DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01255-w

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-04

مكتبة DTU

ترجمة حدود نظام الأرض للمدن والشركات

إجمالي عدد المؤلفين:

24

استدامة الطبيعة

10.1038/s41893-023-01255-w

٢٠٢٤

نسخة محكمة

باي، إكس.، حسن، س.، أندرسن، إل. إس.، بيورن، أ.، كيلكيش، ش.، أوسبينا، د.، ليو، ج.، كورنيل، س. إ.، ساباغ مونوز، أ.، دي بريموند، أ.، كرونا، ب.، ديكليرك، ف.، جوبتا، ج.، هوف، هـ.، ناكيسينوفيتش، ن.، أوبورا، د.، وايتمان، ج.، برودغيت، و.، ليد، س. ج.، … زيم، س. (2024). ترجمة حدود نظام الأرض للمدن والشركات. نيتشر سستينابيليتي، 7، 108-119.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01255-w

ترجمة حدود نظام الأرض للمدن والشركات

الملخص

يتطلب العمل ضمن حدود نظام الأرض الآمنة والعادلة تعبئة الجهات الفاعلة الرئيسية عبر المستويات لتحديد الأهداف واتخاذ الإجراءات وفقًا لذلك. تُعد طرق الترجمة عبر المستويات القوية والشفافة والعادلة ضرورية للمساعدة في التنقل عبر الخطوات المتعددة للأحكام العلمية والمعيارية في الترجمة، مع وعي واضح بالافتراضات والتحيزات والشكوك المرتبطة بها. هنا، من خلال مراجعة الأدبيات واستطلاع خبراء، نحدد الأساليب الشائعة الاستخدام للمشاركة، ونوضح عشرة مبادئ للترجمة، ونقدم بروتوكولًا يتضمن اللبنات الأساسية والخطوات الرقابية في الترجمة. نولي اهتمامًا خاصًا للأعمال التجارية والمدن، وهما جهتان فاعلتان مهمتان ولكن غير مدروستين بشكل كافٍ للانضمام إلى العملية.

الرئيسي

مشاركة الأساليب في الترجمة عبر المقاييس

دورات

(أ) نهج مشاركة واحد يُطبق على مقياس واحد: يخصص هذا النهج مباشرة إلى مقياس نقطة النهاية للترجمة. هناك العديد من الأمثلة حيث تكون المشاركة مستقلة

يُستخدم هذا النهج لتخصيص الحصص الوطنية، مستفيدًا على سبيل المثال من المساواة

(ب) نهج مشاركة واحد يُطبق عبر مقاييس متعددة: يخصص هذا النهج في البداية للمقاييس الوسيطة، قبل التخصيص النهائي لمقياس النقطة النهائية. استخدمت إحدى الدراسات النهج القديم (التوريث) (الذي يُنفذ باستخدام تأثيرات المناخ عبر

(ج) تطبيق عدة أساليب للمشاركة بشكل مشترك على مقياس واحد: تتضمن هذه الطريقة استخدام ما لا يقل عن أسلوبين للمشاركة معًا لتخصيص من مقياس إلى آخر. على سبيل المثال، تم تطبيق المساهمة الاجتماعية من خلال مؤشر التوظيف والمساهمة الاقتصادية من خلال مؤشر الناتج المحلي الإجمالي بشكل مشترك لتخصيص ميزانية الكربون من المستوى الوطني إلى مستوى الصناعة.

(د) تطبيق أساليب مشاركة متعددة عبر مقاييس متعددة: يستخدم هذا الأسلوب طريقة مشاركة فريدة لكل تخصيص عبر المقاييس، وبالتالي يمر عبر مقياس أو عدة مقاييس وسيطة

| مشاركة الأساليب | الوصف | مثال على تنفيذ المقاييس |

| الإرث | الحصص تتناسب مع الاستحقاقات الحالية أو التاريخية، أو التأثيرات البيئية أو البصمات البيئية التي تولدها الكيان (ويشار إليها أيضًا بالتوريث). | بصمات الاستهلاك، بصمات الإنتاج، بصمات المنتج |

| المسؤولية | يتم تخصيص الحصص من خلال احتساب التأثيرات التراكمية والانبعاثات أو البصمات البيئية على مر الزمن (أي الدين التاريخي للأفراد، الدول، المدن، القطاعات، الشركات). | تصريفات التلوث التاريخية، الانبعاثات أو إزالة الأراضي؛ تركيب الطاقة المتجددة |

| السيادة | الحصص تتناسب مع الأسهم الحالية وتدفقات رأس المال الطبيعي المحتفظ به ضمن الحدود الإقليمية. | الأراضي الزراعية والمزارع؛ مخزونات الموارد المتجددة وغير المتجددة؛ القدرة البيولوجية للنظام البيئي |

| المساهمة الاقتصادية | تُخصص الأسهم بنسبة تتناسب مع المساهمة الاقتصادية الحالية للدولة أو القطاع أو الصناعة أو الشركة، على سبيل المثال، مقاسة بالمساهمة في الناتج المحلي الإجمالي. | القيمة المضافة الإجمالية أو الناتج المحلي الإجمالي؛ حجم الإنتاج للشركة أو القطاع؛ إيرادات التشغيل للشركة |

| المساهمة الاجتماعية | تُخصص الحصص بما يتناسب مع المساهمة الحالية للقطاع أو الصناعة أو الشركة في المجتمعات والمجتمع الأوسع، على سبيل المثال، يُقاس ذلك بعدد الأشخاص العاملين. | عدد الموظفين بدوام كامل المكافئ؛ الإنفاق على الأجور والرواتب؛ المساهمة المالية في برامج المجتمع؛ الضرائب المدفوعة |

| كفاءة الموارد | يتم تحديد الحصص للدول (أو المناطق دون الوطنية) بناءً على كفاءة استخدام الموارد الحالية لديها مقارنة بالمستوى العالمي المتوسط، مما يفيد أولئك الذين لديهم كفاءة أعلى؛ أو حيث يمكن توقع أكبر مكاسب في الكفاءة. | استخدام الموارد لكل وحدة من الأرض أو المنتج أو الخدمة أو الناتج الاقتصادي |

| القدرة | يتم تخصيص الحصص من خلال احتساب قدرة الفاعل على اتخاذ الإجراءات بناءً على القدرات النسبية كأساس، على سبيل المثال، من خلال الوسائل المالية. | الثروة؛ فعالية الحوكمة؛ قدرة نمو الطاقة المتجددة؛ قدرة الزراعة التجديدية |

| الاحتياجات والتفضيلات الأساسية | يتم تخصيص الحصص بحيث يتم تلبية الاحتياجات الأساسية للإنسان أولاً، قبل توزيع بقية الموارد على الاحتياجات غير الأساسية الأخرى. | المغذيات والمياه المطلوبة لزراعة الغذاء الأساسي المناسب إقليمياً؛ المحتوى الحراري للطعام؛ كفاية المغذيات في الغذاء |

| المساواة | الحصص تتناسب مع حجم سكان البلد أو المنطقة أو المدينة. | السكان (لكل فرد)؛ الناتج الكلي (لكل دولار من الناتج)؛ الدخل المتاح (لكل دولار من الدخل) |

| الحافز الأخضر (الاستحقاق) | يتم تخصيص الأسهم بطريقة تحفز أو تكافئ الشركات ذات كثافة انبعاثات منخفضة أو الحصص الأعلى من استخدام الطاقة المتجددة. | شدة الانبعاثات؛ حصة الطاقة المتجددة في مزيج مدخلات الطاقة؛ الأنشطة أو البرامج الطوعية للاستدامة البيئية |

| حقوق التطوير | يتم تخصيص الأسهم من خلال مراعاة السياق الاجتماعي والاقتصادي للبلد، وبشكل خاص الموارد المطلوبة لرفع الناس من الفقر في المستقبل. | معدل الفقر؛ مستوى التنمية؛ مؤشرات اجتماعية واقتصادية أخرى |

عشرة مبادئ للترجمة

| عملية الترجمة | ||||

|

P2 شفاف | P5 آمن بما فيه الكفاية | تمكين P7 | P8 تحفيز |

| يوضح النهج/التطبيق بوضوح وبشكل كافٍ مبررات التخصيصات، مع توضيح صريح للفرضيات الأساسية والاعتبارات المعيارية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، فإن البيانات المستخدمة متاحة للأطراف المهتمة الأخرى. | يشمل النهج/التطبيق والنتائج بعض الفواصل في الحصص أو المسؤوليات المخصصة، كطبقة إضافية من الصرامة. | الأهداف هي: (1) شاملة بما يكفي لتحقيق التوافق، ومع ذلك تسمح باتخاذ القرارات المحلية، (2) عملية للتنفيذ (قابلة للقياس والتحكم)، و(3) بسيطة بما يكفي لتسهيل التواصل والفهم من قبل مختلف أصحاب المصلحة. | يتم عرض الأهداف بطريقة تحفز الفاعلين على اتخاذ الإجراءات في ظل ظروف مختلفة. على وجه التحديد، يتم تشجيع الفاعلين الذين يُعتبرون “روادًا” على وضع أهداف أكثر طموحًا، في حين أن “المتأخرين” لديهم مسارات مناسبة للحاق بالركب. | |

| P3 فقط | P4 النظامي | P6 حساس للسياق | P9 ديناميكي ومحدد بالزمن | P10 التآزري |

| يتضمن النهج/التطبيق عناصر من العدالة بين الأجيال وداخل الجيل يتم تنفيذها كتعديلات على الحصص المخصصة في البداية، ويأخذ في الاعتبار الآثار السلبية المحتملة للأهداف المترجمة على الأهداف المجتمعية الرئيسية (مثل أهداف التنمية المستدامة). | يأخذ النهج/التطبيق في الاعتبار العواقب المحتملة على أجزاء أخرى من نظام الأرض الناشئة عن تحديد أهداف محددة تركز بشكل خاص على جزء واحد. كما يأخذ في الاعتبار الاتصالات البعيدة / الترابطات البعيدة التي قد تؤدي إلى عواقب سلبية غير مقصودة على الأهداف المجتمعية الرئيسية (مثل أهداف التنمية المستدامة). | يأخذ النهج/التطبيق والنتائج في الاعتبار السياق البيئي والاجتماعي الاقتصادي. بينما الهدف هو تعزيز التوافق العالمي، فإنه يسمح بوضع استراتيجيات/إجراءات محلية (أي أنه ليس مفرطًا في التحديد). | الأهداف محددة بزمن، ولكنها أيضًا قادرة على عكس الطبيعة الديناميكية لـ ‘مساحة التشغيل الآمنة والعادلة’ وسياقها. ويشمل ذلك إمكانية تحديث/تعديل الأهداف استجابة لتطور علم أنظمة الأرض الأساسي. | يتم تحديد الأهداف بحيث يتم التعرف على الفوائد المشتركة المحتملة في مجالات مفوضية الأرض الأخرى، وكذلك الأهداف المجتمعية (مثل أهداف التنمية المستدامة) وتعزيزها. وعلى العكس من ذلك، يتم تحديد الأهداف بحيث يتم تجنب الآثار السلبية المحتملة وعدم التوازن الظالم في القوى. |

| الأسهم والأهداف المترجمة | ||||

السياق الاجتماعي والاقتصادي والبيئي. وأخيرًا، يؤكد المبدأ العاشر على ضرورة تعظيم التآزر بين الأهداف وتقليل المقايضات مثل الآثار السلبية الخارجية، وضمان تجنب الديناميات القوية المدمرة والاستغلالية. على سبيل المثال، عادةً ما تحدد المدن والشركات أهدافها بشكل منفصل، ولكن هناك حاجة إلى التنسيق

العناصر الأساسية التي تربط حافلات الخدمات المؤسسية (ESBs) بالممثلين

نسخ

التخصيص

الصندوق 1: منظور المواطن البيوريجيوني مقابل المواطن العالمي

التخصيص هو مجموعة من الحصص المترجمة من ميزانيات خدمات النظام البيئي إلى الجهات الفاعلة، مدعومة بعملية علمية قوية (المبدأ 1)، شفافة (المبدأ 2)، عادلة (المبدأ 3) وحساسة للسياق (المبدأ 6).

تحديد الأهداف، المقارنة المرجعية، وفحص التوافق

بروتوكول للترجمة

البنية المكانية للحدود

حالة الحدود

- بالنسبة للحدود المناخية (المبنية عالميًا)، فمن الثابت جيدًا أننا على طريق لتجاوز

مستوى الاحترار العالمي خلال السنوات العشر القادمة، دون تخفيضات جذرية في انبعاثات غازات الدفيئة . بينما ال لم يتم تجاوز الحد بعد، إلا أن الانبعاثات الحالية تتجاوز بكثير ميزانية الكربون السنوية المنقولة إلى الحد. وبناءً عليه، سيكون التركيز على تقاسم الأعباء (توزيع مسؤوليات التخفيض)، بدلاً من توزيع ميزانيات الموارد المتناقصة. - بالنسبة للحدود (البيولوجية) الإقليمية، يتم تقييم التعدي على مقياس كل بناء حدودي، مع إمكانية تأثير الجهات الفاعلة من داخل المنطقة وخارجها. عندما يتم تعريف الحدود على أنها منفصلة مكانياً، فإن الاستعادة في منطقة واحدة لا تعوض التدهور في أخرى، بغض النظر عن التشابه في خدمات النظام البيئي. على سبيل المثال، حدود الغلاف الحيوي القائمة على المناطق البيئية الفريدة، وحدود دورة المغذيات القائمة على معايير جودة المياه المرتبطة بتدفقات المغذيات من الأراضي الزراعية، وحدود المياه العذبة القائمة على معدلات إعادة تغذية المياه الجوفية السنوية، ومعايير التدفق البيئي، أو بدلات تعديل التدفق الشهرية. يتم تقييم حالة التعدي لكل منطقة، لكن يمكن تقييم التأثيرات (والإجراءات) على مقاييس أصغر أو أكبر. مع تقييم حدود المياه السطحية شهرياً، قد يحدث التعدي في كل شهور السنة أو في بعض الشهور فقط.

- بالنسبة للحدود التي يتم فيها تقييم التعدي على أساس كل شبكة على حدة، قد توجد شبكات متعدية وأخرى غير متعدية داخل الحدود الإقليمية للدول.

أو المدن، أو ضمن النطاق المكاني للتأثيرات من الأعمال التجارية، سواء كانت تقع داخل أو خارج الشبكة المحددة.

الطبيعة المتجددة لحالة نطاق ES

- بالنسبة لمجالات خدمات النظام البيئي التي لا تمتلك قدرة تجديد (غير قابلة للتجديد و/أو لها تأثيرات لا رجعة فيها)، فإن تقليل أو حتى وقف التأثيرات لا يغير حالة الحدود. على سبيل المثال،

الانبعاثات تراكمية بطبيعتها مع عدم وجود قدرة تجديدية تقريبًا. تقليل الانبعاثات لن يؤدي إلى تبريد إلى درجات حرارة ما قبل الصناعة في الأطر الزمنية ذات الصلة بالسياسات. - المجالات البيئية ذات القدرة التجديدية البطيئة قادرة على التجديد والاستعادة على مدى زمني يقارب العقود. يمكن اعتبار معدل تجديد تركيزات النيتروجين والفوسفور في المسطحات المائية بطيئًا، على مقياس زمني لدورة المغذيات عبر التربة. وبالمثل، فإن معدل تجديد المياه الجوفية يتماشى مع مقاييس زمنية لإعادة تغذية المكامن المائية. كما يمكن اعتبار معدل تجديد الغلاف الحيوي بطيئًا أيضًا، على مقياس زمني لنمو الغطاء النباتي وتعافي النظام البيئي.

- تجدد أو تتكرر مجالات خدمات النظام البيئي ذات القدرة التجديدية السريعة تقريبًا على فترات زمنية موسمية أو سنوية. يُعتبر مستوى الخلفية من الهباء الجوي يتجدد بسرعة، حيث تنخفض تركيزاته في الهواء إلى مستويات الخلفية في غضون أشهر أو أقل بعد توقف افتراضي للانبعاثات. يُعتبر ميزان المياه السطحية المتاح بفعل الأنشطة البشرية يتجدد بسرعة، حيث يعاد تجديده سنويًا وفقًا لموسمية الهطول.

المنظور الزمني وملاءمة أساليب المشاركة

- بالنسبة للمناخ: تعتبر الأساليب القائمة على النظر إلى الوراء مناسبة لتوزيع مسؤوليات خفض الانبعاثات، وتعتبر الأساليب القائمة على النظر إلى الأمام مناسبة لتوزيع الميزانيات العالمية المحدودة المتبقية وكذلك مسؤوليات الخفض للحفاظ على المسارات التي تعتبر ضرورية للأنظمة البيئية الحيوية.

- بالنسبة للغلاف الحيوي، المغذيات، والمياه الجوفية: فإن الأساليب التشاركية التي تنظر إلى الوراء مناسبة لتخصيص مسؤوليات التخفيض والاستعادة، حيث تؤثر التأثيرات السابقة على الموارد والتركيزات الحالية. أما الأساليب التشاركية التي تنظر إلى الأمام فهي ضرورية لتخصيص استخدام الأراضي بناءً على الاحتياجات والحقوق التنموية، ولتخصيص الإجراءات الاستعادية بناءً على القدرة، ولتخصيص تدفقات المغذيات والمياه الجوفية التي تتجاوز الحدود الإقليمية أو تكون محدودة بناءً على الاحتياجات، ولتخصيص إمكانيات التخفيض بناءً على القدرة.

- بالنسبة للهباء الجوي والمياه السطحية: فإن الإجراءات السابقة أقل صلة بالحالة الحالية للمورد، وتجاوز الحدود في العام الماضي لا يعني تجاوزها هذا العام. يجب أن يكون التركيز بدلاً من ذلك على تخصيص المورد المحدود بشكل عادل بناءً على الاحتياجات والحقوق في التنمية، واتخاذ إجراءات الحفظ بناءً على القدرة، باستخدام مناهج المشاركة المستقبلية.

تنفيذ المقاييس وتوفر البيانات

الفجوات المتبقية والخطوات التالية

آليات المساءلة

References

- Rockström, J. et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 619, 102-111 (2023). This paper proposes eight safe and just Earth system boundaries on climate, the biosphere, freshwater, nutrients and air pollution at global and subglobal scales, and finds seven have been transgressed.

- Rockström, J., Mazzucato, M., Andersen, L. S., Fahrländer, S. F. & Gerten, D. Why we need a new economics of water as a common good. Nature 615, 794-797 (2023).

- Meyer, K. & Newman, P. The Planetary Accounting Framework: a novel, quota-based approach to understanding the impacts of any scale of human activity in the context of the Planetary Boundaries. Sustainable Earth 1, 4 (2018).

- Meyer, K. & Newman, P. Planetary Accounting: Quantifying how to live within planetary limits at different scales of human activity. (Springer Singapore, 2020). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1443-2.

- Wang-Erlandsson, L. et al. A planetary boundary for green water. Nat Rev Earth Environ 3, 380-392 (2022).

- Chen, X., Li, C., Li, M. & Fang, K. Revisiting the application and methodological extensions of the planetary boundaries for sustainability assessment. Science of The Total Environment 788, 147886 (2021).

- Ryberg, M. W., Andersen, M. M., Owsianiak, M. & Hauschild, M. Z. Downscaling the planetary boundaries in absolute environmental sustainability assessments – A review. J Clean Prod 276, 123287 (2020).

- Stewart-Koster, B. et al. How can we live within the safe and just Earth system boundaries for blue water? Nature Sustainability (Forthcoming).

- Bai, X. et al. How to stop cities and companies causing planetary harm. Nature 609, 463466 (2022).

This paper highlights the importance of linking planetary level boundaries to cities and businesses as key actors and elaborate on seven knowledge gaps in crossscale translation. - Whiteman, G., Walker, B. & Perego, P. Planetary Boundaries: Ecological Foundations for Corporate Sustainability. Journal of Management Studies 50, 307-336 (2013).

- Science Based Target Network (SBTN). Science-based targets for nature: Initial guidance for business. https://sciencebasedtargetsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Science-Based-Targets-for-Nature-Initial-Guidance-forBusiness.pdf (2020).

- SBTi. Companies taking action. Target dashboard (Beta version). https://sciencebasedtargets.org/companies-taking-action (2023).

- Bjørn, A., Tilsted, J. P., Addas, A. & Lloyd, S. M. Can Science-Based Targets Make the Private Sector Paris-Aligned? A Review of the Emerging Evidence. Curr Clim Change Rep 8, 53-69 (2022).

- Lucas, P. L., Wilting, H. C., Hof, A. F. & van Vuuren, D. P. Allocating planetary boundaries to large economies: Distributional consequences of alternative perspectives on distributive fairness. Global Environmental Change 60, 102017 (2020).

This paper applies grandfathering, ‘equal per capita’ share and ‘ability to pay’ to allocate and compare planetary boundary (PB)-based global budgets for CO2 emissions (climate change), intentional nitrogen fixation and phosphorus fertiliser use (biogeochemical flows), cropland use (land-use change) and mean species abundance loss (biodiversity loss) for the EU, US, China and India. - Häyhä, T., Lucas, P. L., van Vuuren, D. P., Cornell, S. E. & Hoff, H. From Planetary Boundaries to national fair shares of the global safe operating space – How can the scales be bridged? Global Environmental Change 40, 60-72 (2016).

This paper proposes a conceptual framework for translating planetary boundaries to national or regional implementation, taking into account the biophysical, socioeconomic and ethical dimensions for scaling planetary boundaries to the scales needed for implementation. - Clift, R. et al. The Challenges of Applying Planetary Boundaries as a Basis for Strategic Decision-Making in Companies with Global Supply Chains. Sustainability vol. 9 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020279 (2017).

- Nilsson, M. & Persson, Å. Can Earth system interactions be governed? Governance functions for linking climate change mitigation with land use, freshwater and biodiversity protection. Ecological Economics 75, 61-71 (2012).

- Busch, T., Cho, C. H., Hoepner, A. G. F., Michelon, G. & Rogelj, J. Corporate Greenhouse Gas Emissions’ Data and the Urgent Need for a Science-Led Just Transition: Introduction to a Thematic Symposium. Journal of Business Ethics 182, 897901 (2023).

- Rockström, J. et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009 461:7263 461, 472-475 (2009).

- Steffen, W. et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science (1979) 347, 1259855 (2015).

- Chandrakumar, C. et al. Setting Better-Informed Climate Targets for New Zealand: The Influence of Value and Modeling Choices. Environ Sci Technol 54, 4515-4527 (2020).

- Raupach, M. R. et al. Sharing a quota on cumulative carbon emissions. Nat Clim Chang 4, 873-879 (2014).

- van den Berg, N. J. et al. Implications of various effort-sharing approaches for national carbon budgets and emission pathways. Clim Change 162, 1805-1822 (2020).

- Höhne, N., den Elzen, M. & Escalante, D. Regional GHG reduction targets based on effort sharing: a comparison of studies. Climate Policy 14, 122-147 (2014).

Through a comparison of more than 40 studies on national or regional allocations of future GHG emissions allowances or reduction targets using different effortsharing approaches, this paper finds that the range in allowances within specific categories of effort-sharing can be substantial, the outcome of effort sharing approaches is largely driven by how the equity principle is implemented, and the distributional impacts differed significantly depending on the effort sharing criteria used. - Steininger, K. W., Williges, K., Meyer, L. H., Maczek, F. & Riahi, K. Sharing the effort of the European Green Deal among countries. Nat Commun 13, 3673 (2022).

This paper presents an effort sharing approach that systematically combines different interpretations of justice or equity expressed through capability, equality and responsibility principles to allocate emissions reduction burden amongst European Union member states. - Sun, Z., Behrens, P., Tukker, A., Bruckner, M. & Scherer, L. Shared and environmentally just responsibility for global biodiversity loss. Ecological Economics 194, 107339 (2022).

- Perdomo Echenique, E. A., Ryberg, M., Vea, E. B., Schwarzbauer, P. & Hesser, F. Analyzing the Consequences of Sharing Principles on Different Economies: A Case Study of Short Rotation Coppice Poplar Wood Panel Production Value Chain. Forests 2022, Vol. 13, Page 461 13, 461 (2022).

- Cole, M. J., Bailey, R. M. & New, M. G. Tracking sustainable development with a national barometer for South Africa using a downscaled ‘safe and just space’ framework. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, E4399-E4408 (2014).

- Zhang, Q. et al. Bridging planetary boundaries and spatial heterogeneity in a hybrid approach: A focus on Chinese provinces and industries. Science of The Total Environment 804, 150179 (2022).

- Zipper, S. C. et al. Integrating the Water Planetary Boundary With Water Management From Local to Global Scales. Earths Future 8, e2019EF001377 (2020).

- Zhou, P. & Wang, M. Carbon dioxide emissions allocation: A review. Ecological Economics 125, 47-59 (2016).

- Bjørn, A. et al. Life cycle assessment applying planetary and regional boundaries to the process level: a model case study. Int J Life Cycle Assess 25, 2241-2254 (2020).

- Bjorn, A. et al. Review of life-cycle based methods for absolute environmental sustainability assessment and their applications. Environmental Research Letters 15, 083001 (2020).

- Li, M., Wiedmann, T., Fang, K. & Hadjikakou, M. The role of planetary boundaries in assessing absolute environmental sustainability across scales. Environ Int 152, 106475 (2021).

- European Environment Agency & Federal Office for the Environment (EEA/FOEN). Is Europe living within the limits of our planet? An assessment of Europe’s environmental footprints in relation to planetary boundaries. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/is-europe-living-within-the-planets-limits (2020).

- Hoff, H., Nykvist, B. & Carson, M. ‘Living well, within the limits of our planet’? Measuring Europe’s growing external footprint. https://mediamanager.sei.org/documents/Publications/SEI-WP-2014-05-Hoff-EU-Planetary-boundaries.pdf (2014).

- Nykvist, B. et al. National environmental performance on planetary boundaries. https://www.sei.org/publications/national-environmental-performance-on-planetaryboundaries/ (2013).

- Hoff, H., Häyhä, T., Cornell, S. & Lucas, P. Bringing EU policy into line with the Planetary Boundaries. https://www.sei.org/publications/eu-policy-into-line-planetary-boundaries/ (2017).

- Andersen, L. S. et al. A safe operating space for New Zealand/Aotearoa. Translating the planetary boundaries framework. https://www.stockholmresilience.org/download/18.66e0efc517643c2b810218e/16123411 72295/Updated PBNZ-Report-Design-v6.0.pdf (2020).

- Dao, H., Peduzzi, P. & Friot, D. National environmental limits and footprints based on the Planetary Boundaries framework: The case of Switzerland. Global Environmental Change 52, 49-57 (2018).

- Häyhä, T., Cornell, S. E., Hoff, H., Lucas, P. & van Vuuren, D. Operationalizing the concept of a safe operating space at the EU level – first steps and explorations. https://www.stockholmresilience.org/publications/publications/2018-07-03-operationalizing-the-concept-of-a-safe-operating-space-at-the-eu-level—first-steps-andexplorations.html (2018).

- Sandin, G., Peters, G. M. & Svanström, M. Using the planetary boundaries framework for setting impact-reduction targets in LCA contexts. Int J Life Cycle Assess 20, 1684-1700 (2015).

- Roos, S., Zamani, B., Sandin, G., Peters, G. M. & Svanström, M. A life cycle assessment (LCA)-based approach to guiding an industry sector towards sustainability: the case of the Swedish apparel sector. J Clean Prod 133, 691-700 (2016).

- Ryberg, M. W. et al. How to bring absolute sustainability into decision-making: An industry case study using a Planetary Boundary-based methodology. Science of The Total Environment 634, 1406-1416 (2018).

- Algunaibet, I. M. et al. Powering sustainable development within planetary boundaries. Energy Environ Sci 12, 1890-1900 (2019).

- Lucas, E., Guo, M. & Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Optimising diets to reach absolute planetary environmental sustainability through consumers. Sustain Prod Consum 28, 877-892 (2021).

- Ehrenstein, M., Galán-Martín, Á., Tulus, V. & Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Optimising fuel supply chains within planetary boundaries: A case study of hydrogen for road transport in the UK. Appl Energy 276, 115486 (2020).

- Hjalsted, A. W. et al. Sharing the safe operating space: Exploring ethical allocation principles to operationalize the planetary boundaries and assess absolute sustainability at individual and industrial sector levels. J Ind Ecol 25, 6-19 (2021).

This paper develops and tests a framework for sharing the planetary boundaryderived safe operating space amongst social actors based on a two-step process of downscaling to individual level followed by upscaling from an individual share to a higher-level unit or entity such as company, organisation, product, service, sector, household or nation; different ethical principles were explored in the downscaling and upscaling processes. - Hannouf, M., Assefa, G. & Gates, I. Carbon intensity threshold for Canadian oil sands industry using planetary boundaries: Is a sustainable carbon-negative industry possible? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 151, 111529 (2021).

- Wheeler, J., Galán-Martín, Á., Mele, F. D. & Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Designing biomass supply chains within planetary boundaries. AIChE Journal 67, e17131 (2021).

- Suárez-Eiroa, B. et al. A framework to allocate responsibilities of the global environmental concerns: A case study in Spain involving regions, municipalities, productive sectors, industrial parks, and companies. Ecological Economics 192, 107258 (2022). Using Spain as a case study, this paper presents the responsible operating space framework to allocate responsibilities for managing territorial and global environmental concerns to entities and social actors operating at different scales using a footprint perspective.

- Brejnrod, K. N., Kalbar, P., Petersen, S. & Birkved, M. The absolute environmental performance of buildings. Build Environ 119, 87-98 (2017).

- Chandrakumar, C., McLaren, S. J., Jayamaha, N. P. & Ramilan, T. Absolute Sustainability-Based Life Cycle Assessment (ASLCA): A Benchmarking Approach to Operate Agri-food Systems within the

Global Carbon Budget. J Ind Ecol 23, 906-917 (2019). - Desing, H., Braun, G. & Hischier, R. Ecological resource availability: a method to estimate resource budgets for a sustainable economy. Global Sustainability 3, e31 (2020).

- Bjørn, A. et al. A comprehensive planetary boundary-based method for the nitrogen cycle in life cycle assessment: Development and application to a tomato production case study. Science of The Total Environment 715, 136813 (2020).

- Bjørn, A. et al. A planetary boundary-based method for freshwater use in life cycle assessment: Development and application to a tomato production case study. Ecol Indic 110, 105865 (2020).

- Hachaichi, M. & Baouni, T. Downscaling the planetary boundaries (Pbs) framework to city scale-level: De-risking MENA region’s environment future. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 5, 100023 (2020).

- Wolff, A., Gondran, N. & Brodhag, C. Detecting unsustainable pressures exerted on biodiversity by a company. Application to the food portfolio of a retailer. J Clean Prod 166, 784-797 (2017).

- Ryberg, M. W., Bjerre, T. K., Nielsen, P. H. & Hauschild, M. Absolute environmental sustainability assessment of a Danish utility company relative to the Planetary Boundaries. J Ind Ecol 25, 765-777 (2021).

- Fanning, A. L. & O’Neill, D. W. Tracking resource use relative to planetary boundaries in a steady-state framework: A case study of Canada and Spain. Ecol Indic 69, 836-849 (2016).

- Fang, K., Heijungs, R., Duan, Z. & De Snoo, G. R. The Environmental Sustainability of Nations: Benchmarking the Carbon, Water and Land Footprints against Allocated Planetary Boundaries. Sustainability vol. 7 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3390/su70811285 (2015).

- O’Neill, D. W., Fanning, A. L., Lamb, W. F. & Steinberger, J. K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat Sustain 1, 88-95 (2018).

- Huang, L. H., Hu, A. H. & Kuo, C.-H. Planetary boundary downscaling for absolute environmental sustainability assessment – Case study of Taiwan. Ecol Indic 114, 106339 (2020).

- Sala, S., Crenna, E., Secchi, M. & Sanyé-Mengual, E. Environmental sustainability of European production and consumption assessed against planetary boundaries. J Environ Manage 269, 110686 (2020).

- Dao, Q.-H., Peduzzi, P., Chatenoux, B., De Bono, A. & Schwarzer, S. Environmental limits and Swiss footprints based on Planetary Boundaries. (2015).

- Lucas, P. & Wilting, H. Using planetary boundaries to support national implementation of environment-related sustainable development goals. (2018).

- Kahiluoto, H., Kuisma, M., Kuokkanen, A., Mikkilä, M. & Linnanen, L. Local and social facets of planetary boundaries: right to nutrients. Environmental Research Letters 10, 104013 (2015).

- Li, M., Wiedmann, T. & Hadjikakou, M. Towards meaningful consumption-based planetary boundary indicators: The phosphorus exceedance footprint. Global Environmental Change 54, 227-238 (2019).

- Shaikh, M. A., Hadjikakou, M. & Bryan, B. A. National-level consumption-based and production-based utilisation of the land-system change planetary boundary: patterns and trends. Ecol Indic 121, 106981 (2021).

- Gupta, J. et al. Earth system justice needed to identify and live within Earth system boundaries. Nat Sustain (2023) doi:10.1038/s41893-023-01064-1.

- Armstrong McKay, D. I. et al. Exceeding

global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science (1979) 377, eabn7950 (2023). - Liu, J. Integration across a metacoupled world. Ecology and Society 22, (2017).

- Bai, X. Eight energy and material flow characteristics of urban ecosystems. Ambio 45, 819-830 (2016).

- Liu, J. et al. Nexus approaches to global sustainable development. Nat Sustain 1, 466476 (2018).

- Fang, K., Heijungs, R. & De Snoo, G. R. Understanding the complementary linkages between environmental footprints and planetary boundaries in a footprint-boundary environmental sustainability assessment framework. Ecological Economics 114, 218-226 (2015).

- Kulionis, V. & Pfister, S. A planetary boundary-based method to assess freshwater use at the global and local scales. Environmental Research Letters 17, 094031 (2022).

- Obura, D. O. et al. Achieving a nature- and people-positive future. One Earth 6, 105-117 (2023).

- Dooley, K. et al. Ethical choices behind quantifications of fair contributions under the Paris Agreement. Nat Clim Chang 11, 300-305 (2021).

- Hickel, J. Quantifying national responsibility for climate breakdown : an equality-based attribution approach for carbon dioxide emissions in excess of the planetary boundary. Lancet Planet Health 4, e399-e404 (2020).

- Hickel, J., Neill, D. W. O., Fanning, A. L. & Zoomkawala, H. National responsibility for ecological breakdown : a fair-shares assessment of resource use , 1970 – 2017. Lancet Planet Health 6, e342-e349 (2022).

- Liu, J. et al. Systems integration for global sustainability. Science (1979) 347, 1258832 (2015).

- Xu, H. et al. Ensuring effective implementation of the post-2020 global biodiversity targets. Nat Ecol Evol 5, 411-418 (2021).

- IPCC. Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, . (2022) doi:doi: 10.1017/9781009157926.

- Hoornweg, D., Hosseini, M., Kennedy, C. & Behdadi, A. An urban approach to planetary boundaries. Ambio 45, 567-580 (2016).

- UN DESA. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/en/desa/products/un-desa-databases.

- UNIDO. United Nations Industrial Development Organization. https://www.unido.org/.

- CDP. CDP Cities, States and Regions Open Data Portal. https://data.cdp.net/.

- Freiberg, D., Park, D. G., Serafim, G. & Zochowski, R. Corporate environmental impact: measurement, data and information. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3565533 (2021) doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3565533.

- WBCSD & WRI. The Greenhouse Gas Protocol. A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (Revised Edition). https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/ghg-protocol-revised.pdf (2004).

- Bjørn, A. et al. Increased transparency is needed for corporate science-based targets to be effective. Nat Clim Chang 13, 756-759 (2023).

- Bjorn, A., Lloyd, S. & Matthews, D. From the Paris Agreement to corporate climate commitments: evaluation of seven methods for setting ‘science-based’ emission targets. Environmental Research Letters 16, 054019 (2021).

- Lade, S. J. et al. Human impacts on planetary boundaries amplified by Earth system interactions. Nat Sustain 3, 119-128 (2020).

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

المصالح المتنافسة

- الحقوق العامة

حقوق الطبع والنشر والحقوق المعنوية للمنشورات المتاحة في البوابة العامة محفوظة للمؤلفين و/أو أصحاب حقوق الطبع والنشر الآخرين، ومن شروط الوصول إلى المنشورات أن يعترف المستخدمون بهذه الحقوق ويلتزموا بالمتطلبات القانونية المرتبطة بها.- يجوز للمستخدمين تنزيل وطباعة نسخة واحدة من أي منشور من البوابة العامة لغرض الدراسة أو البحث الخاص.

- لا يجوز لك توزيع المادة بشكل إضافي أو استخدامها لأي نشاط يهدف إلى تحقيق الربح أو مكاسب تجارية

- يمكنك توزيع عنوان URL الذي يحدد المنشور في البوابة العامة بحرية

إذا كنت تعتقد أن هذا المستند ينتهك حقوق الطبع والنشر، يرجى الاتصال بنا مع تقديم التفاصيل، وسنقوم بإزالة الوصول إلى العمل فورًا والتحقيق في مطالبتك.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01255-w

Publication Date: 2024-01-04

DTU Library

Translating Earth system boundaries for cities and businesses

Total number of authors:

24

Nature Sustainability

10.1038/s41893-023-01255-w

2024

Peer reviewed version

Bai, X., Hasan, S., Andersen, L. S., Bjørn, A., Kilkiş, Ş., Ospina, D., Liu, J., Cornell, S. E., Sabag Muñoz, O., de Bremond, A., Crona, B., DeClerck, F., Gupta, J., Hoff, H., Nakicenovic, N., Obura, D., Whiteman, G., Broadgate, W., Lade, S. J., … Zimm, C. (2024). Translating Earth system boundaries for cities and businesses. Nature Sustainability, 7, 108-119. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01255-w

TRANSLATING EARTH SYSTEM BOUNDARIES FOR CITIES AND BUSINESSES

Abstract

Operating within safe and just Earth system boundaries requires mobilizing key actors across scale to set targets and take actions accordingly. Robust, transparent, and fair cross-scale translation methods are essential to help navigate through the multiple steps of scientific and normative judgements in translation, with clear awareness of associated assumptions, bias, and uncertainties. Here, through literature review and expert elicitation, we identify commonly used sharing approaches, illustrate ten principles of translation, and present a protocol involving key building blocks and control steps in translation. We pay particular attention to businesses and cities, two understudied but critical actors to bring on board.

Main

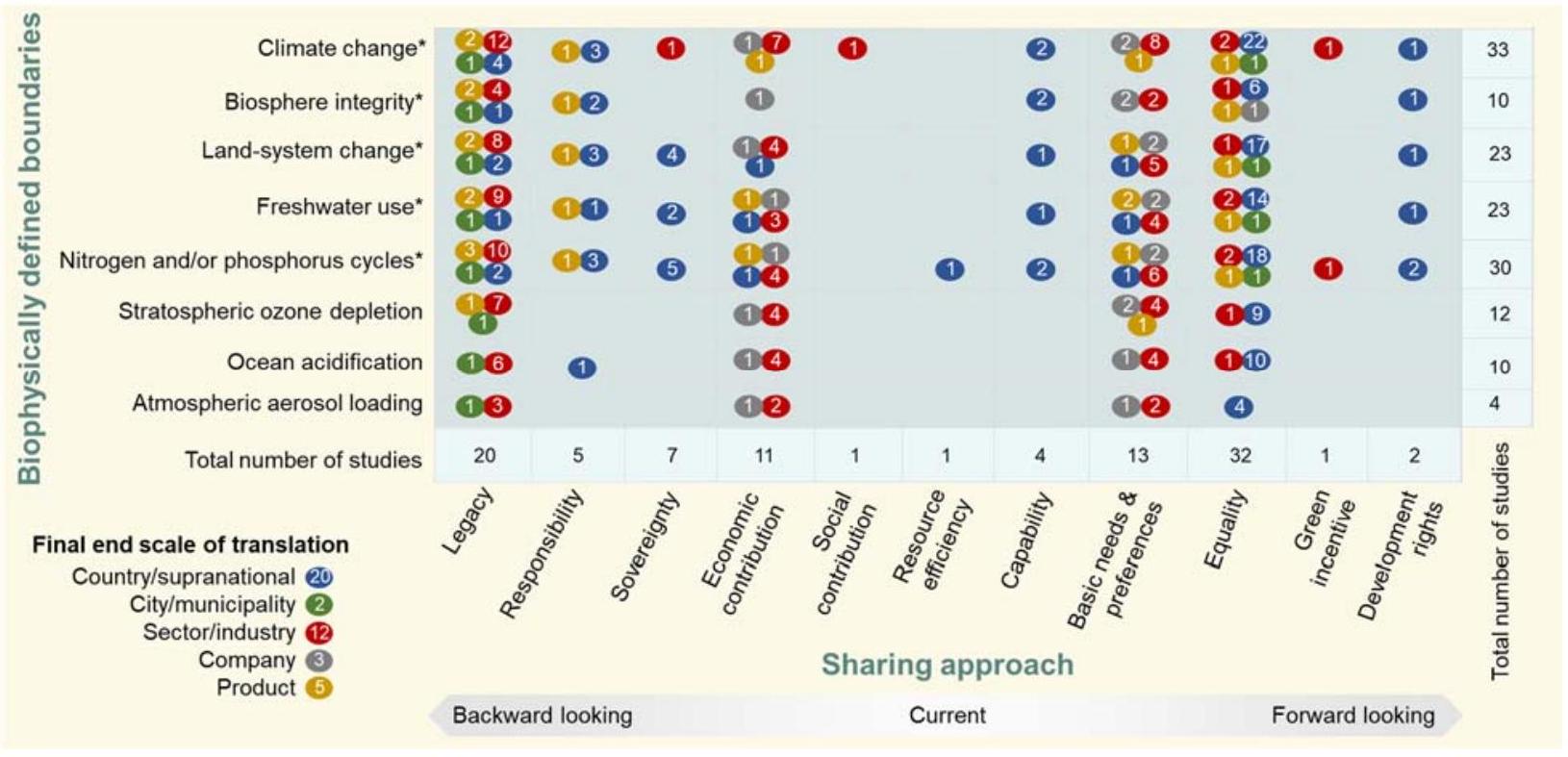

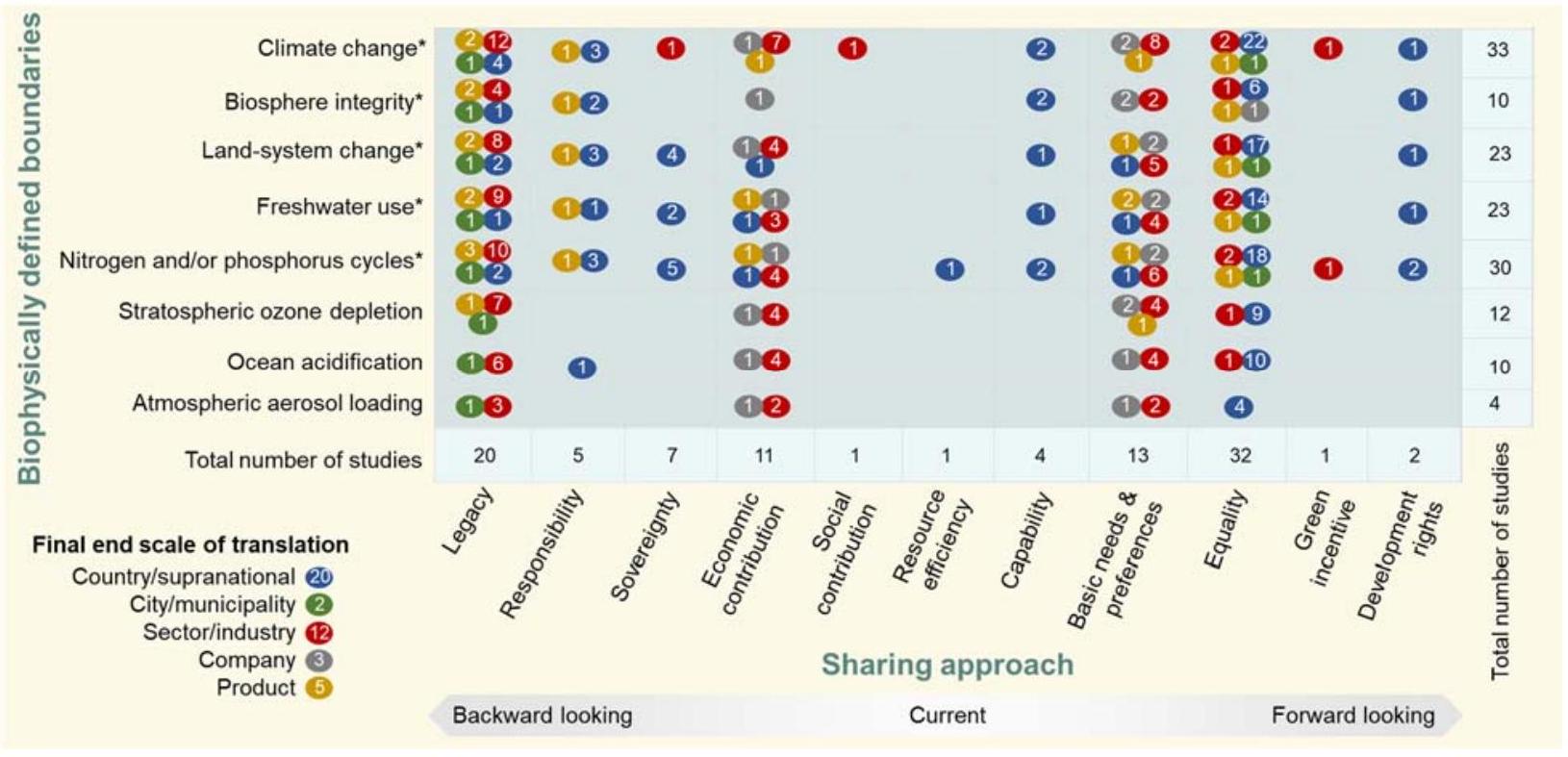

Sharing Approaches in Cross Scale Translation

cycles

(a) A single sharing approach applied to a single scale: This approach allocates directly to the endpoint scale of translation. There are numerous examples where a stand-alone sharing

approach is used to allocate national shares, utilising for example the equality

(b) A single sharing approach applied across multiple scales: This approach allocates initially to intermediate scales, before final allocation to the endpoint scale. One study used legacy (grandfathering) (enacted using climate impacts via

(c) Multiple sharing approaches applied jointly at a single scale: This approach involves utilisation of at least two sharing approaches in combination to allocate from one scale to another. For instance, social contribution through an employment indicator and economic contribution through the GDP indicator have been jointly applied to allocate a carbon budget from national to industry scale

(d) Multiple sharing approaches applied across multiple scales: This approach uses a unique sharing approach for each cross-scale allocation, thus going through one or several intermediate scales

| Sharing approaches | Description | Example of enacting metrics |

| Legacy | Shares are in proportion to current or historical entitlements, ecological impacts or environmental footprints generated by the entity (also referred to as grandfathering). | Consumption footprints, production footprints, product footprints |

| Responsibility | Shares are allocated by accounting for cumulative impacts and emissions or environmental footprints over time (i.e., historical debt of individuals, nations, cities, sectors, businesses). | Historical pollution discharges, emissions or land clearing; renewable energy installation |

| Sovereignty | Shares are in proportion to the current stocks and flows of natural capital in possession within territorial boundaries. | Cropping land and plantations; renewable and non-renewable resource stocks; ecosystem biocapacity |

| Economic contribution | Shares are allocated in proportion to the current economic contribution of the country, sector, industry or company, e.g., measured in contribution to GDP. | Gross Value Added or Gross Domestic Product; company or sectoral production volume; company operating revenues |

| Social contribution | Shares are allocated in proportion to the current contribution of the sector, industry or company to communities and wider society, e.g., measured in numbers of people employed. | Number of full-time equivalent employees; expenditure on wages and salaries; financial contribution to community programs; taxes paid |

| Resource efficiency | Shares are determined for countries (or sub-national regions) based on their current resource use efficiency relative to the global average level, benefiting those with higher efficiency; or where the largest efficiency gains can be expected. | Resource use per area of land, product, service or economic output |

| Capability | Shares are allocated by accounting for the ability of an actor to take actions based on relative capabilities as a basis, e.g., through financial means. | Wealth; governance effectiveness; renewable energy growth capacity; regenerative agriculture capacity |

| Basic needs & preferences | Shares are allocated such that fulfilment of human basic needs comes first, before distributing the rest of the resources to other non-basic needs. | Nutrient and water required to grow regionally suitable staple food; calorific content of food; food nutrient adequacy |

| Equality | Shares are in proportion to population size of the country, region or city. | Population (per capita); total output (per dollar of output); disposable income (per dollar of income) |

| Green incentive (merit) | Shares are allocated in a manner that incentivises or rewards companies with low emission intensity or higher shares of renewable energy use. | Emission intensity; share of renewable energy in energy input mix; voluntary environmental sustainability activities or programs |

| Development rights | Shares are allocated by accounting for the socio-economic context of the country, in particular, the resources required to lift people out of poverty in the future. | Poverty rate; development level; other socio-economic indicators |

Ten Principles of Translation

| Translation process | ||||

|

P2 Transparent | P5 Sufficiently safe | P7 Enabling | P8 Incentivising |

| The approach/application clearly and sufficiently explains the rationale for allocations, being explicit about underlying assumptions and normative considerations. Additionally, the data used is accessible to other interested parties. | The approach/application and the outcomes include some buffers in the allocated shares or responsibilities, as an additional level of stringency. | Targets are: (i) Universal enough for alignment, yet allow local decision making, (ii) Pragmatic for implementation (feasible measurement and controllability), and (iii) Simple enough to facilitate communication and understanding by different stakeholders. | Targets are presented in a manner that incentivise action by actors under different circumstances. Specifically, those actors who are ‘pioneers’ are emboldened to set more ambitious targets, while ‘laggards’ have suitable pathways to catch up. | |

| P3 Just | P4 Systemic | P6 Context sensitive | P9 Dynamic & time bound | P10 Synergetic |

| The approach/application incorporates elements of intergenerational and intragenerational equity implemented as adjustment(s) to initially allocated shares, and considers the potential negative implications of translated targets on key societal goals (e.g. SDGs). | The approach/application considers potential consequences on other parts of the Earth System arising from setting specific targets specifically focused on one part. It also considers teleconnections / telecouplings that have potential for unintended negative consequences on key societal goals (e.g. SDGs) | The approach/application and the outcomes take into account environmental and socio-economic context. While the aims is to foster global alignment, it allows for locally-devised strategies/actions (i.e. it is not overly prescriptive). | Targets are time bound, but also able to reflect the dynamic nature of ‘safe and just’ operating space and its context. This includes the possibility of updating/adjusting targets in response to the development of the underlying Earth systems science. | Targets are set so that potential co-benefits in other Earth Commission domains, as well as societal goals (e.g. SDGs) are recognised and amplified. Conversely, targets are set so that potential negative externalities and unjust power imbalances are avoided. |

| Translated shares and targets | ||||

socioeconomic and environmental context. Finally, Principle 10 stresses the need to maximise synergies among targets and minimise trade-offs such as negative externalities and to ensure that disruptive and exploitative power dynamics are avoided. For example, cities and companies typically set targets separately, but alignment is needed

Key Building Blocks Linking ESBs to Actors

Transcription

Allocation

Box 1: Bioregional vs. global citizen’s perspective

allocation is a set of translated shares of the ES budgets to actors, underpinned by a scientifically robust (Principle 1), transparent (Principle 2), just (Principle 3) and context sensitive (Principle 6) process.

Target setting, benchmarking and alignment checking

A Protocol for Translation

Spatial construct of the boundary

State of the boundary

- For the climate boundary (globally constructed), it is well established that we are on a pathway to transgressing a

level of global warming within the next 10 years, without drastic reductions in GHG emissions . While the boundary has not yet been exceeded, current emissions far exceed the annual carbon budget transcribed to the boundary. Accordingly, the focus would be on burden sharing (allocation of reductions responsibilities), rather than distributing diminishing resource budgets. - For (bio)regional boundaries, transgression is assessed at the scale of each boundary construct, with actors’ impacts possible from both within and outside of the region. When the boundary is defined as spatially discrete, restoration in one region does not offset degradation in another, regardless of the similarities in ecosystem services. For example, biosphere boundaries based on unique ecoregions, nutrient cycle boundaries based on water quality criteria connected to nutrient flows from agricultural lands, and freshwater boundaries based on annual groundwater recharge rates, environmental flow criteria, or monthly flow alteration allowances. Transgression status is assessed per region but impacts (and actions) can be assessed at smaller or larger scales. With the surface water boundary assessed monthly, transgression might occur in every or only some months of the year.

- For boundaries where transgression is assessed on a grid-by-grid basis, there could be both transgressed and non-transgressed grids within the territorial boundaries of nations

or cities, or within the spatial range of impacts from businesses, either located within or outside of the given grid.

Regenerative nature of the state of the ES domain

- For ES domains with no regenerative capacity (non-renewable and/or have irreversible impacts), reducing or even halting impacts does not alter the state of the boundary. For example,

emissions are cumulative in nature with almost no regenerative capacity. Reducing the emission will not result in cooling to pre-industrial temperatures on policyrelevant timescales. - ES domains with slow regenerative capacity are able to renew and restore at approximately decadal time scales. The regenerative rate of nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations in water bodies can be considered slow, at the time scale of nutrient cycling through soil. Similarly, the regenerative rate of groundwater is along the time scales of aquifer recharge. The regenerative rate of the biosphere can also be considered slow, along the time scale of vegetation growth and ecosystem recovery.

- ES domains with rapid regenerative capacity renew or recur at approximately seasonal or annual time scales. Background-levels of aerosols are considered to renew rapidly, as their concentrations in the air would drop to background-levels in a matter of months or less after a hypothetical cessation of emissions. Anthropogenically available surface water budget is considered to regenerate rapidly, as it replenishes annually following the seasonality of precipitation.

Temporal perspective and suitability of sharing approaches

- For Climate: backward looking sharing approaches are appropriate for allocating emission reduction responsibilities, and forward-looking sharing approaches are appropriate for allocating limited remaining global budgets as well as reduction responsibilities for upholding trajectories that are essential for ESBs.

- For biosphere, nutrients, groundwater: backward looking sharing approaches are suitable for allocating reduction and restorative responsibilities, as past impacts affect current resources and concentrations. Forward looking sharing approaches are needed to allocate land use based on needs and developmental rights, to allocate restorative actions based on capability, to allocate regionally exceeded or limited nutrient flows and groundwater based on needs, and reduction possibilities based on capability.

- For aerosols and surface water: past actions are less relevant to the current state of the resource, and transgression last year does not mean transgression this year. Focus should rather be on allocating the limited resource equitably based on needs and rights to development, and conservation actions based on capability, using the forward-looking sharing approaches.

Enacting metrics and data availability

Remaining Gaps and Next Steps

accountability mechanisms

References

- Rockström, J. et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 619, 102-111 (2023). This paper proposes eight safe and just Earth system boundaries on climate, the biosphere, freshwater, nutrients and air pollution at global and subglobal scales, and finds seven have been transgressed.

- Rockström, J., Mazzucato, M., Andersen, L. S., Fahrländer, S. F. & Gerten, D. Why we need a new economics of water as a common good. Nature 615, 794-797 (2023).

- Meyer, K. & Newman, P. The Planetary Accounting Framework: a novel, quota-based approach to understanding the impacts of any scale of human activity in the context of the Planetary Boundaries. Sustainable Earth 1, 4 (2018).

- Meyer, K. & Newman, P. Planetary Accounting: Quantifying how to live within planetary limits at different scales of human activity. (Springer Singapore, 2020). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1443-2.

- Wang-Erlandsson, L. et al. A planetary boundary for green water. Nat Rev Earth Environ 3, 380-392 (2022).

- Chen, X., Li, C., Li, M. & Fang, K. Revisiting the application and methodological extensions of the planetary boundaries for sustainability assessment. Science of The Total Environment 788, 147886 (2021).

- Ryberg, M. W., Andersen, M. M., Owsianiak, M. & Hauschild, M. Z. Downscaling the planetary boundaries in absolute environmental sustainability assessments – A review. J Clean Prod 276, 123287 (2020).

- Stewart-Koster, B. et al. How can we live within the safe and just Earth system boundaries for blue water? Nature Sustainability (Forthcoming).

- Bai, X. et al. How to stop cities and companies causing planetary harm. Nature 609, 463466 (2022).

This paper highlights the importance of linking planetary level boundaries to cities and businesses as key actors and elaborate on seven knowledge gaps in crossscale translation. - Whiteman, G., Walker, B. & Perego, P. Planetary Boundaries: Ecological Foundations for Corporate Sustainability. Journal of Management Studies 50, 307-336 (2013).

- Science Based Target Network (SBTN). Science-based targets for nature: Initial guidance for business. https://sciencebasedtargetsnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Science-Based-Targets-for-Nature-Initial-Guidance-forBusiness.pdf (2020).

- SBTi. Companies taking action. Target dashboard (Beta version). https://sciencebasedtargets.org/companies-taking-action (2023).

- Bjørn, A., Tilsted, J. P., Addas, A. & Lloyd, S. M. Can Science-Based Targets Make the Private Sector Paris-Aligned? A Review of the Emerging Evidence. Curr Clim Change Rep 8, 53-69 (2022).

- Lucas, P. L., Wilting, H. C., Hof, A. F. & van Vuuren, D. P. Allocating planetary boundaries to large economies: Distributional consequences of alternative perspectives on distributive fairness. Global Environmental Change 60, 102017 (2020).

This paper applies grandfathering, ‘equal per capita’ share and ‘ability to pay’ to allocate and compare planetary boundary (PB)-based global budgets for CO2 emissions (climate change), intentional nitrogen fixation and phosphorus fertiliser use (biogeochemical flows), cropland use (land-use change) and mean species abundance loss (biodiversity loss) for the EU, US, China and India. - Häyhä, T., Lucas, P. L., van Vuuren, D. P., Cornell, S. E. & Hoff, H. From Planetary Boundaries to national fair shares of the global safe operating space – How can the scales be bridged? Global Environmental Change 40, 60-72 (2016).

This paper proposes a conceptual framework for translating planetary boundaries to national or regional implementation, taking into account the biophysical, socioeconomic and ethical dimensions for scaling planetary boundaries to the scales needed for implementation. - Clift, R. et al. The Challenges of Applying Planetary Boundaries as a Basis for Strategic Decision-Making in Companies with Global Supply Chains. Sustainability vol. 9 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020279 (2017).

- Nilsson, M. & Persson, Å. Can Earth system interactions be governed? Governance functions for linking climate change mitigation with land use, freshwater and biodiversity protection. Ecological Economics 75, 61-71 (2012).

- Busch, T., Cho, C. H., Hoepner, A. G. F., Michelon, G. & Rogelj, J. Corporate Greenhouse Gas Emissions’ Data and the Urgent Need for a Science-Led Just Transition: Introduction to a Thematic Symposium. Journal of Business Ethics 182, 897901 (2023).

- Rockström, J. et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009 461:7263 461, 472-475 (2009).

- Steffen, W. et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science (1979) 347, 1259855 (2015).

- Chandrakumar, C. et al. Setting Better-Informed Climate Targets for New Zealand: The Influence of Value and Modeling Choices. Environ Sci Technol 54, 4515-4527 (2020).

- Raupach, M. R. et al. Sharing a quota on cumulative carbon emissions. Nat Clim Chang 4, 873-879 (2014).

- van den Berg, N. J. et al. Implications of various effort-sharing approaches for national carbon budgets and emission pathways. Clim Change 162, 1805-1822 (2020).

- Höhne, N., den Elzen, M. & Escalante, D. Regional GHG reduction targets based on effort sharing: a comparison of studies. Climate Policy 14, 122-147 (2014).

Through a comparison of more than 40 studies on national or regional allocations of future GHG emissions allowances or reduction targets using different effortsharing approaches, this paper finds that the range in allowances within specific categories of effort-sharing can be substantial, the outcome of effort sharing approaches is largely driven by how the equity principle is implemented, and the distributional impacts differed significantly depending on the effort sharing criteria used. - Steininger, K. W., Williges, K., Meyer, L. H., Maczek, F. & Riahi, K. Sharing the effort of the European Green Deal among countries. Nat Commun 13, 3673 (2022).

This paper presents an effort sharing approach that systematically combines different interpretations of justice or equity expressed through capability, equality and responsibility principles to allocate emissions reduction burden amongst European Union member states. - Sun, Z., Behrens, P., Tukker, A., Bruckner, M. & Scherer, L. Shared and environmentally just responsibility for global biodiversity loss. Ecological Economics 194, 107339 (2022).

- Perdomo Echenique, E. A., Ryberg, M., Vea, E. B., Schwarzbauer, P. & Hesser, F. Analyzing the Consequences of Sharing Principles on Different Economies: A Case Study of Short Rotation Coppice Poplar Wood Panel Production Value Chain. Forests 2022, Vol. 13, Page 461 13, 461 (2022).

- Cole, M. J., Bailey, R. M. & New, M. G. Tracking sustainable development with a national barometer for South Africa using a downscaled ‘safe and just space’ framework. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, E4399-E4408 (2014).

- Zhang, Q. et al. Bridging planetary boundaries and spatial heterogeneity in a hybrid approach: A focus on Chinese provinces and industries. Science of The Total Environment 804, 150179 (2022).

- Zipper, S. C. et al. Integrating the Water Planetary Boundary With Water Management From Local to Global Scales. Earths Future 8, e2019EF001377 (2020).

- Zhou, P. & Wang, M. Carbon dioxide emissions allocation: A review. Ecological Economics 125, 47-59 (2016).

- Bjørn, A. et al. Life cycle assessment applying planetary and regional boundaries to the process level: a model case study. Int J Life Cycle Assess 25, 2241-2254 (2020).

- Bjorn, A. et al. Review of life-cycle based methods for absolute environmental sustainability assessment and their applications. Environmental Research Letters 15, 083001 (2020).

- Li, M., Wiedmann, T., Fang, K. & Hadjikakou, M. The role of planetary boundaries in assessing absolute environmental sustainability across scales. Environ Int 152, 106475 (2021).

- European Environment Agency & Federal Office for the Environment (EEA/FOEN). Is Europe living within the limits of our planet? An assessment of Europe’s environmental footprints in relation to planetary boundaries. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/is-europe-living-within-the-planets-limits (2020).

- Hoff, H., Nykvist, B. & Carson, M. ‘Living well, within the limits of our planet’? Measuring Europe’s growing external footprint. https://mediamanager.sei.org/documents/Publications/SEI-WP-2014-05-Hoff-EU-Planetary-boundaries.pdf (2014).

- Nykvist, B. et al. National environmental performance on planetary boundaries. https://www.sei.org/publications/national-environmental-performance-on-planetaryboundaries/ (2013).

- Hoff, H., Häyhä, T., Cornell, S. & Lucas, P. Bringing EU policy into line with the Planetary Boundaries. https://www.sei.org/publications/eu-policy-into-line-planetary-boundaries/ (2017).

- Andersen, L. S. et al. A safe operating space for New Zealand/Aotearoa. Translating the planetary boundaries framework. https://www.stockholmresilience.org/download/18.66e0efc517643c2b810218e/16123411 72295/Updated PBNZ-Report-Design-v6.0.pdf (2020).

- Dao, H., Peduzzi, P. & Friot, D. National environmental limits and footprints based on the Planetary Boundaries framework: The case of Switzerland. Global Environmental Change 52, 49-57 (2018).

- Häyhä, T., Cornell, S. E., Hoff, H., Lucas, P. & van Vuuren, D. Operationalizing the concept of a safe operating space at the EU level – first steps and explorations. https://www.stockholmresilience.org/publications/publications/2018-07-03-operationalizing-the-concept-of-a-safe-operating-space-at-the-eu-level—first-steps-andexplorations.html (2018).

- Sandin, G., Peters, G. M. & Svanström, M. Using the planetary boundaries framework for setting impact-reduction targets in LCA contexts. Int J Life Cycle Assess 20, 1684-1700 (2015).

- Roos, S., Zamani, B., Sandin, G., Peters, G. M. & Svanström, M. A life cycle assessment (LCA)-based approach to guiding an industry sector towards sustainability: the case of the Swedish apparel sector. J Clean Prod 133, 691-700 (2016).

- Ryberg, M. W. et al. How to bring absolute sustainability into decision-making: An industry case study using a Planetary Boundary-based methodology. Science of The Total Environment 634, 1406-1416 (2018).

- Algunaibet, I. M. et al. Powering sustainable development within planetary boundaries. Energy Environ Sci 12, 1890-1900 (2019).

- Lucas, E., Guo, M. & Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Optimising diets to reach absolute planetary environmental sustainability through consumers. Sustain Prod Consum 28, 877-892 (2021).

- Ehrenstein, M., Galán-Martín, Á., Tulus, V. & Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Optimising fuel supply chains within planetary boundaries: A case study of hydrogen for road transport in the UK. Appl Energy 276, 115486 (2020).

- Hjalsted, A. W. et al. Sharing the safe operating space: Exploring ethical allocation principles to operationalize the planetary boundaries and assess absolute sustainability at individual and industrial sector levels. J Ind Ecol 25, 6-19 (2021).

This paper develops and tests a framework for sharing the planetary boundaryderived safe operating space amongst social actors based on a two-step process of downscaling to individual level followed by upscaling from an individual share to a higher-level unit or entity such as company, organisation, product, service, sector, household or nation; different ethical principles were explored in the downscaling and upscaling processes. - Hannouf, M., Assefa, G. & Gates, I. Carbon intensity threshold for Canadian oil sands industry using planetary boundaries: Is a sustainable carbon-negative industry possible? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 151, 111529 (2021).

- Wheeler, J., Galán-Martín, Á., Mele, F. D. & Guillén-Gosálbez, G. Designing biomass supply chains within planetary boundaries. AIChE Journal 67, e17131 (2021).

- Suárez-Eiroa, B. et al. A framework to allocate responsibilities of the global environmental concerns: A case study in Spain involving regions, municipalities, productive sectors, industrial parks, and companies. Ecological Economics 192, 107258 (2022). Using Spain as a case study, this paper presents the responsible operating space framework to allocate responsibilities for managing territorial and global environmental concerns to entities and social actors operating at different scales using a footprint perspective.

- Brejnrod, K. N., Kalbar, P., Petersen, S. & Birkved, M. The absolute environmental performance of buildings. Build Environ 119, 87-98 (2017).

- Chandrakumar, C., McLaren, S. J., Jayamaha, N. P. & Ramilan, T. Absolute Sustainability-Based Life Cycle Assessment (ASLCA): A Benchmarking Approach to Operate Agri-food Systems within the

Global Carbon Budget. J Ind Ecol 23, 906-917 (2019). - Desing, H., Braun, G. & Hischier, R. Ecological resource availability: a method to estimate resource budgets for a sustainable economy. Global Sustainability 3, e31 (2020).

- Bjørn, A. et al. A comprehensive planetary boundary-based method for the nitrogen cycle in life cycle assessment: Development and application to a tomato production case study. Science of The Total Environment 715, 136813 (2020).

- Bjørn, A. et al. A planetary boundary-based method for freshwater use in life cycle assessment: Development and application to a tomato production case study. Ecol Indic 110, 105865 (2020).

- Hachaichi, M. & Baouni, T. Downscaling the planetary boundaries (Pbs) framework to city scale-level: De-risking MENA region’s environment future. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 5, 100023 (2020).

- Wolff, A., Gondran, N. & Brodhag, C. Detecting unsustainable pressures exerted on biodiversity by a company. Application to the food portfolio of a retailer. J Clean Prod 166, 784-797 (2017).

- Ryberg, M. W., Bjerre, T. K., Nielsen, P. H. & Hauschild, M. Absolute environmental sustainability assessment of a Danish utility company relative to the Planetary Boundaries. J Ind Ecol 25, 765-777 (2021).

- Fanning, A. L. & O’Neill, D. W. Tracking resource use relative to planetary boundaries in a steady-state framework: A case study of Canada and Spain. Ecol Indic 69, 836-849 (2016).

- Fang, K., Heijungs, R., Duan, Z. & De Snoo, G. R. The Environmental Sustainability of Nations: Benchmarking the Carbon, Water and Land Footprints against Allocated Planetary Boundaries. Sustainability vol. 7 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3390/su70811285 (2015).

- O’Neill, D. W., Fanning, A. L., Lamb, W. F. & Steinberger, J. K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat Sustain 1, 88-95 (2018).

- Huang, L. H., Hu, A. H. & Kuo, C.-H. Planetary boundary downscaling for absolute environmental sustainability assessment – Case study of Taiwan. Ecol Indic 114, 106339 (2020).

- Sala, S., Crenna, E., Secchi, M. & Sanyé-Mengual, E. Environmental sustainability of European production and consumption assessed against planetary boundaries. J Environ Manage 269, 110686 (2020).

- Dao, Q.-H., Peduzzi, P., Chatenoux, B., De Bono, A. & Schwarzer, S. Environmental limits and Swiss footprints based on Planetary Boundaries. (2015).

- Lucas, P. & Wilting, H. Using planetary boundaries to support national implementation of environment-related sustainable development goals. (2018).

- Kahiluoto, H., Kuisma, M., Kuokkanen, A., Mikkilä, M. & Linnanen, L. Local and social facets of planetary boundaries: right to nutrients. Environmental Research Letters 10, 104013 (2015).

- Li, M., Wiedmann, T. & Hadjikakou, M. Towards meaningful consumption-based planetary boundary indicators: The phosphorus exceedance footprint. Global Environmental Change 54, 227-238 (2019).

- Shaikh, M. A., Hadjikakou, M. & Bryan, B. A. National-level consumption-based and production-based utilisation of the land-system change planetary boundary: patterns and trends. Ecol Indic 121, 106981 (2021).

- Gupta, J. et al. Earth system justice needed to identify and live within Earth system boundaries. Nat Sustain (2023) doi:10.1038/s41893-023-01064-1.

- Armstrong McKay, D. I. et al. Exceeding

global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science (1979) 377, eabn7950 (2023). - Liu, J. Integration across a metacoupled world. Ecology and Society 22, (2017).

- Bai, X. Eight energy and material flow characteristics of urban ecosystems. Ambio 45, 819-830 (2016).

- Liu, J. et al. Nexus approaches to global sustainable development. Nat Sustain 1, 466476 (2018).

- Fang, K., Heijungs, R. & De Snoo, G. R. Understanding the complementary linkages between environmental footprints and planetary boundaries in a footprint-boundary environmental sustainability assessment framework. Ecological Economics 114, 218-226 (2015).

- Kulionis, V. & Pfister, S. A planetary boundary-based method to assess freshwater use at the global and local scales. Environmental Research Letters 17, 094031 (2022).

- Obura, D. O. et al. Achieving a nature- and people-positive future. One Earth 6, 105-117 (2023).

- Dooley, K. et al. Ethical choices behind quantifications of fair contributions under the Paris Agreement. Nat Clim Chang 11, 300-305 (2021).

- Hickel, J. Quantifying national responsibility for climate breakdown : an equality-based attribution approach for carbon dioxide emissions in excess of the planetary boundary. Lancet Planet Health 4, e399-e404 (2020).

- Hickel, J., Neill, D. W. O., Fanning, A. L. & Zoomkawala, H. National responsibility for ecological breakdown : a fair-shares assessment of resource use , 1970 – 2017. Lancet Planet Health 6, e342-e349 (2022).

- Liu, J. et al. Systems integration for global sustainability. Science (1979) 347, 1258832 (2015).

- Xu, H. et al. Ensuring effective implementation of the post-2020 global biodiversity targets. Nat Ecol Evol 5, 411-418 (2021).

- IPCC. Climate change 2022: Mitigation of climate change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, . (2022) doi:doi: 10.1017/9781009157926.

- Hoornweg, D., Hosseini, M., Kennedy, C. & Behdadi, A. An urban approach to planetary boundaries. Ambio 45, 567-580 (2016).

- UN DESA. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/en/desa/products/un-desa-databases.

- UNIDO. United Nations Industrial Development Organization. https://www.unido.org/.

- CDP. CDP Cities, States and Regions Open Data Portal. https://data.cdp.net/.

- Freiberg, D., Park, D. G., Serafim, G. & Zochowski, R. Corporate environmental impact: measurement, data and information. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3565533 (2021) doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3565533.

- WBCSD & WRI. The Greenhouse Gas Protocol. A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (Revised Edition). https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/ghg-protocol-revised.pdf (2004).

- Bjørn, A. et al. Increased transparency is needed for corporate science-based targets to be effective. Nat Clim Chang 13, 756-759 (2023).

- Bjorn, A., Lloyd, S. & Matthews, D. From the Paris Agreement to corporate climate commitments: evaluation of seven methods for setting ‘science-based’ emission targets. Environmental Research Letters 16, 054019 (2021).

- Lade, S. J. et al. Human impacts on planetary boundaries amplified by Earth system interactions. Nat Sustain 3, 119-128 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Competing interests

- General rights

Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights.- Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research.

- You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain

- You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal

If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim.