DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40885-023-00259-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38163867

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-02

أثر النظام الغذائي منخفض الصوديوم وعالي البوتاسيوم على خفض ضغط الدم والأحداث القلبية الوعائية

الملخص

إن دمج التعديلات الحياتية العدوانية مع العلاج الدوائي لارتفاع ضغط الدم هو استراتيجية علاجية حاسمة لتعزيز معدل السيطرة على ارتفاع ضغط الدم. يُعتبر تعديل النظام الغذائي أحد التدخلات الحياتية المهمة لارتفاع ضغط الدم، وقد ثبت أن له تأثيرًا واضحًا. من بين مكونات الطعام، وُجد أن الصوديوم والبوتاسيوم لهما أقوى ارتباط بضغط الدم. لقد تم إثبات تأثير النظام الغذائي منخفض الصوديوم وعالي البوتاسيوم في خفض ضغط الدم، خاصة في السكان الذين يعانون من ارتفاع ضغط الدم. كما أن تناول كميات كبيرة من البوتاسيوم، وهو عنصر رئيسي في النظام الغذائي المعروف باسم “النهج الغذائي لوقف ارتفاع ضغط الدم” (DASH)، قد أظهر أيضًا تأثيرًا إيجابيًا على خطر الأحداث القلبية الوعائية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أظهرت الأبحاث التي أجريت باستخدام طرق قياس قوية فوائد قلبية وعائية لتناول كميات منخفضة من الصوديوم. في هذه المراجعة، نهدف إلى مناقشة الأدلة المتعلقة بالعلاقة بين النظام الغذائي منخفض الصوديوم وعالي البوتاسيوم وضغط الدم والأحداث القلبية الوعائية.

الخلفية

لذلك، تهدف هذه الورقة إلى مراجعة تأثير خفض ضغط الدم الناتج عن انخفاض الصوديوم وارتفاع البوتاسيوم

تتعلق الأنظمة الغذائية وأحدث التطبيقات السريرية. عادةً ما تشير كلمة “ملح” إلى كلوريد الصوديوم، ولكن من أجل الوضوح في هذه الورقة، يتم استخدام مصطلح “صوديوم” بشكل موحد باستثناء المصطلحات المحددة. من منظور تركيز الأيونات بين السائل داخل الخلايا والسائل خارج الخلايا، فإن تركيز الأيونات في السائل خارج الخلايا هو تعبير أكثر دقة من تركيز الأيونات في البلازما. ومع ذلك، نظرًا لعدم وجود فرق كبير في تركيز الأيونات بين السائل خارج الخلايا والبلازما، تعتبر هذه الورقة أن تركيز الأيونات بدون إضافات تشير إلى تركيز الأيونات في كل من السائل خارج الخلايا والبلازما.

آثار الصوديوم على ضغط الدم

الصوديوم، توازن السوائل خارج الخلايا، وضغط الدم

يتم تحفيز الشعور بالعطش من خلال حركة الماء خارج الخلايا. ومع ذلك، فإن هذه العملية هي عملية ديناميكية، ويمكن ملاحظة التغيرات في الضغط الأسموزي فقط على أنها زيادة في السائل خارج الخلايا، ومن الصعب ملاحظة زيادة فعلية في تركيز الصوديوم. لذلك، عند استهلاك الصوديوم، تزداد فقط السوائل خارج الخلايا دون تغيير في تركيز الصوديوم، مما يعني أن تناول الصوديوم يعني زيادة في السائل خارج الخلايا. وعلى العكس، فإن تقليل تناول الصوديوم يعني تقليل السائل خارج الخلايا.

في جسم الإنسان، يتم تقسيم السائل خارج الخلايا إلى قسمين: السائل بين الخلايا، الذي يشكل حوالي

مع زيادة تناول الصوديوم، يزداد حجم السائل خارج الخلايا، ويزداد حجم الدم داخل الأوعية بشكل متناسب. ونتيجة لذلك، يزداد الناتج القلبي، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة لاحقة في ضغط الدم. الآلية الفسيولوجية التي تؤدي إلى زيادة ضغط الدم في الشرايين الكلوية والتي تؤدي إلى زيادة في إخراج الملح والماء تُسمى ناتريوريسيس الضغط.

حساسية الملح وضغط الدم

الصوديوم في الأنسجة البشرية

يمكن أن توجد الجلد أو العضلات في شكل مركز، منفصل عن مبدأ الضغط الأسموزي، لتمكين هذا العمل العازل. ومع ذلك، أفادت بعض الدراسات الحديثة أيضًا أن الضغط الأسموزي للصوديوم الموجود في الجلد ليس أعلى من ذلك في السائل خارج الخلية، مما يشير إلى أن التركيز العالي للصوديوم في الجلد قد يعكس فقط وذمة نسيجية تحت السريرية.

آثار البوتاسيوم على ضغط الدم

تنظيم توازن البوتاسيوم

أثر البوتاسيوم على توازن الصوديوم

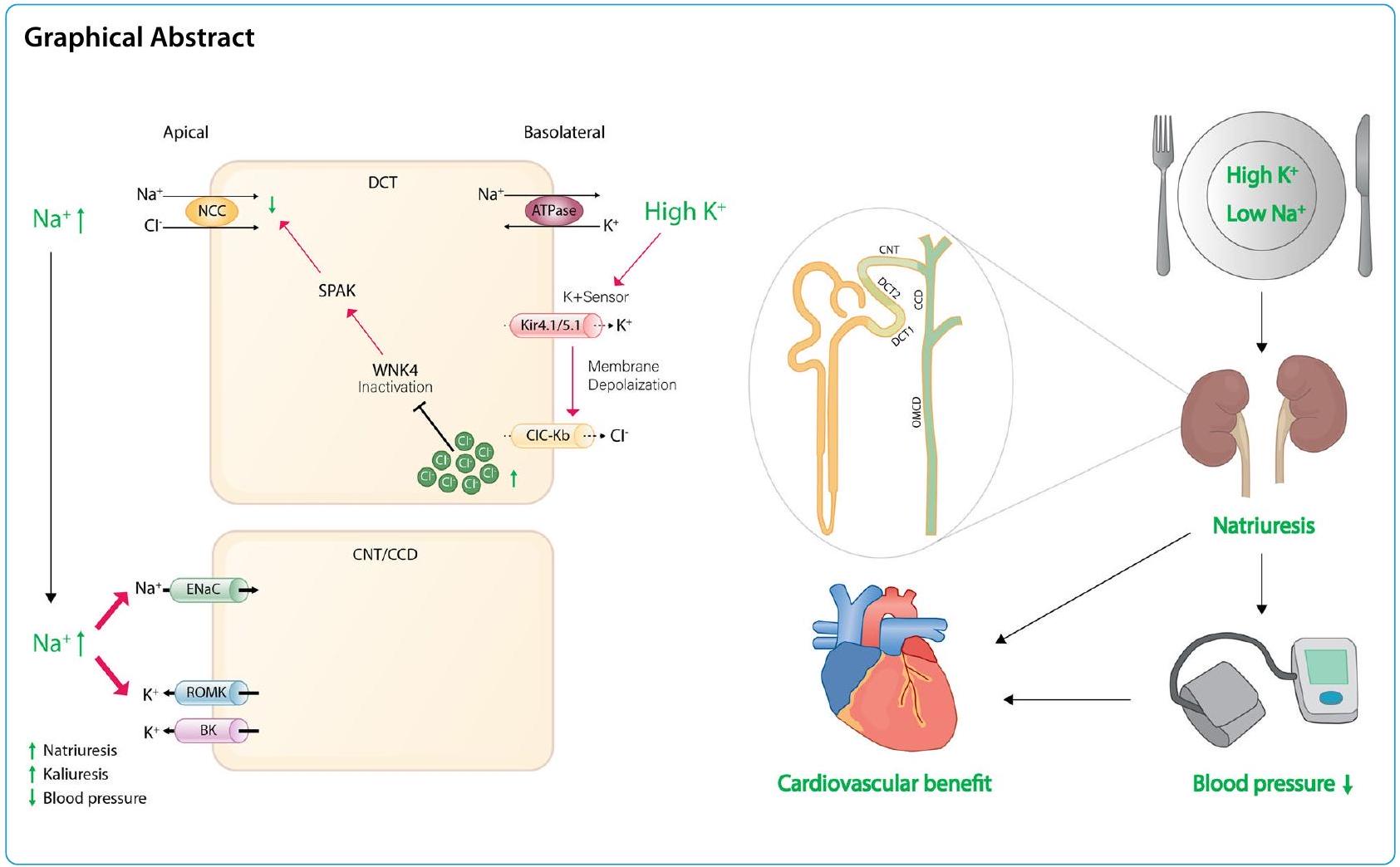

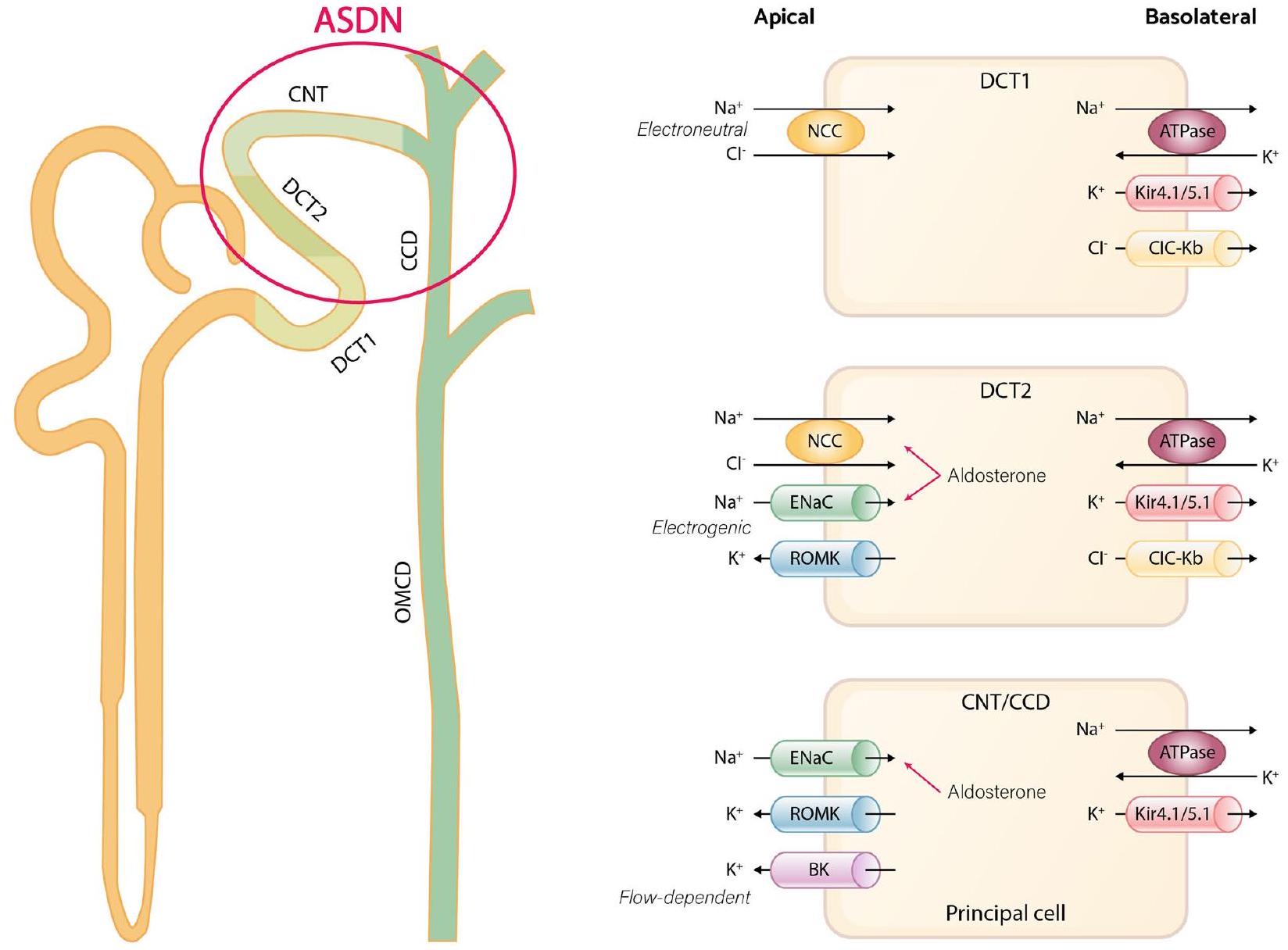

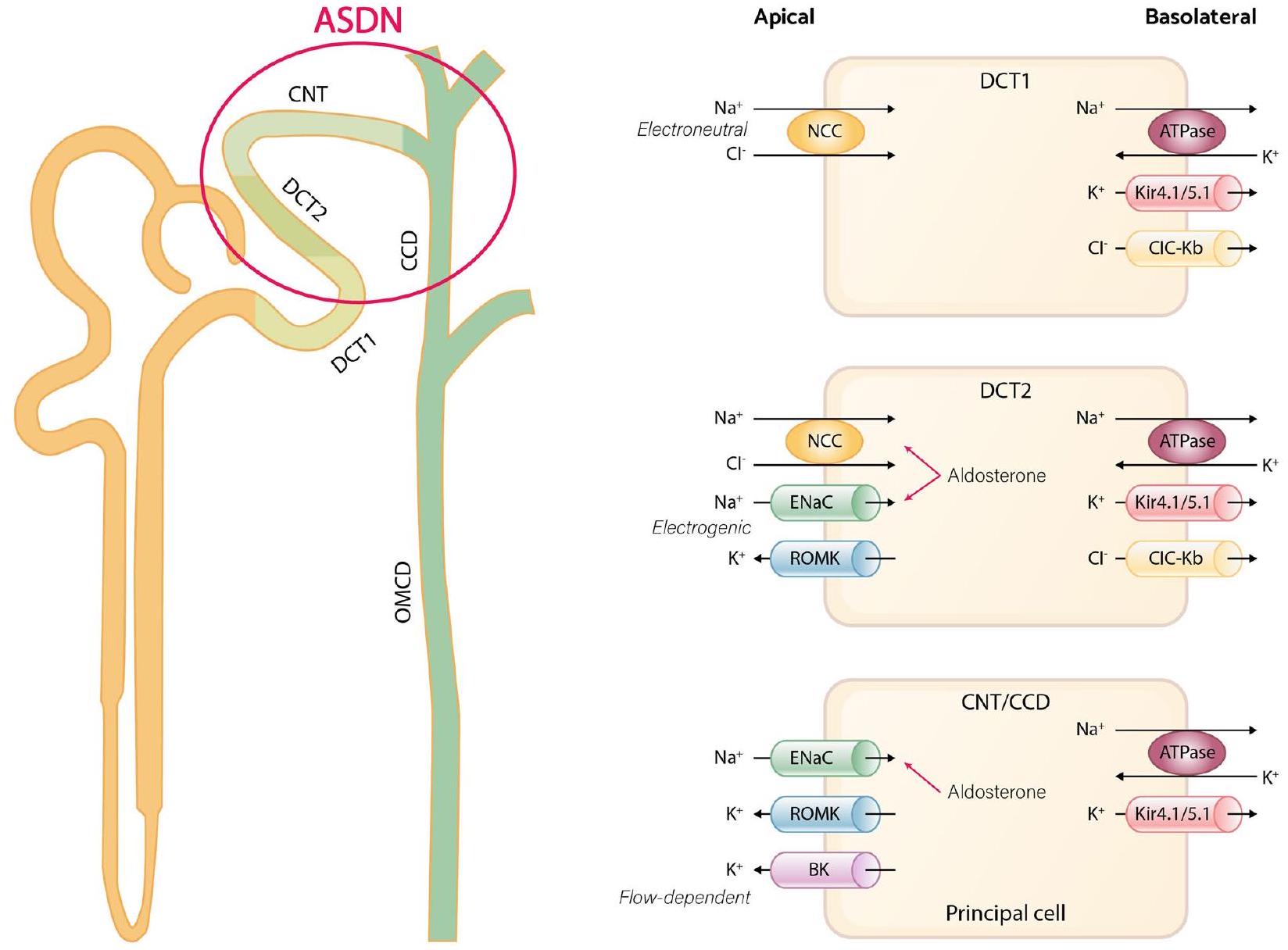

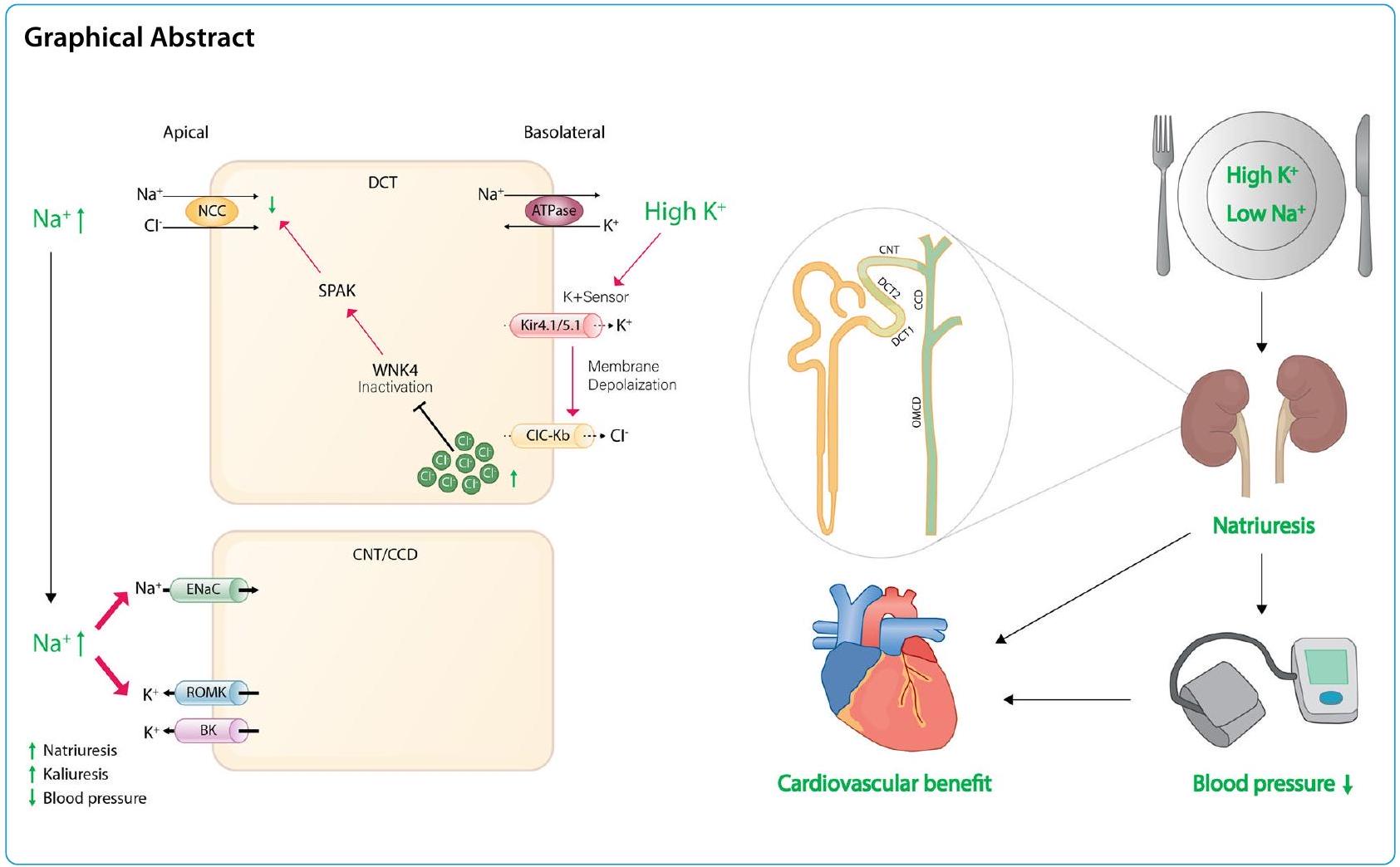

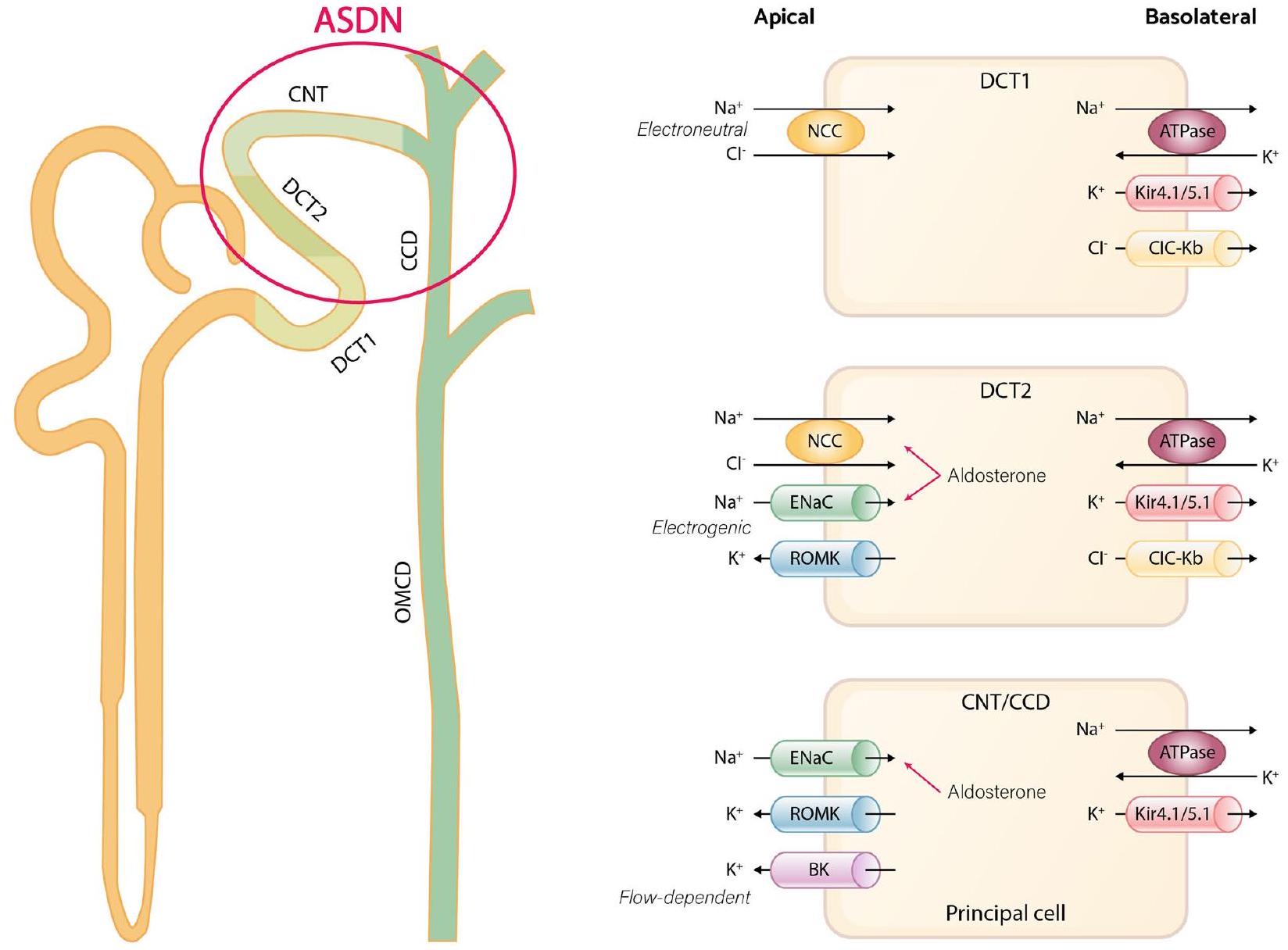

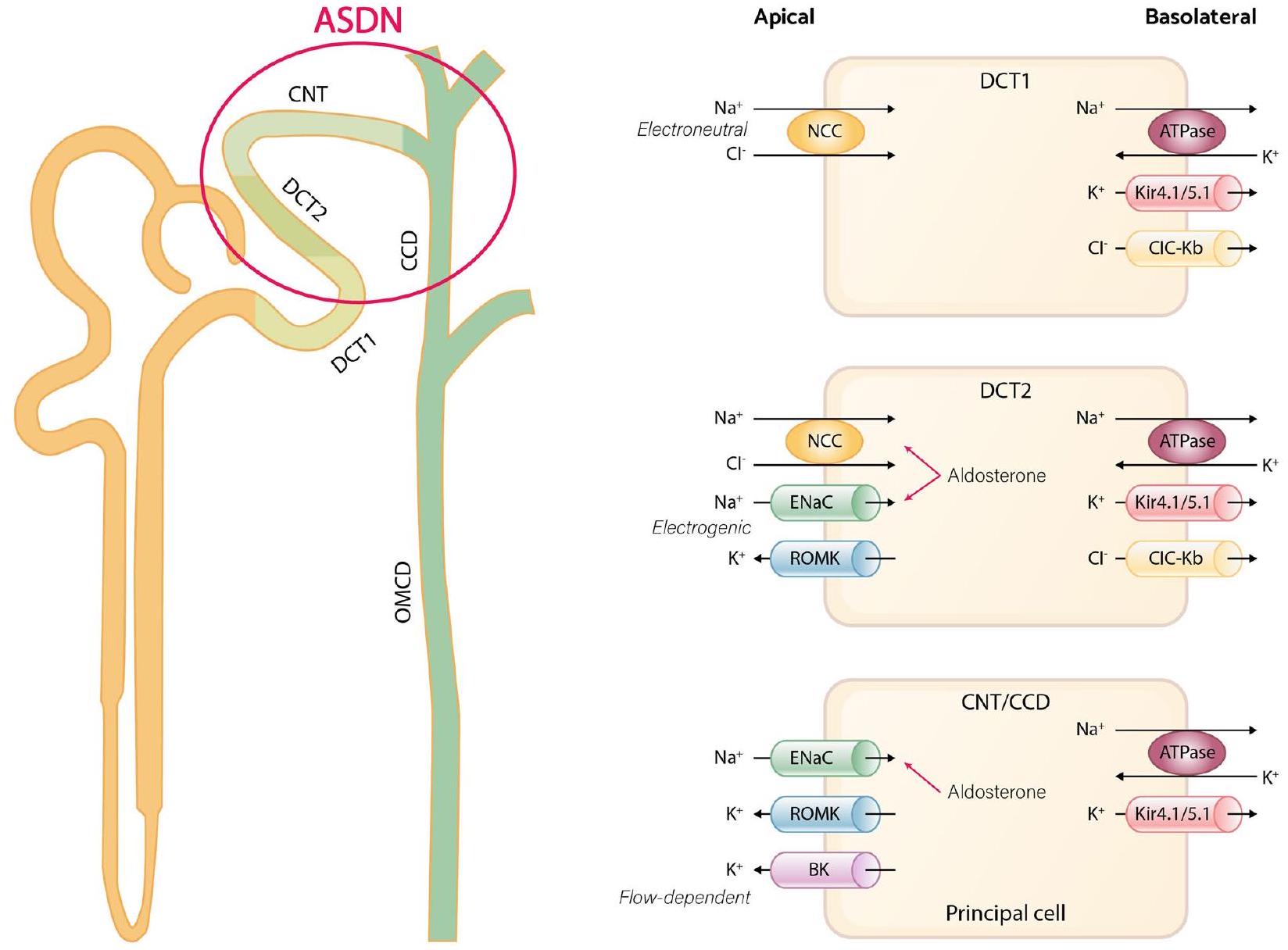

تشير الأبحاث الحديثة إلى أن القناة القريبة من الدائرة (DCT) تعمل كحساس للبوتاسيوم وتؤثر على معالجة البوتاسيوم في الأسفل من خلال تنظيم توصيل الصوديوم.

بشكل عام، يعني القناة الموصلة للداخل أن القناة البوتاسية التي تحفز فرط الاستقطاب تسمح بدخول الأيونات لتثبيت جهد الغشاء. ولكن في الجزء القريب من الأنبوب الكلوي (DCT)، تعتبر قنوات Kir4.1/Kir5.1 هي القناة البوتاسية الوحيدة المعبر عنها على الغشاء القاعدي الجانبي لـ DCT، مما يجعلها تعمل كقناة تسرب بوتاسي بدلاً من كونها موصلة للداخل، وهو أمر حاسم في الحفاظ على جهد الغشاء. كما تلعب دورًا في اكتشاف مستويات البوتاسيوم في البلازما، ومن ثم تعديل نشاط NCC. في ظل ظروف النظام الغذائي المنخفض البوتاسيوم، تكتشف قناة البوتاسيوم Kir4.1/Kir5.1 انخفاض تركيز البوتاسيوم خارج الخلية، مما يؤدي إلى تدفق البوتاسيوم خارج الخلية عبر الغشاء البلازمي القاعدي الجانبي لخلايا DCT. هذه العملية تحفز فرط الاستقطاب للغشاء وتحفز تدفق الكلوريد. الانخفاض الناتج في تركيز الكلوريد داخل الخلية يخفف من تثبيط كينازات حساسة للكلوريد، خاصة كينازات بدون ليسين (K) (WNKs)، مما يحفز الفسفرة الذاتية. ونتيجة لذلك، يؤدي تنشيط هذه الكينازات المفسفرة WNKs إلى تنشيط كينازات وسيطة مثل كيناز البروتين الغني بالبروتين الألانين المرتبط بـ Ste-20 (SPAK)، والتي تنشط بعد ذلك NCC، مما يسهل إعادة امتصاص الصوديوم إلى الخلية عبر NCC ويؤدي إلى انخفاض في النترية، وزيادة في الكاليوريس، وارتفاع ضغط الدم. يرتبط ارتفاع ضغط الدم الحساس للملح بتحفيز NCC تحت تناول منخفض من البوتاسيوم. على العكس من ذلك، مع نظام غذائي مرتفع البوتاسيوم، يتم قمع قنوات Kir4.1/Kir5.1، مما يؤدي إلى إزالة فسفرة NCC وانخفاض النشاط، مما يقلل من إعادة امتصاص الصوديوم. يشجع قمع نشاط NCC على الكاليوريس بينما يحد من الحفاظ على الصوديوم، حتى في ظل ارتفاع مستويات الألدوستيرون. التأثير الكاليوريسي الناتج عن تناول البوتاسيوم الغذائي يسبق في الواقع ارتفاع الألدوستيرون في البلازما ويصاحبه نترية. علاوة على ذلك، بسبب الانخفاض في إعادة امتصاص الصوديوم عبر NCC، هناك زيادة في توصيل الصوديوم إلى ASDN السفلي. هذا يعزز إعادة امتصاص الصوديوم الكهروجنسي الذي يتم بوساطة ENaC، مما يؤدي إلى إنشاء تدرج كهربائي كيميائي يدفع إفراز البوتاسيوم عبر قنوات ROMK. يلعب الألدوستيرون دورًا في تنظيم إفراز البوتاسيوم في البول وإعادة امتصاص الصوديوم من خلال العمل على مستقبلات المعدن الكورتيكويد في CNT المتأخر وCCD بالكامل والتحكم في نشاط الجينات المعنية بتنظيم ENaC.

في الختام، فإن تنظيم تنشيط NCC يستجيب بشكل ملحوظ للتغيرات في مستويات البوتاسيوم خارج الخلايا. تشير هذه الحساسية إلى أنه حتى في ظل ظروف تناول الصوديوم المرتفع، إذا كانت مستويات البوتاسيوم خارج الخلايا مرتفعة أيضًا، فإن نشاط NCC يت hinder، مما يؤدي إلى زيادة إخراج الصوديوم. هذه الآلية تعاكس بشكل فعال ارتفاع ضغط الدم، وهو ما يكون مفيدًا بشكل خاص للأفراد الذين يعانون من حساسية الملح وزيادة ضغط الدم.

فائدة نظام غذائي منخفض الصوديوم

توصية بنظام غذائي منخفض الصوديوم والقضايا المتعلقة بتفسير الأدلة

تقييم استهلاك الصوديوم

عند قياس تناول الصوديوم الغذائي الفردي مقارنةً بالمعيار الذهبي لإخراج الصوديوم في البول على مدار 24 ساعة. يُعتبر إخراج الصوديوم في البول على مدار 24 ساعة الطريقة الأكثر دقة لقياس تناول الصوديوم الغذائي. إنه يعكس حوالي

أثر تقليل الصوديوم على خفض ضغط الدم

ضغط الدم حتى في المرضى الذين يعانون من ارتفاع ضغط الدم المقاوم. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، من المعروف أن تناول الصوديوم بكميات زائدة يضعف تأثير مثبطات نظام الرينين-أنجيوتنسين.

فائدة خفض الصوديوم على القلب والأوعية الدموية

تم إجراء العديد من التجارب العشوائية المضبوطة للتحقيق في تأثير تقليل الملح على أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية، ولكن الغالبية العظمى من هذه الدراسات كانت ذات أحجام عينة ومدة غير كافية. وفقًا لمراجعة سابقة من كوكرين، كانت الأدلة التي تدعم فعالية التدخلات الهادفة إلى تقليل الملح الغذائي على الأحداث القلبية الوعائية ضعيفة. على عكس هذه الادعاءات، تم الإبلاغ عن نتائج متعارضة تشير إلى أن تقليل تناول الملح مرتبط بانخفاض كبير في الأحداث القلبية الوعائية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، خلص تقرير الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم (NAS) إلى أن تقليل تناول الصوديوم الغذائي يمكن أن يمنع الأحداث القلبية الوعائية استنادًا إلى تحليل تلوي لتجارب طويلة الأمد مصممة بشكل جيد، بما في ذلك تجارب الوقاية من ارتفاع ضغط الدم (TOHP) وتجارب التدخل غير الدوائي لدى كبار السن (TONE). مؤخرًا، شمل تحليل تلوي دراسة متابعة المهنيين الصحيين (HPFS)، ودراسة صحة الممرضات (NHS)، وNHS II، والوقاية من مرض الكلى والأوعية الدموية في المرحلة النهائية (PREVEND)، وتجارب TOHP I وTOHP II، والتي

تم إجراء جمع البول على مدار 24 ساعة بشكل متكرر كأكثر الطرق ملاءمة، وأبلغوا عن ارتباط ذو دلالة إحصائية يعتمد على الجرعة بين تناول الصوديوم العالي وخطر الأحداث القلبية الوعائية. وأفادوا أن الزيادة اليومية بمقدار 1 جرام في إخراج الصوديوم كانت مرتبطة بـ

استدامة تقييد تناول الصوديوم

| دراسة (سنة) | السكان | تقدير استهلاك الصوديوم | المتابعة (سنوات) | النتائج | نتيجة | مرجع |

| ستولارز-سكرزيبيك وآخرون (2011) | 3681 مشارك بدون أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية | إخراج الصوديوم في البول على مدار 24 ساعة | 7.9 | وفاة السيرة الذاتية | ارتباط عكسي ضعيف | [109] |

| توماس وآخرون (2011) | 2807 مشاركًا مصابًا بداء السكري من النوع 1 | إخراج الصوديوم في البول على مدار 24 ساعة | 10.0 | الوفاة بسبب جميع الأسباب | ارتباط منحنى J | [110] |

| PREVEND (2014) | 7543 مشاركًا بدون أمراض القلب والأوعية الدموية | إخراج الصوديوم في البول على مدار 24 ساعة | 10.5 | أحداث مرض القلب التاجي | لا ارتباط | [111] |

| سينجر وآخرون (2015) | 3505 مشاركًا يعانون من ارتفاع ضغط الدم | إخراج الصوديوم في البول على مدار 24 ساعة | 18.6 | وفاة بسبب فيروس كورونا والوفاة بسبب جميع الأسباب | ارتباط مباشر بالوفاة من جميع الأسباب | [112] |

| ميلز وآخرون (2016) | 3757 مشاركًا يعانون من مرض الكلى المزمن | إخراج الصوديوم في البول على مدار 24 ساعة | 6.8 | مركب من أحداث مرض القلب والأوعية الدموية | الارتباط الخطي | [95] |

| فوري وآخرون (2020) | 4630 السكان العام | إخراج الصوديوم في البول على مدار 24 ساعة | 14.0 | مركب من أحداث مرض القلب والأوعية الدموية | ارتباط مباشر | [113] |

| TOHP I و II (2016) | 3011 مشاركًا يعانون من ارتفاع ضغط الدم المبدئي | إخراج الصوديوم في البول على مدار 24 ساعة | ٢٣.٩ و ١٨.٨ | الوفاة بسبب جميع الأسباب | الارتباط الخطي | [79] |

| تحليل تلوي لدراسات HPFS و NHS I و NHS II و PREVEND و TOHP I و TOHP II (2022) | 10709 السكان العام | إخراج الصوديوم في البول على مدار 24 ساعة | 8.8 | مركب من أحداث مرض القلب والأوعية الدموية | الارتباط الخطي | [93] |

لدعم تغيير سلوك المرضى الأفراد، يجب أيضًا أخذ الاعتبارات المتعلقة بالعوامل الاجتماعية أو البيئية المرتبطة بتقييد الصوديوم في الاعتبار. على سبيل المثال، من المعروف أنه في معظم الحالات، يتم تزويد الصوديوم الإضافي، بخلاف الصوديوم الطبيعي الموجود في المكونات الخام، أثناء معالجة الطعام أو مبيعات الطعام التجارية. لذلك، من المهم تقليل الأطعمة المعالجة والتحقق من محتوى الصوديوم المشار إليه على ملصقات الطعام. يمكن أن تعطي ملصقات الطعام دافعًا للمستهلكين لاختيار منتجات منخفضة الصوديوم. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن أن تشجع بعض ممارسات التسمية الشركات المصنعة على إعادة صياغة منتجاتها لتحتوي على صوديوم أقل. من أجل اختيار محتوى صوديوم منخفض، من المهم اختيار المنتجات التي لا تحتوي على ملح إضافي، وتقليل الأطعمة المتبلة أو المخللة بالملح أو التوابل، واستخدام التوابل منخفضة الصوديوم ذات النكهات الحارة، واختيار بعناية عند تناول الطعام خارج المنزل، وضبط محتوى العناصر الغذائية في الطعام، وتجنب استخدام الصوديوم على الطاولة. يمكن أن تكون الاستشارة مع أخصائي تغذية ماهر حول تغيير السلوك مفيدة في تنفيذ هذه الطرق. إذا كان من الممكن تقييد الصوديوم من خلال تحسينات اجتماعية أو مؤسسية، فقد يقلل ذلك من الجهد المبذول لتقليل تناول الصوديوم بوعي، مما يزيد من الكفاءة. المراقبة الذاتية ضرورية في إدارة المرضى الذاتية، خاصة للأمراض المزمنة مثل السكري والربو وفشل القلب. الفوائد المحتملة للمراقبة الذاتية واعدة، حيث تشير الأدبيات إلى أنها قد تعزز الإدارة الذاتية، وإدارة الأعراض، وتنظيم الأمراض، مما يؤدي إلى تقليل عدد.

المضاعفات، تحسين التكيف والمواقف تجاه المرض، تحديد الأهداف الواقعية، وتحسين جودة الحياة بشكل عام. لقد أظهرت مراقبة ضغط الدم الذاتي، مثل قياس ضغط الدم في المنزل، أنها تحسن الالتزام بالعلاج في حالات ارتفاع ضغط الدم وتوصى بها بنشاط. على سبيل المثال، عند تقديم المشورة للمرضى حول نتائج قياسات ضغط الدم في المنزل، يمكن أن يساعد عرض نتائج ضغط الدم المرتفعة على مدى عدة أيام المرضى في مراقبة تأثير تناول الصوديوم على ضغط الدم، ويمكن أن يساعدهم في فهم حساسيتهم للصوديوم وتأثير تقليل الصوديوم في خفض ضغط الدم، مما يمكن أن يكون له تأثير إيجابي على تغيير السلوك المستدام.

فائدة نظام غذائي غني بالبوتاسيوم

النتائج [128]. كما أفادت دراسة PURE أنه مع زيادة إخراج البوتاسيوم في البول، انخفض ضغط الدم الانقباضي، وانخفضت معدلات الوفيات والأحداث القلبية الوعائية [129]. وقد أظهرت عدة تحليلات تلوية نتائج مماثلة باستمرار. في تحليل تلوى يضم 33 تجربة عشوائية محكومة (

في تجربة SSaSS [116]، كانت المجموعة التي استبدلت الملح العادي ببديل الملح الذي يتكون من

حمية داش ونسبة الصوديوم إلى البوتاسيوم

الاستنتاجات

الاختصارات

| DCT | الأنبوب الملتوي البعيد |

| سي إن تي | أنبوب موصل |

| CCD | قناة التجميع القشرية |

| NCC | ناقل الصوديوم والكلور |

| ENaC | قناة الصوديوم الظهارية |

| رومك | قناة البوتاسيوم في النخاع الخارجي للكلى |

| بي كيه | قنوات البوتاسيوم الكبيرة-K+ |

| WNK | كينازات بدون ليسين (K) |

| سباك | كيناز البروتين الغني بالبروتينات الألانين والبروتينات البروتينات المرتبطة بـ Ste-20 |

| OSR1 | كيناز 1 المستجيب للإجهاد التأكسدي |

| منظمة الصحة العالمية | منظمة الصحة العالمية |

| آها | جمعية القلب الأمريكية |

| ناس | الأكاديمية الوطنية للعلوم |

| تو إتش بي | تجارب الوقاية من ارتفاع ضغط الدم |

| نغمة | تجارب التدخلات غير الدوائية لدى كبار السن |

| HPFS | دراسة متابعة المهنيين الصحيين |

| NHS | دراسة صحة الممرضات |

| بريفند | الوقاية من مرض الكلى والأوعية الدموية في مراحله النهائية |

| RCT | تجربة سريرية عشوائية |

| SSaSS | دراسة بديل الملح والسكتة الدماغية |

| إنترسال | الدراسة التعاونية الدولية حول الملح وعوامل أخرى والدم |

| نقي | علم الأوبئة الحضري الريفي المحتمل |

| داش | الأساليب الغذائية لوقف ارتفاع ضغط الدم. |

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

نُشر على الإنترنت: 02 يناير 2024

References

- Organization WH. A global brief on hypertension: silent killer, global public health crisis: world health day 2013. In: World Health Organization; 2013.

- Kim HC, Cho SMJ, Lee H, Lee HH, Baek J, Heo JE. Korea hypertension fact sheet 2020: analysis of nationwide population-based data. Clin Hypertens. 2021;27(1):8.

- Zhou B, Carrillo-Larco RM, Danaei G, Riley LM, Paciorek CJ, Stevens GA, et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398(10304):957-80.

- Kim HL, Lee EM, Ahn SY, Kim KI, Kim HC, Kim JH, et al. The 2022 focused update of the 2018 Korean Hypertension Society Guidelines for the management of hypertension. Clin Hypertens. 2023;29(1):11.

- Lee HY, Shin J, Kim GH, Park S, Ihm SH, Kim HC, et al. 2018 Korean Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of hypertension: part II-diagnosis and treatment of hypertension. Clin Hypertens. 2019;25:20.

- Walser M. Phenomenological analysis of renal regulation of sodium and potassium balance. Kidney Int. 1985;27(6):837-41.

- Bie P. Mechanisms of sodium balance: total body sodium, surrogate variables, and renal sodium excretion. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys. 2018;315(5):R945-r962.

- Bie P, Wamberg S, Kjolby M. Volume natriuresis vs. pressure natriuresis. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;181(4):495-503.

- Duda K, Majerczak J, Nieckarz Z, Heymsfield SB, Zoladz JA. Chapter 1 – Human Body Composition and Muscle Mass. In: Zoladz JA, editor. Muscle and exercise physiology. Academic Press; 2019. p. 3-26.

- van Westing AC, Küpers LK, Geleijnse JM. Diet and Kidney Function: a Literature Review. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020;22(2):14.

- Guthrie D, Yucha C. Urinary concentration and dilution. Nephrol Nurs J. 2004;31 (3):297-301. quiz 302-293

- Natochin YV, Golosova DV. Vasopressin receptor subtypes and renal sodium transport. Vitam Horm. 2020;113:239-58.

- Bernal A, Zafra MA, Simón MJ, Mahía J. Sodium Homeostasis, a Balance Necessary for Life. Nutrients. 2023;15(2):395.

- Girardin E, Caverzasio J, Iwai J, Bonjour JP, Muller AF, Grandchamp A. Pressure natriuresis in isolated kidneys from hypertension-prone and hypertension-resistant rats (Dahl rats). Kidney Int. 1980;18(1):10-9.

- Felder RA, White MJ, Williams SM, Jose PA. Diagnostic tools for hypertension and salt sensitivity testing. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013;22(1):65-76.

- Titze J, Dahlmann A, Lerchl K, Kopp C, Rakova N, Schröder A, et al. Spooky sodium balance. Kidney Int. 2014;85(4):759-67.

- Clemmer JS, Pruett WA, Coleman TG, Hall JE, Hester RL. Mechanisms of blood pressure salt sensitivity: new insights from mathematical modeling. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys. 2017;312(4):R451-r466.

- Elijovich F, Weinberger MH, Anderson CA, Appel LJ, Bursztyn M, Cook NR, et al. Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2016;68(3):e7-e46.

- Koomans HA, Roos JC, Boer P, Geyskes GG, Mees EJ. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure in chronic renal failure. Evidence for renal control of body fluid distribution in man. Hypertension. 1982;4(2):190-7.

- Titze J, Shakibaei M, Schafflhuber M, Schulze-Tanzil G, Porst M, Schwind KH, et al. Glycosaminoglycan polymerization may enable osmotically inactive Na+ storage in the skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287(1):H203-8.

- Rossitto G, Mary S, Chen JY, Boder P, Chew KS, Neves KB, et al. Tissue sodium excess is not hypertonic and reflects extracellular volume expansion. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4222.

- Bräxmeyer DL, Keyes JL. The pathophysiology of potassium balance. Crit Care Nurse. 1996;16(5):59-71. quiz 72-53

- Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Physiology and pathophysiology of potassium homeostasis. Adv Physiol Educ. 2016;40(4):480-90.

- Staruschenko A. Beneficial Effects of High Potassium: Contribution of Renal Basolateral K(+) Channels. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1015-22.

- Rodrigues SL, Baldo MP, Machado RC, Forechi L, Molina Mdel C, Mill JG. High potassium intake blunts the effect of elevated sodium intake on blood pressure levels. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8(4):232-8.

- Giebisch G. Renal potassium transport: mechanisms and regulation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1998;274(5):F817-33.

- Gumz ML, Rabinowitz L, Wingo CS. An integrated view of potassium homeostasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):60-72.

- Roy A, Al-bataineh MM, Pastor-Soler NM. Collecting duct intercalated cell function and regulation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(2):305.

- Wade JB, Fang L, Coleman RA, Liu J, Grimm PR, Wang T, et al. Differential regulation of ROMK (Kir1.1) in distal nephron segments by dietary potassium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300(6):F1385-93.

- Gamba G. Molecular biology of distal nephron sodium transport mechanisms. Kidney Int. 1999;56(4):1606-22.

- Masilamani S, Kim GH, Mitchell C, Wade JB, Knepper MA. Aldosteronemediated regulation of ENaC alpha, beta, and gamma subunit proteins in rat kidney. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(7):R19-23.

- Rieg T, Vallon V, Sausbier M, Sausbier U, Kaissling B, Ruth P, et al. The role of the BK channel in potassium homeostasis and flow-induced renal potassium excretion. Kidney Int. 2007;72(5):566-73.

- Wei KY, Gritter M, Vogt L, de Borst MH, Rotmans JI, Hoorn EJ. Dietary potassium and the kidney: lifesaving physiology. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13(6):952-68.

- Gumz ML, Rabinowitz L, Wingo CS. An Integrated View of Potassium Homeostasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):60-72.

- Zhang C, Wang L, Zhang J, Su XT, Lin DH, Scholl UI, et al. KCNJ10 determines the expression of the apical

cotransporter (NCC) in the early distal convoluted tubule (DCT1). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(32):11864-9. - Su X-T, Zhang C, Wang L, Gu R, Lin D-H, Wang W-H. Disruption of KCNJ10 (Kir4. 1) stimulates the expression of ENaC in the collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310(10):F985-93.

- Cuevas CA, Su XT, Wang MX, Terker AS, Lin DH, McCormick JA, et al. Potassium Sensing by Renal Distal Tubules Requires Kir4.1. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(6):1814-25.

- Wang MX, Cuevas CA, Su XT, Wu P, Gao ZX, Lin DH, et al. Potassium intake modulates the thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride cotransporter (NCC) activity via the Kir4.1 potassium channel. Kidney Int. 2018;93(4):893-902.

- Hennings JC, Andrini O, Picard N, Paulais M, Huebner AK, Cayuqueo IK, et al. The CIC-K2 Chloride Channel Is Critical for Salt Handling in the Distal Nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(1):209-17.

- Bazúa-Valenti S, Chávez-Canales M, Rojas-Vega L, González-Rodríguez X, Vázquez N, Rodríguez-Gama A, et al. The Effect of WNK4 on the Na+-ClCotransporter Is Modulated by Intracellular Chloride. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(8):1781-6.

- Castañeda-Bueno M, Cervantes-Perez LG, Rojas-Vega L, Arroyo-Garza I, Vázquez N, Moreno E, et al. Modulation of NCC activity by low and high

intake: insights into the signaling pathways involved. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2014;306(12):F1507-19. - Yang YS, Xie J, Yang SS, Lin SH, Huang CL. Differential roles of WNK4 in regulation of NCC in vivo. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2018;314(5):F999-f1007.

- Terker AS, Zhang C, McCormick JA, Lazelle RA, Zhang C, Meermeier NP, et al. Potassium modulates electrolyte balance and blood pressure through effects on distal cell voltage and chloride. Cell Metab. 2015;21(1):39-50.

- Hoorn EJ, Gritter M, Cuevas CA, Fenton RA. Regulation of the renal NaCl cotransporter and its role in potassium homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 2020;100(1):321-56.

- Jensen IS, Larsen CK, Leipziger J, Sørensen MV. Na(+) dependence of

-induced natriuresis, kaliuresis and cotransporter dephosphorylation. Acta Physiol (Oxford). 2016;218(1):49-61. - Sorensen MV, Grossmann S, Roesinger M, Gresko N, Todkar AP, Barmettler G, et al. Rapid dephosphorylation of the renal sodium chloride cotransporter in response to oral potassium intake in mice. Kidney Int. 2013;83(5):811-24.

- Shoda W, Nomura N, Ando F, Mori Y, Mori T, Sohara E, et al. Calcineurin inhibitors block sodium-chloride cotransporter dephosphorylation in response to high potassium intake. Kidney Int. 2017;91(2):402-11.

- Pearce D, Manis AD, Nesterov V, Korbmacher C. Regulation of distal tubule sodium transport: mechanisms and roles in homeostasis and pathophysiology. Pflug Arch Eur J Physiol. 2022;474(8):869-84.

- Yang LE, Sandberg MB, Can AD, Pihakaski-Maunsbach K, McDonough AA. Effects of dietary salt on renal Na+ transporter subcellular distribution, abundance, and phosphorylation status. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2008;295(4):F1003-16.

- van der Lubbe N, Moes AD, Rosenbaek LL, Schoep S, Meima ME, Danser AH , et al.

-induced natriuresis is preserved during depletion and accompanied by inhibition of the Na+-Cl- cotransporter. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2013;305(8):F1177-88. - Terker AS, Zhang C, Erspamer KJ, Gamba G, Yang CL, Ellison DH. Unique chloride-sensing properties of WNK4 permit the distal nephron to modulate potassium homeostasis. Kidney Int. 2016;89(1):127-34.

- Huang CL , Cheng CJ. A unifying mechanism for WNK kinase regulation of sodium-chloride cotransporter. Pflugers Arch. 2015;467(11):2235-41.

- Fujita T, Ando K. Hemodynamic and endocrine changes associated with potassium supplementation in sodium-loaded hypertensives. Hypertension. 1984;6(2 Pt 1):184-92.

- Wilson DK, Sica DA, Miller SB. Effects of potassium on blood pressure in salt-sensitive and salt-resistant black adolescents. Hypertension. 1999;34(2):181-6.

- Walkowska A, Kuczeriszka M, Sadowski J, Olszyñski KH, Dobrowolski L, Červenka L, et al. High salt intake increases blood pressure in normal rats: putative role of 20-HETE and no evidence on changes in renal vascular reactivity. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2015;40(3):323-34.

- Intersalt Cooperative Research Group. Intersalt: an international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Results for 24 hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 1988;297(6644):319-28.

- Denton D, Weisinger R, Mundy NI, Wickings EJ, Dixson A, Moisson P, et al. The effect of increased salt intake on blood pressure of chimpanzees. Nat Med. 1995;1(10):1009-16.

- Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P, Ezzati M, et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12):e003733.

- WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Guideline: Sodium Intake for Adults and Children. Geneva: World Health Organization Copyright © 2012: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Snetselaar LG, de Jesus JM, DeSilva DM, Stoody EE. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025: Understanding the Scientific Process, Guidelines, and Key Recommendations. Nutr Today. 2021;56(6):287-95.

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition NF, Allergens F, Turck D, Castenmiller J, de Henauw S, Hirsch-Ernst K-I, et al. Dietary reference values for sodium. EFSA J. 2019;17(9):e05778.

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021-104.

- Graudal N, Hubeck-Graudal T, Jürgens G, Taylor RS. Dose-response relation between dietary sodium and blood pressure: a metaregression analysis of 133 randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(5):1273-8.

- Graudal NA, Hubeck-Graudal T, Jurgens G. Effects of low sodium diet versus high sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;12(12):Cd004022.

- Cappuccio FP, Beer M, Strazzullo P. Population dietary salt reduction and the risk of cardiovascular disease. A scientific statement from the European Salt Action Network. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;29(2):107-14.

- He FJ, Campbell NRC, Ma Y, MacGregor GA, Cogswell ME, Cook NR. Errors in estimating usual sodium intake by the Kawasaki formula alter its relationship with mortality: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(6):1784-95.

- He FJ, Campbell NRC, Woodward M, MacGregor GA. Salt reduction to prevent hypertension: the reasons of the controversy. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(25):2501-5.

- He FJ, Li J, Macgregor GA. Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2013;346:f1325.

- Huang L, Trieu K, Yoshimura S, Neal B, Woodward M, Campbell NRC, et al. Effect of dose and duration of reduction in dietary sodium on blood pressure levels: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2020;368:m315.

- Olde Engberink RHG, van den Hoek TC, van Noordenne ND, van den Born BH, Peters-Sengers H, Vogt L. Use of a Single Baseline Versus Multiyear 24-Hour Urine Collection for Estimation of Long-Term Sodium Intake and Associated Cardiovascular and Renal Risk. Circulation. 2017;136(10):917-26.

- McLean RM, Farmer VL, Nettleton A, Cameron CM, Cook NR, Campbell NRC. Assessment of dietary sodium intake using a food frequency questionnaire and 24-hour urinary sodium excretion: a

systematic literature review. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich, Conn). 2017;19(12):1214-30. - McLean RM, Farmer VL, Nettleton A, Cameron CM, Cook NR, Woodward M , et al. Twenty-Four-Hour Diet recall and Diet records compared with 24-hour urinary excretion to predict an individual’s sodium consumption: A Systematic Review. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich, Conn). 2018;20(10):1360-76.

- Lucko AM, Doktorchik C, Woodward M, Cogswell M, Neal B, Rabi D, et al. Percentage of ingested sodium excreted in 24-hour urine collections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich, Conn). 2018;20(9):1220-9.

- Lerchl K, Rakova N, Dahlmann A, Rauh M, Goller U, Basner M, et al. Agreement between 24 -hour salt ingestion and sodium excretion in a controlled environment. Hypertension. 2015;66(4):850-7.

- Tanaka T, Okamura T, Miura K, Kadowaki T, Ueshima H, Nakagawa H, et al. A simple method to estimate populational 24-h urinary sodium and potassium excretion using a casual urine specimen. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16(2):97-103.

- Kawasaki T, Itoh K, Uezono K, Sasaki H. A simple method for estimating 24 h urinary sodium and potassium excretion from second morning voiding urine specimen in adults. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1993;20(1):7-14.

- Brown IJ, Dyer AR, Chan Q, Cogswell ME, Ueshima H, Stamler J, et al. Estimating 24-hour urinary sodium excretion from casual urinary sodium concentrations in Western populations: the INTERSALT study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(11):1180-92.

- O’Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Wang X, Liu L, et al. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):612-23.

- Cook NR, Appel LJ, Whelton PK. Sodium Intake and All-Cause Mortality Over 20 Years in the Trials of Hypertension Prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(15):1609-17.

- Huang L, Crino M, Wu JH, Woodward M, Barzi F, Land MA, et al. Mean population salt intake estimated from 24-h urine samples and spot urine samples: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(1):239-50.

- Cappuccio FP, Sever PS. The importance of a valid assessment of salt intake in individuals and populations. A scientific statement of the British and Irish Hypertension Society. J Hum Hypertens. 2019;33(5):345-8.

- Suckling RJ, He FJ, Markandu ND, MacGregor GA. Modest Salt Reduction Lowers Blood Pressure and Albumin Excretion in Impaired Glucose Tolerance and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Double-Blind Trial. Hypertension. 2016;67(6):1189-95.

- The Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. Effects of weight loss and sodium reduction intervention on blood pressure and hypertension incidence in overweight people with highnormal blood pressure. The Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase II. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(6):657-67.

- Pimenta E, Gaddam KK, Oparil S, Aban I, Husain S, Dell’Italia LJ, et al. Effects of dietary sodium reduction on blood pressure in subjects with resistant hypertension: results from a randomized trial. Hypertension. 2009;54(3):475-81.

- Vegter S, Perna A, Postma MJ, Navis G, Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P. Sodium intake, ACE inhibition, and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(1):165-73.

- Welsh CE, Welsh P, Jhund P, Delles C, Celis-Morales C, Lewsey JD, et al. Urinary Sodium Excretion, Blood Pressure, and Risk of Future Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in Subjects Without Prior Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension. 2019;73(6):1202-9.

- Zanetti D, Bergman H, Burgess S, Assimes TL, Bhalla V, Ingelsson E. Urinary Albumin, Sodium, and Potassium and Cardiovascular Outcomes in the UK Biobank: Observational and Mendelian Randomization Analyses. Hypertension. 2020;75(3):714-22.

- Elliott P, Muller DC, Schneider-Luftman D, Pazoki R, Evangelou E, Dehghan A, et al. Estimated 24-Hour Urinary Sodium Excretion and Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality Among 398628 Individuals in UK Biobank. Hypertension. 2020;76(3):683-91.

- Mente A, O’Donnell M, Rangarajan S, Dagenais G, Lear S, McQueen M, et al. Associations of urinary sodium excretion with cardiovascular events in individuals with and without hypertension: a pooled

analysis of data from four studies. Lancet (London, England). 2016;388(10043):465-75. - O’Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, O’Leary N, Yin L, et al. Joint association of urinary sodium and potassium excretion with cardiovascular events and mortality: prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2019;364:I772.

- Cook NR, Appel LJ, Whelton PK. Lower levels of sodium intake and reduced cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2014;129(9):981-9.

- Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2009;339:b4567.

- Ma Y, He FJ, Sun Q, Yuan C, Kieneker LM, Curhan GC, et al. 24-Hour Urinary Sodium and Potassium Excretion and Cardiovascular Risk. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(3):252-63.

- Mente A, O’Donnell M, Rangarajan S, McQueen M, Dagenais G, Wielgosz A, et al. Urinary sodium excretion, blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: a community-level prospective epidemiological cohort study. Lancet. 2018;392(10146):496-506.

- Mills KT, Chen J, Yang W, Appel LJ, Kusek JW, Alper A, et al. Sodium Excretion and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. Jama. 2016;315(20):2200-10.

- Kieneker LM, Eisenga MF, Gansevoort RT, de Boer RA, Navis G, Dullaart RPF, et al. Association of Low Urinary Sodium Excretion With Increased Risk of Stroke. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(12):1803-9.

- Heaney RP. Sodium: how and how not to set a nutrient intake recommendation. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26(10):1194-7.

- Cook NR, He FJ, MacGregor GA, Graudal N. Sodium and health-concordance and controversy. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2020;369:m2440.

- Adler AJ, Taylor F, Martin N, Gottlieb S, Taylor RS, Ebrahim S. Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(12):Cd009217.

- Taylor RS, Ashton KE, Moxham T, Hooper L, Ebrahim S. Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (Cochrane review). Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(8):843-53.

- He FJ, MacGregor GA. Salt reduction lowers cardiovascular risk: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet (London, England). 2011;378(9789):380-2.

- National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine, Health, Medicine D, Food, Nutrition B, Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for S, Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Oria M, Harrison M, Stallings VA, editors. Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2019 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved; 2019.

- Cook NR, Cutler JA, Obarzanek E, Buring JE, Rexrode KM, Kumanyika SK, et al. Long term effects of dietary sodium reduction on cardiovascular disease outcomes: observational follow-up of the trials of hypertension prevention (TOHP). BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2007;334(7599):885-8.

- Appel LJ, Espeland MA, Easter L, Wilson AC, Folmar S, Lacy CR. Effects of reduced sodium intake on hypertension control in older individuals: results from the Trial of Nonpharmacologic Interventions in the Elderly (TONE). Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(5):685-93.

- Bao Y, Bertoia ML, Lenart EB, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, et al. Origin, Methods, and Evolution of the Three Nurses’ Health Studies. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1573-81.

- Sun Q, Bertrand KA, Franke AA, Rosner B, Curhan GC, Willett WC. Reproducibility of urinary biomarkers in multiple 24-h urine samples. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(1):159-68.

- Yuan C, Spiegelman D, Rimm EB, Rosner BA, Stampfer MJ, Barnett JB, et al. Relative Validity of Nutrient Intakes Assessed by Questionnaire, 24-Hour Recalls, and Diet Records as Compared With Urinary Recovery and Plasma Concentration Biomarkers: Findings for Women. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(5):1051-63.

- The effects of nonpharmacologic interventions on blood pressure of persons with high normal levels. Results of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, Phase I. Jama 1992, 267(9):1213-1220.

- Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Kuznetsova T, Thijs L, Tikhonoff V, Seidlerová J, Richart T, et al. Fatal and nonfatal outcomes, incidence of hypertension, and blood pressure changes in relation to urinary sodium excretion. Jama. 2011;305(17):1777-85.

- Thomas MC, Moran J, Forsblom C, Harjutsalo V, Thorn L, Ahola A, et al. The association between dietary sodium intake, ESRD, and all-cause mortality in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(4):861-6.

- Joosten MM, Gansevoort RT, Mukamal KJ, Lambers Heerspink HJ, Geleijnse JM, Feskens EJ, et al. Sodium excretion and risk of developing coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2014;129(10):1121-8.

- Singer P, Cohen H, Alderman M. Assessing the associations of sodium intake with long-term all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a hypertensive cohort. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(3):335-42.

- Vuori MA, Harald K, Jula A, Valsta L, Laatikainen T, Salomaa V, et al. 24-h urinary sodium excretion and the risk of adverse outcomes. Ann Med. 2020;52(8):488-96.

- Chang HY, Hu YW, Yue CS, Wen YW, Yeh WT, Hsu LS, et al. Effect of potas-sium-enriched salt on cardiovascular mortality and medical expenses of elderly men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6):1289-96.

- Bernabe-Ortiz A, Sal YRVG, Ponce-Lucero V, Cárdenas MK, Carrillo-Larco RM, Diez-Canseco F, et al. Effect of salt substitution on community-wide blood pressure and hypertension incidence. Nat Med. 2020;26(3):374-8.

- Neal B, Wu Y, Feng X, Zhang R, Zhang Y, Shi J, et al. Effect of Salt Substitution on Cardiovascular Events and Death. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(12):1067-77.

- Wang G, Labarthe D. The cost-effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce sodium intake. J Hypertens. 2011;29(9):1693-9.

- Whelton PK, Kumanyika SK, Cook NR, Cutler JA, Borhani NO, Hennekens CH, et al. Efficacy of nonpharmacologic interventions in adults with high-normal blood pressure: results from phase 1 of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention. Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65(2 Suppl):652s-60s.

- Ihm SH, Kim KI, Lee KJ, Won JW, Na JO, Rha SW, et al. Interventions for Adherence Improvement in the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases: Expert Consensus Statement. Korean Circ J. 2022;52(1):1-33.

- Anderson CA, Appel LJ, Okuda N, Brown IJ, Chan Q, Zhao L, et al. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: the INTERMAP study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(5):736-45.

- Cobb LK, Appel LJ, Anderson CA. Strategies to reduce dietary sodium intake. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2012;14(4):425-34.

- Appel L, Miller E. Promoting lifestyle modification in the office setting. In: Hypertension: hot topics. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, Inc; 2004. p. 155-63.

- Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(2):177-87.

- Wilde MH, Garvin S. A concept analysis of self-monitoring. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57(3):339-50.

- Richard AA, Shea K. Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2011;43(3):255-64.

- Jo SH, Kim SA, Park KH, Kim HS, Han SJ, Park WJ. Self-blood pressure monitoring is associated with improved awareness, adherence, and attainment of target blood pressure goals: Prospective observational study of 7751 patients. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich, Conn). 2019;21(9):1298-304.

- Elliott P, Stamler J, Nichols R, Dyer AR, Stamler R, Kesteloot H, et al. Intersalt revisited: further analyses of 24 hour sodium excretion and blood pressure within and across populations. Intersalt Cooperative Res Group BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1996;312(7041):1249-53.

- Kwon YJ, Lee HS, Park G, Lee JW. Association between dietary sodium, potassium, and the sodium-to-potassium ratio and mortality: A 10-year analysis. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1053585.

- Miller V, Yusuf S, Chow CK, Dehghan M, Corsi DJ, Lock K, et al. Availability, affordability, and consumption of fruits and vegetables in 18 countries across income levels: findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(10):e695-703.

- Whelton PK, He J, Cutler JA, Brancati FL, Appel LJ, Follmann D, et al. Effects of oral potassium on blood pressure. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Jama. 1997;277(20):1624-32.

- Aburto NJ, Hanson S, Gutierrez H, Hooper L, Elliott P, Cappuccio FP. Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2013;346:f1378.

- Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Dietary potassium intake and risk of stroke: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Stroke. 2011;42(10):2746-50.

- Gritter M, Wouda RD, Yeung SMH, Wieërs MLA, Geurts F, de Ridder MAJ, et al. Effects of Short-Term Potassium Chloride Supplementation in Patients with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33(9):1779-89.

- Mu F, Betts KA, Woolley JM, Dua A, Wang Y, Zhong J, et al. Prevalence and economic burden of hyperkalemia in the United States Medicare population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(8):1333-41.

- Food Labeling. Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels. Final Rule Fed Regist. 2016;81(103):33741-999.

- Drewnowski A, Rehm CD, Maillot M, Mendoza A, Monsivais P. The feasibility of meeting the WHO guidelines for sodium and potassium: a cross-national comparison study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e006625.

- Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1117-24.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/ NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):e13-e115.

- Lee CH, Shin J. Effect of low sodium and high potassium diet on lowering blood pressure. J Korean Med Assoc. 2022;65(6):368-76.

- He FJ, Pombo-Rodrigues S, Macgregor GA. Salt reduction in England from 2003 to 2011: its relationship to blood pressure, stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e004549.

- Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, Khan NA, Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, et al. 2020 International Society of Hypertension Global Hypertension Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75(6):1334-57.

ملاحظة الناشر

- تقديم سريع ومريح عبر الإنترنت

- مراجعة دقيقة من قبل باحثين ذوي خبرة في مجالك

- نشر سريع عند القبول

- الدعم لبيانات البحث، بما في ذلك أنواع البيانات الكبيرة والمعقدة

- الوصول المفتوح الذهبي الذي يعزز التعاون الأوسع وزيادة الاقتباسات

- أقصى رؤية لبحثك: أكثر من 100 مليون مشاهدة للموقع سنويًا

تعلم المزيدbiomedcentral.com/submissions

- ساهم بيونغ سيك كيم ومي-يون يو بالتساوي في هذا العمل.

*المراسلة:

جينهو شين

jhs2003@hanyang.ac.kr

قسم أمراض القلب، قسم الطب الباطني، مستشفى هانيانغ الجامعي في غوري، غوري، كوريا الجنوبية

قسم أمراض الكلى، قسم الطب الباطني، كلية الطب بجامعة هانيانغ، سيول، كوريا الجنوبية

قسم أمراض القلب، قسم الطب الباطني، مركز هانيانغ الطبي، كلية الطب بجامعة هانيانغ، 222

وانغسيمني-رو، سونغدونغ-غو، سيول 04763، كوريا الجنوبية

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40885-023-00259-0

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38163867

Publication Date: 2024-01-02

Effect of low sodium and high potassium diet on lowering blood pressure and cardiovascular events

Abstract

Incorporating aggressive lifestyle modifications along with antihypertensive medication therapy is a crucial treatment strategy to enhance the control rate of hypertension. Dietary modification is one of the important lifestyle interventions for hypertension, and it has been proven to have a clear effect. Among food ingredients, sodium and potassium have been found to have the strongest association with blood pressure. The blood pressure-lowering effect of a low sodium diet and a high potassium diet has been well established, especially in hypertensive population. A high intake of potassium, a key component of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, has also shown a favorable impact on the risk of cardiovascular events. Additionally, research conducted with robust measurement methods has shown cardiovascular benefits of low-sodium intake. In this review, we aim to discuss the evidence regarding the relationship between the low sodium and high potassium diet and blood pressure and cardiovascular events.

Background

Therefore, this paper aims to review the blood pres-sure-lowering effect of low sodium and high potassium

diets and the latest clinical applications. “Salt” usually refers to sodium chloride, but for clarity in this paper, the term “sodium” is used uniformly except for specific terms. From the perspective of ion concentration between intracellular and extracellular fluid, the ion concentration of extracellular fluid is a more accurate expression than that of plasma ion concentration. However, since there is no significant difference in ion concentration between extracellular fluid and plasma, this paper considers that the concentration of ions without additional modifiers refers to the ion concentration in both extracellular fluid and plasma.

Effects of sodium on blood pressure

Sodium, extracellular fluid balance, and blood pressure

being stimulated by the movement of water out of the cells, causing thirst. However, this process is a dynamic process, and changes in osmotic pressure can only be observed as an increase in extracellular fluid, and it is difficult to observe an actual increase in sodium concentration [8]. Therefore, when sodium is consumed, only extracellular fluid increases without change in sodium concentration, meaning that sodium intake implies an increase in extracellular fluid. Conversely, decreasing sodium intake means decreasing extracellular fluid.

In the human body, the extracellular fluid is divided into two compartments: the interstitial fluid, which constitutes about

As sodium intake increases, extracellular fluid volume increases, and intravascular volume increases in proportion. As a result, cardiac output increases, leading to a subsequent increase in blood pressure. The physiological mechanism by which an increase in BP in the renal arteries leads to an increased salt and water excretion is called pressure natriuresis [14].

Salt sensitivity and blood pressure

Sodium in human tissues

skin or muscle can exist in a concentrated form, separate from the principle of osmotic pressure, to enable this buffering action [20]. However, some recent studies have also reported that the osmotic pressure of sodium present in the skin is not higher than that of the extracellular fluid, suggesting that the high concentration of sodium in the skin may be reflecting only subclinical tissue edema [21].

Effects of potassium on blood pressure

Regulation of potassium balance

Effect of potassium on sodium balance

Recent research indicates that the DCT acts as a potassium sensor and influences downstream potassium handling by regulating sodium delivery [33, 34]. In

general, inward rectifier means hyperpolarization triggered potassium channel permit influx to stabilize the membrane potential. But in DCT, Kir4.1/Kir5.1 is the only potassium channel expressed on the basolateral membrane of the DCT so that it acts not as inward rectifier but as potassium leakage channel which is crucial in maintaining membrane potential [35]. It also has the role in detecting plasma potassium levels, and subsequently, modulating NCC activity [36]. Under conditions of low potassium diet, the potassium channel Kir4.1/ Kir5.1 detects reduced extracellular potassium concentration, leading to potassium efflux through the basolateral plasma membrane of DCT cells [37, 38]. This process induces membrane hyperpolarization and stimulates chloride efflux [39]. The ensuing decrease in intracellular chloride concentration relieves the inhibition of chloride-sensitive kinases, especially with-no-lysine (K) kinases (WNKs), prompting autophosphorylation [40]. As a consequence, the activation of these phosphorylated WNKs triggers intermediate kinases such as Ste-20-related proline alanine-rich protein kinase (SPAK), which subsequently activate NCC, facilitating sodium reabsorption into the cell through NCC and leading to decreased natriuresis, kaliuresis, and elevated blood pressure (Fig. 2A) [41-43]. Salt-sensitive hypertension linked to NCC stimulation under low potassium intake [44]. Conversely, with a heightened potassium diet, Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channels are suppressed, leading to NCC dephosphorylation and diminished activity, subsequently decreasing sodium reabsorption. The suppression of NCC activity encourages kaliuresis while curbing sodium preservation, even in the face of heightened aldosterone levels. The kaliuretic effect resulting from dietary potassium intake actually precedes the rise in plasma aldosterone and is accompanied by natriuresis [3]. Moreover, due to the reduction in sodium reabsorption through NCC, there is an increased sodium delivery to the downstream ASDN. This intensifies the electrogenic sodium reabsorption mediated by ENaC, leading to the creation of an electrochemical gradient that propels the secretion of potassium through ROMK channels (Fig. 2B) [45-47]. Aldosterone plays a role in regulating urinary potassium excretion and sodium reabsorption by acting on the mineralocorticoid receptor at the late CNT and entire CCD and controlling the activity of genes involved in ENaC regulation [31, 48].

To conclude, the regulation of NCC activation is remarkably responsive to alterations in extracellular potassium levels [51, 52]. This sensitivity implies that even under conditions of elevated sodium intake, if extracellular potassium levels are also high, NCC activity is hindered, resulting in increased sodium excretion. This mechanism effectively counteracts blood pressure elevation, particularly beneficial for individuals with salt sensitivity increases in blood pressure [53, 54].

Benefit of low sodium diet

Recommendation of low sodium diet and issues related to interpretation of the evidence

Assessment of sodium intake

when measuring individual dietary sodium intake compared to the gold standard of 24 -hour urinary sodium excretion [71, 72]. The 24 -hour urinary sodium excretion is widely regarded as the most accurate method of measurement of dietary sodium intake. It reflects about

Blood pressure-lowering effect of sodium restriction

blood pressure even in patients with resistant hypertension [84]. In addition, excessive sodium intake is known to weaken the effect of renin-angiotensin system blockers [85].

Cardiovascular benefit of sodium reduction

Several randomized controlled trials also have conducted to investigate the impact of salt reduction on cardiovascular disease, but the majority of these studies had inadequate sample sizes and durations. According to a previous Cochrane review, the evidence supporting the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing dietary salt on cardiovascular events was small [99, 100]. Contrary to these claims, opposing results have also been reported that reducing salt intake is associated with a significant decrease in cardiovascular events [101].. In addition, National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report concluded that reducing dietary sodium intake can prevent cardiovascular events based on a meta-analysis of well-designed relatively long-term trials, including the Trials of Hypertension Prevention (TOHP), and the Trials of Nonpharmacologic Intervention in the Elderly (TONE) [102-104]. More recently, a metaanalysis including the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS), the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), NHS II, the Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-Stage Disease (PREVEND), TOHP I, and TOHP II trials, which

repeatedly conducted 24 -hour urine collection as the most appropriate method, reported a dose-dependent and significant association between high sodium intake and risk of cardiovascular events [83, 96, 105-108]. They reported that daily increment of 1 g in sodium excretion was associated with an

Sustainability of sodium intake restriction

| Study (year) | Population | Estimation of sodium intake | Follow-up (years) | Outcomes | Result | Reference |

| Stolarz-Skrzypek et al. (2011) | 3681 participants without CVD | 24-hour urinary sodium excretion | 7.9 | CV death | Weak inverse association | [109] |

| Thomas et al. (2011) | 2807 participants with type 1 DM | 24-hour urinary sodium excretion | 10.0 | All-cause death | J-curve association | [110] |

| PREVEND (2014) | 7543 participants without CVD | 24-hour urinary sodium excretion | 10.5 | Coronary heart disease events | No association | [111] |

| Singer et al. (2015) | 3505 participants with HTN | 24-hour urinary sodium excretion | 18.6 | CV death and allcause death | Direct association with all-cause death | [112] |

| Mills et al. (2016) | 3757 participants with CKD | Multiple 24-hour urinary sodium excretion | 6.8 | Composite of CVD events | Linear association | [95] |

| Vuori et al. (2020) | 4630 general population | 24-hour urinary sodium excretion | 14.0 | Composite of CVD events | Direct association | [113] |

| TOHP I and II (2016) | 3011 participants with prehypertension | Multiple 24-hour urinary sodium excretion | 23.9 and 18.8 | All-cause death | Linear association | [79] |

| Meta-analysis of HPFS, NHS I, NHS II, PREVEND, TOHP I, and TOHP II (2022) | 10709 general population | Multiple 24-hour urinary sodium excretion | 8.8 | Composite of CVD events | Linear association | [93] |

support individual patient behavioral change, considerations for social or ecological factors related to sodium restriction must also be included [119]. For example, it is known that in most cases, additional sodium beyond the natural sodium found in raw ingredients is supplied during food processing or commercial food sales. Therefore, it is important to reduce processed foods and check the sodium content indicated on food labels [120]. Food labeling can give motivation to consumers choose low sodium products [121]. Additionally, certain labeling practices can encourage manufacturers to reformulate their products to contain less sodium. In order to choose low sodium content, it is important to choose products without additional salt, reduce foods seasoned or pickled with salt or seasonings, use low sodium spices with spicy flavors, choose carefully when eating out, adjust the nutrient content of food, and avoid using sodium at the table. Consultation with a skilled nutritionist on behavior change can be helpful in implementing these methods. If sodium restriction is possible through social or institutional improvements, it can reduce the effort to consciously reduce sodium intake, thus maximizing efficiency [122]. Self-monitoring is crucial in patients’ selfmanagement, particularly for chronic diseases such as diabetes, asthma, and heart failure [123]. The potential benefits of self-monitoring are promising, as literature indicates it may enhance self-management, symptom management, and disease regulation, resulting in fewer

complications, improved coping and attitudes towards the illness, realistic goal setting, and an overall better quality of life [124, 125]. Self-blood pressure monitoring, such as home blood pressure, has been shown to improve treatment adherence in hypertension and is actively recommended [5, 126]. For example, when counseling patients on their home blood pressure measurement results, regularly showing patients with a few days of blood pressure increases can help them monitor the effects of sodium intake on blood pressure and can help them understand their salt sensitivity and the blood pressure-lowering effect of sodium restriction, which can have a positive effect on sustained behavior change.

Benefit of high potassium diet

outcomes [128]. The PURE study also reported that as urinary potassium excretion increased, systolic blood pressure decreased, and the rates of mortality and cardiovascular events were decreased [129]. Several metaanalyses have consistently shown similar results. In a meta-analysis comprising 33 randomized controlled trials (

In a SSaSS trial [116], the group that replaced regular salt with a salt-substitute consisting of

DASH diet and sodium potassium ratio

Conclusions

Abbreviations

| DCT | distal convoluted tubule |

| CNT | connecting tubule |

| CCD | cortical collecting duct |

| NCC | sodium-chloride cotransporter |

| ENaC | epithelial sodium channel |

| ROMK | renal outer medullary K+ channel |

| BK | big-K+ channels |

| WNK | with-no-lysine (K) kinases |

| SPAK | Ste-20-related proline alanine-rich protein kinase |

| OSR1 | oxidative stress-responsive kinase 1 |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| NAS | National Academy of Sciences |

| TOHP | the Trials of Hypertension Prevention |

| TONE | the Trials of Nonpharmacologic Intervention in the Elderly |

| HPFS | the Health Professionals Follow-up Study |

| NHS | the Nurses’ Health Study |

| PREVEND | the Prevention of Renal and Vascular End-Stage Disease |

| RCT | randomized clinical trial |

| SSaSS | the Salt Substitute and Stroke Study |

| INTERSALT | the International Cooperative Study on Salt, Other Factors, and Blood |

| PURE | the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology |

| DASH | the dietary approaches to stop hypertension. |

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 02 January 2024

References

- Organization WH. A global brief on hypertension: silent killer, global public health crisis: world health day 2013. In: World Health Organization; 2013.

- Kim HC, Cho SMJ, Lee H, Lee HH, Baek J, Heo JE. Korea hypertension fact sheet 2020: analysis of nationwide population-based data. Clin Hypertens. 2021;27(1):8.

- Zhou B, Carrillo-Larco RM, Danaei G, Riley LM, Paciorek CJ, Stevens GA, et al. Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398(10304):957-80.

- Kim HL, Lee EM, Ahn SY, Kim KI, Kim HC, Kim JH, et al. The 2022 focused update of the 2018 Korean Hypertension Society Guidelines for the management of hypertension. Clin Hypertens. 2023;29(1):11.

- Lee HY, Shin J, Kim GH, Park S, Ihm SH, Kim HC, et al. 2018 Korean Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the management of hypertension: part II-diagnosis and treatment of hypertension. Clin Hypertens. 2019;25:20.

- Walser M. Phenomenological analysis of renal regulation of sodium and potassium balance. Kidney Int. 1985;27(6):837-41.

- Bie P. Mechanisms of sodium balance: total body sodium, surrogate variables, and renal sodium excretion. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys. 2018;315(5):R945-r962.

- Bie P, Wamberg S, Kjolby M. Volume natriuresis vs. pressure natriuresis. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;181(4):495-503.

- Duda K, Majerczak J, Nieckarz Z, Heymsfield SB, Zoladz JA. Chapter 1 – Human Body Composition and Muscle Mass. In: Zoladz JA, editor. Muscle and exercise physiology. Academic Press; 2019. p. 3-26.

- van Westing AC, Küpers LK, Geleijnse JM. Diet and Kidney Function: a Literature Review. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2020;22(2):14.

- Guthrie D, Yucha C. Urinary concentration and dilution. Nephrol Nurs J. 2004;31 (3):297-301. quiz 302-293

- Natochin YV, Golosova DV. Vasopressin receptor subtypes and renal sodium transport. Vitam Horm. 2020;113:239-58.

- Bernal A, Zafra MA, Simón MJ, Mahía J. Sodium Homeostasis, a Balance Necessary for Life. Nutrients. 2023;15(2):395.

- Girardin E, Caverzasio J, Iwai J, Bonjour JP, Muller AF, Grandchamp A. Pressure natriuresis in isolated kidneys from hypertension-prone and hypertension-resistant rats (Dahl rats). Kidney Int. 1980;18(1):10-9.

- Felder RA, White MJ, Williams SM, Jose PA. Diagnostic tools for hypertension and salt sensitivity testing. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013;22(1):65-76.

- Titze J, Dahlmann A, Lerchl K, Kopp C, Rakova N, Schröder A, et al. Spooky sodium balance. Kidney Int. 2014;85(4):759-67.

- Clemmer JS, Pruett WA, Coleman TG, Hall JE, Hester RL. Mechanisms of blood pressure salt sensitivity: new insights from mathematical modeling. Am J Phys Regul Integr Comp Phys. 2017;312(4):R451-r466.

- Elijovich F, Weinberger MH, Anderson CA, Appel LJ, Bursztyn M, Cook NR, et al. Salt Sensitivity of Blood Pressure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2016;68(3):e7-e46.

- Koomans HA, Roos JC, Boer P, Geyskes GG, Mees EJ. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure in chronic renal failure. Evidence for renal control of body fluid distribution in man. Hypertension. 1982;4(2):190-7.

- Titze J, Shakibaei M, Schafflhuber M, Schulze-Tanzil G, Porst M, Schwind KH, et al. Glycosaminoglycan polymerization may enable osmotically inactive Na+ storage in the skin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287(1):H203-8.

- Rossitto G, Mary S, Chen JY, Boder P, Chew KS, Neves KB, et al. Tissue sodium excess is not hypertonic and reflects extracellular volume expansion. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4222.

- Bräxmeyer DL, Keyes JL. The pathophysiology of potassium balance. Crit Care Nurse. 1996;16(5):59-71. quiz 72-53

- Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Physiology and pathophysiology of potassium homeostasis. Adv Physiol Educ. 2016;40(4):480-90.

- Staruschenko A. Beneficial Effects of High Potassium: Contribution of Renal Basolateral K(+) Channels. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1015-22.

- Rodrigues SL, Baldo MP, Machado RC, Forechi L, Molina Mdel C, Mill JG. High potassium intake blunts the effect of elevated sodium intake on blood pressure levels. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2014;8(4):232-8.

- Giebisch G. Renal potassium transport: mechanisms and regulation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1998;274(5):F817-33.

- Gumz ML, Rabinowitz L, Wingo CS. An integrated view of potassium homeostasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):60-72.

- Roy A, Al-bataineh MM, Pastor-Soler NM. Collecting duct intercalated cell function and regulation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(2):305.

- Wade JB, Fang L, Coleman RA, Liu J, Grimm PR, Wang T, et al. Differential regulation of ROMK (Kir1.1) in distal nephron segments by dietary potassium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300(6):F1385-93.

- Gamba G. Molecular biology of distal nephron sodium transport mechanisms. Kidney Int. 1999;56(4):1606-22.

- Masilamani S, Kim GH, Mitchell C, Wade JB, Knepper MA. Aldosteronemediated regulation of ENaC alpha, beta, and gamma subunit proteins in rat kidney. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(7):R19-23.

- Rieg T, Vallon V, Sausbier M, Sausbier U, Kaissling B, Ruth P, et al. The role of the BK channel in potassium homeostasis and flow-induced renal potassium excretion. Kidney Int. 2007;72(5):566-73.

- Wei KY, Gritter M, Vogt L, de Borst MH, Rotmans JI, Hoorn EJ. Dietary potassium and the kidney: lifesaving physiology. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13(6):952-68.

- Gumz ML, Rabinowitz L, Wingo CS. An Integrated View of Potassium Homeostasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):60-72.

- Zhang C, Wang L, Zhang J, Su XT, Lin DH, Scholl UI, et al. KCNJ10 determines the expression of the apical

cotransporter (NCC) in the early distal convoluted tubule (DCT1). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(32):11864-9. - Su X-T, Zhang C, Wang L, Gu R, Lin D-H, Wang W-H. Disruption of KCNJ10 (Kir4. 1) stimulates the expression of ENaC in the collecting duct. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310(10):F985-93.

- Cuevas CA, Su XT, Wang MX, Terker AS, Lin DH, McCormick JA, et al. Potassium Sensing by Renal Distal Tubules Requires Kir4.1. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(6):1814-25.

- Wang MX, Cuevas CA, Su XT, Wu P, Gao ZX, Lin DH, et al. Potassium intake modulates the thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride cotransporter (NCC) activity via the Kir4.1 potassium channel. Kidney Int. 2018;93(4):893-902.

- Hennings JC, Andrini O, Picard N, Paulais M, Huebner AK, Cayuqueo IK, et al. The CIC-K2 Chloride Channel Is Critical for Salt Handling in the Distal Nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(1):209-17.

- Bazúa-Valenti S, Chávez-Canales M, Rojas-Vega L, González-Rodríguez X, Vázquez N, Rodríguez-Gama A, et al. The Effect of WNK4 on the Na+-ClCotransporter Is Modulated by Intracellular Chloride. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26(8):1781-6.

- Castañeda-Bueno M, Cervantes-Perez LG, Rojas-Vega L, Arroyo-Garza I, Vázquez N, Moreno E, et al. Modulation of NCC activity by low and high

intake: insights into the signaling pathways involved. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2014;306(12):F1507-19. - Yang YS, Xie J, Yang SS, Lin SH, Huang CL. Differential roles of WNK4 in regulation of NCC in vivo. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2018;314(5):F999-f1007.

- Terker AS, Zhang C, McCormick JA, Lazelle RA, Zhang C, Meermeier NP, et al. Potassium modulates electrolyte balance and blood pressure through effects on distal cell voltage and chloride. Cell Metab. 2015;21(1):39-50.

- Hoorn EJ, Gritter M, Cuevas CA, Fenton RA. Regulation of the renal NaCl cotransporter and its role in potassium homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 2020;100(1):321-56.

- Jensen IS, Larsen CK, Leipziger J, Sørensen MV. Na(+) dependence of

-induced natriuresis, kaliuresis and cotransporter dephosphorylation. Acta Physiol (Oxford). 2016;218(1):49-61. - Sorensen MV, Grossmann S, Roesinger M, Gresko N, Todkar AP, Barmettler G, et al. Rapid dephosphorylation of the renal sodium chloride cotransporter in response to oral potassium intake in mice. Kidney Int. 2013;83(5):811-24.

- Shoda W, Nomura N, Ando F, Mori Y, Mori T, Sohara E, et al. Calcineurin inhibitors block sodium-chloride cotransporter dephosphorylation in response to high potassium intake. Kidney Int. 2017;91(2):402-11.

- Pearce D, Manis AD, Nesterov V, Korbmacher C. Regulation of distal tubule sodium transport: mechanisms and roles in homeostasis and pathophysiology. Pflug Arch Eur J Physiol. 2022;474(8):869-84.

- Yang LE, Sandberg MB, Can AD, Pihakaski-Maunsbach K, McDonough AA. Effects of dietary salt on renal Na+ transporter subcellular distribution, abundance, and phosphorylation status. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2008;295(4):F1003-16.

- van der Lubbe N, Moes AD, Rosenbaek LL, Schoep S, Meima ME, Danser AH , et al.

-induced natriuresis is preserved during depletion and accompanied by inhibition of the Na+-Cl- cotransporter. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2013;305(8):F1177-88. - Terker AS, Zhang C, Erspamer KJ, Gamba G, Yang CL, Ellison DH. Unique chloride-sensing properties of WNK4 permit the distal nephron to modulate potassium homeostasis. Kidney Int. 2016;89(1):127-34.

- Huang CL , Cheng CJ. A unifying mechanism for WNK kinase regulation of sodium-chloride cotransporter. Pflugers Arch. 2015;467(11):2235-41.

- Fujita T, Ando K. Hemodynamic and endocrine changes associated with potassium supplementation in sodium-loaded hypertensives. Hypertension. 1984;6(2 Pt 1):184-92.

- Wilson DK, Sica DA, Miller SB. Effects of potassium on blood pressure in salt-sensitive and salt-resistant black adolescents. Hypertension. 1999;34(2):181-6.

- Walkowska A, Kuczeriszka M, Sadowski J, Olszyñski KH, Dobrowolski L, Červenka L, et al. High salt intake increases blood pressure in normal rats: putative role of 20-HETE and no evidence on changes in renal vascular reactivity. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2015;40(3):323-34.

- Intersalt Cooperative Research Group. Intersalt: an international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Results for 24 hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 1988;297(6644):319-28.

- Denton D, Weisinger R, Mundy NI, Wickings EJ, Dixson A, Moisson P, et al. The effect of increased salt intake on blood pressure of chimpanzees. Nat Med. 1995;1(10):1009-16.

- Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P, Ezzati M, et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12):e003733.

- WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Guideline: Sodium Intake for Adults and Children. Geneva: World Health Organization Copyright © 2012: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Snetselaar LG, de Jesus JM, DeSilva DM, Stoody EE. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025: Understanding the Scientific Process, Guidelines, and Key Recommendations. Nutr Today. 2021;56(6):287-95.

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition NF, Allergens F, Turck D, Castenmiller J, de Henauw S, Hirsch-Ernst K-I, et al. Dietary reference values for sodium. EFSA J. 2019;17(9):e05778.

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(33):3021-104.

- Graudal N, Hubeck-Graudal T, Jürgens G, Taylor RS. Dose-response relation between dietary sodium and blood pressure: a metaregression analysis of 133 randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(5):1273-8.

- Graudal NA, Hubeck-Graudal T, Jurgens G. Effects of low sodium diet versus high sodium diet on blood pressure, renin, aldosterone, catecholamines, cholesterol, and triglyceride. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;12(12):Cd004022.

- Cappuccio FP, Beer M, Strazzullo P. Population dietary salt reduction and the risk of cardiovascular disease. A scientific statement from the European Salt Action Network. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;29(2):107-14.

- He FJ, Campbell NRC, Ma Y, MacGregor GA, Cogswell ME, Cook NR. Errors in estimating usual sodium intake by the Kawasaki formula alter its relationship with mortality: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(6):1784-95.

- He FJ, Campbell NRC, Woodward M, MacGregor GA. Salt reduction to prevent hypertension: the reasons of the controversy. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(25):2501-5.

- He FJ, Li J, Macgregor GA. Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2013;346:f1325.

- Huang L, Trieu K, Yoshimura S, Neal B, Woodward M, Campbell NRC, et al. Effect of dose and duration of reduction in dietary sodium on blood pressure levels: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2020;368:m315.

- Olde Engberink RHG, van den Hoek TC, van Noordenne ND, van den Born BH, Peters-Sengers H, Vogt L. Use of a Single Baseline Versus Multiyear 24-Hour Urine Collection for Estimation of Long-Term Sodium Intake and Associated Cardiovascular and Renal Risk. Circulation. 2017;136(10):917-26.

- McLean RM, Farmer VL, Nettleton A, Cameron CM, Cook NR, Campbell NRC. Assessment of dietary sodium intake using a food frequency questionnaire and 24-hour urinary sodium excretion: a

systematic literature review. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich, Conn). 2017;19(12):1214-30. - McLean RM, Farmer VL, Nettleton A, Cameron CM, Cook NR, Woodward M , et al. Twenty-Four-Hour Diet recall and Diet records compared with 24-hour urinary excretion to predict an individual’s sodium consumption: A Systematic Review. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich, Conn). 2018;20(10):1360-76.

- Lucko AM, Doktorchik C, Woodward M, Cogswell M, Neal B, Rabi D, et al. Percentage of ingested sodium excreted in 24-hour urine collections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich, Conn). 2018;20(9):1220-9.

- Lerchl K, Rakova N, Dahlmann A, Rauh M, Goller U, Basner M, et al. Agreement between 24 -hour salt ingestion and sodium excretion in a controlled environment. Hypertension. 2015;66(4):850-7.

- Tanaka T, Okamura T, Miura K, Kadowaki T, Ueshima H, Nakagawa H, et al. A simple method to estimate populational 24-h urinary sodium and potassium excretion using a casual urine specimen. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16(2):97-103.

- Kawasaki T, Itoh K, Uezono K, Sasaki H. A simple method for estimating 24 h urinary sodium and potassium excretion from second morning voiding urine specimen in adults. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1993;20(1):7-14.

- Brown IJ, Dyer AR, Chan Q, Cogswell ME, Ueshima H, Stamler J, et al. Estimating 24-hour urinary sodium excretion from casual urinary sodium concentrations in Western populations: the INTERSALT study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(11):1180-92.

- O’Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Wang X, Liu L, et al. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):612-23.

- Cook NR, Appel LJ, Whelton PK. Sodium Intake and All-Cause Mortality Over 20 Years in the Trials of Hypertension Prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(15):1609-17.

- Huang L, Crino M, Wu JH, Woodward M, Barzi F, Land MA, et al. Mean population salt intake estimated from 24-h urine samples and spot urine samples: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(1):239-50.

- Cappuccio FP, Sever PS. The importance of a valid assessment of salt intake in individuals and populations. A scientific statement of the British and Irish Hypertension Society. J Hum Hypertens. 2019;33(5):345-8.

- Suckling RJ, He FJ, Markandu ND, MacGregor GA. Modest Salt Reduction Lowers Blood Pressure and Albumin Excretion in Impaired Glucose Tolerance and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Double-Blind Trial. Hypertension. 2016;67(6):1189-95.

- The Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. Effects of weight loss and sodium reduction intervention on blood pressure and hypertension incidence in overweight people with highnormal blood pressure. The Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase II. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(6):657-67.

- Pimenta E, Gaddam KK, Oparil S, Aban I, Husain S, Dell’Italia LJ, et al. Effects of dietary sodium reduction on blood pressure in subjects with resistant hypertension: results from a randomized trial. Hypertension. 2009;54(3):475-81.

- Vegter S, Perna A, Postma MJ, Navis G, Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P. Sodium intake, ACE inhibition, and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(1):165-73.

- Welsh CE, Welsh P, Jhund P, Delles C, Celis-Morales C, Lewsey JD, et al. Urinary Sodium Excretion, Blood Pressure, and Risk of Future Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in Subjects Without Prior Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension. 2019;73(6):1202-9.

- Zanetti D, Bergman H, Burgess S, Assimes TL, Bhalla V, Ingelsson E. Urinary Albumin, Sodium, and Potassium and Cardiovascular Outcomes in the UK Biobank: Observational and Mendelian Randomization Analyses. Hypertension. 2020;75(3):714-22.

- Elliott P, Muller DC, Schneider-Luftman D, Pazoki R, Evangelou E, Dehghan A, et al. Estimated 24-Hour Urinary Sodium Excretion and Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality Among 398628 Individuals in UK Biobank. Hypertension. 2020;76(3):683-91.

- Mente A, O’Donnell M, Rangarajan S, Dagenais G, Lear S, McQueen M, et al. Associations of urinary sodium excretion with cardiovascular events in individuals with and without hypertension: a pooled

analysis of data from four studies. Lancet (London, England). 2016;388(10043):465-75. - O’Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, O’Leary N, Yin L, et al. Joint association of urinary sodium and potassium excretion with cardiovascular events and mortality: prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2019;364:I772.

- Cook NR, Appel LJ, Whelton PK. Lower levels of sodium intake and reduced cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2014;129(9):981-9.

- Strazzullo P, D’Elia L, Kandala NB, Cappuccio FP. Salt intake, stroke, and cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2009;339:b4567.

- Ma Y, He FJ, Sun Q, Yuan C, Kieneker LM, Curhan GC, et al. 24-Hour Urinary Sodium and Potassium Excretion and Cardiovascular Risk. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(3):252-63.

- Mente A, O’Donnell M, Rangarajan S, McQueen M, Dagenais G, Wielgosz A, et al. Urinary sodium excretion, blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: a community-level prospective epidemiological cohort study. Lancet. 2018;392(10146):496-506.

- Mills KT, Chen J, Yang W, Appel LJ, Kusek JW, Alper A, et al. Sodium Excretion and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. Jama. 2016;315(20):2200-10.

- Kieneker LM, Eisenga MF, Gansevoort RT, de Boer RA, Navis G, Dullaart RPF, et al. Association of Low Urinary Sodium Excretion With Increased Risk of Stroke. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(12):1803-9.

- Heaney RP. Sodium: how and how not to set a nutrient intake recommendation. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26(10):1194-7.

- Cook NR, He FJ, MacGregor GA, Graudal N. Sodium and health-concordance and controversy. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2020;369:m2440.

- Adler AJ, Taylor F, Martin N, Gottlieb S, Taylor RS, Ebrahim S. Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(12):Cd009217.

- Taylor RS, Ashton KE, Moxham T, Hooper L, Ebrahim S. Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (Cochrane review). Am J Hypertens. 2011;24(8):843-53.

- He FJ, MacGregor GA. Salt reduction lowers cardiovascular risk: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet (London, England). 2011;378(9789):380-2.

- National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine, Health, Medicine D, Food, Nutrition B, Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for S, Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Oria M, Harrison M, Stallings VA, editors. Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2019 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved; 2019.

- Cook NR, Cutler JA, Obarzanek E, Buring JE, Rexrode KM, Kumanyika SK, et al. Long term effects of dietary sodium reduction on cardiovascular disease outcomes: observational follow-up of the trials of hypertension prevention (TOHP). BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2007;334(7599):885-8.

- Appel LJ, Espeland MA, Easter L, Wilson AC, Folmar S, Lacy CR. Effects of reduced sodium intake on hypertension control in older individuals: results from the Trial of Nonpharmacologic Interventions in the Elderly (TONE). Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(5):685-93.

- Bao Y, Bertoia ML, Lenart EB, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, et al. Origin, Methods, and Evolution of the Three Nurses’ Health Studies. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1573-81.

- Sun Q, Bertrand KA, Franke AA, Rosner B, Curhan GC, Willett WC. Reproducibility of urinary biomarkers in multiple 24-h urine samples. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(1):159-68.

- Yuan C, Spiegelman D, Rimm EB, Rosner BA, Stampfer MJ, Barnett JB, et al. Relative Validity of Nutrient Intakes Assessed by Questionnaire, 24-Hour Recalls, and Diet Records as Compared With Urinary Recovery and Plasma Concentration Biomarkers: Findings for Women. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(5):1051-63.