DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-024-00959-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38378660

تاريخ النشر: 2024-02-20

تزامن الزيلزين مع الفنتانيل غير المشروع يشكل تهديدًا متزايدًا في الجنوب العميق: دراسة استعادية لبيانات المتوفين

الملخص

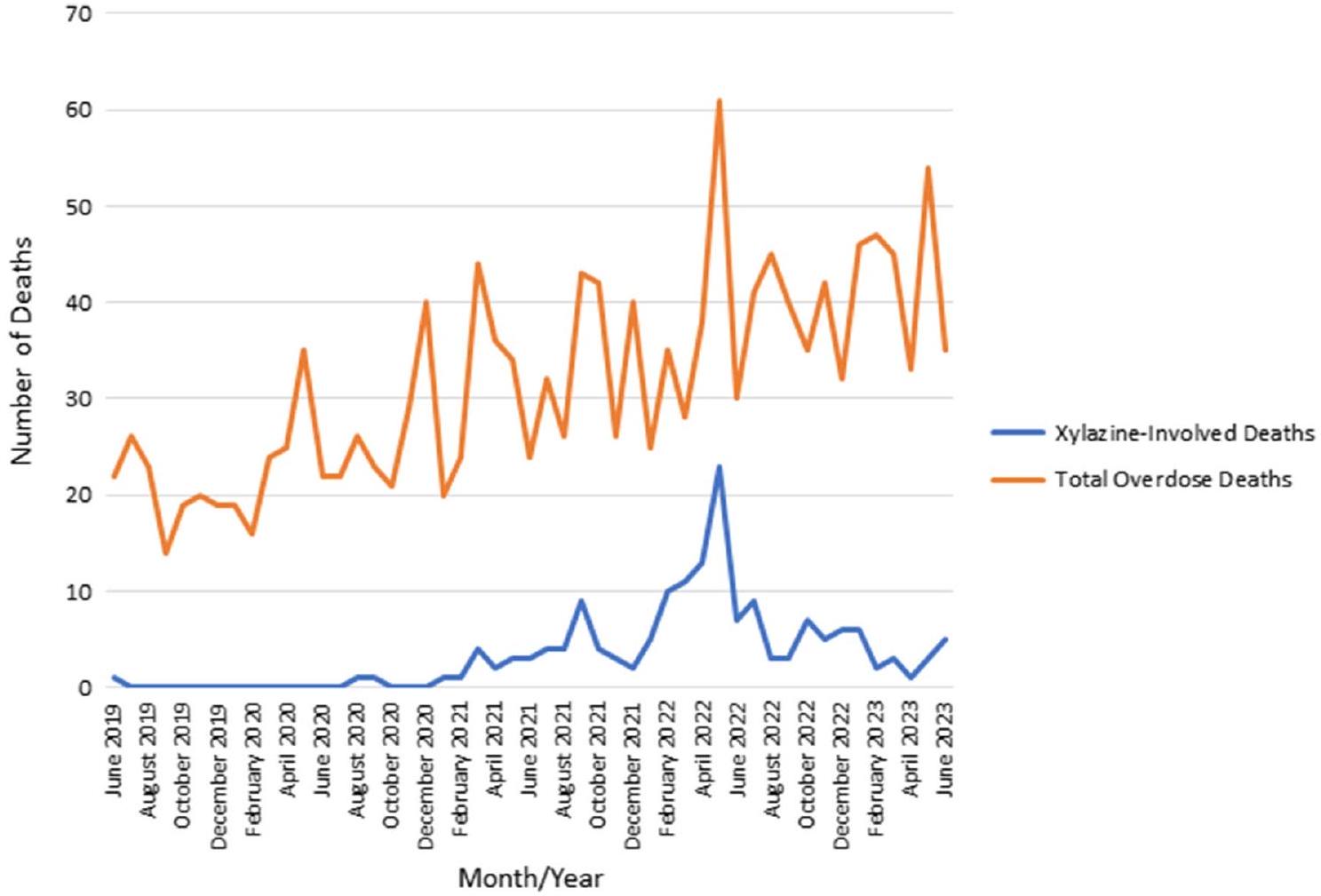

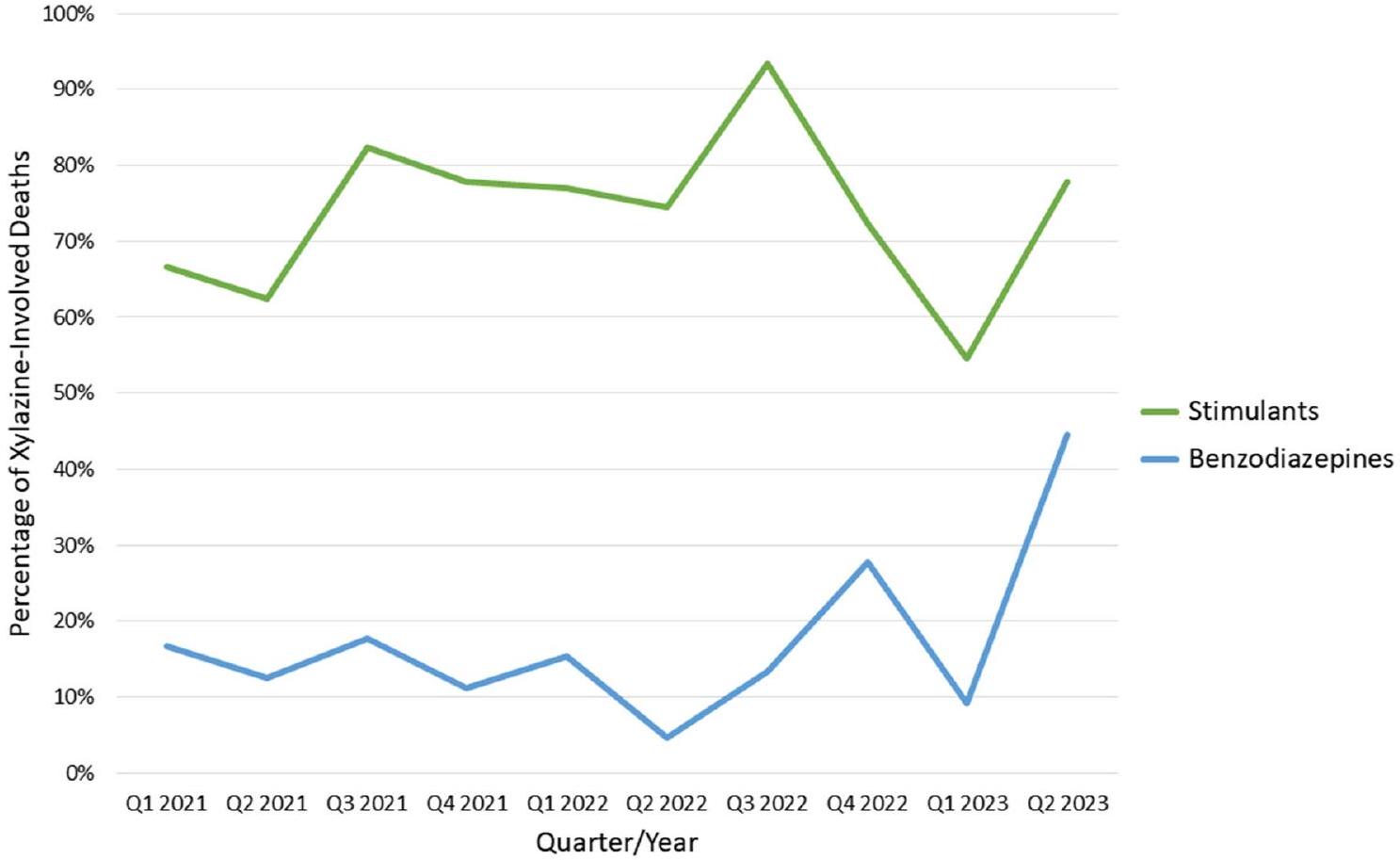

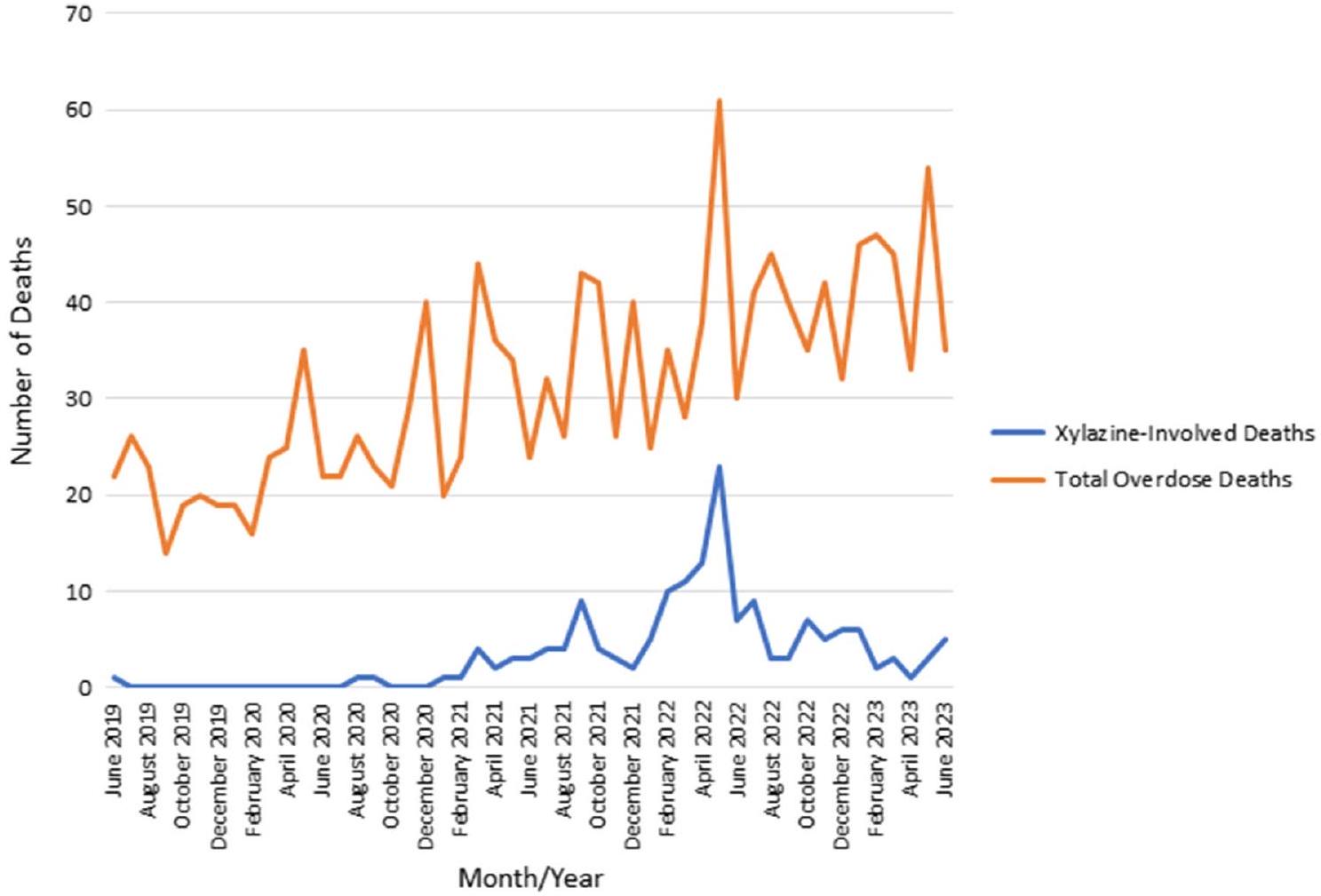

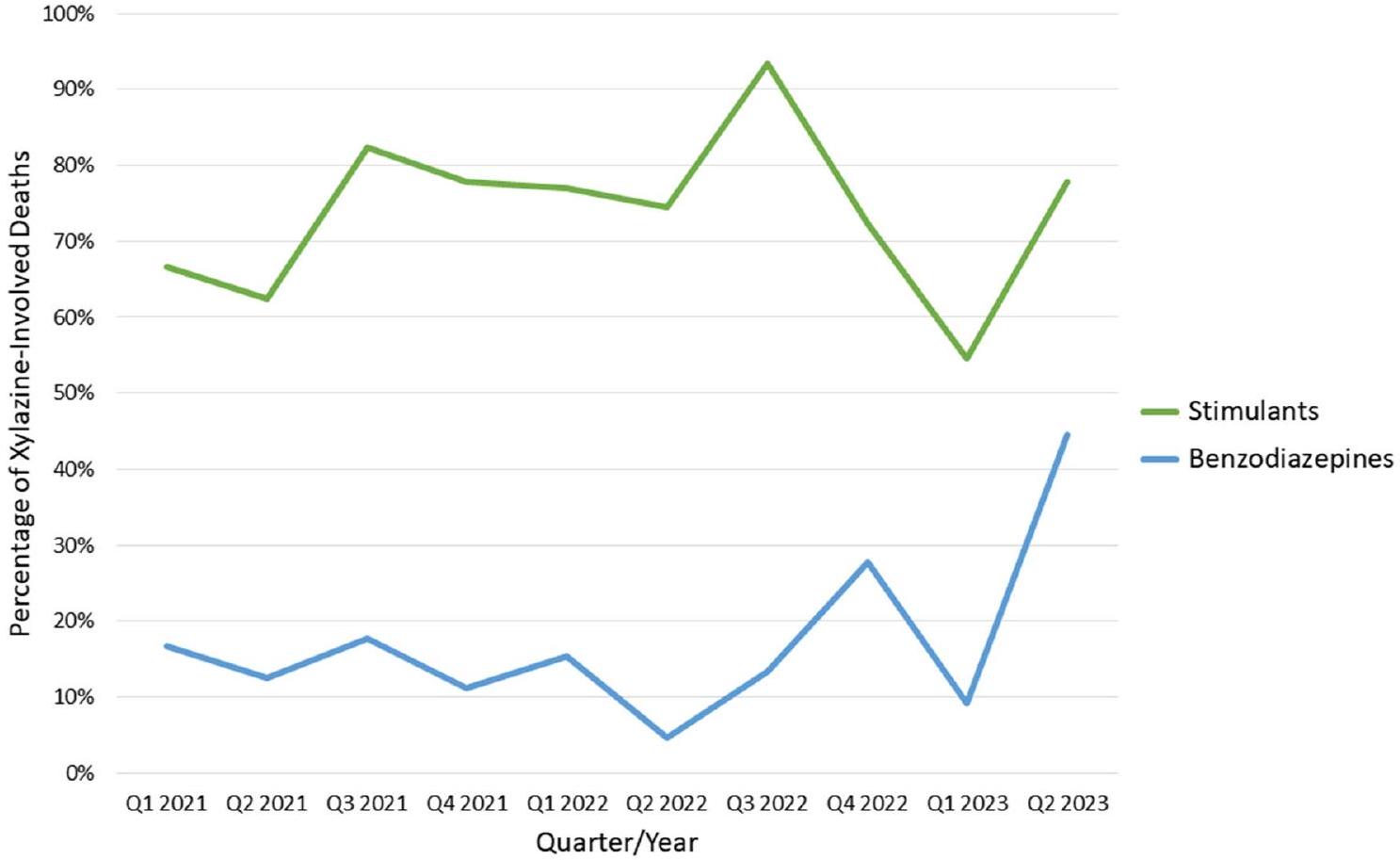

خلفية: الزيلزين هو مهدئ بيطري خطير يوجد بشكل رئيسي في الفنتانيل غير المشروع في شمال شرق ووسط الولايات المتحدة. دورها في أزمة الجرعات الزائدة في الجنوب العميق ليس موصوفًا بشكل جيد. الطرق: قمنا بإجراء مراجعة استعادية لبيانات التشريح في مقاطعة جيفرسون، ألاباما، لتحديد الاتجاهات في انتشار الزيلزين بين الأشخاص الذين توفوا نتيجة الجرعات الزائدة من يونيو 2019 حتى يونيو 2023. النتائج: استوفى 165 متوفى معايير الإدراج. بينما كانت أول حالة جرعة زائدة مرتبطة بالزيلزين في يونيو 2019، أصبح الزيلزين منتشرًا بشكل مستمر منذ يناير 2021. كانت جميع حالات الجرعات الزائدة المميتة المرتبطة بالزيلزين مصحوبة بالفنتانيل، وشارك معظمها (75.4%) في استخدام المنشطات المتعددة. كان متوسط العمر 42.2، وكان معظم المتوفين من البيض (58.8%) والذكور (68.5%). بشكل عام،

الخلفية

طرق

بالنسبة للمرضى الذين استوفوا معايير الإدراج، قمنا باستخراج معلومات من سجلات تشريح الجثة الخاصة بفاحص الطب الشرعي بما في ذلك المعلومات الاجتماعية والديموغرافية وبيانات عن جميع الأدوية التي تم الكشف عنها من اختبارات السموم. كانت وسائل اختبارات السموم هي تقنية المناعية المعززة بالإنزيم (EMIT) للفحص، وكروماتوغرافيا الغاز/ مطياف الكتلة (GC/MS) للتحليل التأكيدي، وكروماتوغرافيا السائل مع مطياف الكتلة (LC-MS/MS) للتحليل التأكيدي في عدد قليل من الحالات حيث كانت هناك حاجة لاختبارات خارجية. تم تحديد الجنس بناءً على نتائج التشريح الشامل. تم تحديد العرق من خلال رخصة القيادة، أو العرق المبلغ عنه من خلال تعريف رسمي آخر، أو من خلال تقرير العائلة. تم تعريف حالة السكن من خلال مراجعتين طبيتين من قبل طبيبين للمعلومات التحقيقية في قاعدة البيانات لكل حالة وفاة مشمولة. في الحالات التي لم يكن من الممكن فيها تحديد ما إذا كان الشخص مقيماً أو بلا مأوى بشكل مؤكد،

تم تعيين التسمية “غير قادر على التحديد”. قمنا بحساب الإحصائيات الوصفية وملخص العوامل الديموغرافية والسريرية باستخدام مقاييس النزعة المركزية (المتوسطات والوسيطات) والتشتت (النطاق والانحراف المعياري) والتوزيع (التكرار والنسبة المئوية). لم تكن هناك بيانات مفقودة عن المتغيرات ذات الاهتمام. تم إجراء جميع التحليلات باستخدام برنامج JMP (الإصدار 17.0) وMicrosoft Excel.

النتائج

| خاصية |

|

| عمر | |

| متوسط

|

|

| الوسيط، من الحد الأدنى إلى الحد الأقصى | 42، 4 إلى 70 |

| جنس | |

| أنثى | 52 (31.5) |

| ذكر | 113 (68.5) |

| سباق | |

| أبيض | 97 (58.8) |

| أسود | 62 (37.6) |

| هسباني | 6 (3.6) |

| حالة السكن | |

| مُسَكَّن | ١٣٣ (٨٠.٦) |

| غير مأوى | 30 (18.2) |

| غير قادر على التحديد | 2 (1.2) |

| سنة التعرف عليها | |

| 2019 | 1 (0.6) |

| ٢٠٢٠ | 2 (1.2) |

| ٢٠٢١ | 40 (24.2) |

| ٢٠٢٢ | ١٠٢ (٦١.٨) |

| 2023 (حتى يونيو) | 20 (12.1) |

| تداخل الأدوية (فئة واسعة) | |

| فنتانيل | ١٦٥ (١٠٠) |

| منبه | 124 (75.2) |

| البنزوديازيبين | 25 (15.2) |

نقاش

من المهم أن العديد من ولايات الجنوب العميق تفتقر إلى جهاز لتقييم الوفيات بشكل شامل، مما قد يؤدي إلى نقص كبير في عدد وفيات الجرعات الزائدة بالإضافة إلى ضعف الكشف عن الزيلزين وغيرها من المواد المضافة الجديدة (مثل الميديتوميدين). تُجرى معظم تحقيقات الوفيات في المناطق الريفية بواسطة طبيب شرعي، وهو مسؤول منتخب لديه تدريب محدود في فحص الوفيات مقارنةً بأطباء الطب الشرعي (ME’s)، الذين غالبًا ما يكونون أطباء تشريح معتمدين (أو أطباء شرعيين) مع تدريب إضافي في تحقيقات الوفيات الطبية القانونية. تعتمد دقة الإبلاغ عن الوفيات المرتبطة بالمخدرات إلى حد كبير على نظام تحقيق الوفيات الطبية القانونية (MDI) الذي يغطي المنطقة. يختلف تدريب وخبرة الأطباء الشرعيين بشكل كبير في جميع أنحاء الولايات المتحدة. أظهرت مراجعة للمعلومات من الوفيات التي حدثت في عام 2014 وعام 2018 أن أنظمة الأطباء الشرعيين كانت مرتبطة بزيادة احتمال عدم الإشارة إلى الدواء (أو الأدوية) التي تسببت في وفاة الجرعة الزائدة. علاوة على ذلك، كان هذا ذا دلالة إحصائية عند مقارنة المقاطعات الريفية والحضرية.

إجراء تشريح للجثث في حالات الوفاة المشتبه بها المتعلقة بالمخدرات. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يرتبط نظام الطب الشرعي بانخفاض احتمال تسجيل الوفيات المرتبطة بالأفيون. تشير هذه البيانات إلى أن الإبلاغ الدقيق عن حالات الوفاة الناتجة عن الجرعات الزائدة يعتمد بشكل كبير على نظام MDI. في ألاباما، يشرف الأطباء الشرعيون على تحقيقات الوفاة في جميع المقاطعات باستثناء مقاطعة جيفرسون، وتحدث معظم تحقيقات الوفاة في الولاية ضمن اختصاصات الأطباء الشرعيين.

زايلزين هو تهديد صحي عام سريع الظهور وخطير يستحق التدخل القوي والمراقبة المستمرة. لقد كان شائعًا في إحدى مقاطعات الجنوب العميق لمدة ثلاث سنوات على الأقل وقد يكون أكثر انتشارًا نظرًا لتوافر الموارد في أنظمة MDI المختلفة عبر المنطقة. يجب أن تركز الأبحاث المستقبلية على تحديد دور تلوث زايلزين في تعزيز الأمراض السريرية خارج عدوى الأنسجة الرخوة وتحسين تنفيذ أفضل ممارسات تقليل الأضرار من أجل تمكين مستخدمي المخدرات من تجنب هذا الملوث الخطير.

| MDI | التحقيق في الوفاة الطبية القانونية |

| أنا | الطبيب الشرعي |

| PWUD | الأشخاص الذين يستخدمون المخدرات |

| SSP | برنامج خدمات الحقن |

شكر وتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

تمويل

توفر البيانات والمواد

الإعلانات

موافقة الأخلاقيات والموافقة على المشاركة

الموافقة على النشر

المصالح المتنافسة

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 20 فبراير 2024

References

- Kariisa M, O’Donnell J, Kumar S, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl-involved overdose deaths with detected xyla-zine-United States, January 2019-June 2022. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(26):721-7.

- Friedman J, Montero F, Bourgois P, Wahbi R, Dye D, Goodman-Meza D, et al. Xylazine spreads across the US: a growing component of the increasingly synthetic and polysubstance overdose crisis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;233: 109380.

- Zagorski CM, Hosey RA, Moraff C, Ferguson A, Figgatt M, Aronowitz S, et al. Reducing the harms of xylazine: clinical approaches, research deficits, and public health context. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1):141.

- Ball NS, Knable BM, Relich TA, Smathers AN, Gionfriddo MR, Nemecek BD, et al. Xylazine poisoning: a systematic review. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2022;60(8):892-901.

- D’Orazio J, Nelson L, Perrone J, Wightman R, Haroz R. Xylazine adulteration of the heroin-fentanyl drug supply: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176(10):1370-6.

- Malayala SV, Papudesi BN, Bobb R, Wimbush A. Xylazine-induced skin ulcers in a person who injects drugs in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e28160.

- McFadden R, Wallace-Keeshen S, Petrillo Straub K, Hosey RA, Neuschatz R, McNulty K, et al. Xylazine-associated wounds: clinical experience

from a low-barrier wound care clinic in Philadelphia. J Addict Med. 2024;18(1):9-12. - Nunez J, DeJoseph ME, Gill JR. Xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer, detected in 42 accidental fentanyl intoxication deaths. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2021;42(1):9-11.

- Zhu DT. Public health impact and harm reduction implications of xylazine-involved overdoses: a narrative review. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1):131.

- Fernández-Viña MH, Prood NE, Herpolsheimer A, Waimberg J, Burris S. State laws governing syringe services programs and participant syringe possession, 2014-2019. Public Health Rep. 2020;135(1_suppl):128s-s137.

- Cain MD, McGwin G, Atherton D. Surveillance of drug overdoses using google fusion tables. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2016;6(2):281-90.

- Love JS, Levine M, Aldy K, Brent J, Krotulski AJ, Logan BK, et al. Opioid overdoses involving xylazine in emergency department patients: a multicenter study. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2023;61(3):173-80.

- Office JCCMEs. Annual Report of the Jefferson County Coroner/Medical Examiner’s Office. Birmingham, AL; 2020-2022.

- Childs E, Biello KB, Valente PK, Salhaney P, Biancarelli DL, Olson J, et al. Implementing harm reduction in non-urban communities affected by opioids and polysubstance use: a qualitative study exploring challenges and mitigating strategies. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;90: 103080.

- Boslett AJ, Denham A, Hill EL, Adams MCB. Unclassified drug overdose deaths in the opioid crisis: emerging patterns of inequity. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(8-9):767-77.

- Denham A, Vasu T, Avendano P, Boslett A, Mendoza M, Hill EL. Coroner county systems are associated with a higher likelihood of unclassified drug overdoses compared to medical examiner county systems. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2022;48(5):606-17.

- County-level provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. 2023.

- Reed MK, Imperato NS, Bowles JM, Salcedo VJ, Guth A, Rising KL. Perspectives of people in Philadelphia who use fentanyl/heroin adulterated with the animal tranquilizer xylazine; Making a case for xylazine test strips. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep. 2022;4: 100074.

- Gupta R, Holtgrave DR, Ashburn MA. Xylazine-medical and public health imperatives. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(24):2209-12.

ملاحظة الناشر

- *المراسلة:

ويليام برادفورد

wsbradford@uabmc.edu

1 قسم الأمراض المعدية، جامعة ألاباما في برمنغهام، مبنى بوشيل للسكري الطابق الثامن 1808 7th Ave S، برمنغهام، AL 35233، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

قسم الطب المخبري، جامعة ألاباما في برمنغهام، برمنغهام، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

قسم طب الطوارئ، جامعة ألاباما في برمنغهام، برمنغهام، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

مكتب الطبيب الشرعي/الفاحص الطبي في مقاطعة جيفرسون، برمنغهام، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

قسم علم الأمراض، جامعة ألاباما في برمنغهام، برمنغهام، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية الاختصارات

GC/MS كروماتوغرافيا الغاز/مطياف الكتلة

LC-MS/MS كروماتوغرافيا السائل/مطياف الكتلة

JCCMEO مكتب الطبيب الشرعي/الفاحص الطبي في مقاطعة جيفرسون

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-024-00959-2

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38378660

Publication Date: 2024-02-20

Xylazine co-occurrence with illicit fentanyl is a growing threat in the Deep South: a retrospective study of decedent data

Abstract

Background Xylazine is a dangerous veterinary sedative found mainly in illicit fentanyl in the Northeast and Midwest. Its role in the Deep South overdose crisis is not well-characterized. Methods We conducted a retrospective review of autopsy data in Jefferson County, Alabama to identify trends in xylazine prevalence among people who fatally overdosed from June 2019 through June 2023. Results 165 decedents met inclusion criteria. While the first identified xylazine-associated overdose was in June 2019, xylazine has become consistently prevalent since January 2021. All cases of xylazine-associated fatal overdoses were accompanied by fentanyl, and most (75.4%) involved poly-drug stimulant use. The average age was 42.2, and most decedents were white (58.8%) and male (68.5%). Overall,

Background

Methods

For patients who met inclusion criteria, we abstracted information from the medical examiner autopsy records including sociodemographic information and data on all drugs detected from toxicology testing. The means of toxicology testing were enzyme multiplied immunoassay technique (EMIT) for screening, gas chromatography/ mass spectrometry (GC/MS) for confirmatory analysis, and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for confirmatory analysis in a small number of cases where send out testing was required. Sex was assigned based on comprehensive autopsy findings. Race was assigned by Driver’s License, other formal identifica-tion-reported race, or by family report. Housing status was defined by two clinician medical review of investigative information in the database for each included death. In situations where it was not possible to determine with certainty whether a person was housed or unhoused,

the designation “unable to determine” was assigned. We calculated descriptive statistics and summarized demographic and clinical factors using measures of central tendency (means and medians), dispersion (range and standard deviation), and distribution (frequency and percentage). There were no missing data on the variables of interest. All analyses were conducted using JMP software (v.17.0) and Microsoft Excel.

Results

| Characteristic |

|

| Age | |

| Mean

|

|

| Median, min to max | 42, 4 to 70 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 52 (31.5) |

| Male | 113 (68.5) |

| Race | |

| White | 97 (58.8) |

| Black | 62 (37.6) |

| Hispanic | 6 (3.6) |

| Housing status | |

| Housed | 133 (80.6) |

| Unhoused | 30 (18.2) |

| Unable to determine | 2 (1.2) |

| Year identified | |

| 2019 | 1 (0.6) |

| 2020 | 2 (1.2) |

| 2021 | 40 (24.2) |

| 2022 | 102 (61.8) |

| 2023 (through June) | 20 (12.1) |

| Drug overlap (broad category) | |

| Fentanyl | 165 (100) |

| Stimulant | 124 (75.2) |

| Benzodiazepine | 25 (15.2) |

Discussion

Significantly, many Deep South states lack an apparatus for comprehensive death evaluation, which may be leading to significant undercounting of both the number of overdose deaths along with poor detection of xylazine and other novel adulterants (e.g., medetomidine). Most death investigations in rural jurisdictions are conducted by a Coroner, an elected lay official who has limited training in death examination compared to Medical Examiners (ME’s), who are most often appointed pathologists (or forensic pathologists) with additional training in medicolegal death investigations. The accuracy of reporting of drug related fatalities depends largely on the Medicolegal Death Investigation (MDI) system that covers the region. The training and experience of coroners vary greatly throughout the United States [15]. A review of information from deaths that occurred in 2014 and in 2018 showed that coroner systems were associated with a greater likelihood of not indicating what drug (or drugs) caused an overdose death. Furthermore, this was statistically significant when comparing rural and urban counties [16]. Coroner systems had a lower likelihood of

performing an autopsy in suspected drug related deaths. In addition, a coroner system is associated with a lower likelihood of recording opioid-related deaths. These data indicate that accurate reporting of overdose deaths depends greatly on the MDI system [15]. In Alabama, coroners oversee death investigations in all counties except Jefferson County, Alabama and most death investigations in the state occur in Coroner jurisdictions.

Xylazine is a rapidly emerging and serious public health threat that merits aggressive intervention and continued close monitoring [19]. It has been prevalent in one Deep South county for at least 3 years and may be more widespread given resource availability in different MDI systems across the region. Future research should focus on establishing the role of xylazine adulteration in promoting clinical diseases outside of soft tissue infection and improving implementation of best harm reduction practices in order to empower PWUD to avoid this dangerous adulterant.

| MDI | Medicolegal Death Investigation |

| ME | Medical examiner |

| PWUD | People who use drugs |

| SSP | Syringe service program |

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Availability of data and materials

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Published online: 20 February 2024

References

- Kariisa M, O’Donnell J, Kumar S, Mattson CL, Goldberger BA. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl-involved overdose deaths with detected xyla-zine-United States, January 2019-June 2022. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(26):721-7.

- Friedman J, Montero F, Bourgois P, Wahbi R, Dye D, Goodman-Meza D, et al. Xylazine spreads across the US: a growing component of the increasingly synthetic and polysubstance overdose crisis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;233: 109380.

- Zagorski CM, Hosey RA, Moraff C, Ferguson A, Figgatt M, Aronowitz S, et al. Reducing the harms of xylazine: clinical approaches, research deficits, and public health context. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1):141.

- Ball NS, Knable BM, Relich TA, Smathers AN, Gionfriddo MR, Nemecek BD, et al. Xylazine poisoning: a systematic review. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2022;60(8):892-901.

- D’Orazio J, Nelson L, Perrone J, Wightman R, Haroz R. Xylazine adulteration of the heroin-fentanyl drug supply: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176(10):1370-6.

- Malayala SV, Papudesi BN, Bobb R, Wimbush A. Xylazine-induced skin ulcers in a person who injects drugs in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e28160.

- McFadden R, Wallace-Keeshen S, Petrillo Straub K, Hosey RA, Neuschatz R, McNulty K, et al. Xylazine-associated wounds: clinical experience

from a low-barrier wound care clinic in Philadelphia. J Addict Med. 2024;18(1):9-12. - Nunez J, DeJoseph ME, Gill JR. Xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer, detected in 42 accidental fentanyl intoxication deaths. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2021;42(1):9-11.

- Zhu DT. Public health impact and harm reduction implications of xylazine-involved overdoses: a narrative review. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1):131.

- Fernández-Viña MH, Prood NE, Herpolsheimer A, Waimberg J, Burris S. State laws governing syringe services programs and participant syringe possession, 2014-2019. Public Health Rep. 2020;135(1_suppl):128s-s137.

- Cain MD, McGwin G, Atherton D. Surveillance of drug overdoses using google fusion tables. Acad Forensic Pathol. 2016;6(2):281-90.

- Love JS, Levine M, Aldy K, Brent J, Krotulski AJ, Logan BK, et al. Opioid overdoses involving xylazine in emergency department patients: a multicenter study. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2023;61(3):173-80.

- Office JCCMEs. Annual Report of the Jefferson County Coroner/Medical Examiner’s Office. Birmingham, AL; 2020-2022.

- Childs E, Biello KB, Valente PK, Salhaney P, Biancarelli DL, Olson J, et al. Implementing harm reduction in non-urban communities affected by opioids and polysubstance use: a qualitative study exploring challenges and mitigating strategies. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;90: 103080.

- Boslett AJ, Denham A, Hill EL, Adams MCB. Unclassified drug overdose deaths in the opioid crisis: emerging patterns of inequity. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(8-9):767-77.

- Denham A, Vasu T, Avendano P, Boslett A, Mendoza M, Hill EL. Coroner county systems are associated with a higher likelihood of unclassified drug overdoses compared to medical examiner county systems. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2022;48(5):606-17.

- County-level provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. 2023.

- Reed MK, Imperato NS, Bowles JM, Salcedo VJ, Guth A, Rising KL. Perspectives of people in Philadelphia who use fentanyl/heroin adulterated with the animal tranquilizer xylazine; Making a case for xylazine test strips. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep. 2022;4: 100074.

- Gupta R, Holtgrave DR, Ashburn MA. Xylazine-medical and public health imperatives. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(24):2209-12.

Publisher’s Note

- *Correspondence:

William Bradford

wsbradford@uabmc.edu

1 Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Boshell Diabetes Building 8th Floor 1808 7th Ave S, Birmingham, AL 35233, USA

Division of Laboratory Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, USA

Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, USA

Jefferson County Coroner/Medical Examiner’s Office, Birmingham, USA

Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, USA Abbreviations

GC/MS Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry

LC-MS/MS Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

JCCMEO Jefferson County Coroner/Medical Examiner’s Office