DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02744-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38183526

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-06

بلورة مشتركة من ترامادول-سيلوكوكسيب مقابل ترامادول أو دواء وهمي للألم الحاد المعتدل إلى الشديد بعد جراحة الفم: تجربة عشوائية مزدوجة التعمية من المرحلة 3 (STARDOM1)

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

الملخص

المقدمة: الكوكرystal من ترامادول-سيلوكوكسيب (CTC) هو أول كوكرystal مسكن للألم للحالات الحادة. تم تقييم فعالية وأمان/تحمل CTC في هذه التجربة متعددة المراكز، مزدوجة التعمية، المرحلة الثالثة مقارنةً بترامادول في سياق الألم المعتدل إلى الشديد حتى 72 ساعة بعد استخراج ضرس العقل الثالث الانتقائي الذي يتطلب إزالة العظام. الطرق: البالغون (

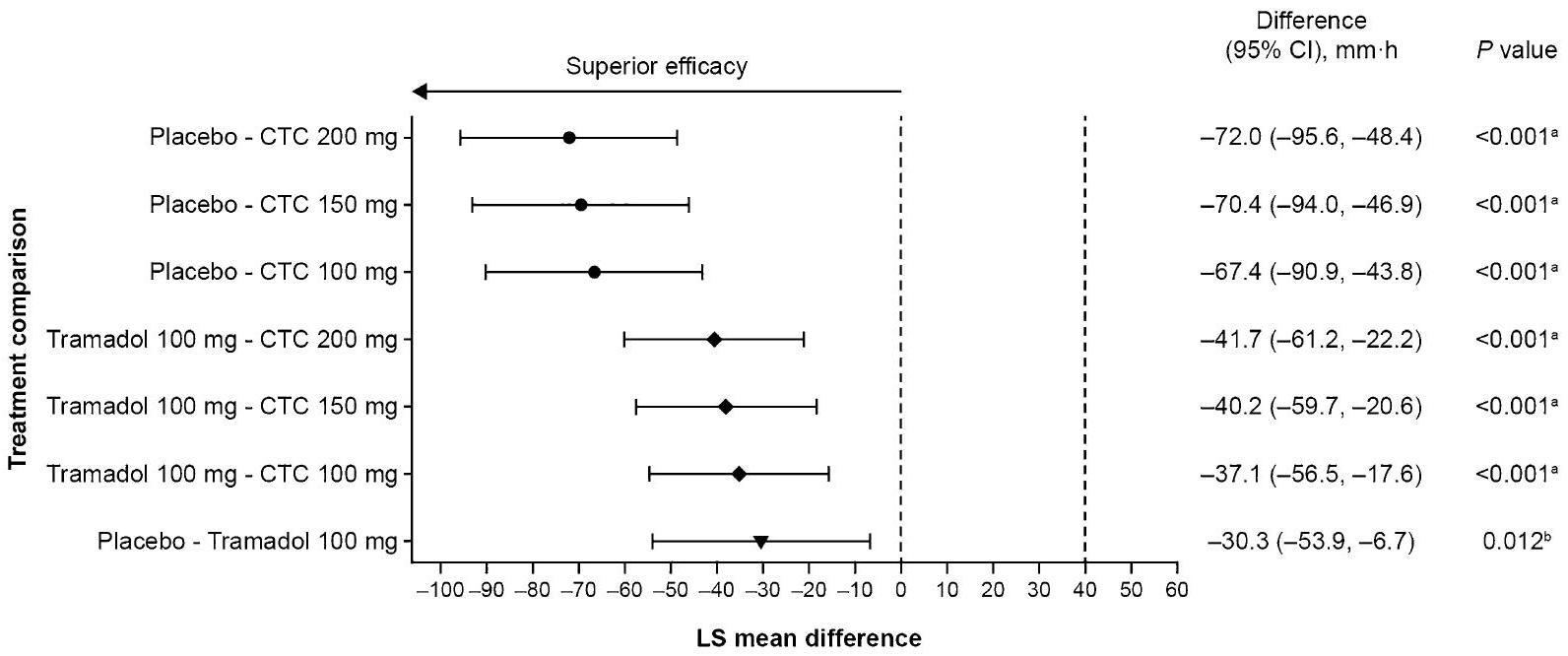

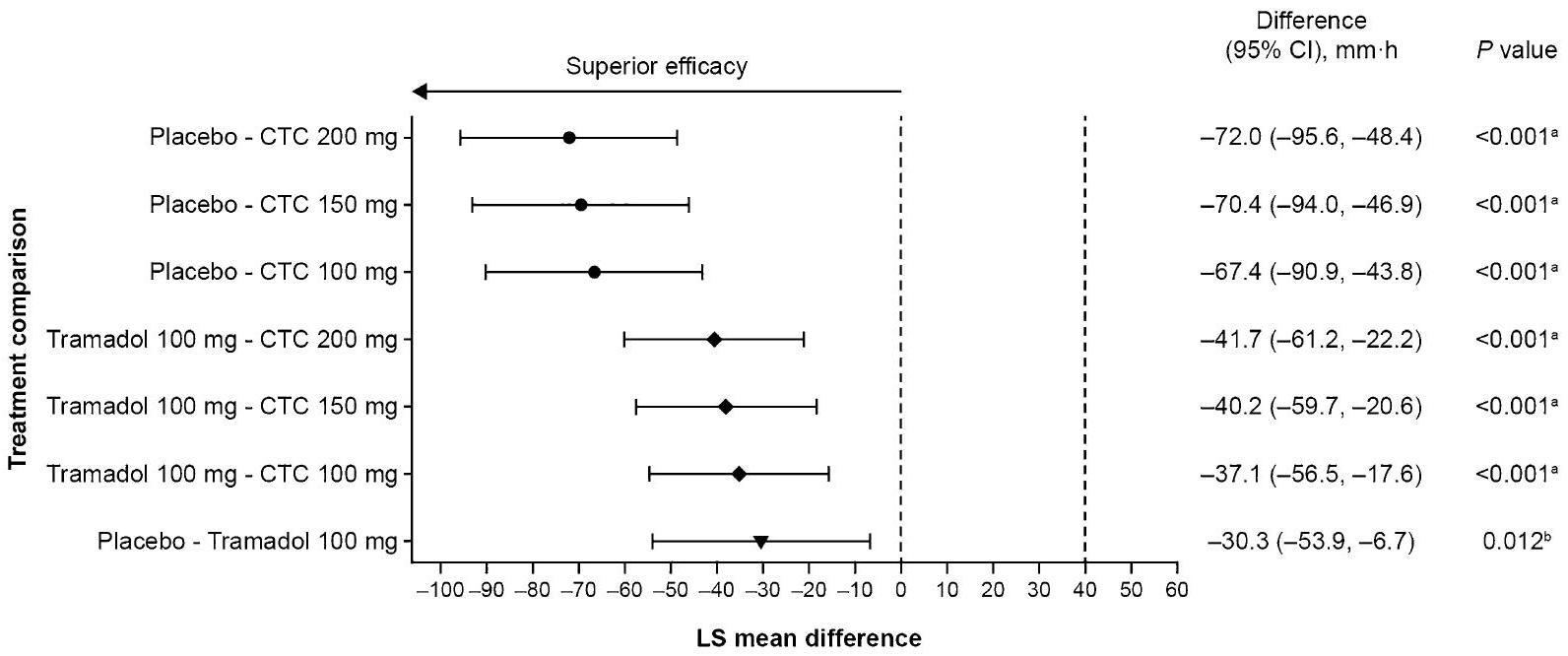

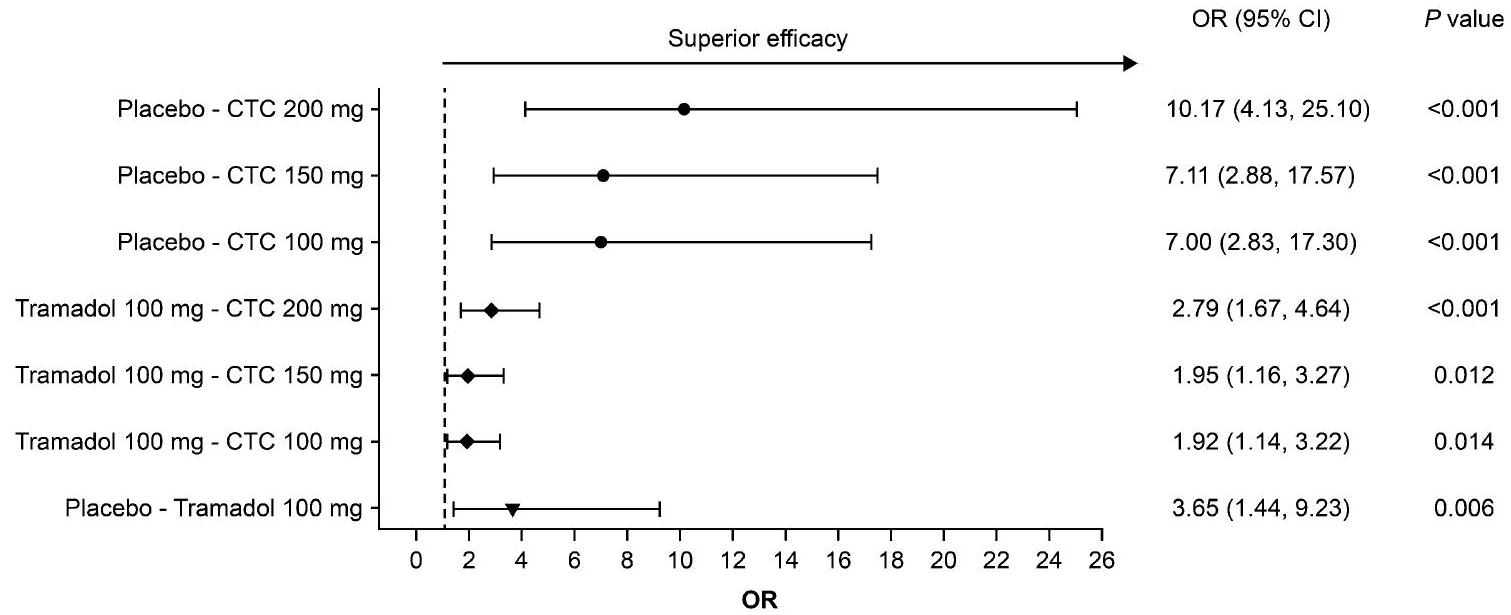

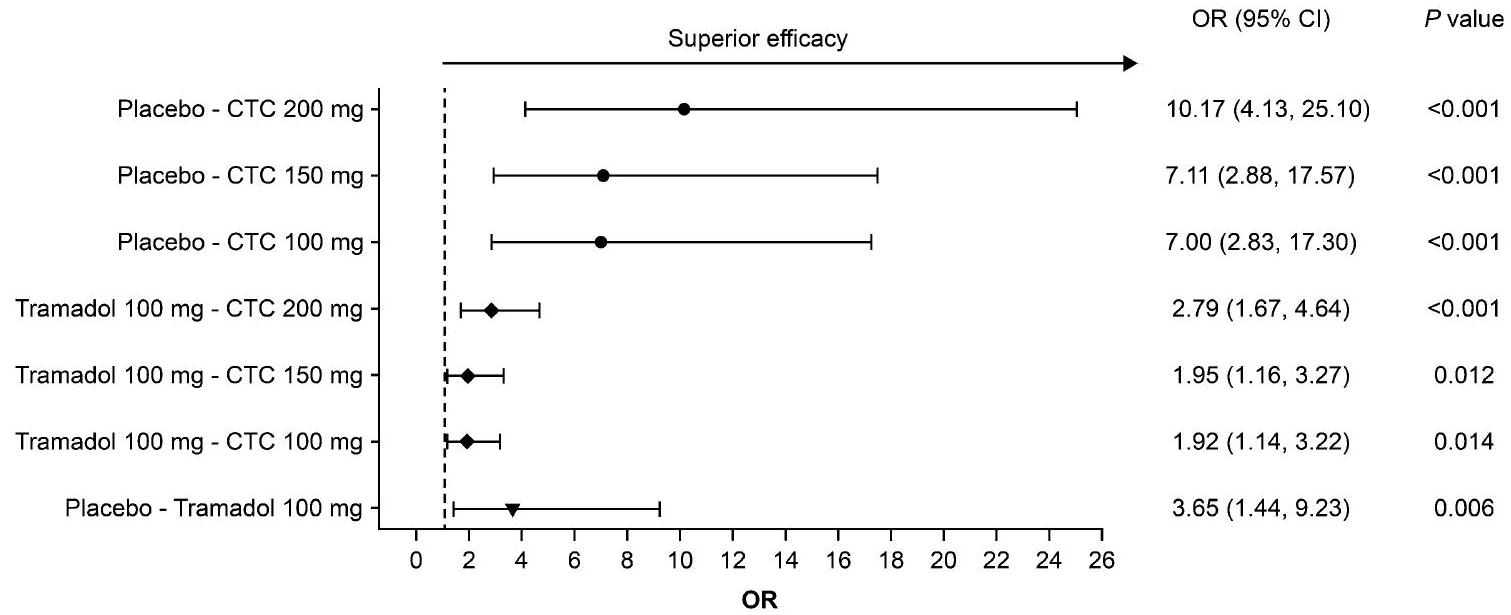

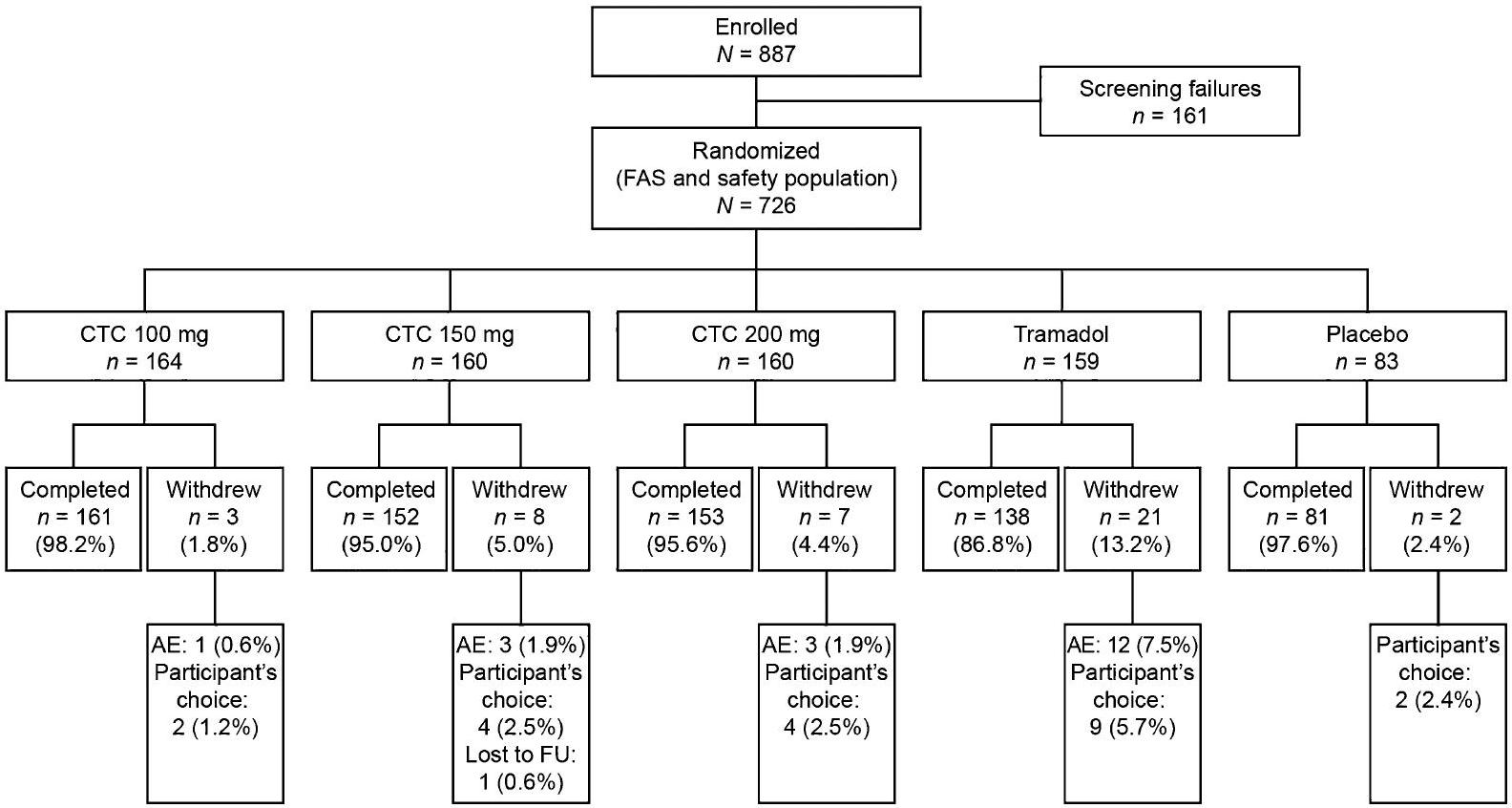

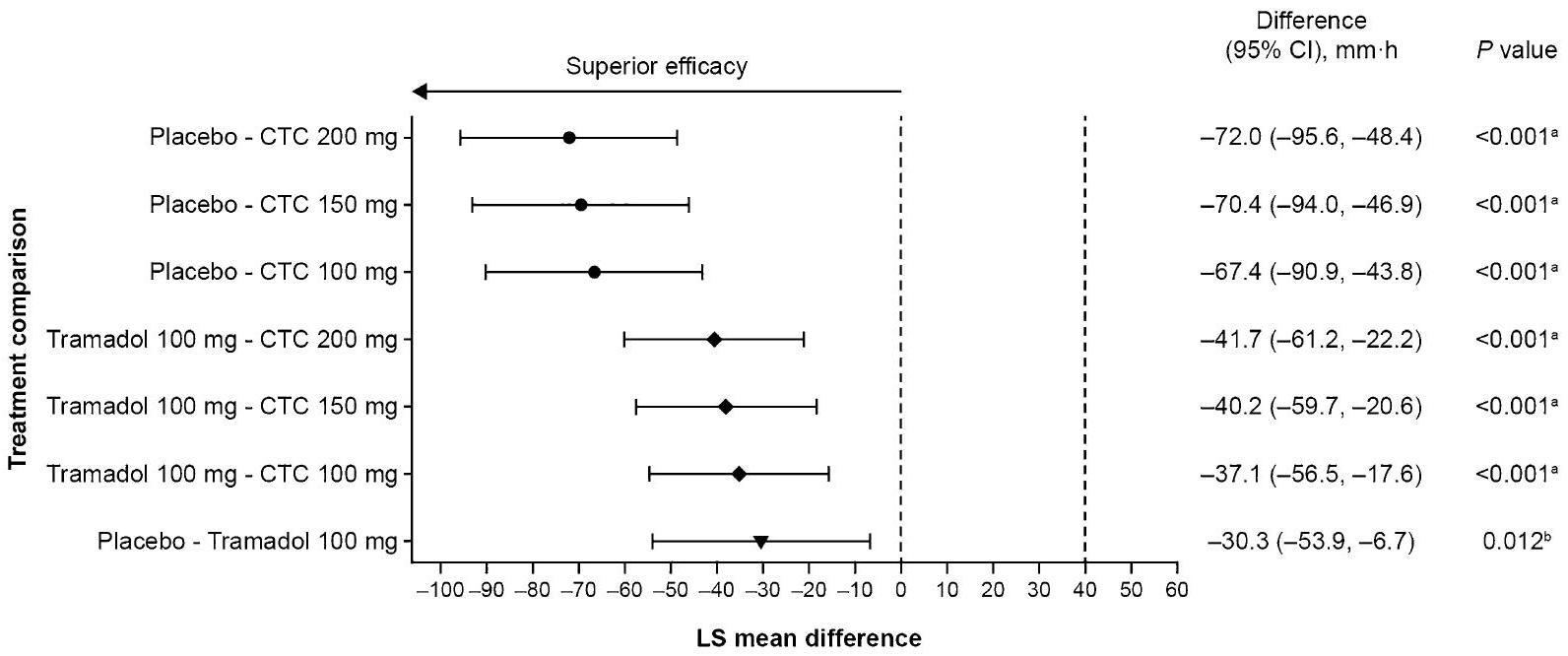

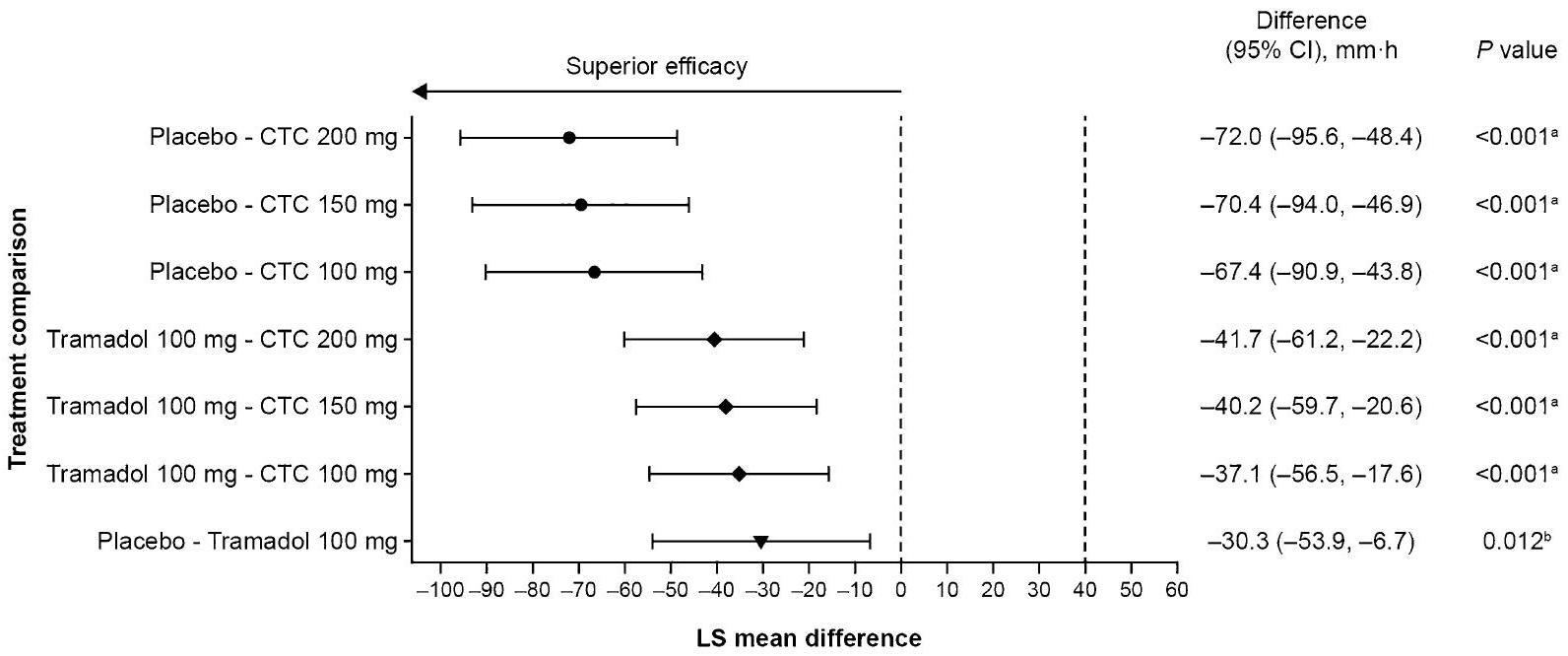

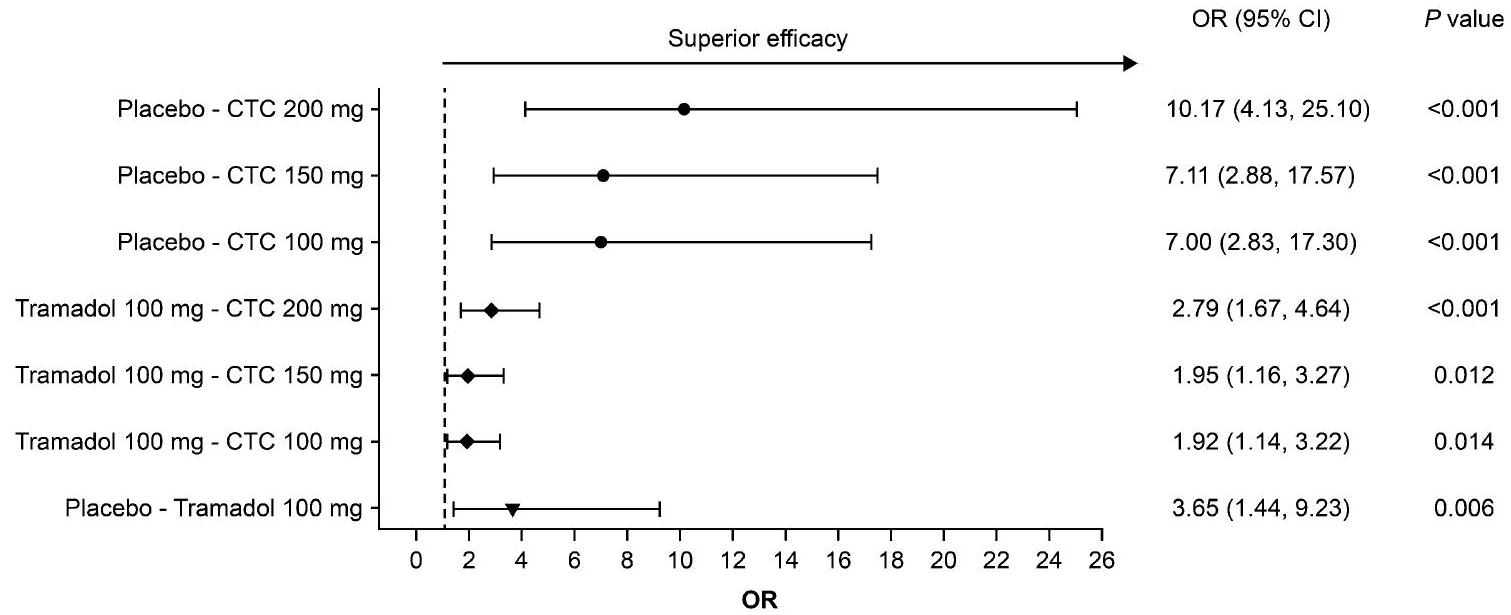

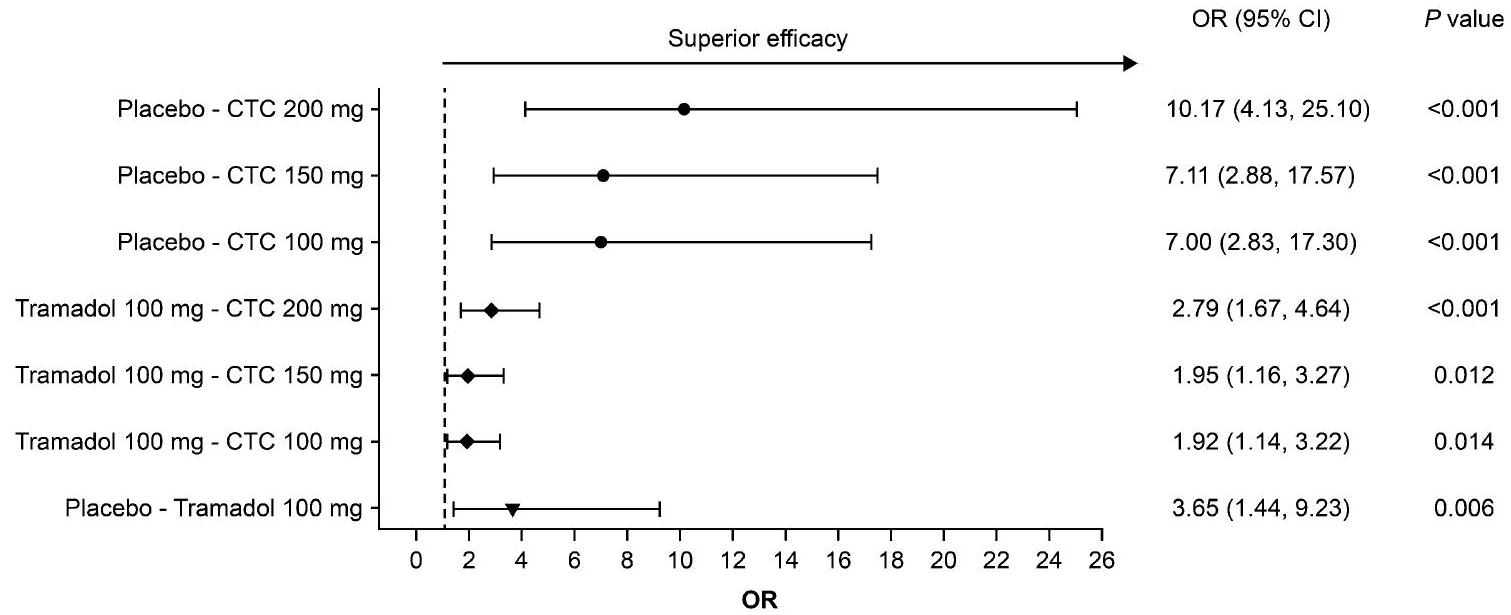

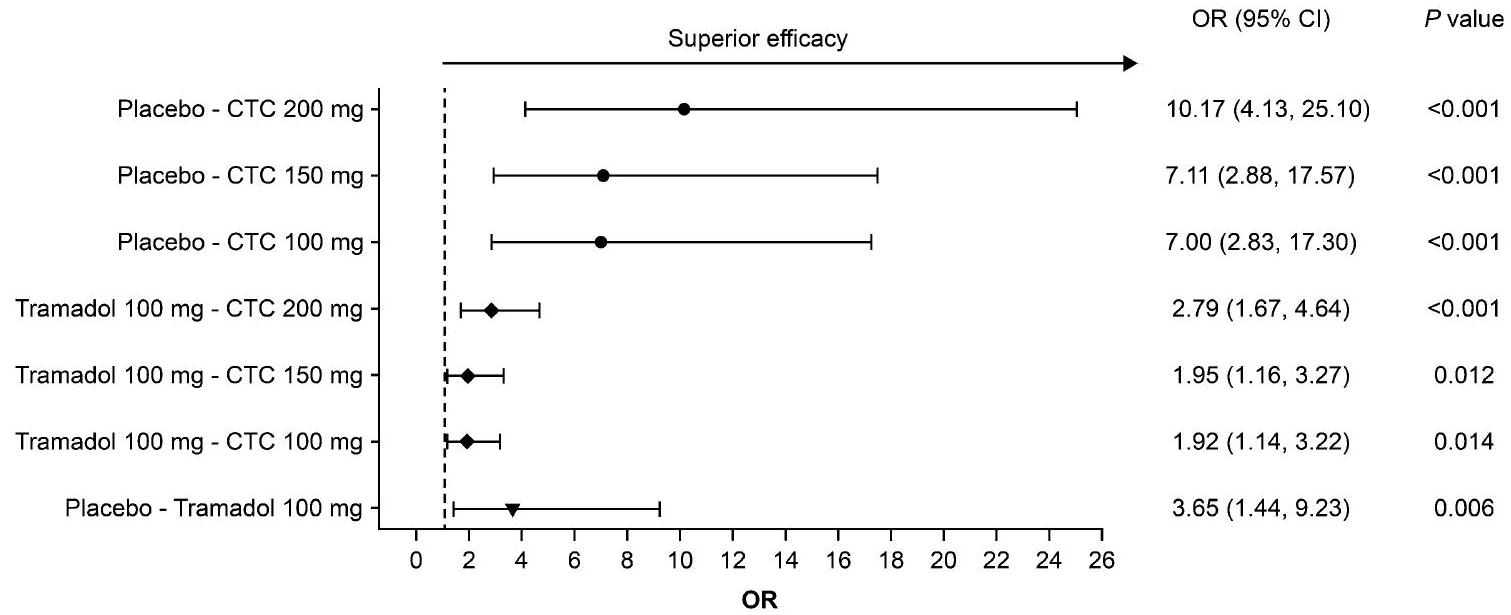

النتائج: كانت جميع جرعات CTC متفوقة على الدواء الوهمي (

الاستنتاجات: أظهر CTC تخفيفًا أفضل للألم مقارنةً بالترامادول أو الدواء الوهمي، بالإضافة إلى تحسين في نسبة الفائدة/المخاطر مقارنةً بالترامادول.

تسجيل التجربة:ClinicalTrials.govمعرف، NCT02982161؛ رقم EudraCT، 2016-00059224.

نقاط ملخص رئيسية

لماذا يتم إجراء هذه الدراسة؟

ماذا تم تعلمه من الدراسة؟

مقدمة

تعدل البنية البلورية لصيغة ‘الكو-كريستال’ الخصائص الفيزيائية والكيميائية وكذلك الحركية الدوائية للجزيئات النشطة، مما يقلل من التركيز الأقصى للتامادول في البلازما بينما يطيل الوقت للوصول إلى هذا التركيز ويقصر الوقت للوصول إلى التركيز الأقصى للسيلوكوكسيب في البلازما، بطريقة لا يمكن تحقيقها من خلال الإعطاء المشترك أو التركيبة الثابتة التقليدية. قد يكون هذا هو السبب وراء نتائج التجارب السريرية. أظهرت CTC ملف فائدة/خطر تم تحسينه بشكل كبير مقارنة بالتامادول والدواء الوهمي في تجربة المرحلة الثانية لإدارة الألم الفموي بعد الجراحة. في تجربة المرحلة الثالثة للألم بعد عملية إزالة عظمة الإبهام مع قطع العظام، كانت CTC مرتبطة بتخفيف أكبر للألم مقارنةً بجرعات يومية مماثلة من التامادول أو السيلوكوكسيب، مع تحمل مشابه للتامادول. كما وُجد أن CTC 200 ملغ ليست أدنى ولديها ملف فائدة/خطر محسّن مقارنة بالتامادول في تجربة المرحلة الثالثة للألم بعد استئصال الرحم البطني. تم اعتماد CTC من قبل إدارة الغذاء والدواء الأمريكية في عام 2021، وتلقت أول موافقة تنظيمية أوروبية (في إسبانيا) في سبتمبر 2023.

الطرق

تصميم الدراسة والإشراف

تم قفل البيانات، وعلى الرغم من أن الدراسة كانت مزدوجة التعمية، إلا أنه تم ذلك بسبب عدم الامتثال لممارسات السريرية الجيدة. تم اعتماد بروتوكول الدراسة من قبل لجنة الأخلاقيات المحلية في كل دولة و/أو موقع دراسة (المذكورة في الطرق S1 في المواد التكميلية الإلكترونية). كان الباحث الرئيسي من إسبانيا، وكانت لجنة الأخلاقيات الإسبانية هي لجنة الأخلاقيات للبحث السريري بالأدوية في مستشفى الأميرة (مدريد)، القرار رقم 20/17 بتاريخ 10 نوفمبر 2016. قدم جميع المرضى موافقة خطية مستنيرة خلال فترة الفحص للدراسة (أي قبل الجراحة). تم إجراء الدراسة وفقًا لإعلان هلسنكي وإرشادات ممارسات السريرية الجيدة.

المرضى

العشوائية والتعتيم

التدخلات

تم السماح باستخدامه كدواء إنقاذ خلال فترة التعمية المزدوجة. كانت الأدوية المرافقة التالية محظورة: الأدوية السيروتونية (بما في ذلك مثبطات استرداد السيروتونين الانتقائية ومثبطات استرداد السيروتونين والنورإبينفرين)، مضادات الاكتئاب ثلاثية الحلقات، مثبطات أكسيد أحادي الأمين، مضادات الذهان، مضادات التشنجات (ومنتجات أخرى تقلل من عتبة النوبات)، الأفيونات، مضادات الالتهاب غير الستيرويدية (بما في ذلك الأسيتامينوفين)، وحمض الأسيتيل ساليسيليك (الأسبرين؛ على الرغم من أنه تم السماح بجرعات منخفضة للوقاية من thrombosis/الوقاية القلبية).

التقييمات والنقاط النهائية

التحليلات الإحصائية

آثار العلاج المتفوقة ذات الصلة لـ CTC مقارنةً بالترامادول، مع الأخذ في الاعتبار الحاجة إلى إثبات تفوق CTC على الدواء الوهمي وعدم تفوقه على الترامادول. لإظهار عدم تفوق CTC مقابل الترامادول (مع افتراض هامش عدم التفوق من

نموذج (ANCOVA)، مع العلاج وQPI كآثار ثابتة، ومركز الدراسة كأثر عشوائي، وPI-VAS قبل الجرعة (0 ساعة) كمتغير مصاحب. تم استخدام طريقة آخر ملاحظة تم حملها للأمام (LOCF) للتعامل مع قيم PI-VAS المفقودة. بالنسبة للمرضى الذين تناولوا أدوية الإنقاذ، تم حمل آخر قيمة متاحة من PI-VAS قبل أول تناول لأدوية الإنقاذ للأمام لجميع النقاط الزمنية المتتالية.

النتائج

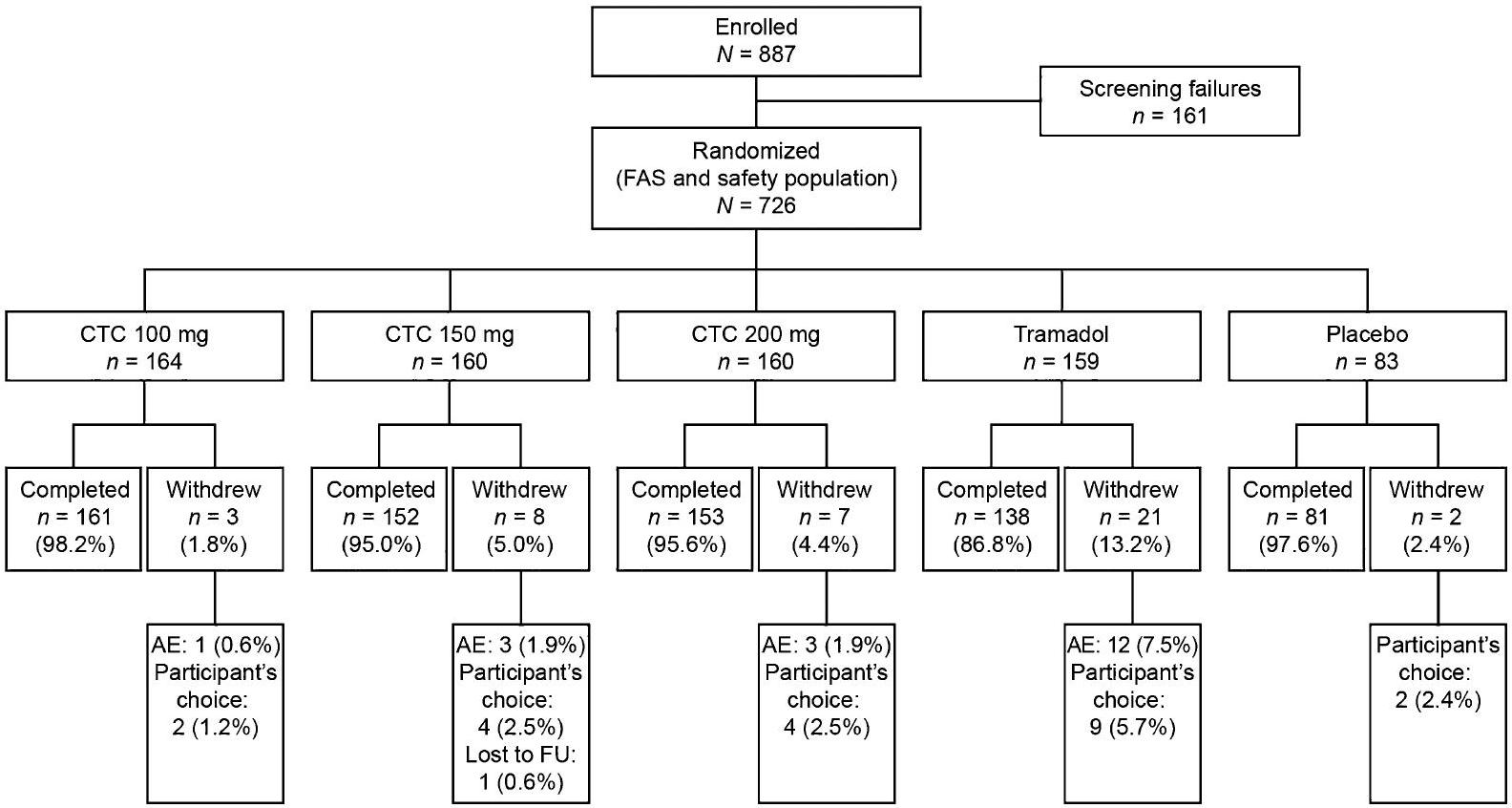

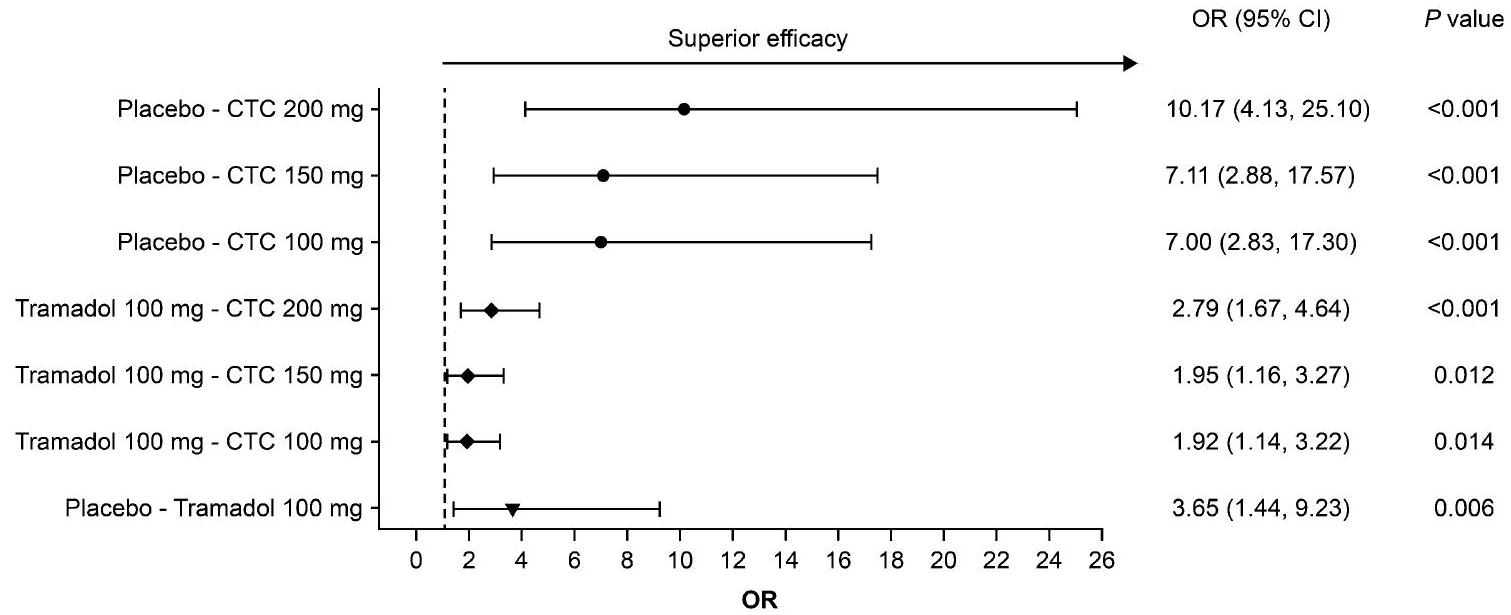

المرضى

النقطة النهائية الأساسية

زيادة إلى 8.1 (28.11) مم بعد 4 ساعات. أدى العلاج الوهمي إلى متوسط (انحراف معياري) PID قدره – 5.5 (23.03) مم بعد 4 ساعات.

النقاط الثانوية الرئيسية

| خاصية | CTC | ترامادول 100 ملغ

|

دواء وهمي (

|

الإجمالي (

|

||

|

|

|

|

||||

| العمر، سنوات | ||||||

|

|

164 | ١٦٠ | ١٦٠ | 159 | 83 | 726 |

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | ٢٦.٠ (٧.١٢) | 25.6 (5.75) | 25.6 (5.95) | 25.8 (6.11) | ٢٥.٨ (٦.٣٣) | 25.8 (6.25) |

| الوسيط | ٢٤.٠ | ٢٤.٠ | ٢٤.٠ | ٢٥.٠ | ٢٦.٠ | ٢٤.٠ |

| الحد الأدنى، الحد الأقصى | 18,69 | 18,52 | 18,47 | 18، 48 | 18، 44 | 18,69 |

| العمر المصنف

|

||||||

|

|

163 (99.4) | ١٦٠ (١٠٠.٠) | 160 (100.0) | 159 (100.0) | 83 (100.0) | 725 (99.9) |

|

|

1 (0.6) | – | – | – | – | 1 (0.1) |

|

|

– | – | – | – | – | – |

| الجنس،

|

||||||

| ذكر | 68 (41.5) | 66 (41.3) | 53 (33.1) | 63 (39.6) | ٢٨ (٣٣.٧) | 278 (38.3) |

| أنثى | ٩٦ (٥٨.٥) | 94 (58.8) | 107 (66.9) | 96 (60.4) | ٥٥ (٦٦.٣) | 448 (61.7) |

| سباق

|

||||||

| الأمريكيون الأصليون أو سكان ألاسكا الأصليون | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| آسيوي | 2 (1.2) | – | – | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.2) | 4 (0.6) |

| أسود أو أمريكي من أصل أفريقي | 2 (1.2) | – | – | 1 (0.6) | – | 3 (0.4) |

| هاواي الأصلي أو غيره من سكان جزر المحيط الهادئ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| أبيض | 158 (96.3) | 157 (98.1) | 156 (97.5) | 155 (97.5) | 80 (96.4) | 706 (97.2) |

| آخر | 2 (1.2) | 3 (1.9) | ٤ (٢.٥) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (2.4) | 13 (1.8) |

| خاصية | CTC | ترامادول 100 ملغ

|

دواء وهمي

|

الإجمالي (

|

||

|

|

|

|

||||

| الوزن، كجم | ||||||

|

|

164 | ١٦٠ | 159 | 159 | 83 | 725 |

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 70.68 (15.75) | 71.02 (16.54) | 69.85 (15.12) | 69.46 (14.11) | 68.82 (14.20) | 70.09 (15.25) |

| الوسيط | 68.75 | 67.05 | 67.00 | ٦٦.٠٠ | 65.00 | 67.00 |

| الحد الأدنى، الحد الأقصى | ٤٠.٠، ١١٧.٩ | ٤٣.٣، ١٢٥.٠ | ٤٤.٦، ١٢٩.٩ | ٤٤.٧، ١٢٤.٠ | ٤٨.٨، ١١٢.٠ | ٤٠.٠، ١٢٩.٩ |

| الطول، سم | ||||||

|

|

164 | ١٦٠ | 159 | 159 | 83 | 725 |

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 171.2 (9.20) | 171.5 (8.82) | 171.0 (9.43) | 170.4 (9.54) | 169.7 (8.68) | 170.9 (9.18) |

| الوسيط | ١٧٠٫٠ | ١٧٠٫٠ | 170.0 | ١٦٩.٠ | 167.0 | 170.0 |

| الحد الأدنى، الحد الأقصى | 154، 202 | 155، 194 | 153، 196 | 148، 197 | 154، 193 | 148، 202 |

| مؤشر كتلة الجسم،

|

||||||

|

|

164 | ١٦٠ | 159 | 159 | 83 | 725 |

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | ٢٣.٩٤ (٤.٢١) | ٢٣.٩٨ (٤.٤٢) | ٢٣.٨٣ (٤.٤٤) | ٢٣.٨٨ (٤.٠٨) | ٢٣.٧٦ (٤.٠٣) | ٢٣.٨٩ (٤.٢٥) |

| الوسيط | ٢٣.٤٠ | ٢٣.٢٠ | ٢٢.٨٠ | 23.10 | ٢٢.٦٠ | 23.10 |

| الحد الأدنى، الحد الأقصى | 16.2، 39.8 | 15.9، 40.8 | 17.0، 39.4 | 17.3، 38.1 | 18.4، 40.2 | 15.9، 40.8 |

| مؤشر كتلة الجسم المصنف

|

||||||

| نقص الوزن | 11 (6.7) | 10 (6.3) | 8 (5.0) | 7 (4.4) | 1 (1.2) | ٣٧ (٥.١) |

| وزن طبيعي | 90 (54.9) | 98 (61.3) | ١٠١ (٦٣.٥) | 98 (61.6) | ٥٦ (٦٧.٥) | ٤٤٣ (٦١.١) |

| زيادة الوزن | ٤٧ (٢٨.٧) | ٣٩ (٢٤.٤) | ٣٦ (٢٢.٦) | 40 (25.2) | 20 (24.1) | 182 (25.1) |

| بدين | 16 (9.8) | 13 (8.1) | 14 (8.8) | 14 (8.8) | 6 (7.2) | 63 (8.7) |

| مفقود | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| مدة الجراحة، دقيقة | ||||||

|

|

164 | ١٦٠ | ١٦٠ | 159 | 83 | 726 |

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | ٣٤.١ (١٥.٧) | ٣٥.٦ (١٧.٠) | ٣٥.٣ (١٥.٦) | ٣٣.٩ (١٨.٢) | ٣٤.٢ (١٨.٧) | ٣٤.٦ (١٦.٩) |

| خاصية | CTC | ترامادول 100 ملغ

|

دواء وهمي (

|

الإجمالي (

|

||

|

|

|

|

||||

| درجة PI-VAS المؤهلة | ||||||

| ن | 164 | ١٦٠ | ١٦٠ | 159 | 83 | 726 |

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | ٥٥.٦ (٨.٣٨) | ٥٦.٢ (١٠.٤٥) | ٥٦.٥ (٩.٤٣) | ٥٦.١ (٨.٥٨) | 55.0 (8.53) | ٥٦.٠ (٩.١٥) |

| الوسيط | 53.0 | 53.0 | ٥٤.٠ | ٥٤.٠ | 52.0 | 53.0 |

| الحد الأدنى، الحد الأقصى | ٤٥، ٨٧ | ٤٠,١٠٠ | ٤٥,١٠٠ | ٤٥، ٨٨ | ٤٥,٧٨ | ٤٠,١٠٠ |

| درجة PI-VAS المؤهلة المصنفة

|

||||||

| معتدل

|

153 (93.3) | 143 (89.4) | 145 (90.6) | 147 (92.5) | 76 (91.6) | 664 (91.5) |

| شديد

|

11 (6.7) | 17 (10.6) | 15 (9.4) | 12 (7.5) | 7 (8.4) | 62 (8.5) |

| درجة PI-VAS قبل الجرعة (0 ساعة)

|

||||||

|

|

163 | ١٦٠ | ١٦٠ | 158 | 83 | 724 |

| المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | 60.8 (11.35) | 60.8 (15.68) | 61.8 (11.77) | 61.1 (12.35) | ٥٩.٠ (١٠.٦٠) | 60.9 (12.64) |

| الوسيط | ٥٧.٠ | 60.0 | 60.0 | ٥٨.٠ | ٥٧.٠ | ٥٨.٠ |

| الحد الأدنى، الحد الأقصى | ٢٣، ٨٩ | ٢, ١٠٠ | ٢٥,٩٩ | ٢٧، ٩١ | ٣٧، ٨٤ | ٢, ١٠٠ |

| CTC | ترامادول | دواء وهمي | إجمالي | |||

|

|

|

|

100 ملغ (

|

(

|

(

|

|

| تحليل بعد الحدث | ||||||

| درجة PI-VAS قبل الجرعة (0 ساعة) المصنفة،

|

||||||

| معتدل

|

125 (76.7) | 121 (75.6) | ١١٩ (٧٤.٤) | ١٢٢ (٧٧.٢) | 66 (79.5) | ٥٥٣ (٧٦.٤) |

| شديد

|

٣٨ (٢٣.٣) | ٣٩ (٢٤.٤) | 41 (25.6) | ٣٦ (٢٢.٨) | 17 (20.5) | 171 (23.6) |

| النسب المئوية تعتمد على عدد المرضى الذين تتوفر لديهم بيانات | ||||||

| مؤشر كتلة الجسم (BMI)، بلورة مشتركة من ترامادول-سيلوكوكسيب (CTC)، شدة الألم – مقياس بصري تماثلي (PI-VAS)، الانحراف المعياري (SD) | ||||||

|

|

||||||

أهمية

من اختبار التفوق أحادي الجانب لاختبار الفرضية الصفرية التي تفيد بأن الفرق في المتوسطات هو

|

|

|

|

دواء وهمي | |||||||||

|

|

٥٤ | ٥٤ | 65 | 32 | ٦ | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CTC | CTC | CTC | ترامادول | دواء وهمي | |

| 100 ملغ | 150 ملغ | 200 ملغ | 100 ملغ | ||

| دواء الإنقاذ | 67 | 71 | 63 | 89 | 66 |

| استخدم في 4 ساعات

|

|

|

|

|

|

مقياس شدة الألم البصري.

اختبار عدم الفرق لاختبار الفرضية الصفرية التي تفيد أن

الترم الثاني: الترم الأول، كما هو موضح.

فترة

نسبة مقياس ستي-المرئي التماثلي.

نسبة نسبة

| CTC | ترامادول 100 ملغ

|

دواء وهمي (

|

|||

| TEAEs | 120 (73.2) | ١١٩ (٧٤.٨) | ١٣٢ (٨٢.٥) | 137 (85.6) | ٤٩ (٥٩.٠) |

| الآثار الجانبية المرتبطة بالعلاج | 98 (59.8) | 106 (66.7) | 120 (74.4) | ١٣٢ (٨٢.٥) | 30 (36.1) |

| آثار جانبية خطيرة | 19 (11.6) | 16 (10.1) | ٢٨ (١٧.٥) | 57 (35.6) | 9 (10.8) |

| الأحداث السلبية التي أدت إلى التوقف | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 12 (7.5) | 0 |

| آثار جانبية خطيرة | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| الوفيات | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| أكثر الأحداث الضائرة المتعلقة بالعلاج تكرارًا

|

|||||

| نعاس | 62 (37.8) | 73 (45.9) | 96 (60.0) | 98 (61.3) | ٢٣ (٢٧.٧) |

| دوار | 41 (25.0) | ٤٧ (٢٩.٦) | ٥٩ (٣٦.٩) | 89 (55.6) | 11 (13.3) |

| إرهاق | 44 (26.8) | ٤٦ (٢٨.٩) | ٥٩ (٣٦.٩) | 69 (43.1) | ٢١ (٢٥.٣) |

| غثيان | 41 (25.0) | 44 (27.7) | ٤٦ (٢٨.٨) | 87 (54.4) | 12 (14.5) |

| التقيؤ | ٣٩ (٢٣.٨) | ٢٩ (١٨.٢) | ٣٥ (٢١.٩) | 84 (52.5) | 6 (7.2) |

| اضطراب في الانتباه | ٢٤ (١٤.٦) | ٢٣ (١٤.٥) | ٣٣ (٢٠.٦) | 50 (31.3) | 14 (16.9) |

| حكة | 4 (2.4) | 18 (11.3) | 25 (15.6) | 44 (27.5) | 3 (3.6) |

| حالة ارتباك | 11 (6.7) | 9 (5.7) | 16 (10.0) | 29 (18.1) | 8 (9.6) |

| إمساك | 11 (6.7) | 12 (7.5) | 16 (10.0) | ٢٨ (١٧.٥) | 4 (4.8) |

| عُسْرُ البَوْل | 1 (0.6) | ٤ (٢.٥) | 13 (8.1) | ٣٣ (٢٠.٦) | 2 (2.4) |

| التقيؤ | 2 (1.2) | ٤ (٢.٥) | ٤ (٢.٥) | 13 (8.1) | 2 (2.4) |

| صداع | 4 (2.4) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 5 (3.1) | 1 (1.2) |

| حكة عامة | 0 | 2 (1.3) | 3 (1.9) | 7 (4.4) | 0 |

| فرط التعرق | 3 (1.8) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | ٤ (٢.٥) | 0 |

| وهن | 0 | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | ٤ (٢.٥) | 1 (1.2) |

| malaise | 0 | 0 | 5 (3.1) | 2 (1.3) | 0 |

| TEAEs ذات الاهتمام الإضافي | |||||

| علامات وأعراض الجهاز الهضمي | ٥٨ (٣٥.٤) | 51 (32.1) | ٥٦ (٣٥.٠) | ١٠٨ (٦٧.٥) | 15 (18.1) |

| غثيان | ٤٨ (٢٩.٣) | ٤٧ (٢٩.٦) | 50 (31.3) | 90 (56.3) | 15 (18.1) |

| التقيؤ | 40 (24.4) | 32 (20.1) | ٣٦ (٢٢.٥) | ٨٨ (٥٥.٠) | 9 (10.8) |

| اضطرابات عصبية | 89 (54.3) | 93 (58.5) | ١١٢ (٧٠.٠) | 114 (71.3) | ٣٣ (٣٩.٨) |

| دوار | ٤٦ (٢٨.٠) | ٤٨ (٣٠.٢) | 61 (38.1) | 90 (56.3) | 12 (14.5) |

| نعاس | 75 (45.7) | 83 (52.2) | ١٠٥ (٦٥.٦) | ١٠١ (٦٣.١) | ٣١ (٣٧.٣) |

نقاط نهاية ثانوية إضافية

كانت الفروق بين العلاج الوهمي وجميع جرعات CTC ذات دلالة إحصائية؛ لم تكن الفروق بين CTC والتامول ذات دلالة إحصائية (الجدول S9).

السلامة، التحمل، والدوائية

تظهر الآثار الجانبية المرتبطة بالعلاج في الجدول 2 والشكل S9. بالنسبة لجميع الآثار الجانبية المرتبطة بالعلاج باستثناء الشعور بالضيق، كانت النسبة الأكبر من المرضى الذين عانوا من كل أثر جانبي مرتبط بالعلاج في مجموعة الترامادول. في مجموعات CTC، لوحظ نمط يعتمد على الجرعة لمعظم الآثار الجانبية المرتبطة بالعلاج. فيما يتعلق بالآثار الجانبية ذات الاهتمام الإضافي، 288 (

نقاش

البيانات السابقة التي تم الإبلاغ عنها من الدراسات ما قبل السريرية والمرحلة 1 تظهر أن CTC له خصائص فيزيائية كيميائية معدلة وحرائك دوائية مقارنة بالترامادول والسيلوكوكسيب، سواء تم استخدامه بمفرده أو في تركيبة حرة [23-26]. في دراسة المرحلة 1 التي تم الإبلاغ عنها مؤخرًا [24]، أدى السيلوكوكسيب من CTC إلى انخفاض في

كانت الأعراض الجانبية التي أدت إلى التوقف عن العلاج هي الغثيان والقيء والدوار (كل منها حدث في 6 مرضى)، حيث كانت حالة واحدة من القيء خطيرة. لم يتوقف أي مريض في أي مجموعة بسبب عدم الفعالية. هذا الأمر ذو صلة خاصة بالجراحة الخارجية، حيث يدير المرضى الألم المفاجئ والأعراض الجانبية في المنزل؛ لذا فإن معدل الأعراض الجانبية المنخفض المبلغ عنه هنا لـ CTC مقارنة بالترامادول، جنبًا إلى جنب مع الفعالية المستمرة على مر الزمن، قد يحسن من التزام المرضى وبالتالي النتائج. حسب علمنا، فإن تقريرنا هو الأول الذي يتناول إضافة السيلوكوكسيب إلى مسكنات الترامادول مما أدى إلى تقليل استهلاك الترامادول (مقارنة بالعلاج الأحادي بالترامادول) وتقليل الأعراض الجانبية. من المحتمل أن يكون لـ CTC فائدة في المرضى الذين يحتاجون إلى مسكنات متعددة الوسائط، والذين لا يتم إدارة ألمهم بشكل كافٍ من خلال العلاج بمضادات الالتهاب غير الستيرويدية أو الأسيتامينوفين وحده، وفقًا للخطوة 2 من سلم المسكنات التابع لمنظمة الصحة العالمية.

تم تأكيد الحساسية من خلال تفوق الترامادول على الدواء الوهمي. وقد أظهر CTC فعالية مسكنة في الدراسة، مع جرعات يومية إجمالية أقل من الأفيونات مقارنة بمجموعة الترامادول.

كما في دراسات أخرى، كانت النسبة متوافقة بشكل أفضل مع تقارير الأدبيات [27، 47، 54].

الاستنتاجات

شكر وتقدير

إعلانات

تسمح بأي استخدام غير تجاري، ومشاركة، وتكييف، وتوزيع وإعادة إنتاج في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت هناك تغييرات قد تم إجراؤها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر ائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

REFERENCES

- Sinatra R. Causes and consequences of inadequate management of acute pain. Pain Med. 2010;11(12): 1859-71.

- Gan TJ, Habib AS, Miller TE, White W, Apfelbaum JL. Incidence, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of post-surgical pain: results from a US national survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(1):149-60.

- Gregory J, McGowan L. An examination of the prevalence of acute pain for hospitalised adult patients: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(5-6):583-98.

- Kaye AD, Urman RD, Rappaport Y, et al. Multimodal analgesia as an essential part of enhanced recovery protocols in the ambulatory settings. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2019;35(Suppl 1): S40-5.

- Walker EMK, Bell M, Cook TM, Grocott MPW, Moonesinghe SR. Patient reported outcome of adult perioperative anaesthesia in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional observational study. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(6):758-66.

- Edgley C, Hogg M, De Silva A, Braat S, Bucknill A, Leslie K. Severe acute pain and persistent post-surgical pain in orthopaedic trauma patients: a cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(3):350-9.

- Galinski M, Ruscev M, Gonzalez G, et al. Prevalence and management of acute pain in prehospital emergency medicine. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010; 14(3):334-9.

- Tan M, Law LS, Gan TJ. Optimizing pain management to facilitate Enhanced Recovery After Surgery pathways. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62(2):203-18.

- Gan TJ. Poorly controlled postoperative pain: prevalence, consequences, and prevention. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2287-98.

- Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Segelcke D, Schug SA. Postoperative pain-from mechanisms to treatment. Pain Rep. 2017;2(2):e588.

- Bier JD, Kamper SJ, Verhagen AP, Maher CG, Williams CM. Patient nonadherence to guideline-recommended care in acute low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(12):2416-21.

- Stessel B, Theunissen M, Marcus MA, et al. Prevalence and predictors of patient nonadherence to pharmacological acute pain therapy at home after day surgery: a prospective cohort study. Pain Pract. 2018;18(2):194-204.

- Callebaut I, Jorissen S, Pelckmans C, et al. Fourweek pain profile and patient non-adherence to pharmacological pain therapy after day surgery. Anesth Pain Med. 2020;10(3):e101669.

- Beverly A, Kaye AD, Ljungqvist O, Urman RD. Essential elements of multimodal analgesia in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) guidelines. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35:e115-43.

- Hagen K, Iohom G. Pain management for ambulatory surgery: what is new? Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2014;4(4):326-33.

- Almansa C, Frampton CS, Vela JM, Whitelock S, Plata-Salamán CR. Co-crystals as a new approach to multimodal analgesia and the treatment of pain. J Pain Res. 2019;12:2679-89.

- Gascón N, Almansa C, Merlos M, et al. Co-crystal of tramadol-celecoxib: preclinical and clinical evaluation of a novel analgesic. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28(5):399-409.

- Suzuki K, Naito T, Tanaka H, et al. Impact of CYP2D6 activity and cachexia progression on enantiomeric alteration of plasma tramadol and its demethylated metabolites and their relationships with central nervous system symptoms in head and neck cancer patients. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2021;128(3):472-81.

- Gillen C, Haurand M, Kobelt DJ, Wnendt S. Affinity, potency and efficacy of tramadol and its metabolites at the cloned human mu-opioid receptor. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362(2):116-21.

- Nissen SE, Yeomans ND, Solomon DH, et al. Cardiovascular safety of celecoxib, naproxen, or ibuprofen for arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(26): 2519-29.

- Arfe A, Scotti L, Varas-Lorenzo C, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of heart failure in four European countries: nested casecontrol study. BMJ. 2016;354:i4857.

- Derry S, Moore RA. Single dose oral celecoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(10):CD004233.

- Almansa C, Mercè R, Tesson N, Farran J, Tomàs J, PlataSalamán CR. Co-crystal of tramadol hydrochlo-ride-celecoxib (CTC): a novel API-API co-crystal for the treatment of pain. Cryst Growth Des. 2017;17: 1884-92.

- Cebrecos J, Carlson JD, Encina G, et al. Celecoxibtramadol co-crystal: a randomized 4-way crossover comparative bioavailability study. Clin Ther. 2021;43(6):1051-65.

- Port A, Almansa C, Enrech R, Bordas M, Plata-Salamán CR. Differential solution behavior of the new API-API co-crystal of tramadol-celecoxib (CTC) versus its constituents and their combination. Cryst Growth Des. 2019;19:3172-82.

- Videla S, Lahjou M, Vaqué A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of multiple doses of co-crystal of tramadolcelecoxib: findings from a four-way randomized open-label phase I clinical trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(1):64-78.

- López-Cedrún J, Videla S, Burgueño M, et al. Cocrystal of tramadol-celecoxib in patients with moderate to severe acute post-surgical oral pain: a dose-finding, randomised, double-blind, placeboand active-controlled, multicentre, phase II trial. Drugs R D. 2018;18(2):137-48.

- Viscusi ER, de Leon-Casasola O, Cebrecos J, et al. Celecoxib-tramadol co-crystal in patients with moderate-to-severe pain following bunionectomy with osteotomy: a phase 3 , randomized, doubleblind, factorial, active-and placebo-controlled trial. Pain Pract. 2023;23(1):8-22.

- Langford R, Morte A, Sust M, et al. Efficacy and safety of co-crystal of tramadol-celecoxib (CTC) in acute moderate-to-severe pain after abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial (STARDOM2). Eur J Pain. 2022;26(10):2083-96.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing information, SEGLENTIS. 2021. https://www. accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/213 426s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov 2021.

- ESTEVE Pharmaceuticals SA. Velyntra Spanish Regulatory Approval. 2023. https://cima.aemps.es/ cima/dochtml/ft/89051/FT_89051.html. Accessed 9 Oct 2023

- Bretz F, Maurer W, Brannath W, Posch M. A graphical approach to sequentially rejective multiple test procedures. Stat Med. 2009;28(4):586-604.

- Videla S, Lahjou M, Vaqué A, et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of co-crystal of tramadol-celecoxib: results of a four-way randomized open-label phase I clinical trial in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(12):2718-28.

- Reines SA, Goldmann B, Harnett M, Lu L. Misuse of tramadol in the United States: an analysis of the National Survey of Drug Use and Health 2002-2017. Subst Abuse. 2020;14: 1178221820930006.

- Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-57.

- Mikosz CA, Zhang K, Haegerich T, et al. Indicationspecific opioid prescribing for US patients with Medicaid or private insurance, 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e204514.

- Echeverria-Villalobos M, Stoicea N, Todeschini AB, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS): a perspective review of postoperative pain management under ERAS pathways and its role on opioid crisis in the United States. Clin J Pain. 2020;36(3): 219-26.

- Malamed SF. Pain management following dental trauma and surgical procedures. Dent Traumatol. 2023;39(4):295-303.

- Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Liedgens H, Hummelshoj L, et al. Developing consensus on core outcome domains for assessing effectiveness in perioperative pain management: results of the PROMPT/IMIPainCare Delphi Meeting. Pain. 2021;162(11): 2717-36.

- Anekar AA, Cascella M. WHO Analgesic Ladder, in StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Mishra H, Khan FA. A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized comparison of pre and postoperative administration of ketorolac and tramadol for dental extraction pain. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012;28(2):221-5.

- Borel JF, Deschaumes C, Devoize L, et al. Treating pain after dental surgery: a randomised, controlled, double-blind trial to assess a new formulation of paracetamol, opium powder and caffeine versus tramadol or placebo [article in French]. Presse Med. 2010;39(5):e103-11.

- Janssen. Ultram (tramadol hydrochloride) prescribing information. https://www.janssenlabels. com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/ULTRAM-pi.pdf (2023). Accessed 12 Jul 2023.

- Fricke JR Jr, Hewitt DJ, Jordan DM, Fisher A, Rosenthal NR. A double-blind placebo-controlled comparison of tramadol/acetaminophen and tramadol in patients with postoperative dental pain. Pain. 2004;109(3):250-7.

- Moore RA, Gay-Escoda C, Figueiredo R, et al. Dexketoprofen/tramadol: randomised double-blind trial and confirmation of empirical theory of combination analgesics in acute pain. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:541.

- Moore RA, McQuay HJ, Tomaszewski J, et al. Dexketoprofen/tramadol

: randomised double-blind trial in moderate-to-severe acute pain after abdominal hysterectomy. BMC Anesthesiol. 2016;16:9. - Singla NK, Desjardins PJ, Chang PD. A comparison of the clinical and experimental characteristics of four acute surgical pain models: dental extraction, bunionectomy, joint replacement, and soft tissue surgery. Pain. 2014;155(3):441-56.

- Pergolizzi JV, Magnusson P, LeQuang JA, Gharibo C, Varrassi G. The pharmacological management of

dental pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020; 21(5):591-601. - Isiordia-Espinoza MA, de Jesús Pozos-Guillén A, Aragon-Martinez OH. Analgesic efficacy and safety of single-dose tramadol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in operations on the third molars: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52(9):775-83.

- Akinbade AO, Ndukwe KC, Owotade FJ. Comparative analgesic effects of ibuprofen, celecoxib and tramadol after third molar surgery: a randomized double blind controlled trial. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2018;19(11):1334-40.

- Edinoff AN, Kaplan LA, Khan S, et al. Full opioid agonists and tramadol: pharmacological and clinical considerations. Anesth Pain Med. 2021;11(4): e119156.

- Health Products Regulatory Authority. Summary of Product Characteristics, Zydol 50 mg Hard Capsules. https://www.hpra.ie/img/uploaded/swedocuments/ Licence_PA2242-005-001_18022022162405.pdf (2022). Accessed 13 Nov 2023.

- Pfizer Inc. CELEBREX (celecoxib) capsule: highlights of prescribing information. http://labeling.pfizer. com/showlabeling.aspx?id=793 (2021) Accessed 7 Aug 2021.

- Gay-Escoda C, Hanna M, Montero A, et al. Tramadol/dexketoprofen (TRAM/DKP) compared with tramadol/paracetamol in moderate to severe acute pain: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo and active-controlled, parallel group trial in the impacted third molar extraction pain model (DAVID study). BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e023715.

- Prior presentation: An abstract reporting these data was presented as a poster at the European Pain Federation (EFIC) 2022 congress, Dublin, Ireland, 27-30 April, 2022.Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https:// doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02744-2.

R. Langford () University Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany

A. MorteM. Sust J. Cebrecos A. Vaqué E. Ortiz - N. Gascón • C. Plata-Salamán

ESTEVE Pharmaceuticals, Barcelona, Spain

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02744-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38183526

Publication Date: 2024-01-06

Co-crystal of Tramadol-Celecoxib Versus Tramadol or Placebo for Acute Moderate-to-Severe Pain After Oral Surgery: Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Trial (STARDOM1)

© The Author(s) 2024

Abstract

Introduction: Co-crystal of tramadol-celecoxib (CTC) is the first analgesic co-crystal for acute pain. This completed phase 3 multicenter, double-blind trial assessed the efficacy and safety/tolerability of CTC in comparison with that of tramadol in the setting of moderate-tosevere pain up to 72 h after elective third molar extraction requiring bone removal. Methods: Adults (

Results: All CTC doses were superior to placebo (

Conclusions: CTC demonstrated superior pain relief compared with tramadol or placebo, as well as an improved benefit/risk profile versus tramadol.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02982161; EudraCT number, 2016-00059224.

Key Summary Points

Why carry out this study?

What was learned from the study?

INTRODUCTION

crystalline structure of the ‘co-crystal’ formulation modifies the physicochemical characteristics as well as the pharmacokinetics of the active molecules-decreasing the maximum concentration of tramadol in plasma while prolonging the time to achieve this and shortening the time to reach the maximum concentration of celecoxib in plasma [24]-in a manner that is not attainable via coadministration or conventional fixed-dose combination. This may underlie clinical trial findings [25, 26]. CTC demonstrated a benefit/risk profile that was significantly improved versus that of tramadol and placebo in a phase 2 trial on postoperative management of oral pain [27]. In a phase 3 trial of pain following bunionectomy with osteotomy, CTC was associated with greater pain relief than similar daily doses of tramadol or celecoxib, with comparable tolerability as tramadol [28]. CTC 200 mg was also found to be noninferior and to have an improved benefit/ risk profile compared with tramadol in a phase 3 trial of pain following abdominal hysterectomy [29]. CTC was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2021 [30], and received its first European regulatory approval (in Spain) in September 2023 [31].

METHODS

Study Design and Oversight

data lock and while the study was blinded, because of non-compliance with Good Clinical Practice. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee for each country and/or study site (listed in Methods S1 in the electronic supplementary material). The principal investigator was from Spain, and the Spanish ethics committee was the Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica con Medicamentos del Hospital Universitario de la Princesa (Madrid), resolution no. 20/17 of 10 November 2016. All patients provided written informed consent during the screening period of the study (i.e. before surgery). The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Patients

Randomization and Masking

Interventions

permitted as rescue medication during the double-blind period. The following concomitant medications were prohibited: serotonergic drugs (including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants (and other products that lower the seizure threshold), opioids, NSAIDs (including acetaminophen), and acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin; although low doses were permitted for anti-thrombosis/cardiac prophylaxis).

Assessments and Endpoints

Statistical Analyses

relevant superior treatment effects of CTC compared with tramadol, also considering the need to demonstrate CTC’s superiority over placebo and its noninferiority to tramadol. To show noninferiority of CTC versus tramadol (assuming a noninferiority margin of

(ANCOVA) model, with treatment and QPI as fixed effects, study center as a random effect, and predose ( 0 h ) PI-VAS as a covariate. The last observation carried forward (LOCF) method was used to account for missing PI-VAS values. For patients who took rescue medication, the last available PI-VAS value before the first intake of rescue medication was carried forward for all consecutive time points.

RESULTS

Patients

Primary Endpoint

increasing to 8.1 (28.11) mm after 4 h . Placebo treatment resulted in a mean (SD) PID of – 5.5 (23.03) mm after 4 h .

Key Secondary Endpoints

| Characteristic | CTC | Tramadol 100 mg (

|

Placebo (

|

Total (

|

||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Age, years | ||||||

|

|

164 | 160 | 160 | 159 | 83 | 726 |

| Mean (SD) | 26.0 (7.12) | 25.6 (5.75) | 25.6 (5.95) | 25.8 (6.11) | 25.8 (6.33) | 25.8 (6.25) |

| Median | 24.0 | 24.0 | 24.0 | 25.0 | 26.0 | 24.0 |

| Min, max | 18,69 | 18,52 | 18,47 | 18, 48 | 18, 44 | 18,69 |

| Categorized age,

|

||||||

|

|

163 (99.4) | 160 (100.0) | 160 (100.0) | 159 (100.0) | 83 (100.0) | 725 (99.9) |

|

|

1 (0.6) | – | – | – | – | 1 (0.1) |

|

|

– | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sex,

|

||||||

| Male | 68 (41.5) | 66 (41.3) | 53 (33.1) | 63 (39.6) | 28 (33.7) | 278 (38.3) |

| Female | 96 (58.5) | 94 (58.8) | 107 (66.9) | 96 (60.4) | 55 (66.3) | 448 (61.7) |

| Race,

|

||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Asian | 2 (1.2) | – | – | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.2) | 4 (0.6) |

| Black or African American | 2 (1.2) | – | – | 1 (0.6) | – | 3 (0.4) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| White | 158 (96.3) | 157 (98.1) | 156 (97.5) | 155 (97.5) | 80 (96.4) | 706 (97.2) |

| Other | 2 (1.2) | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.5) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (2.4) | 13 (1.8) |

| Characteristic | CTC | Tramadol 100 mg (

|

Placebo (

|

Total (

|

||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Weight, kg | ||||||

|

|

164 | 160 | 159 | 159 | 83 | 725 |

| Mean (SD) | 70.68 (15.75) | 71.02 (16.54) | 69.85 (15.12) | 69.46 (14.11) | 68.82 (14.20) | 70.09 (15.25) |

| Median | 68.75 | 67.05 | 67.00 | 66.00 | 65.00 | 67.00 |

| Min, max | 40.0, 117.9 | 43.3, 125.0 | 44.6, 129.9 | 44.7, 124.0 | 48.8, 112.0 | 40.0, 129.9 |

| Height, cm | ||||||

|

|

164 | 160 | 159 | 159 | 83 | 725 |

| Mean (SD) | 171.2 (9.20) | 171.5 (8.82) | 171.0 (9.43) | 170.4 (9.54) | 169.7 (8.68) | 170.9 (9.18) |

| Median | 170.0 | 170.0 | 170.0 | 169.0 | 167.0 | 170.0 |

| Min, max | 154, 202 | 155, 194 | 153, 196 | 148, 197 | 154, 193 | 148, 202 |

| BMI,

|

||||||

|

|

164 | 160 | 159 | 159 | 83 | 725 |

| Mean (SD) | 23.94 (4.21) | 23.98 (4.42) | 23.83 (4.44) | 23.88 (4.08) | 23.76 (4.03) | 23.89 (4.25) |

| Median | 23.40 | 23.20 | 22.80 | 23.10 | 22.60 | 23.10 |

| Min, max | 16.2, 39.8 | 15.9, 40.8 | 17.0, 39.4 | 17.3, 38.1 | 18.4, 40.2 | 15.9, 40.8 |

| Categorized BMI,

|

||||||

| Underweight | 11 (6.7) | 10 (6.3) | 8 (5.0) | 7 (4.4) | 1 (1.2) | 37 (5.1) |

| Normal weight | 90 (54.9) | 98 (61.3) | 101 (63.5) | 98 (61.6) | 56 (67.5) | 443 (61.1) |

| Overweight | 47 (28.7) | 39 (24.4) | 36 (22.6) | 40 (25.2) | 20 (24.1) | 182 (25.1) |

| Obese | 16 (9.8) | 13 (8.1) | 14 (8.8) | 14 (8.8) | 6 (7.2) | 63 (8.7) |

| Missing | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| Duration of surgery, min | ||||||

|

|

164 | 160 | 160 | 159 | 83 | 726 |

| Mean (SD) | 34.1 (15.7) | 35.6 (17.0) | 35.3 (15.6) | 33.9 (18.2) | 34.2 (18.7) | 34.6 (16.9) |

| Characteristic | CTC | Tramadol 100 mg (

|

Placebo (

|

Total (

|

||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Qualifying PI-VAS score | ||||||

| n | 164 | 160 | 160 | 159 | 83 | 726 |

| Mean (SD) | 55.6 (8.38) | 56.2 (10.45) | 56.5 (9.43) | 56.1 (8.58) | 55.0 (8.53) | 56.0 (9.15) |

| Median | 53.0 | 53.0 | 54.0 | 54.0 | 52.0 | 53.0 |

| Min, max | 45, 87 | 40,100 | 45,100 | 45, 88 | 45,78 | 40,100 |

| Categorized qualifying PI-VAS score,

|

||||||

| Moderate (

|

153 (93.3) | 143 (89.4) | 145 (90.6) | 147 (92.5) | 76 (91.6) | 664 (91.5) |

| Severe (

|

11 (6.7) | 17 (10.6) | 15 (9.4) | 12 (7.5) | 7 (8.4) | 62 (8.5) |

| Predose (0 h) PI-VAS score

|

||||||

|

|

163 | 160 | 160 | 158 | 83 | 724 |

| Mean (SD) | 60.8 (11.35) | 60.8 (15.68) | 61.8 (11.77) | 61.1 (12.35) | 59.0 (10.60) | 60.9 (12.64) |

| Median | 57.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | 58.0 | 57.0 | 58.0 |

| Min, max | 23, 89 | 2, 100 | 25,99 | 27, 91 | 37, 84 | 2, 100 |

| CTC | Tramadol | Placebo | Total | |||

|

|

|

|

100 mg (

|

(

|

(

|

|

| Post-hoc analysis | ||||||

| Categorized predose (0 h) PI-VAS score,

|

||||||

| Moderate (

|

125 (76.7) | 121 (75.6) | 119 (74.4) | 122 (77.2) | 66 (79.5) | 553 (76.4) |

| Severe (

|

38 (23.3) | 39 (24.4) | 41 (25.6) | 36 (22.8) | 17 (20.5) | 171 (23.6) |

| Percentages are based on the number of patients with data present | ||||||

| BMI body mass index, CTC co-crystal of tramadol-celecoxib, PI-VAS pain intensity-visual analog scale, SD standard deviation | ||||||

|

|

||||||

significance (

from one-sided test of superiority for testing the null hypothesis that the difference of means is

|

|

|

|

Placebo | |||||||||

|

|

54 | 54 | 65 | 32 | 6 | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CTC | CTC | CTC | Tramadol | Placebo | |

| 100 mg | 150 mg | 200 mg | 100 mg | ||

| Rescue medication | 67 | 71 | 63 | 89 | 66 |

| use in 4 h,

|

|

|

|

|

|

sity-visual analog scale.

test of no difference for testing the null hypothesis that the

as ‘ 2 nd term: 1st term,’ as indicated.

interval,

ratio sity-visual analog scale.

ratio ratio

| CTC | Tramadol 100 mg (

|

Placebo (

|

|||

| TEAEs | 120 (73.2) | 119 (74.8) | 132 (82.5) | 137 (85.6) | 49 (59.0) |

| Treatment-related AEs | 98 (59.8) | 106 (66.7) | 120 (74.4) | 132 (82.5) | 30 (36.1) |

| Severe TEAEs | 19 (11.6) | 16 (10.1) | 28 (17.5) | 57 (35.6) | 9 (10.8) |

| TEAEs leading to discontinuation | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 12 (7.5) | 0 |

| Serious TEAEs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 0 |

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Most frequent treatment-related TEAEs (

|

|||||

| Somnolence | 62 (37.8) | 73 (45.9) | 96 (60.0) | 98 (61.3) | 23 (27.7) |

| Dizziness | 41 (25.0) | 47 (29.6) | 59 (36.9) | 89 (55.6) | 11 (13.3) |

| Fatigue | 44 (26.8) | 46 (28.9) | 59 (36.9) | 69 (43.1) | 21 (25.3) |

| Nausea | 41 (25.0) | 44 (27.7) | 46 (28.8) | 87 (54.4) | 12 (14.5) |

| Vomiting | 39 (23.8) | 29 (18.2) | 35 (21.9) | 84 (52.5) | 6 (7.2) |

| Disturbance in attention | 24 (14.6) | 23 (14.5) | 33 (20.6) | 50 (31.3) | 14 (16.9) |

| Pruritus | 4 (2.4) | 18 (11.3) | 25 (15.6) | 44 (27.5) | 3 (3.6) |

| Confusional state | 11 (6.7) | 9 (5.7) | 16 (10.0) | 29 (18.1) | 8 (9.6) |

| Constipation | 11 (6.7) | 12 (7.5) | 16 (10.0) | 28 (17.5) | 4 (4.8) |

| Dysuria | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.5) | 13 (8.1) | 33 (20.6) | 2 (2.4) |

| Retching | 2 (1.2) | 4 (2.5) | 4 (2.5) | 13 (8.1) | 2 (2.4) |

| Headache | 4 (2.4) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 5 (3.1) | 1 (1.2) |

| Pruritus, generalized | 0 | 2 (1.3) | 3 (1.9) | 7 (4.4) | 0 |

| Hyperhidrosis | 3 (1.8) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.5) | 0 |

| Asthenia | 0 | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) |

| Malaise | 0 | 0 | 5 (3.1) | 2 (1.3) | 0 |

| TEAEs of further interest | |||||

| Gastrointestinal signs and symptoms | 58 (35.4) | 51 (32.1) | 56 (35.0) | 108 (67.5) | 15 (18.1) |

| Nausea | 48 (29.3) | 47 (29.6) | 50 (31.3) | 90 (56.3) | 15 (18.1) |

| Vomiting | 40 (24.4) | 32 (20.1) | 36 (22.5) | 88 (55.0) | 9 (10.8) |

| Neurologic disorders | 89 (54.3) | 93 (58.5) | 112 (70.0) | 114 (71.3) | 33 (39.8) |

| Dizziness | 46 (28.0) | 48 (30.2) | 61 (38.1) | 90 (56.3) | 12 (14.5) |

| Somnolence | 75 (45.7) | 83 (52.2) | 105 (65.6) | 101 (63.1) | 31 (37.3) |

Additional Secondary Endpoints

placebo were significant for all CTC doses; differences between CTC and tramadol were not statistically significant (Table S9).

Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics

treatment-related TEAEs are shown in Table 2 and Fig. S9. For all TEAEs except malaise, the greatest proportion of patients experiencing each treatment-related TEAE occurred in the tramadol group. In CTC groups, a dose-dependent pattern was observed for most treatmentrelated TEAEs. Regarding TEAEs of further interest, 288 (

DISCUSSION

previously reported preclinical and phase 1 data showing that CTC has modified physiochemical properties and pharmacokinetics compared with tramadol and celecoxib, whether used alone or in free combination [23-26]. In a recently reported phase 1 study [24], celecoxib from CTC resulted in a lower

discontinuation were nausea, vomiting, and dizziness (each occurring in 6 patients), of which one case of vomiting was serious. No patients in any group discontinued due to lack of efficacy. This is particularly relevant to ambulatory surgery, as patients manage breakthrough pain and AEs at home; so the lower rate of AEs reported here for CTC versus tramadol, combined with consistent efficacy over time, might improve patient adherence and therefore outcomes. To our knowledge, ours is the first report of the addition of celecoxib to tramadol analgesia resulting in both decreased tramadol consumption (versus tramadol monotherapy) and reduced AEs. CTC is likely to have utility in patients requiring multimodal analgesia, whose pain is not sufficiently managed by treatment with an NSAID or acetaminophen alone, per Step 2 of the World Health Organization’s analgesic ladder [40].

sensitivity was confirmed by superiority of tramadol over placebo. CTC was shown to have analgesic efficacy in the study, with lower cumulative daily opioid doses than in the tramadol group.

as in other studies, the proportion was better aligned with literature reports [27, 47, 54].

CONCLUSIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declarations

permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

REFERENCES

- Sinatra R. Causes and consequences of inadequate management of acute pain. Pain Med. 2010;11(12): 1859-71.

- Gan TJ, Habib AS, Miller TE, White W, Apfelbaum JL. Incidence, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of post-surgical pain: results from a US national survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(1):149-60.

- Gregory J, McGowan L. An examination of the prevalence of acute pain for hospitalised adult patients: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(5-6):583-98.

- Kaye AD, Urman RD, Rappaport Y, et al. Multimodal analgesia as an essential part of enhanced recovery protocols in the ambulatory settings. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2019;35(Suppl 1): S40-5.

- Walker EMK, Bell M, Cook TM, Grocott MPW, Moonesinghe SR. Patient reported outcome of adult perioperative anaesthesia in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional observational study. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(6):758-66.

- Edgley C, Hogg M, De Silva A, Braat S, Bucknill A, Leslie K. Severe acute pain and persistent post-surgical pain in orthopaedic trauma patients: a cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(3):350-9.

- Galinski M, Ruscev M, Gonzalez G, et al. Prevalence and management of acute pain in prehospital emergency medicine. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010; 14(3):334-9.

- Tan M, Law LS, Gan TJ. Optimizing pain management to facilitate Enhanced Recovery After Surgery pathways. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62(2):203-18.

- Gan TJ. Poorly controlled postoperative pain: prevalence, consequences, and prevention. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2287-98.

- Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Segelcke D, Schug SA. Postoperative pain-from mechanisms to treatment. Pain Rep. 2017;2(2):e588.

- Bier JD, Kamper SJ, Verhagen AP, Maher CG, Williams CM. Patient nonadherence to guideline-recommended care in acute low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(12):2416-21.

- Stessel B, Theunissen M, Marcus MA, et al. Prevalence and predictors of patient nonadherence to pharmacological acute pain therapy at home after day surgery: a prospective cohort study. Pain Pract. 2018;18(2):194-204.

- Callebaut I, Jorissen S, Pelckmans C, et al. Fourweek pain profile and patient non-adherence to pharmacological pain therapy after day surgery. Anesth Pain Med. 2020;10(3):e101669.

- Beverly A, Kaye AD, Ljungqvist O, Urman RD. Essential elements of multimodal analgesia in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) guidelines. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35:e115-43.

- Hagen K, Iohom G. Pain management for ambulatory surgery: what is new? Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2014;4(4):326-33.

- Almansa C, Frampton CS, Vela JM, Whitelock S, Plata-Salamán CR. Co-crystals as a new approach to multimodal analgesia and the treatment of pain. J Pain Res. 2019;12:2679-89.

- Gascón N, Almansa C, Merlos M, et al. Co-crystal of tramadol-celecoxib: preclinical and clinical evaluation of a novel analgesic. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28(5):399-409.

- Suzuki K, Naito T, Tanaka H, et al. Impact of CYP2D6 activity and cachexia progression on enantiomeric alteration of plasma tramadol and its demethylated metabolites and their relationships with central nervous system symptoms in head and neck cancer patients. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2021;128(3):472-81.

- Gillen C, Haurand M, Kobelt DJ, Wnendt S. Affinity, potency and efficacy of tramadol and its metabolites at the cloned human mu-opioid receptor. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362(2):116-21.

- Nissen SE, Yeomans ND, Solomon DH, et al. Cardiovascular safety of celecoxib, naproxen, or ibuprofen for arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(26): 2519-29.

- Arfe A, Scotti L, Varas-Lorenzo C, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of heart failure in four European countries: nested casecontrol study. BMJ. 2016;354:i4857.

- Derry S, Moore RA. Single dose oral celecoxib for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(10):CD004233.

- Almansa C, Mercè R, Tesson N, Farran J, Tomàs J, PlataSalamán CR. Co-crystal of tramadol hydrochlo-ride-celecoxib (CTC): a novel API-API co-crystal for the treatment of pain. Cryst Growth Des. 2017;17: 1884-92.

- Cebrecos J, Carlson JD, Encina G, et al. Celecoxibtramadol co-crystal: a randomized 4-way crossover comparative bioavailability study. Clin Ther. 2021;43(6):1051-65.

- Port A, Almansa C, Enrech R, Bordas M, Plata-Salamán CR. Differential solution behavior of the new API-API co-crystal of tramadol-celecoxib (CTC) versus its constituents and their combination. Cryst Growth Des. 2019;19:3172-82.

- Videla S, Lahjou M, Vaqué A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of multiple doses of co-crystal of tramadolcelecoxib: findings from a four-way randomized open-label phase I clinical trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(1):64-78.

- López-Cedrún J, Videla S, Burgueño M, et al. Cocrystal of tramadol-celecoxib in patients with moderate to severe acute post-surgical oral pain: a dose-finding, randomised, double-blind, placeboand active-controlled, multicentre, phase II trial. Drugs R D. 2018;18(2):137-48.

- Viscusi ER, de Leon-Casasola O, Cebrecos J, et al. Celecoxib-tramadol co-crystal in patients with moderate-to-severe pain following bunionectomy with osteotomy: a phase 3 , randomized, doubleblind, factorial, active-and placebo-controlled trial. Pain Pract. 2023;23(1):8-22.

- Langford R, Morte A, Sust M, et al. Efficacy and safety of co-crystal of tramadol-celecoxib (CTC) in acute moderate-to-severe pain after abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial (STARDOM2). Eur J Pain. 2022;26(10):2083-96.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing information, SEGLENTIS. 2021. https://www. accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/213 426s000lbl.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov 2021.

- ESTEVE Pharmaceuticals SA. Velyntra Spanish Regulatory Approval. 2023. https://cima.aemps.es/ cima/dochtml/ft/89051/FT_89051.html. Accessed 9 Oct 2023

- Bretz F, Maurer W, Brannath W, Posch M. A graphical approach to sequentially rejective multiple test procedures. Stat Med. 2009;28(4):586-604.

- Videla S, Lahjou M, Vaqué A, et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of co-crystal of tramadol-celecoxib: results of a four-way randomized open-label phase I clinical trial in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(12):2718-28.

- Reines SA, Goldmann B, Harnett M, Lu L. Misuse of tramadol in the United States: an analysis of the National Survey of Drug Use and Health 2002-2017. Subst Abuse. 2020;14: 1178221820930006.

- Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-57.

- Mikosz CA, Zhang K, Haegerich T, et al. Indicationspecific opioid prescribing for US patients with Medicaid or private insurance, 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e204514.

- Echeverria-Villalobos M, Stoicea N, Todeschini AB, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS): a perspective review of postoperative pain management under ERAS pathways and its role on opioid crisis in the United States. Clin J Pain. 2020;36(3): 219-26.

- Malamed SF. Pain management following dental trauma and surgical procedures. Dent Traumatol. 2023;39(4):295-303.

- Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Liedgens H, Hummelshoj L, et al. Developing consensus on core outcome domains for assessing effectiveness in perioperative pain management: results of the PROMPT/IMIPainCare Delphi Meeting. Pain. 2021;162(11): 2717-36.

- Anekar AA, Cascella M. WHO Analgesic Ladder, in StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Mishra H, Khan FA. A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized comparison of pre and postoperative administration of ketorolac and tramadol for dental extraction pain. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012;28(2):221-5.

- Borel JF, Deschaumes C, Devoize L, et al. Treating pain after dental surgery: a randomised, controlled, double-blind trial to assess a new formulation of paracetamol, opium powder and caffeine versus tramadol or placebo [article in French]. Presse Med. 2010;39(5):e103-11.

- Janssen. Ultram (tramadol hydrochloride) prescribing information. https://www.janssenlabels. com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/ULTRAM-pi.pdf (2023). Accessed 12 Jul 2023.

- Fricke JR Jr, Hewitt DJ, Jordan DM, Fisher A, Rosenthal NR. A double-blind placebo-controlled comparison of tramadol/acetaminophen and tramadol in patients with postoperative dental pain. Pain. 2004;109(3):250-7.

- Moore RA, Gay-Escoda C, Figueiredo R, et al. Dexketoprofen/tramadol: randomised double-blind trial and confirmation of empirical theory of combination analgesics in acute pain. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:541.

- Moore RA, McQuay HJ, Tomaszewski J, et al. Dexketoprofen/tramadol

: randomised double-blind trial in moderate-to-severe acute pain after abdominal hysterectomy. BMC Anesthesiol. 2016;16:9. - Singla NK, Desjardins PJ, Chang PD. A comparison of the clinical and experimental characteristics of four acute surgical pain models: dental extraction, bunionectomy, joint replacement, and soft tissue surgery. Pain. 2014;155(3):441-56.

- Pergolizzi JV, Magnusson P, LeQuang JA, Gharibo C, Varrassi G. The pharmacological management of

dental pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020; 21(5):591-601. - Isiordia-Espinoza MA, de Jesús Pozos-Guillén A, Aragon-Martinez OH. Analgesic efficacy and safety of single-dose tramadol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in operations on the third molars: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52(9):775-83.

- Akinbade AO, Ndukwe KC, Owotade FJ. Comparative analgesic effects of ibuprofen, celecoxib and tramadol after third molar surgery: a randomized double blind controlled trial. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2018;19(11):1334-40.

- Edinoff AN, Kaplan LA, Khan S, et al. Full opioid agonists and tramadol: pharmacological and clinical considerations. Anesth Pain Med. 2021;11(4): e119156.

- Health Products Regulatory Authority. Summary of Product Characteristics, Zydol 50 mg Hard Capsules. https://www.hpra.ie/img/uploaded/swedocuments/ Licence_PA2242-005-001_18022022162405.pdf (2022). Accessed 13 Nov 2023.

- Pfizer Inc. CELEBREX (celecoxib) capsule: highlights of prescribing information. http://labeling.pfizer. com/showlabeling.aspx?id=793 (2021) Accessed 7 Aug 2021.

- Gay-Escoda C, Hanna M, Montero A, et al. Tramadol/dexketoprofen (TRAM/DKP) compared with tramadol/paracetamol in moderate to severe acute pain: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo and active-controlled, parallel group trial in the impacted third molar extraction pain model (DAVID study). BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e023715.

- Prior presentation: An abstract reporting these data was presented as a poster at the European Pain Federation (EFIC) 2022 congress, Dublin, Ireland, 27-30 April, 2022.Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https:// doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02744-2.

R. Langford () University Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany

A. MorteM. Sust J. Cebrecos A. Vaqué E. Ortiz - N. Gascón • C. Plata-Salamán

ESTEVE Pharmaceuticals, Barcelona, Spain