DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00511-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38589501

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-08

تحليل تكاملي يكشف عن ارتباطات بين اختلال ميكروبيوتا الفم والتشوهات الجينية والوراثية المضاعفة في سرطان الخلايا الحرشفية في تجويف الفم

الملخص

تم الإبلاغ عن أن اختلال التوازن في الميكروبيوم الفموي البشري مرتبط بسرطان الخلايا الحرشفية في تجويف الفم (OSCC)، بينما تظل التفاعلات بين المضيف والميكروبيوم فيما يتعلق بالتأثير المحتمل للبكتيريا المسببة للأمراض على الشذوذات الجينومية والإيبيجينية للمضيف غير مدروسة بشكل كافٍ. في هذه الدراسة، تم تحليل المجتمع البكتيري المخاطي، والتعبير الجيني على مستوى الجينوم للمضيف، وميثيلين DNA CpG في وقت واحد في الأورام وأنسجتها الطبيعية المجاورة لمرضى OSCC. لوحظت زيادة ملحوظة في الوفرة النسبية لسبع أنواع من البكتيريا (Fusobacterium nucleatum، Treponema medium، Peptostreptococcus stomatis، Gemella morbillorum، Catonella morbi، Peptoanaerobacter yurli وPeptococcus simiae) في بيئة الورم لـ OSCC. شكلت هذه البكتيريا الغنية بالورم 254 ارتباطًا إيجابيًا مع 206 جينات مضيف مرتفعة التعبير، تتعلق بشكل رئيسي بمسارات الإشارات المرتبطة بالالتصاق الخلوي، والهجرة، والتكاثر. حدد التحليل التكاملي لارتباطات البكتيريا-التعبير الجيني وارتباطات البكتيريا-الميثيلين ما لا يقل عن 20 جينًا مضيفًا غير منظم مع ميثيلين CpG مقلوب في مناطق المحفز الخاصة بها مرتبطة بزيادة البكتيريا المسببة للأمراض، مما يشير إلى إمكانية البكتيريا المسببة للأمراض في تنظيم التعبير الجيني، جزئيًا، من خلال التغيرات الإيبيجينية. أكدت نموذج في المختبر أن Fusobacterium nucleatum قد تساهم في غزو الخلايا من خلال التفاعل مع E-cadherin.

ومضغ جوز البتلة؛ ومع ذلك، فإن انتشار سرطان الفم والبلعوم بدون عوامل الخطر التقليدية قد زاد في السنوات الأخيرة

الميكروبيوم في السرطانات

النتائج

مواضيع الدراسة

اختلال ميكروبيوم الفم في سرطان الفم الحرشفي

عوامل أخرى، بما في ذلك مرحلة T (T1 و T2 مقابل T3 و T4) (وزن GUniFrac

فوسوبكتيريوم نوكليتوم المرتبط بمرضى سرطان الفم والبلعوم الحرشفي دون عوامل خطر تقليدية

تعبير الجينات المضيفة المختلفة في ترانسكريبتوم سرطان الفم والبلعوم

تحليل (الدرجة

الجينات الأكثر تنظيمًا للأعلى

(

| الضرائب | وفرة متوسطة (

|

اختبار LEfSe | اختبار توكي HSD | اختبار MWU | اختبار ANCOM-BC2

|

اختبار ALDEx2

|

اختبار زيكوسيك

|

الممثل ASV | |||||||||||

| أن | ورم | مجموعة LDA | درجة LDA | تحليل التخصيص اللاتيني

|

الفرق (%) |

|

قيمة p |

|

|

|

قيمة p |

|

|

قيمة p |

|

|

|

||

| جنس | |||||||||||||||||||

| فوسوبكتيريوم |

|

|

ورم | ٤.٧٨ | 0.0000 | 12.45 (8.71, 16.20) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.12 | ٤.٢٧ | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | ٥.٧٢ | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0600 | 0.0979 | |

| تريبونيما |

|

|

ورم | ٤.٢٩ | 0.0180 | 4.07 (1.85, 6.29) | 0.0004 | 0.0001 | 0.0028 | 0.81 | 2.57 | 0.0114 | 0.0235 | ٢.٥٧ | 0.0156 | 0.9819 | 0.0100 | 0.0017 | |

| بيبتوانيروباكتير |

|

|

ورم | 3.82 | 0.0017 | 1.19 (0.47, 1.92) | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 1.46 | 6.16 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 3.58 | 0.0012 | 0.3104 | 0.0100 | 0.0070 | |

| بيبتوستربتوكوكوس |

|

|

ورم | 3.80 | 0.0019 | 1.20 (0.26, 2.14) | 0.0125 | 0.0004 | 0.0066 | 0.71 | ٢.٧٤ | 0.0070 | 0.0151 | 3.77 | 0.0004 | 0.1432 | 0.0300 | 0.0468 | |

| كاتونيلا |

|

|

ورم | 3.54 | 0.0001 | 0.62 (0.29، 0.95) | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.72 | 3.23 | 0.0017 | 0.0044 | 3.94 | 0.0003 | 0.1222 | 0.0100 | 0.0063 | |

| بيبتوكوكوس |

|

|

ورم | 3.06 | 0.0002 | 0.23 (0.10, 0.36) | 0.0008 | 0.0001 | 0.0018 | 0.87 | ٤.٢٣ | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 3.78 | 0.0008 | 0.2074 | 0.0100 | 0.0017 | |

| ستربتوكوكوس |

|

|

أن | ٤.٥٥ | 0.0000 | -7.39 (-10.66, -4.13) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.91 | -3.64 | 0.0004 | 0.0013 | -3.04 | 0.0046 | 0.7240 | 0.0100 | 0.0313 | |

| فيلونيلة |

|

|

أن | ٤.٣٠ | 0.0000 | -3.97 (-5.22, -2.71) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -1.11 | -3.95 | 0.0001 | 0.0005 | -3.98 | 0.0002 | 0.0660 | 0.0100 | 0.0067 | |

| روثيا |

|

|

أن | 3.98 | 0.0000 | -1.80 (-3.62, 0.01) | 0.0518 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -1.27 | -4.40 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | -4.38 | 0.0001 | 0.0220 | 0.0100 | 0.0208 | |

| جرانوليكاتيلا |

|

|

أن | 3.69 | 0.0000 | -0.96 (-1.58، -0.34) | 0.0027 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.85 | -3.21 | 0.0017 | 0.0044 | -4.02 | 0.0002 | 0.0768 | 0.0100 | 0.0428 | |

| شاليا |

|

|

أن | ٣.٦٤ | 0.0000 | -0.85 (-1.26، -0.45) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.98 | -4.03 | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | -٤.٠٠ | 0.0003 | 0.0867 | 0.0100 | 0.0013 | |

| أكتينوميس |

|

|

أن | ٣.٥٧ | 0.0000 | -0.68 (-0.93، -0.43) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -1.08 | -5.32 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -4.92 | 0.0000 | 0.0073 | 0.0100 | 0.0081 | |

| لاوتروبيا |

|

|

أن | 3.36 | 0.0002 | -0.42 (-0.68، -0.15) | 0.0023 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | -0.87 | -4.08 | 0.0002 | 0.0007 | -3.18 | 0.0059 | 0.5965 | 0.0100 | 0.0013 | |

| كورينباكتيريوم |

|

|

أن | ٣.٣٠ | 0.0000 | -0.36 (-0.59، -0.14) | 0.0018 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | -0.75 | -3.53 | 0.0008 | 0.0026 | -3.96 | 0.0006 | 0.1612 | 0.0100 | 0.0013 | |

| يوبيكتيريوم |

|

|

أن | 3.28 | 0.0393 | -0.38 (-0.67، -0.09) | 0.0117 | 0.0007 | 0.0113 | -0.56 | -2.42 | 0.0174 | 0.0337 | -0.63 | 0.5459 | 1.0000 | 0.0100 | 0.0208 | |

| هالوموناس |

|

|

أن | 3.22 | 0.0024 | -0.28 (-0.65, 0.09) | 0.1305 | 0.0045 | 0.0545 | -1.15 | -6.82 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | -1.99 | 0.1134 | 0.9503 | 0.0100 | 0.0470 | |

| ميغاسفيرا |

|

|

أن | 3.16 | 0.0028 | -0.27 (-0.47، -0.08) | 0.0063 | 0.0003 | 0.0060 | -0.63 | -2.98 | 0.0042 | 0.0096 | -2.42 | 0.0295 | 0.9625 | 0.0100 | 0.0072 | |

| لانسفيلديلا |

|

|

أن | 3.11 | 0.0115 | -0.24 (-0.55, 0.08) | 0.1447 | 0.0001 | 0.0018 | -1.06 | -4.66 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | -1.20 | 0.2663 | 1.0000 | 0.0100 | 0.0070 | |

| فوكايكولا |

|

|

أن | ٣.٠٤ | 0.0040 | -0.22 (-0.41، -0.03) | 0.0212 | 0.0006 | 0.0109 | -0.74 | -3.57 | 0.0008 | 0.0027 | -2.49 | 0.0387 | 0.8908 | 0.0100 | 0.0070 | |

| نوع | |||||||||||||||||||

| فوسوبكتيريوم نوكليتوم |

|

|

ورم | ٤.٦٨ | 0.0000 | 9.75 (5.91, 13.59) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.15 | ٤.٥٤ | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 3.92 | 0.0002 | 0.1623 | 0.0100 | 0.0229 | 4c305539242bc00f72118f6a70d5d103 |

| تريبونيما ميديوم |

|

|

ورم | ٤.٠٢ | 0.0030 | 2.06 (0.97, 3.16) | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 | 1.01 | ٤.٠١ | 0.0001 | 0.0005 | ٣.١٥ | 0.0036 | 0.8050 | 0.0100 | 0.0043 | 88d5e4fcfd68b0cef9f267bd04d6b934 |

| بيبتوستربتوكوكوس ستوماتيس |

|

|

ورم | ٣.٦٧ | 0.0021 | 0.95 (0.08, 1.82) | 0.0323 | 0.0005 | 0.0094 | 0.67 | 2.78 | 0.0062 | 0.0132 | 3.79 | 0.0004 | 0.2569 | 0.0100 | 0.0183 | feb281c58c97b847d8e32aa9dae2174b |

| جميلة موربيلوروم |

|

|

ورم | 3.52 | 0.0000 | 0.67 (0.23، 1.11) | 0.0034 | 0.0000 | 0.0011 | 0.39 | 1.93 | 0.0569 | 0.0879 | ٤.٧٣ | 0.0000 | 0.0140 | 0.0100 | 0.0488 | 66358cc06be2067caaeab6047c327466 |

| كاتونيلا موربي |

|

|

ورم | 3.51 | 0.0001 | 0.62 (0.29، 0.95) | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.71 | ٣.٤٥ | 0.0008 | 0.0024 | ٤.٠٠ | 0.0003 | 0.1628 | 0.0100 | 0.0092 | de1e79ff05735a3eb21b59e27188410c |

| بيبتوانيروباكتير يورلي |

|

|

ورم | 3.38 | 0.0145 | 0.47 (0.00، 0.95) | 0.0514 | 0.0008 | 0.0133 | 1.08 | ٥.٦٤ | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2.61 | 0.0246 | 0.9239 | 0.0100 | 0.0213 | 74a1666eb102cd17c22028f87467e2e4 |

| بيبتوكوكوس سيمي |

|

|

ورم | 3.06 | 0.0002 | 0.23 (0.10، 0.36) | 0.0008 | 0.0001 | 0.0019 | 0.88 | ٤.٦٨ | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 3.76 | 0.0011 | 0.3176 | 0.0100 | 0.0025 | e5944afd1dc39fe0c43f907049fd6ac4 |

| بورفيروموناس جينجيفاليس |

|

|

أن | 3.96 | 0.0016 | -1.60 (-2.77, -0.42) | 0.0080 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | -0.78 | -3.33 | 0.0013 | 0.0037 | -2.62 | 0.0179 | 0.9642 | 0.0100 | 0.0051 | 204ae45c366a21148f2675b55295831c |

| شاليليا أودونتوليتكا |

|

|

أن | ٣.٥٧ | 0.0000 | -0.72 (-1.11, -0.32) | 0.0004 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.78 | -3.63 | 0.0004 | 0.0015 | -3.86 | 0.0004 | 0.2285 | 0.0200 | 0.0043 | 845954a9086d53d7993b092f560b4fcc |

| لاوتروبيّا ميرا بيلس |

|

|

أن | 3.32 | 0.0004 | -0.42 (-0.66، -0.19) | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | -0.93 | -5.00 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | -2.86 | 0.0166 | 0.8482 | 0.0100 | 0.0025 | 14e61b2c1523a6a67df3d576d3c01fdc |

| أكتينوميسيس أوريز |

|

|

أن | 3.31 | 0.0000 | -0.41 (-0.57، -0.25) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.86 | -5.31 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -4.51 | 0.0001 | 0.0855 | 0.0100 | 0.0025 | 37e783541d8270c9329ce720d8331512 |

| كامبيلوباكتر غراسيليس |

|

|

أن | ٣.٠٠ | 0.0009 | -0.18 (-0.37, 0.01) | 0.0679 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 | -0.72 | -4.73 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | -2.50 | 0.0324 | 0.9517 | 0.0100 | 0.0124 | 42cb1a145d5871ce13065a619775cab6 |

تقدير كابلان-ماير لبقاء المرضى لمدة 3 سنوات بناءً على مستويات وفرة أربعة جينات معبرة بشكل مختلف (MMP1، SERPINE1، COL5A2، وFAP). تم استخدام اختبار لوغ-رانك لتحديد الأهمية.

أداة لتصنيف المخاطر وتخطيط العلاج الشخصي في سرطان الفم والبلعوم.

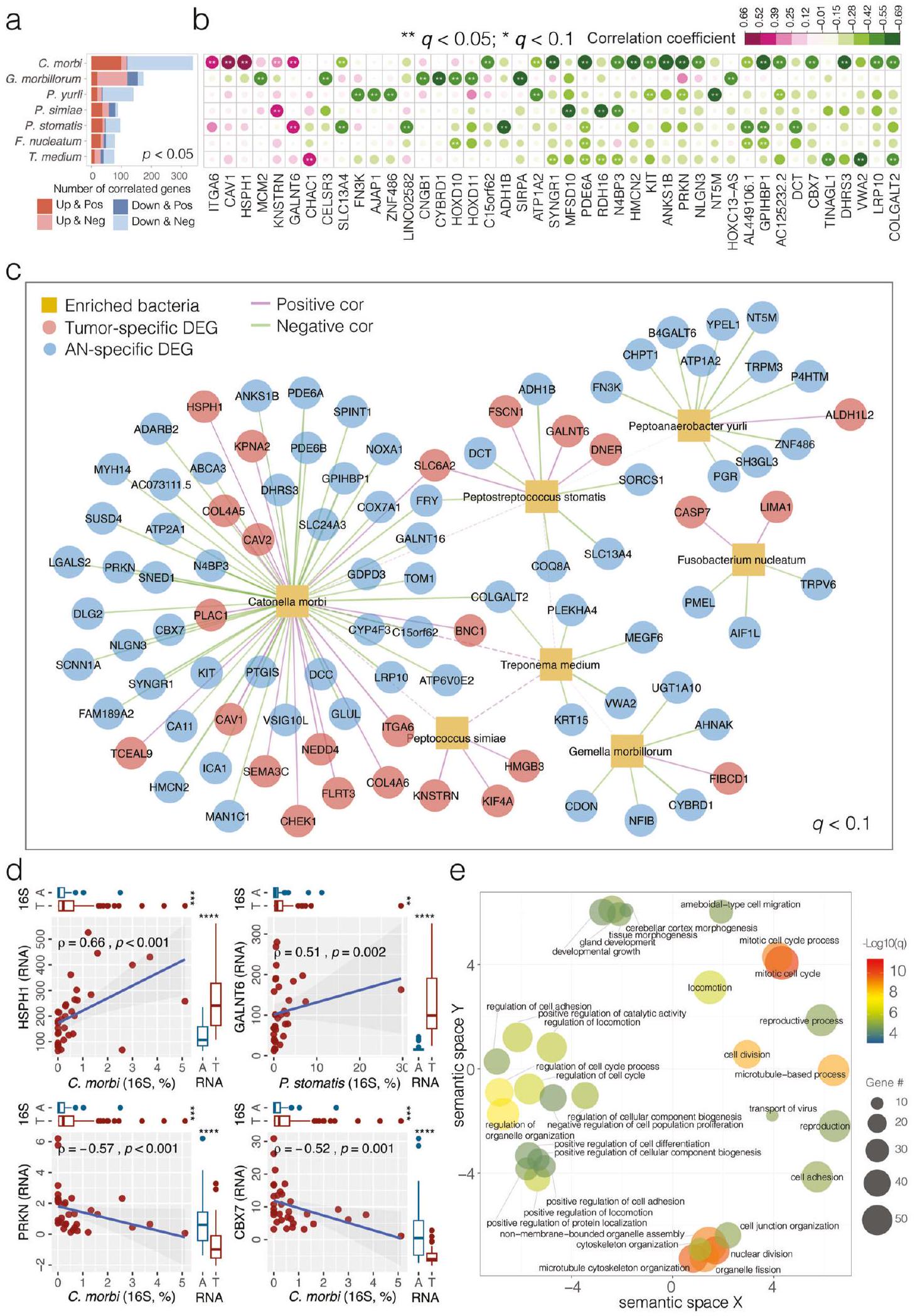

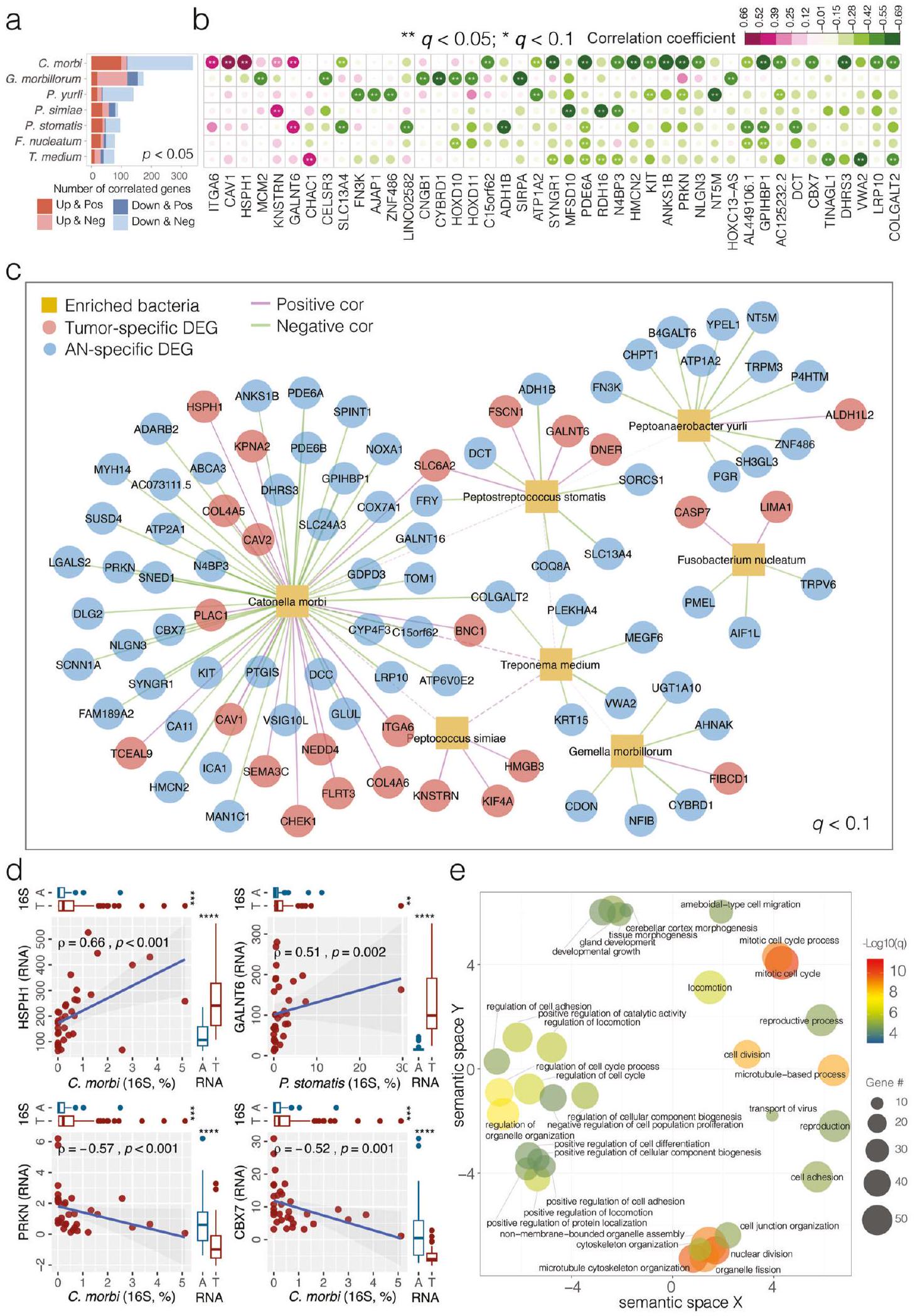

التفاعلات بين الميكروبات الفموية وترانسكريبتوم المضيف في سرطان الفم الحرشفي

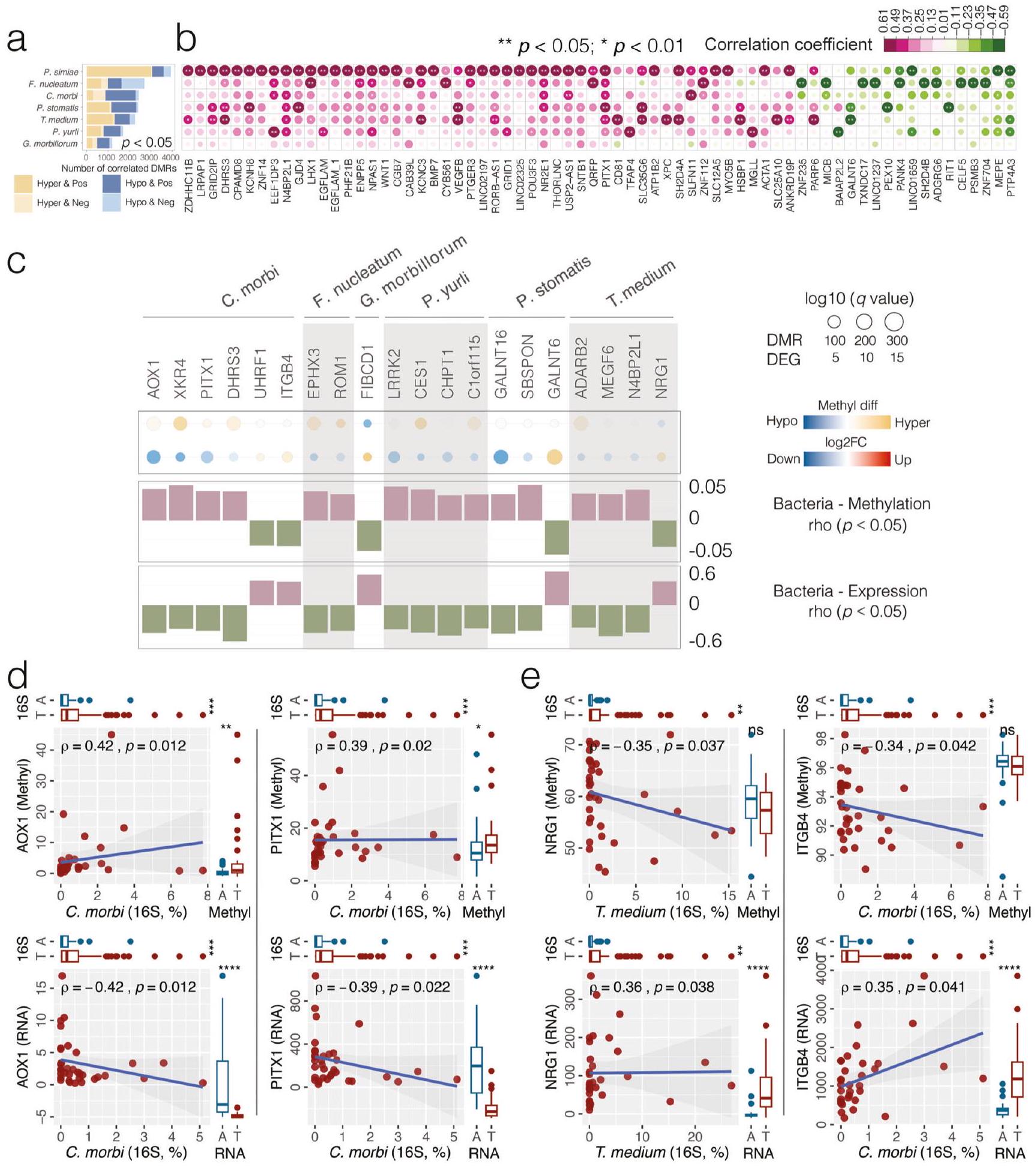

اختلال التعبير الجيني بسبب الميثيلation الحمض النووي

(تحليل المكونات الرئيسية،

الانحرافات الجينية المرتبطة بالبكتيريا في تنظيم الجينات المضيفة في سرطان الفم والبلعوم

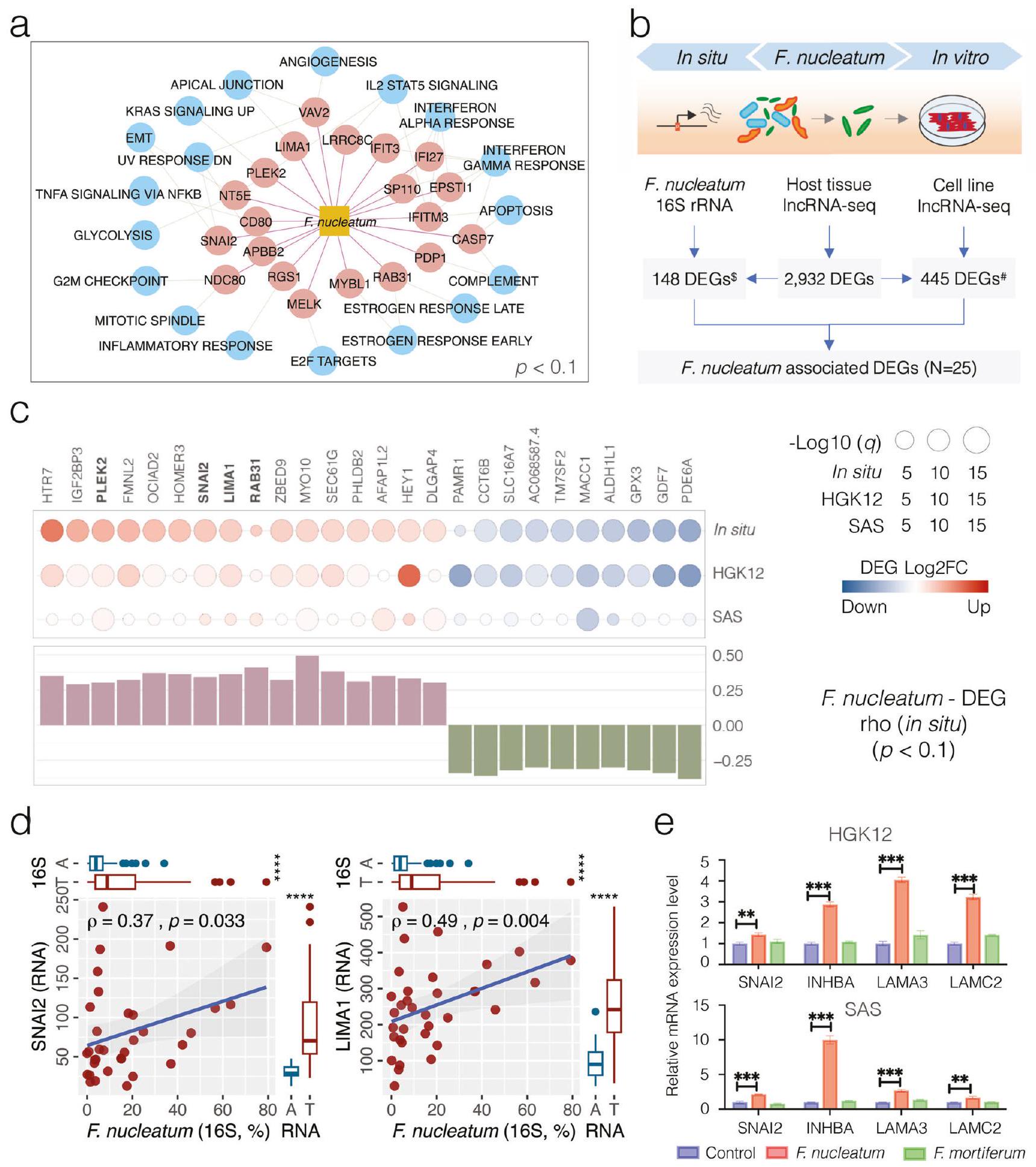

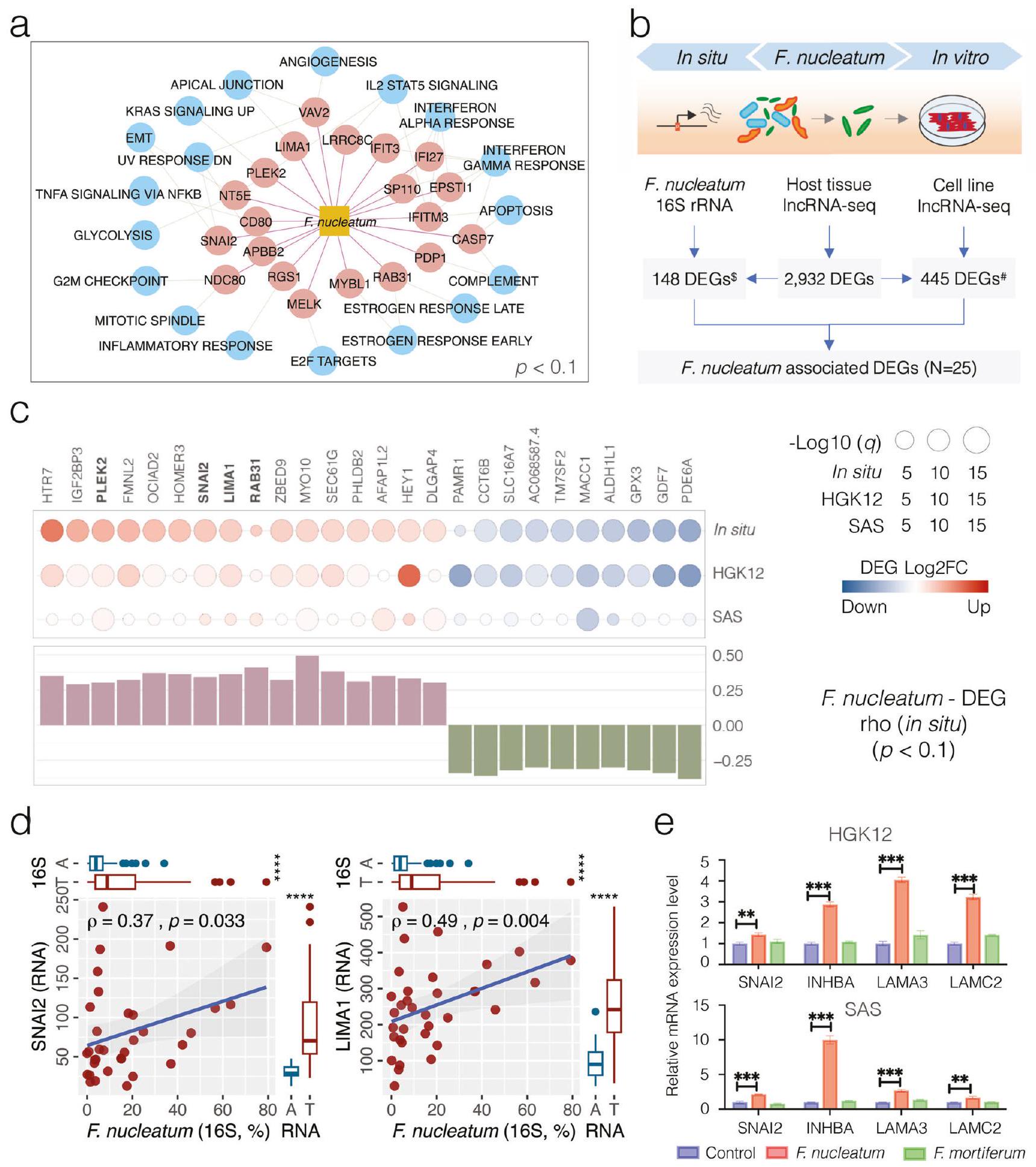

الإمكانات المسرطنة المرتبطة بـ OSCC لبكتيريا Fusobacterium nucleatum في الموقع

الإمكانات المسرطنة المرتبطة بـ OSCC لبكتيريا Fusobacterium nucleatum في المختبر

شبكة تصور الارتباطات المهمة بين البكتيريا والترانسكريبتوم (خط صلب، سبيرمان

تعبيرات النسخ المعبر عنها، مع 820 جينًا معبرًا عنه بشكل مرتفع و478 جينًا معبرًا عنه بشكل منخفض تم اكتشافها بشكل شائع

نقاش

كنقطة انطلاق لدراسة مدفوعة بالفرضيات لفهم أفضل للآليات الجزيئية للبكتيريا المسببة للأمراض التي تكمن وراء نشوء سرطان الفم.

تعبير النسخ الجيني (DEG) ممثل بدوائر مملوءة، مع أحجام تتناسب مع

المقابل لـ

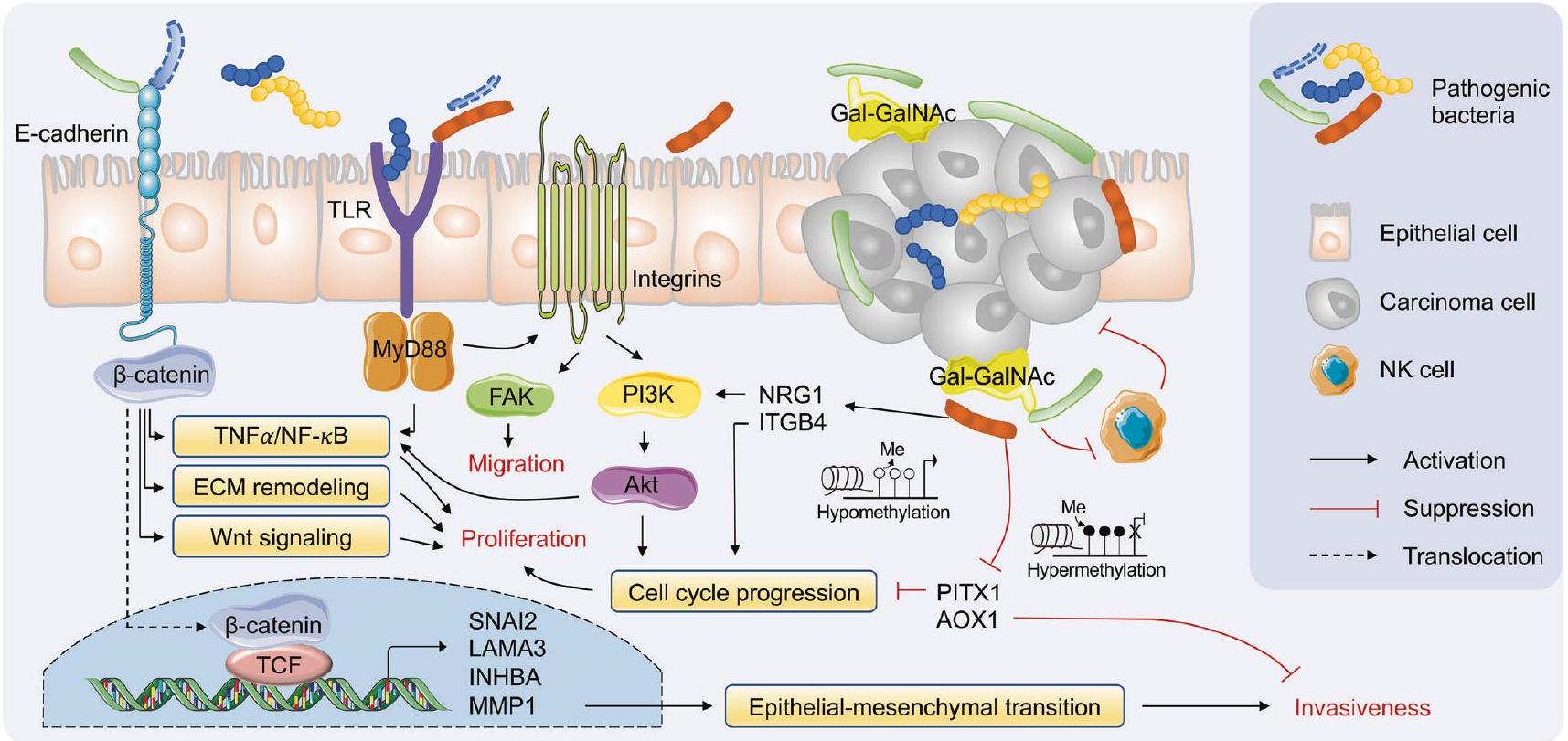

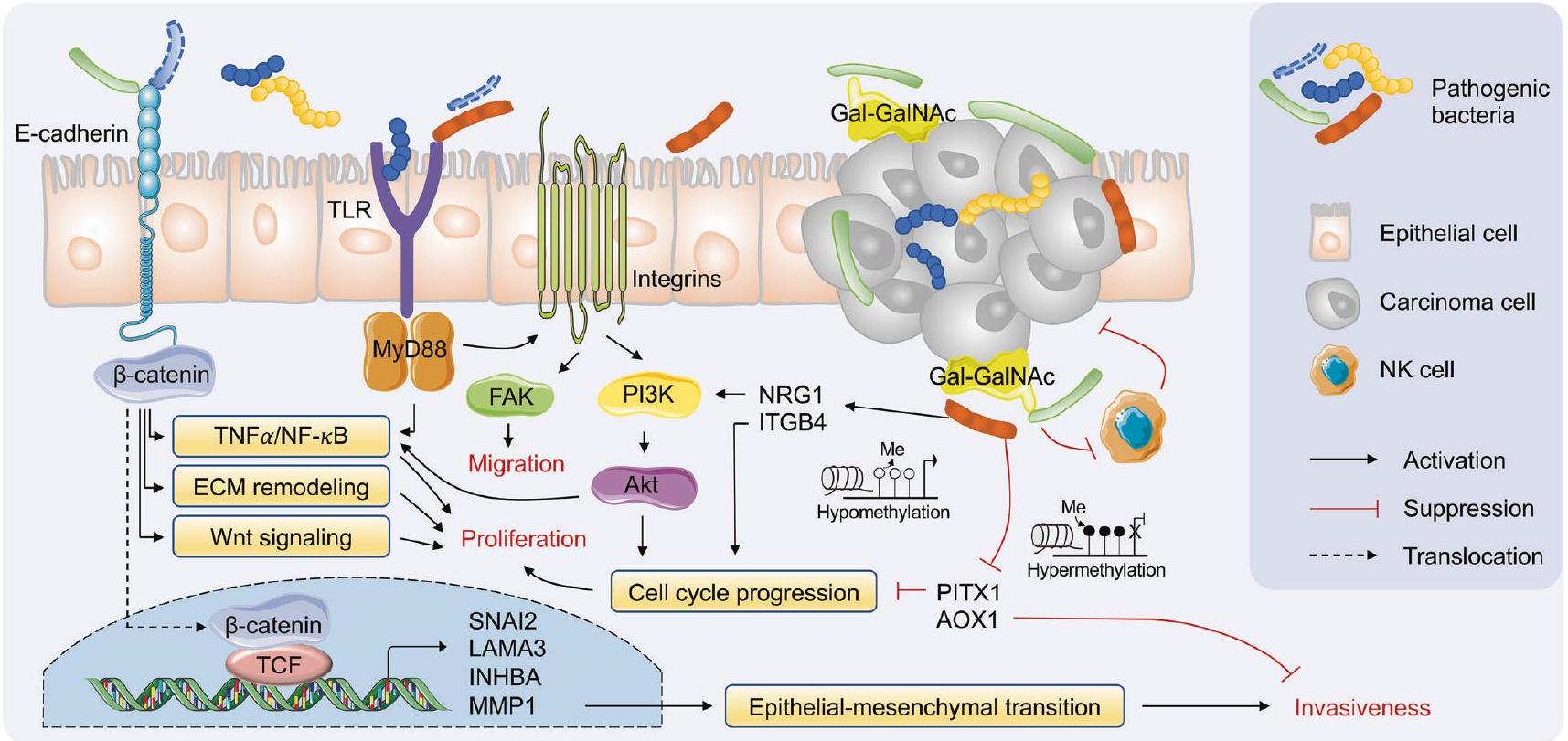

تم الإبلاغ عن تعزيزها لعدوانية السرطان من خلال التفاعل بين مسارات إشارات الإنتجرين/FAK وTLR/MyD88. يمكن تنشيط إشارات PI3K/Akt المرتبطة بالإنتجرين بواسطة

مؤشرًا على أهمية تفاعلات المضيف والميكروبيوم

تعبير الجينات المضيفة غير المنظم، وميثيل الحمض النووي CpG الشاذ في بيئة الورم، مع وظائف غنية تتعلق بمسارات السرطان المختلفة. يكشف التحليل التكاملي بين ترانسكريبتوم البكتيريا وارتباطات ميثيل البكتيريا أن عدم تنظيم ترانسكريبتوم الجينات المضيفة قد يتأثر بالبكتيريا الغنية في الورم أو بواسطة الشذوذات الجينية المرتبطة بالبكتيريا. تمتد نتائجنا الفهم الحالي لتفاعلات المضيف والميكروبات في مسببات سرطان الفم والبلعوم، مما يوفر رؤى مهمة في الأساس الجيني والوظيفي كعلامات تشخيصية محتملة وأهداف علاجية لوضع استراتيجيات أكثر فعالية للوقاية والتدخل لإدارة هذه الكيان المرضي.

طرق

تجنيد المرضى

موافقة الأخلاقيات

جمع عينات الأنسجة واستخراج الحمض النووي/الحمض النووي الريبي

تسلسل الأمبليكون لجين 16S rRNA للميكروبيوتا V3-V4

تحليل البيانات الحيوية والإحصائية لتسلسل 16S للميكروبيوتا

طريقة

كشف فيروس الورم الحليمي البشري وتصنيفه الجيني

تسلسل RNA غير المشفر الطويل للجين المضيف (IncRNA-seq) وتحليل التعبير الجيني

الدلالة الإحصائية

تحليل بيانات تسلسل RNA لسرطان الفم (OSCC) من أطلس جينوم السرطان (TCGA)

تحليل الشبكة بين وفرة البكتيريا وتعبير الجينات المضيفة

ميثيلation CpG في الحمض النووي البشري والتحليل المعلوماتي الحيوي

3000 نقطة أساسية قبل و3000 نقطة أساسية بعد مواقع بدء النسخ (TSSs). عندما تم تحديد عدة مناطق ديميثيلاز (DMRs) داخل نفس منطقة المحفز، استخدمنا طريقة التصويت بالأغلبية لتحديد حالة الميثيل للجين. تم استخدام اختبار ارتباط ترتيب سبيرمان لاستكشاف العلاقة بين DMRs المرتبطة بالمحفز وأنواع البكتيريا الغنية بـ OSCC.

التعايش مع بكتيريا الفوسوبكتيريوم نوكليتوم مع خلايا الظهارة المضيفة في المختبر

تفاعل البوليميراز المتسلسل في الوقت الحقيقي (RT-PCR) لتعبير جينات mRNA

التحليل الغربي للتعبير البروتيني

تم تحديد مستويات التعبير من خلال قياس قيم التدرج الرمادي لشرائط البروتين المستهدفة بالنسبة للبروتين المرجعي بيتا-أكتين باستخدام برنامج ImageJ. جميع البقع والهلامات تأتي من نفس التجربة وتم معالجتها بشكل متوازي.

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

نُشر على الإنترنت: 08 أبريل 2024

References

- Li, Q. et al. Role of oral bacteria in the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers 12, 2797 (2020).

- Johnson, D. E. et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 6, 1-22 (2020).

- Sepich-Poore, G. D. et al. The microbiome and human cancer. Science 371 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc4552 (2021).

- Guerrero-Preston, R. et al. 16 S rRNA amplicon sequencing identifies microbiota associated with oral cancer, human papilloma virus infection and surgical treatment. Oncotarget 7, 51320-51334 (2016).

- Ganly, I. et al. Periodontal pathogens are a risk factor of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma, independent of tobacco and alcohol and human papillomavirus. Int. J. Cancer 145, 775-784 (2019).

- Chen, Z. et al. The intersection between oral microbiota, host gene methylation and patient outcomes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12113425 (2020).

- Kamarajan, P. et al. Periodontal pathogens promote cancer aggressivity via TLR/MyD88 triggered activation of Integrin/FAK signaling that is therapeutically reversible by a probiotic bacteriocin. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008881 (2020).

- Michmerhuizen, N. L., Birkeland, A. C., Bradford, C. R. & Brenner, J. C. Genetic determinants in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and their influence on global personalized medicine. Genes Cancer 7, 182-200 (2016).

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature 517, 576-582 (2015).

- Maruya, S. et al. Differential methylation status of tumorassociated genes in head and neck squamous carcinoma: incidence and potential implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 3825-3830 (2004).

- Rosas, S. L. et al. Promoter hypermethylation patterns of p 16 , O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase, and death-associated protein kinase in tumors and saliva of head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Res. 61, 939-942 (2001).

- Xia, X. et al. Bacteria pathogens drive host colonic epithelial cell promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes in colorectal cancer. Microbiome 8, 108 (2020).

- Jena, P. K. et al. Dysregulated bile acid synthesis and dysbiosis are implicated in Western diet-induced systemic inflammation, microglial activation, and reduced neuroplasticity. FASEB J. 32, 2866-2877 (2018).

- Song, X. et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma diagnosed from saliva metabolic profiling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 16167-16173 (2020).

-

. et al. Oncometabolite 2 -hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell 19, 17-30 (2011). - Janney, A., Powrie, F. & Mann, E. H. Host-microbiota maladaptation in colorectal cancer. Nature 585, 509-517 (2020).

- Dayama, G., Priya, S., Niccum, D. E., Khoruts, A. & Blekhman, R. Interactions between the gut microbiome and host gene regulation in cystic fibrosis. Genome Med. 12, 12 (2020).

- Helmink, B. A., Khan, M. A. W., Hermann, A., Gopalakrishnan, V. & Wargo, J. A. The microbiome, cancer, and cancer therapy. Nat. Med. 25, 377-388 (2019).

- Nejman, D. et al. The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type-specific intracellular bacteria. Science 368, 973-980 (2020).

- Rubinstein, M. R. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/beta-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 14, 195-206 (2013).

- Rousselle, P. & Scoazec, J. Y. Laminin 332 in cancer: when the extracellular matrix turns signals from cell anchorage to cell movement. Semin. Cancer Biol. 62, 149-165 (2020).

- Jung, A. R., Jung, C.-H., Noh, J. K., Lee, Y. C. & Eun, Y.-G. Epithelialmesenchymal transition gene signature is associated with prognosis and tumor microenvironment in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 10, 3652 (2020).

- Hu, Y. et al. Epigenetic suppression of E-cadherin expression by Snail2 during the metastasis of colorectal cancer. Clin. Epigenetics 10, 154 (2018).

- Tang, D. et al. TNF-alpha promotes invasion and metastasis via NFKappa B pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. Basic Res. 23, 141-149 (2017).

- Wu, Y. et al. Stabilization of snail by NF-kappaB is required for inflammation-induced cell migration and invasion. Cancer Cell 15, 416-428 (2009).

- Adjuto-Saccone, M. et al. TNF-alpha induces endothelialmesenchymal transition promoting stromal development of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 12, 649 (2021).

- Coppenhagen-Glazer, S. et al. Fap2 of Fusobacterium nucleatum is a galactose-inhibitable adhesin involved in coaggregation, cell adhesion, and preterm birth. Infect. Immun. 83, 1104-1113 (2015).

- Yang, Y. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum increases proliferation of colorectal cancer cells and tumor development in mice by activating toll-like receptor 4 signaling to nuclear factor-kappaB, and upregulating expression of microRNA-21. Gastroenterology 152, 851-866.e24 (2017).

- Long, X. et al. Peptostreptococcus anaerobius promotes colorectal carcinogenesis and modulates tumour immunity. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 2319-2330 (2019).

- Zhang, L., Liu, Y., Zheng, H. J. & Zhang, C. P. The oral microbiota may have influence on oral cancer. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 9, 476 (2019).

- Huang, X. et al. Wnt7a activates canonical Wnt signaling, promotes bladder cancer cell invasion, and is suppressed by miR-370-3p. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 6693-6706 (2018).

- Xie, H. et al. WNT7A promotes EGF-induced migration of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells by activating

-catenin/MMP9mediated signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 98 (2020). - Chen, L. et al. VEGF promotes migration and invasion by regulating EMT and MMPs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Cancer 11, 7291-7301 (2020).

- Wang, X. et al. Characterization of LIMA1 and its emerging roles and potential therapeutic prospects in cancers. Front. Oncol. 13, 1115943 (2023).

- Zeng, J., Jiang, W. G. & Sanders, A. J. Epithelial protein lost in neoplasm, EPLIN, the cellular and molecular prospects in cancers. Biomolecules 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11071038 (2021).

- Feinberg, A. P., Ohlsson, R. & Henikoff, S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 21-33 (2006).

- Yu, D. H. et al. Postnatal epigenetic regulation of intestinal stem cells requires DNA methylation and is guided by the microbiome. Genome Biol. 16, 211 (2015).

- Fellows, R. et al. Microbiota derived short chain fatty acids promote histone crotonylation in the colon through histone deacetylases. Nat. Commun. 9, 105 (2018).

- Ansari, I. et al. The microbiota programs DNA methylation to control intestinal homeostasis and inflammation. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 610-619 (2020).

- Qiao, F. et al. Downregulated PITX1 modulated by MiR-19a-3p promotes cell malignancy and predicts a poor prognosis of gastric cancer by affecting transcriptionally activated PDCD5. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 46, 2215-2231 (2018).

- Wang, Q., Zhao, S., Gan, L. & Zhuang, Z. Bioinformatics analysis of prognostic value of PITX1 gene in breast cancer. Biosci. Rep. 40 https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20202537 (2020).

- Kolfschoten, I. G. M. et al. A genetic screen identifies PITX1 as a suppressor of RAS activity and tumorigenicity. Cell 121, 849-858 (2005).

- Vantaku, V. et al. Epigenetic loss of AOX1 expression via EZH2 leads to metabolic deregulations and promotes bladder cancer progression. Oncogene 39, 6265-6285 (2020).

- Liu, C. et al. GALNT6 promotes breast cancer metastasis by increasing mucin-type O-glycosylation of alpha2M. Aging 12, 11794-11811 (2020).

- Chen, S. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum reduces METTL3-mediated m(6)A modification and contributes to colorectal cancer metastasis. Nat. Commun. 13, 1248 (2022).

- Xu, C. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer metastasis through miR-1322/CCL20 axis and M2 polarization. Gut Microbes 13, 1980347 (2021).

- Wong, M. C. S. et al. Prevalence and epidemiologic profile of oral infection with alpha, beta, and gamma papillomaviruses in an Asian Chinese population. J. Infect. Dis. 218, 388-397 (2018).

- Chen, Z. et al. Impact of preservation method and 16S rRNA hypervariable region on gut microbiota profiling. mSystems 4 https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00271-18 (2019).

- Matsen, F. A., Kodner, R. B. & Armbrust, E. V. pplacer: linear time maximum-likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic placement of sequences onto a fixed reference tree. BMC Bioinforma. 11, 538 (2010).

- Zhu, H. et al. Convergent dysbiosis of upper aerodigestive microbiota between patients with esophageal and oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 152, 1903-1915 (2023).

- Mirarab, S., Nguyen, N. & Warnow, T. SEPP: SATe-enabled phylogenetic placement. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 247-258 https://doi.org/10.1142/9789814366496_0024 (2012).

- Hamady, M., Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. Fast UniFrac: facilitating highthroughput phylogenetic analyses of microbial communities including analysis of pyrosequencing and PhyloChip data. ISME J. 4, 17-27 (2010).

- Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60 (2011).

- Lin, H. & Peddada, S. D. Analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction. Nat. Commun. 11, 3514 (2020).

- Fernandes, A. D. et al. Unifying the analysis of high-throughput sequencing datasets: characterizing RNA-seq, 16S rRNA gene sequencing and selective growth experiments by compositional data analysis. Microbiome 2, 15 (2014).

- Yang, L. & Chen, J. A comprehensive evaluation of microbial differential abundance analysis methods: current status and potential solutions. Microbiome 10, 130 (2022).

- Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139-140 (2010).

- Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996-998 (2013).

- Bernard, H. U. et al. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology 401, 70-79 (2010).

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Biological agents. Volume 100 B. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 100, 1-441 (2012).

- Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15-21 (2013).

- Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923-930 (2014).

- Chen, J., Bardes, E. E., Aronow, B. J. & Jegga, A. G. ToppGene Suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W305-W311 (2009).

- Colaprico, A. et al. TCGAbiolinks: an R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e71 (2016).

- Friedman, J. & Alm, E. J. Inferring correlation networks from genomic survey data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002687 (2012).

- Saito, R. et al. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nat. Methods 9, 1069-1076 (2012).

- Supek, F., Bosnjak, M., Skunca, N. & Smuc, T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS ONE 6, e21800 (2011).

- Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledgebased approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545-15550 (2005).

- Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114-2120 (2014).

- Krueger, F. & Andrews, S. R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics 27, 1571 (2011).

- Akalin, A. et al. methylKit: a comprehensive

package for the analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles. Genome Biol. 13, R87 (2012). - Yu, G., Wang, L. G. & He, Q. Y. ChIPseeker: an R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics 31, 2382-2383 (2015).

- Manson McGuire, A. et al. Evolution of invasion in a diverse set of Fusobacterium species. mBio 5, e01864 (2014).

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00511-x.

© المؤلفون 2024

قسم علم الأحياء الدقيقة، الجامعة الصينية في هونغ كونغ، منطقة هونغ كونغ الإدارية الخاصة، الصين. قسم الأنف والأذن والحنجرة، جراحة الرأس والعنق، الجامعة الصينية في هونغ كونغ، منطقة هونغ كونغ الإدارية الخاصة، الصين. قسم علم الأمراض الكيميائية، الجامعة الصينية في هونغ كونغ، منطقة هونغ كونغ الإدارية الخاصة، الصين. مركز جورجيا للسرطان، أوغستا، GA 30912، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. قسم الطب، كلية الطب في جورجيا، جامعة أوغستا، أوغستا، GA 30912، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية. كلية العلوم الطبية الحيوية، الجامعة الصينية في هونغ كونغ، منطقة هونغ كونغ الإدارية الخاصة، الصين. قسم الطب والعلاج، الجامعة الصينية في هونغ كونغ، منطقة هونغ كونغ الإدارية الخاصة، الصين. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: ليويانغ كاي، هينغيان زو، تشيان تشيان مو. - البريد الإلكتروني: jasonchan@ent.cuhk.edu.hk; zigui.chen@cuhk.edu.hk

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00511-x

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38589501

Publication Date: 2024-04-08

Integrative analysis reveals associations between oral microbiota dysbiosis and host genetic and epigenetic aberrations in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma

Abstract

Dysbiosis of the human oral microbiota has been reported to be associated with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) while the host-microbiota interactions with respect to the potential impact of pathogenic bacteria on host genomic and epigenomic abnormalities remain poorly studied. In this study, the mucosal bacterial community, host genome-wide transcriptome and DNA CpG methylation were simultaneously profiled in tumors and their adjacent normal tissues of OSCC patients. Significant enrichment in the relative abundance of seven bacteria species (Fusobacterium nucleatum, Treponema medium, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Gemella morbillorum, Catonella morbi, Peptoanaerobacter yurli and Peptococcus simiae) were observed in OSCC tumor microenvironment. These tumor-enriched bacteria formed 254 positive correlations with 206 up-regulated host genes, mainly involving signaling pathways related to cell adhesion, migration and proliferation. Integrative analysis of bacteria-transcriptome and bacteria-methylation correlations identified at least 20 dysregulated host genes with inverted CpG methylation in their promoter regions associated with enrichment of bacterial pathogens, implying a potential of pathogenic bacteria to regulate gene expression, in part, through epigenetic alterations. An in vitro model further confirmed that Fusobacterium nucleatum might contribute to cellular invasion via crosstalk with E -cadherin

and betel nut chewing; however, the prevalence of OSCC without traditional risk factors has been increasing in recent years

microbiome in cancers

Results

Study subjects

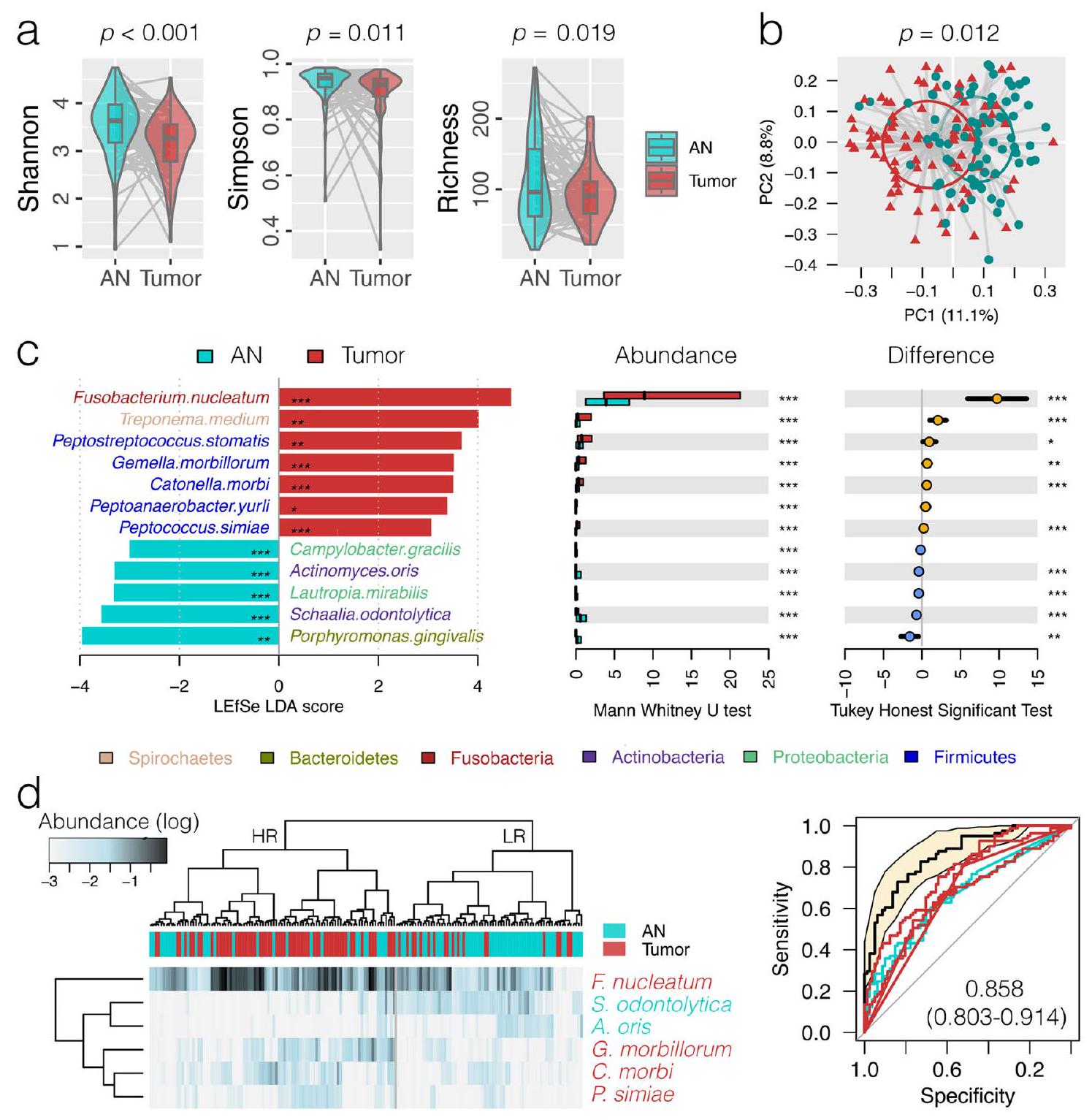

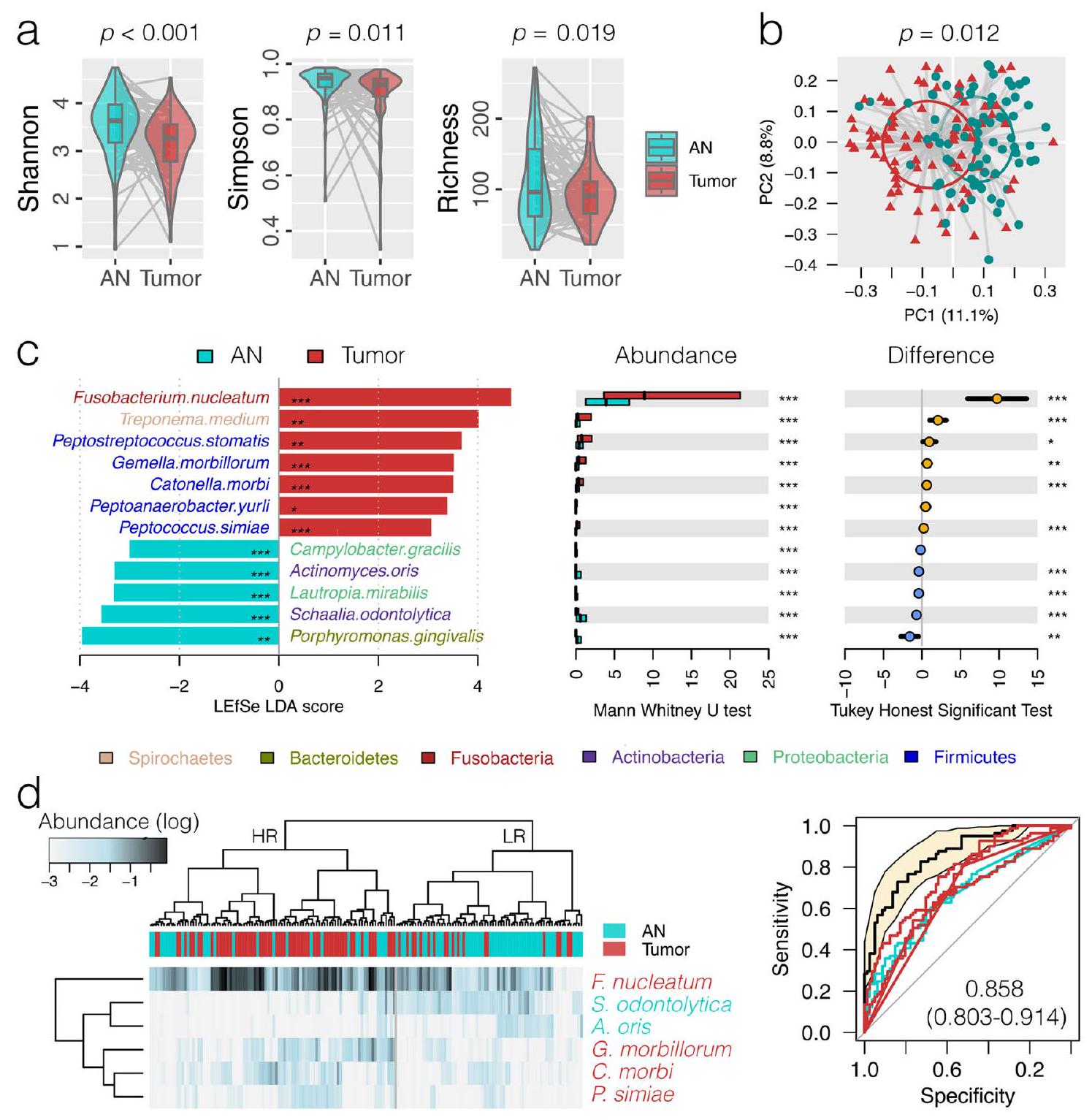

Oral microbiota dysbiosis in OSCC

other factors, including T stage (T1&T2 vs. T3&T4) (weighted GUniFrac

Fusobacterium nucleatum associated with OSCC patients without traditional risk factors

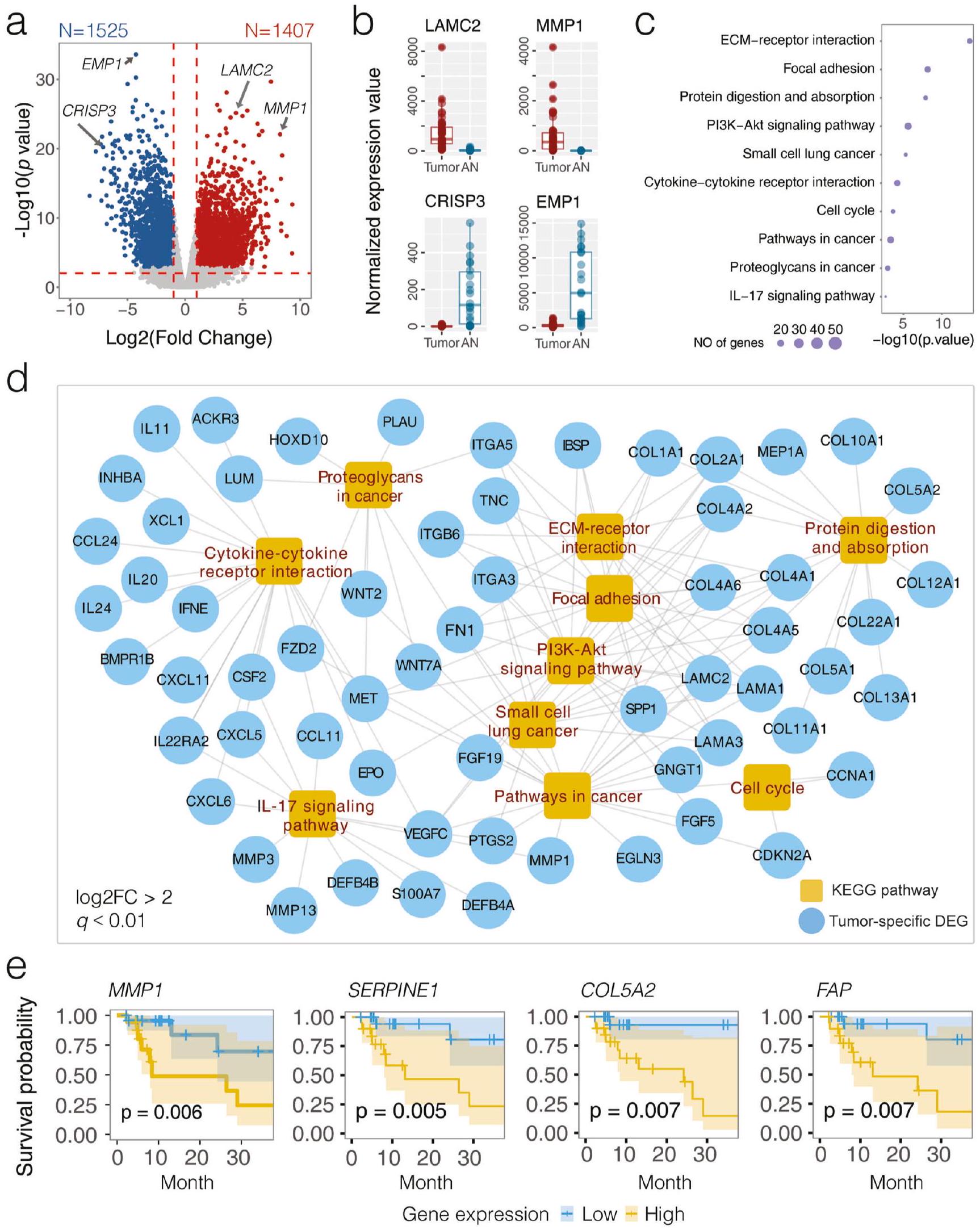

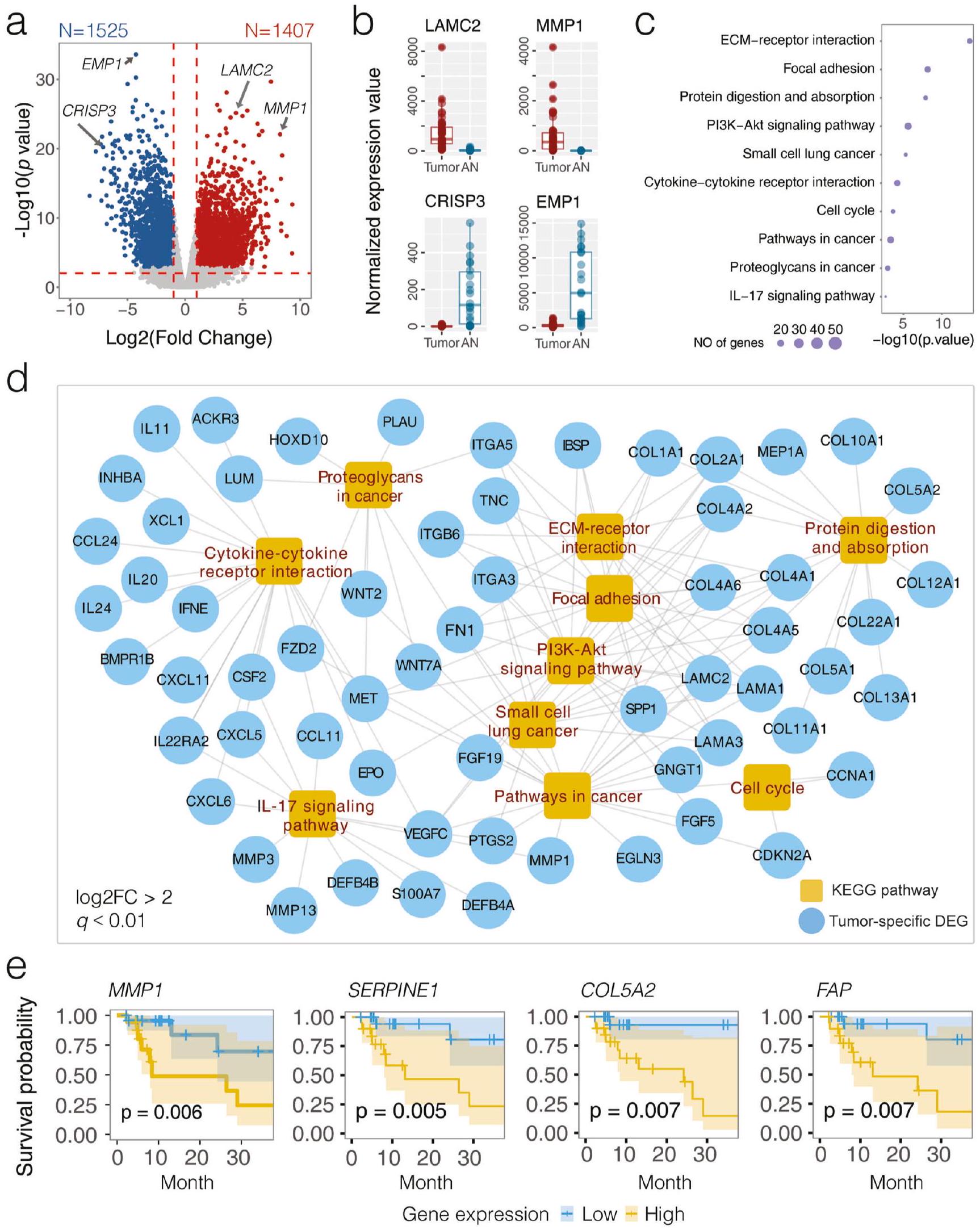

Differentially expressed host gene transcriptome in OSCC

analysis (score

the most up-regulated genes (

(

| Taxa | Mean abundance (

|

LEfSe test | Tukey HSD test | MWU test | ANCOM-BC2 test

|

ALDEx2 test

|

ZicoSeq test

|

Representative ASV | |||||||||||

| AN | Tumor | LDA group | LDA score | LDA

|

Difference (%) |

|

p value |

|

|

|

p value |

|

|

p value |

|

|

|

||

| Genus | |||||||||||||||||||

| Fusobacterium |

|

|

Tumor | 4.78 | 0.0000 | 12.45 (8.71, 16.20) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.12 | 4.27 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 5.72 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0600 | 0.0979 | |

| Treponema |

|

|

Tumor | 4.29 | 0.0180 | 4.07 (1.85, 6.29) | 0.0004 | 0.0001 | 0.0028 | 0.81 | 2.57 | 0.0114 | 0.0235 | 2.57 | 0.0156 | 0.9819 | 0.0100 | 0.0017 | |

| Peptoanaerobacter |

|

|

Tumor | 3.82 | 0.0017 | 1.19 (0.47, 1.92) | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 1.46 | 6.16 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 3.58 | 0.0012 | 0.3104 | 0.0100 | 0.0070 | |

| Peptostreptococcus |

|

|

Tumor | 3.80 | 0.0019 | 1.20 (0.26, 2.14) | 0.0125 | 0.0004 | 0.0066 | 0.71 | 2.74 | 0.0070 | 0.0151 | 3.77 | 0.0004 | 0.1432 | 0.0300 | 0.0468 | |

| Catonella |

|

|

Tumor | 3.54 | 0.0001 | 0.62 (0.29, 0.95) | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.72 | 3.23 | 0.0017 | 0.0044 | 3.94 | 0.0003 | 0.1222 | 0.0100 | 0.0063 | |

| Peptococcus |

|

|

Tumor | 3.06 | 0.0002 | 0.23 (0.10, 0.36) | 0.0008 | 0.0001 | 0.0018 | 0.87 | 4.23 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | 3.78 | 0.0008 | 0.2074 | 0.0100 | 0.0017 | |

| Streptococcus |

|

|

AN | 4.55 | 0.0000 | -7.39 (-10.66, -4.13) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.91 | -3.64 | 0.0004 | 0.0013 | -3.04 | 0.0046 | 0.7240 | 0.0100 | 0.0313 | |

| Veillonella |

|

|

AN | 4.30 | 0.0000 | -3.97 (-5.22, -2.71) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -1.11 | -3.95 | 0.0001 | 0.0005 | -3.98 | 0.0002 | 0.0660 | 0.0100 | 0.0067 | |

| Rothia |

|

|

AN | 3.98 | 0.0000 | -1.80 (-3.62, 0.01) | 0.0518 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -1.27 | -4.40 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | -4.38 | 0.0001 | 0.0220 | 0.0100 | 0.0208 | |

| Granulicatella |

|

|

AN | 3.69 | 0.0000 | -0.96 (-1.58, -0.34) | 0.0027 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.85 | -3.21 | 0.0017 | 0.0044 | -4.02 | 0.0002 | 0.0768 | 0.0100 | 0.0428 | |

| Schaalia |

|

|

AN | 3.64 | 0.0000 | -0.85 (-1.26, -0.45) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.98 | -4.03 | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | -4.00 | 0.0003 | 0.0867 | 0.0100 | 0.0013 | |

| Actinomyces |

|

|

AN | 3.57 | 0.0000 | -0.68 (-0.93, -0.43) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -1.08 | -5.32 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -4.92 | 0.0000 | 0.0073 | 0.0100 | 0.0081 | |

| Lautropia |

|

|

AN | 3.36 | 0.0002 | -0.42 (-0.68, -0.15) | 0.0023 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | -0.87 | -4.08 | 0.0002 | 0.0007 | -3.18 | 0.0059 | 0.5965 | 0.0100 | 0.0013 | |

| Corynebacterium |

|

|

AN | 3.30 | 0.0000 | -0.36 (-0.59, -0.14) | 0.0018 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | -0.75 | -3.53 | 0.0008 | 0.0026 | -3.96 | 0.0006 | 0.1612 | 0.0100 | 0.0013 | |

| Eubacterium |

|

|

AN | 3.28 | 0.0393 | -0.38 (-0.67, -0.09) | 0.0117 | 0.0007 | 0.0113 | -0.56 | -2.42 | 0.0174 | 0.0337 | -0.63 | 0.5459 | 1.0000 | 0.0100 | 0.0208 | |

| Halomonas |

|

|

AN | 3.22 | 0.0024 | -0.28 (-0.65, 0.09) | 0.1305 | 0.0045 | 0.0545 | -1.15 | -6.82 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | -1.99 | 0.1134 | 0.9503 | 0.0100 | 0.0470 | |

| Megasphaera |

|

|

AN | 3.16 | 0.0028 | -0.27 (-0.47, -0.08) | 0.0063 | 0.0003 | 0.0060 | -0.63 | -2.98 | 0.0042 | 0.0096 | -2.42 | 0.0295 | 0.9625 | 0.0100 | 0.0072 | |

| Lancefieldella |

|

|

AN | 3.11 | 0.0115 | -0.24 (-0.55, 0.08) | 0.1447 | 0.0001 | 0.0018 | -1.06 | -4.66 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | -1.20 | 0.2663 | 1.0000 | 0.0100 | 0.0070 | |

| Phocaeicola |

|

|

AN | 3.04 | 0.0040 | -0.22 (-0.41, -0.03) | 0.0212 | 0.0006 | 0.0109 | -0.74 | -3.57 | 0.0008 | 0.0027 | -2.49 | 0.0387 | 0.8908 | 0.0100 | 0.0070 | |

| Species | |||||||||||||||||||

| Fusobacterium nucleatum |

|

|

Tumor | 4.68 | 0.0000 | 9.75 (5.91, 13.59) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.15 | 4.54 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 3.92 | 0.0002 | 0.1623 | 0.0100 | 0.0229 | 4c305539242bc00f72118f6a70d5d103 |

| Treponema medium |

|

|

Tumor | 4.02 | 0.0030 | 2.06 (0.97, 3.16) | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 | 1.01 | 4.01 | 0.0001 | 0.0005 | 3.15 | 0.0036 | 0.8050 | 0.0100 | 0.0043 | 88d5e4fcfd68b0cef9f267bd04d6b934 |

| Peptostreptococcus stomatis |

|

|

Tumor | 3.67 | 0.0021 | 0.95 (0.08, 1.82) | 0.0323 | 0.0005 | 0.0094 | 0.67 | 2.78 | 0.0062 | 0.0132 | 3.79 | 0.0004 | 0.2569 | 0.0100 | 0.0183 | feb281c58c97b847d8e32aa9dae2174b |

| Gemella morbillorum |

|

|

Tumor | 3.52 | 0.0000 | 0.67 (0.23, 1.11) | 0.0034 | 0.0000 | 0.0011 | 0.39 | 1.93 | 0.0569 | 0.0879 | 4.73 | 0.0000 | 0.0140 | 0.0100 | 0.0488 | 66358cc06be2067caaeab6047c327466 |

| Catonella morbi |

|

|

Tumor | 3.51 | 0.0001 | 0.62 (0.29, 0.95) | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.71 | 3.45 | 0.0008 | 0.0024 | 4.00 | 0.0003 | 0.1628 | 0.0100 | 0.0092 | de1e79ff05735a3eb21b59e27188410c |

| Peptoanaerobacter yurli |

|

|

Tumor | 3.38 | 0.0145 | 0.47 (0.00, 0.95) | 0.0514 | 0.0008 | 0.0133 | 1.08 | 5.64 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 2.61 | 0.0246 | 0.9239 | 0.0100 | 0.0213 | 74a1666eb102cd17c22028f87467e2e4 |

| Peptococcus simiae |

|

|

Tumor | 3.06 | 0.0002 | 0.23 (0.10, 0.36) | 0.0008 | 0.0001 | 0.0019 | 0.88 | 4.68 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 3.76 | 0.0011 | 0.3176 | 0.0100 | 0.0025 | e5944afd1dc39fe0c43f907049fd6ac4 |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis |

|

|

AN | 3.96 | 0.0016 | -1.60 (-2.77, -0.42) | 0.0080 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | -0.78 | -3.33 | 0.0013 | 0.0037 | -2.62 | 0.0179 | 0.9642 | 0.0100 | 0.0051 | 204ae45c366a21148f2675b55295831c |

| Schaalia odontolytica |

|

|

AN | 3.57 | 0.0000 | -0.72 (-1.11, -0.32) | 0.0004 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.78 | -3.63 | 0.0004 | 0.0015 | -3.86 | 0.0004 | 0.2285 | 0.0200 | 0.0043 | 845954a9086d53d7993b092f560b4fcc |

| Lautropia mirabilis |

|

|

AN | 3.32 | 0.0004 | -0.42 (-0.66, -0.19) | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | -0.93 | -5.00 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | -2.86 | 0.0166 | 0.8482 | 0.0100 | 0.0025 | 14e61b2c1523a6a67df3d576d3c01fdc |

| Actinomyces oris |

|

|

AN | 3.31 | 0.0000 | -0.41 (-0.57, -0.25) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -0.86 | -5.31 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | -4.51 | 0.0001 | 0.0855 | 0.0100 | 0.0025 | 37e783541d8270c9329ce720d8331512 |

| Campylobacter gracilis |

|

|

AN | 3.00 | 0.0009 | -0.18 (-0.37, 0.01) | 0.0679 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 | -0.72 | -4.73 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | -2.50 | 0.0324 | 0.9517 | 0.0100 | 0.0124 | 42cb1a145d5871ce13065a619775cab6 |

e Kaplan-Meier estimate for 3-year disease-specific survival based on the abundance levels of four DEGs (MMP1, SERPINE1, COL5A2, and FAP). The log-rank test was used to determine significance.

instrumental for risk stratification and personalized treatment planning in OSCC.

Interactions between oral microbiota and host transcriptome in OSCC

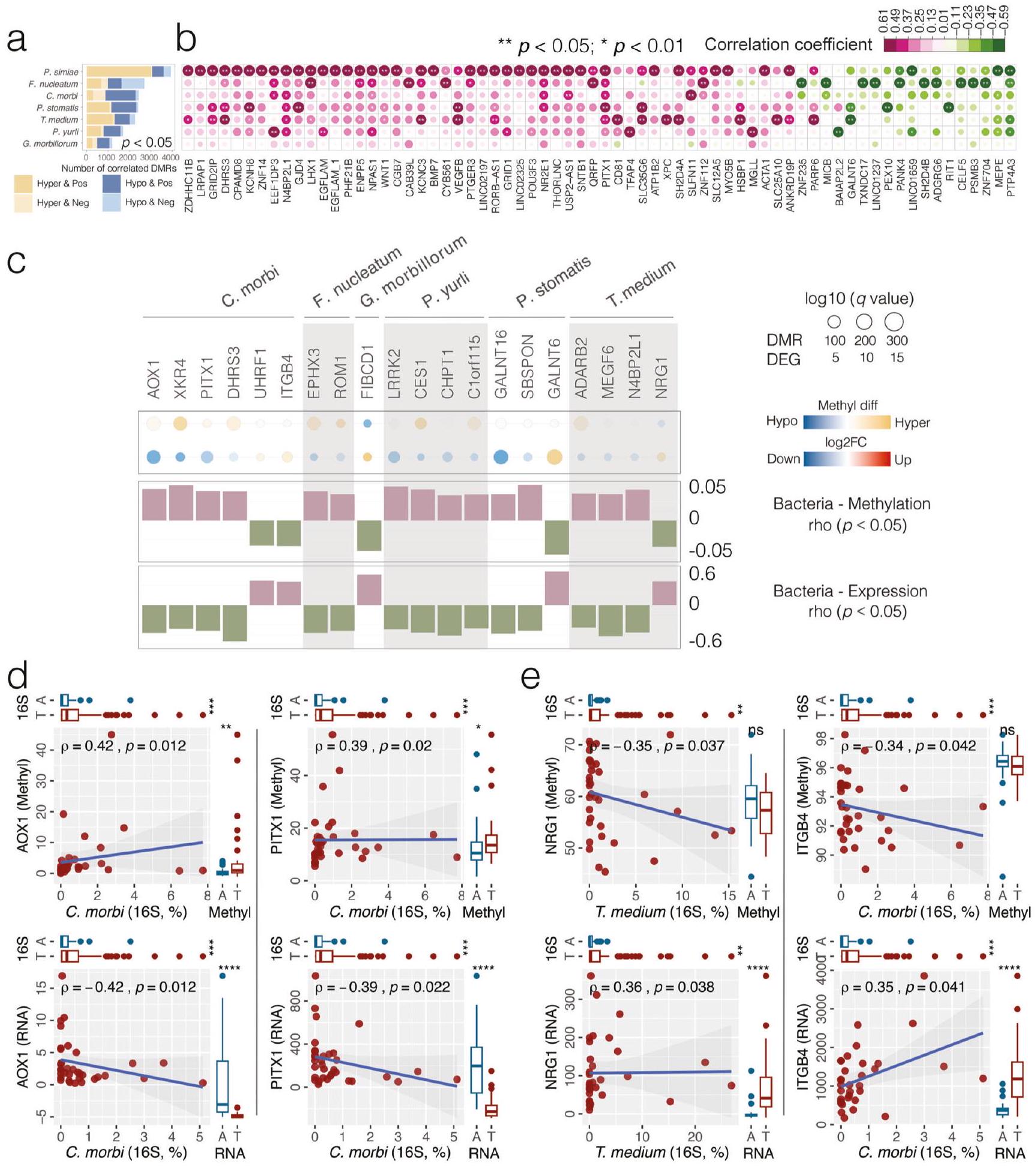

Transcriptome deregulation by DNA methylation

(PCA,

Bacteria-associated epigenetic aberrance on host gene dysregulation in OSCC

OSCC-related carcinogenic potential of Fusobacterium nucleatum in situ

OSCC-related carcinogenic potential of Fusobacterium nucleatum in vitro

c Network visualizing significant correlations between bacteria-transcriptome (solid line, Spearman

expressed transcriptomes, with 820 up- and 478 down-regulated DEGs commonly detected

Discussion

as a precursor for hypothesis-driven study to better understand the molecular mechanisms of pathogenic bacteria underlying OSCC pathogenesis.

transcriptome expression (DEG) are represented by filled circles, with sizes corresponding to the

corresponding to the

been reported to promote cancer aggressivity via crosstalk between the integrin/FAK and TLR/MyD88 signaling pathways. Integrin-associated PI3K/Akt signaling can be activated by

indicating the importance of host-microbiome interactions

dysregulated host gene expression, and aberrant DNA CpG methylation in tumor microenvironment, with enriched functions related to various cancer-related pathways. Integrative analysis between bacteriatranscriptome and bacteria-methylation correlations reveals that dysregulation of host gene transcriptome might be influenced by tumor-enriched bacteria or by bacteria-associated epigenetic abnormality. Our findings extend the current understanding of the host-microbiota interactions in the pathogenesis of OSCC, which provides important insights into the genetic and functional basis as potential diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets for formulating more effective prevention and intervention strategies to manage this morbid entity.

Methods

Patient recruitment

Ethics approval

Tissue specimen collection and DNA/RNA extraction

Microbiota 16S rRNA gene V3-V4 amplicon sequencing

Microbiota 16S sequence data bioinformatics and statistical analysis

method

HPV detection and genotyping

Host gene long non-coding RNA sequencing (IncRNA-seq) and transcriptome profiling

statistical significance (

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) OSCC RNA-seq data analysis

Network analysis between bacterial abundance and host gene expression

Human DNA CpG methylation and bioinformatic analysis

as 3000 bp upstream and 3000 bp downstream of the transcription start sites (TSSs). When multiple DMRs were located within the same promoter region, we used a majority voting method to determine the methylation status of the gene. Spearman’s rank-order correlation test was used to explore the association between promoter-associated DMRs and OSCC-enriched bacterial species. A

Fusobacterium nucleatum co-culture with host epithelial cell in vitro

Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) of mRNA gene expression

Western blot of protein expression

expression levels were determined by quantifying the grayscale values of the target protein bands relative to the reference beta-actin using ImageJ software. All blots and gels derive from the same experiment and they were processed in parallel.

Reporting summary

Data availability

Published online: 08 April 2024

References

- Li, Q. et al. Role of oral bacteria in the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers 12, 2797 (2020).

- Johnson, D. E. et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 6, 1-22 (2020).

- Sepich-Poore, G. D. et al. The microbiome and human cancer. Science 371 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc4552 (2021).

- Guerrero-Preston, R. et al. 16 S rRNA amplicon sequencing identifies microbiota associated with oral cancer, human papilloma virus infection and surgical treatment. Oncotarget 7, 51320-51334 (2016).

- Ganly, I. et al. Periodontal pathogens are a risk factor of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma, independent of tobacco and alcohol and human papillomavirus. Int. J. Cancer 145, 775-784 (2019).

- Chen, Z. et al. The intersection between oral microbiota, host gene methylation and patient outcomes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12113425 (2020).

- Kamarajan, P. et al. Periodontal pathogens promote cancer aggressivity via TLR/MyD88 triggered activation of Integrin/FAK signaling that is therapeutically reversible by a probiotic bacteriocin. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008881 (2020).

- Michmerhuizen, N. L., Birkeland, A. C., Bradford, C. R. & Brenner, J. C. Genetic determinants in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and their influence on global personalized medicine. Genes Cancer 7, 182-200 (2016).

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature 517, 576-582 (2015).

- Maruya, S. et al. Differential methylation status of tumorassociated genes in head and neck squamous carcinoma: incidence and potential implications. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 3825-3830 (2004).

- Rosas, S. L. et al. Promoter hypermethylation patterns of p 16 , O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase, and death-associated protein kinase in tumors and saliva of head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Res. 61, 939-942 (2001).

- Xia, X. et al. Bacteria pathogens drive host colonic epithelial cell promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes in colorectal cancer. Microbiome 8, 108 (2020).

- Jena, P. K. et al. Dysregulated bile acid synthesis and dysbiosis are implicated in Western diet-induced systemic inflammation, microglial activation, and reduced neuroplasticity. FASEB J. 32, 2866-2877 (2018).

- Song, X. et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma diagnosed from saliva metabolic profiling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 16167-16173 (2020).

-

. et al. Oncometabolite 2 -hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell 19, 17-30 (2011). - Janney, A., Powrie, F. & Mann, E. H. Host-microbiota maladaptation in colorectal cancer. Nature 585, 509-517 (2020).

- Dayama, G., Priya, S., Niccum, D. E., Khoruts, A. & Blekhman, R. Interactions between the gut microbiome and host gene regulation in cystic fibrosis. Genome Med. 12, 12 (2020).

- Helmink, B. A., Khan, M. A. W., Hermann, A., Gopalakrishnan, V. & Wargo, J. A. The microbiome, cancer, and cancer therapy. Nat. Med. 25, 377-388 (2019).

- Nejman, D. et al. The human tumor microbiome is composed of tumor type-specific intracellular bacteria. Science 368, 973-980 (2020).

- Rubinstein, M. R. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/beta-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 14, 195-206 (2013).

- Rousselle, P. & Scoazec, J. Y. Laminin 332 in cancer: when the extracellular matrix turns signals from cell anchorage to cell movement. Semin. Cancer Biol. 62, 149-165 (2020).

- Jung, A. R., Jung, C.-H., Noh, J. K., Lee, Y. C. & Eun, Y.-G. Epithelialmesenchymal transition gene signature is associated with prognosis and tumor microenvironment in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 10, 3652 (2020).

- Hu, Y. et al. Epigenetic suppression of E-cadherin expression by Snail2 during the metastasis of colorectal cancer. Clin. Epigenetics 10, 154 (2018).

- Tang, D. et al. TNF-alpha promotes invasion and metastasis via NFKappa B pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. Basic Res. 23, 141-149 (2017).

- Wu, Y. et al. Stabilization of snail by NF-kappaB is required for inflammation-induced cell migration and invasion. Cancer Cell 15, 416-428 (2009).

- Adjuto-Saccone, M. et al. TNF-alpha induces endothelialmesenchymal transition promoting stromal development of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 12, 649 (2021).

- Coppenhagen-Glazer, S. et al. Fap2 of Fusobacterium nucleatum is a galactose-inhibitable adhesin involved in coaggregation, cell adhesion, and preterm birth. Infect. Immun. 83, 1104-1113 (2015).

- Yang, Y. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum increases proliferation of colorectal cancer cells and tumor development in mice by activating toll-like receptor 4 signaling to nuclear factor-kappaB, and upregulating expression of microRNA-21. Gastroenterology 152, 851-866.e24 (2017).

- Long, X. et al. Peptostreptococcus anaerobius promotes colorectal carcinogenesis and modulates tumour immunity. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 2319-2330 (2019).

- Zhang, L., Liu, Y., Zheng, H. J. & Zhang, C. P. The oral microbiota may have influence on oral cancer. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 9, 476 (2019).

- Huang, X. et al. Wnt7a activates canonical Wnt signaling, promotes bladder cancer cell invasion, and is suppressed by miR-370-3p. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 6693-6706 (2018).

- Xie, H. et al. WNT7A promotes EGF-induced migration of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells by activating

-catenin/MMP9mediated signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 98 (2020). - Chen, L. et al. VEGF promotes migration and invasion by regulating EMT and MMPs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J. Cancer 11, 7291-7301 (2020).

- Wang, X. et al. Characterization of LIMA1 and its emerging roles and potential therapeutic prospects in cancers. Front. Oncol. 13, 1115943 (2023).

- Zeng, J., Jiang, W. G. & Sanders, A. J. Epithelial protein lost in neoplasm, EPLIN, the cellular and molecular prospects in cancers. Biomolecules 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11071038 (2021).

- Feinberg, A. P., Ohlsson, R. & Henikoff, S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 21-33 (2006).

- Yu, D. H. et al. Postnatal epigenetic regulation of intestinal stem cells requires DNA methylation and is guided by the microbiome. Genome Biol. 16, 211 (2015).

- Fellows, R. et al. Microbiota derived short chain fatty acids promote histone crotonylation in the colon through histone deacetylases. Nat. Commun. 9, 105 (2018).

- Ansari, I. et al. The microbiota programs DNA methylation to control intestinal homeostasis and inflammation. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 610-619 (2020).

- Qiao, F. et al. Downregulated PITX1 modulated by MiR-19a-3p promotes cell malignancy and predicts a poor prognosis of gastric cancer by affecting transcriptionally activated PDCD5. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 46, 2215-2231 (2018).

- Wang, Q., Zhao, S., Gan, L. & Zhuang, Z. Bioinformatics analysis of prognostic value of PITX1 gene in breast cancer. Biosci. Rep. 40 https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20202537 (2020).

- Kolfschoten, I. G. M. et al. A genetic screen identifies PITX1 as a suppressor of RAS activity and tumorigenicity. Cell 121, 849-858 (2005).

- Vantaku, V. et al. Epigenetic loss of AOX1 expression via EZH2 leads to metabolic deregulations and promotes bladder cancer progression. Oncogene 39, 6265-6285 (2020).

- Liu, C. et al. GALNT6 promotes breast cancer metastasis by increasing mucin-type O-glycosylation of alpha2M. Aging 12, 11794-11811 (2020).

- Chen, S. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum reduces METTL3-mediated m(6)A modification and contributes to colorectal cancer metastasis. Nat. Commun. 13, 1248 (2022).

- Xu, C. et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal cancer metastasis through miR-1322/CCL20 axis and M2 polarization. Gut Microbes 13, 1980347 (2021).

- Wong, M. C. S. et al. Prevalence and epidemiologic profile of oral infection with alpha, beta, and gamma papillomaviruses in an Asian Chinese population. J. Infect. Dis. 218, 388-397 (2018).

- Chen, Z. et al. Impact of preservation method and 16S rRNA hypervariable region on gut microbiota profiling. mSystems 4 https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00271-18 (2019).

- Matsen, F. A., Kodner, R. B. & Armbrust, E. V. pplacer: linear time maximum-likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic placement of sequences onto a fixed reference tree. BMC Bioinforma. 11, 538 (2010).

- Zhu, H. et al. Convergent dysbiosis of upper aerodigestive microbiota between patients with esophageal and oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 152, 1903-1915 (2023).

- Mirarab, S., Nguyen, N. & Warnow, T. SEPP: SATe-enabled phylogenetic placement. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 247-258 https://doi.org/10.1142/9789814366496_0024 (2012).

- Hamady, M., Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. Fast UniFrac: facilitating highthroughput phylogenetic analyses of microbial communities including analysis of pyrosequencing and PhyloChip data. ISME J. 4, 17-27 (2010).

- Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60 (2011).

- Lin, H. & Peddada, S. D. Analysis of compositions of microbiomes with bias correction. Nat. Commun. 11, 3514 (2020).

- Fernandes, A. D. et al. Unifying the analysis of high-throughput sequencing datasets: characterizing RNA-seq, 16S rRNA gene sequencing and selective growth experiments by compositional data analysis. Microbiome 2, 15 (2014).

- Yang, L. & Chen, J. A comprehensive evaluation of microbial differential abundance analysis methods: current status and potential solutions. Microbiome 10, 130 (2022).

- Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139-140 (2010).

- Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996-998 (2013).

- Bernard, H. U. et al. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology 401, 70-79 (2010).

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Biological agents. Volume 100 B. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum. 100, 1-441 (2012).

- Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15-21 (2013).

- Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923-930 (2014).

- Chen, J., Bardes, E. E., Aronow, B. J. & Jegga, A. G. ToppGene Suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W305-W311 (2009).

- Colaprico, A. et al. TCGAbiolinks: an R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e71 (2016).

- Friedman, J. & Alm, E. J. Inferring correlation networks from genomic survey data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002687 (2012).

- Saito, R. et al. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nat. Methods 9, 1069-1076 (2012).

- Supek, F., Bosnjak, M., Skunca, N. & Smuc, T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS ONE 6, e21800 (2011).

- Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledgebased approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545-15550 (2005).

- Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114-2120 (2014).

- Krueger, F. & Andrews, S. R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics 27, 1571 (2011).

- Akalin, A. et al. methylKit: a comprehensive

package for the analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles. Genome Biol. 13, R87 (2012). - Yu, G., Wang, L. G. & He, Q. Y. ChIPseeker: an R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics 31, 2382-2383 (2015).

- Manson McGuire, A. et al. Evolution of invasion in a diverse set of Fusobacterium species. mBio 5, e01864 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00511-x.

© The Author(s) 2024

Department of Microbiology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China. Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China. Department of Chemical Pathology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China. Georgia Cancer Center, Augusta, GA 30912, USA. Department of Medicine, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta University, Augusta, GA 30912, USA. School of Biomedical Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China. Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China. These authors contributed equally: Liuyang Cai, Hengyan Zhu, Qianqian Mou.