DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.04.015

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38723627

تاريخ النشر: 2024-05-01

خلية

التسلل الورمي اليومي ووظيفة CD8

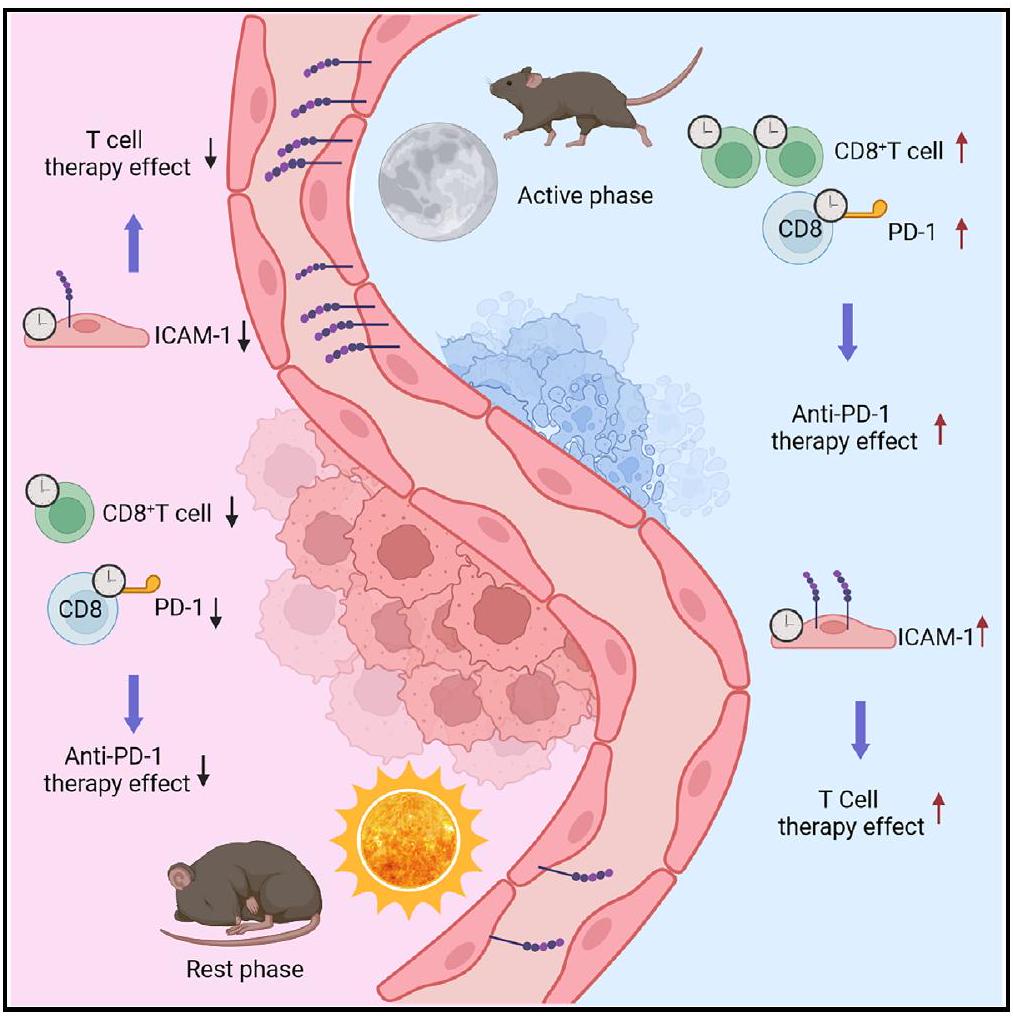

ملخص رسومي

أهم النقاط

تغلغل الأورام الإيقاعي لخلايا T يعتمد على الساعة البيولوجية الوعائية

تعديل وقت الحقن خلال اليوم يحسن فعالية علاج خلايا CAR T

تحسين السيطرة على الورم بواسطة العلاج المضاد لـ PD-1 في الوقت المناسب يعتمد على نشاط خلايا T الدائرية

المؤلفون

المراسلات

باختصار

تسلل الأورام الدائري ووظيفة خلايا CD8+ T تحدد فعالية العلاج المناعي

الملخص

الملخص جودة وكمية اللمفاويات المتسللة إلى الورم، وخاصة

مقدمة

التي تم تعديلها وراثيًا للتعرف على خلايا الورم.

من اليوم.

النتائج

تظهر تسرب الكريات البيضاء إلى الأورام تذبذبات يومية

تتحكم خلايا البطانة في تسرب الكريات البيضاء الدائرية

(أ) الأعداد الكلية المعيارية لكريات الدم البيضاء المتسللة إلى الورم في ورم B16-F10-OVA، التي تم جمعها في 4 أوقات مختلفة من اليوم (وقت الزايتgeber [ZT])؛

(ب) التصوير (يسار) والتquantification (يمين) لـ CD4

(C) أعداد الكريات البيضاء المتسللة إلى الورم في Tyr::CreERT2، BRaf

(د) الأعداد الكلية المعنوية لكريات الدم البيضاء المتسللة إلى الورم في ورم B16-F10-OVA، التي تم جمعها في أوقات مختلفة من اليوم تحت ظروف ظلام دائم (الوقت اليومي [CT])؛

جدول زمني خفيف من الضوء:الظلام (LD)، والظلام:الضوء المعكوس (DL)، وظروف اضطراب الساعة البيولوجية (JL). تشير المناطق المظللة إلى مراحل الظلام، وتدل الأرقام على أوقات الحصاد.

(F) أعداد الكريات البيضاء المتسللة إلى الورم في ورم B16-F10-OVA، التي تم جمعها في النقاط الزمنية المحددة (1 أو 13 ساعة في E) بعد بدء الدورة تحت الضوء: الظلام (LD،

(أ) الأعداد الكلية المعيارية لكريات الدم البيضاء المتسللة إلى الورم في نموذج B16-F10-OVA، التي تم جمعها في ZT1 أو ZT13، بعد 24 ساعة من علاج الأجسام المضادة للتحكم في النمط أو الأجسام المضادة المضادة لـ LFA-1؛

(ب) استراتيجية البوابة وقياس الخلايا المنقولة بالتبني في أورام B16-F10-OVA بعد ساعتين من الحقن الوريدي عند ZT1 أو ZT13؛

(ج) التصوير (يسار) والتquantification (يمين) للتعبير عن ICAM-1 على CD31

(د) أعداد الكريات البيضاء في أورام B16-F10-OVA، التي تم جمعها في ZT1 أو ZT13 من مجموعة التحكم أو Bmal1

الأعداد المعيارية لكريات الدم البيضاء المنقولة بالتبني التي تم جمعها من أورام B16-F10-OVA بعد ساعتين من الحقن الوريدي في ZT1 أو ZT13 إلى مجموعة التحكم من نفس السلالة أو Bmal1

الأعداد المعيارية للخلايا المنقولة بالتبني OT-I في أورام B16-F10-OVA بعد ساعتين من الحقن في ZT1 أو ZT13؛

حجم الورم بعد الحقن الوريدي بـ

(H) حجم الورم بعد الحقن الوريدي لـ

حجم الورم بعد الحقن الوريدي بـ

(ج) عدد خلايا CAR T في أورام DoHH2 بعد 24 ساعة من الحقن الوريدي في ZT1 (

وبذلك تم التركيز على خلايا البطانة كوسائط محتملة لاختراق الكريات البيضاء الدائرية وزرع الأورام في حيوانات تظهر نقصًا قابلًا للتحفيز، محدد النسب، في الجين الدائري.

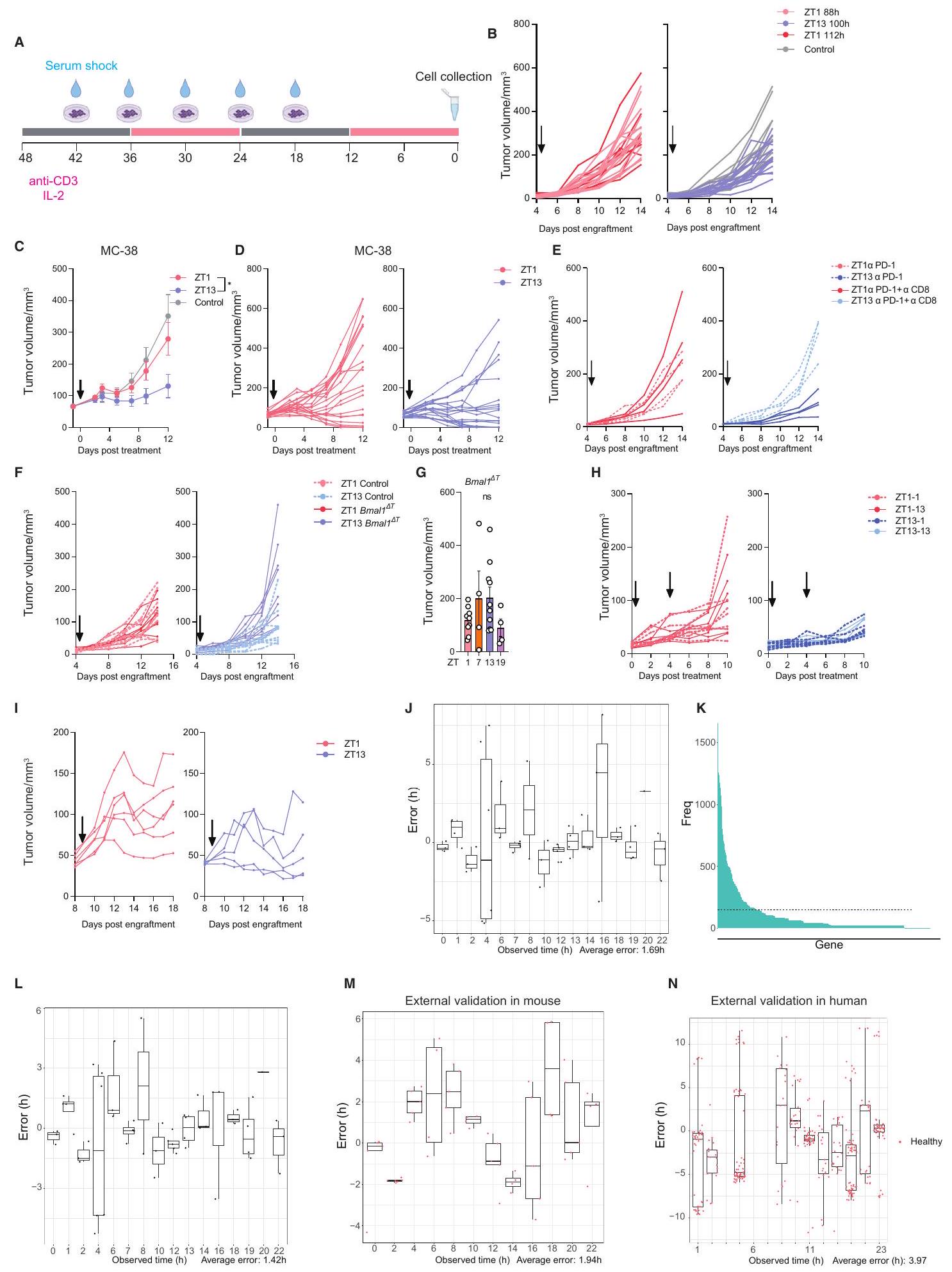

فعالية علاج خلايا CAR T تعتمد على وقت اليوم

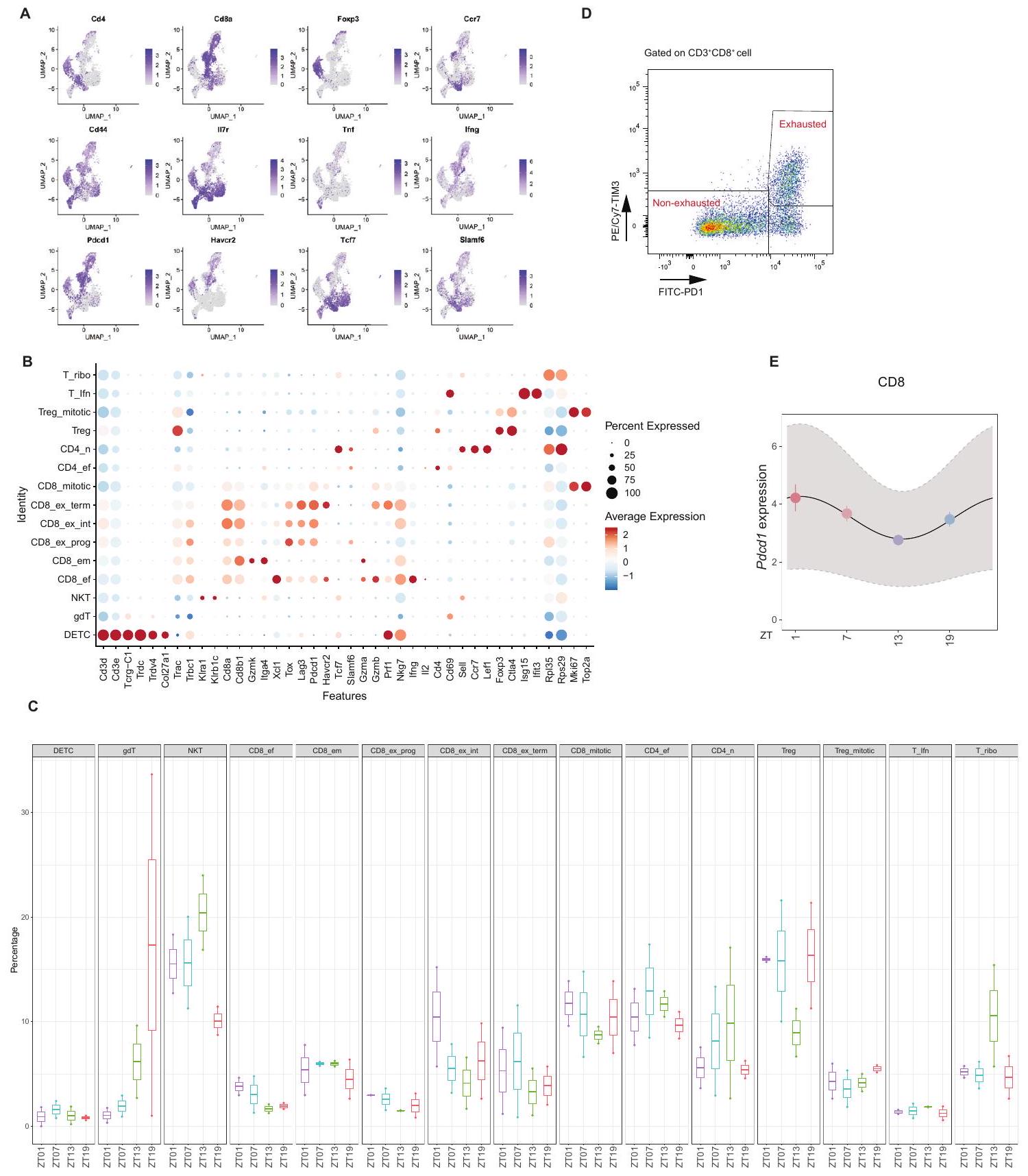

اختلافات يومية في نمط TIL

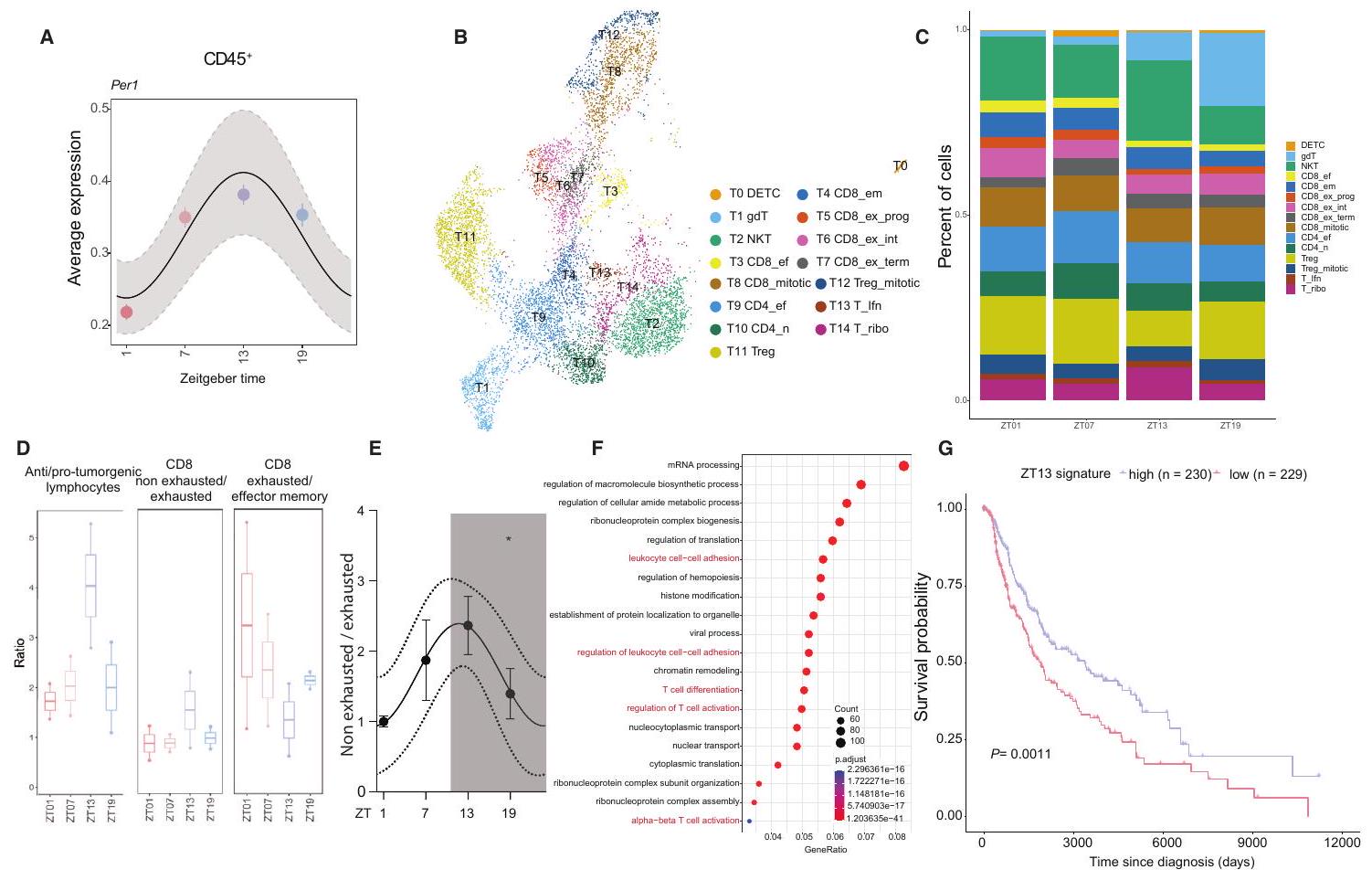

أعلى

اختلافات وقت اليوم في الورم

CD8

(ب) تمثيل UMAP لتحليلات scRNA-seq لخلايا T التي تم جمعها في 4 أوقات مختلفة من اليوم.

(ج) الوفرة النسبية لمجموعات خلايا T عبر أوقات مختلفة من اليوم.

(د) نسبة وفرة مجموعات معينة من خلايا T في أوقات مختلفة من اليوم بواسطة تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية. تشمل “الخلايا اللمفاوية المضادة للورم” خلايا NK،

نسبة طبيعية غير مستنفدة إلى مستنفدة

(F) تحليل علم الأحياء الجيني للجينات المتذبذبة في

(G) تحليل البقاء في مرضى الميلانوما من مجموعة بيانات TCGA باستخدام تعبير مرتفع أو منخفض لتوقيع جين ZT13 الفأري في الجدول S2، اختبار لوغرانك. جميع البيانات ممثلة كمتوسط

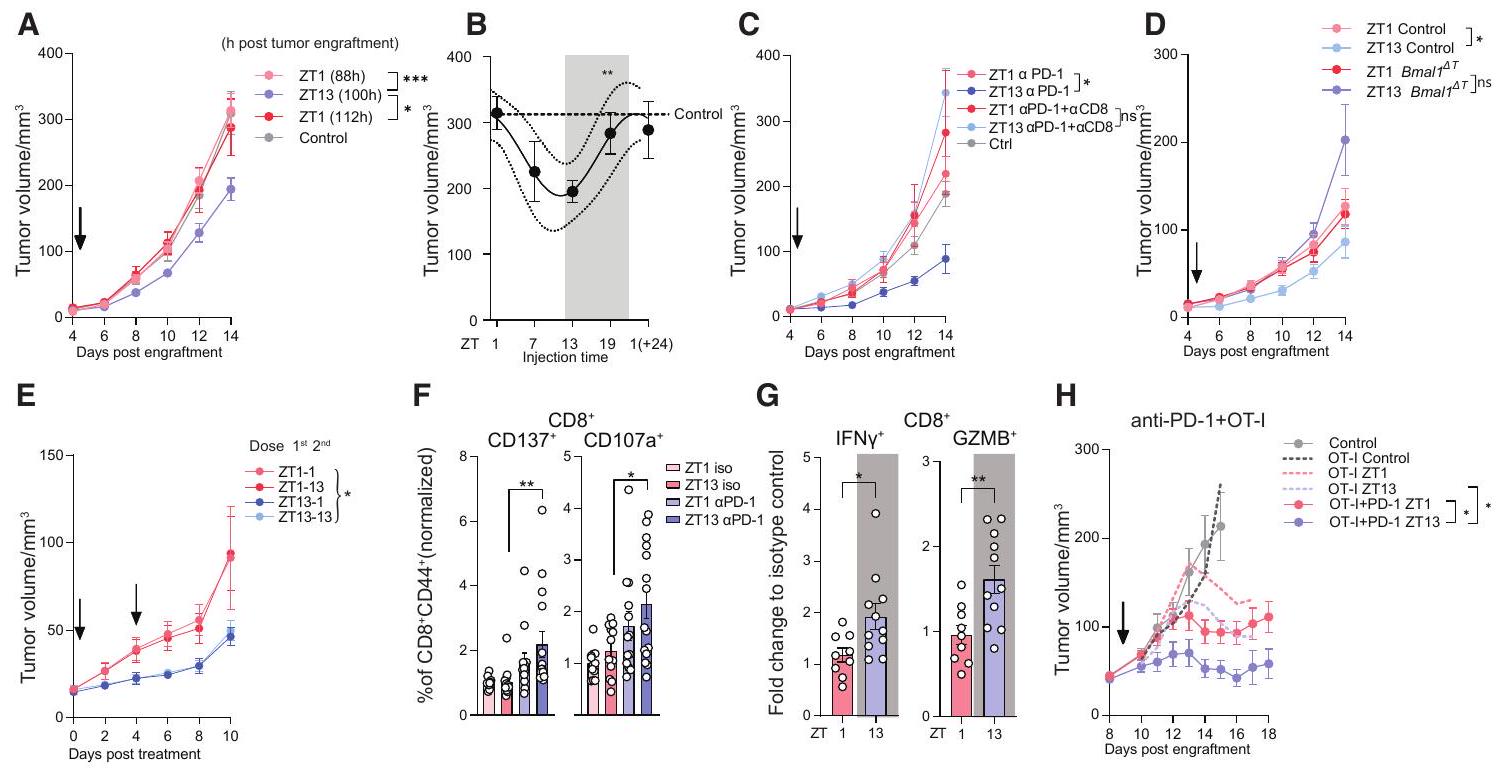

علاج مضاد PD-1 يعتمد على وقت اليوم

نموذج الورم، حيث كانت الأورام تنمو بشكل أقل عندما تم إجراء العلاج في المساء مقارنةً بالصباح (الأشكال 5A و5B وS6B). في الواقع، كان للعلاج في الصباح تأثير ضئيل بشكل مدهش على عبء الورم، حتى عندما سبق إعطاء العلاج في الصباح إعطاء العلاج في المساء بـ 12 ساعة (الأشكال 5A و5B وS6B). يمكننا تأكيد هذه البيانات في نموذج سرطان القولون MC-38، مما يشير إلى أن هذه الظاهرة امتدت إلى نماذج ورم أخرى (الأشكال S6C وS6D). كان تأثير وقت اليوم معتمدًا بشكل حاسم على

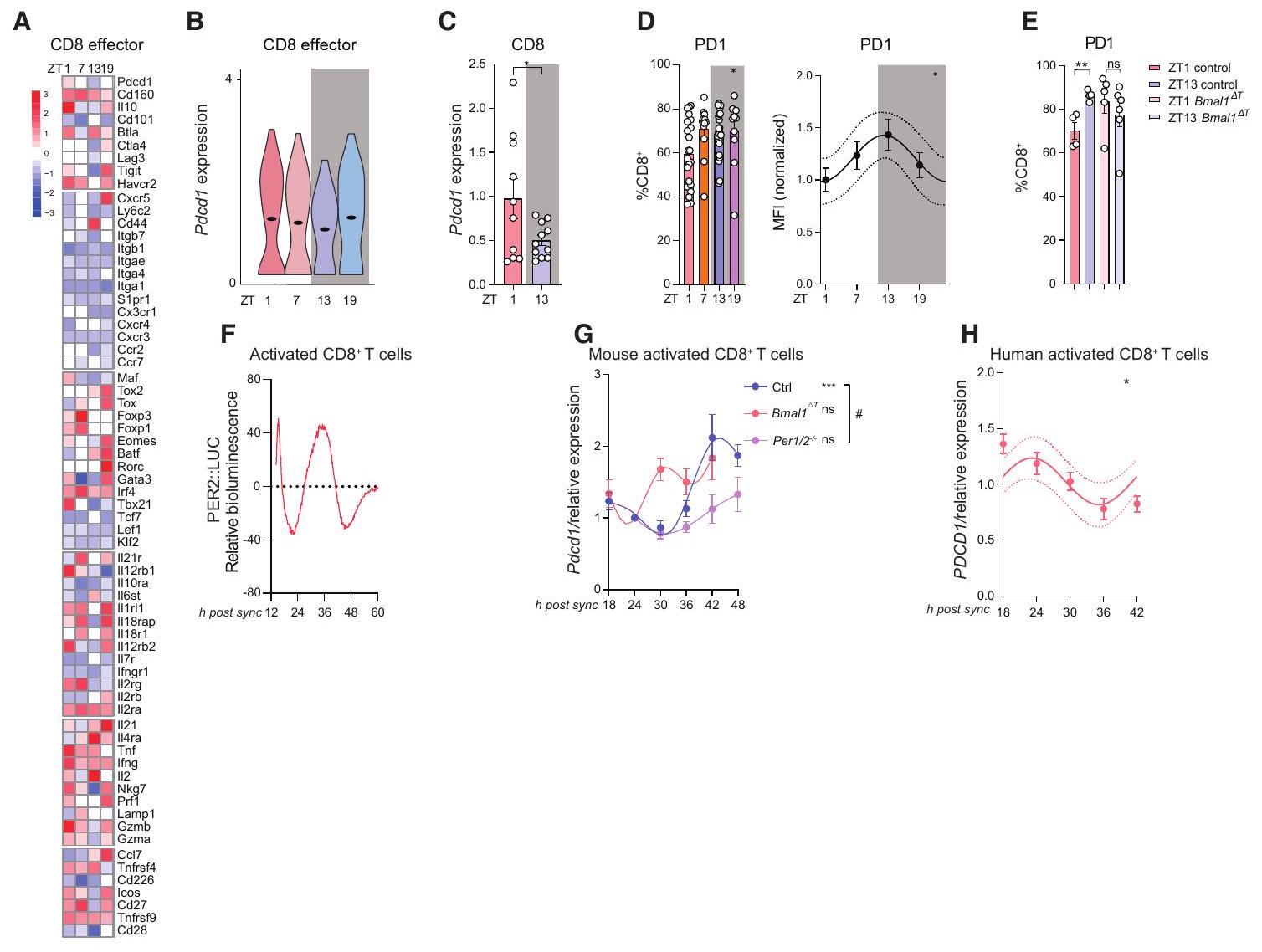

خريطة حرارية لتحليلات تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية

(ب) تعبير Pdcd1 بواسطة تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية لـ CD8

(C) تعبير Pdcd1 بواسطة qPCR لفرز الخلايا المعتمد على الفلورية (FACS) لخلية CD8

(د) تعبير PD-1 بواسطة تحليل تدفق الخلايا للورم

تعبير PD-1 بواسطة تحليل التدفق الخلوي ل CD8 الورمي

الضوء الحيوي النسبي المنشط

(G) تعبير Pdcd1 في CD8 المنشط

(H) تعبير PDCD1 في خلايا CD8 المنشطة لدى البشر

تقليل عبء الورم بشكل أكبر مقارنةً بظروف ZT1 (الأشكال 5 H و S6I). وهذا يشير إلى أن كلا

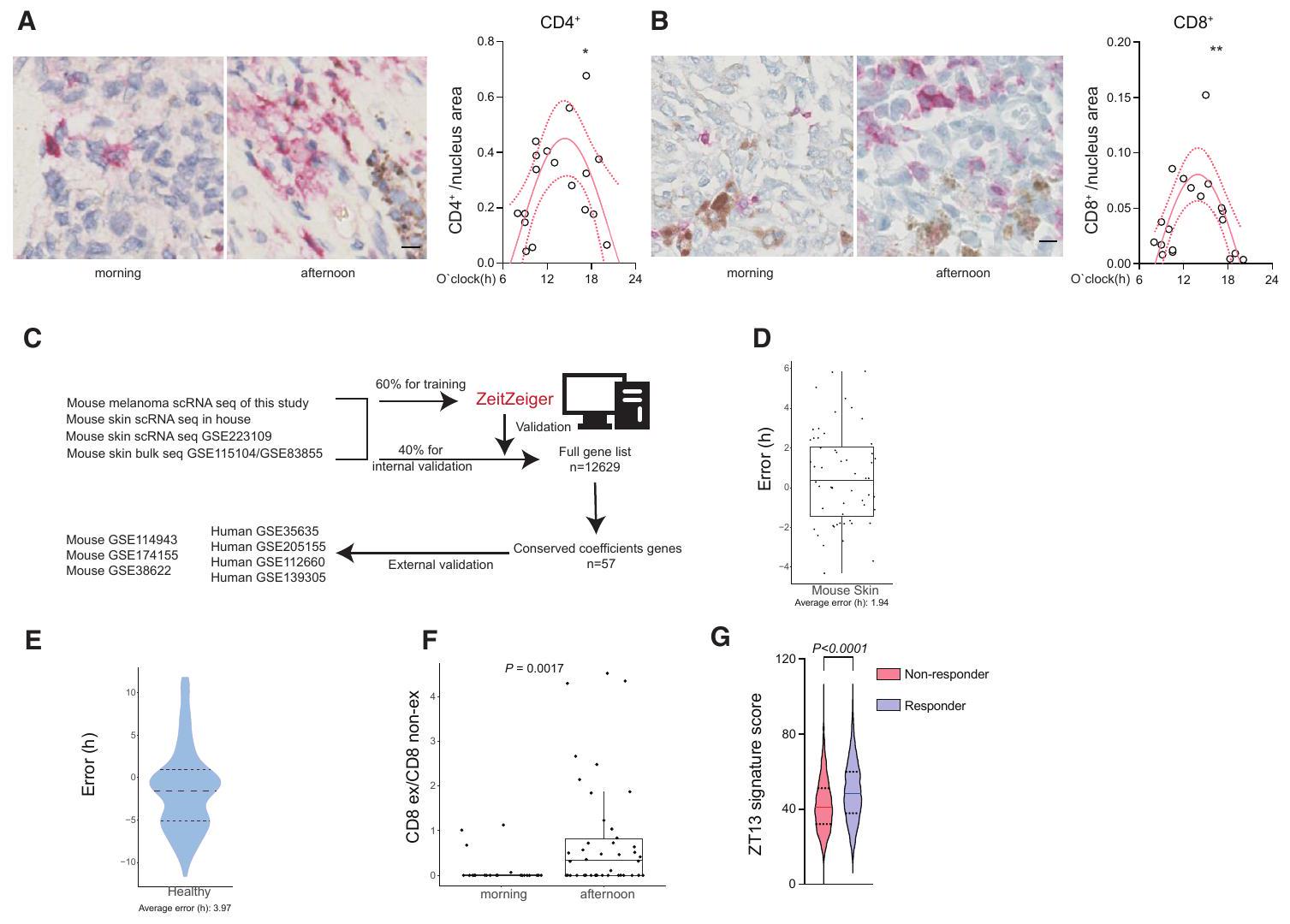

الظاهرة الدورية لخلايا المناعة في السرطانات البشرية

حجم الورم بعد علاج مضاد PD-1 (الأسهم) المطبق في ZT1 أو ZT13، مضاد PD-1 (

(ب) حجم الورم بعد 14 يومًا من زراعة الورم، مضاد PD-1 (

حجم الورم بعد علاج anti-PD-1 (الأسهم) المطبق في ZT1 أو ZT13 مع أو بدون

حجم الورم بعد علاج مضاد PD-1 (الأسهم) المطبق في ZT1 أو ZT13 في المجموعة الضابطة (ZT1،

حجم الورم بعد جرعتين من علاج مضاد PD-1 (الأسهم) المقدم عند ZT1 أو ZT13؛

إنتاج السيتوكينات بواسطة خلايا CD8 الورمية

حجم الورم بعد السيطرة (

البيانات المتاحة من المصفوفات الدقيقة من جلد الإنسان السليم حيث كانت معلومات وقت اليوم معروفة، تمكنا من التنبؤ بشكل كافٍ بوقت اليوم في هذه العينات مع خطأ قدره

(C) مخطط لتدريب الخوارزمية والتحقق منها للتنبؤ بوقت اليوم في العينات غير الموقعة زمنياً. تم استخدام خوارزمية نهائية تحتوي على 57 جينًا للتحقق الخارجي والتنبؤ.

(D و E) خطأ (ساعات) خوارزمية توقع الوقت في التحقق الخارجي في الفأر (

(F) مرهق/غير مرهق

(G) إثراء تعبير جين ZT13 في الفئران لدى المرضى الذين يستجيبون أو لا يستجيبون لعلاج ICB (غير المستجيبين،

نقاش

حساسية وقت اليوم، نظرًا لأننا نرى أيضًا تذبذبات في نمط الخلايا البلعمية في بيئة الورم. لقد ركزنا في هذه الدراسة على خلايا CD8 T، حيث تمثل حاليًا أهدافًا علاجية رئيسية في العيادة. تظهر بياناتنا أن إعطاء الأجسام المضادة يغير نمط خلايا CD8 T داخل الورم بطريقة تعتمد على وقت اليوم، بعد 24 ساعة من الحقن، مما يشير إلى أن هذه الخلايا تشارك في الاستجابات اليومية الأولية. ومع ذلك، قد تكون التذبذبات في سلالات خلايا المناعة الأخرى التي نصفها، ولا سيما خلايا النخاع، ذات أهمية وظيفية إضافية للتأثير اليومي. لا يزال يتعين التحقيق في مساهمة مجموعات خلايا المناعة المختلفة في هذه الاستجابة المناعية المضادة للورم اليومية في الدراسات المستقبلية.

قيود الدراسة

محدد، حيث أن البيانات الحالية تقيم فقط تأثيرات الصباح مقابل بعد الظهر.

طرق النجوم *

- جدول الموارد الرئيسية

- توافر الموارد

- جهة الاتصال الرئيسية

- توفر المواد

- توفر البيانات والشيفرة

- نموذج تجريبي وتفاصيل المشاركين في الدراسة – الحيوانات

- تفاصيل الطريقة

- خطوط خلايا الورم والتطعيم

- تنشيط خلايا T في الفئران

- تزامن خلايا T في الفئران

- إنسان

تنشيط خلايا T والتزامن - تعبير لوكفيراز

خلايا - هضم الأنسجة وتحضير الخلايا المفردة

- تدفق الخلايا

- نقل كريات الدم البيضاء من الفئران

- اختبار EdU

- فرز خلايا CD8 T واستخراج RNA

- استخراج RNA، النسخ العكسي و qPCR

- علاجات الأجسام المضادة في الجسم الحي

- توليد خلايا CAR T البشرية

- نقل خلايا CAR T البشرية

- تصوير المناعة الفلورية

- التشخيص المناعي النسيجي البشري

- تسلسل الخلايا المفردة والتحليل

- تحليل زايتيزايجر

- تقدير تركيبة الخلايا في مرضى الميلانوما في TCGA

- التكميم والتحليل الإحصائي

معلومات إضافية

شكر وتقدير

من مؤسسة ISREC، أبحاث لودفيغ للسرطان، ومن منح المعهد الوطني للصحة P01CA240239 وR01-CA218579. تم تمويل R.B. من خلال زمالة تنقل ما بعد الدكتوراه ومنحة العودة من SNSF (P400PM_183852 وP5R5PM_203164). يتم دعم الأبحاث في مختبر A.D.G. من قبل مؤسسة أبحاث فلاندرز (FWO) (منحة البحث الأساسي، G0B4620N؛ منحة FWO SBO لمجموعة “ANTIBODY”)، جامعة KU Leuven (منحة C1، C14/19/098، ومنح C3، C3/21/037 وC3/22/022)، Kom op Tegen Kanker (KOTK/2018/11509/1 وKOTK/2019/11955/1)، VLIR-UOS (منحة iBOF، iBOF/21/048، لمجموعة “MIMICRY”)، وصندوق أبحاث أوليفيا هندريكس (OHRF Immuunbiomarkers). تم تمويل C.D. من خلال منحة مؤسسة العلوم الوطنية السويسرية 310030_184708/1، مؤسسة فوندوبل، مؤسسة نوفارتس لصحة المستهلك، برنامج EFSD/Novo Nordisk لأبحاث السكري في أوروبا، مؤسسة Swiss Life، مؤسسة أولغا ماينفيش، مؤسسة الابتكار في السرطان وعلم الأحياء، الرابطة الرئوية الجنيفية، رابطة السرطان السويسرية KFS-5266-02-2021-R، مؤسسة فيلوكس، مؤسسة ليناارد، مؤسسة ISREC، ومؤسسة جيرترود فون ميسنر (V.P. وC.D.). حصل Y.W. على دعم من مؤسسة العلوم لمستشفى سرطان بكين (2022-21). تم إنشاء البيانات الموسعة الشكل 6A والملخص الرسومي باستخدام BioRender.

مساهمات المؤلفين

إعلان المصالح

تمت المراجعة: 2 فبراير 2024

تم القبول: 16 أبريل 2024

نُشر: 8 مايو 2024

REFERENCES

- Mellman, I., Coukos, G., and Dranoff, G. (2011). Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 480, 480-489. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nature10673.

- Tawbi, H.A., Schadendorf, D., Lipson, E.J., Ascierto, P.A., Matamala, L., Castillo Gutiérrez, E., Rutkowski, P., Gogas, H.J., Lao, C.D., De Menezes, J.J., et al. (2022). Relatlimab and Nivolumab versus Nivolumab in Untreated Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 24-34. https://doi. org/10.1056/NEJMoa2109970.

- Cappell, K.M., and Kochenderfer, J.N. (2023). Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: what we know so far. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 359-371. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00754-1.

- Flugel, C.L., Majzner, R.G., Krenciute, G., Dotti, G., Riddell, S.R., Wagner, D.L., and Abou-El-Enein, M. (2023). Overcoming on-target, off-tumour toxicity of CAR T cell therapy for solid tumours. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 49-62. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-022-00704-3.

- Tumeh, P.C., Harview, C.L., Yearley, J.H., Shintaku, I.P., Taylor, E.J.M., Robert, L., Chmielowski, B., Spasic, M., Henry, G., Ciobanu, V., et al.

(2014). PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515, 568-571. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13954. - Wang, C., Barnoud, C., Cenerenti, M., Sun, M., Caffa, I., Kizil, B., Bill, R., Liu, Y., Pick, R., Garnier, L., et al. (2023). Dendritic cells direct circadian anti-tumour immune responses. Nature 614, 136-143. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41586-022-05605-0.

- Scheiermann, C., Gibbs, J., Ince, L., and Loudon, A. (2018). Clocking in to immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 423-437. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41577-018-0008-4.

- Arjona, A., Silver, A.C., Walker, W.E., and Fikrig, E. (2012). Immunity’s fourth dimension: approaching the circadian-immune connection. Trends Immunol. 33, 607-612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2012.08.007.

- Curtis, A.M., Bellet, M.M., Sassone-Corsi, P., and O’Neill, L.A.J. (2014). Circadian clock proteins and immunity. Immunity 40, 178-186. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.002.

- Cermakian, N., Stegeman, S.K., Tekade, K., and Labrecque, N. (2022). Circadian rhythms in adaptive immunity and vaccination. Semin. Immunopathol. 44, 193-207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-021-00903-7.

- Man, K., Loudon, A., and Chawla, A. (2016). Immunity around the clock. Science 354, 999-1003. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah4966.

- Palomino-Segura, M., and Hidalgo, A. (2021). Circadian immune circuits. J. Exp. Med. 218, e20200798. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem. 20200798.

- Wang, C., Lutes, L.K., Barnoud, C., and Scheiermann, C. (2022). The circadian immune system. Sci. Immunol. 7, eabm2465. https://doi.org/10. 1126/sciimmunol.abm2465.

- He, W., Holtkamp, S., Hergenhan, S.M., Kraus, K., de Juan, A., Weber, J., Bradfield, P., Grenier, J.M.P., Pelletier, J., Druzd, D., et al. (2018). Circadian Expression of Migratory Factors Establishes Lineage-Specific Signatures that Guide the Homing of Leukocyte Subsets to Tissues. Immunity 49, 1175-1190.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2018.10.007.

- Druzd, D., Matveeva, O., Ince, L., Harrison, U., He, W., Schmal, C., Herzel, H., Tsang, A.H., Kawakami, N., Leliavski, A., et al. (2017). Lymphocyte Circadian Clocks Control Lymph Node Trafficking and Adaptive Immune Responses. Immunity 46, 120-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni. 2016.12.011.

- Shimba, A., Cui, G., Tani-ichi, S., Ogawa, M., Abe, S., Okazaki, F., Kitano, S., Miyachi, H., Yamada, H., Hara, T., et al. (2018). Glucocorticoids Drive Diurnal Oscillations in T Cell Distribution and Responses by Inducing Interleukin-7 Receptor and CXCR4. Immunity 48, 286-298.e6. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2018.01.004.

- Casanova-Acebes, M., Nicolás-Ávila, J.A., Li, J.L., García-Silva, S., Balachander, A., Rubio-Ponce, A., Weiss, L.A., Adrover, J.M., Burrows, K., AGonzález, N., et al. (2018). Neutrophils instruct homeostatic and pathological states in naive tissues. J. Exp. Med. 215, 2778-2795. https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem. 20181468.

- Nguyen, K.D., Fentress, S.J., Qiu, Y., Yun, K., Cox, J.S., and Chawla, A. (2013). Circadian gene Bmal1 regulates diurnal oscillations of Ly6C(hi) inflammatory monocytes. Science 341, 1483-1488. https://doi.org/10. 1126/science. 1240636.

- Cervantes-Silva, M.P., Carroll, R.G., Wilk, M.M., Moreira, D., Payet, C.A., O’Siorain, J.R., Cox, S.L., Fagan, L.E., Klavina, P.A., He, Y., et al. (2022). The circadian clock influences

cell responses to vaccination by regulating dendritic cell antigen processing. Nat. Commun. 13, 7217. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34897-z. - Ince, L.M., Barnoud, C., Lutes, L.K., Pick, R., Wang, C., Sinturel, F., Chen, C.S., de Juan, A., Weber, J., Holtkamp, S.J., et al. (2023). Influence of circadian clocks on adaptive immunity and vaccination responses. Nat. Commun. 14, 476. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-35979-2.

- Nobis, C.C., Dubeau Laramée, G., Kervezee, L., Maurice De Sousa, D., Labrecque, N., and Cermakian, N. (2019). The circadian clock of CD8 T cells modulates their early response to vaccination and the rhythmicity of related signaling pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 2007720086. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1905080116.

- Gibbs, J., Ince, L., Matthews, L., Mei, J., Bell, T., Yang, N., Saer, B., Begley, N., Poolman, T., Pariollaud, M., et al. (2014). An epithelial circadian clock controls pulmonary inflammation and glucocorticoid action. Nat. Med. 20, 919-926. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3599.

- Scheiermann, C., Kunisaki, Y., Lucas, D., Chow, A., Jang, J.E., Zhang, D., Hashimoto, D., Merad, M., and Frenette, P.S. (2012). Adrenergic nerves govern circadian leukocyte recruitment to tissues. Immunity 37, 290-301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.021.

- Hazan, G., Duek, O.A., Alapi, H., Mok, H., Ganninger, A., Ostendorf, E., Gierasch, C., Chodick, G., Greenberg, D., and Haspel, J.A. (2023). Biological rhythms in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in an observational cohort study of 1.5 million patients. J. Clin. Invest. 133, e167339. https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCl167339.

- Long, J.E., Drayson, M.T., Taylor, A.E., Toellner, K.M., Lord, J.M., and Phillips, A.C. (2016). Morning vaccination enhances antibody response over afternoon vaccination: A cluster-randomised trial. Vaccine 34, 26792685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.032.

- Ho, P.C., Bihuniak, J.D., Macintyre, A.N., Staron, M., Liu, X., Amezquita, R., Tsui, Y.C., Cui, G., Micevic, G., Perales, J.C., et al. (2015). Phosphoenolpyruvate Is a Metabolic Checkpoint of Anti-tumor T Cell Responses. Cell 162, 1217-1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.012.

- Raskov, H., Orhan, A., Christensen, J.P., and Gögenur, I. (2021). Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in cancer and cancer immunotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 124, 359-367. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01048-4.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2024). B-Cell Lymphomas. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1480.

- Neelapu, S.S., Dickinson, M., Munoz, J., Ulrickson, M.L., Thieblemont, C., Oluwole, O.O., Herrera, A.F., Ujjani, C.S., Lin, Y., Riedell, P.A., et al. (2022). Axicabtagene ciloleucel as first-line therapy in high-risk large B-cell lymphoma: the phase 2 ZUMA-12 trial. Nat. Med. 28, 735-742. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41591-022-01731-4.

- Arjona, A., and Sarkar, D.K. (2005). Circadian oscillations of clock genes, cytolytic factors, and cytokines in rat NK cells. J. Immunol. 174, 76187624. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7618.

- Hughey, J.J., Hastie, T., and Butte, A.J. (2016). ZeitZeiger: supervised learning for high-dimensional data from an oscillatory system. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e80. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw030.

- Zhao, Y., Liu, M., Chan, X.Y., Tan, S.Y., Subramaniam, S., Fan, Y., Loh, E., Chang, K.T.E., Tan, T.C., and Chen, Q. (2017). Uncovering the mystery of opposite circadian rhythms between mouse and human leukocytes in humanized mice. Blood 130, 1995-2005. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-04-778779.

- Sade-Feldman, M., Yizhak, K., Bjorgaard, S.L., Ray, J.P., de Boer, C.G., Jenkins, R.W., Lieb, D.J., Chen, J.H., Frederick, D.T., Barzily-Rokni, M., et al. (2018). Defining T Cell States Associated with Response to Checkpoint Immunotherapy in Melanoma. Cell 175, 998-1013.e20. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.038.

- Naulaerts, S., Datsi, A., Borras, D.M., Antoranz Martinez, A., Messiaen, J., Vanmeerbeek, I., Sprooten, J., Laureano, R.S., Govaerts, J., Panovska, D., et al. (2023). Multiomics and spatial mapping characterizes human CD8

T cell states in cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eadd1016. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/scitransImed.add1016. - Qian, D.C., Kleber, T., Brammer, B., Xu, K.M., Switchenko, J.M., Jano-paul-Naylor, J.R., Zhong, J., Yushak, M.L., Harvey, R.D., Paulos, C.M., et al. (2021). Effect of immunotherapy time-of-day infusion on overall survival among patients with advanced melanoma in the USA (MEMOIR): a propensity score-matched analysis of a single-centre, longitudinal study. Lancet Oncol. 22, 1777-1786. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21) 00546-5.

- Yeung, C., Kartolo, A., Tong, J., Hopman, W., and Baetz, T. (2023). Association of circadian timing of initial infusions of immune checkpoint inhibitors with survival in advanced melanoma. Immunotherapy 15, 819-826. https://doi.org/10.2217/imt-2022-0139.

- Gonçalves, L., Gonçalves, D., Esteban-Casanelles, T., Barroso, T., Soares de Pinho, I., Lopes-Brás, R., Esperança-Martins, M., Patel, V., Torres, S., Teixeira de Sousa, R., et al. (2023). Immunotherapy around the Clock: Impact of Infusion Timing on Stage IV Melanoma Outcomes. Cells 12, 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12162068.

- Karaboué, A., Collon, T., Pavese, I., Bodiguel, V., Cucherousset, J., Zakine, E., Innominato, P.F., Bouchahda, M., Adam, R., and Lévi, F. (2022). Time-Dependent Efficacy of Checkpoint Inhibitor Nivolumab: Results from a Pilot Study in Patients with Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 14, 896. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14040896.

- Rousseau, A., Tagliamento, M., Auclin, E., Aldea, M., Frelaut, M., Levy, A., Benitez, J.C., Naltet, C., Lavaud, P., Botticella, A., et al. (2023). Clinical outcomes by infusion timing of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 182, 107-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2023.01.007.

- Nomura, M., Hosokai, T., Tamaoki, M., Yokoyama, A., Matsumoto, S., and Muto, M. (2023). Timing of the infusion of nivolumab for patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus influences its efficacy. Esophagus 20, 722-731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10388-023-01006-y.

- Landré, T., Karaboué, A., Buchwald, Z.S., Innominato, P.F., Qian, D.C., Assié, J.B., Chouaïd, C., Lévi, F., and Duchemann, B. (2024). Effect of immunotherapy-infusion time of day on survival of patients with advanced cancers: a study-level meta-analysis. ESMO Open 9, 102220. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.102220.

- Martin, A.M., Cagney, D.N., Catalano, P.J., Alexander, B.M., Redig, A.J., Schoenfeld, J.D., and Aizer, A.A. (2018). Immunotherapy and Symptomatic Radiation Necrosis in Patients With Brain Metastases Treated With Stereotactic Radiation. JAMA Oncol. 4, 1123-1124. https://doi.org/10. 1001/jamaoncol.2017.3993.

- Postow, M.A., Goldman, D.A., Shoushtari, A.N., Betof Warner, A., Callahan, M.K., Momtaz, P., Smithy, J.W., Naito, E., Cugliari, M.K., Raber, V., et al. (2022). Adaptive Dosing of Nivolumab + Ipilimumab Immunotherapy Based Upon Early, Interim Radiographic Assessment in Advanced Melanoma (The ADAPT-IT Study). J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 1059-1067. https://doi. org/10.1200/JCO.21.01570.

- Arlauckas, S.P., Garris, C.S., Kohler, R.H., Kitaoka, M., Cuccarese, M.F., Yang, K.S., Miller, M.A., Carlson, J.C., Freeman, G.J., Anthony, R.M., et al. (2017). In vivo imaging reveals a tumor-associated macrophagemediated resistance pathway in anti-PD-1 therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaal3604. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitransImed.aal3604.

- Conforti, F., Pala, L., Bagnardi, V., De Pas, T., Martinetti, M., Viale, G., Gelber, R.D., and Goldhirsch, A. (2018). Cancer immunotherapy efficacy and patients’ sex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 19, 737-746. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30261-4.

- Lévi, F.A., Okyar, A., Hadadi, E., Innominato, P.F., and Ballesta, A. (2024). Circadian Regulation of Drug Responses: Toward Sex-Specific and Personalized Chronotherapy. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 64, 89-114. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-051920-095416.

- Duan, J., Ngo, M.N., Karri, S.S., Tsoi, L.C., Gudjonsson, J.E., Shahbaba, B., Lowengrub, J., and Andersen, B. (2023). tauFisher accurately predicts circadian time from a single sample of bulk and single-cell transcriptomic data. Preprint at bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.04.535473.

- Welz, P.-S., Zinna, V.M., Symeonidi, A., Koronowski, K.B., Kinouchi, K., Smith, J.G., Guillén, I.M., Castellanos, A., Furrow, S., Aragón, F., et al. (2019). BMAL1-Driven Tissue Clocks Respond Independently to Light to Maintain Homeostasis. Cell 177, 1436-1447.e12. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.cell.2019.05.009.

- Wang, H., van Spyk, E., Liu, Q., Geyfman, M., Salmans, M.L., Kumar, V., Ihler, A., Li, N., Takahashi, J.S., and Andersen, B. (2017). Time-Restricted Feeding Shifts the Skin Circadian Clock and Alters UVB-Induced DNA Damage. Cell Rep. 20, 1061-1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep. 2017.07.022.

- Tsujihana, K., Tanegashima, K., Santo, Y., Yamada, H., Akazawa, S., Nakao, R., Tominaga, K., Saito, R., Nishito, Y., Hata, R.-I., et al. (2022). Circadian protection against bacterial skin infection by epidermal CXCL14mediated innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2116027119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116027119.

- Geyfman, M., Kumar, V., Liu, Q., Ruiz, R., Gordon, W., Espitia, F., Cam, E., Millar, S.E., Smyth, P., Ihler, A., et al. (2012). Brain and muscle Arnt-like protein-1 (BMAL1) controls circadian cell proliferation and susceptibility to UVB-induced DNA damage in the epidermis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11758-11763. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1209592109.

- Spörl, F., Korge, S., Jürchott, K., Wunderskirchner, M., Schellenberg, K., Heins, S., Specht, A., Stoll, C., Klemz, R., Maier, B., et al. (2012). Krüp-pel-like factor 9 is a circadian transcription factor in human epidermis that controls proliferation of keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10903-10908. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118641109.

- del Olmo, M., Spörl, F., Korge, S., Jürchott, K., Felten, M., Grudziecki, A., de Zeeuw, J., Nowozin, C., Reuter, H., Blatt, T., et al. (2022). Inter-layer and inter-subject variability of diurnal gene expression in human skin. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 4, Iqac097. https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/Iqac097.

- Wu, G., Ruben, M.D., Schmidt, R.E., Francey, L.J., Smith, D.F., Anafi, R.C., Hughey, J.J., Tasseff, R., Sherrill, J.D., Oblong, J.E., et al. (2018). Popula-tion-level rhythms in human skin with implications for circadian medicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 12313-12318. https://doi.org/10.1073/ pnas. 1809442115.

- Sherrill, J.D., Finlay, D., Binder, R.L., Robinson, M.K., Wei, X., Tiesman, J.P., Flagler, M.J., Zhao, W., Miller, C., Loftus, J.M., et al. (2021). Transcriptomic analysis of human skin wound healing and rejuvenation following ablative fractional laser treatment. PLoS One 16, e0260095. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0260095.

- Hao, Y., Hao, S., Andersen-Nissen, E., Mauck, W.M., 3rd, Zheng, S., Butler, A., Lee, M.J., Wilk, A.J., Darby, C., Zager, M., et al. (2021). Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 184, 3573-3587.e29. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.048.

- Wu, T., Hu, E., Xu, S., Chen, M., Guo, P., Dai, Z., Feng, T., Zhou, L., Tang, W., Zhan, L., et al. (2021). clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation (Camb) 2, 100141. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141.

- Carlucci, M., Kriščiūnas, A., Li, H., Gibas, P., Koncevičius, K., Petronis, A., and Oh, G. (2019). DiscoRhythm: an easy-to-use web application and

package for discovering rhythmicity. Bioinformatics 36, 1952-1954. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz834. - Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R., and Guinney, J. (2013). GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-7.

- Colaprico, A., Silva, T.C., Olsen, C., Garofano, L., Cava, C., Garolini, D., Sabedot, T.S., Malta, T.M., Pagnotta, S.M., Castiglioni, I., et al. (2016). TCGAbiolinks: an R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e71. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/ gkv1507.

- Leek, J.T., Johnson, W.E., Parker, H.S., Jaffe, A.E., and Storey, J.D. (2012). The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics 28, 882-883. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts034.

- Holtkamp, S.J., Ince, L.M., Barnoud, C., Schmitt, M.T., Sinturel, F., Pilorz, V., Pick, R., Jemelin, S., Mühlstädt, M., Boehncke, W.H., et al. (2021). Circadian clocks guide dendritic cells into skin lymphatics. Nat. Immunol. 22, 1375-1381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-021-01040-x.

- Wittenbrink, N., Ananthasubramaniam, B., Münch, M., Koller, B., Maier, B., Weschke, C., Bes, F., de Zeeuw, J., Nowozin, C., Wahnschaffe, A., et al. (2018). High-accuracy determination of internal circadian time from a single blood sample. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 3826-3839. https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI120874.

- Newman, A.M., Steen, C.B., Liu, C.L., Gentles, A.J., Chaudhuri, A.A., Scherer, F., Khodadoust, M.S., Esfahani, M.S., Luca, B.A., Steiner, D., et al. (2019). Determining cell type abundance and expression from bulk tissues with digital cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 773-782. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41587-019-0114-2.

طرق النجوم

جدول الموارد الرئيسية

| كاشف أو مورد | المصدر | معرف |

| الأجسام المضادة | ||

| مضاد الفأر CD45 النسخة 30-F11 | بي دي بيوساينس | 564279/AB_2651134 |

| مضاد الماوس CD3e النسخة KT3.1.1 | بايو ليجند | 155617/AB_2832541 |

| النسخة GK1.5 المضادة للفأر CD4 | بي دي بيوساينس | 563232/AB_2738083 |

| النسخة 53-6.7 من CD8a المضاد للفأر | بي دي بيوساينس | 563152/AB_2738030 |

| النسخة N418 من مضاد CD11c للفأر | بايو ليجند | 117307/AB_313776 |

| مضاد الفأر CD19 النسخة 1D3 | بي دي بيوساينس | 566412/AB_2744315 |

| النسخة المضادة للفأر NK1.1 PK136 | بايو ليجند | 108715/AB_493591 |

| النسخة المضادة لمستضدات الكريات البيضاء البشرية من نوع MHCII M5/114.15.2 | بايو ليجند | 107643/AB_2565976 |

| مضاد الفأر Ly6G النسخة 1A8 | بايو ليجند | 127645/AB_2566317 |

| مضاد الفأر Ly6C النسخة HK1.4 | بايو ليجند | 128023/AB_10640119 |

| مضاد الفأر CD137 النسخة 17B5 | بايو ليجند | 106106/AB_2287565 |

| مضاد الفأر CD107a النسخة 1D4B | بايو ليجند | 121610/AB_571991 |

| مضاد PD-1 الفأري النسخة 29F.1A12 | بايو ليجند | 135213/AB_10689633 |

| مضاد للجرانزيم B الفأري النسخة QA16A02 | بايو ليجند | 372207/AB_2687031 |

| مضاد IFN- الفأر

|

بايو ليجند | 505837/AB_11219004 |

| النسخة MEC13.3 من مضاد الفأر CD31 | بايو ليجند | 102520/AB_2563319 |

| نسخة مضادة للفأر CD4، GK1.5 | بايو ليجند | 100405/AB_312690 |

| نسخة مضادة للفأر CD54، YN1/1.7.4 | بايو ليجند | 116114/AB_493495 |

| النسخة 53-6.7 من مضاد الفأر CD8 | بايو ليجند | 100724/AB_389326 |

| النسخة 429 من الأجسام المضادة ضد VCAM-1 للفئران | بايو ليجند | 105710/AB_493427 |

| مضاد الفأر مضاد CD11a النسخة M17/4 | بايو إكس سيل | BE0006/ AB_1107578 |

| مضاد الفأر مضاد-CD18 النسخة M18/2 | بايو إكس سيل | BE0009/ AB_1107607 |

| مضاد PD-1 للفأر، النسخة 29F.1A12

|

بايو إكس سيل | BE0273/ AB_2687796 |

| مضاد الفأر CD8a، النسخة YTS 169.4 | بايو إكس سيل | BE0117/ AB_10950145 |

| النسخة UZ6 المضادة للبروتين E-selectin للفئران | إنفيتروجين | MA1-06506/ AB_2186701 |

| نسخة مضادة للبشر CD3 BW264/56 | ميلتيني بيولوجي | 130-113-687/AB_2726228 |

| نسخة مضادة للبشر CD8 RPA-T8 | بي دي بيوساينس | 563795/AB_2722501 |

| نسخة CD4 المضادة للبشر SK3 | بي دي بيوساينس | 565995/AB_2739446 |

| النسخة المضادة للبشر CD19 HIB19 | بايو ليجند | 302219/AB_389313 |

| نسخة مضادة للبشر CD4 EP204 | جسر تشونغشان الذهبي للتكنولوجيا الحيوية | ZA-0519 |

| نسخة CD8 المضادة للبشر SP16 | جسر تشونغشان الذهبي للتكنولوجيا الحيوية | ZA-0508 |

| تحكم إيزوتيب IgG2a للفأر، النسخة 2A3 | بايو إكس سيل | BE0089/ AB_1107769 |

| تحكم إيزوتيب IgG2b للفأر، النسخة LTF-2 | بايو إكس سيل | BE0090/ AB_1107780 |

| دينابيدز ت Activator CD3/CD28 البشري | جيبكو | 11132D/AB_2916088 |

| نسخة مضادة للبشر CD3 BW264/56 | بايو ليجند | 317348/ AB_2571995 |

| دينابيدز

|

جيبكو | 11453D |

| أجسام مضادة ثانوية ماعز مضادة لجرذان IgG (H+L) تم امتصاصها بشكل متقاطع | إنفيتروجين | A21247/ AB_141778 |

| المواد الكيميائية، الببتيدات، والبروتينات المؤتلفة | ||

| DRAQ7 | بيوليجند | 424001 |

| عدّ الخرز | ثيرمو فيشر | C36950 |

| مستمر | ||

| كاشف أو مورد | المصدر | معرف |

| إي بايوساينس

|

إي بايوساينس

|

65-0865-18 |

| مجموعة صبغة عامل النسخ Foxp3 | eBioscience

|

00-5523-00 |

| فوربول 12-ميريستات 13-أسيتات | سيغما-ألدريتش | P1585 |

| أيونيوميسين | سيغما-ألدريتش | I3909 |

| جولجي بلوق

|

بي دي بيوساينس | 555029 |

| حدث الخلية

|

إنفيتروجين | R37167 |

| متتبع الخلايا

|

إنفيتروجين | C34565 |

| محلول تحليل كريات الدم الحمراء | بيوليجند | 420302 |

| إدو أليكس فلور

|

إنفيتروجين | C10646 |

| رياجنت تريزول | إنفيتروجين | 15596018 |

| إنترلوكين-2 البشري | بيبروتيك | 200-02 |

| IL-2 الفأر | بيوليجند | 575406 |

| ريترونيكتين | تاكارا | T100B |

| ستربتافيدين | بيوليجند | 405207 |

| بروتين L المربوط بالبيوتين | ثيرمو فيشر | ٢٩٩٩٧ |

| كولاجيناز IV | شركة وورثينغتون للمواد الكيميائية الحيوية | LS004189 |

| كولاجيناز د | روش | ١١٠٨٨٨٦٦٠٠١ |

| دي إنز I | روش | 04716728001 |

| DAPI | بيوليجند | 422801 |

| بلوك إيد

|

إنفيتروجين | B10710 |

| مجموعة كشف البوليمر بوند ريد | لايكا | دي إس 9390 |

| اختبارات تجارية حاسمة | ||

| مجموعة كواشف كروميم أحادي الخلية 3′ v3.1 مع مؤشرات مزدوجة | 10x جينومكس | 1000269 |

| طقم عزل خلايا T CD8+، بشري | ميلتيني بيولوجي | ١٣٠-٠٩٦-٤٩٥ |

| مجموعة عزل خلايا T CD8a+، فئران | ميلتيني بيولوجي | ١٣٠-١٠٤-٠٧٥ |

| البيانات المودعة | ||

| تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية في الوقت المحدد من الخلايا اللمفاوية التائية المستخرجة من الميلانوما الفأرية | هذه الورقة | جيو: GSE260641 |

| تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية من البشرة في الفأر | دوان وآخرون

|

جيو: GSE223109 |

| تسلسل RNA لجلد الفأر | ويلز وآخرون

|

جيو: GSE115104، GSE114943 |

| تسلسل RNA لجلد الفأر | وانغ وآخرون

|

جيو: GSE83855 |

| تسلسل RNA في البشرة للفأر في ظلام دائم | تسوجيهانا وآخرون

|

جيو: GSE174155 |

| مصفوفة ميكروية لجلد الفأر | جيفمان وآخرون

|

جيو: GSE38622، GSE38623 |

| ميكروأري الفقاعات الشفطية للبشرة البشرية | سبورل وآخرون

|

جيو: GSE35635 |

| ميكروأري جلد الإنسان | دل أولمو وآخرون

|

جيو: GSE205155 |

| ميكروأري جلد الساعد البشري | وو وآخرون

|

جيو: GSE112660 |

| ميكروأري جلد الإنسان (علاج بالليزر الجزئي) | شيريل وآخرون

|

جيو: GSE139305 |

| تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية لميلانوما الإنسان | ساد-فيلدمن وآخرون

|

جيو: GSE120575 |

| بيانات داعمة أخرى | هذه الورقة | (https://doi.org/10.26037/yareta: 5rmtImd5sreo7bmcbe44bbijfm). |

| نماذج تجريبية: خطوط الخلايا | ||

| B16-F10-OVA | ستيفاني هيوغ، جامعة جنيف، سويسرا | غير متوفر |

| مستمر | ||||

| كاشف أو مورد | المصدر | معرف | ||

| خط الخلايا السرطانية القولونية MC38 من الفئران | مارك ج. سميث | RRID: CVCL_B288 | ||

| لمفوما بشرية DoHH2 | فرانشيسكو بيرتوني، IOR، بيلينزونا، سويسرا | غير متوفر | ||

| نماذج تجريبية: الكائنات/السلالات | ||||

| فأر: WT C57BL/6J | مختبر جاكسون | السلالة # 000664 RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 | ||

| فأر: WT C57BL/6N | نهر تشارلز | السلالة # CRL027 RRID:IMSR_CRL:027 | ||

| فأر: B6.129S4(Cg)-Bmal1tm1Weit/J | مختبر جاكسون |

|

||

| فأر: B6.Cg-Tg(Cd4-cre)1Cwi/BfluJ | مختبر جاكسون |

|

||

| فئران Cdh5-cre/ERT2 | رالف آدامز، MPI مونستر، ألمانيا | غير متوفر | ||

| NSG (NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIL2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) | نهر تشارلز | السلالة #:614 | ||

| BRaf

|

بينغ-تشي هو، جامعة الأمم المتحدة، سويسرا | هو وآخرون

|

||

| CD45.1 OT-I | والتر رايث، جامعة جنيف، سويسرا | غير متوفر | ||

| أوليغونوكليوتيدات | ||||

|

مايكروسينث | غير متوفر | ||

|

مايكروسينث | غير متوفر | ||

|

مايكروسينث | غير متوفر | ||

|

مايكروسينث | غير متوفر | ||

|

مايكروسينث | غير متوفر | ||

|

مايكروسينث | غير متوفر | ||

|

مايكروسينث | غير متوفر | ||

|

مايكروسينث | غير متوفر | ||

|

مايكروسينث | غير متوفر | ||

|

مايكروسينث | غير متوفر | ||

| البرمجيات والخوارزميات | ||||

| فاسك ديفا 6 | بي دي بيوساينس | RRID:SCR_001456 | ||

| فلو جو 10 | بي دي بيوساينس | RRID:SCR_008520 | ||

| سلايدبوك | 3 آي | RRID:SCR_014300 | ||

| إيميج جي | فيجي | RRID:SCR_002285 | ||

| سيل رينجر 6.1.2 | 10X جينوميكس | RRID:SCR_017344 | ||

| سورات 4.3.0 | هاو وآخرون

|

https://satijalab.org/seurat/ | ||

| R 4.2.2 | مؤسسة R | https://www.r-project.org/ | ||

| كلاستر بروفايلر | وو وآخرون

|

https://bioconductor.org/packages/ release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html | ||

| كوزينور | المصدر المفتوح | https://github.com/sachsmc/cosinor | ||

| إيقاع الديسكو | كارلوتشي وآخرون

|

https://bioconductor.org/packages/ release/bioc/html/DiscoRhythm.html | ||

| GSVA | هانزلمان وآخرون

|

https://bioconductor.org/packages/ release/bioc/html/GSVA.html | ||

| مستمر | ||

| المُعَايِن أو المورد | المصدر | معرف |

| TCGAbiolinks | كولابريكو وآخرون

|

https://bioconductor.org/packages/ release/bioc/html/TCGAbiolinks.html |

| زيت زايجر | هيوي وآخرون

|

https://github.com/hugheylab/zeitzeiger |

| سفا | ليك وآخرون

|

https://bioconductor.org/packages/ release/bioc/html/sva.html |

| رمز التحليل | هذه الدراسة | https://github.com/zqun1/circadian_immune_mouse_melanoma |

توافر الموارد

جهة الاتصال الرئيسية

توفر المواد

توفر البيانات والشيفرة

- تم إيداع بيانات تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية في GEO: GSE260641 وهي متاحة للجمهور اعتبارًا من تاريخ النشر. أرقام الوصول للبيانات العامة المستخدمة في هذه الدراسة مدرجة في جدول الموارد الرئيسية. جميع البيانات التي تدعم استنتاجات هذه الورقة متاحة على الإنترنت.https://doi.org/10.26037/yareta:5rmtlmd5sreo7bmcbe44bbijfm).

- تم إيداع جميع الشيفرات الأصلية في GitHubhttps://github.com/zqun1/circadian_immune_mouse_melanomaوهو متاح للجمهور اعتبارًا من تاريخ النشر.

- أي معلومات إضافية مطلوبة لإعادة تحليل البيانات المبلغ عنها في هذه الورقة متاحة من جهة الاتصال الرئيسية عند الطلب.

تفاصيل النموذج التجريبي وشارك الدراسة

الحيوانات

تفاصيل الطريقة

خطوط خلايا الورم والتطعيم

تم زراعة (IOR) أبحاث الأورام، بيلينزونا، سويسرا في RPMI (جيبكو) معززة بـ

تنشيط خلايا T في الفئران

تزامن خلايا T في الفئران

إنسان

تعبير لوكفيراز

هضم الأنسجة وتحضير الخلايا المفردة

تدفق الخلايا

نقل كريات الدم البيضاء من الفئران

اختبار EdU

فرز خلايا T CD8 واستخراج RNA

استخراج RNA، النسخ العكسي و qPCR

علاجات الأجسام المضادة في الجسم الحي

إنتاج خلايا CAR T البشرية

نقل خلايا CAR T البشرية

تصوير المناعة الفلورية

التشخيص المناعي النسيجي البشري

تسلسل الخلايا الفردية والتحليل

تحليل ZeitZeiger

تقدير تركيبة الخلايا في مرضى الميلانوما في TCGA

التكميم والتحليل الإحصائي

الرسوم التوضيحية الإضافية

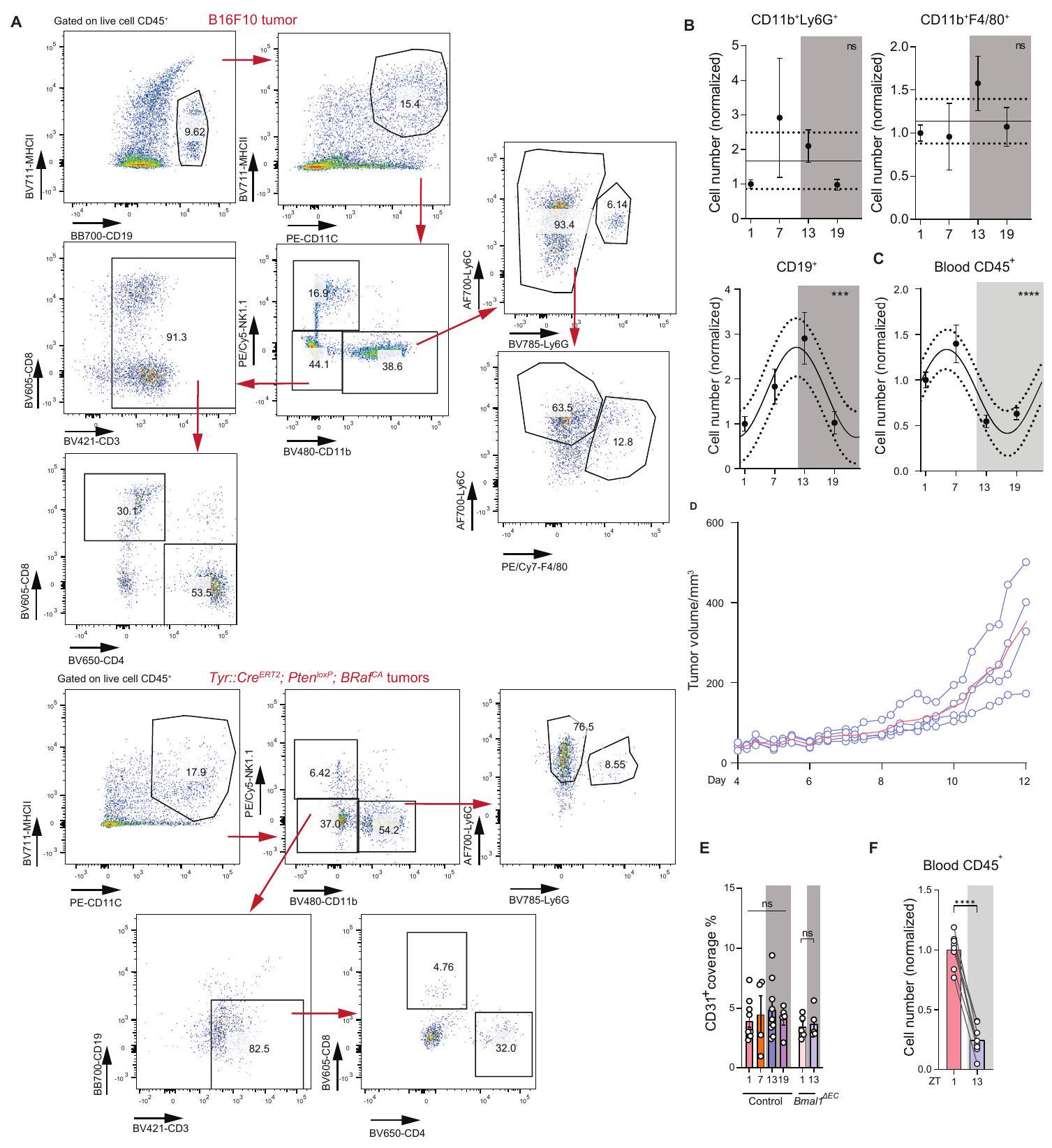

استراتيجية البوابة لكريات الدم البيضاء في B16-F10-OVA و Tyr::Cre

(ب) الأعداد الكلية الطبيعية لمجموعات الكريات البيضاء في أورام B16-F10-OVA، التي تم جمعها في 4 أوقات مختلفة من اليوم (وقت الزايتgeber [ZT])؛

(ج) أعداد كريات الدم البيضاء المأخوذة في 4 أوقات مختلفة من اليوم من فئران تحمل ورم B16-F10-OVA،

حجم ورم B16-F10-OVA، الذي تم قياسه 3 مرات في اليوم،

(هـ) قياس CD31

(F) الأعداد المعيارية لكريات الدم البيضاء المأخوذة عند ZT1 أو ZT13 من Tyr::Cre

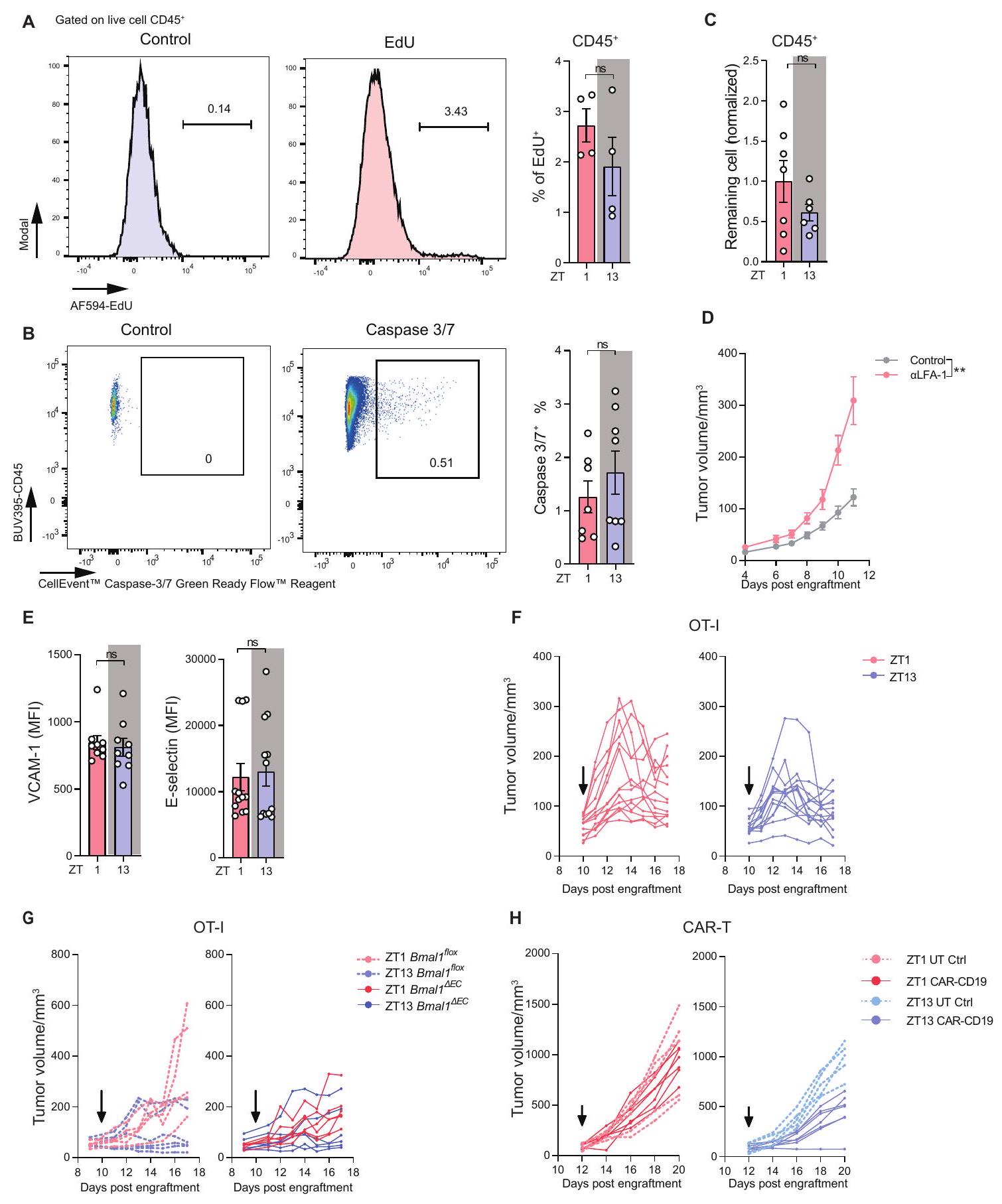

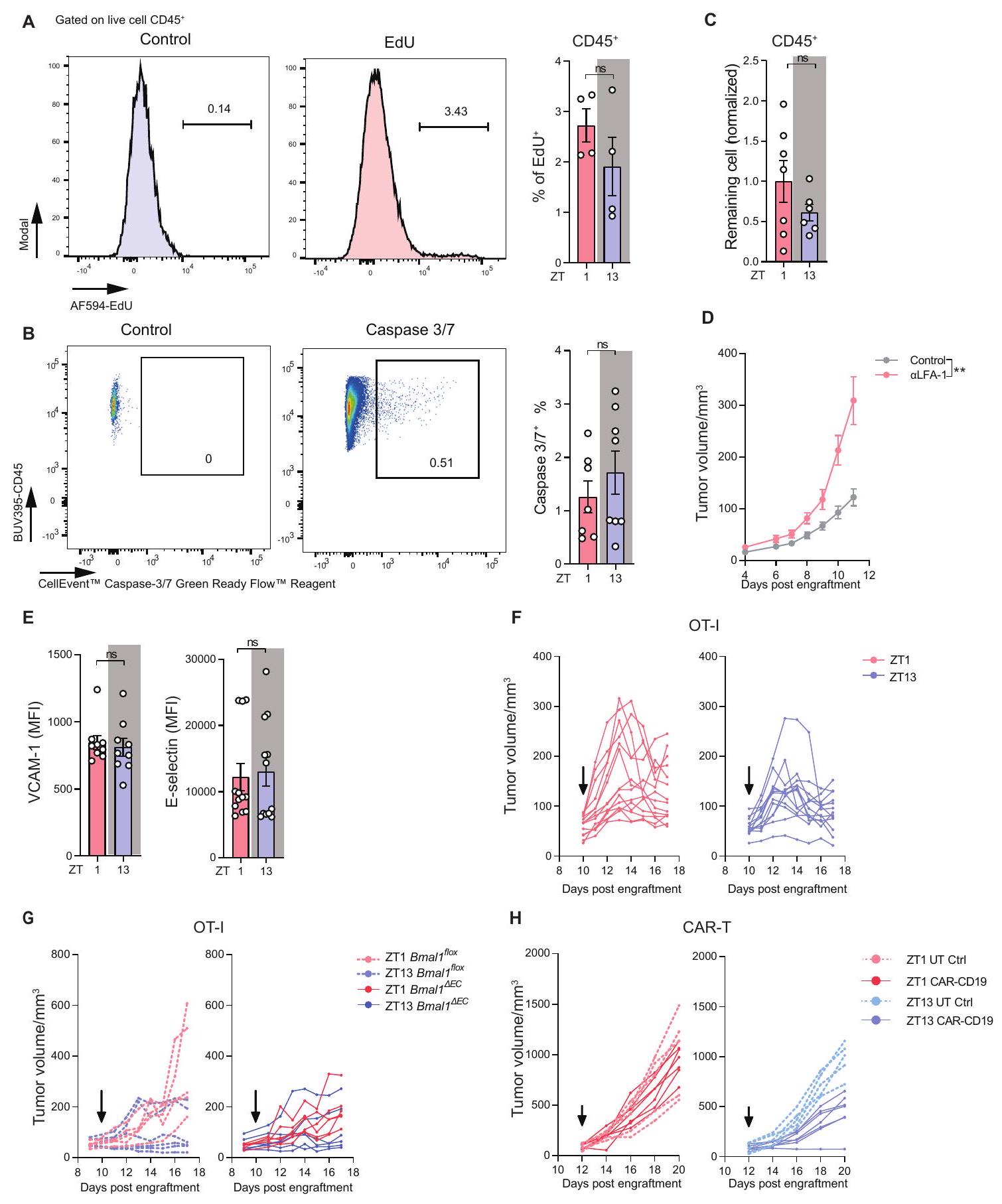

(أ) استراتيجية البوابة وقياس EdU

(ب) استراتيجية البوابة وقياس الكاسبيز-3/-7 في كريات الدم البيضاء في أورام B16-F10-OVA، التي تم جمعها في ZT1 (

(ج) الأعداد المعيارية للخلايا المتبقية في الأورام بعد 24 ساعة من الحقن داخل الورم

حجم الورم بعد علاج مضاد LFA-1 (

(E) قياس VCAM-1 (

حجم الورم بعد الحقن الوريدي بـ

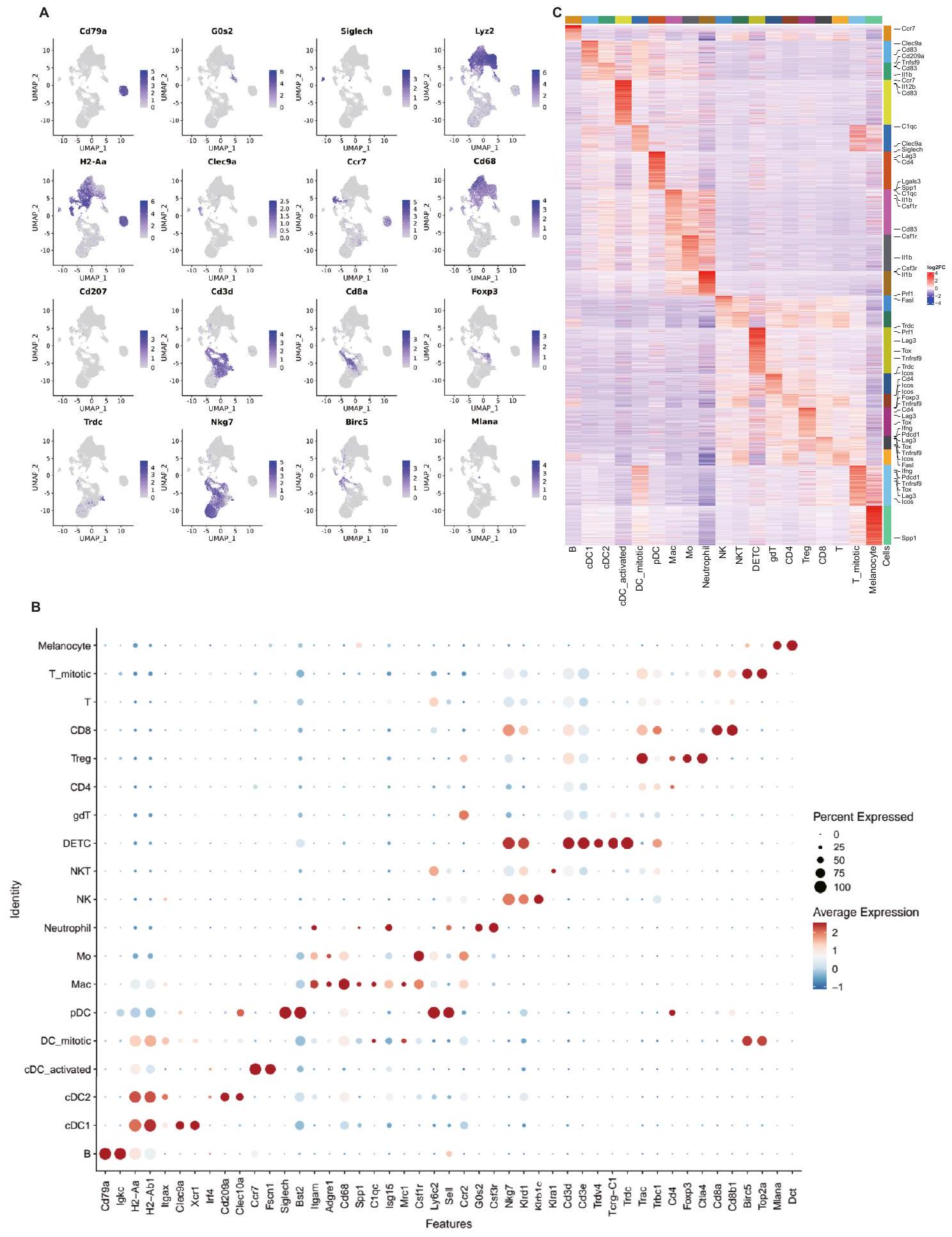

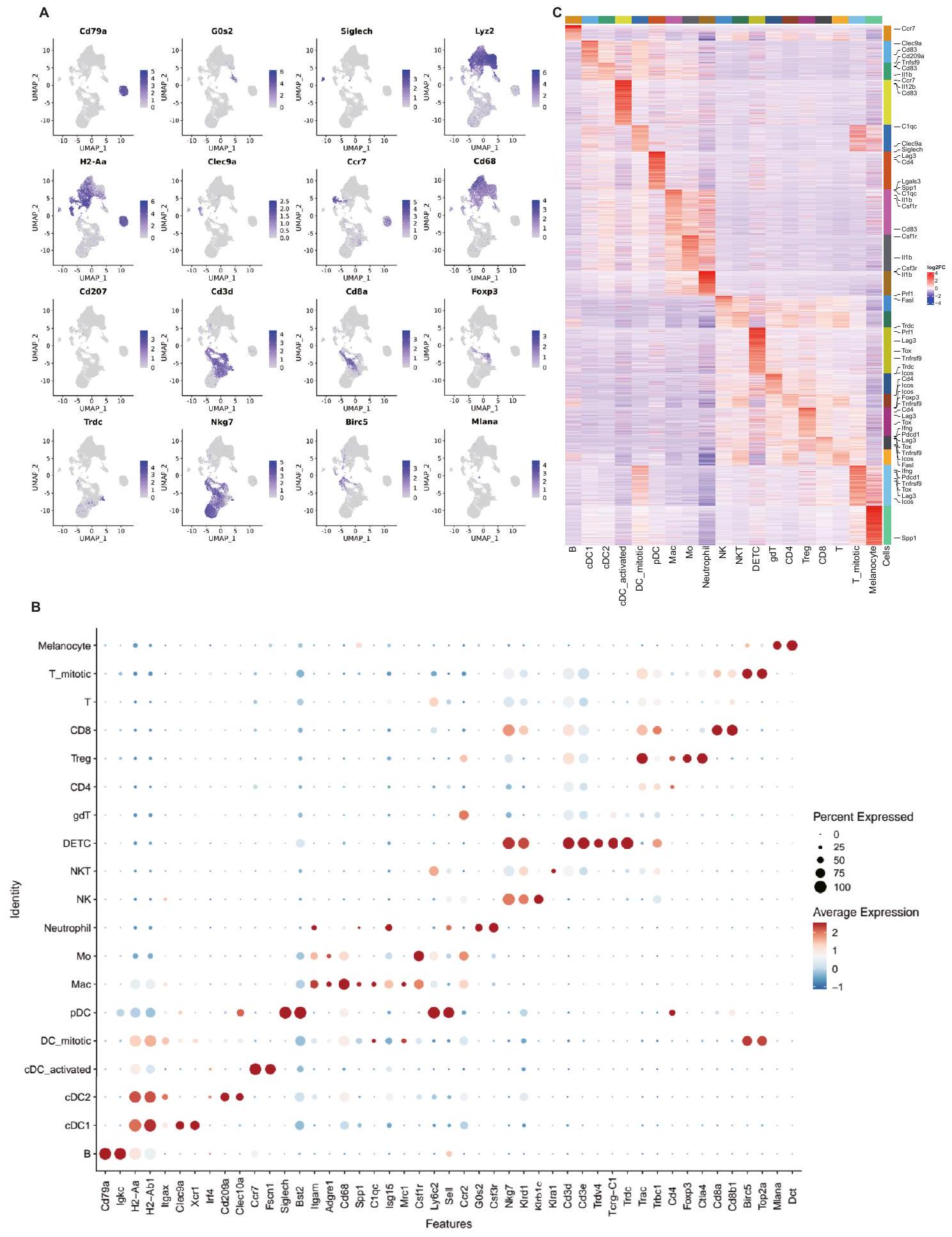

(A-C) رسم ميزات وخريطة حرارية للجينات لتحديد كل مجموعة من كريات الدم البيضاء التي تم الحصول عليها من تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية لأورام B16-F10-OVA، التي تم جمعها في 4 أوقات مختلفة من اليوم.

مقالة

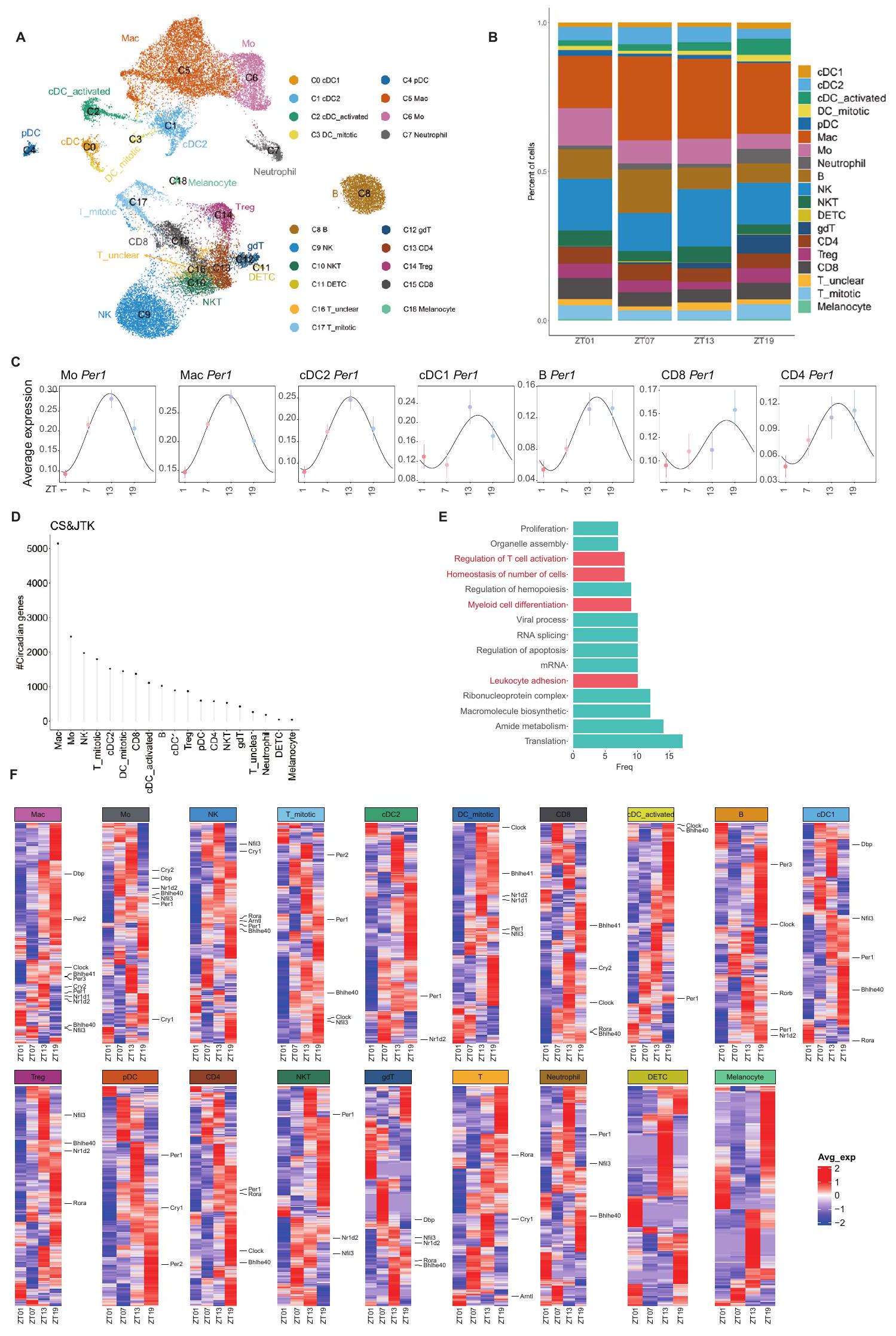

تمثيل UMAP لتحليلات scRNA-seq لـ TILs التي تم جمعها في 4 أوقات مختلفة من اليوم.

(ب) الوفرة النسبية لخلايا المناعة لكل مجموعة عبر أوقات مختلفة من اليوم.

(ج) تعبير الجين الدائري Per1 في كل مجموعة من كريات الدم البيضاء التي تم الحصول عليها من تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية (scRNA-seq) لأورام B16-F10-OVA، التي تم جمعها في 4 أوقات مختلفة من اليوم.

(د) عدد الجينات المتذبذبة بشكل ملحوظ التي تم اكتشافها في كل مجموعة باستخدام تحليلات كوزينور (CS) ودورة JTK.

(E) المسارات الجينية المتذبذبة الشائعة في مجموعات الخلايا المناعية المختلفة.

خريطة حرارية للجينات المتذبذبة لكل مجموعة. تم تمييز الجينات الدائرية.

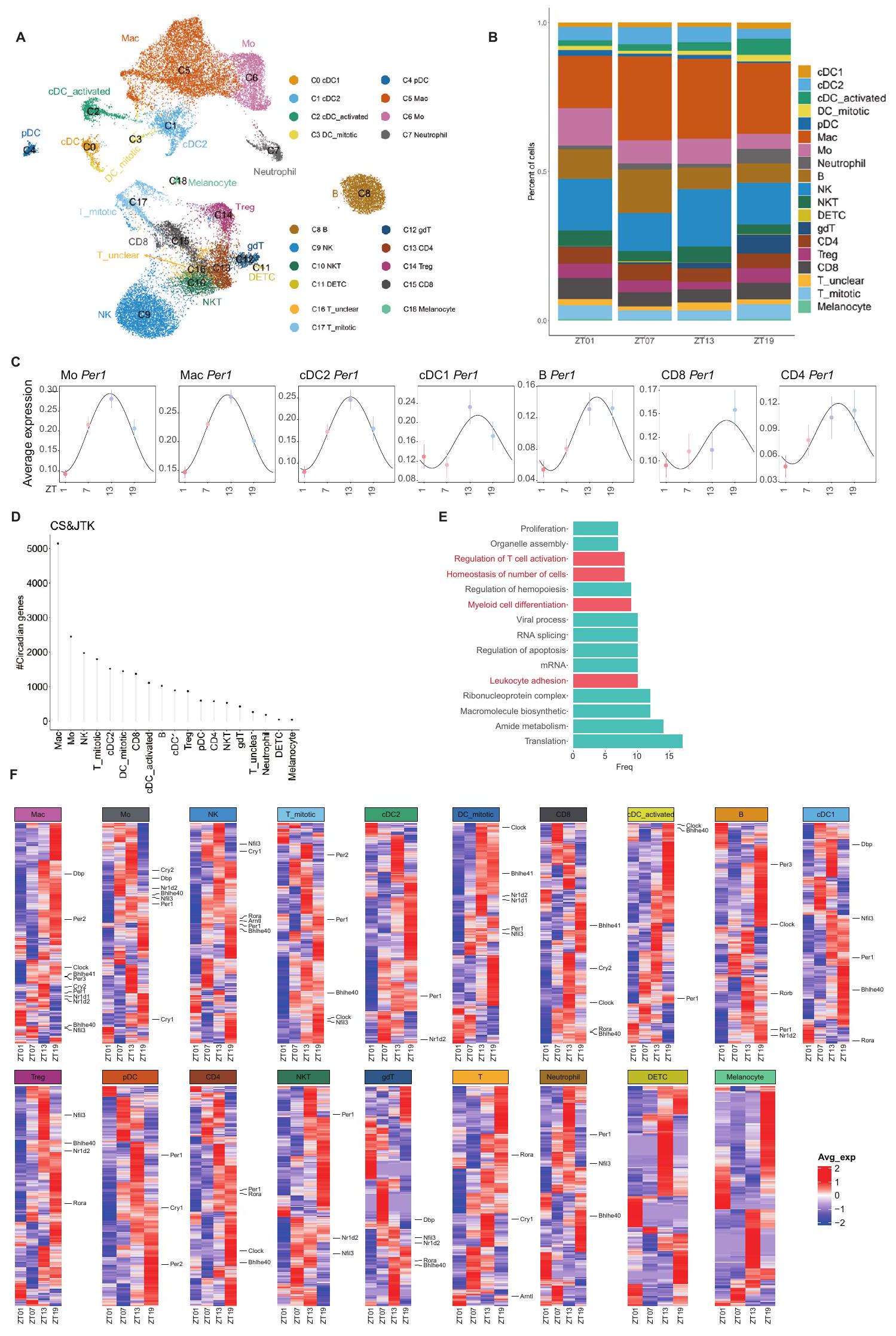

رسم ميزات (A و B) ورسم نقطي للجينات لتحديد مجموعات خلايا T المختلفة التي تم الحصول عليها من تسلسل RNA أحادي الخلية لأورام B16-F10-OVA، التي تم جمعها في 4 أوقات مختلفة من اليوم.

(ج) الوفرة النسبية لكل

(د) استراتيجية البوابة للمستنفدين وغير المستنفدين

(E) تعبير Pdcd1 تم قياسه من خلال تحليل pseudobulk لخلايا CD8

نظرة عامة تخطيطية لـ

(ب) حجم الورم بعد علاج مضاد PD-1 المطبق في ZT1 أو ZT13 في أورام B16-F10-OVA؛

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.04.015

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38723627

Publication Date: 2024-05-01

Cell

Circadian tumor infiltration and function of CD8

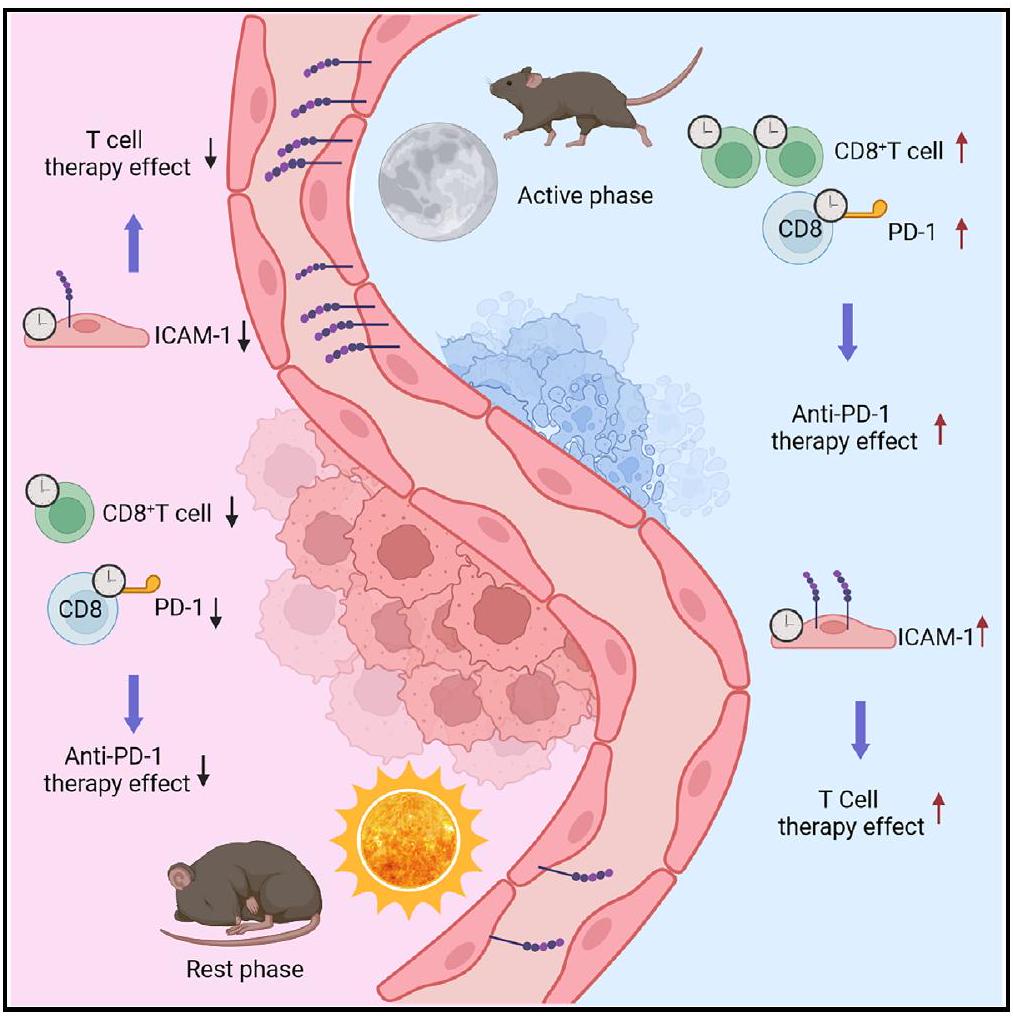

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-Rhythmic tumor infiltration of T cells depends on the endothelial circadian clock

-Adjusting the time of injection during the day improves CAR T cell therapy efficacy

-Enhanced tumor control by timed anti-PD-1 therapy depends on circadian T cell activity

Authors

Correspondence

In brief

Circadian tumor infiltration and function of

Abstract

SUMMARY The quality and quantity of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes,particularly

INTRODUCTION

that are genetically engineered to recognize tumor cells.

of the day.

RESULTS

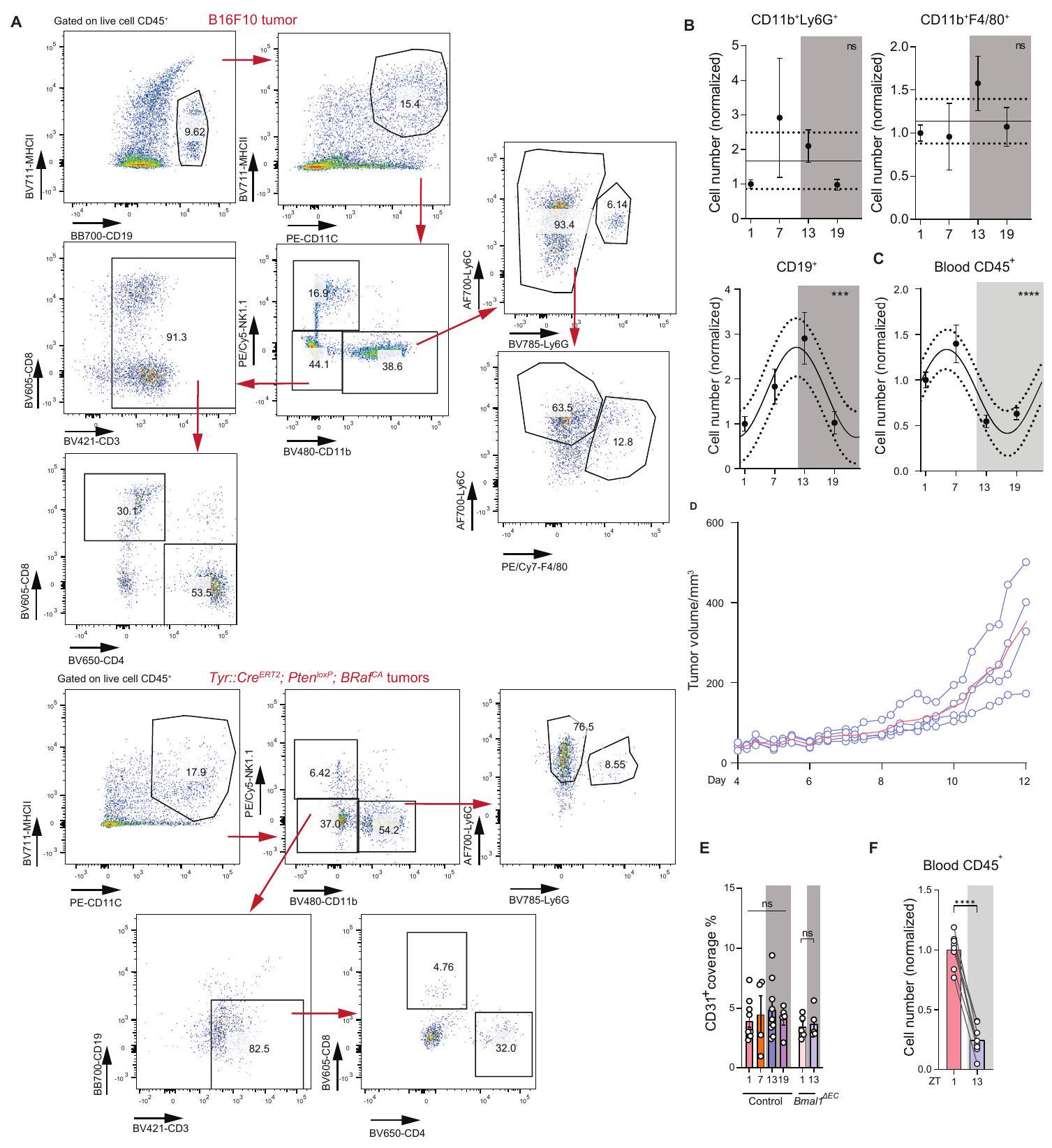

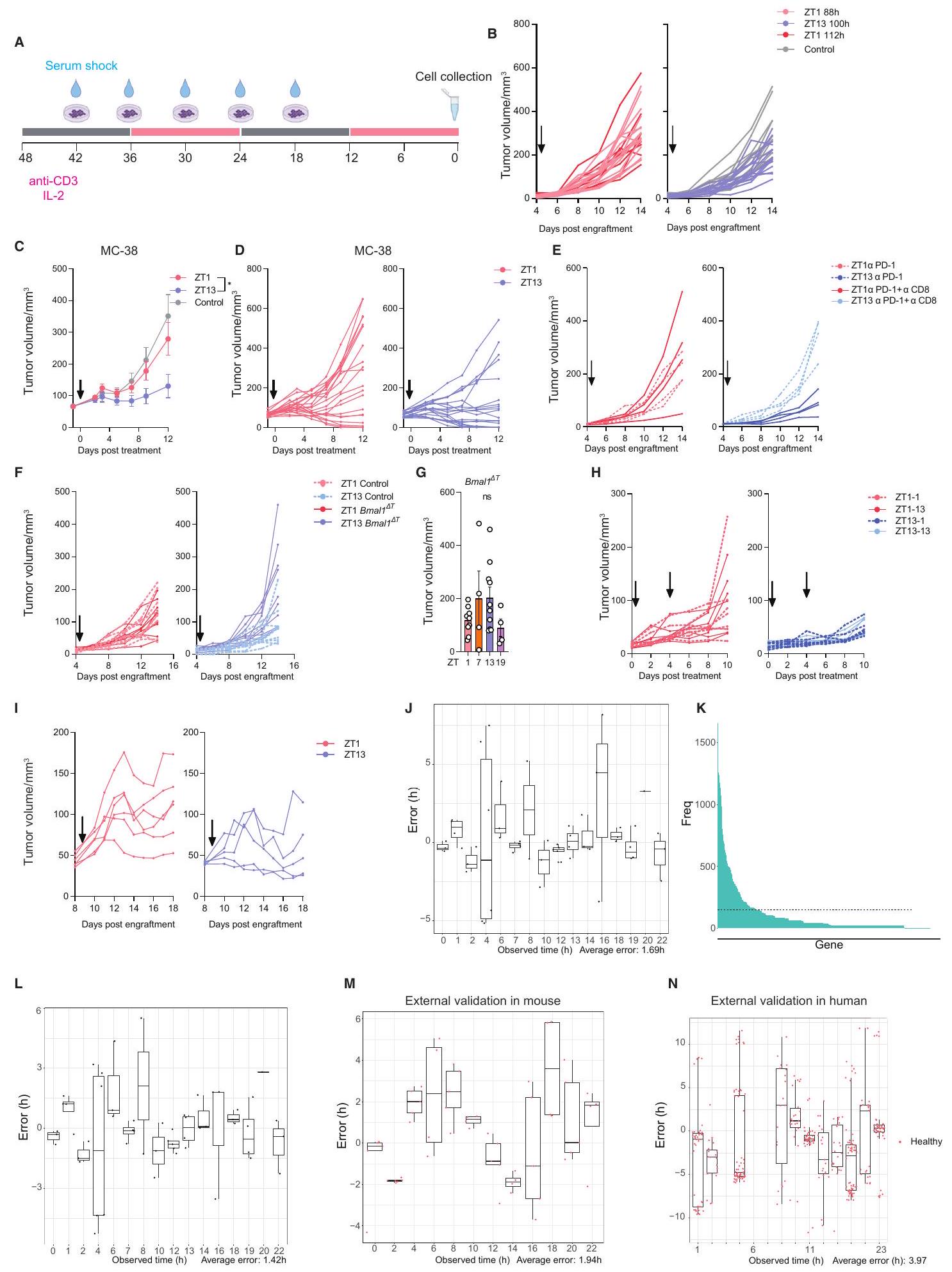

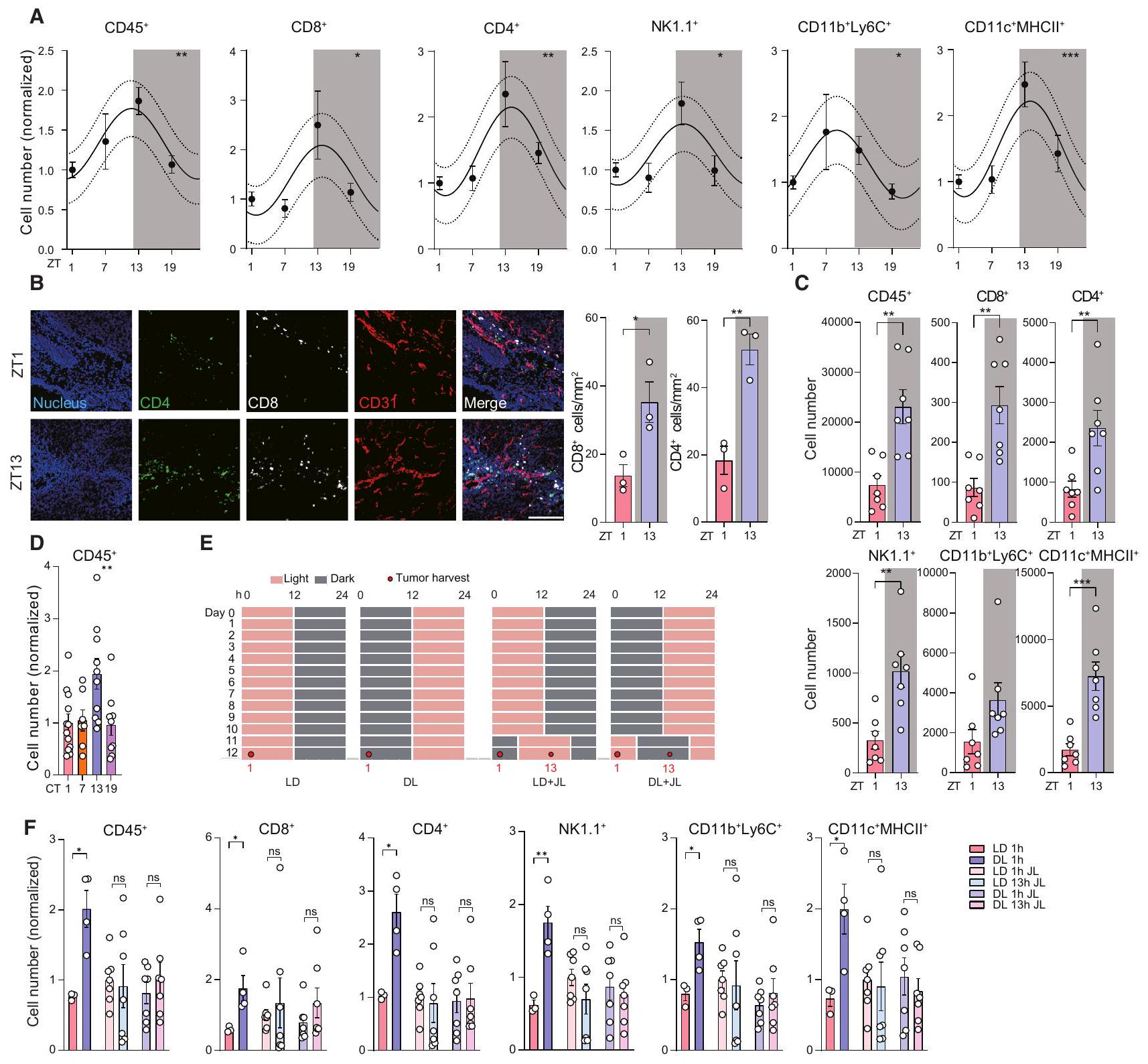

Leukocyte infiltration of tumors exhibits circadian oscillations

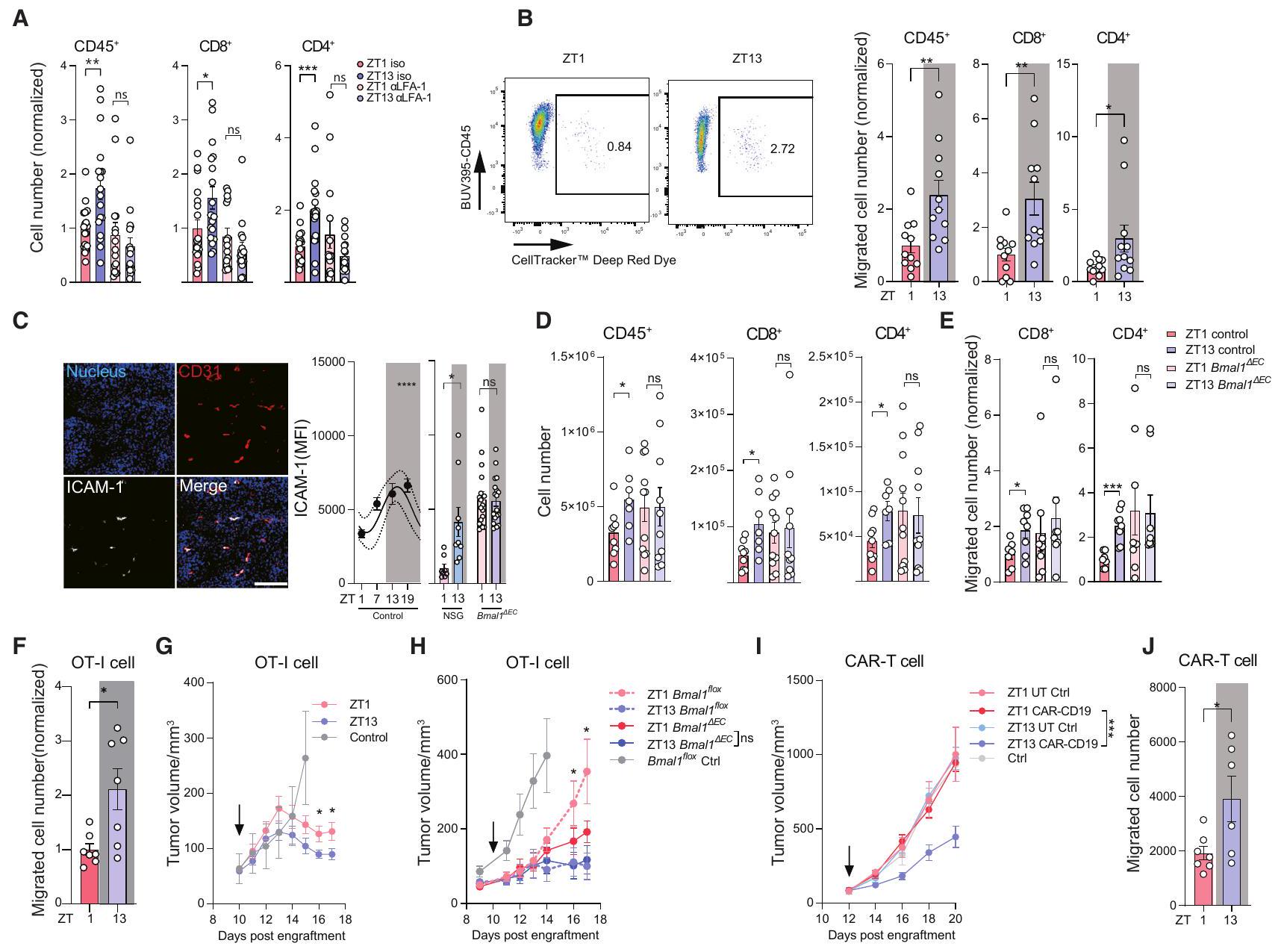

Endothelial cells gate circadian leukocyte infiltration

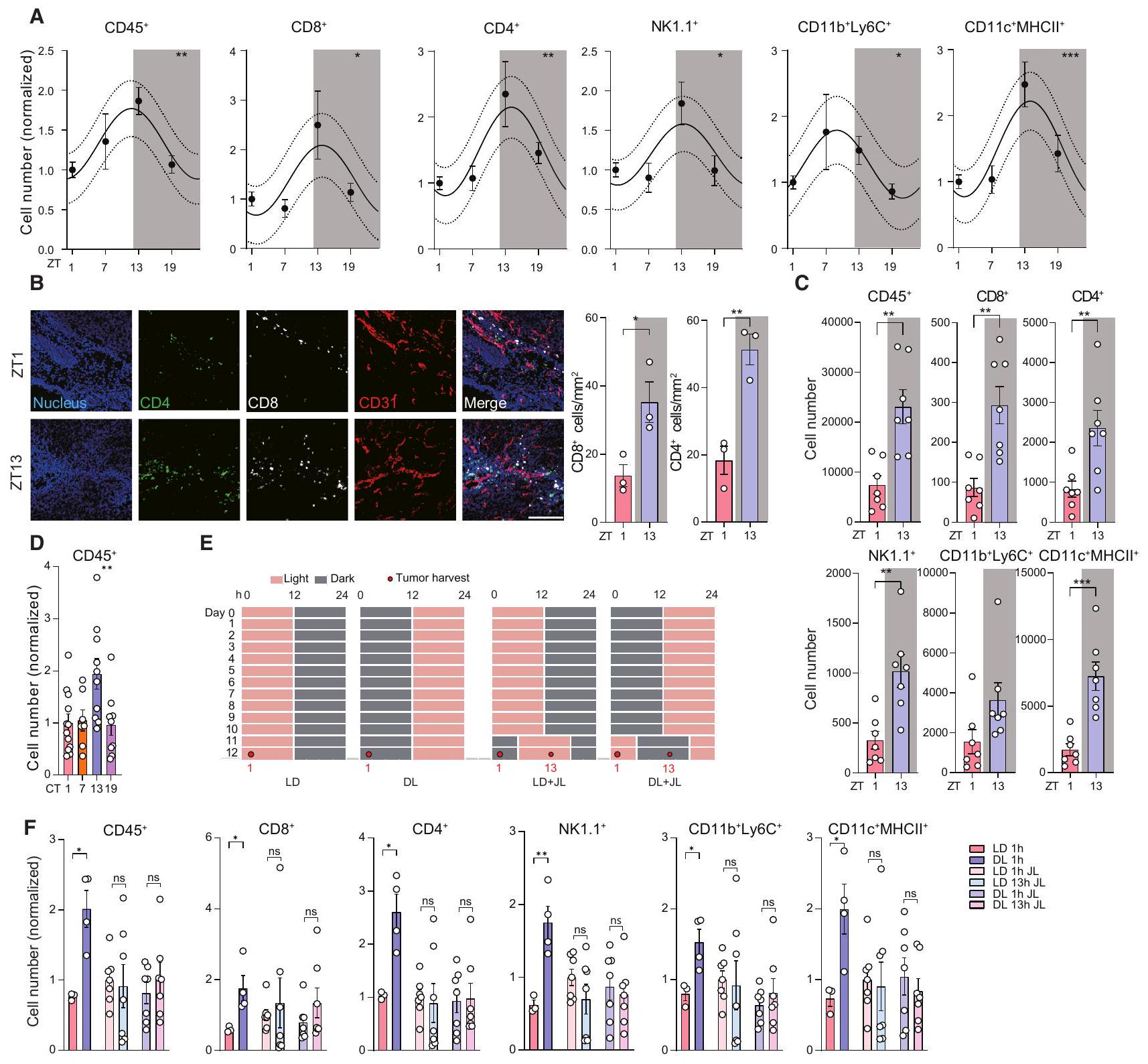

(A) Normalized total numbers of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes in a B16-F10-OVA tumor, harvested at 4 different times of the day (zeitgeber time [ZT]);

(B) Imaging (left) and quantification (right) of CD4

(C) Numbers of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes in Tyr::CreERT2, BRaf

(D) Normalized total numbers of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes in a B16-F10-OVA tumor, harvested at different times of the day under constant darkness conditions (circadian time [CT]);

(E) Light schedule of light:dark (LD), inverted dark:light (DL), and jet lag (JL) conditions. Shaded areas indicate dark phases, and numbers indicate the harvest times.

(F) Numbers of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes in a B16-F10-OVA tumor, harvested as the indicated time points (1 or 13 h in E) after the onset of the cycle under light:dark (LD,

(A) Normalized total numbers of tumor-infiltrating leukocytes in a B16-F10-OVA model, harvested at ZT1 or ZT13, 24 h after the treatment of isotype control or anti-LFA-1 antibodies;

(B) Gating strategy and quantification of adoptively transferred cells in B16-F10-OVA tumors 2 h post i.v. injection at ZT1 or ZT13;

(C) Imaging (left) and quantification (right) of ICAM-1 expression on CD31

(D) Numbers of leukocytes in B16-F10-OVA tumors, harvested at ZT1 or ZT13 from littermate control or Bmal1

(E) Normalized numbers of adoptively transferred leukocytes harvested from B16-F10-OVA tumors 2 h post i.v. injection at ZT1 or ZT13 into littermate control or Bmal1

(F) Normalized numbers of adoptively transferred OT-I cells in B16-F10-OVA tumors 2 h post injection at ZT1 or ZT13;

(G) Tumor volume after i.v. injection of

(H) Tumor volume after i.v. injection of

(I) Tumor volume after i.v. injection of

(J) Number of CAR T cells in DoHH2 tumors 24 h post i.v. injection at ZT1 (

thus focused on endothelial cells as potential mediators of circadian leukocyte infiltration and grafted tumors into animals exhibiting an inducible, lineage-specific lack of the circadian gene

Efficacy of CAR T cell therapy is time-of-day dependent

Diurnal differences in TIL phenotype

up

Time-of-day differences in the tumor

CD8

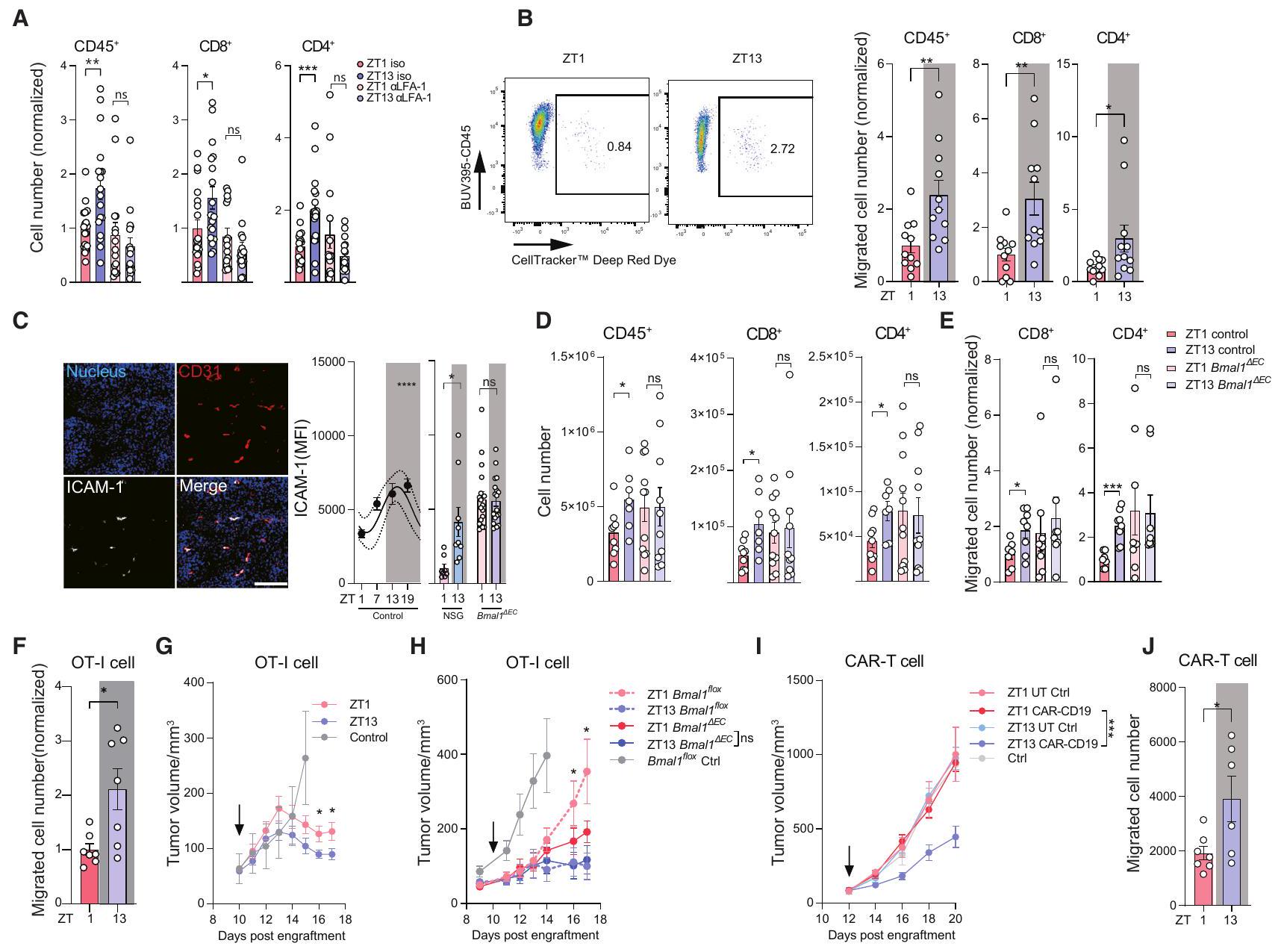

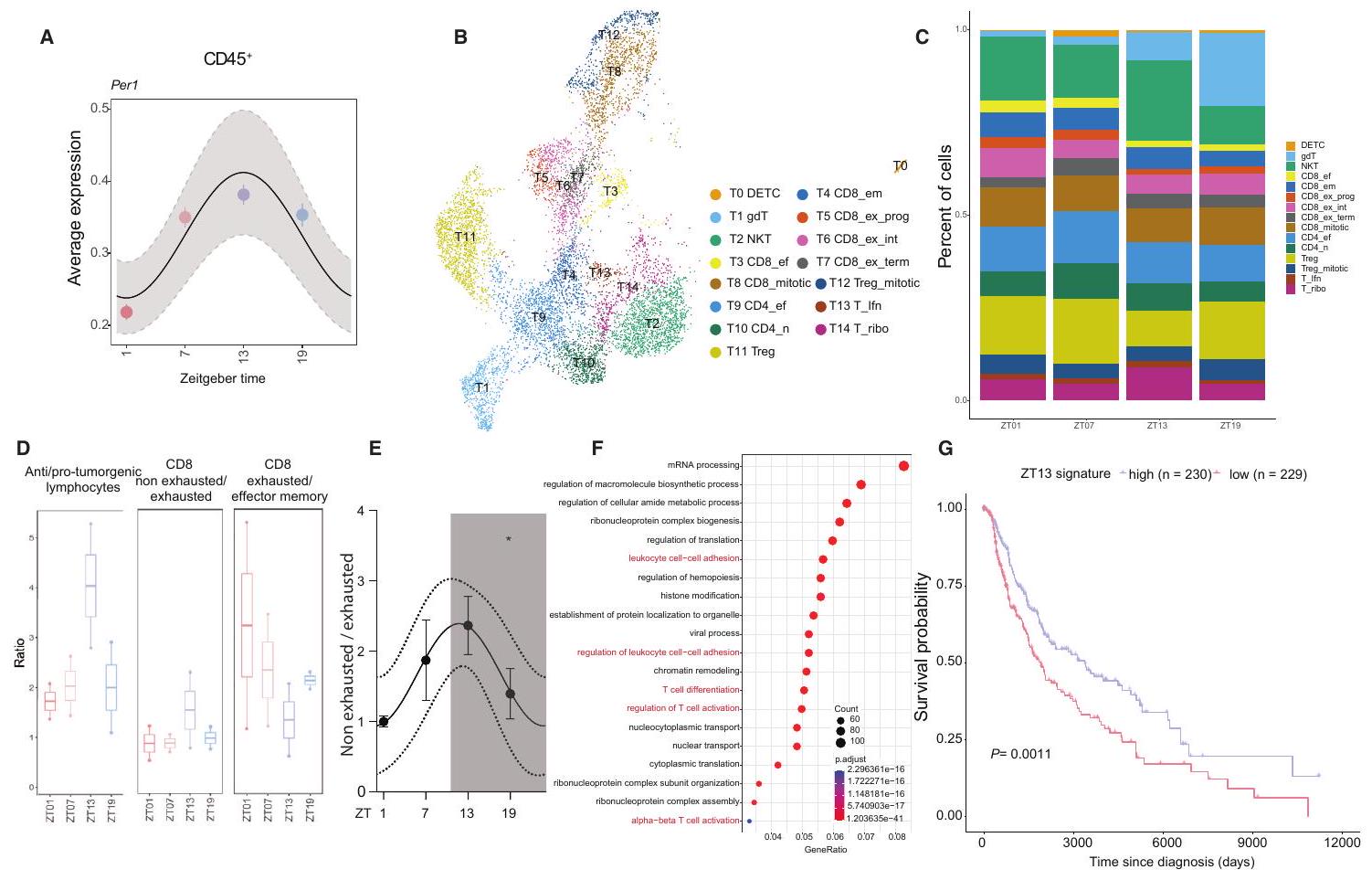

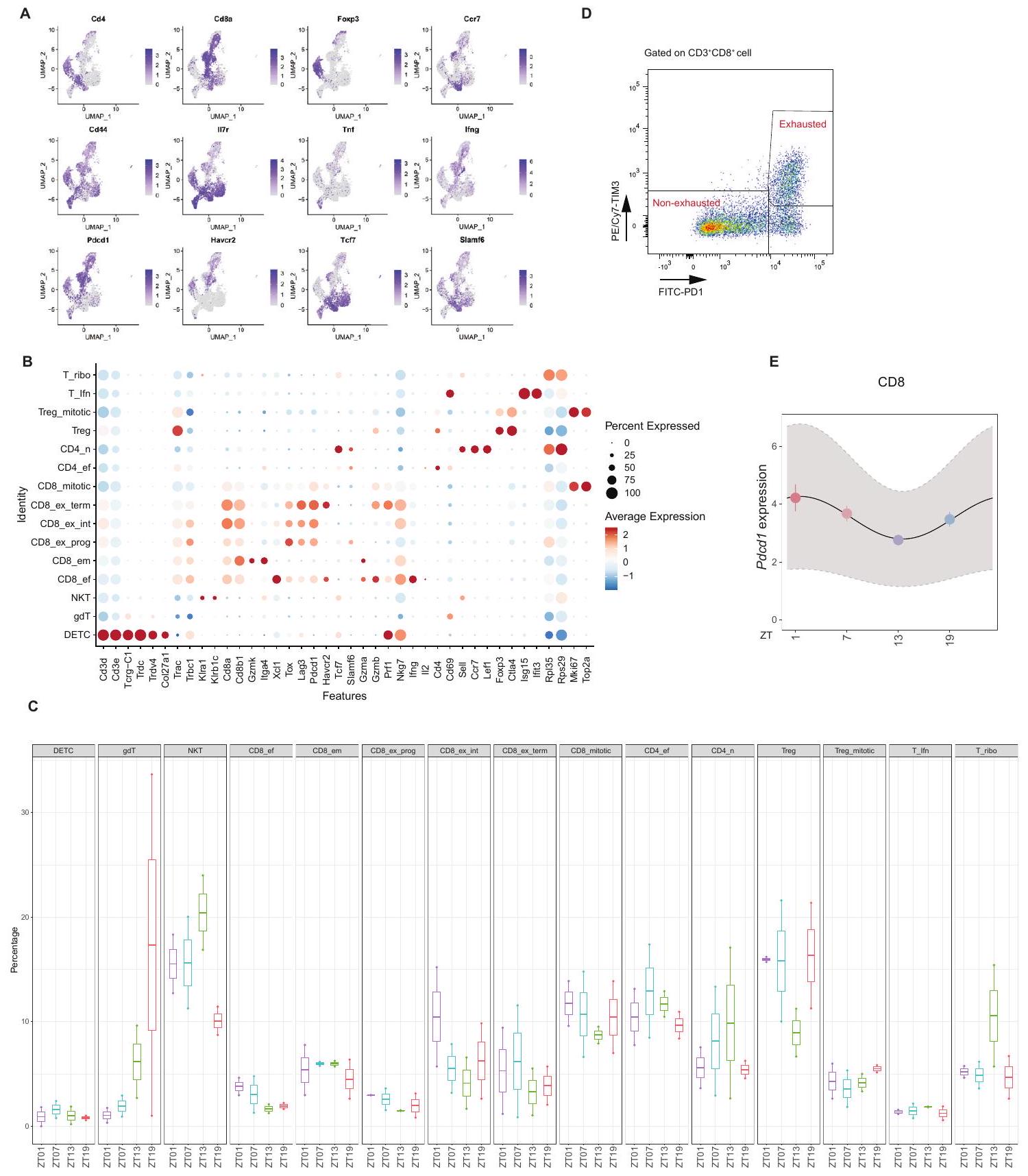

(B) UMAP representation of scRNA-seq analyses of T cells harvested at 4 different times of the day.

(C) Relative abundance of T cell subsets across different times of the day.

(D) Abundance ratio of specific T cell subsets across different times of the day by scRNA-seq. “Anti-tumorigenic lymphocytes” include NK,

(E) Normalized ratio of non-exhausted over exhausted

(F) Gene ontology analysis of genes oscillating in

(G) Survival analysis in melanoma patients from the TCGA dataset using a high or low expression of the murine ZT13 gene signature in Table S2, logrank test. All data are represented as mean

Anti-PD-1 therapy is time-of-day dependent

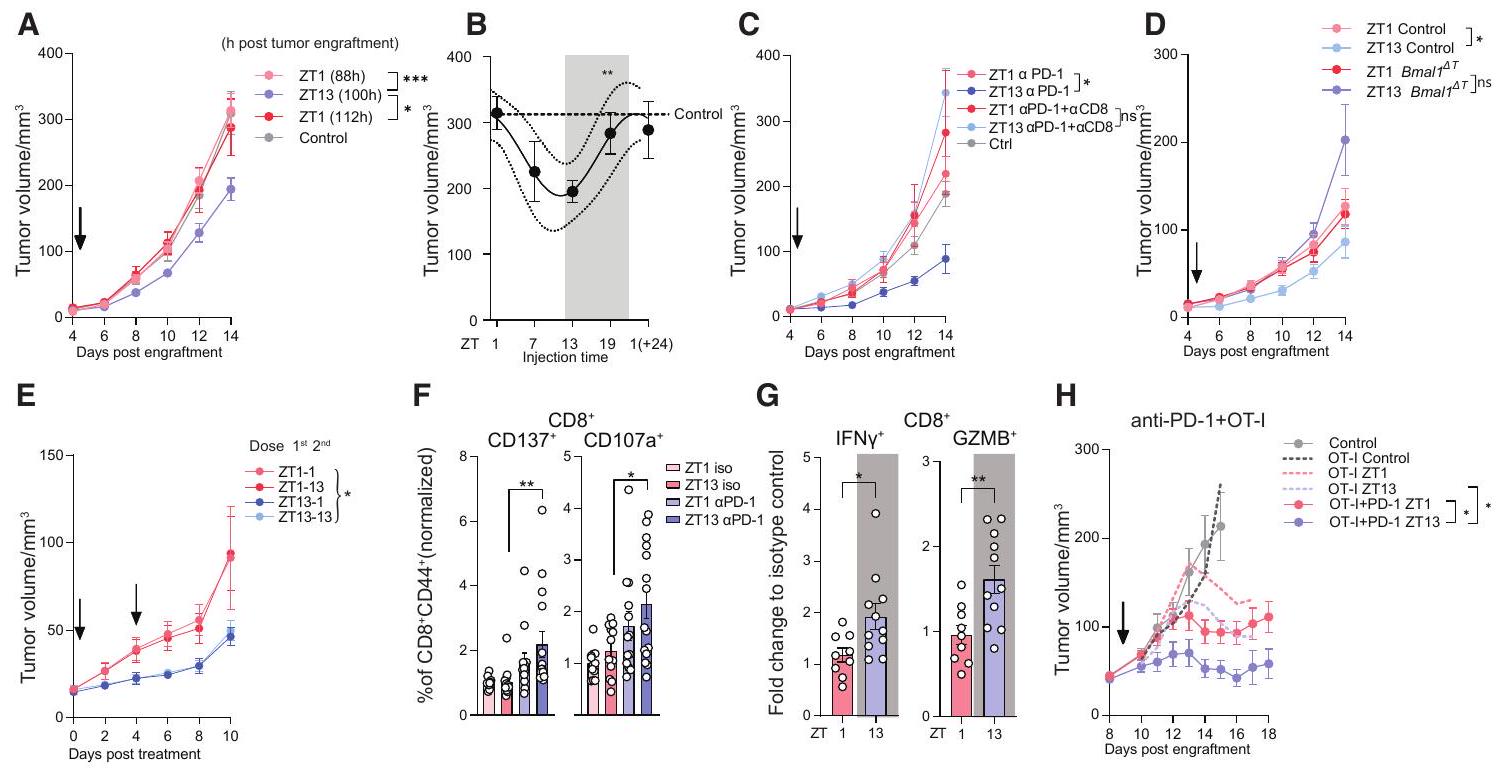

tumor model, with tumors growing less when therapy was performed in the evening compared with the morning (Figures 5A, 5B, and S6B). In fact, therapy in the morning had surprisingly little effect on tumor burden, even when morning administration preceded that of evening administration by 12 h (Figures 5A, 5B, and S6B). We could confirm these data in an MC-38 colon carcinoma model, indicating that this phenotype extended to other tumor models (Figures S6C and S6D). The time-of-day effect was critically dependent on

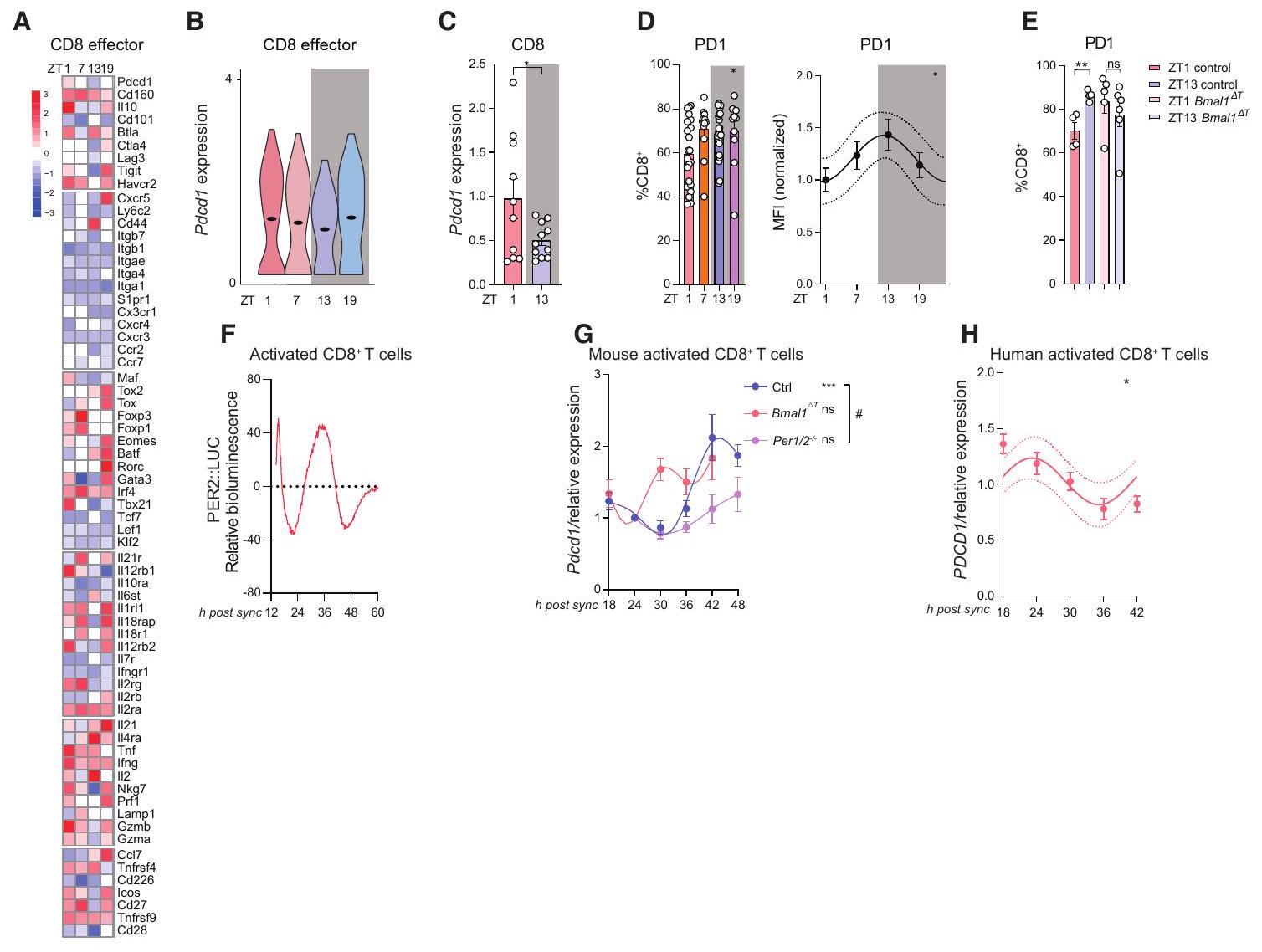

(A) Heatmap of scRNA-seq analyses of

(B) Pdcd1 expression by scRNA-seq of CD8

(C) Pdcd1 expression by qPCR of fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-sorted CD8

(D) PD-1 expression by flow cytometry of tumor

(E) PD-1 expression by flow cytometry of tumor CD8

(F) Relative bioluminescence of activated

(G) Pdcd1 expression of activated CD8

(H) PDCD1 expression in human activated CD8

further reducing tumor burden compared with ZT1 conditions (Figures 5 H and S6I). This indicates that both

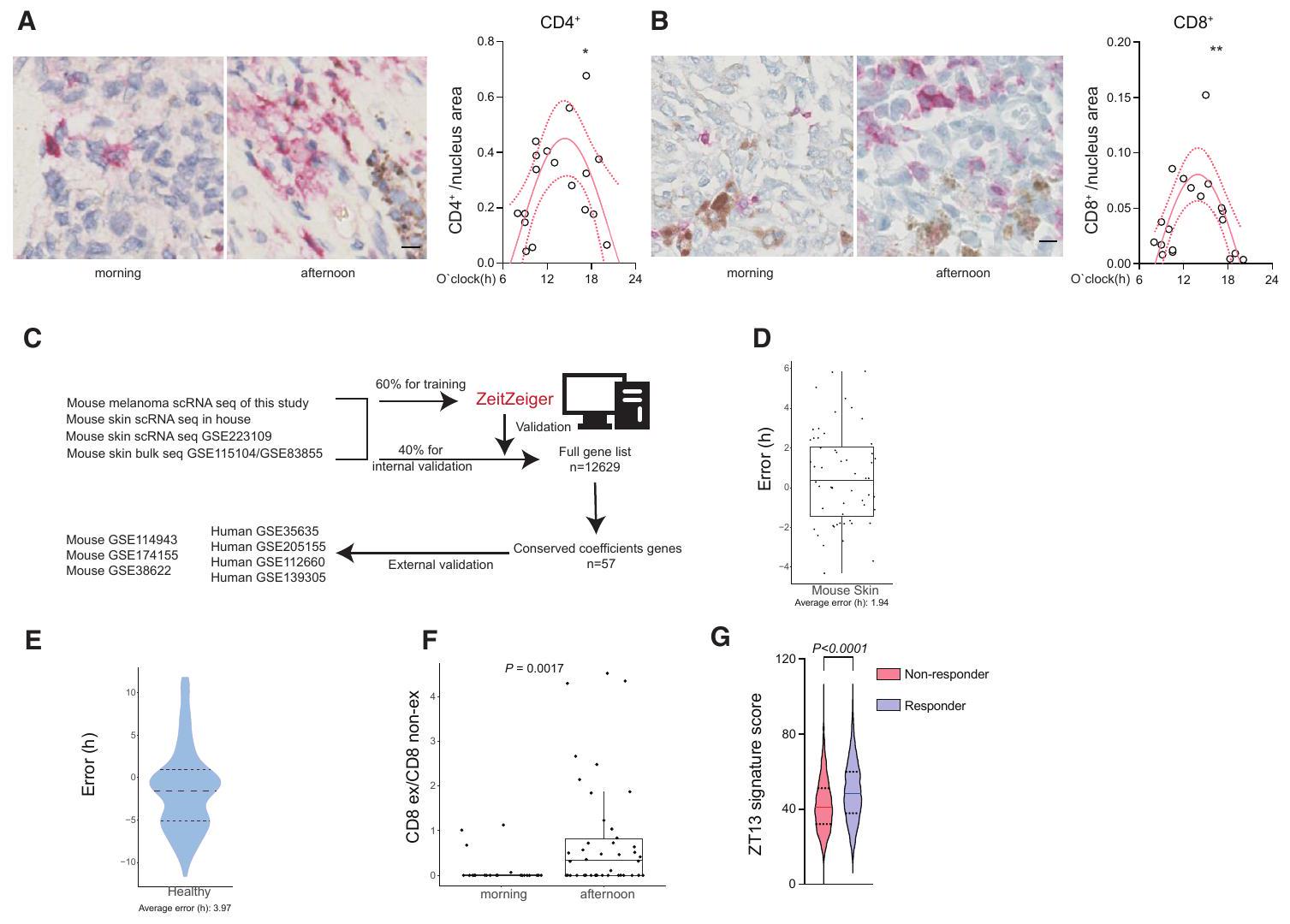

Circadian immune cell phenotype in human cancers

(A) Tumor volume after anti-PD-1 treatment (arrows) administered at ZT1 or ZT13, anti-PD-1 (

(B) Tumor volume 14 days post tumor engraftment, anti-PD-1 (

(C) Tumor volume after anti-PD-1 treatment (arrows) administered at ZT1 or ZT13 with or without (

(D) Tumor volume after anti-PD-1 treatment (arrows) administered at ZT1 or ZT13 in control (ZT1,

(E) Tumor volume after two doses of anti-PD-1 treatment (arrows) administered at ZT1 or ZT13;

(G) Cytokine production by tumor CD8

(H) Tumor volume after control (

available microarray data from healthy human skin where time of day information was known, we could adequately predict the time of day in these samples with an error of

(C) Schematic for the algorithm training and validation to predict time of day in non-time stamped samples. A final algorithm containing 57 genes was used for external validation and prediction.

(D and E) Error (hours) of the time prediction algorithm in external validation in mouse (

(F) Exhausted/non-exhausted

(G) Enrichment of the murine ZT13-gene expression signature in patients responding or not responding to ICB treatment (non-responders,

DISCUSSION

time-of-day sensitivity, given that we also see oscillations in macrophage phenotype in the TME. We have focused on CD8 T cells in this study, as they currently represent major therapeutic targets in the clinic. Our data show that antibody administration alters the phenotype of CD8 T cells within the tumor in a time-of-day-dependent manner, already 24 h after the infusion, indicating that these cells are involved in the initial circadian responses. Nevertheless, oscillations in other immune cell lineages that we describe, notably of myeloid cells, may be of additional functional relevance for the circadian effect. The contribution of different immune cell populations in this circadian anti-tumor response remains to be investigated in future studies.

Limitations of the study

defined, as current data only assessed morning versus afternoon effects.

STAR * METHODS

- KEY RESOURCES TABLE

- RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

- Lead contact

- Materials availability

- Data and code availability

- EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS – Animals

- METHOD DETAILS

- Tumor cell lines and inoculation

- Mouse T cell activation

- Mouse T cell synchronization

- Human

T cell activation and synchronization - Luciferase-expressing

cells - Tissue digestion and single-cell preparation

- Flow Cytometry

- Mouse leukocyte adoptive transfer

- EdU assay

- CD8 T cell sorting and RNA extraction

- RNA extraction, reverse transcription and qPCR

- In vivo antibody treatments

- Human CAR T cell generation

- Human CAR T cell adoptive transfer

- Immunofluorescence imaging

- Human immunohistochemistry

- Single cell sequencing and analysis

- ZeitZeiger analysis

- Estimation of cell composition in TCGA melanoma patients

- QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

from the ISREC Foundation, Ludwig Cancer Research, and NIH grants P01CA240239 and R01-CA218579. R.B. was funded by a Postdoc Mobility fellowship and a Return Grant of the SNSF (P400PM_183852 and P5R5PM_203164). Research in the A.D.G. lab is supported by Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) (Fundamental Research Grant, G0B4620N; FWO SBO grant for “ANTIBODY” consortium), KU Leuven (C1 grant, C14/19/098, and C3 grants, C3/21/ 037 and C3/22/022), Kom op Tegen Kanker (KOTK/2018/11509/1 and KOTK/ 2019/11955/1), VLIR-UOS (iBOF grant, iBOF/21/048, for “MIMICRY” consortium), and Olivia Hendrickx Research Fund (OHRF Immuunbiomarkers). C.D. was funded by Swiss National Science Foundation grant 310030_184708/1, the Vontobel Foundation, the Novartis Consumer Health Foundation, EFSD/Novo Nordisk Programme for Diabetes Research in Europe, Swiss Life Foundation, the Olga Mayenfisch Foundation, the Fondation pour l’innovation sur le cancer et la biologie, the Ligue Pulmonaire Genevoise, Swiss Cancer League KFS-5266-02-2021-R, the Velux Foundation, the Leenaards Foundation, the ISREC Foundation, and the Gertrude von Meissner Foundation (V.P. and C.D.). Y.W. received support from the Science Foundation of Peking University Cancer Hospital (2022-21). Extended data Figure 6A and the graphical abstract were created with BioRender.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

Revised: February 2, 2024

Accepted: April 16, 2024

Published: May 8, 2024

REFERENCES

- Mellman, I., Coukos, G., and Dranoff, G. (2011). Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 480, 480-489. https://doi.org/10.1038/ nature10673.

- Tawbi, H.A., Schadendorf, D., Lipson, E.J., Ascierto, P.A., Matamala, L., Castillo Gutiérrez, E., Rutkowski, P., Gogas, H.J., Lao, C.D., De Menezes, J.J., et al. (2022). Relatlimab and Nivolumab versus Nivolumab in Untreated Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 24-34. https://doi. org/10.1056/NEJMoa2109970.

- Cappell, K.M., and Kochenderfer, J.N. (2023). Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: what we know so far. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 359-371. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00754-1.

- Flugel, C.L., Majzner, R.G., Krenciute, G., Dotti, G., Riddell, S.R., Wagner, D.L., and Abou-El-Enein, M. (2023). Overcoming on-target, off-tumour toxicity of CAR T cell therapy for solid tumours. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20, 49-62. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-022-00704-3.

- Tumeh, P.C., Harview, C.L., Yearley, J.H., Shintaku, I.P., Taylor, E.J.M., Robert, L., Chmielowski, B., Spasic, M., Henry, G., Ciobanu, V., et al.

(2014). PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515, 568-571. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13954. - Wang, C., Barnoud, C., Cenerenti, M., Sun, M., Caffa, I., Kizil, B., Bill, R., Liu, Y., Pick, R., Garnier, L., et al. (2023). Dendritic cells direct circadian anti-tumour immune responses. Nature 614, 136-143. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41586-022-05605-0.

- Scheiermann, C., Gibbs, J., Ince, L., and Loudon, A. (2018). Clocking in to immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 423-437. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41577-018-0008-4.

- Arjona, A., Silver, A.C., Walker, W.E., and Fikrig, E. (2012). Immunity’s fourth dimension: approaching the circadian-immune connection. Trends Immunol. 33, 607-612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2012.08.007.

- Curtis, A.M., Bellet, M.M., Sassone-Corsi, P., and O’Neill, L.A.J. (2014). Circadian clock proteins and immunity. Immunity 40, 178-186. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2014.02.002.

- Cermakian, N., Stegeman, S.K., Tekade, K., and Labrecque, N. (2022). Circadian rhythms in adaptive immunity and vaccination. Semin. Immunopathol. 44, 193-207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-021-00903-7.

- Man, K., Loudon, A., and Chawla, A. (2016). Immunity around the clock. Science 354, 999-1003. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aah4966.

- Palomino-Segura, M., and Hidalgo, A. (2021). Circadian immune circuits. J. Exp. Med. 218, e20200798. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem. 20200798.

- Wang, C., Lutes, L.K., Barnoud, C., and Scheiermann, C. (2022). The circadian immune system. Sci. Immunol. 7, eabm2465. https://doi.org/10. 1126/sciimmunol.abm2465.

- He, W., Holtkamp, S., Hergenhan, S.M., Kraus, K., de Juan, A., Weber, J., Bradfield, P., Grenier, J.M.P., Pelletier, J., Druzd, D., et al. (2018). Circadian Expression of Migratory Factors Establishes Lineage-Specific Signatures that Guide the Homing of Leukocyte Subsets to Tissues. Immunity 49, 1175-1190.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2018.10.007.

- Druzd, D., Matveeva, O., Ince, L., Harrison, U., He, W., Schmal, C., Herzel, H., Tsang, A.H., Kawakami, N., Leliavski, A., et al. (2017). Lymphocyte Circadian Clocks Control Lymph Node Trafficking and Adaptive Immune Responses. Immunity 46, 120-132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni. 2016.12.011.

- Shimba, A., Cui, G., Tani-ichi, S., Ogawa, M., Abe, S., Okazaki, F., Kitano, S., Miyachi, H., Yamada, H., Hara, T., et al. (2018). Glucocorticoids Drive Diurnal Oscillations in T Cell Distribution and Responses by Inducing Interleukin-7 Receptor and CXCR4. Immunity 48, 286-298.e6. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2018.01.004.

- Casanova-Acebes, M., Nicolás-Ávila, J.A., Li, J.L., García-Silva, S., Balachander, A., Rubio-Ponce, A., Weiss, L.A., Adrover, J.M., Burrows, K., AGonzález, N., et al. (2018). Neutrophils instruct homeostatic and pathological states in naive tissues. J. Exp. Med. 215, 2778-2795. https://doi.org/ 10.1084/jem. 20181468.

- Nguyen, K.D., Fentress, S.J., Qiu, Y., Yun, K., Cox, J.S., and Chawla, A. (2013). Circadian gene Bmal1 regulates diurnal oscillations of Ly6C(hi) inflammatory monocytes. Science 341, 1483-1488. https://doi.org/10. 1126/science. 1240636.

- Cervantes-Silva, M.P., Carroll, R.G., Wilk, M.M., Moreira, D., Payet, C.A., O’Siorain, J.R., Cox, S.L., Fagan, L.E., Klavina, P.A., He, Y., et al. (2022). The circadian clock influences

cell responses to vaccination by regulating dendritic cell antigen processing. Nat. Commun. 13, 7217. https:// doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34897-z. - Ince, L.M., Barnoud, C., Lutes, L.K., Pick, R., Wang, C., Sinturel, F., Chen, C.S., de Juan, A., Weber, J., Holtkamp, S.J., et al. (2023). Influence of circadian clocks on adaptive immunity and vaccination responses. Nat. Commun. 14, 476. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-35979-2.

- Nobis, C.C., Dubeau Laramée, G., Kervezee, L., Maurice De Sousa, D., Labrecque, N., and Cermakian, N. (2019). The circadian clock of CD8 T cells modulates their early response to vaccination and the rhythmicity of related signaling pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 2007720086. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1905080116.

- Gibbs, J., Ince, L., Matthews, L., Mei, J., Bell, T., Yang, N., Saer, B., Begley, N., Poolman, T., Pariollaud, M., et al. (2014). An epithelial circadian clock controls pulmonary inflammation and glucocorticoid action. Nat. Med. 20, 919-926. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3599.

- Scheiermann, C., Kunisaki, Y., Lucas, D., Chow, A., Jang, J.E., Zhang, D., Hashimoto, D., Merad, M., and Frenette, P.S. (2012). Adrenergic nerves govern circadian leukocyte recruitment to tissues. Immunity 37, 290-301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.021.

- Hazan, G., Duek, O.A., Alapi, H., Mok, H., Ganninger, A., Ostendorf, E., Gierasch, C., Chodick, G., Greenberg, D., and Haspel, J.A. (2023). Biological rhythms in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in an observational cohort study of 1.5 million patients. J. Clin. Invest. 133, e167339. https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCl167339.

- Long, J.E., Drayson, M.T., Taylor, A.E., Toellner, K.M., Lord, J.M., and Phillips, A.C. (2016). Morning vaccination enhances antibody response over afternoon vaccination: A cluster-randomised trial. Vaccine 34, 26792685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.032.

- Ho, P.C., Bihuniak, J.D., Macintyre, A.N., Staron, M., Liu, X., Amezquita, R., Tsui, Y.C., Cui, G., Micevic, G., Perales, J.C., et al. (2015). Phosphoenolpyruvate Is a Metabolic Checkpoint of Anti-tumor T Cell Responses. Cell 162, 1217-1228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.012.

- Raskov, H., Orhan, A., Christensen, J.P., and Gögenur, I. (2021). Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in cancer and cancer immunotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 124, 359-367. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01048-4.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2024). B-Cell Lymphomas. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1480.

- Neelapu, S.S., Dickinson, M., Munoz, J., Ulrickson, M.L., Thieblemont, C., Oluwole, O.O., Herrera, A.F., Ujjani, C.S., Lin, Y., Riedell, P.A., et al. (2022). Axicabtagene ciloleucel as first-line therapy in high-risk large B-cell lymphoma: the phase 2 ZUMA-12 trial. Nat. Med. 28, 735-742. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41591-022-01731-4.

- Arjona, A., and Sarkar, D.K. (2005). Circadian oscillations of clock genes, cytolytic factors, and cytokines in rat NK cells. J. Immunol. 174, 76187624. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7618.

- Hughey, J.J., Hastie, T., and Butte, A.J. (2016). ZeitZeiger: supervised learning for high-dimensional data from an oscillatory system. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e80. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw030.

- Zhao, Y., Liu, M., Chan, X.Y., Tan, S.Y., Subramaniam, S., Fan, Y., Loh, E., Chang, K.T.E., Tan, T.C., and Chen, Q. (2017). Uncovering the mystery of opposite circadian rhythms between mouse and human leukocytes in humanized mice. Blood 130, 1995-2005. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-04-778779.

- Sade-Feldman, M., Yizhak, K., Bjorgaard, S.L., Ray, J.P., de Boer, C.G., Jenkins, R.W., Lieb, D.J., Chen, J.H., Frederick, D.T., Barzily-Rokni, M., et al. (2018). Defining T Cell States Associated with Response to Checkpoint Immunotherapy in Melanoma. Cell 175, 998-1013.e20. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.038.

- Naulaerts, S., Datsi, A., Borras, D.M., Antoranz Martinez, A., Messiaen, J., Vanmeerbeek, I., Sprooten, J., Laureano, R.S., Govaerts, J., Panovska, D., et al. (2023). Multiomics and spatial mapping characterizes human CD8

T cell states in cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eadd1016. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/scitransImed.add1016. - Qian, D.C., Kleber, T., Brammer, B., Xu, K.M., Switchenko, J.M., Jano-paul-Naylor, J.R., Zhong, J., Yushak, M.L., Harvey, R.D., Paulos, C.M., et al. (2021). Effect of immunotherapy time-of-day infusion on overall survival among patients with advanced melanoma in the USA (MEMOIR): a propensity score-matched analysis of a single-centre, longitudinal study. Lancet Oncol. 22, 1777-1786. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21) 00546-5.

- Yeung, C., Kartolo, A., Tong, J., Hopman, W., and Baetz, T. (2023). Association of circadian timing of initial infusions of immune checkpoint inhibitors with survival in advanced melanoma. Immunotherapy 15, 819-826. https://doi.org/10.2217/imt-2022-0139.

- Gonçalves, L., Gonçalves, D., Esteban-Casanelles, T., Barroso, T., Soares de Pinho, I., Lopes-Brás, R., Esperança-Martins, M., Patel, V., Torres, S., Teixeira de Sousa, R., et al. (2023). Immunotherapy around the Clock: Impact of Infusion Timing on Stage IV Melanoma Outcomes. Cells 12, 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12162068.

- Karaboué, A., Collon, T., Pavese, I., Bodiguel, V., Cucherousset, J., Zakine, E., Innominato, P.F., Bouchahda, M., Adam, R., and Lévi, F. (2022). Time-Dependent Efficacy of Checkpoint Inhibitor Nivolumab: Results from a Pilot Study in Patients with Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 14, 896. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14040896.

- Rousseau, A., Tagliamento, M., Auclin, E., Aldea, M., Frelaut, M., Levy, A., Benitez, J.C., Naltet, C., Lavaud, P., Botticella, A., et al. (2023). Clinical outcomes by infusion timing of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 182, 107-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2023.01.007.

- Nomura, M., Hosokai, T., Tamaoki, M., Yokoyama, A., Matsumoto, S., and Muto, M. (2023). Timing of the infusion of nivolumab for patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus influences its efficacy. Esophagus 20, 722-731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10388-023-01006-y.

- Landré, T., Karaboué, A., Buchwald, Z.S., Innominato, P.F., Qian, D.C., Assié, J.B., Chouaïd, C., Lévi, F., and Duchemann, B. (2024). Effect of immunotherapy-infusion time of day on survival of patients with advanced cancers: a study-level meta-analysis. ESMO Open 9, 102220. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.102220.

- Martin, A.M., Cagney, D.N., Catalano, P.J., Alexander, B.M., Redig, A.J., Schoenfeld, J.D., and Aizer, A.A. (2018). Immunotherapy and Symptomatic Radiation Necrosis in Patients With Brain Metastases Treated With Stereotactic Radiation. JAMA Oncol. 4, 1123-1124. https://doi.org/10. 1001/jamaoncol.2017.3993.

- Postow, M.A., Goldman, D.A., Shoushtari, A.N., Betof Warner, A., Callahan, M.K., Momtaz, P., Smithy, J.W., Naito, E., Cugliari, M.K., Raber, V., et al. (2022). Adaptive Dosing of Nivolumab + Ipilimumab Immunotherapy Based Upon Early, Interim Radiographic Assessment in Advanced Melanoma (The ADAPT-IT Study). J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 1059-1067. https://doi. org/10.1200/JCO.21.01570.

- Arlauckas, S.P., Garris, C.S., Kohler, R.H., Kitaoka, M., Cuccarese, M.F., Yang, K.S., Miller, M.A., Carlson, J.C., Freeman, G.J., Anthony, R.M., et al. (2017). In vivo imaging reveals a tumor-associated macrophagemediated resistance pathway in anti-PD-1 therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaal3604. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitransImed.aal3604.

- Conforti, F., Pala, L., Bagnardi, V., De Pas, T., Martinetti, M., Viale, G., Gelber, R.D., and Goldhirsch, A. (2018). Cancer immunotherapy efficacy and patients’ sex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 19, 737-746. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30261-4.

- Lévi, F.A., Okyar, A., Hadadi, E., Innominato, P.F., and Ballesta, A. (2024). Circadian Regulation of Drug Responses: Toward Sex-Specific and Personalized Chronotherapy. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 64, 89-114. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-051920-095416.

- Duan, J., Ngo, M.N., Karri, S.S., Tsoi, L.C., Gudjonsson, J.E., Shahbaba, B., Lowengrub, J., and Andersen, B. (2023). tauFisher accurately predicts circadian time from a single sample of bulk and single-cell transcriptomic data. Preprint at bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.04.535473.

- Welz, P.-S., Zinna, V.M., Symeonidi, A., Koronowski, K.B., Kinouchi, K., Smith, J.G., Guillén, I.M., Castellanos, A., Furrow, S., Aragón, F., et al. (2019). BMAL1-Driven Tissue Clocks Respond Independently to Light to Maintain Homeostasis. Cell 177, 1436-1447.e12. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.cell.2019.05.009.

- Wang, H., van Spyk, E., Liu, Q., Geyfman, M., Salmans, M.L., Kumar, V., Ihler, A., Li, N., Takahashi, J.S., and Andersen, B. (2017). Time-Restricted Feeding Shifts the Skin Circadian Clock and Alters UVB-Induced DNA Damage. Cell Rep. 20, 1061-1072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep. 2017.07.022.

- Tsujihana, K., Tanegashima, K., Santo, Y., Yamada, H., Akazawa, S., Nakao, R., Tominaga, K., Saito, R., Nishito, Y., Hata, R.-I., et al. (2022). Circadian protection against bacterial skin infection by epidermal CXCL14mediated innate immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2116027119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116027119.

- Geyfman, M., Kumar, V., Liu, Q., Ruiz, R., Gordon, W., Espitia, F., Cam, E., Millar, S.E., Smyth, P., Ihler, A., et al. (2012). Brain and muscle Arnt-like protein-1 (BMAL1) controls circadian cell proliferation and susceptibility to UVB-induced DNA damage in the epidermis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11758-11763. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1209592109.

- Spörl, F., Korge, S., Jürchott, K., Wunderskirchner, M., Schellenberg, K., Heins, S., Specht, A., Stoll, C., Klemz, R., Maier, B., et al. (2012). Krüp-pel-like factor 9 is a circadian transcription factor in human epidermis that controls proliferation of keratinocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 10903-10908. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118641109.

- del Olmo, M., Spörl, F., Korge, S., Jürchott, K., Felten, M., Grudziecki, A., de Zeeuw, J., Nowozin, C., Reuter, H., Blatt, T., et al. (2022). Inter-layer and inter-subject variability of diurnal gene expression in human skin. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 4, Iqac097. https://doi.org/10.1093/nargab/Iqac097.

- Wu, G., Ruben, M.D., Schmidt, R.E., Francey, L.J., Smith, D.F., Anafi, R.C., Hughey, J.J., Tasseff, R., Sherrill, J.D., Oblong, J.E., et al. (2018). Popula-tion-level rhythms in human skin with implications for circadian medicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 12313-12318. https://doi.org/10.1073/ pnas. 1809442115.

- Sherrill, J.D., Finlay, D., Binder, R.L., Robinson, M.K., Wei, X., Tiesman, J.P., Flagler, M.J., Zhao, W., Miller, C., Loftus, J.M., et al. (2021). Transcriptomic analysis of human skin wound healing and rejuvenation following ablative fractional laser treatment. PLoS One 16, e0260095. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0260095.

- Hao, Y., Hao, S., Andersen-Nissen, E., Mauck, W.M., 3rd, Zheng, S., Butler, A., Lee, M.J., Wilk, A.J., Darby, C., Zager, M., et al. (2021). Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 184, 3573-3587.e29. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.048.

- Wu, T., Hu, E., Xu, S., Chen, M., Guo, P., Dai, Z., Feng, T., Zhou, L., Tang, W., Zhan, L., et al. (2021). clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation (Camb) 2, 100141. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141.

- Carlucci, M., Kriščiūnas, A., Li, H., Gibas, P., Koncevičius, K., Petronis, A., and Oh, G. (2019). DiscoRhythm: an easy-to-use web application and

package for discovering rhythmicity. Bioinformatics 36, 1952-1954. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz834. - Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R., and Guinney, J. (2013). GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-7.

- Colaprico, A., Silva, T.C., Olsen, C., Garofano, L., Cava, C., Garolini, D., Sabedot, T.S., Malta, T.M., Pagnotta, S.M., Castiglioni, I., et al. (2016). TCGAbiolinks: an R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e71. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/ gkv1507.

- Leek, J.T., Johnson, W.E., Parker, H.S., Jaffe, A.E., and Storey, J.D. (2012). The sva package for removing batch effects and other unwanted variation in high-throughput experiments. Bioinformatics 28, 882-883. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts034.

- Holtkamp, S.J., Ince, L.M., Barnoud, C., Schmitt, M.T., Sinturel, F., Pilorz, V., Pick, R., Jemelin, S., Mühlstädt, M., Boehncke, W.H., et al. (2021). Circadian clocks guide dendritic cells into skin lymphatics. Nat. Immunol. 22, 1375-1381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-021-01040-x.

- Wittenbrink, N., Ananthasubramaniam, B., Münch, M., Koller, B., Maier, B., Weschke, C., Bes, F., de Zeeuw, J., Nowozin, C., Wahnschaffe, A., et al. (2018). High-accuracy determination of internal circadian time from a single blood sample. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 3826-3839. https://doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI120874.

- Newman, A.M., Steen, C.B., Liu, C.L., Gentles, A.J., Chaudhuri, A.A., Scherer, F., Khodadoust, M.S., Esfahani, M.S., Luca, B.A., Steiner, D., et al. (2019). Determining cell type abundance and expression from bulk tissues with digital cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 773-782. https://doi. org/10.1038/s41587-019-0114-2.

STAR*METHODS

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-mouse CD45 clone 30-F11 | BD Biosciences | 564279/AB_2651134 |

| Anti-mouse CD3e clone KT3.1.1 | BioLegend | 155617/AB_2832541 |

| Anti-mouse CD4 clone GK1.5 | BD Biosciences | 563232/AB_2738083 |

| Anti-mouse CD8a clone 53-6.7 | BD Biosciences | 563152/AB_2738030 |

| Anti-mouse CD11c clone N418 | BioLegend | 117307/AB_313776 |

| Anti-mouse CD19 clone 1D3 | BD Biosciences | 566412/AB_2744315 |

| Anti-mouse NK1.1 clone PK136 | BioLegend | 108715/AB_493591 |

| Anti-mouse MHCII clone M5/114.15.2 | BioLegend | 107643/AB_2565976 |

| Anti-mouse Ly6G clone 1A8 | BioLegend | 127645/AB_2566317 |

| Anti-mouse Ly6C clone HK1.4 | BioLegend | 128023/AB_10640119 |

| Anti-mouse CD137 clone 17B5 | BioLegend | 106106/AB_2287565 |

| Anti-mouse CD107a clone 1D4B | BioLegend | 121610/AB_571991 |

| Anti-mouse PD-1clone 29F.1A12 | BioLegend | 135213/AB_10689633 |

| Anti-mouse Granzyme B clone QA16A02 | BioLegend | 372207/AB_2687031 |

| Anti-mouse IFN-

|

BioLegend | 505837/AB_11219004 |

| Anti-mouse CD31 clone MEC13.3, | BioLegend | 102520/AB_2563319 |

| Anti-mouse CD4 clone, GK1.5 | BioLegend | 100405/AB_312690 |

| Anti-mouse CD54 clone, YN1/1.7.4 | BioLegend | 116114/AB_493495 |

| Anti-mouse CD8 clone 53-6.7 | BioLegend | 100724/AB_389326 |

| Anti-mouse VCAM-1 clone 429 | BioLegend | 105710/AB_493427 |

| Anti-mouse anti-CD11a clone M17/4 | BioXCell | BE0006/ AB_1107578 |

| Anti-mouse anti-CD18 clone M18/2 | BioXCell | BE0009/ AB_1107607 |

| Anti-mouse PD-1, clone 29F.1A12

|

BioXCell | BE0273/ AB_2687796 |

| Anti-mouse CD8a, clone YTS 169.4 | BioXCell | BE0117/ AB_10950145 |

| Anti-mouse E-selectin clone UZ6 | Invitrogen | MA1-06506/ AB_2186701 |

| Anti-human CD3 clone BW264/56 | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-113-687/AB_2726228 |

| Anti-human CD8 clone RPA-T8 | BD Biosciences | 563795/AB_2722501 |

| Anti-human CD4 clone SK3 | BD Biosciences | 565995/AB_2739446 |

| Anti-human CD19 clone HIB19 | BioLegend | 302219/AB_389313 |

| Anti-human CD4 clone EP204 | Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology | ZA-0519 |

| Anti-human CD8 clone SP16 | Zhongshan Golden Bridge Biotechnology | ZA-0508 |

| rat IgG2a isotype control, clone 2A3 | BioXCell | BE0089/ AB_1107769 |

| rat IgG2b isotype control, clone LTF-2 | BioXCell | BE0090/ AB_1107780 |

| Dynabeads human T-Activator CD3/CD28 | Gibco | 11132D/AB_2916088 |

| Anti-human CD3 clone BW264/56 | BioLegend | 317348/ AB_2571995 |

| Dynabeads

|

Gibco | 11453D |

| Goat anti-Rat IgG (H+L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody | Invitrogen | A21247/ AB_141778 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| DRAQ7 | Biolegend | 424001 |

| Counting Beads | ThermoFisher | C36950 |

| Continued | ||

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

| eBioscience

|

eBioscience

|

65-0865-18 |

| Foxp3 / Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set | eBioscience

|

00-5523-00 |

| Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate | Sigma-Aldrich | P1585 |

| Ionomycin | Sigma-Aldrich | I3909 |

| GolgiPlug

|

BD Biosciences | 555029 |

| CellEvent

|

Invitrogen | R37167 |

| CellTracker

|

Invitrogen | C34565 |

| RBC lysis buffer | Biolegend | 420302 |

| EdU Alexa Fluor

|

Invitrogen | C10646 |

| Trizol Reagent | Invitrogen | 15596018 |

| Human IL-2 | PeproTech | 200-02 |

| Mouse IL-2 | Biolegend | 575406 |

| retronectin | Takara | T100B |

| streptavidin | Biolegend | 405207 |

| biotinylated protein L | ThermoFisher | 29997 |

| Collagenase IV | Worthington Biochemical Corporation | LS004189 |

| Collagenase D | Roche | 11088866001 |

| DNase I | Roche | 04716728001 |

| DAPI | Biolegend | 422801 |

| BlockAid

|

Invitrogen | B10710 |

| Bond Polymer Refine Red Detection kit | Leica | DS9390 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Chromium Single Cell 3′ v3.1 Reagent Kit with dual indexes | 10x Genomics | 1000269 |

| CD8+ T Cell Isolation Kit, human | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-096-495 |

| CD8a+ T Cell Isolation Kit, mouse | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-104-075 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Timed scRNA-seq of TILs from murine melanoma | This paper | GEO: GSE260641 |

| Mouse epidermal scRNA-seq | Duan et al.

|

GEO: GSE223109 |

| Mouse skin RNA-seq | Welz et al.

|

GEO: GSE115104, GSE114943 |

| Mouse skin RNA-seq | Wang et al.

|

GEO: GSE83855 |

| Mouse epidermal RNA-seq in constant darkness | Tsujihana et al.

|

GEO: GSE174155 |

| Mouse skin microarray | Geyfman et al.

|

GEO: GSE38622, GSE38623 |

| Human epidermal suction blister microarray | Spörl et al.

|

GEO: GSE35635 |

| Human skin microarray | del Olmo et al.

|

GEO: GSE205155 |

| Human forearm skin microarray | Wu et al.

|

GEO: GSE112660 |

| Human skin microarray (fractional laser treatment) | Sherrill et al.

|

GEO: GSE139305 |

| Human melanoma scRNA-seq | Sade-Feldman et al.

|

GEO: GSE120575 |

| Other supporting data | This paper | (https://doi.org/10.26037/yareta: 5rmtImd5sreo7bmcbe44bbijfm). |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| B16-F10-OVA | Stéphanie Hugues, UNIGE, Switzerland | N/A |

| Continued | ||||

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER | ||

| Murine MC38 colorectal carcinoma cell line | Mark J. Smyth | RRID: CVCL_B288 | ||

| Human lymphoma DoHH2 | Francesco Bertoni, IOR,Bellinzona, Switzerland | N/A | ||

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||||

| Mouse: WT C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | Strain # 000664 RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 | ||

| Mouse: WT C57BL/6N | Charles River | Strain # CRL027 RRID:IMSR_CRL:027 | ||

| Mouse: B6.129S4(Cg)-Bmal1tm1Weit/J | The Jackson Laboratory |

|

||

| Mouse: B6.Cg-Tg(Cd4-cre)1Cwi/BfluJ | The Jackson Laboratory |

|

||

| Cdh5-cre/ERT2 mice | Ralf Adams, MPI Munster, Germany | N/A | ||

| NSG (NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIL2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) | Charles River | Strain #:614 | ||

| BRaf

|

Ping-Chih Ho, UNIL, Switzerland | He et al.

|

||

| CD45.1 OT-I | Walter Reith, UNIGE, Switzerland | N/A | ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||||

|

Microsynth | N/A | ||

|

Microsynth | N/A | ||

|

Microsynth | N/A | ||

|

Microsynth | N/A | ||

|

Microsynth | N/A | ||

|

Microsynth | N/A | ||

|

Microsynth | N/A | ||

|

Microsynth | N/A | ||

|

Microsynth | N/A | ||

|

Microsynth | N/A | ||

| Software and algorithms | ||||

| FACSDiva 6 | BD Biosciences | RRID:SCR_001456 | ||

| FlowJo 10 | BD Biosciences | RRID:SCR_008520 | ||

| Slidebook | 3 i | RRID:SCR_014300 | ||

| ImageJ | FIJI | RRID:SCR_002285 | ||

| Cell Ranger 6.1.2 | 10X Genomics | RRID:SCR_017344 | ||

| Seurat 4.3.0 | Hao et al.

|

https://satijalab.org/seurat/ | ||

| R 4.2.2 | The R Foundation | https://www.r-project.org/ | ||

| clusterProfiler | Wu et al.

|

https://bioconductor.org/packages/ release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html | ||

| Cosinor | Open source | https://github.com/sachsmc/cosinor | ||

| DiscoRhythm | Carlucci et al.

|

https://bioconductor.org/packages/ release/bioc/html/DiscoRhythm.html | ||

| GSVA | Hanzelmann et al.

|

https://bioconductor.org/packages/ release/bioc/html/GSVA.html | ||

| Continued | ||

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

| TCGAbiolinks | Colaprico et al.

|

https://bioconductor.org/packages/ release/bioc/html/TCGAbiolinks.html |

| zeitZeiger | Hughey et al.

|

https://github.com/hugheylab/zeitzeiger |

| sva | Leek et al.

|

https://bioconductor.org/packages/ release/bioc/html/sva.html |

| Analysis code | This study | https://github.com/zqun1/circadian_ immune_mouse_melanoma |

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Materials availability

Data and code availability

- Single-cell RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO: GSE260641 and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers of public data used in this study are listed in the key resources table. All data supporting the conclusions of this paper are available online (https://doi.org/10.26037/yareta:5rmtlmd5sreo7bmcbe44bbijfm).

- All original code has been deposited at GitHub https://github.com/zqun1/circadian_immune_mouse_melanoma and is publicly available as of the date of publication.

- Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Animals

METHOD DETAILS

Tumor cell lines and inoculation

of Oncology Research (IOR), Bellinzona, Switzerland) were cultured in RPMI (Gibco) supplemented with

Mouse T cell activation

Mouse T cell synchronization

Human

Luciferase-expressing

Tissue digestion and single-cell preparation

Flow Cytometry

Mouse leukocyte adoptive transfer

EdU assay

CD8 T cell sorting and RNA extraction

RNA extraction, reverse transcription and qPCR

In vivo antibody treatments

Human CAR T cell generation

Human CAR T cell adoptive transfer

Immunofluorescence imaging

Human immunohistochemistry

Single cell sequencing and analysis

ZeitZeiger analysis

Estimation of cell composition in TCGA melanoma patients

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Supplemental figures

(A) Gating strategy of leukocytes in B16-F10-OVA and Tyr::Cre

(B) Normalized total cell numbers of leukocyte subsets in B16-F10-OVA tumors, harvested at 4 different times of the day (zeitgeber time [ZT]);

(C) Blood leukocyte numbers sampled at 4 different times of the day from B16-F10-OVA tumor-bearing mice,

(D) Tumor volume of B16-F10-OVA tumors, measured 3 times a day,

(E) Quantification of the CD31

(F) Normalized numbers of blood leukocyte sampled at ZT1 or ZT13 from Tyr::Cre

(A) Gating strategy and quantification of EdU

(B) Gating strategy and quantification of caspase-3/-7 leukocytes in B16-F10-OVA tumors, harvested at ZT1 (

(C) Normalized numbers of remaining cells in tumors 24 h post intratumoral injection of

(D) Tumor volume after anti-LFA-1 treatment (

(E) Quantification of VCAM-1 (

(F) Tumor volume after i.v. injection of

(A-C) Feature plot and heatmap of genes to identify each leukocyte cluster obtained by scRNA-seq of B16-F10-OVA tumors, harvested at 4 different times of the day.

Article

(A) UMAP representation of scRNA-seq analyses of TILs harvested at 4 different times of the day.

(B) Relative abundance of immune cells per cluster across different times of the day.

(C) Expression of the circadian gene Per1 in each leukocyte cluster obtained by scRNA-seq of B16-F10-OVA tumors, harvested at 4 different times of the day.

(D) Number of significantly oscillating genes detected in each cluster using cosinor (CS) and JTK cycle analyses.

(E) Top oscillatory Gene Ontology pathways common in the different immune cell clusters.

(F) Heatmap of oscillating genes of each cluster. Circadian genes are highlighted.

(A and B) Feature plot and dot plot of genes to identify different T cell clusters obtained by scRNA-seq of B16-F10-OVA tumors, harvested at 4 different times of the day.

(C) Relative abundance of each

(D) Gating strategy of exhausted and non-exhausted

(E) Expression of Pdcd1 quantified by pseudobulk analysis of the CD8

(A) Schematic overview of

(B) Tumor volume after anti-PD-1 treatment administered at ZT1 or ZT13 in B16-F10-OVA tumors;