DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-023-10337-7

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-16

تحفيز الطلاب من خلال الألعاب يعزز الدافع الداخلي، وإدراك الاستقلالية والترابط، ولكن له تأثير ضئيل على الكفاءة: تحليل ميتا ومراجعة منهجية

© المؤلفون 2024

الملخص

على الرغم من أن العديد من الدراسات في السنوات الأخيرة قد فحصت استخدام الألعاب كاستراتيجية تحفيزية في التعليم، إلا أن الأدلة المتعلقة بتأثيراتها على الدافع الداخلي غير متسقة. لدعم أو معارضة اعتماد الألعاب في التعليم، تفحص هذه الدراسة تأثيراتها على الدافع الداخلي للطلاب والعوامل التحفيزية الأساسية: الكفاءة المدركة، والاستقلالية، والترابط. في هذه المراجعة، قمنا بتحليل نتائج الدراسات التي تقارن التعلم المعزز بالألعاب مع التعلم غير المعزز بالألعاب المنشورة بين عامي 2011 و2022. أظهرت نتائج تحليلنا الشامل لـ 35 تدخلًا مستقلًا (تشمل 2500 مشارك) تأثيرًا كبيرًا ولكنه صغير بشكل عام لصالح التعلم المعزز بالألعاب مقارنة بالتعلم بدون ألعاب (Hedges’

المقدمة

أنها لم تشرح بشكل صريح ما إذا كانت تركز على الدافع الداخلي أو الخارجي، أو ما إذا كانت نتائج دافعها تشمل أيضًا مفاهيم أخرى. على سبيل المثال، أشار سايلر وهومر (2020) إلى نتائج تحفيزية تشمل مجموعة من المفاهيم مثل (الدافع الداخلي) والدوافع والتفضيلات والمواقف والانخراط والثقة والكفاءة الذاتية. وبالمثل، على الرغم من أن ريتزهاوت وآخرون (2021) أفادوا بحجم تأثير إيجابي وذو دلالة لتأثير الألعاب على النتائج العاطفية للطلاب، فإن النتائج العاطفية التي فحصوها شملت ليس فقط الدافع والاهتمام ولكن أيضًا كفاءة المتعلم الذاتية، والتعلم المدرك، وسهولة الاستخدام المدركة، والموقف. لقد تسبب هذا الغموض حول أنواع النتائج التحفيزية التي تم التحقيق فيها في الدراسات السابقة في بعض الارتباك حول تأثير الألعاب على الدافع الداخلي وجعل من الصعب اتخاذ قرار بشأن استخدام الألعاب في التعليم.

أسئلة البحث

RQ2. ما تأثير الألعاب على الدافع الداخلي للطلاب؟

RQ3. ما تأثير الألعاب على الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية للطلاب (أي الكفاءة، والاستقلالية، والترابط)؟

RQ4. ما هي التحديات الحالية لاستخدام الألعاب لتعزيز الدافع الداخلي؟

الخلفية المفاهيمية والنظرية

الدافع

بمهمة من أجل نتيجة خارجية (مثل الحصول على مكافأة أو تجنب العقوبة) هم أكثر عرضة للمشاركة في التعلم السطحي وغير المستدام (لي وآخرون، 2010)، وقد تكون الدافعية الخارجية لدى الطلاب مرتبطة بنتائج سلبية معينة (كلانتون هارباين، 2015). على سبيل المثال، بمجرد توقف المكافأة الخارجية، قد يتوقف هؤلاء الطلاب عن إظهار السلوك المحدد. كما ذكر زيشيرمان وكانينغهام (2011، ص. 27)، “بمجرد أن تبدأ في منح شخص ما مكافأة، يجب أن تبقيها في حلقة المكافأة تلك إلى الأبد.”

| شرط المكافأة | الوصف | ||

| غير مشروط بالمهمة | تُقدم المكافأة مقابل الموافقة على المشاركة، أو الحضور إلى الدراسة، أو الانتظار للباحث | ||

| المكافآت المقدمة لأداء جيد |

|

||

| المكافآت المقدمة للقيام بمهمة |

|

||

| المكافآت المقدمة لإنهاء أو إكمال مهمة |

|

||

| المكافآت المقدمة عن كل وحدة تم حلها | تُقدم المكافأة عن كل وحدة، أو لغز، أو مشكلة، إلخ، تم حلها | ||

| المكافآت المقدمة لتجاوز درجة |

|

||

| المكافآت المقدمة لتجاوز معيار | تُقدم المكافأة لتلبية أو تجاوز أداء الآخرين في المهمة (معيار نسبي) |

نظرية تحديد الذات كإطار عمل

(1) تشير الكفاءة إلى الشعور بإتقان تحدٍ وتزدهر عندما يتم تلقي تعليقات مباشرة وإيجابية (معلوماتية) (ديسي وريان، 2004). تحدث التأثيرات الإيجابية للشعور بالكفاءة على الدافعية الذاتية عادةً عندما تكون مصحوبة بإحساس بالاستقلالية (ديسي وريان، 2004).

(2) تشير الاستقلالية إلى الحرية النفسية والإرادة لأداء المهام (ديسي وريان، 2000، ص. 231؛ فان دن بروك وآخرون، 2010؛ فانستينكيست وآخرون، 2010). إن الشعور باتخاذ قرارات بناءً على اهتمامات الفرد هو تعبير عن الحرية النفسية (ديسي وريان، 2012؛ ريان وديسي، 2002)، بينما الإرادة هي الشعور بالتصرف دون ضغط أو إكراه خارجي (فانستينكيست وآخرون، 2010). عندما يشعر الشخص بإحساس بالاستقلالية، يظهر اهتمامًا أكبر في النشاط وثقة أكبر في المشاركة فيه، مما يعزز الأداء ويزيد من الاستمرارية (ريان وديسي، 2000د).

(3) تشير الترابط إلى إحساس بالانتماء والاتصال (ريان وديسي، 2020). تمثل الرغبة الأساسية للفرد في الاندماج في البيئة الاجتماعية (باوميستر ولياري، 1995؛ ديسي وريان، 2000، 2004). عندما يشكل الأفراد

العلاقات الحميمة والشعور بالاتصال مع الآخرين، يدركون مستويات أكبر من الترابط (ديشي ورايان، 2000). في البيئات التي تتميز بإحساس الترابط، من المرجح أن تزدهر الدوافع الداخلية (رايان وديشي، 2000د؛ رايان ولا غارديا، 2000).

تحفيز الألعاب

تحفيز الألعاب والدافع الداخلي

(1) حيث تشير الكفاءة إلى الشعور بأن الشخص ينجح عند التفاعل مع البيئة (ريغبي ورايان، 2011؛ فانستينكيست ورايان، 2013)، يمكن أن تساعد آليات التغذية الراجعة في التعلم المحفز بالألعاب في تلبية احتياجات الطلاب من الكفاءة. على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن تتواصل آليات التغذية الراجعة مثل النقاط، الميداليات، ولوحات المتصدرين بصريًا إنجازات الطلاب وكفاءتهم (شي وآخرون، 2019). بالإضافة إلى ذلك، لتحفيز الطلاب بشكل فعال، يجب تصميم المهام في التعلم المحفز بالألعاب بحيث لا تكون سهلة ولكنها خارج منطقة الراحة للطلاب عند مستوى من الصعوبة يجدونه قابلًا للتحقيق (روي وزمان، 2017). عندما تكون المهام عند هذا المستوى من الصعوبة، يستمر الطلاب في تحسين أنفسهم لتحقيقها (ديشي ورايان، 1985؛ بينغ وآخرون، 2012).

(2) حيث تشير الاستقلالية إلى شعور الشخص بالحرية في أفعاله (رايان وديشي، 2020)، يمكن أن يساعد توفير الخيارات للطلاب في تلبية احتياجاتهم من الاستقلالية. على سبيل المثال، تناول جونز وآخرون (2022) حاجة الطلاب للاستقلالية من خلال توفير خيارات متعددة للمهام التي يمكن أن يشارك فيها الطلاب، مما سمح لهم باختيار مسارهم الخاص لتحقيق النتائج المرغوبة (الدرجات). النتائج

أظهرت أن الطلاب الذين شاركوا في التعلم المحفز بالألعاب كان لديهم شعور أعلى بالاستقلالية والدافع الداخلي مقارنةً بأولئك الذين شاركوا في التعلم غير المحفز بالألعاب.

(3) حيث تشير الترابط إلى شعور الشخص بالانتماء إلى مجموعة (رايان وديشي، 2017)، يمكن أن تساعد الاتصالات المتكررة ومشاركة الأفكار عبر العمل الجماعي في التعلم المحفز بالألعاب المتعلمين في إدراك الترابط (فرناندز-ريو وآخرون، 2021). علاوة على ذلك، يمكن أن تخلق المنافسة الجماعية شعورًا بالانتماء إلى فريق من خلال تعزيز الإحساس بالمجتمع (فان روي وزمان، 2019).

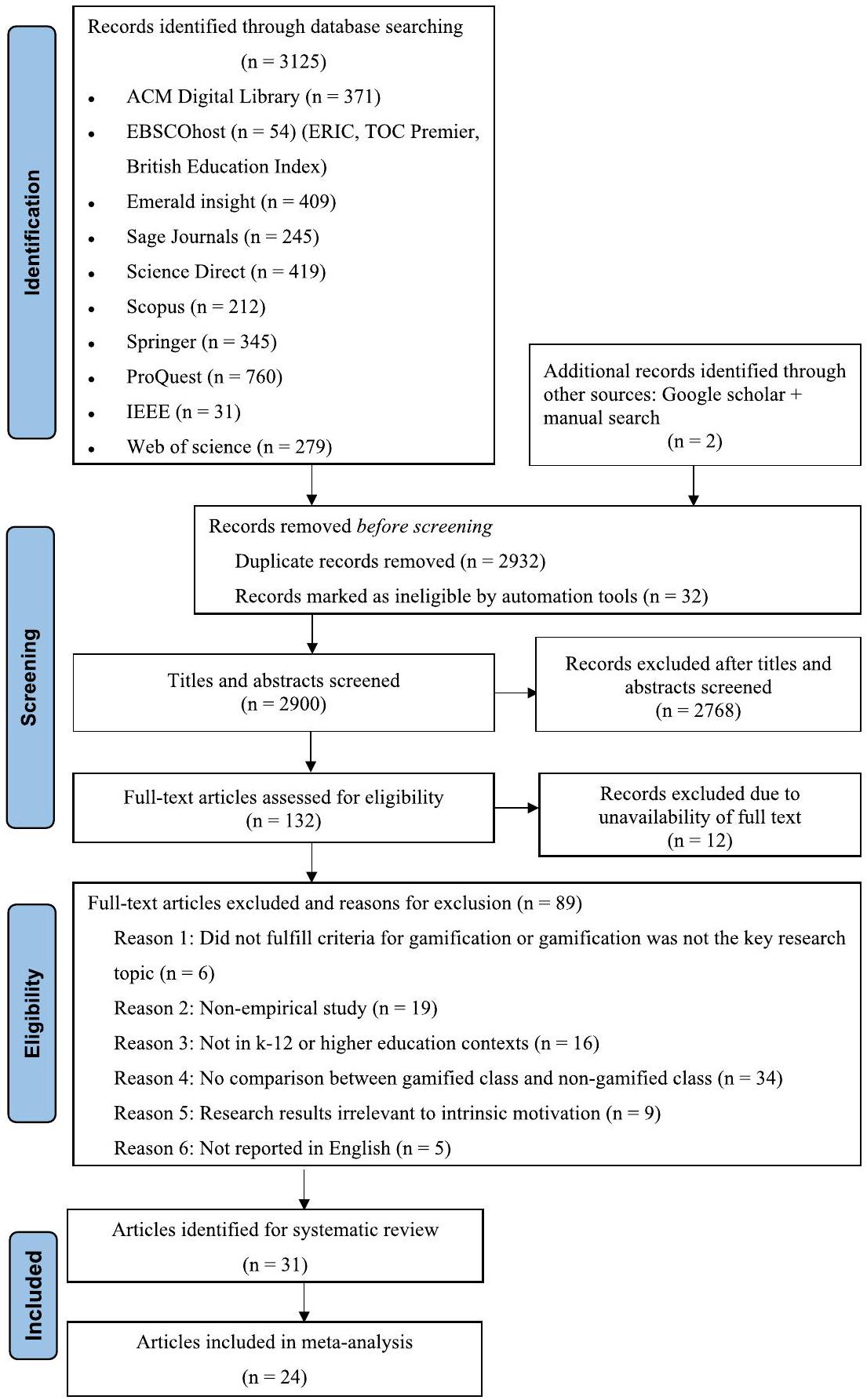

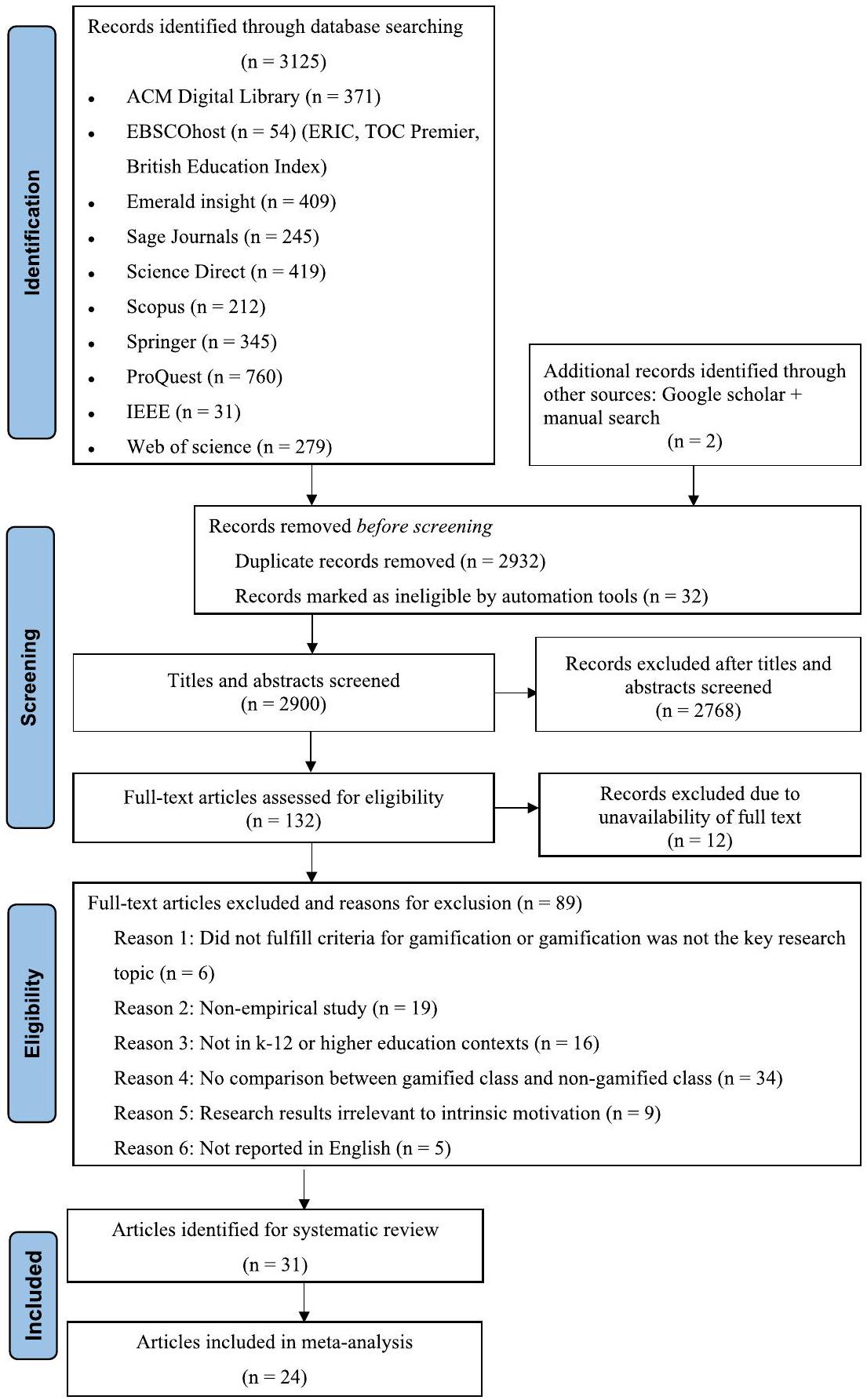

طرق

استراتيجية البحث

سلسلة البحث

التغيرات الصرفية لـ “تحفيز الألعاب”، “محفز بالألعاب”، و”تحفيز”. احتوت المجموعة الثانية من مصطلحات البحث على مصطلحات تتعلق بالدافع الداخلي. استخدمنا التعبير “intrinsic motiva*” لتغطية جميع التغيرات الصرفية لـ “الدافع الداخلي”، “مدفوع داخليًا”، و”مدفوع داخليًا”. احتوت المجموعة الثالثة على مصطلحات تتعلق بالدورة، والفصل الدراسي، والتعليم، أو التعلم. فيما يلي سلسلة البحث التي تم استخدامها: gamif* AND intrinsic motiva* AND (course OR class* OR educat* OR learn*).

معايير الاختيار

اختيار الدراسة

تحليل البيانات

استخراج البيانات

حساب أحجام التأثير

تحليل التباين

(1) خصائص المشاركين. يهدف إلى تحليل ما إذا كانت هناك أي اختلافات بين المشاركين عبر مستويات المدارس والمناطق الجغرافية.

(2) خصائص الدورة. تهدف إلى تحليل ما إذا كانت هناك أي اختلافات عبر مواضيع الدورة وما إذا كانت مدد التدخلات التجريبية وأحجام العينات قد أثرت على حجم التأثير النهائي (تشين وآخرون، 2018؛ زينغ وآخرون، 2016). لضمان تحليل دقيق، استخدمنا نظام ترميز حجم العينة المعدل من تشين وآخرون (2018) ونظام ترميز الوقت من باي وآخرون (2020) (انظر الجدول 3).

(3) مستوى التحكم. يهدف إلى تحديد ما إذا كانت مستويات التحكم المختلفة المطبقة في التدخلات قد أثرت على حجم التأثير النهائي (فريمان وآخرون، 2014). وفقًا لباي وآخرون (2020)، يمكن اعتبار مستويين من التحكم: معادلة الطلاب ومعادلة المعلم. يمكن تصنيف الدراسة إلى واحدة من ثلاثة أنواع بناءً على معادلة الطلاب: (1) مجموعة عدم الفرق الكبير، أي أن الدراسة أجريت وأبلغت عن تقييم إحصائي أولي لمجموعتي التحكم والتجريب، وأظهرت أن الطلاب في المجموعتين كانوا في البداية في نفس المستوى بطريقة ذات دلالة إحصائية؛ (2) مجموعة الفرق الكبير، أي أن نتائج التقييم الإحصائي الأولي أظهرت أن المستويات الأولية للطلاب كانت مختلفة بين المجموعتين؛ و(3) عدم وجود بيانات مقدمة، أي أن الدراسة لم تقدم بيانات إحصائية حول ما إذا كانت المستويات الأولية للطلاب متكافئة. وبالمثل، يمكن تصنيف الدراسة إلى واحدة من ثلاثة أنواع بناءً على معادلة المعلم: (1) معلم متطابق، أي أن نفس المعلم أشرف على مجموعتي العلاج والتحكم؛ (2) معلم مختلف، أي أن معلمين أو أكثر أشرفوا على مجموعتي العلاج والتحكم على التوالي؛ و(3) عدم وجود بيانات مقدمة، أي أن المؤلفين لم يقدموا هذه المعلومات عن المعلمين.

(4) عدد عناصر اللعبة. يهدف إلى التحقيق فيما إذا كان عدد عناصر اللعبة المستخدمة قد أثر على حجم التأثير.

(5) نوع المكافأة وشرط المكافأة. يهدف إلى تحديد ما إذا كان نوع المكافأة وشرط المكافأة قد أثرا على أحجام التأثير. تم تصنيف المكافآت إلى مكافآت لفظية (أي، الثناء أو التعليقات الإيجابية) ومكافآت ملموسة (مثل، الحلويات، الألعاب، والشارات). قمنا بتشفير شروط المكافأة باستخدام إطار عمل شروط المكافأة الذي طوره كاميرون وآخرون (2001) (انظر الجدول 1).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| حجم العينة | <50 | 50-100 | 100-150 |

|

لم يتم تقديم بيانات | |

| مدة التدخل | <1 أسبوع | 1 أسبوع-1 شهر | 1 شهر-3 أشهر | 3 أشهر-1 فصل دراسي |

|

لم يتم تقديم بيانات |

تحليل انحياز النشر

تحليل نوعي

النتائج

خصائص الدراسات

| الجدول 4 مخطط التشفير القائم على نظرية تحديد الذات لتشفير التحديات المرتبطة باستخدام الألعاب | |||||||

| التحديات المتعلقة بالكفاءة | التحديات المتعلقة بالعلاقة | التحديات المتعلقة بالاستقلالية | |||||

| الفشل في تحقيق شعور بالتمكن، شعور بالنجاح | الفشل في تحقيق شعور بالاتصال مع الآخرين | الفشل في تحقيق شعور بالمبادرة وملكية الأفعال الفردية | |||||

|

|

– نقص الاستقلالية في اختيار محتوى التعلم والأنشطة | |||||

RQ1. ما الأدوات التي تم استخدامها لقياس الدافع الداخلي للطلاب في نهج الفصل الدراسي المعتمد على الألعاب؟

استبيانات التقرير الذاتي

مقابلة

RQ2. ما هو تأثير التلعيب على الدافع الداخلي للطلاب؟

حجم التأثير الكلي

| اسم الدراسة | نتيجة | إحصائيات لكل دراسة | g هيدجز وفترة الثقة 95% | |||||||

| g هيدجز | الحد الأدنى | الحد الأقصى | قيمة p | |||||||

| بروما وآخرون (2019). | IM – NC | 0.072 | -0.409 | 0.553 | 0.769 | |||||

| بروما وآخرون (2019). | [M – NF | 0.096 | -0.389 | 0.580 | 0.٦٩٩ | |||||

| تشالكو وآخرون (2019). | أنا | 0.952 | 0.213 | 1.690 | 0.012 | |||||

| تشالكو وآخرون (2017). | أنا | 0.470 | -0.036 | 0.977 | 0.069 | |||||

| دي شوتير_أبيلي (2014). | أنا | -1.148 | -1.812 | -0.484 | 0.001 | |||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020). _ التجربة 1 | [M – التجربة 1 | -0.513 | -1.136 | 0.111 | 0.107 | |||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020). _ التجربة 2 | [M – التجربة 2 | 0.017 | -0.531 | 0.565 | 0.950 | |||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020) _ التجربة 3 | [M – التجربة 3 | 0.009 | -0.541 | 0.559 | 0.974 | |||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020). _ التجربة 4 | [M – التجربة 4 | -1.329 | -1.943 | -0.715 | 0.000 | |||||

| فيريز-فاليرو وآخرون (2020). | أنا | 0.146 | -0.201 | 0.492 | 0.٤٠٩ | |||||

| غارسيا-كابوت وآخرون (2020). | أنا | 0.304 | -0.437 | 1.044 | 0.422 | |||||

| حزان وآخرون (2018). | أنا | 0.276 | -0.317 | 0.869 | 0.361 | |||||

| يورغلايتس وآخرون (2019أ). – هو | أنا | 1.326 | 0.948 | 1.704 | 0.000 | |||||

| كييوسكي وآخرون (2018). | أنا | -0.333 | -1.196 | 0.530 | 0.449 | |||||

| أورتيز روجاس وآخرون (2017). | أنا | 0.183 | -0.207 | 0.572 | 0.358 | |||||

| أورتيز-روخاس وآخرون (2019). | أنا | 0.271 | -0.155 | 0.697 | 0.212 | |||||

| رودريغيز وآخرون (2021). | أنا | 0.١٠٣ | -0.758 | 0.963 | 0.815 | |||||

| سايلر وآخرون (2021). | أنا | 0.835 | 0.550 | 1.120 | 0.000 | |||||

| سيغورا-روبليز وآخرون (2020). | أنا | 1.934 | 1.345 | ٢.٥٢٢ | 0.000 | |||||

| ستانسبوري-إيرنست (2017). | أنا | 0.640 | 0.226 | 1.054 | 0.002 | |||||

| ستويانوفا وآخرون (2017). | أنا | 0.037 | -0.367 | 0.440 | 0.859 | |||||

| تصدق وآخرون (2021). | أنا | -0.322 | -0.928 | 0.284 | 0.298 | |||||

| ترايبلمير وآخرون (2020). | أنا | -0.313 | -0.541 | -0.084 | 0.007 | |||||

| جونز وآخرون (2022). | أنا | -0.271 | -0.820 | 0.277 | 0.332 | |||||

| هونغ ومسعود. (2014). | أنا | 0.587 | 0.076 | 1.097 | 0.024 | |||||

| ليتاو وآخرون (2022). | IM – PT – B | 0.657 | -0.096 | 1.410 | 0.087 | |||||

| ليتاو وآخرون (2022). | IM – PT – L | -0.297 | -1.020 | 0.427 | 0.421 | |||||

| لقطا ct وآخرون. (2022). | IM – PT – PBL | 0.669 | -0.072 | 1.409 | 0.077 | |||||

| ليتاو وآخرون (2022). | [م – المملكة المتحدة – ب | 0.261 | -0.830 | 1.351 | 0.639 | |||||

| ليتاو وآخرون (2022). | LM – المملكة المتحدة – L | 1.123 | -0.059 | 2.305 | 0.063 | |||||

| ليتاو وآخرون (2022). | IM – المملكة المتحدة – P | 0.093 | -0.993 | 1.179 | 0.867 | |||||

| ليتاو وآخرون (2022). | [م – المملكة المتحدة – PBL | 1.393 | 0.162 | ٢.٦٢٥ | 0.027 | |||||

| ليتاو وآخرون (2022). | [M- PT – P | -0.523 | -1.256 | 0.209 | 0.161 | |||||

| فيماندز-ريو وآخرون (2021). | أنا | 1.466 | 0.872 | 2.060 | 0.000 | |||||

| سوتوس-مارتينيز وآخرون (2022) | أنا | 0.499 | 0.259 | 0.738 | 0.000 | |||||

| 0.257 | 0.043 | 0.471 | 0.019 | |||||||

| -٤.٠٠ | -2.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | ٤.٠٠ | ||||||

| المشرف |

|

|

قيمة P |

| خصائص المشاركين | |||

| مستوى المدرسة | 2.820 | 1 | . 093 |

| الجغرافيا | ٥٫٤٩٠ | ٣ | . 139 |

| خصائص المنهج الدراسي | |||

| حجم العينة | 1.231 | ٣ | . 746 |

| تصميم البحث | 3.119 | ٣ | . 374 |

| مدة التدخل | 9.509 | ٤ | .050* |

| مستوى التحكم | |||

| معادلة الطلاب | 0.463 | 2 | . 794 |

| معادلة المدرب | 12.596 | 2 | .002* |

| عدد عناصر اللعبة | |||

| عدد عناصر اللعبة | 0.975 | 2 | . 614 |

| المشرف | ن |

|

|

فترة الثقة 95% |

|

|

| LL | UL | |||||

| نوع تعويض المكافأة | 99.486 (.000*) | |||||

| كل وحدة تم حلها | 10 | . 041 | . 401 | . 016 | . 785 | |

| كل وحدة تم حلها + تجاوز درجة | 2 | . 631 | . 084 | – . 258 | . 425 | |

| إكمال مهمة + كل وحدة تم حلها + تجاوز معيار | 2 | . 768 | – . 085 | – . 647 | . 478 | |

| كل وحدة تم حلها + تجاوز درجة + تجاوز معيار | 2 | . 005 | . ٦٣٣ | . 187 | 1.079 | |

| إكمال مهمة + كل وحدة تم حلها + تجاوز درجة + تخطي معيار | 2 | . 000 | -1.246 | – 1.697 | -. 795 | |

| أداء مهمة + إكمال مهمة + كل وحدة تم حلها + تجاوز درجة | ٣ | . 575 | . 325 | -. 809 | 1.459 | |

| المشرف | ن | تحوطات

|

|

فترة الثقة 95% |

|

|

| LL | UL | |||||

| معادلة المدرب | 12.596 (.002*) | |||||

| مدرسون مختلفون | ٨ | – . 143 | 0.176 | -0.487 | 0.202 | |

| مدرب متطابق | 9 | . 613 | 0.124 | 0.371 | 0.855 | |

| لا توجد بيانات مُبلغ عنها | ١٨ | . 264 | 0.187 | -0.102 | 0.630 | |

| مدة التدخل | 9.509 (.050*) | |||||

| <1 أسبوع | 12 | . 371 | . 153 | . 071 | . 672 | |

| 1 أسبوع – 1 شهر | ٥ | . 243 | . ٢٠٨ | – . 165 | . 651 | |

| 1 شهر – 3 أشهر | ٧ | . 610 | . 253 | . ١١٥ | 1.105 | |

| > = 1 فصل | ٨ | – . 068 | . ٣٣٧ | – . 729 | . ٥٩٢ | |

| لم يتم الإبلاغ | ٣ | – . 127 | . 146 | – . 414 | . 159 | |

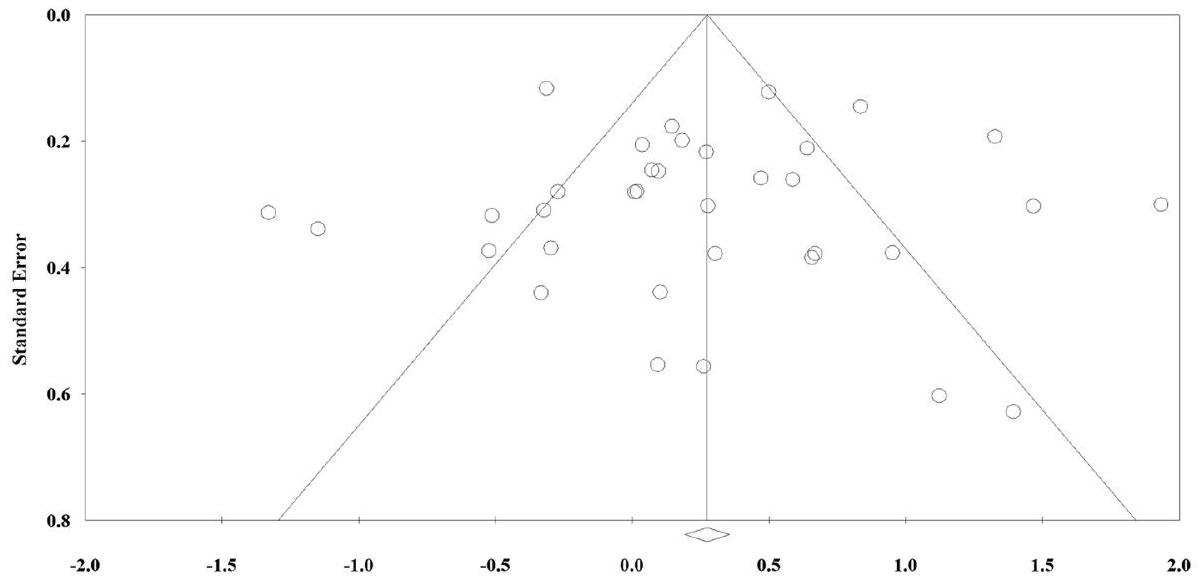

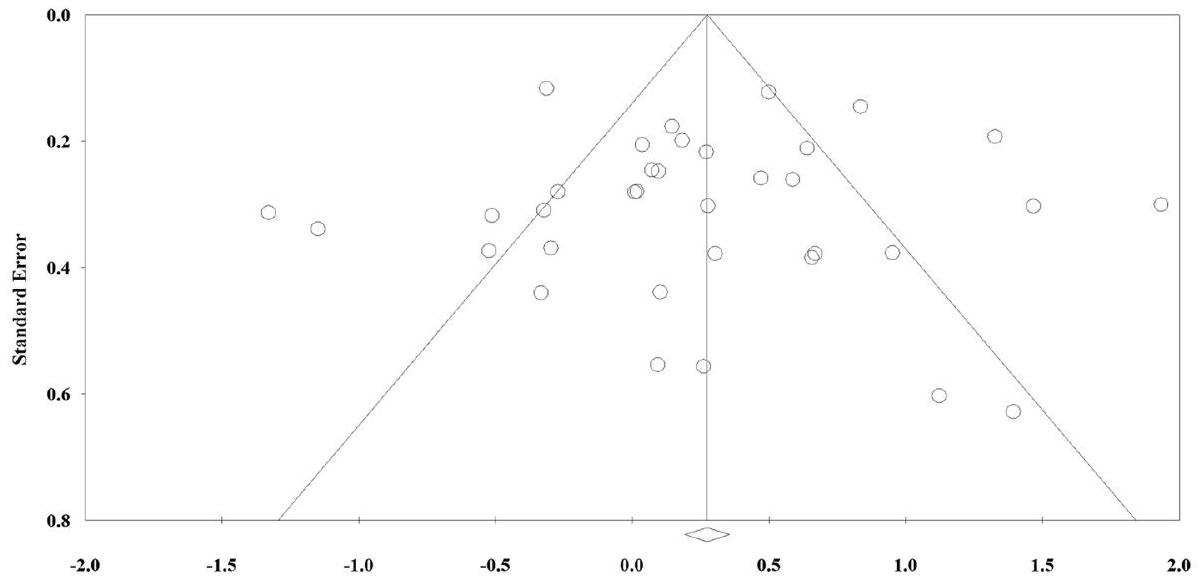

تحيز النشر

RQ3: ما هو تأثير التلعيب على الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية التي تسهم في الدافع الداخلي؟

| اسم الدراسة | نتيجة | إحصائيات لكل دراسة | g هيدجز وفترة الثقة 95% | |||||||

| g هيدجز | الحد الأدنى | الحد الأقصى | قيمة p | |||||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020). التجربة 3 | الكفاءة – التجربة 3 | 0.007 | -0.543 | 0.557 | 0.980 | |||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020)._التجربة 1 | الكفاءة – التجربة 1 | -0.072 | -0.687 | 0.543 | 0.818 | |||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020). التجربة 2 | الكفاءة – الخبرة 2 | 0.020 | -0.528 | 0.568 | 0.942 | |||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020). التجربة 4 | الكفاءة – الخبرة 4 | -0.358 | -0.937 | 0.220 | 0.225 | |||||

| حزان وآخرون (2018). | كفاءة | 0.502 | -0.097 | 1.101 | 0.100 | |||||

| يورغيلاتيس وآخرون (2019أ). – cst | كفاءة | 1.115 | 0.746 | 1.483 | 0.000 | |||||

| سايلر وآخرون (2021). | كفاءة | -0.061 | -0.335 | 0.212 | 0.660 | |||||

| سيغورا-روبليز وآخرون (2020). | كفاءة | -0.433 | -0.923 | 0.057 | 0.083 | |||||

| جونز وآخرون (2022). | كفاءة | 0.696 | 0.133 | 1.259 | 0.015 | |||||

| هونغ ومسعود. (2014). | كفاءة | 0.600 | 0.089 | 1.111 | 0.021 | |||||

| فيماندز-ريو وآخرون (2021). | كفاءة | 0.764 | 0.219 | 1.310 | 0.006 | |||||

| سوتوس-مارتينيز وآخرون (2022) | كفاءة | 0.429 | 0.190 | 0.667 | 0.000 | |||||

| 0.277 | 0.001 | 0.553 | 0.049 | |||||||

| -4.00 | -2.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | ٤.٠٠ | ||||||

| اسم الدراسة | نتيجة | إحصائيات لكل دراسة | g هيدجز وفترة الثقة 95% | ||||||

| g هيدجز | الحد الأدنى | الحد الأقصى | قيمة p | ||||||

| تشالكو وآخرون (2019). | الاستقلالية | 0.810 | 0.083 | 1.537 | 0.029 | ||||

| تشالكو وآخرون (2017). | الاستقلالية | 0.825 | 0.304 | 1.346 | 0.002 | ||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020). التجربة 3 | الاستقلال – التجربة 3 | 0.191 | -0.359 | 0.742 | 0.496 | ||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020)._التجربة الأولى | الاستقلال – التجربة 1 | -0.603 | -1.230 | 0.024 | 0.059 | ||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020). التجربة 2 | الاستقلال – التجربة 2 | 0.168 | -0.381 | 0.716 | 0.549 | ||||

| فاسي-شو وآخرون (2020). التجربة 4 | الاستقلال – تجربة 4 | -0.464 | -1.044 | 0.117 | 0.117 | ||||

| سيغورا-روبليز وآخرون (2020). | الاستقلالية | 3.889 | ٣.٠٦٠ | ٤.٧١٩ | 0.000 | ||||

| جونز وآخرون (2022). | الاستقلالية | 1.310 | 0.706 | 1.913 | 0.000 | ||||

| هونغ ومسعود. (2014). | الاستقلالية | 0.076 | -0.424 | 0.576 | 0.766 | ||||

| فيماندز-ريو وآخرون (2021). | الاستقلالية | 0.644 | 0.104 | 1.183 | 0.019 | ||||

| سوتوس-مارتينيز وآخرون (2022) | الاستقلالية | 0.565 | 0.325 | 0.806 | 0.000 | ||||

| -٤.٠٠ | -2.00 | 0.00 | ٤.٠٠ | ||||||

| اسم الدراسة | نتيجة | إحصائيات لكل دراسة | g هيدجز وفترة الثقة 95% | ||||||||

| g هيدجز | الحد الأدنى | الحد الأقصى | قيمة p | ||||||||

| سايلر وآخرون (2021). | الترابط | 0.594 | 0.315 | 0.874 | 0.000 | ||||||

| سيغورا-روبليز وآخرون (2020). | الترابط | ٥.٨٠٥ | ٤.٦٨٩ | 6.921 | 0.000 | ||||||

| فرنانديز-ريو وآخرون (2021). | الترابط | 0.993 | 0.435 | 1.551 | 0.000 | ||||||

| سوتوس-مارتينيز وآخرون (2022) | الترابط | 0.581 | 0.340 | 0.822 | 0.000 | ||||||

| -٤.٠٠ | -2.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | ٤.٠٠ | |||||||

RQ4. ما هي التحديات الحالية التي يجب أن تتناولها أبحاث الت gamification؟

| المواضيع والمواضيع الفرعية (النسبة المئوية) | استشهادات تمثيلية |

| نظرية تحديد الذات | |

| نقص في الكفاءة المدركة | |

| عدم الراحة بين المشاركين الأقل تصنيفًا في قائمة المتصدرين العامة (23%) | “يمكن أن يكون للطريقة التي تم بها تقديم المكافآت للطلاب دور في تصورهم للبرنامج. على سبيل المثال، بينما حصل جميع الطلاب على نقاط ومكان في لوحة المتصدرين، فإن حقيقة أن الطلاب الثلاثة الأوائل فقط هم من حصلوا على شارات قد تكون قد حدت من تأثير هذا العنصر من عناصر الألعاب. علاوة على ذلك، قد يكون التواجد في المراتب العليا في لوحة المتصدرين أو الحصول على شارة مشجعًا بشكل خاص فقط للطلاب المعنيين، بينما قد يكون بقية الفصل قد تأثر سلبًا” (أندرادي وآخرون، 2020، ص. 17) |

| عدم ملاءمة مستوى صعوبة المهام الم gamified (10%) | “لم يكن الطلاب مهتمين ببعض الشارات، مثل تلك التي تُمنح لمجرد حضور الدروس… بعض الشارات، مثل شارات الحضور، لم تُعتبر ذات قيمة حيث أراد الطلاب شارات تتطلب جهدًا لتحقيق الإنجاز وليس تلك التي ‘يمكن للجميع الحصول عليها’” (FaceyShaw et al., 2020، ص. 42) |

| عدم الإلمام بعناصر الت gamification (10%) | “بعض الطلاب أبلغوا أيضًا عن عدم وعيهم بالشارات. قد يكون هذا قد أدى إلى الانخفاض الملحوظ إحصائيًا في الدرجات المتعلقة بالشعور بالكفاءة” (فاسي-شاو وآخرون، 2020، ص. 46) |

| نقص في الشعور بالاستقلالية | |

| نقص الاستقلالية في اختيار محتوى التعلم والأنشطة (19%) | “استنادًا إلى هذه النتائج والطريقة التي استجاب بها الطلاب للدورة في الفصل، يجب تقديم التوصيات التالية: … منح الطلاب حرية الاختيار في كيفية إظهار إتقانهم للمواد” (De Schutter & Abeele, 2014، ص. 7) |

نقاش

قياس الدافع الذاتي

لقد وجدت الدراسات المتعلقة بالدافع الداخلي نتائج مشابهة لتلك التي توصلت إليها الدراسات التي استخدمت سلوك الاختيار الحر (ديشي وآخرون، 1999). إن اعتماد مقاييس سلوك الاختيار الحر للدافع الداخلي، مثل السماح للمشاركين باختيار الاستمرار في الانخراط في مهمة دون أي مكافأة (ديشي ورايان، 2004) وتسجيل النتائج، قد يوفر رؤى إضافية.

أثر التلعيب على الدافع الداخلي

عندما تكون معايير الأداء مصنفة وقابلة للتحقيق، فإن المكافآت لها تأثير إيجابي (كاميرون وآخرون، 2001).

أثر الت gamification على الاحتياجات النفسية الأساسية

تحديات استخدام التلعيب لتسهيل الدافع الداخلي والحلول المحتملة

القيود

المجرب غير مدرك لما إذا كانوا يستمرون في أداء نشاط خلال فترة الاختيار الحر وبالتالي يقررون ما إذا كانوا سيستمرون بناءً على دافعهم الخاص.

الخاتمة

النتائج عبر الدراسات، يجب أولاً أن يستند تصميم التدخلات التعليمية القائمة على الألعاب إلى إطار نظري شامل، ويجب أن تقدم الدراسات وصفًا واضحًا للتنظيمات التعليمية وأنواع الأنشطة التعليمية المستخدمة. ثانيًا، يجب الإبلاغ عن جميع جوانب تصميم الدراسة، مثل خصائص الدراسة وترتيبات مجموعة التحكم، بشفافية لتسهيل تحقيق شامل للتحليل التلوي للعوامل المؤثرة على فعالية الألعاب.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو صيغة، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت هناك تغييرات قد تم إجراؤها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يُذكر خلاف ذلك في سطر ائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة واستخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارةhttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Andrade, P., Law, E. L.-C., Farah, J. C., & Gillet, D. (2020). Evaluating the effects of introducing three gamification elements in STEM educational software for secondary schools. 32nd Australian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction

Annetta, L. A. (2010). The “I’s” have it: A framework for serious educational game design. Review of General Psychology, 14(2), 105-113.

Armstrong, M. B., & Landers, R. N. (2017). An evaluation of gamified training: Using narrative to improve reactions and learning. Simulation & Gaming, 48(4), 513-538.

Bai, S., Hew, K. F., & Huang, B. (2020). Does gamification improve student learning outcome? Evidence from a meta-analysis and synthesis of qualitative data in educational contexts. Educational Research Review, 30, 100322.

Baker, M. (2016). Statisticians issue warning on P values. Nature, 531(7593), 151-151.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

Boyle, E. A., Hainey, T., Connolly, T. M., Gray, G., Earp, J., Ott, M., Lim, T., Ninaus, M., Ribeiro, C., & Pereira, J. (2016). An update to the systematic literature review of empirical evidence of the impacts and outcomes of computer games and serious games. Computers & Education, 94, 178-192.

Brom, C., Stárková, T., Bromová, E., & Děchtěrenko, F. (2019). Gamifying a simulation: Do a game goal, choice, points, and praise enhance learning? Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(6), 1575-1613.

Cameron, J., Banko, K. M., & Pierce, W. D. (2001). Pervasive negative effects of rewards on intrinsic motivation: The myth continues. The Behavior Analyst, 24(1), 1-44.

Cameron, J., & Pierce, W. D. (1994). Reinforcement, reward, and intrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 64(3), 363-423.

Cameron, J., & Pierce, W. D. (2002). Rewards and intrinsic motivation: Resolving the controversy. Bergin & Garvey.

Cerasoli, C. P., Nicklin, J. M., & Ford, M. T. (2014). Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: A 40-year meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 980.

Challco, G. C., Isotani, S., & Bittencourt, I. I. (2019). The effects of ontology-based gamification in scripted collaborative learning. 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT),

Clanton Harpine, E. (2015). Is Intrinsic Motivation Better Than Extrinsic Motivation? In E. Clanton Harpine (Ed.), Group-centered prevention in mental health: Theory, training, and practice (pp. 87-107). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19102-7_6

Costa, J. P., Wehbe, R. R., Robb, J., & Nacke, L. E. (2013). Time’s up: studying leaderboards for engaging punctual behaviour. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Gameful Design, Research, and Applications,

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2022). Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI). https://selfdeterminationtheory. org/intrinsic-motivation-inventory/#toc-description

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 627.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation in education: Reconsidered once again. Review of Educational Research, 71(1), 1-27.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the selfdetermination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Handbook of self-determination research. University Rochester Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 182.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In R. M. E. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation (pp. 85-107). Oxford University Press.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: defining “gamification”. Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments,

Deterding, S. (2012). Gamification: designing for motivation. Interactions, 19(4), 14-17.

Dicheva, D., Dichev, C., Agre, G., & Angelova, G. (2015). Gamification in education: A systematic mapping study. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 18(3), 75-88.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2013). Teaching and researching: Motivation. Routledge.

Educause. (2011). 7 things you should know about gamification. https://library.educause.edu/resources/ 2011/8/7-things-you-should-know-about-gamification

Facey-Shaw, L., Specht, M., van Rosmalen, P., & Bartley-Bryan, J. (2020). Do Badges Affect Intrinsic Motivation in Introductory Programming Students? Simulation & Gaming, 51(1), 33-54. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1046878119884996

Fernandez-Rio, J., Zumajo-Flores, M., & Flores-Aguilar, G. (2021). Motivation, basic psychological needs and intention to be physically active after a gamified intervention programme. European Physical Education Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X21105288

Ferriz-Valero, A., Østerlie, O., García Martínez, S., & García-Jaén, M. (2020). Gamification in physical education: Evaluation of impact on motivation and academic performance within higher education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4465.

Fransen, K., Boen, F., Vansteenkiste, M., Mertens, N., & Vande Broek, G. (2018). The power of competence support: The impact of coaches and athlete leaders on intrinsic motivation and performance. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(2), 725-745.

Fredricks, J. A., & McColskey, W. (2012). The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 763-782). Springer.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

Fu, R., Gartlehner, G., Grant, M., Shamliyan, T., Sedrakyan, A., Wilt, T. J., Griffith, L., Oremus, M., Raina, P., & Ismaila, A. (2011). Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(11), 1187-1197.

Garcia-Cabot, A., Garcia-Lopez, E., Caro-Alvaro, S., Gutierrez-Martinez, J. M., & de Marcos, L. (2020). Measuring the effects on learning performance and engagement with a gamified social platform in an MSc program. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 28(1), 207-223.

Gnambs, T., & Hanfstingl, B. (2016). The decline of academic motivation during adolescence: An accelerated longitudinal cohort analysis on the effect of psychological need satisfaction. Educational Psychology, 36(9), 1691-1705.

Greene, R. J. (2018). Rewarding performance: Guiding principles; custom strategies. Routledge.

Gurevitch, J., & Hedges, L. V. (1999). Statistical issues in ecological meta-analyses. Ecology, 80(4), 1142-1149.

Hanus, M. D., & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & Education, 80, 152-161.

Hazan, B., Zhang, W., Olcum, E., Bergdoll, R., Grandoit, E., Mandelbaum, F., Wilson-Doenges, G., & Rabin, L. A. (2018). Gamification of an undergraduate psychology statistics lab: Benefits to perceived competence. Statistics Education Research Journal, 17(2), 255-265.

Hewett, R., & Conway, N. (2016). The undermining effect revisited: The salience of everyday verbal rewards and self-determined motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(3), 436-455.

Higgins, J. P., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons.

Hong, G. Y., & Masood, M. (2014). Effects of gamification on lower secondary school students’ motivation and engagement. International Journal of Educational and Pedagogical Sciences, 8(12), 3765-3772.

Huang, B., & Hew, K. F. (2021). Using gamification to design courses. Educational Technology & Society, 24(1), 44-63.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings. Sage.

Jones, M., Blanton, J. E., & Williams, R. E. (2022). Science to practice: Does gamification enhance intrinsic motivation? Active Learning in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/14697874211066882

Jurgelaitis, M., Čeponienè, L., Čeponis, J., & Drungilas, V. (2019). Implementing gamification in a univer-sity-level UML modeling course: A case study. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 27(2), 332-343.

Karabulut-Ilgu, A., Jaramillo Cherrez, N., & Jahren, C. T. (2018). A systematic review of research on the flipped learning method in engineering education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(3), 398-411.

Karimi, S., & Sotoodeh, B. (2020). The mediating role of intrinsic motivation in the relationship between basic psychological needs satisfaction and academic engagement in agriculture students. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(8), 959-975. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1623775

Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191-210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. ijinfomgt.2018.10.013

Korpershoek, H., Harms, T., de Boer, H., van Kuijk, M., & Doolaard, S. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of classroom management strategies and classroom management programs on students’ academic, behavioral, emotional, and motivational outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 86(3), 643-680.

Kyewski, E., & Krämer, N. C. (2018). To gamify or not to gamify? An experimental field study of the influence of badges on motivation, activity, and performance in an online learning course. Computers & Education, 118, 25-37.

La Guardia, J., & Ryan, R. (2002). What adolescents need. Academic motivation of adolescents (Vol. 2, pp. 193-219). IAP Information Age Publishing.

Landers, R. N. (2014). Developing a theory of gamified learning: Linking serious games and gamification of learning. Simulation & Gaming, 45(6), 752-768.

Landers, R. N., Bauer, K. N., Callan, R. C., & Armstrong, M. B. (2014). Psychological theory and the gamification of learning (pp. 165-186). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/ 978-3-319-10208-5_9

Lee, J. Q., McInerney, D. M., Liem, G. A. D., & Ortiga, Y. P. (2010). The relationship between future goals and achievement goal orientations: An intrinsic-extrinsic motivation perspective. Contemporary educational psychology, 35(4), 264-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.04.004

Leitão, R., Maguire, M., Turner, S., & Guimarães, L. (2022). A systematic evaluation of game elements effects on students’ motivation. Education and Information Technologies, 27(1), 1081-1103.

Lepper, M. R., Corpus, J. H., & Iyengar, S. S. (2005). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations in the classroom: Age differences and academic correlates. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(2), 184.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

Mekler, E. D., Brühlmann, F., Tuch, A. N., & Opwis, K. (2017). Towards understanding the effects of individual gamification elements on intrinsic motivation and performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 525-534.

Mitchell, R., Schuster, L., & Drennan, J. (2017). Understanding how gamification influences behaviour in social marketing. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 25(1), 12-19.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine, 6(7), e1000097.

Mula-Falcón, J., Moya-Roselló, I., & Ruiz-Ariza, A. (2022). The active methodology of gamification to improve motivation and academic performance in educational context: A meta-analysis. Review of European Studies. https://doi.org/10.5539/res.v14n2p32

Ortiz-Rojas, M., Chiluiza, K., & Valcke, M. (2019). Gamification through leaderboards: An empirical study in engineering education. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 27(4), 777-788.

Paulhus, D. L., & Vazire, S. (2007). The self-report method. Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 224-239). The Guilford Press.

Peng, W., Lin, J.-H., Pfeiffer, K. A., & Winn, B. (2012). Need satisfaction supportive game features as motivational determinants: An experimental study of a self-determination theory guided exergame. Media Psychology, 15(2), 175-196.

Przybylski, A. K., Rigby, C. S., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). A motivational model of video game engagement. Review of General Psychology, 14(2), 154-166.

Raudenbush, S. W. (2009). Analyzing effect sizes: Random-effects models. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (Vol. 2, pp. 295-316). Russell Sage Foundation.

Raufelder, D., & Kulakow, S. (2021). The role of the learning environment in adolescents’ motivational development. Motivation and Emotion, 45(3), 299-311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-021-09879-1

Rigby, S., & Ryan, R. M. (2011). Glued to games: How video games draw us in and hold us spellbound: How video games draw us in and hold us spellbound. AbC-CLIo.

Ritzhaupt, A. D., Huang, R., Sommer, M., Zhu, J., Stephen, A., Valle, N., Hampton, J., & Li, J. (2021). A meta-analysis on the influence of gamification in formal educational settings on affective and behavioral outcomes. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(5), 2493-2522.

Rodrigues, L., Toda, A. M., Oliveira, W., Palomino, P. T., Avila-Santos, A. P., & Isotani, S. (2021). Gamification Works, but How and to Whom? An Experimental Study in the Context of Programming Lessons. Proceedings of the 52nd ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education,

Rosenthal, R., & DiMatteo, M. R. (2001). Meta-analysis: Recent developments in quantitative methods for literature reviews. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 59-82.

Roy, R. V., & Zaman, B. (2017). Why gamification fails in education and how to make it successful: Introducing nine gamification heuristics based on self-determination theory. Serious Games and edutainment applications (pp. 485-509). Springer.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (1987). When free-choice behavior is not intrinsically motivated: Experiments on internally controlling regulation. Unpublished manuscript, University of Rochester.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Chapter 2 – When rewards compete with nature: The undermining of intrinsic motivation and Self-Regulation. In C. Sansone & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation (pp. 13-54). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012619070-0/ 50024-6

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000b). The darker and brighter sides of human existence: Basic psychological needs as a unifying concept. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532 7965PLI1104_03

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54-67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000d). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1037/ 0003-066X.55.1.68

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. Handbook of self-determination research (Vol. 2, pp. 3-33). University of Rochester Press.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary educational psychology, 61, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Ryan, R. M., Koestner, R., & Deci, E. L. (1991). Ego-involved persistence: When free-choice behavior is not intrinsically motivated. Motivation and Emotion, 15(3), 185-205.

Sailer, M., Hense, J., Mandl, J., & Klevers, M. (2014). Psychological perspectives on motivation through gamification. Interaction Design and Architecture Journal, 19, 28-37.

Sailer, M., Hense, J. U., Mayr, S. K., & Mandl, H. (2017). How gamification motivates: An experimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 371-380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.033

Sailer, M., & Homner, L. (2020). The gamification of learning: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 77-112.

Sailer, M., & Sailer, M. (2021). Gamification of in-class activities in flipped classroom lectures. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(1), 75-90.

Scammacca, N., Roberts, G., & Stuebing, K. K. (2014). Meta-analysis with complex research designs: Dealing with dependence from multiple measures and multiple group comparisons. Review of Educational Research, 84(3), 328-364.

Scherrer, V., & Preckel, F. (2019). Development of motivational variables and self-esteem during the school career: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Review of Educational Research, 89(2), 211-258.

De Schutter, B., & Abeele, V. V. (2014). Gradequest-Evaluating the impact of using game design techniques in an undergraduate course. In 9th international conference on the foundations of digital games., USA.

Segura-Robles, A., Fuentes-Cabrera, A., Parra-González, M. E., & López-Belmonte, J. (2020). Effects on personal factors through flipped learning and gamification as combined methodologies in secondary education. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1103.

Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ, 349, g7647-g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

Stansbury, J. A., & Earnest, D. R. (2017). Meaningful gamification in an industrial/organizational psychology course. Teaching of Psychology, 44(1), 38-45.

Stoyanova, M., Tuparova, D., & Samardzhiev, K. (2017). Impact of motivation, gamification and learning style on students’ interest in maths classes-a study in 11 high school grade. International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning,

Sun, J.C.-Y., & Hsieh, P.-H. (2018). Application of a gamified interactive response system to enhance the intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, student engagement, and attention of English learners. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 21(3), 104-116.

Tasadduq, M., Khan, M. S., Nawab, R. M., Jamal, M. H., & Chaudhry, M. T. (2021). Exploring the effects of gamification on students with rote learning background while learning computer programming. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 29(6), 1871-1891.

Tondello, G. F., Mora, A., & Nacke, L. E. (2017). Elements of gameful design emerging from user preferences. Proceedings of The Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play

Tsay, C.H.-H., Kofinas, A., & Luo, J. (2018). Enhancing student learning experience with technology-mediated gamification: An empirical study. Computers & Education, 121, 1-17.

Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M., Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. F. (1992). The Academic Motivation Scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(4), 1003-1017.

Van den Broeck, A., Vansteenkiste, M., De Witte, H., Soenens, B., & Lens, W. (2010). Capturing autonomy, competence, and relatedness at work: Construction and initial validation of the work-related basic need satisfaction scale. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 981-1002.

van Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2019). Unravelling the ambivalent motivational power of gamification: A basic psychological needs perspective. International Journal of human-computer studies, 127, 38-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2018.04.009

Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Deci, E. L. (2006). Intrinsic versus extrinsic goal contents in self-determination theory: Another look at the quality of academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 41(1), 19-31.

Vansteenkiste, M., Niemiec, C. P., & Soenens, B. (2010). The development of the five mini-theories of self-determination theory: An historical overview, emerging trends, and future directions. The decade ahead: Theoretical perspectives on motivation and achievement. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(3), 263.

Xiang, P., Agbuga, B., Liu, J., & McBride, R. E. (2017). Relatedness need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, and engagement in secondary school physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 36(3), 340-352.

Xu, J., Lio, A., Dhaliwal, H., Andrei, S., Balakrishnan, S., Nagani, U., & Samadder, S. (2021). Psychological interventions of virtual gamification within academic intrinsic motivation: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 444-465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.070

Yaşar, H., Kiyici, M., & Karatas, A. (2020). The views and adoption levels of primary school teachers on gamification, problems and possible solutions. Participatory Educational Research, 7(3), 265-279.

Zarraonandia, T., Diaz, P., Aedo, I., & Ruiz, M. R. (2015). Designing educational games through a conceptual model based on rules and scenarios. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 74(13), 4535-4559.

Zhang, Q., Yu, L., & Yu, Z. (2021). A content analysis and meta-analysis on the effects of classcraft on gamification learning experiences in terms of learning achievement and motivation. Education Research International. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/9429112

Zheng, B., Warschauer, M., Lin, C.-H., & Chang, C. (2016). Learning in one-to-one laptop environments: A meta-analysis and research synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1052-1084. https://doi. org/10.3102/0034654316628645

Zichermann, G., & Cunningham, C. (2011). Gamification by design: Implementing game mechanics in web and mobile apps. O’Reilly Media Inc.

- Khe Foon Hew

kfhew@hku.hk

1 The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

2 Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong, Room 111A, Runme Shaw Building, Hong Kong, China - Meta-analysis

(a) The study reported an empirical examination of gamified practices using at least one clearly described game element

(b) The study was conducted in a K-12 or higher education setting and written in English

(c) The study contained at least one comparison of motivational outcomes between a gamified class and a non-gamified class

(d) The study measured students’ intrinsic motivation in both gamified and non-gamified classes for the same course topic using a survey such as the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory or a scale measuring freechoice behavior. Such surveys have been frequently used by researchers to assess participants’ motivation during an intervention

(e) The study reported sufficient data such as means, standard deviations, sample sizes,values of t-tests, values, and scores of Mann-Whitney U tests

(f) The study was published in a peer-reviewed journal or was a conference paper or thesis/dissertation. The study had to be accessible via a library subscription or freely available onlineSystematic review

(a) The study reported on empirical gamified learning practices using at least one explicitly described game element

(b) The study was conducted in a K-12 or higher education setting

(c) The study involved data collected through student interviews and/or open-ended survey questions

(d) The study was published in a peer-reviewed journal or was a conference paper or thesis/dissertation. The study had to be accessible via a library subscription or freely available online

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-023-10337-7

Publication Date: 2024-01-16

Gamification enhances student intrinsic motivation, perceptions of autonomy and relatedness, but minimal impact on competency: a meta-analysis and systematic review

© The Author(s) 2024

Abstract

Although many studies in recent years have examined the use of gamification as a motivational strategy in education, evidence regarding its effects on intrinsic motivation is inconsistent. To make the case for or against the adoption of gamification in education, this study examines its effects on students’ intrinsic motivation and the underlying motivational factors: perceived competence, autonomy, and relatedness. In this review, we analyzed the results of studies comparing gamified learning with non-gamified learning published between 2011 and 2022. The results of our meta-analysis of 35 independent interventions (involving 2500 participants) indicated an overall significant but small effect size favoring gamified learning over learning without gamification (Hedges’

Introduction

that they did not explicitly explain whether they focused on intrinsic or extrinsic motivation, or their motivation outcomes also included other constructs. For example, Sailer and Homner (2020) referred to motivational outcomes that included a host of constructs such as (intrinsic) motivation, dispositions, preferences, attitudes, engagement, confidence, and self-efficacy. Similarly, although Ritzhaupt et al. (2021) reported a positive and significant effect size for the influence of gamification on students’ affective outcomes, the affective outcomes that they examined included not only motivation and interest but also learner self-efficacy, perceived learning, perceived ease of use, and attitude. This lack of clarity on the types of motivational outcomes investigated in prior studies has caused some confusion about the effect of gamification on intrinsic motivation and made it difficult to decide whether to use gamification in education.

Research questions

RQ2. What is the effect of gamification on students’ intrinsic motivation?

RQ3. What is the effect of gamification on students’ basic psychological needs (i.e., competence, autonomy, relatedness)?

RQ4. What are the current challenges of using gamification to enhance intrinsic motivation?

Conceptual and theoretical background

Motivation

a task for an external consequence (e.g., obtaining a reward or avoiding punishment)are more likely to engage in surface and unsustainable learning (Lee et al., 2010), and extrinsic motivation in students may be associated with certain negative outcomes (Clanton Harpine, 2015). For example, once the external reward stops, such students may stop demonstrating the specific behavior. As Zichermann and Cunningham (2011, p. 27) stated, “once you start giving someone a reward, you have to keep her in that reward loop forever.”

| Reward contingency | Description | ||

| Task noncontingent | Reward is offered for agreeing to participate, for coming to the study, or for waiting for the experimenter | ||

| Rewards offered for doing well |

|

||

| Rewards offered for doing a task |

|

||

| Rewards offered for finishing or completing a task |

|

||

| Rewards offered for each unit solved | Reward is offered for each unit, puzzle, problem, etc., that is solved | ||

| Rewards offered for surpassing a score |

|

||

| Rewards offered for exceeding a norm | Reward is offered to meet or exceed the performance of others on the task (relative standard) |

Self-determination theory as a framework

(1) Competence refers to the feeling of mastering a challenge and flourishes when direct and positive (informative) feedback is received (Deci & Ryan, 2004). The positive effects of perceived competence on intrinsic motivation typically occur when it is accompanied by a sense of autonomy (Deci & Ryan, 2004).

(2) Autonomy refers to psychological freedom and the volition to perform tasks (Deci & Ryan, 2000, p. 231; Van den Broeck et al., 2010; Vansteenkiste et al., 2010). The sense of making decisions based on one’s interests is the expression of psychological freedom (Deci & Ryan, 2012; Ryan & Deci, 2002), whereas volition is the sense of acting with no external pressure or coercion (Vansteenkiste et al., 2010). When a person perceives a sense of autonomy, they show more interest in an activity and greater confidence in engaging in it, which enhances performance and increases persistence (Ryan & Deci, 2000d).

(3) Relatedness refers to a sense of belonging and connection (Ryan & Deci, 2020). It represents an individual’s underlying desire for integration into the social environment (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Deci & Ryan, 2000, 2004). When individuals form

intimate relationships and feel a sense of communion with others, they perceive greater levels of relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2000). In environments characterized by a sense of relatedness, intrinsic motivation is more likely to thrive (Ryan & Deci, 2000d; Ryan & La Guardia, 2000).

Gamification

Gamification and intrinsic motivation

(1) As competence refers to the feeling that one is succeeding when interacting with the environment (Rigby & Ryan, 2011; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013), feedback mechanisms in gamified learning can help satisfy students’ needs for competence. For example, feedback mechanisms such as points, medals, and leaderboards can visually communicate students’ achievements and competence (Xi & Hamari, 2019). In addition, to motivate students effectively, tasks in gamified learning should be designed so that they are not easy but just outside the comfort zone of the students at a level of difficulty they find achievable (Roy & Zaman, 2017). When tasks are at such a level of difficulty, students persist in improving themselves to accomplish them (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Peng et al., 2012).

(2) As autonomy refers to a person’s sense of freedom in their actions (Ryan & Deci, 2020), providing students with choice can help satisfy students’ needs for autonomy. For example, Jones et al. (2022) addressed students’ need for autonomy by providing multiple options for assignments that the students could engage in, which allowed them to choose their own path to achieve their desired outcomes (grades). The results

demonstrated that the students who participated in gamified learning had higher perceived autonomy and intrinsic motivation than those who participated in non-gamified learning.

(3) As relatedness refers to a person’s sense of belonging to a group (Ryan & Deci, 2017), frequent communication and idea-sharing via group work in gamified learning can help learners perceive relatedness (Fernandez-Rio et al., 2021). Furthermore, group competition can create a sense of belonging to a team by reinforcing the sense of community (van Roy & Zaman, 2019).

Methods

Search strategy

Search string

morphological variations of “gamification,” “gamified,” and “gamify.” The second set of search terms contained terms related to intrinsic motivation. We used the expression “intrinsic motiva*” to cover all morphological variations of “intrinsic motivation,” “intrinsic motivated,” and “intrinsically motivated.” The third set contained terms that were related to course, classroom, education, or learning. The following is the search string that was used: gamif* AND intrinsic motiva* AND (course OR class* OR educat* OR learn*).

Selection criteria

Study selection

Data analysis

Data extraction

Computing effect sizes

Analysis of heterogeneity

(1) Participant characteristics. Aimed at analyzing whether there were any differences between participants across school levels and geographic regions.

(2) Course characteristics. Aimed at analyzing whether there were any differences across course subjects and whether the durations and sample sizes of the experimental interventions influenced the final effect size (Chen et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2016). To ensure a precise analysis, we used a sample size coding scheme adapted from Chen et al. (2018) and a time coding scheme from Bai et al. (2020) (see Table 3).

(3) Control level. Aimed at determining whether the various control levels implemented in the interventions may have affected the final effect size (Freeman et al., 2014). According to Bai et al. (2020), two control levels can be considered: student equivalence and instructor equivalence. A study can be categorized into one of three types based on student equivalence: (1) no-significant-difference group, i.e., the study conducted and reported an initial statistical assessment of the control and experimental groups, and showed that the students in the two groups were initially at the same level in a statistically significant manner; (2) significant-difference group, i.e., the results of the initial statistical assessment showed that the initial levels of the students were different between the groups; and (3) no data reported, i.e., the study did not provide statistical data on whether the initial levels of the students were equivalent. Similarly, a study can be categorized into one of three types based on instructor equivalence: (1) identical instructor, i.e., the same instructor oversaw the treatment and control groups; (2) different instructor, i.e., two or more instructors oversaw the treatment and control groups respectively; and (3) no data reported, i.e., the authors did not provide this information about the instructors.

(4) Number of game elements. Aimed at investigating whether the number of game elements used moderated the effect size.

(5) Type of reward and reward contingency. Aimed at determining whether the type of reward and reward contingency moderated the effect sizes. Rewards were categorized into verbal rewards (i.e., praise or positive feedback) and tangible rewards (e.g., sweets, toys, and badges). We coded the reward contingencies using the reward contingency framework developed by Cameron et al. (2001) (see Table 1).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Sample size | <50 | 50-100 | 100-150 |

|

No data provided | |

| Intervention duration | <1 week | 1 week-1 month | 1 month-3 months | 3 months-1 semester |

|

No data provided |

Analysis of publication bias

Qualitative analysis

Results

Characteristics of the studies

| Table 4 Self-determination theory-based coding scheme to code the challenges of using gamification | |||||||

| Challenges related to competence | Challenges pertaining to relatedness | Challenges pertaining to autonomy | |||||

| Failure to achieve a sense of mastery, a feeling of success | Failure to achieve a sense of connection with other people | Failure to attain a sense of initiative and ownership of individual actions | |||||

|

|

– Lack of autonomy in choosing learning content and activities | |||||

RQ1. What instruments have been used to measure students’ intrinsic motivation in the gamified classroom approach?

Self-report questionnaires

Interview

RQ2. What is the effect of gamification on students’ intrinsic motivation?

Overall effect size

| Study name | Outcome | Statistics for each study | Hedges’s g and 95% CI | |||||||

| Hedges’s g | Lower limit | Upper limit | p-Value | |||||||

| Brom et al. (2019). | IM – NC | 0.072 | -0.409 | 0.553 | 0.769 | |||||

| Brom et al. (2019). | [M – NF | 0.096 | -0.389 | 0.580 | 0.699 | |||||

| Challco et al. (2019). | IM | 0.952 | 0.213 | 1.690 | 0.012 | |||||

| Challco et al. (2017). | IM | 0.470 | -0.036 | 0.977 | 0.069 | |||||

| De Schutter_Abeele (2014). | IM | -1.148 | -1.812 | -0.484 | 0.001 | |||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020). _ Exp 1 | [M – Exp 1 | -0.513 | -1.136 | 0.111 | 0.107 | |||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020). _ Exp 2 | [M – Exp 2 | 0.017 | -0.531 | 0.565 | 0.950 | |||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020) _ Exp 3 | [M – Exp 3 | 0.009 | -0.541 | 0.559 | 0.974 | |||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020). _ Exp 4 | [M – Exp 4 | -1.329 | -1.943 | -0.715 | 0.000 | |||||

| Ferriz-Valero et al. (2020). | IM | 0.146 | -0.201 | 0.492 | 0.409 | |||||

| Garcia-Cabot et al. (2020). | IM | 0.304 | -0.437 | 1.044 | 0.422 | |||||

| Hazan et al. (2018). | IM | 0.276 | -0.317 | 0.869 | 0.361 | |||||

| Jurgelaitis et al. (2019a). – est | IM | 1.326 | 0.948 | 1.704 | 0.000 | |||||

| Kyewski et al. (2018). | IM | -0.333 | -1.196 | 0.530 | 0.449 | |||||

| Ortiz Rojas et al. (2017). | IM | 0.183 | -0.207 | 0.572 | 0.358 | |||||

| Ortiz-Rojas et al. (2019). | IM | 0.271 | -0.155 | 0.697 | 0.212 | |||||

| Rodrigues et al. (2021). | IM | 0.103 | -0.758 | 0.963 | 0.815 | |||||

| Sailer et al. (2021). | IM | 0.835 | 0.550 | 1.120 | 0.000 | |||||

| Segura-Robles et al. (2020). | IM | 1.934 | 1.345 | 2.522 | 0.000 | |||||

| Stansbury-Earnest (2017). | IM | 0.640 | 0.226 | 1.054 | 0.002 | |||||

| Stoyanova et al. (2017). | IM | 0.037 | -0.367 | 0.440 | 0.859 | |||||

| Tasadduq et al. (2021). | IM | -0.322 | -0.928 | 0.284 | 0.298 | |||||

| Treiblmaier et al. (2020). | IM | -0.313 | -0.541 | -0.084 | 0.007 | |||||

| Jones et al. (2022). | IM | -0.271 | -0.820 | 0.277 | 0.332 | |||||

| Hong & Masood. (2014). | IM | 0.587 | 0.076 | 1.097 | 0.024 | |||||

| Leitao et al. (2022). | IM – PT – B | 0.657 | -0.096 | 1.410 | 0.087 | |||||

| Leitao et al. (2022). | IM – PT – L | -0.297 | -1.020 | 0.427 | 0.421 | |||||

| Lcitao ct al. (2022). | IM – PT – PBL | 0.669 | -0.072 | 1.409 | 0.077 | |||||

| Leitao et al. (2022). | [M – UK – B | 0.261 | -0.830 | 1.351 | 0.639 | |||||

| Leitao et al. (2022). | LM – UK – L | 1.123 | -0.059 | 2.305 | 0.063 | |||||

| Leitao et al. (2022). | IM – UK – P | 0.093 | -0.993 | 1.179 | 0.867 | |||||

| Leitao et al. (2022). | [M – UK – PBL | 1.393 | 0.162 | 2.625 | 0.027 | |||||

| Leitao et al. (2022). | [M- PT – P | -0.523 | -1.256 | 0.209 | 0.161 | |||||

| Femandez-Rio et al. (2021). | IM | 1.466 | 0.872 | 2.060 | 0.000 | |||||

| Sotos-Martinez ct al. (2022) | IM | 0.499 | 0.259 | 0.738 | 0.000 | |||||

| 0.257 | 0.043 | 0.471 | 0.019 | |||||||

| -4.00 | -2.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | ||||||

| Moderator |

|

|

P-value |

| Participant characteristics | |||

| School level | 2.820 | 1 | . 093 |

| Geography | 5.490 | 3 | . 139 |

| Curriculum characteristics | |||

| Sample size | 1.231 | 3 | . 746 |

| Research design | 3.119 | 3 | . 374 |

| Intervention duration | 9.509 | 4 | .050* |

| Control level | |||

| Student equivalence | 0.463 | 2 | . 794 |

| Instructor equivalence | 12.596 | 2 | .002* |

| Number of game elements | |||

| Number of game elements | 0.975 | 2 | . 614 |

| Moderator | n |

|

|

95% CI |

|

|

| LL | UL | |||||

| Type of Reward Contingency | 99.486 (.000*) | |||||

| Each unit solved | 10 | . 041 | . 401 | . 016 | . 785 | |

| Each unit solved+Surpassing a score | 2 | . 631 | . 084 | – . 258 | . 425 | |

| Completing a task + Each unit solved + Exceeding a norm | 2 | . 768 | – . 085 | – . 647 | . 478 | |

| Each unit solved + Surpassing a score + Exceeding a norm | 2 | . 005 | . 633 | . 187 | 1.079 | |

| Completing a task + Each unit solved + Surpassing a score + Exceeding a norm | 2 | . 000 | -1.246 | – 1.697 | -. 795 | |

| Doing a task + Completing a task + Each unit solved + Surpassing a score | 3 | . 575 | . 325 | -. 809 | 1.459 | |

| Moderator | n | Hedges’

|

|

95% CI |

|

|

| LL | UL | |||||

| Instructor equivalence | 12.596 (.002*) | |||||

| Different instructors | 8 | – . 143 | 0.176 | -0.487 | 0.202 | |

| Identical instructor | 9 | . 613 | 0.124 | 0.371 | 0.855 | |

| No data reported | 18 | . 264 | 0.187 | -0.102 | 0.630 | |

| Intervention duration | 9.509 (.050*) | |||||

| <1 week | 12 | . 371 | . 153 | . 071 | . 672 | |

| 1 week-1 month | 5 | . 243 | . 208 | – . 165 | . 651 | |

| 1 month-3 months | 7 | . 610 | . 253 | . 115 | 1.105 | |

| > = 1 semester | 8 | – . 068 | . 337 | – . 729 | . 592 | |

| Not reported | 3 | – . 127 | . 146 | – . 414 | . 159 | |

Publication bias

RQ3: What is the effect of gamification on the basic psychological needs that contribute to intrinsic motivation?

| Study name | Outcome | Statistics for each study | Hedges’s g and 95% CI | |||||||

| Hedges’s g | Lower limit | Upper limit | p -Value | |||||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020)._Exp 3 | Competence – Exp 3 | 0.007 | -0.543 | 0.557 | 0.980 | |||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020)._Exp 1 | Competence – Exp 1 | -0.072 | -0.687 | 0.543 | 0.818 | |||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020)._Exp 2 | Competence – Exp 2 | 0.020 | -0.528 | 0.568 | 0.942 | |||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020)._Exp 4 | Competence – Exp 4 | -0.358 | -0.937 | 0.220 | 0.225 | |||||

| Hazan et al. (2018). | Competence | 0.502 | -0.097 | 1.101 | 0.100 | |||||

| Jurgelaitis et al. (2019a). – cst | Competence | 1.115 | 0.746 | 1.483 | 0.000 | |||||

| Sailer et al. (2021). | Competence | -0.061 | -0.335 | 0.212 | 0.660 | |||||

| Segura-Robles et al. (2020). | Competence | -0.433 | -0.923 | 0.057 | 0.083 | |||||

| Jones et al. (2022). | Competence | 0.696 | 0.133 | 1.259 | 0.015 | |||||

| Hong & Masood. (2014). | Competence | 0.600 | 0.089 | 1.111 | 0.021 | |||||

| Femandez-Rio et al. (2021). | Competence | 0.764 | 0.219 | 1.310 | 0.006 | |||||

| Sotos-Martinez et al. (2022) | Competence | 0.429 | 0.190 | 0.667 | 0.000 | |||||

| 0.277 | 0.001 | 0.553 | 0.049 | |||||||

| -4.00 | -2.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | ||||||

| Study name | Outcome | Statistics for each study | Hedges’s g and 95% CI | ||||||

| Hedges’s g | Lower limit | Upper limit | p -Value | ||||||

| Challco et al. (2019). | Autonomy | 0.810 | 0.083 | 1.537 | 0.029 | ||||

| Challco et al. (2017). | Autonomy | 0.825 | 0.304 | 1.346 | 0.002 | ||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020)._Exp 3 | Autonomy – Exp3 | 0.191 | -0.359 | 0.742 | 0.496 | ||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020)._Exp I | Autonomy – Exp 1 | -0.603 | -1.230 | 0.024 | 0.059 | ||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020)._Exp 2 | Autonomy – Exp 2 | 0.168 | -0.381 | 0.716 | 0.549 | ||||

| Facey-Shaw et al. (2020)._Exp 4 | Autonomy- Exp4 | -0.464 | -1.044 | 0.117 | 0.117 | ||||

| Segura-Robles et al. (2020). | Autonomy | 3.889 | 3.060 | 4.719 | 0.000 | ||||

| Jones et al. (2022). | Autonomy | 1.310 | 0.706 | 1.913 | 0.000 | ||||

| Hong & Masood. (2014). | Autonomy | 0.076 | -0.424 | 0.576 | 0.766 | ||||

| Femandez-Rio et al. (2021). | Autonomy | 0.644 | 0.104 | 1.183 | 0.019 | ||||

| Sotos-Martinez et al. (2022) | Autonomy | 0.565 | 0.325 | 0.806 | 0.000 | ||||

| -4.00 | -2.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | ||||||

| Study name | Outcome | Statistics for each study | Hedges’s g and 95% CI | ||||||||

| Hedges’s g | Lower limit | Upper limit | p -Value | ||||||||

| Sailer et al. (2021). | Relatedness | 0.594 | 0.315 | 0.874 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Segura-Robles et al. (2020). | Relatedness | 5.805 | 4.689 | 6.921 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Fernandez-Rio et al. (2021). | Relatedness | 0.993 | 0.435 | 1.551 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Sotos-Martinez et al. (2022) | Relatedness | 0.581 | 0.340 | 0.822 | 0.000 | ||||||

| -4.00 | -2.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | |||||||

RQ4. What are the current challenges that gamification research must address?

| Themes and sub-themes (Percentage) | Representative citations |

| Self-determination theory | |

| Lack of perceived competence | |

| Discomfort among the lowest ranked participants in a public absolute leaderboard (23%) | “The way in which the rewards were presented to students could have also played a role in their perception of the software. For example, whereas all students received points and a position on the leaderboard, the fact that only the top three students were awarded badges could have limited the effect of this gamification element. Furthermore, being high on the leaderboards or receiving a badge could have been particularly encouraging only for those students concerned, while the rest of the class could have potentially been negatively affected” (Andrade et al., 2020, p. 17) |

| Unsuitability of the difficulty level of the gamified tasks (10%) | “Students were not interested in certain badges, such as those given for merely attending classes…Some badges, such as attendance badges, were not considered valuable as students wanted badges that required achievement effort and not those that ‘everyone can earn’” (FaceyShaw et al., 2020, p. 42) |

| Unfamiliarity with gamification elements (10%) | “Some students also reported being unaware of the badges. This may have led to the statistically significant drop in scores for perceived competence” (Facey-Shaw et al., 2020, p. 46) |

| Lack of perceived autonomy | |

| Lack of autonomy in choosing learning content and activities (19%) | “Based on these findings and the way the students responded to the course in class, the following recommendations should be made: … Provide students with freedom of choice in how they want to show their mastery of the materials” (De Schutter & Abeele, 2014, p. 7) |

Discussion

Measurement of intrinsic motivation

intrinsic motivation have found similar results to those of studies using free-choice behavior (Deci et al., 1999), the adoption of behavioral free-choice measures of intrinsic motivation, such as by allowing participants the choice to continue engaging in a task without any reward (Deci & Ryan, 2004) and recording the outcome, may yield additional insights.

Effect of gamification on intrinsic motivation

of competence, and when performance criteria are graded and attainable, rewards have a positive effect (Cameron et al., 2001).

Effect of gamification on basic psychological needs

Challenges of using gamification to facilitate intrinsic motivation and potential solutions

Limitations

experimenter is not aware of whether they persist in performing an activity during the freechoice period and thus decide whether to persist based on their own motivation.

Conclusion

findings across studies, first, the design of instructional gamification interventions should be based on a comprehensive theoretical framework, and studies should provide a clear description of the instructional arrangements and the types of instructional activities used. Second, all aspects of a study’s design, such as study characteristics and control group arrangements, should be reported transparently to facilitate a comprehensive meta-analytic investigation of the factors influencing the effectiveness of gamification.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Andrade, P., Law, E. L.-C., Farah, J. C., & Gillet, D. (2020). Evaluating the effects of introducing three gamification elements in STEM educational software for secondary schools. 32nd Australian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction

Annetta, L. A. (2010). The “I’s” have it: A framework for serious educational game design. Review of General Psychology, 14(2), 105-113.

Armstrong, M. B., & Landers, R. N. (2017). An evaluation of gamified training: Using narrative to improve reactions and learning. Simulation & Gaming, 48(4), 513-538.

Bai, S., Hew, K. F., & Huang, B. (2020). Does gamification improve student learning outcome? Evidence from a meta-analysis and synthesis of qualitative data in educational contexts. Educational Research Review, 30, 100322.

Baker, M. (2016). Statisticians issue warning on P values. Nature, 531(7593), 151-151.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

Boyle, E. A., Hainey, T., Connolly, T. M., Gray, G., Earp, J., Ott, M., Lim, T., Ninaus, M., Ribeiro, C., & Pereira, J. (2016). An update to the systematic literature review of empirical evidence of the impacts and outcomes of computer games and serious games. Computers & Education, 94, 178-192.

Brom, C., Stárková, T., Bromová, E., & Děchtěrenko, F. (2019). Gamifying a simulation: Do a game goal, choice, points, and praise enhance learning? Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(6), 1575-1613.

Cameron, J., Banko, K. M., & Pierce, W. D. (2001). Pervasive negative effects of rewards on intrinsic motivation: The myth continues. The Behavior Analyst, 24(1), 1-44.

Cameron, J., & Pierce, W. D. (1994). Reinforcement, reward, and intrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 64(3), 363-423.

Cameron, J., & Pierce, W. D. (2002). Rewards and intrinsic motivation: Resolving the controversy. Bergin & Garvey.

Cerasoli, C. P., Nicklin, J. M., & Ford, M. T. (2014). Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: A 40-year meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 980.

Challco, G. C., Isotani, S., & Bittencourt, I. I. (2019). The effects of ontology-based gamification in scripted collaborative learning. 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT),

Clanton Harpine, E. (2015). Is Intrinsic Motivation Better Than Extrinsic Motivation? In E. Clanton Harpine (Ed.), Group-centered prevention in mental health: Theory, training, and practice (pp. 87-107). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19102-7_6

Costa, J. P., Wehbe, R. R., Robb, J., & Nacke, L. E. (2013). Time’s up: studying leaderboards for engaging punctual behaviour. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Gameful Design, Research, and Applications,

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2022). Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI). https://selfdeterminationtheory. org/intrinsic-motivation-inventory/#toc-description

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 627.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation in education: Reconsidered once again. Review of Educational Research, 71(1), 1-27.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the selfdetermination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Handbook of self-determination research. University Rochester Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 182.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In R. M. E. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation (pp. 85-107). Oxford University Press.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: defining “gamification”. Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments,

Deterding, S. (2012). Gamification: designing for motivation. Interactions, 19(4), 14-17.

Dicheva, D., Dichev, C., Agre, G., & Angelova, G. (2015). Gamification in education: A systematic mapping study. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 18(3), 75-88.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2013). Teaching and researching: Motivation. Routledge.

Educause. (2011). 7 things you should know about gamification. https://library.educause.edu/resources/ 2011/8/7-things-you-should-know-about-gamification

Facey-Shaw, L., Specht, M., van Rosmalen, P., & Bartley-Bryan, J. (2020). Do Badges Affect Intrinsic Motivation in Introductory Programming Students? Simulation & Gaming, 51(1), 33-54. https:// doi.org/10.1177/1046878119884996

Fernandez-Rio, J., Zumajo-Flores, M., & Flores-Aguilar, G. (2021). Motivation, basic psychological needs and intention to be physically active after a gamified intervention programme. European Physical Education Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X21105288

Ferriz-Valero, A., Østerlie, O., García Martínez, S., & García-Jaén, M. (2020). Gamification in physical education: Evaluation of impact on motivation and academic performance within higher education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4465.

Fransen, K., Boen, F., Vansteenkiste, M., Mertens, N., & Vande Broek, G. (2018). The power of competence support: The impact of coaches and athlete leaders on intrinsic motivation and performance. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 28(2), 725-745.

Fredricks, J. A., & McColskey, W. (2012). The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 763-782). Springer.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

Fu, R., Gartlehner, G., Grant, M., Shamliyan, T., Sedrakyan, A., Wilt, T. J., Griffith, L., Oremus, M., Raina, P., & Ismaila, A. (2011). Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(11), 1187-1197.

Garcia-Cabot, A., Garcia-Lopez, E., Caro-Alvaro, S., Gutierrez-Martinez, J. M., & de Marcos, L. (2020). Measuring the effects on learning performance and engagement with a gamified social platform in an MSc program. Computer Applications in Engineering Education, 28(1), 207-223.

Gnambs, T., & Hanfstingl, B. (2016). The decline of academic motivation during adolescence: An accelerated longitudinal cohort analysis on the effect of psychological need satisfaction. Educational Psychology, 36(9), 1691-1705.

Greene, R. J. (2018). Rewarding performance: Guiding principles; custom strategies. Routledge.

Gurevitch, J., & Hedges, L. V. (1999). Statistical issues in ecological meta-analyses. Ecology, 80(4), 1142-1149.

Hanus, M. D., & Fox, J. (2015). Assessing the effects of gamification in the classroom: A longitudinal study on intrinsic motivation, social comparison, satisfaction, effort, and academic performance. Computers & Education, 80, 152-161.

Hazan, B., Zhang, W., Olcum, E., Bergdoll, R., Grandoit, E., Mandelbaum, F., Wilson-Doenges, G., & Rabin, L. A. (2018). Gamification of an undergraduate psychology statistics lab: Benefits to perceived competence. Statistics Education Research Journal, 17(2), 255-265.

Hewett, R., & Conway, N. (2016). The undermining effect revisited: The salience of everyday verbal rewards and self-determined motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(3), 436-455.

Higgins, J. P., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley & Sons.