DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocad259

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38281112

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-27

تحسين نماذج اللغة الكبيرة للتعرف على الكيانات المسماة السريرية من خلال هندسة المطالبات

الملخص

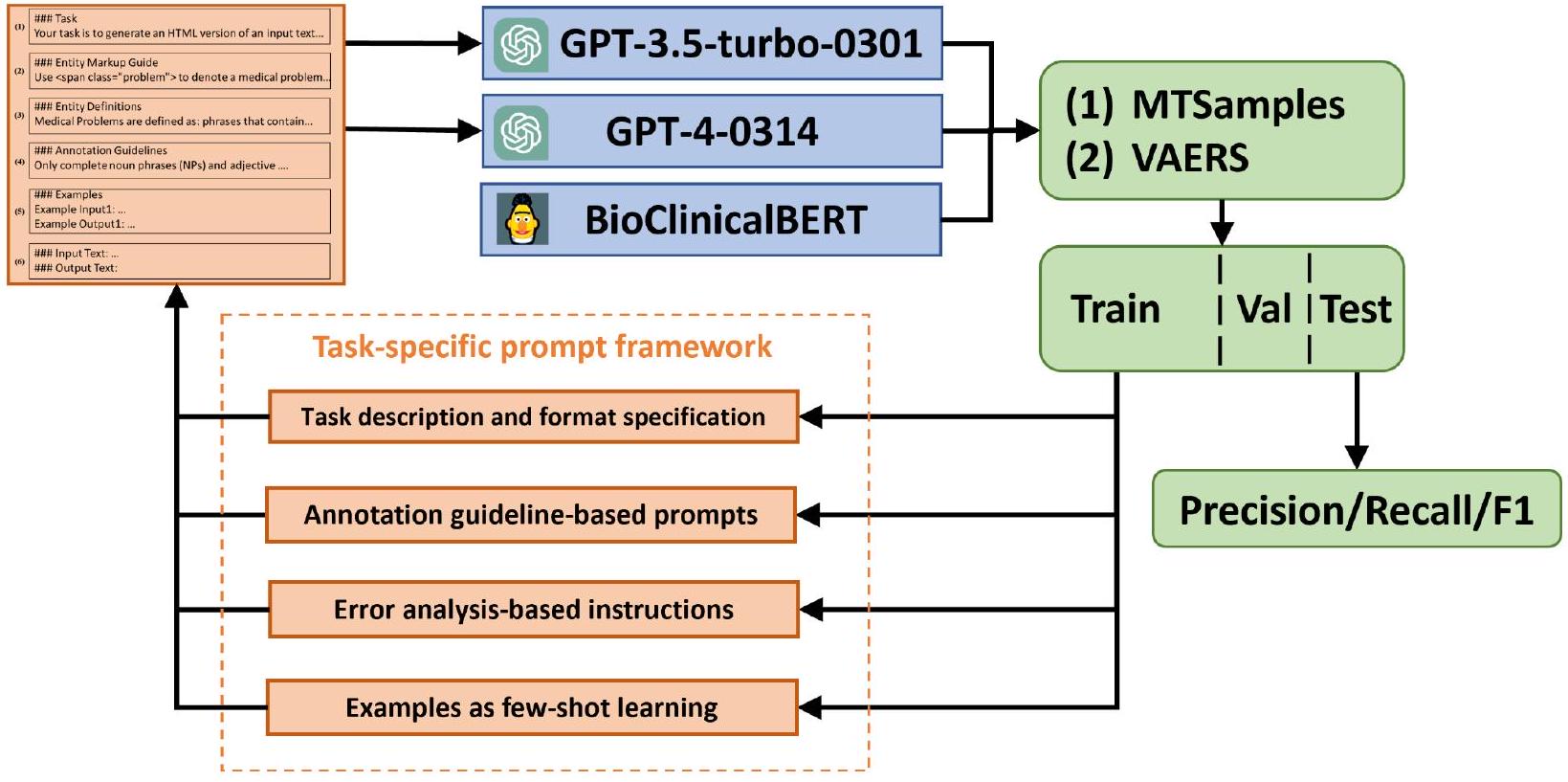

الهدف: تهدف هذه الدراسة إلى قياس قدرات GPT-3.5 و GPT-4 في مهام التعرف على الكيانات المسماة السريرية (NER) وتقترح مطالبات محددة لتحسين أدائها. المواد والأساليب: قمنا بتقييم هذه النماذج على مهمتين سريريتين لـ NER: (1) لاستخراج المشكلات الطبية والعلاجات والاختبارات من الملاحظات السريرية في مجموعة بيانات MTSamples، وفقًا لمهمة استخراج المفاهيم المشتركة i2b2 لعام 2010، و (2) تحديد الأحداث السلبية المتعلقة باضطرابات الجهاز العصبي من تقارير السلامة في نظام الإبلاغ عن الأحداث السلبية للقاحات (VAERS). لتحسين أداء نماذج GPT، قمنا بتطوير إطار عمل لمطالبات محددة للمهام السريرية يتضمن (1) مطالبات أساسية مع وصف المهمة وتحديد التنسيق، (2) مطالبات مستندة إلى إرشادات التوضيح، (3) تعليمات مستندة إلى تحليل الأخطاء، و (4) عينات موضحة للتعلم القليل. قمنا بتقييم فعالية كل مطالبة وقارننا النماذج بـ BioClinicalBERT. النتائج: باستخدام المطالبات الأساسية، حقق GPT-3.5 و GPT-4 درجات F1 مريحة قدرها

1 المقدمة

كطريقة رائدة لتطوير تطبيقات معالجة اللغة الطبيعية السريرية. تمثل تمثيلات المحولات ثنائية الاتجاه (BERT) نموذج لغة مدرب مسبقًا يستخدم على نطاق واسع يتعلم التمثيلات السياقية للنص الحر [7]. باستخدام BERT كأساس، تم تطوير نماذج لغة محددة للمجال مثل BioBERT و PubMedBERT (مدرب على الأدبيات الطبية الحيوية) و ClinicalBERT (مدرب على مجموعة بيانات MIMIC-III) [8، 9، 10]. تم تطبيق هذه النماذج على مهام NER السريرية من خلال التعلم الانتقالي (أي، ضبط النماذج على مجموعات بيانات NER السريرية)، وقد أظهرت أداءً محسنًا مع عدد أقل من العينات الموضحة [8، 9، 10].

2 طرق

2.1 نظرة عامة على المهمة

تم تصوير التحقيق في الشكل ؟؟. تم إعداد محفزين مختلفين لتحديد ثلاثة أنواع من الكيانات السريرية: المشكلة الطبية، العلاج، والاختبار من النصوص السريرية باستخدام كل من ChatGPT وGPT-3. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قمنا بتدريب نموذج BioClinicalBERT تحت الإشراف باستخدام مجموعة بيانات مشروحة من تحدي i2b2 لعام 2010، كخط أساس. ثم تم تقييم النماذج الثلاثة باستخدام مجموعة بيانات مشروحة تتكون من أقسام HPI من 100 ملخص خروج في مجموعة MTSamples (انظر القسم التالي).

2.2 مجموعة البيانات

2.3 النماذج

| مجموعات البيانات | الكيانات | قطار | صالح | اختبار | إجمالي |

| عينات MT | مشكلة طبية | 538 | ٢٠٣ | 199 | 940 |

| علاج | 149 | 43 | ٣٥ | 227 | |

| اختبار | ١٢٠ | ٣٩ | 50 | ٢٠٩ | |

| VAERS | تحقيق | 148 | ٢٩ | ٥٩ | 236 |

| حدث سلبي عصبي | ٤٠٦ | 83 | 162 | 651 | |

| حدث سلبي آخر | ٣٠١ | 62 | 167 | 530 | |

| إجراء | ٣٣٨ | ٥٧ | ١٢٦ | 521 |

فيما يتعلق بنماذج GPT، استخدمنا الإصدارات المحددة GPT-3.5-turbo-0301 و GPT-4-0314 لضمان القابلية للتكرار. تشير درجة الحرارة في نموذج اللغة التوليدي إلى معلمة تتحكم في العشوائية في توقعات النموذج، وعادة ما تتراوح من 0 (حتمي تمامًا) إلى 1 أو أعلى (مخرجات عشوائية ومتنوعة بشكل متزايد). تم ضبط معلمة درجة الحرارة لنماذج GPT على 0 لتقليل العشوائية في توليد الاستجابات. قيمة درجة الحرارة المنخفضة تحد من ميل النموذج لأخذ قفزات إبداعية، مما يضمن مخرجات أكثر توقعًا وثباتًا. هذا أمر حاسم في مهام التعرف على الكيانات المسماة السريرية حيث تكون دقة وموثوقية استخراج المعلومات في غاية الأهمية. في إعدادنا، تم التفاعل مع نماذج GPT في دور “المستخدم”. يحاكي هذا الدور تفاعل المستخدم الحقيقي مع النموذج، حيث يقوم “المستخدم” بإدخال المطالبات وينتج النموذج الاستجابات وفقًا لذلك. تعكس هذه الطريقة سيناريو استخدام نموذجي لهذه النماذج في التطبيقات العملية. جميع مجموعات البيانات المدخلة والمخرجة جنبًا إلى جنب مع متغيرات المطالبات مشمولة مع دفاتر Jypter التي يمكن أن تتفاعل مع واجهة برمجة تطبيقات OpenAI في مستودع GitHub الخاص بنا. في وقت هذه الدراسة، كانت تكاليف GPT-3.5 لكل 1k توكن تقريبًا

2.4 هندسة المطالبات

(1) موجه أساسي مع وصف المهمة ومواصفات التنسيق: توفر هذه المكون معلومات أساسية لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة حول المهام التي نوجهها لها وفي أي تنسيق يجب أن تخرج النماذج النتائج. قمنا بتوجيه النماذج لتسليط الضوء على الكيانات المسماة داخل ملف HTML باستخدام علامات <span> مع سمة فئة تشير إلى أنواع الكيانات. وهذا يسمح بتحويل مخرجات نماذج GPT بسهولة إلى تنسيق تقليدي يُعرف باسم Inside-Outside-Beginning (IOB)، مما يسمح بإجراء مقارنة مباشرة لأداء التعرف على الكيانات المسماة مع النتائج من الدراسات الحالية.

(2) المطالب المستندة إلى إرشادات التوضيح: تحتوي هذه المكونة على تعريفات الكيانات وقواعد لغوية مستمدة من إرشادات التوضيح. تقدم تعريفات الكيانات أوصافًا شاملة وواضحة لكيان ما ضمن سياق مهمة معينة. تلعب دورًا أساسيًا في توجيه النموذج اللغوي الكبير نحو التعرف الدقيق على الكيانات داخل الوثائق النصية. لاحظنا أن توقعات النموذج غالبًا ما تختلف بشكل كبير عن المعيار الذهبي من حيث البنية النحوية. على سبيل المثال، قد تنشأ اختلافات بشأن أنواع العبارات التي يجب تضمينها (مثل، عبارات الأسماء أو عبارات الصفات). لتحسين أداء النموذج، أشرنا إلى ودمجنا القواعد الموجودة في إرشادات التوضيح لمعالجة هذه القضايا.

(3) تعليمات مستندة إلى تحليل الأخطاء: بالإضافة إلى إرشادات التوضيح الأصلية، قمنا أيضًا بإدراج إرشادات إضافية بعد تحليل الأخطاء الناتجة عن مخرجات GPT باستخدام بيانات التدريب. على سبيل المثال، لاحظنا أن نماذج GPT تميل غالبًا إلى تصنيف إجراءات الاستشارة ككيانات اختبار. لمنع ذلك، قمنا بإدراج قاعدة محددة تنص على: “يجب عدم تصنيف إجراءات الاستشارة كاختبارات.”.

(4) عينات مشروحة: لمساعدة نماذج اللغة الكبيرة بشكل أكبر في فهم المهمة وتوليد نتائج دقيقة، قدمنا مجموعة من العينات المشروحة لتحسين أدائها في إعداد التعلم القليل. قمنا باختيار عشوائي إما 1 أو 5 أمثلة مشروحة (تعلم 1 أو 5) من مجموعة التدريب وصغناها وفقًا لوصف المهمة ودليل تعليمات الكيانات. على سبيل المثال، بالنظر إلى جملة ‘تم تشخيصه بالتهاب المفاصل العظمي في الركبتين وقد خضع لعملية تنظير المفاصل قبل سنوات من القبول.’ مع ‘التهاب المفاصل العظمي في الركبتين’ و ‘تنظير المفاصل’ مشروحتين ككيانات مشكلة طبية واختبار، قمنا بإدراج هذه الجملة في الموجه باستخدام التنسيق التالي:

### أمثلة

مثال على المدخل: تم تشخيصه بالتهاب المفاصل العظمي في الركبتين وقد خضع لعملية تنظير المفاصل قبل سنوات من دخوله المستشفى.

مثال على المخرجات: تم تشخيصه بـالتهاب المفاصل العظمي في الركبتينوقد خضعت لـتنظير المفاصلسنوات قبل القبول.

2.5 التقييم

3 نتائج

3.1 الأداء بدون تدريب مع مطالبات مختلفة

| أنواع المطالبات | أمثلة | ||||

| (1) مطالبات الأساس |

|

||||

| (2) مطالبات مستندة إلى إرشادات التعليق |

|

||||

| (3) تعليمات قائمة على تحليل الأخطاء |

|

||||

| (4) عينات مشروحة من خلال التعلم القليل |

|

| نماذج | استراتيجيات التحفيز | عينات MT | VAERS | ||||||||||

| مطابقة دقيقة | مباراة مريحة | مطابقة دقيقة | مباراة مريحة | ||||||||||

| P | ر | فورمولا 1 | P | ر | فورمولا 1 | P | ر | فورمولا 1 | P | ر | فورمولا 1 | ||

| جي بي تي-3.5 | (1) | 0.492 | 0.327 | 0.393 | 0.794 | 0.528 | 0.634 | 0.510 | 0.146 | 0.227 | 0.626 | 0.187 | 0.288 |

| (1)+(2) | 0.453 | 0.405 | 0.428 | 0.736 | 0.680 | 0.707 | 0.575 | 0.200 | 0.297 | 0.687 | 0.243 | 0.359 | |

| (1)

|

0.462 | 0.412 | 0.436 | 0.755 | 0.687 | 0.719 | 0.569 | 0.233 | 0.331 | 0.730 | 0.305 | 0.431 | |

| جي بي تي-4 | (1) | 0.486 | 0.546 | 0.514 | 0.762 | 0.852 | 0.804 | 0.420 | 0.397 | 0.408 | 0.599 | 0.568 | 0.583 |

|

|

0.478 | 0.577 | 0.523 | 0.752 | 0.919 | 0.827 | 0.559 | 0.444 | 0.495 | 0.743 | 0.593 | 0.660 | |

|

|

0.488 | 0.570 | 0.526 | 0.777 | 0.908 | 0.838 | 0.536 | 0.469 | 0.500 | 0.727 | 0.650 | 0.686 | |

3.2 تأثير أمثلة N-Shot على أداء النموذج

| نماذج | استراتيجيات التحفيز | عينات MT | VAERS | ||||||||||

| مطابقة دقيقة | مباراة مريحة | مطابقة دقيقة | مباراة مريحة | ||||||||||

| P | ر | فورمولا 1 | P | ر | فورمولا 1 | P | ر | فورمولا 1 | P | ر | فورمولا 1 | ||

| جي بي تي-3.5 | صفر-لقطة | 0.462 | 0.412 | 0.436 | 0.755 | 0.687 | 0.719 | 0.569 | 0.233 | 0.331 | 0.73 | 0.305 | 0.431 |

| لقطة واحدة | 0.475 | 0.461 | 0.468 | 0.779 | 0.778 | 0.779 | 0.561 | 0.311 | 0.401 | 0.733 | 0.416 | 0.531 | |

| خمس لقطات | 0.515 | 0.472 | 0.493 | 0.827 | 0.764 | 0.794 | 0.526 | 0.432 | 0.474 | 0.735 | 0.626 | 0.676 | |

| جي بي تي-3.5 | صفر-لقطة | 0.488 | 0.570 | 0.526 | 0.777 | 0.908 | 0.838 | 0.536 | 0.469 | 0.500 | 0.727 | 0.650 | 0.686 |

| لقطة واحدة | 0.506 | 0.560 | 0.532 | 0.809 | 0.894 | 0.849 | 0.547 | 0.500 | 0.٥٢٢ | 0.721 | 0.661 | 0.690 | |

| خمس طلقات | 0.555 | 0.637 | 0.593 | 0.804 | 0.926 | 0.861 | 0.513 | 0.574 | 0.542 | 0.701 | 0.774 | 0.736 | |

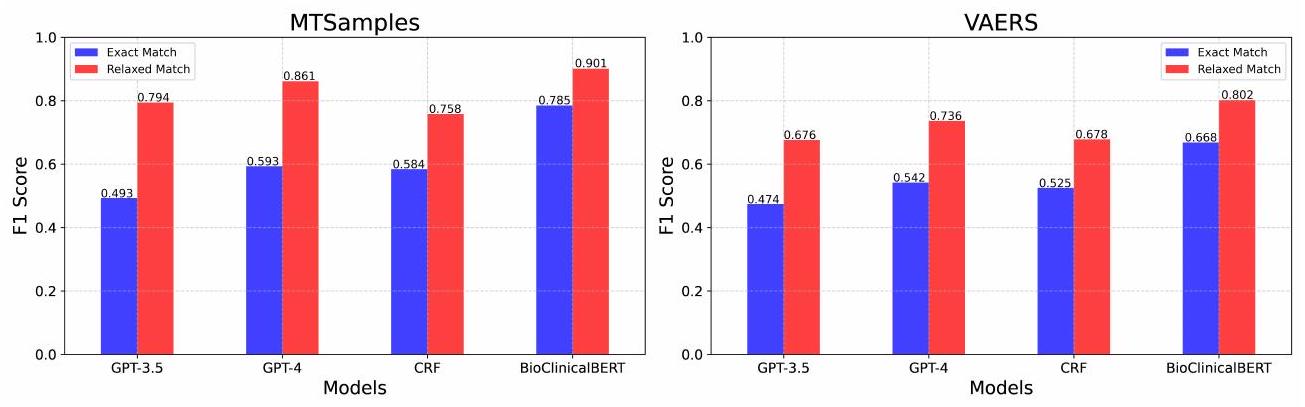

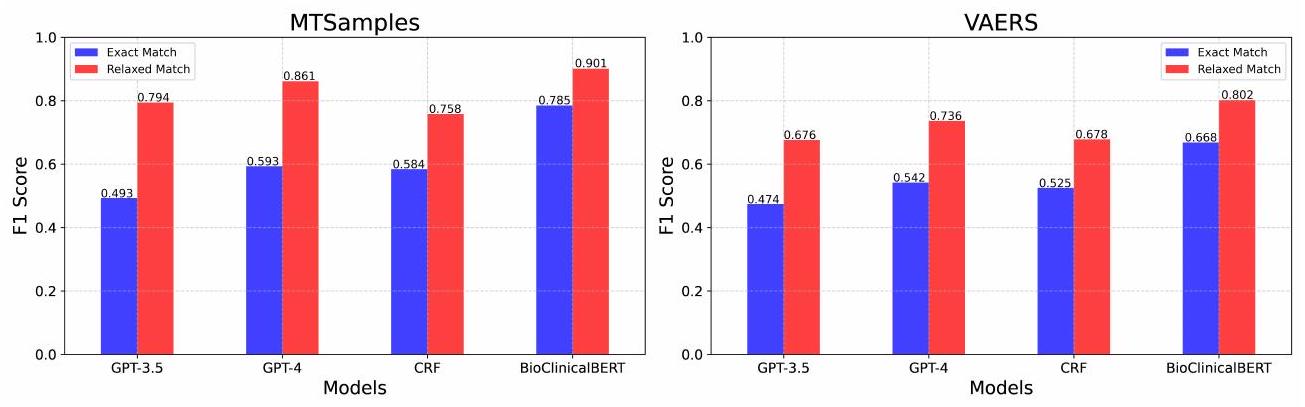

3.3 مقارنة الأداء مع التعلم المراقب

| نماذج | عينات MT | VAERS | ||||||||||

| مطابقة دقيقة | مباراة مريحة | مطابقة دقيقة | مباراة مريحة | |||||||||

| P | ر | فورمولا 1 | P | ر | فورمولا 1 | P | ر | فورمولا 1 | P | ر | فورمولا 1 | |

| جي بي تي-3.5 | 0.515 | 0.472 | 0.493 | 0.827 | 0.764 | 0.794 | 0.526 | 0.432 | 0.474 | 0.735 | 0.626 | 0.676 |

| جي بي تي-4 | 0.555 | 0.637 | 0.593 | 0.804 | 0.926 | 0.861 | 0.513 | 0.574 | 0.542 | 0.701 | 0.774 | 0.736 |

| CRF | 0.511 | 0.681 | 0.584 | 0.662 | 0.887 | 0.758 | 0.473 | 0.591 | 0.525 | 0.609 | 0.764 | 0.678 |

| بايوكلينيكال بيرت | 0.785 | 0.785 | 0.785 | 0.915 | 0.887 | 0.901 | 0.698 | 0.640 | 0.668 | 0.846 | 0.761 | 0.802 |

3.4 تحليل الأخطاء

4 المناقشة

تحدث نماذج اللغة الكبيرة تغييرات جذرية في أبحاث وتطوير معالجة اللغة الطبيعية. تظهر نتائجنا طريقًا سريعًا وسهلاً لبناء أنظمة NER سريرية أكثر قابلية للتعميم من خلال الاستفادة من نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. سيغير هذا بشكل كبير ممارستنا الحالية في معالجة اللغة الطبيعية السريرية. تقليديًا، لبناء نظام NER قائم على التعلم الآلي أو التعلم العميق لأنواع معينة من الكيانات السريرية، يجب علينا بناء مجموعة بيانات معلمة من الوثائق السريرية، وهو أمر يستغرق وقتًا طويلاً ومكلفًا، حيث يتطلب غالبًا خبراء في المجال الطبي. من المRemarkably، تظهر أبحاثنا أن نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، دون الحاجة إلى مزيد من تدريب النموذج أو الضبط الدقيق، قد أظهرت أداءً استثنائيًا. مع مجرد 1 – أو 5 – عينات معلمة، يمكن لهذه النماذج تحقيق أداء قريب من النماذج المضبوطة التي تتطلب مئات من عينات التدريب. يشير هذا إلى إمكانية تقليل بعض التكاليف المرتبطة بتطوير نظام NER السريري، خاصة في مجالات التعليق على البيانات. ومع ذلك، من المهم ملاحظة أن هذا لا يلغي الحاجة إلى مدخلات الخبراء في إنشاء إرشادات التعليق وفي المراحل الأولية من تدريب النموذج. بينما تظهر دراستنا أن نماذج GPT يمكن أن تحقق أداءً تنافسياً مع عدد أقل من الأمثلة المعلمة مقارنة بأنظمة معالجة اللغة الطبيعية التقليدية، تظل دور خبراء الموضوع حاسمة. يحتاج الخبراء إلى كتابة إرشادات تعليق دقيقة، وإجراء تعليقات أولية لتحليل الأخطاء وتوليد الأمثلة، والتحقق من أداء النموذج. على الرغم من أن نماذج GPT تتطلب عددًا أقل من الحالات المعلمة، يجب ألا يتم تجاهل التكاليف المرتبطة بمشاركة الخبراء، واستخدام واجهة برمجة التطبيقات، وتشغيل خدمة نموذج اللغة الكبيرة. سيكون من المفيد إجراء مقارنة شاملة لمتطلبات الموارد والتكاليف بين أنظمة معالجة اللغة الطبيعية التقليدية، ونماذج تضمين الكلمات، وأنظمة القائمة على نماذج اللغة الكبيرة للدراسات المستقبلية. سيوفر ذلك فهمًا أوضح للتداعيات العملية والجدوى من نشر نماذج اللغة الكبيرة في مهام NER السريرية.

علاوة على ذلك، فإن نهجنا قابل للتعميم – يظهر تحسينات أداء متسقة عبر مهمتين مختلفتين من NER السريرية. تم إثبات القدرات الناشئة لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة [36] بشكل أكبر في مهام NER السريرية المتعددة هنا، مما يشير إلى جدوى بناء نموذج كبير واحد لمهام استخراج المعلومات المتنوعة في المجال الطبي، وهو أمر جذاب للغاية.

مع وضع هذه التغييرات في الاعتبار، ستكون هناك حاجة ملحة لإعادة تصميم سير العمل لتطوير أنظمة NER السريرية باستخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. إطار العمل للمطالبات لهاتين المهمتين من NER السريرية هو الخطوة الأولى نحو هذا الاتجاه ويضيء بعض الجوانب التي تستحق النظر. الجانب الأول هو كيفية تعريف مهمة استخراج المعلومات بوضوح. تظهر تجاربنا أن إرشادات التعليق المحددة مفيدة جدًا، مما يشير إلى أن المعرفة الطبية (إما في قاعدة بيانات معرفية أو من خبراء بشريين) لا تزال حاسمة في أنظمة NER القائمة على نماذج اللغة الكبيرة وكيفية الحصول على المعرفة المحددة للمهمة وتمثيلها في المطالبات تحتاج إلى مزيد من التحقيق. كما أظهرنا أن توفير أمثلة معلمة فعال لتحسين الأداء. ومع ذلك، لم يتم التحقيق في كيفية اختيار عينات معلوماتية وتمثيلية في هذه الدراسة ويمكن استكشاف خوارزميات التعلم القليل المتقدمة الأخرى.

قضية مهمة أخرى هي التقييم. في هذه الدراسة، طلبنا من نماذج GPT إخراج الكيانات وفقًا لأساليب NER التقليدية حتى نتمكن من تقييمها باستخدام نصوص التقييم السابقة. ومع ذلك، سنجادل بأن مخطط التقييم الحالي لأنظمة NER قد لا يكون مثاليًا لأنظمة القائمة على نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. تظهر نماذج GPT، بسبب طبيعتها التوليدية والتدريب المسبق الواسع على مجموعات نصية متنوعة، فهمًا دقيقًا للسياق وبنية اللغة. يمكّنها ذلك من تفسير وتوليد النص بطريقة تمتد أحيانًا إلى ما هو أبعد من الحدود الصارمة لفئات الكيانات المحددة مسبقًا. على سبيل المثال، غالبًا ما تتعرف نماذج GPT على اختبارات المعمل ذات القيم غير الطبيعية (مثل “مستوى سكر الدم 40” أو “عدد كريات الدم البيضاء 23,500”) كمشاكل طبية. بينما يكون هذا التفسير ذا صلة سياقية ومعنوية سريرية، فإنه ينحرف عن التعريفات الصارمة للكيانات المستخدمة في تقييمنا، مما يؤدي إلى عدم تطابق واضح. لذلك، سيكون من الضروري وجود مخطط تقييم أفضل لتقييم أداء نماذج اللغة الكبيرة بدقة أكبر.

على الرغم من النتائج الواعدة، فإن دراستنا لها بعض القيود. أولاً، قمنا بتقييد نماذج اللغة الكبيرة بنماذج GPT في هذه الدراسة. في المستقبل، سنشمل نماذج اللغة الكبيرة الشهيرة الأخرى مثل LLaMA و Falcon [37، 38، 39]. ثانيًا، كانت أساليب التعلم القليل لدينا بسيطة نسبيًا، ونخطط لاستكشاف أساليب أخرى مثل طريقة سلسلة الأفكار [40، 41، 42]، على أمل تحقيق نتائج أفضل.

5 الخاتمة

بيان التمويل

تعارض المصالح

توفر البيانات

References

- Jensen PB, Jensen LJ, Brunak S. Mining electronic health records: towards better research applications and clinical care. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2012;13(6):395-405.

- Nadkarni PM, Ohno-Machado L, Chapman WW. Natural language processing: an introduction. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2011;18(5):544-51.

- Névéol A, Dalianis H, Velupillai S, Savova G, Zweigenbaum P. Clinical natural language processing in languages other than English: opportunities and challenges. Journal of biomedical semantics. 2018;9(1):1-13.

- Wang Y, Wang L, Rastegar-Mojarad M, Moon S, Shen F, Afzal N, et al. Clinical information extraction applications: a literature review. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2018;77:34-49.

- Huang Z, Xu W, Yu K. Bidirectional LSTM-CRF models for sequence tagging. arXiv preprint arXiv:150801991. 2015.

- Savova GK, Masanz JJ, Ogren PV, Zheng J, Sohn S, Kipper-Schuler KC, et al. Mayo clinical Text Analysis and Knowledge Extraction System (cTAKES): architecture, component evaluation and applications. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2010;17(5):507-13.

- Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:181004805. 2018.

- Lee J, Yoon W, Kim S, Kim D, Kim S, So CH, et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(4):1234-40.

- Gu Y, Tinn R, Cheng H, Lucas M, Usuyama N, Liu X, et al. Domain-specific language model pretraining for biomedical natural language processing. ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare (HEALTH).

10. Huang K, Altosaar J, Ranganath R. Clinicalbert: Modeling clinical notes and predicting hospital readmission. arXiv preprint arXiv:190405342. 2019.

11. OpenAI. Introducing chatgpt. OpenAI;. Available from: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt.

12. Bang Y, Cahyawijaya S, Lee N, Dai W, Su D, Wilie B, et al. A multitask, multilingual, multimodal evaluation of chatgpt on reasoning, hallucination, and interactivity. arXiv preprint arXiv:230204023. 2023.

13. Brown T, Mann B, Ryder N, Subbiah M, Kaplan JD, Dhariwal P, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems. 2020;33:1877-901.

14. Achiam J, Adler S, Agarwal S, Ahmad L, Akkaya I, Aleman FL, et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:230308774. 2023.

15. Gilson A, Safranek CW, Huang T, Socrates V, Chi L, Taylor RA, et al. How does CHATGPT perform on the United States Medical Licensing Examination? the implications of large language models for medical education and knowledge assessment. JMIR Medical Education. 2023;9(1):e45312.

16. Kung TH, Cheatham M, Medenilla A, Sillos C, De Leon L, Elepaño C, et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLoS digital health. 2023;2(2):e0000198.

17. Rao A, Kim J, Kamineni M, Pang M, Lie W, Succi MD. Evaluating ChatGPT as an adjunct for radiologic decision-making. medRxiv. 2023:2023-02.

18. Antaki F, Touma S, Milad D, El-Khoury J, Duval R. Evaluating the performance of chatgpt in ophthalmology: An analysis of its successes and shortcomings. medRxiv. 2023:2023-01.

19. Jeblick K, Schachtner B, Dexl J, Mittermeier A, Stüber AT, Topalis J, et al. ChatGPT Makes Medicine Easy to Swallow: An Exploratory Case Study on Simplified Radiology Reports. arXiv preprint arXiv:221214882. 2022.

20. Peter L, Goldbert C, Kohane I. The AI Revolution in Medicine: GPT-4 and Beyond. PEARSON; 2023.

21. Chen Q, Du J, Hu Y, Keloth VK, Peng X, Raja K, et al. Large language models in biomedical natural language processing: benchmarks, baselines, and recommendations. arXiv preprint arXiv:230516326. 2023.

22. Tian S, Jin Q, Yeganova L, Lai PT, Zhu Q, Chen X, et al. Opportunities and challenges for ChatGPT and large language models in biomedicine and health. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2024;25(1):bbad493.

23. Jin Q, Yang Y, Chen Q, Lu Z. Genegpt: Augmenting large language models with domain tools for improved access to biomedical information. ArXiv. 2023.

24. Wang J, Shi E, Yu S, Wu Z, Ma C, Dai H, et al. Prompt engineering for healthcare: Methodologies and applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:230414670. 2023.

25. Yu F, Quartey L, Schilder F. Exploring the effectiveness of prompt engineering for legal reasoning tasks. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023; 2023. p. 13582-96.

26. Ma C. Prompt Engineering and Calibration for Zero-Shot Commonsense Reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:230406962. 2023.

27. Hsueh CY, Zhang Y, Lu YW, Han JC, Meesawad W, Tsai RTH. NCU-IISR: Prompt Engineering on GPT-4 to Stove Biological Problems in BioASQ 11b Phase B. In: 11th BioASQ Workshop at the 14th Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum (CLEF); 2023. .

28. Ateia S, Kruschwitz U. Is ChatGPT a Biomedical Expert?-Exploring the Zero-Shot Performance of Current GPT Models in Biomedical Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:230616108. 2023.

29. Chen S, Li Y, Lu S, Van H, Aerts HJ, Savova GK, et al. Evaluation of ChatGPT Family of Models for Biomedical Reasoning and Classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:230402496. 2023.

30. Uzuner Ö, South BR, Shen S, DuVall SL. 2010 i2b2/VA challenge on concepts, assertions, and relations in clinical text. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2011;18(5):552-6.

31. Du J, Xiang Y, Sankaranarayanapillai M, Zhang M, Wang J, Si Y, et al. Extracting postmarketing adverse events from safety reports in the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS) using deep learning. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2021;28(7):1393-400.

32. Alsentzer E, Murphy JR, Boag W, Weng WH, Jin D, Naumann T, et al. Publicly available clinical BERT embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:190403323. 2019.

33. Wolf T, Debut L, Sanh V, Chaumond J, Delangue C, Moi A, et al. Transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. In: Proceedings of the 2020 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing: system

demonstrations; 2020. p. 38-45.

34. Loshchilov I, Hutter F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:171105101. 2017.

35. Jiang M, Chen Y, Liu M, Rosenbloom ST, Mani S, Denny JC, et al. A study of machine-learning-based approaches to extract clinical entities and their assertions from discharge summaries. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2011;18(5):601-6.

36. Wei J, Tay Y, Bommasani R, Raffel C, Zoph B, Borgeaud S, et al. Emergent abilities of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:220607682. 2022.

37. Touvron H, Lavril T, Izacard G, Martinet X, Lachaux MA, Lacroix T, et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:230213971. 2023.

38. Touvron H, Martin L, Stone K, Albert P, Almahairi A, Babaei Y, et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv preprint arXiv:230709288. 2023.

39. Almazrouei E, Alobeidli H, Alshamsi A, Cappelli A, Cojocaru R, Debbah M, et al. The falcon series of open language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:231116867. 2023.

40. Chen W, Ma X, Wang X, Cohen WW. Program of thoughts prompting: Disentangling computation from reasoning for numerical reasoning tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:221112588. 2022.

41. Sun J, Luo Y, Gong Y, Lin C, Shen Y, Guo J, et al. Enhancing Chain-of-Thoughts Prompting with Iterative Bootstrapping in Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:230411657. 2023.

42. Fu Y, Peng H, Sabharwal A, Clark P, Khot T. Complexity-based prompting for multi-step reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:221000720. 2022.

معلومات إضافية:

1 المواد التكميلية

1.1 المطالبات الكاملة لمجموعتين من البيانات

1.1.1 مهمة استخراج المفاهيم i 2 b2 لعام 2010

### المهمة

### دليل وضع علامات الكيانات

استخدم <span class=”treatment”> للدلالة على علاج.

استخدم <span class=”test”> للدلالة على اختبار.

اترك النص كما هو إذا لم يتم العثور على مثل هذه الكيانات.

### تعريفات الكيانات

تُعرف العلاجات بأنها: عبارات تصف الإجراءات، والتدخلات، والمواد المقدمة لمريض في محاولة لحل مشكلة طبية. وهي تستند بشكل فضفاض إلى الأنواع الدلالية UMLS للإجراءات العلاجية أو الوقائية، أو الأجهزة الطبية، أو الستيرويدات، أو المواد الدوائية، أو المواد البيولوجية أو السنية، أو المضادات الحيوية، أو الأدوية السريرية، وأجهزة توصيل الأدوية. تشمل أيضًا مفاهيم أخرى تعتبر علاجات ولكن قد لا توجد في UMLS. يتم وضع علامة على العلاجات التي خضع لها المريض، أو سيخضع لها، أو قد يخضع لها في المستقبل، أو تم ذكرها صراحةً أن المريض لن يخضع لها كعلاجات.

تُعرف الاختبارات بأنها: عبارات تصف الإجراءات، واللوحات، والقياسات التي تُجرى على مريض أو سائل أو عينة من الجسم من أجل اكتشاف، أو استبعاد، أو العثور على مزيد من المعلومات حول مشكلة طبية. وهي تستند بشكل فضفاض إلى الأنواع الدلالية UMLS للإجراءات المخبرية، أو الإجراءات التشخيصية، ولكنها تشمل أيضًا حالات غير مغطاة بواسطة UMLS.

### إرشادات التوصيف

قم بتضمين جميع الموصوفات مع المفاهيم عندما تظهر في نفس العبارة باستثناء موصوفات التأكيد.

يمكنك تضمين ما يصل إلى عبارة جارة واحدة (PP) تتبع مفهومًا يمكن وضع علامة عليه إذا كانت PP لا تحتوي على مفهوم يمكن وضع علامة عليه وتشير إما إلى عضو/جزء من الجسم أو يمكن إعادة ترتيبها لإزالة PP (نسمي هذا لاحقًا اختبار PP).

قم بتضمين الأدوات والملكية.

يجب تضمين الروابط وغيرها من البنية النحوية التي تدل على القوائم إذا حدثت ضمن الموصوفات أو كانت مرتبطة بمجموعة شائعة من الموصوفات. إذا كانت أجزاء القائمة مستقلة بخلاف ذلك، فلا ينبغي تضمينها. وبالمثل، عندما يتم ذكر المفاهيم بأكثر من طريقة في نفس العبارة الاسمية (مثل تعريف اختصار أو حيث يتم استخدام اسم عام واسم علامة تجارية لدواء معًا)، يجب وضع علامات على المفاهيم معًا. يجب ذكر المفاهيم بالنسبة للمريض أو شخص آخر في الملاحظة. يجب عدم وضع علامات على عناوين الأقسام التي توفر تنسيقًا، ولكنها ليست محددة لشخص.

### إرشادات قائمة على تحليل الأخطاء:

لا ينبغي وضع علامات على المتخصصين الطبيين، أو الخدمات، أو المرافق الصحية، حتى لو بدت أنها تناسب فئات ‘الاختبارات’، ‘العلاجات’، أو ‘المشاكل الطبية’. هذه الكيانات هي جزء من نظام تقديم الرعاية الصحية ولا تدل مباشرة على اختبار، أو علاج، أو مشكلة طبية.

لا ينبغي اعتبار إجراءات الاستشارة كاختبارات.

### أمثلة

مثال المخرج 1: عند وقت القبول، أنكر الحمى، التعرق، الغثيان، ألم الصدر أو أعراض نظامية أخرى.

مثال المدخل 2: تم تشخيصه بالتهاب المفاصل العظمي في الركبتين وقد خضع لتنظير المفاصل قبل سنوات من القبول.

مثال المخرج 2: تم تشخيصه بـ التهاب المفاصل العظمي في الركبتين وقد خضع لـ تنظير المفاصل قبل سنوات من القبول.

مثال المدخل 3: بعد أن تم رؤية المريض في العيادة في 10 أغسطس، استمرت الحمى العالية وتم قبوله في 11 أغسطس إلى مستشفى كوتونوود.

مثال المخرج 3: بعد أن تم رؤية المريض في العيادة في 10 أغسطس، استمرت <span class=”problem”

مثال المدخل 4: تاريخ المرض الحالي: المريض هو ذكر يبلغ من العمر 85 عامًا تم إحضاره بواسطة EMS مع شكوى من انخفاض مستوى الوعي.

مثال المخرج 4: تاريخ المرض الحالي: المريض هو ذكر يبلغ من العمر 85 عامًا تم إحضاره بواسطة EMS مع شكوى من انخفاض مستوى الوعي.

مثال المدخل 5: تم زيادة لسيينوبريل الخاص بها إلى 40 ملغ يوميًا.

مثال المخرج 5: تم زيادة لسيينوبريل الخاص بها إلى 40 ملغ يوميًا.

### نص المدخل:

### نص المخرج:

1.1.2 مهمة استخراج الأحداث المتعلقة باضطرابات الجهاز العصبي

### المهمة

### دليل وضع علامات الكيانات

استخدم <span class=”nervous_AE”> للدلالة على حدث سلبي عصبي.

استخدم <span class=”other_AE”> للدلالة على حدث سلبي آخر.

استخدم <span class=”procedure”> للدلالة على إجراء.

إذا لم يتم العثور على كيان، اترك النص كما هو.

### تعريفات الكيانات

يشمل الحدث السلبي العصبي مشاكل مرتبطة عادةً بالجهاز العصبي، مثل متلازمة غيلان باريه، عدم التنسيق، عدم الاستجابة، نقص الإحساس، التنميل، الدوخة، الصداع وغيرها من اضطرابات الجهاز العصبي.

تشمل الإجراءات أحداث المشاكل غير الطبية مثل مضاعفات التطعيم الفردية أو الأحداث الطبية ذات الصلة (يجب تمييز كل تطعيم بشكل منفصل)، والعمليات الجراحية مثل وضع القسطرة، والاستشفاء، ورعاية الطوارئ، والت intubation، إلخ. تشير الإجراء إلى نشاط طبي أو جراحي محدد يتم تنفيذه لتشخيص أو علاج أو مراقبة حالة. يجب عدم اعتبار أنشطة الرعاية الروتينية أو إدارة الرعاية الصحية العامة مثل ‘استدعاء مريض’، ‘زيارة طبيب’، ‘فحص عام’، إلخ. بدون إجراء أو حدث محدد مرتبط كإجراء. لاحظ أن ‘اللقاحات المعطاة’ في غياب أي مضاعفات أو أحداث طبية ذات صلة يجب ألا تعتبر إجراءً.

يرجى ملاحظة أنه في حالة النفي حيث يتم الإشارة بوضوح إلى أن حدث سلبي معين أو تحقيق أو إجراء لم يحدث (على سبيل المثال، ‘لا توجد أعراض في الأمعاء أو المثانة’)، لا تقم بتمييز الكيان.

### إرشادات التوضيح

عند تمييز الأحداث المتعلقة بتحسن الأعراض / التقدم أو أحداث النفي، يجب استخدام الإرشادات التالية. في حالة أبلغ المريض عن حدث سلبي محدد أولاً، ثم أبلغ عن تحسن / تقدم في الحدث السلبي، يجب أن نميزه كأعراض محسنة. ومع ذلك، لا نحتاج إلى تمييز نفي عرض لم يبلغه المريض من قبل.

يجب تمييز الأحداث المبلغ عنها كـ تاريخ (الأحداث التي لم تحدث للمريض المبلغ) . تعتبر التاريخ العائلي مهمًا لتوقع المخاطر وقد يتم تضمينه كمعلومات أساسية (على سبيل المثال، للتحليل الإحصائي).

بعض تقارير VAERS تحتوي على أحداث مكررة. على سبيل المثال، يتم تكرار نفس الأحداث / النص مرتين في التقرير. الحالة التي تهمنا هي تكرار بعض الأحداث السلبية، أي، يتطلب أن يظهر الحدث السلبي، ثم يختفي، ثم يعود. في هذه الحالة، يجب بالتأكيد تمييزه مرتين. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، نحتاج إلى تمييز تخفيف / تحسن الحدث إذا تم ذكره في التقرير. عندما لا توجد معلومات مثل هذه لتحديد ما إذا كان تكرارًا، المبدأ هو أنه إذا كانت هناك طوابع زمنية متعددة لنفس الحدث، نقوم بتمييزه مرتين، إذا لم يكن، يمكننا الاحتفاظ بسجل واحد فقط.

### إرشادات قائمة على تحليل الأخطاء:

يجب اعتبار جميع الأعراض غير الطبيعية كأحداث سلبية.

### أمثلة

مثال إخراج1: تلقيت لقاح الإنفلونزا 11 / 1 / 06.

مثال إدخال2: 1 / 28 / 05 PM : احمرار صاعد في الكوع الأيسر ثم من أطراف الأصابع.

مثال إخراج2: 1 / 28 / 05 PM : احمرار صاعد في الكوع الأيسر ثم من أطراف الأصابع</span

مثال إدخال3: غير قادر على الوقوف بسبب عدم التنسيق الشديد.

مثال إخراج3: غير قادر على الوقوف بسبب عدم التنسيق الشديد<span class=”nervous_AE”

مثال إدخال4: في الساعة 4 صباحًا في 12-16 – 11 استيقظت مرة أخرى للذهاب إلى الحمام وفي الطريق خرجت ساقي اليمنى من تحت قدمي مرة أخرى ورآني زوجي وحاول مساعدتي ثم لم تعمل كلتا الساقين.

مثال إخراج4: في الساعة 4 صباحًا في 12-16 – 11 استيقظت مرة أخرى للذهاب إلى الحمام وفي الطريق خرجت

مثال إدخال5: تم رؤيتي من قبل طبيب أعصاب وتم تشخيصي بمتلازمة غيلان باري.

### نص الإدخال:

### نص الإخراج:

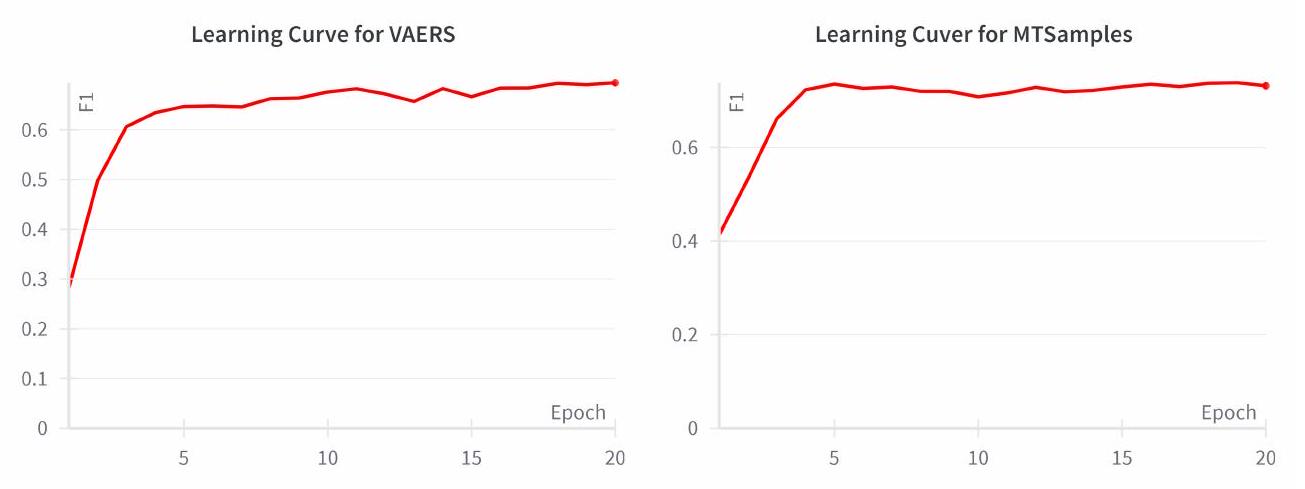

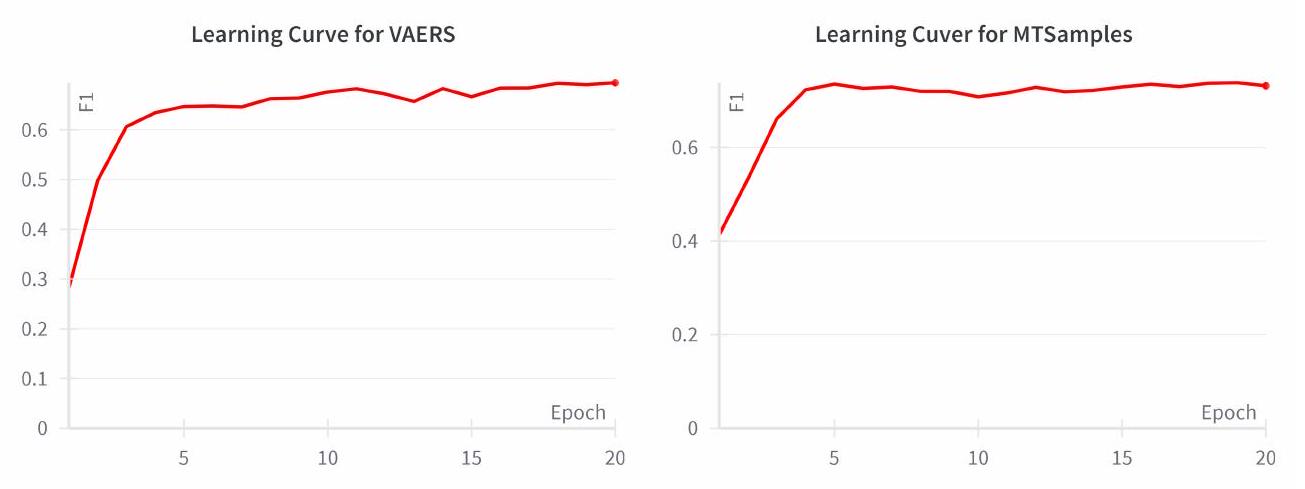

1.2 منحنى التعلم لـ BioClinicalBERT على مجموعات التحقق

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocad259

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38281112

Publication Date: 2024-01-27

Improving Large Language Models for Clinical Named Entity Recognition via Prompt Engineering

Abstract

Objective: This study quantifies the capabilities of GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 for clinical named entity recognition (NER) tasks and proposes task-specific prompts to improve their performance. Materials and Methods: We evaluated these models on two clinical NER tasks: (1) to extract medical problems, treatments, and tests from clinical notes in the MTSamples corpus, following the 2010 i 2 b 2 concept extraction shared task, and (2) identifying nervous system disorder-related adverse events from safety reports in the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS). To improve the GPT models’ performance, we developed a clinical task-specific prompt framework that includes (1) baseline prompts with task description and format specification, (2) annotation guideline-based prompts, (3) error analysis-based instructions, and (4) annotated samples for few-shot learning. We assessed each prompt’s effectiveness and compared the models to BioClinicalBERT. Results: Using baseline prompts, GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 achieved relaxed F1 scores of

1 Introduction

have emerged as the leading method for developing clinical NLP applications. Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) is a widely used pre-trained language model that learns contextual representations of free text [7]. Utilizing BERT as the foundation, domain-specific language models like BioBERT, PubMedBERT (trained on biomedical literature), and ClinicalBERT (trained on the MIMIC-III dataset) have been further developed [8, 9, 10]. These models have been applied to clinical NER tasks via transfer learning (i.e., fine-tuning the models on clinical NER corpora), and have shown improved performance with fewer annotated samples [8, 9, 10].

2 Methods

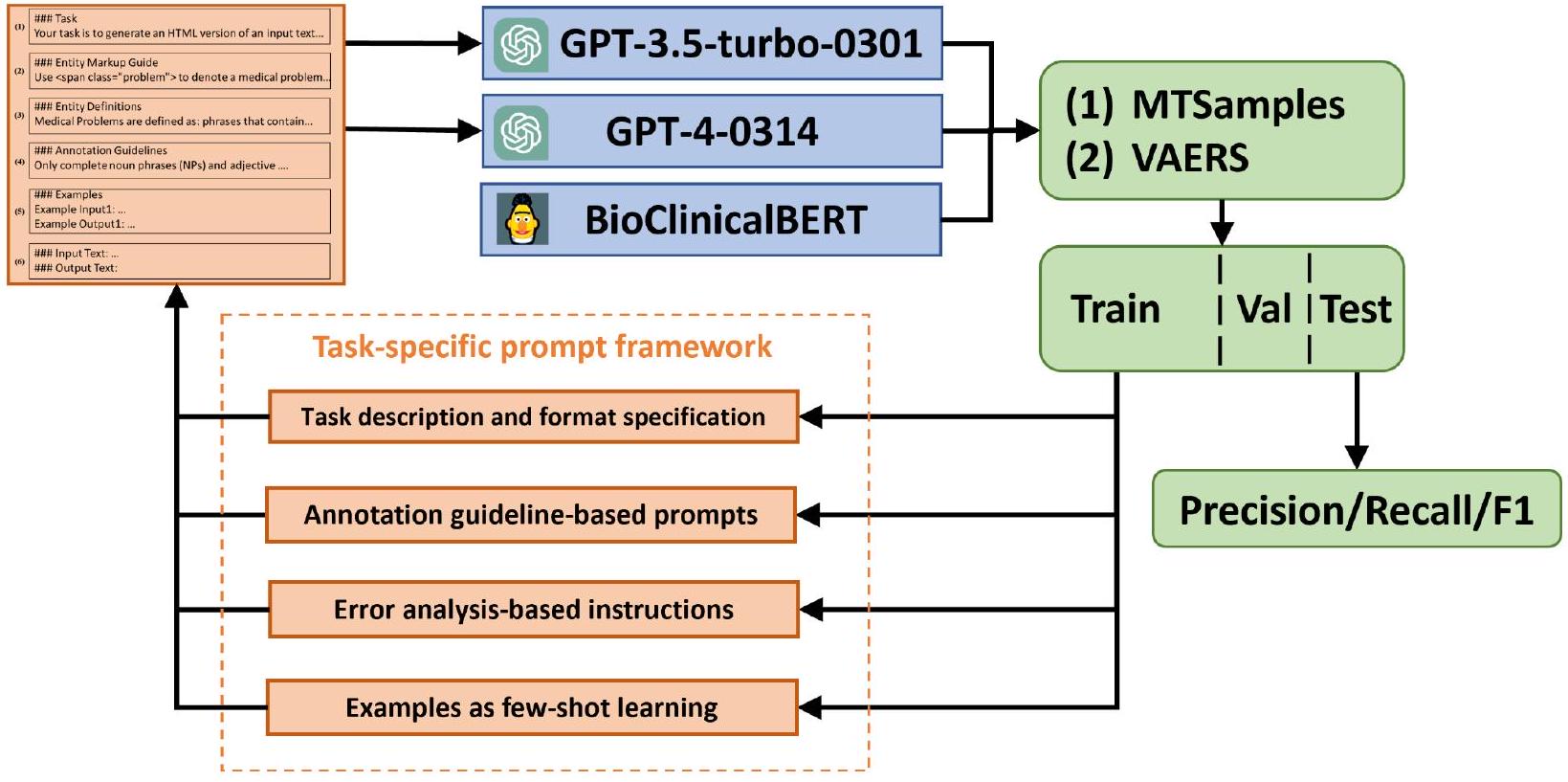

2.1 Task Overview

investigation is depicted in Figure ??. Two different prompts were crafted to identify three types of clinical entities: Medical Problem, Treatment, and Test from clinical text using both ChatGPT and GPT-3. Additionally, we trained a supervised BioClinicalBERT model using an annotated corpus from the 2010 i 2 b 2 challenge, as a baseline. All three models were then evaluated using an annotated corpus consisting of HPI sections from 100 discharge summaries in the MTSamples collection (see next section).

2.2 Dataset

2.3 Models

| Datasets | Entities | Train | Valid | Test | Total |

| MTSamples | Medical Problem | 538 | 203 | 199 | 940 |

| Treatment | 149 | 43 | 35 | 227 | |

| Test | 120 | 39 | 50 | 209 | |

| VAERS | Investigation | 148 | 29 | 59 | 236 |

| Nervous adverse event | 406 | 83 | 162 | 651 | |

| Other adverse event | 301 | 62 | 167 | 530 | |

| Procedure | 338 | 57 | 126 | 521 |

Regarding the GPT models, we used the specific versions GPT-3.5-turbo-0301 and GPT-4-0314 for reproducibility. Temperature in a generative language model refers to a parameter that controls the randomness in the model’s predictions, typically ranging from 0 (completely deterministic) to 1 or higher (increasingly random and diverse outputs). The temperature parameter for GPT models was set to 0 to minimize randomness in response generation. A lower temperature value restricts the model’s tendency to take creative leaps, thereby ensuring more predictable and consistent outputs. This is crucial in clinical NER tasks where accuracy and reliability of information extraction are paramount. In our setup, the GPT models were interacted with in a ‘user’ role. This role simulates a real-world user interaction with the model, where the ‘user’ inputs prompts and the model generates responses accordingly. This approach reflects a typical use-case scenario for these models in practical applications. All input and output datasets along with prompt variants are included with Jypter notebooks that can interface with the OpenAI API in our GitHub repository. At the time of this study, costs of GPT-3.5 per 1k tokens were approximately

2.4 Prompt engineering

(1) Baseline prompt with task description and format specification: This component provides the LLMs with basic information about the tasks we are instructing them to perform and in what format the LLMs should output results. We instructed the models to highlight the named entities within an HTML file using <span>tags with a class attribute indicating the entity types. This allows the output from GPT models to be easily converted into a traditional Inside-Outside-Beginning (IOB) format, which allows for a direct comparison of NER performance with findings from existing studies.

(2) Annotation guideline-based prompts: This component contains entity definitions and linguistic rules derived from annotation guidelines. Entity definitions offer comprehensive, unambiguous descriptions of an entity within the context of a given task. They play an instrumental role in steering the LLM toward the precise identification of entities within text documents. We noticed that the model’s predictions often differed substantially from the gold standard in terms of grammatical structure. For example, discrepancies may arise concerning what types of phrases to be included (e.g., noun phrases or adjective phrases). To enhance the model’s performance, we referred to and incorporated rules in the annotation guidelines to address these issues.

(3) Error analysis-based instructions: In addition to the original annotation guidelines, we also incorporated additional guidelines following error analysis of GPT outputs using the training data. For example, we noticed that GPT models often tend to annotate consultation procedures as test entities. To prevent this, we incorporated a specific rule stating, “Consultation procedures should not be annotated as tests.”.

(4) Annotated samples: To further assist the LLMs in understanding the task and generating accurate results, we provided a set of annotated samples to improve its performance in a few-shot learning setting. We randomly selected either 1 or 5 annotated examples ( 1 or 5 -shot learning) from the training set and formatted them according to the task description and entity markup guide. For instance, given a sentence ‘He had been diagnosed with osteoarthritis of the knees and had undergone arthroscopy years prior to admission .’ with ‘osteoarthritis of the knees’ and ‘arthroscopy’ annotated as medical problem and test entities, we incorporated this sentence into the prompt using the following format:

### Examples

Example Input: He had been diagnosed with osteoarthritis of the knees and had undergone arthroscopy years prior to admission .

Example Output: He had been diagnosed with osteoarthritis of the kneesand had undergone arthroscopyyears prior to admission .

2.5 Evaluation

3 Results

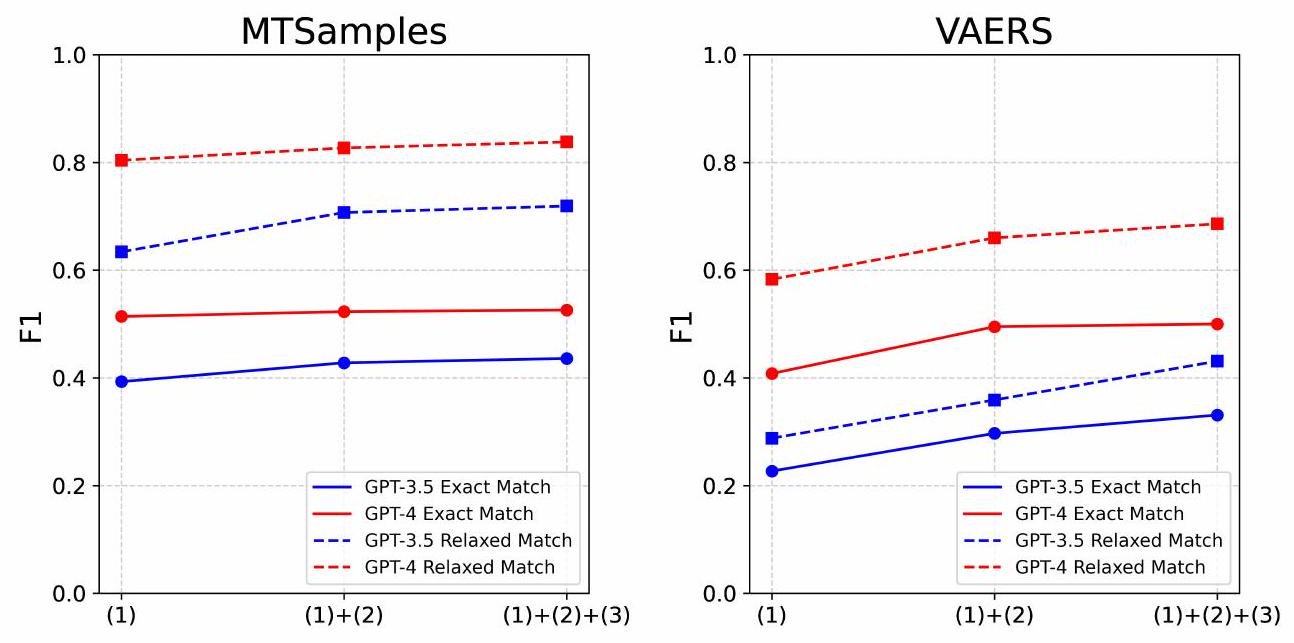

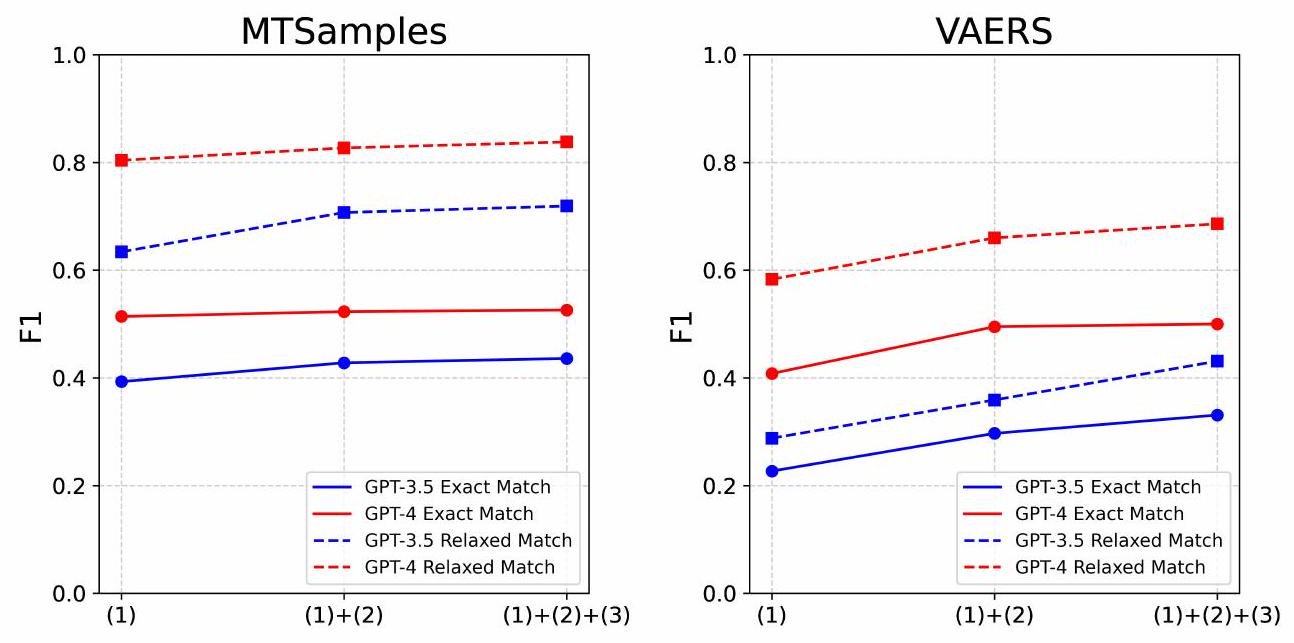

3.1 Zero-shot performance with different prompts

| Prompt Types | Examples | ||||

| (1) Baseline prompts |

|

||||

| (2) Annotation guideline-based prompts |

|

||||

| (3) Error analysis-based instructions |

|

||||

| (4) Annotated samples via few-shot learning |

|

| Models | Prompt Strategies | MTSamples | VAERS | ||||||||||

| Exact-Match | Relaxed-match | Exact-Match | Relaxed-match | ||||||||||

| P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | ||

| GPT-3.5 | (1) | 0.492 | 0.327 | 0.393 | 0.794 | 0.528 | 0.634 | 0.510 | 0.146 | 0.227 | 0.626 | 0.187 | 0.288 |

| (1)+(2) | 0.453 | 0.405 | 0.428 | 0.736 | 0.680 | 0.707 | 0.575 | 0.200 | 0.297 | 0.687 | 0.243 | 0.359 | |

| (1)

|

0.462 | 0.412 | 0.436 | 0.755 | 0.687 | 0.719 | 0.569 | 0.233 | 0.331 | 0.730 | 0.305 | 0.431 | |

| GPT-4 | (1) | 0.486 | 0.546 | 0.514 | 0.762 | 0.852 | 0.804 | 0.420 | 0.397 | 0.408 | 0.599 | 0.568 | 0.583 |

|

|

0.478 | 0.577 | 0.523 | 0.752 | 0.919 | 0.827 | 0.559 | 0.444 | 0.495 | 0.743 | 0.593 | 0.660 | |

|

|

0.488 | 0.570 | 0.526 | 0.777 | 0.908 | 0.838 | 0.536 | 0.469 | 0.500 | 0.727 | 0.650 | 0.686 | |

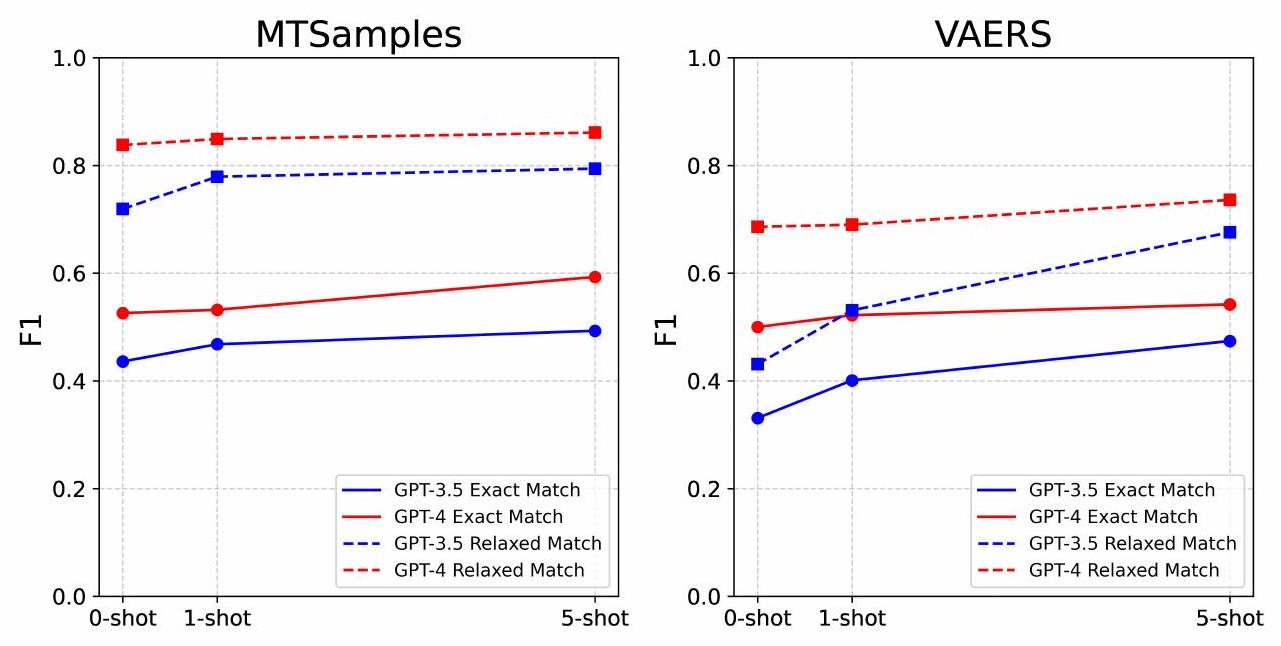

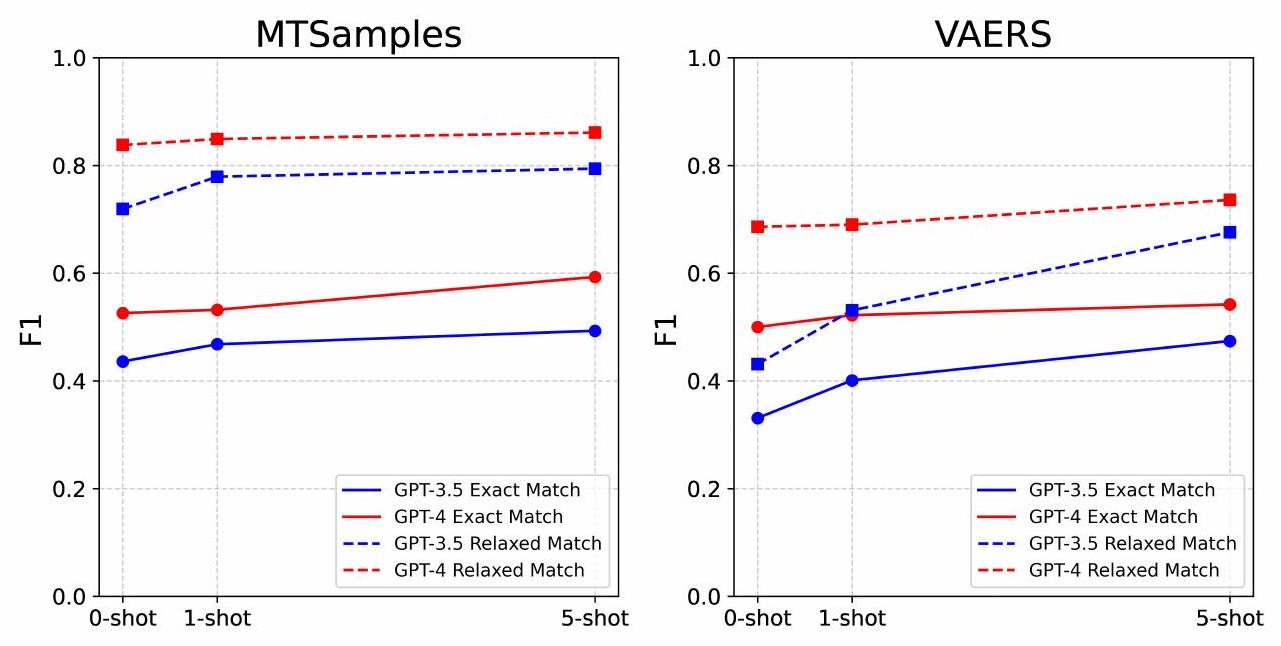

3.2 Effect of N-Shot Examples on Model Performance

| Models | Prompt Strategies | MTSamples | VAERS | ||||||||||

| Exact-Match | Relaxed-match | Exact-Match | Relaxed-match | ||||||||||

| P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | ||

| GPT-3.5 | 0-shot | 0.462 | 0.412 | 0.436 | 0.755 | 0.687 | 0.719 | 0.569 | 0.233 | 0.331 | 0.73 | 0.305 | 0.431 |

| 1-shot | 0.475 | 0.461 | 0.468 | 0.779 | 0.778 | 0.779 | 0.561 | 0.311 | 0.401 | 0.733 | 0.416 | 0.531 | |

| 5-shot | 0.515 | 0.472 | 0.493 | 0.827 | 0.764 | 0.794 | 0.526 | 0.432 | 0.474 | 0.735 | 0.626 | 0.676 | |

| GPT-3.5 | 0-shot | 0.488 | 0.570 | 0.526 | 0.777 | 0.908 | 0.838 | 0.536 | 0.469 | 0.500 | 0.727 | 0.650 | 0.686 |

| 1-shot | 0.506 | 0.560 | 0.532 | 0.809 | 0.894 | 0.849 | 0.547 | 0.500 | 0.522 | 0.721 | 0.661 | 0.690 | |

| 5-shot | 0.555 | 0.637 | 0.593 | 0.804 | 0.926 | 0.861 | 0.513 | 0.574 | 0.542 | 0.701 | 0.774 | 0.736 | |

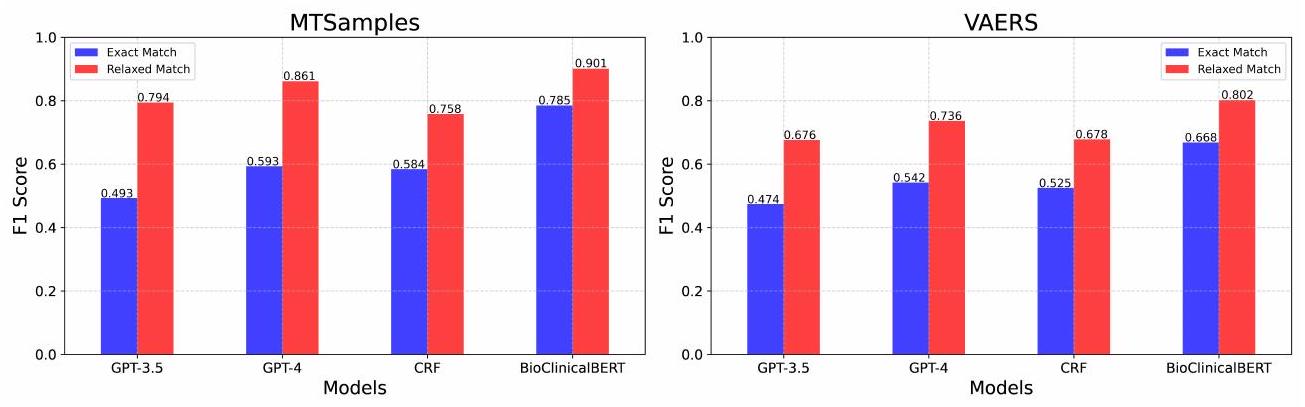

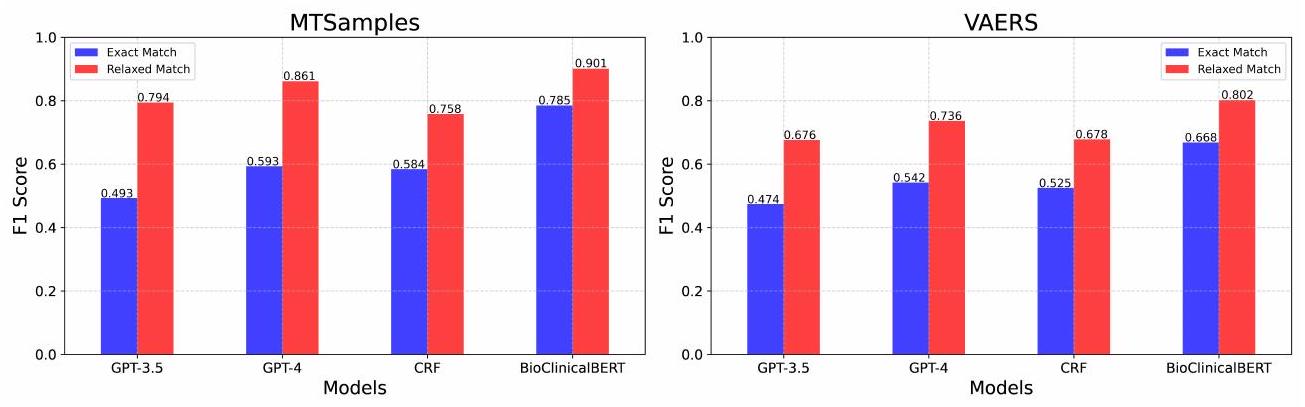

3.3 Performance Comparison to Supervised Learning

| Models | MTSamples | VAERS | ||||||||||

| Exact-Match | Relaxed-match | Exact-Match | Relaxed-match | |||||||||

| P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | |

| GPT-3.5 | 0.515 | 0.472 | 0.493 | 0.827 | 0.764 | 0.794 | 0.526 | 0.432 | 0.474 | 0.735 | 0.626 | 0.676 |

| GPT-4 | 0.555 | 0.637 | 0.593 | 0.804 | 0.926 | 0.861 | 0.513 | 0.574 | 0.542 | 0.701 | 0.774 | 0.736 |

| CRF | 0.511 | 0.681 | 0.584 | 0.662 | 0.887 | 0.758 | 0.473 | 0.591 | 0.525 | 0.609 | 0.764 | 0.678 |

| BioClinicalBERT | 0.785 | 0.785 | 0.785 | 0.915 | 0.887 | 0.901 | 0.698 | 0.640 | 0.668 | 0.846 | 0.761 | 0.802 |

3.4 Error analysis

4 Discussion

LLMs are making paradigm-shifting changes in NLP research and development. Our finding shows a quick and easy path to build more generalizable clinical NER systems by leveraging LLMs. This will significantly change our current practice in clinical NLP. Traditionally, to build a machine learning or deep learning-based NER system for specific types of clinical entities, we have to build an annotated corpus of clinical documents, which is time-consuming and costly, as it often requires medical domain experts. Remarkably, our research shows that LLMs, devoid of further model training or fine-tuning, have exhibited exceptional performance. With merely 1 – or 5 -shot annotated samples, these models can achieve performance that is close to the fine-tuned models that require hundreds of training samples. This suggests a potential reduction in some of the costs associated with clinical NER system development, particularly in the areas of data annotation. However, it is important to note that this does not eliminate the need for expert input in creating annotation guidelines and in the initial phases of model training. While our study demonstrates that GPT models can achieve competitive performance with fewer annotated examples compared to traditional NLP systems, the role of subject matter experts remains crucial. Experts are needed to write precise annotation guidelines, perform initial annotations for error analysis and example generation, and validate the model’s performance. Although the GPT models require fewer annotated instances, the costs associated with expert involvement, API usage, and running an LLM service should not be overlooked. A comprehensive comparison of resource requirements and costs between traditional NLP systems, word embedding models, and LLM-based systems would be valuable for future studies. This will provide a clearer understanding of the practical implications and feasibility of deploying LLMs in clinical NER tasks.

Moreover, our approach is generalizable – it shows consistent performance improvements across two different clinical NER tasks. The emergent abilities of LLMs [36] have been further demonstrated in multiple clinical NER tasks here, indicating the feasibility of building one large model for diverse information extraction tasks in the medical domain, which is very appealing.

With those changes in mind, an urgent need will be to re-design the workflow for developing clinical NER systems using LLMs. The prompt framework for those two clinical NER tasks is the first step toward this direction and it sheds some lights for several aspects that are worth considering. The first aspect is how to clearly define an information extraction task. Our experiments show specific annotation guidelines are very helpful, which indicates medical knowledge (either in a knowledge base or from human experts) are still critical in LLMs-based NER systems and how to obtain and represent task-specific knowledge in prompts need further investigation. We also demonstrated that supplying annotated examples is effective for performance improvement. Nevertheless, how to select informative and representative samples have not been investigated in this study and other advanced few-shot learning algorithms could be explored.

Another important issue is evaluation. In this study, we instructed GPT models to output entities following traditional NER approaches so that we can evaluate them using the previous evaluation scripts. However, we would argue that the current evaluation schema for NER may not be ideal for LLMs-based systems. GPT models, due to their generative nature and extensive pre-training on diverse text corpora, exhibit a nuanced understanding of context and language structure. This enables them to interpret and generate text in a way that sometimes extends beyond the strict boundaries of predefined entity classes. For instance, GPT models often recognized lab tests with abnormal values (e.g., “a blood sugar level of 40 ” or “white blood cell count of 23,500 “) as medical problems. While this interpretation is contextually relevant and clinically meaningful, it deviates from the strict entity definitions used in our evaluation, leading to apparent mismatches. Therefore, a better evaluation schema would be needed to assess LLMs performance more accurately.

Despite the promising results, our study has some limitations. First, we limited LLMs to GPT models in this study. In future, we will include other popular LLMs such as LLaMA and Falcon [37, 38, 39]. Second, our few-shot learning approaches were relatively simple, and we plan to investigate other approaches such as the chain-of-thoughts method [40, 41, 42], hoping to yield better results.

5 Conclusion

Funding Statement

Conflict of Interest

Data Availability

References

- Jensen PB, Jensen LJ, Brunak S. Mining electronic health records: towards better research applications and clinical care. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2012;13(6):395-405.

- Nadkarni PM, Ohno-Machado L, Chapman WW. Natural language processing: an introduction. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2011;18(5):544-51.

- Névéol A, Dalianis H, Velupillai S, Savova G, Zweigenbaum P. Clinical natural language processing in languages other than English: opportunities and challenges. Journal of biomedical semantics. 2018;9(1):1-13.

- Wang Y, Wang L, Rastegar-Mojarad M, Moon S, Shen F, Afzal N, et al. Clinical information extraction applications: a literature review. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2018;77:34-49.

- Huang Z, Xu W, Yu K. Bidirectional LSTM-CRF models for sequence tagging. arXiv preprint arXiv:150801991. 2015.

- Savova GK, Masanz JJ, Ogren PV, Zheng J, Sohn S, Kipper-Schuler KC, et al. Mayo clinical Text Analysis and Knowledge Extraction System (cTAKES): architecture, component evaluation and applications. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2010;17(5):507-13.

- Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:181004805. 2018.

- Lee J, Yoon W, Kim S, Kim D, Kim S, So CH, et al. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(4):1234-40.

- Gu Y, Tinn R, Cheng H, Lucas M, Usuyama N, Liu X, et al. Domain-specific language model pretraining for biomedical natural language processing. ACM Transactions on Computing for Healthcare (HEALTH).

10. Huang K, Altosaar J, Ranganath R. Clinicalbert: Modeling clinical notes and predicting hospital readmission. arXiv preprint arXiv:190405342. 2019.

11. OpenAI. Introducing chatgpt. OpenAI;. Available from: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt.

12. Bang Y, Cahyawijaya S, Lee N, Dai W, Su D, Wilie B, et al. A multitask, multilingual, multimodal evaluation of chatgpt on reasoning, hallucination, and interactivity. arXiv preprint arXiv:230204023. 2023.

13. Brown T, Mann B, Ryder N, Subbiah M, Kaplan JD, Dhariwal P, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems. 2020;33:1877-901.

14. Achiam J, Adler S, Agarwal S, Ahmad L, Akkaya I, Aleman FL, et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:230308774. 2023.

15. Gilson A, Safranek CW, Huang T, Socrates V, Chi L, Taylor RA, et al. How does CHATGPT perform on the United States Medical Licensing Examination? the implications of large language models for medical education and knowledge assessment. JMIR Medical Education. 2023;9(1):e45312.

16. Kung TH, Cheatham M, Medenilla A, Sillos C, De Leon L, Elepaño C, et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLoS digital health. 2023;2(2):e0000198.

17. Rao A, Kim J, Kamineni M, Pang M, Lie W, Succi MD. Evaluating ChatGPT as an adjunct for radiologic decision-making. medRxiv. 2023:2023-02.

18. Antaki F, Touma S, Milad D, El-Khoury J, Duval R. Evaluating the performance of chatgpt in ophthalmology: An analysis of its successes and shortcomings. medRxiv. 2023:2023-01.

19. Jeblick K, Schachtner B, Dexl J, Mittermeier A, Stüber AT, Topalis J, et al. ChatGPT Makes Medicine Easy to Swallow: An Exploratory Case Study on Simplified Radiology Reports. arXiv preprint arXiv:221214882. 2022.

20. Peter L, Goldbert C, Kohane I. The AI Revolution in Medicine: GPT-4 and Beyond. PEARSON; 2023.

21. Chen Q, Du J, Hu Y, Keloth VK, Peng X, Raja K, et al. Large language models in biomedical natural language processing: benchmarks, baselines, and recommendations. arXiv preprint arXiv:230516326. 2023.

22. Tian S, Jin Q, Yeganova L, Lai PT, Zhu Q, Chen X, et al. Opportunities and challenges for ChatGPT and large language models in biomedicine and health. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2024;25(1):bbad493.

23. Jin Q, Yang Y, Chen Q, Lu Z. Genegpt: Augmenting large language models with domain tools for improved access to biomedical information. ArXiv. 2023.

24. Wang J, Shi E, Yu S, Wu Z, Ma C, Dai H, et al. Prompt engineering for healthcare: Methodologies and applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:230414670. 2023.

25. Yu F, Quartey L, Schilder F. Exploring the effectiveness of prompt engineering for legal reasoning tasks. In: Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023; 2023. p. 13582-96.

26. Ma C. Prompt Engineering and Calibration for Zero-Shot Commonsense Reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:230406962. 2023.

27. Hsueh CY, Zhang Y, Lu YW, Han JC, Meesawad W, Tsai RTH. NCU-IISR: Prompt Engineering on GPT-4 to Stove Biological Problems in BioASQ 11b Phase B. In: 11th BioASQ Workshop at the 14th Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum (CLEF); 2023. .

28. Ateia S, Kruschwitz U. Is ChatGPT a Biomedical Expert?-Exploring the Zero-Shot Performance of Current GPT Models in Biomedical Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:230616108. 2023.

29. Chen S, Li Y, Lu S, Van H, Aerts HJ, Savova GK, et al. Evaluation of ChatGPT Family of Models for Biomedical Reasoning and Classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:230402496. 2023.

30. Uzuner Ö, South BR, Shen S, DuVall SL. 2010 i2b2/VA challenge on concepts, assertions, and relations in clinical text. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2011;18(5):552-6.

31. Du J, Xiang Y, Sankaranarayanapillai M, Zhang M, Wang J, Si Y, et al. Extracting postmarketing adverse events from safety reports in the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS) using deep learning. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2021;28(7):1393-400.

32. Alsentzer E, Murphy JR, Boag W, Weng WH, Jin D, Naumann T, et al. Publicly available clinical BERT embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:190403323. 2019.

33. Wolf T, Debut L, Sanh V, Chaumond J, Delangue C, Moi A, et al. Transformers: State-of-the-art natural language processing. In: Proceedings of the 2020 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing: system

demonstrations; 2020. p. 38-45.

34. Loshchilov I, Hutter F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:171105101. 2017.

35. Jiang M, Chen Y, Liu M, Rosenbloom ST, Mani S, Denny JC, et al. A study of machine-learning-based approaches to extract clinical entities and their assertions from discharge summaries. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2011;18(5):601-6.

36. Wei J, Tay Y, Bommasani R, Raffel C, Zoph B, Borgeaud S, et al. Emergent abilities of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:220607682. 2022.

37. Touvron H, Lavril T, Izacard G, Martinet X, Lachaux MA, Lacroix T, et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:230213971. 2023.

38. Touvron H, Martin L, Stone K, Albert P, Almahairi A, Babaei Y, et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv preprint arXiv:230709288. 2023.

39. Almazrouei E, Alobeidli H, Alshamsi A, Cappelli A, Cojocaru R, Debbah M, et al. The falcon series of open language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:231116867. 2023.

40. Chen W, Ma X, Wang X, Cohen WW. Program of thoughts prompting: Disentangling computation from reasoning for numerical reasoning tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:221112588. 2022.

41. Sun J, Luo Y, Gong Y, Lin C, Shen Y, Guo J, et al. Enhancing Chain-of-Thoughts Prompting with Iterative Bootstrapping in Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:230411657. 2023.

42. Fu Y, Peng H, Sabharwal A, Clark P, Khot T. Complexity-based prompting for multi-step reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:221000720. 2022.

Supplementary Information:

1 Supplementary Materials

1.1 Complete prompts for two datasets

1.1.1 The 2010 i 2 b2 concept extraction task

### Task

### Entity Markup Guide

Use <span class=”treatment” >to denote a treatment.

Use <span class=”test” >to denote a test.

Leave the text as it is if no such entities are found.

### Entity Definitions

Treatments are defined as: phrases that describe procedures, interventions, and substances given to a patient in an effort to resolve a medical problem. They are loosely based on the UMLS semantic types therapeutic or preventive procedure, medical device, steroid, pharmacologic substance, biomedical or dental material, antibiotic, clinical drug, and drug delivery device. Other concepts that are treatments but that may not be found in UMLS are also included. Treatments that a patient had, will have, may have in the future, or are explicitly mentioned that the patient will not have are all marked as treatments.

Tests are defined as: phrases that describe procedures, panels, and measures that are done to a patient or a body fluid or sample in order to discover, rule out, or find more information about a medical problem. They are loosely based on the UMLS semantic types laboratory procedure, diagnostic procedure, but also include instances not covered by UMLS.

### Annotation Guidelines

Include all modifiers with concepts when they appear in the same phrase except for assertion modifiers.

You can include up to one prepositional phrase (PP) following a markable concept if the PP does not contain a markable concept and either indicates an organ/body part or can be rearranged to eliminate the PP (we later call this the PP test).

Include articles and possessives.

Conjunctions and other syntax that denote lists should be included if they occur within the modifiers or are connected by a common set of modifiers. If the portions of the list are otherwise independent, they should not be included. Similarly, when concepts are mentioned in more than one way in the same noun phrase (such as the definition of an acronym or where a generic and a brand name of a drug are used together), the concepts should be marked together. Concepts should be mentioned in relation to the patient or someone else in the note. Section headers that provide formatting, but that are not specific to a person are not marked.

### Error-analysis-based Guidelines:

Medical specialists, services, or healthcare facilities should not be annotated, even if they might seem to fit into the categories of ‘tests’, ‘treatments’, or ‘medical problems’. These entities are part of the healthcare delivery system and do not directly denote a test, treatment, or medical problem.

Consultation procedures should not be considered as tests.

### Examples

Example Output1: At the time of admission, he denied fever, diaphoresis, nausea, chest painor other systemic symptoms .

Example Input2: He had been diagnosed with osteoarthritis of the knees and had undergone arthroscopy years prior to admission .

Example Output2: He had been diagnosed with osteoarthritis of the kneesand had undergone arthroscopyyears prior to admission .

Example Input3: After the patient was seen in the office on August 10, she persisted with high fevers and was admitted on August 11 to Cottonwood Hospital .

Example Output3: After the patient was seen in the office on August 10 , she persisted with <span class=”problem”

Example Input4: HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS : The patient is an 85 – year – old male who was brought in by EMS with a complaint of a decreased level of consciousness .

Example Output4: HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS : The patient is an 85 – year – old male who was brought in by EMS with a complaint of a decreased level of consciousness.

Example Input5: Her lisinopril was increased to 40 mg daily .

Example Output5: Her lisinoprilwas increased to 40 mg daily .

### Input Text:

### Output Text:

1.1.2 The nervous system disorder-related event extraction task

### Task

### Entity Markup Guide

Use <span class=”nervous_AE” >to denote a nervous adverse event.

Use <span class=”other_AE” >to denote an other adverse event.

Use <span class=”procedure” >to denote a procedure.

If no entity found, leave the text as it is.

### Entity Definitions

Nervous adverse event includes typically nervous system-related problems, such as guillain-barré syndrome, ataxia, areflexia, hypoaesthesia, paraesthesia, dizziness, headache and other nervous system disorders.

Procedure includes non-medical problem events such as individual immunization complications or related medical events (each immunization should be marked separately), surgeries such as catheter placement, hospitalization, emergence care, intubation, etc. A procedure refers to a specific medical or surgical activity carried out to diagnose, treat, or monitor a condition. Routine care activities or general healthcare administration such as ‘sick call’, ‘doctor’s visit’, ‘general checkup’, etc. without a specific associated procedure or event should not be considered as a procedure. Note that ‘vaccines administered’ in absence of any complications or related medical events should not be considered a procedure.

Please note that in the case of negation where a certain adverse event, investigation, or procedure is clearly indicated NOT to have occurred (e.g., ‘No bowel or bladder symptoms’), do not mark the entity.

### Annotation Guidelines

When annotating events related to symptom improvement / progress or negation events, the following guideline should be used. In the case where the patient reported a specific adverse event first, and then reported improvement / progress of the adverse event, we should annotate it as an improved symptom. However, we do NOT need to annotate the negation of a symptom which the patient never reported before.

Events reported as history (events that did not happen to the reporting patient) should be annotated. Family history is important for risk prediction and may be included as a baseline information (e.g., for statistical analysis).

Some VAERS reports have duplicate events reported. For example, the same events / text are repeated twice in the report. The case we are interested in, is the recurrence of some adverse event, i.e., it requires the adverse event appears, then disappear, and then come back. In this case it should definitely be annotated twice. Additionally, we need to annotate the relief/improvement of the event if it is mentioned in the report. When no such information to decide whether it is a recurrence, the principle is that if there are multiple time stamps of the same event, we annotate it twice, if not, we can just keep one record.

### Error-analysis-based Guidelines:

All abnormal symptoms should be considered as adverse events.

### Examples

Example Output1: Received flu shot 11 / 1 / 06 .

Example Input2: 1 / 28 / 05 PM : ascending redness left elbow then from fingertips .

Example Output2: 1 / 28 / 05 PM : ascending redness left elbow then from fingertips</span

Example Input3: Unable to stand due to severe ataxia .

Example Output3: Unable to standdue to severe <span class=”nervous_AE”

Example Input4: At 4 AM on 12-16 – 11 got up again to go to the bathroom and on the way out my right leg gave out from under me again and my husband saw me and tried to help me and then both legs wouldn’t work.

Example Output4: At 4 AM on 12-16 – 11 got up again to go to the bathroom and on the way out my

Example Input5: Seen by neurologist and diagnosed with Guillain Barre Syndrome .

### Input Text:

### Output Text:

1.2 Learning Curve of BioClinicalBERT on the validation sets