinerant ferromagnets from faraday and kerr measurements, Phys. Rev. B 75, 214416 (2007).

[35] R. Valdés Aguilar, A. V. Stier, W. Liu, L. S. Bilbro, D. K. George, N. Bansal, L. Wu, J. Cerne, A. G. Markelz, S. Oh, and N. P. Armitage, Terahertz response and colossal kerr rotation from the surface states of the topological insulator

[36] H. Ebert, Magneto-optical effects in transition metal systems, Rep. Prog. Phys. 59, 1665 (1996).

[37] C. Aversa and J. E. Sipe, Nonlinear optical susceptibilities of semiconductors: Results with a length-gauge analysis, Phys. Rev. B 52, 14636 (1995).

[38] Y. Yao, L. Kleinman, A. H. MacDonald, J. Sinova, T. Jungwirth, D.-s. Wang, E. Wang, and Q. Niu, First principles calculation of anomalous hall conductivity in ferromagnetic bcc Fe, Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 037204 (2004).

[39] X. Wang, J. R. Yates, I. Souza, and D. Vanderbilt, Ab initio calculation of the anomalous hall conductivity by wannier interpolation, Phys. Rev. B 74, 195118 (2006).

[40] G. Kresse and J. Furthmüller, Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set, Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

[41] J. P. Perdew, K. Burke, and M. Ernzerhof, Generalized gradient approximation made simple, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

[42] A. Togo, F. Oba, and I. Tanaka, First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and

[43] N. Marzari and D. Vanderbilt, Maximally localized generalized wannier functions for composite energy bands, Phys. Rev. B 56, 12847 (1997).

[44] A. A. Mostofi, J. R. Yates, Y.-S. Lee, I. Souza, D. Vanderbilt, and N. Marzari, Wannier90: A tool for obtaining maximally-localised wannier functions, Comput Phys Commun 178, 685 (2008), 0708.0650.

[45] I. Souza, N. Marzari, and D. Vanderbilt, Maximally localized wannier functions for entangled energy bands, Phys. Rev. B 65, 035109 (2001).

[46] K. S. Burch, D. Mandrus, and J.-G. Park, Magnetism in two-dimensional van Der Waals materials, Nature 563, 47 (2018).

[47] M. Cococcioni and S. de Gironcoli, Linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction pa-

rameters in the LDA+U method, Physical Review B 71, 035105 (2005).

Supplementary material for “Two-dimensional fully-compensated Ferrimagnetism”

I. SQUARE LATTICE TIGHT-BINDING MODEL

When the parameters are set to

II. THE REMARKABLE MAGNETO-OPTICAL EFFECT AND ANOMALOUS HALL EFFECT IN GENERAL FFIM MODEL

III. HEXAGONAL LATTICE TIGHT-BINDING MODEL

IV. MATERIALS CALCULATION

[1] C. Aversa and J. E. Sipe, Nonlinear optical susceptibilities of semiconductors: Results with a length-gauge analysis, Phys. Rev. B 52, 14636 (1995).

[2] H. Ebert, Magneto-optical effects in transition metal systems, Rep. Prog. Phys. 59, 1665 (1996).

[3] M.-H. Kim, G. Acbas, M.-H. Yang, I. Ohkubo, H. Christen, D. Mandrus, M. A. Scarpulla, O. D. Dubon, Z. Schlesinger, P. Khalifah, and J. Cerne, Determination of the infrared complex magnetoconductivity tensor in itinerant ferromagnets from faraday and kerr measurements, Phys. Rev. B 75, 214416 (2007).

[4] R. Valdés Aguilar, A. V. Stier, W. Liu, L. S. Bilbro, D. K. George, N. Bansal, L. Wu, J. Cerne, A. G. Markelz, S. Oh, and

| NiICl | ||||

| U (eV) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| E

|

-17.713227 | -16.865274 | -16.077713 | -15.348955 |

|

|

-17.714349 | -16.864369 | -16.073680 | -15.341357 |

|

|

0.001122 | -0.000905 | -0.004033 | -0.007598 |

|

|

||||

| U (eV) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| E

|

-64.108138 | -62.529771 | -61.062467 | -59.686118 |

|

|

– | -61.917934 | -60.410827 | -58.999141 |

|

|

– | -0.611837 | -0.65164 | -0.686977 |

|

|

||||

| U (eV) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|

|

-27.797280 | -26.962275 | -26.161623 | -25.395336 |

|

|

-27.797266 | -26.962107 | -26.161330 | -25.394878 |

|

|

-0.000014 | -0.000168 | -0.000293 | -0.000458 |

[5] Y. Yao, L. Kleinman, A. H. MacDonald, J. Sinova, T. Jungwirth, D.-s. Wang, E. Wang, and Q. Niu, First principles calculation of anomalous hall conductivity in ferromagnetic bcc Fe, Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 037204 (2004).

[6] X. Wang, J. R. Yates, I. Souza, and D. Vanderbilt, Ab initio calculation of the anomalous hall conductivity by wannier interpolation, Phys. Rev. B 74, 195118 (2006).

[7] G. Kresse and J. Furthmüller, Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set, Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

[8] J. P. Perdew, K. Burke, and M. Ernzerhof, Generalized gradient approximation made simple, Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

[9] A. Togo, F. Oba, and I. Tanaka, First-principles calculations of the ferroelastic transition between rutile-type and

[10] N. Marzari and D. Vanderbilt, Maximally localized generalized wannier functions for composite energy bands, Phys. Rev. B 56, 12847 (1997).

[11] A. A. Mostofi, J. R. Yates, Y.-S. Lee, I. Souza, D. Vanderbilt, and N. Marzari, Wannier90: A tool for obtaining maximallylocalised wannier functions, Comput Phys Commun 178, 685 (2008), 0708.0650.

[12] I. Souza, N. Marzari, and D. Vanderbilt, Maximally localized wannier functions for entangled energy bands, Phys. Rev. B 65, 035109 (2001).

[13] K. S. Burch, D. Mandrus, and J.-G. Park, Magnetism in two-dimensional van Der Waals materials, Nature 563, 47 (2018).

[14] B. Huang, G. Clark, E. Navarro-Moratalla, D. R. Klein, R. Cheng, K. L. Seyler, D. Zhong, E. Schmidgall, M. A. McGuire, D. H. Cobden, W. Yao, D. Xiao, P. Jarillo-Herrero, and X. Xu, Layer-dependent ferromagnetism in a van Der Waals crystal down to the monolayer limit, Nature 546, 270 (2017).

[15] M. Cococcioni and S. de Gironcoli, Linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction parameters in the LDA+U method, Physical Review B 71, 035105 (2005).

[16] T. Gorkan, J. Das, J. Kapeghian, M. Akram, J. V. Barth, S. Tongay, E. Akturk, O. Erten, and A. S. Botana, Skyrmion formation in ni-based janus dihalide monolayers: Interplay between magnetic frustration and dzyaloshinskii-moriya interaction, Phys. Rev. Mater 7, 054006 (2023).

[17] P. Wang, D. Wu, K. Zhang, and X. Wu, Two-dimensional quaternary transition metal sulfide

[18] B. Huang, W.-Y. Liu, X.-C. Wu, S.-Z. Li, H. Li, Z. Yang, and W.-B. Zhang, Large spontaneous valley polarization and high magnetic transition temperature in stable two-dimensional ferrovalley

- These authors contributed equally to this work.

ccliu@bit.edu.cn

- These authors contributed equally to this work.