DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-03851-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38212816

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-11

تأثير زاوية البناء على ملاءمة حواف التيجان السنية المطبوعة بتقنية الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد باستخدام معالجة الضوء الرقمي وتقنية الاستريوليثوغرافي: دراسة مخبرية

الملخص

الخلفية تأثير تقنية الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد وزاوية البناء على الملاءمة الهامشية للتاجات المطبوعة غير واضح. كان الهدف من هذا البحث هو استخدام معالجة الضوء الرقمي (DLP) والطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد المعتمدة على الاستريوليثوغرافيا (SLA) لبناء ترميمات فردية بزوايا بناء متنوعة وتحليل الملاءمة الهامشية للتاجات. الطرق تم مسح ضرس أول معدني مُعد باستخدام ماسح ضوئي بصري. تم استخدام ثلاث زوايا بناء لبناء العينات: 0، 45، و

الخلفية

الدقة الحجمية، تقلل من وقت وتكلفة التصنيع، وتقلل من عدد الدعامات المطلوبة للطباعة [14]. من خلال الاستفادة الكاملة من مصدر الضوء، واحدة من الميزات التي قد تحسن الدقة الهندسية والجودة الهيكلية للعنصر النهائي المطبوعة بتقنية الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد هي تخصيص زاوية/اتجاه البناء أثناء عملية البناء [15].

طرق

|

|

|

|

قيمة P | ||

| SLA |

|

|

|

|

||

| DLP |

|

|

|

|

تم التحقق من البيانات المجمعة للتوزيع الطبيعي باستخدام اختبارات Kolomgrov-Smirnov وShapiro-Wilk وتم تحليلها باستخدام تحليل التباين أحادي الاتجاه وثنائي الاتجاه (ANOVA)، تليها اختبار Tukey’s HSD (SPSS Statistics for Windows، الإصدار 20.0؛ IBM، أرمونك، نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) عند مستوى دلالة

النتائج

المناقشة

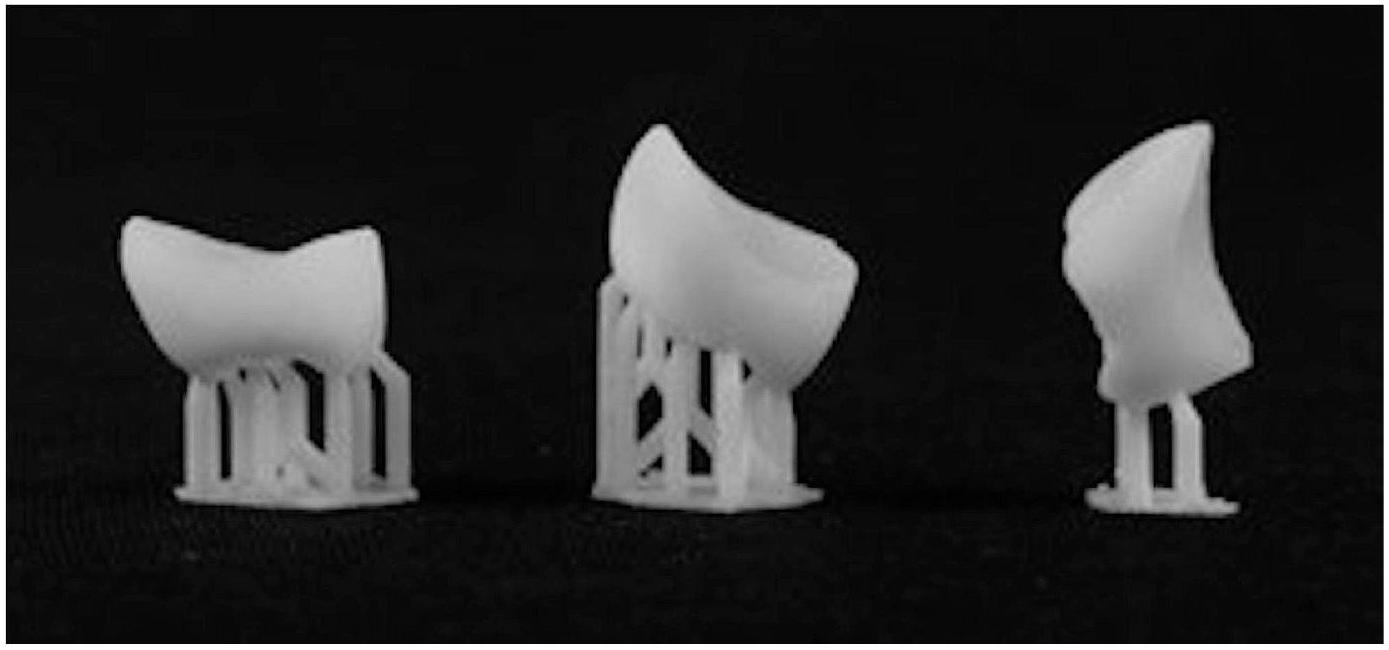

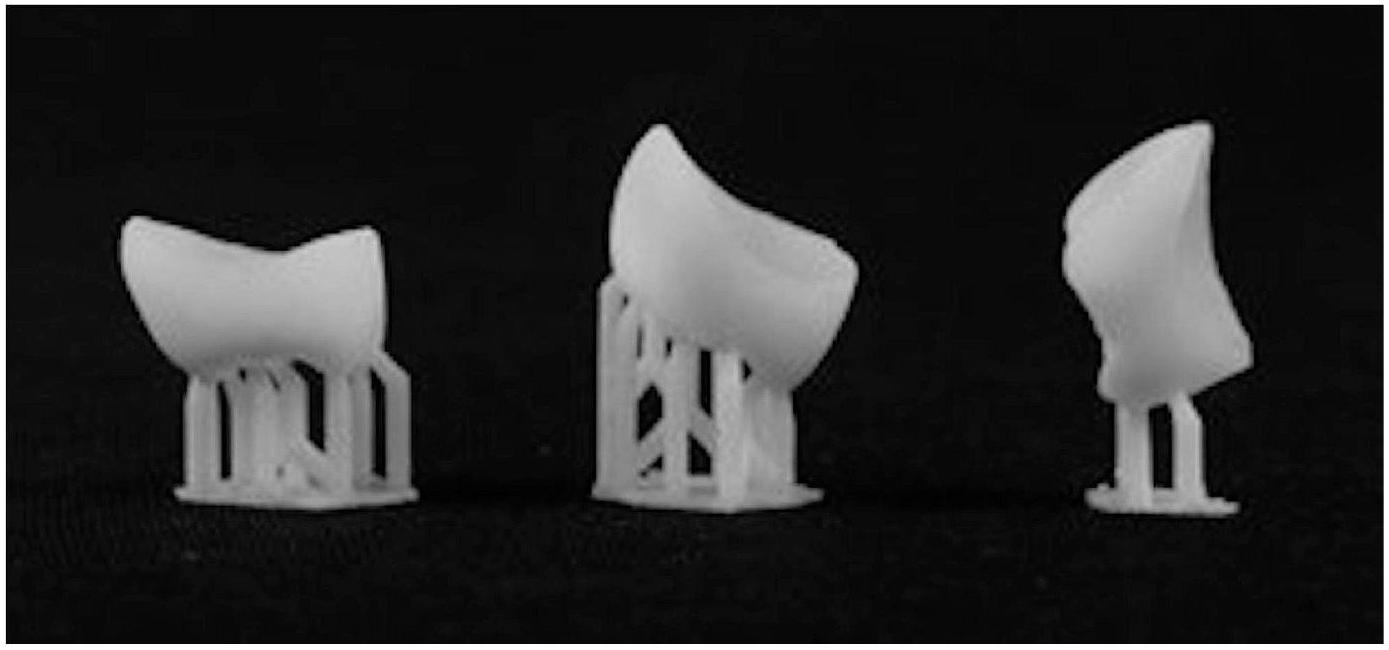

تم استخدام ثلاث زوايا بناء مختلفة لطباعة تاجات الأسنان ذات التغطية الكاملة بتقنية 3D. تم اتخاذ عدة خطوات لتقليل والقضاء على جميع الأخطاء المحتملة في التعامل والمعالجة. في مركز منصة البناء، تم طباعة كل تاج بشكل فردي. تمت عمليات التصنيع والعلاج بعد الطباعة بواسطة ممارس مدرب واحد من التقنيتين. بناءً على الأبحاث السابقة، تم التخطيط لمساحة الأسمنت لتكون

الضوء الذي يدخل منطقة أوسع مع مسافة اختراق أقصر من تلك الخاصة بـ

تقطيع عنصر ثلاثي الأبعاد إلى طبقات، والتي تتم طباعتها بشكل فردي ثم تتكدس لتتفاعل معًا وتبني الجسم المطلوب تدريجيًا، هو الخطوة الأولى في عملية الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد. “تأثير الدرج” هو ظاهرة يمكن أن تحدث عند طباعة العناصر مع اتجاهات بناء مائلة. في هذه الظاهرة، يتم طباعة الطبقات تدريجيًا وتؤدي الحواف بينهما إلى أخطاء [15، 32]. لذلك، من المعقول أن نفترض أن

في العينات ذات الاتجاهات الإنشائية المختلفة، قد تؤدي الجاذبية إلى تشويه المنطقة التي تتدلى فوق الجدران البوكالية واللسانية، مما يغير حجم الفجوات الهامشية. تتماشى هذه النتائج مع تلك الخاصة بـ ريو وآخرون [11]، أن اتجاه

اكتشفت تحقيقات أخرى أيضًا تأثير الهياكل الداعمة. أفاد يو وآخرون أن بروستhesis الراتنجية التي تم إنتاجها باستخدام طابعة SLA ثلاثية الأبعاد كانت ذات جودة رديئة في الحواف القريبة من موصل الدعم وغالبًا ما كانت لها حواف خشنة [6]. يختلف موضع موصل الدعم مع زاوية البناء. قد تؤدي الأجزاء غير المدعومة إلى أخطاء. إذا كان الدعم متصلًا بالقرب من حافة التاج، فقد يتسبب ذلك في ضرر أثناء الإزالة [18]. بحث الحربي وآخرون في دقة الأبعاد لزاوية البناء لتاجات الأسنان المصنوعة باستخدام طابعة DLP ثلاثية الأبعاد، كانت خطأ الجذر التربيعي المتوسط (RMSE) أعلى في المنطقة التي تحتوي على هيكل الدعم [18]. يختلف موضع موصل الدعم مع زاوية البناء. قد تؤدي الأجزاء غير المدعومة إلى أخطاء. إذا كان الدعم متصلًا بالقرب من حافة التاج، فقد يتسبب ذلك في ضرر أثناء الإزالة. في الوقت نفسه، يختلف شكل الطبقة التي أنشأتها الطابعة ثلاثية الأبعاد وفقًا لزاوية البناء، وهو سبب للاختلافات في الملاءمة الهامشية. تقوم طابعة ثلاثية الأبعاد المعتمدة على DLP بتجفيف طبقة واحدة في كل مرة، وأي تغيير في شكل الطبقة يتطلب تغييرات في الشكل ودرجة انكماش البوليمرة. تستخدم تقنية SLA ليزر الأشعة فوق البنفسجية (UV) لعلاج المادة نقطة بنقطة [25، 26].

اختيار زاوية البناء أمر حاسم لأنه يؤثر على كمية الهياكل الداعمة المطلوبة، والتي قد تؤثر على دقة المكونات المصنعة [18]. يزداد عدد الأسطح المدعومة ذاتيًا وينخفض عدد الهياكل الداعمة عندما يتم تدوير التاج من زاوية بناء

قد يتعرض جزء من الترميم للتلف. تم وضع الدعم بعيدًا عن حواف التاج في

الاستنتاجات

- تؤثر تقنية الطباعة بشكل مباشر على الدقة الهامشية للتاج الدائم المطبوعة بتقنية الطباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد.

- زاوية الطباعة لها تأثير على الدقة الهامشية.

- أظهرت جميع المتغيرات المختبرة نتائج ضمن النطاق المقبول سريرياً.

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

موافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تاريخ الاستلام: 13 مايو 2023 / تاريخ القبول: 2 يناير 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 11 يناير 2024

References

- Ebeid K, Nouh I, Ashraf Y, Cesar PF. Accuracy of different laboratory scanners for scanning of implant-supported full arch fixed prosthesis. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2022;34:843-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.12918.

- Ebeid K, Sabet A, El Sergany O, Della Bona A. Accuracy and repeatability of different intraoral instruments on shade determination compared to visual shade selection. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2022;34:988-93. https://doi. org/10.1111/jerd.12884.

- Ellakany P, Tantawi M, El, Mahrous AA, Al-Harbi F. Evaluation of the accuracy of digital impressions obtained from intraoral and extraoral dental scanners with different CAD/CAM scanning technologies: an in vitro study. J Prosthodont. 2022;31:314-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13400.

- Azari A, Nikzad S. The evolution of rapid prototyping in dentistry: a review. Rapid Prototyp J. 2009;15:216-25. https://doi. org/10.1108/13552540910961946.

- Ottoni R, Marocho SMS, Griggs JA, Borba M. CAD/CAM versus 3D-printing/ pressed lithium disilicate monolithic crowns: adaptation and fatigue behavior. J Dent. 2022;123:104181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104181.

- Yu BY, Son KB, Da, Lee KB. Evaluation of intaglio surface trueness and margin quality of interim crowns in accordance with the build angle of stereolithography apparatus 3-dimensional printing. J Prosthet Dent. 2021;126:231-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2020.04.028.

- Andersen UV, Pedersen DB, Hansen HN, Nielsen JS. In-process 3D geometry reconstruction of objects produced by direct light projection. Int J Adv ManufTechnol. 2013;68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-013-4778-3.

- Wu GH, Hsu SH, Review. Polymeric-based 3D printing for tissue engineering. J Med Biol Eng. 2015;35:285-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40846-015-0038-3.

- Mitteramskogler G, Gmeiner R, Felzmann R, Gruber S, Hofstetter C, Stampfl J, et al. Light curing strategies for lithography-based additive manufacturing of customized ceramics. Addit Manuf. 2014;1:110-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. addma.2014.08.003.

- Lee MP, Cooper GJT, Hinkley T, Gibson GM, Padgett MJ, Cronin L. Development of a 3D printer using scanning projection stereolithography. Sci Rep. 2015;5. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09875.

- Ryu JE, Kim YL, Kong HJ, Chang HS, Jung JH. Marginal and internal fit of 3D printed provisional crowns according to build directions. J Adv Prosthodont. 2020;12. https://doi.org/10.4047/jap.2020.12.4.225.

- Yan Y, Li S, Zhang R, Lin F, Wu R, Lu Q, et al. Rapid prototyping and manufacturing technology: principle, representative technics, applications, and development trends. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2009;14:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S1007-0214(09)70001-X.

- Huotilainen E, Salmi M, Chekurov S, Flores Ituarte I. Effect of build orientation in 3D printing production for material extrusion, material jetting, binder jetting, sheet object lamination, vat photopolymerisation, and powder bed fusion. Int J Collab Enterp. 2016;5:218. https://doi.org/10.1504/ ijcent.2016.10003187.

- Hong J, Wu DL, Li DC, Lu BH. Multi-objective optimization of the part building orientation in stereolithography. Hsi-An Chiao Tung Ta Hsueh/Journal Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 2001;35:506-9.

- Oropallo W, Piegl LA. Ten challenges in 3D printing. Eng Comput. 2016;32:135-48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-015-0407-0.

- Habib SR, AI Otaibi AK, AI Anazi TA, AI Anazi SM. Comparison between five CAD/CAM systems for fit of zirconia copings. Quintessence Int. 2018;49:43744. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.qi.a40354.

- Zheng Z, Wang H, Mo J, Ling Z, Zeng Y, Zhang Y, et al. Effect of virtual cement space and restorative materials on the adaptation of CAD-CAM endocrowns. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22:580. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02598-0.

- Alharbi N, Osman R, Wismeijer D. Factors influencing the dimensional accuracy of 3d-printed full-coverage dental restorations using stereolithography technology. Int J Prosthodont. 2016;29:503-10. https://doi.org/10.11607/ ijp.4835.

- Kakinuma H, Izumita K, Yoda N, Egusa H, Sasaki K. Comparison of the accuracy of resin-composite crowns fabricated by three-dimensional printing and milling methods. Dent Mater J. 2022;41:808-15. https://doi.org/10.4012/ dmj.2022-074.

- Abualsaud R, Alalawi H. Fit, precision, and trueness of 3d-printed zirconia crowns compared to milled counterparts. Dent J. 2022;10:215. https://doi. org/10.3390/dj10110215.

- Chaiamornsup P, Iwasaki N, Tsuchida Y, Takahashi H. Effects of build orientation on adaptation of casting patterns for three-unit partial fixed dental prostheses fabricated by using digital light projection. J Prosthet Dent. 2022;128:1047-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2021.01.006.

- Bammani SS, Birajdar PR, Metan SS. Dental crown manufacturing using stereolithography method. Proc Int Conf Adv Ind Prod Eng 2012:7-10.

- Torabi K, Vojdani M, Giti R, Taghva M, Pardis S. The effect of various veneering techniques on the marginal fit of zirconia copings. J Adv Prosthodont. 2015;7:233-9. https://doi.org/10.4047/jap.2015.7.3.233.

- Martínez-Rus F, Suárez MJ, Rivera B, Pradíes G. Evaluation of the absolute marginal discrepancy of zirconia-based ceramic copings. J Prosthet Dent. 2011;105:108-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3913(11)60009-7.

- Tahayeri A, Morgan MC, Fugolin AP, Bompolaki D, Athirasala A, Pfeifer CS, et al. 3D printed versus conventionally cured provisional crown and bridge dental materials. Dent Mater. 2018;34:192-200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. dental.2017.10.003.

- Unkovskiy A, Bui PHB, Schille C, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Huettig F, Spintzyk S. Objects build orientation, positioning, and curing influence dimensional accuracy and flexural properties of stereolithographically printed resin. Dent Mater. 2018;34:e324-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2018.09.011.

- Park GS, Kim SK, Heo SJ, Koak JY, Seo DG. Effects of printing parameters on the fit of implant-supported 3D printing resin prosthetics. Mater (Basel). 2019;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12162533.

- McLean JW, Von F. The estimation of cement film thickness by an in vivo technique. Br Dent J. 1971;131:107-11. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4802708.

- Revilla-León M, Meyers MJ, Zandinejad A, Özcan M. A review on chemical composition, mechanical properties, and manufacturing work flow of additively manufactured current polymers for interim dental restorations. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2019;31:51-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.12438.

- Chaiamornsup P, Iwasaki N, Yasue T, Uo M, Takahashi H. Effects of build conditions and angle acuteness on edge reproducibility of casting patterns fabricated using digital light projection. Dent Mater J. 2020;39:135-40. https://doi. org/10.4012/dmj.2018-401.

- Vitale A, Cabral JT. Frontal conversion and uniformity in 3D printing by photopolymerisation. Mater (Basel). 2016;9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9090760.

- Pandey PM, Venkata Reddy N, Dhande SG. Part deposition orientation studies in layered manufacturing. J Mater Process Technol. 2007;185:125-31. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2006.03.120.

- Derban P, Negrea R, Rominu M, Marsavina L. Influence of the printing angle and load direction on flexure strength in 3d printed materials for provisional dental restorations. Mater (Basel). 2021;14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ma14123376.

- Melchels FPW, Feijen J, Grijpma DW. A review on stereolithography and its applications in biomedical engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.050.

- Liu Q, Leu MC, Schmitt SM. Rapid prototyping in dentistry: technology and application. Int J Adv ManufTechnol. 2006;29:317-35. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00170-005-2523-2.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلات:

كمال عبيد

كمال عبيد@dent.asu.edu.eg

قسم التعويضات الثابتة، كلية طب الأسنان، البريطانية

جامعة في مصر، القاهرة، مصر

قسم التعويضات الثابتة، كلية dentistry، جامعة عين شمس

جامعة، شارع منظمة الوحدة الأفريقية، القاهرة، مصر

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-03851-4

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38212816

Publication Date: 2024-01-11

Build angle effect on 3D-printed dental crowns marginal fit using digital lightprocessing and stereo-lithography technology: an in vitro study

Abstract

Background The effect of 3D printing technology and build angle on the marginal fit of printed crowns is unclear. The objective of this research was to use digital light processing (DLP) and stereo-lithography (SLA)-based 3D printing to construct single restorations with varied build angles and to analyze the crowns’ marginal fit. Methods A prepared resin first molar was scanned utilizing an optical scanner. Three build orientations were used to construct the specimens: 0,45 , and

Background

volumetric accuracy, decreases manufacturing time and cost, and reduces the number of supports required for printing [14]. By making full use of the light source, one of the features that may improve the geometrical precision and structural quality of the final 3D-printed item is customizing build angle/orientation during the build process [15].

Methods

|

|

|

|

P-Value | ||

| SLA |

|

|

|

|

||

| DLP |

|

|

|

|

The data collected was checked for normal distribution using Kolomgrov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests and analyzed using one-way and two-way analysis of variances (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s HSD test (SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0.; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) at a significance level of

Results

Discussion

Three different build angles were utilized to 3D print full-coverage dental crowns. Several steps were made to reduce and eradicate all possible handling and processing faults. In the center of the build platform, each crown was printed individually. The fabrication and post-curing processes were carried out by a single trained practitioner of the two technologies. Based on earlier research, the cement space was planned to be

light entering a broader area with a shorter penetrating distance than that of the

Virtually cutting a 3D item into layers, which are then printed individually and stacked to copolymerize and gradually construct the desired object, is the first step in the 3D printing process. The “staircase effect” is a phenomenon that can happen when printing objects with inclined construction orientations. In this phenomenon, layers are printed gradually and the step edges between them result in errors [15, 32]. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the

In specimens with different construction orientations, gravity may distort the area that hangs over the buccal and lingual walls, changing the size of the marginal gaps. These findings are in line with those of Ryu et al. [11], that a

Other investigations also discovered the impact of the supporting structures. Yu et al. reported that a resin prosthesis produced using a SLA 3D printer had poor quality of the margins close to the support attachment and frequently had roughened edges [6]. The support attachment position varies with the construction angle. Unsupported sections might cause errors. If the support is connected near to the crown margin, it may cause harm during removal [18]. Alharbi et al. investigated the dimensional accuracy of the build orientation of dental crowns fabricated with a DLP 3D printer, the root mean square error (RMSE) was higher in the area with the support structure [18]. The support attachment position varies with the construction angle. Unsupported sections might cause errors. If the support is connected near to the crown margin, it may cause harm during removal. Meanwhile, the form of the layer created by the 3D printer differs according to the build angle which is a reason for the differences in the marginal fit. A DLP-based 3D printer polymerizes one layer at a time, any change in the layer form entails changes in the form and degree of polymerization shrinkage. SLA technology employs an ultraviolet (UV) laser to cure material point by point [25, 26].

The choice of construction angle is crucial since it influences the amount of support structures required, which may have an impact on the precision of the created components [18]. The number of surfaces that are selfsupported increases and the support structures number decreases when the crown is rotated from a

part of the restoration may undergo damage. Support was set back from the crown edges in the

Conclusions

- Printing technology has a direct effect on the marginal accuracy of 3D printed permanent crowns.

- Printing build angle has an effect on the marginal accuracy.

- All tested variables showed results within the clinically acceptable range.

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Received: 13 May 2023 / Accepted: 2 January 2024

Published online: 11 January 2024

References

- Ebeid K, Nouh I, Ashraf Y, Cesar PF. Accuracy of different laboratory scanners for scanning of implant-supported full arch fixed prosthesis. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2022;34:843-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.12918.

- Ebeid K, Sabet A, El Sergany O, Della Bona A. Accuracy and repeatability of different intraoral instruments on shade determination compared to visual shade selection. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2022;34:988-93. https://doi. org/10.1111/jerd.12884.

- Ellakany P, Tantawi M, El, Mahrous AA, Al-Harbi F. Evaluation of the accuracy of digital impressions obtained from intraoral and extraoral dental scanners with different CAD/CAM scanning technologies: an in vitro study. J Prosthodont. 2022;31:314-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopr.13400.

- Azari A, Nikzad S. The evolution of rapid prototyping in dentistry: a review. Rapid Prototyp J. 2009;15:216-25. https://doi. org/10.1108/13552540910961946.

- Ottoni R, Marocho SMS, Griggs JA, Borba M. CAD/CAM versus 3D-printing/ pressed lithium disilicate monolithic crowns: adaptation and fatigue behavior. J Dent. 2022;123:104181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdent.2022.104181.

- Yu BY, Son KB, Da, Lee KB. Evaluation of intaglio surface trueness and margin quality of interim crowns in accordance with the build angle of stereolithography apparatus 3-dimensional printing. J Prosthet Dent. 2021;126:231-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2020.04.028.

- Andersen UV, Pedersen DB, Hansen HN, Nielsen JS. In-process 3D geometry reconstruction of objects produced by direct light projection. Int J Adv ManufTechnol. 2013;68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-013-4778-3.

- Wu GH, Hsu SH, Review. Polymeric-based 3D printing for tissue engineering. J Med Biol Eng. 2015;35:285-92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40846-015-0038-3.

- Mitteramskogler G, Gmeiner R, Felzmann R, Gruber S, Hofstetter C, Stampfl J, et al. Light curing strategies for lithography-based additive manufacturing of customized ceramics. Addit Manuf. 2014;1:110-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. addma.2014.08.003.

- Lee MP, Cooper GJT, Hinkley T, Gibson GM, Padgett MJ, Cronin L. Development of a 3D printer using scanning projection stereolithography. Sci Rep. 2015;5. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09875.

- Ryu JE, Kim YL, Kong HJ, Chang HS, Jung JH. Marginal and internal fit of 3D printed provisional crowns according to build directions. J Adv Prosthodont. 2020;12. https://doi.org/10.4047/jap.2020.12.4.225.

- Yan Y, Li S, Zhang R, Lin F, Wu R, Lu Q, et al. Rapid prototyping and manufacturing technology: principle, representative technics, applications, and development trends. Tsinghua Sci Technol. 2009;14:1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S1007-0214(09)70001-X.

- Huotilainen E, Salmi M, Chekurov S, Flores Ituarte I. Effect of build orientation in 3D printing production for material extrusion, material jetting, binder jetting, sheet object lamination, vat photopolymerisation, and powder bed fusion. Int J Collab Enterp. 2016;5:218. https://doi.org/10.1504/ ijcent.2016.10003187.

- Hong J, Wu DL, Li DC, Lu BH. Multi-objective optimization of the part building orientation in stereolithography. Hsi-An Chiao Tung Ta Hsueh/Journal Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 2001;35:506-9.

- Oropallo W, Piegl LA. Ten challenges in 3D printing. Eng Comput. 2016;32:135-48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-015-0407-0.

- Habib SR, AI Otaibi AK, AI Anazi TA, AI Anazi SM. Comparison between five CAD/CAM systems for fit of zirconia copings. Quintessence Int. 2018;49:43744. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.qi.a40354.

- Zheng Z, Wang H, Mo J, Ling Z, Zeng Y, Zhang Y, et al. Effect of virtual cement space and restorative materials on the adaptation of CAD-CAM endocrowns. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22:580. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02598-0.

- Alharbi N, Osman R, Wismeijer D. Factors influencing the dimensional accuracy of 3d-printed full-coverage dental restorations using stereolithography technology. Int J Prosthodont. 2016;29:503-10. https://doi.org/10.11607/ ijp.4835.

- Kakinuma H, Izumita K, Yoda N, Egusa H, Sasaki K. Comparison of the accuracy of resin-composite crowns fabricated by three-dimensional printing and milling methods. Dent Mater J. 2022;41:808-15. https://doi.org/10.4012/ dmj.2022-074.

- Abualsaud R, Alalawi H. Fit, precision, and trueness of 3d-printed zirconia crowns compared to milled counterparts. Dent J. 2022;10:215. https://doi. org/10.3390/dj10110215.

- Chaiamornsup P, Iwasaki N, Tsuchida Y, Takahashi H. Effects of build orientation on adaptation of casting patterns for three-unit partial fixed dental prostheses fabricated by using digital light projection. J Prosthet Dent. 2022;128:1047-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prosdent.2021.01.006.

- Bammani SS, Birajdar PR, Metan SS. Dental crown manufacturing using stereolithography method. Proc Int Conf Adv Ind Prod Eng 2012:7-10.

- Torabi K, Vojdani M, Giti R, Taghva M, Pardis S. The effect of various veneering techniques on the marginal fit of zirconia copings. J Adv Prosthodont. 2015;7:233-9. https://doi.org/10.4047/jap.2015.7.3.233.

- Martínez-Rus F, Suárez MJ, Rivera B, Pradíes G. Evaluation of the absolute marginal discrepancy of zirconia-based ceramic copings. J Prosthet Dent. 2011;105:108-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3913(11)60009-7.

- Tahayeri A, Morgan MC, Fugolin AP, Bompolaki D, Athirasala A, Pfeifer CS, et al. 3D printed versus conventionally cured provisional crown and bridge dental materials. Dent Mater. 2018;34:192-200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. dental.2017.10.003.

- Unkovskiy A, Bui PHB, Schille C, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Huettig F, Spintzyk S. Objects build orientation, positioning, and curing influence dimensional accuracy and flexural properties of stereolithographically printed resin. Dent Mater. 2018;34:e324-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dental.2018.09.011.

- Park GS, Kim SK, Heo SJ, Koak JY, Seo DG. Effects of printing parameters on the fit of implant-supported 3D printing resin prosthetics. Mater (Basel). 2019;12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12162533.

- McLean JW, Von F. The estimation of cement film thickness by an in vivo technique. Br Dent J. 1971;131:107-11. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4802708.

- Revilla-León M, Meyers MJ, Zandinejad A, Özcan M. A review on chemical composition, mechanical properties, and manufacturing work flow of additively manufactured current polymers for interim dental restorations. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2019;31:51-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jerd.12438.

- Chaiamornsup P, Iwasaki N, Yasue T, Uo M, Takahashi H. Effects of build conditions and angle acuteness on edge reproducibility of casting patterns fabricated using digital light projection. Dent Mater J. 2020;39:135-40. https://doi. org/10.4012/dmj.2018-401.

- Vitale A, Cabral JT. Frontal conversion and uniformity in 3D printing by photopolymerisation. Mater (Basel). 2016;9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9090760.

- Pandey PM, Venkata Reddy N, Dhande SG. Part deposition orientation studies in layered manufacturing. J Mater Process Technol. 2007;185:125-31. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2006.03.120.

- Derban P, Negrea R, Rominu M, Marsavina L. Influence of the printing angle and load direction on flexure strength in 3d printed materials for provisional dental restorations. Mater (Basel). 2021;14. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ma14123376.

- Melchels FPW, Feijen J, Grijpma DW. A review on stereolithography and its applications in biomedical engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.050.

- Liu Q, Leu MC, Schmitt SM. Rapid prototyping in dentistry: technology and application. Int J Adv ManufTechnol. 2006;29:317-35. https://doi. org/10.1007/s00170-005-2523-2.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

Kamal Ebeid

kamal_ebeid@dent.asu.edu.eg

Department of Fixed Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, The British

University in Egypt, Cairo, Egypt

Department of Fixed Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Ain Shams

University, Organization of African Unity Street, Cairo, Egypt