DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3688399

تاريخ النشر: 2024-08-13

تصميم وكلاء LLM غير المتجانسين لتحليل المشاعر المالية

الملخص

لقد غيرت نماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLMs) بشكل جذري الطرق الممكنة لتصميم الأنظمة الذكية، حيث انتقلت التركيزات من جمع البيانات الضخمة وتدريب النماذج الجديدة إلى التوافق البشري والاستنباط الاستراتيجي للإمكانات الكاملة للنماذج المدربة مسبقًا الموجودة. ومع ذلك، لم يتم تحقيق هذا التحول في النموذج بالكامل في تحليل المشاعر المالية (FSA)، بسبب الطبيعة التمييزية لهذه المهمة ونقص المعرفة الإرشادية حول كيفية الاستفادة من النماذج التوليدية في مثل هذا السياق. تبحث هذه الدراسة في فعالية النموذج الجديد، أي استخدام LLMs دون ضبط دقيق لـ FSA. مستندة إلى نظرية مينسكي للعقل والعواطف، يتم اقتراح إطار تصميم مع وكلاء LLM غير المتجانسين. يقوم الإطار بتجسيد وكلاء متخصصين باستخدام المعرفة السابقة في المجال حول أنواع أخطاء FSA والأسباب المتعلقة بمناقشات الوكلاء المجمعة. تظهر التقييمات الشاملة على مجموعات بيانات FSA أن الإطار يحقق دقة أفضل، خاصة عندما تكون المناقشات كبيرة. تسهم هذه الدراسة في أسس التصميم وتفتح آفاق جديدة لتحليل المشاعر المالية المعتمد على LLMs. كما يتم مناقشة الآثار على الأعمال والإدارة.

1 المقدمة

تم تطوير غالبية أنظمة FSA في العقد الماضي ومرت أفكار تصميمها وهندستها بعدة تكرارات مع التقدم في معالجة اللغة الطبيعية. تعتمد الأنظمة المبكرة على قواميس كلمات المشاعر وقواعد بسيطة أو إحصائيات لاستنتاج القطبية على مستوى الجملة أو الرسالة. تم بذل جهود لاكتشاف الكلمات/العبارات المحددة بمجال المالية [24، 40]. تم تطوير عدد كبير من الأنظمة المعتمدة على التعلم لاحقًا. على وجه التحديد، تم إجراء مهمتين مرجعيتين (SemEval 2017 Task 5 [6] وFiQA 2018 Task 1 [7])، و

تم تحقيق أفضل النتائج بواسطة نماذج التجميع الانحداري (RE) والشبكات العصبية التلافيفية (CNN) ونماذج الانحدار باستخدام دعم المتجهات (SVR) بناءً على ميزات مجمعة من قواميس المشاعر وتمثيلات الكلمات الكثيفة. كانت الموجة التالية من التصاميم تعتمد على ضبط دقيق لنماذج اللغة المدربة مسبقًا ذات الأغراض العامة، مثل BERT

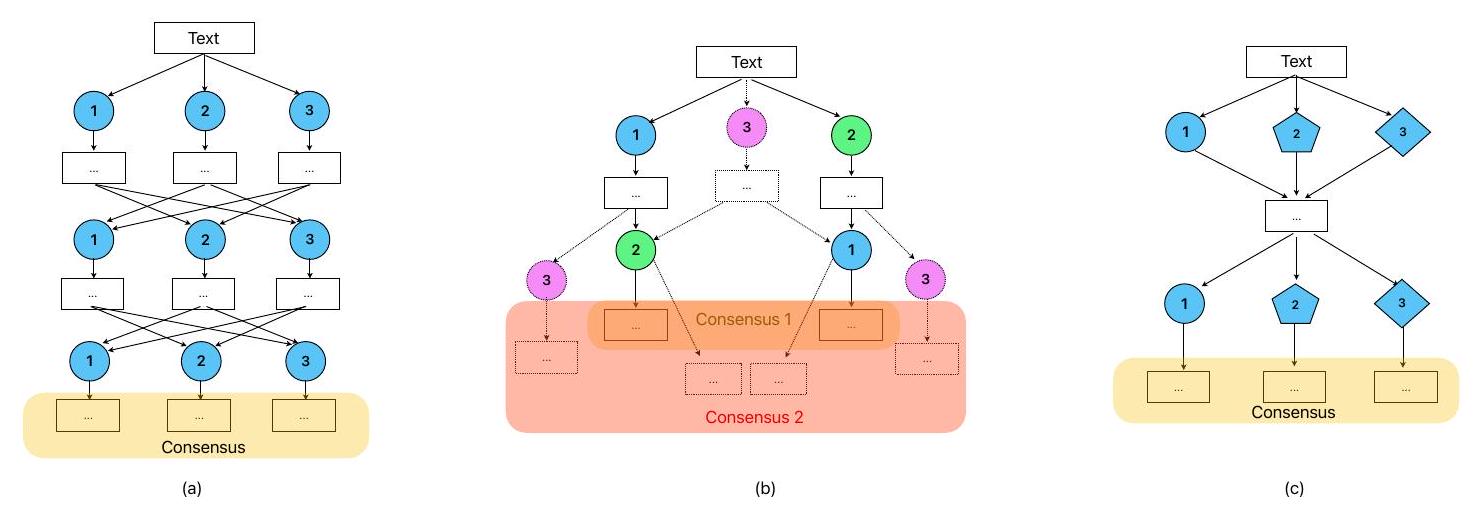

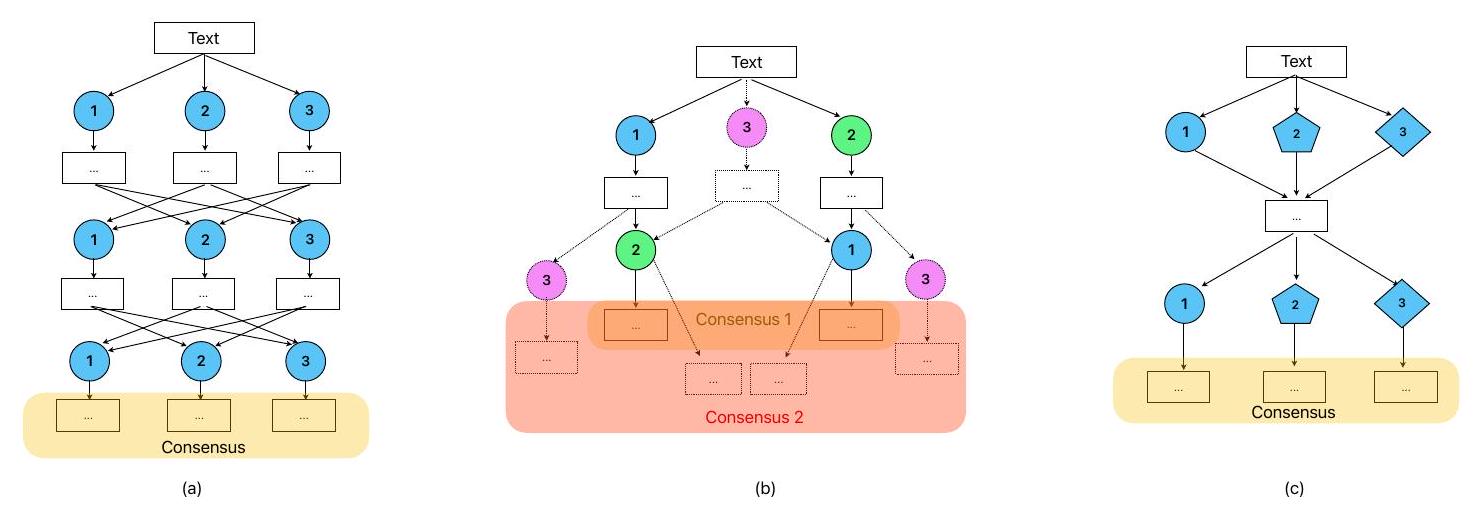

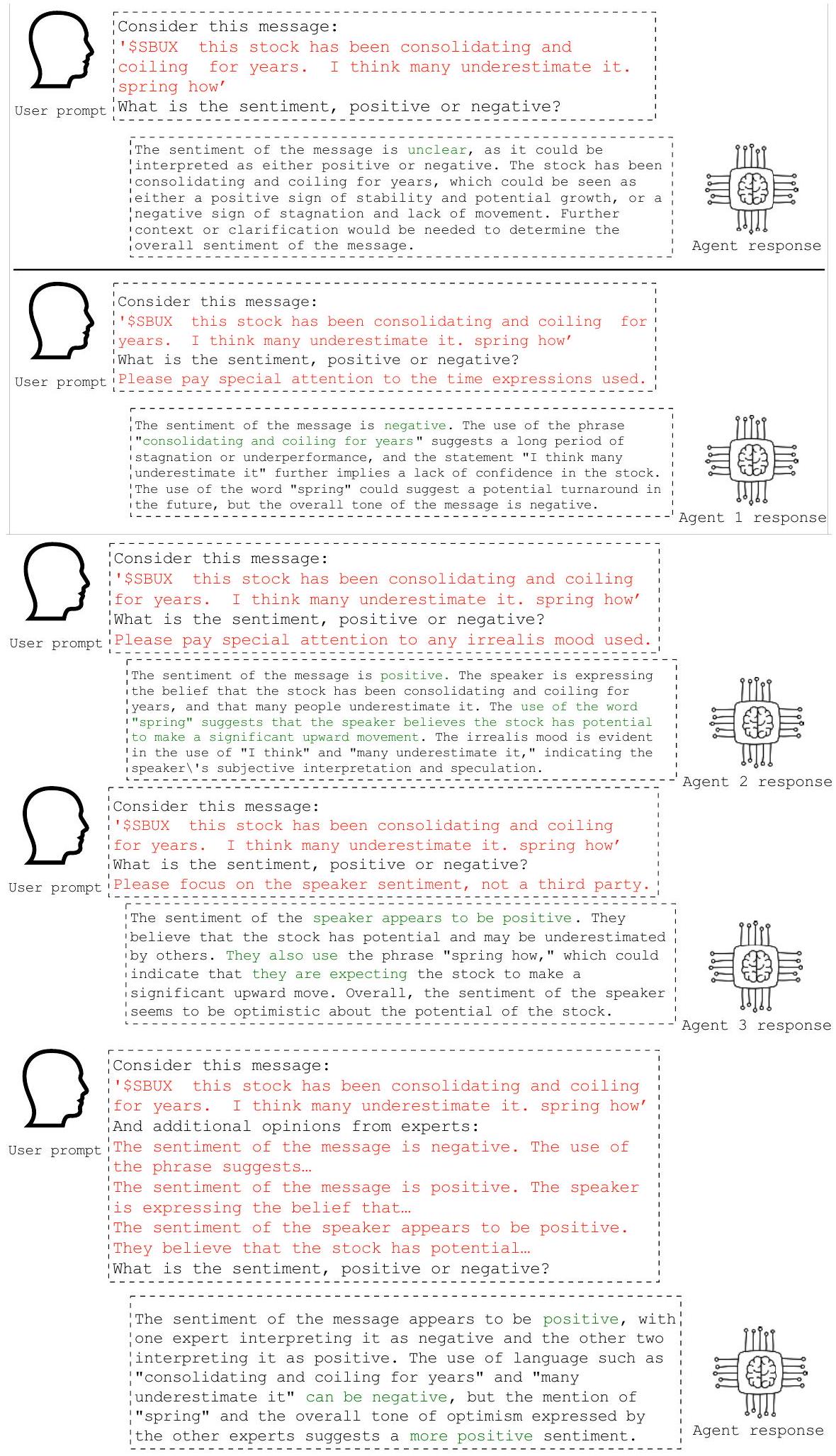

مختلف عن العديد من التصاميم العشوائية التي تم تطويرها من سلسلة الأفكار (CoT) [10]، وشجرة الأفكار (ToT) [42]، والتحقق، وقيود الاتساق الذاتي، والألواح المتوسطة، وإعدادات متعددة الوكلاء متعددة الأدوار، يتبع إطار التصميم المقدم هنا إرشادات علم التصميم من قبل هيفنر وآخرون [18] ويساهم في المعرفة الإرشادية كـ “نظرية تصميم” [15]. بناءً على نظرية مينسكي للعقل والعواطف، فإن “الحالات العاطفية” هي طرقنا للتفكير مع مجموعة محددة من الموارد المفعلة وأخرى غير مفعلة نظرًا لظروف بيئية معينة [27]. لذلك، فإن أحد أساليب FSA هو محاكاة العمليات العقلية الكامنة وراء النصوص، مما يتطلب وكلاء LLM متخصصين للعب أدوار “الموارد”، أي الأجزاء الوظيفية من دماغنا التي تجعلنا نتفاعل مع البيئة. في سياق التحليل المالي، يتم تعلم العديد من الموارد كمعرفة مهنية وليست أجزاء فطرية من أدمغتنا. يختار إطار التصميم (مناقشة متعددة الوكلاء غير المتجانسة) تطوير وكلاء LLM متخصصين من خلال التحفيز، والوظيفة الرئيسية هي الانتباه إلى نوع من الأخطاء التي تميل LLMs إلى ارتكابها لمهمة FSA المعطاة. وبالتالي، يحتوي المنتج التصميمي على خمسة وكلاء مختلفين وتستند نتيجة FSA إلى مناقشة مشتركة تأخذ في الاعتبار المخرجات من جميع الوكلاء. أقوم بتقييم المنتج باستخدام طرق متعددة، وتخلص النتائج عمومًا إلى أن الإطار فعال.

- RQ1: ما مدى فعالية HAD مقارنة بالتحفيز الساذج ونموذج الضبط الدقيق؟

- RQ2: كيف يمكن تحفيز وكلاء LLM للتصرف بشكل متنوع في تحليل المشاعر في المالية؟

- RQ3: ما هي المساهمات الكمية لكل وكيل LLM وأهميتها النسبية؟

تساهم هذه الدراسة في أدبيات علم تصميم العلوم من خلال تقديم عنصر تصميم مستند إلى نظرية أساسية. تم تقديم عدد من النظريات الأساسية من العلوم الطبيعية أو الاجتماعية في تصميم نظم المعلومات، بينما تعتبر النظريات الأساسية من الذكاء الاصطناعي نادرة بالمقارنة. لهذه الدراسة آثار على نظرية العواطف، وأبحاث التعاون بين نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، وممارسات اتخاذ القرار المالي. أولاً، تدعم هذه الدراسة مجتمع العقل وآلات العواطف لتكون نظريات قابلة للتطبيق تفسر كيف تظهر العواطف كنوع مهم من الذكاء البشري؛ ثانياً، تطبق هذه الدراسة نماذج اللغة الكبيرة متعددة الوكلاء في أنظمة التحليل المالي. تم استخدام هذا الإطار للتحقق من الحقائق، والتفكير الحسابي/الرياضي، والتحسين، وتحليل المشاعر العام، ولكن لم يتم استخدامه بعد في أنظمة التحليل المالي حسب علمي. وبالتالي، توفر هذه الدراسة مواد جديدة للتعاون بين نماذج اللغة الكبيرة، وتعزز أيضاً النهج القائم على علم التصميم في تطوير الإطارات؛ وأخيراً، تساهم النتائج في المعرفة التوجيهية لتصميم أنظمة التحليل المالي. قد يقوم المستثمرون والمتداولون بتكرار وتحسين أنظمة التحليل المالي الخاصة بهم بناءً على إطار HAD أو أن يكونوا أكثر اطلاعاً عند اتخاذ قرار اختيار أو شراء حلول تقنية من نوع مشابه.

2 الأعمال ذات الصلة وعملية التصميم

2.1 استخدام نماذج اللغة الكبيرة لتحليل المشاعر المالية

النتائج، على الرغم من أن هذه المعلومات نادراً ما تكون متاحة في بيئات الإنتاج الواقعية. لاحظ زانغ وآخرون [44] أن الأخبار المالية غالباً ما تكون مختصرة بشكل مفرط. وبالتالي، تم تطوير نموذج يسترجع سياقاً إضافياً من مصادر خارجية موثوقة لتشكيل تعليمات أكثر تفصيلاً. وجد دينغ وآخرون [10] أن إجبار النموذج اللغوي الكبير على اتباع عدة مسارات تفكير باستخدام طريقة سلسلة التفكير يساعد في توليد تسميات أكثر استقراراً ودقة. كما أن التسميات التي يولدها النموذج اللغوي الكبير مفيدة وتلبي الجودة اللازمة لتكملة التوصيفات البشرية لطرق التعلم الخاضع للإشراف التقليدية. وبالمثل، طور فاي وآخرون [14] إطار عمل للتفكير ثلاثي القفز مستوحى من طريقة سلسلة التفكير التي تستنتج أولاً الجانب الضمني، وثانياً الرأي الضمني، وأخيراً قطبية المشاعر. ومع ذلك، تم الإشارة [35] إلى أن نموذج لغوي كبير واحد يواجه صعوبات في استغلال الإمكانات الكاملة لمعارف النموذج اللغوي الكبير. وهذا صحيح بشكل خاص بالنسبة للأنظمة المعقدة، حيث تتضمن قدرات متعددة للنموذج اللغوي الكبير، مثل التفكير، والتحقق من الحقائق، والتحليل النحوي/الدلالي، وأكثر من ذلك. ألاحظ ظاهرة مشابهة كما تم الإبلاغ عنها في [45] أن أداء النموذج اللغوي الكبير في المهام الأكثر تعقيداً ليس مرضياً كما هو الحال في مهمة التصنيف الثنائي. علاوة على ذلك، فإن التصاميم المذكورة أعلاه (استرجاع التخزين وطريقة سلسلة التفكير) وتصاميم أخرى لم يتم تطبيقها بعد على الأنظمة المعقدة، مثل التحقق، وقيود الاتساق الذاتي، أو دفاتر الملاحظات الوسيطة، هي أيضاً في الغالب تجريبية، في أحسن الأحوال تعتمد على التجارب، وتفتقر إلى أساس نظري قوي.

الإطار المقترح يعتمد على التعلم في السياق (ICL) ويستفيد من تجسيدات متعددة لنماذج اللغة الكبيرة (LLM) (وكلاء)، والذي يُشار إليه أيضًا بتعاون نماذج اللغة الكبيرة. تشمل استراتيجيات التعاون المهام المساعدة (مثل التحقق) [4]، والنقاش [13]، وتوزيع الأدوار المتنوعة [35] بما في ذلك المولد، والمميز، والمبرمج، والمدير، والمتحكم الفوقي، إلخ. مرة أخرى، يبدو أن تصميم المهام المساعدة والأدوار عشوائي ويفتقر إلى أسس نظرية قوية. كما تم التحقيق في تعاون نماذج اللغة الكبيرة بشكل أكبر في العديد من مهام معالجة اللغة الطبيعية العامة بما في ذلك تحليل المشاعر، ولكن تطبيقها على FSA يفتقر إلى الأدلة المباشرة. ربما الأكثر ارتباطًا بإطار تصميم HAD المقترح هو MedPrompt [29]. يستخدم مجموعة من تسلسلات التفكير (CoT) الم shuffled عشوائيًا من وكلاء متجانسين. التصميم أيضًا أكثر استهلاكًا للموارد الحاسوبية وصعب النقل إلى مجال المالية حيث أن مجموعات بيانات الأسئلة والأجوبة المالية الحالية أكثر ندرة.

2.2 هندسة المطالبات

فيما يتعلق بالبحث التلقائي عن نموذج الطلب، يتم مناقشة الطرق المعتمدة على التحسين العشوائي. على سبيل المثال، اكتشف سورنسن وآخرون [34] أن النموذج الجيد هو الذي يعظم المعلومات المتبادلة بين المدخلات والمخرجات الناتجة.

فيما يتعلق بتصميم المطالبات، درس ليو وتشيلتون [22] نماذج توليد النص إلى صورة وقالب المطالبة “الموضوع بأسلوب الأسلوب”. وقد وجدوا أن وضوح وبارز الكلمات الرئيسية مهمان لجودة التوليد. قدم يو وآخرون [43] فكرة استخدام المعرفة المتخصصة لتوجيه تصميم المطالبات. وقد تم الإبلاغ عن أنه بالنسبة لمهمة استنتاج المعلومات القانونية، يتم الحصول على أفضل النتائج عندما يتم اشتقاق المطالبات من تقنيات التفكير القانوني المحددة، مثل تقنية القضية-القاعدة-التطبيق-الاستنتاج (IRAC) كما يتم تدريسها في كليات الحقوق. ومع ذلك، بالنسبة لـ FSA، فإن إرشادات التصميم غير واضحة ومعظم الدراسات استخدمت مطالبات بسيطة. على سبيل المثال، استخدم تشين وشينغ [3] “أنت مساعد تحليل المشاعر المفيد – [رسالة مثال]:[المشاعر]. المستخدم: [رسالة اختبار].” وقالب FSA الخاص بـ BloombergGPT [36] هو ببساطة “[رسالة اختبار] سؤال: ما هي المشاعر؟ أجب بالسلبية/الحيادية/الإيجابية”.

2.3 نظرية النواة: المشاعر ومجتمع العقل

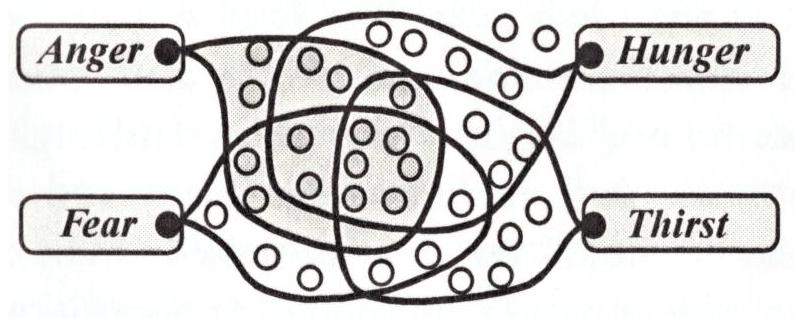

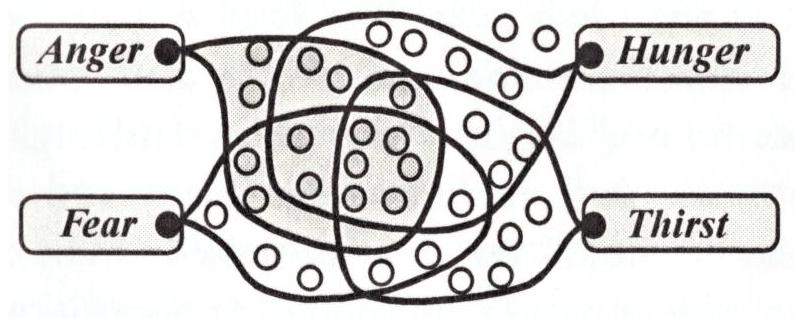

مجتمع العقل هو منظور اختزالي للذكاء البشري أثر بشكل كبير على الذكاء الاصطناعي ويجادل بأن أي وظيفة لا تنتج الذكاء مباشرة. بدلاً من ذلك، يأتي الذكاء من التفاعل المدبر لمجموعة متنوعة من الوكلاء القادرين ولكن الأبسط وغير الذكيين. على سبيل المثال، عند شرب كوب من الشاي، يتم تفعيل وكيل حركي يمسك الكوب، وموازن يمنع انتشار الشاي، ومستشعر حرارة يؤكد أن حلقنا لن يتأذى. ترى هذه النظرية الحالات العاطفية كنماذج من التفعيل. على سبيل المثال، الحالة التي نسميها “غاضب” قد تكون ما يحدث عندما يتم تفعيل سحابة من الموارد التي تساعدك على التفاعل بسرعة وقوة غير عادية – بينما يتم قمع بعض الموارد الأخرى التي تجعلك تتصرف بحذر (الشكل 2).

2.4 المتطلبات الميتا، التصاميم الميتا، والفرضيات

| نظرية النواة |

|

|||

| المتطلبات الميتا |

|

|||

| التصاميم الميتا |

|

|||

| الفرضيات القابلة للاختبار |

|

- تعريف الوكلاء المتنوعين وقوالب مطالباتهم

. - الحصول على تحليل وسيط

(User_Message) - الحصول على نتيجة تحليل تراكمية

User_Message,

لتقييم ما إذا كان الإطار المقترح فعالًا، تم تطوير فرضيتين قابلتين للاختبار. إذا كانت أنواع الأخطاء مفيدة لتوجيه تصميم الوكيل، نتوقع أن تتحسن مقاييس الأداء (H1). بسبب مشكلة عدم توازن البيانات الملحوظة في FSA، يجب أيضًا التحقيق في درجة F-1 بالإضافة إلى الدقة. ملاحظة أخرى هي أن حدوث كل نوع من الأخطاء ليس متساويًا ويختلف عبر مجالات اللغة المختلفة [46، 39]. وبالتالي، يُفترض أن الوكلاء سيكون لديهم أهمية مختلفة ولكن جميعهم يساهمون بشكل إيجابي في مهمة FSA (H2).

3 قطعة تصميم: مناقشة الوكيل المتنوع (HAD)

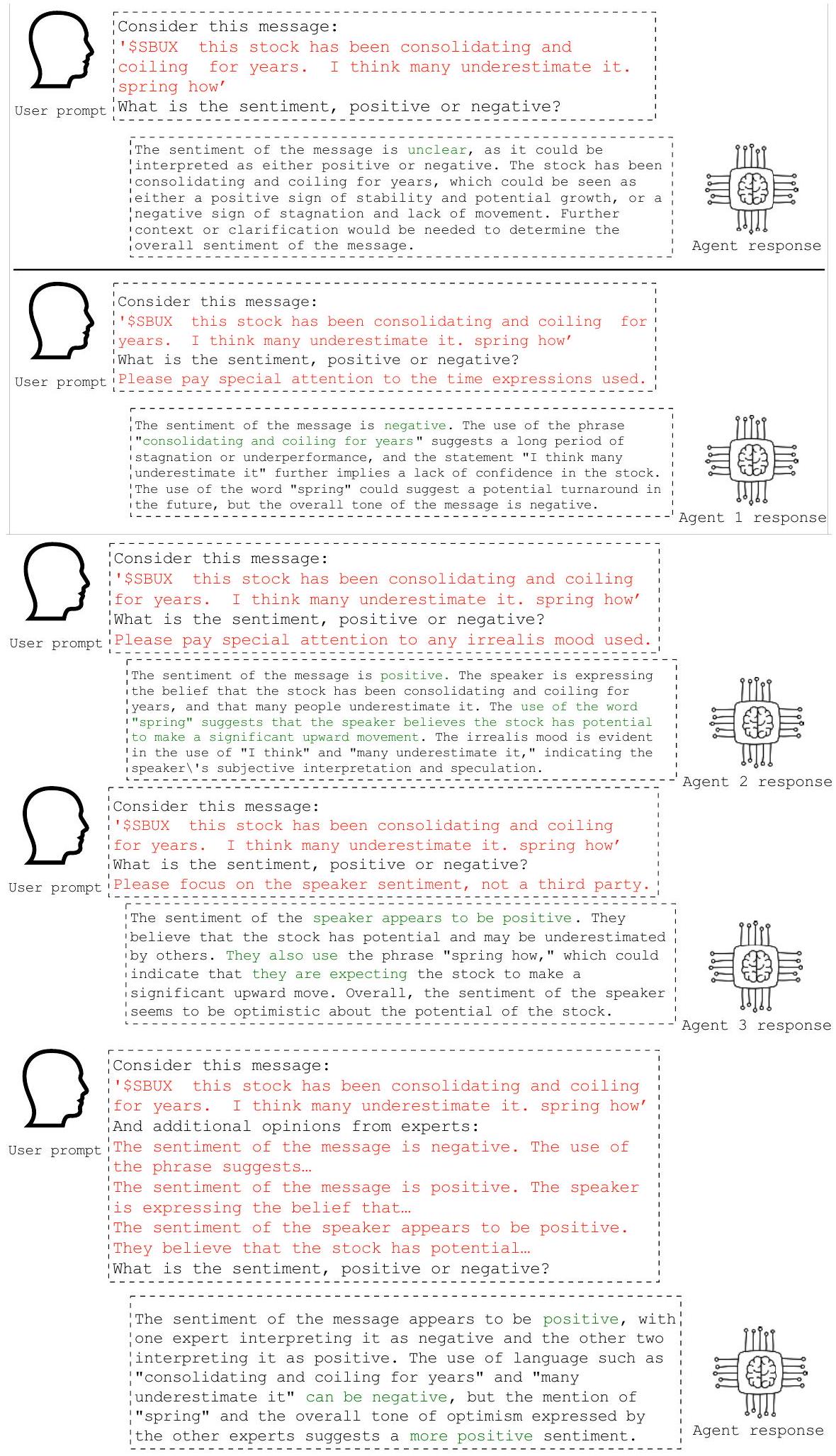

مع هذا الخلفية، تم تصميم خمسة وكلاء بناءً على [39] لأن (1) هذه الفئات أكثر ارتباطًا بـ FSA بشكل مباشر و(2) هذه الفئات أقل عددًا (6 مقارنة بـ 13) وأكثر عملية. نظرًا لأن LLMs لوحظ أنها قوية ضد الكلمات غير المعترف بها والأخطاء الإملائية من الويب، لم يتم تصميم وكيل خاص وفقًا لهذا الخطأ. الوكلاء الخمسة ومطالباتهم المميزة هي:

- A1 (وكيل المزاج): يرجى الانتباه بشكل خاص إلى أي مزاج غير واقعي مستخدم.

- A2 (وكيل البلاغة): يرجى الانتباه بشكل خاص إلى أي بلاغة (سخرية، تأكيد سلبي، إلخ) مستخدمة.

- A3 (وكيل الاعتماد): يرجى التركيز على مشاعر المتحدث، وليس طرف ثالث.

- A4 (وكيل الجانب): يرجى التركيز على رمز السهم/العلامة/الموضوع، وليس الكيانات الأخرى.

- A5 (وكيل المرجع): يرجى الانتباه بشكل خاص إلى تعبيرات الوقت، والأسعار، والحقائق الأخرى غير المعلنة.

4 التقييم

4.1 تحسين الأداء

الملاحظة الأولى هي السلوكيات المختلفة لنموذجي GPT-3.5 وBLOOMZ كنماذج أساسية. تم تدريب GPT-3.5 بشكل رئيسي على مجموعة بيانات Common Crawl [2]، التي أرشفت الويب. بينما تم تدريب BLOOMZ على مجموعة بيانات أكبر من مصادر النصوص المفتوحة في العلوم والتعاون المفتوح [19]، والتي تتكون بشكل رئيسي من مجموعات بيانات علمية تم جمعها من قبل الجمهور. جميع مجموعات البيانات الخمس المستخدمة للاختبار تأتي من الويب: وهذا قد يكون أقرب إلى مجال اللغة الذي تم تدريب GPT-3.5 عليه. لوحظ أن GPT-3.5 يتمتع بتدريب أفضل على التعليمات من خلال التغذية الراجعة البشرية الخاصة به. في المقابل، يميل BLOOMZ إلى مهمة إكمال اللغة. على سبيل المثال، قد تؤدي العبارة “ترجم إلى الإنجليزية: Je t’aime” بدون نقطة (.) في النهاية إلى محاولة النموذج مواصلة الجملة الفرنسية بدلاً من ترجمتها. يميل BLOOMZ إلى الإكمال/الإجابة بلغة مختصرة. بالنسبة للأسئلة المفتوحة المتعلقة بالعواطف تجاه وكلاء متنوعين، غالبًا ما يقدم BLOOMZ حكمًا نهائيًا إيجابيًا/سلبيًا دون الكثير من التبرير، وليس جيدًا في توقع الرسائل “المحايدة”. بالنسبة للعوامل التي تم مناقشتها سابقًا،

| مجموعة بيانات | FPB | ستوك سين | سي إم سي | في كيو إيه | SEntFiN |

| إيجابي | 570 | 4542 | 12022 | ٥٠٧ | ٢٨٣٢ |

| سلبي | ٣٠٣ | 1676 | 1523 | 264 | ٢٣٧٣ |

| محايد | 1391 | – | – | – | ٢٧٠١ |

| الحجم الكلي | 2264 | 6218 | 13545 | ٧٧١ | 7906 |

| مجموعة البيانات النموذجية | FPB | ستوك سين | سي إم سي | في كيو إيه | SEntFiN | |||||

| حساب | فورمولا 1 | حساب | فورمولا 1 | حساب | فورمولا 1 | حساب | فورمولا 1 | حساب | فورمولا 1 | |

| (فين-)بيرت | 91.69 | ٨٩.٧٠ | ٧٦.٩٠ | ٨٤.٥٠ | 93.50 | – | – | – | 94.29 | 93.27 |

| بلومبرغ جي بي تي | – | ٥١.٠٧ | – | – | – | – | – | 75.07 | – | – |

| جي بي تي-3.5 | 78.58 | 81.06 | 67.64 | 73.93 | 85.31 | 91.05 | 90.53 | 92.41 | 67.99 | 63.21 |

| جي بي تي-3.5 (هاد) | 80.48 | 81.41 | 70.44 | ٧٦.٥٥ | ٨٧.٥٥ | 92.50 | 93.91 | 95.22 | 77.45 | ٧٦.٩٣ |

| بلومز | ٣٤.٦٣ | ٣٢.٩٠ | 63.65 | 72.47 | ٨٧.١٦ | 92.62 | 78.33 | ٨٣.٦٤ | ٥١.٣٢ | 41.87 |

| بلومز (هاد) | ٣٤.١٩ | ٣٢.٩٣ | 72.80 | ٨٣.٩٧ | ٨٧.٦٧ | 92.95 | ٧٦.٧٨ | ٨٣.٠٣ | 50.16 | ٤٠.٦٩ |

4.2 تحليل الاستئصال

يلاحظ أن وكيل المزاج (A1) ووكيل البلاغة (A2) ووكيل الجانب (A4) هم الأكثر أهمية: إزالة أي منهم سيكون لها تأثير سلبي بشكل عام على الأداء. وكيل المرجع (A5) أقل أهمية: تأثير إزالته غير مؤكد عبر مجموعات بيانات مختلفة. يبدو أن وكيل الاعتماد (A3) غير فعال: إزالة A3 ستزيد من تحسين الأداء. قد تشير عدم فعالية A3 إلى أن اعتبار هذا النوع من الأخطاء غير ضروري، أو يمكن أن يُعزى إلى تصميم غير فعال للمطالبة. في كلتا الحالتين، تشير الأداءات الملحوظة إلى أن الوكلاء المتنوعين لديهم تفاعلات غير خطية معقدة، ويمكن تحسين التصميم المقدم بشكل أكبر مع مزيد من الأدلة التجريبية.

4.3 دراسة حالة

| مجموعة بيانات النموذج | FPB | في كيو إيه | SEntFiN | متوسط | ||||

| حساب | فورمولا 1 | حساب | فورمولا 1 | حساب | فورمولا 1 | حساب | فورمولا 1 | |

| جي بي تي-3.5 (هاد) | 80.48 | 81.41 | 93.91 | 95.22 | ٧٧.٤٥ | ٧٦.٩٣ | – | – |

| جي بي تي-3.5 | -1.90 | -0.35 | -3.38 | -2.81 | -9.46 | -13.72 | – | – |

| بدون A1 | -0.71 | +0.64 | -0.01 | +0.02 | -0.58 | -0.61 | -0.43 | +0.02 |

| بدون A2 | -2.12 | -0.39 | +0.64 | +0.52 | -0.80 | -0.99 | -0.76 | -0.29 |

| بدون A3 | +3.00 | +3.56 | +0.51 | +0.42 | +0.01 | +0.03 | +1.17 | +1.34 |

| بدون A4 | +0.04 | +0.97 | +0.25 | +0.22 | -0.66 | -0.69 | -0.12 | +0.16 |

| بدون A5 | +4.32 | +4.29 | -0.01 | -0.00 | -0.52 | -0.43 | +1.26 | +1.28 |

الحالة 2 صعبة ويمكن بسهولة أن تُعتبر إيجابية من خلال التوجيه الساذج باستخدام عبارة رئيسية مثل “رفع … أعلى”. لفهم السياق بشكل صحيح، يجب أن يعرف المرء أن تايلور ويمبي وآشتياد هما شركتان في مجال بناء المنازل وتأجير معدات البناء. لذا، فإن “رفع الأسواق أعلى” قد يشير إلى المؤشر أو أسواق العقارات ويضع سيناريو اقتصادي. له تداعيات معقدة على الشركتين وليس مباشرًا مثل “انخفاض باركليز”. A1 و A4 و A5 صحيحة بشأن المشاعر المختلطة. مع كون حكم A3 محايدًا و A2 يتنبأ بالسلبية، تلخص الإطار في النهاية قطبية صحيحة على أنها سلبية.

الحالة 1: بيركشاير تسعى لزيادة حصتها في ويلز فارجو فوق 10٪ (إيجابية)

الحالة 2: افتتاح لندن: تايلور ويمبي وآشتيد يدفعان الأسواق للأعلى، باركليز ينخفض (سلبية)

الحالة 3: تهريب الذهب يشهد انخفاضًا مع تراجع الطلب عليه (سلبي)

الحالة 4: خطة العقارات لبورافانكارا ليست CIS: سيبي (سلبي)

الحالة 5: ويرلبول قد تصل إلى حوالي 450-475: ديفانغ فيساريا (محايد)

الحالة الأخيرة 5 تم التنبؤ بها بشكل خاطئ على أنها إيجابية من خلال التحفيز الساذج، ربما بسبب اللون الإيجابي الطفيف لعبارة “تصل إلى”. A1 و A2 حددوا بشكل صحيح عدم اليقين المرتبط بالمزاج غير الواقعي. A3 اكتشف نفس الإيجابية كما في التحفيز الساذج، بينما جميع الوكلاء الأربعة الآخرين يتنبؤون بأن الرسالة محايدة. مع العدد الغالب من التنبؤات المحايدة (

5 المناقشة، الاستنتاج، والعمل المستقبلي

تحتوي هذه الدراسة الأولية على بعض القيود، التي قد تلهم الأبحاث المستقبلية. القيد الأول هو قابلية التوسع. التنبؤ أو المناقشة مع وكلاء LLM أبطأ مقارنةً بالتحليل الإحصائي ويتطلب تكاليف. لهذا السبب، من الممكن وجود نظام كبير، أي مع المزيد من الوكلاء، لكنه غير مفضل أثناء التصميم والتقييم. القيد الثاني هو سرية مجموعات بيانات التقييم. StockSen و CMC و SEntFiN جديدة نسبيًا، لكن FPB و FiQA موجودتان منذ عدة سنوات. نظرًا لأن المواد التدريبية لـ LLMs عادةً ما تكون غير شفافة تمامًا وبعض LLMs تستمر في التحديث باستخدام التعلم المعزز وتعليقات البشر، لا يمكن استبعاد احتمال تعرض مجموعات بيانات التقييم لـ LLMs من قبل، مما يتسبب في تسرب بعض المعلومات. أخيرًا، تظهر دراسات الحالة أن أنواع الأخطاء المحددة يمكن حلها تقريبًا. لذلك، من المثير للاهتمام استكشاف أسباب الأخطاء الجديدة/المتبقية التي ارتكبتها LLMs وتقييم ما هي الأداءات على مستوى البشر/الخبراء على هذه المجموعات من بيانات FSA.

بعض التحديات الفريدة في FSA، مثل المراجع الخارجية للحقائق والمعرفة العالمية، كانت تُعتبر مستحيلة الحل في المستقبل القريب قبل ظهور نماذج بنية المحولات. مع الأمل في الذكاء العام الاصطناعي (AGI) على الأبواب، تعرض هذه الدراسة القدرات المتنوعة لـ LLM التي تكون مفيدة لـ FSA، وتدعو إلى مزيد من البحث في هذه المهمة المهمة.

References

[2] T. B. Brown, B. Mann, N. Ryder, M. Subbiah, J. Kaplan, P. Dhariwal, A. Neelakantan, P. Shyam, G. Sastry, A. Askell, S. Agarwal, A. Herbert-Voss, G. Krueger, T. Henighan, R. Child, A. Ramesh, D. M. Ziegler, J. Wu, C. Winter, C. Hesse, M. Chen, E. Sigler, M. Litwin, S. Gray, B. Chess, J. Clark, C. Berner, S. McCandlish, A. Radford, I. Sutskever, and D. Amodei. Language models are few-shot learners. In Proceedings of NeuIPS’20, pages 1877-1901, 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2005.14165

[3] S. Chen and F. Xing. Understanding emojis for financial sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of ICIS’23, pages 1-16, 2023. URL https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2023/socmedia_ digcollab/socmedia_digcollab/3/

[4] X. Chen, M. Lin, N. Schärli, and D. Zhou. Teaching large language models to self-debug, 2023. doi,10.48550/ARXIV.2304.05128.

[5] L. Chu, X.-Z. He, K. Li, and J. Tu. Investor sentiment and paradigm shifts in equity return forecasting. Management Science, 68(6):4301-4325, 2022. doi

[6] K. Cortis, A. Freitas, T. Daudert, M. Huerlimann, M. Zarrouk, S. Handschuh, and B. Davis. Semeval-2017 task 5: Fine-grained sentiment analysis on financial microblogs and news. In SemEval Workshop, 2017. doi 10.18653/v1/S17-2089

[7] D. de França Costa and N. F. F. da Silva. Inf-ufg at fiqa 2018 task 1: predicting sentiments and aspects on financial tweets and news headlines. In Companion Proceedings of the The Web Conference 2018, pages 1967-1971, 2018. doi

[8] J. Deng, M. Yang, M. Pelster, and Y. Tan. Social trading, communication, and networks. Information Systems Research, 2023. doi:10.1287/isre.2021.0143

[9] S. Deng, Z. J. Huang, A. P. Sinha, and H. Zhao. The interaction between microblog sentiment and stock returns: An empirical examination. MIS Quarterly, 42(3):895-918, 2018. doi

[10] X. Deng, V. Bashlovkina, F. Han, S. Baumgartner, and M. Bendersky. What do llms know about financial markets? a case study on reddit market sentiment analysis. In Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, 2023. doi

[11] W. Dong, S. Liao, and Z. Zhang. Leveraging financial social media data for corporate fraud detection. Journal of Management Information Systems, 35(2):461-487, 2018. doi, 10.1080/07421222.2018.1451954

[12] K. Du, F. Xing, and E. Cambria. Incorporating multiple knowledge sources for targeted aspectbased financial sentiment analysis. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems, 14(3):1-24, 2023. doi

[13] Y. Du, S. Li, A. Torralba, J. B. Tenenbaum, and I. Mordatch. Improving factuality and reasoning in language models through multiagent debate, 2023. doi 10.48550/ARXIV.2305.14325.

[14] H. Fei, B. Li, Q. Liu, L. Bing, F. Li, and T.-S. Chua. Reasoning implicit sentiment with chain-of-thought prompting. In Proceedings of ACL’23, pages 1171-1182, 2023. doi

[15] S. Gregor and A. R. Hevner. Positioning and presenting design science research for maximum impact. MIS Quarterly, 37(2):337-355, 2013. doi

[16] T. Hendershott, X. M. Zhang, J. L. Zhao, and Z. E. Zheng. Fintech as a game changer: Overview of research frontiers. Information Systems Research, 32(1):1-17, 2021. doi 10.1287/isre.2021.0997

[17] D. Hendrycks, C. Burns, S. Basart, A. Zou, M. Mazeika, D. Song, and J. Steinhardt. Measuring massive multitask language understanding. In Proceedings of ICLR’21, 2021. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2009.03300

[18] A. R. Hevner, S. T. March, J. Park, and S. Ram. Design science in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 28(1):75-105, 2004. doi.10.2307/25148625.

[19] H. Laurençon, L. Saulnier, T. Wang, C. Akiki, A. V. del Moral, T. L. Scao, L. von Werra, C. Mou, E. G. Ponferrada, H. Nguyen, J. Frohberg, M. Sasko, Q. Lhoest, A. McMillan-Major, G. Dupont, S. Biderman, A. Rogers, L. B. Allal, F. D. Toni, G. Pistilli, O. Nguyen, S. Nikpoor, M. Masoud, P. Colombo, J. de la Rosa, P. Villegas, T. Thrush, S. Longpre, S. Nagel, L. Weber, M. Muñoz, J. Zhu, D. van Strien, Z. Alyafeai, K. Almubarak, M. C. Vu, I. Gonzalez-Dios, A. Soroa, K. Lo, M. Dey, P. O. Suarez, A. Gokaslan, S. Bose, D. I. Adelani, L. Phan, H. Tran, I. Yu, S. Pai, J. Chim, V. Lepercq, S. Ilic, M. Mitchell, A. S. Luccioni, and Y. Jernite. The bigscience ROOTS corpus: A 1.6tb composite multilingual dataset. In Proceedings of NeurIPS’22, 2022. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2303.03915

[20] M. Lengkeek, F. van der Knaap, and F. Frasincar. Leveraging hierarchical language models for aspect-based sentiment analysis on financial data. Information Processing & Management, 60(5):103435, 2023. doi. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2023.103435.

[21] P. Liu, W. Yuan, J. Fu, Z. Jiang, H. Hayashi, and G. Neubig. Pre-train, prompt, and predict: A systematic survey of prompting methods in natural language processing. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(9):1-35, 2023. doi

[22] V. Liu and L. B. Chilton. Design guidelines for prompt engineering text-to-image generative models. In Proceedings of CHI ’22, 2022. doi:10.1145/3491102.3501825.

[23] Z. Liu, D. Huang, K. Huang, Z. Li, and J. Zhao. Finbert: A pre-trained financial language representation model for financial text mining. In Proceedings of IJCAI’20, pages 4513-4519, 2020. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2020/622.

[24] T. Loughran and B. McDonald. When is a liability not a liability? textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-ks. Journal of Finance, 66(1):35-65, 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01625.x.

[25] M. Maia, S. Handschuh, A. Freitas, B. Davis, R. McDermott, M. Zarrouk, and A. Balahur. WWW’18 open challenge: financial opinion mining and question answering. In Proceedings of WWW’18, pages 1941-1942, 2018. doi

[26] P. Malo, A. Sinha, P. Korhonen, J. Wallenius, and P. Takala. Good debt or bad debt: Detecting semantic orientations in economic texts. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(4):782-796, 2014. doi.10.1002/asi.23062

[27] M. Minsky. The Emotion Machine: Commonsense Thinking, Artificial Intelligence, and the Future of the Human Mind. Simon & Schuster, 2006.

[28] N. Muennighoff, T. Wang, L. Sutawika, A. Roberts, S. Biderman, T. Le Scao, M. S. Bari, S. Shen, Z. X. Yong, H. Schoelkopf, X. Tang, D. Radev, A. F. Aji, K. Almubarak, S. Albanie, Z. Alyafeai, A. Webson, E. Raff, and C. Raffel. Crosslingual generalization through multitask finetuning. In Proceedings of ACL’23, pages 15991-16111, 2023. doi.

[29] H. Nori, Y. T. Lee, S. Zhang, D. Carignan, R. Edgar, N. Fusi, N. King, J. Larson, Y. Li, W. Liu, R. Luo, S. M. McKinney, R. O. Ness, H. Poon, T. Qin, N. Usuyama, C. White, and E. Horvitz. Can generalist foundation models outcompete special-purpose tuning? case study in medicine, 2023. doi,10.48550/ARXIV.2311.16452

[30] R. L. Peterson. Trading on Sentiment: The Power of Minds Over Markets. Wiley, 2016. doi:10.1002/9781119219149

[31] S. Samtani, H. Zhu, B. Padmanabhan, Y. Chai, H. Chen, and J. F. Nunamaker. Deep learning for information systems research. Journal of Management Information Systems, 40(1):271-301, 2023. doi,10.1080/07421222.2023.2172772.

[32] R. Shah, K. Chawla, D. Eidnani, A. Shah, W. Du, S. Chava, N. Raman, C. Smiley, J. Chen, and D. Yang. When FLUE meets FLANG: Benchmarks and large pretrained language model for financial domain. In Proceedings of EMNLP’22, 2022. doi 10.18653/v1/2022.emnlp-main. 148.

[33] A. Sinha, S. Kedas, R. Kumar, and P. Malo. SEntFiN 1.0: Entity-aware sentiment analysis for financial news. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 73(9):1314-1335, 2022. doi 10.1002/asi.24634.

[34] T. Sorensen, J. Robinson, C. Rytting, A. Shaw, K. Rogers, A. Delorey, M. Khalil, N. Fulda, and D. Wingate. An information-theoretic approach to prompt engineering without ground truth labels. In Proceedings of ACL’22, 2022. doi.

[35] X. Sun, X. Li, S. Zhang, S. Wang, F. Wu, J. Li, T. Zhang, and G. Wang. Sentiment analysis through 1 lm negotiations, 2023. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2311.01876

[36] S. Wu, O. Irsoy, S. Lu, V. Dabravolski, M. Dredze, S. Gehrmann, P. Kambadur, D. Rosenberg, and G. Mann. Bloomberggpt: A large language model for finance, 2023. doi,10.48550/ARXIV.2303.17564.

[37] F. Xing, E. Cambria, and R. Welsch. Intelligent asset allocation via market sentiment views. IEEE Computational Intelligence Magazine, 13(4):25-34, 2018. doi

[38] F. Xing, E. Cambria, and Y. Zhang. Sentiment-aware volatility forecasting. Knowledge Based Systems, 176:68-76, 2019. doi. 10.1016/j.knosys.2019.03.029.

[39] F. Xing, L. Malandri, Y. Zhang, and E. Cambria. Financial sentiment analysis: An investigation into common mistakes and silver bullets. In Proceedings of COLING’20, pages 978-987, 2020. doi: 10.18653/v1/2020.coling-main.85.

[40] F. Xing, F. Pallucchini, and E. Cambria. Cognitive-inspired domain adaptation of sentiment lexicons. Information Processing & Management, 56(3):554-564, 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jpm.2018.11.002

[41] Y. Yang, Y. Qin, Y. Fan, and Z. Zhang. Unlocking the power of voice for financial risk prediction: A theory-driven deep learning design approach. MIS Quarterly, 47(1):63-96, 2023. doi

[42] S. Yao, D. Yu, J. Zhao, I. Shafran, T. Griffiths, Y. Cao, and K. Narasimhan. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. In Proceedings of NeuIPS’23, pages 1-14, 2023.

[43] F. Yu, L. Quartey, and F. Schilder. Exploring the effectiveness of prompt engineering for legal reasoning tasks. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023. doi:

[44] B. Zhang, H. Yang, T. Zhou, M. Ali Babar, and X.-Y. Liu. Enhancing financial sentiment analysis via retrieval augmented large language models. In Proceedings of ICAIF’23, 2023. doi:10.1145/3604237.3626866

[45] W. Zhang, Y. Deng, B. Liu, S. J. Pan, and L. Bing. Sentiment analysis in the era of large language models: A reality check, 2023. doi 10.48550/ARXIV.2305.15005.

[46] D. Zimbra, A. Abbasi, D. Zeng, and H. Chen. The state-of-the-art in twitter sentiment analysis: A review and benchmark evaluation. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems, 9(2):5:1-5:29, 2018. doi

There is no strict definition of “how large” a language model has to be to qualify for the name of LLM. It seems that LLMs are usually far larger than the word2vec models (around 1 million parameters). This definition includes BERT (110-340 M parameters), GPT-3 (around 175 B parameters), and more. Now has been re-branded as ” X “.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3688399

Publication Date: 2024-08-13

Designing Heterogeneous LLM Agents for Financial Sentiment Analysis

Abstract

Large language models (LLMs) have drastically changed the possible ways to design intelligent systems, shifting the focuses from massive data acquisition and new modeling training to human alignment and strategical elicitation of the full potential of existing pre-trained models. This paradigm shift, however, is not fully realized in financial sentiment analysis (FSA), due to the discriminative nature of this task and a lack of prescriptive knowledge of how to leverage generative models in such a context. This study investigates the effectiveness of the new paradigm, i.e., using LLMs without fine-tuning for FSA. Rooted in Minsky’s theory of mind and emotions, a design framework with heterogeneous LLM agents is proposed. The framework instantiates specialized agents using prior domain knowledge of the types of FSA errors and reasons on the aggregated agent discussions. Comprehensive evaluation on FSA datasets show that the framework yields better accuracies, especially when the discussions are substantial. This study contributes to the design foundations and paves new avenues for LLMs-based FSA. Implications on business and management are also discussed.

1 Introduction

The majority of FSA systems were developed in the past decade and their architecture and design ideas have gone through several iterations along with the advances in natural language processing. Early systems rely on sentiment word dictionaries and simple rules or statistics to derive sentencelevel or message-level polarities. Efforts were made to discover words/phrases specific to the finance domain [24, 40]. A great amount of learning-based systems were later developed. Specifically, two benchmark tasks (SemEval 2017 Task 5 [6] and FiQA 2018 Task 1 [7]) were conducted, and the

best results were achieved by regression ensemble (RE), convolutional neural network (CNN), and support vector regression (SVR) models based on combined features of sentiment lexica and dense word representations. The following wave of designs were based on fine-tuning general-purpose pretrained language models, e.g., BERT

Different from many ad hoc designs developed from chain of thought (CoT) [10], tree of thoughts (ToT) [42], verification, self-consistency constraints, intermediate scratchpads, and multi-agent multirole settings, the design framework presented here follows the design science guidelines by Hevner et al. [18] and contributes to the prescriptive knowledge as a “design theory” [15]. Based on Minsky’s theory of mind and emotions, “emotional states” are our Ways to Think with a specific collection of resources turned on and others turned off given certain environment conditions [27]. Therefore, one FSA approach is to simulate the mental processes underlying the texts, requiring specialized LLM agents to play the roles of “resources”, i.e., functional parts of our brain that make us react to the environment. In the context of financial analysis, many resources are learned as professional knowledge and not innate parts of our brains. The design framework (Heterogeneous multi-Agent Discussion) chooses to develop specialized LLM agents by prompting, and the main function is to pay attention to a type of error that LLMs are prone to make for the given FSA task. The design artifact thus has five different agents and the FSA result is based on a shared discussion considering output from all the agents. I evaluate the artifact using multiple methods, and the results generally conclude the framework to be effective.

- RQ1: How effective is HAD compared to naive prompting and to the fine-tuning paradigm?

- RQ2: How to prompt LLM agents to behave heterogeneously for sentiment analysis in finance?

- RQ3: What are the quantitative contributions of each LLM agent and their relative importance?

This study contributes to the design science literature by presenting a kernel theory-informed design artifact. A number of kernel theories from the natural or social sciences were introduced to information system design, whereas kernel theories from AI are comparatively rare. This study has implications for the emotion theory, LLM collaboration research, and financial decision-making practices. Firstly, it supports the society of mind and emotion machines [27] to be actionable theories that explain how emotions emerge as an important type of human intelligence; Secondly, this study applies multi-agent LLMs in FSA. This framework has been used for factuality checking, arithmetic/mathematical reasoning, optimization, general-purpose sentiment analysis, but not yet on FSA to the best of my knowledge. This study thus provides new materials for LLM collaboration, and also reinforces the design science-based approach to framework development; Lastly, the findings contribute to the prescriptive knowledge of FSA system design. Investors and traders may iterate and improve their own FSA systems based on the HAD framework or be more informed when they decide to select or purchase technical solutions of a similar kind.

2 Related Work and Design Process

2.1 Using LLMs for Financial Sentiment Analysis

results, though this information is rarely available in real-world production environments. Zhang et al. [44] observed that financial news is often overly succinct. A model that retrieves additional context from reliable external sources to form a more detailed instruction is consequently developed. Deng et al. [10] found that forcing the LLM through several reasoning paths with CoT helps generate more stable and accurate labels. The LLM generated labels are also useful and meet the quality for complementing human annotations for conventional supervised learning methods. Similarly, Fei et al. [14] developed a three-hop reasoning framework inspired by CoT that infers firstly the implicit aspect, secondly the implicit opinion, and finally the sentiment polarity. However, it has been pointed out [35] that a singular LLM has difficulties in fully exploiting the potential of LLM knowledge. This is especially true for FSA as it involves multiple LLM capabilities, such as reasoning, fact-checking, syntactic/semantic parsing, and more. I observe a similar phenomenon as reported in [45] that LLM performances on more complicated tasks are not as satisfactory as on the binary classification task. Moreover, the aforementioned designs (storage retrieval and CoT ) and more designs that are not yet applied to FSA, such as verification, self-consistency constraints, or intermediate scratchpads, are also largely heuristic, at most based on experiences, and lack solid theoretical foundation.

The proposed framework adopts in-context learning (ICL) and leverages multiple LLM instantiations (agents), which is also referred to as LLM collaboration. Strategies of collaboration include auxiliary tasks (e.g., verification) [4], debate [13], and various role-assignment [35] including generator, discriminator, programmer, manager, meta-controller, etc. Again, the design of auxiliary tasks and roles appears arbitrary and lacks solid theoretical foundations. LLM collaboration is also more investigated on many general natural language processing tasks including sentiment analysis, but their applicability on FSA lacks direct evidence. Perhaps most related to the proposed HAD design framework is MedPrompt [29]. It uses an ensemble of randomly shuffled CoT from homogeneous agents. The design is also more computationally heavy and difficult to transfer to the finance domain as existing financial question-answering datasets are more sparse.

2.2 Prompt Engineering

In terms of automatically searching for the prompt template, stochastic optimization-based methods are discussed. Sorensen et al. [34], for example, discovered that a good template is the one that maximizes the mutual information between input and the generated output.

In terms of designing prompts, Liu and Chilton [22] studied text-to-image generative models and the prompt template “SUBJECT in the style of STYLE”. They found the clarity and salience of keywords are important to the generation quality. Yu et al. [43] presented the idea of using domain knowledge to guide prompt design. It was reported that for the legal information entailment task, the best results are obtained when prompts are derived from specific legal reasoning techniques, such as Issue-Rule-Application-Conclusion (IRAC) as taught at law schools. For FSA, however, the design guidelines are unclear and most studies used naive prompts. For example, Chen and Xing [3] used “You are a helpful sentiment analysis assistant – [example message]:[sentiment]. User: [test message].” and BloombergGPT’s FSA template [36] is simply “[test message] Question: what is the sentiment? Answer with negative/neutral/positive”.

2.3 Kernel Theory: Emotions and the Society of Mind

Society of mind is a reductionistic perspective of human intelligence that influenced AI greatly and argues no function directly produces intelligence. Instead, intelligence comes from the managed interaction of a variety of resourceful but simpler and non-intelligent agents. For example, when drinking a cup of tea, there activates a motor agent that grasps the cup, a balancer that keeps the tea from spreading, and a temperature sensor that confirms our throat will not be hurt. This theory sees emotional states as patterns of activation. For example, the state we call “angry” could be what happens when a cloud of resources that help you react with unusual speed and strength are activated – while some other resources that make you act prudently are suppressed (Fig. 2).

2.4 Meta-requirements, Meta-designs, and Hypotheses

| Kernel theory |

|

|||

| Meta-requirements |

|

|||

| Meta-designs |

|

|||

| Testable hypotheses |

|

- Define heterogeneous agents and their prompt templates

. - Obtain intermediary analysis

(User_Message) - Obtain summative analysis Result

User_Message,

To assess whether the proposed framework is effective, two testable hypotheses are developed. If types of error are useful for guiding agent design, we would expect the performance metrics to improve (H1). Because of the noted data imbalance issue in FSA, F-1 score should also be investigated on top of accuracy. Another observation is that the occurrences of each type of error are not equal and vary across different language domains [46, 39]. It is thus hypothesized that the agents will have different importance but all contribute positively to the FSA task (H2).

3 Design Artifact: Heterogeneous Agent Discussion (HAD)

With this background, five agents are designed based on [39] because (1) these categories are more directly FSA relevant and (2) these categories are less in number (6 compared to 13) and more operational. Since LLMs are observed to be robust to unrecognized words and spellings from the web, no special agent is designed according to this error. The five agents and their characteristic prompts are:

- A1 (the mood agent): Please pay special attention to any irrealis mood used.

- A2 (the rhetoric agent): Please pay special attention to any rhetorics (sarcasm, negative assertion, etc.) used.

- A3 (the dependency agent): Please focus on the speaker sentiment, not a third party.

- A4 (the aspect agent): Please focus on the stock ticker/tag/topic, not other entities.

- A5 (the reference agent): Please pay special attention to the time expressions, prices, and other unsaid facts.

4 Evaluation

4.1 Performance Improvement

The first observation is the different behaviors of GPT-3.5 and BLOOMZ as base models. GPT-3.5 was trained mainly on the Common Crawl corpus [2], which archives the web. BLOOMZ was trained on an even larger Open-science Open-collaboration Text Sources corpus [19], which is mainly crowd-sourced scientific datasets. The five testing datasets are all from the web: this may be closer to GPT-3.5’s trained language domain. It is observed that GPT-3.5 is better instruction-tuned with its proprietary human feedback. In contrast, BLOOMZ inclines to the language completion task. An example is that the prompt “Translate to English: Je t’aime” without a full stop (.) at the end may result in the model trying to continue the French sentence instead of translating it. BLOOMZ inclines to complete/answer with concise language. For the sentiment-related open-ended questions to heterogeneous agents, BLOOMZ often answers a final judgment of positive/negative without much justification, and is not good at predicting “neutral” messages. For the afore-discussed factors,

| Dataset | FPB | StockSen | CMC | FiQA | SEntFiN |

| Positive | 570 | 4542 | 12022 | 507 | 2832 |

| Negative | 303 | 1676 | 1523 | 264 | 2373 |

| Neutral | 1391 | – | – | – | 2701 |

| Total Size | 2264 | 6218 | 13545 | 771 | 7906 |

| ModellDataset | FPB | StockSen | CMC | FiQA | SEntFiN | |||||

| Acc. | F-1 | Acc. | F-1 | Acc. | F-1 | Acc. | F-1 | Acc. | F-1 | |

| (Fin-)BERT | 91.69 | 89.70 | 76.90 | 84.50 | 93.50 | – | – | – | 94.29 | 93.27 |

| BloombergGPT | – | 51.07 | – | – | – | – | – | 75.07 | – | – |

| GPT-3.5 | 78.58 | 81.06 | 67.64 | 73.93 | 85.31 | 91.05 | 90.53 | 92.41 | 67.99 | 63.21 |

| GPT-3.5 (HAD) | 80.48 | 81.41 | 70.44 | 76.55 | 87.55 | 92.50 | 93.91 | 95.22 | 77.45 | 76.93 |

| BLOOMZ | 34.63 | 32.90 | 63.65 | 72.47 | 87.16 | 92.62 | 78.33 | 83.64 | 51.32 | 41.87 |

| BLOOMZ (HAD) | 34.19 | 32.93 | 72.80 | 83.97 | 87.67 | 92.95 | 76.78 | 83.03 | 50.16 | 40.69 |

4.2 Ablation Analysis

It is observed that the mood agent (A1), the rhetoric agent (A2), and the aspect agent (A4) are the most important: removing any of them will generally have a negative impact on the performance. The reference agent (A5) is less important: the effect of removing it is uncertain across different datasets. The dependency agent (A3) seems ineffective: removing A3 will further improve the performance. The ineffectiveness of A3 may suggest considering this error type is unnecessary, or be attributed to an ineffective prompt design. Either way, the observed performances suggest that heterogeneous agents have complicated non-linear interactions, and the presented design can be further optimized with more empirical evidence.

4.3 Case Study

| ModellDataset | FPB | FiQA | SEntFiN | Average | ||||

| Acc. | F-1 | Acc. | F-1 | Acc. | F-1 | Acc. | F-1 | |

| GPT-3.5 (HAD) | 80.48 | 81.41 | 93.91 | 95.22 | 77.45 | 76.93 | – | – |

| GPT-3.5 | -1.90 | -0.35 | -3.38 | -2.81 | -9.46 | -13.72 | – | – |

| w/o A1 | -0.71 | +0.64 | -0.01 | +0.02 | -0.58 | -0.61 | -0.43 | +0.02 |

| w/o A2 | -2.12 | -0.39 | +0.64 | +0.52 | -0.80 | -0.99 | -0.76 | -0.29 |

| w/o A3 | +3.00 | +3.56 | +0.51 | +0.42 | +0.01 | +0.03 | +1.17 | +1.34 |

| w/o A4 | +0.04 | +0.97 | +0.25 | +0.22 | -0.66 | -0.69 | -0.12 | +0.16 |

| w/o A5 | +4.32 | +4.29 | -0.01 | -0.00 | -0.52 | -0.43 | +1.26 | +1.28 |

Case 2 is challenging and can easily be mistaken as positive by naive prompting with key-phrase such as “drive … higher” spotted. To correctly understand the context, one has to know that Taylor Wimpey and Ashtead are home construction and construction equipment rental companies. So “driving the markets higher” may refer to the index or property markets and is setting an economic scenario. It has complicated implications for the two companies and is not as direct as “Barclays falls”. A1, A4, A5 are correct about the mixed sentiment. With A3’s judgment being neutral and A2 predicting negative, the framework finally summarizes a correct polarity as negative.

Case 1: Berkshire applies to boost Wells Fargo stake above 10 pct (positive)

Case 2: London open: Taylor Wimpey and Ashtead drive markets higher, Barclays falls (negative)

Case 3: Smuggling of gold sees a decline as its demand softens (negative)

Case 4: Puravankara’s real estate scheme not a CIS: Sebi (negative)

Case 5: Whirlpool may head to around 450-475: Devang Visaria (neutral)

The last Case 5 was wrongly predicted as positive by naive prompting, probably due to the slight positive color of phrasing “head to”. A1 and A2 correctly identified the uncertainty associated with irrealis mood. A3 detected the same positivity as naive prompting, while the other four agents all predict the message as neutral. With the dominant number of neutral predictions (

5 Discussion, Conclusion, and Future Work

This preliminary study has a few limitations, which may inspire future research. The first limitation is scalability. Predicting or Discussion with LLM agents is slower compared to statistical analysis and incurs costs. For this reason, a large system, i.e., with more agents, is possible, but not preferred during design and evaluation. The second limitation is the confidentiality of evaluation datasets. StockSen, CMC, and SEntFiN are relatively new, but FPB and FiQA have been there for quite a few years. Because the training material for LLMs is usually not fully transparent and some LLMs keep updating using reinforcement learning and human feedback, the possibility that the evaluation datasets have been exposed to the LLMs before, causing some information leaks can not be excluded. Finally, the case studies show that the identified error types can almost be solved. It is therefore interesting to explore what are the reasons for the new/remaining errors made by LLMs and assess what are the human/expert-level performances on these FSA datasets.

Some of the unique challenges in FSA, e.g., external references to facts and world knowledge, were thought to be impossible to solve in the short-term future before the transformer architecture models came into existence. With the hope of artificial general intelligence (AGI) around the corner, this study exhibits the versatile capabilities of LLM that are useful for FSA, and calls for more research on this important task.

References

[2] T. B. Brown, B. Mann, N. Ryder, M. Subbiah, J. Kaplan, P. Dhariwal, A. Neelakantan, P. Shyam, G. Sastry, A. Askell, S. Agarwal, A. Herbert-Voss, G. Krueger, T. Henighan, R. Child, A. Ramesh, D. M. Ziegler, J. Wu, C. Winter, C. Hesse, M. Chen, E. Sigler, M. Litwin, S. Gray, B. Chess, J. Clark, C. Berner, S. McCandlish, A. Radford, I. Sutskever, and D. Amodei. Language models are few-shot learners. In Proceedings of NeuIPS’20, pages 1877-1901, 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2005.14165

[3] S. Chen and F. Xing. Understanding emojis for financial sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of ICIS’23, pages 1-16, 2023. URL https://aisel.aisnet.org/icis2023/socmedia_ digcollab/socmedia_digcollab/3/

[4] X. Chen, M. Lin, N. Schärli, and D. Zhou. Teaching large language models to self-debug, 2023. doi,10.48550/ARXIV.2304.05128.

[5] L. Chu, X.-Z. He, K. Li, and J. Tu. Investor sentiment and paradigm shifts in equity return forecasting. Management Science, 68(6):4301-4325, 2022. doi

[6] K. Cortis, A. Freitas, T. Daudert, M. Huerlimann, M. Zarrouk, S. Handschuh, and B. Davis. Semeval-2017 task 5: Fine-grained sentiment analysis on financial microblogs and news. In SemEval Workshop, 2017. doi 10.18653/v1/S17-2089

[7] D. de França Costa and N. F. F. da Silva. Inf-ufg at fiqa 2018 task 1: predicting sentiments and aspects on financial tweets and news headlines. In Companion Proceedings of the The Web Conference 2018, pages 1967-1971, 2018. doi

[8] J. Deng, M. Yang, M. Pelster, and Y. Tan. Social trading, communication, and networks. Information Systems Research, 2023. doi:10.1287/isre.2021.0143

[9] S. Deng, Z. J. Huang, A. P. Sinha, and H. Zhao. The interaction between microblog sentiment and stock returns: An empirical examination. MIS Quarterly, 42(3):895-918, 2018. doi

[10] X. Deng, V. Bashlovkina, F. Han, S. Baumgartner, and M. Bendersky. What do llms know about financial markets? a case study on reddit market sentiment analysis. In Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, 2023. doi

[11] W. Dong, S. Liao, and Z. Zhang. Leveraging financial social media data for corporate fraud detection. Journal of Management Information Systems, 35(2):461-487, 2018. doi, 10.1080/07421222.2018.1451954

[12] K. Du, F. Xing, and E. Cambria. Incorporating multiple knowledge sources for targeted aspectbased financial sentiment analysis. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems, 14(3):1-24, 2023. doi

[13] Y. Du, S. Li, A. Torralba, J. B. Tenenbaum, and I. Mordatch. Improving factuality and reasoning in language models through multiagent debate, 2023. doi 10.48550/ARXIV.2305.14325.

[14] H. Fei, B. Li, Q. Liu, L. Bing, F. Li, and T.-S. Chua. Reasoning implicit sentiment with chain-of-thought prompting. In Proceedings of ACL’23, pages 1171-1182, 2023. doi

[15] S. Gregor and A. R. Hevner. Positioning and presenting design science research for maximum impact. MIS Quarterly, 37(2):337-355, 2013. doi

[16] T. Hendershott, X. M. Zhang, J. L. Zhao, and Z. E. Zheng. Fintech as a game changer: Overview of research frontiers. Information Systems Research, 32(1):1-17, 2021. doi 10.1287/isre.2021.0997

[17] D. Hendrycks, C. Burns, S. Basart, A. Zou, M. Mazeika, D. Song, and J. Steinhardt. Measuring massive multitask language understanding. In Proceedings of ICLR’21, 2021. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2009.03300

[18] A. R. Hevner, S. T. March, J. Park, and S. Ram. Design science in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 28(1):75-105, 2004. doi.10.2307/25148625.

[19] H. Laurençon, L. Saulnier, T. Wang, C. Akiki, A. V. del Moral, T. L. Scao, L. von Werra, C. Mou, E. G. Ponferrada, H. Nguyen, J. Frohberg, M. Sasko, Q. Lhoest, A. McMillan-Major, G. Dupont, S. Biderman, A. Rogers, L. B. Allal, F. D. Toni, G. Pistilli, O. Nguyen, S. Nikpoor, M. Masoud, P. Colombo, J. de la Rosa, P. Villegas, T. Thrush, S. Longpre, S. Nagel, L. Weber, M. Muñoz, J. Zhu, D. van Strien, Z. Alyafeai, K. Almubarak, M. C. Vu, I. Gonzalez-Dios, A. Soroa, K. Lo, M. Dey, P. O. Suarez, A. Gokaslan, S. Bose, D. I. Adelani, L. Phan, H. Tran, I. Yu, S. Pai, J. Chim, V. Lepercq, S. Ilic, M. Mitchell, A. S. Luccioni, and Y. Jernite. The bigscience ROOTS corpus: A 1.6tb composite multilingual dataset. In Proceedings of NeurIPS’22, 2022. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2303.03915

[20] M. Lengkeek, F. van der Knaap, and F. Frasincar. Leveraging hierarchical language models for aspect-based sentiment analysis on financial data. Information Processing & Management, 60(5):103435, 2023. doi. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2023.103435.

[21] P. Liu, W. Yuan, J. Fu, Z. Jiang, H. Hayashi, and G. Neubig. Pre-train, prompt, and predict: A systematic survey of prompting methods in natural language processing. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(9):1-35, 2023. doi

[22] V. Liu and L. B. Chilton. Design guidelines for prompt engineering text-to-image generative models. In Proceedings of CHI ’22, 2022. doi:10.1145/3491102.3501825.

[23] Z. Liu, D. Huang, K. Huang, Z. Li, and J. Zhao. Finbert: A pre-trained financial language representation model for financial text mining. In Proceedings of IJCAI’20, pages 4513-4519, 2020. doi:10.24963/ijcai.2020/622.

[24] T. Loughran and B. McDonald. When is a liability not a liability? textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-ks. Journal of Finance, 66(1):35-65, 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01625.x.

[25] M. Maia, S. Handschuh, A. Freitas, B. Davis, R. McDermott, M. Zarrouk, and A. Balahur. WWW’18 open challenge: financial opinion mining and question answering. In Proceedings of WWW’18, pages 1941-1942, 2018. doi

[26] P. Malo, A. Sinha, P. Korhonen, J. Wallenius, and P. Takala. Good debt or bad debt: Detecting semantic orientations in economic texts. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(4):782-796, 2014. doi.10.1002/asi.23062

[27] M. Minsky. The Emotion Machine: Commonsense Thinking, Artificial Intelligence, and the Future of the Human Mind. Simon & Schuster, 2006.

[28] N. Muennighoff, T. Wang, L. Sutawika, A. Roberts, S. Biderman, T. Le Scao, M. S. Bari, S. Shen, Z. X. Yong, H. Schoelkopf, X. Tang, D. Radev, A. F. Aji, K. Almubarak, S. Albanie, Z. Alyafeai, A. Webson, E. Raff, and C. Raffel. Crosslingual generalization through multitask finetuning. In Proceedings of ACL’23, pages 15991-16111, 2023. doi.

[29] H. Nori, Y. T. Lee, S. Zhang, D. Carignan, R. Edgar, N. Fusi, N. King, J. Larson, Y. Li, W. Liu, R. Luo, S. M. McKinney, R. O. Ness, H. Poon, T. Qin, N. Usuyama, C. White, and E. Horvitz. Can generalist foundation models outcompete special-purpose tuning? case study in medicine, 2023. doi,10.48550/ARXIV.2311.16452

[30] R. L. Peterson. Trading on Sentiment: The Power of Minds Over Markets. Wiley, 2016. doi:10.1002/9781119219149

[31] S. Samtani, H. Zhu, B. Padmanabhan, Y. Chai, H. Chen, and J. F. Nunamaker. Deep learning for information systems research. Journal of Management Information Systems, 40(1):271-301, 2023. doi,10.1080/07421222.2023.2172772.

[32] R. Shah, K. Chawla, D. Eidnani, A. Shah, W. Du, S. Chava, N. Raman, C. Smiley, J. Chen, and D. Yang. When FLUE meets FLANG: Benchmarks and large pretrained language model for financial domain. In Proceedings of EMNLP’22, 2022. doi 10.18653/v1/2022.emnlp-main. 148.

[33] A. Sinha, S. Kedas, R. Kumar, and P. Malo. SEntFiN 1.0: Entity-aware sentiment analysis for financial news. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 73(9):1314-1335, 2022. doi 10.1002/asi.24634.

[34] T. Sorensen, J. Robinson, C. Rytting, A. Shaw, K. Rogers, A. Delorey, M. Khalil, N. Fulda, and D. Wingate. An information-theoretic approach to prompt engineering without ground truth labels. In Proceedings of ACL’22, 2022. doi.

[35] X. Sun, X. Li, S. Zhang, S. Wang, F. Wu, J. Li, T. Zhang, and G. Wang. Sentiment analysis through 1 lm negotiations, 2023. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2311.01876

[36] S. Wu, O. Irsoy, S. Lu, V. Dabravolski, M. Dredze, S. Gehrmann, P. Kambadur, D. Rosenberg, and G. Mann. Bloomberggpt: A large language model for finance, 2023. doi,10.48550/ARXIV.2303.17564.

[37] F. Xing, E. Cambria, and R. Welsch. Intelligent asset allocation via market sentiment views. IEEE Computational Intelligence Magazine, 13(4):25-34, 2018. doi

[38] F. Xing, E. Cambria, and Y. Zhang. Sentiment-aware volatility forecasting. Knowledge Based Systems, 176:68-76, 2019. doi. 10.1016/j.knosys.2019.03.029.

[39] F. Xing, L. Malandri, Y. Zhang, and E. Cambria. Financial sentiment analysis: An investigation into common mistakes and silver bullets. In Proceedings of COLING’20, pages 978-987, 2020. doi: 10.18653/v1/2020.coling-main.85.

[40] F. Xing, F. Pallucchini, and E. Cambria. Cognitive-inspired domain adaptation of sentiment lexicons. Information Processing & Management, 56(3):554-564, 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jpm.2018.11.002

[41] Y. Yang, Y. Qin, Y. Fan, and Z. Zhang. Unlocking the power of voice for financial risk prediction: A theory-driven deep learning design approach. MIS Quarterly, 47(1):63-96, 2023. doi

[42] S. Yao, D. Yu, J. Zhao, I. Shafran, T. Griffiths, Y. Cao, and K. Narasimhan. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models. In Proceedings of NeuIPS’23, pages 1-14, 2023.

[43] F. Yu, L. Quartey, and F. Schilder. Exploring the effectiveness of prompt engineering for legal reasoning tasks. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2023. doi:

[44] B. Zhang, H. Yang, T. Zhou, M. Ali Babar, and X.-Y. Liu. Enhancing financial sentiment analysis via retrieval augmented large language models. In Proceedings of ICAIF’23, 2023. doi:10.1145/3604237.3626866

[45] W. Zhang, Y. Deng, B. Liu, S. J. Pan, and L. Bing. Sentiment analysis in the era of large language models: A reality check, 2023. doi 10.48550/ARXIV.2305.15005.

[46] D. Zimbra, A. Abbasi, D. Zeng, and H. Chen. The state-of-the-art in twitter sentiment analysis: A review and benchmark evaluation. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems, 9(2):5:1-5:29, 2018. doi

There is no strict definition of “how large” a language model has to be to qualify for the name of LLM. It seems that LLMs are usually far larger than the word2vec models (around 1 million parameters). This definition includes BERT (110-340 M parameters), GPT-3 (around 175 B parameters), and more. Now has been re-branded as ” X “.