DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58425-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38649451

تاريخ النشر: 2024-04-22

تصميم وتقييم اللعب عبر الإنترنت المعزز بالألعاب كاستراتيجية تدريب عن بُعد في التعليم السني: دراسة مختلطة تتابعية تفسيرية

الملخص

تشايانيد تيراوونغبايروج

لقد حظيت الصحة عن بُعد باهتمام كبير من مختلف المنظمات نظرًا لإمكاناتها في تحسين جودة الرعاية الصحية وإمكانية الوصول إليها

- تصميم لعب تفاعلي عبر الإنترنت لتدريب طب الأسنان عن بُعد.

- التحقيق في تصورات المتعلمين بشأن ثقتهم ووعيهم في استخدام طب الأسنان عن بُعد بعد إكمال اللعب التفاعلي عبر الإنترنت.

- استكشاف رضا المستخدمين تجاه استخدام اللعب التفاعلي عبر الإنترنت.

- تطوير إطار مفاهيمي لتصميم وتنفيذ لعب تفاعلي عبر الإنترنت لتدريب طب الأسنان عن بُعد.

المواد والأساليب تصميم البحث

لعبة دور عبر الإنترنت مُعززة بالألعاب لتدريب طب الأسنان عن بُعد

عدم أخذ يوم عطلة من العمل خلال هذه الفترة. على الرغم من هذا القيد، كانت بحاجة إلى استشارة سنية لتلقي نصائح للعناية الذاتية الأولية، حيث كانت أعراضها تؤثر بشكل كبير على حياتها اليومية. علاوة على ذلك، تم تعيينها لمواجهة صعوبات في الاستخدام التكنولوجي لمنصة طب الأسنان عن بُعد.

المشاركون في البحث

المرحلة الكمية

المرحلة النوعية

تقييمات النتائج

الثقة الذاتية والوعي تجاه طب الأسنان عن بُعد

الرضا تجاه اللعب الدورى عبر الإنترنت المعزز بالألعاب

تجارب المتعلمين ضمن لعبة الأدوار عبر الإنترنت المعززة بالعناصر الترفيهية

صلاحية وموثوقية أدوات جمع البيانات

تحليل البيانات

تم إجراء تحليل التباين (ANOVA) لمقارنة ما إذا كانت هناك اختلافات ذات دلالة إحصائية في تقييم الذات ودرجات الرضا بين السنوات الأكاديمية الثلاث.

الاعتبارات الأخلاقية

الموافقة المستنيرة

النتائج

المشاركون في البحث

الاتساق الداخلي لجميع البنى

| مشارك | جنس | عمر | سنة الدراسة | تحسن في الثقة بالنفس المدركة | تحسن في الوعي الذاتي المدرك |

| 1 | أنثى | ٢٩ | ٣ | 2.0 | 0.6 |

| 2 | أنثى | ٢٨ | 1 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

| ٣ | أنثى | ٢٨ | 2 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| ٤ | ذكر | ٢٩ | ٣ | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| ٥ | أنثى | ٢٨ | ٢ | 1.5 | 0 |

| ٦ | أنثى | ٢٩ | ٢ | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| ٧ | أنثى | 27 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.1 |

| ٨ | أنثى | ٢٨ | 2 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| 9 | أنثى | ٢٩ | ٣ | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| 10 | أنثى | ٢٨ | 1 | 0.6 | 0 |

| 11 | ذكر | ٢٩ | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | أنثى | ٢٩ | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| البنى | معامل ألفا |

| الثقة الذاتية المدركة (6 عناصر) | 0.90 |

| الوعي الذاتي المدرك (6 عناصر) | 0.78 |

| الإحساس الذاتي بالفائدة (6 عناصر) | 0.81 |

| سهولة الاستخدام المدركة ذاتياً (6 عناصر) | 0.79 |

| الاستمتاع الذاتي المدرك (6 عناصر) | 0.91 |

| تقييمات ذاتية الإدراك |

|

|

قيمة P | ||||

| الثقة الذاتية المدركة |

|

|

|

||||

| الوعي الذاتي المدرك |

|

|

|

| تقييمات ذاتية الإدراك | متوسط السنة الأولى (الانحراف المعياري) | السنة الثانية المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | السنة 3 المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) |

|

| الثقة الذاتية المدركة | ||||

| درجة التقييم المسبق | 3.06 (0.17) | 3.83 (0.80) | 3.25 (0.71) | 0.115 |

| درجة ما بعد التقييم | 3.97 (0.82) | ٤.٤٤ (٠.٤٦) | ٤.٢٨ (٠.٥٢) | 0.346 |

| تحسين الدرجات | 0.89 (0.67) | 0.61 (0.55) | 1.03 (0.56) | 0.484 |

| الوعي الذاتي المدرك | ||||

| درجة التقييم المسبق | ٤.١٣ (٠.٤٤) | ٤.٣٦ (٠.٤٧) | 3.97 (0.54) | 0.399 |

| درجة ما بعد التقييم | ٤.٤٤ (٠.٤٣) | ٤.٧٥ (٠.١٧) | ٤.٤٤ (٠.٤٤) | 0.787 |

| تحسين الدرجات | 0.31 (0.36) | 0.39 (0.37) | 0.47 (0.34) | 0.728 |

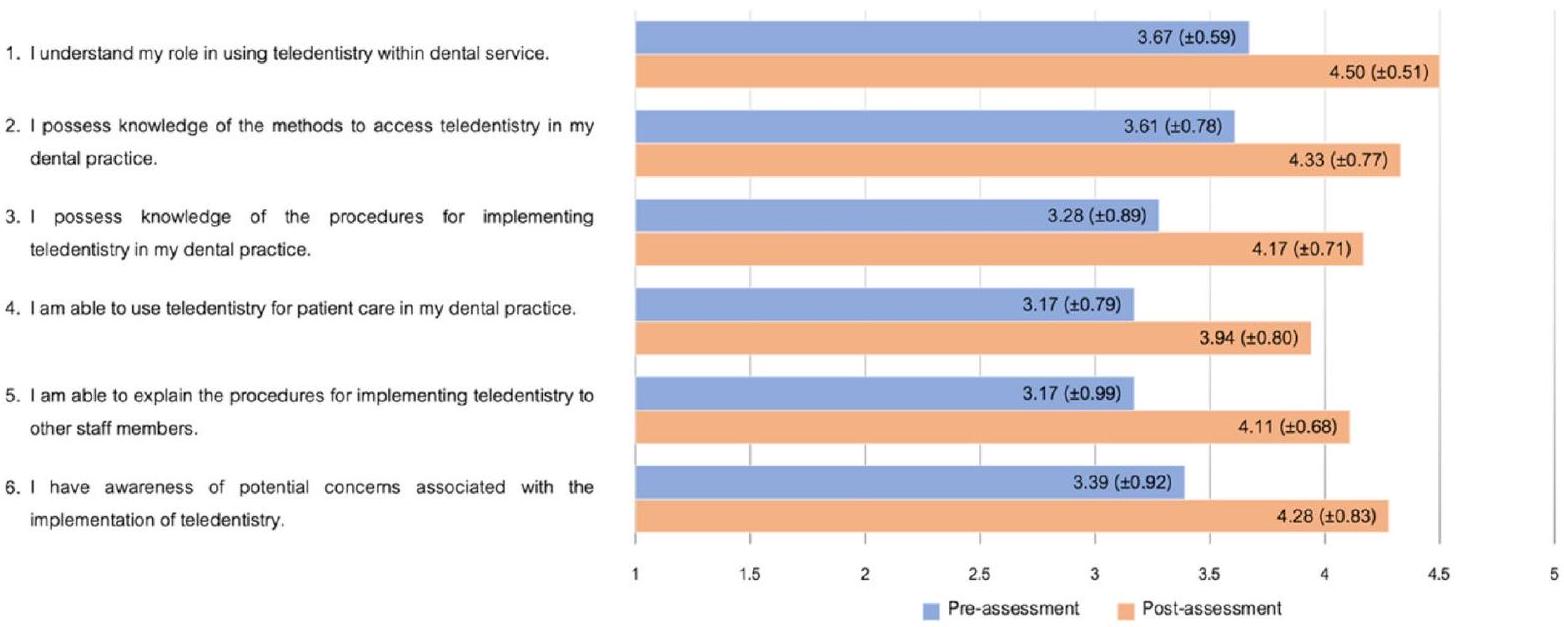

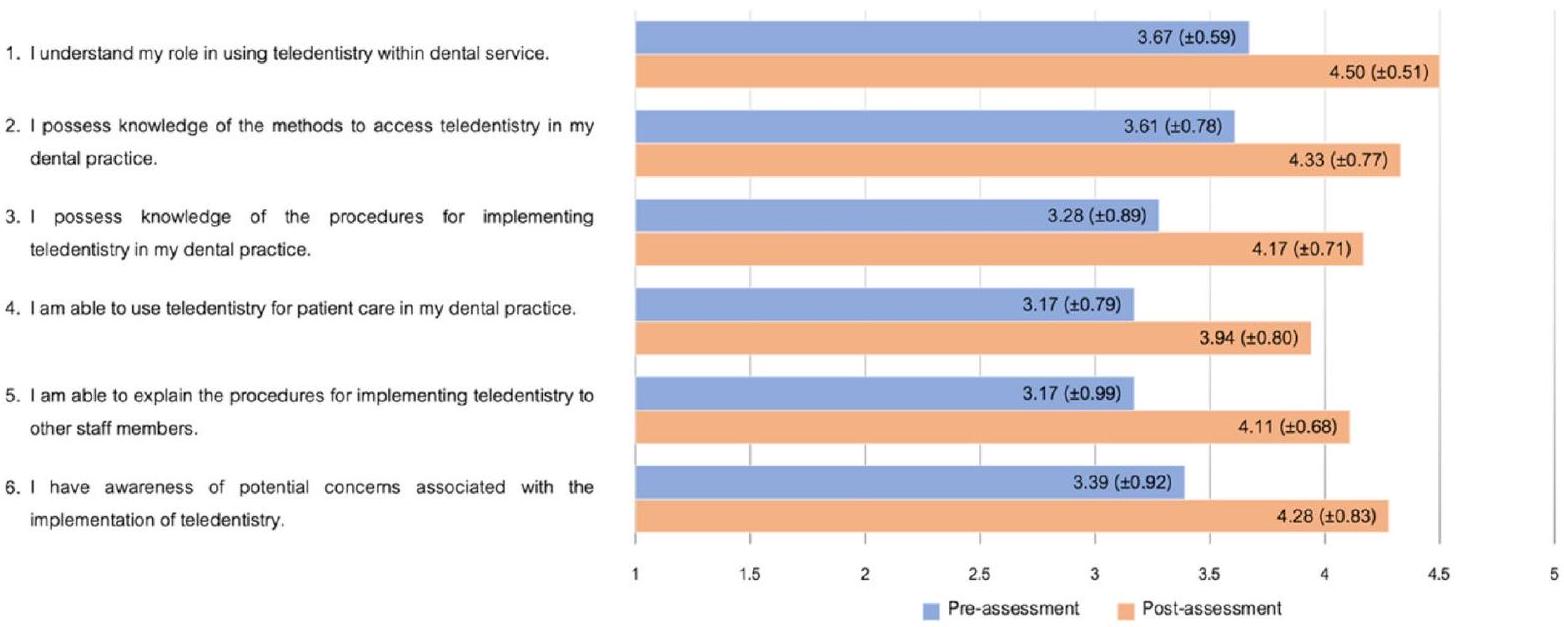

التقييمات الذاتية تجاه الثقة والوعي بتقنية طب الأسنان عن بُعد

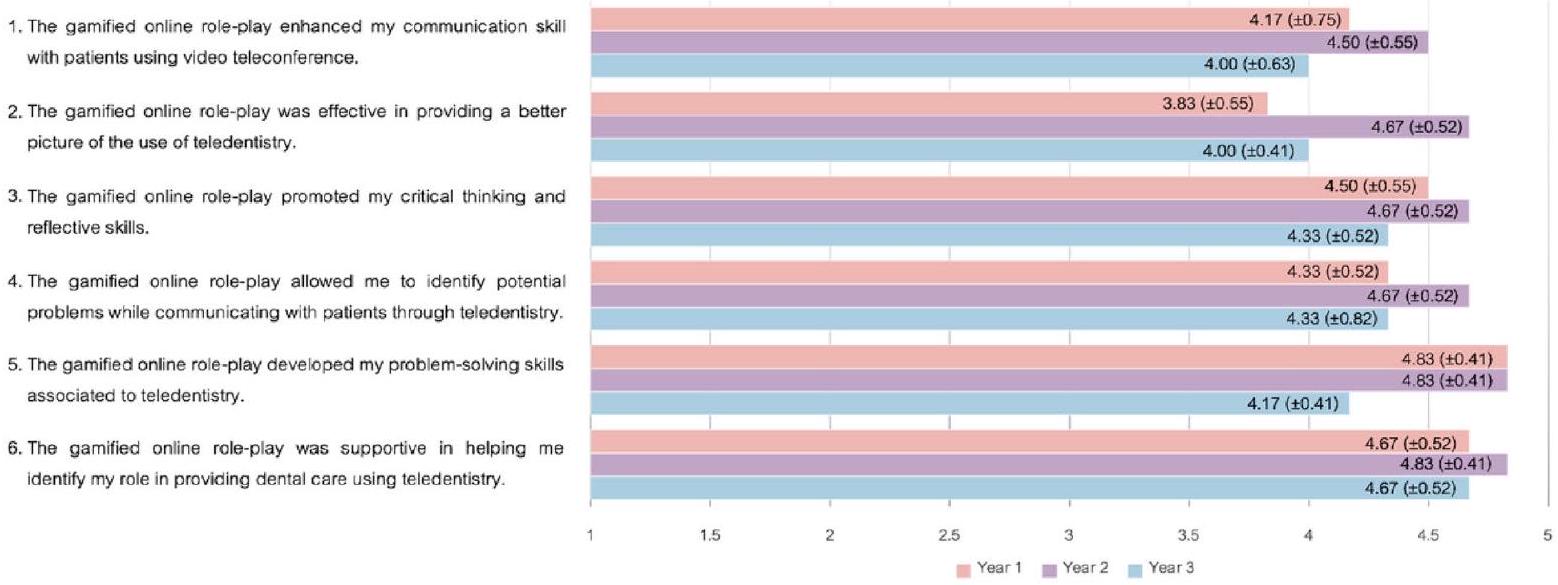

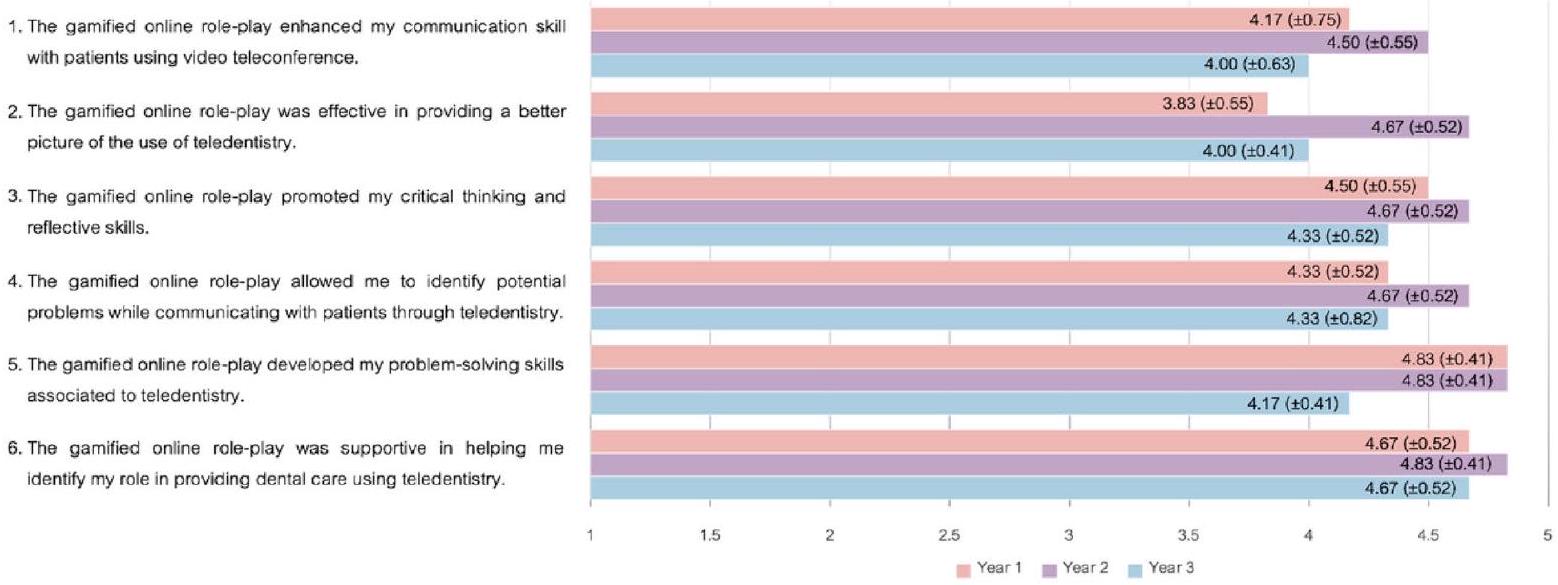

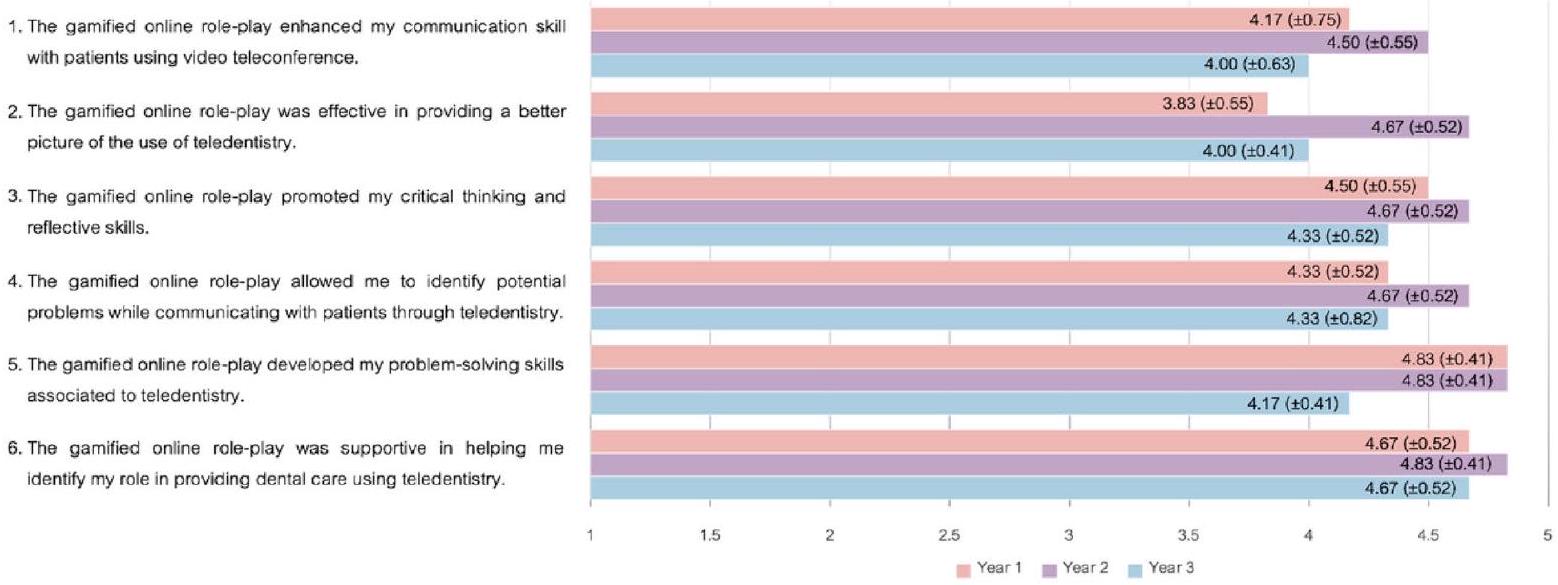

الرضا تجاه استخدام الألعاب التفاعلية عبر الإنترنت

تجارب المتعلمين ضمن لعبة الأدوار عبر الإنترنت المعززة بالعناصر الترفيهية

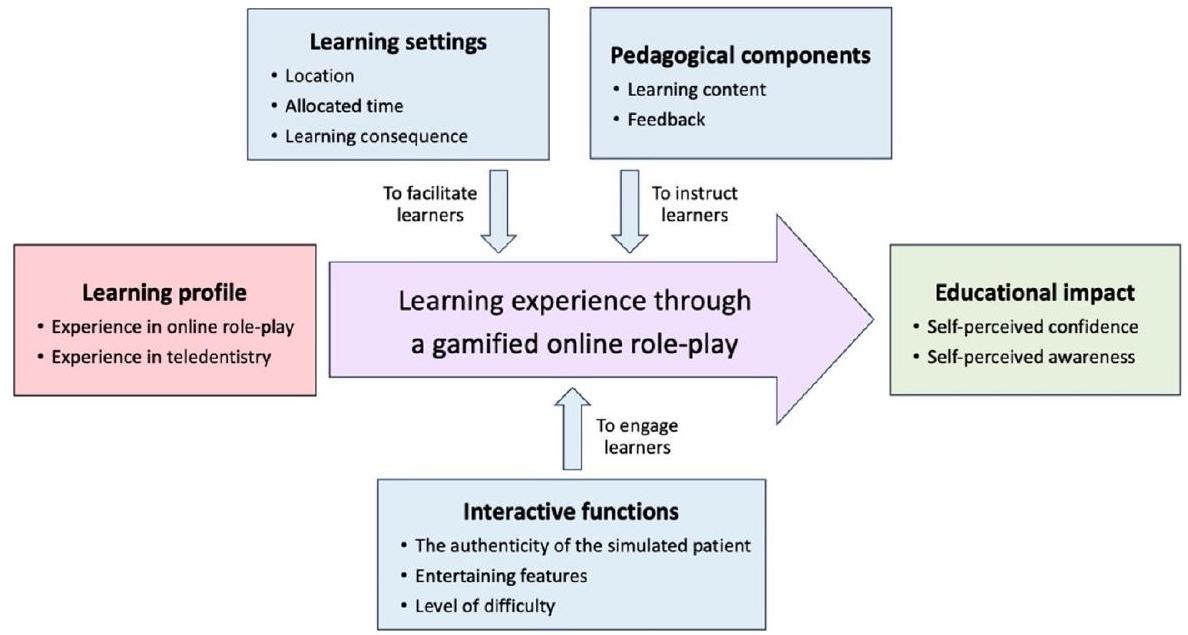

الموضوع 1: ملف المتعلم

لقد كانت لدي تجربة مع نشاط تمثيل الأدوار عندما كنت طالبًا في كلية طب الأسنان، وأحب هذا النوع من التعلم حيث يقوم شخص بتمثيل دور مريض بشخصيات محددة في سياقات مختلفة. قد يكون هذا سببًا في شعوري بالاهتمام للمشاركة في هذه المهمة (تمثيل الأدوار عبر الإنترنت بطريقة م gamified). كما كنت أعتقد أنه سيكون داعمًا لممارستي السريرية.

المشارك 12، السنة 1، أنثى

“في الواقع، لقد رأيت في عدة مقاطع فيديو (عن طب الأسنان عن بُعد) حيث كان الأطباء يعلمون المرضى كيفية إجراء الفحوصات الذاتية، مثل فحص أفواههم والتقاط الصور للاستشارات. لذلك، كان بإمكاني التفكير في ما سأختبره خلال النشاط (داخل لعبة الأدوار عبر الإنترنت الم gamified).” المشاركة 8، السنة الثانية، أنثى

الموضوع 2: إعدادات التعلم في لعبة الأدوار عبر الإنترنت المعززة بالألعاب

الموضوع الفرعي 2.1: الموقع

التواصل وفهم احتياجات المريض، مما يؤدي إلى فهم أفضل لمحتوى الدرس. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يجب أن تكون بيئات المتعلمين والمريض المحاكي حقيقية لتحسين جودة التعلم.

| الرضا | متوسط السنة الأولى (الانحراف المعياري) | السنة الثانية المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) | السنة 3 المتوسط (الانحراف المعياري) |

|

| فائدة ذاتية الإدراك | ٤.٣٩ (٠.٤٦) | ٤.٦٩ (٠.٤٧) | ٤.٢٥ (٠.٦٦) | 0.158 |

| سهولة الاستخدام المدركة ذاتياً | ٤.٥٠ (٠.٢٩) | 4.56 (0.51) | ٤.١٤ (٠.٦٣) | 0.263 |

| التمتع الذاتي المدرك | 4.00 (0.39) | ٤.٢٥ (٠.٢٥) | 3.83 (0.72) | 0.570 |

| بشكل عام | ٤.٣٠ (٠.٢٦) | ٤.٥٠ (٠.٢٣) | ٤.٠٧ (٠.٢٢) | 0.997 |

تم اعتبار الوقت المخصص للعب الأدوار عبر الإنترنت في هذا البحث مناسبًا، حيث اعتقد المشاركون أن فترة 30 دقيقة يجب أن تكون كافية للحصول على المعلومات ومن ثم تقديم بعض النصائح لمريضهم. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، يمكن أن تكون مناقشة لمدة 10 دقائق حول كيفية تفاعلهم مع المريض مفيدة للمشاركين لتعزيز كفاءاتهم في استخدام طب الأسنان عن بُعد.

“… من المحتمل أن يستغرق الأمر حوالي 20 دقيقة لأننا سنحتاج إلى جمع الكثير من المعلومات … قد يحتاج الأمر بعض الوقت لطلب وجمع معلومات متنوعة … ربما 10-15 دقيقة أخرى لتقديم بعض النصائح.” المشاركة 7، السنة 1، أنثى

“أعتقد أنه خلال الحصة … يمكننا تخصيص حوالي 30 دقيقة للعب الأدوار، … قد يكون لدينا مناقشة حول أداء المتعلمين لمدة 10-15 دقيقة … أعتقد أنه يجب ألا يتجاوز المجموع 45 دقيقة.”

المشاركة 6، السنة 2، أنثى

اقترح معظم المشاركين أن يتم تنظيم لعب الأدوار عبر الإنترنت في طب الأسنان عن بُعد في السنة الأولى من برنامج الدراسات العليا الخاص بهم. يمكن أن يزيد ذلك من فعالية لعب الأدوار عبر الإنترنت، حيث سيكونون قادرين على تطبيق طب الأسنان عن بُعد في ممارستهم السريرية منذ بداية تدريبهم. ومع ذلك، اقترح بعض المشاركين أن يمكن إعادة ترتيب هذا النهج التعليمي في السنة الثانية أو الثالثة من البرنامج. حيث إنهم قد اكتسبوا بالفعل خبرة في الممارسة السريرية، فإن لعب الأدوار عبر الإنترنت سيعزز كفاءتهم في طب الأسنان عن بُعد.

“في الواقع، سيكون من الرائع إذا كان يمكن جدولة هذه الجلسة في السنة الأولى … سأشعر بمزيد من الراحة عند التعامل مع مرضاي من خلال منصة عبر الإنترنت.”

المشاركة 11، السنة 2، ذكر

“أعتقد أن هذا النهج يجب أن يتم تطبيقه في السنة الأولى لأنه يسمح للطلاب بالتدريب في طب الأسنان عن بُعد قبل التعرض للمرضى الحقيقيين. ومع ذلك، إذا تم تطبيق هذا النهج في السنة الثانية أو الثالثة عندما يكون لديهم بالفعل خبرة في رعاية المرضى، سيكون بإمكانهم التعلم بشكل أفضل من المحادثات مع المرضى المحاكين.”

المشاركة 4، السنة 3، ذكر

الموضوع 3: المكونات التربوية

الموضوع الفرعي 3.1: محتوى التعلم

“تتيح لي مهام التعلم (ضمن لعب الأدوار عبر الإنترنت) معرفة كيفية إدارة المرضى من خلال مؤتمرات الفيديو.”

المشاركة 5، السنة 2، أنثى

“… بدا أن هناك قيودًا (في طب الأسنان عن بُعد) … قد يكون هناك خطر من التشخيص الخاطئ … قد تؤدي جودة الفيديو الضعيفة إلى أخطاء تشخيصية … من الصعب على المرضى التقاط آفاتهم الفموية.”

المشاركة 3، السنة 2، أنثى

الموضوع الفرعي 3.2: التغذية الراجعة

كنت أعرف (ما إذا كنت قد تفاعلت بشكل صحيح أم لا) من الإيماءات والعواطف للمريض المحاكي خلال المحادثة. كان بإمكاني أن أتعلم من التغذية الراجعة المقدمة خلال لعب الأدوار، خاصة من تعبيرات وجه المريض.

المشاركة 11، السنة 2، ذكر

“التغذية الراجعة المقدمة في النهاية جعلتني أعرف مدى أدائي ضمن مهام التعلم.” المشاركة 2، السنة 1، أنثى

الموضوع 4: الوظائف التفاعلية

اعتقد معظم المشاركين أن المريض المحاكي الذي يتمتع بأداء تمثيلي عالٍ يمكن أن يعزز تدفق لعب الأدوار، مما يسمح للمتعلمين بتجربة عواقب حقيقية. يمكن أن يجذب المستوى المناسب من المصداقية المتعلمين إلى النشاط التعليمي، حيث سيكون لديهم وعي أقل بمرور الوقت في حالة التدفق. لذلك، يمكنهم التعلم بشكل أفضل من لعب الأدوار عبر الإنترنت.

“كان الأمر واقعيًا جدًا. … سمح لي ذلك بالتحدث مع المريض المحاكي بشكل طبيعي … في البداية، عندما كنا نتحدث، لم أكن متأكدًا من كيفية أدائي … لكن بعد ذلك لم أعد أشك في أي شيء وشعرت أنني أريد أن أشرح لها الأمور أكثر.”

المشاركة 3، السنة 2، أنثى

“في البداية، كنت أعتقد أنه إذا كان هناك عامل يمكن أن يؤثر على التعلم، فسيكون على الأرجح مريضًا محاكيًا. لقد تأثرت بكيفية أداء هذا المريض المحاكي بشكل جيد جدًا. جعل المحادثة تتدفق بسلاسة وبشكل تدريجي.”

المشاركة 9، السنة 3، أنثى

الموضوع الفرعي 4.2: الميزات الترفيهية

“كانت تجربة مرحة أثناء التواصل مع المريض المحاكي. هناك عناصر مفاجأة من بطاقات التحدي تجعل المحادثة أكثر جاذبية، ولم أشعر بالملل خلال لعب الأدوار.”

المشاركة 4، السنة 3، ذكر

“أحببت بطاقة التحدي التي اخترناها عشوائيًا، حيث لم يكن لدينا أي فكرة عما سنواجهه … المزيد من السيناريوهات مثل ثمانية خيارات ويمكننا الاختيار عشوائيًا لنكون أكثر حماسًا. أعتقد أننا لا نحتاج إلى بطاقات تحدي إضافية، حيث تم تضمين بعضها بالفعل في ظروف المرضى.”

المشاركة 5، السنة 2، أنثى

الموضوع الفرعي 4.3: مستوى الصعوبة

“كان المريض قد أخفى معلوماته، وكان عليّ أن أستخرجها من المحادثة.”

المشاركة 12، السنة 1، أنثى

“يمكن أن تكون مشاعر المرضى أكثر حساسية لزيادة مستوى التحديات. يمكن أن يوفر لنا ذلك المزيد من الفرص لتعزيز مهاراتنا في إدارة مشاعر المرضى.”

المشاركة 11، السنة 2، ذكر

“… يمكننا زيادة مستوى الصعوبة تدريجيًا، مشابهًا للعب لعبة. يمكن أن تكون هذه التحديات مرتبطة بالمريض المحاكي، مثل المعرفة المحدودة أو صعوبات في التواصل، وهو ما من المحتمل أن يحدث في مهنتنا.”

المشاركة 6، السنة 2، أنثى

الموضوع 5: التأثير التعليمي

مهارات التواصل. كان المشاركون من المحتمل أن يدركوا أنهم يمكن أن يتعلموا من لعب الأدوار عبر الإنترنت وشعروا بمزيد من الثقة في استخدام طب الأسنان عن بُعد. تم تحقيق هذا التأثير التعليمي في الغالب من خلال المحادثة عبر الإنترنت ضمن نشاط لعب الأدوار، حيث يمكن للمشاركين تحسين مهاراتهم في التواصل من خلال منصة مؤتمرات الفيديو.

“أشعر أن لعب الأدوار عبر الإنترنت كان شكلًا فريدًا من التعلم. أعتقد أنني اكتسبت الثقة من التواصل عبر الإنترنت مع المريض المحاكي. كنت قادرًا على تطوير مهارات للتواصل بفعالية مع المرضى الحقيقيين.”

المشاركة 11، السنة 2، ذكر

أعتقد أنه يدعمنا في تدريب مهارات التواصل … لقد أتاح لنا ممارسة مهارات الاستماع والتحدث بشكل أكثر شمولاً.

المشارك 4، السنة 3، ذكر

مهارات التفكير النقدي وحل المشكلات. بالإضافة إلى مهارات التواصل، أفاد المشاركون أن التحديات المدمجة في تمثيل الأدوار سمحت لهم بتعزيز مهارات التفكير النقدي وحل المشكلات، وهي مجموعة من المهارات المطلوبة للتعامل مع المشكلات المحتملة في استخدام طب الأسنان عن بُعد.

المشارك 11، السنة 2، ذكر

الموضوع الفرعي 5.2: الوعي الذاتي المدرك في طب الأسنان عن بُعد

اعتقد المشاركون أنهم يمكنهم إدراك ضرورة طب الأسنان عن بُعد من خلال اللعب التفاعلي عبر الإنترنت. سمحت قصص المرضى أو ظروفهم للمتعلمين بفهم كيف يمكن أن يوفر طب الأسنان عن بُعد دعماً جسدياً ونفسياً لمرضى الأسنان.

من خلال النشاط، أعتبر طب الأسنان عن بُعد أداة مريحة للتواصل مع المرضى، خاصة إذا لم يتمكن المريض من الذهاب إلى عيادة الأسنان.

المشارك 5، السنة 2، أنثى

لقد تعلمت عن فوائد طب الأسنان عن بُعد، خاصة من حيث المتابعة. يمكن أن تدعم منصة مؤتمرات الفيديو تبادل المعلومات، مثل رسم الصور أو تقديم خطط العلاج، للمرضى.

المشارك 8، السنة 2، أنثى

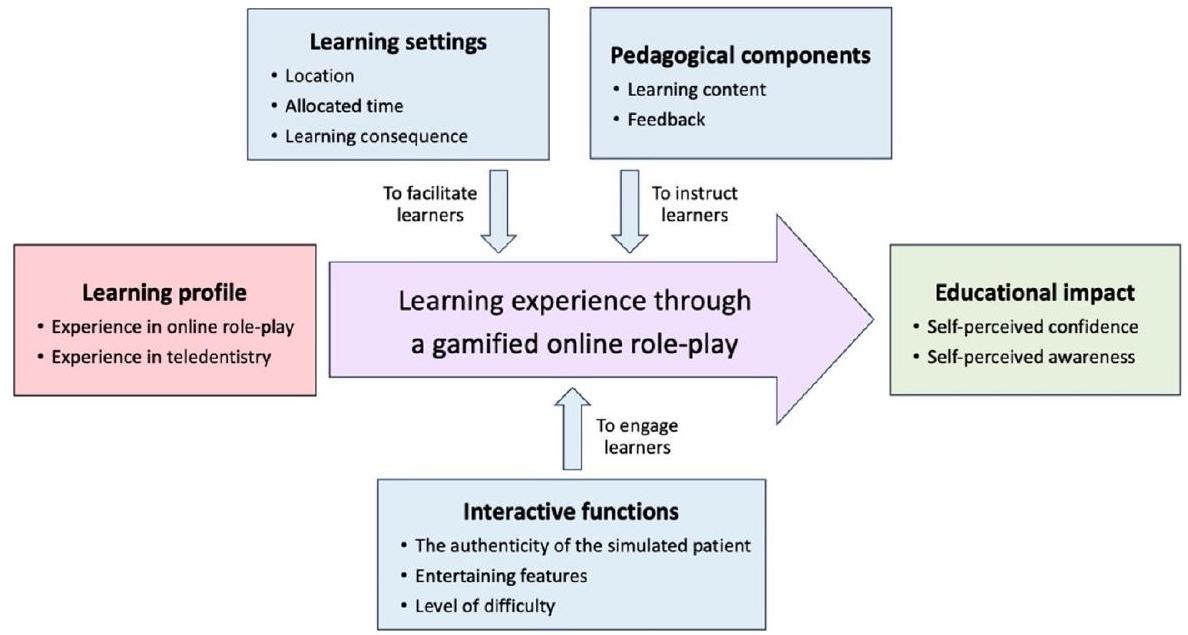

إطار مفاهيمي لتجربة التعلم ضمن لعبة تقمص أدوار عبر الإنترنت مُعزَّزة بالألعاب

نقاش

الاستنتاجات

توفر البيانات

تم النشر عبر الإنترنت: 22 أبريل 2024

References

- Van Dyk, L. A review of telehealth service implementation frameworks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11(2), 1279-1298 (2014).

- Bartz, C. C. Nursing care in telemedicine and telehealth across the world. Soins. 61(810), 57-59 (2016).

- Lin, G.S.S., Koh, S.H., Ter, K.Z., Lim, C.W., Sultana, S., Tan, W.W. Awareness, knowledge, attitude, and practice of teledentistry among dental practitioners during COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 58(1), 130 (2022).

- Wolf, T.G., Schulze, R.K.W., Ramos-Gomez, F., Campus, G. Effectiveness of telemedicine and teledentistry after the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19(21), 13857 (2022).

- Gajarawala, S. N. & Pelkowski, J. N. Telehealth benefits and barriers. J. Nurse Pract. 17(2), 218-221 (2021).

- Jampani, N. D., Nutalapati, R., Dontula, B. S. & Boyapati, R. Applications of teledentistry: A literature review and update. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 1(2), 37-44 (2011).

- Khan, S. A. & Omar, H. Teledentistry in practice: literature review. Telemed. J. E. Health. 19(7), 565-567 (2013).

- Baheti, M. J. B. S., Toshniwal, N. G. & Misal, A. Teledentistry: A need of the era. Int. J. Dent. Med. Res. 1(2), 80-91 (2014).

- Datta, N., Derenne, J., Sanders, M. & Lock, J. D. Telehealth transition in a comprehensive care unit for eating disorders: Challenges and long-term benefits. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53(11), 1774-1779 (2020).

- Bursell, S. E., Brazionis, L. & Jenkins, A. Telemedicine and ocular health in diabetes mellitus. Clin. Exp. Optom. 95(3), 311-327 (2012).

- da Costa, C. B., Peralta, F. D. S. & Ferreira de Mello, A. L. S. How has teledentistry been applied in public dental health services? An integrative review. Telemed. J. E. Health. 26(7), 945-954 (2020).

- Heckemann, B., Wolf, A., Ali, L., Sonntag, S. M. & Ekman, I. Discovering untapped relationship potential with patients in telehealth: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 6(3), e009750 (2016).

- Pérez-Noboa, B., Soledispa-Carrasco, A., Padilla, V. S. & Velasquez, W. Teleconsultation apps in the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Guayaquil City, Ecuador. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 49(1), 27-37 (2021).

- Wamsley, C. E., Kramer, A., Kenkel, J. M. & Amirlak, B. Trends and challenges of telehealth in an academic institution: The unforeseen benefits of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Aesthetic Surg. J. 41(1), 109-118 (2020).

- Jonasdottir, S. K., Thordardottir, I. & Jonsdottir, T. Health professionals’ perspective towards challenges and opportunities of telehealth service provision: A scoping review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 167, 104862 (2022).

- Tan, S. H. X., Lee, C. K. J., Yong, C. W. & Ding, Y. Y. Scoping review: Facilitators and barriers in the adoption of teledentistry among older adults. Gerodontology. 38(4), 351-365 (2021).

- Minervini, G. et al. Teledentistry in the management of patients with dental and temporomandibular disorders. BioMed. Res. Int. 2022, 7091153 (2022).

- Edirippulige, S. & Armfield, N. Education and training to support the use of clinical telehealth: A review of the literature. J. Telemed. Telecare. 23(2), 273-282 (2017).

- Mariño, R. & Ghanim, A. Teledentistry: A systematic review of the literature. J. Telemed. Telecare. 19(4), 179-183 (2013).

- Armitage-Chan, E. & Whiting, M. Teaching professionalism: Using role-play simulations to generate professionalism learning outcomes. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 43(4), 359-363 (2016).

- Spyropoulos, F., Trichakis, I. & Vozinaki, A.-E. A narrative-driven role-playing game for raising flood awareness. Sustainability. 14(1), 554 (2022).

- Jiang, W. K. et al. Role-play in endodontic teaching: A case study. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 23(4), 281-288 (2020).

- Vizeshfar, F., Zare, M. & Keshtkaran, Z. Role-play versus lecture methods in community health volunteers. Nurse Educ. Today. 79, 175-179 (2019).

- Nestel, D. & Tierney, T. Role-play for medical students learning about communication: Guidelines for maximising benefits. BMC Med. Educ. 7, 3 (2007).

- Gelis, A. et al. Peer role-play for training communication skills in medical students: A systematic review. Simulat. Health. 15(2), 106-111 (2020).

- Cornelius, S., Gordon, C. & Harris, M. Role engagement and anonymity in synchronous online role play. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 12(5), 57-73 (2011).

- Bell, M. Online role-play: Anonymity, engagement and risk. Educ. Med. Int. 38(4), 251-260 (2001).

- Sipiyaruk, K., Gallagher, J. E., Hatzipanagos, S. & Reynolds, P. A. A rapid review of serious games: From healthcare education to dental education. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 22(4), 243-257 (2018).

- Sipiyaruk, K., Hatzipanagos, S., Reynolds, P. A. & Gallagher, J. E. Serious games and the COVID-19 pandemic in dental education: An integrative review of the literature. Computers. 10(4), 42 (2021).

- Morse, J.M., Niehaus, L. Mixed Method Design: Principles and Procedures. (2016).

- Creswell, J. W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches 3rd edn. (SAGE Publications, 2009).

- Cheng, V. W. S., Davenport, T., Johnson, D., Vella, K. & Hickie, I. B. Gamification in apps and technologies for improving mental health and well-being: Systematic review. JMIR Ment. Health. 6(6), el3717 (2019).

- Gallego-Durán, F. J. et al. A guide for game-design-based gamification. Informatics. 6(4), 49 (2019).

- Gee, J. P. Learning and games. In The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning (ed. Salen, K.) 21-40 (MIT Press, 2008).

- Cheung, K. L., ten Klooster, P. M., Smit, C., de Vries, H. & Pieterse, M. E. The impact of non-response bias due to sampling in public health studies: A comparison of voluntary versus mandatory recruitment in a Dutch national survey on adolescent health. BMC Public Health. 17(1), 276 (2017).

- Murairwa, S. Voluntary sampling design. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Social Sci. 4(2), 185-200 (2015).

- Chow, S.-C., Shao, J., Wang, H. & Lokhnygina, Y. Sample Size Calculations in Clinical Research (CRC Press, 2017).

- Palinkas, L. A. et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration Policy Mental Health Mental Health Services Res. 42(5), 533-544 (2015).

- McIlvried, D. E., Prucka, S. K., Herbst, M., Barger, C. & Robin, N. H. The use of role-play to enhance medical student understanding of genetic counseling. Genet. Med. 10(10), 739-744 (2008).

- Schlegel, C., Woermann, U., Shaha, M., Rethans, J.-J. & van der Vleuten, C. Effects of communication training on real practice performance: A role-play module versus a standardized patient module. J. Nursing Educ. 51(1), 16-22 (2012).

- Manzoor, I. M. F. & Hashmi, N. R. Medical students’ perspective about role-plays as a teaching strategy in community medicine. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 22(4), 222-225 (2012).

- Cornes, S., Gelfand, J. M. & Calton, B. Foundational telemedicine workshop for first-year medical students developed during a pandemic. MedEdPORTAL. 17, 11171 (2021).

- King, J., Hill, K. & Gleason, A. All the world’sa stage: Evaluating psychiatry role-play based learning for medical students. Austral. Psychiatry. 23(1), 76-79 (2015).

- Arayapisit, T. et al. An educational board game for learning orofacial spaces: An experimental study comparing collaborative and competitive approaches. Anatomical Sci. Educ. 16(4), 666-676 (2023).

- Sipiyaruk, K., Hatzipanagos, S., Vichayanrat, T., Reynolds, P.A., Gallagher, J.E. Evaluating a dental public health game across two learning contexts. Educ. Sci. 12(8), 517 (2022).

- Pilnick, A. et al. Using conversation analysis to inform role play and simulated interaction in communications skills training for healthcare professionals: Identifying avenues for further development through a scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 18(1), 267 (2018).

- Lane, C. & Rollnick, S. The use of simulated patients and role-play in communication skills training: A review of the literature to August 2005. Patient Educ. Counseling. 67(1), 13-20 (2007).

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S. & Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13(1), 117 (2013).

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M. & Ormston, R. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers (Sage, 2014).

- Chen, J. C. & Martin, A. R. Role-play simulations as a transformative methodology in environmental education. J. Transform. Educ. 13(1), 85-102 (2015).

- Davis, F. D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. Manag. Inform. Syst. Quart. 13(3), 319-340 (1989).

- Novak, E., Johnson, T. E., Tenenbaum, G. & Shute, V. J. Effects of an instructional gaming characteristic on learning effectiveness, efficiency, and engagement: Using a storyline for teaching basic statistical skills. Interact. Learn. Environ. 24(3), 523-538 (2016).

- Marchiori, E. J. et al. A narrative metaphor to facilitate educational game authoring. Comput. Educ. 58(1), 590-599 (2012).

- Luctkar-Flude, M. et al. Effectiveness of debriefing methods for virtual simulation: A systematic review. Clin. Simulat. Nursing. 57, 18-30 (2021).

- Joyner, B. & Young, L. Teaching medical students using role play: Twelve tips for successful role plays. Med. Teach. 28(3), 225-229 (2006).

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Performance (HarperCollins Publishers, 1990).

- Buajeeb, W., Chokpipatkun, J., Achalanan, N., Kriwattanawong, N. & Sipiyaruk, K. The development of an online serious game for oral diagnosis and treatment planning: Evaluation of knowledge acquisition and retention. BMC Med. Educ. 23(1), 830 (2023).

- Littlefield, J. H., Hahn, H. B. & Meyer, A. S. Evaluation of a role-play learning exercise in an ambulatory clinic setting. Adv. Health. Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 4(2), 167-173 (1999).

- Alkin, M. C. & Christie, C. A. The use of role-play in teaching evaluation. Am. J. Evaluat. 23(2), 209-218 (2002).

- Lovell, K. L., Mavis, B. E., Turner, J. L., Ogle, K. S. & Griffith, M. Medical students as standardized patients in a second-year performance-based assessment experience. Med. Educ. Online. 3(1), 4301 (1998).

الشكر والتقدير

مساهمات المؤلفين

التمويل

المصالح المتنافسة

معلومات إضافية

معلومات إعادة الطبع والتصاريح متاحة على www.nature.com/reprints.

ملاحظة الناشر تظل Springer Nature محايدة فيما يتعلق بالمطالبات القضائية في الخرائط المنشورة والانتماءات المؤسسية.

© المؤلفون 2024

قسم طب الأسنان العام المتقدم، كلية طب الأسنان، جامعة ماهيدول، بانكوك، تايلاند. قسم تقويم الأسنان، كلية طب الأسنان، جامعة ماهيدول، بانكوك، تايلاند. البريد الإلكتروني: kawin.sip@mahidol.ac.th - يجب أن تكون الغرفة مساحة خاصة بدون أي إزعاج. سيجعلنا هذا نشعر بالثقة ونتفاعل في المحادثات مع المريض المحاكي.

المشارك 10، السنة 1، أنثى

“… محاكاة بيئة واقعية يمكن أن تشجعني على التفاعل مع المريض المحاكي بشكل أكثر فعالية …” المشارك 8، السنة 2، أنثى - كانت وسيلة للتدريب قبل تجربة المواقف الحقيقية … سمحت لنا بالتفكير النقدي فيما إذا كان ما قمنا به مع المرضى المحاكين مناسبًا أم لا.

المشارك 7، السنة 1، أنثى

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58425-9

PMID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38649451

Publication Date: 2024-04-22

The design and evaluation of gamified online role-play as a telehealth training strategy in dental education: an explanatory sequential mixed-methods study

Abstract

Chayanid Teerawongpairoj

Telehealth has gained significant attention from various organization due to its potential to improve healthcare quality and accessibility

- To design a gamified online role-play for teledentistry training.

- To investigate learner perceptions regarding their confidence and awareness in the use of teledentistry after completing the gamified online role-play.

- To explore user satisfactions toward the use of gamified online role-play.

- To develop a conceptual framework for designing and implementing a gamified online role-play for teledentistry training.

Materials and methods Research design

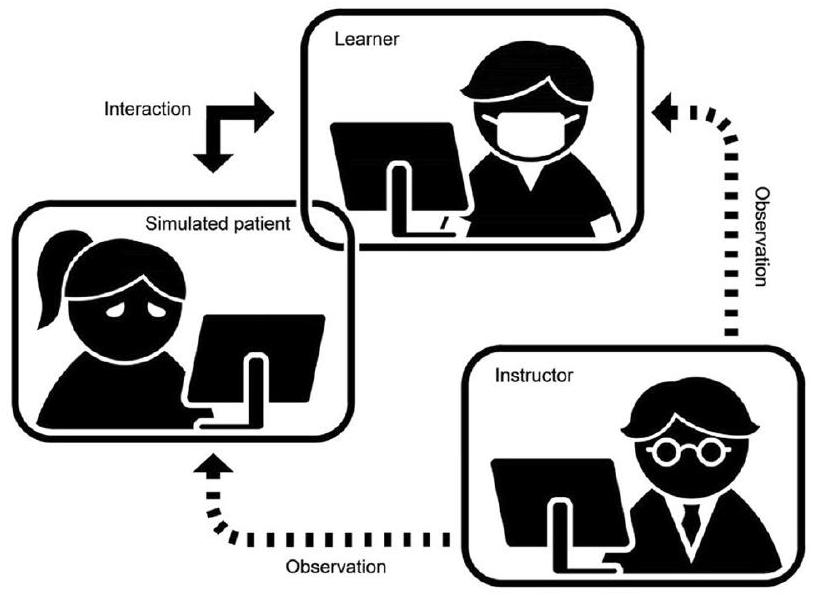

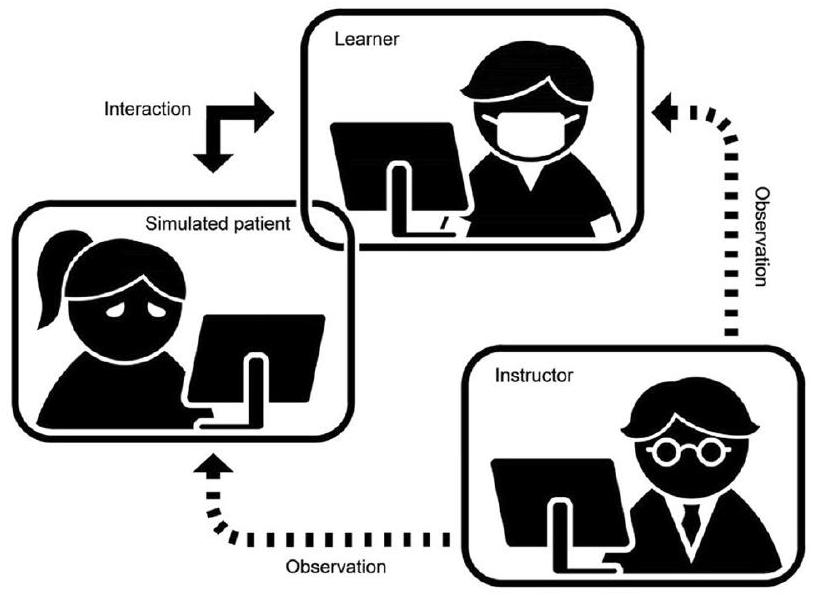

A gamified online role-play for training teledentistry

not take a day off from work during this period. Despite this constraint, she required a dental consultation to receive advice for initial self-care, as her symptoms significantly impacted her daily life. Furthermore, she was designated to encounter difficulties with the technological use of the teledentistry platform.

Research participants

Quantitative phase

Qualitative phase

Outcome assessments

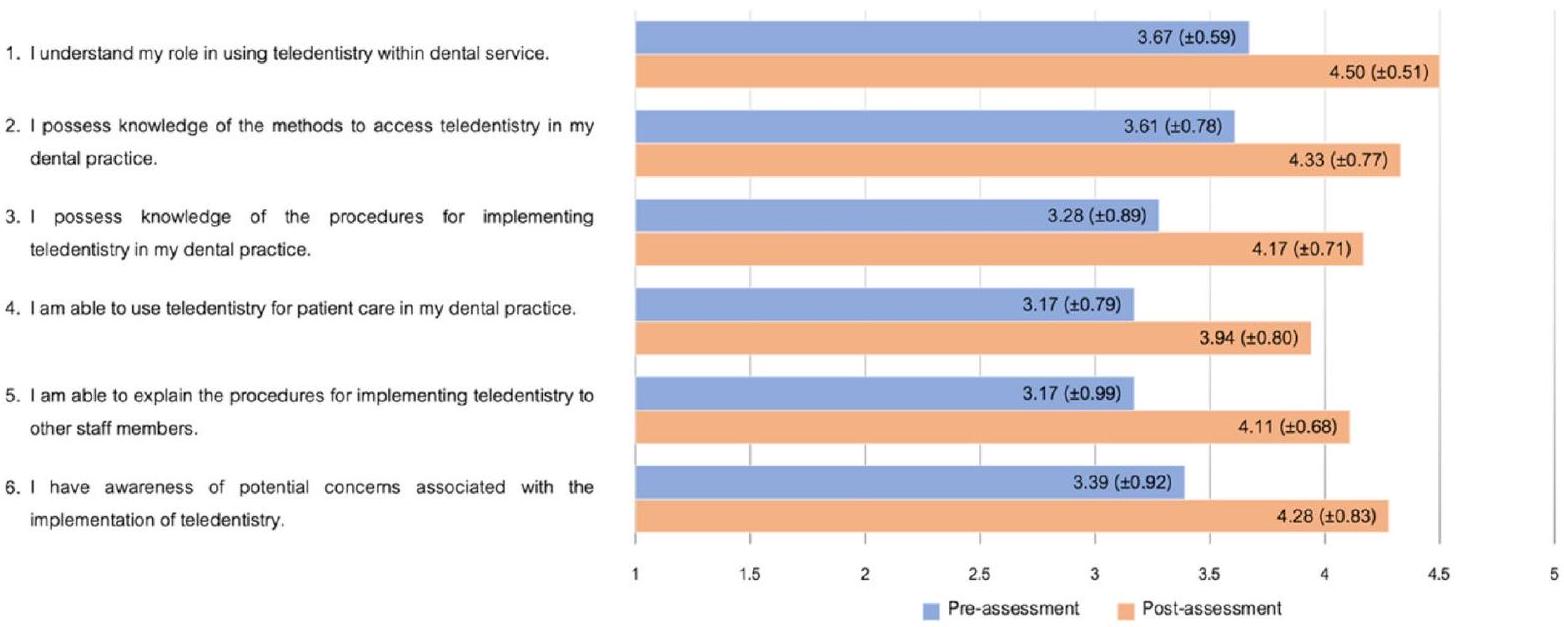

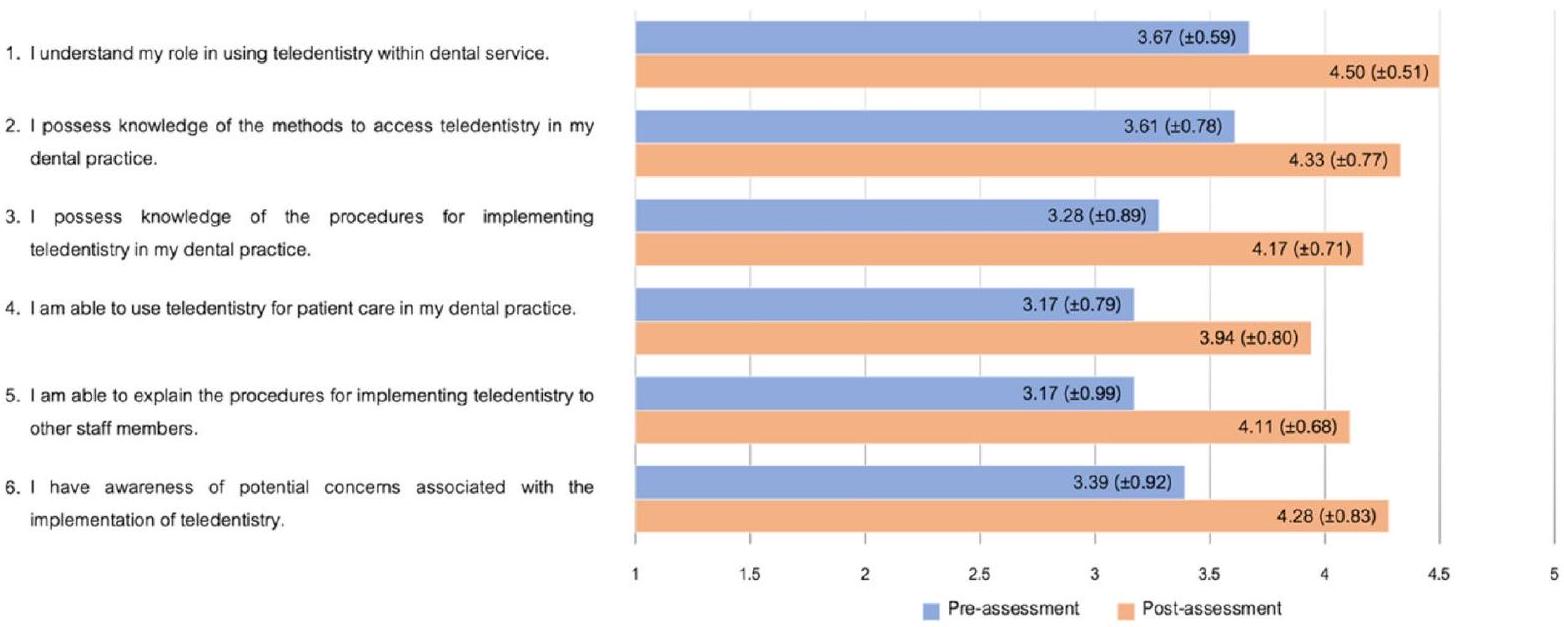

Self-perceived confidence and awareness toward teledentistry

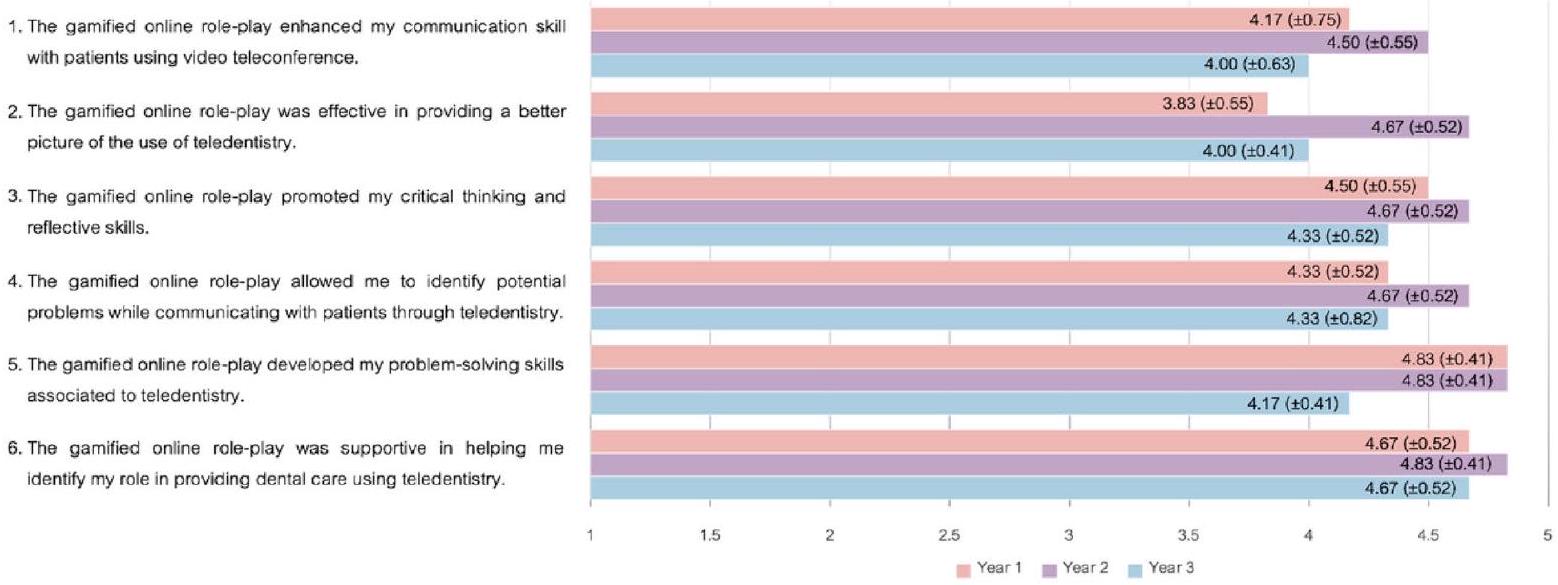

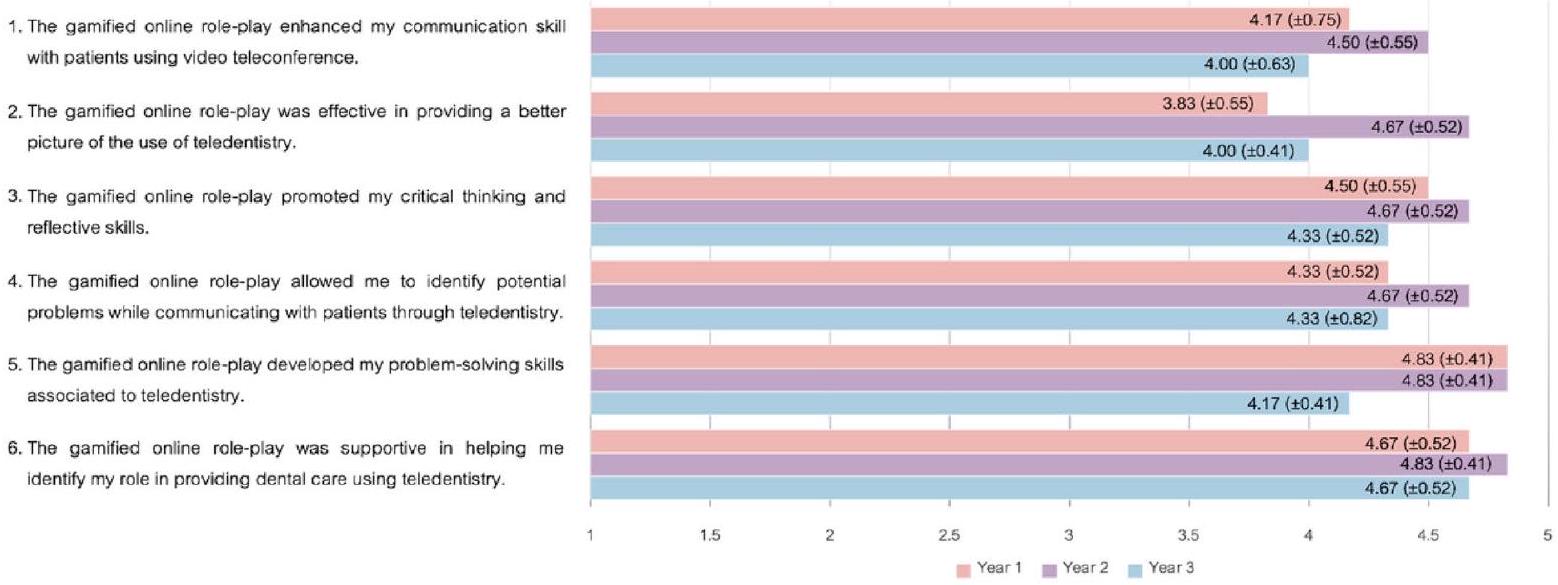

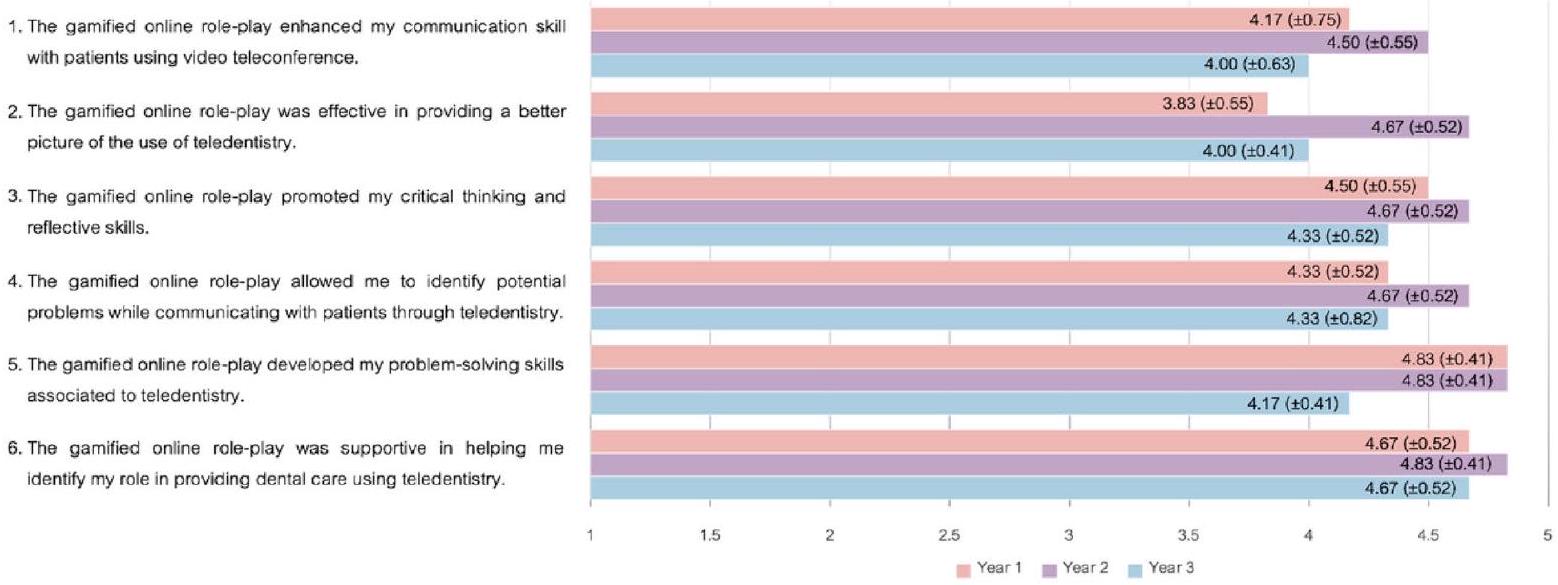

Satisfactions toward the gamified online role-play

Learner experiences within the gamified online role-play

Validity and reliability of data collection tools

Data analysis

variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare whether or not there were statistically significant differences in self-perceived assessment and satisfaction scores among the three academic years.

Ethical consideration

Informed consent

Results

Research participants

Internal consistency of all constructs

| Participant | Sex | Age | Year of study | Improvement in self-perceived confidence | Improvement in self-perceived awareness |

| 1 | Female | 29 | 3 | 2.0 | 0.6 |

| 2 | Female | 28 | 1 | 1.5 | 0.9 |

| 3 | Female | 28 | 2 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| 4 | Male | 29 | 3 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| 5 | Female | 28 | 2 | 1.5 | 0 |

| 6 | Female | 29 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| 7 | Female | 27 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.1 |

| 8 | Female | 28 | 2 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| 9 | Female | 29 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.1 |

| 10 | Female | 28 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 |

| 11 | Male | 29 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | Female | 29 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Constructs | Coefficient alpha |

| Self-perceived confidence (6 items) | 0.90 |

| Self-perceived awareness (6 items) | 0.78 |

| Self-perceived usefulness (6 items) | 0.81 |

| Self-perceived ease of use (6 items) | 0.79 |

| Self-perceived enjoyment (6 items) | 0.91 |

| Self-perceived assessments |

|

|

P-value | ||||

| Self-perceived confidence |

|

|

|

||||

| Self-perceived awareness |

|

|

|

| Self-perceived assessments | Year 1 Mean (SD) | Year 2 Mean (SD) | Year 3 Mean (SD) |

|

| Self-perceived confidence | ||||

| Pre-assessment score | 3.06 (0.17) | 3.83 (0.80) | 3.25 (0.71) | 0.115 |

| Post-assessment score | 3.97 (0.82) | 4.44 (0.46) | 4.28 (0.52) | 0.346 |

| Score improvement | 0.89 (0.67) | 0.61 (0.55) | 1.03 (0.56) | 0.484 |

| Self-perceived awareness | ||||

| Pre-assessment score | 4.13 (0.44) | 4.36 (0.47) | 3.97 (0.54) | 0.399 |

| Post-assessment score | 4.44 (0.43) | 4.75 (0.17) | 4.44 (0.44) | 0.787 |

| Score improvement | 0.31 (0.36) | 0.39 (0.37) | 0.47 (0.34) | 0.728 |

Self-perceived assessments toward confidence and awareness of teledentistry

Satisfactions toward the use of gamified online role-play

Learner experiences within the gamified online role-play

Theme 1: Learner profile

“I had experience with a role-play activity when I was dental undergraduates, and I like this kind of learning where someone role-plays a patient with specific personalities in various contexts. This could be a reason why I felt interested to participate in this task (the gamified online role-play). I also believed that it would be supportive for my clinical practice.”

Participant 12, Year 1, Female

“Actually, I’ have seen in several videos (about teledentistry), where dentists were teaching patients to perform self-examinations, such as checking their own mouth and taking pictures for consultations. Therefore, I could have thought about what I would experience during the activity (within the gamified online role-play).” Participant 8, Year 2, Female

Theme 2: Learning settings of the gamified online role-play

Subtheme 2.1: Location

communicate and understand of the needs of patient, leading to a better grasp of lesson content. In addition, the environments of both learners and simulated patient should be authentic to the learning quality.

| Satisfactions | Year 1 Mean (SD) | Year 2 Mean (SD) | Year 3 Mean (SD) |

|

| Self-perceived usefulness | 4.39 (0.46) | 4.69 (0.47) | 4.25 (0.66) | 0.158 |

| Self-perceived ease of use | 4.50 (0.29) | 4.56 (0.51) | 4.14 (0.63) | 0.263 |

| Self-perceived enjoyment | 4.00 (0.39) | 4.25 (0.25) | 3.83 (0.72) | 0.570 |

| Overall | 4.30 (0.26) | 4.50 (0.23) | 4.07 (0.22) | 0.997 |

The time allocated for the gamified online role-play in this research was considered as appropriate, as participants believed that a 30 -minutes period should be suitable to take information and afterwards give some advice to their patient. In addition, a 10 -minutes discussion on how they interact with the patient could be supportive for participants to enhance their competencies in the use of teledentistry.

“… it would probably take about 20 minutes because we would need to gather a lot of information … it might need some time to request and gather various information … maybe another 10-15 minutes to provide some advice.” Participant 7, Year 1, Female

“I think during the class … we could allocate around 30 minutes for role-play, … we may have discussion of learner performance for 10-15 minutes … I think it should not be longer than 45 minutes in total.”

Participant 6, Year 2, Female

Most participants suggested that the gamified online role-play in teledentistry should be arranged in the first year of their postgraduate program. This could maximize the effectiveness of online role-play, as they would be able to implement teledentistry for their clinical practice since the beginning of their training. However, some participants suggested that this learning approach could be rearranged in either second or third year of the program. As they already had experience in clinical practice, the gamified online role-play would reinforce their competence in teledentistry.

“Actually, it would be great if this session could be scheduled in the first year … I would feel more comfortable when dealing with my patients through an online platform.”

Participant 11, Year 2, Male

“I believe this approach should be implemented in the first year because it allows students to be trained in teledentistry before being exposed to real patients. However, if this approach is implemented in either the second or third year when they have already had experience in patient care, they would be able to better learn from conversations with simulated patients.”

Participant 4, Year 3, Male

Theme 3: Pedagogical components

Subtheme 3.1: Learning content

“The learning tasks (within the gamified online role-play) let me know how to manage patients through the teleconference.”

Participant 5, Year 2, Female

“… there seemed to be limitations (of teledentistry) … there could be a risk of misdiagnosis … the poor quality of video may lead to diagnostic errors … it is difficult for patients to capture their oral lesions.”

Participant 3, Year 2, Female

Subtheme 3.2: Feedback

“I knew (whether or not I interacted correctly) from the gestures and emotions of the simulated patient between the conversation. I could have learnt from feedback provided during the role-play, especially from the facial expressions of the patient.”

Participant 11, Year 2, Male

“The feedback provided at the end let me know how well I performed within the learning tasks.” Participant 2, Year 1, Female

Theme 4: Interactive functions

Most participants believed that a simulated patient with high acting performance could enhance the flow of role-play, allowing learners to experience real consequences. The appropriate level of authenticity could engage learners with the learning activity, as they would have less awareness of time passing in the state of flow. Therefore, they could learn better from the gamified online role-play.

“It was so realistic. … This allowed me to talk with the simulated patient naturally … At first, when we were talking, I was not sure how I should perform … but afterwards I no longer had any doubts and felt like I wanted to explain things to her even more.”

Participant 3, Year 2, Female

“At first, I believed that if there was a factor that could influence learning, it would probably be a simulated patient. I was impressed by how this simulated patient could perform very well. It made the conversation flow smoothly and gradually.”

Participant 9, Year 3, Female

Subtheme 4.2: Entertaining features

“It was a playful experience while communicating with the simulated patient. There are elements of surprise from the challenge cards that make the conversation more engaging, and I did not feel bored during the role-play.”

Participant 4, Year 3, Male

“I like the challenge card we randomly selected, as we had no idea what we would encounter … more scenarios like eight choices and we can randomly choose to be more excited. I think we do not need additional challenge cards, as some of them have already been embedded in patient conditions.”

Participant 5, Year 2, Female

Subtheme 4.3: Level of difficulty

“The patient had hidden their information, and I needed to bring them out from the conversation.”

Participant 12, Year 1, Female

“Patients’ emotions could be more sensitive to increase level of challenges. This can provide us with more opportunities to enhance our management skills in handling patient emotions.”

Participant 11, Year 2, Male

“… we can gradually increase the difficult level, similar to playing a game. These challenges could be related to the simulated patient, such as limited knowledge or difficulties in communication, which is likely to occur in our profession.”

Participant 6, Year 2, Female

Theme 5: Educational impact

Communication skills. Participants were likely to perceive that they could learn from the gamified online role-play and felt more confident in the use of teledentistry. This educational impact was mostly achieved from the online conversation within the role-play activity, where the participants could improve their communication skills through a video teleconference platform.

“I feel like the online role-play was a unique form of learning. I believe that I gained confidence from the online communication the simulated patient. I could develop skills to communicate effectively with real patients.”

Participant 11, Year 2, Male

“I believe it support us to train communication skills … It allowed us to practice both listening and speaking skills more comprehensively.”

Participant 4, Year 3, Male

Critical thinking and problem-solving skills. In addition to communication skills, participants reported that challenges embedded in the role-play allowed them to enhance critical thinking and problem-solving skills, which were a set of skills required to deal with potential problems in the use of teledentistry.

Participant 11, Year 2, Male

Subtheme 5.2: Self perceived awareness in teledentistry

Participants believed that they could realize the necessity of teledentistry from the gamified online role-play. The storytelling or patient conditions allowed learners to understand how teledentistry could have both physical and psychological support for dental patients.

“From the activity, I would consider teledentistry as a convenient tool for communicating with patients, especially if a patient cannot go to a dental office”.

Participant 5, Year 2, Female

“I learned about the benefits of teledentistry, particularly in terms of follow-up. The video conference platform could support information sharing, such as drawing images or presenting treatment plans, to patients.”

Participant 8, Year 2, Female

A conceptual framework of learning experience within a gamified online role-play

Discussion

Conclusions

Data availability

Published online: 22 April 2024

References

- Van Dyk, L. A review of telehealth service implementation frameworks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11(2), 1279-1298 (2014).

- Bartz, C. C. Nursing care in telemedicine and telehealth across the world. Soins. 61(810), 57-59 (2016).

- Lin, G.S.S., Koh, S.H., Ter, K.Z., Lim, C.W., Sultana, S., Tan, W.W. Awareness, knowledge, attitude, and practice of teledentistry among dental practitioners during COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina (Kaunas). 58(1), 130 (2022).

- Wolf, T.G., Schulze, R.K.W., Ramos-Gomez, F., Campus, G. Effectiveness of telemedicine and teledentistry after the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 19(21), 13857 (2022).

- Gajarawala, S. N. & Pelkowski, J. N. Telehealth benefits and barriers. J. Nurse Pract. 17(2), 218-221 (2021).

- Jampani, N. D., Nutalapati, R., Dontula, B. S. & Boyapati, R. Applications of teledentistry: A literature review and update. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 1(2), 37-44 (2011).

- Khan, S. A. & Omar, H. Teledentistry in practice: literature review. Telemed. J. E. Health. 19(7), 565-567 (2013).

- Baheti, M. J. B. S., Toshniwal, N. G. & Misal, A. Teledentistry: A need of the era. Int. J. Dent. Med. Res. 1(2), 80-91 (2014).

- Datta, N., Derenne, J., Sanders, M. & Lock, J. D. Telehealth transition in a comprehensive care unit for eating disorders: Challenges and long-term benefits. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 53(11), 1774-1779 (2020).

- Bursell, S. E., Brazionis, L. & Jenkins, A. Telemedicine and ocular health in diabetes mellitus. Clin. Exp. Optom. 95(3), 311-327 (2012).

- da Costa, C. B., Peralta, F. D. S. & Ferreira de Mello, A. L. S. How has teledentistry been applied in public dental health services? An integrative review. Telemed. J. E. Health. 26(7), 945-954 (2020).

- Heckemann, B., Wolf, A., Ali, L., Sonntag, S. M. & Ekman, I. Discovering untapped relationship potential with patients in telehealth: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open. 6(3), e009750 (2016).

- Pérez-Noboa, B., Soledispa-Carrasco, A., Padilla, V. S. & Velasquez, W. Teleconsultation apps in the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Guayaquil City, Ecuador. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 49(1), 27-37 (2021).

- Wamsley, C. E., Kramer, A., Kenkel, J. M. & Amirlak, B. Trends and challenges of telehealth in an academic institution: The unforeseen benefits of the COVID-19 global pandemic. Aesthetic Surg. J. 41(1), 109-118 (2020).

- Jonasdottir, S. K., Thordardottir, I. & Jonsdottir, T. Health professionals’ perspective towards challenges and opportunities of telehealth service provision: A scoping review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 167, 104862 (2022).

- Tan, S. H. X., Lee, C. K. J., Yong, C. W. & Ding, Y. Y. Scoping review: Facilitators and barriers in the adoption of teledentistry among older adults. Gerodontology. 38(4), 351-365 (2021).

- Minervini, G. et al. Teledentistry in the management of patients with dental and temporomandibular disorders. BioMed. Res. Int. 2022, 7091153 (2022).

- Edirippulige, S. & Armfield, N. Education and training to support the use of clinical telehealth: A review of the literature. J. Telemed. Telecare. 23(2), 273-282 (2017).

- Mariño, R. & Ghanim, A. Teledentistry: A systematic review of the literature. J. Telemed. Telecare. 19(4), 179-183 (2013).

- Armitage-Chan, E. & Whiting, M. Teaching professionalism: Using role-play simulations to generate professionalism learning outcomes. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 43(4), 359-363 (2016).

- Spyropoulos, F., Trichakis, I. & Vozinaki, A.-E. A narrative-driven role-playing game for raising flood awareness. Sustainability. 14(1), 554 (2022).

- Jiang, W. K. et al. Role-play in endodontic teaching: A case study. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 23(4), 281-288 (2020).

- Vizeshfar, F., Zare, M. & Keshtkaran, Z. Role-play versus lecture methods in community health volunteers. Nurse Educ. Today. 79, 175-179 (2019).

- Nestel, D. & Tierney, T. Role-play for medical students learning about communication: Guidelines for maximising benefits. BMC Med. Educ. 7, 3 (2007).

- Gelis, A. et al. Peer role-play for training communication skills in medical students: A systematic review. Simulat. Health. 15(2), 106-111 (2020).

- Cornelius, S., Gordon, C. & Harris, M. Role engagement and anonymity in synchronous online role play. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 12(5), 57-73 (2011).

- Bell, M. Online role-play: Anonymity, engagement and risk. Educ. Med. Int. 38(4), 251-260 (2001).

- Sipiyaruk, K., Gallagher, J. E., Hatzipanagos, S. & Reynolds, P. A. A rapid review of serious games: From healthcare education to dental education. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 22(4), 243-257 (2018).

- Sipiyaruk, K., Hatzipanagos, S., Reynolds, P. A. & Gallagher, J. E. Serious games and the COVID-19 pandemic in dental education: An integrative review of the literature. Computers. 10(4), 42 (2021).

- Morse, J.M., Niehaus, L. Mixed Method Design: Principles and Procedures. (2016).

- Creswell, J. W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches 3rd edn. (SAGE Publications, 2009).

- Cheng, V. W. S., Davenport, T., Johnson, D., Vella, K. & Hickie, I. B. Gamification in apps and technologies for improving mental health and well-being: Systematic review. JMIR Ment. Health. 6(6), el3717 (2019).

- Gallego-Durán, F. J. et al. A guide for game-design-based gamification. Informatics. 6(4), 49 (2019).

- Gee, J. P. Learning and games. In The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning (ed. Salen, K.) 21-40 (MIT Press, 2008).

- Cheung, K. L., ten Klooster, P. M., Smit, C., de Vries, H. & Pieterse, M. E. The impact of non-response bias due to sampling in public health studies: A comparison of voluntary versus mandatory recruitment in a Dutch national survey on adolescent health. BMC Public Health. 17(1), 276 (2017).

- Murairwa, S. Voluntary sampling design. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Social Sci. 4(2), 185-200 (2015).

- Chow, S.-C., Shao, J., Wang, H. & Lokhnygina, Y. Sample Size Calculations in Clinical Research (CRC Press, 2017).

- Palinkas, L. A. et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration Policy Mental Health Mental Health Services Res. 42(5), 533-544 (2015).

- McIlvried, D. E., Prucka, S. K., Herbst, M., Barger, C. & Robin, N. H. The use of role-play to enhance medical student understanding of genetic counseling. Genet. Med. 10(10), 739-744 (2008).

- Schlegel, C., Woermann, U., Shaha, M., Rethans, J.-J. & van der Vleuten, C. Effects of communication training on real practice performance: A role-play module versus a standardized patient module. J. Nursing Educ. 51(1), 16-22 (2012).

- Manzoor, I. M. F. & Hashmi, N. R. Medical students’ perspective about role-plays as a teaching strategy in community medicine. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 22(4), 222-225 (2012).

- Cornes, S., Gelfand, J. M. & Calton, B. Foundational telemedicine workshop for first-year medical students developed during a pandemic. MedEdPORTAL. 17, 11171 (2021).

- King, J., Hill, K. & Gleason, A. All the world’sa stage: Evaluating psychiatry role-play based learning for medical students. Austral. Psychiatry. 23(1), 76-79 (2015).

- Arayapisit, T. et al. An educational board game for learning orofacial spaces: An experimental study comparing collaborative and competitive approaches. Anatomical Sci. Educ. 16(4), 666-676 (2023).

- Sipiyaruk, K., Hatzipanagos, S., Vichayanrat, T., Reynolds, P.A., Gallagher, J.E. Evaluating a dental public health game across two learning contexts. Educ. Sci. 12(8), 517 (2022).

- Pilnick, A. et al. Using conversation analysis to inform role play and simulated interaction in communications skills training for healthcare professionals: Identifying avenues for further development through a scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 18(1), 267 (2018).

- Lane, C. & Rollnick, S. The use of simulated patients and role-play in communication skills training: A review of the literature to August 2005. Patient Educ. Counseling. 67(1), 13-20 (2007).

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S. & Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13(1), 117 (2013).

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M. & Ormston, R. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers (Sage, 2014).

- Chen, J. C. & Martin, A. R. Role-play simulations as a transformative methodology in environmental education. J. Transform. Educ. 13(1), 85-102 (2015).

- Davis, F. D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. Manag. Inform. Syst. Quart. 13(3), 319-340 (1989).

- Novak, E., Johnson, T. E., Tenenbaum, G. & Shute, V. J. Effects of an instructional gaming characteristic on learning effectiveness, efficiency, and engagement: Using a storyline for teaching basic statistical skills. Interact. Learn. Environ. 24(3), 523-538 (2016).

- Marchiori, E. J. et al. A narrative metaphor to facilitate educational game authoring. Comput. Educ. 58(1), 590-599 (2012).

- Luctkar-Flude, M. et al. Effectiveness of debriefing methods for virtual simulation: A systematic review. Clin. Simulat. Nursing. 57, 18-30 (2021).

- Joyner, B. & Young, L. Teaching medical students using role play: Twelve tips for successful role plays. Med. Teach. 28(3), 225-229 (2006).

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Performance (HarperCollins Publishers, 1990).

- Buajeeb, W., Chokpipatkun, J., Achalanan, N., Kriwattanawong, N. & Sipiyaruk, K. The development of an online serious game for oral diagnosis and treatment planning: Evaluation of knowledge acquisition and retention. BMC Med. Educ. 23(1), 830 (2023).

- Littlefield, J. H., Hahn, H. B. & Meyer, A. S. Evaluation of a role-play learning exercise in an ambulatory clinic setting. Adv. Health. Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 4(2), 167-173 (1999).

- Alkin, M. C. & Christie, C. A. The use of role-play in teaching evaluation. Am. J. Evaluat. 23(2), 209-218 (2002).

- Lovell, K. L., Mavis, B. E., Turner, J. L., Ogle, K. S. & Griffith, M. Medical students as standardized patients in a second-year performance-based assessment experience. Med. Educ. Online. 3(1), 4301 (1998).

Acknowledgements

Author contributions

Funding

Competing interests

Additional information

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

© The Author(s) 2024

Department of Advanced General Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. email: kawin.sip@mahidol.ac.th - “The room should be a private space without any disturbances. This will make us feel confident and engage in conversations with the simulated patient.”

Participant 10, Year 1, Female

“… simulating a realistic environment can engage me to interact with the simulated patient more effectively …” Participant 8, Year 2, Female - “It was a way of training before experiencing real situations … It allowed us to think critically whether or not what we performed with the simulated patients was appropriate.”

Participant 7, Year 1, Female