DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-025-03275-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40075491

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-12

الهيدروجيل القابل للحقن مع إطلاق الدواء المحفز بواسطة أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية يمكّن من التوصيل المشترك لعامل مضاد للبكتيريا وجزيئات نانوية مضادة للالتهابات لعلاج التهاب اللثة

الملخص

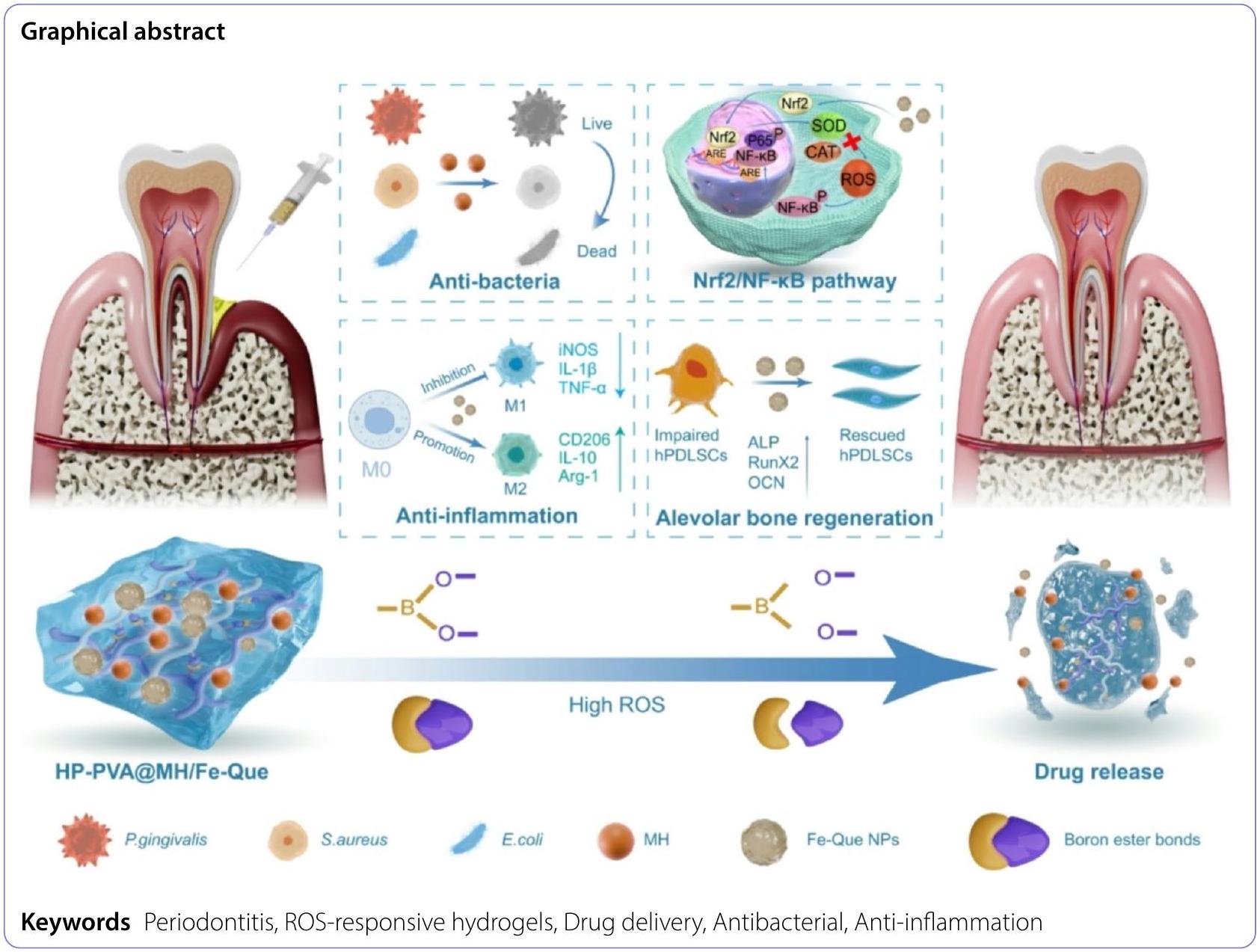

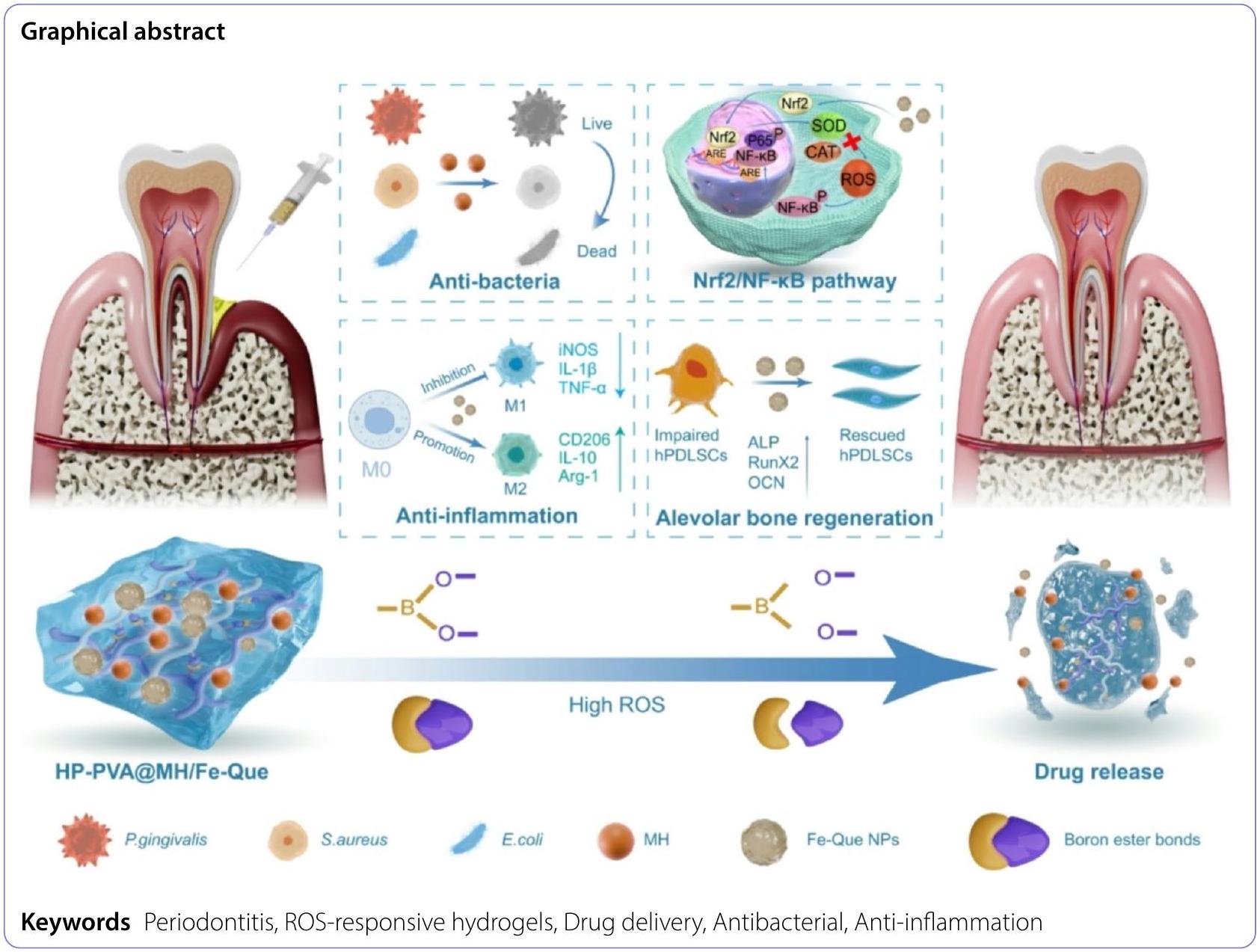

التهاب اللثة، وهو مرض التهابي مزمن تسببه البكتيريا، يتميز بتراكم أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) في مناطق محددة، مما يؤدي إلى استجابة التهابية، والتي بدورها تؤدي إلى تدمير الأنسجة الداعمة للثة. لذلك، فإن استخدام مضادات البكتيريا، والتخلص من ROS، وتقليل الاستجابة الالتهابية، وتنظيم البيئة الدقيقة للثة، وتخفيف امتصاص العظم السنخي هي طرق فعالة لعلاج التهاب اللثة. في هذه الدراسة، قمنا بتطوير هلام قابل للحقن يستجيب لـ ROS عن طريق تعديل حمض الهيالورونيك بحمض الفينيل بورونيك (PBA) والتفاعل معه مع بولي (الكحول الفينيل) (PVA) لتشكيل رابطة بورات. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، احتوى الهلام القابل للاستجابة لـ ROS على العامل المضاد للبكتيريا مينو سيكلين هيدروكلوريد (MH) والجزيئات النانوية المضادة للالتهابات فيرو-كويرسيتين (Fe-Que NPs) لإطلاق الدواء عند الطلب استجابةً لبيئة التهاب اللثة. أظهر هذا الهلام (HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que) خصائص مضادة للبكتيريا فعالة للغاية. علاوة على ذلك، من خلال تعديل مسار Nrf2/NF-kB، قضى بشكل فعال على ROS وعزز استقطاب البلعميات إلى النمط الظاهري M2، مما قلل الالتهاب وزاد من القدرة على التمايز العظمي لخلايا جذع الرباط السني البشري (hPDLSCs) في البيئة الدقيقة للثة. أظهرت الدراسات الحيوانية أن HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que قلل بشكل كبير من فقدان العظم السنخي وزاد من تعبير عوامل التمايز العظمي من خلال قتل البكتيريا وتثبيط الالتهاب. وبالتالي، كان لهلام HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que قدرات فعالة في مكافحة البكتيريا، والتخلص من ROS، ومكافحة الالتهاب، وتخفيف امتصاص العظم السنخي، مما يظهر إمكانات تطبيق ممتازة لعلاج التهاب اللثة.

المقدمة

يمكن أن تنتج مسببات الأمراض اللثوية مجموعة متنوعة من الإنزيمات والسموم والمواد الأيضية السامة، والتي

تتسبب لاحقًا في تلف الأنسجة وتحفيز ردود فعل التهابية، مما يؤدي إلى تدمير الأنسجة اللثوية، مثل فقدان العظام وفقدان الارتباط [6،7]. لذلك، فإن القضاء السريع على البكتيريا المسببة للأمراض اللثوية هو شرط أساسي لعلاج التهاب اللثة. تتوفر مجموعة متنوعة من الأدوية لإزالة البكتيريا المسببة للأمراض اللثوية، مثل المضادات الحيوية، والببتيدات المضادة للميكروبات، والجزيئات النانوية المعتمدة على المعادن [8-11]. في الممارسة السريرية، يُعتبر مينو سيكلين هيدروكلوريد (MH) عاملًا موضعيًا شائع الاستخدام للجيوب اللثوية. لا يتمتع MH فقط بنشاط مضاد للبكتيريا عالي ضد مسببات الأمراض اللثوية، ولكنه أيضًا يمتلك خصائص مثبطة للكولاجيناز. أظهرت العديد من الدراسات أن الجرعات المنخفضة من MH يمكن أن تقلل بشكل كبير من الالتهاب في موقع اللثة، مما يحسن من نجاح علاج التهاب اللثة [12، 13]. لذلك، يُعتبر MH دواءً مثاليًا لعلاج التهاب اللثة بالمضادات الحيوية. ومع ذلك، فإن استخدام MH بمفرده له العديد من القيود، مثل فقدان الدواء السريع، مما لا يمكنه تحقيق إطلاق بطيء وتأثير مضاد للبكتيريا سريع. لذلك، من الضروري تحميل MH في حامل مثل الجزيئات النانوية، أو الكريات الدقيقة، أو الهلامات.

يت disrupted التوازن بين البكتيريا والمضيف في موقع آفات التهاب اللثة. يتم إنتاج ROS الزائدة، مما ينشط مسارات الإشارة الالتهابية المتعددة، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة نسبة البلعميات M1 إلى M2 وإنتاج عدد كبير من السيتوكينات الالتهابية، مثل إنترلوكين-6 (IL-6)، وعامل نخر الورم ألفا (TNF-

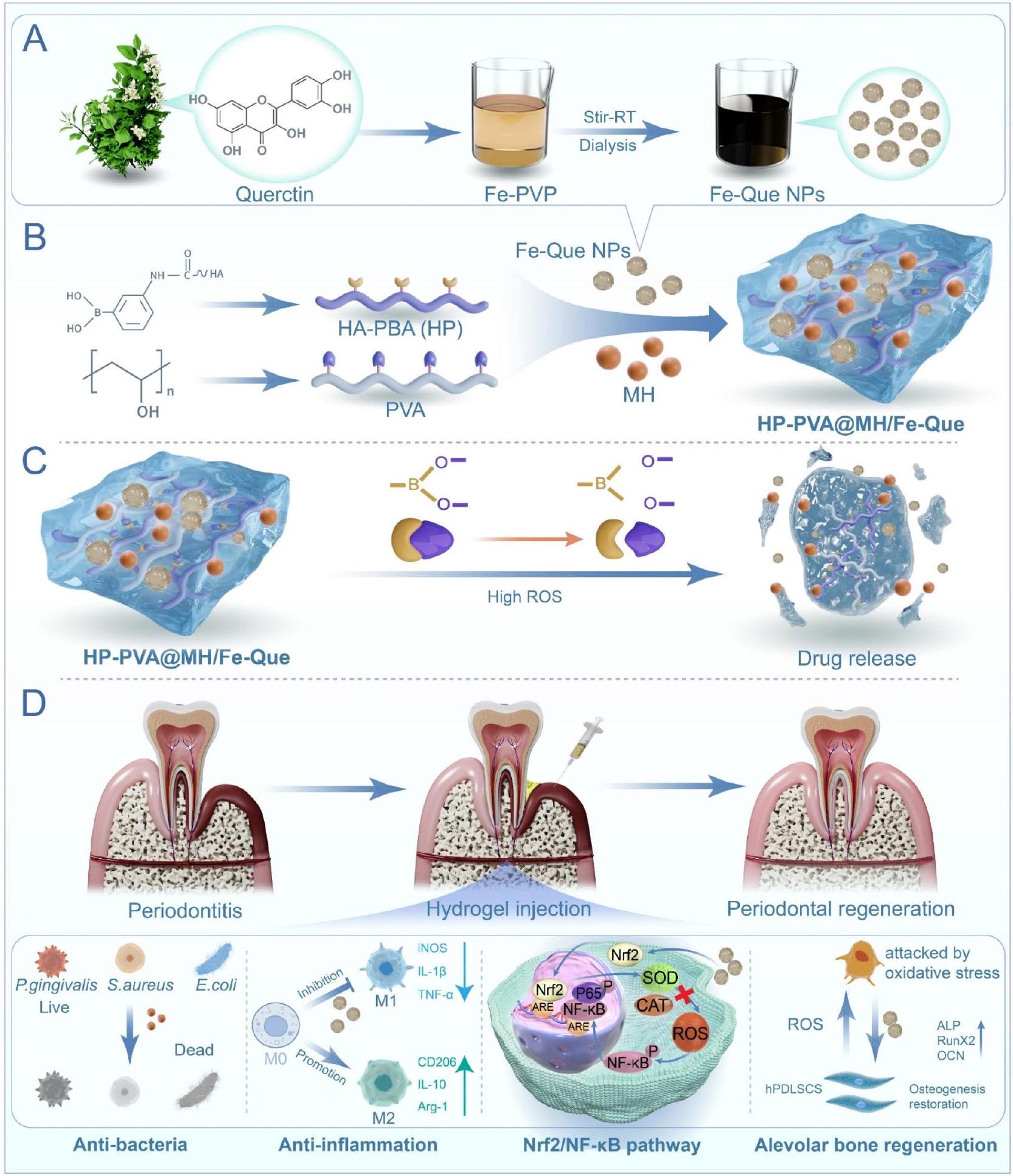

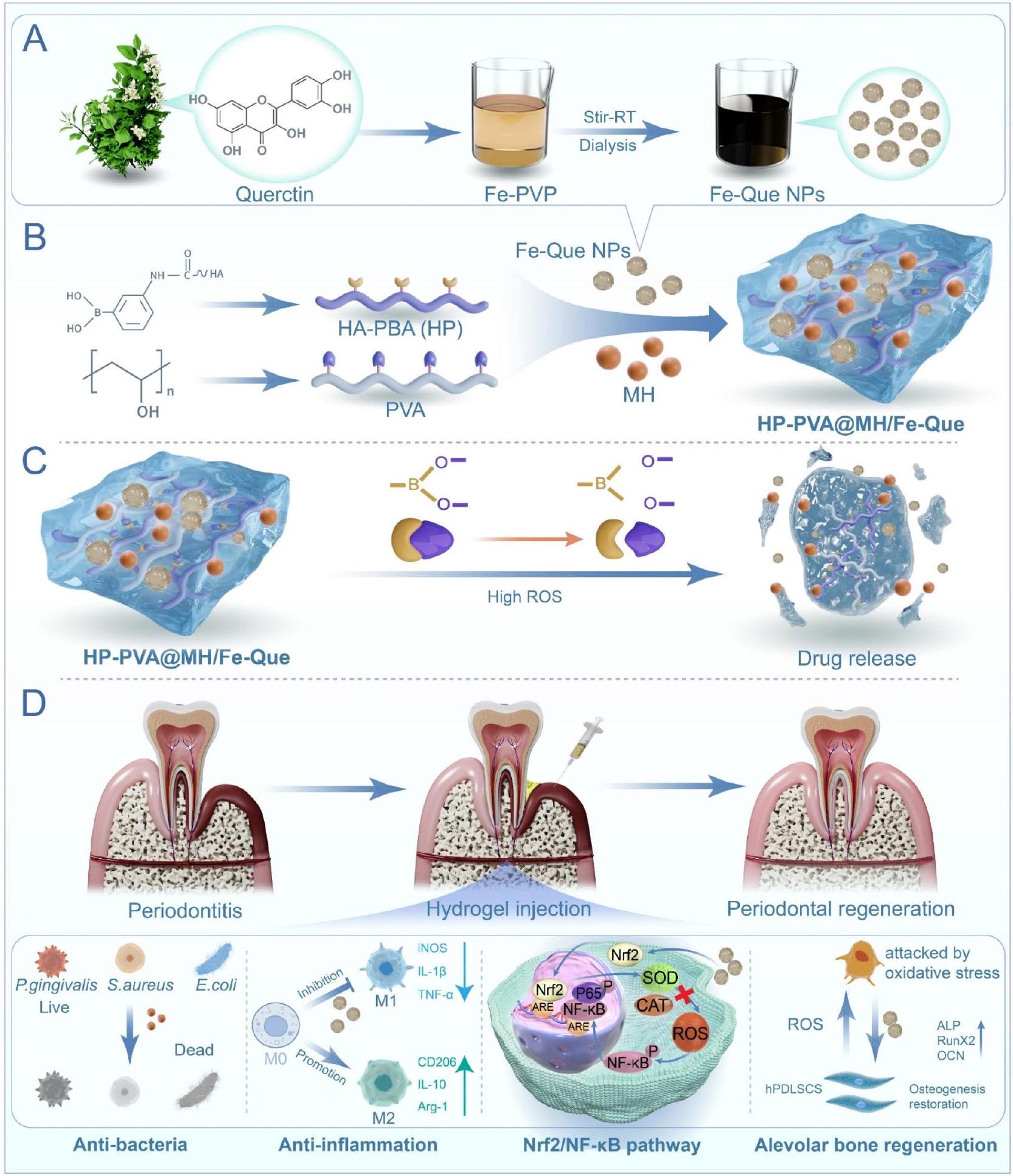

في هذه الدراسة، كما هو موضح في المخطط 1، تم تشكيل جزيئات نانوية فائقة الصغر من Fe-Que أولاً من خلال تنسيق الكيرسيتين مع أيونات الحديد منخفضة السمية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم تطعيم حمض الهيالورونيك (HA) مع 3-أمينوفينيل بورات (HA-PBA، HP)، والذي تفاعل بعد ذلك مع مجموعة 1،3-ديول من بولي (الفينيل الكحول) (PVA) لتشكيل رابطة بورات، مما أدى إلى بناء هيدروجيل بخصائص استجابة ROS. تم إدخال MH وFe-Que لتحضير نظام هيدروجيل HP-PVA (HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que). في بيئة ROS العالية لالتهاب اللثة، تم كسر رابطة البورات، مما أدى إلى تسريع إطلاق MH وFe-Que. الجزيء الصغير MH يقتل البكتيريا بسرعة، ثم تقوم جزيئات Fe-Que بالتخلص من ROS، وتقليل الاستجابة الالتهابية للأنسجة اللثوية، وتخفيف امتصاص العظم السنخي. تم تقييم الخصائص الفيزيائية، وخصائص إطلاق الدواء، والنشاط المضاد للبكتيريا، والتوافق الحيوي لمركب HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que بالتفصيل. أظهرت هذه الدراسة أن هيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que قام في البداية بسرعة بتثبيط نمو البكتيريا من خلال MH. بعد ذلك، قامت Fe-Que بالتخلص من ROS عبر مسار Nrf2/NF-кB، وتنظيم استقطاب البلعميات لتقليل العوامل المؤيدة للالتهاب وزيادة العوامل المضادة للالتهاب، بينما حمت أيضًا hPDLSCs من الأضرار الناتجة عن ROS وعززت التمايز العظمي تحت الضغط التأكسدي. تم تأكيد قدرة هيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que على التخلص من ROS وتخفيف الالتهاب وامتصاص العظم السنخي أيضًا في نموذج التهاب اللثة المزمن SD. لذلك، مع فعالية علاجية ملحوظة في المختبر وفي الجسم الحي، قد يكون لهيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que إمكانات كبيرة لعلاج التهاب اللثة.

المواد والأساليب

المواد

تركيب وتوصيف جزيئات نانوية من الحديد-كيو

تم فحص الشكل والحجم لجزيئات نانو الحديد-كيو باستخدام المجهر الإلكتروني الناقل (TEM، JEM-2100، طوكيو، اليابان). تم قياس توزيع أحجام الجسيمات باستخدام تقنية تشتت الضوء الديناميكي (DLS) (مالفرن، نانو ZS، المملكة المتحدة). تم استخدام مطياف الأشعة فوق البنفسجية والمرئية (TU-1810، شنغهاي، الصين) لتحديد طيف الأشعة فوق البنفسجية والمرئية بالقرب من الأشعة تحت الحمراء (UV-vis-NIR).

تركيب وتوصيف HA المعدل بواسطة PBA (HAPBA، المسمى HP)

تم قياس طيف UV-vis-NIR لـ HA و PBA و HP باستخدام مطياف الأشعة فوق البنفسجية والمرئية (TU1810، شنغهاي، الصين). تم قياس أطياف FTIR لـ HA و PBA و HP باستخدام مطياف FTIR (WQF-530، بكين، الصين). تم تحليل الهياكل الكيميائية لـ HA و HP بواسطة الرنين المغناطيسي النووي للبروتون.

تحضير وتوصيف الهلاميات المائية

تم تثبيت العينات على قاعدة معدنية ورشها بالذهب تحت فراغ. ثم تم ملاحظة الهياكل الدقيقة للعينات بصريًا باستخدام المجهر الإلكتروني الماسح بالانبعاث الميداني (SEM، Sigma 300، ZEISS، ألمانيا)، وعناصر سطح العينات.

تم الكشف عن التركيب والتوزيع بواسطة صور مطياف الطاقة المشتتة (EDS).

خصائص القابلية للحقن، والتكيف مع الشكل، واللصق، والشفاء الذاتي للهلاميات المائية

10 مم، وتركت اللثة في درجة حرارة الغرفة لمدة 15 دقيقة. تم تثبيت العينات المربوطة بعد ذلك على نظام اختبار المواد (INSTRON، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) بمعدل

تم تحميل 2 مل من هيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que في زجاجة عينة. ثم، تم إضافة 1 مل من تركيزات مختلفة من بيروكسيد الهيدروجين (

سلوك التحلل للهيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que في المختبر

إطلاق الدواء في المختبر استجابة لمستويات ROS من هيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que

اختبارات النشاط المضاد للبكتيريا للهيدروجيل في المختبر

لتقييم النشاط المضاد للبكتيريا للهيدروجيل بشكل أكبر، تم إجراء اختبار منطقة التثبيط (ZOI). بالإضافة إلى S. aureus، تم اختبار E. coli، P. gingivalis، والجرثومة الرئيسية ستربتوكوكوس موتانس (S. mutans)، المرتبطة بتكوين الأغشية الحيوية الفموية، لتقييم فعالية الهيدروجيل ضد البكتيريا الخاصة بالفم. تم غمر الهيدروجيل المعقم في PBS عند

اختبار التوافق الحيوي للهيدروجيل

زراعة الخلايا

تم الحصول على hPDLSCs من الأضراس الدائمة الصحية لمرضى تقويم الأسنان الذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 12-18 عامًا. تم أخذ جميع الأسنان الدائمة الشابة المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة من المستشفى السنية التابع لجامعة الطب الجنوبي الغربي، مع موافقة مستنيرة من المرضى والأوصياء، وموافقة من لجنة الأخلاقيات

(20220819002). تم نقع الأنسجة السنية وغسلها عدة مرات بمحلول PBS يحتوي على تركيزات مختلفة من بنسلين-ستربتوميسين. ثم، تم كشط الثلث الأوسط من الأنسجة اللثوية في الجذر باستخدام شفرة معقمة، وتم الطرد المركزي، ونقلها إلى زجاجة زراعة مقلوبة، وزرعها في حاضنة خلايا تحتوي على

توافق الخلايا مع الهيدروجيلات

تم زراعة HPDLSCs و HGFs و RAW264.7 و L929 و HaCaTs بكثافة من

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم زراعة الخلايا بكثافة

اختبار التوافق الحيوي للهيدروجيل

قدرة امتصاص الجذور الحرة والقدرة المضادة للأكسدة للهلاميات

اختبار امتصاص الجذور الحرة DPPH و ABTS

ثم تم تقييم معدلات إزالة الجذور الحرة DPPH للمواد الهلامية المختلفة باستخدام مطياف الأشعة فوق البنفسجية والمرئية (TU-1810، شنغهاي، الصين) لتسجيل قيم OD عند 515 نانومتر وطيف الأشعة فوق البنفسجية والمرئية والأشعة تحت الحمراء القريبة في النطاق من

تأثيرات الحماية الخلوية ضد الإجهاد التأكسدي

تم تقييم قدرة إنقاذ الخلايا من الإجهاد التأكسدي واستعادة حيويتها من خلال صبغة الخلايا الحية/الميتة واختبار CCK-8. باختصار، تم زراعة خلايا L929 و RAW264.7 بكثافة

علاوة على ذلك، تم تقييم قدرة الهيدروجيل المختلفة على القضاء على أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) من خلال قياس شدة الفلورسنت باستخدام نظام تصوير حي متعدد الأوضاع للحيوانات الصغيرة (ABL X6، تانون). تم زراعة خلايا RAW264.7 بكثافة

تقييم استقطاب البلعميات للهيدروجيلات

علاوة على ذلك، تم زراعة خلايا RAW264.7 في طبق يحتوي على ستة آبار وتم معالجتها وفقًا لما ذُكر أعلاه.

ثم تم هضم الخلايا باستخدام

آلية مضادات الأكسدة ومضادات الالتهاب في الهيدروجيل في المختبر من خلال تنظيم مسار Nrf2/NF-кB

ثم تم الكشف عن مستويات التعبير لعوامل الالتهاب و جينات إنزيمات مضادات الأكسدة في خلايا RAW264.7 بواسطة تقنية PCR الكمي في الوقت الحقيقي (qRT-PCR). باختصار، تم زراعة خلايا RAW264.7 بكثافة من

علاوة على ذلك، تم إجراء تحليل Western blot (WB) لتقييم مستويات التعبير المرتبطة بالبروتينات المضادة للأكسدة (Nrf2)، وبروتينات مسار الإشارات NF-кB (NF-кB و

للفصل البروتيني، تلاها نقل إلى غشاء بولي فينيليدين فلوريد (PVDF). بعد حجب

تقييم التمايز العظمي في المختبر للهلامات

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم زراعة hPDLSCs على صفائح 24 بئر وتمت معالجة الخلايا كما فعلنا من قبل. تم صبغ العينات المجمعة لمدة 7 أيام لـ Runx2، بينما تم صبغ تلك المزروعة لمدة 21 يومًا لبروتين التمايز العظمي المتأخر أوستيوكالسين (OCN). بالنسبة لـ IF، تم إجراء hPDLSCs باستخدام مضاد RUNX2 (1:100، Cell Signaling Technology، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) ومضاد OCN (1:100، Proteintech، الصين). علاوة على ذلك، تم ملاحظة شكل الهيكل الخلوي بعد معالجة

باستخدام المجهر الضوئي الليزري. أخيرًا، تم استخدام المجهر الضوئي الفلوري لتصور صور IF، وتم تقييم الخرائط الطبوغرافية ثلاثية الأبعاد باستخدام ImageJ.

العلاج في نموذج التهاب اللثة في الجسم الحي إنشاء نموذج التهاب اللثة في الفئران

خاصية مضادة للأكسدة في الجسم الحي

تحليل Micro-CT

علم الأنسجة و المناعية

رباعي الأسيتيك (EDTA) لمدة شهر، وتم تجفيفها في كحول متدرج، وتم تضمينها في البارافين. بعد ذلك، تم عمل هذه العينات البارافينية إلى مقاطع بسمك

تحليل إحصائي

النتائج والمناقشة

تخليق وتوصيف جزيئات Fe-Que NPs

تخليق وتوصيف HP

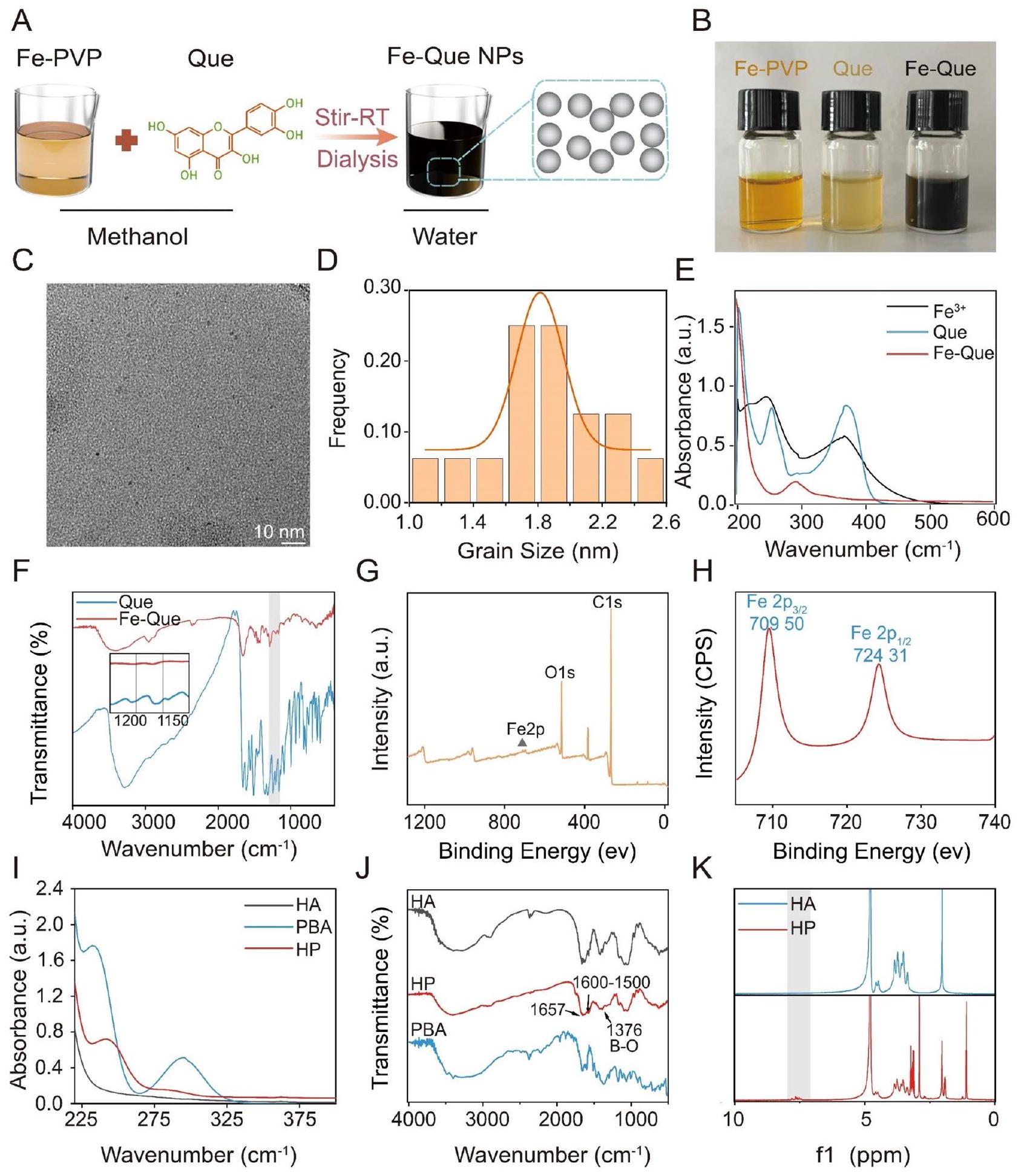

تحضير وتوصيف هيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que

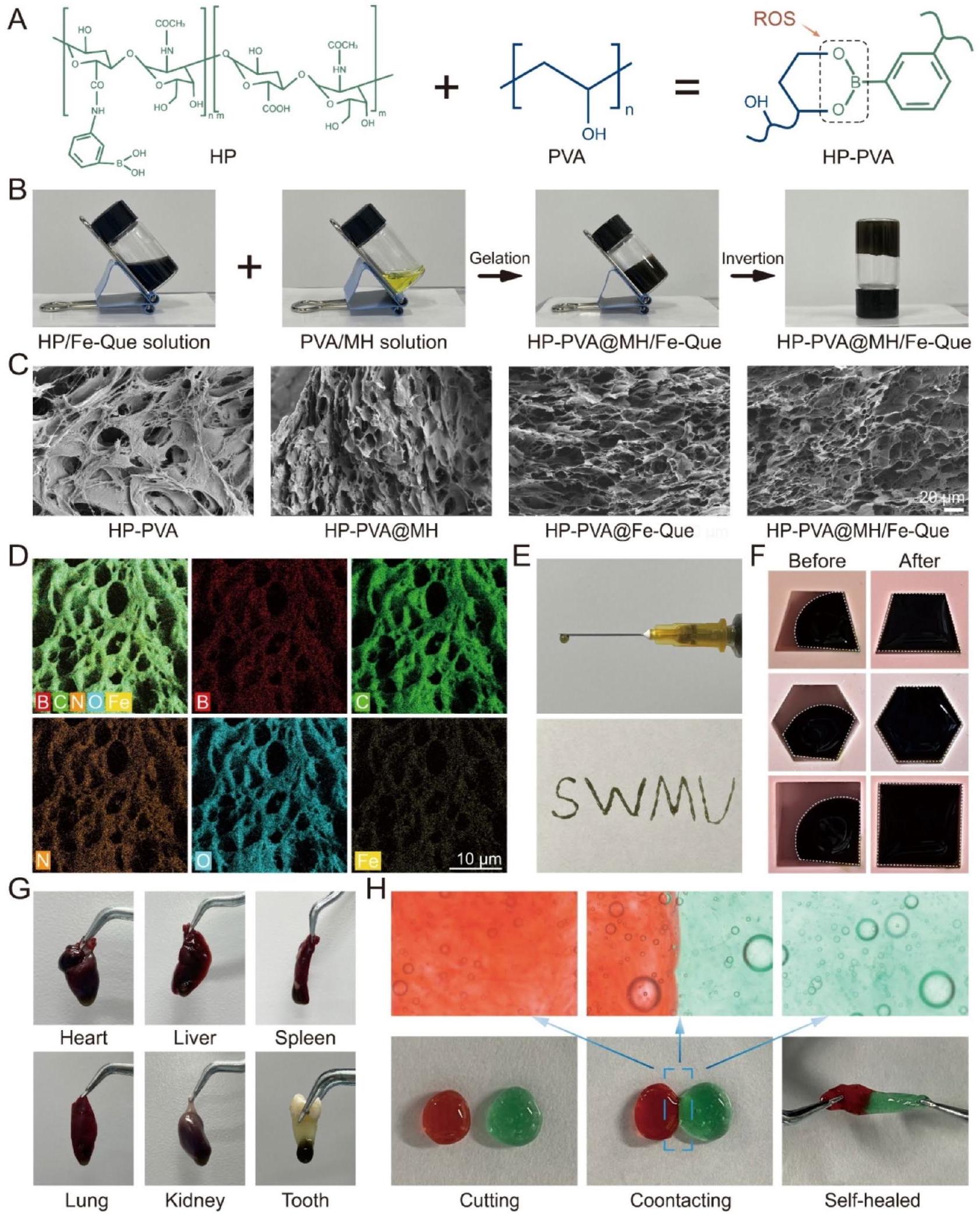

والتي يمكن أن تحسن الأداء المضاد للبكتيريا، وتسريع إزالة ROS وتخفيف الالتهاب وامتصاص العظام. كما هو موضح في الشكل 2A، تم تشكيل شبكة هيدروجيل من خلال إنشاء روابط استر البورات الديناميكية (الحساسة للغاية لـ ROS) بين هياكل مجموعة الديول على PVA ومجموعات حمض phenylboronic على HP. يظهر الشكل 2B حالة هيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que قبل وبعد التجلط. بعد ذلك، تم ملاحظة الشكل المجهري للهيدروجيل بواسطة SEM. كما هو موضح في الشكل 2C، أظهرت جميع الهيدروجيل مسام مترابطة وهياكل مسامية ثلاثية الأبعاد موحدة، مما يسهل احتواء الجزيئات النشطة بيولوجيًا وحمايتها من التحلل. علاوة على ذلك، ضمنت النقل الفعال للمواد الغذائية والأكسجين، مما يعزز اختراق الخلايا، والتكاثر، وتكوين الأنسجة الجديدة. علاوة على ذلك، كشفت تحليل خريطة EDS عن توزيع متجانس للعناصر C وN وO وB وFe في جميع أنحاء هيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que (الشكل 2D)، مما يوفر دليلًا على التحميل الناجح وتشتت جزيئات Fe-Que النانوية داخل الهيدروجيل.

القدرة على الحقن، التكيف، الالتصاق، وخصائص الشفاء الذاتي هي خصائص أساسية للهيدروجيل لتوصيل الأدوية محليًا في جيوب التهاب اللثة [43]. تسهل ميزة الحقن اختراق الهيدروجيل بكفاءة في جيوب التهاب اللثة الضيقة والعميقة، مما يوفر تحكمًا مكانيًا وزمنيًا في إطلاق الدواء العلاجي من خلال تحلل المادة وانتشار الدواء [8]. أظهر الشكل 2E أن هيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/FeQue يمكن نقله بسهولة إلى حقنة وضغطه من إبرة (

في التهاب اللثة، يتم تدمير الأنسجة اللثوية بشكل غير منتظم. يمتلك الهيدروجيل مرونة شبيهة بالهلام وسوائل، مما يظهر تكيفًا ممتازًا مع الشكل، مما يمكّن الهيدروجيل من التكيف تمامًا مع الأنسجة اللثوية التالفة والتكيف مع العيوب اللثوية غير المنتظمة. كما هو موضح في الشكل 2F، يمكن إعادة تشكيل هيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que إلى أشكال مختلفة، مما يمكن استخدامه لملء عيوب مختلفة وكان له تكيف جيد. بعد حقنه في جيب اللثة، يتعرض الهيدروجيل لغسل مستمر بواسطة سائل اللثة واللعاب، لذا يجب أن يمتلك خصائص لاصقة معينة للالتصاق بالأنسجة اللثوية وإطالة وقت احتباسه داخل جيب اللثة. أظهر هيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que التصاقًا قويًا بشق الأسنان والأعضاء الداخلية، بما في ذلك القلب والكبد والطحال والرئتين والكلى وجذر السن الأول للضرس. لتقييم التصاق الأنسجة للهيدروجيل بشكل أكبر، تم إجراء اختبار قص قياسي في المختبر باستخدام لثة الخنازير، وتم تقييم التصاق الهيدروجيل بمينا الأسنان. أظهرت النتائج أن تحميل MH وFe-Que لم يؤثر على خصائص التصاق الهيدروجيل، وكانت قوة التصاق HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que بلثة الخنازير حوالي

ديناميكية إطلاق الأدوية المستجيبة لـ ROS وسلوك التحلل في المختبر للهيدروجيلات

درجة الحموضة ودرجة الحرارة [50]. الشكل S5A يوضح آلية تفاعل الهيدروجيل مع أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية. لذلك، قمنا بمعالجة الهيدروجيلات بطرق مختلفة

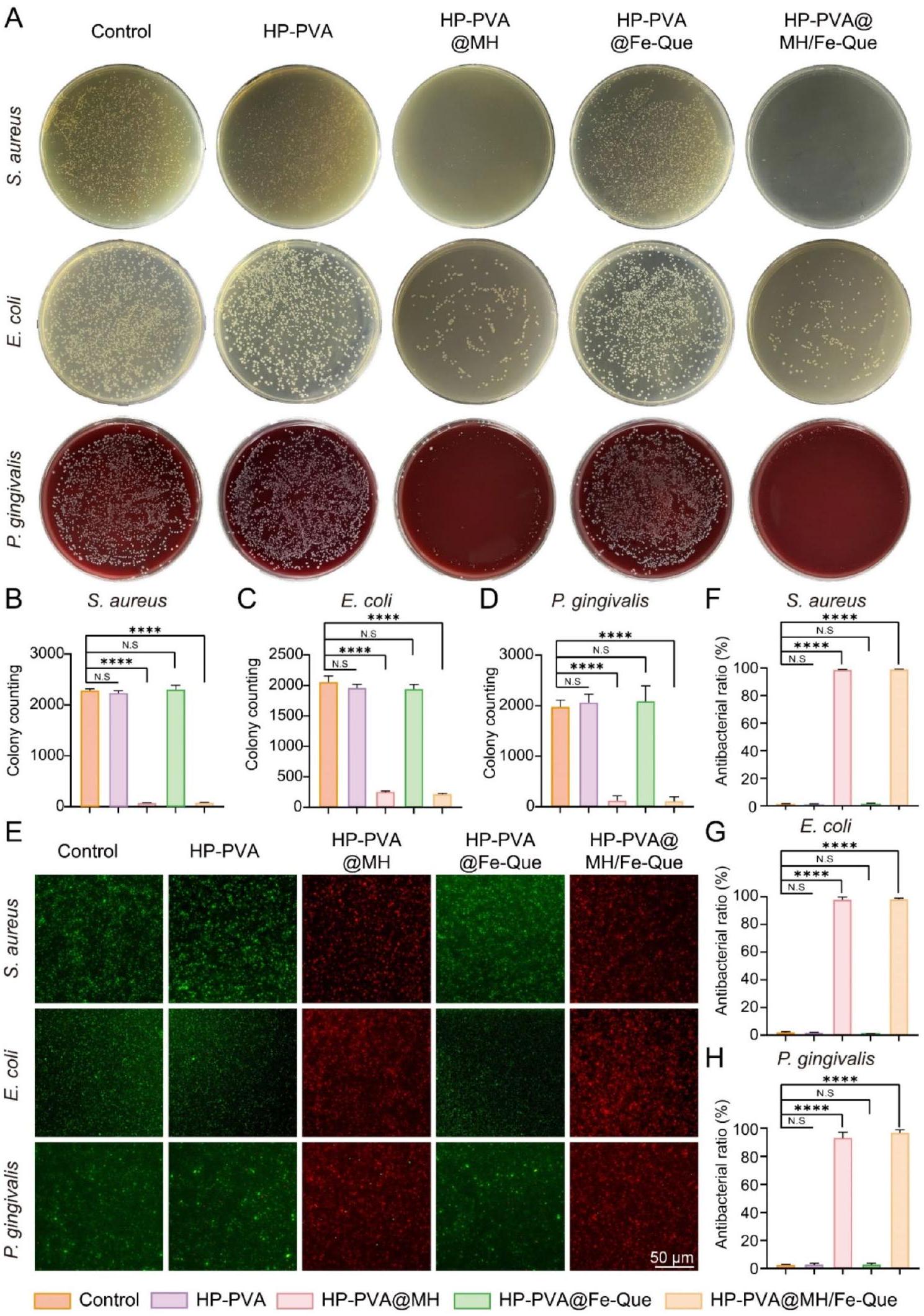

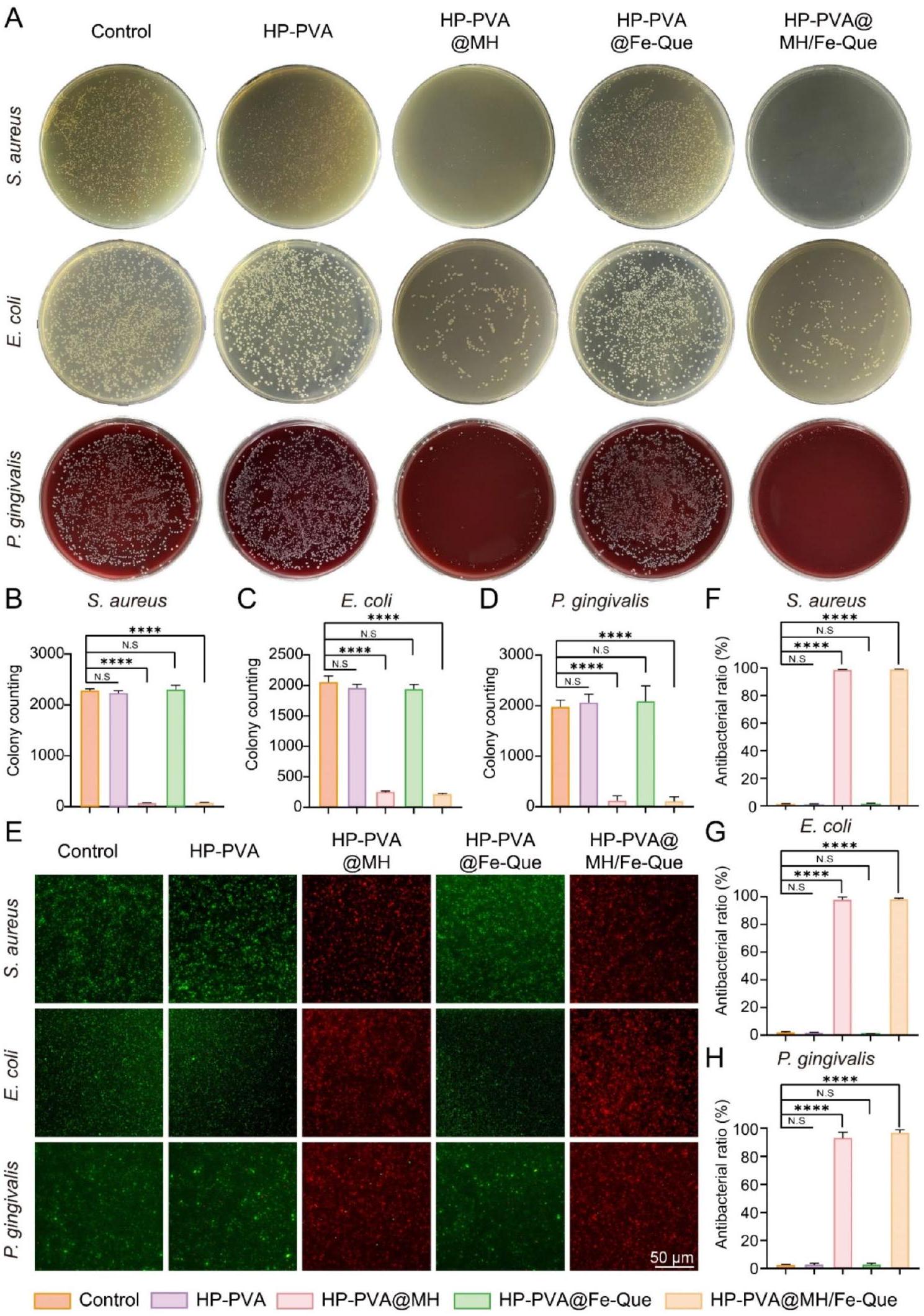

اختبارات النشاط المضاد للبكتيريا في المختبر للهلامات المائية

أشارت النتائج إلى أن الهيدروجيل HP-PVA و HP-PVA@Fe-Que لم يشكلا مناطق تثبيط ملحوظة، بينما أظهرت مجموعات HP-PVA@MH و HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que مناطق تثبيط واضحة ضد جميع البكتيريا المختبرة، بما في ذلك S. mutans (الشكل S7). كانت هذه النتائج متسقة مع نتائج عدّ مستعمرات البكتيريا. لذلك، كان الهيدروجيل المحمّل بمضاد الميكروبات MH يتمتع بقدرة مضادة للميكروبات ممتازة وعمل على المحفزات المسببة لالتهاب اللثة لتحقيق تأثير علاجي كبير.

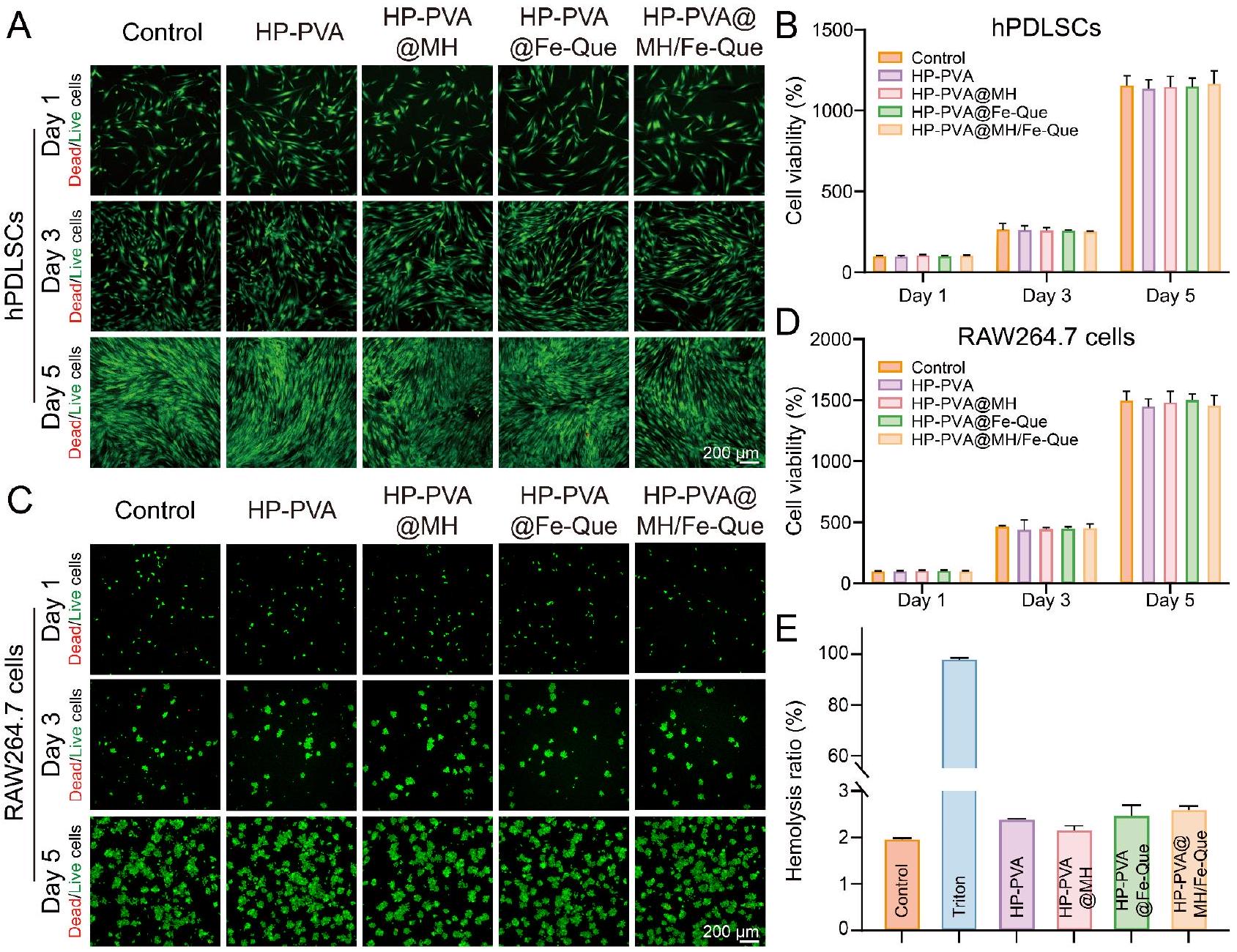

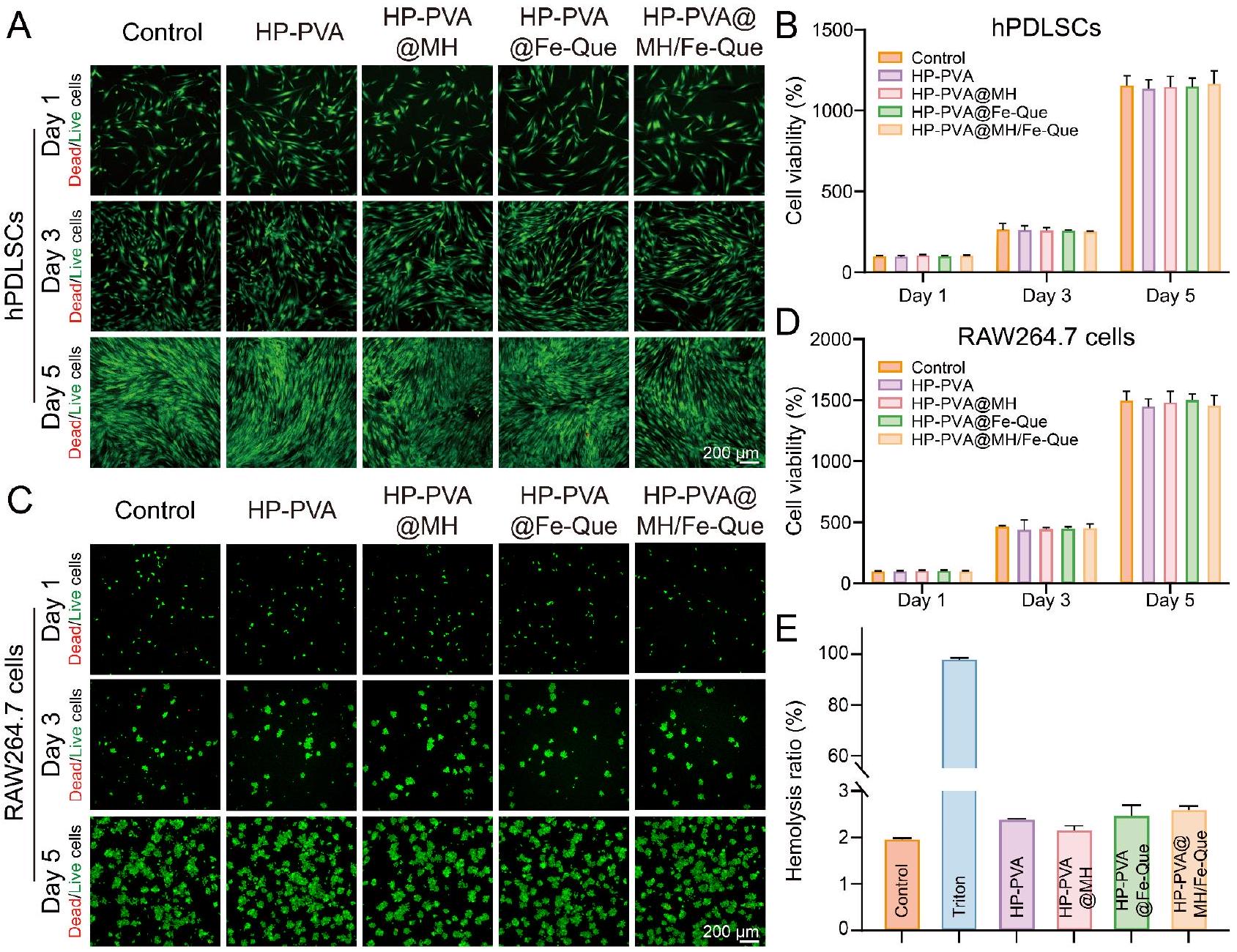

اختبار التوافق الحيوي للهلاميات المائية

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، من أجل إظهار حيوية الخلايا مباشرة في وجود الهلاميات لتحليل التفاعل البيولوجي بدقة، قمنا بزراعة خلايا hPDLSCs على هلام HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que. كما هو موضح في الشكل S9A وS9B، لم يظهر الهلام أي سمية واضحة تجاه hPDLSCs وأظهر توافقاً حيوياً جيداً. علاوة على ذلك، من خلال صبغة DAPI وFITC الفلورية المدمجة مع المجهر الضوئي التداخل الليزري، لوحظ أن الخلايا كانت موزعة بالتساوي على سطح الهلام وأظهرت شكل مغزلي منتشر بشكل جيد، مما يدل على التصاق ممتاز (الشكل S9C). وبالتالي، كان للهلام توافق جيد مع الخلايا.

نزيف اللثة هو عرض سريري مهم لالتهاب اللثة [9]. أثناء علاج التهاب اللثة، يلتصق الهلام لتدمير سطح الأنسجة في جيب اللثة. من منظور التوافق الحيوي، يجب أن يكون له مستوى عالٍ من توافق الدم. مقارنة بمجموعة التحكم، لم يكن هناك ضرر واضح لخلايا الدم الحمراء في مجموعة معالجة الهلام، بينما كانت خلايا الدم الحمراء في مجموعة معالجة Triton X-100 ممزقة (الشكل S10A، B). أظهر الشكل 4E أن معدل انحلال الدم لمجموعة معالجة الهلام كان أقل من

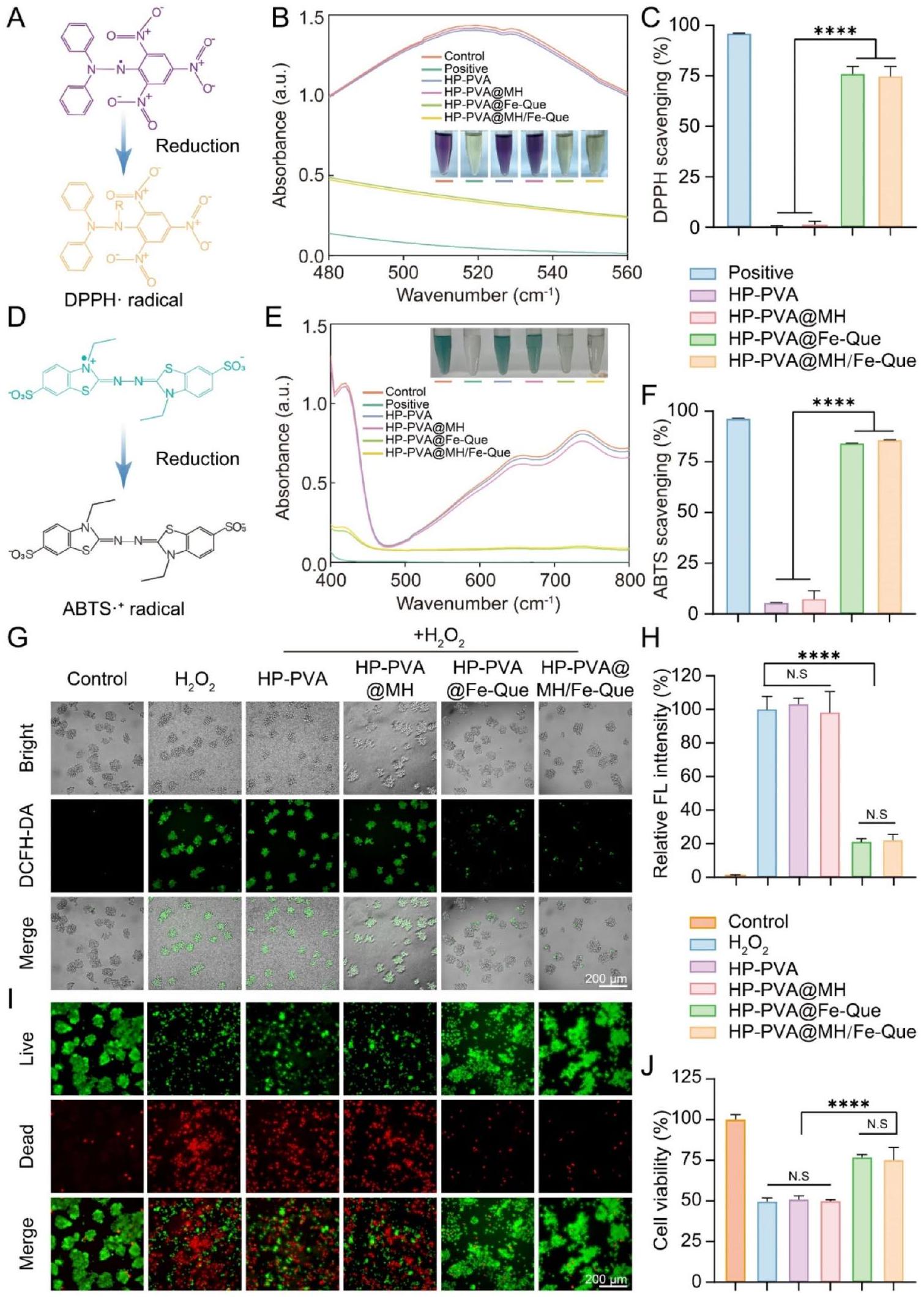

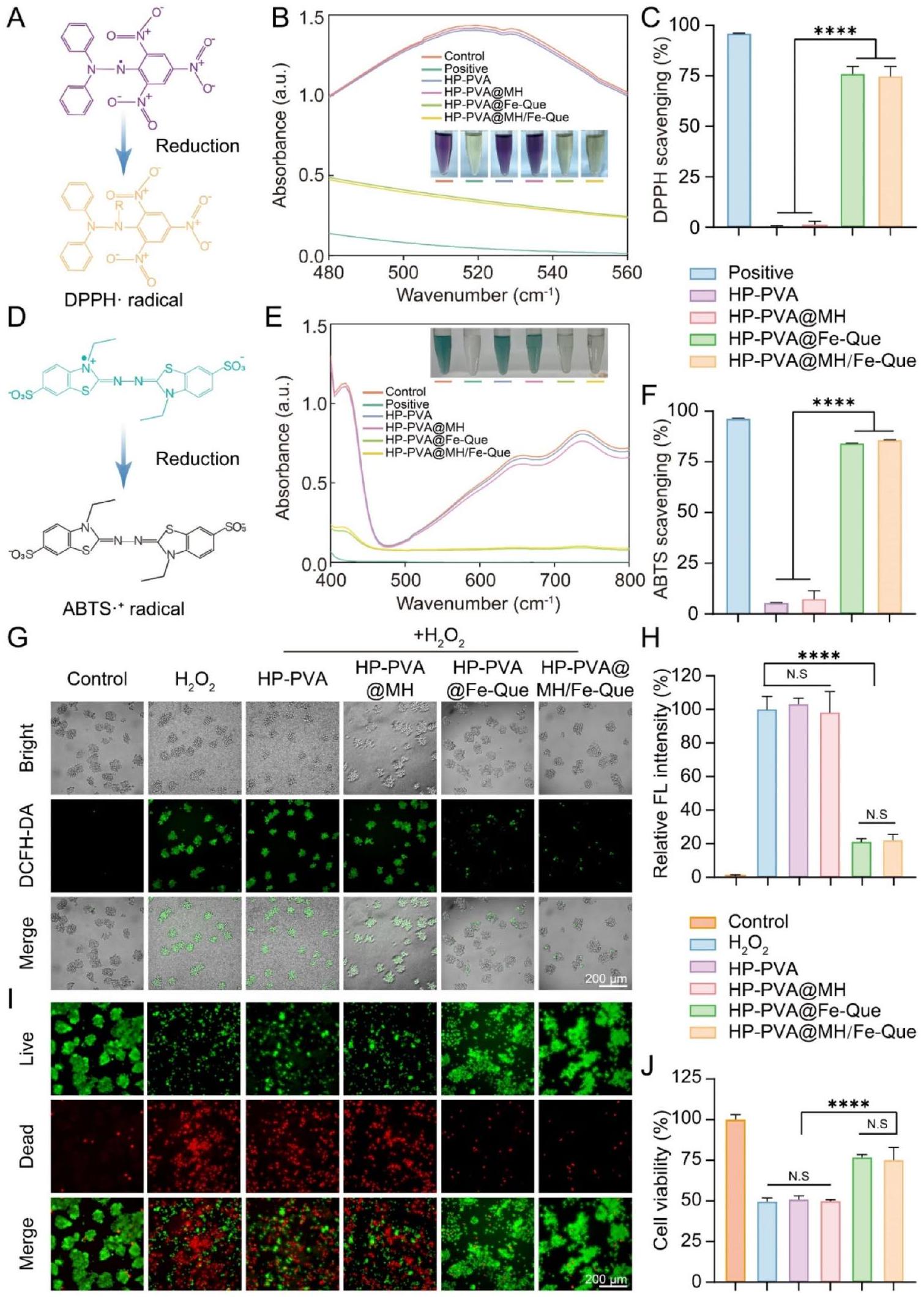

قدرة الهلاميات على التخلص من الجذور الحرة والقدرة المضادة للأكسدة

على التخلص من الجذور الحرة DPPH. على العكس من ذلك، أظهرت كل من مجموعات HP-PVA@Fe-Que وHP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que مستويات امتصاص منخفضة بشكل ملحوظ، مع عرض لون متوسط بين مجموعة التحكم والمجموعة الإيجابية (الشكل 5B). يوضح الشكل 5C نشاط التخلص من الجذور الحرة DPPH لمجموعات الهلام المختلفة. أشارت النتائج إلى أن مجموعات HP-PVA@Fe-Que وHP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que كانت لديها معدلات تخلص متفوقة من DPPH عند

ثانياً، يتعرض ABTS للأكسدة، مما يشكل جذر كاتيوني أخضر مستقر مع ذروة امتصاصه عند 405 نانومتر [57]. عند إدخال العينة إلى محلول جذر ABTS، تتفاعل المركبات المضادة للأكسدة مع جذور ABTS، مما يؤدي إلى تغيير لون نظام التفاعل وانخفاض الامتصاص عند 405 نانومتر (الشكل 5D). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن تغيير امتصاصه ضمن نطاق معين يتناسب مع درجة التخلص من الجذور الحرة. كما أظهر الشكل 5E، كان امتصاص مجموعة التحكم هو الأعلى وظهر باللون الأخضر، بينما عرضت المجموعة الإيجابية أقل امتصاص بلون شفاف. أظهرت مجموعات HP-PVA وHP-PVA@MH قدرة ضئيلة على التخلص من الجذور الحرة ABTS. على العكس من ذلك، عرضت مجموعات HP-PVA@Fe-Que وHP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que لوناً متوسطاً بين مجموعات التحكم والإيجابية، مع عرض مستويات امتصاص منخفضة بشكل ملحوظ. كانت معدلات التخلص من الجذور الحرة ABTS متسقة كما هو موضح أعلاه (الشكل 5F).

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم إثبات قدرة الهلاميات على التخلص من ROS بشكل أكبر من خلال صبغة DCFH-DA داخل الخلايا [58]. في مجموعة التحكم، أظهرت خلايا RAW264.7 أقل كثافة فلورية، بينما كانت كثافة الفلورة لـ

علاوة على ذلك، تم تقييم القدرة الحامية للهلام ضد تلف الخلايا الناتج عن الإجهاد التأكسدي وقدرتها على استعادة حيوية الخلايا باستخدام صبغة الحياة/الموت واختبار CCK-8. كما هو موضح في الشكل 5I، كانت هناك كثافة كبيرة من الفلورة الحمراء

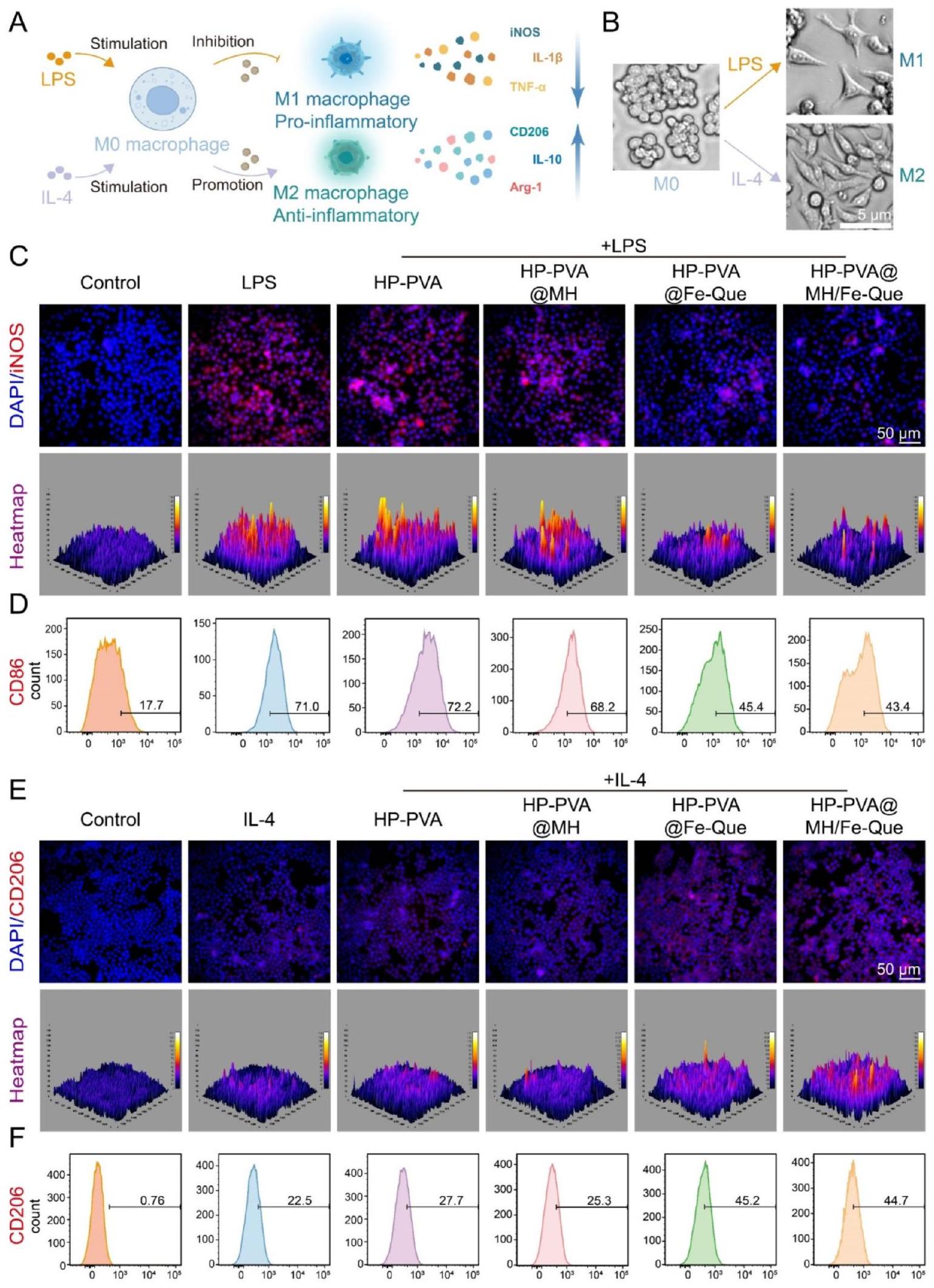

تأثير تنظيم نمط الخلايا البلعمية للهلاميات

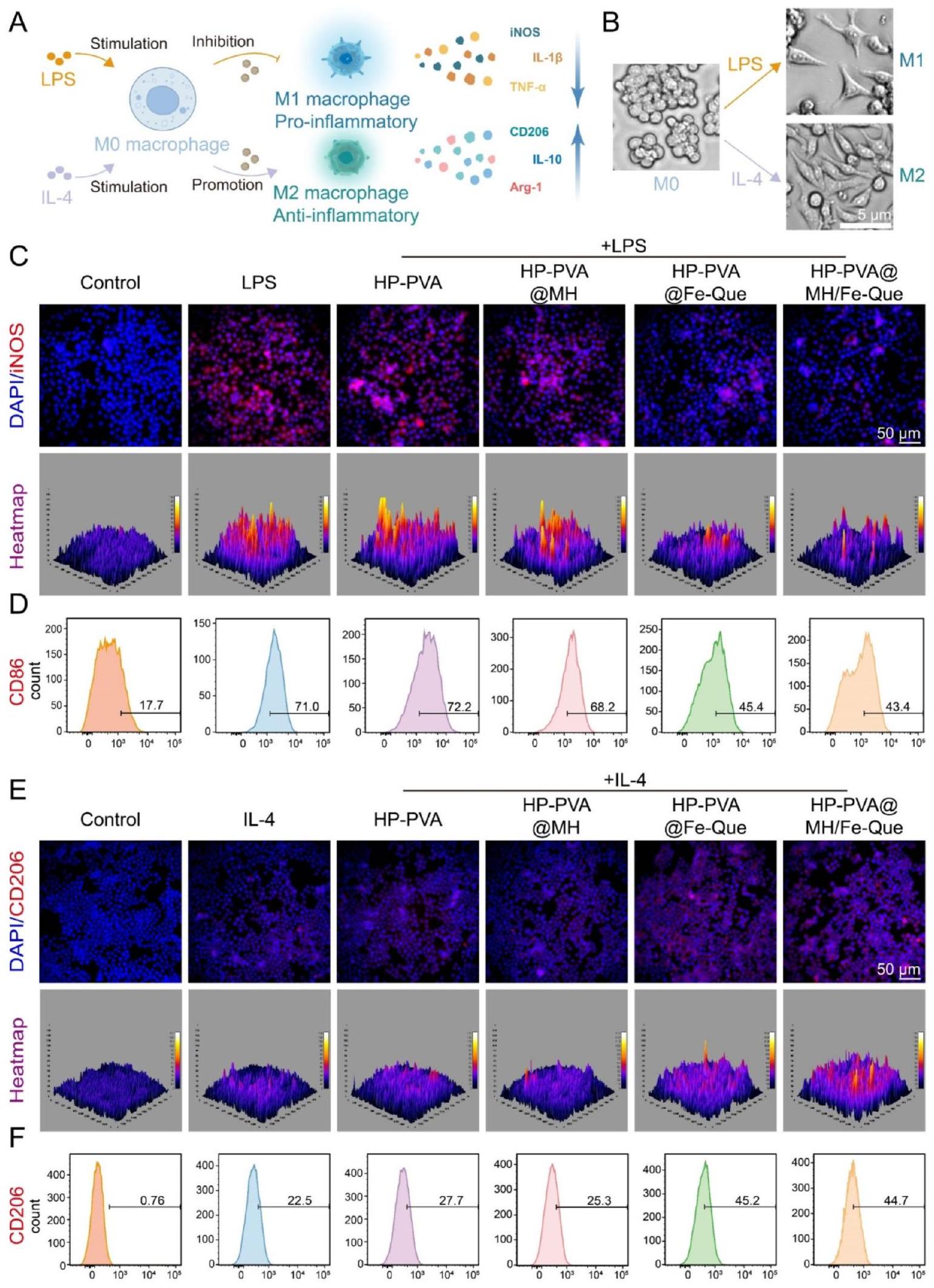

تم إجراء تجارب صبغ IF في البداية على البلعميات لتحديد البلعميات من النوع M1 التي تعبر عن إنزيم أكسيد النيتريك المحفز (iNOS) والبلعميات من النوع M2 التي تعبر عن مستقبل المانوز (CD206). كما هو موضح في الشكل 6C، زادت تعبير iNOS في خلايا RAW264.7 بشكل ملحوظ بعد معالجة LPS. بالمقارنة مع مجموعة LPS، لم يتم ملاحظة فرق كبير في تعبير iNOS في هيدروجيل HP-PVA و HP-PVA@MH. ومع ذلك، لوحظ انخفاض كبير في تعبير iNOS في مجموعات HP-PVA@Fe-Que و HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que. كما هو موضح في الشكل 6E، زاد تعبير CD206 في خلايا RAW264.7 بعد معالجة IL-4. وبالمثل، لم يتم ملاحظة أي تغيير كبير في تعبير CD206 بين هيدروجيل HP-PVA و HP-PVA@MH مقارنة بمجموعة IL-4؛ ومع ذلك، لوحظ زيادة كبيرة في تعبير CD206 داخل مجموعات HP-PVA@Fe-Que و HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que. بعد ذلك، تم إجراء تحليل إضافي باستخدام تقنية قياس التدفق لتقييم استقطاب البلعميات (الشكل 6D، F). أظهرت النتائج أن

آلية مضادات الأكسدة ومضادات الالتهاب في الهيدروجيل في المختبر من خلال تنظيم مسار Nrf2/NF-кB

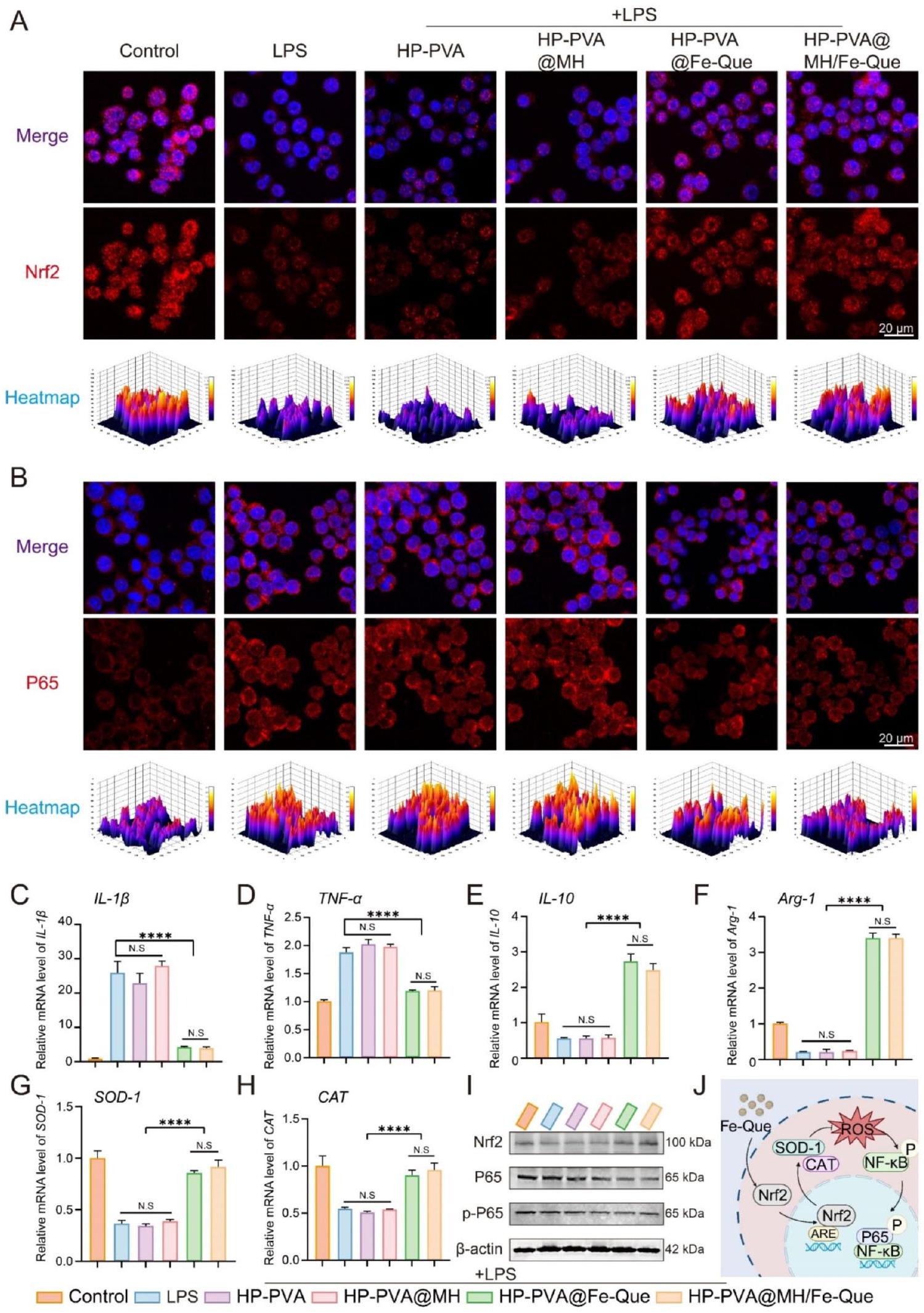

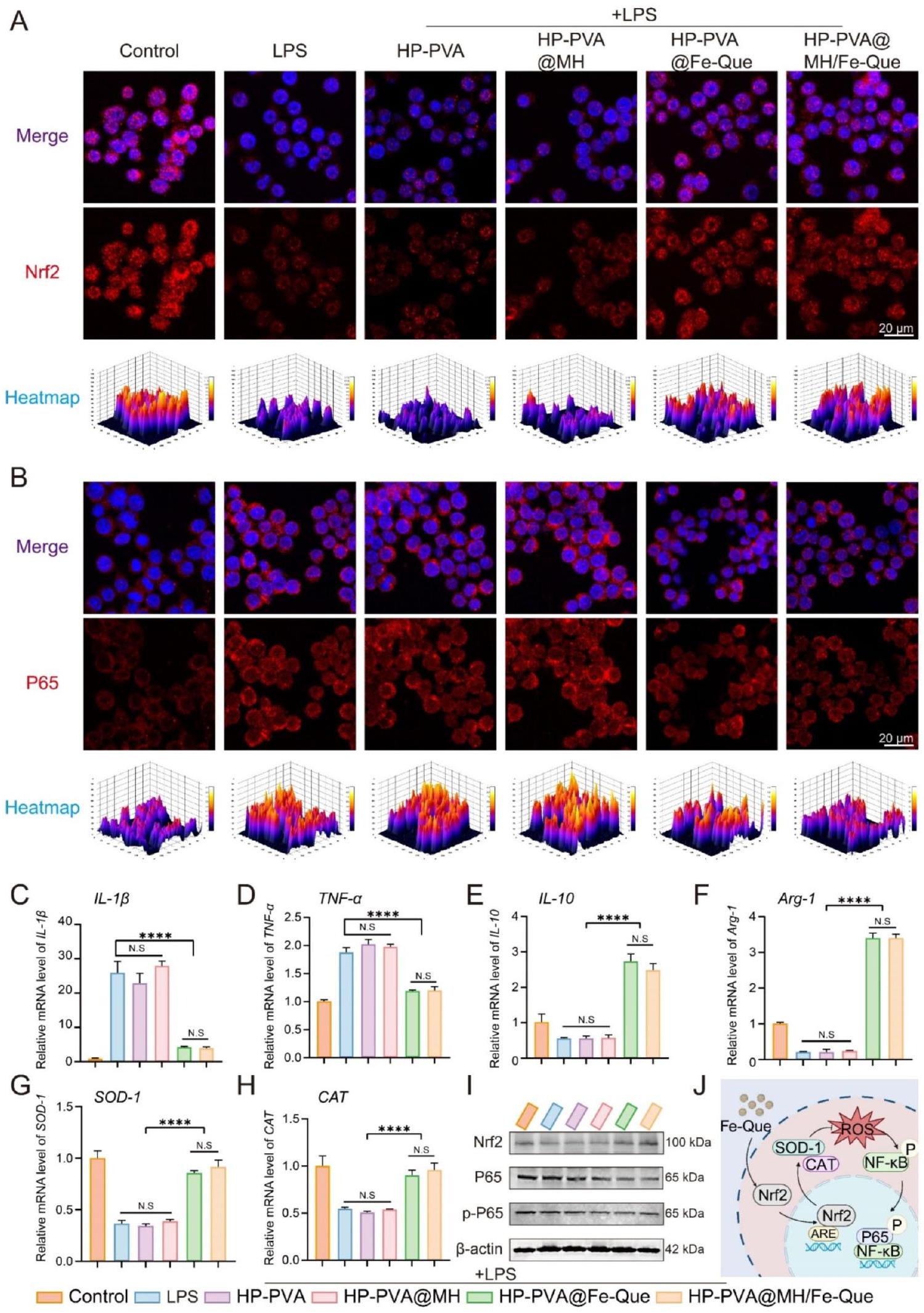

كما هو موضح في الشكل 7A، بعد الالتهاب الناتج عن LPS، أظهرت البلعميات شدة فلورية أقل لنظام Nrf2، كما أظهرت مجموعات HP-PVA و HP-PVA@MH شدة فلورية مشابهة؛ ومع ذلك، كانت إشارة الفلورة لنظام Nrf2 أعلى بشكل ملحوظ في مجموعات HP-PVA@Fe-Que و HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que مقارنة بمجموعة LPS. على العكس من ذلك، بالنسبة لنظام NF-кB، كانت إشارة الفلورة في مجموعات HP-PVA@Fe-Que و HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que أقل من مجموعة LPS (الشكل 7B). وفقًا للنتائج الموضحة في الشكل 7C-H، مقارنة بمجموعة LPS، أظهرت مجموعات HP-PVA@Fe-Que و HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que اتجاهًا هبوطيًا في تعبير السيتوكينات المؤيدة للالتهاب.

علاوة على ذلك، أظهرت نتائج الويسترن بلوت أنه بعد إضافة LPS، انخفض تعبير Nrf2،

تقييم التمايز العظمي في المختبر للهلامات المائية

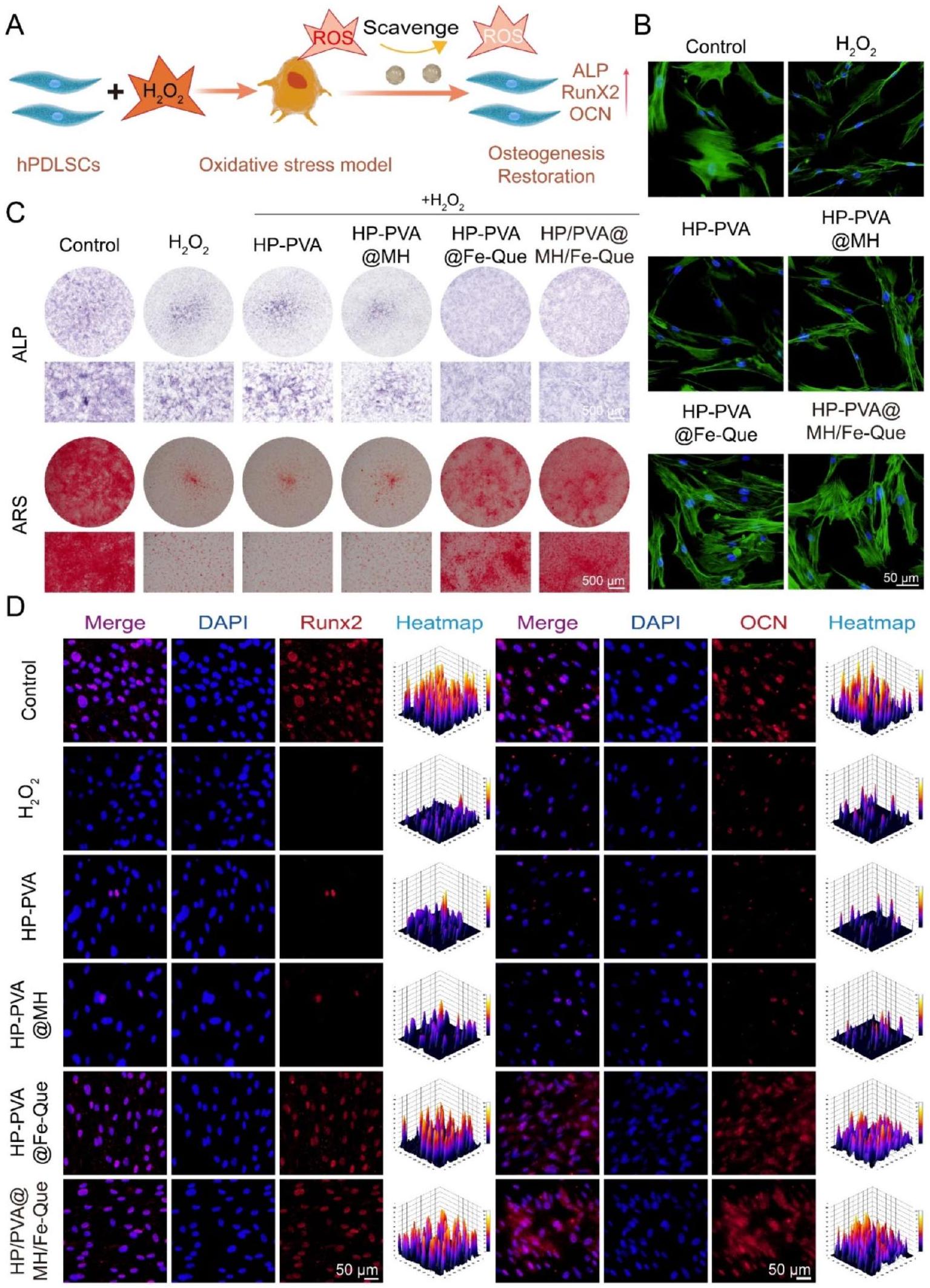

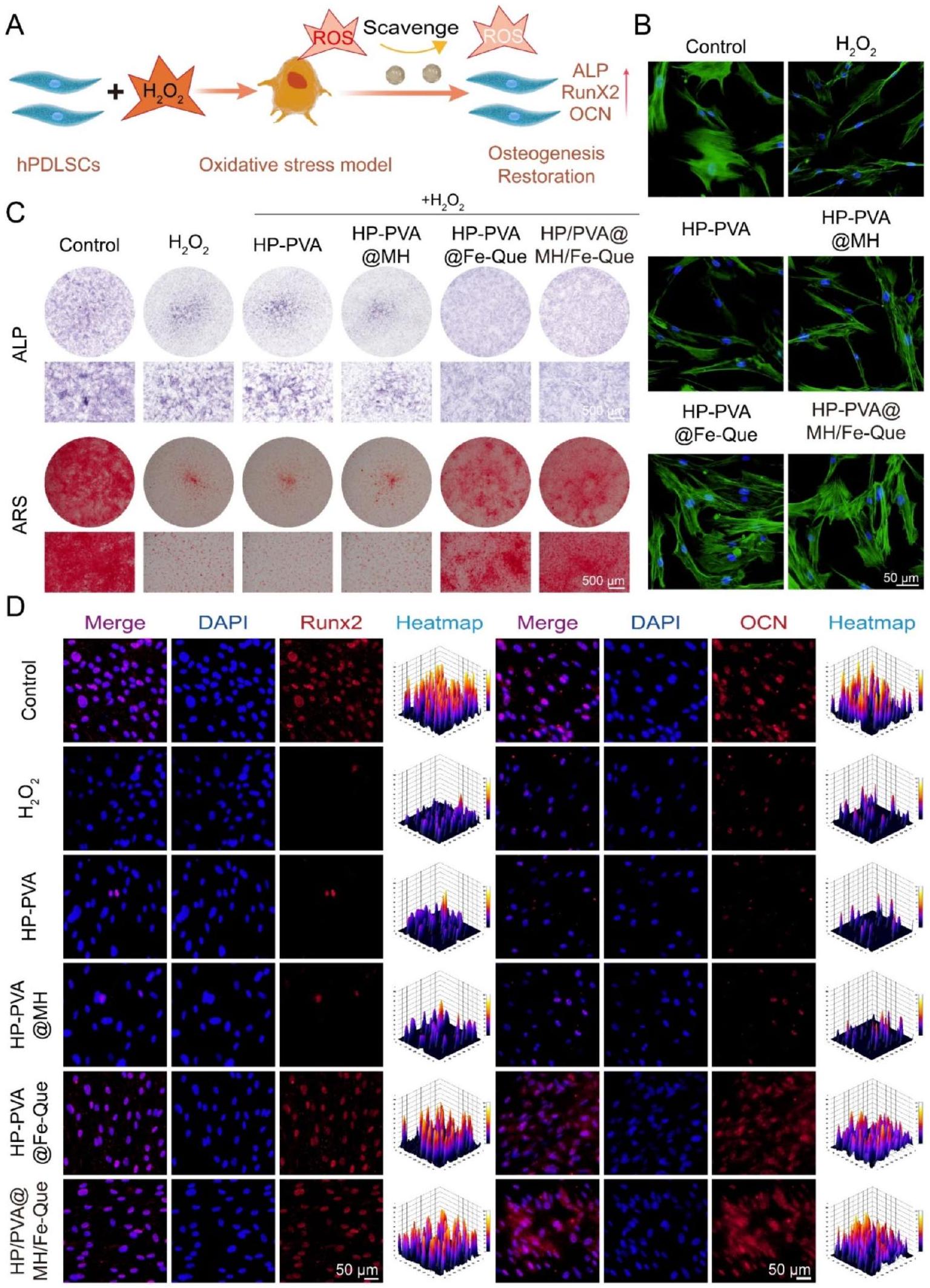

كما هو موضح في الشكل 8A، أظهر هيدروجيل HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que قدرته على حماية خلايا hPDLSCs من التمايز العظمي. تم تقييم الشكل الخلوي لكل مجموعة هيدروجيل تحت

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، للتحقيق بشكل أكبر في قدرة هلام HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que على إنقاذ تمايز hPDLSCs العظمي، تم إجراء تلوين مناعي فلوري لتقييم مستويات التعبير عن Runx2 و OCN. يلعب Runx2 دورًا حاسمًا في تمايز الخلايا العظمية وتشكيل الهيكل العظمي، حيث يظهر تعبيرًا عاليًا مبكرًا وتوطينًا نوويًا [65]. OCN هو بروتين يتم إفرازه من الخلايا العظمية يعكس نشاطها وقدرتها على تشكيل العظام، ويعمل كعلامة في مرحلة متأخرة للتكوين العظمي [66]. مقارنة بمجموعة التحكم، تم تقليل تعبيرات كل من Runx2 و OCN بشكل ملحوظ في

قدرة إزالة ROS للهلاميات في الجسم الحي

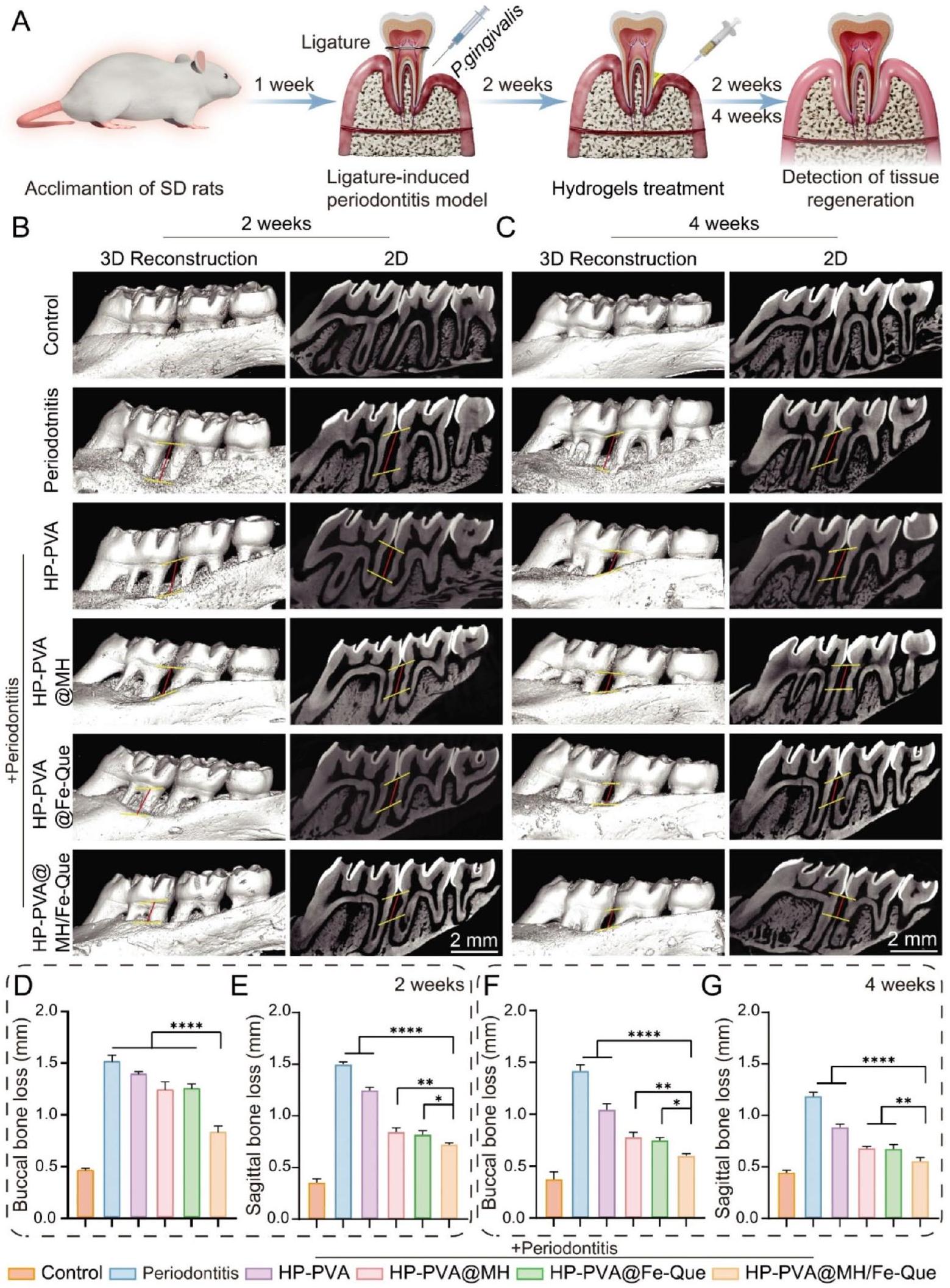

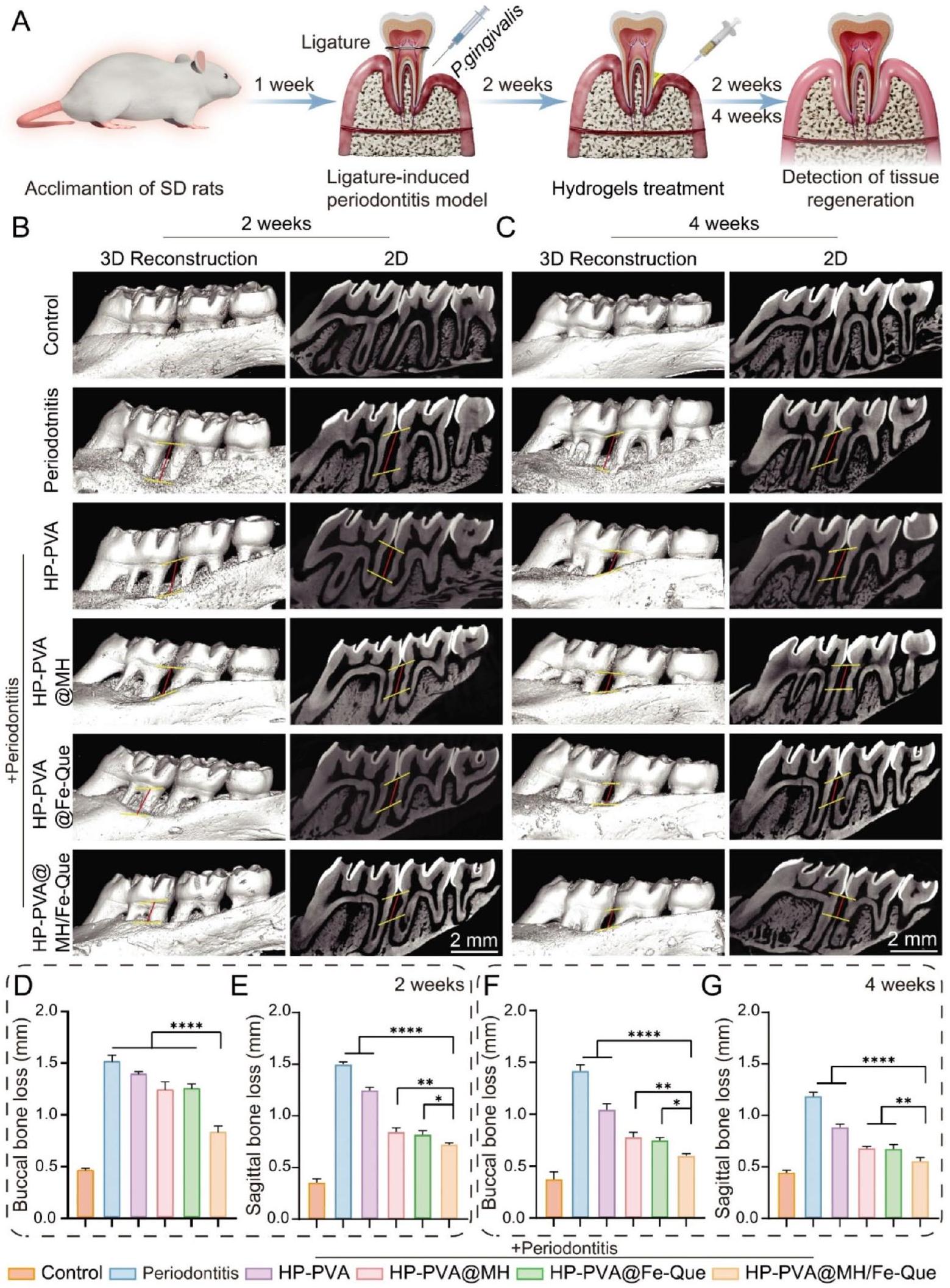

تقييم تجديد العظام للهلاميات في الجسم الحي

إعادة تشكيل وتجديد الأنسجة اللثوية في التهاب دواعم الأسنان في الجسم الحي

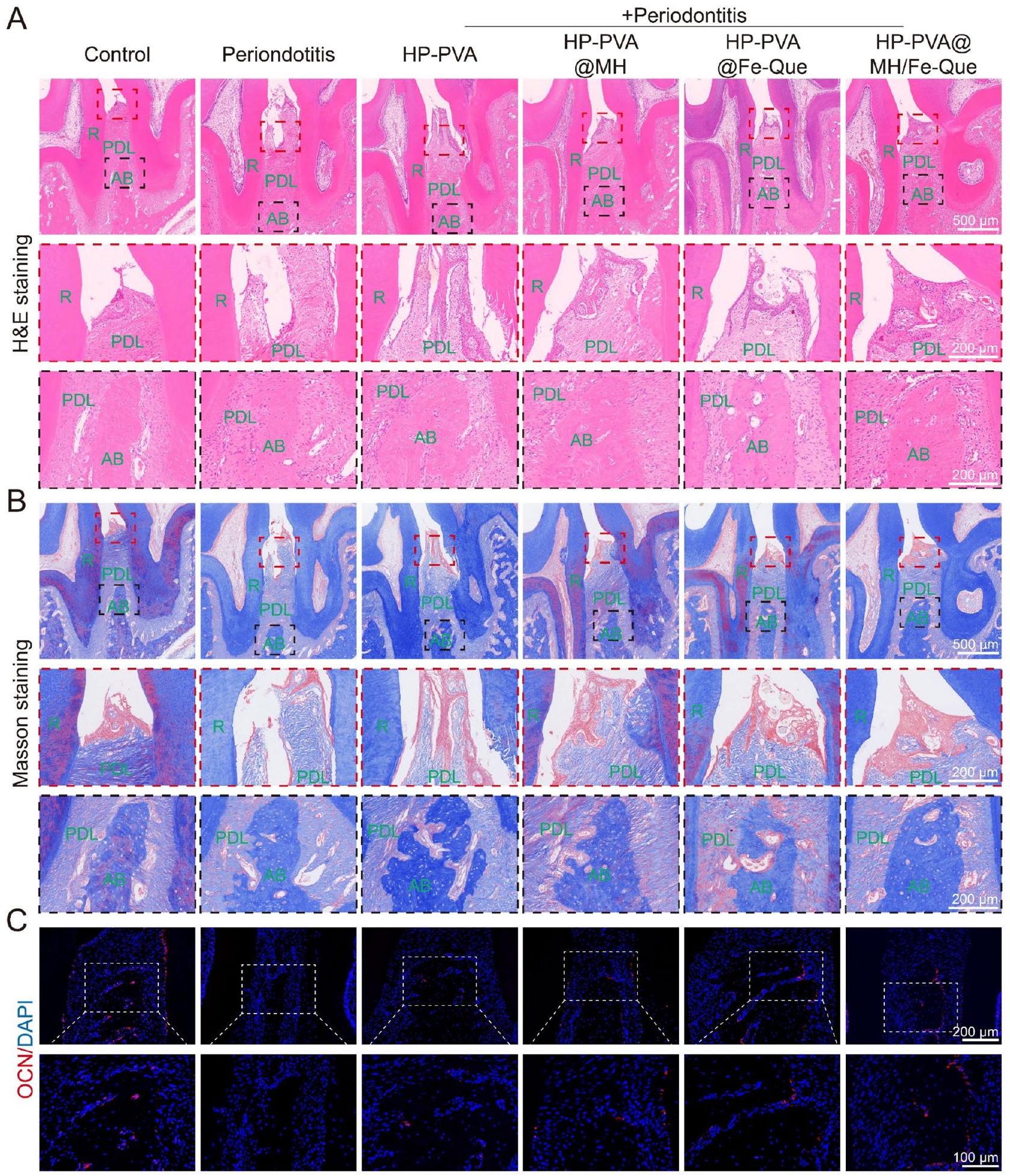

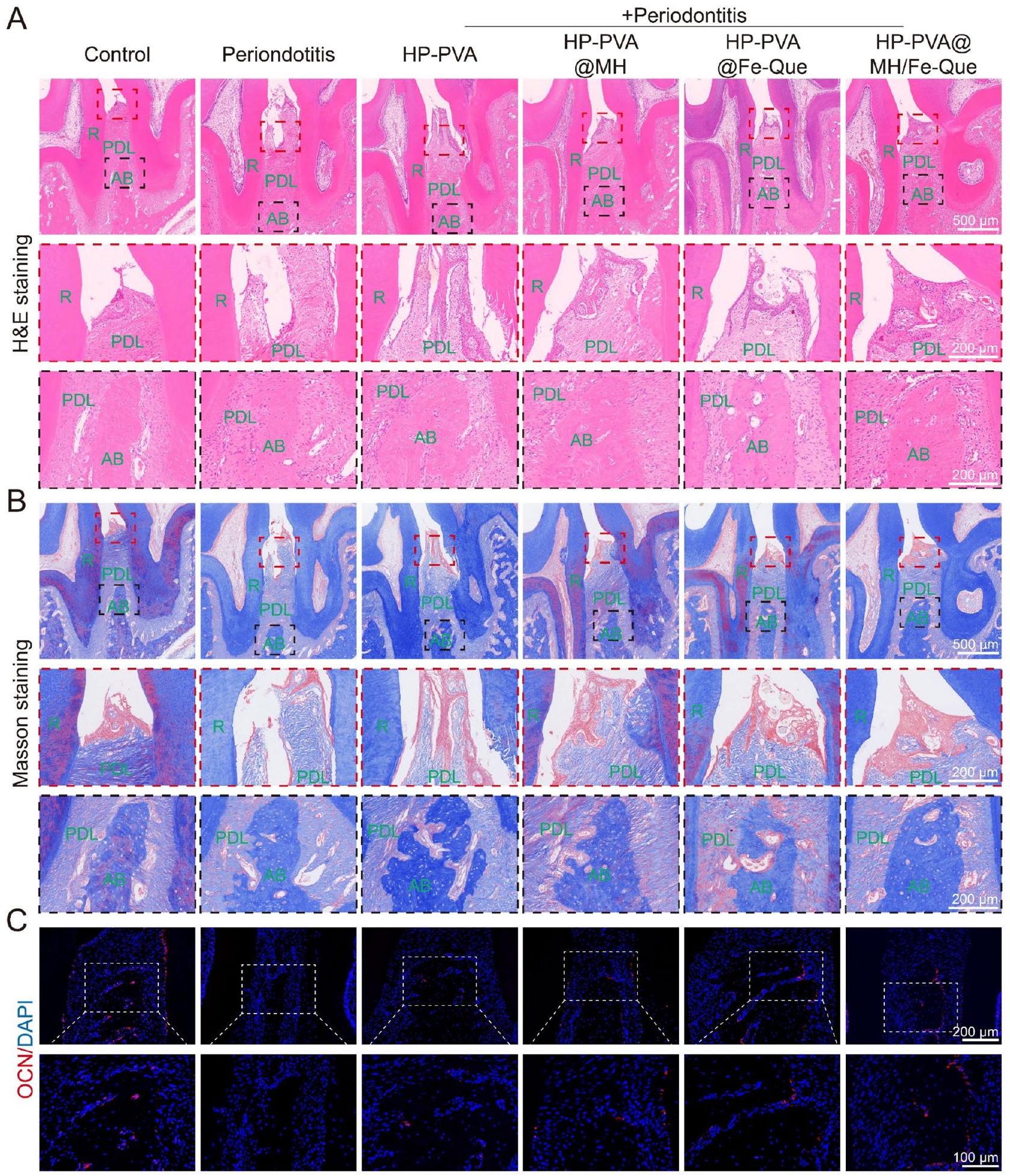

في 4 أسابيع، لاحظنا استعادة محدودة لفقدان العظم في مجموعة التهاب اللثة، مع هيكل نسيج ضام غير منظم (الشكل 10A، B). في مجموعة علاج HP-PVA، كان هناك استعادة طفيفة في النسيج الضام وارتفاع العظم السنخي، دون تأثير كبير على علاج التهاب اللثة. كان تسرب الخلايا الالتهابية أقل بكثير في مجموعة HP-PVA@Fe-Que و

للتحقق من النشاط العظمي لـ HP-PVA@MH/FeQue في مرحلة تجديد الأنسجة بعد الالتهاب، تم استخدام Runx2 (بعد أسبوعين) وOCN (بعد 4 أسابيع) للتحقق من التعبير العظمي المحتمل أثناء تكوين العظم من خلال صبغة IF (الشكل S17C، 10 C). كان التعبير عن Runx2 وOCN منخفضًا في مجموعة التهاب اللثة، مما يشير إلى أن القدرة على تجديد العظم كانت منخفضة خلال التهاب اللثة (الشكل S17F، S18C). مقارنةً بمجموعة التهاب اللثة، كان التعبير عن Runx2 وOCN مرتفعًا بعد العلاج بهلام HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que، مما يظهر أن علاج هلام HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que كان له تأثير تنظيمي إيجابي على استعادة نسيج العظم اللثوي.

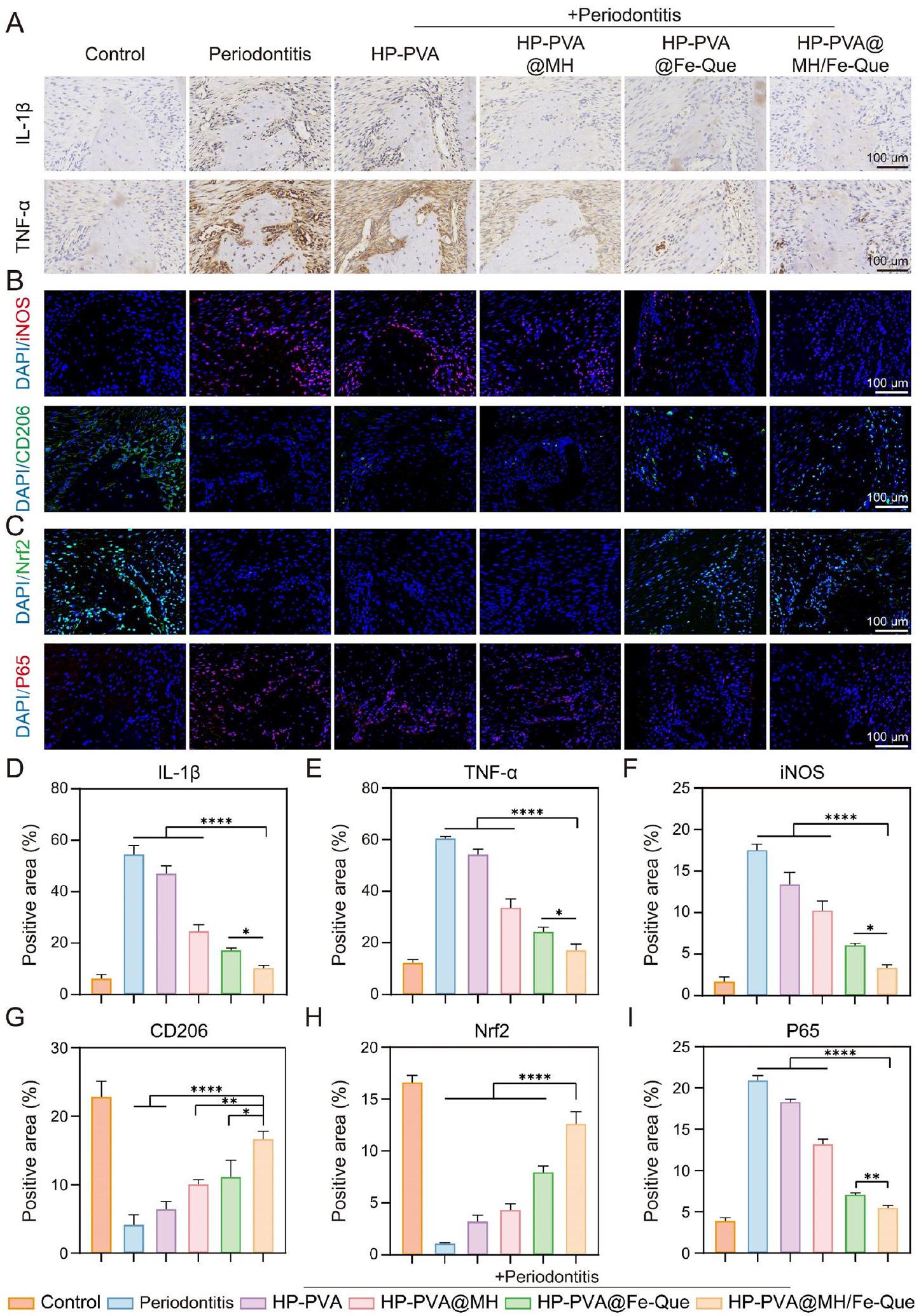

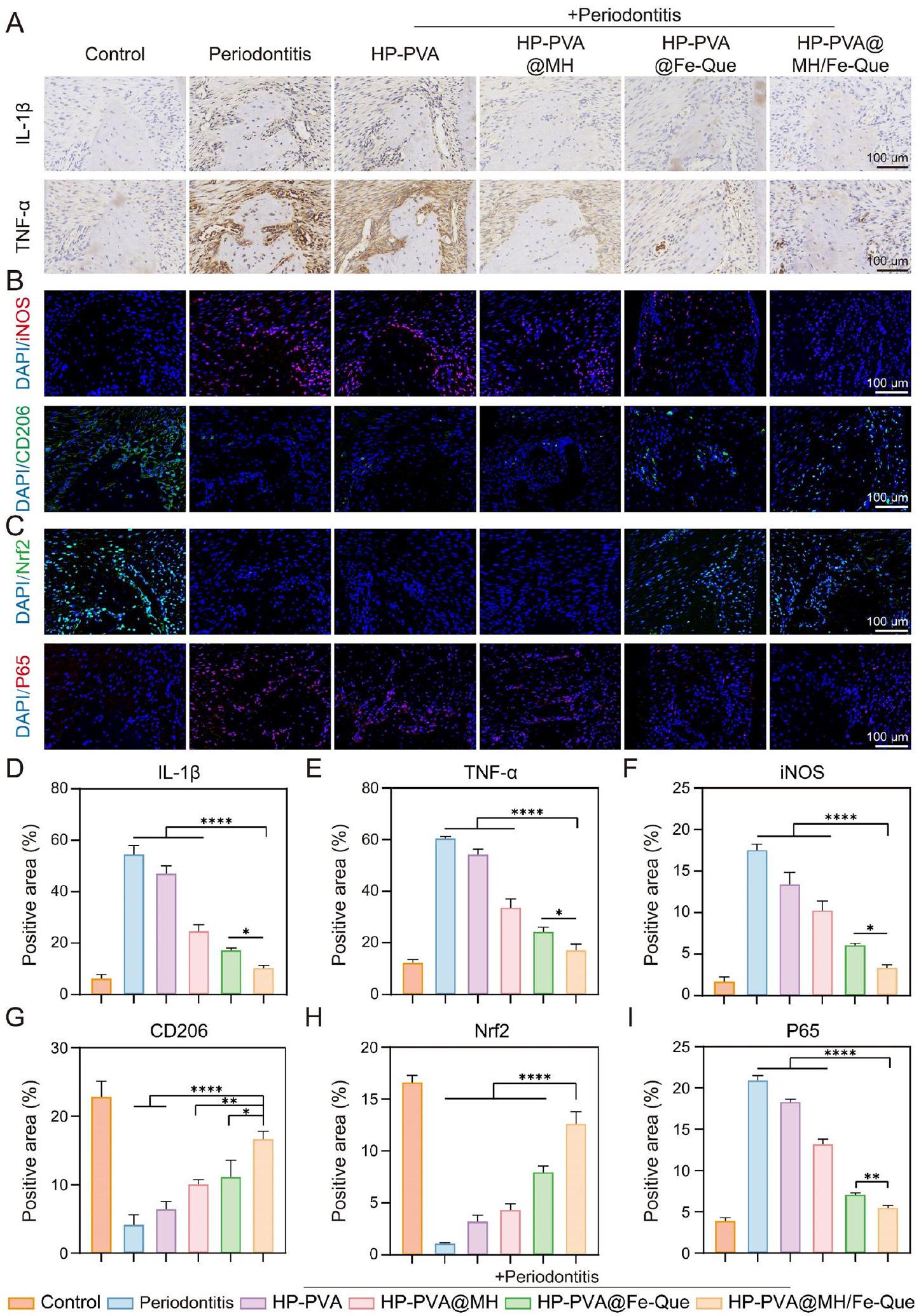

التأثير المضاد للالتهابات للهلاميات في الجسم الحي

في التهاب اللثة، تتكاثر البلعميات M1 بشكل مفرط وتطلق عوامل التهابية مختلفة، مما يزيد من حدة الالتهاب. بعد ذلك، قمنا بتقييم وظيفة تعديل المناعة للهلام. قمنا بإجراء صبغة IF للبلعميات M1 وM2 مع

iNOS وCD206، على التوالي. أظهر الشكل 11B أن شدة الفلورسنت لـ iNOS في مجموعة التهاب اللثة كانت الأعلى، مما يشير إلى زيادة كبيرة في التعبير، بينما كان التعبير عن CD206 أقل. بعد العلاج بهلام HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que، انخفضت شدة الفلورسنت للبلعميات M1 بشكل كبير، بينما زادت شدة الفلورسنت للبلعميات M2 بشكل كبير (الشكل 11F، G)، مما يشير إلى أن مجموعة HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que يمكن أن تثبط استقطاب البلعميات M1 وتعزز استقطاب البلعميات M2، مع وظيفة تعديل مناعي جيدة.

يمكن أن يعزز Nrf2 مقاومة الإجهاد التأكسدي لتقليل الاستجابات الالتهابية من خلال تنشيط جينات معينة مثل NF-кB في التهاب اللثة [40]. بناءً على نتائج نموذج LPS السابقة في المختبر (الشكل 7A، B، I)، استكشفنا المزيد من التعبير عن Nrf2 وNF-кB في الجسم الحي. كما هو موضح في الشكل 11C، كان تعبير Nrf2 منخفضًا في مجموعة التهاب اللثة، بينما كان مستوى بروتين Nrf2 أعلى في مجموعة HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que مقارنةً بمجموعة التهاب اللثة (الشكل 11H). تشير هذه النتيجة إلى أن HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que كان له قدرة أفضل على مكافحة الأكسدة. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، مقارنةً بمجموعة التحكم، كان مستوى بروتين P65 أعلى في مجموعة التهاب اللثة، مما يشير إلى أن مسار إشارات NF-

باختصار، كان لهلام HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que تأثير علاجي كبير على نموذج التهاب اللثة الناتج عن البكتيريا، والذي يمكن أن يزيل ROS ويخفف من الإجهاد التأكسدي في الأنسجة اللثوية. ثانيًا، عزز التعبير عن Nrf2 وكبح التعبير عن P65، منظمًا مسار Nrf2/NF-кB لتحقيق تعديل مناعي، مثبطًا استقطاب البلعميات M1 ومروجًا لاستقطاب البلعميات M2، مما يخفف من الاستجابة الالتهابية في الأنسجة اللثوية. علاوة على ذلك، تم أيضًا زيادة التعبير عن عوامل مضادة للالتهابات وجينات تشكيل العظام. تعمل جميع هذه العوامل معًا على خلق بيئة ميكروبية مناعية ملائمة لحل التهاب اللثة وتجديد الأنسجة اللثوية.

الخلاصة

معلومات إضافية

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تفاصيل المؤلف

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 12 مارس 2025

References

- Armitage GC. Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2004;34:9-21. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0906-6713.20 02.003421.x.

- Williams DW, Greenwell-Wild T, Brenchley L, Dutzan N, Overmiller A, Sawaya AP, Webb S, Martin D, Genomics NN, Computational Biology C, et al. Human oral mucosa cell atlas reveals a stromal-neutrophil axis regulating tissue immunity. Cell. 2021;184:4090-e41044015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021. 05.013.

- Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17038. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.38.

- Tonetti MS, Chapple ILC. Biological approaches to the development of novel periodontal therapies- Consensus of the seventh European workshop on periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:114-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1 600-051X.2010.01675.x.

- Hathaway-Schrader JD, Novince CM. Maintaining homeostatic control of periodontal bone tissue. Periodontol. 2000. 2021;86:157-187. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/prd. 12368

- Feng Z, Weinberg A. Role of bacteria in health and disease of periodontal tissues. Periodontol. 2000. 2006:40:50-76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0757 .2005.00148.x

- Yin Y, Yang S, Ai D, Qin H, Sun Y, Xia X, Xu X, Ji W, Song J. Rational design of bioactive hydrogels toward periodontal delivery: from pathophysiology to therapeutic applications. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33:2301062. https://doi.org/1 0.1002/adfm.202301062.

- Zhao X, Yang Y, Yu J, Ding R, Pei D, Zhang Y, He G, Cheng Y, Li A. Injectable hydrogels with high drug loading through B-N coordination and ROS-triggered drug release for efficient treatment of chronic periodontitis in diabetic rats. Biomaterials. 2022;282:121387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials. 202 2.121387.

- Pan S, Zhong W, Lan Y, Yu S, Yang L, Yang F, Li J, Gao X, Song J. Pathol-ogy-Guided cell Membrane-Coated polydopamine nanoparticles for efficient multisynergistic treatment of periodontitis. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34:202312253. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202312253.

- Yang S, Zhu Y, Ji C, Zhu H, Lao A, Zhao R, Hu Y, Zhou Y, Zhou J, Lin K, Xu Y. A five-in-one novel MOF-modified injectable hydrogel with thermo-sensitive and adhesive properties for promoting alveolar bone repair in periodontitis: antibacterial, hemostasis, immune reprogramming, pro-osteo-/angiogenesis and recruitment. Bioact Mater. 2024;41:239-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioa ctmat.2024.07.016.

- Dong Z, Lin Y, Xu S, Chang L, Zhao X, Mei X, Gao X. NIR-triggered tea polyphenol-modified gold nanoparticles-loaded hydrogel treats periodontitis by inhibiting bacteria and inducing bone regeneration. Mater Design. 2023;225:111487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2022.111487.

- Wang P, Wang L, Zhan Y, Liu Y, Chen Z, Xu J, Guo J, Luo J, Wei J, Tong F, Li Z. Versatile hybrid nanoplatforms for treating periodontitis with chemical/ photothermal therapy and reactive oxygen species scavenging. Chem Eng J. 2023;463:142293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.142293.

- Wang L, Li Y, Ren M, Wang X, Li L, Liu F, Lan Y, Yang S, Song J. pH and lipase-responsive nanocarrier-mediated dual drug delivery system to treat periodontitis in diabetic rats. Bioactive Mater. 2022;18:254-66. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.02.008.

- Lou J, Mooney DJ. Chemical strategies to engineer hydrogels for cell culture. Nat Reviews Chem. 2022;6:726-44. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-022-0042 0-7.

- Ye B, Xiang R, Luo F. Hydrogel-Based drug delivery systems for diabetes bone defects. Chem Eng J. 2024;497:154436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.154 436.

- Huang M, Huang Y, Liu H, Tang Z, Chen Y, Huang Z, Xu S, Du J, Jia B. Hydrogels for the treatment of oral and maxillofacial diseases: current research, challenges, and future directions. Biomater Sci. 2022;10:6413-46. https://doi.org/ 10.1039/d2bm01036d.

- Gan Z, Xiao Z, Zhang Z, Li Y, Liu C, Chen X, Liu Y, Wu D, Liu C, Shuai X, Cao Y. Stiffness-tuned and ROS-sensitive hydrogel incorporating complement C5a receptor antagonist modulates antibacterial activity of macrophages for periodontitis treatment. Bioact Mater. 2023;25:347-59. https://doi.org/10.101 6/j.bioactmat.2023.01.011.

- Wu Y, Wang Y, Long L, Hu C, Kong Q, Wang Y. A Spatiotemporal release platform based on

ROS stimuli-responsive hydrogel in wound repairing. J Control Release. 2022;341:147-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.11.0 27. - Zhang L, Bei Z, Li T, Qian Z. An injectable conductive hydrogel with dual responsive release of Rosmarinic acid improves cardiac function and promotes repair after myocardial infarction. Bioact Mater. 2023;29:132-50. https:/ /doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.07.007.

- Ming P, Liu Y, Yu P, Jiang X, Yuan L, Cai S, Rao P, Cai R, Lan X, Tao G, Xiao J. A biomimetic Se-nHA/PC composite microsphere with synergistic Immunomodulatory and osteogenic ability to activate bone regeneration in periodontitis. Small. 2024;20:e2305490. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 2023054 90.

- Bai X, Peng W, Tang Y, Wang Z, Guo J, Song F, Yang H, Huang C. An NIRpropelled janus nanomotor with enhanced ROS-scavenging, Immunomodulating and biofilm-eradicating capacity for periodontitis treatment. Bioact Mater. 2024;41:271-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2024.07.014.

- Peng S, Fu H, Li R, Li H, Wang S, Li B, Sun J. A new direction in periodontitis treatment: biomaterial-mediated macrophage immunotherapy. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:359. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02592-4.

- Liu X, Wan X, Sui B, Hu Q, Liu Z, Ding T, Zhao J, Chen Y, Wang ZL, Li L. Piezoelectric hydrogel for treatment of periodontitis through bioenergetic activation. Bioact Mater. 2024;35:346-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat. 2024.02.011.

- He Z, Liu Y, Zheng ZL, Lv JC, Liu SB, Zhang J, Liu HH, Xu JZ, Li ZM, Luo E. Periodic Lamellae-Based nanofibers for precise Immunomodulation to treat inflammatory bone loss in periodontitis. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13:e2303549. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202303549.

- Cai G, Ren L, Yu J, Jiang S, Liu G, Wu S, Cheng B, Li W, Xia J. A Microenviron-ment-Responsive, controlled release hydrogel delivering Embelin to promote bone repair of periodontitis via Anti-Infection and Osteo-Immune modulation. Adv Sci. 2024;11:e202403786. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202403786.

- Yang S, Yin Y, Sun Y, Ai D, Xia X, Xu X, Song J. AZGP1 aggravates macrophage M1 polarization and pyroptosis in periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2024;103:631-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345241235616.

- Li J, Wang Y, Tang M, Zhang C, Fei Y, Li M, Li M, Gui S, Guo J. New insights into nanotherapeutics for periodontitis: a triple concerto of antimicrobial activity, Immunomodulation and periodontium regeneration. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02261-y.

- Lei M, Wan H, Song J, Lu Y, Chang R, Wang H, Zhou H, Zhang X, Liu C, Qu X. Programmable Electro-Assembly of collagen: constructing porous Janus films with customized dual signals for Immunomodulation and tissue regeneration in periodontitis treatment. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11:e2305756. https://d oi.org/10.1002/advs.202305756.

- Xie Y, Xiao S, Huang L, Guo J, Bai M, Gao Y, Zhou H, Qiu L, Cheng C, Han X. Cascade and ultrafast artificial antioxidases alleviate inflammation and bone resorption in periodontitis. ACS Nano. 2023;17:15097-112. https://doi.org/10. 1021/acsnano.3c04328.

- Xin X, Liu J, Liu X, Xin Y, Hou Y, Xiang X, Deng Y, Yang B, Yu W. MelatoninDerived carbon Dots with free radical scavenging property for effective periodontitis treatment via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. ACS Nano. 2024;18:8307-24. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c12580.

- Yang GG, Zhou DJ, Pan ZY, Yang J, Zhang DY, Cao Q, Ji LN, Mao ZW. Multifunctional low-temperature photothermal nanodrug with in vivo clearance, ROSScavenging and anti-inflammatory abilities. Biomaterials. 2019;216:119280. ht tps://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119280.

- Yang SY, Hu Y, Zhao R, Zhou YN, Zhuang Y, Zhu Y, Ge XL, Lu TW, Lin KL, Xu YJ. Quercetin-loaded mesoporous nano-delivery system remodels osteoimmune microenvironment to regenerate alveolar bone in periodontitis via the miR-21a-5p/PDCD4/NF-kappaB pathway. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:94. https ://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02352-4.

- Wang Y, Li C, Wan Y, Qi M, Chen Q, Sun Y, Sun X, Fang J, Fu L, Xu L, et al. Quercetin-Loaded ceria nanocomposite potentiate Dual-Directional

immunoregulation via macrophage polarization against periodontal inflammation. Small. 2021;17:e2101505. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202101505. - Zhu H, Cai C, Yu Y, Zhou Y, Yang S, Hu Y, Zhu Y, Zhou J, Zhao J, Ma H, et al. Quercetin-Loaded bioglass injectable hydrogel promotes m6A alteration of Per1 to alleviate oxidative stress for periodontal bone defects. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11:e2403412. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs. 202403412.

- Li Y, Li J, Chang Y, Zhang J, Wang Z, Wang F, Lin Y, Sui L. Mitochondria-targeted drug delivery system based on tetrahedral framework nucleic acids for bone regeneration under oxidative stress. Chem Eng J. 2024;496:153723. https://do i.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.153723.

- Gui S, Tang W, Huang Z, Wang X, Gui S, Gao X, Xiao D, Tao L, Jiang Z, Wang X. Ultrasmall coordination polymer nanodots Fe-Quer nanozymes for preventing and delaying the development and progression of diabetic retinopathy. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33:2300261. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202300261.

- Han Z, Gao X, Wang Y, Cheng S, Zhong X, Xu Y, Zhou X, Zhang Z, Liu Z, Cheng L. Ultrasmall iron-quercetin metal natural product nanocomplex with antioxidant and macrophage regulation in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13:1726-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.11.020.

- Xu Y, Luo Y, Weng Z, Xu H, Zhang W, Li Q, Liu H, Liu L, Wang Y, Liu X, et al. Microenvironment-Responsive Metal-Phenolic nanozyme release platform with antibacterial, ROS scavenging, and osteogenesis for periodontitis. ACS Nano. 2023;17:18732-46. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c01940.

- Zhu S, Zhao B, Li M, Wang H, Zhu J, Li Q, Gao H, Feng Q, Cao X. Microenvironment responsive nanocomposite hydrogel with NIR photothermal therapy, vascularization and anti-inflammation for diabetic infected wound healing. Bioact Mater. 2023;26:306-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.03.00 5.

- Tian Y, Li Y, Liu J, Lin Y, Jiao J, Chen B, Wang W, Wu S, Li C. Photothermal therapy with regulated Nrf2/NF-kappaB signaling pathway for treating bacteria-induced periodontitis. Bioact Mater. 2022;9:428-45. https://doi.org/1 0.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.07.033.

- Boda SK, Fischer NG, Ye Z, Aparicio C. Dual oral tissue adhesive nanofiber membranes for pH -Responsive delivery of antimicrobial peptides. Biomacromolecules. 2020;21:4945-61. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.0c01163.

- Qiao B, Wang J, Qiao L, Maleki A, Liang Y, Guo B. ROS-responsive hydrogels with Spatiotemporally sequential delivery of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory drugs for the repair of MRSA-infected wounds. Regenerative Biomaterials. 2023;11:rbad110. https://doi.org/10.1093/rb/rbad110.

- Luo Q, Yang Y, Ho C, Li Z, Chiu W, Li A, Dai Y, Li W, Zhang X. Dynamic hydrogel-metal-organic framework system promotes bone regeneration in periodontitis through controlled drug delivery. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:287. https://d oi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02555-9.

- Wu Y, Wang Y, Long L, Hu C, Kong Q, Wang Y. A Spatiotemporal release platform based on pH/ROS stimuli-responsive hydrogel in wound repairing. J Controlled Release. 2022;341:147-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.1 1.027.

- Qiao B, Wang J, Qiao L, Maleki A, Liang Y, Guo B. ROS-responsive hydrogels with Spatiotemporally sequential delivery of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory drugs for the repair of MRSA-infected wounds. Regenerative Biomaterials. 2024;11. https://doi.org/10.1093/rb/rbad110.

- Dong Z, Sun Y, Chen Y, Liu Y, Tang C, Qu X. Injectable adhesive hydrogel through a microcapsule Cross-Link for periodontitis treatment. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2019;2:5985-94. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsabm.9b00912.

- Guo H, Huang S, Yang X, Wu J, Kirk TB, Xu J, Xu A, Xue W. Injectable and Self-Healing hydrogels with Double-Dynamic bond tunable mechanical, Gel-Sol transition and drug delivery properties for promoting periodontium regeneration in periodontitis. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13:61638-52. h ttps://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c18701.

- Zhang C, Yan R, Bai M, Sun Y, Han X, Cheng C, Ye L. Pt-Clusters-Equipped Antioxidase-Like biocatalysts as efficient ROS scavengers for treating periodontitis. Small. 2024;20:e2306966. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202306966.

- Wang Y, Yuan Y, Wang R, Wang T, Guo F, Bian Y, Wang T, Ma Q, Yuan H, Du Y, et al. Injectable thermosensitive gel CH-BPNs-NBP for effective periodontitis treatment through ROS-Scavenging and jaw vascular unit protection. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13:e2400533. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202400533.

- Liu Y, Yan J, Chen L, Liao Y, Huang L, Tan J. Multifunctionalized and DualCrosslinked hydrogel promotes inflammation resolution and bone regeneration via NLRP3 Inhibition in periodontitis. Small Struct. 2024;5. https://doi.org /10.1002/sstr.202300281.

- Gong J, Wang S, Liu J, Zhang Y, Li J, Yang H, Liang K, Deng Y. In situ oxygengenerating bio-heterojunctions for enhanced anti-bacterial treatment of

anaerobe-induced periodontitis. Chem Eng J. 2024;498. https://doi.org/10.10 16/j.cej.2024.155083. - Xia P, Yu M, Yu M, Chen D, Yin J. Bacteria-responsive, Cell-recruitable, and osteoinductive nanocomposite microcarriers for intelligent bacteriostasis and accelerated tissue regeneration. Chem Eng J. 2023;465:142972. https://d oi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.142972.

- Thananukul K, Kaewsaneha C, Opaprakasit P, Lebaz N, Errachid A, Elaissari A. Smart gating porous particles as new carriers for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;174:425-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2021.04.023.

- Zhu B, Wu J, Li T, Liu S, Guo J, Yu Y, Qiu X, Zhao Y, Peng H, Zhang J, et al. A glutathione Peroxidase-Mimicking nanozyme precisely alleviates reactive oxygen species and promotes periodontal bone regeneration. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13:e2302485. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm. 202302485.

- Guo J, Xing Z, Liu L, Sun Y, Zhou H, Bai M, Liu X, Adeli M, Cheng C, Han X. Antioxidase-Like nanobiocatalysts with ultrafast and reversible RedoxCenters to secure stem cells and periodontal tissues. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33:202211778. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202211778.

- Xu Z, Zhu Y, Xie M, Liu K, Cai L, Wang H, Li D, Chen H, Gao L. Mackinawite nanozymes as reactive oxygen species scavengers for acute kidney injury alleviation. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21:281. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-02 3-02034-7.

- Zhang Y, Zhang H, Zhao F, Jiang Z, Cui Y, Ou M, Mei L, Wang Q. Mitochondrialtargeted and ROS-responsive nanocarrier via nose-to-brain pathway for ischemic stroke treatment. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13:5107-20. https://doi.or g/10.1016/j.apsb.2023.06.011.

- Hu S, Wang L, Li J, Li D, Zeng H, Chen T, Li L, Xiang X. Catechol-Modified and

-Nanozyme-Reinforced hydrogel with improved antioxidant and antibacterial capacity for periodontitis treatment. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2023;9:5332-46. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.3c00454. - Tian M, Chen G, Xu J, Lin Y, Yi Z, Chen X, Li X, Chen S. Epigallocatechin gallatebased nanoparticles with reactive oxygen species scavenging property for effective chronic periodontitis treatment. Chem Eng J. 2022;433:132197. http s://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.132197.

- Liu X, Hou Y, Yang M, Xin X, Deng Y, Fu R, Xiang X, Cao N, Liu X, Yu W, et al. N-Acetyl-I-cysteine-Derived carbonized polymer Dots with ROS scavenging

via Keap1-Nrf2 pathway regulate alveolar bone homeostasis in periodontitis. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12:e2300890. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm. 202300 890. - Yang G, Fan M, Zhu J, Ling C, Wu L, Zhang X, Zhang M, Li J, Yao Q, Gu Z, Cai

. A multifunctional anti-inflammatory drug that can specifically target activated macrophages, massively deplete intracellular , and produce large amounts CO for a highly efficient treatment of osteoarthritis. Biomaterials. 2020;255:120155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120155. - Liu S, Wang W, Wu P, Chen Z, Pu W, Li L, Li G, Zhang J, Song J. PathogenesisGuided engineering of Multi-Bioactive hydrogel Co-Delivering InflammationResolving nanotherapy and Pro-Osteogenic protein for bone regeneration. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33:2301523. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202301523.

- Sun H, Xu J, Wang Y, Shen S, Xu X, Zhang L, Jiang Q. Bone microenvironment regulative hydrogels with ROS scavenging and prolonged oxygen-generating for enhancing bone repair. Bioact Mater. 2023;24:477-96. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.12.021.

- Wang H, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Li C, Zhang M, Wang J, Zhang Y, Du Y, Cui W, Chen W. Activating macrophage continual efferocytosis via microenvironment biomimetic short fibers for reversing inflammation in bone repair. Adv Mater. 2024;36:e2402968. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202402968.

- Bai L, Feng M, Li Q, Zhao Y, Zhang G, Cai Z, Xiao J, Lin Y. Curcumin delivery using tetrahedral framework nucleic acids enhances bone regeneration in osteoporotic rats. Chem Eng J. 2023;472:144978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej. 2023.144978.

- Dos Santos DM, Moon JI, Kim DS, Bassous NJ, Marangon CA, CampanaFilho SP, Correa DS, Kang MH, Kim WJ, Shin SR. Hierarchical Chitin Nano-crystal-Based 3D printed dual-Layer membranes hydrogels: A dual drug delivery Nano-Platform for periodontal tissue regeneration. ACS Nano. 2024;18:24182-203. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.4c05558.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

روي كاي

cairui@swmu.edu.cn

تشونهوي لي

Ich10221022@163.com

غانغ تاو

taogang@swmu.edu.cn

القائمة الكاملة لمعلومات المؤلف متاحة في نهاية المقال

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-025-03275-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40075491

Publication Date: 2025-03-12

Injectable hydrogels with ROS-triggered drug release enable the co-delivery of antibacterial agent and anti-inflammatory nanoparticle for periodontitis treatment

Abstract

Periodontitis, a chronic inflammatory disease caused by bacteria, is characterized by localized reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, leading to an inflammatory response, which in turn leads to the destruction of periodontal supporting tissues. Therefore, antibacterial, scavenging ROS, reducing the inflammatory response, regulating periodontal microenvironment, and alleviating alveolar bone resorption are effective methods to treat periodontitis. In this study, we developed a ROS-responsive injectable hydrogel by modifying hyaluronic acid with 3-amino phenylboronic acid (PBA) and reacting it with poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) to form a borate bond. In addition, the ROS-responsive hydrogel encapsulated the antibacterial agent minocycline hydrochloride (MH) and Fe-Quercetin anti-inflammatory nanoparticles (Fe-Que NPs) for on-demand drug release in response to the periodontitis microenvironment. This hydrogel (HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que) exhibited highly effective antibacterial properties. Moreover, by modulating the Nrf2/NF-kB pathway, it effectively eliminated ROS and promoted macrophage polarization to the M 2 phenotype, reducing inflammation and enhancing the osteogenic differentiation potential of human periodontal ligament stem cells (hPDLSCs) in the periodontal microenvironment. Animal studies showed that HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que significantly reduced alveolar bone loss and enhanced osteogenic factor expression by killing bacteria and inhibiting inflammation. Thus, HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel had efficient antibacterial, ROS-scavenging, anti-inflammatory, and alveolar bone resorption-alleviation abilities, showing excellent application potential for periodontitis healing.

Introduction

Periodontal pathogens can produce a variety of enzymes, toxins, and toxic metabolites, which

subsequently damage tissues and trigger inflammatory reactions, leading to periodontal tissue destruction, such as bone loss and attachment loss [6,7]. Therefore, rapid elimination of periodontal pathogenic bacteria is a prerequisite for treating periodontitis. Various drugs are available to remove periodontal pathogenic bacteria, such as antibiotics, antimicrobial peptides, and metal-based nanoparticles [8-11]. In clinical practice, minocycline hydrochloride (MH) is a commonly used topical agent for periodontal pockets. MH not only has high antibacterial activity against periodontal pathogens but also has colla-genase-inhibiting properties. Many studies have shown that low doses of MH can significantly reduce inflammation at the periodontal site, thereby improving the success of periodontitis treatment [12, 13]. Therefore, MH is an ideal drug for the antibiotic treatment of periodontitis. However, the use of MH alone has many limitations, such as rapid drug loss, which cannot achieve a slow release and rapid antibacterial effect. Therefore, loading the MH into a carrier such as nanoparticles, microspheres, or hydrogels is necessary.

The balance between bacteria and host is disrupted at the site of periodontitis lesions. Excess ROS are produced, which activates multiple pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, leading to an increase in the ratio of M1 to M2 macrophages and the production of a large number of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleu-kin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-

In this study, as shown in Scheme 1, the ultra-small Fe-Que NPs were first formed by the coordination of quercetin with low-toxicity iron ions. In addition, hyaluronic acid (HA) was grafted with 3-aminophenyl borate (HA-PBA, HP), which was further reacted with the 1,3diol group of poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) to form a borate bond, resulting in the construction of hydrogels with ROS-responsive properties. MH and Fe-Que were introduced to prepare the HP-PVA hydrogel system (HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que). In the high ROS environment of periodontitis, the borate bond was broken, accelerating the release of MH and Fe-Que. The small molecule MH rapidly kills bacteria, and then the Fe-Que NPs scavenge ROS, reduce the inflammatory response of periodontal tissue, and alleviate alveolar bone resorption. The physical properties, drug release characteristics, antibacterial activity, and biocompatibility of the HP-PVA@MH/ Fe-Que compound were evaluated in detail. This study demonstrated that the HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel initially rapidly inhibited bacterial growth through MH. Subsequently, Fe-Que scavenged ROS via the Nrf2/ NF-кB pathway, regulated macrophage polarization to reduce pro-inflammatory factors and up-regulate antiinflammatory factors, while also protecting hPDLSCs from ROS-induced damage and promoting osteogenic differentiation under oxidative stress. The ability of HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel to scavenge ROS and alleviate inflammation and alveolar bone resorption was also confirmed in a chronic periodontitis SD model. Therefore, with remarkable in vitro and in vivo therapeutic efficacy, HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel may have great potential for treating periodontitis.

Materials and methods

Materials

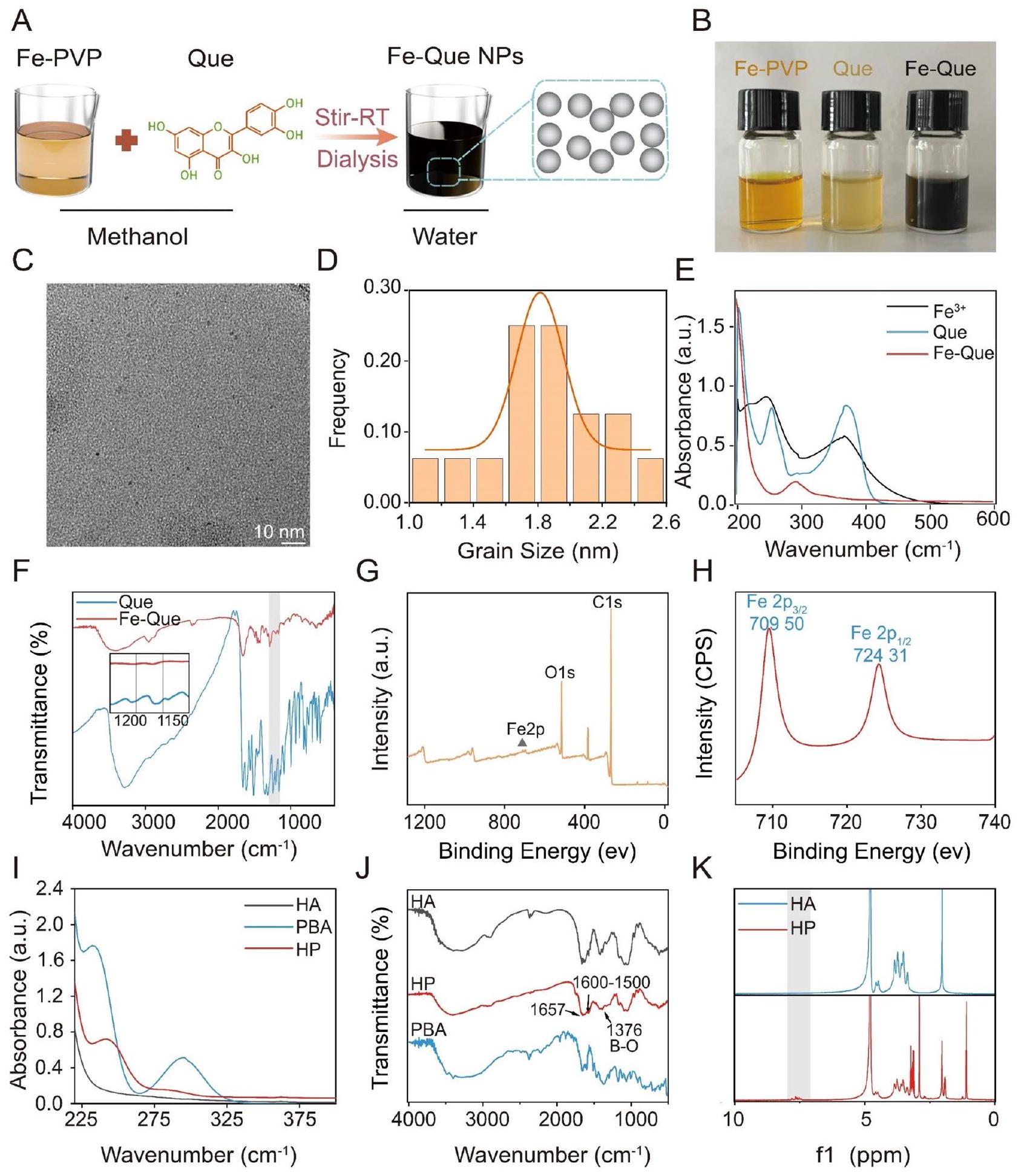

Synthesis and characterization of Fe-Que NPs

The morphology and size of Fe-Que NPs were examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2100, Tokyo, Japan). Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements of particle size distributions (Malvern, Nano ZS, UK). The UV-visible spectrophotometer (TU-1810, Shanghai, China) was used to determine the UV-visible near-infrared (UV-vis-NIR) spectra of

Synthesis and characterization of HA modified by PBA (HAPBA, named HP)

The UV-vis-NIR spectrum of HA, PBA, and HP was measured using the UV-visible spectrophotometer (TU1810, Shanghai, China). The FTIR spectra of HA, PBA, and HP were measured using the FTIR spectrometer (WQF-530, Beijing, China). The chemical structures of HA and HP were analyzed by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (

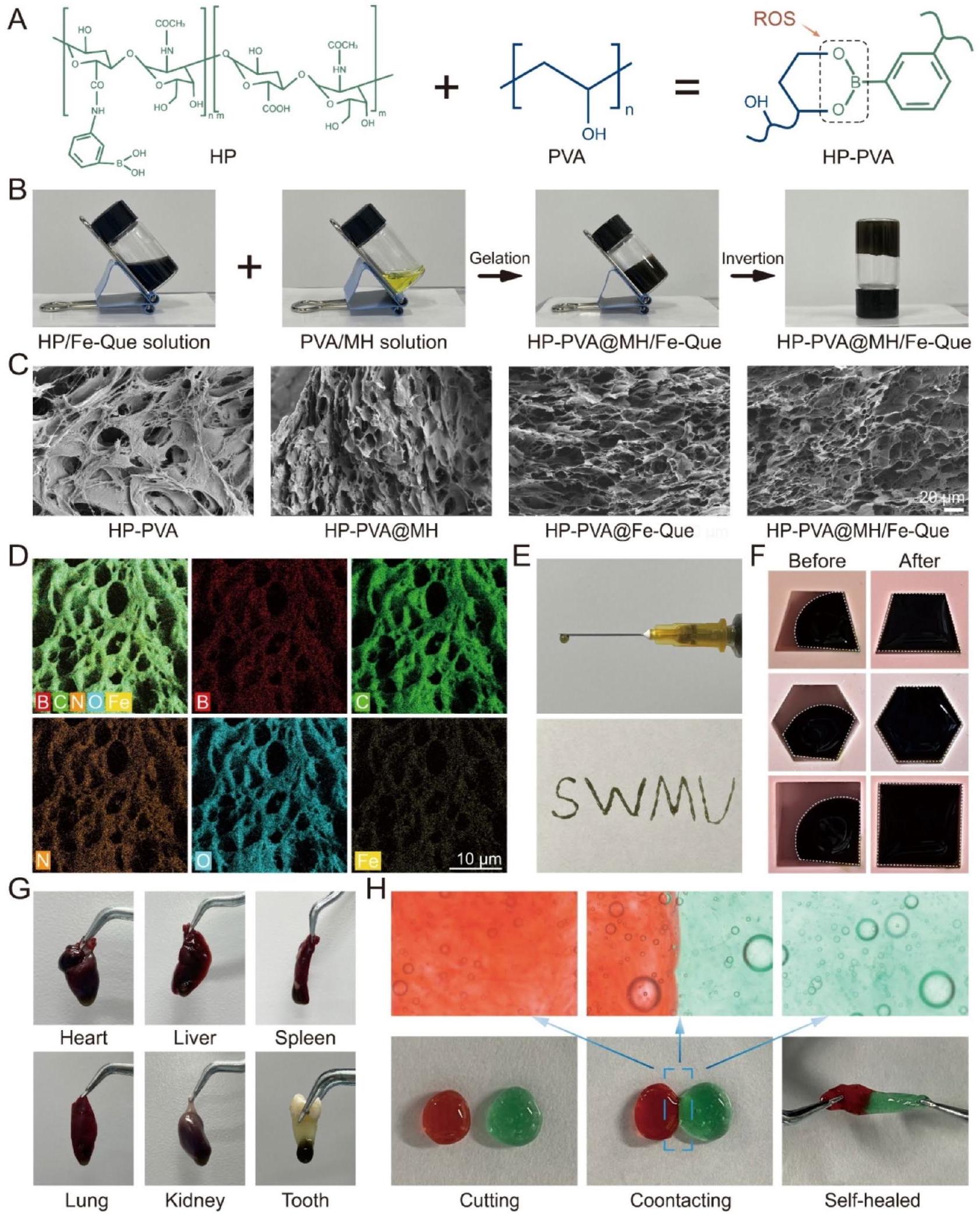

Preparation and characterization of the hydrogels

The samples were fixed on a metal base and sprayed with gold under vacuum. Then, the microstructures of the samples were visually observed by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Sigma 300, ZEISS, Germany), and the samples’ surface elements

composition and distribution were detected by energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) images.

The injectability, shape-adaptive, adhesive, and selfhealing properties of the hydrogels

Next, the HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel was injected into the mold. The state of its adaptation to the mold was observed every 30 s , and the shape of the original hydrogel ( 0 min ) and the hydrogel adapted to the environment ( 2 min ) was recorded. The adhesive properties of the hydrogels were assessed by observing whether they adhered to the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys of SD rats and human orthodontic teeth after being moistened in PBS for 1 min . Moreover, the adhesion of hydrogels to fresh porcine gingiva and human premolar enamel was quantitatively assessed [41]. The porcine gingiva (length: 70 mm , width: 10 mm ) was isolated and washed with PBS. Two pieces of porcine gingiva were then bonded together with hydrogel over an area of

ROS-responsive properties of the HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogels

Degradation behavior of HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogels in vitro

In vitro drug release in response to ROS levels from the HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogels

In vitro antibacterial activity assays of the hydrogels

To further evaluate the antibacterial activity of the hydrogels, a zone of inhibition (ZOI) assay was conducted. In addition to S. aureus, E. coli, P. gingivalis, and the key pathogen Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans), which is associated with oral biofilm formation, was tested to assess the effectiveness of the hydrogels against oral-specific bacteria. The sterilized hydrogels were immersed in PBS at

The biocompatibility test of the hydrogels

Cell culture

The hPDLSCs were derived from healthy premolars of orthodontic patients aged 12-18. All the young permanent teeth used in this study were taken from The Affiliated Stomatological Hospital of Southwest Medical University, with informed consent of patients and guardians, and approved by the Ethics Committee

(20220819002). The dental tissue was soaked and repeatedly rinsed with PBS containing different concentrations of penicillin-streptomycin. Then, the middle-third of the periodontal tissue in the root was scraped with a sterile blade, centrifuged, transferred to an inverted culture bottle, cultured in a cell incubator containing

The cytocompatibility of the hydrogels

HPDLSCs, HGFs, RAW264.7, L929, and HaCaTs, were seeded at a density of

In addition, the cells were seeded at a density of

The hemocompatibility test of the hydrogels

Free radical scavenging ability and antioxidant capacity of the hydrogels

DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assay

Then, the DPPH free radical scavenging rates of different hydrogels were assessed using the UV-visible spectrophotometer (TU-1810, Shanghai, China) to record the OD values at 515 nm and the UV-vis-NIR spectra in the range of

Cytoprotective effects against oxidative stress

of rescuing cells from oxidative stress and restoring their vitality was assessed by cell live/dead staining and the CCK-8 assay. In short, L929 and RAW264.7 cells were plated at a density of

Moreover, the capacity of various hydrogels to eliminate ROS was assessed by measuring fluorescence intensity using a Multimodal Small Animal Live Imaging System (ABL X6, Tanon). RAW264.7 cells were seeded at a density of

Macrophage polarization assessment of the hydrogels

Moreover, RAW264.7 cells were planted in a sixwell plate and treated according to the aforementioned

method. Then, the cells were digested with

In vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanism of the hydrogels through the regulation of the Nrf2/NF-кB pathway

Then, the expression levels of inflammatory factors and antioxidant enzyme genes in RAW264.7 cells were detected by Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR). In brief, RAW264.7 cells were seeded at a density of

Further, western blot (WB) analysis was performed to evaluate the related expression levels of antioxidant protein (Nrf2), NF-кB signaling pathway proteins (NF-кB and

electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) for protein separation, followed by transfer to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. Following a

In vitro osteogenic differentiation assessment of the hydrogels

In addition, the hPDLSCs were seeded on 24-well plates and treated the cells as we did before. Samples collected for 7 days were stained for Runx2, whereas those cultured for 21 days were stained for the late osteogenic protein osteocalcin (OCN). For IF, hPDLSCs were performed using anti-RUNX2 (1:100, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) and anti-OCN (1:100, Proteintech, China). Moreover, the cytoskeleton morphology after

using laser confocal microscopy. Finally, the fluorescence microscope was used to visualize the IF images, and 3D topographic maps were evaluated using ImageJ.

In vivo treatment in periodontitis model In vivo establishment of periodontitis model in rats

In vivo antioxidant property

Micro-CT analysis

Histology and immunohistochemistry

tetraacetic acid (EDTA) for one month, dehydrated in gradient alcohol, and embedded in paraffin. Afterward, these paraffin samples were made into sections at

Statistical analysis

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of Fe-Que NPs

Synthesis and characterization of HP

The Preparation and characterization of the HP-PVA@MH/ Fe-Que hydrogels

which can improve antibacterial performance, accelerate the removal of ROS and alleviate inflammation and bone resorption. As depicted in Fig. 2A, a hydrogel network was formed by establishing dynamic borate ester bonds (highly sensitive to ROS) between the diol group structures on PVA and the phenylboronic acid groups on HP. Figure 2B shows the state of HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel before and after gelation. Next, the microscopic morphology of the hydrogels was observed by SEM. As depicted in Fig. 2C, all the hydrogels exhibited interconnected pores and uniform three-dimensional porous structures, facilitating the encapsulation of biologically active molecules and protecting them from degradation. Moreover, it ensured efficient nutrient and oxygen transport, promoting cellular penetration, proliferation, and new tissue formation. Furthermore, EDS map analysis revealed a homogeneous distribution of elements C , N, O, B, and Fe throughout the HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel (Fig. 2D), providing evidence for the successful loading and dispersion of Fe-Que nanoparticles within the hydrogel.

Injectability, adaptability, adhesion, and self-healing properties are essential properties of hydrogels for local drug delivery in periodontal pockets [43]. The injectability feature facilitates the efficient penetration of hydrogels into narrow and deep periodontal pockets, providing spatiotemporal control of therapeutic drug release through material degradation and drug diffusion [8]. Figure 2E showed that the HP-PVA@MH/FeQue hydrogel could be easily transferred into a syringe and extruded from a needle (

In periodontitis, periodontal tissue is destroyed irregularly. Hydrogel possesses both gel-like elasticity and fluidity, exhibiting excellent shape adaptability, which enables the hydrogel to fit perfectly with the damaged periodontal tissue and adapt to irregularly shaped periodontal defects [45]. As shown in Fig. 2F, the HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel could be reshaped into different shapes, which could be used to fill different defects and had good adaptability. After being injected into the periodontal pocket, the hydrogel is subjected to constant washing by gingival fluid and saliva, so it should have certain adhesion properties to adhere to the periodontal tissue and prolong its retention time within the periodontal pocket [46]. The HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel exhibited a firm adhesion to the dental sulcus and internal organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, and the root of the first premolar tooth (Fig. 2G). To further evaluate the tissue adhesion of the hydrogel, a standardized in vitro lapshear test was conducted using porcine gingiva, and the hydrogel’s adhesion to tooth enamel was assessed (Fig. S4A, S4B, S4D, and S4E). The results showed that MH and Fe-Que loading did not affect the adhesive properties of the hydrogel, and the adhesion strength of HP-PVA@ MH/Fe-Que to pig gingiva was about

ROS-responsive behavior drug release kinetics, and in vitro degradation behavior of the hydrogels

pH and temperature [50]. Fig. S5A shows the reaction mechanism of hydrogel to ROS. Therefore, we treated the hydrogels with different

In vitro antibacterial activity assays of the hydrogels

indicated that the HP-PVA and HP-PVA@Fe-Que hydrogels did not form notable inhibition zones, while the HPPVA@MH and HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que groups exhibited clear inhibition zones against all tested bacteria, including S. mutans (Fig. S7). These findings were consistent with the bacterial colony counting results. Therefore, the hydrogel loaded with antimicrobial MH had outstanding antimicrobial capacity and acted on the initiators of periodontitis to achieve a great therapeutic effect.

The biocompatibility test of the hydrogels

In addition, in order to show cell viability directly in the presence of the hydrogels for accurate biological interaction analysis, we co-cultured hPDLSCs on HP-PVA@ MH/Fe-Que hydrogels. As shown in Fig. S9A and S9B, the hydrogel exhibited no apparent toxicity to hPDLSCs and demonstrated good biocompatibility. Furthermore, through DAPI and FITC fluorescence staining combined with laser confocal microscopy, it was observed that the cells were evenly distributed on the surface of the hydrogel and exhibited a well-spread spindle-shaped morphology, indicating excellent adhesion (Fig. S9C). Hence, the hydrogel had good cell compatibility.

Gingival bleeding is an important clinical symptom of periodontitis [9]. During the treatment of periodontitis, the hydrogel adheres to destroy the tissue surface in the periodontal pocket. From the perspective of biocompatibility, it must have a high level of blood compatibility. Compared with the control group, there was no obvious damage to the red blood cells in the hydrogel-treated group, while the red blood cells in the Triton X-100treated group were ruptured (Fig. S10A, B). Figure 4E showed that the hemolysis rate of the hydrogel-treated group was less than

Free radical scavenging ability and antioxidant capacity of the hydrogels

for DPPH free radical scavenging. Conversely, both the HP-PVA@Fe-Que and HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que groups exhibited significantly reduced absorbance levels, displaying a color intermediate between that of the control and positive groups (Fig. 5B). Figure 5C illustrates the DPPH free radical scavenging activity of different hydrogel groups. The results indicated that the HP-PVA@Fe-Que and HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que groups had superior DPPH scavenging rates at

Secondly, ABTS undergoes oxidation, forming a stable green cationic radical with its peak absorption at 405 nm [57]. When the sample is introduced to the ABTS radical solution, the antioxidant compounds interact with the ABTS radicals, resulting in a color change in the reaction system and a reduction in absorbance at 405 nm (Fig. 5D). Besides, the change of its absorbance within a certain range is proportional to the degree of free radicals being scavenged. As Fig. 5E showed, the absorbance of the control group exhibited the highest value and appeared green, while the positive group displayed the lowest absorbance with transparent color. The HPPVA and HP-PVA@MH groups demonstrated negligible capacity for ABTS free radical scavenging. Conversely, the HP-PVA@Fe-Que and HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que groups displayed a color intermediate between the control and positive groups, exhibiting significantly reduced absorbance levels. The ABTS free radical scavenging rates were consistent as described above (Fig. 5F).

In addition, the ability of hydrogels to scavenge ROS was further demonstrated by intracellular DCFH-DA staining [58]. In the control group, RAW264.7 cells showed the lowest fluorescence intensity, while the fluorescence intensity of the

Furthermore, the cytoprotective potential of hydrogel against oxidative stress-induced cell damage and their ability to restore cellular vitality was evaluated using live/dead cell staining and CCK-8 assay. As depicted in Fig. 5I, the substantial presence of red fluorescence

Macrophage phenotype regulation effect of the hydrogels

IF staining experiments were initially performed on macrophages to label M1 macrophages expressing inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and M2 macrophages expressing mannose receptor (CD206). As shown in Fig. 6C, the expression of iNOS in RAW264.7 cells significantly increased after LPS treatment. Compared to the LPS group, no significant difference in iNOS expression was observed in HP-PVA and HP-PVA@MH hydrogels. However, a significant reduction in iNOS expression was observed in the HP-PVA@Fe-Que and HP-PVA@MH/ Fe-Que groups. As shown in Fig. 6E, the expression of CD206 in RAW264.7 cells increased after IL-4 treatment. Similarly, there was no significant variation observed in CD206 expression between the HP-PVA and HP-PVA@ MH hydrogels compared with the IL-4 group; however, a substantial increase was observed in CD206 expression within the HP-PVA@Fe-Que and HP-PVA@MH/ Fe-Que groups. Subsequently, additional flow cytometry analysis was performed to assess macrophage polarization (Fig. 6D, F). The findings demonstrated that the

In vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanism of the hydrogels by regulating the Nrf2/NF-кB pathway

As shown in Fig. 7A, after LPS-induced inflammation, macrophages exhibited weaker Nrf2 fluorescence intensity, and the HP-PVA and HP-PVA@MH groups also showed similar fluorescence intensity; however, the Nrf2 fluorescence signal was significantly higher in the HP-PVA@Fe-Que and HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que groups than in the LPS group. Conversely, for NF-кB, the fluorescence signal in the HP-PVA@Fe-Que and HP-PVA@ MH/Fe-Que groups was lower than in the LPS group (Fig. 7B). According to the results shown in Fig. 7C-H, compared with the LPS group, the HP-PVA@Fe-Que and HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que groups exhibited a downward trend in pro-inflammatory cytokine expression of

Furthermore, western blot results showed that after the addition of LPS, the expression of Nrf2 decreased,

In vitro osteogenic differentiation assessment of the hydrogels

As illustrated in Fig. 8A, the HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel demonstrated its ability to protect hPDLSCs from osteogenic differentiation. The cellular morphology of each hydrogel group was evaluated under an

In addition, to further investigate the ability of HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel in rescuing hPDLSCs’ osteogenic differentiation, immunofluorescence staining was conducted to evaluate the expression levels of Runx2 and OCN. Runx2 plays a crucial role in osteoblast differentiation and skeletal morphogenesis, exhibiting early high expression and nuclear localization [65]. OCN is an osteoblast’s secreted protein that reflects its activity and bone formation capacity, serving as a late-stage marker for osteogenesis [66]. Compared to the control group, both Runx2 and OCN expressions were significantly reduced in the

ROS removal ability of the hydrogels in vivo

Bone regeneration evaluation of the hydrogels in vivo

Remodeling and regeneration of periodontal tissues in periodontitis in vivo

In 4 weeks, we observed limited bone loss recovery in the periodontitis group, with disordered connective tissue structure (Fig. 10A, B). In the HP-PVA treatment group, there was slight recovery of the connective tissue and alveolar bone height, with no significant effect on the treatment of periodontitis. The inflammatory cell infiltration was significantly less in the HP-PVA@Fe-Que and

To verify the osteogenic activity of HP-PVA@MH/FeQue in the post-inflammatory tissue regeneration stage, Runx2 (2 weeks) and OCN (4 weeks) were used to verify the potential osteogenic expression during bone formation by IF staining (Fig. S17C, 10 C ). The expression of Runx2 and OCN was downregulated in the periodontitis group, indicating that the ability to regenerate bone was reduced during periodontitis (Fig. S17F, S18C). Compared with the periodontitis group, the expression of Runx2 and OCN was upregulated after treatment with HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel, showing that HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel treatment had a positive regulatory effect on the restoration of periodontal bone tissue.

Anti-inflammatory effect of the hydrogels in vivo

In periodontitis, M1 macrophages proliferate excessively and release various pro-inflammatory factors, further aggravating the inflammation. Next, we evaluated the immune-modulating function of the hydrogel. We performed IF staining of M1 and M2 macrophages with

iNOS and CD206, respectively. Figure 11B showed that the fluorescence intensity of iNOS in the periodontitis group was the highest, indicating a significant increase in expression, while the expression of CD206 was lower. After treatment with HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel, the fluorescence intensity of M1 macrophages significantly decreased, while the fluorescence intensity of M2 macrophages significantly increased (Fig. 11F, G), indicating that the HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que group can inhibit the polarization of M1 macrophages and promote the polarization of M2 macrophages, and with good immune modulating function.

Nrf2 can enhance the antioxidant stress resistance to reduce inflammatory responses by activating specific genes such as NF-кB in periodontitis [40]. Based on the previous LPS model results in vitro (Fig. 7A, B, I), we further explored the expression of Nrf2 and NF-кB in vivo. As shown in Fig. 11C, Nrf2 expression was low in the periodontitis group, while the Nrf2 protein level was higher in the HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que group than in the periodontitis group (Fig. 11H). This result indicated that HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que had better antioxidant capacity. Additionally, compared with the control group, the P65 protein level was higher in the periodontitis group, indicating that the NF-

In summary, the HP-PVA@MH/Fe-Que hydrogel had a significant therapeutic effect on the bacteria-induced periodontitis model, which could scavenge ROS and alleviate oxidative stress in periodontal tissues. Secondly, it promoted the expression of Nrf2 and inhibited the expression of P65, regulating the Nrf2/NF-кB pathway to achieve immune modulation, inhibiting the polarization of M1 macrophages and promoting the polarization of M2 macrophages, thereby alleviating the inflammatory response in periodontal tissues. Furthermore, the expression of anti-inflammatory factors and bone-forming genes was also upregulated. All these factors work together to create an immune microenvironment favorable for the resolution of periodontitis and the regeneration of periodontal tissues.

Conclusion

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Author details

Published online: 12 March 2025

References

- Armitage GC. Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2004;34:9-21. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0906-6713.20 02.003421.x.

- Williams DW, Greenwell-Wild T, Brenchley L, Dutzan N, Overmiller A, Sawaya AP, Webb S, Martin D, Genomics NN, Computational Biology C, et al. Human oral mucosa cell atlas reveals a stromal-neutrophil axis regulating tissue immunity. Cell. 2021;184:4090-e41044015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021. 05.013.

- Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17038. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.38.

- Tonetti MS, Chapple ILC. Biological approaches to the development of novel periodontal therapies- Consensus of the seventh European workshop on periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2011;38:114-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1 600-051X.2010.01675.x.

- Hathaway-Schrader JD, Novince CM. Maintaining homeostatic control of periodontal bone tissue. Periodontol. 2000. 2021;86:157-187. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/prd. 12368

- Feng Z, Weinberg A. Role of bacteria in health and disease of periodontal tissues. Periodontol. 2000. 2006:40:50-76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0757 .2005.00148.x

- Yin Y, Yang S, Ai D, Qin H, Sun Y, Xia X, Xu X, Ji W, Song J. Rational design of bioactive hydrogels toward periodontal delivery: from pathophysiology to therapeutic applications. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33:2301062. https://doi.org/1 0.1002/adfm.202301062.

- Zhao X, Yang Y, Yu J, Ding R, Pei D, Zhang Y, He G, Cheng Y, Li A. Injectable hydrogels with high drug loading through B-N coordination and ROS-triggered drug release for efficient treatment of chronic periodontitis in diabetic rats. Biomaterials. 2022;282:121387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials. 202 2.121387.

- Pan S, Zhong W, Lan Y, Yu S, Yang L, Yang F, Li J, Gao X, Song J. Pathol-ogy-Guided cell Membrane-Coated polydopamine nanoparticles for efficient multisynergistic treatment of periodontitis. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34:202312253. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm. 202312253.

- Yang S, Zhu Y, Ji C, Zhu H, Lao A, Zhao R, Hu Y, Zhou Y, Zhou J, Lin K, Xu Y. A five-in-one novel MOF-modified injectable hydrogel with thermo-sensitive and adhesive properties for promoting alveolar bone repair in periodontitis: antibacterial, hemostasis, immune reprogramming, pro-osteo-/angiogenesis and recruitment. Bioact Mater. 2024;41:239-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioa ctmat.2024.07.016.

- Dong Z, Lin Y, Xu S, Chang L, Zhao X, Mei X, Gao X. NIR-triggered tea polyphenol-modified gold nanoparticles-loaded hydrogel treats periodontitis by inhibiting bacteria and inducing bone regeneration. Mater Design. 2023;225:111487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2022.111487.

- Wang P, Wang L, Zhan Y, Liu Y, Chen Z, Xu J, Guo J, Luo J, Wei J, Tong F, Li Z. Versatile hybrid nanoplatforms for treating periodontitis with chemical/ photothermal therapy and reactive oxygen species scavenging. Chem Eng J. 2023;463:142293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.142293.

- Wang L, Li Y, Ren M, Wang X, Li L, Liu F, Lan Y, Yang S, Song J. pH and lipase-responsive nanocarrier-mediated dual drug delivery system to treat periodontitis in diabetic rats. Bioactive Mater. 2022;18:254-66. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.02.008.

- Lou J, Mooney DJ. Chemical strategies to engineer hydrogels for cell culture. Nat Reviews Chem. 2022;6:726-44. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-022-0042 0-7.

- Ye B, Xiang R, Luo F. Hydrogel-Based drug delivery systems for diabetes bone defects. Chem Eng J. 2024;497:154436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.154 436.

- Huang M, Huang Y, Liu H, Tang Z, Chen Y, Huang Z, Xu S, Du J, Jia B. Hydrogels for the treatment of oral and maxillofacial diseases: current research, challenges, and future directions. Biomater Sci. 2022;10:6413-46. https://doi.org/ 10.1039/d2bm01036d.

- Gan Z, Xiao Z, Zhang Z, Li Y, Liu C, Chen X, Liu Y, Wu D, Liu C, Shuai X, Cao Y. Stiffness-tuned and ROS-sensitive hydrogel incorporating complement C5a receptor antagonist modulates antibacterial activity of macrophages for periodontitis treatment. Bioact Mater. 2023;25:347-59. https://doi.org/10.101 6/j.bioactmat.2023.01.011.

- Wu Y, Wang Y, Long L, Hu C, Kong Q, Wang Y. A Spatiotemporal release platform based on

ROS stimuli-responsive hydrogel in wound repairing. J Control Release. 2022;341:147-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.11.0 27. - Zhang L, Bei Z, Li T, Qian Z. An injectable conductive hydrogel with dual responsive release of Rosmarinic acid improves cardiac function and promotes repair after myocardial infarction. Bioact Mater. 2023;29:132-50. https:/ /doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.07.007.

- Ming P, Liu Y, Yu P, Jiang X, Yuan L, Cai S, Rao P, Cai R, Lan X, Tao G, Xiao J. A biomimetic Se-nHA/PC composite microsphere with synergistic Immunomodulatory and osteogenic ability to activate bone regeneration in periodontitis. Small. 2024;20:e2305490. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 2023054 90.

- Bai X, Peng W, Tang Y, Wang Z, Guo J, Song F, Yang H, Huang C. An NIRpropelled janus nanomotor with enhanced ROS-scavenging, Immunomodulating and biofilm-eradicating capacity for periodontitis treatment. Bioact Mater. 2024;41:271-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2024.07.014.

- Peng S, Fu H, Li R, Li H, Wang S, Li B, Sun J. A new direction in periodontitis treatment: biomaterial-mediated macrophage immunotherapy. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:359. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02592-4.

- Liu X, Wan X, Sui B, Hu Q, Liu Z, Ding T, Zhao J, Chen Y, Wang ZL, Li L. Piezoelectric hydrogel for treatment of periodontitis through bioenergetic activation. Bioact Mater. 2024;35:346-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat. 2024.02.011.

- He Z, Liu Y, Zheng ZL, Lv JC, Liu SB, Zhang J, Liu HH, Xu JZ, Li ZM, Luo E. Periodic Lamellae-Based nanofibers for precise Immunomodulation to treat inflammatory bone loss in periodontitis. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13:e2303549. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202303549.

- Cai G, Ren L, Yu J, Jiang S, Liu G, Wu S, Cheng B, Li W, Xia J. A Microenviron-ment-Responsive, controlled release hydrogel delivering Embelin to promote bone repair of periodontitis via Anti-Infection and Osteo-Immune modulation. Adv Sci. 2024;11:e202403786. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202403786.

- Yang S, Yin Y, Sun Y, Ai D, Xia X, Xu X, Song J. AZGP1 aggravates macrophage M1 polarization and pyroptosis in periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2024;103:631-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345241235616.

- Li J, Wang Y, Tang M, Zhang C, Fei Y, Li M, Li M, Gui S, Guo J. New insights into nanotherapeutics for periodontitis: a triple concerto of antimicrobial activity, Immunomodulation and periodontium regeneration. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-023-02261-y.

- Lei M, Wan H, Song J, Lu Y, Chang R, Wang H, Zhou H, Zhang X, Liu C, Qu X. Programmable Electro-Assembly of collagen: constructing porous Janus films with customized dual signals for Immunomodulation and tissue regeneration in periodontitis treatment. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11:e2305756. https://d oi.org/10.1002/advs.202305756.

- Xie Y, Xiao S, Huang L, Guo J, Bai M, Gao Y, Zhou H, Qiu L, Cheng C, Han X. Cascade and ultrafast artificial antioxidases alleviate inflammation and bone resorption in periodontitis. ACS Nano. 2023;17:15097-112. https://doi.org/10. 1021/acsnano.3c04328.

- Xin X, Liu J, Liu X, Xin Y, Hou Y, Xiang X, Deng Y, Yang B, Yu W. MelatoninDerived carbon Dots with free radical scavenging property for effective periodontitis treatment via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. ACS Nano. 2024;18:8307-24. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c12580.

- Yang GG, Zhou DJ, Pan ZY, Yang J, Zhang DY, Cao Q, Ji LN, Mao ZW. Multifunctional low-temperature photothermal nanodrug with in vivo clearance, ROSScavenging and anti-inflammatory abilities. Biomaterials. 2019;216:119280. ht tps://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119280.

- Yang SY, Hu Y, Zhao R, Zhou YN, Zhuang Y, Zhu Y, Ge XL, Lu TW, Lin KL, Xu YJ. Quercetin-loaded mesoporous nano-delivery system remodels osteoimmune microenvironment to regenerate alveolar bone in periodontitis via the miR-21a-5p/PDCD4/NF-kappaB pathway. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:94. https ://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02352-4.

- Wang Y, Li C, Wan Y, Qi M, Chen Q, Sun Y, Sun X, Fang J, Fu L, Xu L, et al. Quercetin-Loaded ceria nanocomposite potentiate Dual-Directional

immunoregulation via macrophage polarization against periodontal inflammation. Small. 2021;17:e2101505. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202101505. - Zhu H, Cai C, Yu Y, Zhou Y, Yang S, Hu Y, Zhu Y, Zhou J, Zhao J, Ma H, et al. Quercetin-Loaded bioglass injectable hydrogel promotes m6A alteration of Per1 to alleviate oxidative stress for periodontal bone defects. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11:e2403412. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs. 202403412.

- Li Y, Li J, Chang Y, Zhang J, Wang Z, Wang F, Lin Y, Sui L. Mitochondria-targeted drug delivery system based on tetrahedral framework nucleic acids for bone regeneration under oxidative stress. Chem Eng J. 2024;496:153723. https://do i.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.153723.

- Gui S, Tang W, Huang Z, Wang X, Gui S, Gao X, Xiao D, Tao L, Jiang Z, Wang X. Ultrasmall coordination polymer nanodots Fe-Quer nanozymes for preventing and delaying the development and progression of diabetic retinopathy. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33:2300261. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202300261.

- Han Z, Gao X, Wang Y, Cheng S, Zhong X, Xu Y, Zhou X, Zhang Z, Liu Z, Cheng L. Ultrasmall iron-quercetin metal natural product nanocomplex with antioxidant and macrophage regulation in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13:1726-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.11.020.

- Xu Y, Luo Y, Weng Z, Xu H, Zhang W, Li Q, Liu H, Liu L, Wang Y, Liu X, et al. Microenvironment-Responsive Metal-Phenolic nanozyme release platform with antibacterial, ROS scavenging, and osteogenesis for periodontitis. ACS Nano. 2023;17:18732-46. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c01940.

- Zhu S, Zhao B, Li M, Wang H, Zhu J, Li Q, Gao H, Feng Q, Cao X. Microenvironment responsive nanocomposite hydrogel with NIR photothermal therapy, vascularization and anti-inflammation for diabetic infected wound healing. Bioact Mater. 2023;26:306-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.03.00 5.

- Tian Y, Li Y, Liu J, Lin Y, Jiao J, Chen B, Wang W, Wu S, Li C. Photothermal therapy with regulated Nrf2/NF-kappaB signaling pathway for treating bacteria-induced periodontitis. Bioact Mater. 2022;9:428-45. https://doi.org/1 0.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.07.033.

- Boda SK, Fischer NG, Ye Z, Aparicio C. Dual oral tissue adhesive nanofiber membranes for pH -Responsive delivery of antimicrobial peptides. Biomacromolecules. 2020;21:4945-61. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.0c01163.

- Qiao B, Wang J, Qiao L, Maleki A, Liang Y, Guo B. ROS-responsive hydrogels with Spatiotemporally sequential delivery of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory drugs for the repair of MRSA-infected wounds. Regenerative Biomaterials. 2023;11:rbad110. https://doi.org/10.1093/rb/rbad110.

- Luo Q, Yang Y, Ho C, Li Z, Chiu W, Li A, Dai Y, Li W, Zhang X. Dynamic hydrogel-metal-organic framework system promotes bone regeneration in periodontitis through controlled drug delivery. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22:287. https://d oi.org/10.1186/s12951-024-02555-9.

- Wu Y, Wang Y, Long L, Hu C, Kong Q, Wang Y. A Spatiotemporal release platform based on pH/ROS stimuli-responsive hydrogel in wound repairing. J Controlled Release. 2022;341:147-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.1 1.027.

- Qiao B, Wang J, Qiao L, Maleki A, Liang Y, Guo B. ROS-responsive hydrogels with Spatiotemporally sequential delivery of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory drugs for the repair of MRSA-infected wounds. Regenerative Biomaterials. 2024;11. https://doi.org/10.1093/rb/rbad110.

- Dong Z, Sun Y, Chen Y, Liu Y, Tang C, Qu X. Injectable adhesive hydrogel through a microcapsule Cross-Link for periodontitis treatment. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2019;2:5985-94. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsabm.9b00912.

- Guo H, Huang S, Yang X, Wu J, Kirk TB, Xu J, Xu A, Xue W. Injectable and Self-Healing hydrogels with Double-Dynamic bond tunable mechanical, Gel-Sol transition and drug delivery properties for promoting periodontium regeneration in periodontitis. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13:61638-52. h ttps://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c18701.

- Zhang C, Yan R, Bai M, Sun Y, Han X, Cheng C, Ye L. Pt-Clusters-Equipped Antioxidase-Like biocatalysts as efficient ROS scavengers for treating periodontitis. Small. 2024;20:e2306966. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll. 202306966.

- Wang Y, Yuan Y, Wang R, Wang T, Guo F, Bian Y, Wang T, Ma Q, Yuan H, Du Y, et al. Injectable thermosensitive gel CH-BPNs-NBP for effective periodontitis treatment through ROS-Scavenging and jaw vascular unit protection. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13:e2400533. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202400533.

- Liu Y, Yan J, Chen L, Liao Y, Huang L, Tan J. Multifunctionalized and DualCrosslinked hydrogel promotes inflammation resolution and bone regeneration via NLRP3 Inhibition in periodontitis. Small Struct. 2024;5. https://doi.org /10.1002/sstr.202300281.

- Gong J, Wang S, Liu J, Zhang Y, Li J, Yang H, Liang K, Deng Y. In situ oxygengenerating bio-heterojunctions for enhanced anti-bacterial treatment of

anaerobe-induced periodontitis. Chem Eng J. 2024;498. https://doi.org/10.10 16/j.cej.2024.155083. - Xia P, Yu M, Yu M, Chen D, Yin J. Bacteria-responsive, Cell-recruitable, and osteoinductive nanocomposite microcarriers for intelligent bacteriostasis and accelerated tissue regeneration. Chem Eng J. 2023;465:142972. https://d oi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.142972.

- Thananukul K, Kaewsaneha C, Opaprakasit P, Lebaz N, Errachid A, Elaissari A. Smart gating porous particles as new carriers for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;174:425-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2021.04.023.