المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 14، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56849-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38485747

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-14

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56849-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38485747

تاريخ النشر: 2024-03-14

افتح

تحديد سلالات بوري فورماناس جينجيفاليس المرتبطة بأمراض اللثة

بروفيورماناس جينجيفاليس، بكتيريا سالبة الغرام لا هوائية توجد عادة في اللويحة تحت اللثة لدى البشر، هي عامل مسبب رئيسي لالتهاب اللثة وقد ارتبطت بالعديد من الأمراض الجهازية. تم تحديد العديد من سلالات P. gingivalis وتمتلك السلالات المختلفة عوامل ضراوة مختلفة. لم تتمكن الأساليب الحالية لدراسة الميكروبيوم الفموي (16S أو شوتغن) من التمييز بين

التهاب اللثة هو من بين أكثر العدوى شيوعًا في الولايات المتحدة، مع انتشار يقدر بـ

تمتاز التهاب اللثة بأنه مرض غير متوازن بسبب التحول في المجتمعات الميكروبية تحت اللثة التي تستعمر جيوب اللثة من بكتيريا هوائية إيجابية الجرام في الغالب، إلى هيمنة البكتيريا سالبة الجرام اللاهوائية. ومن أبرز هذه البكتيريا ما يُعرف بـ “مجموعة الأحمر”: بوريهيموناس جينجيفاليس، تانيريلة فورسيتيا، وتريبوينما دينتيكولا.

تم العثور على ب. جينغفالس في الأفراد الأصحاء وكذلك في المرضى الذين يعانون من مرض اللثة المزمن.

تم العثور على ب. جينغفالس في الأفراد الأصحاء وكذلك في المرضى الذين يعانون من مرض اللثة المزمن.

حالياً، هناك 67 جينوم فريد من P. gingivalis في قاعدة بيانات NCBI. تجريبياً، تختلف سلالات P. gingivalis في تجلّي الصفات الضارة المقاسة.

تشمل الأساليب الحالية لميكروبيوم الأمعاء تسلسل المناطق المتغيرة بشكل كبير من جين 16S rRNA أو تسلسل الشوتغن لجميع الحمض النووي المعزول. كلا الطريقتين محدودتان في قدرتهما على اكتشاف الأنواع الفرعية أو السلالات البكتيرية. على سبيل المثال، على الرغم من أن تجارب ميكروبيوم 16S قد كشفت عن تنوع الميكروبيوتا وكشفت عن ارتباطها بصحة الإنسان والمرض.

لذا، لتحديد سلالات P. gingivalis بطريقة فعالة من حيث التكلفة، قمنا بتكييف الأساليب السابقة التي تفحص منطقة الفاصل بين الجينات (ISR).

النتائج

الخصوصية والحساسية وقابلية التكرار لـ

تم محاذاة تسلسلات ISR المتاحة لـ P. gingivalis لتحديد المناطق التي تتراوح بين 200-250 نقطة أساسية تحتوي على أكبر عدد من الاختلافات بين السلالات والتي تحاط بتسلسلات محفوظة لأمبليكون PCR (الشكل 1). ثم تم فحص تسلسلات البرايمر المحفوظة في قاعدة بيانات NCBI لاختبار الهوية مع البكتيريا غير P. gingivalis. تم تحديد مجموعتين من البرايمرات مع مجموعة واحدة موصوفة أدناه على أنها الأكثر إفادة لتحديد السلالات. تم تحديد خصوصية البرايمرات الخاصة بـ P. gingivalis ISR باستخدام لويحات تحت اللثة من مشارك يعاني من مرض اللثة الشديد، وضوابط إيجابية (سلالة P. gingivalis ATCC33277، لويحات تحت اللثة المجمعة من عدة مشاركين)، وضوابط سلبية (DNA زيمو الوهمي، ماء خالي من الحمض النووي الميكروبي) (الشكل 1B). كانت البرايمرات الخاصة بـ

تحديد

لفحص سلالات P. gingivalis المرتبطة بأمراض اللثة، قمنا بفحص عينات من اللويحات تحت اللثة من دراسة هشاشة العظام وأمراض اللثة في بوفالو (OsteoPerio).

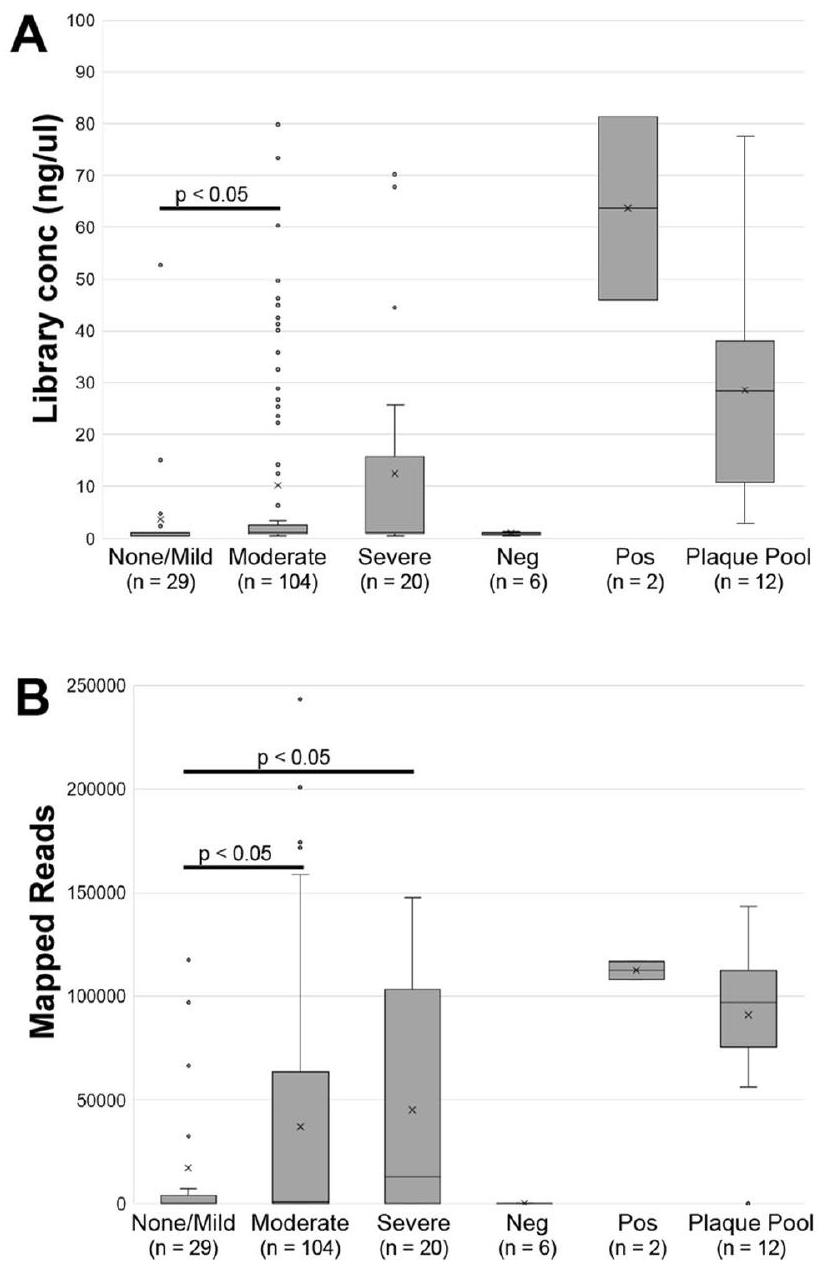

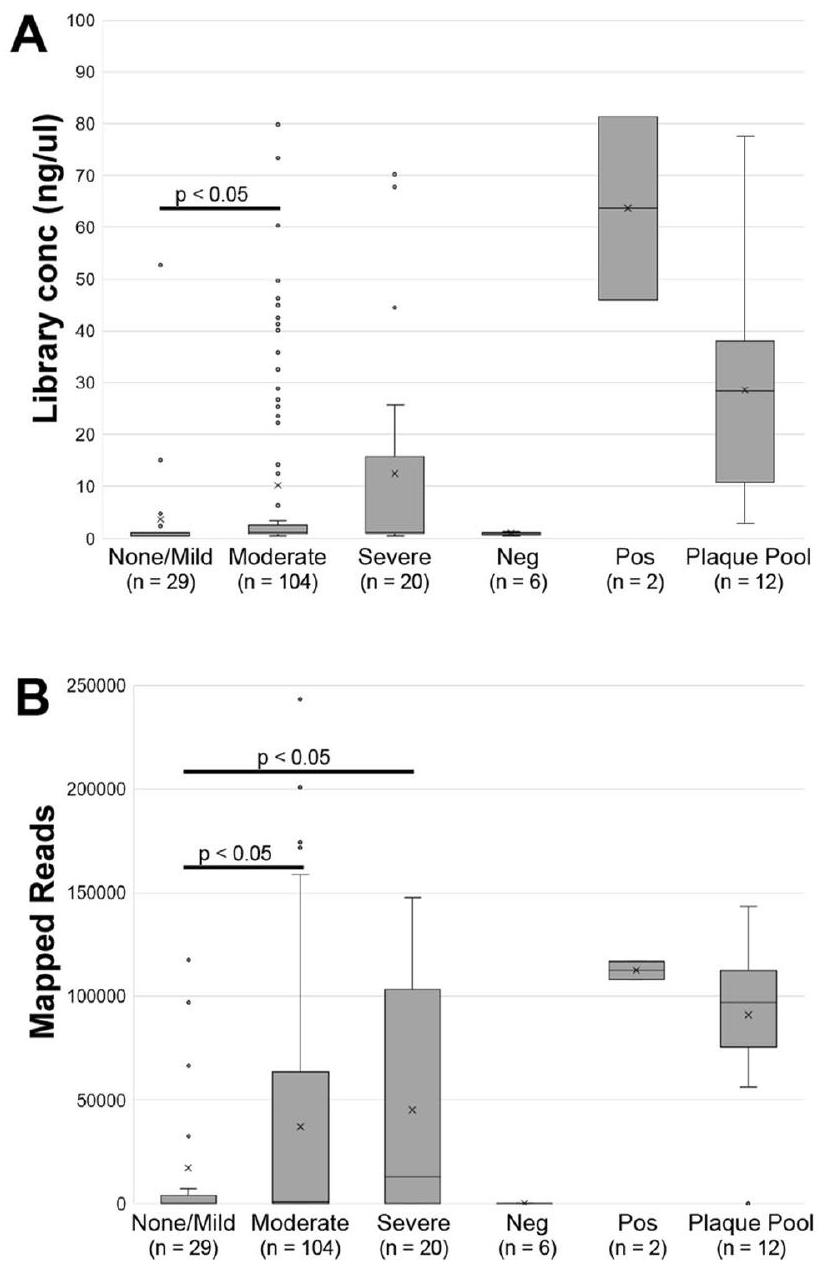

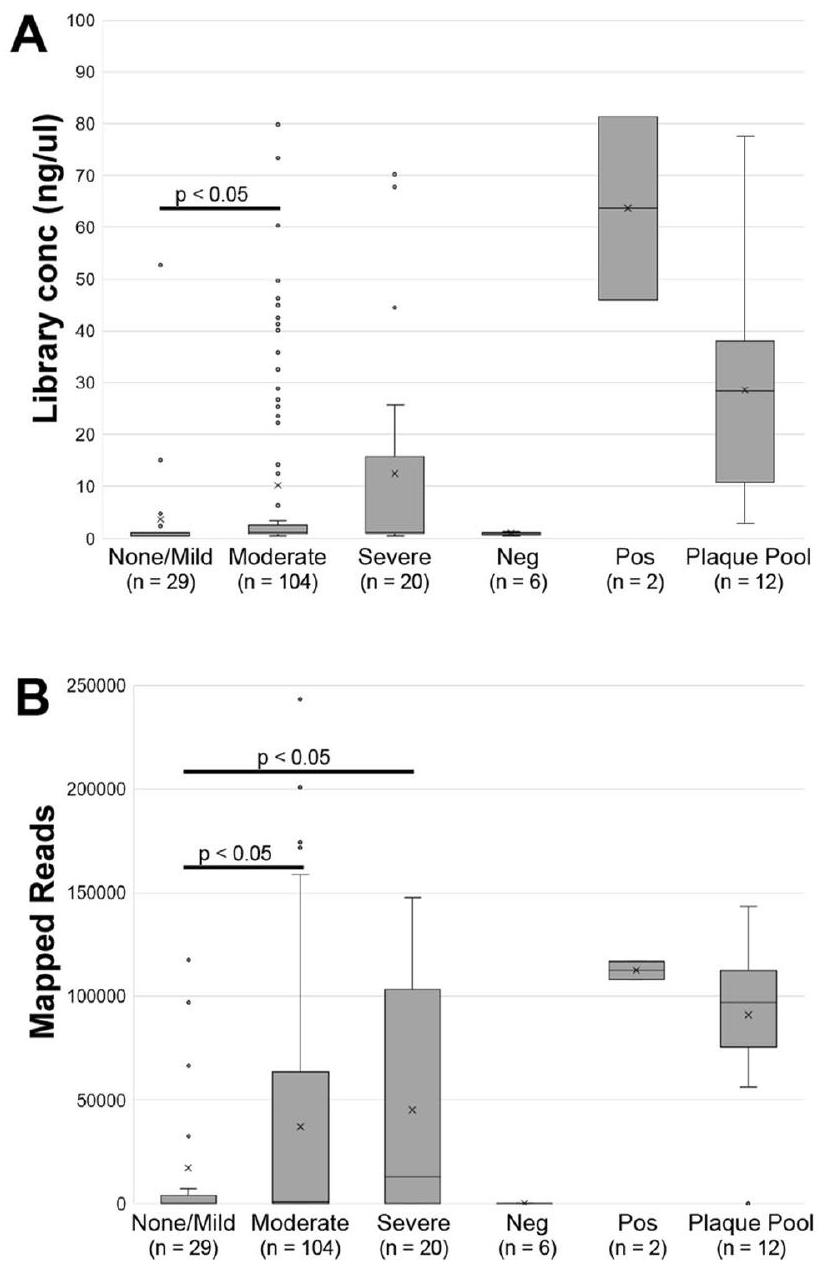

تم إنتاج الأمبليكون المحدد لـ P. gingivalis ISR باستخدام تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل ذو الخطوتين، مشابهًا لتحليل 16S (انظر “الطرق”)

تم إنتاج الأمبليكون المحدد لـ P. gingivalis ISR باستخدام تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل ذو الخطوتين، مشابهًا لتحليل 16S (انظر “الطرق”)

كشف عن

كان هناك 139 تسلسلًا فريدًا من P. gingivalis ISR. يتم تسمية كل سلالة ممكنة بـ

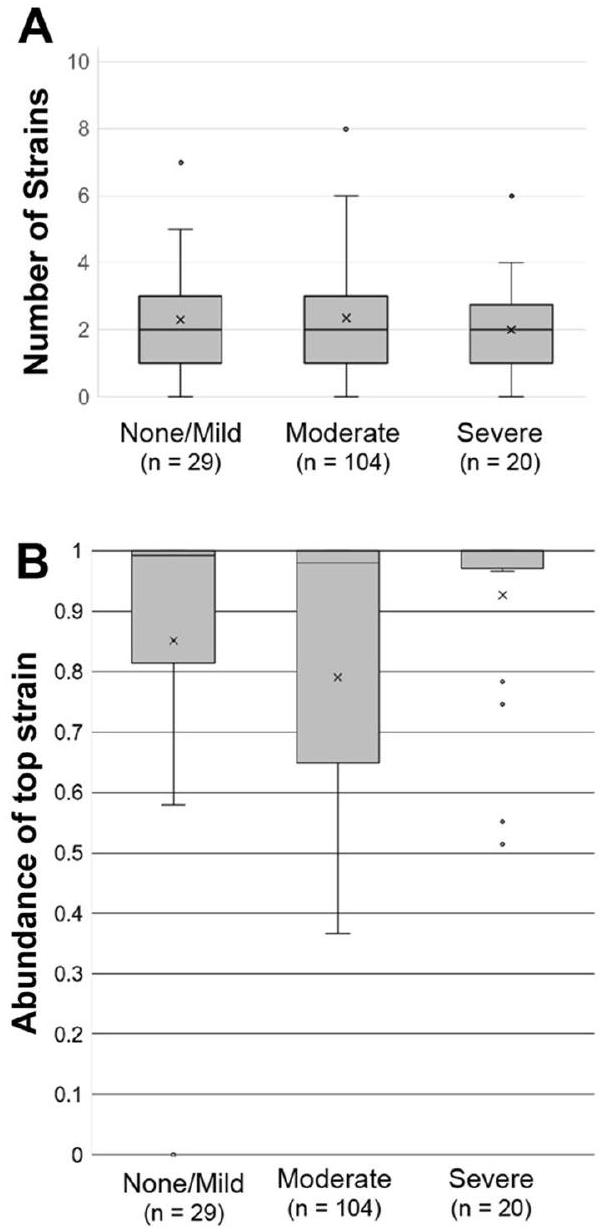

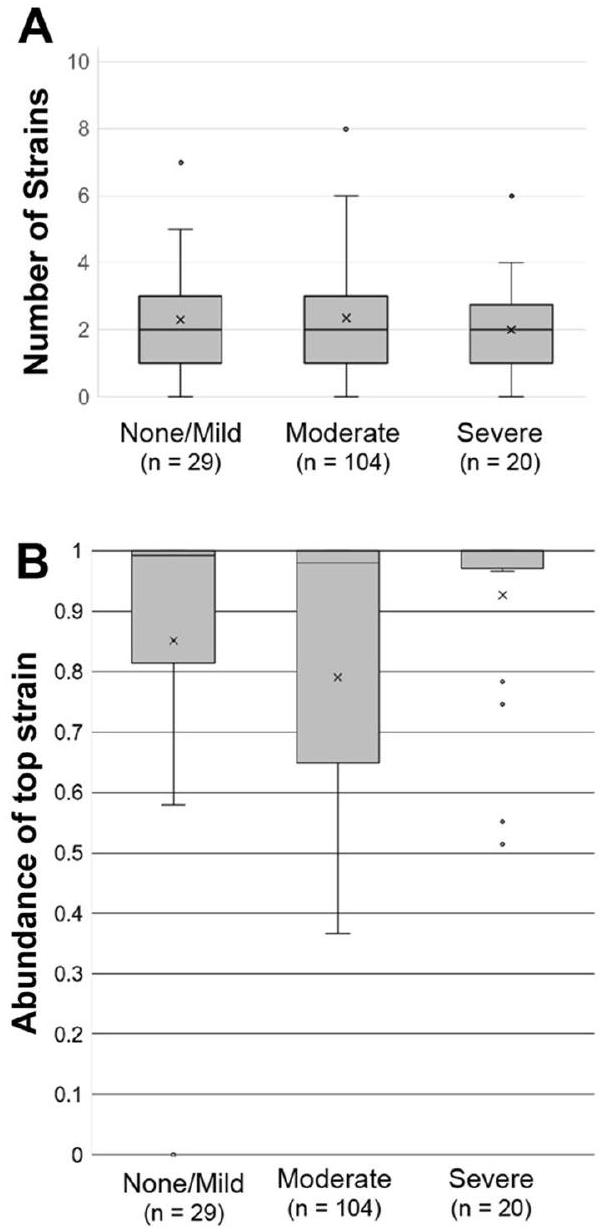

تمت مطابقة معظم عينات المشاركين مع سلالتين مختلفتين من P. gingivalis (الشكل 4A)، وهو ما يتماشى مع النتائج السابقة.

أ

| * | 60 | * | * | * | |||||

| KCOM 2796 |  |

||||||||

| W83 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTG | CTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGG | GCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | ١٢٤ | ||||

| ATCC_33277 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTT | CTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGG | GCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | ١٢٤ | ||||

| ATCC_49417 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTT | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | ١٢٤ | |||||

| AJW4 | : GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGGTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTT | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | ١٢٤ | |||||

| AS2 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTT | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | ١٢٤ | |||||

| A7436 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | ١٢٤ | ||||||

| KCOM_3001 | : GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTCCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | ١٢٤ | ||||||

| HG66 | : | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | ١٢٤ | |||||

| KCOM | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGAGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | ١٢٤ | ||||||

| KCOM | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGGTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTG | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 114 | ||||||

| TDC 60 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTG | CTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG | ———– | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 114 | ||||

| KCOM | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGGTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTG | CTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGAGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 114 | ||||||

| A7A1-28 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTG | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 114 | ||||||

| KCOM | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTT | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———–AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 114 | ||||||

| KCOM 3131 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 114 | |||||||

| KCOM 2800 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTCCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 114 | |||||||

| RMA 4165 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GA-CTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG | ———–AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 113 | ||||||

| RMA | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG | ———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 114 | ||||||

| RMA_ | : | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCCAAAAGG | ———–AAAAATATAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 114 | |||||

| GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC | GAgcTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTgCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCaAAAAGG |

|

|||||||

| * | 180 | ٢٠٠ | 220 | ||||||

| KCOM | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTT | CGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT | –غاتات جي تي أغاغ جي تي سي جي جي سي آي جي تي | 225 | ||||

| W83 | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT | –غاتات جي تي أغاغ جي تي سي جي جي سي آي جي تي تي | 225 | |||||

| ATCC_33277 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| ATCC 49417 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| AJW4 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| AS2 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| A7436 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| KCOM | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | ||||||

| HG66 | : AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| KCOM | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | ||||||

| KCOM | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | ||||||

| TDC_60 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| KCOM | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| A7A1-28 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| KCOM | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGATGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGACAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| KCOM | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| KCOM | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCATAC | GGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGACAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | ||||||

| RMA

|

AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | ٢١٤ | |||||||

| RMA | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| RMA | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAgACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAgAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT | GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | –جاتاات جي تي ايه تي جي ايه جي جي تي سي جي جي سي اج تي تي | 215 | |||

ب

الشكل 1. إنشاء بادئات محددة لـ P. gingivalis. (أ) محاذاة لمناطق سلالة P. gingivalis ISR التمثيلية. تم الإشارة إلى مواقع البادئات. (ب) تم تحسين ظروف تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل (PCR) لتكبير مناطق ISR لـ P. gingivalis دون استهداف بكتيريا أخرى. (ج) تسمح ظروف PCR بتكبير P. gingivalis في عينات مختلطة. يحتوي Zymo Mock على الحمض النووي من Listeria monocytogenes وPseudomonas aeruginosa وBacillus subtilis وEscherichia coli وSalmonella enterica وLactobacillus fermentum وEnterococcus faecalis وStaphylococcus aureus؛ Plaque Pool، تجمع من اللويحات تحت اللثة من عدة مشاركين (تحكم إيجابي لمجموعات التسلسل)؛ Pg. DNA، سلالة P. gingivalis ATCC33277. عينة Perio، لويحات تحت اللثة من مشارك يعاني من مرض اللثة الشديد. تم تصور المنتجات النهائية في

السلالة العليا في كل عينة (الشكل 4ب). بالنسبة لمعظم عينات المشاركين بغض النظر عن حالة المرض، تمثل السلالة العليا

W83/W50 مرتبط بمرض اللثة

لتحديد ما إذا كانت سلالات معينة مرتبطة بمرض اللثة، قمنا بتجميع عيناتنا إلى مجموعتين: لا شيء/خفيف ومتوسط/شديد وقمنا بتصفية تسلسلات ISR بإزالة السلالات ذات الوفرة المنخفضة أو تلك التي تظهر في عينة واحدة فقط (انظر “الطرق”). في المجموع، تم فحص 18 سلالة من P. gingivalis بعد التصفية (الجدول 1).

السلالة الأكثر وفرة في جميع العينات هي السلالة غير الضارة

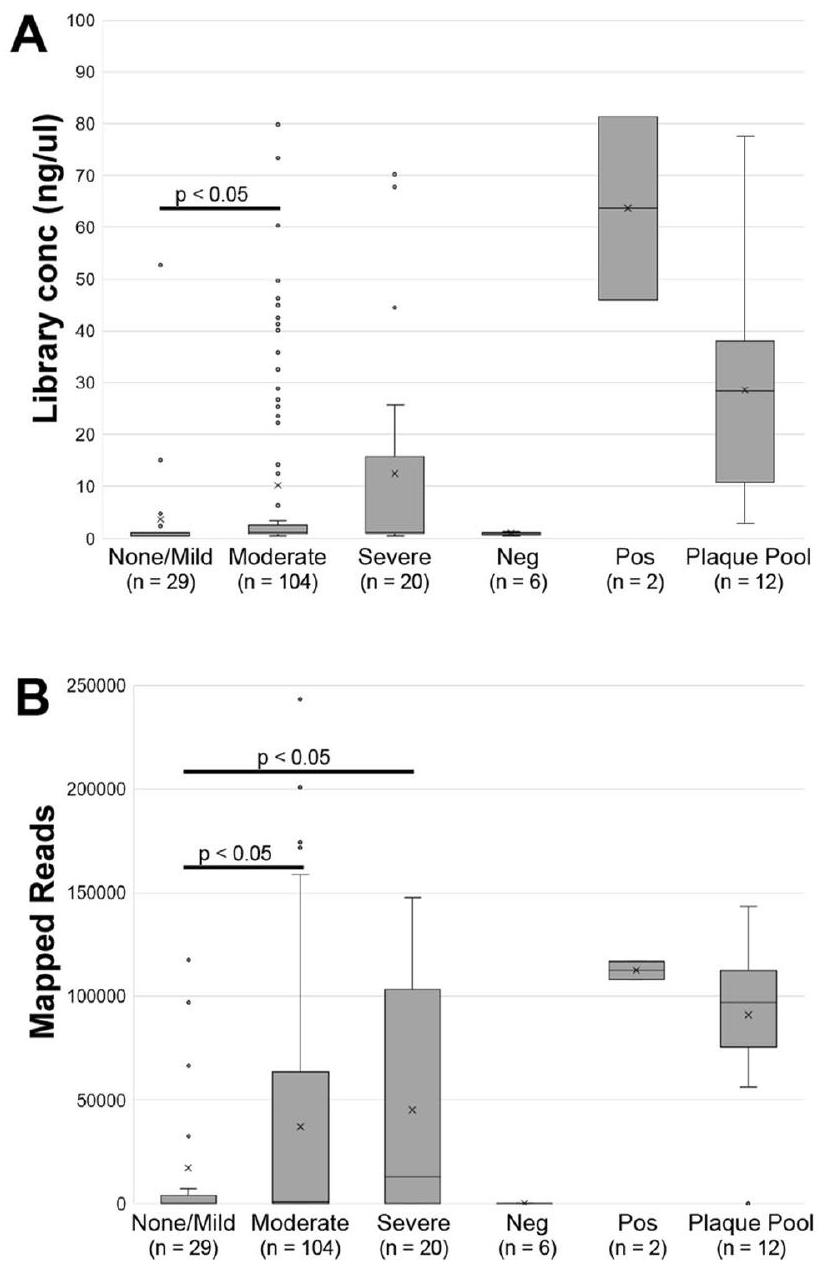

الشكل 2. مكتبات ISR وعدد القراءات المرسومة. (A) تركيزات الحمض النووي بعد تشكيل مكتبة تسلسل الجيل التالي مع جولتين من PCR. (B) أعداد القراءات التي تم رسمها على قاعدة بيانات ISR لـ P. gingivalis. يتم عرض تصنيف العينة اللثوي (لا شيء / خفيف، معتدل، شديد) مع عدد العينات لكل مجموعة. Neg، التحكم السلبي المحدد للدفعة (محلول الاستخراج، فراغ PCR)؛ Pos، التحكم الإيجابي مع DNA من ATCC33277؛ مجموعة اللويحات، DNA المعزول من مزيج من اللويحات تحت اللثة من مجموعة من الأشخاص (تحكم إيجابي).

الشكل 3. النسخ التقنية قابلة للتكرار. الوفرة النسبية لخمسة عينات مكررة، مع معامل الارتباط بيرسون (r) بين النسخ.

الشكل 4. عدد السلالات والوفرة (أ) عدد السلالات المكتشفة في كل عينة. (ب) تكرار السلالة الأكثر وفرة في كل عينة.

مرتبط بالتهاب اللثة

قمنا بعد ذلك بتقييم الارتباطات الخطية لكل متوسط إجهاد CLR مع القياسات السريرية الكاملة للفم لعمق الجيب المتوسط (PD) ومستوى الارتباط السريري (CAL) (الجدول 1). تراوحت الارتباطات من -0.134 إلى 0.142 لعمق الجيب ومن -0.095 إلى 0.152 لمستوى الارتباط السريري. بعد تصحيح الاختبارات المتعددة، لم تكن أي من الارتباطات ذات دلالة إحصائية.

نقاش

تحديد سلالات P. gingivalis باستخدام طرق الميكروبيوم الحالية كان محدودًا. هناك مشكلتان رئيسيتان تحتاجان إلى معالجة. أولاً، وفرة

في هذه الدراسة، حددنا منطقة غنية بالمعلومات تقع داخل

بينما نهجنا واعد، إلا أن له بعض القيود التي يجب أخذها بعين الاعتبار. الحد الأول هو أن عددًا كبيرًا من سلالات P. gingivalis لديها تسلسلات متطابقة ضمن هدفنا.

| ملصق السلالة | فئة أمراض اللثة

|

متوسط الفم بالكامل | ||||||||

| لا شيء/خفيف

|

متوسط/شديد

|

فرانكلين ديلانو روزفلت | PD | كال | ||||||

| يعني

|

تكرار

|

متوسط

|

تكرار

|

قيمة P

|

قيمة-q

|

|

قيمة P

|

|

قيمة P

|

|

| W83_W50 | 0 (0) | 0 | 1.45 (0.38) | 0.13 | 0.0003 | 0.005 | 0.142 | 0.11 | 0.096 | 0.29 |

| PG-strain_10 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.33 (0.2) | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.076 | 0.4 | 0.152 | 0.09 |

| PG-strain_45 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.18 (0.1) | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.271 | 0.002 | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| KCOM2798 | 0.21 (0.21) | 0.05 | 0.77 (0.26) | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.43 | 0.052 | 0.56 | 0.031 | 0.73 |

| PG-strain_16 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.23 (0.17) | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.43 | -0.094 | 0.3 | -0.051 | 0.58 |

| PG-strain_39 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.14 (0.1) | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.43 | -0.075 | 0.4 | -0.025 | 0.78 |

| PG-strain_43 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.12 (0.09) | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.43 | -0.017 | 0.85 | -0.066 | 0.46 |

| KCOM3001 | 0.28 (0.28) | 0.05 | 0.72 (0.27) | 0.06 | 0.27 | 0.61 | -0.134 | 0.14 | -0.064 | 0.48 |

| ATCC33277_381 | 6.38 (0.96) | 0.71 | 5.34 (0.52) | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.66 | -0.028 | 0.75 | -0.014 | 0.88 |

| PG-strain_18 | 0.4 (0.23) | 0.1 | 0.64 (0.17) | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.66 | -0.071 | 0.43 | -0.067 | 0.46 |

| TDC60_KCOM3131 | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.05 | 0.61 (0.24) | 0.05 | 0.43 | 0.66 | -0.057 | 0.53 | -0.095 | 0.29 |

| RMA3725 | 1.46 (0.78) | 0.19 | 2.16 (0.43) | 0.2 | 0.44 | 0.66 | -0.07 | 0.44 | 0.007 | 0.94 |

| KCOM2796 | 0.73 (0.73) | 0.05 | 0.33 (0.16) | 0.04 | 0.60 | 0.82 | -0.024 | 0.79 | -0.032 | 0.72 |

| PG-strain_8 | 0.29 (0.29) | 0.05 | 0.4 (0.18) | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.034 | 0.71 | 0.1 | 0.27 |

| AJW4 | 0.64 (0.46) | 0.1 | 0.78 (0.29) | 0.06 | 0.78 | 0.85 | -0.11 | 0.22 | -0.011 | 0.9 |

| PG-strain_3 | ٢.٢١ (٠.٩٧) | 0.29 | 2.48 (0.43) | 0.28 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.114 | 0.21 | 0.108 | 0.23 |

| PG-strain_14 | 0.17 (0.17) | 0 | 0.23 (0.16) | 0.01 | 0.80 | 0.85 | -0.004 | 0.96 | -0.009 | 0.92 |

| PG-strain_9 | 0.51 (0.51) | 0.05 | 0.44 (0.22) | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.90 | -0.061 | 0.5 | -0.035 | 0.7 |

الجدول 1. سلالات P. gingivalis عبر فئات مختلفة من أمراض اللثة. CAL، مستوى الارتباط السريري؛ PD عمق الجيب.

منطقة ISR. وبالتالي، لا يمكن لطريقتنا الحالية التمييز بين هذه السلالات. إن تحديد مجموعات إضافية من البرايمرات الموجودة في جينات الضراوة من شأنه تعزيز هذه الطريقة وتسهيل تصنيف أنواع سلالات ISR غير المعروفة. ثانياً، تعتمد قدرتنا على تحديد كل سلالة على مطابقة التسلسلات مع قاعدة بيانات للسلالات الموصوفة. ومع ذلك، ستتحسن هذه القيود مع المزيد من

طرق

المشاركون

شملت الدراسة الحالية 153 امرأة بعد انقطاع الطمث تم تسجيلهن في دراسة بوفالو لهشاشة العظام والتهاب اللثة (OsteoPerio)، وهي دراسة مساعدة أجريت في مركز بوفالو (نيويورك) السريري لدراسة المبادرة الصحية للنساء (WHI OS). خضعت كل مشاركة في هذه الدراسة لفحص سريري كامل للفم.

استخراج الحمض النووي الجيني البكتيري

تم عزل الحمض النووي الميتاجينومي من عينات اللويحات تحت اللثة باستخدام نظام QIAsymphony SP الآلي كما هو موصوف سابقًا.

تحكم إيجابي. تم استرجاع 60 ميكرولتر من الحمض النووي من كل عينة. تم قياس كمية الحمض النووي المستخرج باستخدام جهاز QuantiT.

تحكم إيجابي. تم استرجاع 60 ميكرولتر من الحمض النووي من كل عينة. تم قياس كمية الحمض النووي المستخرج باستخدام جهاز QuantiT.

تحضير مكتبة تسلسل الأمبليكون ISR

تم استخدام الحمض النووي الميتاجينومي من كل عينة للتحضير

تحليل البيانات

تم تنزيل الجينومات المتاحة لبكتيريا P. gingivalis من قاعدة بيانات GenBank التابعة لـ NCBI. تم إنشاء قاعدة بيانات ISR الفموية البشرية عن طريق استخراج تسلسلات ISR باستخدام بادئات محيطة بـ ISR باستخدام تطبيق BLASTN الإصدار 2.5.0 من الجينومات المتاحة لجميع سلالات Porphyromonas gingivalis.

خوارزمية إزالة الضوضاء للأمبليكون القابلة للتقسيم 2 (DADA2-متاحة علىhttps://github.com/benjjneb/dada2خط أنابيب الميكروبيوم المستخدم لتمييز المجتمعات الميكروبية من خلال متغيرات التسلسل التي تختلف بمقدار نوكليوتيد واحد فقط الموجودة في البيانات، كمتغيرات تسلسل الأمبليكون (ASVs)

تم تطبيع كل ISR ASV باستخدام تحويل النسبة اللوغاريتمية المركزية (CLR)، مما سيساعد في حساب هيكل البيانات التركيبية، وتقليل احتمالية الارتباطات الزائفة، وزيادة دلالة المقارنة.

توفر البيانات

تم رفع بيانات التسلسل الناتجة إلى قاعدة بيانات أرشيف قراءة التسلسل (SRA) التابعة لمركز المعلومات البيولوجية الوطني (NCBI) مع معرف مشروع البيولوجيا # PRJNA982061.

تاريخ الاستلام: 12 يونيو 2023؛ تاريخ القبول: 12 مارس 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 14 مارس 2024

نُشر على الإنترنت: 14 مارس 2024

References

- Eke, P. I., Borgnakke, W. S. & Genco, R. J. Recent epidemiologic trends in periodontitis in the USA. Periodontology 2000(82), 257-267. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd. 12323 (2020).

- Bole, C., Wactawski-Wende, J., Hovey, K. M., Genco, R. J. & Hausmann, E. Clinical and community risk models of incident tooth loss in postmenopausal women from the Buffalo Osteo Perio Study. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 38, 487-497. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00555.x (2010).

- Bernabe, E. & Marcenes, W. Periodontal disease and quality of life in British adults. J. Clin. Periodontol. 37, 968-972. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01627.x (2010).

- Genco, R. J., Ho, A. W., Grossi, S. G., Dunford, R. G. & Tedesco, L. A. Relationship of stress, distress and inadequate coping behaviors to periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 70, 711-723. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.1999.70.7.711 (1999).

- Fiorillo, L. et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis, periodontal and systemic implications: A systematic review. Dentistry J. 7, 114. https:// doi.org/10.3390/dj7040114 (2019).

- Khan, S. A., Kong, E. F., Meiller, T. F. & Jabra-Rizk, M. A. Periodontal diseases: Bug induced, host promoted. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004952. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat. 1004952 (2015).

- Li, X. et al. Maladaptive innate immune training of myelopoiesis links inflammatory comorbidities. Cell 185, 1709-1727.e1718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.043 (2022).

- Hajishengallis, G. & Chavakis, T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 426-440. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-020-00488-6 (2021).

- Dominy, S. S. et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau3333. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau3333 (2019).

- Mendez, K. N. et al. Variability in genomic and virulent properties of Porphyromonas gingivalis strains isolated from healthy and severe chronic periodontitis individuals. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 9, 246. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00246 (2019).

- Kumawat, R. M., Ganvir, S. M., Hazarey, V. K., Qureshi, A. & Purohit, H. J. Detection of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola in chronic and aggressive periodontitis patients: A comparative polymerase chain reaction study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 7, 481-486. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-237X. 194097 (2016).

- Kulkarni, P. G. et al. Molecular detection of Porphyromonas gingivalis in chronic periodontitis patients. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 19, 992-996 (2018).

- Lau, L. et al. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction versus culture: A comparison between two methods for the detection and quantification of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythensis in subgingival plaque samples. J. Clin. Periodontol. 31, 1061-1069. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00616.x (2004).

- Frandsen, E. V., Poulsen, K., Curtis, M. A. & Kilian, M. Evidence of recombination in Porphyromonas gingivalis and random distribution of putative virulence markers. Infect. Immun. 69, 4479-4485. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.69.7.4479-4485.2001 (2001).

- Menard, C. & Mouton, C. Clonal diversity of the taxon Porphyromonas gingivalis assessed by random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting. Infect. Immun. 63, 2522-2531. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.63.7.2522-2531.1995 (1995).

- Loos, B. G., Dyer, D. W., Whittam, T. S. & Selander, R. K. Genetic structure of populations of Porphyromonas gingivalis associated with periodontitis and other oral infections. Infect. Immun. 61, 204-212. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.61.1.204-212.1993 (1993).

- Leys, E. J., Smith, J. H., Lyons, S. R. & Griffen, A. L. Identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis strains by heteroduplex analysis and detection of multiple strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 3906-3911. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.37.12.3906-3911.1999 (1999).

- Mulhall, H., Huck, O. & Amar, S. Porphyromonas gingivalis, a long-range pathogen: Systemic impact and therapeutic implications. Microorganisms. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8060869 (2020).

- Neiders, M. E. et al. Heterogeneity of virulence among strains of Bacteroides gingivalis. J. Periodontal. Res. 24, 192-198. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0765.1989.tb02005.x (1989).

- Jockel-Schneider, Y. et al. Wild-type isolates of Porphyromonas gingivalis derived from periodontitis patients display major variability in platelet activation. J. Clin. Periodontol. 45, 693-700. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe. 12895 (2018).

- Birkedal-Hansen, H., Taylor, R. E., Zambon, J. J., Barwa, P. K. & Neiders, M. E. Characterization of collagenolytic activity from strains of Bacteroides gingivalis. J. Periodontal. Res. 23, 258-264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0765.1988.tb01369.x (1988).

- Werheim, E. R., Senior, K. G., Shaffer, C. A. & Cuadra, G. A. Oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis can escape phagocytosis of mammalian macrophages. Microorganisms. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8091432 (2020).

- Grice, E. A. et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science 324, 1190-1192. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science. 1171700 (2009).

- Franasiak, J. M. & Scott, R. T. Jr. Reproductive tract microbiome in assisted reproductive technologies. Fertil. Steril. 104, 1364-1371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.012 (2015).

- Oh, J. et al. The altered landscape of the human skin microbiome in patients with primary immunodeficiencies. Genome Res. 23, 2103-2114. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr. 159467.113 (2013).

- Griffen, A. L. et al. Distinct and complex bacterial profiles in human periodontitis and health revealed by 16 S pyrosequencing. ISME J. 6, 1176-1185. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.191 (2012).

- Guerrero-Preston, R. et al. (2016) 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing identifies microbiota associated with oral cancer, human papilloma virus infection and surgical treatment. Oncotarget. 7, 51320-51334. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.9710.

- Marotz, C. A. et al. Improving saliva shotgun metagenomics by chemical host DNA depletion. Microbiome 6, 42. https://doi.org/

(2018). - Mukherjee, C., Beall, C. J., Griffen, A. L. & Leys, E. J. High-resolution ISR amplicon sequencing reveals personalized oral microbiome. Microbiome 6, 153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0535-z (2018).

- Anyansi, C., Straub, T. J., Manson, A. L., Earl, A. M. & Abeel, T. Computational methods for strain-level microbial detection in colony and metagenome sequencing data. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1925. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01925 (2020).

- Genco, R. J. et al. The subgingival microbiome relationship to periodontal disease in older women. J. Dent. Res. 98, 975-984. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0022034519860449 (2019).

- Barry, T., Colleran, G., Glennon, M., Dunican, L. K. & Gannon, F. The

ribosomal spacer region as a target for DNA probes to identify eubacteria. PCR Methods Appl. 1, 51-56. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1.1.51 (1991). - Rumpf, R. W., Griffen, A. L., Wen, B. G. & Leys, E. J. Sequencing of the ribosomal intergenic spacer region for strain identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 2723-2725. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.37.8.2723-2725.1999 (1999).

- Aakra, A., Utåker, J. B. & Nes, I. F. RFLP of rRNA genes and sequencing of the 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacer region of ammoniaoxidizing bacteria: A phylogenetic approach. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49(Pt 1), 123-130. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-49-1-123 (1999).

- Chun, J., Huq, A. & Colwell, R. R. Analysis of 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer regions of Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio mimicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 2202-2208. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.65.5.2202-2208.1999 (1999).

- Stubbs, S. L., Brazier, J. S., O’Neill, G. L. & Duerden, B. I. PCR targeted to the 16S-23S rRNA gene intergenic spacer region of Clostridium difficile and construction of a library consisting of 116 different PCR ribotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 461-463. https:// doi.org/10.1128/jcm.37.2.461-463.1999 (1999).

- Banack, H. R. et al. Cohort profile: The Buffalo OsteoPerio microbiome prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 8, e024263. https:// doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024263 (2018).

- Zheng, W. et al. An accurate and efficient experimental approach for characterization of the complex oral microbiota. Microbiome 3, 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-015-0110-9 (2015).

- Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. P. Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis. ISME J. 11, 2639-2643. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.119 (2017).

- Eke, P. I., Page, R. C., Wei, L., Thornton-Evans, G. & Genco, R. J. Update of the case definitions for population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 83, 1449-1454. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop. 2012.110664 (2012).

- Griffen, A. L., Lyons, S. R., Becker, M. R., Moeschberger, M. L. & Leys, E. J. Porphyromonas gingivalis strain variability and periodontitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 4028-4033. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.37.12.4028-4033.1999 (1999).

- Genco, C. A., Cutler, C. W., Kapczynski, D., Maloney, K. & Arnold, R. R. A novel mouse model to study the virulence of and host response to Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 59, 1255-1263. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.59.4.1255-1263. 1991 (1991).

- Grenier, D. & Mayrand, D. Selected characteristics of pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains of Bacteroides gingivalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25, 738-740. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.25.4.738-740.1987 (1987).

- Laine, M. L. & van Winkelhoff, A. J. Virulence of six capsular serotypes of Porphyromonas gingivalis in a mouse model. Oral. Microbiol. Immunol. 13, 322-325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-302x.1998.tb00714.x (1998).

- Naito, M. et al. Determination of the genome sequence of Porphyromonas gingivalis strain ATCC 33277 and genomic comparison with strain W83 revealed extensive genome rearrangements in P. gingivalis. DNA Res. 15, 215-225. https://doi.org/10.1093/dnares/ dsn013 (2008).

- Igboin, C. O., Griffen, A. L. & Leys, E. J. Porphyromonas gingivalis strain diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 3073-3081. https://doi. org/10.1128/JCM.00569-09 (2009).

- Handelmann, C. R., Tsompana, M., Samudrala, R. & Buck, M. J. The impact of nucleosome structure on CRISPR/Cas9 fidelity. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad021 (2023).

- Brennan, R. M. et al. Bacterial species in subgingival plaque and oral bone loss in postmenopausal women. J. Periodontol. 78, 1051-1061. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2007.060436 (2007).

- Gordon, J. H. et al. Is the oral microbiome associated with blood pressure in older women?. High Blood Press Cardiovasc. Prev. 26, 217-225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40292-019-00322-8 (2019).

- LaMonte, M. J. et al. Composition and diversity of the subgingival microbiome and its relationship with age in postmenopausal women: An epidemiologic investigation. BMC Oral Health 19, 246. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0906-2 (2019).

- Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581-583. https:// doi.org/10.1038/nmeth. 3869 (2016).

- Gloor, G. B., Macklaim, J. M., Pawlowsky-Glahn, V. & Egozcue, J. J. Microbiome datasets are compositional: and this is not optional. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2224. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02224 (2017).

- Chong, J., Liu, P., Zhou, G. & Xia, J. Using MicrobiomeAnalyst for comprehensive statistical, functional, and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nat. Protoc. 15, 799-821. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-019-0264-1 (2020).

مساهمات المؤلفين

قام MJB بتصميم البحث (تصور المشروع، تطوير خطة البحث العامة، والإشراف على الدراسة)؛ قام VM بإجراء البحث (تنفيذ التجارب وجمع البيانات)؛ قام VM وSU وKMH وYS وMJL بتحليل البيانات أو إجراء التحليل الإحصائي؛ كتب VM وSU وMJL وJWW وPID الورقة؛ كان لدى MJB المسؤولية الرئيسية عن المحتوى النهائي؛ قرأ جميع المؤلفين ووافقوا على المخطوطة النهائية.

تمويل

تم دعم هذا المشروع جزئيًا من خلال المنحة رقم OS950077 من وزارة الدفاع، R01DE013505، و R01DE024523 من NIDCR لجون ويليامز.

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

المعلومات التكميلية النسخة الإلكترونية تحتوي على مواد تكميلية متاحة على https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-024-56849-x.

يجب توجيه المراسلات وطلبات المواد إلى م.ج.ب.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا تم إجراء تغييرات. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمواد. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة وكان استخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© المؤلفون 2024

© المؤلفون 2024

قسم الكيمياء الحيوية، مدرسة جاكوبس للطب والعلوم الطبية الحيوية، جامعة بافالو، بافالو، نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم علم الأوبئة والصحة البيئية، مدرسة الصحة العامة والمهن الصحية، جامعة بافالو، بافالو، نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الميكروبيولوجيا والمناعة، مدرسة جاكوبس للطب والعلوم الطبية الحيوية، جامعة بافالو، بافالو، نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. مركز ميكروبيوم جامعة بافالو، بافالو، نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم علم الأحياء الفموية، مدرسة طب الأسنان، جامعة بافالو، بافالو، نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم المعلوماتية الطبية الحيوية، مدرسة جاكوبس للطب والعلوم الطبية الحيوية، جامعة بافالو، بافالو، نيويورك، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. البريد الإلكتروني: mjbuck@buffalo.edu

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 14, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56849-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38485747

Publication Date: 2024-03-14

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56849-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38485747

Publication Date: 2024-03-14

OPEN

Defining Porphyromonas gingivalis strains associated with periodontal disease

Porphyromonas gingivalis, a Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium commonly found in human subgingival plaque, is a major etiologic agent for periodontitis and has been associated with multiple systemic pathologies. Many P. gingivalis strains have been identified and different strains possess different virulence factors. Current oral microbiome approaches ( 16 S or shotgun) have been unable to differentiate

Periodontitis is among the most common infections in the United States, with an estimated prevalence of

Periodontitis has been characterized as a dysbiotic disease owing to a shift in the subgingival microbial communities that colonize the periodontal pockets from a predominantly Gram-positive aerobic bacteria, to a dominance of Gram-negative anaerobes. The most notable are the so-called “red-complex” bacteria: Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, and Treponema denticola

P. gingvalis is found in healthy individuals as well as in patients with chronic periodontal disease

P. gingvalis is found in healthy individuals as well as in patients with chronic periodontal disease

Currently, there are 67 unique P. gingivalis genomes in the NCBI database. Experimentally, strains of P. gingivalis vary in the manifestation of measured virulence traits

Current microbiome approaches involve sequencing of the hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene or shotgun sequencing of all isolated DNA. Both approaches are limited in their ability to detect bacterial subspecies or strains. For example, although 16S microbiome experiments have revealed the diversity of the microbiota and have uncovered a connection with human health and disease

Thus, to determine P. gingivalis strains cost-effectively, we have adapted previous approaches examining the intergenic spacer region (ISR)

Results

Specificity, sensitivity and reproducibility of

Available ISR sequences for P. gingivalis were aligned to identify 200-250 bp regions containing the highest number of differences between strains which are flanked by conserved sequences for PCR amplicons (Fig. 1). The conserved primer sequences were then blasted to the NCBI database to test identity to non- P. gingivalis bacteria. Two sets of primers were identified with a single set described below as being the most informative for strain identification. Specificity of the P. gingivalis ISR-specific primers were determined with subgingival plaque from a participant with severe periodontal disease, positive controls (P. gingivalis strain ATCC33277, pooled subgingival plaque from multiple participants), and negative controls (Zymo mock DNA, Microbial DNA-free water) (Fig. 1B). The primers specific for

Identifying

To examine P. gingivalis strains associated with periodontal disease we examined subgingival plaque samples from the Buffalo Osteoporosis and Periodontal Disease (OsteoPerio) Study

P. gingivalis ISR specific amplicons were generated using two-step PCR, similar to 16 S analysis (see “Methods”)

P. gingivalis ISR specific amplicons were generated using two-step PCR, similar to 16 S analysis (see “Methods”)

Detection of

There were 139 unique sequences of P. gingivalis ISR. Each possible strain is named by

Most participant samples mapped to two different P. gingivalis strains (Fig. 4A), consistent with previous findings

A

| * | 60 | * | * | * | |||||

| KCOM 2796 |  |

||||||||

| W83 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTG | CTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGG | GCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 124 | ||||

| ATCC_33277 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTT | CTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGG | GCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 124 | ||||

| ATCC_49417 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTT | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 124 | |||||

| AJW4 | : GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGGTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTT | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 124 | |||||

| AS2 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTT | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 124 | |||||

| A7436 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 124 | ||||||

| KCOM_3001 | : GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTCCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 124 | ||||||

| HG66 | : | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 124 | |||||

| KCOM | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGGGCAAAAAGAA | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGAGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 124 | ||||||

| KCOM | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGGTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTG | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 114 | ||||||

| TDC 60 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTG | CTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG | ———– | AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 114 | ||||

| KCOM | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGGTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTG | CTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGAGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 114 | ||||||

| A7A1-28 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTG | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 114 | ||||||

| KCOM | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTT | GCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———–AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 114 | ||||||

| KCOM 3131 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 114 | |||||||

| KCOM 2800 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTCCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 114 | |||||||

| RMA 4165 | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GA-CTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG | ———–AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCGCA | 113 | ||||||

| RMA | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCAAAAAGG | ———-AAAAATAAAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 114 | ||||||

| RMA_ | : | GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC–GAGCTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTGCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCCAAAAGG | ———–AAAAATATAGAGAGATAAGGGGCAACGGTCATGCAGCCCA | 114 | |||||

| GGCCTTGGTTCGTTTATCTTTC | GAgcTTTCCCTGCTTCGAACTTTgCTTCTTTTTTTGAAGCGAGGCaAAAAGG |

|

|||||||

| * | 180 | 200 | 220 | ||||||

| KCOM | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTT | CGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT | –GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | ||||

| W83 | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT | –GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||

| ATCC_33277 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| ATCC 49417 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| AJW4 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| AS2 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| A7436 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| KCOM | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | ||||||

| HG66 | : AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | |||||||

| KCOM | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 225 | ||||||

| KCOM | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | ||||||

| TDC_60 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| KCOM | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| A7A1-28 | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| KCOM | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGATGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGACAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| KCOM | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| KCOM | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCATAC | GGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGACAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | ||||||

| RMA

|

AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 214 | |||||||

| RMA | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT–GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||||||

| RMA | : | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAGACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAGAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT | AGGAGCTGCCACAGGCAgACGGAAGAGTTCGAATAAGAGAgAAGCAGTCCTATAGCTCAGTTGGTTAGAGCGCTACACT | GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | –GATAATGTAGAGGTCGGCAGTT | 215 | |||

B

Figure 1. Creating P. gingivalis specific primers. (A) Alignment of representative P. gingivalis strain ISR regions. Primer locations are indicated. (B) PCR conditions were optimized to amplify P. gingivalis ISR regions without targeting other bacteria. (C) PCR conditions allow P. gingivalis amplification in mixed samples. Zymo Mock contains DNA from Listeria monocytogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, Lactobacillus fermentum, Enterococcus faecalis, and Staphylococcus aureus; Plaque Pool, pooled subgingival plaque from multiple participants (positive control for sequencing batches); Pg. DNA, P. gingivalis strain ATCC33277. Perio Sample, subgingival plaque from a participant with severe periodontal disease. Amplicons were visualized in

top strain in each sample (Fig. 4b). For most participant samples regardless of disease state, the top strain represents

W83/W50 is associated with periodontal disease

To determine if specific strains are associated with periodontal disease, we grouped our samples into two groups None/Mild and Moderate/Severe and filtered the ISR sequences removing strains with low abundance or ones appearing in a single sample (see “Methods”). In total 18 P. gingivalis strains were examined after filtering (Table 1).

The most abundant strain across all samples is the avirulent

Figure 2. ISR libraries and number of mapped reads. (A) DNA concentrations after next-generation sequencing library formation with two rounds of PCR. (B) Numbers of reads that mapped to the P. gingivalis ISR database. The sample periodontal classification (none/mild, moderate, severe) with the number of samples is shown for each group. Neg, batch-specific negative control (extraction buffer, PCR blank); Pos, positive control with ATCC33277 DNA; Plaque pool, DNA isolated from a mixture of subgingival plaques from a group of people (positive control).

Figure 3. Technical replicates are reproducible. Relative abundance for 5 replicate samples, with the Pearson correlation (r) between replicates.

Figure 4. Number of strains and abundance (A) Number of detected strains in each sample. (B) Frequency of the most abundant strain in each sample.

associated with periodontitis

We next evaluated the linear correlations for each CLR mean strain with the whole-mouth clinical measurements for mean pocket depth (PD) and clinical attachment level (CAL) (Table 1). Correlations ranged from -0.134 to 0.142 for PD and from -0.095 to 0.152 for CAL. After multiple testing correction none of correlations are significant.

Discussion

Determining P. gingivalis strains with current microbiome methods has been limited. There are two major issues which needed to be addressed. First, abundance of

In this study we identified an information-rich region located within the

While our approach is promising, it does have some limitations that should be taken into consideration. The first limitation is that a significant number of P. gingivalis strains have identical sequences within our targeted

| Strain label | Periodontal disease category

|

Whole-mouth mean | ||||||||

| None/mild (

|

Moderate/severe (

|

FDR | PD | CAL | ||||||

| Mean

|

Freq

|

Mean

|

Freq

|

P value

|

q-value

|

|

P value

|

|

P value

|

|

| W83_W50 | 0 (0) | 0 | 1.45 (0.38) | 0.13 | 0.0003 | 0.005 | 0.142 | 0.11 | 0.096 | 0.29 |

| PG-strain_10 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.33 (0.2) | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.076 | 0.4 | 0.152 | 0.09 |

| PG-strain_45 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.18 (0.1) | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.271 | 0.002 | 0.23 | 0.01 |

| KCOM2798 | 0.21 (0.21) | 0.05 | 0.77 (0.26) | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.43 | 0.052 | 0.56 | 0.031 | 0.73 |

| PG-strain_16 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.23 (0.17) | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.43 | -0.094 | 0.3 | -0.051 | 0.58 |

| PG-strain_39 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.14 (0.1) | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.43 | -0.075 | 0.4 | -0.025 | 0.78 |

| PG-strain_43 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0.12 (0.09) | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.43 | -0.017 | 0.85 | -0.066 | 0.46 |

| KCOM3001 | 0.28 (0.28) | 0.05 | 0.72 (0.27) | 0.06 | 0.27 | 0.61 | -0.134 | 0.14 | -0.064 | 0.48 |

| ATCC33277_381 | 6.38 (0.96) | 0.71 | 5.34 (0.52) | 0.54 | 0.34 | 0.66 | -0.028 | 0.75 | -0.014 | 0.88 |

| PG-strain_18 | 0.4 (0.23) | 0.1 | 0.64 (0.17) | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.66 | -0.071 | 0.43 | -0.067 | 0.46 |

| TDC60_KCOM3131 | 0.3 (0.3) | 0.05 | 0.61 (0.24) | 0.05 | 0.43 | 0.66 | -0.057 | 0.53 | -0.095 | 0.29 |

| RMA3725 | 1.46 (0.78) | 0.19 | 2.16 (0.43) | 0.2 | 0.44 | 0.66 | -0.07 | 0.44 | 0.007 | 0.94 |

| KCOM2796 | 0.73 (0.73) | 0.05 | 0.33 (0.16) | 0.04 | 0.60 | 0.82 | -0.024 | 0.79 | -0.032 | 0.72 |

| PG-strain_8 | 0.29 (0.29) | 0.05 | 0.4 (0.18) | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.85 | 0.034 | 0.71 | 0.1 | 0.27 |

| AJW4 | 0.64 (0.46) | 0.1 | 0.78 (0.29) | 0.06 | 0.78 | 0.85 | -0.11 | 0.22 | -0.011 | 0.9 |

| PG-strain_3 | 2.21 (0.97) | 0.29 | 2.48 (0.43) | 0.28 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.114 | 0.21 | 0.108 | 0.23 |

| PG-strain_14 | 0.17 (0.17) | 0 | 0.23 (0.16) | 0.01 | 0.80 | 0.85 | -0.004 | 0.96 | -0.009 | 0.92 |

| PG-strain_9 | 0.51 (0.51) | 0.05 | 0.44 (0.22) | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.90 | -0.061 | 0.5 | -0.035 | 0.7 |

Table 1. P. gingivalis strains across different categories of periodontal disease. CAL, clinical attachment level; PD pocket depth.

ISR region. Consequently, our current approach cannot differentiate between these strains. Identification of additional primer sets located in virulence genes would strength this approach and facilitate the characterization of unknown ISR strain types. Secondly, our ability to identify each strain is dependent on matching sequences to a database of characterized strains. However, this limitation will improve as more

Methods

Participants

The present study included 153 postmenopausal women enrolled in the Buffalo Osteoporosis and Periodontitis (OsteoPerio) Study, which is an ancillary study conducted at the Buffalo (NY) clinical center of the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study (WHI OS). Each participant in this study had a complete clinical oral examination

Bacterial genomic DNA extraction

Metagenomic DNA was isolated from subgingival plaque samples using an the QIAsymphony SP automated system as described previously

a positive control. 60 ul of DNA was eluted from each sample. Extracted DNA were quantified with the QuantiT

a positive control. 60 ul of DNA was eluted from each sample. Extracted DNA were quantified with the QuantiT

ISR amplicon sequencing library preparation

Metagenomic DNA from each sample was used to prepare

Data analysis

Available genomes for the P. gingivalis bacteria were downloaded from NCBI’s GenBank database. The human oral ISR database was created by extracting ISR sequences with ISR-flanking primers using BLASTN application 2.5.0 from available genomes for all the Porphyromonas gingivalis strains.

The Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm 2 (DADA2-available at https://github.com/benjjneb/dada2) microbiome pipeline used to distinguish the microbial communities by sequence variants differing by as little as one nucleotide present in the data, as amplicon sequence variants (ASVs)

Each ISR ASV was normalized using the centered log (2)-ratio (CLR) transformation, which will help account for the compositional data structure, reduce the likelihood of spurious correlations, and enhance the meaningfulness of comparison

Data availability

The resulting sequencing data has been uploaded to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database with BioProject ID # PRJNA982061.

Received: 12 June 2023; Accepted: 12 March 2024

Published online: 14 March 2024

Published online: 14 March 2024

References

- Eke, P. I., Borgnakke, W. S. & Genco, R. J. Recent epidemiologic trends in periodontitis in the USA. Periodontology 2000(82), 257-267. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd. 12323 (2020).

- Bole, C., Wactawski-Wende, J., Hovey, K. M., Genco, R. J. & Hausmann, E. Clinical and community risk models of incident tooth loss in postmenopausal women from the Buffalo Osteo Perio Study. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 38, 487-497. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00555.x (2010).

- Bernabe, E. & Marcenes, W. Periodontal disease and quality of life in British adults. J. Clin. Periodontol. 37, 968-972. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01627.x (2010).

- Genco, R. J., Ho, A. W., Grossi, S. G., Dunford, R. G. & Tedesco, L. A. Relationship of stress, distress and inadequate coping behaviors to periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 70, 711-723. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.1999.70.7.711 (1999).

- Fiorillo, L. et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis, periodontal and systemic implications: A systematic review. Dentistry J. 7, 114. https:// doi.org/10.3390/dj7040114 (2019).

- Khan, S. A., Kong, E. F., Meiller, T. F. & Jabra-Rizk, M. A. Periodontal diseases: Bug induced, host promoted. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004952. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat. 1004952 (2015).

- Li, X. et al. Maladaptive innate immune training of myelopoiesis links inflammatory comorbidities. Cell 185, 1709-1727.e1718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.043 (2022).

- Hajishengallis, G. & Chavakis, T. Local and systemic mechanisms linking periodontal disease and inflammatory comorbidities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 426-440. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-020-00488-6 (2021).

- Dominy, S. S. et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau3333. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau3333 (2019).

- Mendez, K. N. et al. Variability in genomic and virulent properties of Porphyromonas gingivalis strains isolated from healthy and severe chronic periodontitis individuals. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 9, 246. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2019.00246 (2019).

- Kumawat, R. M., Ganvir, S. M., Hazarey, V. K., Qureshi, A. & Purohit, H. J. Detection of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Treponema denticola in chronic and aggressive periodontitis patients: A comparative polymerase chain reaction study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 7, 481-486. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-237X. 194097 (2016).

- Kulkarni, P. G. et al. Molecular detection of Porphyromonas gingivalis in chronic periodontitis patients. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 19, 992-996 (2018).

- Lau, L. et al. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction versus culture: A comparison between two methods for the detection and quantification of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythensis in subgingival plaque samples. J. Clin. Periodontol. 31, 1061-1069. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00616.x (2004).

- Frandsen, E. V., Poulsen, K., Curtis, M. A. & Kilian, M. Evidence of recombination in Porphyromonas gingivalis and random distribution of putative virulence markers. Infect. Immun. 69, 4479-4485. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.69.7.4479-4485.2001 (2001).

- Menard, C. & Mouton, C. Clonal diversity of the taxon Porphyromonas gingivalis assessed by random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting. Infect. Immun. 63, 2522-2531. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.63.7.2522-2531.1995 (1995).

- Loos, B. G., Dyer, D. W., Whittam, T. S. & Selander, R. K. Genetic structure of populations of Porphyromonas gingivalis associated with periodontitis and other oral infections. Infect. Immun. 61, 204-212. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.61.1.204-212.1993 (1993).

- Leys, E. J., Smith, J. H., Lyons, S. R. & Griffen, A. L. Identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis strains by heteroduplex analysis and detection of multiple strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 3906-3911. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.37.12.3906-3911.1999 (1999).

- Mulhall, H., Huck, O. & Amar, S. Porphyromonas gingivalis, a long-range pathogen: Systemic impact and therapeutic implications. Microorganisms. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8060869 (2020).

- Neiders, M. E. et al. Heterogeneity of virulence among strains of Bacteroides gingivalis. J. Periodontal. Res. 24, 192-198. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0765.1989.tb02005.x (1989).

- Jockel-Schneider, Y. et al. Wild-type isolates of Porphyromonas gingivalis derived from periodontitis patients display major variability in platelet activation. J. Clin. Periodontol. 45, 693-700. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe. 12895 (2018).

- Birkedal-Hansen, H., Taylor, R. E., Zambon, J. J., Barwa, P. K. & Neiders, M. E. Characterization of collagenolytic activity from strains of Bacteroides gingivalis. J. Periodontal. Res. 23, 258-264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0765.1988.tb01369.x (1988).

- Werheim, E. R., Senior, K. G., Shaffer, C. A. & Cuadra, G. A. Oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis can escape phagocytosis of mammalian macrophages. Microorganisms. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8091432 (2020).

- Grice, E. A. et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science 324, 1190-1192. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science. 1171700 (2009).

- Franasiak, J. M. & Scott, R. T. Jr. Reproductive tract microbiome in assisted reproductive technologies. Fertil. Steril. 104, 1364-1371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.012 (2015).

- Oh, J. et al. The altered landscape of the human skin microbiome in patients with primary immunodeficiencies. Genome Res. 23, 2103-2114. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr. 159467.113 (2013).

- Griffen, A. L. et al. Distinct and complex bacterial profiles in human periodontitis and health revealed by 16 S pyrosequencing. ISME J. 6, 1176-1185. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.191 (2012).

- Guerrero-Preston, R. et al. (2016) 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing identifies microbiota associated with oral cancer, human papilloma virus infection and surgical treatment. Oncotarget. 7, 51320-51334. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.9710.

- Marotz, C. A. et al. Improving saliva shotgun metagenomics by chemical host DNA depletion. Microbiome 6, 42. https://doi.org/

(2018). - Mukherjee, C., Beall, C. J., Griffen, A. L. & Leys, E. J. High-resolution ISR amplicon sequencing reveals personalized oral microbiome. Microbiome 6, 153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0535-z (2018).

- Anyansi, C., Straub, T. J., Manson, A. L., Earl, A. M. & Abeel, T. Computational methods for strain-level microbial detection in colony and metagenome sequencing data. Front. Microbiol. 11, 1925. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01925 (2020).

- Genco, R. J. et al. The subgingival microbiome relationship to periodontal disease in older women. J. Dent. Res. 98, 975-984. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0022034519860449 (2019).

- Barry, T., Colleran, G., Glennon, M., Dunican, L. K. & Gannon, F. The

ribosomal spacer region as a target for DNA probes to identify eubacteria. PCR Methods Appl. 1, 51-56. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.1.1.51 (1991). - Rumpf, R. W., Griffen, A. L., Wen, B. G. & Leys, E. J. Sequencing of the ribosomal intergenic spacer region for strain identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 2723-2725. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.37.8.2723-2725.1999 (1999).

- Aakra, A., Utåker, J. B. & Nes, I. F. RFLP of rRNA genes and sequencing of the 16S-23S rDNA intergenic spacer region of ammoniaoxidizing bacteria: A phylogenetic approach. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49(Pt 1), 123-130. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-49-1-123 (1999).

- Chun, J., Huq, A. & Colwell, R. R. Analysis of 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer regions of Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio mimicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 2202-2208. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.65.5.2202-2208.1999 (1999).

- Stubbs, S. L., Brazier, J. S., O’Neill, G. L. & Duerden, B. I. PCR targeted to the 16S-23S rRNA gene intergenic spacer region of Clostridium difficile and construction of a library consisting of 116 different PCR ribotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 461-463. https:// doi.org/10.1128/jcm.37.2.461-463.1999 (1999).

- Banack, H. R. et al. Cohort profile: The Buffalo OsteoPerio microbiome prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 8, e024263. https:// doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024263 (2018).

- Zheng, W. et al. An accurate and efficient experimental approach for characterization of the complex oral microbiota. Microbiome 3, 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-015-0110-9 (2015).

- Callahan, B. J., McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. P. Exact sequence variants should replace operational taxonomic units in marker-gene data analysis. ISME J. 11, 2639-2643. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.119 (2017).

- Eke, P. I., Page, R. C., Wei, L., Thornton-Evans, G. & Genco, R. J. Update of the case definitions for population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 83, 1449-1454. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop. 2012.110664 (2012).

- Griffen, A. L., Lyons, S. R., Becker, M. R., Moeschberger, M. L. & Leys, E. J. Porphyromonas gingivalis strain variability and periodontitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 4028-4033. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.37.12.4028-4033.1999 (1999).

- Genco, C. A., Cutler, C. W., Kapczynski, D., Maloney, K. & Arnold, R. R. A novel mouse model to study the virulence of and host response to Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 59, 1255-1263. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.59.4.1255-1263. 1991 (1991).

- Grenier, D. & Mayrand, D. Selected characteristics of pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains of Bacteroides gingivalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25, 738-740. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.25.4.738-740.1987 (1987).

- Laine, M. L. & van Winkelhoff, A. J. Virulence of six capsular serotypes of Porphyromonas gingivalis in a mouse model. Oral. Microbiol. Immunol. 13, 322-325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-302x.1998.tb00714.x (1998).

- Naito, M. et al. Determination of the genome sequence of Porphyromonas gingivalis strain ATCC 33277 and genomic comparison with strain W83 revealed extensive genome rearrangements in P. gingivalis. DNA Res. 15, 215-225. https://doi.org/10.1093/dnares/ dsn013 (2008).

- Igboin, C. O., Griffen, A. L. & Leys, E. J. Porphyromonas gingivalis strain diversity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 3073-3081. https://doi. org/10.1128/JCM.00569-09 (2009).

- Handelmann, C. R., Tsompana, M., Samudrala, R. & Buck, M. J. The impact of nucleosome structure on CRISPR/Cas9 fidelity. Nucleic Acids Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad021 (2023).

- Brennan, R. M. et al. Bacterial species in subgingival plaque and oral bone loss in postmenopausal women. J. Periodontol. 78, 1051-1061. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2007.060436 (2007).

- Gordon, J. H. et al. Is the oral microbiome associated with blood pressure in older women?. High Blood Press Cardiovasc. Prev. 26, 217-225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40292-019-00322-8 (2019).

- LaMonte, M. J. et al. Composition and diversity of the subgingival microbiome and its relationship with age in postmenopausal women: An epidemiologic investigation. BMC Oral Health 19, 246. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0906-2 (2019).

- Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581-583. https:// doi.org/10.1038/nmeth. 3869 (2016).

- Gloor, G. B., Macklaim, J. M., Pawlowsky-Glahn, V. & Egozcue, J. J. Microbiome datasets are compositional: and this is not optional. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2224. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02224 (2017).

- Chong, J., Liu, P., Zhou, G. & Xia, J. Using MicrobiomeAnalyst for comprehensive statistical, functional, and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nat. Protoc. 15, 799-821. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-019-0264-1 (2020).

Author contributions

MJB designed research (project conception, development of overall research plan, and study oversight); VM conducted research (hands-on conduct of the experiments and data collection); VM, SU, KMH, YS, MJL analyzed data or performed statistical analysis; VM, SU, MJL, JWW, PID wrote paper; MJB had primary responsibility for final content; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This project was partially supported by grant No. OS950077 from DOD, R01DE013505, and R01DE024523 from NIDCR for JWW.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-024-56849-x.

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.J.B.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2024

© The Author(s) 2024

Department of Biochemistry, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA. Department of Epidemiology and Environmental Health, School of Public Health and Health Professions, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA. Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA. UB Microbiome Center, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA. Department of Oral Biology, School of Dental Medicine, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA. Department of Biomedical Informatics, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA. email: mjbuck@buffalo.edu