المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 14، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51371-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38195846

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-09

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51371-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38195846

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-09

تحفيز البذور بالسيلينيوم يحسن نمو وإنتاج نباتات الكينوا التي تعاني من الجفاف

يعتبر إجهاد الجفاف تهديدًا عالميًا لإنتاجية المحاصيل، خاصة في المناطق الجافة وشبه الجافة من العالم. في الدراسة الحالية، تم التحقيق في تأثير نقع بذور السيلينيوم (Se) على محصول الكينوا تحت ظروف طبيعية وظروف جفاف. تم تنفيذ تجربة في أصص لتعزيز تحمل الجفاف في الكينوا من خلال نقع بذور السيلينيوم.

يتمتع عدد سكان العالم بنمو سريع ويقترح أنه سيصل إلى

استكشاف إمكانيات نموه وإنتاجه

أثرت الجفاف بشكل كبير على نمو النباتات وتطورها، مما أدى إلى انخفاض ملحوظ في تراكم الكتلة الحيوية ومعدل نمو المحاصيل.

تم وصف السيلينيوم (Se) كعنصر غذائي حيوي للبشر والحيوانات والنباتات، بالإضافة إلى كونه سمًا بيئيًا.

الجفاف، وهو ضغط متعدد الأبعاد، يؤثر على مختلف الصفات الفسيولوجية والبيوكيميائية في النباتات بما في ذلك معدل التمثيل الضوئي، وإمكانات التوتر، وإمكانات الأسموزة بالإضافة إلى الإصابة الشديدة بالأغشية الخلوية.

ركزت الدراسة على التحقيق في فعالية نقع بذور السيلينيوم في تعزيز قدرة الكينوا على تحمل الجفاف من خلال تحسين خصائصها الفسيولوجية والبيوكيميائية. كان أحد الأهداف الرئيسية للدراسة هو تقييم تأثير نقع بذور السيلينيوم على النمو والإنتاجية والخصائص الفسيولوجية للكينوا المعرضة لظروف إجهاد الجفاف.

المواد والأساليب

إدارة التخطيط والقص

تم الانتهاء من التجربة في مستودع الأسلاك التابع لقسم الزراعة، الجامعة الإسلامية في باهوالبور، باكستان (خط الطول:

| المعلمات | ملف التربة |

| طين (%) | 9.5 |

| الطين (%) | ٣٣.٥ |

| الرمل (%) | ٥٧ |

| درجة الحموضة | 7.37 |

| فئة القوام | تربة رملية طينية |

| المادة العضوية (%) | 0.91 |

| التوصيل الكهربائي

|

٢.٥١ |

| البوتاسيوم المتاح (جزء في المليون) | ١٠٩ |

| الأمونياك ن

|

1.62 |

| الفوسفور المتاح (جزء في المليون) | 6.77 |

الجدول 1. الخصائص الفيزيائية والكيميائية للتربة التجريبية.

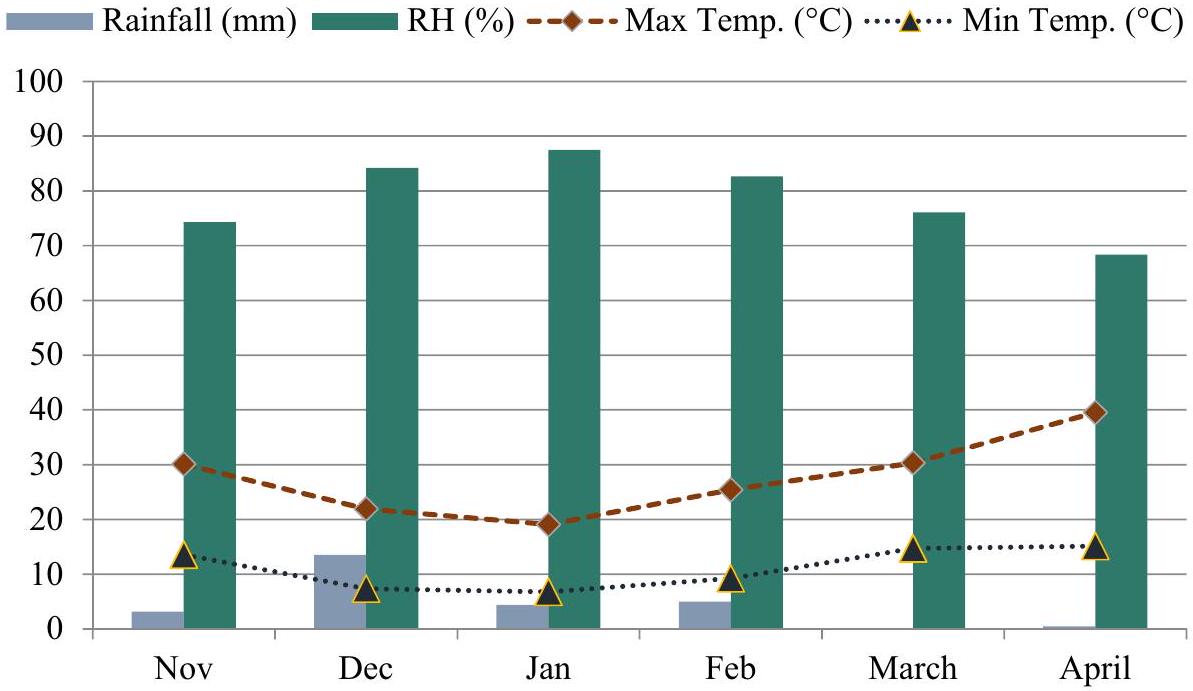

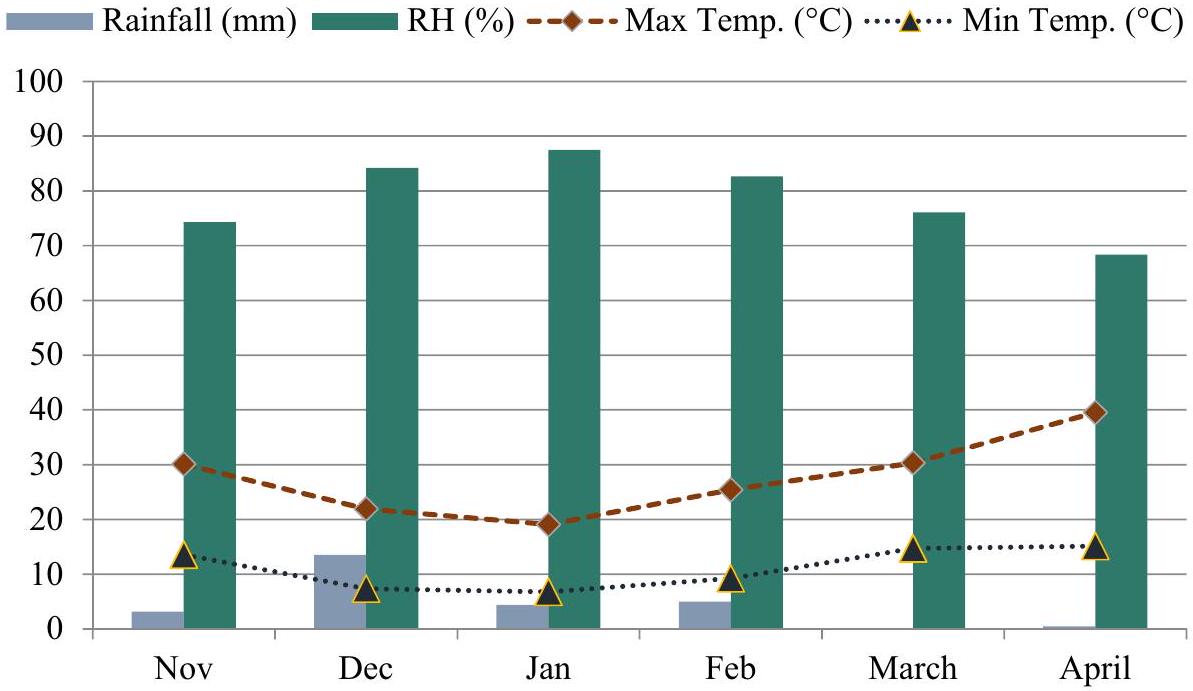

الشكل 1. الرطوبة النسبية (RH)، هطول الأمطار، أقصى وأدنى درجة حرارة خلال فترة نمو الكينوا.

فرض الجفاف وتحفيز Se

تم تنفيذ إجهاد الجفاف في مراحل متعددة من الأوراق (MLS) بعد 30 يومًا من الإنبات (DAG)، ومرحلة الإزهار (FS، 60 DAG) ومرحلة ملء البذور (SFS، 85 DAG)، بينما تم استخدام إمداد الماء العادي كعلاج تحكم (CK). تم فحص نباتات الكينوا يوميًا للكشف عن ظواهرها الفينولوجية لتطبيق دقيق لإجهاد الجفاف القائم على مراحل النمو (DS) كما أوضح سوسا-زونيجا وآخرون.

س selenate الصوديوم

تسجيل البيانات والإجراءات المتعلقة بها

معايير النمو والعائد

تم حصاد النباتات بعد 140 يومًا بعد الزراعة عندما وصلت إلى النضج من أجل قياس ارتفاع النبات، عدد النورات لكل نبات، طول ووزن النورة الرئيسية، وزن الألف حبة، العائد البيولوجي والاقتصادي.

تم حصاد النباتات بعد 140 يومًا بعد الزراعة عندما وصلت إلى النضج من أجل قياس ارتفاع النبات، عدد النورات لكل نبات، طول ووزن النورة الرئيسية، وزن الألف حبة، العائد البيولوجي والاقتصادي.

السمات الفسيولوجية

تم تقييم محتويات الكلوروفيل في الأوراق من الأوراق الشابة المتوسعة بالكامل بعد 50 يومًا بعد الزراعة باستخدام مقياس الكلوروفيل (نموذج CL-01، أدوات هانسيتش المحدودة، المملكة المتحدة)، وكانت حساب كفاءة استخدام المياه (WUE) بناءً على الصيغة المحددة التي وصفها إقبال وآخرون.

تم قياس خصائص تبادل الغاز، أي معدل النتح، ومعدل التمثيل الضوئي، وموصلية الثغور، للأوراق الشابة الخامسة الأكثر اتساعًا باستخدام نظام LI-COR Li-6400 (الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) المحمول للتمثيل الضوئي، في الظهيرة.

علاقات المياه

تم تقييم جهد الماء في الورقة ومحتويات الماء النسبية (RWC) باستخدام ورقتين طازجتين بالكامل بعد خمسين يومًا من الإنبات، وتم استخدام مقياس الرطوبة الحرارية PSYPRO (Wescor، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) لقياس جهد الماء في الورقة. تم إزالة الأوراق الطازجة من النباتات ونقلها على الفور إلى موقع الاختبار (المختبر) لتسجيل الوزن الطازج (FW). ثم تم غمر الأوراق في الماء المقطر لمدة 24 ساعة في

تم استخدام جهاز قياس جهد الماء (تشاس و. كوك، برمنغهام، إنجلترا) لتسجيل جهد الماء في الأوراق.

LTP = LWP – LOP

LTP = LWP – LOP

معايير الجودة

تم طحن حبوب الكينوا (0.1 جرام) إلى مسحوق جاف ووضعها في أنابيب الهضم. إلى كل أنبوب، أضيف 5 مل من محلول صارم

التحليل الإحصائي

تم تحليل البيانات المجمعة لجميع الصفات إحصائيًا باستخدام تقنيات تحليل التباين لفشر. تم إجراء اختبار LSD (أقل فرق ذو دلالة) عند

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

هذه الدراسة لا تشمل البشر أو الحيوانات.

بيان حول الإرشادات

جميع الدراسات التجريبية والمواد التجريبية المعنية في هذا البحث تتوافق تمامًا مع الإرشادات والتشريعات المؤسسية والوطنية والدولية ذات الصلة.

النتائج

خصائص النمو والعائد

أثر إجهاد الجفاف بشكل كبير على إنتاج الكتلة الحيوية وخصائص العائد [عدد السنبيلات لكل نبات (NPPP)، طول السنبلة الرئيسية (MPL)، وزن السنبلة الرئيسية (MPW) ووزن الألف حبة (TGW) في الكينوا (الجدول 2). وقد خفف تنشيط بذور الكينوا باستخدام السيلينيوم من الآثار السلبية للجفاف، مما أظهر القيم القصوى لـ

محتويات الكلوروفيل في الأوراق

تأثرت محتويات الكلوروفيل في أوراق الكينوا (LCC) بشكل كبير بتنفيذ الجفاف كما هو موضح في الجدول 3. تم ملاحظة القيم القصوى لـ LCC (22.52) عندما تم ري المحصول بشكل طبيعي (Ck) تليها DSFS، وكانت أقل قيمة لـ LCC (14.55) عندما تعرض المحصول للجفاف عند مستوى الجفاف الأدنى (MLS). وقد حسّن التمهيد بشكل كبير LCC حيث أظهر القيمة القصوى لـ

كفاءة استخدام المياه

أثر الجفاف وتحميس السيلينيوم بشكل كبير على كفاءة استخدام المياه في الكينوا. تم تسجيل أعلى قيمة (0.56) لكفاءة استخدام المياه في DMLS وأدنى قيمة (0.38) لكفاءة استخدام المياه في Ck. لوحظت أعلى كفاءة لاستخدام المياه عندما تم تحميس بذور الكينوا بـ

إجمالي الفينولات

تأثرت الفينولات الكلية (TP) بشكل كبير بكل من الري الناقص ومعاملة السيلينيوم في الكينوا (الجدول 3). تم الحصول على أعلى مستوى من الفينولات الكلية في المعاملة الضابطة (Ck) بينما تم ملاحظة أدنى قراءة للفينولات الكلية في معاملة DMLS. وقد خفف السيلينيوم بشكل كبير من الآثار السلبية للجفاف وحسن من تراكم الفينولات الكلية في أوراق الكينوا. تم تسجيل أعلى مستوى من الفينولات الكلية (11.41) في

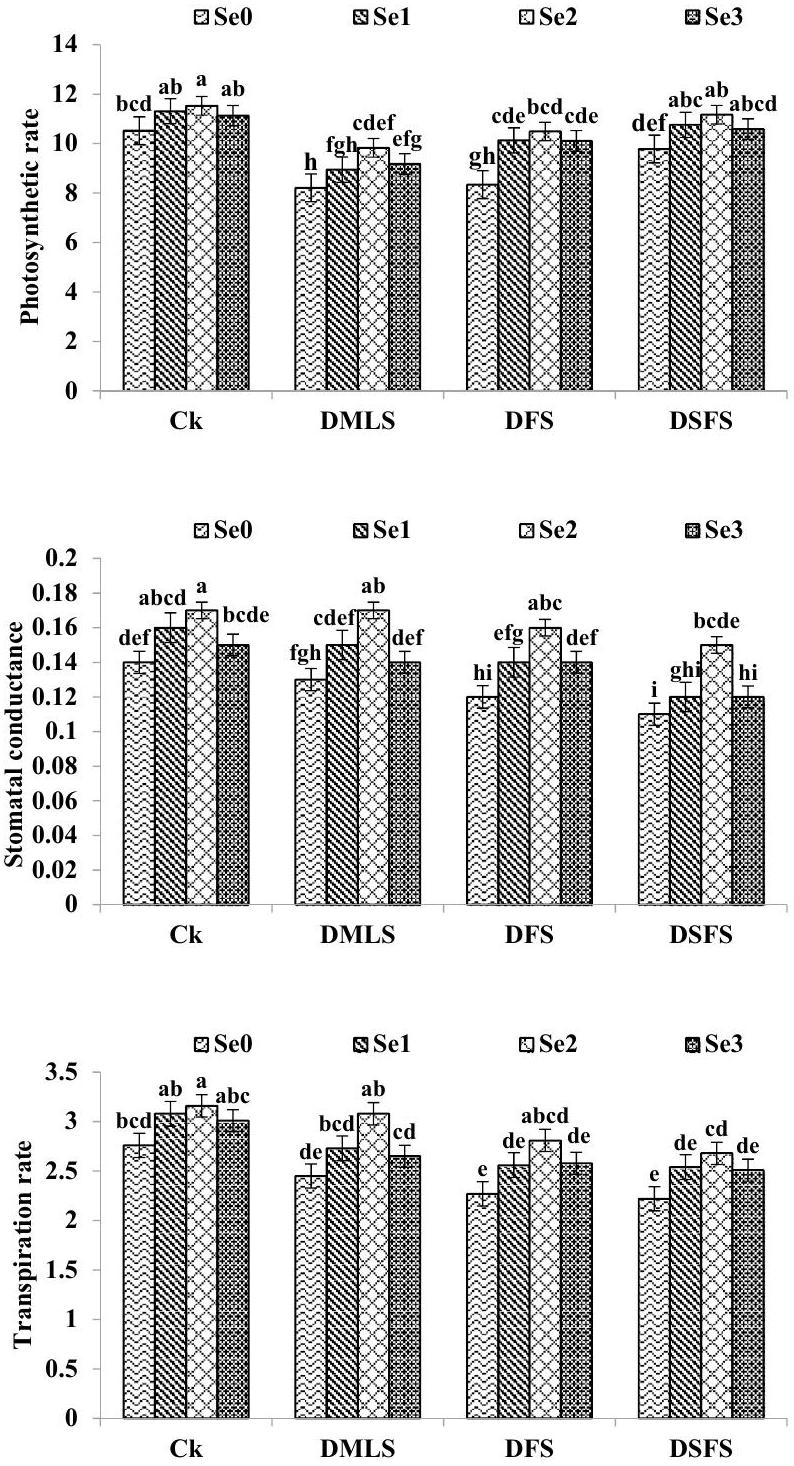

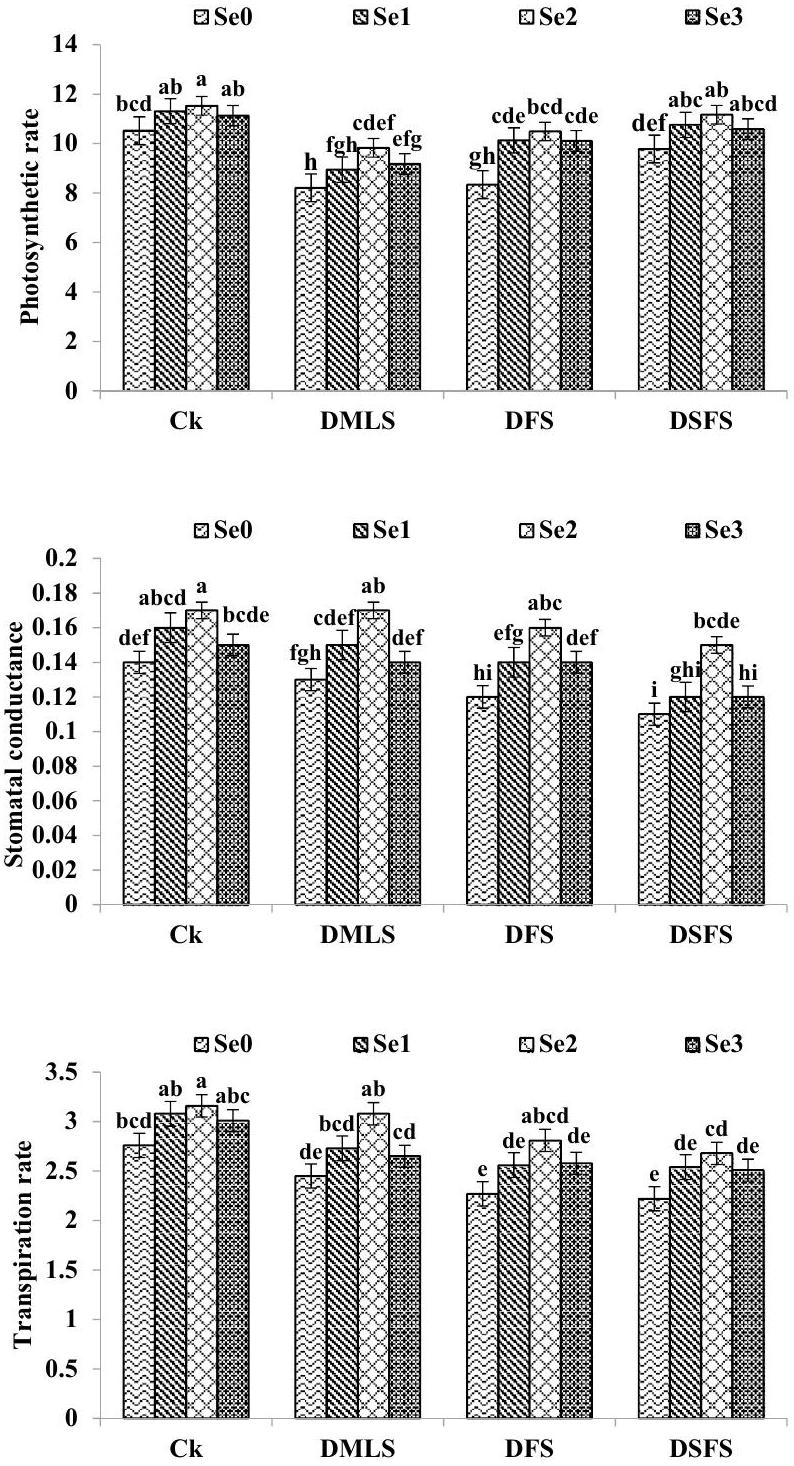

معايير تبادل الغاز

انخفضت معدلات التمثيل الضوئي (PR) وموصلية الثغور (SC) ومعدل النتح (TR) في نباتات الكينوا المعرضة للإجهاد المائي (DS) مقارنة بالنباتات الضابطة (الشكل 2). تم ملاحظة أعلى قيم لـ PR في المعاملة الضابطة تليها DSFS وDFS، بينما تم تحقيق أدنى PR في DMLS. لوحظ نمط متباين (Ck > DMLS > DFS > DSFS) بالنسبة لـ SC وTR تحت ظروف الجفاف. حسنت معالجة البذور بشكل كبير من PR وSC وTR في نباتات DS مقارنة بالمعاملة الضابطة. كانت القيم القصوى لـ PR (11.53) وSC (0.17).

| علاجات | PH | PPP | MPL | MPW | TGW | بواسطة | جي |

| سي كيه | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DMLS | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DFS | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DSFS | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LSD (

|

2.28 | 1.01 | 0.69 | 1.63 | 0.14 | 3.43 | 1.24 |

| أهمية | |||||||

| سي | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| الجفاف | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| سي

|

نس | نس | نس | نس | نس | نس | نس |

الجدول 2. ارتفاع النبات (

وتم تحقيق TR (3.16) عندما تم تنشيط بذور الكينوا بـ

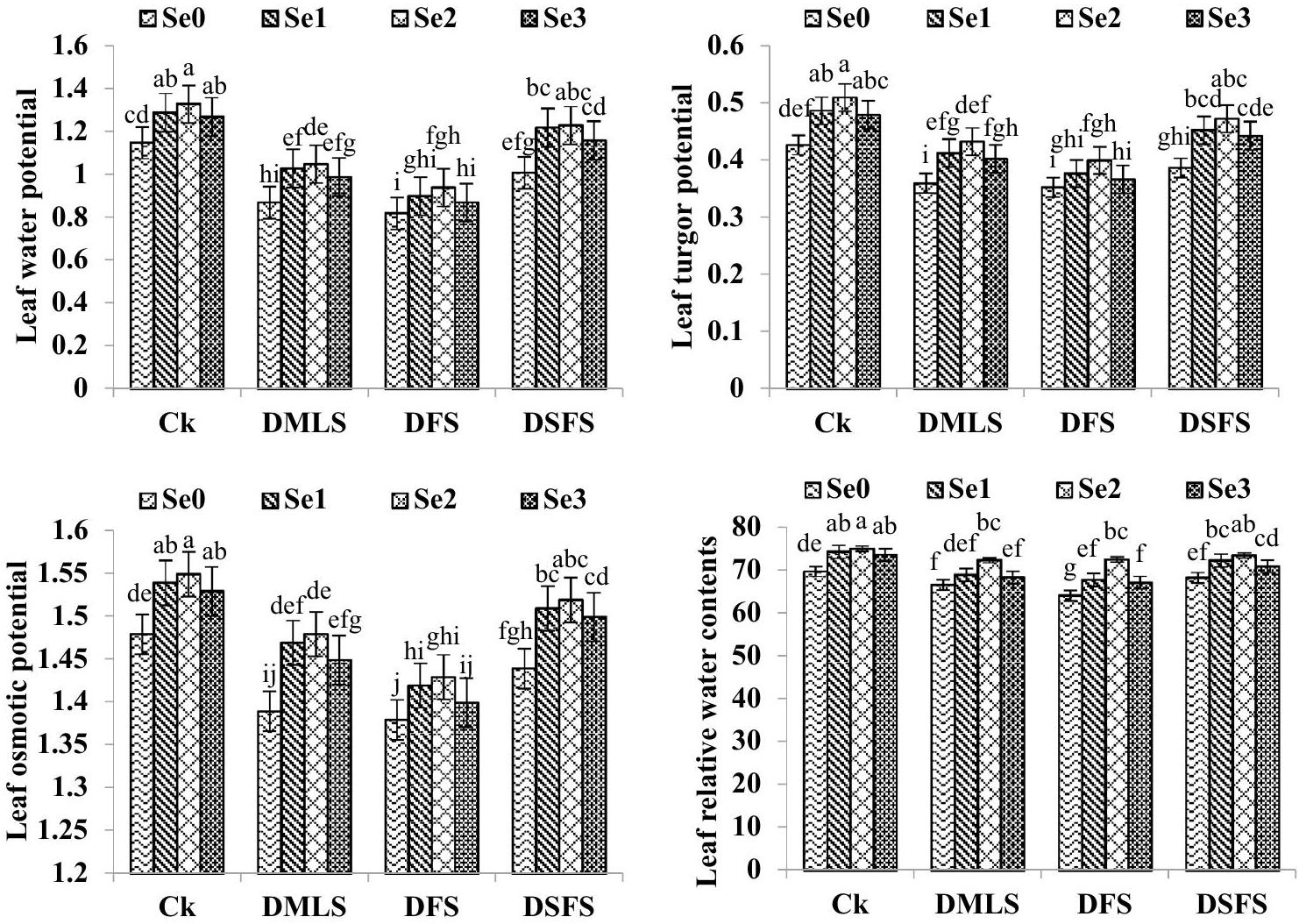

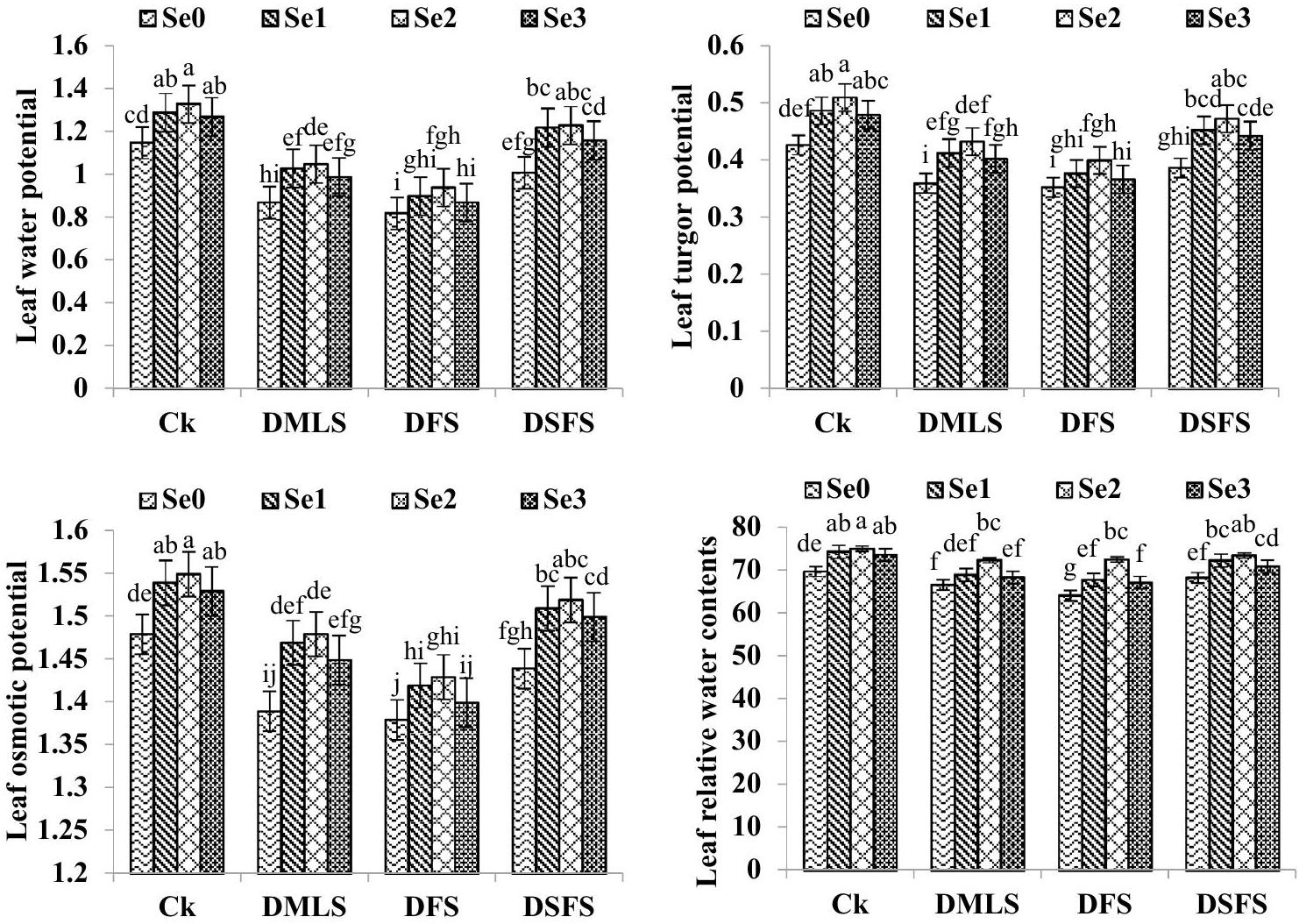

علاقات المياه

تم تقديم التأثير الكبير للجفاف وتغليف بذور السيلينيوم على LWP وLTP وLOP وLRWC في الشكل 3. لوحظ انخفاض كبير في LWP وLTP وLOP وLRWC في معالجة DSFS تليها DMLS وDFS عند مقارنتها بنباتات الكينوا غير المتأثرة بالإجهاد. زاد تغليف بذور السيلينيوم بشكل كبير من LWP وLTP وLOP مقارنة بمعالجة التحكم. علاوة على ذلك، فإن تغليف السيلينيوم (

محتويات بروتين الحبوب

تشير الجدول 3 إلى أن الجفاف له تأثير كبير على محتويات البروتين (PCs) في حبوب الكينوا. تم ملاحظة أعلى القيم لمحتويات البروتين من خلال تنفيذ الجفاف في SFS تليها FS و MLS، وكانت أدنى قيمة ملحوظة في Ck. تم ملاحظة أعلى محتوى بروتين للحبوب (15.62) في

محتويات الفوسفور في الحبوب

أثر نقص الري وتغليف البذور بالسيلينيوم بشكل كبير على محتوى الفوسفور في حبوب الكينوا. وكان أعلى محتوى للفوسفور في الحبوب تحت الري العادي بين ظروف الجفاف.

| علاجات | حاسوب شخصي | P | ك | لجنة التنسيق المحلية | WUE | تي بي |

| سي كيه | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DMLS | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DFS | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DSFS | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| إل إس دي (

|

0.64 | 28.11 | ٨٥.٨١ | 2.06 | 0.08 | 0.93 |

| أهمية | ||||||

| سي | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | * |

| الجفاف | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| سي

|

نس | نس | نس | نس | نس | نس |

الجدول 3. محتويات البروتين

محتويات البوتاسيوم في الحبوب

أثر نقص الري ومعالجة البذور بالسيلينيوم بشكل كبير على محتوى البوتاسيوم (K) في حبوب الكينوا. تم العثور على أعلى قيم للبوتاسيوم (1129.5) في بذور الكينوا مع الري العادي (Ck) تليها DMLS، بينما تم ملاحظة قيم أقل لمحتوى البوتاسيوم (915.8) في معالجة DSFS. حسنت معالجة البذور بالسيلينيوم بشكل كبير تركيز البوتاسيوم في حبوب الكينوا سواء تحت ظروف الري العادي أو نقص المياه (الجدول 3).

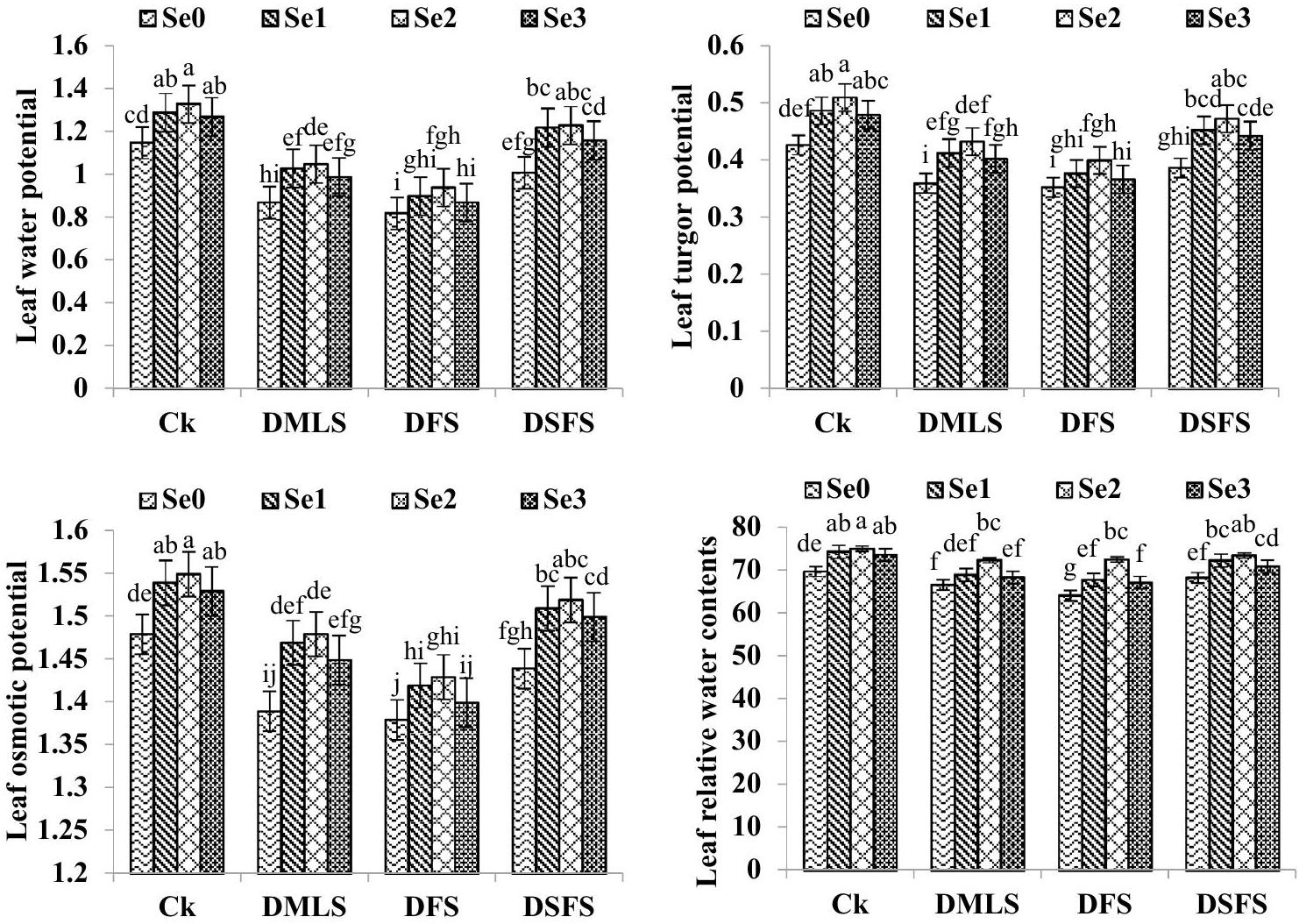

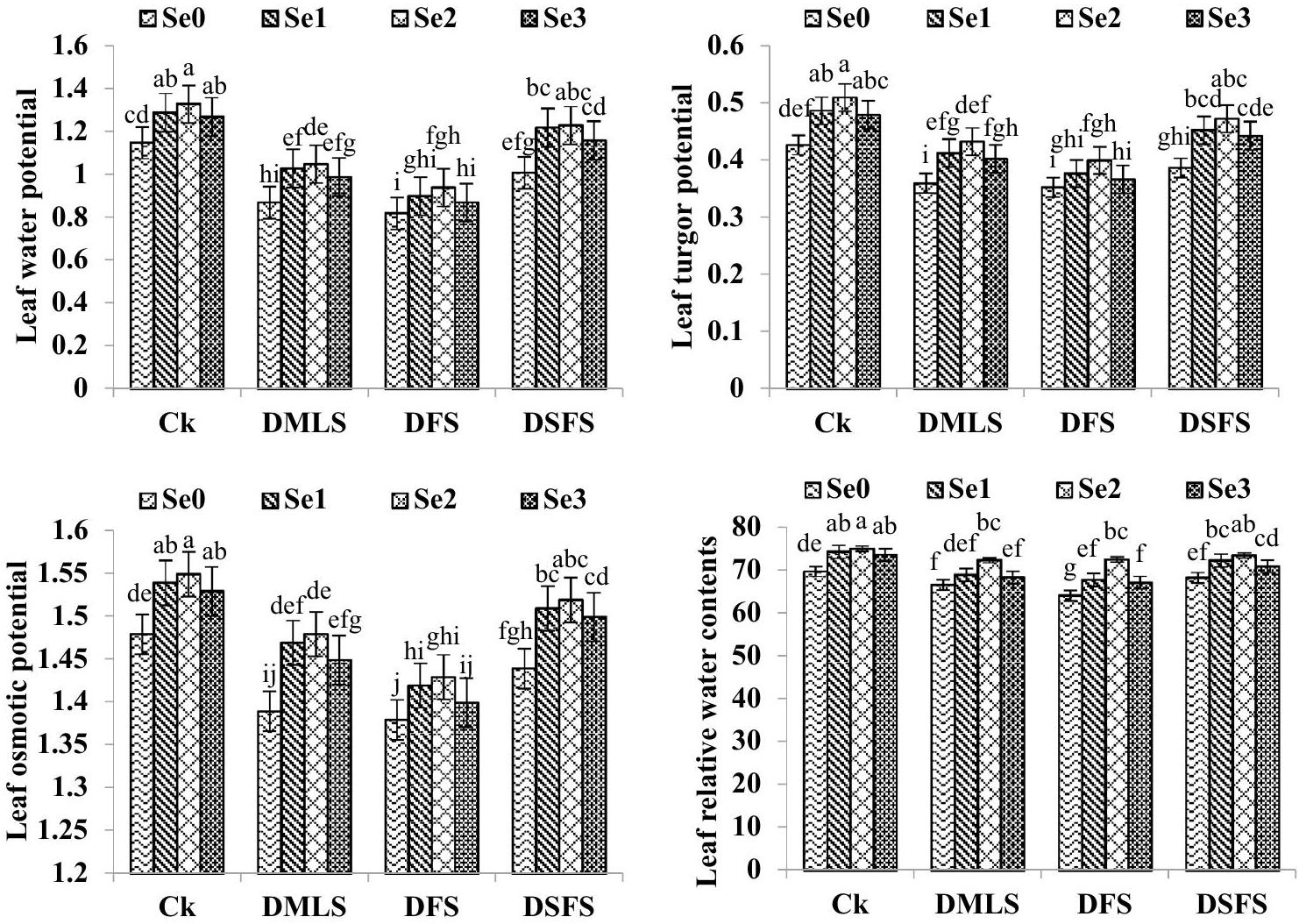

تحليل المكونات الرئيسية (PCA) لاستخراج البيانات

تم تنفيذ تحليل المكونات الرئيسية (PCA) على جميع المعلمات التجريبية لكشف ارتباطها بالعلاجات المجاورة والمتغيرات الأخرى. ومع ذلك، كشف تحليل المكونات الرئيسية عن تمييز واضح بين PC1 و PC2، اللذان يمثلان معًا

نقاش

الجفاف هو أحد العوامل الرئيسية المحددة لتحقيق الاستدامة في إنتاج المحاصيل.

انخفاض كبير في صبغة التمثيل الضوئي (الكلوروفيل) كان بسبب إنتاج أنواع الأكسجين التفاعلية (ROS) مثل

الشكل 2. معدل التمثيل الضوئي (

الذي أدى في النهاية إلى تدمير الكلوروفيل في حالات الضغط. ومع ذلك، أدى تحضير البذور بالسيلينيوم إلى زيادة محتوى الكلوروفيل في كل من البيئات الجافة وغير المتوترة لأن السيلينيوم زاد من تدفق الإلكترونات في سلسلة التنفس، وبالتالي زاد من معدل التمثيل الضوئي في النباتات.

أثرت الجفاف، عندما تم فرضه في FS و SFS، سلبًا على كفاءة استخدام المياه في الكينوا. وقد تم توثيق نتائج مماثلة من قبل زانغ وآخرين.

أدى إجهاد الجفاف إلى تقليص كبير في علاقات المياه (LWP و LTP و LOP و LRWC) في الكينوا مقارنةً بمعاملة التحكم. وقد تم الإبلاغ عن نتائج مماثلة من قبل حيدر وآخرون.

الشكل 3. إمكانات المياه في الأوراق (-MPa)، إمكانات التوتر في الأوراق (MPa)، إمكانات الأسموزية في الأوراق (-MPa) ومحتويات المياه النسبية في الأوراق (%) من الكينوا المتأثرة بتنشيط Se تحت ظروف الجفاف.

الشكل 4. رسم ثنائي يوضح الارتباطات بين ارتفاع النبات (PH)، عدد السنبيلات لكل نبات (PPP)، طول السنبلة الرئيسية (MPL)، وزن السنبلة الرئيسية (MPW)، وزن الألف حبة (TGW)، العائد البيولوجي (BY)، عائد الحبوب (GY)، محتويات البروتين (PC)، محتويات الفوسفور (P) ومحتويات البوتاسيوم (K)، محتوى الكلوروفيل في الأوراق (LCC)، الفينولات الكلية (TP)، كفاءة استخدام المياه (WUE)، معدل التمثيل الضوئي (PR)، الموصلية stomatal (SC)، معدل النتح (TR)، إمكانات المياه في الأوراق (LWP)، إمكانات التوتر في الأوراق (LTP)، إمكانات الأسموزية في الأوراق (LOP) ومحتويات المياه النسبية في الأوراق (LRWC) من الكينوا المتأثرة بتنشيط Se تحت ظروف الجفاف.

LRWC و OP و TP. كشف دوموكوس-سابولكسي وآخرون.

أدى إجهاد الجفاف إلى تقليل كبير في محتوى الفينولات في الكينوا عندما تم فرضه في MLS، والذي قد يكون بسبب انخفاض نشاط هرمونات النبات (فينيل ألانين أمونيا لايز) والإجهاد الأسموزي أثناء تخليق المركبات الفينولية. وبالمثل، أبلغ محرم نجاد وآخرون.

تم تحسين محتويات البروتين (PCs) في حبوب الكينوا بشكل كبير عندما تم تنفيذ إجهاد الجفاف في SFS. كما أبلغ أنجم وآخرون.

أدى إجهاد الجفاف إلى تقليل كبير في تركيز P و K في بذور الكينوا عندما تم فرض الجفاف في DSFS، والذي قد يكون بسبب عدم قدرة جذور النبات على امتصاص العناصر الغذائية الموجودة في التربة وحركتها لأعلى داخل النباتات. وبالمثل، وجد جين وآخرون.

تم تقليل الصفات المساهمة في العائد (NPPP و MPL و MPW و TGW) والعائد البيولوجي (BY) وعائد الحبوب (GY) تحت نقص الري. ومع ذلك، يمكن أن يُعزى الانخفاض في NPPP و BY في MLS إلى امتصاص محدود لـ N و P في بداية نمو النبات.

الاستنتاج

تقلل حلقات الجفاف خلال مراحل النمو الحرجة (الإزهار وملء البذور) من الأداء العام للنبات، وخصائص الجودة وعائد الكينوا. ومع ذلك، أظهر تنشيط بذور Se بتركيزات متفاوتة إمكانات ملحوظة لتعزيز تحمل الجفاف والعائد الكلي للكينوا. من الجدير بالذكر أن تنشيط Se عند

توفر البيانات

تتضمن مجموعات البيانات التي تم تحليلها خلال هذه الدراسة في هذه المخطوطة.

تاريخ الاستلام: 20 أكتوبر 2023؛ تاريخ القبول: 4 يناير 2024

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 09 يناير 2024

تاريخ الاستلام: 20 أكتوبر 2023؛ تاريخ القبول: 4 يناير 2024

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 09 يناير 2024

References

- Amna Ali, B., Azeem, M. A., Qayyum, A., Mustafa, G., Ahmad, M. A., Javed, M. T., & Chaudhary, H. J. (2021). Bio-fabricated silver nanoparticles: A sustainable approach for augmentation of plant growth and pathogen control. in Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 53; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, pp. 345-371. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86876-5_14

- AsmaHussain, I. et al. Alleviating effects of salicylic acid spray on stage-based growth and antioxidative defense system in two drought-stressed rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars. Turk. J. Agric. Forestry. 47(1), 79-99. https://doi.org/10.55730/1300-011X. 3066 (2023).

- Ruiz, K. B. et al. Quinoa biodiversity and sustainability for food security under climate change. A review. Agron. Sustain. Develop. 34, 349-359 (2014).

- Waqas, M. et al. Synergistic consequences of salinity and potassium deficiency in quinoa: Linking with stomatal patterning, ionic relations and oxidative metabolism. Plant Physiol. Biochem 159, 17-27 (2021).

- Choque Delgado, G. T., Carlos Tapia, K. V., Pacco Huamani, M. C. & Hamaker, B. R. Peruvian Andean grains: Nutritional, functional properties and industrial uses. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 63(29), 9634-9647 (2023).

- Filho, A. M. M. et al. Quinoa: Nutritional, functional, and antinutritional aspects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 57(8), 1618-1630 (2017).

- Liu, C., Ma, R., & Tian, Y. (2022). An overview of the nutritional profile, processing technologies, and health benefits of quinoa with an emphasis on impacts of processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1-18.

- Aslam, M. U. et al. Improving strategic growth stage-based drought tolerance in quinoa by rhizobacterial inoculation. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 51(7), 853-868 (2020).

- Kammann, C. I., Linsel, S., Gößling, J. W. & Koyro, H. W. Influence of biochar on drought tolerance of Chenopodium quinoa Willd and on soil-plant relations. Plant Soil 345(1), 195-210 (2011).

- Yang, A., Akhtar, S. S., Amjad, M., Iqbal, S. & Jacobsen, S. E. Growth and physiological responses of quinoa to drought and temperature stress. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 202(6), 445-453 (2016).

- Maestro-Gaitán, I. et al. Genotype-dependent responses to long-term water stress reveal different water-saving strategies in Chenopodium quinoa Willd. Environ. Exp. Bot. 201, 104976 (2022).

- Al-Huqail, A. A. et al. Efficacy of priming wheat (Triticum aestivum) seeds with a benzothiazine derivative to improve drought stress tolerance. Funct. Plant Biol. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP22140 (2023).

- Wahab, A. et al. Plants’ physio-biochemical and phyto-hormonal responses to alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress: A comprehensive review. Plants 11, 1620. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11131620 (2022).

- Yasmeen, S. et al. Melatonin as a foliar application and adaptation in lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) crops under drought stress. Sustainability 14, 16345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416345 (2022).

- Salam, A. et al. Nano-priming against abiotic stress: A way forward towards sustainable agriculture. Sustainability 14, 14880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214880 (2022).

- Ali, J. et al. Biochemical response of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) to selenium (Se) under drought stress. Sustainability 15, 5694. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075694 (2023).

- Hasanuzzaman, M. et al. Selenium toxicity in plants and environment: biogeochemistry and remediation possibilities. Plants 9(12), 1711 (2020).

- Djanaguiraman, M., Prasad, P. V. & Seppanen, M. Selenium protects sorghum leaves from oxidative damage under high temperature stress by enhancing antioxidant defense system. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48(12), 999-1007 (2010).

- Shahzadi, E. et al. Silicic and ascorbic acid induced modulations in photosynthetic, mineral uptake, and yield attributes of mung bean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek) under ozone stress. ACS Omega https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c00376 (2023).

- Mozafariyan, M., Pessarakli, M. & Saghafi, K. Effects of selenium on some morphological and physiological traits of tomato plants grown under hydroponic condition. J. Plant Nutr. 40(2), 139-144 (2017).

- Helaly, M. N., El-Hoseiny, H., El-Sheery, N. I., Rastogi, A. & Kalaji, H. M. Regulation and physiological role of silicon in alleviating drought stress of mango. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 118, 31-44 (2017).

- Wang, W., Vinocur, B. & Altman, A. Plant responses to drought, salinity and extreme temperatures: towards genetic engineering for stress tolerance. Planta 218(1), 1-14 (2003).

- Hasanuzzaman, M., Hossain, M. A. & Fujita, M. Selenium in higher plants: Physiological role, antioxidant metabolism and abiotic stress tolerance. J. Plant Sci. 5(4), 354-375 (2010).

- Shigeoka, S. et al. Regulation and function of ascorbate peroxidase isoenzymes. J. Exp. Bot. 53(372), 1305-1319 (2002).

- Victoria, O., Idorenyin, U. D. O., Asana, M., Shuoshuo, L., & Yang, S. (2023). Seed treatment with 24 -epibrassinolide improves wheat germination under salinity stress. Asian J. Agric. Biol. (3).

- Faryal, S. et al. Thiourea-capped nanoapatites amplify osmotic stress tolerance in Zea mays L. by conserving photosynthetic pigments, osmolytes biosynthesis and antioxidant biosystems. Molecules 27, 5744. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27185744 (2022).

- Taratima, W., Kunpratum, N., & Maneerattanarungroj, P. (2023). Effect of salinity stress on physiological aspects of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duchesne. ‘Laikaotok’) under hydroponic condition. Asian J. Agric. Biol. (2), 202101050.

- Tadina, N., Germ, M., Kreft, I., Breznik, B. & Gaberščik, A. Effects of water deficit and selenium on common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench.) plants. Photosynthetica 45(3), 472-476 (2007).

- Ahmad, Z. et al. Selenium alleviates the adverse effect of drought in oilseed crops camelina (Camelina sativa L.) and canola (Brassica napus L.). Molecules 26(6), 1699 (2021).

- Jóźwiak, W. & Politycka, B. Effect of selenium on alleviating oxidative stress caused by a water deficit in cucumber roots. Plants 8(7), 217 (2019).

- Sosa-Zuniga, V., Brito, V., Fuentes, F. & Steinfort, U. Phenological growth stages of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) based on the BBCH scale. Ann. Appl. Biol. 171(1), 117-124 (2017).

- Iqbal, R. et al. Assessing the potential of partial root zone drying and mulching for improving the productivity of cotton under arid climate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28(46), 66223-66241 (2021).

- Waterhouse, A. L. Determination of total phenolics. Curr. Protocols Food Analyt. Chem. 6(1), I1-1 (2001).

- Iqbal, H., Yaning, C., Waqas, M., Shareef, M. & Raza, S. T. Differential response of quinoa genotypes to drought and foliage-applied H2O2 in relation to oxidative damage, osmotic adjustment and antioxidant capacity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 164, 344-354 (2018).

- Raza, M. A. S. et al. Physiological and biochemical assisted screening of wheat varieties under partial rhizosphere drying. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 116, 150-166 (2017).

- Gonzalez, J. A., Konishi, Y., Bruno, M., Valoy, M. & Prado, F. E. Interrelationships among seed yield, total protein and amino acid composition of ten quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) cultivars from two different agroecological regions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 92(6), 1222-1229 (2012).

- AOAC. (1990). Official Methods of Analysis, 15th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Inc.: Arlington, TX, USA, p. 70. ISBN 0-935584-42-0.

- Rosero, O., Marounek, M. & Břeňová, N. Phytase activity and comparison of chemical composition, phytic acid P content of four varieties of quinoa grain (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Acta Agronómica 62(1), 13-20 (2013).

- Chapman, H. D. & Pratt, P. E. Methods of Analysis for Soils, Plant and Water (California University, 1961).

- Steel, R. G. D., Torrie, J. H. & Dickey, D. A. Principles and Procedure of Statistics 178-182 (McGrow Hill Book Co., 1997).

- El-Fattah, A., Ahmed, D., Elhamid Hashem, F. A. & Abd-Elrahman, S. H. Impact of applying organic fertilizers on nutrient content of soil and lettuce plants, yield quality and benefit-cost ratio under water stress conditions. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2, 202102086 (2021).

- Waraich, E. A., Ahmad, R. & Ashraf, M. Y. Role of mineral nutrition in alleviation of drought stress in plants. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 5(6), 764-777 (2011).

- Nawaz, F. et al. Supplemental selenium improves wheat grain yield and quality through alterations in biochemical processes under normal and water deficit conditions. Food Chem. 175, 350-357 (2015).

- Teimouri, S., Hasanpour, J. & Tajali, A. A. Effect of Selenium spraying on yield and growth indices of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under drought stress condition. Int. J. Adv. Biol. Biomed. Res. 2(6), 2091-2103 (2014).

- Muhammad, F. et al. Ameliorating drought effects in wheat using an exclusive or co-applied rhizobacteria and zno nanoparticles. Biology 11(11), 1564 (2022).

- Chomchan, R., Siripongvutikorn, S. & Puttarak, P. Selenium bio-fortification: an alternative to improve phytochemicals and bioactivities of plant foods. Funct. Foods Health Disease 7(4), 263-279 (2017).

- Dong, J. Z. et al. Selenium increases chlorogenic acid, chlorophyll and carotenoids of Lycium chinense leaves. J. Sci. Food Agric. 93(2), 310-315 (2013).

- Lavu, R. V. S. et al. Use of selenium fertilizers for production of Se-enriched Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus): Effect on Se concentration and plant productivity. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 176(4), 634-639 (2013).

- Hawrylak-Nowak, B. Comparative effects of selenite and selenate on growth and selenium accumulation in lettuce plants under hydroponic conditions. Plant Growth Regul. 70(2), 149-157 (2013).

- Ardebili, Z. O., Ardebili, N. O., Jalili, S. & Safiallah, S. The modified qualities of basil plants by selenium and/or ascorbic acid. Turk. J. Bot. 39(3), 401-407 (2015).

- Khaliq, A. et al. Seed priming with selenium: consequences for emergence, seedling growth, and biochemical attributes of rice. Biol. Trace Element Res. 166(2), 236-244 (2015).

- Zhang, B., Li, F. M., Huang, G., Cheng, Z. Y. & Zhang, Y. Yield performance of spring wheat improved by regulated deficit irrigation in an arid area. Agric. Water Manag. 79(1), 28-42 (2006).

- Geerts, S., Raes, D., Garcia, M., Mendoza, J. & Huanca, R. Crop water use indicators to quantify the flexible phenology of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) in response to drought stress. Field Crops Res. 108(2), 150-156 (2008).

- Telahigue, D. C., Yahia, L. B., Aljane, F., Belhouchett, K., & Toumi, L. (2017). Grain yield, biomass productivity and water use efficiency in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) under drought stress. J. Sci. Agric. 222-232.

- Sajedi, N. A., Ardakani, M. R., Naderi, A., Madani, H. & Boojar, M. M. A. Response of maize to nutrients foliar application under water deficit stress conditions. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 4(3), 242-248 (2009).

- Haider, I. et al. Potential effects of biochar application on mitigating the drought stress implications on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under various growth stages. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 24(12), 974-981 (2020).

- Ahmed, A. H., Harb, E. M., Higazy, M. A. & Morgan, S. H. Effect of silicon and boron foliar applications on wheat plants grown under saline soil conditions. Int. J. Agric. Res. 3(1), 1-26 (2008).

- Domokos-Szabolcsy, E. et al. The interactions between selenium, nutrients and heavy metals in higher plants under abiotic stresses. Environ. Biodiversity Soil Security 1(2017), 5-31 (2017).

- Moharramnejad, S., Sofalian, O., Valizadeh, M., Asgari, A. & Shiri, M. Proline, glycine betaine, total phenolics and pigment contents in response to osmotic stress in maize seedlings. J. Biosci. Biotechnol. 4(3), 313-319 (2015).

- Sofy, M. R., Sharaf, A. E. M., Osman, M. S. & Sofy, A. R. Physiological changes, antioxidant activity, lipid peroxidation and yield characters of salt stressed barely plant in response to treatment with Sargassum extract. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 4(2), 90-109 (2017).

- Salem, N. et al. Effect of drought on safflower natural dyes and their biological activities. EXCLI J. 13, 1-18 (2014).

- Kusvuran, S. & Dasgan, H. Y. Effects of drought stress on physiological and biochemical changes in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Legume Res. 40(1), 55-62 (2017).

- Emam, M. M., Khattab, H. E., Helal, N. M. & Deraz, A. E. Effect of selenium and silicon on yield quality of rice plant grown under drought stress. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 8(4), 596-605 (2014).

- Anjum, S. A. et al. Gas exchange and chlorophyll synthesis of maize cultivars are enhanced by exogenously-applied glycinebetaine under drought conditions. Plant Soil Environ. 57(7), 326-331 (2011).

- Nawaz, F. et al. Selenium supply methods and time of application influence spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) yield under water deficit conditions. J. Agric. Sci. 155(4), 643-656 (2017).

- Jin, J. et al. Interaction between phosphorus nutrition and drought on grain yield, and assimilation of phosphorus and nitrogen in two soybean cultivars differing in protein concentration in grains. J. Plant Nutr. 29(8), 1433-1449 (2006).

- Nawaz, F., Ahmad, R., Waraich, E. A., Naeem, M. S. & Shabbir, R. N. Nutrient uptake, physiological responses, and yield attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) exposed to early and late drought stress. J. Plant Nutr. 35(6), 961-974 (2012).

- Hajiboland, R., Sadeghzadeh, N., Ebrahimi, N., Sadeghzadeh, B. & Mohammadi, S. A. Influence of selenium in drought-stressed wheat plants under greenhouse and field conditions. Acta Agriculturae Slovenica 105(2), 175-191 (2015).

- Samarah, N. H. Effects of drought stress on growth and yield of barley. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 25, 145-149 (2005).

- Fatemi, R., Yarnia, M., Mohammadi, S., Vand, E. K. & Mirashkari, B. Screening barley genotypes in terms of some quantitative and qualitative characteristics under normal and water deficit stress conditions. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2, 2022071 (2023).

- Sadak, M. S. & Bakhoum, G. S. Selenium-induced modulations in growth, productivity and physiochemical responses to water deficiency in Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) grown in sandy soil. Biocatalysis Agric. Biotechnol. 44, 102449 (2022).

- Ibrahim Nossier, M., Hassan Abd-Elrahman, S. & Mahmoud El-Sayed, S. Effect of using garlic and lemon peels extracts with selenium on Vicia faba productivity. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 4, 202107276 (2022).

- Chen, C. C. & Sung, J. M. Priming bitter gourd seeds with selenium solution enhances germinability and antioxidative responses under sub-optimal temperature. Physiologia Plantarum 111(1), 9-16 (2001).

- Rayman, M. P. Selenium and human health. Lancet 379(9822), 1256-1268 (2012).

- Nawaz, F., Ashraf, M. Y., Ahmad, R. & Waraich, E. A. Selenium (Se) seed priming induced growth and biochemical changes in wheat under water deficit conditions. Biol. Trace Element Res. 151(2), 284-293 (2013).

الشكر والتقدير

يقدم المؤلفون تقديرهم للباحثين الذين يدعمون رقم المشروع (RSPD2024R941)، جامعة الملك سعود، الرياض، المملكة العربية السعودية.

مساهمات المؤلفين

تصور، تحقيق، جمع البيانات، وكتابة المسودة الأصلية، م.أ.س.ر.، و م.ع.أ. البرمجيات، تقييم النصوص، وتحريرها، م.ف.، إ.أ، و ر.ي. الكتابة-المراجعة والتحرير، ر.ر.، أ.م.س.إ.، إ.ح.، إ.أ.، و أ.إ.م.م. تنسيق البيانات والتحليل الرسمي، م.س.إ.، إ.أ، و م.ع.أ. التصور والتحقق، م.س.إ.، ر.ي.، م.أ.س.ر. المنهجية والمراجع، ر.ر.، أ.م.س.إ.، ر.ي.، و م.ع.أ. الإشراف، م.أ.س.ر. الحصول على التمويل، ر.ر.، أ.م.س.إ.، إ.أ، و ر.ي. جميع المؤلفين راجعوا المخطوطة ووافقوا على النشر النهائي.

التمويل

تمكين وتنظيم التمويل المفتوح بواسطة مشروع DEAL. تمكين وتنظيم التمويل المفتوح بواسطة مشروع DEAL.

المصالح المتنافسة

يعلن المؤلفون عدم وجود مصالح متنافسة.

معلومات إضافية

يجب توجيه المراسلات وطلبات المواد إلى م.أ.س.ر.، م.ع.أ.، ر.ي. أو ر.ر.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

النفاذ المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا تم إجراء تغييرات. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُشار إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر الائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة واستخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© المؤلفون 2024

© المؤلفون 2024

قسم الزراعة، الجامعة الإسلامية في بهاولبور، بهاولبور 63100، باكستان. قسم الهندسة وتكنولوجيا الهندسة، جامعة ولاية متروبوليتان في دنفر، دنفر، كولورادو 80217، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. المركز الوطني للبحوث الزراعية، الجامعة الإسلامية في بهاولبور، بهاولبور 63100، باكستان. قسم علم النبات والميكروبيولوجيا، كلية العلوم، جامعة الملك سعود، ص.ب. 2455، 11451 الرياض، المملكة العربية السعودية. قسم الوراثة والتنمية، مركز إيرفينغ الطبي بجامعة كولومبيا، نيويورك، نيويورك 10032، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. معهد تغذية النبات وعلوم التربة، جامعة كريستيان ألبريشتس في كيل، 24118 كيل، ألمانيا. قسم الزراعة الحراجية وعلوم البيئة، جامعة سيلهيت الزراعية، سيلهيت 3100، بنغلاديش. مركز دراسات وأبحاث المياه، المركز الوطني للبحوث المائية، القاهرة 81525، مصر. roy@plantnutrition.uni-kiel.de

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 14, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51371-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38195846

Publication Date: 2024-01-09

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51371-6

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38195846

Publication Date: 2024-01-09

Seed priming with selenium improves growth and yield of quinoa plants suffering drought

Drought stress is a worldwide threat to the productivity of crops, especially in arid and semi-arid zones of the world. In the present study, the effect of selenium (Se) seed priming on the yield of quinoa under normal and drought conditions was investigated. A pot trial was executed to enhance the drought tolerance in quinoa by Se seed priming (

The world population is rapidly growing and proposed that it will reach to

exploration of its growth and production potential

Drought significantly hampered the plant growth and development, resulting in a notable decrease in biomass accumulation and crop growth rate

Selenium (Se) has been described as a vital nutrient for humans, animals and plants, as well as an environmental toxin

Drought, a multi-dimensional stress affects various physiological and biochemical attributes in plants including photosynthetic rate, turgor potential, osmotic potential along with severe injury to cellular membranes

The study focused on investigating the effectiveness of Se seed priming in enhancig the drought tolerance potential of quinoa by improving its physiological and biochemical attributes. One of the key objective of the study was to assess the impact of Se seed priming on the growth, yield, and physiological attributes of quinoa subjected to drought stress conditions.

Materials and methods

Layout and crop management

The experiment was completed in the wirehouse of the Department of Agronomy, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan (Longitude:

| Parameters | Soil profile |

| Clay (%) | 9.5 |

| Silt (%) | 33.5 |

| Sand (%) | 57 |

| pH | 7.37 |

| Texture class | Sandy loam soil |

| Organic matter (%) | 0.91 |

| Electric conductivity (

|

2.51 |

| Available Potassium (ppm) | 109 |

| Ammoniac N (

|

1.62 |

| Available Phosphorus (ppm) | 6.77 |

Table 1. Physiochemical properties of the experimental soil.

Figure 1. Relative humidity (RH), rainfall, maximum and minimum temperature during the growing period of quinoa.

Drought imposition and Se priming

Drought stress was executed at multiple leaf (MLS) 30 days after germination (DAG), flowering (FS, 60 DAG) and seed filling (SFS, 85 DAG) stages, whereas, normal supply of water was used as control treatment (CK). Quinoa plants were examined everyday to reveal their phenology for precise application of growth stage-based drought stress (DS) outlined by Sosa-Zuniga et al.

Se as Sodium selenate

Data recording and related procedures

Growth and yield related parameters

The plants were harvested 140 DAS when they reached at maturity in order to measure plant height, number of panicles per plant, length and weight of main panicle, thousand grain weight, biological and economic yield.

The plants were harvested 140 DAS when they reached at maturity in order to measure plant height, number of panicles per plant, length and weight of main panicle, thousand grain weight, biological and economic yield.

Physiological attributes

The chlorophyll contents of leaves were assessed from fully expanded young leaves after 50 DAS using a chlorophyll meter (model CL-01, Hansatech instruments Ltd., United Kingdom), and the calculation of water use efficiency (WUE) was based on the specified formula described by Iqbal et al.

The gas exchange attributes i.e., transpiration rate, photosynthetic rate and stomatal conductance, of fifth topmost fully expanded young leaves were measured using LI-COR Li-6400 (USA) portable photosynthetic system, at noon.

Water relations

The leaf water potential and relative water contents (RWC) were assessed using two completely expanded fresh leaves after fifty days of germination, PSYPRO thermocouple psychrometer (Wescor, USA) was used to measure the leaf water potential. Fresh leaves were removed from plants and instantly shifted to test site (laboratory) to record fresh weight (FW). Then, the leaves were dipped in distilled water for 24 h at

Water potential apparatus (Chas W. Cook, Birmingham, England) was used to record the leaf water potential (

LTP = LWP – LOP

LTP = LWP – LOP

Quality parameters

Quinoa grains ( 0.1 g ) were ground into dry powder and placed in digestion tubes. To each tube, 5 ml of rigorous

Statistical analysis

The data gathered for all attributes were analyzed statistically by Fisher’s analysis of variance techniques. LSD (least significant difference) test was carried out at

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study does not include human or animal subjects.

Statement on guidelines

All experimental studies and experimental materials involved in this research are in full compliance with relevant institutional, national and international guidelines and legislation.

Results

Growth and yield attributes

Drought stress significantly affected the biomass production and yield attributes [number of panicles per plant (NPPP), main panicle length (MPL), main panicle weight (MPW) and thousand grain weight (TGW) in quinoa (Table 2). Priming of quinoa seeds with Se mitigated the negative effects of drought showing the maximum values for

Leaf chlorophyll contents

Leaf chlorophyll contents (LCC) of quinoa were affected significantly by the execution of DS as presented in Table 3. The peak values for LCC (22.52) were observed when crop was nourished with normal irrigation (Ck) followed by DSFS and minimum LCC (14.55) were observed when crop was subjected to drought at MLS. Se priming significantly improved LCC showing maximum value for

Water use efficiency

Drought and Se priming significantly influenced the WUE of quinoa. Maximum values (0.56) for WUE were noted in DMLS and minimum value (0.38) for WUE was found in Ck. Highest WUE was noticed when quinoa seeds were primed with

Total phenolics

Total phenolics (TP) were significantly affected by both deficit irrigation and Se priming in quinoa (Table 3). Maximum TP were obtained in control treatment (Ck) whereas minimum reading was noted for TP in DMLS treatment. Se significantly alleviated the adverse effects of drought and improved the accumulation of TP in quinoa leaves. Maximum TP (11.41) were recorded in

Gas exchange parameters

The quinoa plants subjected to DS decreased the photosynthetic rate (PR), stomatal conductance (SC) and transpiration rate (TR) as compared to control plants (Fig. 2). Highest values for PR were observed in control treatment followed by DSFS and DFS and minimum PR was achieved in DMLS. A disparate fashion (Ck > DMLS > DFS > DSFS) was observed for SC and TR under drought. Se seed priming significantly improved the PR, SC and TR in DS plants as compared to control treatment. Maximum values for PR (11.53), SC (0.17)

| Treatments | PH | PPP | MPL | MPW | TGW | BY | GY |

| Ck | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DMLS | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DFS | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DSFS | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LSD (

|

2.28 | 1.01 | 0.69 | 1.63 | 0.14 | 3.43 | 1.24 |

| Significance | |||||||

| Se | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Drought | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Se

|

ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Table 2. Plant height (

and TR (3.16) were achieved when quinoa seeds were primed with

Water relations

Significant effect of drought and Se seed priming on LWP, LTP, LOP and LRWC has been presented in Fig. 3. Significant reduction in LWP, LTP, LOP and LRWC was observed in DSFS treatment followed by DMLS and DFS when compared with non-stressed quinoa plants. Se seed priming significantly increased the LWP, LTP and LOP in comparison with control treatment. Furthermore, Se priming (

Grain protein contents

Table 3 indicates that drought has significant effect on protein contents (PCs) of quinoa grains. Maximum values for PCs were noted by the execution of drought at SFS followed by FS and MLS and minimum value was noted in Ck. Maximum grain PCs (15.62) were observed in

Grain phosphorus contents

Irrigation deficit and seed priming with Se influenced significantly the grain phosphorus contents of quinoa. Among the drought maximum grain phosphorus contents were under normal irrigation (

| Treatments | PC | P | K | LCC | WUE | TP |

| Ck | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DMLS | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DFS | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| DSFS | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LSD (

|

0.64 | 28.11 | 85.81 | 2.06 | 0.08 | 0.93 |

| Significance | ||||||

| Se | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | * |

| Drought | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Se

|

ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

Table 3. Protein contents (

Grain potassium contents

Irrigation deficit and seed priming with Se influenced significantly the potassium (K) contents in quinoa grains. Maximum K (1129.5) values in quinoa seeds were found with normal irrigation (Ck) followed by DMLS and lower values for K content (915.8) were noted in DSFS treatment. Seed priming with Se significantly improved the concentration of K in quinoa grains both under Ck and water deficit conditions (Table 3).

Principle component analysis (PCA) for data mining

The PCA was executed on all experimental parameters to reveal their correlation with the neighboring treatments and other variables. Yet, the PCA revealed a clear distinction between PC1 and PC2, which accounted for a combined

Discussion

Drought is one of the main limiting factor to achieve sustainability in crop production

A significant decrease in photosynthetic pigment (chlorophyll) was due to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as

Figure 2. Photosynthetic rate (

which ultimately resulted in demolition of chlorophyll under stress situations. However, seed priming with Se resulted in higher chlorophyll contents both in drought and non-stressed environments because Se increased the flow of electrons in the respiratory chain, and hence increased the rate of photosynthesis in plants

Drought, when imposed at FS and SFS negatively affected WUE of quinoa. Analogous results have been documented by Zhang et al.

Drought stress significantly abridged the water relations (LWP, LTP, LOP and LRWC) in quinoa when compared with control treatment. Similar outcomes have been stated by Haider et al.

Figure 3. Leaf water potential (-MPa), Leaf turgor potential (MPa), Leaf osmotic potential (-MPa) and Leaf relative water contents (%) of quinoa influenced by Se priming under drought.

Figure 4. Biplot showing the correlations between plant height (PH), panicles per plant (PPP), main panicle length (MPL), main panicle weight (MPW), thousand grain weight (TGW), biological yield (BY), grain yield (GY), protein contents (PC), phosphorus contents (P) potassium contents (K), leaf chlorophyll content (LCC), total phenolics (TP), water use efficiency (WUE), photosynthetic rate (PR), stomatal conductance (SC), transpiration rate (TR), leaf water potential (LWP), leaf turgor potential (LTP), leaf osmotic potential (LOP) and leaf relative water contents (LRWC) of quinoa affected by Se priming under drought.

LRWC, OP and TP. Domokos-Szabolcsy et al.

Drought stress significantly decreased phenolic content of quinoa when imposed at MLS which may be due to the reduced activity of plant hormones (phenylalaine ammonia lyase) and osmotic stress during the biosynthesis of phenolic compounds. Similarly, Moharramnejad et al.

Protein contents (PCs) in quinoa grains were considerably improved when DS was executed at SFS. Anjum et al.

Drought stress significantly reduced the concentration of P and K in quinoa seeds when drought was imposed at DSFS which may be because of the inability of plant roots to uptake soil nutrients present in soil and their upward movement within plants. Similarly, Jin et al.

The yield contributing attributes (NPPP, MPL, MPW, TGW), biological yield (BY) and grain yield (GY) were lowered under irrigation deficit. However, decrease in NPPP and BY at MLS can be attributed to limited N and P absorption in the begining of plant growth

Conclusion

Drought episodes during critical growth stages (flowering and seed filling) reduce overall plant performance, quality attributes and yield of quinoa. However, Se seed priming at varying concentrations demonstrated a remarkable potential to enhance drought tolerance and overall yield of quinoa. Notably, Se priming at

Data availability

The datasets analysed during this study are included in this manuscript.

Received: 20 October 2023; Accepted: 4 January 2024

Published online: 09 January 2024

Received: 20 October 2023; Accepted: 4 January 2024

Published online: 09 January 2024

References

- Amna Ali, B., Azeem, M. A., Qayyum, A., Mustafa, G., Ahmad, M. A., Javed, M. T., & Chaudhary, H. J. (2021). Bio-fabricated silver nanoparticles: A sustainable approach for augmentation of plant growth and pathogen control. in Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 53; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, pp. 345-371. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86876-5_14

- AsmaHussain, I. et al. Alleviating effects of salicylic acid spray on stage-based growth and antioxidative defense system in two drought-stressed rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars. Turk. J. Agric. Forestry. 47(1), 79-99. https://doi.org/10.55730/1300-011X. 3066 (2023).

- Ruiz, K. B. et al. Quinoa biodiversity and sustainability for food security under climate change. A review. Agron. Sustain. Develop. 34, 349-359 (2014).

- Waqas, M. et al. Synergistic consequences of salinity and potassium deficiency in quinoa: Linking with stomatal patterning, ionic relations and oxidative metabolism. Plant Physiol. Biochem 159, 17-27 (2021).

- Choque Delgado, G. T., Carlos Tapia, K. V., Pacco Huamani, M. C. & Hamaker, B. R. Peruvian Andean grains: Nutritional, functional properties and industrial uses. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 63(29), 9634-9647 (2023).

- Filho, A. M. M. et al. Quinoa: Nutritional, functional, and antinutritional aspects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 57(8), 1618-1630 (2017).

- Liu, C., Ma, R., & Tian, Y. (2022). An overview of the nutritional profile, processing technologies, and health benefits of quinoa with an emphasis on impacts of processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1-18.

- Aslam, M. U. et al. Improving strategic growth stage-based drought tolerance in quinoa by rhizobacterial inoculation. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 51(7), 853-868 (2020).

- Kammann, C. I., Linsel, S., Gößling, J. W. & Koyro, H. W. Influence of biochar on drought tolerance of Chenopodium quinoa Willd and on soil-plant relations. Plant Soil 345(1), 195-210 (2011).

- Yang, A., Akhtar, S. S., Amjad, M., Iqbal, S. & Jacobsen, S. E. Growth and physiological responses of quinoa to drought and temperature stress. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 202(6), 445-453 (2016).

- Maestro-Gaitán, I. et al. Genotype-dependent responses to long-term water stress reveal different water-saving strategies in Chenopodium quinoa Willd. Environ. Exp. Bot. 201, 104976 (2022).

- Al-Huqail, A. A. et al. Efficacy of priming wheat (Triticum aestivum) seeds with a benzothiazine derivative to improve drought stress tolerance. Funct. Plant Biol. https://doi.org/10.1071/FP22140 (2023).

- Wahab, A. et al. Plants’ physio-biochemical and phyto-hormonal responses to alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress: A comprehensive review. Plants 11, 1620. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11131620 (2022).

- Yasmeen, S. et al. Melatonin as a foliar application and adaptation in lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) crops under drought stress. Sustainability 14, 16345. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142416345 (2022).

- Salam, A. et al. Nano-priming against abiotic stress: A way forward towards sustainable agriculture. Sustainability 14, 14880. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214880 (2022).

- Ali, J. et al. Biochemical response of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) to selenium (Se) under drought stress. Sustainability 15, 5694. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075694 (2023).

- Hasanuzzaman, M. et al. Selenium toxicity in plants and environment: biogeochemistry and remediation possibilities. Plants 9(12), 1711 (2020).

- Djanaguiraman, M., Prasad, P. V. & Seppanen, M. Selenium protects sorghum leaves from oxidative damage under high temperature stress by enhancing antioxidant defense system. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48(12), 999-1007 (2010).

- Shahzadi, E. et al. Silicic and ascorbic acid induced modulations in photosynthetic, mineral uptake, and yield attributes of mung bean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek) under ozone stress. ACS Omega https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c00376 (2023).

- Mozafariyan, M., Pessarakli, M. & Saghafi, K. Effects of selenium on some morphological and physiological traits of tomato plants grown under hydroponic condition. J. Plant Nutr. 40(2), 139-144 (2017).

- Helaly, M. N., El-Hoseiny, H., El-Sheery, N. I., Rastogi, A. & Kalaji, H. M. Regulation and physiological role of silicon in alleviating drought stress of mango. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 118, 31-44 (2017).

- Wang, W., Vinocur, B. & Altman, A. Plant responses to drought, salinity and extreme temperatures: towards genetic engineering for stress tolerance. Planta 218(1), 1-14 (2003).

- Hasanuzzaman, M., Hossain, M. A. & Fujita, M. Selenium in higher plants: Physiological role, antioxidant metabolism and abiotic stress tolerance. J. Plant Sci. 5(4), 354-375 (2010).

- Shigeoka, S. et al. Regulation and function of ascorbate peroxidase isoenzymes. J. Exp. Bot. 53(372), 1305-1319 (2002).

- Victoria, O., Idorenyin, U. D. O., Asana, M., Shuoshuo, L., & Yang, S. (2023). Seed treatment with 24 -epibrassinolide improves wheat germination under salinity stress. Asian J. Agric. Biol. (3).

- Faryal, S. et al. Thiourea-capped nanoapatites amplify osmotic stress tolerance in Zea mays L. by conserving photosynthetic pigments, osmolytes biosynthesis and antioxidant biosystems. Molecules 27, 5744. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27185744 (2022).

- Taratima, W., Kunpratum, N., & Maneerattanarungroj, P. (2023). Effect of salinity stress on physiological aspects of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duchesne. ‘Laikaotok’) under hydroponic condition. Asian J. Agric. Biol. (2), 202101050.

- Tadina, N., Germ, M., Kreft, I., Breznik, B. & Gaberščik, A. Effects of water deficit and selenium on common buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench.) plants. Photosynthetica 45(3), 472-476 (2007).

- Ahmad, Z. et al. Selenium alleviates the adverse effect of drought in oilseed crops camelina (Camelina sativa L.) and canola (Brassica napus L.). Molecules 26(6), 1699 (2021).

- Jóźwiak, W. & Politycka, B. Effect of selenium on alleviating oxidative stress caused by a water deficit in cucumber roots. Plants 8(7), 217 (2019).

- Sosa-Zuniga, V., Brito, V., Fuentes, F. & Steinfort, U. Phenological growth stages of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) based on the BBCH scale. Ann. Appl. Biol. 171(1), 117-124 (2017).

- Iqbal, R. et al. Assessing the potential of partial root zone drying and mulching for improving the productivity of cotton under arid climate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28(46), 66223-66241 (2021).

- Waterhouse, A. L. Determination of total phenolics. Curr. Protocols Food Analyt. Chem. 6(1), I1-1 (2001).

- Iqbal, H., Yaning, C., Waqas, M., Shareef, M. & Raza, S. T. Differential response of quinoa genotypes to drought and foliage-applied H2O2 in relation to oxidative damage, osmotic adjustment and antioxidant capacity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safety 164, 344-354 (2018).

- Raza, M. A. S. et al. Physiological and biochemical assisted screening of wheat varieties under partial rhizosphere drying. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 116, 150-166 (2017).

- Gonzalez, J. A., Konishi, Y., Bruno, M., Valoy, M. & Prado, F. E. Interrelationships among seed yield, total protein and amino acid composition of ten quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) cultivars from two different agroecological regions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 92(6), 1222-1229 (2012).

- AOAC. (1990). Official Methods of Analysis, 15th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Inc.: Arlington, TX, USA, p. 70. ISBN 0-935584-42-0.

- Rosero, O., Marounek, M. & Břeňová, N. Phytase activity and comparison of chemical composition, phytic acid P content of four varieties of quinoa grain (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Acta Agronómica 62(1), 13-20 (2013).

- Chapman, H. D. & Pratt, P. E. Methods of Analysis for Soils, Plant and Water (California University, 1961).

- Steel, R. G. D., Torrie, J. H. & Dickey, D. A. Principles and Procedure of Statistics 178-182 (McGrow Hill Book Co., 1997).

- El-Fattah, A., Ahmed, D., Elhamid Hashem, F. A. & Abd-Elrahman, S. H. Impact of applying organic fertilizers on nutrient content of soil and lettuce plants, yield quality and benefit-cost ratio under water stress conditions. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2, 202102086 (2021).

- Waraich, E. A., Ahmad, R. & Ashraf, M. Y. Role of mineral nutrition in alleviation of drought stress in plants. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 5(6), 764-777 (2011).

- Nawaz, F. et al. Supplemental selenium improves wheat grain yield and quality through alterations in biochemical processes under normal and water deficit conditions. Food Chem. 175, 350-357 (2015).

- Teimouri, S., Hasanpour, J. & Tajali, A. A. Effect of Selenium spraying on yield and growth indices of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under drought stress condition. Int. J. Adv. Biol. Biomed. Res. 2(6), 2091-2103 (2014).

- Muhammad, F. et al. Ameliorating drought effects in wheat using an exclusive or co-applied rhizobacteria and zno nanoparticles. Biology 11(11), 1564 (2022).

- Chomchan, R., Siripongvutikorn, S. & Puttarak, P. Selenium bio-fortification: an alternative to improve phytochemicals and bioactivities of plant foods. Funct. Foods Health Disease 7(4), 263-279 (2017).

- Dong, J. Z. et al. Selenium increases chlorogenic acid, chlorophyll and carotenoids of Lycium chinense leaves. J. Sci. Food Agric. 93(2), 310-315 (2013).

- Lavu, R. V. S. et al. Use of selenium fertilizers for production of Se-enriched Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus): Effect on Se concentration and plant productivity. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 176(4), 634-639 (2013).

- Hawrylak-Nowak, B. Comparative effects of selenite and selenate on growth and selenium accumulation in lettuce plants under hydroponic conditions. Plant Growth Regul. 70(2), 149-157 (2013).

- Ardebili, Z. O., Ardebili, N. O., Jalili, S. & Safiallah, S. The modified qualities of basil plants by selenium and/or ascorbic acid. Turk. J. Bot. 39(3), 401-407 (2015).

- Khaliq, A. et al. Seed priming with selenium: consequences for emergence, seedling growth, and biochemical attributes of rice. Biol. Trace Element Res. 166(2), 236-244 (2015).

- Zhang, B., Li, F. M., Huang, G., Cheng, Z. Y. & Zhang, Y. Yield performance of spring wheat improved by regulated deficit irrigation in an arid area. Agric. Water Manag. 79(1), 28-42 (2006).

- Geerts, S., Raes, D., Garcia, M., Mendoza, J. & Huanca, R. Crop water use indicators to quantify the flexible phenology of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) in response to drought stress. Field Crops Res. 108(2), 150-156 (2008).

- Telahigue, D. C., Yahia, L. B., Aljane, F., Belhouchett, K., & Toumi, L. (2017). Grain yield, biomass productivity and water use efficiency in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) under drought stress. J. Sci. Agric. 222-232.

- Sajedi, N. A., Ardakani, M. R., Naderi, A., Madani, H. & Boojar, M. M. A. Response of maize to nutrients foliar application under water deficit stress conditions. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 4(3), 242-248 (2009).

- Haider, I. et al. Potential effects of biochar application on mitigating the drought stress implications on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under various growth stages. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 24(12), 974-981 (2020).

- Ahmed, A. H., Harb, E. M., Higazy, M. A. & Morgan, S. H. Effect of silicon and boron foliar applications on wheat plants grown under saline soil conditions. Int. J. Agric. Res. 3(1), 1-26 (2008).

- Domokos-Szabolcsy, E. et al. The interactions between selenium, nutrients and heavy metals in higher plants under abiotic stresses. Environ. Biodiversity Soil Security 1(2017), 5-31 (2017).

- Moharramnejad, S., Sofalian, O., Valizadeh, M., Asgari, A. & Shiri, M. Proline, glycine betaine, total phenolics and pigment contents in response to osmotic stress in maize seedlings. J. Biosci. Biotechnol. 4(3), 313-319 (2015).

- Sofy, M. R., Sharaf, A. E. M., Osman, M. S. & Sofy, A. R. Physiological changes, antioxidant activity, lipid peroxidation and yield characters of salt stressed barely plant in response to treatment with Sargassum extract. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 4(2), 90-109 (2017).

- Salem, N. et al. Effect of drought on safflower natural dyes and their biological activities. EXCLI J. 13, 1-18 (2014).

- Kusvuran, S. & Dasgan, H. Y. Effects of drought stress on physiological and biochemical changes in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Legume Res. 40(1), 55-62 (2017).

- Emam, M. M., Khattab, H. E., Helal, N. M. & Deraz, A. E. Effect of selenium and silicon on yield quality of rice plant grown under drought stress. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 8(4), 596-605 (2014).

- Anjum, S. A. et al. Gas exchange and chlorophyll synthesis of maize cultivars are enhanced by exogenously-applied glycinebetaine under drought conditions. Plant Soil Environ. 57(7), 326-331 (2011).

- Nawaz, F. et al. Selenium supply methods and time of application influence spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) yield under water deficit conditions. J. Agric. Sci. 155(4), 643-656 (2017).

- Jin, J. et al. Interaction between phosphorus nutrition and drought on grain yield, and assimilation of phosphorus and nitrogen in two soybean cultivars differing in protein concentration in grains. J. Plant Nutr. 29(8), 1433-1449 (2006).

- Nawaz, F., Ahmad, R., Waraich, E. A., Naeem, M. S. & Shabbir, R. N. Nutrient uptake, physiological responses, and yield attributes of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) exposed to early and late drought stress. J. Plant Nutr. 35(6), 961-974 (2012).

- Hajiboland, R., Sadeghzadeh, N., Ebrahimi, N., Sadeghzadeh, B. & Mohammadi, S. A. Influence of selenium in drought-stressed wheat plants under greenhouse and field conditions. Acta Agriculturae Slovenica 105(2), 175-191 (2015).

- Samarah, N. H. Effects of drought stress on growth and yield of barley. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 25, 145-149 (2005).

- Fatemi, R., Yarnia, M., Mohammadi, S., Vand, E. K. & Mirashkari, B. Screening barley genotypes in terms of some quantitative and qualitative characteristics under normal and water deficit stress conditions. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2, 2022071 (2023).

- Sadak, M. S. & Bakhoum, G. S. Selenium-induced modulations in growth, productivity and physiochemical responses to water deficiency in Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) grown in sandy soil. Biocatalysis Agric. Biotechnol. 44, 102449 (2022).

- Ibrahim Nossier, M., Hassan Abd-Elrahman, S. & Mahmoud El-Sayed, S. Effect of using garlic and lemon peels extracts with selenium on Vicia faba productivity. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 4, 202107276 (2022).

- Chen, C. C. & Sung, J. M. Priming bitter gourd seeds with selenium solution enhances germinability and antioxidative responses under sub-optimal temperature. Physiologia Plantarum 111(1), 9-16 (2001).

- Rayman, M. P. Selenium and human health. Lancet 379(9822), 1256-1268 (2012).

- Nawaz, F., Ashraf, M. Y., Ahmad, R. & Waraich, E. A. Selenium (Se) seed priming induced growth and biochemical changes in wheat under water deficit conditions. Biol. Trace Element Res. 151(2), 284-293 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the researchers supporting project number (RSPD2024R941), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, data collection, and writing-original draft, M.A.S.R., and M.U.A. Software, script evaluation, and editing, M.V., I.A, and R.I. Writing-review and editing, R.R., A.M.S.E., I.H., I.A., and A.E.M.M. Data curation and formal analysis, M.S.E., I.A, and M.U.A. Visualization and validation, M.S.E., R.I., M.A.S.R., Methodology and references, R.R., A.M.S.E., R.I., and M.U.A. Supervision, M.A.S.R. Funding Acquisition, R.R., A.M.S.E., I.A, and R.I. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed for final publication.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.A.S.R., M.U.A., R.I. or R.R.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© The Author(s) 2024

© The Author(s) 2024

Department of Agronomy, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Bahawalpur 63100, Pakistan. Department of Engineering and Engineering Technology, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Denver, CO 80217, USA. National Research Center of Intercropping, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Bahawalpur 63100, Pakistan. Department of Botany and Microbiology, College of Science, King Saud University, P.O. 2455, 11451 Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Department of Genetics and Development, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY 10032, USA. Institute of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, Christian-Albrechts-Univers ität Zu Kiel, 24118 Kiel, Germany. Department of Agroforestry & Environmental Science, Sylhet Agricultural University, Sylhet 3100, Bangladesh. Water Studies and Research Complex, National Water Research Center, Cairo 81525, Egypt. roy@plantnutrition.uni-kiel.de