DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03057-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38886626

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-17

تحديد درجات الدوائر الدماغية المخصصة يميز الأنماط البيولوجية السريرية المختلفة في الاكتئاب والقلق

تم القبول: 9 مايو 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 17 يونيو 2024

الملخص

هناك حاجة ملحة لاشتقاق مقاييس كمية تستند إلى خلل عصبي حيوي متماسك أو ‘أنماط حيوية’ لتمكين تصنيف المرضى الذين يعانون من الاكتئاب والقلق. استخدمنا بيانات خالية من المهام وبيانات مستحثة بالمهام من بروتوكول تصوير الرنين المغناطيسي الوظيفي القياسي الذي تم إجراؤه عبر دراسات متعددة في مرضى الاكتئاب والقلق عندما كانوا غير خاضعين للعلاج.

علاج

يمكن تصنيف المرضى بشكل استباقي إلى مجموعات فرعية تشترك في خلل عصبي بيولوجي مشابه، أو ‘أنماط حيوية’، كل منها قد يشير إلى مجموعة مختلفة من أساليب العلاج أو مسار علاج مختلف.

| ميزة | سريري | التحكمات |

| رقم | ٨٠١ | ١٣٧ |

| جنس | ||

| أنثى

|

461 (58) | 67 (49) |

| ذكر،

|

٣٢٩ (٤١) | 70 (51) |

| آخر

|

11 (1) | 0 (0) |

| العمر (سنوات)، المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | ٣٤٫٢٤ (١٣٫٤٠) | ٣٢.١٠ (١٢.٥٧) |

| سباق | ||

| الأمريكيون الأصليون/السكان الأصليون في ألاسكا

|

٣ | 0 (0%) |

| آسيوي

|

181 (23) | ٢٩ (٢١) |

| أسود/أمريكي أفريقي

|

16 (2) | 1 (1) |

| هاواي/جزيرة المحيط الهادئ

|

1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| أكثر من عرق واحد،

|

31 (4) | ٤ (٣) |

| آخر

|

١٠٣ (١٣) | 6 (4) |

| أبيض

|

462 (58) | 97 (71) |

| تمت معالجته في البداية،

|

٤٠ (٥) | 0 (0) |

| ذراع العلاج | ||

| إسيتالوبرام

|

٤٦ (١٢) | 0 (0) |

| سيرترالين

|

٥٥ (١١) | 0 (0) |

| فينلافاكسين

|

50 (10) | 0 (0) |

| أنا أهتم،

|

٤٦ (٩) | 0 (0) |

| يو-كير

|

٤٠ (٨) | 0 (0) |

| تشخيصات | ||

| اضطراب الاكتئاب الرئيسي،

|

375 (48) | 0 (0) |

| اضطراب القلق العام،

|

192 (28) | 0 (0) |

| اضطراب الهلع،

|

75 (10) | 0 (0) |

| اضطراب القلق الاجتماعي،

|

179 (26) | 0 (0) |

| اضطراب الوسواس القهري،

|

47 (7) | 0 (0) |

| اضطراب ما بعد الصدمة،

|

37 (5) | 0 (0) |

| التعايش (تشخيصان أو أكثر) | 221 (28) | 0 (0) |

ملفات تعريف وأداء في اختبارات سلوكية عامة وعاطفية، معرفية، محوسبة. علاوة على ذلك، تم تسجيل جزء كبير من المشاركين في تجارب سريرية عشوائية لمضادات الاكتئاب أو العلاج السلوكي، مما مكننا من إثبات أن أنواعنا البيولوجية تختلف في نتائجها عبر علاجات متعددة.

النتائج

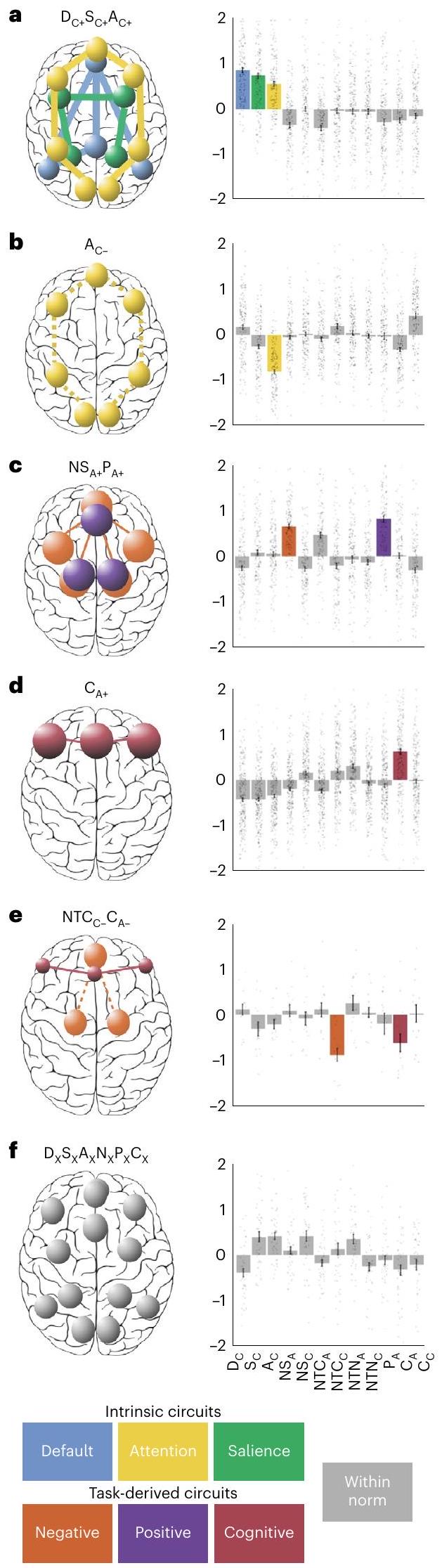

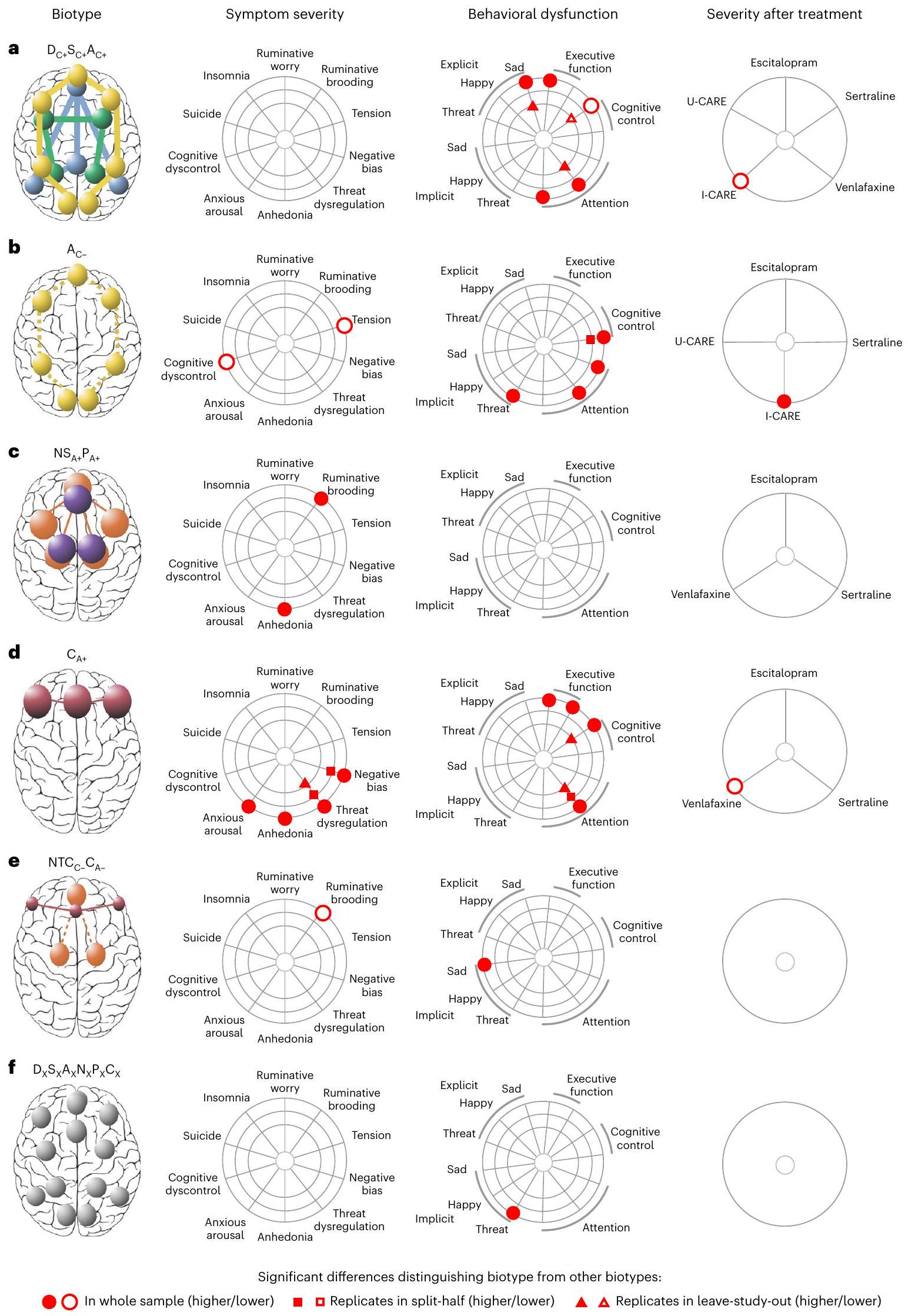

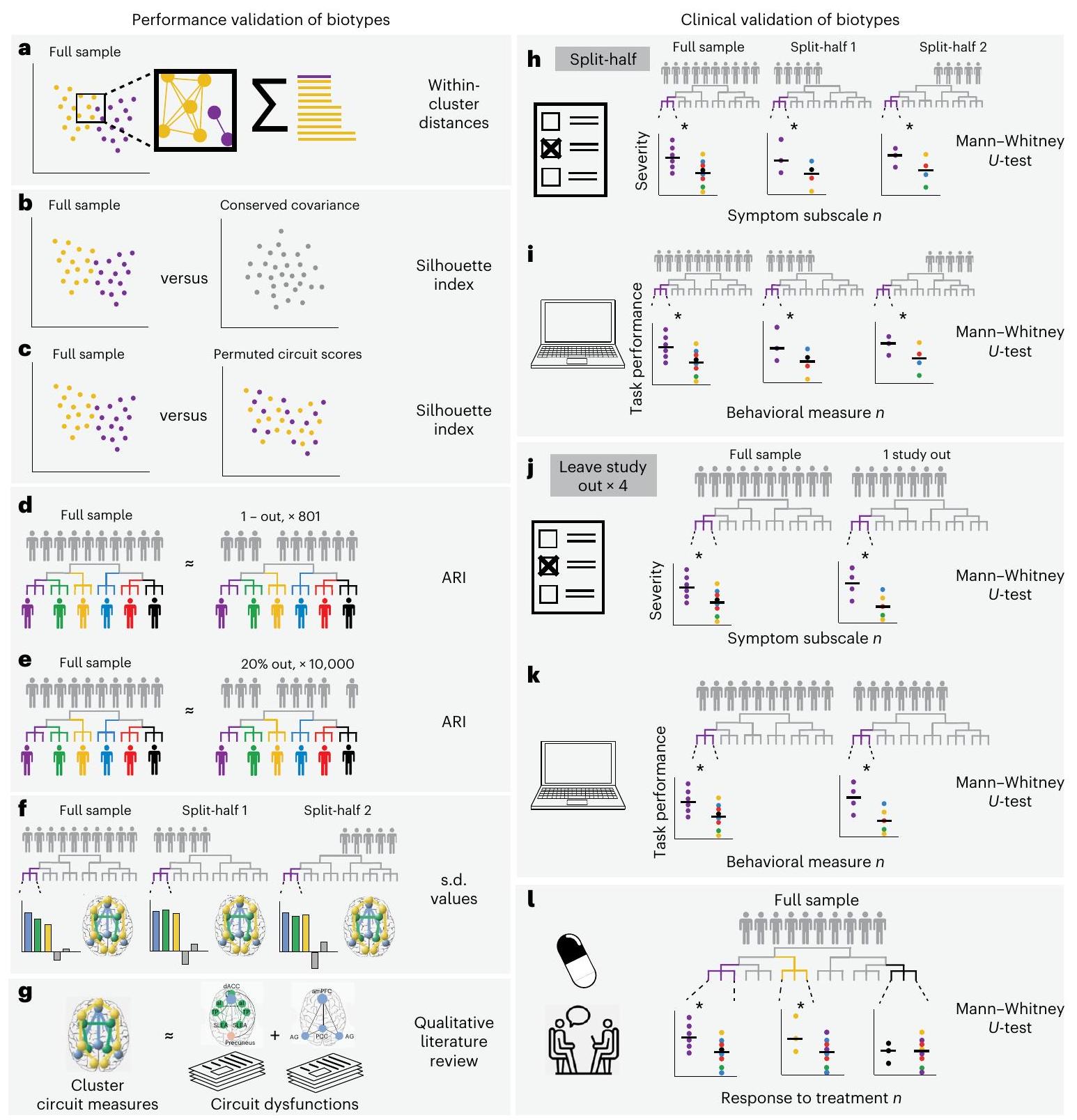

تحدد درجات دوائر الدماغ الشخصية ستة أنواع بيولوجية

بالإضافة إلى 137 ضابطًا صحيًا (الجدول 1 والجدول التكميلية 1). في وقت المسح الأساسي، لم يكن 95% من المشاركين يتلقون أي علاجات مضادة للاكتئاب ولم يتم تشخيص أي من المشاركين باضطراب يعتمد على المواد. استخدمنا نفس إجراء معالجة الصور في مجموعة بيانات العلاج التي تتكون من 250 مشاركًا تم إعادة تقييمهم بعد إكمال تجارب العلاج. خلال هذه التجارب، تم تعيين المشاركين عشوائيًا لتلقي أحد ثلاثة أدوية مضادة للاكتئاب الموصوفة بشكل شائع (إسيتالوبرام، سيرترالين أو فينلافاكسين الممتد الإفراز (XR)

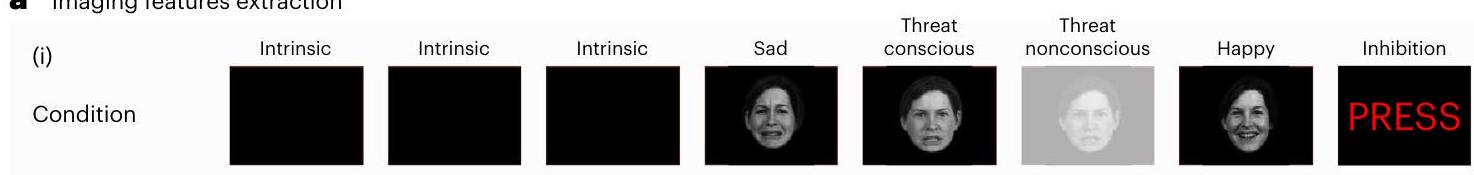

تحقق من أنواع البيولوجية

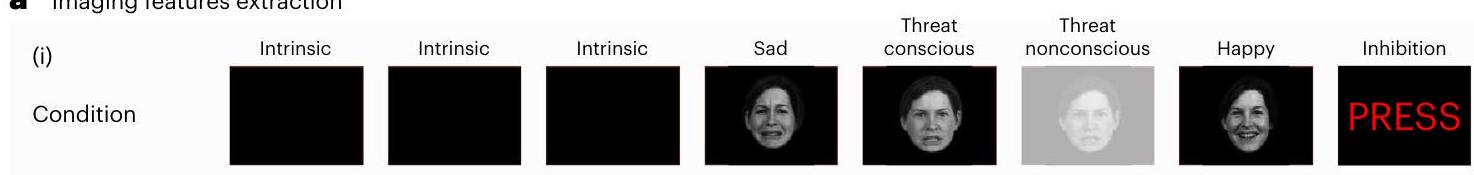

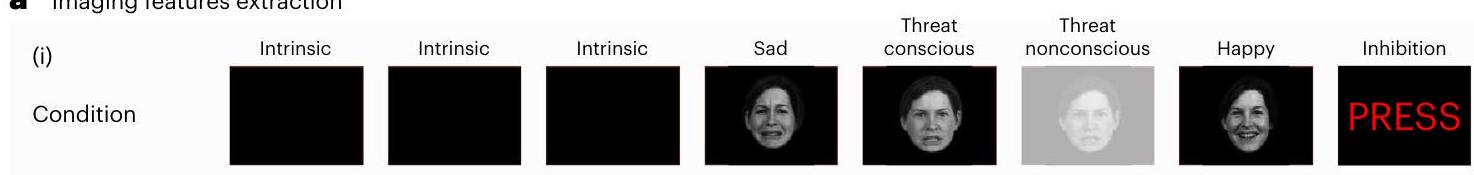

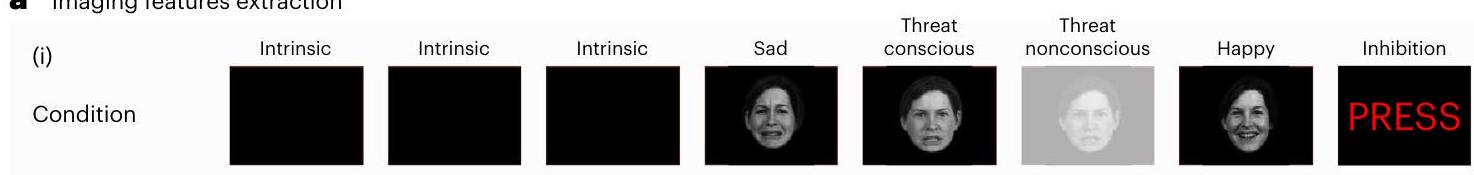

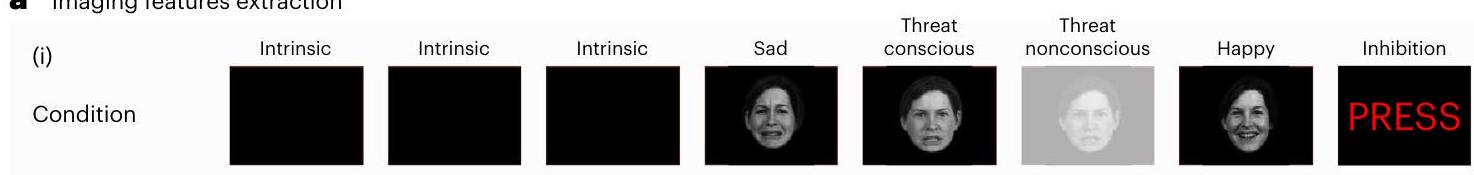

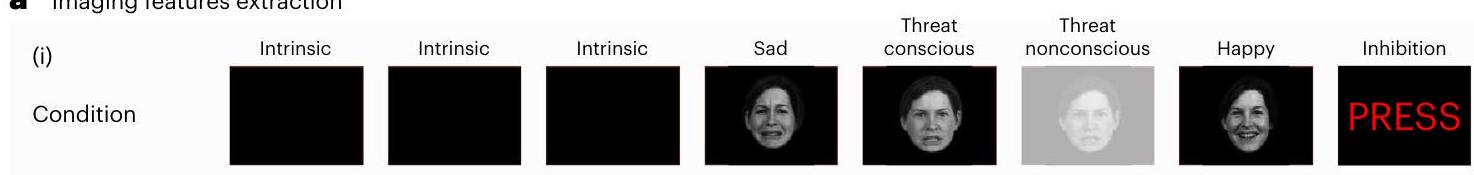

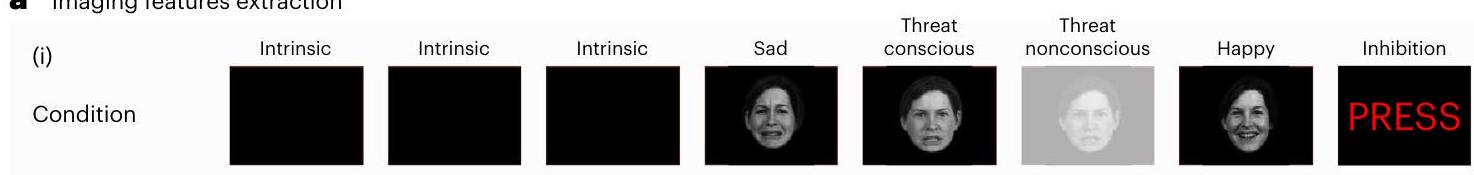

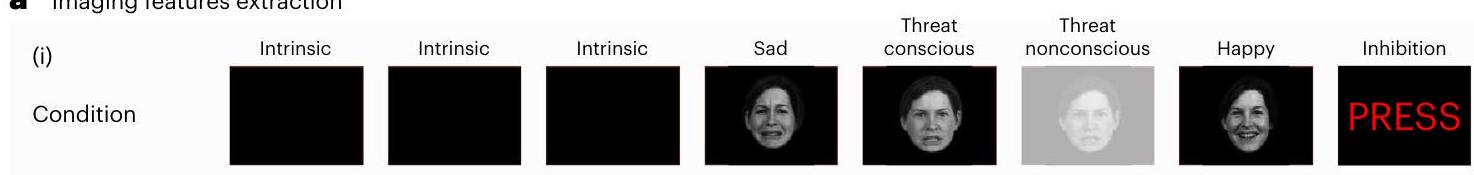

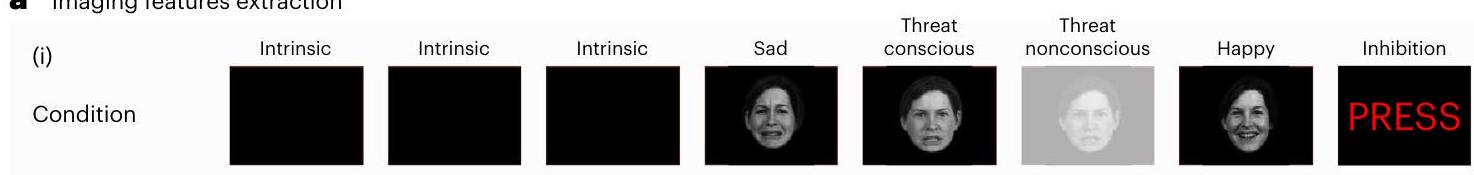

تم استخدام هذه التدابير كقيم انحراف معياري مقارنة بالمشاركين الأصحاء للحصول على درجات دائرية إقليمية مخصصة لكل فرد. انظر الجدول التكميلي 18 للحصول على القائمة الكاملة للدرجات. ج، قمنا بحساب المسافة بين كل زوج من الأفراد كـ 1 – معامل الارتباط لدرجاتهم الدائرية الإقليمية. د، نعرض مصفوفة المسافة بين أول 100 مشارك كخريطة حرارية لأغراض توضيحية. هـ، ثم استخدمنا المسافات التي تم الحصول عليها كمدخلات لتحليل التجميع الهرمي. الأفراد الم depicted تم منحهم الإذن ليتم تضمينهم في مجموعات تحفيز العواطف الوجهية المنشورة.

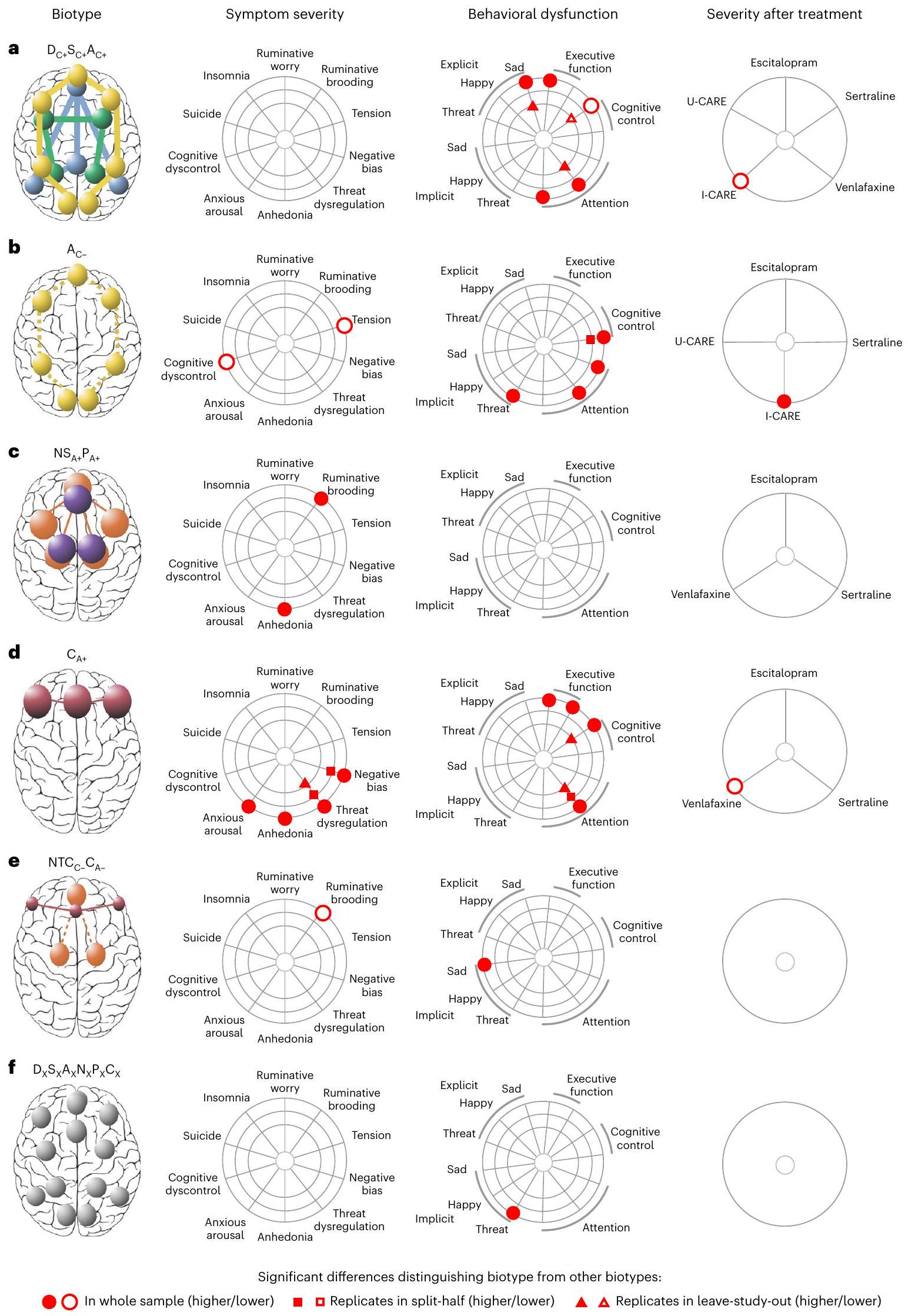

تختلف الأنماط البيولوجية في الأعراض والسلوك واستجابة العلاج

مجالات القياسات السريرية ذات المعنى (الشكل 4): شدة الأعراض، الأداء في الاختبارات المعرفية العامة والعاطفية، واستجابة العلاج التفاضلية. نبرز أن الأنماط البيولوجية للدائرة المستمدة من التجميع تم تمييزها باستخدام مدخلات الدائرة فقط التي تم تقييمها بشكل مستقل عن هذه المجالات من المعلومات السريرية بحيث تمثل الأعراض والأداء واستجابة العلاج مقاييس تحقق خارجية.

قمنا بتقييم الفروقات المحددة حسب المجموعة في الأعراض المبلغ عنها

سؤال، استخدمنا مان-ويتني

(

الأنماط البيولوجية هي عبر التشخيص

تباين التصنيف التشخيصي التقليدي للاكتئاب. بعد ذلك، تساءلنا عما إذا كانت الأنماط البيولوجية تتجاوز التصنيفات التشخيصية عبر التشخيصات المرتبطة والمصاحبة للاكتئاب. كانت عيّنتنا مكونة من مشاركين استوفوا المعايير التشخيصية التقليدية للاكتئاب الشديد.

تتفوق درجات الدوائر الدماغية على الميزات الأخرى في تصنيف الأنماط البيولوجية

نقاش

عطل الدائرة على مستوى الفرد، قمنا بتوصيف ستة أنواع حيوية من الاكتئاب والقلق محددة من خلال ملفات محددة من العطل داخل كل من الدوائر الدماغية غير المرتبطة بالمهام وتلك المرتبطة بالمهام.

|

اضطراب الاكتئاب الشديد | اضطراب القلق العام | اضطراب الهلع | اضطراب القلق الاجتماعي | اضطراب الوسواس القهري | اضطراب ما بعد الصدمة | ||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ب |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| د |  |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| e

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| ف

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

حدود الاكتئاب والقلق والاضطرابات المصاحبة ذات الصلة. ومن المهم بالنسبة للترجمة السريرية، أن هذه الأنماط البيولوجية تتنبأ بالاستجابة لمختلف التدخلات الدوائية والسلوكية.

بدلاً من اتباع نهج يعتمد بالكامل على البيانات، قمنا بدمج تحليل التجميع غير المراقب مع إطار نظري مناسب للتفسير (الجدول التكميلي 16). فعلنا ذلك لتقليل احتمال الإفراط في التكيف ولتوليد حلول مناسبة للاختيار المحتمل للمرضى حسب النوع البيولوجي لتجارب الطب النفسي الدقيق المستقبلية. في هذا النهج الهجين، تم تمييز كل نوع بيولوجي من خلال خلل دائري محدد بالنسبة للمعيار الصحي، والذي تم ربطه بظاهرة سريرية فريدة عبر التشخيص.

العلاج مقارنة مع الأنماط البيولوجية الأخرى. من ناحية أخرى، يتميز النمط البيولوجي بانخفاض الاتصال في دوائر الانتباه (

يجب تفسيرها بحذر حتى يمكن التحقق منها في عينات جديدة. أخيرًا، كانت الفروق في الأعراض بين الأنماط البيولوجية التي اكتشفناها صغيرة في الغالب، مع أحجام تأثير تتراوح من 0.08 إلى 0.90. قد يكون الحجم الصغير لهذه الفروق سببًا في عدم وصول معظم المقارنات إلى دلالة إحصائية عند تقسيم مجموعة البيانات إلى نصفين عشوائيين أو حسب الدراسة وتحليل كل تقسيم بشكل مستقل. أحجام التأثير الصغيرة في العلاقة بين التصوير المتغيرات والأعراض شائعة.

المحتوى عبر الإنترنت

References

- Friedrich, M. J. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA 317, 1517 (2017).

- Ansara, E. D. Management of treatment-resistant generalized anxiety disorder. Ment. Health Clin. 10, 326-334 (2020).

- Ruberto, V. L., Jha, M. K. & Murrough, J. W. Pharmacological treatments for patients with treatment-resistant depression. Pharmaceuticals 13, 116 (2020).

- Drysdale, A. T. et al. Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Nat. Med 23, 28-38 (2017).

- Liang, S. et al. Biotypes of major depressive disorder: neuroimaging evidence from resting-state default mode network patterns. Neuroimage Clin. 28, 102514 (2020).

- Price, R. B., Gates, K., Kraynak, T. E., Thase, M. E. & Siegle, G. J. Data-driven subgroups in depression derived from directed functional connectivity paths at rest. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 2623-2632 (2017).

- Tokuda, T. et al. Identification of depression subtypes and relevant brain regions using a data-driven approach. Sci. Rep. 8, 14082 (2018).

- Patel, A. R. et al. Stress cardiac magnetic resonance myocardial perfusionimaging: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 78, 1655-1668 (2021).

- Goldstein-Piekarski, A. N. et al. Human amygdala engagement moderated by early life stress exposure is a biobehavioral target for predicting recovery on antidepressants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11955-11960 (2016).

- Nguyen, K. P. et al. Patterns of pretreatment reward task brain activation predict individual antidepressant response: key results from the EMBARC randomized clinical trial. Biol. Psychiatry 91, 550-560 (2022).

- Pilmeyer, J. et al. Functional MRI in major depressive disorder: a review of findings, limitations, and future prospects. J. Neuroimaging 32, 582-595 (2022).

- Tozzi, L., Goldstein-Piekarski, A. N., Korgaonkar, M. S. & Williams, L. M. Connectivity of the cognitive control network during response inhibition as a predictive and response biomarker in major depression: evidence from a randomized clinical trial. Biol. Psychiatry 87, 462-472 (2020).

- Krystal, A. D. et al. A randomized proof-of-mechanism trial applying the ‘fast-fail’ approach to evaluating k-opioid antagonism as a treatment for anhedonia. Nat. Med. 26, 760-768 (2020).

- Dinga, R. et al. Evaluating the evidence for biotypes of depression: methodological replication and extension of Drysdale et al. (2017). Neuroimage Clin. 22, 101796 (2019).

- Grosenick, L. et al. Functional and optogenetic approaches to discovering stable subtype-specific circuit mechanisms in depression. Biol. Psychiatry. Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 4, 554-566 (2019).

- Williams, L. M. Defining biotypes for depression and anxiety based on large-scale circuit dysfunction: a theoretical review of the evidence and future directions for clinical translation. Depress. Anxiety 34, 9-24 (2017).

- Williams, L. M. Precision psychiatry: a neural circuit taxonomy for depression and anxiety. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 472-480 (2016).

- Williams, L. M. et al. International Study to Predict Optimized Treatment for Depression (iSPOT-D), a randomized clinical trial: rationale and protocol. Trials 12, 4 (2011).

- Ma, J. et al. Effect of integrated behavioral weight loss treatment and problem-solving therapy on body mass index and depressive symptoms among patients with obesity and depression: the RAINBOW randomized clinical trial. JAMA 321, 869-879 (2019).

- Goldstein-Piekarski, A. N. et al. Mapping neural circuit biotypes to symptoms and behavioral dimensions of depression and anxiety. Biol. Psychiatry 91, 561-571 (2022).

- Gaynes, B. N. et al. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Pschiatr. Serv. 60, 1439-1445 (2009).

- Scangos, K. W., State, M. W., Miller, A. H., Baker, J. T. & Williams, L. M. New and emerging approaches to treat psychiatric disorders. Nat. Med. 29, 317-333 (2023).

- Dichter, G. S., Kozink, R. V., McClernon, F. J. & Smoski, M. J. Remitted major depression is characterized by reward network hyperactivation during reward anticipation and hypoactivation during reward outcomes. J. Affect. Disord. 136, 1126-1134 (2012).

- Keedwell, P. A., Andrew, C., Williams, S. C. R., Brammer, M. J. & Phillips, M. L. The neural correlates of anhedonia in major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 58, 843-853 (2005).

- Groenewold, N. A., Opmeer, E. M., de Jonge, P., Aleman, A. & Costafreda, S. G. Emotional valence modulates brain functional abnormalities in depression: evidence from a meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 152-163 (2013).

- Stuhrmann, A., Suslow, T. & Dannlowski, U. Facial emotion processing in major depression: a systematic review of neuroimaging findings. Biol. Mood Anxiety Disord. 1, 10 (2011).

- Matsuo, K. et al. Prefrontal hyperactivation during working memory task in untreated individuals with major depressive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 12, 158-166 (2007).

- Cuthbert, B. N. & Kozak, M. J. Constructing constructs for psychopathology: the NIMH research domain criteria. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 122, 928-937 (2013).

- Williams, L. M. et al. Identifying response and predictive biomarkers for transcranial magnetic stimulation outcomes: protocol and rationale for a mechanistic study of functional neuroimaging and behavioral biomarkers in veterans with pharmacoresistant depression. BMC Psychiatry 21, 35 (2021).

- Feng, C., Thompson, W. K. & Paulus, M. P. Effect sizes of associations between neuroimaging measures and affective symptoms: a meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 39, 19-25 (2022).

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn (2000).

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn (2013).

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn (1994).

- Sheehan, D. V. et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 59, 22-33 (1998).

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med 16, 606-613 (2001).

- Gur, R. C. et al. A method for obtaining 3-dimensional facial expressions and its standardization for use in neurocognitive studies. J. Neurosci. Methods 115, 137-143 (2002).

- Mathersul, D. et al. Explicit identification and implicit recognition of facial emotions: II. Core domains and relationships with general cognition. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 31, 278-291 (2009).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

طرق

عينات

اكتساب التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي والمعالجة المسبقة

اشتقاق درجات الدوائر الإقليمية

التشريح إلى قياسات تصوير موثوقة وقابلة للتكرار. على سبيل المثال، فإن التنشيطات داخل المناطق المحددة تشريحيًا ذات الاهتمام لها موثوقية مقبولة إلى عالية داخل المشاركين

قياسات الأعراض

التشخيصات السريرية

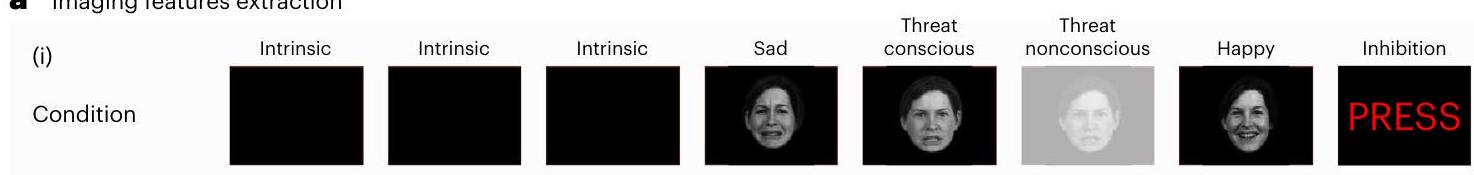

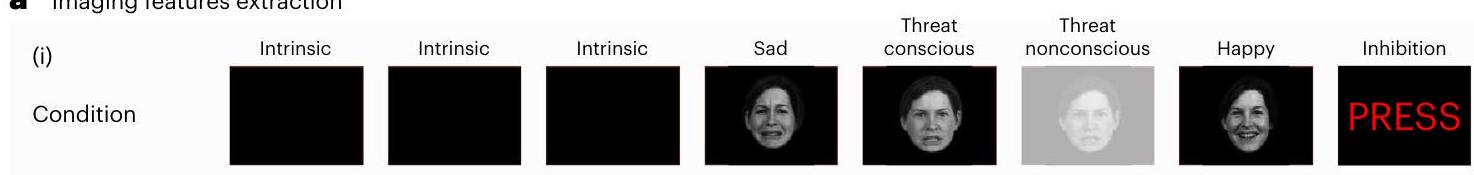

قياسات الأداء السلوكي

التحكم المعرفي (أخطاء التكليف وأوقات رد الفعل في اختبار Go-NoGo)؛ تحديد المشاعر الصريحة (وقت رد الفعل لتحديد الوجوه السعيدة، الحزينة، الخائفة والغاضبة)؛ والتحيز الضمني بالتنبيه بواسطة المشاعر (الفرق في وقت رد الفعل في مهمة تحديد الوجه عند التنبيه ضمنيًا بواسطة الوجوه السعيدة، الحزينة، الخائفة والغاضبة مقارنة بالوجوه المحايدة). لأغراض التحليل، استخدمنا أداء الاختبار المرجع إلى معيار متطابق في العمر تم إنشاؤه بواسطة WebNeuro (

العلاج

تحديد أنواع الاكتئاب

التوصيف السريري للأنواع

عبر نصف الانقسام العشوائي؛ (8) اختلافات الأعراض القابلة للتعميم عبر ترك الدراسة؛ (9) اختلافات السلوك القابلة للتعميم عبر ترك الدراسة؛ و (10) الأنواع البيولوجية تختلف في استجابة العلاج. بالنسبة لكل من مجموعات الميزات البديلة، قمنا بتقييم عدد المجموعات المبلغ عنها في الورقة الأصلية وست مجموعات (العدد الذي اخترناه في تحليلنا). كما أجرينا اختبارين إحصائيين لمقارنة أداء التجميع باستخدام ميزاتنا مع ميزات أخرى. أولاً، اختبار إعادة أخذ العينات: أخذنا عينة من

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشيفرة

References

- Williams, L. M. et al. Developing a clinical translational neuroscience taxonomy for anxiety and mood disorder: protocol for the baseline-follow up Research domain criteria Anxiety and Depression (‘RAD’) project. BMC Psychiatry 16, 68 (2016).

- Tozzi, L. et al. The human connectome project for disordered emotional states: protocol and rationale for a research domain criteria study of brain connectivity in young adult anxiety and depression. Neurolmage 214, 116715 (2020).

- Williams, L. M. et al. The ENGAGE study: integrating neuroimaging, virtual reality and smartphone sensing to understand self-regulation for managing depression and obesity in a precision medicine model. Behav. Res. Ther. 101, 58-70 (2018).

- Elliott, M. L. et al. General functional connectivity: shared features of resting-state and task fMRI drive reliable and heritable individual differences in functional brain networks. Neurolmage 189, 516-532 (2019).

- Korgaonkar, M. S., Ram, K., Williams, L. M., Gatt, J. M. & Grieve, S. M. Establishing the resting state default mode network derived from functional magnetic resonance imaging tasks as an endophenotype: a twins study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 3893-3902 (2014).

- Esteban, O. et al. fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat. Methods 16, 111-116 (2019).

- Yarkoni, T., Poldrack, R. A., Nichols, T. E., Van Essen, D. C. & Wager, T. D. Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data. Nat. Methods 8, 665-670 (2011).

- Holiga, Š. et al. Test-retest reliability of task-based and resting-state blood oxygen level dependence and cerebral blood flow measures. PLoS ONE 13, e0206583 (2018).

- Tozzi, L., Fleming, S. L., Taylor, Z., Raterink, C. & Williams, L. M. Test-retest reliability of the human functional connectome over consecutive days: identifying highly reliable portions and assessing the impact of methodological choices. Netw. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1162/netn_a_00148 (2020).

- Fortin, J.-P. et al. Harmonization of cortical thickness measurements across scanners and sites. Neurolmage 167, 104-120 (2018).

- Fortin, J.-P. et al. Harmonization of multi-site diffusion tensor imaging data. Neurolmage 161, 149-170 (2017).

- Johnson, W. E., Li, C. & Rabinovic, A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 8, 118-127 (2007).

- DeLapp, R. C., Chapman, L. K. & Williams, M. T. Psychometric properties of a brief version of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire in African Americans and European Americans. Psychol. Assess. 28, 499-508 (2016).

- Parola, N. et al. Psychometric properties of the Ruminative Response Scale-short form in a clinical sample of patients with major depressive disorder. Patient Prefer Adherence 11, 929-937 (2017).

- Wardenaar, K. J. et al. Development and validation of a 30-item short adaptation of the Mood and Anxiety Symptoms Questionnaire (MASQ). Psychiatry Res. 179, 101-106 (2010).

- Snaith, R. P. et al. A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone the Snaith-Hamilton pleasure scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 167, 99-103 (1995).

- Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S. & Barratt, E. S. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 51, 768-774 (1995).

- Rush, A. J. et al. The 16 -Item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 573-583 (2003).

- Hamilton, M. in Assessment of Depression (eds Sartorius, D. N. & Ban, D. T. A.) 143-152 (Springer, 1986).

- Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S. & Covi, L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale-preliminary report. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 9, 13-28 (1973).

- Williams, L. M. et al. Explicit identification and implicit recognition of facial emotions: I. Age effects in males and females across 10 decades. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 31, 257-277 (2009).

- Williams, L. M. A platform for standardized, online delivered, clinically applicable neurocognitive assessment. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.28.553107 (2023).

- Urchs, S. G. et al. Functional connectivity subtypes associate robustly with ASD diagnosis. eLife 11, e56257 (2022).

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

natureportfolio

ملخص التقرير

الإحصائيات

تم التأكيد

لاختبار الفرضية الصفرية، إحصائية الاختبار (مثل

للتصاميم الهرمية والمعقدة، تحديد المستوى المناسب للاختبارات والتقارير الكاملة للنتائج

تقديرات أحجام التأثير (مثل حجم تأثير كوهين،

تحتوي مجموعتنا على الويب حول الإحصائيات لعلماء الأحياء على مقالات حول العديد من النقاط المذكورة أعلاه.

البرمجيات والرموز

| جمع البيانات | لم يتم استخدام أي برمجيات. |

| تحليل البيانات | تم استخدام البرمجيات مفتوحة المصدر التالية: SPM الإصدار 8، FSL الإصدار 6، MATLAB الإصدار 2018b، fMRIprep الإصدار 20.2.1، R الإصدار 4.1.3، R Studio الإصدار 2023.06.2+561، حزمة R miceRanger الإصدار 1.5.0. تم استخدام برمجيات مخصصة أيضًا وهي متاحة على GitHub على https:// github.com/leotozzi88/cluster_study_2023. |

البيانات

معلومات السياسة حول توفر البيانات

- رموز الوصول، معرفات فريدة، أو روابط ويب لمجموعات البيانات المتاحة للجمهور

- وصف لأي قيود على توفر البيانات

- بالنسبة لمجموعات البيانات السريرية أو بيانات الطرف الثالث، يرجى التأكد من أن البيان يتماشى مع سياستنا

إجراءات مستودعات عامة وعلمية رسمية أخرى مثل HCP وABCD وNDA. هذا الاختيار يتماشى مع إرشادات FAIRness، ويحترم متطلبات التمويل الأصلية، مما يسمح بمساهمات ومراجع مناسبة من المصادر. تم تصميم نهجنا خصيصًا للاستخدام العلمي، والذي يتضمن تقييد الوصول للكيانات الربحية للامتثال لمتطلبات التمويل الأصلية وموافقة المشاركين. لذلك، فإن الوصول المفتوح الكامل غير ممكن. نهدف إلى توفير الوصول العام الذي يتماشى مع اتفاقيات الموافقة ونوايا التمويل الأصلية، مشابهًا للبيانات المشتركة من خلال مستودعات NIH. على Stanford BRAINnet، أنشأنا نموذج طلب وصول البيانات الذي يقوم بفرز المستخدمين، مشابهًا لمستودعات عامة أخرى.

البحث الذي يشمل المشاركين البشريين، بياناتهم، أو المواد البيولوجية

| التقرير عن الجنس والهوية | تم جمع الجنس المبلغ عنه ذاتيًا واستخدم في التحليلات. | |||||||||||||

| التقرير عن العرق، الاثنية، أو مجموعات اجتماعية ذات صلة | تم جمع العرق والاثنية المبلغ عنه ذاتيًا ولكن لم يتم استخدامه في التحليلات. | |||||||||||||

| خصائص السكان |

|

|||||||||||||

| التجنيد |

|

|||||||||||||

| الإشراف الأخلاقي | قدم جميع المشاركين موافقة خطية مستنيرة. تمت الموافقة على الإجراءات من قبل مجلس مراجعة المؤسسات بجامعة ستانفورد (IRB 27937 و41837) أو لجنة أخلاقيات البحث البشري في خدمة الصحة الغربية في سيدني. |

التقرير الخاص بالمجال

علوم الحياة

لنسخة مرجعية من الوثيقة مع جميع الأقسام، انظر nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

تصميم دراسة علوم الحياة

| حجم العينة | البيانات المستخدمة في هذه الورقة تم تجميعها من أربع دراسات مكتملة: “الدراسة الدولية للتنبؤ بالعلاج الأمثل في الاكتئاب” (iSPOT-D، (ويليامز وآخرون، 2011))، “دراسة البحث عن القلق والاكتئاب” (RAD، (ويليامز وآخرون، 2016))، “مشروع الاتصال البشري لحالات العاطفة المضطربة” (HCP-DES، (توزي وآخرون، 2020c))، و”استهداف التنظيم الذاتي لفهم آليات تغيير السلوك وتحسين المزاج ونتائج الوزن” (ENGAGE، (ويليامز وآخرون، 2018)). |

| كان حجم العينة هو جميع المرضى الذين تلقوا تصوير الرنين المغناطيسي الوظيفي كجزء من تلك الدراسات. لم يتم إجراء حساب لحجم العينة. |

التكرار

قمنا بتكييف الإجراء المقترح من قبل دينغا وآخرين (المرجع 14) لتطبيقنا لتقييم ما إذا كانت تعيينات التجميع مستقرة تحت اضطرابات صغيرة في البيانات. وهذا مكننا من تقييم ما إذا كان تكرار نفس الإجراء باستخدام مجموعة بيانات مشابهة سيحدد مجموعات مشابهة، وما إذا كنا سنعين نفس المشاركين إلى نفس المجموعات. في هذا التحليل، كررنا إجراء التجميع 801 مرة، في كل مرة مع استبعاد مشارك واحد. لكل تشغيل ولكل حل بين 2 و 15 مجموعة، قمنا بحساب تشابه تعيينات المجموعات الجديدة مع تلك من التحليل الأصلي باستخدام مؤشر راند المعدل (ARI)، وهو النسخة المصححة للصدفة من مؤشر راند.

للتحقق مما إذا كانت حل التجميع النهائي لدينا قويًا، قمنا بإجراء إجراء تقسيم النصف كما يلي. أولاً، قمنا بتقسيم مجموعة البيانات الخاصة بنا إلى عينتين عشوائيتين متساويتين في الحجم. ثم، قمنا بتشغيل إجراء التجميع على النصف الأول من التقسيم. بعد ذلك، قمنا بتعيين كل مشارك في النصف الثاني إلى واحدة من المجموعات التي تم الحصول عليها في النصف الأول من التقسيم. للقيام بذلك، قمنا بحساب متوسط درجات الدوائر عبر جميع المشاركين الذين ينتمون إلى كل مجموعة في النصف الأول من التقسيم. ثم، قمنا بحساب معامل ارتباط بيرسون بين ملف درجات الدوائر الكاملة لكل مشارك وهذه الدرجات المتوسطة للمجموعات. تم تعيين كل مشارك خارج العينة إلى المجموعة التي كانت فيها هذه العلاقة هي الأعلى. أخيرًا، حددنا الاختلالات الرئيسية في الدوائر لكل مجموعة في كل تقسيم كما هو موضح أعلاه.

قمنا بتكرار المقارنات الهامة للسلوك والأعراض بين الأنماط البيولوجية الموجودة في العينة الكاملة من خلال تقسيم العينة إلى نصفين عشوائيين، وتكرار إجراء التجميع على النصف الأول، ثم استخدام ارتباطات ملف الدائرة الموضحة أعلاه لتعيين المشاركين في النصف الثاني إلى المجموعات التي تم الحصول عليها في النصف الأول. ثم أجرينا اختبارات ويلكوكسون كما هو موضح أعلاه في كل تقسيم واعتبرنا النتيجة قابلة للتكرار إذا كانت ذات دلالة إحصائية في كل من العينة الأصلية وفي كل من عينات النصف المقسمة (بالنسبة للتقسيم الثاني، أجرينا اختبارًا تأكيديًا أحادي الجانب). كما قمنا أيضًا بحساب الأهمية السريرية للنتائج في كلا التقسيمين بناءً على حجم التأثير.

التوزيع العشوائي

في ENGAGE، تم تخصيص المشاركين عشوائيًا لتلقي علاج I-CARE السلوكي أو العلاج المعتاد.

في الدراسة الحالية، لم يتم تخصيص أي مجموعات تجريبية.

عمى

في الدراسة الحالية، لم يكن المحلل معزولاً عن التوزيع العشوائي في بيانات التجربة السريرية. لم يكن العزل ذا صلة بهذه الدراسة، حيث كانت التحليل بأثر رجعي وقارن بين المتغيرات السريرية لمجموعات من المرضى تم تعريفها بناءً على خصائص أدمغتهم. لم يكن التحليل يهدف إلى إثبات فعالية علاج.

التقارير عن مواد وأنظمة وطرق محددة

البيانات السريرية

معلومات السياسة حول الدراسات السريرية

| تسجيل التجارب السريرية |

|

||||

| بروتوكول الدراسة |

|

||||

| جمع البيانات | تم إعادة تحليل البيانات التي تم جمعها سابقًا للدراسة الحالية. | ||||

| النتائج |

|

النباتات

| مخزونات البذور |

|

||

| أنماط جينية نباتية جديدة |

|

||

| المصادقة |

|

التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي

تصميم تجريبي

| نوع التصميم | المهمة (المتعلقة بالكتل والأحداث) وحالة الراحة | ||||

| مواصفات التصميم |

|

||||

| مقاييس الأداء السلوكي | لم يتم استخدام ضغطات الأزرار الصحيحة وأوقات الاستجابة في التحليل. | ||||

| استحواذ | |||||

| نوع (أنواع) التصوير | هيكلي، وظيفي | ||||

| شدة المجال | 3 ت | ||||

| معلمات التسلسل والتصوير |

|

||||

تم الحصول على المسح الهيكلي الموزون T1 في المستوى السهمي باستخدام تسلسل صدى تدرج مفسد ثلاثي الأبعاد (SPGR)

\section*{برمجيات المعالجة المسبقة}

التطبيع

التطبيع

معالجة البيانات التشريحية

لكل من عمليات BOLD التي تم العثور عليها لكل موضوع (عبر جميع المهام والجلسات)، تم إجراء المعالجة المسبقة التالية. أولاً، تم إنشاء حجم مرجعي وإصداره المنزوع الجمجمة باستخدام منهجية مخصصة من fMRIPrep. تم استبعاد تصحيح تشوه الحساسية (SDC). ثم تم تسجيل مرجع BOLD مع مرجع T1w باستخدام bbregister (FreeSurfer) الذي ينفذ التسجيل القائم على الحدود (Greve وFischl 2009). تم تكوين التسجيل المشترك مع ست درجات من الحرية. تم تقدير معلمات حركة الرأس بالنسبة لمرجع BOLD (مصفوفات التحويل، وستة معلمات دوران وترجمة متCorresponding) قبل أي تصفية زمانية مكانية باستخدام mcflirt (FSL 5.0.9، Jenkinson وآخرون 2002). تم تصحيح أوقات الشرائح لعمليات BOLD باستخدام 3dTshift من AFNI 20160207 (Cox وHyde 1997، RRID:SCR_005927). تم إعادة عينة سلسلة زمنية BOLD على الأسطح التالية (تسميات إعادة بناء FreeSurfer): fsnative، fsaverage. تم إعادة عينة سلسلة زمنية BOLD (بما في ذلك تصحيح توقيت الشرائح عند تطبيقه) إلى مساحتها الأصلية، الأصلية من خلال تطبيق التحويلات لتصحيح حركة الرأس. ستُشار إلى هذه السلاسل الزمنية المعاد عيّنتها BOLD باسم BOLD المعالجة المسبقة في الفضاء الأصلي، أو ببساطة BOLD المعالجة المسبقة. تم إعادة عينة سلسلة زمنية BOLD إلى الفضاء القياسي، مما أدى إلى إنشاء عملية BOLD معالجة مسبقًا في فضاء MNI152NLin6Asym. أولاً، تم إنشاء حجم مرجعي وإصداره المنزوع الجمجمة باستخدام منهجية مخصصة من fMRIPrep.

MNI152NLin6Asym

النمذجة الإحصائية والاستدلال

تم قياس تنشيط المهام باستخدام نموذج خطي عام (GLM) حيث تم دمج أحداث المهام مع دالة استجابة دموية معيارية كما هو مطبق في SPM8. في هذا التحليل، تم تطبيق فلتر تمرير عالي لمدة 128 ثانية على البيانات، وتم إضافة ستة معلمات إعادة المحاذاة بالإضافة إلى إشارات المادة البيضاء والسائل الدماغي الشوكي المستمدة من fMRIPrep إلى مصفوفة التصميم كعوامل مشوشة.

تصوير الرنين المغناطيسي الانتشاري

تم حساب التباينات المحددة ذات الاهتمام لكل مهمة ودائرة كما يلي: 1) دائرة التأثير السلبي: الوجوه الحزينة > الوجوه المحايدة الواعية؛ 2) دائرة التأثير السلبي: التهديد > الوجوه المحايدة الواعية؛ 3) دائرة التأثير السلبي: التهديد > الوجوه المحايدة غير الواعية؛ 4) دائرة التأثير الإيجابي: الوجوه السعيدة > الوجوه المحايدة الواعية؛ 5) دائرة التحكم المعرفي: تجارب NoGo > Go. تم الحصول على مقاييس النشاط لكل منطقة من كل دائرة من خلال استخراج القيمة المتوسطة للتباين ذي الاهتمام.

لا شيء.

(انظر Eklund et al. 2016)

لا شيء.

n/a متضمن في الدراسة

X

X

- (A) تحقق من التحديثات

- حتى يمثل 0 الحد الأدنى من الشدة/الخلل و1 الحد الأقصى من الشدة/الخلل. العمود ‘الشدة بعد العلاج’ يظهر الفروق في شدة الأعراض بعد العلاج (أي أن القيم المنخفضة تتوافق مع استجابة أفضل للعلاج). تم إجراء المقارنات على الشدة بعد العلاج فقط لمجموعات البيوتيب/العلاج التي تحتوي على

, لذا يتم عرض تلك فقط. استخدمنا التسمية البيوتيب المستخدمة سابقًا. يشير الحرف الفرعي x إلى أن البيوتيب السادس لا يتم تمييزه من خلال خلل دائري بارز بالنسبة للبيوتيبات الأخرى. بالإضافة إلى هذه التسمية، نقترح وصفًا قصيرًا باللغة الإنجليزية البسيطة لكل بيوتيب (بين علامات الاقتباس)، والذي يربطها مع بيوتيباتنا النظرية المركبة (كما هو موضح في الشكل 3). - البريد الإلكتروني: leawilliams@stanford.edu

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-03057-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38886626

Publication Date: 2024-06-17

Personalized brain circuit scores identify clinically distinct biotypes in depression and anxiety

Accepted: 9 May 2024

Published online: 17 June 2024

Abstract

There is an urgent need to derive quantitative measures based on coherent neurobiological dysfunctions or ‘biotypes’ to enable stratification of patients with depression and anxiety. We used task-free and task-evoked data from a standardized functional magnetic resonance imaging protocol conducted across multiple studies in patients with depression and anxiety when treatment free (

treatment

measures, patients could be stratified prospectively into subgroups that share similar neurobiological dysfunctions, or ‘biotypes’, each of which would possibly implicate a different set of treatment approaches or a different treatment trajectory.

| Feature | Clinical | Controls |

| Number | 801 | 137 |

| Sex | ||

| Female,

|

461 (58) | 67 (49) |

| Male,

|

329 (41) | 70 (51) |

| Other,

|

11 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Age (years), mean (s.d.) | 34.24 (13.40) | 32.10 (12.57) |

| Race | ||

| American Indian/Alaska Native,

|

3 | 0 (0%) |

| Asian,

|

181 (23) | 29 (21) |

| Black/African American,

|

16 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander,

|

1 (0) | 0 (0) |

| More than one race,

|

31 (4) | 4 (3) |

| Other,

|

103 (13) | 6 (4) |

| White,

|

462 (58) | 97 (71) |

| Treated at baseline,

|

40 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Treatment arm | ||

| Escitalopram,

|

46 (12) | 0 (0) |

| Sertraline,

|

55 (11) | 0 (0) |

| Venlafaxine,

|

50 (10) | 0 (0) |

| I-CARE,

|

46 (9) | 0 (0) |

| U-CARE,

|

40 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Diagnoses | ||

| Major depressive disorder,

|

375 (48) | 0 (0) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder,

|

192 (28) | 0 (0) |

| Panic disorder,

|

75 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Social anxiety disorder,

|

179 (26) | 0 (0) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder,

|

47 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder,

|

37 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Comorbidity (2+ diagnoses) | 221 (28) | 0 (0) |

profiles and performance on general and emotional, cognitive, computerized behavioral tests. Furthermore, a substantial portion of the participants were enrolled into randomized clinical trials of antidepressants or behavioral therapy, which enabled us to demonstrate that our biotypes differ in their outcomes across multiple treatments.

Results

Personalized brain circuit scores define six biotypes

as well as 137 healthy controls (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). At the time of baseline scanning, 95% of participants were not receiving any antidepressant treatments and none of the participants was diagnosed with a substance-dependent disorder. We used the same image-processing procedure in a treatment dataset consisting of 250 participants who were reassessed after completing treatment trials. During these trials, the participants were randomly assigned to receive one of three commonly prescribed antidepressant medications (escitalopram, sertraline or venlafaxine extended release(XR)

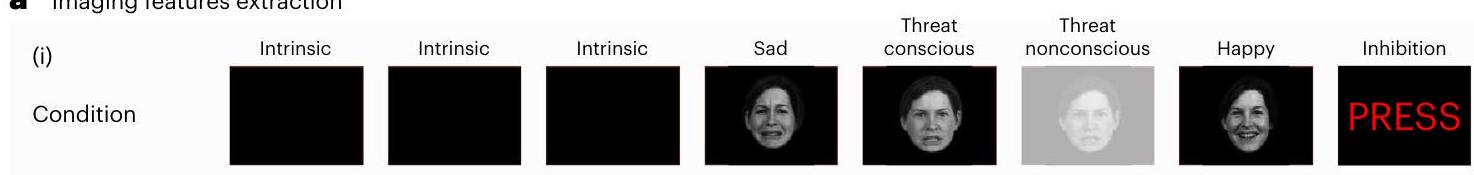

Biotype validation

these measures as s.d. values compared with healthy participants to obtain personalized regional circuit scores for each individual. See Supplementary Table 18 for the full list of scores. c, We computed the distance between each pair of individuals as 1 – the correlation of their regional circuit scores. d, We show the distance matrix between the first 100 participants as a heatmap for illustrative purposes. e, We then used the distances obtained as input for a hierarchical clustering analysis. The individuals depicted have given permission to be included in published facial emotion stimulus sets

Biotypes differ on symptoms, behavior and treatment response

domains of clinically meaningful measures (Fig. 4): severity of symptoms, performance on general and emotional cognitive tests and differential treatment response. We highlight that the circuit biotypes derived from clustering were differentiated using only circuit inputs assessed independently from these domains of clinical information such that symptoms, performance and treatment response represented external validation measures.

we evaluated the cluster-specific differences in reported symptoms (

question, we used Mann-Whitney

(

Biotypes are transdiagnostic

heterogeneity of the traditional diagnostic classification of depression. We next asked whether biotypes transcend diagnostic classifications across the diagnoses that are related to and comorbid with depression. Our sample was composed of participants who met traditional diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (

Brain circuit scores outperform other features for biotyping

Discussion

circuit dysfunction at the level of the individual, we characterized six biotypes of depression and anxiety defined by specific profiles of dysfunction within both task-free and task-evoked brain circuits.

|

Major depressive disorder | Generalized anxiety disorder | Panic disorder | Social anxiety disorder | Obsessivecompulsive disorder | Post-traumatic stress disorder | ||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| b |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| d |  |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| e

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| f

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|||||||||

boundaries of depression, anxiety and related comorbid disorders. Importantly for clinical translation, these biotypes predict response to different pharmacological and behavioral interventions.

than pursuing a fully data-driven approach, we integrated an unsupervised clustering analysis with a theoretical framework suitable for interpretability (Supplementary Table 16). We did this to minimize the possibility of overfitting and to generate solutions suited to the prospective selection of patients by biotype for future precision psychiatry trials. In this hybrid approach, each biotype was typified by a specific circuit dysfunction relative to a healthy norm, which mapped on to a unique transdiagnostic clinical phenotype.

treatment compared with the other biotypes. On the other hand, the biotype characterized by reduced attention circuit connectivity (

should be interpreted prudently until they can be validated in new samples. Finally, the symptom differences between biotypes that we detected were mostly small, with effect sizes ranging from 0.08 to 0.90 . The small size of these differences might be a reason why most comparisons did not reach statistical significance when splitting the dataset in two random halves or by study and analyzing each split independently. Small effect sizes in the association between imaging and symptom variables are common

Online content

References

- Friedrich, M. J. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. JAMA 317, 1517 (2017).

- Ansara, E. D. Management of treatment-resistant generalized anxiety disorder. Ment. Health Clin. 10, 326-334 (2020).

- Ruberto, V. L., Jha, M. K. & Murrough, J. W. Pharmacological treatments for patients with treatment-resistant depression. Pharmaceuticals 13, 116 (2020).

- Drysdale, A. T. et al. Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Nat. Med 23, 28-38 (2017).

- Liang, S. et al. Biotypes of major depressive disorder: neuroimaging evidence from resting-state default mode network patterns. Neuroimage Clin. 28, 102514 (2020).

- Price, R. B., Gates, K., Kraynak, T. E., Thase, M. E. & Siegle, G. J. Data-driven subgroups in depression derived from directed functional connectivity paths at rest. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 2623-2632 (2017).

- Tokuda, T. et al. Identification of depression subtypes and relevant brain regions using a data-driven approach. Sci. Rep. 8, 14082 (2018).

- Patel, A. R. et al. Stress cardiac magnetic resonance myocardial perfusionimaging: JACC review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 78, 1655-1668 (2021).

- Goldstein-Piekarski, A. N. et al. Human amygdala engagement moderated by early life stress exposure is a biobehavioral target for predicting recovery on antidepressants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11955-11960 (2016).

- Nguyen, K. P. et al. Patterns of pretreatment reward task brain activation predict individual antidepressant response: key results from the EMBARC randomized clinical trial. Biol. Psychiatry 91, 550-560 (2022).

- Pilmeyer, J. et al. Functional MRI in major depressive disorder: a review of findings, limitations, and future prospects. J. Neuroimaging 32, 582-595 (2022).

- Tozzi, L., Goldstein-Piekarski, A. N., Korgaonkar, M. S. & Williams, L. M. Connectivity of the cognitive control network during response inhibition as a predictive and response biomarker in major depression: evidence from a randomized clinical trial. Biol. Psychiatry 87, 462-472 (2020).

- Krystal, A. D. et al. A randomized proof-of-mechanism trial applying the ‘fast-fail’ approach to evaluating k-opioid antagonism as a treatment for anhedonia. Nat. Med. 26, 760-768 (2020).

- Dinga, R. et al. Evaluating the evidence for biotypes of depression: methodological replication and extension of Drysdale et al. (2017). Neuroimage Clin. 22, 101796 (2019).

- Grosenick, L. et al. Functional and optogenetic approaches to discovering stable subtype-specific circuit mechanisms in depression. Biol. Psychiatry. Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 4, 554-566 (2019).

- Williams, L. M. Defining biotypes for depression and anxiety based on large-scale circuit dysfunction: a theoretical review of the evidence and future directions for clinical translation. Depress. Anxiety 34, 9-24 (2017).

- Williams, L. M. Precision psychiatry: a neural circuit taxonomy for depression and anxiety. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 472-480 (2016).

- Williams, L. M. et al. International Study to Predict Optimized Treatment for Depression (iSPOT-D), a randomized clinical trial: rationale and protocol. Trials 12, 4 (2011).

- Ma, J. et al. Effect of integrated behavioral weight loss treatment and problem-solving therapy on body mass index and depressive symptoms among patients with obesity and depression: the RAINBOW randomized clinical trial. JAMA 321, 869-879 (2019).

- Goldstein-Piekarski, A. N. et al. Mapping neural circuit biotypes to symptoms and behavioral dimensions of depression and anxiety. Biol. Psychiatry 91, 561-571 (2022).

- Gaynes, B. N. et al. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Pschiatr. Serv. 60, 1439-1445 (2009).

- Scangos, K. W., State, M. W., Miller, A. H., Baker, J. T. & Williams, L. M. New and emerging approaches to treat psychiatric disorders. Nat. Med. 29, 317-333 (2023).

- Dichter, G. S., Kozink, R. V., McClernon, F. J. & Smoski, M. J. Remitted major depression is characterized by reward network hyperactivation during reward anticipation and hypoactivation during reward outcomes. J. Affect. Disord. 136, 1126-1134 (2012).

- Keedwell, P. A., Andrew, C., Williams, S. C. R., Brammer, M. J. & Phillips, M. L. The neural correlates of anhedonia in major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 58, 843-853 (2005).

- Groenewold, N. A., Opmeer, E. M., de Jonge, P., Aleman, A. & Costafreda, S. G. Emotional valence modulates brain functional abnormalities in depression: evidence from a meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 152-163 (2013).

- Stuhrmann, A., Suslow, T. & Dannlowski, U. Facial emotion processing in major depression: a systematic review of neuroimaging findings. Biol. Mood Anxiety Disord. 1, 10 (2011).

- Matsuo, K. et al. Prefrontal hyperactivation during working memory task in untreated individuals with major depressive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 12, 158-166 (2007).

- Cuthbert, B. N. & Kozak, M. J. Constructing constructs for psychopathology: the NIMH research domain criteria. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 122, 928-937 (2013).

- Williams, L. M. et al. Identifying response and predictive biomarkers for transcranial magnetic stimulation outcomes: protocol and rationale for a mechanistic study of functional neuroimaging and behavioral biomarkers in veterans with pharmacoresistant depression. BMC Psychiatry 21, 35 (2021).

- Feng, C., Thompson, W. K. & Paulus, M. P. Effect sizes of associations between neuroimaging measures and affective symptoms: a meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 39, 19-25 (2022).

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn (2000).

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn (2013).

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn (1994).

- Sheehan, D. V. et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 59, 22-33 (1998).

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med 16, 606-613 (2001).

- Gur, R. C. et al. A method for obtaining 3-dimensional facial expressions and its standardization for use in neurocognitive studies. J. Neurosci. Methods 115, 137-143 (2002).

- Mathersul, D. et al. Explicit identification and implicit recognition of facial emotions: II. Core domains and relationships with general cognition. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 31, 278-291 (2009).

(c) The Author(s) 2024

Methods

Samples

MRI acquisition and preprocessing

Derivation of regional circuit scores

anatomy can lead to reliable and reproducible imaging measures. For example, activations within anatomically defined regions of interest have acceptable-to-high within-participant reliability

Symptom measures

Clinical diagnoses

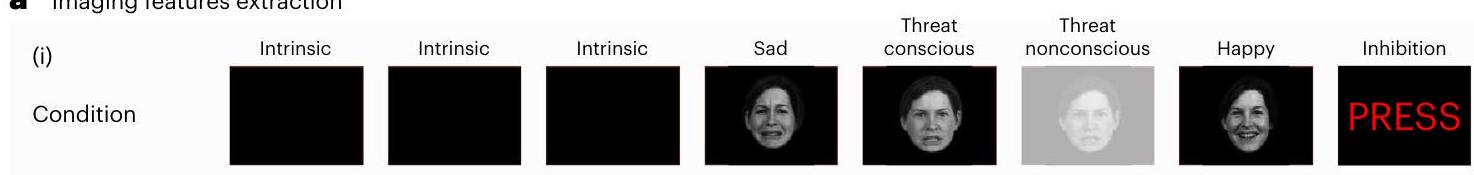

Behavioral performance measures

cognitive control (commission errors and reaction times in a Go-NoGo test); explicit emotion identification (reaction time to identify happy, sad, fearful and angry faces); and implicit priming bias by emotion (difference in reaction time in a face identification task when primed implicitly by happy, sad, fearful and angry faces compared with neutral faces). For analyses, we used the test performance referenced to an age-matched norm generated by WebNeuro (

Treatment

Identification of depression biotypes

Clinical characterization of biotypes

across random split-half; (8) generalizable symptom differences across leave-study-out; (9) generalizable behavior differences across leave-study-out; and (10) biotypes differ in treatment response. For each of the alternative sets of features, we evaluated the number of clusters reported in the original paper and six clusters (the number that we chose in our analysis). We also conducted two statistical tests comparing clustering performance using our features with other features. First, a resampling test: we sampled

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Williams, L. M. et al. Developing a clinical translational neuroscience taxonomy for anxiety and mood disorder: protocol for the baseline-follow up Research domain criteria Anxiety and Depression (‘RAD’) project. BMC Psychiatry 16, 68 (2016).

- Tozzi, L. et al. The human connectome project for disordered emotional states: protocol and rationale for a research domain criteria study of brain connectivity in young adult anxiety and depression. Neurolmage 214, 116715 (2020).

- Williams, L. M. et al. The ENGAGE study: integrating neuroimaging, virtual reality and smartphone sensing to understand self-regulation for managing depression and obesity in a precision medicine model. Behav. Res. Ther. 101, 58-70 (2018).

- Elliott, M. L. et al. General functional connectivity: shared features of resting-state and task fMRI drive reliable and heritable individual differences in functional brain networks. Neurolmage 189, 516-532 (2019).

- Korgaonkar, M. S., Ram, K., Williams, L. M., Gatt, J. M. & Grieve, S. M. Establishing the resting state default mode network derived from functional magnetic resonance imaging tasks as an endophenotype: a twins study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 3893-3902 (2014).

- Esteban, O. et al. fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat. Methods 16, 111-116 (2019).

- Yarkoni, T., Poldrack, R. A., Nichols, T. E., Van Essen, D. C. & Wager, T. D. Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data. Nat. Methods 8, 665-670 (2011).

- Holiga, Š. et al. Test-retest reliability of task-based and resting-state blood oxygen level dependence and cerebral blood flow measures. PLoS ONE 13, e0206583 (2018).

- Tozzi, L., Fleming, S. L., Taylor, Z., Raterink, C. & Williams, L. M. Test-retest reliability of the human functional connectome over consecutive days: identifying highly reliable portions and assessing the impact of methodological choices. Netw. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1162/netn_a_00148 (2020).

- Fortin, J.-P. et al. Harmonization of cortical thickness measurements across scanners and sites. Neurolmage 167, 104-120 (2018).

- Fortin, J.-P. et al. Harmonization of multi-site diffusion tensor imaging data. Neurolmage 161, 149-170 (2017).

- Johnson, W. E., Li, C. & Rabinovic, A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 8, 118-127 (2007).

- DeLapp, R. C., Chapman, L. K. & Williams, M. T. Psychometric properties of a brief version of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire in African Americans and European Americans. Psychol. Assess. 28, 499-508 (2016).

- Parola, N. et al. Psychometric properties of the Ruminative Response Scale-short form in a clinical sample of patients with major depressive disorder. Patient Prefer Adherence 11, 929-937 (2017).

- Wardenaar, K. J. et al. Development and validation of a 30-item short adaptation of the Mood and Anxiety Symptoms Questionnaire (MASQ). Psychiatry Res. 179, 101-106 (2010).

- Snaith, R. P. et al. A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone the Snaith-Hamilton pleasure scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 167, 99-103 (1995).

- Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S. & Barratt, E. S. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 51, 768-774 (1995).

- Rush, A. J. et al. The 16 -Item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 54, 573-583 (2003).

- Hamilton, M. in Assessment of Depression (eds Sartorius, D. N. & Ban, D. T. A.) 143-152 (Springer, 1986).

- Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S. & Covi, L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale-preliminary report. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 9, 13-28 (1973).

- Williams, L. M. et al. Explicit identification and implicit recognition of facial emotions: I. Age effects in males and females across 10 decades. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 31, 257-277 (2009).

- Williams, L. M. A platform for standardized, online delivered, clinically applicable neurocognitive assessment. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.28.553107 (2023).

- Urchs, S. G. et al. Functional connectivity subtypes associate robustly with ASD diagnosis. eLife 11, e56257 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

natureportfolio

Reporting Summary

Statistics

Confirmed

For null hypothesis testing, the test statistic (e.g.

For hierarchical and complex designs, identification of the appropriate level for tests and full reporting of outcomes

Estimates of effect sizes (e.g. Cohen’s

Our web collection on statistics for biologists contains articles on many of the points above.

Software and code

| Data collection | No software was used. |

| Data analysis | The following open source software was used: SPM version 8, FSL version 6, MATLAB version 2018b, fMRIprep version 20.2.1, R version 4.1.3, R Studio version 2023.06.2+561, R package miceRanger version 1.5.0. Custom software was also used and is available on Github at https:// github.com/leotozzi88/cluster_study_2023. |

Data

Policy information about availability of data

- Accession codes, unique identifiers, or web links for publicly available datasets

- A description of any restrictions on data availability

- For clinical datasets or third party data, please ensure that the statement adheres to our policy

procedures of other official public and scientific repositories like HCP, ABCD, and NDA. This choice is in line with the FAIRness guidelines, and it respects the original funding requirements, allowing for appropriate source contributions and citations. Our approach is specifically designed for scientific use, which includes limiting access to for-profit entities to comply with the original funding stipulations and participant consent. Therefore, total open access is not feasible. Our intention is to provide public access that is consistent with the consent agreements and the original funding intentions, similar to the data shared through NIH repositories. On Stanford BRAINnet, we established a data access request form that screens users, similar to other public repositories.

Research involving human participants, their data, or biological material

| Reporting on sex and gender | Self-reported gender was collected and used for the analyses. | |||||||||||||

| Reporting on race, ethnicity, or other socially relevant groupings | Self-reported race and tehnicity was collected but not used for the analyses. | |||||||||||||

| Population characteristics |

|

|||||||||||||

| Recruitment |

|

|||||||||||||

| Ethics oversight | All participants provided written informed consent. Procedures were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (IRB 27937 and 41837) or the Western Sydney Area Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee. |

Field-specific reporting

Life sciences

For a reference copy of the document with all sections, see nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf

Life sciences study design

| Sample size | The data used in this paper were aggregated from four completed studies: “International Study to Predict Optimized Treatment in Depression” (iSPOT-D, (Williams et al., 2011)), “Research on Anxiety and Depression study” (RAD, (Williams et al., 2016)), “Human Connectome Project for Disordered Emotional States” (HCP-DES, (Tozzi et al., 2020c)), and “Engaging self-regulation targets to understand the mechanisms of behavior change and improve mood and weight outcome” (ENGAGE, (Williams et al., 2018)). |

| The sample size was all the patients who had received fMRI as part of those studies. No sample size calculation was performed. |

Replication

We adapted the procedure proposed by Dinga et al. (ref. 14) to our application to evaluate whether the clustering assignment was stable under small perturbations to the data. This enabled us to assess whether repeating the same procedure using a similar dataset would identify similar clusters, and whether we would we assign the same participants to the same clusters. In this analysis, we repeated the clustering procedure 801 times, each time with one participant left out. For each run and for each solution between 2 and 15 clusters, we calculated the similarity of the new cluster assignments to those from the original analysis using the adjusted Rand index (ARI), which is the corrected-forchance version of the Rand index (

To verify if our final clustering solution was robust, we performed a split-half procedure as follows. First, we split our dataset into two random samples of equal size. Then, we ran our clustering procedure on the first half-split. Then, we assigned each participant in the second split to one of the clusters obtained in the first half-split. To do so, we computed the mean circuit scores across all participants belonging to each cluster in the first half-split. Then, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between each participant’s entire brain circuit score profile and these cluster-averaged scores. Each out-of-sample participant was assigned to the cluster for which this correlation was highest. Finally, we identified the primary circuit dysfunctions of each cluster in each split as described above (

We replicated the significant comparisons of behavior and symptoms between biotypes found in the complete sample by splitting the sample into two random halves, repeating the clustering procedure on the first half, and then using the circuit profile correlations described above to assign participants in the second half to the clusters obtained in the first half. We then conducted Wilcoxon tests as described above in each split and considered a result replicable if it was significant both in the original sample and in each of the split-half samples (for the second split we conducted a confirmatory one-sided test). We also calculated the clinical meaningfulness of results in both splits based on the effect size

Randomization

In ENGAGE, participants were randomly allocated to receive I-CARE behavioral treatment or treatment as usual.

In the current study, no allocation into experimental groups was performed.

Blinding

In the current study, the analyst was not blinded to the randomization in the clinical trial data. Blinding was not relevant for this study, since the analysis was retrospective and compared clinical variables of groups of patients defined based on their brain characteristics. The analysis was not aimed at demonstrating the efficacy of a treatment.

Reporting for specific materials, systems and methods

Clinical data

Policy information about clinical studies

| Clinical trial registration |

|

||||

| Study protocol |

|

||||

| Data collection | Data previously collected was re-analyzed for the current study. | ||||

| Outcomes |

|

Plants

| Seed stocks |

|

||

| Novel plant genotypes |

|

||

| Authentication |

|

Magnetic resonance imaging

Experimental design

| Design type | Task (block and event related) and resting state | ||||

| Design specifications |

|

||||

| Behavioral performance measures | Correct button presses and response times were not used in the analysis. | ||||

| Acquisition | |||||

| Imaging type(s) | Structural, functional | ||||

| Field strength | 3 T | ||||

| Sequence & imaging parameters |

|

||||

The T1-weighted structural scan was acquired in the sagittal plane using a 3D spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) sequence (

section*{Preprocessing software}

Normalization

Normalization

Anatomical data preprocessing

For each of the BOLD runs found per subject (across all tasks and sessions), the following preprocessing was performed. First, a reference volume and its skull-stripped version were generated using a custom methodology of fMRIPrep . Susceptibility distortion correction (SDC) was omitted. The BOLD reference was then co-registered to the T1w reference using bbregister (FreeSurfer) which implements boundary-based registration (Greve and Fischl 2009). Co-registration was configured with six degrees of freedom. Head-motion parameters with respect to the BOLD reference (transformation matrices, and six corresponding rotation and translation parameters) are estimated before any spatiotemporal filtering using mcflirt (FSL 5.0.9, Jenkinson et al. 2002). BOLD runs were slice-time corrected using 3dTshift from AFNI 20160207 (Cox and Hyde 1997, RRID:SCR_005927). The BOLD time-series were resampled onto the following surfaces (FreeSurfer reconstruction nomenclature): fsnative, fsaverage. The BOLD time-series (including slice-timing correction when applied) were resampled onto their original, native space by applying the transforms to correct for head-motion. These resampled BOLD time-series will be referred to as preprocessed BOLD in original space, or just preprocessed BOLD. The BOLD time-series were resampled into standard space, generating a preprocessed BOLD run in MNI152NLin6Asym space. First, a reference volume and its skullstripped version were generated using a custom methodology of fMRIPrep .

MNI152NLin6Asym

Statistical modeling & inference

Task-evoked activation was quantified using a generalized linear model (GLM) in which task events were convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function as implemented in SPM8. In this analysis, a 128 s high pass filter was applied to the data, and six realignment parameters as well as white matter and cerebrospinal fluid signals derived by fMRIPrep were added to the design matrix as confounds.

Diffusion MRI

Specific contrasts of interest were computed for each task and circuit as follows: 1) negative affect circuit: sad > neutral conscious faces; 2) negative affect circuit: threat > neutral conscious faces; 3) negative affect circuit: threat > neutral nonconscious faces; 4) positive affect circuit: happy > neutral conscious faces; 5) cognitive control circuit: NoGo > Go trials. Measures of activation for each region of each circuit were obtained by extracting the average value of the contrast of interest.

None.

(See Eklund et al. 2016)

None.

n/a Involved in the study

X

X

- (A) Check for updates

- so that 0 would represent minimum severity/dysfunction and 1 maximum severity/dysfunction. The column ‘Severity after treatment’ shows differences in symptom severity posttreatment (that is, lower values correspond to better treatment response). Comparisons on severity after treatment were conducted only for biotype/treatment combinations having

, so only those are shown. We used the biotype nomenclature used previously. The subscript x indicates that the sixth biotype is not differentiated by a prominent circuit dysfunction relative to other biotypes. Besides this nomenclature, we suggest a short plainEnglish description for each biotype (in quotes), which connects them with our theoretically synthesized biotypes (as shown in Fig. 3). - e-mail: leawilliams@stanford.edu