DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oor.2024.100662

تاريخ النشر: 2024-09-26

تبسيط منهجية البحث: كيفية اختيار تقنية العينة المناسبة وتحديد حجم العينة الملائم للبحث

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

حجم العينة

تقنية أخذ العينات

حسابات حجم العينة

جدول حجم العينة

عملية أخذ العينات

أخذ العينات الاحتمالية

أخذ العينات غير الاحتمالية

البحث الكمي

مستوى الثقة

هامش الخطأ

حجم السكان

حجم التأثير

الصلاحية

الموثوقية

البحث الاستقصائي

تصميم الدراسة

الملخص

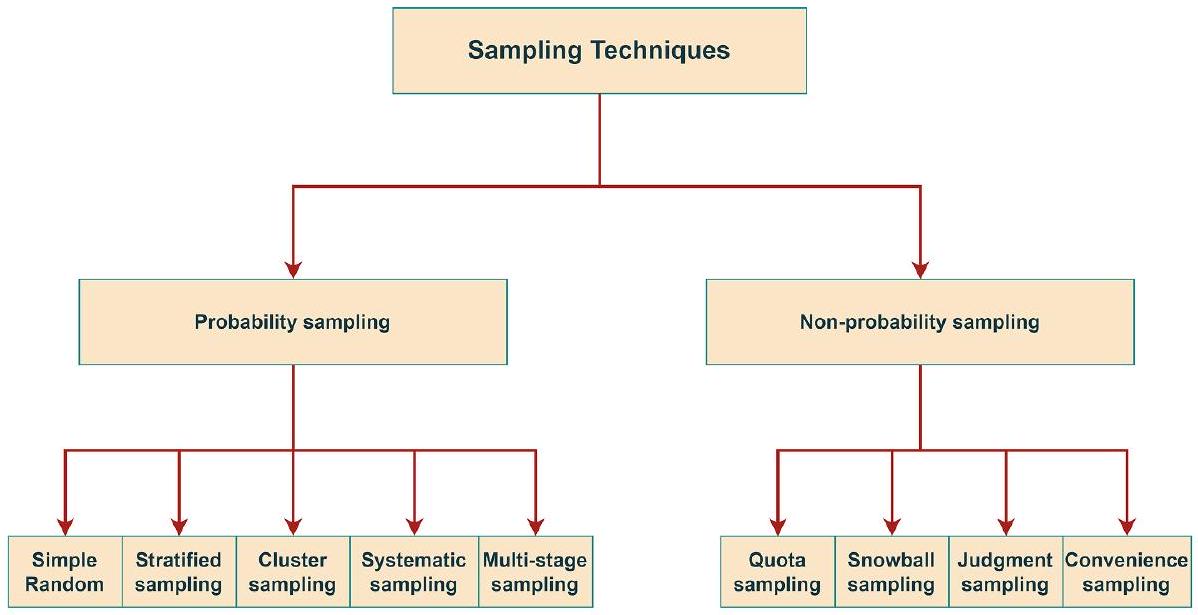

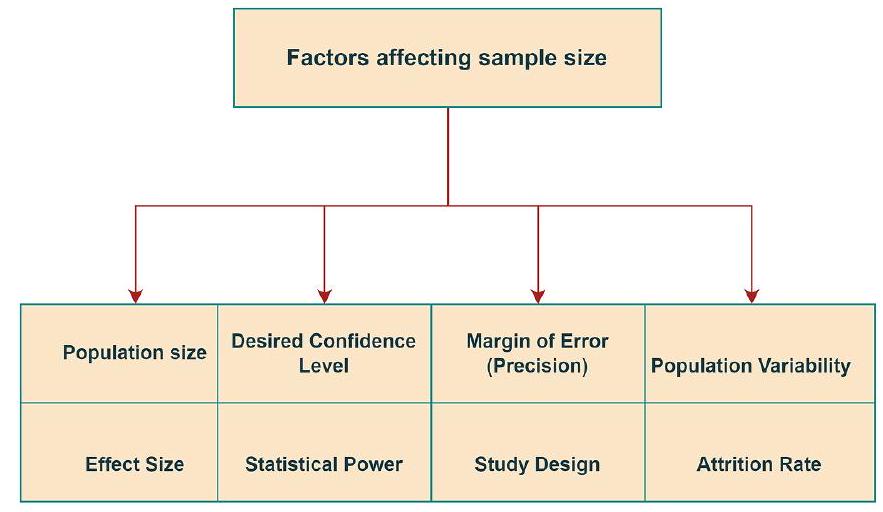

تتطلب تقنية أخذ العينات المناسبة مع التحديد الدقيق لحجم العينة عملية اختيار دقيقة للغاية، وهي في الواقع حيوية لأي بحث تجريبي. من الواضح أن هذه القرارات المنهجية ستؤثر بشكل كبير على الصلاحية الداخلية والخارجية وقابلية تعميم نتائج الدراسة بشكل عام. لقد قامت هذه الورقة بتحديث شامل للإرشادات حول طرق أخذ العينات وحساب حجم العينة، مما يوفر أدلة كافية ستكون مفيدة في مساعدة الباحثين على تعزيز مصداقية وقوة البحث الإحصائية. تم شرح الفروق بين تقنيات أخذ العينات الاحتمالية، بما في ذلك أخذ العينات العشوائية البسيطة، وأخذ العينات الطبقية، وأخذ العينات العنقودية، وطرق أخذ العينات غير الاحتمالية، مثل أخذ العينات المريحة، وأخذ العينات الهادفة، وأخذ العينات الثلجية، بشكل كامل. الاحتمالية هي الوحيدة التي يمكن أن تضمن قابلية التعميم، بينما تعتبر أخذ العينات غير الاحتمالية مفيدة في الحالات الاستكشافية. عملية أخرى مهمة هي تحديد حجم العينة الأمثل، والذي يجب أن يأخذ في الاعتبار، من بين أمور أخرى، الحجم الإجمالي للسكان، وحجم التأثير، والقوة الإحصائية، ومستوى الثقة، وهامش الخطأ. تسهم الورقة في تقديم إرشادات نظرية وأدوات عملية يحتاجها الباحثون في اختيار استراتيجيات مناسبة لأخذ العينات والتحقق من حسابات حجم العينة المناسبة منهجياً. باختصار، تحدد مثل هذه الورقة المعايير لأفضل الممارسات في منهجية البحث التي ستعزز الموثوقية والصلاحية والصرامة التجريبية عبر دراسات متنوعة.

1. المقدمة

أخذ العينات [1،3]. تشمل أخذ العينات الاحتمالية أخذ العينات العشوائية الأساسية، وأخذ العينات الطبقية، وأخذ العينات العنقودية، حيث تعتمد طرق الاختيار على عملية العشوائية كعملية تعزيز لتقليل التحيز في الاختيار. تتمتع هذه الطرق بمبادئ إحصائية سليمة وعادة ما يتم اعتمادها عندما يكون الهدف هو التعميم. تشمل طرق أخذ العينات غير الاحتمالية أخذ العينات المريحة وأخذ العينات الهادفة كلما لم يكن الاختيار العشوائي ممكنًا أو عمليًا. قد تكون هذه مريحة لأغراض عملية، لكنها ستؤدي بسرعة إلى تحيزات في العينة التي ستؤثر بعد ذلك على تعميم النتائج [4].

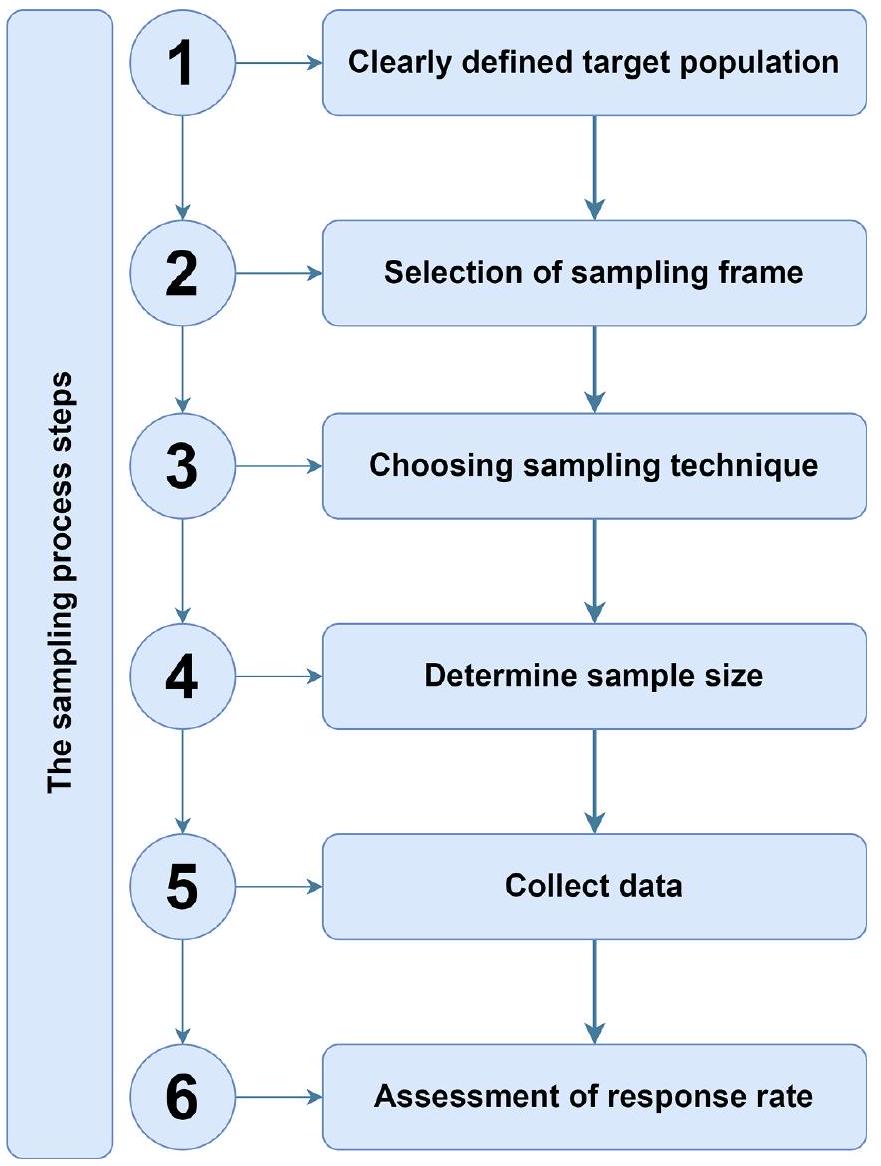

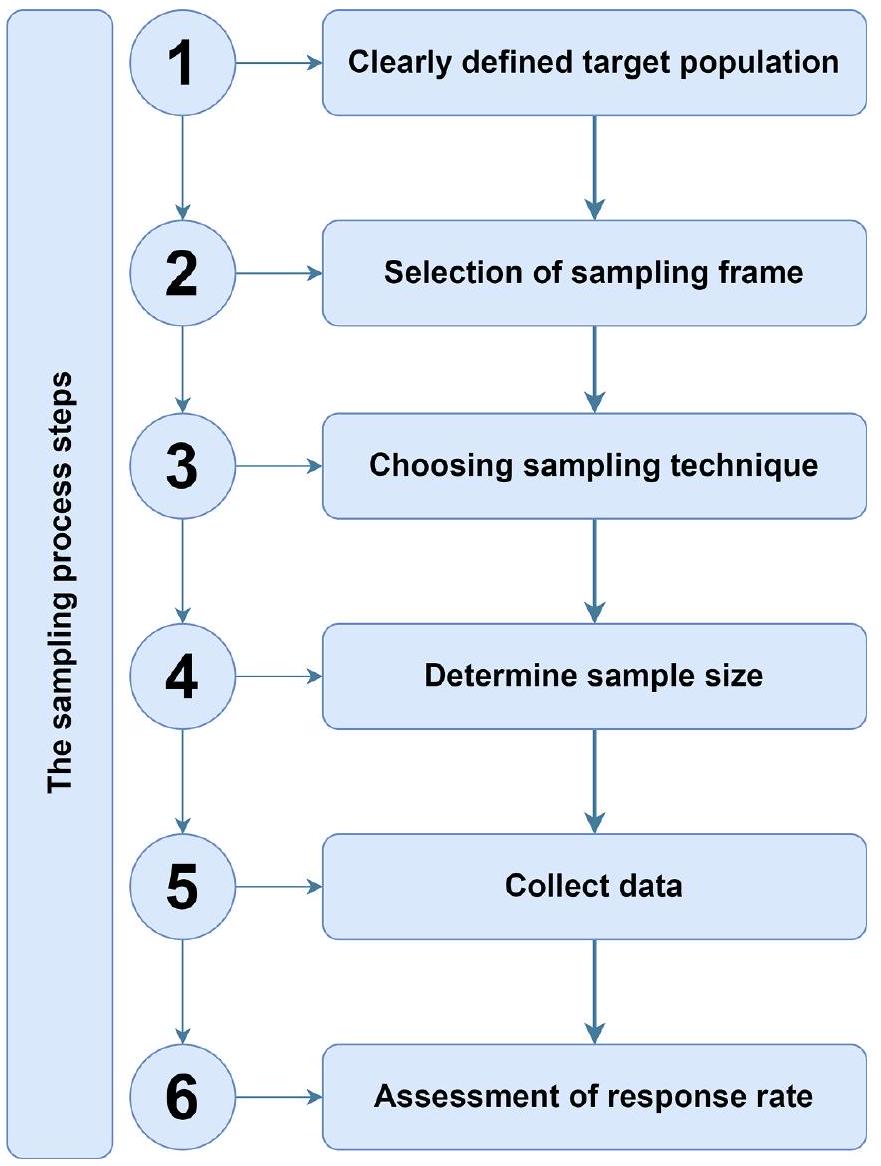

2. عملية أخذ العينات في البحث

3. تقنيات أخذ العينات

3.1. طرق أخذ العينات العشوائية

3.1.1. العينة العشوائية البسيطة

3.1.2. أخذ العينات الطبقية

3.1.3. أخذ العينات العنقودية

3.1.4. أخذ العينات النظامية

3.1.5. أخذ العينات متعددة المراحل

أخذ العينات متعددة المراحل – يتم تقسيم السكان إلى عناقيد كبيرة (على سبيل المثال، مناطق أو مؤسسات)، يتم منها سحب عينات عشوائية إضافية في مراحل متعاقبة. بمجرد اختيار المناطق الجغرافية، على سبيل المثال، يمكن اختيار عينة عشوائية من الأفراد داخل كل منطقة. تعتبر الطبقات المتدرجة مفيدة في الدراسات الكبيرة لتقليل حجم العينة بشكل منهجي من خلال تضييق نطاق السكان الواسع أو المتشتت. بينما قد يوفر ذلك التكاليف والوقت، هناك خطر زيادة خطأ العينة في كل مرحلة من عملية الاختيار، إذا لم تكن العينة في كل مستوى تمثل.

3.2. طرق أخذ العينات غير العشوائية

3.2.1. أخذ العينات المريحة

3.2.2. أخذ العينات الهادفة

3.2.3. أخذ العينات المتساقطة

3.2.4. أخذ العينات الحصصية

الإيجابيات والسلبيات لتقنيات أخذ العينات العشوائية وغير العشوائية.

| تقنيات أخذ العينات | الإيجابيات | السلبيات | ||||||

| أخذ العينات العشوائية البسيطة |

|

|

||||||

| العينة المنهجية |

|

|

||||||

| العينة الطبقية |

|

|

||||||

| العينة العنقودية |

|

|

||||||

| العينة المريحة |

|

|

||||||

| العينة الهادفة |

|

|

| تقنيات أخذ العينات | الإيجابيات | السلبيات | ||||||

| مع المعرفة أو التجارب النادرة. | عند التطبيق على السكان الأوسع. | |||||||

| أخذ العينات بالكرة الثلجية | 2 الثقة في السكان هي النتيجة الأساسية الأخرى؛ ستؤدي إلى معدلات المشاركة من خلال زيادة استعداد الشخص لمشاركة التجارب. |

|

||||||

| أخذ العينات بالحصص |

|

|

4. تحديد حجم العينة في البحث

4.1. صيغة تقدير نسب السكان

حيث.

-

حجم العينة المطلوب، -

– القيمة المرتبطة بمستوى الثقة المطلوب (مثل 1.96 لمستوى ثقة 95%)، -

النسبة المقدرة للسكان (استخدم إذا كانت غير معروفة لزيادة التباين)، -

هامش الخطأ أو الدقة المطلوبة.

4.2. صيغة تقدير متوسطات السكان

حيث.

-

حجم العينة المطلوب، -

– القيمة المرتبطة بمستوى الثقة (مثل 1.96 لمستوى الثقة ، -

الانحراف المعياري المقدّر للسكان، -

هامش الخطأ أو الفرق المسموح به بين متوسط العينة ومتوسط السكان.

4.3. صيغة حجم العينة لكوخران

حيث.

- no = حجم العينة الأولي للسكان الكبار (قبل أي تعديلات للسكان المحدودة)،

– القيمة (مثل 1.96 لمستوى الثقة ، -

النسبة المقدرة للسكان (استخدم 0.5 إذا كانت غير معروفة)، -

هامش الخطأ.

حيث.

-

حجم العينة المعدل، - no

حجم العينة الأولي من صيغة كوخران أو الصيغ الأخرى، -

حجم السكان الكلي.

4.4. صيغة أخذ العينات الطبقية

حيث.

-

حجم العينة للطبقة h، -

حجم السكان للطبقة h، -

حجم السكان الكلي، -

حجم العينة الكلي.

4.5. صيغة ياماني

أين.

-

حجم العينة -

حجم السكان -

هامش الخطأ

4.6. دور الجداول في تحديد حجم العينة

4.7. العوامل المؤثرة على حجم العينة

أحجام العينات المطلوبة لمختلف أحجام السكان عند

|

|||||

| حجم السكان | حجم العينة المطلوب (هامش الخطأ

|

حجم العينة المطلوب (هامش الخطأ

|

حجم العينة المطلوب (هامش الخطأ

|

||

| 50 | ٤٤ | ٤٨ | 50 | ||

| 75 | 63 | 70 | 74 | ||

| 100 | 79 | 91 | 99 | ||

| 150 | ١٠٨ | 132 | 148 | ||

| ٢٠٠ | 132 | 168 | 196 | ||

| ٢٥٠ | 151 | ٢٠٣ | 244 | ||

| ٣٠٠ | 168 | 234 | 291 | ||

| ٤٠٠ | 196 | 291 | 384 | ||

| ٥٠٠ | 217 | ٣٤٠ | ٤٧٥ | ||

| ٦٠٠ | 234 | 384 | 565 | ||

| ٧٠٠ | 246 | 423 | ٦٥٢ | ||

| ٨٠٠ | ٢٦٠ | 457 | 738 | ||

| 1000 | ٢٧٨ | ٥١٦ | 906 | ||

| ١٥٠٠ | 306 | 624 | 1297 | ||

| ٢٠٠٠ | ٣٢٢ | 696 | 1655 | ||

| ٣٠٠٠ | ٣٤١ | 787 | 2286 | ||

| 5000 | ٣٥٧ | 879 | ٣٢٨٨ | ||

| “10,000” in Arabic is “عشرة آلاف”. | 370 | 964 | ٤٨٩٩ | ||

| 25,000 | 378 | ١٠٢٣ | 6939 | ||

| ٥٠٠٠٠ | 381 | 1045 | 8057 | ||

| 100,000 | ٣٨٣ | 1056 | 8762 | ||

| ٢٥٠,٠٠٠ | 384 | 1063 | 9249 | ||

| ٥٠٠,٠٠٠ | 384 | 1065 | 9423 | ||

| 1,000,000 | 384 | 1066 | 9513 | ||

أحجام العينات المطلوبة لمختلف أحجام السكان عند

|

|||||

| حجم السكان | حجم العينة المطلوب (هامش الخطأ

|

حجم العينة المطلوب (هامش الخطأ

|

حجم العينة المطلوب (هامش الخطأ

|

||

| 50 | ٤٦ | ٤٩ | 50 | ||

| 75 | 67 | 72 | 75 | ||

| 100 | 87 | 95 | 99 | ||

| 150 | ١٢٢ | ١٣٩ | 149 | ||

| ٢٠٠ | 154 | 180 | 198 | ||

| ٢٥٠ | 181 | 220 | 246 | ||

| ٣٠٠ | ٢٠٦ | 258 | ٢٩٥ | ||

| ٤٠٠ | 249 | ٣٢٨ | 391 | ||

| ٥٠٠ | ٢٨٥ | ٣٩٣ | ٤٨٥ | ||

| ٦٠٠ | 314 | ٤٥٢ | 579 | ||

| ٧٠٠ | ٣٤٠ | ٥٠٧ | 672 | ||

| ٨٠٠ | ٣٦٢ | ٥٥٧ | 763 | ||

| 1000 | 398 | ٦٤٧ | 943 | ||

| ١٥٠٠ | ٤٥٩ | ٨٢٥ | 1375 | ||

| ٢٠٠٠ | 497 | 957 | 1784 | ||

| ٣٠٠٠ | 541 | 1138 | 2539 | ||

| 5000 | 583 | 1142 | ٣٨٣٨ | ||

| 10,000 | 620 | 1550 | ٦٢٢٨ | ||

| 25,000 | 643 | 1709 | 9944 | ||

| ٥٠٠٠٠ | ٦٥٢ | 1770 | 12,413 | ||

| 100,000 | ٦٥٦ | 1802 | 14,172 | ||

| ٢٥٠,٠٠٠ | 659 | 1821 | 15,489 | ||

| ٥٠٠,٠٠٠ | ٦٦٠ | 1828 | ١٥٩٨٤ | ||

| 1,000,000 | 660 | 1831 | ١٦٢٤٤ | ||

5. الخاتمة

الموافقة الأخلاقية

تمويل

توفر البيانات

بيان مساهمة مؤلفي CRediT

إعلان عن تضارب المصالح

المصالح أو العلاقات الشخصية التي قد تكون بدت وكأنها تؤثر على العمل المبلغ عنه في هذه الورقة.

شكر وتقدير

References

[2] Andrade C. The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian J Psychol Med 2020;43:86-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0253717620977000.

[3] Shorten A, Moorley C. Selecting the sample. Evid Base Nurs 2014;17:32-3. https:// doi.org/10.1136/eb-2014-101747.

[4] Rahman MM. Sample size determination for survey research and non-probability sampling techniques: a review and set of recommendations. J Entrep Bus Econ

[5] Suresh K, V Thomas S, Suresh G. Design, data analysis and sampling techniques for clinical research. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2011;14:287-90. https://doi.org/ 10.4103/0972-2327.91951.

[6] Taherdoost H. Sampling methods in research methodology; how to choose a sampling technique for research. Int J Acad Res Manag 2016;5:18-27.

[7] Krejcie R, Morgan D. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas 1970;30:607-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308.

[8] Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. first ed. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1990. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429258589.

[9] Rodríguez del Águila MM, González-Ramírez AR. Sample size calculation. Allergol Immunopathol 2014;42:485-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aller.2013.03.008.

[10] Daniel WW, Cross CL. Biostatistics: a foundation for analysis in the health sciences. tenth ed. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2018.

[11] Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. second ed. Inc, New York: ohn Wiley and Sons; 1963.

[12] Yamane T. Statistics: an introductory analysis. second ed. New York: Harper and Row; 1967.

[13] Gill J, Johnson P. Research methods for managers. Sage; 2010.

- College of Nursing, University of Raparin, Rania, Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan Region, 46012, Iraq.

E-mail addresses: sirwan.k.ahmed@gmail.com, sirwan.kahmed@uor.edu.krd.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oor.2024.100662

Publication Date: 2024-09-26

How to choose a sampling technique and determine sample size for research: A simplified guide for researchers

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Sample size

Sampling technique

Sample size calculations

Sample size table

Sampling process

Probability sampling

Non-probability sampling

Quantitative research

Confidence level

Margin error

Population size

Effect size

Validity

Reliability

Survey research

Study design

Abstract

An appropriate sampling technique with the exact determination of sample size involves a very vigorous selection process, which is actually vital for any empirical research. It is obvious that these methodological decisions would greatly affect the internal and external validity and the overall generalizability of the study findings. This paper has comprehensively updated the guidelines on sampling methods and sample size calculation, hence giving enough evidence that will be beneficial in assisting researchers to advance the credibility and statistical power of their research work. The differences between probability sampling techniques, including simple random sampling, stratified sampling, and cluster sampling, and non-probability methods, such as convenience sampling, purposive sampling, and snowball sampling, have been fully explained. Probability is the only that can ensure the generalizability, while non-probability sampling is useful in exploratory situations. Another significant process is the determination of an optimal sample size, which, among other things, has to take into account the total population size, effect size, statistical power, confidence level, and margin of error. The paper contributes both theoretical guidance and practical tools that researchers need in choosing appropriate strategies for sampling and validating methodologically appropriate sample size calculations. In sum, such a paper sets the standard for best practice in research methodology that will drive reliability, validity, and empirical rigor across diverse studies.

1. Introduction

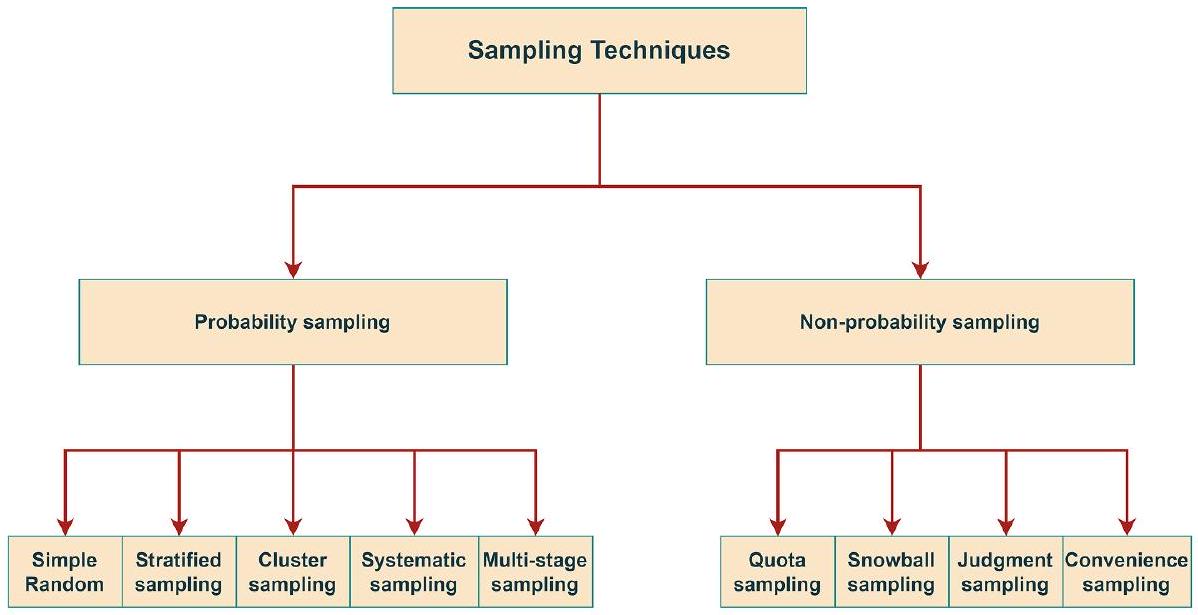

sampling [1,3]. Probability sampling includes basic random sampling, stratified sampling, and cluster sampling, where methods of selection depend on the randomization process as a strengthening process to reduce selection bias. These methods boast of sound statistical tenets and are usually adopted when generalization is intended. Non-probability sampling methods include convenience and purposive sampling whenever random selection is not feasible or practical. These may be convenient for practical purposes, but they will rapidly lead to biases in the sample that then will affect the generalization of results [4].

2. Sampling process in research

3. Sampling techniques

3.1. Probability sampling methods

3.1.1. Simple random sampling

3.1.2. Stratified sampling

3.1.3. Cluster sampling

3.1.4. Systematic sampling

3.1.5. Multi-stage sampling

multi-stage sampling – populations are divided into large clusters (for instance, regions or institutions), from which further random samples are drawn in successive stages. Once geographic areas are selected, for example, a random sample of individuals within each area could be selected. The stepwise stratification is useful in large-scale studies to systematically reduce the sample size by narrowing down through vast or dispersed populations. While this may save costs and time, there is a risk of increased sampling error at each stage in the selection process, if the sampling at each level is not representative.

3.2. Non-probability sampling methods

3.2.1. Convenience sampling

3.2.2. Purposive sampling

3.2.3. Snowball sampling

3.2.4. Quota sampling

Pros and Cons of Probability and Non-Probability Sampling techniques.

| Sampling techniques | Pros | Cons | ||||||

| Simple Random Sampling |

|

|

||||||

| Systematic Sampling |

|

|

||||||

| Stratified Sampling |

|

|

||||||

| Cluster Sampling |

|

|

||||||

| Convenience Sampling |

|

|

||||||

| Purposive Sampling |

|

|

| Sampling techniques | Pros | Cons | ||||||

| with rare knowledge or experiences. | on application to the wider population. | |||||||

| Snowball Sampling | 2 The trust in populations is the other elementary outcome; it will lead to participation rates by increasing a person’s willingness to share experiences. |

|

||||||

| Quota Sampling |

|

|

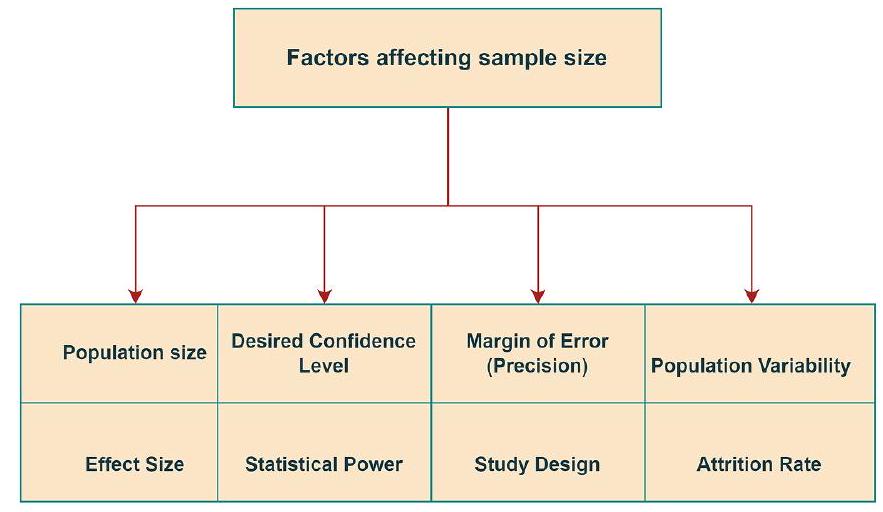

4. Sample size determination in research

4.1. Formula for estimating population proportions

Where.

-

required sample size, -

-value associated with the desired confidence level (e.g., 1.96 for 95 % confidence), -

estimated population proportion (use if unknown to maximize variability), -

margin of error or desired precision.

4.2. Formula for estimating population means

Where.

-

required sample size, -

-value corresponding to the confidence level (e.g., 1.96 for confidence), -

estimated population standard deviation, -

margin of error or allowable difference between the sample mean and the population mean.

4.3. Cochran’s sample size formula

Where.

- no = initial sample size for large populations (before any adjustments for finite populations),

-value (e.g., 1.96 for confidence), -

estimated population proportion (use 0.5 if unknown), -

margin of error.

Where.

-

adjusted sample size, - no

initial sample size from Cochran’s formula or the other formulas, -

total population size.

4.4. Formula for stratified sampling

Where.

-

sample size for stratum h , -

population size for stratum h , -

total population size, -

overall sample size.

4.5. Yamane’s formula

Where.

-

sample size -

population size -

margin of error

4.6. The role of tables in sample size determination

4.7. Factors affecting sample size

Required sample sizes for various population sizes at

|

|||||

| Popultion size | Required sample size (Margin of Error

|

Required sample size (Margin of Error

|

Required sample size (Margin of Error

|

||

| 50 | 44 | 48 | 50 | ||

| 75 | 63 | 70 | 74 | ||

| 100 | 79 | 91 | 99 | ||

| 150 | 108 | 132 | 148 | ||

| 200 | 132 | 168 | 196 | ||

| 250 | 151 | 203 | 244 | ||

| 300 | 168 | 234 | 291 | ||

| 400 | 196 | 291 | 384 | ||

| 500 | 217 | 340 | 475 | ||

| 600 | 234 | 384 | 565 | ||

| 700 | 246 | 423 | 652 | ||

| 800 | 260 | 457 | 738 | ||

| 1000 | 278 | 516 | 906 | ||

| 1500 | 306 | 624 | 1297 | ||

| 2000 | 322 | 696 | 1655 | ||

| 3000 | 341 | 787 | 2286 | ||

| 5000 | 357 | 879 | 3288 | ||

| 10,000 | 370 | 964 | 4899 | ||

| 25,000 | 378 | 1023 | 6939 | ||

| 50,000 | 381 | 1045 | 8057 | ||

| 100,000 | 383 | 1056 | 8762 | ||

| 250,000 | 384 | 1063 | 9249 | ||

| 500,000 | 384 | 1065 | 9423 | ||

| 1,000,000 | 384 | 1066 | 9513 | ||

Required sample sizes for various population sizes at

|

|||||

| Population size | Required sample size (Margin of Error

|

Required sample size (Margin of Error

|

Required sample size (Margin of Error

|

||

| 50 | 46 | 49 | 50 | ||

| 75 | 67 | 72 | 75 | ||

| 100 | 87 | 95 | 99 | ||

| 150 | 122 | 139 | 149 | ||

| 200 | 154 | 180 | 198 | ||

| 250 | 181 | 220 | 246 | ||

| 300 | 206 | 258 | 295 | ||

| 400 | 249 | 328 | 391 | ||

| 500 | 285 | 393 | 485 | ||

| 600 | 314 | 452 | 579 | ||

| 700 | 340 | 507 | 672 | ||

| 800 | 362 | 557 | 763 | ||

| 1000 | 398 | 647 | 943 | ||

| 1500 | 459 | 825 | 1375 | ||

| 2000 | 497 | 957 | 1784 | ||

| 3000 | 541 | 1138 | 2539 | ||

| 5000 | 583 | 1142 | 3838 | ||

| 10,000 | 620 | 1550 | 6228 | ||

| 25,000 | 643 | 1709 | 9944 | ||

| 50,000 | 652 | 1770 | 12,413 | ||

| 100,000 | 656 | 1802 | 14,172 | ||

| 250,000 | 659 | 1821 | 15,489 | ||

| 500,000 | 660 | 1828 | 15,984 | ||

| 1,000,000 | 660 | 1831 | 16,244 | ||

5. Conclusion

Ethical approval

Funding

Data availability

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Declaration of competing interest

interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

References

[2] Andrade C. The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian J Psychol Med 2020;43:86-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0253717620977000.

[3] Shorten A, Moorley C. Selecting the sample. Evid Base Nurs 2014;17:32-3. https:// doi.org/10.1136/eb-2014-101747.

[4] Rahman MM. Sample size determination for survey research and non-probability sampling techniques: a review and set of recommendations. J Entrep Bus Econ

[5] Suresh K, V Thomas S, Suresh G. Design, data analysis and sampling techniques for clinical research. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2011;14:287-90. https://doi.org/ 10.4103/0972-2327.91951.

[6] Taherdoost H. Sampling methods in research methodology; how to choose a sampling technique for research. Int J Acad Res Manag 2016;5:18-27.

[7] Krejcie R, Morgan D. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas 1970;30:607-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447003000308.

[8] Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. first ed. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 1990. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429258589.

[9] Rodríguez del Águila MM, González-Ramírez AR. Sample size calculation. Allergol Immunopathol 2014;42:485-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aller.2013.03.008.

[10] Daniel WW, Cross CL. Biostatistics: a foundation for analysis in the health sciences. tenth ed. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2018.

[11] Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. second ed. Inc, New York: ohn Wiley and Sons; 1963.

[12] Yamane T. Statistics: an introductory analysis. second ed. New York: Harper and Row; 1967.

[13] Gill J, Johnson P. Research methods for managers. Sage; 2010.

- College of Nursing, University of Raparin, Rania, Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan Region, 46012, Iraq.

E-mail addresses: sirwan.k.ahmed@gmail.com, sirwan.kahmed@uor.edu.krd.