DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.109115

تاريخ النشر: 2024-06-27

تطبيق التعلم العميق في التعرف على سلوك الماشية: مراجعة منهجية للأدبيات

معلومات المقال

الكلمات المفتاحية:

التعلم العميق (DL)

الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI)

التعرف على السلوك

الزراعة الدقيقة للماشية

الملخص

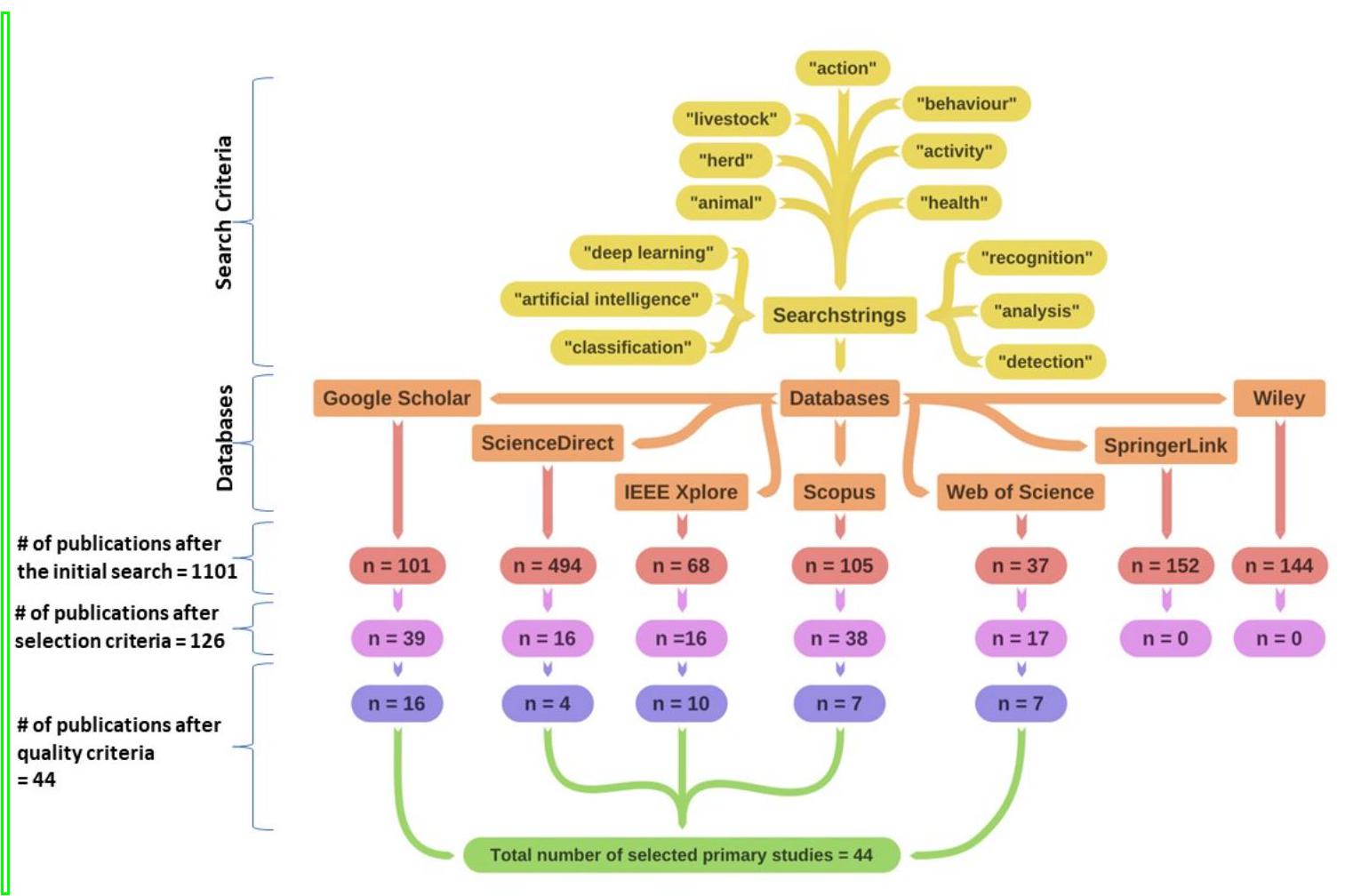

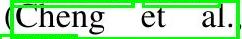

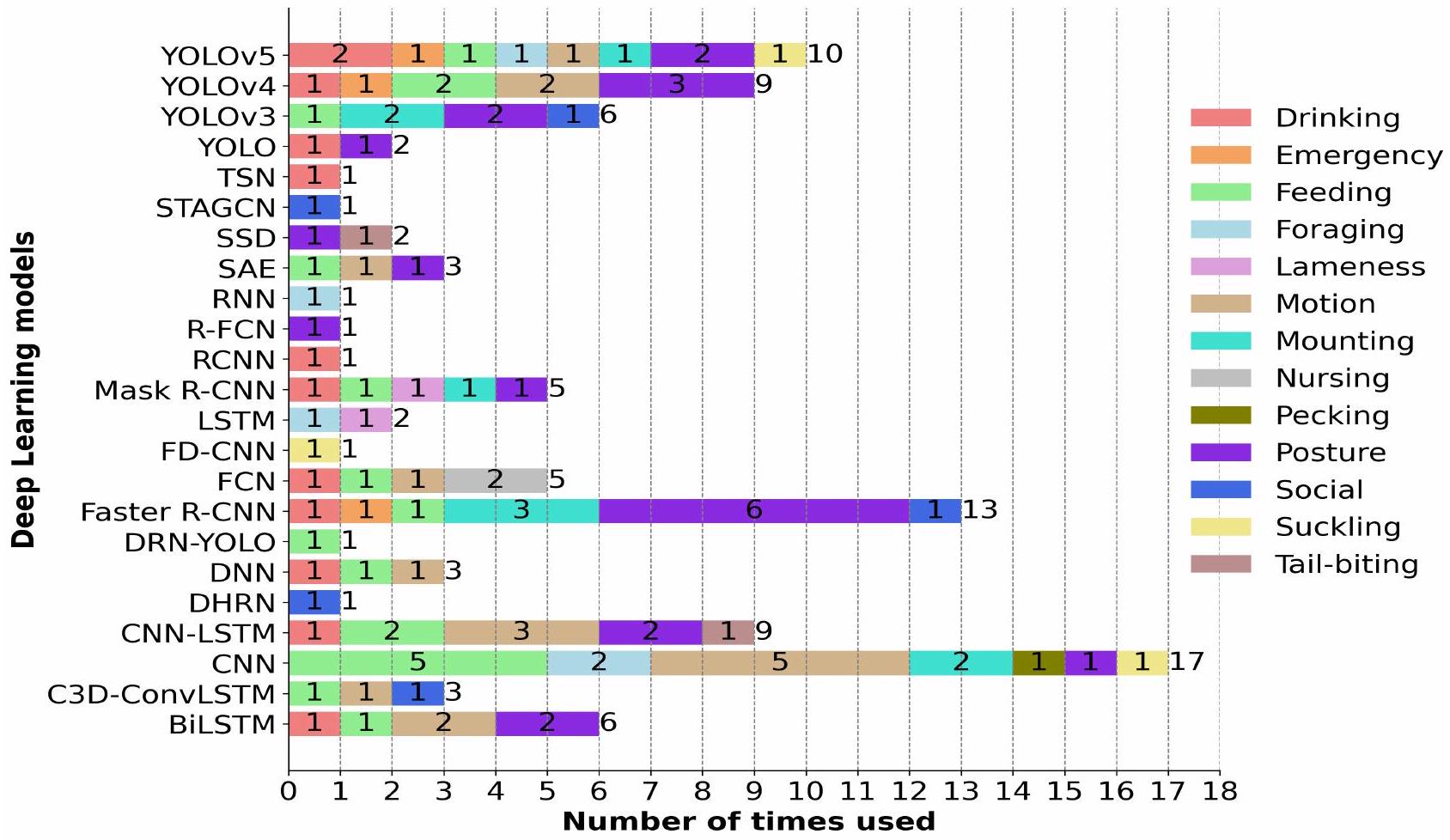

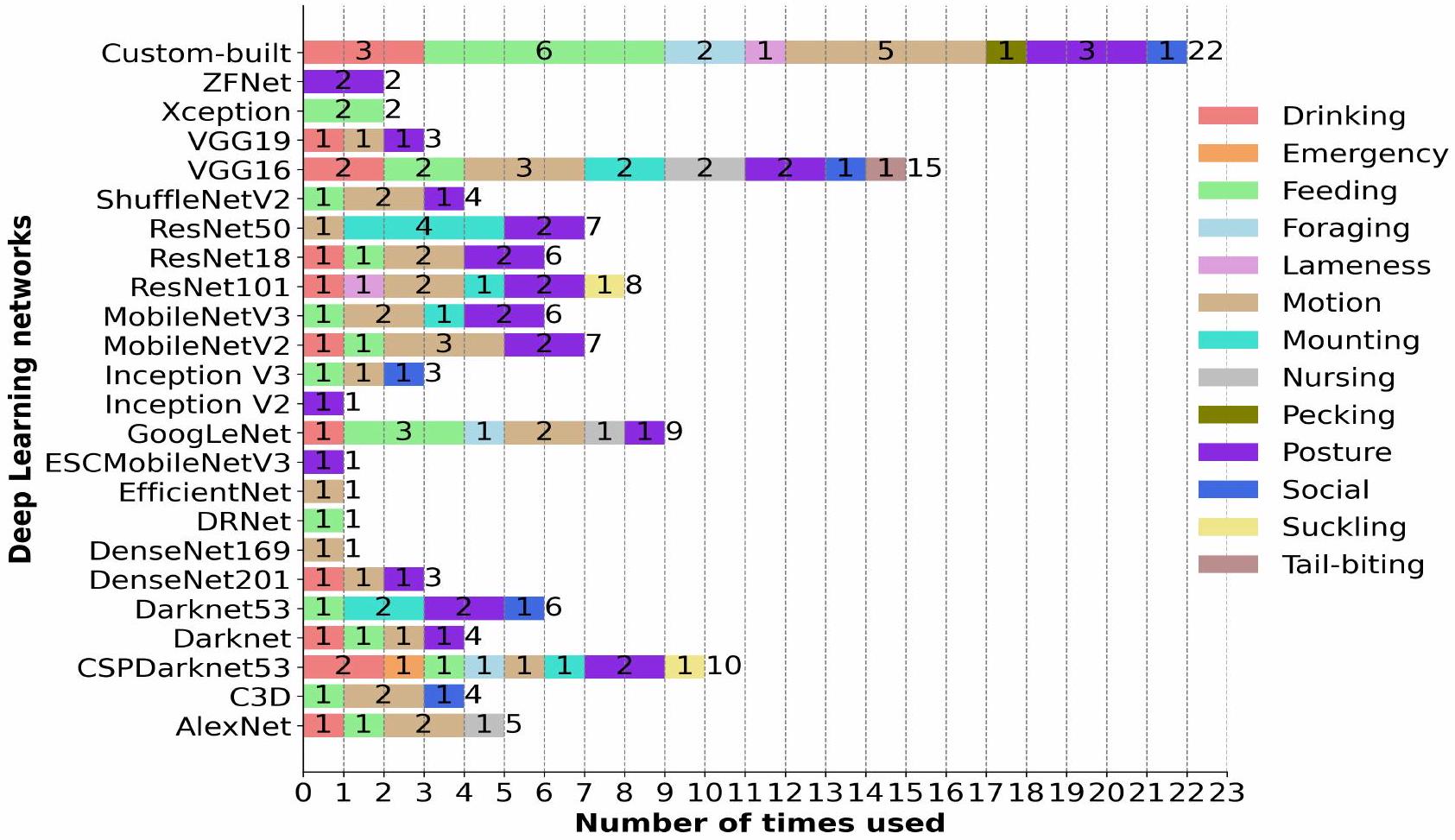

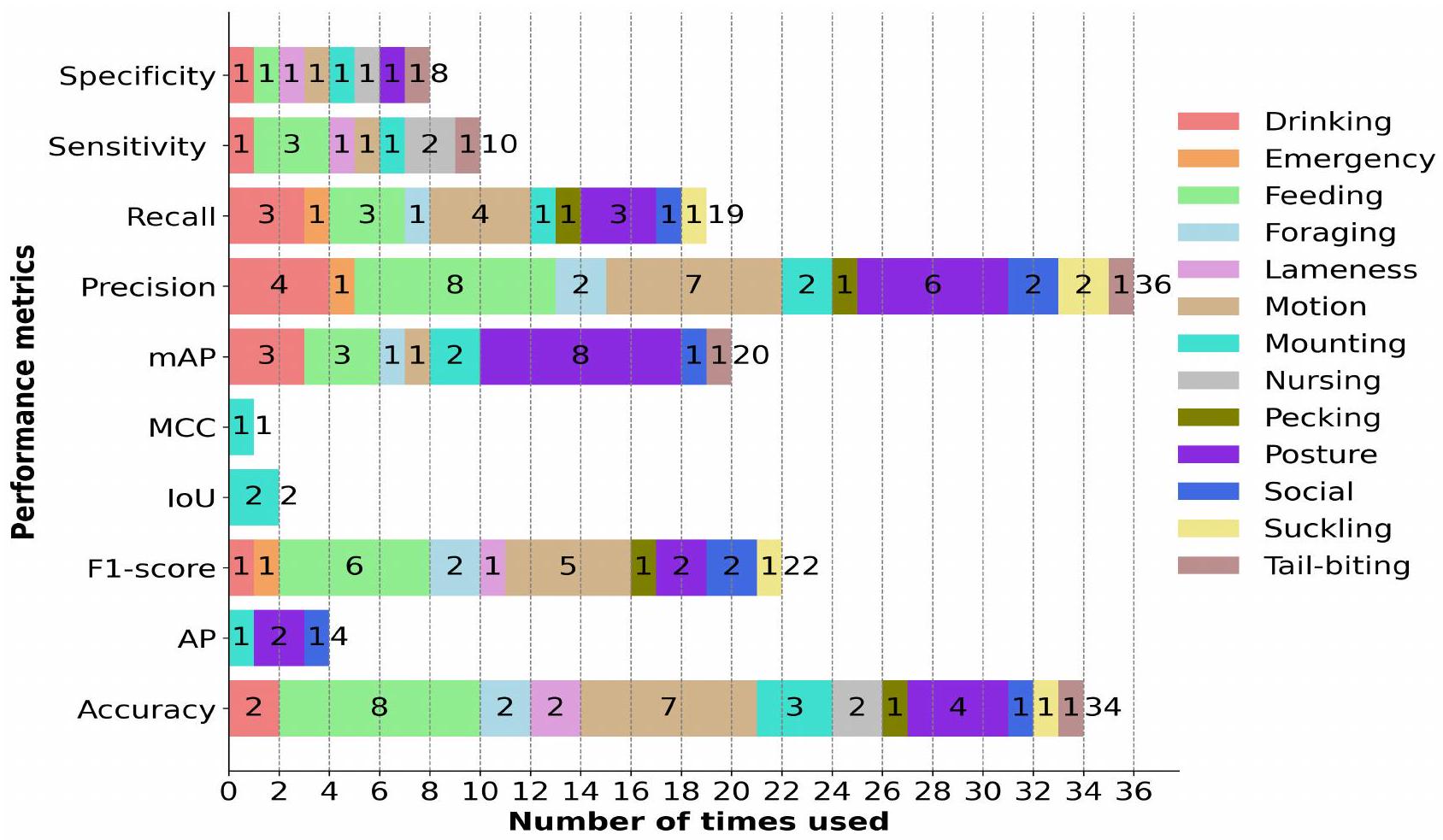

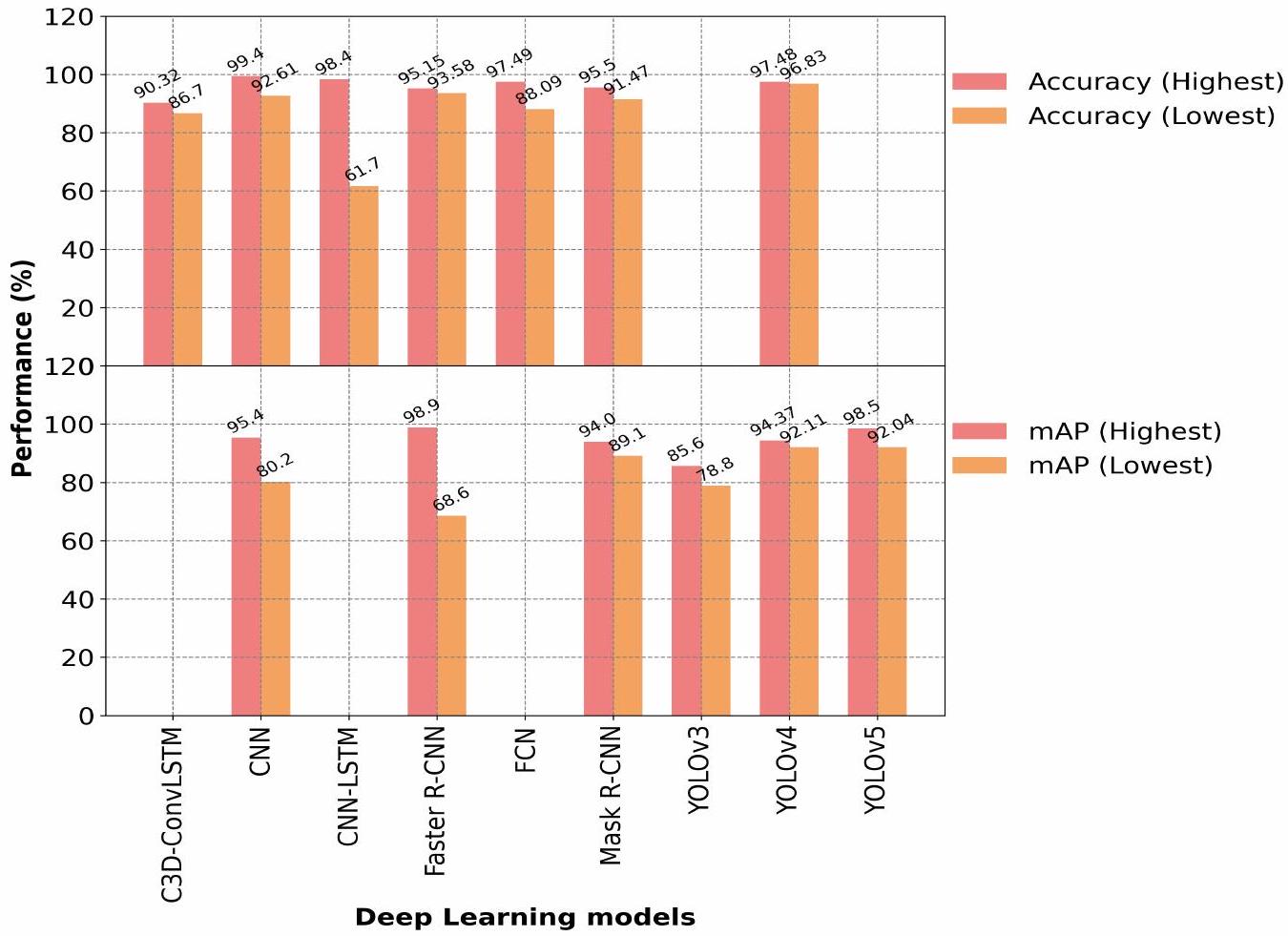

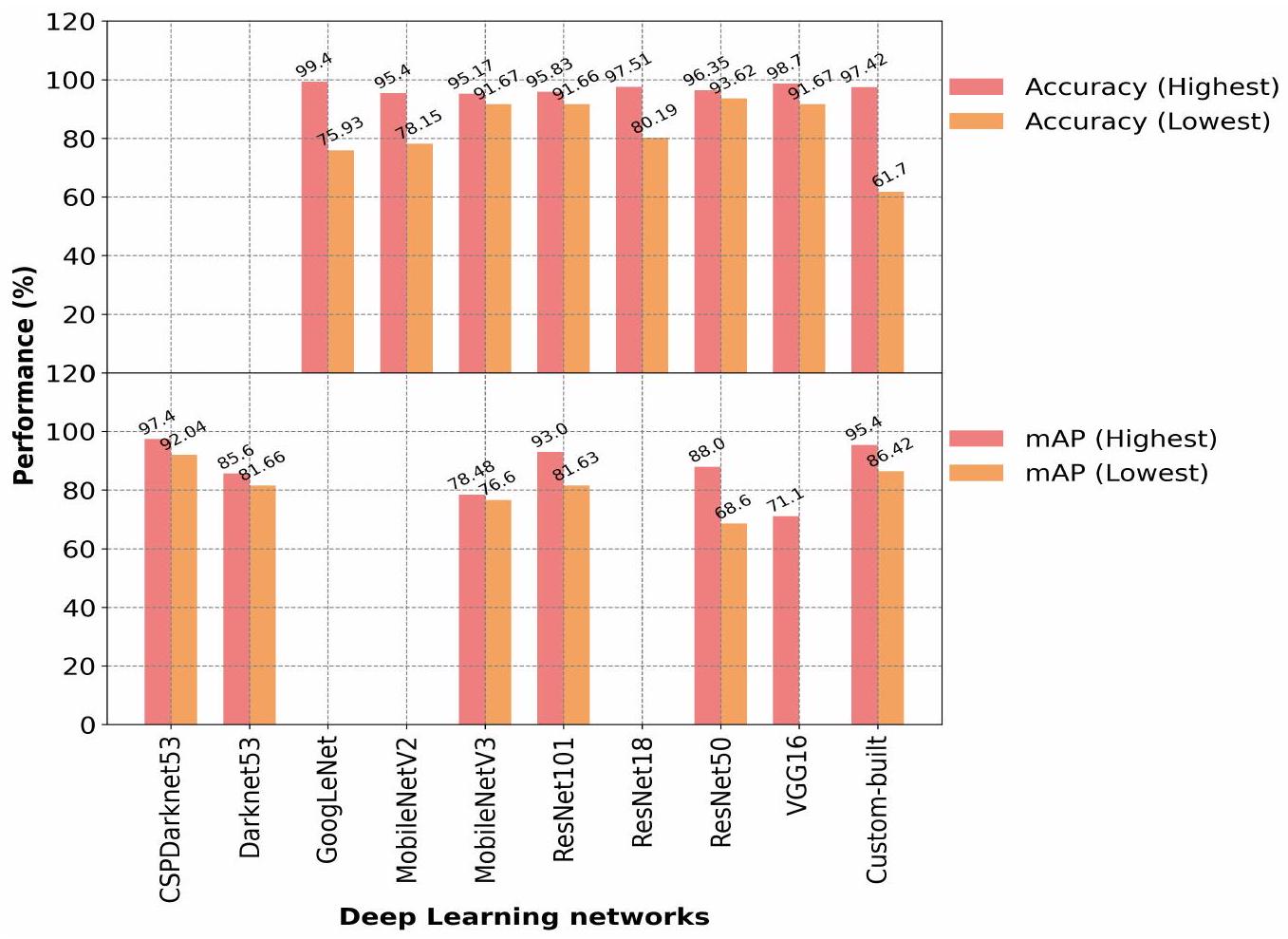

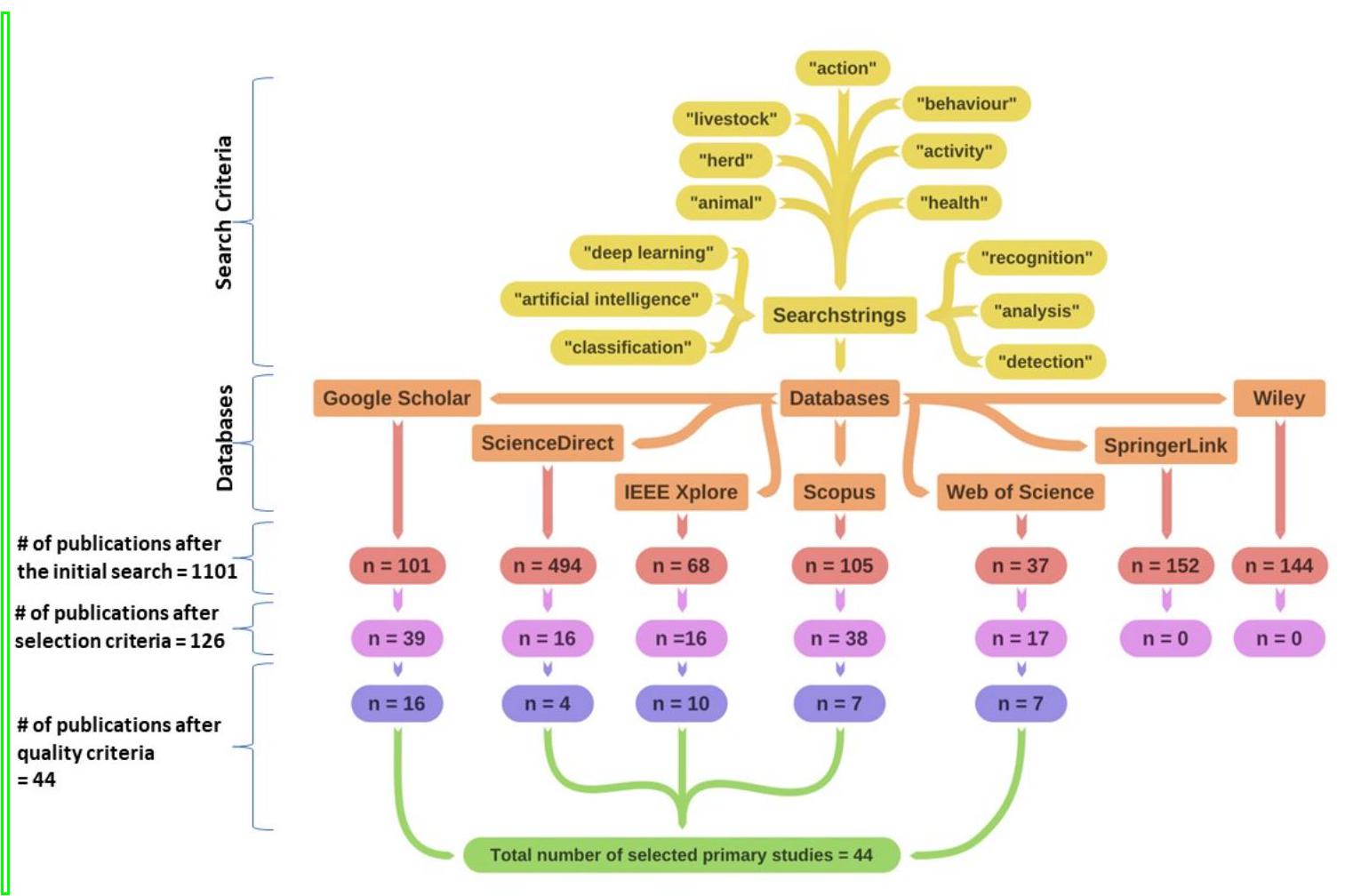

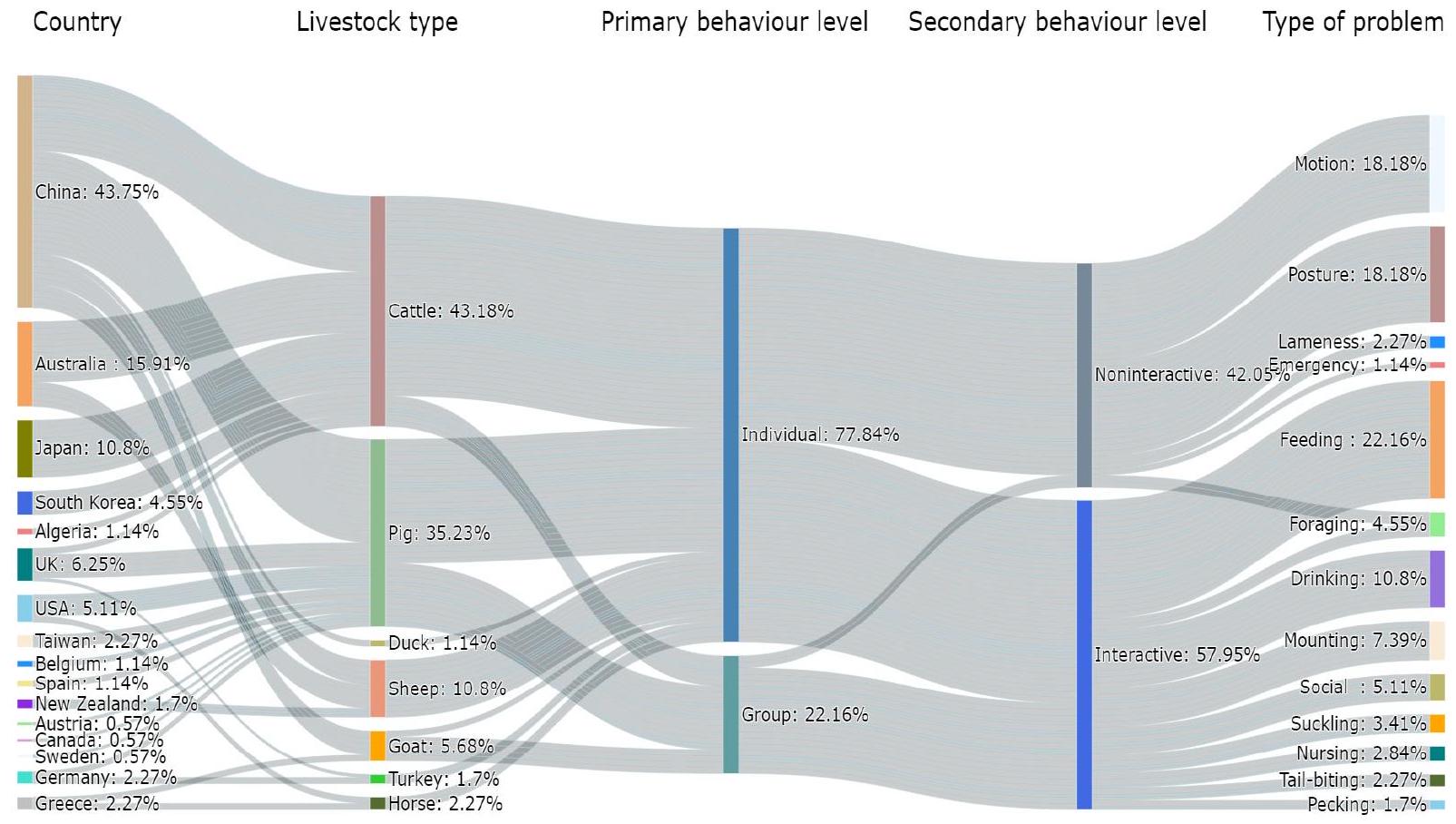

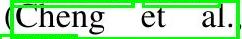

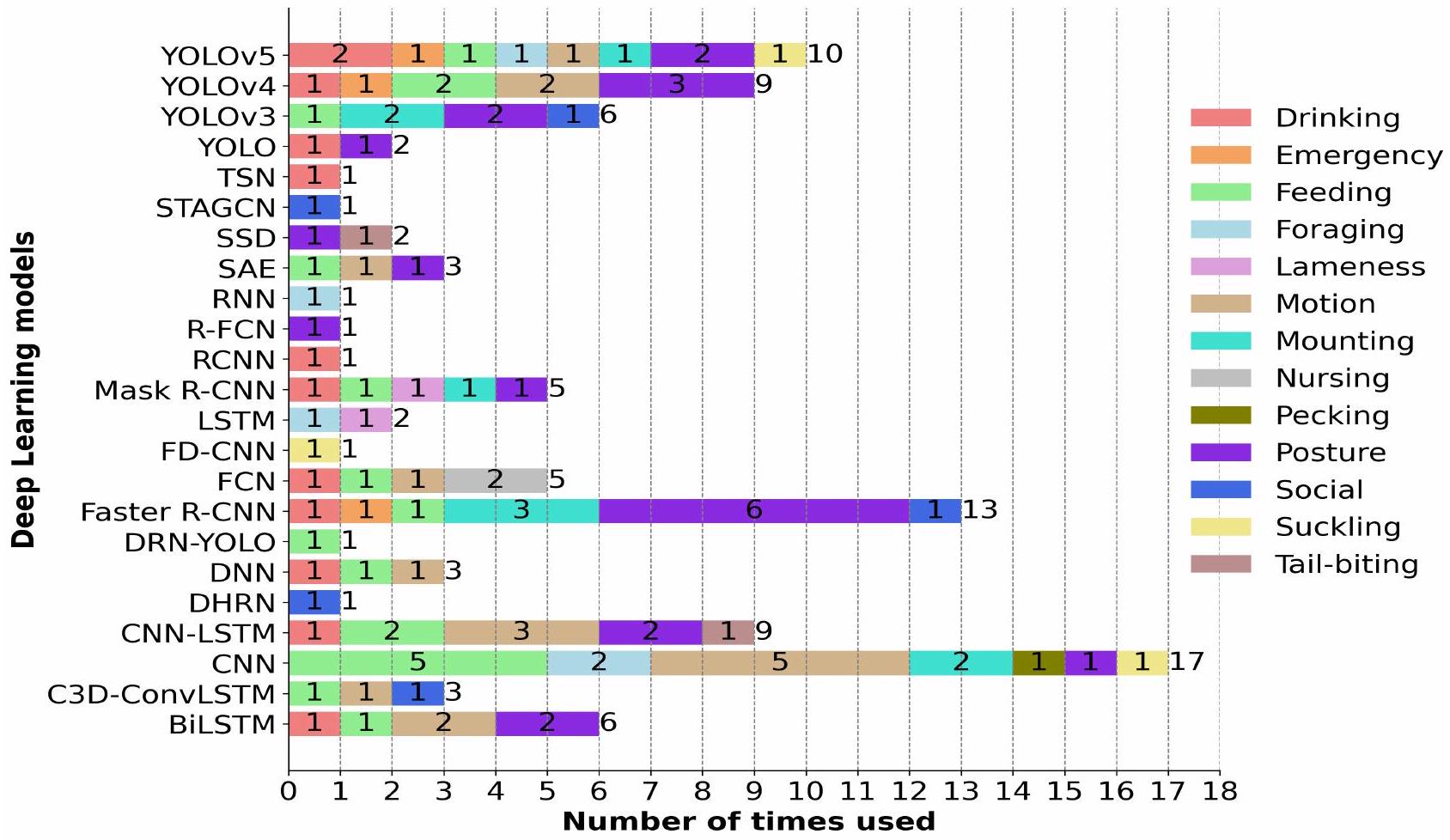

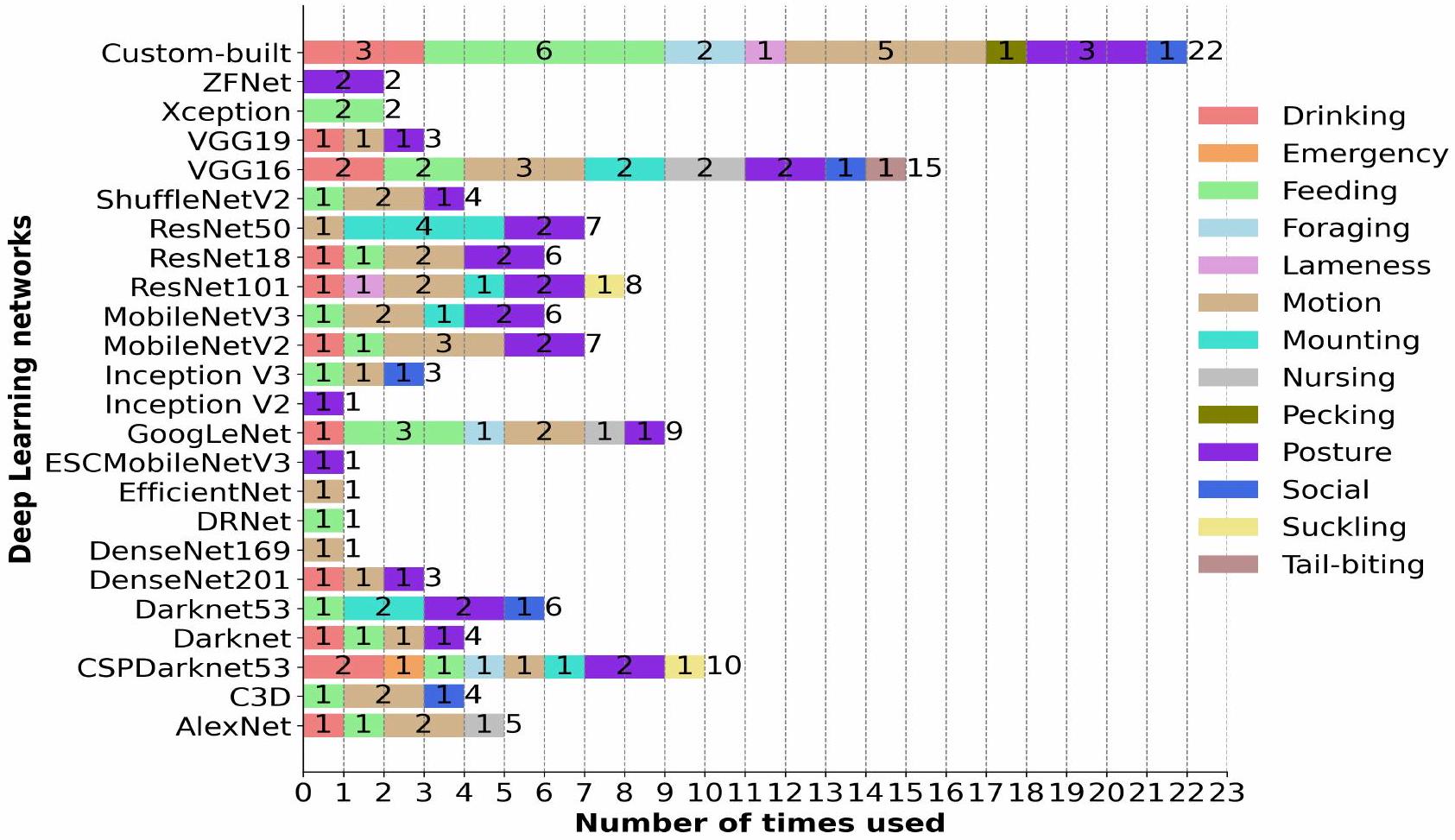

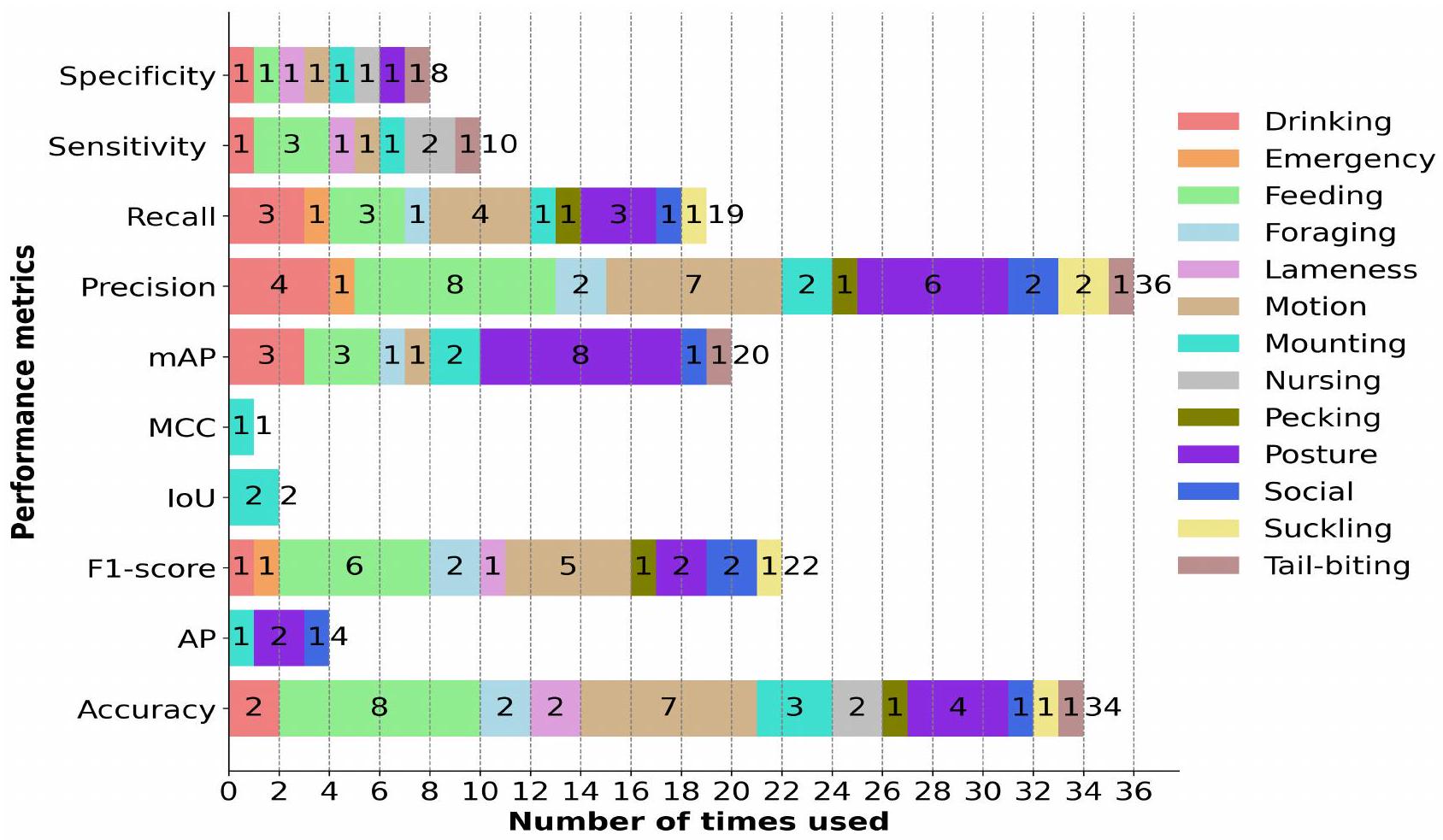

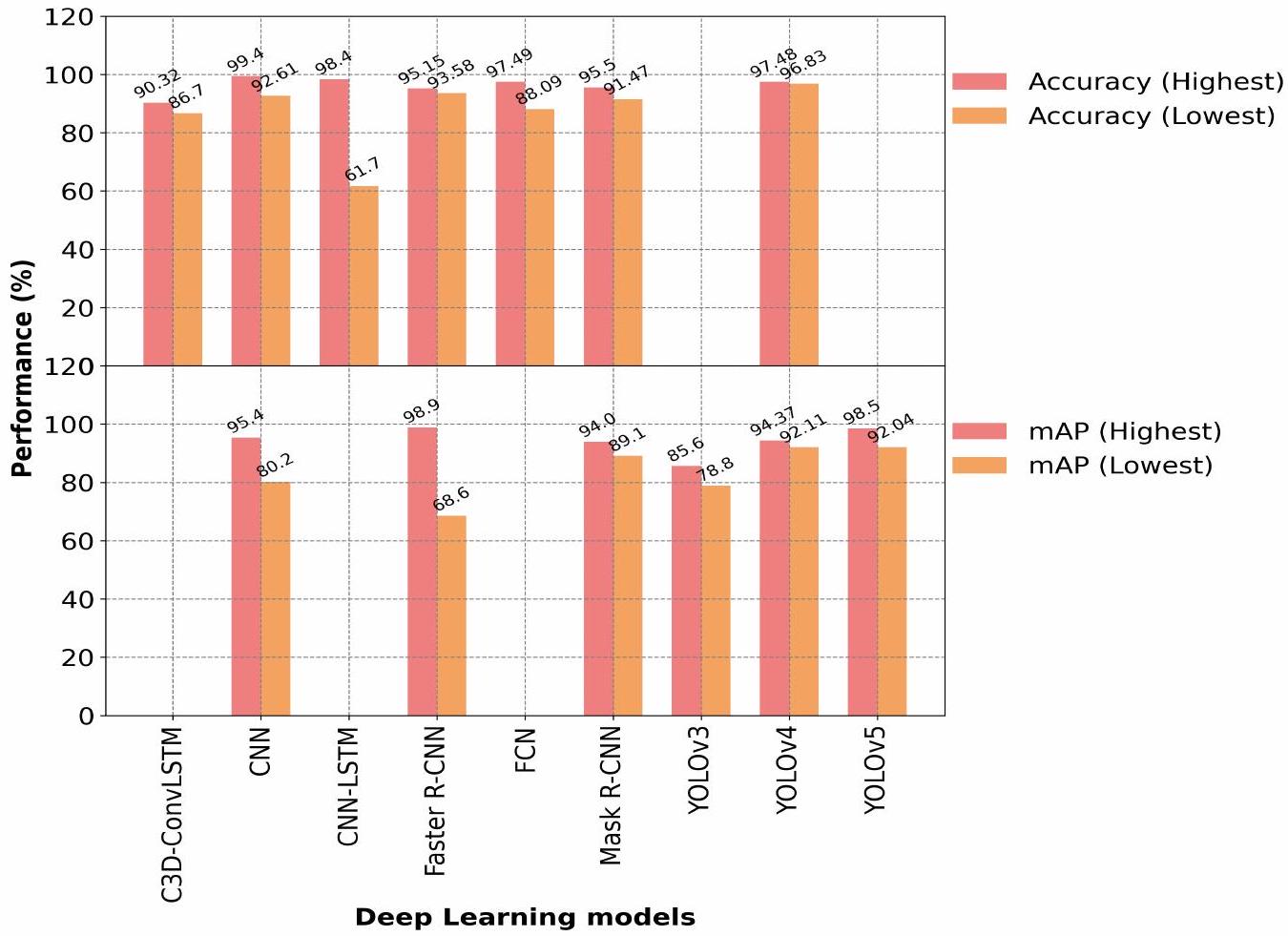

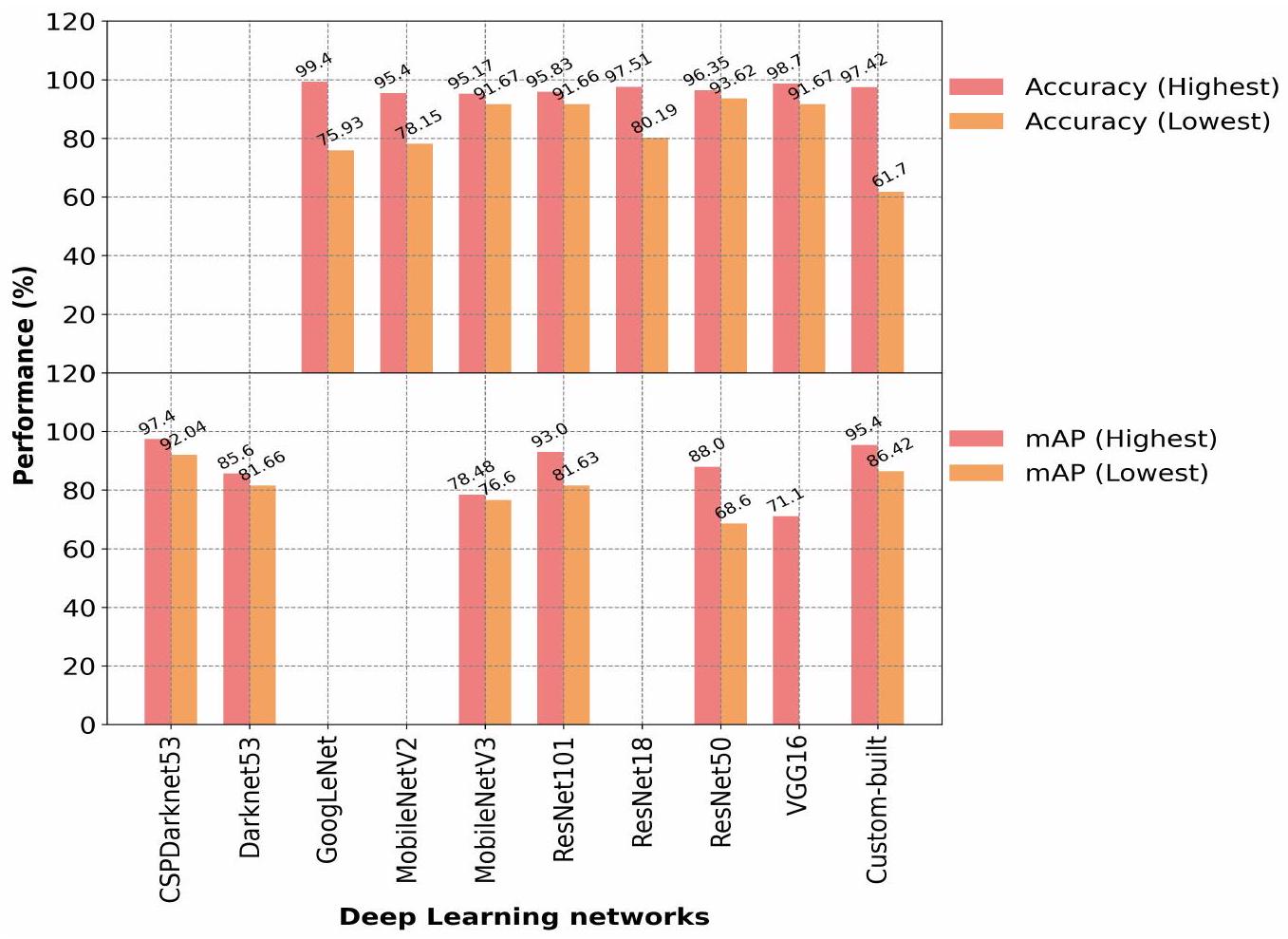

مراقبة صحة ورفاهية الماشية هي مهمة شاقة وتحتاج إلى جهد كبير كانت تُنفذ سابقًا يدويًا بواسطة البشر. ومع ذلك، مع التقدم التكنولوجي الأخير، اعتمدت صناعة الماشية أحدث تقنيات الذكاء الاصطناعي والرؤية الحاسوبية المدعومة بنماذج التعلم العميق (DL) التي تعمل في جوهرها كأدوات لصنع القرار. تم استخدام هذه النماذج سابقًا لمعالجة العديد من القضايا، بما في ذلك تحديد هوية الحيوانات الفردية، تتبع حركة الحيوانات، التعرف على أجزاء الجسم، وتصنيف الأنواع. ومع ذلك، على مدار العقد الماضي، كان هناك اهتمام متزايد باستخدام هذه النماذج لفحص العلاقة بين سلوك الماشية والمشاكل الصحية المرتبطة بها. تم تطوير العديد من المنهجيات المعتمدة على التعلم العميق للتعرف على سلوك الماشية، مما يتطلب مسح وتجميع أحدث ما توصلت إليه الأبحاث. تم إجراء دراسات مراجعة سابقًا بطريقة عامة جدًا ولم تركز على مشكلة محددة، مثل التعرف على السلوك. حسب علمنا، لا توجد حاليًا دراسة مراجعة تركز على استخدام التعلم العميق بشكل خاص للتعرف على سلوك الماشية. نتيجة لذلك، يتم إجراء هذه المراجعة المنهجية للأدبيات (SLR). تم إجراء المراجعة من خلال البحث في عدة قواعد بيانات إلكترونية شهيرة، مما أسفر عن 1101 منشور. بعد تقييمها من خلال معايير الاختيار المحددة، تم اختيار 126 منشورًا. تم تصفية هذه المنشورات باستخدام معايير الجودة التي أسفرت عن اختيار 44 دراسة أولية عالية الجودة، والتي تم تحليلها لاستخراج البيانات للإجابة على أسئلة البحث المحددة. وفقًا للنتائج، حل التعلم العميق 13 مشكلة في التعرف على السلوك تتعلق بـ 44 فئة سلوكية مختلفة. تم استخدام 23 نموذجًا للتعلم العميق و24 شبكة، حيث كانت CNN وFaster R-CNN وYOLOv5 وYOLOv4 هي النماذج الأكثر شيوعًا، وVGG16 وCSPDarknet53 وGoogLeNet وResNet101 وResNet50 هي الشبكات الأكثر شعبية. تم استخدام عشرة مصفوفات مختلفة لتقييم الأداء، حيث كانت الدقة والموثوقية الأكثر استخدامًا. كانت الانسداد والالتصاق، عدم توازن البيانات، والبيئة المعقدة للماشية هي التحديات الأكثر بروزًا التي أبلغت عنها الدراسات الأولية. أخيرًا، تم مناقشة الحلول المحتملة واتجاهات البحث في هذه الدراسة SLR للمساعدة في تطوير أنظمة التعرف على سلوك الماشية بشكل مستقل.

1. المقدمة

التسمية

| التسمية | |

| BiFPN | شبكة هرمية ثنائية الاتجاه |

| Bi-LSTM | ذاكرة طويلة وقصيرة المدى ثنائية الاتجاه |

| C3D | التفاف ثلاثي الأبعاد |

| ConvLSTM | ذاكرة طويلة وقصيرة المدى الالتفافية |

| CNN | شبكة عصبية التفافية |

| LSTM | ذاكرة طويلة وقصيرة المدى |

| CSPDarknet | شبكة جزئية عبر المراحل تعتمد على Darknet |

| DHRN | شبكة عالية الدقة العميقة |

| DNN | شبكة عصبية عميقة |

| DRNet | شبكة كثيفة متبقية |

| DRN-YOLO | DenseResNet-You Only Look Once |

| ESCMobileNet | شبكة موبايل نت مفصولة بشكل كبير |

| R-CNN | شبكة عصبية التفافية قائمة على المنطقة |

| FCN | شبكة تفافية كاملة |

| FD-CNN | اختلافات الإطار-شبكة عصبية تفافية |

| FPN | شبكة هرمية للميزات |

| ResNet | شبكة عصبية متبقية |

| R-FCN | شبكة تفافية كاملة قائمة على المنطقة |

| RNN | شبكة عصبية متكررة |

| RPN | شبكة اقتراح المنطقة |

| SAE | مشفر تلقائي متفرق |

| SSD | كاشف لقطة واحدة |

| STAGCN | شبكة تفافية رسومية زمنية وتكيفية |

| TSN | شبكة مقطع زمني |

| VGG | مجموعة الهندسة البصرية |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| ZFNet | شبكة زيلر وفيرغس |

| mAP | متوسط الدقة |

| AP | الدقة المتوسطة |

| IoU | التقاطع على الاتحاد |

| MCC | معامل ارتباط ماثيو |

| MPA | متوسط دقة البكسل |

تُستغل أنواع الحيوانات في مجموعات كبيرة تُحتجز في أنظمة إنتاج مكثفة، ومن غير الواقعي مراقبة كل نشاط للحيوانات في الوقت الحقيقي. مع ظهور تقنيات الصناعة 4.0 في الأتمتة الصناعية، أصبح من الأكثر عملية إنشاء أنظمة يمكنها أداء هذه المهام بكفاءة واستقلالية أكبر. لقد أعادت التقنيات المتقدمة مثل الذكاء الاصطناعي (AI) تشكيل تربية الماشية الصناعية وأدت إلى ظهور مجالات “الزراعة الذكية” و”الزراعة الدقيقة” و”تربية الماشية الدقيقة” (غونكالفيس وآخرون، 2022). تستفيد هذه المجالات بشكل كبير من الذكاء الاصطناعي لتحليل البيانات وتوفير أدوات جديدة لمراقبة وإدارة سلوك وصحة الحيوانات. تمتلك هذه التقنيات الجديدة القدرة على إحداث ثورة في تربية الماشية التقليدية، مما يمكّن المزارعين من اتخاذ قرارات مستندة إلى البيانات تحسن من صحة ورفاهية وإنتاجية الحيوانات. يمكن أن تساعد تربية الماشية الدقيقة في تحسين عملية الإنتاج، وتقليل التكاليف، وتقليل الآثار البيئية من خلال توفير مراقبة وتحليل في الوقت الحقيقي لسلوك الحيوانات (غارسيا وآخرون، 2020). أيضًا، يمكن أن يؤدي دمج التقنيات المتقدمة في تربية الماشية إلى تحويل الصناعة، مما يؤدي إلى ممارسات أكثر استدامة وكفاءة تفيد كل من الحيوانات والمزارعين. أخيرًا، يمكن أن تساعد هذه التقنيات في مكافحة الأمراض المعدية والمستوطنة، وهي واحدة من التحديات الرئيسية في تربية الماشية المعاصرة، مع تداعيات على كل من الحيوانات (مثل التهاب الضرع) وصحة المستهلكين (غريس، 2019).

بشكل كبير اعتمادًا على المشكلة التي تم تصميمها لحلها. على سبيل المثال، قد يؤدي نموذج التعلم العميق الذي تم إنشاؤه لتصنيف الأشياء في الصور إلى أداء ضعيف في مهمة زمنية مكانية معقدة مثل التعرف على السلوك. لذلك، من الضروري إجراء أبحاث لتحديد حالة التعلم العميق فيما يتعلق بالمشاكل المحددة في تربية الماشية الدقيقة. من خلال القيام بذلك، يمكننا فهم كيفية تصميم وتطوير ونشر نماذج التعلم العميق بشكل فعال، مما يؤدي في النهاية إلى نتائج أفضل لمزارعي الماشية وحيواناتهم. لذلك، يهدف هذا الاستعراض إلى فحص الاتجاهات والتطورات الحديثة في استخدام التعلم العميق لمشكلة محددة تتعلق بالتعرف على السلوك في تربية الماشية الدقيقة. سيوفر هذا الاستعراض نظرة شاملة على الأنواع المختلفة من مشاكل التعرف على السلوك التي تم تناولها باستخدام التعلم العميق. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، سيلخص الأساليب المختلفة المستخدمة لجمع البيانات، بما في ذلك الكمية والجودة ونوع البيانات المستخدمة في هذه الدراسات. علاوة على ذلك، سيناقش الأنواع المختلفة من نماذج التعلم العميق والشبكات التي تم تطويرها للتعرف على السلوك وكيفية تطبيقها على مشاكل محددة، وتحليل أداء نماذج التعلم العميق والشبكات، والتحديات المبلغ عنها في الأدبيات، والحلول المحتملة للتغلب على هذه التحديات.

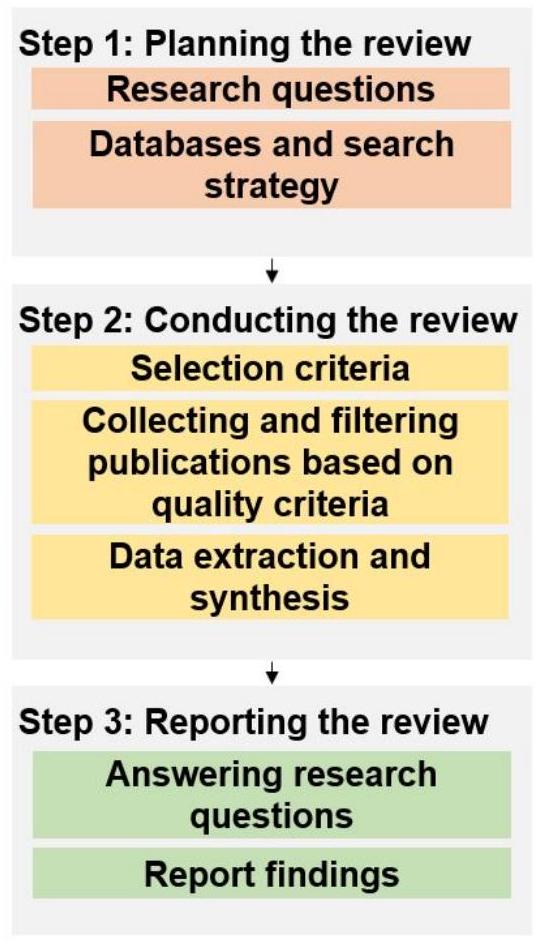

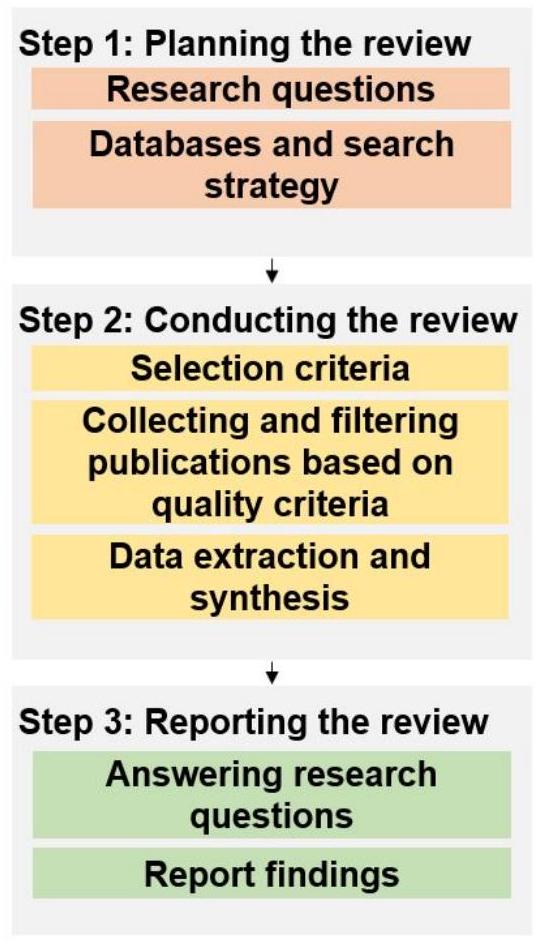

2. المنهجية

2.1. بروتوكول الاستعراض

2.2. أسئلة البحث

2.3. قواعد البيانات واستراتيجية البحث

2.4. معايير الاختيار

- المنشور غير مرتبط بالتعلم العميق للتعرف على سلوك الماشية.

- المنشور مكرر أو تم استرجاعه من قاعدة بيانات أخرى.

- المنشور غير مكتوب باللغة الإنجليزية، والنص الكامل للدراسة غير متاح.

- المنشور هو فصل كتاب، ملخصات مؤتمرات، مقالات بيانات، مراجعات صغيرة، اتصالات قصيرة، أطروحة، مراجعة، أو مقال استقصائي.

- المنشور هو نسخة مسبقة أو غير مراجعة من قبل الأقران.

- تم نشر المنشور قبل عام 2012.

- المنشور مرتبط بتطبيق منهجيات قائمة على التعلم العميق للتعرف على السلوك في الماشية.

- المنشور هو دراسة أولية.

2.5. جمع وتصنيف المنشورات

- هل تم توضيح الأهداف والغايات للدراسة بوضوح؟

- هل تم تعريف نطاق الدراسة، والمنهجية، وتصميم التجربة بوضوح؟

- هل تم توثيق عملية البحث والمنهجية بشكل مناسب؟

- هل تم الإجابة على جميع أسئلة الدراسة؟

- هل تم تقديم النتائج السلبية؟

- هل تتوافق الاستنتاجات مع أهداف الدراسة وغرضها؟

الشكل 2. يظهر العملية العامة لاختيار الدراسات الأولية.

2.6. استخراج البيانات والتركيب

الإيثوجرام الذي يحدد كل سلوك، جمع البيانات ونوعها وكمية وجودة البيانات، نماذج التعلم العميق والشبكات، مقاييس تقييم الأداء، التفاصيل المتعلقة بسنة ومجلة المنشورات، والتحديات المرتبطة بتطبيق التعلم العميق للتعرف على سلوك الماشية. أخيرًا، تم تركيب البيانات المستخرجة للإجابة على كل سؤال بحث. تم تقديم نتائج هذه الدراسة SLR في القسم التالي.

3. النتائج

3.1. أهمية التعرف على السلوك في الماشية وأنواع المشاكل (RQ. 1)

تفاصيل الدراسات الأولية المختارة.

| لا. | المصدر | عنوان المقال | المرجع |

| 1 | Google Scholar | التعرف على سلوك التزاوج للخنازير بناءً على التعلم العميق | Ii وآخرون 2019 |

| 2 | التعرف على سلوك تزاوج الخنازير بناءً على ميزات الفيديو الزمانية المكانية | Tallg er ai. 2021 | |

| 3 | التعرف التلقائي على سلوك إرضاع الخنازير باستخدام تقنيات التقسيم المعتمدة على التعلم العميق والميزات المكانية والزمانية | يانغ وآخرون 2018 | |

| ٤ | استخدام EfficientNet-LSTM للتعرف على سلوكيات حركة الأبقار الفردية في بيئة معقدة | “إليتال. 2020 | |

| ٥ | التعرف التلقائي على سلوك التغذية والبحث عن الطعام في الخنازير باستخدام التعلم العميق | أيامير وآخرون 2020ب | |

| ٦ | إطار عمل للتعرف التلقائي على سلوكيات الخنازير اليومية استنادًا إلى تحليل الحركة والصورة | يانغ إير آي. 2020 | |

| ٧ | التعرف على سلوك تغذية الخنازير وتحديد وقت تغذية كل خنزير بواسطة طريقة التعلم العميق المعتمدة على الفيديو | تشيلتاي. 20200 | |

| ٨ | تصنيف سلوك الأغنام المعتمد على التعلم العميق من بيانات مقياس التسارع مع عدم التوازن | تومر وآخرون 2022 | |

| 9 | طريقة قائمة على رؤية الكمبيوتر للتعرف على الأفعال الزمانية المكانية لسلوك عض الذيل في الخنازير المرباة في مجموعات | ليو وآخرون 2020 | |

| 10 | تحليل سلوك الأغنام التلقائي باستخدام ماسك R-CNN | X́uetal. 2021 | |

| 11 | الكشف الآلي وتحليل سلوك رضاعة الخنازير الصغيرة باستخدام تقسيم الكائنات غير المرئية بدقة عالية | غال إي إل. 2022أ | |

| 12 | تطبيق التعلم العميق في التعرف على سلوكيات الأغنام وتحليل تأثير خصائص بيانات التدريب على فعالية التعرف | تشينجيراي. 2022 | |

| ١٣ | التعرف التلقائي على أوضاع الخنازير المرضعة بواسطة شبكة Faster R-CNN المحسّنة ذات القناتين RGB-D | ZIII إل وآخرون، 2020 | |

| 14 | تحديد وتحليل سلوك الطوارئ للدجاج البياض المُربى في الأقفاص استنادًا إلى YoloV5 | غو وآخرون 2022 | |

| 15 | التعرف على وضعية الخنزير المحجوز بناءً على YOLOv4 المحسن | لورا. 2022 | |

| 16 | كشف وضعية الخنازير الفردية استنادًا إلى الشبكات العصبية التلافيفية الخفيفة واهتمام القنوات الفعال | لو وآخرون، 2021 | |

| 17 | ساينس دايركت | التعرف على سلوك الماشية استنادًا إلى دمج الميزات تحت آلية انتباه مزدوج | شانغ وآخرون 2022 |

| ١٨ | كشف سلوك البحث عن الطعام لدى الخيول باستخدام تقنيات التعرف على الصوت والذكاء الاصطناعي | نوميس وآخرون 2021 | |

| 19 | التعرف على سلوك الماشية القائم على التعلم العميق مع معلومات مكانية زمنية هرمية | فوينتس إير آي. 2020) | |

| 20 | كشف نشاط الخنازير الصغيرة الرضيعة استنادًا إلى تحليل منطقة الحركة باستخدام اختلافات الإطارات بالاقتران مع الشبكة العصبية التلافيفية | دينغ وآخرون، 2022 | |

| 21 | IEEE إكسبلور | الكشف التلقائي عن سلوك التزاوج في الماشية باستخدام التقسيم الدلالي والتصنيف | نو وآخرون 2021 |

| ٢٢ | حل قائم على التعلم العميق لاستخراج منطقة الماشية لكشف العرج | نوف إيل آل.. 2022 | |

| 23 | تحديد الهوية والتعرف على الحركة في الماشية المعتمدة على الفيديو | نغوينتر أي. 2021) | |

| ٢٤ | زيادة البيانات لبيانات المستشعرات القابلة للحركة في الشبكات العصبية التلافيفية لتصنيف سلوك الماشية | ليرا.. 2021 | |

| ٢٥ | نظام قائم على الذكاء الاصطناعي لمراقبة سلوك ونمو الخنازير | تشيل وآخرون 2020ب | |

| ٢٦ | نحو بناء نظام قائم على البيانات لرصد سلوكيات الأبقار السوداء | ناوانو وآخرون 2021 | |

| 27 | مقارنة بين ميزات التشفير التلقائي والميزات الإحصائية لتصنيف سلوك الماشية | رانمان إكاي. 2010 | |

| ٢٨ | كشف العرج في الأبقار باستخدام التعلم العميق الهرمي وتحويل الموجات المتزامنة | جارسي وآخرون 2021 | |

| ٢٩ | عن فوائد الشبكات العصبية التلافيفية العميقة في التعرف على نشاط الحيوانات | دوكاجيت آي. 2020 | |

| 30 | نموذج التعرف الفردي وطريقة لتقدير الرتبة الاجتماعية بين قطيع من الأبقار الحلوب باستخدام YOLOv5 | أوكينيو وأونوادا، 2021 | |

| 31 | سكوبس | شبكة الالتفاف البياني الزمكانية للكشف الآلي وتحليل السلوكيات الاجتماعية بين الخنازير الصغيرة قبل الفطام | غان وآخرون 2022ب |

| ٣٢ | طريقة الكشف التلقائي عن سلوك تغذية الأبقار الحلوب استنادًا إلى نموذج YOLO المحسن والحوسبة الطرفية | أونرال. 2022 | |

| ٣٣ | التعرف على سلوك الحركة الأساسي لفرس الحليب الفردية استنادًا إلى شبكة ركسنت 3D المحسّنة | نيتات أي. 2022 | |

| ٣٤ | تحديد وتصنيف سلوك رعي الأغنام استنادًا إلى الإشارة الصوتية والتعلم العميق | وانجراي.. 2021) | |

| ٣٥ | استخدام شبكة CNN-LSTM لاكتشاف السلوكيات الأساسية لابقار الألبان الفردية في بيئة معقدة | ويرال 2021 | |

| ٣٦ | تحليل الصور لتحديد الهوية الفردية ومراقبة سلوك التغذية للأبقار الحلوب استنادًا إلى الشبكات العصبية التلافيفية (CNN) | أسيور وآي. 2020 | |

| 37 | أساليب التعلم العميق ورؤية الآلة لاكتشاف وضعية الخنازير الفردية | ناسيراهماوي وآخرون، 2019 | |

| ٣٨ | ويب أوف ساينس | تصنيف سلوك الأبقار المعتمد على C3D-ConvLSTM باستخدام بيانات الفيديو للزراعة الحيوانية الدقيقة | أوياو وآخرون. 2022 |

| ٣٩ | التعرف التلقائي على سلوك الماعز المربى في مجموعات باستخدام التعلم العميق | جيانغ إير آي. 2020 | |

| 40 | تصنيف سلوك الماشية المعتمد على التعلم العميق باستخدام تمثيل البيانات الزمنية الترددية المشترك | تيُوسيكيمينوريميت وآخرون 2021 | |

| 41 | التعرف الآلي على الوضعيات وسلوك الشرب للكشف عن الصحة المت compromised في الخنازير | الأمير وآخرون. 2020أ | |

| 42 | كشف نشاط النقر في الديوك الرومية المرباة في مجموعات باستخدام بيانات صوتية وتقنية التعلم العميق | ناسير أحمدي وآخرون. 2020 | |

| 43 | رؤية الكمبيوتر المطبقة للكشف عن الخمول من خلال مراقبة حركة الحيوانات: تجربة على حمى الخنازير الأفريقية في الخنازير البرية | فيمانوكز-كانيون وآخرون، 2020 | |

| ٤٤ | التعرف التلقائي على أوضاع الخنازير المرضعة من صور العمق بواسطة كاشف التعلم العميق | إنينغ وآخرون، 2010 |

صحة غير معاقة وتوقع الأمراض مثل الكيتوزية والتهاب الضرع. يساعد التقييم الدوري لسلوك التغذية في مراقبة صحة وإنتاج الماشية على مستوى الأفراد والمزارع. يمكن أن يساعد التعرف على الوضع غير الطبيعي في الحيوانات في الوقت المناسب في الحد من انتقال الأمراض، وتقليل استخدام المضادات الحيوية البيطرية، وزيادة الفوائد الاقتصادية للمزارع التجارية. تعتبر سلوكيات الحركة والنشاط مؤشرات حاسمة على الحالة الصحية البدنية للحيوانات وظروف الزراعة. يرتبط سلوك الشرب بإنتاج الحليب، والتحكم في درجة حرارة الجسم، واستهلاك العلف الكافي. يساعد سلوك التزاوج في اكتشاف فترات الشبق، ويمكن أن يساعد في تحسين أداء التكاثر للحيوانات. يرتبط سلوك الرضاعة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بالجوع ويؤثر على إنتاج الحليب ونمو الحيوانات. يمكن أن يشير أيضًا إلى الأمراض أو الإصابات المتعلقة بالضرع. يعتبر عض الذيل من أكثر السلوكيات ضررًا التي تؤثر على رفاهية الحيوانات وإنتاجها. لقد أدى التعرف المبكر على العرج إلى تحسين رفاهية الحيوانات، مما أدى إلى فوائد اقتصادية وصحية. تعتبر السلوكيات الاجتماعية مؤشرات حاسمة على نمو الحيوانات وصحتها. ترتبط سلوكيات الطوارئ مثل الدوس في البط بمعدل إصابات مرتفع. قد يعكس سلوك الرضاعة الصحة البدنية للحيوان. لوحظ أن الحيوانات ذات مستويات النشاط الأعلى لديها معدل وفيات أقل. علاوة على ذلك، قد يشير الوقت المخصص للرضاعة أو تدليك الضرع إلى الجوع أو تناول العلف ويمكن استخدامه لتوقع نمو الحيوانات.

نوع مشكلات التعرف على السلوك والفئات السلوكية المرتبطة.

| نوع المشكلة | فئات السلوك |

| التعرف على سلوك التغذية | الأكل، الرعي، المضغ، التجشؤ، التجشؤ واقفًا، التجشؤ مستلقيًا، العض |

| التعرف على الوضع | الراحة، الاستلقاء، الاستلقاء، الاستلقاء على البطن، الاستلقاء على الجانب، الاستلقاء الجانبي، الاستلقاء على الصدر، الوقوف، النهوض، الجلوس، الاستلقاء على الصدر، الاستلقاء البطني، الاستلقاء الجانبي، النوم |

| التعرف على الحركة | المشي، التحرك، تحريك الذيل، تحريك الرأس، غير نشط، خمول |

| التعرف على سلوك الرضاعة | تفاعل الرضاعة |

| التعرف على سلوك التزاوج | تفاعل التزاوج |

| التعرف على سلوك الشرب | تفاعل الشرب |

| التعرف على نشاط النقر | نقر أو عدم نقر |

| التعرف على سلوك عض الذيل | عض الذيل (العض)، عض الذيل (الضحية) |

| التعرف على سلوك البحث عن الطعام | زيارات غير غذائية / غير تغذوية |

| التعرف على السلوك الاجتماعي | البحث، اللعق الاجتماعي، التمشيط، الاستكشاف، الشم الاجتماعي، القتال، اللعب |

| التعرف على سلوك الطوارئ | تمديد الرقبة، الدوس، نشر الأجنحة |

| التعرف على العرج | العرج |

| التعرف على سلوك الرضاعة | الرضاعة أو عدم الرضاعة |

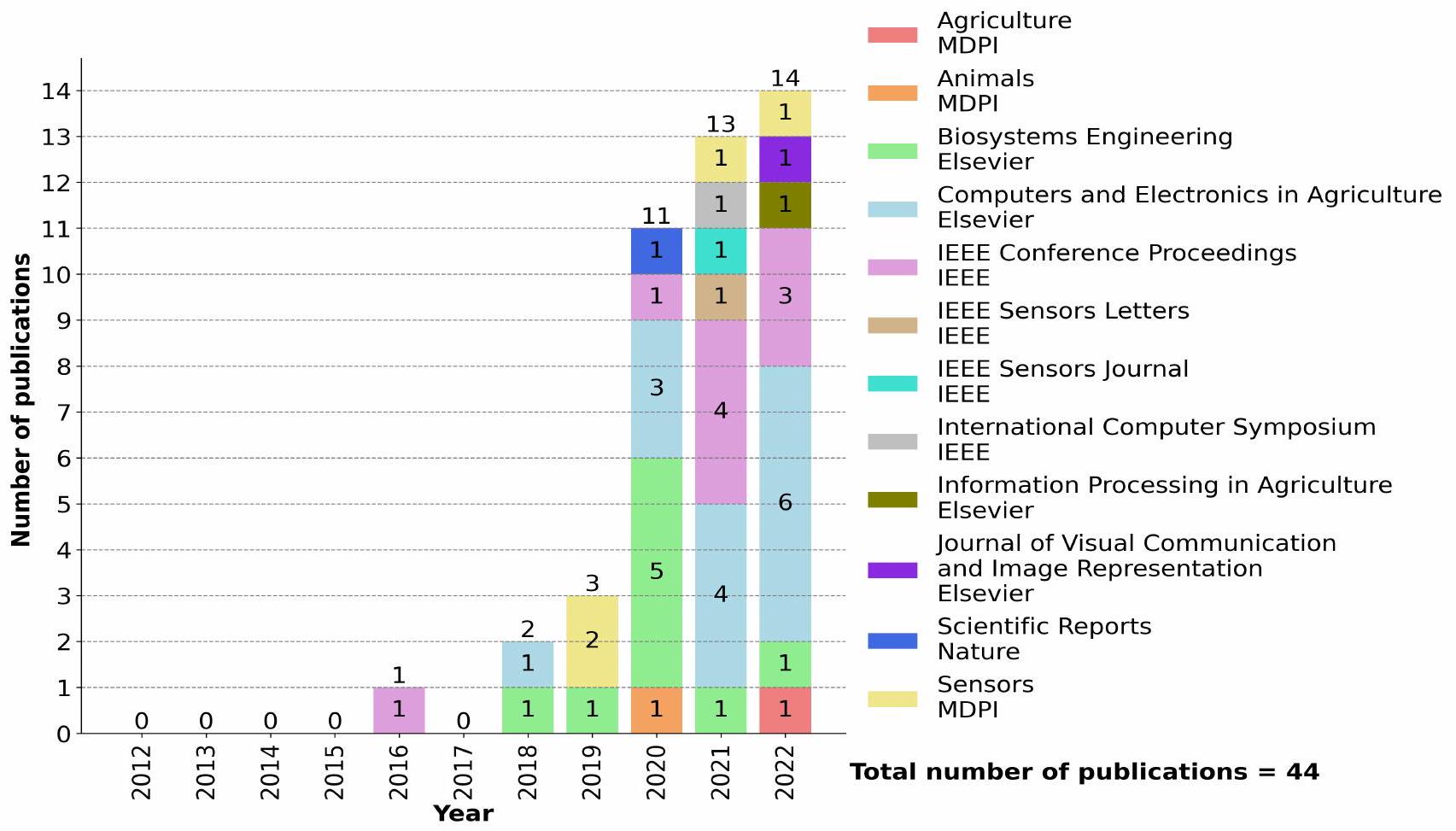

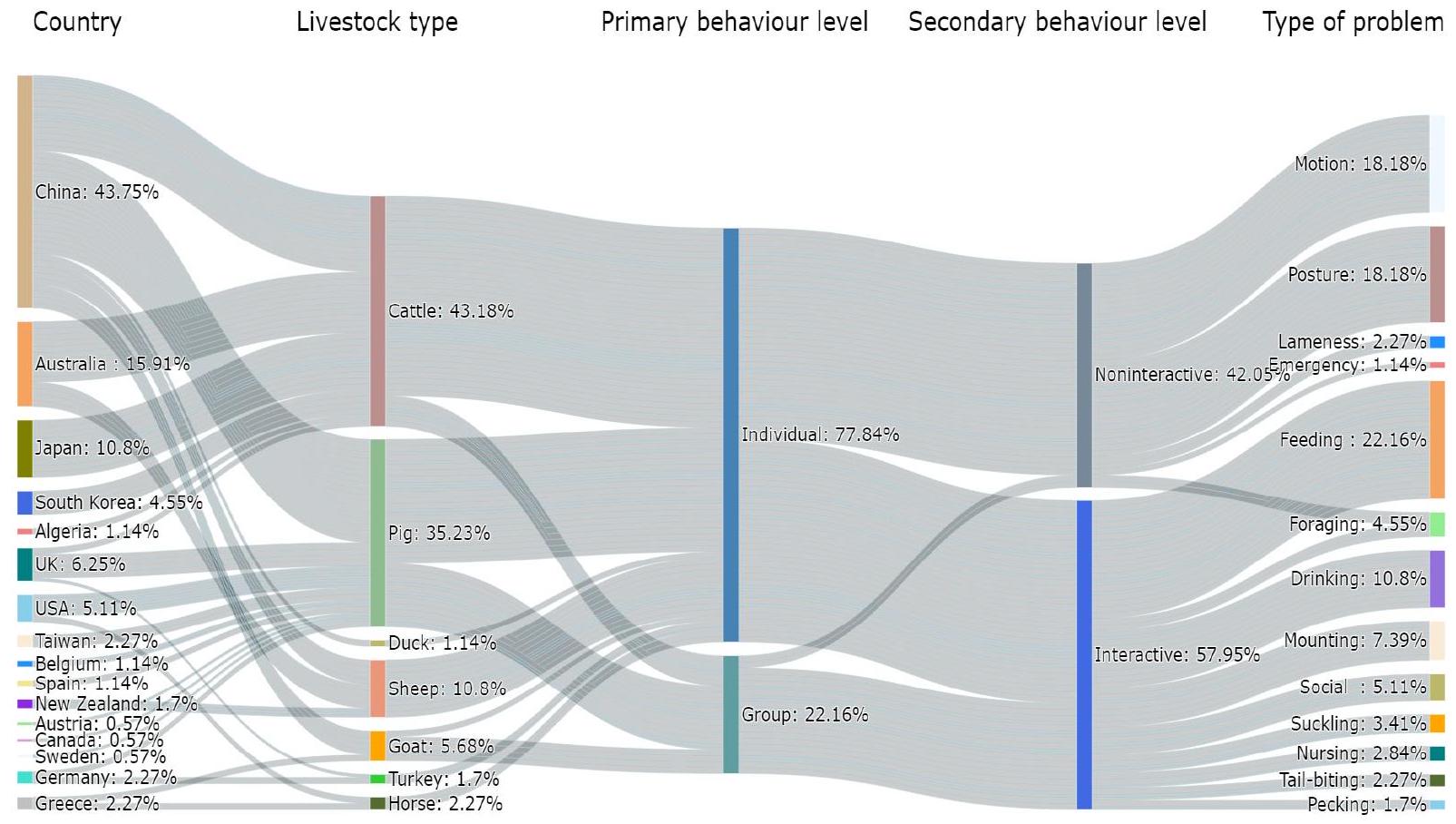

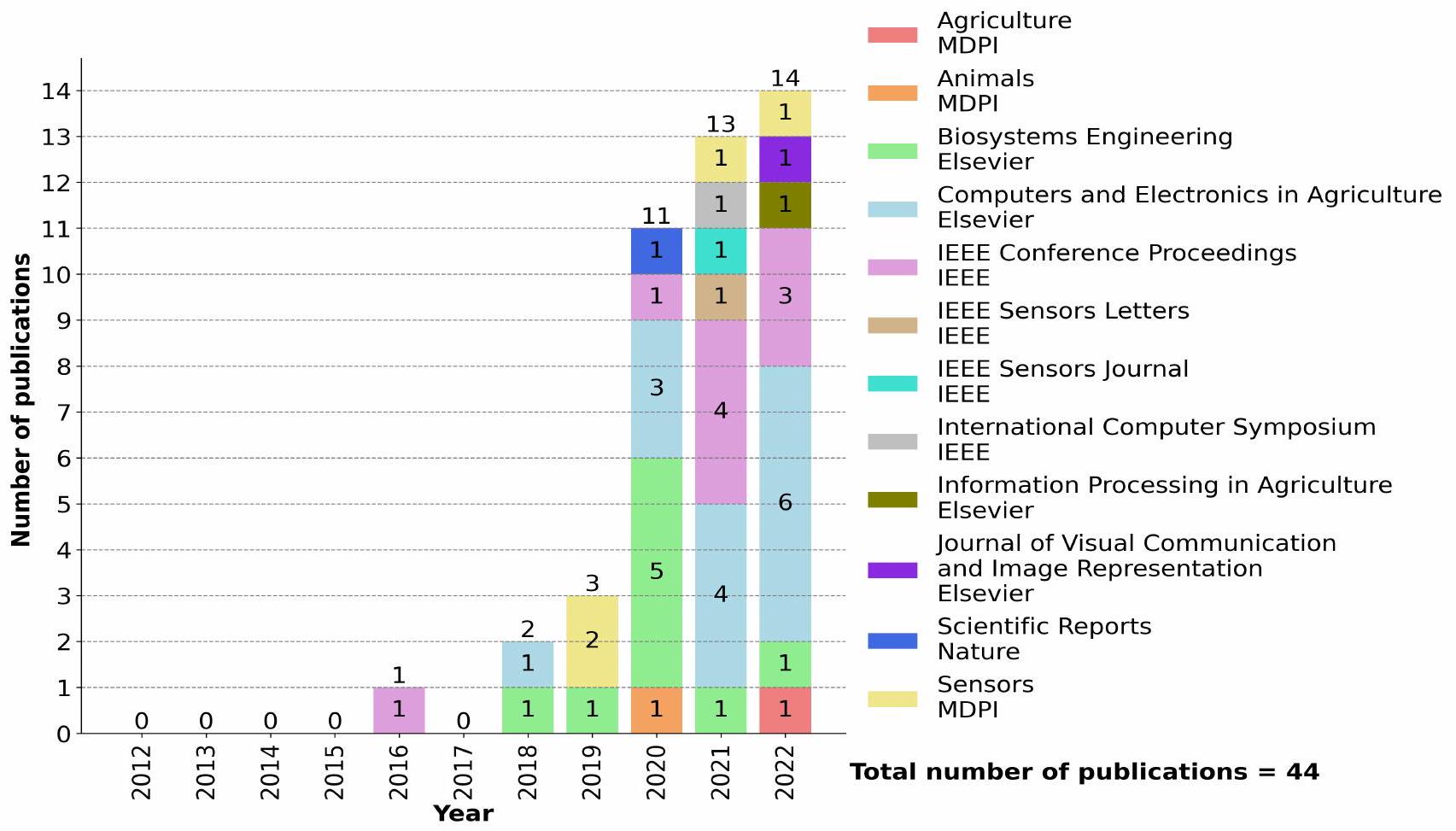

3.1.1. توزيع الدراسات الأولية والاتجاه العالمي للتعرف على سلوك الماشية

إيثوجرام يوضح الفئات السلوكية الموجودة في الدراسات الأولية.

| فئات السلوك | الوصف | المرجع |

| التغذية / الأكل | الوقوف مع الرأس في صينية العلف أو خفض الرأس | (فوينتس وآخرون |

| أو إبقاء الرأس في منطقة الطعام وأداء حركة الأكل أو الرأس داخل حوض الطعام أو إبقاء الرأس في منطقة الطعام أو العض والمضغ على طعامه، والحفر بأنفه في المغذي أو الرأس مائل لأسفل والطعام متاح في المغذي أو عندما يتداخل صندوق الحدود لرأس أي خنزير مع منطقة السرير | 2020)، (يانغ وآخرون 2020)، (الأمير وآخرون 2020ب)، (تشن وآخرون 2020أ)، (أشور وآخرون، 2020)، (تشن وآخرون 2020ب)، (كيو وآخرون، | |

| 2022)، (يو وآخرون، 2022) | ||

| المضغ والتجشؤ | المضغ، ورفع الرأس | (رحمن وآخرون، 2016) |

| 2020)، (وو وآخرون، 2021) | ||

| التجشؤ واقفًا | التجشؤ، والوقوف | (رحمن وآخرون، 2016) |

| التجشؤ مستلقيًا، | التجشؤ، والاستلقاء أو الجلوس | (رحمن وآخرون، 2016) |

| الراحة | الجلوس على الأرض أو الاستراحة، والاستلقاء أو الاستراحة، والوقوف مع رفع الرأس | (فوينتس وآخرون |

| 2020)، (رحمن وآخرون، 2016) | ||

| الكذب | البطن يلتصق بالأرض دون حركة شاقة أخرى أو الوضعية بعد الركوع | (وو وآخرون، 2021)،(ما وآخرون، 2022) |

| مستلقٍ | التحرك من الوقوف إلى الاستلقاء | (فوينتس وآخرون، 2020) |

| الكذب على البطن | مستلقٍ مع الأطراف مطوية تحت الجسم | (ناسراهامدي وآخرون، 2019) |

| مستلقٍ على الجانب | استلقِ في وضعية ممددة بالكامل مع مد الأطراف | |

| (ناسراه مادي وآخرون، 2019) | ||

| الاستلقاء الجانبي | جانب جذع الخنزير ملامس للأرض | (الأمير وآخرون، 2020أ) |

| الاستلقاء على الصدر | صدر الخنزير / عظمة الصدر ملامس للأرض | (الأمير وآخرون، 2020أ) |

| الوقوف | وضعية الجسم المستقيمة على أرجل ممدودة مع وجود الحوافر فقط في | (Zheng وآخرون، |

| 2018)، (لو وآخرون، | ||

| الاتصال مع الأرض أو الساقين مستقيمتين وتدعمان | 2020)، (فوينتس وآخرون، | |

| حالة الوقوف أو الخنزير لديه أقدام (وربما أنف) في اتصال | 2020)، (عشور وآخرون. | |

| مع القلم الأرضي أو الأرجل تبقى عمودية بدون أخرى | 2020)، (العمر وآخرون. | |

| حركة شاقة أو وضع الجسم والأرجل الأربعة | 2020أ)، (وو وآخرون، | |

| لم يتغير OR الوضع قبل الركوع على الأرض | 2021)، (كياو وآخرون | |

| الوقوف | التحرك من الاستلقاء إلى الوقوف | (Fuentes وآخرون، 2020) |

| الجلوس | (Zheng وآخرون، 2018)، (Zhu وآخرون، 2020)، (Alameer وآخرون، 2020أ)، (Lu وآخرون، 2022) | |

| مرفوعة جزئيًا على الأرجل الأمامية الممدودة مع نهاية الجسم الذيلية تلامس الأرض أو فقط أقدام الأرجل الأمامية والجزء الخلفي/الأسفل من جسم الخنزير تلامس الأرض | ||

| الاستلقاء على الصدر | مستلقٍ على البطن/الصدر مع طي الأرجل الأمامية والخلفية تحت الجسم؛ الضرع مخفي تمامًا. | (Zheng وآخرون، 2018)، (Zhu وآخرون، 2020) |

| الاستلقاء البطني | مستلقٍ على البطن/الصدر مع الأرجل الأمامية مطوية تحت | (Zheng وآخرون. |

| الجسم والأرجل الخلفية الظاهرة (الجانب الأيمن، الجانب الأيسر)؛ الضرع هو | 2018)، (تشو وآخرون، | |

| مغطى جزئيًا | 2020)، (لو وآخرون، 2022) | |

| الاستلقاء الجانبي | مستلقٍ على أي جانب مع ظهور جميع الأرجل الأربعة (الجانب الأيمن، الجانب الأيسر) | (Zheng وآخرون، 2018) |

| الجانب)؛ الضرع مرئي تمامًا أو الجانب مستلقٍ على | (تشو وآخرون، 2020)، (لو | |

| الأرض، كتف واحد على الأرض، مع الأطراف ممدودة | ||

| نائم | الجلوس على الأرض والرأس على الأرض | (فوينتس وآخرون، 2020) |

| المشي | التحرك في وضع الوقوف أو رفع الرأس والمشي أو | (فوينتس وآخرون |

| تتحرك الأرجل بشكل متكرر وتختلف وضعية البقرة بشكل كبير أو | 2020)، (وو وآخرون. | |

| حركة لأكثر من 3 ثواني | 2021)، (كياو وآخرون. | |

| (يانغ وآخرون، 2020) | ||

| تحريك | التحرك دون القيام بأي شيء آخر | |

| ذيل متحرك | حركات الذيل | (Fuentes وآخرون، 2020) |

| رأس متحرك | حركات الرأس | (فوينتس وآخرون، 2020) |

| غير نشط | الجلوس، الاستلقاء، الركوع، أو الوقوف دون القيام بأي نشاط آخر | (يانغ وآخرون، 2020) |

| كسل | (فيرنانديز-كاريون وآخرون، 2020) | |

| قيم منخفضة في الحركة اليومية تتزامن مع قمم درجات حرارة مرتفعة | ||

| تفاعل التمريض | على الأقل نصف الخنازير الصغيرة تتلاعب بنشاط بالحلمة عندما تكون الخنزيرة مستلقية جانبياً، ومدة النشاط | (يانغ وآخرون، 2018)، (يانغ وآخرون، 2020) |

| تفاعل متزايد | يتجاوز 60 ثانية | (فوينتس وآخرون |

| البقرة تنحني على بقرة أخرى عادةً عندما تكون إحدى البقرتين في حالة حرارة. | 2021)، (كاوانو وآخرون، 2021)، (لو وآخرون، 2021) |

| فصول السلوك | وصف | مرجع |

| تفاعل الشرب | لمس حلمة الشرب بالخطم أو الخطم في اتصال مع حلمة الشرب، أو الوقوف بجانب خزان الماء وفمه في الخزان | (يانغ وآخرون، 2020)، (العمر وآخرون. |

| 2020أ)، (وو وآخرون. | ||

| نقر أو غير نقر | عندما ضربت الطيور الكرة المعدنية (الجسم المنقاري) بمنقارها | (ناصرهامدي وآخرون 2020) |

| عضة الذيل | عض ذيل زميل القلم، مع رد فعل مفاجئ من زميل القلم | (ترنر وآخرون، 2022) |

| عضة ذيل | بينميت يعض ذيل الموضوع ويثير رد فعل | (ترنر وآخرون، 2022) |

| غير مغذي / غير- | عندما يدخل خنزير منطقة التغذية على قدمين دون أن | (الأمير وآخرون |

| زيارات التغذية | 2020ب)، (يو وآخرون. | |

| تناول أي طعام أو عندما تكون البقرة في منطقة التغذية، ترفع رأسها بعيدًا عن منطقة التغذية للمضغ، والإجراء التالي إما أن تستمر في التغذية أو تترك منطقة التغذية | ||

| البحث | رأس منخفض ويمشي | (رحمن وآخرون 2016) |

| اللعق الاجتماعي | لعق جسم الآخر باللسان | (فوينتس وآخرون، 2020) |

| تجميل | (فوينتس وآخرون | |

| اللعق بجسمه باللسان أو الرأس مائل نحو البطن لتجميل الجسم باللسان | ||

| 2022) | ||

| استكشاف | الرأس قريب من الأرض أو على اتصال بها | (أوياو وآخرون، 2022) |

| التجسس الاجتماعي | الخنزير الصغير الذي يلمس أو يشم أي جزء من رأس أو أنف خنزير صغير آخر | |

| قتال | قتال شخصين أو أكثر أو قتال عنيف، دفع بالرأس، أو عض الأشقاء بشكل عنيف | (فوينتس وآخرون |

| 2020)، (غان وآخرون. | ||

| اللعب | الدفع أو الدفع الخفيف، اللعب، والقتال | (غان وآخرون 2022ب) |

| تمديد الرقبة | البطة التي تضع البيض تمد عنقها خارج القفص من خلف القفص | (Gu وآخرون، 2022) |

| داس | على الأقل، قدم واحدة من بطة تدوس على جسم البطة الأخرى | (Gu وآخرون، 2022) |

| نشر الأجنحة | أجنحة البط منتشرة من زاوية معينة لتكون مفتوحة بالكامل | (Gu وآخرون، 2022) |

| عرج | تقدير تردد المشي، مدة المشي والفترات غير المتعلقة بالمشي، والعرج أو سرعة المشي، وانحناء ظهورهم وخفض رؤوسهم أثناء المشي | (جارشي وآخرون، 2021)،(نوي وآخرون، 2022) |

| الرضاعة | إما الفم على الحلمة أو اتصال الأنف بالضرع مع حركات رأس عمودية وإيقاعية، تتكون من تدليك مسبق للضرع، وتناول/تدفق الحليب، وتدليك بعد ذلك أو إرضاع البقرة للعجل. | (غان وآخرون، 2022أ)، (فوينتس وآخرون، 2020) |

مرتبط بتناول الغذاء والرفاهية العامة للحيوانات. علاوة على ذلك، نظرًا لأن التغذية سلوك فردي، فإن الغالبية العظمى من الدراسات ركزت على التعرف عليها بدلاً من السلوكيات الجماعية المعقدة مثل التزاوج، والتفاعل الاجتماعي، والرضاعة.

3.2. جمع البيانات ونوع وكمية وجودة البيانات (RQ. 2)

كانت بيانات الحركة معلمة حاسمة. ومع ذلك، لم يتم العثور على تفسيرات ملموسة تتعلق بجودة وكمية البيانات. تم استخدام عدد مختلف من العينات، ونطاقات التردد، وأحجام الصور، ومعدل الإطارات في الثانية من قبل دراسات مختلفة حتى للتعرف على نفس نوع السلوك. بغض النظر عن ذلك، في هذه الدراسة المنهجية، تم تلخيص أدوات جمع البيانات، ونوع البيانات، وكمية البيانات، وجودة البيانات، إلى جانب نوع مشاكل التعرف على السلوك التي تم حلها، والنماذج والشبكات العميقة المبلغ عنها، وأدائها، وعدد الفئات المستخدمة، وتم تقديمها في الجدولين 5 و 6.

3.3. نماذج الشبكات العميقة للتعرف على سلوك الماشية (RQ. 3)

3.4. مقاييس الأداء والمنهجيات (RQ. 4)

ملخص لجمع البيانات، النوع، الكمية، والجودة.

| مرجع | نوع المشكلة | جمع البيانات | نوع البيانات | كمية البيانات | جودة البيانات | ||||

| (رحمن وآخرون 2016) | التغذية، الوضعية | طوق مثبت على العنق مزود بأجهزة استشعار، هوني ويل HMC6343 | إشارات مقياس التسارع | 8,62,500 عينة | معدل أخذ العينات 10 هرتز | ||||

| (Zheng وآخرون | وضعية | مستشعر مايكروسوفت كينكت v2 | صور RGB وعمق | 356,000 صورة |

|

||||

| (يانغ وآخرون. | التمريض | كاميرا هيكفيجن (DS-2CD1321D-I) | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 421,972 صورة |

|

||||

| (ناصرهامدي وآخرون، 2019) | وضعية | كاميرتان علوية (VIVOTEK IB836BAHF3، Hikvision DS-2CD2142FWD-I) | صور RGB | 4,900 صورة |

|

||||

| (لي وآخرون، 2019) | تركيب | جي-282C، نورنبيرغ | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 1,500 صورة |

|

||||

| (تشو وآخرون، 2020) | وضعية |

|

|

18,133 زوجًا من الصور |

|

||||

| (يانغ وآخرون 2020) | التغذية، الشرب، الرضاعة، الحركة | كاميرا هيكفيجن (DS-2CD1321D-I) | عصور | 630,000 صورة | 960 × 540 بكسل، 5 إطارات في الثانية | ||||

| (ناصرهامدي وآخرون، 2020) | نقر | ميكروفون (Monacor VB-120MIC) كاميرا (TosiNet Realtime 2K 4 MPPoE-IP-camera) | الإشارات الصوتية، الفيديوهات | 13,100 مقطع صوتي |

|

||||

| (ترنر وآخرون) | عض الذيل | 6 كاميرات IP (GV-BX 1300 KV ، Geovision Inc.، تايبيه، تايوان) | فيديوهات، صور RGB | فيديو مدته 8 ساعات (247 حدثًا لعض الذيل تستمر) |

|

||||

| (الأمير وآخرون | التغذية، البحث عن الطعام | صور RGB وصور تدرج الرمادي | 42,778 صورة | 640 × 360 بكسل، 25 إطار في الثانية | |||||

| 2020ب) | كاميرتان (مايكروسوفت كينكت لجهاز إكس بوكس ون، مايكروسوفت، ريدموند، واشنطن، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) | ||||||||

| (تشن وآخرون 2020أ) | إطعام | كاميرا أمان قبة خارجية بالأشعة تحت الحمراء (CTPTLVA29AV، كانتيك) | فيديوهات |

|

|

||||

| (أشور وآخرون | إطعام | نموذج Raspberry Pi 3 | فيديوهات، صور RGB |

|

|||||

| 2020) | ب متصل بكاميرا ويب USB (كاميرا ويب يوداني USB (يود | 19 ساعة، 25,352 صورة (4 مجموعات بيانات) | |||||||

| (الأمير وآخرون | الوضعية، الشرب | كاميرا (مايكروسوفت) | فيديوهات، RGB im- | 11,3379 صورة | |||||

| 2020أ) | كينكت لجهاز إكس بوكس ون، مايكروسوفت، ريدموند، واشنطن، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية | عصور | |||||||

| (فوينتس وآخرون 2020) | الوضعية، التغذية، الاجتماعية، التزاوج | كاميرات | فيديوهات، RGB وتدفق بصري im- | 350 فيديو، كل واحد 12 دقيقة |

|

||||

| (ين وآخرون، 2020) | حركة | الكاميرات (SONY HDRCX290 ونظام كاميرات المراقبة الشبكية YW7100HR09-SC62-TA12) |

|

1,009 فيديو، 90 ثانية لكل منها، 2,270,250 صورة | 512 × 512 بكسل، 25 إطار في الثانية | ||||

| (بوجاج وآخرون 2020) | التغذية، الحركة | مجموعات البيانات العامة | إشارات مقياس التسارع | مجموعتان بيانات 87621 عينة، 6 مواضيع (حصان) 86557 عينة، 5 مواضيع (ماعز) | معدل أخذ العينات 12 هرتز معدل أخذ العينات 100 هرتز | ||||

| كارريون وآخرون 2020 | حركة | كاميرات القبة الثابتة | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 1,000 صورة | 640 × 360 بكسل، 6 إطارات في الثانية | ||||

| عرج | جهاز قابل للارتداء يعتمد على المتحكم الدقيق Intel QuarkSE C1000 ويجمع بين مستشعر Bosch BMI160 (Boschsensortec.com، 2016) | إشارات مقياس التسارع | 2,04,999 عينة | معدل أخذ العينات 16 هرتز | |||||

| مرجع | نوع المشكلة | جمع البيانات | نوع البيانات | كمية البيانات | جودة البيانات | ||

| (وو وآخرون، 2021) | الوضعية، الشرب، الحركة |

|

فيديوهات، صور RGB | 4566 فيديو، 63

|

224 × 224 بكسل، 25 إطار في الثانية | ||

| (تشن وآخرون 2020ب) | التغذية، الشرب | كاميرا عين السمكة بزاوية واسعة | فيديوهات، صور RGB وصور تدرج الرمادي | يوم واحد |

|

||

| (نونس وآخرون 2021) | التجميع | كاميرا ميكرو LK-SC100B (LKSUMPT، شنتشن، الصين) | صوت، فيديو |

|

|

||

| (نو وآخرون، 2021) | تركيب | كاميرات | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 15 فيديو، 2000 صورة |

|

||

| (يانغ وآخرون. | تركيب | كاميرا شبكة الأشعة تحت الحمراء هايكينغ (DS-2CD3345-I، هيكفيجن، هانغتشو، الصين) | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 1,000 صورة |

|

||

| (كاوانو وآخرون 2021) | تركيب | كاميرات | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 12 ساعة، 5,020 صورة |

|

||

| (حسينينوربين وآخرون، 2021) | التغذية، الحركة | علامات الطوق، مستشعر IMU | إشارات مقياس التسارع |

|

معدل أخذ العينات 50 هرتز | ||

| (وانغ وآخرون 2021) | التجميع | طوق مع ميكروفون 9750 من توين ستار | صوت، فيديو | 21,924 عينة |

|

||

| (لي وآخرون، 2021) | التغذية، الحركة | مجموعة بيانات عامة | إشارات مقياس التسارع | 5,30,485 عينة | معدل | ||

| (نجوين وآخرون | الشرب | ثلاث كاميرات (جوبرو 5 بلاك) | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 1,715 فيديو، 64 ساعة | 256 × 256 بكسل | ||

| (لو وآخرون، 2021) | الوضعية، التركيب | كاميرا الأشعة تحت الحمراء | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 22,509 صورة |

|

||

| (Xu وآخرون، 2021) | التغذية، الاجتماعية | 5 كاميرات برجية (MR832، 1080p) | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 108 صورة | 1280 × 720 بكسل، 15 إطار في الثانية | ||

| (تشياو وآخرون) | جاء IP المدمج DS-2DM1-714 | فيديوهات، RGB im- |

|

||||

| 2022) | كاميرا IP مدمجة (هيكفيجن، هانغتشو، الصين) |

|

|||||

| (دين وآخرون | الرضاعة | كاميرا (DS-2CD3346WD- | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 5,000 صورة | 640 × 640 بكسل، 24 إطار في الثانية | ||

| 2022) | أنا، هيكفيجن، هانغتشو، الصين | ||||||

| (ما وآخرون، 2022) | حركة | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 224 × 224 بكسل، 25 إطار في الثانية | ||||

| الكاميرات (شنتشن، شركة ييوي رويتشانغ للتكنولوجيا المحدودة، YW7100HR09-SC62- TA12 | 406 فيديو، كل واحد من 15-30 ثانية، 256,500 صورة | ||||||

| (Gu وآخرون، 2022) | طوارئ | كاميرا | صور RGB | 5,560 صورة |

|

||

| (غان وآخرون، | اجتماعي | كاميرا (DS- | فيديوهات | 100 فيديو، 30 |

|

||

| 2022ب) | 2CD1321D-I، هيكفيجن، هانغتشو، الصين | ثانية لكل | بكسل، 5 إطارات في الثانية | ||||

| (نو وآخرون، 2022) | عرج | كاميرا | صور RGB | 2,000 صورة |

|

||

| (ترنر وآخرون | الوضعية، الحركة | مثبت على الفك | مقياس التسارع | مجموعتان من البيانات | |||

| 2022) | إطعام | أجهزة استشعار أكتيفغراف (أكتيفغراف، بنساكولا، فلوريدا، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) وأجهزة استشعار النشاط المثبتة على الأذن (أكسيتي في المحدودة، نيوكاسل، المملكة المتحدة) | إشارات | 29,179 و 2,54,087 عينة |

|

||

| (شينغ وآخرون، 2022) | الوضعية، التغذية | مجموعة بيانات عامة، مجموعة بيانات مخصصة مسجلة بواسطة الكاميرا | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 61 فيديو، 4,360 صورة |

|

||

| (يو وآخرون، 2022) | إطعام | كاميرتان عمق ZED2 (STEREOLABS) | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 80 فيديو، 10,288 صورة |

|

||

| (تشن وآخرون) | الوضعية، الشرب | الكاميرات (HIKVISION، هانغتشو، الصين) | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 12 يوم، 100 ساعة | 1920 × 1080، 12 | ||

| (لو وآخرون | وضعية | كاميرا | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 2,310 صورة |

|

||

| (غان وآخرون 2022أ) | الرضاعة | الكاميرات (IPX DDK1700D، الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية) | فيديوهات | 100 فيديو، 60 ثانية لكل واحد و8 ساعات |

|

||

| أوهودا، 2021) | التجميع، الحركة | 4 كاميرات | فيديوهات، صور RGB | 3 أيام، 1,093 صورة |

|

||

| (جيانغ وآخرون. | الوضعية، الشرب | كاميرا EZVIZ (HIKVI- | فيديوهات، RGB im- | 2,000 صورة |

|

||

| جميع روهان وآخرون: مسودة مقدمة إلى إلسفير | الصفحة 13 من 24 |

ملخص لنماذج الشبكات العميقة وعدد الفئات وأدائها

| مرجع | نوع المشكلة | نماذج التعلم العميق | الشبكات | كائنات فئات المرشحين | أداء | |

| (رحمن وآخرون 2016) | التغذية، الوضعية، الحركة | SAE | مصنوع حسب الطلب | غير متوفر | 9 | الدقة المتوسطة: 62% |

| (لينغ وآخرون. | وضعية | فاستر آر-سي إن إن | ZFNet | RPN | ٥ | الدقة: |

| 2018) | ||||||

| وآخرون | التمريض | FCN | VGG16 | غير متوفر | ٢ | الدقة: 96.8% |

| يانغ (ناصرهمدي | وضعية | Faster R-CNN، R-FCN، SSD | إنسيبشن V2، ريزنت50 | غير متوفر | ٣ | mAP: 91% باستخدام Faster R-CNN و Inception V2 |

| (لي وآخرون، 2019) | تركيب | ماسک آر-سيانان | ResNet101 ResNet50، ResNet101 | RPN | ٢ | الدقة: 91.47% |

| (تشو وآخرون، 2020) | وضعية | فاستر آر-سي إن إن | ZFNet | RPN | ٥ | الدقة المتوسطة: |

| (يانغ وآخرون. | FCN | غير متوفر | ٦ | |||

| 2020) | التغذية، الشرب، الرضاعة، الحركة | أليكس نت، في جي جي 16، جوجل نت | الدقة: 97.49% (الشرب)، 95.36% (التغذية)، و88.09% (الرضاعة) | |||

| (ناصرهامدي وآخرون، 2020) | نقر | سي إن إن | مصنوع حسب الطلب | غير متوفر | ٢ | الدقة: 96.8% |

| (ترنر وآخرون 2022) | عض الذيل | SSD، CNNLSTM | VGG16، ResNet50 | غير متوفر | ٢ | الدقة: 96.35% باستخدام |

| (الأمير وآخرون 2020ب) | التغذية، البحث عن الطعام | سي إن إن | غوغل نت، سك غوغل نت | غير متوفر | ٧ | دقة ResNet-50:

|

| (تشن وآخرون | إطعام | سي إن إن – إل إس تي إم | إكسبشن | غير متوفر | 2 | الدقة: 98.4% |

| (آشور وآخرون | إطعام | 4 نماذج CNN | إكسبشن | غير متوفر | ٢، ٢، ٦ | الدقة: |

| 2020) | 17 | 92.61% | ||||

| (الأمير وآخرون 2020أ) | وضعية | Faster R-CNN، YOLO | ريسنت-50 | RPN | ٥ | mAP: 98.9% |

| (فوينتس وآخرون 2020) | الوضعية، التغذية، الاجتماعية، التزاوج | Faster R-CNN، YOLOv3 | VGG16، Darknet53 | غير متوفر | 15 | mAp: 85.6% باستخدام سابتيوا- |

| تحليل زمني (YOLOv3) | ||||||

| (ين وآخرون، 2020) | حركة | سي إن إن – إل إس تي إم | EfficientNet، VGG16، ResNet50، DenseNet169 مصممة خصيصًا | بي إف بي إن | ٥ | الدقة: 97.87% |

| (بوجاج وآخرون | التغذية، الحركة | سي إن إن | غير متوفر | ٦، ٥ | الدقة: | |

| 2020) (فرناندز- | 97.42% | |||||

| حركة | سي إن إن | أليكس نت | غير متوفر | 2 | ||

| كارريون وآخرون | ||||||

| (جارشي وآخرون | عرج | LSTM | مصنوع حسب الطلب | غير متوفر | ٤ | الدقة: |

| 96.73% | ||||||

| (Wuet وآخرون، 2021) | الوضعية، الشرب، الحركة | سي إن إن – إل إس تي إم، بي آي إل إس تي إم | VGG16، VGG19، ResNet18، ResNet101، MobileNetV2، DenseNet201 | غير متوفر | ٥ | |

| (Chen وآخرون 2020ب) | التغذية، الشرب | ماسک آر-سيانان | مصنوع حسب الطلب | FPN | ٣ | mAP: 89.1% |

| مرجع | نوع المشكلة | نماذج التعلم العميق | الشبكات | كائنات فئات المرشحين | أداء | |

| (نونس وآخرون | التجميع | LSTM | مصنوع حسب الطلب | غير متوفر | ٢ | mAP: 86.42% |

| 2021) | تركيب | سي إن إن | VGG16 | غير متوفر | 2 | الدقة: 98% |

| (يانغ وآخرون. | تركيب | Faster R-CNN | ريسنت 50 | RPN | ٢ | الدقة: |

| 2021) | 95.15% | |||||

| (كاوانو وآخرون | تركيب | سي إن إن | ريسنت 50 | غير متوفر | ٤ | mAP: 80.02% |

| حسين نوربين وآخرون، 2021 | التغذية، الحركة، الشرب | DNN | مصنوع حسب الطلب | غير متوفر | 9 | درجة F1: 89.3% |

| (وانغ وآخرون 2021) | التجميع | سي إن إن آر إن إن | مصنوع حسب الطلب | غير متوفر | ٥ | 93.17% استخدام |

| (لي وآخرون، 2021) | التغذية، الحركة | سي إن إن | مصنوع حسب الطلب | غير متوفر | ٥ | RNN mAP: 95.4% دقة:

|

| (نجوين وآخرون | الشرب | RCNN، TSN | مصنوع حسب الطلب | غير متوفر | ٣ | |

| 2021) | ||||||

| (لو وآخرون، 2021) | الوضعية، التركيب | Faster R-CNN، YOLOv3، YOLOv5 | ResNet50، Darknet53، CSPDarknet53، MobileNetV3، | FPN | ٥ | mAP: 92.04% (YOLOv5) |

| وضعية | ماسک آر-سيانان | RPN | ٢ | mAP: 94% | ||

| (شو وآخرون، 2021) (تشياو وآخرون. | حركة | C3D- | C3DLSTM، RNN، Inception | غير متوفر | ٥ | الدقة:

|

| 2022) | الرضاعة | FD-CNN، YOLOv5 | CSPDarknet53 | FPN | ٣ | الدقة: 93.6% |

| حركة | سي إن إن (ريكسنت 3D) | ResNet101، MobileNetV2، MobileNetV3، ShuffleNetV2، C3D | غير متوفر | ٣ | الدقة: 95% | |

| (Gu وآخرون، 2022) | طوارئ | Faster R-CNN، YOLOv5، YOLOv4 | CSPDarknet53 | FPN | ٣ | الدقة المتوسطة: 95.5% (YOLOv5) |

| 2022ب) | اجتماعي | DHRN، STAGCN | مصنوع حسب الطلب | غير متوفر | 2 | الدقة: 94.21% |

| (نو وآخرون، 2022) | عرج | ماسک آر-سيانان | ريسنت101 | غير متوفر | 2 | الدقة: 95.5% |

| (ترنر وآخرون | الوضعية، الحركة | بي إل إس تي إم | مصنوع حسب الطلب | غير متوفر | 9 | الدقة: 61.7% باستخدام BiLSTM |

| (شانغ وآخرون. | الوضعية، الحركة | سي إن إن، يو لو 4 | غير متوفر | ٧، ٤ | دقة 95.17% باستخدام | |

| شوفلننت V2، موبايل نت V2، ريز نت 18، جوجل نت، موبايل نت V3 | ||||||

| (يو وآخرون، 2022) | إطعام | دي آر إن – يولو | دي آر نت | غير متوفر | ٣ | mAP: 96.91% |

|

وضعية | يو لو في 5 | CSPDarknet53 | FPN | ٤ | mAP: 97.4% |

| 2022) | إطعام | |||||

| (لو وآخرون، 2022) | يو لو 4 | ESCMobileNetV3 | غير متوفر | ٤ | الدقة: | |

| (غان وآخرون | الرضاعة | سي إن إن | ريسنت101 | FPN | 2 | 96.83% |

| (أوشينو وأوهوا، 2021) | التجميع، الحركة، الشرب | يو لو في 5 | CSPDarknet53 | FPN | ٥ | الدقة: 95.2% |

| (جيانغ وآخرون 2020) | الوضعية، الشرب، التغذية، الحركة | يو لو 4 | الدارك نت | غير متوفر | ٤ | الدقة: 97.48% |

3.5. نماذج الشبكات العميقة الفعالة (RQ. 5)

أكثر نماذج وشبكات التعلم العميق فعالية بناءً على مشاكل التعرف على السلوك مع الدقة كمقياس للأداء.

| نوع السلوك | نموذج | شبكة | الدقة (%) |

| الشرب | سي إن إن إل إس تي إم | في جي جي 16 | 98 |

| إطعام | سي إن إن | غوغل نت | 99.4 |

| التجميع | سي إن إن | جوجل نت | 99.4 |

| عرج | LSTM | مخصص | ٩٦.٧٣ |

| حركة | سي إن إن إل إس تي إم | VGG16 | 98 |

| تركيب | سي إن إن | VGG16 | 98 |

| التمريض | FCN | في جي جي 16 | 96.8 |

| نقر | سي إن إن | مخصص | 96.8 |

| وضعية | سي إن إن إل إس تي إم | VGG16 | 98 |

| اجتماعي | C3DConvLSTM | مخصص | 90.32 |

| عض الذيل | سي إن إن إل إس تي إم | ريسنت-50 | ٩٦.٣٥ |

3.6. التحديات (RQ. 6)

أكثر نماذج وشبكات التعلم العميق فعالية بناءً على مشاكل التعرف على السلوك مع الدقة كمقياس للأداء.

| نوع السلوك | نموذج | شبكة | الدقة (%) |

| الشرب | يو لو في 5 | CSPDarknet53 95.2 | |

| طوارئ | يو لو في 5 | CSPDarknet53 95.5 | |

| التجميع | يو لو في 5 | CSPDarknet53 95.2 | |

| حركة | يو لو 5 | CSPDarknet53 95.2 | |

| وضعية | فاستر آر-سي إن إن | ZFNet | 95.47 |

| اجتماعي | ستاجكن | مخصص | ٩٤.٢١ |

| الرضاعة | سي إن إن | ريسنت101 | 95.2 |

أكثر نماذج وشبكات التعلم العميق فعالية بناءً على مشاكل التعرف على السلوك مع متوسط الدقة كمعيار للأداء.

| نوع السلوك | نموذج | شبكة | معدل الدقة المتوسطة (%) |

| الشرب | يولو | ريزنت-50 | 98.9 |

| إطعام | يو لو في 5 | CSPDarknet53 | 97.4 |

| التجميع | LSTM | مخصص | ٨٦.٤٢ |

| حركة | سي إن إن | مخصص | 95.4 |

| تركيب | يو لو 5 | CSPDarknet53 | 92.04 |

| وضعية | أسرع | ريسنت-50 | 98.9 |

| آر-سي إن إن | |||

| اجتماعي | يو لو v3 | دارك نت 53 | 85.6 |

البيئة في هذه المزارع غالبًا ما تخلق خلفيات معقدة في الصورة بسبب تأثير مصابيح الحرارة، وبقع الماء والبول، والسماد، وحالة الأرضية المعقدة. بيئة المزرعة متغيرة، وهناك أصوات خلفية غير متوقعة جزئيًا. تجعل التدخلات من الوضعيات والبيئة، والمساحة الواسعة، ووجود عدد كبير من الحيوانات تطبيق التعلم العميق تحديًا كبيرًا. تحدٍ آخر مهم تم الإبلاغ عنه من قبل

4. المناقشة

لتطوير نماذج DL، سيكون من المهم أيضًا أنه حيثما كان ذلك ممكنًا، يتم مشاركة البيانات المستخدمة في الدراسات مع الوصول المفتوح للجمهور لاختبار طرق أخرى محتملة ولإعادة إنتاج النتائج.

5. الخاتمة

النماذج. تم الإبلاغ أيضًا عن أن الأساليب غير التلامسية لها مزايا كبيرة على الأساليب المعتمدة على التلامس. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، قامت بعض النماذج، مثل C3D Conv-LSTM، بدمج ميزات المجال الزمني بالإضافة إلى ميزات المجال المكاني. أظهرت الأبحاث الحديثة حول التعرف على أفعال الإنسان، التي تعتبر أكثر تقدمًا من التعرف على سلوك الماشية، أن التحليل الزمني المكاني، الذي يأخذ في الاعتبار الميزات المكانية والزمنية في الصورة، يمكن أن يسفر عن نتائج واعدة. قد يكون هذا اتجاهًا بحثيًا مثيرًا لتطوير نماذج تعلم عميق أكثر استدامة للتعرف على سلوك الماشية. أخيرًا، تقتصر هذه الدراسة على الأعمال المنشورة بين عامي 2012 وأكتوبر 2022. تم اختيار المقالات من أهم قواعد البيانات البحثية باستخدام المعايير الموضحة في هذه الدراسة؛ لم يتم تضمين المقالات من قواعد بيانات أخرى في هذه المراجعة.

تعارض المصالح

شكر وتقدير

إعلان عن الذكاء الاصطناعي التوليدي والتقنيات المدعومة بالذكاء الاصطناعي في عملية الكتابة

بيان مساهمة تأليف CRediT

References

Alameer, A., Kyriazakis, I., Bacardit, J., 2020a. Automated recognition of postures and drinking behaviour for the detection of compromised health in pigs. Scientific reports 10, 13665 .

Alameer, A., Kyriazakis, I., Dalton, H.A., Miller, A.L., Bacardit, J., 2020b. Automatic recognition of feeding and foraging behaviour in pigs using deep learning. Biosystems engineering 197, 91-104.

Atkinson, G.A., Smith, L.N., Smith, M.L., Reynolds, C.K., Humphries, D.J., Moorby, J.M., Leemans, D.K., Kingston-Smith, A.H., 2020. A computer vision approach to improving cattle digestive health by the monitoring of faecal samples. Scientific Reports 10, 17557.

Bareille, N., Beaudeau, F., Billon, S., Robert, A., Faverdin, P., 2003. Effects of health disorders on feed intake and milk production in dairy cows. Livestock production science 83, 53-62.

Bocaj, E., Uzunidis, D., Kasnesis, P., Patrikakis, C.Z., 2020. On the benefits of deep convolutional neural networks on animal activity recognition, in: 2020 International Conference on Smart Systems and Technologies (SST), IEEE. pp. 83-88.

Chen, C., Zhu, W., Steibel, J., Siegford, J., Han, J., Norton, T., 2020a. Recognition of feeding behaviour of pigs and determination of feeding time of each pig by a video-based deep learning method. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 176, 105642.

Chen, Y.R., Ni, C.T., Ng, K.S., Hsu, C.L., Chang, S.C., Hsu, C.B., Chen, P.Y., 2020b. An ai-based system for monitoring behavior and growth of pigs, in: 2020 International Computer Symposium (ICS), IEEE. pp. 91-95.

Cheng, M., Yuan, H., Wang, Q., Cai, Z., Liu, Y., Zhang, Y., 2022. Application of deep learning in sheep behaviors recognition and influence analysis of training data characteristics on the recognition effect. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 198, 107010.

Chidgey, K.L., Morel, P.C., Stafford, K.J., Barugh, I.W., 2015. Sow and piglet productivity and sow reproductive performance in farrowing pens with temporary crating or farrowing crates on a commercial new zealand pig farm. Livestock Science 173, 87-94.

Chilukuri, D.M., Yi, S., Seong, Y., 2022. A robust object detection system with occlusion handling for mobile devices. Computational Intelligence 38, 1338-1364. URL: https://onlinelibrary.

wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/coin.12511 doihttps:// doi.org/10.1111/coin. 12511

Cohen, J., 1968. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychological bulletin 70, 213.

Ding, Q.a., Chen, J., Shen, M.x., Liu, L.s., 2022. Activity detection of suckling piglets based on motion area analysis using frame differences in combination with convolution neural network. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 194, 106741.

Fernández-Carrión, E., Barasona, J.Á., Sánchez, Á., Jurado, C., CadenasFernández, E., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M., 2020. Computer vision applied to detect lethargy through animal motion monitoring: a trial on african swine fever in wild boar. Animals 10, 2241.

Flower, F., De Passillé, A., Weary, D., Sanderson, D., Rushen, J., 2007. Softer, higher-friction flooring improves gait of cows with and without sole ulcers. Journal of dairy science 90, 1235-1242.

Flower, F., Sanderson, D., Weary, D., 2005. Hoof pathologies influence kinematic measures of dairy cow gait. Journal of dairy science 88, 3166-3173.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2022, . The State of Food and Agriculture 2022: Leveraging agricultural automation for transforming agrifood systems. Number 2022 in The State of Food and Agriculture (SOFA), FAO. URL: https://www. fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cb9479en doi10.4060/ cb9479en

Fuentes, A., Yoon, S., Park, J., Park, D.S., 2020. Deep learning-based hierarchical cattle behavior recognition with spatio-temporal information. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 177, 105627.

Gan, H., Ou, M., Li, C., Wang, X., Guo, J., Mao, A., Ceballos, M.C., Parsons, T.D., Liu, K., Xue, Y., 2022a. Automated detection and analysis of piglet suckling behaviour using high-accuracy amodal instance segmentation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 199, 107162.

Gan, H., Xu, C., Hou, W., Guo, J., Liu, K., Xue, Y., 2022b. Spatiotemporal graph convolutional network for automated detection and analysis of social behaviours among pre-weaning piglets. Biosystems Engineering 217, 102-114.

Garcia, R., Aguilar, J., Toro, M., Pinto, A., Rodriguez, P., 2020. A systematic literature review on the use of machine learning in precision livestock farming. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 179, 105826.

Grace, D., 2019. Infectious diseases and agriculture, 439-447URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/

PMC7161382/ doi 10.1016/B978-0-08-100596-5. 21570-9

Gu, Y., Wang, S., Yan, Y., Tang, S., Zhao, S., 2022. Identification and analysis of emergency behavior of cage-reared laying ducks based on yolov5. Agriculture 12, 485.

Hosseininoorbin, S., Layeghy, S., Kusy, B., Jurdak, R., Bishop-Hurley, G.J., Greenwood, P.L., Portmann, M., 2021. Deep learning-based cattle behaviour classification using joint time-frequency data representation. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 187, 106241.

Hu, H., Dai, B., Shen, W., Wei, X., Sun, J., Li, R., Zhang, Y., 2020. Cow identification based on fusion of deep parts features. Biosystems engineering 192, 245-256.

Jarchi, D., Kaler, J., Sanei, S., 2021. Lameness detection in cows using hierarchical deep learning and synchrosqueezed wavelet transform. IEEE Sensors Journal 21, 9349-9358.

Jiang, M., Rao, Y., Zhang, J., Shen, Y., 2020. Automatic behavior recognition of group-housed goats using deep learning. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 177, 105706.

Kawano, Y., Saito, S., Nakano, T., Kondo, I., Yamazaki, R., Kusaka, H., Sakaguchi, M., Ogawa, T., 2021. Toward building a data-driven system for detecting mounting actions of black beef cattle, in: 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), IEEE. pp. 4458-4464.

Kitchenham, B., Brereton, O.P., Budgen, D., Turner, M., Bailey, J., Linkman, S., 2009. Systematic literature reviews in software

engineering-a systematic literature review. Information and software technology 51, 7-15.

Kitchenham, B.A., Charters, S., 2007. Guidelines for performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. Technical Report EBSE 2007-001. Keele University and Durham University Joint Report. URL: https://www.elsevier.com/_data/promis misc/525444systematicreviewsguide.pdf

Kong, Y., Fu, Y., 2022. Human action recognition and prediction: A survey. International Journal of Computer Vision 130, 1366-1401.

Laradji, I., Rodriguez, P., Kalaitzis, F., Vazquez, D., Young, R., Davey, E., Lacoste, A., 2020. Counting cows: Tracking illegal cattle ranching from high-resolution satellite imagery. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.07369 .

Li, C., Tokgoz, K.K., Fukawa, M., Bartels, J., Ohashi, T., Takeda, K.i., Ito, H., 2021. Data augmentation for inertial sensor data in cnns for cattle behavior classification. IEEE Sensors Letters 5, 1-4.

Li, D., Chen, Y., Zhang, K., Li, Z., 2019. Mounting behaviour recognition for pigs based on deep learning. Sensors 19, 4924.

Liu, D., Oczak, M., Maschat, K., Baumgartner, J., Pletzer, B., He, D., Norton, T., 2020. A computer vision-based method for spatialtemporal action recognition of tail-biting behaviour in group-housed pigs. Biosystems Engineering 195, 27-41.

Lovarelli, D., Bacenetti, J., Guarino, M., 2020. A review on dairy cattle farming: Is precision livestock farming the compromise for an environmental, economic and social sustainable production? Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 121409.

Lu, L., Mao, L., Wang, J., Gong, W., 2022. Reserve sow pose recognition based on improved yolov4, in: 2022 IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Image Processing, Electronics and Computers (IPEC), IEEE. pp. 15381546.

Ma, S., Zhang, Q., Li, T., Song, H., 2022. Basic motion behavior recognition of single dairy cow based on improved rexnet 3d network. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 194, 106772.

Mahmud, M.S., Zahid, A., Das, A.K., Muzammil, M., Khan, M.U., 2021. A systematic literature review on deep learning applications for precision cattle farming. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 187, 106313.

Nasirahmadi, A., Edwards, S.A., Sturm, B., 2017. Implementation of machine vision for detecting behaviour of cattle and pigs. Livestock Science 202, 25-38.

Nasirahmadi, A., Gonzalez, J., Sturm, B., Hensel, O., Knierim, U., 2020. Pecking activity detection in group-housed turkeys using acoustic data and a deep learning technique. Biosystems engineering 194, 40-48.

Nasirahmadi, A., Sturm, B., Edwards, S., Jeppsson, K.H., Olsson, A.C., Müller, S., Hensel, O., 2019. Deep learning and machine vision approaches for posture detection of individual pigs. Sensors 19, 3738.

Ng, X.L., Ong, K.E., Zheng, Q., Ni, Y., Yeo, S.Y., Liu, J., 2022. Animal kingdom: A large and diverse dataset for animal behavior understanding, in: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 19023-19034.

Nguyen, C., Wang, D., Von Richter, K., Valencia, P., Alvarenga, F.A., Bishop-Hurley, G., 2021. Video-based cattle identification and action recognition, in: 2021 Digital Image Computing: Techniques and Applications (DICTA), IEEE. pp. 01-05.

Noe, S.M., Zin, T.T., Tin, P., Kobayashi, I., 2021. Automatic detection of mounting behavior in cattle using semantic segmentation and classification, in: 2021 IEEE 3rd Global Conference on Life Sciences and Technologies (LifeTech), IEEE. pp. 227-228.

Noe, S.M., Zin, T.T., Tin, P., Kobayashi, I., 2022. A deep learningbased solution to cattle region extraction for lameness detection, in: 2022 IEEE 4th Global Conference on Life Sciences and Technologies (LifeTech), IEEE. pp. 572-573.

Nowodziński, P., 2021. Sustainability challenges URL: https:// startsmartcee.org/sustainability-challenges/

Nunes, L., Ampatzidis, Y., Costa, L., Wallau, M., 2021. Horse foraging behavior detection using sound recognition techniques and artificial intelligence. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 183, 106080.

Qiao, Y., Guo, Y., Yu, K., He, D., 2022. C3d-convlstm based cow behaviour classification using video data for precision livestock farming. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 193, 106650.

Qiao, Y., Su, D., Kong, H., Sukkarieh, S., Lomax, S., Clark, C., 2020. Bilstm-based individual cattle identification for automated precision livestock farming, in: 2020 IEEE 16th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), IEEE. pp. 967-972.

Rahman, A., Smith, D., Hills, J., Bishop-Hurley, G., Henry, D., Rawnsley, R., 2016. A comparison of autoencoder and statistical features for cattle behaviour classification, in: 2016 international joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN), IEEE. pp. 2954-2960.

Santoni, M.M., Sensuse, D.I., Arymurthy, A.M., Fanany, M.I., 2015. Cattle race classification using gray level co-occurrence matrix convolutional neural networks. Procedia Computer Science 59, 493-502.

Shang, C., Wu, F., Wang, M., Gao, Q., 2022. Cattle behavior recognition based on feature fusion under a dual attention mechanism. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 85, 103524.

Shankar, B., Madhusudhan, H., DB, H., 2009. Pre-weaning mortality in pig-causes and management. Veterinary world 2.

Slob, N., Catal, C., Kassahun, A., 2021. Application of machine learning to improve dairy farm management: A systematic literature review. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 187, 105237.

Tabak, M.A., Norouzzadeh, M.S., Wolfson, D.W., Sweeney, S.J., VerCauteren, K.C., Snow, N.P., Halseth, J.M., Di Salvo, P.A., Lewis, J.S., White, M.D., et al., 2019. Machine learning to classify animal species in camera trap images: Applications in ecology. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 10, 585-590.

Thorup, V.M., Nielsen, B.L., Robert, P.E., Giger-Reverdin, S., Konka, J., Michie, C., Friggens, N.C., 2016. Lameness affects cow feeding but not rumination behavior as characterized from sensor data. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 3. URL: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ fvets. 2016.00037 doi 10.3389 / fvets. 2016.00037

Turner, K.E., Thompson, A., Harris, I., Ferguson, M., Sohel, F., 2022. Deep learning based classification of sheep behaviour from accelerometer data with imbalance. Information Processing in Agriculture URL: https://www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S2214317322000415. doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inpa.2022.04.001

Uchino, T., Ohwada, H., 2021. Individual identification model and method for estimating social rank among herd of dairy cows using yolov5, in: 2021 IEEE 20th International Conference on Cognitive Informatics & Cognitive Computing (ICCI* CC), IEEE. pp. 235-241.

Wang, K., Wu, P., Cui, H., Xuan, C., Su, H., 2021. Identification and classification for sheep foraging behavior based on acoustic signal and deep learning. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 187, 106275. URL: https://www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S0168169921002921.

doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106275

Wu, D., Wang, Y., Han, M., Song, L., Shang, Y., Zhang, X., Song, H., 2021. Using a cnn-lstm for basic behaviors detection of a single dairy cow in a complex environment. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 182, 106016. URL: https: / /www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S016816992100034X.

doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106016

Xu, B., Wang, W., Guo, L., Chen, G., Li, Y., Cao, Z., Wu, S., 2022. Cattlefacenet: A cattle face identification approach based on retinaface and arcface loss. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 193, 106675. URL: https: //www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S016816992100692X doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106675

Xu, J., Wu, Q., Zhang, J., Tait, A., 2021. Automatic sheep behaviour analysis using mask r-cnn, in: 2021 Digital Image Computing: Techniques and Applications (DICTA), pp. 01-06. doi 10.1109 /DICTA52665. 2021.9647101

Yang, A., Huang, H., Zhu, X., Yang, X., Chen, P., Li, S., Xue, Y., 2018. Automatic recognition of sow nursing behaviour using deep learning-based segmentation and spatial and temporal features. Biosystems Engineering 175, 133-145. URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/ pii/S1537511018304641 doi https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.biosystemseng.2018.09.011

Yang, Q., Xiao, D., Cai, J., 2021. Pig mounting behaviour recognition based on video spatial-temporal features. Biosystems Engineering 206, 55-66. URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/pii/S1537511021000726 doi https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2021.03.011

Yao, L., Hu, Z., Liu, C., Liu, H., Kuang, Y., Gao, Y., 2019. Cow face detection and recognition based on automatic feature extraction algorithm, in: Proceedings of the ACM Turing Celebration Conference – China, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA. URL: https: / /doi.org/10.1145/3321408. 3322628 doi

Yin, X., Wu, D., Shang, Y., Jiang, B., Song, H., 2020. Using an efficientnet-lstm for the recognition of single cow’s motion behaviours in a complicated environment. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 177, 105707. URL: https: / /www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S0168169920315386 doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105707

Yu, Z., Liu, Y., Yu, S., Wang, R., Song, Z., Yan, Y., Li, F., Wang, Z., Tian, F., 2022. Automatic detection method of dairy cow feeding behaviour based on yolo improved model and edge computing. Sensors 22. URL: https: //www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/22/9/3271 doi 10.3390 /s22093271

Zheng, C., Zhu, X., Yang, X., Wang, L., Tu, S., Xue, Y., 2018. Automatic recognition of lactating sow postures from depth images by deep learning detector. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 147, 51-63. URL: https://www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S0168169917309985 doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2018.01.023

Zhu, X., Chen, C., Zheng, B., Yang, X., Gan, H., Zheng, C., Yang, A., Mao, L., Xue, Y., 2020. Automatic recognition of lactating sow postures by refined two-stream rgb-d faster r-cnn. Biosystems Engineering 189, 116-132. URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/pii/S153751101930892X doihttps: //doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2019.11.013

- *Corresponding authors at National Subsea Centre, School of Computing, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen AB10 7AQ, UK (A.R.); School of Veterinary Medicine and Sciences, University of Nottingham, Sutton Bonington Campus, Loughborough, LE12 5RD, UK (T.D.). E-mail addresses: a.rohan@rgu.ac.uk (A.R.), tania.dottorini@nottingham.ac.uk (T. D).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2024.109115

Publication Date: 2024-06-27

Application of deep learning for livestock behaviour recognition: A systematic literature review

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Deep Learning (DL)

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Behaviour recognition

Precision Livestock Farming

Abstract

Livestock health and welfare monitoring is a tedious and labour-intensive task previously performed manually by humans. However, with recent technological advancements, the livestock industry has adopted the latest AI and computer vision-based techniques empowered by deep learning (DL) models that, at the core, act as decision-making tools. These models have previously been used to address several issues, including individual animal identification, tracking animal movement, body part recognition, and species classification. However, over the past decade, there has been a growing interest in using these models to examine the relationship between livestock behaviour and associated health problems. Several DL-based methodologies have been developed for livestock behaviour recognition, necessitating surveying and synthesising state-of-the-art. Previously, review studies were conducted in a very generic manner and did not focus on a specific problem, such as behaviour recognition. To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no review study that focuses on the use of DL specifically for livestock behaviour recognition. As a result, this systematic literature review (SLR) is being carried out. The review was performed by initially searching several popular electronic databases, resulting in 1101 publications. Further assessed through the defined selection criteria, 126 publications were shortlisted. These publications were filtered using quality criteria that resulted in the selection of 44 high-quality primary studies, which were analysed to extract the data to answer the defined research questions. According to the results, DL solved 13 behaviour recognition problems involving 44 different behaviour classes. 23 DL models and 24 networks were employed, with CNN, Faster R-CNN, YOLOv5, and YOLOv4 being the most common models, and VGG16, CSPDarknet53, GoogLeNet, ResNet101, and ResNet50 being the most popular networks. Ten different matrices were utilised for performance evaluation, with precision and accuracy being the most commonly used. Occlusion and adhesion, data imbalance, and the complex livestock environment were the most prominent challenges reported by the primary studies. Finally, potential solutions and research directions were discussed in this SLR study to aid in developing autonomous livestock behaviour recognition systems.

1. Introduction

Nomenclature

| Nomenclature | |

| BiFPN | Bi-directional Feature Pyramid Network |

| Bi-LSTM | Bi-directional Long Short-Term Memory |

| C3D | Convolutional 3D |

| ConvLSTM | Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| CSPDarknet | Cross Stage Partial network based Darknet |

| DHRN | Deep High Resolution Network |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| DRNet | Dense Residual Network |

| DRN-YOLO | DenseResNet-You Only Look Once |

| ESCMobileNet | Extremely Separated ConvolutionMobileNet |

| R-CNN | Region-based Convolutional Neural Network |

| FCN | Fully Convolutional Network |

| FD-CNN | Frame Differences-Convolutional Neural Network |

| FPN | Feature Pyramid Network |

| ResNet | Residual neural Network |

| R-FCN | Region-based Fully Convolutional Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RPN | Region Proposal Network |

| SAE | Sparse Autoencoder |

| SSD | Single-shot detector |

| STAGCN | Spatiotemporal and Adaptive Graph Convolutional Network |

| TSN | Temporal Segment Network |

| VGG | Visual Geometry Group |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| ZFNet | Zeiler & Fergus Net |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

| AP | Average Precision |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| MCC | Matthew’s Correlation Coefficient |

| MPA | Mean Pixel Accuracy |

species of animals are exploited in large groups housed in intensive production systems, it is unrealistic to observe every activity of animals in real time. With the advent of Industry 4.0 technologies in industrial automation, creating systems that can perform these tasks more efficiently and autonomously has become more practical. Advanced technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) have reshaped industrial livestock farming and given rise to the fields of “Smart farming,” “Precision Agriculture,” and “Precision Livestock Farming” (Gonçalves et al., 2022). These fields heavily utilise AI to analyse data and provide new tools for monitoring and managing animal behaviour and health. These new technologies have the potential to revolutionise traditional livestock farming, enabling farmers to make data-driven decisions that improve animal health, welfare, and productivity. Precision livestock farming can help optimise the production process, reduce costs, and minimise environmental impacts by providing real-time monitoring and analysis of animal behaviour (Garcia et al., 2020). Also, integrating advanced technologies in livestock farming can transform the industry, leading to more sustainable and efficient practices that benefit both animals and farmers. Finally, these technologies can help the fight against infectious and endemic diseases, one of the major challenges in contemporary livestock farming, with repercussions on both animals (e.g. mastitis) and consumers’ health (Grace, 2019).

can vary significantly depending on the problem they are designed to solve. For example, a DL model created for object classification in images may perform poorly in a complex spatiotemporal task like behaviour recognition. Therefore, it is essential to research to establish the state of DL concerning specific problems in precision livestock farming. By doing so, we can better understand how to design, develop, and deploy DL models effectively, ultimately leading to better outcomes for livestock farmers and their animals. Therefore, this review aims to examine the recent trends and advancements in the use of DL for a specific problem of behaviour recognition in precision livestock farming. This review will provide a comprehensive overview of the various types of behaviour recognition problems that have been addressed using DL. In addition, it will summarise the different approaches employed for data collection, including the quantity, quality, and type of data used in these studies. Furthermore, it will discuss the different types of DL models and networks developed for behaviour recognition and how they are applied to specific problems, the performance analysis of DL models and networks, challenges reported in the literature, and potential solutions to overcome these challenges.

2. Methodology

2.1. Review Protocol

2.2. Research Questions

2.3. Databases and search strategy

2.4. Selection Criteria

- The publication is not related to deep learning for livestock behaviour recognition.

- The publication is either duplicated or retrieved from another database.

- The publication is not written in English, and the full text of the study is not available.

- The publication is a book chapter, conference abstracts, data articles, mini-reviews, short communications, thesis, review, or survey article.

- The publication is a pre-print or not peer-reviewed.

- The publication was published before 2012.

- The publication is related to the application of DLbased methodologies for behaviour recognition in livestock.

- The publication is a primary study.

2.5. Collecting and filtering publications

- Are the aims & objectives of the study clearly stated?

- Are the study’s scope, methodology, and experimental design clearly defined?

- Is the research process and methodology documented appropriately?

- Are all study questions answered?

- Are negative findings presented?

- Do the conclusions correspond to the study’s goals and purpose?

Figure 2. shows the overall process for the selection of primary studies.

2.6. Data extraction and synthesis

ethogram defining each behaviour, data collection and the type, quantity, and quality of data, DL models and networks, performance evaluation metrics, the details regarding the year and journal of publications, and challenges associated with the application of DL for livestock behaviour recognition. Finally, the extracted data were synthesised to answer each research question. The results of this SLR study are presented in the next section.

3. Results

3.1. Significance of behaviour recognition in livestock and types of problems (RQ. 1)

Details of the selected primary studies.

| No. | Source | Article Title | Reference |

| 1 | Google Scholar | Mounting behaviour recognition for pigs based on deep learning | Ii et al. 2019 |

| 2 | Pig mounting behaviour recognition based on video spatial-temporal features | Tallg er ai. 2021 | |

| 3 | Automatic recognition of sow nursing behaviour using deep learning-based segmentation and spatial and temporal features | Yang er al. 2018 | |

| 4 | Using an EfficientNet-LSTM for the recognition of single Cow’s motion behaviours in a complicated environment | “illetal. 2020 | |

| 5 | Automatic recognition of feeding and foraging behaviour in pigs using deep learning | Aiameer et al. 2020b | |

| 6 | An automatic recognition framework for sow daily behaviours based on motion and image analyses | Yang er ai. 2020 | |

| 7 | Recognition of feeding behaviour of pigs and determination of feeding time of each pig by a video-based deep learning method | Cheiletai. 20200 | |

| 8 | Deep learning based classification of sheep behaviour from accelerometer data with imbalance | Tumer er al. 2022 | |

| 9 | A computer vision-based method for spatial-temporal action recognition of tail-biting behaviour in group-housed pigs | Liu er al. 2020 | |

| 10 | Automatic Sheep Behaviour Analysis Using Mask R-CNN | X́uetal. 2021 | |

| 11 | Automated detection and analysis of piglet suckling behaviour using high-accuracy amodal instance segmentation | Gall EL ai. 2022a | |

| 12 | Application of deep learning in sheep behaviors recognition and influence analysis of training data characteristics on the recognition effect | Chengerai. 2022 | |

| 13 | Automatic recognition of lactating sow postures by refined two-stream RGB-D faster R-CNN | ZIII El al., 2020 | |

| 14 | Identification and Analysis of Emergency Behavior of Cage-Reared Laying Ducks Based on YoloV5 | Gu et al. 2022 | |

| 15 | Reserve sow pose recognition based on improved YOLOv4 | Luerai. 2022 | |

| 16 | Posture Detection of Individual Pigs Based on Lightweight Convolution Neural Networks and Efficient Channel-Wise Attention | Luo et ai., 2021 | |

| 17 | Science Direct | Cattle behavior recognition based on feature fusion under a dual attention mechanism | Shang et al. 2022 |

| 18 | Horse foraging behavior detection using sound recognition techniques and artificial intelligence | Numes et al. 2021 | |

| 19 | Deep learning-based hierarchical cattle behavior recognition with spatio-temporal information | Fuentes er ai. 2020) | |

| 20 | Activity detection of suckling piglets based on motion area analysis using frame differences in combination with convolution neural network | Ding et ai., 2022 , | |

| 21 | IEEE Xplore | Automatic Detection of Mounting Behavior in Cattle using Semantic Segmentation and Classification | Noe et al. 2021 |

| 22 | A Deep Learning-based solution to Cattle Region Extraction for Lameness Detection | Nove el al.. 2022 | |

| 23 | Video-based cattle identification and action recognition | Nguyenter ai. 2021) | |

| 24 | Data Augmentation for Inertial Sensor Data in CNNs for Cattle Behavior Classification | Liera.. 2021 | |

| 25 | An AI-based System for Monitoring Behavior and Growth of Pigs | Chell etal. 2020b | |

| 26 | Toward Building a Data-Driven System For Detecting Mounting Actions of Black Beef Cattle | Nawano et al. 2021 | |

| 27 | A comparison of autoencoder and statistical features for cattle behaviour classification | Ranman ecai. 2010 | |

| 28 | Lameness Detection in Cows Using Hierarchical Deep Learning and Synchrosqueezed Wavelet Transform | Jarciii etal. 2021 | |

| 29 | On the Benefits of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks on Animal Activity Recognition | Docajet ai. 2020 | |

| 30 | Individual identification model and method for estimating social rank among herd of dairy cows using YOLOv5 | Ucnino and Onwada, 2021) | |

| 31 | Scopus | Spatiotemporal graph convolutional network for automated detection and analysis of social behaviours among pre-weaning piglets | Gan et al. 2022b) |

| 32 | Automatic Detection Method of Dairy Cow Feeding Behaviour Based on YOLO Improved Model and Edge Computing | Oneral. 2022 | |

| 33 | Basic motion behavior recognition of single dairy cow based on improved Rexnet 3D network | Nitaet ai. 2022 | |

| 34 | Identification and classification for sheep foraging behavior based on acoustic signal and deep learning | Wangerai.. 2021) | |

| 35 | Using a CNN-LSTM for basic behaviors detection of a single dairy cow in a complex environment | Wheral 2021 | |

| 36 | Image analysis for individual identification and feeding behaviour monitoring of dairy cows based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) | Aciour et ai. 2020 | |

| 37 | Deep learning and machine vision approaches for posture detection of individual pigs | Nasirahmaui et al., 2019 | |

| 38 | Web of Science | C3D-ConvLSTM based cow behaviour classification using video data for precision livestock farming | Oiao et al. 2022 |

| 39 | Automatic behavior recognition of group-housed goats using deep learning | Jiang er ai. 2020 | |

| 40 | Deep learning-based cattle behaviour classification using joint time-frequency data representation | Tiosseciminourimet al. 2021 | |

| 41 | Automated recognition of postures and drinking behaviour for the detection of compromised health in pigs | Alameer el al. 2020a | |

| 42 | Pecking activity detection in group-housed turkeys using acoustic data and a deep learning technique | Nasirahmadi et ai. 2020 | |

| 43 | Computer Vision Applied to Detect Lethargy through Animal Motion Monitoring: A Trial on African Swine Fever in Wild Boar | Femánucz-Cañón et ai., 2020, | |

| 44 | Automatic recognition of lactating sow postures from depth images by deep learning detector | Eneng et al., 2010, |

impaired health and predict diseases like ketosis and mastitis. Periodic evaluation of feeding behaviour helps monitor livestock’s health and production status at the individual and farm levels. Recognising abnormal posture in animals on time can assist in limiting disease transmission, reducing the usage of veterinary antibiotics, and increasing the economic advantages of commercial farms. Motion and activity-related behaviours are critical predictors of the physical health status of animals and farming conditions. Drinking behaviour is linked with milk production, control of body temperature, and adequate feed consumption. Mounting behaviour is helpful in the detection of oestrous periods, and it can help improve animal reproductive performance. Nursing behaviour is closely related to starvation and influences milk output and animal growth. It can also indicate diseases or injuries related to the udder. Tail biting is one of the most harmful behaviours affecting animal welfare and production. Early lameness identification has increased animal welfare, resulting in economic and health benefits. Social behaviours are crucial indicators of animal growth and health. Emergency behaviours such as trampling in ducks are linked with a high rate of injuries. Suckling behaviour might reflect an animal’s physical health. Animals with higher activity levels have been observed to have a lower mortality rate. Furthermore, the time allotted for suckling or udder massage might indicate hunger or feed intake and can be used to anticipate animal growth.

Type of behaviour recognition problems and associated behaviour classes.

| Type of problem | Behaviour classes |

| Feeding behaviour recognition | Eating, Grazing, Chewing, Ruminating, Ruminating standing, Ruminating lying, Bite |

| Posture recognition | Resting, Lying, Lying down, Lying on the belly, Lying on the side, Lateral lying, Sternal lying, Standing, Standing up, Sitting, Sternal recumbency, Ventral recumbency, Lateral recumbency, Sleeping |

| Motion recognition | Walking, Moving, Moving tail, Moving head, Inactive, Lethargy |

| Nursing behaviour recognition | Nursing interaction |

| Mounting behaviour recognition | Mounting interaction |

| Drinking behaviour recognition | Drinking interaction |

| Pecking activity recognition | Peck or Non-peck |

| Tail-biting behaviour recognition | Tail-biter (biter), Tail-bitten (victim) |

| Foraging behaviour recognition | Non-nutritive / Non-feeding visits |

| Social behaviour recognition | Searching, Social licking, Grooming, Exploring, Social nosing, Fighting, Playing |

| Emergency behaviour recognition | Neck extension, Trample, Spreading wings |

| Lameness recognition | Lameness |

| Suckling behaviour recognition | Suckling or Non-suckling |

3.1.1. Distribution of primary studies and global trend for livestock behaviour recognition

Ethogram outlining behaviour classes found in the primary studies.

| Behaviour classes | Description | Reference |

| Feeding /Eating | Standing with the head in the feed tray OR Lowering head | (Fuentes et al |

| OR Keeping head in the food area and performing eating movement OR Head inside a food trough OR Keeping head in the food area OR Biting and chewing on its food, and rooting with snout in the feeder OR Head is downward and the food is available in the feeder OR When the bounding box of any pig’s head overlaps the region of crib | 2020), (Yang et al. 2020), (Alameer et al. 2020b), (Chen et al. 2020a),(Achour et al., 2020), (Chen et al. 2020b),(Qiao et al., | |

| 2022), (Yu et al., 2022) | ||

| Chewing Ruminating | Chewing, and head raised | (Rahman et ai., 2016) |

| 2020),(Wu et al., 2021) | ||

| Ruminating standing | Ruminating, and standing | (Rahman et al., 2016) |

| Ruminating lying, | Ruminating, and lying or sitting | (Rahman et al., 2016) |

| Resting | Sitting on the floor OR Resting, and lying OR Resting, and standing with head up | (Fuentes et al. |

| 2020),(Rahman et al., 2016) | ||

| Lying | Abdomen clings to the ground without other strenuous movement OR The posture after kneeling | (Wu et al., 2021),(Ma et al., 2022) |

| Lying down | Action from standing to lying down | (Fuentes et al., 2020) |

| Lying on the belly | Lying with limbs are folded under the body | (Nasırahmadı et al., 2019) |

| Lying on the side | Lie in a fully recumbent position with limbs extended | |

| (Nasırahmadi et al., 2019) | ||

| Lateral lying | The side of the trunk of the pig is in contact with the floor | (Alameer et al., 2020a) |

| Sternal lying | The chest / sternum of the pig is in contact with the floor | (Alameer et al., 2020a) |

| Standing | Upright body position on extended legs with hooves only in | (Zheng et al., |

| 2018),(Lhu et al., | ||

| contact with the floor OR Legs are straight and supporting the | 2020), (Fuentes et al., | |

| standing state OR Pig has feet (and possibly snout) in contact | 2020), (Achour et al. | |

| with the pen floor OR Legs remain vertical without other | 2020), (Alameer et al. | |

| strenuous movement OR The position of body and four legs | 2020a),(Wu et al., | |

| is unchanged OR The posture before kneeling on the ground | 2021),(Qiao et al. | |

| Standing up | Action from lying down to standing | (Fuentes et ai., 2020) |

| Sitting | (Zheng et al., 2018), (Zhu et al. 2020), (Alameer et al., 2020a), (Lu et al., 2022) | |

| Partly erected on stretched front legs with caudal end of body contacting the floor OR Only the feet of the front legs and the posterior portion/bottom of the pig body are in contact with the floor | ||

| Sternal recumbency | Lying on abdomen/sternum with front and hind legs folded under the body; udder is totally obscured, | (Zheng et al., 2018), (Zhu et al., 2020) |

| Ventral recumbency | Lying on abdomen/sternum with front legs folded under the | (Zheng et al. |

| body and visible hind legs (right side, left side); udder is | 2018), (Zhu et al., | |

| partially obscured | 2020), (Lu et al., 2022) | |

| Lateral recumbency | Lying on either side with all four legs visible (right side, left | (Zheng et al., 2018), |

| side); the udder is totally visible OR Side lying flat on the | (Zhu et al., 2020), (Lu | |

| ground, one shoulder on the ground, with the limbs extended | ||

| Sleeping | Sitting on the floor and head on the ground | (Fuentes et al., 2020) |

| Walking | Moving in a standing position OR Head up and walking OR | (Fuentes et al. |

| Legs move repeatedly and cow position changes greatly OR | 2020),(Wu et al. | |

| Movement for more than 3 sec | 2021), (Qiao et al. | |

| (Yang et ai., 2020) | ||

| Moving | Moving without doing anything else | |

| Moving tail | Tail movements | (Fuentes et ai., 2020) |

| Moving head | Head movements | (Fuentes et al., 2020) |

| Inactive | Sitting, lying, kneeling, or standing without performing any other activity | (Yang et al., 2020) |

| Lethargy | (Fernández-Carrión et al., 2020) | |

| Low values in daily motion matched with high temperature peaks | ||

| Nursing interaction | At least half of the piglets are actively manipulating the udder when the sow is lying laterally, and the period of activity | (Yang et al., 2018), (Yang et al., 2020) |

| Mounting interaction | exceeds 60 sec | (Fuentes et al. |

| Cow bends over another cow usually when either cow is in estrus | 2021),(Kawano et al., 2021),(Luo et al., 2021) |

| Behaviour classes | Description | Reference |

| Drinking interaction | Touching the drinking nipple with snout OR The pig snout is in contact with a nipple drinker, OR Stand by the water tank with its mouth in the tank | (Yang et al., 2020), (Alameer et al. |

| 2020a),(Wu et al. | ||

| Peck or Non-peck | When birds struck the metallic ball (pecking object) with their beak | (Nasirahmadi et al. 2020) |

| Tail-biter | Biting a penmate’s tail, with a sudden reaction of the penmate | (Turner et al., 2022) |

| Tail-bitten | Penmate is biting the subject’s tail and elicits a reaction | (Turner et al., 2022) |

| Non-nutritive / Non- | When a pig enters the feeding area with two feet without ever | (Alameer et al. |

| feeding visits | 2020b),(Yu et al. | |

| consuming any food OR When the cow is in the feeding zone, lifts her head away from the feed area to chew, and the next action is either to continue feeding or to leave the feeding zone | ||

| Searching | Head down and walking | (Rahman et al. 2016) |

| Social licking | Licking another’s body with the tongue | (Fuentes et al., 2020) |

| Grooming | (Fuentes et al. | |

| Licking own body with the tongue OR Head is turned towards abdomen groom the body with the tongue | ||

| 2022) | ||

| Exploring | Head is in close proximity of or in contact with the ground | (Oiao et al., 2022) |