DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14192821

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39409770

تاريخ النشر: 2024-09-30

برمجة وإعداد خوارزمية كشف الكائنات YOLO لتحديد أنشطة التغذية لماشية الأبقار: مقارنة بين YOLOv8m و YOLOv10m

– للاستشهاد بهذه النسخة:

HAL Id: hal-04751826 https://institut-agro-dijon.hal.science/hal-04751826v1

برمجة وإعداد خوارزمية كشف الكائنات YOLO لتحديد أنشطة تغذية الماشية: مقارنة بين YOLOv8m و YOLOv10m

https://doi.org/10.3390/ ani14192821

تمت المراجعة: 12 أغسطس 2024

تم القبول: 2 سبتمبر 2024

تم النشر: 30 سبتمبر 2024

الملخص

تسلط هذه الدراسة الضوء على أهمية مراقبة سلوك تغذية الماشية باستخدام خوارزمية YOLO لكشف الكائنات. تم تسجيل مقاطع فيديو لستة ثيران من سلالة شاروليه في مزرعة فرنسية، وتم تحديد ثلاثة سلوكيات تغذية (عض، مضغ، زيارة) وتم تصنيفها باستخدام Roboflow. تم مقارنة YOLOv8 و YOLOv10 من حيث أدائهما في اكتشاف هذه السلوكيات. تفوقت YOLOv10 على YOLOv8 بدقة أعلى قليلاً، واسترجاع، ودرجات mAP50، و mAP50-95. على الرغم من أن كلا الخوارزميات أظهرت دقة عامة مماثلة (حوالي

1. المقدمة

في قطاع الثروة الحيوانية، ساعدت خوارزميات التعلم الآلي المدمجة مع الكاميرات في هذه المهمة على مدى العقود الماضية. تجعل هذه الخوارزميات، وخاصة خوارزميات كشف الكائنات، من الممكن والفعال تقييم سلوك الحيوانات الفردية عبر أحجام وأنواع المزارع المتنوعة، مما يظهر مرونتها وقابليتها للتطبيق عبر سياقات إدارة الثروة الحيوانية المختلفة [3].

2. المواد والأساليب

2.1. الحيوانات، النظام الغذائي والقياسات

الحيوانات المغذي. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كانت سعة تخزين الفيديو أيضًا عاملًا محددًا. كانت الحيوانات housed في حظيرة مغطاة مع فرشة من القش وتم تغذيتها مرتين يوميًا: أولاً في الساعة 8:00 صباحًا مع قش البرسيم ad libitum، بالإضافة إلى مركز طاقة وبروتين، ومرة أخرى في الساعة 4:00 مساءً مع قش البرسيم فقط [

2.2. نظام التسجيل

2.3. وصف مجموعة البيانات والتسمية

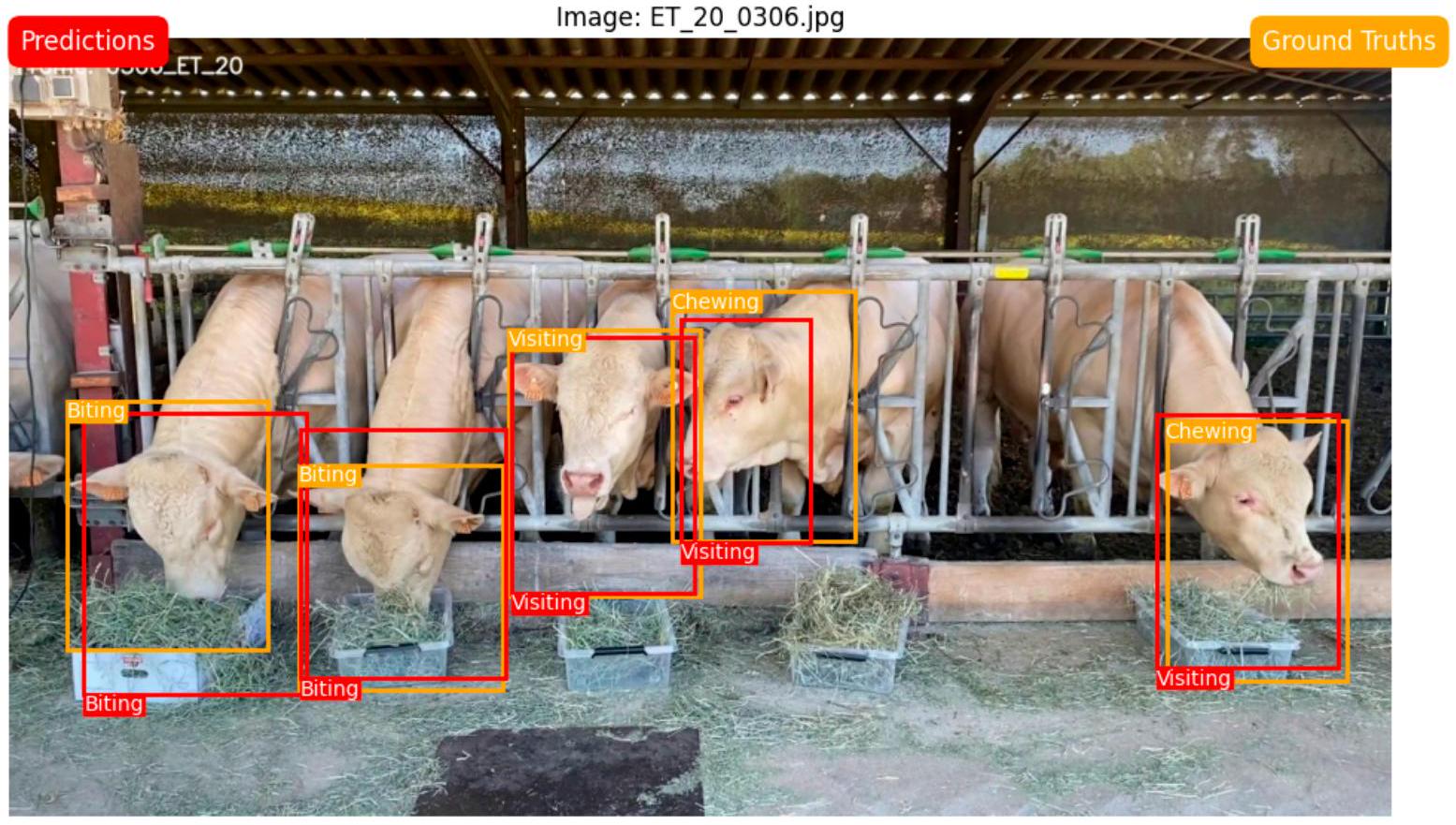

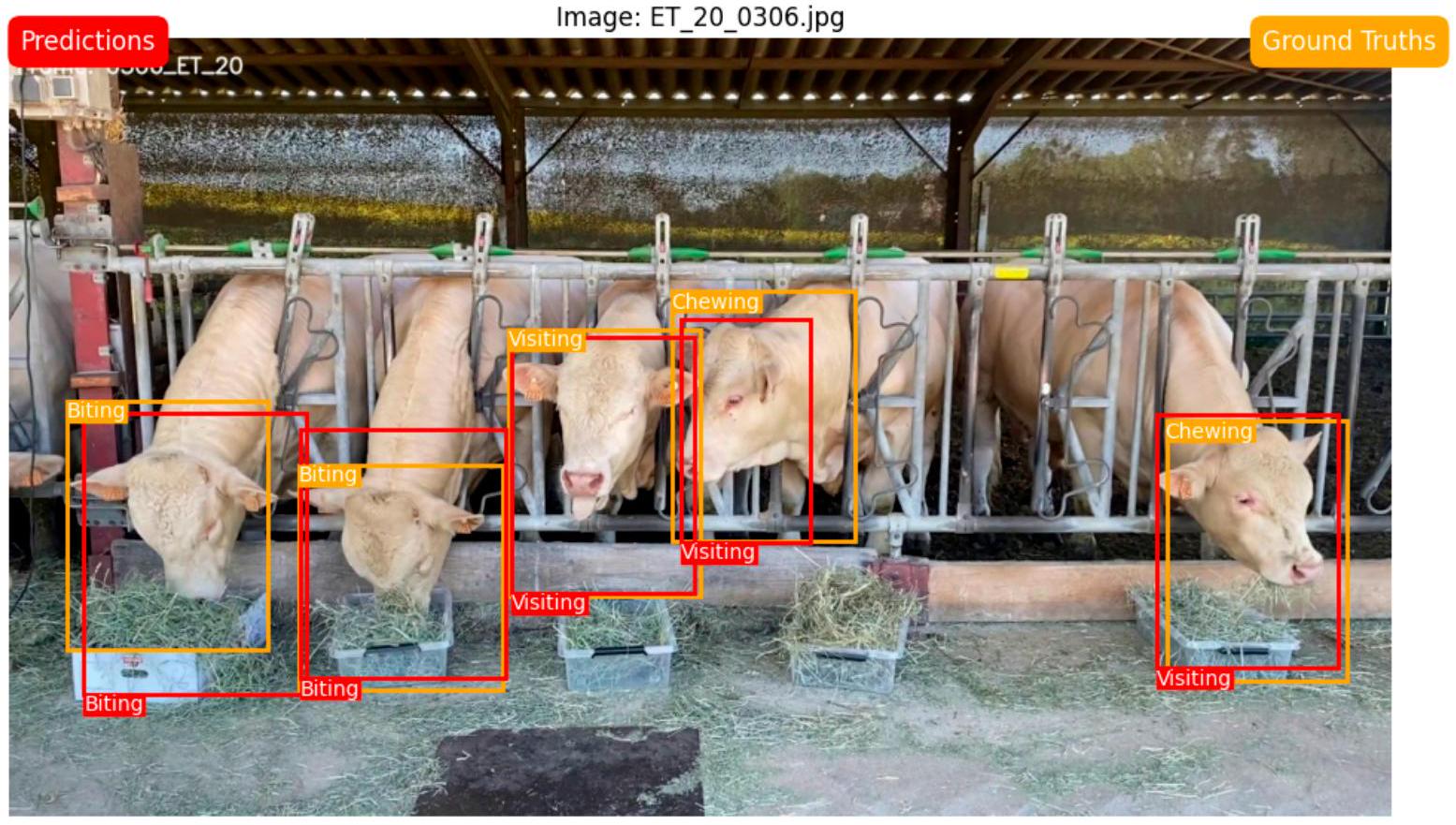

قدرة النموذج على التعميم على ظروف جديدة وغير مرئية. الشكل 2 يظهر أمثلة على تنوع الصور المستخدمة في هذا العمل.

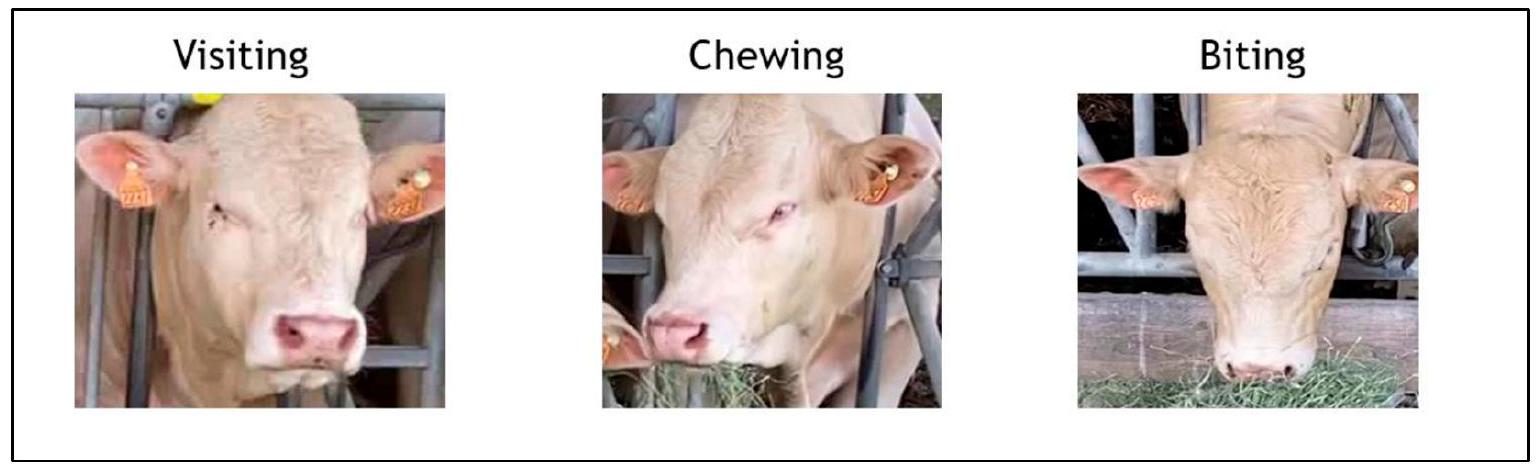

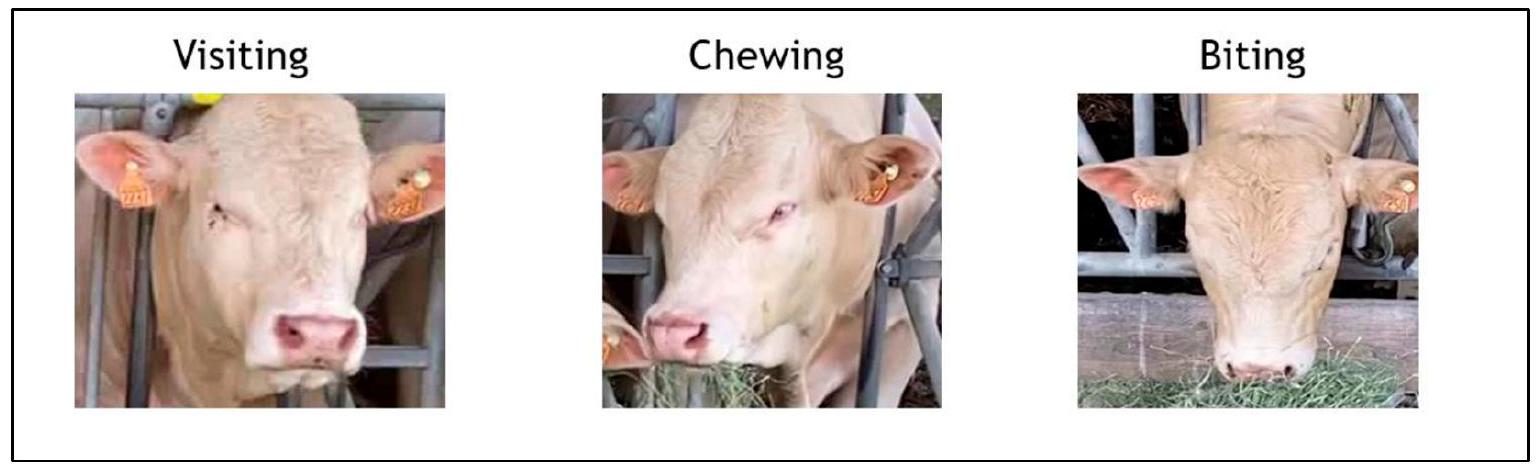

- الزيارة: تتميز بوقوف الحيوان برأسه مرفوعًا وعدم الانخراط في أي نشاط تغذية، مما يدل على غياب استهلاك العلف.

- العض: يتم تعريفه بانخفاض رأس الحيوان نحو المغذي، مما يشير إلى الانخراط النشط مع العلف وعادة ما يدل على الفعل الأولي لتناول العلف.

- المضغ: يتميز برفع الحيوان لرأسه ولكنه يظهر علامات واضحة على المضغ، كما يتضح من وجود العلف في الفم.

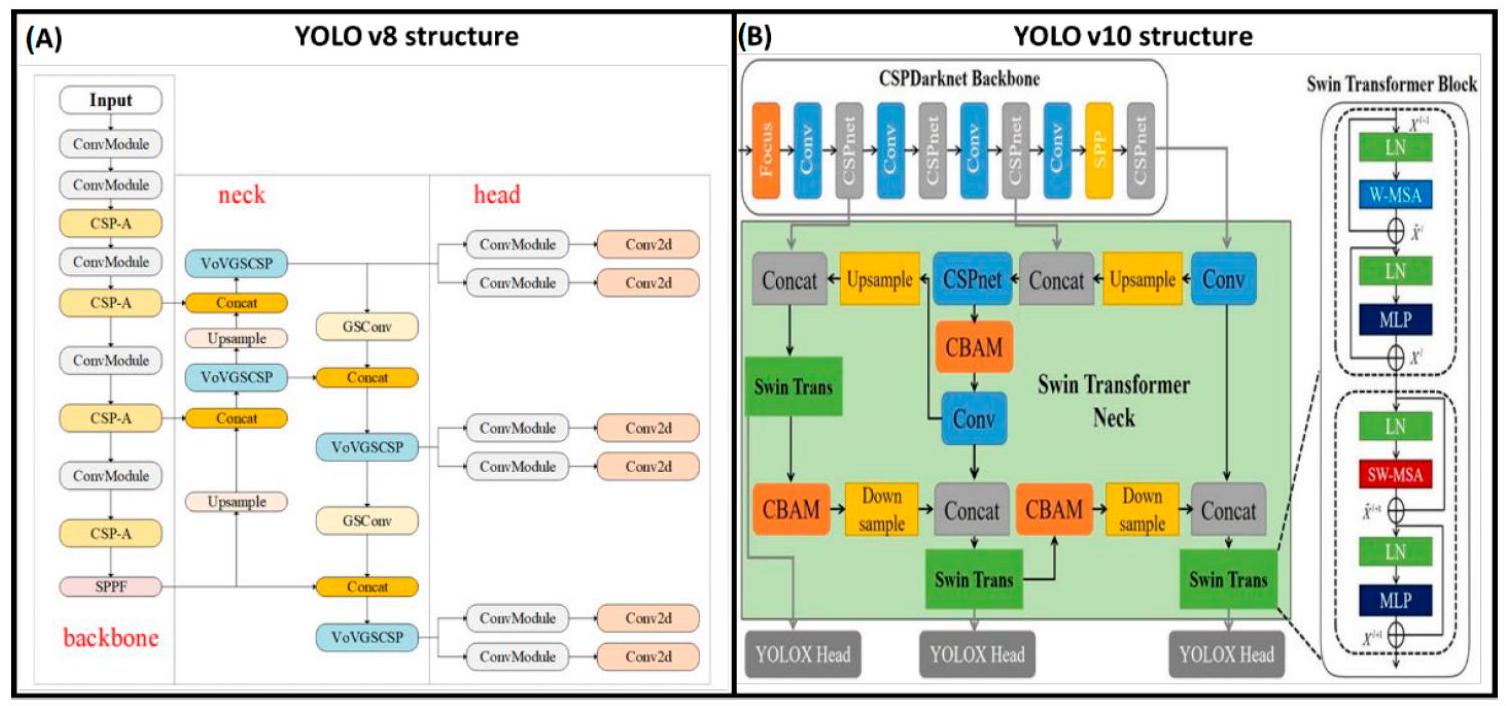

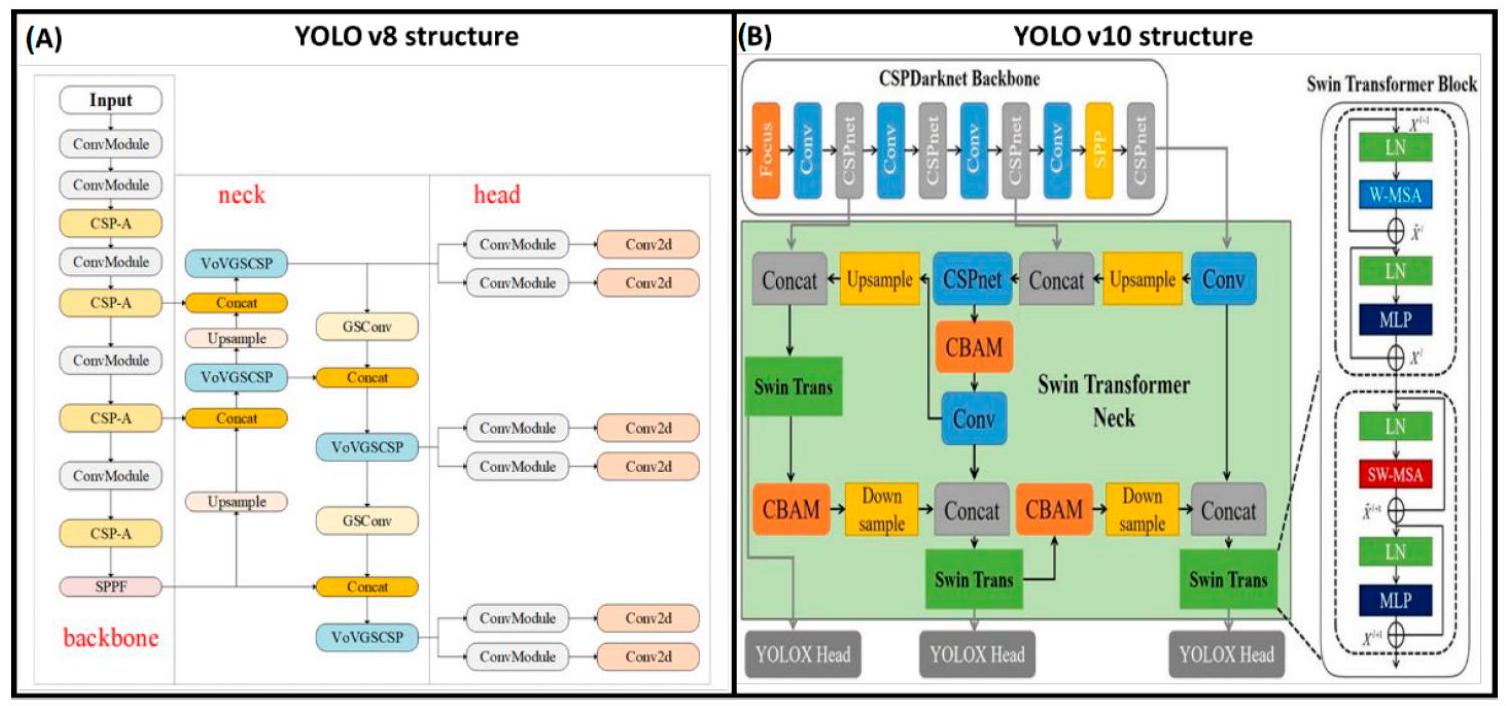

2.4. هيكل شبكة YOLOv8 و v10

2.5. التدريب

2.6. مؤشرات التقييم

و F1-score. من حيث الدقة والاسترجاع، هناك أربعة نتائج محتملة عند توقع عينة اختبار: إيجابي حقيقي (TP)، إيجابي زائف (FP)، سلبي حقيقي (TN)، وسلبي زائف (FN). يتم تعريف هذه المؤشرات التقييمية كما يلي:

- الدقة هي نسبة توقعات TP إلى العدد الإجمالي للتوقعات الإيجابية التي قام بها النموذج (كلا من TP و FP). تعكس دقة التوقعات الإيجابية.

- الاسترجاع هو نسبة توقعات TP إلى العدد الإجمالي للحالات الإيجابية الفعلية (TP و

. يقيس قدرة النموذج على تحديد جميع الحالات ذات الصلة. - متوسط الدقة (AP) يُعرف بأنه المساحة تحت منحنى الدقة والاسترجاع؛ يوفر AP قيمة واحدة تلخص أداء النموذج في الدقة والاسترجاع عند مستويات عتبة مختلفة.

- متوسط الدقة (mAP) هو متوسط قيم متوسط الدقة لجميع الفئات. يعمل كمقياس شامل يقيم الأداء العام للنموذج عبر فئات الأجسام المختلفة.

- F1-Score هو المتوسط التوافقي للدقة والاسترجاع. يوازن بين هذين المقياسين من خلال توفير درجة واحدة تأخذ في الاعتبار كل من الإيجابيات الزائفة والسلبيات الزائفة.

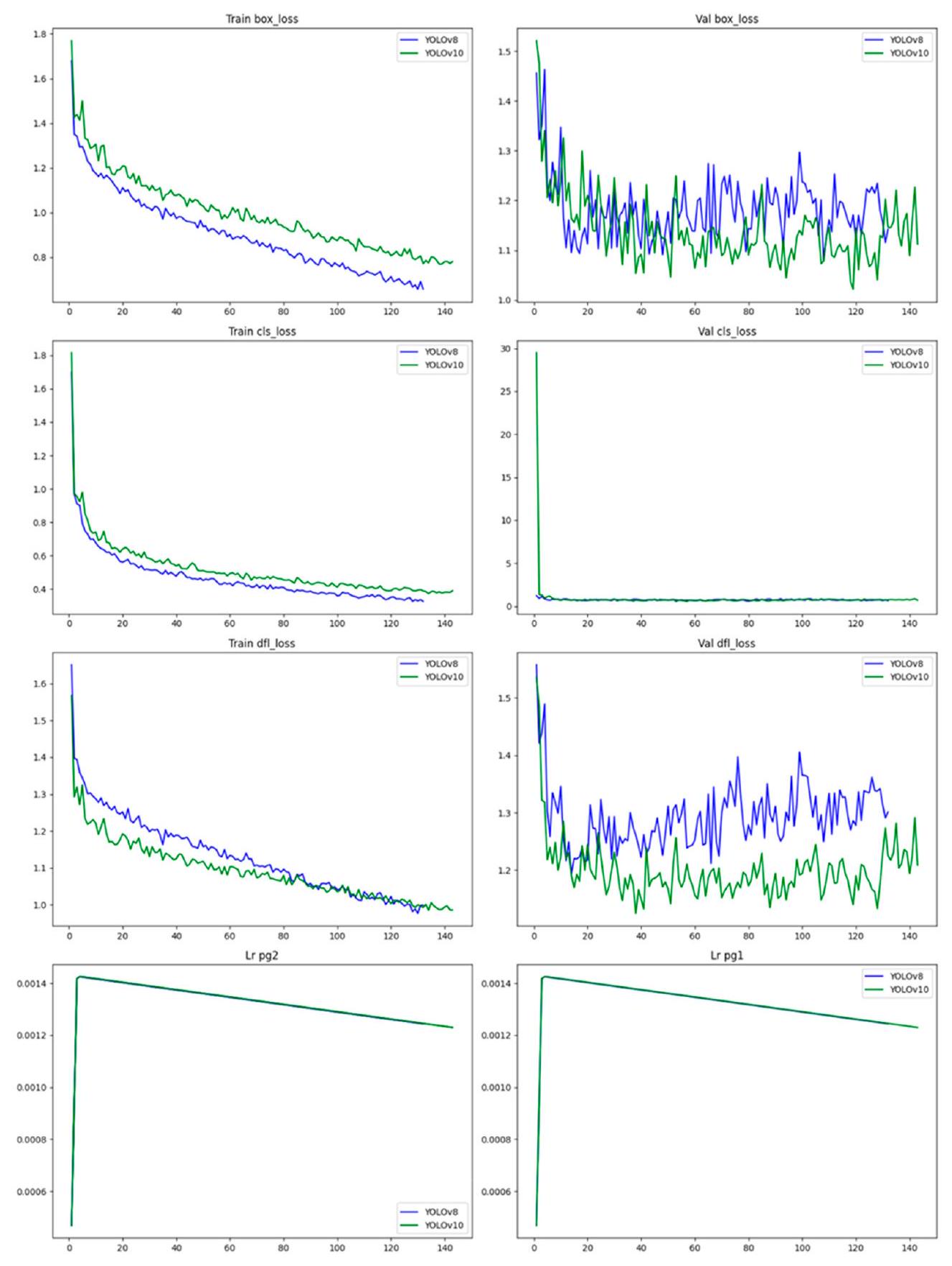

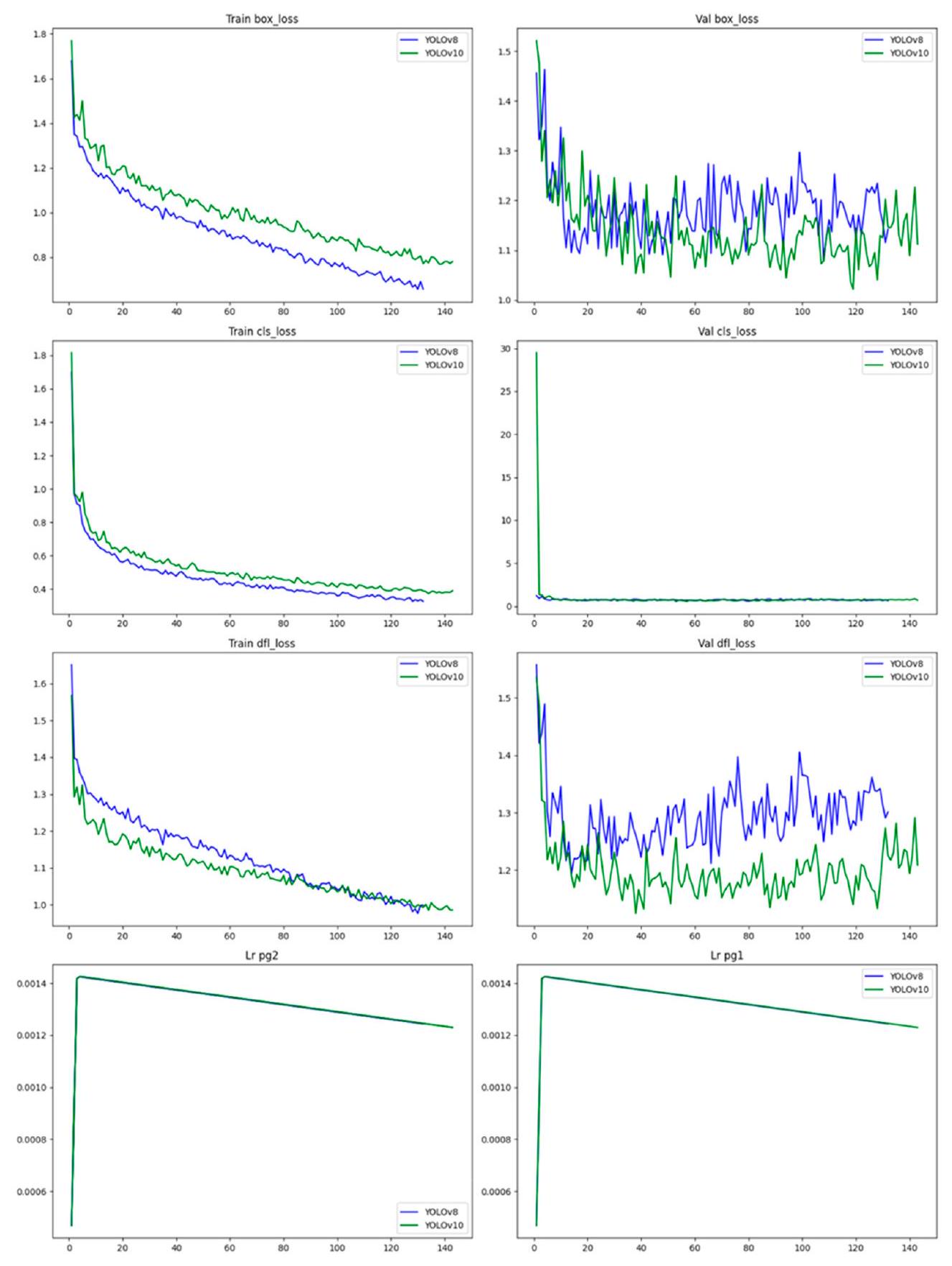

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن استخدام الاتجاه المتغير لمنحنى خسارة النموذج أيضًا لتقييم أداء النموذج. تشير سرعة ملاءمة منحنى الخسارة الأسرع، والملاءمة الأفضل، وقيمة الخسارة النهائية الأقل عمومًا إلى أداء أقوى. علاوة على ذلك، تم تطوير كود بايثون لتقييم أداء نماذج الكشف عن الأجسام المدربة باستخدام مجموعة من صور الاختبار والتعليقات التوضيحية المقابلة لها. تبدأ العملية باستيراد المكتبات الضرورية للعمليات العددية، ومعالجة الصور، والتعامل مع الملفات، وعمليات النموذج. يتم تعريف دالة التقاطع على الاتحاد (IoU) لحساب التداخل بين الصناديق المحيطة المتوقعة والحقيقية، مما يوفر مقياسًا لدقة التوقع. يقرأ الكود التعليقات التوضيحية للحقيقة الأرضية من مجموعة بيانات الاختبار، والتي تم تنسيقها بأسلوب YOLO وتحويلها إلى إحداثيات مطلقة. ثم يتم تحميل نموذج YOLO المدرب باستخدام الأوزان المحددة والدلائل لصور الاختبار، ويتم تعيين تعليقاتها التوضيحية. يقوم الكود بتهيئة القواميس لحساب TP و FP و FN لكل فئة ويعد قوائم لتخزين قيم الدقة والاسترجاع. يقوم الكود بالتكرار عبر كل صورة في دليل الاختبار، وقراءة الصورة وتعليقاتها التوضيحية الحقيقية المقابلة. يقوم النموذج بعمل توقعات، واستخراج الصناديق المحيطة وتسميات الفئات المقابلة لها، والتي تتم مقارنتها بعد ذلك مع التعليقات التوضيحية الحقيقية. إذا كانت التوقعات تتطابق مع الحقيقة الأرضية (لديها نفس معرف الفئة و IoU أكبر من 0.5)، يتم احتسابها كـ TP. إذا لم يتم العثور على تطابق، يتم احتساب الحقيقة الأرضية كـ FN، وأي توقعات متبقية يتم احتسابها كـ FP. بعد معالجة جميع الصور، يقوم الكود بحساب الدقة، والاسترجاع، و F1-score، ومتوسط الدقة لكل فئة.

3. النتائج

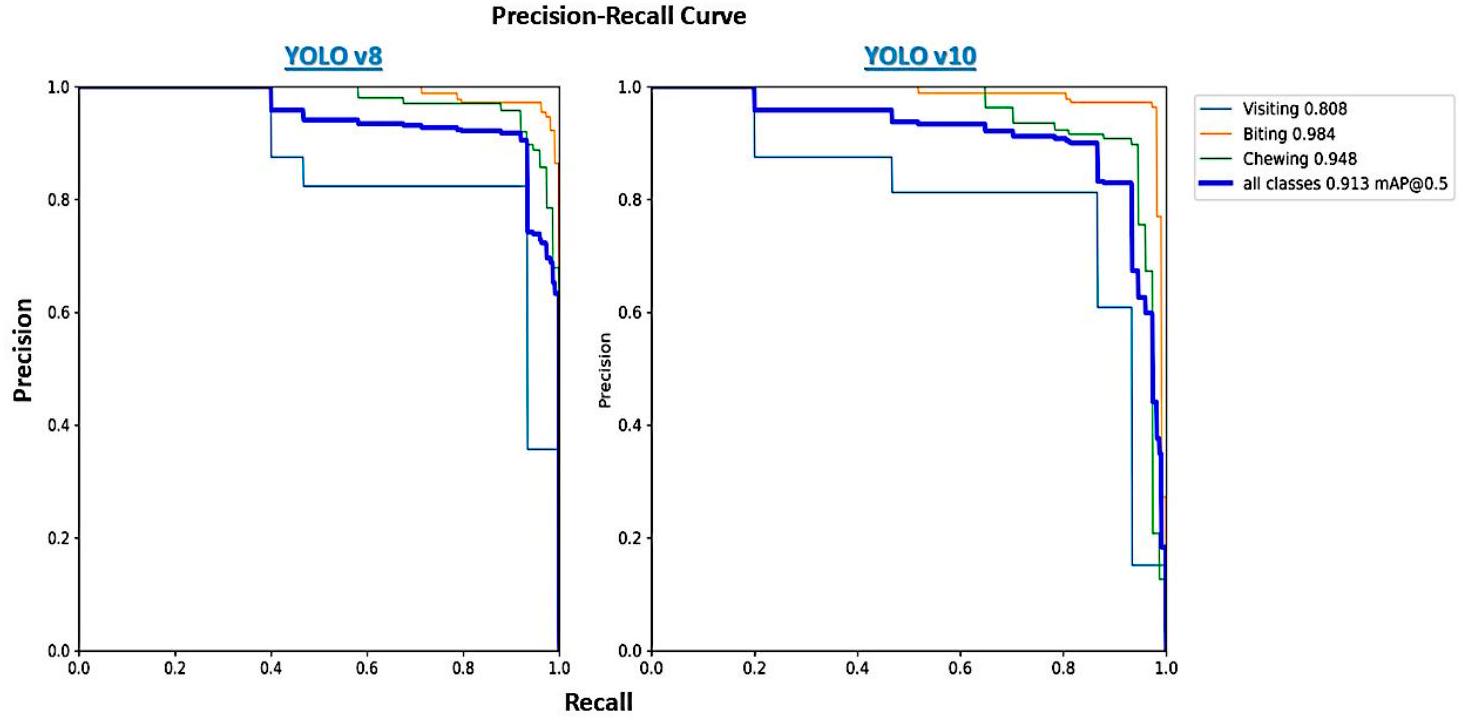

3.1. أداء YOLOv8 و v10 في الكشف عن سلوك التغذية

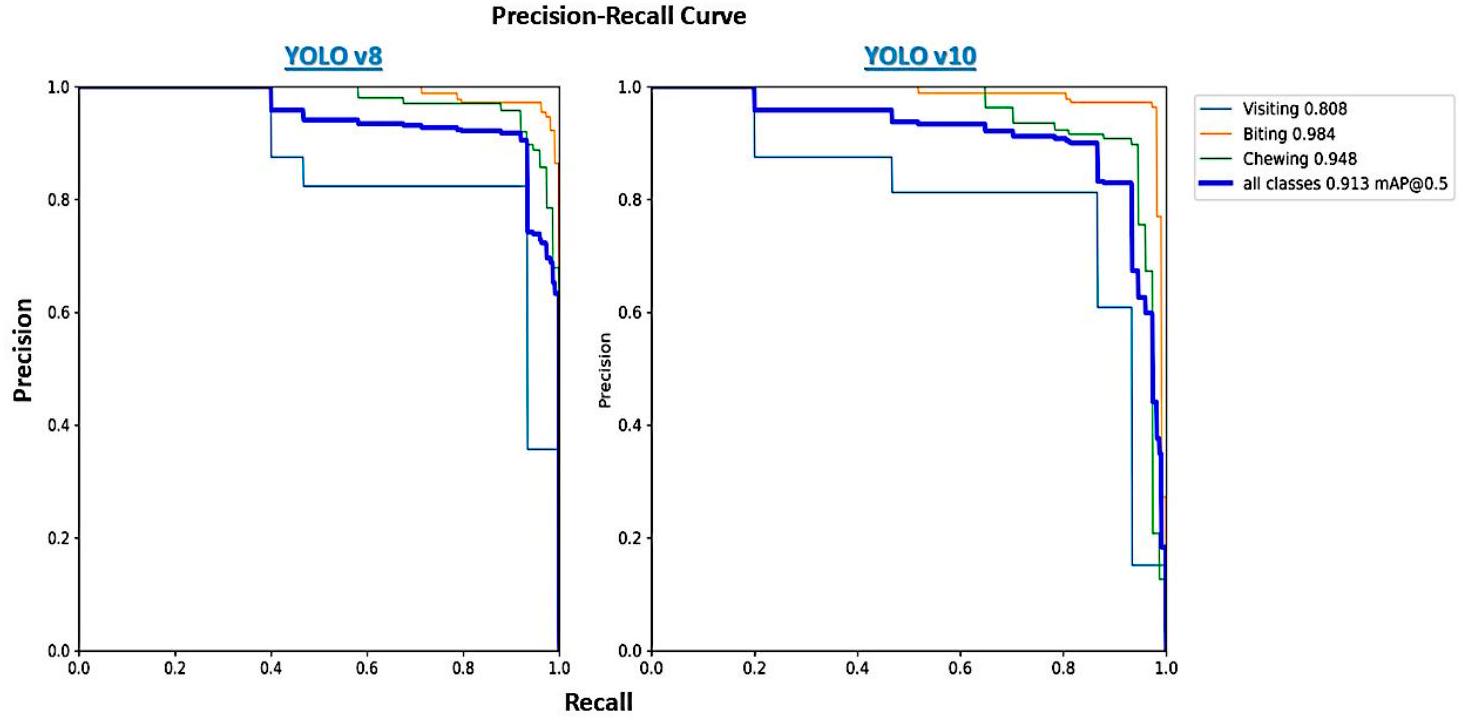

تشير النتائج بشكل جماعي إلى أن YOLOv10 يقدم أداءً أكثر قوة وموثوقية عبر أنشطة مختلفة، مما يجعله خيارًا متفوقًا للتطبيقات التي تتطلب كشف كائنات بدقة عالية في قاعدة بياناتنا. يختلف عدد الحالات بين النماذج لأن YOLOv10 لم يكتشف بعض الحالات التي اكتشفها YOLOv8، مما أدى إلى انخفاض عدد الحالات لبعض الفئات في تقييم YOLOv10. تنشأ هذه الفجوة بسبب اختلاف قدرات النماذج في كشف الكائنات التي لديها تقاطع على اتحاد (IoU) أكبر من 0.5 ومطابقة تسميات الأنشطة بشكل صحيح.

| نموذج | فصل | حالات

|

دقة * | استرجاع * | درجة F1 * | mAP* |

| يو لو 8 | كل | 2040 | – | – | – | 0.92 |

| عض | ١١٢٨ | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | – | |

| مضغ | 762 | 0.84 | 0.98 | 0.91 | – | |

| زيارة | 150 | 1.00 | 0.15 | 0.26 | – | |

| YOLOv10 | كل | 1953 | – | – | – | 0.94 |

| عض | ١٠٨١ | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | – | |

| مضغ | 737 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.93 | – | |

| زيارة | 135 | 0.98 | 0.37 | 0.54 | – |

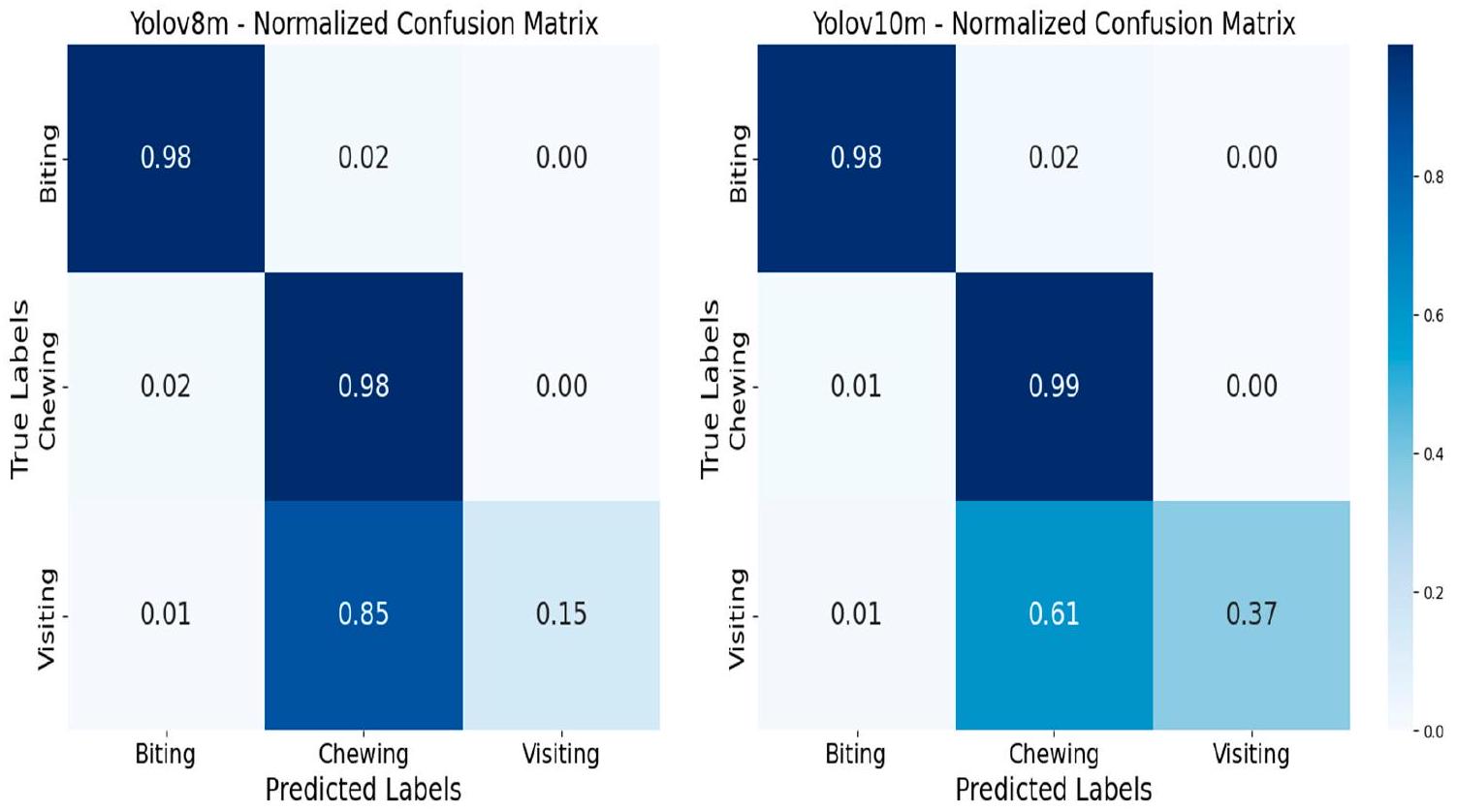

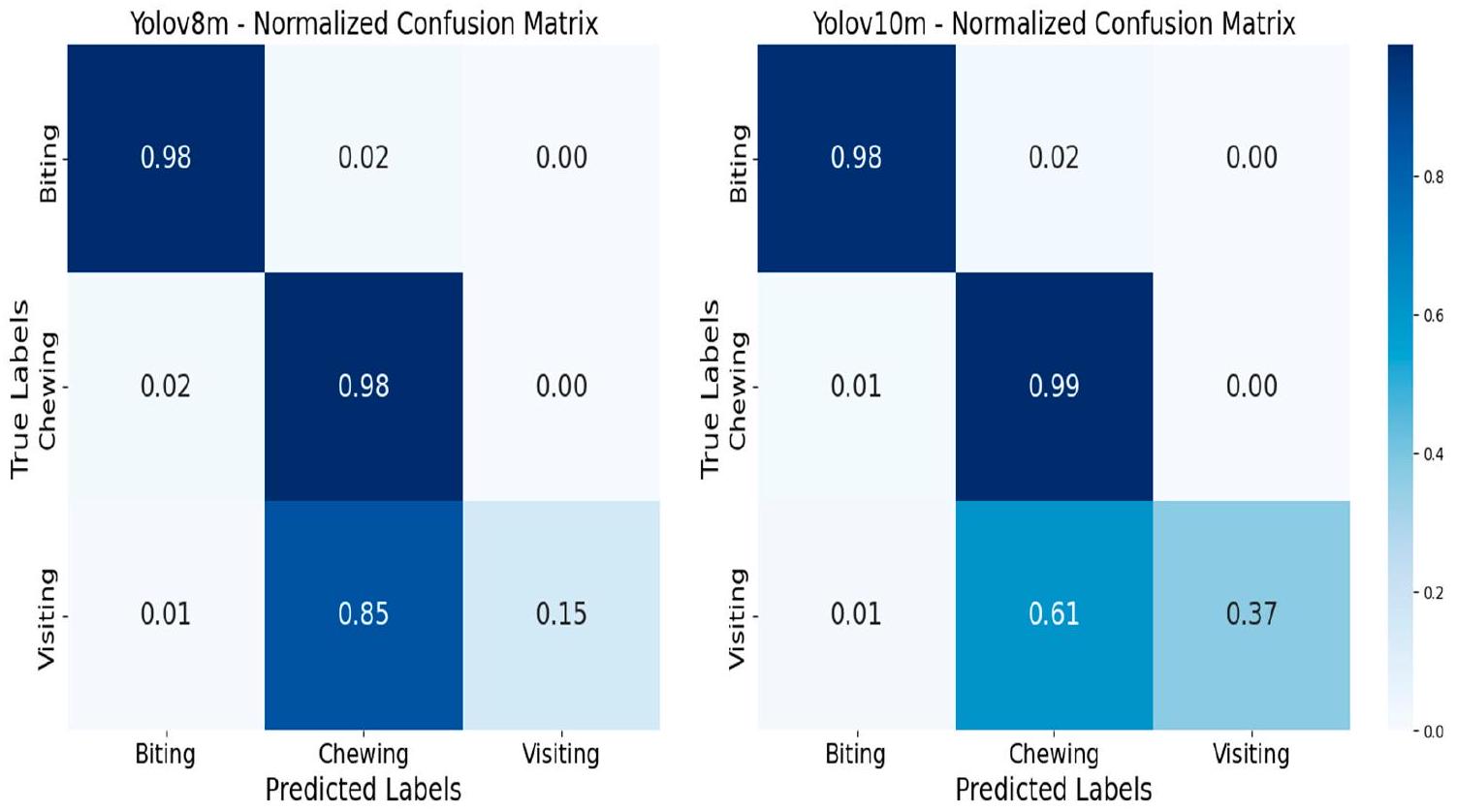

3.2. مصفوفة الارتباك للأنشطة الغذائية المتوقعة باستخدام YOLOv8 مقابل v10

سلوكيات ‘المضغ’، حيث حقق نموذج YOLOv8m دقة 0.98 لكليهما، بينما حقق نموذج YOLOv10m دقة 0.98 و0.99 على التوالي. ومع ذلك، يظهر كلا النموذجين ميلاً لخلط ‘الزيارة’ مع ‘المضغ’. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن YOLOv8m يظهر ارتباكًا أكبر في هذا الصدد، حيث حقق دقة 0.15 فقط في التعرف الصحيح على ‘الزيارة’ مقارنةً بدقة 0.37 التي لوحظت في YOLOv10m. وهذا يشير إلى أنه بينما كلا الخوارزميات فعالة للغاية في التعرف على ‘العض’ و’المضغ’، فإن YOLOv10m، على الرغم من دقته العامة، يواجه صعوبة أكبر في تمييز ‘الزيارة’ عن ‘المضغ’. يمكن تفسير هذا الارتباك من خلال التشابهات بين هذين النشاطين وقلة الحالات المسجلة لـ ‘الزيارة’ في قاعدة البيانات.

3.3. معدلات التعلم ومعلمات YOLOv8 و v10

| ميزة * | يو لو 8 | يو لو v10 |

| طبقات | ٢٩٥ | 498 |

| GFLOPs | 79.1 | 64.0 |

| محسّن | آدم دبليو | آدم دبليو |

| معدل التعلم | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| زخم | 0.937 | 0.937 |

| تآكل الوزن | 0.0005 | 0.0005 |

| فترات الإحماء | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| عصور التدريب | 1000 | 1000 |

| حجم الدفعة | ٨ | ٨ |

| حجم الصورة | 640 | 640 |

| ميزة * | يو لو 8 | يو لو v10 |

| تجميد الطبقات | وزن.22.دفل.كونف | وزن.23.دفل.كونف |

| تعزيزات | تشويش، تشويش متوسط، إلى رمادي، CLAHE | تشويش، تشويش متوسط، إلى رمادي، CLAHE |

| الدقة المختلطة | نعم | نعم |

| أقصى عدد من الاكتشافات | ٣٠٠ | ٣٠٠ |

| فصول | ٣ | ٣ |

| صبر | 50 | 50 |

- لفهم هذه المعايير بشكل أفضل، قام الباحثون السابقون بمراجعتها، موضحين معناها وتأثيرها على توقعات النموذج [28].

4. المناقشة

5. الاستنتاجات

بيان مجلس المراجعة المؤسسية: غير قابل للتطبيق.

بيان الموافقة المستنيرة: غير قابل للتطبيق.

بيان توفر البيانات: البيانات المقدمة في هذه الدراسة متاحة عند الطلب من المؤلف المراسل.

References

- Difford, G.F.; Plichta, D.R.; Løvendahl, P.; Lassen, J.; Noel, S.J.; Højberg, O.; Wright, A.-D.G.; Zhu, Z.; Kristensen, L.; Nielsen, H.B.; et al. Host genetics and the rumen microbiome jointly associate with methane emissions in dairy cows. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007580. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, G.A.; Smith, L.N.; Smith, M.L.; Reynolds, C.K.; Humphries, D.J.; Moorby, J.M.; Leemans, D.K.; Kingston-Smith, A.H. A computer vision approach to improving cattle digestive health by the monitoring of faecal samples. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17557. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zhu, W.; Norton, T. Behaviour recognition of pigs and cattle: Journey from computer vision to deep learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106255. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, J.; Tzimiropoulos, G.; Slinger, K.R.; Huggett, Z.J.; Down, P.M.; Bell, M.J. Detecting dairy cow behavior using vision technology. Agriculture 2021, 11, 675. [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Yoder, J.; Nasiri, A.; Burns, R.T.; Gan, H. Analysis of the drinking behavior of beef cattle using computer vision. Animals 2023, 13, 2984. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Han, M.; Song, H.; Song, L.; Duan, Y. Monitoring the respiratory behavior of multiple cows based on computer vision and deep learning. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 2963-2979. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, A.; Yoon, S.; Park, J.; Park, D.S. Deep learning-based hierarchical cattle behavior recognition with spatio-temporal information. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 177, 105627. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.; Kim, D.-R.; Ryu, J.-H.; Kim, H.-W.; Cho, J.; Lee, E.; Jeong, J.-H. A Monitoring System for Cattle Behavior Detection using YOLO-v8 in IoT Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 5-8 January 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1-4.

- Yu, J.; Ye, X.; Tu, Q. Traffic sign detection and recognition in multiimages using a fusion model with YOLO and VGG network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 16632-16642. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hua, Z.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, X.; Song, H. E-YOLO: Recognition of estrus cow based on improved YOLOv8n model. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122212. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, A.; Han, S.; Nasir, M.F.; Park, J.; Yoon, S.; Park, D.S. Multiview monitoring of individual cattle behavior based on action recognition in closed barns using deep learning. Animals 2023, 13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27-30 June 2016; pp. 779-788.

- Guo, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Sukkarieh, S.; Chai, L.; He, D. Bigru-attention based cow behavior classification using video data for precision livestock farming. Trans. ASABE 2021, 64, 1823-1833. [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, faster, stronger. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21-26 July 2017; pp. 7263-7271.

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767.

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.T.; Mark Liao, H.Y. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934.

- Jocher, G.; Stoken, A.; Chaurasia, A.; Borovec, J.; Kwon, Y.; Michael, K.; Thanh Minh, M. ultralytics/yolov5: v6. 0-YOLOv5n ‘Nano’ Models, Roboflow Integration, TensorFlow Export, OpenCV DNN Support; Zenodo: Genève, Switzerland, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Balasso, P.; Marchesini, G.; Ughelini, N.; Serva, L.; Andrighetto, I. Machine learning to detect posture and behavior in dairy cows: Information from an accelerometer on the animal’s left flank. Animals 2021, 11, 2972. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezen, R.; Edan, Y.; Halachmi, I. Computer vision system for measuring individual cow feed intake using RGB-D camera and deep learning algorithms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 172, 105345. [CrossRef]

- Ciaglia, F.; Zuppichini, F.S.; Guerrie, P.; McQuade, M.; Solawetz, J. Roboflow 100: A rich, multi-domain object detection benchmark. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.13523.

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14-19 June 2020; pp. 390-391.

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9-15 June 2019; Volume 97, pp. 6105-6114.

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. FCOS: Fully Convolutional One-Stage Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October-2 November 2019; pp. 9627-9636.

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21-26 July 2017; pp. 2117-2125.

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458.

- Shao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Lv, C.; Luo, Z.; Che, M. TL-YOLO: Foreign-Object Detection on Power Transmission Line Based on Improved Yolov8. Electronics 2024, 13, 1543. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Feng, Z.; Cao, C.; Yu, C.; Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Ye, S.; Shang, Y. STN-Track: Multiobject tracking of unmanned aerial vehicles by swin transformer neck and new data association method. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 8734-8743. [CrossRef]

- Sohan, M.; Sai Ram, T.; Rami Reddy, C.V. A Review on YOLOv8 and Its Advancements. In Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics: ICDICI 2023; Jacob, I.J., Piramuthu, S., Falkowski-Gilski, P., Eds.; Algorithms for Intelligent Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2024.

- Alif, M.A.R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv1 to YOLOv10: A comprehensive review of YOLO variants and their application in the agricultural domain. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10139.

- Andriamandroso, A.; Bindelle, J.; Mercatoris, B.; Lebeau, F. A review on the use of sensors to monitor cattle jaw movements and behavior when grazing. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2016, 20, 273-286. [CrossRef]

- Tani, Y.; Yokota, Y.; Yayota, M.; Ohtani, S. Automatic recognition and classification of cattle chewing activity by an acoustic monitoring method with a single-axis acceleration sensor. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 92, 54-65. [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, F.; Borges, I.; Oddy, V.; Dobos, R. Discrimination of biting and chewing behaviour in sheep using a tri-axial accelerometer. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 168, 105051. [CrossRef]

- Galli, J.; Cangiano, C.; Pece, M.; Larripa, M.; Milone, D.; Utsumi, S.; Laca, E. Monitoring and assessment of ingestive chewing sounds for prediction of herbage intake rate in grazing cattle. Animal 2018, 12, 973-982. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rau, L.M.; Chelotti, J.O.; Vanrell, S.R.; Giovanini, L.L. Developments on real-time monitoring of grazing cattle feeding behavior using sound. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 26-28 February 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 771-776.

- Chelotti, J.O.; Vanrell, S.R.; Milone, D.H.; Utsumi, S.A.; Galli, J.R.; Rufiner, H.L.; Giovanini, L.L. A real-time algorithm for acoustic monitoring of ingestive behavior of grazing cattle. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 127, 64-75. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Dong, X.; Ma, Y.; Yu, C. A multiple object tracking algorithm based on YOLO detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 11th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI), Beijing, China, 13-15 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1-5.

- Megalingam, R.K.; Babu, D.H.T.A.; Sriram, G.; YashwanthAvvari, V.S. Concurrent detection and identification of multiple objects using YOLO algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 XXIII Symposium on Image, Signal Processing and Artificial Vision (STSIVA), Popayan, Colombia, 15-17 September 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1-6.

- Sapkota, R.; Qureshi, R.; Calero, M.F.; Hussain, M.; Badjugar, C.; Nepal, U.; Poulose, A.; Zeno, P.; Vaddevolu, U.B.; Yan, H.; et al. YOLOv10 to Its Genesis: A Decadal and Comprehensive Review of the You Only Look Once Series. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.19407.

- Zhou, Y. A YOLO-NL object detector for real-time detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122256. [CrossRef]

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14192821

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39409770

Publication Date: 2024-09-30

Programming and Setting Up the Object Detection Algorithm YOLO to Determine Feeding Activities of Beef Cattle: A Comparison between YOLOv8m and YOLOv10m

– To cite this version:

HAL Id: hal-04751826 https://institut-agro-dijon.hal.science/hal-04751826v1

Programming and Setting Up the Object Detection Algorithm YOLO to Determine Feeding Activities of Beef Cattle: A Comparison between YOLOv8m and YOLOv10m

https://doi.org/10.3390/ ani14192821

Revised: 12 August 2024

Accepted: 2 September 2024

Published: 30 September 2024

Abstract

This study highlights the importance of monitoring cattle feeding behavior using the YOLO algorithm for object detection. Videos of six Charolais bulls were recorded on a French farm, and three feeding behaviors (biting, chewing, visiting) were identified and labeled using Roboflow. YOLOv8 and YOLOv10 were compared for their performance in detecting these behaviors. YOLOv10 outperformed YOLOv8 with slightly higher precision, recall, mAP50, and mAP50-95 scores. Although both algorithms demonstrated similar overall accuracy (around

1. Introduction

in the livestock sector, machine learning algorithms coupled with cameras have assisted in this task over the past decades. These machine learning algorithms, specifically object detection algorithms, make it feasible and efficient to assess individual animal behaviors across diverse farm sizes and types, showcasing their versatility and applicability across various livestock management contexts [3].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals, Diet and Measurements

animals left the feeder. In addition, the video storage capacity was also a limiting factor. The animals were housed in a covered barn with straw bedding and were fed twice daily: first at 8:00 AM with alfalfa hay ad libitum, as well as an energy and protein concentrate, and again at 4:00 PM with just alfalfa hay [

2.2. Recording System

2.3. Data Set Description and Labelling

assess the model’s ability to generalize to new, unseen conditions. Figure 2 shows examples of the image diversity used in this work.

- Visiting: Characterized by the animal standing with its head elevated and not engaging in any feeding activity, signifying the absence of feed intake.

- Biting: Defined by the animal lowering its head toward the feeder, suggesting active engagement with the feed and typically indicating the initial action of feed intake.

- Chewing: Marked by the animal raising its head yet displaying clear signs of mastication, evidenced by the presence of feed in the mouth.

2.4. YOLOv8 and v10 Network Structure

2.5. Training

2.6. Evaluation Indicators

and F1-score. In terms of precision and recall, there are four possible outcomes when predicting a test sample: True Positive (TP), False Positive (FP), True Negative (TN), and False Negative (FN). These evaluation indicators are defined as follows:

- Precision is the ratio of TP predictions to the total number of positive predictions made by the model (both TP and FP). It reflects the accuracy of the positive predictions.

- Recall is the ratio of TP predictions to the total number of actual positive cases (TP and

. It measures the model’s ability to identify all relevant instances. - Average Precision (AP) is defined as the area under the precision-recall curve; AP provides a single value that summarizes the model’s precision and recall performance at various threshold levels.

- Mean Average Precision (mAP) is the mean of the average precision values for all classes. It serves as a comprehensive measure that evaluates the overall performance of the model across different object classes.

- F1-Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall. It balances these two metrics by providing a single score that accounts for both false positives and false negatives.

Additionally, the changing trend of the model’s loss curve can also be used to assess the model’s performance. A faster loss curve fitting speed, better fit, and lower final loss value generally indicate stronger performance. Furthermore, a Python code was developed to evaluate the performance of the trained object detection models using a set of test images and their corresponding annotations. The process begins by importing necessary libraries for numerical operations, image processing, file handling, and model operations. The Intersection over Union (IoU) function is defined to calculate the overlap between predicted and ground-truth bounding boxes, providing a measure of prediction accuracy. The code reads the ground truth annotations from the test dataset, which are formatted in YOLO style and converted into absolute coordinates. The trained YOLO model is then loaded using the specified model weights and directories for test images, and their annotations are set. The code initializes dictionaries to count TP, FP, and FN for each class and sets up lists to store precision and recall values. The code iterates through each image in the test directory, reading the image and its corresponding ground truth annotations. The model makes predictions, extracting bounding boxes and their corresponding class labels, which are then compared with the ground truth annotations. If a prediction matches a ground truth (having the same class ID and an IoU greater than 0.5 ), it is counted as a TP. If no match is found, the ground truth is counted as an FN, and any remaining predictions are counted as FP. After processing all images, the code calculates precision, recall, F1-score, and average precision for each class.

3. Results

3.1. YOLOv8 and v10 Performance in Feeding Behavior Detection

collectively suggest that YOLOv10 offers more robust and reliable performance across different activities, making it a superior choice for applications requiring high-accuracy object detection in our database. The number of instances differs between models because YOLOv10 did not detect some instances that YOLOv8 did, leading to a lower count of instances for certain classes in the YOLOv10 evaluation. This discrepancy arises due to the models’ differing abilities to detect objects with an Intersection over Union (IoU) greater than 0.5 and correctly match the activity labels.

| Model | Class | Instances

|

Precision * | Recall * | F1-Score * | mAP* |

| YOLOv8 | All | 2040 | – | – | – | 0.92 |

| Biting | 1128 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | – | |

| Chewing | 762 | 0.84 | 0.98 | 0.91 | – | |

| Visiting | 150 | 1.00 | 0.15 | 0.26 | – | |

| YOLOv10 | All | 1953 | – | – | – | 0.94 |

| Biting | 1081 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | – | |

| Chewing | 737 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.93 | – | |

| Visiting | 135 | 0.98 | 0.37 | 0.54 | – |

3.2. Confusion Matrix of Feeding Activities Predicted with YOLOv8 vs. v10

‘Chewing’ behaviors, with YOLOv8m achieving 0.98 accuracy for both and YOLOv10m achieving 0.98 and 0.99 , respectively. However, both models exhibit a tendency to confuse ‘Visiting’ with ‘Chewing’. Notably, YOLOv8m shows greater confusion in this regard, with only 0.15 accuracy in correctly identifying ‘Visiting’ compared to 0.37 accuracy observed in YOLOv10m. This indicates that while both algorithms are highly effective at recognizing ‘Biting’ and ‘Chewing,’ YOLOv10m, despite its overall precision, struggles more with distinguishing ‘Visiting’ from ‘Chewing.’ This confusion can be explained by the similarities between these two activities and the relatively few instances of ‘Visiting’ recorded in the database.

3.3. Learning Rates and Parameters of YOLOv8 and v10

| Feature * | YOLOv8 | YOLOv10 |

| Layers | 295 | 498 |

| GFLOPs | 79.1 | 64.0 |

| Optimizer | AdamW | AdamW |

| Learning Rate | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Momentum | 0.937 | 0.937 |

| Weight Decay | 0.0005 | 0.0005 |

| Warmup Epochs | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Training Epochs | 1000 | 1000 |

| Batch Size | 8 | 8 |

| Image Size | 640 | 640 |

| Feature * | YOLOv8 | YOLOv10 |

| Freeze Layers | model.22.dfl.conv.weight | model.23.dfl.conv.weight |

| Augmentations | Blur, MedianBlur, ToGray, CLAHE | Blur, MedianBlur, ToGray, CLAHE |

| Mixed Precision | Yes | Yes |

| Max Detections | 300 | 300 |

| Classes | 3 | 3 |

| Patience | 50 | 50 |

- To better understand these parameters, previous researchers have reviewed them, explaining their meaning and influence on model predictions [28].

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement: The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- Difford, G.F.; Plichta, D.R.; Løvendahl, P.; Lassen, J.; Noel, S.J.; Højberg, O.; Wright, A.-D.G.; Zhu, Z.; Kristensen, L.; Nielsen, H.B.; et al. Host genetics and the rumen microbiome jointly associate with methane emissions in dairy cows. PLoS Genet. 2018, 14, e1007580. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, G.A.; Smith, L.N.; Smith, M.L.; Reynolds, C.K.; Humphries, D.J.; Moorby, J.M.; Leemans, D.K.; Kingston-Smith, A.H. A computer vision approach to improving cattle digestive health by the monitoring of faecal samples. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17557. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zhu, W.; Norton, T. Behaviour recognition of pigs and cattle: Journey from computer vision to deep learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106255. [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, J.; Tzimiropoulos, G.; Slinger, K.R.; Huggett, Z.J.; Down, P.M.; Bell, M.J. Detecting dairy cow behavior using vision technology. Agriculture 2021, 11, 675. [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Yoder, J.; Nasiri, A.; Burns, R.T.; Gan, H. Analysis of the drinking behavior of beef cattle using computer vision. Animals 2023, 13, 2984. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Han, M.; Song, H.; Song, L.; Duan, Y. Monitoring the respiratory behavior of multiple cows based on computer vision and deep learning. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 2963-2979. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, A.; Yoon, S.; Park, J.; Park, D.S. Deep learning-based hierarchical cattle behavior recognition with spatio-temporal information. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 177, 105627. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.; Kim, D.-R.; Ryu, J.-H.; Kim, H.-W.; Cho, J.; Lee, E.; Jeong, J.-H. A Monitoring System for Cattle Behavior Detection using YOLO-v8 in IoT Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 5-8 January 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1-4.

- Yu, J.; Ye, X.; Tu, Q. Traffic sign detection and recognition in multiimages using a fusion model with YOLO and VGG network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 16632-16642. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hua, Z.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, X.; Song, H. E-YOLO: Recognition of estrus cow based on improved YOLOv8n model. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122212. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, A.; Han, S.; Nasir, M.F.; Park, J.; Yoon, S.; Park, D.S. Multiview monitoring of individual cattle behavior based on action recognition in closed barns using deep learning. Animals 2023, 13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27-30 June 2016; pp. 779-788.

- Guo, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Sukkarieh, S.; Chai, L.; He, D. Bigru-attention based cow behavior classification using video data for precision livestock farming. Trans. ASABE 2021, 64, 1823-1833. [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, faster, stronger. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21-26 July 2017; pp. 7263-7271.

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767.

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.T.; Mark Liao, H.Y. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934.

- Jocher, G.; Stoken, A.; Chaurasia, A.; Borovec, J.; Kwon, Y.; Michael, K.; Thanh Minh, M. ultralytics/yolov5: v6. 0-YOLOv5n ‘Nano’ Models, Roboflow Integration, TensorFlow Export, OpenCV DNN Support; Zenodo: Genève, Switzerland, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Balasso, P.; Marchesini, G.; Ughelini, N.; Serva, L.; Andrighetto, I. Machine learning to detect posture and behavior in dairy cows: Information from an accelerometer on the animal’s left flank. Animals 2021, 11, 2972. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezen, R.; Edan, Y.; Halachmi, I. Computer vision system for measuring individual cow feed intake using RGB-D camera and deep learning algorithms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 172, 105345. [CrossRef]

- Ciaglia, F.; Zuppichini, F.S.; Guerrie, P.; McQuade, M.; Solawetz, J. Roboflow 100: A rich, multi-domain object detection benchmark. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.13523.

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14-19 June 2020; pp. 390-391.

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9-15 June 2019; Volume 97, pp. 6105-6114.

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. FCOS: Fully Convolutional One-Stage Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October-2 November 2019; pp. 9627-9636.

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21-26 July 2017; pp. 2117-2125.

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.14458.

- Shao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Lv, C.; Luo, Z.; Che, M. TL-YOLO: Foreign-Object Detection on Power Transmission Line Based on Improved Yolov8. Electronics 2024, 13, 1543. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Feng, Z.; Cao, C.; Yu, C.; Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Ye, S.; Shang, Y. STN-Track: Multiobject tracking of unmanned aerial vehicles by swin transformer neck and new data association method. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 8734-8743. [CrossRef]

- Sohan, M.; Sai Ram, T.; Rami Reddy, C.V. A Review on YOLOv8 and Its Advancements. In Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics: ICDICI 2023; Jacob, I.J., Piramuthu, S., Falkowski-Gilski, P., Eds.; Algorithms for Intelligent Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2024.

- Alif, M.A.R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv1 to YOLOv10: A comprehensive review of YOLO variants and their application in the agricultural domain. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10139.

- Andriamandroso, A.; Bindelle, J.; Mercatoris, B.; Lebeau, F. A review on the use of sensors to monitor cattle jaw movements and behavior when grazing. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2016, 20, 273-286. [CrossRef]

- Tani, Y.; Yokota, Y.; Yayota, M.; Ohtani, S. Automatic recognition and classification of cattle chewing activity by an acoustic monitoring method with a single-axis acceleration sensor. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2013, 92, 54-65. [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, F.; Borges, I.; Oddy, V.; Dobos, R. Discrimination of biting and chewing behaviour in sheep using a tri-axial accelerometer. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 168, 105051. [CrossRef]

- Galli, J.; Cangiano, C.; Pece, M.; Larripa, M.; Milone, D.; Utsumi, S.; Laca, E. Monitoring and assessment of ingestive chewing sounds for prediction of herbage intake rate in grazing cattle. Animal 2018, 12, 973-982. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rau, L.M.; Chelotti, J.O.; Vanrell, S.R.; Giovanini, L.L. Developments on real-time monitoring of grazing cattle feeding behavior using sound. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 26-28 February 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 771-776.

- Chelotti, J.O.; Vanrell, S.R.; Milone, D.H.; Utsumi, S.A.; Galli, J.R.; Rufiner, H.L.; Giovanini, L.L. A real-time algorithm for acoustic monitoring of ingestive behavior of grazing cattle. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 127, 64-75. [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Dong, X.; Ma, Y.; Yu, C. A multiple object tracking algorithm based on YOLO detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 11th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI), Beijing, China, 13-15 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1-5.

- Megalingam, R.K.; Babu, D.H.T.A.; Sriram, G.; YashwanthAvvari, V.S. Concurrent detection and identification of multiple objects using YOLO algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2021 XXIII Symposium on Image, Signal Processing and Artificial Vision (STSIVA), Popayan, Colombia, 15-17 September 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1-6.

- Sapkota, R.; Qureshi, R.; Calero, M.F.; Hussain, M.; Badjugar, C.; Nepal, U.; Poulose, A.; Zeno, P.; Vaddevolu, U.B.; Yan, H.; et al. YOLOv10 to Its Genesis: A Decadal and Comprehensive Review of the You Only Look Once Series. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.19407.

- Zhou, Y. A YOLO-NL object detector for real-time detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122256. [CrossRef]