DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44432-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38177128

تاريخ النشر: 2024-01-04

تزداد شذوذات العضلات سوءًا بعد التعب التالي للجهد في كوفيد طويل الأمد

تم القبول: 13 ديسمبر 2023

نُشر على الإنترنت: 04 يناير 2024

(ط) التحقق من التحديثات

الملخص

برنت أبلمان ©

الملخص

تظل مجموعة فرعية من المرضى المصابين بفيروس SARS-CoV-2 يعانون من أعراض مستمرة لأكثر من ثلاثة أشهر بعد الإصابة. من الأعراض المميزة للمرضى الذين يعانون من كوفيد طويل الأمد هو التعب بعد المجهود، والذي يرتبط بتفاقم أعراض التعب والألم بعد ممارسة التمارين الذهنية أو البدنية الحادة، لكن الآلية المرضية الكامنة وراء ذلك غير واضحة. من خلال هذه الدراسة الطولية ذات التصميم الحالة-الشاهد (NCT05225688)، نقدم رؤى جديدة حول الآلية المرضية للتعب بعد المجهود لدى مرضى كوفيد طويل الأمد. نُظهر أن بنية العضلات الهيكلية مرتبطة بانخفاض القدرة على ممارسة التمارين لدى المرضى، وأن الاضطرابات الأيضية المحلية والجهازية، والاعتلال العضلي الشديد الناتج عن التمارين، وتسلل الأنسجة لترسبات تحتوي على الأميلويد في عضلات الهيكل العظمي لدى مرضى كوفيد طويل الأمد تزداد سوءًا بعد تحفيز التعب بعد المجهود. تسلط هذه الدراسة الضوء على مسارات جديدة تساعد في فهم الآلية المرضية للتعب بعد المجهود لدى المرضى الذين يعانون من كوفيد طويل الأمد وأمراض ما بعد العدوى الأخرى.

الإرهاق الناتج عن الجهد، والذي يمثل تفاقم الأعراض بعد الجهد الذهني أو البدني

النتائج

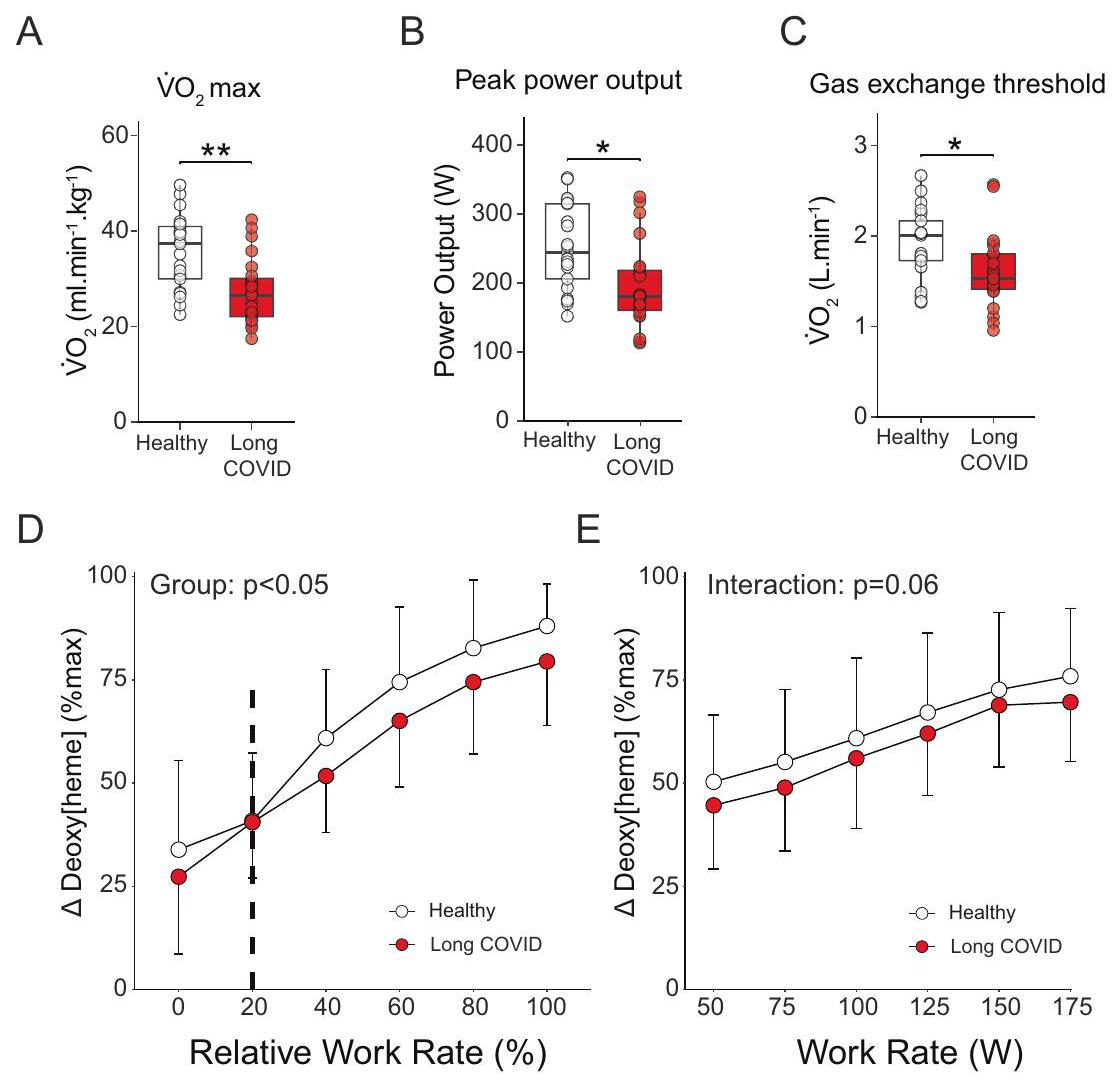

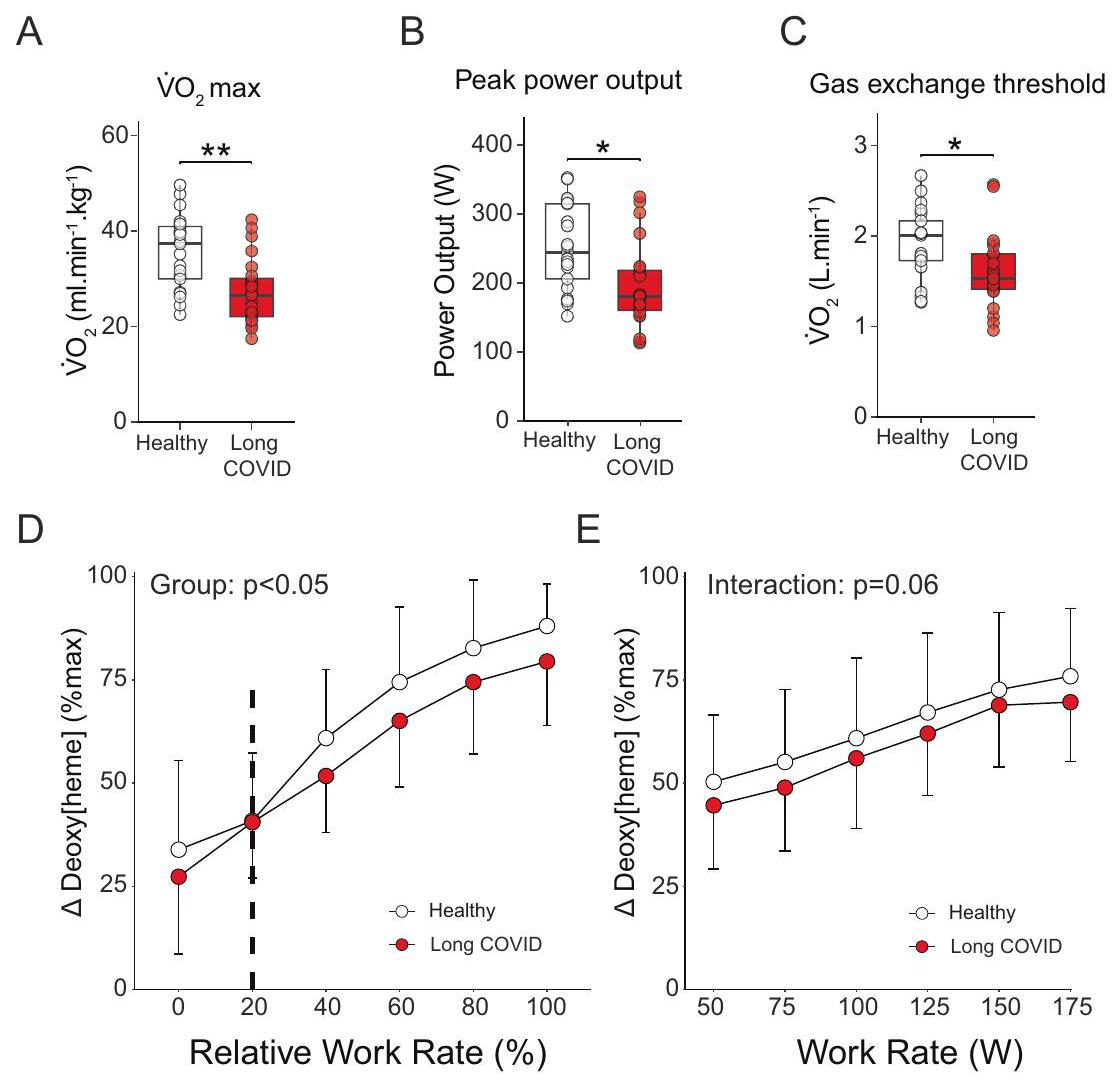

القدرة المحدودة على ممارسة التمارين في كوفيد طويل الأمد

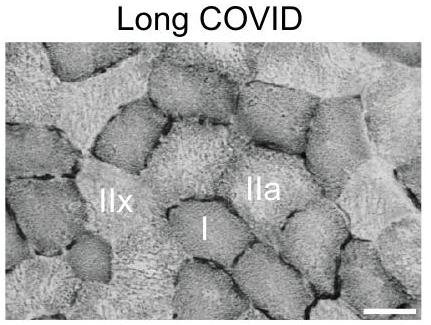

ضعف العضلات لدى المرضى. الجزء السفلي

الخلل الأيضي والتعب بعد المجهود

| المراقبون الأصحاء | كوفيد طويل الأمد |

|

|

| عدد المشاركين | ٢١ | ٢٥ | |

| التركيبة السكانية | |||

| العمر، المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري)، بالسنوات | ٤٢ (١٠) | ٤١ (١١) | 0.82 |

| الجنس، ذكر (%) | 10 (47.6) | 12 (48.0) | >0.99 |

| مؤشر كتلة الجسم، المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري)،

|

٢٤٫١٤ (٣٫٣٧) | ٢٥٫٦٠ (٤٫٦٢) | ٠٫٢٤ |

| مؤشر تشارلسون للأمراض المصاحبة، الوسيط [المدى الربيعي] | صفر، صفر [0, 0] | المجموعة [0,1] | ٠٫٧٦ |

| الاستشفاء بسبب كوفيد-19 | 0 (0) | (0) | >0.99 |

| التطعيم ضد فيروس كورونا المستجد (SARS-CoV-2) قبل المشاركة (%) | ٢١ (١٠٠) | ٢٤ (٩٦.٠) | >0.99 |

| ساعات العمل الأسبوعية قبل الإصابة الأولية بفيروس SARS-CoV-2، الوسيط [المدى الربيعي] | ٣٦ [٣٢، ٤٠] | ٣٦ [٣٢، ٤٥] | 0.520 |

| ساعات العمل الأسبوعية خلال الدراسة، الوسيط [المدى الربيعي] | ٣٦ [٣٢، ٤٠] | ٥ [٠،١٢] | <0.001 |

| المدة منذ الإصابة الأولية بفيروس SARS-CoV-2، الوسيط [المدى الربيعي]، بالأيام | 142 [105، 405] | 545 [455، 686] | 0.001 |

| المدة منذ آخر عدوى بفيروس SARS-CoV-2، الوسيط [المدى الربيعي]، بالأيام | 135 [93، 197] | 504 [329، 665] | 0.002 |

من سوء الحالة بعد الجهد

القدرة في المرضى. كما لاحظنا انخفاض S-أدينوسيل ميثيونين (SAM) في المرضى، مما قد يرتبط بانخفاض التمثيل الميثيلي ونشاط دورة SAM في مرضى كوفيد طويل الأمد. تم تقليل ديوهيدروكسي أسيتون فوسفات، وهو وسيط مهم في تخليق الدهون والتحلل السكري، في عضلات الهيكل العظمي للمرضى بعد التعب الناتج عن الجهد (الشكل 3D). يرتبط انخفاض حمض الهيدروكسي فينيل أسيتيك في المرضى عادة بزيادة إنتاج الميتوكوندريا للجذور الحرة للأكسجين (الشكل التكميلي 6A، B).

الخط الأساسي وأثناء التعب بعد الجهد ولكن انخفض بعد أسبوع واحد من حدوث التعب بعد الجهد.

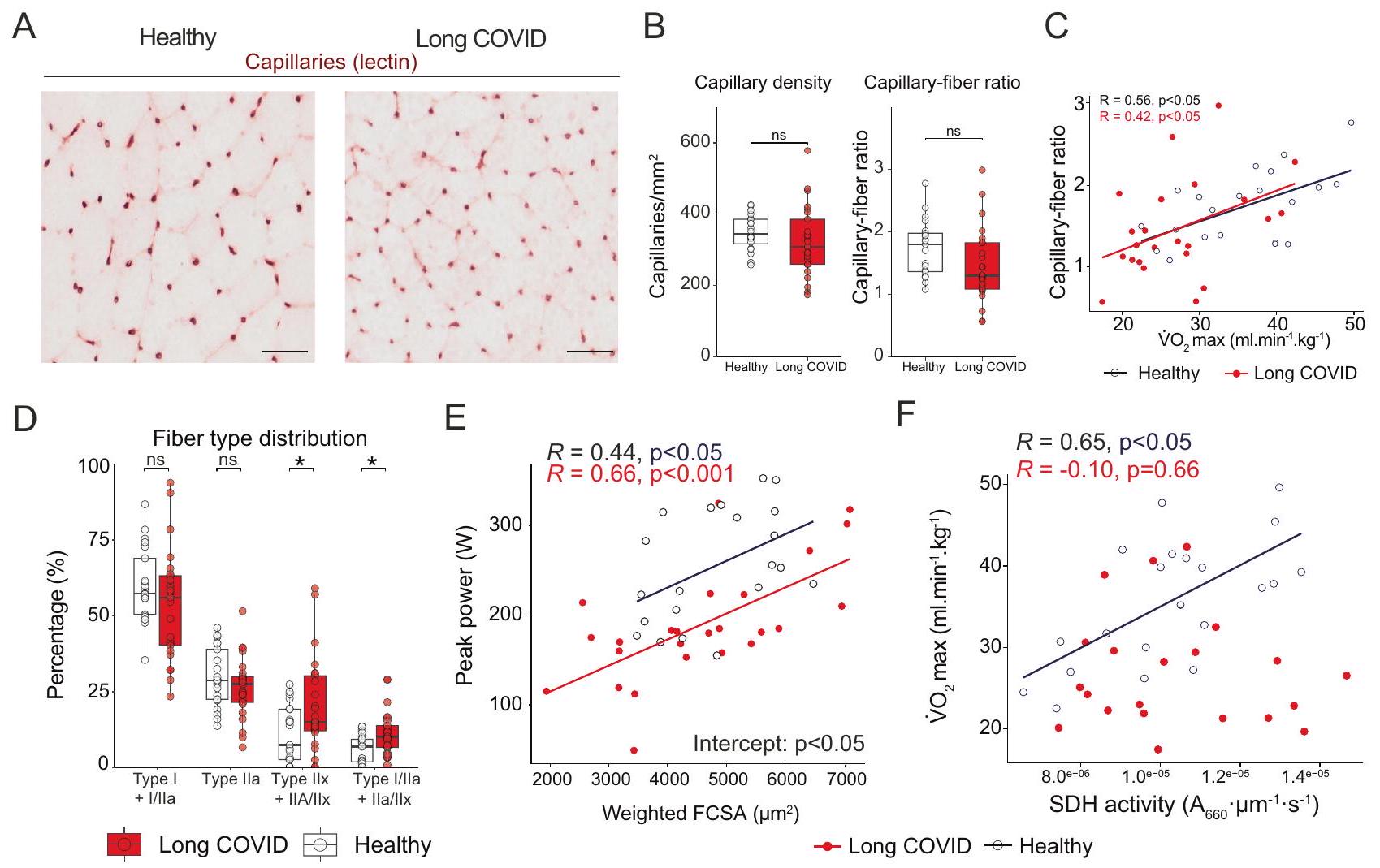

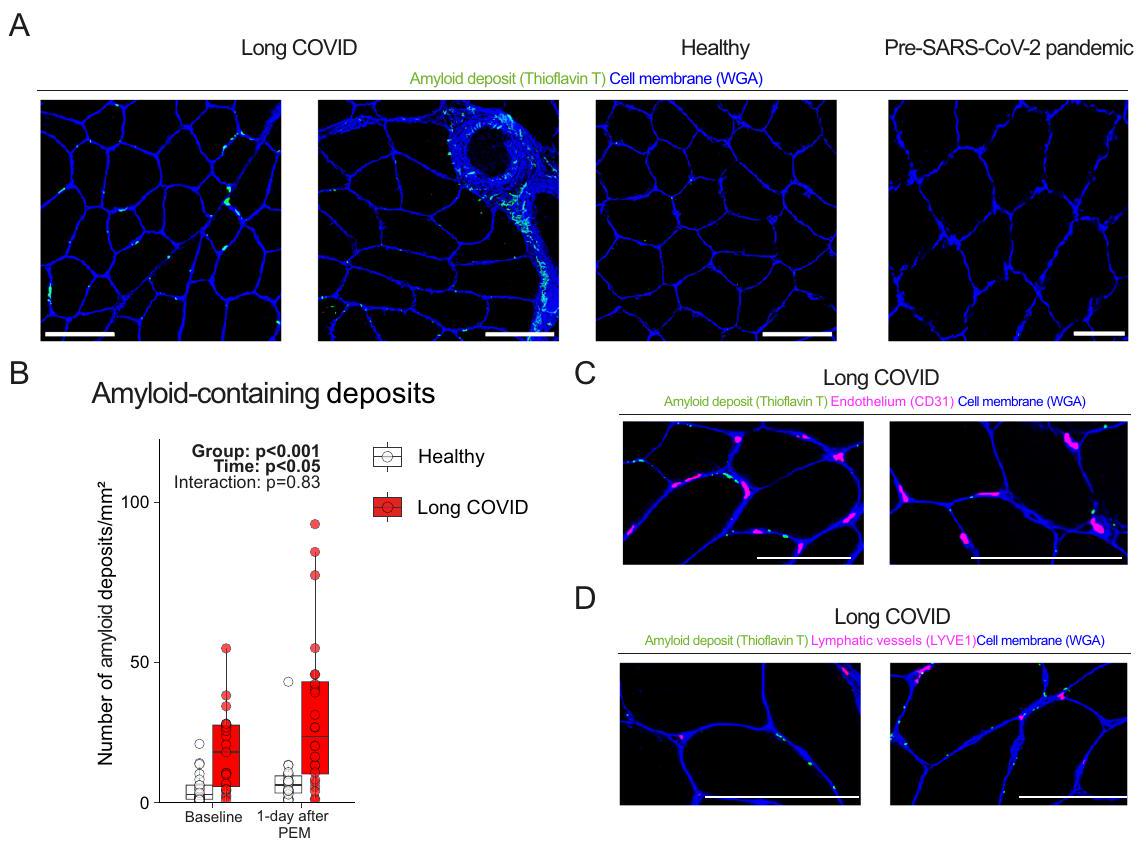

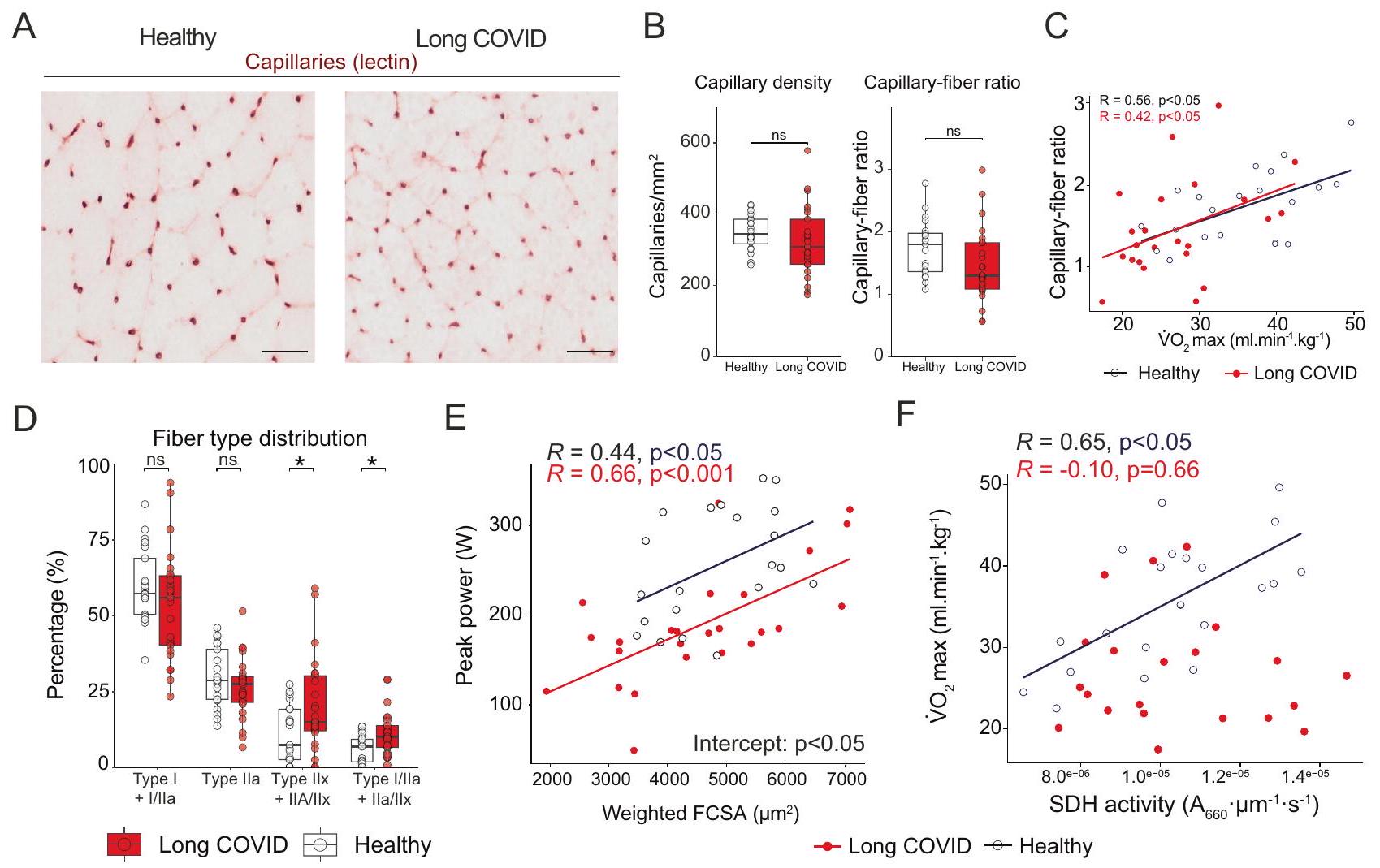

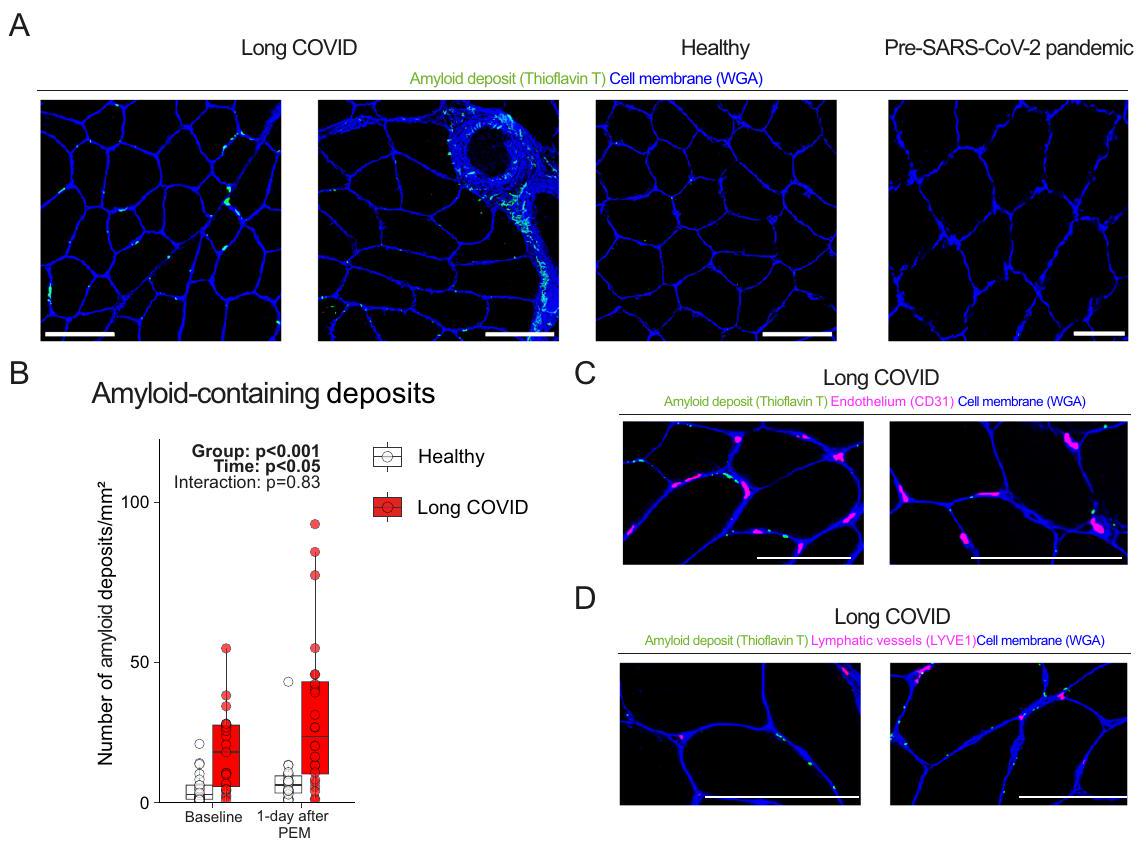

تراكم ترسبات تحتوي على الأميلويد ناتجة عن التمرين في العضلات الهيكلية

مما يشير إلى أن هذه الترسبات تقع خارج الخلايا المتسللة (المناعية). نستنتج أن الترسبات التي تحتوي على الأميلويد غير موجودة داخل الشعيرات الدموية. كما أننا لم نلاحظ أي علامات على نقص الأكسجة في نسيج العضلات الهيكلية، حيث لم يكن هناك اختلاف في نسبة الشعيرات الدموية إلى الألياف العضلية، وكثافة الشعيرات الدموية (الشكل 2ب)، وتركيزات اللاكتات داخل الخلايا وفي الدورة الدموية (الأشكال التكميلية 3ج، 6أ) بين مرضى كوفيد طويل الأمد والمجموعة الضابطة. لذلك، نستنتج أن التعب بعد الجهد لا يمكن تفسيره بالافتراض القائل بأن هذه الترسبات تسد تدفق الأوعية، مما يسبب نقص الأكسجة المحلية في الأنسجة.

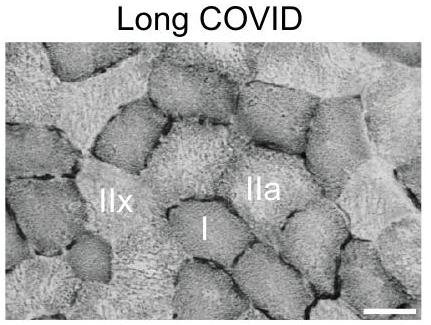

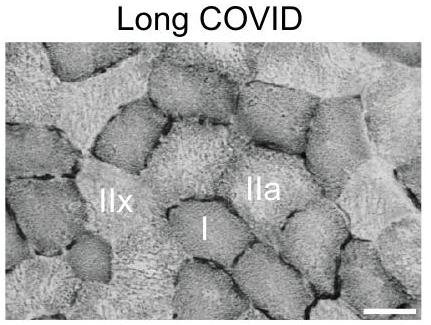

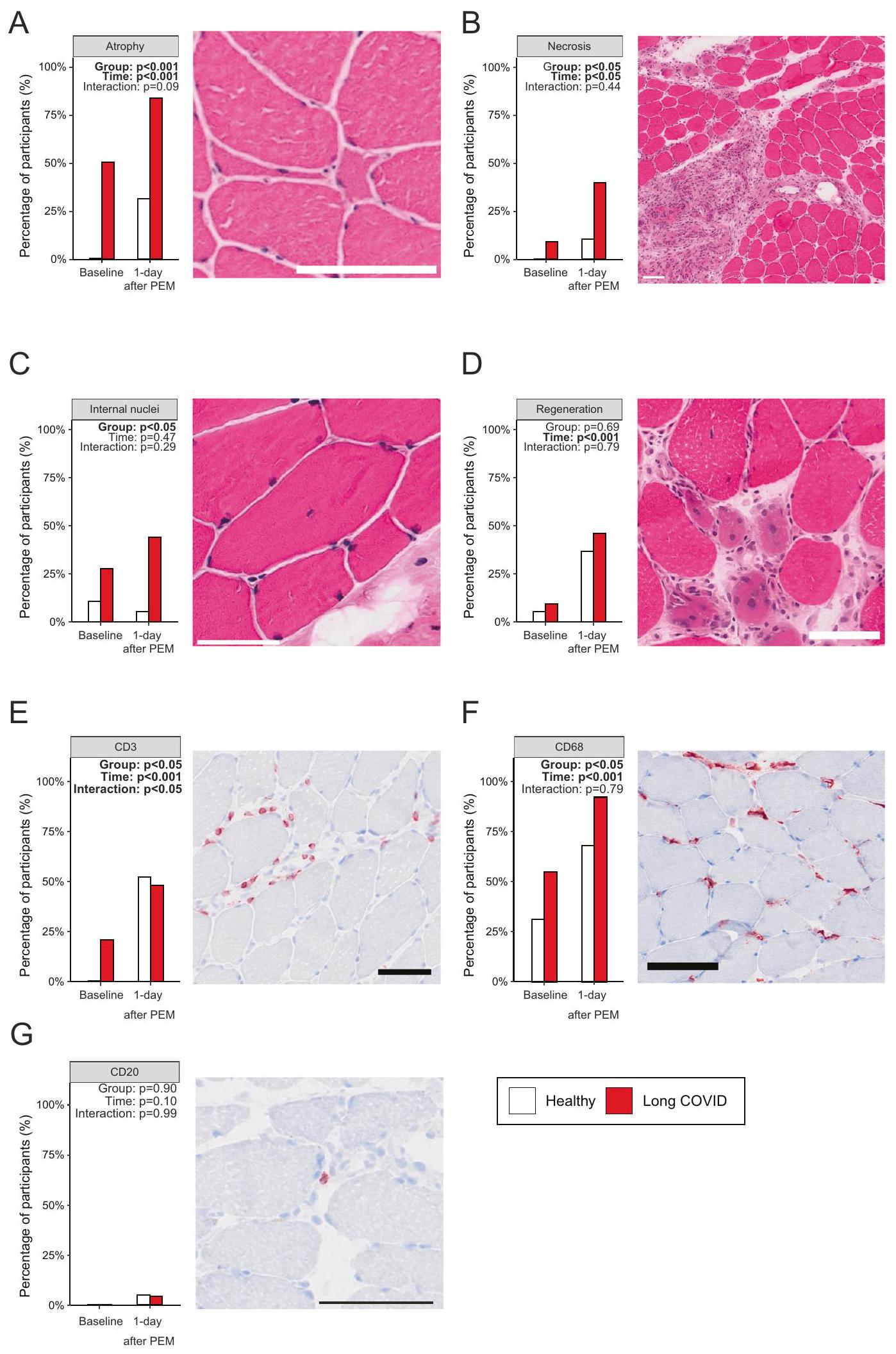

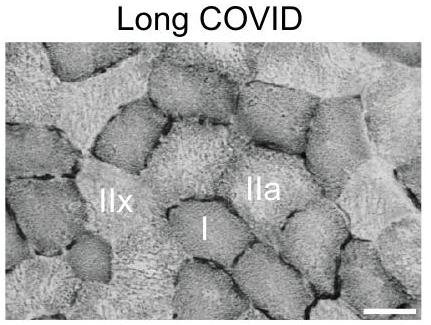

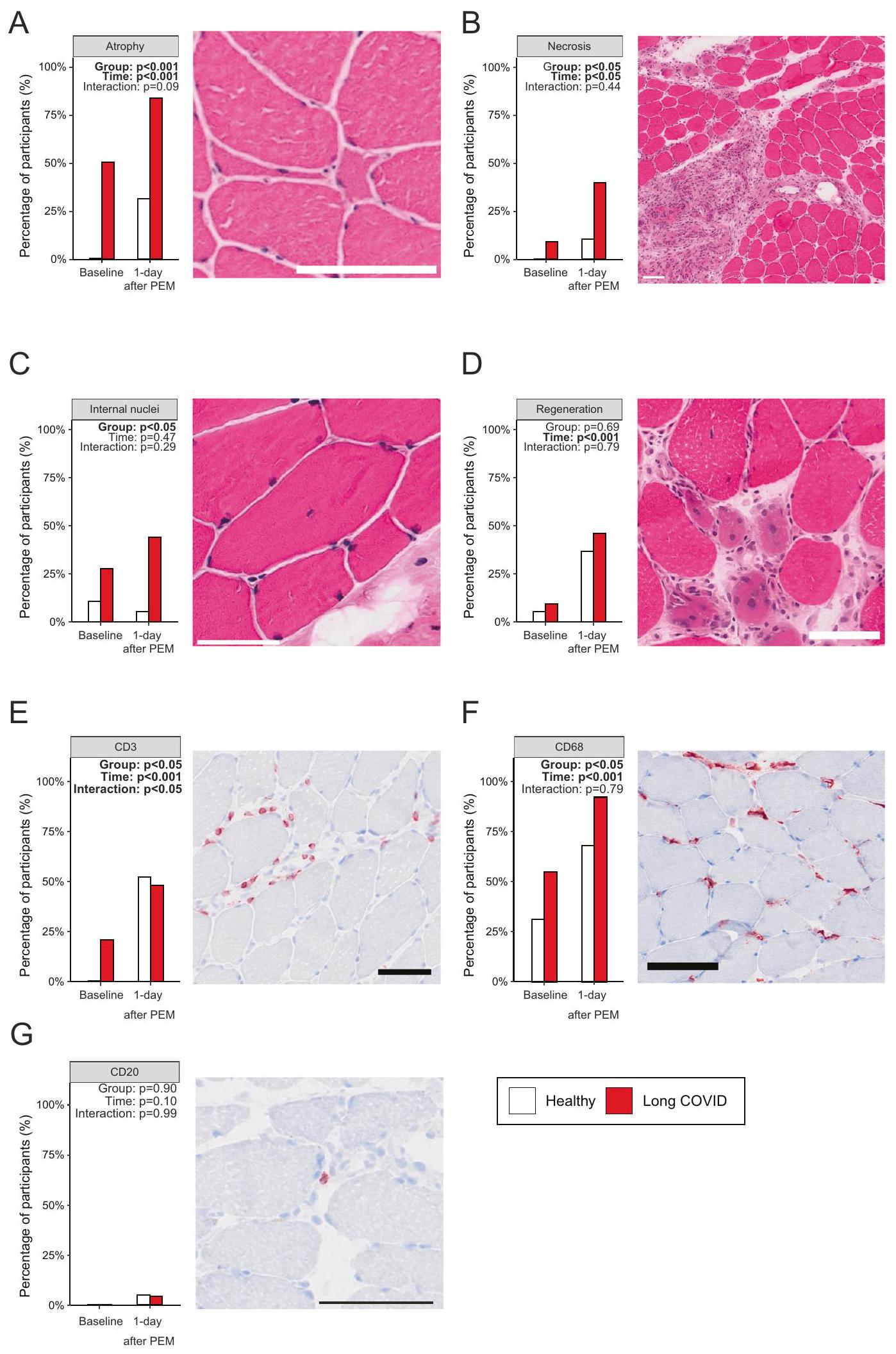

اعتلال العضلات الناجم عن التمرين في كوفيد طويل الأمد

|

|

نستنتج أن تلف العضلات الشديد الناتج عن التمرين والتجدد اللاحق مرتبطان بفيزيولوجيا مرض التعب بعد الجهد، وقد يفسران ألم العضلات والتعب والضعف لدى المرضى الذين يعانون من كوفيد طويل الأمد ويختبرون التعب بعد الجهد.

انخفاض الاعتماد على الأيض التأكسدي في المرضى الذين يعانون من كوفيد طويل الأمد (

| الأعراض | الخط الأساسي

|

بعد يوم واحد من بدء التعب بعد الجهد

|

بعد أسبوع واحد من بدء التعب بعد المجهود

|

|

| الإرهاق | ٢٥ (١٠٠.٠) | ٢٥ (١٠٠.٠) | 24 (96.0) | 0.36 |

| شدة التعب المبلغ عنها ذاتياً (1-10)، الوسيط [المدى الربيعي] | ٦٫٠٠ [٤٫٠٠، ٧٫٠٠] | ٧.٠٠ [٧.٠٠، ٨.٠٠] | ٧٫٠٠ [٦٫٠٠، ٧٫٢٥] | 0.001 |

| مشاكل معرفية | 20 (80.0) | ٢١ (٨٤.٠) | 23 (92.0) | 0.47 |

| شدة شدة الإدراك المبلغ عنها ذاتيًا (1-10)، الوسيط [المدى الربيعي] | ٤.٠٠ [٣.٠٠، ٦.٢٥] | ٦٫٠٠ [٥٫٠٠، ٨٫٠٠] | ٦٫٠٠ [٤٫٠٠، ٧٫٠٠] | ٠٫٠٦ |

| ألم في العضلات أو المفاصل | 16 (64.0) | 20 (80.0) | 15 (60.0) | 0.276 |

| ألم الصدر | ٨ (٣٢٫٠) | 11 (44.0) | ٨ (٣٢٫٠) | 0.59 |

| ضيق التنفس | ٦ (٢٤٫٠) | ٤ (١٦٫٠) | ٧ (٢٨٫٠) | 0.59 |

| فقدان حاسة الشم | ٣ (١٢٫٠) | ٣ (١٢٫٠) | ٣ (١٢٫٠) | >0.99 |

| التهاب الحلق | ٢ (٨.٠) | ٥ (٢٠٫٠) | ٣ (١٢٫٠) | 0.45 |

| أعراض تشبه البرد | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | ٢ (٨٫٠) | 0.35 |

| سعال | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (4.0) | 0.60 |

الوسيط مع المدى الربيعي. لم يتم تصحيح قيم p للاختبارات المتعددة. تم توفير بيانات المصدر في ملف بيانات المصدر.

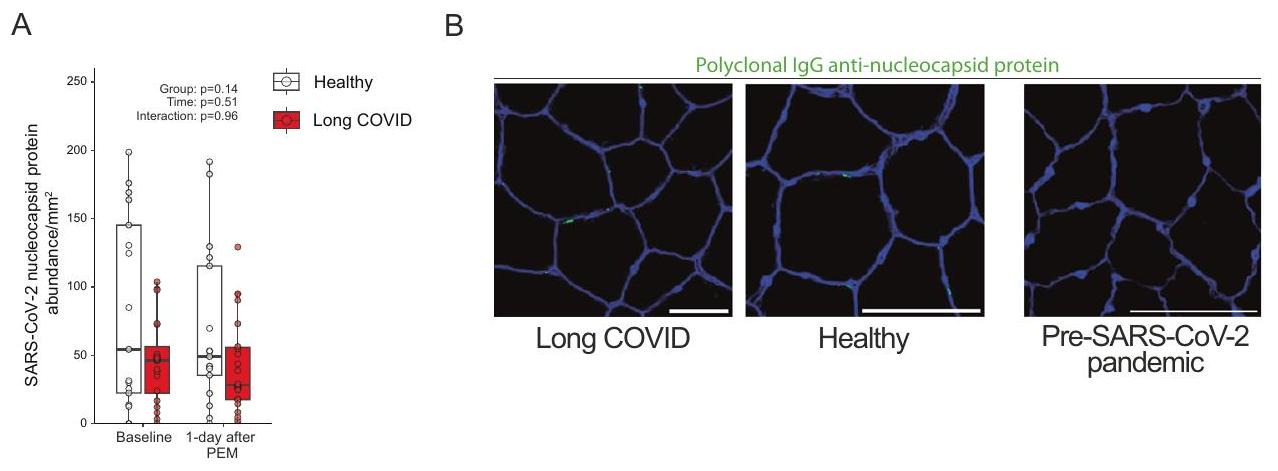

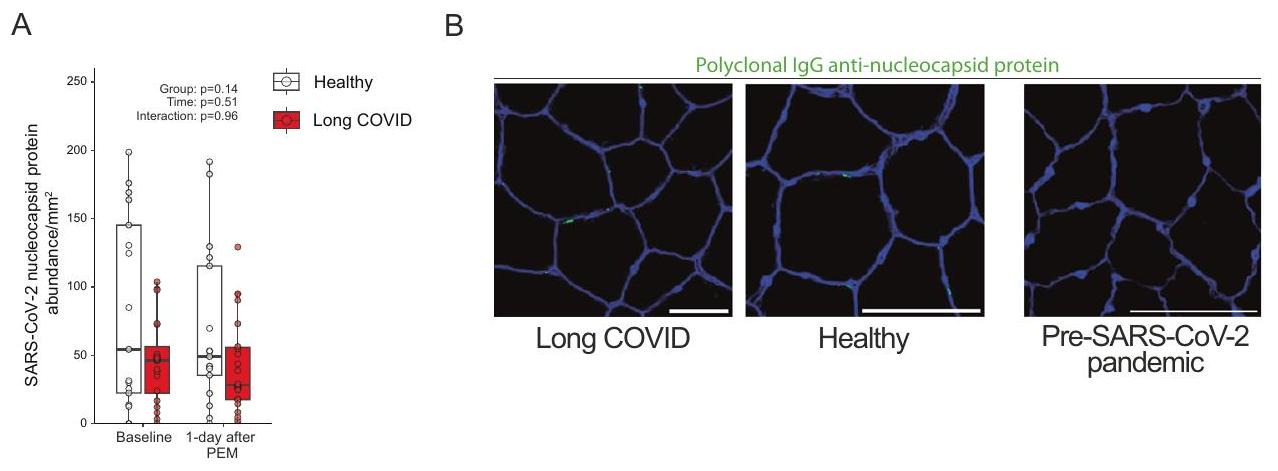

الوسيط مع المدى الربيعي. لم يتم تصحيح قيم p للاختبارات المتعددة. تم توفير بيانات المصدر في ملف بيانات المصدر.وجود نوكليوكابسيد فيروس سارس-كوف-2 في العضلات الهيكلية

دور، يجب أن يكون بروتين النيوكليوكابسيد الخاص بـ SARS-CoV-2، والذي يختص بـ SARS-CoV-2 ولا يتأثر بالتطعيمات، موجودًا على الأقل. بينما لم نلاحظ أي تلوين إيجابي في العينات التي تم الحصول عليها قبل تفشي SARS-CoV-2 (الشكل 6A، B)، وجدنا بروتين النيوكليوكابسيد الخاص بـ SARS-CoV-2 في جميع المرضى تقريبًا وكذلك في الأشخاص الأصحاء (الشكل 6A، B). على الرغم من مرور فترة أطول منذ آخر عدوى لدى مرضى كوفيد طويل الأمد، لم يكن هناك اختلاف في كمية بروتين النيوكليوكابسيد بين المجموعات (الشكل 6A)، سواء قبل أو بعد تعديل الوقت منذ آخر عدوى. المشاركون الذين أصيبوا بالعدوى قبل أكثر من 6 أشهر من تسجيل الدراسة لم يظهروا فروقًا في وفرة بروتين النيوكليوكابسيد، لكن لا يمكننا استبعاد وجود عدوى إضافية غير معروفة بدون أعراض. لم يكن بروتين النيوكليوكابسيد الخاص بـ SARS-CoV-2 موجودًا داخل ألياف العضلات، بل في المصفوفة خارج الخلوية، ومع ذلك، لم يتداخل وجوده بشكل مستمر مع نوى الخلايا. لم يكن هناك ارتباط بين وجود بروتين النيوكليوكابسيد الخاص بـ SARS-CoV-2 والترسبات المحتوية على الأميلويد (

مناقشة

تصميم الدراسة الجماعية. أظهر المرضى المصابون بكوفيد طويل الأمد قدرة تمرين منخفضة بشكل ملحوظ، والتي ارتبطت بتغيرات في أيض عضلات الهيكل العظمي وتحول نحو ألياف سريعة التعب. تشمل الفيزيولوجيا المرضية للإرهاق بعد المجهود انخفاضًا حادًا في نشاط إنزيمات الميتوكوندريا في عضلات الهيكل العظمي الناجم عن التمرين، وتراكمًا متزايدًا لترسبات تحتوي على الأميلويد في عضلات الهيكل العظمي، وعلامات على تلف شديد في نسيج العضلات، إلى جانب استجابة خلوية T ضعيفة ناتجة عن التمرين في عضلات الهيكل العظمي. مجتمعة، تساعد هذه النتائج في فك شفرة الفيزيولوجيا الكامنة وراء التعب والقدرة المحدودة على التمرين الناتجة عن تطور الإرهاق بعد المجهود لدى مرضى كوفيد طويل الأمد.

التركيب، ونشاط إنزيمات الميتوكوندريا، ولكن على الرغم من هذا التباين الكبير، عانى جميع المرضى من التعب بعد الجهد في اليوم التالي لاختبار التمرين. وبناءً عليه، نستنتج أن الفيزيولوجيا المرضية للإرهاق وانخفاض القدرة على التمرين تختلف عن التطور السريع للتعب بعد الجهد لدى مرضى كوفيد طويل الأمد. ومع ذلك، قد يؤدي تطور التعب بعد الجهد إلى مزيد من الانخفاض في القدرة على التمرين لدى المرضى، حيث إن الانخفاض الحاد في نشاط إنزيم SDH الميتوكوندري، وحدوث نخر في الأنسجة، وربما تراكم رواسب تحتوي على الأميلويد داخل العضلات، قد يؤدي إلى تفاقم أيض العضلات الهيكلية وإنتاج القوة مع مرور الوقت، مما يسبب دائرة هبوطية ضارة.

الألياف، والتنخر البؤري بعد تحفيز التعب بعد الجهد مقارنةً بالأشخاص الأصحاء. يمكن أن يحدث ضمور العضلات الهيكلية والتنخر البؤري أثناء الإصابة الحادة الشديدة بفيروس سارس-كوف-2.

(الوقت:

الإرهاق الناتج عن الجهد. علاوة على ذلك، لم نلاحظ زيادة في تسلل خلايا B في العضلات الهيكلية للمرضى قبل وأثناء فترة الإرهاق الناتج عن الجهد. وجود بروتين الغلاف النووي لفيروس SARS-CoV-2 في العضلات الهيكلية ليس أمرًا مفاجئًا، حيث يمكن أن يتواجد بروتين الغلاف النووي حتى عام بعد الإصابة في الدم.

الفيزيولوجيا المرضية متشابهة في جميع فئات المرضى، بما في ذلك الأطفال والمراهقين

طرق

مجتمع الدراسة

تصميم الدراسة

اختبار التمرين التدريجي المتزايد

الميوغلوبين]، وكذلك تشبع العضلات (

مستوى النشاط البدني في الحياة اليومية

قياسات العضلات الهيكلية

| معامل | الأجسام المضادة، التخفيف، البائع | الأجسام المضادة الثانوية (التخفيف)، المورد | معرّف RRID |

| نوع ألياف العضلات | BA-D5 (MHC-I)،

|

ماعز مضاد للفأر IgG2b 555، 1:1000، إنفيتروجين A21147؛ ماعز مضاد للفأر IgG1 647، 1:1000، إنفيتروجين A21240؛ ماعز مضاد للفأر IgM 488، 1:1000، إنفيتروجين A21042 (60 دقيقة) | AB_2235587AB_2147165; AB_1157897; AB_2535783; AB_2535809; AB_2535711 |

| ترسبات تحتوي على الأميلويد | ثيوفلافين تي (

|

غير متوفر | |

| الخلايا البطانية | CD31، IgG1 فأر، 1:50، Abcam ab9498 (حضانة طوال الليل) WGA 350، 1:25، TMO W11263 (30 دقيقة) | الأجسام المضادة من الماعز ضد IgG1 للفأر 647، 1:200، Invitrogen A21240 (60 دقيقة) | AB_726362 |

| الخلايا البطانية | UEA-1 البيوتينيل، 1:100، B-1065، مختبرات فيكتور (30 دقيقة) | مجموعة فيكتاستاين إيليت ABC PK-6100، مختبرات فيكتور (30 دقيقة)؛ مادة إيمباكت™ AMEC الحمراء لبيروكسيداز SK-4285، مختبرات فيكتور (10 دقائق) | AB_2336766 AB_2336819 AB_2336519 |

| الوعاء اللمفاوي | LYVE1، أرنب IgG، 1:50 Abcam 10278 (حضانة طوال الليل) WGA 350،

|

الأجسام المضادة للأرانب من الماعز IgG 647، 1:200، Invitrogen A32733 (60 دقيقة) | AB_881387 |

| بروتين الغلاف النووي لفيروس سارس-كوف-2 | أجسام مضادة لبروتين النوكليوكابسيد لـ SARS-CoV-2، أرانب PAb، منقى بواسطة تقارب المستضد، 1:500؛ SinoBiological (60 دقيقة) WGA 555، 1:25، TMO W32464 (30 دقيقة) | أليكسا فلور ماعز مضاد لأجسام الأرنب IgG 488 بنسبة 1:500، إنفيتروجين A27034 (60 دقيقة) | AB_2892769 |

| سي دي 3 | SP7 (أرنب موآب)، 1:200، ثيرمو ساينتيفيك Rm-9107-S | AB_149924 | |

| CD68 | PG-M1 IgG 3، 1:200، DAKO M0876 | AB_2074844 | |

| سي دي 20 | L26 IgG 2a، 1:1000، DAKO/M0755 | AB_2282030 |

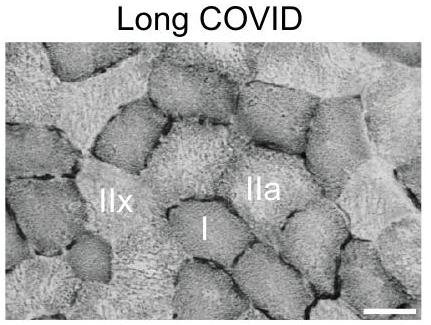

كفاءة التحكم في الفسفرة (

القسم. سمح هذا بالتمييز بين الألياف التي تعبر عن كل من MHC-I و MHC-IIa، و MHC-IIa فقط، وكل من MHC-IIx و MHC-IIa. ثانيًا، تم التعبير عن توزيع الألياف كنسبة مئوية من المساحة المقطعية التي تشغلها كل نوع من الألياف من إجمالي المساحة المقطعية لجميع الألياف. سمح هذا بقياس التضخم/الضمور الذي قد يحدث مع تعبير معين لـ MHC.

النسبة (C/F) وكثافة الشعيرات الدموية (CD) بعدد الشعيرات الدموية لكل

أحادي الفوسفات (5 نانومول)، الأدينوزين.

قياسات الدم الوريدي

| معامل | معدات | طريقة | حدود المرجع |

| الكورتيزول | روش كوباس C8000 | التحليل المناعي الكيميائي الضوئي الكهربائي “ECLIA” شركة روش للتشخيص |

|

| كرياتين كيناز | c702 روش دياغنوستيكس | نشط بواسطة NAC،

|

الذكور < 171 وحدة/لتر الإناث < 145 وحدة/لتر |

| كرياتين كيناز-إم بي | e602 روش دياغنوستيكس | تحليل مناعي ربطي ساندويتش معلم بالإنزيم من روش للتشخيص |

|

التحليل الإحصائي

ملخص التقرير

توفر البيانات

توفر الشفرة البرمجية

References

- Davis, H. E., Mccorkell, L., Vogel, J. M. & Topol, E. J. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 133-146 (2023).

- Hickie, I. et al. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. BMJ 333, 575-578 (2006).

- Ruiz-Pablos, M., Paiva, B., Montero-Mateo, R., Garcia, N. & Zabaleta, A. Epstein-Barr virus and the origin of myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome. Front. Immunol. 12, 4637 (2021).

- Ursinus, J. et al. Prevalence of persistent symptoms after treatment for lyme borreliosis: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 6, 100142 (2021).

- Herridge, M. S. & Azoulay, É. Outcomes after critical illness. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 913-924 (2023).

- Subramanian, A. et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat. Med. 28, 1706-1714 (2022).

- Kedor, C. et al. A prospective observational study of post-COVID-19 chronic fatigue syndrome following the first pandemic wave in Germany and biomarkers associated with symptom severity. Nat. Commun. 13, 1-13 (2022).

- Kerkhoff, T. J., Charlton, B. T., Appelman, B., van Vugt, M. & Wüst, R. C. I. Post COVID-19 condition: critical need for a clear definition and detailed pathophysiology. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13, 2754-2756 (2022).

- Chilunga, F. P. et al. Differences in incidence, nature of symptoms, and duration of long COVID among hospitalised migrant and nonmigrant patients in the Netherlands: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 29, 100630 (2023).

- Al-Aly, Z., Bowe, B. & Xie, Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 28, 1461-1467 (2022).

- Klein, J. et al. Distinguishing features of Long COVID identified through immune profiling. Nature 1-3 (2023) https://doi.org/10. 1038/s41586-023-06651-y.

- Hejbøl, E. K. et al. Myopathy as a cause of fatigue in long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms: evidence of skeletal muscle histopathology. Eur. J. Neurol. 29, 2832-2841 (2022).

- Pretorius, E. et al. Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20, 1-18 (2021).

- Muri, J. et al. Autoantibodies against chemokines post-SARS-CoV-2 infection correlate with disease course. Nat. Immunol. 1-8 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-023-01445-w.

- Wang, E. Y. et al. Diverse functional autoantibodies in patients with COVID-19. Nature 595, 283-288 (2021).

- Kruger, A. et al. Proteomics of fibrin amyloid microclots in long COVID/post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) shows many entrapped pro-inflammatory molecules that may also contribute to a failed fibrinolytic system. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 1-23 (2022).

- Guo, L. et al. Prolonged indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-2 activity and associated cellular stress in post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. EBioMedicine 94, 104729 (2023).

- Soares, M. N. et al. Skeletal muscle alterations in patients with acute Covid-19 and post-acute sequelae of Covid-19. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13, 11-22 (2022).

- World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID). https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition. (2023)

- Frésard, I. et al. Dysfunctional breathing diagnosed by cardiopulmonary exercise testing in ‘long COVID’ patients with persistent dyspnoea. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 9, e001126 (2022).

- Schwendinger, F., Knaier, R., Radtke, T. & Schmidt-Trucksäss, A. Low cardiorespiratory fitness post-COVID-19: a narrative review. Sports Med 53, 51-74 (2023).

- Skjørten, I. et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise capacity and limitations 3 months after COVID-19 hospitalisation. Eur. Respir. J. 58, 2100996 (2021).

- Singh, I. et al. Persistent exertional intolerance after COVID-19: insights from invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Chest 161, 54-63 (2022).

- Germain, A. et al. Plasma metabolomics reveals disrupted response and recovery following maximal exercise in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. JCI Insight 7, e157621 (2022).

- McGregor, N. R., Armstrong, C. W., Lewis, D. P. & Gooley, P. R. Postexertional malaise is associated with hypermetabolism, hypoacetylation and purine metabolism deregulation in ME/CFS cases. Diagnostics 9, 1-11 (2019).

- Missailidis, D. et al. An isolated complex V inefficiency and dysregulated mitochondrial function in immortalized lymphocytes from ME/CFS patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1074 (2020).

- Wüst, R. C. I. et al. The antibiotic doxycycline impairs cardiac mitochondrial and contractile function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 4100 (2021).

- Beloborodova, N. et al. Effect of phenolic acids of microbial origin on production of reactive oxygen species in mitochondria and neutrophils. J. Biomed. Sci. 19, 89 (2012).

- Pedley, A. M., Pareek, V. & Benkovic, S. J. The purinosome: a case study for a mammalian metabolon. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 91, 89-106 (2022).

- Kell, D. B., Laubscher, G. J. & Pretorius, E. A central role for amyloid fibrin microclots in long COVID/PASC: origins and therapeutic implications. Biochem. J. 479, 537-559 (2022).

- Charnley, M. et al. Neurotoxic amyloidogenic peptides in the proteome of SARS-COV2: potential implications for neurological symptoms in COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 13, 3387 (2022).

- Aschman, T. et al. Post-COVID exercise intolerance is associated with capillary alterations and immune dysregulations in skeletal muscles. acta neuropathol commun. 11, 193 (2023).

- Nakahira, K., Hisata, S. & Choi, A. M. K. The roles of mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns in diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 23, 1329 (2015).

- Grazioli, S. & Pugin, J. Mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns: from inflammatory signaling to human diseases. Front. Immunol. 9, 1 (2018).

- Frere, J. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters and humans results in lasting and unique systemic perturbations after recovery. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabq3059 (2022).

- Littlefield, K. M. et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells associate with inflammation and reduced lung function in pulmonary post-acute sequalae of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1010359 (2022).

- Iwasaki, A. & Putrino, D. Why we need a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of long COVID. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 393-395 (2023).

- de Boer, E. et al. Decreased fatty acid oxidation and altered lactate production during exercise in patients with post-acute COVID19 syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 205, 126-129 (2022).

- Colosio, M. et al. Structural and functional impairments of skeletal muscle in patients with postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Appl. Physiol. 135, 902-917 (2023).

- Posthuma, J. J., van der Meijden, P. E. J., ten Cate, H. & Spronk, H. M. H. Short- and long-term exercise induced alterations in haemostasis: a review of the literature. Blood Rev. 29, 171-178 (2015).

- Charfeddine, S. et al. Long COVID 19 syndrome: is it related to microcirculation and endothelial dysfunction? Insights from TUNEndCOV study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 745758 (2021).

- Turner, S. et al. Long COVID: pathophysiological factors and abnormalities of coagulation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 34, 321-344 (2023).

- Swank, Z. et al. Persistent circulating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike is associated with post-acute coronavirus disease 2019 sequelae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, e487-e490 (2023).

- Aschman, T. et al. Association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and immune-mediated myopathy in patients who have died. JAMA Neurol. 78, 948-960 (2021).

- Mageriu, V., Zurac, S., Bastian, A., Staniceanu, F. & Manole, E. Histological findings in skeletal muscle of SARS-CoV2 infected patient. J. Immunoass. Immunochem. 41, 1000-1009 (2020).

- Patterson, B. K. et al. Persistence of SARS CoV-2 S1 protein in CD16+ monocytes in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) up to 15 months post-infection. Front. Immunol. 12, 5526 (2022).

- Buonsenso, D. et al. Viral persistence in children infected with SARS-CoV-2: current evidence and future research strategies. Lancet Microbe 4, e745-e756 (2023).

- Appelman, B. et al. Time since SARS-CoV-2 infection and humoral immune response following BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination. EBioMedicine 72, 103561 (2021).

- Wang, Z. et al. Naturally enhanced neutralizing breadth against SARS-CoV-2 one year after infection. Nature 595, 426-431 (2021).

- Gallais, F. et al. Evolution of antibody responses up to 13 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection and risk of reinfection. EBioMedicine 71, 103561 (2021).

- Hendrickse, P. W. et al. Capillary rarefaction during bed rest is proportionally less than fibre atrophy and loss of oxidative capacity. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13, 2712-2723 (2022).

- Agergaard, J. et al. Myopathy as a cause of Long COVID fatigue: evidence from quantitative and single fiber EMG and muscle histopathology. Clin. Neurophysiol. 148, 65-75 (2023).

- Pizzuto, D. A. et al. Lung perfusion assessment in children with longCOVID: a pilot study. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 58, 2059-2067 (2023).

- Cotler, J., Holtzman, C., Dudun, C. & Jason, L. A. A brief questionnaire to assess post-exertional malaise. Diagnostics 8, 66 (2018).

- Krupp, L. B., Alvarez, L. A., Larocca, N. G. & Scheinberg, L. C. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 45, 435-437 (1988).

- Smets, E. M. A., Garssen, B., Bonke, B. & De Haes, J. C. J. M. The multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J. Psychosom. Res. 39, 315-325 (1995).

- Clevenger, K. A. et al. Effect of sampling rate on acceleration and counts of hip- and wrist-worn ActiGraph accelerometers in children. Physiol. Meas. 40, 095008 (2019).

- Gnaiger E. (2020) Mitochondrial pathways and respiratory control. An introduction to OXPHOS analysis. 5th ed. Bioenerg Commun 2:112 (2020).

- Gnaiger, E. Capacity of oxidative phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle: new perspectives of mitochondrial physiology. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41, 1837-1845 (2009).

- Gnaiger, E. et al. Mitochondrial coupling and capacity of oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle of Inuit and Caucasians in the arctic winter. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 25, 126-134 (2015).

- Horwath, O. et al. Variability in vastus lateralis fiber type distribution, fiber size, and myonuclear content along and between the legs. J. Appl. Physiol. 131, 158-173 (2021).

- Wüst, R. C. I. et al. Region-specific adaptations in determinants of rat skeletal muscle oxygenation to chronic hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H364-74 (2009).

- Van Der Zwaard, S. et al. Critical determinants of combined sprint and endurance performance: an integrative analysis from muscle fiber to the human body. FASEB J. 32, 2110-2123 (2018).

- Grootemaat, A. E. et al. Lipid and nucleocapsid N-protein accumulation in COVID-19 patient lung and infected cells. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0127121 (2022).

- Schomakers, B. V. et al. Polar metabolomics in human muscle biopsies using a liquid-liquid extraction and full-scan LC-MS. STAR Protoc. 3, 101302 (2022).

- Daimon, T. Box-Cox transformation. Int. Encycl. Stat. Sci. 1, 176-1781 (2011).

- Diedenhofen, B. & Musch, J. cocor: a comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PLoS ONE 10, e0121945 (2015).

- Searle, S. R., Speed, F. M. & Milliken, G. A. Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means [

package emmeans version 1.8.5]. Am. Stat. 34, 216-221 (2023). - Hedges, L. V. Distribution Theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 6, 107-128 (1981).

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

قاموا بمراجعة المخطوطة بشكل جوهري. لقد قدم كل من F.B.، M.v.W.، B.S.، P.C.، J.P.، E.A.، وW.J.W. مساهمات كبيرة في التصور، التصميم، تحليل البيانات، صياغة ومراجعة المخطوطة. جميع المؤلفين قد وافقوا على النسخة المقدمة ويوافقون على تحمل المسؤولية الشخصية عن مساهماتهم الخاصة وضمان التحقيق المناسب في الأسئلة المتعلقة بدقة أو نزاهة أي جزء من العمل، حتى تلك التي لم يشارك فيها المؤلف شخصيًا، وحلها وتوثيق الحل في الأدبيات.

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

المواد التكميلية متاحة على

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44432-3.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© المؤلف(ون) 2024

موقع مستشفى أمستردام الجامعي، جامعة أمستردام، مركز الطب التجريبي والجزيئي، ميبرجدريف 9، أمستردام، هولندا. معهد أمستردام للعدوى والمناعة، الأمراض المعدية، أمستردام، هولندا. قسم علوم حركة الإنسان، كلية العلوم السلوكية وعلوم الحركة، جامعة فريجيه أمستردام، أمستردام، هولندا. علوم الحركة بأمستردام، أمستردام، هولندا. قسم الفسيولوجيا، مركز أمستردام الطبي الجامعي، فرع جامعة فريه أمستردام، دي بولان 1117، أمستردام، هولندا. علوم القلب والأوعية الدموية في أمستردام، أمستردام، هولندا. قسم جراحة الصدمات، مركز أمستردام الطبي الجامعي، جامعة أمستردام، ميبيرجدريف 9، أمستردام، هولندا. مختبر الأمراض الوراثية الأيضية، مرفق التحليل الأيضي الأساسي، مستشفى أمستردام الجامعي، فرع جامعة أمستردام، ميبيرجدريف 9، أمستردام، هولندا. خدمة الأعصاب، قسم علوم الأعصاب والصحة النفسية، مستشفى سانتا ماريا، CHULN، لشبونة، البرتغال. كلية الطب، مركز دراسات إيجاس مونيز، جامعة لشبونة، لشبونة، البرتغال. قسم (علم الأمراض العصبي)، علوم الأعصاب بأمستردام، مركز أمستردام الطبي الجامعي، موقع جامعة أمستردام، ميبيرجدريف 9، أمستردام، هولندا. مستشفى فليفوزيكنهوس، قسم الجراحة، طريق المستشفى 1، ألميري، هولندا. قسم الأمراض المعدية، قسم الطب الباطني، مركز أمستردام الطبي الجامعي، موقع جامعة أمستردام، ميبرجدريف 9، أمستردام، هولندا. قسم الأمراض المعدية، الطب الاستوائي، قسم الطب، مركز أمستردام الطبي الجامعي، فرع جامعة أمستردام، ميبرجدريف 9، أمستردام، هولندا. ساهم هؤلاء المؤلفون بالتساوي: برنت أبلمان، بريدن تي. تشارلتون، ميشيل فان فوجت، روب سي. آي. فوست. البريد الإلكتروني:m.vanvugt@amsterdamumc.nl; r.wust@vu.nl  الوسيط مع المدى الربيعي.

الوسيط مع المدى الربيعي.

-لم يتم تصحيح القيم الاحتمالية للاختبارات المتعددة. تم توفير بيانات المصدر في ملف بيانات المصدر.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44432-3

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38177128

Publication Date: 2024-01-04

Muscle abnormalities worsen after postexertional malaise in long COVID

Accepted: 13 December 2023

Published online: 04 January 2024

(i) Check for updates

Abstract

Brent Appelman ©

Abstract

A subgroup of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 remain symptomatic over three months after infection. A distinctive symptom of patients with long COVID is post-exertional malaise, which is associated with a worsening of fatigue- and pain-related symptoms after acute mental or physical exercise, but its underlying pathophysiology is unclear. With this longitudinal casecontrol study (NCT05225688), we provide new insights into the pathophysiology of post-exertional malaise in patients with long COVID. We show that skeletal muscle structure is associated with a lower exercise capacity in patients, and local and systemic metabolic disturbances, severe exerciseinduced myopathy and tissue infiltration of amyloid-containing deposits in skeletal muscles of patients with long COVID worsen after induction of postexertional malaise. This study highlights novel pathways that help to understand the pathophysiology of post-exertional malaise in patients suffering from long COVID and other post-infectious diseases.

exertional malaise, representing the worsening of symptoms after mental or physical exertion

Results

Limited exercise capacity in long COVID

muscle impairments in patients. The lower

Metabolic dysfunction and post-exertional malaise

| Healthy controls | Long COVID |

|

|

| Number of participants | 21 | 25 | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 42 (10) | 41 (11) | 0.82 |

| Sex, male (%) | 10 (47.6) | 12 (48.0) | >0.99 |

| BMI, mean (SD),

|

24.14 (3.37) | 25.60 (4.62) | 0.24 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, median [IQR] | O [0, 0] | O [0,1] | 0.76 |

| Hospitalization for COVID-19 | 0 (0) | (0) | >0.99 |

| SARS-CoV-2 vaccination before participation (%) | 21 (100) | 24 (96.0) | >0.99 |

| Weekly working hours before initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, median [IQR] | 36 [32, 40] | 36 [32, 45] | 0.520 |

| Weekly working hours during the study, median [IQR] | 36 [32, 40] | 5 [0,12] | <0.001 |

| Time since initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, median [IQR], days | 142 [105, 405] | 545 [455, 686] | 0.001 |

| Time since latest SARS-CoV-2 infection, median [IQR], days | 135 [93, 197] | 504 [329, 665] | 0.002 |

of post-exertional malaise

capacity in patients. We also observed lower S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) in patients, possibly linking to reduced methylation and SAM cycle activity in long COVID patients. Dihydroxyacetone phosphate, an important intermediate in lipid biosynthesis and glycolysis was reduced in patient skeletal muscle following post-exertional malaise (Fig. 3D). The lower hydroxyphenyl acetic acid in patients is typically associated with increased mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species (Supplemental Fig. 6A, B)

baseline and during post-exertional malaise but decreased one week after the induction of post-exertional malaise.

Exercise-induced amyloid-containing deposit accumulation in skeletal muscle

suggesting that these deposits are located outside infiltrating (immune) cells. We conclude that amyloid-containing deposits are not present within capillaries. Neither did we observe any signs of skeletal muscle tissue hypoxia, as the skeletal muscle capillary-to-fiber ratio, capillary density (Fig. 2B), and intracellular and circulating lactate concentrations (Supplemental Figs. 3G, 6A) were not different between long COVID patients and controls. Therefore, we conclude that post-exertional malaise cannot be explained by the hypothesis that these deposits block vessel perfusion, causing local tissue hypoxia

Exercise-induced myopathy in long COVID

|

|

conclude that severe exercise-induced muscle damage and subsequent regeneration are associated with the pathophysiology of postexertional malaise, and can possibly explain muscle pain, fatigue, and weakness in patients with long COVID experiencing post-exertional malaise.

lower reliance on oxidative metabolism in patients with long COVID (

| Symptoms | Baseline

|

1 day after induction of post-exertional malaise

|

1 week after induction of postexertional malaise

|

|

| Fatigue | 25 (100.0) | 25 (100.0) | 24 (96.0) | 0.36 |

| Self-reported fatigue severity intensity (1-10), median [IQR] | 6.00 [4.00, 7.00] | 7.00 [7.00, 8.00] | 7.00 [6.00, 7.25] | 0.001 |

| Cognitive problems | 20 (80.0) | 21 (84.0) | 23 (92.0) | 0.47 |

| Self-reported cognitive severity intensity (1-10), median [IQR] | 4.00 [3.00, 6.25] | 6.00 [5.00, 8.00] | 6.00 [4.00, 7.00] | 0.06 |

| Muscle or joint pain | 16 (64.0) | 20 (80.0) | 15 (60.0) | 0.276 |

| Chest pain | 8 (32.0) | 11 (44.0) | 8 (32.0) | 0.59 |

| Dyspnea | 6 (24.0) | 4 (16.0) | 7 (28.0) | 0.59 |

| Anosmia | 3 (12.0) | 3 (12.0) | 3 (12.0) | >0.99 |

| Sore throat | 2 (8.0) | 5 (20.0) | 3 (12.0) | 0.45 |

| Cold-like symptoms | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (8.0) | 0.35 |

| Cough | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) | 1 (4.0) | 0.60 |

median with interquartile range. p-values were not corrected for multiple testing. Source data are provided in the Source Data File.

median with interquartile range. p-values were not corrected for multiple testing. Source data are provided in the Source Data File.SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid presence in skeletal muscle

a role, then the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein, which is specific to SARS-CoV-2 and not influenced by vaccinations, should be at least present. While we did not observe any positive staining in samples obtained before the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 6A, B), we found SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein in almost all patients and healthy controls (Fig. 6A, B). Despite a greater duration since the latest infection in long COVID patients, the amount of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein was not different between groups (Fig. 6A), before and after adjusting for time since the latest infection. Participants with an infection >6 months prior to study enrollment showed no differences in the abundance of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein, but we cannot exclude additional unknown asymptomatic infections. The SARS-CoV2 nucleocapsid protein was not located inside muscle fibers, but rather in the extracellular matrix, however, its presence did not consistently overlap with cell nuclei. There was no correlation between the presence of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein and amyloid-containing deposits (

Discussion

cohort design. Patients with long COVID displayed a markedly lower exercise capacity, which related to skeletal muscle metabolic alterations and a shift towards more fast-fatigable fibers. The pathophysiology of post-exertional malaise includes an acute exercise-induced reduction in skeletal muscle mitochondrial enzyme activity, an increased accumulation of amyloid-containing deposits in skeletal muscle, signs of severe muscle tissue damage, together with a blunted exercise-induced T-cell response in skeletal muscle. Collectively, these findings help to decipher the underlying physiology of fatigue and a limited exercise capacity from the development of post-exertional malaise in patients with long COVID.

composition, and mitochondrial enzyme activity, but despite this large heterogeneity, all patients experienced post-exertional malaise one day after the exercise test. As such, we conclude that the pathophysiology of fatigue and a reduced exercise capacity is distinct from the rapid development of post-exertional malaise in long COVID patients. The development of post-exertional malaise could in turn, however, lead to a further reduction in exercise capacity in patients, as the acute reduction in mitochondrial SDH activity, occurrence of tissue necrosis, and possibly intramuscular accumulation of amyloid-containing deposits could worsen skeletal muscle metabolism and force production over time, causing a vicious downward circle.

fibers, and focal necrosis after induction of post-exertional malaise compared to healthy controls. Skeletal muscle atrophy and focal necrosis can occur during severe acute SARS-CoV-2 infection

(Time:

exertional malaise. Furthermore, we did not observe more B-cell infiltration in the skeletal muscle of patients before and during postexertional malaise. The mere presence of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein in skeletal muscle is unsurprising, as nucleocapsid protein can be present up to a year after infection in blood

pathophysiology is similar in all patient populations, including children and adolescents

Methods

Study population

Study design

Incremental ramp exercise test

myoglobin], as well as muscle saturation (

Daily life physical activity level

Skeletal muscle measurements

| Parameter | Antibody, dilution, vendor | Secondary antibody (dilution), vendor | RRID |

| Muscle fiber type | BA-D5 (MHC-I),

|

Goat-anti-mouse IgG2b 555, 1:1000, Invitrogen A21147; Goat anti-mouse IgG1 647, 1:1000, Invitrogen A21240; Goat anti-mouse IgM 488, 1:1000, Invitrogen A21042 (60 min) | AB_2235587AB_2147165; AB_1157897; AB_2535783; AB_2535809; AB_2535711 |

| Amyloidcontaining deposits | Thioflavin T (

|

N.A. | |

| Endothelial cells | CD31, IgG1 mouse, 1:50, Abcam ab9498 (overnight incubation) WGA 350, 1:25, TMO W11263 ( 30 min ) | Goat anti-mouse IgG1 647, 1:200, Invitrogen A21240 ( 60 min ) | AB_726362 |

| Endothelial cells | Biotinylated UEA-1, 1:100, B-1065, Vector Laboratories ( 30 min ) | Vectastain Elite ABC Kit PK-6100, Vector Laboratories ( 30 min ); ImmPACT™ AMEC Red Peroxidase Substrate SK-4285, Vector Laboratories ( 10 min ) | AB_2336766 AB_2336819 AB_2336519 |

| Lymphatic vessel | LYVE1, IgG rabbit, 1:50 Abcam 10278 (overnight incubation) WGA 350,

|

Goat anti-rabbit IgG 647, 1:200, Invitrogen A32733 ( 60 min ) | AB_881387 |

| SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein | SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Antibody, Rabbit PAb, Antigen Affinity Purified, 1:500; SinoBiological ( 60 min ) WGA 555, 1:25, TMO W32464 ( 30 min ) | Alexa fluor goat-anti rabbit IgG 488 1:500, Invitrogen A27034 (60 min) | AB_2892769 |

| CD3 | SP7 (rabbit moab), 1:200, Thermo Sc. Rm-9107-S | AB_149924 | |

| CD68 | PG-M1 IgG 3, 1:200, DAKO M0876 | AB_2074844 | |

| CD20 | L26 IgG 2a, 1:1000,DAKO/M0755 | AB_2282030 |

phosphorylation control efficiency (

section. This allowed for differentiation between fibers expressing both MHC-I and MHC-IIa, MHC-IIa only, and both MHC-IIx and MHC-Ila. Second, fiber distribution was expressed as the cross-sectional area occupied by each fiber type as a percentage of the cross-sectional area of all fibers. This allowed for quantification of hypertrophy/atrophy that may be occurring with particular MHC expression.

ratio (C/F) and capillary density (CD) by capillaries per

monophosphate ( 5 nmol ), adenosine.

Venous blood measurements

| Parameter | Equipment | Method | Reference limits |

| Cortisol | Roche cobas C8000 | Electro- chemiluminescence immunoassay “ECLIA” Roche Diagnostics |

|

| Creatine kinase | c702 Roche diagnostics | NAC-activated,

|

Male < 171 U/L Female < 145 U/L |

| Creatine kinase-MB | e602 Roche Diagnostics | Enzyme-labeled sandwich immunoassay Roche Diagnostics |

|

Statistical analysis

Reporting summary

Data availability

Code availability

References

- Davis, H. E., Mccorkell, L., Vogel, J. M. & Topol, E. J. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 133-146 (2023).

- Hickie, I. et al. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: prospective cohort study. BMJ 333, 575-578 (2006).

- Ruiz-Pablos, M., Paiva, B., Montero-Mateo, R., Garcia, N. & Zabaleta, A. Epstein-Barr virus and the origin of myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome. Front. Immunol. 12, 4637 (2021).

- Ursinus, J. et al. Prevalence of persistent symptoms after treatment for lyme borreliosis: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 6, 100142 (2021).

- Herridge, M. S. & Azoulay, É. Outcomes after critical illness. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 913-924 (2023).

- Subramanian, A. et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat. Med. 28, 1706-1714 (2022).

- Kedor, C. et al. A prospective observational study of post-COVID-19 chronic fatigue syndrome following the first pandemic wave in Germany and biomarkers associated with symptom severity. Nat. Commun. 13, 1-13 (2022).

- Kerkhoff, T. J., Charlton, B. T., Appelman, B., van Vugt, M. & Wüst, R. C. I. Post COVID-19 condition: critical need for a clear definition and detailed pathophysiology. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13, 2754-2756 (2022).

- Chilunga, F. P. et al. Differences in incidence, nature of symptoms, and duration of long COVID among hospitalised migrant and nonmigrant patients in the Netherlands: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 29, 100630 (2023).

- Al-Aly, Z., Bowe, B. & Xie, Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 28, 1461-1467 (2022).

- Klein, J. et al. Distinguishing features of Long COVID identified through immune profiling. Nature 1-3 (2023) https://doi.org/10. 1038/s41586-023-06651-y.

- Hejbøl, E. K. et al. Myopathy as a cause of fatigue in long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms: evidence of skeletal muscle histopathology. Eur. J. Neurol. 29, 2832-2841 (2022).

- Pretorius, E. et al. Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20, 1-18 (2021).

- Muri, J. et al. Autoantibodies against chemokines post-SARS-CoV-2 infection correlate with disease course. Nat. Immunol. 1-8 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-023-01445-w.

- Wang, E. Y. et al. Diverse functional autoantibodies in patients with COVID-19. Nature 595, 283-288 (2021).

- Kruger, A. et al. Proteomics of fibrin amyloid microclots in long COVID/post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) shows many entrapped pro-inflammatory molecules that may also contribute to a failed fibrinolytic system. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 1-23 (2022).

- Guo, L. et al. Prolonged indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-2 activity and associated cellular stress in post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. EBioMedicine 94, 104729 (2023).

- Soares, M. N. et al. Skeletal muscle alterations in patients with acute Covid-19 and post-acute sequelae of Covid-19. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13, 11-22 (2022).

- World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID). https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition. (2023)

- Frésard, I. et al. Dysfunctional breathing diagnosed by cardiopulmonary exercise testing in ‘long COVID’ patients with persistent dyspnoea. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 9, e001126 (2022).

- Schwendinger, F., Knaier, R., Radtke, T. & Schmidt-Trucksäss, A. Low cardiorespiratory fitness post-COVID-19: a narrative review. Sports Med 53, 51-74 (2023).

- Skjørten, I. et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise capacity and limitations 3 months after COVID-19 hospitalisation. Eur. Respir. J. 58, 2100996 (2021).

- Singh, I. et al. Persistent exertional intolerance after COVID-19: insights from invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Chest 161, 54-63 (2022).

- Germain, A. et al. Plasma metabolomics reveals disrupted response and recovery following maximal exercise in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. JCI Insight 7, e157621 (2022).

- McGregor, N. R., Armstrong, C. W., Lewis, D. P. & Gooley, P. R. Postexertional malaise is associated with hypermetabolism, hypoacetylation and purine metabolism deregulation in ME/CFS cases. Diagnostics 9, 1-11 (2019).

- Missailidis, D. et al. An isolated complex V inefficiency and dysregulated mitochondrial function in immortalized lymphocytes from ME/CFS patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1074 (2020).

- Wüst, R. C. I. et al. The antibiotic doxycycline impairs cardiac mitochondrial and contractile function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 4100 (2021).

- Beloborodova, N. et al. Effect of phenolic acids of microbial origin on production of reactive oxygen species in mitochondria and neutrophils. J. Biomed. Sci. 19, 89 (2012).

- Pedley, A. M., Pareek, V. & Benkovic, S. J. The purinosome: a case study for a mammalian metabolon. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 91, 89-106 (2022).

- Kell, D. B., Laubscher, G. J. & Pretorius, E. A central role for amyloid fibrin microclots in long COVID/PASC: origins and therapeutic implications. Biochem. J. 479, 537-559 (2022).

- Charnley, M. et al. Neurotoxic amyloidogenic peptides in the proteome of SARS-COV2: potential implications for neurological symptoms in COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 13, 3387 (2022).

- Aschman, T. et al. Post-COVID exercise intolerance is associated with capillary alterations and immune dysregulations in skeletal muscles. acta neuropathol commun. 11, 193 (2023).

- Nakahira, K., Hisata, S. & Choi, A. M. K. The roles of mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns in diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 23, 1329 (2015).

- Grazioli, S. & Pugin, J. Mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns: from inflammatory signaling to human diseases. Front. Immunol. 9, 1 (2018).

- Frere, J. J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters and humans results in lasting and unique systemic perturbations after recovery. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabq3059 (2022).

- Littlefield, K. M. et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells associate with inflammation and reduced lung function in pulmonary post-acute sequalae of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1010359 (2022).

- Iwasaki, A. & Putrino, D. Why we need a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of long COVID. Lancet Infect. Dis. 23, 393-395 (2023).

- de Boer, E. et al. Decreased fatty acid oxidation and altered lactate production during exercise in patients with post-acute COVID19 syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 205, 126-129 (2022).

- Colosio, M. et al. Structural and functional impairments of skeletal muscle in patients with postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Appl. Physiol. 135, 902-917 (2023).

- Posthuma, J. J., van der Meijden, P. E. J., ten Cate, H. & Spronk, H. M. H. Short- and long-term exercise induced alterations in haemostasis: a review of the literature. Blood Rev. 29, 171-178 (2015).

- Charfeddine, S. et al. Long COVID 19 syndrome: is it related to microcirculation and endothelial dysfunction? Insights from TUNEndCOV study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 745758 (2021).

- Turner, S. et al. Long COVID: pathophysiological factors and abnormalities of coagulation. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 34, 321-344 (2023).

- Swank, Z. et al. Persistent circulating severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 spike is associated with post-acute coronavirus disease 2019 sequelae. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, e487-e490 (2023).

- Aschman, T. et al. Association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and immune-mediated myopathy in patients who have died. JAMA Neurol. 78, 948-960 (2021).

- Mageriu, V., Zurac, S., Bastian, A., Staniceanu, F. & Manole, E. Histological findings in skeletal muscle of SARS-CoV2 infected patient. J. Immunoass. Immunochem. 41, 1000-1009 (2020).

- Patterson, B. K. et al. Persistence of SARS CoV-2 S1 protein in CD16+ monocytes in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) up to 15 months post-infection. Front. Immunol. 12, 5526 (2022).

- Buonsenso, D. et al. Viral persistence in children infected with SARS-CoV-2: current evidence and future research strategies. Lancet Microbe 4, e745-e756 (2023).

- Appelman, B. et al. Time since SARS-CoV-2 infection and humoral immune response following BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination. EBioMedicine 72, 103561 (2021).

- Wang, Z. et al. Naturally enhanced neutralizing breadth against SARS-CoV-2 one year after infection. Nature 595, 426-431 (2021).

- Gallais, F. et al. Evolution of antibody responses up to 13 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection and risk of reinfection. EBioMedicine 71, 103561 (2021).

- Hendrickse, P. W. et al. Capillary rarefaction during bed rest is proportionally less than fibre atrophy and loss of oxidative capacity. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13, 2712-2723 (2022).

- Agergaard, J. et al. Myopathy as a cause of Long COVID fatigue: evidence from quantitative and single fiber EMG and muscle histopathology. Clin. Neurophysiol. 148, 65-75 (2023).

- Pizzuto, D. A. et al. Lung perfusion assessment in children with longCOVID: a pilot study. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 58, 2059-2067 (2023).

- Cotler, J., Holtzman, C., Dudun, C. & Jason, L. A. A brief questionnaire to assess post-exertional malaise. Diagnostics 8, 66 (2018).

- Krupp, L. B., Alvarez, L. A., Larocca, N. G. & Scheinberg, L. C. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 45, 435-437 (1988).

- Smets, E. M. A., Garssen, B., Bonke, B. & De Haes, J. C. J. M. The multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J. Psychosom. Res. 39, 315-325 (1995).

- Clevenger, K. A. et al. Effect of sampling rate on acceleration and counts of hip- and wrist-worn ActiGraph accelerometers in children. Physiol. Meas. 40, 095008 (2019).

- Gnaiger E. (2020) Mitochondrial pathways and respiratory control. An introduction to OXPHOS analysis. 5th ed. Bioenerg Commun 2:112 (2020).

- Gnaiger, E. Capacity of oxidative phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle: new perspectives of mitochondrial physiology. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 41, 1837-1845 (2009).

- Gnaiger, E. et al. Mitochondrial coupling and capacity of oxidative phosphorylation in skeletal muscle of Inuit and Caucasians in the arctic winter. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 25, 126-134 (2015).

- Horwath, O. et al. Variability in vastus lateralis fiber type distribution, fiber size, and myonuclear content along and between the legs. J. Appl. Physiol. 131, 158-173 (2021).

- Wüst, R. C. I. et al. Region-specific adaptations in determinants of rat skeletal muscle oxygenation to chronic hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 297, H364-74 (2009).

- Van Der Zwaard, S. et al. Critical determinants of combined sprint and endurance performance: an integrative analysis from muscle fiber to the human body. FASEB J. 32, 2110-2123 (2018).

- Grootemaat, A. E. et al. Lipid and nucleocapsid N-protein accumulation in COVID-19 patient lung and infected cells. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0127121 (2022).

- Schomakers, B. V. et al. Polar metabolomics in human muscle biopsies using a liquid-liquid extraction and full-scan LC-MS. STAR Protoc. 3, 101302 (2022).

- Daimon, T. Box-Cox transformation. Int. Encycl. Stat. Sci. 1, 176-1781 (2011).

- Diedenhofen, B. & Musch, J. cocor: a comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PLoS ONE 10, e0121945 (2015).

- Searle, S. R., Speed, F. M. & Milliken, G. A. Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means [

package emmeans version 1.8.5]. Am. Stat. 34, 216-221 (2023). - Hedges, L. V. Distribution Theory for Glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 6, 107-128 (1981).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

substantially revised the manuscript. F.B., M.v.W., B.S., P.C., J.P., E.A., and W.J.W. have made substantial contributions to the conception, design, analysis of the data, drafting, and revision of the manuscript. All authors have approved the submitted version and agree to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Competing interests

Additional information

supplementary material available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-44432-3.

http://www.nature.com/reprints

© The Author(s) 2024

Amsterdam UMC location University of Amsterdam, Center for Experimental and Molecular Medicine, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Amsterdam Institute for Infection and Immunity, Infectious diseases, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Department of Human Movement Sciences, Faculty of Behavioral and Movement Sciences, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Amsterdam Movement Sciences, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Department of Physiology, Amsterdam UMC location Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1117, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Amsterdam Cardiovascular Sciences, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Department of Trauma Surgery, Amsterdam UMC location University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Laboratory Genetic Metabolic Diseases, Core Facility Metabolomics, Amsterdam UMC location University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Serviço de Neurologia, Departamento de Neurociências e Saúde Mental, Hospital de Santa Maria, CHULN, Lisbon, Portugal. Faculdade de Medicina, Centro de Estudos Egas Moniz, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal. Department of (Neuro)pathology, Amsterdam Neuroscience, Amsterdam UMC location University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Flevoziekenhuis, Division of Surgery, Hospitaalweg 1, Almere, the Netherlands. Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Amsterdam UMC location University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Division of Infectious Diseases, Tropical Medicine, Department of Medicine, Amsterdam UMC location University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. These authors contributed equally: Brent Appelman, Braeden T. Charlton, Michèle van Vugt, Rob C. I. Wüst. e-mail: m.vanvugt@amsterdamumc.nl; r.wust@vu.nl  a median with an interquartile range.

a median with an interquartile range.

-values were not corrected for multiple testing. Source data are provided in the Source Data File.