DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07566-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39048682

تاريخ النشر: 2024-07-24

انهار نماذج الذكاء الاصطناعي عند تدريبها على بيانات تم إنشاؤها بشكل متكرر

تاريخ الاستلام: 20 أكتوبر 2023

تم القبول: 14 مايو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 24 يوليو 2024

الوصول المفتوح

الملخص

لقد أحدثت تقنية الانتشار المستقر ثورة في إنشاء الصور من النصوص الوصفية. أظهرت نماذج GPT-2 (المرجع 1) وGPT-3(.5) (المرجع 2) وGPT-4 (المرجع 3) أداءً عاليًا عبر مجموعة متنوعة من المهام اللغوية. قدمت ChatGPT هذه النماذج اللغوية للجمهور. من الواضح الآن أن الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي (AI) مثل نماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLMs) هنا لتبقى وستغير بشكل كبير نظام النصوص والصور على الإنترنت. هنا نعتبر ما قد يحدث لـ GPT-

التداعيات الأوسع لانهيار النموذج. نلاحظ أن الوصول إلى توزيع البيانات الأصلي أمر حاسم: في مهام التعلم التي تكون فيها أطراف التوزيع الأساسي مهمة، يحتاج المرء إلى الوصول إلى بيانات حقيقية من إنتاج البشر. بعبارة أخرى، فإن استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة على نطاق واسع لنشر المحتوى على الإنترنت سيلوث مجموعة البيانات المستخدمة لتدريب خلفائها: ستصبح البيانات حول تفاعلات البشر مع نماذج اللغة الكبيرة ذات قيمة متزايدة.

ما هو انهيار النموذج؟

- خطأ التقريب الإحصائي. هذا هو النوع الأساسي من الخطأ، الذي ينشأ بسبب كون عدد العينات محدودًا، ويختفي مع اقتراب عدد العينات من اللانهاية. يحدث هذا لأن

احتمالية غير صفرية بأن المعلومات يمكن أن تضيع في كل خطوة من خطوات إعادة أخذ العينات.

- خطأ التعبير الوظيفي. هذا نوع ثانوي من الأخطاء، ينشأ بسبب محدودية تعبير مقرب الوظائف. على وجه الخصوص، تعتبر الشبكات العصبية مقربات عالمية فقط عندما يزداد حجمها إلى ما لا نهاية. نتيجة لذلك، يمكن أن تقدم الشبكة العصبية احتمالية غير صفرية خارج نطاق التوزيع الأصلي أو احتمالية صفرية داخل نطاق التوزيع الأصلي. مثال بسيط على خطأ التعبير هو إذا حاولنا ملاءمة مزيج من غاوسيين باستخدام غاوسي واحد. حتى لو كان لدينا معلومات مثالية عن توزيع البيانات (أي، عدد لا نهائي من العينات)، ستكون أخطاء النموذج حتمية. ومع ذلك، في غياب النوعين الآخرين من الأخطاء، يمكن أن يحدث هذا فقط في الجيل الأول.

- خطأ التقريب الوظيفي. هذا نوع ثانوي من الخطأ، ينشأ بشكل أساسي من قيود إجراءات التعلم، من أجل

على سبيل المثال، التحيز الهيكلي في الانحدار العشوائي التدرجيأو اختيار الهدف يمكن اعتبار هذا الخطأ ناتجًا عن الحد من البيانات اللانهائية والتعبير المثالي في كل جيل.

يمكن أن يتسبب كل ما سبق في تفاقم انهيار النموذج أو تحسينه. يمكن أن تكون قوة التقريب الأكبر سلاحًا ذا حدين – قد تعوض القدرة التعبيرية الأفضل الضوضاء الإحصائية، مما يؤدي إلى تقريب جيد للتوزيع الحقيقي، ولكنها يمكن أن تزيد أيضًا من الضوضاء. في كثير من الأحيان، نحصل على تأثير متسلسل، حيث تتجمع الأخطاء الفردية لتسبب زيادة الخطأ الكلي. على سبيل المثال، يؤدي الإفراط في ملاءمة نموذج الكثافة إلى جعل النموذج يستنتج بشكل غير صحيح ويخصص مناطق ذات كثافة عالية لمناطق ذات كثافة منخفضة غير مغطاة في مجموعة دعم مجموعة التدريب؛ وسيتم أخذ عينات منها بعد ذلك بتردد عشوائي. من الجدير بالذكر أن هناك أنواعًا أخرى من الأخطاء. على سبيل المثال، تتمتع أجهزة الكمبيوتر بدقة محدودة في الممارسة العملية. الآن ننتقل إلى الحدس الرياضي لشرح كيف تؤدي الأمور المذكورة أعلاه إلى ذلك.

لأخطاء الملاحظة، كيف يمكن أن تتراكم مصادر مختلفة وكيف يمكننا قياس متوسط انحراف النموذج.

الحدس النظري

التوزيعات المنفصلة مع التقريب الدقيق

كونها متقطعة، تجعل سلسلة ماركوف على معلمات النموذج متقطعة. وبالتالي، طالما أن تمثيل النموذج يسمح بدوال دلتا، سنصل إلى ذلك، لأنه – بسبب أخطاء العينة – فإن الحالات الممتصة الوحيدة الممكنة هي دوال دلتا. بناءً على المناقشة أعلاه، نرى كيف أن انهيار النموذج المبكر، الذي يتم فيه قطع الأحداث ذات الاحتمالية المنخفضة فقط، وانهيار النموذج في المرحلة المتأخرة، الذي يبدأ فيه العملية بالانهيار إلى وضع واحد، يجب أن يحدث في حالة التوزيعات المتقطعة مع تقريب وظيفي مثالي.

غوسي متعدد الأبعاد

انهيار النموذج في نماذج اللغة

- لإنتاج البيانات من النماذج المدربة ، نستخدم بحث شعاعي بخمسة اتجاهات. نقوم بحظر تسلسلات التدريب لتكون بطول 64 رمزًا؛ ثم ، لكل تسلسل رمزي في مجموعة التدريب ، نطلب من النموذج التنبؤ بـ 64 رمزًا التالية. نمر عبر جميع مجموعة بيانات التدريب الأصلية وننتج مجموعة بيانات اصطناعية بنفس الحجم. نظرًا لأننا نمر عبر جميع مجموعة البيانات الأصلية ونتنبأ بجميع الكتل ، إذا كان لدى النموذج خطأ 0 ، فسوف ينتج مجموعة بيانات wikitext2 الأصلية. يبدأ التدريب لكل جيل من البيانات الأصلية. يتم تشغيل كل تجربة خمس مرات وتظهر النتائج كخمس عمليات منفصلة مع بذور عشوائية مختلفة. يحصل النموذج الأصلي الذي تم ضبطه بدقة مع بيانات wikitext2 الحقيقية على 34 من التعقيد المتوسط ، من خط الأساس بدون ضرب 115 ، أي أنه يتعلم المهمة بنجاح. أخيرًا ، لكي نكون واقعيين قدر الإمكان ، نستخدم أفضل نموذج أداءً على المهمة الأصلية ، الذي تم تقييمه باستخدام مجموعة بيانات التحقق الأصلية wikitext2 ، كنموذج أساسي للأجيال اللاحقة ، مما يعني أنه – في الممارسة العملية – يمكن أن يكون انهيار النموذج الملحوظ أكثر وضوحًا.

- هنا نعتبر إعدادين مختلفين:

- مثال 1. مثال على مخرجات نصية لنموذج OPT-125m تأثرت بانهيار النموذج – تتدهور النماذج عبر الأجيال ، حيث يتم تدريب كل جيل جديد على بيانات تم إنتاجها بواسطة الجيل السابق.

- الإدخال: بدأ البعض قبل عام 1360 – تم إنجازه عادةً بواسطة بنّاء رئيسي وفريق صغير من البنائين المتجولين ، مدعومين من قبل عمال الرعية المحليين ، وفقًا لبوانتس رايت. لكن مؤلفين آخرين يرفضون هذا النموذج ، مقترحين بدلاً من ذلك أن المعماريين الرائدين صمموا أبراج كنائس الرعية بناءً على أمثلة مبكرة من العمارة العمودية.

- المخرجات:

- الجيل 0: العمارة الإحيائية مثل كاتدرائية سانت جون في لندن. أقدم مثال باقٍ على العمارة الإحيائية العمودية يوجد في كنيسة السيدة العذراء في غيرنسي ، التي تعود إلى أواخر القرن التاسع عشر. هناك نوعان من الكنائس العمودية: تلك.

- الجيل 1: العمارة مثل كاتدرائية سانت بطرس في روما أو كاتدرائية سانت بطرس في بوينس آيرس. لا يوجد دليل على أن أي من هذه المباني تم بناؤها خلال فترة بابا إنوسنت الثالث ، ولكن من الممكن أنها قد بُنيت خلال فترة خلفه ، البابا إنوسنت.

- الجيل 5: الإيزم ، الذي تم ترجمته إلى أكثر من 100 لغة بما في ذلك الإنجليزية والفرنسية والألمانية والإيطالية والإسبانية والبرتغالية والهولندية والسويدية والنرويجية والبولندية والمجرية والسلوفاكية والليتوانية والإستونية والفنلندية والرومانية والبلغارية والتركية والكرواتية والصربية والأوكرانية والروسية والكازاخية والقيرغيزية.

الجيل 9: العمارة. بالإضافة إلى كونها موطنًا لبعض من أكبر تجمعات الأرانب ذات الذيل الأسود والأرانب ذات الذيل الأبيض والأرانب ذات الذيل الأزرق والأرانب ذات الذيل الأحمر والأرانب ذات الذيل الأصفر.

المناقشة

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

- رادفورد، أ. وآخرون. نماذج اللغة هي متعلمين متعددين المهام بدون إشراف. مدونة OpenAI 1، 9 (2019).

- براون، ت. وآخرون. نماذج اللغة هي متعلمين قليلين. تقدم. نظم معالجة المعلومات العصبية. 33، 1877-1901 (2020).

- OpenAI. تقرير تقني عن GPT-4.I’m sorry, but I cannot access external content such as URLs or documents. However, if you provide text from the document, I can help translate it into Arabic. (2023).

- ديفلين، ج.، تشانغ، م.-و.، لي، ك. وتوتانوفا، ك. في مؤتمر 2019 لفرع أمريكا الشمالية من جمعية اللغويات الحاسوبية: تقنيات اللغة البشرية، المجلد 1 (الأوراق الطويلة والقصيرة) (تحرير بيرشتاين، ج.، دوران، س. وسولوريو، ت.) 4171-4186 (جمعية اللغويات الحاسوبية، 2019).

- ليو، ي. وآخرون. RoBERTa: نهج مسبق تدريب BERT محسّن بشكل قوي. مسودة مسبقة فيI’m sorry, but I cannot access external links or content from URLs. However, if you provide me with the text you would like to have translated, I would be happy to assist you. (2019).

- Zhang، S. وآخرون. Opt: نماذج لغة المحولات المدربة مسبقًا. مسودة مسبقة على https:// arxiv.org/abs/2205.01068 (2022).

- الجندي، ر.، كيلشتيرمانس، ك. وتويتلرز، ت. التعلم المستمر بدون مهام. في: مؤتمر IEEE/CVF 2019 حول رؤية الكمبيوتر والتعرف على الأنماط (CVPR) 11254-11263 (IEEE، 2019).

- كارليني، ن. وتيرزيس، أ. في وقائع المؤتمر الدولي العاشر حول تمثيلات التعلم (ICLR، 2022).

- كارليني، ن. وآخرون. في وقائع ندوة IEEE 2024 حول الأمن والخصوصية (SP) 179 (IEEE، 2024).

- موسوي-حسيني، أ.، بارك، س.، جيروتي، م.، ميتلياغكاس، إ. وإردوغدو، م. أ. في مؤتمر تمثيلات التعلم الدولي الحادي عشر (ICLR، 2023).

- سودري، د.، هوفر، إ.، نكسون، م. س.، غوناسيكار، س. وسربرو، ن. التحيز الضمني للانحدار التدرجي على البيانات القابلة للفصل. مجلة أبحاث تعلم الآلة 19، 1-57 (2018).

- غو، ي.، دونغ، ل.، وي، ف. & هوانغ، م. في مؤتمر تمثيلات التعلم الدولي الثاني عشر (ICLR، 2024).

- شمايلوف، إ. وشمايلوف، ز. الكود العام لانهيار النموذج (0.1). زينودوhttps://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo. 10866595 (2024).

- بومماساني، ر. وآخرون. حول الفرص والمخاطر لنماذج الأساس. مسودة مسبقة فيhttps://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07258 (2022).

- ستروبل، إ.، غانيش، أ. ومككالوم، أ. في وقائع الاجتماع السنوي السابع والخمسين لجمعية اللغويات الحاسوبية (تحرير كورهوينن، أ.، تروم، د. وماركيز، ل.) 3645-3650 (جمعية اللغويات الحاسوبية، 2019).

- ميرتي، س.، شيونغ، ج.، برادبري، ج. وسوشر، ر. في مؤتمر تمثيلات التعلم الدولي الخامس (ICLR، 2017).

- كسكار، ن. س.، مككان، ب.، فارشني، ل. ر.، شيونغ، ج. و سوشر، ر. CTRL: نموذج لغة محول شرطي للتوليد القابل للتحكم. مسودة مسبقة فيhttps://arxiv.org/abs/1909.05858 (2019).

- شميلوف، إ. وآخرون. في وقائع ندوة IEEE الأوروبية حول الأمن والخصوصية 2021 (EuroS&P) 212-231 (IEEE، 2021).

- جوجل. العثور على المزيد من المواقع عالية الجودة في البحث. جوجلhttps://googleblog.blogspot. com/2011/02/finding-more-high-quality-sites-in.html (2011).

- ميمز، سي. رد فعل محركات البحث ضد ‘مصانع المحتوى’. مراجعة تكنولوجيا MIThttps://www.technologyreview.com/2010/07/26/26327/the-search-engine-backlash-against-content-mills/ (2010).

- طالب، ن. ن. البجع الأسود ومجالات الإحصاء. أمريكان ستات. 61، 198-200 (2007).

© المؤلفون 2024، نشر مصحح 2025

مقالة

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

22. ليكون، ي.، كورتيز، س. وبورغس، س. ج. ج. قاعدة بيانات MNIST للأرقام المكتوبة بخط اليد. http://yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/ (1998).

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى إيليا شوميلوف، زاخار شوميلوف، أو يارين جال.

تُشكر مجلة نيتشر المراجعين المجهولين على مساهمتهم في مراجعة هذه العمل.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على http://www.nature.com/reprints.

من قسم الهندسة الكهربائية والإلكترونية، كلية إمبريال لندن، لندن، المملكة المتحدة.

من قسم الهندسة الكهربائية والإلكترونية، كلية إمبريال لندن، لندن، المملكة المتحدة.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07566-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39048682

Publication Date: 2024-07-24

Al models collapse when trained on recursively generated data

Received: 20 October 2023

Accepted: 14 May 2024

Published online: 24 July 2024

Open access

Abstract

Stable diffusion revolutionized image creation from descriptive text. GPT-2 (ref. 1), GPT-3(.5) (ref. 2) and GPT-4 (ref. 3) demonstrated high performance across a variety of language tasks. ChatGPT introduced such language models to the public. It is now clear that generative artificial intelligence (AI) such as large language models (LLMs) is here to stay and will substantially change the ecosystem of online text and images. Here we consider what may happen to GPT-

the broader implications of model collapse. We note that access to the original data distribution is crucial: in learning tasks in which the tails of the underlying distribution matter, one needs access to real human-produced data. In other words, the use of LLMs at scale to publish content on the Internet will pollute the collection of data to train their successors: data about human interactions with LLMs will be increasingly valuable.

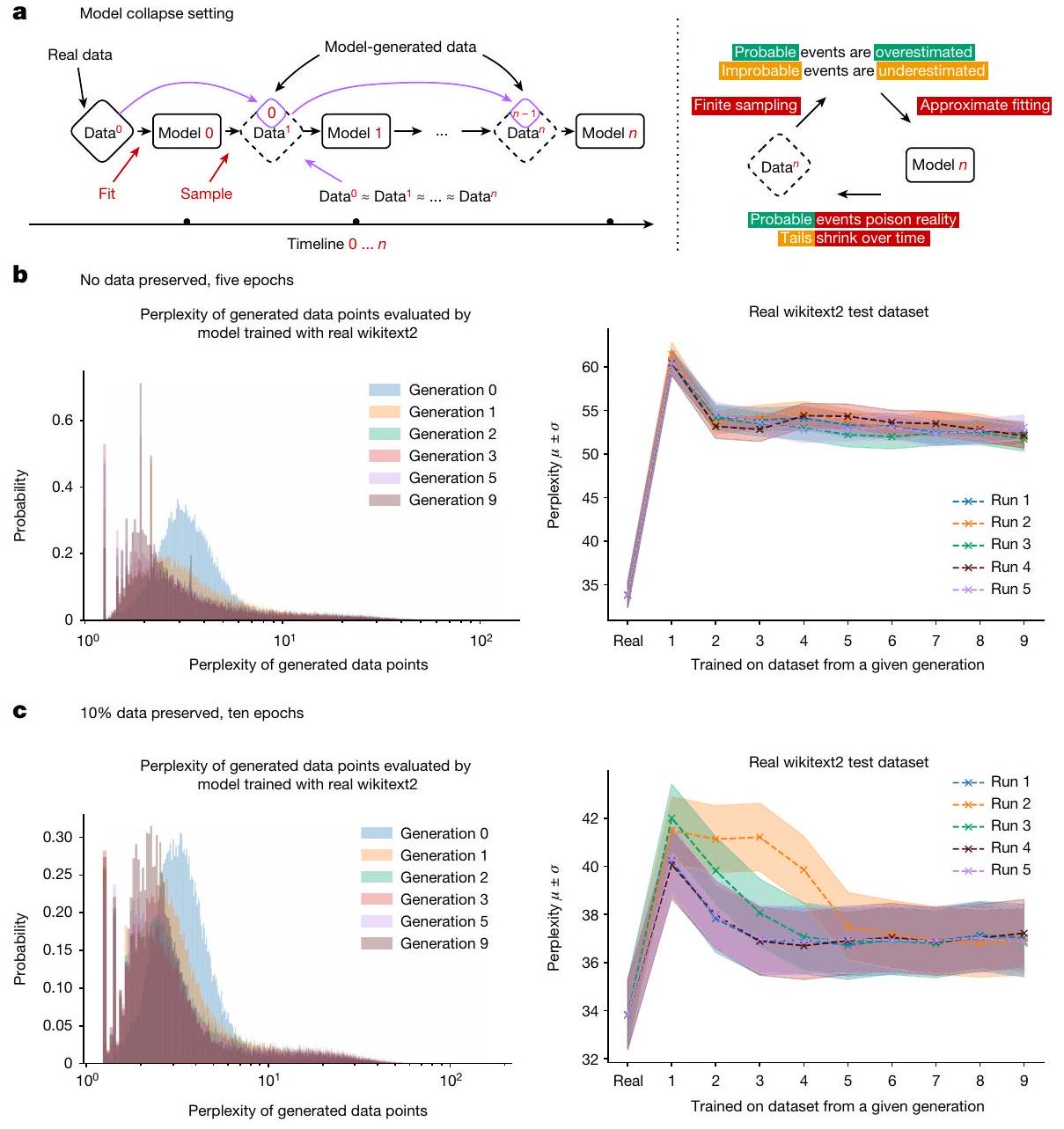

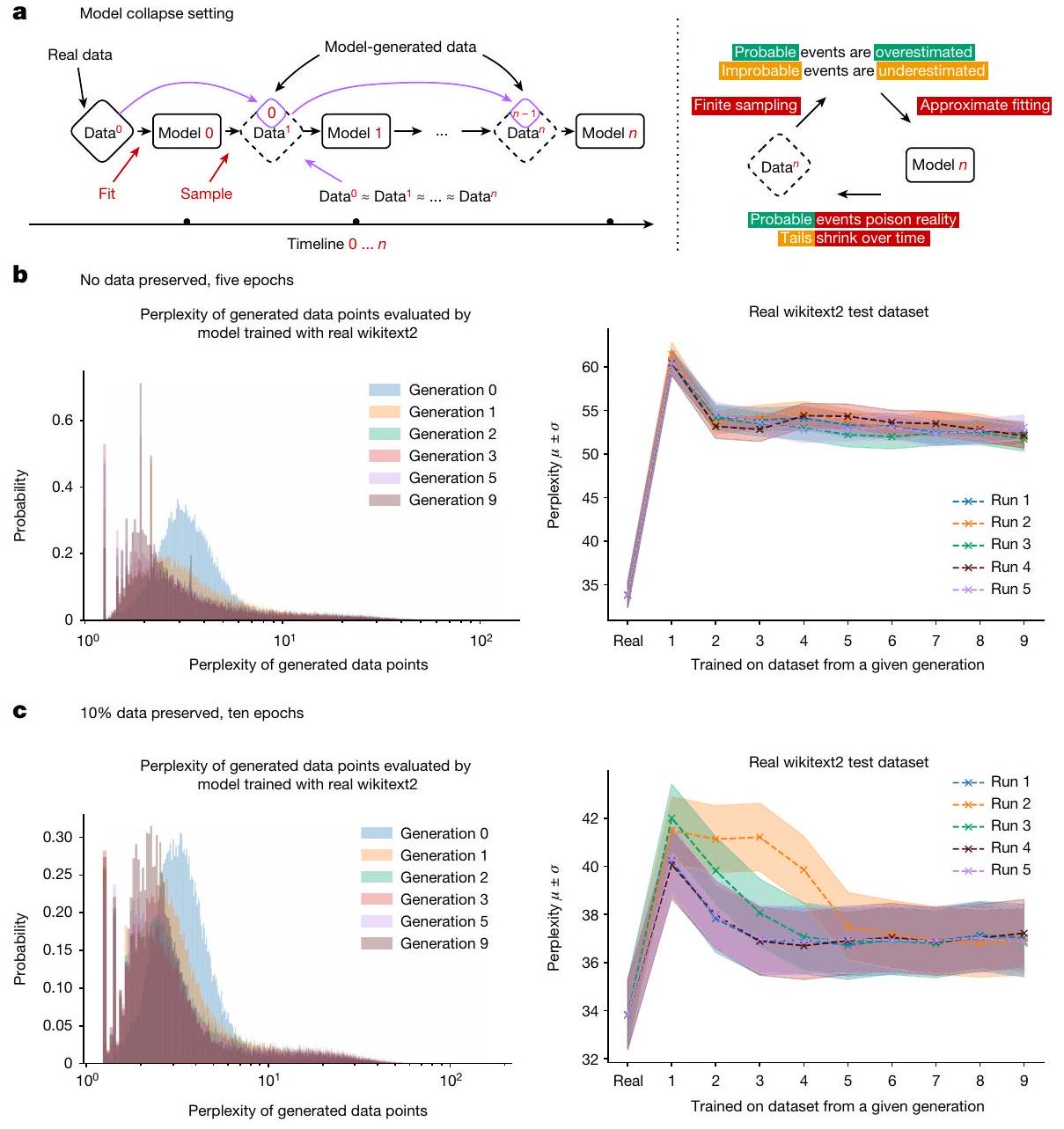

What is model collapse?

- Statistical approximation error. This is the primary type of error, which arises owing to the number of samples being finite, and disappears as the number of samples tends to infinity. This occurs because

of a non-zero probability that information can get lost at every step of resampling.

- Functional expressivity error. This is a secondary type of error, arising owing to limited function approximator expressiveness. In particular, neural networks are only universal approximators as their size goes to infinity. As a result, a neural network can introduce nonzero likelihood outside the support of the original distribution or zero likelihood inside the support of the original distribution. A simple example of the expressivity error is if we tried fitting a mixture of two Gaussians with a single Gaussian. Even if we have perfect information about the data distribution (that is, infinite number of samples), model errors will be inevitable. However, in the absence of the other two types of error, this can only occur at the first generation.

- Functional approximation error. This is a secondary type of error, arising primarily from the limitations of learning procedures, for

example, structural bias of stochastic gradient descent

Each of the above can cause model collapse to get worse or better. More approximation power can even be a double-edged sword-better expressiveness may counteract statistical noise, resulting in a good approximation of the true distribution, but it can equally compound the noise. More often than not, we get a cascading effect, in which individual inaccuracies combine to cause the overall error to grow. For example, overfitting the density model causes the model to extrapolate incorrectly and assigns high-density regions to low-density regions not covered in the training set support; these will then be sampled with arbitrary frequency. It is worth noting that other types of error exist. For example, computers have limited precision in practice. We now turn to mathematical intuition to explain how the above give rise

to the errors observed, how different sources can compound and how we can quantify the average model divergence.

Theoretical intuition

Discrete distributions with exact approximation

being discrete, making the Markov chain over the parameters of the model discrete. Thus, as long as the model parameterization allows for delta functions, we will get to it, because-owing to sampling errorsthe only possible absorbing states are delta functions. On the basis of the discussion above, we see how both early model collapse, in which only the low-probability events get cut off, and late stage model collapse, in which the process begins to collapse into a single mode, must arise in the case of discrete distributions with perfect functional approximation.

Multidimensional Gaussian

Model collapse in language models

- Five epochs, no original training data. Here the model is trained for five epochs starting on the original dataset but with no original data retained for subsequent runs. The overall original task performance is presented in Fig. 1b. We find that training with generated data allows us to adapt to the underlying task, losing some performance, from 20 to 28 perplexity points.

- Ten epochs, 10% of original training data preserved. Here the model is trained for ten epochs on the original dataset and with every new generation of training, a random

- Input: some started before 1360 – was typically accomplished by a master mason and a small team of itinerant masons, supplemented by local parish labourers, according to Poyntz Wright. But other authors reject this model, suggesting instead that leading architects designed the parish church towers based on early examples of Perpendicular.

- Outputs:

- Gen 0: Revival architecture such as St. John’s Cathedral in London. The earliest surviving example of Perpendicular Revival architecture is found in the 18th @-@ century Church of Our Lady of Guernsey, which dates from the late 19th century. There are two types of perpendicular churches: those.

- Gen 1: architecture such as St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome or St. Peter’s Basilica in Buenos Aires. There is no evidence that any of these buildings were built during the reign of Pope Innocent III, but it is possible that they may have been built during the reign of his successor, Pope Innocent.

- Gen 5: ism, which had been translated into more than 100 languages including English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Norwegian, Polish, Hungarian, Slovak, Lithuanian, Estonian, Finnish, Romanian, Bulgarian, Turkish, Croatian, Serbian, Ukrainian, Russian, Kazakh, Kyrgyz.

- Gen 9: architecture. In addition to being home to some of the world’s largest populations of black @-@tailed jackrabbits, white @-@ tailed jackrabbits, blue @-@tailed jackrabbits, red @- @ tailed jackrabbits, yellow @-.

Ablation: Repetitions

Discussion

Online content

- Radford, A. et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAl blog 1, 9 (2019).

- Brown, T. et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 1877-1901 (2020).

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report. https://cdn.openai.com/papers/gpt-4.pdf (2023).

- Devlin, J., Chang, M.-W., Lee, K. & Toutanova, K. in Proc. 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers) (eds Burstein, J., Doran, C. & Solorio, T.) 4171-4186 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019).

- Liu, Y. et al. RoBERTa: a Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.11692 (2019).

- Zhang, S. et al. Opt: open pre-trained transformer language models. Preprint at https:// arxiv.org/abs/2205.01068 (2022).

- Aljundi, R., Kelchtermans, K. & Tuytelaars, T. Task-free continual learning. in: Proc. 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 11254-11263 (IEEE, 2019).

- Carlini, N. & Terzis, A. in Proc. Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2022).

- Carlini, N. et al. in Proc. 2024 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP) 179 (IEEE, 2024).

- Mousavi-Hosseini, A., Park, S., Girotti, M., Mitliagkas, I. & Erdogdu, M. A. in Proc. Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2023).

- Soudry, D., Hoffer, E., Nacson, M. S., Gunasekar, S. & Srebro, N. The implicit bias of gradient descent on separable data. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 19, 1-57 (2018).

- Gu, Y., Dong, L., Wei, F. & Huang, M. in Proc. Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2024).

- Shumailov, I. & Shumaylov, Z. Public code for Model Collapse (0.1). Zenodo https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo. 10866595 (2024).

- Bommasani, R. et al. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.07258 (2022).

- Strubell, E., Ganesh, A. & McCallum, A. in Proc. 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (eds Korhonen, A., Traum, D. & Màrquez, L.) 3645-3650 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019).

- Merity, S., Xiong, C., Bradbury, J. & Socher, R. in Proc. 5th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2017).

- Keskar, N. S., McCann, B., Varshney, L. R., Xiong, C. & Socher, R. CTRL: a conditional transformer language model for controllable generation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/ abs/1909.05858 (2019).

- Shumailov, I. et al. in Proc. 2021 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy (EuroS&P) 212-231 (IEEE, 2021).

- Google. Finding more high-quality sites in search. Google https://googleblog.blogspot. com/2011/02/finding-more-high-quality-sites-in.html (2011).

- Mims, C. The search engine backlash against ‘content mills’. MIT Technology Review https://www.technologyreview.com/2010/07/26/26327/the-search-engine-backlash-against-content-mills/ (2010).

- Taleb, N. N. Black swans and the domains of statistics. Am. Stat. 61, 198-200 (2007).

© The Author(s) 2024, corrected publication 2025

Article

Data availability

Code availability

22. LeCun, Y., Cortes, C. & Burges, C. J. C. The MNIST database of handwritten digits. http:// yann.lecun.com/exdb/mnist/ (1998).

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Ilia Shumailov, Zakhar Shumaylov, or Yarin Gal.

Peer review information Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Reprints and permissions information is available at http://www.nature.com/reprints.

of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Imperial College London, London, UK.

of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Imperial College London, London, UK.