DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-025-11418-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40097976

تاريخ النشر: 2025-03-17

تحليل النسخ الجيني المقارن يكشف عن اختلافات في الاستجابات المناعية لأيونات النحاس في Sepia esculenta تحت ظروف درجات الحرارة العالية

الملخص

سيبيا إسكولنتا هي واحدة من أكثر تجمعات الحبار الموجودة حاليًا وفرة في جنوب شرق آسيا، وتثير اهتمامًا بسبب معدل تكاثرها السريع وقيمتها التجارية العالية. في السنوات الأخيرة، ومع التطور السريع للصناعة، ظهرت قضايا مثل الاحتباس الحراري وتلوث المعادن الثقيلة في المحيطات، مما يشكل تهديدًا خطيرًا على الأنشطة الحيوية للكائنات البحرية. في هذه الدراسة، استخدمنا تقنيات النسخ الجيني للتحقيق في الفروقات في استجابات المناعة للتعرض للنحاس في يرقات S. esculenta تحت ظروف درجات حرارة مختلفة. كان تركيز جينات عائلة ناقلات المحاليل (SLC) والجينات المتعلقة بتكرار الحمض النووي وإصلاحه أعلى بشكل ملحوظ في مجموعة CuT مقارنة بمجموعة Cu. كشفت تحليل إثراء الوظائف أن مسارات البلعمة المعتمدة على FcyR ومسارات الالتهام الذاتي كانت غنية في مجموعة CuT. استنادًا إلى تحليل الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف (DEGs) ونتائج إثراء الوظائف، يمكننا أن نستنتج أوليًا أن مجموعة CuT تسببت في اضطراب أكثر حدة في نقل الأيونات بين الخلايا وتكرار الحمض النووي وإصلاحه في اليرقات مقارنة بمجموعة Cu. قد يكون هذا قد أثر بشكل أكبر على الأنشطة الفسيولوجية الطبيعية ليرقات S. esculenta. بشكل عام، عند درجات حرارة مرتفعة، يؤدي التعرض للنحاس إلى استجابة التهابية أكثر حدة. توفر نتائج هذه الدراسة أساسًا نظريًا للباحثين لفهم تأثيرات العوامل البيئية على مناعة يرقات S. esculenta، بالإضافة إلى رؤى أولية حول التأثيرات السامة المعززة للنحاس المعدني على الكائنات المائية تحت ظروف درجات الحرارة العالية.

مقدمة

لقد أدى التطور السريع في التصنيع إلى زيادة تلوث المعادن الثقيلة، كما زاد من معدل الاحتباس الحراري. أظهرت الدراسات السابقة أن درجة الحرارة تؤدي إلى تغييرات في سمية المعادن الثقيلة للكائنات البحرية. وجد رين وآخرون أن درجات الحرارة العالية تعزز من تسمم المعادن الثقيلة لـ Ruditapes philippinarum، مما يعيق نموه وتطوره بشكل كبير. أظهر مالهوتر وآخرون أن درجة الحرارة ستؤثر على السمية الناتجة عن التعرض للنحاس. مقارنةً بدرجة الحرارة المنخفضة.

س. إسكولنتا هي واحدة من أكثر تجمعات الحبار وفرة التي تعيش في جنوب شرق آسيا، حيث تتميز بلحمها اللذيذ، واحتوائها على نسبة عالية من البروتين، وسرعة تكاثرها. لذلك، جذبت بسرعة انتباه العلماء. نتيجة لتدهور البيئة البحرية والاستغلال الواسع النطاق للموارد البحرية من قبل البشر، انخفضت أعداد س. إسكولنتا بشكل كبير، وفي السنوات الأخيرة، أصبحت حتى نوعًا مهددًا بالانقراض. عادةً ما يتم تربية س. إسكولنتا في الأسر في المياه الساحلية الضحلة. تؤثر التركيزات العالية من المعادن الثقيلة ودرجات الحرارة المرتفعة على طول الساحل البحري بشكل عميق على نموها وتطورها.

آليات الجزيئات لدرجات الحرارة العالية على الأخطبوط العادي واستجابة النسخ الجيني للتعرض للنحاس في Mytilus coruscus [12-14]. لذلك، يمكننا استخدام تسلسل RNA لاستكشاف الآلية السمية للتعرض للنحاس في يرقات S. esculenta عند درجات حرارة عالية.

في دراستنا، استخدمنا تسلسل النسخ الجيني عالي الإنتاجية لاستكشاف الفروق في مناعة التعرض للنحاس في يرقات S. esculenta عند درجات حرارة مختلفة. من خلال تحليل إثراء الوظائف باستخدام GO و KEGG، وُجد أن درجات الحرارة العالية تؤثر بشكل كبير على استجابة المناعة للتعرض للنحاس وتسبب استجابة التهابية أكثر حدة في يرقات S. esculenta. في الوقت نفسه، يمكن أن تؤدي درجات الحرارة العالية إلى إحداث أضرار أكثر شدة في الحمض النووي واضطرابات في نقل الأيونات. توفر نتائجنا أساسًا لاستكشاف الفروق في استجابات التعرض للنحاس في يرقات S. esculenta تحت ظروف درجات حرارة مختلفة وتقديم اقتراحات علمية أكثر لتربية الحبار الذهبي والرأسقدميات.

المواد والطرق

جمع يرقات S. esculenta وتجارب الضغط

و 24 ساعة (CuT_24h) في مجموعة CuT. تم تخزين جميع العينات في خزانات النيتروجين السائل حتى استخراج RNA.

استخراج RNA، بناء المكتبة والتسلسل

فحص الجينات المختلفة وتوصيف وظائف الجينات

تحليل الإثراء

تحليل RT-PCR الكمي

النتائج

نتائج تسلسل الترنسكريبتوم

تحليل الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف

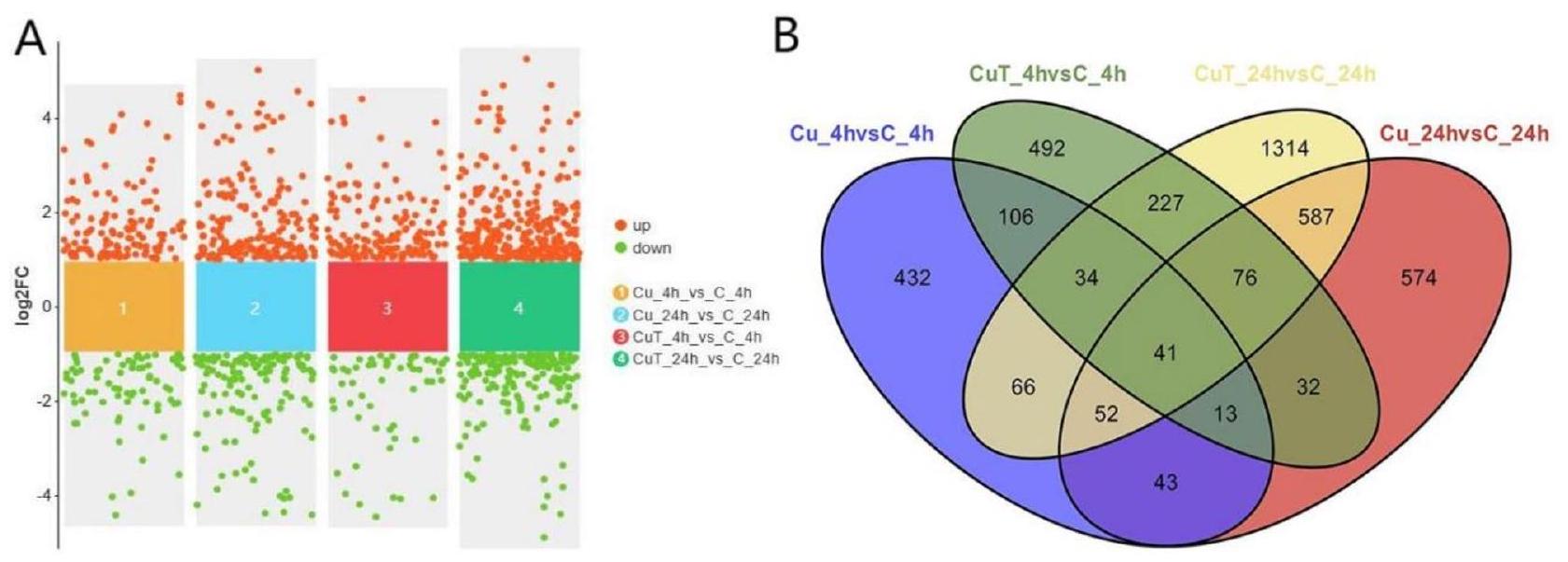

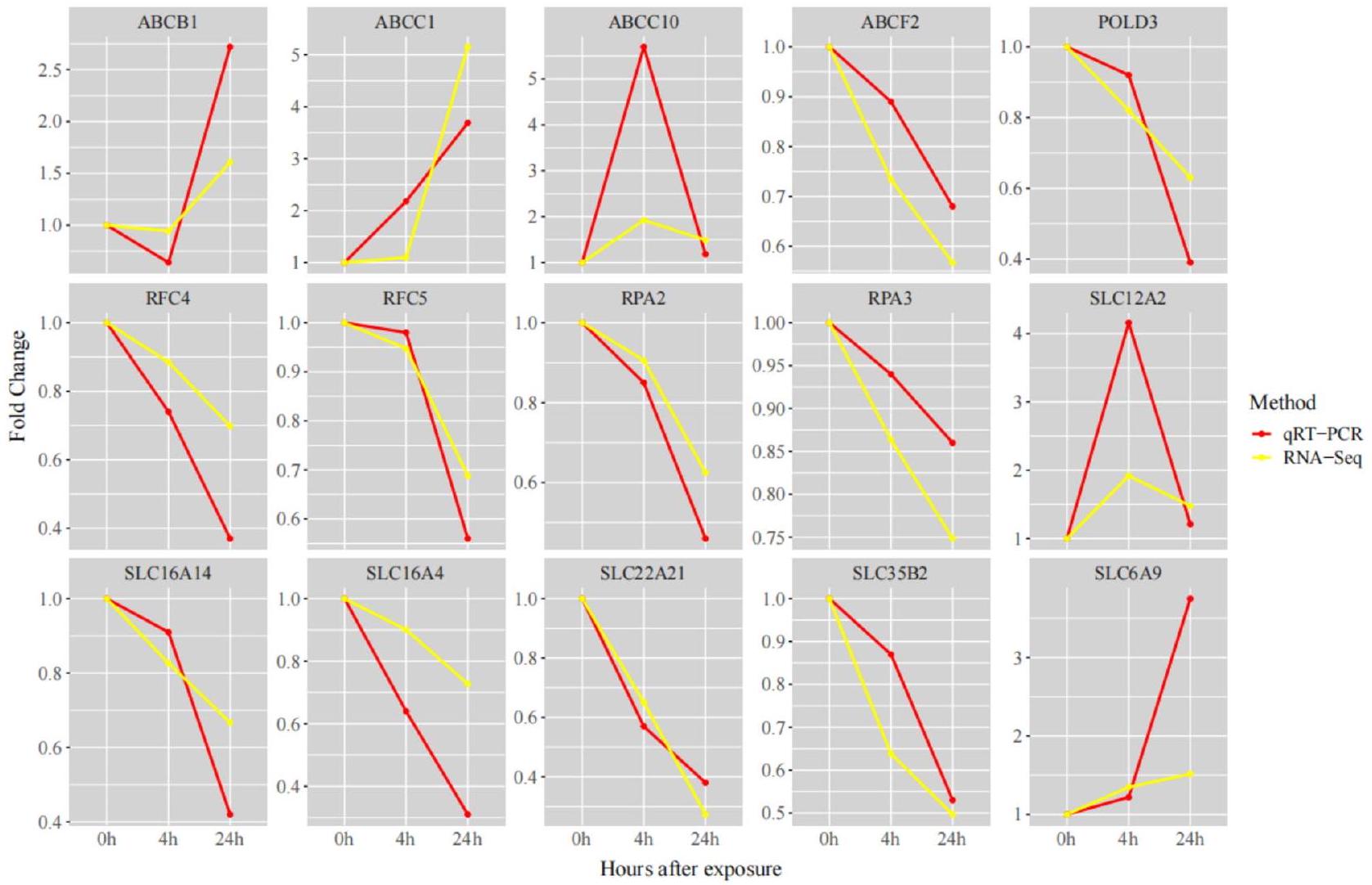

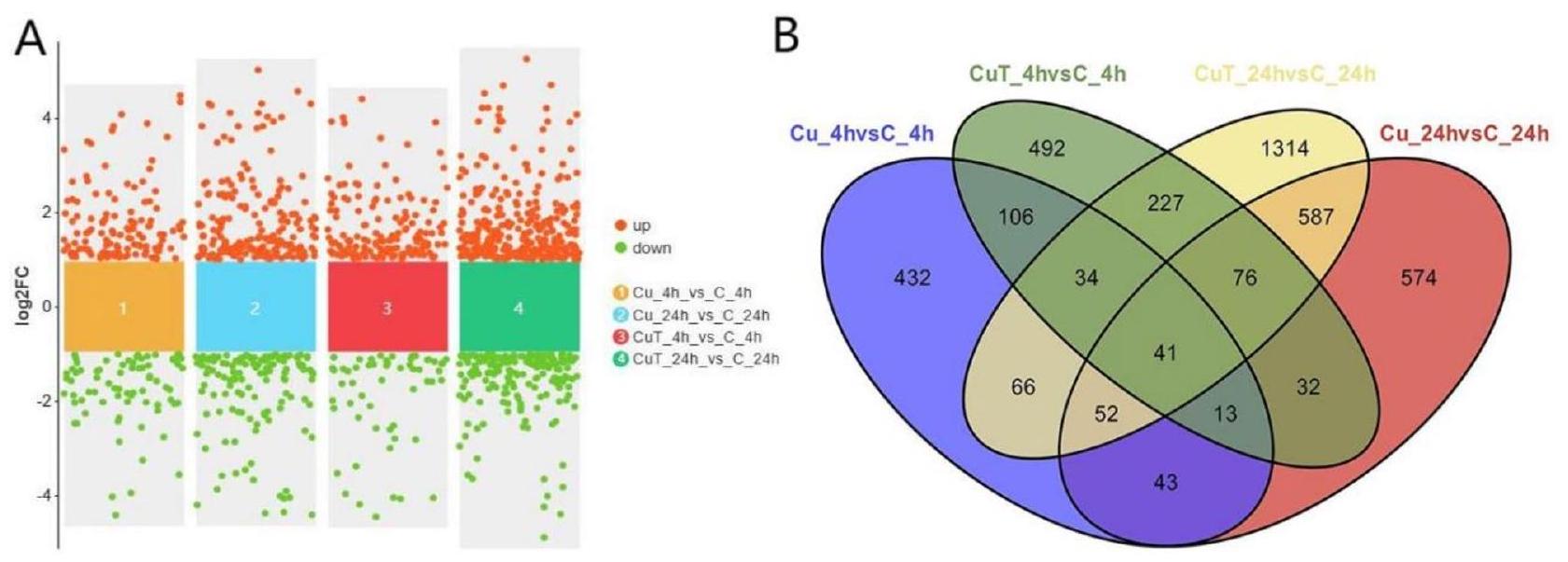

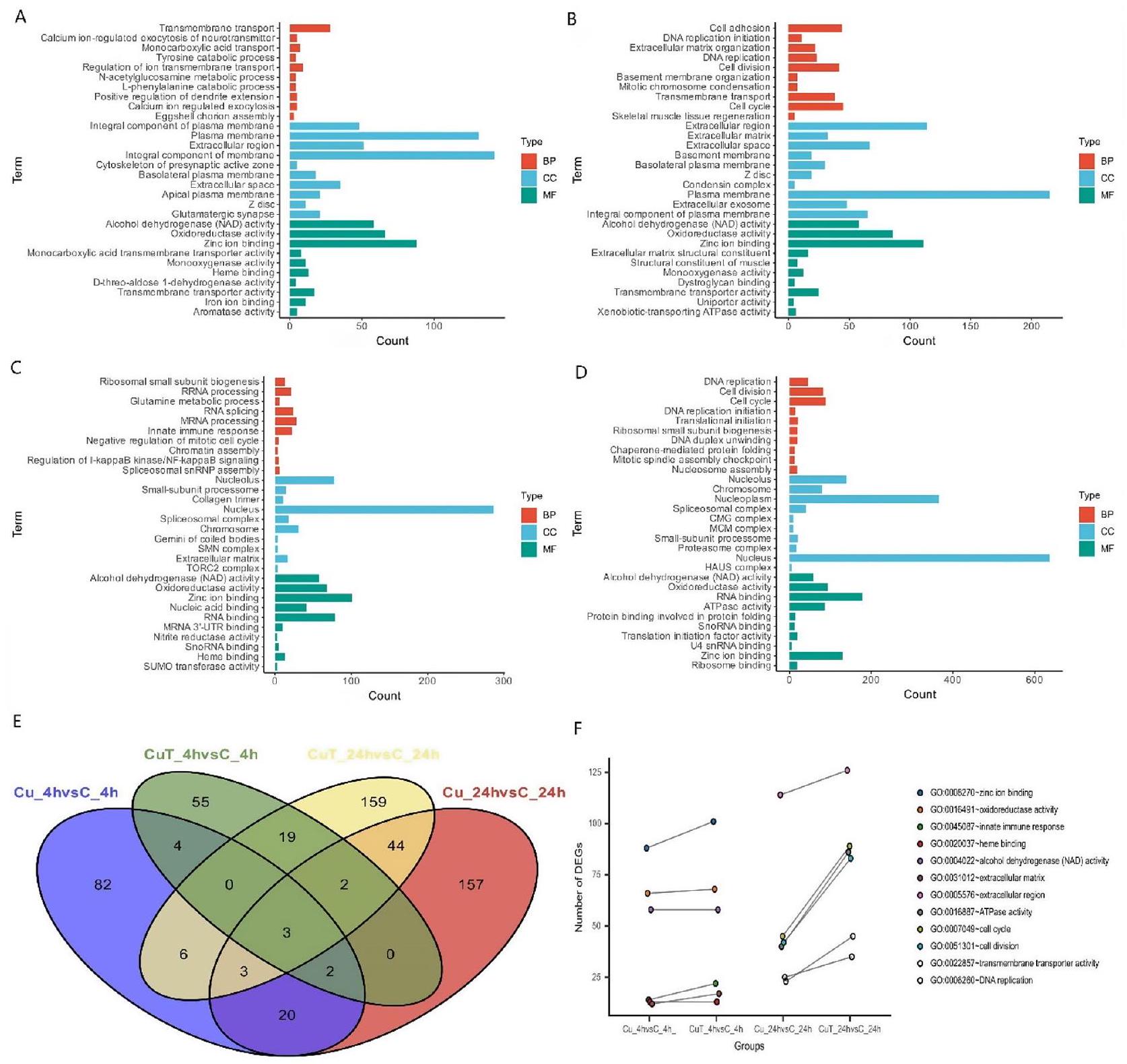

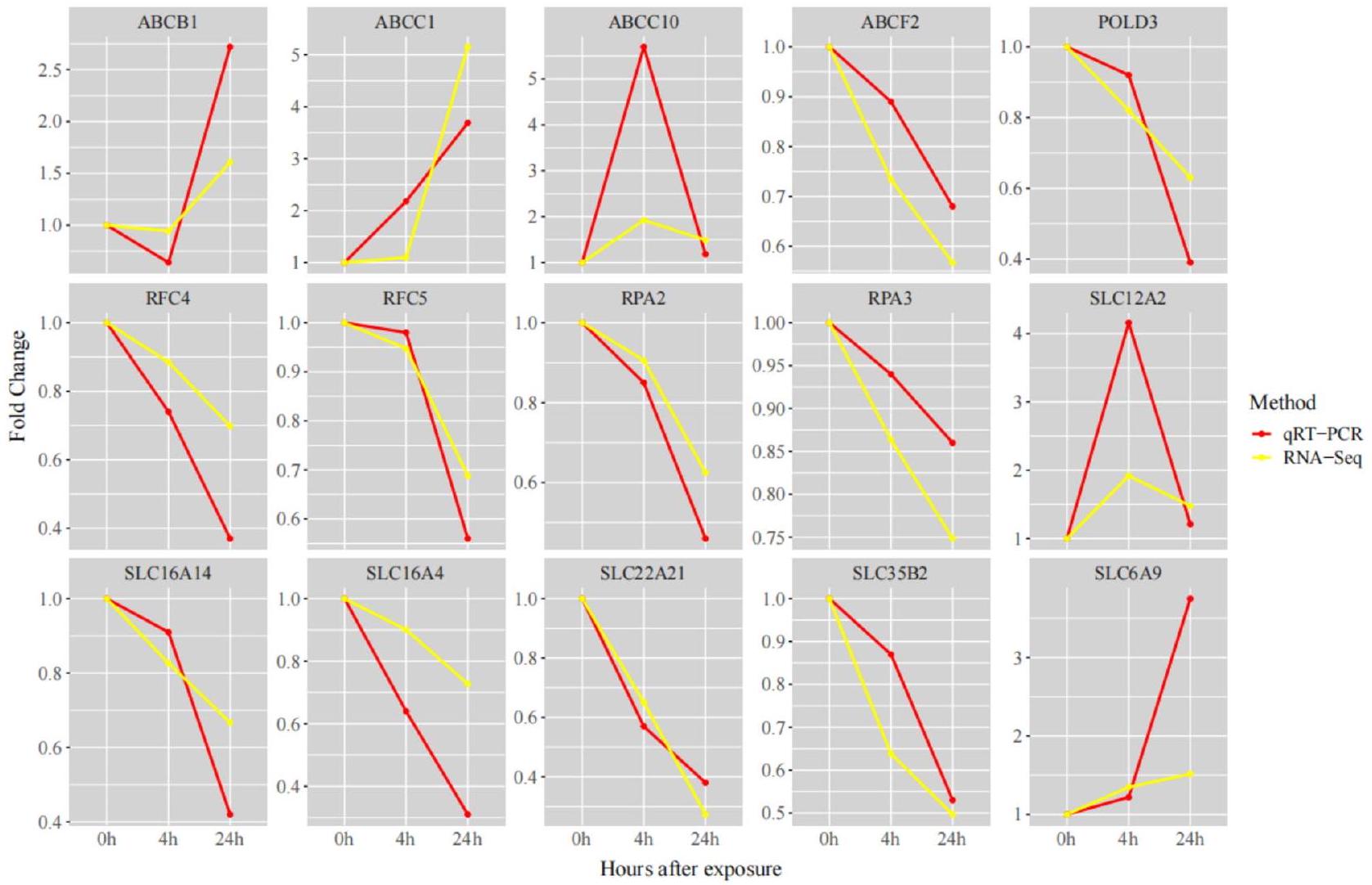

يوضح مخطط Venn للجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف (الشكل 1B) بوضوح الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل فريد والمشتركة بين كل مجموعة. في كل من مجموعتي Cu و CuT، وجدنا وجود جينات من عائلة SLC (SLC6A9) وعائلة ناقلات ATP (ABC) الفرعية (ABCC10، ABCC1، ABCB1). في مجموعة CuT، وجدنا أن عائلة SLC (SLC16A4، SLC16A14، SLC22A21، SLC35B2، SLC6A9، SLC12A2) وعائلة ABC الفرعية (ABCF2) كانت موجودة. تم العثور على جينات مرتبطة بتكرار الحمض النووي والتلف في الجينات الفريدة لمجموعة CuT، مثل RFC4، RFC5، POLD3، RPA2، وRPA3.

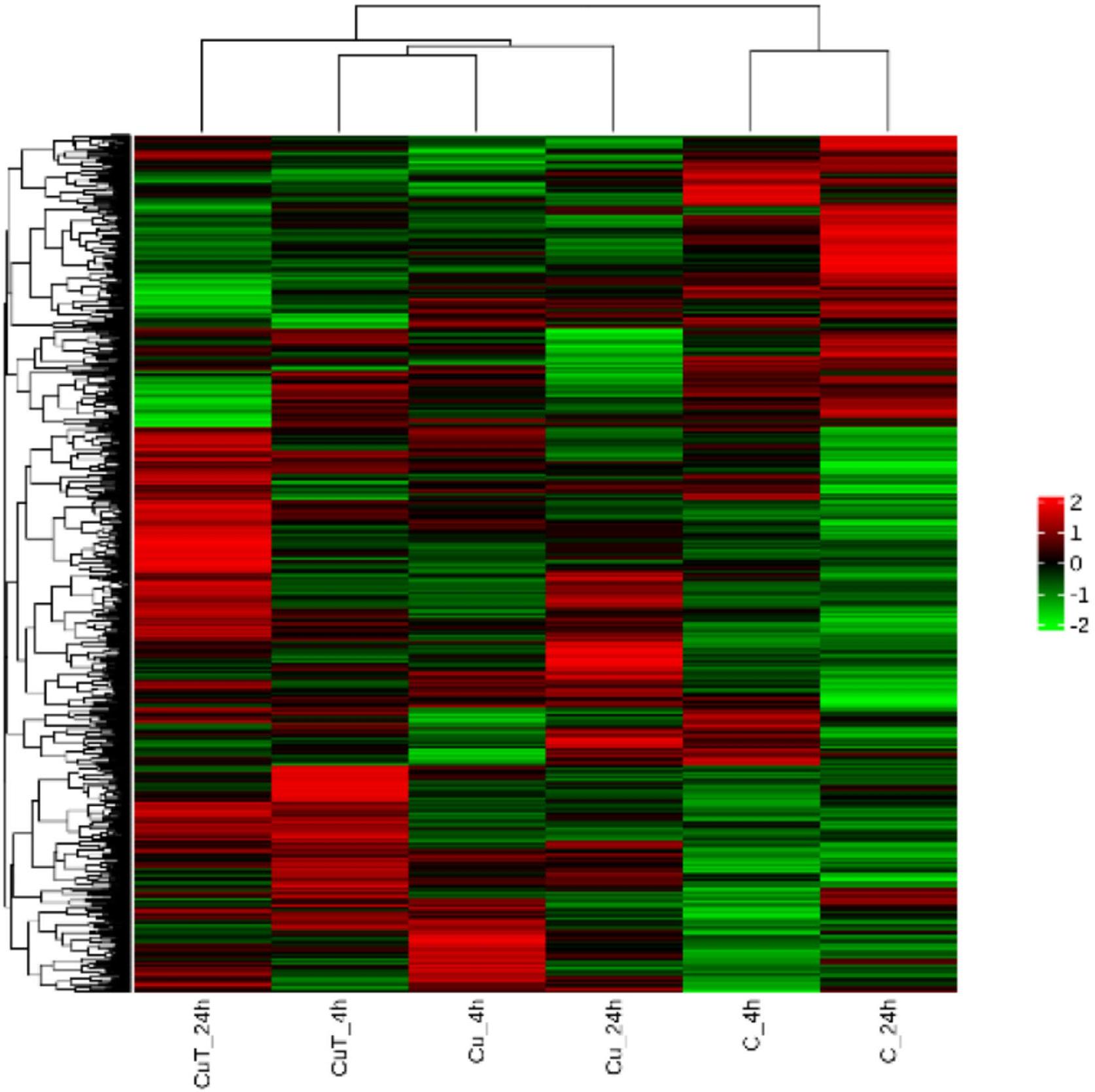

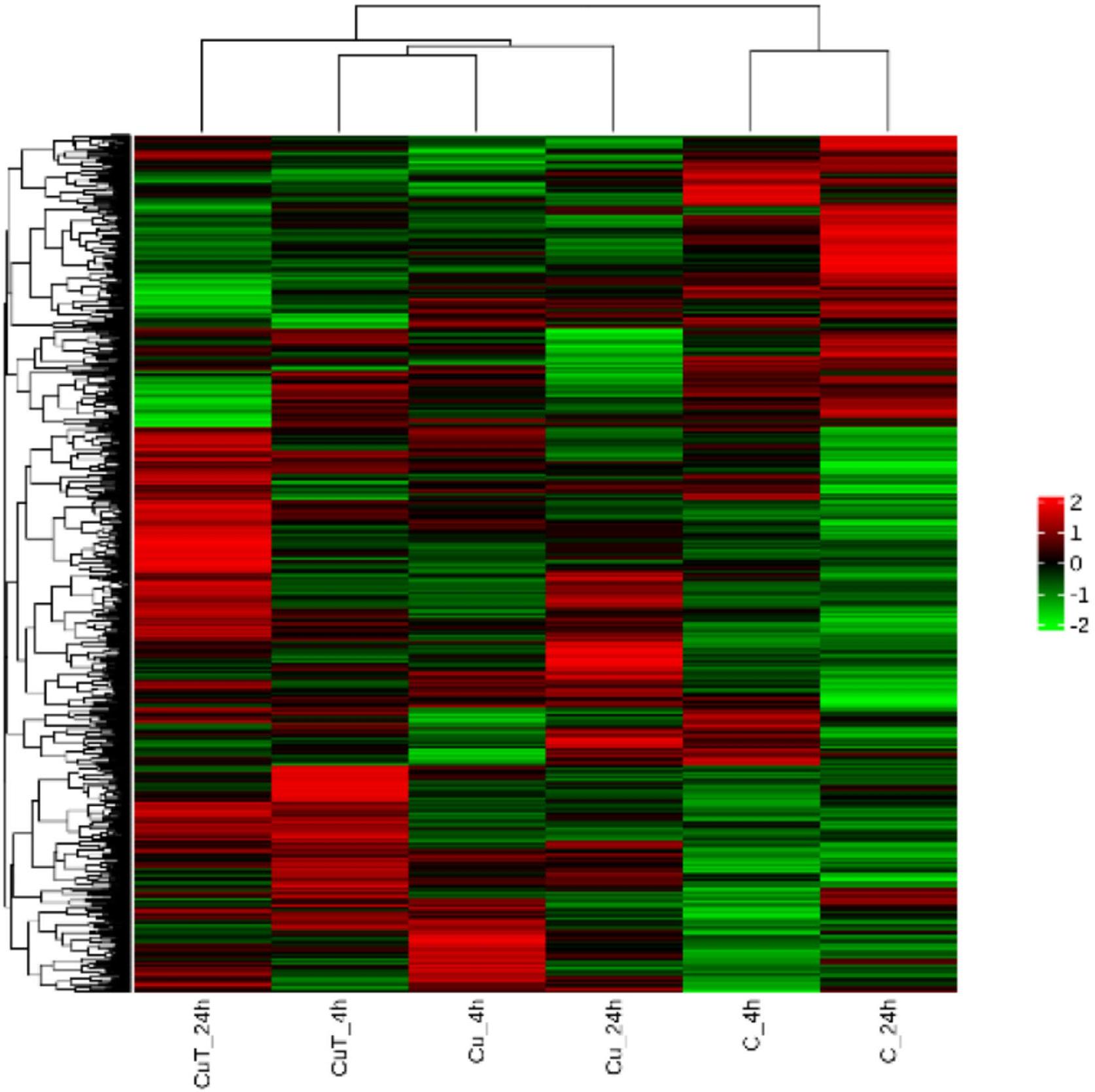

أظهرت نتائج خريطة الحرارة للتجميع أن نمط التعبير لمجموعة CuT كان مختلفًا بوضوح عن نمط مجموعة Cu (الشكل 2).

تحليل GO

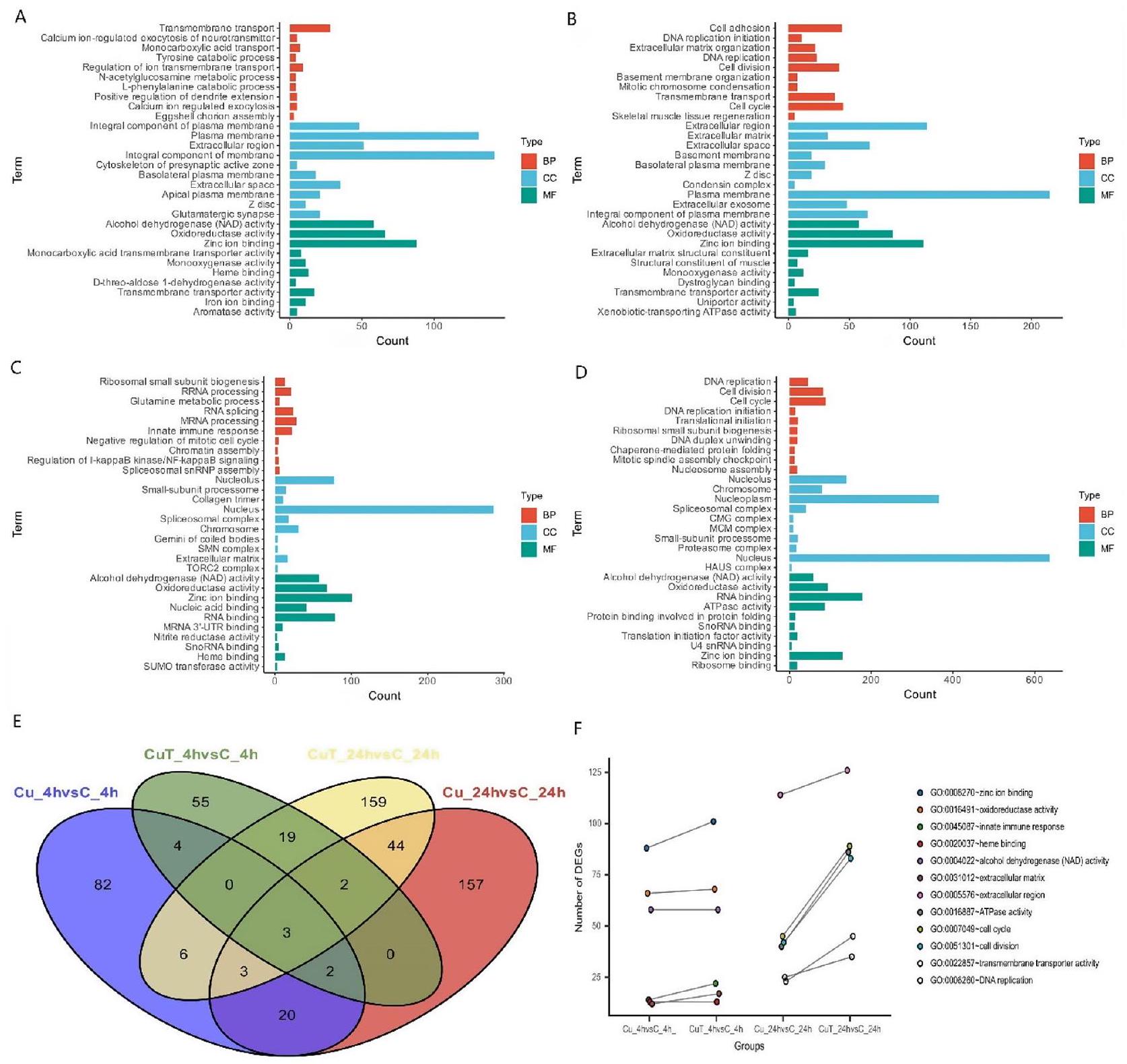

لقد اخترنا مصطلحات GO التي تحتوي على كمية كبيرة من إثراء DEGs وأهمية عالية لمراقبة تغييرات إجهاد النحاس في ظروف إجهاد النحاس ودرجات الحرارة المرتفعة في كمية DEGs، كما هو موضح في الرسم البياني (الشكل 3F). وجدنا أنه خلال عملية التعرض للنحاس، سيؤدي ارتفاع درجة الحرارة إلى تغييرات في كمية إثراء DEGs في هذه المصطلحات، والتي أظهرت اتجاهًا تصاعديًا؛ كلما زادت مدة التعرض لدرجات الحرارة المرتفعة، زاد عدد الجينات المثرية.

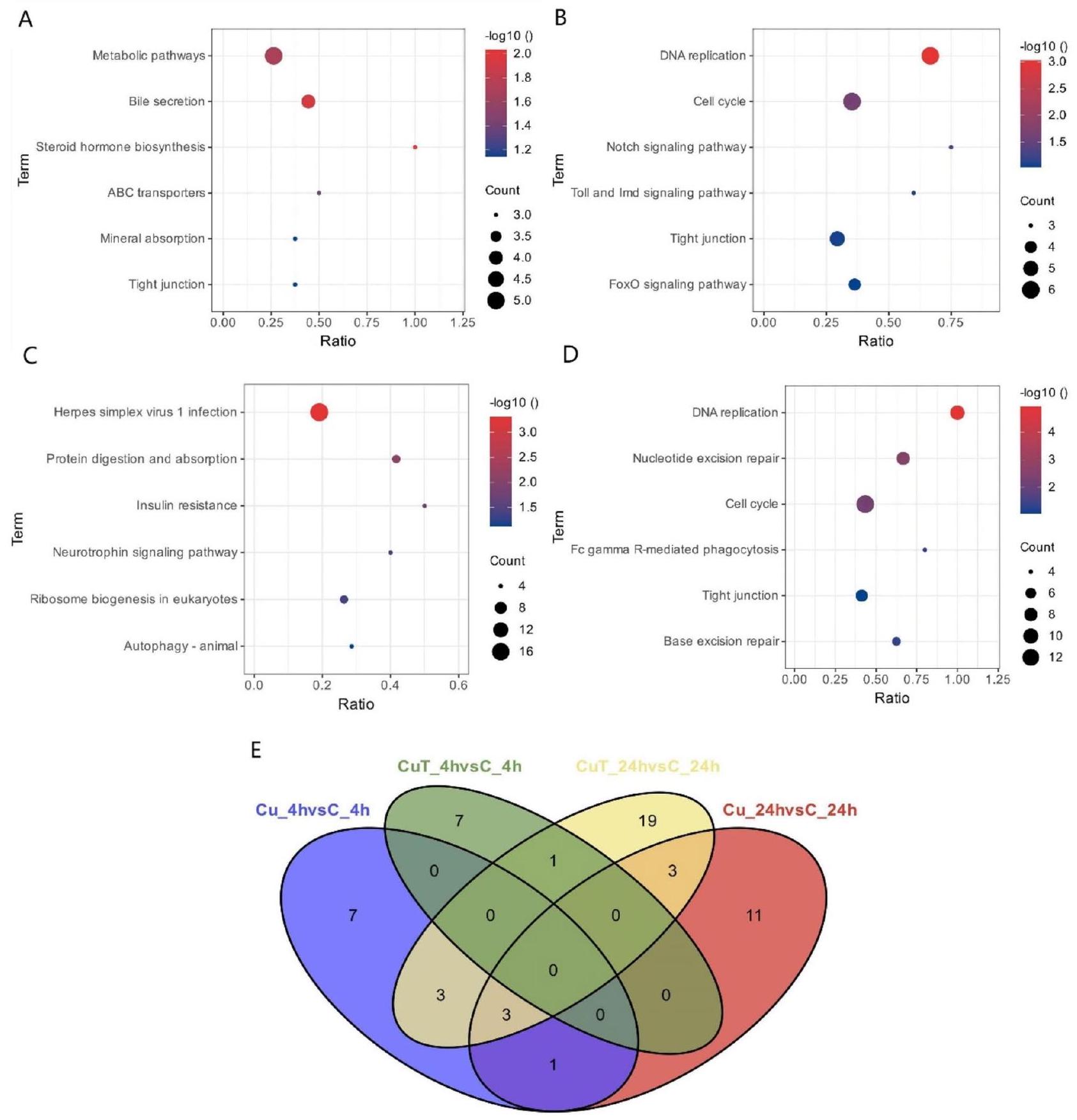

تحليل KEGG

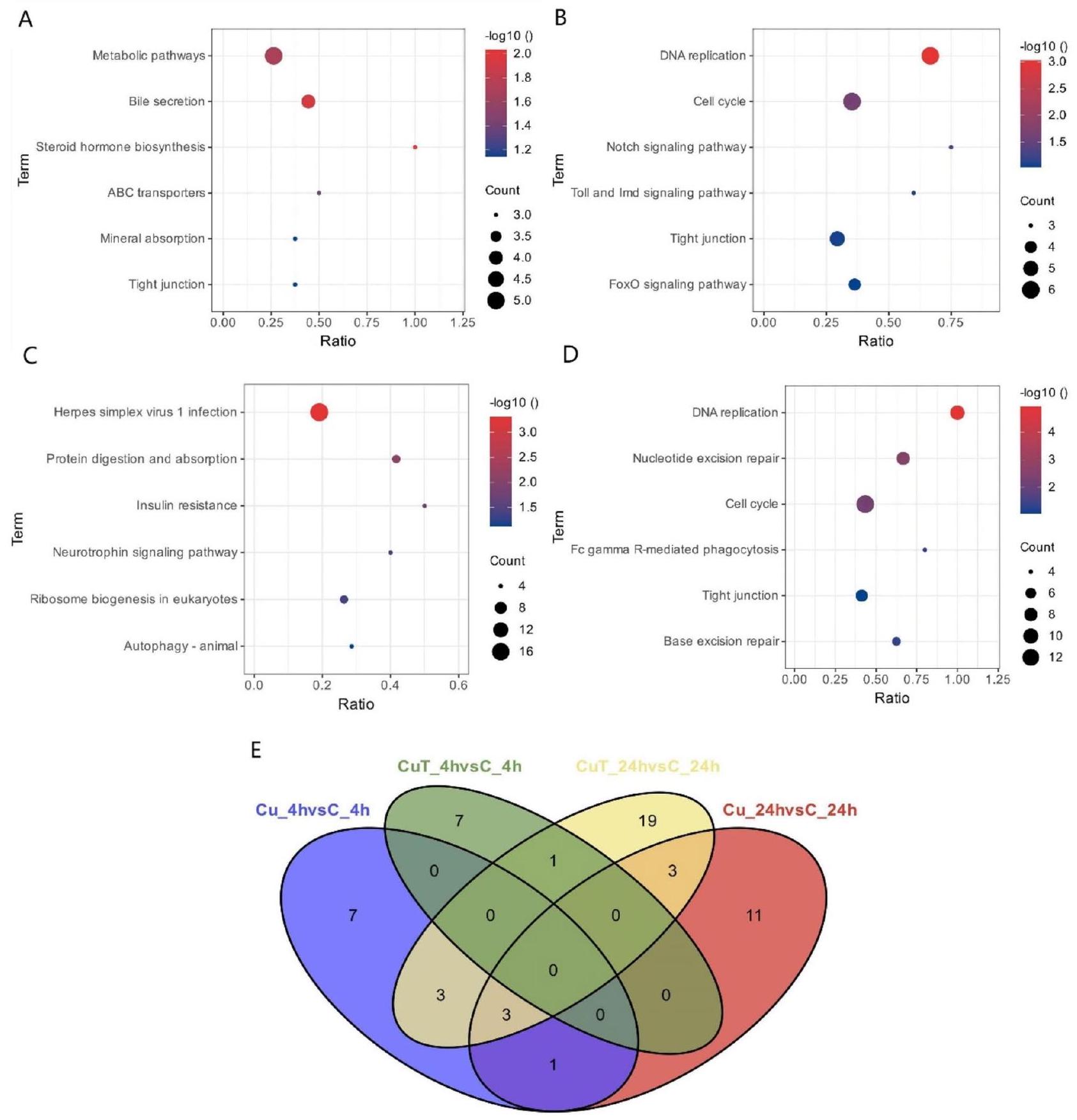

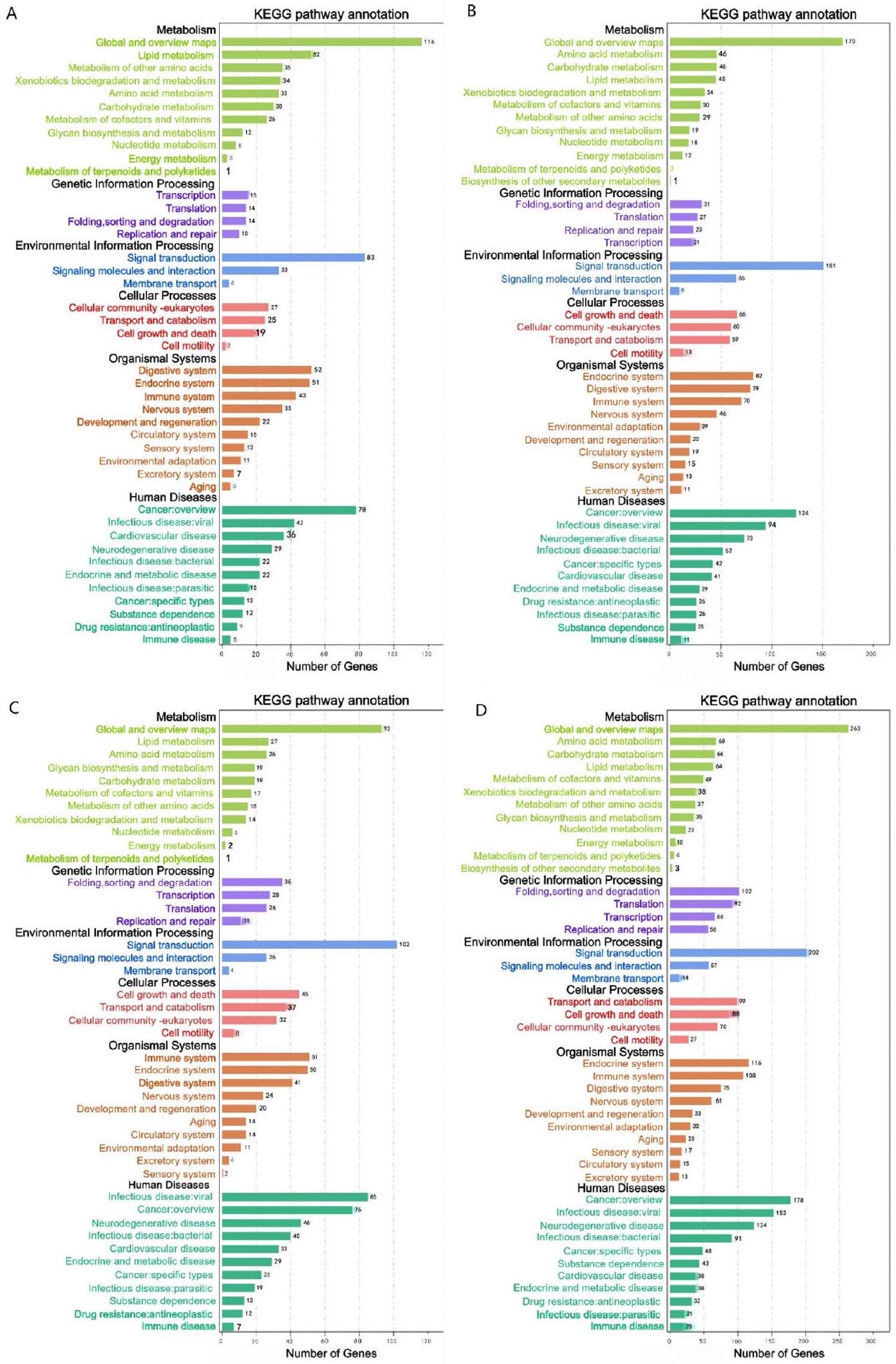

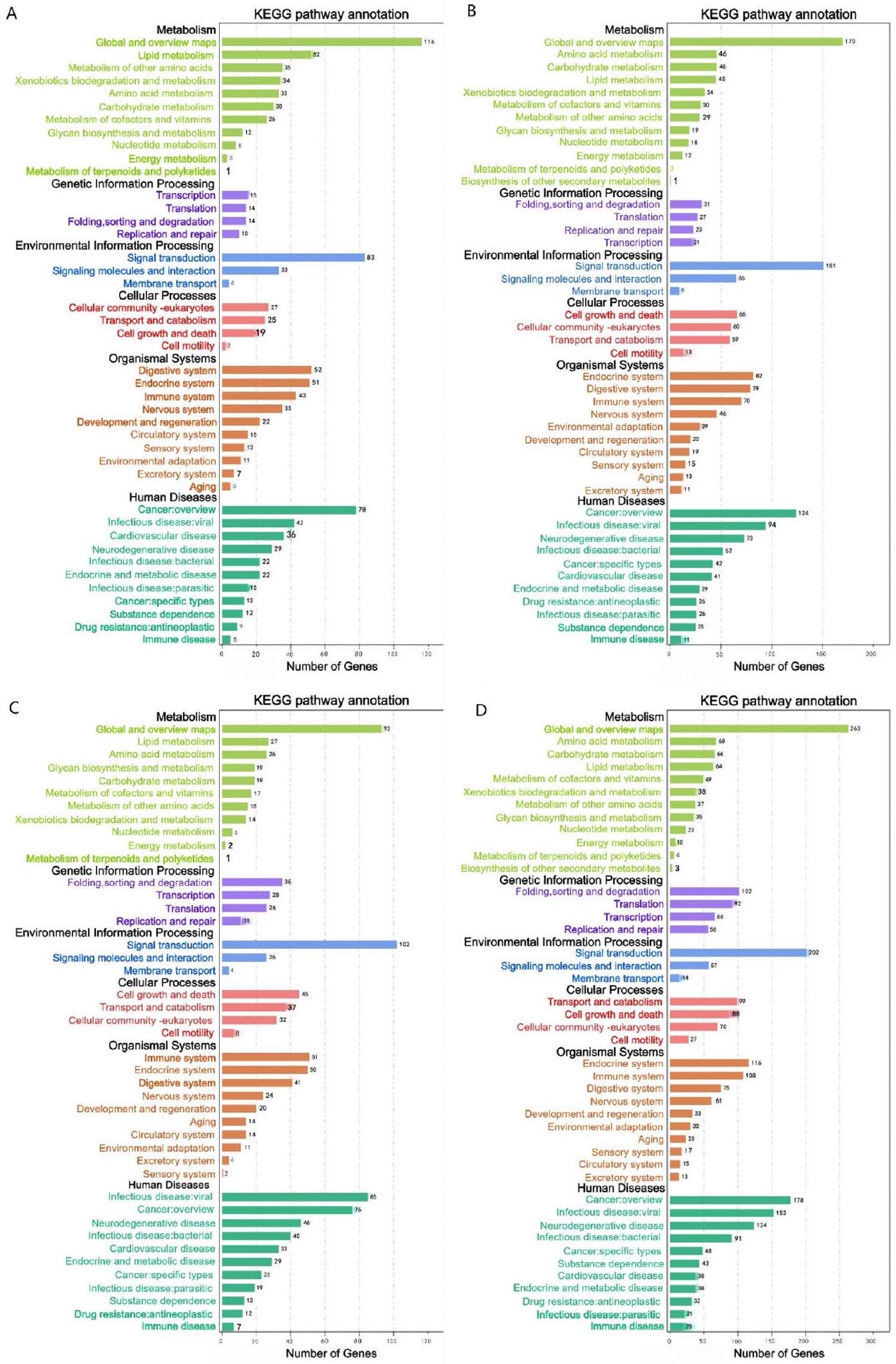

تتركز العديد من الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف (DEGs) في مسار الإشارات الثانوي KEGG المرتبط بالمناعة (الشكل 5AD)، بما في ذلك نظام المناعة والأمراض المناعية. تم إثراء المزيد من الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف في المسارات المتعلقة بالمناعة في مجموعة CuT مقارنة بمجموعة Cu، مما قد يشير إلى أن التعرض للنحاس عند درجات حرارة مرتفعة له تأثير أكبر على نظام المناعة ليرقات S. esculenta.

qRT-PCR للتحقق من الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف (DEGs)

نقاش

تحليل التعبير للجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف

تحليل الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف المرتبطة بعائلات SLC و ABC

لقد أظهرت الدراسات أن عائلة ABC تعتبر تلعب دورًا أساسيًا في الخط الأول من الدفاع الخلوي. عندما يحدث التهاب في الجسم، تقوم الجينات في عائلة ABC بتقليل الالتهاب من خلال تنظيم NF- بشكل إيجابي.

استنادًا إلى وظائف عائلتي ABC و SLC، نفترض أن معدل تراكم أو ذوبان أيونات النحاس في يرقات S. esculenta قد يزداد تحت درجات حرارة مرتفعة، مما يؤدي إلى استجابة مناعية أقوى. في هذه الدراسة، اختلف عدد DEGs في عائلتي SLC و ABC قبل وبعد زيادة درجة الحرارة. نحن نعتقد أن التعرض للنحاس (Cu) تحت

قد تؤدي ظروف درجات الحرارة العالية إلى تفاقم الاستجابة الالتهابية في يرقات S. esculenta.

تحليل DEGs المتعلقة بتكرار الحمض النووي، الضرر، والإصلاح

باختصار، نفترض أن تأثيرات التعرض للنحاس على نقل الأيونات، بالإضافة إلى تكرار الحمض النووي وإصلاحه، أقوى في يرقات S. esculenta عند درجات حرارة مرتفعة، وأن درجات الحرارة العالية قد تؤدي إلى معدلات أعلى

من التجميع أو الذوبان لأيونات النحاس في يرقات S. esculenta.

تحليل إثراء الوظائف GO

تحليل مصطلحات GO المشتركة بين مجموعتي Cu و cut

أظهرت الدراسات السابقة أن أيونات الزنك تلعب دورًا مهمًا في العمليات المناعية وتنظيم الإشارات، وأن نقص أيونات الزنك يؤدي إلى خلل في العديد من الأعضاء والجهاز المناعي [28].

قد يشير إثراء هذه المصطلحات إلى أن التعرض للنحاس قد يؤدي إلى انخفاض في قدرة ربط الأيونات ونشاط الأكسيدوريدوكتاز في يرقات S. esculenta، مما قد يؤدي إلى عدم توازن في جهاز المناعة ليرقات S. esculenta أو تعزيز الالتهاب. وجدنا أيضًا أن عدد DEGs في مصطلحات ربط أيونات الزنك (GO:0008270) ونشاط الأكسيدوريدوكتاز (GO:0016491) اختلف بين مجموعة Cu ومجموعة CuT، مع زيادة في DEGs في مجموعة CuT. قد تشير هذه الاتجاهات إلى أن درجات الحرارة العالية يمكن أن تعزز الآثار الضارة للتعرض للنحاس على S. esculenta.

تحليل مصطلحات GO الفريدة في مجموعة CuT

موت الخلايا المبرمج مهم في الحفاظ على توازن الأنسجة وتقليل الالتهاب، ويمكن للكائنات الحية أن تتخلص تدريجياً من الالتهاب أو تقلله من خلال تجديد الخلايا عبر موت الخلايا المبرمج في الجسم [31]. إصلاح تلف الحمض النووي والمناعة الفطرية هما آليتان محفوظتان تلعبان دورًا في كل من الإجهاد الخلوي

الاستجابات، وقد وُجد أن إصلاح الحمض النووي مرتبط ارتباطًا وثيقًا بالالتهاب وأن الكائنات الحية يمكن أن تتحكم بفعالية في الالتهاب من خلال إصلاح الحمض النووي الخاص بها [32].

من خلال تحليل إثراء GO، تمكنا من الافتراض أن التهاب التعرض للنحاس في

تحليل إثراء الوظائف KEGG تحليل المسارات KEGG المشتركة بين مجموعتي Cu و CuT

يرتبط تكرار الحمض النووي بالمناعة الفطرية في الحيوانات، وبعض الأخطاء المناعية الفطرية ناتجة عن طفرات في عوامل تكرار الحمض النووي. الحمض النووي

مسار النسخ هو مسار إشارة معقد يلعب دورًا مهمًا في تنظيم إصلاح تلف الحمض النووي وتحفيز موت الخلايا المبرمج. في بحثنا، من المحتمل أن يكون الثراء الكبير لمسار نسخ الحمض النووي في يرقات S. esculenta ناتجًا عن التعرض للنحاس مما يؤدي إلى أخطاء في نسخ الحمض النووي في يرقات S. esculenta، مما يؤدي إلى اضطرابات في المناعة الفطرية في يرقات S. esculenta. وقد وجدت الأبحاث أن الالتهاب يمكن أن يزيد من تلف الجهاز العصبي من خلال تدهور بروتينات الوصلات الضيقة. هناك تفاعل بين بروتينات الوصلات الضيقة والالتهاب، وحماية هذه البروتينات يمكن أن تخفف أيضًا من الاستجابات الالتهابية، مما يقلل من إمكانية ضعف الوظيفة العصبية. أظهرت الجينات في مسار الوصلات الضيقة، مثل TUBA1C و MICALL2، تعبيرًا منخفضًا، ونفترض أن يرقات S. esculenta تمر بالتهاب داخل الجسم بعد التعرض للنحاس وتدهور بروتينات الوصلات الضيقة. نشاط دورة الخلية مرتبط بالوظيفة المناعية، وغالبًا ما يشير عدم تنظيم دورة الخلية إلى وجود خلايا مناعية غير طبيعية. يمكن لبعض منظمات دورة الخلية تعديل دورة الخلية لتحقيق تأثيرات مناعية، وقد تكون برامج دورة الخلية مرتبطة بالسلوك المناعي من خلال آليات يمكن أن تؤثر على المناعة. وجدنا انخفاضًا في تعبير جين CDK1، وهو كيناز معتمد على بروتين دورة الخلية، في نتائج النسخ الجيني لدينا. يؤثر CDK1 على نشاطه التحفيزي من خلال تفاعلات فريدة مع مجمعات بروتين دورة الخلية المختلفة، مما يضمن عدم تعطل تقدم دورة الخلية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يلعب CDK1 دورًا تنظيميًا كبيرًا في تعديل استجابات المناعة الخلوية المختلفة أثناء الالتهاب. لذلك، فإن انخفاض تعبير جين CDK1 بعد تحفيز النحاس في يرقات S. esculenta يشير على الأرجح إلى وجود شذوذ في دورة الخلية.

في الختام، قد يكون تفعيل مسار تكرار الحمض النووي، ومسار الوصلات الضيقة، ومسار دورة الخلية بعد التعرض للنحاس مرتبطًا بوجود الالتهاب في يرقات S. esculenta. كما لاحظنا توزيعًا مختلفًا للجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف عبر المسارات الثلاثة المشتركة بين مجموعتي النحاس والنحاس المعالج، مع زيادة عدد الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف في مجموعة النحاس المعالج. تشير هذه الاتجاهات إلى أن التعرض للنحاس في ظل ظروف درجات الحرارة المرتفعة قد يزيد من الآثار السلبية على

تحليل المسارات الفريدة في KEGG في مجموعة CuT

إصلاح الإخراج النووي فريد من نوعه لأنه يتعرف على الأضرار المقطوعة في الحمض النووي ويزيلها و

المشاركة في إصلاح الحمض النووي، والذي يرتبط ارتباطًا وثيقًا بالمناعة الذاتية والالتهاب الموجود في الذات [39-41]. إصلاح الإخراج القاعدي (BER) هو المسار الرئيسي للخلايا حقيقية النواة لحل الأضرار الناتجة عن قاعدة مفردة، مما يمكّن من إصلاح الأضرار في الحمض النووي بسرعة وكفاءة [42]. لذلك، استنتجنا أن إثراء الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف في مسار إصلاح الإخراج النووي ومسار إصلاح الإخراج القاعدي كان على الأرجح ناتجًا عن التعرض للنحاس عند درجات حرارة مرتفعة، مما أدى إلى مزيد من تعطيل عملية تكرار

في الختام، أدت درجات الحرارة المرتفعة إلى زيادة سمية أيونات النحاس المعدنية، مما أدى بدوره إلى تلف الحمض النووي في يرقات S. esculenta وتداخل مع قدرة اليرقات على تكرار وإصلاح الحمض النووي. كان التعرض للنحاس في ظل ظروف درجات الحرارة المرتفعة قادرًا على التسبب في التهاب أكثر حدة في يرقات S. esculenta، مما خفف من الاستجابة الالتهابية من خلال تعزيز الالتهام الذاتي والبلعمة في الكائن الحي.

الخاتمة

لزيادة الالتهاب. كانت الاستجابات الالتهابية أكثر حدة في مجموعة CuT، كما يتضح من زيادة تلف الحمض النووي واستجابة المناعة الأقوى التي لوحظت في اليرقات. تسهم هذه الدراسة في سد الفجوة المعرفية بشأن التأثيرات المشتركة لدرجة الحرارة والمعادن الثقيلة على يرقات S. esculenta، مقدمة رؤى جديدة حول كيفية تفاقم تفاعلاتها للمخاطر الصحية على هذه الكائنات. علاوة على ذلك، توفر نتائجنا مرجعًا قيمًا لفهم تحديات البقاء والتكاثر التي تواجهها الرخويات الأخرى في ظروف بيئية مماثلة. في سياق ارتفاع درجات الحرارة العالمية وزيادة تلوث المعادن الثقيلة، تعتبر هذه الدراسة دليلًا عمليًا مهمًا لتربية S. esculenta وغيرها من الرخويات. ستساعد البيانات المرجعية والنظريات التي نقدمها مؤسسات تربية الأحياء المائية أو الأفراد على فهم هذه التحديات والتعامل معها بشكل أفضل، مما يعزز التنمية المستدامة للصناعات ذات الصلة.

الاختصارات

| تسلسل RNA | تسلسل RNA |

| RT-qPCR | تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل العكسي الكمي |

| جينات التعبير المختلفة | الجينات المعبر عنها بشكل مختلف |

| اذهب | علم الجينات |

| كيج | موسوعة كيوتو للجينات والجينومات |

معلومات إضافية

المادة التكميلية 2

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 17 مارس 2025

References

- Bhuyan MS, Haider SMB, Meraj G, Bakar MA, Islam MT, Kunda M, et al. Assessment of heavy metal contamination in beach sediments of Eastern St. Martin’s Island, Bangladesh: implications for environmental and human health risks[J]. Water. 2023;15:2494.

- Ali MM, Ali ML, Bhuyan MS, Islam MS, Rahman MZ, Alam MW, et al. Spatiotemporal variation and toxicity of trace metals in commercially important fish of the tidal Pasur river in Bangladesh[J]. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:40131-45.

- Wang

, Wang , Jiang , Jordan RW, Gu -G. Bioenrichment preference and human risk assessment of arsenic and metals in wild marine organisms from Dapeng (Mirs) Bay, South China Sea[J]. Mar Pollut Bull. 2023;194:115305. - Sfakianakis DG, Renieri E, Kentouri M, Tsatsakis AM. Effect of heavy metals on fish larvae deformities: a review[J]. Environ Res. 2015;137:246-55.

- Al-Ghussain L. Global warming: review on driving forces and mitigation[J]. Environ Prog Sustain Energy. 2019;38:13-21.

- Bethke K, Kropidłowska K, Stepnowski P, Caban M. Review of warming and acidification effects to the ecotoxicity of pharmaceuticals on aquatic organisms in the era of climate change[J]. Sci Total Environ. 2023;877:162829.

- Ren J, Liu S, Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Shang S. Effects of cadmium exposure on haemocyte immune function of clam Ruditapes philippinarum at different temperatures[J]. Mar Environ Res. 2024;195:106375.

- Malhotra N, Ger T-R, Uapipatanakul B, Huang J-C, Chen KH-C, Hsiao C-D. Review of copper and copper nanoparticle toxicity in fish[J]. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:1126.

- Wang Y, Liu X, Wang W, Sun G, Feng Y, Xu X, et al. The investigation on stress mechanisms of Sepia esculenta larvae in the context of global warming and ocean acidification[J]. Aquaculture Rep. 2024;36:102120.

- Gong H, Li C, Zhou Y. Emerging global ocean deoxygenation across the 21st century[J]. Geophys Res Lett. 2021;48:e2021GL095370.

- Liu X, Bao X, Yang J, Zhu X, Li Z. Preliminary study on toxicological mechanism of golden cuttlefish (Sepia esculenta) larvae exposed to Cd[J]. BMC Genomics. 2023;24:503.

- García-Fernández P, Prado-Alvarez M, Nande M, De La Garcia D, Perales-Raya C, Almansa E, et al. Global impact of diet and temperature over aquaculture of Octopus vulgaris paralarvae from a transcriptomic approach[J]. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10312.

- Zapata M, Tanguy A, David E, Moraga D, Riquelme C. Transcriptomic response of Argopecten purpuratus post-larvae to copper exposure under experimental conditions[J]. Gene. 2009;442:37-46.

- Xu M, Jiang L, Shen K-N, Wu C, He G, Hsiao C-D. Transcriptome response to copper heavy metal stress in hard-shelled mussel (Mytilus coruscus)[J]. Genomics Data. 2016;7:152-4.

- Liu Y, Chen L, Meng F, Zhang T, Luo J, Chen S, et al. The effect of temperature on the embryo development of cephalopod Sepiella japonica suggests crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis[J]. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:15365.

- Liu X, Li Z, Li Q, Bao X, Jiang L, Yang J. Acute exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics induced oxidative stress in Sepia esculenta larvae[J]. Aquaculture Rep. 2024;35:102004.

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2[J]. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550.

- Li Z, Ndandala CB, Guo Y, Zhou Q, Huang C, Huang H, et al. Impact of IGF3 stimulation on spotted scat (Scatophagus argus) liver: implications for a role in ovarian development. Agric Commun. 2023;1:100016.

- Liu X, Li Z, Wu W, Liu Y, Liu J, He Y, et al. Sequencing-based network analysis provides a core set of gene resources for Understanding kidney immune response against Edwardsiella tarda infection in Japanese flounder[J]. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017;67:643-54.

- Wang Y, Chen X, Xu X, Yang J, Liu X, Sun G, et al. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis based on stimulation by lipopolysaccharides and polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid provides a core set of genes for Understanding hemolymph immune response mechanisms of Amphioctopus fangsiao[J]. Animals. 2023;14:80.

- Bao X, Li Y, Liu X, Feng Y, Xu X, Sun G, et al. Effect of acute Cu exposure on immune response mechanisms of golden cuttlefish (Sepia esculenta)[J]. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022;130:252-60.

- Sheng L, Luo Q, Chen L. Amino acid solute carrier transporters in inflammation and autoimmunity[J]. Drug Metab Dispos. 2022;50:1228-37.

- Luo S-S, Chen X-L, Wang A-J, Liu Q-Y, Peng M, Yang C-L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter in Penaeus vannamei and identification of two ABC genes involved in immune defense against Vibrio parahaemolyticus by affecting NF-kB signaling pathway[J]. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;262:129984.

- Luckenbach T, Epel D. ABCB- and ABCC-type transporters confer multixenobiotic resistance and form an environment-tissue barrier in bivalve gills[J]. Am J Physiology-Regulatory Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1919-29.

- Cui K, Qin L, Tang X, Nong J, Chen J, Wu N, et al. A single amino acid substitution in RFC4 leads to endoduplication and compromised resistance to DNA damage in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Genes. 2022;13:1037.

- Murga M, Lecona E, Kamileri I, Díaz M, Lugli N, Sotiriou SK, et al. POLD3 is haploinsufficient for DNA replication in mice[J]. Mol Cell. 2016;63:877-83.

- Elmayan T, Proux F, Vaucheret H. Arabidopsis RPA2: A genetic link among transcriptional gene silencing, DNA repair, and DNA replication[J]. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1919-25.

- Li T, Jiao R, Ma J, Zang J, Zhao G, Zhang T. Zinc binding strength of proteins dominates zinc uptake in Caco-2 cells[J]. RSC Adv. 2022;12:21122-8.

- Abou-Hamdan A, Mahler R, Grossenbacher P, Biner O, Sjöstrand D, Lochner M, et al. Functional design of bacterial superoxide:quinone oxidoreductase[J]. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA) – Bioenergetics. 2022;1863:148583.

- Mahida RY, Lax S, Bassford CR, Scott A, Parekh D, Hardy RS, et al. Impaired alveolar macrophage

-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 reductase activity contributes to increased pulmonary inflammation and mortality in sepsis-related ARDS[J]. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1159831. - Arienti S, Barth ND, Dorward DA, Rossi AG, Dransfield I. Regulation of apoptotic cell clearance during resolution of inflammation[J]. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:891.

- Shah A, Bennett M. Controlling inflammation through DNA damage and repair[J]. Circul Res. 2016;119:698-700.

- Willemsen M, Staels F, Gerbaux M, Neumann J, Schrijvers R, Meyts I, et al. DNA replication-associated inborn errors of immunity[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;151:345-60.

- Zhao B, Yin Q, Fei Y, Zhu J, Qiu Y, Fang W, et al. Research progress of mechanisms for tight junction damage on blood-brain barrier inflammation[J]. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2022;128:1579-90.

- Li J, Stanger BZ. Cell cycle regulation Meets tumor immunosuppression[J]. Trends Immunol. 2020;41:859-63.

- Bonelli M, La Monica S, Fumarola C, Alfieri R. Multiple effects of CDK4/6 Inhibition in cancer: from cell cycle arrest to immunomodulation[J]. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;170:113676.

- Jones MC, Askari JA, Humphries JD, Humphries MJ. Cell adhesion is regulated by CDK1 during the cell cycle[J]. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:3203-18.

- Yamamura M, Sato Y, Takahashi K, Sasaki M, Harada K. The cyclindependent kinase pathway involving CDK1 is a potential therapeutic target for cholangiocarcinoma[J]. Oncol Rep. 2020;43:306-17.

- Kuper J, Kisker C. At the core of nucleotide excision repair[J]. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2023;80:102605.

- Li W, Jones K, Burke TJ, Hossain MA, Lariscy L. Epigenetic regulation of nucleotide excision repair[J]. Front Cell Dev Biology. 2022;10:847051.

- Cohen I. DNA damage talks to inflammation[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2017;33:35-9.

- Raper AT, Maxwell BA, Suo Z. Dynamic processing of a common oxidative DNA lesion by the first two enzymes of the base excision repair pathway[J]. J Mol Biol. 2021;433:166811.

- Tanguy E, Tran Nguyen AP, Kassas N, Bader M-F, Grant NJ, Vitale N. Regulation of phospholipase D by Arf6 during FcyR-mediated phagocytosis[J]. J Immunol. 2019;202:2971-81.

- Huang F, Lu X, Kuai L, Ru Y, Jiang J, Song J, et al. Dual-site biomimetic Cu/ZnMOF for atopic dermatitis catalytic therapy via suppressing FcyR-mediated phagocytosis[J]. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146:3186-99.

- Hortová-Kohoutková M, Tidu F, De Zuani M, Šrámek V, Helán M, Frič J. Phagocytosis-inflammation crosstalk in sepsis: new avenues for therapeutic intervention[J]. Shock. 2020;54:606-14.

- Shao B-Z, Yao Y, Zhai J-S, Zhu J-H, Li J-P, Wu K. The role of autophagy in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Front Physiol. 2021;12:621132.

- Lee J, Kim HS. The role of autophagy in eosinophilic airway inflammation[J]. Immune Netw. 2019;19:e5.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

زان لي

lizanlxm@163.com

شيوميي ليو

xiumei0210@163.com

جيانمين يانغ

ladderup@126.com

كلية مصايد الأسماك، جامعة لودونغ، يانتاي 264025، الصين

كلية علوم الحياة، جامعة يانتاي، يانتاي 264005، الصين

مركز رصد ومراقبة المصايد البحرية والتخفيف من المخاطر، رشان 264500، الصين

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-025-11418-y

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40097976

Publication Date: 2025-03-17

Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals differences in immune responses to copper ions in Sepia esculenta under hightemperature conditions

Abstract

Sepia esculenta is one of the most abundant extant squid populations in Southeast Asia and is of interest due to its rapid reproductive rate and high commercial value. In recent years, with the rapid development of industrialization, issues such as global warming and heavy metal pollution in the oceans have emerged, posing a serious threat to the life activities of marine organisms. In this study, we used transcriptomic techniques to investigate the differences in Cu exposure immune responses in S . esculenta larvae under different temperature conditions. The enrichment of solute carrier family (SLC) genes and genes related to DNA replication and damage was significantly higher in the CuT group than in the Cu group. Functional enrichment analysis revealed that the FcyR-mediated phagocytosis and autophagy pathways were enriched in the CuT group. Based on the analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and functional enrichment results, we can preliminarily infer that the CuT group caused more severe disruption of intercellular ion transport and DNA replication and repair in larvae compared to the Cu group. This may have further interfered with the normal physiological activities of S. esculenta larvae. Overall, at high temperatures, Cu exposure induces a more intense inflammatory response. The results of this study provide a theoretical foundation for researchers to further understand the effects of environmental factors on the immunity of S. esculenta larvae, as well as preliminary insights into the enhanced toxic effects of metallic copper on aquatic organisms under high-temperature conditions.

Introduction

The rapid development of industrialization has not only led to the intensification of heavy metal pollutions but has also increased the rate of global warming [5]. Previous studies have shown that temperature induces changes in the toxicity of heavy metals to marine organisms [6]. Ren et al. found that high temperatures enhanced the intoxication of heavy metals to Ruditapes philippinarum, significantly inhibiting its growth and development [7]. Malhotra et al. showed that temperature would affect the toxicity induced by Cu exposure. Compared with low temperature (

S. esculenta is one of the most abundant squid populations surviving in Southeast Asia, with tasty meat, high protein content, and rapid reproduction [9], Therefore, it quickly attracted the attention of scholars. As a result of the degradation of the marine environment and the largescale exploitation of marine resources by human beings, the population of S. esculenta has declined drastically, and in recent years, it has even become an endangered species [10]. Usually, S. esculenta is cultured in captivity in shallow coastal waters. High concentrations of heavy metals and high temperatures along the ocean coast have a profound effect on the growth and development of

molecular mechanisms of high temperature on Octopus vulgaris and the response of the transcriptome to Cu exposure in Mytilus coruscus [12-14]. Therefore, we can use RNA-Seq to preliminarily explore the toxicological mechanism of Cu exposure in S. esculenta larvae at high temperature.

In our study, we used high-throughput transcriptome sequencing to explore differences in Cu exposure immunity in S. esculenta larvae at different temperatures. By GO and KEGG functional enrichment analysis, it was found that high temperature significantly affected the Cu exposure immune response and induced a more intense inflammatory response in S. esculenta larvae. At the same time, high temperatures can induce more severe DNA damage and ion transport disorders. Our findings provide a basis for further exploration of differences in Cu exposure imaginal responses in S. esculenta larvae under different temperature conditions and provide more scientific breeding suggestions for golden squid and cephalopods.

Materials and methods

Collection of S. esculenta larvae and stress experiments

and 24 h (CuT_24h) in the CuT group. All samples were stored in liquid nitrogen tanks until RNA extraction.

RNA extraction, library construction and sequencing

Screening of differential genes and annotation of gene functions

Enrichment analysis

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Results

Transcriptome sequencing results

Analysis of DEGs

The DEGs Venn diagram (Fig. 1B) clearly shows the unique and shared DEGs between each group. In both the Cu and CuT groups, we found the presence of genes from the SLC family (SLC6A9) and the ATP-binding cassette(ABC) subfamily (ABCC10, ABCC1, ABCB1). In the CuT group, we found that the SLC family (SLC16A4, SLC16A14, SLC22A21, SLC35B2, SLC6A9, SLC12A2) and the ABC subfamily (ABCF2) were present. Genes related to DNA replication and damage were found in genes unique to the CuT group, such as RFC4, RFC5, POLD3, RPA2, and RPA3.

The results of the clustering heat map showed that the expression pattern of the CuT group was obviously not the same as that of the Cu group (Fig. 2).

GO analysis

We selected the GO terms with a large amount of DEGs enrichment and high significance to observe their copper stress and elevated temperature conditions copper stress changes in the amount of DEGs, as shown in the line chart (Fig. 3F). We found that during the Cu exposure process, the increase in temperature would lead to changes in the amount of DEGs enrichment in these terms, which showed an upward trend; the longer the high-temperature duration, the greater the number of enriched genes.

KEGG analysis

Many DEGs are concentrated in the secondary KEGG signaling pathway associated with immunity (Fig. 5AD), including the immune system and immune diseases. More DEGs were enriched in immune-related pathways in the CuT group than in the Cu group, which may imply that Cu exposure at high temperatures has a greater impact on the immune system of S. esculenta larvae.

qRT-PCR to verify DEGs

Discussion

Expression analysis of DEGs

Analysis of SLC and ABC family-related DEGs

It has been shown that the ABC family is considered to play an essential role in the first line of cellular defense. When inflammation occurs in the body, genes in the ABC family reduce inflammation by positively regulating the NF-

Based on the functions of the ABC and SLC families, we hypothesize that the accumulation or dissolution rate of copper ions in S. esculenta larvae may increase under elevated temperatures, leading to a stronger immune response. In this study, the number of DEGs in the SLC and ABC families varied before and after the temperature increase. We speculate that copper ( Cu ) exposure under

high-temperature conditions may exacerbate the inflammatory response in S. esculenta larvae.

Analysis of DEGs related to DNA replication, damage, and repair

In summary, we speculate that Cu exposure effects on ion transport, as well as DNA replication and repair, are stronger in S. esculenta larvae at high temperatures, and that high temperatures may be able to lead to higher rates

of aggregation or solubilization of Cu ions in S. esculenta larvae.

GO functional enrichment analysis

Analysis of common GO terms between Cu and cut groups

Previous studies have shown that zinc ions play an important role in immune processes and signal regulation, and that a deficiency of zinc ions leads to dysfunction in many organs and the immune system [28].

The enrichment of these terms may indicate that Cu exposure may lead to a decrease in ion binding ability and reductase activity in S. esculenta larvae, which may result in an imbalance of the immune system of S. esculenta larvae or promote inflammation. We also found that the number of DEGs in the terms zinc ion binding (GO:0008270) and oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491) differed between the Cu group and CuT group, with an increase in DEGs in the CuT group. This trend may indicate that high temperature can enhance the harmful effects of copper exposure on S. esculenta.

Analysis of unique GO terms in the CuT group

Apoptosis is important in the maintenance of tissue homeostasis and the reduction of inflammation, and organisms can gradually eliminate or reduce inflammation by renewing cells through apoptosis in vivo [31]. DNA damage repair and innate immunity are two conserved mechanisms that play a role in both cellular stress

responses, and it has been found that DNA repair is closely linked to inflammation and that organisms can effectively control inflammation through their own DNA repair [32].

Through GO enrichment analysis, we were able to speculate that Cu exposure inflammation in

KEGG functional enrichment analysis Analysis of common KEGG pathways between Cu and CuT groups

DNA replication is associated with innate immunity in animals, and some innate immune errors are caused by mutations in DNA replication factors. The DNA

replication pathway is a complex signaling pathway that plays an important role in regulating the repair of DNA damage and inducing cell apoptosis [33]. In our research, the significant enrichment of the DNA replication pathway in S. esculenta larvae is likely due to Cu exposure leading to errors in DNA replication in S. esculenta larvae, which results in innate immune disorders in S. esculenta larvae. Research has found that inflammation can increase damage to the nervous system by degrading tight junction proteins. There is an interaction between tight junction proteins and inflammation, and protecting these proteins can also alleviate inflammatory responses, thereby reducing the potential for impaired neurological function [34]. Genes in the tight junction pathway, such as TUBA1C and MICALL2, showed down-regulated expression, and we speculate that S. esculenta larvae undergo in vivo inflammation following Cu exposure and degradation of tight junction proteins. Cell cycle activity is related to immune function, and dysregulation of the cell cycle often indicates the presence of abnormal immune cells. Some cell cycle regulators can modulate the cell cycle to exert immunomodulatory effects, and cell cycle programs may be linked to immune behavior through mechanisms that can influence immunity [35, 36]. We found down-regulation of the CDK1 gene, a cell cycle protein-dependent kinase, in our transcriptome results. CDK1 influences its catalytic activity through unique interactions with various cell cycle protein complexes, ensuring that cell cycle progression is not impaired. Additionally, CDK1 plays a significant regulatory role in modulating various cellular immune responses during inflammation [37, 38]. Therefore, the downregulation of the CDK1 gene after copper induction in S. esculenta larvae likely indicates an abnormality in the cell cycle.

In conclusion, the activation of the DNA replication pathway, tight junction pathway, and cell cycle pathway following Cu exposure may be linked to the presence of inflammation in S. esculenta larvae. We also observed a differential distribution of DEGs across the three shared pathways between the Cu and CuT groups, with an increased number of DEGs in the CuT group. This trend suggests that copper exposure under elevated temperature conditions may exacerbate the adverse effects on

Analysis of unique KEGG pathways in the CuT group

Nucleotide excision repair is unique in that it recognizes and removes truncated damage in DNA and is

involved in the repair of DNA, which is closely linked to autoimmunity and inflammation present in the self [39-41]. Base excision repair (BER) is the primary pathway for eukaryotic cells to resolve single-base damage, enabling rapid and efficient DNA damage repair [42]. Therefore, we deduced that the enrichment of DEGs in the nucleotide excision repair pathway and base excision repair pathway was most likely caused by high-temperature Cu exposure, resulting in further disruption of the replication of

In conclusion, high temperatures enhanced the toxicity of metallic copper ions, which further led to DNA damage in S. esculenta larvae and interfered with the ability of the larvae to replicate and repair DNA. Cu exposure under high-temperature conditions was able to cause more severe inflammation in S. esculenta larvae, which attenuated the inflammatory response by enhancing autophagy and phagocytosis in vivo.

Conclusion

to enhanced inflammation. Inflammatory responses were more intense in the CuT group, as indicated by the increased DNA damage and stronger immune response observed in the larvae. This study contributes to bridging the knowledge gap regarding the combined effects of temperature and heavy metals on S. esculenta larvae, offering new insights into how their interactions exacerbate the health risks to these organisms. Furthermore, our findings provide a valuable reference for understanding the survival and reproductive challenges faced by other cephalopods in similar environmental conditions. In the context of rising global temperatures and increasing heavy metal pollution, the present study is an important practical guide for the breeding of S. esculenta and other cephalopods. The reference data and theories we provide will help aquaculture enterprises or individuals to better understand and cope with these challenges, thus promoting the sustainable development of related industries.

Abbreviations

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| RT-qPCR | Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 2

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Data availability

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 17 March 2025

References

- Bhuyan MS, Haider SMB, Meraj G, Bakar MA, Islam MT, Kunda M, et al. Assessment of heavy metal contamination in beach sediments of Eastern St. Martin’s Island, Bangladesh: implications for environmental and human health risks[J]. Water. 2023;15:2494.

- Ali MM, Ali ML, Bhuyan MS, Islam MS, Rahman MZ, Alam MW, et al. Spatiotemporal variation and toxicity of trace metals in commercially important fish of the tidal Pasur river in Bangladesh[J]. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:40131-45.

- Wang

, Wang , Jiang , Jordan RW, Gu -G. Bioenrichment preference and human risk assessment of arsenic and metals in wild marine organisms from Dapeng (Mirs) Bay, South China Sea[J]. Mar Pollut Bull. 2023;194:115305. - Sfakianakis DG, Renieri E, Kentouri M, Tsatsakis AM. Effect of heavy metals on fish larvae deformities: a review[J]. Environ Res. 2015;137:246-55.

- Al-Ghussain L. Global warming: review on driving forces and mitigation[J]. Environ Prog Sustain Energy. 2019;38:13-21.

- Bethke K, Kropidłowska K, Stepnowski P, Caban M. Review of warming and acidification effects to the ecotoxicity of pharmaceuticals on aquatic organisms in the era of climate change[J]. Sci Total Environ. 2023;877:162829.

- Ren J, Liu S, Zhang Q, Zhang Z, Shang S. Effects of cadmium exposure on haemocyte immune function of clam Ruditapes philippinarum at different temperatures[J]. Mar Environ Res. 2024;195:106375.

- Malhotra N, Ger T-R, Uapipatanakul B, Huang J-C, Chen KH-C, Hsiao C-D. Review of copper and copper nanoparticle toxicity in fish[J]. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:1126.

- Wang Y, Liu X, Wang W, Sun G, Feng Y, Xu X, et al. The investigation on stress mechanisms of Sepia esculenta larvae in the context of global warming and ocean acidification[J]. Aquaculture Rep. 2024;36:102120.

- Gong H, Li C, Zhou Y. Emerging global ocean deoxygenation across the 21st century[J]. Geophys Res Lett. 2021;48:e2021GL095370.

- Liu X, Bao X, Yang J, Zhu X, Li Z. Preliminary study on toxicological mechanism of golden cuttlefish (Sepia esculenta) larvae exposed to Cd[J]. BMC Genomics. 2023;24:503.

- García-Fernández P, Prado-Alvarez M, Nande M, De La Garcia D, Perales-Raya C, Almansa E, et al. Global impact of diet and temperature over aquaculture of Octopus vulgaris paralarvae from a transcriptomic approach[J]. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10312.

- Zapata M, Tanguy A, David E, Moraga D, Riquelme C. Transcriptomic response of Argopecten purpuratus post-larvae to copper exposure under experimental conditions[J]. Gene. 2009;442:37-46.

- Xu M, Jiang L, Shen K-N, Wu C, He G, Hsiao C-D. Transcriptome response to copper heavy metal stress in hard-shelled mussel (Mytilus coruscus)[J]. Genomics Data. 2016;7:152-4.

- Liu Y, Chen L, Meng F, Zhang T, Luo J, Chen S, et al. The effect of temperature on the embryo development of cephalopod Sepiella japonica suggests crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis[J]. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:15365.

- Liu X, Li Z, Li Q, Bao X, Jiang L, Yang J. Acute exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics induced oxidative stress in Sepia esculenta larvae[J]. Aquaculture Rep. 2024;35:102004.

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2[J]. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550.

- Li Z, Ndandala CB, Guo Y, Zhou Q, Huang C, Huang H, et al. Impact of IGF3 stimulation on spotted scat (Scatophagus argus) liver: implications for a role in ovarian development. Agric Commun. 2023;1:100016.

- Liu X, Li Z, Wu W, Liu Y, Liu J, He Y, et al. Sequencing-based network analysis provides a core set of gene resources for Understanding kidney immune response against Edwardsiella tarda infection in Japanese flounder[J]. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2017;67:643-54.

- Wang Y, Chen X, Xu X, Yang J, Liu X, Sun G, et al. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis based on stimulation by lipopolysaccharides and polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid provides a core set of genes for Understanding hemolymph immune response mechanisms of Amphioctopus fangsiao[J]. Animals. 2023;14:80.

- Bao X, Li Y, Liu X, Feng Y, Xu X, Sun G, et al. Effect of acute Cu exposure on immune response mechanisms of golden cuttlefish (Sepia esculenta)[J]. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022;130:252-60.

- Sheng L, Luo Q, Chen L. Amino acid solute carrier transporters in inflammation and autoimmunity[J]. Drug Metab Dispos. 2022;50:1228-37.

- Luo S-S, Chen X-L, Wang A-J, Liu Q-Y, Peng M, Yang C-L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter in Penaeus vannamei and identification of two ABC genes involved in immune defense against Vibrio parahaemolyticus by affecting NF-kB signaling pathway[J]. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;262:129984.

- Luckenbach T, Epel D. ABCB- and ABCC-type transporters confer multixenobiotic resistance and form an environment-tissue barrier in bivalve gills[J]. Am J Physiology-Regulatory Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R1919-29.

- Cui K, Qin L, Tang X, Nong J, Chen J, Wu N, et al. A single amino acid substitution in RFC4 leads to endoduplication and compromised resistance to DNA damage in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Genes. 2022;13:1037.

- Murga M, Lecona E, Kamileri I, Díaz M, Lugli N, Sotiriou SK, et al. POLD3 is haploinsufficient for DNA replication in mice[J]. Mol Cell. 2016;63:877-83.

- Elmayan T, Proux F, Vaucheret H. Arabidopsis RPA2: A genetic link among transcriptional gene silencing, DNA repair, and DNA replication[J]. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1919-25.

- Li T, Jiao R, Ma J, Zang J, Zhao G, Zhang T. Zinc binding strength of proteins dominates zinc uptake in Caco-2 cells[J]. RSC Adv. 2022;12:21122-8.

- Abou-Hamdan A, Mahler R, Grossenbacher P, Biner O, Sjöstrand D, Lochner M, et al. Functional design of bacterial superoxide:quinone oxidoreductase[J]. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA) – Bioenergetics. 2022;1863:148583.

- Mahida RY, Lax S, Bassford CR, Scott A, Parekh D, Hardy RS, et al. Impaired alveolar macrophage

-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 reductase activity contributes to increased pulmonary inflammation and mortality in sepsis-related ARDS[J]. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1159831. - Arienti S, Barth ND, Dorward DA, Rossi AG, Dransfield I. Regulation of apoptotic cell clearance during resolution of inflammation[J]. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:891.

- Shah A, Bennett M. Controlling inflammation through DNA damage and repair[J]. Circul Res. 2016;119:698-700.

- Willemsen M, Staels F, Gerbaux M, Neumann J, Schrijvers R, Meyts I, et al. DNA replication-associated inborn errors of immunity[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;151:345-60.

- Zhao B, Yin Q, Fei Y, Zhu J, Qiu Y, Fang W, et al. Research progress of mechanisms for tight junction damage on blood-brain barrier inflammation[J]. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2022;128:1579-90.

- Li J, Stanger BZ. Cell cycle regulation Meets tumor immunosuppression[J]. Trends Immunol. 2020;41:859-63.

- Bonelli M, La Monica S, Fumarola C, Alfieri R. Multiple effects of CDK4/6 Inhibition in cancer: from cell cycle arrest to immunomodulation[J]. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;170:113676.

- Jones MC, Askari JA, Humphries JD, Humphries MJ. Cell adhesion is regulated by CDK1 during the cell cycle[J]. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:3203-18.

- Yamamura M, Sato Y, Takahashi K, Sasaki M, Harada K. The cyclindependent kinase pathway involving CDK1 is a potential therapeutic target for cholangiocarcinoma[J]. Oncol Rep. 2020;43:306-17.

- Kuper J, Kisker C. At the core of nucleotide excision repair[J]. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2023;80:102605.

- Li W, Jones K, Burke TJ, Hossain MA, Lariscy L. Epigenetic regulation of nucleotide excision repair[J]. Front Cell Dev Biology. 2022;10:847051.

- Cohen I. DNA damage talks to inflammation[J]. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2017;33:35-9.

- Raper AT, Maxwell BA, Suo Z. Dynamic processing of a common oxidative DNA lesion by the first two enzymes of the base excision repair pathway[J]. J Mol Biol. 2021;433:166811.

- Tanguy E, Tran Nguyen AP, Kassas N, Bader M-F, Grant NJ, Vitale N. Regulation of phospholipase D by Arf6 during FcyR-mediated phagocytosis[J]. J Immunol. 2019;202:2971-81.

- Huang F, Lu X, Kuai L, Ru Y, Jiang J, Song J, et al. Dual-site biomimetic Cu/ZnMOF for atopic dermatitis catalytic therapy via suppressing FcyR-mediated phagocytosis[J]. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146:3186-99.

- Hortová-Kohoutková M, Tidu F, De Zuani M, Šrámek V, Helán M, Frič J. Phagocytosis-inflammation crosstalk in sepsis: new avenues for therapeutic intervention[J]. Shock. 2020;54:606-14.

- Shao B-Z, Yao Y, Zhai J-S, Zhu J-H, Li J-P, Wu K. The role of autophagy in inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Front Physiol. 2021;12:621132.

- Lee J, Kim HS. The role of autophagy in eosinophilic airway inflammation[J]. Immune Netw. 2019;19:e5.

Publisher’s note

- *Correspondence:

Zan Li

lizanlxm@163.com

Xiumei Liu

xiumei0210@163.com

Jianmin Yang

ladderup@126.com

School of Fisheries, Ludong University, Yantai 264025, China

College of Life Sciences, Yantai University, Yantai 264005, China

Rushan Marine and Fishery Monitoring and Hazard Mitigation Center, Rushan 264500, China