المجلة: Scientific Reports، المجلد: 14، العدد: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55249-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38413739

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-27

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55249-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38413739

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-27

افتح

تحليل الميتابولوم غير المستهدف لمصل الدم من القطط المملوكة للعملاء المصابة بمرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة والمتأخرة

يمكن أن يكشف تقييم الميتابولوم عن مؤشرات حيوية جديدة للأمراض. حتى الآن، لم يتم الإبلاغ عن توصيف الميتابولوم في مصل الدم للقطط المملوكة من قبل العملاء المصابة بمرض الكلى المزمن (CKD)، الذي يشترك في العديد من التشابهات الفسيولوجية المرضية مع مرض الكلى المزمن لدى البشر. يُعتبر مرض الكلى المزمن سببًا رئيسيًا للمراضة والوفيات في القطط، ويمكن تقليله من خلال الكشف المبكر والعلاج المناسب. وبالتالي، هناك حاجة ملحة لمؤشرات حيوية مبكرة لمرض الكلى المزمن. كان الهدف من هذه الدراسة المستعرضة والمستقبلية هو توصيف الميتابولوم العالمي غير المستهدف في مصل الدم للقطط في مراحل مبكرة مقارنة بمراحل متأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن مقارنة بالقطط السليمة. أظهرت التحليلات فصلًا مميزًا للميتابولوم في مصل الدم بين القطط السليمة ومرحلة مبكرة ومرحلة متأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن. كانت المستقلبات الدهنية والأحماض الأمينية ذات الوفرة المختلفة هي المساهمين الرئيسيين في هذه الاختلافات، وشملت المستقلبات المركزية في استقلاب الأحماض الدهنية والأحماض الأمينية الأساسية والسموم اليوريمية. إن ارتباط العديد من المستقلبات الدهنية والأحماض الأمينية مع البيانات السريرية المهمة لمراقبة مرض الكلى المزمن وعلاج المرضى (مثل الكرياتينين، ودرجة حالة العضلات) يوضح بشكل أكبر أهمية استكشاف هذه الفئات من المستقلبات لمزيد من قدرتها على العمل كمؤشرات حيوية للكشف المبكر عن مرض الكلى المزمن في كل من القطط والبشر.

| اختصارات | |

| بي دي بي | منتج تحلل البيليروبين |

| بي سي إس | درجة حالة الجسم |

| بي سي إيه إيه | حمض أميني متفرع السلسلة |

| كعكة | نيتروجين اليوريا في الدم |

| مرض الكلى المزمن | مرض الكلى المزمن |

| فا | حمض دهني |

| FS | أنثى، تم تعقيمها |

| معدل الترشيح الكبيبي | معدل تصفية الكبيبات |

| جي بي سي | غليسيروفوسفوريلي كولين |

| جي بي إي | غليسيروفوسفوريليثانولامين |

| جي بي آي | غليسيروفوسفوريليزيتول |

| HCA | تحليل التجميع الهرمي |

| هود | حمض الهيدروكسي أوكتاديسينويك |

| إيريس | الجمعية الدولية لاهتمام الكلى |

| إم سي | ذكر، مُخصي |

| نسبة الكتلة إلى الشحنة | نسبة الكتلة إلى الشحنة |

| MCFA | حمض دهني متوسط السلسلة |

| موفا | حمض دهني أحادي غير مشبع |

| MCS | درجة حالة العضلات |

| تحليل المكونات الرئيسية للحدود الجزئية | تحليل التمييز باستخدام المربعات الصغرى الجزئية |

| بيس | درجة إثراء المسار |

| SCFA | حمض دهني قصير السلسلة |

| SDMA | ثنائي ميثيل الأرجينين المتماثل |

| TMAO | أكسيد ن-ثلاثي ميثيل الأمين |

| USG | الكثافة النوعية للبول |

| كروماتوغرافيا السائل عالية الأداء مع قياس الطيف الكتلي | الكروماتوغرافيا السائلة عالية الأداء المتسلسلة مع مطياف الكتلة |

مرض الكلى المزمن (CKD) هو حالة طبية شائعة في القطط مرتبطة باضطرابات فسيولوجية واستقلابية كبيرة، بما في ذلك الهزال، وسوء التغذية، واضطراب استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية، والإجهاد التأكسدي.

تُصنع المستقلبات وتُستخدم خلال الوظائف الخلوية الطبيعية، وتسبب الأمراض اضطرابًا في المسارات الكيميائية الحيوية مما يخلق ملفات مستقلبية محددة. يمكن تمييز هذه الملفات من خلال توصيف المستقلبات في مصفوفة بيولوجية باستخدام علم المستقلبات غير المستهدفة ومقارنة العينات الصحية مقابل العينات المريضة. لقد تم تنفيذ هذه الطريقة بشكل موسع في الأشخاص الذين يعانون من مرض الكلى المزمن وتم استخدامها بنجاح لاكتشاف المؤشرات الحيوية للتشخيص المبكر وتحديد الأسباب.

حتى الآن، لا توجد دراسات بيطرية منشورة تقارن بين ملفات الميتابوليتات في القطط التي تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن (CKD) في مراحله المبكرة والمتأخرة. إن القدرة على تحديد المحركات الأيضية لمرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة مقابل المتأخرة، على الرغم من الظروف البيئية المتغيرة (مثل النظام الغذائي، العلاجات الطبية، المنزل) والظروف الفسيولوجية المرضية (مرض الكلى المزمن الذي يحدث بشكل طبيعي مع أو بدون حالات مصاحبة مثل التهاب الأمعاء المزمن، اعتلال عضلة القلب، إلخ)، أمر ضروري لتطبيق المؤشرات الحيوية بنجاح على مجموعات المرضى المتنوعة. كان الهدف من هذه الدراسة هو تحديد الميتابوليتات الخاصة بالمرض والمرحلة لتحسين فهم فسيولوجيا مرض الكلى المزمن، وخاصة في المرض في مراحله المبكرة، وبالتالي اقتراح أهداف علاجية محتملة ومؤشرات حيوية لمرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة. لتعريف الاضطرابات الأيضية بشكل أفضل في القطط المصابة بمرض الكلى المزمن، قمنا بتطبيق علم الميتابولوميات غير المستهدف على مصل الدم لمقارنة القطط المملوكة من قبل العملاء التي تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة والمتأخرة مع القطط الصحية.

النتائج

التقييم السريري للقطط الصحية وذات المرحلة المبكرة والمتأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن

من بين 56 قطة مسجلة في هذه الدراسة، كانت هناك 25 قطة صحية (الوسيط، تسع سنوات؛ النطاق، 1-14 سنة) و30 قطة تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن (الوسيط، 14 سنة؛ النطاق،

تُعرض الفحوصات البدنية والمعايير المخبرية للقطط الصحية، ومرحلة CKD 1 و2، ومرحلة CKD 3 و4 في الجدول 1، وتُقدم المعلومات الديموغرافية للقطط الفردية في الملف التكميلي 1. الغالبية العظمى من القطط الصحية (

لم يكن معظم القطط الصحية تتلقى أدوية، باستثناء الوقاية الموضعية من البراغيث والديدان القلبية (سيلامكتين) في ثلاثة قطط والجلوكوزامين الفموي في قط واحد. كان هناك ثمانية قطط مصابة بأمراض الكلى المزمنة تتناول دواء أو أكثر أو مكملات، بما في ذلك هيدروكسيد الألمنيوم (قطتان)، غلوكونات البوتاسيوم (قطتان)، بروبيوتيك (خمسة قطط)، بولي إيثيلين غليكول 3350 (قطتان)، سيلامكتين موضعي وجلوكوزامين فموي (قط واحد لكل منهما). كانت جميع القطط الصحية تتغذى على نظام غذائي تجاري مصمم لتلبية الملف الغذائي لجمعية مسؤولي مراقبة الأعلاف الأمريكية لصيانة القطط البالغة.

| متغير | صحي

|

مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة (المراحل 1 و 2)

|

مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المتأخرة (المرحلتان 3 و 4)

|

| جنس | 14 MC، 11 FS | 9 MC; 8 FS | 8 MC; 5 FS |

| العمر (بالسنوات) | 9 (1-14) | 14 (4-17) | 13 (3-19) |

| وزن الجسم (كجم) | 4.6 (2.8-8.1) | 3.9 (3.2-6.4) | 4.3 (2.4-5.8) |

| BCS (1-9) | 5 (4-9) | 5 (4-7) | 5 (2-6) |

| MCS (0-3)* | 0 (0-2)

|

|

|

| الهيماتوكريت (%) |

|

٣٥ (٣١-٤٣) | ٣٦ (٢٣-٤٢)

|

| الكرياتينين (ملغ/دل) | 1.4 (1.1-2.2)

|

|

3.7 (3.1-7.4)

|

| بولة نيتروجينية (ملغ/دل) | 22 (18-31)

|

|

55 (42-90)

|

| إجمالي الكالسيوم (ملغ/دل) |

|

10.1 (9.2-14.4) |

|

| الفوسفور (ملغ/دل) | 3.7 (2.9-4.6)

|

3.9 (2.3-6.2) |

|

| البوتاسيوم (مEq/L) | 4.2 (3.5-5.2) | ٤.٧ (٣.٧-٥.٣) | ٤.٦ (٢.٤-٥.١) |

| الألبومين (غ/دل) | 3.7 (2.9-4.4) | 3.5 (3.2-4.0) | 3.6 (3.2-3.9) |

| USG | 1.049 (1.038-1.073)

|

1.018 (1.010-1.039)

|

1.016 (1.009-1.025)

|

الجدول 1. الخصائص السكانية للمرضى، الفحص البدني، والمتغيرات المخبرية. الأرقام خارج الأقواس تمثل القيمة المتوسطة لكل مجموعة من المرضى، والأرقام داخل الأقواس تظهر النطاق. بالنسبة لكل متغير، كانت الأعمدة داخل كل صف التي تحمل حرفًا مختلفًا كحرف علوي مختلفة إحصائيًا عن بعضها البعض.

القطط المصابة بأمراض الكلى المزمنة في مراحلها المبكرة والصحية والمراحل المتأخرة لها ميتابولومات مصلية مميزة

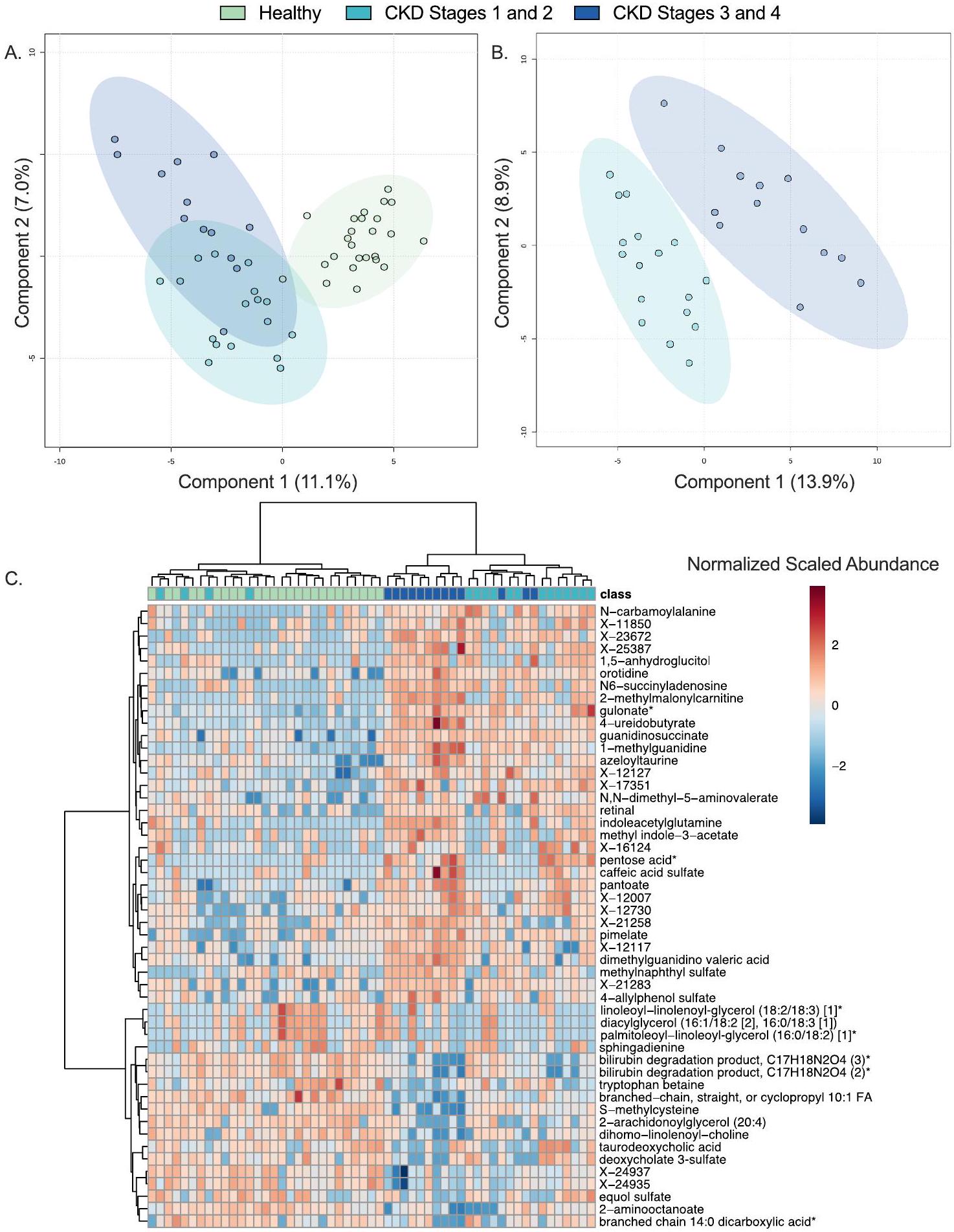

تم تقييم الميتابولوم السيرومي العالمي غير المستهدف في 55 قطة. يوضح الجدول 2 توزيع الفئات الكيميائية، بما في ذلك أعداد الميتابوليتات ذات الوفرة المختلفة عند مقارنة المجموعات الثلاث باستخدام اختبار كروسكال-واليس مع قيم p المعدلة وفقًا لأسلوب بنجاميني-هوشبرغ. يوفر الملف التكميلي 2 فروق الطي وقيم p الزوجية لجميع الميتابوليتات ذات الوفرة المختلفة بين كل مجموعة. عبر جميع العينات، تم الكشف عن 918 ميتابوليت، بما في ذلك 830 ميتابوليت مسمى و88 ميتابوليت غير معروف. مثلت الدهون

بالإضافة إلى اختبار كروسكال-واليس، تم استخدام تحليل التمييز بالحد الأدنى من المربعات (PLS-DA) كمعيار متعدد المتغيرات ثانٍ لتحديد المستقلبات التي كانت مساهمات مهمة في تفسير الفروق.

| فئة كيميائية | الصحة مقابل مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة (المراحل 1 و 2) | الصحة مقابل مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المتأخرة (المراحل 3 و 4) | مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة (المراحل 1 و 2) مقابل مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المتقدمة (المراحل 3 و 4) |

| الأحماض الأمينية (206) | 62 (

|

100 (

|

55 (

|

| الببتيدات (36) |

|

9 (

|

٤ (

|

| الكربوهيدرات (22) | 5 (

|

10 (

|

٥ (

|

| الفيتامينات والعوامل المساعدة (30) | 13 (

|

16 (

|

٥ (

|

| أيض الطاقة (9) | ٦ (

|

٨ (

|

|

| الدهون (369) | ١٠٤ (

|

195 (

|

٥٨ (

|

| النيوكليوتيدات (51) | ١٣ (

|

٢٦ (

|

12 (

|

| الزنوبيوتيك (100) | 12 (

|

٢٩ (

|

17 (

|

| المستقلبات غير المعروفة والتي تم توصيفها جزئيًا (95) | ٢٣ (

|

٤٤ (

|

٢٢ (

|

| الإجمالي (918) | 240 (

|

٤٣٧ (

|

١٨٠ (

|

الجدول 2. المستقلبات ذات الوفرة المختلفة في القطط الصحية والقطط المصابة بمرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة مقابل المتأخرة. تشير الأقواس بجانب الفئة الكيميائية إلى العدد الإجمالي للمستقلبات المحددة. لكل مقارنة، تشير الأرقام إلى العدد الإجمالي للمستقلبات ذات الوفرة المختلفة.

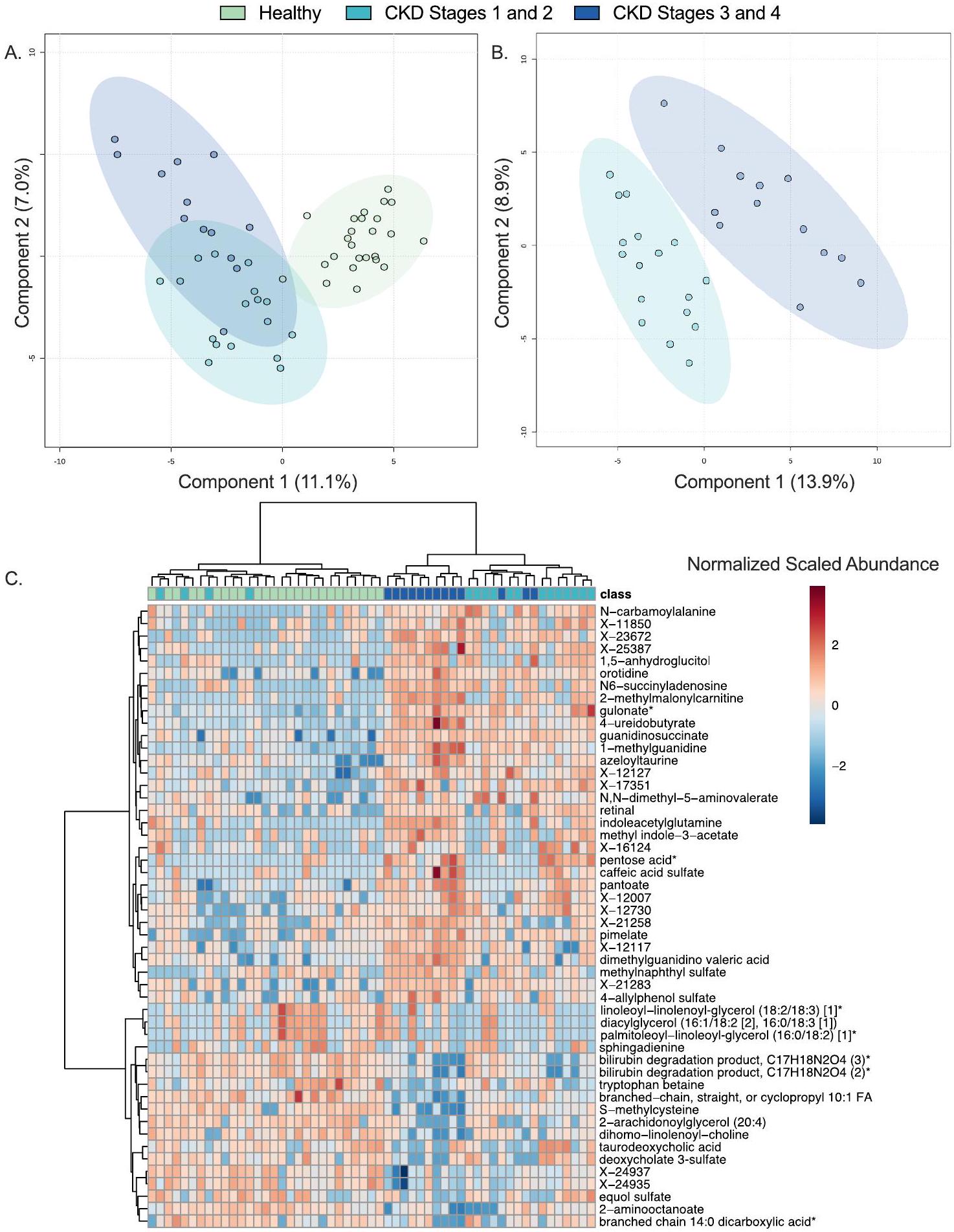

بين القطط الصحية، وتلك التي تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة، وتلك التي تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المتأخرة. أظهر نموذج PLS-DA فصلًا واضحًا عند مقارنة ملفات الميتابوليت للقطط الصحية مع تلك التي تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة والمتأخرة، مع

يعتبر استقلاب الدهون محركًا رئيسيًا للاختلافات في الميتابولوم بين القطط الصحية وقطط مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة وقطط مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المتأخرة.

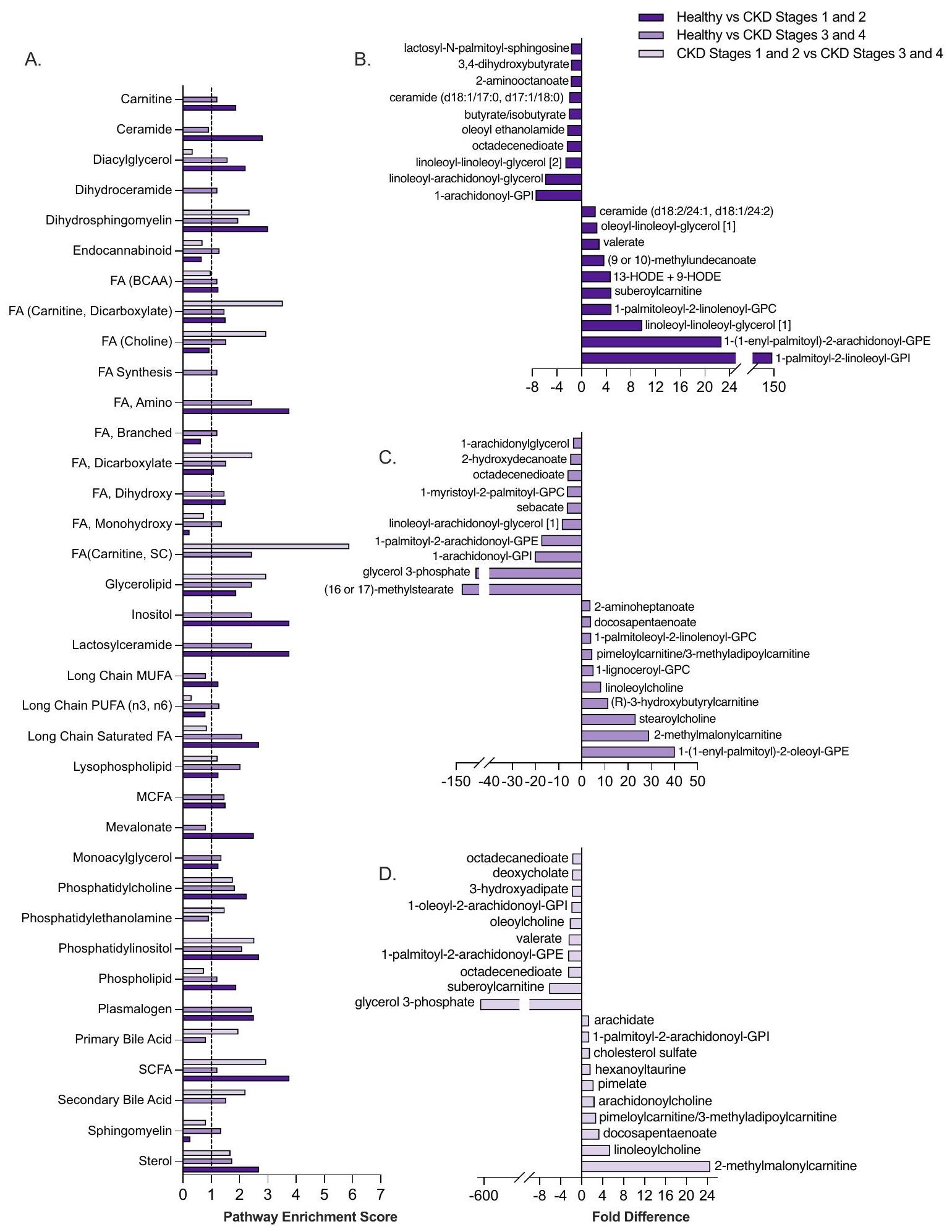

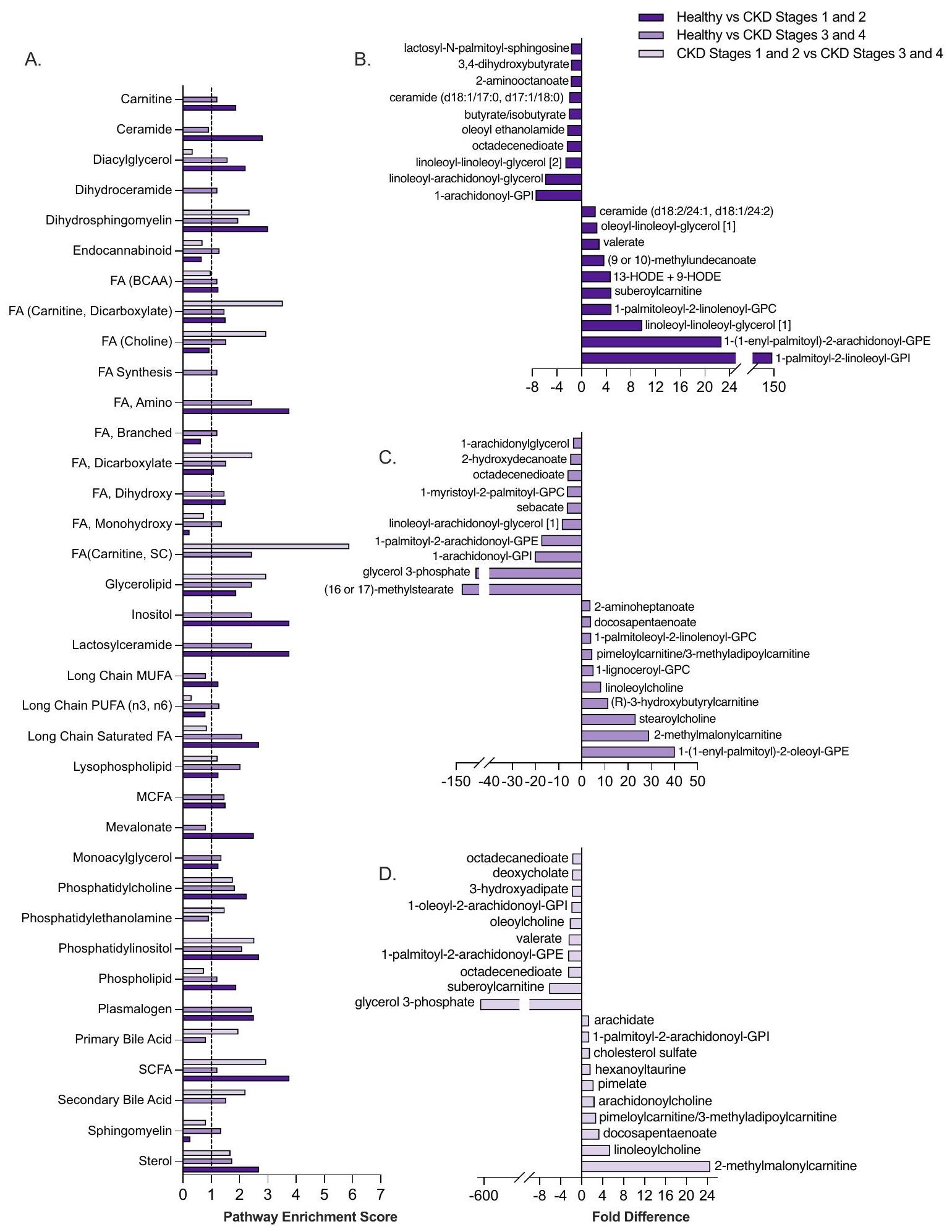

تم فحص الدهون، التي تشكل معظم الميتابولوم في مصل الدم لدى القطط الصحية وذات المرحلة المبكرة والمتأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن، بشكل أعمق لتحديد المسارات الأيضية والمواد الأيضية التي تسهم في أكبر الفروقات بين حالات المرض (الشكل 2). نظرًا لتنوع الدهون والمسارات الأيضية ضمن هذه الفئة الكيميائية، تم استخدام درجات إثراء المسار (PES) لتحديد المسارات الدهنية الرئيسية والمواد الأيضية التي تسهم في الفروقات بين مجموعات المرضى. عند مقارنة القطط الصحية وذات المرحلة المبكرة من مرض الكلى المزمن، تم تحديد 26 مسارًا كعوامل مساهمة هامة في اختلافات المواد الأيضية (الشكل 2A). من بين هذه المسارات الأيضية، كان لتمثيل الأحماض الدهنية (FA) (الأحماض الأمينية والأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة [SCFA]) وعمليات الأيض لللاكتوسيلسيراميد كل منهما درجة PES تبلغ 3.76، وهي أعلى درجة PES تم ملاحظتها بين هاتين المجموعتين من المرضى. عند ترتيب المواد الأيضية الدهنية حسب حجم الفرق بين القطط الصحية وذات المرحلة المبكرة من مرض الكلى المزمن، كانت المواد الأيضية للأحماض الدهنية 2-أمينوكتانوات (انخفاض بمقدار 1.73 مرة في المرحلة المبكرة من مرض الكلى المزمن مقابل الصحية،

في القطط الصحية مقابل القطط في مراحل متأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن، كانت 31 مسارًا من مسارات الأيض الدهني مساهمات مهمة في اختلافات الميتابولوم. مشابهًا للقطط الصحية مقابل القطط في مراحل مبكرة من مرض الكلى المزمن، كانت مسارات الأيض الدهني (الكارنيتين الأسيل، الأحماض الأمينية، السلسلة القصيرة) أيضًا مساهمات مهمة في الاختلافات بين القطط الصحية مقابل القطط في مراحل متأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن (جميعها PES 2.44). ساهم أيض البلازمالوجين والدهون الجليسرولية (كلاهما PES 2.44) وأيض الأحماض الدهنية ذات السلسلة المتفرعة (PES 1.22) بعدة من أعلى المكونات المتباينة في الوفرة بين القطط الصحية مقابل القطط في مراحل متأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن (الشكل 2A). شملت هذه المكونات الدهون الجليسرولية الجليسرول-3-فوسفات (انخفاض بمقدار 57.55 مرة في القطط في مراحل متأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن مقابل القطط الصحية،

عند مقارنة القطط في مراحل مبكرة ومتأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن، كانت 14 مسارًا لتمثيل الدهون مساهمات مهمة في اختلافات الميتابولوم. كانت مسارات تمثيل الأحماض الدهنية تمثل عدة من هذه المسارات وشملت الكارنيتين الأسيل والأحماض الدهنية ثنائية الكربوكسيل (PES 3.53)، الكولين الأسيل (PES 2.94)، وعمليات الأيض للأحماض الدهنية قصيرة السلسلة (PES 2.94 (الشكل 2A). من بين أكثر المستقلبات الدهنية اختلافًا في الوفرة ضمن هذه المسارات كان المستقلب الكارنيتين الأسيل والأحماض الدهنية ثنائية الكربوكسيل بيميلويلكارنيتين/3-ميثيلأديبويكارنيتين (زيادة بمقدار 2.77 مرة في مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة مقارنة بالمراحل المتأخرة،

بالنسبة للقطط الصحية، يتم ملاحظة اضطرابات في الأحماض الأمينية في مصل الدم لدى القطط المصابة بمرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة والمتأخرة.

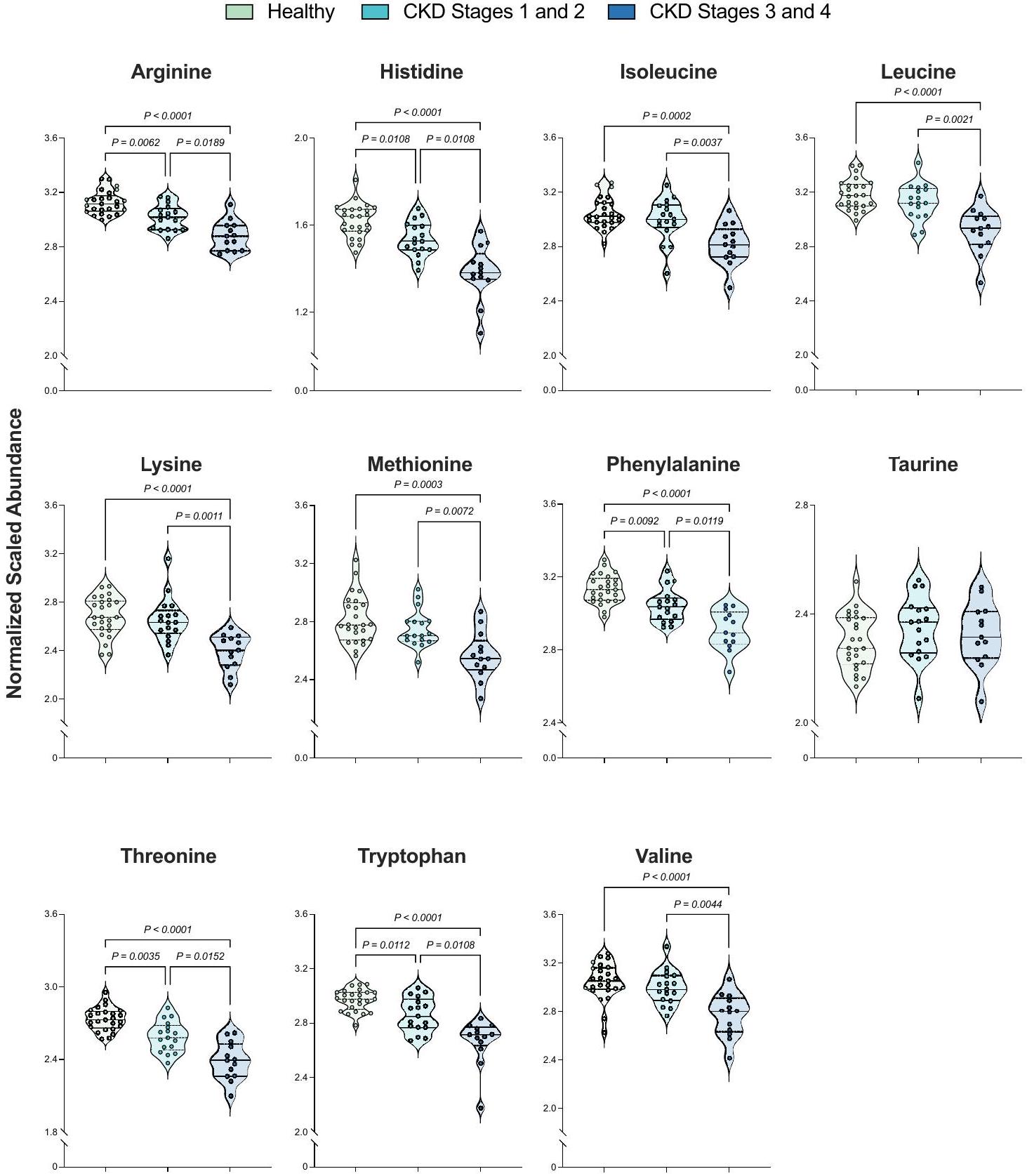

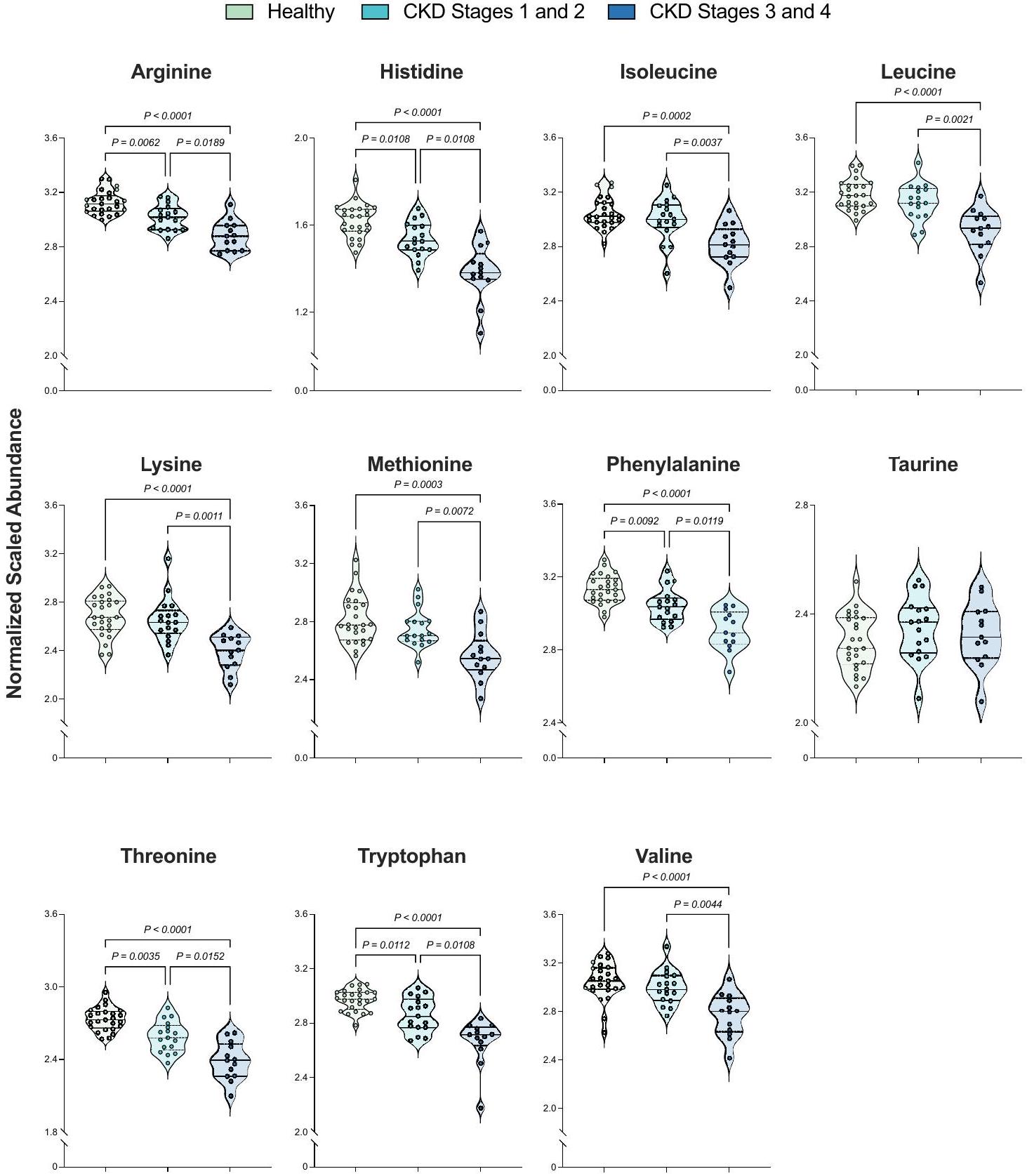

كانت الأحماض الأمينية ثاني أكبر فئة كيميائية تساهم في الفروق بين القطط الصحية وقطط مرض الكلى المزمن، بما في ذلك الفروق بين القطط في المراحل المبكرة من مرض الكلى المزمن وقطط المراحل المتأخرة. بالنظر إلى انتشار الهزال وفقدان العضلات النحيفة في القطط مع

يختلف استقلاب سموم اليوريمية بين القطط الصحية وقطط مرض الكلى المزمن، وعند المقارنة بين قطط مرض الكلى المزمن في المراحل المبكرة والمراحل المتأخرة.

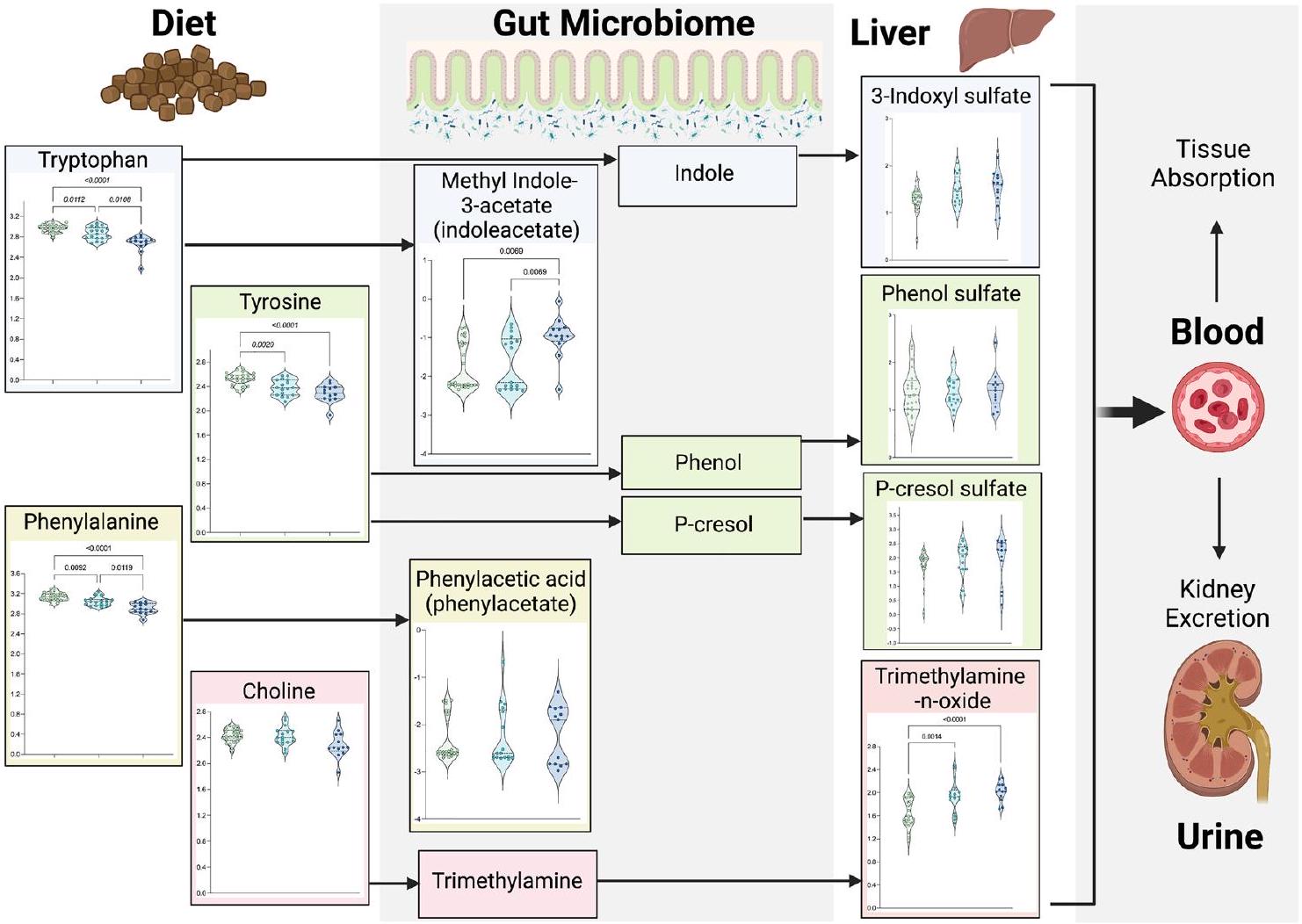

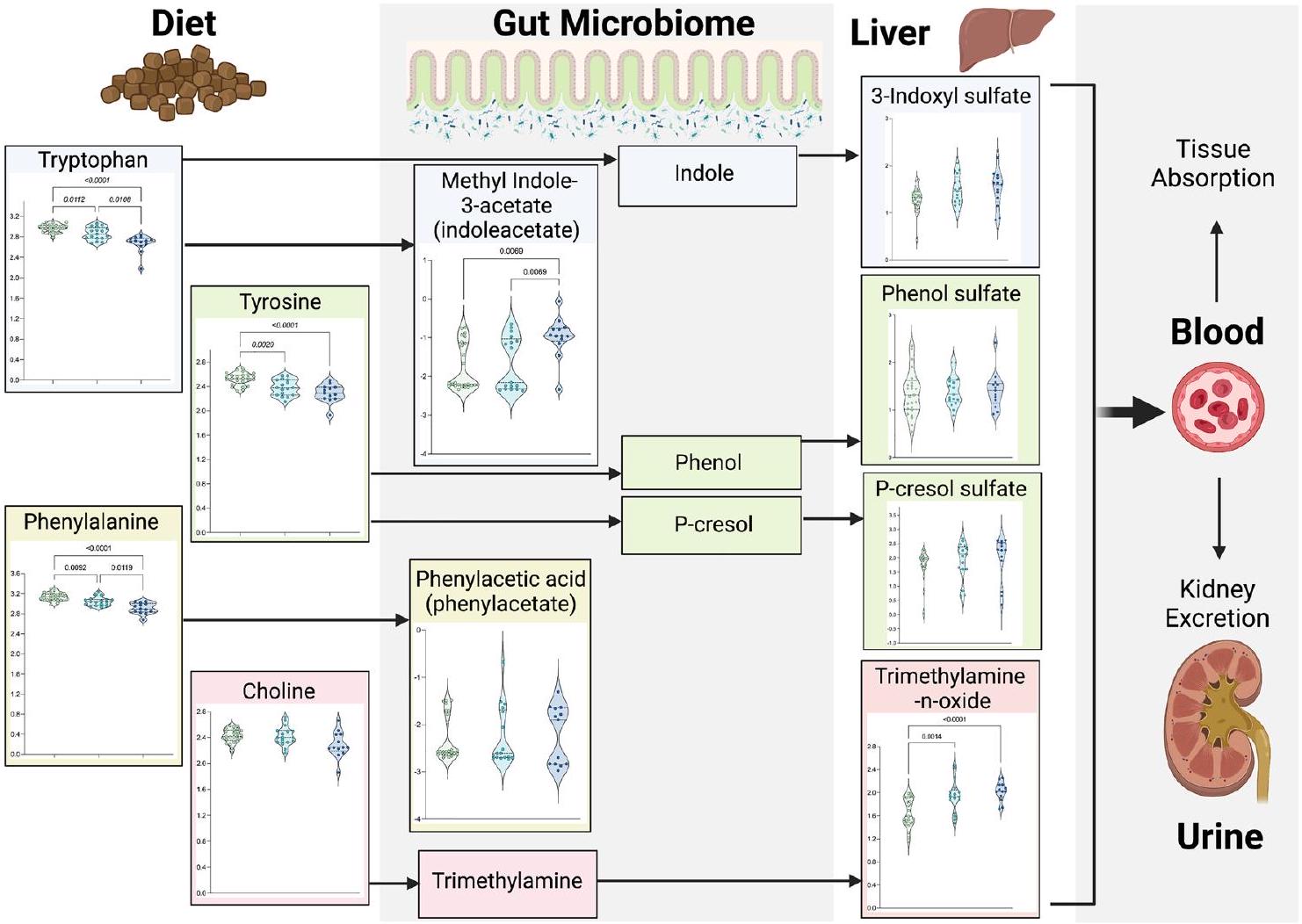

نظرًا للرابط بين ميكروبيوم الأمعاء والسموم اليوريمية، تم تقييم الاختلافات في عشرة مستقلبات متعلقة بتمثيل السموم اليوريمية الرئيسية المشتقة من الأمعاء في الشكل 4. عند مقارنة القطط المصابة بمرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة والقطط الصحية، لوحظت انخفاضات كبيرة في التربتوفان (انخفاض بمقدار 0.96 ضعف،

الشكل 1. مرحلة المرض تميز بوضوح الميتابولوم المصل للقطط الصحية، وقطط المرحلة المبكرة من مرض الكلى المزمن، وقطط المرحلة المتأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن. تحليلات التمييز باستخدام تحليل المربعات الجزئية (PLS-DA) للقطط الصحية، وقطط المرحلة المبكرة من مرض الكلى المزمن (المراحل 1 و2)، وقطط المرحلة المتأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن (المراحل 3 و4) (أ) وقطط المرحلة المبكرة من مرض الكلى المزمن مقابل المرحلة المتأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن (ب). كل دائرة تمثل الميتابولوم المصل لقط واحد. تمثل البيضات المظللة المحيطة بكل مجموعة مرضى

الشكل 2. يعد استقلاب الدهون محركًا رئيسيًا للاختلافات في الميتابولوم المصل بين القطط الصحية وقطط مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة والمتأخرة. درجات إثراء المسار لمسارات استقلاب الدهون مقارنةً بالقطط الصحية وقطط المرحلة المبكرة (المراحل 1 و 2) وقطط المرحلة المتأخرة (المراحل 3 و 4) (أ). الخط المنقط عند 1.0 يظهر المسارات الأيضية التي تم تعريفها كمساهمين ذوي مغزى في اختلافات مجموعة المرضى (درجة إثراء المسار لـ

الشكل 3. القطط التي تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المتأخرة تظهر انخفاضًا في مستويات السيروم من الأحماض الأمينية الأساسية مقارنة بالقطط الصحية وتلك التي تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة. تمثل الوفرة المعيرة والمقاسة لـ 11 حمضًا أمينيًا أساسيًا في القطط. كل دائرة تمثل قطة واحدة، حيث تشير الألوان إلى مجموعات المرضى: الأخضر = قطة صحية؛ الأزرق الفاتح = قطة تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة (المراحل 1 و 2)؛ الأزرق الداكن = قطة تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المتأخرة (المراحل 3 و 4). تظهر الخطوط المنقطة على كل مخطط كمان النسب المئوية 25 و 50 (الوسيط) و 75 من توزيعات وفرة المستقلبات المعيرة والمقاسة لكل حمض أميني. تم تعريف الأهمية على أنها

| حمض أميني | مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة (المراحل 1 و 2) مقابل الأصحاء | الفشل الكلوي المزمن في مراحله المتأخرة (المراحل 3 و 4) مقابل الصحة | مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة (المراحل 1 و 2) مقابل مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المتأخرة (المراحل 3 و 4) |

| أرجينين |

|

|

|

| هيستيدين |

|

|

|

| إيزوليوسين | 0.98 (0.38) |

|

|

| ليوسين | 0.91 (0.25) |

|

|

| ليسين | 0.99 (0.47) |

|

|

| ميثيونين | 0.91 (0.36) |

|

|

| فينيل ألانين |

|

|

|

| التورين | 1.02 (0.36) | 0.98 (0.50) | 1.01 (0.50) |

| ثريونين |

|

|

|

| تريبتوفان |

|

|

|

| فالين | 0.91 (0.24) |

|

|

الجدول 3. اختلافات الأحماض الأمينية الأساسية بين القطط الصحية وقطط المرحلة المبكرة مقابل المرحلة المتأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن. لكل مقارنة، تشير الأرقام إلى الفرق المضاعف عند مقارنة كل مجموعة من القطط، حيث تم حساب الفروق المضاعفة عن طريق قسمة المجموعة الأولى على المجموعة الثانية. الفروق المضاعفة والدلالات الإحصائية تستند إلى اختبار كروسكال-واليس لوفرة المستقلبات المحولة إلى لوغاريتمات مقاسة بالوسيط، وتم تعريف الدلالة على أنها

الشكل 4. تزداد وفرة السموم اليوريمية في مصل الدم لدى القطط في مراحل متأخرة مقارنة بالقطط في مراحل مبكرة من مرض الكلى المزمن والقطط الصحية. وفرة السموم اليوريمية العشر مقاسة ومعيارية. كل دائرة تمثل قطة واحدة، حيث تشير الألوان إلى مجموعات المرضى: الأخضر = قطة صحية؛ الأزرق الفاتح = قطة في مرحلة مبكرة من مرض الكلى المزمن (المراحل 1 و 2)؛ الأزرق الداكن = قطة في مرحلة متأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن (المراحل 3 و 4). الخطوط المنقطة على كل رسم بياني توضح النسب المئوية 25 و 50 (الوسيط) و 75 من توزيعات وفرة المستقلبات المقاسة والمعيارية لكل حمض أميني. الأسهم بين المستقلبات تشير إلى علاقاتها ببعضها البعض في مسارات استقلاب السموم اليوريمية، حيث تكون المستقلبات على يسار السهم هي المستقلبات العليا (المواد الأولية) للمستقلبات على الجانب الأيمن من الأسهم. تم تعريف الأهمية على أنها

تمت ملاحظة سموم اليوريا ثلاثي ميثيل أمين N – أكسيد (TMAO) عند مقارنة مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة بالقطط الصحية (زيادة بمقدار 1.17 مرة،

أثرت شدة المرض بشكل أكبر على استقلاب السموم اليوريمية. مقارنةً بمرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة، أظهرت القطط في المراحل المتأخرة من مرض الكلى المزمن انخفاضًا كبيرًا في التربتوفان (انخفاض بمقدار 0.93 مرة،

الارتباطات بين المستقلبات المختارة مع الكرياتينين ودرجة حالة العضلات

تم تقييم العلاقات بين 110 مستقلبات تم تقييمها في الأشكال 1 و 2 و 3 و 4 والمتغيرات السريرية المختارة باستخدام ارتباطات سبيرمان وبييرسون (الجدول 4، الملف التكميلي 3). نظرًا لأدوارها في تقدير معدل الترشيح الكبيبي وعمليات الأيض العضلي على التوالي.

نقاش

كان هدف هذه الدراسة هو مقارنة الميتابولوم في مصل الدم للقطط المملوكة من قبل العملاء التي كانت صحية مع تلك التي تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن (CKD) الذي يحدث بشكل طبيعي، لتحديد المستقلبات التي تميز بسهولة بين الصحة ومرحلة المرض المبكرة مقابل المرحلة المتأخرة. هذه هي أول دراسة منشورة تصف الميتابولوم في مصل الدم للقطط المملوكة من قبل العملاء. بينما ترتبط بعض المؤشرات الحيوية التقليدية في المصل، مثل الكرياتينين وSDMA، بشكل جيد مع معدل الترشيح الكبيبي (GFR) وتستخدم بشكل روتيني لتشخيص مرض الكلى المزمن وتصنيفه، إلا أن هناك قيودًا على استخدامها السريري. يتأثر الكرياتينين بالاضطرابات خارج الكلى، بما في ذلك كتلة العضلات النحيفة، وأمراض الغدد الصماء، والنظام الغذائي، ويمكن أن يقع ضمن النطاقات المرجعية الطبيعية خلال مرحلة مرض الكلى المزمن المبكرة.

هذه الدراسة فحصت 55 قطة مملوكة للعميل تم تأكيد تشخيصها بالفشل الكلوي المزمن عند التسجيل. الزيادات الكبيرة التي لوحظت في مستوى اليوريا في الدم والكرياتينين

| فئة كيميائية | مسار الأيض | مستقلب | كرياتينين | MCS |

| حمض أميني | ألانين، أسبارتات | N-carbامويل-ألانين | 0.54 (

|

0.47 (0.00033) |

| جلايسين، سيرين، ثريونين | ثريونين | -0.71 (

|

-0.51 (

|

|

| غوانيدينو، أسيتاميدو | 1-ميثيلغوانيدين | 0.66 (

|

0.35 (

|

|

| غوانيدينوسكسينات | 0.58 (

|

0.47 (

|

||

| هيستيدين | هيستيدين | -0.68 (

|

-0.34 (

|

|

| ليوسين، إيزوليوسين، فالين | إيزوليوسين | -0.55 (

|

-0.25 (

|

|

| ليوسين | -0.59 (

|

-0.28 (

|

||

| فالين | -0.54 (

|

-0.33 (

|

||

| ليسين | ليسين | -0.53 (

|

-0.10 (

|

|

| ميثيونين، سيستين، S-أدينوزيل-ميثيونين، تورين | ميثيونين | -0.54 (

|

-0.21 (

|

|

| أس-ميثيل سيستين | -0.57 (

|

-0.27 (

|

||

| تيروزين | -0.63 (

|

-0.48 (

|

||

| فينيل ألانين | فينيل ألانين | -0.73 (

|

-0.44 (

|

|

| تريبتوفان | إندول أسيتيل غلوتامين | 0.57 (

|

0.14 (

|

|

| تريبتوفان | -0.69 ((

|

-0.47 (

|

||

| دورة اليوريا، أرجينين، برولين | أرجينين | -0.67 (

|

-0.40 (

|

|

| حمض ديميثيلغوانيدينو فاليريك | 0.62

|

0.37 (

|

||

| كربوهيدرات | تحلل السكر، تكوين الجلوكوز، البيروفات | 1,5-أنهدروغلوكيتول | 0.35 (

|

0.62 (

|

| عامل مساعد، فيتامين | غولونات | 0.76 (

|

0.76 (

|

|

| شبكي | 0.61 (

|

0.34 (

|

||

| بانتوثينات، إنزيم مساعد أ | بانتوات | 0.51 (

|

0.32 (

|

|

| دهون | دياسيلغليسيرول | غليسيرول لينوليول-لينولينيك [1] | -0.45 (

|

-0.50 (

|

| القنبانويد الداخلي | أزيلويلتاورين | 0.58 (

|

0.21 (

|

|

| أوليول إيثانولاميد | -0.51 (

|

-0.28 (

|

||

| حمض دهني، أستيل كولين | أراكيدونيل كولين | -0.53 (

|

-0.10 (

|

|

| ديهيمو-لينولينيك-كولين | -0.53 (

|

-0.23 (

|

||

| لينوليويل كولين | -0.60 (

|

-0.31 (

|

||

| أوليوايل كولين | -0.53 (

|

-0.24 (

|

||

| حمض دهني، أحماض أمينية | 2-أمينوكتانوات | -0.51 (

|

-0.53 (

|

|

| حمض دهني متفرع | (9 أو 10)-ميثيلوندكانوات | -0.51 (

|

-0.52 (

|

|

| حمض دهني/أحماض أمينية متفرعة السلسلة | 2-ميثيلمالونيلكارنيتين | 0.61 (

|

0.20 (

|

|

| بيميلويلكارنيتين/3-ميثيلاديبوييلكارنيتين | 0.59 (

|

0.34 (

|

||

| حمض دهني (كارنيتين أسيل، ثنائي الكربوكسيل) | سوبروليكارتين | 0.71 (

|

0.26 (

|

|

| حمض دهني، ثنائي الكربوكسيل | أوكتاديسينديوات | -0.68 (

|

-0.53 (

|

|

| حمض دهني، ثنائي الهيدروكسي | 3,4-ديهيدروكسي بيوتيرات | 0.44 (

|

0.58 (

|

|

| حمض دهني، متعدد غير مشبع طويل السلسلة (n3 و n6) | دوكوسابنتاينوات | -0.51 (

|

-0.063 (

|

|

| حمض دهني، مشبع طويل السلسلة | أراشيدات | -0.60 (

|

-0.16 (

|

|

| حمض دهني، أحادي الهيدروكسي | 13-HODE + 9-HODE | -0.62 (

|

-0.37 (

|

|

| فوسفatidylcholine | ستيارويل كولين | -0.51 (

|

-0.23 (

|

|

| فوسفatidylethanolamine | 1-بالميتويل-2-أراشيدونويل-GPE | -0.51 (

|

-0.14 (

|

|

| فوسفاتيديلينوزيتول | 1-بالميتويل-2-أراشيدونويل-GPI | -0.58 (

|

-0.28 (

|

|

| فوسفوليبيد | أكسيد ثلاثي ميثيل الأمين | 0.53 (

|

0.52 (

|

|

| بلازمالوجين | 1-(1-إينيل-بالميتويل)-2-أوليول-جي بي إي | -0.50 (

|

-0.36 (

|

|

| نوكليوتيد | بيورين، أدينين | N6-سكسينيل أدينوزين | 0.57 (

|

0.38 (

|

| بيريميدين، أوروتات | أوروتيدين | 0.72 (

|

0.44 (

|

|

| بيريميدين، يوراسيل | 4-يوريدوبوتيرات | 0.72 (

|

0.44 (

|

|

| غير معروف | BDP، C17H18N2O4 (2) | -0.56 (

|

-0.25 (

|

|

| BDP، C17H18N2O4 (3) | -0.53 (

|

-0.25 (

|

||

| FA (1) 10:1 متفرع/مستقيم/سيكلوبروبيل | -0.64 (

|

-0.47 (

|

||

| إكس-12117 | 0.50 (

|

0.37 (

|

||

| إكس-12730 | 0.42 (

|

0.51 (

|

||

| إكس-17351 | 0.55 (

|

0.18 (

|

||

| إكس-21283 | 0.71 (

|

0.25 (

|

||

| إكس-24935 | -0.55 (

|

-0.27 (

|

||

| إكس-24937 | -0.59 (

|

-0.30 (

|

||

| إكس-25387 | 0.43 (

|

0.51 (

|

الجدول 4. ارتباطات بعض المستقلبات مع الكرياتينين في المصل ودرجة حالة العضلات. تشمل المستقلبات المختارة لتحليل الارتباط 110 مستقلبات تم تحديدها كعوامل تمييز رئيسية للمرضى من تحليل خريطة الحرارة + التحليل العنقودي الهرمي، والأحماض الأمينية الأساسية، وتحليل السموم اليوريمية. لكل مقارنة، تظهر القيم معامل الارتباط وقيمة p (بين قوسين) من اختبارات ارتباط سبيرمان. تم تعريف الدلالة على أنها

على الرغم من أن أدوار اضطراب استقلاب الدهون في بداية وتقدم مرض الكلى المزمن هي مجال نشط للبحث في الطب البشري، إلا أن القليل معروف عن ذلك في الكلاب والقطط.

تدمير أنبوبي تدريجي

تدمير أنبوبي تدريجي

تعتبر الأحماض الأمينية الأساسية (EAAs) علامات تشخيصية وعلاجية محتملة في مرض الكلى المزمن (CKD) حيث يمكن قياسها بسهولة وتعديلها بشكل فريد في القطط المصابة بـ CKD. إن فهم العلاقات المتبادلة بين CKD واضطراب استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية هو مجال آخر قيد البحث النشط في الطب البيطري، حيث ترتبط التغيرات في استقلاب الأحماض الأمينية بالهزال وإنتاج السموم اليوريمية في القطط.

تم تحديد انخفاضات في خمسة أحماض أمينية في مصل القطط المصابة بمرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة مقارنة بالقطط الصحية (الأرجينين، الهيستيدين، الفينيل ألانين، الثريونين، التريبتوفان) (الشكل 3، الجدول 3). وقد انخفضت هذه الأحماض الأمينية بشكل أكبر عند مقارنة القطط المصابة بمرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المتأخرة مع القطط في مراحله المبكرة، مما يشير إلى أنه قد تكون هناك تغييرات تدريجية تحدث مع تقدم المرض. في دراسة سابقة، انخفضت مستويات الفينيل ألانين والتريبتوفان والثريونين في المصل بشكل متناسب مع مرحلة مرض الكلى المزمن.

حددت مجموعة عمل السموم اليوريمية الأوروبية أكثر من 100 سمّ يوريمي مصنفة إما على أنها قابلة للذوبان في الماء الحر ذات الوزن الجزيئي المنخفض (

تشمل نقاط القوة في هذه الدراسة تطبيق نهج الميتابولوميات العالمية على القطط الصحية المملوكة من قبل العملاء وتلك التي تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة والمتأخرة باستخدام مصل الدم، وهو عينة تشخيصية تُستخدم بشكل روتيني وغير جراحية. على الرغم من أن هذه الدراسة لم تكن مدعومة بشكل كافٍ لمقارنة القطط بين مراحل أو مراحل فرعية منفصلة من IRIS بسبب انخفاض عدد تسجيل القطط في المرحلة 1 و4 من CKD، إلا أن فصل القطط إلى مجموعات مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة (المراحل 1 و2) والمتأخرة (المراحل 3 و4) لا يزال يسمح بإجراء مقارنات أوسع؛ وقد تم تطبيق هذا التصنيف سابقًا لمقارنة قطط CKD.

يتميز ميتابولوم المصل بسهولة بتمييز القطط الصحية عن تلك التي تعاني من مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة والمتأخرة، ويدعم ذلك أن هناك اضطرابات استقلابية كبيرة تحدث في مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة. تعتبر المستقلبات الدهنية والأحماض الأمينية محددات رئيسية لشدة المرض وعادة ما تكون مرتبطة بشكل جيد بالمتغيرات السريرية المستخدمة في توجيه اتخاذ القرارات السريرية لمرض الكلى المزمن. لذلك، هناك وعد كبير في التحقيق فيما إذا كانت هذه المستقلبات يمكن أن تعمل كعلامات حيوية تمييزية وقابلة للقياس بشكل عملي تميز بين القطط الصحية ومرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة. نظرًا للتشابهات بين مرض الكلى المزمن في القطط والبشر، قد تسهم العلامات الحيوية التي تم تحديدها لاكتشاف مرض الكلى المزمن في مراحله المبكرة لدى القطط في تحسين تشخيصات البشر، مما يؤدي إلى تحسين جودة الحياة للحيوانات والبشر الذين يعانون من مرض الكلى المزمن.

طرق

السكان المدروسون

شملت الدراسة عينات مصل من 55 قطة تم الحصول عليها من دراسات سابقة. تم الموافقة على جميع الدراسات من قبل إما مجلس المراجعة السريرية (VCS 2018-168؛ VCS 2019-198) في جامعة ولاية كولورادو أو لجنة رعاية واستخدام الحيوانات المؤسسية (IACUC) في جامعة ولاية أوريغون (IACUC 2020-0069؛ IACUC 2020-0065) وتمت وفقًا للإرشادات واللوائح ذات الصلة. تم تجنيد القطط الصحية والقطط التي تم تشخيصها بمرض الكلى المزمن (CKD) من عملاء مستشفى التعليم البيطري بجامعة ولاية كولورادو من 2018 إلى 2019 ومستشفى التعليم البيطري بجامعة ولاية أوريغون من 2020 إلى 2021. تم تجنيد القطط الصحية خصيصًا لهذه التجارب السريرية المتعلقة بمرض الكلى المزمن الجارية في جامعة ولاية كولورادو أو جامعة ولاية أوريغون وتمت عملية الفحص في مستشفياتهم المعنية. لكي تكون مؤهلة للإدراج، خضعت القطط لتقييم شامل شمل تاريخ العميل، ومراجعة السجل الطبي السابق، وفحص بدني أجراه أخصائي طب داخلي معتمد. تم إجراء تعداد دم كامل، ولوحة كيمياء مصل، وتحليل البول وفي معظم الحالات، تم قياس نسبة البروتين إلى الكرياتينين في البول (UPC)، وفحص الطفيليات بواسطة الطرد المركزي للسكر في البراز، وقياس تركيز الثيروكسين الكلي في المصل، وقياس ضغط الدم بواسطة قياس ضغط الدم دوبلر. تم الحصول على درجة حالة الجسم (BCS؛ نستله بيورينا، سانت لويس، ميزوري، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) ودرجة حالة العضلات (MCS).

جمع العينات

تم جمع المصل كجزء من دراسات غير مرتبطة. قدم جميع مالكي القطط المشاركين موافقة خطية قبل جمع العينات. تم جمع عينات المصل عن طريق وخز الوريد الوداجي أو الوريد السافن الأوسط، وتم تجميدها في الموقع، وتخزينها في

تحضير عينة الميتابولوم

تم إجراء تحليل ملفات الأيض المصلية العالمية بواسطة مختبر تجاري (Metabolon Inc.، موريسفيل، NC) كما هو موصوف سابقًا. باختصار، تم إرسال المصل لكل مريض على ثلج جاف. عند الوصول، تم تخزين العينات في

كروماتوغرافيا السائل التفاعلي المحب للماء مع مطيافية الكتلة بالتزامن (HILIC/UPLC-MS/MS) باستخدام التأين السالب، وتم حفظ العينة الخامسة كاحتياطي. تم تخزين جميع العينات تحت النيتروجين قبل التحليل اللاحق.

كروماتوغرافيا السائل التفاعلي المحب للماء مع مطيافية الكتلة بالتزامن (HILIC/UPLC-MS/MS) باستخدام التأين السالب، وتم حفظ العينة الخامسة كاحتياطي. تم تخزين جميع العينات تحت النيتروجين قبل التحليل اللاحق.

تحليل UPLC-MS/MS

تم تجفيف كل عينة وإعادة تكوينها في مذيبات تم تحسينها لأحد طرق الاستخراج الكروماتوغرافية الأربعة. شمل هذا الإعداد عينة واحدة تم تحسينها لاستخراج المستقلبات المحبة للماء والتي تم إزالتها بالتدرج من خلال عمود C18 (Waters UPLC BEH C18-2.1).

لجميع التحليلات، تم تضمين عينة فارغة في كل عملية تشغيل، حيث تم استخدام استخراج أولي من الماء النقي للغاية لتحديد إشارة الشحن الأساسية التي تمر عبر مطياف الكتلة. تضمنت الضوابط الإيجابية معايير خارجية تتكون من عينات بلازما بشرية موصوفة جيدًا تم تشغيلها سابقًا على معدات الكروماتوغرافيا ومطياف الكتلة، بالإضافة إلى عينة مجمعة تتكون من كميات متساوية من كل عينة تجريبية. كانت الضوابط الثالثة تتكون من كوكتيل معيار داخلي يتكون من مستقلبات بتركيزات معروفة لن تتداخل مع تحليل المستقلبات الذاتية (أي، المستقلبات غير الموجودة في المصل). تضمنت الضوابط السلبية مقادير من المذيبات المستخدمة في عمليات استخراج العينات المختلفة. للتحكم في انحراف الكروماتوغرافيا، تم عشوائية إزاحة العينات عبر الكروماتوغراف، وتم توزيع عينات التحكم بشكل متناسب بين حقن العينات التجريبية.

استخراج البيانات، تحديد المركبات وقياس الكمية

تم استخراج بيانات الطيف الكتلي ومعالجتها باستخدام تقنيات مملوكة لشركة ميتابولون. باختصار، يتم تحديد قمم الطيف الكتلي كمواد من خلال مقارنة القمم بمكتبة داخلية تضم أكثر من 4500 معيار نقي ومجهولات متكررة (أي، المستقلبات التي تم التعرف عليها فقط إلى “

أين

التحليل الإحصائي

بالنسبة لكل من البيانات السريرية والمستقلبات في المصل، تم تصنيف القطط المصابة بالفشل الكلوي المزمن إلى فشل كلوي مبكر (المراحل 1 و 2) وفشل كلوي متأخر (المراحل 3 و 4) لغرض التحليل الإحصائي. تم مقارنة المتغيرات السريرية (معايير تحاليل الدم، الوزن، BCS، MCS، العمر) بين الأصحاء (

تم إجراء التحليل الإحصائي والتصور لبيانات المستقلبات باستخدام Metaboanalyst 5.0 و GraphPad Prism

باستخدام أكبر خمسة مكونات تساهم في اختلافات العينات. تم حساب كل من Q2 (دقة توقع النموذج) و

باستخدام أكبر خمسة مكونات تساهم في اختلافات العينات. تم حساب كل من Q2 (دقة توقع النموذج) و

توفر البيانات

بيانات المستقلبات و/أو البيانات السريرية التي تم تحليلها في هذه الدراسة متاحة عند الطلب وتحت تقدير المؤلف المراسل.

تاريخ الاستلام: 1 نوفمبر 2023؛ تاريخ القبول: 21 فبراير 2024

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 27 فبراير 2024

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 27 فبراير 2024

References

- Marino, C. L. et al. Prevalence and classification of chronic kidney disease in cats randomly selected from four age groups and in cats recruited for degenerative joint disease studies. J. Feline Med. Surg. 16(6), 465-472 (2014).

- O’Neill, D. G. et al. Longevity and mortality of cats attending primary care veterinary practices in England. J. Feline Med. Surg. 17(2), 125-133 (2015).

- IRIS Staging of CKD. http://www.iris-kidney.com/pdf/2_IRIS_Staging_of_CKD_2023.pdf. Accessed 24 Sep 2023.

- Bradley, R. et al. Predicting early risk of chronic kidney disease in cats using routine clinical laboratory tests and machine learning. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 33(6), 2644-2656 (2019).

- Hall, J. A. et al. Positive impact of nutritional interventions on serum symmetric dimethylarginine and creatinine concentrations in client-owned geriatric cats. PLoS ONE 11(4), e0153654 (2016).

- Perini-Perera, S. et al. Evaluation of chronic kidney disease progression in dogs with therapeutic management of risk factors. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, 621084 (2021).

- Benito, S. et al. Untargeted metabolomics for plasma biomarker discovery for early chronic kidney disease diagnosis in pediatric patients using LC-QTOF-MS. Analyst 143(18), 4448-4458 (2018).

- Hall, J. A., Jewell, D. E. & Ephraim, E. Changes in the fecal metabolome are associated with feeding fiber not health status in cats with chronic kidney disease. Metabolites 10(7), 281 (2020).

- Hall, J. A., Jewell, D. E. & Ephraim, E. Feeding cats with chronic kidney disease food supplemented with betaine and prebiotics increases total body mass and reduces uremic toxins. PLoS ONE 17(5), e0268624 (2022).

- Jewell, D. E. et al. Metabolomic changes in cats with renal disease and calcium oxalate uroliths. Metabolomics 18(8), 68 (2022).

- Ruberti, B. et al. Serum metabolites characterization produced by cats CKD affected, at the 1 and 2 stages, before and after renal diet. Metabolites 13(1), 43 (2022).

- Kim, Y. et al. In-depth characterisation of the urine metabolome in cats with and without urinary tract diseases. Metabolomics 18(4), 19 (2022).

- AAFCO methods for substantiating nutritional adequacy of dog and cat foods, 13-24 (2023).

- Summers, S. C. et al. Serum and fecal amino acid profiles in cats with chronic kidney disease. Vet. Sci. 9(2), 84 (2022).

- Liao, Y.-L., Chou, C.-C. & Lee, Y.-J. The association of indoxyl sulfate with fibroblast growth factor-23 in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 33(2), 686-693 (2019).

- Chen, C. N. et al. Plasma indoxyl sulfate concentration predicts progression of chronic kidney disease in dogs and cats. Vet. J. 232, 33-39 (2018).

- Freeman, L. M. Cachexia and sarcopenia: Emerging syndromes of importance in dogs and cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 26(1), 3-17 (2012).

- Paepe, D. & Daminet, S. Feline CKD: Diagnosis, staging and screening: What is recommended?. J. Feline Med. Surg. 15(Suppl 1), 15-27 (2013).

- Kongtasai, T. et al. Renal biomarkers in cats: A review of the current status in chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 36(2), 379-396 (2022).

- Peterson, M. E. et al. Evaluation of serum symmetric dimethylarginine concentration as a marker for masked chronic kidney disease in cats with hyperthyroidism. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 32(1), 295-304 (2018).

- Sagawa, M. et al. Plasma creatinine levels and food creatinine contents in cats. J. Jpn. Vet. Med. Assoc. 48(11), 871-874 (1995).

- Mack, R. M. et al. Longitudinal evaluation of symmetric dimethylarginine and concordance of kidney biomarkers in cats and dogs. Vet. J. 276, 105732 (2021).

- Hall, J. A. et al. Comparison of serum concentrations of symmetric dimethylarginine and creatinine as kidney function biomarkers in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 28(6), 1676-1683 (2014).

- Paltrinieri, S. et al. Serum symmetric dimethylarginine and creatinine in Birman cats compared with cats of other breeds. J. Feline Med. Surg. 20(10), 905-912 (2017).

- Reynolds, B. S. & Lefebvre, H. P. Feline CKD: Pathophysiology and risk factors: What do we know?. J. Feline Med. Surg. 15(1 suppl), 3-14 (2013).

- Martino-Costa, A. L. et al. Renal interstitial lipid accumulation in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Comp. Pathol. 157(2-3), 75-79 (2017).

- Behling-Kelly, E. Serum lipoprotein changes in dogs with renal disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 28(6), 1692-1698 (2014).

- Gai, Z. et al. Lipid accumulation and chronic kidney disease. Nutrients 11(4), 722 (2019).

- Magliocca, G. et al. Short-chain fatty acids in chronic kidney disease: Focus on inflammation and oxidative stress regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(10), 5354 (2022).

- Simic, P. et al. Glycerol-3-phosphate is an FGF23 regulator derived from the injured kidney. J. Clin. Invest. 130(3), 1513-1526 (2020).

- Summers, S. C. et al. The fecal microbiome and serum concentrations of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresol sulfate in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 33(2), 662-669 (2019).

- Hall, J. A. et al. Cats with IRIS stage 1 and 2 chronic kidney disease maintain body weight and lean muscle mass when fed food having increased caloric density, and enhanced concentrations of carnitine and essential amino acids. Vet. Rec. 184(6), 190-190 (2019).

- Freeman, L. M. et al. Evaluation of weight loss over time in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 30(5), 1661-1666 (2016).

- Brusach, K. et al. Measurement of Ghrelin as a marker of appetite dysregulation in cats with and without chronic kidney disease. Vet. Sci. 10(7), 464 (2023).

- Casperson, S. L. et al. Leucine supplementation chronically improves muscle protein synthesis in older adults consuming the RDA for protein. Clin. Nutr. 31(4), 512-519 (2012).

- Hammer, V. A., Rogers, Q. R. & Freedland, R. A. Threonine is catabolized by L-threonine 3-dehydrogenase and threonine dehydratase in hepatocytes from domestic cats (Felis domestica). J. Nutr. 126(9), 2218-2226 (1996).

- Tang, Q. et al. Physiological functions of threonine in animals: beyond nutrition metabolism. Nutrients 13(8), 2592 (2021).

- Duranton, F. et al. Normal and pathologic concentrations of uremic toxins. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23(7), 1258-1270 (2012).

- Lim, Y. J. et al. Uremic toxins in the progression of chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Toxins 13(2), 142 (2021).

- Bhargava, S. et al. Homeostasis in the gut microbiota in chronic kidney disease. Toxins 14(10), 648 (2022).

- Cheng, F. P. et al. Detection of indoxyl sulfate levels in dogs and cats suffering from naturally occurring kidney diseases. Vet. J. 205(3), 399-403 (2015).

- Mertowska, P. et al. A link between chronic kidney disease and gut microbiota in immunological and nutritional aspects. Nutrients 13(10), 3637 (2021).

- Hall, J. A. et al. Relationship between lean body mass and serum renal biomarkers in healthy dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 29(3), 808-814 (2015).

- Muscle Condition Score. https://wsava.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Muscle-Condition-Score-Chart-for-Dogs.pdf. Accessed 6 Aug 2023.

- Body Condition Score. https://wsava.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Body-Condition-Score-cat-updated-August-2020.pdf. Accessed 6 Aug 2023.

- Pang, Z. et al. Using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 for LC-HRMS spectra processing, multi-omics integration and covariate adjustment of global metabolomics data. Nat. Protoc. 17(8), 1735-1761 (2022).

- Krasztel, M. M. et al. Correlation between metabolomic profile constituents and feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 36(2), 473-481 (2022).

الشكر والتقدير

نود أن نشكر هيئة التدريس والموظفين والطلاب في مستشفى جيمس إل. فوس لتعليم الطب البيطري بجامعة ولاية كولورادو ومستشفى تعليم الطب البيطري بجامعة ولاية أوريغون الذين ساعدوا في تجنيد المالكين وإدارة المرضى وجمع العينات. نشكر أيضًا الملاك وقططهم الذين وافقوا على المشاركة.

مساهمات المؤلفين

تم تأمين تمويل هذه الدراسة بواسطة S.S. و J.Q. تم تصور هذه الدراسة بواسطة J.Q. و S.S. تم جمع عينات سريرية وبيانات المرضى بواسطة J.Q. و S.S. تم تنسيق وتحليل البيانات السريرية بواسطة S.S.، و N.J.N. لبيانات المستقلبات. ساهمت N.J.N، S.S.، J.A.W. و J.Q. في تفسير البيانات. كانت N.J.N. و S.S. و J.A.W. مسؤولين عن إنشاء الأشكال والجداول. تم الانتهاء من كتابة المخطوطة بواسطة N.J.N. و S.S. تم مراجعة وتحرير المخطوطة بواسطة N.J.N. و S.S. و J.A.W. و J.Q. راجع جميع المؤلفين وأيدوا المخطوطة النهائية للنشر.

المصالح المتنافسة

ليس لدى N.J.N. أي مصالح متنافسة للإعلان. S.S. هي مستشارة بحثية لشركة IDEXX Laboratories، Inc. ولديها أعمال سابقة ممولة من Nestle Purina و IDEXX Laboratories، Inc. لقد تلقت مكافأة متحدث من Royal Canin و IDEXX Laboratories، Inc. و Boehringer-Ingelheim. تم تقديم النتائج الأولية من هذا التحليل في شكل ملخص في المنتدى السنوي لعام 2022 لكلية الطب البيطري الأمريكية للطب الباطني، الذي عقد في أوستن، تكساس (ePoster NU30: تحليل المستقلبات غير المستهدفة للمصل من القطط المصابة بمرض الكلى المزمن). تم تمويل عمل J.Q. من قبل مؤسسة EveryCat Health، ومؤسسة موريس للحيوانات، وNestle Purina، وTrivium Vet، وZoetis. لقد تلقت تعويضًا كعضو في المجلس الاستشاري العلمي لشركة Nestle Purina وElanco وZoetis. كما أنها استشارت أو خدمت كقائد رأي رئيسي لشركة Boehringer Ingelheim وDechra وElanco وGallant وHeska وHill’s وIDEXX وNestle Purina وRoyal Canin وSN Biomedical وVetoquinol وZoetis وتلقت تعويضًا. تم تمويل مختبر J.A.W. من قبل مؤسسة EveryCat Health، ومؤسسة موريس للحيوانات، ومؤسسة صحة الكلاب التابعة لنادي الكلاب الأمريكي، وNestle Purina، وإدارة الغذاء والدواء، والمعاهد الوطنية للصحة. لقد تلقت مكافآت متحدث من Royal Canin وNestle Purina وDVM360.

معلومات إضافية

المعلومات التكميلية تحتوي النسخة عبر الإنترنت على مواد تكميلية متاحة على https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-024-55249-5.

يجب توجيه المراسلات والطلبات للحصول على المواد إلى J.A.W.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

الوصول المفتوح هذه المقالة مرخصة بموجب رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للاستخدام والمشاركة والتكيف والتوزيع وإعادة الإنتاج في أي وسيلة أو شكل، طالما أنك تعطي الائتمان المناسب للمؤلفين الأصليين والمصدر، وتوفر رابطًا لرخصة المشاع الإبداعي، وتوضح ما إذا كانت هناك تغييرات قد تم إجراؤها. الصور أو المواد الأخرى من طرف ثالث في هذه المقالة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة، ما لم يتم الإشارة إلى خلاف ذلك في سطر ائتمان للمادة. إذا لم تكن المادة مشمولة في رخصة المشاع الإبداعي للمقالة واستخدامك المقصود غير مسموح به بموجب اللوائح القانونية أو يتجاوز الاستخدام المسموح به، ستحتاج إلى الحصول على إذن مباشرة من صاحب حقوق الطبع والنشر. لعرض نسخة من هذه الرخصة، قم بزيارة http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

© المؤلفون 2024

© المؤلفون 2024

قسم العلوم السريرية البيطرية، كلية الطب البيطري، جامعة ولاية أوهايو، كولومبوس، أوهايو 43210، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم العلوم السريرية، كلية كارلسون للطب البيطري، جامعة ولاية أوريغون، كورفاليس، أوريغون 97331، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: نورة جان نيلون وستاسي سامرز. البريد الإلكتروني: Winston.210@osu.edu

Journal: Scientific Reports, Volume: 14, Issue: 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55249-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38413739

Publication Date: 2024-02-27

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55249-5

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38413739

Publication Date: 2024-02-27

OPEN

Untargeted metabolomic profiling of serum from client-owned cats with early and late-stage chronic kidney disease

Evaluation of the metabolome could discover novel biomarkers of disease. To date, characterization of the serum metabolome of client-owned cats with chronic kidney disease (CKD), which shares numerous pathophysiological similarities to human CKD, has not been reported. CKD is a leading cause of feline morbidity and mortality, which can be lessened with early detection and appropriate treatment. Consequently, there is an urgent need for early-CKD biomarkers. The goal of this crosssectional, prospective study was to characterize the global, non-targeted serum metabolome of cats with early versus late-stage CKD compared to healthy cats. Analysis revealed distinct separation of the serum metabolome between healthy cats, early-stage and late-stage CKD. Differentially abundant lipid and amino acid metabolites were the primary contributors to these differences and included metabolites central to the metabolism of fatty acids, essential amino acids and uremic toxins. Correlation of multiple lipid and amino acid metabolites with clinical metadata important to CKD monitoring and patient treatment (e.g. creatinine, muscle condition score) further illustrates the relevance of exploring these metabolite classes further for their capacity to serve as biomarkers of early CKD detection in both feline and human populations.

| Abbreviations | |

| BDP | Bilirubin degradation product |

| BCS | Body condition score |

| BCAA | Branched chain amino acid |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| FA | Fatty acid |

| FS | Female, spayed |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| GPC | Glycerophosphorylcholine |

| GPE | Glycerophosphorylethanolamine |

| GPI | Glycerophosphorylinositol |

| HCA | Hierarchical clustering analysis |

| HODE | Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid |

| IRIS | International Renal Interest Society |

| MC | Male, castrated |

| m/z | Mass-to-charge ratio |

| MCFA | Medium-chain fatty acid |

| MUFA | Mono-unsaturated fatty acid |

| MCS | Muscle condition score |

| PLS-DA | Partial least squares discriminant analysis |

| PES | Pathway enrichment score |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| SDMA | Symmetric dimethylarginine |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

| USG | Urine specific gravity |

| UPLC-MS/MS | Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass-spectrometry |

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common medical condition of cats associated with significant physiological and metabolic disturbances, including cachexia, malnutrition, deranged amino acid metabolism, and oxidative stress

Metabolites are made and used during normal cellular functions, and disease causes disruption of biochemical pathways creating specific metabolomic profiles. These profiles can be discerned by characterizing the metabolome in a biological matrix using untargeted metabolomics and comparing healthy versus diseased samples. This method has been extensively performed in people with CKD and was successfully used for biomarker discovery for early diagnosis and etiology identification

To date, no published veterinary studies compare metabolite profiles between client-owned early-stage and late-stage CKD in cats. The ability to identify metabolic drivers of early- versus late-stage CKD, despite variable environmental conditions (e.g. diet, medical treatments, household) and pathophysiological conditions (naturally-occurring CKD with and without comorbidities including chronic enteropathy, cardiomyopathy, etc.), is imperative for biomarkers to be applied successfully to diverse patient populations. The objective of this study was to identify disease- and stage-specific metabolites to improve understanding of CKD pathophysiology, particularly in early-stage disease, and thereby suggest potential therapeutic targets and biomarkers of earlystage CKD. To better define metabolic disturbances in CKD cats, we applied untargeted serum metabolomics to compare client-owned cats with early- and late-stage CKD and healthy cats.

Results

Clinical evaluation of healthy, early-stage and late-stage CKD cats

Of the 56 cats enrolled in this study, 25 healthy cats (median, nine years; range, 1-14 years) and 30 CKD cats (median, 14 years; range,

Physical examination and laboratory parameters for healthy, CKD Stage 1 and 2, and CKD Stage 3 and 4 cats are presented in Table 1 and demographic information for individual cats is provided in Supplementary File 1. The majority of healthy cats (

Most healthy cats were not receiving medications, except for topical flea and heartworm preventative (selamectin) in three cats and oral glucosamine in one cat. Eight CKD cats were on one or more medications or supplements, including aluminum hydroxide (two cats), potassium gluconate (two cats), probiotic (five cats), polyethylene glycol 3350 (two cats), topical selamectin and oral glucosamine (one cat each). All healthy cats were fed a commercial diet formulated to meet the Association of American Feed Control Officials Nutritional Profile for adult feline maintenance

| Variable | Healthy (

|

Early-stage CKD (Stages 1 and 2) (

|

Late-stage CKD (Stages 3 and 4) (

|

| Sex | 14 MC, 11 FS | 9 MC; 8 FS | 8 MC; 5 FS |

| Age (years) | 9 (1-14) | 14 (4-17) | 13 (3-19) |

| Body weight (kg) | 4.6 (2.8-8.1) | 3.9 (3.2-6.4) | 4.3 (2.4-5.8) |

| BCS (1-9) | 5 (4-9) | 5 (4-7) | 5 (2-6) |

| MCS (0-3)* | 0 (0-2)

|

|

|

| Hematocrit (%) |

|

35 (31-43) | 36 (23-42)

|

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.4 (1.1-2.2)

|

|

3.7 (3.1-7.4)

|

| BUN (mg/dL) | 22 (18-31)

|

|

55 (42-90)

|

| Total Calcium (mg/dL) |

|

10.1 (9.2-14.4) |

|

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 3.7 (2.9-4.6)

|

3.9 (2.3-6.2) |

|

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.2 (3.5-5.2) | 4.7 (3.7-5.3) | 4.6 (2.4-5.1) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.7 (2.9-4.4) | 3.5 (3.2-4.0) | 3.6 (3.2-3.9) |

| USG | 1.049 (1.038-1.073)

|

1.018 (1.010-1.039)

|

1.016 (1.009-1.025)

|

Table 1. Patient demographics, physical examination, and laboratory variables. Numbers outside of parentheses represent the median value for each patient group, and numbers inside of parentheses show the range. For each variable, columns within each row bearing a different superscript letter were statistically different from each other (

Healthy, early-stage CKD and late-stage CKD cats have distinct serum metabolomes

The global, non-targeted serum metabolome was evaluated in 55 cats. Table 2 shows the distribution of chemical classes, including numbers of differentially abundant metabolites when comparing the three groups using a Kruskal-Wallis test with Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-values. Supplementary File 2 provides fold differences and pairwise p-values for all differentially abundant metabolites between each group. Across all samples, 918 metabolites were detected and included 830 named and 88 unknown metabolites. Lipids represented

In addition to Kruskal-Wallis testing, partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was used as a second multivariate metric to identify metabolites that were important contributors to explaining differences

| Chemical class | Healthy versus early-stage CKD (Stages 1 and 2) | Healthy versus late-stage CKD (Stages 3 and 4) | Early-stage (Stages 1 and 2) versus latestage CKD (Stages 3 and 4) |

| Amino acids (206) | 62 (

|

100 (

|

55 (

|

| Peptides (36) |

|

9 (

|

4 (

|

| Carbohydrates (22) | 5 (

|

10 (

|

5 (

|

| Vitamins and cofactors (30) | 13 (

|

16 (

|

5 (

|

| Energy metabolism (9) | 6 (

|

8 (

|

|

| Lipids (369) | 104 (

|

195 (

|

58 (

|

| Nucleotides (51) | 13 (

|

26 (

|

12 (

|

| Xenobiotics (100) | 12 (

|

29 (

|

17 (

|

| Unknown and partially characterized metabolites (95) | 23 (

|

44 (

|

22 (

|

| Total (918) | 240 (

|

437 (

|

180 (

|

Table 2. Differentially abundant metabolites in healthy cats and cats with early- versus late-stage chronic kidney disease. Parentheses next to chemical class indicates total number of identified metabolites. For each comparison, numbers refer to the total number of differentially abundant metabolites (

between healthy cats, those with early-stage CKD, and those with late-stage CKD. The PLS-DA model showed clear separation when comparing metabolite profiles of healthy cats to those with early-stage CKD and late-stage CKD, with

Lipid metabolism is a key driver of metabolome differences between healthy, early-stage CKD and late-stage CKD cats

Lipids, which comprised most of the serum metabolome in healthy, early-stage, and late-stage CKD cats, were examined further to identify the metabolic pathways and metabolites contributing to the largest differences between disease states (Fig. 2). Given the diversity of lipids and metabolic pathways within this chemical class, pathway enrichment scores (PES) were used to identify key lipid pathways and metabolites contributing to differences between patient groups. When comparing healthy and early-stage CKD cats, 26 pathways were identified as significant contributors to metabolite differences (Fig. 2A). Among these metabolic pathways, fatty acid (FA) (amino and shortchain fatty acid [SCFA]) and lactosylceramide metabolism each had a PES of 3.76 , which was the highest PES observed between these two patient groups. When ranking lipid metabolites by their magnitude of fold difference between healthy and early-stage CKD cats, the FA metabolites 2-aminooctanoate (1.73-fold decrease in early-stage CKD versus healthy,

In healthy versus late-stage CKD cats, 31 lipid metabolic pathways were significant contributors to metabolome differences. Similar to healthy versus early-stage CKD cats, FA metabolic pathways (acyl carnitine, amino, short-chain) were also significant contributors to differences among healthy versus late-stage CKD cats (all PES 2.44). Plasmalogen and glycerolipid metabolism (both PES 2.44) and branched chain FA metabolism (PES 1.22) further contributed several of the highest-magnitude differentially abundant metabolites for healthy versus latestage CKD cats (Fig. 2A). These metabolites included the glycerolipid glycerol-3-phosphate (57.55 fold-decrease in late-stage CKD versus healthy cats,

When comparing early-stage CKD versus late-stage CKD cats, 14 lipid metabolic pathways were significant contributors to metabolome differences. FA metabolic pathways accounted for several of these pathways and included acyl carnitine and dicarboxylate FA (PES 3.53), acyl choline (PES 2.94), and SCFA metabolism (PES 2.94 (Fig. 2A). Among the most differentially abundant lipid metabolites within these pathways included the acyl carnitine and dicarboxylate metabolite pimeloylcarnitine/3-methyladipoylcarnitine (2.77-fold increase in early-stage CKD versus late-stage CKD,

Compared to healthy cats, derangements in serum amino acids are observed in early-stage and late-stage CKD cats

Amino acids were the second largest chemical class contributing to differences between healthy and CKD cats, including between early-stage CKD versus late-stage CKD cats. Considering the prevalence of cachexia and lean muscle loss in cats with

Uremic toxin metabolism differs between healthy versus CKD cats and when comparing early-stage versus late-stage CKD cats

Given the link between the gut microbiome and uremic toxins, differences in ten metabolites involved metabolism of major gut-derived uremic toxins were evaluated in Fig. 4. When comparing early-stage CKD and healthy cats, significant decreases were observed for tryptophan ( 0.96 -fold decrease,

Figure 1. Disease stage distinctly differentiates the serum metabolome of healthy, early-stage CKD, and late-stage CKD cats. Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) projections of healthy cats, cats with early-stage CKD (Stages 1 and 2), and cats with late-stage CKD (Stages 3 and 4) (a) and cats with early-stage CKD versus late-stage CKD (b). Each circle represents the serum metabolome of one cat. Shaded ellipses surrounding each patient group represent

Figure 2. Lipid metabolism is a key driver of serum metabolome differences between healthy, early-stage CKD and late-stage CKD cats. Pathway enrichment scores of lipid metabolic pathways comparing healthy cats, early-stage (Stages 1 and 2) and late-stage (Stages 3 and 4) cats (a). Dotted line at 1.0 shows metabolic pathways that were defined as meaningful contributors to patient group differences (pathway enrichment score of

Figure 3. Cats with late-stage CKD exhibit decreased serum abundances of essential amino acids compared to healthy cats and those with early-stage CKD. Normalized, scaled abundances of 11 feline essential amino acids. Each circle represents one cat, where colors refer to patient groups: Green=Healthy cat; Teal=Early-stage CKD cat (Stages 1 and 2); Navy=Late-stage CKD cat (Stages 3 and 4). Dotted lines on each violin plot show the 25th, 50th (median) and 75th percentiles of normalized, scaled metabolite abundance distributions for each amino acid. Significance was defined as

| Amino acid | Early-stage CKD (Stages 1 and 2) versus healthy | Late-stage CKD (Stages 3 and 4) versus healthy | Early-stage (Stages 1 and 2) versus late-stage CKD (Stages 3 and 4) |

| Arginine |

|

|

|

| Histidine |

|

|

|

| Isoleucine | 0.98 (0.38) |

|

|

| Leucine | 0.91 (0.25) |

|

|

| Lysine | 0.99 (0.47) |

|

|

| Methionine | 0.91 (0.36) |

|

|

| Phenylalanine |

|

|

|

| Taurine | 1.02 (0.36) | 0.98 (0.50) | 1.01 (0.50) |

| Threonine |

|

|

|

| Tryptophan |

|

|

|

| Valine | 0.91 (0.24) |

|

|

Table 3. Essential amino acid differences across healthy cats and cats with early-stage versus late-stage chronic kidney disease. For each comparison, numbers indicate the fold difference when comparing each group of cats, where fold differences were calculated by dividing the first group by the second group. Fold differences and statistical significances are based on Kruskal-Wallis testing of median-scaled log-transformed metabolite abundances, and significance was defined as

Figure 4. Increased abundances of uremic toxins are present in the serum of cats with late-stage versus early-stage CKD and healthy cats. Normalized, scaled abundances of ten uremic toxins. Each circle represents one cat, where colors refer to patient groups: Green=Healthy cat; Teal=Early-stage CKD cat (Stages 1 and 2); Navy = Late-stage CKD cat (Stages 3 and 4). Dotted lines on each violin plot show the 25th, 50th (median) and 75th percentiles of normalized, scaled metabolite abundance distributions for each amino acid. Arrows between metabolites indicate their relationships to each other in uremic toxin metabolic pathways, where metabolites to the left of an arrow are upstream metabolites (precursors) to the metabolites on the right side of arrows. Significance was defined as

uremic toxin trimethylamine N -oxide (TMAO), were observed when comparing early-stage CKD to healthy cats (1.17-fold increase,

Disease severity further impacted uremic toxin metabolism. Compared to early-stage CKD, late-stage CKD cats exhibited significant decreases in tryptophan ( 0.93 -fold decrease,

Correlations between selected metabolites with creatinine and muscle condition score

Associations between the 110 metabolites assessed in Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 and selected clinical variables were further evaluated using Spearman and Pearson correlations (Table 4, Supplementary File 3). Given their roles in GFR estimation and muscle metabolism respectively

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to compare the serum metabolome of client-owned cats that were healthy to those with naturally-occurring CKD to identify metabolites that readily distinguished between health and early-stage versus late-stage disease. This is the first published study that characterizes the serum metabolome in clientowned cats. While some conventional serum biomarkers, such as creatinine and SDMA, are well correlated with GFR and routinely used for CKD diagnosis and staging, there are limitations to their clinical use. Creatinine is affected by extra-renal disorders, including lean muscle mass, endocrinopathies, diet, and it can fall within normal reference intervals during early-stage CKD

This study examined 55 client-owned cats with a confirmed diagnosis of CKD at enrollment. The significant increases observed in serum BUN and creatinine (

| Chemical Class | Metabolic Pathway | Metabolite | Creatinine | MCS |

| Amino Acid | Alanine, Aspartate | N-carbamoyl-alanine | 0.54 (

|

0.47 (0.00033) |

| Glycine, Serine, Threonine | Threonine | -0.71 (

|

-0.51 (

|

|

| Guanidino, Acetamido | 1-methylguanidine | 0.66 (

|

0.35 (

|

|

| Guanidinosuccinate | 0.58 (

|

0.47 (

|

||

| Histidine | Histidine | -0.68 (

|

-0.34 (

|

|

| Leucine, Isoleucine, Valine | Isoleucine | -0.55 (

|

-0.25 (

|

|

| Leucine | -0.59 (

|

-0.28 (

|

||

| Valine | -0.54 (

|

-0.33 (

|

||

| Lysine | Lysine | -0.53 (

|

-0.10 (

|

|

| Methionine, Cysteine, S-Adenosyl-methionine, Taurine | Methionine | -0.54 (

|

-0.21 (

|

|

| S-methylcysteine | -0.57 (

|

-0.27 (

|

||

| Tyrosine | -0.63 (

|

-0.48 (

|

||

| Phenylalanine | Phenylalanine | -0.73 (

|

-0.44 (

|

|

| Tryptophan | Indoleacetylglutamine | 0.57 (

|

0.14 (

|

|

| Tryptophan | -0.69 ((

|

-0.47 (

|

||

| Urea Cycle, Arginine, Proline | Arginine | -0.67 (

|

-0.40 (

|

|

| Dimethylguanidino valeric acid | 0.62 ((

|

0.37 (

|

||

| Carbohydrate | Glycolysis, Gluconeogenesis, Pyruvate | 1,5-anhydroglucitol | 0.35 (

|

0.62 (

|

| Cofactor, Vitamin | Gulonate | 0.76 (

|

0.76 (

|

|

| Retinal | 0.61 (

|

0.34 (

|

||

| Pantothenate, Co-enzyme A | Pantoate | 0.51 (

|

0.32 (

|

|

| Lipid | Diacylglycerol | linoleoyl-linolenoyl-glycerol [1] | -0.45 (

|

-0.50 (

|

| Endocannabinoid | Azeloyltaurine | 0.58 (

|

0.21 (

|

|

| Oleoyl ethanolamide | -0.51 (

|

-0.28 (

|

||

| Fatty Acid, Acyl Choline | Arachidonoylcholine | -0.53 (

|

-0.10 (

|

|

| Dihomo-linolenoyl-choline | -0.53 (

|

-0.23 (

|

||

| Linoleoylcholine | -0.60 (

|

-0.31 (

|

||

| Oleoylcholine | -0.53 (

|

-0.24 (

|

||

| Fatty Acid, Amino | 2-aminooctanoate | -0.51 (

|

-0.53 (

|

|

| Fatty Acid, Branched | (9 or 10)-methylundecanoate | -0.51 (

|

-0.52 (

|

|

| Fatty Acid/BCAA | 2-methylmalonylcarnitine | 0.61 (

|

0.20 (

|

|

| Pimeloylcarnitine/3-methyladipoylcarnitine | 0.59 (

|

0.34 (

|

||

| Fatty Acid (Acyl Carnitine, Dicarboxylate) | Suberoylcarnitine | 0.71 (

|

0.26 (

|

|

| Fatty Acid, Dicarboxylate | Octadecenedioate | -0.68 (

|

-0.53 (

|

|

| Fatty Acid, Dihydroxy | 3,4-dihydroxybutyrate | 0.44 (

|

0.58 (

|

|

| Fatty Acid, Long Chain Polyunsaturated (n3 and n6) | Docosapentaenoate | -0.51 (

|

-0.063 (

|

|

| Fatty Acid, Long Chain Saturated | Arachidate | -0.60 (

|

-0.16 (

|

|

| Fatty Acid, Monohydroxy | 13-HODE + 9-HODE | -0.62 (

|

-0.37 (

|

|

| Phosphatidylcholine | Stearoylcholine | -0.51 (

|

-0.23 (

|

|

| Phosphatidylethanolamine | 1-palmitoyl-2-arcahidonoyl-GPE | -0.51 (

|

-0.14 (

|

|

| Phosphatidylinositol | 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonoyl-GPI | -0.58 (

|

-0.28 (

|

|

| Phospholipid | Trimethylamine-N-oxide | 0.53 (

|

0.52 (

|

|

| Plasmalogen | 1-(1-enyl-palmitoyl)-2-oleoyl-GPE | -0.50 (

|

-0.36 (

|

|

| Nucleotide | Purine, Adenine | N6-succinyladenosine | 0.57 (

|

0.38 (

|

| Pyrimidine, Orotate | Orotidine | 0.72 (

|

0.44 (

|

|

| Pyrimidine, Uracil | 4-ureidobutyrate | 0.72 (

|

0.44 (

|

|

| Unknown | BDP, C17H18N2O4 (2) | -0.56 (

|

-0.25 (

|

|

| BDP, C17H18N2O4 (3) | -0.53 (

|

-0.25 (

|

||

| Branched/straight/cyclopropyl 10:1 FA (1) | -0.64 (

|

-0.47 (

|

||

| X-12117 | 0.50 (

|

0.37 (

|

||

| X-12730 | 0.42 (

|

0.51 (

|

||

| X-17351 | 0.55 (

|

0.18 (

|

||

| X-21283 | 0.71 (

|

0.25 (

|

||

| X-24935 | -0.55 (

|

-0.27 (

|

||

| X-24937 | -0.59 (

|

-0.30 (

|

||

| X-25387 | 0.43 (

|

0.51 (

|

Table 4. Correlations of selected metabolites with serum creatinine and muscle condition score. Metabolites selected for correlation analysis included the 110 metabolites identified as key patient differentiators from heatmap + HCA, essential amino acid, and uremic toxin analyses. For each comparison, values show the correlation coefficient and p-value (parentheses) from Spearman’s correlations tests. Significance was defined as

Although the roles of lipid dysmetabolism in CKD onset and progression is an active area of investigation in human medicine, little is known in dogs and cats

progressive tubular destruction

progressive tubular destruction

EAAs are potential diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers in CKD as they are easily measured and uniquely modified in CKD cats. Understanding the interrelationships between CKD and amino acid dysmetabolism is a second area of active investigation within veterinary medicine, where alterations to amino acid metabolism are linked to cachexia and uremic toxin production in feline

Decreases in five amino acids were identified in the serum of cats with early-stage CKD versus healthy cats (arginine, histidine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan) (Fig. 3, Table 3). These amino acids were further decreased when comparing late-stage CKD to early-stage CKD cats, suggesting that there may be progressive changes occurring with disease advancement. In a previous investigation, serum phenylalanine, tryptophan, and threonine levels decreased proportionately with CKD stage

The European Uremic Toxin Work Group identified > 100 uremic toxins that are classified as either free water-soluble low molecular weight (

The strengths of this study include applying a global metabolomics approach to healthy client-owned cats and those with both early-stage and late-stage CKD using serum, which is a routinely-used and non-invasive diagnostic sample. While this study was not sufficiently powered to compare cats between separate IRIS stages or sub-stages due to low enrollment of CKD Stage 1 and 4 cats, separation of cats into early-stage CKD (Stages 1 and 2) and late-stage CKD (Stages 3 and 4) groups still allows for broader comparisons; this grouping has been applied previously to compare CKD cats

The serum metabolome readily differentiates healthy cats from those with early-stage and late-stage CKD and supports that substantial metabolic derangements occur in early-stage CKD. Lipid and amino acid metabolites are key determinants of disease severity and are generally well-correlated with clinical variables used to guide CKD clinical decision-making CKD. Therefore, there is immense promise in investigating if these metabolites can serve as discriminative and feasibly measured biomarkers that distinguish healthy versus early-stage CKD. Given the similarities between feline and human CKD, biomarkers identified for feline early-stage CKD detection may advance human diagnostics, resulting in improved life quality for animals and people with CKD.

Methods

Study population

The study included serum samples from 55 cats sourced from previous studies. All studies were approved by either the Clinical Review Board (VCS 2018-168; VCS 2019-198) at Colorado State University or the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Oregon State University (IACUC 2020-0069; IACUC 2020-0065) and were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Healthy cats and cats diagnosed with CKD were recruited from clients of the Colorado State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital from 2018 to 2019 and Oregon State University Veterinary Teaching Hospital from 2020 to 2021. Healthy cats were recruited specifically for these CKD clinical trials ongoing at Colorado State University or Oregon State University and performed screening at their respective hospitals. To be eligible for inclusion, cats underwent a thorough evaluation that included a client history, review of past medical record, and physical examination performed by a boardcertified internal medicine specialist. Cats had a complete blood count, serum biochemistry panel, urinalysis and in most cases, urine protein-to-creatinine (UPC) ratio, fecal sugar centrifugation parasite screen, serum total thyroxine concentration, and blood pressure measurement by Doppler sphygnomanometry was performed. A nine-point body condition score (BCS; Nestle Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA) and MCS was obtained (

Sample collection

Sera were collected as part of unrelated studies. All participating cat owners provided written consent prior to sample collection. Serum samples were collected via jugular or medial saphenous venipuncture, frozen on site, and stored at

Metabolome sample preparation

Analysis of global serum metabolic profiles was performed by a commercial laboratory (Metabolon Inc., Morrisville, NC) as previously described. Briefly, serum was submitted for each patient on dry ice. Upon arrival, samples were stored at

hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HILIC/UPLC-MS/MS) with negative ESI, and a fifth aliquot saved as a spare. All aliquots were stored under nitrogen prior to downstream analysis.

hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (HILIC/UPLC-MS/MS) with negative ESI, and a fifth aliquot saved as a spare. All aliquots were stored under nitrogen prior to downstream analysis.

UPLC-MS/MS analysis

Each aliquot was dried and reconstituted in solvents optimized for one of four chromatographic extraction methods. This setup included one aliquot optimized for elution of hydrophilic metabolites that was gradienteluted through a C18 column (Waters UPLC BEH C18-2.1

For all analyses, a blank was included in each sample run, where initial extraction of ultra-pure water was used to establish the baseline charge signal running through the mass spectrometer. Positive controls included external standards comprised of well-characterized human plasma samples previously run on the chromatography and mass spectrometry equipment as well as a pooled sample consisting of equal amounts of each experimental sample. A third control consisted of an internal standard cocktail that consisted of metabolites at known concentrations that would not interfere with endogenous metabolite analysis (i.e., metabolites not found in serum). Negative controls included aliquots of the solvents used in the various sample extractions. To control for chromatographic drift, sample elution through the chromatographer was randomized and control samples were proportionately spaced between experimental sample injections.

Data extraction, compound identification and quantitation

Mass spectral data was extracted and processed using proprietary technologies owned by Metabolon Inc. Briefly, mass spectral peaks are identified as compounds through peak comparison to an internal library of over 4,500 purified standards and recurrent unknowns (i.e., metabolites identified only to the

where ”

Statistical analysis

For both clinical metadata and the serum metabolome, CKD cats were grouped as early-stage CKD (Stages 1 and 2) and late-stage CKD (Stages 3 and 4) for the purpose of statistical analysis. Clinical variables (bloodwork parameters, weight, BCS, MCS, age) were compared between healthy (

Statistical analysis and visualization for metabolomics data was performed using Metaboanalyst 5.0 and GraphPad Prism

using the five largest components contributing to sample differences. Both Q2 (model predictive accuracy) and

using the five largest components contributing to sample differences. Both Q2 (model predictive accuracy) and

Data availability

Metabolomics and/or clinical metadata analyzed in this study is available by request and under the discretion of the corresponding author.

Received: 1 November 2023; Accepted: 21 February 2024

Published online: 27 February 2024

Published online: 27 February 2024

References

- Marino, C. L. et al. Prevalence and classification of chronic kidney disease in cats randomly selected from four age groups and in cats recruited for degenerative joint disease studies. J. Feline Med. Surg. 16(6), 465-472 (2014).

- O’Neill, D. G. et al. Longevity and mortality of cats attending primary care veterinary practices in England. J. Feline Med. Surg. 17(2), 125-133 (2015).

- IRIS Staging of CKD. http://www.iris-kidney.com/pdf/2_IRIS_Staging_of_CKD_2023.pdf. Accessed 24 Sep 2023.

- Bradley, R. et al. Predicting early risk of chronic kidney disease in cats using routine clinical laboratory tests and machine learning. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 33(6), 2644-2656 (2019).

- Hall, J. A. et al. Positive impact of nutritional interventions on serum symmetric dimethylarginine and creatinine concentrations in client-owned geriatric cats. PLoS ONE 11(4), e0153654 (2016).

- Perini-Perera, S. et al. Evaluation of chronic kidney disease progression in dogs with therapeutic management of risk factors. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, 621084 (2021).

- Benito, S. et al. Untargeted metabolomics for plasma biomarker discovery for early chronic kidney disease diagnosis in pediatric patients using LC-QTOF-MS. Analyst 143(18), 4448-4458 (2018).

- Hall, J. A., Jewell, D. E. & Ephraim, E. Changes in the fecal metabolome are associated with feeding fiber not health status in cats with chronic kidney disease. Metabolites 10(7), 281 (2020).

- Hall, J. A., Jewell, D. E. & Ephraim, E. Feeding cats with chronic kidney disease food supplemented with betaine and prebiotics increases total body mass and reduces uremic toxins. PLoS ONE 17(5), e0268624 (2022).

- Jewell, D. E. et al. Metabolomic changes in cats with renal disease and calcium oxalate uroliths. Metabolomics 18(8), 68 (2022).

- Ruberti, B. et al. Serum metabolites characterization produced by cats CKD affected, at the 1 and 2 stages, before and after renal diet. Metabolites 13(1), 43 (2022).

- Kim, Y. et al. In-depth characterisation of the urine metabolome in cats with and without urinary tract diseases. Metabolomics 18(4), 19 (2022).

- AAFCO methods for substantiating nutritional adequacy of dog and cat foods, 13-24 (2023).

- Summers, S. C. et al. Serum and fecal amino acid profiles in cats with chronic kidney disease. Vet. Sci. 9(2), 84 (2022).

- Liao, Y.-L., Chou, C.-C. & Lee, Y.-J. The association of indoxyl sulfate with fibroblast growth factor-23 in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 33(2), 686-693 (2019).

- Chen, C. N. et al. Plasma indoxyl sulfate concentration predicts progression of chronic kidney disease in dogs and cats. Vet. J. 232, 33-39 (2018).

- Freeman, L. M. Cachexia and sarcopenia: Emerging syndromes of importance in dogs and cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 26(1), 3-17 (2012).

- Paepe, D. & Daminet, S. Feline CKD: Diagnosis, staging and screening: What is recommended?. J. Feline Med. Surg. 15(Suppl 1), 15-27 (2013).

- Kongtasai, T. et al. Renal biomarkers in cats: A review of the current status in chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 36(2), 379-396 (2022).

- Peterson, M. E. et al. Evaluation of serum symmetric dimethylarginine concentration as a marker for masked chronic kidney disease in cats with hyperthyroidism. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 32(1), 295-304 (2018).

- Sagawa, M. et al. Plasma creatinine levels and food creatinine contents in cats. J. Jpn. Vet. Med. Assoc. 48(11), 871-874 (1995).

- Mack, R. M. et al. Longitudinal evaluation of symmetric dimethylarginine and concordance of kidney biomarkers in cats and dogs. Vet. J. 276, 105732 (2021).

- Hall, J. A. et al. Comparison of serum concentrations of symmetric dimethylarginine and creatinine as kidney function biomarkers in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 28(6), 1676-1683 (2014).

- Paltrinieri, S. et al. Serum symmetric dimethylarginine and creatinine in Birman cats compared with cats of other breeds. J. Feline Med. Surg. 20(10), 905-912 (2017).

- Reynolds, B. S. & Lefebvre, H. P. Feline CKD: Pathophysiology and risk factors: What do we know?. J. Feline Med. Surg. 15(1 suppl), 3-14 (2013).

- Martino-Costa, A. L. et al. Renal interstitial lipid accumulation in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Comp. Pathol. 157(2-3), 75-79 (2017).

- Behling-Kelly, E. Serum lipoprotein changes in dogs with renal disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 28(6), 1692-1698 (2014).

- Gai, Z. et al. Lipid accumulation and chronic kidney disease. Nutrients 11(4), 722 (2019).

- Magliocca, G. et al. Short-chain fatty acids in chronic kidney disease: Focus on inflammation and oxidative stress regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(10), 5354 (2022).

- Simic, P. et al. Glycerol-3-phosphate is an FGF23 regulator derived from the injured kidney. J. Clin. Invest. 130(3), 1513-1526 (2020).

- Summers, S. C. et al. The fecal microbiome and serum concentrations of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresol sulfate in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 33(2), 662-669 (2019).

- Hall, J. A. et al. Cats with IRIS stage 1 and 2 chronic kidney disease maintain body weight and lean muscle mass when fed food having increased caloric density, and enhanced concentrations of carnitine and essential amino acids. Vet. Rec. 184(6), 190-190 (2019).

- Freeman, L. M. et al. Evaluation of weight loss over time in cats with chronic kidney disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 30(5), 1661-1666 (2016).

- Brusach, K. et al. Measurement of Ghrelin as a marker of appetite dysregulation in cats with and without chronic kidney disease. Vet. Sci. 10(7), 464 (2023).

- Casperson, S. L. et al. Leucine supplementation chronically improves muscle protein synthesis in older adults consuming the RDA for protein. Clin. Nutr. 31(4), 512-519 (2012).

- Hammer, V. A., Rogers, Q. R. & Freedland, R. A. Threonine is catabolized by L-threonine 3-dehydrogenase and threonine dehydratase in hepatocytes from domestic cats (Felis domestica). J. Nutr. 126(9), 2218-2226 (1996).

- Tang, Q. et al. Physiological functions of threonine in animals: beyond nutrition metabolism. Nutrients 13(8), 2592 (2021).

- Duranton, F. et al. Normal and pathologic concentrations of uremic toxins. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23(7), 1258-1270 (2012).

- Lim, Y. J. et al. Uremic toxins in the progression of chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Toxins 13(2), 142 (2021).

- Bhargava, S. et al. Homeostasis in the gut microbiota in chronic kidney disease. Toxins 14(10), 648 (2022).

- Cheng, F. P. et al. Detection of indoxyl sulfate levels in dogs and cats suffering from naturally occurring kidney diseases. Vet. J. 205(3), 399-403 (2015).